The Project Gutenberg EBook of Sumerian Liturgies and Psalms by Stephen Langdon

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Sumerian Liturgies and Psalms Author: Stephen Langdon Release Date: April 10, 2010 [Ebook #31935] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SUMERIAN LITURGIES AND PSALMS***

Sumerian Liturgies and Psalms

By

Stephen Langdon

Professor of Assyriology

at Oxford University

Philadelphia

Published by The University Museum

1919

Contents

- Introduction.

- Lamentation of Ishme-Dagan Over Nippur. 13856 (No. 1)

- Liturgy of Ishme-Dagan. 11005 (No. 2)

- Liturgical Hymn to Innini. 7847 (No. 3 and duplicate No. 4)

- Psalm to Enlil Containing a Long Intercession by the Mother Goddess. 15204 (No. 5)

- Lamentation on the Pillage of Lagash by the Elamites. 2154 (No. 6)

- Lamentation to Innini on the Sorrows of Erech. 13859 (Poebel No. 26)

- Liturgical Hymn to Sin. 8097 (No. 7)

- Lamentation on the Destruction of Ur. 7080 (No. 11)

- Liturgical Hymns of the Tammuz Cult. 3656 (Myhrman No. 5)

- A Liturgy to Enlil, Series e-lum gud-sun (Zimmern KL. No. 11)

- Reverse of Tablet Virolleaud (The titular litany)

- Early Form of the Series d.Babbar-gim-è-ta 11359 (Myhrman No. 8)

- Liturgy of the Cult of Kes (Nippur Fragments and Ashmolean Prism.)

- Ashmolean Prism, Col. II

- Third Tablet of the Series “The Exalted One Who Walketh” (e-lum didara) (No. 13)

- Babylonian Cult Symbols. 6060 (No. 12)

- Addendum On Obv. I 10 F.

- Description Of Tablets

- Index Of Tablets

- Index To Vol. X

- Autographed Texts

- Footnotes

Introduction.

[Transcriber's Note: This e-book is Number 4 of Volume X of a series, which had a single page numbering system throughout the Volume. Thus, although this e-book is pages 233 through 351, it contains references to pages outside of this range in the same Volume.]

With the publication of the texts included in this the last part of volume X, Sumerian Liturgical and Epical Texts, the writer arrives at a definite stage in the interpretation of the religious material in the Nippur collection. Having been privileged to examine the collection in Philadelphia as well as that in Constantinople, I write with a sense of responsibility in giving to the public a brief statement concerning what the temple library of ancient Nippur really contained. Omitting the branches pertaining to history, law, grammar and mathematics, the following résumé is limited to those tablets which, because of their bearing upon the history of religion, especially upon the origins of Hebrew religion, have attracted the attention of the public on two continents to the collections of the University Museum.

Undoubtedly the group of texts which have the most human interest and greatest literary value is the epical group, designated in Sumerian by the rubric zag-sal.1 This literary term was employed by the Sumerian scribes to designate a composition as didactic and theological. Religious texts of such kind are generally composed in an easy and graceful style and, although somewhat influenced by liturgical mannerisms, may be readily distinguished from the hymns and psalms sung in the temples to musical accompaniment. The zagsal [pg 234] compositions2 are mythological and theological treatises concerning the deeds and characters of the great gods. The most important didactic hymns of the Nippur collection and in fact the most important religious texts in early Sumerian literature are two six column tablets, one (very incomplete) on the Creation and the Flood published by Dr. Poebel, and one (all but complete) on Paradise and the Fall of Man. Next in importance is a large six column tablet containing a mythological and didactic hymn on the characteristics of the virgin mother goddess.3 A long mythological hymn in four columns4 on the cohabitation of the earth god Enlil and the mother goddess Ninlil and an equally long but more literary hymn to the virgin goddess Innini5 are good examples of this group of tablets in the Nippur collection.6 One of the most interesting examples of didactic composition is a hymn to the deified king Dungi of Ur. By accident both the Philadelphia and the Constantinople collections possess copies of this remarkable poem and the entire text has been reconstructed by the writer in a previous publication.7 1 have already signaled the unique importance of this extraordinary hymn to the god-man Dungi in which he is described as the divinely born king who was sent by the gods [pg 235] to restore the lost paradise.8 The poem mentions the flood which, according to the Epic of Paradise, terminated by divine punishment the Utopian age. The same mythological belief underlies the hymn to Dungi. Paradise had been lost and this god-man was sent to restore the golden age. There is a direct connection between this messianic hymn to Dungi and the remarkable Epic of Paradise. All other known hymns to deified kings are liturgical compositions and have the rubrics which characterize them as songs sung in public services. But the didactic hymn to Dungi has the rubric [dDungi] zag-sal, “O praise Dungi.” It would be difficult to claim more conclusive evidence than this for the correctness of our interpretation of the group of zagsal literature and of the entire mythological and theological exegesis propounded in the edition of the Epic of Paradise, edited in part one of this volume.9

When our studies shall have reached the stage which renders appropriate the collection of these texts into a special corpus they will receive their due valuation in the history of religion. That they are of prime importance is universally accepted.

From the point of view of the history of religion I would assign the liturgical texts to the second group in order of importance. Surprisingly few fragments from the long canonical daily prayer services have been found. In fact, about all of the perfected liturgies such as we know the Sumerian temples to have possessed belong to the cults of deified kings. In the [pg 236] entire religious literature of Nippur, not one approximately complete canonical prayer service has survived. Only fragments bear witness to their existence in the public song services of the great temples in Nippur. A small tablet10 published in part two of this volume carries a few lines of the titular or theological litany of a canonical or musically completed prayer book as they finally emerged from the liturgical schools throughout Sumer. Long liturgical services were evolved in the temples at Nippur as we know from a few fragments of large five column tablets.11 The completed composite liturgies or canonical breviaries as they finally received form throughout Sumer in the Isin period were made by selecting old songs of lament and praise and re-editing them so as to develop theological ideas. Characteristic of these final song services is the titular litany as the penultimate song and a final song as an intercession. A considerable number of such perfected services exist in the Berlin collection. These were obtained apparently from Sippar.12 The writer has made special efforts to reconstruct the Sumerian canonical series as they existed in the age of Isin and the first Babylonian dynasty. On the basis of tablets not excavated at Nippur but belonging partly to the University Museum and partly to the Berlin collection the writer restored the greater part of an Enlil liturgy in part 2, pp. 155-167.13 In the present and final part of this volume another Enlil liturgy has been largely reconstructed on pages 290-306.14 From these two partially reconstructed song services the reader will obtain an [pg 237] approximate idea of the elaborate liturgical worship of the late Sumerian period. These were adopted by the Babylonians and Assyrians as canonical and were employed in interlinear editions by these Semitic peoples. Naturally the liturgical remains of the Babylonian and Assyrian breviaries are much more numerous and on the basis of these the writer was able in previous volumes to identify and reconstruct a large number of the Sumerian canonical musical services. But a large measure of success has not yet attended his efforts to reconstruct the original unilingual liturgies commonly written on one huge tablet of ten columns. Obviously the priestly schools of the great religious center at Nippur possessed these perfected prayer books but their great size was fatal to their preservation. It must be admitted that the Nippur collection has contributed almost nothing from the great canonical Sumerian liturgies which surely existed there.

Much better is the state of preservation of the precanonical liturgies, or long song services constructed by simply joining a series of kišubs or songs of prostration. These kišub liturgies are the basis of the more intricate canonical liturgies and in this aspect the Nippur collection surpasses in value all others. Canonical and perfected breviaries may be termed liturgical compositions and the precanonical breviaries may be described as liturgical compilations, if we employ “composition” and “compilation” in their exact Latin sense. Since Sumerian song services of the earlier type, that is liturgical compilations, are more extensively represented in the Nippur temple library than in any other, this is an appropriate place to give an exact description of this form of prayer service which preceded and prepared the way to the greatest system of musical ritual in any ancient religion. If we may judge from the literary remains of [pg 238] Nippur now in the University Museum, the priestly schools of temple music in that famous city were extremely conservative about abandoning the ancient liturgical compilations. These daily song services, all of sorrowful sentiment and invariably emphasizing humility and human suffering, are constructed by simply compiling into one breviary a number of ancient songs, selected in such manner that all are addressed to one deity. In this manner arose intricate choral compilations of length suitable to a daily prayer, each addressed to a great god. Hence we have in the temple libraries throughout Sumer and Babylonia liturgies to each of the great gods. Even in the less elaborate kišub compilations there is in many cases revealed a tendency to recast and arrange the collection of songs upon deeper principles. A tendency to include in all services a song to the wrathful word of the gods and a song to the sorrowful earth mother is seen even in the Nippurian breviaries of the precanonical type. I need not dilate here upon the great influence which these principles exercised upon the beliefs and formal worship of Assyria and Babylonia, upon the late Jewish Church and upon Christianity. The personified word of god and the worship of the great mater dolorosa, or the virgin goddess, are ancient Sumerian creations whose influence has been effective in all lands.

As examples of the liturgical compilation texts the reader is referred especially to the following tablets. On pages 290-292 the writer has described the important compiled liturgy found by Charles Virolleaud.15 It is an excellent example of a Nippurian musical prayer service. It contained eleven kišubs, or prayers, and they are recast in such manner that the whole set forth one idea which progresses to the end. The liturgy has in fact almost reached the stage of a composition. And in these same pages [pg 239] the reader will see how this service finally resulted in a canonical liturgy, for the completed product has been recovered. On pages 309-310 will be found a fragment, part of an ancient liturgy to Enlil of the compiled type. Here again we are able to produce at least half of the great liturgy into which the old service issued. In the preceding part of this volume, pages 184-187, is given the first song of a similar liturgy addressed to the mother goddess.

Undoubtedly the most important liturgical tablet which pertains to the ordinary cults in the Nippur collection is discussed on pages 279-285. The breviary, which probably belongs to the cult of the moon-god, derives importance from its great length, its theological ideas, especially the mention of the messengers which attend the Logos or Word of Enlil, and its musical principles. Here each song has an antiphon which is unusual in precanonical prayer books of the ordinary cults.16 Students of the history of liturgies will be also particularly interested in the unique breviary compiled from eight songs of prostration, a lamentation for the ancient city of Keš with theological references. This song service was popular at Nippur, for remains of at least two copies have been found in the collection. A translation is given on pages 311-323.

The oldest public prayer services consisted of only one psalm or song. A good number of these ancient psalms are known from other collections, especially from those of the British Museum. In view of the conservative attitude of the liturgists at Nippur it is indeed surprising that so few of the old temple songs have survived as they were originally employed; ancient single song liturgies in this collection are rare. The following [pg 240] list contains all the notable psalms of this kind. Radau, Miscellaneous Sumerian Texts No. 317 is a lamentation of the mother goddess and her appeal to Enlil on behalf of various cities which had been visited by wars and other afflictions. Radau, ibid., No. 16 has the rubric ki-šu18 sìr-gal dEnlil, “A prayer of prostration, a great song unto Enlil.” A psalm of the weeping mother goddess similar in construction to Radau No. 3 is edited on pages 260-264 of this volume.19 No. 7 of this part, edited on pages 276-279, is an excellent illustration of the methods employed in developing the old single song psalms into compiled liturgies. Here we have a short song service to the moon god constructed by putting together two ancient psalms. The rubrics designate them as sagar melodies,20 or choral songs, and adds that it is sung to the lyre.21 An especially fine psalm of a liturgical character was translated on pages 115-117. It is likewise a lament to the sorrowful mother goddess.

The student of Sumero-Babylonian religion will not fail to comment upon one remarkable lacuna in the religious literature of every Sumerian city which has been excavated. Prayers of the private cults are almost entirely nonexistent. Later Babylonian religion is rich in penitential psalms written in Sumerian for use in private devotions. These are known by the rubric eršagģunga, or prayers to appease the heart. Only one has been found in the Nippur collection,22 and none at all have been recovered elsewhere. Seals of Sumerians showing them in [pg 241] the act of saying their private prayers abound from the earliest period. Most of these seals represent the worshipper saluting a deity with a kiss thrown with the hand. The attitude was described as šu-illa, or “Lifting of the Hand.” Semitic prayers of the lifting of the hand abound in the religion of Babylonia and Assyria. Here they are prayers employed in the incantation ritual. We know from the great catalogue of Sumerian liturgical literature compiled by the Assyrians that the Sumerians had a large number of prayers of the lifting of the hand.23 In Sumerian religion these were apparently purely private prayers unconnected with the rituals of atonement. At any rate the Nippur collections in Constantinople and Philadelphia contain a large number of incantation services for the atonement of sinners and the afflicted. These resemble and are the originals of the Assyrian incantation texts of the type utukku limnuti, and contain no prayers either by priest (kišub in later terminology is the rubric of priest's prayers in incantations) or by penitent (šu-il-la's). The absence of prayers of private devotion in the temple library of Nippur is absolutely inexplicable. Does it mean that the Sumerians were so deficient in providing for the religious cure of the individual? Their emphasis of the social solidarity of religion is truly in remarkable contrast to the religious individualism of the Semite. But the Sumerian historical inscriptions often contain remarkable prayers of individuals. The seals emphasize the act of private devotion. The catalogue of their prayers states that they possessed a good literature for private devotions. When one considers the evidence which induces to assume that they possessed such a literature, its total absence in every Sumerian collection is an enigma which the writer fails to explain.

[pg 242]In the introduction to part two of this volume24 the writer has emphasized the peculiarly rich collection of tablets in this collection pertaining to the cults of deified kings. In the present part is published a most important tablet of that class. This liturgy of the compiled type in six kišubs sung in the cult of the god-man Ishme-Dagan, fourth king of the Isin dynasty, is unique in the published literature of Sumer. Its musical intricacy and theological importance have been duly defined on pages 245-247. With the publication of these texts the important song services of the cults of deified kings are exhausted. In addition to the texts of this class translated or noted in part two, I call attention to the very long text concerning Dungi, king of Ur, published by Barton, Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions No. 3. In that extremely long poem in six columns of about 360 lines25 there are no rubrics, which shows at once that it is not a cult song service. Moreover, Dungi had not been deified when the poem was written. It is really an historical poem to this king whose deification had at any rate not yet been recognized at Nippur. It belongs in reality to the same class of literature as the historical poem on his father Ur-Engur, translated on pages 126-136.

The only Sumerian cult songs to deified kings not in the Nippur collection have now been translated by the writer and made accessible for wider study. One hymn to Ur-Engur which proves that he had been canonized at his capitol in Ur will be found in the Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Literature, 1918, 45-50. The twelfth song of a liturgy to Ishme-Dagan published by Zimmern from the Berlin collection is translated on pages 52-56 of the same article. Finally a long liturgy to [pg 243] Libit-Ishtar, son of Ishme-Dagan, likewise in Berlin, has been translated there on pages 69-79.26 Since the Berlin texts probably came from Sippar their existence in that cult is important. For they prove not only the practice of cult worship of deified kings in that city, but the domination of Isin over this north Semitic city is thus documented for a period as late as Libit-Ishtar.

Nearly all the existing prayer services in the cults of the deified kings of Ur and Isin are now published and translated. The student will observe that they are all of the compiled type but that there is in most cases much musical arrangement and striving for combined effect. A few, and especially the Ishme-Dagan liturgy published as No. 1 of this part, reveal theological speculation and an effort to give the institution of god-man worship its proper place in their religion. The hymns of these cults comparatively so richly represented in this volume will be among the most interesting groups of religious texts supplied by the excavations at Nippur.27

Oxford, July 9, 1919.

Lamentation of Ishme-Dagan Over Nippur. 13856 (No. 1)

The liturgical character of this tablet is unique among all the numerous choral compositions of the Isin period. It is a large two column tablet containing six long kišub melodies. Liturgies of such kind, compiled by joining a series of kišubs, or melodies, attended by prostrations, represent an advanced stage in the evolution of these compositions in that the sections are not mechanically joined together by selecting older melodies without much regard for their connection, but as a whole they are apparently original compositions so arranged that they develop a motif from the beginning to the end of the liturgy. Choral services composed of kišubs in the cults of deified kings have been found28 wherein the deeds and personality of the king are sung, his divine claims are emphasized and his Messianic promises rehearsed. But the liturgy here published resembles in literary style the classical lamentations which always formed the chief temple services of Sumer and Babylonia. It more especially resembles the weeping mother liturgies, but here Ishme-Dagan appears in the lines of the service in a rôle similar to that of the sorrowful mother goddess of the ordinary liturgies, as he weeps for Nippur.

“Her population like cattle of the fields within her have perished. Helas my land I sigh.”

So reads a line from the second melody.

[pg 246]Lines of similar character occur repeatedly in the laments of the mother goddess as she weeps for her people in the standard liturgies. In other words, the cult of the deified kings issues here into its logical result. The god man created to live and die for his people usurps the sphere of the earth mother herself. And like her he is intimately associated with the fortunes of mankind, of nature and all living creatures. The great gods and the hosts of their attendants rule over man and the various phases of the universe from afar. But the mother goddess is the incarnation of fruitful nature, the mother of man whose joys and sorrows she feels. So also in this remarkable liturgy the deified son of the great gods lives among men, becomes their patron and divine companion.

The tablet contained originally about fifty lines in each column, or 200 in all. About one-third of the first column is gone. The first melody contained at least fifty lines and ended somewhere shortly after the first line of Col. II of the obverse. It began by relating how Enlil had ordered the glory of Nippur, and then had become angered against his city, sending upon it desolation at the hands of an invader. When we take up the first lines of Obv. II we are well into the second melody which represents Ishme-Dagan mourning for fathers and mothers who had been separated from their children; for brothers who had been scattered afar; for the cruel reign of the savage conqueror who now rules where the dark-headed people had formerly dwelled in peace.

At about the middle of Obv. II begins the third melody which consists of 38 lines extending to Rev. I 19. In this section the psalmist ponders upon the injustice of his city's fate, and looks for the time when her woes will cease, and Enlil will be reconciled.

[pg 247]The fourth section begins at line 24 of Rev. I and ended near the bottom of this column which is now broken away. Here Ishme-Dagan joins with the psalmists weeping for Nippur.

Section 5 began near the end of Rev. I, and ends at line 16 of Rev. II. Here begins the phase of intercession to Enlil to repent and revenge Nippur upon the foe. Section 6, beginning at Rev. II 17, probably continued to the end of the column and the tablet. Here the liturgy promises the end of Nippur's sorrow. Enlil has ordered the restoration of his city and has sent Ishme-Dagan, his beloved shepherd, to bring joy unto the people.

After sections 2 and 3 follows the antiphon of one or two lines. The ends of sections 1 and 4 are lost but we may suppose that antiphons stood here also. Section 5 does not have an antiphon. Since section 6 ended the liturgy it is not likely that an antiphon stood there.

[Transcriber's Note: In the original book, throughout the book, all of the transcriptions and translations were done in two columns. The left column showed the transcription, and the right the English translation; each line had the line number. In this e-book, the transcription and translation of each line will be shown in succeeding lines.]

Obverse. Col. I

(About eighteen lines broken away.)

(End of Col. I.)

Col. II

(About fifteen lines broken away.)50

Reverse, Col. I

(About twelve lines broken away.)97

Reverse II

(About twelve lines broken away, in case this section continued to the end of the tablet.)

Liturgy of Ishme-Dagan. 11005 (No. 2)

Col. II.

Reverse I

Liturgical Hymn to Innini. 7847 (No. 3 and duplicate No. 4)

Col. I

Col. II

Psalm to Enlil Containing a Long Intercession by the Mother Goddess. 15204 (No. 5)

This liturgical psalm in one melody adds one more document of this kind to the classical Sumerian corpus of old short musical services on which the later complex liturgies were based.162 The title, árabu-(ģu) árabu-(ģu) múzu kúrra munmállašu záe alménna, arranged in seven dactyls, does not appear in the catalogue of old songs given in the Assyrian list, IV Raw. 53 Col. III. Since the greater part of the psalm consists in an address of the mother goddess to Enlil on behalf of Nippur, the composition is defined as an adoration of “my mother,”163 an epithet applied to Innini by the singers in most liturgies. The psalm begins with twelve lines sung by the choir and addressed to Enlil. They then in lines 13-15 introduce Innini whom they represent in discourse before Enlil in lines 16-47. This part of the song service contains refrains characteristic of public worship. Theologically the text illustrates one of the most profound principles of Sumerian religion, the sympathy and concern of the virgin mother for mankind.164 The great daily services of the standard prayer books represent her as a mater dolorosa and she with Tammuz shares the vicissitudes of mortal life. Our text is unique and noteworthy for one salient fact. It illustrates the scenes so common on Babylonian seals, where the mother goddess stands in intercession before the god, with one or both hands raised in supplication and the left foot advanced as though about to set it on the paved approach to the throne of the deity.

[pg 266]...173

Lamentation on the Pillage of Lagash by the Elamites. 2154 (No. 6)

This neatly written but seriously damaged single column tablet carried when complete about fifty-five lines. In style the liturgical lamentation has a striking resemblance to the lamentation [pg 269] on the invasion of Sumer by the people of Gutium, published in the author's Sumerian Liturgical Texts, 120-124. The same refrain, “How long? oh my destroyed city and my destroyed temple, sadly I wail,” distinguishes both compositions.183 Other lines are common to both threnodies. The contents are similar to the lamentation on Lagash published in Cuneiform Texts of the British Museum, Vol. XV 22, of which Zimmern has published a variant VAT. 617 Rev. II 10-42, in his Sumerische Kultleider. A translation of the British Museum text will be found in the author's Sumerian and Babylonian Psalms, p. 284, an edition which can now be improved.

Lamentation to Innini on the Sorrows of Erech. 13859 (Poebel No. 26)

This well preserved single column tablet is published by Poebel in PBS. V 26. The composition reflects the standard theological ideas found in the canonical psalms and liturgies. The mother goddess Innini is represented as a divine mother wailing for the misery of her city and her people. The calamity [pg 273] consists in the pillage of the city and its holy places by a foreign invader, who is repeatedly compared to an ox. Like the ordinary psalms of public service the singers abruptly introduce the goddess speaking in the first person as in lines 16; 18-20; 33-4. But the lamentation does not have refrains and at the end the style approaches nearly that of a prayer. The tablet also bears no liturgical note at the end. For these reasons and because of the general impression which the lines leave with the present interpreter, he classifies this text as the product of a scholastic liturgist of the Ur or Isin period whose work was not incorporated into the corpus of the official breviary.

Obverse

Liturgical Hymn to Sin. 8097 (No. 7)

This liturgical composition consists of two melodies each designated by the rubric sagarram, “It is a sagar.” The entire service is sung to the tigû, a kind of flute. In the first melody of fifteen lines the choir chant the glory of the moon god and his city Ur. The second melody of twenty-four lines is apparently an address of the earth god Enlil to his son the moon god. This melody must remain obscure as long as the recurring liturgical phrase áb-mu-ba-ši-in-dib is unexplained.

[pg 277]Reverse

Lamentation on the Destruction of Ur. 7080 (No. 11)

The fragment Ni. 7080 carries the right half of one of the largest literary tablets in the Museum. Broken evenly at the center from top to bottom the right half of this tablet preserves part of Col. III and all of Cols. IV, V of the obverse. The reverse correspondingly contains Cols. I, II and half of Col. III. Like so many similar liturgical compositions of the period of Ur this lamentation is divided into a series of kišubs or songs, here of unusually great length. The third song ends at Obv. III 38; [pg 280] its first line stood in Obv. II, which has been lost. The fourth song began at Obv. III 42 and ends at Obv. IV 23, containing thirty-four lines. The fifth song begins at Obv. IV 27 and ends at Obv. V 7, containing forty-seven lines. In the following pages will be found a translation of twenty-three lines of the end of the fourth song which describes the wrathful word of the gods Anu and Enlil. The fifth song, a remarkable ode to the wrathful word of Enlil, has been translated so far as the text permits.

The sixth song begins at Obv. V 11, and probably terminated in the broken passage at the top of Rev. I. Its length was also unusual, having at least forty-five lines. This song was edited on a small tablet Ni. 4584 on which the beginning and the end of the section are preserved. It has been published as No. 10 in Sumerian Liturgical Texts, Vol. X of the Publications of the Babylonian Section. Only a few lines at the commencement of this song have been translated here. From this point onward the language of the liturgy presents such difficulty that the writer has been unable to offer a translation.

Section seven probably ended at the top of Rev. II and refers throughout to the mother goddess who weeps over the ruins of Ur. The eighth song probably began at the top of Rev. II and ended perhaps at the top of Rev. III. It is another doleful ode to the weeping mother and many of its lines are clear and translatable. The entire song is marked by sorrowful refrains: me-li-e-a uru-mu nu-me-a, Oh woe is me, my city is no more.242 a-uru-mu im-me, How long? oh my city I cry.243 me-li-e-a uru-ta è-a-mèn, Oh woe is me, from the city I depart.244 dingir ga-ša-an-gal-mèn é-ta è-a-mèn, Great divine queen am I, [pg 281] from the temple I depart.245 er-gig ni-šéš-šéš, She weeps bitterly.246

Only the ends of lines of a large part of the ninth song are preserved in Rev. III. The tenth song probably occupied most of the space in Rev. IV. Speculation concerning the number of songs in the entire liturgy is limited to the number of about 11-13. The liturgy was, therefore, extremely long, attaining to a content of about 500 lines. We know from the single tablet variant of the sixth song that another edition of this series existed in which small tablets carried each a single kišub. A similar condition of editorial redaction is revealed by Zimmern, KL. 200, a small tablet which contains the twelfth song of a liturgy to the deified king of Isin, Išme-Dagan.

The historical event referred to in this liturgy is undoubtedly the destruction of Ur in the time of Ibi-Sin, last of the kings of the Ur dynasty. This calamity left many traces in the temple songs of Sumer, and the Sumerian prayer books of Nippur contain other lamentations on the fall of Ur, written perhaps during the Isin period. The writer has already published a single column tablet which rehearses the same catastrophe, mentioning Ibi-Sin himself and naming the Elamites as his captors.247

Obverse IV

(Lines 47-55 mostly illegible.)

Col. V.

(Lines 1-6 mostly illegible.)

Liturgical Hymns of the Tammuz Cult. 3656 (Myhrman No. 5)

The obverse of this fine single column tablet contained a hymn in thirty-eight lines to the departed Tammuz. It represents the people wailing for the lord of life who now sleeps in the lower world. Thirteen lines have been completely broken away from the top. The reverse carried a long liturgical song of the cult of this god in which the mother goddess is represented wailing for her ravished lover. Songs of the weeping mother are common enough in these wailings for Tammuz, but all other known examples of this motif represent the major unmarried type of mother goddess Innini-Ishtar wandering on earth, crying for her departed son. The hymn on our tablet reveals in a wholly unexpected manner the close relation between the mother goddess Gula of Isin and Innini. It was known that both sprang from a common source, a prehistoric unmarried goddess, but one had hardly supposed that the liturgists went so far as to introduce [pg 286] the married goddess of Isin in the rôle of the virgin mother Innini. The great mother divinity of Isin, although attached in a loose way to a male consort Ninurta, in that city retained, nevertheless, much of her ancient unattached character. In the standard liturgies she is almost invariably the type of Weeping mother, whereas Innini is this type in the Tammuz liturgies. Since Gula of Isin was the ordinary liturgical type we find the influence of the ordinary liturgies effective in the composition of the Tammuz hymn. It explains the extraordinary phenomenon of the introduction of a long passage (Rev. 3-10) from one of the wailing liturgies. And the short litany refrain lines 11-20 is obviously an imitation of numberless similar passages of the ordinary liturgies in which the goddess wails for various temples; here only for Nippur and Isin, since the composition was written for the services at Nippur in the period of the Isin dynasty. In a most gratifying manner our tablet shows how the lamentations of the mother goddess in the canonical prayer books express sorrows for certain concrete misfortunes and certain defined temples and cities and find their general expression in the lamentations for Tammuz, the representative of all human vicissitudes. This edition has been made from my own copy. The tablet was first published by Myhrman, PBS. Vol. I No. 5, and by Radau, BE. 30 No. 2. To these copies I have been able to make only slight additions.

Hymns of the Tammuz Cult

Reverse

A Liturgy to Enlil, Series e-lum gud-sun (Zimmern KL. No. 11)

The history of the text of this long and intricate Enlil liturgy elucidates in unusual manner the evolution of Sumerian prayer books until they attained canonical and permanent form. The earliest text of this liturgy is partially preserved on the Tablet Virolleaud published in the Revue d'Assyriologie, Vol. XVI. The fragment was brought to Europe in 1909 by the assyriologist Charles Virolleaud, having been purchased by him during his excavations in Persia. It is light brown and varies from the center to the edge by two inches to one inch in thickness. The fragment is from the upper left corner of a large three(?) column tablet. About half of the first melody is preserved on the obverse. The reverse preserves the last two melodies. From their rubrics we learn that the entire series contained eleven sections. This tablet has the rubric ki-šub-gú after each strophe. The titular litany281 occupies as usual the next to the last place but only the opening lines giving the motif and a few titles are given. The redactor indicates the remaining titles by a rubric “(Recite the title) of a [pg 291] god until they are finished.” The rubric is in Semitic which shows that the redaction was done by Semitic scholars.

The series as it finally issued from the hands of the liturgists in the Isin period was written upon a huge five(?) column tablet, the lower half of which has been published by Zimmern, Altsumerische Kultlieder, No. 11. Each column contained about fifty lines. There are no giš-gí-gal or antiphons after the melodies, ten of which I have been able to restore. By borrowing from old songs and other liturgies the redactors have greatly increased the length of this service. At least ten songs have been lost on Cols. III, IV of the obverse and I, II of the reverse.

The late Assyrian redaction is mentioned in the catalogue of prayer books IV Raw. 53 I 13 and in BL. No. 103 Obv. 13. SBH. No. 21, edited in SBP. 112-119, is tablet one of the late Babylonian School282 and contains the first four songs, duplicates of the first four on K.L. 11. SBH. No. 25, edited in SBP. 120-123,283 carries on the obverse two songs (e-lum di-da-ra and me-e ur-ri men) found on Col. III of K.L. No. 11, Rev., or the two last melodies before the titular litany. A fragment published by Meek in BA. X pt. 1, No. 11, contains the end of e-lum di-da-ra and all of me-e ur-ri men. SBH. 25 and Meek No. 11 belong to the series e-lum di-da-ra, entered in the Assyrian catalogue, IV Raw. 53a 8, and form tablet one of that service.

The titular litany of the e-lum gud-sun series is identical (except for some variants) with the famous titular litany of the mother goddess series mu-ten NU-NUNUZ gim-ma, tablet five, edited in SBP. 149-167. Portions of the titular litany of the Enlil series have been edited in PBS. X 155-167, see pages 163-4. The titular litany of ní-ma-al gù-de-de occurs at the end [pg 292] of tablet two of that series, SBP. 24-9 = BL. 72-3. Not every series has a theological litany of this kind, which ordinarily comes before the er-šem-ma, or intercessional song at the end. The song to the “word,” which occurs in all series, is partially preserved on Obv. III and begins a-ma-ru na-nam. The indispensable song to the weeping mother comes just before the titular litany. This little nine-line melody me-e ur-ri-mèn me-e kàs-mèn must have been a national religious song. It was copied into another Enlil song service as we have seen. The same song introduces tablet four of an Innini series of which we have only the end of tablet three, K. 2759, in BL. 93 f.

Finally the reader will note that the first song e-lum gud-sun of this series has been copied into one of the tablets of ame baranara, SBH. No. 22 = SBP. 126 f. A fragment of some unknown series, K. 8603 = BL. 14 also employs this song in the body of its text.

Obverse II

Col. III

(Here began a melody of which ten lines at least are lost.)

(Here followed Obv. IV; eight or ten lines continued this melody to the word. Their contents were similar to SBP. 100, 49-57 ff.)

Reverse III331

(Lines 1-11 of this melody, i. e., 40-51 on KL. 11, III, are supplied by Tablet Virolleaud, Rev. 1-11, and restores the entire section.)

Reverse IV(?)

(Here supply twenty-eight lines = SBP 154, 24-156, 51.)

Reverse V(?)

About twenty-four lines completed this column and ended the liturgy. The void is to be completed by part of the titular litany, SBP. 160, 19-164, 38, and by a short intercession similar to the fragmentary intercession at the end of KL. No. 8. It is possible that the eleventh and last section on Tablet Virolleaud was retained as the final melody of this later redaction.

Reverse of Tablet Virolleaud (The titular litany)

Early Form of the Series d.Babbar-gim-è-ta 11359 (Myhrman No. 8)

Ni. 11359, published by Myhrman, PBS. I. No. 8, is the left upper corner of a large four column tablet. It contained a series of ki-šub melodies which formed the prototype of the later Enlil series of which three tablets have been edited by the writer, see Sumerian Liturgical Texts 167. It stands to the completed series as the similar tablet of the e-lum gud-sun series, Tablet Virolleaud, is related to its completed canonical form in Zimmern, KL. 11. Both Ni. 11359 and Tablet Virolleaud show the evolution of two great Enlil liturgies arrested midway in their evolution. They still consist of unmethodically joined melodies. Both have the same rubric at the end. The first melody of d.Babbar-gim-è-ta after line four agrees with the first melody of the Enlil series zi-bu-ù sud-du-ám in Zimmern, KL. 8 and 9 after line five of that series. A duplicate will be found in BL. pp. 37-39, which see for critical notes on the reconstructed text.

Obverse 1

Reverse II

Liturgy of the Cult of Kes (Nippur Fragments and Ashmolean Prism.)

Keš and Opis, two closely associated but unlocated southern cities of Sumer, lay apparently somewhere in the region between Erech and Šuruppak. So closely were they united that the same cult of the great mother goddess obtained in both.413 According to II Raw. 60a 26, Innini of Hallab was the queen of Keš. The Sumerian liturgy, BL. p. 54, names Nintud as the goddess of this city, but the list of mother goddesses in PSBA. 1911 Pl. XII calls her by the name Ninharsag,414 where she is associated with Ninmenna, epithet of the earth mother in Adab a city near Šuruppak. A fragment, No. 102 in BL., reads her title at Keš as Aruru. These various epithets all refer to the earth mother whose principal married type is Ninlil. In fact one liturgy actually names Ninlil as the goddess of Keš, SBP. 24, 74. On the other hand, a cult document of the Neo-Babylonian period names Kallat Ekur, the bride of Ekur, as the goddess of U-pi-ia or Opis, VS. VI. 213, 21.415 The bride of Ekur is Ninlil. Thus the twin cities Keš and Opis of Sumer with their cult of the earth mother Ninharsag or Nintud were imitated in later times in Akkad and located on the Tigris where Opis survived into Greek times (ωπις) and Keš seems to have become confused in writing with Kiš a famous city near Babylon. At Opis in Akkad a male satellite Igi-du was associated with the mother goddess and we [pg 312] may be safe in assuming that he was borrowed from the original southern cult.416 Of the names Ninharsag, Aruru, Nintud, Ninmah, Innini of Hallab, we are not certain which one applied especially to Keš and Opis. In any case the liturgy which we are about to discuss had some special name for the goddess here. In a refrain which recurs at the end of each melody the psalmists say that the god of Keš, that is probably Igidu,417 was made like Ašširgi, or Ninurta, and that its goddess was made like Nintud, hence the special name of the mother goddess in this liturgy cannot have been Nintud.

So far as the text of this important liturgy in eight melodies can be established, it leads to the inference that, like all other Sumerian choral compositions, the subject is the rehearsal of sorrows which befell a city and its temple. Here the glories of Keš, its temple and its gods are recorded in choral song, and the woes of this city are referred to as symbolic of all human misfortunes. The name of the temple has not been preserved in the text. But we know from other liturgies that the temple in Keš bore the name Uršabba.418 The queen of the temple Uršabba is called the mother of Negun, also a title of Ninurta in Elam.419 The close connection between the goddess of Keš and Ninlil is again revealed, for Negun is the son of Ninlil in the theological lists, CT. 24, 26, 112. Therefore at Keš we have a reflection of the Innini-Tammuz cult or the worship of mother and son, mother goddess Ninlil or Ninharsag, and Igidu or Negun.420

[pg 313]Keš and Opis must have been closely associated with both Erech and Šuruppak, and of traditional veneration in Sumer. Keš is mentioned in a list with Ur, Kullab (part of Erech) and Šuruppak, Smith, Miscellaneous Texts 26, 5. Gudea speaks of a part of the temple in Lagash which was pure as Keš and Aratta (i. e. Šuruppak).421 The various mother goddesses of Eridu, Kullab, Kêši, Lagaš and Šuruppak are invoked in an incantation, CT. 16, 36, 1-9. The first melody of the Ashmolean Prism contains a reference to the horse of Šuruppak.

The textual history of this liturgy is interesting. The major text is written upon a four-sided prism now in the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford. The object is eight inches high, four inches wide on each surface and is pierced from top to bottom at the center by a small hole, so that the liturgy could be turned on a spindle. The writer published a copy of this prism or prayer wheel in his Babylonian Liturgies. The elucidation of this exceedingly difficult text was lightened somewhat by the discovery of a four column tablet in Constantinople, which originally contained the entire text. It was afterwards published as No. 23 of my Historical and Religious Texts. Since the edition of these two sources, the Nippur Collection in Philadelphia has been found to contain several fragments of the same liturgy. A portion of the redaction on several single column tablets had been already published by Radau in his Miscellaneous Sumerian Texts, No. 8 (=Ni. 11876), last tablet of the series containing melodies six, seven, and eight. I failed to detect the connection of Radau's tablet at the time of the first edition but referred to it with a rendering in my Epic of Paradise, p. 19. [pg 314] Another tablet, also from a single column tablet redaction at Nippur, has been recovered in Philadelphia, Ni. 8384.422 This text utilized here in transcription contains a section marked number 4 on that tablet but all the other sources omit it. Hence this redaction probably contained nine melodies. The new melody has been inserted between melodies three and four of the standard text. If evidence did not point otherwise the editor would have supposed that Ni. 8384 and 11876 belonged to the same tablet. But Ni. 8384 has melodies four, five and six of its redaction with the catch-line of the next or its seventh melody which partly duplicates the Radau tablet. Moreover, these two tablets have not the same handwriting and differ in color and texture of the clay. Finally a small fragment, Ni. 14031, contains the end of the second melody and the beginning of the third on its obverse. The reverse contains the end of the sixth melody. This small tablet undoubtedly belongs to the four column tablet in Constantinople. The two fragments became separated by chance when the Nippur Collection was divided between Philadelphia and the Musée Imperial of Turkey. Ni. 14031 will be found in my Sumerian Liturgical Texts, No. 22.

Under ordinary circumstances a text for which so many duplicates exist should have yielded better results than I have been able to produce. But the contents are still obscure owing largely to the bad condition of the prism. My first rendering of the interesting refrain in which I saw a reference to the creation of man and woman was apparently erroneous. The refrain refers rather to the creation of the mother goddess of Keš and to her giving birth to her son Negun.423

[pg 315]Col. I (Lines 1-22 defaced)

Col. II

8384.

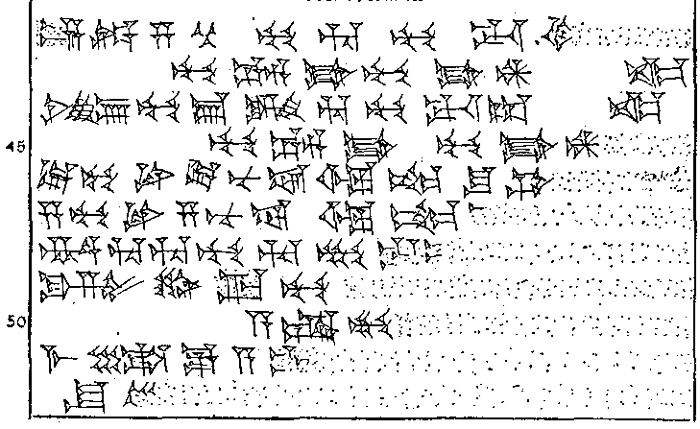

Ashmolean Prism, Col. II

Col. III

Col. IV

Third Tablet of the Series “The Exalted One Who Walketh” (e-lum didara) (No. 13)

The series elum didara is entered in the Assyrian liturgical catalogue, IV Raw. 53a 8, and the first tablet of this Enlil liturgy has been found in the Berlin collection and published by Reisner, SBH. No. 25.477 The Berlin tablet belongs to a great Babylonian temple library of the Greek period redacted by a family of liturgists descendants of Sin-ibni. A fragment of the same first tablet of another Babylonian copy has been found, BM. 81-7-27, 203.478 The catch line of tablet two is lost on SBH. 25 and no part of tablet two has been identified. In 1914 [pg 324] I copied BM. 78239 (=88-5-12, 94) the upper half of a large tablet carrying according to the colophon ninety-six Sumerian lines. The number of lines provided with an interlinear translation on this fragment is only two, which increases the actual number of lines to ninety-eight. Probably a few more should be added for Semitic lines on the lost portion. This tablet, also from a Babylonian redaction, belongs to an edition made by another school of liturgists and contains tablet three of elum didara.

The third tablet of elum didara began with a melody nin-ri nin-ri gû-am-me to the mother goddess Bau (I. 2), who in line 7 is identified with Nanâ. Lines 3-6 introduce by interpolation other local forms of the mother goddess, as a concession to cities whose liturgists succeeded in inserting these lines before the canon of sacred songs were closed in the Isin period. Hence Babylon is favored by a reference to Zarpanit in line 3; Barsippa by a reference to Tašmet in lines 4-6. Bau or Gula wails for Nippur whose destruction is here attributed to the moon-god, Sin. The introduction of a long passage to the moon-god in the weeping mother melody of an Enlil liturgy is unusual. The entire passage reflects the phraseology and ideas of the well-known Sumerian hymn to the moon-god magur azag anna.479 The composer desiring to utilize these fine lines makes a setting for them by describing Sin as the god who visited Nippur with wrath, regardless of the inconsistency of placing such a passage in an Enlil song service which attributed the sorrows of Nippur to Enlil himself.

According to the catch line of tablet two of the Ninurta liturgy gud-nim kurra the third tablet of that series began by the same melody as tablet three of the elum didara.480 It is probable [pg 325] that the first melody of tablet three of both series was identical. Melodies are always identified by their first lines and when these agree we assume that the entire melodies are identical. Since the musicians referred to all melodies by their first lines it was manifestly impossible to begin two different melodies with the same line. But tablet three of the weeping mother liturgy muten nu-nunuz-gim begins its first melody481 nin-ri nin-ri gù-ám, etc., otherwise both melodies differ completely. This is the first known of example of two different melodies bearing the same title. It is curious indeed that an Enlil, a Ninurta and a mater dolorosa series all begin their third tablets in the same manner.

The obverse of BM. 78239 breaks away before the end of the melody nin-ri ninri gú-ám-me. Here forty-five Sumerian lines are lost; one or two melodies at least stood in this break. For the last passage on tablet three, the scribe borrows the first melody of the Ninurta series gud-nim kurra.482 The litanies which begin these melodies or series of addresses to Ninurta differ greatly in the two redactions. Since SBH. No. 18 belongs to a Ninurta series the addresses therein are much more extensive. The composer of the Enlil series elum didara obviously introduced this irrelevant melody to obtain the fine passage to the weeping mother, Rev. 10-21 on BM. 78239. These lines are lost on the Berlin text SBH. No. 18. On the whole the liturgy elum didara is more inconsistent in the development of ideas than any song service of which extensive portions are known. Only tablets one and three are as yet identified and neither of these is much more than half complete.

[pg 326]Reverse

Babylonian Cult Symbols. 6060 (No. 12)

Ni. 6060, a Cassite tablet in four columns, yields a notable addition to the scant literature we now possess concerning Babylonian mystic symbols. A fragmentary Assyrian copy from the library of Ašurbanipal was published by Zimmern as No. 27 of his Ritual Tafeln. The Assyrian copy contains only fifteen symbols with their mystic identifications, in Col. II of the obverse. The ends of the lines of the right half of Col. I are preserved on Zimmern 27, and these are all restored by the Cassite original. The obverse of these two restored tablets contained about sixty symbols with their divine implications. Most of them are the names of plants, metals, cult utensils and sacrificial animals, each being identified with a deity. A tablet in the British Museum, dated in the 174th year of the Seleucid era or 138 B. C., Spartola Collection I 131, published by Strassmaier, ZA. VI 241-4, begins with an astronomical myth concerning the summer and winter solstices503 and then inserts a passage on the mystic meanings of ten symbols. The myth of the solstices runs as follows:

“In the month Tammuz, 11th day, when the deities Miniṭṭi and Kaṭuna, daughters of Esagila,504 go unto Ezida505 and in the month Kislev, 3d day, when the deities Gazbaba and Kazalsurra, daughters of Ezida, go unto Esagila—Why do they go? In the month Tammuz the nights are short. To lengthen the nights the daughters of Esagila go unto Ezida. Ezida is the house of [pg 331] night. In the month Kislev, when the days are short, the daughters of Ezida to lengthen the days go unto Esagila. Esagila is the house of day.” The tablet then explains the Sumerian ideogram gubarra=Ašrat, the western mother goddess Ashtarte, and says that Ašrat of Ezida is poverty stricken.506 But Ašrat of Esagila is full of light and mighty.507 Some mystic connection between Ašrat or Geštinanna, mistress of letters and astrology,508 scribe of the lower world, and the daughters of night and day existed. This cabalistic tablet here refers to a mirror which she holds in her hand and says she appeared on the 15th day to order the decisions. The 15th of the month Tammuz is probably referred to or the beginning of the so-called dark period when the days begin to shorten and Nergal the blazing sun descends to the lower world to remain 160 days.509 For some reason Ašrat, here called the queen,510 appears to order the decisions, probably the fates of those that die. The phrase “The divine queen appeared” is usually said of the rising of stars or astral bodies, but the reference here is wholly obscure. As a star she was probably Virgo. At any rate some mystic pantomime must have been enacted in the month of Tammuz in which the daughters of Esagila and Ezida and the queen recorder of Sheol were the principal figures. The pantomime represented the passing of light, the reign of night and the judgment of the dead. Clearly an elaborate ritual attended by magic ceremonies characterized the ceremony. At this point the tablet gives a commentary on [pg 332] the mystic meaning of cult objects used for the healing of the sick or the atonement of a sinner. Obviously some connection exists between this mystagogy and the myth described. The commentary is probably intended to explain the hidden powers of the objects employed in the weird ritual, at any rate the mystery is thus explained.511

(1) Gypsum is the god Ninurta.512 (2) Pitch is the asakku-demon.513 (3) Meal water (which encloses the bed of the sick man) is Lugalgirra and Meslamtaea.514 [A string of wet meal was laid about the bed of a sick man or about any object to guard them against demons. Hence meal water symbolizes the two gods who guard against demons. See especially Ebeling, KTA. No. 60 Obv. 8 zisurrá talamme-šu, “Thou shalt enclose him with meal water.”]

(4) Three meal cakes are Anu, Enlil and Ea.515 (5) The design which is drawn before the bed is the net which overwhelms all evil. (6) The hide of a great bull is Anu. [Here the hide of the bull is the symbol of the heaven god as of Zeus Dolichaîos in Asia Minor.]

(7) The copper gong516 is Enlil. But in our tablet II 13 symbol of Nergal and in CT. 16, 24, 25 apparently of Anu. The term of comparison in any case is noise, bellowing.

(8) The great reed spears which are set up at the head of the [pg 333] sick man are the seven great gods sons of Išhara. The seven sons of Išhara are unknown, but this goddess was a water and vegetation deity closely connected with Nidaba goddess of the reed.517 The reed, therefore, symbolizes her sons.

(9) The scapegoat is Ninamašazagga. Here the scapegoat typifies the genius of the flocks who supplies the goat. See, however, another explanation below Obv. II 17.

(10) The censer is Azagsud. The deity Azagsud in both theological and cult texts is now male and now female. As a male deity he is the great priest of Enlil, CT. 24, 10, 12, and always a god of lustration closely connected with the fire god Gibil, Meek, BA. X pt. 1 No. 24,4.518 But ordinarily Azagsud is a form of the grain goddess who was also associated with fire in the rites of purification. As a title of the grain goddess, see CT. 24, 9, 35 = 23, 17; SBP. 158, 64 A-sug where Zimmern, KL. 11 Rev. III 11 has Azag-sug. She is frequently associated with Ninḫabursildu and Nidaba (the grain goddess) in rituals, Zimmern, Rt. 126, 27 and 29; 138, 14, etc. The censer probably symbolizes both male and female aspects, the fire that burns and the grain that is burned. See below II 9, where the censer is symbol of Urashâ a god of light.

(11) The torch is Nusku the fire god in the Nippur pantheon. Below (II 10) the torch is Gibil, fire god in the Eridu pantheon.

The mystic identifications do not always agree, but the term of comparison can generally be found if the origin and character of the deities are known and the nature of the symbol determined. Each god was associated with an animal and a plant and with other forms of nature over which they presided. When the cult utensils are symbols the term of comparison is generally clear. [pg 334] Below will be found such interpretations of these mysteries as the condition of the tablet and the limits of our knowledge permit. Most difficult of all are the metal symbols which begin with Obv. I 10. Here silver is heaven, but it can hardly be explained after the manner of the same connection of Zeus Dolichaîos with silver in Kommagene. The cult of this Asiatic heaven god is said to have been chiefly practiced at a city in the region of silver mines.519 That is an impossible explanation in the case of Anu whose chief cult center was at Erech. The association of gold with Enmesharra, here obviously the earth god, is completely unintelligible. In Obv. I 31 he is possibly associated with lead or copper as the planet Saturn. In lines I 14-18 the symbols are broken away, but they are probably based upon astronomy. Metals seem to be connected with fixed stars and planets on the principle of color. The metallic symbolism of the planets was well known to Byzantine writers who did not always agree in these matters. Their identifications are certainly a Græco-Roman heritage which in turn repose upon Babylonian tradition.520 The following table taken from Cook, Zeus, p. 626, will illustrate Græco-Roman ideas on this point:

Kronos—lead (Saturn); Zeus—silver (Jupiter); Ares—iron (Mars); Helios—gold (Sun); Aphrodite—tin (Venus); Hermes—bronze (Mercury); Selene—crystal (Moon).

Our tablet preserves only the names of the deities at this [pg 335] point, and if metals stood at the left we are clearly authorized to interpret the divine names in their astral sense. This assumes, of course, that these astral identifications obtained in the Cassite period. Assuming this hypothesis we should have the metals for Betelgeuze, Ursa Major, Venus, Jupiter, Mars, Saturn, New-moon(?), a star in Orion, Venus as evening and morning star, Virgo, and perhaps others.

The reverse of the tablet is even more mystic and subtle. The first section connects various cult substances with parts of the body. White wine and its bottle influence the eyes. White figs pertain to a woman's breasts. Must or mead have power over the limbs as the members of motion. Terms of comparison fail to suggest themselves here and we are completely disconcerted by the fancy of the Babylonian mystagogue. In the next section, which is only partially preserved, we have twelve gods of the magic rituals. The province of each in relation to the city and state is defined. Kushu, the evil satyr who receives the sin-bearing scapegoat, hovers over the homes of men. Muḫru, the deity who receives burnt offerings, or incarnation of the fires of sacrifice, dwells at the city-gate. Sakkut, a god of light and war, inexplicably protects the pools. Then follow hitherto undefined and unknown Cassite deities and a break in the tablet.

As in the Assyrian duplicate, Zimmern Rt. 27, so also here, the reverse contains a lexicographical commentary on mythological phrases. The name of the god Negun is commented upon here and most timely information is given. Both the phonetic reading of the name and the character of the deity are defined. The colophon at the end has the usual formula attached to cult instructions whose contents are forbidden to the uninitiated.

[pg 336]Obverse II

Reverse I

Reverse II

Addendum On Obv. I 10 F.

Anu in this passage really denotes Sin, the moon, which has been connected with silver on account of its color. The identification of Anu, the heaven god, with the moon god rests upon the astronomical connection between the moon and the summer solstice, see Weidner, Handbuch der Babylonischen Astronomie, 32. Sin is called “Anu of heaven,” King, Magic, No. I, 9, and for the connection with silver, see Virolleaud, Astrologie, Supplement, V II, kaspu ilu A-nu huraṣu ilu Enlil erû ilu Ea. Enlil is connected with gold in Virolleaud, Astrologie, Second Supplement, XVII 14, and Enlil is not infrequently identified with Shamash, see p. 158, 1-2 and p. 308, 18, and gold is the traditional metal of the sun.

The Greek identification of Zeus, the sky-god, with silver is certainly borrowed from Babylonia; see p. 334.

Description Of Tablets

| Number in this Volume | Museum Number | Description |

| 1 | 13856 | Large two column tablet. Unbaked; light brown with dark spots. Top broken away and left lower corner damaged. H. 6-½ inches; W. 4-¼; T. 1-¾ - ¾. Liturgy of the cult of Ishme-Dagan. See pages 245-257. |

| 2 | 11005 | Upper part of a large two column tablet. Unbaked; light brown. Top and left edge of the fragment damaged. H. 3-¾; W. 3-¾; T. 1-½ - ¾. Liturgy of Ishme-Dagan. See pages 258-259. |

| 3 | 7847 | Dark brown unbaked tablet. Right upper corner slightly damaged. Right lower corner broken away. Two columns. H. 8; W. 5-¼; T. 1 - ½. Mythological hymn to Innini. The obverse is translated on pages 260 to 264, but the reverse is too badly damaged to permit an interpretation. The text ends with the line, “Oh praise Innini,” the literary note characteristic of epical compositions. The scribe adds a note stating that there are 153 lines. Written by the hand of Lugal-ģe-a ... son of E-a-i-lù(?).... |

| 4 | 7878 | Light brown fragment from the left upper corner of a large unbaked tablet. H. 3-½; W. 1-½ - 1; T. 1-½ - 1. Duplicate of 7847. This tablet omits the liturgical note, “Oh praise Innini.” It has the colophon, “Written by the hand of Ninurash-mu..., in the presence of Nidaba-igi-pa(?)-...ģe-en.” |

| 5 | 15204 | Single column, dark brown tablet. Partly baked. Left lower corner broken away. H. 4-½; W. 2-½; T. 1-¼ - ½. Psalm to Enlil. See pages 265-268. |

| 6 | 2154 | Single Column, light brown tablet. Top and left lower corner broken. H. 4-¼; W. 2-½; T. 1-¼-½. Lamentation for Lagash. See pages 268-272. |

| 7 | 8097 | Single column, light brown tablet. Lower edge damaged. H. 4-¼; W. 2-¼; T. ¾-½. Liturgical hymn to Sin. See pages 276-279. |

| 8 | 346 | Single column, dark unbaked tablet. Damaged at top and bottom. H. 4; W. 2-½; T. 1--½. Bilingual hymn. See plate 86. |

| 9 | 8334 | Single column, light brown tablet, unbaked. Left upper corner and top of reverse damaged. H. 4-¾; W. 2-½; T. 1-¼-½. Hymn to Innini. |

| 10 | 8533 | Upper part of a large two column tablet. Light brown, soft and crumbling. Purchased by the Expedition in 1895, from Abu Hatab. H. 3-¼; W. 5-½; T. 1-¼-½. Hymn to Enlil. |

| 11 | 7080 | Large light brown tablet; five columns; broken perpendicularly at the middle. Isin period. H. 8-¼; W. 4; T. 2. Liturgy to Enlil. Lamentation for the city of Ur. See pages 279-285. |

| 12 | 6060 | Nearly complete tablet; baked. Temple library (IV). Second Exp. Two column tablet; Cassite period. H. 4; W. 3-½; T. 1-½. Cult symbols. See pages 320-342. |

| 13 | B.M. 78239 | Upper half of large single column tablet. Light brown, partially baked. H. 7; W. 6; T. 2. Acquired by the British Museum in 1888. Late Babylonian edition of the third tablet of the liturgy elum didara to Enlil. See pages 323-329. |

| 14 | 11327 | Lower part of a large unbaked tablet, two columns. Right half almost wholly broken away. Myth of the water god Enki. H. 6; W. 6-½; T. 1-¾. Probably a zag-sal hymn. |

Index Of Tablets

Tablets in this Volume.

| Museum Number | Number in this Volume |

| 346 | 8 |

| 2154 | 6 |

| 6060 | 12 |

| 7080 | 11 |

| 7847 | 3 |

| 7848 | 4 |

| 8097 | 7 |

| 8334 | 9 |

| 8533 | 10 |

| 11005 | 2 |

| 11327 | 14 |

| 13856 | 1 |

| 15204 | 5 |

| B.M. 78239 | 13 |

Other Tablets Translated Or Discussed

Nies 1315, Tablet Virolleaud, 290-308

Poebel, PBS. V No. 26, 272-276

Myhrman, PBS. I No. 5, Radau, BE. 30, No. 2, 285-290

Myhrman, PBS. I No. 8, 309-310

Zimmern, KL. No. 11, 290-308

Zimmern, Ritual Tafeln, No. 27, 330-340

Ashmolean Prism, 311-323

Strassmaier, ZA. VI 241-4, 330-333

Reisner, SBH. No. 18, 327-329

Reisner, SBH. No. 21, 292-297

Reisner, SBH. No. 22, 292-295

Reisner, SBH. No. 25, 300-302

Index To Vol. X

Autographed Texts

Plate LXXI. 1. Obverse. Col. 1.

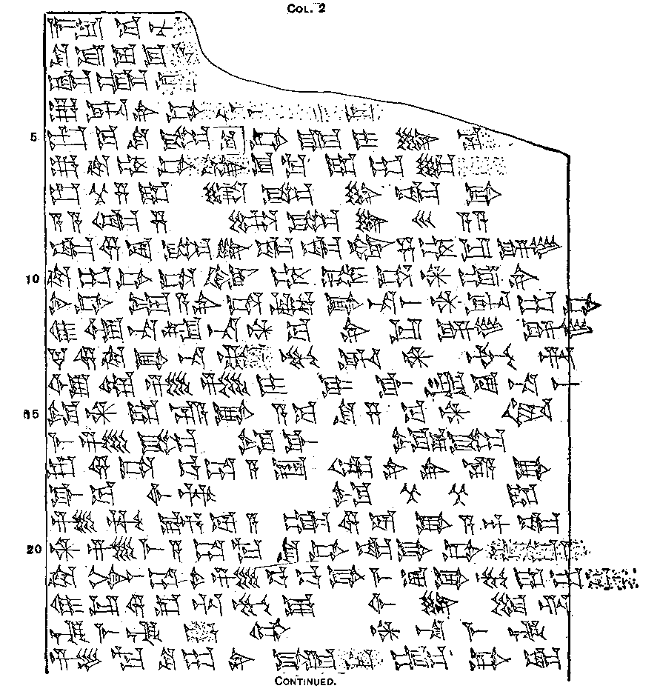

Plate LXXII. 1. Obverse. Col. 2.

Plate LXXIII. 1. Reverse. Col. 1.

Plate LXXIV. 1. Reverse. Col. 2.

Plate LXXV. 2. Obverse.

2. Reverse.

Plate LXXVI. 3. Obverse. Col. 1 Initial.

Plate LXXVII. 3. Obverse. Col. 1 Continued.

3. Obverse. Col. 2 Initial.

Plate LXXVIII. 3. Obverse. Col. 2 Continued.

3. Reverse. Col. 1 Initial.

Plate LXXIX. 3. Reverse. Col. 1 Continued.

3. Reverse. Col. 2 Initial.

Plate LXXX. 3. Reverse. Col. 2 Continued.

4. Obverse.

4. Reverse.

Plate LXXXI. 5. Obverse.

Plate LXXXII. 5. Reverse.

Plate LXXXIII. 6. Obverse.

Plate LXXXIV. 6. Reverse.

Plate LXXXV. 7. Obverse.

7. Reverse.

8. Reverse.

Plate LXXXVII. 9. Obverse.

9. Reverse.

Plate LXXXVIII. 10. Obverse. Col. 1. (Col. 2 Destroyed)

Plate LXXXIX. 10. Reverse. Col. 1.

10. Reverse. Col. 2.

Plate XC. 11. Obverse. Col. 3 Initial.

Plate XCI. 11. Obverse. Col. 3 Continued.

11. Obverse. Col. 4 Initial.

Plate XCII. 11. Obverse. Col. 4 Continued.

Plate XCIII. 11. Obverse. Col. 4 Final.

11. Obverse. Col. 5 Initial.

Plate XCIV. 11. Obverse. Col. 5 Continued.

Plate XCV. 11. Reverse. Col. 1. Initial.

Plate XCVI. 11. Reverse. Col. 1 Continued.

11. Reverse. Col. 2 Initial.

Plate XCVII. 11. Reverse. Col. 2 Continued.

11. Reverse. Col. 3. Initial.

Plate XCVIII. 11. Col. 3 Continued.

Plate XCIX. 12. Obverse. Cols. 1 and 2.

Plate C. 12. Reverse. Cols. 1 and 2.

Plate CI. 13. Obverse.

Plate CII. 13. Reverse.

Plate CIII. 14. Obverse. Col. 1

Plate CIV. 14. Obverse. Col. 2.

14. Reverse. Col. 1.

Plate CV. 14. Reverse. Col. 2.

Footnotes

- 1.

- In addition to the examples of epical poems and hymns cited on pages 103-5 of this volume note the long mythological hymn to Innini, No. 3 and the hymn to Enlil, No. 10 of this part. An unpublished hymn to Enlil, Ni. 9862, ends a-a dEn-lil zag-sal, “O praise father Enlil.” For Ni. 13859, cited above p. 104, see Poebel, PBS. V No. 26.

- 2.

- So far as the term is properly applied. Being of didactic import it was finally attached to grammatical texts in the phrase dNidaba zag-sal, “O praise Nidaba,” i. e., praise the patroness of writing.

- 3.

- Poebel, PBS. V No. 25; translated in the writer's Le Poème Sumérien du Paradis, 220-257. Note also a similar epical poem to Innini partial duplicate of Poebel No. 25 in Myhrman's Babylonian Hymns and Prayers, No. 1. Here also the principal actors are Enki, his messenger Isimu, and “Holy Innini” as in the better preserved epic. Both are poems on the exaltation of Innini.

- 4.

- Ni. 9205 published by Barton, Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions, No. 4. This text is restored by a tablet of the late period published by Pinches in JRAS. 1919.

- 5.

- Ni. 7847, published in this part, No. 3 and partially translated on pages 260-264.

- 6.

- Undoubtedly Ni. 11327, a mythological hymn to Enki in four columns, belongs to this class. It is published as No. 14 of this part. A similar zagsal to Enki belongs to the Constantinople collection, see p. 45 of my Historical and Religious Texts.

- 7.

- Historical and Religious Texts, pp. 14-18.

- 8.

- See PSBA. 1919, 34.

- 9.

- One of the most remarkable tablets in the Museum is Ni. 14005, a didactic poem in 61 lines on the period of pre-culture and institution of Paradise by the earth god and the water god in Dilmun. Published by Barton, Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions, No. 8. The writer's exegesis of this tablet will be found in Le Poème Sumérien du Paradis, 135-146. It is not called a zag-sal probably because the writer considered the tablet too small to be dignified by that rubric. Similar short mythological poems which really belong to the zag-sal group are the following: hymn to Shamash, Radau, Miscel. No. 4; hymn to Ninurta as creator of canals, Radau, BE. 29, No. 2, translated in BL., 7-11; hymn to Nidaba, Radau, Miscel. No. 6.

- 10.

- Ni. 112; see pp. 172-178.

- 11.

- For example, Myhrman, No. 3; Radau, Miscel. No. 13; both canonical prayer books of the weeping mother class. For a liturgy of the completed composite type in the Tammuz cult, see Radau, BE. 30, Nos. 1, 5, 6, 8, 9.

- 12.

- See Zimmern, Sumerische Kultlieder, p. V, note 2.

- 13.

- The base text here is Zimmern, KL. No. 12.

- 14.

- The base of this text is Zimmern, KL. No. 11.

- 15.

- Now in the Nies Collection, Brooklyn, New York.

- 16.

- A similar liturgy is Ni. 19751, published by Barton, Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions, No. 6.

- 17.

- Translated by Radau on pages 436-440.

- 18.

- Abbreviation for ki-šub-gú-da = šêru, strophe, song of prostration.

- 19.

- No. 3 of the texts in part 4.

- 20.

- sa-gar = pitnu šaknu, choral music, v. Zimmern, ZA. 31, 112. See also the writer's PBS. Vol. XII, p. 12.

- 21.

- nar-balag. The liturgists classified the old songs according to the instrument employed in the accompaniment. See SBP. p. ix.

- 22.

- See page 118 in part 2.

- 23.

- See IV Raw. 53, III 44-IV 28 restored from BL. 103 Reverse, a list of 47 šu-il-lá prayers to various deities.

- 24.

- Pages 106-109.

- 25.

- Less than half the tablet is preserved.

- 26.

- Note that this breviary of the cult of Libit-Ishtar terminates with two ancient songs, one to Innini and one to Ninâ, both types of the mother goddess who was always intimately connected with the god-men as their divine mother.

- 27.

- For a list of the abbreviations employed in this volume, see page 98 of Part I.

- 28.

- The twelfth kišub of a liturgy to Ishme-Dagan is published in Zimmern's Kultlieder, No. 200. A somewhat similar song service of the cult of this king has been published in the writer's Sumerian Liturgical Texts, 178-187. A portion of a series to Dungi was published by Radau in the Hilprecht Anniversary Volume, No. 1. The liturgy to Libit-Ishtar in Zimmern, K L. 199 I—Rev. I 7, is composed of a series of sa-(bar)-gid-da.

- 29.

- na-ba- is for nam-ba, emphatic prefix. See PBS. X pt. 1 p. 76 n. 4. Cf. na-ri-bi, verily she utters for thee, BE. 30, No. 2, 20.

- 30.

- On the philological meaning of this name, see VAB. IV 126, 55.

- 31.

- For the suffixes eš, uš, denoting plural of the object, see Sum. Gr. p. 168.

- 32.

- On ki-dúr-gar cf. Gudea, Cyl. B 12, 19.

- 33.

- Usually written dù-azag, throne room. On the meaning of du in this word, see AJSL. 33, 107. Written also dû-azag, in Ni. 11005 II 9.

- 34.

- Cf. Gudea, Cyl. A 25, 14, the kin-gi of the unu-gal.

- 35.

- Br. 7720. The sign TE is here gunufied. Cf. OBI. 127, Obv. 5.

- 36.

- Tin alone may mean “wine,” as in Gudea, Cyl. B, 5, 21; 6, 1. See also Nikolski, No. 264, duk-tin, a jar of wine.

- 37.

- a-gim = dimêtu, ban, SBH. 59, 25. a-gim ģe-im-bal-e, The ban may he elude, Ni. 11065 Rev. II 25. Unpublished. The line is not entirely clear; cf. Brünnow, No. 3275.

- 38.

- For en-na in the sense of “while,” see Pery, Sin in LSS. page 41, 16.

- 39.

- The sign is imperfectly made on the tablet.

- 40.

- Cf. SBP. 328, 11.

- 41.

- ḪA is probably identical in usage with PEŠ, and the idea common to both is “be many, extensive, abundant.” Note Zimmern, Kultlieder 19 Rev. has ḪA where SBP. 12, 2 has PEŠ. šu-peš occurs in Gudea, Cyl. A 16, 23; 11, 9; 19, 9 and CT. 15, 7, 27.

- 42.

- On ugu-de = ḇalāku, na'butu, to run away, see Delitzsch, Glossar p. 43. Also ugu-bi-an-de-e, V R. 25a 17; ù-gù-dé, RA. 10, 78, 14; ú-gu ba-an-dé, if he run away, VS. 13, 72 9 and 84, 11, with variant 73, 11 u-da-pa-ar = udtappar, if he take himself away. ú-gu-ba-an-de-zu, when thou fleest, BE. 31, 28, 23. ú-gu-ba-de, Genouillac, Inventaire 944; Clay Miscellen 28 V 71: má ú-gu-ba-an-de, “If a boat float away,” ibid. IV 14. See also Grant AJSL. 33, 200-2.

- 43.

- Sic! gú-sa-bi is expected; cf. RA. 11, 145, 31 gú-sa-bi = napḫar-šu-nu.

- 44.

- Sign obliterated; the traces resemble SU.

- 45.

- Read perhaps dū-šub = nadû ša rigmi, to shout loudly. Cf. dúg sir-ra šub-ba-a-zu = rigme zarbiš addiki, ASKT. 122, 12. Passim in astrological texts.

- 46.

- The tablet has MAŠ. The Semitic would be adi mati kabattu iparrad.

- 47.

- ri is apparently an emphatic element identical in meaning with ám; cf. SBP. 10, 7-12. Note ri, variant of nam, SBH. 95, 23 = Zimmern, KL. 12 I 8.

- 48.

- Sic! Double plural. eš probably denotes the past tense, see Sum. Gr. § 224.

- 49.

- Sign Brünnow, No. 11208.

- 50.

- The first melody or liturgical section probably ended somewhere in this lost passage at the top of Col. II.

- 51.

- Text A-ÁŠ!

- 52.

- The subject is Ishme-Dagan.

- 53.

- The sign is a clearly made Br. No. 10275 but probably an error for 10234. For sùr-ri-eš see BA. V 633, 22; SBH. 56 Rev. 27; Zimmern, KL. 12 Rev. 17.

- 54.

- This compound verb di-e-sud here for the first time. di-e is probably connected with de to flee. At the end AŠ is written for AN. Read a-áš and construe šeš as a plural?

- 55.

- gul = kalû, restrain, is ordinarily construed with the infinitive alone; še-du nu-uš-gul-e-en = damāma ul ikalla, Lang. B.L. 80, 25; SBH. 133, 65; 66, 15, etc.

- 56.

- Confirms SAI. 6507 = uḳḳu, dumb, grief stricken.

- 57.

- Variant of sīg-sīg, etc. See Sum. Gr. p. 237 sig. 3. Also Poebel, PBS. V 26, 29.

- 58.

- On the liturgical use of balag-di, see BL. p. XXXVII.

- 59.

- Var. of ad-du-ge = bêl nissāti, IV R. 11a 23: ad-da-ge, Zim. K.L. 12 II 3. See for discussion, Lang. PBS. X 137 n. 7.

- 60.

- A new ideogram. Perhaps uššu kînu, “sure foundation.”

- 61.

- For suffixed ni, bi, ba in interrogative sentences note also a-na an-na-ab-duģ-ni, What can I add to thee? Genouillac, Drehem, No. 1, 12, a-ba ku-ul-la-ba, Who shall restrain? Ni. 4610 Rev. 1.

- 62.

- See BL. p. XLV, and PBS. X 151 note 1.

- 63.

- On the anticipative construct, see § 138 of the grammar.

- 64.

- nu-mal are uncertain. The tablet is worn at this point.

- 65.

- On the use of this term, see PBS. X 151 n. 1 and 182, 33.

- 66.

- Cf. BL. 110, 11.

- 67.

- Written Br. 3046, but the usual form is the gunu, Br. 3009. suģ-ám-bi = aḫulap-šu. Poebel, PBS. V 152 IX 8: cf. also lines 9 and 10 ibid. In later texts suģ-a = aḫulap, Haupt, ASKT. 122, 12. Delitzsch, H. W. 44a. aḫulap has the derived meaning of mercy, the answer to the “How long” refrain as in this passage. See also SBP. 241 note 27 and Schrank, LSS. III 1, 53.

- 68.

- Cf. nar-balag nig-dug-ga, Poebel, PBS. V 25 IV 48. Our text has the emesal form ag-zib.

- 69.

- For dû-na = šalṭiš, see RA. 11, 146, 33.

- 70.

- Written Br. 3046 = nasāḳu.

- 71.

- For ta-šú. Cf. BA. V 679, 14.

- 72.

- Probably a variant of namģalam, namģilim = šaḫluḳtu.

- 73.

- The demonstrative pronoun ģur, ūr

- 74.

- mûši ù urra, IV R. 5a 65; CT. 16, 20, 68.

- 75.

- Text A-AŠ.

- 76.

- Sign AL. šitim, šidim = idinnu is usually written with the sign GIM, Poebel, PBS. V 117, 14 f. amelu ĢIM = idinnu, passim in Neo-Babylonian contracts.

- 77.

- Literally, “caused to enter.”

- 78.

- munga with ra, to carry away property as booty, see SBH. No. 32 Rev. 21 and BL. No. 51. The comparison with line 11 suggests, however, another interpretation, immer-e be-in-ne-ra-ám, “the storm-wind carried away.”

- 79.

- In lines 7 and 9 the verb tur is employed in the sense of “to cause an event to enter,” to bring about the entrance of a condition or state of affairs.

- 80.

- Br. 11208.

- 81.

- The passage refers to the priests' robes and garments of the temple service. See also SBP. 4, 9.

- 82.

- Variant of nam-rig-aga = šalālu.

- 83.

- See Obv. II 23.

- 84.

- Enlil.

- 85.

- Rendered ša ṣirḫi, BL. 95, 19. On this title for a psalmist, see BL. XXIV.

- 86.

- uš has evidently some meaning similar to the one given in the translation but it has not yet been found in this sense in any other passage. We have here the variant of iš, eš = bakû with vowel u. See Sum. Gr. 213 and 222.

- 87.

- DUL-DU. The sign DUL is erroneously written REC. 236. In the text change si to ši.

- 88.

- Br. 3739.

- 89.

- Here treated as plural.

- 90.

- The tablet has SU. For šag-zu synonym of teṣlitu, see IV R. 21b Rev. 5.

- 91.

- libbu rûḳu; see Zimmern, KL. No. 8 I 3 and IV 28.

- 92.

- The sign like many others on this tablet is imperfectly made. ma-pad? or ma-šig? The meaning is obscure.

- 93.

- Text uncertain. Perhaps PI-SI-gà-bi.

- 94.

- Written A-KA. An unpublished Berlin syllabar gives A-KA (uga) = muḫḫu.

- 95.

- Br. 5515. For this sign with value maštaku, see Delitzsch, H. W., sub voce and BA., V 620, 20. The Sumerian value is ama, Chicago Syllabar, 241 in AJSL. 33, 182.

- 96.