DELANO

BY

JANE A. DELANO, R. N.

Chairman of the National Committee, Red Cross Nursing Service; Director,

Department of Nursing, American Red Cross; Late Superintendent

of the Nurse Corps, U. S. A.; of the Training Schools

for Nurses, Bellevue Hospital, New York City; and of the

Training School for Nurses, Hospital of the University

of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

REVISED AND REWRITTEN

BY

ANNE HERVEY STRONG, R. N.

Professor of Public Health Nursing, Simmons College, Boston

This is the Second Edition of the American Red Cross

Text-book in Elementary Hygiene and Home Care of

the Sick by Jane A. Delano and Isabel McIsaac.

PREPARED FOR AND ENDORSED BY

THE AMERICAN RED CROSS

PHILADELPHIA

P. BLAKISTON'S SON & CO.

1012 WALNUT STREET

Copyright, 1918, by American Red Cross

THE MAPLE PRESS YORK PA

To the woman who wishes to protect her family from preventable diseases and is anxious to fit herself in the absence of a trained nurse to give intelligent care to those who are sick, this revision of the Red Cross text-book on Elementary Hygiene and Home Care of the Sick is particularly directed. It should appeal to men and to women who are interested in maintaining the health of their neighborhoods and communities and in affording effective coöperation to the public health authorities. To teachers wishing to impart protective health information to high school pupils, the book also should be useful as a class text as well as a guide.

The war, which has caused the withdrawal from private practice of thousands of physicians and graduate nurses, makes it peculiarly important to the nation for every adult to have sound knowledge as to how to prevent contagion and epidemics, especially by precautionary attention to home and local sanitation. With nurses becoming more difficult to secure, the safety of the family demands that some member in each household know enough about elementary nursing to make a patient comfortable and to carry out accurately the instructions of the physician.

[vi] The work of revision, based upon the latest knowledge of hygiene, sanitation and methods of home-nursing has been done by Miss Anne Hervey Strong, Professor of Public Health Nursing, Simmons College, under the personal direction of the author and the National Committee on Red Cross Nursing Service. The material has been painstakingly read by Dr. H. W. Rucker and Dr. Taliaferro Clarke of the United States Public Health Service, and Lieutenant Colonel Clarence H. Connor, Medical Corps, United States Army. Indebtedness to Dr. H. M. McCracken, President of Vassar College and Director of the Red Cross Junior Membership, for his valuable suggestion as to adapting the book for high school use as well as for the assistance rendered by his Department, also is gladly acknowledged.

J. A. D.

I wish to express my gratitude to those who have so kindly helped in the work of preparing the present edition. Thanks are especially due to Professor Isabel Stewart, Miss Anna C. Jamme, Professor Curtis M. Hilliard, Professor Maurice Bigelow, Miss Katharine Lord, Miss Josephine Goldmark, and Miss Evelyn Walker.

A. H. S.

| Preface | v |

| Introduction | xi |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Page | |

| Causes and Prevention of Sickness

Communicable diseases, 1. Micro-organisms and bacteria, 1. Parasites, 3. Structure and development of parasites, 4. Bacteria, 4. Shape, 4. Size, 5. Motion, 5. Multiplication, 5. Spores, 7. Distribution, 8. Protozoa, 8. Visible parasites, 8. Transmission of pathogenic organisms, 9. Defenses of the body, 12. Immunity, 13. Vaccination and inoculation, 15. Carriers, 17. Non-communicable diseases, 20. Physical examinations, 22. | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Health and the Home

Heredity, 27. Hygiene of environment and person, 28. Ventilation, 29. Lighting, 32. Cleanliness of houses, 33. Garbage, 37. Insects, 38. Sewage, 39. Personal cleanliness, 41. Oral hygiene, 44. Treatment of teeth, 46. Clothing, 47. Food, 48. Elimination, 52. Rest and fatigue, 53. Sleep, 55. Recreation, 55. | 27 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Babies and Their Care

Growth and development, 64. Average size, 64. Muscular development, 65. Development of special senses, of speech, of teeth, 66. Normal excretions, 67. Clothing, 68. Sleep, 70. Fresh air, 72. Diet, 72. Intervals of feeding, 73. Water, 75. Weaning, 75. Nursing bottles and nipples, 75. Tables of diet, 78. Bathing, 78. Eyes, 80. Mouth, 81. Nostrils, 81. Genital organs, 81. Development of habits, 82. Exercise, 83. Play and toys, 85. | 60 |

| [viii] CHAPTER IV | |

| Indications of Sickness

Objective symptoms, 92. Temperature, 92. Pulse, 96. Respiration, 99. General appearance, 100. Special senses, 101. Voice, tongue, throat, gums, 102. Cough, 103. Appetite, 103. Excretions, 103. Loss of weight, 104. Sleep, 104. Mental conditions, 104. Subjective symptoms, 105. Pain, 105. Records, 107. Tuberculosis, cancer and mental illness, 107. Tuberculosis, 109. Cancer, 111. Mental illness, 112. |

88 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Equipment and Care of the Sick Room

Choice of a sick room, 118. Furnishing, 120. Ventilation, 123. Heating, 124. Lighting, 124. Cleaning, 126. The attendant, 127. | 117 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Beds and Bedmaking

Bedsteads, 133. Mattresses, 135. Care of the mattress, 136. Pillows, 136. Protection of the mattress and pillows, 137. Rubber sheets and pillow-cases, 138. Sheets, 139. Draw sheets, 139. Pillow covers, 140. Blankets, 140. Comforters and quilts, 141. Counterpanes, 141. Bedmaking, 141. To make an unoccupied bed, 143. To change a patient's pillows, 146. Lifting a patient in bed, 146. To turn a patient in bed, 147. To change sheets while patient is in bed, 147. To move patient from one bed to another, 150. |

132 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Baths and Bathing

Cleansing baths, 154. Bed bath, 156. Care of the mouth and teeth, 160. Care of the hair, 163. To wash the hair of a bed patient, 164. Hot foot-baths, 165. Cool sponge bath, 166. |

154 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Appliances and Methods for the Sick-Room

Devices to give support, 172. Bedpans, 176. Daily routine in the sick-room, 179. Time for visitors, 182. |

169 |

| [ix] CHAPTER IX | |

| Feeding the Sick

The digestive process, 188. Feeding the sick, 191. Liquid diet, 192. Semi-solid diet, 192. Light or convalescent diet, 193. Full diet, 193. Serving food for the sick, 195. To feed a helpless patient, 197. |

187 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Medicines and Other Remedies

Action of drugs, 200. Amateur dosing, 202. Patent remedies, 205. Administration of medicine, 206. Suppositories, 209. Enemata, 210. Sprays and gargles, 213. Inhalation, 213. Inunction, 214. Household medicine cupboard, 215. |

200 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Application of Heat, Cold and Counter-Irritants

Inflammation, 220. Hot applications, 225. Dry heat, 225. Moist heat, 227. Stupes or hot fomentations, 229. Cold applications, 231. Dry cold, 231. Moist cold, 232. Cold compresses for the eyes, 232. Counter-irritants, 233. Mustard paste, 233. Mustard leaves, 234. |

220 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Care of Patients with Communicable Diseases

Incubation period, 238. Care of patients with colds or other slight infections, 238. Care during more serious infections, 242. Children's diseases, 246. Rules for isolation and exclusion from school, 247. Disinfection, 248. Care of nose and throat discharges, 249. Care of discharges from the bowels and bladder, 249. Bath water, 250. Care of the hands, 250. Care of utensils, 251. Care of linen, 251. Disinfection of the person, 252. Termination of quarantine, 252. Terminal disinfection, 253. Fumigation, 254. |

236 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Common Ailments and Emergencies

Conditions in which the nervous system is involved, 257. Headache, 257. Sleeplessness, 258. Fainting, 259. Convulsions, 260. Shock, 261. Stimulants, 263. Sunstroke and heat exhaustion, 264. Conditions in which the digestive tract is affected, 265. Nausea and vomiting, 265. Hiccough, 265.[x] Diarrhœa, 266. Constipation, 266. Colic, 266. Conditions in which the eyes or ears are affected, 267. Styes, 267. Foreign bodies in the eye, 267. Disorders affecting the ears, 268. Conditions in which the skin is affected, 269. Prickly heat, 269. Insect bites and stings, 270. Ivy poisoning, 270. Other emergencies, 270. Chills, 270. Croup, 271. Bleeding, 272. Treatment of slight wounds, 272. Nose bleed, 274. Profuse menstruation, 275. Other injuries, 275. Sprains, 275. Bruises, 276. Burns and scalds, 277. Brush burn, 278. |

257 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Special Points in the Care of Children, Convalescents,

Chronics, and the Aged

Children, 281. Physical defects, 283. Eye-strain, 284. Enlarged tonsils and adenoids, 284. Defective hearing, 285. Defective teeth, 286. Posture, 286. Predisposition to nervousness, 292. Convalescent patients, 294. Chronic patients, 299. Care of the aged, 303. |

280 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| Questions for Review | 312 |

| Appendix

Circulars of information issued by Division of Child Hygiene, New York Department of Health. |

319 |

| Glossary | 326 |

| Index | 331 |

Health and sickness, at all times momentous factors in the welfare of our nation, now as never before are matters of vital importance. To win its victories both in peace and in war, the nation needs all its citizens with all their powers, and it is a matter of more than passing interest that, as conservative estimates show, at least three persons out of every hundred living in the United States are constantly incapacitated by serious sickness. In 1910 these seriously sick persons numbered more than 3,000,000. Even more significant, perhaps, is the fact that at least half of our national sickness could be prevented if knowledge and resources that we now possess were fully utilized.

The problem of sickness is by no means peculiar to our own day and generation. It has been a medical, a religious, and a social problem in every age. From the time of Job its meaning has baffled philosophers; from his day to ours thoughtful men have devoted their lives to searching for causes and cures. Yet before the middle of the last century little progress was made, either in scientific treatment or in prevention of disease.

[xii] The invention of the microscope first made possible a real understanding of sickness. Through the microscope a new world was revealed,—a world of the infinitely small, swarming with tiny forms of animal and vegetable life. No one, however, appreciated the significance of these hitherto invisible plants and animals until the latter part of the 19th century, when the great French savant, Pasteur, proved that little vegetable forms, now called bacteria, cause putrefaction and fermentation, and also certain diseases of animals and man. Pasteur's discoveries were carried still further by other scientists, with the result that bacteriology has revolutionized medicine, agriculture, and many industries, and has made possible the brilliant achievements of modern sanitary science. For the first time in history the prevention of epidemics has become possible, and sickness is no longer regarded as a punishment for sin.

Actual care of the sick, both in homes and in hospitals, has always been one of the responsibilities of women. The first general public hospital was built in Rome in the 4th century after Christ by Fabiola, a patrician lady. There she nursed the sick with her own hands, and from her day to ours extends an unbroken line of devoted women, handing down through the[xiii] centuries their tradition of compassionate nursing service. It remained for Florence Nightingale, however, to give to the training its technical and scientific foundation, and thus to found the profession of nursing. As a result of her work, effectiveness was added to the spirit of service, that spirit which inspires the modern nurse no less than in an earlier day it inspired the Sisters of Charity who died nursing the wounded on the battlefields of Poland.

But different generations have different needs, and to meet them the spirit of service must manifest itself in widely varying ways. The sick need care today no less than they did when St. Elizabeth bathed the feet of the lepers; but such limited service, however beautiful, is no longer enough. Today we serve best by preventing sickness. Cure of sickness and alleviation of suffering must never be neglected; not in cure, however, but in prevention lies the hope of modern sanitary science, of modern medicine, and of modern nursing.

Nearly every woman at some time in her life is called upon to assist in caring for the sick. Indeed, approximately 90% of all sick persons in the United States are cared for at home, even in cities where hospital facilities are good. Moreover, every woman is largely responsible for maintaining her own health, and few escape[xiv] responsibility at some time for maintaining the health of others. For such responsibility most women are poorly prepared. Every year in our own country thousands of persons, many of them babies and children, die merely because someone, in many cases a woman, is fatally ignorant of the laws governing sickness and health.

Only prolonged and careful training, such as good hospital training-schools afford, can furnish the skill and judgment required in nursing persons who are seriously ill. Upon the trained nurse the modern practice of medicine makes great and ever-increasing demands: a nurse must perform complicated duties, meet critical situations, and carry out a wide variety of measures based on scientific principles which she must understand. Good will and sympathy are no longer enough; amateur nursing, even when performed with the best intentions, may involve grave dangers for those who are seriously ill.

On the other hand, although it is true that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, it is no less true that total ignorance may be more dangerous still. For instance, in cases of incipient, slight, or chronic illness, and in certain emergencies a little knowledge may be safer far than no knowledge at all; and no one, surely, should be ignorant of the principles of hygiene.

[xv] The American Red Cross, recognizing the part that women can and should play in preventing sickness and in building up the health and vigor of the nation, has added to its larger patriotic services this elementary course of instruction in hygiene and home care of the sick. The lessons are not intended to take the place of a nurse's training, and procedures requiring technical skill are necessarily omitted. The object of the book is to supply a little knowledge of sickness, which though limited may yet be safe. The book is also designed to set forth some general laws of health; to make possible earlier recognition of symptoms; to teach greater care in guarding against communicable disease; and to describe some elementary methods of caring for the sick, which, however simple, are essential to comfort, and sometimes indeed to ultimate recovery.

Diseases of two kinds have long been recognized: first, those transmitted directly or indirectly from person to person, like smallpox, measles, and typhoid fever; and second, diseases like heart disease and apoplexy, which are not so transmitted. These two classes are popularly called "catching" and "not catching;" the former are the infectious or communicable diseases, and the latter the non-infectious or non-communicable. The term contagious, formerly applied to diseases supposed to be spread only by direct contact, is no longer an accurate or useful term.

The invention of the microscope, as we have seen, revealed the existence of innumerable little plants and animals, so small that even many millions crowded together are invisible to the naked eye. These tiny living creatures are called micro-organisms or germs. The plant forms are called bacteria (singular, bacterium), and the animal[2] forms protozoa (singular, protozoön). The common belief that all or even most bacteria are harmful is quite unfounded. As a matter of fact, while not less than 1500 different kinds of micro-organisms or germs are known, only about 75 varieties are known to produce disease.

Most bacteria belong to the class of micro-organisms called saprophytes, which find their food in dead organic matter, both animal and vegetable, and cannot flourish in living tissues. These saprophytes act upon the tissues of dead animals and vegetables, and resolve them into simpler substances, which are then ready to serve as nourishment for plants higher in the vegetable kingdom. Thus the processes which we know as fermentation and putrefaction are due to the action of saprophytes. Higher plants in turn furnish food for men and animals, and so the food supply is used over and over in different forms, making what is known as the food cycle. If it were not for bacterial activities vegetation would be robbed of its supply of nourishment, and plant life would speedily end; destruction of plant life would deprive the animal kingdom of food and thus all life would become extinct. The saprophytes are consequently essential to the existence of both animals and vegetables.

There are, however, other organisms called[3] parasites, which can exist in living tissues of animals or vegetables. The organisms at whose expense the parasites live are called their hosts. Parasites not only contribute nothing to their hosts, but generally harm them by producing poisonous substances or depriving them of food. Some parasites are able to lead a saprophytic existence also, but as a rule they live at the expense of animal or plant life. Pathogenic, or disease-producing, germs belong to the group of parasites. The pathogenic germs which find favorable soil in the body produce poisons called toxins. These poisons or toxins interfere with the bodily functions, and thus cause what we know as communicable disease. Communicable diseases are caused by specific germs only: that is, a certain disease cannot develop unless its particular germs are present; the germs of typhoid for instance, can cause typhoid fever only, and not tuberculosis or other disease.

A number of diseases are caused by micro-organisms that are now well known. Chief among these diseases are colds, septicæmia (blood poisoning), influenza, pneumonia, diphtheria, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, whooping cough, Asiatic cholera, bubonic plague, meningitis, tetanus ("lock jaw"), leprosy, gonorrhœa, syphilis, relapsing fever, typhus fever, glanders, and anthrax. Micro-[4]organisms not yet identified probably cause the communicable diseases whose origin is not known with certainty. These include infantile paralysis, smallpox, scarlet fever, measles, mumps, chicken-pox, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, yellow fever, hydrophobia (rabies), foot-and-mouth disease. We can hardly doubt that the intensive laboratory research now in progress will reveal in the near future the specific germs of these diseases also.

The group of parasites consists of two general classes, the vegetable, and the animal. In the former class belong the bacteria, and in the latter the protozoa. The two classes are not sharply differentiated, but in general the vegetable parasites are less highly organized than the animal.

—Bacteria are composed of single cells and are consequently called unicellular organisms. Under the microscope individual cells are seen to differ in size, shape, and structure. In shape bacteria show three different types; the rod-shaped (bacillus), the spherical (coccus), and the spiral (spirillum). The organisms causing[5] typhoid fever for example are a variety of bacilli, those causing pneumonia are cocci, while those causing Asiatic cholera are spirilla.

Fig. 1.—Bacilli of Various Forms. (Williams.)

Fig. 1.—Bacilli of Various Forms. (Williams.)

—Bacteria vary greatly in size. Average rod-shaped bacteria are about 1/25000 of an inch long, but there are undoubtedly organisms so small that they cannot be seen, even by means of the strongest microscopes we now possess.

Staphylococci. Streptococci. Diplococci. Tetrads. Sarcinæ.

Staphylococci. Streptococci. Diplococci. Tetrads. Sarcinæ.—The power of motion in certain species of bacteria is due to hair-like appendages called flagella. These flagella by a lashing movement somewhat resembling the action of oars enable the organisms to move through fluids.

—After bacteria have fully developed, each cell divides into two equal parts; the process of division is called fission. Each[6] of these two parts rapidly grows into a full-sized organism. Then fission again takes place, so that four bacteria replace the original one. In each of the four, fission occurs again, and so the process of multiplication continues. As bacteria develop they group themselves in characteristic ways. Some, like the streptococci, arrange themselves in chains; the diplococci, in pairs; the tetrads, in groups of four; others in packets called sarcinæ, and still others, the staphylococci, form masses supposed to resemble bunches of grapes.

Fig. 3.—Spirilla of Various Forms. (Williams.)

Fig. 3.—Spirilla of Various Forms. (Williams.)

Fig. 4.—Bacteria showing Flagella. (Williams.)

Fig. 4.—Bacteria showing Flagella. (Williams.)

Under favorable conditions fission occurs rapidly; in some types a new generation may appear as often as every 15 minutes. Enormous[7] multiplication would result if nothing occurred to check the process. But in nature such increase never continues unhindered, and bacteria, acting upon their food substances, produce acids and other materials injurious to themselves. Furthermore, lack of proper food, moisture, or favorable temperature, and competition with other organisms tend to prevent their unrestricted growth and multiplication.

Fig. 5.—Bacteria with Spores. (Williams.)

Fig. 5.—Bacteria with Spores. (Williams.)

—Most bacteria die if conditions become unfavorable to their growth, but some enter into a resting stage. This stage is characterized by the development of round or oval glistening bodies called spores, which are of dense structure and possess an extraordinary power to withstand heat, chemicals, and unfavorable surroundings. Except in rare instances a single cell produces but one spore. As soon as favorable conditions of temperature, moisture, and food supply are restored, the spore develops into the active form of the germ; it may, however, remain dormant[8] for months or years. Spore formation, however, occurs in only a very few varieties of pathogenic bacteria.

—Bacteria are very widely distributed in nature; they are in fact found practically everywhere on the surface of the earth. They are present in plants and water and food; on fabrics and furniture, walls and floors; and they are found in great numbers on the skin, hair, many mucous surfaces, and other tissues of the body.

The protozoa are the lowest group of the animal kingdom. Like bacteria they are composed of single cells so small as to be visible only under the microscope. They play an important part in causing certain diseases of man, especially in the tropics. Among the well-known human diseases of protozoan origin are malaria, amoebic dysentery, and sleeping-sickness. Protozoa also cause several wide-spread and serious plagues of domestic animals.

A few diseases are caused by parasites large enough to be seen with the naked eye. One of the most important is hookworm disease. This[9] disease is caused by a tiny worm which penetrates the victim's skin and ultimately finds its way into the intestine. Other diseases also are caused by parasitic worms, such as tapeworms, pinworms, and trichinæ. The latter are acquired as a result of eating infected meat, particularly infected pork that has not been thoroughly cooked.

Pathogenic or disease producing organisms need for their development food, moisture, darkness, and warmth, conditions that exist within the human body. When one or more of these factors is unfavorable, development of germs is checked; if unfavorable conditions are extreme or long continued, the organisms begin to die. It is difficult to say at exactly what moment they will die if deprived of moisture or exposed to extremes of temperature or other unfavorable conditions, just as it would be impossible to state at exactly what moment a collection of house plants would all be dead if water were withheld, or if the room temperature were greatly reduced.

Most pathogenic organisms, however, do not flourish long outside the body, and owe their[10] continued existence to a fairly direct transfer from person to person. They gain access to the body through mucous surfaces such as the respiratory and digestive tracts, and through breaks in the skin, such as cuts, abrasions, and the bites of certain insects. They leave the body chiefly in the nasal and mouth discharges, as in coughing, sneezing, and spitting, in the urine and bowel discharges, and in pus or "matter."

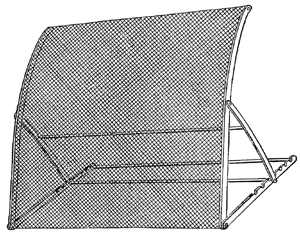

Fig. 6. (L. H. Wilder.)

Fig. 6. (L. H. Wilder.)

The problem of controlling communicable diseases, consequently, lies in preventing the bodily discharges of one person from travelling[11] directly into the body of another. If a person is not expelling pathogenic germs, it is clear that he cannot pass diseases on to others. But both pathogenic and harmless germs follow the same routes from person to person, so that safety as well as decency lies in preventing so far as possible all exchanges of bodily discharges.

There are five routes by which the bodily discharges most frequently travel from one person to another. Four of these routes of infection are called public, because in most cases efforts of individuals alone are not sufficient to control them. The public routes are water, milk, food, and insects. The fifth, or private route, includes all means by which fresh discharges of one person are passed to another, as when nose and mouth discharges are carried in coughing, sneezing, and kissing, or when bowel and bladder discharges are carried by the hands. These five routes in a given case differ greatly in relative importance, but the fifth, or direct route plays an immense part, although its importance in causing sickness has only lately been recognized. It cannot be too strongly emphasized that the chief agent in the spread of human diseases is man himself, and the human hand is the great carrier of disease germs both to and from the body. If unclean hands could be kept away from the orifices of the body,[12] particularly the mouth, many diseases would soon cease to exist.

In view of all the dangers from disease-producing germs it may seem surprising that the human race has not long ago succumbed to its invisible enemies. But the body has various defenses by means of which it may prevent invasion, or successfully combat its enemies in case they do gain access.

The unbroken skin is usually impassable to bacteria. Virulent organisms are often found upon the skin of perfectly healthy persons, where they appear to be harmless unless an abrasion occurs which affords entrance into the deeper tissues. Most bacteria breathed in with the air cling to the moist surfaces of the air-passages and never reach the lungs.

Mucous membranes lining the mouth and other cavities of the body would prove favorable sites for the growth of bacteria if the mucus secreted by them were not frequently removed. The mouth of a healthy person may contain bacteria of many kinds, but the saliva has a slight disinfectant power and serves as a constant wash to the membranes. The normal gastric (stomach) juice is decidedly unfavorable to the growth of bacteria,[13] although it does not always kill them; they often pass through the stomach and are found in large numbers in the intestines. Other bodily secretions, such as the tears and perspiration, tend to discourage bacterial growth.

Tissues of the body vary greatly in their power to resist invading germs, so that the route by which germs enter influences the severity of their effects. Typhoid bacilli and the spirilla of Asiatic cholera when taken with food or water produce far more serious disturbances than when injected under the skin; infections from pus germs through an abrasion of the skin may result in a slight local disturbance, while the same amount introduced into a deeper wound might cause a fatal infection. Certain germs nourish in certain tissues only; even tuberculosis, which attacks practically all tissues, has its favorite locations.

—In addition to its mechanical defenses against disease, the body shows a varying degree of immunity, or the power possessed by living organisms to resist infections. Immunity or resistance is the opposite of susceptibility. It is exceedingly variable, being greater or less in different people and under different conditions, but the exact ways in which it is brought about are still in many cases far from clear.

Immunity may be natural or acquired. By[14] natural immunity is meant an inherited characteristic by which all individuals of a species are immune to a certain disease. The natural immunity of certain species of animals to the diseases of other animals is well known. Man is immune to many diseases of lower animals, and they in turn are immune to many diseases of man. Cattle, for instance, are immune to typhoid and yellow fever, while man shows high resistance to rinderpest and Texas fever; both, however, are susceptible to tuberculosis, to which goats are immune. There are all gradations of immunity within the same species. Moreover, certain individuals have a personal immunity against diseases to which others of the same race or species are susceptible.

Immunity may be acquired in several ways. It is commonly known that one attack of certain communicable diseases renders the individual immune for a varying length of time, and sometimes for life. Among these diseases are smallpox, measles, whooping-cough, scarlet fever, infantile paralysis, typhoid fever, chicken-pox, and mumps; erysipelas and pneumonia on the other hand appear to diminish resistance and to leave a person more susceptible to later attacks.

Again, in some cases immunity may be artificially acquired by introducing certain substances[15] into the body to increase its resistance. Examples of this method include the use of antitoxin as a protection against diphtheria, of sera in pneumonia and other infections, and vaccination against smallpox and typhoid fever whereby a slight form of the disease is artificially induced. Laboratory research goes on constantly, and doubtless many more substances will eventually be discovered that will reduce human misery as vaccines and antitoxin have already reduced it.

Vaccination and inoculation have saved thousands of lives. Smallpox, once more prevalent than measles, was the scourge of Europe until vaccination was introduced. During the 18th century it was estimated that 60,000,000 people died of it, and at the beginning of the 19th century one-fifth of all children born died of smallpox before they were 10 years old. In countries where vaccination is not practised the disease is as serious as ever; in Russia during the five years from 1893-97, 275,502 persons died of smallpox, while in Germany where vaccination is compulsory, only 8 people died of it during the year 1897. Death rates from diphtheria and typhoid fever have been greatly reduced by the use of antitoxin and antityphoid vaccine. Thus in New York State in 1894, before antitoxin was generally used, 99 out of every 100,000 of the population died of[16] diphtheria, while only 20 out of 100,000 died of it in 1914. In 1911 a United States Army Division of more than 12,000 men camped at San Antonio, Texas, for four months. All of these men were vaccinated against typhoid fever and only a single case occurred during the summer, although conditions of camp life always tend to spread the disease.

While many and various factors tend to lower resistance rather than to increase it, the idea that these factors act equally in all kinds of infection is erroneous.

"The principal causes which diminish resistance to infection are: wet and cold, fatigue, insufficient or unsuitable food, vitiated atmosphere, insufficient sleep and rest, worry, and excesses of all kinds. The mechanism by which these varying conditions lower our immunity must receive our attention, for they are of the greatest importance in preventive medicine. It is a matter of common observation that exposure to wet and cold or sudden changes of temperature, overwork, worry, stale air, poor food, etc., make us more liable to contract certain diseases. The tuberculosis propaganda that has been spread broadcast with such energy and good effect has taught the value of fresh air and sunshine, good food, and rest in increasing our resistance to this infection.

"There is, however, a wrong impression abroad that because a lowering of the general vitality favors certain diseases, such as tuberculosis, common colds, pneumonia, septic and other infections, it plays a similar rôle in all[17] communicable diseases. Many infections, such as smallpox, measles, yellow fever, tetanus, whooping-cough, typhoid fever, cholera, plague, scarlet fever, and other diseases, have no particular relation whatever to bodily vigor. These diseases often strike down the young and vigorous in the prime of life. The most robust will succumb quickly to tuberculosis if he receives a sufficient dose of the virulent micro-organisms. A good physical condition does not always temper the virulence of the disease; on the contrary, many infections run a particularly severe course in strong and healthy subjects, and, contrariwise, may be mild and benign in the feeble. Physical weakness, therefore, is not necessarily synonymous with increased susceptibility to all infections, although true for some of them. In other words, 'general debility' lowers resistance in a specific, rather than in a general, sense."—(Rosenau: Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, pp. 403 and 404.)

Well persons who carry in their bodies pathogenic germs but who themselves have no symptoms of disease are called carriers. Thus typhoid carriers have typhoid bacilli in the intestinal tract, while they themselves show no symptoms of typhoid fever; diphtheria carriers have bacilli of diphtheria in the throat or nose, but have themselves no symptoms of diphtheria, and so on. It has now been proved that many patients harbor bacteria for weeks, months, or even years following an infection, and are dangerous distributors of[18] disease; also, some healthy individuals without a history of illness harbor living bacteria which may infect susceptible persons in the usual ways. Transmission by healthy carriers goes far to explain the occurrence of diseases among persons who have apparently not been exposed. This explanation has greatly clarified the whole problem of the spread of communicable diseases. Carriers, unfortunately, exist in large numbers, and render the ultimate control of disease exceedingly difficult. They can usually be identified by bacteriological tests. To some extent they can be supervised; food handlers at least should be legally obliged to submit to physical examinations, and should be licensed only when proved free from communicable disease.

Diseases are also spread by persons suffering from them in a form so mild or so unusual that they pass unrecognized. These persons are known as "missed" cases. Carriers of disease and "missed" cases go freely about the community, handling food, using common drinking cups, travelling in crowded street cars, standing in crowded shops; in various ways coming into close contact with other people, coughing and sneezing and kissing their friends no less often than normal individuals. It is consequently clear that the bodily discharges of supposedly normal persons[19] may be hardly less a menace than those of persons known to be infected.

Diseases that depend for transmission upon milk, water, food, and insects may be controlled by public action, that is, by specific measures taken by a large group of people in order to protect the individual. Such action constitutes public sanitation. There is, however, a large group of diseases, chiefly sputum-borne, that cannot be controlled except by individual action. Such individual action constitutes a large part of personal hygiene.

The whole problem of controlling infections sounds simple, depending as it does for the most part upon unpolluted water, milk, and food, extermination of certain insects, and cleanliness in personal behaviour. In practice the problem is not so easy. Public sanitation has performed miracles in the past, and will do much in the future; behaviour, however, will continue to be influenced by many factors, social and economic as well as personal. Ignorance of the laws of health is an obstacle to progress, but in modern conditions even the instructed may be unable to control their ways of living and working. Indeed, such control is at present limited to the privileged few. On the ignorant and the poor, those least able to bear it, society loads the heaviest burden of sickness. Only when ignorance and poverty are[20] abolished, as one day they will be, can the final stage be reached in the fight for public health.

In this group is included a great variety of maladies. Of some the causes are known, while in the case of others, origin, prevention, and remedy are still obscure. Here belong defects in structure of the body, both hereditary and acquired; insanity and other nervous diseases; new growths, like tumors and cancer; disturbances of bodily processes, as malnutrition and gout; and the important class of degenerative diseases, like arteriosclerosis, in which tissues become hardened and fibrous and hence less able to perform their normal functions.

The degenerative diseases are playing a menacing part in national health. The average length of life in the United States has shown a marked increase it is true, during the last 40 years. But this gain represents chiefly the saving of life through prevention of communicable diseases, especially among babies and children; among people who have passed the 30th year on the other hand, death rates are actually increasing. This increase is most marked after the age of 45, and is caused chiefly by the increase of cancer, and of degenerative diseases of the heart, blood vessels, and[21] kidneys. Degeneration of tissues is normally a condition typical of old age, and in aged persons it may occur in any tissue. There is no elixir of youth, and for old age there is no cure. But the important facts in this connection are that degenerative changes now occur prematurely, and that among a vast number of people, in various classes of society and various occupations, the vital organs show a marked tendency to break down after the age of 45.

This condition is not inevitable. Before the beginning of the present war, death rates at all ages were decreasing in England, Sweden, and other European countries. In America also degenerative diseases can be checked or prevented to a large extent, and it is highly important that their causes should be generally understood.

The two groups following include some of the probable causes:

1. Conditions of life which result in continued overwork, and mental overwork in particular; worry, excitement, insufficient recreation and exercise, and other kinds of nervous strain typical of modern life, especially in cities.

2. Irritating substances in the body, including poisonous substances resulting from infectious diseases, and from syphilis in particular; poisons from chronic infections, alcohol, and industrial[22] poisons such as lead and other metals; overeating and improper eating, especially of meat and other proteins, and rich or highly seasoned food; faulty digestion, constipation, and imperfect elimination through the kidneys.—(See Dr. A. E. Shipley, in bulletin of the N. Y. City Dept. of Health, Feb., 1915.)

The importance of early recognition cannot be overemphasized. In many of these troubles the symptoms are not pronounced, and the victims have no knowledge of their condition until they happen to be examined for life insurance, or until the disease is far advanced. And even when they realize that trouble exists, as for example constipation or overwork, most people absolutely fail to realize how serious the consequences may be. The first step toward remedy is periodic complete physical examination by a competent physician, in order to learn in time how to prevent these degenerative diseases, if present, from growing worse. The custom of undergoing an annual physical examination is becoming more common, and "such a course, conservatively estimated, would add 5 years to the average life of persons between 45 and 50."—(Winslow.)

"Recently, we have been making examinations of the employees of whole institutions, large banks and other industrial concerns in New York City, and we[23] find almost the same conditions there. Out of 2000 such examinations among young men and women of an average age of 33, just in the early prime of life, men and women supposedly picked because of their especial fitness for work, only 3.14% were found free of impairment or of habits of living which are obviously leading to impairment. Of the remaining persons, 96.69% were unaware of impairment; 5.38% of the total number examined were affected with chronic heart trouble; 13.10% with arteriosclerosis; 25.81% with high or low blood pressure; 35.65% with sugar, casts or albumen in the urine; 12.77% with combination of both heart and kidney disease; 22.22% with decayed teeth or infected gums; 16.03% with faulty vision uncorrected.... The fact of greatest import, however, was that impairment, sufficiently serious to justify the examiner in referring the examinee to his family physician for medical treatment, was found in 59% of the total number of cases, while 37.86% were on the road to impairment because of the use of "too much alcohol," or "too much tobacco," constipation, eye-strain, overweight, diseased mouths, errors of diet, and so forth....

"And what is the cause of this appalling increase, in the United States, of these and other degenerative diseases? I believe it can be shown to the satisfaction of any reasonable person that the increase is largely due to the neglect of individual hygiene in United States....

"If a man were suddenly afflicted with smallpox or typhoid fever or any other acute malady, he would lose no time in getting expert advice and applying every known means to save his life. But his life may be threatened just as seriously, though possibly not so imminently, by arteriosclerosis, heart disease, or Bright's disease,[24] and he will do nothing to prevent the encroachment of these diseases until it is too late, but will continue to eat as he pleases, drink as he pleases, smoke as he pleases, or overwork, and worry himself into a premature grave."—("Conservation of Life at Middle Age," Prof. Irving Fisher, Am. Journal of Public Health, July, 1915.)

Periodic physical examinations are as necessary for children as for adults, in order to detect physical defects. These defects are known to have such an immense bearing upon health that routine examinations of all children have become an integral part of the work of enlightened public schools.

Prevention of degenerative disease, then, as well as of the enormous numbers of preventable accidents and injuries, depends in large measure upon proper living conditions and proper personal habits. The infectious diseases, according to Dr. Hill, cost us annually at least 10 billion dollars in addition to the loss of life, and he adds: "The infectious diseases in general radiate from and are kept going by women."—(Hill—New Public Health, p. 30.) Women, it is true, can prevent many of the infections, but they can do still more, for hygienic habits to be effective must be acquired early, and mothers and teachers, because they have practically the entire control of children, have the power to prevent many cases[25] of degenerative as well as of communicable disease.

Of all the considerations that determine health, heredity is the one unalterable factor. Although certain characteristics are obviously hereditary,—complexion, height, and mental and physical traits in great variety,—yet in the past heredity has been little understood. In consequence it has served too often as a scape goat for faults and failings not beyond an individual's control. Our first clear understanding of the principles underlying heredity resulted from experiments made by Mendel, an Austrian monk, during the last century, and it is now possible to predict with a high degree of accuracy the inheritance of certain characteristics.

Many diseases, formerly considered hereditary because their actual causes were unknown, are now known to be communicable. Thus, it is now understood that tuberculosis is not hereditary, although little children may be infected by tuberculous parents. No germ diseases are inherited in the strict sense of the word; but a[28] baby may be infected with syphilis before birth if his father or his mother has the disease.

It is true, however, that certain tissue weaknesses of the body seem to be hereditary, and in consequence one family is more susceptible to digestive disorders, another to diseases of the lungs, a third to deafness, and so on. Moreover, general low vitality may be inherited. It should be emphasized, however, that hereditary weakness does not inevitably lead to disease. Many persons have succeeded in preventing the development of active disease by guarding against strain in directions where they are weak by inheritance.

Of all tissue weaknesses that may be inherited, defects of the nervous system are the most serious. Nervous disorders of every degree of severity, from slight nervous instability even to insanity, may result when these tissues are defective; but it is now a recognized fact that nervous disorders in many cases can be prevented from developing. Feeblemindedness, another condition due to defective tissue, is known to be inherited in the majority of cases, and in all cases it is incurable.

By environment is meant everything outside the body that affects it; taken in its complete[29] meaning the word might include everything that is or ever was in the whole universe. It is possible to consider here a few only of the many environmental and personal factors affecting the health of individuals.

The home constitutes the important part of environment for most persons, and for children in particular, since they spend the greater part of their time in or about it, and get there the foundation on which their health in later years depends. For persons employed away from home, industrial and occupational hygiene is hardly less important; but those subjects are too extensive to be considered here.

Most people live where they must, and few have any part in planning the construction of their own houses. In choosing a house, however, one should remember that rooms where sunshine never enters are unfit for continued occupation. For children in particular fresh air and sunshine are essential, and it may be economy in the end to pay a comparatively high rent for an apartment having sunshine during at least a part of the day. Ignorance and carelessness, unfortunately, can spoil the best living conditions, and sometimes even in the country fresh air and sunshine are excluded from sleeping and living rooms.

—Ventilation has a direct bearing[30] on health, although, contrary to former belief, the actual amount of oxygen in the air is not ordinarily the most important factor; even badly ventilated rooms contain more than enough oxygen to support life. The factors of prime importance in ventilation are temperature, humidity, air movement, and the number of persons in a given space since the greater the distance from one another the less is the probability that diseases will be spread.

Room temperature should not be above 70° F. and, except for the aged or sick, it is better to be between 60° and 65°. Some moisture in the air is desirable; the amount needed is from 50% to 55% of the total moisture that the air can hold at a given temperature. We have no apparatus to decrease humidity in the air of houses, and in summer we are obliged to endure humidity, if excessive, no matter how uncomfortable we may be. But in winter the air in most houses is too dry, so that the mucous membranes of the nose and throat often become irritated and susceptible to infection. Most heating systems, particularly in small buildings, make no provision for supplying moisture. Keeping water in open dishes on or near radiators is often recommended, and would greatly improve the condition of the air, if people remembered to keep the dishes filled.

[31] The following is a simple but effective device to increase humidity: Roll an ordinary desk blotter into a cone about 8 inches in diameter at the base, and keep it constantly submerged for about one inch in a dish of water. The water rises to the top of the blotter and a large surface for evaporation is thus afforded.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Stagnant air is harmful. Air should be in constant though not necessarily perceptible motion. Air about the body, if motionless, acts like a warm moist blanket, preventing the passage of heat from the body.

The three factors, heating, humidity, and air motion, must be considered together. Every person requires each hour about 3000 cubic feet of air, and the problem of heating and ventilating is that of providing this amount in gentle motion, at a temperature of about 65° F., and of humidity from 50-55%. Higher temperatures[32] and stagnant air cause disinclination to work, headache, nausea, restlessness, or sleepiness, and if continued are likely to result in loss of appetite, and anemia. The tuberculosis movement has clearly shown the benefits both for the sick and the well of living in the open air, and has caused great and beneficial changes within a generation. The more time spent in the open air the better; since however most persons who work must spend the greater part of the day indoors, ventilation is a matter of great importance.

Although fresh air enthusiasts are still too few, yet some go to the extreme and think that because cool air in motion is good, the colder the air and more violent the motion the better. On the contrary, chilling the whole body or a part of the body lowers resistance. Draughts of air have no bad effects upon persons in good health, particularly those accustomed to changes in temperature. But draughts are likely to be injurious to aged or sick persons and babies, by diminishing their resistance to such infections as common colds and pneumonia. It should be remembered that draughts or cold alone cannot cause colds; the specific germs must be present.

—Amount and direction of light are physiologically important. Defects of the eyes,[33] too prolonged use, and insufficient light are the commonest causes of eye strain. Most eye defects can be relieved by glasses. Children's eyes should be examined upon entering school, and as often afterward as the oculist advises. Prolonged use causes fatigue of the eyes, especially when the illumination is poor; within limits, the amount of light needed depends on the nature of the work. Light should come from the left side of right handed people; never from the front. Light reflected from snow, sand, glazed white paper of books, or other bright surfaces is fatiguing from its intensity, and from the unusual angle at which it enters the eyes. Too much light is harmful, and probably causes some of the effects, such as nausea and headache, commonly attributed to poor ventilation.

Almost all blindness is preventable, and blindness due to industrial accidents and processes is no exception to this rule. Surely no individual precautions or legal measures are too great in order to guard against this saddest of all physical defects.

—A clean, well-cared for house is desirable from every point of view, but certain kinds of cleanliness affect health more than others.

The most scrupulous care should be exercised[34] wherever food is stored or prepared. The kitchen is in reality a laboratory; in it either intelligently or ignorantly are formed chemical compounds which have a far-reaching effect upon family health. From the standpoint of health no other room in the house is so important. It should be bright, airy, and easy to clean. In cleaning kitchen tables and woodwork water should not be allowed to soak into cracks and dark corners, carrying with it particles of food for the nourishment of bacteria and insects. Linoleum, if used to cover the floor, should be well fitted at the edges to prevent water from running underneath. There should be neither cracks nor crevices in wall or floor, and no dark corners or out-of-the-way cupboards in which dust, food particles, and moisture can accumulate. Such conditions not only attract mice and roaches, but furnish favorable soil for the development of moulds and fungi which by their growth affect food deleteriously. Waging a constant warfare against the development of bacteria constitutes a large part of good housekeeping.

All cooking utensils should be thoroughly washed, scalded, and dried before they are put away; the use of carelessly washed dishes is bad. Enameled or agate ware which has begun to chip should be discarded. Dish-cloths and[35] towels should be washed and boiled after using, and if possible dried in the sun.

Every place in which food is kept should have constant care. The refrigerator is particularly important. Its linings should be water-tight, and the drain freely open at all times; otherwise the surrounding wood will become foul and saturated with drainings. At least once a week it should be entirely emptied and cleaned in the following way: The racks should be thoroughly washed in hot soapsuds to which a small amount of washing soda has been added, rinsed in boiling water, dried and placed in the sun and air. All parts of the refrigerator should be washed in the same manner, especially grooves and projections where food or dirt may lodge. The drainpipe should be flushed, the whole interior rinsed again with plain hot water, thoroughly dried with a clean cloth, and left to air for at least an hour. The drainage pan should be washed and scalded frequently. Food showing the slightest evidence of spoiling should be removed from the refrigerator at once.

Even more attention should be paid to the hands of the cook. They should be washed always before handling food, and always after visiting the toilet, using the handkerchief, or otherwise coming in contact with nose, mouth, or other[36] bodily secretions. Theoretically coughing and sneezing ought not to occur in the neighborhood of food, especially of food to be eaten raw; and persons with coughs, colds, or other communicable disease, however slight, ought not to handle food. If this rule were observed in practice, more persons would go hungry, but fewer would be sick.

Thorough cleaning of rooms involves soap, water, sunshine, air, and elbow grease, just as it did before germs were discovered. Cleaning means actually removing dirt and dust, not merely stirring it up to settle again; consequently dry sweeping and dusting are ineffectual. Vacuum cleaning, and sweeping and dusting with damp or "dustless" mops and dusters are good. Deodorants and disinfectants do not take the place of ordinary cleanliness.

Dust does not carry living disease germs to an appreciable extent; the fact is now well established that diseases formerly thought to be transmitted by dust or even supposed to travel directly through the air, are carried on tiny particles of moisture and mucus expelled in coughing and sneezing. This mode of transmission is called droplet or spray infection; it is one of the most active agents in spreading certain kinds of communicable diseases.

[37] Nevertheless dust in motion is harmful; it irritates the lining membranes of the nose, throat, bronchial tubes, and lungs, even causing tiny wounds through which disease germs enter. Thus tuberculosis is especially prevalent among stone cutters, felt workers, and others engaged in dusty trades. Metallic dust is especially harmful, because it is harder and sharper than dust from organic substances like wool and cotton. Furthermore, presence of dust indicates a low standard of cleanliness. People who tolerate it generally tolerate uncleanliness in other forms, more serious though less apparent.

Cleaning would not be so great a problem if most houses were not littered with such dust catchers as carpets, so-called ornaments, carved and upholstered furniture, banners, draperies, and a vast collection of articles that can only be classified as Christmas presents. In actual practice things that are difficult or expensive to clean seldom are cleaned; carpets for example are considered unhygienic, not because they cannot be cleaned, but because they are not. William Morris' advice to exclude from houses all articles not known to be useful or believed to be beautiful would, if followed, add years to the lives of housekeepers.

, has little bearing on health, except[38] in so far as it affords a breeding place for flies. If it contains disease germs it may be dangerous, but statistics show that garbage handlers, although they can hardly be called especially careful, are not more subject to sickness than other men of their class. Garbage disposal is chiefly a question of preventing a public nuisance; it is a matter of cleanliness and public decency.

—Flies, cockroaches, and other scavenging insects may carry disease germs on their feet and thus infect food on which they walk. Typhoid, cholera, dysentery, and other diseases have been carried by flies. Flies are always a menace, and should not be tolerated; moreover, the thought of their coming to food directly from manure piles and privy vaults is disgusting. Houses should be thoroughly screened in the fly season, but it is better to destroy the nuisance at its source. The chief breeding places of flies[39] are garbage cans and manure piles. If the garbage can is water tight, closely covered, frequently emptied, and thoroughly cleaned, flies will not develop in it; about ten days must elapse from the time when the egg is laid until the insect is ready to fly. Fly traps to fit on the garbage can are useful. Manure should be screened and removed frequently, or it can be treated chemically. Methods for treating it are given in "Preventive Medicine and Hygiene."—Rosenau, p. 255, and in Bulletin No. 118, of the U. S. Dept. of Agriculture, July 14, 1914.

Fig. 8.—A Fly with Germs (Greatly Magnified) on Its Legs.

Fig. 8.—A Fly with Germs (Greatly Magnified) on Its Legs.Other diseases carried by insects are malaria and yellow fever, each by a special species of mosquito; typhus fever, by lice; and bubonic plague, by rat fleas. Various diseases less common in this country are carried by other insects. Even when mosquitoes are not carrying disease germs their bites may be harmful since they are often rubbed, especially by children, until the skin is broken, and various infections may enter through the wounds. Insects of every kind, rats, mice, and vermin should be excluded from houses.

—Discharges from the bowels and bladder contain various germs, and constitute one of the most important routes by which germs of typhoid fever, cholera and certain other diseases[40] travel from person to person. Keeping sewage out of the water supply is consequently of great importance. Where a system of sewage disposal exists, the responsibility of making the system adequate and thus safeguarding public health rests upon the community as a whole. Communities ordinarily get just as much, or just as little typhoid fever as they are willing to endure.

Fig. 9.—How a well may be polluted. (From "The Human Mechanism." Copyright by Theodore Hough and William T. Sedgwick. Ginn and Company, publishers. Used by permission.)

In places having no system of drainage privies must be used. They can be made harmless, as army camps prove, but they require scrupulous[41] care. Fecal matter must be prevented from draining into wells and other water supplies, and must be screened from flies. The privy should be located at a distance from the well. The minimum distance that is safe depends in each case upon the nature of the soil and the direction of the natural drainage. Even when the privy is situated below the well on sloping ground, drainage may still occur from the privy to the well; however, a well-made, properly located pit privy is safe unless it is near a limestone formation. The dry earth system is satisfactory in places having an efficient public scavenger system; in this system pails or cans are used to receive the discharges, which are then covered with sand, ashes, earth or, preferably, chloride of lime. The buckets are frequently emptied and the contents buried at least one foot below the surface of the ground. The objection to this method for more extended use is that proper care of the cans is a disagreeable duty of which most households soon tire.

—The main functions of the skin are three: to protect underlying tissues, to excrete waste matter, and to regulate bodily heat by checking or allowing the evaporation of perspiration. After perspiration has evaporated solid matter is left upon the skin, and oily matter also is deposited on it by the glands that keep the[42] skin lubricated. Removing these and other materials at least once a day is desirable to improve the bodily tone and sense of well-being. Real cleanliness is impossible without frequent use of warm water and soap.

Cold baths are stimulating, though not very efficacious for cleansing purposes. They are valuable tonics if properly used, but delicate or elderly persons should use them only by a physician's advice. Chilly feelings or depression following should be the signal for any person to discontinue cold bathing or swimming in cold water.

Warm baths are soothing in their effects, and are appropriate at bed time, particularly for persons inclined to sleeplessness. Very hot baths, especially if prolonged, may be harmful, and should not be taken often.

There is no clear connection between general cleanliness and disease. Frequent bathing does not protect a person from any particular disease, except in so far as bathing necessarily includes washing the hands. If typhoid germs for example have actually been swallowed, a clean bodily exterior is of no avail in preventing typhoid fever or in diminishing its severity. The same is true of other diseases.

But it is impossible to emphasize unduly the[43] importance of clean hands. Hands are prime offenders in distributing fresh bodily secretions, and germs both innocent and harmful. All health authorities agree on this point.

"Perhaps 90% of all infections are taken into the body through the mouth. They reach the mouth in water, food, fingers, dust, and upon the innumerable objects that are sometimes placed in the mouth. The fact that the great majority of infections are taken by way of the mouth gives scientific direction to personal hygiene. Sanitary habits demand that the hands should be washed after defecation and again before eating, and fingers should be kept away from the mouth and nose, and that no unnecessary objects should be mouthed. All food and drink should be clean or thoroughly cooked. These simple precautions alone would prevent many a case of infection."—(Rosenau: Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, p. 366.)

As Dr. Chapin says:

"Probably the chief vehicle for the conveyance of nasal and oral secretion from one to another is the fingers. If one takes the trouble to watch for a short time his neighbors, or even himself, unless he has been particularly trained in such matters, he will be surprised to note the number of times that the fingers go to the mouth and the nose. Not only is the saliva made use of for a great variety of purposes, and numberless articles are for one reason or another placed in the mouth, but for no reason whatever, and all unconsciously, the fingers are with great frequency raised to the lips or the nose. Who can[44] doubt that if the salivary glands secreted indigo the fingers would continually be stained a deep blue, and who can doubt that if the nasal and oral secretions contain the germs of disease these germs will be almost as constantly found upon the fingers? All successful commerce is reciprocal, and in this universal trade in human saliva the fingers not only bring foreign secretions to the mouth of their owner, but there exchanging them for his own, distribute the latter to everything that the hand touches. This happens not once, but scores and hundreds of times during the day's round of the individual. The cook spreads his saliva on the muffins and rolls, the waitress infects the glasses and spoons, the moistened fingers of the peddler arrange his fruit, the thumb of the milkman is in his measure, the reader moistens the pages of his book, the conductor his transfer tickets, the "lady" the fingers of her glove. Every one is busily engaged in this distribution of saliva, so that the end of each day finds this secretion freely distributed on the doors, window sills, furniture and playthings in the home, the straps of trolley cars, the rails and counter and desks of shops and public buildings, and indeed upon everything that the hands of man touch. What avails it if the pathogens do die quickly? A fresh supply is furnished each day."—(Chapin: The Sources and Modes of Infection, p. 188.)

—Cleanliness and proper care of the mouth and teeth can hardly be over emphasized. Their bearing upon health is direct. Long ago it was recognized that persons with decayed or missing teeth frequently suffered[45] from dyspepsia, a natural result of inability to masticate properly, but only within recent years has it been realized that decayed teeth give rise to many other diseased conditions. Bacteria are constantly present in the mouth. If the mucus of the mouth is not removed, it forms a sticky coat upon the surfaces of the teeth and gums. In this bacteria collect, and pus or matter may also be formed, which, if carried by the blood to other parts of the body, may cause digestive troubles, rheumatism, and diseases of heart and kidneys. (See Dr. T. B. Hartzell, Health News, Oct., 1915, "The Importance of Mouth Hygiene and How to Practise it.")

To keep the mouth and teeth healthy they must have:

1. Proper use.

2. Proper care.

3. Proper treatment.

1. Teeth, like other parts of the body, need exercise. Foods that require a considerable amount of chewing should be included in the diet. Such food is needed by children as soon as their first teeth have come, but care must be exercised to see that the food is actually chewed before it is swallowed.

2. A good brush should be provided. The stiffness of the bristles should be regulated according[46] to the individual. The brush should be thoroughly rinsed after using, and discarded as soon as it is worn. Dental floss is generally needed to remove particles that have lodged between the teeth.

Brushing the teeth by passing the bristles across them is not efficacious. They should be brushed not across but with the cracks, as a good housewife sweeps a floor.

"In the light of recent investigation conducted by some of the leading students of mouth hygiene, the most effective way to use the toothbrush is to place the bristles of the brush firmly against the teeth, applying firm pressure, as though trying to force the bristles between the teeth, using a slight rotary or scrubbing motion.... After a little practice the user of this method will be surprised at the results obtained. Care should be used to go over all the surfaces of the teeth in this manner."—(See Dr. W. G. Ebersole. "The Importance of Mouth Hygiene and How to Practice it," Health News, Oct., 1915.)

After brushing the teeth, the mouth should be rinsed by forcing lukewarm water about the teeth, using all the force that can be brought to bear by the cheeks, lips, and tongue.

3.

—The teeth, including the first teeth of children, should be inspected by a competent dentist at least twice a year. Periodic cleansing by a dentist, and early attention to[47] small cavities, may prevent serious ill health and impairment of the body, as well as the acute suffering generally accompanying treatment of advanced dental defects.

—Clothing was originally used for purposes of ornament. Desire for protection from cold and dampness came later. The amount of clothing required varies greatly according to individual needs and habits, but it is increasingly recognized that light clothing is best, provided that the wearer is really protected from cold. Clothing should be porous in order to allow ventilation of the body, supported so far as possible from the shoulders, and clean and well aired. Dampness favors the growth of germs which may cause irritation of the skin.

Clothing should not constrict the body or hamper its movements. Perhaps the worst health menace for which clothing is to blame comes from the high heeled shoes on which many women prefer to limp through life. From the health standpoint shoes are of great importance. Bad shoes are responsible for many cases of flat feet, whose muscles have degenerated through non-use, and for much so-called "rheumatism," which is merely the protest of abused muscles. Bad shoes also, by distorting the feet, prevent comfortable walking, which is the only out-of-door exercise readily[48] available for the vast majority of people; and still worse, the resulting unnatural position of the body sometimes has serious consequences by bringing injurious strains on other muscles and organs.

—Two distinct problems are encountered here: the problem of nutrition, and the problem of preventing sickness. Nutrition, or proper feeding, is a subject beyond the scope of this book; it is nevertheless one of the most important, if not the most important, factor in maintaining health. Food preparation and care of children, the two most important functions of the home, are unfortunately relegated to the least intelligent and least interested members of most households in which servants are employed.

Most American families eat too much protein food, such as meat and eggs. Excess of protein probably leads to degeneration of tissues, and plays a part in causing the degenerative diseases already mentioned. Habit is important here as in other ways of living, but cereals and vegetables should in large measure make up the diet of sedentary persons and indeed of everyone in warm weather.

The amount of food required in 24 hours depends on many factors: age, height, weight, occupation, season, and habit. Underweight and[49] overweight are both abnormal conditions; probably the latter is the more easily remedied. Both require the advice of a physician. Rapid reduction of weight involves certain dangers, especially for persons with weak hearts.

Food may cause sickness either because it is in itself harmful, or because it carries disease germs. Meat from diseased animals should be destroyed before it reaches the market, but bacterial activities in food originally wholesome may form in it poisonous substances.

The chief diseases known to be carried by food, water, or milk are typhoid fever, paratyphoid, dysentery and other diarrhœal diseases, scarlet fever, diphtheria, septic sore throat, and tuberculosis. The sole problem here is to keep human and animal excretions out of food, water, and milk. Since thorough cooking kills disease germs, danger arises chiefly from raw foods. All fruits and vegetables eaten raw should first be thoroughly washed.

Water is essential to health. At least three pints should be taken daily, the amount varying somewhat according to diet, exercise, temperature, and so forth. Most persons drink too little water.

Cities and towns should of course have public supplies of pure water. Contamination of water,[50] when it occurs, is caused chiefly by sewage from cesspools, privies, and drains. All well or spring water must be constantly watched and Boards of Health are always ready to examine samples of water and to report whether it is safe to drink. At the present time a porcelain filter is the only satisfactory kind for a household, but many domestic filters are so badly cared for that in actual practice they are worse than none. Danger from a filter containing an accumulation of impurities is greater than the danger from most ordinary water supplies. Boiling water for ten minutes kills all pathogenic germs, but this method is inconvenient on a large scale and is not practical for continued family use.

Every effort should be made to insure a regular supply of pure water in every house. It is not satisfactory to have two kinds, one for drinking and one for other purposes, since mistakes are sure to be made, especially by children. Some families who use only bottled or filtered water for drinking purposes habitually run the risk involved in using impure water from the tap for cleaning the teeth.

Freezing destroys most germs, but ice is not necessarily free from bacterial life, and should be used in drinking water only when known to be free from impurities. Neither does freezing milk[51] or cream necessarily kill germs that may be contained in it.

Raw milk plays so important a part in the spread of disease that its fitness for human consumption is open to serious question. Certified milk, where obtainable, is safe but expensive. Boiled milk is safe, but changed in taste and to some extent in quality. If milk is heated to 142°-145° F. and kept at that temperature for 30 minutes all disease germs in it are killed. This process, called pasteurization, renders milk safe. The objection is sometimes made that continued use of pasteurized milk for infants causes scurvy, but in New York City where over 90 per cent. of the milk is pasteurized no increase in scurvy has been noticed, while a large diminution in deaths of infants from diarrhœal diseases has resulted, as in all cities where pasteurization is required.

The following is a simple method for pasteurizing a quart bottle of milk. If the directions are exactly followed the milk will be pasteurized at the end of the process; no thermometer need be used. To prevent the bottle from breaking, it is first warmed by placing it for a few minutes in a pail of warm water.

"From the results of the experiments it was concluded that any housewife can pasteurize a one quart bottle of milk by:

[52] 1. Boiling 2½ quarts of water in a large agate saucepan; or better

2. Boiling 2 quarts of water in a 10 pound tin lard pail, placing the slightly warmed bottle from the ice chest in it, covering with a cloth and setting in a warm place. At the end of one hour the bottle of milk should be removed and chilled promptly. The water must be boiled in the container in which the pasteurization is to be done."—(Ruth Vories, in "Health News," Sept., 1916.)

—Careful attention should be paid to elimination through the bowels and kidneys. Constipation is responsible for many common ailments; among them are headache, disinclination to work, irritable temper, and lowered resistance. If long continued, constipation becomes serious both from congestion and displacement of pelvic organs, and from absorption over a considerable time of even small amounts of the poisonous substances resulting from decomposition of food in the large intestine. The bowels can best be regulated by diet, water, exercise, and habit. The habitual use of cathartic and laxative drugs is most unwise, because they tend to aggravate the trouble. Moreover the habitual and continued use of injections and "internal baths" is harmful, and would not be considered necessary if bran and coarse flour and vegetables were substituted for concentrated foods. Greed, laziness, and lack of[53] intelligence lead most persons suffering with constipation to prefer pills to the restraints demanded by hygienic living. The habit of evacuating the bowels at a regular time, if established in early childhood and rigidly adhered to, will prevent constipation among most healthy people. Any person who thinks drugs necessary should consult a physician, and be prepared to follow the régime he advises over a considerable period of time and at the cost of some self-denial.

For healthy people, voiding urine presents no difficulty if a sufficient amount of water is taken; but some persons reduce the amount of liquid taken in order to escape the inconvenience of urination. This practice is harmful, and may involve insufficient cleansing of the entire system. If frequent urination disturbs sleep, liquids may be withheld during the evening; but the total amount of water taken in 24 hours should not be diminished.

—A fatigued person is a poisoned person. Muscular exertion burns the fuel constituents of the body, as we recognize by the greater heat generated within us during muscular exertion. Waste products, resulting from this burning process, accumulate if not removed, and clog the body in somewhat the same way that ashes and cinders clog a furnace. The fatigued[54] person remains fatigued, consequently, until the accumulations of waste matter are removed by the normal action of the lungs, skin, and kidneys.

Fatigue is caused by both mental and physical work, and when excessive, affects the nervous system most disastrously. The body can and should respond to occasional extra drafts on strength and endurance; its flexibility and power of adjusting to varying conditions may even be stimulated thereby. But even slight fatigue, if continued and especially if associated with anxiety or worry, has caused many nervous and mental breakdowns.