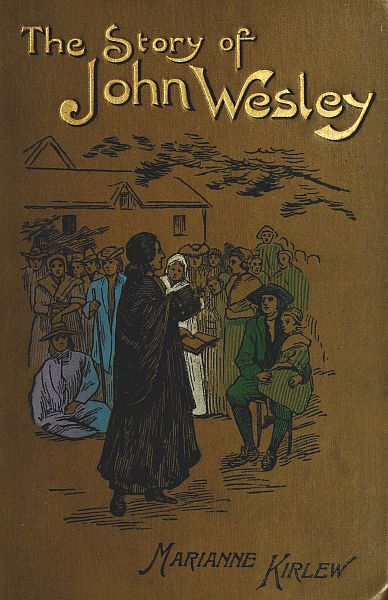

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Story of John Wesley, by Marianne Kirlew

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Story of John Wesley

Told to Boys and Girls

Author: Marianne Kirlew

Release Date: June 3, 2010 [EBook #32669]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STORY OF JOHN WESLEY ***

Produced by Emmy, Darleen Dove and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

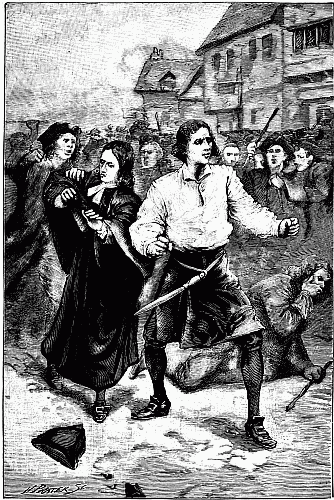

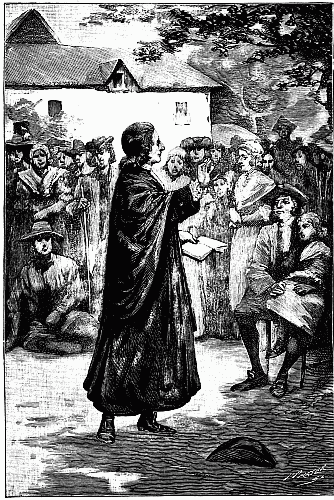

Frontispiece.

Frontispiece.

"That our sons may be as plants grown up in their youth; that our daughters may be as corner stones, polished after the similitude of a palace."—Psalm cxliv. 12.

It is specially important that this remarkable history should be re-told for young people. The youth of England ought to be fully conversant with John Wesley's unique personality and immortal work.

John Wesley's name is far above mere denominationalism. He belongs to all the churches, for he belongs to the "Holy Catholic Church." He is a great national and historic figure. It has ever been claimed by some, whose authority is high, that John Wesley was the saviour of modern England. Surely there is large truth in this. The great religious leader was indeed one of the most potent political forces England has known. If there be even an approximation towards fact in such a claim, then how important for young England to know the record of a man so supremely distinguished.

Certainly, on any ground, these pages meet a distinct want; and I think it will be the judgment of readers, that[vi] they meet it admirably well. Here John Wesley's life is traced clearly, even to the point of vividness. The style in which the story is told, will be found to add to the intrinsic interest of the recital.

The author of this life of Wesley is thoroughly imbued with the spirit of her subject, nor does she forget to apply the lessons, with which this wonderful life-story is crowded.

If the children of our land could be fired with enthusiasm for the truths John Wesley taught and lived, what a blessed outlook would there be for England!

We earnestly pray, that many a young reader may be stirred to the very depths of his being, by the narration here so attractively given. "'Tis a consummation devoutly to be wished."

Manchester,

June, 1895.

| Chapter | Page |

| I. | 1 |

| II. | 6 |

| III. | 10 |

| IV. | 13 |

| V. | 19 |

| VI. | 23 |

| VII. | 28 |

| VIII. | 32 |

| IX. | 35 |

| X. | 38 |

| XI. | 45 |

| XII. | 49 |

| XIII. | 54 |

| XIV. | 59 |

| XV. | 63 |

| XVI. | 68 |

| XVII. | 73 |

| [viii]XVIII. | 77 |

| XIX. | 82 |

| XX. | 86 |

| XXI. | 89 |

| XXII. | 92 |

| XXIII. | 98 |

| XXIV. | 102 |

| XXV. | 106 |

| XXVI. | 110 |

| XXVII. | 116 |

| XXVIII. | 120 |

| XXIX. | 123 |

| XXX. | 128 |

| XXXI. | 134 |

| XXXII. | 138 |

| XXXIII. | 142 |

| XXXIV. | 145 |

| XXXV. | 149 |

| XXXVI. | 152 |

| XXXVII. | 156 |

| XXXVIII. | 159 |

| XXXIX. | 163 |

Jacky.—His brothers and sisters.—His cottage home.—What happened to the little pet-dog.—How Jacky's father forgave the wicked men of Epworth.—"Fire! Fire!"

But Jacky did not mind all this houseful, I think he[2] rather liked it, for you see he always had plenty of playmates. His home was in a country village called Epworth, in Lincolnshire. If you look on your map I think you will find it. The house was like a big cottage; the roof had no slates on like ours, but was thatched with straw, the same as some of the cottages you have seen in the country; and the windows had tiny panes of glass, diamond-shaped, and they opened like little doors. The walls of the cottage were covered with pretty climbing plants, and what was best of all, there was a beautiful big garden where apple and pear trees grew, and where there was lots of room for Jacky and Charlie and the others to run about and play "hide and seek."

But I must tell you that a great many wicked people lived at Epworth, and Jack's father, who was a minister, tried to teach them how wrong it was to steal and fight, and do so many cruel things. But his preaching only made them very angry with good Mr. Wesley, and one of the men, out of spite, cut off the legs of his little pet-dog. Was not that a dreadfully cruel thing to do?

But Jack's father, because he loved Jesus so much, loved these wicked men, and always forgave them. He knew if he could get them to love Jesus, they would soon stop being cruel and unkind.

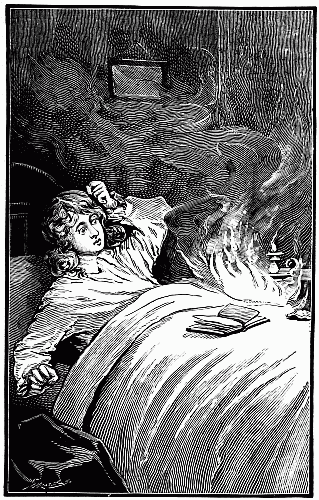

One night in winter, when everybody was fast asleep, Kitty woke up feeling something very hot on her feet. Opening her eyes she was dreadfully[3] frightened to see the bedroom ceiling all on fire. She was only a very little girl, but she jumped out of bed, and ran to the room where her mother and two of her sisters were sleeping. Her father, who was in another room, hearing a great noise outside, and people calling "Fire! Fire!" jumped up and found it was his own house that was in flames. Telling the elder girls to be quick and get dressed and to help their mother, who was very ill, he ran to the nursery, and burst open the door. "Nurse, nurse!" he shouted, "be quick and get the children up, the house is on fire."

Snatching up baby Charles in her arms, and calling to the other children to follow her, the nurse hurried down-stairs. But there they found the hall full of flames and smoke, and to get out of the front-door was impossible. So some of the children got through the windows and some through the back-door into the garden.

Just as the minister thought he had all his family safe, he heard a cry coming from the nursery, and on looking round, he found Jacky was missing. He rushed into the burning house, and tried to get up the stairs, but they were all on fire. What should he do? He didn't know. So he just knelt down in the hall surrounded by the dreadful flames, and asked God to take care of little Jack, and if he couldn't be saved to take him to heaven.

Now I must tell you how it was Jack was still in[4] the burning house. He had been fast asleep when the nurse called, and did not hear her and the other children go out of the room. All at once he woke up, and seeing a bright light in the room, thought it was morning. "Nursie, nursie!" he called, "take me up; I want to get up." Of course there was no answer. Then he put his head out of the curtains which surrounded his little bed, and saw streaks of fire on the top of the room. Oh, how frightened he was!

Jacky was only five years old, but he was a brave boy, and instead of lying still and screaming and crying, he jumped up and ran to the door in his night-gown. But the floor and the stairs were all on fire. What should he do? He ran back again into the room, and climbed on a big box that stood near the window. Then some one in the yard saw him and shouted: "Fetch a ladder, quick! I see him."

"There's no time," called out somebody else; "the roof is falling in. Look here!" said the same man, "I'll stand against this wall, and let a man that's not very heavy stand on my shoulders, and then we can reach the child."

So the strong man fixed himself against the wall, and another man climbed on his shoulders, and Jacky put out his arms as far as he could, and the man lifted him out of the burning room, and he was safe. Two minutes afterwards the roof fell in with a big crash.

Jack was carried into a neighbour's house, and they all knelt down while the minister thanked God for[5] taking care of them, and so wonderfully preserving all their lives.

Jack never forgot that terrible night, and all his life afterwards he felt that God had saved him from being burnt to death, in order that he might do a great deal of work for Him.

You will not be surprised to hear, that it was the wicked people in Epworth who had set the minister's house on fire. But as Jesus forgave His enemies, so Mr. Wesley forgave these men, and tried more than ever to show them how much Christ loved them.

Jacky learns his A B C.—A wise mother.—Christ's little soldier.—A chatterbox.—The big brother and the little one.—Jacky poorly.—The bravest of the brave.—A proud father.

Mrs. Wesley was a dear, kind mother, and took a great deal of trouble, and often put herself to much pain to train her little boys to be Christian gentlemen, and her little girls to be Christian ladies. As soon as they could speak, they were taught to say their prayers every night and morning, and to keep the Sabbath day holy. They were never allowed to have anything they cried for, and they were always[7] taught to speak kindly and politely to the servants. Bad words were never heard among them, and no loud talking or rough play was allowed. This wise mother also knew that little people are sometimes tempted to tell untruths to hide a fault for fear of punishment, so she made it a rule that if any of the children did what was naughty, and at once confessed and promised not to do it again, they should not be whipped.

One of the little boys—I'm afraid it was Jacky—did not always follow this rule, and so he sometimes got what he did not like. But Mrs. Wesley never allowed her children to taunt one another with a fault, especially when they were trying to do better.

Another thing the children were taught, was to respect the rights of property; that is, if Jacky wanted Charlie's top, he was not to take it without Charlie's leave; and if Emily wanted Sukey's brooch, she must ask her sister's permission before taking it.

"Oh, how dreadfully strict!" I fancy I hear some of my readers say. Not at all, dears, it was a mother's kindness to her children; for it took far more time, and a great deal more trouble to teach them all these things than it would have done to let them do as they liked. And when Emily and Mollie and Jack and Charlie and all the others grew up to be men and women, they thanked God for giving them such a wise mother.[8]

Once a week Mrs. Wesley used to take each of the children into her room, separately, for a quiet little talk. They each had their own day for having mother all to themselves. Jack had every Thursday, and Saturday was Charlie's day. So helpful were these little talks with mother, that years afterwards when Jack had left home, he wrote and asked his mother if she would spare the same time every Thursday to pray for him.

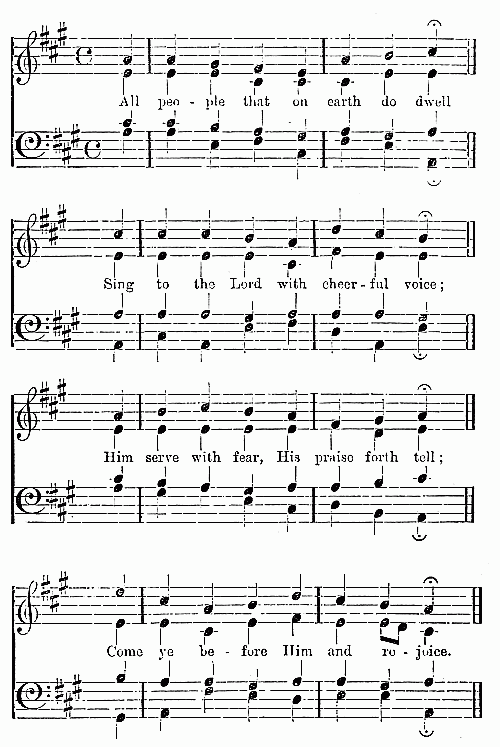

Before Jacky was eight years old he loved Jesus so much that he wanted every one to know he meant to be one of His faithful soldiers. So he asked his father if he might go to the communion, which, you know, is doing what Christ asked all His followers to do, taking bread and drinking wine "in remembrance of Him." Though Jack was such a little boy, his father knew, by his conduct, that he meant what he said, and so he admitted him to the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper. I wish all my young readers could say, as Jacky could:—

Mrs. Wesley used to have services in her big kitchen on a Sunday night, for the servants, and[9] the poor people who could not walk all the long way to church; and little Jack used to sit and listen so attentively, while his mother told the people how God's Son was put to death on the cruel cross, to save them from sin, and to gain for them a place in heaven.

Jack, like many another little boy, had rather a long tongue, indeed, he was a regular chatterbox. His big brother Sam did not always like Jack putting his word in, and giving his opinion; he would put him down and say: "Child, don't talk so much, when you're older you'll find that nothing much is done in the world by arguing." His father used to stand up for Jack, and would say: "There's one thing, our Jack will never do anything without giving a good reason for doing it, I know."

You will be sorry to hear that Jacky had a dreadful illness when he was nine years old. It was a disease that causes a great deal of pain and suffering. But Jack remembered that a soldier must be brave, and, as Christ's little soldier, he must be the bravest of the brave. So Jacky was very patient, and gave his nurse as little trouble as he could. His mother wrote to Mr. Wesley, who was in London at the time, and said, "Jack has borne his illness bravely, like a man, and like a little Christian, he has never uttered a word of complaint;" and the father, as he folded the letter and put it into his pocket, felt proud of his little son.

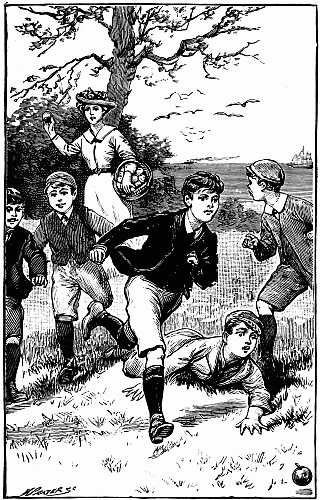

Jacky at boarding school.—Bullying.—Hard lines.—A morning run.—A Christ-like schoolboy.—Charlie at Westminster.—Scotch Jamie.—"Bravo, Captain Charlie!"

Here poor Jacky had a very unhappy time for two or three years. The big boys took a delight in bullying the little ones, especially the new-comers; and as Jack had never been from home before, their unkindness was hard to bear. Every meal-time each boy had to go to the cook's house for his allowance of food, and the big boys used to lay wait for the little ones as they came out, and snatch away their meat; so for a long time Jack had nothing but bread to eat at every meal.[11]

Those of my readers who know what boarding-school life is to-day, will think this a very funny way of getting your food; and so it was, but, you must remember, this was in 1714, one hundred and eighty years ago, and every thing then was very different to what it is now.

Before Jack went to the Charterhouse, his father had said to him: "Jack, I should like you to run round the school garden every morning before breakfast, it will give you an appetite and help to make you grow up a strong man." And all the long years Jack was at school he never failed to obey his father's wish; and, when he grew up, he said this morning run had helped to make him the healthy, strong man he had always been. But, poor little fellow, it was very hard for him, when, feeling dreadfully hungry with the fresh air and exercise, the big boys ran off with his meat, and left him with only some bread for his breakfast.

However, by and by, Jack grew old enough to fight for his meat. And when this time came, do you think he took his turn at stealing from the little boys, and bullying them? Of course you will all say: "No, indeed, Jack would never be so mean." You are right; instead of treating others as others had treated him, he just did what he thought Jesus would have done when he was a boy at school. He stood up for the little fellows, and fought the big boys who tried to steal their meat.[12]

Jack was so quiet and diligent at school, and so careful to obey rules, that he soon became a favourite with the head-master, Dr. Walker; and when he grew to be a man, he forgot all about the hard times he had had, and never failed to visit the Charterhouse once a year.

When Jack had been two years at this school, his brother Charlie was sent to a school at Westminster, where his elder brother Samuel was a teacher. Charlie was then a bright little boy of nine; he was strong, full of spirit and fun, and afraid of nothing. He became a great favourite, and was soon looked upon as the "captain" of the school. Charlie was as generous as he was brave; his great dream was to be a good man, and to help others to be good too.

There was a little Scotch laddie at the school whom all the other boys used to tease and mock. The captain wouldn't stand this; he took Jamie under his special protection, shielded him, fought for him, and saved him from what would otherwise have been a life of misery.

I fancy I hear you all say: "Bravo, Captain Charlie!"

Jack at Westminster.—At Oxford.—Life at College.—Jack a deserter.—His good angel.—"He that goes a borrowing, goes a sorrowing."—A bitter disappointment.—A letter from "Mother."—Jack's decision.—Father's advice.

At first he was much shocked at the drinking and gambling, and wickedness of all sorts that went on among the students at the university. But when day after day we witness wrong-doing, gradually we get[14] less and less shocked, and after a time think little about it. This only happens though when we get down from our watch-tower, and the enemy has a chance to get near to us. Jack's temptations to join his fellow students were very great, and I am sorry to say, he got "off his guard," and yielded. For a time he quite disgraced the colours of his regiment, and became a deserter from Christ's army. But it was not for long, he remembered what he had learnt at home, and how his dear mother had prayed for him. He remembered how he had been saved from the burning house, and he felt sure that God had not spared his life for him to grow up a wicked or a worldly man.

He had found it hard work to be a Christian at the Charterhouse School, now he found it harder still at Christ Church College. He loved fun and merry company, and this sometimes led him to seek the society of young men who loved their own pleasure better than any thing else; and many times Jack, following their bad example, did things for which he was afterwards very sorry and very much ashamed.

I have somewhere read this line of poetry:

I told you before, I think, that Jack's parents were not rich; they had never been able to allow him much pocket-money, and now at Oxford, when his expenses were greater, he somehow could never manage to make his money last out. I am afraid he was not always as careful as he might have been, and I am sorry to say when he was spent up—which was very often—he did what so many boys and young fellows do, borrowed money. This is always foolish, for, of course, it cannot make things any better, and indeed only makes them worse; because when the allowance comes, the debts have to be paid, and there is little or no money left. However, neither debt nor being short of money troubled Jack at this time; indeed he said it was just as well to be poor, for there were so many rogues at Oxford, that if you carried anything worth stealing, it was not safe to be out at night.

One of his friends was once standing at the door of a coffee-house about seven o'clock in the evening, and happening to look round, in an instant his hat[16] and his wig—they wore wigs in those days—were snatched off his head by a thief, who managed to get clear off with his booty. Jack writing home about this said: "I am safe from these rogues, for all my belongings would not be worth their stealing."

When Jack had been four years at Oxford, and was about twenty-one, his brother Samuel wrote to tell him he had had the misfortune to break his leg. He also told him his mother was coming to London, and if he liked he might go and meet her there.

It was a long, long time since Jack had seen his mother, and you may imagine his delight when he got this letter. He wrote back:

"Dear Brother Samuel,

"I am sorry for your misfortune, though glad to hear you are getting better. Have you heard of the Dutch sailor who having broken one of his legs by a fall from the mast, thanked God that he had not broken his neck? I expect you are feeling thankful that you did not break both legs.

"I cried for joy at the last part of your letter. The two things I most wished for of almost anything in the world were to see my mother and Westminster again. But I have been so often disappointed when I have set my heart on some great pleasure, that I will never again be sure of anything before it comes.

Poor Jack! it was well he did not anticipate this treat too much, for when the time came he hadn't[17] enough money to take him to London, and as he was already in debt he could not borrow any more. It was a bitter disappointment; but when his mother got back home again after her visit to London, she wrote one of her bright, loving, encouraging letters, which did something towards comforting the heart of this "mother's boy." This was the letter:

"Dear Jack,

"I am uneasy because I have not heard from you. Don't just write letter for letter, but let me hear from you often, and tell me if you are well, and how much you are still in debt.

"Dear Jack, don't be discouraged; do your duty; keep close to your studies, and hope for better days. Perhaps we may be able to send you a few pounds before the end of the year.

"Dear Jacky, I pray Almighty God to bless thee!

When boys get to be fourteen or sixteen, they begin to think and wonder what they will be when they are men. Very little boys generally mean to be either cab-drivers or engine-drivers; and I did hear of one who meant to have a wild beast show when he grew up. Jack reached the age of twenty-one, and had not decided what he would be.

At last the time came when he must make up his mind. After thinking about it very seriously, he thought he would like to be a minister like his father. So he wrote home and told them his decision.[18]

His father who had been ill and was unable to use his right hand properly, wrote to him that he must be quite sure that God had called him to this work before he undertook it. "At present," he said, "I think you are too young." Then, referring to his illness, he said: "You see that time has shaken me by the hand; and death is but a little behind him. My eyes and heart are almost all I have left, and I bless God for them."

Mrs. Wesley was very glad when she heard that her boy wished to be a minister. "God Almighty direct and bless you," she wrote to him.

A few months afterwards, Jack's father wrote, and told him that he had changed his mind about his being too young, and that he would like him to "take Orders," that is, to become a minister, the following summer. "But in the first place," he said, "if you love yourself or me, pray very earnestly about it."

To choose to be Christ's minister, a preacher of the gospel, Mr. Wesley knew was a very solemn and responsible choice, and he wished Jack to think very seriously, and to pray very earnestly before he took the important step.

Books.—Two books that left impressions on Jack.—Must a Christian boy be miserable?—Jack says "No."—So says Jack's mother.—Father gives his opinion.—"The Enchanted Rocks;" a fairy story.

I remember, when I was somewhere about the mischievous age of eight or nine, how fond I used to be of getting to the putty round a newly-put-in window pane. It was lovely to press my thimble on it, and see all the pretty little holes it left; or to push a naughty finger deep down into the nice soft stuff. Then, when the putty had dried hard,[20] I used to look with great interest on my work, for every impression was there, and could not now be removed.

So it is with books, they make an impression on you; and you are either a little bit better or a little bit worse for every book you read. Take care only to read those books that will make you better.

The summer after Jack decided to be a minister, he read two books which made some big impressions on his mind, and left him better than he was before reading them. One was called "The Imitation of Christ," and the other "Holy Living and Dying." They taught him that true religion must be in the heart, and that it is not enough for our words and actions, as seen and heard by men, to be right, but our very thoughts must be pure and good, such as would be approved of God. He did not at all agree with Thomas à Kempis, the writer of the first book I mentioned, in everything, though, for he made out, according to Jack's idea, that we should always be miserable.

I think Jack would never have persevered in his determination to follow Christ, if he had been convinced that "to be good you must be miserable," for he loved fun, and could not help being happy. He felt sure Thomas à Kempis was mistaken, especially when he remembered that verse in the Bible which says religion's ways "are ways of pleasantness" (Prov. iii. 17). When he wrote home, he[21] asked his mother what she thought, for although he was now a young man of twenty-two, he was still the old Jack that thought father and mother knew better than anybody else.

His mother wrote back that she thought Thomas à Kempis was mistaken, for so many texts in the Bible show us that God intends us to be happy and full of joy. "And," she said, "if you want to know what pleasures are right and wrong, ask yourself: 'Will it make me love God more, and will it help me to be more like my great example, Jesus Christ?'"

Jack's father wrote: "I don't altogether agree with Thomas à Kempis; but the world is like a siren, and we must beware of her. If the young man would rejoice in his youth, let him take care that his pleasures are innocent; and in order to do this, remember, my son, that for all these things God will bring us into judgment."

Some of my readers will hardly understand what Mr. Wesley meant when he said the world is "like a siren." Most of you have read fairy tales; well, a kind of Greek fairy story tells of some beautiful maidens, called sirens, who used to sit on some dangerous rocks, and play sweetest music. When sailors saw them and heard their singing, they were drawn by magic nearer and nearer to where they were, until at last their boats struck on the rocks, and the poor deluded sailors were dragged[22] by the sirens to the bottom of the sea and were drowned.

Now, do you see why the world is like a siren? Its pleasures all look so beautiful that we are tempted to draw nearer and nearer, until at last we are lost to all that is holy and good.

Jack a minister.—A letter from father.—Jack's first sermon.—"Mr. John."—Back at college.—Temptations and persecutions.—"For Jesus' sake."—Mr. John's long hair.—Clever, but not proud.—Young soldiers for Christ.

"God fit you for your great work. Watch and pray; believe, love, endure, and be happy, towards which you shall never want the most ardent prayers of

Jack's first sermon was preached at a small town near Oxford, and his second at his dear home-village,[24] Epworth. Mr. Wesley was getting old, and as he had now two churches to look after, the one at Epworth and another at a place called Wroote, where he and Mrs. Wesley had gone to live, he was very glad when his son offered to go and help him. And now that Jack has grown up and got to be a proper minister, I think we must begin to call him Mr. John. Well, Mr. John stayed some time helping his father at Wroote and Epworth, and then went back again to Oxford, to study for a place in a college there—Lincoln College.

There were several others trying to get this same place, and they didn't like Mr. John because he would not do the wicked things they did, so they made great fun of him, and laughed at him for being good. Nobody likes being laughed at; and Mr. John didn't, but he bore it bravely; and his father comforted him when he wrote: "Never mind them, Jack; he is a coward that cannot bear being laughed at. Jesus endured a great deal more for us, before He entered glory; and unless we follow His steps we can never hope to share that glory with Him. Bear it patiently, my boy, and be sure you never return evil for evil." His mother, too, sent loving letters to cheer and comfort him.

So Mr. John worked hard, and bore his persecutions patiently—for Jesus' sake; and in spite of all his enemies he won the coveted place, and became Fellow of Lincoln College. Oh, how glad and thankful he[25] was! And his father and mother were so proud and happy.

It was just about this time that Mr. Wesley was afraid he would have to leave Wroote, and it was a great trouble to him. "But," he said, proudly, "wherever I am, my Jacky is Fellow of Lincoln." As for Jack, he felt it was worth everything to give his father and mother such pleasure.

Though he was properly grown up, twenty-three years old, Mr. and Mrs. Wesley always thought of him as their "boy." Fathers and mothers always do this. It doesn't matter how old their children grow to be, they love to think of them, and speak of them as their "boys" and "girls." Dear readers, remember there is no one on earth that loves you, or ever will love you with such a big love as father and mother. No matter how tall, or how strong, or how clever you may grow, they will always love you with the same big love they did when you were little boys and girls. And, oh! whatever you do, never, never grieve these dearest of all dear friends.

Mrs. Wesley had been longing to see her "boy" again, especially now that he had become Fellow of Lincoln College. At last her wish was granted. There were a great many things that puzzled Jack which he wanted to ask his father and mother about. So he went and spent a long summer at home, getting his hard questions answered, and helping his father with the work that was now almost too much for[26] him. He had such a happy time that he was almost sorry when the autumn came and he had to return to Oxford.

Being at school and college costs a great deal of money, and Jack knew that his father was not a rich man, and that he had hard work often to pay his college expenses. Jack had been very sorry to be such a burden to his parents, and tried to be as careful as he could. Have you ever seen a picture of Mr. John Wesley? If you have, you will have noticed his long hair. Every one at Oxford wore their hair short; but having it cut cost money, and John used to say: "I've no money to spend on hair-dressers." So, though his fellow-students made great fun of him, he saved his money and wore his hair long, and in time got so accustomed to it, that he wore it long all his life. Now that he was Fellow of Lincoln College he received enough money to pay his own expenses, and it made him very happy to think he need no longer be an expense to his dear father. But he resolved still to be as careful as he could, and never again to go into debt.

When he went back to his new College, after spending the summer at home, he said to himself: "I will give up all the old friends who have so often tempted me to do things that a Christian ought not to do, and I will make new friends of those who will help me on my way to heaven." So, though he was always polite to the many worldly young men who[27] wanted to make his acquaintance, he would not have them for his friends. This made some of them say very unkind things about him; but Mr. John bore it all quietly, and never said unkind things back again. He felt he was only treading the path Jesus had trod before him, the path which all His disciples must follow.

Mr. John got to be so clever that soon he was made professor, or teacher of Greek. Some boys and girls—yes, and grown-up people, too—become proud when they get to be clever, but Mr. John did not. He determined, more than ever, to be a faithful and humble follower of the Lord Jesus. He was very patient with his scholars, and tried not only to make them learned, but to make them Christians. "I want these young soldiers of Christ to be burning and shining lights wherever they may go," he said. "If they are not all intended to be clergymen, they are all intended to be Christians."

In the beginning of the next year (1727), Mr. John went home again to help his father, who was getting very old, and was often ill. He stayed at Wroote about two years, and then went back again to Oxford.

Charlie goes to Oxford.—Won't have his brother interfere with him.—A change in Charlie.—Somebody's prayers.—Charlie's chums, and how he treated them.—Dividing time.—Nickname.—A nickname honoured.

Charlie was not a Christian, and made companions of the worldly young students who spent their time in all sorts of wrong-doings. John was very sorry for this, and spoke to him about it; but Charlie became very angry at what he called his brother's interference, and said: "Do you want me to become a saint all at once?"

However, while Mr. John was away at home those two years helping his father, Charlie changed very much. He became steadier and more thoughtful, and even wrote to his brother, and asked for the advice he would not have before. "I don't exactly know how or when I changed," he said in his letter; "but it was soon after you went away. It is owing, I believe, to somebody's prayers (my mother's most likely) that I am come to think as I do."

When boys and girls or grown-up people become Christians, those around them soon find it out. Charlie's giddy companions soon saw something was wrong with him. He used to be lazy and shirk his studies, spending his time with them in pleasure and amusement, now he was diligent and worked hard.

The next thing they noticed was that he went to church regularly and took the Sacrament. And here I must tell you how he behaved towards these friends, and I know it will make you like Charlie more than ever.

I told you before how loving and genial he was,[30] and now he did not at all like to give up his old chums, and yet he knew that if he meant to travel heavenwards he must have companions that were going the same way. He longed for his friends to become Christians, and talked to them so lovingly and so wisely that before very long he got two or three of them to join him in fighting against the evils of their nature, and encouraging and seeking after everything that was good.

You have all read in your English history how good King Alfred the Great divided his time; well, Charles and his companions divided theirs in a similar way. So many hours were spent in study, so many in prayer, and so many in sleeping and eating. They made other strict rules for themselves, and lived so much by what we call "method," that at last they got to be called "Methodists."

Boys and girls are very fond of giving nicknames to their companions; sometimes it is done in fun, and then there is no harm in it,—but often spite and ill-nature suggest the nickname, then it is very wrong and very unkind.

Most of the young men at Oxford thought religion and goodness were only things to make fun of, so Charles and his friends were a butt for their ridicule. Because they read their Bibles a great deal they called them "Bible Bigots," and "Bible Moths," and their meetings they called the "Holy Club."

But "Methodists" was the name that fastened most[31] firmly to them, and, as you know, after all these years, this is the name we call ourselves by to-day. Just think; a nickname given to a few young men at Oxford, more than one hundred and fifty years ago, is now held in honour by hundreds of thousands of people all over the world.

The Christian band at Oxford.—How they spent their time.—Mr. John and the little ragged girl.—A very early bird.—Methodist rules, and the Methodist guide-book.

Do you remember a verse in the Bible that, speaking of Jesus, says: "He went about doing good"? Well, these young men who were taking Jesus for their copy, just did the same; all their spare time was spent in "doing good." Some of them tried to rescue their fellow-students from bad companions and get them to become Christians; others visited and helped the poor. Some taught the children in the workhouse, and some got leave to go[33] into the prison and read to the prisoners. Very few of them were rich, but they denied themselves things they really wanted in order to buy books, and medicine for the poor. Every night they used to have a meeting to talk over what they had done, and settle their work for the next day.

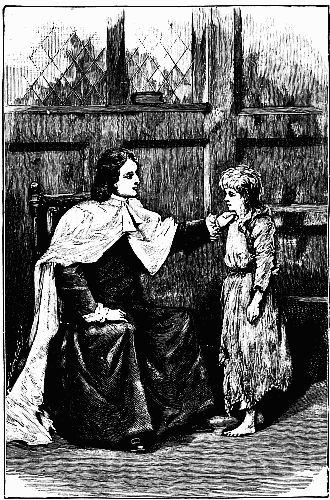

Mr. John started a school for poor little children; he paid a teacher to teach them, and bought clothes for the boys and girls whose parents could not afford to buy them. Once a little girl from the school called to see Mr. John. It was a cold winter's day, and she was very poorly clad.

"You seem half starved, dear," he said; "have you nothing to wear but that cotton frock?"

"No, sir," she answered; "this is the only frock I have."

Mr. John put his hand into his pocket, but, alas! he found no money there, it had all gone. Just then he caught sight of the pictures on the walls of his room, and he thought: "How can I allow these beautiful pictures to hang here while Christ's poor are starving?"

We are not told, but I think we can be quite sure that the pictures were sold, and that the little girl got a warm winter's frock.

Mr. John was just as careful of his time as his money, he never wasted a moment. He believed in the proverb you have often heard: "Early to bed and early to rise." Some people say: "Get up with[34] the lark," but I think Mr. John was always up before that little bird even awoke. Every morning when the clock struck four he jumped out of bed, and began his work. Wasn't that early? I wonder which of us would like to get up at that time? And he did not do this only when he was young, he did it all his life, even when he was an old, old man.

I told you these "Methodists" made rules for themselves. One of them was to set apart special days for special prayer for their friends and pupils. And another one which we all should copy was: Never to speak unkindly of any one. The Bible was their Guide Book, and it told them, as it will tell us, all they ought to do, and all they ought not to do.

A long walk.—More persecutions.—Mr. John's illness.—Not afraid to die.—Mrs. Wesley scolds.—Home again.—A proud father.—Mr. Wesley's opinion about fasting.—At Wroote once more.—Mr. Wesley's "Good-bye."

Well, do you know Mr. John and Mr. Charles Wesley used often to walk all that long way to see a friend. You know there were no railways in those days, and to go by coach cost a great deal of money. This friend's name was Mr. Law; he was a very good man, and encouraged and helped the two brothers very much. He taught them that "religion is the simplest thing in the world." He said: "It is just this, 'We love Jesus, because Jesus first loved us.'"

At Oxford, the Methodists were still called all sorts of names and made great fun of, not only by the idle, wicked students, but even by clever and learned men[36] who ought to have known better. Some of their enemies said: "They only make friends with those who are as queer as themselves." But Mr. John showed them this was not true, for in every way he could he helped and showed kindness to those who said the most unkind things.

Hard work, close study, and fasting, at last made Mr. John very ill; one night he thought he was going to die. He was not at all afraid, he just prayed, "O God, prepare me for Thy coming." But God had a great deal of work for His servant to do, and did not let him die. With care and a doctor's skill he got quite better.

Poor Mrs. Wesley was often anxious about her two Oxford sons, and once wrote them quite a scolding letter. "Unless you take more care of yourselves," she said, "you will both be ill. You ought to know better than to do as you are doing." Mrs. Wesley did not agree with them fasting so much; she believed God meant us to take all the food necessary to support our bodies.

Just about this time, Mr. Samuel—the big brother—got an appointment as master of a boys' school somewhere in the West of England; but before he went to his new place he thought he would like to go home, and see his dear father and mother.

When his brothers at Oxford heard this, they thought they would go too, so that they might all be together in the old home once more. And, oh, what[37] a happy time they had! Mr. Wesley was getting very old, and he was so proud to have his "boys" with him again. He talked very seriously to John and Charles, and told them he did not at all approve of their way of living. He said he was sure God never meant us to fast so much as to injure our health, or to shut ourselves up and be so much alone. Jesus said: "Let your light shine before men;" our light should be where everybody can see it. I am sure old Mr. Wesley was right.

A few months later, and the brothers were again at Wroote, standing by the bedside of their dying father. "I am very near heaven," he said, as they gathered round him, "Good-bye!" And "father" went Home.

A corner in America.—Wanted a missionary.—Mrs. Wesley gives up her sons to God's work.—At the dock-side.—The good ship "Simmonds."—Life on board.—A terrible storm.—The German Christians who were not afraid.

When people are driven out of their own country like this, they are called "exiles," and though this little band of exiles found work and food, and freedom to worship God in the new land, they had no minister. So the gentlemen who had raised the money, and who knew what brave, good men Mr. John and Mr. Charles Wesley were, asked them if they would go out and minister to these poor people in Georgia. "You are just the men to comfort and teach them," they said.

Then, too, a number of Indians lived in Georgia, and they wanted to be friends with the white strangers, and General Oglethorpe and Dr. Burton, the gentlemen I mentioned, thought it would be a good opportunity to preach the gospel to them.

When Mr. John Wesley was first asked, he said: "No, I cannot go, I cannot leave my mother." Then they said: "Will you go if your mother gives her consent?"

"Yes," said John, feeling quite sure she would never give it.

So he went to Epworth and told his mother all about the matter. Then he waited for her reply. Mrs. Wesley loved her "boy" John very, very dearly, and if he went to America she might never see him again, and yet her answer came: "If I had twenty sons, I would give them all up for such a work."

Even after obtaining this unexpected consent, John did not decide to go until he had asked[40] the advice of his brother Samuel and his friend Mr. Law, both of whom advised him to undertake the work. Then both he and his brother sent in their decision to General Oglethorpe, and began making preparations for their long journey across the Atlantic Ocean.

Now I want us to imagine ourselves at Gravesend, a place on the river Thames near London. Look at all those ships in the docks! See, there is one that looks just ready to sail! Can you read the name of it? "S i m m o n d s"—"Simmonds." Yes, that is its name. Let us button up our coats, as it is a sharp October day, and watch the passengers go on board.

Look at that little man with the nice face, and a lot of colour in his cheeks! What long hair he has! and how smooth it is! It looks as if he brushed it a great deal. See, he is looking this way, and we can notice his beautiful forehead and his bright eyes. Why that must be Mr. John Wesley! And, of course, that is his brother Charles talking to some gentlemen on the deck. See, he is holding a book close to his eyes—he must be short-sighted. Listen, how the others are laughing! I expect he is making a joke. Now he is walking off arm in arm with one of his companions. He seems to be still loving-hearted and full of fun, the same Charlie he was at Westminster School only grown big.

A number of Germans were also on board the "Simmonds," all bound for Georgia. Before they[41] had been many days at sea, John Wesley found out that they were earnest Christians, and he began at once to learn German in order that he might talk to them.

The brothers had not taken their father's advice about fasting; they and some other Methodists who were their fellow-passengers still thought they ought to do with as little food as possible, and with as few comforts. They ate nothing but rice, biscuits, and bread, and John Wesley slept on the floor. He was obliged to do it one night, because the waves got into the ship and wet his bed, and because he slept so well that night, he thought the floor was good enough for him, and continued to sleep on it.

I expect you wonder how they spent their time during the long, long voyage to Georgia. I will tell you. They made the same strict rules for themselves that they did at Oxford. They got up every morning at four o'clock, and spent the time in private prayer until five o'clock. Then they all read the Bible together until seven. After that they had breakfast, and then public prayers for everybody on the ship who would come. Then from nine to twelve—just your school-time, little readers, is it not?—Mr. John studied his German; somebody else studied Greek, another taught the children on board, and Mr. Charles wrote sermons. Then at twelve o'clock they all met and told each other how they had been getting along, and what they had been doing. At[42] one o'clock they had dinner, and after that they read or preached to those on board until four o'clock. Then they studied and preached and prayed again until nine, when they went to bed. Were not these strict rules? I wonder if they ever had the headache? I am afraid we should, if we studied so hard and so long.

Have you ever been to Liverpool, and seen one of those beautiful vessels that go to America? They are as nice and as comfortable as the best of your own homes, and you can get to the other side of the Atlantic in about ten days. But at the time of which I write, more than one hundred and fifty years ago, travelling was very different. The ships were much smaller, and tossed about a great deal more, and the passengers had to put up with a great many discomforts. Then again, it took weeks, instead of days, to get across to America.

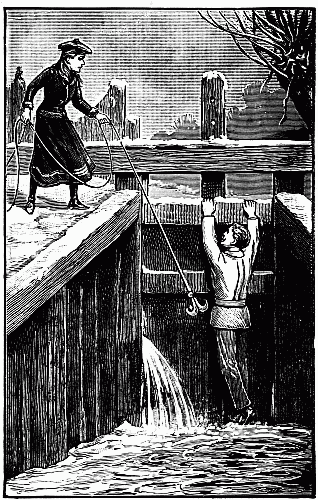

The passengers on board the "Simmonds" met with some terrible storms; often the great waves would dash over their little ship, until it seemed as if it must sink and never rise again.

One of these storms began on a Sunday, about twelve o'clock in the middle of the day. The wind roared round them, and the waves, rising like mountains, kept washing over and over the decks. Every ten minutes came a shock against the side of the boat, that seemed as if it would dash the planks in pieces.[43]

During this storm as Mr. Wesley was coming out of the cabin-door, a big wave knocked him down. There he lay stunned and bruised, until some one came to his help. When he felt better, he went and comforted the poor English passengers, who were dreadfully afraid, and were screaming and crying in their fear. Then he went among the Germans, but they needed no comfort from him. He heard them singing as he got near, and found them calm and quiet, not the least bit frightened.

"Were you not afraid?" Mr. Wesley asked them when the storm was over.

"No," they answered, "we are not afraid to die."

"But were not the children frightened?" he said.

"No," they said again, "our children are not afraid to die either."

During that terrible storm they had remembered how Jesus stilled the tempest on the Lake of Galilee, and His voice seemed to say to them now: "Peace, be still."

This reminds me of a piece of poetry, which I dare say some of you have read. It is about a little girl whose father was a captain, and once when there was an awful storm, and even the captain himself was frightened:

"The Lord on high is mightier than the noise of many waters, yea, than the mighty waves of the sea:" Psa. xciii. 4.

"He maketh the storm a calm, so that the waves thereof are still:" Psa. cvii. 29.

In the Savannah river.—Landed.—A prayer meeting on the top of a hill.—German Christians.—The Indians.—Tomo Chachi and his squaw.—Their welcome to Mr. Wesley.—A jar of milk and a jar of honey.

The first thing they did on landing was to go to the top of a hill, kneel down together, and thank God for bringing them safely across the ocean. You remember Noah's first act after leaving the ship that God put him into when the world was drowned, was to offer a sacrifice of thankfulness for God's care over him. And when Abraham got safely into the strange land to which God sent him, the first thing he did[46] was to offer sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving. In the same way the little missionary band from England showed their reverence and gratitude to the God who rules earth, sky, and sea.

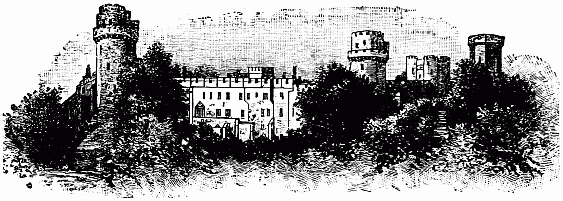

When they got to the town of Savannah they found it a very small place. There were only about forty houses, besides a church, a prison built of logs of wood, and a mill where everybody took their corn to be ground.

I told you, if you remember, that besides the poor English exiles there were a number of German Christians. These were called Moravians, and they were so glad to have a minister that they came to meet Mr. Wesley, and told him how pleased they were to see him. Mr. Wesley and one of his friends lived with them in Savannah for a long time, and they soon found what earnest real Christians they were, true followers of the Lord Jesus. You know it is the people you live with that know you the best, and this is what Mr. Wesley wrote about these Moravians. "We were in the same room with them from morning till night, except when we went out for a walk. They were never idle, were always happy, and always kind to one another. They were true copies in all things of their Saviour Jesus Christ." Was not that a splendid character to have, and would it not be nice if those whom we live with could say the same of us?

There was something near Savannah that you would have liked to see, especially the boys, and that[47] was an Indian town. If there was one thing more than another that drew Mr. Wesley to Georgia it was the Indians. I expect, like you, he had loved to read and hear about them; now he had a chance to see them. But what he longed for most of all was to tell them about Jesus, and to get them to become Christians. The Indians lived in tents or tepees as they are called, and a number of these tepees all put up close together was called a town; one of these towns was only about twenty minutes' walk from Savannah.

After Mr. Wesley had been a week or two in America, who should come to see him but the Indian chief. Think how excited Mr. Wesley would be! The chief's name was Tomo Chachi, and he came looking so grand in all his war paint, with his great feather head-dress, and moccasins made of buffalo skin, ornamented with pretty coloured beads, just as you have seen them in pictures.

Mr. Wesley thought he must dress up too, to receive his distinguished visitor, so he put on his gown and cassock, and down he went to see Tomo Chachi. Of course Mr. Wesley did not understand the Indian language, but there was a woman who did, and she acted as interpreter. "I am glad you are come," said Tomo Chachi. "I will go up and speak to the wise men of our nation, and I hope they will come and hear you preach."

Then Tomo Chachi's wife, or squaw as she is called,[48] who had come with her husband, presented the missionaries with a jar of milk. She meant by this that she wanted them to make the story of Jesus Christ very plain and simple so that they could understand it, for she said "we are only like children." Then she gave them a jar of honey, and by this she meant that she hoped the missionaries would be very sweet and nice to them. Then Tomo Chachi and his squaw went back to their tepee.

A few months after, Mr. Wesley had a long talk with another tribe of Indians, a very wicked tribe called the Chicasaws; but they would not allow him to preach to them. They said: "We don't want to be Christians, and we won't hear about Christ." So Mr. Wesley had to leave them and go back disappointed to Savannah.

Proud children.—Edie.—Boys in Georgia.—John and Charles Wesley in the wrong.—Signal failure.—Disappointment.—Return to England.—Mr. Wesley finds out something on the voyage home.—An acrostic.

I remember seeing a little girl, and it was in a Sunday School too, who had on a new summer frock and a new summer hat; and oh! Edie did think she looked nice. She kept smoothing her frock down and looking at it, and then tossing her head. By her side sat a sweet-faced little girl about a year younger than Edie. Annie's dress was of print and quite plainly made, but very clean and tidy. After admiring herself a little while, Edie turned to Annie and thinking, I suppose, that she might be wearing[50] a pinafore, and have a frock underneath, she rudely lifted it up, and finding it really was her dress, she turned away with a very ugly, disgusted look on her face, and said, scornfully "What a frock!" Proud, thoughtless boys and girls never know the hurts they give, and the harm they do.

The boys in Georgia were no better than some boys in England. At a school where one of the Methodists taught there were some poor boys who wore neither shoes nor stockings, and their companions who were better off taunted them and made their lives miserable. Their teacher did not know what to do, and asked Mr. Wesley for advice. "I'll tell you what we'll do," he said; "we'll change schools"—Mr. Wesley taught a school too—"and I'll see if I can cure them."

So the two gentlemen changed schools, and when the boys came the next morning they found they had a new teacher, and this new teacher, to their astonishment, wore neither shoes nor stockings. You can imagine how the boys stared; but Mr. Wesley said nothing, just kept them to their lessons. This went on for a week, and at the end of that time the boys were cured of their pride and vanity.

Though Mr. John and Mr. Charles Wesley were so good, they were not perfect. They said and did many unwise things, and only saw their mistake when it was too late. One thing was they expected the people to lead the same strict lives they did, and[51] to believe everything they believed. This, of course, the people of Georgia would not do, they thought their ways were just as good as Mr. Wesley's, and I dare say in some things they were. Instead of trying to persuade them and explaining why one way was better than another, Mr. Wesley told them they must do this, and they mustn't do that, until at last they got to dislike him very much. One woman got so angry that she knocked him down.

I am sure you will all feel very sorry when you read this, for Mr. Wesley was working very hard amongst them, and thought he was doing what was right. Mr. Charles did not get on any better at Frederica, where he had gone to work and preach. Like his brother, he was very strict and expected too much from the people. He tried and tried, not seeing where he was to blame, and at last wearied and disappointed he returned to England.

After he had gone, Mr. John took his place at Frederica, hoping to get on better than he had done at Savannah. It was of no use; he stayed for twelve weeks, but things only seemed to get worse and worse. At last he had to give up and go back to Savannah. Things, however, were no better there, and before long he too began to see that his mission had been a failure, and he returned to England a sadder and a wiser man.

In spite of all their mistakes Mr. John and his brother must have done some good in Georgia, for[52] the missionary who went after them wrote and said: "Mr. Wesley has done much good here, his name is very dear to many of the people." It must have made the brothers glad to read this, for it is hard when you have been doing what you thought was right, and then find it was all wrong.

On his return voyage to England Mr. Wesley had time to think about all the things that happened in Georgia. He was feeling dreadfully disappointed and discouraged; he had given up everything at home on purpose to do good to the people out there. He had meant to convert the Indians and comfort and help the Christian exiles, and he was coming back not having done either. Poor Mr. Wesley! And the worst of it was, the more he thought about it all, the more he began to see that the fault was his own.

There was another thing he discovered about himself on that voyage home. They encountered a fearful storm, when every one expected to be drowned. During those awful hours Mr. Wesley found out, almost to his own surprise, that the very thought of death was a terror to him. He knew then that there was something wrong, for no Christian ought to fear to die. So Mr. Wesley went down on his knees and told God how wrong he had been, that he had thought too much of his own opinions and trusted too much in himself. He asked God to give him more faith, more peace, more love.[53]

He was always glad afterwards that he had gone to Georgia, and thanked God for taking him into that strange land, for his failure there had humbled him and shown him his weakness and his failings.

It is a grand thing when we get to know ourselves. Let us be always on the look-out for our own faults, and when we see them, fight them.

I would like to close this chapter with an acrostic I once heard on the word "Faith." It is a thing little folks, yes, and big folks often find hard to understand, perhaps this may help you.

What is Faith?

| F | ull |

| A | ssurance (confidence, having no doubt) |

| I | n |

| T | rusting |

| H | im (Jesus). |

George Whitefield, the "boy parson."—The Wesleys back in England.—Long walks.—Preaching by the way-side.—A talk in a stable.—Sermon in Manchester.—Mr. Charles in London.—Wants something he has not got.—Gets it.—Mr. John wants it too.—A top place in the class.

When he heard that the two Wesleys were leaving Georgia he determined to go and take their place, and see what he could do for the poor exiles. Before he left England he preached a good-bye sermon, and told the people that he was going this long and dangerous voyage, and perhaps they might never see his face again. When they heard this, the children and the grown-up people, rich and poor, burst into tears, they loved him so much. But as this book is to be about Mr. John Wesley, we must not follow Mr. Whitefield across the Atlantic. Try to remember his name though, for he and the Wesleys were life-long friends, and you will hear about him again further on.

When Mr. John and Mr. Charles got back to England they took up George Whitefield's work, going from town to town telling the people about Jesus Christ. As there were no railways they had to walk a great deal, and they used to speak to the people they met on the roads and in the villages through which they passed. Once, when Mr. Wesley and a friend were on their way to Manchester, they stayed one night in an inn at Stafford. Before they went to bed, Mr. Wesley asked the mistress of the house if they might have family prayer. She was quite willing, and so all the servants were called in. Next morning, after breakfast,[56] Mr. Wesley had a talk with them all again, and even went into the stables and spoke to the men there about their sins and about the love of Jesus Christ.

He preached in Manchester the next Sunday, and this was his text: "If any man be in Christ, he is a new creature" (2 Cor. v. 17). He explained to them that when any one begins to love Jesus, and tries to copy His life, they grow more and more like what He was. Then everything becomes different; the things they loved to do before cease to be a pleasure to them, and the places they liked to go to they no longer care to visit; they are "new creatures in Christ Jesus."

The next morning (Monday) Mr. Wesley, and the friend who was with him, left Manchester and went on to Knutsford. Here, too, the people listened attentively, while they preached the gospel of Jesus Christ. They visited other towns, and then Mr. Wesley returned to Oxford.

He had not been long there when he heard that his brother Charles was very ill in London, and went at once to see him. Charles Wesley had been living and working there with some German Christians, or Moravians, as they were called, and before long he found that these people had something in their lives that he did not possess. Like the Germans he met in Georgia, their religion gave them peace and joy on week-days as well as on Sundays.[57]

When he was ill, one of these Moravians, named Peter Böhler, came to see him. During the little talk they had, the visitor said:

"What makes you hope you are saved?"

"Because I have done my best to serve God," answered Mr. Charles.

You see, he was trusting in all the good deeds he had done, and not on Jesus Christ's suffering and death for him.

Mr. Böhler shook his head, and did not say any more then. But he left Charles Wesley longing for the something he had not got.

When he was a little better, he was carried to the house of a poor working-man named Bray. He was not clever, indeed, he hardly knew how to read, but he was a happy believer in Jesus; and he explained to Mr. Charles that doing was not enough, that we must believe that Jesus Christ died on the cross for us, and that it is only through Him that we can pray to God, and only by His death that we can hope to go to heaven.

Then a poor woman came in, and she made him understand better than any one; and at last Mr. Charles saw where he had been in the wrong, and instead of trusting in his own goodness and in all the kind things he had done, he just gave up his faith in these, and trusted alone in the dying love of his Saviour, and ours.

I expect all my readers have classes in the schools[58] they go to. Some of you are at the top of your class, some of you are in the middle, and some of you are—well—near the bottom. I think this is very much the way in Christ's school, the only difference is that in your class at school there can only be one at the top. In Christ's school there can be any number at the top. There are a great number of Christians who are only half-way up in the class, and I am afraid there are a still greater number at the bottom. That is a place none of us like to be in at school; then don't let us be content to keep that place in Christ's school; let us all seek and obtain top places.

When Mr. John Wesley visited his brother, he found he had got above him in Christ's school; he had taken a top place in the class, and John could not rest until he had got a top place too. So he prayed very earnestly, and got the people that had helped his brother to talk to him, but still he did not seem to understand. Four days after he went to a little service, and while the preacher was explaining the change that comes in us, when we trust in Jesus alone, John Wesley saw it all, took a top place in Christ's school, and joyfully went and told his brother.

Methodist rules.—Pulpits closed against Mr. Wesley.—A visit to Germany.—A walk in Holland.—Christian David, the German carpenter.—The Fellow of Lincoln College takes lessons in a cottage.

The people who attended the Methodist meetings were divided into little bands or companies, no band to have fewer than five persons in it, and none more than ten. They were to meet every week, and each one in turn was to tell the rest what troubles and temptations they had had, and how God, through Jesus Christ, had helped them since the last meeting.

Every Wednesday evening, at eight o'clock, all the bands joined together in one large meeting, which[60] began and ended with hymns and prayer. There were many other rules, some of which I will tell you later on, others you can read about when you are older.

All this time you must remember that Mr. Wesley was a church clergyman. He loved the Church of England very dearly, though there were a great many things in it with which he did not agree.

Wherever he preached he told the people just what he believed, and as very few clergymen thought as he did, they did not like him speaking his opinions so freely. At last, first one and then another said he should never preach in their churches again. Yet the message Mr. Wesley gave to the people, was the very same message that Christ spoke long before on the shores of Galilee.

Mr. Wesley still longed to understand his Bible better, and to learn more of Jesus Christ, so he determined to go and visit the Moravians at a place called Herrnhuth in Germany, and see if he could get some help from them. So one June day, he said good-bye to his mother, and with eight of his friends set off. One of these friends was an old member of the Holy Club at Oxford. On their way to Herrnhuth, they had to pass through Holland. This is what Mr. Wesley says about a walk they had in that country:

I never saw such a beautiful road. Walnut trees grow in rows on each side, so that it is like walking[61] in a gentleman's garden. We were surprised to find that in this country the people at the inns will not always take in travellers who ask for food and bed. They refused to receive us at several inns. At one of the towns we were asked to go and see their church, and when we went in we took off our hats in reverence, as we do in England, but the people were not pleased, they said: "You must not do so, it is not the custom in this country."

After a long, long journey through Germany, the little party at last reached Herrnhuth.

Mr. Wesley had only been a few days there, when he wrote to his brother Samuel: "God has given me my wish, I am with those who follow Christ in all things, and who walk as He walked."

I must just tell you about one of these Moravians, because he helped Mr. Wesley more than any of the others. His name was Christian David. He was only an ignorant working-man, and when not preaching was always to be found working at his carpenter's bench. But David was Christian in life as well as in name; he "walked with God," and whether he preached and prayed, or worked with chisel and plane, he did all "in the name of the Lord Jesus." He was never tired of telling people about the Saviour he loved, and trying to get them to love Him too. He was a man who often made mistakes, but as some one has said, "the man who never makes mistakes never makes anything;" and Christian David was[62] always ready to own his faults when they were pointed out to him.

You remember to what a high position Mr. Wesley had risen at Oxford, and how clever he was? Yet Christian David knew more than he did about Jesus Christ and His love; and the Fellow of Lincoln College was not too proud to go and sit in a cottage and be taught by this humble carpenter, who so closely followed the Holy Carpenter of Nazareth.

Fetter Lane.—Popular preachers.—Old friends meet again.—Love-feasts.—1739—Small beginning of a great gathering.—A crowded church.—A lightning thought.—But a shocking thing.—George Whitefield's welcome at Bristol.—"You shall not preach in my pulpit."—"Nor mine."—"Nor mine."—Poor Mr. Whitefield.

He and his brother still preached in any church where they were allowed, and wherever they went crowds of poor people followed to hear them. They used to go, too, to the prisons, and the hospitals, and preach to the sinful and the suffering. They told them how Jesus forgave sins, and how He used to heal the sick; and the sinful were made sorry, and the suffering ones were comforted, and many believed in Jesus and prayed for forgiveness.

Mr. Wesley had returned from Germany in September; a few months later Mr. George Whitefield came back from Georgia. He had got on very well with the people there, because he did not try to alter the ways they had been accustomed to, unless it was really necessary.

Mr. Wesley went to meet his old friend, and, oh! how pleased they were to see each other again. Mr. Whitefield joined the little society in Fetter Lane, and they all worked together most happily.

I dare say most of my Methodist readers will have been to a love-feast; those of you who have not, will at any rate have heard of them. Well, it was just about this time that love-feasts were first started. The little bands or companies that I told you about used to join together, and have a special prayer meeting once a month on a Saturday; and the following day, which, of course, was Sunday, they all used to meet again between seven o'clock and ten in the evening for a love-feast—a meal of bread and water[65] eaten altogether and with prayer. It was a custom of the Moravians, and it was from them Mr. Wesley copied it.

I have also heard that the love-feast was provided for the people, who had walked a great many miles to hear Mr. Wesley preach, and were tired and hungry. If this was the idea of the love-feast, they would have to give the people a great deal more bread than they do now, or they would still be hungry when they had done.

The year after Mr. Whitefield returned from Georgia, 1739, was a wonderful year for the Methodists. It started with a love-feast and prayer meeting, which lasted half through the night. Then a few days later, on January 5th, the two Mr. Wesleys and Mr. Whitefield, with four other ministers, met together to talk about all they hoped to do during the year, and make rules and plans for their helpers and members.

I told you, if you remember, that first one pulpit and then another was closed against these clergymen. At last there were only two or three churches where they were allowed to preach. One day when Mr. Whitefield was preaching in one of these, the people came in such crowds to hear him, that hundreds could not get into the church. Some of them went away, but a great number stood outside.

All at once there flashed across Mr. Whitefield's mind this thought: "Jesus preached in the open air[66] to the people, why can't I?" Numbers had often before been turned away when he preached, but he had never thought of having a service outside a church, it seemed a most shocking thing. However, the message seemed to come straight from God. He dared not act on it at once, for you see he was a clergyman, and had always been brought up to believe that inside the church was the only place where people can properly worship God.

When he mentioned the matter to his friends, some of them were very much shocked, and thought to preach in the open air would be a very wrong thing. But some said: "We will pray about it, and ask God to show us what we ought to do." So they knelt down and prayed to be guided to do the right thing.

Soon after this Mr. Whitefield went to Bristol, where he had been liked so much before he went to America. When he got there he was invited to preach first in one church and then in another, all were open to him. But before very long the clergymen in the place showed that they disapproved of the plain way in which he spoke to the people, and they told him they would not allow him to preach in their pulpits again.

By and by all the churches were closed against him, and there was nowhere but the prison where he was allowed to preach. Soon the mayor of Bristol closed that door also.

Poor Mr. Whitefield! what could he do now?[67] I think I know one thing he would do. He would turn to his Bible, and there he would read: "In all thy ways acknowledge Him, and He shall direct thy paths."

In the next chapter you shall hear how God fulfilled His promise to George Whitefield.

Kingswood.—Grimy colliers.—The shocking thing is done.—A beautiful church.—From 200 to 20,000.—John Wesley shocked.—Drawing lots.—To be or not to be.—To be.—Mr. Wesley gets over the shock.—George Whitefield's "good-bye" to the colliers.

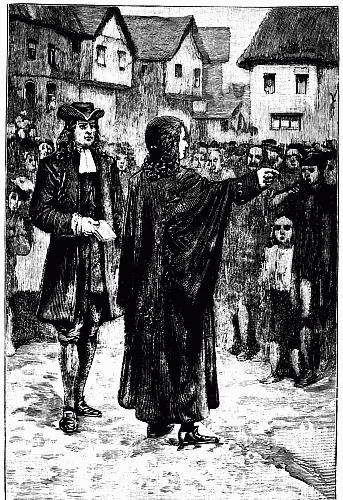

Surely, Mr. Whitefield thought, these people ought to have the gospel of Jesus Christ preached to them; they have no church, it cannot be wrong to preach to them in the open air. So, one Saturday in this year, 1739, Mr. Whitefield set off to Kingswood. It was a cold winter's day, but his heart was warm[69] inside with love for these poor neglected colliers, and he soon got warm outside with his long walk.

When he reached Kingswood he found an open space called Rose Green, which he thought was just the place for a service. Standing on a little mound which did for a pulpit, he commenced to preach; and surely that was the grandest church in which a Methodist minister ever held a service. The blue sky of heaven was his roof, the green grass beneath him the floor; and as Mr. Whitefield stood in his FIRST FIELD PULPIT, his thoughts went back, down the ages, to the dear Master whose steps he was seeking to follow—the Preacher of Nazareth, whose pulpit was the mountain-side, and whose hearers were the publicans and sinners. Two hundred grimy colliers stood and listened to that earnest young preacher.

Mr. Whitefield continued his visits to Kingswood; the second time, instead of two hundred there were 2,000 eager listeners. The next time over 4,000 came to hear; and so the numbers went on increasing until he had a congregation of 20,000.

Once, after he had been preaching, he wrote this: "The trees and the hedges were all in full leaf, and the sun was shining brightly. All the people were silent and still, and God helped me to speak in such a loud voice that everybody could hear me. All in the surrounding fields were thousands and thousands of people, some in coaches and some on horseback,[70] while many had climbed up into the trees to see and hear."

As Mr. Whitefield preached, nearly all were in tears. Many of the men had come straight from the coal-pits, and the tears that trickled down their cheeks made little white gutters on their grimy faces. Then, in the gathering twilight, they sang the closing hymn, and when the last echoes died away in the deepening shadows, Mr. Whitefield felt how solemn it all was, and he, too, could hardly keep back the tears.

Mr. Whitefield soon found there was more work at Kingswood than he could do alone, so he wrote and asked Mr. John Wesley to come and help him. Being very proper sort of clergymen, John and Charles Wesley could not help thinking it a dreadful, and almost a wrong thing to preach anywhere but in a church, or, at any rate, in a room; and for some time they could not decide what to do.

They asked the other members at Fetter Lane what they thought about it; some said Mr. John ought to go, and some said he ought not. So at last they decided to draw lots. You know what that is, don't you? If you look in your Bible, in Acts i. 26, you will see that the disciples drew lots when they wanted to make up their number to twelve, after wicked Judas had killed himself. And in John xix. 24, you can read how the soldiers cast lots for the coat that had belonged to Jesus, which[71] they took away after they had crucified Him. And in many other places in the Bible we read about people casting lots.

So the society at Fetter Lane cast lots, and it came out that Mr. John Wesley should go. Everybody was satisfied after this, and even Mr. Charles, who more than any of the others had objected, now felt that it was right. So Mr. John set off for Bristol and joined his friend.

The first Sunday he was there he heard Mr. Whitefield preach in the open air, and this is what he wrote about it: "It seemed such a strange thing to preach in the fields, when all my life I had believed in everything being done properly and according to the rules of the Church. Indeed, I should have thought it almost a sin to preach anywhere else."

However, because of the lots, he felt it was all right; and he was still more sure of this when he saw the crowds, who would never have gone into a church, listening so intently to God's Word. He very soon got used to open-air preaching, and by and by Mr. Whitefield left the work at Kingswood to him.

When the people heard that Mr. Whitefield was going to leave them, they were very, very sorry; and the day he rode out of Bristol, a number of them, about twenty, rode on horseback with him, they could not bear to say "good-bye."

As he passed through Kingswood, the poor colliers, who were so grateful for all he had done for them,[72] came out to meet him, and told him they had a great surprise for him. They had been very busy collecting money for a school for poor children, and now they wanted their dear friend, Mr. Whitefield, to lay the corner-stone of their new building.

He was surprised and delighted; and when the ceremony was over, he knelt down and prayed that the school might soon be completed, and that God's blessing might ever rest upon it; and all those rough colliers bowed their heads, and uttered a fervent "Amen."

At last "good-bye" was said to the dear minister who had brought them the glad tidings of salvation, and leaving them in charge of Mr. Wesley, George Whitefield rode away.

John Wesley's moral courage.—What some carriage people thought of him.—And why.—The fashionable Beau in the big, white hat.—Interrupts Mr. Wesley.—Gets as good as he gives.—And better.—The King of Bath slinks away.

Now, I think John Wesley showed a great deal of moral courage when he started to preach in the open air. Remember, he was born a gentleman, he was educated as a gentleman, and as Fellow of an Oxford College had always mixed with distinguished gentlemen. Then he was brought up a strict Churchman, and had always believed that the ways and[74] rules of the Church were the only right and proper ways.

Fancy this most particular Church clergyman, wearing his gown and bands, just as you have seen him in the pictures, and getting upon a table in the open air, or on the stump of a tree, or climbing into a cart and preaching to a lot of dirty, ignorant men and women. This was, indeed, moral courage; he did it because he felt it was the right thing to do, and that God wanted him to do it.

Mr. Wesley was quite as much liked by the people as Mr. Whitefield had been, and the sight of him preaching was such a wonderful one, that ladies and gentlemen came in their carriages to see and to hear.

In his sermons, Mr. Wesley spoke as plainly to the rich as he did to the poor. He told them how God hated sin, and that it was impossible for a sinner to get to heaven. Some of the ladies and gentlemen did not like this at all, and called Mr. Wesley "rude and ill-mannered," but it made them feel uncomfortable all the same.

You have heard of a place called Bath, and that it is noted for its mineral waters. It is a fashionable place now, but it was a great deal more fashionable in Mr. Wesley's time. Not being far from Bristol, Mr. Wesley used sometimes to go and preach there. Once when he went, some of his friends said: "Don't preach to-day, for Beau Nash means to come and oppose you."[75]

Beau Nash was a gambler, and in other ways, too, a very bad man. But, somehow, he always managed to get enough money to make a great show, and many of the people looked up to him as a leader of fashion. Indeed, he was quite popular among most of the visitors to Bath.

Of course when Mr. Wesley heard that this man was coming to oppose him, instead of being frightened, he was all the more determined to preach.

A great number of people had assembled, many of them Nash's friends, who had come to see "the fun." By and by Beau Nash himself came, looking very grand in a big white hat, and riding in a coach drawn by six grey horses, with footmen and coachmen all complete.

Soon after Mr. Wesley had commenced his sermon, Beau Nash interrupted him by asking: "Who gave you leave to do what you are doing?"