Project Gutenberg's The Goddess of Atvatabar, by William R. Bradshaw

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Goddess of Atvatabar

Being the history of the discovery of the interior world

and conquest of Atvatabar

Author: William R. Bradshaw

Release Date: June 15, 2010 [EBook #32825]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GODDESS OF ATVATABAR ***

Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Juliet Sutherland, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| artist, | page | |

| Map of the interior world, | Frontispiece. | |

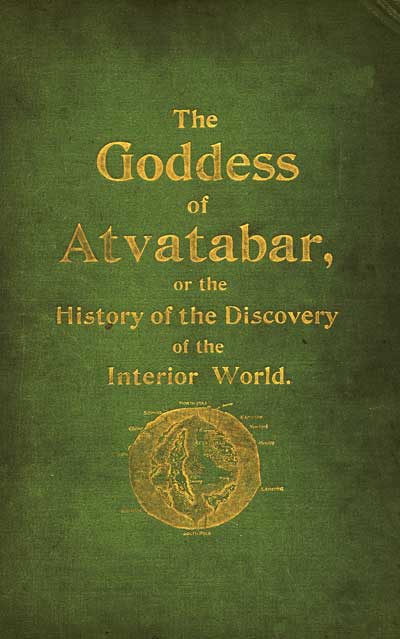

| I signalled the engineer full speed ahead, and in a short time we crossed the ice-foot and entered the chasm, | C. Durand Chapman, | 17 |

| A semi-circle of rifles was discharged at the unhappy brutes. Two of them, fell dead in their tracks, | " | 29 |

| The terror inspired by the professor's words was plainly visible on every face, | " | 35 |

| At this moment a wild cry arose from the sailors. With one voice they shouted, "The sun! The sun!" | " | 41 |

| One of the flying men caught Flathootly by the hair of the head, and lifted him out of the water, | R. W. Rattray, | 55 |

| One of the mounted police got hold of the switch on the back of the bockhockid, and brought it to a standstill, | Carl Gutherz, | 69 |

| The sacred locomotive stormed the mountain heights with its audacious tread, | C. Durand Chapman, | 75 |

| The king embraced me, and I kissed the hand of her majesty, | " | 81 |

| A procession of priests and priestesses passed down the living aisles, bearing trophies of art, | Harold Haven Brown, | 87 |

| On the throne sat the Supreme Goddess Lyone, the representative of Harikar, the Holy Soul, | C. Durand Chapman, | 97 |

| The throne of the gods was indeed the golden heart of Atvatabar, the triune symbol of body, mind, and spirit, | " | 101 |

| Her holiness offered both his majesty the king and myself her hand to kiss, | " | 111 |

| Zoophytes of Atvatabar, | Paul de Longpré | |

| The Lilasure, | 117 | |

| The Laburnul, | 118 | |

| The Green Gazzle of Glockett Gozzle, | 119 | |

| Jeerloons, | 120 | |

| A Jeerloon, | 120 | |

| The Lillipoutum, | 121 | |

| The Jugdul, | 122 | |

| The Yarphappy, | 123 | |

| The Jalloast, | 124 | |

| The Gasternowl, | 125 | |

| The Crocosus, | 126 | |

| The Jardil, or Love-pouch, | 127 | |

| The Blocus, | 128 | |

| The Funny-fenny, or Clowngrass, | 129 | |

| The Gleroseral, | 130 | |

| The Eaglon, | 131 | |

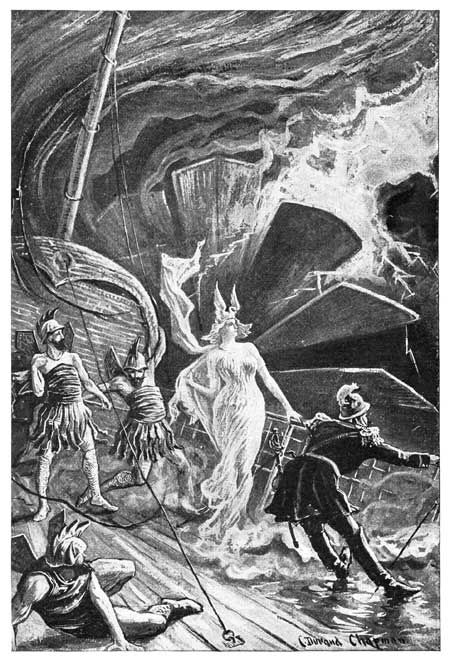

| The goddess stood holding on to the outer rail of the deck, the incarnation of courage, | C. Durand Chapman, | 135 |

| Then the ship rose again toward the mammoth rocks, adorned

with the tapestries of falling wave, | " | 141 |

| Lyone was borne on a litter from the aerial ship to the palace, | " | 147 |

| The priest and priestess stood beside the altar, each reading an alternate stanza from the ritual of the goddess, | R. W. Rattray, | 155 |

| Her kiss was a blinding whirlwind of flame and tears, | C. Durand Chapman, | 181 |

| The labyrinth was a subterranean garden, whose trees and flowers were chiselled out of the living rock, | Paul de Longpré, | 187 |

| As i gazed, lo! a shower of blazing jewels issued from the mouth of the hehorrent, | Leonard M. Davis, | 191 |

| "By virtue of the spirit power in this cable," said the sorcerer, "I will that the magical Island of Arjeels shall rise above the waves," | C. Durand Chapman, | 197 |

| The ship in company with a vast volume of water sprang into the air to a great height, | " | 223 |

| We slowly dragged ourselves across the range of icy peaks, | " | 241 |

| I mounted the trunk and proposed the health of Her Majesty Lyone, Queen of Atvatabar, | R. W. Rattray, | 261 |

| Lyone reached for a flower, and in doing so touched the vase, and immediately fell dead upon the floor, | C. Durand Chapman, | 273 |

| At this juncture a shell of terrorite exploded among the foe with thrilling effect, destroying at least two hundred bockhockids, | Walter M. Dunk, | 285 |

| Heavens and earth! He was holding Lyone in his arms, alive from the living battery! Lyone, the peerless soul of souls, alive once more and triumphant over death, | C. Durand Chapman, | 293 |

| We sat thus crowned amid the tremendous excitement. The people shouted, "Life, health and prosperity to our sovereign lord and lady, Lexington and Lyone, King and Queen of Atvatabar," | Allan B. Doggett, | 307 |

| Oi made Bhooly an' Koshnili kneel down, an' a sojer tied their hands behind their backs. Then Oi ordhered a wayleal to behead thim wid their own swords, | Allan B. Doggett, | 313 |

It is proper that some explanation be made as to the position occupied by the following story in the realm of fiction, and that a brief estimate should be made of its literary value.

Literature may be roughly classified under two heads—the creative and the critical. The former is characteristic of the imaginative temperament, while the latter is analytical in its nature, and does not rise above the level of the actual. Rightly pursued, these two ways of searching out truth should supplement each other. The poet finds in God the source of matter; the man of science traces matter up to God. Science is poetry inverted: the latter sees in the former confirmation of its airiest flight; it is synthetic and creative, whereas science dissects and analyzes. Obviously, the most spiritual conceptions should always maintain a basis in the world of fact, and the greatest works of literary art, while taking their stand upon the solid earth, have not feared to lift their heads to heaven. The highest art is the union of both methods, but in recent times realism in an extreme form, led by Zola and Tolstoi, and followed with willing though infirm footsteps by certain American writers, has attained a marked prominence in literature, while romantic writers have suffered a corresponding obscuration. It must be admitted that the influence of the realists is not entirely detrimental; on the contrary, they have imported into literature a nicety of observation, a heedfulness of workmanship, a mastery of technique, which have been greatly to its advantage. Nevertheless, the novel of hard facts has failed to prove its claim to infallibility. Facts in themselves are impotent to account for life. Every material fact is but the representative on the plane of sense of a corresponding truth on the spiritual plane. Spirit is the substance; fact the shadow only, and its whole claim to existence lies in its relation to spirit. Bulwer declares in one of his early productions that the Ideal is the only true Real.

In the nature of things a reaction from the depression of the realistic school must take place. Indeed, it has already set in, even at the moment of the realists' apogee. A dozen years ago the author of "John Inglesant," in a work of the finest art and most delicate spirituality, showed that the spell of the ideal had not lost its efficacy, and the books that he has written since then have confirmed and emphasized the impression produced by it. Meanwhile, Robert Louis Stevenson and Rider Haggard have cultivated with striking success the romantic vein of fiction, and the[10] former, at least, has acquired a mastery of technical detail which the realists themselves may envy. It is a little more than a year, too, since Rudyard Kipling startled the reading public with a series of tales of wonderful force and vividness; and whatever criticism may be applied to his work, it incontestably shows the dominance of a spiritual and romantic motive. The realists, on the other hand, have added no notable recruits to their standard, and the leaders of the movement are losing rather than gaining in popularity. The spirit of the new age seems to be with the other party, and we may expect to see them enjoy a constantly widening vogue and influence.

The first practical problem which confronts the intending historian of an ideal, social, or political community is to determine the locality in which it shall be placed. It may have no geographical limitations, like Plato's "Republic," or Sir Philip Sidney's "Arcadia." Swift, in his "Gulliver's Travels," appropriated the islands of the then unknown seas, and the late Mr. Percy Greg boldly steered into space and located a brilliant romance on the planet Mars. Mr. Haggard has placed the scene of his romance "She" in the unexplored interior of Africa. After all, if imagination be our fellow-traveller, we might well discover El Dorados within easy reach of our own townships.

Other writers, like Ignatius Donnelly and Edward Bellamy, have solved the problem by anticipating the future. Anything will do, so that it be well done. The real question is as to the writer's ability to interest his readers with supposed experiences that may develop mind and heart almost as well as if real.

"The Goddess of Atvatabar," like the works already mentioned, is a production of imagination and sentiment, the scene of action being laid in the interior of the earth. It is true that the notion has heretofore existed that the earth might be a hollow sphere. The early geologists had a theory that the earth was a hollow globe, the shell being no thicker in proportion to its size than that of an egg. This idea was revived by Captain Symmes, with the addition of polar openings. Jules Verne takes his readers, in one of his romances, to the interior of a volcano, and Bulwer, in his "Coming Race," has constructed a world of underground caverns. Mr. Bradshaw, however, has swept aside each and all of these preliminary explorations, and has kindled the fires of an interior sun, revealing an interior world of striking magnificence. In view of the fact that we live on an exterior world, lit by an exterior sun, he has supposed the possibility of similar interior conditions, and the crudity of all former conceptions of a hollow earth will be made vividly apparent to the reader of the present volume. "The Goddess of Atvatabar" paints a picture of a new world, and the author must be credited with an original conception. He has written out of his own heart and brain, without reference to or dependence upon the imaginings of others, and it is within the truth to say that in boldness of design, in wealth and ingenuity of detail, and in lofty purpose, he has not fallen below the highest standard that has been erected by previous writers.

Mr. Bradshaw, in his capacity of idealist, has not only created a new world, but has decorated it with the skill and conscientiousness of the[11] realist, and has achieved a work of art which may rightfully be termed great. Jules Verne, in composing a similar story, would stop short with a description of mere physical adventure, but in the present work Mr. Bradshaw goes beyond the physical, and has created in conjunction therewith an interior world of the soul, illuminated with the still more dazzling sun of ideal love in all its passion and beauty. The story is refreshingly independent both in conception and method, and the insinuation, "Beati qui ante nos nostra dixerunt," cannot be quoted against him. He has imagined and worked out the whole thing for himself, and he merits the full credit that belongs to a discoverer.

"The Goddess of Atvatabar" is full of marvellous adventures on land and sea and in the aerial regions as well. It is not my purpose at present to enumerate the surprising array of novel conceptions that will charm the reader. The author, by the condition of his undertaking, has given carte blanche to his imagination. He has created a complete society, with a complete environment suited to it. The broadest generalization, no less than the minutest particulars, have received careful attention, and the story is based upon a profound understanding of the essential qualities of human nature, and is calculated to attain deserved celebrity. Among the subjects dear to the idealist's heart, perhaps none finds greater favor than that which involves the conception of a new social and political order, and our author has elaborated this subject on fresh lines of thought, making his material world enclose a realm of spiritual tenderness, even as the body is the continent and sensible manifestation of the soul.

The forces, arts, and aspirations of the human soul are wrought into a symmetrical fabric, exhibiting its ideal tendencies. The evident purpose of the writer is to stimulate the mind, by presenting to its contemplation things that are marvellous, noble, and magnificent. He has not hesitated to portray his own emotions as expressed by the characters in the book, and is evidently in hearty sympathy with everything that will produce elevation of the intellectual and emotional ideals.

The style in which the story is told is worthy of remark. In the beginning, when events are occurring within the realm of things already known or conceived of, he speaks in the matter-of-fact, honest tone of the modern explorer; so far as the language goes we might be reading the reports of an arctic voyage as recounted in the daily newspaper; there is the same unpretentiousness and directness of phrase, the same attention to apparently commonplace detail, and the same candid portrayal of wonder, hope, and fear. But when the stupendous descent into the interior world has been made, and we have been carried through the intermediary occurrences into the presence of the beautiful goddess herself, the style rises to the level of the lofty theme and becomes harmoniously imaginative and poetic. The change takes place so naturally and insensibly that no jarring contrast is perceived; and a subdued sense of humor, making itself felt at the proper moment, redeems the most daring flights of the work from the reproach of extravagance.

Mr. Bradshaw is especially to be commended for having the courage of his imagination. He wastes no undue time on explanations, but proceeds[12] promptly and fearlessly to set forth the point at issue. When, for example, it becomes necessary to introduce the new language spoken by the inhabitants of the interior world, we are brought in half a dozen paragraphs to an understanding of its characteristic features, and proceed to the use of it without more ado. A more timid writer would have misspent labor and ingenuity in dwelling upon a matter which Mr. Bradshaw rightly perceived to be of no essential importance; and we should have been wearied and delayed in arriving at the really interesting scenes.

The philosophy of the book is worthy of more serious notice. The religion of the new race is based upon the worship of the human soul, whose powers have been developed to a height unthought of by our section of mankind, although on lines the commencement of which are already within our view. The magical achievements of theosophy and occultism, as well as the ultimate achievements of orthodox science, are revealed in their most amazing manifestations, and with a sobriety and minuteness of treatment that fully satisfies what may be called the transcendental reader. The whole philosophic and religious situation is made to appear admirably plausible: but we are gradually brought to perceive that there is a futility and a rottenness inherent in it all, and that for the Goddess of Atvatabar, lofty, wise, and immaculate though she be, there is, nevertheless, a loftier and sublimer experience in store. The finest art of the book is shown here: a deep is revealed underneath the deep, and the final outcome is in accord with the simplest as well as the profoundest religious perception.

But it would be useless to attempt longer to withhold the reader from the marvellous journey that awaits him. A word of congratulation, however, is due in regard to the illustrations. They reach a level of excellence rare even at this day; the artists have evidently been in thorough sympathy with the author, and have given to the eye what the latter has presented to the understanding. A more lovable divinity than that which confronts us on the golden throne it has seldom been our fortune to behold; and the designs of animal-plants are as remarkable as anything in modern illustrative art: they are entirely unique, and possess a value quite apart from their artistic grace.

The chief complaint I find to urge against the book is that it stops long before my curiosity regarding the contents of the interior world is satisfied. There are several continents and islands yet to be heard from. But I am reassured by the termination of the story that there is nothing to prevent the hero from continuing his explorations; and I shall welcome the volume which contains the further points of his extraordinary and commendable enterprise.

Julian Hawthorne.

I had been asleep when a terrific noise awoke me. I rose up on my couch in the cabin and gazed wildly around, dazed with the feeling that something extraordinary had happened. By degrees becoming conscious of my surroundings, I saw Captain Wallace, Dr. Merryferry, Astronomer Starbottle, and Master-at-Arms Flathootly beside me.

"Commander White," said the captain, "did you hear that roar?"

"What roar?" I replied. "Where are we?"

"Why, you must have been asleep," said he, "and yet the roar was enough to raise the dead. It seemed as if both earth and heaven were split open."

"What is that hissing sound I hear?" I inquired.

"That, sir," said the doctor, "is the sound of millions of flying sea-fowl frightened by the awful noise. The midnight sun is darkened with the flight of so many birds. Surely, sir, you must have heard that dreadful shriek. It froze the blood in our veins with horror."

I began to understand that the Polar King was safe, and that we were all still alive and well. But what could my officers mean by the terrible noise they talked about?

I jumped out of bed saying, "Gentlemen, I must investigate this whole business. You say the Polar King is safe?"

"Shure, sorr," said Flathootly, the master-at-arms, "the ship lies still anchored to the ice-fut where we put her this afthernoon. She's all right."

I at once went on deck. Sure enough the ship was as safe as if in harbor. Birds flew about in myriads, at times obscuring[14] the sun, and now and then we heard growling reverberations from distant icebergs, answering back the fearful roar that had roused them from their polar sleep.

The sea, that is to say the enormous ice-pack in which we lay, heaved and fell like an earthquake. It was evident that a catastrophe of no common character had happened.

What was the cause that startled the polar midnight with such unwonted commotion?

Sailors are very superstitious; with them every unknown sound is a cry of disaster. It was necessary to discover what had happened, lest the courage of my men should give way and involve the whole expedition in ruin.

The captain, although alarmed, was as brave as a lion, and as for Flathootly, he would follow me through fire and water like the brave Irishman that he was. The scientific staff were gentlemen of education, and could be relied upon to show an example of bravery that would keep the crew in good spirits.

"Do you remember the creek in the ice-foot we passed this morning," said the captain, "the place where we shot the polar bear?"

"Quite well," I said.

"Well, the roar that frightened us came from that locality. You remember all day we heard strange squealing sounds issuing from the ice, as though it was being rent or split open by some subterranean force."

The entire events of the day came to my mind in all their clearness. I did remember the strange sounds the captain referred to. I thought then that perhaps they had been caused by Professor Rackiron's shell of terrorite which he had fired at the southern face of the vast range of ice mountains that formed an impenetrable barrier to the pole. The men were in need of a change of diet, and we thought the surest way of getting the sea-fowl was to explode a shell among them. The face of the ice cliffs was the home of innumerable birds peculiar to the Arctic zone. There myriads of gulls, kittiwakes, murres, guillemots, and such like creatures, made the ice alive with feathered forms.

The terrorite gun was fired with ordinary powder, and although we could approach no nearer the cliffs than five miles, on account of the solid ice-foot, yet our chief gun was good for that distance.[15]

The shell was fired and exploded high up on the face of the crags. The effect was startling. The explosion brought down tons of the frosty marble. The débris fell like blocks of iron that rang with a piercing cry on the ice-bound breast of the ocean. Millions of sea-fowl of every conceivable variety darkened the air. Their rushing wings sounded like the hissing of a tornado. Thousands were killed by the shock. A detachment of sailors under First Officer Renwick brought in heavy loads of dead fowl for a change of diet. The food, however, proved indigestible, and made the men ill.

We resolved, as soon as the sun had mounted the heavens from his midnight declension, to retrace our course somewhat and discover the cause of the terrible outcry of the night. We had been sailing for weeks along the southern ice-foot that belonged to the interminable ice hills which formed an effectual barrier to the pole. Day after day the Polar King had forced its way through a gigantic floe of piled-up ice blocks, floating cakes of ice, and along ridges of frozen enormity, cracked, broken, and piled together in endless confusion. We were in quest of a northward passage out of the terrible ice prison that surrounded us, but failed to discover the slightest opening. It had become a question of abandoning our enterprise of discovering the North Pole and returning home again or abandoning the ship, and, taking our dogs and sledges, brave the nameless terrors of the icy hills. Of course in such case the ship would be our base of supplies and of action in whatever expedition might be set on foot for polar discovery.

About six o'clock in the morning of the 20th of July we began to work the ship around, to partially retrace our voyage. All hands were on the lookout for any sign of such a catastrophe as might have caused the midnight commotion. After travelling about ten miles we reached the creek where the bear had been killed the day before. The man on the lookout on the top-mast sung out:

"Creek bigger than yesterday!"

Before we had time to examine the creek with our glasses he sung out:

"Mountains split in two!"

Sure enough, a dark blue gash ran up the hills to their very summit, and as soon as the ship came abreast of the creek we saw that the range of frozen precipices had been riven apart,[16] and a streak of dark blue water lay between, on which the ship might possibly reach the polar sea beyond.

Dare we venture into that inviting gulf?

The officers crowded around me. "Well, gentlemen," said I, "what do you say, shall we try the passage?"

"We only measure fifty feet on the beam, while the fissure is at least one hundred feet wide; so we have plenty of room to work the ship," said the captain.

"But, captain," said I, "if we find the width only fifty feet a few miles from here, what then?"

"Then we must come back," said he, "that's all."

"Suppose we cannot come back—suppose the walls of ice should begin to close up again?" I said.

"I don't believe they will," said Professor Goldrock, who was our naturalist and was well informed in geology.

"Why not?" I inquired.

"Well," said he, "to our certain knowledge this range of ice hills extends five hundred miles east and west of us. The sea is here over one hundred and fifty fathoms deep. This barrier is simply a congregation of icebergs, frozen into a continuous solid mass. It is quite certain that the mass is anchored to the bottom, so that it is not free to come asunder and then simply close up again. My theory is this: Right underneath us there is a range of submarine rocks or hills running north and south. Last night an earthquake lifted this submarine range, say, fifty feet above its former level. The enormous upward pressure split open the range of ice resting thereon, and, unless the mountains beneath us subside to their former level, these rent walls of ice will never come together again. The passage will become filled up with fresh ice in a few hours, so that in any case there is no danger of the precipices crushing the ship."

"Your opinion looks feasible," I replied.

"Look," said he; "you will see that the top of the crevasse is wider than it is at the level of the water, one proof at least that my theory is correct."

The professor was right; there was a perceptible increase in the width of the opening at the top.

To make ourselves still more sure we took soundings for a mile east and west of the chasm, and found the professor's theory of a submarine range of hills correct. The water was shallowest right under the gap, and was very much deeperonly[17] a short distance on either side. I said to the officers and sailors: "My men, are you willing to enter this gap with a view of getting beyond the barrier for the sake of science and fortune and the glory of the United States?"

I SIGNALLED THE ENGINEER FULL SPEED AHEAD, AND IN A

SHORT TIME WE CROSSED THE ICE-FOOT AND ENTERED THE CHASM.

I SIGNALLED THE ENGINEER FULL SPEED AHEAD, AND IN A

SHORT TIME WE CROSSED THE ICE-FOOT AND ENTERED THE CHASM.

They gave a shout of assent that robbed the gulf of its terrors. I signalled the engineer full speed ahead, and in a short time we crossed the ice-foot and entered the chasm.

It could be nothing else but an upheaval of nature that caused the rent, as the distance was uniform between the walls however irregular the windings made. And such walls! For a distance of twenty miles we sailed between smooth glistening precipices of palæocrystic ice rising two hundred feet above the water. The opening remained perceptibly wider at the top than below.

After a distance of twenty miles the height gradually decreased until within a distance of another fifty miles the ice sank to the level of the water.

The sailors gave a shout of triumph which was echoed from the ramparts of ice. To our astonishment we found we had reached a mighty field of loose pack ice, while on the distant horizon were glimpses of blue sea!

The Polar King, in lat. 84', long. 151' 14", had entered an ocean covered with enormous ice-floes. What surprised us most was the fact that we could make any headway whatever, and that the ice wasn't frozen into one solid mass as every one expected. On the contrary, leads of open water reached in all directions, and up those leading nearest due north we joyfully sailed.

May the 10th was a memorable day in our voyage. On that day we celebrated the double event of having reached the furthest north and of having discovered an open polar sea.

Seated in the luxurious cabin of the ship, I mused on the origin of this extraordinary expedition. It was certain, if my father were alive he would fully approve of the use I was making of the wealth he had left me. He was a man utterly without[20] romance, a hard-headed man of facts, which quality doubtless was the cause of his amassing so many millions of dollars.

My father could appreciate the importance of theories, of enthusiastic ideals, but he preferred others to act upon them. As for himself he would say, "I see no money in it for me." He believed that many enthusiastic theories were the germs of great fortunes, but he always said with a knowing smile, "You know it is never safe to be a pioneer in anything. The pioneer usually gets killed in creating an inheritance for his successors." It was a selfish policy which arose from his financial experiences, that in proportion as a man was selfish he was successful.

I was always of a totally different temperament to my father. I was romantic, idealistic. I loved the marvellous, the magnificent, the miraculous and the mysterious, qualities that I inherited from my mother. I used to dream of exploring tropic islands, of visiting the lands of Europe and the Orient, and of haunting temples and tombs, palaces and pagodas. I wished to discover all that was weird and wonderful on the earth, so that my experiences would be a description of earth's girdle of gold, bringing within reach of the enslaved multitudes of all nations ideas and experiences of surpassing novelty and grandeur that would refresh their parched souls. I longed to whisper in the ear of the laborer at the wheel that the world was not wholly a blasted place, but that here and there oases made green its barrenness. If he could not actually in person mingle with its joys, his soul, that neither despot nor monopolist could chain, might spread its wings and feast on such delights as my journeyings might furnish.

How seldom do we realize our fondest desires! Just at the time of my father's death the entire world was shocked with the news of the failure of another Arctic expedition, sent out by the United States, to discover, if possible, the North Pole. The expedition leaving their ship frozen up in Smith's Sound essayed to reach the pole by means of a monster balloon and a favoring wind. The experiment might possibly have succeeded had it not happened that the car of the balloon struck the crest of an iceberg and dashed its occupants into a fearful crevasse in the ice, where they miserably perished. This calamity brought to recollection the ill-fated Sir John Franklin and Jeanette expeditions; but, strange to say, in my mind at least, such disasters[21] produced no deterrent effect against the setting forth of still another enterprise in Arctic research.

From the time the expedition I refer to sailed from New York until the news of its dreadful fate reached the country, I had been reading almost every narrative of polar discovery. The consequence was I had awakened in my mind an enthusiasm to penetrate the sublime secret of the pole. I longed to stand, as it were, on the roof of the world and see beneath me the great globe revolve on its axis. There, where there is neither north, nor south, nor east, nor west, I could survey the frozen realms of death. I would dare to stand on the very pole itself with my few hardy companions, monarch of an empire of ice, on a spot that never feels the life-sustaining revolutions of the earth. I knew that on the equator, where all is light, life, and movement, continents and seas flash through space at the rate of one thousand miles an hour, but on the pole the wheeling of the earth is as dead as the desolation that surrounds it.

I had conversed with Arctic navigators both in England and the United States. Some believed the pole would never be discovered. Others, again, declared their belief in an open polar sea. It was generally conceded that the Smith's Sound route was impracticable, and that the only possible way to approach the pole was by the Behring Strait route, that is, by following the 170th degree of west longitude north of Alaska.

I thought it a strange fact that modern sailors, armed with all the resources of science and with the experience of numerous Arctic voyages to guide them, could get only three degrees nearer the pole than Henry Hudson did nearly three hundred years ago. That redoubtable seaman possessed neither the ships nor men of later voyagers nor the many appliances of his successors to mitigate the intense cold, yet his record in view of the facts of the case remains triumphant.

It was at this time that my father died. He left me the bulk of his property under the following clause in his will:

"I hereby bequeath to my dear son, Lexington White, the real estate, stocks, bonds, shares, title-deeds, mortgages, and other securities that I die possessed of, amounting at present market prices to over five million dollars. I desire that my said son use this property for some beneficent purpose, of use[22] to his fellow-men, excepting what money may be necessary for his personal wants as a gentleman."

I could scarcely believe my father was so wealthy as to be able to leave me so large a fortune, but his natural secretiveness kept him from mentioning the amount of his gains, even to his own family. No sooner did I realize the extent of my wealth than I resolved to devote it to fitting out a private expedition with no less an object than to discover the North Pole myself. Of course I knew the undertaking was extremely hazardous and doubtful of success. It could hardly be possible that any private individual, however wealthy and daring, could hope to succeed where all the resources of mighty nations had failed.

Still, these same difficulties had a tremendous power of attracting fresh exploits on that fatal field. Who could say that even I alone might not stumble upon success? In a word, I had made up my mind to set forth in a vessel strong and swift and manned by sailors experienced in Arctic voyages, under my direct command. The expedition would be kept a profound secret; I would leave New York ostensibly for Australia, then, doubling Cape Horn, would make direct for Behring Sea. If I failed, none would be the wiser; if I succeeded, what fame would be mine!

I determined to build a vessel of such strength and equipment as could not fail, with ordinary good fortune, to carry us through the greatest dangers in Arctic navigation. Short of being absolutely frozen in the ice, I hoped to reach the pole itself, if there should be sufficient water to float us. The vessel, which I named the Polar King, although small in size was very strong and compact. Her length was 150 feet and her width amidships 50 feet. Her frames and planking were made of well-seasoned oak. The outer planking was sheathed in steel plates from four to six inches in thickness. This would protect us from the edges of the ancient ice that might otherwise cut into the planking and so destroy the vessel.[23]

The ship was armed as follows: A colossal terrorite gun that stood in the centre of the deck, whose 250-pound shell of explosive terrorite was fired by a charge of gunpowder without exploding the terrorite while leaving the gun. This was to destroy icebergs and heavy pack-ice. A battery of twelve 100-pounder terrorite guns, with shells also fired with powder. All shells would explode by percussion in striking the object aimed at. A battery of six guns of the Gatling type, to repel boarding parties in case we reached a hostile country. There was also an armory of magazine rifles, revolvers, cutlasses, etc., as well as 50 tons of gunpowder, terrorite, and revolver-rifle cartridges.

The ship was driven by steam, the triple-expansion engine being 500-horse power and the rate of speed twenty-five miles an hour. By an important improvement on the steam engine, invented by myself, one ton of coal did the work of 50 tons without such improvement. The bunkers held 250 tons of coal, which was thus equal to 12,500 tons in any other vessel. There was also an auxiliary engine for working the pumps, electric dynamo, cargo, anchors, etc. One of the most useful fittings was the apparatus that both heated the ship and condensed the sea water for consumption on board ship, and for feeding the boilers.

The ship's company was as follows:

OFFICERS.

Lexington White, Commander of the Expedition.

Captain, William Wallace.

First Officer Renwick, Navigating Lieutenant.

Second Officer Austin, Captain of the terrorite gun.

Third Officer Haddock, Captain of the main deck battery.

SCIENTIFIC STAFF.

Professor Rackiron, Electrician and Inventor.

Professor Starbottle, Astronomer.

Professor Goldrock, Naturalist.

Doctor Merryferry, Ship's Physician.

PETTY OFFICERS.

Master-at-Arms Flathootly.

First Engineer Douglass.

Second Engineer Anthoney.

Pilot Rowe.

[24]Carpenter Martin.

Painter Hereward.

Boatswain Dunbar.

Ninety-five able-bodied seamen, including mechanics, gunners, cooks, tailors, stokers, etc.

Total of ship's company, 110 souls.

Believing in the absolute certainty of discovering the pole and our consequent fame, I had included in the ship's stores a special triumphal outfit for both officers and sailors. This consisted of a Viking helmet of polished brass surmounted by the figure of a silver-plated polar bear, to be worn by both officers and sailors. For the officers a uniform of navy-blue cloth was provided, consisting of frock coat embroidered with a profusion of gold striping on shoulders and sleeves, and gold-striped pantaloons. For each sailor there was provided a uniform consisting of outer navy-blue cloth jacket, with inner blue serge jacket, having the figure of a globe embroidered in gold on the breast of the latter, surmounted by the figure of a polar bear in silver. Each officer and sailor was armed with a cutlass having the figure of a polar bear in silver-plated brass surmounting the hilt. This was the gala dress, but for every-day use the entire company was supplied with the usual Arctic outfit to withstand the terrible climate of high latitudes.

Foreseeing the necessity of pure air and freedom from damp surroundings, I had the men's berths built on the spar deck, contrary to the usual custom. The spar deck was entirely covered by a hurricane deck, thus giving complete protection from cold and the stormy weather we would be sure to encounter on the voyage.

Our only cargo consisted of provisions, ship's stores, ammunition, coal, and a large stock of chemical batteries and a dynamo for furnishing electricity to light the ship. We also shipped largely of materials to manufacture shells for the terrorite guns.

The list of stores included an ample supply of tea, coffee, canned milk, butter, pickles, canned meats, flour, beans, peas, pork, molasses, corn, onions, potatoes, cheese, prunes, pemmican, rice, canned fowl, fish, pears, peaches, sugar, carrots, etc.

The refrigerator contained a large quantity of fresh beef, mutton, veal, etc. We brought no luxuries except a few barrels[25] of rum for special occasion or accidents. Exposure and hard work will make the plainest food seem a banquet.

Thus fully equipped, the Polar King quietly left the Atlantic Basin in Brooklyn, N. Y., ostensibly on a voyage to Australia. The newspapers contained brief notices to the effect that Lexington White, a gentleman of fortune, had left New York for a voyage to Australia and the Southern Ocean, via Cape Horn, and would be gone for two years.

We left on New Year's Day, and had our first experience of a polar pack in New York Bay, which was thickly covered with crowded ice. Gaining the open water, we soon left the ice behind, and, after a month's steady steaming, entered the Straits of Magellan, having touched at Monte Video for supplies and water.

Leaving the Straits we entered the Pacific Ocean, steering north. Touching at Valparaiso, we sailed on without a break until we arrived at Sitka, Alaska, on the 1st of March.

Receiving our final stores at Sitka, the vessel at once put to sea again, and in a week reached Behring Strait and entered the Arctic Ocean. I ordered the entire company to put on their Arctic clothing, consisting of double suits of underclothing, three pairs of socks, ordinary wool suits, over which were heavy furs, fur helmets, moccasins and Labrador boots.

All through the Straits we had encountered ice, and after we had sailed two days in the Arctic Sea, a hurricane from the northwest smote us, driving us eastward over the 165th parallel, north of Alaska. We were surrounded with whirlwinds of snow frozen as hard as hail. We experienced the benefit of having our decks covered with a steel shell. There was plenty of room for the men to exercise on deck shielded from the pitiless storm that drove the snow like a storm of gravel before it. Exposure to such a blizzard meant frost-bite, perhaps death. The outside temperature was 40 below zero, the inside temperature 40 above zero, cold enough to make the men digest an Arctic diet.

We kept the prow of the ship to the storm, and every wave that washed over us made thicker our cuirass of ice. It was gratifying to note the contrast between our comfortable quarters and the howling desolation around us.

While waiting for the storm to subside we had leisure to speculate on the chances of success in discovering the pole.

Captain Wallace had caused to be put up in each of our four cabins the following tables of Arctic progress made since Hudson's voyage in 1607:

| RECORD OF HIGHEST LATITUDES REACHED. | |

| Hudson | 80' 23" in 1607 |

| Phipps | 80' 48" in 1773 |

| Scoresby | 81' 12" in 1806 |

| Payer | 82' 07" in 1872 |

| Meyer | 82' 09" in 1871 |

| Parry | 82' 45" in 1827 |

| Aldrich | 83' 07" in 1876 |

| Markham | 83' 20" in 1876 |

| Lockwood | 83' 24" in 1883 |

"Does it not seem strange," said I, "that nearly three hundred years of naval progress and inventive skill can produce no better record in polar discovery than this? With all our skill and experience we have only distanced the heroic Hudson three degrees; that is one degree for every hundred years. At this rate of progress the pole may be discovered in the year 2600."

"It is a record of naval imbecility," said the captain; "there is no reason why our expedition cannot at least touch the 85th degree. That would be doing the work of two hundred years in as many days."

"Why not do the work of the next 700 years while we are at it?" said Professor Rackiron. "Let us take the ship as far as we can go and then bundle our dogs and a few of the best men into the balloon and finish a job that the biggest governments on earth are unable to do."

"That's precisely what we've come here for," said I, "but we must have prudence as well as boldness, so as not to throw away our lives unnecessarily. In any case we will beat the record ere we return."

The storm lasted four days. On its subsidence we discovered ourselves completely surrounded with ice. We were beset by a veritable polar pack, brought down by the violence of the gale. The ice was covered deeply with snow, which made a dazzling scene when lit by the brilliant sun. We seemed transported to a new world. Far as the eye could see huge masses of ice interposed with floe bergs of vast dimensions. The captain[27] allowed the sailors to exercise themselves on the solidly frozen snow. It was impossible to get any fresh meat, as the pack, being of a temporary nature, had not yet become the home of bear, walrus, or seal.

We saw a water sky in the north, showing that there was open water in that direction, but meantime we could do nothing but drift in the embrace of the ice in an easterly direction. In about a week the pack began to open and water lanes to appear. A more or less open channel appearing in a northeasterly direction, we got the ship warped around, and, getting up steam, drew slowly out of the pack.

Birds began to appear and flocks of ducks and geese flew across our track, taking a westerly course. We were now in the latitude of Wrangel Island, but in west longitude 165. We had the good fortune to see a large bear floating on an isolated floe toward which we steered. I drew blood at the first shot, but Flathootly's rifle killed him. The sailors had fresh meat that day for dinner.

The day following we brought down some geese and elder ducks that sailed too near the ship. We followed the main leads in preference to forcing a passage due north, and when in lat. 78' long. 150' the watch cried out "Land ahead!" On the eastern horizon rose several peaks of mountains, and on approaching nearer we discovered a large island extending some thirty miles north and south. The ice-foot surrounding the land was several miles in width, and bringing the ship alongside, three-fourths of the sailors, accompanied by the entire dogs and sledges, started for the land on a hunting expedition.

It was a fortunate thing that we discovered the island, for, with our slow progress and monotonous confinement, the men were getting tired of their captivity and anxious for active exertion.

The sailors did not return until long after midnight, encouraged to stay out by the fact that it was the first night the sun remained entirely above the horizon.

It was the 10th of April, or rather the morning of the 11th, when the sailors returned with three of the five sledges laden with the spoils of the chase. They had bagged a musk ox, a bear, an Arctic wolf, and six hares—a good day's work. Grog was served all around in honor of the midnight sun and the capture of fresh meat. We dressed the ox and bear, giving the[28] offal as well as the wolf to the dogs, and revelled for the next few days in the luxury of fresh meat.

The island not being marked on our charts, we took credit to ourselves as its discoverers, and took possession of the same in the name of the United States.

The captain proposed to the sailors to call it Lexington Island in honor of their commander, and the men replied to his proposition with such a rousing cheer that I felt obliged to accept the distinction.

Flathootly reported that there was a drove of musk oxen on the island, and before finally leaving it we organized a grand hunting expedition for the benefit of all concerned.

Leaving but five men, including the first officer and engineer, on board to take care of the ship, I took charge of the hunt. After a rough-and-tumble scramble over the chaotic ice-foot, we reached the mainland in good shape, save that a dog broke its leg in the ice and had to be shot. Its companions very feelingly gave it a decent burial in their stomachs.

Mounting an ice-covered hillock, we saw, two miles to the southeast in a valley where grass and moss were visible, half a dozen musk oxen, doubtless the entire herd. We adopted the plan of surrounding the herd, drawing as near the animals as possible without alarming them. Sniffing danger in the southeasterly wind, the herd broke away to the northwest. The sailors jumped up and yelled, making the animals swerve to the north. A semi-circle of rifles was discharged at the unhappy brutes. Two fell dead in their tracks and the remaining four, badly wounded, wheeled and made off in the opposite direction. The other wing of the sailors now had their innings as we fell flat and heard bullets fly over us. Three more animals fell, mortally wounded. A bull calf, the only remnant of the herd on its legs, looked in wonder at the sailor who despatched it with his revolver. The dogs held high carnival for an hour or more on the slaughtered oxen. We packed the sledges with a carcass on each, and in due time regained the ship, pleased with our day's work.

Leaving Lexington Island we steered almost due north through a vast open pack. On the 1st of May we arrived in lat. 78' 30" west long. 155' 50", our course having been determined by the lead of the lanes in the enormous drifts of ice. Here another storm overtook us, travelling due east. We were oncemore[29] beset, and drifted helplessly for three days before the storm subsided. We found ourselves in long. 150' again, in danger of being nipped. The wind, suddenly drifting to the east, reopened the pack for us to our intense relief.

A SEMICIRCLE OF RIFLES WAS DISCHARGED AT THE UNHAPPY

BRUTES, AND TWO FELL DEAD IN THEIR TRACKS.

A SEMICIRCLE OF RIFLES WAS DISCHARGED AT THE UNHAPPY

BRUTES, AND TWO FELL DEAD IN THEIR TRACKS.

Taking advantage of some fine leads and favorable winds, we passed through leagues of ice, piled-up floes and floebergs, forming scenes of Arctic desolation beyond imagination to conceive. At last we arrived at a place beyond which it was impossible to proceed. We had struck against the gigantic barrier of what appeared to be an immense continent of ice, for a range of ice-clad hills lay only a few miles north of the Polar King. At last the sceptre of the Ice King waved over us with the command, "Thus far and no further."

How the Polar King penetrated what appeared an insurmountable obstacle, and the joyful proof that the hills did not belong to a polar continent, but were a continuous congregation of icebergs, frozen in one solid mass, are already known to the reader.

The gallant ship continued to make rapid progress toward the open water lying ahead of us. Mid-day found us in 84' 10" north latitude and 150' west longitude. The sun remained in the sky as usual to add his splendor to our day of deliverance and exultation.

We felt what it was to be wholly cut off from the outer world. The chances were that the passage in the ice would be frozen up solid again soon after we had passed through it. Even with our dogs and sledges the chances were against our retreat southward.

The throbbing of the engine was the only sound that broke the stillness of the silent sea. The laugh of the sailors sounded hollow and strange, and seemed a reminder that with all our freedom we were prisoners of the ice, sailing where no ship had ever sailed nor human eye gazed on such a sea of terror and beauty.

Happily we were not the only beings that peopled the solitudes[32] of the pole. Flocks of gulls, geese, ptarmigan, and other Arctic fowls wheeled round us. They seemed almost human in their movements, and were the links that bound us to the beating hearts far enough off then to be regretted by us.

Every man on board the vessel was absorbed in thought concerning our strange position. The beyond? That was the momentous question that lay like a load on every soul.

While thinking of these things, Professor Starbottle inquired, if with such open water as we sailed in, how soon I expected to reach the pole.

"Well," said I, "we ought to be at the 85th parallel by this time. Five more degrees, or 300 miles, will reach it. The Polar King will cover that distance easily in twenty hours. It is now 6 p.m.; at 2 p.m. to-morrow, the 12th of May, we will reach the pole."

Professor Starbottle shook his head deprecatingly. "I am afraid, commander," said he, "we will never reach the pole."

His look, his voice, his manner, filled me with the idea that something dreadful was going to happen. My lips grew dry with a sudden excitement, as I hastily inquired why he felt so sure we would never reach the object of our search.

"What time is it, commander?" said he.

I pulled forth my chronometer; it was just six o'clock.

"Well, then," said he, "look at the sun. The sun has swung round to the west, but hasn't fallen any."

I looked at the sun, which, sure enough, stood as high as at mid-day. I was paralyzed with a nameless dread. I stood rooted to the deck in anticipation of some dreadful horror.

"Good heavens!" I gasped, "what—what do you mean?"

"I mean," said he, "the sun is not going to fall again on this course. It's we who are going to fall."

"The sun will fall to its usual position at midnight," I stammered; "wait—wait till midnight."

"The sun won't fall at midnight," said the professor. "I am afraid to tell you why," he added.

"In God's name," I shouted, "tell me the meaning of this!"

I will never forget the feeling that crazed me as the professor said: "I fear, commander, we are falling into the interior of the earth!"

"You are mad, sir!" I shouted. "It cannot be—we are sailing to the North Pole."[33]

"Wait till midnight, commander," said he, shaking my hand.

I took his hand and echoed his words—"Wait till midnight." After a pause I inquired if he had mentioned his extraordinary fears to any one else.

"Not a soul," he replied.

"Then," said I, "say nothing to anybody until midnight."

"Ay, ay, sir," said he, and disappeared.

The sailors evidently expected that something was going to happen on account of the sun standing still in the heavens. They were gathered in groups on deck discussing the situation with bated breath. I noticed them looking at me with wild eyes, like sheep cornered for execution. The officers avoided calling my attention to the unusual sight, possibly divining I was already fully excited by it.

Never was midnight looked for so eagerly by any mortal on earth as I awaited the dreadful hour that would either confirm or dispel my fears.

Midnight came and the sun had not fallen in the sky! There he stood as high as at noonday, at least five degrees higher than his position twenty-four hours before.

Professor Starbottle, approaching me, said: "Commander, my prognostication was correct; you see the sun's elevation is unchanged since mid-day. Now one of two things has happened—either the axis of the earth has approached five degrees nearer the plane of its orbit since mid-day or we are sailing down into a subterranean gulf! That the former is impossible, mid-day to-day will disprove. If my theory of a subterranean sea is correct, the sun will fall below the horizon at mid-day, and our only light will be the earth-light of the opposite mouth of the gulf into which we are rapidly sinking."

"Professor," said I, "tell the officers and the scientific staff to meet me at once in the cabin. This is a tremendous crisis!"

Ere I could leave the deck the captain, officers, doctor, naturalist, Professor Rackiron, and many of the crew surrounded me, all in a state of the greatest consternation.

"Commander," said Captain Wallace, "I beg to report that the pole star has suddenly fallen five degrees south from its position overhead, and the sun has risen to his mid-day position in the sky! I fear we are sailing into a vast polar depression something greater than the description given in our geographies, that the earth is flattened at the poles."

"Do you really think, captain," I inquired, "that we are sailing into a hollow place around the pole?"

"Why, I am sure of it," said he. "Nothing else can explain the sudden movement of the heavenly bodies. Remember, we have only passed the 85th parallel but a few miles and ought to have the pole star right overhead."

"Professor Starbottle has a theory," I said, "that may account for the strange phenomena we witness. Let these gentlemen hear your theory, professor."

The professor stated very deliberately what he had already communicated to me, viz.: that we were really descending to the interior of the earth, that the bows of the ship were gradually pointing to its centre, and that if the voyage were continued we would find ourselves swallowed up in a vast polar gulf leading to God knows what infernal regions.

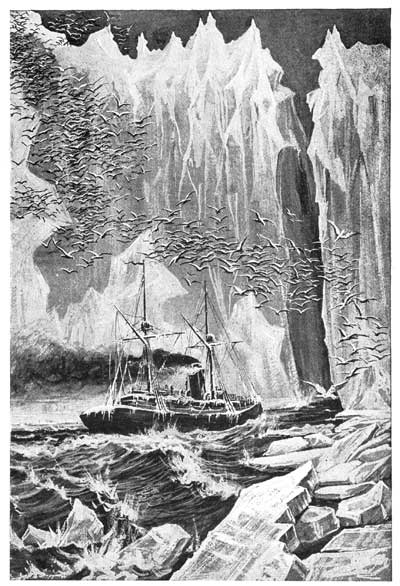

The terror inspired by the professor's words was plainly visible on every face.

"Let us turn back!" shouted some of the sailors.

"My opinion," said the captain, "is that we have entered a polar depression; it is impossible to think that the earth is a hollow shell into which we may sail so easily as this."

"If I might venture a remark," said Pilot Rowe, "I think Professor Starbottle is right. If the earth is a hollow shell having a subterranean ocean, we can sail thereon bottom upward and masts downward, just as easily as we sail on the surface of the ocean here."

"I believe an interior ocean an impossibility," said the captain.

"You're right, sorr," said the master-at-arms, "for what would keep the ship sticking to the wather upside down?"

THE TERROR INSPIRED BY THE PROFESSOR'S WORDS WAS

PLAINLY VISIBLE ON EVERY FACE.

THE TERROR INSPIRED BY THE PROFESSOR'S WORDS WAS

PLAINLY VISIBLE ON EVERY FACE.

"I don't say that the earth is absolutely a hollow sphere," said the professor, "but I do say this, we are now sailing into a polar abyss, and if the sun disappears at noon to-day it will be because we have sailed far enough into the gulf to put the ocean over which we have sailed between us and that luminary. If the sun disappears at noon, depend upon it we will never reach the pole, which will forever remain only the ideal axis of the earth."

"Do you mean to say," I inquired, "that what men have called the pole is only the mouth of an enormous cavern, perhaps the vestibule of a subterranean world?"

"That is precisely the theory I advance to account for this strange ending of our voyage," said the professor.

The murmurs of excitement among the men again broke out into wild cries of "Turn back the ship!"

I encouraged the men to calm themselves. "As long as the ship is in no immediate danger," said I, "we can wait till noonday and see if the professor's opinion is supported by the behavior of the sun. If so, we will then hold a council of all hands and decide on what course to follow. Depart to your respective posts of duty until mid-day, when we will decide on such action as will be for the good of all."

The men, terribly frightened, dispersed, leaving Captain Wallace, First Officer Renwick, Professors Starbottle, Goldrock, and Rackiron, the doctor and myself together.

Dreadful as was the thought of quietly sinking into a polar gulf from which possibly there might be no escape, yet the bare possibility of returning to tell the world of our tremendous discovery created a desire to explore still further the abyss into which we had entered. I confess that my first feeling of terror was rapidly giving way to a passion for discovery. What fearful secrets might not be held in the darkness toward which we undoubtedly travelled! Would it be our fortune to pierce the darkness and silence of a polar cavern? When I thought of the natural terror of the sailors, I dared not think of our sailing further than mid-day, in case we had really entered an abyss.

"Commander," said Professor Starbottle, "this is the most important day, or rather night, of the voyage. I propose we stay on deck and enjoy the sunlight as long as we can."

One glance at the sun sufficed to tell us the truth; he was[38] rapidly falling from the sky. At midnight he was 20 degrees and at 1 a.m. only 18 degrees above the waste of waters.

This proved we were as rapidly taking leave of the glorious orb, on an expedition fraught with the greatest peril and unknown possibilities of science, conquest, and commerce.

By a tacit consent we turned our attention to the scene around us. The water was very free from ice, only here and there icebergs floated. The diminished radiation of light produced a weird effect, growing more spectral as the sun sank in the heavens.

Professor Goldrock pointed out a flock of geese actually flying ahead of us into the gulf, if gulf indeed it were. We considered this a good omen and took heart accordingly.

The captain pointed out a strange apparition in the north, but which was really south of the pole, and discoverable with the glass. It appeared to be the limb of some rising planet between us and the sun that seemed faintly illuminated by moonlight. Professor Starbottle said it was the opposite edge of the polar gulf that was about to envelop us. It was illuminated by the earth-light reflected from the same ocean on which the Polar King floated.

The sun, as he swung round to the south, fell rapidly to the horizon, and at eight o'clock disappeared below the water. Was there ever a day in human experience as portentous as that? When did the sun set at 8 a.m. in the Arctic summer, leaving the earth in darkness? We knew then that Professor Starbottle's theory of a polar gulf was a truth beyond question. It was a fearful fact!

But the grandest spectacle we had yet seen now lay before us. The opposite rapidly rising limb of the polar gulf, 500 miles away, was brilliantly illuminated by the sun's rays far overhead, and its splendid earth-light, twenty times brighter than moonlight, falling upon us, compensated for the sudden obliteration of the daylight.

It was mid-day, and our only light was the earth-light of the gulf. There stood over us the still rising circular rim of the ocean, sparkling like an enormous jewel. It was a bewildering experience. In the light of that distant ocean I assembled the men on deck and thus addressed them:

"My men, when we started on the present expedition you stipulated for a voyage of discovery to the North Pole (if possible[39]) and return to New York again. The first part of the voyage is happily accomplished. We alone of all the explorers who have essayed polar discovery have been rewarded with a sight of the pole. The mystery of the earth's axis is no longer a secret. Here before your eyes is the axis on which the earth performs its daily revolution. The North Pole is an immense gulf 500 miles in diameter and of unknown depth. Within this gulf lies our ship, at least a hundred miles below the level of the outer ocean!

"The question we are now called upon to decide is this: Are we to remain satisfied with our present achievement, turn back the ship, and go home without attempting to discover whither leads this enormous gulf? As far as the officers of the ship and the scientific staff are concerned, as far as I myself am concerned, I am satisfied if we were once back in New York again, our first thought would be to return hither, and, taking up the thread of our journey, endeavor to explore the farthest recesses of the gulf."

I was here interrupted by loud applause from the entire officers and many of the men.

"This being so, why should we waste a journey to New York and back again for nothing? Why not, with our good ship well armed and provisioned, that has in safety carried us so far, why not, I say, proceed further, taking advantage of the only opportunity the ages of time have ever offered to man to explore earth's profoundest secrets?

"Who knows what oceans, what continents, what nations, it may be of men like ourselves, may not exist in a subterranean world? Who knows what gold, what silver, what precious stones are there piled perhaps mountains high? Are we to tamely throw aside the possibility of such glory on account of base fears, and, returning home, allow others to snatch from our grasp the golden prize?

"My men, I cannot think you will do this. Our future lies entirely in your hands. We cannot proceed further on our voyage without your assistance. I will not compel a single man to go further against his will. I call for volunteers for the interior world! I am willing to lead you on; who will follow me?"

The officers and sailors responded to my speech with ringing cheers. Every man of them volunteered to stay by the ship and continue our voyage down the gulf. Whatever malcontents there may have been among the sailors, those, influenced by the prevailing enthusiasm, were afraid to exhibit any cowardice, and all were unanimous for further exploration.

I signalled our resolution by a discharge of three guns, which created the most thrilling reverberations in the mysterious abyss.

Starting the engine again, the prow of the Polar King was pointed directly toward the darkness before us, toward the centre of the earth. We were determined to explore the hollow ocean to its further confines, if our provisions held out until such a work would be accomplished.

We hoped at midnight to obtain our last look at the sun, as we would then be brought into the position of the opposite side of the watery crater down which we sailed. At eleven o'clock the sun rose above the limb of the gulf, which was now veiled in darkness. We were gladdened with two hours of sunlight, the sun promptly setting at 1 a.m. of the new day.

We continued our voyage in the semi-darkness, the prow of the vessel still pointed to the centre of the earth, while the polar star shone in the outer heavens on the horizon directly over the rail of the vessel's stern.

It did not appear to us that we were dropping straight down into the interior of the earth; on the contrary, we always seemed to float on a horizontal sea, and the earth seemed to turn up toward us and the polar cavern to gradually engulf us. The sight we beheld that day was inexpressibly magnificent. Five hundred miles above us rose the crest of the circular polar sea. Its upper hemisphere glowed with the light of the unseen sun. We were surrounded by fifteen hundred miles of perpendicular ocean, crowned with a diadem of icebergs!

AT THIS MOMENT A WILD CRY AROSE FROM THE SAILORS. WITH

ONE VOICE THEY SHOUTED, "THE SUN! THE SUN!"

AT THIS MOMENT A WILD CRY AROSE FROM THE SAILORS. WITH

ONE VOICE THEY SHOUTED, "THE SUN! THE SUN!"

Glorious as was the sight, the sailors were terribly apprehensive of nameless disasters in such monstrous surroundings. It was impossible for them to understand how the ocean roof could remain [43] suspended above us like the vault of heaven. The idea of being able to sail down a tubular ocean, the antechamber of some infernal world, was incomprehensible. We were traversing sea-built corridors, whose oscillating floors and roof remained providentially apart to permit us to explore the mystery beyond.

Mid-day on the 13th of May brought no sight of the sun, but only a deepening twilight, the dim reflection of the bright sky we had left behind. The further we sailed into the gulf the less its diameter grew. When we had penetrated the vast aperture some two hundred and fifty miles, we found the aërial diameter was reduced to about fifty miles, thus forming a conical abyss. We were clearly sailing down a gigantic vortex or gulf of water, and we began to feel a diminishing gravity the further we approached the central abyss.

The cavernous sea was subject to enormous undulations, or tidal waves, either the result of storms in the interior of the earth or mighty adjustments of gravity between the interior and exterior oceans. As we were lifted up upon the crest of an immense tidal wave several of the sailors, as well as the lookout, declared they had seen a flash of light, in the direction of the centre of the earth!

We were all terribly excited at the news, and as the ship was lifted on the crest of the next wave, we saw clearly an orb of flame that lighted up the circling undulations of water with the flush of dawn! We were now between two spectral lights—the faint twilight of the outer sun and the intermittent dawn of some strange source of light in the interior of the earth.

The sailors crowded to the top of both masts and stood upon cross-trees and rigging, wildly anxious to discover the meaning of the strange light and whatever the view from the next crest of waters would reveal.

"What do you think is the source of this strange illumination," I inquired of the captain, "unless it is the radiance of fires in the centre of the earth?"

"It comes from some definite element of fire," said the professor, "the nature of which we will soon discover. It certainly does not belong to the sun, nor can I attribute it to an aurora dependent on solar agency."

"Possibly," said Professor Rackiron, "we are on the threshold of if not the infernal regions at least a supplementary edition[44] of the same. We may be yet presented at court—the court of Mephistopheles."

"You speak idle words, professor," said I. "On the eve of confronting unknown and perhaps terrible consequences you walk blindfold into the desperate chances of our journey with a jest on your lips."

"Pardon me, commander," said he, "I do not jest. Have not the ablest theologians concurred in the statement that hell lies in the centre of the earth, and that the lake of fire and brimstone there sends up its smoke of torment? For aught we know this lurid light is the reflection of the infernal fires."

At this moment a wild cry arose from the sailors. With one voice they shouted:

"The sun! The sun! The sun!"

The Polar King had gained at last the highest horizon or vortex of water, and there, before us, a splendid orb of light hung in the centre of the earth, the source of the rosy flame that welcomed us through the sublime portal of the pole!

As soon as the astonishment consequent on discovering a sun in the interior of the earth had somewhat subsided, we further discovered that the earth was indeed a hollow sphere. It was now as far to the interior as to the exterior surface, thus showing the shell of the earth to be at the pole at least 500 miles in thickness. We were half way to the interior sphere.

Professor Starbottle, who had been investigating the new world with his glass, cried out: "Commander, we are to be particularly congratulated; the whole interior planet is covered with continents and oceans just like the outer sphere!"

"We have discovered an El Dorado," said the captain, with enthusiasm; "if we discover nothing else I will die happy."

"The heaviest elements fall to the centre of all spheres," said Professor Goldrock. "I am certain we shall discover mountains of gold ere we return."

"I think we ought to salute our glorious discovery," said Professor Rackiron. "You see the infernal world isn't nearly so bad a place as we thought it was."

I ordered a salute of one hundred terrorite guns to be given in honor of our discovery, and the firing at once began. The echoed roaring of the guns was indescribably grand. The trumpet-shaped caverns of water, both before and behind us,[45] multiplied the heavy reverberations until the air of the gulf was rent with their thunder. The last explosion was followed by long-drawn echoes of triumph that marked our introduction to the interior world.

Strange to say that on the very threshold of success there are men who suddenly take fright at the new conditions that confront them. It appeared that Boatswain Dunbar and eleven sailors who had unwillingly sailed thus far refused to proceed further with the ship, being terrified at the discovery we had made. I could have obliged them to have remained with us, but their reason being possibly affected, I saw that their presence as malcontents might in time cause a mutiny, or at all events an ever-present, source of trouble. They were wildly anxious to leave the ship and return home; consequently I gave them liberty to depart. The largest boat was lowered, together with a mast and sails. I gave the command to Dunbar, and furnished the boat with ample stores and plenty of clothing. I also gave them one-half of the dogs and two sledges for crossing the ice. When the men were finally seated Dunbar cast off the rope and steered for the outer sea. We gave them a parting salute by firing a gun, and in a short time they were lost in the darkness of the gulf.

The first thought that occurred to us after the excitement of discovery had somewhat subsided was that the interior of the earth was in all probability a habitable planet, possessing as it did a life-giving luminary of its own, and our one object was to get into the planet as quickly as possible. A continual breeze from the interior ocean of air passed out of the gulf. Its temperature was much higher than that of the sea on which we sailed, and it was only now that we began to think of laying off our Arctic furs.

A closer observation of the interior sun revealed the knowledge that it was a very luminous orb, producing a climate similar to that of the tropics or nearly so. As we entered the[46] interior sphere the sun rose higher and higher above us, until at last he stood vertically above our heads at a height of about 3,500 miles. We saw at once what novel conditions of life might exist under an earth-surrounded sun, casting everywhere perpendicular shadow, and neither rising nor setting, but standing high in heaven, the lord of eternal day. We seemed to sail the bottom of a huge bowl or spherical gulf, surrounded by oceans, continents, islands, and seas.

A peculiar circumstance, first noticed immediately after arriving at the centre of the gulf, was that each of us possessed a sense of physical buoyancy, hitherto unfelt.

Flathootly told me he felt like jumping over the mast in his newly-found vigor of action, and the sailors began a series of antics quite foreign to their late stolid behavior. I felt myself possessed of a very elastic step and a similar desire to jump overboard and leap miles out to sea. I felt that I could easily jump a distance of several miles.

Professor Starbottle explained this phenomenal activity by stating that on the outer surface of the earth a man who weighs one hundred and fifty pounds, would weigh practically nothing on the interior surface of an earth shell of any equal thickness throughout. But the fact that we did weigh something, and that the ship and ocean itself remained on the under surface of the world, proved that the shell of the earth, naturally made thicker at the equator by reason of centrifugal gravity than at the poles, has sufficient equatorial attraction to keep open the polar gulf. Besides this centrifugal gravity confers a certain degree of weight on all objects in the interior sphere.

"I'll get a pair of scales," said Flathootly, "an' see how light I am in weight."

"Don't mind scales," said the professor, "for the weights themselves have lost weight."

"Well, I'm one hundred and seventy-five pounds to a feather," said Flathootly, "an' I'll soon see if the weights are right or not."

"The weights are right enough," said the professor, "and yet they are wrong."

"An' how can a thing be roight and wrang at the same time, I'd loike to know? We'll thry the weights anyway," said the Irishman.

So saying, Flathootly got a little weighing machine on deck,[47] and, standing thereon, a sailor piled on the weights on the opposite side.

He shouted out: "There now, do you see that? I'm wan hundred and siventy-siven pounds, jist what I always was."

"My dear sir," said the professor, "you don't seem to understand this matter; the weights have lost weight equally with yourself, hence they still appear to you as weighing one hundred and seventy-seven pounds."

"Excuse me, sorr," said Flathootly. "If the weights have lost weight, the chap that stole it was cute enough to put it back again before I weighed meself. Don't you see wid yer two eyes I'm still as heavy as iver I was?"

"You will require ocular demonstration that what I say is correct. Here, sir, let me weigh you with this instrument," said the professor.

The instrument referred to was a huge spring-balance with which it was proposed to weigh Flathootly. One end of it was fastened to the mast, and to the hook hanging from the other end the master-at-arms secured himself. The hand on the dial plate moved a certain distance and stopped at seventeen pounds. The expression on the Irishman's face was something awful to behold.

"Does this machine tell the thruth?" he inquired in a tearful voice.

We assured him it was absolutely correct. He only weighed seventeen pounds.

"Oh, howly Mother of Mercy!" yelled Flathootly. "Consumption has me by the back of the neck. I've lost a hundred and sixty pounds in three days. Oh, sir, for the love of heaven, take me back to me mother. I'm kilt entoirely."

It was some time before Flathootly could understand that his lightness of weight was due to the lesser-sized world he was continually arriving upon, together with centrifugal gravity, and that we all suffered from his affliction of being each "less than half a man" as he termed it. The weighing of the weights wherewith he had weighed himself proved conclusively that the depreciation in gravity applied equally to everything around us.

The extreme lightness of our bodies, and the fact that our muscles had been used to move about ten times our then weight, was the cause of our wonderful buoyancy.[48]

The sailors began leaping from the ship to a large rock that rose out of the water about half a mile off. Their agility was marvellous, and Flathootly covered himself with glory in leaping over the ship hundreds of feet in the air and alighting on the same spot on deck again.

Their officers and scientific staff remained on deck as became their dignity, although tempted to try their agility like the sailors.

Flathootly surprised us by leaping on a yardarm and exclaiming: "Gintlemen, I tell ye what it is, I'm no weight at all."

"How do you make that out?" said the professor.

"Well, Oi've been thinking," said he, "that, as you say, we're in the middle of the two wurrlds. Now it stands to sense that the wan wurrld, I mane the sun up there, is pullin' us up an' the t'other wurrld is pullin' us down, an' as both wurrlds is pulling aqually, why av corse we don't amount to no weight at all. How could I turn fifteen summersaults at wance if I was any weight? That shows yer weighing machine is all wrang again."

"How can you stand on the deck if you are no weight?" inquired the professor.

"Why, I'm only pressing me feet on the boards," said the Irishman; "look here!" So saying, he leaped from the yard and revolved in the air at least twenty times before alighting on the deck.

"Now," said the professor, "I'll explain why you only weigh seventeen pounds as indicated by the spring-balance. We have sailed, down the gulf 500 miles, haven't we?"

"Yis, sorr."

"And here we are sailing upside down on the inside roof of the world——"

"Sailin' upside down? Indeed, sorr, an' ye can't make me believe that, for shure I'm shtandin' on me feet like yourself, head uppermost."

"Well, whether you believe it or not, we are sailing upside down, just as ships going to Australia sail upside down as compared with ships sailing the North Atlantic. But the point of gravity is this: Here we are surrounded on all sides by the shell of the earth, which attracts equally in all directions. Hence all objects in the interior world have no weight as regards whatever thickness of the earth's shell surrounds them. You[49] see, weight is caused by an object having the world on one side of it. Thus both the world and the object attract each other according to the density and distance apart. What we call a pound weight is a mass of matter attracted by the earth on its surface with a force equal to the weight of sixteen ounces. A pound weight on the surface of the earth weighs sixteen ounces, and all the mighty volume of our planet, with all its mountains, continents and seas, weighs only sixteen ounces on the surface of a pound weight. The earth may still weigh many millions of tons as regards the sun, but as regards a pound weight it only weighs sixteen ounces."