The Project Gutenberg EBook of Harper's New Monthly Magazine, No. 22, March, 1852, Volume 4.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Harper's New Monthly Magazine, No. 22, March, 1852, Volume 4. Release Date: June 26, 2010 [Ebook #32983] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE, NO. 22, MARCH, 1852, VOLUME 4.***

Harper's

New Monthly Magazine

No. XXII.—March, 1852.—Vol. IV.

Contents

- Rodolphus.—A Franconia Story. By Jacob Abbott.

- Recollections Of St. Petersburg.

- A Love Affair At Cranford.

- Anecdotes Of Monkeys.

- The Mountain Torrent.

- A Masked Ball At Vienna.

- The Ornithologist.

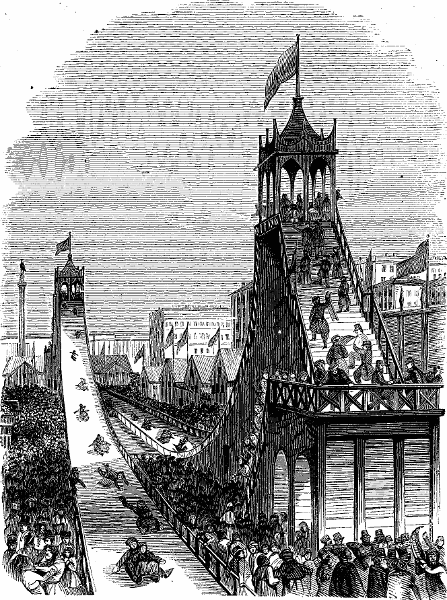

- A Child's Toy.

- “Rising Generation”-Ism.

- A Taste Of Austrian Jails.

- Who Knew Best?

- My First Place.

- The Point Of Honor.

- Christmas In Germany.

- The Miracle Of Life.

- Personal Sketches And Reminiscences. By Mary Russell Mitford.

- Recollections Of Childhood.

- Married Poets.—Elizabeth Barrett Browning—Robert Browning.

- Incidents Of A Visit At The House Of William Cobbett.

- A Reminiscence Of The French Emigration.

- The Dream Of The Weary Heart.

- New Discoveries In Ghosts.

- Keep Him Out!

- Story Of Rembrandt.

- The Viper.

- Esther Hammond's Wedding-Day.

- My Novel; Or, Varieties In English Life.

- A Brace Of Blunders By A Roving Englishman.

- Public Executions In England.

- What To Do In The Mean Time?

- The Lost Ages.

- Blighted Flowers.

- Monthly Record of Current Events.

- United States.

- Mexico.

- Great Britain.

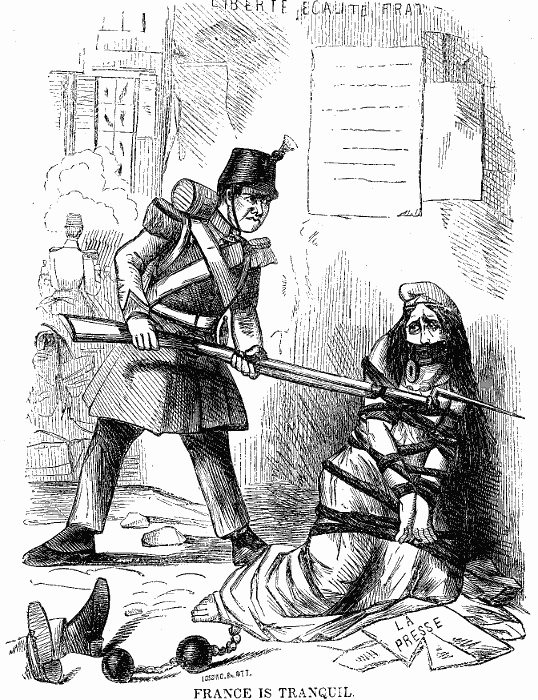

- France.

- Austria And Hungary.

- Editor's Table.

- Editor's Easy Chair

- Editor's Drawer.

- Literary Notices.

- A Leaf from Punch.

- Fashions for March.

- Footnotes

Rodolphus.—A Franconia Story.1 By Jacob Abbott.

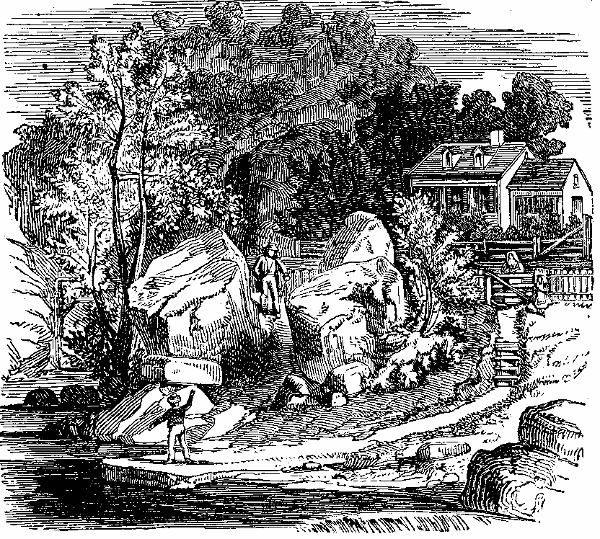

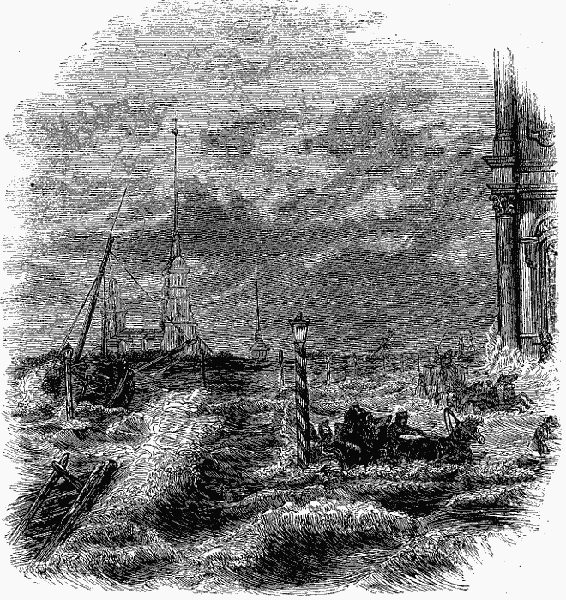

scene of the story.

Franconia, a village among the mountains at the North.

principal persons.

Rodolphus.

Ellen Linn: his sister, residing with her aunt up the glen.

Annie Linn, a younger sister.

Antoine Bianchinette, a French boy, at service at Mrs. Henry's, a short distance from the village. He is called generally by grown people Antonio, and by the children Beechnut.

Malleville, Mrs. Henry's niece.

Alphonzo, called commonly Phonny, her son.

Mr. Keep, a lawyer.

Chapter I.

The manner in which indulgence and caprice on the part of the parent, lead to the demoralization and ruin of the child, is illustrated by the history of Rodolphus.

I. Bad Training.

Rodolphus, whatever may have been his faults, was certainly a very ingenious boy. When he was very young he made a dove-house in the end of his father's shed, all complete, with openings for the doves to go in and out in front, and a door for himself behind. He made a ladder, also, by which he could mount up to the door. He did all this with boards, which he obtained from an old fence, for material, and an ax, and a wood saw, for his only tools. His father, when he came to see the dove-house, was much pleased with the ingenuity which Rodolphus had displayed in the construction of it—though he found fault with him for taking away the boards from the fence without permission. This, however, gave Rodolphus very little concern.

When the dove house was completed, Rodolphus obtained a pair of young doves from a farmer who lived about a mile away, and put them into a nest which he made for them in a box, inside.

At another time not long after this, he formed a plan for having some rabbits, and accordingly he made a house for them in a corner of the yard where he lived, a little below the village of Franconia. He made the house out of an old barrel. He sawed a hole in one side of the barrel, near the bottom of it, as it stood up upon one end—for a door, in order that the rabbits might go in and out. He put a roof over the top of it, to keep out the rain and snow. He also placed a keg at the side of the barrel, by way of wing into the building. There was a roof over this wing, too, as well as over the main body of the house, or, rather, there was a board placed over it, like a roof, though in respect to actual use this covering was more properly a lid than roof, for the keg was intended to be used as a store-room, to keep the provisions in, which the rabbits were to eat. The board, therefore, which formed the roof of the wing of the building, was fastened at one edge, by leather hinges, and so could be lifted up and let down again at pleasure.

Rodolphus's mother was unwilling that he should have any rabbits. She thought that such animals in Rodolphus's possession would make her a great deal of trouble. But Rodolphus said that he would have some. At least, he said, he would have one.

Rodolphus was standing in the path, in front of the door of his mother's house, when he said this. His mother was upon the great flat stone which served for a step.

“But Beechnut asks a quarter of a dollar for his rabbits.” said his mother, in an expostulating tone, “and you have not got any money.”

“Ah, but I know where I can get some money,” said Rodolphus.

“Where?” said his mother.

[pg 434]“Father will give it to me,” said Rodolphus.

“But I shall ask him not to give it to you,” said his mother.

“I don't care,” said Rodolphus. “I can get it, if you do.”

“How?” asked his mother.

Rodolphus did not answer, but began to turn summersets and cut capers on the grass, making all sorts of antic gestures and funny grimaces toward his mother. Mrs. Linn, for that was his mother's name, laughed, and then went into the house, saying, as she went, “Oh, Rolf, Rolf, what a little rogue you are!”

Rodolphus's father was a workman, and he was away from home almost all the day, though sometimes Rodolphus himself went to the place where he worked, to see him. When Mr. Linn came home at night, sometimes he played with Rodolphus, and sometimes he quarreled with him: but he never really governed him.

For example, when Rodolphus was a very little boy, he would climb up into his father's lap, and begin to feel in his father's waistcoat pockets for money. If his father directed him not to do so, Rodolphus would pay no regard to it. If he attempted to take Rodolphus's hands away by force, Rodolphus would scream, and struggle; and so his father, not wishing to make a disturbance, would desist. If Mr. Linn frowned and spoke sternly, Rodolphus would tickle him and make him laugh.

Finally, Rodolphus would succeed in getting a cent, perhaps, or some other small coin, from his father's pocket, and would then climb down and run away. The father would go after him, and try all sorts of coaxings and threatenings, to induce Rodolphus to bring the cent back—while Mrs. Linn would look on, laughing, and saying, perhaps, “Ah; let him have the cent, husband. It is not much.”

Being encouraged thus by his mother's interposition, Rodolphus would of course persevere, and the contest would end at last by his keeping the money. Then he would insist the next day, on going into the little village close by, and spending it for gingerbread. He would go, while eating his gingerbread, to where his father was at work, and hold it up to his father as in triumph—making it a sort of trophy, as it were, of victory. His father would shake his finger at him, laughing at the same time, and saying, “Ah, Rolf! Rolf! what a little rogue you are!”

Rodolphus, in fact, generally contrived to have his own way in almost every thing. His mother did not attempt to govern him; she tried to manage him; but in the end it generally proved that he managed her. In fact, whenever he was engaged in any contest with his mother, his father would usually take the boy's part, just as his mother had done in his contests with his father.

For instance, one winter evening when he was quite a small boy, he was sitting in a corner playing with some blocks. He was building a saw-mill. His mother was at work in a little kitchen which opened into the room where he was at play. His father was sitting on the settle, by the fire, reading a newspaper. The door was open which led into the kitchen, and Rodolphus, while he was at work upon his mill, watched his mother's motions, for he knew that when she had finished the work which she was doing, and had swept up the room, she would come to put him to bed. So Rodolphus went on building the mill, and the bridge, and the flume which was to convey the water to his mill, listening all the time to the sounds in the kitchen, and looking up from time to time, with a very watchful eye, at the door.

At length he heard the sound of the sweeping, and a few minutes afterward his mother appeared at the door, coming in. Rodolphus dropped his blocks, sprang to his feet, and ran round behind the table—a round table which stood out in the middle of the room.

“Now, Rodolphus,” said his mother, in a tone of remonstrance, looking at the same time very seriously at him. “It is time for you to go to bed.”

Rodolphus said nothing, but began to dance about, looking at his mother very intently all the time, and moving this way and that, as she moved, so as to keep himself exactly on the opposite side of the table from her.

“Rodolphus!” said his mother, in a very stern and commanding tone. “Come to me this minute.”

Rodolphus continued his dancing.

Rodolphus's mother was a very beautiful young woman. Her dark glossy hair hung in curls upon her neck.

When she found that it did no good to command Rodolphus, the stern expression of her face changed into a smile, and she said,

“Well, if you won't come, I shall have to catch you, that's all.”

So saying, she ran round the table to catch him. Rodolphus ran too. His mother turned first one way and then the other, but she could not get any nearer to the fugitive. Rodolphus kept always on the farthest side of the table from her. Presently Mr. Linn himself looked up and began to cheer Rodolphus, and encourage him to run; and once when Mrs. Linn nearly caught him and he yet escaped, Mr. Linn clapped his hands in token of his joy.

Mrs. Linn was now discouraged: so she stopped, and looking sternly at Rodolphus again, she said,

“Now, Rodolphus, you must come to me. Come this minute. If you don't come, I shall certainly punish you.” She spoke these words with a great deal of force and emphasis, in order to make Rodolphus think that she was really in earnest. But Rodolphus did not believe that she was in earnest, and so it was evident that he had no intention to obey.

Mrs. Linn then thought of another plan for catching the fugitive, which was to push the table along to one side of the room, or up into a corner, and get Rodolphus out from behind it in that way. So she began to push. Rodolphus [pg 435] immediately began to resist her attempt, by pushing against the table himself, on the other side. His mother was the strongest, however, and she succeeded in gradually working the table, with Rodolphus before it, over to the further side of the room, notwithstanding all the efforts that he made to prevent it. When he found at last that he was likely to be caught, he left the table and ran behind the settle where his father was reading. His mother ran after him and caught him in the corner.

She attempted to take him, but Rodolphus began to struggle and scream, and to shake his shoulders when she took hold of them, evincing his determination not to go with her. At the same time he called out, “Father! father!”

His father looked around at the end of the settle to see what was the matter.

“He won't let me put him to bed,” said Mrs. Linn, “and it was time half an hour ago.”

“Oh, let him sit up a little while longer if he likes,” said Mr. Linn. “It's of no use to make him cry.”

Mrs. Linn reluctantly left Rodolphus, murmuring to herself that he ought to go to bed. Very soon, she said, he would be asleep upon the floor. “I would make him go,” she added, “only if he cries and makes a noise, it will wake Annie.”

In fact Annie was beginning to move a little in the cradle then. The cradle in which Annie was sleeping was by the side of the fire, opposite to the settle. Mrs. Linn went to it, to rock it, so that Annie might go to sleep again, and Rodolphus returned victorious to his mill.

These are specimens of the ways in which Rodolphus used to manage his father and mother, while he was quite young. He became more and more accomplished and capable in attaining his ends as he grew older, and finally succeeded in establishing the ascendency of his own will over that of his father and mother, almost entirely.

He was about four years old when the incidents occurred which have been just described. When he was about five years old, he used to begin to go and play alone down by the water. His father's house was near the water, just below the bridge. There were some high rocks near the shore, and a large flat rock rising out of the water. Rodolphus liked very much to go down to this flat rock and play upon it. His mother was very much afraid to have him go upon this rock, for the water was deep near it, and she was afraid that he might fall in. But Rodolphus would go.

The road which led to Mr. Linn's from the village, passed round the rocks above, at some distance above the bank of the stream. There was a fence along upon the outer side of the road, with a little gate where Rodolphus used to come through. From the gate there was a path, with steps, which led down to the water. At one time, in order to prevent Rodolphus from going down there, Mr. Linn fastened up the gate. Then Rodolphus would climb over the fence. So his father, finding that it did no good to fasten up the gate, opened it again.

Not content with going down to the flat stone contrary to his mother's command, Rodolphus would sometimes threaten to go there and jump off, by way of terrifying her, when his mother would not give him what he wanted. This would frighten Mrs. Linn very much, and she would usually yield at once to his demands, in order to avert the danger. Finally she persuaded her husband to wheel several loads of stones there and fill up the deep place, after which she was less uneasy about Rodolphus's jumping in.

Rodolphus was about ten years old when he made his rabbit house. Annie, his sister, had grown up too. She was two years younger than Rodolphus, and of course was eight. She was beautiful like her mother. She had blue eyes, and her dark hair hung in curls about her neck. She was a gentle and docile girl, and was often much distressed to see how disobedient and rebellious Rodolphus was toward his father and mother.

She went out to see the rabbit house which Rodolphus had made, and she liked it very much See wished that her mother would allow them to have a rabbit to put into it, and she said so, as she stood looking at it, with her hands behind her.

“I am sorry, that mother is not willing that you should have a rabbit,” said she.

“Oh, never mind that,” said Rodolphus, “I'll have one for all that, you may depend.”

That evening when Mr. Linn came home from his work, he took a seat near the door, where he could look out upon the little garden. His mother was busy setting the table for tea.

“Father,” said Rodolphus, “I wish you would give me a quarter of a dollar.”

“What for,” said Mr. Linn.

“To buy a rabbit,” said Rodolphus.

“No,” said his mother, “I wish you would not give him any money. I have told him that I don't wish him to have any rabbits.”

“Yes,” said Rodolphus, speaking to his father. “Do, it only costs a quarter of a dollar to get one, and I have got the house all ready for him.”

“Oh, no, Rolfy,” said his father. “I would not have any rabbits. They are good for nothing but to gnaw off all the bark and buds in the garden.”

Here there followed a long argument between Rodolphus on the one side, and his father and mother on the other, they endeavoring in every possible way to persuade him that a rabbit would be a trouble and not a pleasure. Of course, Rodolphus was not to be convinced. His father however, refused to give him any money, and Rodolphus ceased to ask for it. His mother thought that he submitted to his disappointment with very extraordinary good-humor. But the fact was, he was not submitting to disappointment at all. He had formed another plan.

He began playing with Annie about the yard [pg 436] and garden, saying no more, and apparently thinking no more about his rabbit, for some time. At last he came up to his father's side and said,

“Father, will you lend me your keys?”

“What do you want my keys for?” asked his father.

“I want to whistle with them,” said Rodolphus. “Annie is my dog, and I want to whistle to her.”

“No,” said his father, “you will lose them. You must whistle with your mouth.”

“But I can't whistle with my mouth, Annie makes me laugh so much. I must have the keys.”

So saying, Rodolphus began to feel in his father's pockets for the keys. Mr. Linn resisted his efforts a little, remonstrating with him all the time, and saying that he could not let his keys go. Rodolphus, however, persevered, and finally succeeded in getting the keys, and running away with them.

His father called him to come back, but he would not come.

Rodolphus whistled in one of the keys a few minutes, playing with Annie, and then, after a little while, he said to her, in a whisper, and in a very mysterious manner,

“Annie, come with me!”

So saying, he went round the corner of the house, and there entering the house by means of a door which led into the kitchen, he passed through into the room where his father was sitting, without being seen by his father. He walked very softly as he went, too, and so the sound of his footsteps was not heard. Annie remained at the door when Rodolphus went in. She asked him as he went in what he was going to do, but Rodolphus only answered by saying in a whisper, “Hush! Wait here till I come back.”

Rodolphus crept slowly up to a bureau which stood behind a door. There was a certain drawer in this bureau where he knew that his father kept his money. He was going to open this drawer and see if he could not find a quarter of a dollar. He succeeded in putting the key into the key-hole, and in unlocking the drawer without making much noise. He made a little noise, it is true, and though his father heard it as he sat at the door looking out toward the garden, his attention was not attracted by it. He thought, perhaps, that it was Rodolphus's mother, doing something in that corner of the room.

Rodolphus pulled the drawer open as gently and noiselessly as he could. In a corner of the drawer he saw a bag. He knew that it was his father's money-bag. He pulled it open and put his hand in, looking round at the same time stealthily, to see whether his father was observing him.

Just at that instant, Mr. Linn looked round.

“Rolf, you rogue,” said he, “what are you doing'”

Rodolphus did not answer, but seized a small handful of money and ran. His father started up and pursued him. Among the coins which Rodolphus had seized there was a quarter of a dollar, and there were besides this several smaller silver coins, and two or three cents. Rodolphus took the quarter of a dollar in one hand, as he ran, and threw the other money down upon the kitchen floor. His father stopped to pick up this money, and by this means Rodolphus gained distance. He ran out from the kitchen into the yard, and from the yard into the road—his father pursuing him. Rodolphus went on at the top of his speed, filling the air with shouts of laughter.

He scrambled up a steep path which led to the top of the rocks; his father stopped below.

“Ah, Rolfy!” said his father, in an entreating sort of tone. “Give me back that money; that's a good boy.”

Rolfy did not answer, but stood upon a pinnacle of the rock, holding one of his hands behind him.

“Did you throw down all the money that you took,” said his father.

“No,” said Rodolphus.

“How much have you got now?” said his father.

“A quarter of a dollar,” said the boy.

“Come down, then, and give it to me,” said his father. “Come down this minute.”

“No,” said Rodolphus, “I want it to buy my rabbit.”

Mr. Linn paused a moment, looking perplexed, as if uncertain what to do.

At length he said,

“Yes, bring back the money, Rolfy, that's a good boy, and to-morrow I'll go and buy you a rabbit myself.”

Rodolphus knew that he could not trust to such a promise, and so he would not come. Mr. Linn seemed more perplexed than ever. He began to be seriously angry with the boy, and he resolved, that as soon as he could catch him, he would punish him severely: but he saw that it was useless to attempt to pursue him.

Rodolphus looked toward the house, and there he saw his mother standing at the kitchen-door, laughing. He held up the quarter of a dollar toward her, between his thumb and finger, and laughed too.

“If you don't come down, I shall come up there after you,” said Mr. Linn.

“You can't catch me, if you do,” said Rodolphus.

Mr. Linn began to ascend the rocks. Rodolphus, however, who was, of course, more nimble than his father, went on faster than his father could follow. He passed over the highest portion, of the hill, and then clambered down upon the other side, to the road. He crossed the road, and then began climbing down the bank, toward the shore. He had often been up and down that path before, and he accordingly descended very quick and very easily.

When he reached the shore, he went out to the flat rock, and there stopped and turned round to look at his father. Mr. Linn was standing on the brink of the cliff, preparing to come down.

“Stop,” said Rodolphus to his father. “If you come down, I will throw the quarter of a dollar into the water.”

[pg 437]So saying, Rodolphus extended his hand as if he were about to throw the money off, into the stream.

Mrs. Linn and Annie had come out from the house, to see how Mr. Linn's pursuit of the fugitive would end; but instead of following Rodolphus and his father over the rocks, they had come across the road to the little gate, where they could see the flat rock on which Rodolphus was standing, and his father on the cliffs above. Mrs. Linn stood in the gateway. Annie had come forward, and was standing in the path, at the head of the steps. When she saw Rodolphus threatening to throw the money into the river, she seemed very much concerned and distressed. She called out to her brother, in a very earnest manner.

“Rodolphus! Rodolphus! That is my father's quarter of a dollar. You must not throw it away.”

“I will throw it away,” said Rodolphus, “and I'll jump into the water myself, in the deepest place that I can find, if he won't let me have it to buy my rabbit with.”

“I would let him have it, husband,” said Mrs. Linn, “if he wants it so very much. I don't care much about it, on the whole. I don't think the rabbit will be any great trouble.”

When Rodolphus heard his mother say this, he considered the case as decided, and he walked off from the flat rock to the shore, and from the shore up the path to his mother. There was some further conversation between Rodolphus and his parents in respect to the rabbit, but it was finally concluded that the rabbit should be bought, and Rodolphus was allowed to keep the quarter of a dollar accordingly.

Such was the way in which Rodolphus was brought up in his childhood. It is not surprising that he came in the end to be a very bad boy.

II. Ellen.

The next morning after Rodolphus had obtained his quarter of a dollar in the manner we have described, he proposed to Annie to go with him to buy his rabbit. It would not be very far, he said.

“I should like to go very much,” said Annie, “if my mother will let me.”

“O, she will let you,” said Rodolphus, “I can get her to let you.”

Rodolphus waited till his father had gone away after breakfast, before asking his mother to let Annie go with him. He was afraid that his father might make some objection to the plan. After his father had gone, he went to ask his mother.

At first she said very decidedly that Annie could not go.

“Why not?” asked Rodolphus.

“Oh, I could not trust her with you so far,” replied his mother, “she is too little.”

There followed a long and earnest debate between Rodolphus and his mother, which ended at last in her consent that Annie should go.

Rodolphus found a basket in the shed, which he took to bring his rabbit home in. He put a cloth into the basket, and also a long piece of twine. The cloth was to spread over the top of the basket, and the twine to tie round it, in order to keep the rabbit in.

When Rodolphus was ready to go, his mother told him that she was afraid that he might lose his quarter of a dollar on the way, and in order to make it more secure, she proposed to tie it up for him in the corner of a pocket handkerchief.

“Why, that would not do any good, mother,” said Rodolphus, “for then I should only lose handkerchief and all.”

“No,” replied his mother. “You would not be so likely to lose the handkerchief. The handkerchief could not be shaken out of your pocket so easily, nor get out through any small hole. Besides, if you should by any chance lose the money, you could find it again much more readily if it was tied up in a handkerchief, that being so large and easily seen.”

So Mrs. Linn tied the money in the corner of a pocket handkerchief, and then put the handkerchief itself in Rodolphus's pocket.

The place where Rodolphus lived was in Franconia, just below the village. There was a bridge in the middle of the village with a dam across the stream just above it. There were mills near the dam. Just below the dam the water was very rapid.

Rodolphus walked along with Annie till he came to the bridge. On the way, as soon as he got out of sight of the house, he pulled the handkerchief out of his pocket, and began untying the knot.

“What are you going to do?” asked Annie.

“I am going to take the money out of this pocket handkerchief,” said Rodolphus.

So saying he untied the knot, and when he had got the money out he put the money itself in one [pg 438] pocket and the handkerchief in the other, and then walked along again.

When Rodolphus reached the bridge he turned to go over it. Annie was at first afraid to go over it. She wanted to go some other way.

“There is no other way,” said Rodolphus.

“Where is it that you are going to get the rabbit?” asked Annie.

“To Beechnut's,” said Rodolphus.

“Beechnut's,” repeated Annie, “that's a funny name.”

“Why, his real name is Antonio,” said Rodolphus. “But, come, walk along; there is no danger in going over the bridge.”

Notwithstanding her brother's assurances that there was no danger, Annie was very much afraid of the bridge. She however walked along, but she kept as near the middle of the roadway as she could. Sometimes she came to wide cracks in the floor of the bridge, through which she could see the water foaming and tumbling over the rocks far below. There was a sort of balustrade or railing each side of the bridge, but it was very open. Rodolphus went to this railing and putting his head between the bars of it, looked down.

Annie begged him to come back. But he said he wished to look and see if there were any fishes down there in the water. In the mean time Annie walked along very carefully, taking long steps over the cracks, and choosing her way with great caution. Presently she heard a noise behind her, and looking round she saw a wagon coming. This frightened her more than ever. So she began to run as fast as she could run, and very soon she got safely across the bridge. When she reached the land, she went out to the side of the road to let the wagon go by, and sat down there to wait for her brother.

Presently Rodolphus came. Annie left her seat and went back into the road to meet him, and so they walked along together.

“If his name is truly Antonio,” said Annie, “why don't you call him Antonio?”

“Oh, I don't know,” said Rodolphus, “the boys always call him Beechnut.”

“I mean to call him Antonio,” said Annie, “if I see him.”

“Well, you will see him,” said Rodolphus, “for we go right where he lives.”

“Where does he live?” asked Annie.

“He lives at Phonny's,” said Rodolphus.

“And where is Phonny's?” asked Annie.

“Oh, it is a house up here by the valley. Didn't you ever go there?”

“No,” said Annie.

“It is a very pleasant house,” said Rodolphus. “There is a river in front of it, and a pier, and a boat. There is a boat-house, too. There used to be a little girl there, too—just about as big as you.”

“What was her name?” asked Annie.

“Malleville,” replied Rodolphus.

“I have heard about Malleville,” said Annie.

“How did you hear about her?” asked Rodolphus.

“My sister Ellen told me about her,” said Annie.

“We can go and see Ellen,” said Rodolphus, “after we have got the rabbit.”

“Well,” said Annie, “I should like to go and see her very much.”

Rodolphus and Annie had a sister Ellen. She was two years older than Rodolphus. Rodolphus was at this time about ten. Ellen was twelve. Antonio was fourteen. Ellen did not live at home. She lived with her aunt. She went to live with her aunt when she was about eight years old. Her aunt lived in a small farm-house among the mountains, and when Ellen was about eight years old, she was taken sick, and so Ellen went to the house to help take care of her.

Ellen was a very quiet and still, and at the same time a very diligent and capable girl. She was very useful to her aunt in her sickness. She took care of the fire, and kept the room in order; and she set a little table very neatly at the bedside, when her aunt got well enough to take food.

It was a long time before her aunt was well enough to leave her bed, and then she could not sit up much, and she could not walk about at all. She could only lie upon a sort of sofa, which her husband made for her in his shop. So Ellen remained to take care of her from week to week, until at last her aunt's house became her home altogether.

Ellen liked to live at her aunt's very much, for the house was quiet, and orderly, and well-managed, and every thing went smoothly and pleasantly there. At home, on the other hand, every thing was always in confusion, and Rodolphus made so much noise and uproar, and encroached so much on the peace and comfort of the family by his self-will and his domineering temper, that Ellen was always uneasy and unhappy when she was at her mother's. She liked to be at her aunt's, therefore, better; and as her aunt liked her, she gradually came to make that her home. Rodolphus used frequently to go and see her, and even Annie went sometimes.

Annie was very much pleased with the plan of going now to make Ellen a visit. They walked quietly along the road, talking of this plan, when Annie suddenly called out;

“Oh, Rodolphus, look there!”

Rodolphus looked, and saw a drove of cattle coming along the road. It was a very large drove, and it filled up the road almost entirely.

“Who cares for that?” said Rodolphus.

Annie seemed to care for it very much. She ran out to the side of the road.

Rodolphus walked quietly after her, saying, “Don't be afraid, Annie. You can climb up on the fence, if you like, till they get by.”

There was a large stump by the side of the fence, at the place where Rodolphus and Annie approached it, and Rodolphus, running to it, said, “Quick, Annie, quick! climb up on this stump.”

Rodolphus climbed up on the stump, and then helped Annie up after him. They had, however, but just got their footing upon it, when Rodolphus looked down at his feet and saw a hornet [pg 439] crawling out of a crevice in the side of the stump. “Ah, Annie, Annie! a hornet's nest! a hornet's nest!” exclaimed Rodolphus; “we must run.”

So saying, Rodolphus climbed down from the stump, on the side opposite to where he had seen the hornet come out, and then helped Annie down.

“We must run across to the other side of the road,” said he.

So saying, he hurried back into the road again, leading Annie by the hand. They found, however, that they were too late to gain the fence on the other side, for several of the cattle had advanced along by the green bank on that side so far that the fence was lined with them, and Rodolphus saw at a glance, that he could not get near it.

“Never mind, Annie,” said Rodolphus, “we will stay here, right in the middle of the road. Stand behind me, and I will keep the cattle off with my basket.”

So Annie took her stand behind Rodolphus, in the middle of the road, while Rodolphus, by swinging his basket to and fro, toward the cattle as they came on, made them separate to the right and left, and pass by on each side. Rodolphus, besides waving his basket at the cattle, shouted to them in a very stern and authoritative manner, saying, “Hie! Whoh! Hie-up, there! Ho!” The cattle were slow to turn out—but they did turn out, just before they came to where Rodolphus and Annie were standing—crowding and jamming each other in great confusion. The herd closed together again as soon as they had passed the children, so that for a time Rodolphus and Annie stood in a little space in the road, with the monstrous oxen all around them.

At length the herd all passed safely by, and then Rodolphus and Annie went on. After walking along a little farther, they came to the bank of a river. The road lay along the bank of this river. There was a smooth sandy beach down by the water. Rodolphus and Annie went down there a few minutes to ploy. There was an old raft there. It was floating in the water, but was fastened by a rope to a stake in the sand.

“Ah, here is a raft, Annie,” said Rodolphus. “I'll tell you what we will do. We will go the rest of the way by water, on this raft. I'm tired of walking so far.”

“Oh, no,” said Annie, “I'm afraid to go on that raft. It will sink.”

“O, no,” said Rodolphus, “it will not sink. See.” So saying, he stepped upon the raft, to show Annie how stable it was.

“I'll get a block,” he continued, “for you to sit on.”

Annie was very much afraid of the raft, though she was not quite so much afraid of it as she had been of the bridge, because the bridge was very high up above the water, and there was, consequently as she imagined, danger of a fall. Besides the water where the raft was lying, was smooth and still, while that beneath the bridge was a roaring torrent. Finally, Annie allowed herself to be persuaded to get upon the raft. Rodolphus found a block lying upon the shore, and he put that upon the raft for Annie to sit upon. When Annie was seated, Rodolphus stepped upon the raft himself, and with a long pole he pushed it out from the shore, while Annie balanced herself as well as she could upon the block.

The water was not very deep, and Rodolphus could push the raft along very easily, by setting the end of his pole against the bottom Annie sat upon her block very still. It happened, however, unfortunately, that the place where Antonio lived was up the stream, not down, and Rodolphus found that though he could move his raft very easily round and round, and even back and forth, he could not get forward much on his way, on account of the force of the current, which was strong against him. He advanced a little way, however, and then he began to be tired of so difficult a navigation.

“I don't think we shall go very far, on the raft,” said he, to Annie, “there is such a strong tide.”

Just then Rodolphus began to look very intently into the water before him. He thought he saw a pickerel. He was just going to attempt to spear him with his pole, when his attention was arrested by hearing Annie call out, “Oh, Rolfy! Rolfy! the raft is all coming to pieces”

Rodolphus looked round, and saw that the boards of which the raft had been made, were separating from each other at the end of the raft where Annie was sitting, and one of the boards was shooting out entirely.

“So it is,” said Rodolphus. “Why didn't they nail it together? You sit still, and I will push in to the shore.”

Rodolphus attempted to push in to the shore, but in the strenuous efforts which he made for that purpose, he stepped about upon the raft irregularly and in such a manner, as to make the boards separate more and more. At length the water began to come up around Annie's feet, and Rodolphus alarmed at this, hurriedly directed her to stand up, on the block. Annie tried to do so, but before she effected her purpose, the raft seemed evidently about going to pieces. It had, however, by this time got very near the shore, so Rodolphus changed his orders, and called out, “Jump, Annie, jump!”

Annie jumped; but the part of the raft on which she was standing gave way under her feet, and she came down into the water. The water was not very deep. It came up, however, almost to Annie's knees. Rodolphus himself had leaped over to the shore, and so had, himself, escaped a wetting. He took Annie by the hand, and led her also out to the dry land.

Annie began to cry. Rodolphus soothed and quieted her as well as he could. He took off her stockings and shoes. He poured the water out of the shoes, and wrung out the stockings. He also wrung out Annie's dress as far as possible. He told her not to mind it; her clothes would soon get dry. It was all the fault of the boys, he said, who made the raft, for not nailing it together.

Rodolphus had had presence of mind enough to seize his basket, when he leaped ashore, so that that was safe. The raft, however, went all to pieces, and the fragments of it floated away down the stream.

Rodolphus and Annie then resumed their journey. Rodolphus talked fast to Annie, and told her a great many amusing stories, to divert her mind from the misfortune which had happened to them. He charged her not to tell her mother, when she got home, that she had been in the water, and made her promise that she would not.

At length they came to a large house which stood back from the road a little way, at the entrance to a valley. This was the house, Rodolphus said, where Beechnut lived. Rodolphus opened a great gate, and he and Annie went into the yard.

“I think that Beechnut is in some of the barns, or sheds, or somewhere,” said Rodolphus.

So he and Annie went to the barns and sheds. There was a horse standing in one of the sheds, harnessed to a wagon, but there were no signs of Beechnut.

“Perhaps he is in the yard,” said Rodolphus.

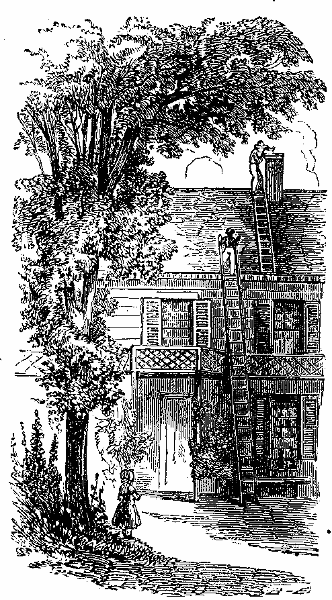

So Rodolphus led the way through a shed to a sort of back-yard, where there was a plank-walk, with lilac-bushes and other shrubbery on one side of it. Rodolphus and Annie walked along upon the planks. Presently, they came to a place where there was a ladder standing up against the house.

“Ah!” said Rodolphus, “he is upon the house. Here is the ladder. I think he is doing something on the house. I mean to go and see.”

“No,” said Annie, “you must not go up on such a high place.”

“Oh, this is not a very high ladder,” said Rodolphus. So saying he began to go up. Annie stood below, looking up to him as he ascended, and feeling great apprehension lest he should fall.

The top of the ladder reached up considerably above the top of the house, and Rodolphus told Annie that he was not going to the top of the ladder, but only high enough to see if Beechnut was on the house. He told her, too, that if she walked back toward the garden gate, perhaps she could see too. Annie accordingly walked back, and looking upward all the time, she presently saw a young man who she supposed was Beechnut, doing something to the top of one of the chimneys. By this time Rodolphus had reached the eaves of the house, in climbing up the ladder, and he came in sight of Beechnut, too.

“Hie-yo! Dolphin!” said Beechnut, “is that you!”

Beechnut often called Rodolphus, Dolphin.

“May I come up where you are?” said Rodolphus.

“No,” said Beechnut.

When Rodolphus heard this answer, he remained quietly where he was upon the ladder.

“What are you doing?” said Rodolphus.

“Putting a wire netting over the chimney,” said Beechnut.

“What for!” asked Rodolphus.

[pg 441]“To keep the chimney-swallows from getting in,” said Beechnut.

“Are you coming down pretty soon?” asked Rodolphus.

“Yes,” said Beechnut. “Go down the ladder and wait till I come.”

So Rodolphus went down the ladder again to Annie.

“What is the reason,” said Annie, “that you obey Beechnut so much better than you do my father?”

“Oh, I don't know,” said Rodolphus. “He makes me, I suppose.”

It was true that Beechnut made Rodolphus obey him—that is, in all cases where he was under any obligation to obey him. One day, when he first became acquainted with Beechnut, he went out upon the pond in Beechnut's boat. He wished to row, but Beechnut preferred that some other boy should row, and directed Rodolphus to sit down upon one of the thwarts. Rodolphus would not do this, but was determined to row, and he attempted to take away one of the oars by force. Beechnut immediately turned the head of the boat toward the shore, and when he reached the shore he directed four of the strongest boys to put Rodolphus out upon the sand, and then when they had done this he sailed away in the boat again. Rodolphus took up clubs and stones, and began to throw them at the boat. Beechnut came back again, and seizing Rodolphus, he tied his hands behind him with a strong cord. When he was thus secured Beechnut said to him,

“Now, you may have your choice of two things. You may stay here till we come back from our excursion, and then, if you seem pretty peaceable, I will untie you. Or you may go home now, as you are, with your hands tied behind you in disgrace.”

Rodolphus concluded to remain where he was; for he was well aware that if he were to go home through the village with his hands tied behind him, every body would know that the tying was one of Beechnut's punishments, and that it had not been resorted to without good reason. Some of the boys thought that after this occurrence Beechnut would not be willing to have Rodolphus go with them again in the boat, but Beechnut said “Yes; he may go with us whenever he pleases. I don't mind having a rebel on board at all. I know exactly what to do with rebels.”

“But it is a great trouble,” said one of the boys, “to have them on board.”

“Not at all,” said Beechnut, “on the other hand it is a pleasure to me to discipline them.”

Rodolphus very soon found that it was useless to resist Beechnut's will, in any case where Beechnut had the right to control; and so he soon formed the habit of obeying him. He liked Beechnut too, very much. He liked him in fact, all the better, on account of his firmness and decision.

When Beechnut came down from the housetop, Rodolphus told him he had come to get a rabbit, and at the same time held out the quarter of a dollar to view.

“Where did you get the money?” said Beechnut.

“My father gave it to me,” said Rodolphus.

“No,” said Annie, very earnestly, “my father did not give it to you. You took it away from him.”

“But he gave it to me afterward,” said Rodolphus.

Beechnut inquired what this meant, and Annie explained to him, as well as she could, the manner in which Rodolphus had obtained his money. Beechnut then said, that he would not take the quarter of a dollar. The money was not honestly come by, he said. It was not voluntarily given to Rodolphus, and therefore was not honestly his. “The money was stolen,” said he, “and I will not have any stolen money for my rabbits. I would rather give you a rabbit for nothing.”

This, Beechnut said finally, he would do. “I will give you a rabbit,” said he, “for the present, and whenever you get a quarter of a dollar, which is honestly your own, you may come and pay for it, if you please, and if not, not. But don't bring me any money which is not truly your own. And carry that quarter of a dollar back and give it to your father.”

So saying, Beechnut led the way, and Rodolphus and Annie followed him, into one of the barns. They walked along a narrow passageway, between a hay-mow on one side, and a row of stalls for cattle on the other. Then they turned and passed through an open room, and finally came to a place which Beechnut called a bay. Here there was a little pen, with a house in it, for the rabbits, and a hole at one side where the rabbits could run in under the barn. Beechnut called “Benny! Benny! Benny!” and immediately several rabbits came running out from the hole.

“There,” said Beechnut, “which one will you have?”

The children began immediately to examine the different rabbits, and to talk very fast and very eagerly about them. Finally, Rodolphus decided in favor of a gray one, though there was one which was perfectly white, that Annie seemed to prefer. Beechnut said that he would give Rodolphus the gray one.

“As to the white one,” said he, “I am going to let you take it, Annie, for Ellen. I can't give it to you. I give it to Ellen; but, perhaps, she will let you carry it home with you, and take care of it for her, and so keep it with Rodolphus's.”

Annie seemed very much pleased with this plan, and so the two rabbits were caught and put into the basket. The cloth was then tied over them, and Rodolphus and Annie prepared to go away.

“But, stop,” said Beechnut, “I am going directly by your aunt's in my wagon, and I can give you a ride.”

“Well,” said Annie, dancing about and clapping her hands. It was very seldom that Annie had an opportunity to take a ride. [pg 442] She ran to the wagon. Rodolphus followed her slowly, carrying the basket. Beechnut helped in the two children, and then got in himself, and took his seat between them. Rodolphus held the basket between his knees, peeping in under the cloth, now and then, to see if the rabbits were safe.

The party traveled on by a winding and very pleasant road among the mountains, for about a mile, and at length they drove up to the door of a pleasant little farm-house in a sort of dell. There was a high hill behind it—overhung with forest trees. There was a spacious yard at the end of the house, with ducks, and geese, and chickens, in the back part of it. There was a large dog lying asleep on the great flat stone step when the wagon came up, but when he heard the wagon coming, awoke, opened his eyes, got up, and walked away. There was a well in the middle of the yard. Beechnut rode round the well, and drove up to the door. Ellen was sitting at the window. As soon as she saw the wagon, she got up and ran to the door.

“How do you do, Ellen!” said Beechnut.

“How do you do, Antonio!” said Ellen, “I am much obliged to you for bringing my brother and sister to see me.”

So saying, she came to the wagon and helped Annie out. Rodolphus, who was on the other side of Beechnut, then handed her his basket, saying, “Here, Ellen, take this very carefully. There are two rabbits in it, and one of them is for you.”

“For me,” said Ellen.

“Yes,” said Annie, “only I am to take care of it for you.”

“Good-by,” said Beechnut. He was just beginning, as he said this, to drive the wagon away.

“Good-by, Beechnut,” said Rodolphus.

“I am much obliged to you for my ride,” said Annie.

“Stop a minute, Antonio,” said Ellen, “I have got something for you.”

So saying, Ellen went into the house and brought out a small flat parcel, neatly put up and addressed on the outside, Antonio.

She took it out to the wagon, and handed it up to Antonio, saying that there were the last drawings that he had lent her. In fact, Ellen was one of Beechnut's pupils in drawing. He was accustomed to lend her models, which, when she had copied them, she sent back to him. Ellen was one of Antonio's favorite pupils; she was so faithful, and patient, and persevering. Besides, she was a very beautiful girl.

“I must not stop to see your copies now,” said Antonio, “but I shall come again pretty soon. Good-by.”

“Good-by,” said Ellen: and then she went back to the door where Rodolphus and Annie were standing.

Rodolphus lifted up the corner of the cloth, which covered the basket, and let Ellen see the rabbits. Ellen was very much pleased to find that one of them was hers. She said that she would put a collar on its neck, as a mark that it was hers, and she asked Rodolphus and Annie to go in with her into the house, where she said she would get the collar.

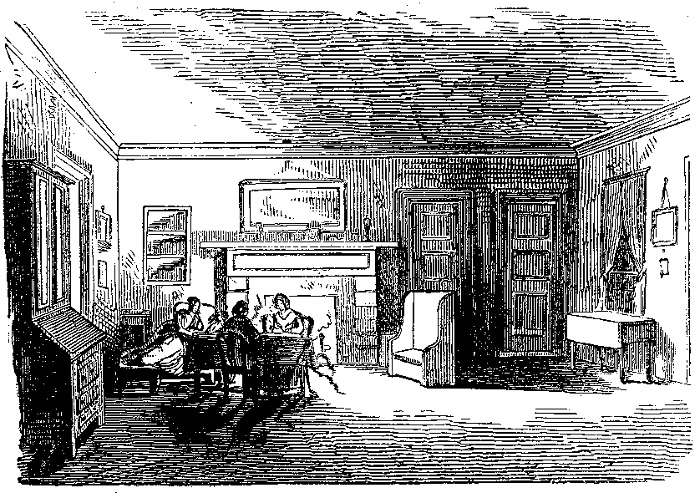

So they all went in. The room was a very pleasant room, indeed. It was large and it was in perfect order. There was a very spacious fire-place in it, but scarcely any fire. As it was summer, no fire was necessary. At one side of the room, near a window, there was a table, which Ellen said was her table. There were two drawers in this table. These drawers contained books, and papers, and various articles of apparatus for writing and drawing. In one corner of one of the drawers there was a little paint box.

There was a small bedroom adjoining the room where the children were. They all pretty soon heard a voice calling from this room, in a pleasant tone, “Ellen, bring the children in here.”

“Yes; come Rolfy,” said Ellen—“and Annie—come and see aunt.” So all the children went into their aunt's room.

They found her half-sitting and half-lying upon her sofa, by a pleasant window, which looked out upon a green yard and upon an orchard which was beyond the yard. She was sewing. She looked pale, but she seemed contented and happy—and she said that she was very glad to see Rodolphus and Annie. She talked with them some time, and then asked Ellen to get them some luncheon. Ellen accordingly went into the other room and set the table for luncheon, by her window as she called it. This window was a very pleasant one, near her table. The luncheon consisted [pg 443] of a pie, some cake, warm from the oven, and some baked apples, and cream. Ellen said that she made the cake, and the pie, and baked the apples herself.

The children ate their luncheon together very happily, and then spent some time in walking about the yards, the barns, and the garden, to see what was to be seen. Rodolphus walked about quietly and behaved well. In fact, he was always a good boy at his aunt's, and obeyed all her directions—she would not allow him to do otherwise.

At length Rodolphus and Annie set out on their return home. It was a long walk, but in due time they reached home in safety. Rodolphus determined not to give the money back to his father, and so he hid it in a crevice, which he found in a part of the fence behind his rabbit house. He put the rabbits in their house, and put a board up before the door to keep them in.

That night when Mrs. Linn took off Annie's stockings by the kitchen fire, when she was going to put her to bed, she found them very damp.

“Why, Annie,” she said, “what makes your stockings so damp? You must have got into the water somewhere to-day.”

Annie did not answer. Rodolphus had enjoined it upon her not to tell their mother of their adventure on the raft, and so she did not know what to say.

“Damp?” said Rodolphus. “Are they damp? Let me feel.” So he began to feel of Annie's stockings.

“No,” said he, “they are not damp. I can't feel that they are damp.”

“They certainly are,” said his mother. “They are very damp indeed.”

“Then,” said Rodolphus, “we must have spilled some water into them when we were getting a drink, Annie, at the well.” Annie said nothing, and Mrs. Linn hung the stockings up to dry.

III. Sickness.

Ellen's aunt was the sister of Mr. Linn, Ellen's father; and her name was Anne. Ellen used to call her Aunt Anne. Her husband's name was Randon, so that sometimes Ellen called her Aunt Randon.

Though Mr. Randon's house appeared rather small, as seen from the road by any one riding by, it was pretty spacious and very comfortable within. Mr. Randon owned several farms in different places, and he was away from home a great deal attending to his other farms and to the flocks of sheep and herds of cattle which he had upon them. During these absences Mrs. Randon of course remained at home with Ellen. There was a girl named Martha who lived at the house to do the work of the family, and also a young man named Hugh. Hugh was employed in the mornings and evenings in taking care of the barns and the cattle, and in the day-time, especially in the winter, he hauled wood—sometimes to the house for the family to burn, and sometimes to the village for sale.

The family lived thus very happily together, whether Mr. Randon was at home or away. Mrs. Randon could not walk about the house at all, but was, on the other hand, confined all day to her bed or her sofa; but she knew every thing that was done; and gave directions about every thing. Ellen was employed as messenger to carry her aunt's directions out, and to bring back intelligence and answers. Mrs. Randon knew exactly what was in every room, and where it was in the room. She knew what was in every drawer, and what was on every shelf in every closet, and what and how much was in every bin in the cellar. So that if she wanted any thing she could direct Ellen where to go to get it with a certainty that it would be exactly there. The house was very full of furniture, stores, and supplies, and all was so well arranged and in such an orderly and complete condition, that in going over it every room that the visitor entered seemed pleasanter than the one seen before.

On one occasion, Rodolphus himself had proof of this admirable order. He had cut his finger, in the shed, and when he came in, Mrs. Randon, after binding it up very nicely, turned to Ellen, and said,

“Now, Ellen, we must have a cot. Go up into the garret, and open the third trunk, counting from the west window. In the right-hand front corner of this trunk you will find a small box. In the box you will find three cots. Bring the smallest one to me.”

Ellen went and found every thing as Mrs. Randon had described it.

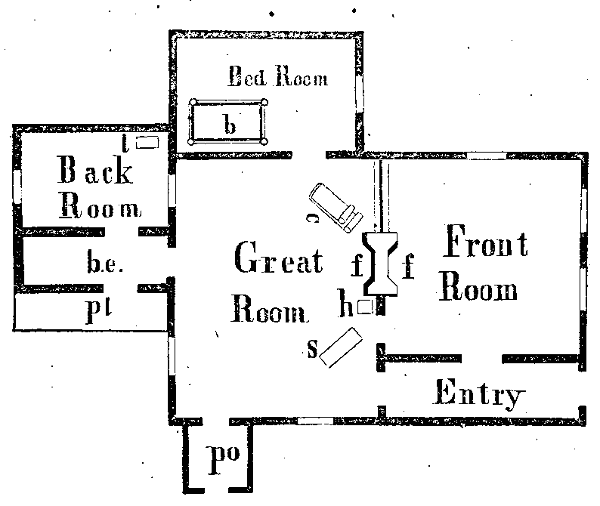

There was a room in the front part of the house called the Front Room, which was usually kept shut up. It was furnished as a parlor very prettily. It had very full curtains to the windows, a soft carpet on the floor, and a rug before the fire-place. There was a bookcase in this room, with a desk below. Mr. Randon kept his valuable papers in this desk, and the book-case above was filled with interesting books. There were several very pretty pictures on the walls of this room, and some curious ornaments on the mantle shelf. The blinds of the windows in this apartment were generally closed and the curtains drawn, and Ellen seldom went into it, except to get a new book to read to her aunt, out of the secretary.

The room which the family generally used, was a back room. It was quite large, and it had a very spacious fire-place in it. Being larger than any other room in the house it was generally called the Great Room. The windows of this room looked out upon a pretty green yard, with a garden and an orchard beyond. There was a door too at one end of the room opening to a porch. In this porch was an outer door, which led to a large yard at the end of the house. This was the door that Antonio had driven up to, when he brought Rodolphus and Annie to see Ellen. On the other side of the kitchen from the porch-door, was a door leading to Mrs. Randon's bed-room. The situation of these rooms, and of the other apartments of the house as well as of the principal articles of furniture hereafter [pg 444] to be described, may be perfectly understood by the means of the following plan.

Mrs. Randon was accustomed to remain in her bedroom almost all the time in the summer, but in the winter she had her sofa or couch brought out and placed by the side of the fire-place in the great room, as represented in the plan. Here, in the long stormy evenings of winter, the family would live together very happily. Mrs. Randon would lie reclining upon her sofa, knitting, and talking to Martha and Ellen while they were getting supper ready. Ellen would set the table, while Martha would bake the cakes and bring up the milk out of the cellar, and make the tea; and then when all was ready, they would move the table up close to Mrs. Randon's sofa, and after lifting her up and supporting her with pillows at her back, they would themselves sit down on the other side of the table, and all eat their supper together in a very happy manner.

Then, after supper, when the table had been put away, and a fresh fire had been made on the great stone hearth, Ellen would sit in a little rocking-chair by her aunt's side, and read aloud some interesting story, while Martha sat knitting on the settle, at the other side of the fire, and Hugh, on a bench in the corner, occupied himself with making clothes-pins, or shaping teeth for rakes, or fitting handles into tools, or some other work of that kind. Hugh found that unless he had such work to do, he always fell asleep while Ellen was reading.

Ellen found that her aunt, instead of growing better, rather grew worse. She was very pale, though very delicate and beautiful. Her fingers were very long, and white, and tapering. Ellen thought that they grew longer and more tapering every day. At last, one winter evening, just after tea, and before Hugh and Martha had come in to sit down, Ellen went up to the sofa, and kneeling down upon a little bear-skin rug which was there, and which had been put there to look warm and comfortable, although the poor invalid could never put her feet upon it, she bent down over her aunt and said,

“It seems to me Aunt Anne, that you don't get better very fast.”

The patient, putting her arm over Ellen's neck, and drawing Ellen down closely to her, kissed her, but did not answer.

“Do you think you shall ever get well, aunty?” said Ellen.

“No,” said her aunt, “I do not think that I shall. I think that before a great while I shall die.”

“Why, aunty!” said Ellen. She was much shocked to hear such a declaration. “I hope you will not die,” she continued presently, speaking in a very low and solemn manner. “What shall I do if you should die!—What makes you think that you will die?”

“There are two reasons why I think that I shall die,” said her aunt. “One is, that I feel that I am growing weaker and weaker all the time. I have grown a great deal weaker within a few days.”

“Have you?” said Ellen, in a tone of great anxiety and concern.

“Yes,” said her aunt. “The other reason that makes me think that I am going to die is greater still; and that is I begin to feel so willing to die.”

“I thought that you were always willing to die,” said Ellen. “I thought we ought to be all willing to die, always.”

“No,” said her aunt, “or yes, in [pg 445] one sense we ought. We ought always to be willing to submit to whatever God shall think best for us. But as to life and death, we ought undoubtedly, when we are strong and well, to desire to live.”

“God means,” she continued, “that we should desire to live, and that we should do all that we can to prolong life. He has given us an instinct impelling us to that feeling. But when sickness comes and death is nigh, then the instinct changes. We do not wish to live then—that is, if we feel that we are prepared to die. It is a very kind and merciful arrangement to have the instinct change, so that when we are well, we can be happy in the thought of living, and when we are sick and about to die, we can be happy in the thought of dying. Our instincts often change thus, when the circumstances change.”

“Do they?” said Ellen, thoughtfully.

“Yes,” said her aunt. “For instance, when you were an infant, your mother's instinctive love for you led her to wish to have you always near her, with your cheek upon her cheek, and your little hand in her bosom. Mothers all have such an instinct as that, while their children are very young. It is given to them so that they may love to have their children very near them while they are so young and tender that they would not be safe if they were away.

“But now,” she continued, “you have grown older, and the instinct has changed. Your mother loves you just as much as she did when you were an infant, but she loves you in a different way. She is willing to have you absent from her, if you are only well provided for and happy.”

“And is it so with death?” asked Ellen.

“Yes,” replied her aunt; “when we are well, we love life, and we ought to love it. It then seems terrible to die. God means that it should seem terrible to us then. But when sickness comes and we are about to die, then he changes the feeling. Death seems terrible no more. We become perfectly willing to die.”

Here Mrs. Randon paused, and Ellen remained still, thinking of what she had heard, but without speaking. After a few minutes her aunt continued.

“I have had a great change in my feelings within a short time, about dying,” said she, “I have always, heretofore, desired to live and to get well; and it has seemed to me a terrible thing to die;—to leave my pleasant home, and my husband, and my dear Ellen, and to see them no more. But somehow or other, lately, all this is changed. I feel now perfectly willing to die. It does not seem terrible at all. I have been a great sinner all my days, but I feel sure that my sins are forgiven for Christ's sake, and that if I die I shall be happy where I go, and that I shall see my husband and you too there some day.”

Ellen laid her head down by the side of her aunt's, with her face to the pillow and her cheek against her aunt's cheek, but said nothing.

“When I am gone,” continued her aunt, “you will go home and live with your mother again.”

“Shall I?” said Ellen, faintly.

“Yes,” replied her aunt, “it will be better that you should. You can do a great deal of good there. You can gradually get the house in order, taking one thing at a time, and so not only help your mother, but make it more pleasant and comfortable for your father. You can also teach Annie, and be a great help to her as she grows up; and you can also perhaps do a great deal of good to Rodolphus.”

“I don't know what I shall do with Rodolphus,” said Ellen. “He troubles my mother very much indeed.”

“I know he does,” said her aunt, “but then you will soon get a great influence over him, and it is possible that you will succeed in making him a good boy.”

As Mrs. Randon said this, Ellen heard the sound of a door opening in the back entry, and a stamping of feet upon the floor, as if some one were coming in out of the snow.

“There comes Hugh,” said Ellen, “and I think there is going to be a storm.”

Signs of a gathering storm had in fact been appearing all that day. For several days before, the weather had been very clear and cold, but that morning the cold had diminished, and a thin haze had gradually extended itself over the sky. At sunset the sky looked thick and murky toward the southeast, and it became dark much sooner than usual. A moment after Ellen had spoken, Hugh came in. He said that it was snowing, and that two or three inches of snow had already fallen; and that if it snowed much during the night he should not be able to go into the woods the next morning.

When Ellen rose the next morning and looked at the windows, she saw that the snow was piled up against the panes of glass on the outside, and on going to the window to look out, she found that it was snowing still, and that all the old snow and all the roads and tracks upon it, were entirely covered. Ellen went out into the great room, and there she found a blazing fire in the fireplace, and Martha before it getting breakfast ready. Pretty soon Hugh came in.

“What a great snow-storm,” said Ellen.

“No,” said Hugh, “it is not a very great snow-storm. It does not snow very fast.”

“Can you go into the woods to-day?” said Ellen.

“Yes,” said Hugh, “I am going into the woods for a load of wood to haul to the village. The snow is not very deep yet.”

Hugh went to the woods, got his load, hauled it to the village, and returned to dinner. After dinner he went again. Ellen was almost afraid to have him go away in the afternoon, for her aunt appeared to be more and more unwell. She lay upon her sofa by the side of the fire, silent and still, apparently without pain, but very faint and feeble. She spoke very seldom, and then only in a whisper. At one time about the middle of the afternoon, Ellen went and stood a moment at the window to see the snow driving by—blown by the wind along the crests of the drifts, and over the walls, down the road. When she turned round, she saw that her aunt was [pg 446] beckoning to her with her white and slender finger. Ellen went immediately to her.

“Is Hugh going to the village this afternoon?” she asked.

“Yes, aunt,” said Ellen, “I believe he is.”

“I wish you would ask him to call at my brother George's, and tell him that I am very sick, and ask him if he can not come up and see me this evening.”

“Yes, aunt,” said Ellen, “I will.”

Ellen accordingly watched for Hugh when he came down the mountain-road with the load of wood, on the way to the village. She gave him the message, standing at the stoop-door. The wind howled mournfully over the trees of the forest, and the air was thick with falling and driving snow. Hugh said that he had almost concluded not to go to the village. The snow had become so deep, and the storm was increasing so fast, that he doubted very much whether he could get back if he should go. On receiving Ellen's message, however, he decided at once to go on. He could get to the village well enough, he said, for it was a descending road all the way; but there would be more uncertainty about the return.

So he started his four oxen again, and they went wallowing on, followed by the great loaded sled, with the runners buried in the drift. Hugh's cap and shaggy coat, and the handkerchief which he had tied about the collar of his coat, after turning it up to cover his ears, were all whitened with the snow, and from among all these various mufflings his face, reddened with the cold, peeped out, though almost wholly concealed from view.

As soon as Hugh was gone, Ellen, who was by this time almost blinded by the snow which the wind blew furiously into her face and eyes, came into the house and shut the door.

Ellen watched very diligently all the afternoon for the coming of her father. She hoped that he would bring her mother with him. She went to the window again and again, and looked anxiously down the road, but nothing was to be seen but the thick and murky atmosphere, the increasing drifts, and the scudding wreaths of snow. The fences and the walls gradually disappeared from view; the great wood pile in the yard was soon completely covered and concealed; and a deep drift, of the form of a wave just curling over to break upon the shore, slowly rose directly across the entrance to the yard, until it was higher than the posts on each side of the gateway, so that Ellen began to fear that if her father and mother should come, they would not be able to get into the yard.

At length it gradually grew dark, and then, though Ellen went to the window as often as before, and attempted to shade her eyes from the reflection of the fire, by holding up her hands to the side of her face, she could watch these changes no longer. Nothing was to be seen, but the trickling of the flakes down the panes of glass on the outside, and a small expanse of white immediately below the window.

In the mean time, within the room where Ellen's aunt was reposing, all seemed, at least in appearance, very bright and cheerful. A great log was lying across the andirons, behind and beneath which there was a blazing and glowing fire. There was a tin baker before this fire, with a pan of large apples in it, which Martha was baking, to furnish the table with, for the expected company. Martha herself was busy at a side-table too, making cakes for supper. The tea-kettle was in a corner, with a column of steam rising gently from the spout, and Ellen's little gray kitten, Lutie, was in the other corner asleep. Ellen herself was busy, here and there, about the room. She went often to the window, even after it was too dark to see, and she watched her aunt continually with a countenance expressive of much affection and concern. Her aunt lay perfectly quiet and still, as if she were asleep, only she would now and then open her eyes and smile upon Ellen, if she saw Ellen looking at her, and then close them again.

The couch that she was lying upon had little wheels at the four corners of it toward the floor, so that it could be moved to and fro. Ellen had been accustomed, when the time arrived for her aunt to go to bed, to ask Martha to help her move the couch into the bedroom, by the side of the bed, and then assist her in moving the patient from one to the other. Ellen, accordingly, about an hour after it became dark, went to her aunt's couch, and asked her in a gentle tone if she would not like to go to bed. But her aunt said no. She would not be moved, she said, but would remain as she was until her brother should come. She said, too, that Martha and Ellen might eat their supper when it was ready, and leave her where she was.

Martha and Ellen finished their supper about seven o'clock. Martha then took her place upon the settle with her knitting-work as usual, and Ellen went and sat down upon the little bear-skin rug, and leaned her head toward her aunt. Her aunt put out her hand toward Ellen's cheek and pressed her head gently down upon the pillow, by the side of her own, and then very slowly and feebly moved her fingers, once or twice, down the hair on Ellen's temple, as if she were pleased to have her little niece lying near her. Ellen shut her eyes, and for a few minutes enjoyed very much the thought that she was such an object of affection to one whom she loved so much; but after a few minutes, she began to lose her consciousness, and soon fell fast asleep.

She slept more than an hour. It was in fact nearly half-past eight when she awoke. She raised her head and looked up. She found that Martha had fallen asleep too. Her knitting-work had dropped from her hand. Ellen did not wish to disturb her, so she rose softly, went to the fire, and put up a brand which had fallen down, and then crossed the room to the window, parted the curtains, and putting her face close to the glass, attempted to look out. Nothing was to be seen. She listened. Nothing was to be heard but the dreadful roaring of the wind, and [pg 447] the clicking of the snow-flakes against the windows.

Ellen came back to the couch again, and looked at her aunt as she lay with her cheek upon her pillow, apparently asleep. At first Ellen thought that she was really asleep, but when she came near, she found that her eyes were not entirely closed. She kneeled down by the side of the couch and said gently, “Aunt Anne, Aunt Anne, how do you feel now?”

Ellen saw that her aunt moved a little, and she heard a faint whispering sound, but there was no audible answer.

Ellen was now frightened. She feared that her aunt might be dying. She went to Martha and woke her. Martha started up much alarmed. Ellen told her that she was afraid that her aunt was dying. Martha went to the couch. She thought so too.

“I must go,” said she, “to some of the neighbors and get them to come.”

“But you can not get to any of the neighbors,” said Ellen.

“Perhaps I can,” said Martha, “and at any rate I must try.”

So Martha began to prepare herself, as well as she could, to go out into the storm, Ellen standing by, full of apprehension and anxiety, and helping her so far as she was able to do so. There was a neighbor who lived about a quarter of a mile from the house, by a road which lay through the woods, and which was, therefore, ordinarily not very much obstructed with the snow. It was to this house that Martha was going to attempt to make her way. When she was ready, she went forth, leaving Ellen with her aunt alone.

(To Be Continued.)

Recollections Of St. Petersburg.

“To-morr punkt at 'leven wir schiff for St. Petersburg,” was the polyglot announcement by which all of us, Swedes, Germans, English, and one solitary American, were given to understand at what hour on the ensuing day we were to commence our voyage from Stockholm for the Russian capital. With praiseworthy punctuality the steam was up at the appointed hour of eleven, and as our steamer shot out into the Baltic we took our farewell view of Stockholm, the “City of Piles.” As we steamed northward we dashed through archipelago after archipelago of islands, some with bold and rocky shores, and others sloping greenly down to the tranquil sea. Having passed the Aland Islands, one of which, not thirty miles from the coast of Sweden, has been seized and strongly fortified by her powerful and unscrupulous neighbor, we turned into a narrow inlet, and touched Russian soil at Abo, the ancient capital of Finland.

Here we made our first acquaintance with those fascinating gentry, whom his Imperial Majesty deputes to watch that nothing treasonable or contraband finds entrance into his dominions. Our intercourse here was, however, brief, our passports merely being demanded, and permission granted us to go on shore while the steamer was detained. At Cronstadt and St. Petersburg we formed a more intimate if not more agreeable acquaintance with these functionaries. Setting out again we coasted eastward up the Gulf of Finland, passing the grim fortress of Sveaborg, with its eight hundred guns, and garrison of fifteen thousand men, and shot up the beautiful bay to Helsingfors, one of the great naval stations of Russia. Touching at Revel, on the opposite shore of the Gulf of Finland, we ran due east up the Gulf, encountering the great Russian summer fleet, which was performing its annual manœuvres, and on the morning after leaving Helsingfors came in sight of the shipping and fortifications of Cronstadt. As we crept slowly up the narrow and winding channel, by which alone the harbor can be reached, and passed successively the grim lines of batteries which command every portion of it, we were forced to confess that it formed a fitting outpost to a great military power.

Cronstadt is not only the chief naval dépôt of Russia, but is properly the port of St. Petersburg, as the capital is inaccessible to vessels drawing more than eight or nine feet of water. Hence Cronstadt is included in the St. Petersburg customs-district, and vessels clear indifferently for either, and are subject to only a single customs-house examination. It forms the key to the capital, which would be entirely at the mercy of any fleet which should once pass its batteries. It has therefore been fortified so strongly as to be apparently impregnable to all the navies of the world. We came to anchor under the guns of the fortress; and were soon put under the charge of our amiable friends of the custom-house, who took complete possession of the deck, while the passengers and officers of the vessel were directed to repair to the cabin to give an account of themselves, their occupations, pursuits, and designs to these rude and filthy representatives of the Czar. It was well for us that we had been in a measure hardened to these annoyances by our previous Continental experiences. Police and custom-house functionaries are nowhere famous for civility, but the rudest and most unendurable specimens of that class whom it has ever been my fortune to encounter are the lower orders of the Russian officials. We could, however, congratulate ourselves that the infliction was light in comparison to what it would have been had we proceeded by land from Abo. There trunks, pockets, and pocket-books are liable to repeated searches at different stations along the route. We were told of travelers who had their boxes of tooth-powder carefully emptied, and their soap-balls cut in two, in quest of something treasonable or contraband.

But there is an end to all things human, even to Russian police-examinations. Our passports were luckily all in order, and as our steamer was cleared for St. Petersburg we escaped the vexations attendant upon an inspection of luggage and a change of vessel. Every thing was put under seal, even to an ancient umbrella which [pg 448] had borne the brunt of many a shower in half the countries of Europe, to say nothing of storms it had weathered previous to its transatlantic voyage.

After our seven hours' detention, we found ourselves at last steaming up the transparent Neva, and straining our eyes to get a first view of the City of Peter. After something more than an hour's paddling against the rapid current of the river, the gilt dome of the Cathedral first caught the eye, followed by the sight of dome after dome, tower upon tower, spire after spire, gilt and spangled with azure stars, long before the flat roofs and walls of the city were visible.

No sooner had our steamer touched the granite quai than it was taken possession of by a horde of custom-house and police officers, a shade or two less filthy and disgusting than their Cronstadt brethren; for it is a noticeable fact, the higher you proceed in official grade, the more endurable do the Russian officials become, till you reach the heads of the departments, who are as civil and well-behaved a body of functionaries as ever clasped fingers upon a bribe. A few copecks or rubles, as the case may require, insinuated into the expectant palms of the searching officials have a wonderful tendency to abate the rigor of the examinations, which being completed, and a silver ruble paid to the officer in attendance, the traveler is at liberty to go on shore in search of a hotel or lodgings.