The Project Gutenberg EBook of Hair-Breadth Escapes, by H.C. Adams

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Hair-Breadth Escapes

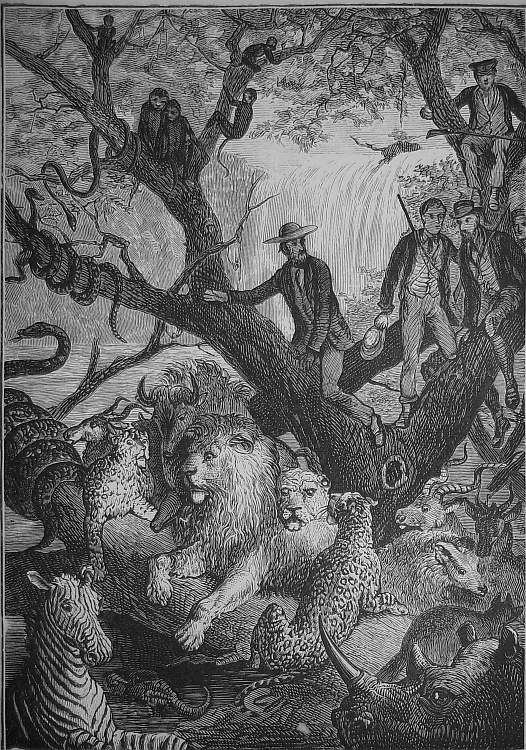

The Adventures of Three Boys in South Africa

Author: H.C. Adams

Release Date: July 31, 2010 [EBook #33304]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HAIR-BREADTH ESCAPES ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Rev. H.C. Adams

"Hair-Breadth Escapes"

Dedication.

To the Rev. G.G. Ross, D.C.L., Principal of St. Andrew’s College, Grahamstown, Cape Colony.

My dear Ross,

I dedicate this Tale to you for two reasons: first, because it is, in some sort, a souvenir of a very interesting visit to South Africa, rendered pleasant by the kind hospitality shown us by so many in Grahamstown, and by no one more than yourself. Secondly and chiefly, because it gives me the opportunity of expressing publicly to you my sympathy in the noble work you are carrying on, under the gravest difficulties—difficulties which (I am persuaded) many would help to lighten, who possess the means of doing so, were they but acquainted with them.

H.C. Adams.

Dry Sandford, August 1876.

Chapter One.

The Hooghly—Old Jennings—Short-handed—The Three Boys—Frank—Nick—Ernest—Dr Lavie—Teneriffe.

It was the afternoon of a day late in the November of the year 1805. His Majesty’s ship Hooghly, carrying Government despatches and stores, as well as a few civil and military officers of the East India Company’s service, was running easily before the trade wind, which it had caught within two days’ sail of Madeira—and was nearing the region of the tropics. The weather, which had been cold and stormy, when the passengers left England some weeks before, had been gradually growing bright and genial; until for the last three or four days all recollections of fog and chill had vanished from their minds. The sky was one vast dome of the richest blue, unbroken by a single cloud, only growing somewhat paler of hue as it approached the horizon line. The sea stretched out into the distance—to the east, an endless succession of purple wavelets, tipped here and there with white; to the west, where the sun was slowly sinking in all its tropical glory, one seething mass of molten silver.

It was indeed a glorious sight, and most of our readers will be of opinion that those who had the opportunity of beholding it, would—for the time at least—have bestowed little attention on anything else. But if they had been at sea as long as Captain Wilmore, they might perhaps have thought differently. Captain Wilmore had been forty years a sailor; and whether given, or not given, to admire brilliant skies and golden sunsets in his early youth, he had at all events long ceased to trouble himself about them. He was at the outset of this story sitting in his cabin—having just parted from his first lieutenant, Mr Grey—and was receiving with a very dubious face the report of an old quartermaster. A fine mastiff was seated by the captain’s chair, apparently listening with much gravity to what passed.

“Well, Jennings, Mr Grey tells me you have something to report, which he thinks ought to be brought straight to me, in order that I may question you myself about it. What is it? Is it something about these gentlemen we have on board? Are they dissatisfied, or has Lion here offended them?”

“No, cap’en,” said the old sailor; “I wish ’twas only something o’ that sort. That would be easy to be disposed of, that would.”

“What is it, then? Is it the men, who are grumbling—short rations, or weak grog, or what?”

“There’s more rations and stronger grog than is like to be wanted, cap’en,” said Jennings, evasively, for he was evidently anxious to escape communicating his intelligence, whatever it might be, as long as possible.

“What do you mean, Jennings?” exclaimed Captain Wilmore, roused by the quartermaster’s manner. “More rations and stronger grog than the men want? I don’t understand you.”

“Well, cap’en, I’m afraid some on ’em won’t eat and drink aboard this ship no more.”

“What, are any of them sick, or dead—or, by heaven, have any of them deserted?”

“I’m afeared they has, cap’en. You remember the Yankee trader, as sent a boat to ask us to take some letters to Calcutta?”

“Yes, to be sure; what of him?”

“Well, I’ve heard since, as his crew was going about among our chaps all the time he was aboard, offering of ’em a fist half full of guineas apiece, if they’d sail with him, instead of you.”

“The scoundrel!” shouted Captain Wilmore. “If I’d caught him at it, I’d have run him up to the mainyard, as sure as he’s alive.”

“Ay, cap’en; and I’d have lent a hand with all my heart,” said the old seaman. “But you see he was too cunning to be caught. He went back to his ship, which was lying a very little way off, for there wasn’t a breath of wind, if you remember. But he guessed the breeze would spring up about midnight, so he doesn’t hoist his boats up, but hides ’em under his lee, until—”

“I see it all plain enough, Jennings,” broke in the captain. “How many are gone?”

“Well, we couldn’t make sure for a long time, Captain Wilmore,” said Jennings, still afraid to reveal the whole of his evil tidings. “Some of the hands had got drunk on the rum fetched aboard at Madeira, and they might be lying about somewhere, you see—”

“Well, but you’ve found out now, I suppose?” interjected his questioner sharply.

“I suppose we has, cap’en. There’s Will Driver, and Joel Grigg, and Lander, and Hawkins, and Job Watson—not that he’s any great loss—and Dick Timmins, and—”

“Confound you, Jennings! how many?” roared the captain, so fiercely, that the dog sprang up, and began barking furiously. “Don’t keep on pottering in that way, but tell me the worst at once. How many are gone? Keep quiet, you brute, do you hear? How many, I say?”

“About fifteen, cap’en,” blurted out the quartermaster, shaking in his shoes. “Leastways there’s fifteen, or it may be sixteen, as can’t be found, or—”

“Fifteen or sixteen, or some other number,” shouted the skipper. “Tell me the exact number, you old idiot, or I’ll disrate you! Confound that dog! Turn him out.”

“Sixteen’s the exact number we can’t find,” returned Jennings, “but some of ’em may be aboard, and turn up sober by-and-by.”

“Small chance of that,” muttered the captain. “Well, it’s no use fretting; the question is, What’s to be done? We were short-handed before—so you thought, didn’t you, Jennings?”

“Well, cap’en, we hadn’t none too many, that’s sartain; and we should have been all the better for half a dozen more.”

“That comes to the same thing, doesn’t it?” said the skipper, who, vexed and embarrassed as he was, could not help being a little diverted at the old man’s invincible reluctance to speaking out.

“Well, I suppose it does, sir,” he answered, “only you see—”

“I don’t see anything, except that we are in a very awkward scrape,” interposed the other. “It will be madness to attempt to make the passage with such a handful as we have at present. If there came a gale, or we fall in with a French or Spanish cruiser—” He paused, unwilling to put his thoughts into words.

“’Twouldn’t be pleasant, for sartain,” observed Jennings.

“But, then, if we put back to England—for I know no hands are to be had at Madeira, we should be quite as likely to encounter a storm, or a Frenchman.”

“A good deal more like,” assented the quartermaster.

“And there would be the loss and delay, and the blame would be safe to be laid on me,” continued the captain, following out his own thoughts rather than replying to his companion’s observations. “No, we must go on. But then, where are we to pick up any fresh hands?”

“We shall be off the Canaries this evening, cap’en,” said Jennings. “We’ve been running along at a spanking rate with this wind all night. The peak’s in sight even now.”

“The Canaries are no good, Jennings. The Dons are at war with us, you know. And though there are no ships of war in the harbour at Santa Cruz, they’d fire upon us from the batteries if we attempted to hold communication with the shore.”

“They ain’t always so particular, are they, sir?” asked the sailor.

“Perhaps not, Jennings. But the Dons here have never forgiven the attack made on them seven or eight years ago, by Nelson.”

“Well, sir, they might have forgiven that, seeing as they got the best of it I was in that, sir—b’longed to the Foxy and was one of Nelson’s boat’s crew, and we got nothing out of the Dons but hard knocks and no ha’pence that time.”

“That’s true. But you see Nelson has done them so much harm since, that the damage they did him then seems very little comfort to them. No, we mustn’t attempt anything at the Canaries.”

“Very good, sir. Then go on to the Cape Verdes. If this wind holds, we shall soon be there, and the Cape Verdes don’t belong to the Dons.”

“No; to the Portuguese. Well, I believe that will be best. I have received information that the French and Spanish fleets are off Cape Trafalgar; and our fellows are likely to have a brush with them soon, if they haven’t had it already.”

“Indeed, sir! Well, Admiral Nelson ain’t likely to leave many of ’em to follow us to the Cape. We’re pretty safe from them, anyhow.”

“You’re right there, I expect, Jennings,” said the skipper, relaxing for the first time into a grim smile. “Well, then, shape the ship’s course for the Cape Verdes, and, mind you, keep the matter of those scoundrels deserting as quiet as possible. If some of the passengers get hold of it, they’ll be making a bother. Now you may go, Jennings. Stay, hand me those letters about the boys that came on board at Plymouth. I’ve been too busy to give any thought to them till now. But I must settle something about them before we reach the Cape, and I may as well do so now.”

The quartermaster obeyed. He handed his commanding officer the bundle of papers he had indicated, and then left the cabin, willing enough to be dismissed. The captain, throwing himself with an air of weariness back on his sofa, broke the seal of the first letter, muttering to himself discontentedly the while.

“I wonder why I am to be plagued with other people’s children? Because I have been too wise to have any of my own, I suppose! Well, Frank is my nephew, and blood is thicker than water, they say—and for once, and for a wonder, say true. I suppose I am expected to look after him. And he’s a fine lad too. I can’t but own that. But what have I to do with old Nat Gilbert’s children, I wonder? He was my schoolfellow, and pulled me out of a pond once, when I should have been drowned if he hadn’t I suppose he thought that was reason enough for putting off his boy upon me, as his guardian. Humph! I don’t know about that. Let us see, any way, what sort of a boy this young Gilbert is. This is from old Dr Staines, the schoolmaster he has been with for the last four or five years. I wonder what he says of the boy? At present I know nothing whatever about him, except that he looks saucy enough for a midshipman, and laughs all day like a hyena!

“‘Gymnasium House, Hollingsley,

“‘September 29th, 1805.

“‘Sir,—You are, no doubt, aware that I have had under my charge, for the last five years, Master George Gilbert, the son of the late Mr Nathaniel Gilbert, of Evertree, a most worthy and respectable man. I was informed, at the time of the parent’s decease, that you had been appointed the guardian of the infant; but as Mr Nathaniel had, with his customary circumspection, lodged a sum in the Hollingsley bank, sufficient to cover the cost of his son’s education for two years to come, there was no need to trouble you. You were also absent from England, and I did not know your direction.

“‘The whole of the money is not yet exhausted; but I regret to say I am unable to retain Master George under my tuition any longer. I must beg you to take notice that his name is George, as his companions are in the habit of calling him “Nick,” giving the idea that his name, or one of his names, is Nicodemus. Such, however, is not the case, George being his only Christian appellative. Why his schoolfellows should have adopted so singular a nomenclature I am unable to say. The only explanation of it, which has ever been suggested to me, is one so extremely objectionable, that I am convinced it must be a mistake.

“‘But to proceed’—(‘A long-winded fellow this!’ muttered the captain as he turned the page; ‘who cares what the young scamp’s called?’)—‘But to proceed. I cannot retain Master George any longer. His continually repeated acts of mischief render it impossible for me any longer to temper the justice due to myself and family with the mercy which it is my ordinary habit to exercise. I will not detail to you his offences against propriety’—(‘thank goodness for that,’ again interjected Captain Wilmore, ‘though I dare say some of his offences would be entertaining enough’)—‘I will not detail his offences—they would fill a volume. I will only mention what has occurred to-day. If there is any practice I consider more objectionable than another, it is that of using the dangerous explosives known as fireworks. Master Gilbert is aware that I strictly interdict their purchase; in consequence of which they cannot be obtained at the only shop in Hollingsley where they are sold, by any of my scholars. But what were my feelings—I ask you, sir—when I ascertained that he had obtained a large number of combustibles weeks ago, and had concealed them—actually concealed them in a chest under Mrs Staines’s bed! The chest holds a quantity of linen, and under this he had hidden the explosives, thinking, I conclude, that it was seldom looked into. Seldom looked into! Why, merciful heaven, Mrs Staines is often in the habit of examining even by candlelight’—(‘I say, I can’t read any more of this,’ exclaimed the captain; ‘anyhow, I’ll skip a page or two.’ He turned on a long way and resumed.)—‘When I found out this morning that he was missing, I felt no doubt that my words had produced even a deeper effect than I had designed. Mrs Staines and myself both feared that in his remorse he had been guilty of some desperate act; and we made every effort, immediately after breakfast, to discover the place of his retreat. Being St Michael’s day, it was a whole holiday, and we were thus enabled to devote the entire day to the quest. It has been extremely rainy throughout; but when we returned, two hours ago, exhausted and wet to the skin, after a fruitless search, we found him, dry and warm, awaiting us in the hall. This was some relief; but judge of our feelings when we discovered that the shameless boy had put on my camlet-cloak and overalls—they had been missing, and I had been obliged to go without them! he had taken Mrs Staines’s large umbrella, and had waited for us, from breakfast time, round the corner, under the confident assurance that we should go to look for him. Sir, it has been his amusement to follow us about all day, gratifying his malevolent feelings with the spectacle of our exposure to the elements, our weariness, our ever-increasing anxiety! You will not wonder after this, sir—’”

“There, that will do,” once more exclaimed the skipper, throwing aside the letter with a chuckle of amusement. “I must say I don’t wonder at the doctor’s refusing to keep him any more after that! Well, his father wanted him to be a sailor, and maybe he won’t make a bad one. Only we must have none of his tricks on board ship. I’ll have a talk with him, when I can spare the time. That’s settled. And now I can see Dr Lavie about this other lad, young Warley. Hallo there, Matthews, tell the doctor I am at liberty now.”

In a few minutes the person named was ushered into Captain Wilmore’s presence. The new comer was a gentlemanly and well-looking young man, and bore a good character, so far as he was known, in the ship. The captain was pleased with his appearance, and felt at the moment more than usually gracious—possibly in consequence of his recent mirth over George Gilbert’s exploits. He spoke with unusual kindness.

“Well, doctor, what can I do for you? You have come to speak to me about young Ernest Warley, I think?”

“Yes, Captain Wilmore, I want to ask your advice. His father was the best friend I ever had. He took me by the hand when I was left an orphan without a sixpence, and put me to school, and took care of me. When he was dying, he made me promise to do my best for his boy, as he had for me. But I’m afraid I can’t do that, glad as I should be to do it, if I could—”

“But I don’t understand, doctor. Old Warley—I knew a little of him—was a wealthy man, partner in Vanderbyl and Warley’s house, one of the best in Cape Town. The lad can’t want for money.”

“Ah, he does, though. His elder brother has all the money. He was the son of the first wife, old Vanderbyl’s daughter, and all the money derived from the business went to him. The second wife’s fortune was settled on Ernest; but it was lost, every farthing of it, in the failure of Steinberg’s bank last year.”

“Won’t the elder brother do anything?”

“No more than very shame may oblige him to do. He hated his father’s second wife, and hates her son now.”

“How old is the lad?”

“Past nineteen; very steady and quiet, but plenty of stuff in him. He wouldn’t take his brother’s money, if he had the chance; says he means to work for himself. He wanted to be a parson, and would have gone this autumn to the University, but for the smash of the bank. He’ll do anything now that I advise him, but I don’t know what to advise.”

“‘Nineteen!’—too old for the navy. ‘Wanted to be a parson!’—wouldn’t do for the army. ‘Do anything you advise!’ Are you sure of that? Few young fellows now-a-days will do anything but what they themselves like.”

“Yes, he’ll do anything I advise, because he knows I really care for him. Where he fancies he’s put upon, he can be stiff-backed and defiant enough. I’ve seen that once or twice. Ernest hasn’t your nephew Frank’s temper, which is hot and hasty for the moment, but is right again the next. He doesn’t come to in a minute, as Frank does, but he’s a good fellow for all that.”

The captain’s brow was overcast as he heard his nephew’s name. “Frank’s spirit wants breaking, Mr Lavie,” he said in an angry tone. “I shall have to teach him that there’s only one will allowed aboard ship, and that’s the captain’s. Frank can ride and leap and shoot to a bead they tell me, but he can’t command my ship, and he shan’t. I won’t have him asking for reasons for what I order, and if he does it again—he’ll wish he hadn’t. But this is nothing to the purpose, Mr Lavie,” he added, recovering himself. “We were talking about young Warley. You had better try to get him a clerkship in a house at Cape Town. You mean to settle there yourself after the voyage, do you not?”

“Well, no, sir, I think not I had meant it, but my inclination now rather is to try for a medical appointment in Calcutta. You see it would be uncomfortable for Ernest at the Cape with his brother—”

“I see. Well, then, both of you had better go on to Calcutta with me. I dare say—if I am pleased with the lad—I may be able to speak to one of the merchants or bankers there. What does he know? what can he do?”

“He is a tolerable classical scholar, sir, and a good arithmetician, Dr Phelps told me—”

“That’s good,” interposed the captain.

“And he knows a little French, and is a fair shot with a gun, and can ride his horse, though he can’t do either like Frank—”

“Never mind Frank,” broke in Captain Wilmore hastily. “He’d behave himself at all events, which is more than Frank does. Well, that will do, then. You two go on with the Hooghly to Calcutta, and then I’ll speak to you again.”

Mr Lavie rose and took his leave, feeling very grateful to his commanding officer, who was not in general a popular captain. He was in reality a kind-hearted man, but extremely passionate, as well as tenacious of his authority, and apt to give offence by issuing unwelcome orders in a peremptory manner, without vouchsafing explanations, which would have smoothed away the irritation they occasioned. In particular he and his nephew, Frank Wilmore, to whom reference more than once has been made, were continually falling out Frank was a fine high-spirited lad of eighteen, for whom his uncle had obtained a military cadetship from a director, to whom he had rendered a service; and the lad was now on his way to join his regiment. Frank had always desired to be a soldier, and was greatly delighted when he heard of his good fortune. But his uncle gave him no hint that it was through him it had been obtained. Indeed, the news had been communicated in a manner so gruff and seemingly grudging, that Frank conceived an aversion to his uncle, which was not removed when they came into personal contact on board the Hooghly.

The three lads, however, soon fraternised, and before they had sighted Cape Finisterre were fast friends. Many an hour had already been beguiled by the recital of adventures on shore, and speculation as to the future, that lay before them. Nor was there any point on which they agreed more heartily than in denunciation of the skipper’s tyranny, and their resolve not to submit to it. When Mr Lavie came on deck, after his interview in the captain’s cabin, they were all three leaning over the bulwarks, with lion crouching at Frank’s side, but all three, for a wonder, quite silent. Mr Lavie cast a look seaward, and saw at once the explanation of their unusual demeanour. The ship had been making good way for the last hour or two, and was now near enough to the Canaries to allow the Peak of Teneriffe to be clearly seen, like a low triangular cloud, and the rest of the island was coming gradually into clearer sight Mr Lavie joined the party, and set himself to watch what is perhaps the grandest spectacle which the bosom of the broad Atlantic has to exhibit. At first the outline of the great mountain, twelve thousand feet in height, presented a dull cloudy mass, formless and indistinct. But as the afternoon wore on, the steep cliffs scored with lava became visible, and the serrated crests of Anaga grew slowly upon the eye. Then, headland after headland revealed itself, the heavy dark grey masses separating themselves into hues of brown and red and saffron. Now appeared the terraced gardens which clothe the cultivated sides, and above them the picturesque outlines of the rocks intermingled with the foliage of the euphorbia and the myrtle, and here and there opening into wild mountain glens which the wing of the bird alone could traverse. Lastly, the iron-bound coast became visible on which the surf was breaking in foaming masses, and above the rocky shelf the long low line of spires and houses which distinguish the town of Santa Cruz. For a long time the red sunset light was strong enough to make clearly distinguishable the dazzling white frontages, the flat roofs, and unglazed windows, standing out against the perpendicular walls of basaltic rock. Then a dark mist, rising upwards from the sea, like the curtain in the ancient Greek theatre, began to hide the shipping in the port, the quays, and the batteries, till the whole town was lost in the darkness. Higher it spread, obscuring the masses of oleander, and arbutus, and poinsettia in the gardens, and the sepia tints of the rocks above. Then the white lava fissures were lost to the eye, and the Peak alone stood against the darkening sky, its masses of snow bathed in the rich rosy light of the expiring sun. A few minutes more and that too was swallowed up in darkness, and the spell which had enchained the four spectators of the scene was suddenly dissolved.

Chapter Two.

The Cape Verdes—Dionysius’s Ear—Unwelcome News—French Leave—The Skipper’s Wrath—A Scrape.

Three or four days had passed, the weather appearing each day more delicious than the last. The Hooghly sped smoothly and rapidly before the wind, and at daybreak on the fifth morning notice was given that the Cape Verde Islands were in sight. The sky, however, grew thick and misty as they neared land; and it was late in the forenoon before they had approached near enough to obtain a clear view of it.

“I wonder why they call these islands Verdes?” observed Gilbert, as the vessel ran along the coast of one of the largest of the group, which was low and sandy and apparently barren; “there doesn’t seem to be much green about them, that I can see.”

“No, certainly,” said Warley; “a green patch here and there is all there is to be seen, so far as the sea-coast is concerned But the interior seems a mass of mountains. There may be plenty of verdure among them, for all we know.”

“No,” said Mr Lavie, who was standing near them. “Their name has nothing to do with forests or grass-fields. There is a mass of weed on the other side of the group, extending for a long distance over the sea, which is something like a green meadow to look at—that’s the meaning of the name. There are very few woods on any of the islands, and this one in particular produces hardly anything but salt.”

“They belong to the Portuguese, don’t they?” asked Frank.

“Yes; the Portuguese discovered them three centuries and a half ago, and have had possession of them ever since. Portuguese is the only language spoken there, but there are very few whites there, nevertheless.”

“Why, there must be a lot of inhabitants,” remarked Ernest, his eye resting on the villages with which the shores were studded.

“Yes, from forty to fifty thousand, I believe. But they are almost all of them half-breeds between the negroes and the Portuguese.”

“Well, I suppose there’s some fun to be had there, isn’t there?” inquired Frank.

“And something to be seen?” added Warley.

“And first-chop grub?” wound up Gilbert. “There’s plenty to see at Porto Prayo,” returned Mr Lavie. “The town, Ribeira Grande they call it, is curious, and there are some fine mountain passes and grand views in the interior. As for grub, Master Nick” (for this sobriquet had already become young Gilbert’s usual appellative), “there are pretty well all the fruits that took your fancy so much at Madeira—figs, guavas, bananas, oranges, melons, grapes, pine-apples, and mangos—and there’s plenty of turtle too, though I’m not sure you’ll find it made into soup. But as to fun, Frank, it depends on what you call fun, I expect—”

“Let us go ashore,” interrupted Nick, “and we shall be safe to find out lots of fun for ourselves. It would be jolly fun, in itself, to be walking on hard ground again, instead of these everlasting planks. I suppose, as these islands belong to the Portuguese, and we’ve no quarrel with them, the skipper will go ashore, and allow the passengers to do so too?”

“He’ll go ashore, no doubt,” said a voice close at hand; “but he won’t let you go, I’ll answer for that.”

The boys turned quickly round, and were not particularly pleased to see the first lieutenant, Mr Grey, who had come aft, to give some orders, and had overheard the last part of their conversation. Mr Grey was no favourite of theirs. He was not downright uncivil to the boys, but he was fond of snubbing them whenever an occasion offered itself. It was generally believed also that a good deal of the captain’s harshness was due to the first lieutenant’s suggestions.

“You’d better leave the captain to answer for himself,” remarked Frank, his cheek flushing with anger. “I don’t see how you can know what he means to do.”

“Perhaps you mayn’t see it, and yet I may,” returned Mr Grey calmly.

“Why shouldn’t he let us go ashore, as he did at Madeira?” asked Warley. “Nothing went wrong there.”

“I beg your pardon,” replied the lieutenant; “things did go wrong there, and he was very much displeased.”

“Displeased,” repeated Warley, “displeased with us? What do you mean, Mr Grey?”

“I mean that you are not to go ashore,” returned the other curtly, and walking forward as he spoke.

Ernest’s cheek grew almost as crimson as Frank’s had done. The apparent insinuation that he had misconducted himself while on his parole of good behaviour, was one of the things he could least endure. Mr Lavie laid his hand on the boy’s arm.

“Hush, Ernest!” he said, checking an angry exclamation to which he was about to give vent. “Most likely Mr Grey is not serious. Anyway, if the captain does forbid your going ashore, you may be assured he has good reasons—”

“What reasons can he have?” interposed Gilbert; “we are no more likely to get into trouble here than at Madeira, and who has a right to say we did anything wrong there?”

“The first lieutenant didn’t say so,” observed the surgeon. “I think there is some mistake. I’ll make inquiries about the matter before we enter the harbour.”

He moved away, and the boys resolved to retreat to their den, where they might hold an indignation meeting without molestation. This den, to which its occupants had given the classical name of “Dionysius’s ear,” or more briefly, “Dionysius,” was an empty space on the lower deck, about six foot square, where various stores had been stowed away. By some oversight of the men a dozen chests or so had been left ashore, and a vacant place in a corner was reserved for them. When, however, they were brought aboard, they could not conveniently be lowered, and were secured on deck. Master Nick, in the course of his restless wandering, had lighted on this void space, and it occurred to him that it would make a snug place of retreat, when he wished to be alone, as he not unfrequently did, in order to escape the consequences of some piece of mischief. When his friendship with his companions had been sufficiently cemented, he had communicated the secret to them, and Frank at once appreciated its value. Advantage had been already taken of it on one or two occasions, to evade an unwelcome summons from the skipper, or smoke a pipe at interdicted hours.

To be sure it was not a very desirable retiring room, and most persons would have considered a Russian or Neapolitan dungeon greatly preferable to it. As the reader has heard, it was about six foot square. It was lighted by a dead light in the deck above, which had fortunately been inserted just in that spot. Whatever air there was, came through the barrels, or along the ship’s sides. But it is needless to say it was at all times suffocatingly close, and nothing but a boy or a salamander could have long continued to breathe such an atmosphere. Entrance was obtained by pulling aside a small keg; the removal of which allowed just enough room for any one to work his way in, like an earthworm, on his stomach. Then the keg was drawn by the rope attached to it into its place again, and firmly secured to a staple in the ship’s side. Whatever might be its other defects, it was certainly almost impossible of detection.

Arrived here, our three heroes lay down at their leisure on some sacks with which they had garnished their domicile, and proceeded to discuss the matter in hand, lowering their voices as much as possible, as they had discovered that conversation might be heard through the barrels by any one on the other side, which fact, indeed, was the explanation of the name bestowed on their retreat. They were not at first agreed as to the steps to be adopted. Nick was for going ashore under any circumstances—the difficulty of accomplishing his purpose, and the fact of his having been forbidden to essay it, being, in his eyes, only additional incentives. Frank was not disposed to make the attempt, if his uncle really had interdicted it; but he professed himself certain that no such order had been given by anybody but the first lieutenant, and he was not, he said, going to be under his orders. Warley for once was inclined to go beyond Frank, and declared that though he would obey the captain’s order if any reasonable ground for it was assigned, he would not be debarred from what he considered his right as a passenger, by any man’s mere caprice. He added, however, that he thought it would be better to hear what Lavie had found out, before coming to any resolution.

“Well, it is time we should see the doctor, if we mean to do so,” remarked Frank, after an hour or so had passed in conversation. “We must be entering Porto Prayo by this time, or be near it at all events; and he must have had lots of time to find out everything.”

“Very good; one of us had better see Mr Lavie at once,” said Ernest. “I’ll go, if you like, and come back to ‘Dionysius’ here, as soon as I have anything to tell.”

He departed accordingly, and returned in about half an hour, looking very cool, but very much annoyed.

“Hallo, Ernest, what’s up now?” exclaimed Nick, as he caught sight of his face. “What does the doctor say?”

“I haven’t seen the doctor,” answered Warley. “One of the crew has been taken dangerously ill, and the doctor has been with him ever since he left us.”

“What have you learned, then?” asked Frank. “Are we in the harbour?”

“We’re in the harbour, and the skipper’s gone ashore. I saw his boat half-way to the beach. Captain Renton, Mr May, and Mr De Koech have gone with him. They are the only passengers who wanted to go.”

“Well, but I suppose there are some shore boats that would take passengers to and fro.”

“The captain has given orders that no shore boat is to be allowed alongside. He won’t even allow the fresh provisions, or the water, to be brought aboard by any but the ship’s boats. I saw the largest cutter with the empty water-casks in her, lying ready to go ashore presently.”

“Who told you this?” inquired Wilmore, half incredulous.

“Old Jennings, the quartermaster. He has charge of the boat. He said the captain’s resolved we shan’t leave the ship.”

“It’s an infamous shame,” said Frank. “I declare I’ve half a mind to swim ashore. It can’t be very far.”

“No,” said Nick, “but it wouldn’t be pleasant to land soaking wet, to say nothing of the chance of ground sharks. Even Lion had better not try that dodge. But I’ll tell you what—if the boat is lying off the ship’s side, with a lot of ankers in her, why shouldn’t we creep in among them, and go ashore unbeknown to the first lieutenant?”

“We should be seen getting aboard,” said Frank.

“No, we shouldn’t. The men are at dinner just now, and we can slip in when the backs of the fellows on deck are turned.”

“I forgot that,” said Frank; “but we should be certain to be seen when we landed.”

“Ay, no doubt. But that will be too late, won’t it? Once ashore, I guess they must be pretty nimble to catch us; and besides, old Jennings is too good-natured to do anything against us, which he isn’t obliged to do.”

“Well, that’s true, certainly,” returned Wilmore. “What do you say, Warley? Are you game to make the trial?”

“Yes, I am,” returned Ernest. “I think it is regular tyranny to oblige us to stay in the ship, when there is no reason for it, except the captain’s caprice. But if we mean to try this, we must make haste.”

The three lads hurried on deck; and a glance showed them they were just in time. There were only two or three men to be seen, and they were at the other end of the ship. They skimmed nimbly down the ladder, and found no difficulty in concealing themselves at the bow end of the boat, which was completely hidden from sight by the empty casks. They had not been in their hiding-place very long, before the old quartermaster and his men were heard coming down the side. The shore was soon reached, and the keel had no sooner grated on the sand, than the boys sprang out and ran up the beach, saluting old Jennings with a parting cheer as they went.

“Well, I never,” muttered the old man. “The cap’en ’ull be in a nice taking when he hears of this! And there ain’t no chance but what he will hear of it. We’ve Andy Duncan in the boat, and he carries everything to the first lieutenant, as sure as it happens. Well, I ain’t bound to peach, anyhow—that’s one comfort!”

Meanwhile the captain had gone on shore, his temper not improved by the report of the doctor which had been brought to him as he was leaving the vessel, that another of his best hands was rendered useless—for several weeks to come at all events—by a bad attack of fever, which might very possibly spread through the ship. He returned on board after nightfall, still more provoked and vexed. He had met with the greatest difficulty in his attempts to fill the places of his missing men. There were, as the reader has been told, very few whites on the island, and none of them were sailors. The blacks were very unwilling to engage, except upon exorbitant terms, and hardly one of those with whom he spoke appeared good for anything. He had at one time all but given up the matter in despair. But late in the afternoon he was accosted by a dark-complexioned man, lean and sinewy as a bloodhound, who informed him that the vessel in which he traded between the South African ports and the West Indian Islands, had been driven on the Cape Verdes and totally wrecked. But the crew had escaped, he said, and were willing to engage with Captain Wilmore for the voyage to Calcutta.

The captain hesitated. He had little doubt that the lost vessel had been a slaver, and he had an instinctive abhorrence of all engaged in that horrible traffic. Still there seemed no other hope of successfully prosecuting the voyage, and after all it would be a companionship of only a few months. He resolved to make one effort more to obtain less questionable help, and if that should fail, to accept the offer. Desiring the stranger to bring his men to the quay in an hour’s time, he once more entered the town, and made inquiries at all the houses to which sailors were likely to resort. His success was no better than it had been before, and he was obliged to close with the proposal of the foreign captain. He liked the looks of the crew even less than those of their captain. There were eighteen of them, however, and all strong serviceable fellows, if they chose to work. He must hope for the best; but even the best did not appear very promising; and if the Yankee captain, who had been the prime cause of the mischief, had been delivered into his hands at that moment, it is to be feared he would have met with small mercy.

In this frame of mind he regained the Hooghly, and shortly after his arrival was informed by the first lieutenant of the escapade of the three boys, with the gratuitous addition that he had himself delivered them the captain’s message—that no one was to be permitted to leave the ship, except those who had gone ashore with the captain.

The skipper’s wrath fairly boiled over. He vowed he would straightway give his nephew a smart taste of the cat-o’-nine-tails, and put the other two into irons, to teach them obedience. The boatswain accordingly was summoned, and the delinquents ordered into custody, but after a delay of half an hour, during which the captain’s wrath seemed to be every moment growing hotter, it was announced that the boys could not be found, and the boat’s crew sent ashore with the water-casks positively declared that they did not return with them. As no other boats but theirs and the captain’s had held any communication with the land, it appeared certain that the young gentlemen were still on shore, intending probably to return by a shore boat later in the evening.

“Do they?” exclaimed Captain Wilmore fiercely, when this likelihood was suggested to him by Mr Grey. “They’ll find themselves mistaken, then. Up with the anchor, Crossman, and hoist the mainsail. Before their boat has left the quay, we shall be twenty miles from land. Not a word, Mr Lavie. A month or two’s stay in these islands will be a lesson they’ll keep by them all their lives.”

No one ventured to remonstrate. The anchor was lifted, the great sails were set, and in half an hour they were moving southward at a pace which soon left the lights of Porto Prayo a mere speck in the distance.

But the boys had not been left behind, though no one but themselves and old Jennings was aware of the fact. He had kept the boat from putting off on her return to the ship, on one pretext or another, as long as he could venture to do so, in the hope that the lads would make their appearance. But he was aware that Andy Duncan’s eye was upon him, and could not venture to delay longer. It happened, however, that soon after his return, Mr Lavie had found it necessary to send on shore to the hospital for some ice, of which they had none on board, and old Jennings had volunteered to go. He took the smallest boat and no one with him but his nephew, Joe Cobbes, who was completely under his orders. He landed at a different place from that at which the boat had been moored in the morning, and sent his nephew with the message to the hospital. He then made search after the boys, whom he soon discovered at the regular landing-place, waiting anxiously for some means of regaining the Hooghly.

“Hallo, Jennings,” exclaimed Frank, as he caught sight of the old man’s figure through the fast gathering darkness; “that’s all right, then. I was afraid we were going to stay ashore all night?”

“I hope it is all right, sir,” answered Jennings, “but if the captain finds out that you’ve been breaking his orders—”

“I don’t believe he has given any order—” interrupted Frank. “And it would be monstrous if he had,” exclaimed Ernest in the same breath.

“I don’t know what you believe, Mr Frank, but it’s sartain he has ordered that no one shall leave the ship; and I don’t know as it’s so unreasonable, Mr Warley, after the desertion of the hands at Madeira.”

“We never heard of their deserting,” cried Warley.

“I dare say not, sir. It was kep’ snug. But that’s why the cap’en would allow no boats to go ashore, except what couldn’t be helped. You see, sir, if more of the men were to make off, there mightn’t be enough left to work the ship, and if there came a gale—”

“Yes, yes; I understand that,” again broke in Frank, “but we didn’t know anything about their deserting.”

“Well, sir, it was giv’ out this morning as that was the reason, and every one, I thought, knew it. But anyways, sir, you’d best come and get aboard my boat, and keep out of the skipper’s way. He’ll be sure to find out about your doings. Andy ’ull tell the first lieutenant, and he’ll tell the skipper—”

“I am sure I don’t care if he does,” exclaimed Warley.

“Ah, you don’t know him, sir. He’s not a man as it’s wise to defy. Wait a bit; let him cool down and he’s as pleasant a man as any one. But when he’s put up, old Nick himself can’t match him. I don’t mind a gale of wind off the Cape, or boarding a Frenchman, or a tussle with a pirate, but I durstn’t face the cap’en, when he’s in one of his takings. Come along, and get into the boat.”

The lads obeyed, somewhat subdued by Jennings’ representations, which were evidently given in good faith. They allowed the old man to cover them with a tarpaulin, which he had brought for the purpose, and in accordance with his directions lay perfectly still.

Presently Cobbes returned with the ice, and the boat was rowed back to the ship. It was pitch dark before she came alongside, and her approach was hardly noticed. Jennings made for the gangway, and having ascertained that Captain Wilmore was still on shore, sent his nephew with the ice to the doctor’s cabin. He then suffered the boat to float noiselessly to the stern, where he had purposely left one of the cabin windows open; through this the boys contrived, with his help, to scramble.

“You’d better hide somewhere in the hold, Mr Frank,” he whispered, as young Wilmore, who was the last, prepared to follow his companions.

“No, on the lower deck, Jennings; we’ve a hiding-place there, no one will find out. When you think it’s safe for us to show ourselves, come down, and whistle a bar or two of one of your tunes, and I’ll creep out to you. But I hope we shan’t be kept very long, or we shall run a risk of being starved, though we have got some grub in our pockets. Good night, Jennings, and thank you. You’re a good fellow, any way, whatever the captain may be.”

“Good night, Mr Frank; mind you keep close till I come to let you out. I won’t keep you waiting no longer than I can help, you may be sure of that.”

Wilmore followed his friends; and the three boys, creeping cautiously along in the darkness, gained the lower deck unperceived, and were soon safely ensconced in “Dionysius.” Tired out with their day’s work, they all three fell sound asleep.

Chapter Three.

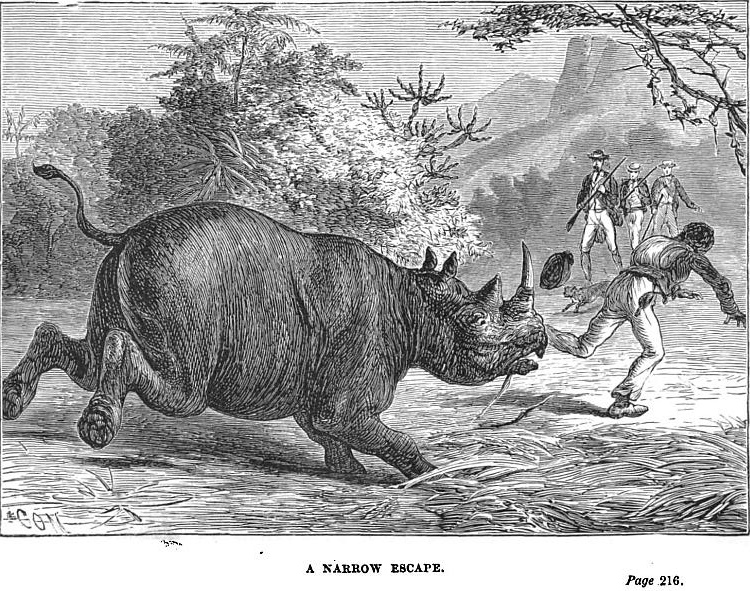

Strange Tidings—Pirates on Board—A Revel—A Narrow Escape—Death of Jennings.

The boys were awakened next morning by the pitching and tossing of the ship. A storm had come on during the night, which increased in violence as the morning advanced. It was well for the Hooghly that the fresh hands had been taken on board, or she would have become wholly unmanageable. Frank and his friends, in their place of retreat, could hear the shouts and cries on deck, the rolling of the barrels which had broken loose from their fastenings, and the washing of the heavy seas which poured over the gunwales. They made their breakfasts on some of the fruit and sausages with which they had filled their pockets on the previous evening, and waited anxiously for old Jennings’ arrival. It was late in the afternoon before he came, and when he did appear, he would not hear of their venturing to show themselves for the present.

“The cap’en wasn’t altogether in a pleasant state of mind yesterday,” he remarked, “but he’s in a wuss to-day. He’s found out that the most part of his crew ain’t worth a tobacco stopper. I must say the Yankee made a good pick of it. He got away pretty nigh every smart hand we had aboard. These new chaps is the best we has now.”

“New chaps?” asked Frank. “Has my uncle got any fresh hands?”

“Picked up nineteen new ’uns at Port Prayo,” replied Jennings. “Stout nimble fellows they are, no doubt. But I don’t greatly conceit them neither. They keep together, and hardly speak to any one aboard, except Andy Duncan and Joel White and Bob O’Hara and that lot. They’re no good either, to my mind. Well, young gents, you must stay here till the gale breaks, as I guess it will to-morrow, or the next day, and then the skipper will be in good-humour again. I’ve brought you a heap of biscuits and some fruit and a keg of water. But I mustn’t be coming down here often, or we shall be found out I’ve tied the dog up in the fo’castle, or he’d be sniffing about after Mr Frank here, and most likely find him out.”

“Very well, Tom,” said Frank, “then we’ll wait here. But it’s terribly dull work. Nothing to do but to sleep and smoke.”

“I think the skipper would let us off, if he knew what we’d gone through during the last twenty-four hours,” observed Nick, yawning. “Well, I suppose one must grin and bear it.” So saying, he rolled himself into his corner and endeavoured to lose the recollection of his désagréments in sleep.

The evening wore on heavily enough. It was past midnight before the gale began to lull, and the lads at length fell sound asleep. But they were roused soon afterwards by a loud commotion on deck. Voices were heard shouting and cursing; one or two shots were fired, and Frank fancied he could once or twice distinguish the clash of cutlasses. But presently the tumult died away, and the ship apparently resumed her customary discipline. Daylight came at last, glimmering faintly through the crevices of their prison, and the boys lay every minute expecting the advent of the old quartermaster. But the morning passed, and the afternoon began to slip away, and still there was no sign of Jennings’s approach. The matter was more than once debated whether they should issue from their hiding-place, which was now becoming intolerable to them, altogether disregarding his advice; or at any rate send out one of the party to reconnoitre. But Ernest urged strongly the wisdom of keeping to their original resolution, and Frank after awhile sided with him. It was agreed, however, that if Jennings did not appear on the following morning, Warley should betake himself to the doctor’s cabin and ask his advice.

Accordingly they once more lay down to sleep, and were again awoke in the middle of the night, but this time by a voice calling to them in a subdued tone through the barrels.

Wilmore, who was the lightest sleeper, started up. “Who is that?” he asked.

“It is I—Tom Jennings,” was the answer. “Don’t speak again, but push out the barrel that stops the way into your crib there. I’ll manage to crawl in, I dare say, though I am a bit lame.”

Wilmore saw there was something wrong. He complied literally with Tom’s request, and pushed the keg out in silence. Presently he heard the old man making his way, stopping every now and then as if in pain. At last there came the whisper again: “Pull the barrel back into its place, I’ve got a lantern under my coat which I’ll bring out when you’ve made all fast.”

Frank again obeyed his directions, having first enjoined silence on his two companions, who were by this time wide awake. Then Jennings drew out his lantern, and lighted it by the help of a flint and steel. As the light fell on his face and figure, the boys could hardly suppress a cry of alarm. His cheeks were as white as ashes, and in several places streaked with clotted blood. His leg too was rudely bandaged from the knee to the ankle, and it was only by a painful effort that he could draw it after him.

“What’s the matter, Tom?” exclaimed Frank. “How have you hurt your leg in that manner?”

“Hush! Mr Frank. We mustn’t speak above a whisper. There’s pirates on board. They’ve got possession of the ship.”

“Pirates!” repeated Wilmore. “What, have we been attacked, and my uncle—”

“He’s safe, Mr Frank—at least I hope so. Look here. You remember them foreign chaps as he brought aboard at Porto Prayo? It was all a lie they told the cap’en, about their ship having been lost. They were part of a crew of pirates—that’s my belief, any way—as had heard Captain Wilmore was short-handed, and wanted to get possession of his ship. They was no sooner aboard than they made friends with some of the worst of our hands—Andy and White and O’Hara and the rest on ’em—and I make no doubt persuaded them to join ’em. About ten o’clock last night, when the men were nearly all in their berths, worn out with their work during the gale, these foreigners crept up on deck, cut down and pitched overboard half a dozen of our chaps as were on deck, and then clapped down the hatches.”

“That was what we heard, then,” remarked Gilbert. “Were you on deck, Tom?”

“Yes, sir, I was, and got these two cuts over the head and leg. By good luck I fell close to the companion-ladder and was able at once to crawl to my berth, or I should have been pitched overboard. Well, as soon as it was daylight, the captain and the officers laid their heads together to contrive some means of regaining the ship; but, before they could settle anything, a vessel came in sight, and the fellows on deck hove to and let her come up—”

“The pirate ship, I suppose, hey?” cried Frank.

“Yes, sir, no other. She’d followed us beyond a doubt from Porto Prayo, and would have come up before, if it hadn’t been for the gale. There wasn’t nothing to be done, of course. The pirates threatened the captain, if he didn’t surrender at once, that they’d fire down the hatchways and afterwards pitch every mother’s son overboard. And they’d have done it too.”

“Not a doubt,” assented Frank. “So my uncle surrendered?”

“Yes, sir, he did, but he didn’t like it. I must say, from what I’ve heard of these fellows, I judged that they’d have thrown us all in to the sea without mercy. But it seems White and O’Hara and the rest wouldn’t allow that, and insisted on it that every one, who chose it, should be allowed to leave the ship. I did ’em injustice, I must say.”

“What did they go in?” inquired Wilmore, a good deal surprised.

“In the two biggest of the ship’s boats, sir. You see we’ve been driven a long way south by that gale, and are not more than a few hundred miles from Ascension. They’ll make for that, and with this wind they’ve a good chance of getting there in three or four days.”

“Are all the officers and passengers gone?” asked Warley.

“Well, no, sir. Mr Lavie ain’t gone. The men stopped him as he was stepping into the boat, and declared he shouldn’t leave the ship. But all the rest is gone—no one’s left except those who’ve joined the mutineers, unless it’s poor old Lion, who’s still tied up in the fo’castle.”

“Why, you haven’t joined them, Jennings, to be sure?”

“I! no, sir; but with my leg I couldn’t have gone aboard the boats; and to be sure, I hadn’t the chance, for I fainted dead off as soon as I’d reached my berth, and didn’t come to till after they was gone. And there’s my nevvy too—he wouldn’t go, but chose to stay behind and nurse me. I hadn’t the heart to scold the lad for it.”

“Scold him! I should think not,” observed Warley.

“Well, sir, it may get him into trouble if he’s caught aboard this ship, and I expect he’ll get into troubles with these pirates too. But there’s no use fretting about what can’t be helped. I’m thinking about you young gents. You see if I’d been in my right senses when they went away, I should have told the cap’en about you, and he’d have taken you away with him. But I wasn’t sensible like, and no one else then knew as you was aboard.”

“No one knew it then?” repeated Warley. “No one knows it now, I suppose.”

“Yes, sir, Mr Lavie knows it, and Joe too; I told them an hour ago, and we had a long talk about it. The doctor’s resolved he won’t stay in the ship, and I suppose you don’t want to stay neither?”

“We stay, Tom!” replied Frank. “No, I should think not indeed, if we can help it. But how are we to get away?”

“This way, sir. These pirates have been choosing their officers to-day, and they’ve made O’Hara captain. They say he’s the only man who’s up to navigating the ship. Anyhow, they’ve made him captain, and one of the foreign chaps, first mate. They’re to have a great supper to-morrow night in honour of ’em, and most of the crew—pretty nigh all I should say—will be drunk. Well, then, we claps a lot of things, that Mr Lavie has got together, aboard one of the boats—there are enough of us to lower her easy enough—and long before daylight you’ll be out of sight.”

“You’ll be out of sight. Don’t you mean to go yourself, Jennings?” asked Frank.

“My leg won’t let me, Mr Frank. I couldn’t get down the ship’s side; and besides, I ain’t in no danger. My old messmates won’t let me be hurt, nor Joe Cobbes neither. I’d best stay here till my leg’s right. Mr Lavie says it wants nothing but rest, and a little washing now and then. No, sir; Joe and I would rather stay on board here and take the first opportunity of leaving the ship that offers. Mr Lavie and you all ’ull bear witness how it happened.”

“That we will, Tom,” said Warley. “Well, then, if I understand you, we’ve nothing to do but to remain quiet until to-morrow night, and you and Mr Lavie will make all the preparations?”

“Yes, sir, that’s right. Stay quietly here till you’ve notice that everything’s ready.”

“But I don’t like you having all the risk and trouble, Tom,” said Wilmore.

“You’d do as much for me, sir, and more too, I dare say, if you had the chance. Besides, I am anxious you should get away safe, because you’re my witnesses that I and Joe had no hand in this. I shall get well all the sooner, when you’re gone.”

“All right, Jennings,” said Warley. “And now I suppose you want to get out of this again?”

“Yes, sir; you must help me. Getting out will be worse than getting in, I am afraid.”

The lantern was extinguished, the keg removed, and with much pain and difficulty the old man was helped out. The next twenty-four hours were passed in the utmost anxiety by the three lads, who would hardly allow themselves even to whisper to one another, for fear of being overheard by the pirates. All the morning they could hear the preparations for the feast going on. Some casks in the lower deck, which, as they knew, contained some unusually fine wine, were broken open, and the bottles carried on deck. Planks also were handed up to make tables and benches. From the conversation of the men employed in the work, they learned that the feast was to take place in the forecastle, none of the cabins being large enough to hold the entire party. Once they caught a mention of Mr Lavie’s name, and learned that he had been all night in attendance on Amos Wood, the sailor who had been attacked by fever at Porto Prayo, and that the man had died that morning, and been thrown overboard. The doctor, it was said, had now turned in for a long sleep. The boys guessed that his day would be differently employed. About six o’clock in the evening, everything seemed to be in readiness. The tramp of feet above was heard as the men took their places at table, and was followed by the rattling of plates and knives and forks, and the oaths and noisy laughter of the revellers. These grew more vociferous as the evening passed on, and after an hour or two the uproar was heightened by the crash of glass, and the frequent outbreak of quarrels among the guests, which were with difficulty suppressed by their more sober comrades. Then benches were overturned, and the noise of bodies falling on the deck was heard, as man after man became stupidly intoxicated. The uproar gradually died out, until nothing was audible, but drunken snores, or the unsteady steps of some few of the sailors, who were supposed to be keeping watch.

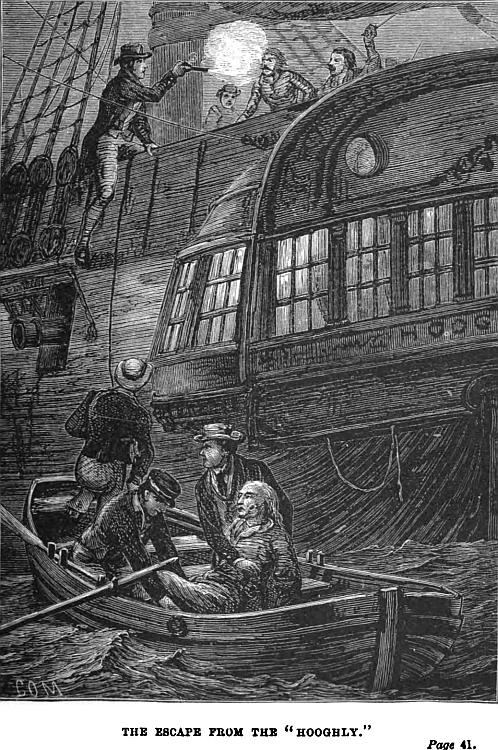

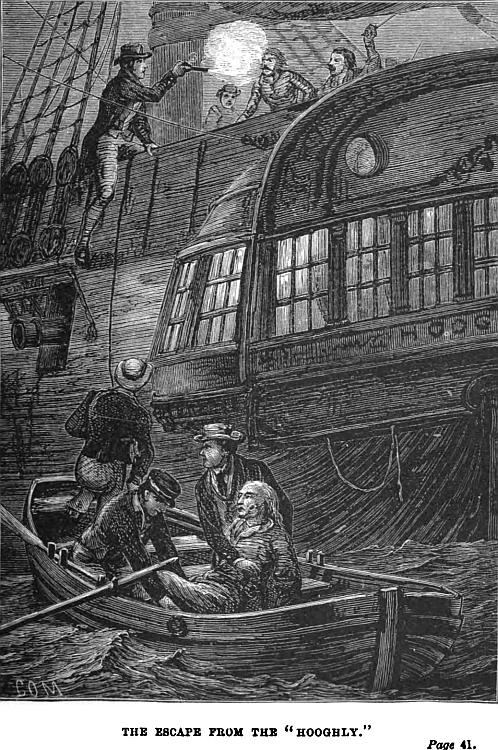

It was about two hours after midnight when the expected summons came. Frank crept out first, followed by Nick and Ernest. They found Mr Lavie and Joe Cobbes waiting for them.

“Everything is ready, Ernest,” whispered the doctor. “We’ve put as many provisions and arms into the jolly-boat as we can safely carry; but you had better take a brace of pistols apiece. There are some one or two of the men who are the worse for drink, but still sober enough to know what they are doing, and we may have a tussle. Put on these caps and jackets, and come as quick as you can. The jolly-boat is on the starboard side, near the stern. She’s not in the water yet, but everything is ready for lowering her. Quiet’s the word.”

The boys obeyed. They crept cautiously on deck, pulling the caps over their foreheads, and imitating as well as they could the movements of drunken men. They soon reached the jolly-boat, where old Jennings was waiting for them. The helm had been lashed, but every ten minutes or so one of the watch came aft to see that all was right. Jennings had unfastened the lashings and taken the rudder, telling the first man who came up that he would see to it for the rest of the watch. The man willingly enough accepted his services, and this skilful manoeuvre saved them for the time from further interruption.

“Lower quickly, Mr Lavie,” he whispered in the doctor’s ear. “Andy Duncan has had liquor enough to make half a dozen men drunk, but he knows what he’s doing for all that. He’s keeping an eye on the ship, and may be down upon us any minute.”

He was obeyed promptly and in silence. The boat was lowered without attracting notice. Warley was the first to slip down the rope, and was safely followed by Nick. Frank was just climbing over the bulwark when a man staggered up, and accused them with a volley of drunken oaths of intending to desert.

“No, no, Andy,” said Jennings quickly, “no one means to desert. There’s a man overboard, and we’re lowering a boat to pick him up. Make haste, my lad,” he continued, addressing Wilmore, “or he’ll be too far astern for us to help him.”

Frank promptly took the cue, and vanished over the side. For a moment Duncan was staggered by the old quartermaster’s readiness, but the next he caught a momentary glimpse of Frank’s features.

“Hallo, that’s young Wilmore, that’s the captain’s nevvy, as you said had been left behind,” he shouted. “There’s some devilry here! Help, my lads, there!” He drew a pistol as he spoke, and fired at Mr Lavie’s head, who was attempting to seize him.

His nerves were unsteady from drink, and the bullet missed its mark; but it struck Joe Cobbes on the temple, who fell on the instant stone dead. Some of the men, startled by the pistol shot, came reeling up from the forecastle.

The doctor struck Andy a heavy blow with the butt end of his pistol, and the man dropped insensible on the deck. He then turned to Jennings. “You must go with us now, Tom,” he said, “or they will certainly murder you. Go, I tell you, or I’ll stay behind myself.”

The old man made a great effort and rolled himself over the bulwarks, reaching the boat by the help of the rope, and the hands of the boys below, though he fainted from pain and exhaustion immediately afterwards.

Mr Lavie fired at the nearest man, who dropped with a broken leg. The others hung back alarmed and stupefied. Lavie skimmed down the rope, and disengaged her before they had recovered their senses. Just at this moment there was a heavy splash close beside them.

“Hallo!” cried Ernest, “one of the fellows has fallen overboard. We must take him in. We can’t leave him to drown.”

“It isn’t any of the crew,” said Frank. “It’s old Lion. I can see his head above water. He has broken his fastenings and followed us. Haul him aboard, Nick.”

The dog was soon got in, and Lavie and Warley, seizing the oars, rowed away from the ship. An attempt was made to lower a boat, and one or two shots were fired. But the crew were in no condition for work of any kind, and in a few minutes the Hooghly was lost sight of in the darkness. Lavie and Wilmore, who understood the management of a boat, hoisted the sail and took the rudder.

Meanwhile, Warley and Gilbert were endeavouring to restore the old quartermaster from his swoon. They threw water in his face, and poured some brandy from a flask down his throat, but for a long time without any result. At last the boat was in proper trim, and Mr Lavie set at liberty to attend to his patient. Alarmed at the low state of the pulse, and the failure of the efforts to restore consciousness, he lighted his lantern, and then discovered that the bottom of the boat was deluged with blood. The bandages had been loosened in the struggle to get on board, and the wound had broken out afresh. The surgeon saw that there was now little hope of saving the old man’s life. He succeeded, however, in stanching the flow of blood, and again bound up the wound, directing that Jennings should be laid in as comfortable a position as possible on a heap of jackets in the bow.

This had not been long effected, when morning appeared. Those who have witnessed daybreak in the tropics, will be aware how strange and brilliant a contrast it presents to that of northern climates. The day does not slowly gather in the East, changing by imperceptible degrees from the depth of gloom to the fulness of light, but springs as it were with a single effort into brilliant splendour—an image of the great Creator’s power when He created the earth and skies—not toiling through long ages of successive processes and formations, as some would have us believe, but starting at one bound from shapeless chaos into life and harmony.

The doctor cast an anxious look at the horizon, and was relieved to find that the Hooghly was nowhere visible. “Well out of that,” he muttered. “If we could only bring poor Jennings round, I shouldn’t so much regret what has happened. But I am afraid that can’t be.” He again felt the old man’s pulse, and found that he was now conscious again, though very feeble.

“Is that Mr Lavie?” he said, opening his eyes. “I’m glad to see you’ve come off safe, sir. I hope the young gentlemen are safe too.”

“All three of them, Jennings, thank you,” was the answer; “not one of them has so much as a scratch on him.”

“That’s hearty, sir. I am afraid poor Joe—it’s all over with him, isn’t it?”

“I am afraid so, Tom. But he didn’t suffer. The ball struck him right on the temple, and he was gone in a moment.”

“Yes, sir, and he was killed doing his duty. Perhaps if he’d remained among them villains, he’d have been led astray by them. It’s best as it is, sir. I only hope you may all get safe to land.”

“And you too, Tom,” added Frank, who with his two companions had joined them unperceived.

“No, Mr Frank, I shall never see land—never see the sun set again, I expect. But I don’t know that I’m sorry for that I’m an old man, sir, and my nevvy was the last of my family, and I couldn’t have lived very long any way.”

“No,” said Mr Lavie, “and you too have met your death in the discharge of your duty. When my time comes, I hope I may be able to say the same.”

“Ah, doctor, it’s little good any on us can do in this world. It’s well that there’s some one better able to bear the load of our sins than we are! But I want to say a word or two, sir, while I can. I advised you, you’ll remember, to run straight for the nearest point of the coast, which I judge is about eight hundred miles off. But I didn’t know then where them pirates meant to take the Hooghly to. Their officers only let it out last night over their drink. They were to make the mouth of the Congo river, where they’ve one of their settlements, or whatever they call them. Now, that happens to be just the point you’d be running for, and they’d be pretty sure to overhaul you before you reached it. You’d better now try to reach the Cape, sir. It is a long way off—a good fortnight’s sail, I dare say, even with this wind. But there’s food and water enough to last more than that time; and besides, you may fall in with an Indiaman.”

“We’ll take your advice, you may be sure, Jennings.”

“I’m glad to hear that, sir. It makes my mind more easy. Make for the coast, Dr Lavie, but don’t try for it north of Cape Frio—that’s my advice, sir; and I know these latitudes pretty well by this time.”

“We’ll take care, Jennings,” said Warley. “And now, isn’t there anything we can do for you?”

“You can say a prayer or two with me, Mr Ernest,” replied the old man feebly. “You can’t do anything else, that I knows of.”

Warley complied, and all kneeling down, he repeated the Lord’s Prayer, and one or two simple petitions for pardon and support, in which old Jennings feebly joined. Before the sun had risen high in the heavens his spirit had passed away. His body was then reverently committed to the deep, and the survivors, in silence and sorrow, sailed away from the spot.

Chapter Four.

A Fog—Wrecked—A Consultation—Survey of the Shore—A Strange Spectacle—The First Night on Shore.

It was early morning. Lavie and Warley were sitting at the helm conversing anxiously, but in subdued tones, unwilling to break the slumbers of their two companions, who were lying asleep at their feet, with Lion curled up beside them. It was now sixteen days since they had left the ship; and so far as they could ascertain, Table Bay was still seven or eight hundred miles distant. They had been unfortunate in their weather. For the first few days indeed the wind had been favourable, and they had made rapid progress. But on the fifth morning there had come a change. The wind lulled, and for eight and forty hours there fell a dead calm. This was followed by a succession of light baffling breezes, during the prevalence of which they could hardly make any way. On the twelfth day the wind was again fair; but their provisions, and especially their supply of water, had now run so low, that there was little hope of its holding out, even if no further contretemps should occur. Under these circumstances, they had thought it better to steer for the nearest point of the African coast. They were now too far to the southward to run any great risk of falling in with the pirates, and at whatever point they might make the land, there would be a reasonable prospect of obtaining fresh supplies. The course of the boat had accordingly been altered, and for the last three days they had been sailing due east.

According to the doctor’s calculations they were not more than sixty or seventy miles from shore, when the sun set on the previous evening; and as they had been running steadily before the wind all night, he fully expected to catch sight of it as soon as the morning dawned. But the sky was thick and cloudy, and there was a mist over the sea, rendering objects at the distance of a few hundred yards quite undistinguishable.

“We cannot be far from shore,” said the doctor. “My observations, I dare say, are not very accurate; but I think I cannot be more than twenty or thirty miles wrong, and according to me we ought to have sighted land, or rather have been near enough to sight it, three or four hours ago.”

“I think I can hear the noise of breakers,” said Warley, “I have fancied so for the last ten minutes. But there is such a fog, that it is impossible to make out anything.”

“You are right,” said Mr Lavie, setting himself to listen. “That is the beating of surf; we must be close to the shore, but it will be dangerous to approach until we can see it more clearly. We must go about.”

Ernest obeyed; but the alarm had been taken too late. Almost at the same moment that he turned the rudder, the boat struck upon a reef, though not with any great force. Lavie sprang out and succeeded in pushing her off into deep water again, but the blow had damaged her bottom, and the water began to come in.

“Bale her out,” shouted Lavie to Frank and Nick as he sprang on board again. “I can see the land now. It’s not a quarter of a mile off, and she’ll keep afloat for that distance. Take the other oar, Ernest; while they bale we must row for that point yonder.”

The fog had partially cleared away, and a low sandy shore became here and there visible, running out into a long projecting spit on their left hand. This was the spot which Lavie had resolved to make for. It was not more than two or three hundred yards distant, and there was no appearance of surf near it. They rowed with all their strength, the other two baling with their hats, in lieu of any more suitable vessels. But the water continued to gain on them, nevertheless, though slowly, and they had approached within thirty yards of the beach, when she struck a second time on a sunk rock, and began to fill rapidly. They all simultaneously leaped out into four-foot water, and by their united strength contrived to drag the boat on until her keel rested on the sand. Lavie then seized the longest rope, and running up the low, shelving shore, secured the end to a huge mass of drift-wood which lay just above high-water mark. Fortunately the tide was now upon the turn, so that in three-quarters of an hour or so she would be left high and dry on the beach.

The first impulse of all four was to fall on their knees and return thanks for their deliverance, even the thoughtless Nick being, for the time, deeply impressed by his narrow escape from death. Then they looked about them. The fog had now almost disappeared, and a long monotonous line of sand hills presented itself in the foreground. Behind this appeared a dreary stretch of sand, unenlivened by tree, grass, or shrub, for two or three miles at least, when it terminated in a range of hills, covered apparently with scrub. Immediately beyond the narrow strip of beach lay a lagoon, extending inland for about a mile. This was evidently connected with the sea at high-water; for a great many fish had been left stranded in the mud, where they were obliged to remain, until the return of the tide again set them at liberty. Presently a low growl from Lion startled them, and they noticed an animal creeping up round a neighbouring sand hill, which on nearer approach they perceived to be a hyena. It was followed by several others of the same kind, which forthwith began devouring the stranded fish, while the latter flapped their tails in vain attempts to escape from the approach of their enemy. Availing themselves of the hint thus offered them, the boys, who had not yet breakfasted, pulled off their shoes and stockings, and followed by Lion, waded into the mud. The hyenas skulked off as they approached, and they soon possessed themselves of several large eels and barbel Mr Lavie, whose appetite also reminded him that he had eaten nothing that morning, gathered a heap of dry weed and drift-wood, and drawing out his burning-glass, soon set them ablaze. Frank undertook to clean and broil the fish, which was soon afterwards served up, and pronounced excellent.

By the time they had finished their meal, all the water had run out of the boat, and the sand was sufficiently dry to enable them to convey their stores on shore. Having completed this, and covered them with tarpaulin to prevent damage from the broiling sun, their next task was to turn her over and examine her bottom. It took the united strength of the four to accomplish this; but it had no sooner been done, than it became evident that it would be useless to bestow further trouble upon her. The first concussion had merely loosened her timbers, but the second had broken a large hole in the bottom; which it was beyond their powers of carpentry to repair, even had they possessed all the necessary tools.

“Thank God she didn’t strike on that sharp rock the first time,” exclaimed Lavie, as he saw the fracture; “we should not be standing here, if she had.”

“Why, we can all swim, Mr Lavie, and it was not more than a quarter of a mile from land,” observed Gilbert, surprised.

The doctor made no reply, but he pointed out to sea where the black fins of more than one shark were visible above the surface.

Nick shuddered and turned pale, and all present again offered an inward thanksgiving.

“Well,” resumed Frank, after a few moments’ silence, “what is to be done, then? I suppose it is pretty certain that she will never float again.”

“Well, not certain, Frank,” suggested Warley. “There may be some fishermen—settlers, or natives—living about here, and they of course would have boats, and would therefore be able to repair ours. The best thing will be to make search in all directions, and see if we can discover anywhere a fisherman’s hut.”

“I am afraid there’s not much chance of that, Ernest,” said Wilmore. “If there were any fishermen about here, we should see their boats, or any way their nets, not to say their cottages; for they would be tolerably sure to live somewhere near the beach.”

“The boats might be out to sea, and the nets on board them,” suggested Gilbert, “and the huts may be anywhere—hidden behind those hillocks of sand, perhaps.”

“So they may, Nick,” observed Mr Lavie, “though I fear there is no very great chance of it. It is worth trying for, at all events. Look here, one of us had better go along the shore to the right, and another to the left, until they get to the end of the bay. From thence they will, in all likelihood, be able to see a long way along the coast, and if no villages or single dwellings are visible, it will be of no use making further search for them. It will take several hours to reach the end to the left there, and that to the right is probably about as far off; but it is still so hidden by the fog that, at this distance, it can’t be made out.”

“And what are the other two to do?” asked Frank.

“They had better stay here and make preparations for supper and passing the night,” said Mr Lavie. “It is still tolerably early, but whoever goes out to explore won’t be back till late in the afternoon, and will be too tired, I guess, to be willing to set out on a fresh expedition then. Besides, the night falls so rapidly in these latitudes that it wouldn’t be safe. Now, I have some skill in hut making, and I think you had better leave that part of the job to me.”

“By all means, Charles,” said Warley; “and Frank here showed himself such a capital cook this morning, that I suppose he’ll want to undertake that office again. Well, I’m quite ready. I should like to take the left side of the bay, Nick, if you’ve no objection.”

“It’s all the same to me,” said Nick; “anything for a quiet life—and it seems quiet enough out there anyway. Well, then, I suppose we had better be off at once, as I don’t want to have to walk very fast. I should like to have Lion, but I suppose he wouldn’t follow me.”

“No, he’s safe to stay with Frank, but you two had better take your guns with you,” said Mr Lavie. “I don’t suppose you are likely to meet any wild animals on these sand flats—nothing worse than a hyena, at any rate.”

“Thank you kindly, Mr Lavie, I don’t particularly want to meet even a hyena,” said Nick.

“Pooh, Nick, he wouldn’t attack you, if he did meet you. But you may want our help for some reason or other, which we can’t foresee, and we shall be sure to hear you, if you fire. Here, Nick, you shall have my rifle for the nonce. It is an old favourite of mine, and has seen many a day’s sport. And here’s Captain Renton’s rifle for you, Ernest. By good luck he had asked me to take care of it, so it was safe in my cabin the day we got away. I’ve never seen it perform; but if it is only one half as good an article as he declares, you’ll have no cause to complain of it.”

“How was it that the captain didn’t take it with him?” asked Gilbert.

“Because they wouldn’t let him,” said the surgeon. “He asked to be allowed to fetch it, and looked as savage as he dared to look, when they swore they’d allow no firearms to be taken.”

“I don’t wonder at their not permitting it,” observed Wilmore.

“Nor I, Frank. The wonder to me has always been that they let the officers and passengers go at all. But it seems that such of our men as agreed to join these Congo pirates would not do so, except on the express condition that the lives of all on board were to be spared; and the pirates daren’t cross them. But we mustn’t dawdle here talking. There’s plenty to be done by all of us, and more than we can do, too.”