The Project Gutenberg EBook of Left on the Prairie, by M. B. Cox This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Left on the Prairie Author: M. B. Cox Illustrator: A. Pierce Release Date: September 26, 2010 [EBook #34003] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LEFT ON THE PRAIRIE *** Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | AT LONGVIEW |

| II. | JACK IN TROUBLE |

| III. | JACK'S RESOLUTION |

| IV. | JACK STARTS ON HIS JOURNEY |

| V. | JACK GOES IN SEARCH OF NIGGER |

| VI. | JACK IS DESERTED |

| VII. | JACK IS RESCUED |

| VIII. | WHAT JACK LEARNED FROM PEDRO |

| IX. | JACK ARRIVES AT SWIFT CREEK RANCH |

| X. | JACK'S VISIT AT SWIFT CREEK RANCH |

| XI. | JACK CROSSES THE RANGE WITH CHAMPION JOE |

| XII. | AT LAST! |

Little Jack Wilson had been born in England; but when he was quite a baby his parents had sailed across the sea, taking him with them, and settled out on one of the distant prairies of America. Of course, Jack was too small when he left to remember anything of England himself, but as he grew older he liked to hear his father and mother talk about the old country where he and they had been born, and to which they still seemed to cling with great affection. Sometimes, as they looked out-of-doors over the burnt-up prairie round their new home, his father would tell him about the trim green fields they had left so far behind them, and say with a sigh, 'Old England was like a garden, but this place is nothing but a wilderness!'

Longview was the name of the lonely western village where George Wilson, his wife, and Jack had lived for eight years, and although we should not have thought it a particularly nice place, they were very happy there. Longview was half-way between two large mining towns, sixty miles apart, and as there was no railway in those parts, the people going to and from the different mines were obliged to travel by waggons, and often halted for a night at Longview to break the journey.

It was a very hot and dusty village in summer, as there were no nice trees to give pleasant shade from the sun, and the staring rows of wooden houses that formed the streets had no gardens in front to make them look pretty. In winter it was almost worse, for the cold winds came sweeping down from the distant mountains and rushed shrieking across the plains towards the unprotected village. They whirled the snow into clouds, making big drifts, and whistled round the frame houses as if threatening to blow them right away.

Jack was used to it, however, and, in spite of the heat and cold, was a happy little lad. His parents had come to America, in the first place, because times were so bad in England, and secondly, because Mrs. Wilson's only sister had emigrated many years before them to Longview, and had been so anxious to have her relations near her.

Aunt Sue, as Jack called her, had married very young, and accompanied her husband, Mat Byrne, to the West. He was a miner, and when he worked got good wages; but he was an idle, thriftless fellow, who soon got into disfavour with his employers, and a year or two after the Wilsons came he took to drink, and made sad trouble for his wife and his three boys. George Wilson had expostulated with him often, and begged him to be more steady, but Mat was jealous of his honest brother-in-law, who worked so hard and was fairly comfortable, and therefore he resented the kind words of advice, and George was obliged to leave him alone.

George Wilson made his living by freighting—that is, carrying goods from place to place by waggons, as there was no rail by which to send things. Sometimes, when he took extra long journeys, he would have to leave his wife and boy for some weeks to keep each other company.

'Take care of your mother, Jack, my boy,' he would say, before starting. 'She has no man to look after her or do things for her but ye till I get home.' And right well did the little fellow obey orders. He was a most helpful boy for his age, and was devoted to his mother, who was far from strong. He got up early every morning, and did what are called the chores in America; these are all the small daily jobs that have to be done in and around a house. First, he chopped wood and lit a fire in the stove; after that he carried water in a bucket and filled the kettle, and then leaving the water to boil, he laid the breakfast-table and ground the coffee.

When breakfast was over, he ran off to school, and afterwards had many a good romp with his cousins, Steve, Hal, and Larry Byrne, who lived quite close to his home. Jack was very fond of his Aunt Sue; she was so like his gentle mother. He often ran in to see her, but he always fled when he heard his Uncle Mat coming, whose loud, rough voice frightened him.

Jack was very sorry for his cousins, as they did not seem to care a bit for their father; indeed, at times they were very much afraid of him, and Steve, the eldest, who was a big fellow, nearly sixteen, told Jack that if it wasn't for his mother, he would run away from home and go off to be a cowboy, instead of working as a miner with his father. But he knew what a sad trouble it would be to the poor woman if he went away from her, and he was too good a son to give her pain.

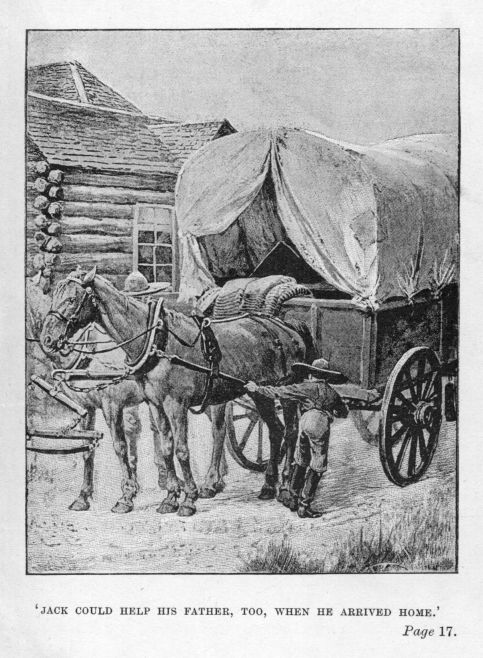

When his father was away freighting, Jack, even while he was at play, kept a good look-out across the prairie, watching every day for his return. He could see for miles, and when he spied the white top of the familiar waggon appearing in the distance, he would rush home shouting, 'Mother! Mother! Daddy's coming! I see the waggon ever such a long way off.' And then the two would get to work and prepare a nice supper for him.

Jack could help his father, too, when he arrived home, for there were four tired horses to unharness, and water, and feed. Jack knew them all well; Buck and Jerry in front as leaders, and Rufus and Billy harnessed to the waggon. George Wilson was very proud of his horses, and they certainly had a good master, for he always looked after them first, and saw them comfortably into their stable before he began his own supper.

Trouble, however, was dawning over the happy household. The life in the hot village had never suited Mrs. Wilson, and it told on her more as time went on. She looked white and thin, and felt so tired and weary if she did any work, that her husband got alarmed and brought in a doctor to see her. The doctor frightened him still more. He said the place was slowly killing her, as the air was so close and hot.

'You must take her away at once,' he said emphatically, 'if you want to save her life. She has been here too long, I fear, as it is. Go away to the mountains and try the bracing air up there; she may come back quite strong after a year there if she avoids all unnecessary fatigue. Take my advice and go as soon as you can. There's no time to lose!'

These words came as an awful shock to George Wilson, who had no idea his wife was so ill, and had hoped a few bottles of tonic from the doctor would restore her failing strength. But the medical warning could not be disregarded, and he could see for himself now how fast she was wasting away. They must go away from Longview as soon as possible.

It was a sad thing for the Wilsons to contemplate the breaking up of their home, but there was no help for it. They talked matters well over, and came at last to the conclusion that it would be better not to take Jack with them. They would probably be moving on from place to place, and in a year he would forget all he had learnt at school. After a long consultation with Aunt Sue, it was arranged that Jack should stay at the Byrnes' house and keep on at his lessons, his Uncle Mat having given his consent after hearing the Wilsons would pay well for his keep.

George Wilson and his wife felt keenly the idea of leaving Jack, and it was agreed that if they decided to stay in the mountains altogether, someone should be found who would take the boy to them.

It was terrible breaking the news to poor little Jack that his parents were going away from him, and for a time he was quite inconsolable. His father talked very kindly and quietly to him, and at last made him see that the arrangement was really all for the best.

'Ye see, Jack,' he said, 'the doctor says your mother is seriously ill, an' the only chance for her is to take her off to the mountains.'

'Can't I go too, Daddy?' pleaded Jack, with tears in his eyes. 'I'll do such lots o' work.'

'No, my lad; it won't do for ye to miss yer schoolin', as ye'd be bound to do if ye came wanderin' about with us. It's only fur a year, so ye must try an' be a brave boy, an' stay with yer good Aunt Sue until we come back agin or send fur ye. We know what's best fur ye, an', laddie, won't it be fine if Mother gets strong and well agin?'

'Aye, dad! That would be grand!' said Jack, brightening up.

'Well, it's a sad partin' fur us all; but there's nothin' else to be done, an' ye must try an' keep up a good heart fur yer mother's sake, as I doubt she'll fret sadly o'er leavin' ye.'

Jack promised to be brave, but there was a troubled look on his usually bright face as he watched the rapid preparations going on for the departure. The things had to be sold out of the house, as they could not take much with them. The sale at first excited Jack, as so many people came to buy; but when he saw their furniture, beds, chairs and tables all being carried oft by strangers, he realized fully what the breaking up of his home meant, and it made him feel very sad.

There was a lot to be done. Jack went with his father to buy a stock of provisions for their long journey, and then they tried to make the clumsy waggon as comfortable as possible for the sick mother. Aunt Sue packed up, as her sister was so weak, and the trial of leaving Jack was proving almost too much for her slender stock of strength. All the same, she bravely tried to hide the pain the parting gave her, and for her boy's sake tried to be cheerful even to the last.

Alone with Aunt Sue, she opened her heart, and received true sympathy in her trouble from that good woman, who knew well that the chief sorrow to her sister was the fear she might never see her little lad again.

'You mustn't get so down-hearted, Maggie,' said Mrs. Byrne kindly, 'but hope for the best. I have heard the air in them mountains is just wonderful to cure cases like yours, and perhaps ye'll get quite strong afore long.'

'If it pleases God,' said her sister gently. 'And now, Sue, ye'll promise me to look well after Jack. I know ye're fond o' him fur his own sake as well as mine; but I'm feared if Mat gets one o' his mad fits on he might treat him badly.'

'Don't you fear, Maggie,' returned Mrs. Byrne soothingly; 'I'll treat him as one o' my boys, an' ye know I manage to keep them out o' their father's way when he's too quarrelsome. Besides, Mat knows as ye're payin' well for Jack, and that, if naught else, will keep him civil to the lad.'

'I hope so,' murmured the mother sadly; 'an' if all goes well we'll have our boy with us again in a year.'

'Aye, a year'll go quick enough, never fear!' concluded her sister cheerfully; 'an' Jack'll get on finely at his schoolin' in that time.'

The night before they started came, and Jack, who had gone early to bed, lay sobbing quietly to himself, quite unable to go to sleep. Before long his mother came softly into the room and stood beside him. She noticed the flushed, tear-stained face on the pillow, and exclaimed in a grieved voice, 'Oh, Jack, darling, don't take on so! It'll break my heart if I think o' ye frettin' all the time.'

'I can't help it, Mother!' cried Jack. 'What shall I do without Dad an' ye?'

'Ye must think o' the meeting ahead, dearie. P'raps if Daddy does well in this new part of the country, an' I can get strong again, we may make our home up near the grand mountains as ye've never seen. It's so different from this hot prairie, fur there are big trees to shade ye from the sun, an' little brooks, called creeks, running down the sides of the hills.'

'Aye, I'd like to go an' live up thar,' cried Jack. 'I hope ye'll send fur me soon, an' I'll try an' be good. I do love Aunt Sue, but I'm scared o' Uncle Mat at times.'

'Never fear, Jack,' said his mother, putting her arms round him; 'Aunt Sue'll see as ye come to no harm. But, oh! dearie, how I wish I could take ye with me!' And the poor woman broke down and mingled her tears with Jack's.

But the boy suddenly remembered his promise to his father, and, knowing how bad the excitement was for his mother, he made a great effort to stop crying, and, rubbing his tears away, he said, 'Mother! this won't do; I promised Dad I'd be brave!'

'You're right, Jack. We mustn't give way again. I ought to have kept up better. I must be goin' now, dearie, an' before I say good-night, will ye promise me not to forget to say yer prayers every day, an' ask God to take care of us all till we meet again?'

'I promise,' said Jack gravely.

'An' ye'll sing the hymns I've taught ye sometimes, won't ye, laddie?' asked his mother softly.

'I won't forget,' returned Jack, as he kissed her wet cheek; and then she went away with a feeling of comfort in her heavy heart.

'A year isn't so very long,' murmured the boy to himself, and before long fell asleep.

Next morning his parents started, and Jack, after the terrible good-byes had been said, stood watching the retreating waggon until it became like a speck in the distance. At last it vanished altogether, and then the boy's loss seemed to overwhelm him. In a frenzy of grief he rushed off to the woodshed, and wept as if his heart would break.

But Aunt Sue guessed the tumult of sorrow that was going on in the young heart, and she soon came to find him and offer comfort. She was so like his dear mother, with her sweet voice and gentle manner, that she soothed him in his trouble; and when she proposed he should help her to get the house brushed out and tidied up, he gladly threw himself into the work.

He was helping his aunt to lay the things on the table when his uncle came in. He had not seen the boy before, and even he felt a bit sorry for the poor lad, so he said not ungraciously, 'That's right, Sue, make him useful. There's nothin' so good fur sick hearts as work.'

Poor Jack flushed at this speech, as it touched him on a sore point; but he saw his uncle did not intend to hurt his feelings by the words, and he tried to swallow the lump that would rise in his throat. The three boys came in for supper, and Hal and Larry looked curiously to see how Jack was taking his trouble; but he was determined they should see no sign of tears from him, and they did not suspect that the little heart was nearly bursting.

Steve was a most good-natured lad, rough to look at, but with a large slice of his mother's kind heart, and he now looked quietly after Jack, seeing that he had a good supper. He was very fond of his small cousin, who in return was devoted to him, and the big boy felt sorry when he noticed the effort Jack was making to keep up a brave face before Hal and Larry.

Very soon Aunt Sue suggested he should go to bed, which he was glad to do, and once there, he was so tired out with his grief he fell fast asleep.

Over a year had passed away since Jack's parents had left Longview for the mountains, and the boy was just nine and a half; but he was no longer the same happy little fellow as when we first knew him. Great changes for the worse had taken place, and misfortunes had come thick and fast upon him.

He lost his good Aunt Sue, for she died of heart disease ten months after his parents' departure. How poor Jack missed her! His uncle very soon afterward married again, and his new wife was a loud-voiced, harsh woman, who treated Jack most unkindly.

Steve, too, his great friend, had gone away, as he had long threatened, to be a cowboy, for he found the life at home unbearable without his mother. Hal and Larry, who had not improved as they grew older, took good care to keep away from the house, except for meals; and thus Jack, as the youngest, had to bear the brunt of everything. He no longer went to school, for his uncle's wife wanted him to wash floors, carry water, and go endless errands for her. Every morning and evening he had to look for Roanie, the cow, who was given to wandering off on the prairie for long distances, searching for better pasture. When he had driven her home he had to milk her, and if he chanced to be late getting her in he was severely scolded, and oftentimes deprived of his supper.

It was a hard life for the little lad, and many a night he sobbed himself to sleep as he thought sadly of the happy days before his parents left him.

There was another thought troubling him, and that was, Why hadn't his people sent for him, as they promised? Was it possible that they had forgotten him, or meant to leave him for years with Uncle Mat?

It was dreadful to think about, but there was no getting over the facts of the case, and Jack knew right well that it was long past the time they had said he should be away from them. Only one year! He remembered it as if it were but yesterday, but not even a message had come for him. He could not understand it, and his heart felt sad and sore as he often crept away to escape his uncle's drunken wrath or the wife's cruel blows.

One evening he could not find Roanie for nearly two hours, and when he got home, tired and hungry, he found Mrs. Byrne in a bad temper. She gave him a little dry bread for supper, and, anxious to get away from her tongue, Jack stole off across the prairie for some way, where, lying on the short, burnt-up grass, he gave vent to his misery, and burying his head in his hands, had a good cry.

Suddenly he heard the sound of horse's hoofs approaching him, and a great jingling of spurs, as someone dashed up close to him and stopped abruptly. Jack looked up, and was surprised to see his cousin Steve, looking very smart and happy.

'Hello, young un!' he cried, jumping off his horse. 'I thought it was you, so I turned off the prairie road to see. What's the trouble? You'll drown everyone in Longview if you cry so hard.'

Jack sat up and wiped his streaming eyes with his sleeve. 'Oh, Steve!' he exclaimed, 'I'm so unhappy. I'm glad you've come, for they're so unkind to me, and I'm beginning to doubt as Father and Mother have forgot me. They've never sent for me.'

'Don't fret, Jack,' said Steve; 'they haven't forgot you, never fear. D'you know,' he went on slowly, 'I've found out as they sent for you long ago, an' he'll not let you go.' Steve nodded towards his home.

'He!' repeated Jack in astonishment. 'Uncle Mat! Why, he hates me, Steve, an' I guess he'd be only too glad to get rid o' me.'

'Not he!' returned Steve. 'You're better than a servant to that woman, for she'd never get anyone to work as hard as you, an' she ain't a-goin' to let you leave. I heard a tale from Long Jim Taylor, as worked in the mine with Father, an' it's that as brought me home now. Father was drunk one day, an' let out about a mean trick as he'd played on your folks, an' you, too, for the matter o' that; an' though he denied it afterwards, I'm sure it's true, an' I'll talk my mind to him afore I'm done.'

Steve looked so furious, Jack felt almost frightened as he asked timidly, 'What was it, Steve? Tell me what he has done.'

'Well, then, kid, listen!' said the cowboy. 'He never wrote to say Mother was dead, but gave your folks to understand as it was you as was buried; said as how you'd had a bad fall an' died terrible sudden, an' there was no time to get 'em over.'

Jack's eyes had grown rounder and larger with horrified surprise as he listened to Steve's story.

'How wicked of him!' he cried. 'But, Steve, I wonder he wasn't afraid o' their hearin' about it.'

'Aye, and so do I,' answered his cousin. 'I believe, however, he has been meanin' to move to some other part o' the country an' take you. Your folks are settled a long way off, an', thinkin' as you're dead, they'll probably never come back here again, so he'd be pretty safe.'

'What shall I do, Steve?' asked Jack piteously. 'I'll ask Uncle Mat about it this very night.'

'Don't make him angry,' returned the cowboy kindly; 'but tell him you have heard what he's done, an' you are bound to go to your folks somehow. I'll tell him what I think when I meet him in the street. I ain't a-goin' near that house with that woman there, so if you want to see me, come here to-morrow evening.'

'I will, Steve. Good-night.' And Jack darted away.

Jack felt very brave and determined when he left his cousin, but his courage failed a little as he approached the house. The door was open, and as he drew near he heard his uncle and his wife talking loudly, and caught his own name.

'I'm not such a fool as to let Jack go back to them,' he heard his uncle say, 'in spite o' what Jim Taylor wrote sayin' he'd told Steve, an' the lad was so angry he was comin' over to make things right for Jack. The boy's worth fifty cents a day to us, an'll make more afore long; so the sooner we clear out o' here, an' make for a part o' the country where we ain't known the better. I guess we needn't let Steve into the secret o' our whereabouts, if we can get off afore he comes.'

Jack's pulses were beating fast as he listened to this speech. He shook with indignation, and at last, unable to stand it any longer, he rushed into the kitchen, exclaiming: 'Uncle Mat, I heard what you were sayin', an' I must go to my folks. I thought as they'd forgot me, an' now I know they haven't, but you've told 'em a lie.'

A look almost of fear crossed the man's face at first when Jack burst in, but it was quickly replaced by a hard and cruel smile.

'Listenin', were you?' he said angrily, 'Well, listeners hear no good o' themsel's, an' it's a mighty bad habit to give way to. Perhaps a touch o' the whip will make you forget what wasn't meant for you to hear.'

'Oh! don't beat me, please, Uncle Mat,' cried poor Jack.

But there was no mercy to be had this time, and when his punishment was over, Jack, quite exhausted, made his way to his miserable bed, which was in a shed adjoining the house. Through the thin wooden walls he could hear the two Byrnes talking and planning to leave Longview as soon as possible, and he felt sick with fright as he heard them arrange to take him too.

'Oh dear! oh dear!' murmured the boy sadly. 'What will become o' me? If Steve don't save me I don't know what they'll do to me. But I'm glad I didn't say I'd seen him.'

In spite of his aching bones, Steve's assurance that his parents had not forgotten him, as he feared, was a great comfort to the lonely little lad, and, thinking hopefully of his interview with Steve the next day, he fell asleep and forgot his troubles.

Jack could hardly get up the next morning, he was so stiff and bruised from the beating his uncle had given him, but he was not the kind of boy to moan and groan in bed. He dragged himself up and dressed, and after washing and dipping his head into cool water in the back yard, he felt better, and soon got to work, lighting the fire and getting the things ready for breakfast. He rather dreaded meeting his Uncle Mat, but although the man looked surly enough, he did not allude to the occurrence of the previous evening, and after breakfast, to Jack's relief, he left the house. The day seemed longer than usual, but Jack finished his work at last, and hastened away to the place where he and Steve had arranged to meet.

His cousin was already waiting there, lying on the ground, lazily watching his horse quietly grazing the herbage near. He hailed Jack heartily.

'Well! how did you get on last night?'

'Very badly, Steve,' returned the boy, and related how he had been treated. Great was Steve's indignation when he heard what had taken place and looked at Jack's bruised back.

'Poor little lad!' he said pityingly. 'He has been hard on you, I can see. He licked me once in a rage, an' I wouldn't stay a day longer in his house, for I hadn't done wrong. I saw him to-day, an' we had a terrible row over you. I gave him a piece o' my mind about the way he was keepin' you from your folks under false pretences.'

'Steve!' cried Jack suddenly, a ray of joy crossing his face, 'I've got a plan in my head. You ran away from home, an' why shouldn't I?'

'Aye! but I was a big fellow over sixteen, an' you're but a little un, not much more than a baby yet,' returned Steve.

'But I shouldn't be afraid to try,' declared Jack stoutly. 'I might get lifts from folks goin' along the road.'

'You're right there,' exclaimed Steve. 'It isn't such a bad idea after all. You're a plucky boy, for I never thought as you had the grit to make a bolt on it. If you're sure you aren't frightened to go so far alone, I do believe as I might be able to help you a bit on your way.'

'Could you, Steve?' cried Jack. 'Oh! do tell me how.'

'Well! There's a waggon here now belongin' to some miners who are on their way to the "Rockies" to prospect. I know one o' them, an' it would be a grand scheme if he would let you go along with him. Shall I ask him?'

'Please do,' said Jack. 'I'm ready to start any minute they want to go, an' I promise I won't give 'em any trouble. Oh, Steve, I must get away from here!'

'All right! I'll try an' fix it for you,' returned Steve. 'Wouldn't it be a surprise for your folks if they saw you walk in one fine day? I don't quite know where they live, except that they're somewhere on the Cochetopa Creek, but I reckon if you do get that far as you'll find 'em. I'll see the miner to-morrow. He's campin' t'other side o' the village. I guess he won't object to takin' you, as I'll tell him you're a handy little chap. I believe I'd have gone an' seen you safe there myself, but I'm goin' to look after cattle down on the Huerfano.'

'You are good to me, Steve!' cried Jack, throwing his arms round the cowboy's neck and hugging him. 'I thought you'd save me somehow, an' I do love you so.'

'There! That'll do, young un,' said Steve good-naturedly. 'Go home an' keep quiet, for if that woman gets wind o' our plans, it'll be all up, for she ain't goin' to give up a slavey like you. But, look here! How shall I let you know if he'll take you?' as Jack was turning to go.

He stopped, and after a little more talking it was decided that Steve was to interview the miner on Jack's behalf, and if the man agreed to let the boy go with him to the mountains, Steve was to ride past his father's house the next morning and wave a red handkerchief as a sign of success.

They parted in great spirits, for both were too young to understand what a great undertaking they were contemplating for a little child. Jack had no notion of the distance it was to his parents' new home, and Steve was rather vague about it. Jack's one idea was to start off and find his father and mother somehow.

The next day Mrs. Byrne was in a very bad temper and was a great trial to poor Jack. Nothing he could do was right in her eyes, and being in a state of anxious excitement himself over the result of Steve's mission, he made some trifling blunders which brought swift correction upon him, and many a time his ear tingled from a blow from her hand.

He was busily engaged in washing the kitchen floor when he heard a horse coming rapidly along the dusty road. He knew what it was, and, unable to resist the temptation, he jumped up from his knees and rushed to the door. Unluckily for him, Mrs. Byrne came in from the garden at that moment and met him at the doorway. Seeing him, as she thought, neglecting his work, she seized him by the arm, and pulling him back roughly into the kitchen, said angrily, 'You lazy imp, the moment my back's turned you leave the washin'! I thought your uncle had taught you a lesson two nights ago; an', mark you, I'll give you another hidin' as you'll remember if I catch you shirkin' your work.'

But Jack cared nothing for her threatening words now. In the one glimpse he had got through the doorway he had seen Steve galloping past, and waving in his hand the red handkerchief of success.

Hope sprang high in the boy's heart, and with a bright smile on his face he set to work once more at the dirty floor, scrubbing with a will. Nothing put him out again that day. He carried pail after pail of water through the hot sun without a sigh, although it blistered his hands, for there was a great thought of joy to cheer him on: 'The last time for her!'

When he met Steve in the evening he heard the waggon was to start at daybreak, and Jeff Ralston, the miner, was willing to take him as far as the mountains if he were there in time, but on no consideration would he wait one moment for him.

'I'll be there, never fear!' exclaimed Jack joyfully.

'This Jeff seems a rough, good-natured fellow,' went on Steve, 'an' he'll be kind to you, I guess, if he don't get drunk. He's like my father when he's drunk: he ain't no use at all; but there isn't much to drink on the prairie, so I expect you'll be all right.'

Jack was quite grateful enough to please Steve, although the little boy did not know that his kind-hearted cousin had given the miner some of his own hard-earned dollars to secure his goodwill towards the youthful traveller.

'You'd better get home an' to bed now,' said Steve at last, 'or you'll miss getting up in time. I hope you'll get through safe, Jack, an' perhaps I'll come an' look you up myself some day.'

'Good-bye, Steve; I won't ever forget you, an' I'll tell Father an' Mother how you helped me off to see them,' said Jack gratefully, and after an affectionate farewell the cousins parted.

Jack went to bed directly he got into the house, but never a wink of sleep did he get. He lay quite still for hours, until the deep breathing through the thin partitions told him that the rest of the family were slumbering soundly. Then he arose and dressed himself. Making no noise, and carrying his boots and a blanket which was his own property, he quietly got out of his window, and in a few minutes was hurrying along the road towards the outskirts of the village in the direction of the miners' camp.

It was a starlight night, which enabled him before very long to make out a big prairie schooner a little way ahead of him, with four horses tethered near by long ropes. Close up under the waggons he saw the figures of two men sleeping on the ground, and not wishing to disturb them, he lay down near them to wait until they awoke. But his long hours of wakefulness had tired him out and he fell asleep.

He was aroused by a stir in camp to find preparations going on for breakfast. He felt chilly from lying on the ground, and was not sorry to see a nice fire of sticks burning near him. A man was putting a kettle of water on to boil, and as Jack rose up and approached him, he welcomed him in a gruff but not unkindly way.

'How do, kid? I reckoned I'd leave you to sleep it out? Are you the young un as Steve Byrne came to inquire about? You want to go along with our outfit as far as the Range, don't you?'

'Yes, please,' answered Jack. 'I'm goin' to my father. He's way over in the San Luis Valley, up on the Cochetopa Creek.'

'Cochetopa Creek!' ejaculated the man. 'Why, boy, that's over two hundred an' fifty miles from here, an' you'll have to cross the "Rockies," too. Say, Lem,' he called out, 'here's an enterprising young un. He's startin' off alone for Cochetopa Creek. What d'you think o' that?'

'He'll never get there,' returned his companion, who had been looking after the horses and came up at that moment.

'You're right, Lem, I do believe,' said the first speaker. 'Just listen to me, boy! A kid like you can never travel so far. Take my advice an' go back to the folks as look after you here.'

'No, I won't,' answered Jack sturdily; 'I've started now, an' I ain't going back for no one. If you won't take me I'll go on an' walk. My father sent for me, but my uncle won't let me go. I guess he shan't stop me now.'

'Well, you're a plucky kid, as sure as my name's Jeff Ralston,' declared the miner.

'How soon is grub to be ready?' asked Lem impatiently. 'I'd better harness up the team while I'm waitin', as we want to get away soon.'

'All right. I'll call you when I've made some oatmeal porridge. Here, kid, go to the waggon an' get out the tin cups an' plates.'

Jack obeyed, and was so quick getting out the things, he pleased Jeff, who remarked to him, when he saw Lem was safe out of earshot: 'Look here! Ye're a sharp lad, an' I'm glad I promised Steve Byrne as I'd do my best for you. All the same, I'm a bit afraid as to how Lem'll take it, for he can't abide kids, an' I haven't told him as you're a-comin' along with us. He's my mate an' a terribly cranky chap.'

'I won't bother him a bit,' cried Jack, delighted to find one of his escort inclined to be so friendly, and hoping to be able in time to please the doubtful Lem too.

Jack confessed to himself he did not like the man's looks at all, and when Jeff at breakfast intimated to him that he intended to take 'the kid' along, he only received a disapproving 'Humph' in return. Jack, distrusting the dark, sullen face, determined to have as little as possible to do with him while he formed one of their party.

The sun had not risen far above the horizon when the waggon started. The men very carefully extinguished every ember of their camp fire before they left the place, by pouring buckets of water over it, as the laws were very strict on that point. Many of the terrible prairie fires are traced from time to time to sparks left by careless people camping out, which, blown by the wind, ignite the dry grass near, and start the destructive flames which spread and rush on for miles, carrying ruin in their track.

Lem sat in front of the waggon, driving the four horses, while Jeff was beside him, both smoking. As Jack was afraid of being pursued, Jeff suggested it would be safer for him to ride inside the waggon for the first day or two. They had only got a few miles from Longview, when Jeff perceived a horseman tearing after them, evidently bent on overtaking them.

'Lie down, boy!' he called through the waggon opening to Jack. 'We're followed already. Get under the blankets.'

Poor Jack obeyed, trembling with fright, and not daring to look out and see who it was. How relieved he felt when the horse came up close behind and he heard Steve's cheery voice hailing them: 'Hi, stop!'

'Hold on, Lem, for a bit,' cried Jeff. 'It's the young un he wants to see.'

Lem pulled up with evident reluctance.

'Have you got the kid?' asked Steve anxiously.

'Yes, there he be,' returned Jeff, as Jack's happy face looked out through the canvas curtains; 'I guess we can take care o' him for a spell of the way; but though he's got his head screwed on right, an' he has plenty of pluck, I doubt if he'll ever get as far as Cochetopa Creek.'

'He's bound to go,' said Steve, 'an' I leave him now in your trust, Jeff.'

Steve could not help laying a slight emphasis on the your, when speaking to Jeff, for there was no doubt his face had fallen considerably when he perceived that Lem Adams was Jeff's mate. He had known two men were going, but Jeff Ralston was the only one he had seen the day before, when he went over to the camp to negotiate on Jack's behalf.

He had not thought of asking the other man's name, and now he was sorry enough to find that Lem was one of Jack's companions. Some months before, Steve had seen a good deal of Lem Adams in a mining town, and disliked him intensely, having found him a bad, untrustworthy man. Lem hated Steve, too, and the scowl on his face was not pleasant to see, as he looked at the young cowboy.

Jack had jumped out of the back of the waggon upon Steve's arrival, and now the latter pulled his horse round to where the boy stood, and leaning from his saddle, he whispered, so that the others could not hear, 'Look out as you don't vex that black-lookin' fellow. He's a mean chap, and hates me, so I'm feared as he'll plague ye if he gets the chance; but Jeff'll see as ye ain't bullied, if he don't get drunk. Take this, lad; it may be useful; but don't let on as you have it.' He slipped a small paper packet into Jack's hand, and shook his head warningly to stop his words of thanks.

Then calling out, 'Good-bye, Jack. Keep a good heart up, an' good luck go with you!' he put spurs to his horse and galloped away.

Jack stood gazing after him until he was lost to sight in a cloud of dust; then, holding the packet tight in his hand, he remounted the waggon, and they moved on once more over the dusty road.

It was August, and the hot sun poured down its relentless rays on the prairie schooner and its occupants travelling slowly on; but Jack never grumbled. He was happy enough, knowing that he had started out on his long journey; and what cared he for the heat when he found himself moving along the same road over which his dear father and mother had travelled before?

But to return for a time to Longview. Jack's absence from his uncle's house was not noticed until breakfast-time. When he was first missed, the Byrnes concluded he had gone to look for the cow, as there was no morning's milk in the place where Jack usually left it. A few hours later they were surprised to hear Roanie lowing near the yard gate, and knew that the wandering animal must have actually come back of her own accord to be milked. But where was Jack? Roanie's arrival caused quite a stir. Mat Byrne began to think something was wrong, and he and the two boys sallied forth to look for the truant in the village.

They asked various people, but no one had seen Jack, and though they hunted every spot they could not find him. His uncle got very angry, and vowed to pay him out when he caught him again.

Luckily for Jack, his uncle never once supposed so young a boy would think of running away, and he made sure that by evening Jack would return to his house hungry and repentant.

He at first thought he would find Jack with his own son, Steve, and therefore was greatly surprised to see the latter riding carelessly about the village all day. Steve rode past him, giving him an indifferent nod, and his father little thought how closely the cowboy was watching every movement he made.

Never for one moment did Mat Byrne connect Jack's disappearance with the departure of the two miners that morning, and when it dawned on the searchers the next day, after having ransacked every shed and building in Longview, that they must look further afield, for the missing boy, our fugitive was too far away to fear recapture. Byrne made many inquiries from incoming travellers as to whether they had seen a lad anywhere along the different roads; but, thanks to Jeff's precautions, not a soul passing their waggon had seen the small boy hiding under the blankets; and, unable to get any clue to the direction Jack had gone in, his uncle was at last obliged to give up the search.

For three or four days Jack was very careful to keep out of sight; but as they got farther away from Longview, he felt safer and breathed more freely. He was always glad when they stopped to camp for the night, as his legs got very cramped in the waggon. If possible, they halted each time near some spring or creek of water, where they could get plenty for man and beast to drink.

Everyone had his own work allotted to him, and in this way, knowing what each one had to do, much confusion was saved when forming the camps. Lem looked after the four horses, unharnessed them, watered them, gave them their feeds, and picketed them out where the grass grew most plentifully. Jeff was cook, and Jack helped them both. Jeff found him most useful. He collected fir cones and bits of piñon or birch-bark to start the fires with, and kept them going with sticks; he filled the camp-kettle from the spring, while Jeff fried the beefsteak or sausage-meat; and even Lem looked less sullen when he found how much quicker he got his meals than before Jack came.

Always after they had eaten their food Jack washed up the things in a bucket, and put them tidily by in their places in the waggon, while the men lounged by the fire and smoked. Jack soon got used to the life, although it seemed very strange to him to find himself every night farther away from Longview, and getting nearer and nearer to the grand mountains which they could just see stretching along in a huge range miles ahead of them.

Jeff liked Jack better every day, and asked him a great deal about his people. One day he questioned him about his mother, and being a subject dear to the boy's heart, he launched forth into a glowing description of her, which quickly showed the rough miner what a good influence she had exercised over her little son.

'Well,' said he slowly, 'I understand you now, my lad. Your mother was one worth having. But you say she taught you prayers an' hymns. I don't care about prayers, but I'm powerful fond o' singin'. Could you give us one o' your mother's hymns now?'

They were gathered round the fire after supper, but Lem seemed half asleep as Jack and Jeff talked. In answer to the latter's questions, the boy said:

'Aye, of course I can. I'll sing you the one as father liked best, for he used to sing it when he was freightin' an' campin' out as we're doin' now.'

'Give it us, my lad,' said Jeff, as he refilled his pipe, and prepared to listen.

Jack had a sweet young voice, and, possessing a good ear for music, he had quickly picked up the tunes of his favourite hymns from his parents, who both sang well.

Delighted to please his new friend, he struck up 'For ever with the Lord,' repeating the last half of the first verse as a chorus after all the verses. Fresh and clear his voice rang out, and when he came to the last two lines—

'Yet nightly pitch my moving tent

A day's march nearer home'—

he seemed to throw his whole energy into the words.

The hymn struck home to rough Jeff, and when it was ended he said:

'That's the way, lad. It's almost as if them words were written for such rovin' chaps as us. Don't stop. I like it. Give us another.'

Jack was only too glad to go on. He sang his mother's favourite, 'My God, my Father, while I stray,' and followed it by many more, until his voice got tired. Sometimes he forgot a verse here and there, but he remembered enough to show Jeff that he must have sung the hymns day after day, to know them so well by heart.

Lem had sat silently on the far side of the camp fire, and as Jack ceased singing, he said sneeringly: 'Say, Jeff, you ain't been much o' a hymn-fancier afore to-night, I reckon.'

'No, I ain't,' returned the miner quietly; 'more's the pity, perhaps. If I'd had such a mother to teach me, I dare say I'd have lived a deal straighter life than I have done. I don't remember my mother. She died when I was a babby, but if she'd been like Jack's, I reckon I'd have gone as far to see her as he's agoin'.'

Lem grunted. In spite of himself he had liked listening to the boy's singing, but the words that he sang had made no impression on him.

Jeff always sent Jack early to bed, for the unusual fatigue made the little fellow feel very tired and weary towards night. He slept in the waggon, for Jeff had said after the first day, 'Jest roll yersel' up cosy in there. Lem an' I are used to sleepin' on the ground an' like it best, but it's different for a kid like you.'

Jack soon became attached to the good-natured miner, and he felt as long as he was present he need not feel in the least afraid of Lem troubling him.

For nearly three weeks the horses dragged the waggon slowly on over the prairie, and although it was very hot and dusty, Jack was as happy as a sandboy.

For some days they had made very short journeys, as one of the horses had rubbed a sore place on its shoulder, and consequently refused to pull at all. Lem at last had to tie it on at the back of the waggon, and arrange the other three animals in unicorn fashion—that is, one in front of two. This, of course, delayed their progress a good deal.

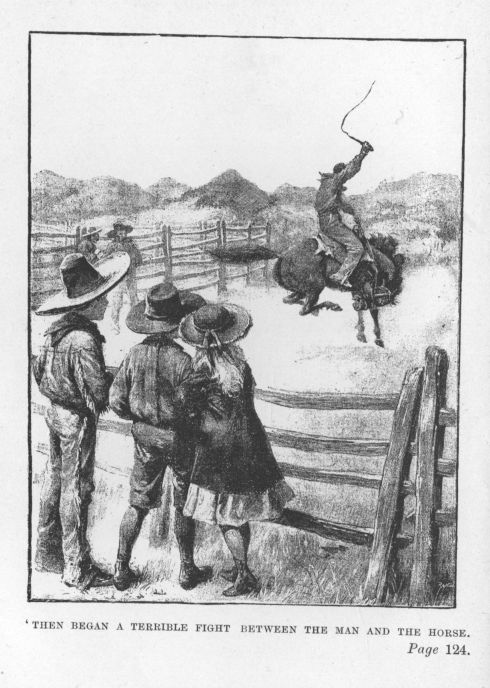

Jack was delighted with the novelty of all he saw, and a band of antelopes bounding away in the distance nearly drove him wild with excitement. One evening they came upon some cowboys who had just bunched up a huge herd of cattle for the night. There were nearly three thousand beasts, and it was a wonderful sight to see how a few men managed to keep so many cattle in check. The cowboys were stationed on their horses at near distances all round the herd like so many sentinels.

If an animal broke away, a horseman was after it at lightning speed. With a swift turn of his arm he would throw the lariat with a true aim over the horns of the runaway, and the sagacious horse, knowing what was expected from it, would twist round on his hind-legs, and the jerk on the rope would bring the fugitive down to the ground. Sometimes the cowboys galloped round the running beast, and headed it back to the herd without using the lariat or long leather rope.

Jack and his companions camped for the night close to the cowboys, and Jack took a great interest in them for Steve's sake. They relieved each other like guards all through the night.

The way they rode was wonderful in Jack's eyes, and their horses were so well trained, they turned to the right or left as their riders bent their bodies in the direction in which they wanted to go, and if the reins were thrown over an animal's head it would stand quite still.

There was great work next morning, as the cowboys made an early start, and the bustle was most exciting to Jack as he watched them standing or sitting in groups round their grub-waggon eating their breakfast. Then, directly after, they tightened their saddles, and before long the gigantic herd of cattle moved slowly on. Such a bellowing they made, and the dust rose in a huge cloud behind them, in which they were soon lost to sight. Their grub-waggon followed them, and shortly after Lem got his horses harnessed, and he, Jeff, and Jack, taking their places in their prairie schooner, rolled on once more towards the mountains.

These mountains, which were getting nearer every day, were a fresh source of wonder to Jack. He had lived all his life on the flat prairie where there was not even a hill to be seen, and he was speechless with surprise as he gazed on the snow-capped peaks in front of him, stretching up into the blue sky. Lower down the sides of the mountains the dark forests of trees spread for miles, and Jeff pointed out to him where the deep ravines or cañons could be seen where the mountain creeks rushed down to the valleys, fringed all along their banks with quaking aspens and cotton-wood trees.

How pleased Jack felt to think that his new home must be somewhere in sight of these glorious mountains, and already the air they breathed seemed very different from the hot, close atmosphere at Longview.

One evening they made their camp for the night just outside a Mexican village. It was a very queer-looking place, and Jack stared about him in astonishment. He had seen Mexicans passing through Longview occasionally, and now he had come to a village where no one but Mexicans lived. The houses were not built of wood, like those at Longview, but were made of a kind of mud called adobe. This adobe was shaped into bricks and baked. The houses looked so funny. Some were quite round like beehives, and it amused Jack very much when he noticed that many of the doors were halfway up the front wall of the houses, and when people wanted to go in and out, they went up and down ladders placed to reach the openings.

That evening, after supper, Lem persuaded Jeff to walk into the village, leaving Jack as usual to wash up the things. The boy felt a mistrust of Lem when he saw how maliciously triumphant he looked as he strolled away from the camp accompanied by Jeff. He watched them as far as the village and then returned to his work. When it was finished he sat contentedly down by the fire to wait for them. It got later and later, but his companions did not return, and at last, unable to keep awake any longer, he went to bed.

He fell into a troubled sleep, from which he was roused by hearing men's voices. Starting up, he listened and heard his companions returning. They were singing and shouting in a wild, boisterous way that struck terror to Jack's heart, for he knew from such sounds that they must have been drinking heavily. Their loud, rough voices frightened him, and he lay very still inside the waggon for fear they should see him. He could tell Lem was in a quarrelsome mood, and trembled as they hunted about in the back of the waggon for their blankets, swearing and growling all the time. At last they sank into heavy slumbers, but all sleep had fled from Jack's eyes at the fresh trouble that had arisen for him. The two men were evidently given to drink, the awful curse in the West, and had taken the opportunity of a first halt at a village to satisfy their craving for it. It was a terrible thought for poor Jack, for he knew, from what they had said, there must be many mining camps ahead of them, and of course in such places there would be great temptations for men like them, and his heart sank at the idea of being alone with such companions.

He lay awake for hours, but dropped into a kind of doze towards morning. He rose early and moved very quietly, fearful of disturbing Jeff and Lem after their night's carousal. He went to water the horses, and to his surprise found one had disappeared.

It had evidently dragged its picket-rope from the pegs that secured it, doubtless frightened by the noise in camp the previous night. It was the horse that had been led behind the waggon on account of its sore shoulder, and it probably was fresher than the other three horses and more likely to run away. It was not shod, and unfortunately had made no impression on the short, dry herbage, to show Jack which way it had gone. He wandered away a short distance from the camp looking for the fugitive, but, unable to see anything of it, he returned, and began to prepare breakfast.

Just as it was ready Lem roused up, and came grumbling towards the fire. Jack deemed it wiser not to speak to him, as he looked very cross indeed, and the boy could not help wishing his friend Jeff would also wake up, as he always felt safer in his presence.

They silently ate their breakfast, until Lem, looking over towards the group of horses, asked suddenly:

'Where's Nigger?'

'He was right enough when I went to bed last night,' returned Jack, 'but I found him gone this mornin'. I expect he dragged his picket-rope and got away.'

Lem darted an angry look at the boy. 'I believe you loosed him yoursel',' he exclaimed furiously, 'to pay Jeff and me out for goin' for a bit of a spree into the village!'

'I didn't,' cried Jack indignantly; 'I wouldn't do such a mean trick nohow.'

'I don't believe you, there!' declared Lem insultingly. 'I can't abide kids, an' I wouldn't trust one of 'em anywhere. I was mad when I heard as Jeff was bent on bringin' you along with us.'

In vain Jack protested he knew nothing about the horse's escape. Lem's temper was bad from the effects of his drinking bout, and as ill-luck would have it, the boy was the victim of it.

'Look here, kid,' he said sternly, 'it was your business to see to them creatures when we were gone away, an' I guess you'll skip out an' find that there Nigger as quick as you can. Not a step on with us do you go, till he's brought back again!'

'I've looked all round the camp this mornin',' said Jack dolefully, 'but I haven't seen no tracks of him. Would you let me get on Yankee Boy an' ride over to that clump of trees over there?'

'No! I guess you can walk that far,' returned Lem, 'an' I reckon you'd better not come back again without the horse. I mayhap would like to ride Yankee Boy mysel' an' have a look round.'

Poor Jack! He looked wistfully at the recumbent figure of Jeff, who was still in a deep slumber, and then, seeing there was no help for it, bravely put the best face he could on the matter, and set forth. He carried a long leather rope to catch the horse with, and walked towards the trees, which were about a couple of miles from the camp.

As he approached them, he noticed they were growing at the entrance of a deep ravine that ran back towards the mountains, with a creek running through it. It was a very rough place; boulders lay strewed about, but here and there were patches of grass which looked so much fresher and greener than that which grew on the prairie, that Jack noticed the difference. It also struck him that the grass looked as if it had been freshly trampled, and in a moment the idea flashed into his mind that Nigger had, without doubt, wandered up the ravine. Jack never hesitated a moment, but started to follow up the tracks he saw so plainly. It was a pleasant change from the hot prairie, as the trees shaded him from the sun, and he climbed steadily on over the stony path, hoping every minute to come on the truant. The ravine ran between towering walls of rock, covered with piñon and oak-scrub, and completely hid all the adjoining prairie from view.

At last Jack turned a corner of rock, and saw ahead a small band of bronchos or prairie horses. He hurried on, hoping to find the object of his search, but, alas! Nigger was not amongst them, and his weary toil up the long ravine had been on a false trail, after all! The wild ponies were scared at the sight of a human being appearing in the lonely cañon, and scampered away up the steep sides of the precipice like goats, leaving Jack gazing sadly after them. It was a great disappointment, and tears were not far from the boy's eyes as, tired out, he sat down on a rock for a rest. It was no use pursuing the hunt for Nigger any higher up there, and seeing it would be quicker to retrace his steps than climb up the sides of the rock, he turned to make his way down again. It was long past noon by the time he had scrambled out of the ravine and stood once more on the prairie.

There was no time to lose, and with many misgivings as to the reception he would receive from the indignant Lem, Jack hurried back as fast as he could towards the camp. He was afraid that his long and, alas! useless delay might also have vexed his friend Jeff, which was a thing to be avoided, if possible.

Ahead of him he saw the quaint Mexican village, but something strange had taken place in his absence! What could have happened? Quite puzzled, he rubbed his eyes and ran on faster towards the place where they had camped, and reaching it, could hardly believe his own eyes when he saw nothing of the prairie waggon, or the horses, or the camp he had left in the morning!

Jack stood on the forsaken camping-ground, and the truth dawned slowly on him—his companions had gone on and left him behind! He noticed the still damp embers of the extinguished fire, and though there was every indication of their recent presence, not a sign could he see of the two men.

He was very indignant at this unkind way of treating him.

'That's Lem's doing,' he muttered. 'He's done it on purpose to spite me. I don't care much; they'll go very slow, an' I guess I can overtake them by night. I hope Jeff will be right again by then.'

All the same, it gave him a feeling of forlornness to know he was absolutely alone on the prairie. He felt very hungry, and of course there was nothing to eat, as all the provisions had gone on in the waggon.

How glad he now felt that he had a little money of his own—the precious packet Steve had given him. He took a quarter-dollar (about one shilling in our English money) out of his store and returned the rest to a safe place inside his shirt. He knew his road lay through the Mexican village, and decided to follow it, hoping to see a shop where he could buy some bread.

Lem and Jeff had picked up a few Mexican words, but, of course, Jack neither understood nor could speak any of the language. He lost no time in entering the village, trusting to make someone understand what he wanted; but he had not proceeded a couple of hundred yards up the main street of the place when he found himself surrounded by a crowd of Mexican boys, all shouting at him in a tongue he did not know.

He tried at first to show them he was hungry, by pointing to his mouth, but they only jeered and laughed, instead of helping him. He got out of patience at last, and endeavoured to make his way through the noisy band towards the centre of the village; but the boys pushed him back each time, evidently thinking it great sport to tease an unprotected little lad.

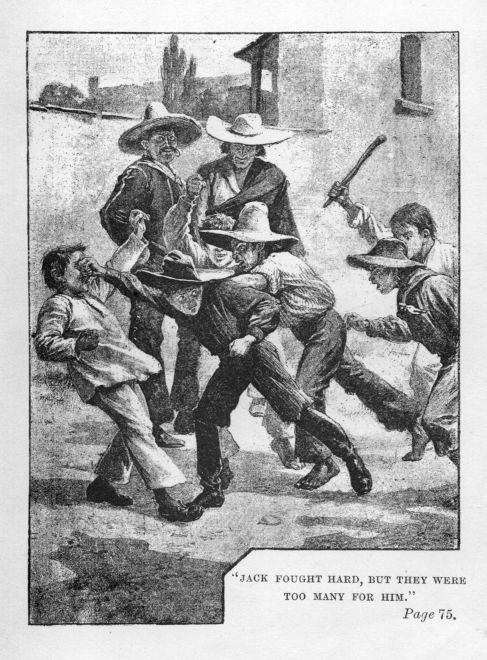

Jack appealed in English to two Mexican men who were lounging near, but they seemed to enjoy watching the group of cruel boys tormenting him. Jack was no coward, although he was so young, and after receiving a hard push from a bigger boy than himself, he lost his temper, and hit his opponent a good blow between the eyes.

This was the signal for a general outburst. The Mexicans are a fierce, passionate race, and the boys retaliated on poor Jack by all setting on him at once. Jack fought hard, and dealt out many a telling blow; but they were too many and strong for him, and at last he found himself being hustled out of the village where he had entered it, while his tormentors formed a long line to prevent his coming in again. Bleeding and bruised, Jack felt too worn out and faint from hunger and the fight to attempt another tussle with the enemy, so, like a wise boy, he deemed 'discretion the better part of valour,' and skirting the village, he recommenced his weary trudge along the road leading towards the mountains.

The range loomed up at no great distance in front of him, and the peaks towered up so high, they seemed to pierce the bright blue sky. But as the afternoon lengthened, Jack noticed that the sky was assuming a very threatening aspect. Big clouds came rolling up over the mountains, making them look almost black in the shadow. Jack went on bravely, hoping to reach some place of shelter before the storm broke, but it was getting rapidly darker, and his heart began to sink at the prospect ahead.

Blacker and blacker it grew around him. Bright flashes of lightning shot from the murky clouds, followed by loud, crashing thunder, which shook the ground, and echoed and re-echoed through the rocky cañons. In a short time Jack was in the midst of a bad specimen of a Rocky Mountain thunderstorm, and no shelter near him. The poor lad was terrified, and crouched near the ground, while the lightning played about him and the thunder roared overhead.

'Oh, dear! oh, dear! I'm so frightened!' cried the little fellow; and then he remembered his mother's words: 'Ask God to take care of us until we meet again'—an injunction he had followed every day since she left. Now he knelt down and prayed to God, Who rules the storms, asking Him to send him help and keep him safe, and he felt comforted in his fear. Soon the rain began to come down in torrents, and Jack was quickly drenched to the skin. The rain, however, broke the power of the storm, and before long the thunder-clouds rolled away and the sky began to clear.

Chilled to the bone and tired out, Jack rose from his crouching position and moved on again, not knowing whither he was going. He had wandered off the road, and was aimlessly walking on over the prairie.

He began to feel very queer. First he shivered, and his teeth chattered with cold, and a few minutes after he was burning hot all over. His head ached and throbbed as if it would burst, and at times a feeling of giddiness came over him. He tried to think what direction he ought to move in, but everything was buzzing and humming in his brain. He thought he heard people shouting after him, and suddenly imagined he could distinguish his Uncle Mat's harsh voice calling him. How it seemed to ring through his head! It struck terror into his weak, over-strained mind, and he rushed on wildly into the gathering darkness. Poor Jack! It was only the fatigue and hunger, combined with the soaking he had endured, that was bringing on an attack of fever, and all these pursuing noises were purely imaginary. He ran on, trying to get away from the mocking sounds, which seemed to grow louder and nearer every minute.

'They'll catch me, I'm feared,' he moaned in an agony of mind as he tore on, but suddenly his headlong career was stopped. His foot tripped, and he fell heavily, knocking his head against a stone.

'Oh! Mother, Mother, save me!' he shrieked; 'he'll get me and take me back!' And the next moment he lost all consciousness.

In the meantime our readers may wonder how it came to pass that Jeff had deserted his little friend, and in order to tell you I must go back to the time when Jack left the camp to look for the horse. Soon after he had set out for the clump of trees, Lem had saddled Yankee Boy, and after riding a few miles, came upon Nigger, whom he at once secured and brought back to camp. He then harnessed up the four horses ready to start, and as Jack did not return, he grew very impatient, and while idling about doing nothing an evil thought took possession of him. What a good opportunity he had now to pay off an old score against Steve Byrne by leaving Jack behind! It was a cruel thing to think of doing, but Lem was an unprincipled fellow who cared little who suffered as long as he got his revenge.

He quickly finished his preparations for starting, the last being to hoist Jeff into the waggon, where he immediately dozed off again, quite unconscious of what was going on. All day he remained half-stupefied, and as Lem drove the horses a long way before making a halt, it was not far off evening when Jeff discovered what had happened.

The indignation it roused in him cleared his torpid brain as if by magic.

'D'ye mean to say as you've been and left the young un behind?' he demanded.

'That's so,' returned Lem coolly; 'I found as he'd been at some tricks, so I guessed we'd get rid of him. I sent him to look for Nigger, and skipped out afore he got back.'

'I don't believe it,' declared Jeff. 'Jack wasn't a kid to play tricks, and I call it a crying shame to desert him. You daren't have done it if I'd known what was goin' on. I blame mysel' for it most, and I'm agoing right back to look for him.'

'Eat your supper first, man, and don't be a fool,' said Lem, somewhat staggered at Jeff's concern over his desertion of Jack; but the miner heeded him not. He mounted one of the tired horses and rode all the weary way back to the place they had camped at, but not a sign did he see of the boy. On the way he endured the whole of the awful storm, which he hardly noticed. In his anxiety he pressed on, arriving late in the Mexican village, where he made inquiries, but received such purposely conflicting answers to his questions about the way the boy had gone, that he got quite confused, and in the end had to turn back and retrace his steps. He stopped at short intervals to shout, but no reply came out of the darkness, and at last he got back to the waggon utterly wearied out, and as unhappy as a man could be.

Lena's surly voice sounded out from the blankets asking, 'Well, I suppose you've got the precious kid all right, haven't you?'

'No, I haven't,' returned Jeff savagely; 'and I'm feared as he's come to grief somewhere, for there ain't a house 'twixt here and the village for him to shelter in. I'll never forgive mysel' nor you either for this day's work, and the sooner we part company the better I'm pleased. I knew you were a cranky chap, but I didn't reckon ye were as mean as this.'

Lem angrily growled out something about making such a fuss over a bit of a kid, but poor Jeff's conscience was at work, and he blamed himself over and over again for Jack's misfortune.

'It's the drink that has done it,' he murmured, 'and I swear I'll never touch another drop again as long as I live. But that won't bring back the little lad,' he went on sadly to himself, 'and I'm scared as a night up so high 'll kill him, with nothing to keep him warm, for it gets terrible cold towards daybreak.'

Jeff could not sleep. He tossed about, listening to Lem's deep breathing.

'I promised to see to him, and I might have known Lem wasn't to be trusted. He did it for spite, I'm pretty sure, and nothin' else,' he argued to himself; and he was right, as we already know.

He and Lem parted company on the first opportunity, and certain it was, from the day Jack was lost, Jeff was a changed man. He kept his word, and never touched a drop of drink. It was no easy matter to break off a long-indulged habit, but when he found the desire for it growing too strong, and felt inclined to yield to the temptation, he would think of little Jack sitting by the camp fire singing his hymns, and as the bright face of the boy rose before him, it would break the evil spell and the longing for drink would pass away. He stayed about for some days, hoping to hear something of Jack, but he was obliged at last to believe that in all human probability the boy had died of exposure on the prairie.

'We may never know for certain,' said he, 'but I'm feared as his mother 'll never see him again, for I think he's dead.'

But Jack was not dead. When he returned to consciousness, he was surprised to find himself no longer on the prairie, but lying on sheep-skins spread over a wooden couch, and covered with a blanket.

He was in a rough kind of tent, and through the turned-back flap of canvas at the entrance, he could see the prairie. He could remember nothing of what had happened, and tried to imagine how in the world he had got into such a place. His head still ached badly, and, putting his hand up, he found his forehead was bandaged. He felt very weak and ill, but his surroundings were so strange to him, he tried to sit up and look about him. The effort was too much for him, and with a groan of pain he fell back on the sheep-skins.

At the sound he made, a man appeared at the tent-door, and approached the couch. He was a fine-looking fellow, evidently a Mexican, from his swarthy complexion, but there was a look of compassion in his dark eyes that inspired Jack with confidence, and made him feel that he had found a friend in need.

'Where am I?' he asked feebly, fearing the man would not understand the English words, and his relief was great when the Mexican answered:

'In my tent. I had lost some sheep last night that scattered in the storm, and while looking for them, my dog Señor found you lyin' on the prairie. You were hurt here'—pointing to his forehead—'and I thought you were dead. I carried you here, and you were nearly gone, but I got you round at last. You've got mountain fever, and you must keep very still if you want to get well. Here, drink this.'

As he spoke he handed Jack a cup, and the boy, thanking him, drank the liquid, which the Mexican told him was a kind of tea he made from the wild sage which grew all over the prairie and was a grand remedy for agues and fevers.

Jack was suffering from the chill he received in his state of fatigue, and it was fortunate for him he had been rescued in time by the shepherd's dog, and had fallen into the hands of such a kind-hearted, sensible man as Pedro Gomez, who had lived all his life on the prairie near the mountains, and knew how to treat most of the maladies that people were subject to in that part of the country.

He saw Jack was excited, so wisely said, 'I shan't listen to you for a day or two, but when you're better, then you can tell me where you come from. It was lucky I found you in time.'

'Yes,' said Jack. 'I believe I asked God to help me, and I expect He heard, for, ye see, He sent you to me.'

The Mexican listened gravely, and said, 'I reckon you've got Him to thank for it arter all, for it was strange we should come across you, and not another soul near you for miles.'

He then gave Jack injunctions to lie very still until he returned again, and prepared to go back to his sheep. He first called his dog and put him on guard.

'There,' he said; 'if you want me, just tell Señor. He knows more than many a man, and 'll come for me at once.'

Jack looked gratefully at him, and said wistfully, 'I guess ye don't hate kids, like Lem?'

'Hate 'em?' repeated Pedro. 'No! My boss has two little uns at his ranch, and I've nursed 'em often. They just love to play with Señor, and want me to tell them prairie tales when I'm there all day long.'

Left by himself with Señor, Jack prepared to make friends with him. He was not a beautiful animal, being a long, thin, vagabond-looking dog; but faithfulness was stamped in his honest, intelligent face, and Pedro was right in saying he knew more than many a human being. Jack was fond of animals, and made the first advances towards his guardian, but Señor was not disposed to be friendly incautiously. His life had made him suspicious of strangers, and he hated boys.

Like Jack, he had a rough time of it when he went to the Mexican village with his master, as dogs and boys invariably attacked him. He therefore avoided them, and at first deemed it wiser not to notice this boy who spoke to him in a coaxing voice. He had stretched himself down on the ground near the tent-door, and prepared to spend his hours of watching with one eye on his charge and the other out-of-doors.

Jack, however, was restless and lonely, and anxious to make friends, so he continued calling him in a caressing way, until at last Señor thought he might as well investigate him closer. Accordingly he rose up, and in a slow, cautious way walked up to the couch, and looked up in the boy's face.

Apparently he was satisfied with his scrutiny, for when Jack ventured to pat his rough head, he returned the friendly act by licking his hand. As Jack talked and caressed him further, Señor gradually threw off all reserve, and when Pedro returned he was surprised to find the dog curled up on the couch, as friendly as possible with the invalid.

'Well, that's good! I see Señor has taken to you, boy,' he said approvingly. 'He can't abide strangers as a rule, so I take it as a sign as we'll get on all right.'

Pedro was a good nurse, and looked after Jack so well that in a few days he was able to get up for a bit and sit at the tent-door. He was very weak, and Pedro told him it was madness to think of trying to continue his journey for some time.

When Jack was strong enough to tell him his story, Pedro proved a most interested listener.

'An' where are your folks now?' he asked.

'Over on the Cochetopa Creek,' answered Jack.

'Why, that's way over t'other side o' the range. You'll never get across the mountain pass alone,' exclaimed Pedro. 'It ain't safe for a child to wander up there with no one near him. There's bears an' mountain lions—let alone the timber wolves! You'd be eaten, boy, afore you'd crossed the divide.'

Jack shuddered. He was afraid of bears. He had never seen one, but they had always been a terror to him.

'I'm terrible afraid o' bears,' he said truthfully; 'but p'raps I'd meet someone going over as would let me go with them.'

'You might,' agreed Pedro; 'but winter's coming on fast, an' it'll be bad getting over the range after November comes. You bide here for a few weeks with me until my boss comes over again, an' I promise you as he'll help you along a bit. He'll be right along shortly to bring me flour an' grub, an' to look at the sheep.'

And so it was decided that Jack should stay on with the Mexican until Mr. Stuart came again, when they would ask him his opinion as to the wisest course for Jack to take to get safely over the mountains.

Pedro took a great fancy to his little visitor, and the quiet life in the tent was very pleasant to Jack after his rough experiences. He was astonished at the Mexican's cleverness: he seemed able to do anything with his fingers, and had a wonderful store of knowledge about plants, insects, and animals, which he had acquired by study and observation in the long, monotonous hours he spent on the prairie.

Jack's clothes, which at his start from Longview were none of the best, had suffered a good deal from the wear and tear of travelling, and by the time he arrived at Pedro's tent they were nothing but rags, and his boots were all to pieces. He was much distressed at his tattered garments, whereupon Pedro said he would soon make it all right for him, and proceeded to hunt out some buckskin leather, which he had tanned himself. It was quite thin and soft, and out of it he cut a suit for Jack, and sewed it together. When the clothes were finished, Jack was delighted with them. They were so comfortable, and the leather shirt and long-fringed trousers made him look like a little cowboy.

His worn-out boots hurt his feet, so his friend made him a pair of mocassin shoes, cut out of a single piece of leather, which fitted him nicely.

Pedro was pleased with the success of his tailoring, and said: 'There, lad; them clothes 'll never wear out, but 'll last after you've outgrown 'em.'

The herd of sheep that Pedro looked after numbered over a thousand, and as winter approached he began driving them towards a place on the prairie where there were corrals, or yards, to put them in at nights, and where a hut had been erected for his own use.

As long, however, as the weather permitted, they lived in the tent, and as Jack grew stronger every day, he was allowed to accompany the sheep-herder and Señor and help to drive home the sheep in the evening. Although they never saw anyone, Jack was never dull or lonely, as Pedro was excellent company. He showed him how to prepare the different skins of animals they found near their camp, and when Jack was tired of work, he and Señor would go off to hunt for chipmunks and gophers. Chipmunks were like small squirrels, and gophers were pretty striped little animals that played about on the prairie.

It had puzzled Jack very much to find a lonely Mexican sheep-herder could speak English so well, until he learned from Pedro that he had lived from the time he was a boy with English people. He had spent many months every year with his young master, hunting, shooting, or minding cattle with him, and thus had learnt to speak the language fluently. He said when Mr. Stuart married and settled down on his ranch, he wanted him (Pedro) to live in a shanty, and look after things for him, but the love of camp life was too strong in him, and he begged his master to give him a situation as a sheep-herder. Mr. Stuart had done as he wished, and he was as happy and contented as possible in his rough old tent.

Some weeks passed, and still Jack stayed on with his new friend. The time had not been lost for the boy, as he had learnt many things which he had not known before, and which were very useful to him in after-life. He was quick and deft with his lingers, and Pedro taught him in a few days how to cut and plait long strips of leather into lariats and bridle-reins, and to make ornamental belts.

'I wish you'd teach me to throw a lariat like the cowboys,' said Jack one day.

'Come and try, then,' returned Pedro, taking down a long leather rope that was coiled round the tent-pole and going outside. 'Now watch me. I take the rope up in loops, leaving the noose end out. Then swing it round in a circle over your head, quicker and quicker, while you take aim and try and throw it over the beast's head like that;' and as he spoke, Pedro let the noose fall gently over Señor's neck, who was running past at some distance away.

He then put up a post, and showed Jack how to drop the noose over it. It was very hard at first to aim straight, but Jack had a quick eye, and after two or three days' hard practising, he made a very good attempt at throwing the rope in the right place. Day after day he went at it, until one never-to-be-forgotten morning he also succeeded in lariating Señor as he trotted by. This was a great achievement, and quite repaid Jack for the trouble of practising so hard to accomplish it.

One place that pleased Jack very much was a prairie-dog village close by. Many an hour did he spend watching the fearless little prairie dogs, who came out of their holes and barked defiantly at him like so many cheeky puppies, until the tears ran down his face from laughing at their antics. Sometimes for fun Jack pretended to throw stones at them, and the instant he raised his arm they disappeared down their holes as if by magic, but peeped out again in a minute or two, quite ready to venture forth again.

Jack saw a great many rattlesnakes when he wandered about with Pedro on the prairie. He was very much afraid of them—and no wonder, for their poisonous bite is often fatal. Pedro was so familiar with them from his childhood, that he did not mind them in the least, and killed them by an extraordinary native trick. He would fearlessly follow a retreating snake, seize it by the tail, swing it rapidly round, and with a dexterous twist of his wrist would crack it like a whip, and dislocate its spine. Being thus rendered helpless, the reptile was easily despatched. As a rule, they tried to escape, but if by chance one showed fight, it was harder to kill, as it would twist itself up in a coil, shaking its rattles noisily, with its head out ready to spring and strike.

Jack had a boy's love for possessing things, and in a short time, with Pedro's help, had a small collection of treasures to carry away with him. He found plenty of rattles on the prairie, as the snakes cast off their rattles every year, and Pedro gave him a skin of a horned toad, a curious creature covered with tiny horns all over its body.

One day Pedro killed a strange-looking animal called a skunk. It was very handsome, like a large black-and-white striped cat with a magnificent bushy tail, but it had such a disagreeable smell it made Jack feel ill.

'You surely can't skin that nasty thing?' he asked.

'Wait and see,' returned Pedro, carrying the dead animal towards a creek. 'I'll show you how the Indians skin 'em.'

He put the skunk quite under the water and kept it there while he took off the skin, as this process destroyed the strong odour belonging to the creature. Jack was very interested, and watched him until the skin was hung out to dry.