The Project Gutenberg EBook of Story Lessons of Character Building (Morals) and Manners, by Loïs Bates This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Story Lessons of Character Building (Morals) and Manners Author: Loïs Bates Release Date: November 3, 2010 [EBook #34200] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STORY LESSONS OF CHARACTER BUILDING *** Produced by Emmy, Darleen Dove and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Incidents often occur in the school or home life which afford fitting opportunity for the inculcation of some special moral truth, but maybe the teacher or mother has no suitable illustration just at hand, and the occasion is passed over with a reproof. It is hoped that where such want is felt this little book may supply the need.

The stories may be either told or read to the children, and are as suitable for the home as the school. "The Fairy Temple" should be read as an introduction to the Story Lessons, for the teaching of the latter is based on this introductory fairy tale. If used at home the blackboard sketch may be written on a slate or slip of paper. The children will not weary if the stories are repeated again and again (this at least was the writer's experience), and they will be eager to pronounce what is the teaching of the tale. In this way the lessons are reiterated and enforced. The method is one which the writer found exceedingly effective during long years of[vi] experience. Picture-teaching is an ideal way of conveying truths to children, and these little stories are intended to be pictures in which the children may see and contrast the good with the bad, and learn to love the good. The faults of young children are almost invariably due either to thoughtlessness or want of knowledge, and the little ones are delighted to learn and put into practice the lessons taught in these stories, which teaching should be applied in the class or home as occasion arises. E.g., a child is passing in front of another without any apology, the teacher says, immediately: "Remember Minnie, you do not wish to be rude, like she was" (Story Lesson 111). Or if a child omits to say "Thank you," he may be reminded by asking: "Have you forgotten 'Alec and the Fairies'?" (Story Lesson 95). The story lessons should be read to the children until they become perfectly familiar with them, so that each may be applied in the manner indicated.

| 1.—MORALS. | ||||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |||

| I. | Introductory Story— | |||

| 1. | The Fairy Temple | 1 | ||

| II. | Obedience— | |||

| 2. | The Two Voices | 4 | ||

| 3. | (Why we Should Obey.) The Pilot | 6 | ||

| 4. | (Why we Should Obey.) The Dog that did not like to be Washed | 7 | ||

| 5. | (Ready Obedience.) Robert and the Marbles | 9 | ||

| 6. | (Unready, Sulky Obedience.) Jimmy and the Overcoat | 9 | ||

| III. | Loyalty— | |||

| 7. | Rowland and the Apple Tart | 10 | ||

| IV. | Truthfulness— | |||

| 8. | (Direct Untruth.) Lucy and the Jug of Milk | 12 | ||

| 9. | (Untruth, by not Speaking.) Mabel and Fritz | 13 | ||

| 10. | (Untruth, by not Telling All.) A Game of Cricket | 14 | ||

| 11. | (Untruth, by "Stretching"—Exaggeration.) The Three Feathers | 16 | ||

| V. | Honesty— | |||

| 12. | Lulu and the Pretty Coloured Wool | 17 | ||

| 13. | (Taking Little Things.) Carl and the Lump of Sugar | 19 | ||

| 14. | (Taking Little Things.) Lilie and the Scent | 19 | ||

| 15. | Copying | 20 | ||

| 16. | On Finding Things | 22 | ||

| VI. | Kindness— | |||

| 17. | Squeaking Wheels | 23 | ||

| 18. | Birds and Trees | 24 | ||

| 19. | Flowers and Bees | 25[viii] | ||

| 20. | Lulu and the Bundle | 26 | ||

| VII. | Thoughtfulness— | |||

| 21. | Baby Elsie and the Stool | 27 | ||

| 22. | The Thoughtful Soldier | 28 | ||

| VIII. | Help One Another— | |||

| 23. | The Cat and the Parrot | 29 | ||

| 24. | The Two Monkeys | 30 | ||

| 25. | The Wounded Bird | 31 | ||

| IX. | On Being Brave— | |||

| 26. | (Brave in Danger.) How Leonard Saved his Little Brother | 32 | ||

| 27. | (Brave in Little Things.) The Twins | 33 | ||

| 28. | (Brave in Suffering.) The Broken Arm | 34 | ||

| 29. | (Brave in Suffering.) The Brave Monkey | 35 | ||

| X. | Try, Try Again— | |||

| 30. | The Sparrow that would not be Beaten | 35 | ||

| 31. | The Railway Train | 36 | ||

| 32. | The Man who Found America | 37 | ||

| XI. | Patience— | |||

| 33. | Walter and the Spoilt Page | 38 | ||

| 34. | The Drawings Eaten by the Rats | 39 | ||

| XII. | On Giving In— | |||

| 35. | Playing at Shop | 40 | ||

| 36. | The Two Goats | 41 | ||

| XIII. | On Being Generous— | |||

| 37. | Lilie and the Beggar Girl | 41 | ||

| 38. | Bertie and the Porridge | 42 | ||

| XIV. | Forgiveness— | |||

| 39. | The Two Dogs | 43 | ||

| XV. | Good for Evil— | |||

| 40. | The Blotted Copy-book | 43 | ||

| XVI. | Gentleness— | |||

| 41. | The Horse and the Child | 45 | ||

| 42. | The Overturned Fruit Stall | 46 | ||

| XVII. | On Being Grateful— | |||

| 43. | Rose and her Birthday Present | 47 | ||

| 44. | The Boy who was Grateful | 47 | ||

| XVIII. | Self-help— | |||

| 45. | The Crow and the Pitcher | 48 | ||

| XIX. | Content—[ix] | |||

| 46. | Harold and the Blind Man | 49 | ||

| XX. | Tidiness— | |||

| 47. | The Slovenly Boy | 50 | ||

| 48. | Pussy and the Knitting | 51 | ||

| 49. | The Packing of the Trunks | 53 | ||

| XXI. | Modesty— | |||

| 50. | The Violet | 54 | ||

| 51. | Modesty in Dress | 55 | ||

| XXII. | On Giving Pleasure to Others— | |||

| 52. | "Selfless" and "Thoughtful". A Fairy Tale | 56 | ||

| 53. | The Bunch of Roses | 56 | ||

| 54. | Edwin and the Birthday Party | 57 | ||

| 55. | Davie's Christmas Present | 59 | ||

| XXIII. | Cleanliness— | |||

| 56. | Why we Should be Clean | 61 | ||

| 57. | Little Creatures who like to be Clean | 62 | ||

| 58. | The Boy who did not like to be Washed | 63 | ||

| 59. | The Nails and the Teeth | 64 | ||

| XXIV. | Pure Language— | |||

| 60. | Toads and Diamonds. A Fairy Tale | 66 | ||

| XXV. | Punctuality— | |||

| 61. | Lewis and the School Picnic | 67 | ||

| XXVI. | All Work Honourable— | |||

| 62. | The Chimney-sweep | 69 | ||

| XXVII. | Bad Companions— | |||

| 63. | Playing with Pitch | 70 | ||

| 64. | Stealing Strawberries | 71 | ||

| XXVIII. | On Forgetting— | |||

| 65. | Maggie's Birthday Present | 73 | ||

| 66. | The Promised Drive | 74 | ||

| 67. | The Boy who Remembered | 75 | ||

| XXIX. | Kindness to Animals— | |||

| 68. | Lulu and the Sparrow | 76 | ||

| 69. | Why we Should be Kind to Animals | 77 | ||

| 70. | The Butterfly | 78 | ||

| 71. | The Kind-hearted Dog | 78 | ||

| XXX. | Bad Temper— | |||

| 72. | How Paul was Cured | 79 | ||

| 73. | The Young Horse | 80 | ||

| XXXI. | Selfishness—[x] | |||

| 74. | The Child on the Coach | 82 | ||

| 75. | Edna and the Cherries | 82 | ||

| 76. | The Boy who liked always to Win | 83 | ||

| 77. | The two Boxes of Chocolate | 84 | ||

| 78. | Eva | 85 | ||

| XXXII. | Carelessness— | |||

| 79. | The Misfortunes of Elinor | 86 | ||

| XXXIII. | On Being Obstinate— | |||

| 80. | How Daisy's Holiday was Spoilt | 87 | ||

| XXXIV. | Greediness— | |||

| 81. | Stephen and the Buns | 89 | ||

| XXXV. | Boasting— | |||

| 82. | The Stag and his Horns | 90 | ||

| XXXVI. | Wastefulness— | |||

| 83. | The Little Girl who was Lost | 91 | ||

| XXXVII. | Laziness— | |||

| 84. | The Sluggard | 91 | ||

| XXXVIII. | On Being Ashamed— | |||

| 85. | The Elephant that Stole the Cakes | 92 | ||

| XXXIX. | Ears and No Ears— | |||

| 86. | Heedless Albert | 94 | ||

| 87. | Olive and Gertie | 95 | ||

| XL. | Eyes and No Eyes— | |||

| 88. | The Two Brothers | 97 | ||

| 89. | Ruby and the Wall | 98 | ||

| XLI. | Love of the Beautiful— | |||

| 90. | The Daisy | 99 | ||

| XLII. | On Destroying Things— | |||

| 91. | Beauty and Goodness | 100 | ||

| XLIII. | On Turning Back When Wrong— | |||

| 92. | The Lost Path | 101 | ||

| XLIV. | One Bad "Stone" may Spoil the "Temple"— | |||

| 93. | Intemperance | 103 | ||

2.—MANNERS. | ||||

| XLV. | Preliminary Story Lesson— | |||

| 94. | The Watch and its Springs | 104 | ||

| XLVI. | On Saying "Please" and "Thank You"—[xi] | |||

| 95. | Fairy Tale of Alec and his Toys | 105 | ||

| XLVII. | On Being Respectful— | |||

| 96. | Story Lesson | 108 | ||

| XLVIII. | Putting Feet Up— | |||

| 97. | Alice and the Pink Frock | 109 | ||

| XLIX. | Banging Doors— | |||

| 98. | How Maurice came Home from School | 110 | ||

| 99. | Lulu and the Glass Door | 111 | ||

| L. | Pushing in Front of People— | |||

| 100. | The Big Boy and the Little Lady | 112 | ||

| LI. | Keeping to the Right— | |||

| 101. | Story Lesson | 113 | ||

| LII. | Clumsy People— | |||

| 102. | Story Lesson | 114 | ||

| LIII. | Turning Round When Walking— | |||

| 103. | The Girl and her Eggs | 115 | ||

| LIV. | On Staring— | |||

| 104. | Ruth and the Window | 116 | ||

| LV. | Walking Softly— | |||

| 105. | Florence Nightingale | 117 | ||

| LVI. | Answering when Spoken To— | |||

| 106. | The Civil Boy | 118 | ||

| LVII. | On Speaking Loudly— | |||

| 107. | The Woman who Shouted | 119 | ||

| LVIII. | On Speaking when Others are Speaking— | |||

| 108. | Margery and the Picnic | 120 | ||

| LIX. | Look at People when Speaking to Them— | |||

| 109. | Fred and his Master | 122 | ||

| LX. | On Talking Too Much— | |||

| 110. | Story Lesson | 122 | ||

| LXI. | Going in Front of People— | |||

| 111. | Minnie and the Book | 124 | ||

| 112. | The Man and his Luggage | 124 | ||

| LXII. | When to Say "I Beg Your Pardon"— | |||

| 113. | Story Lesson | 125 | ||

| 114. | The Lady and the Poor Boy | 126 | ||

| LXIII. | Raising Cap— | |||

| 115. | Story Lesson | 126 | ||

| LXIV. | On Offering Seat to Lady— | |||

| 116. | Story Lesson | 127 | ||

| LXV. | On Shaking Hands—[xii] | |||

| 117. | Reggie and the Visitors | 129 | ||

| LXVI. | Knocking Before Entering a Room— | |||

| 118. | The Boy who Forgot | 130 | ||

| LXVII. | Hanging Hats Up, Etc.— | |||

| 119. | Careless Percy | 130 | ||

| LXVIII. | How to Offer Sweets, Etc.— | |||

| 120. | How Baby did it | 132 | ||

| LXIX. | Yawning, Coughing and Sneezing— | |||

| 121. | Story Lesson | 132 | ||

| LXX. | How a Slate Should Not be Cleaned— | |||

| 122. | Story Lesson | 133 | ||

| LXXI. | The Pocket-handkerchief— | |||

| 123. | Story Lesson | 135 | ||

| LXXII. | How to Behave at Table— | |||

| 124. | (On Sitting Still at Table.) Phil's Disaster | 136 | ||

| 125. | (On Sitting Still at Table.) Fidgety Katie | 136 | ||

| 126. | (Thinking of Others at Table.) The Helpful Little Girl | 137 | ||

| 127. | (Upsetting Things at Table.) Leslie and the Christmas Dinner | 138 | ||

| 128. | Cherry Stones | 138 | ||

| LXXIII. | On Eating and Drinking— | |||

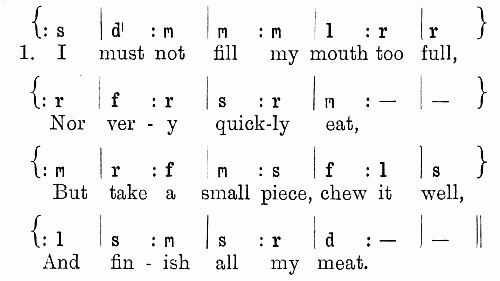

| 129. | Rhymes | 140 | ||

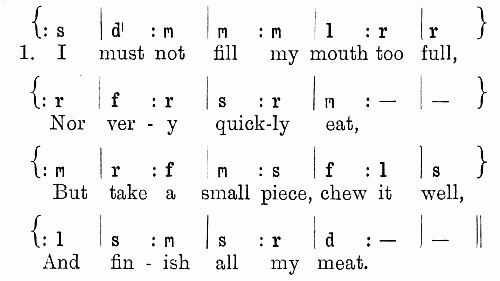

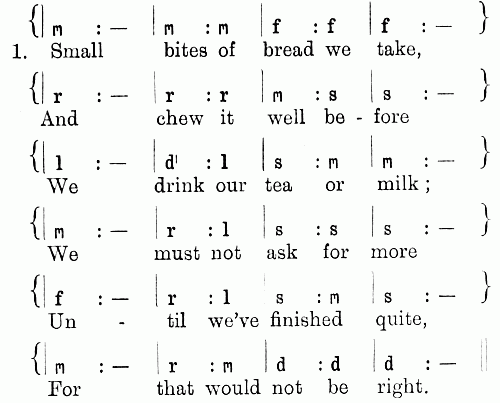

| 130. | Rhymes | 141 | ||

| LXXIV. | Finale— | |||

| 131. | How another Queen Builded | 142 | ||

1.—MORAL SUBJECTS. | |

| PAGE | |

| All Work Honourable | 69 |

| Ashamed, On being | 92 |

| Bad Companions | 70 |

| Boasting | 90 |

| Brave, On being | 32 |

| Carelessness | 86 |

| Cleanliness | 61 |

| Content | 49 |

| Copying | 20 |

| Destroying Things, On | 100 |

| Ears and no Ears | 94 |

| Exaggeration | 16 |

| Eyes and no Eyes | 97 |

| Fairy Temple | 1 |

| Finding Things | 22 |

| Forgetting | 73 |

| Forgiveness | 43 |

| Generous, On being | 41 |

| Gentleness | 45 |

| Giving In, On | 40 |

| Giving Pleasure to Others, On | 56 |

| Good for Evil | 43 |

| Grateful, On being | 47 |

| Greediness | 89 |

| Help one Another | 29 |

| Honesty | 17 |

| How another Queen Builded | 142[xiv] |

| Intemperance | 103 |

| Introductory Story | 1 |

| Kindness | 23 |

| Kindness to Animals | 76 |

| Laziness | 91 |

| Love of the Beautiful | 99 |

| Loyalty | 10 |

| Modesty | 54 |

| Nails, The | 64 |

| Obedience | 4 |

| Obstinate, On being | 87 |

| Patience | 38 |

| Punctuality | 67 |

| Pure Language | 66 |

| Self-Help | 48 |

| Selfishness | 82 |

| Teeth, The | 65 |

| Thoughtfulness | 27 |

| Tidiness | 50 |

| Truthfulness | 12 |

| Try, Try Again | 35 |

| Turning Back when Wrong | 101 |

| Wastefulness | 91 |

2.—MANNERS. | |

| Answering when Spoken To | 118 |

| Banging Doors | 110 |

| Cherry Stones (see "How to Behave at Table") | 138 |

| Clumsy People | 114 |

| Coughing | 132 |

| Eating and Drinking, On | 140 |

| Excuse Me, Please (see "Going in Front of People") | 124 |

| Going in Front of People | 124 |

| Hanging Hats Up, etc. | 130 |

| How to Behave at Table | 136 |

| "I Beg Your Pardon," When to say | 125 |

| [xv]Keeping to the Right | 113 |

| Knocking Before Entering a Room | 130 |

| Look at People when Speaking to Them | 122 |

| Manners | 104 |

| Offering Seat to Lady | 127 |

| Offer Sweets, How to | 132 |

| "Please," On Saying | 105 |

| Pocket-handkerchief, The | 135 |

| Preliminary Story Lesson | 104 |

| Pushing in Front of People | 112 |

| Putting Feet Up | 109 |

| Raising Cap | 126 |

| Respectful, On being | 108 |

| Shaking Hands, On | 129 |

| Sitting Still at Table, On | 136 |

| Sneezing | 132 |

| Speaking Loudly, On | 119 |

| Speaking when Others are Speaking, On | 120 |

| Spitting (see "How a Slate Should Not be Cleaned") | 133 |

| Staring, On | 116 |

| Talking Too Much, On | 122 |

| "Thank You," On Saying | 105 |

| Thinking of Others at Table | 137 |

| Turning Round when Walking | 115 |

| Upsetting Things at Table (see "Leslie and the Christmas Dinner") | 138 |

| Walking Softly | 117 |

| Yawning | 132 |

(The following story should be read to the children first, as it forms a kind of groundwork for the Story Lessons which follow.)

It was night—a glorious, moonlight night, and in the shade of the leafy woods the Queen of the fairies was calling her little people together by the sweet tones of a tinkling, silver bell. When they were all gathered round, she said: "My dear children, I am going to do a great work, and I want you all to help me". At this the fairies spread their wings and bowed, for they were always ready to do the bidding of their Queen. They were all dressed in lovely colours, of a gauzy substance, finer than any silk that ever was seen, and their names were called after the colours they wore. The Queen's robe was of purple and gold, and glittered grandly in the moonlight.

"I have determined," said the Queen, "to build a Temple of precious stones, and your work will be to bring me the material." "Rosy-wings," she continued, turning to a little fairy clad in delicate pink, and fair as a rose, "you shall bring rubies." "Grass-green," to a fairy dressed in green, "your work is to find emeralds; and Shiny-wings, you will go to the mermaids and ask them to give you pearls."[2]

Now there stood near the Queen six tiny, fairy sisters, whose robes were whiter and purer than any. The sisters were all called by the same name—"Crystal-clear," and they waited to hear what their work was to be.

"Sisters Crystal-clear," said the Queen, "you shall all of you bring diamonds; we shall need so many diamonds."

There was another fairy standing there, whose robe seemed to change into many colours as it shimmered in the moonlight, just as you have seen the sky change colour at sunset, and to her the Queen said, "Rainbow-robe, go and find the opal".

Then there were three other fairy sisters called "Gold-wings," who were always trying to help the other fairies, and to do good to everybody, and the Queen told them to bring fine gold to fasten the precious stones together.

These are not all the fairies who were there; some others wore blue, some yellow, and the Queen gave them all their work. Then she rang a tiny, silver bell, and they all spread their wings and bowed before they flew away to do her bidding.

After many days the fairies came together to bring their precious treasures to the Queen. How they carried them I scarcely know, but there was a little girl, many years ago, who often paused at the window of a jeweller's shop to gaze at a tiny, silver boy, with silver wings, wheeling a silver wheel-barrow full of rings, and the little girl thought that perhaps the fairies carried things in the same way. Anyhow, they all came to the Queen bringing their burdens, and she soon set to work on the Temple.

"The foundations must be laid with diamonds," said the Queen. "Where are the six sisters? Ah! here they come with the lovely, shining diamonds, which are like themselves, 'clear as crystal'. Now little Gold-wings, bring your treasure," and the three little sisters brought the[3] finest of gold. So the work went merrily on, and the fairies danced in glee as they saw the glittering Temple growing under the clever hands of the Queen. She made the doors of pearls and the windows of rubies, and the roof she said should be of opal, because it would show many colours when the light played upon it.

At last the lovely building was finished, and after the fairies had danced joyfully round it in a ring again and again, until they could dance no longer, they gathered in a group round the dear Queen, and thanked her for having made so beautiful a Temple.

"It is quite the loveliest thing in the world, I am sure," said Rosy-wings.

"Not quite," replied the Queen, "mortals have it in their power to make a lovelier Temple than ours."

"Who are 'mortals'?" asked Shiny-wings.

"Boys and girls are mortals," said the Queen, "and grown-up people also."

"I have never seen mortals build anything half so pretty as our Temple," said Grass-green; "their houses are made of stone and brick."

"Ah! Grass-green," answered the Queen, smiling, "you have never seen the Temple I am speaking of, but it is better than ours, for it lasts—lasts for ever. Wind and rain, frost and snow, will spoil our Temple in time; but the Temple of the mortals lives on, and is never destroyed."

"Do tell us about it, dear Queen," said all the fairies; "we will try to understand."

"It is called by rather a long word," said the Queen, "its name is 'character'; that is what the mortals build, and the stones they use are more precious than our stones. I will tell you the names of some of them. First there is Truth, clear and bright like the diamonds; that must be the foundation; no good character can be made without Truth."[4]

Then the sisters Crystal-clear smiled at each other and said, "We brought diamonds for truth".

"There are Honesty, Obedience, and many others," continued the Queen, "and Kindness, which is like the pure gold that was brought by Gold-wings, and makes a lovely setting for all the other stones."

The little fairies were glad to hear all this about the Temple which the mortals build, and Gold-wings said that she would like above everything to be able to help boys and girls to make their Temple beautiful, and the other fairies said the same; so the Queen said they all might try to help them, for each boy and girl must build a Temple, and the name of that Temple is Character.

There was once a little boy who said that whenever he was going to do anything wrong he heard two voices speaking to him. Do you know what he meant? Perhaps this story will help you.

The boy's name was Cecil. Cecil's father had a very beautiful and rare canary, which had been brought far over the sea as a present to him.

Cecil often helped to feed the canary and give it fresh water, and sometimes his father would allow him to open the door of the cage, and the bird would come out and perch on his hand, which delighted Cecil very much, but he was not allowed to open the door of the cage unless his father was with him.[5]

One day, however, Cecil came to the cage alone, and while he watched the canary, a little voice said, "Open the door and take him out; father will never know". That was a wrong voice, and Cecil tried not to listen. It would have been better if he had gone away from the cage, but he did not; and the voice came again, "Open the door and let him out". And another little voice said, "No, don't; your father said you must not". But Cecil listened to the wrong voice; he opened the door gently, and out flew the pretty bird. First it perched on his finger, then it flew about the room, and then—Cecil had not noticed that the window was open—then, before he knew, out of the window flew the canary, and poor Cecil burst into tears. "Oh! if I had listened to the good voice, the right voice, and not opened the door! Father will be so angry." Then the bad voice came again and said, "Don't tell your father; say you know nothing about it ". But Cecil did not listen this time; he was too brave a boy to tell his father a lie, and he determined to tell the truth and be punished, if necessary.

Of course his father was very sorry to lose his beautiful canary, and more sorry still that his little son had been disobedient, but he was glad that Cecil told him the truth.

Now do you know the two things that the wrong voice told Cecil to do? It told him (1) Not to obey; (2) Not to tell the truth. I think we have all heard those two voices, not with our ears, but within us. Let us always listen to the good voice—the right voice.

You know that the country in which you live is an island? That means there is water all round it, and that water is the sea.

England and Scotland are joined together in one large island; and if you want to go to any other country, you must sail in a ship. A great many ships come to England, bringing us tea, coffee, sugar, oranges and many other things, and the towns they come to are called ports. London is a port, so is Liverpool; and in the North of England is another port called Hull. To get to Hull from the sea we have to sail up a wide river called the Humber for more than twenty miles. This river has a great many sandbanks in it, and there are men called pilots who know just where these sandbanks lie, and they are the ones who can guide the ships safely into port.

One day there was a captain who brought his ship into the river, and said to himself, "I do not want the pilot on board, I can guide the ship myself". So he did not hoist the "union jack" on the foremast head, which means "Pilot come on board"; and the pilot did not come.

For a little time the good ship sailed along all right, but presently they found that she was not moving at all. What had happened? The ship was stuck fast on a sandbank, and the foolish captain wished now that he had taken the pilot on board. First he had to go out in the little boat and fetch a "tug-boat" to pull the ship off the sandbank, and then he was glad enough to have the pilot on board, and to let him guide the ship just as he liked. Why could not the captain guide the ship? Because he did not know the way.[7]

Have you ever known children who did not like to do as they were told? who thought that they knew best—better than father or mother? They are like the foolish captain, who tried to guide his ship when he did not know the way. Fathers and mothers are like the pilot, who knew which was the best way to take; and wise children are willing to be guided, for they do not know the way any more than the captain did.

The story and its teaching may be further impressed on the minds of the children by a sand lesson:—

Place a blackboard or large piece of oil-cloth on the floor, and make an "island" in sand, and in the "island" form a large "estuary," with little heaps of sand dotted about in it, to represent sandbanks. The sailors cannot see the sandbanks, for they are all covered with water in the real river, so we will take a duster and spread it over these sandbanks. Now, take a tiny boat and ask one of the children to sail it up the river, keeping clear of the sandbanks. The children will soon see that it cannot be done, and the "blackboard" lesson may be again enforced.

A lady once had a dog of which she was very fond. The dog was fond of his mistress also, and loved to romp by her side when she was out walking, or to lie at her feet as she[8] sat at work. But the dog had one serious fault—he did not like to be washed, and he was so savage when he was put into the bath, that at last none of the servants dare do it.

The lady decided that she would not take any more notice of the dog until he was willing to have his bath quietly, so she did not take him out with her for walks, nor allow him to come near her in the house. There were no pattings, no caresses, no romps, and he began to look quite wretched and miserable. You see the dog did not like his mistress to be vexed with him, and he felt very unhappy—so unhappy that at last he could bear it no longer.

Then one morning he crept quietly up to the lady and gave her a look which she knew quite well meant, "I cannot bear this any longer; I will be good".

So he was put in the bath, and though he had to be scrubbed very hard—for by this time he was unusually dirty—he stood still quite patiently, and when it was all over, he bounded to his mistress with a joyous bark and a wag of the tail, as much as to say, "It is all right now".

After this he was allowed to go for walks as usual, and was once more a happy dog, and he never objected to his bath afterwards.

The dog could not bear to grieve his mistress; and how much more should children be sorry to grieve kind father and mother, who do so much for them.

A little boy named Robert was having a game at marbles with a number of other boys, and it had just come his turn to play. He meant to win, and was carefully aiming the marble, when he heard his mother's voice calling, "Robert, I want you". Quick as thought the marbles were dropped into his pocket, and off he ran to see what mother wanted.

I was in a house one day where a boy was getting ready to go to school. His bag was slung over his shoulder, and he was just reaching his cap from the peg, when his mother said, "Put on your overcoat, Jimmy; it is rather cold this morning". Oh, what a fuss there was! How he argued with his mother, "It was not cold; he hated overcoats. Could he not take it over his arm, or put it on in the afternoon?" Many more objections he made, and when at last he had put it on, he went out grumbling, and slammed the door after him.

Can you guess how his mother felt? "Unhappy," you will say. And do you think it is right, dear children, to make mother unhappy? I am sure you do not.

You see Jimmy thought that he knew better than his mother, but he did not. Children need to be guided like the boat in the Humber (Story Lesson 3), for they are not very wise; and when we obey, we are building up our Temple with beautiful stones.

Perhaps you have never heard the word Loyalty before, and maybe Rowland had not either, but he knew what it meant, and tried to practise it.[11]

Rowland was not a very strong little boy, and he could not eat so many different kinds of food as some children can, for some of them made him sick. Among other things he was forbidden to take pastry. His mother, who loved him very dearly, had one day said to him, "Rowland, my boy, I cannot always be with you, but I trust you to do what I wish," and Rowland said he would try always to remember.

One time he was invited to go and stay with his cousins, who lived in a fine old house in the country. They were strong, healthy, rosy children, quite a contrast to their delicate little cousin, and perhaps they were a little rough and rude as well.

There was a large apple tart for dinner one day, and when Rowland said, "I do not wish for any, Auntie, thank you," his cousins looked at him in surprise, and the eldest said scornfully, "I am glad that I am not delicate," and the next boy remarked, "What a fad!" while the third muttered "Baby". This was all very hard to bear, and when his Aunt said, "I am sure a little will not hurt you," Rowland felt very much inclined to give in, but he remembered that his mother trusted him, and he remained true to her wishes.

This is Loyalty, doing what is right even when there is no one there to see.

"Lucy," said her mother, "just run to the dairy and fetch a pint of milk for me, here is the money; and do remember, child, to look where you are going, so that you do not stumble and drop the jug." I am afraid Lucy was a little like another girl you will hear of (Story Lesson 103); she was too fond of staring about, and perhaps rather careless.

However, she went to the dairy and bought the milk, and had returned half-way home without any mishap, when she met a flock of sheep coming down the road, followed by a large sheep-dog. Lucy stood on the pavement to watch them pass; it was such fun to see the sheep-dog scamper from one side to the other, and the timid sheep spring forward as soon as the dog came near them. So far the milk was safe; but, after the sheep had passed, Lucy thought she would just turn round to have one more peep at them, and oh, dear, her foot tripped against a stone, and down she fell, milk, and jug, and all, and the jug was smashed to pieces.

Lucy was in great trouble, and as she stood there and looked at the broken jug, and the milk trickling down the gutter, she cried bitterly.

A big boy who was passing by at the time, and had seen the accident, came across the road and said to her: "Don't cry, little girl, just run home and tell your mother that the sheep-dog bounced up against you and knocked the jug out of your hand; then you will not be punished".[13]

Lucy dried her eyes quickly, and gazed at the boy in astonishment. "Tell my mother a lie!" said she; "no, I would rather be punished a dozen times than do so. I shall tell her the truth," and she walked away home. Lucy was careless, but she was not untruthful; surely the boy must have felt ashamed!

You remember the Fairy Queen said that Truth was the foundation of our beautiful Temple (Story Lesson 1), and the building will all tumble down in ruins if we do not have a strong foundation, so we must be brave to bear punishment (as Lucy was) if we deserve it, and be sure to

This is a story of a dear little curly-headed girl called Mabel, whom everybody loved. She was so bright, and happy, and good-tempered, one could not help loving her, and when you looked into her clear, blue eyes, you could see that she was a frank, truthful child, who had nothing to hide, for she tried to listen to the Good Voice, and do what was right.

One day Mabel was having a romp with her little dog, Fritz, in the kitchen. Up and down she chased him, and away he went, jumping over the chairs, hiding under the dresser, always followed by Mabel, until at last he leaped on the table, and in trying to make him come down, Mabel and the dog together overturned a tray full of clean, starched linen that was on the table. Mabel had been giving Fritz[14] some water to drink a little before this, and in doing so had spilt a good deal on the floor, so the clean cuffs and collars rolled over in the wet, and were quite spoiled.

Mabel's mother happened to come in just when the tray fell with a bang, and as the dog jumped down from the table at the same moment she thought he had done it, and Mabel did not tell that she was in fault, so poor Fritz was chained up in his kennel, and kept without dinner as a punishment.

Mabel felt sad about it all the rest of the day, and when she was put to bed at night, and mamma had left her, she did not go to sleep as usual, but tossed about on the pillow, until her little curly head was quite hot and tired. Then she began to cry. Mabel was listening to the Good Voice now, and it said, "Oh, Mabel, you helped Fritz to overturn the tray, and he got all the blame, how mean of you!" Mabel sobbed louder when she thought of herself as being mean, and her mother hearing the noise came to see what was the matter. Then Mabel confessed all, and her mother said, "Perhaps my little girl did not know that we could be untruthful by not speaking at all, but you see it is quite possible".

I do not think Mabel ever forgot the lesson which she learnt that

Two boys were playing at bat and ball in a field. There was a high hedge on one side of the field, and on the other[15] side of the hedge was a market garden, where things are grown to be afterwards sold in the market. The boys had been playing some time, when the "batter," giving the ball a very hard blow, sent it over the hedge, and both the boys heard a loud crash as of breaking glass. They picked up the wickets quickly, and carried them, with the bat, to a hut that stood in the field, and were hurrying away when the gardener came and stopped them, asking, "Have you sent a cricket-ball over the hedge into my cucumber frame?" The boy who had struck the ball answered, "I did not see a ball go into your frame," and the other boy said, "Neither did I".

They did not see the ball break the glass, but they both knew that it had crashed into the frame, and though the words they spoke might be true, the lie was there all the same.

Supposing the sisters "Crystal-clear" had brought to the Fairy Queen a diamond that was only good on one side, do you think she would have put it in the Temple? No, indeed, she would have said it was only half true; and so we must put away anything that looks like truth, but is not truth. How wrong it is to make believe we have not done a thing, when all the time we have.

Dear children, be true all through! Have you ever seen a glass jar of pure honey, no bits of wax floating in it, all clear and pure? Let your heart be like that, sincere, which means "without wax, clear and pure".

One day three little girls were talking about hats and feathers.

The first girl said: "I have such a long feather in my best hat; it goes all down one side".

Then the next girl said: "Oh! my feather is longer than that, for it goes all round the hat"; and the third girl said: "Ah! but my feather is longer than either of yours, for it goes round the hat and hangs down behind as well".

On the next Sunday each of these little girls went walking in the park with her parents, wearing her best hat with the wonderful feather; it never occurred to one of them that she might meet the other two, but that is just what happened, and the three "long" feathers proved to be nothing but three short, little feathers, one in each hat! Can you guess how ashamed each girl felt?

You have seen a piece of elastic stretched out. How long you can make it, and how short it goes when you leave off stretching! Each girl wanted to be better than the other, and to appear so, each "stretched" the story of her feather, just as the length of elastic was stretched, forgetting that

The little children who went to school long years ago did not have pretty things to play with as you have—no kindergarten balls with bright colours, nor nice bricks with which to build houses and churches! There was a little girl named Lulu who went to a dame's school in those far-off days, and most of the time she had to sit knitting a long, grey stocking, though she was only six years old.

Some of the older girls were sewing on canvas with pretty coloured wools, and making (what appeared to little Lulu) most beautiful pictures. How she longed for a length of the pink or blue wool to have for her very own!

The school was in a room upstairs, and at the head of the stair there was a window, with a deep window-sill in front of it. As Lulu came out of the schoolroom one day to take a message for the teacher, and turned to close the door after her, she saw (oh, lovely sight!) that the window-sill was piled up with bundles of the pretty coloured wool that she liked so much. Oh! how she wished for a little of it! And, see, there is some rose-pink wool on the top, cut into lengths ready for the girls to sew with! It is too much for poor little Lulu; she draws out one! two! three lengths of the wool, folds it up hastily, puts it in her pocket, and runs down the stair on the errand she has been sent.

But is she happy? Oh, no! for a little Voice says: "Lulu, you are stealing; the wool is not yours!" For a few minutes the wool rests in her pocket, and then she[18] runs back up the stair; the schoolroom door is still closed as Lulu draws the wool from her pocket, and gently puts it back on the window-sill. Then she takes the message and returns to her place in the schoolroom, and to the knitting of her long stocking, hot and ashamed at the thought of what she has done, but glad in her heart that she listened to the Good Voice, and did not keep the wool.

Had any one seen her? Did any one know about it? Yes, there were loving Eyes watching little Lulu, and the One who looked down was very glad when she listened to the Good Voice. Do you know who it was?

Note.—To the mother or teacher who can read between the lines, this little story (which is not imaginary, but a true record of fact) bears another meaning. It shows the child's passionate love for objects that are pretty, especially coloured objects, and how the withholding of these may open the way to temptation. Let the child's natural desire be gratified, and supply to it freely coloured wools, beads, etc., at the same time teaching the right use of them, according to kindergarten[3] principles.

There are some people who think that taking little things is not stealing. But it is.

There was a little boy, named Carl, who began his wrong-doing by taking a piece of sugar. Then he took another piece, and another; but he always did it when his mother was not looking. We always want to hide the doing of wrong—we feel so ashamed.

One day Carl's mother sent him to the shop for something, and he kept a halfpenny out of the change. His mother did not notice it; she never thought her little boy would steal.

So it went on from bad to worse, until one day he stole a shilling from a boy in the school, and was expelled.

As Carl grew older he took larger sums, and you will not be surprised to hear that in the end he was sent to prison, and nearly broke his mother's heart.

Lilie's cousin had a bottle of scent given to her, and it had such a pleasant smell that one day, when Lilie was alone in the room, she thought she would like a little, so she unscrewed the stopper, and sprinkled a few drops on her handkerchief. I do not suppose her cousin would have been angry if she had known, but Lilie knew the scent was not hers, and she was miserable the moment she had taken it, and had no peace until she confessed[20] the fault, and asked her cousin's forgiveness. I wish Carl had felt like that about the piece of sugar; do not you? Then he would never have taken the larger things, and been sent to prison.

It was the Christmas examination at school, and the boys were all at their desks ready for the questions in arithmetic. Will Jones's desk was next Tom Hardy's, and everybody thought that one of these two boys would win the prize.

As soon as the questions had been given out, the boys set to work. Tom did all his sums on a scrap of paper first, then he copied them out carefully, and, after handing his paper to the master, left the room. Unfortunately he left the scrap of paper on which he had worked his sums lying on the desk. Will snatched it up, and looked to see if his answers were the same. No! two were different. Tom's would be sure to be right; so he copied the sums from Tom's scrap of paper. It was stealing, of course; just as much stealing as if he had taken Tom's pen or knife. Besides, it is so mean to let some one else do the work and then steal it from them—even the birds know that.

Some little birds were building themselves a nest, and to save the trouble of gathering materials, they went and[21] took some twigs and other things from another bird's nest that was being built. But when the old birds saw what the little ones had done, they set to work and pulled the nest all to pieces. That was to teach them to go and find their own twigs and sticks, and not to steal from others.

Of course Will was not happy. There was a little Voice within that would not let him rest, and when the boys kept talking about the arithmetic prize, and wondering who would get it, he felt as though he would like to go and hide somewhere, he was so ashamed. That is one of the results of wrong-doing, as we said before—it always makes us ashamed.

At last the day came when the master would tell who were the prize-winners. The boys were all sitting at their desks listening as the master read out these words:—

"Tom Hardy and Will Jones have all their sums right, but as Will's paper is the neater of the two, he will take the first prize".

The boys clapped their hands, but Will was not glad. The Voice within spoke louder and louder, so loudly that Will was almost afraid some of the other boys would hear it, and his face grew red and hot. At last he determined to obey the Good Voice and tell the truth, so he rose from his seat, walked up to the master, and said: "Please, sir, the prize does not belong to me, for I stole two of my answers from Tom Hardy. I am very sorry."

The master was greatly surprised, but he could see that Will was very sorry and unhappy. He held out his hand to him, and said: "I am glad, Will, that you have been brave enough to confess this. It will make you far happier than the prize would have done, seeing that you had not honestly won it." So the prize went to Tom, and Will[22] was never guilty of copying again; he remembered too well the unhappiness that followed it.

When Lulu reached her fifteenth birthday she had a watch given to her. One afternoon she was walking through a wood, up a steep and rocky path, and when she reached the top she stood for a few moments to rest. Looking back down the wood she saw a boy coming by the same path, and when about half-way up he stooped down as if to raise something from the ground, but the thought did not occur to Lulu that it might be anything belonging to her.

When she was rested she walked on until she came to a house just outside the wood, where she was to take tea with a friend.

After tea they sat and worked until the sun began to go down. Then Lulu said, "I think I must be going home; I will see what time it is," and she was going to take out her watch, when, alas! she found it was gone. "Oh, dear!" said she, "what shall I do? How careless of me to put it in my belt; it was a present from my brother!" Then she suddenly remembered standing at the top of the path and seeing the boy pick something up. "That would be my watch," said she. And so it was.

The boy had followed her up the wood, and had seen her go into the house, but he did not give up the watch. He waited until some bills were posted offering a reward of[23] £1, then he brought the watch and took the sovereign. If he had been an honest boy he would not have waited, but would have given up the watch at once. We ought not to wish any reward for doing what is right. It is quite enough to have the happiness that comes from obeying the Good Voice. We cannot build up a good character without honesty.

A lady was one day taking a walk along a country lane, and just as she was passing the gate of a field a horse and cart came out, and went down the road in the same direction as she was going, and oh! how the wheels did squeak! The lady longed to get away from the sound of them. First she walked very quickly, hoping to get well ahead; but no, the horse hurried up too, and kept pace with her. Perhaps he disliked the squeaking, and wanted his journey to be quickly finished. Then she lingered behind, and sauntered along slowly, but squeak, squeak—the hateful sound was still[24] there. At last the cart was driven down a lane to the right, and now the lady could listen to the songs of the birds, the humming of the bees, and the sweet rustle of the leaves as the wind played amongst them. "How much pleasanter," thought she, "are these sounds than the squeaking of the wheels."

I wonder if you have ever seen any little children who make you think of those disagreeable wheels? They are children who do not like to lend their toys, or to play the games that their companions suggest, but who like, instead, to please themselves.

Do you know what the wheels needed to make them go sweetly? They needed oil. And the disagreeable children who grate on us with their selfish, unkind ways, need another sort of oil—the oil of kindness. That will make things go sweetly; so we will write on the blackboard

Did you know that trees and birds, bees and flowers could be kind to each other? They can; I will tell you how.

See the pretty red cherries growing on that tree. All little children like cherries, and the birds like them too.

A little bird comes flying to the cherry tree and asks, "May I have one of these rosy little balls, please?"

"Yes, little bird," says the cherry tree; "take some, by all means."[25]

So the bird has a nice fruit banquet with the cherries, and then, what do you think he does for the tree?

"Oh!" you say, "a little bird cannot do anything that would help a big tree." But he can.

When he has eaten the cherry he drops the stone, and sometimes it sinks into the ground, and from it a young cherry tree springs up. The tree could not do that for itself, so we see that

When you have been smelling a tiger-lily, has any of the yellow dust ever rested on the tip of your nose? (Let the children see a tiger-lily, or a picture of one, if possible.) Look into the large cup of the lily, and there, deep down, you will see some sweet, delicious juice. What is it for? Ask the bee; she will tell you.

Here she comes, and down goes her long tongue into the flower. "Ah! Mrs. Bee, the honey is for you, I see. And pray, what have you done for the flower? Nothing, I'm afraid."

"Oh, yes, I have," hums the bee. "I brought her some flower-dust (pollen) on my back from another tiger-lily that I have been visiting to make her seeds grow. When I dip down into the flower some of the 'dust' clings to me, so I take it to the next tiger-lily that I visit, and she is very much obliged to me."[26]

You see, dear children, how the flowers help each other, and how the bee carries messages from one to another; so if

Do you remember the story of "Lulu and the Wool"? This is a true tale of the same little girl when she was grown older.

Lulu's home was at the top of a hill, and the road leading up to it was very steep. One summer evening, as Lulu walked home from town, she overtook a woman coming from market, and carrying a heavy basket as well as a bundle which was tied up in a blue checked handkerchief.

The poor woman stopped to rest just as Lulu came up to her. "Let me carry your bundle," said Lulu. And before the woman could answer she had picked it up and was trudging along.

"Perhaps your mother would not be pleased to see you carrying my bundle?" sighed the woman. "Some people think it is vulgar to be seen carrying parcels."

"It is never vulgar to be kind," answered Lulu. "That is what mother would say." So they walked on until they came to the cottage, and Lulu left the grateful woman at her own door, and forgot all about it.

Some years after, Lulu had been away from home, and, missing her train, she returned laden with parcels one dark,[27] wet night. There was no one to meet her, no one to help to carry her parcels, and the rain was pouring down. She hurried outside to look for a cab, but there was not one to be had, so she began to walk up the hill. After going a very little way she stopped to rest, the parcels were so heavy; and just then a man came up and said: "Give me your parcels, miss, they seem too heavy for you". And Lulu, astonished, handed them to him. He carried them to the door of her mother's house, and hardly waited to hear the grateful thanks Lulu would have poured out.

Have you ever heard these words: "Give, and it shall be given unto you". I think they came true in this little story. Do not you?

Let us all try to build a good deal of the "pure gold" of Kindness into our "Temple".

If you place your hand on your head you will feel something hard just beneath the hair. What is it? It is bone. Pass your hand all over your head and you will still feel the bone. It is called the skull, and it covers up a wonderful thing called the brain, with which we think, and learn, and remember.

A little baby girl was toddling about the room one afternoon while her mother sat sewing. The baby was a year and a half old. She had only just learned to walk, and could not talk much, but she had begun to think. Presently she noticed a little stool under the table, and[28] after a great deal of trouble she managed to get it out. Can you guess what she wanted it for? (Let children try to answer.) She wanted it for mother's feet to rest upon. Elsie could not say this, but she dragged the stool until it was close to her mother, and then she patted it, and said "Mamma," which meant, "Put your feet on it".

Was not that a sweet, kind thing for a one-year-old baby to do? You see she was learning to think—to think for others, and you will not be surprised to hear that she grew up to be a kind, helpful girl, and was so bright and happy that her mother called her "Sunshine".

If any one asked me what kind of child I liked best, I believe the answer would be this: "A child who is thoughtful of others"; for a child who thinks of others will not be rude, or rough, or unkind. Who was it slammed the door when mother had a headache? It was a child who did not think. Who left his bat lying across the garden path so that baby tumbled over it and got a great bump on his little forehead? It was thoughtless Jimmy. Do not be thoughtless, dear children, for you cannot help hurting people, if you are thoughtless; and we are in the world to make it happy, not to hurt. Thoughtfulness is a lovely jewel; let us all try to build it into our "Temple".

A great soldier, Sir Ralph Abercromby, had been wounded in battle, and was dying. As they carried him on board the ship in a litter a soldier's blanket was rolled up and placed beneath his head for a pillow to ease his pain. "Whose blanket is this?" asked he.[29]

One of the soldiers answered that it only belonged to one of the men. "But I want to know the name of the man," said Sir Ralph. He was then told that the man's name was Duncan Roy, and he said: "Then see that Duncan Roy gets his blanket this very night".

You see how thoughtful he was for the other man's comfort, so thoughtful that he did not wish to keep Duncan's blanket even though he himself was dying. Is it not true that "thoughtfulness" is one of the most beautiful of the precious stones that you build with.

A cat and a parrot lived in the same house, and were very kind and friendly towards each other. One evening there was no one in the kitchen except the bird and the cat. The cook had gone upstairs, leaving a bowl full of dough to rise by the fire. Before long the cat rushed upstairs, mewing and making signs for the cook to come down, then she jumped up and seized her apron, and tried to pull her along. What could be the matter, what had happened? Cook went downstairs to see, and there was poor Polly shrieking, calling out, flapping her wings, and struggling with all her[30] might "up to her knees" in dough, and stuck quite fast. Of course the cook lifted the parrot out, and cleaned the dough from her legs, but if pussy had not been her kind friend, and run for help, she would have sunk farther and farther into the dough, and perhaps in the end would have been smothered.

A ship that was crossing the sea had two monkeys on board; one of them was larger and older than the other, though she was not the mother of the younger one. Now it happened one day that the little monkey fell overboard, and the bigger one was immediately very much excited. She had a cord tied round her waist, with which she had been fastened up, and what do you think she did? She scrambled down the outside of the ship, until she came to a ledge, then she held on to the ship with one hand, and with the other she held out the cord to the poor little monkey that was struggling in the water. Was not she a clever, thoughtful, kind monkey? The cord was just a little too short, so one of the sailors threw out a longer rope, which the little monkey grasped, and by this means she was brought safely on board.

You will remember the story of the monkey, who tried to save her little friend, and remember, also, that

There is a beautiful story about birds helping each other in a book[6] which you must read for yourselves when you grow older.

One day a man was out with his gun, and shot a sea-bird, called a tern, which fell wounded into the sea, near the water's edge. The man stood and waited until the wind should blow the bird near enough for him to reach it, when, to his surprise, he saw two other terns fly down to the poor wounded bird and take hold of him, one at each wing, lift him out of the water, and carry him seawards. Two other terns followed, and when the first two had carried him a few yards and were tired, they laid him down gently and the next two picked him up, and so they went on carrying him in turns until they reached a rock a good way off, where they laid him down. The sportsman then made his way to the rock, but when they saw him coming, a whole swarm of terns came together, and just before he reached the place, two of them again lifted up the wounded bird and bore him out to sea. The man was near enough to have hindered this if he had wished, but he was so pleased to see the kindness of the birds that he would not take the poor creature from them.

So we have learnt another lesson from the birds, and will write it down.

Have you ever known a little girl who cried whenever her face was washed? or a little boy who screamed each time he had a tumble, although he might not be hurt in the least? You would not call those brave children, would you? We say that people are brave when they are not afraid to face danger, like the men who go out in the life-boat when the sea is rough to try and save a crew from shipwreck; or the brave firemen who rescue the inmates of a burning house. Perhaps you think it is only grown-up people who can be brave, but that is not so; little children can be brave also, as you will see from this story of a little boy, about whom we read in the papers not long ago, and who lived not far from London. Some children were playing near a pool, when, by some means, one of them, a little boy named Arthur, three years old, fell in. All the children, except one, ran away. (They were not brave, were they?) The one who remained was little Arthur's brother, Leonard. He was only five years old, but he[33] had a brave heart, and he went into the water at once, although he could not see Arthur, who had fallen on his back under the water, and was too frightened to get up. Leonard had seen where he fell, and though he did not know how deep the water was, he walked in, lifted his little brother up, and pulled him out. It was all done much more quickly than I have told you. If Leonard had run away to fetch some one, instead of doing what he could himself, his brother must have been drowned, because he was fast in the mud. I am sure you will say that Leonard was a brave little boy, and we should not think that he cries when he is washed, or when he has a little tumble. Leonard teaches us to

What a fuss some children make when they are hurt ever so little, and if a finger should bleed how dreadfully frightened they are!

A lady told me this story of two little twin boys whom she knew. Their names were Bennie and Joey, and they were just two years old.

One day as they were playing together Bennie cut his finger, and the blood came out in little drops. Now, the twins had never seen blood before, and you will think, maybe, that Bennie began to cry; but he did not. He looked at his finger and said: "Oh! Joey, look! what is[34] this?" "Don't know," said Joey, shaking his head. Then they both watched the bleeding finger for a little, and at last Bennie said: "I know, Joey; it is gravy". He had seen the gravy in the meat, and he thought this was something like it. Anyhow, it was better than crying and making a fuss, do you not think?

It was recreation time, and the boys were pretending to play football, when a boy of six, named Robin, had an awkward fall and broke his arm. The teacher bound it up as well as she could, and Robin did not cry, though the poor arm must have pained him. He walked quietly through the streets with the teacher, who took him to the doctor to have the broken bone set, and when the doctor pulled his arm straight out to get the bones in place before he bound it up, Robin gave one little cry; that was all. He is now a grown-up man, but the teacher still remembers how brave he was when his arm was broken, and feels proud of her pupil.

Did you ever hear of a monkey having toothache? There was a monkey once who lived in a cage in some gardens in London, and he had a very bad toothache, which made a large swelling on his face. The poor creature was in such great pain that a dentist was sent for. (A dentist, tell the children, is a man who attends to teeth.) When the monkey was taken out of the cage he struggled, but as soon as the dentist placed his hand on the spot he was quite still. He laid his head down so that the dentist might look at his bad tooth, and then he allowed him to take it out without making any fuss whatever. There was a little girl once who screamed and struggled dreadfully when she was taken to have her hair cut, and that, you know, does not hurt at all. Let us learn from the monkey, as we did from Robin, to

A sparrow was one day flying over a road when he saw lying there a long strip of rag.

"Ah!" said he, "that would be nice for the nest we are building; I will take it home." So he picked up one end[36] in his beak and flew away with it, but the wind blew the long streamer about his wings, and down he came, tumbling in the dust. Soon he was up again, and, after giving himself a little shake, he took the rag by the other end and mounted in the air. But again it entangled his wings, and he was soon on the ground. Next he seized it in the middle, but now there were two loose ends, and he was entangled more quickly than before.

Then he stopped to think for a minute, and looked at the rag as much as to say: "What shall I do with you next"? An idea struck him. He hopped up to the rag, and with his beak and claws rolled it into a nice little ball. Then he drove his beak into it, shook his head once or twice to make sure that the ends were fast, and flew away in triumph.

Remember the sparrow and the rag, and

If you had been a little child a hundred years ago, instead of now, and had wished to travel to the seaside or any other place, do you know how you would have got there? You would have had to travel in a coach, for there were no trains in those days. I am afraid the little children who lived then did not get to the seashore as often as you do, unless they lived near it, for it cost so much money to ride in the coaches. How is it that we have trains now?

There was a man called George Stephenson—a poor man[37] he was; he did not even know how to read until he went to a night school when he was eighteen years old, but he worked and worked at the steam-engine until he had made one that could draw a train along. So you see that because this man and others tried and tried again, all those years ago, we have the nice, quick trains to take us to the seaside cheaply, and to other places as well. Like the sparrow, George Stephenson teaches us to

A long, long time ago the people in this country did not even know there was such a place as America; it was another "try, try again" man that found it out. His name was Christopher Columbus, and he thought there must be a country on the other side of that great ocean, if he could only get across. But it would take a good ship, and sailors, and money, and he had none of these. He was in a country called Spain, and he asked the king and queen to help him, but for a great while they did not. However, he waited and never gave it up, and at last the queen said he should go, and off he started with two or three ships and a number of sailors.

It was more than two months before the new land appeared, and sometimes the sailors were afraid when it was very stormy, and wanted to turn back, but Columbus encouraged them to go on, and at last they saw the land. They all went on shore, and the first thing they did was[38] to kneel down and thank God for bringing them safe to land; then they kissed the ground for very gladness, and wept tears of joy.

When Columbus came home again, bringing gold, and cotton, and wonderful birds from the new country, he was received with great rejoicing by the king and queen and all the people. Do not forget this lesson:—

Walter was busy doing his home lessons; he wanted to get them finished quickly, so that he could join his playmates at a game of cricket before it was time to go to bed. He was nearly at the end, and the page was just as neat as it could be—for Walter worked very carefully—when, in turning the paper over, he gave the pen which was in his hand a sharp jerk, and a great splash of ink fell in the very middle of the neat, clean page.

"Oh, dear!" cried Walter, "all my work is wasted. I shall get no marks for this lesson unless I write it all over again; and I wanted so much to go out and have a game." However, he was a brave boy, and his mother was glad to notice that he set to work quietly, and soon had it written over again. When bedtime came, she said: "Walter, your[39] accident with the ink made me think of a story. Shall I tell it to you?"

"Oh, yes, mother! please do," said Walter, for he loved stories.

"There was once a gentleman (Audubon) in America," said his mother, "who was very fond of studying birds. He would go out in the woods to watch them, and he also made sketches of them, and worked so hard that he had nearly a thousand of these drawings, which, of course, he valued very much. One time he was going away from home for some months, and before he went he collected all his precious drawings together, put them carefully in a wooden box, and gave them to a relative to take care of until he came back.

"The time went by and he returned, and soon after asked for the box containing his treasures. The box was there, but what do you think? Two rats had found their way into it, and had made a home there for their young ones, and the beautiful drawings were all gnawed until nothing was left but tiny scraps of paper. You can guess how dreadfully disappointed the poor man would feel. But he tells us that in a few days he went out to the woods and began his drawings again as gaily as if nothing had happened; and he was pleased to think that he might now make better drawings than before. It was nearly three years before he had made up for what the rats had eaten. This man must have possessed the precious jewel of patience. Do you not think so?"

"What is patience, mother?" asked Walter.

"The little Scotch girl said it meant 'wait a wee, and no weary,'" said his mother; "and I think that is a very good[40] meaning. It is like saying that we must wait, and do the work over again, if necessary, without getting vexed or worried."

Patience is a good "stone" to have in the Temple of Character.

You have often played at keeping shop, have you not? Winnie and May were very fond of this game, and when it was holiday time they played it nearly every day. One morning they made the "shop" ready as usual; a stool was to be the "counter," and upon this they placed the scales, with all the things they meant to sell. When all was ready, Winnie stood behind the "counter," and said, "I will be the 'shopman'!"

"No!" exclaimed May, "I want to be 'shopman'; let me come behind the 'counter'." But Winnie would not move, then May tried to pull her away, and Winnie pushed May, and in the end both little girls were crying, and the game was spoilt. Were not they foolish?

How easy it would have been to take it in turns to be "shopman," and that would have been quite fair to both little girls. I am afraid we sometimes forget to be fair in our games. We will tell Winnie and May the story of the two goats.[41]

Perhaps you know that goats like to live on the rocks, and as they have cloven feet (that is, feet that are split up the middle) they can walk in places that would not be at all safe for your little feet.

One day two goats met each other on a narrow ledge of rock where there was not room to pass. Below them was a steep precipice; if they fell down there they would soon be dashed to pieces. How should they manage?

It was now that one of the goats did a polite, kind, graceful act.

She knelt down on the ledge so that the other goat might walk over her, and when this was done, she rose up and went on her way, so both the goats were safe and unhurt.

The goat teaches us a beautiful lesson on "giving in".

You will think "generous" is a long word, but the stories will help you to understand what it means.

Lilie was staying with her auntie, for her mother had gone on a voyage with father in his ship.

One day Lilie heard a timid little knock at the back door. She ran to open it, and saw standing outside a poor little[42] girl about her own size, with no shoes or stockings on. She asked for a piece of bread, and Lilie's auntie went into the pantry to cut it. While she was away Lilie noticed the little girl's bare feet, and, without thinking, she took off her own shoes and gave them to her.

When the girl had gone, auntie asked, "Where are your shoes, Lilie?" And she replied, "I gave them to the little girl, auntie. I do not think mother would mind." It would have been better if Lilie had asked auntie before she gave away her shoes; but auntie did not scold her; she only said to herself, "What a generous little soul the child has".

Bertie was a rosy-faced, healthy boy. His mother lived in a little cottage in the country, and she was too poor to buy dainties for her child, but the good, plain food he ate was quite enough to make him hearty and strong.

His usual breakfast was a basin of porridge mixed with milk, and one bright, sunny morning he was sitting on the doorstep, waiting until it should be cool enough for him to eat, when he saw a very poor, old man leaning on the garden gate. Bertie felt sure the old man must be wanting something to eat, he looked so pale and thin, and being a generous-hearted boy, he carried down his basin of porridge to the old man, and asked him to eat it, which he did with great enjoyment, for he was very hungry. I think you will understand now what being Generous means. We may do good by giving away things that are of no use to us, but that is not being generous.

One day two dogs had been quarrelling, and when they parted at night, they had not made it up, but went to rest, thinking hard things of each other, I fear. Next day, however, one of the dogs brought a biscuit to the other, and laid it down beside him, as much as to say, "Let us be friends". I think the other dog would be sure to forgive him after that, and we are sure they would both be much happier for being friends once more.

Gladys and Dora were in the same class at school, and when the teacher promised to give a prize for the cleanest, neatest and best-written copy-book, they determined to try and win the prize. Both the little girls wrote their copies very carefully for several days, but by-and-by Gladys grew a little careless, and her copies were not so well written as Dora's. Gladys knew this quite well, and yet she longed for the prize. What should she do? There was only one copy more to be written, and then it would have to be decided[44] who should get the prize. Sad to say, Gladys thought of a very mean way by which she might spoil Dora's chance of it.

She went to school one morning very early—no one was there; softly she walked to Dora's desk, and drew out her neat, tidy copy-book, which she opened at the last page, and, taking a pen, she dipped it in ink, and splashed the page all over; then she put it back in the desk, and said to herself, "There, now, the prize will be mine".

But why does Gladys feel so wretched all at once? A little Voice that you have often heard spoke in her heart, and said, "Oh! Gladys, how mean, how unkind!" and she could not help being miserable.

Presently the school assembled, and when the writing lesson came round the teacher said, "Now, girls, take out your copy-books and finish them". Dora drew hers out, and when she opened it and saw the blots her cheeks grew scarlet and her eyes filled with tears. Just then she turned and saw Gladys glancing at her in an ashamed sort of way (as the elephant looked at his driver when he had stolen the cakes—Story Lesson 85), and Dora knew in her heart that it was Gladys who had spoilt her copy-book. But she did not tell any one, not even when the teacher said, "Oh! Dora, what a mess you have made on your nice copy-book!" but she was thinking all the time, and when she went home she said to her mother, "Mamma, may I give my little tin box with the flowers painted on it to Gladys?" "Why, Dora," said her mother, "I thought you were very fond of that pretty box!" "So I am," replied Dora, "that is why I want Gladys to have it; please let me give it to her, mother!" So Dora's mother consented, and next morning Gladys found a small parcel on her desk, with a scrap of paper at the top, on which was written, "Gladys, with love from Dora". Dora was[45] generous, you see; she returned good for evil, and Gladys felt far more sorrow for her fault than she would have done had Dora caused her to be punished. Neither Gladys nor Dora won the prize, but Gladys learnt a lesson that was worth more than many prizes, and Dora had a gladness in her heart that was better than a prize—the gladness that comes from listening to the Good Voice. "Good for Evil" is a beautiful "stone" to have in your Temple.

Gentleness is a beautiful word, and I daresay you know what it means. When you are helping baby to walk, mother will say, "Be gentle with her," which means, "Do not be rough, do not hurt her". A gentleman is a man who is gentle, who will not hurt.

Did you ever hear of a horse who could behave like a gentleman? Here is the story.[10]

"A horse was drawing a cart along a narrow lane in Scotland when it spied a little child playing in the middle of the road. What do you think the kind, gentle horse did? It took hold of the little child's clothes with its teeth, lifted it up, and laid it gently on the bank at the side of the road, and then it turned its head to see that the cart had not hurt the child in passing. Did not the horse behave like a gentleman?"

I have seen boys and girls helping the little ones to dress in the cloakroom at school, or leading them carefully down the steps, or carrying the babies over rough places; this is gentleness, and the gentle boy will grow up to be a gentle man.

You have seen boys playing the game of "Paper Chase," or, as it is sometimes called, "Hare and Hounds". One or two boys start first, each carrying a bag full of small pieces of paper, which they scatter as they run. Then all the other boys start, and follow the track made by the scattered paper.

A number of boys were starting for a "Paper Chase" one Saturday afternoon, and, passing quickly round a corner of the street, some of them ran against a little fruit stall and overturned it. The apples, pears and plums were all rolling on the ground, and the old woman who belonged to the stall looked at them in dismay. The boys all ran on except one, and he stayed behind to help to put the stall right, and to gather up all the fruit. That boy was gentle and kind, and the poor old woman could not thank him enough.

A little girl called Rose had a kind auntie who sent her half a sovereign for a birthday present. Rose was delighted with the money, and was always talking of the many nice things it would buy, but she never thought of writing and thanking her auntie. That was not grateful, was it? When we receive anything, we should always think at once of the giver, and express our thanks without delay. That is why we say "grace" before eating: we wish to thank our kind Father above for giving us the nice food to eat.

The days went by, and still auntie received no word of thanks from her little niece. Then a letter came asking, "Has Rosy had my letter with the present?" Rose answered this, and said she had received the letter, and sent many thanks for the present. But how ashamed she must have felt that she had not written before! It is not nice to have to ask people for their thanks or gratitude; it ought to be given freely without asking.

Little Vernon's father had a tricycle, and one day he fixed up a seat in front for his little boy, and took him for a nice, long ride.

Vernon sat facing his father, and he was so delighted with the ride, and so grateful to his kind father for bringing him, that he could not help putting his arms round his father's neck sometimes, and giving him a kiss as they went along.[48] Vernon's father told me this himself, and I was glad to know that the little boy possessed this precious gift of gratitude, for it is a lovely "stone" to have in the Temple we are building.

Perhaps you have heard the fable of the crow who was thirsty. He found a pitcher with a little water in it, but he could not get at the water, for the neck of the jug was narrow.

Did he leave the water and say, "It is of no use to try"? No; he set to work, and found a way out of the difficulty. The crow dropped pebbles into the jug, one by one, and these made the water rise until he could reach it.

(Illustrate by a tumbler with a few tablespoonfuls of water in it. Drop in some pebbles, and show how the water rises as the pebbles take its place.) If you have a steep hill to climb, or a hard lesson to learn, do not sit down and cry, and think you cannot do it, but be determined that, like the crow, you will master the difficulty. When you were a little, tiny child, your father carried you over the rough places, but as you grow older, you walk over them yourself. You do not want to be carried now, for you are not helpless any longer. But I am afraid there are some children who like to be helpless, and to let mother do everything for[49] them. I once knew a girl of ten who could not tie her own bootlaces; she was helpless. And I knew a little fellow of six who, when his mother was sick, could put on the kettle, and make her a cup of tea; he was a helpful boy.

It is brave and nice of boys and girls to help themselves all they can, and not to be beaten by a little difficulty. Remember the Sparrow and the Rag (Story Lesson 30), as well as the Crow, and

Do you know what it is to be contented? It is just the opposite of being dissatisfied and unhappy.

Little Harold was looking forward to a day in the glen on the morrow, but when the morning came it was wet and cold, and the journey had to be put off. Harold had lots of toys to play with, but he would not touch any of them; he just stood with his face against the window-pane, discontented and unhappy.

After a time he saw an old man with a stick coming up the street, and a little dog was walking beside him. As they drew nearer, Harold saw that the old man held the dog by a string, and that it was leading him, for he was blind. The discontented little boy began to wonder what it must be like to be blind, and he shut his eyes very tight[50] to try it. How dark it was! he could see nothing. How dreadful to be always in darkness! Then he opened his eyes again, and looked at the old man's face; it was a peaceful, pleasant face. The old man did not look discontented and unhappy, and yet it was far worse to be blind than to be disappointed of a picnic. Harold had yet to learn that it is not outside things that give content, but something within. He could not help being disappointed at the wet day, but he could have made the best of it and played with his toys, as indeed he did after seeing the blind man.

Of all the untidy children you ever saw Leo must have been the worst. His hair was unbrushed, his boots were uncleaned, and the laces were always trailing on the floor. Why did he not learn to tie a bow? (For full instructions, with illustrations, on the "Tying of a bow," see Games Without Music.) It must be very uncomfortable to have one's boots all loose about the ankles, besides looking so untidy.

Can you guess how his stockings were? They were all in folds round his legs, instead of being drawn and held up tight, and he had always a button off somewhere. The worst of it was that Leo did not seem to mind being[51] untidy. I hope you are not like that. Do all the little girls love to have smooth, clean pinafores? and do the boys like to have a clean collar and smooth hair? and do all of you keep your hands and faces clean? Then you are like the children in these verses.

1. The Tidy Boy:—

2. The Tidy Girl:—