The Project Gutenberg EBook of Comrades, by Elizabeth Stuart Phelps This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Comrades Author: Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Illustrator: Howard E. Smith Release Date: November 8, 2010 [EBook #34255] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK COMRADES *** Produced by Al Haines

In the late May evening the soul of summer had gone suddenly incarnate, but the old man, indifferent and petulant, thrashed upon his bed. He was not used to being ill, and found no consolations in weather. Flowers regarded him observantly—one might have said critically—from the tables, the bureau, the window-sills: tulips, fleurs-de-lis, pansies, peonies, and late lilacs, for he had a garden-loving wife who made the most of "the dull season," after crocuses and daffodils, and before roses. But he manifested no interest in flowers; less than usual, it must be owned, in Patience, his wife. This was a marked incident. They had lived together fifty years, and she had acquired her share of the lessons of marriage, but not that ruder one given chiefly to women to learn—she had never found herself a negligible quantity in her husband's life. She had the profound maternal instinct which is so large an element in the love of every experienced and tender wife; and when Reuben thrashed profanely upon his pillows, staring out of the window above the vase of jonquils, without looking at her, clearly without thinking of her, she swallowed her surprise as if it had been a blue-pill, and tolerantly thought:

"Poor boy! To be a veteran and can't go!"

Her poor boy, being one-and-eighty, and having always had health and her, took his disappointment like a boy. He felt more outraged that he could not march with the other boys to decorate the graves to-morrow than he had been, or had felt that he was, by some of the important troubles of his long and, on the whole, comfortable life. He took it unreasonably; she could not deny that. But she went on saying "Poor boy!" as she usually did when he was unreasonable. When he stopped thrashing and swore no more she smiled at him brilliantly. He had not said anything worse than damn! But he was a good Baptist, and the lapse was memorable.

"Peter?" he said. "Just h'ist the curtain a mite, won't you? I want to see across over to the shop. Has young Jabez locked up everything? Somebody's got to make sure."

Behind the carpenter's shop the lush tobacco-fields of the Connecticut valley were springing healthily. "There ain't as good a crop as there gener'lly is," the old man fretted.

"Don't you think so?" replied Patience. "Everybody say it's better. But you ought to know."

In the youth and vigor of her no woman was ever more misnamed. Patient she was not, nor gentle, nor adaptable to the teeth in the saw of life. Like wincing wood, her nature had resented it, the whole biting thing. All her gentleness was acquired, and acquired hard. She had fought like a man to endure like a woman, to accept, not to writhe and rebel. She had not learned easily how to count herself out. Something in the sentimentality or even the piety of her name had always seemed to her ridiculous; they both used to have their fun at its expense; for some years he called her Impatience, degenerating into Imp if he felt like it. When Reuben took to calling her Peter, she found it rather a relief.

"You'll have to go without me," he said, crossly.

"I'd rather stay with you," she urged. "I'm not a veteran."

"Who'd decorate Tommy, then?" demanded the old man. "You wouldn't give Tommy the go-by, would you?"

"I never did—did I?" returned the wife, slowly.

"I don't know's you did," replied Reuben Oak, after some difficult reflection.

Patience did not talk about Tommy. But she had lived Tommy, so she felt, all her married life, ever since she took him, the year-old baby of a year-dead first wife who had made Reuben artistically miserable; not that Patience thought in this adjective; it was one foreign to her vocabulary; she was accustomed to say of that other woman: "It was better for Reuben. I'm not sorry she died." She added, "Lord forgive me," because she was a good church member, and felt that she must. Oh, she had "lived Tommy," God knew. Her own baby had died, and there were never any more. But Tommy lived and clamored at her heart. She began by trying to be a good stepmother. In the end she did not have to try. Tommy never knew the difference; and his father had long since forgotten it. She had made him so happy that he seldom remembered anything unpleasant. He was accustomed to refer to his two conjugal partners as "My wife and the other woman."

But Tommy had the blood of a fighting father, and when the Maine went down, and his chance came, he, too, took it. Tommy lay dead and nameless in the trenches at San Juan. But his father had put up a tall, gray slate-stone slab for him in the churchyard at home. This was close to the baby's; the baby's was little and white. So the veteran was used to "decorating Tommy" on Memorial Day. He did not trouble himself about the little, white gravestone then. He had a veteran's savage jealousy of the day that was sacred to the splendid heroisms and sacrifices of the sixties.

"What do they want to go decorating all their relations for?" he argued. "Ain't there three hundred and sixty-four days in the year for them?"

He was militant on this point, and Patience did not contend. Sometimes she took the baby's flowers over the day after.

"If you can spare me just as well's not, I'll decorate Tommy to-morrow," she suggested, gently. "We'll see how you feel along by that."

"Tommy's got to be decorated if I'm dead or livin'," retorted the veteran. The soldier father struggled up from his pillow, as if he would carry arms for his soldier son. Then he fell back weakly. "I wisht I had my old dog here," he complained—"my dog Tramp. I never did like a dog like that dog. But Tramp's dead, too. I don't believe them boys are coming. They've forgotten me, Peter. You haven't," he added, after some slow thought. "I don't know's you ever did, come to think."

Patience, in her blue shepherd-plaid gingham dress and white apron, was standing by the window—a handsome woman, a dozen years younger than her husband; her strong face was gentler than most strong faces are—in women; peace and pain, power and subjection, were fused upon her aspect like warring elements reconciled by a mystery. Her hair was not yet entirely white, and her lips were warm and rich. She had a round figure, not overgrown. There were times when she did not look over thirty. Two or three late jonquils that had outlived their calendar in a cold spot by a wall stood on the window-sill beside her; these trembled in the slant, May afternoon light. She stroked them in their vase, as if they had been frightened or hurt. She did not immediately answer Reuben, and, when she did, it was to say, abruptly:

"Here's the boys! They're coming—the whole of them!—Jabez Trent, and old Mr. Succor, and David Swing on his crutches. I'll go right out 'n' let them all in."

She spoke as if they had been a phalanx. Reuben panted upon his pillows. Patience had shut the door, and it seemed to him as if it would never open. He pulled at his gray flannel dressing-gown with nervous fingers; they were carpenter's fingers—worn, but supple and intelligent. He had on his old red nightcap, and he felt the indignity, but he did not dare to take the cap off; there was too much pain underneath it.

When Patience opened the door she nodded at him girlishly. She had preceded the visitors, who followed her without speaking. She looked forty years younger than they did. She marshaled them as if she had been their colonel. The woman herself had a certain military look.

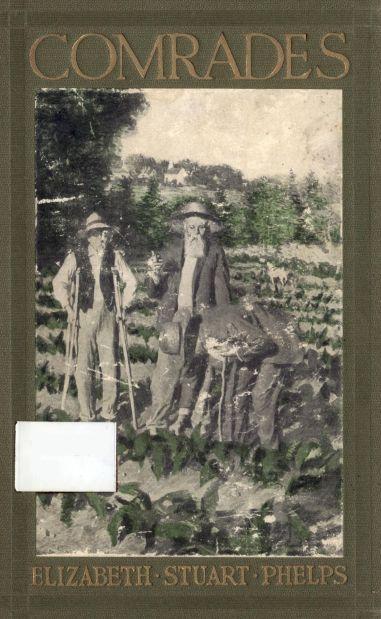

The veterans filed in slowly—three aged, disabled men. One was lame, and one was palsied; one was blind, and all were deaf.

"Here they are, Reuben," said Patience Oak. "They've all come to see you. Here's the whole Post."

Reuben's hand went to his red night-cap. He saluted gravely.

The veterans came in with dignity—David Swing, and Jabez Trent, and old Mr. Succor. David was the one on crutches, but Jabez Trent, with nodding head and swaying hand, led old Mr. Succor, who could not see.

Reuben watched them with a species of grim triumph. "I ain't blind," he thought, "and I hain't got the shakin' palsy. Nor I hain't come on crutches, either."

He welcomed his visitors with a distinctly patronizing air. He was conscious of pitying them as much as a soldier can afford to pity anything. They seemed to him very old men.

"Give 'em chairs, Peter," he commanded. "Give 'em easy chairs. Where's the cushions?"

"I favor a hard cheer myself," replied the blind soldier, sitting solid and straight upon the stiff bamboo chair into which he had been set down by Jabez Trent. "I'm sorry to find you so low, Reuben Oak."

"Low!" exploded the old soldier. "Why, nothing partikler ails me. I hain't got a thing the matter with me but a spell of rheumatics. I'll be spry as a kitten catchin' grasshoppers in a week. I can't march to-morrow—that's all. It's darned hard luck. How's your eyesight, Mr. Succor?"

"Some consider'ble better, sir," retorted the blind man. "I calc'late to get it back. My son's goin' to take me to a city eye-doctor. I ain't only seventy-eight. I'm too young to be blind. 'Tain't as if I was onto crutches, or I was down sick abed. How old are you, Reuben?"

"Only eighty-one!" snapped Reuben.

"He's eighty-one last March," interpolated his wife.

"He's come to a time of life when folks do take to their beds," returned David Swing. "Mebbe you could manage with crutches, Reuben, in a few weeks. I've been on 'em three years, since I was seventy-five. I've got to feel as if they was relations. Folks want me to ride to-morrow," he added, contemptuously, "but I'll march on them crutches to decorate them graves, or I won't march at all."

Now Jabez Trent was the youngest of the veterans; he was indeed but sixty-eight. He refrained from mentioning this fact. He felt that it was indelicate to boast of it. His jerking hand moved over toward the bed, and he laid it on Reuben's with a fine gesture.

"You'll be round—you'll be round before you know it," he shouted.

"I ain't deef," interrupted Reuben, "like the rest of you." But the palsied man, hearing not at all, shouted on:

"You always had grit, Reuben, more'n most of as. You stood more, you was under fire more, you never was afraid of anything— What's rheumatics? 'Tain't Antietam."

"Nor it ain't Bull Run," rejoined Reuben. He lifted his red nightcap from his head. "Let it ache!" he said. "It ain't Gettysburg."

"It seems to me," suggested Jabez Trent, "that Reuben he's under fire just about now. He ain't used to bein' disabled. It appears to me he's fightin' this matter the way a soldier 'd oughter— Comrades, I move he's entitled to promotion for military conduct. He'd rather than sympathy—wouldn't you, Reuben?"

"I don't feel to deserve it," muttered Reuben. "I swore to-day. Ask my wife."

"No, he didn't!" blazed Patience Oak. "He never said a thing but damn. He's getting tired, though," she added, under breath. "He ain't very well." She delicately brushed the foot of Jabez Trent with the toe of her slipper.

"I guess we'd better not set any longer," observed Jabez Trent. The three veterans rose like one soldier. Reuben felt that their visit had not been what he expected. But he could not deny that he was tired out; he wondered why. He beckoned to Jabez Trent, who, shaking and coughing, bent over him.

"You'll see the boys don't forget to decorate Tommy, won't you?" he asked, eagerly. Jabez could not hear much of this, but he got the word Tommy, and nodded.

The three old men saluted silently, and when Reuben had put on his nightcap he found that they had all gone. Only Patience was in the room, standing by the jonquils, in her blue gingham dress and white apron.

"Tired?" she asked, comfortably. "I've mixed you up an egg-nog. Think you could take it?"

"They didn't stay long," complained the old man. "It don't seem to amount to much, does it?"

"You've punched your pillows all to pudding-stones," observed Patience Oak. "Let me fix 'em a little."

"I won't be fussed over!" cried Reuben, angrily. He gave one of his pillows a pettish push, and it went half across the room. Patience picked it up without remark. Reuben Oak held out a contrite hand.

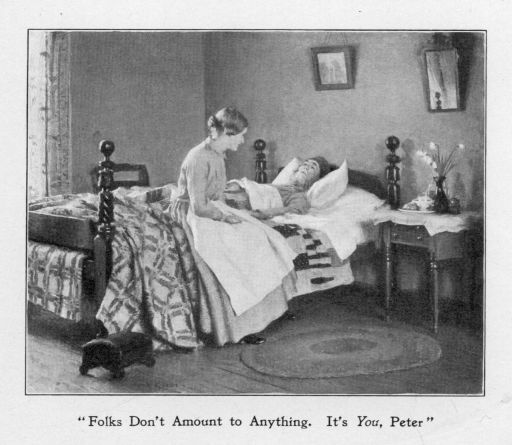

"Peter, come here!" he commanded. Patience, with her maternal smile, obeyed.

"You stay, Peter, anyhow. Folks don't amount to anything. It's you, Peter."

Patience's eyes filled. But she hid them on the pillow beside him—he did not know why. She put up one hand and stroked his cheek.

"Just as if I was a johnnyquil," said the old man. He laughed, and grew quiet, and slept. But Patience did not move. She was afraid of waking him. She sat crouched and crooked on the edge of the bed, uncomfortable and happy.

Out on the street, between the house and the carpenter's shop, the figures of the veterans bent against the perspective of young tobacco. They walked feebly. Old Mr. Succor shook his head:

"Looks like he'd never see another Decoration Day. He's some considerable sick—an' he ain't young."

"He's got grit, though," urged Jabez Trent.

"He's pretty old," sighed David Swing. "He's consider'ble older'n we be. He'd ought to be prepared for his summons any time at his age."

"We'll be decorating him, I guess, come next year," insisted old Mr. Succor. Jabez Trent opened his mouth to say something, but he coughed too hard to speak.

"I'd like to look at Reuben's crop as we go by," remarked the blind man. "He's lucky to have the shop 'n' the crop too."

The three turned aside to the field, where old Mr. Succor appraised the immature tobacco leaves with seeing fingers.

"Connecticut's a great State!" he cried.

"And this here's a great town," echoed David Swing. "Look at the quota we sent—nigh a full company. And we had a great colonel," he added, proudly. "I calc'late he'd been major-general if it hadn't 'a' been for that infernal shell."

"Boys," said Jabez Trent, slowly, "Memorial Day's a great day. It's up to us to keep it that way— Boys, we're all that's left of the Charles Darlington Post."

"That's a fact," observed the blind soldier, soberly.

"That's so," said the lame one, softly.

The three did not talk any more; they walked past the tobacco-field thoughtfully. Many persons carrying flowers passed or met them. These recognized the veterans with marked respect, and with some perplexity. What! Only old blind Mr. Succor? Just David Swing on his crutches, and Jabez Trent with the shaking palsy? Only those poor, familiar persons whom one saw every day, and did not think much about on any other day? Unregarded, unimportant, aging neighbors? These who had ceased to be useful, ceased to be interesting, who were not any longer of value to the town, or to the State, to their friends (if they had any left), or to themselves? Heroes? These plain, obscure old men?—Heroes?

So it befell that Patience Oak "decorated Tommy" for his father that Memorial Day. The year was 1909. The incident of which we have to tell occurred twelve months thereafter, in 1910. These, as I have gathered them, are the facts:

Time, to the old, takes an unnatural pace, and Reuben Oak felt that the year had sprinted him down the race-track of life; he was inclined to resent his eighty-second March birthday as a personal insult; but April cried over him, and May laughed at him, and he had acquired a certain grim reconciliation with the laws of fate by the time that the nation was summoned to remember its dead defenders upon their latest anniversary. This resignation was the easier because he found himself unexpectedly called upon to fill an extraordinary part in the drama and the pathos of the day.

He slept brokenly the night before, and waked early; it was scarcely five o'clock. But Patience, his wife, was already awake, lying quietly upon her pillow, with straight, still arms stretched down beside him. She was careful not to disturb him—she always was; she was so used to effacing herself for his sake that he had ceased to notice whether she did or not; he took her beautiful dedication to him as a matter of course; most husbands would, if they had its counterpart. In point of fact—and in saying this we express her altogether—Patience had the genius of love. Charming women, noble women, unselfish women may spend their lives in a man's company, making a tolerable success of marriage, yet lack this supreme gift of Heaven to womanhood, and never know it. Our defects we may recognize; our deficiencies we seldom do, and the love deficiency is the most hopeless of human limitations. Patience was endowed with love as a great poet is by song, or a musician by harmony, or an artist by color or form. She loved supremely, but she did not know that. She loved divinely, but her husband had never found it out. They were two plain people—a carpenter and his wife, plodding along the Connecticut valley industriously, with the ideals of their kind; to be true to their marriage vows, to be faithful to their children, to pay their debts, raise the tobacco, water the garden, drive the nails straight, and preserve the quinces. There were times when it occurred to Patience that she took more care of Reuben than Reuben did of her; but she dismissed the matter with a phrase common in her class, and covering for women most of the perplexity of married life: "You know what men are."

On the morning of which we speak, Reuben Oak had a blunt perception of the fact that it was kind in his wife to take such pains not to wake him till he got ready to begin the tremendous day before him; she always was considerate if he did not sleep well. He put down his hand and took hers with a sudden grasp, where it lay gentle and still beside him.

"Well, Peter," he said, kindly.

"Yes, dear," said Patience, instantly. "Feeling all right for to-day?"

"Fine," returned Reuben. "I don't know when I've felt so spry. I'll get right up 'n' dress."

"Would you mind staying where you are till I get your coffee heated?" asked Patience, eagerly. "You know how much stronger you always are if you wait for it. I'll have it on the heater in no time."

"I can't wait for coffee to-day," flashed Reuben. "I'm the best judge of what I need."

"Very well," said Patience, in a disappointed tone. For she had learned the final lesson of married life—not to oppose an obstinate man, for his own good. But she slipped into her wrapper and made the coffee, nevertheless. When she came back with it, Reuben was lying on the bed in his flannels, with a comforter over him; he looked pale, and held out his hand impatiently for the coffee.

His feverish eyes healed as he watched her moving about the room. He thought how young and pretty her neck was when she splashed the water on it.

"Goin' to wear your black dress?" he asked. "That's right. I'm glad you are. I'll get up pretty soon."

"I'll bring you all your clothes," she said. "Don't you get a mite tired. I'll move up everything for you. Your uniform's all cleaned and pressed. Don't you do a thing!"

She brushed her thick hair with upraised, girlish arms, and got out her black serge dress and a white tie. He lay and watched her thoughtfully.

"Peter," he said, unexpectedly, "how long is it since we was married?"

"Forty-nine years," answered Patience, promptly. "Fifty, come next September."

"What a little creatur' you were, Peter—just a slip of a girl! And how you did take hold—Tommy and everything."

"I was 'most twenty," observed Patience, with dignity.

"You made a powerful good stepmother all the same," mused Reuben. "You did love Tommy, to beat all."

"I was fond of Tommy," answered Patience, quietly. "He was a nice little fellow."

"And then there was the baby, Peter. Pity we lost the baby! I guess you took that harder 'n I did, Peter."

Patience made no reply.

"She was so dreadful young, Peter. I can't seem to remember how she looked. Can you? Pity she didn't live! You'd 'a' liked a daughter round the house, wouldn't you, Peter? Say, Peter, we've gone through a good deal, haven't we—you 'n' me? The war 'n' all that—and the two children. But there's one thing, Peter—"

Patience came over to him quietly, and sat down on the side of the bed. She was half dressed, and her still beautiful arms went around him.

"You'll tire yourself all out thinking, Reuben. You won't be able to decorate anybody if you ain't careful."

"What I was goin' to say was this," persisted Reuben. "I've always had you, Peter. And you've had me. I don't count so much, but I'm powerful fond of you, Peter. You're all I've got. Seems as if I couldn't set enough by you, somehow or nuther."

The old man hid his face upon her soft neck.

"There, there, dear!" said Patience.

"It must be kinder hard, Peter, not to like your wife. Or maybe she mightn't like him. Sho! I don't think I could stand that.... Peter?"

"Don't you think you'd better be getting dressed, Reuben? The procession's going to start pretty early. Folks are moving up and down the street. Everybody's got flowers—See?"

Reuben looked out of the window and over the pansy-bed with brilliant, dry eyes. His wife could see that he was keeping back the thing that he thought most about. She had avoided and evaded the subject as long as she could. She felt now that it must be met, and yet she parleyed with it. She hurried his breakfast and brought the tray to him. He ate because she asked him to, but his hands shook. It seemed as if he clung wilfully to the old topic, escaping the new as long as he could, to ramble on.

"You've been a dreadfully amiable wife, Peter. I don't believe I could have got along with any other kind of woman."

"I didn't used to be amiable, Reuben. I wasn't born so. I used to take things hard. Don't you remember?"

But Reuben shook his head.

"No, I don't. I can't seem to think of any time you wasn't that way. Sho! How'd you get to be so, then, I'd like to know?"

"Oh, just by loving, I guess," said Patience Oak.

"We've marched along together a good while," answered the old man, brokenly.

Unexpectedly he held out his hand, and she grasped it; his was cold and weak; but hers was warm and strong. In a dull way the divination came to him—if one may speak of a dull divination—that she had always been the strength and the warmth of his life. Suddenly it seemed to him a very long life. Now it was as if he forced himself to speak, as he would have charged at Fredericksburg. He felt as if he were climbing against breastworks when he said:

"I was the oldest of them all, Peter. And I was sickest, too. They all expected to come an' decorate me to-day." Patience nodded, without a word. She knew when her husband must do all the talking; she had found that out early in their married life. "I wouldn't of believed it, Peter; would you? Old Mr. Succor he had such good health. Who'd thought he'd tumble down the cellar stairs? If Mis' Succor 'd be'n like you, Peter, he wouldn't had the chance to tumble: I never would of thought of David Swing's havin' pneumonia—would you, Peter? Why, in '62 he slept onto the ground in peltin', drenchin' storms an' never sneezed. He was powerful well 'n' tough, David was. And Jabez! Poor old Jabez Trent! I liked him the best of the lot, Peter. Didn't you? He was sorry for me when they come here that day an' I couldn't march along of them.... And now, Peter, I've got to go an' decorate them.

"I'm the last livin' survivor of the Charles Darlington Post," added the veteran. "I'm going to apply to the Department Commander to let me keep it up. I guess I can manage someways. I won't be disbanded. Let 'em disband me if they can! I'd like to see 'em do it. Peter? Peter!"

"I'll help you into your uniform," said Patience. "It's all brushed and nice for you."

She got him to his swaying feet, and dressed him, and the two went to the window that looked upon the flowers. The garden blurred yellow and white and purple—a dash of blood-red among the late tulips. Patience had plucked and picked for Memorial Day, she had gathered and given, and yet she could not strip her garden. She looked at it lovingly. She felt as if she stood in pansy lights and iris air.

"Peter," said the veteran, hoarsely, "they're all gone, my girl. Everybody's gone but you. You're the only comrade I've got left, Peter.... And, Peter, I want to tell you—I seem to understand it this morning. Peter, you're the best comrade of 'em all."

"That's worth it," said Patience, in a strange tone—"that's worth the—high cost of living."

She lifted her head. She had an exalted look. The thoughtful pansies seemed to turn their faces toward her. She felt that they understood her. Did it matter whether Reuben understood her or not? It occurred to her that it was not so important, after all, whether a man understood his wife, if he only loved her. Women fussed too much, she thought; they expected to cry away the everlasting differences between the husband and the wife. If you loved a man you must take him as he was—just man. You couldn't make him over. You must make up your mind to that. Better, oh, better a hundred times to endure, to suffer—if it came to suffering—to take your share (perhaps he had his—who knew?) of the loneliness of living. Better any fate than to battle with the man you love, for what he did not give or could not give. Better anything than to stand in the pansy light, married fifty years, and not have made your husband happy.

"I 'most wisht you could march along of me," muttered Reuben Oak. "But you ain't a veteran."

"I don't know about that," Patience shook her head, smiling, but it was a sober smile.

"Tommy can't march," added Reuben. "He ain't here; nor he ain't in the graveyard either. He's a ghost—Tommy. He must be flying around the Throne. There's only one other person I'd like to have go along of me. That's my old dog—my dog Tramp. That dog thought a sight of me. The United States army couldn't have kep' him away from me. But Tramp's dead. He was a pretty old dog. I can't remember which died first, him or the baby; can you? Lord! I suppose Tramp's a ghost, too, a dog ghost, trottin' after—I don't know when I've thought of Tramp before. Where's he buried, Peter? Oh yes, come to think, he's under the big chestnut. Wonder we never decorated him, Peter."

"I have," confessed Patience. "I've done it quite a number of times. Reuben? Listen! I guess we've got to hurry. Seems to me I hear—"

"You hear drums," interrupted the old soldier. Suddenly he flared like lightwood on a camp-fire, and before his wife could speak again he had blazed out of the house.

The day had a certain unearthly beauty—most of our Memorial Days do have. Sometimes they scorch a little, and the processions wilt and lag. But this one, as we remember, had the climate of a happier world and the temperature of a day created for marching men—old soldiers who had left their youth and strength behind them, and who were feebler than they knew.

The Connecticut valley is not an emotional part of the map, but the town was alight with a suppressed feeling, intense, and hitherto unknown to the citizens. They were graver than they usually were on the national anniversary which had come to mean remembrance for the old and indifference for the young. There was no baseball in the village that day. The boys joined the procession soberly. The crowd was large but thoughtful. It had collected chiefly outside of the Post hall, where four old soldiers had valiantly sustained their dying organization for now two or three astonishing years.

The band was outside, below the steps; it played the "Star-spangled Banner" and "John Brown's Body" while it waited. For some reason there was a delay in the ceremonies. It was rumored that the chaplain had not come. Then it went about that he had been summoned to a funeral, and would meet the procession at the churchyard. The chaplain was the pastor of the Congregational Church. The regimental chaplain, he who used to pray for the dying boys after battle, had joined the vanished veterans long ago. The band struck up "My Country, 'tis of Thee." The crowd began to press toward the steps of the Post hall and to sway to and fro restlessly.

Then slowly there emerged from the hall, and firmly descended the steps, the Charles Darlington Post of the Grand Army of the Republic. People held their breaths, and some sobbed. They were not all women, either.

Erect, with fiery eyes, with haughty head—shrunken in his old uniform, but carrying it proudly—one old man walked out. The crowd parted for him, and he looked neither to the right nor to the left, but fell into the military step and began to march. In his aged arms he carried the flags of the Post. The military band preceded him, softly playing "Mine Eyes have Seen the Glory," while the crowd formed into procession and followed him. From the whole countryside people had assembled, and the throng was considerable.

They came out into the street and turned toward the churchyard—the old soldier marching alone. They had begged him to ride, though the distance was small. But he had obstinately refused.

"This Post has always marched," he had replied.

Except for the military music and the sound of moving feet or wheels, the street was perfectly still. No person spoke to any other. The veteran marched with proud step. His gray head was high. Once he was seen to put the flag of his company to his lips. A little behind him the procession had instinctively fallen back and left a certain space. One could not help the feeling that this was occupied. But they who filled it, if such there had been, were invisible to the eye of the body. And the eyes of the soul are not possessed by all men.

Now, the distance, as we have said, was short, and the old soldier was so exalted that it had not occurred to him that he could be fatigued. It was an astonishing sensation to him when he found himself unexpectedly faint.

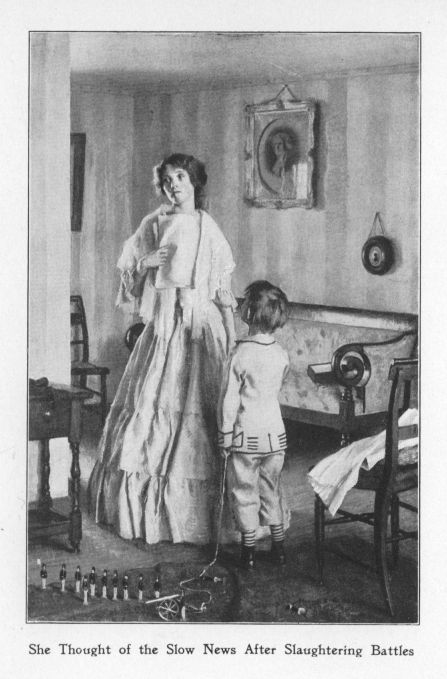

Patience Oak, for some reasons of her own hardly clear to herself, did not join the procession. She chose to walk abreast of it, at the side, as near as possible, without offense to the ceremonies, to the solitary figure of her husband. She was pacing through the grass, at the edge of the sidewalk—falling as well as she could into the military step. In her plain, old-fashioned black dress, with the fleck of white at her throat, she had a statuesque, unmodern look. Her fine features were charged with that emotion which any expression would have weakened. Her arms were heaped with flowers—bouquets and baskets and sprays: spiraea, lilacs, flowering almond, peonies, pansies, all the glory of her garden that opening summer returned to her care and tenderness. She was tender with everything—a man, a child, an animal, a flower. Everything blossomed for her, and rested in her, and yearned toward her. The emotion of the day and of the hour seemed incarnate in her. She embodied in her strong and sweet personality all that blundering man has wrought on tormented woman by the savagery of war. She remembered what she had suffered—a young, incredulous creature, on the margin of life, avid of happiness, believing in joy, and drowning in her love for that one man, her husband. She thought of the slow news after slaughtering battles—how she waited for the laggard paper in the country town; she remembered that she dared not read the head-lines when she got them, but dropped, choking and praying God to spare her, before she glanced. Even now she could feel the wet paper against her raining cheek. Then her heart leaped back, and she thought of the day when he marched away—his arms, his lips, his groans. She remembered what the dregs of desolation were, and mortal fear of unknown fate; the rack of the imagination; and inquisition of the nerve—the pangs that no man-soldier of them all could understand. "It comes on women—war," she thought.

Now, as she was stepping aside to avoid crushing some young white clover-blossoms in the grass where she was walking, she looked up and wondered if she were going blind, or if her mind were giving way.

The vacant space behind the solitary veteran trembled and palpitated before her vision, as if it had been peopled. By what? By whom? Patience was no occultist. She had never seen an apparition in her life. She felt that if she had not lacked a mysterious, unknown gift, she should have seen spirits, as men marching, now. But she did not see them. She was aware of a tremulous, nebulous struggle in the empty air, as of figures that did not form, or of sights from which her eyes were holden. Ah—what? She gasped for the wonder of it. Who was it, that followed the veteran, with the dumb, delighted fidelity that one race only knows of all created? For a wild instant this sane and sensible woman could have taken oath that Reuben Oak was accompanied on his march by his old dog, his dead dog, Tramp. If it had been Tommy— Or if it had been Jabez Trent— And where were they who had gone into the throat of death with him at Antietam, at Bull Run, at Fair Oaks, at Malvern Hill? But there limped along behind Reuben only an old, forgotten dog.

This quaint delusion (if delusion we must call it) aroused her attention, which had wavered from her husband, and concentrated it upon him afresh. Suddenly she saw him stagger.

A dozen persons started, but the wife sprang and reached him first. As she did this, the ghost dog vanished from before her. Only Reuben was there, marching alone, with the unpeopled space between him and the procession.

"Leave go of me!" he gasped. Patience quietly grasped him by the arm, and fell into step beside him. In her heart she was terrified. She was something of a reader in her way, and she thought of magazine stories where the veterans died upon Memorial Day.

"I'll march to decorate the Post—and Tommy—if I drop dead for it!" panted Reuben Oak.

"Then I shall march beside you," answered Patience.

"What 'll folks say?" cried the old soldier, in real anguish.

"They'll say I'm where I belong. Reuben! Reuben! I've earned the right to."

He contended no more, but yielded to her—in fact, gladly, for he felt too weak to stand alone. Inspiring him, and supporting him, and yet seeming (such was the sweet womanliness of her) to lean on him, Patience marched with him before the people; and these saw her through blurred eyes, and their hearts saluted her. With every step she felt that he strengthened. She was conscious of endowing him with her own vitality, as she sometimes did, in her own way—the love way, the wife way, powerfully and mysteriously.

So the veteran and his wife came on together to the cemetery, with the flags and the flowers. Nor was there a man or a woman in the throng who would have separated these comrades.

In the churchyard it was pleasant and expectant. The morning was cool, and the sun climbed gently. Not a flower had wilted; they looked as if they had been planted and were growing on the graves. When they had come to these, Patience Oak held back. She would not take from the old soldier his precious right. She did not offer to help him "decorate" anybody. His trembling mechanic's fingers clutched at the flowers as if he had been handling shot or nails. His breath came short. She watched him anxiously; she was still thinking of those stories she had read.

"Hadn't you better sit down on some monument and rest?" she whispered. But he paid no attention to her, and crawled from mound to mound. She perceived that it was his will to leave the new-made graves until the others had been remembered. Then he tottered across the cemetery with the flowers that he had saved for David Swing and old Mr. Succor and Jabez Trent, and the cheeks of the Charles Darlington Post were wet. Last of all he "decorated Tommy."

The air ached with the military dirge, and the voice of the chaplain faltered when he prayed. The veteran was aware that some persons in the crowd were sobbing. But his own eyes had now grown dry, and burned deep in their sunken sockets. As his sacred task drew to its end he grew remote, elate, and solemn. It was as if he were transfigured before his neighbors into something strange and holy. A village carpenter? A Connecticut tobacco-planter? Rather, say, the glory of the nation, the guardian of a great trust, proudly carried and honored to its end.

Taps were sounding over the old graves and the new, when the veteran slowly sank to one knee and toppled over. Patience, when she got her arms about him, saw that he had fallen across the mound where he had decorated Tommy with her white lilacs. Beyond lay the baby, small and still. The wife sat down on the little grave and drew the old man's head upon her lap. She thought of those Memorial Day stories with a deadly sinking at her heart. But it was a strong heart, all woman and all love.

"You shall not die!" she said.

She gathered him and poured her powerful being upon him—breath, warmth, will, prayer, who could say what it was? She felt as if she took hold of tremendous, unseen forces and moved them by unknown powers.

"Live!" she whispered. "Live!"

Some one called for a doctor, and she assented. But to her own soul she said:

"What's a doctor?"

The flags had fallen from his arms at last; he had clung to them till now. The chaplain reverently lifted them and laid them at his feet.

Once his white lips moved, and the people hushed to hear what outburst of patriotism would issue from them—what tribute to the cause that he had fought for, what final apostrophe to his country or his flag.

"Peter?" he called, feebly. "Peter!"

But Patience had said he should not die. And Patience knew. Had not she always known what he should do, or what he could? He lay upon his bed peacefully when, with tears and smiles, in reverence and in wonder, they had brought him home—and the flags of the Post, too. By a gesture he had asked to have these hung upon the foot-board of his bed.

He turned his head upon his pillow and watched his wife with wide, reflecting eyes. It was a long time before she would let him talk; in fact, the May afternoon was slanting to dusk before he tried to cross her tender will about that matter. When he did, it was to say only this:

"Peter? I was goin' to decorate the baby. I meant to when I took that turn."

Patience nodded.

"It's all done, Reuben."

"And, Peter? I've had the queerest notions about my old dog Tramp to-day. I wonder if there's a johnnyquil left to decorate him?"

"I'll go and see," said Patience. But when she had come back he had forgotten Tramp and the johnnyquil.

"Peter," he muttered, "this has been a great day." He gazed solemnly at the flags.

Patience regarded him poignantly. With a stricture at the heart she thought:

"He has grown old fast since yesterday." Then joyously the elderly wife cried out upon herself: "But I am young! He shall have all my youth. I've got enough for two—and strength!"

She crept beside him and laid her warm cheek to his.

THE END

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Comrades, by Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK COMRADES ***

***** This file should be named 34255-h.htm or 34255-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/3/4/2/5/34255/

Produced by Al Haines

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

https://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: https://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.