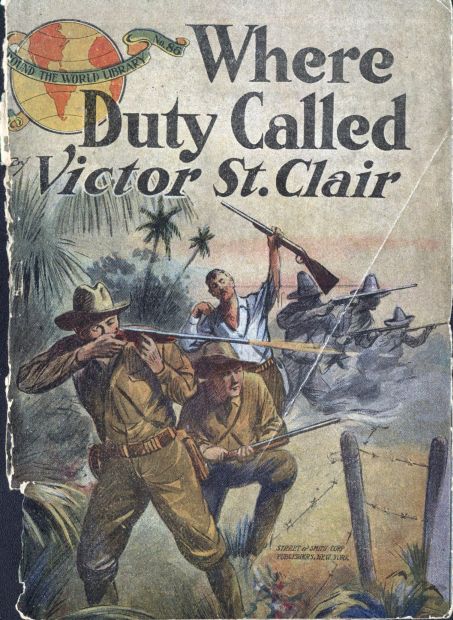

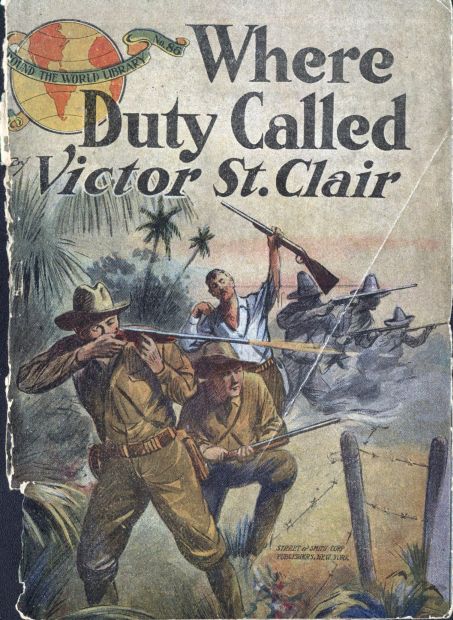

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Where Duty Called, by Victor St. Clair

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Where Duty Called

or, In Honor Bound

Author: Victor St. Clair

Release Date: December 30, 2010 [EBook #34792]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WHERE DUTY CALLED ***

Produced by Al Haines

| Chapter | |

| I. | "A Grand Opportunity." |

| II. | A Suspicious Craft. |

| III. | The Young Exile. |

| IV. | Put in Irons. |

| V. | Escape from the Libertador. |

| VI. | A Swim for Life. |

| VII. | Taken Ashore. |

| VIII. | Jaguar Claws. |

| IX. | The Mystery of the Photograph. |

| X. | "We have been Betrayed!" |

| XI. | A Perilous Flight. |

| XII. | A Lonely Ride. |

| XIII. | In the Enemy's Country. |

| XIV. | Indian Warfare. |

| XV. | A Friendly Voice. |

| XVI. | Colonel Marchand. |

| XVII. | A Cunning Ruse. |

| XVIII. | Ronie Receives a Commission. |

| XIX. | The Scout in the Jungle. |

| XX. | Adventures and Surprises. |

| XXI. | "The Mountain Lion." |

| XXII. | A Fight with the Guerillas. |

| XXIII. | The News at La Guayra. |

| XXIV. | Interview with General Castro. |

| XXV. | The Spy of Caracas. |

| XXVI. | "It is Manuel Marlin!" |

| XXVII. | Good News. |

| XXVIII. | Victory and Peace. |

"Hurrah, boys! here is a letter from home. At least, it is from the homeland, as it is postmarked New York. Who can be writing us from that city?" and the youthful speaker, in his exuberance of feeling, waved the missive over his head, while he began to dance a lively step.

"I know of no better way to find out than to open it, Harrie, or let one of us do it for you; you seem suddenly to have lost your faculty for doing anything rational yourself. Hand it to Jack if you do not want to trust me with it."

"Your very words, to say nothing of your impatient gestures, Ronie, show that you are not one whit less excited than I am over receiving some news from the great world outside of this lost corner," replied the first speaker, beginning to tear open the end of the bulky envelope he held in his hand.

"There must be a lot of news, judging by the size of the package," said the second, approaching so he could look over the shoulder of his companion while he tore open the covering.

"Go slow, lads," said a third person, who had been sitting slightly apart from the others, but who moved near to the twain now. "It won't do to get unduly excited in this climate."

The three were none other than our old friends of the jungles of Luzon, Ronie Rand, Harrie Mannering and Jack Greenland, whose exploits in opening up one of the great forest tracts on that island were described in "Cast Away in the Jungle," first of THE ROUND WORLD SERIES. They had not been long in Manilla, the capital of the island, since completing that hazardous undertaking, when an incoming steamer brought them the letter which awakened such an interest, and which was to play such an important part in their future actions. As its bulk indicated, it was a lengthy epistle, and this length was more than doubled in reading matter by the fine chirography which covered its large pages.

Standing where he could not scan the mysterious pages, Professor Jack fell to watching the countenance of Harrie Mannering as he followed with his eye the closely written pages. As he read, his features began to change their expression from gayety to seriousness, and by the time he had finished a puzzled look had settled upon his sunburned but good-looking face, and his lips, forming themselves unconsciously into a pucker, gave vent to a prolonged whistle. Then, as if to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the message, he returned to the beginning, and was about to read it through again, when Jack said:

"Look here, boy, you are taking an unfair advantage of a fellow. You must know that I am just as much interested in news from the homeland as you, so read it aloud this time. If it is good news, I want to enjoy it with you; if it is bad news, then I certainly ought to share it with you."

"Forgive me, or rather us, Jack—for I am sure Ronie has seen every word—but it is all so strange and unexpected that my head is not quite clear yet as to whether I have been reading or dreaming."

"Then it is all the more necessary that I should hear it, as it is possible my poor head may help unravel the skein. You remember the story of the great novelist, Sir Walter Scott, who, upon recovering from a long illness, was given a book to read for amusement. But upon reading the book, he could get so little sense out of it that he feared he had lost his reason. In this perplexed state of mind he handed the work to another to read without giving his reason, while he waited anxiously for the result. She, after reading a few chapters, threw the book aside, declaring it was such senseless twaddle that she did not care to follow it any further, whereupon the great author breathed easier."

"No offense was meant, Jack, and I will try and make amends at once. In the first place, this is an invitation for us to start upon another undertaking somewhat similar to the one we have just completed."

"What! return to the jungles of Luzon?"

"No; it is to South America this time—to Venezuela. A party of men, some of whom are connected with the local government, are anxious to open up the interior of the country in quest of rubber trees. The writer, who is one of the company, and, I judge, an influential member, has recommended us as 'capable persons'—you needn't laugh, Ronie, for those are his words—to survey and engineer for the party. If we conclude to go, he wants us to meet him at Caracas as soon as possible. In the meantime, he will get everything in readiness to start as soon as we arrive. I am at a loss to know what to think of it. The writer, who is Colonel Rupert Marchand, is very enthusiastic over the scheme, and he seems anxious that we should come. I never thought the colonel was one to get wild over anything that was not likely to prove successful."

Jack made no reply in words, but took the letter from the hand of his young friend, and began to hastily run over its contents, saying, by way of apology for his action:

"You will pardon me, Harrie, but it may not be best for us to read aloud or talk to any great extent here. There may be those about whose motives are not friendly."

Thinking this suggestion a wise one, Harrie and Ronie willingly followed their companion to a more retired place, where the three spent fully five minutes looking over the lengthy missive together before one of them spoke. Then Ronie said:

"Well, what do you think of it, Jack?"

"That it is a grand opportunity for two such adventure-loving fellows as you are to embrace. But I would not advise less daring and energetic youths to think of it for a moment."

"So you think there is likely to be some dangerous experiences attached to the journey?"

"It has all of that appearance, though you may come out of it without a scratch. Colonel Marchand, unless I have misjudged him, is just such a man as would throw all thought of hazard to the wind if the prize was worth striving for."

"You do not believe he would lead any one into needless danger, Jack?"

"Certainly not; he is too good a soldier for that, and you know he made an honorable record in our recent war with Spain."

"I judge, then, you think the people we should be likely to fall among might be a dangerous element," said Ronie.

"That is just what I meant. The inhabitants of the interior of the country where he would have you go are treacherous and dangerous, if they happen to take a dislike to you; and that they are more prone to dislike than to like has been my experience."

"What about this rubber business?" said Harrie. "Colonel Marchand speaks as if he wants us to take an interest in the company as part pay for our work. He seems very enthusiastic over that."

"His excuse for having us take some shares is that we might possibly have more interest in the venture," said Ronie. "That stipulation makes me think there may be some sort of a trap to inveigle us into a profitless adventure, though I do not think the colonel would do that."

"You are as well able to judge of that as I am. In regard to the rubber part of the venture, to use a poor simile, that is very elastic. Unless you have given the matter some consideration you will not, at first thought, realize the importance of that commodity, which must govern the possibilities of the article in the markets. I will acknowledge that I am very favorably impressed with the idea. Rubber is fast becoming one of the most important commercial articles in existence. Turn whichever way you will, do whatever you wish, and you will almost invariably find that rubber is the most necessary thing needed.

"Not only is it used in large quantities toward helping clothe men and creatures, but it is used in house furnishings, such as mattings for floors, stairs and platforms, on board of ships, as well as in houses, and in hundreds of other places. It is utilized largely in the manufacture of druggists' materials; in the manufacture of all kinds of instruments and machinery that require pliable bearings and supporters, printers' rollers, wheel tires, rings on preserve jars. Erasers on lead pencils call for tons of the article.

"Then steam mills must have rubber belts, cars rubber bearings, and gas works call for miles of rubber hose, to say nothing of that used in gardens and on lawns. Billiard tables alone call for nearly a third of a million dollars' worth of rubber every year, while over a million dollars are spent for the rubber used in baseball and football! Typewriters call for a vast amount; so do the makers of rubber stamps, water bottles, trimmings for harness, and fittings for pipes of one kind and another. Altogether, the rubber factories of the United States alone utilize sixty million pounds of rubber annually. You will not wonder now if I say that rubber ranks as third among the imports of the country, and that its handling is one of the most profitable callings of the day. If this is the electrical age, as it has been called, it is rubber that makes possible the many applications of electricity."

"I had not thought it of such importance," remarked Harrie, frankly. "Where does it all come from?"

"A very pertinent question," replied Jack. "Originally it came from India, hence the name of India rubber, which still clings to it, though the great bulk now, and that which is of the better quality, comes from other countries. Foremost among these is South America. It is true a large amount comes from Central America, the west part of Africa, and the islands of the Indian Archipelago, but the best rubber comes from the great belt of lowlands bordering upon the Amazon, the Rio Negro and the Orinoco, the last named tract lying largely in Southern Venezuela. This country in many respects is the Eldorado of South America."

"Then we shall not be going into a country without at least one source of wealth."

"No; Venezuela is wonderfully well favored by nature. Capable of producing abundant supplies of first quality coffee, sugar cane, cocoa palm and cotton plant, it has its rich gold mines, its mines of asphalt, affording paving enough for the cities of the world; while last, but not least, are its rubber forests, which have only very recently been considered as a valuable and available resource. It is here American capital has entered the field of conquest."

"Do you think we had better go there, Jack?"

"That is a question you must answer yourselves. I know you will not act hastily, and, having acted, will not regret the step taken."

"What about the climate, Jack?" asked Harrie. "I believe you have been there?"

"Yes, I have been there," replied the other, shaking his grizzled head slowly, "and it was likely at one stage of the scene that I should stay there forever. But I am not answering your question. The climate of South America, as a whole, is not very bad, though much of its territory lies within the torrid zone. This is largely due to local modifications. The burning heat of the plains of Arabia is unknown in the western hemisphere. The hottest region of South America, as far as I know, is the steppes of Caracas, the capital of Venezuela; but even there the temperature does not reach a hundred degrees in the shade, while it rises to one hundred and twelve degrees in the sand deserts surrounding the Red Sea. In the basin of the Amazon, owing to the protection of vast forests and the influence of prevailing easterly winds, offshoots of the trade winds, which follow the great river nearly to the Andes, the climate is not very hot or unhealthy."

"What do you say, Ronie? Is it go, or stay here until something else comes our way?"

"I will suggest the way I would settle it. Let each one take a slip of paper, and, without consulting the Others, write upon it his answer. Whatever two of us shall say to be our decision, to go or to remain here."

His companions were nothing loath to agree to this, so paper and pencils were quickly obtained, and each one wrote his reply. Upon comparing notes a moment later, it was found that all three had written the short but decisive word:

"Go!"

"I tell you, boys, there is something wrong about this vessel."

The speaker was Jack Greenland, and his companions were Ronie and Harrie, but the scene is now many leagues from the quiet corner where they took their vote to hazard a journey to the rubber forests of Venezuela. Instead of the quaint old buildings of Manilla on the one hand, and the sullen old bay, filled with its odd-looking crafts, on the other, roll the blue waters of the Caribbean Sea, almost as placid as the southern sky that bends so benignly over their heads, while they stand by the taffrail of the rakish ship upon which they have only recently taken passage to the South American coast.

To explain in detail this change of base would require too much space. A few words will suffice to describe the long journey by water and land necessary to make this stupendous change. In the first place, having decided unanimously to undertake the trip, they were exceedingly fortunate in finding that they could leave Manilla within twenty-four hours by steamer for San Francisco. This required some smart hustling, but our trio were used to this, and the next morning found them safely aboard ship, looking hopefully forward to a speedy and safe arrival in the city of the Golden Gate. In this they were not disappointed, while the run down the coast to Panama was also made under favorable conditions. Then the isthmus was crossed with some delay and vexation, when their adventures and misadventures began in earnest.

At Colon tidings of war in Venezuela reached them. These being somewhat indefinite, and the republic in question being a land of revolutions and uprisings, but little attention was given these vague reports. They had barely left port, however, before the captain of the little coastwise vessel declared that they were likely to have trouble.

The next day they were, indeed, fired upon by a strange craft, and instead of keeping on toward La Guayra, the port of Caracas, he put to sea. While bent upon this aimless quest, they were overtaken by a tropical storm, and were eventually driven upon one of the small isles forming the lower horn of that huge crescent of sea isles known as the Windward Islands. From this they managed to reach, after repairing their damages somewhat, Martinique, where our three heroes were only too glad to part with such uncertain companions.

There was a strange ship in this port, which immediately attracted them. Learning that the captain, though he had taken out papers for Colon, intended to stop at La Guayra, they engaged passage. At the outset they had felt some distrust in doing this, while the commander showed equal hesitation in taking them. Still, it was their only chance to get away, so they resolved to take their chances, with the determination to keep their eyes and ears open. Thus they had frequently expressed the opinion among themselves that they had been justified in their suspicions, though this was the first outspoken belief in the fact.

"I agree with you, Jack," declared Ronie.

"What have you learned that is new, Jack?" asked Harrie.

"Enough to confirm what doubts I already had as to her character. Captain Willis does not intend to put in at La Guayra, as he claimed he should to us."

"Perhaps he dares not," said Ronie.

"Ay, lad, that's where you hit the bull's-eye. He dares not do it."

"That means either that his intentions are not honest, or that the war in Venezuela is more than a civil war," said Harrie.

"Now you've hit the bull's-eye with a double shot. I do not believe he is honest," nodding in the direction of the commander, "and that this is an international war!"

"Whew!" exclaimed the young engineers in the same breath. While both had really about come to this conclusion, the proposition seemed more startling when expressed in so many words.

"Before we fully agree to this," continued Professor Jack, "let's compare notes. In the first place this vessel before undergoing some slight alterations came to Martinique as a Colombian vessel, officered and manned by Englishmen. Upon reaching this island she was immediately sold, and her English crew discharged. But her captain remained the same, while she still carried the English colors. The next day it was claimed she had been again sold, this time passing into the possession of followers of General Matos, the leader of the Venezuelan revolutionists. Her English flag was now replaced by the colors of Venezuela, and she was renamed from the Ban Righ to the Libertador. Can the chameleon beat that in changing colors? It is my private opinion she is a cruiser in the employ of the insurgents, and that we are booked for lively times."

"With small chance of reaching Caracas for a long time, if at all," added Ronie.

"How came England to allow such a vessel to leave her port?" asked Harrie.

"She must have been deceived as to her real character. Thinking she was a Colombian ship, and being on peaceful terms with that republic, she had no business to stop her.[1] Hi! what have we here?"

Jack's abrupt question was called forth by the sudden appearance almost by his side of a tall, slender youth, whose tawny skin and dark features proclaimed that he belonged to the mixed blood of the South American people. He had risen from the midst of a coil of rope, and in such close proximity that it was evident he had overheard what had been said. The three Americans realized their situation, though the opening speech of the young stranger reassured them.

"Señors speak very indiscreetly," he said, "of affairs which they must know bode them ill, in case their words reach the ears of others."

"Who are you?" demanded Jack, who was the first to speak. He remembered having seen this youth among the men on board, but had not given him any particular notice, although he noticed that he presented an appearance that showed he did not belong to the class of common sailors, while dressed no better than the poorest. There was an air of superiority about him which they did not possess.

"It is not always well for one to be too outspoken to strangers," he answered, glancing cautiously about as he said the words. "Even coils of rope have ears," he added, significantly.

"You overheard what we said?" queried Jack, who continued to act as spokesman for the party.

"Si, señor. I could not help hearing some of it, though you did speak in a low tone. My ears are very keen, and not every one would have heard the little I did."

"It is not well for one to repeat what one hears, sometimes," said Jack, by way of reply.

"I have a mind as well as ears, señors," replied the youth. "While I can see as well as I can hear, I can think for both eyes and ears. You are not satisfied with the appearance of the Libertador?"

"I judge you are pretty well informed as to our opinion," replied Jack, more vexed than he was willing to show that they should have been caught off their guard. "Listeners are not apt to hear any good of themselves, we are told."

"Had I been a spy," retorted the youth, with some animation, "I should have remained quietly in my concealment, and not shown my head at all, and most assuredly not when I was likely to hear that which was to prove the most important."

"Please explain, then, your motive in addressing us at all."

"Not here—not now," he answered. "When the Southern Cross appears in the sky, and the sharp-eyed, doubting Englishman at the head sleeps, I will meet one of you here, and make plain many things you do not understand."

"Why not meet all of us?" demanded Jack, suspiciously.

"Because one of you in conversation with me would create less suspicion than all of you would be likely to do. That is my only reason, señor."

"By the horn of rock—Gibraltar, if you please," exclaimed Professor Jack, "there is a bit of common sense in that. One of us will be here, if we find it convenient."

"Good, señor. Now, as we seem to be attracting attention, it may be well for us to separate. I will be on hand at the appointed time."

A moment later the unknown youth mingled with the motley crew, leaving our friends wondering what their meeting with him portended.

"He seems honest," declared Ronie.

"He must be half Spaniard, and the other is doubtless something worse, if that is possible," said Jack, who confessed that he had no liking for the South American races.

"Shall we accept his proposition?" asked Harrie. "I will confess I am curious to know what he has to tell."

"I do not understand what this disturbance between the countries means," said Ronie. "When foreign nations take a hand in the affair it would seem to show that something more serious than a civil revolt is likely to follow. There could not have been a suspicion of this outside preparation of war in the United States, or Colonel Marchand would have known of it. I do not see how this has gone on under the American eyes."

"It is probably due to the fact that these republics of South America are almost continually at war. Venezuela has had a stormy time of it from the very first. I think one of us had better listen to what this young Venezuelan has to say. He is evidently not in sympathy with the commander of this vessel."

"Who is working in the interest of Matos, the leader of the revolutionists?"

"As President Castro is at the head of the government, and the target for the fire of the whole world at this time."

It was finally decided that Harrie should meet the stranger at the appointed time, while Ronie and Jack were to remain nearby to lend their assistance in case the youth showed any signs of treachery. Having come to this decision, the three waited, as may be imagined, with considerable anxiety for the hour to come.

[1] Jack hit nearer the truth than he realized at the time. The Ban Righ had, in fact, awakened the suspicions of the English authorities, and the attention of the custom officers was directed to her by the placing of a searchlight on her foremast. An examination disclosed the fact that parts of guns and gun-mountings had been stowed away below deck, where passages had been cut to allow the crew to move about with facility. She was released and permitted to leave port because the Colombian official in London claimed that she was being fitted out for the service of his government. Sailing ostensibly for Colon, she called at Antwerp, where she was loaded with 175 tons of Mausers and 180 tons of ammunition, besides field guns, billed as "hardware, musical instruments and kettledrums." She also took on here a French artillery captain, a doctor, and two sergeants. The guns were mounted before she reached Martinique, and while there a sham sale was made. So it will be seen that Jack and the young engineers had ample reason for mistrusting the vessel whose career reads like a chapter from romance rather than the actual history of a ship that, possibly, did more to foment international disputes concerning the Venezuelan war than anything else.—AUTHOR.

The night proved clear and beautiful, a typical southern evening most fitly closing a day that had been flawless. All the afternoon the sky and sea, so nearly of the same cerulean hue that where they met they matched so perfectly as to seem a curtain of the same texture, had appeared to vie with each other in their placidity, while now the stars overhead were scarcely brighter than their reflections in the waters below. On the rim of the distant horizon shone with a soft luster the glorious radii of the gem of the Antipodes, the Southern Cross.

Harrie was promptly on hand to keep his meeting with the strange youth, but no earlier than the other, who greeted him in his musical voice:

"Señor is in good season. It is well, for our time cannot be long in which to talk. While we speak let us walk slowly back and forth, arm in arm, so we shall not be overheard."

He spoke in a low tone, a little above a whisper, while Harrie allowed his arm to be drawn into the other's grasp, though he was very watchful not to be taken unawares in case of an attack on him.

"In the first place," said the young Venezuelan, "I judge señor is anxious to know who it is who has placed himself in his way. But before that I would speak of the ship which is at this moment bearing us whither we fain would not go."

"What about the ship?" asked Harrie, as he hesitated. "What have you to say of that?"

Lowering his voice so our hero could barely catch his words, he said:

"It is a pirate ship, señor!"

Harrie could not repress a low exclamation at this startling announcement, but he quickly recovered his presence of mind, saying, as he recalled the wild deeds of Morgan and his freebooters, Conrad and his Blue Water Rovers, who once boasted dominion over these seas:

"How can that be?"

"At least it is outlawed by the Venezuelan Government, and a big reward offered for its capture. It is a conscript working in the interest of Matos, the outlaw."

"Who are you who says this, and how come you by this information? You appear to be one of the crew; why is this so?"

"I could answer the last question by asking the same of señor. I am here solely with the hope of getting back to my native land, and to the side of my dear mother. Perhaps you will understand my situation better when I tell you that I belong to a family that once ruled Venezuela. The two Guzman Blancos, the elder of whom was an American, were my ancestors. My name is Francisco de Caprian. My family is hated by Matos, while father, who is not living now, did something to incur the displeasure of Castro, so I am in ill-favor all around," he added, with a smile which disclosed two rows of very white teeth.

"Notwithstanding this," he added, "I am anxious to get back to Caracas, to protect my dear mother in these perilous times, and, it may be, strike one blow more for my country. The De Caprians can trace their ancestry back to Juan Ampues, who founded the first Spanish settlement in Venezuela, and one of them was a captain under Bolivar. Whatever they may say of my family, they have ever been true to their native land. The illustrious General Blanco did much for downtrodden Venezuela, if some complained of him. You cannot suit all, señor, at the same time. Whither do you wish to go?"

"To Caracas," replied Harrie.

"I am glad to hear that, señor, for it will enable us to join fortunes. That is, if you do not hesitate to associate with me. I am frank to say that I am likely to involve you in trouble; but, at the same time, judging you are strangers there, I may be able to help you. Then, too, I do not believe they will dare to molest you to any serious extent, so long as your country is not mixed up in this imbroglio. Yet a South American aroused is like a wild bull, whose coming actions are not to be gauged by his former behavior. I never have found an American who could not take care of himself."

"Thank you, Señor Francisco. I trust you have not found one who would desert a comrade in an hour of need."

Quick and earnest came the reply, while the young Venezuelan grasped Harrie's hand.

"Never, señor."

"You shall find my friends and me faithful to our promises."

"I was confident of that, or I should not have dared to address you. Believe me, the risk was greater than you may realize. Were my identity to become known on this ship I have no doubt but I should be hung at the yardarm, or shot down like a brute, within an hour."

The youthful speaker showed great earnestness, and with what appeared to be genuine honesty and candor. At any rate, Harrie was fain to believe in his honor, and without further delay related enough of his experiences for the other to understand the situation of his friends and himself.

"I was very sure you were here involuntarily," said Francisco, when he had finished. "It is likely we can be of service to each other. From what I have been able to pick up, we are to coast along the shore of Venezuela, leaving here and there arms and ammunition for Matos and his insurgents. It is possible we shall stop at Maracaibo. In case we do so, that will be the place for us to leave the Libertador. If there is a chance before, we shall be remiss as to our personal welfare if we do not discover and improve it. The eyes of the watch are upon us," he said, in a lower tone, "and we had better separate. Keep your eyes and ears open until we have opportunity to speak to each other again."

Before Harrie could reply, the other had slipped away, and he was fain to return to his companions, whom he found anxiously awaiting him. In a few words he apprized them of what had passed between him and the young Venezuelan outlaw, Francisco de Caprian.

"His words only confirm what we had concluded, and for that I am inclined to believe the young man in part, at least. I was in Venezuela at the time of the downfall of that pompous patriot Guzman Blanco, and I knew something of the De Caprians. Possibly it was this fellow's father who was mixed up in the muddle, and who was killed, according to report, soon after I got away. Mind you, I say this, but it will be well for us if we are careful whom we trust. In Venezuela every man is a revolutionist, and where revolutions reign the sacredness of human faith is lost. As we seem to be in for our share of lively times, it may be well for us to look at the situation intelligently."

"I am surprised at the small amount I know of these South American republics," declared Harrie. "Though they are much nearer to us, I really know far less of them than I do of European nations of to-day, or the ancient empires that crumbled away long years ago."

"It is usually so," replied Jack. "It is a trait of human nature to be reaching after the things beyond our reach, while we push right over those near us. The history of South America is a most interesting one, but the most interesting chapter is close at hand, when out of the crude material shall crystallize a government and a people that shall place themselves among the powers of the world. I should not know as much as I do of Venezuela if it had not been for the two years I spent there quite recently—years I am not likely to forget."

"Ojeda, the Spanish adventurer who followed Columbus, named the country Venezuela, which means "Little Venice," from the fact that he found people living in houses built on piles, which suggested to him the 'Queen of the Adriatic,'" said Ronie.

"Very true," argued [Transcriber's note: agreed?} Jack. "These were natives living about Lake Maracaibo, but the name was extended to cover the whole country, though its original inhabitants did not, as a whole, live in dwellings on poles, and move about in canoes. This Alonso de Ojeda carried back to his patrons much gold and many pearls that he stole from the simple but honest natives."

"If I am not mistaken, Vespucci, who had so much to do with naming the new continent,[1] accompanied Ojeda's expedition," said Harrie.

"Very true," replied Jack. "I am glad to think that he was more humane than the majority of the early discoverers, who treated the natives so cruelly. The Indians of this country were not only rapidly despoiled of their gold and pearls, but they were themselves inhumanly butchered or seized and sold into captivity. The result was they soon became bitter enemies to the newcomers, who thus found colonization and civilization not only difficult but dangerous. Among those of a kinder heart who came here was Juan Ampues, whom your young friend, Harrie, claims was an ancestor of his. Ampues succeeded, through his kindness, in winning over the natives to his side, and he was thus enabled to found the first settlement in Venezuela. This was in 1527, and the town whose foundations he laid still exists under the name he gave it, Santa Ana de Coro. But for the most part the Spaniards treated the Indians in a brutal manner, and in the end the unfortunate race was looted and slain."

"But I have read that the people of Venezuela fell into worse hands when the country was leased for a while to the Germans," said Ronie.

"Right!" declared Jack, earnestly. "You are evidently well posted on history. Germany's hold was broken in 1546, but it took two hundred years to conquer and settle Venezuela, while all the slaughter of human lives and vast outlay of wealth proved in the end a poor investment for old Spain. One by one her American dependencies have slipped away from her control, and Venezuela has the honor of being the first to gain her freedom from Old World tyranny.

"The first effort to break the chains was made in 1797. This was unsuccessful, and another attempt was made in 1806, this time by General Francisco Miranda, who invaded Venezuela with an expedition organized in the United States, This revolution was successful only so far as it served to awaken the people to the possibility that lay before them. The prime opportunity came when Napoleon dethroned Ferdinand of Spain, and the inhabitants of this dependency declared that they would not submit to this Napoleonic usurpation. Though this movement was made under a claim of allegiance to the deposed king of Spain, he was incapable of seeing that it was for his interest to stand by them, so he renounced their declaration. The result was another declaration made on July 5, 1811, a declaration of independence and a constitution in some respects like ours."

"It seems a bit strange that they should have an independence day that comes so close to ours," said Harrie.

"Yes; and it is quite as singular that the first blow for liberty was struck by their ancestors on the same day in April that our forefathers fired their opening guns upon the British at Concord and Lexington," replied Jack.

"What means that confusion and those loud voices upon the deck?" asked Ronie, as they were arrested in the midst of their conversation by the sounds of a great commotion having suddenly begun over their heads.

"There is something new afoot!" declared Jack. "It sounds as if there was going to be a fight. Follow me, and we will find out what it means."

[1] Our geographies were wont to credit this nobleman with having given his name to the continent, but modern research has shown this to be an error. The country was already called by the native inhabitants Amarca, or America, which Vespucci very appropriately retained in his written account of the New World, the first that was given to the scholars of that day. From this fact his name became associated with that country, and he became known as "Amerigo" Vespucci, which was very appropriate, though his real name was Albertigo. Later writers, without stopping to investigate, declared that the continent had been named for him, and in that way others accepted the mistake as a fact. The truth is the name of "America" is older and grander than that of any of those who followed in the train of Columbus, and was that appellation given it by the ancient Peruvians, the most highly civilized people on the Western Continent at the coming of the Great Discoverer.—AUTHOR.

As the three hurried to the deck of the Libertador they found the noise and confusion increasing, though the seamen were fast falling into their line of duty with greater regularity. Captain Willis was on hand giving out his orders in his brusque manner.

"Where away has it been sighted, lookout?" called the commander.

"Off our windward quarter, captain."

"Maintain your watch, sir, and report if there is any change."

"They have sighted land," whispered Jack. "It must be one of the islands lying off the Venezuelan coast."

Both of his companions could not help feeling a thrill of pleasure at this announcement, while they hoped it might lead to their speedy escape from their present uncertain situation. But, from their position, no trace of the looked-for shore could be discovered, and it is safe to say no three upon the vessel watched and waited for the morning light with greater anxiety than the two young engineers and their faithful companion.

At different intervals the lookout announced the situation as viewed from his vantage ground, but no satisfactory word came until the dawn of day, when even those upon deck saw in plain sight the shore of one of the tropical islands dotting the sea.

While our friends were looking on the scene with intense interest, Francisco de Caprian passed by them, whispering as he did so:

"The island of Curacao. It looks as though we were going to touch at the port."

He did not stop for any reply from our party, but Jack said to his companions a moment later:

"If I am not mistaken Curacao belongs to the Dutch. It is about fifty miles from the Venezuelan coast, and westward of Caracas."

"Which means that we have passed the line of that city," said Ronie.

"Exactly."

"Had we better try and land here?"

"I am in doubt. Perhaps young De Caprian will be able to advise us. There is no doubt but they intend to stop here."

This was now evident to his companions, and half an hour was filled with the exciting emotions of entering harbor after a voyage at sea. As they moved slowly toward the pier it became evident that they had been expected, for, early as it was, quite a throng of spectators were awaiting them, and among the crowd were to be seen a small body of troops.

At this moment Francisco managed to pause a minute beside them, saying:

"They are stopping here to take off one of Matos' officers. The island seems to have been turned into a sort of recruiting ground for the insurgents."

"Aren't the Dutch neutral in this quarrel?"

"They are supposed to be, but it is my opinion considerable secret assistance is being given the insurgents from Europe—particularly from the Germans. But I shall create suspicion if I talk longer. Above all, appear to be indifferent to whatever may take place."

"You do not think we had better try and leave the vessel here?"

"You could not if you would. Every movement of yours is watched. Be careful what you say or——"

Francisco de Caprian did not stop to finish his sentence, though his unspoken words were very well understood by the anxious trio, who saw him among the most active of the mixed crew a moment later.

Then they were witnesses of the embarkation of a small squad of Venezuelan soldiers under charge of an officer who appeared in a supercilious mood.

"Whoever he is," whispered Jack, "he stands pretty near the head, and he evidently intends that every one shall know it. Our stop is going to be short. Well, the shorter the better, perhaps, for us. If we should succeed in getting ashore we should find ourselves in the power of the insurgents, which, it may be, we are at present," he added, with a smile. "All we can do is to keep our eyes open and await further developments."

Jack realized that his companions knew this as well as he, so he did not expect a reply, while they watched the following scenes in silence. They saw the last of the little party of insurgents on shipboard, and soon after the Libertador was once more ploughing her way through the blue water of the Caribbean. Their course was now south-southwest, but nothing occurred during the rest of the day to break the monotony of the voyage. The newcomers went below immediately, so that our friends saw nothing of them. Toward night Francisco found opportunity to speak a few words to the three.

"We are steering directly for the Venezuelan shore," he said. "I overheard Captain Willis say that he intended to land somewhere near Maracaibo, where, I judge, our passengers are going. We may find opportunity to escape then."

"Do you think we shall touch port again soon?" asked Ronie.

"The officer and his followers whom we took aboard at Curacao are to be left somewhere near Maracaibo. That is all I have been able to learn. They are extremely careful what they say."

The following morning it was found that the Libertador was flying signals, which Jack declared were intended to attract the insurgents.

"Mark my words, we are approaching the shore so closely that we shall soon sight land."

Jack proved himself a true prophet, but before this announcement came from the lookout, something of a more startling nature took place. About an hour after sunrise the sail of a small coastwise vessel was sighted, and within another hour the stranger had been so closely overtaken that she was hailed in no uncertain tones.

The reply was uttered in defiance, and the sloop showed that she was crowding ahead with all the speed she could, a steady breeze lending its favor. But it soon became evident that it would be a short race, and then the bow-chaser of the Libertador was brought to bear upon the fugitive.

As the first shot our heroes had heard in the war rang out over the sea, and the leaden messenger struck in close proximity to its target, the strange sloop was seen to soon slacken its flight. A few minutes later, in answer to the stentorian command of Captain Willis, she lay to.

"It is war in earnest," said Harrie, as they saw a boat let down from the cruiser, and the second officer, accompanied by half a dozen men, started toward the prize. "I wonder what they will do with the sloop now she has capitulated?"

"We shall know as soon as the mate and his men return," replied Jack.

It proved in the end that an officer and half a dozen men were sent from the Libertador to take charge of the captured sloop, which took an opposite course from that pursued by her captor. The latter continued along the coast, flying her signals, but did not offer to touch shore until Jack assured his companions that they must be near to Maracaibo. Then an unexpected thing happened. Though aware that they were continually under close surveillance, they had not been molested in any way until now they were ordered below. Upon showing a little hesitation in obeying, Ronie Rand was sent headlong to the deck by a blow from one of the sailors, sent to see that the order was carried out.

"Our only way is to obey at present," whispered Jack, leading the way to their berths below, followed by their enemies. They were left here by the latter. For a little time the three remained silent, each busy with his own thoughts. Finally Harrie said:

"This begins to look serious. Why is it done?"

"It looks to me as if they were afraid we might try to leave them as soon as we come to port, and they have taken this precaution."

"What can they wish to keep us for?" asked Ronie. "We have been of no benefit to them."

"True. But they may possibly fear to let us go free, as we are Americans, and would be likely to inform our government about some things they think we may have learned of them."

"Hark! I believe they are coming back."

While this did not prove true at the time, it was less than an hour later when an officer, with four companions, did visit them, the former saying he had received orders to put them in irons.

Upon listening to this announcement, the three looked upon their captors and then each upon his companions, Unable, at first, to comprehend the statement.

"Why should we be accorded such treatment?" demanded Jack. "We have done no harm to any one, but have come and remained as peaceful citizens of a country that has no trouble with your government or its subjects."

The officer shook his head, as much as to say: "I know nothing of this. My orders must be obeyed." Then he motioned for his men to carry out their purpose.

Although they were not armed, except for their small firearms, and the Venezuelans carried heavy pistols and cutlasses, the first thought that flashed simultaneously through the minds of our heroes was the idea that they could overpower the party, and thus escape the indignity about to be heaped upon them. But, fortunately, as later events proved, the calmer judgment of Jack prevailed. If they succeeded in overpowering these men, they must stand a slim chance of escaping. In fact, it would be folly to hope for it under the present conditions. Thus they allowed the irons to be clasped upon their wrists and about their ankles. This task, which did not seem an unpleasant one to them, accomplished to their satisfaction, the men returned to the deck, leaving our friends prisoners amid surroundings which seemed to make their situation hopeless.

During the hours which followed—hours that seemed like ages—the imprisoned trio were aware of a great commotion on deck, and Jack assured his companions that the Libertador had come to anchor.

"We are in some port near Maracaibo," he said. "I feel very sure of that."

"If we were only free," said Harrie, "there might be a possibility that we could get away. It begins to look as if we are not going to regain our freedom."

"I wish we had resisted them," exclaimed the more impulsive Ronie. "I know we could have overpowered them."

"It would have done no good in the end," replied Jack. "In fact, it would have worked against us in almost any turn affairs may take. In case we do escape, we shall be able to show that we have not given cause for this treatment. The United States Government will see that we are recompensed for this."

"If we live to get out of it," said Ronie.

"That is an important consideration, I allow," declared Jack. "But I never permit myself to worry over my misfortunes. So long as there is life there is hope."

"I wonder if Francisco knows of this," said Ronie.

"If he does, and he must learn of it sooner or later, he will come to us if it is in his power," replied Harrie, whose faith in the outlawed Venezuelan was greater than his companions'.

Some time later, just how long they had no way of knowing, it became evident to them that the Libertador was again upon the move. Whither were they bound? No one had come near them, and so long had they been without food and drink that they began to feel the effects. Had they been forgotten by their captors, or was it a premeditated plan to kill them by starvation and thirst? Such questions as these filled their minds and occupied most of their conversation.

"I wonder where Colonel Marchand thinks we are?" asked Harrie.

"I tell you what let's do, boys," suggested the fertile Jack Greenland. "Let's remind them that we are human beings, and that we must have food and drink or perish. Now, together, let us call for water!"

The young engineers were not loath to do this, and a minute later, as with one voice that rang out loud and deep in that narrow place of confinement, they shouted three times in succession:

"Water! water! water!"

This cry they repeated at intervals for the next half hour without bringing any one to their side, when they relapsed into silence. But it was not long before an officer and two companions brought them both food and drink. They partook of these while their captors stood grimly over them, ready to return the irons to their wrists as soon as they had finished their simple meal. The only reply they could get to their questions was an ominous shake of the head from the leader of the party. So Jack gave up, and he and his companions relapsed into silence which was not broken until the disappearance of the men.

"This beats everything I ever met with," declared Jack, "though I must confess I have been in some peculiar situations in my time."

Nothing further occurred to break the monotony of their captivity for what they judged to be several hours. Then they suddenly became aware of a person approaching them in a stealthy manner. At a loss to know who could be creeping upon them in such a manner, they could only remain silent till the mystery should be solved. This was done in a most unexpected way by a voice that had a familiar sound to it, though it spoke scarcely above a whisper:

"Have no fear, señors, it is I."

The speaker was Francisco de Caprian, and he was not long in gaining their side.

"How fares it with you, señors?"

"Poorly," replied Jack, speaking for his captors as well as himself. "What does this mean?"

"I cannot stop to explain now. This ship is now bound to Porto Colombia for some repairs. It stopped off Maracaibo to land General Riera and his staff. From what I have overheard the present commander will leave her there, and one of Matos' more intimate followers will become the captain. It is possible we may fare better in Porto Colombia than out to sea here. But I am not certain. The captain seems concerned over what to do with you, and desperate measures may be carried out. I cannot say. But one fact remains. Every moment we are being carried farther and farther from Caracas. As far as I could I have arranged for immediate flight. I have bribed a sailor, who will help us get a boat. The night promises to be dark, which will materially aid us in escaping. But there is a lookout who stands in fear of his life lest he lets anything pass his gaze. It is not more than an even chance that we can succeed in evading him and the others. Do you care to take that chance with me, señors, or remain here and possibly escape with more or less harm?"

"For one," said Ronie, "I am in favor of getting away as soon as possible."

"Will it be possible for us to take our trunk with us?" asked Harrie. "We can ill afford to lose that."

"I thought as much, señor," replied Francisco. "I think we can manage to take it along."

Though it was too dark for them to see the countenance of their companion, the young engineers looked anxiously toward him while they waited for his answer. Jack spoke in a moment:

"I know how you feel, boys, and I think I have some of that spirit myself. I have always found, too, that the bold dash for freedom always counted best. If you think we had better take our chances now, I am with you, by the horn of rock—Gibraltar, if you please!"

"Good!" exclaimed Harrie and Ronie together. "You hear, Francisco, that we are going with you?"

"Si, señors. We will begin at once. For I will free you from those irons. Then you must follow my directions to the letter."

While he was speaking Francisco began to work upon the manacles upon Ronie's wrists, and he showed that he had come prepared for his task, as inside of five minutes the three were free, very much to their relief.

"Now," said Francisco, "you had better remain quietly here for what you judge to be an hour. Then you come upon deck, being careful to get astern without being seen. During this interval of waiting I will have a boat in readiness, and be prepared to lower your chest into it at short notice. You will have to bring this with you, and if it is too heavy to handle easily and rapidly, I should advise you to remove whatever of its contents you can spare. You understand?"

"We do, Francisco, and we will not fail to be on hand."

"I will be there to assist you. In case I fail to accomplish my purpose in getting the boat, you will hear an alarm, in which case you had better replace your irons and stay where you are until the excitement blows over. Under these circumstances it will be for your interest to look out for yourselves, as you will know that I cannot help you."

"We shall not desert you," replied the young engineers, while they clasped his hands as he started to leave them.

"He is a brave fellow, and thoroughly unselfish," said Harrie.

Exchanging now and then a few words, they waited and listened while the silence remained unbroken. At times the sound of footsteps reached their ears, and constantly the steady swish of waters, but nothing to warn them that the plans of Francisco had miscarried.

"The hour must be passed," declared Jack at last.

"And we must be moving," added Ronie.

"Can you find your chest easily?" asked the first.

"I think so," replied Harrie. "Follow me."

The next five minutes were occupied in reaching the deck with their burden. Upon feeling the salt sea breath the three breathed easier, while they glanced about to see if the way was clear. As Francisco had prophesied, the night was quite dark, though there were signs in the west that the clouds were breaking away. No one was to be seen nearby, and silently the three stole along toward the place where they expected to meet Francisco, bearing the chest containing the instruments, charts and papers of the young engineers. Fortunately, this was small, as they had not taken more than was necessary.

Harrie and Ronie bore this between them, while Jack followed with every sense strained to catch the first sight or hear the first movement of their enemies. In this way they had passed half the distance, and had caught a glimpse of one ahead whom they believed to be their friend, when a sharp voice rang out an alarm that for a moment fairly took away their breath. Before they had fairly recovered the cry was answered from the fore part of the vessel, and they realized that their flight had been discovered.

"Quick, señors!" called Francisco. "In a moment we shall be too late."

Ronie and Harrie quickened their advance, while Jack prepared to meet the enemy hand-to-hand, if it should be necessary, while he kept close beside his companions.

"The boat is ready," said Francisco. "Let me fasten the rope about the chest. If we can lower that before they get here, we will give them the slip."

Already they could hear the crew of the Libertador rushing wildly about, uttering confusing cries, which told that they had little idea of what was taking place, the majority doubtless thinking they had been attacked by some unknown and mysterious foes. Above this medley of voices rang the stern command of the captain, trying to bring order out of the excitement.

Francisco had now arranged the rope about the chest, and then it was lowered down the ship's side, rapidly, hand over hand.

"They are coming!" exclaimed Jack, hoarsely. "If I only had a weapon of some kind I would show them the mettle of my arm."

"Over the rail!" said Francisco, and he and Harrie shot down the line at a furious rate. But before Ronie and Jack could follow they found their retreat cut off, and themselves confronted by a dozen armed men, with others coming swiftly toward the scene.

Thinking that his friends were close beside him, Harrie dropped into the boat arranged for their flight. At the same moment Francisco landed in the bow of the slight craft rocking at its moorings, while flashes of light and wild orders of men under the stress of great excitement came from the deck of the Libertador.

"Are you all here?" asked the young Venezuelan, while he looked hurriedly upward to the scene of excitement Over their heads, rather than about him.

"Jack and Ronie are not here!" replied Harrie. "Hark! That must be them engaged in a hand-to-hand fight."

"We must cut loose!" exclaimed Francisco, through his clinched teeth. "Some of them are coming over the rail!"

"Boat ahoy!" thundered a stentorian voice from the vessel.

Francisco was in the act of cutting the boat adrift at that moment, and before the sound of the speaker's voice had died away the fugitives were several yards astern.

"Ply the oars, for your life!" said Francisco. "Our lives depend on our work for the next few minutes."

Loath as he was to make this flight without his friends, it was really all that Harrie could do, and he lent his arm to that of his companion, and with each stroke of the oar they were taken farther and farther from the scene of wild commotion reigning upon the deck of the outlawed ship.

"They are laying to," panted Francisco. "They have sighted us, and boats will be lowered to give us pursuit. Ha! that shows they mean business."

A volley of firearms at that instant awoke the night scene, illuminating the sea for a considerable distance. But the shots flew wide of their mark, though the light from the guns had disclosed their position, so the following volley whistled uncomfortably near. A darkness deeper than ever succeeded the discharge of firearms, and under this cover the fugitives managed to get beyond range before the third volley could be sent after them.

Harrie had improved the passing gleams to look for Ronie and Jack, but he had failed to learn aught of their fates, and his heart was very heavy, as he concluded that he alone had been permitted to escape. Francisco was silently bending over his oar, sending the boat swiftly through the water into the unknown dangers that must lie in their pathway.

Meanwhile, how has it fared with Jack and Ronie, who found their escape cut off at the very moment they were about to follow their companions?

"By the horn of rock—Gibraltar, if you please!" gritted the first, seizing upon a stout lever that some one had dropped nearby, and which promised to be a formidable club when wielded by his nervous arms, "when ye keelhaul old Jack Greenland ye'll hear Gabriel's trumpet sounding not far away!"

Then, as the mob rushed forward, he sprang in front of Ronie, who had suddenly found himself flung back from the ship's rail, to be sent headlong to the deck, and swinging his primitive weapon over his head he mowed down a semi-circle of the seamen as if he was cutting a swath of grain. By that time Ronie, whose determined nature was aroused by this rough treatment, was upon his feet, holding in his right hand a serviceable small arm that he had been able to pick up.

Shots were fired upon them by the crew of the Libertador, but, fortunately, the assailants proved but poor marksmen. One burly ruffian attempting to fell Ronie, the latter pointed at his body and discharged his firearm. At least he cocked the weapon and pulled the trigger, but it failed to respond. Realizing that it was empty, he used it as a club, and a moment later had cleared his path of the big seaman. At that moment Jack cried out:

"Quick—into the sea!"

An instant later their forms disappeared over the rail, and they shot headforemost into the water. Almost simultaneously with their escape the deck where they had just stood swarmed with the armed rabble.

Ronie for a brief while lost consciousness, and then the voice of Jack came faintly to his ears:

"Where are you, lad?"

"Here, Jack."

"Good! I will be with you in a minute. Drop astern as fast as you can."

Ronie was a good swimmer, and as soon as he had recovered from the shock of his headlong leap from the vessel he gathered himself together, and when Jack came alongside he felt equal to the task which seemed to lie ahead.

"Are you hurt, my lad?" asked Jack.

"No, Jack."

"Then keep beside me, and mind that you do not waste any of your strength, for if we do not find Harrie and the boat it is likely to be a long swim."

"Where can he be? I believe they are lowering a boat from the ship."

"Let them lower away, lad. It'll be a long chase before they overhaul us. Let's keep a little more to the right, for the boat has in all probability gone that way, if they got away. I am not sure they did, but it looked like it."

Then, the cries of the excited officers and crew of the Libertador growing fainter, as they swam on and on, Ronie and Jack steadily forged ahead, peering with anxious gaze into the gloom about them for a sight of their friends.

At the end of an hour the dark hulk of the Libertador had faded from view, and no more did the shouts of the exasperated men on board reach their ears, while they, feeling the fearful strain upon them, moved slowly through the water, hope slowly dying out in their breasts.

"We shall not find them!" declared Ronie.

"We must!" said Jack. "Let's shout to them again, now, together:

"Boat a-h-o-y!"

As they had done a dozen times before without receiving any welcoming reply, they sent their united voices far out over the sea, shimmering now in the starlight. Still no response—no sound to break the dreadful silence of their watery surroundings.

"My old arms are not quite tired out yet, lad; hold upon me."

"No—no, Jack. I am young and strong. I can bear up a while longer. If I only knew Harrie had escaped I should feel better."

"We can only hope that they have, and fight for our lives a little longer."

Nothing more was said for some time, while they continued their battle with the sea, each stroke of the arm leaving them a little weaker, until it seemed to the castaways that they could not hold up much longer.

"The race is almost over, lad," said Jack, at last. "I feel worse for you than for myself. You have been a true boy. It does not matter so much with an old wornout veteran like me, but you are——"

"Look, Jack!" exclaimed Ronie, in the midst of his speech. "I believe that is the boat!"

His companion glanced in the direction pointed out by Ronie, and a glad cry escaped his lips.

"Boat, ahoy!" he cried. "Help! H-e-l-p!"

Then they listened for a reply, fearing lest the other should fail to catch their faint appeal, for both were so hoarse and exhausted that their united voices could not reach far.

"It is a sloop," declared Jack. "It is coming straight down upon us. They cannot miss us—ay, they are veering away! They have not heard us—they have not seen us—they are going to pass us. Once again, lad, shout for your life. It is our only hope."

Never did two poor mortals appeal with greater desperation for succor, and a moment later a low cry of rejoicing left their sea-wet lips as the reply rang over the water in a piercing tone:

"Ahoy—there! Where away?"

"Here—to your lee!" replied the castaways, and then, quite overcome, they suddenly lost consciousness.

Neither Jack or Ronie had a full realization of what followed. The sound of a voice that seemed to be muffled rang dimly in their ears, and soon after strong arms lifted them bodily from the water, to place them in the bottom of a boat. Some one spoke in a language they could not understand, when the boat started back to the larger craft awaiting its return. By the time they had been taken upon the deck of this strange sloop both had recovered sufficiently to understand their situation.

A motley-looking crew stood around them, but they did not give these particular attention at the time, as one who was in command immediately caught their notice. He was a stout-framed, bewhiskered man of middle age, and in spite of his foreign dress, plainly an American. But he seemed to be the only American on board the sloop. Prefacing his question with an oath, he demanded:

"Who are you, and where did you come from?"

Understanding the suspicious character of the Libertador, Jack was wise enough not to acknowledge that they had come from that vessel until he should deem it good policy to do so. Accordingly he answered:

"We are two castaways who fell overboard from a ship just out from Maracaibo."

"Pretty seamen!" declared the other, showing that he scouted the idea. "Is it a trick of yours to fall overboard every time you step on deck?"

"We were only passengers," replied Jack. "As you will see, like yourself, we are Americans, who have come to this country with peaceful intentions."

"As if anybody was peaceful at such a time as this. What are your names?"

"Mine is Jack Greenland, and my friend's is Roland Rand," replied Jack, respectfully.

"Names are nothing," grunted the other. "You look like drowned rats. If you will go below with one of the men he will see that you have a change of clothing."

"We do not care for that, sir, Captain——"

"Captain Hawkins, sirrah. If you prefer wet duds to dry ones it is not my fault. Shift for yourselves while I look after my men, who are as lazy a lot of devils as ever swore in Spanish."

Jack and Ronie were in a dilemma. While they hesitated about arousing further the other regarding their identity, it seemed cowardly not to say or do something for Harrie and Francisco, whom they believed afloat in the boat, though not certain of this. Exchanging a few hurried words, Jack then ventured to address the captain again, though he felt he was treading upon dangerous ground. There was that air of mystery about the sloop and those who manned her, which already created a feeling in the breasts of our twain of doubt as to the honesty of the craft. What was this single American doing in these waters with a Venezuelan crew, not one of whom did they believe could speak a word of English, and certainly not one of whom appeared as if he would shrink from cutting a man's throat in case that person stood between him and any purpose he may have had in view.

"Captain Hawkins," said Jack, frankly and fearlessly, "we wish to ask whither you are bound. We realize we are under great favor to you, but we are very anxious to learn the fate of a couple of friends whom we have reason to believe were adrift at the time we found ourselves in the sea."

"Humph!" grunted the captain. "I should like to know what you expect of me. You may thank your stars that I am an American, as that fact alone has spared your lives."

"For which we are very grateful. But for the sake——"

"If you haven't been on this craft long enough to know that I am her master it's because you —— —— idiots, and fit food for the fishes only. I will leave you at the first sod of earth that I see. Is that enough?"

It was a trying situation. It was evident that it would be worse than useless to continue this subject under his present mood.

"They are better off than we were," declared Jack, aside to Ronie. "That is, if they really gained the boat."

"I would give a good deal to know," said Ronie.

"Captain Hawkins is tacking ship," declared Jack, a moment later.

"What does that mean?"

"I cannot tell, unless, by the great horn of rock—Gibraltar, if you please! he means to keep his word, and run us ashore at the first point of land to be reached."

"That will take us away from Harrie," said Ronie.

"Too true, lad; too true!"

"Jack, what do you make of Captain Hawkins and his men?"

"They are greater mysteries to me than the officers and crew of the Libertador. I set them down at once as pirates, but these fellows stump me out of my boots. All we can do is to watch and wait. They have done us one good turn, anyway."

Standing by the rail of this strange sloop, Jack and Ronie watched in silence the scenes that followed. Dark clouds had again risen on the sky, obscuring the stars in the west, while throwing a gloom over the sea far and wide. Captain Hawkins paid no further attention to them, but appeared oblivious of their presence.

"Are all of the ships that ply in these waters like those we have found?" asked Ronie, in a low tone.

"Not all, lad," replied Jack; "but I fear by far too many have followed in the wake of Sir Henry Morgan and his buccaneers. By my faith, lad, we must be going over very nearly the same course pursued by that infamous outlaw of the sea when he sailed with his expedition to sack the coast of Venezuela in the last half of the seventeenth century. In 1668 he captured the important city of Puerto Bello, the booty obtained amounting to over 250,000 pieces of eight, to say nothing of rich merchandise and precious gems. Encouraged in his unholy warfare by these ill-gotten gains, he rallied his lawless forces for another raid. So, early in 1669, he sailed with fifteen vessels and 800 men in this direction, making the rich city of Maracaibo his object. Again success came to him, and at that city and Panama he reaped a greater harvest of spoils than he had done at Puerto Bello. But this time Spain had got wind of his intentions, and sent a mighty squadron to intercept and capture him. At last it seemed as though the bold outlaw must yield, but his daring stood him still in hand, and by a sudden and unexpected swoop upon his unsuspecting foe he carried confusion and dismay into their midst, burning several of their ships and actually routing the fleet. There was still a blockading fort to pass, but throwing his colors to the breeze, now bearing directly down upon the guns, and then veering off, he succeeded in running the gantlet without the loss of a vessel.

"As may be imagined, Morgan was king of the buccaneers now. Did he need more men he had but to say so, and they flocked to his standard by scores. So a year later, in command of thirty-seven vessels and over two thousand men, he started upon the most difficult and the most audacious expedition ever planned by the wild outlaws of this coast. The outcome was too horrible to contemplate. The Spaniards fought well, for their all was at stake, but against the demoniac followers of a man who knew neither mercy nor hesitation in carrying out his infamous purposes. Panama was laid in ruins, and her unhappy inhabitants were nearly all inhumanly butchered or spared to fates even worse. Following this terrible expedition, the infamous leader was knighted by an infamous king, and for a time it seemed as if his evil deeds were to bear him only fruits of contented peacefulness. But it was not long before his old spirit began to reassert itself, he fell into trouble, was seized for some of his crimes, thrown into prison, where his history ends in oblivion."

Ronie was about to speak, when the cry of "land—oh!" came from the lookout, when their attention was quickly turned toward a dark line that had seemed to come up on the distant horizon.

"The sloop is about to lay to," declared Jack.

"And it looks as if they were going to lower a boat," added Ronie.

"By the horn of rock—Gibraltar, if you please! that is what they are doing. I wonder what is on hand now?"

They were kept in suspense but a short time, when Captain Hawkins approached them, saying:

"Whatever else Jerome Hawkins may have to answer for, it cannot be said that he ever failed to keep his word. You said you wanted to go to Venezuela. Yonder lies its shore, and I bid you a hearty God-speed. No thanks, sirrah," as Jack was about to speak, "you go your way and I'll go mine."

Without further words he turned upon his heel, and our twain had no further opportunity to exchange speech with him. A moment later they were ordered by gestures more forcible than speech to enter the boat, and knowing they could do no better, they obeyed. A crew of four accompanied them, and in a short time the keel of the boat grated upon the sandy shore of a point of land jutting out into the sea.

Understanding what was expected of them, and knowing it would avail nothing to resist, Jack and Ronie sprang out upon the land. Without even a parting gesture, the boatmen started upon their return to the sloop, whose dark hull loomed up gloomily in the distance. So intense was the feeling of the utter loneliness hanging over the hapless couple that neither of them spoke until they had seen the boat reach the strange sloop and the four seamen climb to the deck, when Jack said:

"Well, my lad, we are in Venezuela at last."

"But how different is our coming from what we had expected."

Jack Greenland made no reply to the remark of Ronie. In fact, there did not seem anything for him to say by way of answer. They saw that the country which lay back of them appeared barren and desolate. A few sickly shrubs pushed their crabbed heads above the sand dunes, but as far as they could see in the night the country was nearly level, and nothing more inviting than a sandy plain. The only cheerful sight that greeted their gaze was the crimson streak marking the eastern horizon, and which announced the breaking of a new day.

"I would give a good deal to know where Harrie is at this moment," said Ronie.

"We can only hope that he is able to look after himself," replied Jack. "And we can only make the most of our situation. As for me, I feel better on this sand bar than I have felt on board such ships as we have known since leaving Colon."

"If this is a sample of Venezuela," said Ronie, "I am heartily sick of it already."

"It is not. From what Captain Hawkins said, I judge we are on or near the shore, where the narrow tongue of water connects Lake Maracaibo with the sea. If this is the case we are twenty miles from the city. The lake is about one hundred and twenty miles long and ninety miles wide."

"But there must be some town nearer than the city you mention," said Ronie.

"Quite likely. As we can do no good by remaining here we might as well do a little prospecting. It may be well for us to move cautiously, as it is uncertain how we shall be treated. It is unfortunate that our letters of credit and other papers were lost with our chest."

"And all of our instruments and charts. Truly, Jack, it would seem as if we had been prompted to undertake this trip under the influence of an unlucky star."

Jack made no reply to this, but led the way from the shore, closely followed by Ronie. It was getting light enough for them to move with ease, as well as to get a good idea of their surroundings, which were not very inviting so far. But in the distance could be seen the dim outlines of the mountains and the borders of one of those luxuriant forests for which South America is noted.

Something like half a mile was passed in silence, when Jack paused, saying:

"If I am not mistaken, there is a small settlement off to our right. Perhaps we had better get a little nearer, though I hardly believe it will be good policy for us to be seen until we get a better understanding of our situation. We certainly cannot boast of being able to present a very attractive appearance," he added, ruefully, while he looked over his companion and himself.

In their bedraggled garments, not yet fully dry, it was small wonder if they did present a decidedly disheveled appearance.

"Do you think we are liable to an attack from the inhabitants in case we should be seen?"

"I do not know what to think. If this rebellion is general then we are in constant danger. I know of no better way than for us to push ahead and find out."

Suiting action to his words, Jack resumed the advance, with Ronie still beside him. It was now rapidly growing lighter, which was a source of satisfaction to them, as the cover of the growth they were entering promised to prove as effective a shield as the darkness had been when upon the sand plain.

Contrary to the expectations of Jack, they had not found the settlement looked for. In fact, as far as they could see, there were no signs of habitation anywhere in that vicinity. Thus, as they advanced, a feeling of loneliness came upon them that they could not throw off.

"I would give a good sum, if I had it, just to hear some one speak," declared Jack, thrusting his hands into his pockets, to pull them out the next moment with a prolonged whistle, which caused Ronie to start with fear at the unexpected sound.

"What is it, Jack?"

"By the horn of rock—Gibraltar, if you please! talk of being penniless when one pulls out of his pockets a whole handful of Spanish coin."

"It must be what you took in exchange at Colon," said Ronie, appearing relieved to find that nothing worse than a happy discovery had for a moment seemed to upset his companion. "I may have a little, too," beginning to search his pockets. "If I have not got money, then I have something here that may prove of use to us," producing a small pocket compass.

"Right, lad," said Jack. "Zounds! here's something that pleases me quite as much as the Spanish silver pieces. Here is the old knife I have carried with me on so many jaunts that it seems a part of myself. It had slipped down between the lining and the outside cloth of my jacket. In this jungle one feels better to have something with which to defend himself, even if it is nothing more than a good, stout knife, with a blade that has been tried and tested in some tough scrimmages. I think more of the old knife than ever."

The revival of Jack's usual good spirits served to encourage Ronie to somewhat forget their perils and uncertainty.

"Let's see," said Jack, dropping the coin back into his pocket, but holding the knife firmly in his hand, "if I'm not mistaken, by going due west we shall eventually reach the shore of Lake Maracaibo. We shall not have much difficulty then in reaching the city, from which we can go by rail to Caracas; if not all of the way, nearly so."

"In that case the compass will come in handy," said Ronie, and having selected their course, they now pushed forward with better courage than at any period since they had come to land.

It must have been half an hour later, and the sun was now sending its bright bars of light down through the umbrageous branches of the forest trees, one kind of which was laden with a profusion of bright and beautiful flowers, making the largest and most magnificent bouquets of floral offerings Ronie had ever seen, even in the Philippines, where the vegetation abounds on the grandest scale, when they were attracted by the sound of a human voice.