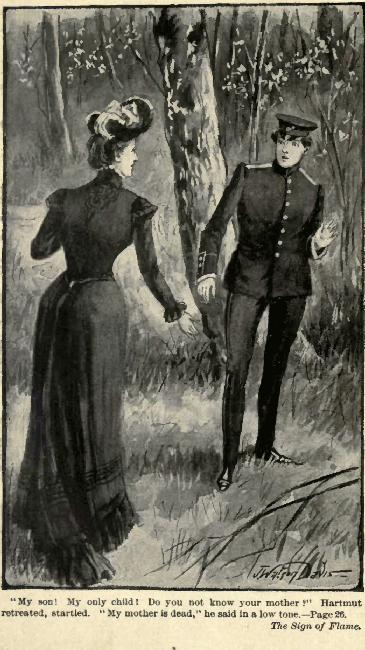

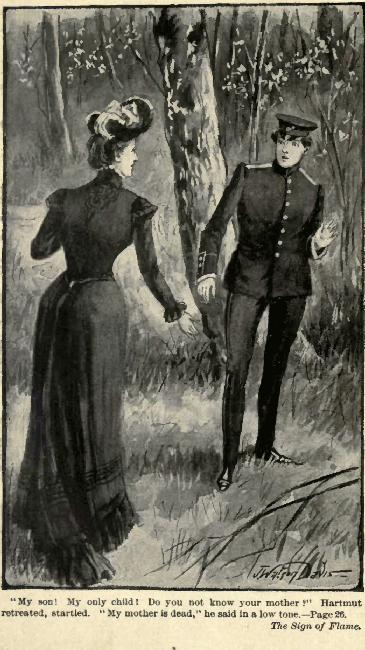

"My son'. My only child! Do you not know your mother?"

Hartmut retreated, startled. "My mother is dead," he said

in a low tone. Page 26. The Sign of Flame.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Sign of Flame, by E. Werner

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Sign of Flame

Author: E. Werner

Translator: Eva Freeman Hart

E. Van Gerpen

Release Date: January 25, 2011 [EBook #35069]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SIGN OF FLAME ***

Produced by Charles Bowen, from page scans provided by the Web Archive

Transcriber's Note:

Page scan source: http://www.archive.org/details/signofflame00werniala

"My son'. My only child! Do you not know your mother?"

Hartmut retreated, startled. "My mother is dead," he said

in a low tone. Page 26. The Sign of Flame.

"Give me a nook and a book,

And let the proud world spin round."

Through the gray fog of an autumn morning a flock of birds took flight; sweeping now, as if in farewell, close to the firs, so recently their home--rising now to a goodly height, directing their flight toward the south, and disappearing slowly in the veiled distance.

The gloomy eyes of a man standing at a window of the large castle-like mansion situated at the edge of the forest, followed this flight.

He was of tall stature and powerful in physique; the erect bearing would have betrayed the soldier even without the uniform which he wore: his features not handsome but strong; hair light, and eyes blue; in short, a typical German in appearance; but something like a shadow rested on those features, and the high brow bore deeper furrows than the years seemed to warrant.

"There, the birds are already leaving," he said, pointing to the flock which fluttered in the distance until lost entirely in the mass of fog. "The autumn is here in nature and also in our lives."

"Not yet in yours," interrupted his companion. "You are standing in full strength at the height of your life."

"Perhaps so considering years; but I feel as if old age would approach me sooner than any one else. I feel much like the autumn of the year."

The other gentleman, who was in civilian dress, was probably older than his companion. His stature was of medium height and frail. At first sight he appeared almost insignificant beside the powerful form of the officer, but the pale, sharply outlined face bore an expression of cold, superior calm; and the sarcastic line around the thin lips proved that behind the cold composure expressed in his whole manner something deeper lay concealed.

He now shook his head with displeasure.

"You take life too hard, Falkenried," he said reproachfully; "you have changed remarkably in these last years. He who has seen you as a young officer, merry as the day, would not recognize you now. And why all this? The shadow which once clouded your life has long ago vanished; you are heart and soul a soldier; you receive distinction at every opportunity; an important position is assured you in the near future; and, what is best--you have kept your son."

Falkenried did not reply; he folded his arms and again looked out into the gray distance. The other continued:

"The boy has grown as handsome as a picture in these last few years. I was quite surprised when I saw him, and even you confess that he is extraordinarily gifted, and, moreover, in several respects is endowed with absolute genius."

"I wish Hartmut were less gifted and had more character instead," Falkenried said in almost harsh tones. "He can make poetry and learn languages as if it were play, but as soon as he begins earnest study he remains far behind the others; while as to military strategy, nothing whatever can be done with him. You have no idea, Wallmoden, what iron severity I have to bring to bear on that."

"I only fear that you do not accomplish much with this severity," interrupted Wallmoden. "You should have followed my advice and sent your son to the University. That he is not cut out for a soldier you ought now finally to see."

"He must and shall be fit for it; it is the only thing possible for his unruly disposition, which chafes under every curb and feels every duty a burden. The University--the life of a student--would give him fullest liberty. Nothing but the iron discipline to which he has to bow keeps him in check."

"Yes, for a while; but can it force him in the future? You should not deceive yourself. His are, unfortunately, inherited faults, which may possibly be suppressed, but never uprooted. Hartmut is in appearance the image of his mother; he has her features--her eyes."

"Yes, I know," Falkenried said, gloomily, "her dark, demoniacal, glowing eyes, which knew how to charm everything----"

"And which became your ruin," completed Wallmoden. "How did I not warn and implore against them, but you would not listen to anything. Passion had taken hold of you like a fever and held you in bonds altogether. I have never been able to understand it."

A bitter smile flitted around Falkenried's mouth.

"I believe that. You, the cool, calculating diplomat who carefully measure every step, are safe from such charms."

"I should at least be more careful in my choice. Your marriage brought misfortune with it from the beginning. A wife of foreign race and blood--of wild Slavian nature, without character, without any understanding for that which is custom and duty to us, and you with your strict principles--your irritable sense of honor--it had finally to come to such an end. And I believe you loved her up to the separation in spite of everything!"

"No," said Falkenried harshly. "The illusion vanished in the first year. I saw only too clearly--but I shuddered at the idea of laying my domestic miseries open to the world by a divorce. I bore it until no choice was left me--until I finally--but enough of it!"

He turned quickly, and again looked out of the window. There was suppressed torture in the sudden breaking off.

"Yes, it needed much to tear a nature like yours from the roots," Wallmoden said seriously; "but nevertheless the separation left you free from the unfortunate claim, and with that you should have also buried the reminiscences."

"One cannot bury such reminiscences; they always rise up again from the supposed grave, and just now----" Falkenried broke off suddenly.

"Just now--what do you mean?"

"Nothing; let us speak of other things. You have been at Burgsdorf since the day before yesterday. How long do you intend to stay?"

"Perhaps two weeks. I have not much time at my disposal, and am Willibald's guardian really only in name, since the diplomatic service keeps me mostly in foreign countries. In fact, the guardianship rests in the hands of my sister, who rules everything, anyhow."

"Yes, Regine is well up to her position," assented Falkenried. "She rules the large estates and numerous people like a man."

"And issues commands from morning to night like a sergeant," completed Wallmoden. "With all due appreciation for her excellent qualities, I always feel a slight rising of the hair at the prospect of a visit to Burgsdorf, and I return from there regularly with shattered nerves. Real primitive conditions rule in that place. Willibald is actually a young bear, but the ideal of his mother for all that. She does her best to raise him an ignorant young country squire. All interposition is of no use, for he has every inclination for it, anyway."

The entrance of a servant interrupted them. He handed a card to Falkenried, which the latter glanced at hastily.

"Herr Egern, Solicitor. Very well, show the gentleman in."

"Have you a business engagement?" asked Wallmoden, rising. "I will not disturb you."

"On the contrary, I beg you to remain. I have been advised of this visit, and know what will be discussed. It concerns----"

He did not conclude, for the door opened and the one announced entered.

He seemed surprised not to find the officer alone, as he had expected, but the latter took no notice of the surprise.

"Herr Egern, Solicitor--Herr von Wallmoden, Secretary of the Ambassador."

The barrister bowed with cool courtesy, and accepted the offered chair.

"I probably have the honor of being familiar to you, Herr Major," he began. "As counsel for your wife, I had occasional cause to meet you personally in that suit for divorce."

He stopped, and seemed to expect an answer, but Major Falkenried only bowed in mute assent. Wallmoden now began to be attentive. He could now understand the strangely irritable mood in which he had found his friend upon his arrival.

"I come to-day also in the name of my former client," continued the lawyer. "She has asked me--may I speak freely?"

He cast a glance at the Secretary, but Falkenried said shortly:

"Herr von Wallmoden is my friend, and as such is familiar with the case. I beg you to speak without restraint."

"Very well, then--the lady has returned to Germany after long years of absence, and naturally wishes to see her son. She has already written to you on that behalf, but has not received an answer."

"I should consider that a sufficient answer. I do not desire this meeting, and therefore shall not permit it."

"That sounds very harsh, Herr Major. Frau von Falkenried has surely----"

"Frau Zalika Rojanow, you mean to say," interrupted the Major. "She resumed her maiden name, so far as I know, when she returned to her country."

"The name is of no consequence," replied the lawyer calmly. "The sole consideration here is the perfectly justifiable wish of a mother, which the father cannot and must not deny, even when, as in this case, the son is given to him unconditionally."

"Must not! And if he should do it, notwithstanding?"

"Then he oversteps the borders of his rights. I would like to ask you, Herr Major, to consider the matter calmly before speaking such a decided 'No.' The rights of a mother cannot be so completely cancelled by a decision of the court that one may even deny her a meeting with her only child. The law is upon the side of my client in this case, and she will enforce it, if my personal appeal is ignored as was her written request."

"She may try it then. I will let it come to the test. My son does not know that his mother is alive, and shall not learn it just yet. I do not wish that he should see and speak to her, and I shall know how to prevent it. My 'No' remains unchanged."

These remarks were given quietly, but upon Falkenried's features there lay an ashy paleness, and his voice sounded hollow and threatening. The awful excitement under which he labored was apparent; only with supreme effort could he force himself to outward calm. The lawyer seemed to understand the fruitlessness of further effort. He only shrugged his shoulders.

"If this be your final decision, then my errand is, of course, finished, and we must decide later upon further moves. I am sorry to have disturbed you, Herr Major."

He took his leave with the same cool politeness with which he had entered.

Falkenried sprang up and paced the room stormily after the door had closed upon the lawyer. A depressing silence reigned for a few moments, after which Wallmoden spoke half audibly.

"You ought not to have done that. Zalika will hardly submit to your 'No.' If you remember, she carried on a life-and-death struggle for her child at that time."

"But I remained victor. I hope she has not forgotten that."

"At that time it concerned the possession of the boy," interrupted the friend. "The mother now only requests to see him again, and you will not be able to deny her that when she demands it with decision."

The Major came to a sudden standstill, but there was a scarcely veiled contempt in his voice as he said:

"She dares not do that after all that happened. Zalika learned to know me in our parting hour. She will take care not to force me to extremes a second time."

"But she will perhaps try to obtain secretly what you refuse her openly."

"That will be impossible; the discipline of our school is too strict. No relations could be started there of which I would not be notified immediately."

Wallmoden did not seem to share this confidence; he shook his head doubtingly.

"I confess that I consider your keeping, with such persistence, the knowledge of his mother's existence from your son a mistake. If he should hear it now from another source--what then? And you will have to tell him finally."

"Perhaps after two years, when he enters life independently. He is still but a scholar--a mere boy. I cannot yet draw the veil from the tragedy which was once enacted in the home of his parents--I cannot."

"Then at least be upon your guard. You know your former wife--know what can be expected from her. I fear there are no impossibilities for that woman."

"Yes, I know her," said Falkenried with boundless bitterness, "and just for that reason I will protect my son from her at any cost. He shall not breathe the poison of her presence for even an hour. Rest assured, I do not underrate the danger of Zalika's return, but as long as Hartmut remains at my side he will be safe from her, for she will not approach me again. I pledge you my word for that."

"We will hope so," returned Wallmoden, rising and giving his hand, "but do not forget that the greatest danger lies in Hartmut himself. He is in every respect the son of his mother. I hear you will come with him to Burgsdorf the day after tomorrow?"

"Yes; he always spends the short autumn vacation with Willibald. I myself can probably stay only for the day, but I shall surely come with him. Au revoir!"

The Ambassador's Secretary departed, and Falkenried again approached the window, glancing only hastily after the friend, who bowed once more. His glance was again lost with the former gloom, in the gray masses of fog.

"The son of his mother!"

The words rang in his ears, but there was no need for another to tell him that. He had long known it, and it was this knowledge that furrowed his brow so deeply and caused those heavy sighs.

He was a man to offer himself to every open danger, but he had struggled in vain, with all his energy for years, against this unfortunate inheritance of the blood in his only son.

"Now I request that this utter foolishness shall end, for my patience is exhausted. There has been an awful turmoil in all Burgsdorf for three days, as if the place were conjured. Hartmut is full of foolishness from head to toe. When once he gets free from the rein which his father draws so tight there is no getting on with him. And you, of course, go with him through thick and thin, following obediently everything that your lord and master starts. You are a fine team!"

This lecture, delivered in very loud tones, came from the lips of Frau von Eschenhagen of Burgsdorf, who sat at breakfast with her son and brother.

The large dining-room was in the lower story of the old mansion, and was a rather bare room, the glass doors of which led to a broad terrace, and from there into the garden. Some antlers hung upon the whitewashed walls, giving evidence of the Nimrod proclivities of former owners. They were also the only ornament of the room.

A dozen straightback chairs standing in stiff rows like grenadiers, a heavy dining table, and two old-fashioned sideboards constituted all of the furniture, which, as one could see, had already served several generations.

Articles of luxury, such as carpets, wallpaper or paintings, were not there. The inmates were apparently satisfied with the old, inherited things, although Burgsdorf was one of the richest estates in the vicinity.

The appearance of the lady of the house corresponded fully with the surroundings. She was about forty years old; of tall, powerful figure, blooming complexion, and strong, heavy features, which were very energetic, but which could never have been beautiful. Nothing escaped easily the glance of those sharp, gray eyes; the dark hair was combed back plainly; the dress was simple and serviceable, and one could see that her hands knew how to work.

This robust person lacked gracefulness, certainly, but possessed something decidedly masculine in carriage and appearance.

The heir and future lord of Burgsdorf, who was scolded in this way, sat opposite his mother, listening, as in duty bound, while he helped himself bountifully to ham and eggs. He was a handsome, ruddy-faced boy of about seventeen years, with features which might portray great good nature, but no surplus of intellect. His sunburned face was full of glowing health, but otherwise bore little resemblance to his mother's. It lacked her energetic expression. The blue eyes and light hair must have been an inheritance from the father. With his powerful but awkward limbs he looked like a young giant, and offered the completest contrast to his Uncle Wallmoden, who sat at his side, and who now said with a tinge of sarcasm:

"You really ought not to make Willibald responsible for the pranks and tricks. He is certainly the ideal of a well-raised son."

"I should advise him not to be anything else. Obeying of orders is what I insist upon," exclaimed Frau von Eschenhagen, slapping the table with such force as to cause her brother to start nervously.

"Yes, one learns that under your regime," he replied, "but I would like to advise you, dear Regine, to do a little more for the mental training of your son. I do not doubt that he will grow up a splendid farmer under your leadership, but something more is required in the education of a future lord, and as Willibald has outgrown tutors, it may be time to send him off."

"Send him----" Frau Regine laid down knife and fork in boundless amazement. "Send him off!" she repeated indignantly. "In gracious name, where to?"

"Well, to the University, and later on let him travel, that he may see something of the world and its people."

"And that he may be totally ruined in this world and among these people! No, Herbert, that will not do. I tell you right now. I have raised my boy in honesty and the fear of God, and have no idea of letting him go into that Sodom and Gomorrah from which our dear Lord keeps the rain of fire and brimstone by His long-suffering alone."

"But you know this Sodom and Gomorrah only by hearsay, Regine," interrupted Herbert sarcastically. "You have lived in Burgsdorf ever since your marriage, but your son must one day enter life as a man--you must acknowledge that."

"I do not acknowledge anything," declared Frau von Eschenhagen stubbornly. "Willy shall be a thoroughly capable farmer. He is fitted for that and does not need your learned trash for it. Or do you, perhaps, wish to take him in training for a diplomat. That would be capital fun!"

She laughed loudly, and Willy, to whom this proposition seemed as ridiculous, joined in in the same key.

Herr von Wallmoden did not indulge in this hilarity, which seemed to jar upon his nerves. He only shrugged his shoulders.

"I do not intend that, indeed; it would probably be lost pains; but I and Willibald are now the only representatives of the family, and if I should remain unmarried----"

"If? Are you contemplating marriage in your old age?" interrupted his sister in her inconsiderate manner.

"I am forty-five years old, dear Regine. That is not usually considered old in a man," said Wallmoden, somewhat offended. "At any rate, I consider a late contracted marriage the best, because then one is not influenced by passion as was Falkenried to his great misfortune, but one allows reason to guide the decision."

"May God help me! Must Willy wait until he has fifty years upon his back and gray hairs upon his head before he marries!" exclaimed Frau von Eschenhagen, horrified.

"No; for he must consider the fact that he is an only son and future lord of the estates; besides, it will depend upon an individual attachment. What do you say, Willibald?"

The young future lord, who had just finished his ham and eggs, and was now turning with unappeased appetite to the wurst, was apparently greatly surprised at having his opinion asked. Such a thing happened so seldom that he was now thrown into a spell of deep musing, declaring as the result of it:

"Yes; I shall probably have to marry some time, but mamma will find me a wife when the time comes."

"That she will, my boy," affirmed Frau von Eschenhagen. "That is my affair; you do not need to worry about it at all. You will remain here in Burgsdorf, where I shall have you under my eyes. Universities and travels are not to be considered--that is decided."

She threw a challenging glance at her brother, but he was regarding with a kind of horror the enormous amount of eatables which his nephew was piling upon his plate for the second time.

"Do you always have such a healthy appetite, Willy?" he asked.

"Always," assured Willy with satisfaction, taking another huge piece of bread and butter.

"Yes; God be thanked, we do not suffer from indigestion here," said Frau Regine, somewhat pointedly. "We deserve our meals honestly. First play and work, then eat and drink, and heartily--that keeps soul and body together. Just look at Willy, how he has prospered with that treatment. He need never be ashamed to be seen."

She slapped her brother upon the shoulder in a friendly manner at these words, but so heartily that Wallmoden hastily pushed his chair out of her reach. His face betrayed plainly that his hair was "standing on end" again; but he gave up the enforcing of his rights as guardian in the face of these primitive conditions.

Willy, on the contrary, apparently discovered that he had turned out extraordinarily well, and looked very pleased at this praise of his mother, who continued now rather vexedly:

"And Hartmut has not come to breakfast again! He seems to allow himself all sorts of irregularities here at Burgsdorf, but I shall lecture the young man when he comes, and make him----"

"Here he is already!" cried a voice from the garden.

A shadow fell athwart the bright sunshine that poured in through the open window, in which there suddenly appeared a youthful form, which swung itself through from the outside.

"Boy, are you out of your senses that you enter through the window?" exclaimed Frau von Eschenhagen indignantly. "What are the doors for?"

"For Willy and other well-raised people," laughed the intruder mirthfully. "I always take the shortest route, and this time it led through this window."

With one jump he landed in the middle of the room from the high sill.

Hartmut Falkenried, like the future lord of Burgsdorf, stood at the border between boyhood and manhood, but beyond that likeness it required but a glance to see the superiority of Hartmut in every respect.

He wore the cadet uniform, which became him wonderfully, but there was something in his whole appearance indicative of a revolt against the strict military cut.

The tall, slender boy was a true picture of youth and beauty, but this beauty had something strange and foreign about it; the movement and whole appearance had a wild, unruled element; and not a feature reminded one of the powerful, soldierly figure and grave composure of the father. The thick, curly hair of a blue-black color, falling over the high brow, denoted a son of the South, rather than a German; the eyes also, which glowed in the youthful face, did not belong to the cold, calm North; they were mysterious eyes, dark as night, yet full of hot, passionate fire. Beautiful as they were, there was something uncanny about them.

And now the laugh, with which Hartmut looked from one to another of the assembly, had more of the supercilious about it than of a boy's hearty mirth.

"You introduce yourself in a very unconventional manner," said Wallmoden sharply; "you seem to think that no etiquette is to be observed at Burgsdorf. I hardly think your father would have permitted such an entrance into a dining-room."

"He does not take such liberties with his father," said Frau von Eschenhagen, who fortunately did not feel the stab which lay for her also in her brother's words. "So you finally come now, Hartmut, when we have finished breakfast? But late people do not get anything to eat--you know that."

"Yes, I know it," returned Hartmut, quite unconcerned; "therefore I got the housekeeper to give me some breakfast. You can't starve me out, Aunt Regine. I am on too good terms with all your people."

"So you think you will be able to take all sorts of liberties unpunished," cried the lady of the house angrily. "You break all the rules of the house; you leave no person nor thing in peace; you stand all Burgsdorf upon its head! We shall know how to stop all that, my boy. I shall send a messenger over to your father to-morrow, to ask him to kindly come for his son, who can be taught no punctuality or obedience."

This threat was effective; the boy grew serious and found it best to yield.

"Oh, all that is only jesting," he said. "Am I not to utilize the short vacation----"

"For all sorts of foolishness?" interrupted Frau von Eschenhagen. "Willy in all his life has not done so many pranks as you in these last three days. You will ruin him for me by your bad example and make him also disobedient."

"Oh, Willy can't be ruined; all pains are thrown away with him," confessed Hartmut frankly.

The young lord did not look, indeed, as if he had any inclination to disobedience. Quite unconcerned by all this conversation, he calmly finished his breakfast by still another piece of bread and butter; but his mother was highly incensed over this remark.

"You are doubtless extremely sorry for that," she exclaimed. "You have taken pains enough to ruin him. Very well, it remains as I said--to-morrow I write to your father."

"To come for me? You will not do that, Aunt Regine. You are too good to do that. You know very well how strict papa is--how harshly he can punish. You surely will not accuse me to him--you have never done so before."

"Leave me alone, boy, with your flatteries." Frau Regine's face was still very grim, but her voice already betrayed a perceptible wavering, and Hartmut knew how to take the advantage offered. With the artless frankness of a boy, he laid his arm around her shoulders.

"I thought you loved me a little bit, Aunt Regine. I--I have anticipated this trip to Burgsdorf so joyously for weeks. I have longed until I was sick, for forest and lake, for the green meadows and the wide, blue sky; I have been so happy here--but, of course, if you do not want me, I shall leave immediately; you do not need to send me away."

His voice sank to a soft, coaxing whisper, while the large, dark eyes helped with the pleading only too effectively. They could speak more fervently than the lips; they seemed, indeed, to have peculiar power.

Frau von Eschenhagen, who to Willy and all Burgsdorf, was the stern, absolute ruler, now allowed herself to be moved to compliance.

"Well, then, behave yourself, you Eulenspiegel," she said, running her fingers through his thick curls. "As to sending you away, you know only too well that Willy and all my people are perfectly foolish about you--and so am I."

Hartmut shouted in his happiness at these last words, and kissed her hand in fervent gratitude. Then he turned to his friend, who had now happily mastered his last sandwich, and was regarding the scene before him in quiet amazement.

"Are you through with your breakfast at last, Willy? Come on; we wished to go to the Burgsdorf pond--now don't be so slow and deliberate. Good-by, Aunt Regine. I see that Uncle Wallmoden is not pleased in the least that you have pardoned me. Hurrah! Now we are off for the woods."

And away he dashed over the terraces and down to the garden. There was in this unruliness an overflowing youthful happiness and strength that were enchanting; the lad was all life and fire. Willy trotted behind him like a young bear, and they disappeared in a few seconds behind the trees and shrubberies.

"He comes and goes like a whirlwind," said Frau von Eschenhagen, looking after them. "That boy cannot be restrained when once the reins are slackened."

"A dangerous lad!" declared Wallmoden. "He understands how to rule even you, who otherwise rule supreme. It is the first time in my knowledge that you pardon disobedience and unpunctuality."

"Yes, Hartmut has something about him that really bewitches a body," exclaimed Frau von Eschenhagen, half vexed over her yielding. "When he looks at one with those glowing, black eyes, and begs and pleads besides, I would like to see the one who could say no. You are right; he is a dangerous lad."

"Yes, very true; but let us leave Hartmut alone now and consider the education of your own son. You have really decided----"

"To keep him at home. Do not trouble yourself, Herbert. You may be an important diplomat and carry the whole political business in your pockets, but nevertheless I do not surrender my boy to you. He belongs to me alone, and I keep him--settled!"

A hearty slap upon the table accompanied this "settled," with which the reigning mistress of Burgsdorf arose and walked out of doors; but her brother shrugged his shoulders, and muttered half audibly: "Let him become a country squire, for all I care--it may be best, anyhow."

In the meantime, Hartmut and Willibald had reached the forest belonging to the estate. The Burgsdorf pond, a lonely water bordered by rushes in the midst of the forest, lay motionless, shining in the sunlight of the quiet morning hour.

The young lord found for himself a shady place upon the bank, and devoted himself comfortably and persistently to the interesting occupation of fishing, while the impatient Hartmut roamed around, starting a bird here, plucking rushes and flowers there, and finally indulging in gymnastics upon the trunk of a tree which lay half in the water.

"Can you never be quiet in one place? You scare off all the fishes," said Willy, displeased. "I have not caught a thing to-day."

"How can you sit for hours in one spot waiting for the stupid fishes--but, of course, you can roam through field and forest all the year round whenever you like. You are free--free!"

"Are you imprisoned?" asked Willy. "Are not you and your companions out of doors every day?"

"But never alone--never without restraint and supervision. We are eternally on duty, even in the hours of recreation. Oh, how I hate it--this duty and life of slavery!"

"But, Hartmut, what if your father should hear that?"

"He would punish me again, then, as usual. He has nothing for me but severity and punishment. I don't care--it's all the same to me."

He threw himself upon the grass, but harsh and disagreeable as his words sounded, there was in them something like a pained, passionate complaint.

Willy only shook his head deliberately fastening a new bait to his hook meanwhile, and deep silence reigned for a few moments.

Suddenly something dashed down from on high, lightning-like; the water, just now so motionless, splashed and foamed, and in the next moment a heron rose high in the air, carrying the struggling, silver-shining prey in his bill.

"Bravo! that was a splendid shot," cried Hartmut, starting up, but Willy scolded vexedly. "The con---- robber strips our whole pond. I shall tell the forester to keep an eye on him."

"A robber!" repeated Hartmut, as his eyes followed the heron, which now disappeared behind the tree-tops. "Yes, surely; but it must be beautiful--such a free robber's life high up in the air. To dash down from the heights like a flash of lightning--to grab the booty, then soar high with it again where no one can follow--that is worthy of the chase."

"Hartmut, I actually believe you have a good notion to lead such a robber's life," said Willy, with the deep horror of a well-raised boy for such inclinations.

His companion laughed, but it was again that harsh, strange laugh which had in it nothing youthful.

"And if I should have it, they would know how to get it out of me at the cadets' school. There is obedience--discipline--the Alpha and Omega of all things, and one finally learns it, too. Willy, have you never longed for wings?"

"I? Wings?" ejaculated Willy, whose full attention was again directed to hook and line. "Nonsense! who could wish for impossibilities?"

"I wish I had some," cried Hartmut, flaming up. "I wish I were one of the falcons of which we hear. Then I would soar high up into the blue air--always higher and higher toward the sun, and would never, never come back."

"I think you are crazy," said the young lord calmly; "but I have not caught anything yet; the fish will not bite at all to-day. I must try another spot."

He gathered up his fishing paraphernalia and went to the other side of the pond.

Hartmut threw himself upon the ground again.

How could he expect that the stolid, matter-of-fact Willibald should harbor thoughts of flying!

It was one of those autumn days which seem to charm back the summer for a few short hours--the sunshine was so golden, the air so mild, the woods so fresh and fragrant. Thousands of brilliant sparkles danced upon the water; the rushes whispered low and mysteriously as the air breathed through them.

Hartmut lay quite motionless, listening to this mystery of whispering and fluttering. The wild, passionate flame, which had flared up almost uncannily when he spoke of the bird of prey, had disappeared from his eyes. Now they were riveted dreamily upon the shining blue of the sky, with a consuming longing in their depths.

Light footsteps drew near, almost inaudible on the soft forest soil; the bushes rustled as if brushed by a silken garment, and parted; a female figure emerged noiselessly and stopped short, fixing an intent look upon the young dreamer.

"Hartmut!"

He started and sprang up quickly. He did not know the voice, nor the stranger, but it was a lady, and he bowed chivalrously.

"Gracious lady----"

A slender and trembling hand was laid hastily and warningly upon his arm.

"Hush--not so loud--your companion might hear us, and I must speak with you, Hartmut--with you alone."

She stepped back again and motioned him to follow. Hartmut hesitated a moment. How came this stranger, whose face was closely veiled, but who, to judge by her dress, belonged to the highest class, at this lonely forest pond? And what was the meaning of the familiar "thou" from her to him, whom she saw now for the first time? But the mystery of the encounter began to interest him, and he followed her.

They stopped under the protection of the bushes where they could not be seen from the other side, and the stranger slowly raised her veil.

She was no longer in her youth--a woman still in her thirties--but the face with the dark, flashing eyes possessed a strange fascination, and the same charm was in the voice, which, even in the whisper, was soft and deep, with a foreign accent, as if the German which she spoke so fluently was not her native tongue.

"Hartmut, look at me. Do you really not remember me? Have you not kept some recollection from your childhood that tells you who I am?"

The young man shook his head slowly, and yet there arose in his mind a remembrance, misty and dreamlike, that told him he did not now hear this voice for the first time--that he had seen this face before in times long, long past. Half timidly, half transfixed, he stood there gazing upon the stranger, who suddenly stretched out both arms toward him.

"My son! my only child! do you not know your mother?"

Hartmut retreated, startled.

"My mother is dead," he said in a low tone.

The stranger laughed bitterly; it sounded exactly like that harsh, unchildlike laugh which had come from the lips of the lad only a short while ago.

"So that is it; they have called me dead. They would not leave you even the memory of your mother. But it is not true, Hartmut. I live--I stand before you. Look at me! look at my features, which are yours also. They could not take those from you. Child of my heart, do you not feel that you belong to me?"

Still Hartmut stood motionless, looking into the face in which he saw his own reflected as in a mirror. There were the same features, the same abundant, blue-black hair; the same large, deep black eyes--yes--even the strange demoniac expression which glowed like a flame in the mother's eyes, glimmered as a spark in the eyes of the son. The natural resemblance showed that they were of the same blood, and now the voice of that blood woke up in the young man.

He did not ask for explanations--for proofs; the confused, dream-like recollections suddenly became clear. Only one more second of hesitation, then he threw himself into the arms which were open for him.

"Mother!"

In the exclamation lay the glowing devotion of the lad, who had never known what it was to possess a mother, and who had longed for it with all his passionate nature.

His mother! As he lay in her arms while she overwhelmed him with passionate caresses--with tender, fond names such as he had never heard, all else disappeared in the flood of overwhelming delight.

Several minutes passed thus, then Hartmut disengaged himself from the embrace which would have detained him.

"Why have you never been with me, mamma?" he asked vehemently. "Why did they tell me that you were dead?"

Zalika drew back. In a moment all the tenderness vanished from her face; a light kindled there of wild, deadly hatred, and the answer came hissing from her lips:

"Because your father hates me, my son, and because he did not wish to leave me even the love of my only child when he thrust me from him."

Hartmut was silent with consternation. He knew well that no one dared mention his mother's name in his father's presence--that his father had once silenced him with the greatest harshness when he had ventured to ask for her, but he had been too young to muse over the why.

Zalika did not give him time for it now. She stroked the dark, curly hair back from the high forehead, and a shadow rested on her face.

"You have his brow," she said slowly, "but that is the only thing to remind of him; everything else belongs to me--to me alone. Every feature tells that you are wholly mine. I knew it would be so."

Again she embraced him, overwhelming him with caresses, which Hartmut returned as passionately. It was an intoxication of happiness to him--like one of the fairy tales of which he had so often dreamed, and he gave himself up to the charm unquestioningly and unreservedly.

But now Willy made himself heard on the opposite bank, calling loudly for his friend, and reminding him that it was time to return home.

Zalika started.

"We must part. Nobody must know that I have seen you and spoken with you, particularly your father. When do you return to him?"

"In eight days."

"Not until then?" The tone was triumphant. "I shall see you every day until then. Be here at the pond to-morrow at the same hour. Dispense with your companion under some pretext, so that we may be undisturbed. You will come, Hartmut?"

"Certainly mother, but----"

She did not give him time for an excuse, but continued in the same passionate whisper:

"Above all, be silent to everybody; do not forget that. Farewell, my child, my beloved only son. Au revoir!"

One more fervent kiss upon Hartmut's brow, then she vanished in the bushes as mysteriously as she had appeared. It was quite time, for Willy appeared on the scene, his approach being heralded by his heavy stamping upon the forest ground.

"Why do you not answer?" he demanded. "I have called three times. Did you fall asleep? You look as if you had been startled from a dream."

Hartmut stood as if stunned, gazing upon the bushes in which his mother had disappeared. At his cousin's words he straightened himself and drew his hand across his brow.

"Yes, I have been dreaming," he said, slowly; "quite a wonderful, strange dream."

"You might rather have been fishing," said Willy; "just see what a splendid catch I got over on the other bank. A person ought not to dream in broad daylight. He ought to be properly occupied, my mother says--and my mother is always right."

The families of Falkenried and Wallmoden had been friendly for years. As owners of adjoining estates they visited each other frequently; the children grew up together, and many mutual interests drew the bonds of friendship still closer.

As both families were only comfortably well off, the sons had their own way to make, which, after completing their education, Major Hartmut von Falkenried and Herbert Wallmoden had done. They had been playmates as children, and had remained true to that friendship when grown to manhood.

At one time the parents thought to cement this friendship by a marriage between the--at that time--Lieutenant Falkenried and Regine Wallmoden. The young couple seemed in perfect accord with it, and all looked propitious for the match, when something took place which brought the plan to a sudden end.

A cousin of the Wallmoden family--an incorrigible fellow who, through divers bad capers, had made it impossible to remain at home, had, long ago, gone out into the wide world. After much travel and a rather adventurous life, he had landed in Roumania, where he acted as inspector upon the estates of a rich Bojar. The rich man died, and the inspector thought best to retrieve his lost fortunes and position in life by marriage with the widow.

It was consummated, and he returned to his old home, accompanied by his wife, for a visit to his relatives, after an absence of more than ten years.

Frau von Wallmoden's bloom of youth had long passed, but she brought with her her daughter by her first marriage--Zalika Rojanow.

The young girl, hardly seventeen years old, with her foreign beauty and charm of her glowing temperament, burst like a meteor upon the horizon of this German country nobility, whose life flowed in such calm, even channels.

And she was a strange object in this circle, whose forms and manners she disregarded with sovereign indifference, and who stared at her as at a being from another world. There was many a serious shaking of heads and much condemnation, which was not uttered aloud, because they saw in the girl only a temporary visitor, who would disappear as suddenly as she had come into view.

Just about this time Hartmut Falkenried came from his garrison to the paternal estates, and became acquainted with the new relatives of his friends. He saw Zalika and recognized in her his fate. It was one of those passions which spring up lightning-like--which resemble the intoxication of a dream, and are paid for only too frequently with the penance of the whole life.

Forgotten were the wishes of the parents, his own plans for the future--forgotten the quiet affection which had drawn him to his playmate Regine. He no longer had eyes for the domestic flower which bloomed young and fresh for him; he breathed only the intoxicating perfume of the foreign wonder-plant. All else disappeared before her, and in a quiet hour with her he threw himself at her feet, confessing his love.

Strangely enough, his feelings were returned. Perhaps it was the truth of extremes meeting which drew Zalika to a man who was her opposite in every respect; perhaps she was flattered by the fact that a glance, a word from her could change the grave, calm and almost gloomy nature of the young officer to enthusiasm.

Enough, she accepted his proposal and he was permitted to embrace her as his betrothed.

The news of this engagement created a storm in the whole family circle; entreaties and warnings came from all sides; even Zalika's mother and stepfather opposed it, but the universal disapproval only increased the determination of the young couple, and six months later Falkenried led his young wife into his home.

But the voices who prophesied misfortune to this marriage were in the right. The bitterest disappointment followed the short term of happiness. It had been a dangerous mistake to believe that a woman like Zalika Rojanow, grown up in boundless freedom and accustomed to the uncontrolled, extravagant life of the families of the Bojars of her country, could ever submit herself to German views and conditions.

To gallop about on fiery horses; to associate freely with men who spent their time in hunting and gambling, and who surrounded themselves in their homes with a splendor which went hand in hand with the most corrupted indebtedness of estates--such was life as she had known it so far, and the only life which suited her.

A conception of duty was as foreign to her as the knowledge of her new position in life. And this woman was to accommodate herself now to the household of a young officer of but limited means, and to the conditions of a small German garrison!

That this was impossible was proved in the first weeks. Zalika began by throwing aside every consideration, and furnishing her house in her usual style, squandering heedlessly her by no means insignificant dowry.

In vain her husband entreated, remonstrated; he found no hearing. She had only sarcasm for forms and rules which were holy to him; only a shrug of the shoulder for his strict sense of honor and ideas of decorum.

Very soon they had the most vehement controversies, and Falkenried recognized too late the serious error which he had committed. He had counted upon the all-powerful efficacy of love to battle against those warning voices which had pointed out the difference of descent, education and character, but he was forced now to recognize that Zalika had never loved him; that caprice alone, or a sudden outburst of passion, which died as suddenly, had brought her to his arms.

She saw in him now only the uncomfortable companion who begrudged her every pleasure of life; who, with his foolish--his ridiculous ideas of honor, fettered and bound her on every side. Still, she feared this man, whose dominant will succeeded always in bowing her characterless nature under his rod.

Even the birth of little Hartmut was not sufficient to reconcile this unhappy marriage; it only held it, apparently, together. Zalika loved her child passionately; she knew her husband would never permit her to keep it if they separated. This alone retained her at his side, while Falkenried bore his domestic misery with concealed pain, putting forth every effort to hide it at least from the world.

Nevertheless, the world knew the truth; it knew things of which the husband did not even dream and which were kept concealed from him through sheer compassion.

But finally the day came when the deceived husband was told what was no secret to others.

The immediate result following was a duel in which Falkenried's opponent fell. Falkenried himself was imprisoned, but was soon pardoned.

Every one knew that the offended husband had only vindicated his honor.

In the meantime, steps were taken for a divorce, which was granted in due time. Zalika made no opposition. She dared not approach her husband; she trembled before him since that hour of separation, when he had called her to account; but she made desperate efforts to secure the possession of her child, fighting as for life.

It was in vain. Hartmut was given unconditionally to his father, who knew how to prevent every approach of the mother with iron inflexibility.

Zalika was not even allowed to see her son again, and it was only after convincing herself entirely on that point that she left--returning to the home of her mother.

She had seemed lost to and forgotten by her former husband until she suddenly reappeared in Germany, where Major Falkenried now held an important position in the large military school at the Residenz.

* * * * *

It was about a week after the arrival of Hartmut at Burgsdorf. Frau von Eschenhagen was in her sitting-room with Major Falkenried, who had but just arrived.

The topic of their conversation seemed to be very serious and of a rather disagreeable nature, for Falkenried listened with a gloomy face to his friend, who was speaking.

"I noticed Hartmut's changed demeanor the third or fourth day. The boy, whose mirth at first knew no bounds, so that I even threatened to send him back home, suddenly became subdued. He committed no more foolish pranks, but roamed for hours through the woods alone, and when he returned was always dreaming with his eyes open, to such an extent that one had almost to awake him. 'He is beginning to get sensible,' said Herbert; but I said, 'Things are not going right; there is something behind all this,' and I questioned my Willy, who also appeared quite peculiar. He was actually in the plot. He had surprised the two one day. Hartmut had made him promise to keep silent, and my boy positively hid something from me, his mother! He confessed only when I got after him seriously. Well, he will not do it a second time. I have taken care of that."

"And Hartmut? What did he say?" interrupted the Major hastily.

"Nothing at all, for I have not spoken a syllable to him about it. He would probably have asked me why he should not see and speak to his own mother, and only--his father can give him the answer to that question."

"He has probably heard it already from the other side," said Falkenried bitterly; "but he has hardly learned the truth."

"I fear so, too, and therefore I did not lose a minute in notifying you after discovering the affair. But what next?"

"I shall have to interfere now," replied the Major with forced composure. "I thank you, Regine. I apprehended trouble when your letter called me so imperatively. Herbert was right. I ought not to have allowed my son to leave my side for an hour under the circumstances. But I believed him safe from every approach here at Burgsdorf. And he anticipated the trip with such pleasure--he longed for it almost passionately. I did not have the heart to refuse him. He is happy, anyway, only when absent from me."

There was deep pain in the last words, but Frau von Eschenhagen only shrugged her shoulders.

"That is not the fault of the boy alone," she said straightforwardly. "I also keep my Willy under good control, but nevertheless he knows that he has a mother whose heart is full of him. Hartmut does not know that of his father. He knows him only from a grave, unapproachable side. If he had an idea that you idolize him secretly----"

"He would abuse the knowledge and disarm me with his caressing tenderness. Shall I allow myself to be ruled by him as every one else is who comes into his presence? His comrades follow him blindly although he brings punishment upon them by his pranks. He has your Willibald completely under control--yes, even his teachers treat him with particular indulgence. I am the only one he fears, and consequently the only one he respects."

"And you think by fear alone to succeed with the boy, who is doubtless now being overwhelmed with the most senseless caresses! Do not turn away, Falkenried; you know I have never mentioned that name to you, but now that it is brought forward so prominently, one may speak it. And since we happen to be upon the subject, I tell you frankly that nothing else could be expected since Frau Zalika's appearance. It would have done no good to have kept Hartmut from Burgsdorf, for one cannot treat a seventeen-year-old lad like a little child. The mother would have found her way to him in spite of all--and it was her right. I would have done just so, too."

"Her right!" cried the Major angrily. "And you tell me that, Regine?"

"I say it because I know what it is to have an only child. That you should take the child from its mother was right--such a mother was not fit for the raising of a boy--but that you now refuse to let her see her son again after twelve years is harshness and cruelty, which hatred alone can teach you. However great her faults may be, that punishment is too severe."

Falkenried stared gloomily before him--he might have felt the truth of the words. Finally he said, slowly:

"I would never have thought that you would take Zalika's part. I offended you bitterly once for her sake--I broke a bond----"

"Which had not even been tied," interrupted Frau von Eschenhagen. "It was a plan of our parents--nothing more."

"But the idea was dear and familiar to us from childhood. Do not attempt to excuse me, Regine; I only know too well what I did at that time to you and--to myself."

Regine fixed her clear, gray eyes upon him, but there was a moist gleam in them as she replied:

"Well, yes, Hartmut; now since we are both long past our youth, I may, perhaps, confess that I liked you then. You might have been able to make something better of me than I am now. I was always a self-willed child--not easy to rule; but I would have followed you--perhaps you alone of all the world. When I went to the altar with Eschenhagen three months after your marriage, matters were reversed.

"I took the reins into my own hands and began to command, and since then I have learned it thoroughly---- But now, away with that old story, long since past. I have not thought hard of you because of it--you know that.

"We have remained friends in spite of it, and if you need me now, in advice as well as deed, I am ready to help you."

She offered her hand, which he grasped.

"I know it, Regine, but I alone can advise here. Please send Hartmut to me. I must speak to him."

Frau von Eschenhagen arose and left the room, murmuring as she went: "If only it is not too late already! She blinded and enraptured the father once. She has probably secured her son now."

Hartmut entered the room and closed the door behind him, but remained standing near it. Falkenried turned toward him.

"Come nearer, Hartmut; I must speak with you."

The youth obeyed, drawing near slowly.

He already knew that Willibald had had to confess; that his rendezvous with his mother had been betrayed; but the awe with which he always approached his father was mingled to-day with defiance, which was not unnoticed by the Major.

He scanned the youthful, handsome person of his son with a long, gloomy glance.

"My sudden arrival does not seem to surprise you," he began; "you probably know what brought me here."

"Yes, father, I surmise it."

"Very well, we do not need then to continue with preliminaries. You have learned that your mother is still living. She has approached you and you are in communication with her. I know it already. When did you see her for the first time?"

"Five days ago."

"And since then you have spoken with her daily?"

"Yes, near the Burgsdorf pond."

Question and reply alike sounded curt and calm.

Hartmut was accustomed to this strict, military manner, even in his private intercourse with his father, who never allowed a superfluous word, a hesitation or evasion in the answers. This tone was kept up even to-day to veil his painful excitement from the eyes of his son. Hartmut saw only the grave, unmoved face; heard only the sound of cold severity as the Major continued:

"I will not make it a reproach to you, as I have never forbidden you anything regarding it; the subject has never been mentioned between us. But since matters have gone so far, I will have to break the silence. You thought your mother dead, and I have silently allowed you to think so, for I wished to save you from reminiscences which have poisoned my life. I meant that your youth, at least, should be free from it. It seems that it cannot be, so you may hear the truth."

He paused for a moment. It was torture to the man, with his delicate sense of honor, to talk on this subject before his son, but there was no longer a choice--he must speak on.

"I loved your mother passionately when a young officer, and married her against the wish of my parents, who saw no good to result from a marriage with a woman of foreign race. They were right, the marriage was deeply unfortunate, and we finally separated at my desire. I had an undeniable right to demand the separation, and also the possession of my son, which was granted me unconditionally. I cannot tell you any more, for I will not accuse the mother to the son; therefore let this suffice you."

Short and harsh as this explanation sounded, it yet made a strange impression upon Hartmut. The father would not accuse the mother to him, who had been hearing daily the most bitter accusation, abuse and slander against the father.

Zalika had put the whole blame of the separation upon her husband, upon his unheard-of tyranny, and she found only too willing a listener in the youth whose unruly nature suffered so intensely under that severity. And yet those short, earnest words now weighed more than all the passionate outbursts of the mother. Hartmut felt instinctively upon which side the truth stood.

"But now to the most important point," resumed Falkenried. "What has been the subject of your conversation?"

Hartmut had not expected this question, and a burning blush suffused his face. He was silent and looked to the ground.

"Ah, so! you do not dare to repeat it to me; but I request to know it. Answer, I command you!"

But Hartmut remained silent; he only closed his lips more firmly, and his eyes met his father's with dark defiance.

Falkenried now drew nearer.

"You will not speak? Has a command from that side, perhaps, made you silent? Never mind, your silence says more than words. I see how much estranged from me you have become, and you would become lost entirely to me if I should leave you longer under that influence. These meetings with your mother must be ended. I forbid them. You will accompany me home to-day and remain under my supervision. Whether it seems cruel to you or not, it must be so, and you will obey."

But the Major was mistaken when he thought to bow his son to his will by a simple command.

Hartmut had been in a school during these last days where defiance against the father had been taught him in the most effectual manner.

"Father, you will not--you cannot command that," he burst forth now with overpowering vehemence. "It is my mother who is found again; the only one in the whole world who loves me. I shall not let her be taken from me again as she has already been taken. I shall not allow myself to be forced to hate her because you hate her. Threaten--punish me do whatever you will with me, but I do not obey this time. I will not obey."

The whole unruly, passionate nature of the young man was in these words; the uncanny fire flamed again in his eyes; the hands were clenched; every fibre throbbed in wild rebellion. He was apparently decided to do battle against the long-feared father.

But the burst of anger which he so confidently expected did not come. Falkenried only looked at him silently, but with a glance of grave, deep reproach.

"The only one in the whole world who loves you!" he repeated slowly. "You have, perhaps, forgotten that you still have a father."

"Who does not love me, though," cried Hartmut in overwhelming bitterness. "Only since I have found my mother have I known what love is."

"Hartmut!"

The youth looked up, startled by the strange, pained tone which he heard for the first time, and the defiance which was about to break forth again died on his lips.

"Because I have no pet names and caresses for you; because I have raised you with seriousness and firmness, do you doubt my love?" said Falkenried, still in the same voice. "Do you know what this severity toward my only, my beloved child has cost me?"

"Father!"

The word sounded still timid and hesitating, but no longer with the old fear and awe; it now contained something like budding faith and trust; like a happy but half-comprehended surprise, and with it Hartmut's eyes hung as if riveted upon his father's features. Falkenried now put his hand upon his son's arm, drawing him nearer, while he continued:

"I once had high ambitions, proud hopes of life, great plans and aspirations, which came to an end when a blow fell upon me from which I shall never be able to rally. If I still aspire and struggle, it is from a sense of duty and because of you, Hartmut. In you centers all my ambition; to make your future great and happy is the only thing which I yet desire of life; and your future can be made great, my son, for your gifts are extraordinary ones; your will is strong in good as well as evil. But there is yet something dangerous in your nature, which is less your fault than your doom, and which must be taken in hand in time, if it is not to develop and dash you into destruction. I had to be severe to banish this unfortunate tendency; it has not been easy for me."

The face of the youth was covered by a deep blush. With panting breath he seemed to read every word from his father's lips, and now he said in a whisper, in which the suppressed joy could scarcely be hidden:

"I have not dared to love you so far. You have always been so cold--so unapproachable, and I----"

He broke off and glanced up at his father, who now put his arm around Hartmut's shoulders, drawing him still closer to him. Then eyes looked deep into eyes, and the voice of the iron man broke as he said, lowly:

"You are my only child, Hartmut, the only thing which has remained to me from a dream of happiness that dispersed in bitterness and disappointment. I lost much at that time and have borne it; but if I should lose you--you--I could not bear it."

His arms closed around his son tightly, as if they could never be detached. Hartmut had thrown himself sobbing upon his father's breast, and father and son held each other in a long, passionate embrace.

Both had forgotten that a shadow from the past still stood threateningly and separatingly between them.

* * * * *

In the meantime, Frau von Eschenhagen, in her dining-room, was giving Willy a curtain lecture. She had done so, in fact, this morning, but was of the opinion that a double portion would not come amiss in this case. The young heir looked completely crushed. He felt himself in the wrong, as well toward his mother as toward his friend, and yet he was quite blameless. He allowed himself to be lectured patiently, like an obedient son, only throwing an occasional sad look over at the supper which already stood upon the table, although his mother did not take any notice of it at all.

"This is what comes of having secrets behind the backs of parents," she said severely, concluding her lecture.

"Hartmut is getting what he deserves in yonder; the Major will not treat him very mildly. I think you will let playing helpmate in such, a plot alone in the future."

"But I have not helped in it," Willy defended himself. "I had only promised to be silent and I had to keep my word."

"You ought not dare to keep silence to your mother; she is always an exception," Frau Regine said decidedly.

"Yes, mamma, Hartmut probably thought so, too, when it concerned his mother," remarked Willibald, and the remark was so correct that she could not well say anything against it; but that angered her the more.

"That is different--entirely different," she said curtly; but the young lord asked persistently:

"Why is it entirely different?"

"Boy, you will kill me yet with your questions and talking," cried his mother angrily. "That is an affair which you do not and shall not understand. It is bad enough that Hartmut has brought you in connection with it at all. Now do you keep quiet, and do not concern yourself further about it. Do you hear?"

Willy was dutifully silent. It was perhaps the first time in his life that he had been reproved for too much talking; besides, his Uncle Wallmoden, who had just returned from a drive, entered now.

"Falkenried has already arrived, I hear," he said, approaching his sister.

"Yes," she replied. "He came immediately upon receiving my letter."

"And how has he borne the news?"

"Outwardly very calm, but I saw only too well how it rent his heartstrings. He is alone now with Hartmut, and the storm will probably burst."

"I am sorry; but I prophesied this turn of affairs when I learned of Zalika's return. He ought to have spoken then to Hartmut. Now I fear he will but add a second mistake to the first one by trying to accomplish a separation by force and dictating. This unfortunate obstinacy which knows only 'either--or'! It is least of all in the right place here."

"Yes, the meeting yonder lasts too long for me," said Frau von Eschenhagen with concern. "I shall go and see how far the two have gotten, whether it offends the Major or not. Remain here, Herbert; I shall return directly."

She left the room, which Wallmoden paced disconsolately. His nephew sat alone at the supper table, about which nobody seemed to think. He did not dare to begin eating by himself, for a regular turmoil reigned to-day in Burgsdorf, and the Frau Mamma was in a very ungracious mood. But fortunately she returned after a few minutes, and her face was beaming with satisfaction.

"The affair is settled in the best way," she said in her short and decided tone. "He has the boy in his embrace. Hartmut is hanging upon his father's neck, and the rest will arrange itself easily now. God be praised! And now you may eat your supper, Willy. The confusion which has disturbed our whole household has come to an end."

Willy did not allow himself to be told twice, but made brisk use of the coveted permission. But Wallmoden shook his head and muttered: "If it were only truly at an end!"

Neither Falkenried nor his son had noticed that the door had been quietly opened and closed again. Hartmut still clung to his father's neck. He seemed to have lost in a moment all awe and reserve, and was overwhelmingly lovable in his new-found, stormy caresses, the charm of which the Major had rightly feared would disarm him. He spoke but little, but again and again he pressed his lips upon the brow of his son, looking steadily into the beautiful face, full of life, which pressed so close to his own.

Finally Hartmut asked in a low voice: "And--my mother?"

A shadow passed again over Falkenried's brow, but he did not release his son from his arms.

"Your mother will leave Germany as soon as she is convinced that she must in the future, as in the past, stay away from you," he said, this time without harshness, but with decision. "You may write to her. I will allow a correspondence with certain restrictions, but I cannot--I dare not permit a personal intercourse."

"Father, think----"

"I cannot, Hartmut; it is impossible."

"Do you hate her, then, so very much?" asked the youth reproachfully. "You wished the separation--not my mother--I know it from herself."

Falkenried's lips quivered. He was about to speak the bitter words and tell his son that the separation had been at the command of honor; but he looked again in those dark, inquiring eyes, and the words died unspoken. He could not accuse the mother to the son.

"Let that question rest," he replied gloomily; "I cannot answer it to you. Perhaps you will learn my reasons later and will understand them. I cannot spare you the hard choice now. You can belong only to one--the other you must shun. Accept it as a doom."

Hartmut bowed his head; he might have felt that nothing further could be gained. That the meetings with his mother had to end when he returned to the strict discipline of the school, he knew; but now a correspondence was permitted, which was more than he had dared to hope for.

"Then I will tell mamma so," he said in a crestfallen way. "Now, since you know everything, I may see her openly, may I not?"

The Major started; he had not considered this possibility.

"When were you to see her again?" he asked.

"To-day, at this hour, at the Burgsdorf pond. She is surely awaiting me there now."

Falkenried seemed to battle with himself. A warning voice arose in him not to allow this leave-taking, yet he felt that to refuse would be cruel.

"Will you be back in two hours?" he asked finally.

"Certainly, father; even earlier if you desire it."

"Go, then," said the Major, with a deep breath. One could hear how reluctant was the permission which his sense of duty forced from him. "We shall drive home as soon as you return. Your vacation ends shortly, anyway."

Hartmut, who was just about to leave, came to a standstill. The words recalled to him what he had entirely forgotten in the last half hour: the discipline and severity of the service which was awaiting him. Heretofore he had not dared to betray his aversion to it openly, but this hour which banished the awe of his father broke also the seal from his lips. Obeying a sudden impulse, he turned and put his arms again around the neck of his father.

"I have a request," he whispered, "a great, great request which you must grant me; and I know you will do it as a proof that you love me."

A furrow appeared between the Major's eyebrows as he asked with slight reproach: "Do you require proofs of it? Well, let's hear it."

Hartmut nestled still more closely to him; his voice had again that sweet, coaxing sound which made his prayers so irresistible, and the dark eyes implored intensely, beseechingly.

"Do not let me become a soldier, father. I do not love the calling for which you have decided me. I shall never learn to love it. If I have bowed until now to your will, it has been with aversion, with secret grumbling, and I have been unbearably unhappy, only I did not dare to confess it to you."

The furrow on Falkenried's brow sank deeper, and he released his son slowly from his embrace.

"That means, in other words, that you do not like to obey," he said harshly, "and just that is more important to you than to any one else."

"But I cannot bear any compulsion," Hartmut burst forth passionately, "and the military service is nothing but duty and fetters. To obey always and eternally--never to have a will of your own--to bow day after day to an iron discipline and strict, cold forms by which every individual movement is suppressed. I cannot bear it any longer. Everything in me demands freedom for light and life. Let me go, father; do not keep me any longer in these bonds. I die--I suffocate under them."

To a man, who was heart and soul a soldier, he could not have done his cause greater harm than by these imprudent words. It sounded like a stormy, glowing prayer. His arm yet lay around his father's neck, but Falkenried now straightened himself suddenly and pushed him back.

"I should consider the service an honor and no fetter," he said cuttingly. "It is sad that I should have to recall that to my son's mind. Freedom--light--life! You think perhaps that one can throw himself at seventeen years into life and grasp all its treasures. The longed-for freedom for you would be only recklessness, ruin, destruction."

"And what if it should be so!" cried Hartmut, totally beside himself. "Better go to ruin in freedom than to live in this depression. To me it is a chain--a fetter--slavery----"

"Be silent! not a word further," commanded Falkenried so threateningly that the youth grew silent despite his awful excitement. "You have no choice, and take care that you do not forget your duty. You must become an officer and fulfill your duty completely as does every one of your comrades. When you are of age, I no longer have any power to hinder you. You may then resign, even if it give me my deathblow to see my only son flee the service."

"Father, do you consider me a coward?" Hartmut burst forth. "I could stand a war--I could fight----"

"You would fight foolhardily and rush blindly into every danger; and with this obstinacy which knows no discipline you would destroy yourself and your men. I know this wild, boundless desire for freedom and life to which no barrier, no duty is sacred. I know from whom you have inherited it and where it will finally lead; therefore I keep you securely in the 'fetters,' no matter whether you hate it or not. You shall learn to obey and to bow your will while yet there is time; and you shall learn it. I pledge my word to that."

Again the old, inflexible harshness sounded in his voice; every line of tenderness, of softness, had disappeared, and Hartmut knew his father too well to continue supplication or defiance. He did not answer a syllable, but his eyes glowed again with that demoniac spark which robbed him of all his beauty; and around his lips, which were pressed closely together, there settled a strange, bad expression as he now turned to go.

The Major's eyes followed him. Again the warning voice came to him like a presentiment of evil, and he called his son back.

"Hartmut, you are sure to be back in time? You give me your word?"

"Yes, father." The answer sounded grim, but firm.

"Very well. I shall trust you as a man. I let you go in peace with this promise which you have given me. Be punctual."

Hartmut had been gone but a few moments when Wallmoden entered.

"Are you alone?" he asked, somewhat surprised. "I did not wish to disturb you, but I saw Hartmut hasten through the garden just now. Where was he going so late?"

"To his mother, to take leave of her."

The Secretary started at this news. "With your consent?" he asked quickly.

"Certainly, I have permitted him to go."

"How imprudent! I should think that you knew now how Zalika manages to get her own way, and yet you leave your son to her mercy."

"For only half an hour to say farewell. I could not refuse that. What do you fear? Surely no force. Hartmut is no longer a child to be borne into a carriage and carried off in spite of his resistance."

"But if he should not refuse a flight?"

"I have his word that he will return in two hours," said the Major with emphasis.

"The word of a seventeen-year-old lad!"

"Who has been raised a soldier and who knows the importance of a word of honor. That gives me no care; my fear lies in another direction."

"Regine told me that you were reconciled," remarked Wallmoden, with a glance upon the still clouded brow of his friend.

"For a few moments only; after that I had to become again the firm, severe father. This hour has showed me how hard the task is to bend, to educate this roving nature. Nevertheless I shall conquer him."

The Secretary approached the window and looked out in the garden.

"It is twilight already, and the Burgsdorf pond is half an hour's distance," he said, half aloud. "You ought to have allowed the rendezvous only in your presence, if it had to take place."

"And see Zalika again? Impossible! I could not and would not do that."

"But if the leave-taking end differently from what you expect--if Hartmut does not return?"

"Then he would be a scoundrel to break his word!" burst out Falkenried; "a deserter, for he carries the sword already at his side. Do not offend me with such thoughts, Herbert; it is my son of whom you speak."

"He is also Zalika's son; but do not let us quarrel about that now. They await you in the dining room. And you will really leave us to-day?"

"Yes, in two hours," the Major said, calmly and firmly. "Hartmut will have returned by that time. My word stands for that."

The gray shadows of twilight were gathering in forest and field, becoming closer and denser with every moment. The short, foggy autumn day drew near its close. Through the heavy-clouded sky the night lowered sooner than usual.

A female figure paced impatiently and restlessly up and down the bank of the Burgsdorf pond. She had drawn the dark cloak tightly around her shoulders, but was unmindful of her shivering, caused by the cold evening air. Her whole manner was feverish expectation and intense listening for the sound of a step which could not as yet be heard.

Zalika had arranged the meetings with her son for a later hour, when it was desolate and dim in the forest, since the day Willibald had surprised them and had to be admitted into the secret. They had parted, however, before dark, so that Hartmut's late return should not cause suspicion at Burgsdorf. He had always been punctual, but now his mother had waited in vain for an hour.

Did a trifle detain him, or was the secret betrayed? One had to expect that, since a third party knew it.

Deathlike silence reigned in the forest; the dry leaves alone rustled beneath the hem of the gown of the restlessly moving woman.

Night shades already lingered under the tree-tops; a cloud of mist floated over the pond where it was lighter and more open; and over there where the water was bordered by a marsh, whitish-gray veils of mist arose yet more thickly. The wind blew damp and cold from over there, like the air of a vault. A light footstep finally sounded at a distance, coming nearer in the direction of the pond with flying haste. Now a slender figure appeared, scarcely recognizable in the gathering dusk. Zalika flew toward him, and in the next moment her son was in her arms.

"What has happened?" she demanded, amidst the usual stormy caresses. "Why do you come so late? I had given up in despair seeing you to-day. What kept you back?"

"I could not come any sooner," panted Hartmut, still breathless from his rapid run. "I come from my father."

Zalika started.

"From your father? Then he knows----"

"Everything."

"So he is at Burgsdorf? Since when? Who notified him?"

The young man, with fluttering breath, reported what had happened, but he had not finished when the bitter laugh of his mother interrupted him.

"Naturally they are all in the plot when it concerns the tearing of my child from me. And your father, he has probably threatened and punished and made you suffer for the heavy crime of having been in the arms of your mother?"

Hartmut shook his head.

The remembrance of that moment when his father drew him to his breast stood firm, in spite of the bitterness with which that scene had ended.

"No," he said in a low voice; "but he commanded me not to see you again, and requested irrevocable separation from you."

"And yet you are here? Oh, I knew it!"