The Rustle of Silk

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: The Rustle of Silk

Author: Cosmo Hamilton

Release Date: January 25, 2011 [EBook #35079]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE RUSTLE OF SILK ***

Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

THE RUSTLE OF SILK

BY

COSMO HAMILTON

Author of Scandal, Etc.

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Made in the United States of America

PART I

I

The man had followed her from Marble Arch,—not a mackerel-eyed old man, sensual and without respect, but one who responded to emotions as an artist and was still young and still interested. He had seen her descend from a motor omnibus, had caught his breath at her disturbing femininity, had watched her pass like a sunbeam on the garden side of the road, and in the spirit of a man who sees the materialization of the very essence of woman, turned and followed.

All the way along, under branches of trees that were newly peppered with early green, he watched her and saw other men’s heads turn as she passed,—on busses, in taxicabs, in cars and in the infrequent horse-drawn carriage that was like a Chaucerian noun dropped into the pages of a modern book. He saw men stop as he had stopped and catch their breath and then pursue their way reluctantly. He noticed that women, especially passée, tired women, paid her tribute by a flash of smile or a sudden brightness of the eye. There was no conscious effort to attract in the girl’s manner, nothing bizarre or even smart in her clothing. Her young figure, the perfection of form, was plainly dressed. She wore the clothes of a student of the lower middle class, of the small shopkeeping class, and probably either made them herself or bought them off the peg. There was no startling beauty in her face or anything wonderful in her eyes, and certainly nothing of challenge, of coquetry,—nothing but the sublime unself-consciousness of a child. And yet there was so definite and disordering a sense of sex about her that she passed through a very procession of tribute.

The man was a dramatist whose business was to play upon the emotions of sex, and to watch this child and the stir she made seemed to him to refute once more the ludicrous attempts of would-be reformers to remold humanity and prohibit the greatest of the urges of nature, and made him laugh. He wondered all the way along not who she was, because that didn’t matter, but what she would do and become,—this girl with her wide-apart eyes, oval face and full red lips, with the nose of a patrician and the sensitive nostrils of a horse,—if she would quickly marry in her own class and drift from early motherhood into a discontented drabness, or burst the bonds and be transferred from her probable back yard into a great conservatory.

He marveled at her astonishing detachment and was amused to discover that she was playing at some sort of game all by herself. From time to time, as she danced along, she assumed suddenly a dignified and gracious personality, walking slowly, with a high chin, bowing to imaginary acquaintances and looking through the railings of Kensington Gardens with an air of proprietorship. Then she as quickly returned to her own obviously normal self and hurried a little, conscious of approaching dusk. Finally, with the cunning of city breeding, she nicked across the road, and he saw her stop outside the tube station at Bayswater, arrested by the bill of an evening paper,—“Fallaray against reprisals. New crisis in the Irish Question. Notable defection from Lloyd-George forces.”

He watched the girl stand in front of these glaring words and read them over and over with extraordinary interest. Standing at her elbow, he heard her heave a quick excited sigh. He imagined that she must be Irish and watched her enter the station, linger about the bookstall and fasten eagerly upon a magazine,—so eagerly that he slipped again to her elbow and looked to see why. On the cover of this fiction monthly was the photograph of the man whose name was set forth on the poster,—the Right Hon. Arthur Napier Fallaray, Home Secretary. He knew the face well. It was one of the few arresting faces in public life; one in which there was something medieval, something also of Savonarola, Manning, and, in the eyes, of Christ,—a clean-shaven face, thin and hawk-like, with a hatchet jaw line, a sad and sensitive mouth and thick brown hair that went into one or two deep kinks. It might have been the face of a hunchback or one who had been inflicted from babyhood with paralysis, obliged to stand aloof from the rush and tear of other children. Only the head was shown on the cover, not the body that stood six foot one, the broad shoulders and the long arms suggestive of the latent strength of a wrestler.

The flush that suffused the girl’s face surprised the watcher and piqued his curiosity. Fallaray, the ascetic, the married bachelor who lived in one wing of his house while Lady Feodorowna entertained the resuscitated Souls in the other,—and this young girl of the lower middle class, worshiping at his shrine! He would have followed her for the rest of the afternoon with no other purpose than to study her moods and watch her stir the passers-by like the whir of an aeroplane or the sudden scent of lilac. But the arrival of a train swept a crowd between them and he lost her. He took a ticket to see if she were on one or other of the platforms, returned to the street and searched up and down. She had gone. Before he left, another bill was posted upon the board of the Evening Standard. “Fallaray sees Prime Minister. May resign from cabinet. Uneasiness in Downing Street,” and as he walked away, no longer interested in the psychology of crowds, but with his imagination all eager and alight, the playwright in him had grasped at the germ of a dramatic experiment.—Take the man Fallaray, a true and sensitive patriot, working for no rewards; humanitarian, scholar, untouched by romance, deaf to the rustle of silk—and that girl, woman to the tips of her ears, Eve in every movement of her body——

II

“Lola’s late,” said Mrs. Breezy. “She ought to have been home half an hour ago.”

Without taking from his eye the magnifying glass through which he was peering into the entrails of a watch, John Breezy gave a fat man’s chuckle. “Don’t you worry about Lola. She’s the original good girl and has more friends among strangers than the pigeons in Kensington Gardens. She’s all right, old dear.”

But Mrs. Breezy never gave more than one ear to her husband. She was not satisfied. She left her place behind the glistening counter of the little jewelry shop in Queen’s Road, Bayswater, and went out into the street to see if she could see anything of her ewe lamb,—the one child of her busy and thrifty married life. On a rain-washed board above her head was painted “John Breezy, Watchmaker and Jeweler, Founded in 1760 by Armand de Brézé.” The name had been Bowdlerized as a concession to the careless English ear.

On the curb a legless man was seated in a sort of perambulator with double wheels, playing a concertina and accompanying another man with no arms and a glass eye who sang with a gorgeous cockney accent, “Come hout, Come hout, the Spring is ’ere.” A few yards farther down a girl with the remains of prettiness was playing the violin at the side of an elderly woman with the smile of professional supplication who held a small tin cup. The incessant crowd which passed up and down Queen’s Road paid little attention either to these stray dogs or to those who occupied other competitive positions in this street of constant noises. Flappers with very short skirts and every known specimen of leg added to the tragic-comedy of a thoroughfare in which provincialism and sophistication were like oil and water. Here was drawn the outside line of polite pretence. The tide of hoi polloi washed up to it and over. Ex-governors of Indian provinces, utterly unrecognized, ex-officers and men of gallant British regiments, mostly out of employment, nurse girls with children, and women of semi-society who lived in those dull barrack houses of Inverness Terrace, where cats squabbled and tradesmen’s boys fought, passed the anxious mother.

Not a day went by that she did not hear from Lola of one or perhaps a series of attempts, in the street, in the Tube, in busses and in the Park, to win her into conversation. The horror stirred by these accounts in the heart of the little woman, to say nothing of the terror, seemed oddly exaggerated to the daughter, who, with her eyes large and gleaming with fun, described the manner in which she left her unrestrained admirers flat and inarticulate. There was nothing vain in this acceptance of male admiration, the mother knew. It was something of which the child had been aware ever since she could remember; had accepted without regret; had hitherto put to no use; but which, deep down in her soul, was recognized as the all-powerful asset of a woman, not to be bought with money, achieved by art or simulated by acting.

Not in so many words had this “gift,” as Lola called it, been interpreted and discussed by Mrs. Breezy. On the contrary, she tried to ignore and hide it away as a dangerous thing which she would have been ashamed to possess. In the full flower of her own youth there had been nothing in herself, she thanked God, to lift her out of the great ruck of women except, as Breezy had discovered, a shrewd head, a tactful tongue and the infinite capacity for taking pains. And she was ashamed of it in Lola. It gave her incessant and painful uneasiness and fright and made her feel, in sleepless hours and while in church, that she had done some wicked thing before her marriage that must be punished. With unusual fairness she accepted all the blame but never had had the courage to tell the truth, either to herself or her husband, as to her true feelings towards this uncanny child, as she sometimes inwardly called her. Had she done so, she must have confessed that Lola was the only human being with whom she had come into touch that remained a total stranger; she must have owned to having been divided from her child almost always by a sort of wall, a division of class over which it was increasingly impossible to cross.

There were times, indeed, when the little woman had gone down to the overcrowded parlor behind the shop so consumed with the idea that she had brought into the world the offspring of another woman that she had sat down cold and puzzled and with an aching heart. It had seemed to her then, as now, that something queer and eerie had happened. At the back of her mind there had been and was still a sort of superstition that Lola was a changeling, that the fairies or the devil or some imp of mischief had taken her own baby away at the moment of her birth and replaced it with an exquisite little creature stolen from the house of an aristocrat. How else could she account for the tiny wrists, small delicate hands, those wide blue eyes, those sensitive nostrils and above all that extraordinary capacity for passing with superb unconsciousness and yet with supreme sophistication through everyday crowds.

There was nothing of John in this girl, of that fat Tomcat-like man, with no more brain than was necessary to peer into watches and repair jewelry, to look with half an eye at current events and grow into increasing content on the same small patch of earth. Neither was there anything of herself, nothing so vulgar as shrewdness, nothing so commonplace as tact and nothing so legitimate as taking pains. Either she did things on the spur of an impulse, by inspiration, or she dropped them, like the shells of nuts.

In spite of this uncanny idea, Mrs. Breezy loved her little girl, adopted though she seemed to be, and constant anxiety ran through her heart like a thread behind a needle. If any man had spoken to her on the street, she would have screamed or called a policeman. She certainly would have been immediately covered with goose flesh. Beyond that, if she had ever discovered that she had been born with the power to stir the feelings of men at first sight, as music stirs the emotions of an audience or wind the surface of water, she would have been tempted to have turned Catholic and taken the veil.

Not an evening went by, therefore, that did not find Mrs. Breezy on the step of the shop in Queen’s Road, Bayswater, looking anxiously up and down for the appearance of Lola among the heterogeneous crowd which infested that street. Always she expected to see at her side a man, perhaps the man who would take her child away. She had her worries, poor little woman, more perhaps than most mothers.

That evening, the light reluctant to leave the sky, Spring’s hand upon the city trees, Lola did bring some one home,—a woman.

III

Miss Breezy, sister of John, made a point of spending every Thursday evening at the neat and gleaming shop in Queen’s Road. It was her night off. Sometimes she turned up with tickets for the theater given to her by the great lady to whom she acted as housekeeper, sometimes to a concert and once or twice during the season for the opera. If there were only two tickets, it was always Lola who enjoyed the other. Mr. and Mrs. Breezy were contented to hear the child’s account of what they gladly missed on her behalf. Frequently they got more from the girl’s description than they would have received had they used the tickets themselves.

It was this woman who unconsciously had made Fallaray the hero of Lola’s dreams. She had brought all the latest gossip from the Fallaray house in which she had served since that strange wedding ten years before, when the son of the Minister for Education, himself in the House of Commons, had gone in a sort of trance to St. Margaret’s, Westminster, and come out of it surprised to find himself married to the eldest daughter of the Marquis of Amesbury,—the brilliant, beautiful, harum-scarum member of a pre-war set that had given England many rude shocks, stepped over all the conventions of an already careless age and done “stunts” which sent a thrill of horror and amazement all through the body of the old British Lion; a set whose cynicism, egotism, perversion, hobnobbing with political enemies, manufacture of erotic poetry and ribald jests had spread like an epidemic.

Miss Breezy, whose Christian name was Hannah, as well it might be, entered in great excitement. “Have you seen the paper?” she asked, giving her sister-in-law peck to the watchmaker’s wife. “Mr. Fallaray’s declared himself against reprisals. He’s condemned the methods of the Black and Tans. They yelled at him in the House this afternoon and called him Sinn Feiner. Just think of that! If any other man had done it, I mean any other Minister, Lloyd George could have afforded to smile. But Mr. Fallaray! It may kill the coalition government, and then what will happen?”

All this was given out in the shop itself, luckily empty of customers. “Woo,” said John. “Good gracious me,” said Mrs. Breezy. “Just as I expected,” said Lola, and she entered the parlor and threw her books into a corner and perched herself on the table, swinging her legs.

“‘Just as you expected?’ What do you know about it all, pray?” Miss Breezy regarded the girl with the irritation that goes with those who forget that little pitchers have ears. She also forgot that the question of Ireland, of little real importance among all the world’s troubles, was being forced into daily and even hourly notice by brutal murders and by equally brutal reprisals and that England was, at that moment, racked from end to end with passionate resentment and anger with which even children were tainted.

And Lola laughed,—that ripple of laughter which had made so many men stand rooted to their shoes after having had the temerity to speak to her on the spur of the moment, or after many manœuverings. “What I know of Mr. Fallaray,” she said, “you’ve taught me. I read the papers for the rest.” And she heaved an enormous sigh and seemed to leave her body and fly out like a homing pigeon.

“Don’t say anything more until I come back,” cried Mrs. Breezy, rapping her energetic heels on the floor on the way out to close the shop.

Beamingly important, the bearer of back-stairs gossip, Miss Breezy removed her coat,—one of those curious garments which seem to be made especially for elderly spinsters and are worn by them proudly as a uniform and with the certain knowledge that everybody can see that they have gone through life in single blessedness, dependent neither for happiness nor livelihood on a mere man.

John Breezy, who had lost all suggestion of his French ancestry and spoke English with the ripest Bayswater, removed his apron. He liked, it is true, to remember his Huguenot grandfather and from time to time indulged in Latin gestures, but when he ventured into a few words of French his accent was atrocious. “Mong Doo,” he said, therefore, and shrugged his fat shoulders almost up to his ears. He had no sympathy with the Irish. He considered that they were screaming fanatics, handicapped by a form of diseased egotism and colossal ignorance which could not be dealt with in any reasonable manner. He belonged to the school of thought, led by the Morning Post, which would dearly like to put an enormous charge of T. N. T. under the whole island and blow it sky high. “Of course you buck a good deal about your Fallaray,” he said to his sister, “that’s natural. You take his money and you live on his food. But I think he’s a weakling. He’s only making things more difficult. I wish to God I was in the House of Commons. I’d show ’em what to do to Ireland.”

There was a burst of laughter from Lola who jumped off the table and threw her arms around her father’s neck. “How wonderful you are, Daddy,” she said. “A regular old John Bull!”

Returning before anything further could be said, Mrs. Breezy shut the parlor door and made herself extremely comfortable to hear the latest from behind the scenes. It was very wonderful to possess a sister-in-law who regularly, once a week, came into that dull backwater with the sort of thing that never got into the papers and who was able to bandy great names about without turning a hair. “Now, then, Hannah, let’s have it all from the beginning and please, John, don’t interrupt.” She would have liked to have added, “Please, Lola,” too, but knew better.

Then it was that Miss Breezy settled henwise among the cushions on the sofa and let herself go. It was a good thing for her that her family was unacquainted with any of those unscrupulous illiterates who wrote the chit-chat in the Daily Mirror.

“It was last night that I knew about all this,” she said. “I went in to see Lady Feo about engaging a new personal maid. Her great friend was there,—Mrs. Malwood, who was Lady Glayburgh in the first year of the War, Lady Pytchley in the second, Mrs. Graham Macoover in the third, married Mr. Aubrey Malwood in the fourth and still has him on her hands. I was kept waiting while they finished their talk. Mrs. Malwood had to hurry home because she was taking part in the theatricals at the Eastminsters. I heard Lady Feo say that Mr. Fallaray had decided to throw his bomb in the House this afternoon. She was frightfully excited. She said she didn’t give a damn about the Irish question—and I wish she didn’t speak like that—but that it would be great fun to have a general election to brighten things up and give her a chance to win some money. I don’t know how Lady Feo knew that her husband had decided to take this step, because they never meet and I don’t believe he ever tells her anything that he has on his mind. I shouldn’t be surprised if she got it from Mr. Fallaray’s secretary. I’ve seen them whispering in corners lately and once she starts her tricks on any man, good-by loyalty. My word, but she’s a wonderful woman. A perfect devil but very kind to me. I’ve no grumbles. If we do have a general election, and I hope to goodness we don’t, there’s only one man to be Prime Minister, and that’s Mr. Fallaray. But there’s no chance of it. All the Prime Minister’s newspapers are against him, and all his jackals, and he has more enemies than any man in the Cabinet, and not a soul to back him up. Office means too much to them all and they’re all in terror of being defeated in the country. He’s the loneliest man in the whole of London and one of the greatest. That’s what I say. I’ve been with the family ten years and there are things I like about Lady Feo, for all her rottenness. But I know this. If she’d been a good wife to that man and had given him a home to come back to and the love that he needs and two or three children to romp with even for half an hour a day, there’d be a very much better chance for England in this mess than there is at present.”

Stopping for breath, she looked up and caught the eyes of the girl whose face had flushed at the sight of the picture on the cover of the magazine. They were filled with something that startled her, something in which there was so great a passion that it threw a hot dart at her spinsterhood and left her rattled and confused.

IV

Miss Breezy was to receive another shock that evening.

It happened that several neighbors came in unexpectedly and stayed to play cards. It was necessary, therefore, to adjourn from the cosy little parlor behind the shop and go up to the drawing-room on the second floor,—a stiff uncomfortable room used only on Sundays and when the family definitely entertained. It smelt of furniture polish, cake and antimacassars. Lola had no patience with cards and helped her mother to make coffee and sandwiches. Miss Breezy, who clung to certain old shibboleths with the pathetic persistence of a limpet, regarded a pack of cards as the instrument of the devil. Besides, she resented the intrusion of every one who put her out of the limelight. Her weekly orgy of talk emptied the cistern of her brain.

She suspected something out of the way when Lola suddenly jumped on the sofa like an Angora kitten, snuggled up and began to purr at her side, saying how nice it was to see her, how terribly they would miss her visits, and how well-informed she was. The little head pressed against her bosom was not uncomforting to the childless woman. The warm arm clasped about her shoulder flattered her vanity. But this display of affection was unusual. It drew from her a rather shrewd question. “Well, my dear, and what do you want to get out of me? I know you. This is cupboard love.”

She won a gleam of teeth and a twinkle of congratulation from those wide-apart eyes. “How clever you are, Auntie. But it isn’t cupboard love, at least not quite. I want to consult you about my future because you’re so sensible and wise.”

“Your future.—Your future is to get married and have babies. That was marked out for you before you began to talk. I never saw such a collection of dolls in a little girl’s room in all my life. A born mother, my dear, that’s what you are. I hope to goodness you have the luck to find the right sort of man in your own walk of life.”

Lola shook her head and snuggled a little closer, putting her lips to the spinster’s ear. “There’s plenty of time for that,” she said. “And, anyway, the right man for me won’t be in my own walk of life, as you call it.”

“What! Why not?”

“Because I want to better myself, as you once said that every girl should do. I haven’t forgotten. I remember everything that you say, Auntie.”

“Oh, you do, do you? Well, go on with it.” What a pretty thing she was with her fine skin and red lips and disconcerting nostrils. Clever as a monkey, too, my word. Amazing that Ellen should be her mother!

“And so I want to get away from Queen’s Road, if I can. I want to take a peep, just a peep for a little while into another world and learn how to talk and think and hold myself. Other girls like me have become ladies when they had the chance. I can’t, I know I can’t, become a teacher as Mother says I must. You know that, too, when you think about me. I should teach the children everything they ought not to know, for one thing, you know I should, and throw it all up in a week. I overheard you say that to Mother the very last time you were here.”

“My dear, your ears are too long. But you’re right all the same. I can’t see you in a school for the shabby genteel.” A warm fierce kiss was pressed suddenly to her lips. “But what can I do to help you out? I don’t know.”

“But I do, Auntie. You’re trying to find a personal maid for Lady Feo. Engage me. I may work up to become a housekeeper like you some day even. Who knows?”

So that was it.—Good heavens!

Miss Breezy unfolded herself from the girl’s embrace and sat with her back as stiff as a ramrod. “I couldn’t think of such a thing,” she said. “You don’t belong to the class that ladies’ maids come from, nor does your mother. A funny way to better yourself, that, I must say. Don’t mention it again, please.” She got up and shook herself as though to cast away both the girl’s spell and her absurd request. Her sister-in-law, after a long day’s work, was impatient for bed and yawning in a way which she hoped would convey a hint to her husband’s friends. She had already wound up the clock on the mantelpiece with extreme deliberation. “I think my cab must be here,” said Miss Breezy loudly, in order to help her. “I ordered him to fetch me. Don’t trouble to come down but do take the trouble to find out what’s the matter with Lola. She’s been reading too many novels or seeing too many moving pictures. I don’t know which it is.”

To Mrs. Breezy’s entire satisfaction, her sister-in-law’s departure broke up the party. There was always a new day to face and she needed her eight hours’ rest. Mr. Preedy, the butcher whose inflated body bore a ludicrous resemblance to a punch ball and who smelt strongly of meat fat, his hard-bosomed spouse and Ernest Treadwell, the young man from the library who would have sold his soul for Lola, followed her down the narrow staircase. But it was Lola who got the last word. She stood on the step of the cab and put a soft hand against Miss Breezy’s cheek. “Do this for me, Auntie,” she wheedled. “Please, please. If you don’t——”

“Well?”

“There are other great ladies and very few ladies’ maids, and if I go to one of them, how will you be able to keep your eye on me,—and you ought to keep your eye on me, you know.”

“Well!” said Miss Breezy to herself, as the cab rattled home. “Did you ever? What an extraordinary child! Nothing of John about her and just as little of Ellen. Where does she get these strange things from?” It was not until she arrived finally at Dover Street that she added two words to her attempted diagnosis which came in the nature of an inspiration. “She’s French!”

V

It was a lukewarm night, without wind and without moon, starless. Excited at having got in her request, which she knew from a close study of her aunt’s character was bound to be refused and after a process of flattery eventually conceded, Lola waved her hand to the Preedys and graciously consented to give a few minutes to Ernest Treadwell. The butcher and his wife, after a lifetime of intimacy with animals, had both taken on a marked resemblance to sheep. They walked away in the direction of their large and prosperous corner shop with wide-apart legs and short quick steps, as though expecting to be rounded up by a bored but conscientious dog. As she leaned against the private door of her father’s shop, with the light of the lamp-post on hair that was the color of buttercups, she did look French. If Miss Breezy were to take the trouble to read a well-known book of memoirs published during the reign of Louis XIV, it would dawn upon her that the little Lola of Queen’s Road, Bayswater, daughter of the cockney watchmaker and Ellen who came from a flat market garden in Middlesex, threw back to a certain Madame de Brézé, the famous courtesan. Whether her respect for her brother would become less or grow greater for this discovery it is not easy to say. Probably, being a snob, it would increase.

“Don’t stand there without a hat, Lola dear. You may catch cold.”

“Mother always says that,” said Lola, “even in the middle of the summer, but she won’t call again for ten minutes, so let’s steal a little chat.” She put her hand on Treadwell’s shoulder with a butterfly touch and held him rooted and grateful. He had the pale skin that goes with red hair as well as the pale eyes, but as he looked at this girl of whom he dreamed by day and night, they flared as they had flared when he had seen her first as a little girl with her hair in a queue at the other end of a classroom. He stood with his foot on the step and his hands clasped together, inarticulate. Behind his utter commonplaceness there was the soul of Romeo, the passion of self-sacrifice that goes with great lovers. He had been too young for gun fodder in the war but he had served in spirit for Lola’s sake and had performed a useful job in the capacity of a boy scout messenger in the War Office. His bony knees and awkward body had been the joke of many a ribald subaltern, mud-stained from the trenches.

“What are you doing on Saturday afternoon?” asked Lola. “Shall we walk to Hampton Court and see the crocuses? They’re all up now like little soldiers in a pantomime.”

“I’ll call for you at two o’clock,” answered the boy, thrilling as though he had been decorated. “We’ll have tea there and come back on top of a bus. I suppose your mother wouldn’t let me take you to the theater? There’s a great piece at the Hammersmith,—Henry Ainley. He’s fine.”

Lola laughed softly. “Mother’s a dear,” she said. “She lets me do everything I want to do after I’ve told her that I’m simply going to do it. Besides, she likes you.”

“Do you like me, Lola?” The question came before the boy could be seized with his usual timidity. It was followed by a rush of blood to the head.

The girl’s answer proved her possession of great kindness and an amazing lack of coquetry. “You are one of my oldest friends, Ernest,” she replied, thereby giving the boy something to hope for but absolutely nothing to grasp. He had never dared to go so far as this before and like all the other boys who hung round Lola had never been able, by any of his crude efforts, to get her to flirt. Friend was the only word that any of them could apply to her. And yet even the least precocious of these boys was convinced of the fact that she was not innocent of her power.

“I love the spring,—just smell it in the air,” said Lola, going off at a tangent, “but I shall never live in the country—I mean all the time. I shall go there and see things grow and get all the scent and the whispers and the music of the stars and then rush back to town. Do you believe in reincarnation, Ernest? I do. I was a canary once and lived in a cage, a big golden cage, full of seeds and water and little bells that jingled. It stood on the table in a room filled with tapestry and lovely old furniture. Servants in livery gave me a saucer for a bath and refilled my seed pans.—I feel like a canary now sometimes. I like to fly out, perfectly tame, and with no cats about, sing a little and imagine that I am perfectly free, and then flick back, stand on a perch and do my best singing to the noise of traffic.” And she laughed again and added, “What rot we talk when we’re young, don’t we? I must go.”

“No, not yet. Please not yet.” And the boy put his hands out to touch her and was afraid. He would gladly have died then and there in that street just to be allowed to kiss her lips.

“It’s late. I must go, Ernest. I have to get up so awfully early. I hate getting up early. I would like breakfast in bed and a nice maid to bring me my letters and the papers. Besides, I don’t want to worry Mother. She has all the worries of the shop. Good night and don’t be late on Saturday.” She held out her hand.

The boy seized it and held it tight, his brain reeling, and his blood on fire. He stood for an instant unable to give expression to the romance that she stirred in him, with his mouth open and his rather faulty teeth showing, and his big awkward nose very white. And when she had gone and the door of her castle was closed, the poor knight, who had none of the effrontery of the troubadour, paced up and down for an hour in front of the shop, saying half aloud all the things from Shakespeare which alone seemed fit for the ears of that princess,—princess of Queen’s Road, Bayswater!

VI

The room at the back of the house in which Lola had been installed since she had been old enough to sleep alone had been her parents’ bedroom and was larger than the one to which they had retired. While Breezy had argued that he damned well didn’t intend to turn out for that kid, Mrs. Breezy had moved the furniture. The best room only was good enough for Lola. The window gave a sordid view of back yards filled with packing cases, washing, empty bottles and one or two anæmic laburnum trees which for a few days once a year burst into a sort of golden smile and then became sullen again,—observation posts for the most corrupt of animals, the London cat. It was in this room that Mrs. Breezy, trespassing sometimes, stood for a few moments lost in amazement, feeling more than ever the changeling sense that she did her best to forget.

With the money that she had saved up—birthday money, Christmas money and a small allowance made to her by her father—Lola had bought a rank imitation of an old four-poster bed made probably in Birmingham. Over it she had hung a canopy of chintz with a tapestry pattern on a black background, copied from an illustration in the life of Du Barry. From time to time pillows with lace covers had been added to the luxurious pile, a little footstool placed at the side of the bed and—the latest acquisition—an eiderdown now lent an air of swollen pomp to the whole thing, which, to the puzzled and concerned mother, was immoral. Hers was one of those still existing minds which read immorality into all attempts to break away from her own strict set of conventions, especially when it was in the direction of beautifying a bed, to her, of course, an unmentionable thing. In America, without doubt, she would be a cherished and respected member of the Board of Motion Picture Censors, as well as—having a cellar—a militant prohibitionist.

For the rest, the room possessed a sofa which was an English cousin to an Italian day bed and curtains of china silk in which there was a faint tinge of pink. A small table on which there was a collection of dainty things for writing, mementos of many Christmases and several lines of shelves crammed with books gave the room something of the appearance of a boudoir, and this was added to by half a dozen cheap French prints framed in gold which looked rather well against a wall paper of tiny bouquets tied up with blue ribbon. Lola’s collection of books had frequently sent John Breezy into gusts of mirth. There was nothing among them that he could read. Very few of them were in English and those were of French history. The rest were the lives and memoirs of famous courtesans, including those of the Madame de Brézé, to whom the watchmaker always referred with a mixture of pride and levity,—but not when his wife was in hearing. A bulky French dictionary, old and dog-eared, stood in solitude upon the writing table.

It was to this room that Lola withdrew as often as possible to cut herself off from every suggestion of Queen’s Road, Bayswater, and the shop below, and to forget her daily journeys to and from the Polytechnic where she was supposed to be taking a commercial course in bookkeeping and shorthand with a view either to going into an office or becoming a teacher in one of the many small schools which endeavored to keep their heads up in and about that portion of London.

The game of make-believe, which the dramatist who followed Lola from Hyde Park corner that afternoon had watched her play, had been carried on in this bed-sitting room ever since she had fallen under the spell of the de Brézé memoirs. It was here, especially on Sunday mornings, that this young thing let her imagination have full play while her father and mother, dressed in their Sabbath best, attended the Methodist Church near-by. Then, playing the part of her celebrated ancestress, she put on a little lace cap and a peignoir over her nightgown and sat up in bed to receive the imaginary friends, admirers and sycophants who came to her with the latest gossip, with rare and beautiful gifts and with the flattery of their kind, which, while it pleased her very much, failed to turn her head, because, after all, she had inherited much of her mother’s shrewdness. With her door locked, her nose powdered and her lips the color of a cherry, Lola conducted, for her own amusement, a brilliant series of monologues which, if given on the stage in a setting a little more elaborate, would have set all London laughing.

The girl’s mimicry of the people whom she brought to life from the pages of those French books was perfectly delightful. She brought her master to life. With a keen sense of characterization she built him up—unconsciously assisted by Aunt Hannah—into as close a resemblance to Fallaray as she could,—a tired, world-worn man, starving for love and adoration, weighed down by the problems of a civilization in chaos, distrait and sometimes almost brusque, but always chivalrous and kind, who came to her for refreshment and inspiration and left her with a lighter tread and renewed optimism. Ancient dames whose days were over came to her with envy in their hearts and the hope of charity in their withered souls to tell her of their triumphs and the scandals of their time. But the character upon whom she concentrated all her humor and sarcasm was the friend of her master, an unscrupulous person who loved her and never could resist the opportunity of pressing his suit in flowery but passionate terms and with an accent which, elaborately Parisian, was reproduced from that of the French journalist who had taught Lola his language in a class that she had attended for several years. These word fencings had begun, of course, as a child would naturally have begun them, with the stilted sentences and high-flown remarks which she had lifted from Grimm’s Fairy Tales. They had become more and more sophisticated as the years had passed and were now full of subtleties and insinuations against which, egging the man on, Lola defended herself with what she took to be great wit and cleverness.

If her little mother had ever gone so far as to put her ear to the keyhole of that bedroom, she would have listened to something which would probably have sent her to a doctor to consult him as to her daughter’s mental condition. She would have heard, for instance, the well-modulated voice of that practised lovemaker and the laughing high-pitched replies of a girl not unpleased with his attentions but adamant to his pleadings and perfectly sure of herself. It is true that Mrs. Breezy would not have understood one word that was spoken because it was all in French, but the mere act of conducting long conversations with imaginary characters as a hobby would have struck deep at her sense of the fitness of things, especially as Sunday was the day chosen for such a game. The Methodist mind is strangely inelastic.

What would have been said to all this by a disciple of Freud it is easy to conceive. He would have read into it the existence of a complex proving a suppressed desire which must have landed Lola in a lunatic asylum. Common sense and a rudimentary knowledge of heredity might, however, have given to the mother and the psychoanalyst the key to all this. The fact was that Lola threw back to her French ancestress who, like herself, was the daughter of humble, honest people, and the glamor of the de Brézé memoirs had not only caught and colored her imagination, which was her strongest trait, but had shown her how to exploit the gift of sex appeal in a way that would make her essential to a man who had it in him to become a great political figure, the only way in which she, like the de Brézé, could be placed in a golden cage with all the luxuries, share in the secrets of government, meet the men who counted, bask in the reflected glory of power, and give in return so whole-hearted a love, devotion, encouragement and refreshment that her “master” would go out to the affairs of his country grateful and humanized. She could not, of course, ever hope to achieve this ambition by marriage. No such man would marry the daughter of a watchmaker. It was that the spirit of this woman lived again in the Breezys’ little daughter; that in her there had been revived the same desire to force a place for herself in a world to which she had not been born, and that she had been endowed with the same feminine qualities that were necessary to such a scheme. In the knowledge of this and pinning her faith to a similar cause—the word was hers—Lola Breezy had gone through those curious years of double life more and more determined to perform this kind of courtesanship, believing that she had inherited the voice with which to sing the little songs of a canary in the secret cage of no less a man than one of proved ability and idealism, who was within an ace of premiership, and—so that her vanity might be satisfied in the proof of her own ability to help him—against whom was pitted all that was mean, ignorant, jealous and reactionary in a bad political system.

What more natural, therefore, than that the man who fulfilled all these requirements and whom she would give her life to serve was Fallaray. He had been brought home to her every Thursday evening by her aunt for ten years. She had read in the papers every word that he had spoken; had followed his course of action through all the years of the War which he had done his best to prevent; had watched his lonely struggle to substantiate a League of Nations free from blood lust and territorial greed; had seen him pelted with lies and calumny when he had cried out that Germany must be allowed to live if Europe were to live; and that very day had stood trembling in front of the billboard which announced that he would not stand for the bloody and disastrous reprisals in Ireland that were backed by the Prime Minister. He was the one honest man, the one idealist in English politics; the one great humanitarian who possessed that strength and fairness of mind which permitted him to see both sides of a question; to belong to a party without being a slave to its shibboleths; to commit the sudden volt-faces so impossible to brass hats and to the Junkers of all nationality; the one man in the House of Commons who didn’t give a damn for limelight, self-aggrandizement, titles, graft and all the rest of the things which have been brought into that low and unclean business by men who would sell the country for a drink. And above all he was unhappy with his wife.

The housekeeper aunt had built up for this girl a hero who fitted exactly into the niche in her heart and ambitions. All the stories and backstairs gossip about him had excited her desire to become a second Madame de Brézé in his life and bring the rustle of silk to this Eveless man. Never once did there enter into her game of make-believe or her dreams of achievement the idea of becoming Fallaray’s wife, even if, at any time, he should be free to marry again. She had too keen a sense of psychology for that. She saw the need to Fallaray, as to other such men in his position, of a secret romance,—stolen meetings, brief escapes, entrancing interludes, and the desire—the paradox of asceticism—for feminine charms. She had read the story of Parnell and understood it; of Nelson and sympathized with it. She knew the history of other men of absorbing patriotism and great intellect who had kept their optimism and their humanity because of a woman’s tenderness and flattery, and whenever she looked at the picture of Fallaray, in whom she recognized a modern Quixote tilting at windmills, she saw that he stood in urgent need of a woman who could do for him what Madame de Brézé had done for that minister of Louis XIV. During all her intelligent years, therefore, she had conducted herself in the hope, vague and futile as it seemed, of some day being discovered to Fallaray, and in her heart there had grown up a love and a hero worship so strong and so passionate that it could never be transferred to any other man.

The reason, then, why Lola had turned the whole force of her concentration upon entering the house in Dover Street as lady’s maid becomes clear. Here, suddenly, was her chance. Once in this house, in attendance upon Lady Feo, it would be possible for her not only to learn the manners and the language of the only women who were known to Fallaray, but eventually, with luck and strategy, to exercise her gift, as she called it, upon Fallaray himself. What did she care whether, as her aunt had said, she went down a peg in the social scale by becoming a lady’s maid? She would willingly become a crossing sweeper or a beggar girl.

If it were true that Fallaray never went into the side of the house that was occupied by his wife, then she would eventually, when she felt that her apprenticeship had been served, slip into the other side. Like all women she had cunning and like very few courage. Opportunity comes to those who make it and she was ready and eager to undergo any humiliation to try herself, so to speak, on Fallaray. Ernest Treadwell loved her and would, she knew, die for her willingly. There was the hero stuff in him. Other boys, too numerous to mention, would go through fire and water for her kisses. Life was punctuated with turned heads, sudden flashes of eye and everyday attempts to win her favor. Once in that house in Dover Street——

VII

Saturday came. Ernest Treadwell arrived early, his face shining with Windsor soap. He had bought a spring tie at Hope Brothers, the name and the season going well with his mood. It was a ghastly affair,—yellow with blobs of red. It was indeed much more suited to Mr. Prouty, the butcher. It illustrated something at which he frequently looked,—animal blood on a sawdust floor. But Ernest Treadwell was one of those men who could always be persuaded into wearing anything that was offered to him. He was a dreamer, the stuff that poets are made of, impractical, embarrassed. He went about with his young and incoherent brain seething with the tail end of big thoughts. If he had not been watched by a fond mother, he would probably have left the house with his trousers around his neck and his legs thrust through the sleeves of his coat. He walked up and down the street for half an hour with his cap on the back of his head and a tuft of hair sticking out in front of it,—an earnest, ungainly, intelligent, heroic person who might one day become a second Wells and write a Joan and Peter about the children of Joan and Peter.

Saturday was a good day for the Breezys and much of Friday night had been spent cleaning and rearranging the cheap and alluring silverware—birthday presents, wedding presents, lovers’ presents—which invariably filled the windows. Twice Lola had looked down and watched her young friend as he marched up and down beneath, with an ecstatic smile on his face. It was after her second look that she made up her mind to desert the crocuses in Hampton Court and make that boy escort her to Dover Street. Acting under a sudden inspiration she determined to go and see her aunt. She knew perfectly well that Miss Breezy had had time to think over the point which had been suggested to her and was by now probably quite ready to accept it. That was the woman’s character. She began by saying no to everything and ended, of course, by saying yes to most of them, and the more emphatic she was in the beginning the more easily she caved in finally. After all, she was very fond of her niece and would welcome the opportunity of having the girl’s company at night and during the hours when Lady Feo was out. Lola knew all that and her entrance into Dover Street had become an obsession, a fixed idea, and if her aunt should develop a hitherto undemonstrated stiff back,—well then her hand must be forced, that’s all, either by hook or by crook. Dressed as simply as usual but wearing her Sunday hat, Lola passed through the shop, dropped a kiss on her father’s head, twiddled her fingers at her mother, who was “getting off” a perfectly hideous vase stuck into a filigree silver support and must not, therefore, be interrupted in her diplomatic flow of persuasion. She was met at the door by Ernest Treadwell, who sheepishly removed his cap. He would have given ten years of his life to have been able to doff it in the manner of Sir Walter Raleigh and utter a string of highly polished phrases suitable to that epoch-making occasion. Instead of which he said, “’Ello,” and dropped his “h” at her feet.

Queen’s Road wore its usual Saturday afternoon appearance and its narrow pavement was filled with people shopping for Sunday,—the tide of semi-society clashing with that of mere respectability. “Hampton Court’ll look great to-day,” said Ernest, who felt that with the assistance of the crocuses he might be able to stammer a few words of love and admiration.

Lola glanced up at the clear sky and the April sun which was in a very kindly mood. “I’m sure it will,” she said, “but I’m afraid I’ve got a disappointment for Ernie. I want you to be a dear and take me to see my aunt in Dover Street. It’s—it’s awfully important.”

The boy’s eyes flicked and a curious whiteness settled about his nose. But he played the knight. “Whatever you say, Lola,” he said, and forced himself to smile. Poor boy, it was a sad blow. He had gone to bed the night before, dreaming of this little adventure. It would have been the first time that he had ever spent an afternoon and evening alone with the girl who occupied the throne of his heart.

Lola knew this. She could see the whole story behind the boy’s smile. So she took his arm to compensate him,—knowing how well it would. “There are crocuses in Kensington Garden,” she said. “We’ll have a look at those as we pass.”

Every head that turned and every eye that flared made Ernest Treadwell swell with pride as well as resentment. A policeman held up the traffic for Lola at the top of the road and one of the keepers of the Gardens, an old soldier, saluted her as she went through the gates. She rewarded these attentions with what she called her best de Brézé smile. Some day other and vastly more important men should gladly show her deference. They followed the broad path which led to Marble Arch, raising their voices in order to overcome the incessant roar of traffic in the Bayswater Road. Lola did most of the talking that afternoon and it was all inspirational, to fire the boy into greater ambition and effort. She had read some of his poetry,—strange stuff that showed the influence of Masefield, crude and half-baked but not untouched with imagery. She believed in Ernest Treadwell and took a very real delight in his improvement. But for her encouragement it might have been some years before he broke out of hobble-de-hoydom and the semi-vicious ineptitude that goes with it. He was very happy as he went along with the warm hand on his arm. His vanity glowed under her friendship, as she intended that it should.

The old Gardens were green and fresh, gay with new leaves and daffodils. Only the presence of smashed men made it look different from the good days before the War. Would all those children who played under the eyes of mothers and nurses be laid presently in sacrifice upon the altars of the old Bad Men of politics who had done nothing to avert the recent cataclysm?

Lola was excited and on her mettle. She was nearing the crossroads. On the one that she had marked out stood Fallaray,—the merest speck. Success with Aunt Hannah meant the first rung of her ladder. Oxford Street was like a once smart woman who had become déclassé. It seemed to be competing with High Street, Putney. There was something pathetically blatant in the shop window arrangements, a strained effort to catch what little money was left to the public after the struggle to make both ends meet and pay the overwhelming taxation. The two young people were unconscious of the change. Lola babbled incessantly. Among other things she said, “I suppose you’re a socialist, aren’t you, Ernest? You’ve never discussed it with me, but I think you must be because you write poetry, and somehow all poets seem to be socialists. I suppose it’s because poetry’s so badly paid.”

“I dunno about that. I’ve never tried to sell my stuff. I’m against everything and everybody, if that’s what you mean. But I don’t know whether it’s true to call it Socialism. There’s a new word for it which suits me,—intelligensia. I don’t think that’s the way to pronounce it but it’s near enough. It’s in all the weekly papers now and stands for anarchy with hair oil on the bombs. Why do you ask me?”

Lola still had her hand on his arm. “Well, I’m afraid I’m going to give you a shock soon. I’m going to be a servant.”

“Good God,” said Ernest. His grandfather had been a valet, his father a piano tuner, he himself had risen to the heights of assistant librarian in a public library, and if his ambition to become a Labor member ever was realized he might very easily wind up as a peer. His children would then belong to the new aristocracy with Lola as Lady Treadwell. He gasped under the blow. “What will your mother say?”

“I’m afraid Mother will hang her head in shame until she gets my angle of it. Luckily I can always point to Aunt. She’s a housekeeper, you see, and after all that’s only a sort of upper servant, isn’t it?”

“But,—what’s the idea?”

This was not a question to which Lola had any intention of giving an answer. It was a perfectly private affair. She went off at one of her inevitable tangents so useful in order to dodge issues. She pointed to an enormous Rolls-Royce which stood outside Selfridge’s. On the panel was painted a coat of arms as big as a soup tureen. She held Ernest back to watch the peculiar people who descended from it,—the man small and fat, with bandy legs and a great moustache waxed into points; the woman bulbous and wobbly, cluttered up with diamonds, made pathetic by a skirt that was almost up to her knees. What an excellent thing the War had been for them.

“New rich,” said Lola. “I saw them the other day coming out of a house at the top of Park Lane which Father told me used to belong to a Duke. Good Lord, why shouldn’t I be a servant without causing a crack in the constitution of the country?”

Fundamentally snobbish as all socialists are, the boy shook his head. “You should lead, not serve,” he said, quoting from one of his masters. And that was all he could manage. Lola,—a servant! They turned into Bond Street in which all the suburban ladies who were not enjoying the matinées were gluing their noses to the shop windows. Ernest Treadwell was unfamiliar with this part of London. He preferred the democratic Strand when he could get away from his duties. He felt more and more sheepish and self-conscious as Lola drew up instinctively at every shop in which corsets were displayed and diaphanous underwear spread out. The silk stockings on extremely well-shaped wooden legs she admired extremely and desired above all things. The bootmakers’ shops also came in for her close attention. The little French shoes with high vamps and stubby noses drew exclamations of delight and envy. Several spots on the window of Aspray’s bore the impression of her nose before she could tear herself away. A set of dressing-table things made of gold and tortoiseshell made her eyes widen and her lips part. Ernest Treadwell would willingly have sacrificed all his half-baked socialism to be able to buy any one of those things for Lola.

Finally they came to Dover Street, that oasis in the heart of Mayfair where even yet certain houses remain untouched by the hand of trade. The Fallaray house was on the sunny side, where it stood gloomily with frowning windows and an uninviting door. It was the oldest house in the street and wore its octogenarian appearance without camouflage. It had belonged originally to the Throgmorton family upon whom Fate had laid a hoodoo. The last of the line was glad to sell it to Fallaray’s grandfather, the cotton man. What he would have said if he could have returned to his old haunts, opened his door with his latch key and walked in to find Lady Feo and her gang God only knows.

It was well known to Lola. Many times she had walked up and down Dover Street in order to gaze at the windows behind which she thought that Fallaray might be sitting, and several times she had been into her aunt’s rooms which overlooked the narrow yards of Bond Street.

“Wait for me here, Ernest,” she said. “I don’t think I shall be very long. If I’m more than half an hour, give me up and we’ll have another afternoon later on.”

She waved her hand, went down the area steps and rang the bell. Ernest Treadwell, to whom the house had taken on a sinister appearance, sloped off with rounded shoulders and a tight mouth. They might have been in Hampton Court looking at the crocuses.—Lola,—a servant. Good God!

VIII

Albert Simpkins opened the door.

It wasn’t his job to open doors, because he was a valet. But it so happened that he was the only person in the servants’ quarters who was not either dressing, lying down after a heavy lunch or out to enjoy an hour’s fresh air.

“Miss Breezy, please,” said Lola.

Simpkins gasped. If he had been passing through the hall and a footman had opened the front door to this girl he would have slipped into a dark corner to watch her enter, believing that she had come to visit Lady Feo. He knew a thoroughbred when he saw one. That she should have come to the area of all places seemed to him to be irregular, not in conformity with the rules of social rectitude which were his religion. All the same he thrilled, and like every other man who caught sight of Lola and stood near enough to catch the indefinable scent of her hair, stumbled over his words.

Lola repeated her remark and gave him a vivid friendly smile. If she carried her point with her aunt presently, this man would certainly be useful. “If you will please come in,” said Simpkins, “I’ll go and see if Miss Breezy’s upstairs. What name shall I say?”

“Lola Breezy.”

“Miss Lola Breezy. Thank you.” He paused for a moment to bask, and then with a little bow in which he acknowledged her irresistible and astonishing effect, disappeared,—valet stamped upon his respectability like a Cunard label on a suit case.

Lola chuckled and remained standing in the middle of what was used by the servants as a sitting room. How easy it was, with her gift, to shatter men’s few senses. She knew the place well,—its pictures of Queen Victoria and of famous race horses cut from illustrated papers cheaply framed and its snapshots of the gardens of Chilton Park, Whitecross, Bucks. Discarded books of all sorts were piled up on various tables. The Spectator and The New Statesman, Massingham’s peevish weekly, Punch, The Sketch and The Tatler, Eve and the Bystander, which had come downstairs from the higher regions, were scattered here and there. They had been read and commented upon first by the butler and then downwards through all the gradations of servants to the girl who played galley slave to the cook. Lola wondered how long it would be before she also would be spending her spare time in that room, hobnobbing with the various members of the family below stairs. A few days, perhaps, not more,—now that she had fastened on this plan.

Simpkins returned almost immediately. “If you will follow me,” he said, and gave her an alluring smile which disclosed a row of teeth that were peculiarly English. He led the way along a narrow passage up the back staircase and out upon a wide and imposing corridor, hung with Flemish tapestry and old portraits, which appealed to Lola’s sense of the decorative and sent her head up with a tilt of proprietorship. This was her atmosphere. This was the corridor along which her imaginary sycophants had passed so often to her room in Queen’s Road, Bayswater. “We’re not supposed to go through here,” said Simpkins, eager to talk, “except on duty. But it’s a short cut to the housekeeper’s quarters and there’s no one in to catch us. You look well against that hanging,” he added. “Like a picture in the Academy,”—which to him was the Temple of Art.

A door opened and there were heavy footsteps.

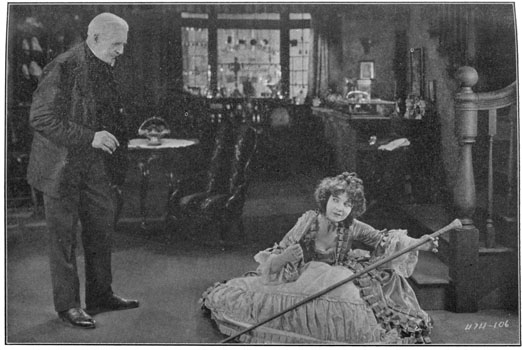

“Look out. The governor.” He seized Lola’s arm and in a panic drew her into the shadow of a large armoire.

Her heart jumped into her mouth!—It was her hero in the flesh, the man at whose feet she had worshipped,—within a few inches of her, walking slowly, with his hands behind his back, his mouth compressed and a sort of hit-me-why-don’t-you in his eye. Still with Simpkins’s hand upon her arm she slipped out,—not to be seen, not with any thought of herself, but to watch Fallaray stride along the corridor; and get the wonder of a first look.

A door banged and he was gone.

“A pretty near thing,” said Simpkins. “It always happens like that. I don’t suppose he would have noticed us. Mostly he sees nothing but his thoughts,—looks inwards, I mean. But rules is rules. He lives in that wing of the ’ouse,—has a library and a bedroom there and another room fitted up as a gym where he goes through exercises to keep hisself fit. Give ’im enough in the House to keep ’im fit, you’d think, wouldn’t yer? A wonderful man.—Come on, Miss, nick through here.” He opened a door, ran lightly up a short flight of stairs and came back again into the servant’s passage. “’Ere you are,” he said and smiled brilliantly, putting in, as he thought, good work. This girl——! “I’ll be glad to see you ’ome,” he added anxiously.

Lola said, “Thank you, but I have some one waiting for me,” and entered.

IX

“Well!” said Miss Breezy.

“I hope so,” said Lola, kissing the ear that was presented to her.

“I’m just rearranging my things. Her Ladyship’s just given me some new pictures. They used to be in the morning room, but she got sick of them and handed ’em over to me. I’m going to hang them up.” She might have added that nearly everything that the room contained had been given to her by Lady Feo with a similar generosity but her sense of humor was not very keen or else her sense of loyalty was. At any rate, there she stood in the middle of a nice airy room with something around her head to keep the dust out of her hair, wearing a pair of gloves, a stepladder near at hand.

There were six fair-sized canvases in gold frames,—seascapes; bold, excellent work, with the wind blowing over them and spray coming out that made the lips all salty. They made you hear the mewing of sea gulls.

“Lady Feo bought them to help a young artist. He was killed in the War. She hates the sea, it makes her sick, and doesn’t want to be reminded of anything sad. I don’t wonder, and anyway, they’ll look very nice here. Do you like them?”

Lola had sized them up in a glance. She too would have turned them out. They seemed to her rough and draughty. “Yes,” she said, “they’re very good, aren’t they?” She mounted the ladder and held out her hands. She had come to ask a favor. She might as well make herself popular at once. “Hand them up, Auntie, and I’ll hang them for you.”

“Oh, well now, that’s very nice. I get giddy on a ladder. You came just at the right moment. Can you manage it? It’s very heavy. The first time I’ve ever seen you making yourself useful, my dear.”

This enabled Lola to get in her first point. “Mother never allows me to be useful,” she said, “and really doesn’t understand the sort of thing that I can do best.” She stretched up, hung the cord over a brass bracket and straightened it.

“Well, you can certainly do this job! Go on and do the rest while you’re at it. I was looking forward to a very tiring afternoon. I didn’t want to have any of the maids to help me. They resent being asked to do anything that is outside their regular duty.”

And so Lola proceeded, hating to get her hands dirty and not very keen on indulging in athletics, but with a determination made doubly firm by the fleeting sight of Fallaray.

Miss Breezy was in an equable mood that afternoon,—less pompous than usual, less consumed with the importance of being the controlling brain in the management of the Fallaray “establishment,” as she called it in the stilted language of the auctioneer. She became almost human as she watched Lola perform the task which would have put her to a considerable amount of physical inconvenience. When one is relieved of anything in the nature of work, equability is the cheapest form of gratitude.

The room was a particularly nice one, large, with a low ceiling and two windows which overlooked Dover Street. It didn’t in the least indicate the character of the housekeeper because not a single thing in it was her own except a few books. Everything else had been given to her by Lady Feo, and like the pictures, had been discarded from one or other of the rooms below. The Sheraton sofa had come from the drawing-room. A Dowager Duchess had sat on it one evening after dinner and let herself go on the question of the Feo gang. It had been thrown out the following morning. The armoire of ripe oak, made up of old French altarpieces—an exquisite thing worth its weight in gold—had suffered a similar fate. Rappé the ubiquitous photographer had taken a picture of Lady Feo leaning against one of its doors. It turned out badly. In fact, the angel on the other door looked precisely as though it were growing on Lady Feo’s nose. It might have been good art but it was bad salesmanship. Away went the armoire. The story of all the other things was the same so that the room had begun to assume the appearance of the den of a dealer in old furniture. There were even a couple of old masters on the walls,—a Reynolds and a Lely, portraits of the members of Lady Feo’s family whose faces she objected to and whose admonishing eyes she couldn’t bear to have upon her when she came down to luncheon feeling a little chippy after a night out. These also were priceless. It had become indeed one of the nicest rooms in the house. Every day it added something to Miss Breezy’s increasing air of dignity and beatitude.

Lola did not fail to admire the way in which her aunt had arranged her wonderful presents and used all her arts of flattery before she came round to the reason of her visit. This she did as soon as Miss Breezy had prepared tea with something of the ceremony of the Japanese and arranged herself to be entertained by the child for whose temperament she had found some excuse by labelling it French. Going cunningly to work, she began by saying, “What do you think? You remember Mother’s friends, the Proutys, who were playing cards the other night?”

“Indeed I do,” replied Miss Breezy. “Whenever I meet those people it takes me some time to get over the unpleasant smell of meat fat. What about them?”

“Cissie, the daughter, has gone into the chorus of the Gaiety, and is very happy there. She’s going to be in the second row at first, but she’s bound to be noticed, she says, because she has to pose as a statue in the second act covered all over with white stuff.”

“Nothing else?”

“No, but it will take an hour to put on every night. And before the end of the run she’ll probably be married at St. Margaret’s to an officer in the Guards, she says. She told me that she couldn’t hope to become a lady in any other way. I was wondering what you would say if I did the same thing?”

Miss Breezy almost dropped her cup as Lola knew that she would. “You don’t mean to say you’ve come to tell me that you’ve got that fearful scheme in the back of your head, you alarming child? A chorus girl?”

Lola laughed. “You know my way of improving myself: to serve an apprenticeship as a lady’s maid, a respectable way,—the way in which you’re going to help me now that you’ve thought it all over.”

The answer came like the rapping of a machine gun. “I’ve not thought it over and what’s more, I’m not going to begin to think it over. I told you so.”

Without turning a hair Lola handed a plate of cakes. “But you wouldn’t like me to follow Cissie’s example, would you,—and that’s the alternative.” Poor dear old Aunt! What was the use of pretending to be firm. All the trumps were against her.

But for once Lola miscalculated her hand and the woman. “If you must make a fool of yourself,” said Miss Breezy, “you must. I’m not your mother and luckily you can’t break my heart. I told you the other night and I tell you again that I do not intend to be a party to your lowering yourself by becoming a servant and there’s an end of it.” And she waved her disengaged hand.

It was almost a minute before Lola recovered her breath. She sat back, then, and put her head on one side. “In that case,” she said in a perfectly even voice, “I must try to get used to the other idea. I think I might look rather well in tights and Cissie tells me that if I were to join her at the Gaiety I should be put into a number in which five other girls will come on in underclothes in a bedroom scene. Of course I should keep my own name and before long you’d see my photograph in the Tatler as ‘the latest recruit to the footlights,—the great-great-granddaughter of the famous Madame de Brézé.’ I should tell the first reporter that, of course, to make it interesting.”

Miss Breezy rocked to and fro, gripping her cup. How often had she shuddered at the sight of scantily dressed precocious girls sitting in alarming attitudes on the shiny paper of the Tatler. To think of Lola in underclothes, debasing a highly respectable name! Nevertheless, “I am not to be bullied,” she said, wobbling like a turkey. “I have always given way to you before, Lola, but in this case my mind is made up. Can’t you understand how awkward it would be to have you in the house on a level with servants who have to be kept in order by me? It would undermine my authority.” That was the point, and it was a good one. And then her starchiness left her under the horror of the alternative. “As for that other thing,—well, you couldn’t go a better way to kill your poor mother and surely you don’t want to do that?”

“Of course I don’t, Auntie.”

“There’s no call for you to think about any way of earning a living, Lola. Your parents don’t want to get rid of you, Heaven knows, and even in these bad times they can get along very nicely and keep you too. You know that.”

Lola had never dreamed of this adamantine attitude. Her aunt had been so easy to manage before. What was she to do?

Thinking that she was winning, Miss Breezy went at it again. “Come, now. Be a good child and forget both these schemes. Go on with your classes and it won’t be long before a suitable person will turn up and ask you to marry him. Your type marries young. Now, will you promise me to think no more about it all?”

But this was Lola’s only chance to enter the first stage of her crusade. She would fight for it to the last gasp. “The chorus, yes,” she said. “As for the other thing, no, Auntie. If you won’t help me I must get the paper in the morning and search through the advertisements. I’m sure to come across some one who wants a lady’s maid and after all, it won’t very much matter who it is. You see, I want to earn my living, and I have made up my mind to do it in this way. There’s good pay, a beautiful house to live in, no early trains to catch, no bad weather to go through, holidays in the country and with any luck foreign travel. I can’t understand why many more girls like me don’t go in for this sort of life. I only thought, of course, it would be so nice to be under your eye and guidance. Mother would much prefer it to be that way, I’m sure.”

But even this practical argument had no effect except to rouse the good lady’s dander. “You are a very nagging girl,” she cried. “I can see perfectly well what you’re driving at but you won’t undermine my decision, I can tell you that. I will not have you in this house and that’s final.”

Lola was beaten. To her astonishment and chagrin she found that her nail was not to be hammered in. There was steel in the old lady’s composition, after all. But there was steel in her own and she quickly decided to leave things as they stood and think out another line of attack before the following Thursday. And then, remembering Ernest Treadwell, who was living up to his name from one end of the street to the other and back, she rose to tear herself away with an air of great patience and affection. Just as she was about to bend down and touch the usual ear with her lips, the door suddenly swung open and a woman with bobbed hair, wearing a red velvet tam-o’-shanter and a curious one-piece garment of brown velvet which disclosed a pair of very admirable legs, stood smiling in the doorway. Her face was as white as the petals of a white rose. Her large violet eyes had lashes as black as her eyebrows and her wanton mouth showed a set of teeth as white and strong as a negro’s. “Oh, hello, Breezy,” she cried out, her voice round and ringing. “Excuse my barging in like this. I want to know what you’ve done about the table decorations for to-morrow night.”

Miss Breezy rose hurriedly to her feet, and Lola, although she had never seen this woman before, followed her example, sensing the fact that here was the famous Lady Feo.

“I sent Mr. Biddle round to Lee and Higgins in Bond Street, my lady. You need have no anxiety about it.”

“That’s all right but I’ve altered my mind. I don’t want flowers. I’ve bought a set of caricatures and I’m going to put one in front of every place. If it’s too late to cancel the order, telephone to Lee and Higgins and tell them to send the flowers to any old hospital that occurs to them.” Lady Feo had spotted Lola immediately and during all this time had never taken her eyes away from the girl’s face and figure, which she looked over with frank and unabashed curiosity and admiration. With characteristic effrontery she made her examination as thorough as she would have done if she had been sizing up a horse with a view to purchase. “Attractive little person,” she said to herself. “As dainty as a piece of Sèvres. What the devil’s she doing here?” Making conversation with a view to discover who Lola was, she added aloud, “I see you’ve hung the pictures, Breezy.—Breezy and seascapes; they go well together, don’t they?” And she laughed at the little joke,—a gay and boyish laugh.

With her heart thumping and a ray of hope in front of her, Lola marked her appreciation of the joke with her most delighted smile.

And Miss Breezy indulged in a diplomatic titter.

“Isn’t it a little remiss of you, Breezy, not to introduce me to your friend?”

“Oh, I beg your ladyship’s pardon, I’m sure. This is my niece Lola.” She wished the child in the middle of next week and dreaded the result of this most unfortunate interruption.

Lady Feo stretched out her hand,—a long-fingered able hand, born for the violin. “How do you do,” she said, as though to an equal. “How is it that I haven’t seen you before? Breezy and I are such old friends. I call her Breezy in that rather abrupt manner—forgive me, won’t you?—because I’m both rude and affectionate. I hope I didn’t cut in on a family consultation?”

Lola braced herself. Here was her opportunity indeed! “Oh, no, my lady. It was a sort of consultation, because I came to talk to Aunt about my future. It’s time I earned my own living and as she doesn’t want me to go on the stage, she’s going to be kind enough to help me in another way.” She got all this in a little breathlessly, with charming naïveté.

“What way?” asked Lady Feo bluntly. “I should think you’d make a great success on the stage.”

Lola took no notice of her aunt’s angry and frantic signs. She stood demure and modest under the searching gaze of Lady Feo and with a sense of extreme triumph took the jump. “The way I most wanted to begin,” she said, “was to be your ladyship’s maid. That’s my great ambition.”

“And for the love of heaven, why not? Breezy, why the deuce haven’t you told me about this girl? I would like to have her about me. She’s decorative. I wouldn’t mind being touched by her and I’m sure she’d look after my things. Look how neat she is. She might have come out of a bandbox.”

Miss Breezy bit her lip. She was bitterly annoyed. She was unaware of the expression but she felt that Lola had double-crossed her,—as indeed she had. “Well, my lady,” she said, “to tell you the truth, I didn’t think that you would care to have two people of the same family in your house. It always leads to trouble.”

“Oh, rot,” said Lady Feo, “I loathe those old shibboleths. They’re so silly.” She turned to Lola. “Look here, do you really mean to say that you’d rather be a lady’s maid than kick your heels about in the chorus?”

“If you please, my lady,” said Lola.

“Well, I think you’ll miss a lot of fun, but as far as I’m concerned, you’re an absolute Godsend. The girl I’ve had for two years is going to be married. Of course, I can’t stop that, as much as I shall miss her. The earth needs repeopling, so I must let her go. The question has been where to get another. With all the unemployment no one seems very keen on doing anything but work in factories. I’d love to have you. Come by all means. Breezy, engage her. I hope we shall rub along very nicely together.”

As much to hide the gleam in her eyes from her aunt as to show deference to her new mistress, Lola bowed. “I thank you, my lady,” she said.

“Fine,” said Lady Feo, “fine. That’s great. Saves me a world of trouble. Pretty lucky thing that I looked in here, wasn’t it?” She went to the door and turned. “When can you come, Lola?”

“To-morrow.—To-night.”

“To-night. I will let Emily off at once. She’ll be glad enough. I’ll send you home in the car. You can pack your things and get back in time to brush my hair. I suppose you know something about your job?”

Miss Breezy broke in hurriedly. Even now perhaps it might not be too late to beat this girl at her own game. “That’s it, my lady,” she said, tumbling over her words. “She doesn’t know anything about it. I’m afraid I ought to say——”