The Project Gutenberg EBook of Handbook of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts by Joseph Breck and Henry Wehle

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Handbook of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts Author: Joseph Breck and Henry Wehle Release Date: February 13, 2011 [Ebook #35269] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HANDBOOK OF THE MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ARTS ***

With 143 Illustrations Published by the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts

1917

Contents

- THE MINNEAPOLIS SOCIETY OF FINE ARTS

- PREFACE

- THE MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ARTS

- GENERAL INFORMATION

- PLAN OF THE FIRST FLOOR

- PLAN OF THE SECOND FLOOR

- THE FIRST FLOOR

- THE CAST COLLECTION

- THE PRINT DEPARTMENT

- NEAR EASTERN ART

- JAPANESE ART

- CHINESE ART

- EGYPTIAN ART

- ANCIENT ART

- GOTHIC ART

- RENAISSANCE ART

- SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ART

- EIGHTEENTH CENTURY ART

- THE SECOND FLOOR

- MODERN AMERICAN PAINTINGS

- MODERN EUROPEAN PAINTINGS

- MODERN DRAWINGS

- MODERN SCULPTURE

- THE BRADSTREET ROOM

Illustrations

- FIRST FLOOR PLAN.

- SECOND FLOOR PLAN.

- View of the South Hall. Renaissance Casts.

- The East Corridor: Greek and Roman Casts

- Gallery B-10: Gothic Casts

- The Print Study Room

- Christ Healing the Sick, Etching, Rembrandt, 1607-1669

- Portrait of Sir Joshua Reynolds by Himself Mezzotint by Valentine Green, 1739-1813

- The Breaking up of the Agamemnon. Sir Francis Seymour Haden, 1818-1910

- Weary, Dry-point, by James McNeil Whistler, 1834-1903

- La Gallerie Notre-Dame, Etching by Meryon, 1821-1868

- The Diggers, Etching (Third State), by F. Millet, 1814-1875

- Plate, with Floral Design Asia Minor, XVI Century

- Two Fragments of Bowls, Persian, Rhages, XIII Century. Left: Polychrome Decoration, Right: Lustred Decoration

- Velvet Brocade Turkish, XVI Century

- Mosque Doors, Carved Wood, Persian, about 1500

- Autumn, Six-fold Screen, by Yeitoku, 1543-1590

- Winter, Six-fold Screen, by Yeitoku, 1543-1590

- Tiger, Attributed to Sesshu, 1420-1506. After a Design by Yen-Hiu, 1082-1135. Gift of Charles L. Freer

- Covered Box, Cloisonne Enamel. Japanese, XIX Century. Decorated in the Old Korean Style.

- Cloisonne Vase Chinese, Ming Dynasty

- Horse's Head. Han Period

- Mortuary Vase. Han Period

- Painting On Silk by Ma Yuan

- Ancient Chinese Jades

- Painting attributed to Pien Chin-Stan

- Tung Fang So. Jade

- Princess Yang. Ming Period

- Vase. Ming Period

- Chinese Porcelain of the XVII and XVIII Centuries

- Detail of the Cartonnage Enclosing the Mummy of the “Lady of the House, Tesha”. Dynasty XXII-XXV

- Coffin and Mummy of the “Lady of the House, Tesha” From Thebes, Dynasty XXII-XXV.

- Lower Part of Coffin. Dynasty XXI

- Statuette, Wood. Dynasty XII

- Goddess Neith, Bronze Dynasty XXVI

- Funerary Papyrus

- Ushabti, Wood

- Cover of a Canopic Jar, Terracotta

- Group of Egyptian Alabaster Vessels

- Bronze Mirror

- Amulet

- Sacred Eye and Scarab

- Piriform Vase. Cypriote, Mycenaean Style. ca. 1500-1200 B.C.

- Cypriote Pottery

- Babylonian Tablet From Jokha, ca. 2350 B. C.

- A Pope, Statuette in Oak. Flemish, about 1500

- Head of the Virgin, Stone. French, late XIV Century

- A View of the Gothic Room

- Hunting Party with Falcons. Burgundian Tapestry, about 1450

- Detail: Falcons Attacking a Heron; Hunter with Lure

- Two Scenes from the Story of Esther. Flemish Tapestry, late XV Century

- The Virgin and St. John. Flemish, about 1500

- Virgin and Child, Stone. French, XIV Century

- A Saint, Lindenwood. German, School of Ulm, about 1500

- St. Mary Magdalene, Linden Wood. Attributed to Jorg Syrlin the Younger, 1425-after 1521

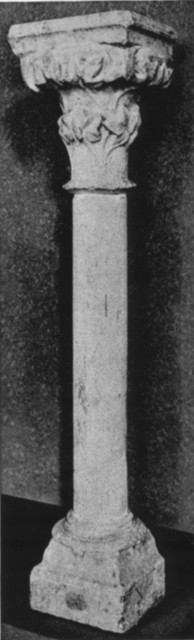

- Small Column, Marble. Southern French, XIV Century

- St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata. School of Giotto, about 1330

- Madonna and Child. The Master of the St. Ursula Legend

- Madonna and Angels. Atelier of Jean Bourdichon, 1457-1521

- The Miraculous Field of Wheat. Joachim Patinir and Quentin Massys

- A Group in the First Renaissance Gallery

- The Second Renaissance Gallery

- Madonna and Child. The Master of the San Miniato Altar-piece

- Portrait of an Ecclesiastic. Giovanni Battista Moroni, ca. 1520-1578.

- Madonna and Child. Giampietrino, fl. first half of XVI Century

- Madonna and Saints. Palma il Vecchio, about 1480-1528

- Stucco Relief. Workshop of Antonio Rossellino

- Glass. Venetian, XVI Century

- Chair. Florentine, XVI Century

- Pomona, Glazed Terracotta Statuette. Giovanni Delia Robbia, 1469-1529 (?)

- Candlestick, Wood, Carved and Gilded. Florentine, XVI Century

- Virgil Appearing to Dante, Tapestry. Florentine, Middle of XVI Century

- Joseph Ruler Over Egypt, Tapestry. Brussels, Second Quarter of XVI Century

- Lectern, Walnut. Italian, Umbrian, XVI Century

- Cassone, with Gilded Decoration. Florentine, Third Quarter of XV Century

- Cassone, Carved Walnut. Sienese, 1514

- Chair, Portuguese. XVII Century

- Henry Hyde, Lord Clarendon. Sir Peter Lely, 1618-1680

- The Concert. Michiel van Musscher, 1645-1705

- Portrait of a Lady. Michiel Mierevelt, 1567-1641

- Tapestry, Hunting Scenes. Flemish, about 1600

- Chest, Oak. English, XVII Century

- Head of an Old Man. Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, 1727-1804

- Portrait of James Ward. Gilbert Stuart, 1755-1828

- Death on the Pale Horse. Benjamin West, 1738-1820

- Large Embroidered Hanging. French, Early XVIII Century Subject, Spring: from a set representing the Four Seasons, in memory of Mrs. Thomas Lowry by Mrs. Gustav Schwyzer, Mrs. Percy Hagerman and Horace Lowry

- Needlepoint, Reticello. Italian, Early XVII Century

- Lace, Needlepoint, Point d'Argentan, French, XVIII Century Lace, Needlepoint, Point d'Alencon, French, XVIII Century Lace, Needlepoint, Rosepoint, Venetian, Early XVIII Century Bobbin Lace, Point d'Angleterre, Flemish, XVIII Century

- Chair, Pearwood Venetian. Early XVIII Century

- Tripod Table with Top Tilted Back

- Tripod Table, Mahogany, English, about 1760-1765

- Card Table, Mahogany English or American, about 1750-1775

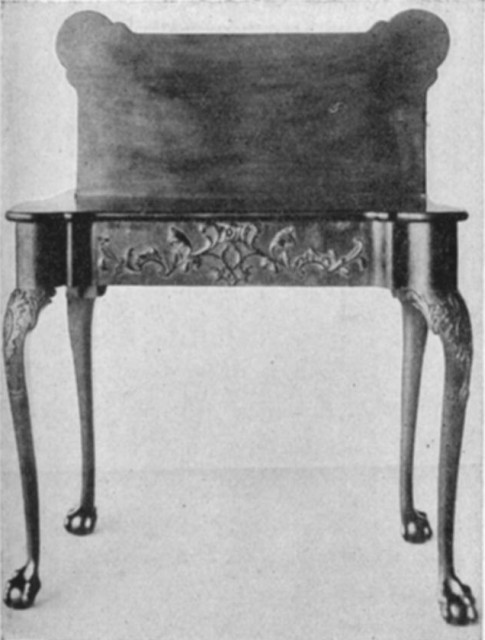

- Dressing-table, Mahogany. American, about 1760-1775

- Large Flip Glass and Two Liquor Bottles. Stiegel Glass, American, XVIII Century.

- Le Beurre, by Ovide Yenesse.

- Mount Whitney. Albert Bierstadt, 1830-1902

- The Conch Divers. Winslow Homer, 1836-1910

- Moonlit Surf, Paul Dougherty, 1877-

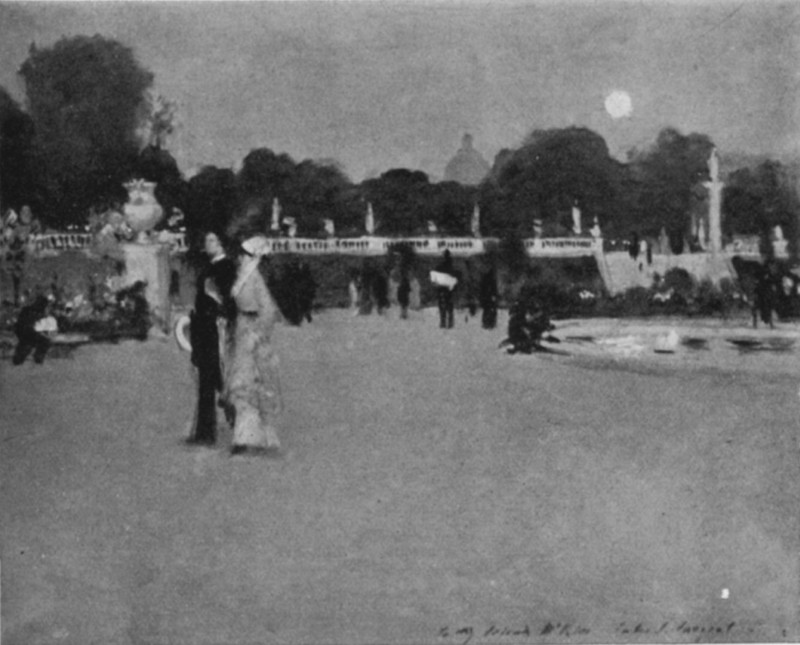

- Luxembourg Gardens at Twilight. John S. Sargent, 1856-

- The White Bridge. John H. Twachtman, 1853-1902

- A Ray of Sunlight. John W. Alexander, 1857-1915.

- River in Winter. Gardner Symons, 1861-

- Garden in June. Frederick C. Frieseke, 1874-

- The Open Sea. Emil Carlsen, 1853

- The Yellow Flower. Albert Reid, 1863-

- Midsummer. R. Sloan Bredin, 1881-

- Night's Overture. Arthur B. Davies, 1862-

- Landscape. Georges Michel, 1763-1843

- Child with Cherries. Gillaume Adolphe Bouguereau, 1825-1905

- The Bath. Jean Leon Gerome, 1824-1903

- The Storming of Tel-el-Kebir. Alphonse de Neuville, 1836-1883

- Napoleon's Retreat from Russia. Jan V. Chelminski, 1851-

- The Roe Covert. Gustave Courbet, 1819-1877

- Woodland Scene. N. V. Diaz de la Pena, 1809-1879

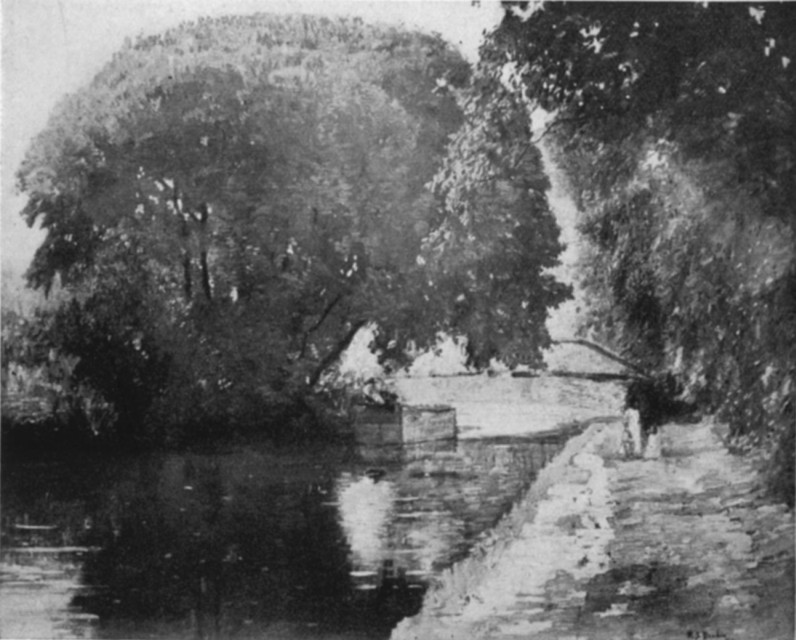

- River Scene. Charles Francois Daubigny, 1817-1878

- Landscape with Cattle. Constant Troyon, 1810-1865

- Fording the River. Constant Troyon, 1810-1865

- The Beach at Trouville. Eugene Boudin, 1824-1898

- Geranium. Albert Andre, 1869-

- The Conversion. Gabriel Max, 1840-

- The Scouts. Adolph Schreyer, 1828-1899

- Mountain Village. Paul Crodel, 1862-

- Cattle in Sunshine. Heinrich von Zugel, 1850-

- Summer Evening at the River. Gustav Adolf Fjaestad, 1870-

- Dalecarlian Peasant. Helmer Mas-Olle, 1884-

- Mother and Children. Josef Israels, 1824-1911

- On the Beach. Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida, 1863-

- Landscape. Alexander Nasmyth, 1758-1840

- Psyche's Wedding. Sir Edward Burne-Jones, 1833-1898

- Silver and Green. Hilda Fearon, English, ?-1917

- Studies of Draped Figures, Pencil Drawing. Sir Edward Burne-Jones, English, 1833-1898

- Fire in Ingram Street, Pencil Drawing. Muirhead Bone, Scotch, 1876-

- Portrait, Drawing in Chalk and Wash. William Strang, Scotch, 1859-

- Mucherach Castle, Drawing in Pen and Wash. David Young Cameron, Scotch, 1865-

- Tuscan Landscape, Drawing in Pen and Wash. Muirhead Bone, Scotch, 1876-

- Study for an Illustration, Drawing in Lithographic Crayon. Theophile Alexandre Steinlen, French, 1859-

- An Old Rabbi, Pencil Drawing. William Rothenstein, English, 1872-

- Playfulness. Paul Manship, 1885-

- Plaque, La Guerre. Hubert Ponscarme, 1827-1903

- Medal, L'Art Decorative, by Ovide Yencesse, 1869-

- A Corner of the Room

- Color Print. Yeizan, flourished 1800-1830

- Carved Panel. XVIII Century

THE MINNEAPOLIS SOCIETY OF FINE ARTS

OFFICERS AND MEMBER OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

| John R. Van Derlip | President |

| Eugene J. Carpenter | First Vice President |

| Edward C. Gale | Second Vice President |

| Russell M. Bennett | Third Vice President |

| Harry W. Rubins | Secretary |

| Perry Harrison | Treasurer |

| Joseph Breck | Director |

TRUSTEES

TERM EXPIRES 1918

| Charles C. Bovey | |

| Charles L. Freer | |

| Francis W. Little | |

| John R. Van Derlip | |

| William C. Whitney |

TERM EXPIRES 1919

| Russell M. Bennett | |

| William Y. Chute | |

| Charles L. Hutchinson | |

| Thomas B. Janney | |

| Horace Lowry | |

| Louis W. Hill |

TERM EXPIRES 1920

| William H. Bovey | |

| Edward C. Gale | |

| Edmund J. Phelps | |

| Richardson Phelps | |

| Oliver C. Wyman |

TERM EXPIRES 1921

| Eugene J. Carpenter | |

| Edwin H. Hewitt | |

| Herschel V. Jones | |

| Angus W. Morrison | |

| Fendall G. Winston | |

| James Ford Bell |

TERM EXPIRES 1922

| Harington Beard | |

| Edmund D. Brooks | |

| Elbert L. Carpenter | |

| Robert W. De Forest | |

| Alfred F. Pillsbury | |

| Laurits S. Swenson |

EX-OFFICIO MEMBERS

| The Mayor of Minneapolis | |

| The President of the Board of Park Commissioners | |

| The President of the Library Board | |

| The President of the Board of Education |

PREFACE

When the Institute was first opened, little more than two and one half years ago, the permanent collection occupied but a small part of the exhibition space. Since then the collection has increased in size and importance to an extent that warrants us, we feel, in publishing this illustrated handbook, which, although intended primarily for the use and convenience of visitors, at the same time may not be without interest as a record of accomplishment within so brief a period. This rapid development of our collection has been made possible, first of all, by the great liberality of numerous friends, but it has been facilitated by firm adherence to a well defined policy in respect to acquisitions. This policy is based on two cardinal beliefs. The first is that an art museum is of the greatest value to a community when its collections embrace both the major and minor arts of all countries and all times. The second is that the standard must be high. It would be idle to pretend that every object in our collection is a masterpiece of the highest order, but it is better to have an ideal, which may not be wholly realized, than to have none.

Through the munificent bequest of William Hood Dunwoody, the Institute has had for its purchases the income of one million dollars. Several important paintings have come to the Institute through the bequest of Mrs. W. H. Dunwoody (Child with Cherries, Landscape with Cattle, Fording the River). In memory of their mother the late Mrs. Thomas Lowry, Mrs. Gustav Schwyzer, Mrs. Percy Hagerman and Horace Lowry have made a welcome gift of paintings and other works of art (Tapestry, Hunting Scenes, Large Embroidered Hanging, The Conversion, The Scouts). Among the numerous gifts must be instanced the Ladd Collection of Prints, the gift of an anonymous donor (see the Print Department chapter); the Charles Jairus Martin Memorial Collection of Tapestries, the gift of Mrs. C. J. Martin (Hunting Party with Falcons, Two Scenes from the Story of Esther, Joseph, Ruler over Egypt, Virgil Appearing to Dante); the Martin B. Koon Memorial Collection of Contemporary American Paintings, the gift of Mrs. C. C. Bovey and Mrs. C. D. Velie (Luxembourg Gardens at Twilight, The White Bridge, River in Winter, Garden in June, The Open Sea, The Yellow Flower, Night's Overture); the Bradstreet Memorial Collection of Japanese Art, the gift of Mrs. Elizabeth B. Carleton and Mrs. Margaret Kimball (The Bradstreet Room, Color Print by Yeizan, Carved Panel); and the Cast Collection, the gift of Russell M. Bennett (see the Cast Collection chapter). The Oriental collection has been enriched by a gift of Chinese porcelain from Mrs. E. C. Gale (Chinese Porcelain), and by a collection of Japanese paintings and other material from Charles L. Freer (Tiger). Valuable paintings and other works of art have been given by James J. Hill (Landscape, The Storming of Tel El Kebir, Napoleon's Retreat from Russia, The Roe Covert), Mrs. Frederick B. Wells (The Bath, Woodland Scene, River Scene, Mother and Children), James Ford Bell (Madonna with Saints), T. B. Walker, and others to whose generosity the Society of Fine Arts is greatly indebted.

In the preparation of this handbook, I have been aided by Mr. Harry B. Wehle, Assistant to the Institute Staff, who is responsible for the notes on XIX Century and modern art. My part of the work, except for general supervision, has been confined to the earlier periods.

THE MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ARTS

[pg viii]The Institute is maintained by the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, incorporated in 1883 for the purpose of promoting a knowledge and love of art in the community. The purpose of the Society found its first expression in a school of art, established in 1886 and for many years carried on in rooms in the building of the Public Library. Since November, 1916, the School has occupied its own building, the Julia Morrison Memorial Building, situated in the same Park as the Institute. From its inception, however, the members of the Society of Fine Arts had purposed establishing, in addition to the art school, a museum of art. In 1911 this hope suddenly began to take the shape of reality. In January of that year, Clinton Morrison offered as a gift to the Society the ten acre tract of land at Twenty-fourth Street between Stevens and Third Avenues, valued at $250,000, as a site for museum and school buildings, provided $500,000 should be secured for the erection of the museum. Immediately upon the announcement of Mr. Morrison's generous offer, William Hood Dunwoody, then President of the Society, promised $100,000 for the building fund. At a dinner held on January 10, 1911, approximately $250,000 additional was pledged by other public-spirited citizens, and by the end of the month the entire sum for building had been obtained.

Plans for a building which could be constructed in successive units, to occupy eventually the entire tract, were prepared by McKim, Mead & White of New York. In August, 1912, the construction work was begun on the main unit, and late in 1914 the building was completed. The Institute was opened to the public on January 7, 1915.

The present museum is about 325 feet long and 100 feet deep, and comprises approximately one-seventh of the entire plan. The total cost was $537,000. The construction is of brick, concrete, and steel, with a facade of white granite. The classical design of the building is considered exceptionally beautiful in its proportions and in the refinement of its details. There are two main exhibition floors. The First Floor contains sixteen exhibition halls and galleries, as well as the entrance hall, information office, check room, library and print-study. The Second Floor comprises thirteen galleries, ten of which are devoted to permanent exhibitions, one to exhibitions of prints, and two to transient exhibitions. On the Ground Floor are located the administration offices, the Trustees' room, toilets, women's rest room, lunch room, class room, shipping room and store rooms.

For the purchase of works of art, the Society has the income from $1,000,000, the munificent bequest of William Hood Dunwoody, who died February 8, 1914. This fund can be used only for the purchase of works of art. For the maintenance of the Institute, the Society is dependent upon membership dues and upon a city tax levy of one-eighth of a mill.

GENERAL INFORMATION

LOCATION. The Institute is located on East 24th Street between Stevens and Third Avenues. It can be reached easily from either the Nicollet Avenue or the Fourth Avenue car line.

HOURS OF OPENING. The Institute is open to the public daily from 10:00 A.M. to 5:00 P.M. except on Sunday and Monday, when the hours are 1:00 P.M. to 5:00 P.M.

ADMISSION. Admission is free on Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday; other days, a charge of twenty-five cents is made, except to members of the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, to school children accompanied by teachers, and to art students, teachers in the public schools, and special students holding annual admission cards, which will be issued upon application.

INFORMATION DESK. Admission tickets, a public telephone, post cards and publications of the Institute may be found at the Information Desk (at the left on entering the building). Application should be made here to see any officer of the Institute. The use of a wheel-chair in the galleries may be obtained here without charge; when an attendant is provided, the charge is $1.00 per hour.

EXPERT GUIDANCE. Visitors wishing docent service, or guidance through the galleries, should make application at the Information Desk.

COPYING AND PHOTOGRAPHING. Application for permission to copy or photograph must be made to the Director.

LUNCH ROOM. The lunch room is located on the Ground Floor at the west end of the corridor. Luncheon is served from 12:30 to 2:00; tea from 3:30 to 4:45. Closed during the summer.

REST ROOM. The rest room for women is located near the lunch room.

BULLETIN. The Institute publishes an illustrated bulletin monthly, October to June. It is free to members; subscription rate to non-members, $.75; single copies, $.10.

ART SCHOOL. For information concerning the Art School apply to the Director, Minneapolis School of Art, 200 East 25th Street.

MEMBERSHIP. The Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts offers, through its various classes of membership, the opportunity of sharing in the support of the Institute and School of Art and of enjoying the privileges afforded by the Society. Membership tickets are issued upon application to the Secretary at the Institute accompanied by membership fee. All classes of membership, except associate and club membership, entitle members to: (1) free admission, at all times when the Institute is open to the public, for themselves and members of their families and out-of-town guests; (2) invitations to all receptions given at the Institute by the Trustees; (3) free admission to all lectures and entertainments given under the auspices of the Society; (4) free guide service; (5) a subscription to the monthly Bulletin published by the Society.

CLASSES OF MEMBERSHIP

| BENEFACTOR. Any person contributing money or property to the value of $25,000. | |

| PATRON. Any person contributing money or property to the value of $10,000. | |

| FELLOW IN PERPETUITY. Any person contributing money or property to the value of $5,000. | |

| FELLOW FOR LIFE. Any person contributing money or property to the value of $1,000 | |

| The above constitute the Governing Members of the Society. | |

| LIFE MEMBERS. Any person paying the life membership fee of $100.00. | |

| ANNUAL MEMBERS. Any person paying the annual membership fee of $10.00. | |

| ASSOCIATE MEMBERS. Privileges restricted to person paying an annual membership fee of $2.00. Limited to teachers and students. | |

| CLUB MEMBERSHIP. Clubs may become members of the Society of Fine Arts by special arrangements, which entitle such groups to meet in the galleries or to use the lecture room and stereopticon. |

PLAN OF THE FIRST FLOOR

Works of art earlier than the XIX century, the cast collection, and the Print Department are located on the First Floor. The visitor who wishes to make a general tour of the collections is advised to proceed from the entrance through the octagonal hall to the corridor at the left. At the end of this corridor is the entrance to the Oriental collections. The Egyptian collection in the adjacent gallery may then be visited. Returning to the corridor, the visitor will come to the Library and Print Study Room. (The Print Department will eventually be given space on the Ground Floor, and the galleries now occupied devoted to Greek and Roman art.) Casts of classical sculpture are exhibited in the corridor. The cast collection is continued in Gallery B-10 (Gothic art) and in Galleries B-11, 12, and the west corridor (Renaissance and later periods). Opposite the stairs to the Second Floor is the entrance to a series of rooms in which original examples of European art are exhibited according to period. The first gallery is devoted to Gothic art; the next two to Renaissance art; these are followed by the gallery of XVII and the two galleries of XVIII century art.

The stairs opposite Gallery B-15 lead to the Ground Floor, where are the lunch room, women's rest room, toilets, class room, administration offices, and work rooms.

PLAN OF THE SECOND FLOOR

Nineteenth century and modern works of art are exhibited on the Second Floor. On this floor are also the Print Exhibition Gallery and the Bradstreet Collection. The visitor is advised to enter the series of galleries through the Print Exhibition Gallery, C-1. From this room the visitor may proceed to the galleries in which paintings of the American and European schools are exhibited. Having completed the circuit along the north front of the building, the visitor may return by way of the corridors and galleries to the south (modern drawings and sculpture, the Bradstreet Room). Galleries C-8 and 9 are used for transient exhibitions, generally changed each month.

[pg xii]THE FIRST FLOOR

THE CAST COLLECTION

The cast collection is installed in Galleries B-2, 10, 11, 12 and the J corridors on the First Floor. To view the collection in chronological sequence, the visitor should proceed from the octagonal Gallery B-2 (V century Greek sculpture) down the north side of corridor B-3 (V century Greek sculpture). Returning, the visitor will find in the alcoves on the south side of the corridor casts of Greek sculpture of the IV century and Hellenistic periods, and casts of Roman sculpture. The collection is continued in Gallery B-10 (Gothic sculpture), which should be entered from the corridor. Casts of Renaissance sculpture are exhibited in Gallery B-1 (Early Renaissance, XV century) and Gallery B-12 (Late Renaissance, XVI century). Other casts of sculptures of the Renaissance and later periods are exhibited in the west corridor.

The educational value of a cast collection is beyond question. Through these mechanical reproductions, it is possible to obtain a fairly adequate idea of the great masterpieces of sculpture, that are inaccessible to many, except in this form. In the plaster cast one may study proportions, composition, style and even technical procedure; but it must be remembered that the qualities of color and texture, which contribute so much to the effect of the original, are almost, if not entirely, lost in the plaster [pg 2] cast. This defect may be overcome in part by treating the plaster in various ways so that it conveys some suggestion of the original material. This has been done with our casts, adding materially to the attractiveness of the collection.

In connection with the casts of Greek and Roman sculpture in our collection, the following notes on classical art may be of interest. As to the characteristics of Gothic and Renaissance art, the reader is referred to the notes on pages 31-32 and 47-48.

A remarkable civilization (Minoan, Cretan, Aegean, or Prehellenic, as it is variously called), extending over a thousand years, preceded the classical period of Greek art. This earlier civilization was brought to an end by the so-called Dorian invasion at the close of the second millennium, and several hundred years had to elapse before conditions once again were right for the flourishing of art. Greece of the classical period begins to emerge towards the end of the VII century B. C. The Archaic Period (about 625-480 B. C.) was one of experimentation, preparatory to the age of perfection, when, technical difficulties having been overcome and aesthetic aims defined, Greek art attained an eminence never surpassed.

Victorious at Salamis and Plataea, the Greek world arose triumphant from its struggles with Asia. The birth of national consciousness ushered in a new period of art, the Golden Age of Greece (480-400 B. C.). The conventions of the archaic style gave place to a free style, adequate to the sculptor's every need. Grace, simplicity, and truth in the representation of the living form characterize the sculpture of this period; draperies are rendered with marvelous skill. Liberal patronage was extended to the arts, particularly by the state. Under these favorable conditions, which reached their climax in the Age of Pericles (461-431 B. C.), Hellenic ideals of proportion, sanity and self-command found perfect embodiment in sculpture. From about the middle of the V century, Athens was the unquestioned leader in the field of art, her nearest rival, the ancient school of Argos. Among the great sculptors of the V century, three stand out in particular prominence: Myron, who excelled in the representation of bodily forms and action; Polyclitus, the sculptor of athletes and the exponent of academic perfection; and above all Phidias, the great genius of the age, who combined technical skill with the expression of lofty, spiritual ideals.

In the next period, that of the IV century (400-323 B. C.) individualism began to dominate Greek thought and action, replacing the earlier civic and religious influences. Art became more individual and more emotional. Portraiture grew in favor. The austere style of Phidias gave place to the dreamy sentiment of Praxiteles, to the fiery passion of Scopas. The gods descended from high Olympus and walked the earth in human guise. The three great sculptors of this age were Praxiteles, Scopas and Lysippus.

[pg 3]

Sculpture of the Hellenistic Period (323-146 B. C.) shows a further development of tendencies already manifested in the preceding century. Individualism led to a vigorous development of portraiture and genre sculpture. Art ran the whole gamut of passion, from the bestial to the ideal, and this amplification of the emotional theme was accompanied by a wider range of subject material than had yet occurred. With these changes came a lowering of ideals. Spiritual emptiness, sensationalism, and lack of self-restraint are only too often characteristic of Hellenistic art. The chief centres of art in this period were not in Greece, but at Pergamon, Rhodes and Alexandria.

The development of Roman sculpture was influenced, on the one hand, by native Italian realistic tendencies, and on the other, by the example of Greek sculpture. Not only were there in Rome numerous Greek sculptures to serve as models, but also many transplanted Greek artists, who had left their native land to seek employment in Italy. To the copies of famous masterpieces executed by these eclectic artists, it may be remarked, we owe our knowledge of many celebrated works of Greek sculpture, which otherwise would have been lost to us. In studying Roman art we note first one tendency, then the other, predominating, but neither is ever lost to sight. It is this dualism that gives to Roman art its distinctive character.

[pg 4]THE PRINT DEPARTMENT

The Print Department occupies two rooms on the Main Floor (Print Study Room and Library) and a large exhibition gallery on the Second Floor. The collection, comprising over 5,000 prints, was the munificent gift to the Society in 1916 of an anonymous donor. The collection, formerly owned by William M. Ladd of Portland, Oregon, represents the work of years in collecting, and illustrates in a comprehensive way the history of the graphic arts. The strength of the collection lies in its splendid representation of the work of XIX century and modern etchers. In this respect it may be said to be second only to the famous Avery Collection in New York. The collection offers an exceptional opportunity for the study and enjoyment of a branch of art that is intimately related to drawing and painting and yet has distinctive qualities of its own.

Selections of prints, frequently changed, are exhibited in the large gallery devoted to this purpose on the Second Floor. Prints not on exhibition are kept in the Print Study Room on the First Floor, to the left of the entrance. Visitors are welcome. The curator is glad to show any prints not on exhibition and to assist the student in every way possible. Adjoining the Study Room is the Library, where in addition to general reference books deposited by the Minneapolis Athenaeum, there is a valuable reference library on the subject of prints, which formed part of the former Ladd Collection. Students will also find useful a collection which is now being made of photographs and other reproductions of works of art.

It is difficult, of course, to give any adequate idea in so brief a space of the scope of the collection, but the following comments may be of interest. Among the prints by the early masters, of the XV and XVI centuries, there are examples of the work of Martin Schongauer; a large group of 106 engravings and wood-cuts by the great German master, Albrecht Durer; some characteristic prints by the so-called “Little Masters,” Beham, Pencz, and Aldegrever; and a small group of engravings by the XV century Italian master, Andrea Mantegna.

By Rembrandt, the outstanding figure in the graphic arts of the XVII century, we are fortunate in possessing 127 etchings, all of them good and many in brilliant impressions. Other engravers and etchers of the XVII century are well represented. Among the Dutch masters may be instanced Paul Potter, Ruysdael, A. van de Velde; among the French, Callot, Claude Lorrain, and the portrait engravers, Nanteuil, Morin and Masson. The XVII century group is an interesting one. We may note 34 etchings by Piranesi and an important collection of English mezzotints by McArdell, S. D. Reynolds, Earlom, Valentine Green, and others.

As to modern etchers and engravers, the collection presents an [pg 5] embarrassment of riches. The masters of this period are finely represented. There are 34 etchings by Meryon; 103 etchings and lithographs by Whistler, including beautiful impressions of the Venetian and Amsterdam sets; 242 prints by Sir Francis Seymour Haden, a collection particularly interesting for the number of trial proofs and different states which it includes. There is a notable group of 242 etchings by Jacque, including a large number of rare early dry-points; an important collection of Millet's etchings and woodcuts; 124 prints by Buhot; 119 prints by Legros; 53 prints by Lepere; 156 prints by van Muyden; a characteristic group of lithographs by Fantin Latour; 90 prints by Storm van's Gravesande, including all his important plates; 32 examples of the work of M. A. J. Bauer. Turner's famous Liber Studiorum is represented by a nearly complete set, including 24 first states. The collection is rich in the work of contemporary British artists. There are, in addition to the large group of Hadens, 138 prints by Sir Frank Short; 72 prints by the Scotch etcher, D. Y. Cameron; and fine examples of the work of Muirhead Bone, Brangwyn, Strang, and other contemporary artists. Modern German work is represented by an interesting collection of etchings, woodcuts, lithography and color-printing. To conclude this brief summary of the European artists represented in the collection, we may mention the group of 20 etchings by the Swedish painter and etcher, Anders Zorn.

Coming to the work of American etchers, we find a large group of prints by Joseph Pennell, including his Panama Canal lithographs; the complete work of D. Shaw MacLaughlan, down to about 1912; the almost complete work of Charles Platt; 55 prints by Stephen Parrish; and a representative group of dry-points by Mary Cassatt.

[pg 6]

This is a fine impression of the second state of Rembrandt's masterpiece known as The Hundred Guilder Print, so-called because it is supposed to have brought that price—a high one for the period—in Rembrandt's own time. Rembrandt is not only the greatest artist of the Dutch school, but also the greatest master of etching the world has ever known.

The art of mezzotint engraving attained its highest development in England during the XVIII century. The English portrait painters were quick to recognize that the mezzotint process with its delicacy of tone and beautiful, velvety quality was admirably suited to the reproduction of their works. Reynolds is said to have employed, under his supervision, one hundred mezzotint engravers in the reproduction of his portraits. English mezzotints are well represented in our collection.

Mezzotint by Valentine Green, 1739-1813

The subject of this large etching is the breaking up of one of England's famous old ships of war, called the Agamemnon. Haden was not only a surgeon eminent in his profession, but also one of the greatest of English etchers. The revival of interest in etching during the XIX century in England was largely due to his efforts. Characteristic works of Whistler and Meryon are illustrated below.

Our print collection is notably rich in the work of Millet. The etchings are all fine impressions, in some cases exceptional in quality. The collection also includes Millet's lithograph, The Sower, and his rare heliogravure, Maternal Precaution. Of the six wood-engravings drawn by Millet and cut by his brothers, three are represented in the collection.

Millet was a thoughtful artist, to whom the spirit of things was at least as important as their visual aspect. His deep and sincere sympathy with the life of the peasant, to whose class he himself belonged, determined to a large extent his choice of subject. But Millet never descended to anecdotal trivialities; he avoided the pale sentimentality of such a painter as Jules Breton. His thought, like his technique, was virile, positive, honest. Millet was far above any trickery, either of thought or of execution.

The very intensity of his intellectual interests led Millet to evolve a personal style that is distinguished by its simplicity and directness. As an artist, Millet is more allied to Durer than to Rubens. Color plays but a small part in his pictures. Significant, expressive line is the first essential of his art, and with this simple means he secures a surprising effect of plastic form. When color is added to outline, he is primarily interested in establishing accurately the values of the different planes. Both in his use of line and of mass, it is Millet's invariable practice to simplify, omitting everything that is not essential to his purpose.

NEAR EASTERN ART

The art of the Nearer Orient is the product of many races. The phrase covers in general the art of India, Persia, Syria, Mohammedan Egypt, Turkey, and even, in certain aspects, the art of Spain, Portugal and southern Italy. Although the development of this art was by no means uniform or along the same lines, the products are all related in style, which is unmistakable and distinct from other types of design. The most typical manifestation of this style would appear to have originated in Egypt about the time of the Mohammedan conquest in 638 A. D., and almost simultaneously in Syria and northern Persia. Since the Koran forbade the representation of any living creature, Mohammedan artists developed the so-called arabesque style, based on geometric and floral motives. This limitation, however, was not observed by the Persians, who introduced human and animal life into their designs with beautiful results.

[pg 10]

The earliest lustred ware of Persia is that found in the ruins of the ancient city of Rhages. This prosperous city was destroyed in 1221 during the Mongol invasion. It may be assumed that most of the fragments found in the tumuli at Rhages date from the early years of the XIII century. Non-lustred pottery with polychrome decoration was also produced at Rhages during this period.

The mosque doors, from Ispahan, illustrated on the opposite page, are particularly fine examples of Persian wood carving. The arabesque designs are especially beautiful. The inscriptions in the upper and lower small panels have been translated as follows:

Panel, Upper Right: Oh God, do not indifferently drive me from your door.

Panel, Upper Left: For if you do, there will be no other door open to me.

Panel, Lower Right: Oh, my heart, do not be far off from the door of those who are sincere and faithful.

Panel, Lower Left: Anyone who is far from the door is near to God.

JAPANESE ART

In the middle of the VI century of the Christian era, Buddhism was introduced into Japan by way of Korea. Through the vehicle of this new religion, Chinese art began to exert a fructifying influence upon the native art of Japan, which up to this time had achieved nothing worthy of mention. Chinese influence continued in succeeding ages a potent factor in the development of Japanese art. In the art of the Suiko (552-644), Hakuho (645-709), Tempyo (710-793), Jogan (794-899), and Fujiwara (900-1190) periods, the inspiration was largely Chinese, but more and more the native genius manifested itself in modifications of the spirit and technique. This evolution toward a distinctive national art and culture made considerable advances in the Fujiwara period, which ended in social revolution and the establishment of a military vice-royalty at Kamakura.

The Kamakura period (1190-1337) is the feudal era of Japan. The spirit of individualism and hero-worship which distinguishes this age brought about a great development in portraiture, even the gods assuming a more individualized character. Battle scenes and the achievements of famous warriors and heroes were popular subjects. To overawe the populace, religious artists for the first time pictured the horrors of hell. Forceful delineation and the vigorous expression of action are characteristic of Kamakura art.

Zenism, a metaphysical doctrine introduced from China to Japan in the Kamakura period, had a very great influence in the succeeding Ashikaga period (1337-1582) in shaping the course of art. The Zen sect of Buddhism, discarding ritual, sought salvation through self-concentration and meditation. Subjective idealism and the search of the inner spirit of things, fostered by Zenism, led the Ashikaga artists to practice a rigorous economy of means, eliminating color in general and all details not essential to the expression of the artist's idea. The search for the hidden beauty [pg 13] in all things was not confined to the major arts but led to the beautification of the humblest household utensils. In the ornamentation of sword guards the metal workers showed extraordinary ability. The Ashikaga era ended in turmoil. In 1582 Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a man of the humblest origin, brought order out of chaos, and became virtual ruler over a unified Japan.

Under the patronage of Hideyoshi and his ennobled generals, the sober refinement of Ashikaga art gave way to gorgeous decoration, resplendent with gold and brilliant colors, that shows the influence of the mature Ming style of China. The leading artist of this period in Japan was Yeitoku (1543-1590), who with his numerous pupils painted sumptuous decorations for the palaces of the wealthy nobles. By Yeitoku are the two large screens illustrated above. This artist created perhaps the greatest purely decorative style of painting that the world has ever known.

After the death of Hideyoshi in 1602, Iyeyasu founded the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1867). During the long “Tokugawa peace” various schools of art developed. Koetsu (d. 1637) and his great followers, Sotatsu (middle XVIII century) and Korin (d. 1716), established the so-called Korin school, seeking to combine the rich coloring of pre-Ashikaga days with the bold treatment of the Zen school. Kano Tanyu and his followers attempted to return to the purity of the Ashikaga masters, but met with only partial success. Patronage was largely in the hands of a prosperous middle class who demanded something more easily understood than the aristocratic art of the earlier periods. To meet this demand a more democratic school arose, and many gifted artists through their paintings of popular festivals and other familiar scenes prepared the way for the Ukiyo-e, or school of common life. Under the inspiration of this popular school, the art of printing in colors from wood blocks was brought to a high state of perfection. Little original work of any importance has been produced in Japan since the Restoration in 1868.

CHINESE ART

The study of ancient Chinese art is attended by discouraging uncertainties. Only a few bronzes, jades, and possibly a small quantity of pottery, have survived to testify to the early development of art in China. To add to the difficulty, the exact dating of this material is at best only tentative. But whether the most ancient of these bronzes and jades are to be attributed to the Shang Dynasty (1766-1122 B. C.) or, with more probability, to the succeeding Chou Dynasty (1122-255), the technical skill which they display postulates so long a period of preparation that the origins of Chinese art must be referred to a past too remote for our present discernment. With the Han Dynasty (B. C. 206-221 A. D.), we find ourselves on surer ground, since many works of art of various kinds and materials, and unquestionably of this era, have come down to us. Not only bronzes and jades but also pottery and sculpture bear witness to the flourishing art of this period. During the Han Dynasty, probably in the first century of our era, Buddhism reached China from India. It does not appear, however, to have exerted much influence upon the arts until about the V century. The Han Dynasty was followed by a succession of shorter reigns known as the Three Kingdoms and the Six Dynasties.

Early in the VII century, the great house of T'ang (618-907) came to power, and for three hundred years held sway over a vast empire. It was the period of China's greatest external power; the period of her greatest poetry; and of her grandest and most vigorous, if not, perhaps, her most perfect art. The surviving works of art of this era are far from numerous, but they are sufficient to warrant the belief that China, except in the field of ceramic art, rarely if ever surpassed the achievements of this golden age. Chinese Buddhist sculpture attained its noblest development in the T'ang period. As to T'ang painting—unfortunately, surviving examples are of the utmost rarity—it is characterized by austere beauty and spiritual elevation. Admirable also are the productions of the metal worker, the weaver, and the potter.

A short period of half a century succeeded the fall of the T'ang Dynasty. We come then to another of the great periods of Chinese civilization, that of the Sung Dynasty (960-1280). From now on, surviving monuments permit us greater certainty in studying the continuous development of Chinese art. Under the Sung emperors we find a complex civilization marked by luxury of living, refinement and elegance of [pg 16] taste. These characteristics are reflected in the arts. Although religeous painting was largely practiced, Sung artists show a predilection for landscape and for subjects allied to landscape, such as birds and flowers. Exceptional qualities of poetic imagination, observation of nature and technical proficiency characterize these paintings. Achievements in the field of minor arts are conspicuous; in particular, we may note the productions of potters.

The Sung Dynasty was succeeded by that of the Mongol invaders who founded the Yuan Dynasty (1280-1368). With the art of this period, the decline begins. The Mongols were followed by a native dynasty, the Ming (1368-1644), under whom the art of porcelain making began to progress rapidly toward perfection. Ming paintings show an excessive refinement, an elegance that is not without its charm, but they lack the nobility and spirituality of the earlier periods. In the Ch'ing, or Manchu, Dynasty (1644-1912), under the Emperors K'ang Hsi and his grandson, Ch'ien Lung, the art of porcelain manufacture and decoration reached its apogee. Today, after forty centuries of liberal harvest, the art soil of China would seem to be sterile and abandoned.

THE CHINESE DYNASTIES

| Shang Dynasty 1766-1122 B. C. | |||||||

| Chou Dynasty 1122-255 B. C. | |||||||

| Ch'in Dynasty 255-206 B. C. | |||||||

| Han Dynasty B. C. 206-221 A. D. | |||||||

| Three Kingdoms 221-265 A. D. | |||||||

| Six Dynasties 265-618 A. D. | |||||||

| T'ang Dynasty 618-907 A. D. | |||||||

| Five Dynasties 907-960 A. D. | |||||||

| Sung Dynasty 960-1280 A. D. | |||||||

| Yuan Dynasty 1280-1368 A. D. | |||||||

| Ming Dynasty 1368-1644 A. D. | |||||||

Ch'ing Dynasty 1644-1912 A. D.

| |||||||

| Republic from 1912 |

The early Chinese believed in the resurrection of the physical man, and only after many centuries did the idea of mere spiritual survival vaguely supplant the earlier superstition. To minister to the needs of the dead the Chinese of the Han period (206 B. C.-221 A. D.) stocked their tombs with jars containing wine and pickled meats, with articles of jade, with clothes, mirrors and weapons. To these were added costly treasures, furniture, chariots, live animals; even immolation of relatives and retainers was practiced in early times. As the conception of spiritual survival gradually replaced that of bodily life after death, simulacra of the objects used in life came to be substituted in burial for real objects. To this class belongs the horse's head, illustrated on this page, intended to take the place of a living sacrifice. The material is a soft grey earthenware, covered with a layer of buff clay, perhaps an original slip or perhaps an adhering soil incrustation. The modeling of the head, which has been made from a mould, combines a close study of nature with monumental elimination of the non-essential. Designs of the period engraved on stone show a similar enthusiasm for the horse and a similar method of treatment, the interest being in the decorative and linear aspect more than in the realistic and plastic.

The vase is a typical piece of mortuary pottery of the Han period. It is made of hard reddish clay covered with a thick translucent green glaze, in parts become iridescent. The form is derived from an earlier bronze type; the simulated rings which originally formed the handles of the earlier type of vessel should be noted. The vase is decorated with a band of hunting scenes and animals, real and fabulous, modeled in low relief.

[pg 18]

During the Sung dynasty, a period of highly developed civilization landscape painting occupied the attention of the greatest artists. Wearying of the complexity of life, men of culture turned with eager desire to the peace and solitude of nature. This love of nature finds beautiful expression in the paintings of Ma Yuan, one of the three greatest landscape painters of the period. By this artist, who flourished in the latter part of the XII century and the first part of the following century, is the large kakemono painted in monochrome on silk, which is illustrated opposite. The subject is the meeting between the Taoist teacher, Lee Erh, and his disciple, Ying Hai, on the mountain Wah Shan, one of the five largest mountains of China. Characteristic of the period is the loftiness and simplicity of the style, an austerity tempered by the serene and silent joy of the true lover of nature. Irrelevant details are omitted; only those which are significant expressing the artist's mood in contemplation of nature are recorded.

The earliest Chinese religion was essentially astronomical and cosmic. Heaven, earth, and the four quarters were the six cosmic powers worshiped as deities. The symbol of earth was a yellow jade “tube” or hollow cylinder, round inside and square outside, with a short, projecting neck at either end. The earth was thought of as round in its interior and square outside. The jade earth “tube” or “huang t'sung” in our collection is a very ancient piece, possibly dating from the Chou period (1122-255 B.C.). To the Sung period (960-1280 A. D.) may be assigned the beautiful jade reproduced in the illustration, although the type is reminiscent of Han productions.

[pg 19]

Attributed to Pien Chin-Stan, an artist of the Yuan period (1280-1368), is the painting of birds and flowers reproduced on this page. The mellow harmony of the colors is particularly delightful. Exquisite sensitiveness to beauties of line and form, combined with loving observation of nature, distinguishes the drawing. Although paintings of the Yuan period, generally speaking, are inferior to the Sung, lacking the spiritual qualities that characterize the earlier period, in such work as this the great traditions of Chinese painting are worthily continued. To appreciate Chinese painting one must rid oneself of the mistaken idea, so common to Occidentals, that a work of art depends for success upon its “likeness” to nature. Petty imitation of the appearance of things plays no part in Chinese painting. It is the expression in terms of beauty of the inner and informing spirit, rather than the outward semblance, that constitutes the aim of the Chinese artist.

From remote antiquity, jade has been highly prized by the Chinese as the most precious of precious stones. In the ornamental carving of this beautiful mineral, the Chinese may justly claim pre-eminence. The little statuette here reproduced represents one of the Chinese immortals, Tung Fang So, who carries the peaches of longevity. The jade is light greyish-green in color. The carving probably dates from the late Ming period.

[pg 20]

This painting represents Princess Yang Kwei-Fei, the celebrated favorite of the Emperor T'ang Huan Tsung, returning from her bath. It is an excellent example of the Ming period (1368-1644 A. D.), lovely in color, distinguished by courtly elegance and refinement of drawing. It has been attributed to Yiu Kiu, also named Tze-Kiu. The daughter of a petty functionary, the Princess Yang became in 735 A. D. one of the concubines of the Emperor's eighteenth son. Her surpassing beauty and accomplishments won the affections of the Emperor himself. So great was her ascendancy over this weak voluptuary that the Imperial favorite was treated by the court with demonstrations of respect that justly appertained to none save the Empress Consort; members of her family were raised to high office; and no outlay was spared in gratifying the caprice and covetousness of the Princess or her relatives. It is not surprising that a rebellion resulted. During the flight of the court in 756 A. D. the Imperial guard revolted, and the Emperor was constrained to order the Princess Yang to be strangled.

The porcelain vase is decorated in five colors on a white ground with a design showing a peacock, a phoenix and smaller birds among rocks, foliage and blossoms. It is a characteristic and fine production of the late Ming Period (1368-1644). Altogether admirable is the way in which the design, drawn with great freedom and boldness, is adapted to the shape of the vase. The colors are skillfully harmonized; the beautiful blue should be particularly noted.

[pg 21]

Apple-green, ashes-of-rose, mirror-black, camellia-green, lemon-yellow, and celadon are some of the beautiful glazes exemplified in this group of remarkable “solid-color” porcelains dating from the reigns of K'ang Hsi, Yung Cheng and Ch'ien Lung (second half of XVII century and the XVIII century). The large plate is a fine piece of K'ang Hsi decorated porcelain. Most of the pieces in this case were formerly in the celebrated Morgan Collection. Gift of Mrs. E. C. Gale.

EGYPTIAN ART

The Egyptian collection, purchased from the Drexel Institute, includes over seven hundred objects, ranging from sculpture and painting to furniture and utensils of daily life. It affords an adequate illustration of the conditions under which art flourished in the ancient land of the Nile, and of the characteristic forms of art expression which were evolved to meet these conditions.

After monumental architecture, the system of decoration evolved by the Egyptians is perhaps their greatest contribution to the world's art. A few characteristics of Egyptian painting and sculpture may be noted. Color is used in flat areas without gradation and effects of light and shade. [pg 23] In drawing, outline is the principal mode of representation. Various conventions originating in the primitive stages of art, such as the representation of the human body with head and legs in profile and the shoulder to the front, became traditional and were continued with little change throughout later periods. These conventions, however, did not prevent the artist in the more vigorous periods of Egyptian art from noting with great keenness of observation many truths of nature. This curious conflict between realistic observation and conventional means of representation is characteristic of Egyptian art. In free-standing sculpture, the variety of postures was limited to a few unvarying poses. On the whole, in the figurative arts, types and subjects remain unchanged throughout Egyptian history, although from time to time the informing spirit was different.

This immutable character of Egyptian art is thoroughly consonant with the idea of duration which was so strongly a controlling factor in Egyptian life. We cannot consider here the manifold ramifications of Egyptian religious belief, but one central tenet—that existence continued after death—must receive some attention, since this belief in the after-world explains many features that might otherwise be puzzling. The tomb, for example, was thought of as the real dwelling house, “the eternal house of the dead”; the houses of the living were merely “wayside inns.” As a result, domestic architecture was inconsequential; all efforts were concentrated on the construction and decoration of tombs and temples.

The mummy is enclosed in a cartonnage, made of many layers of linen held together by plaster, elaborately decorated by inscriptions and figures of the gods. The anthropoid coffin is made of wood, and is also richly decorated. Tesha was the daughter of the Doorkeeper of the Golden House (or Treasury) of Amon at Thebes.

[pg 24]It was believed that man was composed of different entities each having its separate life and function. First, there was the body itself; then, the Ka or double—the ethereal projection of the individual, corresponding in a way to our ghost. Two other elements were the Ba or soul and the Khu or luminous spark from the divine fire. Each of these elements was in itself perishable. Left to themselves, they would hasten to dissolution, and the man, as an entity, would be annihilated. This catastrophe, however, could be averted through the piety of the survivors. The decomposition of the body could be prevented, or at least suspended, by the process of embalming; prayers and offerings saved the other elements from the second death and secured for them all that was necessary for the prolongation of their existence. The influence upon the arts of these religious beliefs is interesting to note. Scenes of harvesting, hunting, and similar episodes connected with the offering of food were painted or carved upon the tomb walls, generally for an utilitarian purpose. Through the recitation of prayers and magic formulae, the pictured semblances of food became reality and saved the hungry Ka from annihilation in case actual offerings should fail him. In the same way, portrait statues were placed in tombs to provide a semblance of the deceased to which the Ka could return were the actual body destroyed. These instances are perhaps sufficient to show us how closely art was related to religion in ancient Egypt.

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE

| Pre-Dynastic Period about 4000-3400 B.C. | |||||||||

| Accession of Menes and Beginning of Egyptian History 3400 B.C. | |||||||||

| Early Dynastic Period, I and II Dynasties 3400-2980 B.C. | |||||||||

Old Kingdom

| |||||||||

Transitional Period

| |||||||||

Middle Kingdom

| |||||||||

Hyksos Period

| |||||||||

The Empire

| |||||||||

Late Dynastic Period

| |||||||||

Saite Period

| |||||||||

| Persian Conquest of Egypt 525 B.C. | |||||||||

Persian Period

| |||||||||

| Ptolemaic Period. 332-30 B.C. | |||||||||

| Roman Period 30 B.C.-364 A.D. | |||||||||

| Byzantine (Coptic) Period 364-640 A.D. | |||||||||

| Arab Conquest of Egypt 640 A.D. |

The exterior of this wooden coffin is decorated with figures of gods and minor divinities in shrines, alternating with invocations to various divinities. The most interesting scene is that next the foot on the right side, showing the goddess Hathor in the form of a cow. Beside her is a suggestion of the Theban cliffs and the open door of her shrine, which was hewn in the mountain side. This very shrine was discovered on February 7, 1906, and in it intact was a life-size cult statue of Hathor as a cow. Hathor was supposed to receive the setting sun and to welcome the dead on the brink of the next world. The decoration of the interior of the coffin is bolder and more highly colored than the exterior. On the floor may be noted the large standing figure of Osiris of Busiris. Various divinities are represented surrounding him. On the sides of the coffin are three registers containing each three mummiform figures with human or animal heads; at the top is the soul of the deceased, represented as a human-headed bird. This coffin doubtless comes from Thebes. The absence of the cover makes it impossible to determine the ownership. The coffin was perhaps originally decorated in advance for a woman's burial, and held in stock for any burial. In one place, however, a man's titles are given, although the name is not recorded, so that possibly, before the decoration of the coffin was completed, it was adapted to the use of a man.

Standing figure of a woman, carved in wood, with traces of painting; found at Deir; a fine example of carving in Dynasty XII. An inscription on the base may be read: “Funerary offerings, beef, fowl (?), things (?), good and pure for the honorable Kai.” Doubtless a portrait statue. The pose, with one foot advanced and the arms held stiffly at the sides, is a familiar one in Egyptian art. Note costume details: the thick wig and the tight dress supported by two shoulder straps.

This bronze statuette represents the Goddess Neith wearing the crown of Lower Egypt; probably of the Saite period. An excellent example of votive bronzes, of which there is a considerable number in the collection. These statuettes probably served as votive or propitiatory offerings; that is to say, they were offered at shrines in gratitude for favors experienced or in the hope of winning favors to come.

[pg 27]

Fragment of the funerary papyrus of the Priest of Amon, Jekhonsefonkh; part of a scroll buried with the deceased for his instruction in the afterworld; Dynasty XXI.

Ushabti, Dynasty XIX (?), part of the burial equipment of “The Lady of the House, the Chantress of Amon, Aay.” Ushabtiu were placed in the tomb to answer for the deceased when called upon to labor in the afterworld. The inscription reads: “To illuminate the Osiris, the Lady of the House, Aay, beatified in peace. He says: O this ushabti, if one be drafted to do all the labors which are performed in the underworld—the Osiris, the Lady of the House, Aay, beatified, in peace—to cultivate the fields, to irrigate the banks, to carry the sand of the east to the west, behold, there will be smitten down ...” Here the text, which is part of Chapter VI of the Book of the Dead, breaks off because the available space was filled. It omits final instructions to the ushabti to reply, should the deceased be drafted, “Behold, here am I!” and thereupon relieve the deceased Lady of the House of the onerous task of laboring in the fields.

Cover of a canopic jar used in the burial to contain the human viscera; if not earlier than the Empire period, to which it is attributed, it represents the genius Amset.

[pg 28]

From left to right: spherical vase, Early Dynastic; kohl jar used to contain antimony or other preparations for the eyes, Dynasty XII or XVIII; the three vessels following are of the Empire period, Dynasty XVIII-XIX.

Bronze mirror, originally highly polished, probably of the Ptolemaic period. Note the lotus column serving as handle and the two sacred falcons at the side of the handle.

The sacred falcon below is a charm or amulet of the XII or XVIII Dynasty in polished gray stone.

Heart scarab, Dynasty XX or later. Inscription is a prayer from the Book of the Dead, adjuring the heart, over which the scarab was placed, not to bear false witness against the deceased at the time of judgment. The Horus eye is a beautiful piece of faience inlaid with stone and glass, probably of Dynasty XIX.

ANCIENT ART

Except for Egyptian material, the representation of ancient art in our collections is unfortunately limited to comparatively few original examples. These include, however, an interesting group of Cypriote pottery (duplicate material from the Cesnola Collection) which has considerable importance from the archaeological as well as from the artistic point of view. This collection of pottery from the island of Cyprus shows an almost unbroken succession of styles from the Early Bronze Age, about 3000 B. C., down to the Roman period, and thus gives us a complete picture of the art of pottery in an important center of ancient civilization for about three thousand years. Artistically, it is probably the most successful product of the Cypriote artist. His sense of form and decoration could here find full expression without disclosing the lack of high artistic inspiration, which is apparent in his sculptural creations. Moreover, a certain fanciful originality which shows itself now in a fantastic shape, now in the addition of handles and bosses in unexpected places, gives to his vases a refreshing variety. The interest of this collection will be greatly increased when we are able to exhibit examples of the Greek painted pottery of the V and IV centuries B. C., which represents the culmination of ancient ceramic art. A small collection of Cypriote glass, dating from the I century B. C. to the V century A. D., attracts attention by its beautiful color, or iridescence, due to burial in the earth. Although we have as yet no original sculptures of the classical period, except for a few fragments, the development of sculpture in Greece and Rome may be studied in our cast collection.

From left to right: Amphora, white ware painted in black and red, X-V centuries B. C.; jug, red slip ware, XX-XV centuries B. C.; amphora, white ware painted in black and red, X-V centuries B. C.; jug, base ring ware, XV-XII centuries B. C.; oinochoe, white ware painted in black and brown, X-V centuries B. C. The earliest of the fabrics illustrated, i.e., the red slip ware, though usually not polished, is made evidently in imitation of the still earlier red polished ware. Base-ring ware is so called from the distinct standing base found on most specimens. With the white painted ware of the Early Iron Age, we come to a wheel-made pottery, usually having painted geometrical decoration.

This is one of a small collection of Babylonian tablets. It was made during the reign of Dungi, King of Ur. The inscription records an offering to the temple. The tablet is sealed to prevent the alteration of the record by the priests or attendants; the seal impression bears the figure of Sin, the Moon God, who was the deity of Ur of the Chaldees, and before the deity stand two priests in the act of worship. These inscribed clay tablets were used by the ancient Babylonians in place of papyrus or parchment.

GOTHIC ART

Since the Goths, a rude and barbarous ancient people, were in no wise concerned with the splendid art of that period intervening between Romanesque and Renaissance, which misguided later generations called Gothic because, forsooth, it was not classical, it is unfortunate that this inappropriate designation should be perpetuated by custom. But the misnomer is now used so generally—needless to say, without any sense of disparagement—that we must perforce accept it.

It is impossible to date any period of art with absolute accuracy; for art is always in the process of change, and the flourishing of any period of art is long anticipated by preliminary manifestations. In a general way, however, it may be said that the Gothic period extends from the second half of the XII century through the XV century. Italy presents an exception. The tentative Gothic art of the XIII century in Italy gave place to the new movement, founded upon enthusiasm for antiquity, as well as for nature, which we call the Renaissance. The classical element in Renaissance art is the feature which principally distinguishes it from Gothic. In the latter part of the XV century, the Renaissance spread from Italy into the northern countries, and, in the XVI century, accomplished a triumphant ascendancy over the late Gothic style.

The crowning achievement of Gothic art was the cathedral, where architect, sculptor and painter combined to create monuments which rank with the greatest works of human genius. Never has sculpture more perfectly adorned architecture; never has architecture more beautifully expressed the hopes and aspirations of a people. In this age the plastic arts were truly “the language of faith.”

From France, Gothic art spread to other lands, to Germany, Flanders, Spain, and England, and even to Italy. During the XIII and XIV centuries, the highest development of Gothic art took place in France, but, in the XV century, Burgundy and the merchant cities of Flanders gained pre-eminence. France required many years after the battle of Agincourt, in 1415, to recover from the exhaustion brought about by internal conflict and foreign wars. In the meantime, the rich cities of Flanders and the powerful Dukes of Burgundy offered the artist generous patronage.

[pg 32]If the artist in this late period lost something of the spirituality and noble simplicity of earlier times, he was more skillful technically and more realistic. Not that the earlier artist had not observed nature! On the contrary, he was eminently successful in discerning significant truths, but he subordinated objective representation to the requirements of a monumental style.

Save for a distinguished list of painters, headed by the great Flemish masters, the Van Eycks (?-1426, 1381-1440), Rogier van der Weyden (1400-1464), and Hans Memling (1425-1495), Gothic art is largely anonymous. In the minor arts, such as glass painting, the illumination of manuscripts, metal work and enameling, furniture, and textiles, woven and embroidered, the Gothic Age excelled, and the rare surviving examples of these beautiful crafts are treasured among the most precious relics of this great period of the world's art.

The large well-head of Istrian stone in the foreground comes from the Palazzo Zorzi in Venice, and is a fine example of Venetian stone-carving in the XV century. The well-head, with its acanthus leaves at the four corners, reminds one of the Corinthian capital of classical times, and, as a matter of fact, ancient capitals were sometimes used in later periods for well-heads. On one side is an angel holding a shield supported by two lions passant. Doubtless, this shield was originally painted the owner's coat of arms.

[pg 34]

The two XV century Gothic tapestries in the Charles Jairus Martin Memorial Collection are masterpieces of the weaver's art. They rank among the most beautiful and characteristic examples of the Golden Age of tapestries. The earlier of the two, The Falconers, was woven, presumably in the ateliers of Arras, about 1450. It is similar in style to the famous Hardwicke Hall hunting tapestries, owned by the Duke of Devonshire. These tapestries have been justly called “the finest of the XV century in England.” They formerly ornamented the walls of a great room in Hardwicke Hall, Devonshire, but were removed from there in the XVI century and cut to adapt them to walls pierced with windows in a new location. Taking into consideration the similarity in size, subject, costume, and style of representation, it is not at all impossible that The Falconers may have belonged originally to this celebrated set. Our tapestry, which comes from the Cathedral of Gerona in Spain, was [pg 35] evidently part of a still larger tapestry (tapestries at this time were often woven of great length), and may have been separated from the other pieces of the set at the time of their removal from Hardwicke Hall.

In the XV century, hunting and hawking—the latter also called falconry—played a significant part in the social life of the nobility. These sports and the ability to pursue them in a generous and polite fashion set the nobility apart from the commoners, and formed the chief topic of conversation, when war did not call from the slaughter of animals to the slaughter of men. One of the most necessary implements in falconry is the lure, used to recall the falcon. In the upper right-hand corner of the tapestry a man is shown waving a lure in his right hand. The lure is a pair of wings attached to a cord, to which the falcon is trained to return because accustomed to find food there. The mode of carrying the falcon on the gloved hand is illustrated by several of the personages in the tapestry. Several of the falcons are still on leash; one has just been released and thrown up into the air; another is having the hood removed from his head. The rich costumes illustrate the extravagant fashions which prevailed in the middle of the XV century, when there was great competition in dress between the wealthy commoners and the nobility.

Great beauty of color distinguishes this tapestry. The greens and browns of the foliage form an agreeable contrast with the rich crimson and blue of the costumes, relieved by passages of green and violet. The Gothic artist was not afraid to use strong colors, but he knew how to keep them in harmonious relationship. The simplicity of the design, the purposeful abstention from realistic effects, which we note in this tapestry, are virtues in the art of mural decoration that can not be too highly commended.

[pg 36]

About fifty years later than The Falconers, this beautiful tapestry with scenes from the Story of Esther, in the Charles Jairus Martin Memorial Collection, represents the tendency toward a more ornate and sumptuous art that characterized the late XV century. In the lower right-hand corner of the tapestry, just above the scroll, may be noted a small fleuron, which is probably the mark of an atelier, but tapestries before 1528 can rarely be assigned to any definite atelier or weaver. We must be content to designate our tapestry as Flemish, woven at the close of the XV century. The story of Esther was popular among the Flemish weavers at this time. Our tapestry, which formed part of a set, may be compared with three hangings of the same subject belonging to the Cathedral of Saragossa.

The reproduction can give but an unsatisfactory idea at best of the original. Not only do we lose the mellow harmonies of color, but in reducing the design of so large a tapestry to a few square inches many of the most beautiful details are necessarily lost. In the left-hand compartment, Queen Esther, kneeling before the King, kisses the golden scepter which Ahasuerus extends to her. Having won favor in the King's eyes, Esther asks as a boon that the King and Haman, the King's favorite, whose plot for the persecution of the Jews Esther intends to circumvent, shall attend a feast which she has prepared for them. In the upper left-hand corner are two little scenes; Esther kneeling in prayer, and Esther receiving instructions from Mordecai. In the compartment at the right is pictured Esther's banquet, the second feast, related in Chap. VII of the Book of Esther, which brought about the fall of Haman. Particularly interesting in this scene is the representation of table furnishings, the damask cloth, the enameled ewer in the shape of a boat, the knives with their handles of ivory and ebony, the hanap, the cup of Venetian glass, and the various pieces of plate. We have in this composition a remarkable document illustrating the luxury that characterized the life of the great nobles at the close of the XV century. In the scrolls at the bottom of the tapestry are Latin mottoes referring to the scenes above. Our tapestry was formerly in the J. Pierpont Morgan Collection.

In such tapestries as this and The Falconers, we may note the perfect relationship which exists between the nature of the design and the purpose to which the tapestry was put. Gothic tapestries of the XV century illustrate the true principle of mural decoration. Designers deliberately avoided realistic imitation of nature with spatial effects and tricks of illusion. They strove to achieve a decorative flatness of design which would emphasize rather than destroy the architectonic quality of the wall the tapestry was to cover.

A tapestry is woven, not embroidered, and forms a single fabric. Only two elements are employed in the making of it, the warp and the woof (or weft). These are the upright and the horizontal threads. The [pg 37] weaving is done upon a loom or frame. The bobbin, or shuttle, filled with thread of the weft, is passed from right to left behind the odd warp threads, and in passing leaves a bit of the weft thread in front of the even warp threads. On the backward trip, from left to right, the shuttle reverses its course and leaves the weft in front of the odd warp threads. Thus, all the warp threads are covered with the weft. A comb is used to press down the threads, so that they form an almost even line. Wool is generally used for the weft, linen or hemp for the warp. The texture was sometimes enriched with passages of gold and silver thread or perhaps a bit of silk.

[pg 38]

Part of a large tapestry representing the Crucifixion. Its vigorous design and harmonious color make one regret all the more the loss of the other part of this splendid tapestry.

This life-size statue, which still retains traces of the painting and gilding with which Gothic sculptures were almost invariably enriched, is an important example of French Gothic sculpture. The monumental character of this great art is shown in the conventional rendering of the hair, and in the simplification of the modeling; its grace and naturalness in the pose of the Divine Mother. The beautiful, rhythmic lines of the drapery should be particularly noted. Representations of the Virgin in French XIV century art have neither the austerity of earlier periods nor the worldliness of later. They are characterized by charming sensibility and tenderness.

[pg 40]

This statue of a holy woman, probably one of the half-sisters of the Virgin, Mary Cleophas, the wife of Alpheus, or Mary Salome, the wife of Zebedee formed part originally, it may be presumed, of a Pieta group. This remarkable example of German sculpture at the close of the XV century is carved in linden wood, and preserves largely intact the original gilding and polychromy which add so much to the decorative effect of the piece. A second figure from this group, a kneeling Magdalene, is in the Kaiser-Friedrich Museum in Berlin. There has been noted a similarity in style between these two sculptures and the work of the Meister des Blaubeurer Hochaltars (so called from the sculptured high altar in the choir of the cloister-church at Blaubeuren). We have represented, perhaps, a late phase of his art, stronger and more realistic than in his early period. It would be most interesting if the connection with this well-known master could be established, but, failing that, the figure may be confidently attributed to the school of Ulm, about 1500.

We do not expect to find in German sculpture of the XV century that spirituality which characterizes the great achievements of the Italian school. German plastic art was one of realism, modified by a strong decorative tradition centuries old, based not only on precedent but on propriety. If the carved altarpiece were to tell in the subdued light of the Gothic church, the artist had to resort to exaggeration, to sharp contrasts in modeling, to the added emphasis of gold and color, to secure his effect. The skillful artist converted his exaggerations of form and movement into beautiful decoration; seized upon the necessity of contrasting planes as a pretext for crumpling his draperies into numerous rhythmic folds, and used the resources of gilding and polychromy to enrich as well as to emphasize form.