Slave Narratives

Volume XVI: Texas Narratives—Part 4

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: Slave Narratives: a Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves: Volume XVI, Texas Narratives, Part 4

Author: Work Projects Administration

Release Date: February 23, 2011 [EBook #35381]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SLAVE NARRATIVES: A FOLK HISTORY OF SLAVERY IN THE UNITED STATES FROM INTERVIEWS WITH FORMER SLAVES: VOLUME XVI, TEXAS NARRATIVES, PART 4 ***

Produced by the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

SLAVE NARRATIVES

A Folk History of Slavery in the United States

From Interviews with Former Slaves

TYPEWRITTEN RECORDS PREPARED BY

THE FEDERAL WRITERS' PROJECT

1936-1938

ASSEMBLED BY

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PROJECT

WORK PROJECTS ADMINISTRATION

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

SPONSORED BY THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Illustrated with Photographs

WASHINGTON 1941

VOLUME XVI

TEXAS NARRATIVES—PART 4

Prepared by the Federal Writers' Project of

the Works Progress Administration

for the State of Texas

[HW:] Handwritten note

[TR:] Transcriber's note

INFORMANTS

- Mazique Sanco

- Clarissa Scales

- Hannah Scott

- Abram Sells

- George Selman

- Callie Shepherd

- Betty Simmons

- George Simmons

- Ben Simpson

- Giles Smith

- James W. Smith

- Jordon Smith

- Millie Ann Smith

- Susan Smith

- John Sneed

- Mariah Snyder

- Patsy Southwell

- Leithean Spinks

- Guy Stewart

- William Stone

- Yach Stringfellow

- Bert Strong

- Emma Taylor

- Mollie Taylor

- Jake Terriell

- J.W. Terrill

- Allen Thomas

- Bill and Ellen Thomas

- Lucy Thomas

- Philles Thomas

- William M. Thomas

- Mary Thompson

- Penny Thompson

- Albert Todd

- Aleck Trimble

- Reeves Tucker

- Lou Turner

- Irella Battle Walker

- John Walton

- Sol Walton

- Ella Washington

- Rosa Washington

- Sam Jones Washington

- William Watkins

- Dianah Watson

- Emma Watson

- James West

- Adeline White

- Sylvester Sostan Wickliffe

- Daphne Williams

- Horatio W. Williams

- Lou Williams

- Millie Williams

- Rose Williams

- Steve Williams

- Wayman Williams

- Willie Williams

- Lulu Wilson

- Wash Wilson

- Willis Winn

- Rube Witt

- Ruben Woods

- Willis Woodson

- James G. Woorling

- Caroline Wright

- Sallie Wroe

- Fannie Yarbrough

- Litt Young

- Louis Young

- Teshan Young

ILLUSTRATIONS

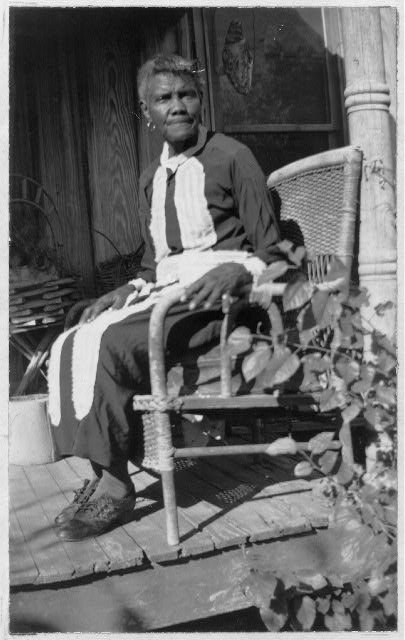

Mazique Sanco

Mazique Sanco was born a slave of Mrs. Louisa Green, in Columbia, South Carolina, on February 10, 1849. Shortly after Mazique was freed, he enlisted in the army and was sent with the Tenth Cavalry to San Angelo, then Fort Concho, Texas. After Mazique left the army he became well-known as a chef, and worked for several large hotels. Mazique uses little dialect. When asked where Mazique is, his young wife says, "In his office," and upon inquiry as to the location of this office, she replies mirthfully, "On de river," for since he is too old to work, Mazique spends most of his time fishing.

"My mistress owned a beautiful home and three hundred twenty acres of land in the edge of Columbia, in South Carolina, just back of the state house. Her name was Mrs. Louisa Green and she was a widow lady. That's where I was born, but when her nephew, Dr. Edward Flemming, married Miss Dean, I was given to him for a wedding present, and so was my mother and her other children. I was a very small boy then, and when I was ten Dr. Flemming gave me to his crippled mother-in-law for a foot boy. She got crippled in a runaway accident, when her husband was killed. He had two fine horses, fiery and spirited as could be had. He called them Ash and Dash, and one day he and his wife were out driving and the horses ran the carriage into a big pine tree, and Mr. Dean was killed instantly, and Mrs. Dean couldn't ever help herself again. I waited on her. I had a good bed and food and was let to earn ten cent shin plasters.

"When the war was over she called up her five families of slaves and told us we could go or stay. Some went and some stayed. I was always an adventurer, wanting to see and learn things, so I left and went back to my mother with Mrs. Flemming.

"I only stayed there a few months and hired out to Major Legg, and worked for him several years. I felt I wasn't learning enough, so I joined the United States Army and with a hundred and eighty-five boys went to St. Louis, Missouri. From there we were transferred with the Tenth Cavalry to Fort Concho. I helped haul the lumber from San Antonio to finish the buildings at the fort. I was there five years.

"After I went to work at private employment I did some carpenter work, but most of the houses were adobe or pecan pole buildings, so I got a job from Mr. Jimmy Keating as mechanic for awhile, and then drifted to Mexico. Odd jobs were all I could get for awhile, so I landed in El Paso and got a job in a hotel.

"That was the start of my success, for I learned to be a skilled chef and superintended the kitchens in some of the largest hotels in Texas. I made as high as $80.00, in Houston. My last work was done at the St. Angelus Hotel here in San Angelo and if you don't believe I'm a good cook, just look at my wife over there. When I married her she was fourteen years old and weighed a hundred and fifteen pounds. Now it's been a long time since I could get her on the scales, not since she passed the two hundred pound mark."

Clarissa Scales

Clarissa Scales, 79, was born a slave of William Vaughan, on his plantation at Plum Creek, Texas. Clarissa married when she was fifteen. She owns a small farm near Austin, but lives with her son, Arthur, at 1812 Cedar Ave., Austin.

"Mammy's name was Mary Vaughan and she was brung from Baton Rouge, what am over in Louisiana, by our master. He went and located on Plum Creek, down in Hays County.

"Mammy was a tall, heavy-set woman, more'n six foot tall. She was a maid-doctor after freedom. Dat mean she nussed women at childbirth. She allus told me de last thing she saw when she left Baton Rouge was her mammy standin' on a big, wood block to be sold for a slave. Dat de last time she ever saw her mammy. Mammy died 'bout fifty years ago. She was livin' on a farm on Big Walnut Creek, in Travis County. Daddy done die a year befo' and she jes' grieves herself to death. Daddy was sho' funny lookin', 'cause he wore long whiskers and what you calls a goatee. He was field worker on de Vaughan plantation.

"Master Vaughan was good and treated us all right. He was a great white man and didn't have no over seer. Missy's name was Margaret, and she was good, too.

"My job was tendin' fires and herdin' hawgs. I kep' fire goin' when de washin' bein' done. Dey had plenty wood, but used corn cobs for de fire. Dere a big hill corn cobs near de wash kettle. In de evenin' I had to bring in de hawgs. I had a li'l whoop I druv dem with, a eight-plaited rawhide whoop on de long stick. It a purty sight to see dem hawgs go under de slip-gap, what was a rail took down from de bottom de fence, so de hawgs could run under.

"Injuns used to pass our cabin in big bunches. One time dey give mammy some earrings, but when they's through eatin' they wants dem earrings back. Dat de way de Injuns done. After feedin' dem, mammy allus say, 'Be good and kind to everybody.'

"One day Master Vaughan come and say we's all free and could go and do what we wants. Daddy and mammy rents a place and I stays until I's fifteen. I wanted to be a teacher, but daddy kep' me hoein' cotton most de time. Dat's all he knowed. He allus told me it was 'nough larnin' could I jes' read and write. He never even had dat much. But he was de good farmer and good to me and mammy.

"Dere was a school after freedom. Old Man Tilden was de teacher. One time a bunch of men dey calls de Klu Klux come in de room and say, 'You git out of here and git 'way from dem niggers. Don' let us cotch you here when we comes back.' Old Man Tilden sho' was scart, but he say, 'You all come back tomorrow.' He finishes dat year and we never hears of him 'gain. Dat a log schoolhouse on Williamson Creek, five mile south of Austin.

"Den a cullud teacher named Hamlet Campbell come down from de north. He rents a room in a big house and makes a school. De trustees hires and pays him and us chillen didn't have to pay. I got to go some, and I allus tells my granddaughter how I's head of de class when I does go. She am good in her studies, too.

"When I's fifteen I marries Benjamin Calhoun Scales and he was a farmer. We had five chillen and three boys is livin'. One am a preacher and Arthur am a cement laborer and Chester works in a printin' shop.

"Benjie dies on February 15th, dis year (1937). I lives with Arthur and de gov'ment gives me $10.00 de month. I has de li'l farm of nineteen acres out near Oak Hill and Floyd, de preacher, lives on dat. All my boys is good to me. Dey done good, and better'n we could, 'cause we couldn't git much larnin' dem days. I's had de good life. But we 'preciated our chance more'n de young folks does nowadays. Dey has so much dey don't have to try so hard. If we'd had what dey got, we'd thunk we was done died and gone to Glory Land. Maybe dey'll be all right when deys growed."

Hannah Scott

Hannah Scott was born in slavery, in Alabama. She does not know her age but says she was grown when her last master, Bat Peterson, set her free. Hannah lives with her grandson in a two-room house near the railroad tracks, in Houston, Texas. Unable to walk because of a paralytic stroke, Hannah asked her grandson to lift her from the bed to a chair, from which she told her story.

"Son, move de chair a mite closer to de stove. Dere, dat's better, 'cause de heat kind of soople me up. Ain't nothin' left of me but some skin and bones, nohow.

"Lemme see now. I's born in Alabama and I think dey calls it Fayette County. Mama's name was Ardissa and she 'long to Marse Clark Eccles, but us chillen allus call him White Pa. Miss Hetty, his wife, we calls her White Ma.

"I never knowed my own pa, 'cause he 'long to 'nother man and was sold away 'fore I's old 'nough to know him. Mama has five us chillen, but dey all dead 'ceptin' me. Dey didn't have no marriage back den like now. Dey just puts black folks together in de sight of man and not in de sight of Gawd, and dey puts dem asunder, too.

"Marse Eccles didn't have no big place and only nine slaves. I guess he what you calls 'poor folks,' but he mighty good to he black folks. I 'member when he sold us to Bat Peterson. He and White Ma break down and cry when old Bat puts us in de wagon and takes us off to Arkansas. I heared mama say something 'bout White Pa sellin' us for debt and he gits a hunerd dollars for me.

"Whoosh, it sho' was a heap dif'ent from Alabama. Marse Bat had niggers. I reckon he must of had a hunerd of dem and two nigger drivers, Uncle Green and Uncle Jake, and a overseer. Marse Bat was mean, too, and work he slaves from daylight till nine o'clock at night. I carries water for de hands. I carries de bucket on my head and 'fore long I ain't got no more hair on my head den you has on de palm of you hand. No, suh!

"When I gits bigger, de overseer puts me in de field with de rest. Marse Bat grow mostly cotton and it don't make no dif'ence is you big or li'l, you better keep up or de drivers burn you up with de whip, sho' 'nough. Old Marse Bat never put a lick on me all de years I 'longs to him, but de drivers sho' burnt me plenty times. Sometime I gits so tired come night, I draps right in de row and gone to sleep. Den de driver come 'long and, wham, dey cuts you 'cross de back with de whip and you wakes up when it lights on you, yes, suh! 'Bout nine o'clock dey hollers 'cotton up' and dat de quittin' signal. We goes to de quarters and jes' drap on de bunk and go to sleep without nothin' to eat.

"On old Bat's place dat all us know, is work and more work. De onlies' time we has off am Sunday and den we has to wash and mend clothes. De first Sunday of de month a white preacher come, but all he say is 'bedience to de white folks, and we hears 'nough of dat without him tellin' us.

"I 'member when White Pa come to try git mama and us chillen back. We been in Arkansas five, six year, and, whoosh, I sho' wants to go back to my White Pa, but old Bat wouldn't let us go. He come to our quarters dat night and tell mama if she or us chillen try to run off he'll kill us. Dey sho' watch us for awhile.

"Sometimes one of de niggers runs off but he ain't gone long. He gits hongry and comes back. Den he gits a burnin' with de bullwhip. Does he run 'way again, Marse Bat say he got too much rabbit in him and chains him up till he goes to Little Rock and sells him.

"I heared some white folks treat dey slaves good and give dem time off, but Marse Bat don't. We has plenty to eat and clothes, but dat all. Dat de way it was till we's freed, only it wasn't in Arkansas. It was down to Richmond, here in Texas, 'cause Marse Bat rents a farm at Richmond. He thunk if he brung us to Texas he wouldn't have to set us free. But he got fooled, 'cause a gov'ment man come tell us we's free. We had de crop planted and old Bat say if we'll stay through pickin' he'll pay us. Mama and us stayed awhile.

"I gits married legal with Richard Scott and we comes to Harrisburg and he gits a job on de section of de railroad. I's lived here ever since. My husban' and me raises five chillen, but only de one gal am alive now. My grandson takes care of me. He tells me iffen my husband lived so long, he be 107 years old. I know he was older dan me, but not 'xactly how much.

"Sometime I feel I's been here too long, 'cause I's paralyzed and can't move round none. But maybe de Lawd ain't ready for me yet, and de Debbil won't have me."

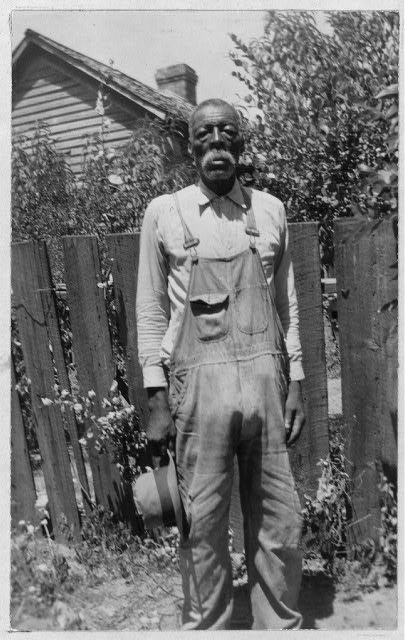

Abram Sells

Abram Sells was born a slave on the Rimes Plantation, which was located about 18 miles southeast of Newton, Texas. He does not know his age, but must be well along in the 80's, as his recollections of slavery days are keen. He lives at Jamestown, Texas.

"I was birthed on the Rimes Plantation, now called Harrisburg. My great-grand-daddy's name was Bowser Rimes and he was brung to Texas from Louisiana and die at 138 year old. He's buried on the old Ben Powell place close to Jasper. My grand-daddy, that's John, he lives to be 103 year old and he buried on the Eddy plantation at Jasper. My daddy, Mose Rimes, he die young at 86 and he buried in Jasper County, too. My mammy's name was Phoebe and she was birthed a Rimes nigger and brung to Texas from back in Louisiana. The year slaves was freed I was inherit by a man named Sells, what marry into the Rimes family and that's why my name's Sells, 'cause it change 'long with the marriage. Us was jes' ready to be ship back to Louisiana to the new massa's plantation when the end of the war break up the trip.

"You see, we all had purty good time on Massa Rimes's plantation. None of them carin' 'bout being sot free. They has to work hard all time, but that don' mean so much, 'cause they have to work iffen they was on they own, too. The old folks was 'lowed Saturday evenin' off or when they's sick, and us little ones, us not do much but bring in the wood and kindle the fires and tote water and he'p wash clothes and feed the little pigs and chickens.

"Us chillen hang round close to the big house and us have a old man that went round with us and look after us, white chillen and black chillen, and that old man was my great grand-daddy. Us sho' have to mind him, 'cause iffen we didn't, us sho' have bad luck. He allus have the pocket full of things to conjure with. That rabbit foot, he took it out and he work that on you till you take the creeps and git shakin' all over. Then there's a pocket full of fish scales and he kind of squeak and rattle them in the hand and right then you wish you was dead and promise to do anything. Another thing he allus have in the pocket was a li'l old dry-up turtle, jes' a mud turtle 'bout the size of a man's thumb, the whole thing jes' dry up and dead. With that thing he say he could do mos' anything, but he never use it iffen he ain't have to. A few times I seed him git all tangle up and boddered and he go off by hisself and sot down in a quiet place, take out this very turtle and put it in the palm of the hand and turn it round and round and say somethin' all the time. After while he git everything ontwisted and he come back with a smile on he face and maybe whistlin'.

"They fed all us nigger chillen in a big trough made out'n wood, maybe more a wood tray, dug out'n soft timber like magnolia or cypress. They put it under a tree in the shade in summer time and give each chile a wood spoon, then mix all the food up in the trough and us goes to eatin'. Mos' the food was potlicker, jes' common old potlicker; turnip green and the juice, Irish 'taters and the juice, cabbages and peas and beans, jes' anything what make potlicker. All us git round like so many li'l pigs and then us dish in with our wood spoon till it all gone.

"We has lots of meat at times. Old grand-daddy allus ketchin' rabbit in some kind of trap, mostly make out'n a holler log. He sot 'em round in the garden and sho' kotch the rabbits. And possums, us have a good possum dog, sometimes two or three, and every night you heered them dogs barkin' in the field down by the branch. Sho' 'nuf, they git possum treed and us go git him and parbile him and put him in the oven and bake him plumb tender. Then we stacks sweet 'taters round him and po' the juice over the whole thing. Now, there is somethin' good 'nuf for a king.

"There was lots of deer and turkey and squirrel in the wil' wood and somebody out huntin' nearly every day. Course Massa Rime's folks couldn't eat up all this meat befo' it spile and the niggers allus git a great big part of it. Then we kilt lots of hawgs and then talk 'bout eatin'! O, them chitlin's, sousemeat and the haslets, thats the liver and the lights all biled up together. Us li'l niggers fill up on sich as that and go to bed and mos' dream us is li'l pigs.

"Us allus have plenty to eat but didn't pay much 'tention to clothes. Boys and gals all dress jes' alike, one long shirt or dress. They call it a shirt iffen a boy wear it and call it a dress iffen the gal wear it. There wasn't no difference, 'cause they's all made out'n somethin' like duck and all white. That is, they's white when you fus' put them on, but after you wears them a while they git kind of pig-cullud, kind of grey, but still they's all the same color. Us all go barefoot in summer, li'l ones and big ones, but in winter us have homemake shoes. They tan the leather at home and make the shoe at home, allus some old nigger that kin make shoe. They was more like moc'sin, with lace made of deerskin. The soles was peg on with wood pegs out'n maple and sharpen down with a shoe knife.

"Us have hats make out'n pine straw, long leaf pine straw, tied together in li'l bunches and platted round and round till it make a kinder hat. That pine straw great stuff in them days and us use it in lots of ways. Us kivered sweet 'taters with it to keep them from git freeze and hogs made beds out'n it and folks too. Yes, sir, us slep' on it. The beds had jes' one leg. They bored two hole in the wall up in the corner and stuck two pole in them holes and lay plank on that like slats and pile lots of pine straw on that. Then they spread a homemake blanket or quilt on that and sometime four or five li'l niggers slep' in there to keep us warm.

"The li'l folks slep' mos' as long as they want to in daylight, but the big niggers have to come out'n that bed 'bout fo' o'clock when the big horn blow. The overseer have one nigger, he wake up early for to blow the horn and when he blow this horn he make sich a holler then all the res' of the niggers better git out'n that bed and 'pear at the barn 'bout daylight. He might not whip him for being late the fus' time, but that nigger better not forgit the secon' time and be late!

"Massa Rimes didn't whip them much, but iffen they was bad niggers he jes' sold them offen the place and let somebody else do the whippin'. Never have no church house or school, but Massa Rimes, he call them in and read the Bible to them. Then he turn the service over to some good, old, 'ligious niggers and let them finish with the singin' and prayin' and 'zorting. After peach [HW: "?"] cleared, a school was 'stablish and a white man come from the north to teach the cullud chillen, but befo' that they didn' take no pains to teach the niggers nothin' 'ceptin' to work, and the white chillen didn't have much school neither.

"That was one plantation what was run 'sclusively by itself. Massa Rimes have a commissary or sto' house, whar he kep' whatnot things—them what make on the plantation and things the slaves couldn' make for themselfs. That wasn't much, 'cause we make us own clothes and shoes and plow and all farm tools and us even make our own plow line out'n cotton and iffen us run short of cotton sometime make them out'n bear grass and we make buttons for us clothes out'n li'l round pieces of gourds and kiver them with cloth.

"That wasn't sich a big plantation, 'bout a t'ousand acre and only 'bout forty niggers. There was'n no jail and they didn't need none. Us have no real doctor, but of course there was a doctor man at Jasper and one at Newton, but a nigger have to be purty sick 'fore they call a doctor. There's allus some old time nigger what knowed lots of remedies and knowed all dif'rent kinds of yarbs and roots. My grand-daddy, he could stop blood, and he could conjure off the fever and rub his fingers over warts and they'd git away. He make ile out'n rattlesnake for the rheumatis'. For the cramp he git a kind of bark offen a tree and it done the job, too. Some niggers wo' brass rings to keep off the rheumatis' and punch hole in a penny or dime and wear that on the ankle to keep off sickness.

"'Member the war? Course I does. I 'member how some of them march off in their uniforms, lookin' so grand, and how some of them hide out in the wood to keep from lookin' so grand. They was lots of talkin' 'bout fighting, and rubbing and scrubbing the old shotgun. The oldes' niggers was settin' round the fire late in the night, stirrin' the ashes with the poker and rakin' out the roas' 'taters. They's smokin' the old corn cob pipe and homemake tobacco and whisperin' right low and quiet like what they's gwineter do and whar they's gwineter to when Mister Lincoln, he turn them free.

"The more they talk, the more I git scared that the niggers is going to git sot free and wondering what I's gwine to do if they is. No, I guess I don't want to live back in them times no mo', but I sho' seed lots of niggers not doin' so well as they did when they was slaves and not havin' nigh as much to eat."

George Selman

George Selman was born in 1852, five miles east of Alto, Texas. His father was born in Virginia and his mother in South Carolina, and were brought to Texas by Mr. Dan Lewis. Green has been a Baptist minister since his youth. He lives in Jacksonville, Texas.

"We was a big fam'ly, nine children. I was born a slave of the Selmans, Marster Tom and Missus Polly, and they lived in Mississippi. Mother's name was Martha and my father's name was John Green Selman.

"Marster's folks come from Mississippi a long ways back and they had a big house made from hewed logs with a big hallway down the middle. The kitchen was out in the yard, 'bout forty steps from the house. The yard had five acres in it and a big garden was in it. Marster had five slave families and our cabins was built in a half circle in the back yard. I seemed to be the pet and always went with Marster Tom to town or wherever he was goin'. Then I learned to plow by my mother letting me hold the handles and walk along with her. Finally she let me go 'round by myself.

"Marster Tom was always good to us and he taught me religion. He was the best man I ever knew. Then Saturday noon come, they blew the horn and we quit workin'. We went to church one Sunday a month and we sat on one side and the white folks on the other.

"I never learnt to read and write, but I learned to work in the house and the fields. Late in the day Aunt Dicey, who was the cook, called all us children out under the big trees and give us supper. This was in summer, but nobody ever fed us but Aunt Dicey. We all ate from one bowl, or maybe I'd call it a tray 'cause it was made of wood, like a bread tray but bigger, big enough to hold three, four gallons. She put the food in the tray and give each chil' a spoon. Mostly we had pot likker and corn-bread. In winter we ate from the same tray, but in the kitchen.

"I never seen runaway slaves, but Marster Tom had a neighbor mean to slaves and sometimes when they was whipped we could hear 'em holler. The neighbor had one slave called Sallie, and she was a weaver and was so mean she had to wear a chain. After she died, I heered her ghost one night. I was stayin' with a white man who had the malaria-typhoid-pneumonia fever, and one night I heered Sallie scream and seen her chain drag back and forth. I tol' the man I knowed it was Sallie, 'cause I'd heered that scream for years. But the man said she was dead, so it mus' have been her ghost. I heered her night after night, screamin' and draggin' her chain up and down.

"When Marster Tom says we's free, I goes to his sister, Miss Ca'line and works for her. After sev'ral years I larned to preach and I's the author of most the Baptist churches in this county."

Callie Shepherd

Callie Shepherd, age 84, lives at 4701 Spring Ave., Dallas, Texas. She was born near Gilmer, Texas, in 1852, a slave of the Stevens family. At present she is cared for by her 68 year old son and his wife.

"Course I kin tell you. I got 'memberance like dey don't have nowadays. Dat 'cause things is goin' round and round too fast without no settin' and talkin' things over.

"I's native born right down here at Gilmer on de old place and Miss Fannie could tell you de same if she could be in your presence, but she went on to Glory many a year ago. She de one what raised me, right in de house with her own chillen. I slep' right in de house, in de chillens' room, in a little trundle bed what jus' pushed back under de big bed when de mornin' come. If her chillen et one side de table I et t'other side, right by Miss Fannie's elbow.

"Miss Fannie, she Dr. Steven's wife and dey from Georgia and lived near Gilmer till de doctor goes off to de war and takes a sickness what he ain't never get peart from and died. Died right there on de old place. He was a right livin' man and dey allus good to me and my mammy, what dey done brought from Georgia and she de main cook.

"My mammy don't think they ain't nobody like Miss Fannie. My mammy, she a little red-Indian nigger woman not so big as me, and Miss Fanny tell her, 'Don't you cry 'cause dey tryin' make freedom, 'cause de doctor done say we is gwine help you raise your babies.'

"Some de niggers don't like de treatment what dey white folks gives 'em and dey run away to de woods. I'd hear de nigger dogs a-runnin' and when dey cotch de niggers dey bites 'em all over and tears dey clothes and gits de skin, too. And de niggers, dey'd holler. I seed 'em whip de niggers, 'cause dey tolt de chillen to look. Dey buckled 'em down on de groun' and laid it on dey backs. Sometimes dey laid on with a mighty heavy hand. But I ain't never git no whippin' 'cause I never went with de cullud gen'ration. I set right in de buggy with de white chillen and went to hear Gospel preachin'.

"I danced at de balls in de sixteen figure round sets and everybody in dem parts say I de principal dancer, but I gits 'ligion and left de old way to live in de 'termination to live beyon' dis vale of tears.

"I have my trib'lations after my old daddy die, 'cause he good to us little chillen. But my next daddy a man mighty rough on us. Dat after Miss Fannie done gone back to Georgia and my back done hurt me all de time from pullin' fodder and choppin' cotton. It make a big indif'rence after Miss Fannie gone, and de war de cause of it all. I heered de big cannons goin' on over there jus' like de bigges' clap of thunder.

"Me and de little chillen playin' in de road makin' frog houses out of sand when we hear de hosses comin'. We looks and see de budallions shinin' in de sun and de sojers have tin cups tied on side dere saddles and throwed dem cups to us chillen as dey passed. Dey say war is over and we is free. Miss Fannie say she a Seay from Georgia and she go back dere, but I jus' stay on where I's native born."

Betty Simmons

Betty Simmons, 100 or more, was born a slave to Leftwidge Carter, in Macedonia, Alabama. She was stolen when a child, sold to slave traders and later to a man in Texas. She now lives in Beaumont, Texas.

"I think I's 'bout a hunnerd and one or two year old. My papa was a free man, 'cause his old massa sot him free 'fore I's born, and give him a hoss and saddle and a little house to live in.

"My old massa when I's a chile, he name Mr. Leftwidge Carter and when he daughter marry Mr. Wash Langford, massa give me to her. She was call Clementine. Massa Langford has a little store and a man call Mobley go in business with him. Dis man brung down he two brothers and dey fair clean Massa Langford out. He was ruint.

"But while all dis goin' on I didn't know it and I was happy. Dey was good to me and I don't work too hard, jus' gits in de mischief. One time I sho' got drunk and dis de way of it. Massa have de puncheon of whiskey and he sell de whiskey, too. Now, in dem days, dey have frills 'round de beds, dey wasn't naked beds like nowdays. Dey puts dis puncheon under de beds and de frills hides it, but I's nussin' a little boy in dat room and I crawls under dat bed and drinks out of de puncheon. Den I poke de head out and say 'Boo' at de little boy, and he laugh and laugh. Den I ducks back and drinks a little more and I say 'Boo' at him 'gain, and he laugh and laugh. Dey was lots of whiskey in dat puncheon and I keeps drinkin' and sayin' 'Boo'. My head, it gits funny and I come out with de puncheon and starts to de kitchen, where my aunt Adeline was de cook. I jes' a-stompin' and sayin' de big words. Dey never lets me 'round where dat puncheon is no more.

"When Massa Langford was ruint and dey goin' take de store 'way from him, dey was trouble, plenty of dat. One day massa send me down to he brudder's place. I was dere two days and den de missy tell me to go to de fence. Dere was two white men in a buggy and one of 'em say, 'I thought she bigger dan dat.' Den he asks me, 'Betty, kin you cook?' I tells him I been cook helper two, three month, and he say, 'You git dressed and came on down three mile to de other side de post office.' So I gits my little bundle and whan I gits dere he say, 'Gal, you want to go 'bout 26 mile and help cook at de boardin' house?' He tries to make me believe I won't be gone a long time, but when I gits in de buggy dey tells me Massa Langford done los' everything and he have to hide out he niggers for to keep he credickers from gittin' dem. Some of de niggers he hides in de woods, but he stole me from my sweet missy and sell me so dem credickers can't git me.

"When we gits to de crossroads dere de massa and a nigger man. Dat another slave he gwine to sell, and he hate to sell us so bad he can't look us in de eye. Dey puts us niggers inside de buggy, so iffen de credickers comes along dey can't see us.

"Finally dese slave spec'laters puts de nigger man and me on de train and takes us to Memphis, and when we gits dere day takes us to de nigger traders' yard. We gits dere at breakfast time and waits for de boat dey calls de 'Ohio' to git dere. De boat jus' ahead of dis Ohio, Old Capt. Fabra's boat, was 'stroyed and dat delay our boat two hours. When it come, dey was 258 niggers out of dem nigger yards in Memphis what gits on dat boat. Dey puts de niggers upstairs and goes down de river far as Vicksburg, dat was de place, and den us gits offen de boat and gits on de train 'gain and dat time we goes to New Orleans.

"I's satisfy den I los' my people and ain't never goin' to see dem no more in dis world, and I never did. Dey has three big trader yard in New Orleans and I hear de traders say dat town 25 mile square. I ain't like it so well, 'cause I ain't like it 'bout dat big river. We hears some of 'em say dere's gwineter throw a long war and us all think what dey buy us for if we's gwine to be sot free. Some was still buyin' niggers every fall and us think it too funny dey kep' on fillin' up when dey gwineter be emptyin' out soon.

"Dey have big sandbars and planks fix 'round de nigger yards and dey have watchmans to keep dem from runnin 'way in de swamp. Some of de niggers dey have jus' picked up on de road, dey steals dem. Dey calls dem 'wagon boy' and 'wagon gal.' Dey has one bit mulatto boy dey stole 'long de road dat way and he massa find out 'bout him and come and git him and take him 'way. And a woman what was a seamster, a man what knowed her seed her in de pen and he done told her massa and he come right down and git her. She sho' was proud to git out. She was stole from 'long de road, too. You sees, if dey could steal de niggers and sell 'em for de good money, dem traders could make plenty money dat way.

"At las' Col. Fortescue, he buy me and kep' me. He a fighter in de Mexican war and he come to New Orleans to buy he slaves. He takes me up de Red River to Shreveport and den by de buggy to Liberty, in Texas.

"De Colonel, he a good massa to us. He 'lows us to work de patch of ground for ourselves, and maybe have a pig or a couple chickens for ourselves, and he allus make out to give us plenty to eat.

"De massa, when a place fill up, he allus pick and move to a place where dere ain't so much people. Dat how come de Colonel fus' left Alabama and come to Texas, and to de place dey calls Beef Head den, but calls Gran' Cane now.

"When us come to Gran' Cane a nigger boy git stuck on one us house girls and he run away from he massa and foller us. It were a woodly country and de boy outrun he chasers. I heered de dogs after him and he torn and bleedin' with de bresh and he run upstair in de gin house. De dogs sot down by de door and de dog-man, what hired to chase him, he drug him down and throw him in de Horse Hole and tells de two dogs to swim in and git him. De boy so scairt he yell and holler but de dogs nip and pinch him good with de claws and teeth. When dey lets de boy out de water hole he all bit up and when he massa larn how mean de dog-man been to de boy he 'fuses to pay de fee.

"I gits married in slavery time, to George Fortescue. De massa he marry us sort of like de justice of de peace. But my husban', he git kilt in Liberty, when he cuttin' down a tree and it fall on him. I ain't never marry no more.

"I sho' was glad when freedom come, 'cause dey jus' ready to put my little three year old boy in de field. Dey took 'em young. I has another baby call Mittie, and she too young to work. I don't know how many chillen I's have, and sometimes I sits and tries to count 'em. Dey's seven livin' but I had 'bout fourteen.

"Dey was pretty hard on de niggers. Iffen us have de baby us only 'lowed to stay in de house for one month and card and spin, and den us has to get out in de field. Dey allus blow de horn for us mammies to come up and nuss de babies.

"I seed plenty soldiers 'fore freedom. Dey's de Democrats, 'cause I never seed no Yankees. Us niggers used to wash and iron for dem. At night us seed dose soldiers peepin' 'round de house and us run 'way in de bresh.

"When freedom come us was layin' by de crop and de massa he give us a gen'rous part of dat crop and us move to Clarks place. We gits on all right after freedom, but it hard at first 'cause us didn't know how to do for ourselves. But we has to larn."

George Simmons

George Simmons, born in Alabama in 1854, was owned by Mr. Steve Jaynes, who lived near Beaumont, Texas. George has a good many memories of slavery years, although he was still a child when he was freed. He now lives in Beaumont, Tex.

"I's bo'n durin' slavery, somewhar in Alabama, but I don' 'member whar my mammy said. Dey brung me here endurin' de War and I belonged to Massa Steve Jaynes, and he had 'bout 75 other niggers. It was a big place and lots of wo'k, but I's too little to do much 'cept errands 'round de house.

"Massa Jaynes, he raised cotton and co'n and he have 'bout 400 acres. He 'spected de niggers to wo'k hard from mornin' till sundown, but he was fair in treatin' 'em. He give us plenty to eat and lots of cornbread and black-eye' peas and plenty hawg meat and sich. We had possum sometimes, too. Jus' took a nice, fat possum we done cotched in de woods and skinned 'im and put 'im in a oven and roas' 'im with sweet 'tatoes all 'round and make plenty gravy. Dat was good.

"Massa Jaynes, he 'lowed de slaves who wanted to have a little place to make garden, veg'tables and dose kin' of things. He give 'em seed and de nigger could have all he raised in his little garden. We was all well kep' and I don' see whar freedom was much mo' better, in a way. Course, some massas was bad to dere slaves and whipped 'em so ha'd dey's nearly dead. I know dat, 'cause I heered it from de neighbors places. Some of dere slaves would run away and hide in de woods and mos' of 'em was kotched with dogs. Fin'ly dey took to puttin' bells on de slaves so iffen dey run away, dey could hear 'em in de woods. Dey put 'em on with a chain, so dey couldn' get 'em off.

"We could have church on Sunday and our own cullud church. Sam Watson, he was de nigger preacher and he's a slave, too.

"I didn' know much 'bout de war, 'cause we couldn' read and de white folks didn' talk war much 'fore us. But we heered things and I 'member de sojers on dere way back after it's all over. Dey wasn' dressed in a uniform and dey clothes was mos'ly rags, dey was dat tore up. We seed 'em walkin' on de road and sometimes dey had ole wagons, but mos' times dey walk. I 'member some Yankee sojers, too. Dey have canteens over de shoulder, and mos' of 'em has blue uniforms on.

"Massa, he tell us when freedom come, and some of us stays 'round awhile, 'cause whar is we'uns goin'? We didn' know what to do and we didn' know how to keep ourselves, and what was we to do to get food and a place to live? Dose was ha'd times, 'cause de country tore up and de business bad.

"And de Kluxes dey range 'round some. Dey soon plays out but dey took mos' de time to scare de niggers. One time dey comes to my daddy's house and de leader, him in de long robe, he say, 'Nigger, quick you and git me a drink of water.' My daddy, he brung de white folks drinkin' gourd and dat Klux, he say, 'Nigger, I say git me a big drink—bring me dat bucket. I's thirsty.' He drinks three buckets of water, we thinks he does, but what you think we learns? He has a rubber bag under his robe and is puttin' dat water in dere!"

Ben Simpson

Ben Simpson, 90, was born in Norcross, Georgia, a slave of the Stielszen family. He had a cruel master, and was afraid to tell the truth about his life as a slave, until assured that no harm would come to him. Ben now lives in Madisonville, Texas, and receives a small old age pension.

"Boss, I's born in Georgia, in Norcross, and I's ninety years old. My father's name was Roger Stielszen and my mother's name was Betty. Massa Earl Stielszen captures them in Africa and brung them to Georgia. He got kilt and my sister and me went to his son. His son was a killer. He got in trouble there in Georgia and got him two good-stepping hosses and the covered wagon. Then he chains all he slaves round the necks and fastens the chains to the hosses and makes then walk all the way to Texas. My mother and my sister had to walk. Emma was my sister. Somewhere on the road it went to snowin' and massa wouldn't let us wrap anything round our feet. We had to sleep on the ground, too, in all that snow.

"Massa have a great, long whip platted out of rawhide and when one the niggers fall behind or give out, he hit him with that whip. It take the hide every time he hit a nigger. Mother, she give out on the way, 'bout the line of Texas. Her feet got raw and bleedin' and her legs swoll plumb out of shape. Then massa, he jus' take out he gun and shot her, and whilst she lay dyin' he kicks her two, three times and say, 'Damn a nigger what can't stand nothin'.' Boss, you know that man, he wouldn't bury mother, jus' leave her layin' where he shot her at. You know, then there wasn't no law 'gainst killin' nigger slaves.

"He come plumb to Austin through that snow. He taken up farmin' and changes he name to Alex Simpson, and changes our names, too. He cut logs and builded he home on the side of them mountains. We never had no quarters. When night-time come he locks the chain round our necks and then locks it round a tree. Boss, our bed were the ground. All he feed us was raw meat and green corn. Boss, I et many a green weed. I was hongry. He never let us eat at noon, he worked us all day without stoppin'. We went naked, that the way he worked us. We never had any clothes.

"He brands us. He brand my mother befo' us left Georgia. Boss, that nearly kilt her. He brand her in the breast, then between the shoulders. He brand all us.

"My sister, Emma, was the only woman he have till he marries. Emma was wife of all seven Negro slaves. He sold her when she's 'bout fifteen, jus' befo' her baby was born. I never seen her since.

"Boss, massa was a outlaw. He come to Texas and deal in stolen hosses. Jus' befo' he's hung for stealin' hosses, he marries a young Spanish gal. He sho' mean to her. Whips her 'cause she want him to leave he slaves alone and live right. Bless her heart, she's the best gal in the world. She was the best thing God ever put life in the world. She cry and cry every time massa go off. She let us a-loose and she feed us good one time while he's gone. Missy Selena, she turn us a-loose and we wash in the creek clost by. She jus' fasten the chain on us and give us great big pot cooked meat and corn, and up he rides. Never says a word but come to see what us eatin'. He pick up he whip and whip her till she falls. If I could have got a-loose I'd kilt him. I swore if I ever got a-loose I'd kill him. But befo' long after that he fails to come home, and some people finds him hangin' to a tree. Boss, that long after war time he got hung. He didn't let us free. We wore chains all the time. When we work, we drug them chains with us. At night he lock us to a tree to keep us from runnin' off. He didn't have to do that. We were 'fraid to run. We knew he'd kill us. Besides, he brands us and they no way to get it off. It's put there with a hot iron. You can't git it off.

"If a slave die, massa made the rest of us tie a rope round he feet and drug him off. Never buried one, it was too much trouble.

"Massa allus say he be rich after the war. He stealin' all the time. He have a whole mountain side where he keep he stock. Missy Selena tell us one day we sposed to be free, but he didn't turn us a-loose. It was 'bout three years after the war they hung him. Missy turned us a-loose.

"I had a hard time then. All I had to eat was what I could find and steal. I was 'fraid of everybody. I jus' went wild and to the woods, but, thank God, a bunch of men taken they dogs and run me down. They carry me to they place. Gen. Houston had some niggers and he made them feed me. He made them keep me till I git well and able to work. Then he give me a job. I marry one the gals befo' I leaves them. I'm plumb out of place there at my own weddin'. Yes, suh, boss, it wasn't one year befo' that I'm the wild nigger. We had thirteen chillen.

"I farms all my life after that. I didn't know nothin' else to do. I made plenty cotton, but now I'm too old. Me and my wife is alone now. This old nigger gits the li'l pension from the gov'ment. I not got much longer to stay here. I's ready to see God but I hope my old massa ain't there to torment me again."

Giles Smith

Giles Smith, 79, now residing at 3107 Blanchard St., Fort Worth, Texas, was born a slave of Major Hardway, on a plantation near Union Springs, Alabama. The Major gave Giles to his daughter when he was an infant and he never saw his parents again. In 1874 Frank Talbot brought Giles to Texas, and he worked on the farm two years. He then went to Brownwood and worked in a gin seventeen years. In 1908 he moved to Fort Worth and worked for a packing company. Old age led to his discharge in 1931 and he has since worked at any odd jobs he could find.

"My name am Giles Smith, 'cause my pappy was born on the Smith plantation and I took his name. I's born at Union Springs, in Alabama and Major Hardway owned me and 'bout a hundred other slaves. But he gave me to Mary, his daughter, when I's only a few months old and had to be fed on a bottle, 'cause she am jus' married to Massa Miles. She told me how she carried me home in her arms. She say I was so li'l she have a hard time to make me eat out the bottle, and I put up a good fight so she nearly took me back.

"I don't 'member the start of the war, but de endin' I does. Massa Miles called all us together and told us we's free and it give us all de jitters. He treated all us fine and nobody wanted to go. He and Missy am de best folks de Lawd could make. I stayed till I was sixteen years old.

"It am years after freedom Missy Mary say to me what massa allus say, 'If the nigger won't follow orders by kind treatin', sich nigger am wrong in the head and not worth keepin'. He didn't have to rush us. We'd just dig in and do the work. One time Massa clearin' some land and it am gittin' late for breakin' the ground. Us allus have Saturday afternoon and Sunday off. Old Jerry says to us, 'Tell yous what us do,—go to the clearin' this afternoon and Sunday and finish for the Massa. That sho' make him glad.'

"Saturday noon came and nobody tells the massa but go to that clearin' and sing while us work, cuttin' bresh and grubbin' stomps and burnin' bresh. Us sing

"'Hi, ho, ug, hi, ho, ug.De sharp bit, de strong arm,Hi, ho, ug, hi, ho, ug,Dis tree am done 'fore us warm.'

"De massa come out and his mouth am slippin' all over he face and he say, 'What this all mean? Why you workin' Saturday afternoon?'

"Old Jerry am a funny cuss and he say, 'Massa, O, massa, please don't whop us for cuttin' down yous trees.'

"I's gwine whop you with the chicken stew,' Massa say. And for Sunday dinner dere am chicken stew with noodles and peach cobbler.

"So I stays with massa and after I's fifteen he pays me $2.00 the month, and course I gits my eats and my clothes, too. When I gits the first two I don't know what to do, 'cause it the first money I ever had. Missy make the propulation to keep the money and buy for me and teach me 'bout it. There ain't much to buy, 'cause we make nearly everything right there. Even the tobaccy am made. They put honey 'twixt the leaves and put a pile of it 'twixt two boards with weights. It am left for a month and that am a man's tobaccy. A weaklin' better stay off that kind tobaccy.

"First I works in the field and then am massa's coachman. But when I's 'bout sixteen I gits a idea to go off somewheres for myself. I hears 'bout Mr. Frank Talbot, whom am takin' some niggers to Texas and I goes with him to the Brazos River bottom, and works there two years. I's lonesome for massa and missy and if I'd been clost enough, I'd sho' gone back to the old plantation. So after two years I quits and goes to work for Mr. Winfield Scott down in Brownwood, in the gin, for seventeen years.

"Well, shortly after I gits to Brownwood I meets a yaller gal and after dat I don't care to go back to Alabama so hard. I's married to Dee Smith on December the eighteenth, in 1880, and us live together many years. She died six years ago. Us have six chillen but I don't know where one of them are now. They all forgit their father in his old age! They not so young, either.

"My woman could write a little so she write missy for me, and she write back and wish us luck and if we ever wants to come back to the old home we is welcome. Us write back' forth with her. Finally, us git the letter what say she sick, and then awful low. That 'bout twenty-five years after I marries. That am too much for me, and I catches the next train back to Alabama but I gits there too late. She am dead, and I never has forgive myself, 'cause I don't go back befo' she die, like she ask us to, lots of times.

"I comes here fifteen years ago and here I be. The last six year I can't work in the packin' plants no more. I's too old. Anything I can find to do I does, but it ain't much no more.

"The worst grief I's had, am to think I didn't go see missy 'fore she die. I's never forgave myself for that."

James W. Smith

James W. Smith, 77, was born a slave of the Hallman family, in Palestine, Texas. James became a Baptist minister in 1895, and preached until 1931, when poor health forced him to retire. He and his wife live at 1306 E. Fourth St., Fort Worth, Texas.

"Yes, suh, I'm birthed a slave, but never worked as sich, 'cause I's too young. But I 'members hearin' my mother tell all about her slave days and our master. He was John Hallman and owned a place in Palestine, with my mother and father and fifty other slaves. My folks was house servants and lived a little better'n the field hands. De cabins was built cheap, though, no money, only time for buildin' am de cost. Dey didn't use nails and helt de logs in place by dovetailin'. Dey closed de space between de logs with wedges covered with mud and straw. De framework for de door was helt by wooden pegs and so am de benches and tables. Master Hallman always had some niggers trained for carpenter work, and one to be blacksmith and one to make shoes and harness.

"We was lucky to have de kind master, what give us plenty to eat. If all de people now could have jus' so good food what we had, there wouldn't be no beggin' by hungry folks or need for milk funds for starved babies.

"We didn't have purty clothes sich as now, with all de dif'rent colors mixed up, but dey was warm and lastin', dyed brown and black. De black oak and cherry made de dyes. Our shoes wasn't purty, either. I has to laugh when I think of de shoes. There wasn't no careful work put on dem, but dey covered de feets and lasted near forever.

"Master always wanted to help his cullud folks live right and my folks always said de best time of they lives was on de old plantation. He always 'ranged for parties and sich. Yes, suh, he wanted dem to have a good time, but no foolishment, jus' good, clean fun. There am dancin' and singin' mostest every Saturday night. He had a little platform built for de jiggin' contests. Cullud folks comes from all round, to see who could jig de best. Sometimes two niggers each put a cup of water on de head and see who could jig de hardest without spillin' any. It was lots of fun.

"I must tell you 'bout de best contest we ever had. One nigger on our place was de jigginest fellow ever was. Everyone round tries to git somebody to best him. He could put de glass of water on his head and make his feet go like triphammers and sound like de snaredrum. He could whirl round and sich, all de movement from his hips down. Now it gits noised round a fellow been found to beat Tom and a contest am 'ranged for Saturday evenin'. There was a big crowd and money am bet, but master bets on Tom, of course.

"So dey starts jiggin'. Tom starts easy and a little faster and faster. The other fellow doin' de same. Dey gits faster and faster and dat crowd am a-yellin'. Gosh! There am 'citement. Dey jus' keep a-gwine. It look like Tom done found his match, but there am one thing yet he ain't done—he ain't made de whirl. Now he does it. Everyone holds he breath, and de other fellow starts to make de whirl and he makes it, but jus' a spoonful of water sloughs out his cup, so Tom am de winner.

"When freedom come, the master tells his slaves and says, 'What you gwine do?' Wall, suh, not one of dem knows dat. De fact am, dey's scared dey gwine be put off de place. But master says dey can stay and work for money or share crop. He says they might be trouble 'twixt de whites and niggers and likely it be best to stay and not git mixed in dis and dat org'ization. Mostest stays, only one or two goes away. My folks stays for five years after de war. Den my father moves to Bertha Creek, where he done 'range for a farm of his own. They hated to leave master's plantation, he's so good and kind.

"Some the cullud folks thinks they's to take charge and run the gov'ment. They asks my father to jine their org'ization. He goes once and some eggs am served. Dey am served by de crowd and dem eggs ain't fresh yard eggs. Father 'cides he wants his eggs served dif'rent, and he likes dem fresh, so he takes master's advice and don't jine nothing.

"When de Klux come, de cullud org'ization made their scatterment. Plenty gits whipped round our place and some what wasn't 'titled to it. Den soldiers comes and puts order in de section. Dey has trouble about votin'. De cullud folks in dem days was non-knowledge, so how could dey vote 'telligent? Dat am foolishment to 'sist on de right to vote. It de non-knowledge what hurts. Myself, I never voted and am too far down de road now to start.

"I worked at farmin' till 1895 when I starts preachin' in de Baptist church. I kept that up till 1931, but my health got too bad and I had to quit. I has de pressure bad. When I preaches, I preaches hard, and de doctor says dat am danger for me.

"The way I learns to preach am dis: after surrender, I 'tends de school two terms and den I studies de Bible and I's a nat'ral talker and gifted for de Lawd's work, so I starts preachin'.

"Jennie Goodman and me marries in 1885 and de Lawd never blessed us with any chillen. We gits de pension, me $16.00 and her $14.00, and gits by on dat. It am for de rations and de eats, but de clothes am a question!"

Jordon Smith

Jordon Smith, 86, was born in Georgia, a slave of the Widow Hicks. When she died, Jordon, his mother and thirty other slaves were willed to Ab Smith, his owner's nephew, and were later refugeed from Georgia to Anderson Co., Texas. When freed, Jordon worked on a steamboat crew on the Red River until the advent of railroads. For thirty years Jordon worked for the railroad. He is now too feeble to work and lives with his third wife and six children in Marshall, Texas, supported by the latter and his pension of $10.00 a month.

"I's borned in Georgia, next to the line of North Car'lina, on Widow Hick's place. My papa died 'fore I's borned but my mammy was called Aggie. My ole missus died and us fell to her nephew, Ab Smith. My granma and granpa was full-blooded Africans and I couldn't unnerstand their talk.

"My missus was borned on the Chattahoochee River and she had 2,000 acres of land in cul'vation, a thousand on each side the river, and owned 500 slaves and 250 head of work mules. She was the richest woman in the whole county.

"Us slaves lived in a double row log cabins facin' her house and our beds was made of rough plank and mattresses of hay and lynn bark and shucks, make on a machine. I's spinned many a piece of cloth and wove many a brooch of thread.

"Missus didn't 'low her niggers to work till they's 21, and the chillen played marbles and run round and kick their heels. The first work I done was hoeing and us worked long as we could see a stalk of cotton or hill of corn. Missus used to call us at Christmas and give the old folks a dollar and the rest a dinner. When she died me and my mother went to Ab Smith at the dividement of the property. Master Ab put us to work on a big farm he bought and it was Hell 'mong the yearlin's if you crost him or missus either. It was double trouble and a cowhidin' whatever you do. She had a place in the kitchen where she tied their hands up to the wall and cowhided them and sometimes cut they back 'most to pieces. She made all go to church and let the women wear some her old, fine dresses to hide the stripes where she'd beat them. Mammy say that to keep the folks at church from knowin' how mean she was to her niggers.

"Master Ab had a driver and if you didn't do what that driver say, master say to him, 'Boy, come here and take this nigger down, a hunerd licks this time.' Sometimes us run off and go to a dance without a pass and 'bout time they's kickin' they heels and getting sot for the big time, in come a patterroller and say, 'Havin' a big time, ain't you? Got a pass?' If you didn't, they'd git four or five men to take you out and when they got through you'd sho' go home.

"Master Ab had hunerds acres wheat and made the women stack hay in the field. Sometimes they got sick and wanted to go to the house, but he made them lay down on a straw-pile in the field. Lots of chillen was borned on a straw-pile in the field. After the chile was borned he sent them to the house. I seed that with my own eyes.

"They was a trader yard in Virginia and one in New Orleans and sometimes a thousand slaves was waitin' to be sold. When the traders knowed men was comin' to buy, they made the slaves all clean up and greased they mouths with meat skins to look like they's feedin' them plenty meat. They lined the women up on one side and the men on the other. A buyer would walk up and down 'tween the two rows and grab a woman and try to throw her down and feel of her to see how she's put up. If she's purty strong, he'd say, 'Is she a good breeder?' If a gal was 18 or 19 and put up good she was worth 'bout $1,500. Then the buyer'd pick out a strong, young nigger boy 'bout the same age and buy him. When he got them home he'd say to them, 'I want you two to stay together. I want young niggers.'

"If a nigger ever run off the place and come back, master'd say, 'If you'll be a good nigger, I'll not whip you this time.' But you couldn't 'lieve that. A nigger run off and stayed in the woods six month. When he come back he's hairy as a cow, 'cause he lived in a cave and come out at night and pilfer round. They put the dogs on him but couldn't cotch him. Fin'ly he come home and master say he won't whip him and Tom was crazy 'nough to 'lieve it. Master say to the cook, 'Fix Tom a big dinner,' and while Tom's eatin', master stand in the door with a whip and say, 'Tom, I's change my mind; you have no business runnin' off and I's gwine take you out jus' like you come into the world.

"Master gits a bottle whiskey and a box cigars and have Tom tied up out in the yard. He takes a chair and say to the driver, 'Boy, take him down, 250 licks this time.' Then he'd count the licks. When they's 150 licks it didn't look like they is any place left to hit, but master say, 'Finish him up.' Then he and the driver sot down, smoke cigars and drink whiskey, and master tell Tom how he must mind he master. Then he lock Tom up in a log house and master tell all the niggers if they give him anything to eat he'll skin 'em alive. The old folks slips Tom bread and meat. When he gits out, he's gone to the woods 'gain. They's plenty niggers what stayed in the woods till surrender.

"I heared some slaves say they white folks was good to 'em, but it was a tight fight where us was. I's thought over the case a thousand times and figured it was 'cause all men ain't made alike. Some are bad and some are good. It's like that now. Some folks you works for got no heart and some treat you white. I guess it allus will be that way.

"They was more ghosts and hants them days than now. It look like when I's comin' up they was common as pig tracks. They come in different forms and shapes, sometimes like a dog or cat or goat or like a man. I didn't 'lieve in 'em till I seed one. A fellow I knowed could see 'em every time he went out. One time us walkin' 'long a country lane and he say, 'Jordon, look over my right shoulder.' I looked and see a man walkin' without a head. I broke and run plumb off from the man I's with. He wasn't scart of 'em.

"I's refugeed from Georgia to Anderson County 'fore the war. I see Abe Lincoln onct when he come through, but didn't none of know who he was. I heared the president wanted 'em to work the young niggers till they was twenty-one but to free the growed slaves. They say he give 'em thirty days to 'siderate it. The white folks said they'd wade blood saddle deep 'fore they'd let us loose. I don't blame 'em in a way, 'cause they paid for us. In 'nother way it was right to free us. We was brought here and no person is sposed to be made a brute.

"After surrender, Massa Ab call us and say we could go. Mammy stayed but I left with my uncles and aunts and went to Shreveport where the Yanks was. I didn't hear from my mammy for the nex' twenty years.

"In Ku Klux times they come to our house and I stood tremblin', but they didn't bother us. I heared 'em say lots of niggers was took down in Sabine bottom and Kluxed, just 'cause they wanted to git rid of 'em. I think it was desperados what done that, 'stead of the Ku Klux. That was did in Panola County, in the Bad Lands. Bill Bateman and Hulon Gresham and Sidney Farney was desperados and would kill a nigger jus' to git rid of him. Course, lots of folks was riled up at the Kluxers and blamed 'em for everything.

"I's voted here in Marshall. Every nation has a flag but the cullud race. The flag is what protects 'em. We wasn't invited here, but was brought here, and don't have no place else to go. We was brought under this government and it's right we be led and told what to do. The cullud folks has been here more'n a hunerd years and has help make the United States what it is. The only thing that'll help the cause is separation of the races. I'll not be here when it comes, but it's bound to, 'cause the Bible say that some day all the races of people will be separated. Since 1865 till now the cullud race have done nothing but go to destruction. There was a time a man could control his wife and family, but you can't do that now.

"After surrender I went to Shreveport and steamboated from there to New Orleans, then to Vicksburg. Old hands was paid $15.00 a trip. I come here in 1872 and railroaded 30 years, on the section gang and in the shops. Since then I farmed and I's had three wives and nineteen chillen and they are scattered all over the state. Since I's too old to farm I work at odd jobs and git a $10.00 a month pension."

Millie Ann Smith

Millie Ann Smith was born in 1850, in Rusk Co., Texas, a slave of George Washington Trammell, a pioneer planter of the county. Trammell bought Millie's mother and three older children in Mississippi before Millie's birth, and brought them to Texas, leaving Millie's father behind. Later he ran away to Texas and persuaded Trammell to buy him, so he could be with his family.

"I's born 'fore war started and 'members when it ceased. I guess mammy's folks allus belonged to the Trammells, 'cause I 'member my grandpa, Josh Chiles, and my grandma, call Jeanette. I's a strappin' big girl when they dies. Grandpa used to say he come to Texas with Massa George Trammell's father when Rusk County was jus' a big woods, and the first two years he was hunter for the massa. He stay in the woods all the time, killing deer and wild hawgs and turkeys and coons and the like for the white folks to eat, and the land's full of Indians. He kinda taken up with them and had holes in the nose and ears. They was put there by the Indians for rings what they wore. Grandpa could talk mos' any Indian talk and he say he used to run off from his massa and stay with the Indians for weeks. The massa'd go to the Indian camp looking for grandpa and the Indians hided him out and say, 'No see him.'

"How mammy and we'uns come to Texas, Massa George brung his wife and three chillen from Mississippi and he brung we'uns. Pappy belonged to Massa Moore over in Mississippi and Massa George didn't buy him, but after mammy got here, that 'fore I's born, pappy runs off and makes his way to Texas and gits Massa George to buy him.

"Massa George and Missy America lived in a fine, big house and they owned more slaves and land than anybody in the county and they's the richest folks 'round there. Us slaves lived down the hill from the big house in a double row of log cabins and us had good beds, like our white folks. My grandpa made all the beds for the white folks and us niggers, too. Massa didn't want anything shoddy 'round him, he say, not even his nigger quarters.

"I's sot all day handin' thread to my mammy to put in the loom, 'cause they give us homespun clothes, and you'd better keep 'em if you didn't want to go naked.

"Massa had a overseer and nigger driver call Jacob Green. If a nigger was hard to make do the right thing, they ties him to a tree, but Massa George never whip 'em too hard, jus' 'nough to make 'em 'have.

"The slaves what worked in the fields was woke up 'fore light with a horn and worked till dark, and then there was the stock to tend to and cloth to weave. The overseer come 'round at nine o'clock to see if all is in the bed and then go back to his own house. When us knowed he's sound asleep we'd slip out and run 'round, sometimes. They locked the young men up in a house at night and on Sunday to keep 'em from runnin' 'round. It was a log house and had cracks in it and once a little nigger boy pokes his hand in tryin' to tease them men and one of 'em chops his fingers off with the ax.

"Massa didn' 'low no nigger to read and write, if he knowed it. George Wood was the only one could read and write and how he larn, a little boy on the 'jining place took up with him and they goes off in the woods and he shows George how to read and write. Massa never did find out 'bout that till after freedom.

"We slips off and have prayer but daren't 'low the white folks know it and sometime we hums 'ligious songs low like when we's workin'. It was our way of prayin' to be free, but the white folks didn't know it. I 'member mammy used to sing like this:

"'Am I born to die, to lay this body down.Must my tremblin' spirit fly into worlds unknown,The land of deepes' shade,Only pierce' by human thought.'

"Massa George 'lowed them what wanted to work a little ground for theyselves and grandpa made money sellin' wild turkey and hawgs to the poor white folks. He used to go huntin' at night or jus' when he could.

"Them days we made our own med'cine out of horsemint and butterfly weed and Jerusalem oak and bottled them teas up for the winter. Butterfly Weed tea was for the pleurisy and the others for the chills and fever. As reg'lar as I got up I allus drank my asafoetida and tar water.

"I 'member Massa George furnishes three of his niggers, Ed Chile and Jacob Green and Job Jester, for mule skinners. I seed the government come and take off a big bunch of mules off our place. Mos' onto four year after the war, three men comes to Massa George and makes him call us up and turn us loose. I heered 'em say its close onto four year we's been free, but that's the first we knowed 'bout it.

"Pappy goes to work at odd jobs and mammy and I goes to keep house for a widow woman and I stays there till I marries, and that to Tom Smith. We had five chillen and now Tom's dead and I lives on that pension from the government, what is $16.00 a month, and I's glad to git it, 'cause I's too old to work."

Susan Smith

Susan Smith is not sure of her age, but appears to be in the late eighties. She was a slave of Charles Weeks, in Iberia, Louisiana. Susan was dressed in a black and white print, a light blue apron and a black velvet hat when interviewed, and seemed to be enjoying the generous quid of tobacco she took as she started to tell her story.

"I 'lieve I was nine or ten when freedom come, 'cause I was nursing for the white folks. Old massa was Charlie Weeks and he lived in Iberia. His sons, Willie and Ned, dey run business in de court house. One of dem tax collector and de other lookin' after de land, and am de surveyor. Old missus named Mag Weeks.

"My pa named Dennis Joe and ma named Sabry Joe, and dey borned and raised on Weeks Island, in Louisiana. After dey old massa die, dey was 'vided up and falls to Massa Charlie Weeks, and dat where I borned, in Iberia on Bayou Teche.

"Massa Charlie, he live in de big brick house with white columns and everybody what pass dere know dat place. Dey have de great big tomb in corner de yard, where dey buries all dey folks, but buries de cullud folks back of de quarters. Dey's well fix in Louisiana, but not so good after dey come to Texas.

"Dey used to have big Christmas in Louisiana and lots of things for us, and a big table and kill hawgs and have lots to eat. But old Missus Mag, she allus treat me like her own chillen and make me set at de table with dem and eat.

"I was with Missus Mag on a visit to Mansfield when de war starts at six o'clock Sunday and go till six o'clock Monday. I went over dat battlefield and look at dem sojers dey kill. David McGill, a young massa, he git kill. He uncle, William Weeks, what done hired him to jine the army in he place, he goes to the battlefield to look for Massa David. De only way he knowed it was him, he have two gold eyeteeth with diamonds in dem. Some dem hurt sojers was prayin' and some cussin'. You could hear some dem hollerin', 'Oh, Gawd, help me.' Dey was layin' so thick you have to step over dem.

"I seed de sojers in Iberia. Dey take anythin' dey wants. Dey cotch de cow and kill it and eat it. Dey have de camp dere and dey jus' carry on. I used to go to de camp, 'cause dey give me crackers and sardines. But after dat Mansfield battle dey have up white flags and dey ain't no more war dere. But while it gwine on, I go to de camp and sometimes dem sojers give me meat and barbecue. Dey one place dere a lump salt big as dis house, and dey set fire to de house and left dat big lump salt. Anywhere dey camp dey burns up de house.

"I didn't know I'm free till a man say to me, 'Sissy, ain't you know you ain't got no more massa or missus?' I say, 'No, suh.' But I stays with dem till I git marry, and slep' right in dey house and nuss for dem. Dey give me de big weddin', too. De noter public in Iberia, he marry us. My husband name Henry Smith and dat when I'm fifteen year old. I so big-limb and fat den I bigger den what I is now.

"I ain't had no husband for a time. I can't cast de years, he been dead so long. Us have fifteen chillen, and seven livin' now.

"Sperrits? I used to see dem. I scart of dem. Sometime dey looks nat'ral and sometime like de shadow. Iffen dey look like de shadow, jus' keep on lookin' at dem till dey looks nat'ral. Iffen you walks 'long, dey come right up side you. Iffen you looks over you left shoulder, you see dem. Dey makes de air feel warm and you hair rise up, and sometime dey gives you de cold chills. You can feel it when dey with you. I set here and seed dem standin' in dat gate. Dey goes round like dey done when dey a-livin'. Some say dey can't cross water.

"I heared talk of de bad mouth. A old woman put bad mouth on you and shake her hand at you, and befo' de day done you gwine be in de acciden'.

"I seed de Klu Klux. Po' Cajuns and redbones, I calls dem. Dey ought to be sleepin'. One time I seed a man hangin' in de wood when I'n pickin' blackberries. His tongue hangin' out and de buzzards fly down on he shoulder. De breeze sot him to swingin' and de buzzards fly off. I tells de people and dey takes him down to bury. He a fine, young cullud man. I don't know why dey done it. Dat after peace and de Yankees done gone back home.

"I been here in Texas a good while, and it such a rough road it got my 'membrance all stir up. I never been to school, 'cause I bound out to work. I lives with my daughter and dis child here my grandchild. I can't 'member no more, 'cause my head ain't good as it used to be."

John Sneed

John Sneed, born near Austin, Texas, does not know his age, but was almost grown when he was freed. He belonged to Dr. Sneed and stayed with him several years after Emancipation.

"I's borned on de old Sneed place, eight miles south of Austin, and my mammy was Sarah Sneed and pappy was Ike. Dey come from Tennessee and dere five boys and two gals. De boys am Dixie and Joe and Jim and Bob and me, and de gals name Katy and Lou. Us live in quarters what was log huts. Dere's one long, log house where dey spinned and weaved de cloth. Dere sixteen spinnin' wheels and eight looms in dat house and my job was turnin' one dem wheels when they'd thresh me out and git me to do it. Mos' all de clothes what de slaves and de white folks have was made in dat house.

"Mos' and usual de chillen sleept on de floor, unless with de old folks. De bedsteads make of pieces of split logs fasten with wooden pegs and rope criss-cross. De mattress make of shucks tear into strips with maybe a li'l cotton or prairie hay. You could go out on de prairie mos' any time and get 'nough grass to make de bed, and dry it 'fore it put in de tick. De white folks have bought beds haul by ox teams from Austin and feather beds.

"Dr. Sneed raise cotton and corn and wheat. Sometime five or six oxen hitch to de wagon and 25 or 30 wagons make what am call de wagon train. Dey haul cotton and corn and wheat to Port Lavaca what am de nearest shipping point. On de return trip, dey brung sugar and coffee and cloth and other things what am needed on de plantation. First time massa 'low me go with dat ox-train, I thunk I's growed.

"Dere a big gang of white and cullud chillen on de plantation but Dr. Sneed didn't have no chillen of he own. De neighbor white chillen come over dere and played. Us rip and play and fight and kick up us heels, and go on. Massa never 'low no whippin' of de chillen. He make dem pick rocks up and make fences out dem, but he didn't 'low no chillen work in de field till dey 'bout fourteen. De real old folks didn't work in de fields neither. Dey sot 'round and knit socks and mend de shoes and harness and stuff.

"Massa John mighty good to us chillen. He allus give us a li'l piece money every Sunday. When he'd git in he buggy to go to Austin to sell butter, de chillen pile in dat buggy and all over him so you couldn't see him and he'd hardly see to drive.

"Us had possum and rabbit and fish and trap birds for eatin'. Dere all kind wild green dem days. Us jus' go in de woods and git wild lettuce and mustard and leather-britches and polk salad and watercress, all us want to eat. Us kilt hawgs and put up de lard by de barrel. Us thresh wheat and take it to de li'l watermill at Barton Creek to grind. Dey'd only grind two bushel to de family, no matter how big dat family, 'cause dere so many folks and it such a small mill.

"Each family have de li'l garden and raise turnips and cabbage and sweet 'taters and put dem in de kiln make from corn stalks and cure dem for winter eatin'. Us have homemake clothes and brogan shoes, come from Austin or some place. Us chillen wear shirt-tail till us 'bout thirteen.

"Massa live in de big two-story rock house and have he office and drug-store in one end de house. Missy Ann have no chillen so she 'dopt one from Tennessee, name Sally.

"Dere 'bout four or five hunerd acres and 'bout sixty slaves. Dey git up 'bout daylight and come from de field in time to feed and do de chores 'fore dark. After work de old folks sot 'round, fiddle and play de 'cordian and tell stories. Dat mostly after de crops laid by or on rainy days. On workin' time, dey usually tired and go to bed early. Dey not work on Saturday afternoon or Sunday, 'cept dey gatherin' de crop 'gin a rain. Old man Jim Piper am fiddler and play for black and white dances. On Sunday massa make us go to church. Us sing and pray in a li'l log house on de plantation and sometimes de preacher stop and hold meetin'.

"Massa John Sneed doctored from Austin to Lockhart and Gonzales and my own mammy he train to be midwife. She good pneumonia doctor and massa 'low her care for dem.

"On Christmas all us go to de big house and crowd 'round massa. He a li'l man and some black boys'd carry him 'round on dere shoulders. All knowed dey gwine git de present. Dere a big tree with present for everyone, white and black. Lots of eggnog and turkey and baked hawgs and all kind good things. Dere allus lots of white folks company at massa's house and big banquets and holidays and birthdays. Us like dem times, 'cause work slack and food heavy. Every las' chile have he birthday celebrate with de big cake and present and maybe de quarter in silver from old massa, bless he soul. Us play kissin' games and ring plays and one song am like dis:

"'I'm in de well,How many feet?Five. Who'd git you out?'

"Iffen it a man, he choose de gal and she have to kiss him to git him out de well. Iffen a gal in de well, she choose a man.

"I well 'member de day freedom 'clared. Us have de tearin'-down dinner dat day. De niggers beller and cry and didn't want leave massa. He talk to us and say long as he live us be cared for, and us was. Dere lots of springs on he place and de married niggers pick out a spring and Massa Doctor give dem stuff to put up de cabin by dat spring, and dey take what dey have in de quarters. Dey want to move from dem slave quarters, but not too far from massa. Dey come to de big house for flour and meal and meat and sich till massa die. He willed every last one he slaves somethin'. Mos' of 'em git a cow and a horse and a pig and some chickens. My mammy git two cows and a pair horses and a wagon and 70 acres land. She marries 'gain when my daddy die and dat shif'less nigger she marry git her to sign some kind paper and she lose de land.