The Project Gutenberg EBook of Odd People, by Mayne Reid

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Odd People

Being a Popular Description of Singular Races of Man

Author: Mayne Reid

Release Date: April 19, 2011 [EBook #35911]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ODD PEOPLE ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Captain Mayne Reid

"Odd People"

"Being a Popular Description of Singular Races of Man"

Chapter One.

Bosjesmen, or Bushmen.

Perhaps no race of people has more piqued the curiosity of the civilised world than those little yellow savages of South Africa, known as the Bushmen. From the first hour in which European nations became acquainted with their existence, a keen interest was excited by the stories told of their peculiar character and habits; and although they have been visited by many travellers, and many descriptions have been given of them, it is but truth to say, that the interest in them has not yet abated, and the Bushmen of Africa are almost as great a curiosity at this hour as they were when Di Gama first doubled the Cape. Indeed, there is no reason why this should not be, for the habits and personal appearance of these savages are just now as they were then, and our familiarity with them is not much greater. Whatever has been added to our knowledge of their character, has tended rather to increase than diminish our curiosity.

At first the tales related of them were supposed to be filled with wilful exaggerations, and the early travellers were accused of dealing too much in the marvellous. This is a very common accusation brought against the early travellers; and in some instances it is a just one. But in regard to the accounts given of the Bushmen and their habits there has been far less exaggeration than might be supposed; and the more insight we obtain into their peculiar customs and modes of subsistence, the more do we become satisfied that almost everything alleged of them is true. In fact, it would be difficult for the most inventive genius to contrive a fanciful account, that would be much more curious or interesting than the real and bonâ fide truth that can be told about this most peculiar people.

Where do the Bushmen dwell? what is their country? These are questions not so easily answered, as in reality they are not supposed to possess any country at all, any more than the wild animals amidst which they roam, and upon whom they prey. There is no Bushman’s country upon the map, though several spots in Southern Africa have at times received this designation. It is not possible, therefore, to delineate the boundaries of their country, since it has no boundaries, any more than that of the wandering Gypsies of Europe.

If the Bushmen, however, have no country in the proper sense of the word, they have a “range,” and one of the most extensive character—since it covers the whole southern portion of the African continent, from the Cape of Good Hope to the twentieth degree of south latitude, extending east and west from the country of the Cafires to the Atlantic Ocean. Until lately it was believed that the Bushman-range did not extend far to the north of the Orange river; but this has proved an erroneous idea. They have recently “turned up” in the land of the Dammaras, and also in the great Kalahari desert, hundreds of miles north from the Orange river and it is not certain that they do not range still nearer to the equatorial line—though it may be remarked that the country in that direction does not favour the supposition, not being of the peculiar nature of a Bushman’s country. The Bushman requires a desert for his dwelling-place. It is an absolute necessity of his nature, as it is to the ostrich and many species of animals; and north of the twentieth degree of latitude, South Africa does not appear to be of this character. The heroic Livingstone has dispelled the long-cherished illusion of the Geography about the “Great-sanded level” of these interior regions; and, instead, disclosed to the world a fertile land, well watered, and covered with a profuse and luxuriant vegetation. In such a land there will be no Bushmen.

The limits we have allowed them, however, are sufficiently large,—fifteen degrees of latitude, and an equally extensive range from east to west. It must not be supposed, however, that they populate this vast territory. On the contrary, they are only distributed over it in spots, in little communities, that have no relationship or connection with one another, but are separated by wide intervals, sometimes of hundreds of miles in extent. It is only in the desert tracts of South Africa that the Bushmen exist,—in the karoos, and treeless, waterless plains—among the barren ridges and rocky defiles—in the ravines formed by the beds of dried-up rivers—in situations so sterile, so remote, so wild and inhospitable as to offer a home to no other human being save the Bushman himself.

If we state more particularly the localities where the haunts of the Bushman are to be found, we may specify the barren lands on both sides of the Orange river,—including most of its headwaters, and down to its mouth,—and also the Great Kalahari desert. Through all this extensive region the kraals of the Bushmen may be encountered. At one time they were common enough within the limits of the Cape colony itself, and some half-caste remnants still exist in the more remote districts; but the cruel persecution of the boers has had the effect of extirpating these unfortunate savages; and, like the elephant, the ostrich, and the eland, the true wild Bushman is now only to be met with beyond the frontiers of the colony.

About the origin of the Bushmen we can offer no opinion. They are generally considered as a branch of the great Hottentot family; but this theory is far from being an established fact. When South Africa was first discovered and colonised, both Hottentots and Bushmen were found there, differing from each other just as they differ at this day; and though there are some striking points of resemblance between them, there are also points of dissimilarity that are equally as striking, if we regard the two people as one. In personal appearance there is a certain general likeness: that is, both are woolly-haired, and both have a Chinese cast of features, especially in the form and expression of the eye. Their colour too is nearly the same; but, on the other hand, the Hottentots are larger than the Bushmen. It is not in their persons, however, that the most essential points of dissimilarity are to be looked for, but rather in their mental characters; and here we observe distinctions so marked and antithetical, that it is difficult to reconcile them with the fact that these two people are of one race. Whether a different habit of life has produced this distinctive character, or whether it has influenced the habits of life, are questions not easily answered. We only know that a strange anomaly exists—the anomaly of two people being personally alike—that is, possessing physical characteristics that seem to prove them of the same race, while intellectually, as we shall presently see, they have scarce one character in common. The slight resemblance that exists between the languages of the two is not to be regarded as a proof of their common origin. It only shows that they have long lived in juxtaposition, or contiguous to each other; a fact which cannot be denied.

In giving a more particular description of the Bushman, it will be seen in what respect he resembles the true Hottentot, and in what he differs from him, both physically and mentally, and this description may now be given.

The Bushman is the smallest man with whom we are acquainted; and if the terms “dwarf” and “pigmy” may be applied to any race of human beings, the South-African Bushmen presents the fairest claim to these titles. He stands only 4 feet 6 inches upon his naked soles—never more than 4 feet 9, and not unfrequently is he encountered of still less height—even so diminutive as 4 feet 2. His wife is of still shorter stature, and this Lilliputian lady is often the mother of children when the crown of her head is just 3 feet 9 inches above the soles of her feet. It has been a very common thing to contradict the assertion that these people are such pigmies in stature, and even Dr Livingstone has done so in his late magnificent work. The doctor states, very jocosely, that they are “not dwarfish—that the specimens brought to Europe have been selected, like costermongers’ dogs, for their extreme ugliness.”

But the doctor forgets that it is but from “the specimens brought to Europe” that the above standard of the Bushman’s height has been derived, but from the testimony of numerous travellers—many of them as trustworthy as the doctor himself—from actual measurements made by them upon the spot. It is hardly to be believed that such men as Sparmann and Burchell, Barrow and Lichtenstein, Harris, Campbell, Patterson, and a dozen others that might be mentioned, should all give an erroneous testimony on this subject. These travellers have differed notoriously on other points, but in this they all agree, that a Bushman of five feet in height is a tall man in his tribe. Dr Livingstone speaks of Bushmen “six feet high,” and these are the tribes lately discovered living so far north as the Lake Nagami. It is doubtful whether these are Bushmen at all. Indeed, the description given by the doctor, not only of their height and the colour of their skin, but also some hints about their intellectual character, would lead to the belief that he has mistaken some other people for Bushmen. It must be remembered that the experience of this great traveller has been chiefly among the Bechuana tribes, and his knowledge of the Bushman proper does not appear to be either accurate or extensive. No man is expected to know everybody; and amid the profusion of new facts, which the doctor has so liberally laid before the world, it would be strange if a few inaccuracies should not occur. Perhaps we should have more confidence if this was the only one we are enabled to detect; but the doctor also denies that there is anything either terrific or majestic in the “roaring of the lion.” Thus speaks he: “The same feeling which has induced the modern painter to caricature the lion has led the sentimentalist to consider the lion’s roar as the most terrific of all earthly sounds. We hear of the ‘majestic roar of the king of beasts.’ To talk of the majestic roar of the lion is mere majestic twaddle.”

The doctor is certainly in error here. Does he suppose that any one is ignorant of the character of the lion’s roar? Does he fancy that no one has ever heard it but himself? If it be necessary to go to South Africa to take the true measure of a Bushman, it is not necessary to make that long journey in order to obtain a correct idea of the compass of the lion’s voice. We can hear it at home in all its modulations; and any one who has ever visited the Zoological Gardens in Regent’s Park—nay, any one who chances to live within half a mile of that magnificent menagerie—will be very much disposed to doubt the correctness of the doctor’s assertion. If there be a sound upon the earth above all others “majestic,” a noise above all others “terrific,” it is certainly the roar of the lion. Ask Albert Terrace and Saint John’s Wood!

But let us not be too severe upon the doctor. The world is indebted to him much more than to any other modern traveller, and all great men indulge occasionally in the luxury of an eccentric opinion. We have brought the point forward here for a special purpose,—to illustrate a too much neglected truth. Error is not always on the side of exaggeration; but is sometimes also found in the opposite extreme of a too-squeamish moderation. We find the learned Professor Lichtenstein ridiculing poor old Hernandez, the natural historian of Mexico, for having given a description of certain fabulous animals—fabulous, he terms them, because to him they were odd and unknown. But it turns out that the old author was right, and the animals exist! How many similar misconceptions might be recorded of the Buffons, and other closet philosophers—urged, too, with the most bitter zeal! Incredulity carried too far is but another form of credulity.

But to return to our proper theme, and complete the portrait of the Bushman. We have given his height. It is in tolerable proportion to his other dimensions. When young, he appears stout enough; but this is only when a mere boy. At the age of sixteen he has reached all the manhood he is ever destined to attain; and then his flesh disappears; his body assumes a meagre outline; his arms and limbs grow thin; the calf disappears from his legs; the plumpness from his cheeks; and altogether he becomes as wretched-looking an object as it is possible to conceive in human shape. Older, his skin grows dry, corrugated, and scaly; his bones protrude; and his knee, elbow, and ankle-joints appear like horny knobs placed at the ends of what more resemble long straight sticks than the arms and limbs of a human being.

The colour of this creature may be designated a yellow-brown, though it is not easy to determine it to a shade. The Bushman appears darker than he really is; since his skin serves him for a towel, and every species of dirt that discommodes his fingers he gets rid of by wiping it off on his arms, sides, or breast. The result is, that his whole body is usually coated over with a stratum of grease and filth, which has led to the belief that he regularly anoints himself—a custom common among many savage tribes. This, however, the Bushman does not do: the smearing toilet is merely occasional or accidental, and consists simply in the fat of whatever flesh he has been eating being transferred from his fingers to the cuticle of his body. This is never washed off again—for water never touches the Bushman’s hide. Such a use of water is entirely unknown to him, not even for washing his face. Should he have occasion to cleanse his hands—which the handling of gum or some like substance sometimes compels him to do—he performs the operation, not with soap and water, but with the dry dung of cattle or some wild animal. A little rubbing of this upon his skin is all the purification the Bushman believes to be needed.

Of course, the dirt darkens his complexion; but he has the vanity at times to brighten it up—not by making it whiter—but rather a brick-red. A little ochreous earth produces the colour he requires; and with this he smears his body all over—not excepting even the crown of his head, and the scant stock of wool that covers it.

Bushmen have been washed. It requires some scrubbing, and a plentiful application either of soda or soap, to reach the true skin and bring out the natural colour; but the experiment has been made, and the result proves that the Bushman is not so black as, under ordinary circumstances, he appears. A yellow hue shines through the epidermis, somewhat like the colour of the Chinese, or a European in the worst stage of jaundice—the eye only not having that complexion. Indeed, the features of the Bushman, as well as the Hottentot, bear a strong similarity to those of the Chinese, and the Bushman’s eye is essentially of the Mongolian type. His hair, however, is entirely of another character. Instead of being long, straight, and lank, it is short, crisp, and curly,—in reality, wool. Its scantiness is a characteristic; and in this respect the Bushman differs from the woolly-haired tribes both of Africa and Australasia. These generally have “fleeces” in profusion, whereas both Hottentot and Bushman have not enough to half cover their scalps; and between the little knot-like “kinks” there are wide spaces without a single hair upon them. The Bushman’s “wool” is naturally black, but red ochre and the sun soon convert the colour into a burnt reddish hue.

The Bushman has no beard or other hairy encumbrances. Were they to grow, he would root them out as useless inconveniences. He has a low-bridged nose, with wide flattened nostrils; an eye that appears a mere slit between the eyelids; a pair of high cheek-bones, and a receding forehead. His lips are not thick, as in the negro, and he is furnished with a set of fine white teeth, which, as he grows older, do not decay, but present the singular phenomenon of being regularly worn down to the stumps—as occurs to the teeth of sheep and other ruminant animals.

Notwithstanding the small stature of the Bushman, his frame is wiry and capable of great endurance. He is also as agile as an antelope.

From the description above given, it will be inferred that the Bushman is no beauty. Neither is the Bushwoman; but, on the contrary, both having passed the period of youth, become absolutely ugly,—the woman, if possible, more so than the man.

And yet, strange to say, many of the Bush-girls, when young, have a cast of prettiness almost amounting to beauty. It is difficult to tell in what this beauty consists. Something, perhaps, in the expression of the oblique almond-shaped eye, and the small well-formed mouth and lips, with the shining white teeth. Their limbs, too, at this early age, are often well-rounded; and many of them exhibit forms that might serve as models for a sculptor. Their feet are especially well-shaped, and, in point of size, they are by far the smallest in the world. Had the Chinese ladies been gifted by nature with such little feet, they might have been spared the torture of compressing them.

The foot of a Bushwoman rarely measures so much as six inches in length; and full-grown girls have been seen, whose feet, submitted to the test of an actual measurement, proved but a very little over four inches!

Intellectually, the Bushman does not rank so low as is generally believed. He has a quick, cheerful mind, that appears ever on the alert,—as may be judged by the constant play of his little piercing black eye,—and though he does not always display much skill in the manufacture of his weapons, he can do so if he pleases. Some tribes construct their bows, arrows, fish-baskets, and other implements and utensils with admirable ingenuity; but in general the Bushman takes no pride in fancy weapons. He prefers having them effective, and to this end he gives proof of his skill in the manufacture of most deadly poisons with which to anoint his arrows. Furthermore, he is ever active and ready for action; and in this his mind is in complete contrast with that of the Hottentot, with whom indolence is a predominant and well-marked characteristic. The Bushman, on the contrary, is always on the qui vive; always ready to be doing where there is anything to do; and there is not much opportunity for him to be idle, as he rarely ever knows where the next meal is to come from. The ingenuity which he displays in the capture of various kinds of game,—far exceeding that of other hunting tribes of Africa,—as also the cunning exhibited by him while engaged in cattle-stealing and other plundering forays, prove an intellectual capacity more than proportioned to his diminutive body; and, in short, in nearly every mental characteristic does he differ from the supposed cognate race—the Hottentot.

It would be hardly just to give the Bushman a character for high courage; but, on the other hand, it would be as unjust to charge him with cowardice. Small as he is, he shows plenty of “pluck,” and when brought to bay, his motto is, “No surrender.” He will fight to the death, discharging his poisoned arrows as long as he is able to bend a bow. Indeed, he has generally been treated to shooting, or clubbing to death, wherever and whenever caught, and he knows nothing of quarter. Just as a badger he ends his life,—his last struggle being an attempt to do injury to his assailant. This trait in his character has, no doubt, been strengthened by the inhuman treatment that, for a century, he has been receiving from the brutal boers of the colonial frontier.

The costume of the Bushman is of the most primitive character,—differing only from that worn by our first parents, in that the fig-leaf used by the men is a patch of jackal-skin, and that of the women a sort of fringe or bunch of leather thongs, suspended around the waist by a strap, and hanging down to the knees. It is in reality a little apron of dressed skin; or, to speak more accurately, two of them, one above the other, both cut into narrow strips or thongs, from below the waist downward. Other clothing than this they have none, if we except a little skin kaross, or cloak, which is worn over their shoulders;—that of the women being provided with a bag or hood at the top, that answers the naked “piccaninny” for a nest or cradle. Sandals protect their feet from the sharp stones, and these are of the rudest description,—merely a piece of the thick hide cut a little longer and broader than the soles of the feet, and fastened at the toes and round the ankles by thongs of sinews. An attempt at ornament is displayed in a leathern skullcap, or more commonly a circlet around the head, upon which are sewed a number of “cowries,” or small shells of the Cyprea moneta.

It is difficult to say where these shells are procured,—as they are not the product of the Bushman’s country, but are only found on the far shores of the Indian Ocean. Most probably he obtains them by barter, and after they have passed through many hands; but they must cost the Bushman dear, as he sets the highest value upon them. Other ornaments consist of old brass or copper buttons, attached to the little curls of his woolly hair; and, among the women, strings of little pieces of ostrich egg-shells, fashioned to resemble beads; besides a perfect load of leathern bracelets on the arms, and a like profusion of similar circlets on the limbs, often reaching from the knee to the ankle-joint.

Red ochre over the face and hair is the fashionable toilette, and a perfumery is obtained by rubbing the skin with the powdered leaves of the “buku” plant, a species of diosma. According to a quaint old writer, this causes them to “stink like a poppy,” and would be highly objectionable, were it not preferable to the odour which they have without it.

They do not tattoo, nor yet perforate the ears, lips, or nose,—practices so common among savage tribes. Some instances of nose-piercing have been observed, with the usual appendage of a piece of wood or porcupine’s quill inserted in the septum, but this is a custom rather of the Caffres than Bushmen. Among the latter it is rare. A grand ornament is obtained by smearing the face and head with a shining micaceous paste, which is procured from a cave in one particular part of the Bushman’s range; but this, being a “far-fetched” article, is proportionably scarce and dear. It is only a fine belle who can afford to give herself a coat of blink-slip,—as this sparkling pigment is called by the colonists. Many of the women, and men as well, carry in their hands the bushy tail of a jackal. The purpose is to fan off the flies, and serve also as a “wipe,” to disembarrass their bodies of perspiration when the weather chances to be over hot.

The domicile of the Bushman next merits description. It is quite as simple and primitive as his dress, and gives him about equal trouble in its construction. If a cave or cleft can be found in the rocks, of sufficient capacity to admit his own body and those of his family—never a very large one—he builds no house. The cave contents him, be it ever so tight a squeeze. If there be no cave handy, an overhanging rock will answer equally as well. He regards not the open sides, nor the draughts. It is only the rain which he does not relish; and any sort of a shed, that will shelter him from that, will serve him for a dwelling. If neither cave, crevice, nor impending cliff can be found in the neighbourhood, he then resorts to the alternative of housebuilding; and his style of architecture does not differ greatly from that of the orang-outang. A bush is chosen that grows near to two or three others,—the branches of all meeting in a common centre. Of these branches the builder takes advantage, fastening them together at the ends, and wattling some into the others. Over this framework a quantity of grass is scattered in such a fashion as to cast off a good shower of rain, and then the “carcass” of the building is considered complete. The inside work remains yet to be done, and that is next set about. A large roundish or oblong hole is scraped out in the middle of the floor. It is made wide enough and deep enough to hold the bodies of three or four Bush-people, though a single large Caffre or Dutchman would scarcely find room in it. Into this hole is flung a quantity of dry grass, and arranged so as to present the appearance of a gigantic nest. This nest, or lair, becomes the bed of the Bushman, his wife, or wives,—for he frequently keeps two,—and the other members of his family. Coiled together like monkeys, and covered with their skin karosses, they all sleep in it,—whether “sweetly” or “soundly,” I shall not take upon me to determine.

It is supposed to be this fashion of literally “sleeping in the bush,” as also the mode by which he skulks and hides among bushes,—invariably taking to them when pursued,—that has given origin to the name Bushman, or Bosjesman, as it is in the language of the colonial Dutch. This derivation is probable enough, and no better has been offered.

The Bushman sometimes constructs himself a more elaborate dwelling; that is, some Bushmen;—for it should be remarked that there are a great many tribes or communities of these people, and they are not all so very low in the scale of civilisation. None, however, ever arrive at the building of a house,—not even a hut. A tent is their highest effort in the building line, and that is of the rudest description, scarce deserving the name. Its covering is a mat, which they weave out of a species of rush that grows along some of the desert streams; and in the fabrication of the covering they display far more ingenuity than in the planning or construction of the tent itself. The mat, in fact, is simply laid over two poles, that are bent into the form of an arch, by having both ends stuck into the ground. A second piece of matting closes up one end; and the other, left open, serves for the entrance. As a door is not deemed necessary, no further construction is required, and the tent is “pitched” complete. It only remains to scoop out the sand, and make the nest as already described.

It is said that the Goths drew their ideas of architecture from the aisles of the oak forest; the Chinese from their Mongolian tents; and the Egyptians from their caves in the rocks. Beyond a doubt, the Bushman has borrowed his from the nest of the ostrich!

It now becomes necessary to inquire how the Bushman spends his time? how he obtains subsistence? and what is the nature of his food? All these questions can be answered, though at first it may appear difficult to answer them. Dwelling, as he always does, in the very heart of the desert, remote from forests that might furnish him with some sort of food—trees that might yield fruit,—far away from a fertile soil, with no knowledge of agriculture, even if it were near,—with no flocks or herds; neither sheep, cattle, horses, nor swine,—no domestic animals but his lean, diminutive dogs,—how does this Bushman procure enough to eat? What are his sources of supply?

We shall see. Being neither a grazier nor a farmer, he has other means of subsistence,—though it must be confessed that they are of a precarious character, and often during his life does the Bushman find himself on the very threshold of starvation. This, however, results less from the parsimony of Nature than the Bushman’s own improvident habits,—a trait in his character which is, perhaps, more strongly developed in him than any other. We shall have occasion to refer to it presently.

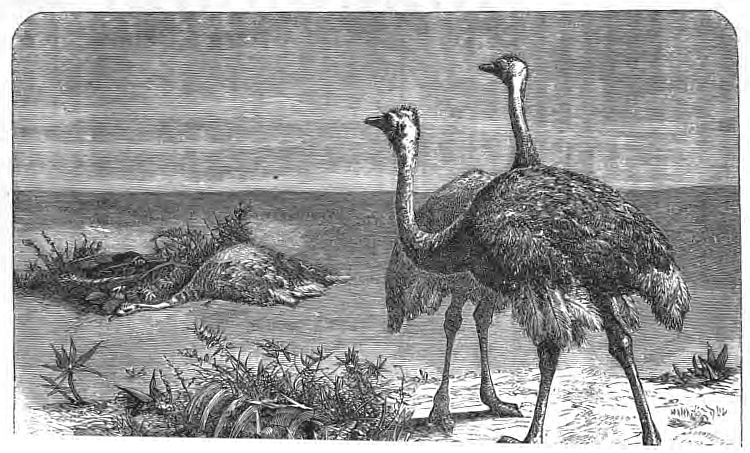

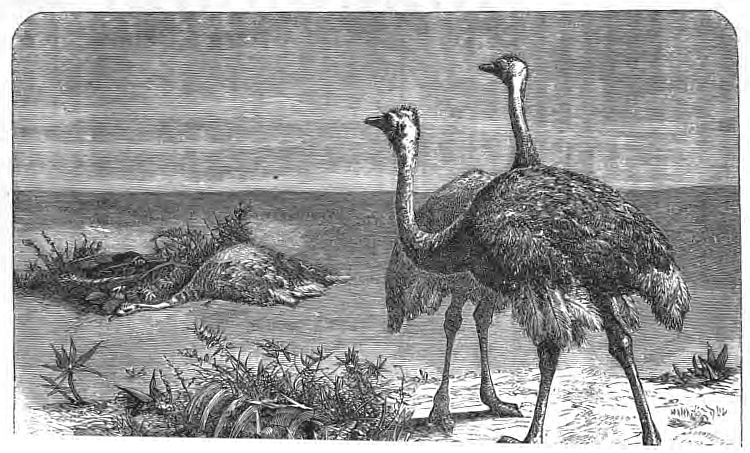

His first and chief mode of procuring his food is by the chase: for, although he is surrounded by the sterile wilderness, he is not the only animated being who has chosen the desert for his home. Several species of birds—one the largest of all—and quadrupeds, share with the Bushman the solitude and safety of this desolate region. The rhinoceros can dwell there; and in numerous streams are found the huge hippopotami; whilst quaggas, zebras, and several species of antelope frequent the desert plains as their favourite “stamping” ground. Some of these animals can live almost without water; but when they do require it, what to them is a gallop of fifty miles to some well-known “vley” or pool? It will be seen, therefore, that the desert has its numerous denizens. All these are objects of the Bushman’s pursuit, who follows them with incessant pertinacity—as if he were a beast of prey, furnished by Nature with the most carnivorous propensities.

In the capture of these animals he displays an almost incredible dexterity and cunning. His mode of approaching the sly ostrich, by disguising himself in the skin of one of these birds, is so well-known that I need not describe it here; but the ruses he adopts for capturing or killing other sorts of game are many of them equally ingenious. The pit-trap is one of his favourite contrivances; and this, too, has been often described,—but often very erroneously. The pit is not a large hollow,—as is usually asserted,—but rather of dimensions proportioned to the size of the animal that is expected to fall into it. For game like the rhinoceros or eland antelope, it is dug of six feet in length and three in width at the top; gradually narrowing to the bottom, where it ends in a trench of only twelve inches broad. Six or seven feet is considered deep enough; and the animal, once into it, gets so wedged at the narrow bottom part as to be unable to make use of its legs for the purpose of springing out again. Sometimes a sharp stake or two are used, with the view of impaling the victim; but this plan is not always adopted. There is not much danger of a quadruped that drops in ever getting out again, till he is dragged out by the Bushman in the shape of a carcass.

The Bushman’s ingenuity does not end here. Besides the construction of the trap, it is necessary the game should be guided into it. Were this not done, the pit might remain a long time empty, and, as a necessary consequence, so too might the belly of the Bushman. In the wide plain few of the gregarious animals have a path which they follow habitually; only where there is a pool may such beaten trails be found, and of these the Bushman also avails himself; but they are not enough. Some artificial means must be used to make the traps pay—for they are not constructed without much labour and patience. The plan adopted by the Bushman to accomplish this exhibits some points of originality. He first chooses a part of the plain which lies between two mountains. No matter if these be distant from each other: a mile, or even two, will not deter the Bushman from his design. By the help of his whole tribe—men, women, and children—he constructs a fence from one mountain to the other. The material used is whatever may be most ready to the hand: stones, sods, brush, or dead timber, if this be convenient. No matter how rude the fence: it need not either be very high. He leaves several gaps in it; and the wild animals, however easily they might leap over such a puny barrier, will, in their ordinary way, prefer to walk leisurely through the gaps. In each of these, however, there is a dangerous hole—dangerous from its depth as well as from the cunning way in which it is concealed from the view—in short, in each gap there is a pit-fall. No one—at least no animal except the elephant—would ever suspect its presence; the grass seems to grow over it, and the sand lies unturned, just as elsewhere upon the plain. What quadruped could detect the cheat? Not any one except the sagacious elephant. The stupid eland tumbles through; the gemsbok goes under; and the rhinoceros rushes into it as if destined to destruction. The Bushman sees this from his elevated perch, glides forward over the ground, and spears the struggling victim with his poisoned assagai.

Besides the above method of capturing game the Bushman also uses the bow and arrows. This is a weapon in which he is greatly skilled; and although both bow and arrows are as tiny as if intended for children’s toys, they are among the deadliest of weapons, their fatal effect lies not in the size of the wound they are capable of inflicting, but in the peculiar mode in which the barbs of the arrows are prepared. I need hardly add that they are dipped in poison;—for who has not heard of the poisoned arrows of the African Bushmen?

Both bow and arrows are usually rude enough in their construction, and would appear but a trumpery affair, were it not for a knowledge of their effects. The bow is a mere round stick, about three feet long, and slightly bent by means of its string of twisted sinews. The arrows are mere reeds, tipped with pieces of bone, with a split ostrich-quill lapped behind the head, and answering for a barb. This arrow the Bushman can shoot with tolerable certainty to a distance of a hundred yards, and he can even project it farther by giving a slight elevation to his aim. It signifies not whether the force with which it strikes the object be ever so slight, if it only makes an entrance. Even a scratch from its point will sometimes prove fatal.

Of course the danger dwells altogether in the poison. Were it not for that, the Bushman, from his dwarfish stature and pigmy strength, would be a harmless creature indeed.

The poison he well knows how to prepare, and he can make it of the most “potent spell,” when the “materials” are within his reach. For this purpose he makes use of both vegetable and animal substances, and a mineral is also employed; but the last is not a poison, and is only used to give consistency to the liquid, so that it may the better adhere to the arrow. The vegetable substances are of various kinds. Some are botanically known: the bulb of Amaryllis disticha,—the gum of a Euphorbia,—the sap of a species of sumac (Rhus),—and the nuts of a shrubby plant, by the colonists called Woolf-gift (Wolf-poison).

The animal substance is the fluid found in the fangs of venomous serpents, several species of which serve the purpose of the Bushman: as the little “Horned Snake,”—so called from the scales rising prominently over its eyes; the “Yellow Snake,” or South-African Cobra (Naga haje); the “Puff Adder,” and others. From all these he obtains the ingredients of his deadly ointment, and mixes them, not all together; for he cannot always procure them all in any one region of the country in which he dwells. He makes his poison, also, of different degrees of potency, according to the purpose for which he intends it; whether for hunting or war. With sixty or seventy little arrows, well imbued with this fatal mixture, and carefully placed in his quiver of tree bark or skin,—or, what is not uncommon, stuck like a coronet around his head,—he sallies forth, ready to deal destruction either to game, animals, or to human enemies.

Of these last he has no lack. Every man, not a Bushman, he deems his enemy; and he has some reason for thinking so. Truly may it be said of him, as of Ishmael, that his “hand is against every man, and every man’s hand against him;” and such has been his unhappy history for ages. Not alone have the boers been his pursuers and oppressors, but all others upon his borders who are strong enough to attack him,—colonists, Caffres, and Bechuanas, all alike,—not even excepting his supposed kindred, the Hottentots. Not only does no fellow-feeling exist between Bushman and Hottentot, but, strange to say, they hate each other with the most rancorous hatred. The Bushman will plunder a Namaqua Hottentot, a Griqua, or a Gonaqua,—plunder and murder him with as much ruthlessness, or even more, than he would the hated Caffre or boer. All are alike his enemies,—all to be plundered and massacred, whenever met, and the thing appears possible.

We are speaking of plunder. This is another source of supply to the Bushman, though one that is not always to be depended upon. It is his most dangerous method of obtaining a livelihood, and often costs him his life. He only resorts to it when all other resources fail him, and food is no longer to be obtained by the chase.

He makes an expedition into the settlements,—either of the frontier boers, Caffres, or Hottentots,—whichever chance to live most convenient to his haunts. The expedition, of course, is by night, and conducted, not as an open foray, but in secret, and by stealth. The cattle are stolen, not reeved, and driven off while the owner and his people are asleep.

In the morning, or as soon as the loss is discovered, a pursuit is at once set on foot. A dozen men, mounted and armed with long muskets (röers), take the spoor of the spoilers, and follow it as fast as their horses will carry them. A dozen boers, or even half that number, is considered a match for a whole tribe of Bushmen, in any fight which may occur in the open plain, as the boers make use of their long-range guns at such a distance that the Bushmen are shot down without being able to use their poisoned arrows; and if the thieves have the fortune to be overtaken before they have got far into the desert, they stand a good chance of being terribly chastised.

There is no quarter shown them. Such a thing as mercy is never dreamt of,—no sparing of lives any more than if they were a pack of hyenas. The Bushmen may escape to the rocks, such of them as are not hit by the bullets; and there the boers know it would be idle to follow them. Like the klipspringer antelope, the little savages can bound from rock to rock, and cliff to cliff, or hide like partridges among crevices, where neither man nor horse can pursue them. Even upon the level plain—if it chance to be stony or intersected with breaks and ravines—a horseman would endeavour to overtake them in vain, for these yellow imps are as swift as ostriches.

When the spoilers scatter thus, the boer may recover his cattle, but in what condition? That he has surmised already, without going among the herd. He does not expect to drive home one half of them; perhaps not one head. On reaching the flock he finds there is not one without a wound of some kind or other: a gash in the flank, the cut of a knife, the stab of an assagai, or a poisoned arrow—intended for the boer himself—sticking between the ribs. This is the sad spectacle that meets his eyes; but he never reflects that it is the result of his own cruelty,—he never regards it in the light of retribution. Had he not first hunted the Bushman to make him a slave, to make bondsmen and bondsmaids of his sons and daughters, to submit them to the caprice and tyranny of his great, strapping frau, perhaps his cattle would have been browsing quietly in his fields. The poor Bushman, in attempting to take them, followed but his instincts of hunger: in yielding them up he obeyed but the promptings of revenge.

It is not always that the Bushman is thus overtaken. He frequently succeeds in carrying the whole herd to his desert fastness; and the skill which he exhibits in getting them there is perfectly surprising. The cattle themselves are more afraid of him than of a wild beast, and run at his approach; but the Bushman, swifter than they, can glide all around them, and keep them moving at a rapid rate.

He uses stratagem also to obstruct or baffle the pursuit. The route he takes is through the driest part of the desert,—if possible, where water does not exist at all. The cattle suffer from thirst, and bellow from the pain; but the Bushman cares not for that, so long as he is himself served. But how is he served? There is no water, and a Bushman can no more go without drinking than a boer: how then does he provide for himself on these long expeditions?

All has been pre-arranged. While off to the settlements, the Bushman’s wife has been busy. The whole kraal of women—young and old—have made an excursion halfway across the desert, each carrying ostrich egg-shells, as much as her kaross will hold, each shell full of water. These have been deposited at intervals along the route in secret spots known by marks to the Bushmen, and this accomplished the women return home again. In this way the plunderer obtains his supply of water, and thus is he enabled to continue his journey over the arid Karroo.

The pursuers become appalled. They are suffering from thirst—their horses sinking under them. Perhaps they have lost their way? It would be madness to proceed further. “Let the cattle go this time?” and with this disheartening reflection they give up the pursuit, turn the heads of their horses, and ride homeward.

There is a feast at the Bushman’s kraal—and such a feast! not one ox is slaughtered, but a score of them all at once. They kill them, as if from very wantonness; and they no longer eat, but raven on the flesh.

For days the feasting is kept up almost continuously,—even at night they must wake up to have a midnight meal! and thus runs the tale, till every ox has been eaten. They have not the slightest idea of a provision for the future; even the lower animals seem wiser in this respect. They do not think of keeping a few of the plundered cattle at pasture to serve them for a subsequent occasion. They give the poor brutes neither food nor drink; but, having penned them up in some defile of the rocks, leave them to moan and bellow, to drop down and die.

On goes the feasting, till all are finished; and even if the flesh has turned putrid, this forms not the slightest objection: it is eaten all the same.

The kraal now exhibits an altered spectacle. The starved, meagre wretches, who were seen flitting among its tents but a week ago, have all disappeared. Plump bodies and distended abdomens are the order of the day; and the profile of the Bushwoman, taken from the neck to the knees, now exhibits the outline of the letter S. The little imps leap about, tearing raw flesh,—their yellow cheeks besmeared with blood,—and the lean curs seem to have been exchanged for a pack of fat, petted poodles.

But this scene must some time come to an end, and at length it does end. All the flesh is exhausted, and the bones picked clean. A complete reaction comes over the spirit of the Bushman. He falls into a state of languor,—the only time when he knows such a feeling,—and he keeps his kraal, and remains idle for days. Often he sleeps for twenty-four hours at a time, and wakes only to go to sleep again. He need not rouse himself with the idea of getting something to eat: there is not a morsel in the whole kraal, and he knows it. He lies still, therefore,—weakened with hunger, and overcome with the drowsiness of a terrible lassitude.

Fortunate for him, while in this state, if those bold vultures—attracted by the débris of his feast, and now high wheeling in the air—be not perceived from afar; fortunate if they do not discover the whereabouts of his kraal to the vengeful pursuer. If they should do so, he has made his last foray and his last feast.

When the absolute danger of starvation at length compels our Bushman to bestir himself, he seems to recover a little of his energy, and once more takes to hunting, or, if near a stream, endeavours to catch a few fish. Should both these resources fail, he has another,—without which he would most certainly starve,—and perhaps this may be considered his most important source of supply, since it is the most constant, and can be depended on at nearly all seasons of the year. Weakened with hunger, then, and scarce equal to any severer labour, he goes out hunting—this time insects, not quadrupeds. With a stout stick inserted into a stone at one end and pointed at the other, he proceeds to the nests of the white ants (termites), and using the point of the stick,—the stone serving by its weight to aid the force of the blow,—he breaks open the hard, gummy clay of which the hillock is formed. Unless the aard-vark and the pangolin—two very different kinds of ant-eaters—have been there before him, he finds the chambers filled with the eggs of the ants, the insects themselves, and perhaps large quantities of their larvae. All are equally secured by the Bushman, and either devoured on the spot, or collected into a skin bag, and carried back to his kraal.

He hunts also another species of ants that do not build nests or “hillocks,” but bring forth their young in hollows under the ground. These make long galleries or covered ways just under the surface, and at certain periods—which the Bushman knows by unmistakable signs—they become very active, and traverse these underground galleries in thousands. If the passages were to be opened above, the ants would soon make off to their caves, and but a very few could be captured. The Bushman, knowing this, adopts a stratagem. With the stick already mentioned he pierces holes of a good depth down; and works the stick about, until the sides of the holes are smooth and even. These he intends shall serve him as pitfalls; and they are therefore made in the covered ways along which the insects are passing. The result is, that the little creatures, not suspecting the existence of these deep wells, tumble head foremost into them, and are unable to mount up the steep smooth sides again, so that in a few minutes the hole will be filled with ants, which the Bushman scoops out at his leisure.

Another source of supply which he has, and also a pretty constant one, consists of various roots of the tuberous kind, but more especially bulbous roots, which grow in the desert. They are several species of Ixias and Mesembryanthemums,—some of them producing bulbs of a large size, and deeply buried underground. Half the Bushman’s and Bushwoman’s time is occupied in digging for these roots; and the spade employed is the stone-headed staff already described.

Ostrich eggs also furnish the Bushman with many a meal; and the huge shells of these eggs serve him for water-vessels, cups, and dishes. He is exceedingly expert in tracking up the ostrich, and discovering its nest. Sometimes he finds a nest in the absence of the birds; and in a case of this kind he pursues a course of conduct that is peculiarly Bushman. Having removed all the eggs to a distance, and concealed them under some bush, he returns to the nest and ensconces himself in it. His diminutive body, when close squatted, cannot be perceived from a distance, especially when there are a few bushes around the nest, as there usually are. Thus concealed he awaits the return of the birds, holding his bow and poisoned arrows ready to salute them as soon as they come within range. By this ruse he is almost certain of killing either the cock or hen, and not infrequently both—when they do not return together.

Lizards and land-tortoises often furnish the Bushman with a meal; and the shell of the latter serves him also for a dish; but his period of greatest plenty is when the locusts appear. Then, indeed, the Bushman is no longer in want of a meal; and while these creatures remain with him, he knows no hunger. He grows fat in a trice, and his curs keep pace with him—for they too greedily devour the locusts. Were the locusts a constant, or even an annual visitor, the Bushman would be a rich man—at all events his wants would be amply supplied. Unfortunately for him, but fortunately for everybody else, these terrible destroyers of vegetation only come now and then—several years often intervening between their visits.

The Bushmen have no religion whatever; no form of marriage—any more than mating together like wild beasts; but they appear to have some respect for the memory of their dead, since they bury them—usually erecting a large pile of stones, or “cairn,” over the body.

They are far from being of a melancholy mood. Though crouching in their dens and caves during the day, in dread of the boers and other enemies, they come forth at night to chatter and make merry. During fine moonlights they dance all night, keeping up the ball till morning; and in their kraals may be seen a circular spot—beaten hard and smooth with their feet—where these dances are performed.

They have no form of government—not so much as a head man or chief. Even the father of the family possesses no authority, except such as superior strength may give him; and when his sons are grown up and become as strong as he is, this of course also ceases.

They have no tribal organisation; the small communities in which they live being merely so many individuals accidentally brought together, often quarrelling and separating from one another. These communities rarely number over a hundred individuals, since, from the nature of their country, a large number could not find subsistence in any one place. It follows, therefore, that the Bushman race must ever remain widely scattered—so long as they pursue their present mode of life—and no influence has ever been able to win them from it. Missionary efforts made among them have all proved fruitless. The desert seems to have been created for them, as they for the desert; and when transferred elsewhere, to dwell amidst scenes of civilised life, they always yearn to return to their wilderness home.

Truly are these pigmy savages an odd people!

Chapter Two.

The Amazonian Indians.

In glancing at the map of the American continent, we are struck by a remarkable analogy between the geographical features of its two great divisions—the North and the South,—an analogy amounting almost to a symmetrical parallelism.

Each has its “mighty” mountains—the Cordilleras of the Andes in the south, and the Cordilleras of the Sierra Madre (Rocky Mountains) in the north—with all the varieties of volcano and eternal snow. Each has its secondary chain: in the north, the Nevadas of California and Oregon; in the south, the Sierras of Caraccas and the group of Guiana; and, if you wish to render the parallelism complete, descend to a lower elevation, and set the Alleghanies of the United States against the mountains of Brazil—both alike detached from all the others.

In the comparison we have exhausted the mountain chains of both divisions of the continent. If we proceed further, and carry it into minute detail, we shall find the same correspondence—ridge for ridge, chain for chain, peak for peak;—in short, a most singular equilibrium, as if there had been a design that one half of this great continent should balance the other!

From the mountains let us proceed to the rivers, and see how they will correspond. Here, again, we discover a like parallelism, amounting almost to a rivalry. Each continent (for it is proper to style them so) contains the largest river in the world. If we make length the standard, the north claims precedence for the Mississippi; if volume of water is to be the criterion, the south is entitled to it upon the merits of the Amazon. Each, too, has its numerous branches, spreading into a mighty “tree”; and these, either singly or combined, form a curious equipoise both in length and magnitude. We have only time to set list against list, tributaries of the great northern river against tributaries of its great southern compeer,—the Ohio and Illinois, the Yellowstone and Platte, the Kansas and Osage, the Arkansas and Red, against the Madeira and Purus, the Ucayali and Huallaga, the Japura and Negro, the Xingu and Tapajos.

Of other river systems, the Saint Lawrence may be placed against the La Plata, the Oregon against the Orinoco, the Mackenzie against the Magdalena, and the Rio Bravo del Norte against the Tocantins; while the two Colorados—the Brazos and Alabama—find their respective rivals in the Essequibo, the Paranahybo, the Pedro, and the Patagonian Negro; and the San Francisco of California, flowing over sands of gold, is balanced by its homonyme of Brazil, that has its origin in the land of diamonds. To an endless list might the comparison be carried.

We pass to the plains. Prairies in the north, llanos and pampas in the south, almost identical in character. Of the plateaux or tablelands, those of Mexico, La Puebla, Perote, and silver Potosi in the north; those of Quito, Bogota, Cusco, and gold Potosi in the south; of the desert plains, Utah and the Llano Estacado against Atacama and the deserts of Patagonia. Even the Great Salt Lake has its parallel in Titicaca; while the “Salinas” of New Mexico and the upland prairies, are represented by similar deposits in the Gran Chaco and the Pampas.

We arrive finally at the forests. Though unlike in other respects, we have here also a rivalry in magnitude,—between the vast timbered expanse stretching from Arkansas to the Atlantic shores, and that which covers the valley of the Amazon. These were the two greatest forests on the face of the earth. I say were, for one of them no longer exists; at least, it is no longer a continuous tract, but a collection of forests, opened by the axe, and intersected by the clearings of the colonist. The other still stands in all its virgin beauty and primeval vigour, untouched by the axe, undefiled by fire, its path scarce trodden by human feet, its silent depths to this hour unexplored.

It is with this forest and its denizens we have to do. Here then let us terminate the catalogue of similitudes, and concentrate our attention upon the particular subject of our sketch.

The whole valley of the Amazon—in other words, the tract watered by this great river and its tributaries—may be described as one unbroken forest. We now know the borders of this forest with considerable exactness, but to trace them here would require a too lengthened detail. Suffice it to say, that lengthwise it extends from the mouth of the Amazon to the foothills of the Peruvian Andes, a distance of 2,500 miles. In breadth it varies, beginning on the Atlantic coast with a breadth of 400 miles, which widens towards the central part of the continent till it attains to 1,500, and again narrowing to about 1,000, where it touches the eastern slope of the Andes.

That form of leaf known to botanists as “obovate” will give a good idea of the figure of the great Amazon forest, supposing the small end or shank to rest on the Atlantic, and the broad end to extend along the semicircular concavity of the Andes, from Bolivia on the south to New Granada on the north. In all this vast expanse of territory there is scarce an acre of open ground, if we except the water-surface of the rivers and their bordering “lagoons,” which, were they to bear their due proportions on a map, could scarce be represented by the narrowest lines, or the most inconspicuous dots. The grass plains which embay the forest on its southern edge along the banks of some of its Brazilian tributaries, or those which proceed like spurs from the Llanos of Venezuela, do not in any place approach the Amazon itself, and there are many points on the great river which may be taken as centres, and around which circles may be drawn, having diameters 1,000 miles in length, the circumferences of which will enclose nothing but timbered land. The main stream of the Amazon, though it intersects this grand forest, does not bisect it, speaking with mathematical precision. There is rather more timbered surface to the southward than that which extends northward, though the inequality of the two divisions is not great. It would not be much of an error to say that the Amazon river cuts the forest in halves. At its mouth, however, this would not apply; since for the first 300 miles above the embouchure of the river, the country on the northern side is destitute of timber. This is occasioned by the projecting spurs of the Guiana mountains, which on that side approach the Amazon in the shape of naked ridges and grass-covered hills and plains.

It is not necessary to say that the great forest of the Amazon is a tropical one—since the river itself, throughout its whole course, almost traces the line of the equator. Its vegetation, therefore, is emphatically of a tropical character; and in this respect it differs essentially from that of North America, or rather, we should say, of Canada and the United States. It is necessary to make this limitation, because the forests of the tropical parts of North America, including the West-Indian islands, present a great similitude to that of the Amazon. It is not only in the genera and species of trees that the sylva of the temperate zone differs from that of the torrid; but there is a very remarkable difference in the distribution of these genera and species. In a great forest of the north, it is not uncommon to find a large tract covered with a single species of trees,—as with pines, oaks, poplars, or the red cedar (Juniperus Virginiana). This arrangement is rather the rule than the exception; whereas, in the tropical forest, the rule is reversed, except in the case of two or three species of palms (Mauritia and Euterpe), which sometimes exclusively cover large tracts of surface. Of other trees, it is rare to find even a clump or grove standing together—often only two or three trees, and still more frequently, a single individual is observed, separated from those of its own kind by hundreds of others, all differing in order, genus, and species. I note this peculiarity of the tropic forest, because it exercises, as may easily be imagined, a direct influence upon the economy of its human occupants—whether these be savage or civilised. Even the habits of the lower animals—beasts and birds—are subject to a similar influence.

It would be out of place here to enumerate the different kinds of trees that compose this mighty wood,—a bare catalogue of their names would alone fill many pages,—and it would be safe to say that if the list were given as now known to botanists, it would comprise scarce half the species that actually exist in the valley of the Amazon. In real truth, this vast Garden of God is yet unexplored by man. Its border walks and edges have alone been examined; and the enthusiastic botanist need not fear that he is too late in the field. A hundred years will elapse before this grand parterre can be exhausted.

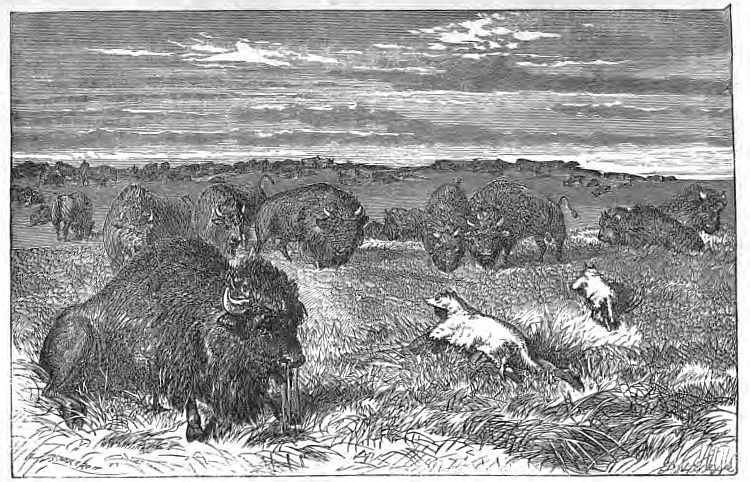

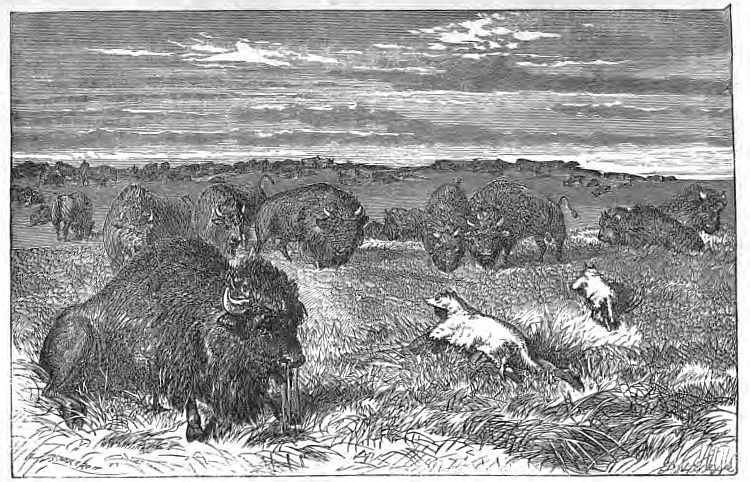

At present, a thorough examination of the botany of the Amazon valley would be difficult, if not altogether impossible, even though conducted on a grand and expensive scale. There are several reasons for this. Its woods are in many places absolutely impenetrable—on account either of the thick tangled undergrowth, or from the damp, spongy nature of the soil. There are no roads that could be traversed by horse or man; and the few paths are known only to the wild savage,—not always passable even by him. Travelling can only be done by water, either upon the great rivers, or by the narrow creeks (igaripes) or lagoons; and a journey performed in this fashion must needs be both tedious and indirect, allowing but a limited opportunity for observation. Horses can scarce be said to exist in the country, and cattle are equally rare—a few only are found in one or two of the large Portuguese settlements on the main river—and the jaguars and blood-sucking bats offer a direct impediment to their increase. Contrary to the general belief, the tropical forest is not the home of the larger mammalia: it is not their proper habitat, nor are they found in it. In the Amazon forest but few species exist, and these not numerous in individuals. There are no vast herds—as of buffaloes on the prairies of North America, or of antelopes in Africa. The tapir alone attains to any considerable size,—exceeding that of the ass,—but its numbers are few. Three or four species of small deer represent the ruminants, and the hog of the Amazon is the peccary. Of these there are at least three species. Where the forest impinges on the mountain regions of Peru, bears are found of at least two kinds, but not on the lower plains of the great “Montaña,”—for by this general designation is the vast expanse of the Amazon country known among the Peruvian people. “Montes” and “montañas,” literally signifying “mountains,” are not so understood among Spanish Americans. With them the “montes” and “montanas” are tracts of forest-covered country, and that of the Amazon valley is the “Montana” par excellence.

Sloths of several species, and opossums of still greater variety, are found all over the Montana, but both thinly distributed as regards the number of individuals. A similar remark applies to the ant-eaters or “ant-bears,” of which there are four kinds,—to the armadillos, the “agoutis,” and the “cavies,” one of which last, the capibara, is the largest rodent upon earth. This, with its kindred genus, the “paca,” is not so rare in individual numbers, but, on the contrary, appears in large herds upon the borders of the rivers and lagoons. A porcupine, several species of spinous rats, an otter, two or three kinds of badger-like animals (the potto and coatis), a “honey-bear” (Galera barbara), and a fox, or wild dog, are widely distributed throughout the Montana.

Everywhere exists the jaguar, both the black and spotted varieties, and the puma has there his lurking-place. Smaller cats, both spotted and striped, are numerous in species, and squirrels of several kinds, with bats, complete the list of the terrestrial mammalia.

Of all the lower animals, monkeys are the most common, for to them the Montana is a congenial home. They abound not only in species, but in the number of individuals, and their ubiquitous presence contributes to enliven the woods. At least thirty different kinds of them exist in the Amazon valley, from the “coatas,” and other howlers as large as baboons, to the tiny little “ouistitis” and “säimiris,” not bigger than squirrels or rats.

While we must admit a paucity in the species of the quadrupeds of the Amazon, the same remark does not apply to the birds. In the ornithological department of natural history, a fulness and richness here exist, perhaps not equalled elsewhere. The most singular and graceful forms, combined with the most brilliant plumage, are everywhere presented to the eye, in the parrots and great macaws, the toucans, trogons, and tanagers, the shrikes, humming-birds, and orioles; and even in the vultures and eagles: for here are found the most beautiful of predatory birds,—the king vulture and the harpy eagle. Of the feathered creatures existing in the valleys of the Amazon there are not less than one thousand different species, of which only one half have yet been caught or described.

Reptiles are equally abundant—the serpent family being represented by numerous species, from the great water boa (anaconda), of ten yards in length, to the tiny and beautiful but venomous lachesis, or coral snake, not thicker than the shank of a tobacco-pipe. The lizards range through a like gradation, beginning with the huge “jacare,” or crocodile, of several species, and ending with the turquoise-blue anolius, not bigger than a newt.

The waters too are rich in species of their peculiar inhabitants—of which the most remarkable and valuable are the manatees (two or three species), the great and smaller turtles, the porpoises of various kinds, and an endless catalogue of the finny tribes that frequent the rivers of the tropics. It is mainly from this source, and not from four-footed creatures of the forest, that the human denizen of the great Montana draws his supply of food,—at least that portion of it which may be termed the “meaty.” Were it not for the manatee, the great porpoise, and other large fish, he would often have to “eat his bread dry.”

And now it is his turn to be “talked about.” I need not inform you that the aborigines who inhabit the valley of the Amazon, are all of the so-called Indian race—though there are so many, distinct tribes of them that almost every river of any considerable magnitude has a tribe of its own. In some cases a number of these tribes belong to one nationality; that is, several of them may be found speaking nearly the same language, though living apart from each other; and of these larger divisions or nationalities there are several occupying the different districts of the Montana. The tribes even of the same nationality do not always present a uniform appearance. There are darker and fairer tribes; some in which the average standard of height is less than among Europeans; and others where it equals or exceeds this. There are tribes again where both men and women are ill-shaped and ill-favoured—though these are few—and other tribes where both sexes exhibit a considerable degree of personal beauty. Some tribes are even distinguished for their good looks, the men presenting models of manly form, while the women are equally attractive by the regularity of their features, and the graceful modesty of expression that adorns them.

A minute detail of the many peculiarities in which the numerous tribes of the Amazon differ from one another would fill a large volume; and in a sketch like the present, which is meant to include them all, it would not be possible to give such a detail. Nor indeed would it serve any good purpose; for although there are many points of difference between the different tribes, yet these are generally of slight importance, and are far more than counterbalanced by the multitude of resemblances. So numerous are these last, as to create a strong idiosyncrasy in the tribes of the Amazon, which not only entitles them to be classed together in an ethnological point of view, but which separates them from all the other Indians of America. Of course, the non-possession of the horse—they do not even know the animal—at once broadly distinguishes them from the Horse Indians, both of the Northern and Southern divisions of the continent.

It would be idle here to discuss the question as to whether the Amazonian Indians have all a common origin. It is evident they have not. We know that many of them are from Peru and Bogota—runaways from Spanish oppression. We know that others migrated from the south—equally fugitives from the still more brutal and barbarous domination of the Portuguese. And still others were true aboriginals of the soil, or if emigrants, when and whence came they? An idle question, never to be satisfactorily answered. There they now are, and as they are only shall we here consider them.

Notwithstanding the different sources whence they sprang, we find them, as I have already said, stamped with a certain idiosyncrasy, the result, no doubt, of the like circumstances which surround them. One or two tribes alone, whose habits are somewhat “odder” than the rest, have been treated to a separate chapter; but for the others, whatever is said of one, will, with very slight alteration, stand good for the whole of the Amazonian tribes. Let it be understood that we are discoursing only of those known as the “Indios bravos,” the fierce, brave, savage, or wild Indians—as you may choose to translate the phrase,—a phrase used throughout all Spanish America to distinguish those tribes, or sections of tribes, who refused obedience to Spanish tyranny, and who preserve to this hour their native independence and freedom. In contradistinction to the “Indios bravos” are the “Indios mansos,” or “tame Indians,” who submitted tamely both to the cross and sword, and now enjoy a rude demi-semi-civilisation, under the joint protectorate of priests and soldiers. Between these two kinds of American aborigines, there is as much difference as between a lord and his serf—the true savage representing the former and the demi-semi-civilised savage approximating more nearly to the latter. The meddling monk has made a complete failure of it. His ends were purely political, and the result has proved ruinous to all concerned;—instead of civilising the savage, he has positively demoralised him.

It is not of his neophytes, the “Indios mansos,” we are now writing, but of the “infidels,” who would not hearken to his voice or listen to his teachings—those who could never be brought within “sound of the bell.”

Both “kinds” dwell within the valley of the Amazon, but in different places. The “Indios mansos” may be found along the banks of the main stream, from its source to its mouth—but more especially on its upper waters, where it runs through Spanish (Peruvian) territory. There they dwell in little villages or collections of huts, ruled by the missionary monk with iron rod, and performing for him all the offices of the menial slave. Their resources are few, not even equalling those of their wild but independent brethren; and their customs and religion exhibit a ludicrous mélange of savagery and civilisation. Farther down the river, the “Indio manso” is a “tapuio,” a hireling of the Portuguese, or to speak more correctly, a slave; for the latter treats him as such, considers him as such, and though there is a law against it, often drags him from his forest-home and keeps him in life-long bondage. Any human law would be a dead letter among such white-skins as are to be encountered upon the banks of the Amazon. Fortunately they are but few; a town or two on the lower Amazon and Rio Negro,—some wretched villages between,—scattered estancias along the banks—with here and there a paltry post of “militarios,” dignified by the name of a “fort:” these alone speak the progress of the Portuguese civilisation throughout a period of three centuries!

From all these settlements the wild Indian keeps away. He is never found near them—he is never seen by travellers, not even by the settlers. You may descend the mighty Amazon from its source to its mouth, and not once set your eyes upon the true son of the forest—the “Indio bravo.” Coming in contact only with the neophyte of the Spanish missionary, and the skulking tapuio of the Portuguese trader, you might bring away a very erroneous impression of the character of an Amazonian Indian.

Where is he to be seen? where dwells he? what like is his home? what sort of a house does he build? His costume? his arms? his occupation? his habits? These are the questions you would put. They shall all be answered, but briefly as possible—since our limited space requires brevity.

The wild Indian, then, is not to be found upon the Amazon itself, though there are long reaches of the river where he is free to roam—hundreds of miles without either town or estancia. He hunts, and occasionally fishes by the great water, but does not there make his dwelling—though in days gone by, its shores were his favourite place of residence. These were before the time when Orellana floated down past the door of his “malocca”—before that dark hour when the Brazilian slave-hunter found his way into the waters of the mighty Solimoes. This last event was the cause of his disappearance. It drove him from the shores of his beloved river-sea; forced him to withdraw his dwelling from observation, and rebuild it far up, on those tributaries where he might live a more peaceful life, secure from the trafficker in human flesh. Hence it is that the home of the Amazonian Indian is now to be sought for—not on the Amazon itself, but on its tributary streams—on the “canos” and “igaripes,” the canals and lagoons that, with a labyrinthine ramification, intersect the mighty forest of the Montana. Here dwells he, and here is he to be seen by any one bold enough to visit him in his fastness home.

How is he domiciled? Is there anything peculiar about the style of his house or his village?

Eminently peculiar; for in this respect he differs from all the other savage people of whom we have yet written, or of whom we may have occasion to write.

Let us proceed at once to describe his dwelling. It is not a tent, nor is it a hut, nor a cabin, nor a cottage, nor yet a cave! His dwelling can hardly be termed a house, nor his village a collection of houses—since both house and village are one and the same, and both are so peculiar, that we have no name for such a structure in civilised lands, unless we should call it a “barrack.” But even this appellation would give but an erroneous idea of the Amazonian dwelling; and therefore we shall use that by which it is known in the “Lingoa geral,” and call it a malocca.

By such name is his house (or village rather) known among the tapuios and traders of the Amazon. Since it is both house and village at the same time, it must needs be a large structure; and so is it, large enough to contain the whole tribe—or at least the section of it that has chosen one particular spot for their residence. It is the property of the whole community, built by the labour of all, and used as their common dwelling—though each family has its own section specially set apart for itself. It will thus be seen that the Amazonian savage is, to some extent, a disciple of the Socialist school.

I have not space to enter into a minute account of the architecture of the malocca. Suffice it to say, that it is an immense temple-like building, raised upon timber uprights, so smooth and straight as to resemble columns. The beams and rafters are also straight and smooth, and are held in their places by “sipos” (tough creeping plants), which are whipped around the joints with a neatness and compactness equal to that used in the rigging of a ship. The roof is a thatch of palm-leaves, laid on with great regularity, and brought very low down at the eaves, so as to give to the whole structure the appearance of a gigantic beehive. The walls are built of split palms or bamboos, placed so closely together as to be impervious to either bullet or arrows.

The plan is a parallelogram, with a semicircle at one end; and the building is large enough to accommodate the whole community, often numbering more than a hundred individuals. On grand festive occasions several neighbouring communities can find room enough in it—even for dancing—and three or four hundred individuals not unfrequently assemble under the roof of a single malocca.

Inside the arrangements are curious. There is a wide hall or avenue in the middle—that extends from end to end throughout the whole length of the parallelogram—and on both sides of the hall is a row of partitions, separated from each other by split palms or canes, closely placed. Each of these sections is the abode of a family, and the place of deposit for the hammocks, clay pots, calabash-cups, dishes, baskets, weapons, and ornaments, which are the private property of each. The hall is used for the larger cooking utensils—such as the great clay ovens and pans for baking the cassava, and boiling the caxire or chicha. This is also a neutral ground, where the children play, and where the dancing is done on the occasion of grand “balls” and other ceremonial festivals.

The common doorway is in the gable end, and is six feet wide by ten in height. It remains open during the day, but is closed at night by a mat of palm fibre suspended from the top. There is another and smaller doorway at the semicircular end; but this is for the private use of the chief, who appropriates the whole section of the semicircle to himself and his family.

Of course the above is only the general outline of a malocca. A more particular description would not answer for that of all the tribes of the Amazon. Among different communities, and in different parts of the Montaña, the malocca varies in size, shape, and the materials of which it is built; and there are some tribes who live in separate huts. These exceptions, however, are few, and as a general thing, that above described is the style of habitation throughout the whole Montaña, from the confines of Peru to the shores of the Atlantic. North and south we encounter this singular house-village, from the headwaters of the Rio Negro to the highlands of Brazil.

Most of the Amazonian tribes follow agriculture, and understood the art of tillage before the coming of the Spaniards. They practise it, however, to a very limited extent. They cultivate a little manioc, and know how to manufacture it into farinha or cassava bread. They plant the musaceae and yam, and understand the distillation of various drinks, both from the plantain and several kinds of palms. They can make pottery from clay,—shaping it into various forms, neither rude nor inelegant,—and from the trees and parasitical twiners that surround their dwellings, they manufacture an endless variety of neat implements and utensils.

Their canoes are hollow trunks of trees sufficiently well-shaped, and admirably adapted to their mode of travelling—which is almost exclusively by water, by the numerous canos and igaripes, which are the roads and paths of their country—often as narrow and intricate as paths by land.

The Indians of the tropic forest dress in the very lightest costume. Of course each tribe has its own fashion; but a mere belt of cotton cloth, or the inner bark of a tree, passed round the waist and between the limbs, is all the covering they care for. It is the guayuco. Some wear a skirt of tree bark, and, on grand occasions, feather tunics are seen, and also plume head-dresses, made of the brilliant wing and tail feathers of parrots and macaws. Circlets of these also adorn the arms and limbs. All the tribes paint, using the anotto, caruto, and several other dyes which they obtain from various kinds of trees, elsewhere more particularly described.

There are one or two tribes who tattoo their skins; but this strange practice is far less common among the American Indians than with the natives of the Pacific isles.

In the manufacture of their various household utensils and implements, as well as their weapons for war and the chase, many tribes of Amazonian Indians display an ingenuity that would do credit to the most accomplished artisans. The hammocks made by them have been admired everywhere; and it is from the valley of the Amazon that most of these are obtained, so much prized in the cities of Spanish and Portuguese America. They are the special manufacture of the women, the men only employing their mechanical skill on their weapons: