The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Great Steel Strike and its Lessons, by William Z. Foster This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Great Steel Strike and its Lessons Author: William Z. Foster Release Date: May 5, 2011 [EBook #36032] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GREAT STEEL STRIKE AND *** Produced by Odessa Paige Turner, Barbara Kosker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

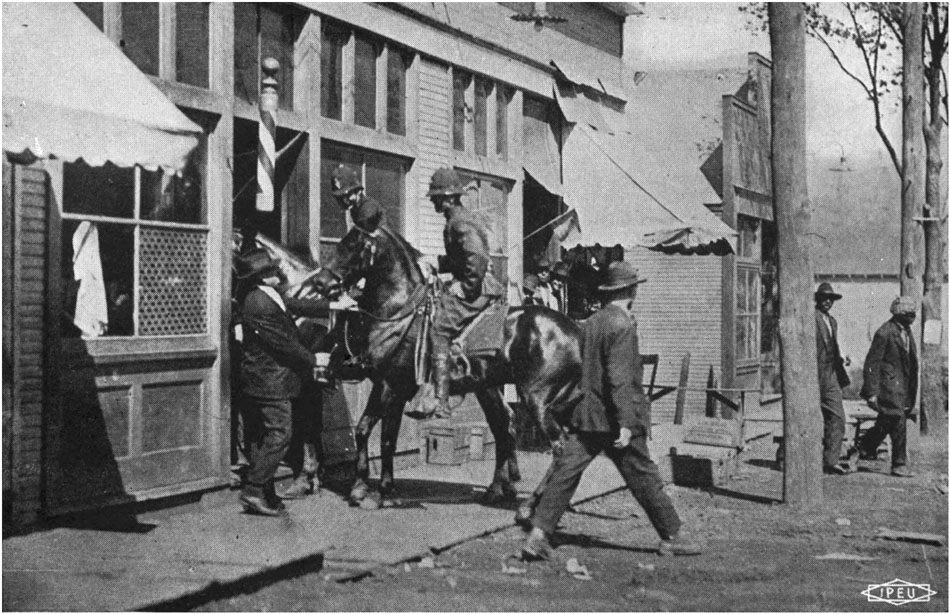

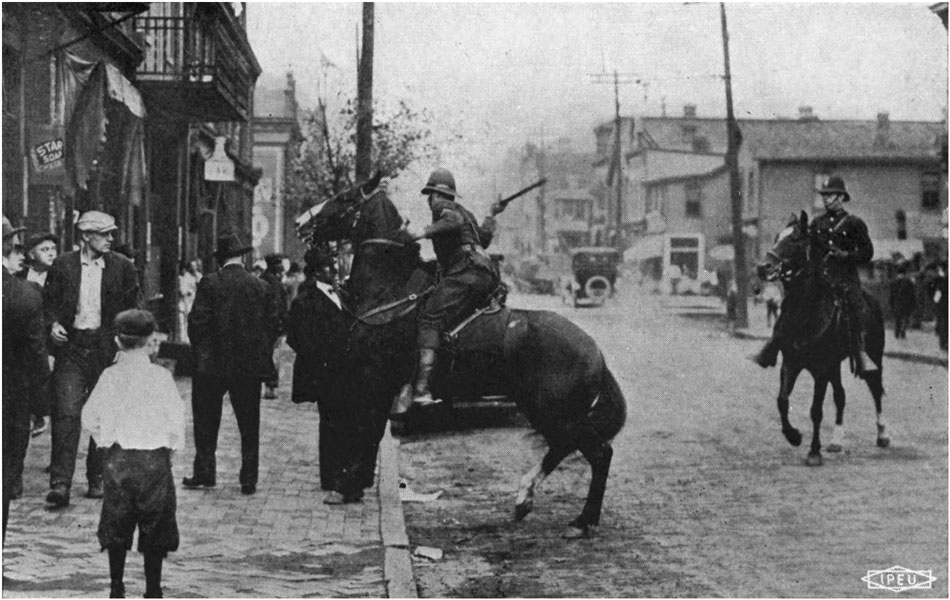

PENNSYLVANIA LAW AND ORDER

State Police driving peaceful citizens out of business places, Clairton, Pa.

Photo by International

Half a million men are employed in the steel industry of the United States. At a period in which eight hours is rapidly coming to be accepted as the standard length of the working day, the principal mills in this industry are operating on a 12-hour work schedule, and many of their workmen are employed seven days in every week. These half million men have, for the most part, no opportunity to discuss with their employers the conditions of their work. Not only are they denied the right of bargaining collectively over the terms of the labor contract, but if grievances arise in the course of their employment they have no right in any effective manner to take up the matter with their employer and secure an equitable adjustment.[1] The right even of petition has been at times denied and, because of the organized strength of the steel companies and the disorganized weakness of the employees, could be denied at any time.

The right of workers in this country to organize and to bargain[Pg vi] collectively is unquestioned. On every hand the workers are exercising this right in order to protect and advance their interests. In the steel mills not only is the right generally denied but the attempt to exercise it is punished by expulsion from the industry. Through a system of espionage that is thoroughgoing and effective the steel companies know which of their employees are attending union meetings, which of them are talking with organizers. It is their practice to discharge such men and thus they nip in the bud any ordinary movement toward organization.

Their power to prevent their employees from acting independently and in their own interest, extends even to the communities in which they live. In towns where the mayor's chair is occupied by company officials or their relatives—as was the case during the 1919 strike in Bethlehem, Duquesne, Clairton and elsewhere—orders may be issued denying to the workers the right to hold meetings for organizing purposes, or the police may be instructed to break them up. Elsewhere—as in Homestead, McKeesport, Monessen, Rankin and in Pittsburgh itself—the economic strength of the companies is so great as to secure the willing cooperation of officials or to compel owners of halls and vacant lots to refuse the use of their property for the holding of union meetings.

One who has not seen with his own eyes the evidences of steel company control in the towns where their plants are located will have difficulty in comprehending its scope and power. Social and religious organizations are profoundly affected by it. [Pg vii]In many a church during the recent strike, ministers and priests denounced the "agitators" and urged the workmen in their congregations to go back to the mills. Small business men accepted deputy sheriffs' commissions, put revolvers in their belts and talked loudly about the merits of a firing squad as a remedy for industrial unrest.

For twenty or more years in the mill towns along the Monongahela—since 1892 in Homestead—the working men have lived in an atmosphere of espionage and repression. The deadening influence of an overwhelming power, capable of crushing whatever does not bend to its will, has in these towns stifled individual initiative and robbed citizenship of its virility.

The story of the most extensive and most courageous fight yet made to break this power and to set free the half million men of the steel mills is told within the pages of this book by one who was himself a leader in the fight. It is a story that is worth the telling, for it has been told before only in fragmentary bits and without the authority that comes from the pen of one of the chief actors in the struggle.

Mr. Foster has performed a public service in setting down as he has the essential facts attendant upon the calling of the strike. The record of correspondence with Judge Gary and with President Wilson indicates clearly enough where responsibility for its occurrence lies. It answers the question also of who it was that flouted the President—the strike committee that refused to enter into a one sided truce, or Judge Gary, who would not accept Mr. Wilson's suggestion that he confer with a union committee, [Pg viii]but who was willing to take advantage of the proposed truce to undermine and destroy the union.

This thoughtful history, remarkably dispassionate upon the whole, considering the fact that the author was not only an actor in the events he describes but the storm center of a countrywide campaign of slanderous falsehood, is an effective answer to those whose method of opposing the strike was to shout "Bolshevism" and "Revolution." Not thus are fomenters of revolution accustomed to write. It is this very quality which will make the book of great value both to the student and to the labor organizer. Never before has a leader in a great organizing campaign like the one preceding the steel strike sat down afterward to appraise so calmly the causes of defeat. Explanations of failure are common, usually in the form of "alibis." Mr. Foster has been willing to look the facts steadily in the face and his analysis of the causes of the loss of the strike—laying the responsibility for it at the doors of the unions themselves—cannot fail to be helpful to every union leader, no matter what industry his union may represent. On the other hand his account of such a feat as the maintenance of a commissary adequate to meet the needs of the strikers at a cost of $1.40 per man is suggestive and encouraging to the highest degree. This achievement must stand as a monument to the integrity and practical ability of the men who conducted the strike.

It is with no purpose of underwriting every statement of fact or of making his own every theory advanced in the book that the writer expresses his confidence in it. It is because the book as a whole is so [Pg ix]well done and because the essential message that it conveys is so true, that it is a pleasure to write these words of introduction. Other books have been written about the steel industry. Some have concerned themselves with metallurgy, others with the commercial aspects of steel manufacture, and still others with certain phases of the labor problem. This book is different from all the others. It sets forth as no other book has, and as no other writer could, the need of the workers in this great basic industry for organization, and the extreme difficulty of achieving this essential right. It shows also in the sanity, good temper, and straightforward speech of the author what sort of leadership it is that the steel companies have decreed their workers shall not have!

John A. Fitch.

New York, June 4, 1920.

[1] See for example Judge Gary's testimony before the Senate Committee investigating the steel strike—October 1, 1919, pp. 161-162, of committee hearings. He told of a strike which occurred because a grievance remained unadjusted after a committee of the workers had tried to take it up with the management. The president of the company involved was for crushing the strike without knowing what the grievance was or even of the existence of the committee.

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | v | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | The Present Situation | 1 |

| The strike—"Victory" of the employers—Industrial democracy abroad, industrial serfdom at home—What the workers won—The outlook. | ||

| II. | A Generation of Defeat | 8 |

| The urge for mastery—Democratic resistance—The Homestead strike—The strikes of 1901 and 1909—The Steel Trust victorious. | ||

| III. | The Giant Labor Awakes | 16 |

| A bleak prospect—Hope springs eternal—A golden chance—Disastrous delay—The new plan—A lost opportunity— The campaign begins—Gary fights back. | ||

| IV. | Flank Attacks | 28 |

| A sea of troubles—The policy of encirclement—Taking the outposts—Organizing methods—Financial systems —The question of morale—Johnstown. | ||

| V. | Breaking into Pittsburgh | 50 |

| The flying squadron—Monessen—Donora—McKeesport —Rankin—Braddock—Clairton—Homestead— Duquesne—The results. | ||

| [Pg xi]VI. | Storm Clouds Gather | 68 |

| Relief demanded—The Amalgamated Association moves —A general movement—The conference committee— Gompers' letter unanswered—The strike vote—Gary defends steel autocracy—President Wilson acts in vain —The strike call. | ||

| VII. | The Storm Breaks | 96 |

| The Steel Trust Army—Corrupt officialdom—Clairton—McKeesport—The strike—showing by districts—A treasonable act—Gary gets his answer. | ||

| VIII. | Garyism Rampant | 110 |

| The White Terror—Constitutional Rights denied— Unbreakable solidarity—Father Kazincy—The Cossacks—Scientific barbarity—Prostituted courts—Servants rewarded. | ||

| IX. | Efforts at Settlement | 140 |

| The National Industrial Conference—The Senate committee—The red book—The Margolis case—The Interchurch World Movement. | ||

| X. | The Course of the Strike | 162 |

| Pittsburgh district—The railroad men—Corrupt newspapers—Chicago district—Federal troops at Gary —Youngstown district—The Amalgamated Association—Cleveland—The Rod and Wire Mill strike—The Bethlehem plants—Buffalo and Lackawanna—Wheeling and Steubenville—Pueblo—Johnstown—Mob rule—The end of the strike. | ||

| XI. | National and Racial Elements | 194 |

| A modern Babel—Americans as skilled workers— Foreigners as unskilled workers—Language difficulties —The Negro in the strike—The race problem. | ||

| [Pg xii]XII. | The Commissariat—The Strike Cost | 213 |

| The Relief organization—Rations—System of distribution —Cost of Commissariat—Steel Strike Relief Fund—Cost of the strike to the workers, the employers, the public, the Labor movement. | ||

| XIII. | Past Mistakes and Future Problems | 234 |

| Labor's lack of confidence—Inadequate efforts—Need of alliance with miners and railroaders—Radical leadership as a strike issue—Railroad shopmen, Boston police, miners, railroad brotherhood strikes—Defection of Amalgamated Association. | ||

| XIV. | In Conclusion | 255 |

| The point of view—Are trade unions revolutionary?—Camouflage in social wars—Ruinous dual unionism—Radicals should strengthen trade unions—The English renaissance—Tom Mann's work. |

| Pennsylvania Law and Order | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| National Committee Delegates | 38 |

| Strike Ballot | 78 |

| Cossacks in Action | 122 |

| Mrs. Fannie Sellins, Trade Union Organizer | 148 |

| Steel Trust Newspaper Propaganda | 188 |

| John Fitzpatrick | 216 |

| A Group of Organizers | 244 |

THE STRIKE—"VICTORY" OF THE EMPLOYERS—INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY ABROAD, INDUSTRIAL SERFDOM AT HOME—WHAT THE WORKERS WON—THE OUTLOOK

The great steel strike lasted three months and a half. Begun on September 22, 1919, by 365,600 men quitting their places in the iron and steel mills and blast furnaces in fifty cities of ten states, it ended on January 8, 1920, when the organizations affiliated in the National Committee for Organizing Iron and Steel Workers voted to permit the 100,000 or more men still on strike to return to work upon the best terms they could secure.

The steel manufacturers "won" the strike. By forcing an unconditional surrender, they drove their men back to the old slavery. This they accomplished in their wonted and time-honored way by carrying on a reign of terror that outraged every just conception of civil and human rights. In this [Pg 2]unholy task they were aided by a crawling, subservient and lying press, which spewed forth its poison propaganda in their behalf; by selfish and indifferent local church movements, which had long since lost their Christian principles in an ignominious scramble for company favors; and by hordes of unscrupulous municipal, county, state and federal officials, whose eagerness to wear the steel collar was equalled only by their forgetfulness of their oaths of office. No suppression of free speech and free assembly, no wholesale clubbing, shooting and jailing of strikers and their families was too revolting for these Steel Trust[2] hangers-on to carry out with relish. With the notable exception of a few honorable and courageous individuals here and there among these hostile elements, it was an alignment of the steel companies, the state, the courts, the local churches and the press against the steel workers.

Upon the ending of the strike the steel workers got no direct concessions from their employers. Those who were able to evade the bitter blacklist were compelled to surrender their union cards and to return to work under conditions that are a shame and a disgrace. They were driven back to the [Pg 3]infamous peonage system with its twelve hour day, a system which American steel workers, of all those in the world, alone have to endure. In England, France, Italy and Germany, the steel workers enjoy the right of a voice in the control of their industry; they regularly barter and bargain with their employers over the questions of hours, wages and working conditions; they also have the eight hour day. One must come to America, the land of freedom, to find steel workers still economically disfranchised and compelled to work twelve hours a day. In this country alone the human rights of the steel workers are crushed under foot by the triumphant property rights of their employers.

Who can uphold this indefensible position? Are not our deposits of coal and iron immeasurably greater, our mills more highly developed, our labor force more numerous and more skilled than those of any other country? Who then will venture to assert that American workingmen are not entitled to exercise all the rights and privileges enjoyed by European workingmen? If the steel workers of England, or France, or Italy, or Germany can practice collective bargaining, why not the steel workers of America? And why should the steel workers here have to work twelve hours daily when the eight hour day obtains abroad?

There are a hundred good reasons why the principles of collective bargaining and the shorter workday should prevail in the steel industry of America, and only one why they should not. This one reason is that the industry is hard and fast in the grip of absentee capitalists who take no part in production [Pg 4]and whose sole function is to seize by hook or crook the product of the industry and consume it. These parasites, in their voracious quest of profits, know neither pity nor responsibility. Their reckless motto is "After us the deluge." They care less than naught for the rights and sufferings of the workers. Ignoring the inevitable weakening of patriotism of people living under miserable industrial conditions, they go their way, prostituting, strangling and dismembering our most cherished institutions. And the worst of it is that in the big strike an ignorant public, miseducated by employers' propaganda sheets masquerading under the guise of newspapers, applauded them in their ruthless course. Blindly this public, setting itself up as the great arbiter of what is democratic and American, condemned as bolshevistic and ruinous the demands of almost 400,000 steel workers for simple, fundamental reforms, without which hardly a pretense of freedom is possible, and lauded as sturdy Americanism the desperate autocracy of the Steel Trust. All its guns were turned against the strikers.

In this great struggle the mill owners may well claim the material victory; but with just as much right the workers can claim the moral victory. For the strike left in every aspiring breast a spark of hope which must burn on till it finally bursts into a flame of freedom-bringing revolt. For a generation steel workers had been hopeless. Their slavery had overwhelmed them. The trade-union movement seemed weak, distant and incapable. The rottenness of steel districts precluded all thought of relief through political channels. The employers [Pg 5]seemed omnipotent. But the strike has changed all this. Like a flash the unions appeared upon the scene. They flourished and expanded in spite of all opposition. Then boldly they went to a death grapple with the erstwhile unchallenged employers. It is true they did not win, but they put up a fight which has won the steel workers' hearts. Their earnest struggle and the loyal support, by money and food, which they gave the strikers, have forever laid at rest the employers' arguments that the unions are cowardly, grafting bodies organized merely to rob and betray the workers. Even the densest of the strikers could see that the loss of the strike was due to insufficient preparation; that only a fraction of the power of unionism had been developed and that with better organization better results would be secured. And the outcome is that the steel workers have won a precious belief in the power of concerted action through the unions. They have discovered the Achilles' heel of their would-be masters. They now see the way out of their slavery. This is their tremendous victory.

No less than the steel workers themselves, the whole trade-union movement won a great moral victory in the steel strike and the campaign that preceded it. This more than offsets the failure of the strike itself. The gain consists of a badly needed addition to the unions' thin store of self-confidence. To trade-union organizers the steel industry had long symbolized the impossible. Wave after wave of organizing effort they had sent against it; but their work had been as ineffectual as a summer sea lapping the base of Gibraltar. Pessimism [Pg 6]regarding its conquest for trade unionism was abysmal. But now all this is changed. The impossible has been accomplished. The steel workers were organized in the face of all that the steel companies could do to prevent it. Thus a whole new vista of possibilities unfolds before the unions. Not only does the reorganization of the steel industry seem strictly feasible, but the whole conception that many of the basic industries are immune to trade unionism turns out to be an illusion. If the steel industry could be organized, so can any other in the country; for the worst of them presents hardly a fraction of the difficulties squarely vanquished in the steel industry. The mouth has been shut forever of that insufferable pest of the labor movement, the large body of ignorant, incompetent, short-sighted, visionless union men whose eternal song, when some important organizing project is afoot, is "It can't be done." After this experience in the steel industry the problem of unionizing any industry resolves itself simply into selecting a capable organizer and giving him sufficient money and men to do the job.

The ending of the strike by no means indicates the abandonment of the steel workers' battle for their rights. For a while, perhaps, their advance may be checked, while they are recovering from the effects of their great struggle. But it will not be long before they have another big movement under way. They feel but little defeated by the loss of the strike, and the trade unions as a whole feel even less so. Both have gained wonderful confidence in themselves and in each other during the fight. The unions will not desert the field and leave the workers [Pg 7]a prey to the demoralizing propaganda of the employers, customary after lost strikes. On the contrary they are keeping a large crew of organizers at work in an educational campaign, devised to maintain and develop the confidence the steel workers have in themselves and the unions. Then, when the opportune time comes, which will be but shortly, the next big drive will be on. Mr. Gary and his associates may attempt to forestall the inevitable by the granting of fake eight hour days, paper increases in wages and hand-picked company unions, but it is safe to say that the steel workers will go on building up stronger and more aggressive combinations among themselves and with allied trades until they finally achieve industrial freedom. So long as any men undertake to oppress the steel workers and to squeeze returns from the industry without rendering adequate service therefor, just that long must these men expect to be confronted by a progressively more militant and rebellious working force. The great steel strike of 1919 will seem only a preliminary skirmish when compared with the tremendous battles that are bound to come unless the enslaved steel workers are set free.

[2] Throughout this book the term "Steel Trust" is used to indicate the collectivity of the great steel companies. It is true that this is in contradiction to the common usage, which generally applies the term to the United States Steel Corporation alone, but it is in harmony with the facts. All the big steel companies act together upon all important matters confronting their industry. Beyond question they are organized more or less secretly into a trust. This book recognizes this situation, hence the broad use of the term "Steel Trust." It is important to remember this explanation. Where the writer has in mind any one company that company is named.

THE URGE FOR MASTERY—DEMOCRATIC RESISTANCE—THE HOMESTEAD STRIKE—THE STRIKES OF 1901 AND 1909—THE STEEL TRUST VICTORIOUS

The recent upheaval in the steel industry was but one link in a long chain of struggles, the latest battle in an industrial war for freedom which has raged almost since the inception of the industry.

The steel manufacturers have always aggressively applied the ordinary, although unacknowledged, American business principles that our industries exist primarily to create huge profits for the fortunate few who own them, and that if they have any other utility it is a matter of secondary importance. The interests of society in the steel business they scoff at. And as for their own employees, they have never considered them better than so much necessary human machinery, to be bought in the market at the lowest possible price and otherwise handled in a thoroughly irresponsible manner. They clearly understand that if they are to carry out their policy of raw exploitation, the prime essential [Pg 9]is that they keep their employees unorganized. Then, without let or hindrance, wages may be kept low, the work day made longer, speeding systems introduced, safety devices neglected, and the human side of the industry generally robbed and repressed in favor of its profit side; whereas, if the unions were allowed to come in, it would mean that every policy in the industry would first have to be considered and judged with regard to its effects upon the men actually making steel and iron. It would mean that humanity must be emphasized at the expense of misearned dividends. But this would never do. The mill owners are interested in profits, not in humanity. Hence, if they can prevent it, they will have no unions. Since the pioneer days of steel making their policy has tended powerfully on the one hand towards elevating the employers into a small group of enormously wealthy, idle, industrial autocrats, and on the other towards depressing the workers into a huge army of ignorant, poverty-stricken, industrial serfs. The calamity of it is that this policy has worked out so well.

Against this will-to-power of their employers the steel workers have fought long and valiantly. In the early days of the industry, when the combinations of capital were weak, the working force skilled, English-speaking and independent, the latter easily defended themselves and made substantial progress toward their own inevitable, even if unrecognized goal of industrial freedom; but in later years, with the growth of the gigantic United States Steel Corporation, the displacement of skilled labor by automatic machinery and the introduction of multitudes [Pg 10]of illiterate immigrants into the industry, their fight for their rights became a desperate and almost hopeless struggle. For the past thirty years they have suffered an unbroken series of defeats. Their one-time growing freedom has been crushed.

At first the fight was easy, and by the later '80's, grace to the activities of many unions, notable among which were the old Sons of Vulcan, the Knights of Labor and the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers, considerable organization existed among the men employed in the iron and steel mills throughout the country. The Amalgamated Association, the dominating body, enjoyed great prestige in the labor movement generally. It consisted almost entirely of highly skilled men and paid little or no attention to the unskilled workers. In the heyday of its strength, in 1891, it numbered about 24,000 members. Its stronghold was in the Pittsburgh district. Its citadel was Homestead. During the period of its greatest activity some measure of democracy prevailed in the industry, and prospects seemed bright for its extension.

But about that time Andrew Carnegie, grown rich and powerful, began to chafe uneasily under the restrictions placed upon his rapacity by his organized employees. He wanted a free hand and determined to get it. As the first step towards enshackling his workers he brought into his company that inveterate enemy of democracy in all its forms, Henry C. Frick. Then the two, Carnegie and Frick, neither of whom gave his workers as much consideration as the Southern slave holder gave his bondmen—for chattel slaves were at least assured sufficient food, warm [Pg 11]clothes, a habitable home and medical attendance—began to war upon the union. They started the trouble in Homestead, where the big mills of the Carnegie Company are located. In 1889 they insisted that the men accept heavy reductions in wages, write their agreements to expire in the unfavorable winter season instead of in summer, and give up their union. The men refused, and after a short strike, got a favorable settlement. But Carnegie and Frick were not to be lightly turned from their purpose. When the contract in force expired, they renewed their old demands, and thus precipitated the great Homestead strike.

This famous strike attracted world-wide attention, and well it might, for it marked a turning point in the industrial history of America. It began on June 23, 1892, and lasted until November 20 of the same year. Characterized by extreme bitterness and violence, it resulted in complete defeat for the men, not only in Homestead, but also in several other big mills in Pittsburgh and adjoining towns where the steel workers had struck in support of their besieged brothers in Homestead. This unsuccessful strike eliminated organized labor from the mills of the big Carnegie Company. It also dealt the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers a blow from which it has not yet recovered. It ended the period of trade-union expansion in the steel industry and began an era of unrestricted labor control by the employers. At Homestead Carnegie and Frick stuck a knife deep into the vitals of the young democracy of the steel workers.

Recuperating somewhat from the staggering [Pg 12]defeat at Homestead, the Amalgamated Association managed to retain a firm hold in the industry for a few years longer. Its next big setback, in 1901, was caused by the organization of the United States Steel Corporation. Foreseeing war from this monster combination dominated by the hostile Carnegie interests, the union, presided over at that time by Theodore J. Shaffer, decided to take time by the forelock and negotiate an agreement that would extend its scope and give it a chance to live. But the plan failed; the anti-union tendencies of the employers were too strong, and a strike resulted. At first the only companies affected were the American Tin Plate Company, the American Sheet Steel Company and the American Steel Hoop Company. Finally, however, all the organized men in all the mills of the United States Steel Corporation were called out, but to no avail; after a few weeks' struggle the strike was utterly lost.

The failure of the 1901 strike broke the backbone of the Amalgamated Association. Still, with characteristic trade-union tenacity, it lingered along in a few of the Trust plants in the sheet and tin section of the industry. Its business relations with the companies at this stage of its decline, according to the testimony of its present President, M. F. Tighe, before the Senate Committee investigating the 1919 strike, consisted of "giving way to every request that was made by the companies when they insisted upon it." But even this humble and pliant attitude of the once powerful Amalgamated Association was intolerable to the haughty steel kings. They could not brook even the most shadowy opposition to their [Pg 13]industrial absolutism. Accordingly, early in the summer of 1909, they served notice upon the union men to accept a reduction in wages and give up their union. It was practically the same ultimatum delivered by Carnegie and Frick to the Homestead men twenty years before. With a last desperate rally the union met this latest attack upon its life. The ensuing strike lasted fourteen months. It was bitterly fought, but it went the way of all strikes in the steel industry since 1892. It was lost; and in consequence every trace of unionism was wiped out of the mills not only of the United States Steel Corporation, but of the big independent companies as well.

Although the union was not finally crushed in the mills until the strike of 1909, the steel mill owners were for many years previous to that time in almost undisputed control of the situation. During a generation, practically, they have worked their will unhampered; and the results of their policy of unlimited exploitation are all too apparent. For themselves they have taken untold millions of wealth from the industry; for the workers they have left barely enough to eke out an existence in the miserable, degraded steel towns.

At the outbreak of the World war the steel workers generally, with the exception of the laborers, who had secured a cent or two advance per hour, were making less wages than before the Homestead strike. The constant increase in the cost of living in the intervening years had still further depressed their standards of life. Not a shred of benefit had they received from the tremendously [Pg 14]increased output of the industry. While the employers lived in gorgeous palaces, the workers found themselves, for the most part, crowded like cattle into the filthy hovels that ordinarily constitute the greater part of the steel towns. Tuberculosis ran riot among them; infant mortality was far above normal. Though several increases in wages were granted after the war began, these have been offset by the terrific rise in the cost of living. If the war has brought any betterment in the living conditions of the steel workers, it cannot be seen with the naked eye.

The twelve hour day prevails for half of the men. One-fourth work seven days a week, with a twenty-four hour shift every two weeks. Their lives are one constant round of toil. They have no family life, no opportunity for education or even for recreation; for their few hours of liberty are spoiled by the ever-present fatigue. Furthermore, working conditions in the mills are bad. The men are speeded up to such a degree that only the youngest and strongest can stand it. At forty the average steel worker is played out. The work, in itself extremely dangerous, is made still more so by the employers' failure to adopt the necessary safety devices. Many a man has gone to his death through the wanton neglect of the companies to provide safeguarding appliances that they would have been compelled to install were the unions still in the plants.[4] [Pg 15]Not a trace of industrial justice remains. The treatment of the men depends altogether upon the arbitrary wills of the foremen and superintendents. A man may give faithful service in a plant for thirty years and then be discharged offhand, as many are, for some insignificant cause. He has no one to appeal to. His fellow workers, living in constant terror of discharge and the blacklist, dare not even listen to him, much less defend his cause. He must bow to the inevitable, even though it means industrial ruin for him and his family.

Such deplorable conditions result naturally from a lack of unionism. It is expecting too much of human nature at this stage of its development to count on employers treating their employees fairly without some form of compulsion. Even in highly organized industries the unions have to be constantly on guard to resist the never-ending encroachments of their employers, manifested at every conceivable point of attack. For the workers, indeed, eternal vigilance is the price of liberty. Hence nothing but degradation for them and autocracy for their employers may be looked for in industries where they are systematically kept unorganized and thus incapable of defending their rights, as is the case in the steel industry. This system of industrial serfdom has served the steel barons well for a generation. But it is one the steel workers will never accept. Regardless of the cost they will rebel against it at every opportunity till they finally destroy it.

[3] Students desiring a full account of the early struggles of the steel unions are advised to read Mr. John A. Fitch's splendid book, "The Steel Workers."

[4] The practice of the different steel companies varies with respect to safety devices. Some of them are still in the dark ages that all were in a few years ago, with reckless disregard of human life. Others have made some progress. Of these the U. S. Steel Corporation is undoubtedly in the lead, for it has installed many safety appliances and has safety committees actively at work. At best, however, steel making is an exceedingly dangerous industry and the risk is intensified by the great heat of the mills and the long hours of work—the twelve hour day and the seven day week—which lead inevitably to exhaustion.

A BLEAK PROSPECT—HOPE SPRINGS ETERNAL—A GOLDEN CHANCE —DISASTROUS DELAY—THE NEW PLAN—A LOST OPPORTUNITY—THE CAMPAIGN BEGINS—GARY FIGHTS BACK

From just previous to, until some time after the beginning of the world war the situation in the steel industry, from a trade-union point of view, was truly discouraging. It seemed impossible for the workers to accomplish anything by organized effort. The big steel companies, by driving the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers from the mills, had built up a terrific reputation as union crushers. This was greatly enhanced by their complete defeat of Labor in the memorable strikes of the structural iron workers, the lake sailors, the iron miners, and the steel workers at McKees Rocks in 1909, Bethlehem in 1910 and Youngstown in 1915-16. It was still further enhanced by their blocking every attempt of the individual trades to re-establish themselves, and by the failure of the A. F. of L. steel campaign, inaugurated by the convention of 1909, to achieve even the slightest tangible results. The endless round of defeat had reduced almost to zero the trade unions' confidence in their [Pg 17]ability to cope with the militant and rapacious steel manufacturers.

But as the war wore on and the United States joined the general slaughter, the situation changed rapidly in favor of the unions. The demand for soldiers and munitions had made labor scarce; the Federal administration was friendly; the right to organize was freely conceded by the government and even insisted upon; the steel industry was the master-clock of the whole war program and had to be kept in operation at all costs; the workers were taking new heart and making demands—already they had engaged in big strike movements in the mills in Pittsburgh (Jones and Laughlin Company), Bethlehem and Birmingham (U. S. Steel). The gods were indeed fighting on the side of Labor. It was an opportunity to organize the industry such as might never again occur. That the trade union movement did not embrace it sooner was a calamity.

The writer was one of those who perceived the unparalleled opportunity. But being at that time Secretary-Treasurer of the committee organizing the packing industry I was unable to do anything substantial in the steel situation until the handing down of Judge Alschuler's decision giving the packing house workers the eight hour day and other vital concessions enabled me to slacken my efforts in that important movement. Immediately thereafter, on April 7, 1918, I presented a resolution to the Chicago Federation of Labor requesting the executive officers of the American Federation of Labor to call a general labor conference and to inaugurate thereat a national campaign to organize the steel workers. [Pg 18]The resolution was endorsed by twelve local unions in the steel industry. It was adopted unanimously and forwarded to the A. F. of L. The latter took the matter up with the rapidly reviving Amalgamated Association, and the affair was slowly winding along to an eventual conference, with a loss of much precious time, when the resolution was resubmitted to the Chicago Federation of Labor, re-adopted and sent to the St. Paul convention of the A. F. of L., June 10-20, 1918. It follows:

RESOLUTION #29

Whereas, the organization of the vast armies of wage-earners employed in the steel industries is vitally necessary to the further spread of industrial democracy in America, and

Whereas, Organized Labor can accomplish this great task only by putting forth a tremendous effort; therefore, be it

Resolved, that the executive officers of the A. F. of L. stand instructed to call a conference during this convention of delegates of all international unions whose interests are involved in the steel industries, and of all the State Federations and City Central bodies in the steel districts, for the purpose of uniting all these organizations into one mighty drive to organize the steel plants of America.

The resolution was adopted by unanimous vote. Accordingly, a number of conferences were held during the convention, at which the proposed campaign was discussed and endorsed. The outcome was that provisions were made to have President Gompers call another conference, in Chicago thirty days later, of responsible union officials who would [Pg 19]come prepared to act in the name of their international unions. This involved further waste of probably the most precious time for organizing work that Labor will ever have.

From past events in the steel industry it was evident that in the proposed campaign radical departures would have to be made from the ordinary organizing tactics. Without question the steel workers' unions have always lacked efficiency in their organizing departments. This was a cardinal failing of the Amalgamated Association and it contributed as much, if not more than anything else to its downfall. If, when in its prime, this organization had shown sufficient organizing activity in the non-union mills, and especially by taking in the unskilled, it would have so intrenched itself that Carnegie and his henchman, Frick, never could have dislodged it. But, unfortunately, it undertook too much of its organization work at the conference table and not enough at the mill gates. Consequently, more than once it found itself in deadly quarrels with the employers over the unionization of certain mills, when a live organizer working among the non-union men involved would have solved the problem in a few weeks.

Nor had the other unions claiming jurisdiction over men employed in the steel industry developed an organizing policy equal to the occasion. Their system of nibbling away, one craft at a time in individual mills, was entirely out of place. Possibly effective in some industries, it was worse than useless in the steel mills. Its unvarying failure served only to strengthen the mill owners and to further [Pg 20]discourage the mill workers and Organized Labor. It is pure folly to organize one trade in one mill, or all trades in one mill, or even all trades in all the mills in one locality, when, at any time it sees fit to do so, the Steel Trust can defeat the movement by merely shutting down its mills in the affected district and transferring its work elsewhere, as it has done time and again. It was plain, therefore, that the proposed campaign would have to affect all the steel mills simultaneously. It would have to be national in scope and encompass every worker in every mill, in every steel district in the United States.

The intention was to use the system so strikingly successful in the organization of the packing industry. The committee charged with organizing that industry, when it assembled, a year before, to begin the work, found three possible methods of procedure confronting it, each with its advocates present. It could go along on the old, discredited craft policy of each trade for itself and the devil take the hindmost; it might attempt to form an industrial union; or it could apply the principle of federating the trades, then making great headway on the railroads. The latter system was the one chosen as the best fitted to get results at this stage in the development of the unions and the packing industry. And the outcome proved the wisdom of the decision. In the steel campaign the unions were to be similarly linked together in an offensive and defensive alliance.

But all this relates merely to the shell of the plan behind Resolution No. 29. Its breath of life was in its strategy; in the way the organization work was to be prosecuted. The best plans are [Pg 21]worthless unless properly executed. The idea was to make a hurricane drive simultaneously in all the steel centers that would catch the workers' imagination and sweep them into the unions en masse despite all opposition, and thus to put Mr. Gary and his associates into such a predicament that they would have to grant the just demands of their men. It was intended that after the Chicago conference a dozen or more general organizers should be dispatched immediately to the most important steel centers, to bring to the steel workers the first word of the big drive being made in their behalf, and to organize local committees to handle the detail work of organization. In the meantime the co-operating international unions were to recruit numbers of organizers and to send them to join the forces already being developed everywhere by the general organizers. They should also assemble and pay in as quickly as possible their respective portions of the fund of at least $250,000 to be provided for the work. The essence of the plan was quick, energetic action.

At the end of three or four weeks, when the organizing forces were in good shape and the workers in the mills acquainted with what was afoot, the campaign would be opened with a rush. Great mass meetings, built up by extensive advertising, would be held everywhere at the same time throughout the steel industry. These were calculated to arouse hope and enthusiasm among the workers and to bring thousands of them into the unions, regardless of any steps the mill owners might take to prevent it. After two or three meetings in each place, [Pg 22]the heavy stream of men pouring into the unions would be turned into a decisive flood by the election of committees to formulate the grievances of the men and present these to the employers. The war was on; the continued operation of the steel industry was imperative; a strike was therefore out of the question; the steel manufacturers would have been compelled to yield to their workers, either directly or through the instrumentality of the Government. The trade unions would have been re-established in the steel industry, and along with them fair dealing and the beginnings of industrial democracy.

The plan was not only a bold one, but also under the circumstances the logical and practical one. The course of events proved its feasibility. The contention that it involved taking unfair advantage of the steel manufacturers may be dismissed as inconsequential. These gentlemen in their dealings with those who stand in their way do not even know the meaning of the word fairness. Their workers they shoot and starve into submission; their competitors they industrially strangle without ceremony; the public and the Government they exploit without stint or limit. The year before the campaign began, 1917, when the country was straining every nerve to develop and conserve its resources, the United States Steel Corporation alone, not to mention the many independents, after paying federal taxes and leaving out of account the vast sums that disappeared in the obscure and mysterious company funds, unblushingly pocketed the fabulous profit of $253,608,200.

It now remained to be seen how far the unions [Pg 23]would sustain such a general and energetic campaign. The fateful conference met in the New Morrison Hotel, Chicago, August 1-2, 1918. Samuel Gompers presided over its sessions. Representatives of fifteen international unions were present. These men showed their progressive spirit by meeting many difficult issues squarely with the proper solutions. They realized fully the need of co-operation along industrial lines, from the men who dig the coal and iron ore to those who switch the finished products onto the main lines of the railroads. Plainly no trade felt able to cope single-handed with the Steel Trust; and joint action was decided upon almost without discussion. Likewise the conference saw the folly of trying to organize the steel industry with each of the score of unions demanding a different initiation fee. Therefore, after much stretching of constitutions, the international unions, with the exception of the Bricklayers, Molders and Patternmakers (who charged respectively $7.25, $5.00 and $5.00), agreed to a uniform initiation fee of three dollars, one dollar of which was to be used for defraying expenses of the national organization work.

At the same meeting the National Committee for Organizing Iron and Steel Workers was formed. It was made to consist of one representative from each of the co-operating international unions. Its given function was to superintend the work of organization. Its chairman had to be a representative of the A. F. of L. Mr. Gompers volunteered to fill this position; the writer was elected Secretary-Treasurer. Including later additions, the constituent unions were as follows:

International Brotherhood of Blacksmiths, Drop-Forgers and Helpers

[Pg 24]

Brotherhood of Boilermakers and Iron Ship Builders and Helpers of America

United Brick and Clay Workers

Bricklayers', Masons' and Plasterers' International Union of America

International Association of Bridge, Structural and Ornamental Iron Workers

Coopers' International Union of North America

International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers

International Brotherhood of Foundry Employees

International Hod Carriers', Building, and Common Laborers' Union of America

Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers

International Association of Machinists

International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers

United Mine Workers of America

International Molders' Union of North America

Patternmakers' League of North America

United Association of Plumbers and Steam Fitters

Quarry Workers' International Union of North America

Brotherhood Railway Carmen of America

International Seamen's Union of America

Amalgamated Sheet Metal Workers' International Alliance

International Brotherhood of Stationary Firemen and Oilers

International Union of Steam and Operating Engineers

International Brotherhood of Steamshovel and Dredgemen

Switchmen's Union of North America.

[Pg 25]This group of unions, lined up to do battle with the Steel Trust, represents the largest body of workers ever engaged in a joint movement in any country. Their members number approximately 2,000,000, and comprise about one-half of the entire American Federation of Labor.

So far, so good. The conference had removed the barriers in the way of the campaign. But when it came to providing the large sums of money and the numerous crews of organizers that were immediately and imperatively needed to insure success, it failed dismally. The internationals assessed themselves only $100 apiece; they furnished only a corporal's guard of organizers to go ahead with the work; and future reinforcements looked remote.

This was a facer. The original plan of a dashing offensive went to smash instanter, and with it, likewise, the opportunity to organize the steel industry. The slender resources in hand at once made necessary a complete change of strategy. To undertake a national movement was out of the question. The work had to be confined to the Chicago district. This was admittedly going according to wrong principles. The steel industry is national in scope and should be handled as such. To operate in one district alone would expose that district to attacks, waste invaluable time and give the employers a chance to adopt counter measures against the whole campaign. It meant playing squarely into Mr. Gary's hands. But there was no other way out of the difficulty.

The writer had hoped that the favorable industrial situation and the organization of the packing [Pg 26]industry, which had long been considered hopeless, would have heartened the trade-union movement sufficiently for it to attack the steel problem with the required vigor and confidence. But such was not the case. The tradition of defeat in the steel industry was too strong,—thirty years of failure were not so easily forgotten. Lack of faith in themselves prevented the unions from pouring their resources into the campaign in its early, critical days. The work in the Chicago district was undertaken, nevertheless, with a determination to win the hearty support of Labor by giving an actual demonstration of the organizability of the steel workers.

During the first week of September the drive for members was opened in the Chicago district. Monster meetings were held in South Chicago, Gary, Indiana Harbor and Joliet—all the points that the few organizers could cover. The inevitable happened; eager for a chance to right their wrongs, the steel workers stormed into the unions. In Gary 749 joined at the first meeting, Joliet enrolled 500, and other places did almost as well. It was a stampede—exactly what was counted upon by the movers of Resolution #29. And it could just as well have been on a national scale, had the international unions possessed sufficient self-confidence and given enough men and money to put the original plan into execution. In a few weeks the unions would have been everywhere firmly intrenched; and in a few more the entire steel industry would have been captured for trade unionism and justice.

But now the folly of a one-district movement made itself evident. Up to this time the steel barons, like many union leaders, apparently had viewed the [Pg 27]campaign with a skeptical, "It can't be done" air. But events in Gary and elsewhere quickly dissipated their optimism. The movement was clearly dangerous and required heroic treatment. The employers, therefore, applying Mr. Gary's famous "Give them an extra cup of rice" policy, ordered the basic eight hour day to go into effect on the first of October. This meant that the steel workers were to get thereafter time and one half after eight hours, instead of straight time. It amounted to an increase of two hours pay per day but the actual working hours were not changed. It was a counter stroke which the national movement had been designed to forestall.

Although this concession really spelled a great moral victory for the unions its practical effect was bad. Just a few months before the United States Steel Corporation had publicly announced that, come what might, there would be no basic eight hour day in the steel industry. Its sudden adoption, almost over night, therefore, was a testimonial to the power of the unions. But this the steel workers as a whole could not realize. In the Chicago district, where the campaign was on, they understood and gave the unions credit for the winning; but in other districts, where nothing had been done, naturally they believed it a gift from the companies. Had the work been going on everywhere when Mr. Gary attempted this move, the workers would have understood his motives and joined the unions en masse,—the unions would have won hands down. But with operations confined to one district he was able to steal the credit from the unions, partially satisfy his men, and strip the campaign of one of its principal issues. No doubt he thought he had dealt it a mortal blow.

A SEA OF TROUBLES—THE POLICY OF ENCIRCLEMENT—TAKING THE OUTPOSTS—ORGANIZING METHODS—FINANCIAL SYSTEMS—THE QUESTION OF MORALE—JOHNSTOWN

Pittsburgh is the heart of America's steel industry. Its pre-eminence derives from its splendid location for steel making. It is situated at the point where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers join their murky waters to form the Ohio, this providing excellent water transportation. Immense deposits of coal surround it; the Great Lakes, the gateway to Minnesota's iron ore, are in easy reach; highly developed railway facilities make the best markets convenient. In the city itself there are only a few of the larger steel mills; but at short distances along the banks of its three rivers, are many big steel producing centers, including Homestead, Braddock, Rankin, McKeesport, McKees Rocks, Duquesne, Clairton, Woodlawn, Donora, Midland, Vandergrift, Brackenridge, New Kensington, etc. Within a radius of seventy-five miles lie Johnstown, Youngstown, Butler, Farrell, Sharon, New Castle, Wheeling, Mingo, Steubenville, Bellaire, Wierton and [Pg 29]various other important steel towns. The district contains from seventy to eighty per cent. of the country's steel industry. The whole territory is an amazing and bewildering network of gigantic steel mills, blast furnaces and fabricating shops.

It was into this industrial labyrinth, the den of the Steel Trust, that the National Committee for Organizing Iron and Steel Workers moved its office on October 1, 1918, preparatory to beginning its work. Success in the Chicago district had made it imperative to overcome the original tactical blunder by extending the campaign, just as quickly as possible, to a national scope.

The outlook was most unpromising. Even under the best of circumstances the task of getting the enormous army of steel workers to thinking and acting together in terms of trade unionism would be tremendous. But the disastrous mistake of not starting the campaign soon enough and with the proper vigor multiplied the difficulties. Unfavorable winter weather was approaching. This was complicated by the influenza epidemic, which for several weeks suspended all public gatherings. Then came the end of the war. The workers had also just been given the basic eight hour day. All these things tended to still them somewhat and to weaken their interest in organization. What was left of this interest was almost entirely wiped out when the mills, dependent as they were on war work, began to slacken production. The workers became obsessed with a fear of hard times, a timidity which was intensified by the steel companies' discharging every one suspected of union affiliations or [Pg 30]sympathies. And to cap the climax, the resources of the National Committee were still pitifully inadequate to the great task confronting it.

But worst of all, the steel companies were now on the qui vive. The original plan had been conceived to take them by surprise, on the supposition that their supreme contempt for Labor and their conceit in their own power would blind them to the real force and extent of the movement until it was too late to take effective counteraction. And it would surely have worked out this way, had the program been followed. But now the advantage of surprise, vital in all wars, industrial or military, was lost to the unions. Wide awake and alarmed, the Steel Trust was prepared to fight to the last ditch.

Things looked desperate. But there was no other course than to go ahead regardless of obstacles. The word failure was eliminated from the vocabulary of the National Committee. Preparations were made to begin operations in the towns close to Pittsburgh. But the Steel Trust was vigilant. It no longer placed any reliance upon its usual methods—its welfare, old age pension, employees' stockholding, wholesale discharge, or "extra cup of rice" policies—to hold its men in line, when a good fighting chance to win their rights presented itself to them. It had gained a wholesome respect for the movement and was taking no chances. It would cut off all communication between the organizers and the men. Consequently, its lackey-like mayors and burgesses in the threatened towns immediately held a meeting and decided that there would be no assemblages of steel workers in the Monongahela [Pg 31]valley. In some places these officials, who for the most part are steel company employees, had the pliable local councils hurriedly adopt ordinances making it unlawful to hold public meetings without securing sanction; in other places they adopted the equally effective method of simply notifying the landlords that if they dared rent their halls to the American Federation of Labor they would have their "Sunday Club" privileges stopped. In both cases the effect was the same—no meetings could be held. In the immediate Pittsburgh district there had been little enough free speech and free assembly for the trade unions before. Now it was abolished altogether.

At this time the world war was still on; our soldiers were fighting in Europe to "make the world safe for democracy"; President Wilson was idealistically declaiming about "the new freedom"; while right here in our own country the trade unions, with 500,000 men in the service, were not even allowed to hold public meetings. It was a worse condition than kaiserism itself had ever set up. This is said advisedly, for the German workers were at least permitted to meet when and where they pleased. The worst they had to contend with was a policeman on their platform, who would jot down "seditious" remarks and require the offenders to report next day to the police. I remember with what scorn I watched this system in Germany years ago, and how proud I felt to be an American. I was so sure that freedom of speech and assembly were fundamental institutions with us and that we would never tolerate such imposition. But now I have changed my [Pg 32]mind. In Pennsylvania, not to speak of other states, the workers enjoy few or no more rights than prevailed under the czars. They cannot hold meetings at all. So far are they below the status of pre-war Germans in this respect that the comparative freedom of the latter seems almost like an unattainable ideal. And this deprival of rights is done in the name of law and patriotism.

In the face of such suppression of constitutional rights and in the face of all the other staggering difficulties it was clearly impossible for our scanty forces to capture Pittsburgh for unionism by a frontal attack. Therefore a system of flank attacks was decided upon. This resolved itself into a plan literally to surround the immediate Pittsburgh district with organized posts before attacking it. The outlying steel districts that dot the counties and states around Pittsburgh like minor forts about a great stronghold, were first to be won. Then the unions, with the added strength, were to make a big drive on the citadel.

It was a far-fetched program when compared with the original; but circumstances compelled it. An important consideration in its execution was that it must not seem that the unions were abandoning Pittsburgh. That was the center of the battle line; the unions had attacked there, and now they must at least pretend to hold their ground until they were able to begin the real attack. The morale of the organizing force and the steel workers demanded this. So, all winter long mass meetings were held in the Pittsburgh Labor Temple and hundreds of thousands of leaflets were distributed in the [Pg 33]neighboring mills to prepare the ground for unionization in the spring. Besides, a lot of noise was made over the suppression of free speech and free assemblage. Protest meetings were held, committees appointed, investigations set afoot, politicians visited, and much other more or less useless, although spectacular, running around engaged in. These activities did not cost much, and they camouflaged well the union program.

But the actual fight was elsewhere. During the next several months the National Committee, with gradually increasing resources, set up substantial organizations in steel towns all over the country except close in to Pittsburgh, including Youngstown, East Youngstown, Warren, Niles, Canton, Struthers, Hubbard, Massillon, Alliance, New Philadelphia, Sharon, Farrell, New Castle, Butler, Ellwood City, New Kensington, Leechburg, Apollo, Vandergrift, Brackenridge, Johnstown, Coatesville, Wheeling, Benwood, Bellaire, Steubenville, Mingo, Cleveland, Buffalo, Lackawanna, Pueblo, Birmingham, etc. Operations in the Chicago district were intensified and extended to take in Milwaukee, Kenosha, Waukegan, De Kalb, Peoria, Pullman, Hammond, East Chicago, etc., while in Bethlehem the National Committee amplified the work started a year before by the Machinists and Electrical Workers.

Much of the success in these localities was due to the thoroughly systematic way in which the organizing work was carried on. This merits a brief description. There were two classes of organizers in the campaign, the floating and the stationary. Outside of a few traveling foreign speakers, the [Pg 34]floating organizers were those sent in by the various international unions. They usually went about from point to point attending to their respective sections of the newly formed local unions, and giving such assistance to the general campaign as their other duties permitted. The stationary organizers consisted of A. F. of L. men, representatives of the United Mine Workers, and men hired directly by the National Committee. They acted as local organizing secretaries, and were the backbone of the working force. The floating organizers were controlled mostly by their international unions; the stationary organizers worked wholly under the direction of the National Committee.

Everywhere the organizing system used was the same. The local secretary was in full charge. He had an office, which served as general headquarters. He circulated the National Committee's weekly bulletin, consisting of a short, trenchant trade-union argument in four languages. He built up the mass meetings, and controlled all applications for membership. At these mass meetings and in the offices all trades were signed up indiscriminately upon a uniform blank. But there was no "one big union" formed. The signed applications were merely stacked away until there was a considerable number. Then the representatives of all the trades were assembled and the applications distributed among them. Later these men set up their respective unions. Finally, the new unions were drawn up locally into informal central bodies, known as Iron and Steel Workers' councils. These were invaluable as they knit the movement together and [Pg 35]strengthened the weaker unions. They also inculcated the indispensable conception of solidarity along industrial lines and prevented irresponsible strike action by over-zealous single trades.

A highly important feature was the financial system. The handling of the funds is always a danger point in all working class movements. More than one strike and organizing campaign has been wrecked by loose money methods. The National Committee spared no pains to avoid this menace. The problem was an immense one, for there were from 100 to 125 organizers (which was what the crew finally amounted to) signing up steel workers by the thousands all over the country; but it was solved by the strict application of a few business principles. In the first place the local secretaries were definitely recognized as the men in charge and placed under heavy bonds. All the application blanks used by them were numbered serially. They alone were authorized to sign receipts[5] for initiation fees received. Should other organizers wish to enroll members, as often happened at the monster mass meetings, they were given and charged with so many receipts duly signed by the secretaries. Later on they were required to return these receipts or three dollars apiece for them. The effect of all this was to make one man, and him bonded, responsible in each locality for all paper outstanding against the National Committee. This was [Pg 36]absolutely essential. No system was possible without this foundation.

The next step was definitely to fasten responsibility in the transfer of initiation fees from the local secretaries to the representatives of the various trade unions. To do so was most important. It was accomplished by requiring the local secretaries to exact from these men detailed receipts, specifying not only the amounts paid and the number of applications turned over, but also the serial number of each application. Bulk transfer of applications was prohibited, there being no way to identify the paper so handled.

The general effect of these regulations was to enable the National Committee almost instantly to trace any one of the thousands of applications continually passing through the hands of its agents. For instance, a steel worker who had joined at an office or a mass meeting, hearing later of the formation of his local union, would go to its meeting, present his receipt and ask for his union card. The secretary of the union would look up the applications which had been turned over to him. If he could not find one to correspond with the man's receipt he would take the matter up with the National Committee's local secretary. The latter could not deny his own signature on the receipt; he would have to tell what became of the application and the fee. On looking up the matter he would find that he had turned them over to a certain representative. Nor could the latter deny his signature on the detailed receipt. He would have to make good.

To facilitate the work, district offices were [Pg 37]established in Chicago and Youngstown. Organizers and secretaries held district meetings weekly. Local secretaries at points contiguous to these centers reported to their respective district secretaries. All others dealt directly with the general office of the National Committee.

It will be recalled that the co-operating unions, at the August 1-2 conference, agreed that the sum of one dollar should be deducted from each initiation fee for organization purposes. The collection of this money devolved upon the National Committee and presented considerable difficulty. It was solved by a system. The local secretaries, in turning over to the trades the applications signed up in their offices or at the mass meetings, held out one dollar apiece on them. For the applications secured at the meetings of the local unions they collected the dollars due with the assistance of blank forms sent to the unions. Each week the local secretaries sent reports to the general office of the National Committee, specifying in detail the number of members enrolled and turned over to the various trades, and enclosing checks to cover the amounts on hand after local expenses were met. These reports were duly certified by the representatives of the organizations involved, who signed their names on them at the points where the reports referred to the number of members turned over to their respective bodies. The whole system worked well.

Practical labor officials who have handled mass movements understand the great difficulties attendant upon the organization of large bodies of workingmen. In the steel campaign these were more [Pg 38]serious than ever before. The tremendous number of men involved; their unfamiliarity with the English language and total lack of union experience; the wide scope of the operations; the complications created by a score of international unions, each with its own corps of organizers, directly mainly from far-distant headquarters; the chronic lack of resources; and the need for quick action in the face of incessant attacks from the Steel Trust—all together produced technical difficulties without precedent. But the foregoing systems went far to solve them. And into these systems the organizers and secretaries entered whole-heartedly. They realized that modern labor organizations cannot depend wholly upon idealism. They bore in mind that they were dealing with human beings and had to adopt sound principles of responsibility, standardization and general efficiency.

But another factor in the success of the campaign possibly even more important than the systems employed was the splendid morale of the organizers. A better, more loyal body of men was never gathered together upon this continent. They knew no such word as defeat. They pressed on with an irresistible assurance of victory born of their faith in the practicability of the theory upon which the campaign was worked out.

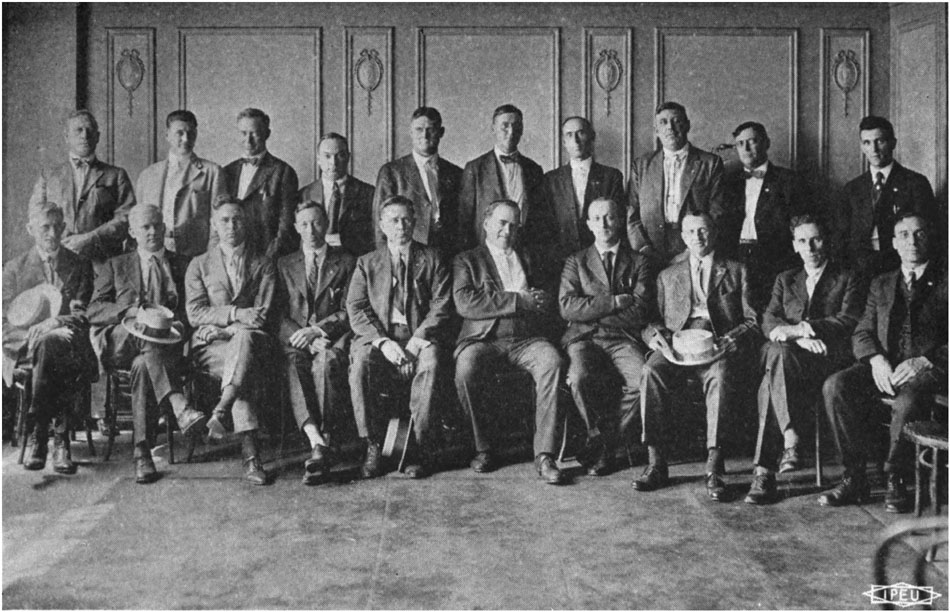

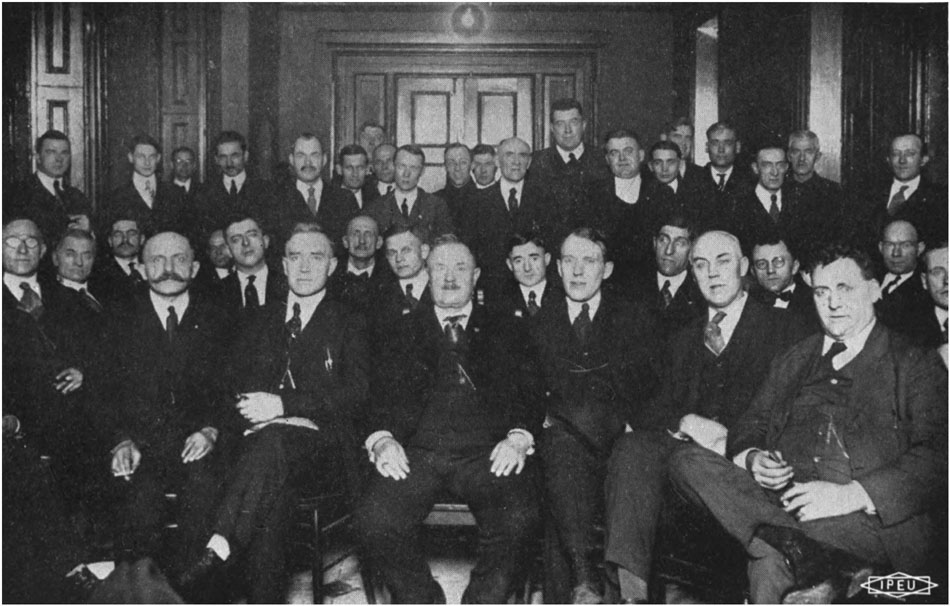

NATIONAL COMMITTEE DELEGATES

Youngstown, Ohio Meeting, Aug. 20, 1919.—Standing, left to right: F. P. Hanaway, Miners; D. Hickey, Miners; C. Claherty, Blacksmiths; R. J. Barr, Machinists; H. F. Liley, Railway Carmen; R. L. Hall, Machinists; R. T. McCoy, Molders; R. W. Beattie, Firemen; J. W. Morton, Firemen; P. A. Trant, Amalgamated Association. Seated, left to right: E. Crough, J. D. Cannon, Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers; F. J. Hardison, Blacksmiths; J. Manley, Iron Workers; Wm. Hannon, Machinists; John Fitzpatrick, Chairman; Wm. Z. Foster, Sec.-Treasurer; C. N. Glover, Blacksmiths; T. C. Cashen, Switchmen; D. J. Davis, Amalgamated Association.

The organization of workingmen into trade unions is a comparatively simple matter when it is properly handled. It depends almost entirely upon the honesty, intelligence, power and persistence of the organizing forces. If these factors are strongly present, employers can do little to stop the [Pg 39]movement of their employees. This is because the hard industrial conditions powerfully predispose the workers to take up any movement offering reasonable prospects of bettering their miserable lot. All that union organizers have to do is to place before these psychologically ripe workers, with sufficient clarity and persistence, the splendid achievements of the trade-union movement, and be prepared with a comprehensive organization plan to take care of the members when they come. If this presentation of trade unionism is made in even half-decent fashion the workers can hardly fail to respond. It is largely a mechanical proposition. In view of its great wealth and latent power, it may be truthfully said that there isn't an industry in the country which the trade-union movement cannot organize any time it sees fit. The problem in any case is merely to develop the proper organizing crews and systems, and the freedom-hungry workers, skilled or unskilled, men or women, black or white, will react almost as naturally and inevitably as water runs down hill.

This does not mean that there should be rosy-hued hopes held out to the workers and promises made to them of what the unions will get from the employers once they are established. On the contrary, one of the first principles of an efficient organizer is never, under any circumstances, to make promises to his men. From experience he has learned the extreme difficulty of making good such promises and also the destructive kick-back felt in case they are not fulfilled. The most he can do is to tell his men what has been done in other cases by organized workingmen and assure them that if they will stand [Pg 40]together the union will do its utmost to help them. Beyond this he will not venture. And this position will enable him to develop the legitimate hope, idealism and enthusiasm which translates itself into substantial trade-union structure. The wild stories of extravagant promises made to the steel workers during their organization are pure tommyrot, as every experienced union man knows.

The practical effect of this theory is to throw on the union men the burden of responsibility for the unorganized condition of the industries. This is as it should be. In consequence, they tend to blame themselves rather than the unorganized men. Instead of indulging in the customary futile lamentations about the scab-like nature of the non-union man, "unorganizable industries," the irresistible power of the employers, and similar illusions to which unionists are too prone, they seek the solution of the problem in improvements of their own primitive organization methods.

This conception worked admirably in the steel campaign. It filled the organizers with unlimited confidence in their own power. They felt that they were the decisive factor in the situation. If they could but present their case strongly enough, and clearly enough to the steel workers, the latter would have to respond, and the steel barons would be unable to prevent it. A check or a failure was but the signal for an overhauling of the tactics used, and a resumption of the attack with renewed vigor. At times it was almost laughable. With hardly an exception, when the organizers went into a steel town to begin work, they would be met by the local union [Pg 41]men and solemnly assured that it was utterly impossible to organize the steel mills in their town. "But," the organizers would say, "we succeeded in organizing Gary and South Chicago and many other tough places." "Yes, we know that," would be the reply, "but conditions are altogether different here. These mills are absolutely impossible. We have worked on them for years and cannot make the slightest impression. They are full of scabs from all over the country. You will only waste your time by monkeying with them." This happened not in one place alone, but practically everywhere—illustrating the villainous reputation the steel companies had built up as union smashers.

Side-stepping these pessimistic croakers, the organizers would go on to their task with undiminished self-confidence and energy. The result was success everywhere. The National Committee can boast the proud record of never having set up its organizing machinery in a steel town without ultimately putting substantial unions among the employees. It made little difference what the obstacles were; the chronic lack of funds; suppression of free speech and free assembly; raises in wages; multiplicity of races; mass picketing by bosses; wholesale discharge of union men; company unions; discouraging traditions of lost local strikes; or what not—in every case, whether the employers were indifferent or bitterly hostile, the result was the same, a healthy and rapid growth of the unions. The National Committee proved beyond peradventure of a doubt that the steel industry could be organized in spite of all the Steel Trust could do to prevent it.

[Pg 42]Each town produced its own particular crop of problems. A chapter apiece would hardly suffice to describe the discouraging obstacles overcome in organizing the many districts. But that would far outrun the limits of this volume. A few details about the work in Johnstown will suffice to indicate the tactics of the employers and the nature of the campaign generally.

Johnstown is situated on the main line of the Pennsylvania railroad, seventy-five miles east of Pittsburgh. It is the home of the Cambria Steel Company, which employs normally from 15,000 to 17,000 men in its enormous mills and mines. It is one of the most important steel centers in America.

For sixty-six years the Cambria Company had reared its black stacks in the Conemaugh valley and ruled as autocratically as any mediæval baron. It practically owned the district and the dwellers therein. It paid its workers less than almost any other steel company in Pennsylvania and was noted as one of the country's worst union-hating concerns. According to old residents, the only record of unionism in its plants, prior to the National Committee campaign, was a strike in 1874 of the Sons of Vulcan, and a small movement a number of years later, in 1885, when a few men joined the Knights of Labor and were summarily discharged. The Amalgamated Association, even in its most militant days, was unable to get a grip in Johnstown. That town, for years, bore the evil reputation of being one where union organizers were met at the depot and given the alternative of leaving town or going to the lockup.

[Pg 43]Into this industrial jail of a city the National Committee went in the early winter of 1918-19, at the invitation of local steel workers who had heard of the campaign. A. F. of L. organizer Thomas J. Conboy was placed in charge of the work. Immediately a strong organization spirit manifested itself—the wrongs of two-thirds of a century would out. It was interesting to watch the counter-moves of the company. They were typical. At first the officials contented themselves by stationing numbers of bosses and company detectives in front of the office and meeting halls to jot down the names of the men attending. But when this availed nothing, they took the next step by calling the live union spirits to the office and threatening them with dismissal. This likewise failed to stem the tide of unionism, and then the company officials applied their most dreaded weapon, the power of discharge. This was a dangerous course; the reason they did not adopt it before was for fear of its producing exactly the revolt they were aiming to prevent. But, all else unavailing, they went to this extreme.