The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Maid of Many Moods, by Virna Sheard This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: A Maid of Many Moods Author: Virna Sheard Release Date: August 21, 2011 [EBook #37152] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A MAID OF MANY MOODS *** Produced by Al Haines

A MAID

OF

MANY

MOODS

By VIRNA SHEARD

Toronto, THE COPP, CLARK

COMPANY, Ltd. MCMII

Copyright, 1902, By James Pott & Co.

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London

First Impression, September, 1902

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

It was Christmas Eve, and all the small diamond window panes of One Tree Inn, the half-way house upon the road from Stratford to Shottery, were aglitter with light from the great fire in the front room chimney-place and from the many candles Mistress Debora had set in their brass candlesticks and started a-burning herself. The place, usually so dark and quiet at this time of night, seemed to have gone off in a whirligig of gaiety to celebrate the Noel-tide.

In vain had old Marjorie, the housekeeper, scolded. In vain had Master Thornbury, who was of a thrifty and saving nature, followed his daughter about and expostulated. She only laughed and waved the lighted end of the long spill around his broad red face and bright flowered jerkin.

"Nay, Dad!" she had cried, teasing him thus, "I'll help thee save thy pennies to-morrow, but to-night I'm of another mind, and will have such a lighting up in One Tree Inn the rustics will come running from Coventry to see if it be really ablaze. There'll not be a candle in any room whatever without its own little feather of fire, not a dip in the kitchen left dark! So just save thy breath to blow them out later."

"Come, mend thy saucy speech, thou'lt light no more, I tell thee," blustered the old fellow, trying to reach the spill which the girl held high above her head. "Give over thy foolishness; thou'lt light no more!"

"Ay, but I will, then," said she wilfully, "an' 'tis but just to welcome Darby, Dad dear. Nay, then," waving the light and laughing, "don't thou dare catch it. An' I touch thy fringe o' pretty hair, dad—thy only ornament, remember—'twould be a fearsome calamity! I' faith! it must be most time for the coach, an' the clusters in the long room not yet lit. Hinder me no more, but go enjoy thyself with old Saddler and John Sevenoakes. I warrant the posset is o'erdone, though I cautioned thee not to leave it."

"Thou art a wench to break a man's heart," said Thornbury, backing away and shaking a finger at the pretty figure winding fiery ribbons and criss-crosses with her bright-tipped wand. "Thou art a provoking wench, who doth need locking up and feeding on bread and water. Marry, there'll be naught for thee on Christmas, and thou canst whistle for the ruff and silver buckles I meant to have given thee. Aye, an' for the shoes with red heels." Then with dignity, "I'll snuff out some o' the candles soon as I go below."

"An' thou do, dad, I'll make thee a day o' trouble on the morrow!" she called after him. And well he knew she would. Therefore, it was with a disturbed mind that he entered the sitting-room and went towards the hearth to stir the simmering contents of the copper pot on the crane.

John Sevenoakes and old Ned Saddler, his nearest neighbours and friends, sat one each side of the fire in their deep rush-bottomed chairs, as they sat at least five nights out of the week, come what weather would. Sevenoakes held a small child, whose yellow, curly head nodded with sleep. The hot wine bubbled up as the inn-keeper stirred it and the little spiced apples, brown with cloves, bobbed madly on top.

"It hath a savoury smell, Thornbury," remarked Saddler. "Methinks 'tis most ready to be lifted."

"'Twill not be lifted till Deb hears the coach," answered Sevenoakes. "'Twas so she timed it. 'On it goes at nine,' quoth she, 'an' off it comes at ten, Cousin John. Just when Darby will be jumping from the coach an' running in. Oh! I can't wait for the hour to come!' she says."

"She's a headstrong, contrary wench as ever heaven sent a man," put in Thornbury, straightening himself. "'Twere trouble saved an' I'd broken her in long ago."

"'Twas she broke thee in long ago," said Saddler, rubbing his knotty hands. "She hath led thee by the ear since she was three years old. An' I had married now, an' had such a lass, I'd a brought her up different, I warrant. Zounds! 'tis a show to see. She coaxes thee, she bullies thee, she comes it over thee with cajolery and blandishments an' leads thee a pretty dance."

"Thou art an old fool," returned Thornbury, mopping his face, which was sorely scorched, "What should thou know of the bringing up of wenches? Thou—a crabbed bachelor o' three score an' odd. Thou hast no way with children;—i' truth I've heard Will Shakespeare say the tartness of that face o' thine would sour ripe grapes."

Sevenoakes trotted the baby gently up and down, a look of troubled apprehension disturbing his usually placid features. His was ever the office of peace-maker between these two ancient cronies, and he knew to a nicety the moment when it was wisest to try and adjust matters.

"'Tis well I mind the night this baby came," he began retrospectively, looking up as the door opened and a tall young fellow entered, stamping the snow off his long boots. "Marry, Nick! thou dost bring a lot o' cold in with thee," he ended briskly, shifting his chair. "Any news o' the coach?"

"None that I've heard," replied the man, going to the hearth and turning his broad back to the fire. "'Tis a still night, still and frosty, but no sound of the horn or wheels reached me though I stood a-listening at the cross-roads. Then I turned down here an' saw how grandly thou had'st lit the house up to welcome Darby. My faith! I'll be glad to see him, for 'tis an age since he was home, Master Thornbury, an' he comes now in high feather. Not every lad hath wit and good looks enough to turn the head o' London after him. The stage is a great place for bringing a man out. Egad! I'm half minded to try it myself."

"I doubt not thou wilt, Nick, sooner or later; thou art a jack-o'-all-trades," answered Thornbury, in surly tones.

Nicholas Berwick laughed and shrugged his well-set shoulders, as he bent over and touched the child sleeping sweetly in old Sevenoakes' arms.

"What was't I heard thee saying o' the baby as I came in; he is not ailing, surely?"

"Not he!" answered Sevenoakes, stroking the moist yellow curls. "He's lusty as a year-old robin, an' as chirpy when he's awake; but he's in the land o' nod now, though his will was good to wait up for Darby like the rest of us."

"He's a rarely beautiful little lad," said Berwick. "I've asked Deb about him often, but she will tell me naught."

"I warrant she will na," piped up old Ned Saddler, in his reedy voice. "I warrant she will na; 'tis no tale for a young maid's repeating. Beshrew me! but the coach be late," he wound up irrelevantly.

"How came the child here?" persisted the young fellow, knocking back a red log with his foot. "An' it be such a tale as you hint, Saddler, I doubt not it's hard to keep it from slipping off thy tongue."

"'Tis a tale that slips off some tongue whenever this time o' year comes," answered Thornbury. "I desire no more Christmas Eves like that one four years back—please God! We were around the hearth as it might be now, and a grand yule log we had burning, I mind me; the room was trimmed gay an' fine with holly an' mistletoe as 'tis to-night. Saddler was there, Sevenoakes just where he be now, an' Deb sitting a-dreaming on the black oak settle yonder, the way she often sits, her chin on her hand—you mind, Nick!"

"Ay!" said the man, smiling.

"She wore her hair down then," went on Thornbury, "an' a sight it were to see."

"'Twere red as fox-fire," interrupted Saddler, aggrieved that the tale-telling had been taken from him. "When thou start'st off on Deb, Thornbury, thou know'st not where to bring up."

"An' Deb was sitting yonder on the oak settle," continued the innkeeper calmly.

"An' she had not lit the house up scandalously that year as 'tis now—for Darby was home," put in Saddler again.

"Ay! Darby was home—an' thou away, Nick—but the lad was worriting to try his luck on the stage in London, an' all on account o' a play little Judith Shakespeare lent him. I mind me 'twas rightly named, 'The Pleasant History o' the Taming o' a Shrew,' for most of it he read aloud to us. Ay, Darby was home, an' we were sitting here as it might be now, when the door burst open an' in come my lad carrying a bit of a baby muffled top an' toe in a shepherd's plaid. 'Twas crying pitiful and hoarse, as it had been long in the night wind."

"'Quick, Dad!' called Darby, 'Quick,' handing the bundle to Deb, 'there be a woman perished of cold not thirty yards from the house.'

"I tramped out after him saying naught. 'Twas a bitter night an' the road rang like metal under our feet. The country was silver-white with snow, an' the sky was sown thick with stars. Darby'd hastened on ahead an' lifted the wench in his arms, but I just took her from him an' carried her in myself. Marry! she were not much more weight than a child.

"We laid her near the fire and forced her to drink some hot sherry sack. Then she opened her eyes wild, raised herself and looked around in a sort o' terror, while she cried out for the baby. Deb brought it, an' the lass seemed content, for she smiled an' fell back on the pillow holding a bit of the shepherd's plaid tight in her small fingers.

"She was dressed in fashion of the Puritans, with kirtle of sad-coloured homespun. The only bright thing about her was her hair, and that curled out of the white coif she wore, golden as ripe corn.

"Well-a-day! I sent quickly for Mother Durley, she who only comes to a house when there be a birth or a death. I knew how 'twould end, for there was a look on the little wench's face that comes but once. She lived till break o' day and part o' the time she raved, an' then 'twas all o' London an' one she would go to find there; but, again she just lay quiet, staring open-eyed. At the last she came to herself, so said Mother Durley, an' there was the light of reason on her face. 'Twas then she beckoned Deb, who was sitting by, to bend down close, and she whispered something to her, though what 'twas we never knew, for my girl said naught—and even as she spoke the end came.

"Soul o' me! but we were at our wits' end to know what to do. Where she came from and who she was there was no telling, an' Deb raised such a storm when I spoke o' her being buried by the parish, that 'twas not to be thought of. One an' another came in to gaze at the little creature till the inn was nigh full. I bethought me 'twould mayhap serve to discover whom she might be. And so it fell. A lumbering yeoman passing through to Oxford stood looking at her a moment as she lay dressed the way we found her in the sad-coloured gown an' white coif.

"'Why! Od's pitikins!' he cried. 'Marry an' Amen! This be none but Nell Quinten! Old Makepeace Quinten's daughter from near Kenilworth. I'd a known her anywhere!'

"Then I bid Darby ride out to bring the Puritan in all haste, but he had the devil's work to get the man to come. He said the lass had shamed him, and he had turned her out months before. She was no daughter o' his he swore—with much quoting o' Scripture to prove he was justified in disowning her.

"Darby argued with him gently to no purpose; so my lad let his temper have way an' told the fellow he'd come to take him to One Tree Inn, an' would take him there dead or alive. The upshot was, they came in together before nightfall. The wench was in truth the old Puritan's daughter, and he took her home an' buried her. But for the child, he'd not touch it.

"''Tis a living lie!' he cried. ''Tis branded by Satan as his own! Give it to the Parish or to them that wants it, or marry, let it bide here! 'Tis a proper place for it in good sooth, for this be a public house where sinful drinking goeth on an' all worldly conversation. Moreover I saw one Master William Shakespeare pass out the door but now—a play actor, an' the maker o' ungodly plays. 'Twas such a one who wrought my Nell's ruin!'

"So he went on an' moore o' the sort. Gra'mercy! I had the will to horsewhip him, an' but for the little dead maid I would. I clenched my hands hard and watched him away; he sitting stiff atop o' Stratford hearse by the driver. Thus he took his leave, calling back at me bits o' Holy Writ," finished Thornbury grimly.

"And Debora told naught of what the girl said at the last?" asked Nicholas Berwick. "That doth seem strange."

"Never a word, lad, beyond this much—she prayed her to care for the child till his father be found."

"By St. George! but that was no modest request. What had'st thou to say in the matter? Did'st take the heaven-sent Christmas box in good part, Master Thornbury?"

"Nay, Nick! thou should know him some better than to ask that," said Saddler. "Gadzooks, there were scenes! 'Twas like Thornbury to grandfather a stray infant now, was't not?" rubbing his knees and chuckling. "Marry! I think I see the face he wore for a full month. ''Twill go to the Parish!' he would cry, stamping around and speaking words 'twould pass me to repeat. 'A plague on't! Here be a kettle of fish! Why should the wench fall at my door in heaven's name? Egad! I am a much-put-upon man.' Ay, Nick, 'twas a marvellous rare treat to hear him."

"How came you to keep the child, sir?" asked Berwick, gravely.

The innkeeper shrugged his shoulders. "'Twas Deb would have it so," he answered. "She was fair bewitched by the little one. Thou knowest her way, Nick, when her heart is set on anything. Peradventure, I have humoured the lass too much, as Saddler maintains. But she coaxed and she cried, an' never did I see her cry so before, such a storm o' tears—save for rage," reflectively.

"Well put!" said Saddler. "Well put, Thornbury!"

"Ever had she wished for just such a one to pet, she pleaded, an' well I knew no small child came in sight o' the inn but Deb was after it for a plaything. Nay, there never was a stray beast about the place, that it did not find her and follow her close, knowing 'twould be best off so.

"Well do I mind her cuffing a big lad she found drowning some day-old kittens in the stable—and he minds it yet I'll gainsay! She fished out the blind wet things, an' gathering them in her quilted petticoat brought them in here a-dripping. I' fecks! she made such a moan over them as never was."

"Ay, Deb always has a following o' ugly, ill-begotten beasts that nobody wants but she," said Sevenoakes. "There be old Tramp for one now—did'st ever see such an ill-favoured beast? An' nowhere will he sit but fair on the edge o' her gown."

"He is a dog of rare discernment—and a lucky dog to boot," said Berwick.

"So, the outcome of it, Master Thornbury, was that the little lad is here."

"What could a man do?" answered Thornbury, ruefully. "Hark!" starting up as the old housekeeper entered the room, "Where be the lass, Marjorie? An' the candles—are they burning safe?"

"Safe, but growing to the half length," she answered, peering out of the window. "The coach must a-got overtipped, Maister."

"Where be Deb—I asked thee?"

"Soul o' me! then if thou must know, Mistress Debora hath just taken the great stable lantern and gone along the road to meet the coach. 'An' thou dost tell my father I'll pinch thee, Marjorie!' she cried back to me. 'When I love thee—I love thee; an' when I pinch—I pinch! So tell him not.' But 'tis over late an' I would have it off my mind, Maister."

"Did Tramp go with her?" asked Berwick, buttoning on his great cape and starting for the door.

"Odso! yes! an' she be safe enow. Thou'lt see the lantern bobbing long before thou com'st up with her."

"'Tis a wench to break a man's heart!" Thornbury muttered, standing at the door and watching the tall figure of Berwick swing along the road.

The innkeeper waited there though a light snow was powdering his scanty fringe of hair—white already—and lying in sparkles on his bald pate and holiday jerkin. He was a hardy old Englishman and a little cold was nought to him.

The night was frosty, and the "star-bitten" sky of a fathomless purple. About the inn the snow was tinted rosily from the many twinkling lights within.

The great oak, standing opposite the open door and stretching out its kindly arms on either side as far as the house reached, made a network of shadows that carpeted the ground like fine lace.

Thornbury bent his head to listen. Far off sounded the ripple of a girl's laugh. A little wind caught it up and it echoed—fainter—fainter. Then did his old heart take to thumping hard, and his breath came quick.

"Ay! they be coming!" he said half aloud. "My lad—an' lass. My lad—an' lass." He strained his eyes to see afar down the road if a light might not be swaying from side to side. Presently he spied it, a merry will-o'-the-wisp, and the sound of voices came to him.

So he waited tremblingly.

Darby it was who saw him first.

"'Tis Dad at the door!" he called, breaking away from Debora and Berwick.

The girl took a step to follow, then stopped and glanced up at the man beside her. "Let him go on alone, Nick," she said. "He hath not seen Dad close onto two years, an' this play-acting of his hath been a bitter dose for my father to swallow. In good sooth I have small patience with Dad, yet more am I sorry for him. I' faith! I would that maidens might also be in the play. Judith Shakespeare says some day they may be—but 'twill serve me little. One of us at that business is all Dad could bear with—an' my work is at home."

"Ay, Deb!" he answered; "thy work is at home, for now."

"For always," she answered, quickly; then, her tone changing, "think'st thou not, Nick, that my Darby is taller? An' did'st note how handsome?"

"He is a handsome fellow," answered Berwick. "Still, I cannot see that he hath grown. He will not be of large pattern."

"Marry!" cried the girl, "Darby is a good head taller than I. Where dost thou keep thine eyes, Nick?"

"Nay, verily, then, he is not," answered the other; "thou art almost shoulder to shoulder, an' still as much alike—I saw by the lantern—as of old, when save for thy dress 'twas a puzzle to say which was which. 'Tis a reasonable likeness, as thou art twins."

Debora pursed up her lips. "He is much taller than I," she said, determinedly. "Thou art no friend o' mine, Nicholas Berwick, an' thou dost cut three full inches off my brother's height. He is a head taller, an' mayhap more—so."

They were drawing up to the inn now, and through the window saw the little group about the fire, Darby with the baby, who was fully awake, perched high on his shoulder.

Berwick caught Deb gently, swinging her close to him, as they stood in the shadow of the oak.

"Ah, Deb!" he said, bending his face to hers, "thou could'st make me swear that black was white. As for Darby, the lad is as tall as thou dost desire. Thou hast my word for't."

"'Tis well thou dost own it," she said, frowning; "though I like not the manner o' it. Let me go, Nick."

"Nay, I will not," he said, passionately. "Be kind; give me one kiss for Christmas. I know thou hast no love for me; thou hast told me so often enough. I will not tarry here, Sweet; 'twould madden me—but give me one kiss to remember when I be gone."

She turned away and shook her head.

"Thou know'st me better than to ask it," she said, softly. "Kisses are not things to give because 'tis Christmas."

The man let go his hold of her, his handsome face darkening.

"Dost hate me?" he asked.

"Nay, then, I hate thee not," with a little toss of her head. "Neither do I love thee."

"Dost love any other? Come, tell me for love's sake, sweetheart. An' I thought so!"

"Marry, no!" she said. Then with a short, half-checked laugh, "Well—Prithee but one!"

"Ah!" cried Berwick, "is't so?"

"Verily," she answered mockingly. "It is so in truth, an' 'tis just Dad. As for Darby, I cannot tell what I feel for him. 'Twould be full as easy to say were I to put it to myself, 'Dost love Debora Thornbury?' 'Yea' or 'Nay,' for, Heaven knows, sometimes I love her mightily—and sometimes I don't; an' then 'tis a fearsome 'don't,' Nick. But come thee in."

"No!" answered Berwick, bitterly. "I am not one of you." Catching her little hands he held them a moment against his coat, and the girl felt the heavy beating of his heart before he let them fall, and strode away.

She stood on the step looking after the solitary figure. Her cheeks burned, and she tapped her foot impatiently on the threshold.

"Ever it doth end thus," she said. "I am not one of you," echoing his tone. "In good sooth no. Neither is old Ned Saddler or dear John Sevenoakes. We be but three; just Dad, an' Darby, an' Deb." Then, another thought coming to her. "Nay four when I count little Dorian. Little Dorian, sweet lamb,—an' so I will count him till I find his father."

A shade went over her face but vanished as she entered the room.

"I have given thee time to take a long look at Darby, Dad," she cried. "Is't not good to have him at home?" slipping one arm around her brother's throat and leaning her head against him.

"Where be the coach, truant?" asked Saddler.

"It went round by the Bidford road—there was no other traveller for us. Marry, I care not for coaches nor travellers now I have Darby safe here! See, Dad, he hath become a fine gentleman. Did'st note how grand he is in his manner, an' what a rare tone his voice hath taken?"

The handsome boy flushed a little and gave a half embarrassed laugh.

"Nay, Debora, I have not changed; 'tis thy fancy. My doublet hath a less rustical cut and is of different stuff from any seen hereabout, and my hose and boots fit—which could not be said of them in olden times. This fashion of ruff moreover," touching it with dainty complacency, "this fashion of ruff is such as the Queen's Players themselves wear."

Old Thornbury's brows contracted darkly and the girl turned to him with a laugh.

"Oh—Dad! Dad! thou must e'en learn to hear of the playhouses, an' actors with a better grace than that. Note the wry face he doth make, Darby!"

"I have little stomach for their follies and buffooneries—albeit my son be one of them," the innkeeper answered, in sharp tone. Then struggling with some intense inward feeling, "Still I am not a man to go half-way, Darby. Thou hast chosen for thyself, an' the blame will not be mine if thy road be the wrong one. Thou canst walk upright on any highway, lad."

"Ay!" put in old Saddler, "Ay, neighbour, but a wilful lad must have his way."

Soon old Marjorie came in and clattered about the supper table, after having made a great to-do over the young master.

Thornbury poured the hot spiced wine into an ancient punch-bowl, and set it in the centre of the simple feast, and they all drew their chairs up to the table as the bells in Stratford rang Christmas in.

Never had the inn echoed to more joyous laughing and talking, for Thornbury and his two old friends mellowed in temper as they refilled their flagons, and they even added to the occasion by each rendering a song. Saddler bringing one forth from the dim recesses of his memory that related, in seventeen verses and much monotonous chorus, the love affairs of a certain Dinah Linn.

The child slumbered again on the oak settle in the inglenook. The firelight danced over his yellow hair and pretty dimpled hands. The candles burned low. Then Darby sang in flute-like voice a carol, that was, as he told them, "the rage in London," and, afterwards, just to please Deb, the old song that will never wear out its welcome at Christmas-tide, "When shepherds watched their flocks."

The girl would have joined him, but there came a tightness in her throat, and the hot stinging of tears to her eyes, and when the last note of it went into silence she said good night, lifted the sleeping child and carried him away.

"Deb grows more beautiful, Dad," said the young fellow, looking after her. "Egad! what a carriage she hath! She steps like a very princess of the blood. Hark! then," going to the latticed window and throwing it open. "Here come the waits, Dad, as motley a crowd as ever."

The innkeeper was trimming the lantern and seeing his neighbours to the door.

"Keep well hold of each other," called Darby after them. "I trow 'tis a timely proverb—'United we stand, divided we fall.'"

Saddler turned with a chuckle and shook his fist at the lad, but lurched dangerously in the operation.

"The apples were too highly spiced for such as thee," said Thornbury, laughing. "Thou had'st best stick to caudles an' small beer."

"Nay, then, neighbour," called back Sevenoakes, with much solemnity, "Christmas comes but once a year, when it comes it brings good cheer—'tis no time for caudles, or small beer!"

At this Darby went into such a peal of laughter—in which the waits who were discordantly tuning up joined him—that the sound of it must have awakened the very echoes in Stratford town.

During the days following Christmas, One Tree Inn was given over to festivity. It had always been a favoured spot with the young people from Stratford and Shottery. In spring they came trooping to Master Thornbury's meadow, bringing their flower-crowned queen and ribbon-decked May-pole. It was there they had their games of barley-break, blindman's buff and the merry cushion dance during the long summer evenings; and when dusk fell they would stroll homeward through the lanes sweet with flowering hedges, each one of them all carrying a posy from Deb Thornbury's garden—for where else grew such wondrous clove-pinks, ragged lady, lad's love, sweet-william and Queen Anne's lace, as there? So now these old playmates of Darby's came one by one to welcome him home and gaze at him in unembarrassed admiration.

Judith Shakespeare, who was a friend and gossip of Debora's, spent many evenings with them, and those who knew the little maid best alone could say what that meant, for never was there a gayer lass, or one who had a prettier wit. To hear Judith enlarging upon her daily experiences with people and things, was to listen to thrilling tales, garnished and gilded in fanciful manner, till the commonplace became delightful, and life in Stratford town a thing to be desired above the simple passing of days in other places.

No trivial occurrence went by this little daughter of the great poet without making some vivid impression upon her mind, for she viewed the every-day world lying beside the peaceful Avon through the wonderful rose-coloured glasses of youth, and an imagination bequeathed to her direct from her father.

It was on an evening when Judith Shakespeare was with them and Deb was roasting chestnuts by the hearth, that they fell to talking of London, and the marvellous way people had of living there.

A sudden storm had blown up, flakes of frozen snow came whirling against the windows, beating a fairy rataplan on the frosted glass, while the heavy boughs of the old oak creaked and groaned in the wind. Darby and the two girls listened to the sounds without and drew their chairs nearer the fire with a sense of the warm comfort of the long cheery room. They chatted about the city and the pleasures and pastimes that held sway there, doings that seemed so extravagant to country-bred folk, and that often turned night into day—a day moreover not akin to any spent elsewhere on top of the earth.

"Dost sometimes act in the same play with my father, Darby, at the Globe Theatre?" asked Judith, after a pause in the conversation, and at a moment when the innkeeper had just left the room.

The girl was sitting in a chair whose oaken frame was black with age. Now she grasped the arms of it tightly, and Darby noted the beautiful form of her hands and the tapering delicate fingers; he saw also a nervous tremor go through them as she spoke.

"Oh! I would know somewhat of my father's life in London," continued Judith, "and of the people he meets there. He hath acquaintance with many gentlemen of the Queen's Court and Parliament, for he hath twice been bidden to play in Her Majesty's theatre in the palace at Greenwich. Yet of all those doings of his and of the nobles who make much of him he doth say so little, Darby."

Debora, who was standing by the high mantel, turned towards her brother expectantly. She said nothing, but her eyes—shadowy eyes of a blue that was not all blue, but had a glint of green about it—her eyes burned as though they held imprisoned a bit of living light, like the fire in an opal.

The young player smiled; he was looking intently into the glowing coals and for the instant his thoughts seemed far away from the tranquil home scene.

There was no pose of Darby's figure which was not graceful; he was always a picture even to those who knew him best, and it was to this unconscious grace probably more than actual talent that his measure of success upon the stage was due. Now as he leant forward, his elbow on his knee, his chin on his white, almost girlish hand, the burnished auburn love-locks shading his oval face, and matching in colour the outward sweeping lashes of his eyes, Judith could not look away from him the while she waited his tardy answer.

After a moment he came out of his brown study with a little start, and glanced over at her.

"Ah, Judith, an' the master will give you but scant information on those points, why should I give more? As for the playhouses where he is constantly, now peradventure he is fore-wearied of them when once at home, or," with a slight uplifting of his brows, "or else he think'th them no topics for a young maid," he ended somewhat priggishly.

"'Tis ever so!" Judith answered with impatience. "Thou wilt give a body no satisfaction either. Soul o' me! but men be all alike. If ever I have a husband—which heaven forbid!—I shall fare to London four times o' the year an' see for myself what it be like."

"I am going to London with Darby when he doth go back again," said Debora, speaking with quiet deliberation. Thornbury entered the room at the moment and heard what his daughter said. The man caught at the edge of the heavy table by which he stood, as though needing to hold by it. He waited there, unheeded by the three around the hearth.

"Thou art joking, Deb," answered her brother after an astonished pause. "Egad! how could'st thou fare to London?"

"I' faith, how could I fare to London?" she said with spirit, mimicking his tone. "An' are there no maids in London then? An' there be not, my faith, t'were time they saw what one is like! Prithee, I have reason to believe I could pass a marvellous pleasant month there if all I hear be true. What say'th thou, Judith, to coming with me?"

"Why, sweetheart," answered the girl, rising, "for all I have protested, I would not go save my father took me. His word is my will always, know'st thou not so? An' if it be his pleasure that I go not to London—well then, I have no mind to go. That is just my thought of it. But," sighing a little, "thou art wiser than I, for thou can'st read books, an' did'st keep pace with Darby page for page, when he went to Stratford grammar school. Furthermore, thou art given thy own way more than I, and art so different—so vastly different—Deb."

"Truly, yes," Debora answered. Then, flinging out her arms, and tossing her head up with a quick, petulant gesture, "Oh, I wish, I wish ten thousand-fold that I were a man and could be with thee, Darby. 'Tis so tame and tantalizing to be but a maid with this one to say 'Gra'mercy! Thou can'st not go there,' an' that one to add 'Alack! an' alack! however cam'st thou to fancy thou could'st do so? Art void o' wit? Beshrew me but ladies never deport themselves in such unmannerly fashion—no, nor even think on't. There is thy little beaten track all bordered with box—'tis precise, yet pleasant—walk thou in it thankfully. Marry, an' thou must not gaze over the hedges neither!'"

A deep, sweet laugh followed her words as an echo, and a man tall and finely built came striding over from the door where he had been standing in shadow, an amused listener. He put his two hands on the girl's shoulders and looked down into the beautiful, rebellious face.

"Heigho, and heigho!" he said. "Just listen to this mutinous one, good Master Thornbury! Here is a whirlwind in petticoats equal to my pretty shrew who was so well tamed at the last. Marry, an' I could show them such a brilliant bit of acting at the new Globe—such tone! such intensity! 'twould surely inspire the Company and so lighten my work by a hundred-fold. But, alas! while we have but lads to play the parts that maidens should take, acting is oft a very weariness and giveth one an ache o' the heart!"

"Thou would'st not have me upon the stage, father?" said Judith, looking at him.

The man smiled down at her, then his face grew suddenly grave and his hazel eyes narrowed.

"By all the gods—No!—not thee sweetheart. But," his voice changing, "but there are those I would. We must away, neighbour Thornbury. I am due in London shortly, and need the night's rest."

They pressed him to stay longer, but he would not tarry. So Judith tied on her hooded cloak, and many a warm good-bye was spoken.

The innkeeper, with Darby and Debora, stood on the threshold and watched the two take the road to Stratford; and the sky was pranked out with many a golden star, for the storm had blown over, and the night winds were at peace.

After they entered the house a silence settled over the little group. The child Dorian slept on the cushioned settle, for he was sorely spoilt by Debora, who would not have him go above stairs till she carried him up herself. The girl sat down beside him now and watched Darby, who was carving a strange head upon a stout bit of wood cut from the tree before the door.

"What art so busy over, lad?" asked Thornbury. His voice trembled, and there was an unusual pallor on his face.

"'Tis but a bit of home I will take away with me, Dad. In an act of 'Romeo and Juliet,' the new play we are but rehearsing, I carry a little cane. I am a dashing fellow, one Mercutio. I would thou could'st see me. Well-a-day! I have just an odd fancy for this bit o' the old tree."

Debora rose and went over to her father. She laid one hand on his arm and patted it gently.

"I would go to London, Dad," she said coaxingly. "Nay, I must go to London, Dad. I pray thee put no stumbling blocks in the way o' it—but be kind as thou art always. See! an' thou dost let me away I will stay but a month, a short month—but four weeks—it doth seem shorter to say it so—an' then I'll fare home again swiftly an' bide in content. Oh! think of it, Dad! to go to London! It is to go where one can hear the heart of the whole world beat!"

The old man shook his head in feeble remonstrance.

"Thou wilt fare there an' thou hast the mind, Deb, but thou wilt never come back an' bide in peace at One Tree Inn."

The girl suddenly wound her arms about his neck and laid her cool sweet face against his. When she raised it, it glistened with tears.

"I will, Dad! I will, I will," she cried softly, then bent and caught little Dorian up and went swiftly out of the room.

The house in London where Darby Thornbury lodged was on the southern side of the Thames in the neighbourhood of the theatres, a part of the city known as Bankside. The mistress of the house was one Dame Blossom, a wholesome-looking woman who had passed her girlhood at Shottery, and remembered Darby and Debora when they were but babies. It was on this account, probably, that she gave to the young actor an amount of consideration and comfort he could not have found elsewhere in the whole of Southwark. When he returned from his holiday, bringing his sister with him, she welcomed them with a heartiness that lacked no tone of absolute sincerity.

The winter had broken when the two reached London; there was even a hint of Spring in the air, though it was but February, and the whole world seemed to be waking after a sleep. At least that was the way it felt to Debora Thornbury. For then began a life so rich in enjoyment, so varied and full of new delights that she sometimes, when brushing that heavy hair of hers before the little copper mirror in the high room that looked away to the river, paused as in a half dream, vaguely wondering if she were in reality the very maid who had lived so long and quietly at the old Inn away there in the pleasant Warwickshire country.

Her impulsive nature responded eagerly to the rapid flow of life in the city, and she received each fresh impression with vivid interest and pleasure. There was a new sparkle in her changeful blue eyes, and the colour drifted in and out of her face with every passing emotion.

Darby also, it struck the girl, was quite different here in London. There was an undefined something about him, a certain assurance both of himself and the situation that she had never noticed before. Truly they had not seen anything of each other for the past two years, but he appeared unchanged when he came home at Christmas. A trifle more manly looking perchance, and with a somewhat greater elegance of manner and speech, yet in verity the same Darby as of old; here in the city it was not so, there was a dashing way about him now, a foppishness, an elaborate attention to every detail of fashion and custom that he had not burdened himself with at the little half-way house. The hours he kept moreover were very late and uncertain, and this sorely troubled his sister. Still each morning he spoke so freely of the many gentlemen he had been with the evening before—at the Tabard—or the Falcon—or even the Devil's Tavern near Temple Bar—where Debora had gazed open-eyed at the flaunting sign of St. Dunstan tweaking the devil by the nose—indeed, all these places he mentioned so entirely as a matter of course, that she soon ceased to worry over the hour he returned. The names of Marlowe and Richard Burbage, Beaumont, Fletcher, Lodge, Greene and even Dick Tarleton, became very familiar to her, beside those of many a lesser light who was wont to shine upon the boards. It seemed reasonable and fair that Darby should wish to pass as much time with reputable players as possible, and moreover he was often, he said, with Ned Shakespeare—who was playing at Blackfriars—and the girl knew that where he was, the master himself was most likely to be for shorter or longer time, for he ever shadowed his brother's life with loving care.

Through the day, when he was not at the theatre, Darby took his sister abroad to see the sights. The young actor was proud to be seen with her, and though he loved her for her own sweet sake, perhaps there was more than a trifle of vanity mixed with the pleasure he obtained from showing the city to one so easily charmed and entertained.

The whispered words of admiration that caught his ear as Debora stood beside him here and there in the public gardens and places of amusement, were as honey to his taste. And it may be because they were acknowledged to be so strikingly alike that it pleased his fancy to have my lord this—and the French Count of that—the beaus and young bloods of the town who haunted the playhouses and therefore knew the actors well—plead with him, after having seen Debora once, to be allowed to pay her at least some slight attention and courtesy.

But Darby Thornbury knew his time and the men of it, and where his little sister was concerned his actions were cool and calculating to a degree.

He was careful to keep her away from those places where she would chance to meet and become acquainted with any of the players whom she knew so well by name, and this the girl thought passing strange. Further, he would not take her to the theatres, though in truth she pleaded, argued, and finally lost her temper over it.

"Nay, Deb," said her brother loftily, "let me be the best judge of where I take thee and whom thou dost meet. I have not lived in London more than twice twelve months for naught. Thou, sweeting, art as fresh and dew-washed as the lilac bushes under Dad's window—and as green. Therefore, I pray thee allow me to decide these matters. Did I not take thee to Greenwich but yesterday to view the Queen's Plaisance, as the place is rightly named?—Methinks I can smell yet that faint scent of roses that so pervaded the place. Egad! 'tis not every lass hath luck enow to see the very rooms Her Majesty hath graced. Marry no! Such tapestries and draperies laced with Spanish gold-thread! Such ancient portraits and miniatures set on ivory! Such chairs and tables inlaid thick with mother o' pearl and beaten silver! That feast of the eye should last thee awhile and save thy temper from going off at a tangent."

Debora lifted her straight brows by way of answer, and her red curved mouth set itself in a dangerously firm line; but Darby appeared not to notice these warning signals and continued in more masterful tone:—

"Moreover, I took thee to the Paris Gardens on a day when there was a passable show, and one 'twas possible for a maid to view, yet even then much against my will and better judgment. I have taken thee to the notable churches and famous tombs. Thou hast seen the pike ponds and the park and palace of the Lord Bishop of Winchester! And further, thou hast walked with me again and again through Pimlico Garden when the very fashion of the city was abroad. Ah! and Nonsuch House! Hast forgotten Nonsuch House on London Bridge, and how we climbed the gilded stairway and went up into the cupola for a fair outlook at the river? 'Tis a place to be remembered. Why, they brought it over from France piecemeal, so 'tis said, and put it together with great wooden pegs instead of nails. The city was sorely taxed for it all, doubtless." He waited half a moment, apparently for some response, but as none came, went on again:

"As for the shops and streets, thou know'st them by heart, for there has not been a day o' fog since we came to keep us in. Art not satisfied, sweet?"

"Nay then I am not!" she answered, with an impatient gesture. "Thou dost know mightily well 'tis the playhouses, the playhouses I would see!"

"'Fore Heaven now! Did a man ever listen to such childishness!" cried Darby. "And hast not seen them then?"

"Marry, no!" she exclaimed, her lovely face reddening.

"Now, by St. George! Then 'twas for naught I let thee gaze so long on 'The Swan,' and I would thou could'st just have seen thine eyes when they ran up the red flag with the swan broidered upon it. Ay! and also when their trumpeter blew that ear-splitting blast which is their barbarous unmannerly fashion of calling the masses in and announcing the play hath opened."

The girl made no reply, but beat a soft, quick tattoo with her little foot on the sanded floor.

After watching her in amused silence Darby again returned to his tantalising recital.

"And I pointed out, as we passed it, the 'Rose Theatre' where the Lord High Admiral's men have the boards. Fine gentlemen all, and hail-fellow-well-met with the Earl of Pembroke's players, though they care little for our Company. Since we have been giving Will Shakespeare's comedies, the run of luck hath been too much with us to make us vastly popular. Anon, I showed thee 'The Hope,' dost not remember the red-tiled roof of it? 'Tis a private theatre, an' marvellous comfortable, they tell me. An' thou has forgotten all those; thou surely canst bring to mind the morning we were in Shoreditch, how I stopped before 'The Fortune' and 'The Curtain' with thee? 'Tis an antiquated place 'The Curtain,' but the playhouse where Master Shakespeare first appeared, and even now well patronised, for Ben Jonson's new comedy 'Every Man in his Humour' is running there to full houses, an' Dick Burbage himself hath the leading part."

He paused again, a merry light in his eyes and his lips twitching a little.

"Thou didst see 'The Globe' an' my memory fails me not, Deb? 'Tis our summer theatre—where I fain we could play all year round—but that is so far impossible as 'tis open to the sky, and a shower o' cold rain or an impromptu sprinkling of sleet on one, in critical moments of the play, hath disastrous effect. Come, thou surely hast not forgotten 'The Globe,' where we of the Lord High Chamberlain's Company have so oft disported ourselves. Above the entrance there is the huge sign of Atlas carrying his load and beneath, the words in Latin, 'All the world acts a play.'"

Debora tossed her head and caught her breath quickly. "My patience is gone with thee, since thou art minded to take me for a very fool, Darby Thornbury," she said with short cutting inflection. "Hearts mercy! 'Tis not the outside o' the playhouses I desire to see, as thou dost understand—'tis the inside—where Master Shakespeare is and the great Burbage, an' Kemp, an' all o' them. Be not so unkind to thy little sister. I would go in an' see the play—Marry an' amen! I am beside myself to go in with thee, Darby!"

The young actor frowned. "Nay then, Deb," he answered, "those ladies (an' I strain a point to call them so) who enter, are usually masked. I would not have thee of them. The play is but for men, like the bear-baiting and bull-baiting places."

"How can'st thou tell me such things," she cried, "an' so belittle the stage? Listen now! this did I hear thee saying over and over last night. So wonderful it was—and rarely, strangely beautiful—yet fearful—it chilled the blood o' my heart! Still I remembered."

Rising the girl walked to the far end of the room with slow, pretty movement, then lifted her face, so like Darby's own—pausing as though she listened.

Her brother could only gaze at her as she stood thus, her plain grey gown lying in folds about her, the sun burnishing the red-gold of her hair; but when she began to speak he forgot all else and only for the moment heard Juliet—the very Juliet the world's poet must have dreamed of.

On and on she spoke with thrilling intensity. Her voice, in its full sweetness, never once failed or lost the words. It was the long soliloquy of the maid of Capulet in the potion scene. After she finished she stood quite still for a moment, then swayed a little and covered her face with her hands.

"It taketh my very life to speak the words so," she said slowly, "yet the wonder of them doth carry me away from myself. But," going over to Darby, "but, dear heart, how dost come thou art studying such a part? 'Tis just for the love of it surely!"

The player rose and walked to the small window. He stood there quite still and answered nothing.

Debora laid one firm, soft hand upon his and spoke, half coaxingly, half diffidently, altogether as though touching some difficult question.

"Dost take the part o' Juliet, dear heart?"

"Ay!" he answered, with a short, hard laugh. "They have cast me for it, without my consent. At first I was given the lines of Mercutio, then, after all my labour over the character—an' I did not spare myself—was called on to give it up. There has been difficulty in finding a Juliet, for Cecil Davenant, who hath the sweetest voice for a girl's part of any o' us, fell suddenly ill. In an evil moment 'twas decided I might make shift to take the character, for none other in the Company com'th so near it in voice, they say, though Ned Shakespeare hath a pink and white face, comely enow for any girl. Beshrew me, sweetheart—but I loathe the taking of such parts. To succeed doth certainly bespeak some womanish beauty in one—to fail doth mar the play. At best I must be as the Master says, 'too young to be a man, too old to be a boy.' 'Tis but the third time I have essayed such a role, an 't shall be the last, I swear."

"I would I could take the part o' Juliet for thee, Darby," said the girl, softly patting the sleeve of his velvet tabard.

"Thou art a pretty comforter," he answered, pinching her ear lightly and trying to recover himself.

"'Twould suit thee bravely, Deb, yet I'd rather see thee busy over a love affair of thine own at home in Shottery. Ah, well! I'd best whistle 'Begone dull care,' for 'twill be a good week before we give the people the new play, though they clamour for it now. We are but rehearsing as yet, and 'Two Gentlemen of Verona' hath the boards."

"I would I could see the play if but for once," said Debora, clasping her hands about his arm. "Indeed," coaxingly, "thou could'st manage to take me an' thou did'st have the will."

Darby knit his brows and answered nothing, yet the girl fancied he was turning something in his mind. With a fair measure of wisdom for one so eager she forebore questioning him further, but glanced up in his face, which was grave and unreadable.

Perchance when she had given up all hope of any favourable answer, he spoke.

"There is a way—though it pleases me not, Deb—whereby thou might be able to see the rehearsals at least. The Company assembles at eight of the morning, thou dost know; now I could take thee in earlier by an entrance I wot of, at Blackfriars, a little half-hidden doorway but seldom used—thence through my tiring-room—and so—and so—where dost think?"

"Nay! I know not," she exclaimed. "Where then, Darby?"

"To the Royal Box!" he answered. "'Tis fair above the stage, yet a little to the right. The curtains are always drawn closely there to save the tinselled velvet and cloth o' gold hangings with which 't hath lately been fitted. Now I will part these drapings ever so little, yet enough to give thee a full sweeping view o' the stage, an' if thou keep'st well to the back o' the box, Deb, thou wilt be as invisible to us as though Queen Mab had cast her charmed cloak about thee. Egad! there be men amongst the High Chamberlain's Players I would not have discover thee for many reasons, my little sister," he ended, watching her face.

For half a moment the girl's lips quivered, then her eyes gathered two great tears which rolled heavily down and lay glittering on her grey kirtle.

"'Tis ever like this with me!" she exclaimed, dashing her hand across her eyes, "whenever I get what I have longed and longed for. First com'th a ball i' my throat, then a queer trembling, an' I all but cry. 'Tis vastly silly is't not, but 'tis just by reason o' being a girl one doth act so." Then eagerly, "Thou would'st not fool me, Darby, or change thy mind? Thou art in earnest? Swear it! Cross thy heart!"

"Ay! I am in earnest," he replied, smiling; "in very truth thou shalt see thy brother turn love-sick maid and mince giddily about in petticoats. I warrant thou'lt be poppy-red, though thou art hidden behind the gold curtains, just to hear the noble Romeo vow me such desperate lover's vows."

"By St. George, Deb! we have a Romeo who might turn any maid's heart and head. He is a handsome, admirable fellow, Sherwood, and hath a way with him most fascinating. He doth act even at rehearsals as though 'twere all most deadly passionate reality, and this with only me for inspiration. I oft' fancy what 'twould be—his love-making—an' he had a proper Juliet—one such as thou would'st make, for instance."

"I will have eyes only for thee, Darby," answered Debora, softly, "but for thee, an', yes, for Master Will Shakespeare, should he be by."

"He is often about the theatre, sweet, but hath no part in this new play. No sooner hath he one written, than another is under his pen; and I am told that even now he hath been reading lines from a wonderful strange history concerning a Jew of Venice, to a party of his friends—Ben Jonson and Dick Burbage, and more than likely Lord Brooke—who gather nightly at 'The Mermaid,' where, thou dost remember, Master Shakespeare usually stays."

"I forget nothing thou dost tell me of him," said the girl, as she turned to leave the room. "O wilt take me with thee on the morrow, Darby? Wilt really take me?——"

"On the morrow," he answered, watching her away.

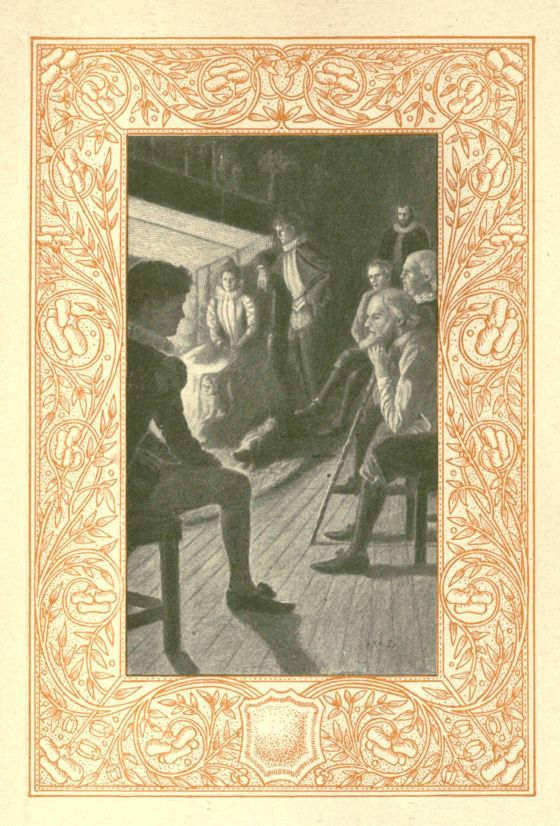

Thus it fell that each morning for one heavenly week Debora Thornbury found herself safely hidden away in what was called by courtesy "The Royal Box." In truth her Majesty had never honoured it, but commanded the players to journey down to Greenwich when it was her whim to see their performances. Now, in 1597, the Queen had grown too world-weary to care much for such pastimes, and rarely had any London entertainment at Court, save a concert by her choir boys from St. Paul's—for these lads with their ofttimes beautiful faces, and their fine voices, she loved and indulged in many ways.

At first Debora felt strangely alone after Darby left her in the little compartment above the stage at Blackfriars. Lingering about it was a passing sweet odour, for the silken cushions were stuffed with fragrant grasses from the West Indies, and the hand-railings and footstools were of carven sandalwood. Mingled with these heavy perfumes was the scent of tobacco, since the young nobles who usually filled the box indulged much in the new weed.

The girl would lean back against the seat in this dim, richly coloured place, and give her mind up to a perfect enjoyment of the moment.

From her tiny aperture in the curtains, skilfully arranged by Darby, she could easily see the stage—all but the east wing—and, furthermore, had a fair view of the two-story circular building.

How gay it must be, she thought, when filled in gallery and pit with a merry company! How bright and glittering when all the great cressets and clusters of candles were alight! How charming to feel free to come and go here as one would, and not have to be conveyed in by private doorways like a bale of smuggled goods!

Then she would dream of olden times, when the sable friars went in and out of the old Dominican friary that stood upon the very place where the theatre was now built.

"'Twas marvellous strange," she thought, "that it should be a playhouse that was erected on this ground that used to be a place of prayer."

So the time would pass till the actors assembled. They were a jovial, swaggering, happy-go-lucky lot, and it took all their Master-player's patience to bring them into straight and steady work. But when the play once began each one followed his part with keen enthusiasm, for there was no half-hearted man amongst the number.

Debora watched each actor, listened for each word and cue the prompter gave them with an absorbed intensity she was scarcely conscious of.

She soon discovered that play-goers were not greatly beguiled through the eye, for the stage-settings changed but little, and the details of a scene were simplified by leaving them to the imagination. Neither did the music furnished by a few sad-looking musicians who appeared to have been entrapped in a small balcony above the stage appeal to her, for it was a thing the least said about the soonest mended.

The actors wore no especial dress or makeup during these rehearsals, save Darby, and he to grow better accustomed to such garments as befitted the maid of Capulet, disported himself throughout in a cumbersome flowing gown of white corduroy that at times clung about him as might a winding sheet, and again dragged behind like a melancholy flag of truce. Yet with the auburn love-locks shading his fair oval face, now clean shaven and tinted like a girl's, and his clear-toned voice, even Debora admitted, he was not so far amiss in the role.

What struck her most from the moment he came upon the stage was his wonderful likeness to herself.

"I' faith," she half whispered, "did I not know that Deb Thornbury were here—an' I have to pinch my arm to make that real—I should have no shadow of a doubt but that Deb Thornbury were there, a player with the rest, though I never could make so sad a tangle of any gown however bad its cut—an' no woman e'er cut that one. Darby doth lose himself in it as if 'twere a maze, and yet withal doth, so far, the part fair justice."

When Don Sherwood came upon the boards the girl's eyes grew brilliant and dark. Darby had but spoken truth regarding this man's fascinating personality. He was a strong, straight-limbed fellow, and his face was such as it pleased the people to watch, though it was not of perfect cast nor strictly beautiful; but he was happy in possessing a certain magnetism which was the one thing needful.

Yet it was not to manner or stage presence that Sherwood owed his success, but rather to his voice, for there was no other could compare to it in the Lord Chamberlain's Company. Truly the gods had been good to this player—for first of all their gifts is such a golden-toned voice as he had brought into this world of sorry discords. Never had Debora listened to anything like it as it thrilled the stillness of the empty house with the passionate words of Romeo.

She followed the tragedy intensely from one scene to another till the ending that stirs all tender hearts to tears.

The lines of the different characters seemed branded upon her brain, and she remembered them without effort and knew them quite by heart. Sometimes Darby, struggling with the distressing complications of his detested dress, would hesitate over some word or break a sentence, thereby marring the perfect beauty of it, and while Sherwood would smile and shrug his shoulders lightly as though as to say, "Have I not enough to put up with, that thou art what thou art, but thou must need'st bungle the words!" Then would Debora clench her hands and tap her little foot against the soft rugs.

"Oh! I would I had but the chance to speak his lines," she said to herself at such times. "Prithee 'twould be in different fashion! 'Tis not his fault, in sooth, for no living man could quite understand or say the words as they should be said, but none the less it doth sorely try my patience."

So the enchanted hours passed and none came to disturb the girl, or discover her till the last morning, which was Saturday. The rehearsal had ended, and Debora was waiting for Darby. The theatre looked gray and deserted. At the back of the stage the great velvet traverses through which the actors made their exits and entrances, hung in dark folds, sombre as the folds of a pall. A chill struck to her heart, for she seemed to be the only living thing in the building, and Darby did not come.

She grew at last undecided whether to wait longer or risk going across the river, and so home alone, when a quick step came echoing along the passage that led to the box. In a moment a man had gathered back the hangings and entered. He started when he saw the slight figure standing in the uncertain light, then took a step towards her.

The girl did not move but looked up into his face with an expression of quick, glad recognition, then she leaned a little towards him and smiled. "Romeo!" she exclaimed softly. "Romeo!" and as though compelled to it by some strange impulse, followed his name with the question that has so much of pathos, "Wherefore," she said, "Wherefore art thou Romeo?"

The man laughed a little as he let the curtains drop behind him.

"Why, an' I be Romeo," he answered in that rare voice of his, full and sweet as a golden bell, "then who art thou? Art not Juliet? Nay, pardon me, mademoiselle," his tone changing, "I know whom thou art beyond question, by thy likeness to Thornbury. 'Fore Heaven! 'tis a very singular likeness, and thou must be, in truth, his sister. I would ask your grace for coming in with such scant announcement. I thought the box empty. The young Duke of Nottingham lost a jewelled pin here yestere'en—or fancied so—and sent word to me to have the place searched. Ah! there it is glittering above you in the tassel to the right."

"I have seen naught but the stage," she said, "and now await my brother. Peradventure he did wrong to bring me here, but I so desired to see the play that I persuaded and teased him withal till he could no longer deny me. 'Twas not over-pleasant being hidden i' the box, but 'twas the only way Darby would hear of. Moreover," with a little proud gesture, "I have the greater interest in this new tragedy that I be well acquainted with Master William Shakespeare himself."

"That is to be fortunate indeed," Sherwood answered, looking into her eyes, "and I fancy thou could'st have but little difficulty in persuading a man to anything. I hold small blame for Thornbury."

Debora laughed merrily. "'Tis a pretty speech," she said, "an' of a fine London flavour." Then uneasily, "I would my brother came; 'tis marvellous unlike him to leave me so."

"I will tell thee somewhat," said Sherwood, after a moment's thought. "A party o' the players went off to 'The Castle Inn'—'tis hard by—an' I believe their intention was to drink success to the play. Possibly they will make short work and drink it in one bumper, but I cannot be sure—they may drink it in more."

"'Tis not like my brother to tarry thus," the girl answered. "I wonder at him greatly."

"Trouble nothing over it," said Sherwood; "indeed, he went against his will; they were an uproarious lot o' roisterers, and carried him off willy-nilly, fairly by main force, now I think on't. Perchance thou would'st rather I left thee alone, mademoiselle?" he ended, as by afterthought.

"'Twould be more seemly," she answered, the colour rising in her face.

"I do protest to that," said the man quickly. "And I found thee out—here alone—why, marry, so might another."

"An' why not another as well?" Debora replied, lifting her brows; "an' why not another full as well as thee, good Sir Romeo? There is no harm in a maid being here. But I would that Darby came," she added.

"We will give him license of five minutes longer," he returned. "Come tell me, what dost think o' the play?"

"'Tis a very wonder," said Debora; "more beautiful each time I see it." Then irrelevantly, "Dost really fancy in me so great a likeness to my brother?"

"Thou art like him truly, and yet no more like him than I am like—well, say the apothecary, though 'tis not a good instance."

"Oh! the poor apothecary!" she cried, laughing. "Prithee, hath he been starved to fit the part? Surely never before saw I one so altogether made of bones."

"Ay!" said Sherwood. "He is a very herring. I wot heaven forecasted we should need such a man, an' made him so."

"Think'st thou that?" she said absently. "O heart o' me! Why doth Darby tarry. Perchance some accident may have happened him or he hath fallen ill! Dost think so?"

The player gave a short laugh, but looked as suddenly grave.

"Do not vex thyself with such imaginings, sweet mistress Thornbury. He hath not come to grief, I give thee my word for it. There is no youth that know'th London better than that same brother o' thine, an' I do not fear that he is ill."

"Why, then, I will not wait here longer," she returned, starting. "I can take care o' myself an' it be London ten times over. 'Tis a simple matter to cross in the ferry to Southwark on the one we so oft have taken; the ferry-man knoweth me already, an' I fear nothing. Moreover, many maids go to and fro alone."

"Thou shalt not," he said. "Wait till I see if the coast be clear. By the Saints! 'twill do Thornbury no harm to find thee gone. He doth need a lesson," ended the man in a lower tone, striding down the narrow passage-way that led to the green-room.

"Come," he said, returning after a few moments, "we have the place to ourselves, and there is not a soul between Blackfriars an' the river house, I believe, save an old stage carpenter, a fellow short o' wit, but so over-fond of the theatre he scarce ever leaves it. Come!"

As the girl stepped eagerly forward to join him, Sherwood entered the box again.

"Nay," on second thought—"wait. Before we go, I pray thee, tell me thy name."

"'Tis Debora," she said softly; "just Debora."

"Ah!" he answered, in a tone she had heard him use in the play—passing tender and passionate. "Well, it suiteth me not; the rest may call thee Debora, an' they will—but I, I have a fancy to think of thee by another title, one sweeter a thousand-fold!" So leaning towards her and looking into her face with compelling eyes that brought hers up to them, "Dost not see, an' my name be Romeo, thine must be——?"

"Nay then," she cried, "I will not hear, I will not hear; let me pass, I pray thee."

"Pardon, mademoiselle," returned the player with grave, quick courtesy, and holding back the curtain, "I would not risk thy displeasure."

They went out together down the little twisted hall into the green-room where the dried rushes that strewed the floor crackled beneath their feet; through the empty tiring rooms, past the old half-mad stage carpenter, who smiled and nodded at them, and so by the hidden door out into the pale early spring sunshine. Then down the steep stairs to Blackfriars Landing where the ferryman took them over the river. They did not say a word to each other, and the girl watched with unfathomable eyes the little curling line of flashing water the boat left behind, though it may be she did not see it. As for Sherwood, he watched only her face with the crisp rings of gold-red hair blown about it from out the border of her fur-edged hood. He had forgotten altogether a promise given to dine with some good fellows at Dick Tarleton's ordinary, and only knew that there was a velvety sea-scented wind blowing up the river wild and free; that the sky was of such a wondrous blue as he had never seen before; that across from him in the old weather-worn ferry was a maid whose face was the one thing worth looking at in all the world.

When the boat bumped against the slippery landing, the player sprang ashore and gave Debora his hand that she might not miss the step. There was a little amused smile in his eyes at her long silence, but he would not help her break it.

Together they went up and through the park where buds on tree and bush were showing creamy white through the brown, and underfoot the grass hinted of coming green. Then along the Southwark common past the theatres. Upon all the road Sherwood was watchful lest they should run across some of his company.

To be seen alone and at mid-day with a new beauty was to court endless questions and much bantering.

For some reason Thornbury had been silent regarding his sister, and the man felt no more willing to publish his chance meeting with Debora.

He glanced often at her as though eager for some word or look, but she gave him neither. Her lips were pressed firmly together, for she was struggling with many feelings, one of which was anger against Darby. So she held her lovely head high and went along with feverish haste.

When they came to the house, which was home now out of all the others in London, she gave a sweeping glance at the high windows lest at one might be discovered the round, good-tempered, yet curious face of Dame Blossom. But the tiny panes winked down quite blankly and her return seemed to be unnoticed.

Running up the steps she lifted her hand to the quaint knocker of the door, turned, and looked down at the man standing on the walk.

"I give thee many thanks, Sir Romeo," said the girl; "thou hast in verity been a most chivalrous knight to a maiden in distress. I give thee thanks, an' if thou art ever minded to travel to Shottery my father will be glad to have thee stop at One Tree Inn." Then she raised the knocker, a rap of which would bring the bustling Dame.

Quickly the man sprang up the steps and laid his hand beneath it, so that, though it fell, there should be no sound.

"Nay, wait," he said, in a low, intense voice. "London is wide and the times are busy; therefore I have no will to leave it to chance when I shall see thee again. Fate has been marvellous kind to-day, but 'tis not always so with fate, as peradventure thou hast some time discovered."

"Ay!" she answered, gently, "Ay! Sir Romeo. Thou art right, fate is not always kind. Yet 'tis best to leave most things to its disposal—at least so it doth seem to me."

"Egad!" said Sherwood, with a short laugh, "'tis a way that may serve well enow for maids but not for men. Tell me, when may I see thee? To-night?"

"A thousand times no!" Debora cried, quickly. "To-night," with a little nod of her head, "to-night I have somewhat to settle with Darby."

"He hath my sympathy," said Sherwood. "Then on the morrow?——"

"Nay, nay, I know not. That is the Sabbath; players be but for week-days."

"Then Monday? I beseech thee, make it no later than Monday, and thou dost wish to keep me in fairly reasonable mind."

"Well, Monday, an' it please the fate thou has maligned," she answered, smiling. Noticing that the firm, brown hand was withdrawn a few inches from the place it had held on the panelling of the door, the girl gave a mischievous little smile and let the knocker fall. It made a loud echoing through the empty hall, and the player raised his laced black-velvet cap, gave Debora so low a bow that the silver-gray plume in it swept the ground, and, before the heavy-footed Mistress Blossom made her appearance, was on his way swiftly towards London Bridge.

Debora went up the narrow stairs with eyes ashine, and a smile curving her lips. For the moment Darby was forgotten. When she closed the chamber door she remembered.

It was past high noon, and Dame Blossom had been waiting in impatience since eleven to serve dinner. Yet the girl would not now dine alone, but stood by the gabled window which looked down on the road, watching, watching, and thinking, till it almost seemed that another morning had passed.

Along Southwark thoroughfare through the day went people from all classes, groups of richly-dressed gentlemen, beruffled and befeathered; their laces and their hair perfuming the wind. Officers of the Queen booted and spurred; sober Puritans, long-jowled and over-sallow, living protests against frivolity and light-heartedness. Portly aldermen, jealous of their dignity. Swarthy foreigners with silver rings swinging in their ears. Sun-browned sailors. Tankard-bearers carrying along with their supply of fresh drinking water the cream of the hour's gossip. Keepers of the watch with lanterns trimmed for the night's burning adangle from oaken poles braced across their shoulders. Little maidens whose long gowns cut after the fashion of their mothers, fretted their dancing feet. Ruddy-hued little lads, turning Catherine wheels for the very joy of being alive, and because the winter time was over and the wine of spring had gone to the young heads.

Debora stood and watched the passing of the people till she wearied of them, and her ears ached with sounds of the street.

Something had gone away from the girl, some carelessness, some content of the heart, and in its place had come a restlessness, as deep, as impossible to quiet, as the restlessness of the sea.

After a time Mistress Blossom knocked at the door, and coaxed her to go below.

"There is no sight o' the young Master, Mistress Debora. Marry, but he be over late, an' the jugged hare I made ready for his pleasuring is fair wasted. Dost think he'll return here to dine or hast gone to the Tabard?"

"I know not," answered Debora, shortly, following the woman down stairs. "He gave me no hint of his intentions, good Mistress Blossom."

"Ods fish!" returned the other, "but that be not mannerly. Still thou need'st not spoil a sweet appetite by tarrying for him. Take thee a taste o' the cowslip cordial, an' a bit o' devilled ham. 'Tis a toothsome dish, an' piping hot."

"I give thee thanks," said Debora, absently. Some question turned itself over in her mind and gave her no peace. Looking up at the busy Dame she spoke in a sudden impulsive fashion.

"Hath my brother—hath my brother been oft so late? Hath he always kept such uncertain hours by night—and day also—I mean?" she ended falteringly.

"Why, sometimes. Now and again as 'twere—but not often. There be gay young gentlemen about London-town, and Master Darby hath with him a ready wit an' a charm o' manner that maketh him rare good company. I doubt his friends be not overwilling to let him away home early," said the woman in troubled tones.

"Hath——he ever come in not—not—quite himself, Mistress Blossom? 'Tis but a passing fancy an' I hate to question thee, yet I must know," said the girl, her face whitening.

"Why then, nothing to speak of," Mistress Blossom replied, bustling about the table, with eyes averted. "See then, Miss Debora, take some o' the Devonshire cream an' one o' the little Banbury cakes with it—there be caraways through them. No? Marry, where be thy appetite? Thou hast no fancy for aught. Try a taste of the conserved cherries, they be white hearts from a Shottery orchard. Trouble not thy pretty self. Men be all alike, sweet, an' not worth a salt tear. Even Blossom cometh home now an' again in a manner not to be spoken of! Ods pitikins! I be thankful to have him make the house in any form, an' not fall i' the clutch o' the watch! They be right glad of the chance to clap a man i' the stocks where he can make a finish o' the day as a target for all the stale jests an' unsavoury missiles of every scurvy rascal o' the streets. But, Heaven be praised!—'tis not often Blossom breaks out—just once in a blue moon—after a bit of rare good or bad luck."

Debora took no heed but stared ahead with wide, unhappy eyes. The old blue plates on the table, the pewter jugs and platters grew strangely indistinct. Then 'twas true! So had she fancied it might be. He had been drinking—drinking. Carousing with the fast, unmannerly youths who haunted the club-houses and inns. Dicing, without doubt, and gambling at cards also peradventure, when she thought he was passing the time in good fellowship with the worthy players from the Lord Chamberlain's Company.

"He hath never come home so by day, surely, good Mistress Blossom? Not by day?" she asked desperately.

"Well—truly—not many times, dearie. But hark'e. Master Darby is one who cannot touch a glass o' any liquor but it flies straightway to his brains; oft hath he told me so, ay! often and over often; 'I am not to blame for this, Blossom,' hath he said to my goodman when he worked over him—cold water and rubbing, Mistress Debora—no more, no less. 'Nay, verily—'tis just my luck, one draught an' I be under the table, leaving the other men bolt upright till they've swallowed full three bottles apiece!"

Debora dropped her face in her hands and rocked a little back an' forth. "'Tis worse than I thought!" she cried, looking up drawn and white. "Oh! I have a fear that 'tis worse—far, far worse. I have little doubt half his money comes from play an' betting, ay! an' at stakes on the bear-baiting, an'—an'—anything else o' wickedness there be left in London—while we at home have thought 'twas earned honestly." As she spoke a heavy rapping sounded down the hall, loud, uneven, yet prolonged.

Mistress Blossom went to answer it quickly, and Debora followed, her limbs trembling and all strength seeming to slip away from her. Lifting the latch the woman flung the outer door open and Darby Thornbury lurched in, falling clumsily against his sister, who straightened her slight figure and hardly wavered with the shock, for her strength had come swiftly back with the sight of him.

The man who lay in the hall in such a miserable heap, had scarce any reminder in him of Darby Thornbury, the dainty young gallant whose laces were always the freshest, and whose ruffs and doublets never bore a mark of wear. Now his long cordovan boots were mud-stained and crumpled about the ankles. His broidered cuffs and collar were wrenched out of all shape. But worse and far more terrible was his face, for its beauty was gone as though a blight had passed across it. He was flushed a purplish red, and his eyes were bloodshot, while above one was a bruised swelling that fairly closed the lid. He tried to get on his feet, and in a manner succeeded.

"By St. George, Deb!" he exclaimed in wrath, "I swear thou 'r a fine sister to take f' outing. I was a double-dyed fool e'er to bring thee t' London. Why couldn't y' wait f' fellow? When I go f' y'—y' not there."

Then he smiled in maudlin fashion and altered his tone. "Egad! I'm proud o' thee, Deb, thou art a very beauty. All the bloods i' town ar' mad to meet thee—th' give me no peace."

"Oh! Mistress Blossom," cried Debora, clasping her hands, "can we not take him above stairs and so to bed? Dear, dear Mistress Blossom, silence him, I pray thee, or my heart will break."

"Be thee quiet, Master Darby, lad," said the woman, persuasively. "Wait, then, an' talk no more. I'll fetch Blossom; he'll fix thee into proper shape, I warrant. 'Tis more thy misfortune than thy fault. Yes, yes, I know thou be sore upset—but why did'st not steer clear o' temptation?"

"Temp-ation, Odso! 'tis a marvellous good word," put in Thornbury. "Any man'd walk a chalk—line—if he could steer clear o' temptation." So, in a state of verbose contrition, was he borne away to his chamber by the sympathetic Blossom, who had a fellow-feeling for the lad that made him wondrous kind.

All Saturday night Debora waited by her window—the one that looked across the commonland to the Thames. The girl could not face what might be ahead. Darby—her Darby—her father's delight. Their handsome boy come to such a pass. "'Twas nothing more than being a common drunkard. One whom the watch might have arrested in the Queen's name for breaking the peace," she said to herself. "Oh! the horror of it, the shame!" In the dark of her room her face burned.

Never had such a fear come to her for Darby till to-day. When was it? Who raised the doubt of him in her mind? Yes, she remembered; 'twas a look—a strange look—a half smile, satirical, pitying, that passed over the player Sherwood's face when he spoke of Darby's being persuaded to drink with the others. In a flash at that moment the fear had come, though she would not give it room then. It was a dangerous life, this life in the city, and she knew now what that expression in the actor's eyes had meant; realised now the full import of it. So. It was all summed up in what she had witnessed to-day. But if they knew—if Master Shakespeare and James Burbage knew—these responsible men of the Company—how did they come to trust Darby with such parts as he had long played. What reliance could be placed upon him?