THE POSTMASTER

"So you're through with the sea for good, are you, Cap'n Zeb," says Mr. Pike.

"You bet!" says I. "Through for good is just what I am."

"Well, I'm sorry, for the firm's sake," he says. "It won't seem natural for the Fair Breeze to make port without you in command. Cap'n, you're goin' to miss the old schooner."

"Cal'late I shall—some—along at fust," I told him. "But I'll get over it, same as the cat got over missin' the canary bird's singin'; and I'll have the cat's consolation—that I done what seemed best for me."

He laughed. He and I were good friends, even though he was ship-owner and I was only skipper, just retired.

"So you're goin' back to Ostable?" he says. "What are you goin' to do after you get there?"

"Nothin'; thank you very much," says I, prompt.

"No work at all?" he says, surprised. "Not a hand's turn? Goin' to be a gentleman of leisure, hey?"

"Nigh as I can, with my trainin'. The 'leisure' part'll be all right, anyway."

He shook his head and laughed again.

"I think I see you," says he. "Cap'n, you've been too busy all your life even to get married, and—"

"Humph!" I cut in. "Most married men I've met have been a good deal busier than ever I was. And a good deal more worried when business was dull. No, sir-ee! 'twa'n't that that kept me from gettin' married. I've been figgerin' on the day when I could go home and settle down. If I'd had a wife all these years I'd have been figgerin' on bein' able to settle up. I ain't goin' to Ostable to get married."

"I'll bet you do, just the same," says he. "And I'll bet you somethin' else: I'll bet a new hat, the best one I can buy, that inside of a year you'll be head over heels in some sort of hard work. It may not be seafarin', but it'll be somethin' to keep you busy. You're too good a man to rust in the scrap heap. Come! I'll bet the hat. What do you say?"

"Take you," says I, quick. "And if you want to risk another on my marryin', I'll take that, too."

"Go you," says he. "You'll be married inside of three years—or five, anyway."

"One year that I'll be at work—steady work—and five that I'm married. You're shipped, both ways. And I wear a seven and a quarter, soft hat, black preferred."

"If I don't win the first bet I will the second, sure," he says, confident. "'Satan finds some mischief still for idle hands,' you know. Well, good-by, and good luck. Come in and see us whenever you get to New York."

We shook hands, and I walked out of that office, the office that had been my home port ever since I graduated from fust mate to skipper. And on the way to the Fall River boat I vowed my vow over and over again.

"Zebulon Snow," I says to myself—not out loud, you understand; for, accordin' to Scriptur' or the Old Farmers' Almanac or somethin', a feller who talks to himself is either rich or crazy and, though I was well enough fixed to keep the wolf from the door, I wa'n't by no means so crazy as to leave the door open and take chances—"Zebulon Snow," says I, "you're forty-eight year old and blessedly single. All your life you've been haulin' ropes, or bossin' fo'mast hands, or tryin' to make harbor in a fog. Now that you've got an anchor to wind'ard—now that the one talent you put under the stock exchange napkin has spread out so that you have to have a tablecloth to tote it home in, don't you be a fool. Don't plant it again, cal'latin' to fill a mains'l next time, 'cause you won't do it. Take what you've got and be thankful—and careful. You go ashore at Ostable, where you was born, and settle down and be somebody."

That's about what I said to myself, and that's what I started to do. I made Ostable on the next mornin's train. The town had changed a whole lot since I left it, mainly on account of so many summer folks buyin' and buildin' everywhere, especially along the water front. The few reg'lar inhabitants that I knew seemed to be glad to see me, which I took as a sort of compliment, for it don't always foller by a consider'ble sight. I got into the depot wagon—the same horse was drawin' it, I judged, that Eben Hendricks had bought when I was a boy—and asked to be carted to the Travelers' Inn. It appeared that there wa'n't any Travelers' Inn now, that is to say, the name of it had been changed to the Poquit House; "Poquit" bein' Injun or Portygee or somethin' foreign.

But the name was the only thing about that hotel that was changed. The grub was the same and the wallpaper on the rooms they showed to me looked about the same age as I was, and wa'n't enough handsomer to count, either. I hired a couple of them rooms, one to sleep in and smoke in, and t'other to entertain the parson in, if he should call, which—unless the profession had changed, too—I judged he would do pretty quick. I had the rooms cleaned and papered, bought some dyspepsy medicine to offset the meals I was likely to have, and settled down to be what Mr. Pike had called a "gentleman of leisure."

Fust three months 'twas fine. At the end of the second three it commenced to get a little mite dull. In about two more I found my mind was shrinkin' so that the little mean cat-talks at the breakfast table was beginnin' to seem interestin' and important. Then I knew 'twas time to doctor up with somethin' besides dyspepsy pills. Ossification was settin' in and I'd got to do somethin' to keep me interested, even if I paid for Pike's hats for the next generation.

You see, there was such a sameness to the programme. Turn out in the mornin', eat and listen to gossip, go out and take a walk, smoke, talk with folks I met—more gossip—come back and eat again, go over and watch the carpenters on the latest summer cottage, smoke some more, eat some more, and then go down to the Ostable Grocery, Dry Goods, Boots and Shoes and Fancy Goods Store, or to the post-office, and set around with the gang till bedtime. That may be an excitin' life for a jellyfish, or a reg'lar Ostable loafer—but it didn't suit me.

I was feelin' that way, and pretty desperate, the night when Winthrop Adams Beanblossom—which wa'n't the critter's name but is nigh enough to the real one for him to cruise under in this yarn—told me the story of his life and started me on the v'yage that come to mean so much to me. I didn't know 'twas goin' to mean much of anything when I started in. But that night Winthrop got me to paddlin', so's to speak, and, later on, come Jim Henry Jacobs to coax me into deeper water; and, after that, the combination of them two and Miss Letitia Lee Pendlebury shoved me in all under, so 'twas a case of stickin' to it or swimmin' or drownin'.

I was in the Ostable Store that evenin', as usual. 'Twas almost nine o'clock and the rest of the bunch around the stove had gone home. I was fillin' my pipe and cal'latin' to go, too—if you can call a tavern like the Poquit House a home. Beanblossom was in behind the desk, his funny little grizzly-gray head down over a pile of account books and papers, his specs roostin' on the end of his thin nose, and his pen scratchin' away like a stray hen in a flower bed.

"Well, Beanblossom," says I, gettin' up and stretchin', "I cal'late it's time to shed the partin' tear. I'll leave you to figger out whether to spend this week's profits in government bonds or trips to Europe and go and lay my weary bones in the tomb, meanin' my private vault on the second floor of the Poquit. Adieu, Beanblossom," I says; "remember me at my best, won't you?"

He didn't seem to sense what I was drivin' at. He lifted his head out of the books and papers, heaved a sigh that must have started somewheres down along his keelson, and says, sorrowful but polite—he was always polite—"Er—yes? You were addressin' me, Cap'n Snow?"

"Nothin' in particular," I says. "I was just askin' if you intended spendin' your profits on a trip to Europe this summer."

Would you believe it, that little storekeepin' man looked at me through his specs, his pale face twitchin' and workin' like a youngster's when he's tryin' not to cry, and then, all to once, he broke right down, leaned his head on his hands and sobbed out loud.

I looked at him. "For the dear land sakes," I sung out, soon's I could collect sense enough to say anything, "what is the matter? Is anybody dead or—"

He groaned. "Dead?" he interrupted. "I wish to heaven, I was dead."

"Well!" I gasps. "Well!"

"Oh, why," says he, "was I ever born?"

That bein' a question that I didn't feel competent to answer, I didn't try. My remark about goin' to Europe was intended for a joke, but if my jokes made grown-up folks cry I cal'lated 'twas time I turned serious.

"What is the matter, Beanblossom?" I says. "Are you in trouble?"

For a spell he wouldn't answer, just kept on sobbin' and wringin' his thin hands, but, after consider'ble of such, and a good many unsatisfyin' remarks, he give in and told me the whole yarn, told me all his troubles. They were complicated and various.

Picked over and b'iled down they amounted to this: He used to have an income and he lived on it—in bachelor quarters up to Boston. Nigh as I could gather he never did any real work except to putter in libraries and collect books and such. Then, somehow or other, the bank the heft of his money was in broke up and his health broke down. The doctors said he must go away into the country. He couldn't afford to go and do nothin', so he has a wonderful inspiration—he'll buy a little store in what he called a "rural community" and go into business. He advertises, "Country Store Wanted Cheap," or words to that effect. Abial Beasley's widow had the "Ostable Grocery, Dry Goods, Boots and Shoes and Fancy Goods Store" on her hands. She answers the ad and they make a dicker. Said dicker took about all the cash Beanblossom had left. For a year he had been fightin' along tryin' to make both ends meet, but now they was so fur apart they was likely to meet on the back stretch. He owed 'most a thousand dollars, his trade was fallin' off, he hadn't a cent and nobody to turn to. What should he do? What should he do?

That was another question I couldn't answer off hand. It was plain enough why he was in the hole he was, but how to get him out was different. I set down on the edge of the counter, swung my legs and tried to think.

"Hum," says I, "you don't know much about keepin' store, do you, Beanblossom? Didn't know nothin' about it when you started in?"

He shook his head. "I'm afraid not, Cap'n Snow," he says. "Why should I? I never was obliged to labor. I was not interested in trade. I never supposed I should be brought to this. I am a man of family, Cap'n Snow."

"Yes," I says, "so'm I. Number eight in a family of thirteen. But that never helped me none. My experience is that you can't count much on your relations."

Would I pardon him, but that was not the sense in which he had used the word "family." He meant that he came of the best blood in New England. His ancestors had made their marks and—

"Made their marks!" I put in. "Why? Couldn't they write their names?"

He was dreadful shocked, but he explained. The Beanblossoms and their gang were big-bugs, fine folks. He was terrible proud of his family. During the latter part of his life in Boston he had become interested in genealogy. He had begun a "family tree"—whatever that was—but he never finished it. The smash came and shook him out of the branches; that wa'n't what he said, but 'twas the way I sensed it. And now he had come to this. His money was gone; he couldn't pay his debts; he couldn't have any more credit. He must fail; he was bankrupt. Oh, the disgrace! and likewise oh, the poorhouse!

"But," says I, considerin', "it can't be so turrible bad. You don't owe but a thousand dollars, this store's the only one in town and Abial used to do pretty well with it. If your debts was paid, and you had a little cash to stock up with, seems to me you might make a decent v'yage yet. Couldn't you?"

He didn't know. Perhaps he could. But what was the use of talkin' that way? For him to pick up a thousand would be about as easy as for a paralyzed man with boxin' gloves on to pick up a flea, or words to that effect. No, no, 'twas no use! he must go to the poorhouse! and so forth and so on.

"You hold on," I says. "Don't you engage your poorhouse berth yet. You keep mum and say nothin' to nobody and let me think this over a spell. I need somethin' to keep me interested and ... I'll see you to-morrow sometime. Good night."

I went home thinkin' and I thought till pretty nigh one o'clock. Then I decided I was a fool even to think for five minutes. Hadn't I sworn to be careful and never take another risk? I was sorry for poor old Winthrop, but I couldn't afford to mix pity and good legal tender; that was the sort of blue and yeller drink that filled the poor-debtors' courts. And, besides, wasn't I pridin' myself on bein' a gentleman of leisure. If I got mixed up in this, no tellin' what I might be led into. Hadn't I bragged to Pike about—Oh, I was a fool!

Which was all right, only, after listenin' to the breakfast conversation at the Poquit House, down I goes to the store and afore the forenoon was over I was Winthrop Adams Beanblossom's silent partner to the extent of twenty-five hundred dollars. I was busy once more and glad of it, even though Pike was goin' to get a hat free.

This was in January. By early March I was twice as busy and not half as glad. You see I'd cal'lated that the store was all right, all it needed was financin'. Trade was just asleep, taking a nap, and I could wake it up. I was wrong. Trade was dead, and, barrin' the comin' of a prophet or some miracle worker to fetch it to life, what that shop was really sufferin' for was an undertaker. My twenty-five hundred was funeral expenses, that's all.

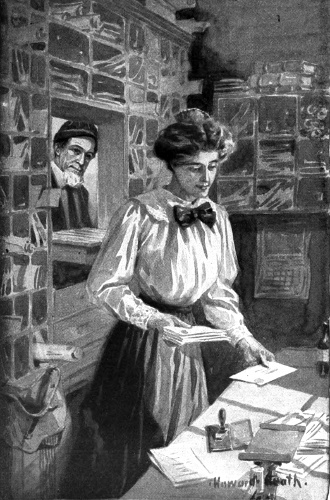

But the prophet came. Yes, sir, he came and fetched his miracle with him. One evenin', after all the reg'lar customers, who set around in chairs borrowin' our genuine tobacco and payin' for it with counterfeit funny stories, had gone—after everybody, as we cal'lated, had cleared out—Beanblossom and I set down to hold our usual autopsy over the remains of the fortni't's trade. 'Twas a small corpse and didn't take long to dissect. We'd lost twenty-one dollars and sixty-eight cents, and the only comfort in that was that 'twas seventy-six cents less than the two weeks previous. The weather had been some cooler and less stuff had sp'iled on our hands; that accounted for the savin'.

Beanblossom—I'd got into the habit of callin' him "Pullet" 'cause his general build was so similar to a moultin' chicken—he vowed he couldn't understand it.

"I think I shall give up buyin' so liberally, Cap'n Snow," says he. "If we didn't keep on buyin' we shouldn't lose half so much," he says.

"Yes," says I, "that's logic. And if we give up sellin' we shouldn't lose the other half. You and me are all right as fur as we go, Pullet, and I guess we've gone about as fur as we can."

"Please don't call me 'Pullet,'" he says, dignified. "When I think of what I once was, it—"

"S-sh-h!" I broke in. "It's what I am that troubles me. I don't dare think of that when the minister's around—he might be a mind-reader. No, Pul—Beanblossom, I mean—it's no use. I imagined because I could run a three-masted schooner I could navigate this craft. I can't. I know twice as much as you do about keepin' store, but the trouble with that example is the answer, which is that you don't know nothin'. We might just exactly as well shut up shop now, while there's enough left to square the outstandin' debts."

He turned white and began the hand-wringin' exercise.

"Think of the disgrace!" he says.

"Think of my twenty-five hundred," says I.

"Excuse me, gentlemen," says a voice astern of us; "excuse me for buttin' in; but I judge that what you need is a butter."

Pullet and I jumped and turned round. We'd supposed we was alone and to say we was surprised is puttin' it mild. For a second I couldn't make out what had happened, or where the voice came from, or who 'twas that had spoke—then, as he come across into the lamplight I recognized him. 'Twas Jim Henry Jacobs, the livin' mystery.

Jim Henry was middlin'-sized, sharp-faced, dressed like a ready-tailored advertisement, and as smooth and slick as an eel in a barrel of sweet ile. Accordin' to his entry on the books of the Poquit House he hailed from Chicago. He'd been in Ostable for pretty nigh a month and nobody had been able to find out any more about him than just that, which is a some miracle of itself—if you know Ostable. He was always ready to talk—talkin' was one of his main holts—but when you got through talkin' with him all you had to remember was a smile and a flow of words. He was at the seashore for his health, that he always give you to understand. You could believe it if you wanted to.

He'd got into the habit of spendin' his evenin's at Pullet's store, settin' around listenin' and smilin' and agreein' with folks. He was the only feller I ever met who could say no and agree with you at the same time. Solon Saunders tried to borrow fifty cents of him once and when the pair of 'em parted, Saunders was scratchin' his head and lookin' puzzled. "I can't understand it," says Solon. "I would have swore he'd lent it to me. 'Twas just as if I had the fifty in my hand. I—I thanked him for it and all that, but—but now he's gone I don't seem to be no richer than when I started. I can't understand it."

Pullet and I had seen him settin' abaft the stove early in the evenin', but, somehow or other, we got the notion that he'd cleared out with the other loafers. However, he hadn't, and he'd heard all we'd been sayin'.

He walked across to where we was, pulled a shoe box from under the counter, come to anchor on it and crossed his legs.

"Gentlemen," he says again, "you need a butter."

Poor old Pullet was so set back his brains was sort of scrambled, like a pan of eggs.

"Er-er, Mr. Jacobs," he says, "I am very sorry, extremely sorry, but we are all out just at this minute. I fully intended to order some to-day, but I—I guess I must have forgotten it."

Jacobs couldn't seem to make any more out of this than I did.

"Out?" he says, wonderin'. "Out? Who's out? What's out? I guess I've dropped the key or lost the combination. What's the answer?"

"Why, butter," says Pullet, apologizin'. "You asked for butter, didn't you? As I was sayin', I should have ordered some to-day, but—"

Jim Henry waved his hands. "Sh-h," he says, "don't mention it. Forget it. If I'd wanted butter in this emporium I should have asked for somethin' else. I've been givin' this mart of trade some attention for the past three weeks and I judge that its specialty is bein' able to supply what ain't wanted. I hinted that you two needed a butter-in. All right. I'm the goat. Now if you'll kindly give me your attention, I'll elucidate."

We give the attention. After he'd "elucidated" for five minutes we'd have given him our clothes. You never heard such a mess of language as that Chicago man turned loose. He talked and talked and talked. He knew all about the store and the business, and what he didn't know he guessed and guessed right. He knew about Pullet and his buyin' the place, about my goin' in as silent partner—though that nobody was supposed to know. He knew the shebang wa'n't payin' and, also and moreover, he knew why. And he had the remedy buttoned up in his jacket—the name of it was James Henry Jacobs.

"Gentlemen," he says, "I'm a specialist. I'm a doctor of sick business. Ever since my medicine man ordered me to quit the giddy metropolis and the Grand Central Department Store, where I was third assistant manager, I've been driftin' about seekin' a nice, quiet hamlet and an opportunity. Here's the ham and, if you say the word, here's the opportunity. This shop is in a decline; it's got creepin' paralysis and locomotive hang-back-tia. There's only one thing that can change the funeral to a silver weddin'—that's to call in Old Doctor Jacobs. Here he is, with his pocket full of testimonials. Now you listen."

We'd been listenin'—'twas by long odds the easiest thing to do—and we kept right on. He had testimonials—he showed 'em to us—and they took oath to his bein' honest and the eighth business wonder of the world. He went on to elaborate. He had a thousand to invest and he'd invest it provided we'd take him in as manager and give him full swing. He'd guarantee—etcetery and so on, unlimited and eternal.

"But," says I, when he stopped to eat a throat lozenge, "sellin' goods is one thing; gettin' the right goods to sell is another. Me and Pullet—Mr. Beanblossom here—have tried to keep a pretty fair-sized stock, but it's the kind of stock that keeps better'n it sells."

"Sell!" he puts in. "You can sell anything, if you know how. See here, let me prove it to you. You think this over to-night and to-morrow forenoon I'll be on hand and demonstrate. Just put on your smoked glasses and watch me. I'll show you."

He did. Next mornin' old Aunt Sarah Oliver came in to buy a hank of black yarn to darn stockin's with. With diplomacy and patience the average feller could conclude that dicker in an hour and a quarter—if he had the yarn. Pullet was just out of black, of course, but that Jim Henry Jacobs stepped alongside and within twenty minutes he sold Aunt Sarah two packages of needles, a brass thimble and a half dozen pair of blue and yellow striped stockin's that had been on the shelves since Abial Beasley's time, and was so loud that a sane person wouldn't dare wear 'em except when it thundered. She went out of the store with her bundles in one hand and holdin' her head with the other. Then that Jim Henry man turned to Pullet and me.

"Well?" he says, serene and smilin'.

It was well, all right. At just quarter to twelve that night the arrangements was made. Jacobs was partner in and manager of the "Ostable Grocery, Dry Goods, Boots and Shoes and Fancy Goods Store."

In less than two months that store of ours was a payin' proposition. Jim Henry Jacobs was responsible, that is all I can tell you. Don't ask me how he did it. 'Twas advertisin', mainly. Advertisin' in the papers, advertisin' on the fences, things set out in the windows, a new gaudy delivery cart, special bargain days for special stuff—they all helped. Of course if we'd limited ourselves to Ostable the cargo wouldn't have been so heavy that we'd get stoop-shouldered, but that Jim Henry was unlimited. He advertised in the county weekly and sent a special cart to take orders for twenty mile around. The early summer cottages was beginnin' to open and 'twas summer trade, rich city folks' trade, that the Jacobs man said we must have. And we got it, one way or another we got it all. Most of the swell big-bugs had been in the habit of orderin' wholesale from Boston, but he soon stopped that. One after another Jim Henry landed 'em. When I asked him how, he just winked.

"Skipper," says he—he most generally called me "Skipper" same as I called Beanblossom "Pullet"—"Skipper," he says, "you can always hook a cod if there's any around and you keepin' changin' bait; ain't that so? Um-hm; well, I change bait, that's all. Every man, woman and suffragette has got a weak p'int somewheres. I just cast around till I find that particular weak p'int; then they swaller hook, line and sinker."

"Humph!" I says, "Miss Letitia ain't swallowed nothin' yet, that I've noticed. Her weak p'ints all strong ones? or what is the matter?"

He made a face. "Sister Pendlebury," says he, "is the frostiest proposition I ever tackled outside of an ice chest. But I'll get her yet. You wait and see. Why, man, we've got to get her."

Well, I could find more truth in them statements than I could satisfaction. We'd got to get her—yes. But she wouldn't be got. She was the richest old maid on the North Shore; lived in a stone and plaster house bigger'n the Ostable County jail, which she'd labeled "Pendlebury Villa"; had six servants, three cats and a poll parrot; and was so tipped back with dignity and importance that a plumb-line dropped from her after-hair comb would have missed her heels by three inches. Her winter port was Brookline; summers she condescended to shed glory over Ostable.

To get the trade of Pendlebury Villa had been Jim Henry's dream from the start. And up to date he was still dreamin'. The other big-bugs he had caged, but Letitia was still flyin' free and importin' her honey from Boston, so to speak. Jacobs had tried everything he could think of, bribin' the servants, sendin' samples of fancy breakfast food and pickles free gratis, writin' letters, callin' with his Sunday clothes on, everything—but 'twas "Keep Off the Grass" at Pendlebury Villa so far as we was concerned. 'Twas the biggest chunk of trade under one head on the Cape and it hurt Jim Henry's pride not to get it. However, he kept on tryin'.

One mornin' he comes back to the store after a cruise to the Villa and it seemed to me that he looked happier than was usual after one of these trips.

"Skipper," says he, "I think—I wouldn't bet any more'n my small change, but I think I've laid a corner stone."

"With Miss Pendlebury?" says I, excited.

"With Letitia," he says, noddin'. "I haven't got an order, but I have got a promise. She's agreed to drop in one of these days and look us over."

"Well!" says I, "I should say that was a corner stone."

"We'll hope 'tis," he says. "Ho, ho! Skipper, I wish you might have been present at the exercises. They were funny."

Seems he'd managed—bribery and corruption of the hired help again—to see Letitia alone in what she called her "mornin' room." He said that, if he'd paid any attention to the temperature of that room when he and she first met in it, he'd have figgered he'd struck the morgue; but he warmed it up a little afore he left. Miss Pendlebury just set and glared frosty while he talked and talked and talked. She said about three words to his two hundred thousand, but every one of hers was a "no." She didn't care to patronize the local merchants. The city ones were bad enough—she had all the trouble she wanted with them. She was not interested; and would he please be careful when he went out and not step on the flower beds.

He was about ready to give it up when he happened to notice an ile portrait in a gorgeous gold frame hangin' on the wall. 'Twas the picture of a man, and Jim Henry said there was a kind of great-I-am look to it, a combination of fatness and importance and wisdom, same as you see in a stuffed owl, that give him an idea. He started to go, stopped in front of the picture and began to look it over, admirin' but reverent, same as a garter snake might look at a boa-constrictor, as proof of what the race was capable of.

"Excuse me, Miss Pendlebury," he says, "but that is a wonderful portrait. I have had some experience in judgin' paintin's—" he was clerk in the Grand Central Store framed picture department once—"and I think I know what I'm talkin' about."

Would you believe it, she commenced to unbend right off.

"It is a Sargent," says she.

Now I should have asked: "Sergeant of militia, or what?" and upset the whole calabash; but Jim Henry knew better. He bows, solemn and wise, and says he'd been sure of it right along.

"But any painter," he says, "would have made a success with a subject like that gentleman before him. There is somethin' about him, the height of his brow, and his wonderful eyes, etcetery, which reminds me—You'll excuse me, Miss Pendlebury, but isn't that a portrait of one of your near relatives?"

She unbent some more and almost smiled. The painted critter was her pa and he was considered a wonderful likeness.

Well, that was enough for your uncle Jim Henry. He settled down to his job then and the way he poured gush over that painted Pendlebury man was close to sacreligion. But Letitia never pumped up a blush; worship was what she expected for her and her pa. He'd been a member of the Governor's staff and a bank president and a church warden and an alderman and land knows what. His daughter and Jacobs had a real sociable interview and it ended by her promisin' to drop in at the store and look our stock over. 'Course 'twa'n't likely 'twould suit her—she was very exacting, she said—but she'd look it over.

We looked it over fust. We put in the rest of that day changin' everything around on the counters and shelves, puttin' the canned stuff in piles where they'd do the most good, and settin' advertisin' signs and such in front of the empty places where they'd been afore. Even Pullet worked, though he couldn't understand it, and growled because he had to leave the musty old book he was readin' and the "genealogical tree" he'd begun to cultivate once more. Jacobs was pretty well disgusted with Pullet. Said he was an incumbrance on the concern and hadn't any business instinct.

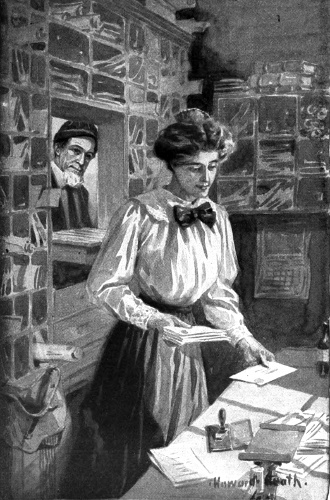

All the next day and the next we hung around, dressed up to kill—that is, Jim Henry's togs would have killed anything with weak eyes—waitin' for Letitia Pendlebury to come aboard and inspect. But she didn't come that day, or the next either. Jacobs was disapp'inted, but he wouldn't give in that he was discouraged. The fourth forenoon, when there was still nothin' doin', he and I went on a cruise with a hired horse and buggy over to Bayport, where we had some business. We left Pullet in charge of the store and when we came back he was lookin' pretty joyful.

"Who do you think has been here?" he says, in his thin, polite little voice. "Miss Letitia Pendlebury called this afternoon."

"She did!" shouts Jacobs.

"Did she buy anythin'?" I wanted to know.

No, it appeared that she hadn't bought anythin'. Fact is, Pullet had forgot he was supposed to be a storekeeper. When Letitia came in he was roostin' in his family tree, had the chart spread out on the counter and was fillin' in some of the twigs with the names of dead and gone Beanblossoms. He couldn't climb down to common things like crackers and salt pork.

"But she was very much interested," he says, his specs shinin' with joy. "When she found out what I was busy with she was very much interested, really. She is a lady of family, too."

"She is?" I sings out. "What are you talkin' about? She's an old maid and an only child besides, and—"

"Hush up, Skipper," orders Jacobs. "Go on, Pullet—Mr. Beanblossom, I mean—go on."

So on went Pullet, both wings flappin'. Letitia and he had talked "family" to beat the cars. She had 'most everything in the Villa except a family tree. She must have one right away. She simply must.

"And I am to help her in preparin' it," says Pullet, puffed up and vainglorious. "The Pendlebury family tree will be an honor to prepare. Of course it will require much labor and research, but I shall enjoy doing it. I told her so. Her father would have prepared one himself, had often spoken of it, but he was a very busy man of affairs and lacked the time."

My, but I was mad! I cal'late if I had a marlinspike handy our coop would have been a Pullet short. But Jim Henry Jacobs was so full of tickle he couldn't keep still. He fairly dragged me into the back room.

"Skipper," he says, "here it is at last! We've got it!"

"Yes," I sputters, thinkin' he was referrin' to Beanblossom, "we've got it; and, if you ask me, I'd tell you we'd ought to chloroform it afore it does any more harm."

"No, no," he says, "you don't understand. We've got the old girl's weak p'int at last. It's genealogy. Pullet shall grow her a family tree if I have to buy a carload of fertilizer to-morrer. Think of it! think of it! Why, she won't give him a minute's rest from now on. She'll be after him the whole time."

"But I can't see where the trade comes in," says I.

"You can't! With our senior pardner head forester? My boy, if any other shop sells Pendlebury Villa a dollar's worth after this, I'll Fletcherize my hat, that's all!"

He knew what he was talkin' about, as usual. The very next forenoon Letitia was in to consult with Pullet about huntin' up her family records. Afore she left Jacobs took orders for thirty-two dollars' worth and I'd have bet she didn't know a thing she bought. After dinner, Jim Henry sent Pullet up to see her. He stayed until supper time. Next day he had supper at the Villa. A week later he made his first trip to Boston, to the Genealogical Society, to hunt for records. And Jacobs stayed in Ostable and kept the Villa supplied with the luxuries of life. If the Pendlebury servants didn't die of gout and overeatin', it wasn't our fault.

By August the whole town was talkin'. They had it all settled. 'Cordin' to the gossip-spreaders there could be only one reason for Pullet and Miss Letitia bein' together so much—they was cal'latin' to marry. The weddin' day was prophesied and set anywheres from to-morrer to next Christmas. I thought such talk ought to be stopped. Jim Henry didn't.

"Why?" says he.

"Why!" I says. "Because it's foolishness, that's why. 'Cause there's no truth in it and you know it."

"No, I don't know," says he. "Stranger things than that have happened."

"She marry that old fossilized pauper!"

"Why not? He's a gentleman and a scholar, if he is poor. She's rich, but if there's one thing she isn't, it's a scholar."

"Humph! fur's that goes," says I, "she ain't a gentleman, either—though she's next door to it."

"That's all right. Skipper, there's some things money can't buy. Pullet's got book learnin' and treed ancestors and she ain't. She's got money and he ain't. Both want what t'other's best fixed in. If old Beanblossom had any sand, I should believe 'twas a sure thing. I guess I'll drop him a hint."

"My land!" I sang out; "don't you do it. The fat'll all be in the fire then."

"Skipper," says he, "you're a cagey old bird, but you don't know it all. There's some things you can leave to me. And, anyhow, whether the weddin' bells chime or not, all this talk is good free advertisin' for the store."

'Twa'n't long after this that the genealogical man begun to seem less gay-like. He and Letitia was together as much as ever, the Pendlebury tree and the Beanblossom tree—he worked on both at the same time—was flourishin', after the topsy-turvy way of such vegetables—from the upper branches down towards the trunks; but there was a look on Pullet's face as he pawed through his books and papers that I couldn't understand. He looked worried and troubled about somethin'.

"What's the matter?" I asked him, once. "Ain't your ancestors turnin' up satisfactory?"

"Yes," he says, polite as ever, but sort of condescendin' and proud, "the Beanblossom history is, if you will permit me to say so, a very satisfactory record indeed."

"And the Pendleburys?" says I. "George Washin'ton was first cousin on their ma's side, I s'pose."

He didn't answer for a minute. Then he wiped his specs with his handkerchief. "The Pendlebury records are," he says, slow, "a trifle more confused and difficult. But I am progressin'—yes, Cap'n Snow, I think I may say that I am progressin'."

The thunderbolt hit us, out of a clear sky, the fust week in September. Yet I s'pose we'd ought to have seen it comin' at least a day ahead. That day the Pendlebury gasoline carryall come buzzin' up to the front platform and Letitia steps out, grand as the Queen of Sheba, of course.

"Cap'n Snow," says she, and it seemed to me that she hesitated just a minute, "is Mr. Beanblossom about?"

"No," says I, "he ain't. I don't know where he is exactly. He was in the store this mornin' askin' about a letter he's expectin' from the Genealogical Society folks, but he went out right afterwards and I ain't seen him since. I s'posed, of course, he was up to your house."

"No," she says, and I thought she colored up a little mite; "he has not been there since day before yesterday. Perhaps that is natural, under the circumstances," speakin' more to herself than to me, "but ... however, will you kindly tell him I called before leavin' for the city. I am goin' to Boston on a shoppin' excursion," she adds, condescendin'. "I shall return on Wednesday."

She went away. Pullet didn't show up until night and then the first thing he asked for was the mail. When I told him about the Pendlebury woman he turned round and went out again.

Next day was Saturday and we was pretty busy, that is, Jim Henry and the clerk was busy. I was about as much use as usual, and, as for Pullet, he was no use at all. A big green envelope from the Genealogical Society come for him in the morning mail—he was always gettin' letters from that Society—and he grabbed at it and went out on the platform. A little while afterwards I saw him roostin' on a box out there, with his hair, what there was of it, all rumpled up, and an expression of such everlastin', world-without-end misery on his face that I stopped stock still and looked at him.

"For the mercy sakes," says I, "what's happened?"

He turned his head, stared at me fishy-eyed, and got up off the box.

"What's wrong?" I asked. "Is the world comin' to an end?"

He put one hand to his head and waved the other up and down like a pump handle.

"Yes," he sings out, frantic like. "It is ended already. It is all over. I—I—"

And with that he jumps off the platform and goes staggerin' up the road. I'd have follered him, but just then Jim Henry calls to me from inside the store and in a little while I'd forgot Beanblossom altogether. I thought of him once or twice durin' the day, but 'twa'n't till about shuttin'-up time that I thought enough to mention him to Jacobs. Then he mentioned him fust.

"Whew!" says he, settin' down for the fust time in two hours. "Whew! I'm tired. This has been the best day this concern has had since I took hold of it, and I've worked like a perpetual motion machine. We'll need another boy pretty soon, Skipper. Pullet's no good as a salesman. By the way, where is Pullet? I ain't seen him since noon."

Neither had I, now that I come to think of it.

"I wonder if the poor critter's sick," I says. Then I started to tell how queer he'd acted out on the platform. I'd just begun when Amos Hallett's boy come into the store with a note.

"It's for you, Cap'n Zeb," he says, all out of breath. "I meant to give it to you afore, but I just this minute remembered it. Mr. Beanblossom, he give it to me at the depot when he took the up train."

"Took the up train?" says I. "Who did? Not Pul—Mr. Beanblossom?"

"Yes," says the boy. "He's gone to Boston, leastways the depot-master said he bought a ticket for there. Why? Didn't you know it? He—"

I was too astonished to speak at all, but Jim Henry was cool as usual.

"Yes, yes, son," he says. "It's all right. You trot right along home afore you catch cold in your freckles." Then, after the youngster'd gone, he turns to me quick. "Open it, Skipper," he orders. "Somethin's happened. Open it."

I opened the envelope. Inside was a sheet of foolscap covered from top to bottom with mighty shaky handwritin'. I read it out loud.

"Captain Zebulon Snow,

"Dear Sir:

"Polite as ever, ain't he?" I says. "He'd been genteel if he was writin' his will."

"Go on!" snaps Jacobs. "Hurry up."

"Dear Sir: When you receive this I shall have left Ostable, it may be forever. I have made a horrible discovery, which has wrecked all my hopes and my life. In accordance with Mr. Jacob's kindly counsel, I recently summoned courage to ask Miss Pendlebury to become my wife.

"Good heavens to Betsy!" I sang out, almost droppin' the letter.

"Go on!" shouts Jacobs. "Don't stop now."

"But he asked her to marry him!" I gasps. "In accordance with your advice—yours! Did you have the cheek to—"

"Will you go on? Of course I advised him. We'd got the Pendlebury trade, hadn't we? Can you think of any surer way to cinch it than to have those two idiots marry each other? Go on—or give me the letter."

I went on, as well as I could, everything considered.

"She did not refuse. She was kinder than I had a right to expect. I realized my presumption, but—"

"Skip that," orders Jim Henry. "Get down to brass tacks."

I skipped some.

"She told me she must have a few days' time to consider. I waited. To-day I received a communication from the Genealogical Society which has dashed my hopes to the ground. It was in connection with my work on the Pendlebury family tree. For some time I have been very much troubled concerning developments in that work. The later Pendleburys have been ladies and gentlemen of repute and worth, but as I delved deeper into the past and approached the early generations in this country, I—"

"Skip again," says Jacobs.

I skipped.

"And now, to my horror, I find the fact proven beyond doubt. Ezekiel Jonas Pendlebury—whose name should be inscribed upon the trunk of the tree, he being the original settler in America—was hanged in the Massachusetts Bay Colony for stealing a hog upon the Sabbath Day."

Then I did drop the letter. "My land of love!" was all I could say. And what Jacobs said was just as emphatic. We stared at each other; and then, all at once, he began to laugh, laugh till I thought he'd never stop. His laughin' made me mad until I commenced to see the funny side of the thing; then I laughed, too, and the pair of us rocked back and forth and haw-hawed like loons.

"Oh, dear me!" says Jim Henry, wipin' his eyes. "The original Pendlebury hung for hog stealin'!"

"Stealin' it on Sunday," says I. "Don't forget that. Sabbath-breakin' was worse than thievin' in them days."

"Well, go on, go on," says he. "There's more of it, ain't they?"

There was. The writing got finer and finer as it got close to the bottom of the page. Poor Pullet had caved in when that revelation struck him. Honor compelled him to tell Letitia the truth and how could he tell her such a truth as that? She, so proud and all. He had led her into this dreadful research work and she would blame him, of course, and dismiss him with scorn and contempt. Her contempt he could not bear. No, he must go away. He could never face her again. He was goin' to Boston, to his cousin's house in Newton, and stay there for a spell. Perhaps some day, after she had shut up her summer villa and gone, too, he might return; he didn't know. But would we forgive him, etcetery and so forth, and—good-by.

His name was squeezed in the very corner. I looked at Jacobs.

"Well," I says, some disgusted, "it looks to me, as a man up a tree—not a family tree, neither, thank the Lord—as if instead of cinchin' the Pendlebury trade your 'advice' had queered it forever."

He didn't say nothin'. Just scowled and kicked his heels together. Then he grabbed the letter out of my hand and begun to read it again. I scowled, too, and set starin' at the floor and thinkin'. All at once I heard him swear, a sort of joyful swear-word, seemed to me. I looked up. As I did he swung off the counter, crumpled up the letter, jammed it in his pocket and grabbed up his hat.

"Skipper," he says, his eyes shinin', "there's a night freight to Boston, ain't there?"

"Yes, there is, but—"

"So long, then. I'll be back soon's I can. You and Bill"—that was the clerk—"must do as well as you can for a day or so. So long. But you just remember this: Old Doctor James Henry Jacobs, specialist in sick businesses, ain't given up hopes of this patient yet, not by any manner of means. By, by."

He was gone afore I could say another word, and for the rest of that night and all day Sunday and until Monday evenin's train come in, I was like a feller walkin' in his sleep. All creation looked crazy and I was the only sane critter in it.

On Monday evenin' he came sailin' into the store, all smiles. 'Twas some time afore I could get him alone, but, when I could, I nailed him.

"Now," says I, "perhaps you'll tell me why you run off and left me, and where you've been, and what you mean by it, and a few other things."

He grinned. "Been?" he says. "Well, I've been to see the last of Miss Letitia Pendlebury of Pendlebury Villa, Ostable, Mass. Miss Pendlebury is no more."

"No more!" I hollered. "No more! Don't tell me she's dead!"

"I sha'n't," says he, "because she isn't. She's alive, all right, but she's no more Miss Pendlebury. She's Mrs. Winthrop Adams Beanblossom now," he says. "They were married this forenoon."

"Married?"

"Married."

"But—but—after the hangin' news—and the hog-stealin'—and—Does she know it? She wouldn't marry him after that?"

"She knows and she was tickled to death to marry him. Skipper, there was a P.S. on the back of that letter of Pullet's. You didn't turn the page over; I did and I recognized the life-saver right off. Here it is."

He passed me Beanblossom's letter, back side up. There was a P.S., but it looked to me more like the finishin' knock on the head than it did like a life-saver. This was it:

"P.S. I have neglected to state another fact which my researches have brought to light and which makes the affair even more hopeless. My own ancestor, at that time Governor of the Colony, was the person who sentenced Ezekiel Pendlebury and caused him to be hanged."

"And that," says I, "is what you call a life-saver! My nine-times great-granddad has your nine-times great-granddad hung and that removes all my objections to marryin' you. Oh, sure and sartin! Yes, indeed!"

He smiled superior. "Listen, you doubtin' Thomas," says he. "You can't see it, but Sister Letitia saw it right off when I put Pullet's case afore her at the Hotel Somerset, where she was stoppin'. Her ancestor was a hog-stealer and a hobo; but Beanblossom's ancestor was a Governor and a nabob from way back. If by just sayin' yes you could swap a pig-thief for a governor, you'd do it, wouldn't you? You would if you'd been braggin' 'family' as Letitia has for the past three months. I saw her, turned on some of my convincin' conversation, saw Pullet at his cousin's and convinced him. They were married at Trinity parsonage this very forenoon."

"My! my! my!" I says, after this had really sunk in. "And the Pendlebury tree is—"

"There ain't any Pendlebury tree," he interrupts. "It's the kindlin'-bin for that shrub. But the Beanblossom tree, with governors and judges and generals proppin' up every main limb, is goin' to hang right next to Pa Pendlebury's picture in the mornin' room of Pendlebury Villa. And the head of Pendlebury Villa is the senior partner in the Ostable Grocery, Dry Goods, Boots and Shoes and Fancy Goods Store."

He was wrong there. Letitia Pendlebury Beanblossom had another surprise under her bonnet and she sprung it when she got back. She sent for Jacobs and me and made proclamation that her husband would withdraw from the firm.

"I trust that Mr. Beanblossom and I are democratic," she says. "Of course we shall continue to purchase our supplies from you gentlemen. But, really," she says, "you must see that a man whose ancestor by direct descent was Governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony could scarcely humiliate himself by engaging in trade."

So, instead of gettin' out of storekeepin', I was left deeper in it than ever. But Jim Henry cheered me up by sayin' I hadn't really been in it at all yet.

"This foundlin' is only beginnin' to set up and take notice," he says. "Skipper, you put your faith in old Doctor Jacobs' Teethin' Syrup and Tonic for Business Infants."

"I guess that's where it's put," says I, drawin' a long breath.

"It couldn't be in a better place, could it? No, we've got a good start, but that's all it is. Before I get through you'll see. We've got to make this store prominent and keep it prominent, and the best way to do that is to be prominent ourselves. Skipper, I wish you'd go into politics."

"Politics!" says I, soon as I could catch my breath. "Well, when I do, I give you leave to order my room at the Taunton Asylum. What do you cal'late I'd better try to get elected to—President or pound-keeper?"

He laughed.

"Both of them jobs are filled at the present time," I went on, sarcastic. "So is every other I can think of off-hand."

"That's all right," says he. "Some of these days you'll hold office right in this town. We need political prestige in our business and you, Cap'n Snow, bein' the solid citizen of this close corporation, will have to sacrifice yourself on the altar of public duty."

"Nary sacrifice," says I. Which shows how little the average man knows what's in store for him.

When I shook hands with Mary Blaisdell and left her standin' under the wistaria vine at the front door of the little old house that had belonged to Henry, all I said was for her to keep a stiff upper lip and not to be any bluer than was necessary. "Ostable's lost a good postmaster," says I, "and you've lost a kind, thoughtful, providin' brother. I know it looks pretty foggy ahead to you just now and you can't see how you're goin' to get along; but you keep up your pluck and a way'll be provided. Meantime I'm goin' to think hard and perhaps I can see a light somewheres. My owners used to tell me I was consider'ble of a navigator, so between us we'd ought to fetch you into port."

Her eyes were wet, but she smiled, rainbow fashion, through the shower, and said I was awful good and she'd never forget how kind I'd been through it all.

"Whatever becomes of me, Cap'n Snow," she says, "I shall never forget that."

What I'd done wa'n't worth talkin' about, so I said good-by and hurried away. At the top of the hill I turned and looked back. She was still standin' in the door and, in spite of the wistaria and the hollyhocks and the green summer stuff everywheres, the whole picture was pretty forlorn. The little white buildin' by the road, with the sign, "Post-office" over the window, looked more lonesome still. And yet the sight of it and the sight of that sign give me an inspiration. I stood stock still and thumped my fists together.

"Why not?" says I to myself. "By mighty, yes! Why not?"

You see, Henry Blaisdell was one of the few Ostable folks that I'd known as a boy and who was livin' there yet when I came back. He was younger than I, and Mary, his sister, was younger still. I liked Henry and his death was a sort of personal loss to me, as you might say. I liked Mary, too. She was always so quiet and common-sense and comfortable. She didn't gossip, and the way she helped her brother in the post-office was a treat to see. She wa'n't exactly what you'd call young, and the world hadn't been all fair winds and smooth water for her, by a whole lot; but, in spite of it, she'd managed to keep sweet and fresh. She and Henry and I had got to be good friends and I gen'rally took a walk up towards their house of a Sunday or managed to run in at the post-office buildin' at least once every week-day and have a chat with 'em.

When I heard of Henry's dyin' so sudden my fust thought was about Mary and what would she do. How was she goin' to get along? I thought of that even durin' the funeral, and now, the day after it, when I went up to see her, I was thinkin' of it still. And, at last, I believed I had got the answer to the puzzle.

Half the way back to the "Ostable Grocery, Dry Goods, Boots and Shoes and Fancy Goods Store," I was thinkin' of my new notion and makin' up my mind. The other half I was layin' plans to put it through. When I walked into the store, Jim Henry met me.

"Hello, Skipper," says he, brisk and fresh as a no'theast breeze in dog days, "did you ever hear the story about the office-seekin' feller in Washin'ton, back in President Harrison's time? He wanted a gov'ment job and he happened to notice a crowd down by the Potomac and asked what was up. They told him one of the Treasury clerks had been found drowned. He run full speed to the White House, saw the President, and asked for the drowned chap's place. 'You're too late,' says Harrison, 'I've just app'inted the man that saw him fall in.'"

I'd heard it afore, but I laughed, out of politeness, and wanted to know what made him think of the yarn.

"Why," says he, "because that's the way it's workin' here in Ostable. Poor old Blaisdell's funeral was only yesterday and it's already settled who's to be the new postmaster."

Considerin' what I'd been goin' over in my mind all the way home from Mary's, this statement, just at this time, knocked me pretty nigh out of water.

"What?" I gasped. "How did you know?"

"Why wouldn't I know?" says he. "I got the advance information right from the oracle. I was told not ten minutes since that the app'intment was to go to Abubus Payne."

I stared at him. "Abubus Payne!" says I. "Abubus—Are you dreamin'?"

He laughed. "I'd never dream a name like 'Abubus,' he says, 'even after one of our Poquit House dinners. No, it's no dream. The Major was just in and he says his mind is made up. That settles it, don't it? You wouldn't contradict the all-wise mouthpiece of Providence, would you, Cap'n Zeb?"

I never said anything—not then. I was realizin' that, if I wanted Mary Blaisdell to be postmistress at Ostable—which was the inspiration I was took with when I looked back at her from the hill—I'd got to do somethin' besides say. I'd got to work and work hard. And even at that my work was cut out from the small end of the goods. To beat Major Cobden Clark in a political fight was no boy's job. But Abubus Payne! Abubus Payne postmaster at Ostable!! Think of it! Maybe you can; I couldn't without stimulants.

You see, this critter Abubus—did you ever hear such a name in your life?—had lived around 'most every town on the Cape at one time or another. He and his wife wa'n't what you'd call permanent settlers anywhere, but had a habit of breakin' out in new and unexpected places, like a p'ison-ivy rash. He worked some at carpenterin', when he couldn't help it, but his main business, as you might say, had always been lookin' for an easier job. In Ostable he'd got one. He was caretaker and general nurse of Major Cobden Clark. His wife, who was about as shiftless as he was, was the Major's housekeeper.

And the Major? Well, the Major was a star, a planet—yes, in his own opinion, the whole solar system. He was big and fleshy and straight and gray-haired and red-faced. He belonged to land knows how many clubs and societies and milishys, includin' the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Boston and the Old Guard of New York. He had political influence and a long pocketbook and a short temper. Likewise he suffered from pig-headedness and chronic indigestion. 'Twas the indigestion that brought him to Ostable and Abubus; or rather 'twas his doctor, Dr. Conquest Payne, the celebrated food and diet specializer—see advertisements in 'most any newspaper—who sent him there. Abubus was Doctor Conquest's cousin and I judge the two of 'em figgered the Clark stomach and income as things too good to be treated outside of the family.

Anyway, the spring afore I landed in Ostable, down comes the Major, buys a good-sized house on the lower road nigh the water front, hires Abubus and his wife to look out for the place and him, and settles down to the simple life, which wa'n't the kind he'd been livin', by a consider'ble sight. But he lived it now; yes, sir, he did! He lived by the clock and he ate and slept by the clock, and that clock was wound up and set accordin' to the rules prescribed by Dr. Conquest Payne, "World Famous Dietitian and Food Specialist"—see more advertisin', with a tintype of the Doctor in the corner.

Nigh as I could find out the diet was a queer one. It give me dyspepsy just to think of it. Breakfast at seven sharp, consistin' of a dozen nut meats, two raw prunes, some "whole wheat bread"—whatever that is—and a pint of hot water. Luncheon at quarter to eleven, with another assortment of similar truck. Afternoon snack at three and dinner at half-past seven. He had two soft b'iled eggs for dinner, or else a two-inch slice of rare steak, and, with them exceptions, the whole bill of fare was, accordin' to my notion, more fittin' for a goat than a human bein'. He mustn't smoke and he mustn't drink: Considerin' what he'd been used to afore the "World Famous" one hooked him it ain't much wonder that he was as crabbed and cranky as a liveoak windlass.

However, it—or somethin' else—had made him feel better since he landed in Ostable and he swore by that Conquest Payne man and everybody connected with him. And if he once took a notion into his tough old head, nothin' short of a surgeon's operation could get it out. He'd decided to make Abubus postmaster and he'd move heaven and earth to do it. All right, then, it was up to me to do some movin' likewise. I can be a little mite pig-headed myself, if I set out to be.

And I set out right then. It may seem funny to say so, but I was about as good a friend as the Major had in Ostable. Course he had a tremendous influence with the selectmen and the like of that, owin' to his soldier record and his pompousness and the amount of taxes he paid. And he and I never agreed on one single p'int. But just the same he spent the heft of his evenin's at the store and I was always glad to see him. I respected the cantankerous old critter, and liked him, in a way. And I'm inclined to think he respected and liked me. I cal'late both of us enjoyed fightin' with somebody that never tried for an under-holt or quit even when he was licked.

So that night, when he comes puffin' in and sets down, as usual, in the most comfortable chair, I went over and come to anchor alongside of him.

"Hello," he grunts, "you old salt hayseed. Any closer to bankruptcy than you was yesterday?"

"Your bill's a little bigger and more overdue, that's all," says I. "See here, I want to talk politics with you. Mary Blaisdell, Henry's sister, is goin' to have the post-office now he's gone, and I want you to put your name on her petition. Not that she needs it, or anybody else's, but just to help fill up the paper."

Well, sir, you ought to have seen him! His red face fairly puffed out, like a young-one's rubber balloon. He whirled round on the edge of his chair—he was too big to move in any other part of it—and glared at me. What did I mean by that? Hey? Was my punkin head sp'ilin' now that warm weather had come, or what? Had I heard what he told my partner that very mornin'?

"Yes," says I, "I heard it. But I judged you must have broke your rule about drinkin' liquor, or else your dyspepsy has struck to your brains. No sane person would set out to make Abubus Payne anythin' more responsible than keeper of a pig pen. You didn't mean it, of course."

He didn't! He'd show me what he meant! Abubus was the most honest, able man on the whole blessed sand-heap, and he was goin' to be postmaster. Mary Blaisdell was an old maid, good enough of her kind, maybe, but the place for her was some kind of an asylum or home for incompetent females. He'd sign a petition to put her in one of them places, but nothin' else. Abubus was just as good as app'inted already.

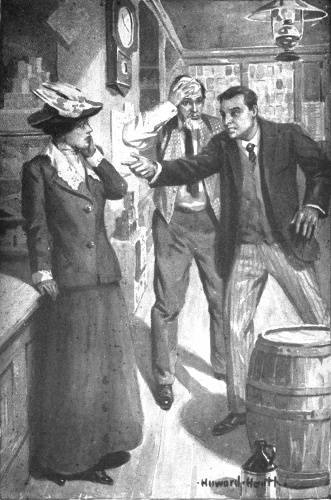

We had it back and forth. There was consider'ble chair thumpin' and hollerin', I shouldn't wonder. Anyhow, afore 'twas over every loafer on the main road was crowdin' 'round us and Jim Henry Jacobs was pacin' up and down back of the counter with the most worried look on his face ever I see there. It ended by the Major's jumpin' to his feet and headin' for the door.

"You—you—you tarry old imbecile," he hollers, shakin' a fat forefinger at me, "I'll show you a few things. I'll never set foot in this rathole of yours again."

"You better not," I sung out. "If you dare to, I'll—"

"What?" he interrupts. "You'll what? I'll be back here to-morrow night. Then what'll you do?"

"I'll show you Mary Blaisdell's petition," I says. "And the names on it'll make you curl up and quit like a sick caterpillar."

"Humph! I'll show you a petition for Abubus Payne, next postmaster of Ostable, with a string of names on it so long you'll die of old age afore you can finish readin' 'em. Bah!"

With that he went out and I went into the back room to wash my face in cold water.

I wrote the headin' to the Blaisdell petition afore I turned in that very night. Next mornin' I hurried over and, after consider'ble arguin', I got Mary to say she'd try for the place. All the rest of that day I put in drivin' from Dan to Beersheby gettin' signatures. And I got 'em, too, a schooner load of 'em. I had the petition ready to show the Major that evenin'; but, when he come into the store, he had a petition, too, just as long as mine. And the worst of it was, in a lot of cases the same names was signed to both papers. Accordin' to those petitions the heft of Ostable folks wanted somebody to keep post-office and they didn't much care who. They wanted to please me and they didn't like to say no to the Major.

He was mad and I was mad and we had another session. But he wouldn't cross the names off and neither would I and so, after another week, both petitions went in as they was. All the good they seemed to do was that we each got a letter from the Post-office Department and Mary Blaisdell was allowed to hold over her brother's place until somebody was picked out permanent. And every evenin' Major Clark came into the store to tell me Abubus was sure to win and get my prediction that Mary was as good as elected. One week dragged along and then another, and 'twas still a draw, fur's a body could tell. The Washin'ton folks wa'n't makin' a peep.

But old Ancient and Honorable Clark was workin' his wires on the quiet and I must give in that he pulled one on me that I wa'n't expectin'. The whole town had got sort of tired of guessin' and talkin' about the post-office squabble and had drifted back into the reg'lar rut of pickin' their neighbors to pieces. The Major had set 'em talkin' on a new line durin' the last fortni't. He'd been fixin' up his house and havin' the grounds seen to, and so forth. Likewise he'd bought an automobile, one of the nobbiest kind. This was somethin' of a surprise, 'cause afore that he'd been pretty much down on autos and did his drivin' around in a high-seated sort of buggy—"dog cart" he called it—though 'twas hauled by a horse and he hated dogs so that he kept a shotgun loaded with rock salt on his porch to drive stray ones off his premises.

"Who's goin' to run that smell-wagon of yours?" I asked him, sarcastic. He kept comin' to the store just the same as ever and we had our reg'lar rows constant. I cal'late we'd both have missed 'em if they'd stopped. I know I should.

"Humph!" he snorts; "smell-wagon, hey? If it smells any worse than that old fish dory of yours, I'll have it buried, for the sake of the public health."

By "fish dory" he meant a catboat I'd bought. She was named the Glide and she could glide away from anything of her inches in the bay.

"But who's goin' to run that auto?" I asked again. "'Tain't possible you're goin' to do it yourself. If she went by alcohol power, I could understand, but—"

"Hush up!" he says, forgettin' to be mad for once and speakin' actually plaintive. "Don't talk that way, Snow," says he. "If you knew how much I wanted a drink you wouldn't speak lightly of alcohol."

"Why don't you take one, then?" I wanted to know. "I believe 'twould do you good. That and a square meal. If you'd forget your prunes and your nutmeats and your quack doctorin'—"

He was mad then, all right. To slur at the "World Famous" was a good deal worse than murder, in his mind. He expressed his opinion of me, free and loud. He said I'd ought to try Doctor Conquest, myself, for developin' my brains. The Doctor was pretty nigh a vegetarian, he said, and my head was mainly cabbage—and so on. Incidentally he announced that Abubus was to run the new auto.

"Abubus!" says I. "Why, he don't know a gas engine from a coffee mill! He wouldn't know what the craft's for."

"That's all right," he says. "He's been takin' lessons at the garage in Hyannis and he can run it like a bird. He knows what it's for. He! he! so do I. By the way, Snow, are you ready to give up the post-office to my candidate yet?"

"Give up?" says I. "Tut! tut! tut! I hate to hear a supposed sane man talk so. Mary Blaisdell handles the mail in the Ostable post-office for the next three years—longer, if she wants to."

"Bet you five she don't," he says.

"Take the bet," says I.

He went out chucklin'. I wondered what he had up his sleeve. A week later I found out. Congressman Shelton, our district Representative at Washin'ton, came to Ostable to look the post-office situation over and, lo and behold you, he comes as Major Cobden Clark's guest, to stay at his house.

When Jim Henry Jacobs learned that, he took me to one side to give me some brotherly advice.

"It's all up for Mary now," he says. "She can't win. Clark and Shelton are old chums in politics. There's only one chance to beat Payne and that's to bring forward a compromise candidate—a dark horse."

"Rubbish!" I sung out. "Dark horse be hanged! Shelton's square as a brick. Nobody can bribe him."

"It ain't a question of bribin'," he says. "If it was, you could bribe, too. Shelton is square, and that's why he'd welcome a compromise candidate. But if it comes to a fight between Mary Blaisdell and Abubus Payne, Abubus'll win because he's the Major's pet. Shelton knows the Major better than he knows you. Take my advice now and look out for the dark horse."

But I wouldn't listen. All the next hour I was ugly as a bear with a sore head and long afore dinner time I told Jacobs I was goin' for a sail in the Glide. "Goin' somewheres on salt water where the air's clean and not p'isoned by politics and automobiles and congressmen and Paynes," I told him.

I headed out of the harbor and then run, afore a wind that was fair but gettin' lighter all the time, up the bay. I sailed and sailed until some of my bad temper wore off and my appetite begun to come back. All the time I was settin' at the tiller I was thinkin' over the post-office situation and, try as hard as I could to see the bright side for Mary Blaisdell, it looked pretty dark. The Major would give that Shelton man the time of his life and he'd talk Abubus to him to beat the cars. I couldn't get at the Congressman to put in an oar for Mary and—well, I'd have discounted my five-dollar bet for about seventy-five cents, at that time.

I thought and thought and sailed and sailed. When I came to myself and realized I was hungry the Glide was miles away from Ostable. I came about and started to beat back; then I saw I was in for a long job. Let alone that the wind was ahead, 'twas dyin' fast, and if I knew the signs of a flat calm, there was one due in half an hour. I took as long tacks as I could, but I made mighty little progress.

On the second tack inshore I came up abreast of Jonathan Crowell's house at Heron P'int. Jonathan's just a no-account longshoreman or he wouldn't live in that place, which is the fag-end of creation. There's a twenty-mile stretch of beach and pines and such close to the shore there, with a road along it. The first eight mile of that road is pretty good macadam and hard dirt. A land company tried to develop that section of beach once and they put in the road; but the land didn't sell and the company busted and after that eight mile the road is just beach sand, soft and coarse. The strip of solid ground, with its pines and scrub-oaks, is, as I said afore, twenty mile long, but it's only a half mile or so wide. Between it and the main cape is a tremendous salt marsh, all cut up with cricks that nobody can get over without a boat. Jonathan's is the only house for the whole twenty mile, except the lighthouse buildin's down at the end. The land company put up a few summer shacks on speculation, but they're all rickety and fallin' to pieces.

I knew Jonathan had gone to Bayport, quahaug rakin', and that his wife was visitin' over to Wellmouth, so when the Glide crept in towards the beach and I saw a couple of folk by the Crowell house, I was surprised. I didn't pay much attention to 'em, however, until I was just about ready to put the helm over and stand out into the bay again. Then they come runnin' down to the beach, yellin' and wavin' their arms. I thought one of 'em had a familiar look and, as I come closer, I got more and more sure of it. It didn't seem possible, but it was—one of those fellers on the beach was Major Cobden Clark.

"Hi-i!" yells the Major, hoppin' up and down and wavin' both arms as if he was practicin' flyin'; "Hi-i-i! you man in the boat! Come here! I want you!"

That was him, all over. He wanted me, so of course I must come. My feelin's in the matter didn't count at all. I run the Glide in as nigh the beach as I dared and then fetched her up into what little wind there was left.

"Ahoy there, Major," I sung out. "Is that you?"

"Hey?" he shouts. "Do you know—Why, I believe it's Snow! Is that you, Snow?"

"Yes, it's me," I hollers. "What in time are you doin' way over here?"

"Never mind what I'm doin'," he roared. "You come ashore here. I want you."

If I hadn't been so curious to know what he was doin', I'd have seen him in glory afore I ever thought of obeyin' an order from him; but I was curious. While I was considerin' the breeze give a final puff and died out altogether. That settled it. I might as well go ashore as stay aboard. I couldn't get anywhere without wind. So I hove anchor and dropped the mains'l.

"Come on!" he kept yellin'. "What are you waitin' for? Don't you hear me say I want you?"

I had on my long-legged rubber boots and the water wa'n't more'n up to my knees. When I got good and ready, I swung over the side and waded to the beach.

"Hello, Maje," I says, brisk and easy, "you ought not to holler like that. You'll bust a b'iler. Your face looks like a red-hot stove already."

He mopped his forehead. "Shut up, you old fool," says he. "Think I'm here to listen to a lecture about my face? You carry Mr. Shelton and me out to that boat of yours. We want you to sail us home."

So the other chap was the Congressman. I'd guessed as much. I went up to him and held out my hand.

"Pleased to know you, Mr. Shelton," says I. "Had the pleasure of votin' for you last fall."

Shelton shook and smiled. "This is Cap'n Snow, isn't it?" he says, his eyes twinklin'. "Glad to meet you, I'm sure. I've heard of you often."

"I shouldn't wonder," says I. "Major Clark and me are old chums and I cal'late he's mentioned my name at least once. Hey, Maje?"

The Major grinned. I grinned, too; and Shelton laughed out loud.

"I never saw such a talkin' machine in my life," snaps Clark. "Don't stop to tell us the story of your life. Take us aboard that boat of yours. You've got to get us back to Ostable, d'you understand?"

"Have, hey?" says I. "I appreciate the honor, but.... However, maybe you won't mind tellin' me what you're doin' here, twelve miles from nowhere?"

The Major was too mad to answer, so Shelton did it for him.

"Well," he says, smilin' and with a wink at his partner, "we came in the Major's auto, but—"

He stopped without finishin' the sentence.

"The auto?" says I. "You came in the auto? Well, why don't you go back in it? What's the matter? Has it broke down? Humph! I ain't surprised; them things are always breakin' down, 'specially the cheap ones."

That stirred up the kettle. The Major give me to understand that his auto cost six thousand dollars and was the best blessedty-blank car on earth. It wa'n't the auto's fault. It hadn't broke down. It had stuck in the eternal and everlastin' sand and they couldn't get it out, that was the trouble.

"But Abubus can get it out, can't he?" says I. "Abubus runs it like a bird, you told me so yourself. Now a bird can fly, and if you want to get from here to Ostable in anything like a straight line, you've got to fly. By the way, where is Abubus?"

Three or four more questions, and a hogshead of profanity on the Major's part, and I had the whole story. He and Shelton had started for a ride way up the Cape. They was cal'latin' to get home by eleven o'clock, but the machine went so fast that they got where they was goin' early and had time to spare. Shelton happened to remember that he'd sunk some money in the land company I mentioned and he thought he'd like to see the place where 'twas sunk. He asked Abubus if they couldn't run along the beach road a ways. Abubus hemmed and hawed and didn't know for sure—he never was sure about anything. But the Major said course they could; that car could go anywhere. So they turned in way up by Sandwich and come b'ilin' down alongshore. Long's the old land company road lasted they was all right, but when, runnin' thirty-five miles an hour, they whizzed off the end of that road, 'twas different. The automobile lit in the soft sand like a snow-plow and stopped—and stayed. They tried to dig it out with boards from Jonathan Crowell's pig pen, but the more they dug the deeper it sunk. At last they give it up; nothin' but a team of horses could haul that machine out of that sand. So Abubus starts to walk the ten or eleven miles back to civilization and livery stables and the Major and Shelton waited for him. And the more they waited the hungrier and madder Clark got. 'Twas all Abubus's fault, of course. He ought to have had more sense than to run that way on that road, anyhow. He ought to have known better than to get into that sand, a feller that had lived in sand all his life. He was an incompetent jackass. Well, I knew that afore, but it certainly did me good to hear the Major confirm my judgment.

I went over and looked at the automobile. It had always acted like a mighty lively contraption, but now it looked dead enough. And not only dead, but two-thirds buried.

"Well?" fumes Clark, "how much longer have we got to stay in this hole?"

"It's consider'ble of a hole," says I, "and it looks to me as if she'd stay there till Abubus gets back with a pair of horses. Considerin' how far he's got to tramp and how long it'll be afore he can get a pair, I cal'late the hole'll be occupied until some time in the night."

That wa'n't what he meant and I knew it. Did I suppose he and Shelton was goin' to wait and starve until the middle of the night? No, sir; the auto could stay where it was; he and the Congressman would sail home with me in the Glide.

"I hope you ain't in any partic'lar hurry," says I, lookin' out over the bay. There wa'n't a breath of air stirrin' and the water was slick and shiny as a starched shirt. "The Glide runs by wind power and there's no wind. This calm may last one hour or it may last two. As long as it lasts I stay where I am."

What! Did I think they would stay there just because I was too lazy to get my whoopety-bang fish-dory under way? Stay there in that sand-heap—sand-heap was the politest of the names he called Crowell's plantation—and starve?

"Oh," says I. "I won't starve. I'm goin' to get dinner."

Dinner! The very name of it was like a life-preserver to a feller who'd gone under for the second time.

"Can you get us dinner?" roars the Major. "By George, if you can I'll—"

"Not for you I can't," I says. "You live accordin' to the Payne schedule, on prunes and pecans and such. The prune crop 'round here is a failure and I don't see a pecan tree in Jonathan's back yard. No, any dinner I'd get would give you compound, gallopin' dyspepsy, and I can't be responsible for your death—I love you too much. But I cal'late I can scratch up a meal that'll keep folks with common insides from perishin' of hunger. Anyhow, I'm goin' to try."

Well, sir, even the Major's guns was spiked for a minute. I cal'late that, for once, he'd forgot all about his dietizin' and only remembered his appetite. He gurgled and choked and glared. Afore he could get his artillery ready for a broadside I walked off and left him. He'd riled me up a little and I saw a chance to rile him back.

I went around to the back part of the Crowell house and tried the kitchen door. 'Twas locked, for a wonder, but the window side of it wasn't. I pushed up the sash and reached in fur enough to unhook the door. Then I went into the house and begun to overhaul the supplies in the galley. I found flour and sugar and salt and pepper and coffee and butter and canned milk and salt pork—about everything I wanted. Jonathan and I was friendly enough so's I knew he wouldn't care what I used so long as I paid for it. If he had I'd have taken the risk, just then.

The wood-box was full and I got a fire goin' in the cookstove, and put on a couple of kettles of water to heat. Then I went out to the shed and located a clam hoe and a bucket. There's clams a-plenty 'most anywheres along that beach and the tide was out fur enough for me to get a bucket-full of small ones in no time. I fetched 'em up to the house and set down on the back step to open 'em.

The Major and Shelton was watchin' me all this time and they looked interested—that is, the Congressman did, and Clark was doin' his best not to. Pretty soon Shelton walks over and asks a question. "What are you doin' with those things, Cap'n Snow?" says he, referrin' to the clams.

"Oh," says I, cheerful, "I'm figgerin' on makin' a chowder, if nothin' busts."

"A chowder," he says, sort of eager. "A clam chowder? Can you?"

"I can. That is, I have made a good many and I cal'late to make this one, unless I'm struck with paralysis."

"A clam chowder!" he says again, sort of eager but reverent. "By George! that's good—er—for you, I mean."

"I hope 'twill be good for you, too," says I. "I'm sorry that Major Clark's dyspepsy's such that 'twon't be good for him, but that's his misfortune, not my fault."

Shelton looked sort of queer and went away to jine his chum. The two of 'em did consider'ble talkin' and the Major appeared to be deliverin' a sermon, at least I heard a good many orthodox words in the course of it. I finished my clam openin', went in and got my cookin' started. The flour and the butter made me think that some hot spider-bread would go good with the chowder and I started to mix a batch. Then I got another idea.

'Twas too late for huckleberries and such, but out back of the shed, beyond the pines, was a little swampy place. I took a tin pail, went out there and filled the pail with early wild cranberries in five minutes. As I was comin' back I noticed an onion patch in the garden. A chowder without onions is like a camp-meetin' Sunday without your best girl—pretty flat and impersonal. Most of those left in the patch had gone to seed, but I got a half dozen.