The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 105 September 23, 1893, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 105 September 23, 1893 Author: Various Editor: Sir Francis Burnand Release Date: January 25, 2012 [EBook #38671] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, OR THE LONDON *** Produced by Malcolm Farmer, Lesley Halamek and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Although professional engagements (not wholly unconnected with the holding of high judicial office in the Tropics) have recently prevented me from contributing to the paper which specially represents Bench and Bar, I have never lost sight of the fact that when I have a duty to perform, the pages of Punch are open to me. Under these circumstances I find myself once again writing to the familiar address, and signing myself, as of yore, with the old name, and the ancient head-quarters. I must confess that although I date this communication from Pump-Handle Court, I am, as a matter of fact, staying at Callerherring, a health resort greatly patronised by all patients of that eminent doctor Sir Peter Twitwillow.

It is unnecessary to describe a place so well known to all lovers of the picturesque. I may hint that the far-famed view of twelve Scotch, Irish, and Welsh counties, and the Channel and the Atlantic Ocean, can still be enjoyed by those who ascend Mount MacHaggis, and that the table-d'h˘te at the Royal Hibernian Hotel yet costs, with its seven courses, five-and-sixpence. And now to perform my duty.

My son, George Lewis Bolton Rollit (he is christened after some professional friends of mine, in the hope that at some distant date he may be assisted by them in the characters of good fairy godfathers in the profession to which it is hoped he may ornamentally belong), is extremely partial to sweetstuff. He is a habitual glutton of a sticky comestible known, I believe, in the confectionery trade as "Chicago Honey Shells." This toothsome (I have his word for the appropriateness of the epithet) edible he devours in large quantities, spending at times as much as five shillings to secure an ample store of an article of commerce generally bought in quantities estimated at the usually convenient rate of "two ounces for three halfpence."

It was after a long gastronomic debauch connected with Chicago Honey Shells that I noticed that George Lewis Bolton Rollit was suffering from a swollen face. My son, although evidently in great pain, declared that there was nothing the matter with him. However, as for three successive days he took only two helpings of meat and refused his pudding, I, in consultation with his mother, came to the conclusion that it was necessary to seek the advice of a local medical man. George Lewis Bolton Rollit raised objections to this course, but they were overruled.

"No, Sir, the doctor is not in. He's out for the day."

Such was the answer to my question put twice at the doors of two medical-looking houses with brass plates to match. On the second occasion I expressed so much annoyance that the servant quite sympathised with me.

"Perhaps Master Sammy might do, Sir?" suggested the kind-hearted janitor.

On finding that "Master Sammy" was a nephew of the owner of the house and a qualified medical man, I consented, and "Master Sammy" was sent for. There was some little delay in his appearance, as, although the morning was fairly well advanced, he was not up. However, after making a possibly hasty toilette, he soon appeared. No doubt he was much older, but he looked about eighteen. He was very pleasant, and listened to my history of the case. He seemed, so it appeared to me, to recognise the Chicago Honey Shells as old acquaintances. It may have been my fancy, but I think he smacked his lips when I suggested that George Lewis Bolton Rollit had probably eaten five shillings' worth at a sitting.

"You see," I said, "he has had a bad face ever since; and as our dentist in town told us about a fortnight ago that sooner or later he must have a tooth out, I think this must be the one to which he referred. Won't you see?"

When, after some persuasion, George Lewis Bolton Rollit had been induced to open his mouth, "Master Sammy" did see.

"Yes," observed the budding doctor, after he had looked into my lad's mouth as if it were a sort of curiosity from India that he was regarding for the first time, "yes, I think it ought to come out."

And armed with this opinion I asked my medical friend if he knew any one in Callerherring capable of performing the operation.

"Well, yes," he replied, after some consideration; "there's a nice little dentist round the corner. He's called Mr. Leo Armstrong."

Then "Master Sammy" smiled, and I felt sure that he and "the nice little dentist" must have quite recently been playing marbles together. Next came the question of the fee. "Master Sammy" was disinclined to accept anything, evidently taking a low estimate of the value of his professional services. However, he ultimately said "Three-and-sixpence," and got the money. I would willingly have increased it to a crown had I not feared that the moment my back was turned "Master Sammy" would have followed the example of George Lewis Bolton Rollit, and himself indulged in five shillings' worth of Chicago Honey Shells.

Mr. Leo Armstrong lived in a rather fine-looking house, ornamented with an aged brass plate, suggesting that he had been established for very many years. A buttons opened the door, and, on my inquiring as to whether Mr. Leo Armstrong was at home, promptly answered "Yes."

From the venerable appearance of the brass plate I had expected to see a rather elderly dentist, with possibly white hair and certainly spectacles; so I was rather taken aback when a dapper young fellow, who seemed about the age of "Master Sammy," entered the waiting-room. The juvenile new-comer made himself master of the situation. He seized upon the jaw of poor trembling George Lewis Bolton Rollit, and declared that "it must come out."

"He'd better have gas," he observed. "But as I am full of engagements this morning, you really must let me fix a time."

Then he took out a pocket-book which I could not help noticing contained such items as "Soda-water—3s.," "Washing—5s.," and "Church collection—6d.," and placed our name and time amidst the other entries.

We kept our appointment. The buttons was in a state of excitement. Mr. Leo Armstrong received us, and pointed to the gas apparatus with an air of triumph, as if he had had some difficulty in getting it entrusted to him in consequence of his youth. Then "Master Sammy" made his appearance. He was going to administer the gas. It was a pleasant family party, and I felt quite parental. Had it not been for poor George Lewis Bolton Rollit's swollen face, I should have said to Mr. Leo Armstrong, "Master Sammy," my boy, and the buttons, "Here, lads, let us make a day of it. I will take you all to Madame Tussaud's and the Zoological Gardens."

"You have had the gas, haven't you?" said "Master Sammy," who had been fumbling with the apparatus. "How do you put it on?"

Poor George Lewis Bolton Rollit, under protest, described the modus operandi. Then the mouth was opened, and "Master Sammy" applied the gas. I am sorry to say he performed the operation rather clumsily, and my poor lad never "went off." George Lewis Bolton Rollit subsequently described every detail of the performance, and said that he had suffered excruciating pain. Then Mr. Leo Armstrong went to work, and, after several struggles, got out a bit of tooth, and then another. Then George Lewis Bolton Rollit came to himself, and the usual comforts were supplied to him.

"I think there's a bit of the tooth still in the gum," said Mr. Leo Armstrong; and then, after a pause, with the air of Jack Horner pulling out a plum, he produced an immense pair of forceps from the instrument drawer. "There." he added, triumphantly, as he exhibited another piece of ivory, "I told you so!"

George Lewis Bolton Rollit had now sufficiently recovered to complain bitterly of the pain he had suffered.

"Impossible," I observed; "remember this is painless dentistry."

I had not intended the remark as a witticism, but rather as a solace to the sufferer. Still, "Master Sammy" and Mr. Leo Armstrong accepted it as first-class waggery, and indulged in roars of laughter. Then the former took his departure. I found that I was indebted to the latter to the extent of 15s. 6d. I don't know how my dentist had arrived at the sum, but he said it with such determination that I could only offer a sovereign and receive the change.

"I want my tooth," said George Lewis Bolton Rollit, who is of an affectionate nature. "I want to give it to Mother."

Then Mr. Leo Armstrong interposed. He desired to keep the tooth (in several pieces) himself. I understood him to say that he regarded it as a memorial of an initial victory—his first extraction.

"Dear me!" I exclaimed. "Why I thought you had been established at least twenty years, Mr. Leo Armstrong."

"Well, to tell the truth," was the reply, "I am not Mr. Leo Armstrong. He's away for the day, and I am taking his place!"

Then George Lewis Bolton Rollit and I bowed ourselves out. As I left the premises I fancied I heard the click of marbles. No doubt "Master Sammy" and "Mr. Leo Armstrong" had resumed the game our visit had interrupted. I was relieved to find myself safe from a fall caused perchance by one of their runaway hoops.

And now to perform my duty. I need scarcely say that it is to add my recommendation to that of Sir Peter Twitwillow anent Callerherring. You should not fail to visit the place, especially if you have a son suffering from "a raging tooth," that "must come out."

Pump-Handle Court, Temple, September, 1893.

[pg 134]It's of three jovial huntsmen, an' a hunting they did go;

An' they hunted, an' they hollo'd, an' they blew their horns also.

Look ye there!

An' one said, "Mind yo'r 'ayes,' and keep yo'r 'noes' well down th' wind,

An' then, by scent or seet, we'll leet on summat to our mind."

Look ye there!

They hunted, an' they hollo'd, an' the first thing they did find

Was a tatter't boggart, in a field, an' that they left behind.

Look ye there!

One said it was a scarecrow, an' another he said "Nay;

It's just the British Farmer, an' he seems in a bad way."

Look ye there!

[pg 135]They hunted, an' they hollo'd, an' the next thing they did find

Was a gruntin', grindin' grindlestone, an' that they left behind.

Look ye there!

One said it was a grindlestone, another he said "Nay;

It's just th' owd Labour Question, which is always in the way."

Look ye there!

They hunted, an' they hollo'd, an' the next thing they did find

Was a bull-calf in a pinfold, an' that too they left behind.

Look ye there!

One said it was a bull-calf, an' another he said "Nay;

It is just a Rural Voter who has lately learned to bray."

Look ye there!

They hunted, an' they hollo'd, an' the next thing they did find

Was a two-three children leaving school, an' these they left behind.

Look ye there!

One said that they were children, but another he said "Nay;

They're Denominational-divvels, who want freedom plus State-pay."

Look ye there!

They hunted, an' they hollo'd, and the next thing they did find

Was two street-spouters and a crowd, an' these they left behind.

Look ye there!

One said they were street-spouters, but another he said, "Nay;

They're just teetotal lunatics who on Veto want their say."

Look ye there!

They hunted an' they hollo'd, an' the next thing they did find

Was a dead sheep hanging by it's heels, an' that they left behind.

Look ye there!

One said it was Welsh Mutton, but another he said, "Nay;

It's the ghost of a Suspensory Bill; we'd better get away!"

Look ye there!

They hunted, an' they hollo'd, an' the next thing they did find

Was a fat pig boltin' thro' a hedge, an' that they left behind.

Look ye there!

One said it was an Irish hog, but another he said "Nay;

It's our plump, pet Home-Rule porker, which the Lords have driven away!"

Look ye there!

So they hunted, an' they hollo'd, till the setting of the sun;

An' they'd nought to bring away at last, when th' huntin'-day was done.

Look ye there!

Then one unto the other said, "This huntin' doesn't pay;

But we've powler 't up an' down a bit, an' had a rattlin' day."

Look ye there!

She. "So much nicer now that all the Visitors have gone. Don't you think so?"

He. "Yes, by Jove! So jolly nice and quiet! Often wonder that Everybody doesn't come now, when there's Nobody here, don't you know!"

Parson and Premier.—I see that a person who is called "the Episcopal Vicar of Blairgowrie" said that he would decline to shake hands with the Prime Minister, in the utterly improbable event of the Prime Minister wishing to shake hands with him. May I inquire how there can be a "Vicar of Blairgowrie" at all? Is not the Established Church in Scotland the Presbyterian one? I know that they have "Lord Rectors" up north, and so perhaps there are Rectors as well, but I never heard of a Lord Vicar. "The Lord Vicar of Blairgowrie" would sound rather well. But what would his Lord Bishop say? Can any genuine Scotchman kindly assist me in unravelling this puzzle?—Southron Body.

Our Auxiliaries.—When are we likely to have a Minister of War who will do real justice to Officers of the Volunteers? I may say that I am thinking of becoming an Officer myself, and I fancy that the following inducements would be likely to bring in a fresh supply of these deserving men:—(1) Exemption from Taxes. (2) Ditto from Rates, and Serving on Juries. (3) More gold braid everywhere. (4) A Volunteer Captain to rank equal to a Lieutenant-General, and a Major of Volunteers equal to the Commander-in-Chief. (5) Retiring pension, and not less than six medals or decorations, after half a year's service. Do you think that there would be much good in my writing to Mr. Campbell-Bannerman and suggesting this?—Modest Merit.

[pg 136]Scene IV.—An Up-platform at Clapham Junction.

Time—Monday afternoon.

Curphew (to himself, as he paces up and down with a pre-occupied air). I ought to have been up at the Hilarity rehearsing hours ago. Considering all that depends on that play of mine—but there'll be time enough to pull Flattery together before Saturday. And this is the only chance I have of seeing Althea for days. Her mother hinted last night that she was obliged to let her travel up to Waterloo alone, and if I did happen to be going up about this time—and of course I do happen to be. I must tell Althea; I can't go on playing a part any longer. I felt such a humbug last night over that confounded Eldorado business. But if I'd revealed myself then as "Walter Wildfire, Comedian and Vocalist," those puritanical parents of hers would probably have both had a fit on the floor, and have kicked me out of the house as soon as they were sufficiently recovered! That's the worst of becoming intimate with a serious Evangelical family in the character of a hard-working journalist. I ought to have undeceived them, I suppose, but it was such a blessing to sink the shop—and besides, I'd seen Althea. It would have been folly to speak until—but she must know now, I'll have no more false pretences. After all, there's no disgrace in being a music-hall singer. I've no reason to be ashamed of the means by which I've got my reputation. Ah! but she won't understand that—the name will be enough for her! And I can't blame her if she fails to see the glory of bringing whisky and water nightly to the eyes of an enraptured audience by singing serio-comic sentiment under limelight through clouds of tobacco-smoke. Heaven knows I'm sick enough of it, and if Flattery only makes a hit, I'd cut the profession at once. If I could only hear her say she—there she is—at last—and alone, thank goodness! I wish I didn't feel so nervous—I'm not likely to get a better opportunity. (Aloud, as he meets Althea.) Mrs. Toovey said I might—can I get your ticket, or see after your luggage, or anything?

Althea. Oh, thank you, Mr. Curphew, but Phœbe is doing all that.

Curph. (to himself, his face falling). That's the maid; then she's not alone! I must get this over now, or not at all. (Aloud.) Miss Toovey, I—I've something I particularly want to say to you; shall we walk up to the other end of the platform?

Alth. (to herself). It looks more serious than ever! Is he going to give me good advice? It's kind of him to care, but still——(Aloud.) Oh, but we shan't have time. See, there's our train coming up now. Couldn't you say it in the railway carriage?

[The train runs in.

Curph. (to himself). For Phœbe's edification! No, I don't quite——(Aloud, desperately.) It—it's something that concerns—something I can't very well say before anyone else—there'll be another train directly—would you mind waiting for it?

Alth. (to herself). It's very mysterious. I should like to know what it can be! (Aloud.) I—I hardly know. I think we ought, perhaps, to—but this doesn't look a very nice train, does it?

Curph. (with conviction). It's a beastly train! One of the very worst they run, and full of the most objectionable people. It—it's quite noted for it.

Alth. (to Phœbe, who hurries up with her hand-bag). No, never mind; I'm not going by this train, Phœbe; we'll wait for a more comfortable one.

Phœbe. Very good, Miss. (To herself, as she retires.) Well, if that isn't downright barefaced—I don't know what it is! I hope they'll find a train to suit 'em before long, and not stay here picking and choosing all day, or I shan't get back in time to lay the cloth for dinner. But it's the way with all these quiet ones!

Alth. Did you want to speak to me about last night, Mr. Curphew? Has my cousin Charles been getting into any mischief? I only came in afterwards; but you were looking so shocked about something. Was it because he had been to a theatre, and do you think that very wicked of him?

Curph. (to himself). I ought to manage to lead up to it now. (Aloud.) It was not a theatre exactly—it was—well, it was a music-hall.

Alth. Oh! but is there any difference?

Curph. Not much—between a music-hall and some theatres. At theatres, you see, they perform a regular play, with a connected plot—at least, some of the pieces have a connected plot. At a music-hall the entertainment is—er—varied. Songs, conjuring-tricks, ventriloquism, and—and that kind of thing.

Alth. Why, that's just like the Penny Readings at our AthenŠum!

Curph. Well, I should hardly have—but I'm not in a position to say. (To himself.) I'm further off than ever!

Alth. It couldn't be that, then; for Papa has presided at Penny Readings himself. But Charles must have told him something that upset him, for he came down to breakfast looking perfectly haggard this morning. Charles had a long talk in the library with him last night after you left, and then Papa went to bed.

Curph. (to himself). I felt sure that fellow spotted me. So he's let the cat out to old Toovey! If I don't tell her now. (Aloud.) Did Mr. Toovey seem—er—annoyed?

Alth. He looked worried, and I believe he wanted to consult you.

Curph. (to himself). The deuce he did! (Aloud.) He mentioned me?

Alth. He talked of going round to see you, but Mamma insisted on his staying quietly indoors.

Curph. (to himself). Sensible woman, Mrs. Toovey! But I've no time to lose. (Aloud.) I think I can explain why he wished to see me. He has discovered my—my secret.

Alth. Have you a secret, Mr. Curphew? (To herself.) He can't mean that, and yet—oh, what am I to say to him?

Curph. I have. I always intended to tell him—but—but I wanted you to know it first. And it was rather difficult to tell. I—I risk losing everything by speaking.

Alth. (to herself). He does mean that! But I won't be proposed to like this on a railway platform; I don't believe it's proper; and I haven't even made up my mind! (Aloud.) If it was difficult before, it will be harder than ever now—just when another train is coming in, Mr. Curphew.

Curph. (angrily, as the train passes). Another—already! The way they crowd the traffic on this line is simply dis——But it's an express. It isn't going to stop, I assure you it isn't!

Alth. It has stopped. And we had better get in.

Phœbe. I don't know if you fancy the look of this train, Miss, but there's an empty first-class in front.

Curph. This train stops everywhere. We shall get in just as soon by the next—sooner in fact.

Alth. If you think so, Mr. Curphew, wait for it, but we really must go. Come, Phœbe.

Phœbe. I only took a second for myself, Miss, not knowing you'd require——

Curph. (to himself). There's a chance still, if I can get a carriage to ourselves. (Aloud.) No, Miss Toovey, you must let me come with you. Your mother put you under my care, you know. (To Phœbe.) Here, give me Miss Toovey's bag. Now, Miss Toovey, this way—we must look sharp. (He opens the door of an empty compartment, puts Althea in, hands her the bag, and is about to follow when he is seized by the arm, and turns to find himself in the grasp of Mr. Toovey.) How do you do, Mr. Toovey? We—we are just off, you see.

Mr. Toovey (breathlessly). I—I consider I am very fortunate in [pg 137] catching you, Mr. Curphew. I accidentally learnt from my wife that you were going up about this time—so I hurried down, on the bare chance of——

Curph. (impatiently). Yes, yes, but I'm afraid I can't wait now, Sir. I—Mrs. Toovey asked me to take care of your daughter——

Mr. Toov. Althea will be perfectly safe. And I must have a few words with you at once on a matter which is pressing, Sir, very pressing indeed. Althea will excuse you.

Alth. (from the window). Of course. You mustn't think of coming, Mr. Curphew. Phœbe will look after me.

Curph. But—but I have an important engagement in Town myself!

Alth. (unkindly). You will get up quite as soon by the next train, Mr. Curphew, or even sooner—you said so yourself, you know! (In an under-tone.) Stay. I'd rather you did—you can tell me your—your secret when I come back.

The Guard. Vauxhall and Waterloo only, this train. Stand back there, please!

[He slams the door; the train moves on, leaving Curphew on the platform with Mr. Toovey.

Curph. (to himself, bitterly). What luck I have! She's gone now—and I haven't told her, after all. And I'm left behind, to have it out with this old pump! (Aloud.) Well, Sir, you've something to say to me?

Mr. Toov. (nervously). I have—yes, certainly—only it—it's of rather a private nature, and—and perhaps we should be freer from interruption in the waiting-room here.

Curph. (to himself). I wish I'd thought of that myself—earlier. Well, he doesn't seem very formidable; it strikes me I shan't find it difficult to manage him. (Aloud.) The waiting-room, by all means.

[He follows Mr. Toovey into the General Waiting-room, and awaits developments.

End of Scene IV.

Note.—When I am travelling due South, as I am now, per L. & S. W. R., to join my party, all I require may be summed up in the accompanying "Mem.," which is to this effect:—

Mem.—Give me a Pullman car, my favourite beverage, a good cigar, or an old pipe charged with well-conditioned bird's-eye, an amiable companion possessed of sufficient ready money in small change, give me likewise a pack of playing cards, let the gods grant me more than average luck at ÚcartÚ or spoof, and never can I regret the two hours and forty minutes occupied by the journey from "W't'r'o" to "P'm'th."

To start with, the line to Pinemouth is one of those "lines" that have "fallen," in the pleasantest of "pleasant places." On a broiling summer's day you pass through a wide expanse of landscape, refreshingly painted in Nature's brightest water colours—plenty of colour, plenty of water. All over the sandy plains of Aldershot, boxes of toy soldiers, with white toy tents and the smartest little flags, have been emptied out; and everywhere about the tiny figures may be seen marching, lounging, digging, riding, firing, surveying, performing evolutions to the sound of the warlike trumpet, and generally employed in a sort of undressed rehearsal of such martial business as is incidental to a Great Campaign Drama. Then, lest the spirits of the travelling tourist should rise so high that he might run the chance of "getting a bit above hisself," as horse-dealers graphically express it, he is whirled away from the war-like scene, and is taken through the peaceful grounds of Wokingham. Here to the unwonted military ardour so recently aroused in the bosom of the travelling civilian will be administered a succession of dampers in the shape of attractively-placed and most legibly printed reminders to the effect that "eligible plots" for burial are "still to be let," and that the terms for intending residents in the thriving country town of Necropolis can be obtained on application to Messrs. Somebody and Sons at Suchandsucher Place, London; the tone of these notices suggesting, in a generally festive spirit, that the good old maxim "first come first served" will be strictly observed in all matters of Necropolitan business.

Then we come to fair Southampton Water, with its marine kind of flymen waiting to take you to the boats, and the boats waiting to take you from the flymen to the yachts. On we speed through the New Forest, where those historically inclined remember William Rufus, and others, with a modern political bias, think of William Harcourt; while the grateful novel-devourer remembers that away in the forest resides the authoress of Lady Audley's Secret, and many other plots. Here, within ten minutes of our appointed time, is Terminus Number One, East Pinemouth, and, finally, West Pinemouth, which, speaking for myself individually and collectively, I prefer to East Pinemouth; at all events, at this particular time of year. Moreover, it appears that a rapidly increasing number are of my opinion, seeing how house-building, and very good house-building, too, is extending westward, and, alas and alack-a-day, threatening immediate destruction to heather, pine, fir, and forest generally. I sing:—

"How happy could I be with heather

If builder were only away!"

No sooner is a house (most of them excellently-planned houses) set up, with garden and lovely view of sea, than down in front of him squats another squatter, up goes another house, the situation is robbed of the charm of privacy, and unless the owner of the first house sits on his own roof or has a special tower built, which erection would probably involve him in difficulties with his neighbours, his view of the sea is reduced to a mere peep, and in course of time will, it is probable, be altogether blocked out. However, as Boys will be Boys, so Builders will be Builders.

One of the chief advantages offered by Pinemouth as a place where a summer holiday may be happily spent, is the facility afforded for getting away from it, in every possible direction; by sea, river, rail, and road. └ propos of "road," the fly-drivers, shopkeepers, and livery-stable keepers of P'm'th, are, for the most part, like the fly-drivers, livery-stablers, and shopkeepers at any place which boasts a recognised season. The eccentric visitor, who chooses to come out of the regulation time, must take his chance, and be content with out-of-season manners to suit his out-of-season custom; still, in the words of the immortal bard, "They're all right when you know 'em, but you've got to know 'em fust!"

As to the hiring of flys and midgets, there is a board of rules and regulations stuck up in the railway station and elsewhere, the interpretation whereof may possibly be mastered by those able and willing to devote a few days to the study of its dark sayings.

"What's the meaning of this rule?" I inadvertently ask a ruddy-faced policeman, on whose broad shoulders time unoccupied seems to be weighing somewhat heavily, at the same time pointing to one of the regulations on the board in question.

"Well, Sir," replies the civil constable, in a carefully measured tone, "it is this way"—and then he commences.

* * * * * *

I breathe again; it is half an hour since I addressed that ruddy-faced official, from whom, thank goodness, I have at last contrived to escape. He has kept me there, giving me, as it were, a lecture on the black board, telling me what this rule might mean if it were read one way, and what that rule might mean if it were read another way, and what both rules might mean if they were each of them read in totally different ways; and how one was labelled "a" (which I saw for myself), and how another was distinguished by being lettered "b"; and how he (my constabulary instructor) "wasn't quite sure himself whether his reading of 'em was quite right;" then going over all the paragraphs again in detail, indicating each syllable with his finger, as though he were teaching an infant spelling-class, and finally coming to the conclusion whereat Bottom the Weaver arrived when he surmised that it was all "past the wit of man to understand," and advising me that, on the whole, if any particular case of attempted extortion should happen to arise, I should do well not to appeal to these rules and regulations, but to summon the extortionist before the nearest police magistrate. "But," said he, as if struck by a new light, "it may be that this rule 'a'"——And here he faced round, in order more closely to inspect the mysterious cryptogram. Taking advantage of his eye being off me for one second, which it had never once been during the previous thirty minutes, I stepped as lightly and rapidly away as my thirteen stone will permit, and fled. I fancied I heard him calling after me that he had discovered something or other; but not even if he had shouted "Stop thief!" should I have paused in my Mazeppa-like career. "Once aboard the lugger," I exclaim to myself, quoting the melodramatic pirate, "and I am free!" So saying, I entered the hospitable gates of my present tenancy, and sank exhausted on the sofa.

Mem.—Never again ask a policeman to explain strange cab-rules and regulations.

["Mr. Gosse holds a middle station between the older and the younger schools of criticism. He is neither a distinguished and respectable fossil nor a wild and whirling catherine-wheel."—AthenŠum.]

Oh, luckiest of Critics! What

A joy unquestioning to feel

On such authority he's not

"A wild and whirling catherine-wheel."

And is it such a wild idea

To think that clever Mr. Gosse'll

Rejoice he's reckoned not to be a

"Respectable, distinguished fossil?"

Would-be Considerate Hostess (to Son of the House). "How inattentive you are, John! You really must look after Mr. Brown. He's helping himself to Everything!"

[Discomfiture of Brown, who, if somewhat shy, is conscious of a very healthy appetite.

["The overwhelming vote of the Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Lancashire miners against accepting any reduction, or even submitting the wages question to arbitration, does not encourage any very sanguine hopes of the Nottingham Conference."—Westminster Gazette.]

"My sentence is for open war!" Thus spake

Fierce Moloch, when within the marly lake

"The Stygian Council" in dark conference met!

"The scepter'd king's" advice prevaileth yet,

And Mammon's self, who in his pristine might

Stooped to the avowal that "all things invite

To peaceful counsels," now in stubborn mood

Urges resistance—at the cost of blood!

Yes, Mammon, musing on "the settled state

Of order," at that dim chaotic date,

Speaks, in the mighty-voiced Miltonic way,

"Of Peace," and "how in safety best we may

Compose our present evils, with regard

Of what we are and were." Mammon's award

Is now more martial: Mammon, swoln and proud

With domination o'er the moiling crowd,

Lifts a most arrogant head, and coldly curls

An insolent lip against the clod-soul'd churls

Whose destiny and duty 'tis to slave

'Twixt cradle comfortless and cheerless grave,

To glut his maw insatiate!

Proud is Pelf;

But might not Legend lesson Labour's self?

"Thus sitting, thus consulting, thus in arms!"

Comes not the echo loud of wild alarms

To Labour's Conference? Violence and wreck,

Incendiary hate that sense should check,

Mad mob-intimidation, brutal wrath,—

These are strange warders for the pleasant path

Of human progress! While they crowd and clash

In headlong stubbornness and anger rash,

Whilst factories burn, and workmen fall in blood,

And women mourn, and children moan for food,

Unnumbered multitudes the misery feel

Who share not in its making!

Mars' red steel

Is sheathed to-day at Arbitration's nod;

Hath this no lesson for the milder god?

Vulcan, the smithy-toiler, and his crowd

Of sooty Cyclops, raging fierce and loud,

Impetuous, implacable, whilst Mars,

That savage god of sanguinary wars,

Awaits the award of Arbiters of Peace!

Strange contrast!

"Cease, great hammer-wielder, cease!"

Says the Sword-bearer. "Cease this frenzied fray.

Try Arbitration—'tis the gentler way,

And wiser. I have tried it—shall not you?

Call back your Cyclops, let not them imbrue

Swart hands in Battle's sanguinary hue.

Shall War, now partly driven from the field,

Find refuge in the factory, nor there yield

To the sage suasion of mild Equity,

At whose just Arbitration even I

Suspend or drop the sword?"

So Mars, and so

All friends of Labour. Raise no stubborn "No!"

At Arbitration's offering, seeing that there

Lies fairest hope of an adjustment fair

'Twixt clashing claims, which if they "fight it out"

In war's wild way may put to utter rout

Humanity's fairest hopes. Oh, time enough

When Arbitration fails to essay the rough

And ruddy road of Mars. Stay, Vulcan stay!

Or blameless hosts long-menaced by your fray

May have a stern effective word to say!

And you, as once of old, though stout and tall,

Kicked out of heaven may have a maiming fall!

(Doctor to Stanley's Emin Pasha Relief Expedition. Died September 10, aged 35.)

"Rarest doctor in the world!"

Tribute rare from sturdy Stanley!

Skilful, tender, modest, manly!

England's flag may well be furled

Over the young hero's bier,

Whose memory is to England dear.

Africa has cost us much.

Fortune send us many such!

Mrs. R. says she understands that disaffecting (disinfecting) fluid was discovered by the great Condy, a celebrated Frenchman.

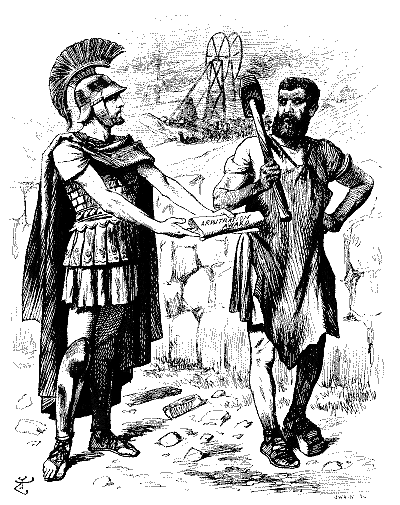

Mars. "LOOK HERE, BROTHER VULCAN!—WHEN EVEN I HAVE KNOCKED UNDER TO 'ARBITRATION,' SURELY YOU MIGHT TRY IT?"

You're not in-fal'be'-le, Doctor dear—

Excuse the painful pun,

Though you merit treatment e'en more severe

For all the ill you've done.

You held a nasty cloud of doubt

Above our sunlit sky,

And now at length we've found you out,

Our summer is near gone by.

Yes, a summer indeed we've had this year,

In spite of your doleful croak,

Though perhaps your early prediction drear

Was simply a practical joke—

A wearisome joke that wouldn't die,

For every man one met

Would remind one of Falbe and his prophecy—

"We're soon to have lots of wet."

But what of the tradesmen who laid in store

Of "brollies" and mackintosh

On the strength of your hint as to rain galore

And unlimited Autumn slosh?

Oh, Falbe, if they but got hold of you,

What a tune they would perform!

There's one prediction we'd warrant true—

You'd find it extremely warm!

Mrs. R. "Christopher darling, I never can remember whether 'Soda-water' is written as One Word or Two joined together by a Syphon?!"

(By One of the "Thirty-six Tyrants" of the Liberal Party.)

Hanbury, Bowles, and Bartley,

Talk and wrangle tartly;

Sour as unripe cranberry

Are Bartlet, Bowles, and Hanbury;

Three most sorrel souls

Are Hanbury, Bartley, Bowles!

They the blame would fix

On the Liberal Thirty-six.

As "tyrants," what are we

Compared with that "Tartar Three,"

Who—but I'll be mum:—

"I hear the Tartar drum!"

Loudly thumped, and smartly,

By Hanbury, Bowles, and Bartley!

["The appearance of a Ladies' Eight on the Thames in the Cookham district has attracted considerable attention.... Mr. R. C. Lehmann has handled the rudder-lines on more than one occasion, and General Hammersley has also been out as coxswain."—Daily News.]

The Ladies' Eight at Cookham rows right well,

There's many a crew of men would not get near them;

But is it not a saddening truth to tell?

The ladies often take a man to steer them!

Summers come and Summers go, Sir,

As appints the course of Nater:

In the winter I'm a grocer,

In the Summer I'm a waiter.

I'm a waiter at the sea-side;

There's the "Grand Hotel" up yonder—

Never hancient Rome or Greece eyed

Poet of the Summer fonder.

Though I'm quite self-heddycated,

Yet I love the Summer golden;

Every gent on whom I've waited

Feels 'isself to me beholden;

As appropriate verse I quote, Sir,

I can watch 'em growing gladder:

They're aweer 'ow much I dote, Sir,

On the golden light and shadder.

"Tipped with gold" the clouds and copses,

"Tipped with gold" yon arf-awake ox,

"Tipped with gold" the sheep and wapses,

"Tipped with gold" the 'arvest 'aycocks;

"Tipped with gold" the cows as browses,

Ditto waves and fish and sea-things,

Ditto shops and dwellin'-'ouses,

Ditto our hotel and tea-things.

"Tipped with gold." It's langwidge splendid,

Summing hup the Summer brightly—

Good for Nater, good for men, did

Gentlemen but read it rightly.

"Tipped with gold" still what I quote is:

'Umble folk should not be proud, Sir,—

Which I 'opes you've marked our notice—

"No gratuities allowed," Sir!

O dubious hybrid, what your patronymic

Or pedigree may be, does not much matter;

But if my own attire you mean to mimic,

And flaunt the fact that you, too, have a hatter—

Well then, in self-defence I'll pick with you

A bone or two.

Perchance you have a motive, deep, ulterior,

In donning head-gear borrowed from banditti?

You wish to show an intellect superior,

(And hide a profile which is not too pretty?)

Or is it, simply, you prefer to go

Incognito?

A transmigrated Balaam's self you may be,

But still I bar your method of progression;

For while I sit, as helpless as a baby,

And scale each precipice in steep succession,

You scorn the mule-track, and pursue the edge

Of ev'ry ledge.

How can I scan with rapt enthusiasm

These Alpine heights, when balanced Ó la Blondin,

While you survey with bird's-eye view each chasm?

I cry Eyupp! Avanti!—you respond in

Attempts straightway to improvise a

"chute" For me, you brute!

Basta! per Bacco! I'll no longer straddle

(With cramp in each adductor and extensor)

This seat of torture that they call a saddle!

Va via! in plain English, get thee hence, or——

On second thoughts, to leave unsaid the rest,

I think, were best!

A little saint! At church I see you pray,

As if a worldly thought would make you faint,

Serenely walking on your heavenly way,

A little saint.

And yet—although I would make no complaint.—

You quickly doff the grave to don the gay.

Your cheeks aren't wholly innocent of paint,

You flirt outrageously the livelong day.

Colloquially, dear Maude, in fact you ain't

I'm thoroughly rejoiced to say

A little saint.

["It would be distinctly an advantage to girls to serve as clerks in a lawyer's office before they launched forth on the world."—Weekly Paper.

Edwin was sad indeed, for all had gone against him. He had lost everything. Even the furniture in the house he occupied was scarcely his—for all he knew, at any moment it might be seized in execution.

"What shall I do?" he asked again, wringing his hands and tearing his hair.

"Cheer up," was the reply, spoken in a soft voice and by a sweet-faced girl. It was Angelina.

"And you have come to me in my distress—after I have treated you so badly?" he said, with a flush of shame colouring his hitherto pale face.

"No, darling," returned the golden-haired maiden, looking into his brown eyes with optics of an azure hue. "Do not say that you have behaved badly to me. You wrong yourself; you do, indeed."

"Have I not deserted you?" he asked in a tone of bitter sorrow.

"But only after you had written me letters upon which I could base an action for breach of promise," murmured the forgiving girl.

"But do you propose to proceed upon them?" he asked earnestly.

"Yes, my own. To quote that touching song you so frequently sang to me in the gilded days of the golden past, 'it will be the best for you and best for me.' I shall certainly ask for substantial damages."

"And is there no way to avoid this crushing, this final disaster?" asked the young man, in deep distress.

"Dearest, you know that I have studied the law. Well, I would propose that you should carry out your contract. I have here the form which requires but the registrar's signature to make us man and wife. What do you say to the matter being settled to-morrow?"

"If it must be so, it must," returned Edwin, in a tone of resignation. "And now, as we are to be married to-morrow, let us dine together. I have an invitation from my aunt at Putney to stay with her until my goods have been seized and sold. I am off. She will extend to you her hospitality."

"Oh, my betrothed, I cannot come." she sobbed. "I am kept here by duty."

"Well, as you will," he replied, carelessly. "But I suppose we meet at noon at the registrar's to-morrow?"

"Yes, for by that time all will be over. The goods will be removed, and I shall be free—free to become your wife."

"But what have you got to do with my property?"

Then came the sorrowful admission.

"Oh, Edwin, my own. You know I am in a lawyer's office. For the moment I am their guardian. Yes, darling, I am the woman in possession!"

Cook (to Vicar's Wife). "And what's to be done with the Sole that was saved yesterday, Ma'am?"

When mirthful humours reign supreme,

And heated revellers are prone

To make sound wisdom kick the beam,

While vain wine-bubble wit alone

Has weight, we, mostly, can depone

To feeling joy to blankness fade

On finding, now our chance has flown,

The repartee we might have made.

One prating fool is apt to deem

No jesting pretty save his own;

Another strives, whate'er the theme,

To make all comers, passive grown,

"Perform the office of a hone"*

For sharpening his witty blade;—

Too late below our breath we moan

The repartee we might have made.

Of course, it now contrives to seem

So patent to the dullest drone;

And, if we wake or if we dream,

It weighs upon us like a stone,

But, unlike, cannot now be thrown;

And thus we languish in the shade,

Because the world has never known

The repartee we might have made.

Envoi.

My friends, a certain sage has shown

What paving-stones below are laid;

Now learn that on each blast is blown

The repartee we might have made!

"Fungar vice cotis, acutum

Reddere quŠ ferrum valet, exsors ipsa secandi."

Horace. De Arte Poetica.

["Every organism must have sprung from a unicellular ancestor."—Dr. Burdon Sanderson's Presidential Address to the British Association.

That life is a sell we most of us know,

But Doctor Burdon Sanderson tells

It began in a cell oh! Šons ago!

And Progress is merely the growth of cells.

And is that what you were fashioned for

Our "unicellular ancestor"?

"The specific energy of cells"

Is a taking phrase, but what does it mean?

Is it merely the Life that in most things dwells,

Or must we go reading the lines between,

To find what you really were fashioned for,

Our "unicellular ancestor"?

Words, words, words! What matter if

They're scientific and pseudo-oracular.

Or, scouting a terminology stiff,

Couched in sciolist's plain vernacular!

Do they tell us what you were fashioned for,

Our "unicellular ancestor"?

Burdon's burden, like Villon's of old

Leaves us a prey to doubt and fear.

Your meaning and purpose when shall we be told

Oh cells—or snows—of yester-year?

Or what you truly were fashioned for

Our "unicellular ancestor"?

The Modern "Tender" Passion.—Bimetallism.

House of Commons, Monday, September 11.—Alpheus Cleophas walking about the Lobby with a new foot-rule obtrusively held in his hand. Thought at first he was going to probe somebody, after the fashion of Swift MacNeill, in rare access of ferocity.

"No," he said, when I asked him if that was his business; "we are presently going to debate question of appointment of Duke of Connaught to command at Aldershot. I want to know precisely how far out of the line of fighting the Duke was at Tel-el-Kebir. You know Campbell-Bannerman's suave manner. When I put question to him, he'll say, 'How can I tell the Hon. Member, not having a foot rule in my pocket.' As soon as he says that, I whip this out; he will sit confounded, and either we shall get at the truth of a matter with which country is deeply concerned, or Campbell-Bannerman must go. I have no personal interest in such a contingency. If there were a vacancy at the War Office, it is, of course, quite possible that Mr. G. might think of me. I fancy in Committee on the Army Estimates I have shown I know a thing or two. But that is neither here nor there. It will be time to decide on the offer when it is made, if indeed prejudices, from which even Liberal Ministry are not free, do not stand in the way. At present I want to know, within a foot or two—no one can say I'm unreasonable—how far off the fighting the Duke of Connaught stood, and Campbell-Bannerman will have to answer the question."

[pg 143] [pg 144]Turned out that Alpheus did not find opportunity of bringing in the foot measure. Dalziel raised question Appointment of Royal Duke to command at Aldershot; a ticklish subject for young Member to take up. Dalziel's manner excellent; gave tone to debate, happily preserved throughout; several times Alpheus Cleophas brought out foot-rule and shook it at Campbell-Bannerman. War Minister, naturally well up in strategy, had observed precaution of placing on his flank his Financial Secretary, Woodall, V.C. If there was any probing to be done that veteran would receive first onslaught. Thus assured, Campbell-Bannerman made admirable defence of a position held in advance to be shaky. Came out of Division Lobby with flying colours and majority of 117.

Business done.—Army Votes in Committee of Supply.

House of Lords, Tuesday.—Lords met to-day—at least Lord Denman and the Bishop of Ely did. They, facing each other from either side of otherwise empty chamber, heard Royal assent given to number of bills, and House adjourned for seven days. Don't know what we should have done this week in Lords but for Denman. Everyone else gone out of town. He still treads the burning deck, his plum-hued skull-cap giving touch of chastened colour to passages leading to and from the House. Severe taste might object that it is a little painful in conjunction with the brilliant red of the leather-covered benches. But whoever responsible for selection of that decoration should have thought of Denman's skull-cap. He was here yesterday; did quite a lot of business; moved Second Reading of his Woman's Suffrage Bill.

"My Lords," he said, rising from the seat which the burly figure of the Markiss usually fills, "I think there is an opportunity of making substantial progress with this important measure. If your Lordships will be so good as to suspend the Standing Orders, as has just been done in case of Naval Defence Amendment Bill, we could carry the measure through all the stages before your Lordships rise."

For all answer Kensington, on Woolsack in absence of Lord Chancellor pacing the battlements of his lordly castle at Deal, put the question that the Bill be read a second time; declared in same breath "the Not-Contents have it;" and so Denman and his little Bill contemptuously swept aside.

"I thought better of them, Toby," he said, when I met him an hour later still hovering round the closed doors of the House. Over his arm was his rusty old coat; in one hand a stick; in the other a hat that had seen silkier days. There was a tear in his eye, and a tremor in his still musical voice. "It seemed as if a better day had dawned; and that the House of Lords was about at last to recognise in me the worthy son of a father once their pride. Last week the change suddenly came. It was Denman this and Denman that, and 'we must see what we can do about your Suffrage Bill.' The Markiss going to his seat on Wednesday gave me a friendly nod and smile. Usually he never sees me except when I get on my legs, when he forthwith moves the Adjournment of House. As for the Whips, I fancied they must have been looking up my speeches in Hansard, and learned what they had lost by not being in their place to hear them. 'I trust your lordship is well, and do not find the electric light too glaring?' 'You must take a place by the table so that you can hear Salisbury and Rosebery.' 'We shan't keep you up late on Friday; have arranged to take Division at midnight so that you may get home in good time. But you'll be there, of course?'"

"And were you there?" I asked.

"Of course I was there, and voted in majority against Home-Rule Bill. Came down yesterday prepared to make most of this new and pleasant turn. Got up to ask Kimberley question as to whether postponement of Home-Rule Bill would date from Friday or Saturday. Nice point, you know. Everything depends upon it. No one had discovered point but me. Expected Government and House would be grateful. What happened? Kimberley snubbed me; House sniggered; my Woman's Suffrage Bill, about which Opposition Whips so anxious last week, treated with usual contumely. I propose to deal with Coal Strike; they move the Adjournment, and leave me speechless at the table. Begin to think that all they wanted was my vote to swell majority against Home-Rule Bill. A weary world, Toby. Saddest of all for neglected statesmen in our gilded Chamber. Should you ever be made a peer take an old man's advice and do everything you can to obscure your native abilities. Once you excite the jealousy of men like the Markiss, and implant in their bosom suspicion that if they don't look out you may supplant them, you are lost. Perhaps I made a mistake when I admitted Farmer-Atkinson to my councils. You remember him in the other House as Member for Boston? We had a plan——but no matter. Still, if Farmer-Atkinson had led the Commons and I the Lords, you would have seen something. Perhaps we were too reckless in our open colloguing in the Lobby. Gladstone smelt a rat. Salisbury saw it moving in the air; the instincts of self-preservation triumphed over political animosity and the rivalry of a lifetime. They put their heads together; the coffers of the secret-service money were depleted; the illimitable resources of the State were in other ways drawn upon. Where is Farmer-Atkinson now? I am left solitary and friendless. For a while the Unholy Alliance triumphs; but they will find they have not done with Denman yet."

The old gentleman took off his skull-cap; carefully wrapped it up; hid its plumage in his tail-pocket; and pressing his hat over his brow, shook his grey head, and walked wearily down the corridor.

Business done.—House of Lords adjourned for a week.

Saturday, 2.40 A.M.—"Who goes home?" I hear the cry resounding through the Lobby. Well, if no one minds, I think I will. Been here since half-past three yesterday. For the matter of that, been here since the 31st of January. Coming down again at noon to sit till Squire of Malwood can see his prospect clear to bringing about Adjournment next Saturday.

Business done.—Mostly all.

Calf-love is a passion most people scorn,

Who've loved, and outlived, life and love's young morn;

But there is a calf-love too common by half,

And that's the love of the Golden Calf!

["The occupation for women exclusively is that of charing."—Daily Paper.]

Whilst year by year men kinder grow.

And from employments won't debar Woman,

It's quite astonishing to know

Man's everything except a charwoman.

Q. Why is a modern advertiser like an ancient knight-errant?

A. Because he is inspired by the spirit of "ad"-venture.

Transcriber's Note:Sundry damaged or missing punctuation has been repaired. Corrections are also indicated, in the text, by a dotted line underneath the correction. Scroll the mouse over the word and the original text will appear. Page 135: 'hallo'd' corrected to 'hollo'd', to match the others. ("They hunted and they hollo'd,an' the next thing they did find") |

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol.

105 September 23, 1893, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, OR THE LONDON ***

***** This file should be named 38671-h.htm or 38671-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/8/6/7/38671/

Produced by Malcolm Farmer, Lesley Halamek and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.