Project Gutenberg's Voices from the Past, by Paul Alexander Bartlett

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

** This is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg eBook, Details Below **

** Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. **

Title: Voices from the Past

Author: Paul Alexander Bartlett

Editor: Steven James Bartlett

Illustrator: Paul Alexander Bartlett

Release Date: April 17, 2012 [EBook #39468]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK VOICES FROM THE PAST ***

Produced by Al Haines

From the cover

of Voices from the Past:

From the cover

of Voices from the Past:

In Voices from the Past, a daring group of five

independent novels, acclaimed author Paul Alexander Bartlett accomplishes a tour

de force of historical fiction, allowing the reader to enter for the first

time into the private worlds of five remarkable people: Sappho of Lesbos, the

famous Greek poet; Jesus; Leonardo da Vinci; Shakespeare; and Abraham Lincoln.

Each novel appears here in its entirety within a single unique volume of 644

pages beautifully illustrated by the author-artist.

Bartlett’s writing has

been praised by many leading authors, reviewers, and critics, among them:

James Michener, novelist: “I am much

taken with Bartlett’s work and commend it highly.”

Charles Poore in The New York Times:

“...believable characters who are stirred by intensely personal concerns.”

Grace Flandrau, author and historian:

“...Characters and scenes are so right and living...it is so beautifully done,

one finds oneself feeling it is not fiction but actually experienced fact.”

James Purdy, novelist: “An important

writer... I find great pleasure in his work. Really beautiful and

distinguished.”

Alice S. Morris in Harper’s Bazaar:

“He tells a haunting and beautiful story and manages to telescope, in a

brilliantly leisurely way, a lifetime, a full and eventful lifetime.”

Russell Kirk, novelist: “The scenes are drawn with power. Bartlett is an

accomplished writer.”

Paul Engle in The Chicago Tribune: “...articulate,

believable ... charms with an expert knowledge of place and people.”

Michael Fraenkel, novelist and poet:

“His is the authenticity of the true and original creator. Bartlett is

essentially a writer of mood.”

Willis Barnstone, Sappho scholar and

translator: “A mature artist, Bartlett writes with ease and taste.”

J. Donald Adams in The New York Times: “...the

freshest, most vital writing I have seen for some time.”

Pearl S. Buck, Nobel Laureate in

Literature: “He is an excellent writer.”

Herbert Gorman, novelist and

biographer: “He possesses a sensitivity in description and an acuteness in the

delineation of character.”

Ford Madox Ford, English novelist,

about Bartlett: “...a writer of very considerable merit.”

Lon Tinkle in the Dallas Morning

News: “Vivid, impressive, highly pictorial.”

Joe Knoefler in the L.A. Times:

“...an American writer gifted with...perception and sensitivity.”

Frank Tannenbaum, historian:

“...written with great sensibility”

Worchester

Telegram: “Between realism and poetry...brilliant, colorful.”

²

eaders of this book who would

like to acquire the bound illustrated volume can do this through any bookstore

by giving the store the published book’s ISBN, which is

ISBN 978-0-6151-4120-6

or you can order the book online through

Barnes & Noble:

http://search.barnesandnoble.com/booksearch/results.asp?ATH=Paul+Alexander+Bartlett&z=y

Amazon.com:

http://www.amazon.com/s/ref=ntt_athr_dp_sr_1?_encoding=UTF8&sort=relevancerank&search-alias=books&field-author=Paul%20Alexander%20Bartlett

If you would like to ask your local library to acquire a copy, it’s

helpful to the library to give the book’s ISBN, mention that the book is

distributed by Ingram and by Baker & Taylor, and give the book’s Library of

Congress Catalog Card Number, which is 2006030830.

²

About Autograph Editions

Autograph Editions is committed to bringing readers some

of the best of fine quality contemporary literature in unique, beautifully

designed books, many of them illustrated with original art specially created

for each book. Each of our books aspires to be a work of art in itself—in both

its content and its design.

The press was established in 1975. Over the years Autograph

Editions has published a variety of distinguished and widely commended books of

fiction and poetry. Our most recent publication is the remarkable quintet, Voices

from the Past, by bestselling author Paul Alexander Bartlett, whose novel, When

the Owl Cries, has been widely acclaimed by many authors, reviewers, and

critics, among them James Michener, Pearl S. Buck, Ford Madox Ford, Charles

Poore, James Purdy, Russell Kirk, Michael Fraenkel, and many others.

eBook Notice

n

addition to this book’s availability in a printed edition, the copyright holder

has chosen to issue this work as an eBook through Project Gutenberg as a free

open access publication under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs

license, which allows anyone to distribute this work without changes to its

content, provided that both the author and the original URL from which this

work was obtained are mentioned, that the contents of this work are not used

for commercial purposes or profit, and that this work will not be used without

the copyright holder’s written permission in derivative works (i.e., you may

not alter, transform, or build upon this work without such permission). The

full legal statement of this license may be found at

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode

Voices from the Past

A Quintet:

Sappho’s

Journal

Christ’s

Journal

Leonardo

da Vinci’s Journal

Shakespeare’s

Journal

Lincoln’s

Journal

Books by

PAUL ALEXANDER BARTLETT

Novels

Voices

from the Past:

Sappho’s Journal ` Christ’s Journal ` Leonardo da Vinci’s Journal

Shakespeare’s Journal ` Lincoln’s Journal

When the Owl Cries

Adiós Mi México

Forward, Children!

Poetry

Wherehill

Spokes

for Memory

Nonfiction

The Haciendas of Mexico:

An Artist’s Record

Voices from the Past

A Quintet:

Sappho’s

Journal

Christ’s

Journal

Leonardo

da Vinci’s Journal

Shakespeare’s

Journal

Lincoln’s

Journal

by

Paul Alexander Bartlett

and

Illustrated by the Author

AUTOGRAPH EDITIONS

Salem, Oregon

AUTOGRAPH EDITIONS

P. O.

Box 6141 Salem, Oregon 97304

Î Established

1975 Ó

This book is protected by

copyright. No part

may be reproduced in any

manner without

written permission from the

publisher.

Copyright © 2007 by Steven James Bartlett

First Edition

ISBN 978-0-6151-4120-6

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2006030830

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Bartlett, Paul

Alexander.

Voices from the past : a

quintet : Sappho's journal, Christ's journal, Leonardo

da Vinci's journal, Shakespeare's journal, Lincoln's journal / by Paul

Alexander

Bartlett and illustrated by the author ; edited by Steven James Bartlett. --

1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: "A

collection of five historical novels written in the form of

journals by the Greek poet Sappho of Lesbos, Christ, Leonardo da Vinci,

Shakespeare, and Lincoln, integrating their thought, writings, and the

testimony

of others"--Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-6151-4120-6

1. Sappho--Diaries--Fiction. 2. Jesus

Christ--Diaries--Fiction. 3. Leonardo, da Vinci,

1452-1519--Diaries--Fiction. 4.

Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616--

Diaries--Fiction. 5. Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865--Diaries--Fiction. I.

Bartlett,

Steven J. II. Title.

PS3602.A8396V65

2006

813'.6--dc22

2006030830

Voices from the Past

CONTENTS

Preface by Steven James Bartlett xiii

Sappho’s Journal

Foreword by Willis Barnstone 3

Sappho’s Journal 5

Christ’s Journal 155

Leonardo da Vinci’s Journal 221

Shakespeare’s Journal 343

Lincoln’s Journal 511

About the Author 621

Colophon 625

PREFACE

Steven James Bartlett

Senior Research Professor of

Philosophy, Oregon State University

and

Visiting Scholar in Psychology

& Philosophy, Willamette University

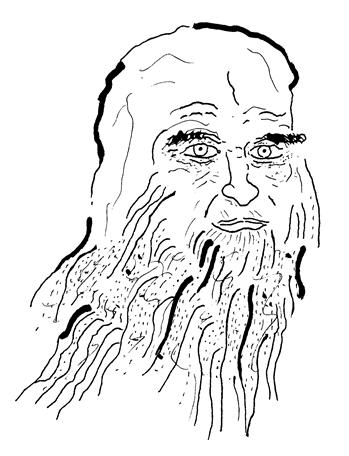

oices from the Past is a

quintet of novels that describe the inner lives of five extraordinary people.

Progressing through time from the most distant to the most recent they are:

Sappho of Lesbos, the famous Greek poet; Jesus; Leonardo da Vinci; Shakespeare;

and Abraham Lincoln. For the most part, little is known about the inward

realities of these people, about their personal thoughts, reflections, and the

quality and nature of their feelings. For this reason they have become no more

than voices from the past: The contributions they have left us remain, but

little remains of each person, of his or her personality, of the loves, fears,

pleasures, hatreds, beliefs, and thoughts each had.

Voices from the Past was written by Paul Alexander

Bartlett over a period of several decades. After his death in an automobile

accident in 1990, the manuscripts of the five novels were discovered among his

as yet unpublished papers. He had been at work adding the finishing touches to

the manuscripts. Now, more than a decade and a half after his death, the

publication of Voices from the Past is overdue.

Bartlett is known for his fiction, including When the Owl

Cries and Adiós Mi México, historical novels set during the Mexican

Revolution of 1910 and descriptive of hacienda life, Forward, Children!,

a powerful antiwar novel, and numerous short stories. He was also the author of

books of poetry, including Spokes for Memory and Wherehill, the

nonfiction work, The Haciendas of Mexico: An Artist’s Record, the

first extensive artistic and photographic study of haciendas throughout

Mexico, and numerous articles about the Mexican haciendas. Bartlett was also an

artist whose paintings, illustrations, and drawings have been exhibited in more

than 40 one-man shows in leading museums in the U.S. and Mexico. Archives of

his work and literary correspondence have now been established at the American

Heritage Center of the University of Wyoming, the Nettie Lee Benson Latin

American Collection of the University of Texas, and the Rare Books Collection

of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Paul Alexander Bartlett’s life was lived with a single value

always central: a sustained dedication to beauty, which he believed was the

most vital value of living and his reason for his life as a writer and an

artist. Voices from the Past reflects this commitment, for he believed

that these five voices, in their different ways, express a passion for life,

for the creative spirit, and ultimately for beauty in a variety of its

forms—poetic and natural (Sappho), spiritual (Jesus), scientific and artistic

(da Vinci), literary (Shakespeare), and humanitarian (Lincoln). In this work,

he has sought, as faithfully as possible, to relay across time a renewed lyrical

meaning of these remarkable individuals, lending them his own voice, with a

mood, simplicity, depth of feeling, and love of beauty that were his, and, he

believed, also theirs.

The journal form has been used only rarely in works of

fiction. Bartlett believed that as a form of literature the journal offers the

most effective way to bring back to life the life-worlds of significant,

unique, highly individual, and important creators. In each of the novels that

make up Voices from the Past, his interest is to portray the inner

experience of exceptional and special people, about whom there is scant

knowledge on this level. During the many years of research he devoted to a

study of the lives and thoughts of Sappho, Jesus, Leonardo, Shakespeare, and

Lincoln, he sought to base the journals on what is known and what can be

surmised about the person behind each voice, and he wove into each journal

passages from their writings and the substance of the testimony of others. Yet

the five novels are fiction: They re-express in an author’s creation lives now

buried by the passage of centuries.

I am deeply grateful to my wife, Karen Bartlett, for her

faithful, patient, and perceptive help with this long project.

✧

For

my father,

Paul

Alexander Bartlett,

whose

kindness, love of beauty and of place

will

always be greatly missed.

Sappho’s Journal

“Violet-haired, pure

honey-smiling Sappho”

– Alcaeus

FOREWORD

Willis Barnstone

Distinguished Professor

Emeritus of Comparative Literature

Indiana University

aul Alexander Bartlett’s journal of

Sappho is a masterful work. I had recently completed a translation of the

extant lines of Sappho and am familiar with his problems. He was faced with the

almost impossible task of reconstructing the personality of Sappho and her

background in ancient Lesbos. To my happy surprise he did so, in a work which

is at once poetic, dramatic and powerful. In Sappho’s Journal he

does more than create a vague illusion of the past. He conveys the character of

real people, their interior life and outer world. A mature artist, he writes

with ease and taste.

Sappho’s poetry, quoted

in this novel, is included with the translator’s permission. The poems appeared

in Sappho, Lyrics in the Original Greek, with translations by Willis

Barnstone, Anchor Books, Doubleday, 1965.

For clarity, the

calendar used by Sappho has been translated into our modern calendar.

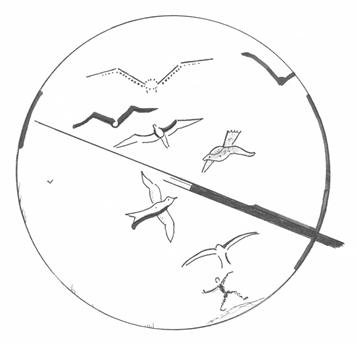

Sappho, walking on her island beach,

pauses by a broken amphora:

With one foot, she nudges the terra cotta and black jar,

its painted chariot, charioteer and horses:

The charioteer wears a laurel wreath.

Sappho, about 30 years old,

her hair braided around her head,

naked, sandaled, saunters along the Mediterranean,

gulls and pelicans flying, surf and gull sounds in early morning

yellow.

Villa

Poseidon, Mytilene

Villa

Poseidon, Mytilene

642 B.C.

he great storm beats across the

island, rattling the olive and the cypress, piling the surf on the beach,

hissing the rain across my roof. It is cold and the light of my terra cotta

lamp is cold. Some say that a storm will wash away our island, but I do not

believe it. Our island will be here long after I have gone, and so will our

town, my dear Mytilene, so wrong, so right.

Alcaeus would revel in this gale and go out in it and let

the rain lash him and then he would come and take me in his arms.

The storm will rage all night and the gutters spew, and I

will rage at my solitude, a solitude that grows and grows.

Growl on, spew on, beat and tramp—tomorrow’s sun will return

and the sea’s eye will glitter and I will gaze across the bay—and Alcaeus will

not be here.

My feet are cold and the lamp is weak and the wax hard, and

I must go to bed.

P

Yesterday, the wine workers gathered at a nearby vineyard,

old men and girls, in tattered clothes, some lazy, some hard-working, pressing

the grapes, many of them my friends. Spade-bearded Niko directed the pressing,

sitting at the base of an oak, wearing a stained robe, his voice low. Women carried

hampers of grapes loaded with purple clusters, the women’s skirts wet with dew,

the grapes mottled with damp. Clouds made the day cool. Someone toyed with a

flute, the men treading, emptying husks over sandy soil, now and then pausing

to talk under the oak, the circular press letting out its red, everyone

tasting. Many amphorae were broken, before they were finally filled and capped.

I wanted to help. How sweet the smell flooding my nose.

P

Atthis has been my girl-child today and we have strolled

together up the long, long path to the outcrop, beyond the temple. Atthis and

tall white marble columns, with their busy apricot-breasted swallows, have

assuaged my loneliness. How lonely we become, as we grow older, even when there

is someone to share. The key to self gets lost; self-assurance diminishes.

Once, it was only necessary to dash around the garden or throw back one’s head

and laugh...

Yellow-headed Atthis, lazy-eyed, sitting on the steps of the

temple ruin, wove a flower wreath for me and I wove one for her. Then,

returning home, we bathed at our fountain, splashing each other, the sun on us

and the slippery marble. Afterwards, we lay down and slept, and I dreamed of a

ship at sea, her mast broken, her tangled sail and rigging dragging.

Will the war never end?

P

Fog, as grey as a shepherd’s cloak, ruffled the bay for a day

and a night. Then, stabbing us, came clarity, and inside that clarity, centered

in it, a brown intaglio, a small wooden carving, first one ship and then

another. Our fleet had sailed back to us! I watched from the terrace, unable to

speak. Atthis ran up to me. Anaktoria came. Gyrinno came. Boys yelled. Old men

rushed past the house. Dogs barked. Someone banged a drum. Such clamoring!

But was it joyous news, I asked myself? Why were the women

in a knot at the corner? Why hadn’t fast rowers raced to tell us? Had the fog

tricked the fleet?

Changing my clothes, putting on new sandals, I walked to the

pier and the seagulls screamed and we waited and waited. People surged all

about, saying wild things, shrieking—then, ominously, fell silent. Their shouts

were better than their silence. The ocean seemed too calm, as if it had been

smothered by the fog or dreaded the arrival of our fleet.

I had pictured the ships as fast moving, bright on bright

water.

As the first one approached, I saw no happy faces, no lifted

hands, no raised shields, no plumed helmets at the rail, no flags.

I heard an oar drag and in that sound I heard the rasp of

death. If Alcaeus is dead, I will take poison—and I saw myself going to Xerxes,

our Persian chemist, and asking for the powder. We had agreed, years back,

during another crisis, that he would allow me this gift to free myself, if I

must. His yellow face vanished, as I watched an anchor plunge slowly and saw the

sail topple into the water and heard a man cry some name.

Shouts went up.

A chorus began.

Voices caught our song, way out at sea, assuring us that

these were not phantoms.

Alcaeus?

Ten years ago, almost ten—ten years ago, he had left

Mytilene, the wars sweeping him away. Ten years we had lived with fear creeping

about our island. Ten years—how my fingers trembled. I saw those years, there

on the wharf, saw them in the gulls’ wings, in the distraught faces about me,

my girls’, my friends’, my neighbors’. We had all waited for this homecoming.

And now, now our fleet was gliding toward us, grey-hulked, no flags raised,

oars shuffling like sick crabs.

Was it defeat or half-victory? Who, among our men, was lost,

dead, or wounded? Gull on the masthead, apple at the end of the bough, what can

you tell us at such crucial times? For an infinitude, the oars paced, a boat

swung, another boat anchoring alongside, the armor on deck flashing, the waves

gulping at the gulls.

I turned away, moved back.

And then I saw someone helping Alcaeus ashore—wounded or

ill—and old, old, I thought.

Beauty said to me: This is only change.

And I said: But what is change?

And I slipped away, not daring to meet him, hoping someone

would shout a name and confirm that this was another, not Alcaeus. But no, I

knew. A woman knows a man she has loved, however battered he may be. I turned

to watch his blundering progress.

The chorus had dwindled—only those at sea, the far off

crews, still carried the hymn. I could not remain any longer. I hurried home, past

his house to mine, wondering what kind of haven it could be, wondering what

people would say at my flight. Yet this was not flight; it was merely a

postponement, waiting for a sign, a chance to prepare myself. Alcaeus...must I

send someone to him? What must I do? Go to his home? Shall I be there for him

when he arrives?

At my door I turned and retraced my steps to his house, the

laces of my sandals making a sound I had never heard before, the gulls

wailing, the sounds from the wharf intermingling and incomprehensible.

And I was there when he came with his servant, an ugly

Parthian, helping him. Yes, I was there and put out my hand to touch him,

hearing his troubled breathing, seeing his torn and disheveled clothes, his

rank beard, and knowing he was ill. I remembered the dream, the ship with its

broken sail. And I remembered our love and I said to him:

“Alcaeus...it is I, Sappho...”

He squared his shoulders, his cloak slipping away. His arms

went out to me, then dropped to his side.

His eyes had the marble core of nothingness in them.

Appalled, I could scarcely stand. O God, what is this that

can happen to a man? Why has it happened? His arms in bandages, his eyes

forever bandaged by the dark.

“Alcaeus...”

He heard my whisper and shuffled backwards, bumping his

servant; he moved forward then and gripped me hard, twisting my flesh, his

great muscles rising in his hands.

“Take me to my room... You haven’t forgotten the way, have

you?”

I took his arm and the Parthian opened the door and servants

bowed about us; yes, I took his arm and silently we climbed the stairs to his

room, his clothes rough against me, his sea smell around me. We passed his

library that held the books he had loved. We passed his mother’s room, where

she had died. We passed where light fell around us, though no light entered his

eyes.

“You are in your room,” I said.

“Where?”

“Beside your Egyptian chair.”

“Can I sit down on it?”

“Yes, it’s ready for you.”

Grasping the heavy frame, he lowered himself and the taut

leather squeaked. I placed a pillow behind him and drew a fur across his knees,

then sat next to him. The door had shut itself and we were alone. We listened

to each other’s breathing and his hand sought mine and climbed my robe to my

face and the coarse fingers felt my cheek and I felt them reach my heart, with

the past roaring around me like the recent storm.

I couldn’t speak. I felt that the war was forever between us

and I hated those years, those battles, the lines on his face. My hate was

there, between us. Then, then, tears came to his eyes. Silently, he wept. And I

drew him to me.

I heard the wind cross over his house.

Voices shuffled below us in the courtyard, the excited

voices of the caretakers, the idle, the hangers-on. I could imagine their

leers, their whispers. I lifted his face toward mine and kissed him, his heavy

beard sticking my mouth.

There was a sob—a broken gasp. How ill he looked, how

tired...

“You must lie down, Alcaeus. Come, I’ll help you.”

And when he was settled, I brought him water.

“Water...there hasn’t been much water these last few days at

sea...”

P

So he had come home, “homeward from earth’s far end,” on the

shield of blindness. I saw him next day and the next, but he seemed strange,

withdrawn. I found two of his servants but he wasn’t interested.

I thought of him as old. But was he old? Age was in his

scars, in his streaked hair and beard, the hands lifting and settling

awkwardly.

Warm under the stars, the daphne fragrant, his sea terrace

tiles smooth underneath our feet, we sat alone, some rooster vaguely saluting

the night, the movement of the surf faint, almost lost. I crushed some daphne

in my palm, remembering their four-pronged flowers, remembering—remembering

Alcaeus after his field games, his javelin and discus throwing, his flushed

face, his eyes lit, his mouth hungry for mine. Remembering—was he remembering,

too?

“There was no daphne where I was,” he said, his voice

sullen. “It would have been better to have died there, than come home like

this.”

“It’s spring, Alcaeus, don’t talk like that,” I said, and

wondered what spring might signify to him.

He did not speak for a while, then quietly, as though to

himself, or from another world, he repeated lines we had loved:

“The gods held me in Egypt, longing to sail for home, for I

had failed to seek their blessing with an offering...”

His voice had not changed, I realized with a start.

Surcharged with new meaning, it entered my being, as he went on about the

galleys and the old men “deep in the sea’s abyss.”

The phrase haunted me because it was he who lived in an

abyss.

As days passed, defeat was all that we heard in our town,

not outright defeat, but capitulation—retreat combined with truce, truce

necessitated by deception. Or was it confusion? The soldiers I met, after their

drunken reunions, spoke of the war with bitterness. Ten years, they said. Ten

years, for what? And how many of us came back? Those who had been away longest

considered themselves outcasts and those who had returned during the war

complained, unable to recognize their families.

Standing on the wharf, I familiarized myself with the fleet,

its remnants, anchored forlornly in the bay, boys swimming around the hulls,

the decks bone dry, hawsers trailing, a door off its hinges, the cordage so

rotten a gull might topple a spar. Disgust in my mouth, I tasted the waste of

life, Alcaeus’, my own, my friends’.

What is life for, but love?

And love sent Atthis and me along the beach, stretching our

legs, running, dashing in and out of shallows, finding periwinkles, the day

even-tempered, goats nibbling at wild celery, their bells lazy, a fisherman

waving at us as he cast his net, clouds over the mountain. I noticed Atthis

against the luminous water, her fragile face trusting life. Her yellow ringlets

in my lap, she sang to me and then, eyes shut, fingers in the sand, she seemed

to steal away.

“What are you thinking about, darling?”

“You...”

“What about?”

“You and Alcaeus—you are so troubled for him.”

“Then you have seen him?”

“Yesterday. And I’m afraid.”

“Why?”

“Because what is there left for him—and you?”

“I can’t answer you, Atthis. Time answers such questions.”

I sense my old loneliness, a loneliness that was distorted

like a ship’s rib, tossed on the beach, warped because of bad luck.

“His arms have been injured, too,” Atthis said.

“They will get better, in time...” And I heard time in the

receding wave and felt it in her ringlets and in her hands.

“You’re so sweet,” she said and I saw myself mirrored in her

eyes. And it occurred to me that Alcaeus and I would never again be able to

exchange notes, those hasty, affectionate scribbles. Would he ever again

dictate his bawdy poems, lampoon dictators and brag about war? Had pen and desk

become his enemies?

Many things occurred to me, there on the sand, as Atthis and

I talked softly.

Sappho’s garden, terraces of roses, shrubbery and cypress,

has the ocean below: moonlit, she stands white-robed

close to marble statuary:

a nude Hermes, a bust of Aphrodite,

a niobe, an athlete from Delphi.

Sappho sits down on a bench and fingers a lyre.

Mytilene

onight, I have returned to my

poetry, for the solace and sound of my pen. Here in my library, time will be

defeated for a moment, at least. The sun’s last rays stream in, so yellow, they

might be made of acacia. The cooling light covers my desk and bookshelves and

relinquishes its hold of my vase. A fragment clings to the amphora Alcaeus gave

me long ago. Its dancing, singing men seem somehow out of focus; yet it seems I

hear the flute and lyre of the ceramic players.

I dreamed I talked with Cyprus-born...

No, that is a poor line.

Maybe this is a better theme for tonight:

But I, I love delicate living, and for me,

richness and beauty belong to the sun...

P

There was a symposium and Gyrinno danced for the guests and

afterwards brought me news about Alcaeus, how he left the party and wandered to

the beach. There he quarreled with Charaxos, both armed with sticks and

staggering drunk. At first, Gyrinno garbled the news, mixing it with the

symposium’s talk of war, the defeat, the hatreds of many kinds, including

punishment and forfeit. It must have been a sorry meeting, this reunion of our

warriors. Gyrinno reached me drenched with wine the men hard thrown on her.

Other girls had been treated the same.

Welcome home—men!

When I had soothed Gyrinno and bathed and perfumed and

powdered her, I went to the beach, thinking I might find them. Yes, they were

there, quarreling on the sand, my lover and my brother, kicking their naked

shins on driftwood, their servants standing by, only half interested and half

awake.

“Charaxos,” I began.

“Ah...I rather expected you.”

“Sappho?” called Alcaeus.

“Get up, both of you.” I moved past the servants

indignantly.

“Just leave us alone,” growled Charaxos.

“Leave a blind man with you, when it is you who is really

blind?”

“Let’s not resume our quarrel,” said Charaxos.

“When have we stopped?”

“Please go away,” said Alcaeus, “I can take care of him,

myself.”

“I’ll not go! I intend to see you home!” And I ordered the

servants to separate them and leave me with Alcaeus.

Mumbling, he followed along the shore, walking uncertainly,

but keeping out of the way of the inrushing water. Where rocks littered the

beach, he allowed me to help him, and was soon apologizing.

“I haven’t been home a month and already I act the fool.

What right have I to criticize anybody? So he brought home a slave woman.

Haven’t I had my share?”

I did not interrupt, preoccupied as I was with guiding him.

Besides, my anger with Charaxos was too old, too deep-seated, too complex. It

was not a subject to pursue on the beach, with the wind carrying our words and

the breakers drowning them. This was, I preferred, a private quarrel.

With Charaxos and his men following a distance apart, we

made a pretty picture, hiccoughing through Mytilene! Its silent streets were

topped by a new moon; Venus seemed swallowed by a single window. Why were we in

such contrast?

Laughter and outworn songs...swaying and shuffling...until

the shutting of my door.

Alone, I sit beside my lamp to consider its flame, the why

and wherefore of its integrity, fragility. Shadows are commonplace when we

ignite a lamp. Yet, without a light, there are profounder shadows.

P

I hear that Alcaeus goes out alone, forbidding his servants

to follow. Everyone has become uneasy.

Today, he dismissed his secretary. So poor Gogu has sought

me out to explain what happened.

“Someday he will do me in. He has threatened this often

enough!” He was trembling so hard, he could hardly speak. It is no wonder

Alcaeus calls him a “stick of driftwood.” He has an abandoned air that begs to

be found and picked up.

“The least word, the least word upsets him. And you know how

Alcaeus can rant!”

“Yes, well...”

“He says our great fight at Sigeum was lost through sheer

carelessness. Of course, he blames the other officers...”

But then, Gogu has never held anyone’s interest or respect

for long. Who but Alcaeus would have hired an epileptic, in the first place?

Almost everyone has rescued Gogu, at one time or another, from the surf, the

wine shop, the brothel or the forum. How does this knobby skeleton manage to

survive and endure?

“You will speak to Alcaeus? You promise?”

I promised. The dread of having Gogu permanently abandoned

is worse than imploring Alcaeus to take him back. Besides, his scholarship is

often surprising, and Alcaeus can use his help.

So later, I invited Alcaeus and some friends to supper. We

sat around the courtyard fountain and listened to the harpists playing under

the burning lamps. Libus, Nanno, Suidas—they are good company for Alcaeus. He

seemed more like himself again, joking and talking. Again he lampooned

Mimnermos and mimicked “that strange-smelling country poet from Smyrna.” But I

detected a morbid note, a self-hostility that cut him more than it did those he

scorned.

Will he ever write again?

He left early, insisting he would find his way home by

himself. A soldier, reduced to being treated like an irresponsible infant—of

course he resented it. But I know he did not return home. Instead, he has

rambled into the hills again.

Now the others are gone. And I wonder, looking towards the

slope, what it is that Alcaeus hopes to find, a new life?

I shall not be able to sleep indoors tonight. My bed will

have to be under the trees. Perhaps the wind can bring me some special message.

P

The banquet honoring the warriors was held last night.

Alcaeus had his collection of war shields displayed on his

dining room walls. Of hide and metal, in various shapes, they united the room

and its glazing lamps and candles. I felt myself the focal point of a painted

eye on a circular hide, as I sat by him. I could not recall such an assembly in

years: Scythian, Etruscan, Turkish, Negro. Bowls of incense sent threads to the

ceiling. Wisps floated in front of me where a man in Egyptian clothes, headband

studded with rubies, sat beside his courtesan.

Alcaeus made his way to the dais, when everyone was seated,

about fifty of us. Hands resting on a table, arms healed and ringed with copper

bands, he leaned forward, waiting for silence. His hair had been freshly

curled, and his beard trimmed and brushed with oil. I was troubled, thinking he

might be impudent or truculent. Instead he spoke gravely and it was difficult

to believe he could not see us. I thought he glanced straight at me.

“Tonight, friends, there will be no tirade, no poetry. I

wish to pay my respects, and offer my thanks for our return to our island. I

know how beautiful it is...”

There was a murmur of appreciation.

“Soldiers have a way of talking out of turn,” he went on,

reminding them of the gossip that had come to his ears, shameful talk that made

faces blush with guilt and anger.

“It’s time for me, as their commander, to speak. Very well,

I will!” And his voice thundered across the room, to make sure that none would

miss or mistake its message. Was this the Alcaeus who had joked and sported and

sung ribald songs, as the popular friend of young men who were proud, rich,

playful and naive? Here was someone speaking out of experience...

“I assure you the truce was an honorable truce—and will be

respected.” An older, solemn Alcaeus...who reviewed the war with wisdom.

“And now let us forget fear and enjoy life and see that our

people prosper.” It was an impressive speech, one they would long remember.

Our personal servants, assisted by the usual naked boys,

waited on us, pouring the Chian wine. Gradually, people began to move about,

to talk and drink together. Men long absent from such gatherings moved

nervously or waited glumly—alone or in knots of two or three, feeling separate.

How does one forget the battlefield? I heard the burr of ancient Egyptian.

Persian was spoken by men from Ablas. Women gathered about the newly returned;

some were excited, some were beautifully dressed, their hair piled in curls,

their shoulders bare, wearing gold sandals.

As the evening wore on, the old familiar sense of freedom

returned. Restraint dropped away. Voices and laughter increased. Then applause

broke out as a Negro entertainer entered, carrying a smoking torch.

Under the edge of the portico, he freed a basket of birds

and juggled several wicker balls. I had never seen this gaunt, ribbed giant,

beautifully naked; some said he had come on a wine ship as a crewman. He spun

the cages higher and higher and as they whirled in the torch light, he tore

open first one and then anther, to liberate the birds. A magnificent

performance.

The suggestion worried Pittakos and he pushed through the

crowd to take the floor. Pittakos, with his rasping tongue and fish eyes—was

there a more dishonest ruler? How ironical that he should represent us! As he

kept folding and unfolding his robe, he spoke about our fleet, how he would

have the ships repaired and converted into fishing boats for the use of the

community...never mentioning that our fleet was rotted!

Presently, the musicians and dancers wandered among us and

the party went on. After many songs and a lot of wine, Alcaeus slipped his arm

through mine and suggested we go upstairs. It was all very obvious, of

course—that he was drunk and I unwilling, that times had changed and everything

with it. When was it we had dashed, hand in hand, up his staircase, giggling

and pushing one another? How many years ago?

Ah, deception and illusion, do we dare recreate the past and

its former happiness? Only in memory is it done successfully. Yet, here we

were in his room.

Life

is for love!

Life

is for love!

In the old days, when we had made love, we had closed our

eyes, to intensify sensations. Now he would not need to shut his eyes. And his

arms, hands, fingers—once young and sure—what could they remember?

I could not keep back tears, tears he would never know, as

he stumbled, laughed, then sprawled over the fur covering of his bed. While

the music filtered in to us, I cushioned him in my lap and wiped the

perspiration from his face, hating the war and the years behind us. After

mumbling a few words, he turned over and fell into profound sleep.

So, that was the resumption of our love...and, as I leaned

against a hillside olive, the salt air fresh about me, I accepted defeat, aware

that my loneliness would appear again and again. There, on the hill, gazing

seaward, where fishing smacks moved, I rubbed the horny bark, envying the

tree’s longevity and its years ahead. Would I trade places, to brood over

Mytilene, for centuries?

Alone?

Then Atthis circled me in her arms, creeping up behind me and

cupping my eyes. I recognized her by her laughter and perfume.

“Atthis...”

P

Alcaeus’ home is much older than mine, with patina walls,

Parian marble floors, and a collection of rare Athenian busts. His library has

a Corinthian copy of Homer and a collection of Periander’s maxims, while I have

been contented with some papyri, of choral lyrics and dithyrambs.

As I stretch out in a leather chair in his library and read

to him, the honeysuckle makes its fragrance outside, surely a woman’s flower,

so fecund. I try to keep my voice and thoughts within the room, beyond the

reach of its fragrance. The honeysuckle does not suit us or the room. And

Alcaeus knows this, too. His impassive features grow stern, as though to

reprimand me. Insatiable Sappho! Yet how can I help it? I must love and be

loved.

Laying down the book, I kneel and place my cheek against his

knee. His hands, gliding over my hair and neck, are dead. His voice, out of its

black, reproaches me.

I want to cry: but I didn’t blind you!

The other day in the library, he said:

“I wanted to write something great... During the war, I

conceived of a series of island poems, bucolic, legendary, praise of this

life.” And he motioned toward the ocean and our island.

“Dictate to me,” I said, hoping to rouse his impulse.

His silence, at first natural enough, went on, and I became

embarrassed by his stare at the bookshelves.

“I want to help you, Alcaeus.”

Again the silence. How was I to get through it?

Taking a volume of his poems, I read aloud several of his

favorites. Slowly, his face relaxed and he settled deeper in his chair. After a

while, he said:

“Read some of yours, Sappho.”

I opened a book, one of my earliest ones, and read several

passages. But I could not continue; I felt my mind wrapped in fog; my hands became

icy. I shut my eyes and said to myself: See, this is what it’s like to be

blind. You’re blind, blind to love and life...

As I kissed him good-bye, I longed for our youth, its

freedom, its daring, its quarrels and fun.

Walking home, I told myself I should never return to his

house.

P

In looking back over the pages of my journal, I am alarmed

by the passage of time. When I was young, I thought time was a philanthropist.

I remember so well that day mama took me to the ocean, and

the rain fell unexpectedly, lashing and soaking us. We finally discovered a

shepherd’s hut, but I got colder and colder in its windowless gloom. Lying on

the floor, among stiff hides, with the rain sounding loud and the hides

smelling strong, I thought the storm would never end. Toward dusk, a shepherd

and his boy came, dripping with wet and shivering, and my mother dried the boy

and made him lie down with me under the hides. Were we seven or eight?

Together, our bodies grew warm and we lay still, listening to the wind and the

rain thud across the green roof, while the shepherd went about building a fire

and preparing supper. I have forgotten the boy’s name, but not his face.

Forever after, I thought of him as my first lover. I doubt whether we spoke a

word all that delicious evening.

Now I find it hard to renew ties with the past. Not only

Alcaeus...but Dioscurides...Pylades...Milo...the very names make me unhappy.

All destroyed by war. What special stupidity do men possess that they must

involve themselves in such a gamble, with loss inevitable, anyhow?

P

The columns of the temple of Zeus, in Athens,

stand white against the moonlit sky.

A woman walks among columnar cypress,

her sandals scraping sand and gravel.

A hawk wheels above.

he masks I have on my bedroom

walls seem less clever than they appeared years ago. Our theatre, too, has

changed through the years, become more mediocre.

Yesterday, at the play, I sat closer than usual and was

delighted by the comic faces, so new and frightful that children screamed and

squealed. Good, I thought. Perhaps the play may take on life.

...A man with a tambourine strutted about...an old beggar,

pack on back, pulled at his beard and mimicked words sung by the chorus. He

seemed to be one of us or a Chian, maybe. It was pleasant enough to soak myself

in comedy for a while, for right after the play, Charaxos found me and

suggested we stroll in private. Obviously, he had something on his mind!

He began by offering me an exquisite scarab, saying he had

purchased it for me, from a sailor who had touched port.

“For me?” I became suspicious! I fingered the beetle-shaped

oval, unlike any I had seen. An amethyst was set in the center with characters

engraved around it.

“An Etruscan scarab should make a pretty keepsake,” he said.

“Then I think you should keep it.”

“Why? Are you afraid?” he asked.

“Of what?”

“That it might bring bad luck.”

He laughed ironically, as he flipped and caught the scarab,

with a flick of his wrist.

“What is it you want?” I asked, coming directly to the

point.

“To be treated with respect, Rhodopis and I—not criticized.”

“Do I say too much?”

“I don’t like your tongue.” He was scowling now.

“Nor I your woman’s!”

“Leave her out! I warn you—she’s no longer a slave!”

“It wasn’t that she was a slave that bothered me.”

“A courtesan, then!”

“No, you should know better than that. Oh, no...it was your

assumption that our family funds could be lifted, without my consent and

without my knowledge. Taken to buy Rhodopis. You sold three or four wine ships

to pay her price, along with the money taken from me.”

“Can’t you forget...”

“Not conveniently. Nobody enjoys being robbed.”

“I have said I would repay you.”

“But that was nearly two years ago. And you go right on

selling wine and buying equipment. I have heard that you added a ship last

month. Wasn’t it convenient to pay me then?”

His fist tightened over the scarab, and he bowed and turned

away, rejoining his wife who was strolling behind us with her friends and

servants.

Theatre!

P

Villa Poseidon

Atthis, Gyrinno, Anaktoria and I went swimming in the bay by

the driftwood tree. It was late, the sun misty, its eye sleepy, pelicans

roosting, a dolphin or two frolicking close to shore. I had been unable to

forget my meeting with Charaxos, until Anaktoria, who is the best swimmer among

us, grabbed me by the heels as I floated by, and towed me to the bottom. That

ended my anger and irritation. I lit after her, snatching for her long hair.

Arms around her, I forced her to tow me toward shore, making myself as heavy as

possible.

As the four of us played on the beach, I thought: When will

this happen again? Something about the late afternoon—its hammered out sun, its

tempered air, its windlessness, its smell of spring—seemed unreal even as it

happened. We tossed our blankets on the sand, dashed back and forth to the

water’s edge, splashed each other, then arranged ourselves in a circle and

began combing each other’s hair. We sang and laughed, comparing, whose was

finest, whose was thickest.

Atthis, whose hair was shortest, bragged she could swim the

farthest. That started an argument.

“Who swam halfway round the island last year?” demanded

Gyrinno.

“Who was born at sea?” said Anaktoria.

“You can tell the best swimmer by the shape of her

buttocks,” said Atthis. “Look at mine, how flat they are.” She jumped up, to

show us.

“A boy’s buttocks,” laughed Gyrinno.

“Here. Measure. Mine are smaller,” said Anaktoria.

So we measured, laughing, fussing, pushing, our hair

streaming around us—a gull on the shore padding back and forth, scolding.

Atthis won, but Anaktoria had the loveliest breasts, so round, almost

transparent in that evening light. I have rarely seen a girl of such grace, not

the childish grace of some, but the accomplished grace of true femininity. As

the others became aware of my admiration, they became jealous and peevish, and

tried to shift the praise.

They talked about my smallness, my violet hair... “your deep

blue eyes”... “your melodious voice...”

But this was Anaktoria’s hour. She had been away, visiting

in Samnos, staying with her family, and I was eager to hear the news.

“I thought I was homesick... But it is Mytilene I love

best... My brother has a girl now. He goes to her house whenever he is not

working. I saw very little of him... Life there was very dull. Family visits

from door to door. The same cup of wine, the same paste of nuts and fruit, the

same questions, answers, family anecdotes and jokes... How lonesome I was!”

Growing quiet, all of us responded to the evening, the

lingering sea-light, the arrival of the stars, the whispering shingle, the

breeze, carrying the scents and sounds from Mytilene.

Anaktoria and I walked home together, feeling our bond

closer, stronger than before. I had missed her more than I thought: I had

missed her a dozen times a day.

P

I have been sick today and to amuse myself I have made some

jottings about my girls:

Atthis—lover of yellow ribbons, scared of the dark. To avoid

going out, will invent a headache, a toothache or a stomachache. An orphan, she

gets homesick for the home she never had. Prefers women to men. Tells amusing

jokes and stories. Loves laughter. Mimics. Is made jealous easily. Speaks

slowly...ivory-skinned.

Gyrinno—the daughter of a wine merchant, can outdrink most

men. Worries about her figure, eats next to nothing. Uses violet perfume. Our

best dancer. Otherwise, is lazy, careless of dress and makeup. Never reads.

Wants to marry someone wealthy and entertain lavishly. Snores.

Anaktoria—hair yellower than torchlight, soft-girl, dabbler

in poetry, dreamer, lovely singer. Plays lyre and flute equally well. Adores

games, trees, flowers, swimming, archery. Wants to travel, be a priestess.

Then there are the new girls: Heptha, with copper hair...

Myra, who is Turkish... Helen, a scatterbrained darling... Ah, but each is

exquisite in her own way. No two are alike. I love them all.

And yet, I am grieved, since my own daughter is jealous of

them. Dear, foolish Kleis, who pretends she has never been a child and is yet

so far from being a woman.

P

I have spent weeks over a poem, revising, revising.

I do my best writing in the morning, when the sea light is

sparking my room. How important the harmony is to me: harmony in my house, on

the island, in my heart.

Sometimes, I call my girls to let them hear what I have

written. Sometimes, in the evenings, I recite my poems for friends. Sometimes,

I go days, unable to write a word. They are cold days.

Shall I use eleven syllables?

A poem does not grow like a leaf, but has to be shaped. I

often think of a lyric as an amphora; little by little I must mold its lines on

the wheel of my mind. It is the structure, containing the song. It must be

graceful, strong, so that the words and the music can flow...

The wings of the swans have drawn you toward the dark ground,

with yoke chariot bearing down from heaven...

Come to me...free me from trouble...

P

Today I received a letter from Aesop, written at Adelphi. It

is a joy to hear from him. I thought he had forgotten me. What a good companion

he was, all those days in Corinth... Companion? He was more like a father!

His handwriting is the most perfect I have ever seen. Each

letter formed so patiently, each thought expressed so beautifully. Does he

strive for perfection because be cannot forget his deformity?

I remember his eyes used to transfix me with their brown

hypnosis.

He must be fifty, I think.

He had his beard trimmed and his hair curled, every morning.

His robes, so elegant, so clean, were always perfumed. I seldom saw him without

his doll, that bull-leaping doll of Cretan ivory, brightly painted! But his

apartment was simple, tastefully furnished, elegant as his clothes. Each bath

towel, I recall, bore a brilliant red octopus.

When he looked after Alcaeus and me, we ate with him every

day at least one meal. Through all the years of our exile, he remained our most

faithful friend. His friends were our friends. His house was ours. His

servants. He treated everyone with equal respect.

“I never forget that I was a slave,” he often said.

He was much sought after, not only for his humor, but for

his wisdom. His reddish whiskers and black brows gave him a comic look. But he

sensed his profundity, as he guided me about Corinth and sat beside me at the

temple of Apollo, watching the people and the boats and the sea birds, and

hearing the choral virgins sing.

Evenings, he would lay aside his doll and tell me fables. He

had learned many from his father, a Persian, and he was constantly visiting

orientals to pick up their stories and jokes. I hear his smooth, somnolent

voice...an effortless story- teller!

“I will certainly come and visit you,” he writes. “I am

tired of Adelphi. The people make me uncomfortable. I want to roam over Lesbos,

to be with you and Alcaeus. I want to see your home.”

Will he come? I hope he can. His letter has taken weeks to

reach me. I suppose he could be on his way, by this time.

P

It must have been almost dawn, when Alcaeus and a group of

revelers came banging at my door, shouting, laughing. We let them in and they

demanded breakfast, some of the more intoxicated trying to seduce my girls, who

were quite amused.

When the others were gone, Alcaeus drew me aside to speak in

earnest.

“Do you know that Kleis goes to Charaxos’ house?”

“What do you mean by that?”

“That she visits your brother’s house frequently.”

“Do you know this...or is it gossip?”

“We just went by his place. She’s there now. I would know

her voice anywhere.”

“Yes, of course...”

“I don’t like his slaves, as you know, and I don’t think

they are fit company for Kleis.”

“No, no, certainly, I shall speak to her...”

“It will take more than that, I’m afraid.”

“Why, Alcaeus, she’s a mere child...”

“Oh come now, Kleis must be fourteen or more. If she were my

daughter, a pretty girl...” He held up a warning finger, then left.

P

Fourteen? No doubt he meant well, was sincere, but I

resented the implication.

Have I really been lax? Is my little girl in need of

direction? It seems she was ten or eleven only yesterday. Fourteen, indeed!

Kleis never knew her father. He is one of a thousand dead,

because of the wars. If he were here, she would not think of slipping off at

night. She looks much like him. I remember his face, the candid eyes and lips.

I remember the ivory gleam of his body. Ah, if he were

here...

How am I to forbid Kleis?

Where is my frivolity? Where is my enthusiasm?

The sun’s color whitened my shutters and I threw them open

on the sea and the light burnished the tiles and splashed the masks and my bed

and I stared into its eye, to surprise its oracle.

P

I am criticized for my simple dress, my tastes. The

townspeople say I should not be aloof. They say I am too aristocratic. They say

my parties are too gay and exclusive. They say my wealth is insufficient. They

say...Yes, I could go on with this pettiness. But why should I?

I have my work and I must live to see beyond the moment, below

the surface; I must interpret the whole heart. For I know too well the

inexorability of time, the disappointments that nibble one’s heels. I must

offset the pain, the loss. There is no one to take my arm, there is no one to

lean on. There is only my work—and my girls.

P

All day in the fragrant lemon forest, fallen fruit

underneath the trees...all day alone. I have hated loneliness and yet I must be

able to rest and get away from responsibilities, to welcome the gods of trees

and ocean and those long dead, whose marble shrines dot a corner of this wood.

There are so many dead. However, life must be better than death or the gods

would have chosen to die. Life must be day-by-day and hour-by-hour. And I talk

to myself and totally convince myself and then the mew of a gull shatters my

conviction.

P

Our spring revel saw us high on the mountain, the ocean

misty blue, our erotic flutes wailing the dawn. Kleis and I danced together, my

girls joining us one by one, the deepest notes growing in volume, the slight notes

dropping away. How the wet grass slid our feet!

I closed my

eyes, remembering nothing, letting the song have me; then, eyes open, I went on

forgetting, forgetting where I was, what this was: I was simply dancing,

flashing with someone, alone, dancing for myself and the oncoming sun, dancing

because I love to dance, dancing because I love life and time is dead. Yes, time

is dead at our spring festival and the flowers never spill from our hair.

I closed my

eyes, remembering nothing, letting the song have me; then, eyes open, I went on

forgetting, forgetting where I was, what this was: I was simply dancing,

flashing with someone, alone, dancing for myself and the oncoming sun, dancing

because I love to dance, dancing because I love life and time is dead. Yes, time

is dead at our spring festival and the flowers never spill from our hair.

Girls bared their breasts and arms to the light. Men clapped

in unison. The music sped up and the faster pace widened our circle of dancers.

Our bare feet kicked blossoms thrown by boys. We ate and danced, drank and

danced again. Kleis, it seemed to me, danced more beautifully than anyone.

Beauty, I said: We are here again, help us to find life’s

meaning.

Beauty said: There is always meaning, look for it.

The step and re-step, circle and re-circle, gulp of air,

ache of chest, ache of legs and arms, sullen eyes, eyes longing for

embrace...longing... longing...isn’t that what life is?

Our tumbled-down temple rose behind us, whitish pillars,

roofless phalli, our gowns, arms and faces, circling.

Through my blur of happiness, I saw Anaktoria, Libus, Gorgo,

Nano, old friends, fishermen, villagers. Old women went about hawking oranges.

Old men drank and talked.

In the afternoon, resting under trees, I became aware that

the crowd had scattered into small groups. How hungry we were! How thirsty!

Then more dancing and, with tiny fires in the twilight, food cooking, pots bubbling,

love-making, songs. It was the dusk I love. And it was easy to grow

sentimental, to talk of Alcaeus and miss him, to remember our fun at other

festivals. Crickets bubbled like little pots. Frogs burped. A bat fluttered

over our fires. Below, somewhere on the bay, a ship winked and made me feel

that the sky had gotten below us.

A warm wind and some scarves, that was all I needed to

sleep, a sleep somewhat troubled because Kleis was not with me. But during the

night she appeared and slipped into my arms, where she began to cry. I

comforted her and slept and thought no more about her girlish tears till

morning, when she whispered about Charaxos, his heavy drinking, then the

darkness and torches, the wild games and dances higher up the mountain...

“I shouldn’t have gone with him! I should have stayed with

the other boys and girls right here. This time, he has changed me. I’ll never

be the same! And I can’t bear the sight of him!”

...A journal is for solace, for strength.

I write in my library, the rain falling, Kleis in her room,

asleep. How sad when youth is tricked! One speaks of treachery, stupidity, ugliness.

One thinks of family honor. And then I realize that Charaxos has no sense of

honor, that my code is incomprehensible to him. So, I’ll not show my distress—our

distress.

Life is for the strong, they say.

How strong must a person be?

P

I feel like dry smoke. And smoke twists and turns inside,

not knowing which way to go. Nothing is hotter than the heat of anger.

Charaxos—how the name burns my tongue, sears my tablet. It

is impossible to concentrate!

It wasn’t enough for us to quarrel over money! You, with

your scarab, your Egyptian clothes, your obelisks, your slaves, your woman!

Perhaps Kleis is mistaken. Children are given to

exaggeration.

I don’t know what to believe.

P

Today, an earthquake shook our island, sloshing water from

our courtyard fountain, making birds cry out. As the walls of the house

trembled, I shut my eyes, thinking: No, not yet...there’s still so much.

And I made up my mind to go out more, to get about more.

With Kleis. We need more time together.

P

How tall she is! With golden hair and mint eyes, she grows

more like her father each day. I detect a restlessness in her nature. Is it

because of what happened, or because she is with me? Or do I imagine it?

Her shoulders stoop, her face is sad. When I speak to her

about it, she straightens and gazes far off, her eyes worried. Perhaps we make

a strange pair.

P

Gems:

A horseman on a gold agate,

a Nike on chalcedony,

a nude girl on jasper,

a fighting lion on rock crystal...

Sappho is enjoying her collection:

the sun, in her bedroom, is all white.

She is all white.

The gems flash:

We see Sappho’s face in her hand mirror,

the faces of her girls around her,

girls singing.

Mytilene

ne of my girls has had a birthday.

It should have been a happy day. There were garlands, songs, dances... Then,

someone came to me, brimming with the amusing story: Kleis has been heard to

say that she doesn’t know how old she is!

“I’ve had so many double birthdays, I’ve lost count,” were

the words repeated to me.

Why do we wish to be older, younger, always in protest? Why

are we never satisfied?

I wish there were no birthdays.

P

For several days, Kleis and I have sailed, our boat a good

fishing boat, captained by a young man named Phaon.

It was our first excursion around the whole island, in

years. We sailed past Malea Point to Eresos, to Antiss, then Methymn, and round

our island, back to Mytilene. I have never seen the water so calm. Probably

because of the recent hot spell, the captain said.

What a peaceful island, our Lesbos... We saw Mt. Ida, olive

groves, cypress, temples, bouldered shores, goatherds, date palms, sailboats,

dolphins... We thought of Odysseus, trying to identify ourselves with that

heroic past, we—only islanders enjoying a holiday!

A striped awning sheltered us during the hot hours of the

day. Nights were cool and comfortable. Our handsome captain was attentive. I

thought he was particularly agreeable. Our food was tasty. How time drifted

along.

Of course it was our being together, lulled by the sea, that

made the trip so happy for Kleis and me. It was our shared regrets, our resolve

for the future, that brought us close. It was the little things we did for one

another, the sleeping together...the voiceless communication.

P

How wonderful it is to get out of bed and stand by the

window and take in the sea and breathe deeply.

How good it is to dream a little.

Phaeon...it is such a beautiful name.

P

There are days when my girls seem utterly listless. Their

activities have no meaning to them. Nothing pleases them. I hear them arguing

among themselves, apart. It is as though a stranger had come to be with them.

And Kleis seems more withdrawn. Does she resent the others

or do they resent her? A curious unease creeps about the place.

Sometimes, I wonder whether it is I who lacks.

P

I do not feel well.

Time is slipping by...

I don’t know what to do about Kleis: she goes off by

herself, and does not tell me where she goes. I can’t very well send someone to

check on her. That’s an ugly thing to do.

I think she isn’t visiting Charaxos’ house, because he has

sailed for Egypt on one of his wine ships. Of course she could be seeing

someone else.

Is it possible that she is interested in Phaon...how shall I

find out?

P

I met him on the pier, the wind blowing, the water choppy

under grey skies. He left off caulking his boat with a cheery “Hello” and

climbed onto the pier. How pleased he was to see me! Was I planning another

trip?

Sitting on piles of rope, he told me of an underwater city

he had seen, with a great bronze statue of Poseidon by a temple...

“The water was like glass, not a seaweed moving, not a

current...” His hand swept sideways, spread flat. “Oh yes, coral...and plenty

of fish, big ones. I swam halfway down to the city, but there was no air in me

to swim deeper. A fish watched me, from one side of Poseidon, its body curving

behind the statue. Poseidon’s eyes were made of jewels...”

Phaon is a handsome young man: I think a man is a man when

he is handsome all over. I measured him with my eyes, as he talked to me. I

measured his feet, hands, thighs, shoulders—the symmetry is unusual. His skin

is the color of oakum and his muscles glide perceptibly under his skin. He smells

of the sea.

I stayed a long while, talking on the piles of rope,

exciting talk. What would it be like to swim with him? To dive deep with him?

We talked and talked. He never mentioned Kleis. And I forgot

why I came.

P

I went to Alcaeus, to tell him about the submerged city.

“You mean Helike?” he asked. “A quake tore apart the coast

and it went under,” he said, and described something of what I had heard.

“Phaon says the city is visible when the water’s clear, and

still,” I said.

“Phaon?”

“Yes, you remember, the captain who took me on a trip around

the island...”

“He fixed his sightless eyes on me and I felt stunned, as

one hypnotized. I trembled. Then his expression altered and he changed the

subject as quickly as a man might draw a sword during battle.

“I never thought I’d be blind. I never memorized any faces.

My home, our bay, the ships—I can’t recall things at will, with certainty.

There’s so little difference now between sleeping and waking. Anything may

come to mind.

“A soldier stares at his hand, slashed by a spear. He can’t

believe he’s wounded. It’s not his blood spattering the rocks...

“A man lies beside his shield, a hole in his side. He can’t

believe he sees what he sees...”

P

Mytilene

For several days, I have been working with Alcaeus in his library.

He has taken heart, at last, and is pouring out words, political invective. I

sit, amazed. Even his dead eyes have gathered light. He jabs out phrase after

phrase, juggling his agate paperweight from hand to hand, steadily, slowly. I

barely have time to write. He breathes deeply, his voice sonorous.

Facing the sea, afternoon light on his face, he could be my

old Alcaeus.

Thasos brought us wine.

And we worked still late, our lamps guttering in the wind,

the air rough from the mainland, tasting of salt. Shutters groaned.

“To strike a balance between common sense and law, this is

the cause to which we must pledge ourselves. Our local tyrants must go. They

realize there isn’t enough corn. Poverty, we must grind against poverty. If our

established life and prosperity can’t be made to serve, they, too, will go...”

Walking home, I was hardly aware that a gale had sprung up.

Exekias, carrying my cloak, seemed surprised at my singing.

P

A note from Rhodopis—naturally, I was astonished. Her note

concerned Kleis: could we talk together?

It was hard to order my thoughts. Rhodopis writing to me,

especially with Charaxos gone...

I fixed an hour and we met at a discreet distance from the

square, a bench in the rear of a small temple.

Despite the extravagant clothes, the careful makeup, how

hard the eyes, the mouth. And I wondered how I looked to her, in my simple

dress. But Rhodopis knows the sister of Charaxos is not naive.

It was a brief meeting, cold, the matter quickly attended

to.

After waving her servants to stand apart, she faced me with

unveiled scorn:

“You daughter’s visits are making my household a difficult

one,” she said.

I flushed.

“So the plaintiff has become the accused? An interesting

reversal,” I murmured.

“I will expect thanks,” she said, with a mocking smile,

twisting her parasol into the sand, “for sparing you public embarrassment.”

I knew she was sharpening her wits, and paused. She lifted a

scented handkerchief to her mouth and took a slow breath.

“I have waited a long time for this, but I’m more charitable

than you think. I won’t keep you waiting. It is Mallia—a servant boy, who has

caught Kleis’ fancy...”

Vaguely, I had the flash of an image: a fair, slim, country

boy, not one of the slaves.

“And what is it you want?” I said, in the same level voice.

The parasol twirled.

“Oh, things could be arranged...”

I did not doubt this. But not knowing the relationship

between Kleis and Mallia, remained silent. My silence seemed to exasperate

Rhodopis.

“Of course, you could send Kleis to a thiase in

Andros,” she exclaimed. I refused to flinch. Sending one’s daughter to school

elsewhere was to admit one’s own school had failed. Rhodopis knew this, as well

as I.

“Or, I could dismiss Mallia, but then, where would the

lovers meet? And if he took her home with him...”

I still waited. Somewhere there was a trap. Rhodopis had not

written, then met me, without a purpose.

“Perhaps you have given too much thought to family honor,

Sappho. So critical of Charaxos...of me.” Her voice had grown confidential.

“If Kleis has done anything foolish, I am willing to accept

the responsibility,” I said.

“And the consequence, too...with my husband?”

I stood up, brushing off the bench dust.

The interview was over: obviously, further discussion was

useless. Why let Rhodopis press her advantage? I nodded and left, with the

sound of her laughter behind me.

P

Why?

It is a question I must answer: it is a multiple question.

Has Rhodopis done this to spite me, wound me, shame me?

Is Kleis doing this to assert herself, to prove that she is not

a child? In protest, against me, my house? To estrange us farther?

Did Kleis tell the whole truth about that day at the

spring-revel? If I knew what happened...

She seemed so happy on our ocean trip. Or was it I who was

happy? Perhaps I teased her too much before Phaon. Did she think I had no right

to be attracted to him? Do I make her out to be more sensitive than she really

is?

Love is a jealous companion.

Right now, all I can see clearly is that perfumed

handkerchief and twirling parasol.

P

I have never been afraid of consequences attached to my own

actions. Must one learn to be braver than that? Or is this a matter of

impersonal wisdom?

P

I have sent for Kleis...

It is true she is fond of Mallia, the boy acting as guardian

to her in the house of Charaxos, protecting her from Charaxos.

It was Mallia who served as wine boy at the spring festival.

Curiously, it is Rhodopis who has sided with them in

opposing and blocking Charaxos. Yet, that is not so curious, either.

“You’re wrong to distrust Rhodopis,” says Kleis.

But my doubts persist and I consider her a foolish child.

For why would she make a confidante of Rhodopis?

“I wish you could be happier with me,” I said.

Our talk seemed to unlock her heart and she burst into tears

and I learned how much of a child she is. For it is still filial jealousy that

makes her difficult. She cannot bear to share me with my girls, my friends,

even my work.

Poor, darling Kleis, how hard it is for some of us to grow

up, to learn to walk gracefully alone. I kissed and comforted her as best I

could, assuring her of my love.

“There’s a place for you here, Kleis. Please try to find it.

I know the girls are eager to help you, if you’ll let them.”

She promised, but the far-away look remained in her eyes.

A thiase in Andros—the thought saddens me, for then

she would be far away.

P

I have hurled myself into work. During long silences, while

I am thinking, composing, I hear the water clock outside my door. Drop after

drop, it fastens itself to my memory.

The wind has continued for days on end, the sun hazy, the

surf magnificent in its wildness, all craft beached, no gulls anywhere, a sense

of abandonment throughout our town, people scurrying to get indoors.

Only in the garden is there shelter, near the fountain. An

angle of the house shuts off the strongest blasts.

I have ordered everyone to work. At least they appear busy.

While the wind howled, a tempest rose in me.

I woke during the night to fight it. Yet, there it was, that

perfect symmetry, stripped to the waist, brown caulking material in his hands.

I did not need to light a lamp. I had memorized his body. We were moving toward

the submerged city; I saw myself swimming beside him; in the water, he was

above me, then below me; then we were one, diving together.

I have fought other storms in my blood, and yet this one,

with the wind howling, the surf beating, threatens to overcome me. I have never

felt more deserted. Death and blindness have made my bed sterile.

Beauty, stay with me! I said.

Beauty said: Don’t be afraid.

How shall I cope with this whirlwind? What does it know of

surfeit, satiety?

I’m too old, compared to his twenty or twenty-two. He may

have a woman of his own, a country girl, a young, simple, laughing slip of a

thing who satisfies him.

In my dream I saw him at the prow of his boat, talking with

Kleis.

I should send her to Andros.

I need to go to Andros, myself!

I must seek Alcaeus...he must help me...

I see Phaon in his bed, his young arms, his young legs, his

close-cropped hair, blue eyes, smooth face.

Like a storm punishing the olives, love shakes me.

I must go to sleep.

Forget!

P

Another letter has reached me from Aesop. Still in Adelphi,

he writes he has been sick with fever.

“My consolation is that I am sick for good reasons. I am

sick of men being mistreated. I am sick of injustice.

“As you know, I have been more than a fly on a chariot

wheel. I have spoken out publicly and this has raised dust and stones. People

stare at me on the streets.

“I am sick of the aristocrats. I am sick of prejudice and

ignorance. There must be a better life.

“A free society...this is the most fabulous joke of all

time. The ones who rant loudest about it would run the farthest, were it to

happen.

“I may have to flee soon, back to Corinth, it seems. These

rulers here have friends. They know how to apply pressure.

“Write me, Sappho. I need your sense of the gracious. Beauty

foremost—I wish I could think as you think.

“Tell Alcaeus I send him my best, that I miss him...”

I took my letter to Alcaeus and read it aloud in his

library.

“I’m afraid it is serious this time,” I said.

“It is always serious, when we speak out,” said Alcaeus,

laying his palms flat on the desk.

“He says it is dangerous for him to come here.”

“He must learn restraint!”

“And you, Alcaeus, do you think you have learned restraint?”

There was silence and then he said:

“Those of us who are free must speak, or there will be no

freedom, no free men left to restrain those who think in terms of chains.”

P

Sitting in the square the other day, I listened to Alcaeus

speaking, excited because he had taken cudgel in hand. Blind though he is, he

strikes an imposing figure, even majestic. Leaning on his cane, staring over

the townsmen who crowd the forum, he looks a pillar, his head shaggy, beard

glistening with oil, clothes immaculate.

Something about the day had a timeless quality, as though

none of it was old, the exorbitant taxes, the stringent laws, the situation of