Upon him, Mohammad, Salvation.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life of Mohammad, by

Etienne Dinet and Sliman Ben Ibrahim

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Life of Mohammad

The Prophet of Allah

Author: Etienne Dinet

Sliman Ben Ibrahim

Illustrator: Etienne Dinet

Release Date: April 23, 2012 [EBook #39523]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIFE OF MOHAMMAD ***

Produced by Andrea Ball, Christine Bell & Marc D'Hooghe

at http://www.freeliterature.org (From images generously

made available by Internet Archive.)

"The man's words were not false...

a fiery mass of Life cast-up from

the great bosom of Nature herself."

("On Heroes," by THOMAS CARLYLE,

London, 1841.)

THIS

WORK

IS DEDICATED

BY THE AUTHOR-PAINTER

AND HIS ARAB COLLABORATOR

TO THE MEMORY OF THE VALIANT MOSLEM SOLDIERS

PARTICULARLY THOSE OF FRANCE AND ENGLAND

WHO, IN THE SACRED CAUSE OF

RIGHT, JUSTICE AND HUMANITY

HAVE PIOUSLY SACRIFICED

THEIR LIVES IN

THE GREAT WAR

OF THE

NATIONS

An existence, so full of stirring events as that of the Prophet Mohammad, cannot be described by us in all its details. As there are limits to all books, we have had to rest content with a selection of the most important episodes, so that each might be developed as we deemed necessary. Thus we present to the reader a series of pictures and not a complete history.

Our scaffolding and sketches are borrowed from very ancient authors such as Ibn Hisham, Ibn Sad, etc., without forgetting a more modern writer, Ali Borhan id-Din Al-Halabi who, in his book known by the title of "Es Sirat'al Halabia," gathered together different versions from all the best-known historians. An incontestable proof of their veracity, in our opinion, is that these narratives, some dating as far back as twelve centuries, fit in perfectly with the manners, customs, hopes and language of the Moslems of the desert; those who at the present day, by their mode of living, are more akin to the Arabs of the Hijaz among whom Mohammad accomplished his Mission.

These remarks will serve to warn the reader that in this work will be found none of those learned paradoxes destined to destroy traditions, such sophisms delighting modern Orientalists by reason of their love of novelty.

The study of innovations introduced in this way into the Prophet's history has caused us to note that they were often prompted by feelings inimical to Islam which were not only out of place in scientific research, but were also unworthy of our epoch. As displayed by their authors, they generally denoted strange ignorance of Arab customs, notwithstanding that these commentaries were accompanied by considerable erudition, although too bookish. In order to refute such new-fangled assertions, it was enough to check each in turn. Being so contradictory, one killed the other. Their extreme improbabilities, from the standpoint of Oriental psychology, only served to enhance with still greater clarity the perfect likelihood of those traditions sanctioned in the world of Islam.

We have been guided by them. We have been satisfied to choose those that seemed most characteristic, setting each in its proper place, thanks to information gleaned in long interviews with pilgrims visiting the Holy Cities of the Hijaz, while reviewing these episodes in the light of our experience of Moslem life, in the Great Desert of Sahara, where one of us two had lived from birth and the other for the last thirty years and more.

In strict agreement with the Qur'an, the only indisputable book according to the Moslem Doctors of the earliest times and those imbued with the modern liberal spirit, such as the celebrated Shaikh Abdu, we have put aside all the posthumous miracles attributed to the Arab Prophet and which only serve to blur his true physiognomy.

Among all the Prophets founders of religions, Mohammad is the only one who, relying solely on the evidence shown by his Mission and the divine eloquence of the Qur'an, was able to do without the assistance of miracles, thus performing the greatest of all—the one which Ernest Renan, forgetting his example, declared to be utterly impossible. "The greatest miracle," said he, speaking of Jesus Christ, "would have been if he had wrought not any. Never would the laws of history and popular psychology have been more violently infringed."

On the other hand, we have taken care not to turn a deaf ear to tales in legendary shape. A legend, and above all, an Oriental legend, is an incomparable means of expression. It serves to paint mere facts in lasting colours and make them stand out in bold relief, far removed from the icy and so-called impartial account of an up-to-date reporter.

Our readers, enlightened by the foregoing warning, must therefore not let themselves be the victims of the numerous errors committed by Hellenism, Latinism and Scholasticism, when interpreting "literally" the sacred books of the East, while beneath seeming magic allegories scattered here and there in this narrative, will easily be discerned realities, poetically transposed, but not at all disfigured by the imagination of the Arabs.

With still more reason, the Qur'an should be read in the same way, for is it not written: "God setteth forth these similitudes to men that haply they may be admonished." (The Qur'an, xiv, 30.)

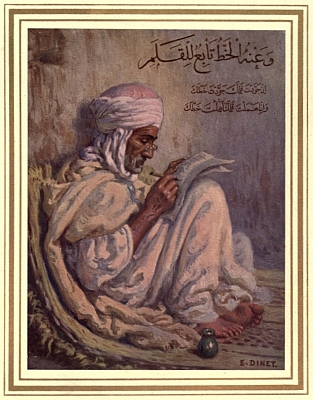

It may also seem strange that in the illustrations accompanying the text, no portrait of the Prophet will be found, nor any picturing of events in which he figured as the hero.

And this is why: being sincere Moslems, we do not want to run counter to the true principles of Islam, far less hostile than is supposed to the portrayal of mortals' faces, but strictly forbidding the image of the Divinity, considered to be rank blasphemy leading to idolatry more or less disguised. To represent the likenesses of the Prophets is to belittle them inevitably and sacrilegiously.

And after all, in the eyes of the Believer, what does the prim effigy of one of God's messengers on earth, however marvellously painted, look like in comparison with the sublime idea that the mind of the Faithful creates, under the influence of fervid faith? This has been so well understood by certain Persian painters of miniatures, that, having to sketch Mohammad in the varied phases of his nocturnal ascension, they veiled his face entirely, because they found themselves powerless to picture it, and feared also to impair features so revered. There is no greater proof of their intention than the meticulous care with which in the same pictures all other faces are treated, including that of Buraq, the winged steed with the head of a human being; and also the lineaments of the angels in the celestial procession.

In place, therefore, of an imaginary portrait and necessarily falsified drawings, we have adopted a more indirect style of illustration, but by its means we hope to have succeeded in evoking a few lights and shadows, undoubtedly emanating from the superman who came into the world at Makkah (Mecca).

His features, solely known by the descriptions of those who penned his history, appear to us dimly through a gauzy veil of dreamland that we shall not try to rend asunder, for behind this mysterious filmy mask, the sacred lineaments will enjoy the rare and precious advantage of not having been spoilt, like so many others, by impossible attempts of pictorial reconstitution. On the other hand, his ways and doings have been brought down to our own times, with religious fidelity, by three hundred millions of disciples, scattered all over the earth's surface.

The constant thought of all Moslems, of whatever race, is to imitate in everything, in the most humble as well as in the highest, of life's functions, the habits of the Prophet whose image is engraved in their hearts. And this is so true, that simply by the way in which he washes his hands, the difference can be seen between an Arab Moslem and an Arab Christian.

Looking upon true Believers going to and fro, we consequently view the movements of Mohammad. It is but a pale reflection, but nevertheless incontestably authentic; whereas, despite the perfection of their statues, the Roman Emperors can only offer to us their limbs and faces, stiffened in attitudes of awkward pride; remaining as corpses that our imagination is powerless to resuscitate.

Impressed by these facts, we had the idea of illustrating this history of Mohammad by picturing the religious doings of his disciples; a few scenes of Arab life, and views of the Hijaz, his native land.

rosy ray lit up

the horizon; the stars paled, and a voice cried out in

cadence, in the silence of dawn:

rosy ray lit up

the horizon; the stars paled, and a voice cried out in

cadence, in the silence of dawn:

"Allah is the greatest! There is no God but Allah, and Mohammad is the Prophet of Allah! Come and pray! Come to Salvation!"

High up above the flat housetops and the palm-trees of the oasis, the last notes of the Muazzin's call, wafted from the balcony of the slender minaret, died away in the infinite space of the Desert....

Mohammedans who were still slumbering, enwrapped in the white folds of their shroud-like mantles, sprung to their feet with a start, like dead men coming to life. They hurried to fountains where they performed their ablutions; and then, with clean skins and pure thoughts, they gathered together in long processions, elbow to elbow, all turned in one direction: that of the Holy Ka'bah of Makkah (Mecca).

Standing erect, heads slightly bent, eyes downcast, perfectly still in the long folds of their garments, they seemed as if metamorphosed into a crowd of statues. Following the example of the Imam, in front of them, but in the same direction, and announcing each phase of the prayer by the Takbir: "Allah is the greatest!" they all lifted their open hands on a level with their foreheads, to bear witness to their ecstasy in the presence of the Almighty power of the Master of the Worlds. Then, every man made the same movement, bending their backs and bowing low before the throne of His Supreme Majesty.

But this did not suffice to express all the humility of their souls, so they dropped to the ground and prostrated themselves, piously pressing their faces against the earth. For a few moments they remained in this supplicating posture, as if crushed by the weight of the entire firmament which might have been prostrated with them.

They held up their heads at last and rose to a sitting posture, both knees on the ground, their heads bowed under the burden of their fervour. The prayer terminated by salutation, accompanied by the face being turned first to the right, then to the left, addressed to the two recording angels who unceasingly attend every true Believer.

Generally, however, the Faithful who ask nothing from Allah, not even their daily bread, remain a little longer on their knees, and placing, breast-high, their open palms under their eyes, as if reading a book, they implore Divine Mercy for the salvation of their souls, for their relatives, and for Islam.

Only a few parts of the Prayer: the Takbir, the Fatihah and the final salutation are loudly intoned by the Imam. The congregation pray inwardly; the Takbir alone is murmured in whispers that are barely audible.

Such half-silence enhances the grandeur of their gestures, so expressive and simple, in which dignity is closely allied to humility; and being totally devoid of affectation, constitutes the most poignant display of adoration imaginable.

Every day, each time the rays of the sun change colour: at rosy dawn; flaming noon; during gilded sunset, when it descends below the horizon in all the yellow sadness of its disappearance; and at the moment it is enshrouded in the blue veiling of night, not only in the Mosques, but also in the houses and streets, in cafés and market-places, in the country or the desert, all Moslems, alone or grouped together, wherever they may be, without needing to be called by the Muazzin or led by the Imam, are bound to stop short in their work and even interrupt their trend of thought, for a few minutes, thus glorifying the Benefactor.

For more than thirteen centuries, from the Atlantic's African shore as far as the Chinese coast-line of the Pacific, more than two hundred millions of the Faithful turn five times daily in the direction of the Holy Ka'bah of Makkah; their millions of prayers being garnered there to be offered up to the Most High, bearing witness to the undying gratitude of the souls of Islam.

This mysterious town, upon which the aspirations of so many human beings close in, was almost unknown in ancient times. What is it like?

Is it one of those cities, picturesquely situated, where ostentatious kings built splendid palaces, accumulating therein all the treasures of creation? Is it one of those vast commercial boroughs dominating land and sea routes to which the riches and produce of the universe came in abundance? Or was it an extensive imperial capital whose valiant warriors bent neighbouring peoples beneath their yoke?

Makkah has nothing in common with all this, being established in one of the most arid and forsaken spots on earth; and in olden times its only commerce consisted in desert caravan traffic, so that it was neither rich nor powerful. Nevertheless, many opulent towns are jealous of its glory, for it shelters in its midst the Holy Temple of the Ka'bah, besides being the birthplace of Our Lord Mohammad, the Prince of Prophets!

In our own times, despite gifts brought from the furthermost corners of the world by the hundred thousand pilgrims who come each year to prostrate themselves in its temple, Makkah, "The Mother of Cities," by the splendour of its palaces and mosques, cannot vie with any great capital. In the eyes of the True Believers, its treasures are radiant with incomparable brilliancy, but which is not terrestrial.

As a matter of fact, the aspect of Makkah—"Allah's Delight"—is no different from other Arab desert centres. There are more numerous and loftier dwellings, better decorated than in general, but its characteristics, on the whole, are unchanged.

From the top of the Jabal Abi-Kubeis which dominates it on the eastern side, it can be viewed stretching from north to south in a narrow valley. At first, it seems to form part of the earth on which it stands, because the bare and rocky mountains surrounding it are not separated from these heights by any oasis or verdant strip, and the terrace-roofs of the houses do not stand out from the heaps of stony fragments that have rolled down from the crags. The spectator's eyes gradually get used to the landscape and pick out architectural lines; mysterious entrances to dwellings; lace-work of tall, straight minarets; and then, astonished at the sudden apparition of a big town that he never thought was there, he sees it, as in a kind of mirage, increasing excessively. Now it is the turn of the rocks to look as if changed into houses; hills becoming immense suburbs extending boundlessly.

If, in this chaos of sharply-outlined shapes, it is difficult for the eye to distinguish dwellings from steep rocks; one cannot fail to be startled at once by the strange aspect of a great cube of masonry, built up in the middle of a spacious quadrangular courtyard and veiled by black silk, shining in violent contrast to the dull tints of the entire sun-scorched landscape.

This black cube is the Holy Ka'bah, the veritable heart of Islam, and like so many veins bringing blood to the heart to vivify the body, all the prayers of Islam flow towards this Temple to vivify souls. It is the only spot on earth where Moslems, when adoring the Eternal, can meet face to face.

The Ka'bah is not the tomb of the Prophet, nor an object to be worshipped, as many Europeans imagine. It is a temple called "Beit Allah al Haram" (the Holy House of Allah), and its origin can be traced to the most distant days of antiquity.

According to the Arab tradition, it was built by Adam, the father of the human race. Destroyed by the Flood, it was rebuilt on the same foundations, by the Prophet Abraham, with the help of his son, Ishmael, the ancestor of the Arabs. Since then, often repaired, but retaining the same lines and proportions, the Ka'bah became the goal of Arab pilgrims flocking to adore Allah, the Only One, and perform seven ritual circuits instituted by their forefathers under the title of "Tawaf."

Little by little, the worship of Allah, the Only One, having degenerated in the memory of the pilgrims who added the practice of idolatry, Mohammad was sent to destroy the three hundred and sixty images they adored.

In the east angle of the monument is incrusted the famous black stone "Hajaru'l-Aswad", framed in a silver circle.

This stone, which came down from Paradise, was brought by the angel Jibra'il (Gabriel) to Abraham and his son, during the rebuilding of the Temple, and they placed it where it is still to be seen this day, in order to serve pilgrims as a starting-point for their ritual circuits. Primitively as white as milk, its present characteristic ebony tint is due to the pollution of the sins of the pilgrims who came to touch and kiss it, while imploring the Merciful to pardon them.

Close to the Ka'bah is the well of Zamzam. Its miraculous water gushed forth from the earth to save Ishmael from the tortures of thirst when lost in the desert with his mother, Hajar (Hagar). Neglected by the Arab tribes, in the dark Days of Ignorance, it became choked up by sand and was dug anew by Abdul Muttalib, a few years before the birth of Mohammad. The water, ever since, is revered by pilgrims who use it for drinking purposes and for their ablutions, thereby sanctifying themselves by the remembrance of their ancestors.

The two functions of "Siqayah," (Management of Water Supply), and of "Hajaba," (Superintendence of the Ka'bah) were posts greatly sought after on account of their prerogatives. At the epoch at which our story begins, they were both united in the hands of Abdul Muttalib bin Hashem, of the Quraish tribe, the grandfather of the future Prophet.

One day, Abdul Muttalib, custodian of the Ka'bah, set forth from the Sanctuary, his favourite son, Abdullah, holding his hand.

On the threshold of the temple was seated Quotila, a woman of the Bani Asad tribe. On catching sight of the lad, she started to her feet, evincing sudden surprise. She stared at him with strange persistence, because she was fascinated by a supernatural light that radiated from his brow. 'Whither art thou going?' she called to him.—'To where my father leadeth me.'—'Stop and listen to me. I offer thee a hundred camels, being as many as thy father was bound to sacrifice to save thy life, if thou wilt consent to throw thyself upon me, now at once.'—'I am in my father's company and cannot disobey him, nor leave him,' replied Abdullah, petrified at such shamelessness, especially in the presence of such a respectable person as Abdul Muttalib.

The young man turned away, filled with confusion, and rejoined Abdul Muttalib who took him to the house of Wahb ibn Abdi Manaf, whose daughter the Superintendent of the Well thought would make a good wife for his boy.

Wahb was one of the chieftains of the Bani Zahrah tribe and Abdul Muttalib being numbered among the princes of the Quraish, a most noble tribe, an alliance between two such authentically aristocratic families would be easily brought about and so the marriage of Abdullah, with Aminah, daughter of Wahb, took place without further loss of time.

Abdullah went off with his bride to the dwelling of Abu Talib, his uncle. There the marriage was consummated during the young couple's sojourn of three days and three nights. When the newly-married young man went out of the house, he came face to face again with Quotila, the woman who had previously hailed him with such lack of decency and he was surprised at her complete indifference as she saw him pass by. Abdullah was considered to be the handsomest youth in Makkah. His manly bearing had aroused the sensual passions of most of the women of the city to such an extent that, when his marriage was announced, they fell ill by dint of jealousy and disappointment. Quotila, however, was not a victim to vulgar lust, being the sister of Waraqah ibn Taufal, the learned man renowned throughout Arabia for his knowledge of the Sacred Books. From him she had learnt how, in that part of the country, a Prophet was about to come into the world, whose father would be known by rays of light illuminating his face with a pearly or starry sheen. This sign she had detected on the brow of Abdullah, and was haunted by the ambitious desire of becoming the mother of the coming Apostle. Her hopes dashed to the ground, she no longer heeded Abdullah, notwithstanding his good looks.

Knowing nothing of all this, he felt hurt at her indifference, following so quickly on her great ardour. 'How comes it that thou dost not ask me again for what thou hungered for but a little while ago?' he asked Quotila.—'Who art thou?' she replied.—'I am Abdullah bin Abdul Muttalib.'—'Art thou the stripling whose brow seemed to me to be surrounded with a luminous aureola which has now disappeared? What hath befell thee, since we first met?'

He apprised her of his marriage, and Quotila guessed that the radiance surrounding the future Prophet had passed away from the forehead of Abdullah into the womb of Aminah, his wife.—'By Allah, I made no mistake!' she told him. 'On thy brow I discovered the pure light that I would have dearly liked to possess in the depths of my body. But now it belongeth to another who will be delivered of "The Best Among Created Beings," and there remaineth naught of thee that I care for.'

Thus it came about that Abdullah, by the words that fell from the lips of this learned woman, got to hear of his wife's pregnancy and the future in store for his son. Abdullah did not live long enough to have the happiness of knowing his offspring, for Mohammad's father died at Yasrib two months before Aminah was delivered.

Aminah, mother of Allah's Chosen One, spoke thus:

"Since the day I carried my son in my womb, until I brought him forth, I never suffered the least pain. I never even felt his weight and should not have known the state I was in, if it had not been that after I conceived and was about to fall asleep, an angel appeared to me, saying: 'Dost thou not see that thou art pregnant with the Lord of thy Nation; the Prophet of all thy people? Know it full well.' At the same instant, a streak of light, darting out of my body, went up northwards—yea, even unto the land of Syria.

"When the day of my deliverance came due, the angel appeared to me again and gave me a warning: 'When thou shalt bring forth thy child into the world, thou must utter these words: 'For him I implore the protection of Allah, the Only One, against the wickedness of the envious,' and thou shalt call him by the name of Mohammad which means The Lauded, as he is announced in the Taurat and the Injil, for he will be lauded by all the inhabitants of Heaven and Earth.'"

When the planet Al-Moushtari passed, a line of light darted for the second time from Aminah's body in the direction of faraway Syria and it illuminated the palace of the town of Busra. At the same time, other prodigies astonished the world: the Lake Sowa suddenly dried up; a violent earthquake made the palace of Chosroes the Great tremble, and shattered fourteen of its towers; the Sacred Fire, kept alight for more than a thousand years, went out, in spite of the exertions of its Persian worshippers, and all the idols of the universe were found with their heads bowed down in great shame.

All these portents caused fear in the hearts of those who witnessed them; but, despite the predictions of Al Moudzenab, the Parsee sorcerer, who had been warned in a dream that a great upheaval in the destiny of the universe would be caused by an event to take place in Arabia, the occurrence was unperceived: the birth of a child of the Quraish tribe at Makkah, a tiny town lost in the midst of the wilderness, unknown to the gorgeous monarchs of East and West alike, or else despised by them.

ur Lord Mohammad (May Allah shower His Blessings upon Him and grant

Him Salvation!) was born a few seconds before the rising of the

Morning Star, on a Monday, the twelfth day of the month Rabi-ul-Awwal

of the first year of the Era of the Elephant. (August 29th, A.D. 570).

ur Lord Mohammad (May Allah shower His Blessings upon Him and grant

Him Salvation!) was born a few seconds before the rising of the

Morning Star, on a Monday, the twelfth day of the month Rabi-ul-Awwal

of the first year of the Era of the Elephant. (August 29th, A.D. 570).

When he came into the world, he was devoid of all pollution, circumcised naturally and the umbilical cord had been cut by the hand of the angel Jibra'il. The atmosphere of the city being fatal to infants, the leading citizens were in the habit of confiding their children to Bedouin wet-nurses who brought them up in their Badya-land, where dwelt the Bedouins, or nomads. Shortly after the birth of Mohammad, about a dozen women belonging to the tribe of the Bani Sad, all bronzed by the bracing breezes of their country, arrived at Makkah, to seek nurslings. Upon one of them devolved the honour of suckling the Prophet of Allah. And she was Halimah, signifying "The Gentle".

Quoth Halimah bint Zuib: "It was a barren year, and both my husband, Haris bin Abdul Ozza and myself, were plunged in dire distress. We made up our minds to go to Makkah where I purposed to seek a foster-child whose grateful parents would help us out of our miserable plight. We joined a caravan where there were many women of our tribe, bound likewise on the same errand.

"The she-ass I was riding was so thin and exhausted by privation that she came nigh upon breaking down on the road and we did not get a wink of sleep all night by reason of our poor child being tortured by the pangs of hunger. Neither in my breasts, nor in the udder of a female camel driven by my husband, did there remain one drop of milk to relieve my baby's pain.

"All sleepless as I was, I fell a prey to despair. In my parlous state, could I hope to take charge of a suckling?

"Lagging far behind the caravan, we arrived in Makkah at last, but all the new-born babes had already been allotted to the other women, except one child and that was Mohammad.

"His father being dead and his family far from rich, despite the high rank it held in Makkah, none of the wet-nurses cared to take charge of the baby boy.

"We likewise turned away from him at first, but I was full of shame at thinking I should have to journey back empty-handed, for I feared the mockery of my friends luckier than I. Besides, my feelings were deeply stirred when I gazed upon that fine infant, bound to wither away in the unwholesome air of the town.

"My heart became filled with compassion; I felt my milk welling up miraculously in my breasts, so I said to my husband: 'I swear by Allah that I have a good mind to adopt that orphan boy, notwithstanding that we have but slight hopes of ever earning anything worth talking about by so doing.'—'I cannot say thou art wrong,' he replied. 'Perhaps with him, the blessing of Allah may once more favour our tent.'

"Scarcely listening, I could no longer restrain myself and rushed towards the handsome baby fast asleep. I placed my hand on its pretty little breast; he smiled and opened his eyes sparkling with light. I kissed his brow between them. Holding him tightly in my embrace, I made my way back to where our caravan was encamped. Once there, I offered him my right breast so that he should enjoy such nourishment as Allah chose to grant him. To my extreme astonishment, he found enough milk to satisfy his hunger. I proffered my left breast, but he refused it, leaving it to his foster-brother, and he always behaved in like fashion.

"A greater marvel still was when from our she-camel's teats, dried-up that morning, my husband drew enough milk to appease the hunger that gnawed my entrails, and for the first time for many a month, the shades of night brought us refreshing sleep. 'By Allah, O Halimah!' exclaimed my husband, next day, on awaking, 'thou hast adopted a child that is verily blessed!'

"With the little boy, I mounted my she-ass who started off at a rapid pace. She was not long in coming up with my surprised companions and even trotted in front of them. Thereupon they cried out: 'O Halimah! pull up thy ass, in order that we may journey home all together. Is that the same animal you bestrode when we departed?'—'Aye; 'tis she and no other.'—'Then she is under some spell that we cannot unravel!'

"We reached our tents of the Bani Sad. I know no more arid soil than ours and our flocks had been mowed down by famine. But we marvelled at finding them in more thriving condition than during the most prosperous seasons, and the swollen teats of our ewes yielded more milk than we knew what to do with.

"Our neighbour's flocks, on the contrary, were in a grievous state and their masters threw the blame on their shepherds. 'Woe to ye all, stupid serving-men!' cried the sheep-owners. 'Lead our lambs to graze with those of Halimah!'

"The men obeyed, but all in vain: the sweet grass that seemed to spring up out of the earth offering its tender sprigs to our sheep, withered immediately they were gone on their way.

"Prosperity and blessings remained in our tent unceasingly. Mohammad attained his second year and it was then I weaned him. His disposition was truly uncommon. At the age of nine months, he talked in a charming way with accents that touched all hearts. He was never dirty; nor did he ever sob or scream, except peradventure when his nakedness chanced to be seen. If he was uneasy at nights and refused to close his eyes, I would bring him out of the tent, when he would fix his gaze immediately with admiration on the stars. He showed great joy, and when his glances were sated with the sight, he let his eyelids droop and allowed slumber to claim him."

But when he was weaned, Halimah was obliged to take Mohammad back to his mother who was eager to have him with her. What grief therefore for the poor wet-nurse! She could not resign herself to such cruel separation. As soon as she got to Makkah, she threw herself at Aminah's feet and burst out supplicating as she kissed them. 'See how the bracing air of the Badya hath profited thy child. Think that those breezes will do him still greater good now that he is beginning to walk. Fear the pestilential air of the city! Thou wouldst see him waste away before thine eyes and remember my words when it was too late.'

Moved by these touching prayers and thinking only of her son's health, Aminah stifled her motherly feelings and finished by consenting to let Halimah take Mohammad back to the Badya. His good-hearted nurse, buckling him securely to her loins, went off, overjoyed, on the road leading to her encampment.

Home again at the Badya of the Bani Sad, Mohammad's first footsteps were printed on the ripple-marked carpet of the immaculate sands, where he inhaled with welcome nostrils the sweet odours of the aromatic plants growing on the hillocks. And there it was he slept under the dark blue tent of the star-studded sky and his chest expanded, breathing the limpid air of desert nights. He grew strong, thanks to the healthy, wholesome food of the nomads: milk and cheese, with unleavened bread baked under hot ashes and, now and again, camel's flesh or mutton, devoid of the sickening smell of wool-grease that comes from animals bred in confined stabling.

Such moral and physical well-being, that he owed to the Badya, was of great help to him, during ordeals later in life. He was always pleased to recur to his childhood's days. 'Allah granted me two inestimable favours,' he would often say. 'First came the privilege of being born in the most noble of all the Arab tribes, the Quraish; secondly, that of being brought up in the Bani Sad region, the most salubrious of the entire Hijaz.'

Never were there effaced from his mind those pictures of the desert which were impressed on his earliest glances when, in company with other nomadic lads, he would climb to the top of a rock to watch over a grazing flock.

Notwithstanding, being inclined to dream and meditate, he did not agree very well with the turbulence and high spirits of the little Bedouins of his own age, and preferred to hide away from them, and ramble in solitude not too far from the tents.

He went out, one morning, with his foster-brother leading the flocks of his foster-father to the pasturage.

All of a sudden, about the middle of the day, Mohammad's young companion went back alone. 'Come hither quickly!' he shouted to his father and mother, his voice hoarse with affright. 'My brother, the Quraish, having slipped away from us, according to his wont, two men, clothed all in white, seized hold of him, threw him on the ground and split his chest open.'

In mad fear, poor Halimah, followed by her husband, ran as fast as her legs would carry her, following the road pointed out by the youthful shepherd. Mohammad was found seated on the top of a hill. He was perfectly calm, but his face had taken on the sinister tint of the dust and ashes to which we must all return. They fondled him gently and put question after question to him. 'What ails thee, O child of ours? What hath befell thee?'—'While I was intent upon looking after the grazing sheep,' he replied, 'I saw two white forms appear. At first, I took them to be two great birds, but as they drew nearer, I saw my mistake: they were two men clad in tunics of dazzling whiteness.'—'Is that the boy?' said one of them to his companion, pointing to me. 'Yea! 'Tis he!' As I stood stupefied with fear, they seized me; threw me down and cut my breast open. They drew out of my heart a black clot of blood which they cast far away; and then closing up my chest, they disappeared like phantoms.'

The words of Allah, in the Qur'an, seem to allude to this incident: "Have we not opened thy breast for thee? * And taken off from thee thy burden. * Which galled thy back?" (The Qur'an, xciv. 1, 2, 3).

This story, together with many others to be met with in the pages of this work, must be taken to be a parable, which, in this case, signifies that Allah opened Mohammad's breast when quite young, so that the joy of monotheistic truth should penetrate therein and permeate his being, relieving him of the heavy burden of idol-worship.

Mohammad's foster-parents continued to live in a state of bewilderment and Haris said to his wife: 'I fear the boy is a prey to falling sickness, evidently due to spells cast by neighbours, jealous of the prosperity and the Blessing that the child hath brought into our tent. But whether possessed by the Evil One who conjured up this hallucination; or because, on the contrary, the boy's vision is a true one and pointeth to a glorious future, our responsibility is none the less heavy. Let us give him back to his family, before his disease becometh more violent.'

Halimah was regretfully obliged to agree with such wise arguments and, taking Mohammad with her, she turned in the direction of Makkah.

The boy, now four years of age, walked by her side, and, on the outskirts of the town, they found themselves in the midst of a great crowd wending their way to the market or the Temple pilgrimage. Night had come on. Hustled in the dense throng, Halimah was soon separated from her foster-son and was unable to find him in the dark, despite her active search and desperate shouts. Without losing time, she hurried to apprise Abdul Muttalib, whose high social position made it easy for him to send out clever men on the track of his grandson, while he rode on horseback to head the searchers.

In the Tihamah water-course, one of the trackers soon found a child seated among some shrubs. He was amusing himself by pulling the branches. 'Who art thou, child?' he was asked. 'I am Mohammad, son of Abdullah bin Abdul Muttalib.'

Well pleased at having found the boy he was looking for, the man lifted up the child and carried him to the arms of his grandfather following behind. Abdul Muttalib embraced Mohammad affectionately, sat him on the pommel of his saddle in front of him and brought him back to Makkah. To show his joy, the old man slaughtered some sheep and distributed their flesh to the poor of the city. Then, taking his grandson astride on his shoulder, he performed the ritual circuits round the Ka'bah in token of gratitude.

Accompanied by poor Halimah, now recovered from her anguish, he led Mohammad into the presence of Aminah, his mother. After she had given way to the effusive joy of a loving mother, she turned to Halimah: 'What doth this signify? O nurse, thou wast so desirous of keeping my son by thy side, and now thou dost bring him back to me, all of a sudden?'—'I considered that he had reached an age when I could do no more for him than I have done; and fearing unlucky accidents, I bring him back to thee, knowing how thou wert longing to set eyes on him again.'

Nevertheless, perplexity and sadness were only too clearly to be read on the kind nurse's features. Not being deceived by her explanations, Aminah continued: 'Thou dost hide from me the true motive of thy return. I wait to hear thee tell the whole truth.'

Halimah then thought it best to repeat what her husband had said, and Aminah's maternal pride was sorely wounded. 'Can it be that thou art afraid lest my son should fall a victim to the devil?' she quickly retorted.—'I confess that such is my fear.'—'Know then that the demon's wiles are powerless to do him harm, for a glorious destiny is in store for him.' Aminah made the nurse acquainted with the marvellous events that had happened during her pregnancy and lying-in. After having thanked and rewarded Halimah for her devotion, Aminah kept her child with her, and his health, fortified by life in the open air, had now nothing to fear from unhealthy conditions of town life.

Under the vigilant eyes of the most loving of mothers, Mohammad grew up handsome and intelligent; but he was not fated to long enjoy maternal affection which no other love can equal. On returning from a journey to Yasrib, whither she had taken him, Aminah died suddenly, halfway on the road, in the straggling village of Al-Abwa, where she was buried.

The sorrowing orphan boy, scarce seven years of age, was brought back to Makkah by a black slave-girl, Umm Aiman; entirely devoted to his young master and who, including five camels, constituted his sole inheritance.

He was taken in hand by his grandfather, Abdul Muttalib, who had always shown him great affection, and the old man's love increased daily, as he saw the lad growing up more and more like Abdullah, his father, so much regretted.

The following anecdote gives an idea of Abdul Muttalib's boundless affection for his grandson:

In Makkah, where the streets are narrow and crooked like those of all the towns of the desert, there is only one open space of any size—the square in which stands the Ka'bah, and where, morning and evening, the citizens gathered together, resting and gossiping about their business as well as performing their devotions. Not a day passed without the servants of Abdul Muttalib throwing down a carpet in the Temple's shade; and round the rug sat his sons, grandsons and the leading townsmen, awaiting his coming. The respect shown to the Superintendent of "The House of Allah" was so great, that never did anyone ever dare to put his foot even on the outer edge of his carpet.

It came to pass one day that young Mohammad took up a position right in the middle of the revered carpet, scandalising in the highest degree his uncles who drove him away immediately. But Abdul Muttalib was coming, and he had witnessed the conflict from afar. 'Let my grandson go back at once to where he was seated!' he called out. 'He is the delight of my old age and his great audacity ariseth from the presentiment he hath of his destiny, for he shall occupy higher rank than any Arab hath ever attained.'

So saying, he made Mohammad sit by his side and fondled his cheeks and his shoulders, while in ecstasies at the least thing the boy said or did.

Again the fates decreed, that Mohammad should be deprived of gentle love: Abdul Muttalib died at the age of ninety-five, unanimously regretted by his fellow-citizens.

The unlucky orphan boy was received into the house of his uncle Abu Talib, who had been chosen for this kind succour by his grandsire, for the reason that, alone among his uncles, he was the brother of both the mother and father of Abdullah, Mohammad's father.

Having a large family and not being very well off, although the management of the Ka'bah had been bequeathed to him, Abu Talib was obliged to do business with the lands of Yaman and Syria.

Shortly after sheltering his nephew under his roof, he undertook the task of organising a caravan of Quraish men, and he was to lead them back to their tents.

All was in readiness; the loads were shared and divided, corded and balanced on the pack-saddles of the kneeling camels, grunting according to their habit. Their drivers began, by dint of blows and shouts, to force them to rise to their feet and direct their swaying stride in a northerly direction. This sight caused Mohammad to remember his beloved Badya, where caravans resembling this one about to depart passed to and fro continually. Fresh separation, this time from his beloved uncle, was about to plunge him into the sadness of solitude. He stood still, gloomy and silent. At last, heartbroken, he threw himself into Abu Talib's embrace, casting his young arms round him, and hiding his face in the folds of his uncle's mantle, to conceal his tears brought on by longing and despair.

Greatly moved by this spontaneous manifestation of affection, and guessing how ardent was his nephew's wish to accompany him, Abu Talib declared: 'By Allah! we'll take him with us; he'll not leave me and I'll not leave him.'

Mohammad dried his tears and, jumping for joy, he busied himself in hastening the final preparations for the journey. At a sign from his uncle, he perched himself on the female camel, getting up behind him.

When the caravan began to pass along the tracks made by the Bedouin tribes, Mohammad's lungs, contracted by breathing the vitiated air of houses and streets, were deliciously dilated, revelling in liberally gulping down the life-giving air of the Badya to which he was accustomed. Being used to a nomadic existence from childhood, the young traveller was able to support most valiantly the exhausting privations and terrible fatigue of such an interminable journey in the midst of the Hijaz deserts.

For more than a year, the countries he passed through were so much alike in their sands and rocks, that the caravan seemed as if marking time. In the pitiless desert there was no other sign of life, except the presence of Him who is everywhere, eternally existant, but not to be seen by mortal eyes.

On the terrace-roof of a convent perched, like a turban on a tall man's head, on the top of a steep hill, the lesser chain of the Jabal Hauran, the most learned monk, Bahira, looked out afar over the Syrian plains, stretching away in infinite space in the direction of Arabia. All of a sudden, his attention was drawn to the strange aspect of a solitary cloud, white and oblong, that stood out in bold relief on the immaculate blue background of the sky. Like some enormous bird, the cloud hovered above a small caravan winding its way northwards. The fleecy mass in the heavens covered the straggling procession with its azure shade and moved with the line of travellers.

At the foot of the hill on which the monastery was built, the caravan halted, close to a great tree that grew on the brink of a dried-up wady, and began to organise the encampment. At that moment, the cloud stopped still and vanished in the celestial canopy, while the branches of the tree were bent, as if beneath the gusts of a breeze acting on those twigs and leaves, at the same time throwing their shade over one of the caravaneers, as if to protect him from the blazing rays of the sun. Seeing these prodigies, Bahira guessed that among these wayfarers coming from the Hijaz, would be found the man he had been awaiting so long: the Prophet announced by the Sacred Books. So Bahira hurried down from the flat roof, gave orders to prepare a bountiful meal and sent a messenger to invite all the folks of the caravan without exception, young or old, nobles or slaves.

The messenger returned, in company with the men of Makkah whose coming Bahira awaited on the threshold of his monastery. 'By Lat and Uzza! thy conduct doth puzzle me, O Bahira!' exclaimed one of the guests. 'Many a time and oft have we passed by the convent; yet, until now thou hast never heeded us; never didst thou dream of showing us the least sign of hospitality. What maggot biteth thee this day?'—'Thou dost not err,' replied Bahira. 'I have cogent reasons for behaving as I do. But ye are my guests at this hour and I pray that ye honour me by gathering together to partake of the repast that I have prepared for you all.'

While the people he had invited were enjoying the food with the appetites of men having recently been sorely deprived, Bahira scrutinised them all in turn, trying to find the one answering to the description given in his Books. Much to his disappointment, he did not succeed. There was no one to be seen whose appearance agreed with the description. But as he had just witnessed marvels that could not be explained, otherwise than by the reason that one of Allah's elect was surely present, he refused to be discouraged. 'O men of the Quraish tribe!' he asked; 'is there not one of you remaining in your tents?'—'Aye, one only,' was the reply. 'We left him alone at rest on account of his extreme youth.'—'Why did ye not bring him hither? Go, call him at once, so that he shareth the meal in your company.'—'By Lat and Uzza!' swore one of the guests; 'we give you right. Of a surety we are to blame for having left one of us behind, while we profit by thine invitation, especially as he is a son of Abdullah bin Abdul Muttalib.'

Rising, he went and fetched Mohammad and brought him into the midst of the group of guests. Bahira eyed the newcomer with great attention and when the men had done eating and drinking, the monk went to him, taking him on one side. 'O young man!' said the monk, 'I have a question to ask. By Lat and Uzza, wilt thou consent to answer?'

Bahira desired to put him to the test by invoking the idols Lat and Uzza, exactly as he had just heard his guests swearing, but Mohammad replied thus: 'Put no question to me in the name of Lat and Uzza, for there is nothing on this earth that I hate more than them.'—'Well then, by Allah! wilt thou answer me?'—' Question me and, by Allah! I'll answer thee!'

Thereupon Bahira interrogated him on everything that was of interest, such as his family, his position in life, his dreams that, now and again, disturbed his slumbers, and many other things. Finally, just as the youth, after having taken leave of the saintly scholar, turned to go away, the collar of his tunic yawned slightly and Bahira caught sight of the "Seal of Prophecy," imprinted on the lad's back, below the nape of the neck, on the exact spot indicated by the Sacred Texts. Bahira's last doubts vanished—here, indeed, standing in his presence, was the Prophet whose advent had been foretold. Therefore, the monk went up to Abu Talib and spoke to him, saying: 'What relation is this lad to thee?'—'He is my son.'—'No! He is no son of thine!'—'True enough! He is not my son, but that of my brother.'—'What hath become of thy brother?'—'He died while his wife was still pregnant with my nephew.'—'Thou dost speak the truth. Mark then my words: lose no time in returning to thy country with thy brother's son and watch over him with constant vigilance. Above all, beware of Jews! If they saw him and learnt what I have just learnt about him, by Allah! they would do him harm, for this son of thy brother is chosen to play a great part in the world!'

Abu Talib, much impressed by the warnings of a man whose scientific reputation was universally recognised, made haste to finish his business at Busra in Syria, and started back home to Makkah with his nephew, where they arrived safe and sound.

Protected by Allah and guided by his uncle, who watched over him with true paternal care, Mohammad grew up and became an accomplished young man. He was extremely chaste. Abu Talib being busily engaged in executing some repairs in the Zamzam well, several Quraish striplings, among them being Mohammad, fetched and carried big stones fitted to the work. So as to be more at their ease, they lifted up their izars (a kind of tunic) in front, passing them over their head and rolling them round the neck, thus protected from the sharp edges of the stones carried on the shoulders; and all this was done without troubling about the fact that they were showing their nakedness. Mohammad was obliged to imitate them; but so soon as he felt his nakedness exposed to every eye, he was seized with a fit of atrocious anguish; great drops of sweat stood out on his brow; a shudder of shame shook his entire frame and he fainted away.

Such innate modesty, and the protection granted by Allah to his Elect, safeguarded the young man from the excesses in which lads often fall at the period of puberty. Among all the youths of the same age, he was the best-looking; the most generous; the most easygoing; the most truth-telling; the most devoted friend; and the most devoid of debauchery, to such an extent that his fellow-citizens called him "Al-Amin," which means: "The Reliable Man."

Like Abu Talib, most of the men of Makkah were obliged, to eke out a living, to traffic with Syria and the Yaman.

Their town, situated in one of the most frightfully barren countries of the world, offered no resources and its citizens only made both ends meet by dint of trading with these two countries between which it served as a link.

Its caravans crawled to the Yaman to procure raw materials from that region, known as Arabia Felix; and also products brought from overseas, imported from Ethiopia, India and even far China. The camels came laden with fragrant spices, sweet-smelling incense, ivory, gold dust, silks and many other articles of luxury. Arriving in the Hijaz, they added dates from Yasrib or Taif. Then they wended their way into Syria, to exchange these goods for agricultural produce, such as grain, wheat, barley, rice, figs and raisins, as well as for imports of Greek and Roman civilisation.

Even women carried on this kind of trade, confiding their goods to those who organised caravans. These female traffickers sold the merchandise in return for a share of the profits.

Khadijah bint Khuaild, a rich and noble widow, at the head of a thriving enterprise of this kind, hearing that everybody was unanimous in extolling Mohammad's well-merited reputation for prudence and probity, thought it would be well to entrust him with the direction of her commerce. She sent for him and, as a beginning, proposed that he should take charge of a caravan she was despatching to Syria and offered a salary twice as large as she was generally in the habit of paying.

Mohammad accepted; but Abu Talib, calling to mind what the monk Bahira had told him, grew uneasy when the camels were ready to start. He spoke privately to each of the caravaneers, urging them to watch over his nephew, and making them responsible for any harm that might come to him. It was with Maisarah, a slave, Khadijah's right-hand man, that Abu Talib was most solemn in his warnings. About to travel with Mohammad, Maisarah, a good servant, simple-minded and devoted, already greatly impressed by the confidential observations of such a prominent citizen as Abu Talib, fell under the sway of the charm and influence exercised by his young master over all who approached him. Maisarah felt great liking and boundless admiration for Mohammad.

In every incident of the journey, Maisarah noted miraculous tokens, proving the superhuman disposition of the man he served, and indeed, certain events showed that the slave guessed aright. The road he had so often travelled, knowing all its fatigue and danger; the interminable tracks where the inexorable orb of day dried up the water-skins and gave the mortals who went that way a foretaste of the flames of Jahannam; the paths marked out by the bones of men and animals that had succumbed to pitiless thirst, were passed as easily as if they had been enchanted.

Every day, at the hour when the sun, rising high over the heads of the travellers, threatened them with its deadly, blazing rays, light clouds, like the feathers of a bird, floated in the azure sky. They increased and met; then they were stretched out in long lines resembling the beam-feathers of enormous wings, opened to protect Mohammad beneath their shade. When the sun, losing its formidable power, began to sink gradually below the horizon, the feathers of these clouds dropped away one by one, vanishing in the last golden rays that the incandescent orb threw out through space before disappearing. The protecting wings, now useless, closed, making room for the stars which sparkle nowhere in the world so brilliantly as over deserts. Even the camels seemed overjoyed; they doubled the stride of their great long legs and the path seems to fold itself backwards as they advance. No dead body of any of them was added to the sinister skeletons left behind by previous caravans.

Once only during the whole journey, a couple of Khadijah's camels showed signs of exhaustion and lagged behind the convoy. Despite the insults and blows showered on them, Maisarah failed to bring them in line with the others. The two wretched beasts were completely bathed in sweat, a certain sign that they would soon fall, never to rise again. Maisarah, devoted to his mistress's interests, was extremely perplexed. He did not want to forsake his tired camels; but on the other hand, he had not forgotten Abu Talib's pressing recommendations concerning the young man then leading the caravan, so the slave ran to apprise him of what was taking place.

Mohammad halted and came back with Maisarah to see the pair of camels who were lying down, uttering painful, pitiful groans each time an effort was made to make them get up. He leant over them and, with his blessed hands, touched their feet hacked by the sharp pebbles of the Hammadah, and the poor beasts that had not even stirred under the lash, suddenly rose to their feet and with enormous strides, grunting joyously, caught up with the leaders of the caravan.

Good luck lasted when the caravan reached Busra, in Syria. Mohammad sold out all the goods he brought with unexpected profit, and found, at extraordinarily advantageous rates, what he had come to get, without even having to undergo the horrors of never-ending haggling, according to Oriental custom.

He awakened the sympathy and interest of everyone by his winning ways, frankness and honesty; but above all, by that mysterious radiance emanating from Predestinated Beings; which the old masters interpreted by a golden aureola, called magnetism by the scientists of the present day, because they lack the power of explaining its nature.

In this region, where enthusiasm for questions of religion ran high; where every hill is topped by a monastery and where every stone calls up the remembrance of a Prophet, this young traveller, before whom Nature itself seemed to bow down, excited in the highest degree the curiosity of all these monks. They were renowned for researches in sacred texts and lived in hopes of the coming of a new Apostle of Allah. All flocked to put questions to Maisarah, known to many among them during previous journeys. They soon divined that he was Mohammad's confidential slave; and a Nestorian monk, named Jordis, predicted great things to the devoted serving-man, making the same kind of recommendations as Bahira had made to Abu Talib.

All transactions being terminated, the caravan turned homewards, and immediately the mysterious cloud, that seemed to be awaiting the travellers, took its place over Mohammad's head and never ceased to accompany him until the journey's end. On the outskirts of Makkah, at the spot called Bathen Mou, Maisarah prevailed on Mohammad to go on ahead of the convoy, so as to carry to Khadijah, without the least delay, the good news of their return.

The widow was in the habit of going up with her servants to the top of her house whence she could see the road to Syria, dipping, in a north-easterly direction, into the ravine overlooked by the Jabal Quayqwan. She certainly felt no anxiety concerning her goods, but without confessing as much to herself as yet, she was fearful lest anything harmful should happen to the man to whom she had confided them: young Mohammad who, by his noble bearing and upright disposition, had so deeply impressed her that his absence weighed her down. It seemed to be never-ending.

One day, among all these weary weeks of waiting, when the sun at its zenith was setting the town in a blaze, preventing the inhabitants from stirring out in the streets or mounting to the housetops, Khadijah lingered at her usual observatory. Her beautiful eyes, their lids scorched by dint of staring searchingly into the depths of the white-hot horizon, had just reluctantly closed, in despair at not seeing the caravan so impatiently desired ... All of a sudden, the house became filled with delicious, cool air; while the blinding reverberation of sunlight on the white terraces and calcined rocks was softened by a gauzy veil of sheltering violet shade ... Just then, the door opened and Mohammad entered Khadijah's dwelling.

Doing his duty like a scrupulous manager, he turned in all the accounts of his expedition, and enumerated the magnificent results thereof. She thanked and complimented him warmly, but without being very much astonished at his success, for she began to think he was predestinated.

The coincidence of his arrival with that of the cloud which granted such beneficent shade had not failed to strike her, and she divined the obvious connection of the circumstances. 'Where is Maisarah?' quoth she.—'With the caravan over which he watches.'—'Go back at once and fetch him; increase the camels' speed, for great is my haste to admire the riches thou dost bring me.'

Mohammad heard and obeyed; and the cloud, flying away from the house, followed and accompanied him on the Syrian road. Henceforward, Khadijah's doubts were dispelled, and her faithful slave Maisarah, who soon arrived, confirmed her opinion. 'The cloud thou didst remark,' he told her, 'accompanied us unceasingly from the day we left Makkah until we returned. Ever since we went out of Busra, and enlightened by the predictions of the learned monks of the Hauran, I am forced to acknowledge that it was formed by the wings of two angels whose mission was to protect my master from the sun's ardent rays.'

He then narrated all those incidents of the journey in which he could make out miraculous tokens and Khadijah never grew tired of questioning him.

This noble, generous woman rewarded Mohammad by giving him double the salary she had promised and thenceforward had but one idea: to get him to take care of her entire wealth. The best way was to marry him, and the dictates of her heart urged her to carry out her plan. There was but one objection: the difference in their ages. Mohammad had only just attained his twenty-fifth year, while she was close upon forty. Nevertheless, Khadijah's age did not prevent her from being the most marrigeable lady in all the town, not, as might be rightly thought, on account of her riches (according to Arab customs, the husband brings the dowry and has no right to his wife's property), but because of her personal qualities, charming ways, distinguished manners, chastity and aristocratic descent, Khadijah being the daughter of Khuaild bin Asad, bin Abdul Ozza, bin Qusaiy, bin Kilab, bin Morra, bin Kab, bin Lawaiy, bin Ghalib....

She was therefore the queen of a court of suitors trying to dazzle her, some by the purity of their pedigrees; others by the extent of their riches. But all in vain. Since the death of her second husband, Abu Hala, it seemed as if she had made up her mind to end her days without contracting a third alliance. When she met Mohammad and began to appreciate his moral qualities, all her resolutions soon weakened and the feelings that drew her towards him increased each day in intensity. She determined to sound him.

Maisarah has said: "Two months and twenty days after our return from Syria, my mistress sent me to my master and I questioned him thus: 'O Mohammad! hast thou any reason for remaining a bachelor?'—'My hands are empty. I do not possess the wherewithal to furnish the dowry of a betrothed bride.'—'But if the small amount thou hast should be considered enough by a rich, worthy and noble lady—what then?'—'To whom dost thou allude?'—'I mean Khadijah!'—'Why joke with me? How, with the trifle I could offer as a dowry, should I dare to seek her presence and offer to take her in marriage?'—'Rest easy on that score. I'll see to it.' My master's accents and looks sufficed for me to become aware of his feelings towards my mistress. Without further delay, I sought her out and told her what I thought. Beaming with joy, she made all her arrangements for speedy nuptials."

At first, Khadijah had to obtain the consent of Khuaild, her father, who so far had inexorably repulsed all suitors, as he never found any rich or noble enough for his daughter. To gain her ends, she resorted to trickery.

Coached by her, Mohammad made arrangements for a big feast, inviting his uncles, Khuaild and a group of Quraish tribesmen of the highest rank. Khuaild's weak point was a love of fermented beverages and, as was his wont, he drank a little more than was reasonable. His daughter seized the opportunity to speak to him thus: 'O my father? Mohammad ben Abdullah asks me to marry him and I beg thee to bring about our union.'

Khuaild, giddy with the fumes of wine, and seeing everything tinted with a rosy hue, gave his consent without reflecting, and Khadijah, immediately, following the custom prevailing at that epoch, bedewed her betrothed with perfumes and threw a sumptuous mantle over his shoulders.

Khuaild woke up out of his fit of drunkenness and interrogated his daughter: 'What doth all this signify?'—'Thou knowest full well, O my father! Thou hast just now settled my betrothal with Mohammad, son of Abdullah.'—'Could I have done this thing: marry thee to the orphan adopted by Abu Talib? Ah no! Never will I consent while I live!'—'Dost desire then to dishonour thyself in the eyes of the Quraish chiefs here this day, by confessing thou wert drunk just now?'

She continued in this strain, until at last Khuaild, finding nothing to say in response, was obliged to give his definite consent. Thereupon Abu Talib made the following speech: 'Praise be to Allah who created us, the Bani Hashem, descendants of Ibrahim (Abraham) and of the seed of Ishmael, who did appoint us to be custodians of His House, the Holy Ka'bah, and Administrators of His Sacred Territory; and who made us as Lords over the Arabs. Here before ye standeth my brother's son, Mohammad bin Abdullah; no man can be weighed in the balance with him, for he is far above all others as regards nobility, merit, generosity and wisdom. If he be not favoured by fortune, remember that wealth is naught else than a passing, inconstant shadow; a loan to be repaid eventually. Now the soul of Mohammad bin Abdullah leaneth towards the noble dame Khadijah, whose soul eke leaneth towards him; and he doth beg at this hour that thou, O Khuaild! in thy generosity, should give her to him to be his wife. As dowry, he bringeth twenty young female camels, and I call upon ye to be my witnesses, O my Quraish brethren!'

The marriage took place, and so as to celebrate it duly, Khadijah had her young and graceful slaves to dance to the sound of tabors, before the company assembled; all unanimously overjoyed at this alliance between two such noble families.

Khadijah was Mohammad's first wife. She never had a rival in her husband's heart, and, until the day of her death, she was his sole, beloved spouse. She gave him seven children; three sons: al-Qasim, at-Tahir and at-Taiyib; and four daughters: Ruqaiyah, Fatimah, Zainab and Ummu Kulsum.

After the birth of al-Qasim, the eldest boy, a familiar surname, "Abul Qasim," that is to say, the Father of Qasim, was bestowed on Mohammad, full of joy at the coming of a scion of his house. Unfortunately, the poor child, greatly cherished by his father, was destined to die in infancy. The same fate overtook his brothers, at-Tahir and at-Taiyib, who passed away in like fashion in "The Days of Ignorance." Only Mohammad's daughters witnessed the advent of Islam and were counted among its first and most faithful servants.

After partial destruction by fire, the Ka'bah had been badly restored. The roof fell in, and thieves took advantage of the breach to get into the Sanctuary and carry off part of the treasure, constituted by pilgrims' offerings.

Fresh repairs were urgently needed; but as bad luck would have it, the walls were so dilapidated that they could no longer bear the least weight. There was nothing to be done but to raze them to the ground. If, however, the idea of rebuilding such a revered monument met with no objection, its demolition seemed to be the most dangerous sacrilege imaginable.

After much hesitation, finally dispelled by a series of obvious miracles, the Quraish men came to the resolution of tearing down the old walls of which the remains were in heaps on the ground. Then, as the ancient foundations were formed of blocks of stone admirably fitting one into the other, each clan of the Quraish tribe undertook part of the task of rebuilding.

The workers, actuated by the zeal that always arises from rivality, soon built up the walls to the height at which the famous Black Stone, "al-Hajaru'l-Aswad," should be fixed. Who was to have the honour of putting the precious relic back in its place? There was not the slightest chance of coming to an agreement on this point, and, in consequence of each party pleading the precedence of the purest noble descent or the greatest merit, the discussion grew so heated that most tragical results were to be feared. Under the influence of jealousy, groups were formed and stood face to face. The Bani Abed-Dar, joining the Bani Adiyy bin Kab, brought forth a bowl filled with blood, plunging their hands therein, and swearing they would die sooner than relinquish the privilege in anyone else's favour, because they thought it devolved upon them by right.

For four days and four nights, the adversaries, with threatening mien, remained on the look-out, absorbed in the task of vigilantly watching each other. At last, Abu-Ummayah, their senior, spoke out, saying: 'There will come a time when all this must finish and this is what I propose: name as umpire the first man who cometh into our midst, and let him settle the dispute that destroyeth our union.'

The advice given was not displeasing to the stubborn rivals and they finally agreed to follow it. It happened then, at that very moment, that they saw coming towards them a young man about thirty years of age. They recognised him as "Al-Amin" (The Reliable); in other words: Mohammad. Nothing could have been more fortunate, and all being as of one mind on this point, they accepted him as arbitrator at once, submitting the cause of their conflict to his judgment. When they terminated explaining the case, Mohammad, instead of hearkening to their respective claims, only said: 'Bring a mantle and spread it out on the ground.'

When they had obeyed his behest, he took the Black Stone in his hands and placing it in the middle of the cloak, he went on: 'Let the most influential person of each party take hold of the mantle by the corner that is in front of him.' All did as they were told, and then he turned towards those who held the corners of the mantle. 'Now, lift the cloak,' he continued; 'all together, up to the height of the wall which is being built.'

They obeyed and when the lifted cloak was level with the spot where the Black Stone was to be built in, Mohammad took the Relic and with his own hands, put it in its place.

Thanks to his presence of mind, all cause of discord disappeared. He had given satisfaction to each of the rival groups, without favouring one more than the other; and caused the proud Arabs to be reconciled without bloodshed, for the first time in all their history; in short, there was honour due to him which no one contested.

High above the Black Stone, the walls rose rapidly, carried up by the workers toiling as friends. The ribs of a ship wrecked on the Jeddah coast furnished a flat terrace-roof, and when the monument was finished, it was entirely draped with a veil of the finest lawn, woven by the Copts.

In later years, the veil consisted of striped Yaman cloth; and still later, the Ka'bah was covered by Hajaj bin Yusef with the "Kiswah," or garment of black silk, such as is still thrown over it at the present day, being renewed yearly.

o him they called "Al-Amin," (the Reliable), his fellow-citizens were

ready to grant the highest and most coveted honours, with a post of

preponderance in their city.

o him they called "Al-Amin," (the Reliable), his fellow-citizens were

ready to grant the highest and most coveted honours, with a post of

preponderance in their city.

But being of a disposition equally devoid of vanity or ambition, he disdainfully refused to reply to their flattering advances, and his fortuitous intervention in the dispute arising from the rebuilding of the Ka'bah was the only time he was mixed up with public affairs during a period of fifteen years, dating from his wedding-day.

How did he pass his time? Allah had inspired him with the love of solitude, and Mohammad loved more than anything to wander all alone on great empty plains stretching away farther than the eye could reach.

What were the causes of this liking? Doubtless, in the gloomy desert surrounding Makkah, he conjured up over and over again the delightful memories of his childhood, passed in the Badya; but his highly-gifted soul found satisfaction of a more exalted kind. In the first place, he was spared the sight of the moral and religious errors of the Arabs at that period.

The Arabs were, in the highest degree, aristocratic, proud, independent and courageous. Their generosity towards their guests was exemplified in a refined manner that has never been surpassed; and, among them, a certain Hatim Tay may be looked upon as the Prince of Generous Hosts.

By their natural gifts of eloquence and poetry, they can bear comparison with the most brilliant orators or magnificent poets of the universe. Their poetry, above all, allowing them to celebrate heroic exploits; and their open-minded generosity by which they were led to sing love's joy and sadness, became, for such hot-blooded men, the object of passionate adoration, marvellously well served by the most enchanting language ever known.

Their public fairs, particularly that held at Okaz, furnished an opportunity for real poetical contests, where the winner heard his poem applauded by a madly delighted throng, and then it was written out fully in letters of gold, and hung up in the Temple of the Ka'bah. Of these poetical triumphs, called "Al-Muaalaquate," ("The Suspended"), seven have been handed down to us and prove what great heights were attained by the genius of the Bedouin primitive poets.

But, at the same time as we admire such brilliant qualities innate in the Arabs, we have to deplore great errors. The monotheistic religion of their great ancestor Ibrahim (Abraham) was entirely forgotten, despite their continued veneration for the Temple built with their own hands. They had become "Mushrikun," ("Associates"). To Allah, the Only One, partners were adjoined in the shape of idols, who were generally preferred. Every tribe and family possessed a favourite idol; and, at that epoch, three hundred and sixty false gods, of wood or stone, dishonoured the Holy Ka'bah.

The most gross superstition flourished in addition to idolatry. Games of chance, divining by arrows, drunkenness and sorcery debased the brains of these men, all otherwise remarkably gifted. Fretting under all restraint, lacking all ideas of decency, they married as many women as they could afford to feed; and as widows were considered to belong to their husbands' estate, revolting unions took place between stepmothers and stepsons.

Still more abominable was the custom of the "Wa'du'l-Binat," (Burying Girls Alive). By some strange morbid decay of the feeling of honour, and also through fear that the debauchery of daughters or their capture by an enemy might one day bring opprobrium on their families, many unnatural fathers preferred to get rid of their female offspring, by burying them alive as soon as they were born.

To sum up: the Arabs' leaning towards ostentation, their aristocratic prejudice and overweening pride, caused them to rebel against all discipline or authority. Consequently, union and progress becoming impossible, incessant warfare and pitiless vendettas between tribes and families submerged all Arabia in a sea of blood.

Such were the errors that saddened Mohammad. He could no longer bring himself to look upon them, and as he saw no cure for such deep-rooted and general evil, which he thought was infallibly destined to draw down on his people the terrible punishment of Heaven, such as annihilated the inhabitants of Thamud and Ad, he hid himself away in the most deserted spots he could find. Far from the contact of human beings, he was able to drive out of his memory the odious remembrance of their iniquity.

It was then that he gave way entirely to the imperious need of meditation and religious worship that mastered his soul. He wandered in sandy ravines, following capricious meandering watercourses, or climbing up the steep sides of rocky mountains, to recline at their summits and let his glance and imagination be lost in the depths of the arid expanse that stretched away at his feet as far as the most unattainable horizon.

During many long hours, stock-still in the midst of such impressive empty space; in this ocean of light where deathly silence reigned, he would be engrossed in mute and ecstatic contemplation of the sight—incomparably grand and varied—offered to him by the elements of heaven and earth obeying a mysterious, unknown, inconceivable, universal and unique Power....

He gazed on dunes and rocks, veiled at first by the dawn's rosy gauze, studded with humble pebbles that became sparkling precious stones when the early rays of the sun broke forth. Next came the shroud of dazzling light which the orb of day, at its zenith, spread over the tired earth that was as still as a corpse. Then followed a golden flood that the sun, as it declined, let loose in great waves all over the world, as if wishing that its departure should give rise to even greater regret. At last was seen the moon's scarf, irisated like a pigeon's breast, splashing the sky with its sparks that changed into myriads of stars.

And there arose proud columns that in still weather the sand erected joyously, as if trying to reach the blue vault above; or furious spouts which, on stormy days, gushed from the bottom of ravines, to attack dark, lightning-loaded mists. Caravans of clouds sometimes careered, shaped like flocks of white sheep, driven by the wind away from the high peaks where they were formed; forced to depart before they could bedew their birthplace with rainy tears. On other days, diluvian storms broke in cascades over bare mountains, vomiting forth impetuous torrents, thundering in the valleys.

In comparison with these formidable elements, which never dared to rebel against the law imposed upon them by Supreme Power, how weak and arrogant Humanity seemed to be! It relied upon the strength of mundane institutions, and now such feeble trifles were liquefied by the mirage viewed by Mohammad in the mirrored waves of seething ether, as if to proffer the image of the absolute vanity of the things of this world.

The "Khelous" (Desert Retirement), was the main source of Mohammad's education. It cleansed his heart of all worldly thoughts. That is why tradition has named it "Safat as Safa,"—The Purity of Purity.

Little by little, the soul of the boundless Desert penetrated his soul, bringing him the intuition of the unlimited grandeur of the Lord of All the Worlds. The most imperceptible secrets of Nature communed in the uttermost hidden depths of his being, impregnating his mind so violently that these eternal truths were on the point of escaping from his lips. Carlyle, the great thinker, cannot restrain his admiration in this connection. "The word of such a man is a Voice direct from Nature's own heart. Men do and must listen to that as to nothing else;—all else is wind in comparison." (The Hero as Prophet, London, 1840.)

How is it that some Orientalists of the West have put forward the theory that Mohammad profited by this retirement to arrange and elaborate his future task in its most minute details? Some of these scholars have even gone so far as to insinuate that, during his seclusion, he composed the Qur'an in its entirety. Have they not noticed that, in this Divine Book, there is no preconceived plan according to human methods; and that each of the Surahs, taken alone, is applicable to events that happened later, extending over a period of more than two decades and which it was impossible for Mohammad to foresee?