The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Young People's Wesley, by W. McDonald This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Young People's Wesley Author: W. McDonald Commentator: Bishop W. F. Mallalieu Release Date: May 31, 2012 [EBook #39864] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE YOUNG PEOPLE'S WESLEY *** Produced by Emmy, Dave Morgan, Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

My sole object in the preparation of this little volume has been to meet what I regard as a real want—a Life of John Wesley which shall include all the essential facts in his remarkable career, presented in such a comprehensive form as to be quickly read and easily remembered by all; not so expensive as to be beyond the reach of those of the most limited means, and not so large as to require much time, even of the most busy worker, to master its contents. I have sought to give my readers a faithful view of the man—his origin, early life, conversion, marvelous ministry, what he did, how he did it, the doctrines he preached, the persecutions he encountered, and his triumphant end.

This revised and enlarged edition will be found to contain many interesting features not found in the first edition. I have added, also, a brief account of the introduction of Methodism into America, as well as John Wesley's influence at the opening of the twentieth century. For this interesting chapter I am indebted to Rev. W. H. Meredith, of the New England Conference, who kindly consented to[6] assist me, in view of the pressure to get the manuscript ready on time.

It will appear, from all that has been said, that Mr. Wesley was the most remarkable character of the last century; and the influence of his life is more potent for good to-day than ever before, and must continue to augment—if his followers are true to their trust—till the end of time.

| Page. | ||

| Preface, | 5 | |

| Introduction, | 9 | |

| CHAPTER. | ||

| I. | Born in Troublous Times, | 13 |

| II. | The Wesley Family, | 20 |

| III. | Wesley's Early Life, | 32 |

| IV. | Epworth Rappings, | 41 |

| V. | Origin of the Holy Club, | 49 |

| VI. | Wesley in America, | 58 |

| VII. | Wesley's Religious Experience, | 71 |

| VIII. | Wesley's Multiplied Labors, | 83 |

| IX. | Wesley's Domestic Relations, | 93 |

| X. | Wesley's Persecutions, | 101 |

| XI. | Wesley and His Theology, | 115 |

| XII. | Wesley as a Man, | 132 |

| XIII. | Wesley as a Preacher, | 136 |

| XIV. | Wesley as a Reformer, | 144 |

| XV. | Wesley and American Methodism Prior to 1766, | 153 |

| XVI. | Wesley and American Methodism, | 161 |

| XVII. | Wesley Approaching the Close of Life, | 173 |

| XVIII. | Wesley and His Triumphant Death, | 179 |

| XIX. | Wesley's Character as Estimated by Unbiased Judges, | 185 |

| XX. | The Greater Wesley of the Opening Century, | 193 |

| Conclusion, | 203 | |

| Portrait of John Wesley, | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| An Unusual View of the Epworth Rectory, | 16 |

| The Wesleyan Memorial Church, Epworth, England, | 32 |

| Jeffrey's Attic Room, Whence the Mysterious Noises Came, | 48 |

| Wesley's Armchair, | 64 |

| Wesley's Clock, | 96 |

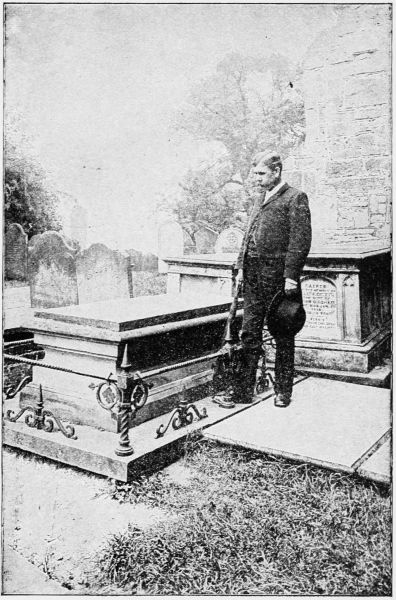

| Samuel Wesley's Grave, upon Which John Preached His Famous Sermon, | 112 |

| Wesley's Teapot. Wesley's Bible and Case, | 144 |

| St. Andrew's Church at Epworth. Epworth Memorial Church at Cleveland, O., | 160 |

| The Room in Which Wesley Died, | 176 |

| John Wesley's Grave, | 192 |

What, another Life of John Wesley! Why not? This time a "Young People's Wesley." If ever the common people had an interest in any man, living or dead, that man is John Wesley. It is true that we already have many "Lives" of this remarkable man. They range from the massive volumes of Tyerman down to the booklet of a few pages. The truth abides that of making many books there is no end, and so more Lives of Wesley will be written from time to time as the years and centuries come and go. The reason of this is that John Wesley is one of the greatest men of all the Christian centuries. When we undertake to enumerate the five greatest men that the English race has ever produced we must of necessity include the name of John Wesley. As the distance increases between the present time and the days of his protracted activity the grander does he appear. The majority of the men of his day and generation did not comprehend him. They could not, for the plan of his aspirations and achievements was far above their thinking or living. They did not realize his greatness; they did not foresee the[10] influence he was destined to exert on all future generations. He has been dead more than a hundred years, and yet to-day he is larger, vaster, and more powerful in the wide realm of intellectual and spiritual activities than he was at any time during his long and vigorous life. So far as we can judge, this development of the stature of this wonderful man will continue for ages.

Remember that John Wesley was well bred. On both his father's and mother's side he inherited the qualities of the best blood of England. So far as we know, his ancestry was purely Saxon, and of the best type of English-Saxon lineage. On sea or land, in military affairs, as a diplomat or statesman, he would have been eminent. He was one of the most thorough and comprehensive scholars of his century. He was fully abreast of his times in all matters of natural science; he was a linguist of rare excellency; he was a metaphysician; he was at home in philosophy. He had the rare ability of using all he knew for the best and highest purposes. He was a real genius, not a crank. A genius utilizes environment; a genius dominates circumstances; a genius makes old things new; a genius pioneers mankind in its career of progress. Because of these qualities and characteristics, men will never tire of reading the life, and men will never stop[11] writing the life, of this man. Born in the humble rectory of Epworth, in the midst of the fens of Lincolnshire, his name and fame reach to the ends of the earth. Men know him not for what he might have been, but for what he was—a friend of all, and a prophet of God.

Just now when the common people are more and more educated, and nearly all of them are readers of books, and many of them interested in good books, it is important that we have a Life of Wesley that is perfectly adapted to those who are not critical historical students, but rather to those who want the gist of things, who want the substantial and essential facts in compressed shape.

It is believed that this volume will meet all these requirements, and that a careful perusal of its pages will put any person of ordinary intelligence in very close touch with one of the greatest religious and social reformers the world has ever known. This volume is one that might be read with great profit by every member of our Church, and by all Methodists everywhere. Especially would its reading help all our young people, and particularly the members of our Epworth League. It is certain that its reading would give them clear, definite, and correct views of the life and work of the founder of Methodism; and such views would be sure to lead to a more healthful and vigorous personal religious experience, and would encourage[12] all heroic aspirations for the highest attainments in holy living, and excite the most ardent and persistent efforts for the salvation of all men. John Wesley knew that humanity had been redeemed by the sufferings and death of the Lord Jesus Christ. He knew that every redeemed soul might be saved. He knew that it was his business to bring redeemed humanity to the feet of its Redeemer. Would that all his followers might share in this threefold knowledge; and that by the reading of this volume all might be led to consecrate themselves to the accomplishment of the supremely glorious task at which John Wesley wrought until he ceased at once to work and live. O, that all Methodists might follow John Wesley even as he followed Christ!

Auburndale, Mass., April 8, 1901.

During the latter part of the seventeenth and the first part of the eighteenth century England was the theater of stirring events. War was sounding its clarion notes through the land. Marlborough had achieved a series of brilliant victories on the Continent, which had filled and fired the national heart with the spirit of military glory.

The English, at that time, had an instinctive horror of popery and power. James II, cruel, arbitrary, and oppressive, had been hurled from the throne as a plotting papal tyrant, and his grandson, Charles Edward, known as the Pretender, was making every possible effort to regain the throne and to subject the people to absolute despotism. To add to their dismay, the fleets of France and Spain were hovering along the English coast, ready, at any favorable moment, to pounce upon her. The means of public communication by railroad[14] and telegraph were unknown. There were few mails, and reliable information could not be readily or safely obtained. Under these circumstances it is not surprising that strange and exaggerated reports should have kept the public mind in a state of great excitement and general consternation.

It was also, pre-eminently, an infidel age. Disrespect for the Bible and the Christian religion prevailed among all classes. Hobbes, with his scorpion tongue; Toland, with his papal-poisoned heart; Tindal, with his infidel dagger concealed under a cloak of mingled popery and Protestantism; Collins, with a heart full of deadly hate for Christianity; Chubb, with his deistical insidiousness; and Shaftesbury, with his platonic skepticism, hurled by wit and sarcasm—these, with their corrupt associates, made that the infidel age of the world. Christianity was everywhere held up to public reprobation and scorn.

It is true that Steele, Addison, Berkeley, Samuel Clarke, and Johnson exposed the follies and sins of the times, but the character of these efforts was generally more humorous and sarcastic than serious. Occasionally they gave a sober rebuke of the religion of the day. Berkeley attacked, with his keen logic and finished style, the skeptical opinions which prevailed. Most of his articles were on the subject of "Free Thinking." Johnson, the great[15] moralist, stood up, it is said, "a great giant to battle, with both hands against all error in religion, whether in high places or low."

These men, and Young, with his vast religious pretentiousness, are said to have walked in the garments of literary and social chastity; but Swift, greater intellectually than any of them, and a high church dignitary to boot, would have disgraced the license of the "Merry Monarch's" court and outdone it in profanity. Even Dryden made the literature of Charles II's age infamous for all time.

"Licentiousness was the open and shameless profession of the higher classes in the days of Charles, and in the time of Anne it still festered under the surface. Gambling was an almost universal practice among men and women alike. Lords and ladies were skilled in knavery; disgrace was not in cheating, but in being cheated. Both sexes were given to profanity and drunkenness. Sarah Jennings, Duchess of Marlborough, could swear more bravely than her husband could fight. The wages of the poor were spent in guzzling beer, in wakes and fairs, badger-baiting and cockfighting."[A] And yet the reign of Anne claims to have been the golden age of English literature. It did show a polish on the surface, but within it was "full of corruption and dead men's bones."

AN UNUSUAL VIEW OF THE EPWORTH RECTORY.

AN UNUSUAL VIEW OF THE EPWORTH RECTORY.

Added to this, the Church, which should have been the light of the world, was in a most deplorable state. Irreligion and spiritual indifference had taken possession of priest and people, and ministers were sleeping over the threatened ruins of the Church, and, in too many instances, were hastening, by their open infidelity, the day of its ruin. The Established Church overtopped everything. She possessed great power and little piety. Her sacerdotal robes had been substituted for the garments of holiness; her Prayer Book had extinguished those earnest, spontaneous soul-breathings which bring the burdened heart into sympathetic union with the sympathizing Saviour. Spirituality had well-nigh found a grave, from which it was feared there would be no resurrection. Isaac Taylor says: "The Church had become an ecclesiastical system, under which the people of England had lapsed into heathenism;" and "Nonconformity had lapsed into indifference, and was rapidly in a course to be found nowhere but in books." In France hot-headed, rationalistic infidelity was invading the strongholds of the Reformation, and French philosophers were spreading moral contagion through Europe, which resulted in the French Revolution. The only thing which saved England from the same catastrophe was the sudden rise of Methodism, which, as one writer says, "laid hold of the lower classes and[17] converted them before they were ripe for explosion." When preachers of the Gospel celebrated holy communion and preached to a handful of hearers on Sabbath morning, and devoted the afternoon to card-playing, and the rest of the week to hunting foxes, what else could have been expected? It is doubtful if in any period of the history of the Church the outlook had been darker.

The North British Review says: "Never has a century risen on Christian England so void of soul and faith; it rose a sunless dawn following a dewless night. The Puritans were buried, and the Methodists were not born." The Bishop of Lichfield said, in a sermon: "The Lord's day now is the devil's market day. More lewdness, more drunkenness, more quarrels and murders, more sin is conceived and committed, than on all the other days of the week. Strong drink has become the epidemic distemper of the city of London. Sin in general has become so hardened and rampant that immoralities are defended, yea, justified, on principle. Every kind of sin has found a writer to teach and vindicate it."

"The philosopher of the age was Bolingbroke; the moralist was Addison; the minstrel was Pope; and the preacher was Atterbury. The world had an idle, discontented look of a morning after some mad holiday."

Over this state of moral and religious apostasy a few were found who made sad and bitter lamentations. Bishop Burnet was "filled with sad thoughts." "The clergy," he said, "were under more contempt than those of any other Church in Europe; for they were much more remiss in their labors and least severe in their lives. I cannot look on," he says, "without the deepest concern, when I see imminent ruin hanging over the Church, and, by consequence, over the Reformation. The outward state of things is black enough, God knows, but that which heightens my fears arises chiefly from the inward state into which we are fallen."

Bishop Gibson gives a heart-saddening view of the matter: "Profaneness and iniquity are grown bold and open." Bishop Butler declared the Church to be "only a subject of mirth and ridicule." Guyes, a Nonconformist divine, says that "preacher and people were content to lay Christ aside." Hurrian, another Dissenter, sees "faith, joy, and Christian zeal under a thick cloud." Bishop Taylor declares that "the spirit was grieved and offended by the abominable corruption that abounded;" while good Dr. Watts sings sadly of the "poor dying rate" at which the friends of Jesus lived, saying: "I am well satisfied that the great and general reason of this is the decay of vital religion in the hearts and lives of men,[19] and the little success that the administration of the Gospel has made of late in the conversion of sinners to holiness."

This was the state of the English Church, and of Dissenters as well, at the opening of the eighteenth century. And well it might be when, as has been said, the philosopher of the age was Bolingbroke, the moralist was Addison, the minstrel was Pope, and the preacher was Atterbury. But when darkness seems most dense the day-star of hope is near to rising.

On the 17th of June, 1703, was born in the obscure parish at Epworth, of Samuel and Susannah Wesley, John Wesley, the subject of this sketch. He was one of nineteen children. The names of fifteen have been recorded; the others, no doubt, died in infancy. Of these fifteen, John was the twelfth. He was born in the third year of the eighteenth century. His long life of eighty-eight years covered eleven of the twelve years of Queen Anne's reign, thirteen of that of George I, thirty-three of George II, and more than thirty of George III. This remarkable child was to more than revive the dead embers of the Reformation; he was chosen of God to inaugurate a spiritual movement which was to fill the world with the spirit of holy being and doing, and bring to the people ransomed by Jesus, in every clime and of every race, "freedom to worship God."

Samuel Wesley, father of John, was for forty years rector of Epworth Parish. He was an honest, conscientious, stern old Englishman; a firmer never clung to the mane of the British lion. He was the son of John Wesley, a Dissenting minister, who enjoyed, for a time, all the rights of churchmen. But, after the death of Cromwell, Charles II, whom the Dissenters had aided in restoring to the throne, and who had promised them toleration and liberty of conscience, on his return, finding the Church party in the ascendency, violated his pledge and approved of the most cruel and oppressive laws passed by Parliament against Dissenters. By one of these inhuman acts more than two thousand ministers, and among them many of the most pious, useful, learned, and conscientious in the land, were deprived of their places in the Church, of their homes and support, and were compelled to wander homeless and friendless, without being allowed to remain anywhere, until they found rest in the grave.

"Stopping the mouths of these faithful[21] men," says Dr. Adam Clarke, "was a general curse to the nation. A torrent of iniquity, deep, rapid, and strong, deluged the whole land, and swept away godliness and vital religion from the kingdom. The king had no religion, either in power or in form, though a papist at heart. He was the most worthless that ever sat on a British throne, and profligate beyond all measure, without a single good quality to redeem his numerous bad ones; and Church and State joined hand in hand in persecution and intolerance. Since those barbarous and iniquitous times, what hath God wrought!"[N]

Mr. Wesley had been for some years pastor of Whitchurch, Dorchestershire, and was greatly beloved by his people. But the law forbade anyone attending a place of worship conducted by Dissenters. Whoever was found in such an assembly was tried by a judge without a jury, and for the third offense was sentenced to transportation beyond the seas for seven years; and if the offender returned to his home before the seven years expired he was liable to capital punishment. This was an example of refined cruelty. The minister who had grown gray in the service of his Lord, whose annual income was barely sufficient to meet the pressing needs of his family, was turned adrift upon the world without support,[22] and the poor man was not permitted to live within five miles of his charge, nor of any other which he might have formerly served. As Mr. Wesley could not teach, or preach, or hold private meetings, he, for a time, turned his attention to the practice of medicine for the support of his family.

He bade his weeping church adieu, and removed to Melcomb, a town some twenty miles away. He had preached for a time in Melcomb before he became vicar of Whitchurch, and hoped to find there a quiet retreat and sympathizing friends. But his family was scarcely settled when an order came prohibiting his settlement there, and fining a good lady twenty pounds for receiving him into her house. Driven from Melcomb, he sought shelter in Preston, by invitation of a kind friend, who offered him free rent. Then came the passage of what was known as the "five-mile act," which required that Dissenting ministers should not reside within five miles of an incorporated town. Preston, though not an incorporated town, was within five miles of one. Finding no place for rest from the relentless persecution of the Established Church—persecution as cruel as Rome ever inflicted, save the death penalty, and that was imposed under certain conditions—he concluded to leave his home for a time and retire to some obscure village until he could, by prayer and deliberation,[23] determine what to do. Here, alone with God, his decision was made. He fully decided that he could not, with a good conscience, obey the law of Conformity, as it was called. Conformity was to him apostasy.

Mr. Wesley determined to remove to some place in South America, and, if not there, to Maryland. He hoped, by so doing, to find a quiet home for himself and family. In Maryland, settled and ruled by Catholics, he could enjoy freedom to worship God, but not in oppressive, Protestant England, just rescued from the domination of Rome.

No one can adequately comprehend how such a removal would have affected the religious life of the world. But the good man finally determined to abandon his plan and remain in his native land and do the best he could. God, without doubt, was in that decision. But he felt that God had called him to preach, and preach he would.

In spite of every precaution, he was frequently interrupted, suffering imprisonment for months together, and at four different times within a few years. At last, by frequent imprisonment, poverty, and failing health, the poor man's crushed spirit could stand it no longer, and he died at the early age of forty-two years, leaving wife and children homeless and helpless. All this the grandfather of John Wesley endured for conscience' sake. He was[24] a graduate of Oxford; as a classical scholar he had few equals—a man of deep piety and distinguished talents. His father, Bartholomew Wesley, had early dedicated his son to the Gospel ministry, and God seems to have accepted the dedication. And because he conscientiously objected to conducting public worship strictly according to the Prayer Book, the unchristian laws regarding Conformity were enforced, and the tears, blood, and suffering which befell those godly men lay at the door of the Established Church. Cruel persecution marked this man for its prey even after death. When his inanimate body, followed by weeping wife, little children, and sympathizing neighbors, was borne on a bier to the gates of the consecrated burial place of Preston, the gates were closed against it by order of the minister of the Established Church. So the remains of this good and great man were deposited in an unknown and unmarked grave.

Samuel Wesley was sixteen years old at the time of his father's death. He had been under the careful tuition of his learned father, and under such training his mind had become highly educated for one of his years. He had a genius for poetry, and possessed a highly sensitive nature. His associations with Dissenters were not the most favorable, and what he saw and heard at the meetings of what was known as the "Calf's Head Club" disgusted him.[25] Added to this, he was not pleased with the school of the Dissenters in which he was being educated, and, being not a little impulsive and hasty in his decisions, he concluded that all Dissenters were of the same character. He determined to examine the grounds of Dissent and Conformity, and, as might be expected, being more or less controlled by youthful prejudice, he concluded to renounce his former opinions and the faith of ancestors, and unite with the Established Church. And, as is often the case in such sudden changes, he did not stop until he had become a high churchman. But, notwithstanding his change, he had too much good practical common sense to carry out his theory. While it is true that he became a high Tory, he possessed too much benevolence, and too nice a sense of right, to give countenance to arbitrary power, such as had been exercised toward his ancestors. He could not forget what his honored father had suffered at the hands of churchmen.

Having become a churchman, at the age of sixteen he left his home for Oxford University. He traveled all the distance on foot, with only about thirteen dollars in his pocket and with no hopeful outlook for further supplies. And from that time until he graduated he received from his friends but a single crown ($1.20). But, Yankeelike, he made everything turn to his advantage. Being a bright scholar, he[26] composed college exercises for those students who, it is said, "had more money than brains;" he read over lessons for those who were too lazy to study, and gave instruction to such as were dull of apprehension. He wrote also for the press, and left the university, at the close, with four times as much money as he had when he entered.

After his graduation he went to London and was ordained. He served one year as curate in London, one year as chaplain on shipboard, and two years more as curate in London.

When James II was expelled, and William and Mary were called to the throne, Mr. Wesley was the first man to write in their defense. For this timely support Queen Mary appointed him rector of Epworth, Lincolnshire, which position he held to the end of his life. The village was far from being attractive, and the people were generally hard cases; but he was a faithful pastor there for forty years. He was always poor, but always honest. He was frequently in jail for debt, and as often relieved by donations from the Duke of Buckingham, the Archbishop of York, the queen, and others. "No man," he says, "has worked truer for bread than I have done, and no one has fared harder."

In politics Mr. Wesley was no conservative. Whatever he did, he did with his might. He espoused the cause of William, Prince of[27] Orange, regarding him as a perfect antitype of Job's war horse, and for such heroic support he received the anathemas of his parishioners; they stabbed his cow, cut off his dog's legs, burned his flax, and twice fired his house. But still he had the courage of his convictions. As an example of his moral courage the following story is told of him: Mr. Wesley was in a London coffee house taking refreshments. A colonel of the guards, near by, was uttering fearful oaths. Wesley, a young man, was greatly moved, and felt that a rebuke was demanded. He called the waiter to bring him a glass of water. He did so, and in a loud, clear voice Wesley said, "Carry this to that young man in the red coat, and request him to wash his mouth after his oaths." The colonel heard him, became much enraged, and made a bold attempt to rush upon his reprover. His companion interfered, saying, "Nay, colonel, you gave the first offense. You see, the gentleman is a clergyman." The colonel subsided, but did not forget the reproof. Years after he met Mr. Wesley in St. James Park, and said to him: "Since that time, sir, thank God! I have feared an oath and everything that is offensive to the Divine Majesty. I cannot refrain from expressing my gratitude to God and to you."

Samuel Wesley possessed many virtues, with some faults. He was often impetuous, hasty, and sometimes rash. In the heat of controversy,[28] in which he at times engaged, he was often unsparing in his invectives. But this must be set down, in part, to the spirit of the time. He was a faithful pastor and a fine oriental scholar. Mr. Tyerman says, "He was learned, laborious, and godly." He had the reputation of being a good poet, a fair commentator, and an able miscellaneous writer.

Susannah Wesley, mother of John Wesley, was in most respects the perfect antipode of her husband. She is said by some to have been beautiful, and by all to have been devout, energetic, and intelligent. She had mastered the Greek, Latin, and French languages, and was the mother of nineteen children. And such a mother, for the careful, wise, religious training of her children, modern times has never furnished a superior.

She was the daughter of Dr. Samuel Annesley, one of the many sufferers under the cruel law of Nonconformity; but he does not seem to have suffered as severely as John Wesley, whose fate we have recorded. It must have been that he, for some cause, was more fortunate than his contemporary. Miss Annesley became the wife of Samuel Wesley at the age of nineteen years. It seems quite remarkable that Samuel Wesley and his wife[29] should have both been connected with Dissenters, and their parents, on both sides, should have suffered by the oppression of the Established Church, and that both of them, while young, should have left the Dissenters and joined the Establishment. It could not have been the result of careful investigation, but, more likely, of youthful prejudice.

Mrs. Wesley was a noble woman. Of her Dr. Adam Clarke says: "Such a woman, take her all in all, I have never read of, nor with her equal have I been acquainted. Many daughters have done virtuously, but Susannah Wesley has excelled them all." She was the sole instructor of her numerous family, "and such a family," continues Dr. Clarke, "I have never read of, heard of, or known; nor since the days of Abraham and Sarah, Joseph and Mary of Nazareth, has there been a family to which the human race has been more in debt."

Many have supposed that Samuel Wesley was a sour and disagreeable husband. But he was one of the kindest of husbands, and his children are said to have "idolized" him. His affection for his wife is seen in a portrait he gives of her, a few years after their marriage, in his Life of Christ, in verse:

Mrs. Wesley's attachment to her husband was undying. When some disagreement occurred between her brother and her husband Mrs. Wesley took the side of her husband, and wrote to her brother as follows: "I am on the wrong side of fifty, infirm and weak, but, old as I am, since I have taken my husband for better, for worse, I'll keep my residence with him. Where he lives, I will live; where he dies, I will die, and there will I be buried. God do unto me, and more also, if aught but death part him and me."

In giving directions to her son John in regard to the right or wrong of worldly pleasure she says: "Take this rule: Whatever weakens your reason, impairs the tenderness of your conscience, obscures your sense of God, or takes off the relish for spiritual things—in[31] short, whatever increases the strength and authority of your body over your mind, that thing is sin to you, however innocent it may be in itself." Did ever divine or philosopher state the question more clearly? Whoever follows these directions will not err in regard to the question of amusements.

Such a woman as this is worthy to be the mother of the founder of Methodism, for had not Susannah Wesley been the mother of John Wesley it is not likely that John Wesley would have been the founder of Methodism. We shall have occasion to speak of this woman and her husband further on.

During the first eleven years of Wesley's life two events occurred worthy of note. At the age of five he was rescued from the burning parsonage almost by miracle. On a winter night, February 9, 1709, while all the family were wrapped in slumber, the cry of "Fire! fire!" was heard on the street. The rector was suddenly awakened, and, though half naked, sought to arouse his family. He rushed to the chamber, called the nurse and the children, and bade them "rise quickly and shift for themselves." After great effort they succeeded in making their escape from the burning house. They are all safe except "Jack." He had not been seen by anyone. In a few moments his voice was heard, crying for help. The flames were everywhere. The father, greatly excited, attempted to rush upstairs, but the flames drove him back. He fell on his knees and commended the soul of his boy to God.

THE WESLEYAN MEMORIAL CHURCH, EPWORTH, ENGLAND.

THE WESLEYAN MEMORIAL CHURCH, EPWORTH, ENGLAND.

While the father was on his knees the boy had mounted a trunk and called from the window. There was no time for ladders, for the house was nigh to falling. One cried, "Come here! I will stand against the wall, and you mount my shoulders quickly." In a moment it was done, and the child was pulled through the casement, and the next moment the walls fell—inward, through mercy—and the child, as well as the one who rescued him, was saved. His father received him as "a brand plucked from the burning," and in the joy of his heart cried out: "Come, neighbors, let us kneel down, and give thanks to God! He has given me all my children. Let the house go; I am rich enough."

There is no doubt but that some of his dastardly parishioners fired his house, and now house, books, furniture, manuscripts, and clothing were all gone. But this foul act made him many friends. A new house was built, but it was many years before he recovered from the loss, if, indeed, he ever did.

John's wonderful escape deeply impressed his mother that God intended him for some work of special importance in the history of the Church and the world, and she felt that she ought to devote special attention to him and train him for God.

At eight years of age John contracted that

most dreaded disease, smallpox. His father

was from home at the time. Mrs. Wesley,

writing, says: "Jack has borne his disease

bravely, like a man—and, indeed, like a Christian—without[33]

[34]

any complaint; though he seems

angry at the smallpox when they are sore, as

we guess by his looking sourly at them; for

he never says anything." Brave boy!

Passing from the watchful eye of his father and the tender, loving, and almost unexampled care and instruction of his mother, he entered, at about the age of eleven, the famous Charterhouse School, London. This was built originally for a monastery. It was purchased by Thomas Sutton, Esq., and under a charter from King James he established a school for the young. In this school forty-four boys, between the ages of ten and fifteen, were gratuitously fed, clothed, and instructed in the classics. Here such notables as Addison, Steele, Blackstone, Isaac Barrows, and others were educated.

Young Wesley was largely aided in securing this position by the Duke of Buckingham, who seems to have been a fast friend of the family. He secured for him a scholarship, which gave him about two hundred dollars a year. By the direction of his father he ran around the playgrounds three times every morning for the benefit of his health. It was a school of trial. Being a charity scholar, he did not escape the taunts of his fellow-students more highly favored than he; but he[35] bore all with meekness, patiently suffering wrongfully. He remained there some six years, and, though a mere youth, he distinguished himself in every branch of scholarship to which he turned his attention.

Mr. Tyerman, who seems to have searched for every spot on this rising sun, is bold to say that Wesley "lost the religion which had marked his character from the days of his infancy. He entered the Charterhouse a saint, and left it a sinner." We cannot find this marked change on the record with the clearness with which it appears to Mr. Tyerman. There is no evidence that Wesley had ever known the converting grace of God up to this time, and, if not, we are unable to see how he could have lost it. That he was a sinner at this time there can be no doubt. But, while he confesses that he was a sinner, he declares that his "sins were not scandalous in the eyes of the world." Instead of being the wicked boy that Mr. Tyerman represents him to have been, he declares: "I still read the Scriptures, and said my prayers morning and evening. And what I now hoped to be saved by was: (1) Not being as bad as other people; (2) Having still a kindness for religion; and (3) Reading my Bible, going to church, and saying my prayers." Should an unconverted young man in these times, in passing through our high schools or seminaries, give evidence[36] that he read his Bible, prayed morning and evening, attended church regularly, joined in all the devotions, went to the sacrament, and manifested a kindness for religion, who would say that "he entered the school a saint, and left it a sinner"? There is no evidence that Wesley, during his six years' course at the Charterhouse, ever contracted vicious habits or became a flagrant sinner. The wonder is that, with such corrupt and corrupting influences surrounding him, he had not been morally ruined.

At the age of seventeen he entered Christ College, Oxford, one of the noblest colleges of that famous seat of learning, where he remained five years, under the care of Dr. Wigon, a gentleman of fine classical attainments. His excellent standing at the Charterhouse gave him a high position at Oxford. His means of support were very limited. His mother laments their inability to assist him. In a letter to him she says:

Dear Jack: I am uneasy because I have not heard from you. If all things fail, I hope God will not forsake us. We have still his good providence to depend on. Dear Jack, be not discouraged. Do your duty. Keep close to your studies, and hope for better days. Perhaps, after all, we shall pick up a few crumbs for you before the end of the year. Dear Jack, I beseech Almighty God to bless thee.

This indicates the great financial embarrassment in which they were often found, as well as their abiding trust in God.

His mother seems deeply concerned for his religious life. She writes, "Now in good earnest resolve to make religion the business of life; for, after all, that is the one thing that, strictly speaking, is necessary. All things besides are comparatively little to the purposes of life. I heartily wish you would now enter upon a strict examination of yourself, that you may know whether you have a reasonable hope of salvation by Jesus Christ. If you have it, the satisfaction of knowing it will abundantly reward your pains; if you have it not, you will find a more reasonable occasion for tears than can be met with in any tragedy."

His brother Samuel writes hopefully to his father: "My brother Jack, I can faithfully assure you, gives you no manner of discouragement from believing your third son a scholar. Jack is a brave boy, learning Hebrew as fast as he can."

At the age of twenty-one, while yet a student at Oxford, "he appears," says a writer of the time, "the very sensible and acute collegian; a young fellow of the finest classical taste, of the most liberal and manly sentiments." Alexander Knox says: "His countenance, as well as his conversation, expressed[38] an habitual gayety of heart, which nothing but conscious innocence and virtue could have bestowed." Then, referring to him in more advanced life, he says: "He was, in truth, the most perfect specimen of moral happiness I ever saw; and my acquaintance with him has done more to teach me what a heaven upon earth is implied in the maturity of Christian piety than all I have elsewhere seen or heard or read, except in the sacred volume." "Strange," says another writer, "that such a man should have become a target for poisoned arrows, discharged, not by the hands of mad-cap students only, but by college dignitaries, by men solemnly pledged to the work of Christian education!"

About this time Wesley became Fellow of Lincoln College, and his brother Charles, who was five years younger, became a student of Christ Church College. He had prepared for college at Westminster grammar school, and was a "gay young fellow, with more genius than grace," loving pleasure more than piety. When John sought to revive the "fireside devotion" of the Epworth home he rejoined, with some degree of earnestness, "What! would you have me be a saint all at once?"

In September of 1725 John was ordained deacon by Bishop Potter, and in March of the following year was elected Fellow of Lincoln College, with which his aged father seems to[39] have been greatly delighted, saying, "Wherever I am, Jack is Fellow of Lincoln!"

His father's health failing, John was urged to become his curate. He responded to his father's request, but does not seem to have had a very high appreciation of his father's flock, for he describes them as "unpolished wights, as dull as asses and impervious as stones." But for about two years he hammers away, preaching the law as he then understood it, confessing that "he saw no fruit for his labor."

He then returned to Oxford as Greek lecturer, devoting himself to the study of logic, ethics, natural philosophy, oratory, Hebrew, and Arabic. He perfected himself in French, and spoke and wrote Latin with remarkable purity and correctness. He gave considerable attention to medicine. In this way Providence was fitting him for the great work of which he was to be the God-ordained leader. About the time that Wesley entered upon his ministry, by episcopal ordination, and commenced his lifework, Voltaire was expelled from France and fled to England. During a long life he and Wesley were contemporaries. Mr. Tyerman gives a graphic description of these two remarkable men. "Perhaps of all the men then living," he says, "none exercised so great an influence as the restless philosopher[40] and the unwearied minister of Christ. Wesley, in person, was beautiful; Voltaire was of a physiognomy so strange, and lighted up with fire so half-hellish and half-heavenly, that it was hard to say whether it was the face of a satyr or man. Wesley's heart was filled with a world-wide benevolence; Voltaire, though of a gigantic mind, scarcely had a heart at all—an incarnation of avaricious meanness, and a victim to petty passions. Wesley was the friend of all and the enemy of none; Voltaire was too selfish to love, and when forced to pay the scanty and ill-tempered homage which he sometimes rendered it was always offered at the shrine of rank and wealth. Wesley had myriads who loved him; Voltaire had numerous admirers, but probably not a friend. Both were men of ceaseless labor, and almost unequaled authors; but while the one filled the land with blessings, the other, by his sneering and mendacious attacks against revealed religion, inflicted a greater curse than has been inflicted by the writings of any other author either before or since. The evangelist is now esteemed by all whose good opinions are worth having; the philosopher is only remembered to be branded with well-merited reproach and shame." Voltaire ended his life as a fool by taking opium, while Wesley ends his life in holy triumph, exclaiming, "The best of all is, God is with us."

It does not seem as if a Life of John Wesley would be complete without an account of what was known as the "Epworth rappings," which occurred in the home of Samuel Wesley in 1716, while John was at the Charterhouse School, London. They occasioned no little speculation among philosophers and doubters in general, not only at the time they occurred, but down to the present day. A brief description of these strange noises, and how they were regarded at the time, may be proper in this place.

On the night of December 2, 1716, Robert Brown, Mr. Wesley's servant, and one of the maids of the family were alone in the dining room. About ten o'clock they heard a strong knocking on the outside of the door which opened into the garden. They answered the call, but no one was there. A second knock was heard, accompanied by a groan. The door was again and again opened, as the knocks were repeated, with the same result. Being startled, they retired for the night.

As Mr. Brown reached the top of the stairs[42] a hand mill, at a little distance, was seen whirling with great velocity. On seeing the strange sight he seemed only to regret that it was not full of malt. Strange noises were heard in and about the room during the night. These were related to another maid in the morning, only to be met with a laugh, and, "What a pack of fools you are!" This was the beginning of these strange noises in the Epworth parsonage.

Subsequently, knocking was heard on the doors, on the bedstead, and at various times in all parts of the house.

Susannah and Ann were one evening below stairs in the dining room and heard knockings at the door and overhead. The next night, while in their chamber, they heard knockings under their feet, while no person was in the chamber at the time, nor in the room below. Knockings were heard at the foot of the bed and behind it.

Mr. Wesley says that, on the night of the 21st of December, "I was wakened, a little before one o'clock, by nine distinct and very loud knocks, which seemed to be in the next room to ours, with a short pause at every third knock." The next night Emily heard knocks on the bedstead and under the bed. She knocked, and it answered her. "I went down stairs," says Mr. Wesley, "and knocked with my stick against the joists of the kitchen.[43] It answered me as loud and as often as I knocked." Knockings were heard under the table; latches of doors were moved up and down as the members of the family approached them. Doors were violently thrust against those who attempted to open or shut them.

When prayer was offered in the evening, by the rector, for the king, a knocking began all around the room, and a thundering knock at the amen. This was repeated at morning and evening, when prayer was offered for the king. Mr. Wesley says, "I have been thrice pushed by an invisible power, once against the corner of my desk in my study, and a second time against the door of the matted chamber, and a third time against the right side of the frame of my study door, as I was going in."

Mr. Poole, the vicar of Haxey, an eminently pious and sensible man, was sent for to spend the night with the family. The knocking commenced about ten o'clock in the evening. Mr. Wesley and his brother clergyman went into the nursery, where the knockings were heard. Mr. Wesley observed that the children, though asleep, were very much affected; they trembled exceedingly and sweat profusely; and, becoming very much excited, he pulled out a pistol and was about to fire it at the place from whence the sound came. Mr. Poole caught his arm and said: "Sir, you are convinced that this is something preternatural. If so, you[44] cannot hurt it, but you give it power to hurt you." Then going close to the place, Mr. Wesley said: "Thou deaf and dumb devil, why dost thou frighten these children, who cannot answer for themselves? Come to me in my study, who am a man." Instantly the particular knock which the rector always gave at the gate was given, as if it would shiver the board in pieces. The next evening, on entering his study, of which no one but himself had the key, the door was thrust against him with such force as nearly to throw him down.

A sound was heard as if a large iron bell was thrown among bottles under the stairs; and as Mr. and Mrs. Wesley were going down stairs they heard a sound as if a vessel of silver were poured upon Mrs. Wesley's breast and ran jingling down to her feet; and at another time a noise as if all the pewter were thrown about the kitchen. But on examination all was found undisturbed.

The dog, a large mastiff, seemed as much disturbed by these noises as the family. On their approach he would run to Mr. and Mrs. Wesley, seeking shelter between them. While the disturbances continued the dog would bark and leap, and snap on one side and on the other, and that frequently before any person in the room heard any noise at all. But after two or three days he used to tremble and creep away before the noise began; and by this the family[45] knew of its approach. Footsteps were heard in all parts of the house, from cellar to garret. Groans and every sort of noise were heard all over the house too numerous to relate. Whenever it was attributed to rats and mice the noises would become louder and fiercer.

These disturbances continued for some four months and then subsided, except that some members of the family were annoyed by them for several years.

Mr. Wesley was frequently urged to quit the parsonage. His reply was eminently characteristic: "No," said he, "let the devil flee from me. I will never flee from the devil."

Every effort was made to discover the cause of these disturbances, but without satisfactory results, save that all believed they were preternatural. The whole family were unanimous in the belief that it was satanic.

A full account of these noises was prepared from the most authentic sources by John Wesley and published in the Arminian Magazine. Dr. Priestley, an unbeliever, confessed it to have been the best-authenticated and best-told story of the kind that was anywhere extant; and yet, so strongly wedded was he to his materialistic views, he could not accept them, nor find what might be regarded as a commonsense solution of them. He thought it quite probable that it was a trick of the servants,[46] assisted by some of the neighbors, and that nothing was meant by it except puzzling the family and amusing themselves. But Mrs. Wesley and other members of the household declared that the noises were heard above and beneath them when all the family were in the same room.

Dr. Southey, though he does not express an opinion of these noises in his Life of Wesley, in a letter to Mr. Wilberforce avows his belief in their preternatural character. In his Life of Wesley he does say, "The testimony upon which it rests is far too strong to be set aside because of the strangeness of the relation."

Dr. Priestley observes in favor of the story that all the parties seemed to have been sufficiently void of fear, and also free from credulity, except the general belief that such things were supernatural. But he claims that "where no good end is answered we may safely conclude that no miracle was wrought."

Mr. Southey replies to Priestley thus: "The former argument would be valid if the term 'miracle' were applicable to the case; but by 'miracle' Mr. Priestley intends a manifestation of divine power, and in the present case no such meaning is supposed, any more than in the appearance of departed spirits. Such things may be preternatural and yet not miraculous; they may be in the ordinary course of[47] nature, and yet imply no alteration of its laws. And in regard to the good end which it may be supposed to answer, it would be end sufficient if sometimes one of those unhappy persons, who, looking through the dim glass of infidelity, sees something beyond this life and the narrow sphere of mortal existence, should, from the well-established truth of such a story (trifling and objectless as it may appear), be led to conclude that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in their philosophy."[M]

Mr. Coleridge finds a satisfactory solution of this knotty question in attributing the whole thing to "a contagious nervous disease" with which he judged the whole family to have been afflicted, "the acme or intensest form of which is catalepsy." The poor dog, it would seem, was as badly afflicted as the rest.

This notion does not need refutation. Dr. Adam Clarke, who collected all the accounts of these disturbances and published them in his Wesley Family, claims that they are so circumstantial and authentic as to entitle them to the most implicit credit. The eye and ear witnesses were persons of strong understanding and well-cultivated minds, untinctured by superstition, and in some instances rather skeptically inclined.

JEFFREY'S ATTIC ROOM, WHENCE THE MYSTERIOUS NOISES CAME.

JEFFREY'S ATTIC ROOM, WHENCE THE MYSTERIOUS NOISES CAME.

These unexplained noises in the Epworth rectory found their counterpart in what was known a little earlier as "New England witchcraft," and in our times as the Rochester and Hidsville knockings in 1848, which have ripened into modern Spiritualism, which, if real, is satanic.

There is but little doubt that these remarkable occurrences at his Epworth home made a deep and lasting impression on John Wesley's mind and life. There was ever present to his mind the reality of an invisible world, and he was convinced that satanic as well as angelic forces were all about us, both to bless and to ruin us if permitted to do so by Him who rules all the world.

It was while he was a member of Lincoln College that that unparalleled religious career of Mr. Wesley, which has always been regarded as the most wonderful movement of modern times, began. "Whoever studies the simplicity of its beginning, the rapidity of its growth, the stability of its institutions, its present vitality and activity, its commanding position and prospective greatness, must confess the work to be not of man, but of God."

The heart of the youthful collegian was profoundly

stirred by the reading of the Christian

Pattern, by Thomas à Kempis, and Holy

Living and Dying by Jeremy Taylor. He

learned from the former "that simplicity of

intention and purity of affection were the

wings of the soul, without which he could never

ascend to God;" and on reading the latter he

instantly resolved to dedicate all his life to

God. He was convinced that there was no medium;

every part must be a sacrifice to either

God or himself. From this time his whole

life was changed. How much he owed under

God to these two works eternity alone will[49]

[50]

reveal. Law's Call and Perfection greatly

aided him.

A little band was formed of such as professed to seek for all the mind of Christ. They commenced with four; soon their number increased to six, then to eight, and so on. Their object was purely mutual profit. They read the classics on week days and divinity on the Sabbath. They prayed, fasted, visited the sick, the poor, the imprisoned. They were near to administer religious consolation to criminals in the hour of their execution. The names of these remarkable religious reformers were: John and Charles Wesley, Robert Kirkham, William Morgan, George Whitefield, John Clayton, T. Broughton, B. Ingham, J. Harvey, J. Whitelamb, W. Hall, J. Gambold, C. Kinchin, W. Smith, Richard Hutchins, Christopher Atkinson, and Messrs. Salmon, Morgan, Boyce, and others.

As might have been expected, they were ridiculed and lampooned by those who differed from them, and who could not comprehend the motive to such a religious life. They were called in derision "Sacramentarians," "Bible Bigots," "Bible Moths," "The Holy Club," "The Godly Club," "Supererogation Men," and finally "Methodists." Their strict, methodical lives in the arrangement of their studies and the improvement of their time, their serious deportment and close attention to religious[51] duties, caused a jovial friend of Charles Wesley to say, "Why, here is a new sect of Methodists springing up!" alluding to an ancient school of physicians, or to a class of Nonconforming ministers of the seventeenth century, or to both, who received this title from some things common to each. The name took, and the young men were known throughout the university as the Methodists. The name thus given in derision was finally accepted, and has been retained in honor to this day by the followers of Wesley.

A writer in one of the most respectable journals of the day, in describing these inoffensive men, employed the most unwarrantable language. It was affirmed that they had a near affinity to the Essenes among the Jews, and to the Pietists of Switzerland; they excluded what was absolutely necessary to the support of life; they afflicted their bodies; they let blood once a fortnight to keep down the carnal man; they allowed none to have any religion but those of their own sect, while they themselves were farthest from it. They were hypocrites, and were supposed to use religion only as a veil to vice; and their greatest friends were ashamed to stand in their defense. They were enthusiasts, madmen, fools, and zealots. They pretended to be more pious than their neighbors. These were but the beginning of sorrows, as we shall see later.

Wesley says: "Ill men say all manner of evil of me, and good men believe them. There is a way, and there is but one, of making my peace. God forbid I should ever take it."

"As for reputation," he says, "though it be a glorious instrument of advancing our Master's service, yet there is a better than that—a clean heart, a single eye, a soul full of God." What words are these for a minister of the Lord Jesus! It implies heroic, unselfish devotion to a glorious object. He had discovered the secret of success.

What golden words are these: "I once desired to make a fair show in language and philosophy. But that is past. There is a more excellent way; and if I cannot attain to any progress in one without throwing up all thoughts of the other, why, fare it well." This gives the reader an idea of the motive which governed him to the end of life.

In the midst of these scenes of persecution Wesley addressed a letter to his venerable father, still living at Epworth, asking his advice. The old man urged him to go on and not be weary in well-doing; "to bear no more sail than necessary, but to steer steady. As they had called his son the father of the Holy Club, they might call him the grandfather, and he would glory in that name rather than in the[53] title of His Holiness." These were noble words from sire to son at such a time and in such a conflict.

In years after, when looking back upon the scenes of Oxford and that mustard-seed beginning, Wesley said: "Two young men, without name, without friends, without either power or fortune, set out from college with principles totally different from those of the common people, to oppose all the world, learned and unlearned, to combat popular prejudices of every kind. Their first principle directly attacked all wickedness; their second, all the bigotry in the world. Thus they attempted a reformation not of opinions (feathers, trifles not worth naming), but of men's tempers and lives; of vice of every kind; of everything contrary to justice, mercy, or truth. And for this it was that they carried their lives in their hands, and that both the great vulgar and the small looked upon them as mad dogs, and treated them as such." Such was the beginning of the religious career of this wonderful man. Wesley refers to three distinct periods of the rise of Methodism. He says: "The first rise of Methodism was in November, 1729, when four of us met at Oxford. The second was at Savannah, in April, 1736, when twenty or thirty persons met at my house. The last was at London, May 1, 1738, when forty or fifty of us agreed to meet together every[54] Wednesday evening, in order to free conversation, begun and ended with singing and prayer. God then thrust us out to raise a holy people."

It would be interesting to follow these men and learn the results of their lives; but our space does not permit. We refer the reader to that most excellent work, The Oxford Methodists, by Tyerman. Of Robert Kirkham little or nothing is known. William Morgan died while a mere youth, and died well. John Clayton became a Jacobite Churchman, and treated Wesley and his brother Charles with utter contempt. Thomas Broughton became secretary of the "Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge," and was faithful to his trust till death. He died suddenly upon his knees, on a Sabbath morning just before he was to have preached. James Harvey, author of Meditations, was a man of beautiful character, but opposed Wesley's Arminian views. Charles Kinchin, unlike most of the "Holy Club," remained the fast friend of Wesley until death. John Whitelamb married John Wesley's sister Mary, who died within one year, leaving her husband broken-hearted and despondent. He seems to have lost much of his early devotion, causing Mr. Wesley to say, "O, why did he not die forty years ago?" Wesley Hall married John Wesley's sister Martha, a lady of superior talents and sweetness of disposition.[55] Wesley regarded Hall as a man "holy and unblamable in all manner of conversation." After some years Hall went to the bad. He became, first, a Dissenter, then a Universalist, then a deist, after that a polygamist. He abandoned his charming wife, nine of his ten children having died, and the tenth soon followed. He went to the West Indies with one of his concubines, living there until her death. Broken in health and awakened to his terrible condition, he returned to England, where he soon after died. His lawful and faithful wife, hearing of his condition, like an angel of mercy hastened to his bedside. He died in great sorrow of heart, saying—and they were his last words—"I have injured an angel, an angel that never reproached me." Wesley says: "I trust he died in peace, for God gave him deep repentance." John Gambold became a Moravian bishop, and was so opposed to Wesley that he frankly told him he was "ashamed to be seen in his company." Wesley, however, always held him in high esteem. Of Richard Hutchins little is known, except that he was rector of Lincoln College, and never seems to have opposed the Wesleys. Christopher Atkinson was for twenty-five years vicar of Shorp-Arch and Walton. His last words were, "Come, Lord Jesus, and come quickly." Charles Delamotte was one who accompanied the Wesleys to Georgia. Little further is[56] known of him, except that he became a Moravian and died in peace at Barrow upon the Humber.

Here ends our account of the "Holy Club." All of them maintained a correct life except Hall. They were nearly all Calvinists, and in this they came in conflict with Wesley. Had they remained with Wesley, what a record they might have made! We trust their end was peace.

Go with me to the Epworth rectory. The venerable Samuel Wesley is dying; no, not dying, but languishing into life. John and Charles have been summoned from Oxford, and they are at the bedside. The faithful wife is so overcome that she cannot be present to witness the dying scene.

John sympathetically inquires, "Do you suffer much, father?" The dying man responds, "Yes, but nothing is too much to suffer for heaven. The weaker I am in body the stronger and more sensible support I feel from God." The dying saint lays his trembling hand on the head of Charles, and, like a true prophet, says, "Be steady! The Christian faith will surely revive in this kingdom. You shall see it, though I shall not." John inquires again, "Are you near heaven?" The dying rector joyfully responds, "Yes, I am." "Are all the[57] consolations of God small with you, father?" The emphatic answer is, "No! no! no!"

He then called his children each by name, and said to them, "Think of heaven; talk of heaven! All the time is lost when we are not thinking of heaven." The hour came for his departure. The children knelt beside his bed; John prayed. As the prayer ended, in a feeble whisper the rector said, "Now you have done all." Again John prayed, commending the soul of his honored father to God. All was silent as the tomb. They opened their eyes, and the rector was with the Lord, "beholding the King in his beauty." "Can anything on earth be more beautiful," says one writer, "than such a death? It was indeed fitting that this tried, scarred Christian warrior should pass thus peacefully to his reward."

"Now," said his widow, in great sorrow, "I am appeased in his having so easy a death, and I am strengthened to bear it."

On the very day of the rector's funeral a heartless parishioner, to whom the rector owed seventy-five dollars, seized the widow's cattle to secure the debt. But it was such a deed as his godless people were ever ready to perpetrate. John came to the relief of his poor mother, and gave the woman his note for the amount.

Wesley is again at Oxford, intent on service for his Lord.

One of the most remarkable chapters in the life of John Wesley relates to his mission to America.

There was a tract of land in North America, lying between South Carolina and Florida, over which the English held a nominal jurisdiction. It was a wild, unexplored wilderness, inhabited only by Indian tribes. Under the sanction of a royal charter in 1732 a settlement was made in this territory, and as a compliment to the king, George II, it was named Georgia.

The object of such a settlement was twofold: first, to supply an outlet for the redundant population of the English metropolis; and, secondly, to furnish a safe asylum for foreign Protestants who were the subjects of popish intolerance. No Roman Catholic could find a home there. James Edward Oglethorpe, an earnest friend of humanity, was appointed the first governor of the territory, and he and twenty others were named as trustees, to hold the territory twenty years in trust for the poor.

The first company of emigrants, one hundred[59] and twenty-four in number, had already landed at Savannah and were breathing its balmy air, and the enthusiastic governor was on his return to inspire in the mind of the English people increased confidence in the new enterprise.

Having long been a personal friend of the Wesley family, Oglethorpe knew well the sterling worth of the two brothers, John and Charles, who were still at Oxford. An application was made to some of the Oxford Methodists to settle in the new colony as clergymen. Such sacrifices as they were ready to endure, and such a spirit as seemed to inflame them, were regarded as excellent qualities for the hardships of such a country as Georgia. Mr. Wesley was earnestly pressed by no less a person than the famous Dr. Burton to undertake a mission to the Indians of Georgia, Dr. Burton telling him that "plausible and popular doctors of divinity were not the men wanted in Georgia," but men "inured to contempt of the ornaments and conveniences of life, to bodily austerities, and to serious thoughts." He finally consented, his brother Charles, Benjamin Ingham, and Charles Delamotte joining him.

When the project was made public it was regarded by many as a Quixotic scheme. One inquired of John: "Do you intend to become a knight-errant? How did Quixotism get into your head? You want nothing. You have a[60] good provision for life. You are in a fair way for promotion, and yet you are leaving all to fight windmills."

"Sir," replied Mr. Wesley, "if the Bible be not true, I am as very a fool and madman as you can conceive. But if that book be of God, I am sober-minded; for it declares, 'There is no man that hath left houses, and friends, and brethren for the kingdom of God's sake, who shall not receive manifold in this present time, and in the world to come everlasting life.'"

He submitted his plans to his widowed mother, asking her advice. She replied, "Had I twenty sons, I should rejoice to see them all so employed." His sister Emily said, "Go, my brother;" and his brother Samuel joined with his mother and sister in bidding him Godspeed.

All things being in readiness, on the 14th of October, 1735, the company embarked on board the Simmonds, off Gravesend, and after a few days' detention set sail for the New World.

This was a voyage of discovery—the discovery of holiness.

"Our end in leaving our native land," Wesley says, "was not to avoid want, God having given us plenty of temporal blessings; nor to gain the dung and dross of riches and honor; but simply to save our souls, to live wholly to the glory of God."

Wesley hoped by subjecting himself to the[61] hardships of such a life to secure that holiness for which his soul so ardently longed. He had no clear conception as yet of the doctrine of salvation by faith alone. He hoped by spending his life among rude savages to escape the temptations of the great metropolis. In the wilds of America he could live on "water and bread and the fruits of the earth," and speak "without giving offense." He justly concluded that "pomp and show of the world had no place in the wilds of America." "An Indian hut offered no food for curiosity." "My chief motive," he says, "is the hope of saving my own soul. I hope to learn the true sense of the Gospel of Christ by preaching it to the heathen." "I cannot hope to attain the same degree of holiness here which I do there." "I hope," he continues, "from the moment I leave the English shore, under the acknowledged character of a teacher sent from God, there shall be no word heard from my lips but what properly flows from that character."

But Wesley could not get away from himself. The greatest hindrance to holiness was in his own heart. He had looked for holiness in works, sacrifices, austerities, etc., but had failed to see that it was by faith alone.

The voyage, though of almost unparalleled roughness, was of infinite profit to Wesley. A company of Moravians, with David Nitschmann as their bishop, were passengers, bound[62] to the New World, fleeing from popish persecutions. Wesley, observing their behavior in the midst of great peril, was convinced that they were in possession of that to which he was a stranger. Ingham represented them as "a heavenly minded people."

Fifty-seven days of sea life brought them within sight of the beautiful Savannah. Soon they were kneeling upon its soil, thanking God for his merciful care and providential deliverance.

An event occurred on the voyage to Georgia illustrating Wesley's character. General Oglethorpe had become offended at his Italian servant. Hearing a disturbance in the cabin, Wesley stepped in. The general, observing him, and being in a high temper, sought to apologize. "You must excuse me, Mr. Wesley," he said; "I have met with a provocation too great for a man to bear. You know I drink nothing but Cyprus wine. I provided myself with several dozens of it, and this villain, Grimaldi, has drank nearly the whole lot of it. I will be avenged. He shall be tied hand and foot, and carried to the man-of-war. [A man-of-war accompanied the expedition for protection.] The rascal should have taken care how he used me so, for I never forgive." Wesley, fixing his eye upon the general—an eye that seemed to penetrate his soul—said, "Then I hope, general, you never sin!"

The general's heart was touched, his conscience smitten. He stood speechless before the youthful evangelist for a moment, and then threw his bunch of keys on the floor before his poor, cringing servant, saying, "There, villain, take my keys; and behave better in the future." Wesley, it seems, had the moral courage, which probably no other man possessed on that ship, to reprove General Oglethorpe to his face.

Soon after landing in Georgia, Wesley met Spangenberg, the Moravian elder, and desired to know of him how he should prosecute his new enterprise. The devout man of God saw clearly the need of the young evangelist, and inquired of him: "Have you the witness within yourself? Does the Spirit of God bear witness with your spirit that you are a child of God?" Wesley seemed surprised at such questions. Spangenberg continued, "Do you know Jesus Christ?" Wesley replied, "I know him as the Saviour of the world." "True," responded the Moravian elder, "but do you know that he saves you?" Wesley replied, "I hope he has died to save me." Spangenberg gravely added, "Do you know yourself?" Wesley answered, "I do;" and here the interview ended.

WESLEY'S ARM-CHAIR.

WESLEY'S ARM-CHAIR.

Charles Wesley was Oglethorpe's secretary, in place of Rev. Samuel Quincy, a native of Massachusetts, who retired from the office, desiring[64] to return to England, where he had been educated. Ingham seems to have attached himself to Charles Wesley, and devoted himself to the children and the poor, and was the first to follow Charles to England. Delamotte was impelled to go to Georgia from his love of John Wesley and his desire to serve him in any capacity; and he never left him for a day while Wesley remained in America. He was the last to leave the colony. John Wesley was the sole minister of the colony, and stood next to Oglethorpe himself.

The Georgia to which Wesley came was very different from the Georgia of to-day. It had only a few English settlements, the most of the territory being the home of savage Indians. These tribes being at war with each other, all access to them was cut off. Not being able to extend their mission among them, Wesley and his colaborers turned their attention to the whites, hoping that God would before long open their way to preach the Gospel to the Indians. In the prosecution of their mission they practiced the most rigid austerities. They slept on the ground instead of on beds, lived on bread and water, dispensing with all the luxuries and most of the necessities of life. They were, in season and out of season, everywhere urging the people to a holy life. Wesley set apart three hours of each day for visiting the people at their homes, choosing[65] the midday hours when the people were kept indoors by the scorching heat.

Charles Wesley and Mr. Ingham were at Frederica, where the people were frank to declare that they liked nothing they did. Even Oglethorpe himself had become the enemy of his secretary, and falsely accused him of inciting a mutiny.

Their plain, earnest, practical public preaching and private rebukes aroused the spirit of persecution, which broke upon them without mixture of mercy. Scandal, with its scorpion tongue; backbiting, with its canine proclivities; and gossip, which also does immense business on borrowed capital—these ran like fires over sun-scorched prairies, until these devoted servants of God were well-nigh consumed.

At Frederica, Charles narrowly escaped assassination. So general and bitter was the hate that he says: "Some turned out of the way to avoid me." "The servant that used to wash my linen sent it back unwashed." "I sometimes pitied and sometimes diverted myself with the odd expressions of their contempt, but found the benefit of having undergone a much lower degree of obloquy at Oxford."

While very sick he was unable to secure a few boards to lie upon, and was obliged to lie on the ground in the corner of Mr. Reed's hut. He thanked God that it had not as yet become[66] a "capital offense to give him a morsel of bread." Though very sick, he was able to go out at night to bury a scout-boatman, "but envied him his quiet grave." He procured the old bedstead on which the boatman had died, upon which to rest his own sinking and almost dying frame; but the bedstead was soon taken from him by order of Oglethorpe himself. But through the mercy of God and the coming of his brother and Mr. Delamotte he recovered.

After about six months (February 5 to July 25) spent in labors more abundant, and almost in stripes above measure, Providence opened his way to return to England as bearer of dispatches to the government. He took passage in a rickety old vessel with a drunken captain, and all came near being lost at sea. The ship put into Boston in distress, and there Charles Wesley remained for more than a month, sick much of the time, but preaching several times in King's Chapel, corner of School and Tremont Streets, and in Christ Church, on Salem Street. This latter church remains as it was when Wesley occupied its pulpit.

John remained in Georgia—at Frederica and Savannah—battling with sin and Satan, with a Christian boldness which might almost have inspired wonder among the angels. His life was frequently threatened at Frederica,[67] and at Savannah there was no end to the insults he endured. Hearing of his conflicts, Whitefield writes to him to "go on and prosper, and, in the strength of God, make the devil's kingdom shake about his ears."

Through the cunning craftiness and manifest hypocrisy of one Miss Hopkey, niece of the chief magistrate, and a lady of great external accomplishments, he came near being ruined. She sought his company; bestowed on him every attention; watched him when sick; was always at his early morning meetings; dressed in pure white because she learned that he was pleased with that color; was always manifesting great interest in his spiritual state; and all, without doubt, to cover up deeper designs. Mr. Wesley, always unsuspecting and confiding, became strongly attached to her for a time, but was subsequently convinced that God did not approve of an alliance in that direction, and at once determined to cut every cord which bound them. At this the lady became greatly exasperated, and within a few days was married to another man—Williamson—and then, with her husband and uncle to aid her, she sought in every way the overthrow of Mr. Wesley.

Mr. Tyerman seeks to make this case, as, in fact, many others, turn to the disadvantage of Wesley. He will have it that Wesley had promised to marry Miss Hopkey, though[68] Henry Moore declares that Wesley told him that no such thing ever occurred. Mr. Tyerman gives credit to the testimony of the hypocritical Miss Hopkey rather than to that of Henry Moore and John Wesley.

After a time Wesley, for just causes, excluded Mrs. Williamson from the Lord's table, and gave his reasons for so doing. For this he was prosecuted before the courts, a packed and paid grand jury bringing against him ten indictments, and the minority presenting a strong counter report. The case never came to trial, though Wesley made seven fruitless efforts to have it tried.

The prejudice excited against him by the chief magistrate and others became so strong that he could accomplish but little good among the people.

In the midst of these conflicts he held every Sunday, from five to six, a prayer service in English; at nine, another in Italian; from 10:30 to 12:30 he preached a sermon in English and administered the communion; at one he held a service in French; at two he catechised the children; at three he held another service in English; still later he conducted a service in his own house, consisting of reading, prayer, and praise; and at six attended the Moravian service.