The Project Gutenberg EBook of Bonaparte in Egypt and the Egyptians of To-day, by Haji A. Browne This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Bonaparte in Egypt and the Egyptians of To-day Author: Haji A. Browne Release Date: June 11, 2012 [EBook #39971] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BONAPARTE IN EGYPT *** Produced by StevenGibbs, Julia Neufeld and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

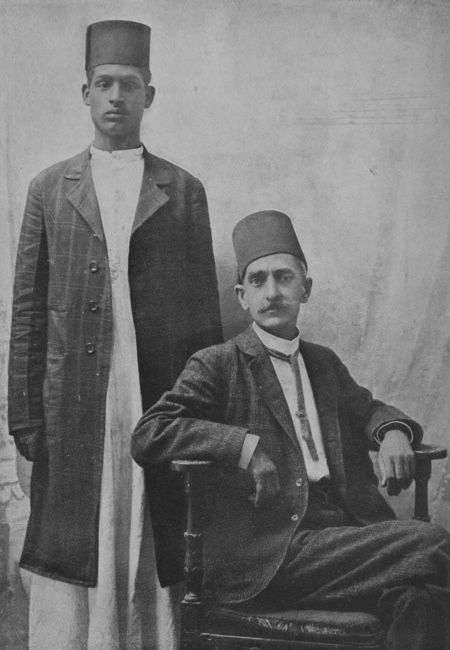

HAJI BROWNE (SEATED) AND HIS SERVANT.

HAJI BROWNE (SEATED) AND HIS SERVANT.

LONDON: T. FISHER UNWIN

ADELPHI TERRACE. MCMVII

"In proportion as we love truth more and victory less, we shall become anxious to know what it is which leads our opponents to think as they do."

(All rights reserved.)

Eight years have passed since I first conceived the idea of writing this book, but it was not until about two years ago that I was able to find time to put together a first rough outline of the form I wished it to take. In the interval I have been obliged from time to time to lay it aside altogether; and, at the most favourable times, have never had more than a few hours a week to devote to it. I had just completed what I had intended to be the last chapter, when events occurred that obliged me to rewrite it, and, that I might do so fitly, await the issue of those events. As the book now stands it is at best but a mere outline. A larger volume than this might easily be written upon each of several of the subjects I have but glanced at, yet I hope I have succeeded in giving a connected and intelligible sketch and one sufficient for the attainment of the chief object I have had in view, that of presenting the Egyptian as he really is to the many who, whether living in Egypt or out of it, have but few and imperfect opportunities of learning to understand him. For over thirty years[6] I have given of all I have had to give, for the promotion of two objects: first, that Pan-Islamism, which I conceive to be the true interest of the Islamic world; and, secondly, the development of friendly relations between the Moslems of the East and the British Empire. How much, or how little, I have been able to accomplish towards the fulfilment of my aims it is impossible for me to estimate, but from boyhood I have had an earnest faith in the belief that right and truth must in the end prevail, and that he who works for these, or for what he honestly believes these to be, never works in vain.

Knowing the Egyptian as I know him, I cannot but think that he is greatly misunderstood, even by those who are sincerely anxious to befriend him. His faults and his failings are to be found at large in almost any of the scores of books that have of late years been written about him and his country; but, though not a few have given him credit for some of his more salient good points, yet none that I have seen have shown any just appreciation of him as he really is.

Cairo, May, 1907.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Story of One Hundred Years | 9 |

| II. | Links with the Past | 22 |

| III. | The Dawn of the New Period | 34 |

| IV. | A Council of State | 48 |

| V. | The Proclamation that Failed | 64 |

| VI. | A Long March and a Short Battle | 79 |

| VII. | After the Battle | 94 |

| VIII. | Victors and Vanquished | 109 |

| IX. | The Gathering of a Storm | 128 |

| X. | The Bursting of the Storm | 150 |

| XI. | After the Storm | 174 |

| [8] | ||

| XII. | Peace without Honour | 197 |

| XIII. | The Siege of Cairo | 217 |

| XIV. | The Price of Peace | 237 |

| XV. | An Ungrateful People | 259 |

| XVI. | Mahomed Ali and his Successors | 275 |

| XVII. | Fachoda and After | 294 |

| XVIII. | Healthy Influences | 311 |

| XIX. | Unhealthy Influences | 336 |

| XX. | More Unhealthy Influences | 359 |

| XXI. | To-day and To-morrow | 382 |

| Index | 401 | |

It was the 23rd of June, 1898. The day in Cairo had been unusually hot and oppressive, but as the sun went down, a cool wind from the north came blowing softly over the city.

I was then living in a little corner of the old town still wholly untouched by the ruthless hand of the "reform" that, in every other part, was busy marring with modern "improvements" the old-time charm of the "City of the Caliphs."

As midnight approached, I went up on the roof to enjoy the cool freshness and quiet of the night, and the stillness was almost unbroken. Now and then in the narrow lanes below, the watchmen, who in their drab-coloured coats and with long staffs and lanterns in their hands, made one think of Old London and the days of Dogberry, called to one another or challenged some belated passer-by, and at times a[10] murmuring echo told of the restless traffic and turbulent life yet stirring in the carriage-crowded streets of the European quarters of the town, but otherwise the silence was undisturbed.

As I stood there, leaning on the parapet of the roof, my thoughts wandered back to the night, just one hundred years before, the 23rd of June, 1798, when possibly some wakeful citizen had stood, perhaps on the very spot on which I was then standing, and gazed upon the very scene, the same limited range of housetops and sidewalls, that was around me. That distant night is one of which the historians of the country make no mention, and yet it is one most worthy of note, as having been at once one of the most peaceful and one of the most memorable Cairo has ever known. Peaceful, for, when not lured from his slumbers by one of the night-quenching festivals he so dearly loves, the Cairene is an early and a sound sleeper, and being then, as now, blessed with an easy-going conscience and unbounded faith in the beneficence of Destiny, we may be certain that on that night he slept the sleep of the just man who is weary. Nor was that night less memorable than peaceful, for little as he could foresee it, it was the last for over a century of time on which the Cairene was to sleep so free from care or thought of the morrow. For, while the city slumbered, away in the villages on the banks of the Nile, sleepers were being unwontedly awakened and dismayed by the sounds of horsemen hurrying through the night with the rushing haste of men who are bearers of tidings of life and death.

[11]Onward, onward they came, these messengers of the night, weary with their long forced ride from Alexandria, the city of the sea, which they had left the day before. Onward, onward as rapidly as they could press forward the steeds that, as one after another failed, were replaced by others seized from the nearest stables "for the service of the State." Onward and onward on their trying ride, spreading as they went the news they bore, news that murdered the sleep of those who heard it, and flung a pall of panic fear over the land.

They were still on the road when the Cairenes rising, as all good Mahomedans should, with the first dawn of day, proceeded to the duties of the morning with the leisurely diligence that is one of their characteristics. But long before mid-day the messengers had discharged their task, and the fateful news they had brought was being discussed throughout the town. It was news that, to the Cairene, was fraught with most direful possibilities, for it was news that a fleet of English ships of war had arrived at Alexandria, and that the Governor of the town, feeling utterly incapable with the scanty resources at his disposal, of offering any effective resistance to a hostile landing, had sent to beg for immediate assistance in men and munitions of war. Many and fervent were the prayers said in the mosques that day, and loud and deep were the anathemas launched against the foreigner who was at their gates. It is not surprising that it should be so, for, of all evils he could imagine, a foreign invasion was, to the[12] Cairene, as to the people of Egypt generally, the one most suggestive of personal loss and misery.

Exactly one hundred years had passed since that day, and the dying hours of that century of time left the Egyptian, as its opening hours had found him, distrustful of the English, rejecting their friendship, and cursing them as foes. That it should have been thus, is one of the problems that perplex those who attempt to know or understand the Egyptian, and as I thought of these things, it seemed to me that living as I then was amongst the most conservative class of the people, the class that still prides itself on living the life its fathers and grandfathers led, and holds all things foreign to be abominations, and yet meeting from day to day with the modern half-Europeanised citizens, and being myself almost an Oriental in thought and sympathy, I could read the story of that one hundred years and comprehend the feelings of the people through all its incidents, better perhaps than any other European, and that by sketching the history of that century as it appears to me, I might help others to understand the people and their history better, and thus aid in promoting the mutual goodwill that is as essential to the interests of the Egyptian himself, as to those of the great army of foreigners who are dwellers in his hospitable land.

As told by the writers of to-day, the history of Egypt extends over nearly seven thousand years—three score and ten centuries—just one for every year allotted by the Psalmist to man as the period[13] of his life. But of all that great stretch of time the hundred and odd years lying between the fateful 23rd of June in 1798 and the present day, although unfortunately the materials available for a study of it are scant and for the most part unreliable, has more of human interest as a chapter in the history of mankind, than all the long ages that preceded it.

Yet if the reader would rightly comprehend the lesson of this period, he must grasp the fact that in a very full and ample sense all history is a part of one—nay, is but one and the same story writ in different characters. How utterly unlike in all externals are the Gospels written in the Latin, Greek, Arabic, Nagri, or Chinese characters and languages, but the essence and the spirit of all these versions are the same. So it is with the histories of men and nations. The stories of England, France, Spain, India, Egypt, how different! and yet in all that is the final essential of true history—the story of man's combat with his surroundings—the same. It is so because in the last analysis all men are the same, like the ocean, "His Sea in no showing the same—his Sea and the same 'neath all showing."

Scattered in the deserts of Persia, the traveller comes upon isolated villages wherein men and women are born, grow up, marry, beget families, and die, and never once pass beyond the mirage-haunted horizon of their little oasis. With world-encircling ideas and ambitions, the traveller thinks of the mad maelstrom of life in the crowded cities[14] of the West, and wonders that men can be so different and still be men, and yet more so, that between himself and these Persians of the desert, drifting through life in a daily round that never changes, never varies, there should be anything in common. And the wonder is, not that they have the same shape and form as he, that they can cry with Shylock, "If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you poison us, do we not die?" All that is as nothing, since it lifts the man no higher than the brutes of the field, but in all else, in all that is the essential differentia of man, even in these, these children of the waste are such as we, moved by the same passions, stirred by the same affections, urged by the same desires, however variously all these may find expression.

Further yet afield. The miserable Mahars and Mangs of the Indian Deccan, who, living or dead, are held by all the peoples around them as not less vile than the carrion they do not scorn to eat. Even there among these if you will, you may trace, as the venerable missionary Wilson did, deep buried under the man-debasing foulness of their lives, the humanity of the man as the dominating, all-controlling element, severing them by an immeasurable and impassable distance from the noblest of the animals, and linking them by an inseverable bond to the noblest of their fellow-men. All that may characterise the individual outside of this is but the accident of his life and being; the essential element, guiding and swaying him in all things, is this fundamental, ineradicable humanity.

[15]It is the fashion nowadays to speak of the "Brotherhood of man," but how few realise how absolutely, how completely the phrase expresses the simple truth! a truth that nullifies all the arrogantly-arrayed arguments and fancy-founded fallacies of Haeckel and the whole field of Monists and Materialists. If, then, we would understand the Egyptian or any other people, we must start by recognising that, however wide and apparently unbridgable may be the gulf that divides us from them, whether physical, mental, or moral, it has been caused by the rushing flow of the multitudinous circumstances that have moulded the life and character of each, and, as Mill and Buckle have said, not to any originating difference in our natures.

As a boy at school to me history was the dullest of dull tasks, but when I came to mix with the peoples of foreign lands, and, fascinated by the charm of the living kaleidoscope of Indian life, sought some clue to the myriad-minded moods and manners of its peoples, I longed for a history that should tell me how and why these peoples were so different from, and yet so like, my own. But histories, as they are written, are rarely more than chafing-dish hashes of the "funeral baked meats" of court chronicles served up with a posset of platitudes and pedantry for sauce. From such histories we may gather a great array of useless, and, for the most part, perfectly uncertain and unreliable "facts," but of the true story of a people scarce anything more than a few doubtful indications. For true history is no bald chronicle of events but the history of man's, too often blind but[16] always intuitive, struggle towards happiness. Back in those memory forsaken ages, of which even myth and legend now tell us nothing, men strove in the same ceaseless, never-ending struggle. What if the immediate aim of that struggle varied then and now with time and place? What if the dweller in the ice-cold lands of the North should be ever seeking the warmth from which the sunburnt inhabitant of the torrid zone would fain escape? To neither is the heat or the cold a thing to be desired or shunned save only as either serves to swell the total of his enjoyment of life. But just as the nature of the climate in which they dwell modifies their conception of enjoyment, so also a host of other circumstances, some minute and scarcely traceable in their influence, others broad and plainly visible, mould the ideas and ideals of men and nations. Thus, and thus only, is it that the Egyptian and the Englishman are so far apart in all that constitutes the individual or national characteristics of each. Thus it is that the restless activity and energy of the one is abhorrent to the other, and that the Englishman to-day finds the Egyptians, as Herodotus found them so long ago, men "distinguished from the rest of mankind by the singularity of their institutions and their manners." I would, therefore, have my readers avoid the error of judging the Egyptians merely from comparison with their own standards and without due regard to the study of the causes that have made them what they are. If the Egyptian be found lacking in qualities upon the possession of which we justly pride ourselves, he is not for that reason alone to be condemned[17] or despised. He has, even as we have, faults and imperfections that may be justly censured. Like Meredith's Captain de Creye, we are all "variegated with faults." These but attest our common humanity, and for the Egyptian it may at least be said, that he has that charity that covereth a multitude of sins, the charity of heart that far outvalues the charity of the purse. Judged with equity he compares favourably in many points with many other men. Less backward than the Spaniard, less bigoted than the Portuguese, less fanatical than any other Oriental, not embittered in spirit as the Irish Celts, "patient in tribulation," "long-suffering," placable, forgiving, hospitable; honest and withal one who, like Abou ben Edhem, loves his fellow-men, there is much, very much, in the Egyptian that may well serve to gain him the friendship and goodwill of those who seek to know him as he really is. But with all this there is one difference between the Egyptian and all European peoples that, as it seems to me, forms an almost impassible barrier to the growth of close friendship, or even intimate companionship, between the European and the Egyptian. This difference is in their modes of thinking and reasoning, for not until the Ethiopian changes his skin will the Oriental think or reason as a European does.

There are hundreds of volumes wherein the Egyptian is portrayed as he has been seen or known by the authors, but like all other Easterns, the Egyptian is, and perhaps always will be, something of a mystery to the European. The thoughts and reasonings of the two peoples are so constantly and so[18] utterly at variance on points and matters that seem to each to admit of little or no controversy, that any attempt to reconcile them must be abandoned as impossible. It is a natural result of this incompatibility that the Egyptian as commonly described by Europeans is a very different being to the Egyptian as he really is. It is so all over the East, through all the widely differing races, nationalities, and religions of the Asiatic continent with, perhaps, the single exception of the Armenians, who in this respect are as distinctly allied to the races of Europe as the Egyptians are to those of Asia. Tourists wander for an hour or two through the bazaars of Egypt or India and flatter themselves that they have seen and can describe the people: young officials tell you glibly that they can read them as a book: the veteran who has grown grey in their service will tell you that the longer he has known them the less is he able to comprehend them.

Orientals generally are capable of a high degree of education or training according to our standards: in India we have men who, in debate and authorship in our language, are entitled to rank with some of our own best men; but mentally even these are apart from us, and in this respect, as Kipling says, "East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet." Nor is it we only who cannot understand them, since they stumble as often and err as widely in their efforts to comprehend us, and even, as I think, more grossly and more hopelessly. None the less, it is, I believe, quite possible for a European to at least partly bridge the gulf and become familiar[19] with Eastern thought and sentiment, but to do so he must pay a heavy price, for it is to be done only by one who will give not merely years of time, but years of self-abnegation, of self-suppression, of self-isolation to the task. Abandoning all that he has been he must seek to become that which he is not, and severing his life from all that has made it his, forego his tastes, stifle his prejudices, ignore his predilections, suppress his emotions, thwart his inclinations, and laughing when he would weep, weep when he would laugh. And with this slaying of his own individuality he must in all things strive to identify himself with those alien to him, ever seeking to see, hear, think, and act as they do. And he must do this not for a week, a month, or a year, but for many years. Not in one city, town or country, but in several, not merely mixing as best he may with the wealthy and the poor, the illiterate and the learned, but learning to be at home in the abodes of the prosperous and the haunts of the miserable, become equally so with the merchant in the bazaar and the wandering fakir in the desert. And through it all he must ever be other than his home life and training have made him. Ceaselessly on the alert to detect the nature, feelings, and impulses of others and to hide his own. And he must be and do all this day and night, in the loneliness of the desert as in the busy haunts of men. And in doing this he is treading a road over which there is no return. The further he goes, the more perfect is his success, the more impossible it becomes for him to regain his starting-point. Never again can he be that which he has been before. He may[20] quit the East, return to the home of his childhood and mix again with his fellows as one of them, but he can never recover the place he has left and lost, for he who goes down into the East, though his heart never cease to yearn for home and the things of home, is daily, slowly, imperceptibly, yet surely, being estranged, and he goes home to find that he no longer has a home, that neither in the East nor in the West, is there any rest for him. Thenceforth and for ever he is alone in the world and, with his own sympathies enlarged and enriched, can hope for no sympathy, no fellowship, amidst all the teeming millions of the earth. Friends and kindred may crowd around his board, ties of love and affection may be renewed, but even with the nearest and dearest the fulness of old-time sympathies can never be revived, for though the East is a bourne from which the traveller may return, it is one from the glamour of which he may never free himself, and as in the East his heart for ever looked yearningly to the West, so from the West it will for ever look back with desire to the East. To him the whole world is clothed with the horror with which "the lonely, terrible streets of London" so bruised the heart of the Irish poet. Such is the price that he who would know the East must pay for his knowledge, a price that few have paid, that none would willingly or wittingly pay. "I speak that which I know," for over thirty years have passed away since I first went down into the East, and as "a mere boy," as Lady Burton disdainfully described me, set myself the task I have never abandoned. Consequently, as[21] it is my object in this book to try and show what, as he appears to me, the Egyptian of to-day is and how he has become that which he is, the picture I shall draw of him will necessarily be unlike those drawn by others, but, although I freely admit that it will be my aim throughout to seek to gain for the Egyptian more generous consideration than he is commonly accorded, my sketch will be as faithful to truth as I can make it: should it fail to be interesting, the fault will assuredly be with the writer and not with the subject.

To understand the Egyptian as he is, we must go back to that memorable 23rd of June in 1798, and learn not only what he then was, but how he had become that which he was. Happily, it needs no long historical details, or wearisome discussion of remote or doubtful causes to gain this necessary knowledge. A few words to show how the Egyptian of to-day is linked with his ancestors of far distant ages, and a short sketch of the social and political conditions existing in the country at the close of the eighteenth century will tell the reader all he need know to enable him to comprehend the story of the years that have since elapsed.

Although the people were then well established in the land and possessed a high degree of civilisation, their history, as we now know it, dates only from the reign of Menes, somewhere over five thousand years before the birth of Christ. From that date down to the present time we have a continuous record, the whole course of which may be divided into three clearly distinguished periods. Of these the first was not only by far the longest, but in every way the most[23] brilliant. In it Egypt was an independent country with a social system of an advanced type, the spontaneous product of the genius of the people, and it was the one in which, under native rulers, the land was filled with the marvellous pyramids, temples, and sculptures that, though now in ruins, still excite the admiration and wonder of the world.

The second period began in 529 B.C. with the conquest of the country by Cambyses. In it after nearly two hundred years of Persian rule, interrupted by a brief restoration of the native power, Egypt was for a little more than three and half centuries in the hands of the Greeks, from whom in the thirtieth year of the Christian Era it passed to the Roman Empire. Six centuries later, in 638, when the flood tide of Islamic conquest first swept westward from Arabia, the country became a prey to the Arabs who, in 1171, were in their turn succeeded by their revolting slaves, under whom as the Mameluk Sultans it remained, until, in 1517, it became a province of the Turkish Empire. In this period, under the sway of foreigners, the country suffered from all the ills we are accustomed to associate with the idea of the dark ages of Europe, and everything that was great or noble in the people or their civilisation perished. It was, indeed, during this time that the world-famous cities of Alexandria and Cairo were built as well as the magnificent mosques that are the pride of all Islam, but these were all the work, not of the people themselves, but of the foreigners by whom they were held in thraldom, and are therefore monuments not of the country's glory but of its shame.

[24]The third and present period began in 1798 when the landing of Bonaparte was the first of the series of events that by the introduction and gradual development of European influence have brought about the now existing social and political condition of the country. In this period Egypt has ceased to be a province of the Turkish Empire, and having acquired the semi-independent position of a tributary State, has been lifted from an appalling condition of social and commercial destitution produced by the ruinous misgovernment and reckless tyranny of a dominant class, to one of unexampled prosperity and of social and political freedom not exceeded in any country of the world.

The three periods into which I have thus divided Egyptian history are then distinguished by differences so deep and so far-reaching that almost the only links by which they can be bound into one consistent whole are the persistence of the people and the preservation of the monuments that testify to their former greatness.

That the Egyptian of to-day is in truth the lineal descendant of those who inhabited the country six thousand years ago is beyond all doubt. Wherever we go in the Nile valley or in the Delta we meet with men and women whose faces and features are living reproductions of the portraits of the kings and people of the most ancient times as sculptured by the artists of their days. And in their habits, manners, and customs, we find to-day striking traces of those that seem to have prevailed when four thousand years before Christ, Ptah-hotep wrote his book of "Instructions,"[25] now believed to be the oldest book in the world. And from their building in those far-off ages down to the present day the pyramids, temples, and tombs have stood surviving witnesses of the early greatness of the country, and, though but heedless spectators of its vicissitudes, silent guardians of its departed glory, ever linking its present with its past.

Closely united as the living Egyptian thus is with his earliest ancestors, all the men and almost all the events that preceded the French invasion are as nothing to the Egypt of to-day. Not a single ruler, patriot, statesman, demagogue, artist or author, in short, no man or woman that lived before the dawn of the modern period, has been instrumental in the making of Egypt or the Egyptians what they now are. Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Turks; all these have held the people in bondage, but their influence never reached below the surface of the life of the country, and has vanished completely with the men upon whom it depended, and though some of these have left monuments, all but imperishable, of their greatness and glory, these to the Egyptians, heirs of their creators, are but idle relics of a forgotten and unheeded past. And as it has been with the men almost so has it been with events, for there are but two of these that, preceding the French invasion, have exercised an influence of such vitality as to survive the great change in the condition of the country that has since been wrought. These two events, with four that belong to the modern period, are indeed all that the whole history of the country[26] presents to us as still clearly and prominently exerting an important and permanent influence upon both the character of the people and the existing circumstances and condition of their country. Of these six events the two that belong to the second period are, the conquest of the land by the Arabs and its subsequent seizure by the Turks. The other four are, the French invasion, the rise of Mahomed Ali, the English occupation and the evacuation of Fachoda by the French.

Each and all of these six events have played important parts in moulding the present-day aspect of Egypt and its people, and the more closely do we study the existing conditions, the more strikingly do these six events stand out from all others as the great and dominating landmarks in the history of modern Egypt. Compared with these all the other incidents of that story of seventy centuries—the long procession of dynasties of Pharaohs, Ptolemies, Caliphs, Sultans, Khedives—are all but shadows that have come and gone. It is not so with the landmarks I have named, for not only are these events that have influenced and are still influencing the thoughts and feelings of the people, but the influence they exert is recognised by the people themselves and must be taken into account in any endeavour either to understand the present condition of the country, or to forecast its future. Although, therefore, the third of these landmarks forms, as we have already seen, the starting-point of the story of modern Egypt, to rightly comprehend that story it is necessary we should have a clear conception of the effects wrought by the first two events[27] and of the influence these have had and still have upon the affairs of the country.

Let us remember here that Egypt, like most civilised countries, has in reality two stories, one the history of the nation as a political body; in other words, its history as history is commonly understood and written, the record of the rise and fall of its rulers, the tale of their triumph and of their failures, and chronicle of their wars, victories, defeats, and all the events that have made or marred their destinies: the other the story of the people themselves, of the growth of their character and institutions, and of the development of their social and moral surroundings. It is with this latter story that we have to deal, and it is, therefore, from the point of view thus assumed that I have estimated the importance of the events of which I have just spoken.

In the history of some countries the two stories, if rightly told, are so interwoven that they become as one, but in the first and second periods of Egyptian history they have scarce anything in common, for so long as the people remained under the rule of the Pharaohs or of the foreigners who succeeded them they were little more than passive victims of the varying fortunes that affected their rulers, and almost the only fluctuations in their state during the long ages stretching from the time of Menes to the French invasion were those occasioned by the varying degrees of the tyranny to which they were subjected. Now and again under some ruler of more humanity or of greater laxity than others their condition may be said to have for the time improved, but such changes[28] were far too slight and their possible duration always far too uncertain for these benefits to be more to the people than as the grateful but passing pleasure a fleeting morning cloud brings to the traveller in a sunburnt desert. Hence, such as the fellaheen or peasantry were when Cheops was building his pyramid, such they remained in almost all respects down to the arrival of the French. The history of the country has, therefore, in the first two periods little to say of the people. In the modern period the two stories touch each other more closely, for in it the people have begun to have a political existence. They have not, indeed, a representative government, and so they have no direct power, but they have a press, the freedom of which is absolutely unrestricted, and they have a "Legislative Council" as a body of elected representatives, through whom, though they cannot control the action of the Government, they are at least able to make their voices heard and their wishes known. More important still, they have begun to comprehend the right of a people to be governed, not only justly, but with a regard to their interests as well as to those of their rulers—a fundamental principle that in the past would have been deemed an unpardonable heresy.

The first step towards the realisation of this improvement, though one for long wholly unproductive of any political benefit to the people, was the Arab conquest, which by the resulting conversion of almost the whole population to the Mahomedan religion, brought about a change still fruitful in its influence upon their ideals and aspirations. To fully[29] describe the importance of this event it would be necessary to enlarge upon the character and tendency of the Mahomedan religion at a length my limits forbid, and I must here therefore content myself with noting that, great as was the moral and mental revolution this conversion occasioned, it was by no means commensurate with that which followed the introduction of Islam into other countries. On the everyday life of the people it seems indeed to have had but little effect other than that of altering their moral standard and modifying in some slight degree their habits and mode of living. It was, perhaps, inevitable that this should be so, for of all the peoples of the East the Egyptians were, and are, the least susceptible of imbibing the spirit that marked the early spread of Islam, gave it the energy that carried it to victory, and still gives it such vitality as it continues to possess. Christianity had been for a long time the State religion of the country, but it seems clear that the great majority of the people were never more than mere nominal followers of the Cross, and the arrival of the Arabs was, therefore, quickly succeeded by the voluntary adoption of Islam by all but the small minority to whom Christianity was something more than a name and whose descendants constitute the Coptic Church of to-day. The political condition of the people was little, if at all, affected by the change in their religion; and consequently, under the Caliphs and their successors, the Egyptian continued to be as he had been before—a man with no higher ambition than that of passing through life with the least possible trouble. From[30] year to year his one prayer was for an abundant Nile and a plentiful crop, not that he might thereby enrich himself, but that he might thereby secure a sufficiency for himself and his family and suffer less from the rapacious tyranny and heartless cruelty of those never-resting oppressors, his rulers and all who, as officials or favourites, were lifted even a little above his own level. It was, and is, of the essence of Islam that it appeals to freemen and favours that love of freedom that is the birthright of every man; but Islam brought no freedom to the Egyptians, save, indeed, the spiritual and moral one their rulers could not rob them of. So such as he had been before, such he remained after the Arab conquest, but with a loftier sense of the dignity of manhood, a nobler conception of life and of its duties, and a stronger faith in a hereafter that should compensate him for all his sufferings and privations in this life. As an individual, therefore, he was somewhat altered, but as a member of the State—if we may apply that term to one who had no political existence save that involved in yielding to his rulers the utmost pennyworth of value they could wrest from him by tyranny and cruelty—he was the same helpless, hopeless, downtrodden being, less valued and less cared for than the beasts in his fields. But the conversion of the Egyptians has filled them with that intense attachment to the faith of Islam that, shared by all Mahomedans, has given rise to the charge of fanaticism so commonly brought against them—a charge that, in the case of the Egyptians, if not wholly unjust, is too often exaggerated, although none the[31] less there is nothing excites the wrathful passions of the people or, in milder moods, sways their actions more than their fidelity to their religion. It is the fact that this is so that renders the Arab conquest the first great landmark in the story of modern Egypt, for it is not too much to say that this attachment of the Egyptians to their faith is to the present day the most important factor with which all who are concerned in the administration of the country have to deal.

If socially and otherwise the Egyptians profited but little from the establishment of the Caliphate, they gained still less from the domination of the Turks. To the people, indeed, this change was scarcely more than a mere nominal one. It left them practically under the same rulers, for though the system of government was modified, it placed the executive power, if not in the hands of the same men as before, at least in those of men of the same stamp, who ruled them as their predecessors had done, in the same manner, through the same agents, and with the same cruelty and wanton oppression. Yet the Turkish, like the Arab, conquest wrought one important effect, the influence of which time has strengthened so that it is only second to that in the urgency of its bearing upon existing conditions. Under the Arabs the Egyptians had been ruled by foreigners, but by foreigners who were in some degree allied to them. Under the Turks their sovereign was, and is, not only a foreigner, but one of an utterly alien race, wholly separated from them by language, character, habits, by everything, indeed,[32] save the bond of their common religion. None the less a spirit of loyalty to the Turkish Empire has grown and spread among the people, which, though it would be an error to credit it with the intensity popular writers of the country ascribe to it, has unquestionably a powerful influence upon the views and opinions of the great majority of the people. To Europeans this loyalty, which, it is worthy of mention here, is shared by the Moslems of India, has always appeared somewhat of an enigma. No one, however, who knows the peoples of the two countries can doubt that, apart from the fact of the Sultan being the official head of their religion, their loyalty to him is largely due to the desire of peoples who have lost the place they once held in the comity of nations to associate themselves with such kindred peoples as have in some extent maintained their ancient status. The Indian and the Egyptian Mahomedans alike look back to the time when Islam was the one dominant, unopposable power in their native lands, and, conscious of their own fallen condition, would fain relieve the darkness of their destiny by seeking a place, however humble, within the only radiance they can claim to share. While, therefore, the loyalty of the Egyptians to the Turkish Empire is only a part of their loyalty to their religion, it has this, from the political point of view, important difference—that it is not irrevocable, but more or less dependent upon the Sultan maintaining his political supremacy in the Mahomedan world, for should he lose the position he holds as the most powerful ruler in Islam, not only the Egyptians, but[33] his own immediate subjects, would feel justified in transferring their allegiance to any ruler who might succeed him. But absolutely as the Sultan may depend upon the loyalty of the Egyptians as against any non-Moslem Power, yet, as we shall have occasion to see, not only can he not do so as against a Moslem rival, but he can only ensure their loyalty and obedience as his subjects by ceding to conditions they hold they have a right to impose upon him. Were, therefore, the hopes of the large section of the Mahomedans which is filled with the desire for the restoration of an Arab Caliphate to be realised it would entirely depend upon circumstances that it is quite impossible to foresee—whether the Egyptians would or would not remain faithful to the Empire. Meanwhile the revival of the Arabic power being a possibility too far removed from probability to take a place in the politics of the day, the loyalty of the Egyptians to the Turkish Empire must be accepted as a controlling feature in the affairs of the country.

Such, then, are the links that bind the Egypt of the present day to the Egypt of the past, but important as has been, and is, the part that the Arab and Turkish conquests have played in shaping the present and will yet have in moulding the future of the people, it was not to these events but to others occurring outside the country that we owe the inauguration of the modern period of Egyptian history.

What these events were and how they affected the making of the Egyptian what he now is we have now to see.

The period which was to be that of the regeneration of Egypt and its people was ushered in by social and political storm and tempest. But the first warning note of its coming, after a brief moment of panic, was unheeded by the people. Nearly three centuries had passed since the country had been invaded by an enemy. That enemy was now the sovereign Power, and under the grasping, selfish rule of its executive the trade and commerce of the country had almost entirely disappeared, and thus isolated from the rest of the world the people had no conception of the growth of the power and civilisation of the European nations. They were, therefore, completely ignorant of the events and political impulses that were, though for the moment indirectly only, shaping the future that lay before them.

There were both Englishmen and Frenchmen in the country at the time, but the rulers of the land, arrogant in their petty might, and the people not less so in their degradation, alike held all foreigners in contempt, and thus profited nothing from their[35] presence. They had, therefore, no means of knowing what the relations between the two great European Powers were, or of anticipating how those relations were liable to affect their country. Yet the fact that brought about the opening of the modern period in their history and thus decreed the ultimate fate of the country was the mutual hostility that swayed the two Powers. This hostility had no relation to Egypt or its people, and, but for contributing causes, could never have affected these, yet it was the desire of the French Government to strike what it fondly hoped would prove a decisive blow at the growth of English power in the East, that was the chief inspiring cause of its decision to order the invasion of Egypt. The Directory, which was at the time the governing body in France, had indeed more than one reason for taking this step, nor was it under the Directory that the eyes of the French had been turned to the valley of the Nile for the first time. Leibnitz, in 1672, had urged upon Louis XIV. the conquest of the country as an object worthy of his attention, declaring that the possession of it would render France the mistress of the world, and though nothing was done at that time to realise the far-seeing policy he advocated, there can be no doubt that the idea was never abandoned. Talleyrand, indeed, said that on his accession to office, he had found more than one project for its accomplishment lying in the pigeon-holes of the Foreign Office, and he himself entered heartily into the scheme, believing that it would be a most important move towards the fulfilment of his theory that the future of France[36] depended upon the extension of her influence along the shores of the Mediterranean. Volney, the traveller and author of the "Ruins of Empires," having visited Egypt had, in 1786, reported that it was in a practically defenceless condition, and Magallon, the French Consul at Alexandria, having for years urged the Government to interfere on behalf of its subjects in Egypt, had, in 1796, made a voyage to France with the express purpose of protesting against the indignities and ill-usage from which they were suffering, and fully confirmed the views of Volney and Leibnitz. The Directory were thus at once shown the possibility of acquiring a colony of the utmost value and provided with a reasonable excuse for its annexation. These and other arguments, against which the fact that the French nation was then at peace and on good terms with the Sultan of Turkey, the sovereign of the country, weighed as nothing, decided the Directory. In March, 1798, therefore, the order to organise an expedition for the conquest of Egypt was given to Bonaparte, and two months later, on May 19th, he set out in command of a vast armada, sailing from Toulon and other ports of the south of France.

Thus it was the aspirations of the French nation for the extension of its influence in the Mediterranean and for the acquisition of new colonies and its conquest rivalry with England, and not events in the country itself, that heralded the dawn of the new period, and eventually, though chiefly indirectly, produced the greatest change in the condition and prospects of the people that their history records.

[37]The rapidity with which the French expedition was prepared, and the secrecy with which its destination was concealed, led the Directory and Bonaparte himself to hope that it would escape all risk of interference on its way to Egypt. In this they were not disappointed, but hearing of the assembling of a great military and naval force in the south of France, and believing that it was intended to make a descent upon the Irish coast with a view to co-operation with the rebels there, Lord Vincent warned Nelson to watch for, and, if possible, destroy it. The people of India were then, however, like those of Ireland, in negotiation with the French, and in particular the famous Tippoo Sultan, "The Tiger of Mysore," longing to be revenged for the defeat and losses Lord Cornwallis had inflicted upon him, had sought their aid. Nelson was aware of this, and having a strong sense of the danger to English interests in India and the East generally the possession of Egypt by the French would be, guessed the real destination of the expedition, and finding that the French had got away to sea, immediately started in pursuit, and, acting upon his own conception as to its aim, steered straight for Egypt. Bonaparte had, however, after leaving the French coast, proceeded to Malta, which he seized, and being thus delayed some days on his way to Egypt, Nelson passed without falling in with him, and thus it was that on June 21st the Alexandrians were startled by the approach of the English Fleet.

As soon as the character of the ships thus unexpectedly[38] appearing on their coast became known the town was thrown into a state of the greatest excitement, and the Governor, believing that the fleet was a hostile one, sent off to Cairo the messengers whose arrival there I have already chronicled, and at the same time sent other messengers to summon the Bedouins, or nomad Arabs, inhabiting the neighbouring deserts, to assist in the defence of the town.

Nelson lost no time in sending ashore to seek news of the French, but the reception given to his officers was far from friendly. Refusing to credit the statement that the English came as friends and protectors and not as enemies, the Governor openly expressed his distrust, and in doing so simply voiced the feelings of the people. Utterly ignorant of everything outside the narrow range of their own experience, it was indeed impossible for these to comprehend how the occupation of Egypt by the French could be a matter of vital importance to the English. So when Nelson's officers assured the Governor that they asked nothing more than to await the arrival of the French and to buy a few supplies of which the fleet was in need, he answered them that they could have nothing. "Egypt," said he, "belongs to the Sultan, and neither the French nor any other people have anything to do with it, so please go away."

It was a bold speech, and as foolish as it was bold, for no one knew better than the Governor himself that he was quite powerless to oppose the English if they wished to land, or to take what they needed[39] by force. It was a speech, too, worth noticing, for it affords a clue to much that puzzles the ordinary critic of Egyptian history. Judged by any known canon of social or international courtesy or policy, it was not less inexcusable than indiscreet, for it was as likely to enrage an enemy as to anger a friend, but it was just what one knowing the people might have expected—the utterance of the impulse of the moment, and, therefore, a full and truthful statement of the speaker's thought. For to the Egyptian mind the visit of a fleet of foreign ships of war could have no other object than the conquest or raiding of the country, hence the English Fleet must be a hostile one. It was neither lawful nor wise to give provision or succour of any kind to an enemy, therefore they had nothing to say to the English but "Please go away."

It was thus that the people of Alexandria argued then, and it is thus that the people of Egypt generally still argue. For they have always been incapable of taking a broad or general view of any subject. No matter how many-sided a question may be, they, as a rule, can see but one aspect of it at a time. They look, in fact, at all things through a mental telescope that, bringing one narrow and limited aspect of a subject into bold and clear relief, shuts from their vision all that surrounds it. Hence when, as they can and sometimes do, they change their point of view, the change is commonly as abrupt as it is thorough, and those who see only the surface tax them with fickleness. Of late years there have been signs that, at all events, the educated[40] classes are learning to reason on surer and safer grounds; but if the reader would understand their story, he must ever bear in mind the narrow basis of their judgments and, therefore, of their actions.

While the answer of the Governor to the English is thus illustrative of a point to be remembered in the character of the Egyptians, the life-story of the man himself also helps us to more fully grasp their mental attitude under the changing circumstances of the period. This Governor, Sayed Mahomed Kerim, was an Egyptian of humble birth, but one of Arab blood, claiming to be a Sayed or Shereef; that is to say, a descendant of the Prophet Mahomed's family, and thus one of the Arab nobility. In his early manhood this man, who as a Sayed, was and is blessed and prayed for by every Mahomedan in the world at every time of praying, was glad to fill the modest post of a weigher in the Customs. Gifted with intelligence and other qualities that commended him to his superiors, by their favour and his own ability he rose rapidly to become the local Director of Customs, and eventually, as we find him, Governor of the town. That in this position he had the confidence and respect of his townsmen seems clear; and it is thus evident that, tyrannical and oppressive as was the rule under which they lived, there was an open path to place and power for able men. Bribery and corruption, it is true, were rife, so much so, that we may safely assume that Sayed Mahomed did not attain his high position wholly without their aid, but they did not[41] play the dominating part assigned them by historians of the time.

We shall see but little more of this Sayed Mahomed, for though still a young man, he had but a short span of life to run, yet the little we shall see makes him a notable man, and one that should be studied. Bold, impulsive, proud and fearless, with that decision of character so praised by Foster; quick to decide and unalterable in his decisions, deciding rightly from his own standpoint, but often with too limited a view—emphatically more of an Arab than an Egyptian type, and yet in the few glances we get of him, illustrating, most aptly, the Egyptian character. Thus, as his answer to the English was essentially Egyptian and not Arab in substance and manner, so also was his subsequent action. For an Arab in such a strait would have sought to gain time by fair-speaking, so that he might take such measures as he could, or at the worst secure better terms, whereas Sayed Mahomed spoke in a manner that, had the English been, as he supposed, enemies, must have precipitated hostilities, and having done so, again Egyptian-like, made no adequate attempt to protect the town from the possible consequences of his rashness.

Whether fortunately or otherwise no man can say, Nelson, too intent upon the object he had in view to be moved from his immediate purpose, took the rebuff offered him calmly, and, after a day's rest off the port, sailed away, leaving the Alexandrians to congratulate themselves upon their own astuteness and to indulge themselves in vain-glorious[42] anticipations of the prodigies of valour they were to perform should the French land upon their shores.

A week having passed by without the appearance of an enemy, the people had regained their wonted calm, when as unexpectedly as though no warning had been given of its coming the French fleet of twenty-one vessels of war and over three hundred transports was seen in the offing heading for the port. This sudden and unlooked-for proof of the reality of the danger they had refused to credit produced the utmost consternation.

Once more the Governor despatched messengers in all haste to the capital, and describing the French fleet as one "without beginning or end," begged earnestly, but all too late, for aid.

The people of Cairo, like those of Alexandria, when their first alarm at the arrival of Nelson's fleet had passed away, seeing in his departure a confirmation of their own conception of his visit, ceased to think of the matter save as the subject of jest, but were overwhelmed with dismay at the new alarm, even the Government, which had been but little moved by the first, being now stirred to activity and a sense of danger.

The Government of Egypt was then, at least nominally, such as it had been constituted after the Turkish conquest in 1517 by Sultan Selim. Keenly recognising the impossibility of enforcing his authority in a province of the Empire so far off and so difficult of access from his own capital, the Sultan had, not unwisely, contented himself[43] with organising a system of government that was, in his opinion, the one most likely to ensure the permanency of his sovereignty and guarantee him the receipt of a goodly share of the wealth of his new possession. Egypt was placed, therefore, as the other provinces of the Empire then were, and still are, under the government of a Pacha, who was in effect, though he was accorded neither the style nor the honour of that rank, a viceroy. But the Sultan, anxious to hold the Pacha in check by some power ever present and active, divided the territory under his charge into twenty-four districts, and placed each of these, as a kind of local governorship, in the hands of a Mamaluk chief or Bey. Of the Beys chosen for these posts seven were to form a Dewan, or Council of State, nominally to advise and assist, but in reality to control the Pacha, whose decisions this Council was empowered to veto. All real power was therefore vested in the Mamaluks, who, it is perhaps scarcely necessary to recall, were the troops that, originally brought into the country as slaves by the Fatimite Caliphs, had gradually developed their power and influence until their chiefs had become feudal lords, holding lands and keeping, according to their individual means, troops of mounted followers, whose physical qualities and effective training rendered them one of the finest bodies of cavalry that has ever existed. As must invariably happen when a weak and incompetent Government seeks the aid of slaves or mercenaries to sustain its failing dominion, the Mamaluks had eventually acquired such power that[44] they were enabled to usurp the government of the country, and had, as we have seen, maintained their position as Sultans of Egypt from the time of Salah ed Deen up to the Turkish conquest. Under the system of government established by the Sultan Selim, though unable to regain the absolute independence they had lost, they soon recovered almost all their former influence and power, and as they controlled the military strength of the country, the small Turkish garrison being quite helpless to oppose them, they soon became, as before, the real rulers of the land. Being invariably foreigners, or the immediate descendants of foreigners, Circassians, Armenians, or other slaves, it was but natural that these Beys should have no sympathy for the people of the country, and, with the arrogance characteristic of a military body that has attained political power, despised all outside of their own ranks, and held it a disgrace to intermarry with the Egyptians. Actuated by none but the most selfish aims, they sought and cared for nothing but their own interests, each of them being a veritable Ishmael, looking upon all men as his enemies, only accepting the co-operation of his fellow Mamaluks as a necessary measure of defence, confiding in the loyalty of his immediate followers only so far as he was able to control them by rendering their faithfulness to him conducive to their own interests. Among themselves they of necessity accepted the domination of the one who by force of arms, intrigues, or other favouring circumstances, was in a position to enforce his will against that[45] of the others, and, as might be expected, the Bey who held this prominent position was the one to whom the post of Sheikh el Beled, or Governor of Cairo, was accorded, that being the post of all others the most coveted by them, this Bey being, in practice, the real Governor of the country, his power being only limited by the necessity he was under of consulting and conciliating the wishes of the other members of the Dewan.

It may seem strange that with the power they thus possessed the Mamaluks should continue to offer even a faint show of respect to the Pacha, or of loyalty to the Empire, for light as was the yoke these laid upon them, it was sufficiently galling to men who lived as they did each wholly absorbed in the prosecution of his own personal aims and interests, and the more so that, as the wealth of the country declined under their greedy and ruthless rule, the remittances of revenue exacted by the Sultan was a yearly draft that seriously limited their resources. But if the Mamaluk hated and despised all men not of his own class, he was in turn hated by all others with a hatred all the fiercer and more bitter that it had no outlet. Thus, with no friend upon whom he could rely save his own right arm, the Mamaluk chief, however powerful, was fain to accept the patronage of the Sultan as the only aid he could look for in his combat with the world, and he must needs, therefore, be content to pay for that aid with a certain tribute of grudging loyalty. Nor must it be forgotten that, ever ready to combine and co-operate against[46] a common foe, each Mamaluk was equally ready to turn his hand and sword against his fellow if thereby he might gain aught for himself. Had it not been for the mutual distrust the knowledge of this fact forced upon them, they might easily have regained the independence wrested from them by the Turks. This had, indeed, been momentarily accomplished by Ali Bey, who, in 1766, not only succeeded in setting himself up as Sultan of Egypt, but aspiring to extend his rule, had attacked and conquered the Mahomedan holy cities of Mecca and Medina in Arabia. His triumph was, however, but shortlived, for Mahomed Bey, the most trusted of his favourites, to whom he had confided the command of an army for the conquest of Syria, abandoned his task, and revolting, took his master Ali prisoner by a treacherous ambush. Unable alone to maintain the power he had thus for the moment seized, the traitor at once tendered his submission to the Sultan, and was, in reward for his "fidelity," appointed Pacha of Egypt. His tenancy of this office was, however, but brief, his death soon after, leaving the country once more a prey to the mutual rivalries of the Beys. In the contest for supremacy that followed, two of these, freed slaves of his, though constantly opposed to and frequently in arms against each other, eventually agreed to share the power between them, the one, Murad Bey, becoming the military chief of the Mamaluks, and the other, Ibrahim Bey, the Sheikh el Beled.

Under the joint sway of these two men the[47] country enjoyed a brief period of greater quiet and peace than it had known for a long time, and although the tyranny and oppression from which they suffered was little if at all abated, the people had been so completely despoiled before and had so little to lose that, as "He that is down need fear no fall," they had but small anxiety for the morrow.

This was the condition that existed on that memorable night of the 23rd of June in 1798, the eve of the day upon which Cairo had its first warning of the approach of the French. Could a plebiscite of the hopes and fears of the people have been taken on that evening, we may be sure that it would have been unfavourable to any change, and that they would have elected to bear the ills they had, rather than face the possibly far worse any change might bring to them.

As soon as the news of the arrival of the French Fleet had been received by Murad Bey, he rode to the country house of Ibrahim Bey, now the Kasr el Aini Hospital, on the east bank of the Nile overlooking the Island of Rhodah.

There a council of the leading men of the city was hastily summoned to consider the steps to be taken for the defence of the country, and it was characteristic of the conditions under which the people were then living, that all those present, with the single exception of Bekir Pacha, the Governor and representative of the Sultan's authority, belonged to one of two classes—the military rulers and the religious leaders of the people. The excitement that prevailed in either class was plainly evident at the meeting, though the feelings and fears induced in each by the news they had met to discuss were very different.

The military element consisted entirely of the Mamaluk Beys, who formed, as we have seen, the real ruling power, their title of Bey—or, as it is written in the Turkish language from which it is[49] taken, Beg—being fairly equivalent to that of Baron as used in our own country in the days of King John, though it has long since ceased to signify any more than the French Legion of Honour, save that, like our Knighthood, it carries a personal title. By the people generally, these Beys were spoken of as Emirs, a title properly nearly equal to that of Prince, and the one employed by the rulers of Afghanistan, so well known to us as the Ameers of that country. I have already spoken of the dominant position the Beys held, but I may add here, as further illustrating their character, that if they had not, as the French nobles had in the days of Louis IX. and Philip the Fair, the right of carrying on war among themselves, they did not hesitate to put their rivalries to the test of battle. Confident in the prowess of their own body, these men had treated with indifference the alarm occasioned by the arrival of Nelson, but when the warning he had given was confirmed by the presence of the French, and the extent of the fleet that was gathering at Alexandria was known, not only through the exaggerated terms in which Sayed Mahomed had described it, but also by the arrival of reports from Rosetta and Damietta to the same effect, they awoke to the necessity for action.

Centuries had then passed since the Arabs or their Mamaluks had measured their strength against that of European armies, and altogether unacquainted with the advance their ancient foes had made in the art of war, it was perhaps natural enough that they should be a little over-confident in their own might, especially as such stories of the Crusades as[50] still lingered among them were not of a kind to excite any very lively fears of an enemy that, according to these traditions, they had never met but to defeat. Moreover, ignorant as they were of the progress of the world outside their own country, they knew that the Moslem corsairs of the Mediterranean were a constant terror to all ships of Christian countries that had to pass the inhospitable coasts of the Barbary States, and that throughout the north of Africa European Christians were found as the slaves of Moslem masters. Added to this the fact that the insulting treatment they themselves accorded to European ships visiting their ports, and their tyrannous behaviour to European subjects resident in the country, long continued as these abuses had been, had brought no effective or warlike protest from the nations thus gravely injured and insulted, and we can easily conceive that they placed no high value upon the military or naval power of peoples who thus meekly, as it seemed to them, submitted to such outrages upon their subjects. Hence, while they regarded the present occasion as one calling for active measures of defence, they had no presentiment of the disastrous fate that was so soon to overtake them, and so, undismayed by the news of the arrival of the French, cried vauntingly, "Let them come that we may trample them under our horses' feet!"

As to the second class of those present at the Council, the Ulema, or "learned men," that is to say, those who in virtue of their proficiency in the study of the laws of Islam were the acknowledged and duly[51] graduated religious leaders of the people, these looked upon the danger with very different eyes. Unlike the Mamaluks they were men of the country, allied by blood to its people, and therefore, though like priests and ministers of all religions in all countries, forming a class severed from the great body of the people by special and mutually conflicting ideals, aims, and interests, they were not, and could not be, wholly indifferent to the welfare of the people, of whom, by kinship of every degree, birth, marriage, and parentage, they never ceased to form an integral part. These, therefore, had a lively fear of the inevitable distress any warlike operations in the country must bring upon the people, while the fact that the enemy approaching was a Christian one, gave to their anticipations a personal character they would not have borne had the invader been of the Moslem faith. Like those of the Mamaluks their conceptions of the character of the European peoples were mainly founded upon the traditions of the Crusades—traditions that included only too many incidents, such as that of the soldiers of the Cross, at the taking of Jerusalem, dashing out the brains of innocent infants; traditions that are still recalled in Moslem lands, and are in no small degree responsible for the anti-Christian and anti-European spirit that exists among Mahomedan peoples. Their feelings at the thought of the possibility of a French victory were, therefore, quite apart from those of the Mamaluks, if, indeed, these ever gave such an idea a moment's thought. If they did, they still had before them three possibilities—victory, which to them meant gain in many ways;[52] defeat and flight, leaving them at least the hope of retrieving their fortune later on, or in some other land; or death in honourable and glorious warfare, warfare too, that being in defence of Islam, would give them the rank and, better still, the rewards of martyrs for the faith. On their part the Ulema could see only two possibilities: a victory that, however glorious, would have to be paid for at a heavy cost of suffering to the people, or a defeat involving all that they could imagine of dire disaster and woe.

That we may fully comprehend the influences swaying the members of the two classes of which the Council was composed, we must recall their mutual relations. The Mamaluks, then, being Mahomedans in little more than name, yielding their loyalty to the Sultan and to Islam simply from a regard to their own interests, were commonly looked upon by the Ulema, as well as by the people generally, as scarcely better than heretics, while their ceaseless rapacity and heartless cruelty made them at once feared and hated. Conscious of these facts, but not daring to place themselves in open opposition to the Ulema, they sought in every way to gain these to their support, and more especially by their professions of loyalty to the faith, and by treating the Ulema with all dignity and respect. This, indeed, they were bound to do, since not only was it in the power of the Ulema to incite the people against them, but with the aid of the Ulema of Constantinople to secure the Sultan's action on their own behalf in case of need. In a word, therefore, while despising the Ulema with the man of action's contempt for the mere student or scholar,[53] the Mamaluks found it essential to their own safety to cultivate their toleration, knowing well that this was all they could obtain from them.

As to the Ulema, fully recognising the insincerity of the Mamaluks, they were fain to accept their homage as the only course for them to follow except one of open hostility, which, however little they, as a body, need fear its results, to each one individually involved risks not lightly to be run.

Having no power of excommunication, such as that possessed by the priests of the Catholic Church or the Brahmins, the Ulema had no direct means of coercing those who displeased them, and were thus not infrequently obliged to accept or adopt a line of conduct that under other circumstances they would have refused to follow. It is, therefore, to their credit that throughout the history of their class, they have always been an independent and, on the whole, a fearless set of men, and that it is but rarely indeed they have been opposed to reason or right as they have understood it, though, unhappily, their conceptions of these have not always been such as enlightened minds could approve. Like the clergy of all Churches, with, perhaps, the exception of the Catholic, they have not seldom been compelled to choose between interest and principle. That they should never err in such a case, they must have been more than human.

Diverse as were the interests of the Beys and those of the Ulema at this Council, the aims and hopes of the two classes were in the most perfect accord, both being dominated by the single desire to[54] concert such measures as should seem best for the protection of the country.

In this they were heartily joined by Bekir Pacha. As the representative of the Sultan's authority, his chief duty and personal interest lay in seeing that the annual remittances to the Sultan were made as early and as large as possible, and that the country was kept as free from wars and seditions as might be. So long as he could in some fair measure secure these aims, though always, like all servants of the Empire, at the mercy of intriguing aspirants, he might hope to retain, if not his post, at least the Sultan's favour. Although thus constrained to court the goodwill of both the Beys and of the Ulema, his personal sympathies were strongly with the latter, and were not weakened by his keen sense of the treacherous nature of the friendship for himself and of the loyalty to the Empire professed by the former.

The relations thus existing between the three parties at the Council—the one-man party of Bekir Pacha, and those of the Mamaluks and Ulema—had then been in force for some years, and, coupled with the fact that Ibrahim Bey was a man who, though of approved courage, was withal a constant promoter of peace and concord, had contributed not a little to gain for the people the few years of comparative immunity from care and trouble they had been enjoying.

Murad Bey was a man of different stamp. Of great energy, proud and ambitious, ever ready to sacrifice friends as well as foes for his own profit, he is said to have been at times daring to foolhardiness,[55] and again timid to poltroonery, but always consistently selfish, grasping, and tyrannical. From the time that he and Ibrahim Bey had agreed to work together in the government of the country they had shared between them the greater part of the revenue; and Murad, while constantly adding to his private property large areas of land confiscated from the people under various pretexts, spent large sums of money in developing the military resources at his disposal, constructing cannon, storing ammunition, and building vessels for military service on the Nile. Passionate, impulsive, and keenly conscious of the fact that the Sultan looked upon him and his fellow-Mamaluks with no friendly eye, upon hearing of the arrival of the French he jumped to the conclusion that they had come, if not as the allies of the Sultan, yet with his connivance. For Bekir Pacha, both as an individual and as the Sultan's representative, he had a contempt that, though veiled under the courtesy of pretended amity, lost no opportunity of wounding his feelings or depreciating his authority. Swayed by these sentiments, he did not hesitate on joining the Council to charge the Pacha with being privy to the invasion, alleging it as inconceivable that the French should venture upon such an undertaking if they had not some reason to look for the support, or at least the countenance of the Turkish Government. The spirit and tact with which the Pacha repelled this accusation showed that had he been in a position of greater power he might have proved himself a man better able to deal with the danger they had to meet than was his accuser. It[56] was soon evident, however, that the Pacha had the confidence of the assembly. Murad was obliged, therefore, to accept his denial, and the attention of those present being turned to the more practical aspects of the subject that had brought them together, after a brief consultation it was arranged that Murad should advance to meet and oppose the French, and, as they all hoped, drive them back into the sea, while Ibrahim Bey was to remain at Cairo and provide for the defence of the capital in the event of the enemy pushing their way so far.

Had the Council limited itself to the discussion of these points I might have passed it with briefer notice; but perhaps the only really debatable issue brought before it was one the reception of which throws some light upon the important question of the feelings of those present towards the Christians then living in the country.

Urged, mainly, in all probability, by the desire not to remain a mere silent member of the Council, one of those present suggested, as a measure of defence, a massacre of all the Christians in the town. There is, I believe, no record as to who made this wild proposal, but we may be certain that it was one of the youngest, and a man little read in either the history or teaching of his religion.

To the tolerant spirit that now happily prevails in England and the West of Europe, such a suggestion, made, even as it was, in an hour of panic, seems savagely revolting. But in our criticisms of this and other incidents in history we too often overlook the lapse of time and compare the Egyptians and[57] other peoples of the past to that which we are at present, and not to that which we ourselves were at the same time. Thus when we condemn the fanaticism of those who made and supported this proposal at the Kasr El Aini Council, we forget to remember what was even then passing in our own country. This Council was held on the 4th of July, in 1798, and on that day the Irish rebels who had been defeated at Vinegar Hill, on the 21st of June, the very day on which Nelson had reached the Egyptian coast, these rebels were still trembling fugitives sheltering in the mountains and bogs of their native land from the ruthless "no-quarter" pursuit of the vengeance-wrecking soldiers of the Crown. Nor let it be thought that in speaking of this I am taking a partial or party view of the events of those days, for my ancestors were with the pursuers, not with the pursued. And if it be objected that this was in Ireland, and that the atrocities perpetrated by both parties were due rather to political than to religious rancour, let us go back but eighteen years, for was it not in 1780 that for four days the Gordon rioters held London in their hands, and, crying "Death to the Catholics!" sacked and pillaged, burned and wrecked the churches, shops, and houses of Catholics and of those who favoured the cause of Catholic emancipation? Let it be remembered, too, that the fanatics of Cairo had at least this excuse, that they were in terror of an approaching foe to whom those they proposed to slay were friendly, while the only danger that the London mob had to face was at most a political one, and that one based[58] upon mere possibilities, and not even on probabilities. Let us—but no! the Reign of Terror in France, the echoes of which were then still ringing throughout Europe, the one unsurpassable horror of all time, that was the maniac outbreak of a people frenzied by the long pent-up wrath of their endless wrongs and sufferings, a horror only possible when the inhumanity of a class had shattered the humanity of the mass. But we may recall the crimes of the Commune, which in our own days washed the streets of Paris with blood, and was an unreasoning, insensate outburst of political fanaticism, and also the recent massacres of Jews in Russia.

These events have had but little in common, except that they were alike the products of fanaticism—whether political or religious—but they show that in condemning the fanaticism of the Cairo Council we must make allowance for time, place, and circumstances, and, remembering how much more grievously we ourselves and our European kinsmen have sinned, hesitate to accept such incidents as these as stamping the people as in this respect other than ourselves.

Bearing these facts and dates in mind, let us now learn what was the fate of the bloodthirsty proposal thus brought before the Cairo Council, but first a word as to who and what the Christians were whose lives were thus endangered.