NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1904

Copyright, 1904, by

The Century Co.

The DeVinne Press

TO THE STUDENTS

OF THREE UNIVERSITIES

—INDIANA, STANFORD, AND CORNELL—

FOR WHOM, WITH WHOM, AND BY WHOSE AID

THIS BOOK CAME TO BE WRITTEN

PAGE

The Value of Material Things 1-169

DIVISION A—WANTS AND PRESENT GOODS

CHAPTER

1 The Nature and Purpose of Political Economy: Name

and Definition; Place of Economics Among the

Social Sciences; The Relation of Economics to Practical Affairs 3

2 Economic Motives: Material Wants, The Primary

Economic Motives; Desires for Non-material Ends,

as Secondary Economic Motives 9

3 Wealth and Welfare: The Relation of Men and

Material Things to Economic Welfare; Some Important

Economic Concepts Connected with Wealth

and Welfare 15

4 The Nature of Demand: The Comparison of Goods

in Man's Thought; Demand for Goods Grows Out

of Subjective Comparisons 21

5 Exchange in a Market: Exchange of Goods Resulting

from Demand; Barter Under Simple Conditions;

Price in a Market 30

6 Psychic Income: Income as a Flow of Goods; Income

as a Series of Gratifications[Pg viii] 39

DIVISION B—WEALTH AND RENT

7 Wealth and Its Direct Uses: The Grades of Relation

of Indirect Goods to Gratification; Conditions of

Economic Wealth 46

8 The Renting Contract: Nature and Definition of

Rent; The History of Contract Rent and Changes

in It 53

9 The Law of Diminishing Returns: Definition of the

Concept of (Economic) Diminishing Returns; Other

Meanings of the Phrase "Diminishing Returns";

Development of the Concept of Diminishing Returns 61

10 The Theory of Rent: The Market Value of the

Usufruct: Differential Advantages in Consumption

Goods; Differential Advantages in Indirect Goods 73

11 Repair, Depreciation, and Destruction of Wealth:

Relation to its Sale and Rent: Repair of Rent-bearing

Agents; Depreciation in Rent-earning

Power of Agents Kept in Repair; Destruction of

Natural Stores of Material 81

12 Increase of Rent-bearers and of Rents: Efforts of

Men to Increase Products and Rent-bearers;

Effects of Social Changes in Raising the Rents

of Indirect Agents 90

DIVISION C—CAPITALIZATION AND TIME-VALUE

13 Money as a Tool in Exchange: Origin of the Use of

Money; Nature of the Use of Money; The Value of

Typical Money 98

14 The Money Economy and the Concept of Capital: The

Barter Economy and its Decline; The Concept of

Capital in Modern Business 108

15 The Capitalization of All Forms of Rent: The Purchase

of Rent-charges as an Example of Capitalization;

Capitalization Involved in the Evaluating

of Indirect Agents; The Increasing Role of Capitalization

in Modern Industry 118

16 Interest on Money Loans: Various Forms of Contract

Interest; The Motive for Paying Interest[Pg ix] 131

17 The Theory of Time-value: Definition and Scope

of Time-value; The Adjustment of the Rate of Time-discount 141

18 Relatively Fixed and Relatively Increasable Forms

of Capital: How Various Forms of Capital May

Be Increased; Social Significance of These Differences 152

19 Saving and Production as Affected by the Rate of

Interest: Saving as Affected by the Interest Rate;

Conditions Favorable to Saving; Influence of the

Interest Rate on Methods of Production 159

PART II

The Value of Human Services 171-355

DIVISION A—LABOR AND WAGES

20 Labor and Classes of Laborers: Relation of Labor

to Wealth; Varieties of Talents and of Abilities

in Men 173

21 The Supply of Labor: What Is a Doctrine of Population?

Population in Human Society; Current Aspect

of the Population Problem 184

22 Conditions for Efficient Labor: Objective Physical

Conditions; Social Conditions Favoring Efficiency;

Division of Labor 195

23 The Law of Wages: Nature of Wages and the Wages

Problem; The Different Modes of Earning Wages;

Wages as Exemplifying the General Law of Value 205

24 The Relation of Labor to Value: Relation of Rent

to Wages, Relation of Time-value to Wages; The

Relation of Labor to Value 215

25 The Wage System and its Results: Systems of Labor;

The Wage System as it Is; Progress of the Masses

Under the Wage System[Pg x] 226

26 Machinery and Labor: Extent of the Use of Machinery;

Effect of Machinery on the Welfare and Wages

of the Masses 236

27 Trade-unions: The Objects of Trade-unions; The

Methods of Trade-unions; Combination and Wages 245

DIVISION B—ENTERPRISE AND PROFITS

28 Production and the Combination of the Factors: The

Nature of Production; Combination of the Factors 257

29 Business Organization and the Enterpriser's Function:

The Direction of Industry; Qualities of a Business

Organizer; The Selection of Ability 265

30 Cost of Production: Cost of Production from the Enterpriser's

Point of View; Cost of Production from

the Economist's Standpoint 273

31 The Law of Profits: Meaning of Terms; The Typical

Enterpriser's Services Reviewed; Statement of the

Law of Profits 282

32 Profit-sharing, Producers' and Consumers' Coöperation:

Profit-sharing; Producers' Coöperation; Consumers'

Coöperation 292

33 Monopoly Profits: Nature of Monopoly; Kinds of

Monopoly; The Fixing of a Monopoly Price 302

34 Growth of Trusts and Combinations in the United

States: Growth of Large Industry in the United

States; Advantages of Large Production; Causes

of Industrial Combinations 312

35 Effect of Trusts on Prices: How Trusts Might

Affect Prices; How Trusts Have Affected Prices 323

36 Gambling, Speculation, and Promoters' Profits: Gambling

vs. Insurance; The Speculator as a Risk taker;

Promoter's and Trustee's Profits[Pg xi] 333

37 Crises and Industrial Depressions: Definition and

Description of Crises; Crises in the Nineteenth

Century; Various Explanations of Crises 345

PART III

The Social Aspects of Value 357-563

DIVISION A—RELATION OF PRIVATE INCOME

TO SOCIAL WELFARE

38 Private Property and Inheritance: Impersonal and

Personal Shares of Income; The Origin of Private

Property; Limitations of the Right of Private

Property 359

39 Income and Social Service: Income from Property;

Income from Personal Services 370

40 Waste and Luxury: Waste of Wealth; Luxury 381

41 Reaction of Consumption on Production: Reaction

upon Material Productive Agents; Reaction upon

the Efficiency of the Workers; Effects on the

Abiding Welfare of the Consumer 392

42 Distribution of the Social Income: The Nature of

Personal Distribution; Methods of Personal Distribution 402

43 Survey of the Theory of Value: Review of the Plan

Followed; Relation of Value Theories to Social

Reforms; Interrelation of Economic Agents 412

DIVISION B—RELATION OF THE STATE TO INDUSTRY

44 Free Competition and State Action: Competition and

Custom; Economic Harmony through Competition;

Social Limiting of Competition 422

45 Use, Coinage, and Value of Money: The Precious

Metals as Money; The Quantity Theory of Money[Pg xii] 431

46 Token Coinage and Government Paper Money: Light-Weight

Coins; Paper Money Experiments; Theories

of Political Money 443

47 The Standard of Deferred Payments: Function of the

Standard; International Bimetallism; The Free-silver

Movement in America 453

48 Banking and Credit: Functions of a Bank; Typical

Bank Money; Banks of the United States To-day 462

49 Taxation in its Relation to Value: Purposes of Taxation;

Forms of Taxation; Principles and Practice 471

50 The General Theory of International Trade: International

Trade as a Case of Exchange; Theory of

Foreign Exchanges of Money; Real Benefits of

Foreign Trade 480

51 The Protective Tariff: The Nature and Claims of

Protection; The Reasonable Measure of Justification

of Protection; Values as Affected by Protection 491

52 Other Protective Social and Labor Legislation:

Social Legislation; Labor Legislation 504

53 Public Ownership of Industry: Examples of Public

Ownership; Economic Aspects of Public Ownership 514

54 Railroads and Industry: Transportation as a Form of

Production; The Railroad as a Carrier; Discrimination

in Rates on Railroads 525

55 The Public Nature of Railroads: Public Privileges

of Railroad Corporations; Political and Economic

Power of Railroad Managers; Commissions to Control

Railroads 534

56 Public Policy as to Control of Industry: State

Regulation of Corporate Industry; Difficulties of

Public Control of Industry; Trend of Policy as to

Public Industrial Activity 544

57 Future Trend of Values: Past and Present of Economic Society;

The Economic Future of Society 555

Questions and Critical Notes 565

Index 595

This book had its beginning ten years ago in a series of brief discussions supplementing a text used in the class-room. Their purpose was to amend certain theoretical views even then generally questioned by economists, and to present most recent opinions on some other questions. These critical comments evolved into a course of lectures following an original outline, and were at length reduced to manuscript in the form of a stenographic report made from day to day in the class-room. The propositions printed in italics were dictated to the class, to give the key-note to the main divisions of the argument. Repeated revisions have shortened the text, cut out many digressions and illustrations, and remedied many of the faults both of thought and of expression; but no effort has been made to conceal or alter the original and essential character of the simple, informal, class-room talks by teacher to student. To this origin are traceable many conversational phrases and local illustrations, and the occasional use of the personal form of address.

The lectures, at the outset, sought to give merely a summary of widely accepted economic theory, not to offer any contribution to the subject. While they were in progress, however, special studies in the evolution of the economic concepts were pursued, and the manuscript of a book on that more special subject was carried well toward completion. That work, which it is hoped some time to complete, was, for several reasons, put aside while the present text was preparing for publication. The economic theories of the present transition period show many discordant elements,[Pg xiv] yet the author felt that his attempt to unify the statement of principles, in an elementary text explaining modern problems, and consistent in its various parts, helped to reveal to him both difficulties and possible solutions in the more special theoretical field. The unforeseen outcome of these varied studies is an elementary text embodying a new conception of the theory of distribution, an outline of which will be found in Chapter Forty-three. It is, in brief, a consistently subjective analysis of the relations of goods to wants, in place of the admixture of objective and subjective distinctions found in the traditional conceptions of rent, interest, and price.

The beginning of the systematic study of economics, like the first steps in a language, is difficult because of the entire strangeness of the thought, and it is not to be hoped that any pedagogic device can do away with the need of strenuous thinking by the student. The aim, however, in the development of this theory of distribution, has been to proceed by gradual steps, as in a series of geometrical propositions, from the simple and familiar acts and experiences of the individual's every-day life, through the more complex relations, to the most complex, practical, economic problems of the day. The hope has long been entertained by economists that a conception of the whole problem of value would be attained that would coördinate and unify the various "laws,"—those of rent, wages, interest, etc. This solution has here been sought by a development of recent theories, the unit of the complex problem of value being the simplest, immediate, temporary gratification.

Possibly some teachers will observe and regret the almost entire absence of critical discussions of controverted points in theory, which make up so large a part of some of the older texts. The more positive manner of presentation has been purposely adopted, and only such reference is made to conflicting views as is needed to guard the student against misunderstanding in his further reading. The author would[Pg xv] not have it thought that he doubts the disciplinary value of economic theory or its scientific worth for more advanced students, for, on the contrary, he believes in it, perhaps to an extreme degree; but, for his own part, he has become convinced of the unwisdom of carrying on these subtle controversies in classes of beginners. The inherent difficulties of the subject are great enough, without the creation of new ones.

The fifty-seven chapters represent the work of the typical college course in elementary economics, allowing two chapters a week, and a third meeting weekly for review and for the discussion of questions, exercises, and reports. The subject is so large that the text is, in many places, hardly more than a suggestive outline. In class-room work it should be supplemented by other sources of information, such as personal observation by the students (many of the questions following the text serving to stimulate the attention); visits to local industries; interchange of opinions; examples given by the teacher; study and discussion, in the light of the principles stated in the text, of some such problems as are suggested in the appended list of questions; collateral reading; the preparation of exercises and the use of statistical material from the census, labor reports, etc.; history and description of industries; history of the growth of economic ideas. Suggestions, from teachers, of changes that will make the text more useful in their classes, will be thankfully received by the author.

Lack of space makes it impossible to mention by name the many sources to which the writer is indebted. Special acknowledgment, however, is gratefully made to C. H. Hull, of Cornell University; to E. W. Kemmerer, now of the Philippine Treasury Department, and to U. G. Weatherly, of Indiana University, who have read large portions of the manuscript, and have made many valuable suggestions; to W. M. Daniels, of Princeton University, who has read every page of the copy, and to whom are due the greatest[Pg xvi] obligations for his numerous and able criticisms both of the argument and of the expression; to R. C. Brooks, now of Swarthmore College, for a number of the questions in the appended list, and for helpful comments given while the course was developing; and to R. F. Hoxie and to A. C. Muhse, whose thoughtful reading of the proof has eliminated many errors. For the defects remaining, not these friendly critics, but the author alone, should be held accountable.

No book on economics can to-day satisfy everybody—"Or even anybody," adds a friend. But with this book may go the hope that what has been written with love of truth and of democracy may serve, in its small way, both to further sound economic reasoning and to extend among American citizens a better understanding of the economic problems set for this generation to solve.

Frank A. Fetter.

Ithaca, N. Y., August, 1904.

1. Economics, or political economy, may be defined, briefly, as the study of men earning a living; or, more fully, as the study of the material world and of the activities and mutual relations of men, so far as all these are the objective conditions to gratifying desires. To define, means to mark off the limits of a subject, to tell what questions are or are not included within it. The ideas of most persons on this subject are vague, yet it would be very desirable if the student could approach this study with an exact understanding of the nature of the questions with which it deals. Until a subject has been studied, however, a definition in mere words cannot greatly aid in marking it off clearly in our thought. The essential thing for the student is to see clearly the central purpose of the study, not to decide at once all of the puzzling cases.

2. A definition that suggests clear and familiar thoughts to the student seem at first much more difficult to get in any social science than in the natural sciences. These deal with concrete, material things which we are accustomed to see, handle, and measure. If a mere child is told that botany is a study in which he may learn about flowers, trees, and plants, the answer is fairly satisfying, for he at once thinks of many things of that kind. When, in like manner zoölogy is defined as the study of animals, or geology as the study of rocks and the earth, the words call up memories of many familiar objects. Even so difficult and foreign-looking a word as ichthyology seems to be made clear by the statement that it is the name of the study in which one learns about fish. It is true that there may be some misunderstanding as to the way in which these subjects are studied, for botany is not in the main to teach how to cultivate plants in the garden, nor ichthyology how to catch fish or to propagate them in a pond. But the main purpose of these studies is clear at the outset from these simple definitions. Indeed, as the study is pursued, and knowledge widens to take in the manifold and various forms of life, the boundaries of the special sciences become not more but less sharp and definite.

Political economy, on the other hand, as one of the social sciences, which deal with men and their relations in society, seems to be a very much more complex thought to get hold of. We are tempted to say that it deals with less familiar things; but the truth may be, as a thoughtful friend suggests, that the simple social acts and relations are more familiar to our thought than are lions, palm-trees, or even horses. Every hour in the streets or stores, one may witness thousands of acts, such as bargains, labor, payments, that are the subject-matter of economic science. Their very familiarity may cause men to overlook their deeper meaning.

Many other definitions have been given of political economy. It has been called the science of wealth, or the science of exchanges. Evidently there are various ways in which[Pg 5] wealth may be considered or exchanges made. The particular aspects that are dealt with in political economy will be made clear by considering two other questions, the place of economics among the social sciences and the relation of economics to practical affairs.

1. Political economy, as one of the social sciences, may be contrasted with the natural sciences, which deal with material things and their mutual relations, while it deals with one aspect of men's life in society, namely, the earning of a living, or the use of wealth. It is true that political economy also has to do with plants and animals and the earth—in fact, with all of those things which are the subject-matter of the natural sciences; but it has to do with them only in so far as they are related to man's welfare and affect his estimate of the value of things; only in so far as they are related to the one central subject of economic interest, the earning of a living.

2. The social sciences deal with men and their relations with each other. The word "social" comes from the Latin socius, meaning a fellow, comrade, companion, associate. As men living together have to do with each other in a great many different ways, and enter into a great many different relations, there arise a great many different social problems. Each of the social sciences attempts to study man in some one important aspect—that is, to view these relations from some one standpoint.

Man's acts, his life, and his motives are so complex that it is not surprising that there has been less definiteness in the thought of the social sciences, and that they have advanced less rapidly toward exactness in their conclusions, than have the natural sciences. This complexity also explains the discouragement of the beginner in the early lessons in this subject. Usually the greatest difficulties appear in the first few[Pg 6] weeks of its study. The thought is more abstract than in natural science; it requires a different, I will not say higher, kind of ability than does mathematics. But little by little the strangeness of the language and ideas disappears; the bare definitions become clothed with the facts of observation and recalled experiences; and soon the "economic" acts and relations of men in society come to be as real and as interesting to the student as are the materials in the natural world about him—often, indeed, more interesting.

3. Political economy is related to all the other social sciences, it being the study of certain of men's relations, while politics, law, and ethics have to do with other relations or with relations under a different aspect. Politics treats of the form and working of government and is mainly concerned with the question of power or control of the individual's actions and liberty. Law treats of the precepts and regulations in accordance with which the actions of men are limited by the state, and the contracts into which they have seen fit to enter are interpreted. Ethics treats the question of right or wrong, studies the moral aspects of men's acts and relations. The attempt just made to distinguish between the fields occupied by the various social sciences betrays at once the fundamental unity existing among them. The acts of men are closely related in their lives, but they may be looked at from different sides. The central thought in economics is the business relation, the relation of men in exchanging their services or material wealth. In pursuing economic inquiries we come into contact with political, legal, and ethical considerations, all of which must be recognized before a final practical answer can be given to any question. Nevertheless the province of economics is limited. It is because of the feebleness of our mental power that we divide and subdivide these complex questions and try to answer certain parts before we seek to answer the whole. When we attempt this final and more difficult task, we should rise to the standpoint of the social philosopher.

1. The ideal of political economy here set forth is that it should be a science, a search for truth, a systematized body of knowledge, arriving at a statement of the laws to which economic actions conform. It is not the advocacy of any particular policy or idea, but if it arrives at any conclusions, any truths, these cannot fail to affect the practical action of men.

Political economy, because defined as the science of wealth, has been described by some as a gospel of Mammon. It is hardly necessary to refute such a misconception. Political economy is not the science of wealth-getting for the individual. Its study is not primarily for the selfish ends and interest of the individual. (Certainly some of its lessons may be of practical value to men in active business) for many economic "principles" are but the general statement of those ideas that have been approved by the experience of business men, of statesmen, and of the masses of men. Some of its lessons must have educational value in practical business, for political economy is not dreamed out by the closet philosopher, but more and more it is the attempt to describe the interests and the action of the practical world in which men must live. Many men are working together to develop its study—those who collect statistics and facts bearing on all kinds of practical affairs, and those who search through the records of the past for illustrations of experiments and experiences that may help us in our life to-day.

2. But, in the main, the study of political economy is a social study for social ends and not a selfish study for individual advantage. The name political economy was first suggested in France when the government was monarchical and despotic in the extreme. As domestic economy indicates a set of rules or principles to guide wisely the action of the[Pg 8] housekeeper or the owner of an estate, so political economy was first thought of as a set of rules or principles to guide the king and his counselors in the control of the state. The term has continued to bear something of that suggestion in it, though of late the term "economics," as being broader and less likely to be confused with politics, has very generally come into use. But in the degree in which unlimited monarchy has given way to the rule of the people, the conception of political economy has been modified. In a democracy there is need for a general diffusion of knowledge. The power now rests not with the king and a few counselors, but in the last resort with the people, and therefore the people must be acquainted with the experience of the past, must have all possible systematic knowledge to enlighten public policy and to guide legislation.

Moreover, with the growth of the modern state, with the interest increasing importance of business, and of industrial and commercial interests, as compared with changes of dynasty or the personal rivalries of rulers, economic questions have grown in relative importance. In our own country, particularly since the subjects of slavery and of States' rights ceased to absorb the attention of our people, economic questions have pushed rapidly into the foreground. Indeed, it has of late been more clearly seen that many of the older political questions, such as the American Revolution and slavery, formerly discussed almost entirely in their political and constitutional aspects, were at bottom questions of economic rivalry and of economic welfare. The remarkable increase in the attention given to this study in colleges and universities in the last twenty years is but the index of the greatly increased interest and attention felt in it by citizens generally.

To sum up, it may be said that in the study of political economy we are seeking the reason, connection, and relations in the great multitude of acts arising out of the dependence of desires on the world of things and men.

1. A logical explanation of industry must begin with a discussion of the nature of wants, for the purpose of industry is to gratify wants. An economic want may be defined as a feeling of incompleteness, because of the lack of a part of the outer world or of some change in it. Often the question asked when one first sees a moving trolley car or automobile or bicycle is: What makes it go? The first question to ask in the part of the study of economic society here undertaken is: What is its motive force? Without an answer to that question one cannot hope to understand the ceaseless and varied activities of men occupied in the making of a living. The question merits long and careful study, but the general answer is so simple that it seems almost self-evident: The motive force in economics is found in the feelings of men. It is men's desire to make use of men and things about them which calls forth all the manifold phenomena studied in economics.

2. Wants among animals depend on the environment; that is to say, the utmost that creatures of a lower order than man can do is to take things as they find them. The imagination and intelligence of animals are not developed enough to lead them to desire much beyond that which is ordinarily to be obtained. And so the environment shapes and affects the animal. The fish is fitted to live in the water and thrives there, and we must believe, enjoys living there.[Pg 10] The horse and the cow like best the food of the fields, and so each species of animal, in order to survive in the severe struggle for existence, has been forced to fit itself to the conditions in which it lives. After the animal has been thus fitted, its desire is for those things normally to be found in its surroundings. So different animals desire or want different things, but always it is the environment that determines the want, and not the want that determines the environment.

3. In simpler human societies, wants are mostly confined to physical necessities; that is, in the earlier stages of society, man's wants are very much like those of the animals. Man bends his energies to securing the things necessary to survival. He feels the pangs of hunger and he strives to secure food. He feels the need of companionship, for it is only through association and mutual help that men, so weak as compared with many kinds of animals, are able to resist the enemies which beset them. He needs clothing to protect him against the harsher climates of the lands to which he moves. For the same purpose, to protect himself against the cold and rain, he needs a shelter, a cave, a wigwam, or a hut; for a house is but a larger dress.

4. In human society, wants develop and transform the world. In the rudest societies of which there is any record, savages are found with wants developed in a great number of directions beyond the wants of any animals. Man is not a passive victim of circumstances; his wants are not determined solely by his environment; his desires soar beyond the things about him. As men become more the masters of circumstances, their desires anticipate mere physical wants; they seek a more varied food of finer flavor and more delicately prepared. Dress is not limited by physical comfort, for one of the earliest of the esthetic wants to develop is the love of personal ornament. The rude hut or communal lodge to protect against rain and cold becomes a home. Out of the earlier rude companionship develop the[Pg 11] noblest sentiments of friendship and family life. Seeking to gratify the senses and the love of action, men develop esthetic tastes, the love of the beautiful in sound, in form, in taste, in color, in motion. And finally, as the imagination and intellect develop, there grow up the various forms of intellectual pleasures—the love of reading, of study, of travel, and of thought.

The various wants of man are sometimes classified as necessities, comforts, and luxuries, but all economists take care to emphasize that these terms have only relative meanings which, in the rapidly changing conditions of modern life, are changing constantly. The comforts of one generation, or of one country, become the necessities in another; and luxuries becoming comforts, are looked upon finally as necessities. And as the desires grow, they more and more alter the world. Man has changed the face of the earth; he has affected its climate, its fertility, its beauty, because, either for better or for worse, his desires have impressed themselves upon the world about him.

5. In human society the growth of wants is necessary to progress. From the earliest times teachers of morals have argued for simplicity of life and against the development of refinements. We do not now raise the moral question, but there is no doubt that the economic effect of developing wants is in the main to impel to greater effort. They are the mainspring of economic progress. In recent discussion of the control of the tropics, the too great contentedness of tropical peoples has been brought out prominently. Some one has said that if a colony of New England school-teachers and Presbyterian deacons should settle in the tropics, their descendants would, in a single generation, be wearing breech-clouts and going to cock-fights on Sunday. Certain it is that the energy and ambition of the temperate zone are hard to maintain in warmer lands. The negro's content with hard conditions, so often counted as a virtue, is one of the difficulties in the way of solving the race problem in our[Pg 12] South to-day. Booker T. Washington, and others who are laboring for the elevation of the American negroes, would try first to make them discontented with the one-room cabins, in which hundreds of thousands of families live. If only the desire for a two- or three-room cabin can be aroused, experience shows that family life and industrial qualities may be improved in many other ways.

Not only in America, but in most civilized lands to-day, is seen a rapid growth of wants in the working-classes. The incomes and the standard of living have become increasing, but not so fast as have the desires of the working-classes. Regret has been expressed by some that the workers of Europe are becoming "declassed." Increasing wages, it is said, bring not welfare, but unhappiness, to the complaining masses. If discontent with one's lot goes beyond a moderate degree, if it is more than the desire to better one's lot by personal efforts, if it becomes an unhappy longing for the impossible, then indeed it may be a misfortune. But a moderate ambition to better one's condition is the "divine discontent" absolutely indispensable if energy and enterprise are to be called into being.

It is a suggestive fact that civilized man, equipped with all of the inventions and the advantages of science, spends more hours of effort in gaining a livelihood than does the savage with his almost unaided hands. Activity is dependent not on bare physical necessity, but on developed wants—in the economic sense of the term. Such social institutions as property and inheritance owe their origin and their justification to their average effect on the motives to activity. If society is to develop, if progress is to continue, human wants—not of the grosser sort, but ever more refined—must continue to emerge and urge men to action.

1. The spiritual nature of man must not be ignored in economic reasoning. There has been much and just criticism of the earlier writers and of their conclusions because so little account was taken by them of any but the motive of self-interest in economic affairs. Generally it was assumed that men knew their own interest, and sought in a very unsympathetic way those things which would gratify their material wants. Thus man in economic reasoning was made an abstraction, differing from real men in his lack of manifold spiritual and social elements.

2. The main classes of non-material wants that are secondarily economic are fear of temporal punishment; sentiments of moral and religious duty; pride, honor, and fear of disgrace; and pleasure in work for itself, for social approval, or for a social result. The first is best illustrated by slavery, where the slave is not impelled to seek wealth for his own welfare, but is driven by punishment to perform the task. The object is to create within the mind of the slave a motive that will take the place of the ordinary economic motive. The feeling of religious or moral duty leads men to act often in direct opposition to the usual economic motive. The taboo is faithfully observed by the members of a savage tribe who suffer as a result the severest hardships. A religious injunction prevents the use of food that would save from starvation. Pride, either of family or of calling; the soldier's honor leading him to sacrifice not only his future but his life; the love of social approval, holding men to the most disagreeable tasks—these illustrate how strongly social sentiments oppose the narrower motive of immediate self-interest as generally thought of. Pleasure in work for work's sake, and pride in the result, may act as motives quite as strong in some cases as desire for the product that can[Pg 14] be used. And even where this does not change the kind of work done, it comes in to influence the interest and earnestness with which the work is performed.

3. Whatever motive in man's complex nature makes him desire things more or less, becomes for the time, and in so far, an economic motive. These various social and spiritual motives sometimes work positively, in the direction of magnifying man's desire for things; sometimes negatively, to diminish it. If we are to understand economic action, we must take men as they are. A religious motive that leads men to refrain from the eating of meat or to eat fish in preference on certain days, is a fact which the economist has but to accept, for it is sure to affect the value of meat and fish at that place and time. Moral convictions, whatever be their origin, whether due to the teaching of parents, to unconscious influences, or to native temperament, may be quite as effective as the pangs of hunger in determining what men desire. Therefore, while these various motives are primarily social or moral or religious, they may be said to be secondarily economic motives, and they may become in certain cases the most important influences of which the economist must take account.

1. The gratifying of economic wants depends on things outside of the man who feels the wants. Man is to himself the center of the world. He groups things and estimates things with reference to their bearing on his desires, be these what are called selfish or unselfish. If we were discussing the economics of an inferior species of animals, things would be grouped in a very different way. But economics being the study of man's welfare, everything must be judged from his standpoint, and things are or are not of economic importance according as they have relation to his wants and satisfactions. Things needful for any of the lower animals are spoken of as "ministering to welfare" in the economic sense only in case these animals are useful to men. Examples are the mulberry-tree on which the silkworm feeds, the flower visited by the honey-bee. In the same view some men are seen to minister to the welfare of other men and therefore bear the same relation for the moment to the welfare of the others as do material things. In any case we study man's welfare as affected by the world which surrounds him.

2. Material things and natural forces differ in kind and nature. This is an axiom which we must take as a basis for reasoning in economics. Things have certain physical qualities quite apart from any action or influence of man.[Pg 16] They are operated on by mechanical laws; the force of gravitation causes them to fall at a certain rate under given conditions. They differ in specific gravity, reflect the rays of light, absorb or transmit heat. All these things are for man ultimate physical facts, but unless he knows these facts he cannot take full advantage of the favorable qualities of things or weigh properly their importance to his welfare. Things differ in a multitude of ways in their chemical qualities. Niter, charcoal, and saltpeter, combined in certain proportions, give certain reactions; different combinations give various results. Solids combine to form gases, and liquids unite to form solids, and these qualities and reactions of material things are for man ultimate truths of chemistry. Likewise many things have certain physiological effects. Sunshine acts on living bodies, whether plant, animal, or man, in certain ways. Some plants are nourishing to man, others are poisonous. If man were not on the earth, things would have the same physical and chemical qualities, mechanical laws would be the same as at present so far as we can conclude. Man cannot change the nature of things; but he can acquaint himself with that nature and then put the things into the relations where a given result will follow.

3. As a result of these differences, things have different relations to wants. These various qualities, physical, chemical, physiological, are important in an economic sense only as they produce psychological effects, that is, as they affect the feelings and judgments of men. We come to some general thoughts which it will be well to define.

Gratification is the feeling that results when a want has been met. Feelings are hard to define in words; the best definition is found in the experience of each individual. We can only say, therefore, that gratification is the attainment of desire, the fulfilment of wants. The word that has usually been employed in this sense in economic discussion is "satisfaction"; but by its derivation and general usage satisfaction[Pg 17] means "the complete or full gratification" of a desire, and this meaning is quite inconsistent with the thought in many connections in which the word is used. We shall therefore prefer here the word gratification, and its corresponding verb, gratify.

Wealth is the collective term for those things which are felt to be related to the gratification of wants. The word is applied in economic discussion to any part of those things, no matter how small. We shall have occasion later to define and discuss this term more fully.

Welfare, in an immediate or narrow sense, is the same as gratification of the moment; in a broader sense, it means the abiding condition of well-being. We have here a distinction very much like that often made between pleasure and happiness. If we think of only the present moment, welfare is the absence of pain, and the presence of the pleasureable feeling; but if we consider a longer period in a man's life or his entire lifetime, it is seen that many things that afford a momentary gratification do not minister to his ultimate, or abiding, welfare. Moralists and philosophers often have dwelt on this contrast. The difference is illustrated by the thoughtlessness and impulsiveness of a child or savage as contrasted with the more rational life of those with foresight and patience.

Wealth, in the general economic sense, is judged with reference to gratification rather than with reference to abiding welfare. It is the first duty of the economist not to preach what should be, but to understand things as they are. He must, in studying the problem of value, recognize any motive that leads men to attach importance to acts and things. He will therefore take account of abiding welfare and of immediate gratification to exactly the degree that men in general do, and the sad fact is that the present impulse rules a large part of the acts of men. Whether tobacco or alcohol or morphine minister to the abiding happiness of those who use them does not alter the immediate fact that[Pg 18] here and now they are sought and an importance is attached to them because of their power to gratify an immediate desire.

5. In studying the question of social prosperity, however, we must rise to the standpoint of the social philosopher and consider the more abiding effects of wealth. Wants may be developed and made rational, and the permanent prosperity of a community depends upon this result. Any species of animal that continued regularly to enjoy that which weakens the health and strength would become extinct. Any society or individual that continues to derive gratification, to seek its pleasure, in ways that do not, on the average, minister to permanent welfare, sinks in the struggle of life and gives way to those men or nations that have a sounder and healthier adjustment of wants and welfare. We touch here, therefore, on the edge of the great problems of morals, and while we must recognize the contrast that often exists in the life of any particular man between his "pleasures" and his health and happiness, we see that there is a reason why, on the whole, and in the long run, these two cannot remain far apart. The old proverbs, "Be virtuous and you will be happy," "Honesty is the best policy," and "Virtue is its own reward," have a sound basis in the age-long experience of the world. Cynics or jesters may easily disprove these truths in a multitude of particular cases.

6. Wealth does not include such personal qualities as honesty, integrity, good health. Some economists speak of these as "internal goods," but it is far better not to speak of free men or of their qualities as wealth. Many difficulties arise from such a use of the term in practical discussion. One of the most important of all distinctions to maintain in economics is that between material things and men. Only in the case of human slavery may persons be counted as economic wealth. It is a different thing, however, to consider human services as wealth of an ephemeral kind at the moment they are rendered. We are, thus merely recognizing[Pg 19] that men may bear at the given moment the same relation to our wants as do material things.

1. Utility, in its broadest usage, is the general capability that things have of ministering to human well being. The term is evidently one without any scientific precision. It expresses only a general or average impression that we have in reference to the relation of a class of goods to human wants. Every one would agree to the statement that "water is useful," thinking of the fact that it is indispensable to life and that it ministers to life in a multitude of ways. But what of water in one's cellar, water soaking one's clothes on a cold day, water breaking through the walls of a mountain reservoir and carrying death and destruction in its path? The poison that is doing what we at the moment desire, we call useful; that doing what we would prevent, we call harmful. Noxious weeds become "useful" by the discovery of some new process by which they can be worked into other forms, though they may still continue to be noxious in many a farmer's fields. The utility of anything, therefore, is seen to be of a relative and limited nature. The term "utility" in popular speech is very inexact. It can be employed in economic discussion only when carefully modified and defined.

2. Goods consist of all those things objective to the user which have a beneficial relation to human wants. They fall into several classes. We may first distinguish between free and economic goods. Free goods are things that exist in superfluity, that is, in quantities sufficient not only to gratify, but to satisfy all the wants that may depend on them. Economic goods are things so limited in quantity that all of the wants to which they could minister are not satisfied. The whole thought of economy begins with scarcity; indeed,[Pg 20] even the conception of free goods is hardly possible until some limitation of wants is experienced. Practical economics is the study of the best way to employ things to secure the highest amount of gratification. The problem itself arises out of the fact that many things are used up before all wants dependent on them are completely satisfied.

A distinction is often made between consumption and production goods, or it may be better to say immediate and intermediate goods. Consumption goods are those things which are immediately at the point of gratifying man's desires. Production goods are those things which are not yet ready to gratify desires; some of them, being merely means of securing consumption goods, never will themselves immediately gratify desire.

3. Value, in the narrow personal sense, may be defined as the importance attributed to a good by a man. The vagueness and inexactness of the word "utility," or the word "good," disappears when we reach the word "value." It is not a usual relation or a vague degree of benefit sometimes present and sometimes absent, but it refers to a particular thing, person, time, and condition. Value is in the closest relation with wants, and in this narrow sense depends on the individual's estimate. From the meeting and comparison of the estimates of individuals, arise market values or prices, which are the central object of study in economics.

1. As wants differ in kind and degree, so goods differ in their power to gratify wants. This general and simple statement unites the leading thoughts of the two chapters preceding. Confirmation of its truth may be found in observation and experience. The purpose of this chapter is to show how, starting from the general nature of wants and the nature of goods, we can arrive at an explanation of the exchange of goods. Recognizing the simple but fundamental fact stated at the opening of this paragraph, an exchange may be seen to be a rational and a logical result when men are living together in society.

2. Immediately enjoyable goods are the first objective things whose value is to be explained. Goods come into relation with wants in a multitude of ways. Some things will not gratify a want until after the lapse of a long time, as ice cut in December and stored for summer use. Other things will never themselves directly gratify a want, but will be of help in getting things that do; such are the young fruit trees planted in the orchard, and the hammer that will be used to drive nails in a house that will shelter men. Still other things are gratifying wants at this moment, or are ready for use and will be used up in a very short time; examples of such are the food on the table and in the pantry, and the cigar in the pocket. All these things are called goods, because of their beneficial relation to man's desires, but the[Pg 22] relation is very immediate in some cases, very remote in others. The value of all goods is to be explained, but the explanation will be more or less complex according to the directness or indirectness of their relation with wants. As it is the power of goods to gratify wants that alone causes value to be attributed to them, those goods which are ripest, which are ready to gratify wants, are nearest to the source of an explanation. The value of unripe enjoyments must be traced to some expected gratification as its cause or basis. In order to attack the difficulties one by one we will, therefore, in the following discussion, deal first with this class of ripe, consumable goods, as food, personal services, enjoyments of any sort that are immediately available. The explanation of these cases of value must precede that of cases in which the relation to wants is less obvious and direct.

3. As the amount of any good increases, after a certain point the gratification that the added portions afford decreases. This is called the law of the diminishing utility of goods or of the decreasing gratification afforded by goods. The reason for the truth of this proposition is found in the very nature of man and his nervous organization. Any stimulus to the nerves, however pleasant at first, becomes painful when long continued or increased unduly. The trumpet too distant at first for the ear to distinguish its notes, may swell to pleasing tones as it approaches, until at length its volume and its din may become absolutely painful. If we were to express the degree of gratification by a curve, we should see the curve rising gradually to a maximum, and then falling somewhat suddenly and becoming a negative quantity, when pain, not pleasure, resulted. The same change could be illustrated by any sensation or by any of men's activities.

The proposition must be understood as applying to the gratification resulting from each added portion of the sensation. There is a maximum point in the gratification afforded by any nerve-stimulus. A man coming in from[Pg 23] the winter's storm and holding out his hands before the fire, feels an intense pleasure in the grateful warmth; a few moments later, the same heat becomes unpleasant. In winter we wish for a moderation of the temperature; on the sultry days of summer, we think of a cool breeze as the most to be desired of all things. Whether the temperature rises or falls, there is a point beyond which the change is no longer an addition to, but a subtraction from, pleasure. A man, however hungry at first, may be made miserable if forced to eat beyond his capacity. Each added portion of the good consumed contributes to the gratification up to a certain point. The sum of these pleasurable sensations may be called the total gratification, which finally reaches satisfaction or fullness. Then begins what may be called in algebraic phrase a "negative gratification" which, if it becomes large enough, will make the total gratification a negative quantity. Each added portion, dose or increment beyond a certain point reduces thus the welfare of the user. One may have too much of a good thing.

4. Marginal utility is the gratification afforded by the added portion of the good. The marginal dose, increment, or portion is that which may be logically considered as coming last in the case of any good or group of goods divisible into small parts. In considering the strict theory of the case, in order to get at the principle involved, the doses may be spoken of as infinitesimally small. The marginal utility expresses the importance that men attach to one unit of this kind of goods under the particular circumstances at the moment existing, and not under certain conceivable conditions which do not in fact exist or need to be taken into account by the persons affected. The marginal unit of a homogeneous supply cannot be considered to have a greater utility than any other unit at the moment, and therefore the product of the marginal utility by the number of units, gives the total measure of importance of the supply then and there, and this is the value.

The value of goods, as has been indicated, is the measure of the dependence felt by men on a portion of the outer world, as the condition of gratifying their wants. From the very nature of wants, which reside in feelings, a dependence that is not felt, a relation between things and gratification that is not recognized, can have no influence on value. Now, it is at this margin of supply that dependence is felt. Men do not concern themselves about that which they have in superfluity—unless, indeed, the excess causes them some discomfort. It is well that they do not, for a wise direction of effort can only take place when men think mainly of their need of things that they want, and want most, and direct their efforts toward securing them.

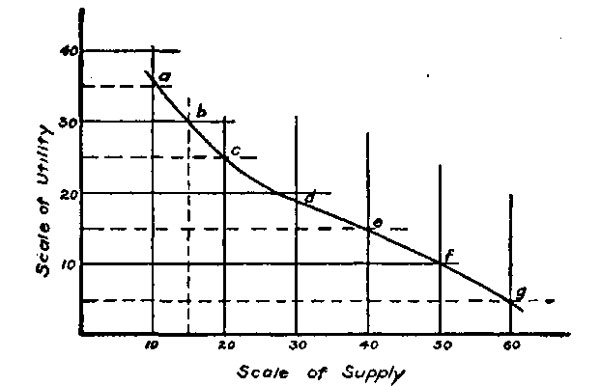

The diminishing utility of successive portions (doses or increments, as they are called) may be represented by a curve of utility.

Scale of Supply

Scale of Supply

The diagram is constructed on the hypothesis that a tenth unit of a certain good would have a utility expressed as 36; a fifteenth unit of 30, etc., and that the value of the whole supply is estimated according to these marginal units. Of course if the conditions were that "all or none" was to be taken, the result would be different.

| Unit of Supply | Marginal Utility | Value of Whole Supply |

| 10 | 36 | 360 |

| 15 | 30 | 450 |

| 20 | 25 | 500 |

| 30 | 19 | 570 |

| 40 | 15 | 600 |

| 50 | 10 | 500 |

| 60 | 5 | 300 |

This diagram is frequently used, and it is important to guard against some misunderstandings. The marginal unit of any given supply—for example, ten units—is not any particular unit, it is any one of the ten units. In the presence of nine units of the good the person or persons find all the various wants that are dependent on that good gratified to such a degree that the tenth unit has an importance expressed by 36. But as this last or marginal unit of supply may be used for any of the purposes, the importance of each and every unit likewise will be expressed by 36. Any one of the units, when once present is, in a logical sense, a marginal unit. When, however, it is a question of increasing the supply, some one unit may properly be looked upon as marginal. The dependence felt by men on the whole group is the product of the units by the marginal utility. As the number of units increases, the marginal utility decreases, until at length it may reach zero, and the total value would be nothing. A point of maximum value evidently will be found somewhere between the two extremes.

Note carefully that on the one diagram are represented a large number of marginal utilities which never exist at one and the same moment. At any one moment there is a given number of units and there is but one marginal utility, and this is the same for each of the units. It is quite erroneous to say that when there are 30 units the utility of the tenth unit is 36; of the twentieth, 25; of the thirtieth, 19. It is equally incorrect to say that when there are 60 units the "total utility" is equal to the area between the right angle and the[Pg 26] curve a-g, while the value is equal to the rectangle below and to the left of the point g. The curve from a-g but marks the height of marginal utilities that have no existence when the supply is 30. The "total utility," often spoken of in this connection, if it has any existence certainly cannot be calculated. The diagram must be understood as representing indicatively at any given moment but one marginal utility, the same for every unit of like goods. The other perpendicular lines are expressed in the conditional mood; they are what the marginal utility would be were the numbers of units different.

5. Since goods possess utility only as they gratify wants, it follows that if wants change, the utility changes. Utility does not rest unchanging in the goods as something "intrinsic," but it depends on the relation of goods to men. This truth, unrecognized for many centuries, is now seen to be fundamental to the whole problem of value. The portions of a good added later do not appeal to the same man as the earlier portions. The man has been changed by what he has enjoyed. In changing his feelings, goods have also changed his wants. Hence, the added portions of the good are changed in respect to their utility or power to gratify a man's wants. Though physically and chemically, i.e., in every material way, they are exactly like the earlier portions, they cannot have the same want-gratifying power until he again changes, for they are not in the presence of the same feelings.

Wants are constantly shifting; different kinds of goods are compared in man's thought and arranged on a scale at every moment according to their felt utility. An increase in the amount of a good will drop the marginal utility of the added portions down the scale of usefulness for the next moment. When we rise in the morning, we want our breakfast; the breakfast eaten, another breakfast does not appeal to us. Our tasks done, we take a boat-ride or go golfing; then, appetite returning, we are tempted to our dinner. And thus from hour to hour wants are gratified, are altered and[Pg 27] are shifted, until, wearied with the day's labor and pastimes, we go to rest. In a well-ordered life, in an advanced economic society, the means for gratifying our wants as they arise are provided in advance. The changing series of desires is met by a changing series of goods. Life has been defined as a constant adjustment of inner relations to outer conditions. Economic life is therefore like physical life, a constant adjustment; and this adjustment of goods but reflects the shifting and adjustment of feelings.

6. The substitution of goods in men's thought is the shifting of the choice from a good that does not give the highest gratification economically possible at the time, to another good that does. The shifting that takes place on the scale of gratification makes it necessary for man to shift constantly his choice of goods. This again is the problem of "economy." Waste results when goods continue to be used to secure a lower degree of gratification, if they might be used to secure a higher. The change of choice may be because of a change in the man, or because of a change in the quality or the quantity of the goods; or because of a change in the ratio at which the goods can be secured.

1. Demand is desire for goods united with the power to give something in exchange. An example frequently given to show the difference between desire and demand is the hungry boy looking longingly at the sweetmeats in the confectioner's window. He represents desire, but not until the kind-hearted gentleman gives him a nickel does he represent effective demand. Desire, therefore, must be united with power to give something in exchange before it can be called demand. It must be for something that is attainable; yearning for something beyond reach, sighing for the moon, is desire that never can become effective demand.

2. Demand is the social aspect of the individual man's comparison of utilities. It is the expression of the man's wish to substitute some of his goods for some one else's goods in order to get a higher satisfaction. This comparison is often made between two goods owned in different quantities. When men are constantly comparing things in their own possession, it is a short step to compare their goods with their neighbor's.

Demand for consumption goods is thus the manifestation of the man's desire to redistribute his enjoyments. In demand for goods men virtually say: "Part of what I have I am ready to give for part of what you have." The strength of their desire is expressed by the amount of their offer. When he makes this comparison and this offer, man enters into a social, economic relation with his fellows.

3. The law of individual demand is: The trader will reduce his stock of a particular good to the point where its marginal utility equals that of the alternative goods. The greater the divergence in his estimates of the marginal utilities of two goods, the more ready is he to trade the lower utility for the higher one. Exchange is but the effort to adjust goods to wants in the best way. The less useful (marginally viewed) is traded for the more useful. The greater the difference, in the one trader's judgment, between the marginal utilities of the two goods, the greater is the maladjustment, and the greater, therefore, is the motive to seek readjustment by means of exchange. As the quantity of the good parted with declines, its marginal utility increases; and as more of the other good is acquired, its marginal utility declines. The marginal utility of the two exchangeable units must come to equilibrium in the individual's judgment. At this point demand ceases, not because an additional unit of the one good could afford no gratification, but because it would afford less gratification than the other good in which demand must be expressed to be effectual.

4. Demand thus varies at different ratios of exchange between goods, and may be expressed graphically by a demand curve. This would show for any one man the decline of the marginal utility of each added portion of a good, and these individual demand curves may be united into a demand curve for a group of men. The demand curve expresses graphically what a man would be willing to pay at each particular stage in the increase of goods. We have here come to the very threshold of the subject of markets and exchange.

5. Elasticity of demand, in the case of any good, expresses the degree in which a change in its ratio to other goods will increase the demand. Elasticity varies for different classes of men according to their wealth and to the cost of the goods. If strawberries are a dollar a box in the city market, a slight fall in the price, say to seventy-five cents, will increase the demand but slightly. But if the price is fifteen cents and falls to ten, the increase in the demand will be marked, for the number of consumers to whom a difference of five cents is important is then very great. The demand for the staples is comparatively inelastic. A certain amount of simple food is necessary to support life; an increase in its price will not quickly check the demand. On the other hand, if the price of staple foods falls, no very great increase will take place in the demand.

1. Exchange in the usual economic sense is the transfer of two goods by two owners, each of whom deems the good taken more than a value-equivalent for the one given. The comparison of goods that has been discussed above is a kind of exchange. When a person chooses one thing rather than another, one form of gratification may be said to be mentally exchanged for another. This is exchange in that person's mind, or subjective exchange. But the word "exchange" as usually employed means an exchange of goods between persons. It is objective exchange, and when the word is used without modification, it is to be understood in the objective sense. In the last chapter were analyzed the motives of the individual man. Robinson Crusoe on his desert island would in very many ways be acted upon by the same motives in reference to economic goods that men are in society. Yet, it is exchange in society and the complicated problems arising from this transfer of goods from person to person that constitute nearly the whole of the subject-matter of political economy.

Exchange is seen to arise out of the differences in the situations of men with reference to goods. The different subjective valuations give rise to demand, and demand leads to exchange. In early societies differences in natural products were the most usual causes of exchange. Salt, though so essential to life, is found in few places. The metals early became[Pg 31] indispensable for weapons of defense or for the chase, and were sought far and wide. Rare shells, feathers, jewels, and the precious metals appealed in early times to a universal desire for ornament. Products like these are the objects of a rude sort of exchange in the first simple efforts made to adjust possessions to wants. Within the tribe, differences in the skill and ability of men to produce arrow heads or weapons or ornaments, bring about the exchange of goods.

2. The advantage of exchange consists in the raising of the want-gratifying power of goods to both parties. It generally was assumed by medieval thinkers that if one party to an exchange gained, the other must lose. The mistaken idea prevailed that value is something fixed in the good, and unchangeable. Where the exchange is voluntary (and only that kind is here being considered), it is mutual advantages which make the exchange rational. Many false conclusions on practical questions still result from a failure to grasp this simple truth. It follows from this that the act of exchange is itself useful, for goods having a small importance to men are given a higher importance by being brought into better relations with wants. Merchants, peddlers, traders, and common carriers of all sorts, therefore, are adding to the utility of goods. This idea has been only slowly apprehended, but is now one of the least disputed propositions in economics.

3. Barter is the exchange of goods without the use of money. Either one of the goods traded in cases of barter may be considered as sold, and either one as bought, according as the matter is looked at from the standpoint of the one or the other party to the exchange. Demand, therefore, is supply, and supply is demand when the point of view is shifted from one party to another. The fisherman's demand for venison is expressed in terms of fish; the hunter's demand for fish is expressed in terms of venison. But to the fisherman the venison is the supply offered to[Pg 32] him. The term "marginal utility" of a good, therefore, does not refer merely to the demand of the consumer; for it expresses by a single phrase the idea both of demand and of supply. The utility of the goods composing the supply is expressed in terms of the goods that represent demand and vice versa. The only way in which man can give definite, concrete, numerical expression to his desire for goods is to state it in terms of other goods. In expressing numerically, in terms of other objects, an estimate of the utility of an apple, a horse or a house, one inevitably gives expression to a ratio of exchange; demand for one good is the offer of another good.

1. In isolated exchange, where only two traders engage in barter, their estimates give respectively the upper and the lower figures of the ratio at which the trade can take place. Let us recall the fact that a difference in the relative estimates that men place on goods is the first essential of exchange. Those estimates may be expressed in a ratio; we may say that A will give four apples for one orange, would be glad to give fewer, but will not give more; while B will give one orange for three apples, would be glad to get more apples, but will not take fewer. The outside limits of the ratio at which the exchange must take place will, therefore, be one orange for three or four apples.

A, seller of apples, offers 4 (or fewer) apples for 1 orange.

B, buyer of apples, demands 3 (or more) apples for 1 orange.

There is, in entirely isolated exchange, therefore, a lack of definiteness in the price, much depending on what Adam Smith called the "higgling of the market." In the old-time American horse trade much depended on "bluff"; in such cases it was as important to be able to judge character as to judge horses. A thorough analysis of the trade, however,[Pg 33] would probably show that the bargain is concluded at a point which exactly balances the hopes of gain and fears of loss of one of the parties.

2. Where one-sided competition exists, the ratio of the exchange will be somewhere between the estimates of the two buyers most eager for the last portion offered. By competition is here meant the independent seeking of the same thing at one time by two or more persons. Where there is one market price paid by a number of buyers, it may be that no two of the subjective estimates are alike; the exchange value may differ from all of their estimates, and yet must correspond closely to two. Auction sales well illustrate the principle. If there is one ax to be sold and ten possible buyers for an ax, and there is no combination among them, the bidding will go on until the estimate of the buyer next to the most eager, has been reached. The most eager buyer can then secure the ax by bidding just a little above his next competitor. But if there are ten axes and ten buyers who know that there will be ten axes offered, the more eager buyers will refuse to bid much above the less eager ones. A shrewd auctioneer, therefore, often conceals the fact that there is more than one of an article, and having sold it off, brings out a second or a third one of the same kind, thus keeping the buyers in ignorance of the supply and getting somewhere near the estimate of the most eager buyer in each case. Advertisements of "a limited supply," "the last chance," "positively the last appearance," are meant to stimulate the demand of the patrons, and to lead them to buy at once. In general, therefore, where competition exists on one side, price is fixed with greater definiteness than in isolated exchange. Not so much depends on shrewd bargaining, on bluff, or on the stubbornness of an individual. Far more depends on forces outside the control of any one man. The bidders are impelled by self-interest to outbid their competitors, and thus the limits within which the market price must fall are narrowly fixed.

If things already brought to market must be sold at any price that can be secured, the buyers may be said to fix the price. This does not mean that they can buy it for any sum that they wish, but it means that when each one is trying to get it as cheap as possible, their bids finally determine how much it will sell for. In such cases, therefore, the competition is for the moment one-sided.

If a part of the supply can be withdrawn and kept without great loss, this will be done if the price is low. Strawberries, fish, and meat may be sold Saturday night at any price that will secure purchasers, but every thing that can be kept with little or no depreciation will be withheld from sale for a time. It may even be of advantage to the seller to destroy a part of the supply, when the increased price of the smaller amount will give a larger total.

3. Where two-sided competition exists, the bidding goes on until a price is reached where the least eager seller and the least eager buyer have the narrowest possible motive to exchange. As the market ratio varies from those in the minds of the individuals when they come to the market, there is left a considerable margin to some and a very small one to others. This difference between the market value and the ratio of exchange at which any given individual would continue to exchange for the good may be called the margin of advantage. Moreover, the buyers will have a margin and the sellers a margin, and as that margin narrows there is less and less motive to continue the exchange until, finally, the margin disappearing, the buyer or seller, withdrawing from the market, ceases to be an exchanger, at least for that particular part of the goods.

The least eager buyer and the least eager seller may be called the marginal pair. They are the buyer and the seller respectively having the narrowest margin of advantage. Their outside estimates are nearest to the market ratio. If the market ratio shifts slightly in either direction, one of them will drop out of the exchange. It is evident that a buyer[Pg 35] who is taking ten units may be on the margin with reference to the tenth unit, and yet may continue to be one of the most eager buyers to secure one unit. Thus, the marginal buyer is to be thought of as that person who, logically considered, is the least eager, or on the margin, with reference to a particular unit of supply, however eager he may be with reference to any other unit of supply. It would be well to recall here the discussion of the nature of wants and the variation in the intensity of demand.

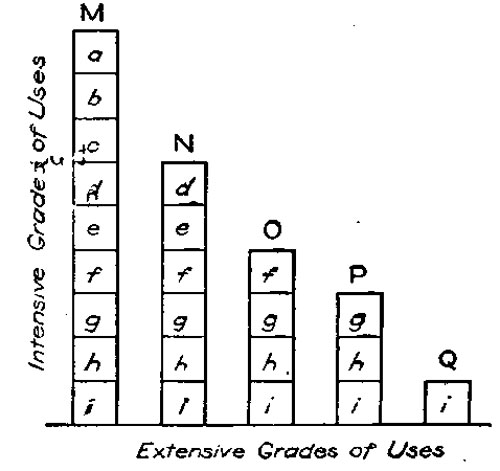

Units of Goods

Units of Goods

4. Market values are built up on subjective valuations. The idea of market values, therefore, is that of the want-gratifying power of goods as expressed in terms of other goods, where there are various buyers and sellers. They are not an average of the subjective valuations, nor are they made up of the extremes. They correspond closely with the subjective estimates of two of the exchangers. The other parties to the exchange are willing to accept the market ratio, for it offers them more inducements than it does to either one of the marginal pair.

1. A market is a body of buyers and sellers in such close business relations that the actual price conforms closely to the valuation of the marginal pair. The word "price" which we have used, may be defined as value expressed in terms of some commonly exchanged commodity. The term is used more broadly of anything given in exchange. The very terms of this definition imply that there can be but one price in a market. This is a somewhat abstract but a useful economic proposition. Very often within sound of each other's voices traders are paying different prices for a good. On the occasion of a break in the stock-market, excited traders within ten feet of each other make bids that differ by thousands of dollars. Retail and wholesale merchants may be purchasing goods in the same room at the same time at very different prices. But within a group of buyers and sellers where competition is approximately complete, price is fixed with some degree of exactness. The more nearly the actual conditions approach to the ideal of a market, the less are prices fixed by higgling, and the more impersonal they become, the buyers and sellers being compelled to adjust their bids to the needs of the market, and not being able to vary them greatly one way or the other.

2. Markets are steadily widening through the improvement of means of communication and transportation. The earliest markets were established on the borders between tribes, villages or nations as a common ground where strangers met to trade. At such markets were brought together from sparsely settled districts a comparatively large number of merchants and customers. Buyers had the opportunity of wide selection both in kind and quality, and the sellers found a large body of customers gathered at one point. Throughout the Middle Ages purchases were made by the more prosperous husbandmen in great quantities once a[Pg 37] year at the fairs or markets. As both the buyers and sellers came from widely separated places, there was, in most respects, no combination, and the conditions of a competitive market were present.

The number of buyers and sellers that can constitute a single market is limited both directly and indirectly by the means of transportation. A dense population cannot usually be maintained without easy means of transportation to bring in a large supply of food, and to carry back manufactured goods great distances. The remarkable growth in the means of commerce since the application of steam to water traffic, and the invention of the railroad, have made it possible for goods to be gathered from most distant points. A market implies a common understanding among traders. Modern means of communication such as newspapers, post-offices, telegraph and cable, trade bulletins, commercial travelers, the consular service, and many forms of special agencies, are diffusing information widely. As a result of these changes, there has been a widening of the village-market to the markets of the province, of the nation, and finally of the world. While a part of every one's purchases continues to be made in the neighborhood, a greater and greater portion of the total business is done by traders who are widely separated and who are indeed members of the world market. Various articles produced in the same locality may seek different markets. The market for wheat may be in Liverpool, while that for fruit and eggs is in the village near the farm-house. If a given product of any community is sold in different markets, the net prices secured must be very nearly equal.