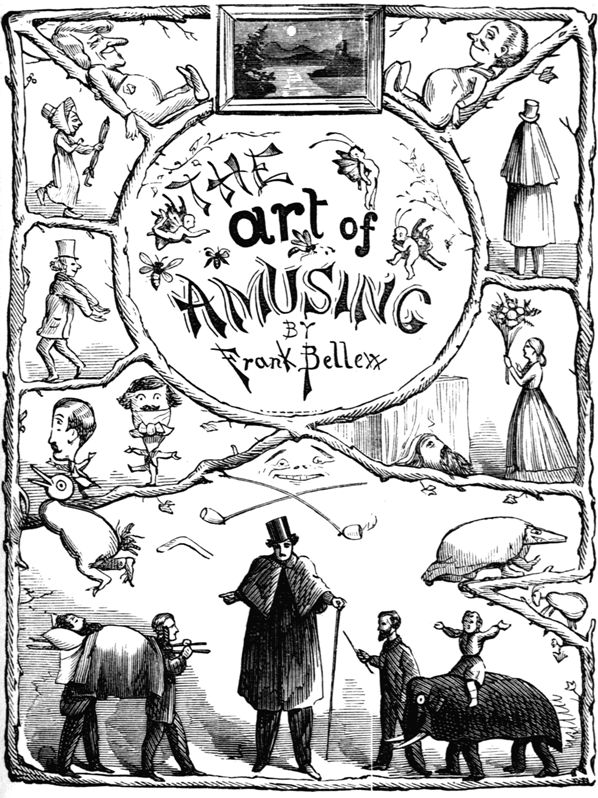

THE

art of

AMUSING

THE

art of

AMUSING

BY Frank Bellew

Beautifully printed and elegantly bound.

The Art of Conversation,

With Directions for Self-Culture. An admirably conceived and entertaining book—sensible, instructive, and full of suggestions valuable to every one who desires to be either a good talker or listener, or who wishes to appear to advantage in good society. ⁂ Price $1.50.

The Habits of Good Society.

A Handbook for Ladies and Gentlemen. With thoughts, hints, and anecdotes concerning social observances; nice points of taste and good manners; and the art of making oneself agreeable. The whole interspersed with humorous social predicaments; remarks on fashion, etc. ⁂ Price $1.75.

The Art of Amusing.

A collection of graceful arts, merry games, and odd tricks, intended to amuse everybody, and enable all to amuse everybody else. Full of suggestions for private theatricals, tableaux, charades, and all sorts of parlor and family amusements. With nearly 150 illustrative pictures. ⁂ Price $2.00.

These three books are the most perfect of their kind ever published. They

are made up of no dry stupid rules that everybody knows, but

are fresh, sensible, good-humored, entertaining, and

readable. Every person of taste should possess

them, and cannot be otherwise than delighted

with them. ⁂ Each will be sent

by mail, free, on receipt

of price, or the

three books

for $5.00.

Carleton, Publisher,

New York.

THE

art of

AMUSING

THE

art of

AMUSING

CARLETON, Publisher, NEW YORK.

A VOLUME INTENDED TO AMUSE EVERYBODY AND ENABLE ALL TO AMUSE EVERYBODY

ELSE; THUS BRINGING ABOUT AS NEAR AN APPROXIMATION TO

THE MILLENNIUM AS CAN BE CONVENIENTLY

ATTAINED IN THE COMPASS OF

ONE SMALL VOLUME.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1866, by

GEO. W. CARLETON,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York.

To J. C. W.

|

To you, my little kinsman, I dedicate these pages, Tho' not so wise, perhaps, as some you've read by graver sages; They're not without a purpose, and I trust a kind and true one, Older than eighteen hundred years, still good as any new one. If they could cheer some winter nights, and make some days seem brighter, I'd feel I'd paid a groat or so, Of that great debt of love I owe, To one at rest who, long ago, dealt kindly by the writer. |

| F. B. |

| CHAPTER I.—Something censorious.—Declaration of Independence.—Card puzzle.—The magic coin.—A hoax.—The telescopic visitor.—Boy's head knocked off. | 7 |

| CHAPTER II.—Colored mesmerism. | 17 |

| CHAPTER III.—Lemon pig and root dragon.—Portrait of the gorilla.—Creature comforts.—High shoulders.—Theatre and theatrical performances.—Nose turned up and teeth knocked out without pain.—The Long-nosed Night-howler, or Vulgaris Pueris cum Papyrus Capitus.—Imitation banjo on piano.—Some conjuring tricks.—The reduced gentleman, or dwarf perforce. | 20 |

| CHAPTER IV.—The voice of the Night-howler.—The play of Punch and Judy, with full directions for producing the same.—Charade on rattan. | 38 |

| CHAPTER V.—Parlor arts and ornaments, comprising apple-seed mice, turnip roses, beet dahlias, and carrot marigolds.—Counting a billion.—The algebraic paradox.—Answer to charade on rattan.—Riddles, etc. | 56 |

| CHAPTER VI.—A patent play. | 72 |

| CHAPTER VII.—Pragmatic and didactic discourse.—Aunty Delluvian, her party.—The duck and double-barrelled speech.—The dwarf.—Trick with four grains of rice.—Riddles, etc. | 81 |

| CHAPTER VIII.—The dancing Highlander and Matadore. | 99 |

| CHAPTER IX.—Answer to trick with four grains of rice.—How to make an old apple-woman out of your fist. | 105 |

| CHAPTER X.—About giants, and how to make them. | 110 |

| CHAPTER XI.—A merry Christmas.—The boomerang.—Optical illusion.—How to turn a young man's head.—The tiger-dog, how to make him.—The elephant, how to make him.—Two queer characters.—Captain Dawk and Colonel Gurramuchy. | 113 |

| CHAPTER XII.—Hanky-panky, instruction in the art.[Pg vi] | 134 |

| CHAPTER XIII.—A tranquil mood.—Transparencies of paper.—The dancing pea.—Artificial teeth. | 138 |

| CHAPTER XIV.—Artemus Ward, parlor edition. | 157 |

| CHAPTER XV.—Bullywingle the Beloved. A drama for private performance. | 164 |

| CHAPTER XVI.—A quiet evening.—Fruit animals.—Window staining.—Oddities with pen and ink. | 189 |

| CHAPTER XVII.—A country Christmas.—The trick trumpet.—Eatable candle.—How to cut off a head.—Ventriloquism.—The jumping rabbit.—Santa Claus arrives. | 199 |

| CHAPTER XVIII.—The bird-whistle, how to make it. | 219 |

| CHAPTER XIX.—A quiet party.—Electric nose.—Miniature camera.—The hat trick.—The magician of Morocco. | 222 |

| CHAPTER XX.—Theatrical red and green fire, how to make them.—How to get up a theatrical storm. | 232 |

| CHAPTER XXI.—Card-board puzzles, the cross, the horseshoe, the arch. | 238 |

| CHAPTER XXII.—The muffin man.—Earth, air, fire, and water.—The broken mirror. | 243 |

| CHAPTER XXIII.—At a watering-place.—A ladies' fair.—Three sticks a penny.—Smoking a cigar under water.—Firing at a target behind you.—Firing firewater.—A practical joke.—Explosive spiders. | 254 |

| CHAPTER XXIV.—Arithmetical puzzles.—The wolf, the goat, and the cabbage.—Alderman Gobble's six geese, etc., etc. | 264 |

| CHAPTER XXV.—Charades. | 271 |

| CHAPTER XXVI.—The art of transmuting everything into coral. | 274 |

| CHAPTER XXVII.—Acting charades. | 279 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII.—The worship of Bud. | 299 |

|

“All work and no play, Makes Jack a dull boy.” |

erhaps one of the great social faults of the American is, that he does not amuse himself enough, at least in a cheerful, innocent manner. We are never jolly. We are terribly troubled about our dignity. All other nations, the French, the German, the Italian, and even the dull English, have their relaxation, their merry-making; but we—why, a political or prayer-meeting is about the most hilarious affair in which we ever indulge. The French peasant has his ducas almost every week, when in some rustic[Pg 8] orchard, lighted with variegated lamps, ornamented with showy booths, he dances the merry hours away with Pauline and Josephine, or sips his glass of wine with the chosen of his heart in a canvas cabaret, whilst the music of a band and the voices of a hundred merry laughers regale his ears. He has, too, numberless fêtes, which he celebrates with masquerades and other undignified kinds of jollification. At these entertainments all are welcome, high and low, and all conduct themselves with a politeness worthy of our best society—only more. We, the writer of this, have often and often danced at these bals champêtres with a hired girl, a cook, or a nurse for our partner. Does it not sound plebeian? The Germans enjoy endless festivals and gift periods, when they have the meanness to offer each other little presents "that an't worth more than two or three cents;" but they are tokens of love and kindness, which make them all feel better and happier. Then our grumpy friend, John Bull, has his free-and-easies, and his cosy tavern parlor-meetings, and song-singings, and his dinner-parties, and his tea-fights, at which latter, be the host rich or poor, you will get a good cup of tea, and tender muffins, and buttered toast, and cake, and shrimps, and fresh radishes, and Scotch marmalade, or similar delicacies.[Pg 9]

A delightful repast and a cosy chat, followed, perhaps, by a rubber of whist and a glass of wine or whiskey-punch, or mug of ale, according to the condition of the entertainer; then there is a general "unbending of the bow," and no one is troubled about his dignity. We have seen, ourselves, in England, in a stately old castle, a party of lords and ladies—for we, like the boy who knew what good victuals were, having been from home several times—even we have seen good company—we say that we have seen a party of lords and ladies, knights and dames of high degree, and of mature years, romping and frolicking together, like a lot of children, playing Hunt the Slipper, Puss in the Corner, and Blindman's Buff, without the remotest idea that they had such a thing as dignity to take care of; and no one seemed to have the slightest fear that any one of the party could by any possibility do anything that would offend or mortify any one else. The fact is, gentlemen or gentlewomen can do anything; all depends on the way of doing it. If you are a snob, for heaven's sake don't be playful; keep a stiff upper lip and look grave; it is your only safety.

However, we are improving. We have skating clubs. We play cricket and base ball. We dine later, and take things a trifle more leisurely.[Pg 10] Theatre-going, our chief amusement, can hardly be reckoned a healthy relaxation, though well enough now and then. Sitting in a cramped attitude, in a stifling atmosphere, is not conducive to moral or physical development. What we need are informal social gatherings, where we may laugh much and think little, and where dignity won't be invited; where we need not make ourselves ill with bad champagne and ice-starch, nor go into the other extreme of platitudes, ice-water and doughnuts: but where both body and mind will be treated considerately, tenderly, generously.

Now we are going to give a few hints that may help to make little meetings such as we mention pass pleasantly; and should any of our austere readers be afraid to risk our programme in full, they can call in the children and make them shoulder the responsibility. "It is," you can say, "a child's party," and then you can enjoy all the fun yourself. The juveniles will not object.

If merely for the purpose of promoting conversation, something ought to be done, on all occasions of social gatherings, something to talk about, something that will afford people an excuse for getting from their seats, something to bring people together, something to break the ice. We have seen a whole party of very estimable people sit round the[Pg 11] room for hours together in an agony of silence, only broken now and then by a small remark fired off by some desperate individual, in the forlorn hope that he would bring on a general conversation.

In our little sketches we shall be discursive, erratic, and unsystematic, just as the fancy takes us. Still, there will be a method in our madness; we shall try to give in each chapter a programme somewhat suited to some one season, and of sufficient variety and quantity to afford amusement for one evening.

In the first place, we must remark, in a general way, that we like a large centre-table. It is something to rally round, it is handy to put things on, and convenient for the bashful to lean against. On this table I would accumulate picture-books, toys, and knick-knacks—little odds and ends which will serve as subjects for conversation. If you can do no better, make a pig out of a lemon and four lucifer matches, or an alligator out of a carrot. But we will give some detailed instructions on this point in a future chapter. Any simple puzzles, numbers of which can be made out of cards, will be found helpful. Take, for example, a common visiting-card, and bend down the two ends, and place it on a smooth table, as represented in the annexed diagram, and then ask any one to blow it over. [Pg 12]This seems easy enough; yet it is next door to an impossibility. Still, it is to be done by blowing sharply and not too hard on the table, about an inch from the card. Another little trick consists in making a coin (if such a thing is to be found nowadays) stick to the door. This is done by simply making a little notch with a knife on the edge of the coin, so that a small point of metal may project, which, when it is pressed against the woodwork, will penetrate, and so cause the dime or half-dime to appear to adhere magically to a perpendicular surface. When you have exhibited one or two tricks of this kind, some other member of the party may have something to show. Then, having secured the confidence of your audience, you may venture to play a hoax upon them. Never mind how trifling or how old these things are, they will serve the purpose of making people talk. Say, for example: "Now, ladies and gentlemen, I will show a trick that is worth seeing. There are only two people in the United States that can execute it[Pg 13]—myself and the Siamese Twins. First of all, I must borrow two articles from two ladies—a pocket-handkerchief and—a boot-jack." Of course no one has the boot-jack; so, pretending to be a little disappointed, you say: "Never mind; I must do without it. Will some gentleman be kind enough to lend me three twenty-dollar gold pieces?" Of course no one has these, either; so you content yourself with borrowing two cents. You place one in each hand, and extending your arms wide apart, assure your audience that you will make both pennies pass into one hand without bringing your arms together. This you do by laying one on the mantel-piece, and turning your whole body round, your arms still extended, till the hand containing the other coin comes over the place where you laid down the cent; then you quietly take it up, and the trick is performed.

After a little conversation, you can try something which requires a little more preparation. The servant, whom you have previously instructed, comes into the room and announces that "that" gentleman has called to look at the pictures. You desire him to be shown in, and a short, broad-shouldered man makes his appearance. Soon after he enters, he turns his back on the company and begins to examine the works of art on the wall, lengthening[Pg 14] and shortening his body to suit the height of the object he wishes to inspect. This is performed by your little brother or son, aided by a broom, a couple of cloaks, and a hat. How, you will doubtless be able to understand by looking at the subjoined picture.

Another trick of the same order can be per[Pg 15]formed in this wise: The servant comes in to inform you that a naughty little boy—Jacky or Willy—in another room won't eat his custard, but will cry for ice-cream, or roast-beef, or alligator-soup. Every one is invited into the room to see this singular child. You find him seated on a high[Pg 16] chair, with a very dirty face, making grimaces. You take the dish of custard in one hand and a large spoon (the larger the better) in the other, and begin to expostulate with him on his perversity, but all to no effect; he only cries and makes faces. You then tell him if he does not behave better you will be obliged to knock his head off. He continues not to behave better, whereupon you give him a tap with the spoon, and, to the surprise of all, his head rolls off on to the floor. Your audience then find out that the naughty boy was made of a pillow and a few children's clothes, whilst the head was supplied by Master Jacky or Willy, ingeniously concealed behind the chair.

A good practical joke to play in a rollicking party, where you can venture to do it, is that of mesmerizing; you of course manage beforehand to lead the conversation to the subject of mesmerism, then profess to have wonderful powers in that line yourself. After more or less persuasion, allow yourself to be induced to operate. You then say:

"Well, I will try if there is any person in the company who is susceptible to the magnetic influence. It is only in rare cases we find this susceptibility; the person must be of exquisitely fine organization and steady nerve. Few people can look one long enough in the face to come under the influence; and, if the current be suddenly broken, the result is apt to be very serious, if not fatal, by producing suspended action of the heart and vital organs generally."[Pg 18]

Having now fully impressed on your audience the absolute necessity of keeping still, you begin to look into the eyes of different persons, press their hands, make passes at them, etc., as though you were searching for the right temperament. At last you come to your intended victim, and pronounce him just the man. You now seat him in a chair, whilst you go into another room to prepare the necessary implements. These are two plates, each having on it a tumblerful of water. One plate, however, must be thoroughly blackened at the bottom, by holding it in the smoke of a lamp or candle. This done, you carry the plates and tumblers into the audience, and hand the one which is black to the victim, who is seated in a chair.

Before commencing operations, you must warn the audience that it is absolutely necessary that they observe strict silence, as the least word or exclamation will break the charm, and be attended with painful effects to both operation and operatee. You may tell how, after being once disturbed in this manner, you had most painful shooting-pains in your nose for fifteen minutes, that being the point in contact with your finger at the moment of interruption. All this is to prevent any one giving vent to some exclamation calculated to betray the trick to your victim.

COLORED MESMERISM.—See page 19.

COLORED MESMERISM.—See page 19.

You now seat yourself opposite the subject, and desire him to keep his eyes steadily on yours, and imitate the motions of your fingers. You then commence. First, you dip your finger in the water, and draw it down the centre of your nose; he does the same; then you rub the bottom of your plate with your fingers, and draw it over your chin; he follows your example, and makes a black smudge on his face; you rub the bottom of the plate again, and draw your finger over your nose, and so on for several minutes, till the victim has smeared himself all over with black. You then rise and compliment him on the steadiness with which he underwent the ordeal, adding, however, that he has too powerful a nervous organization for you to operate on. The victim will generally rise with a rather complacent smile at these compliments, at which point the audience will generally explode with laughter. The victim looks puzzled—more laughter—the victim, thinking they are laughing at your failure, joins in the merriment, which generally has the effect of convulsing every one, when the climax is reached by handing a mirror to the unhappy operatee, who usually looks glum, and does not see much fun in the joke.

We will now describe a little party we attended at a country house one Christmas, some years ago; and should any of our readers find aught in the entertainment they think worth copying, they can do so.

When we arrived at Nix's house all the company had assembled—it consisted of about ten grown people and a dozen children. All were in a chatter over a couple of little objects on the centre-table. The one a pig manufactured out of a lemon, and the other a dragon, or what not, adapted from a piece of some kind of root our friend Nix had picked up in the garden. We alluded to these works of art in our last chapter, and now give a couple of sketches of them. As will be seen, they are very easy of manufacture, and not excessively exciting when made, but they serve to set [Pg 21]people talking. One person told the story of Foote, or some other old wit, who, at a certain dinner-table, after numerous fruitless efforts to cut a pig out of orange-peel, retorted on his friend who was quizzing him on his failure: "Pshaw! you've only made one pig, but (pointing to the mess on the table) I have made a litter." Then some one else discovered a likeness between the dragon and a mutual friend, which produced a roar of laughter. Then a child exclaimed, "Oh! what a little pig!" and some one answered her: "Yes, my dear, it's a pigmy." Then a young lady asked how the eyes were painted, and a young gentleman replied: "With pigment." Whereupon a small boy called out, "Go in lemons!" which was considered rather smart in the small boy, and he was told so, which induced him to be unnecessarily forward and pert for the rest of the evening; but as he never succeeded in making another hit, he gradually simmered down to his normal condition towards the end of the entertainment. One group got into con[Pg 22]versation about the dragon, the dragon led to fabulous animals generally, fabulous animals to antediluvian animals, these to pre-Adamite animals, and so in a few minutes they were found deep in the subject of Creation; whilst the group next to them, owing to some one's having conjectured whether my friend's piece of sculpture could walk, and some one else having suggested that it might be made to do so by means of clock-work or steam, had got on to the subject of machinery, modern improvements, flying-machines, and were away two thousand years off in the future, making a difference of no less than ten thousand years between themselves and the other party. At about this juncture of affairs, we happened to notice a book on the table treating of a certain very interesting animal, the newly discovered African ape, a subject which was attracting a good deal of attention at that time. We took the work in our hand and read on the cover the inscription: "Portrait of the Gorilla." "Nix," we said to our friend, still holding the book in our hand, "if all we hear of this gorilla be true, it must be a most extraordinary animal, although I am rather inclined to be sceptical in the matter; however, I have no right, perhaps, to form an opinion, as I have never looked into the subject; but I'll get you to lend me this book to-morrow. I will take[Pg 23] the greatest care of it, and return it; yes, I will, upon my word of honor. You never knew me fail to return any work you lent me." This we said rather warmly, thinking we detected a somewhat suspicious smile playing round the corner of our friend's mouth. "Oh! yes, certainly," replied he; "you can have it with pleasure—though I think your doubts will vanish when you have looked into it." We did not notice specially that all eyes were upon us. We carelessly opened the volume, and there, by all the spirits ever bought and sold! was a neat little mirror between the covers of the book, and reflected in it our own lovely countenance. Portrait of the Gorilla! eh? This was what the boys would call rather rough, but every one except ourself seemed to think it quite funny. It was some satisfaction, however, to know that every one of the party had been taken in in like manner before our arrival.

A slight but pleasant tinkling now fell upon our ear, and behold! a maiden entered, bearing a tray covered with tall crystal minarets, and transparent goblets, which sparkled and twinkled in the lamplight, followed by a more youthful figure supporting vessels of porcelain and implements of burnished silver, above which wreathed and curled clouds of aromatic incense; or, in other and better words, two[Pg 24] hired girls brought in coffee and punch. Punch! was it punch, or was it negus, or was it sherbet? We don't know, but it was a pleasant, moderately exhilarating beverage, compounded of whiskey, raspberry syrup, sugar, and orange-flower water, and manufactured by Nix, as he subsequently explained, at a cost of about thirty cents per bottle. A few little cakes and some plates of thin, daintily cut slices of bread-and-butter accompanied the beverages, and were handed round with them. We are great believers in eating and drinking at all social gatherings. It is convenient to have something to do with your mouth when you are stumped in the way of conversation. If suddenly asked a puzzling question, or hit in the chest with a sarcasm, what a resource is a glass of wine or cup of coffee, in which to dip your nose whilst you collect your ideas, or recover your breath. Besides, they give you something to do, generally, in a small way. They afford opportunities for small attentions, and excuses for rising from your seat, or moving from one part of the room to the other. Added to which, wine and coffee and cakes are nice things to take—you have the gratification of an additional sense. Then, too, these little things are refreshing, and put you all in good-humor. Therefore, for all these good reasons, and many more, we insist on refreshments, and we[Pg 25] insist, too, upon some kind of vinous stimulant; this ice-water and doughnut business has been carried altogether too far; had we less of it in our homes, less money would pour into the coffers of the bar-keeper. If persons are teetotallers, all very well; we respect their opinions, and, perhaps, decline their invitations; but for people who have no moral scruples on the subject, to ask you to visit them, and then insist on your drinking red-hot weak green tea, when you are already nervous, perspire readily, have a tender gullet, and hate the confounded stuff any way, is downright tyranny, and the very opposite of all hospitality and true Christian charity. However, our friend Nix held orthodox views on this question; so all went well. By dint of helping each other to things we did want, and offering each other things we didn't want, with the aid of a cup of coffee for those that liked coffee, and a glass of punch for those who liked punch, not to forget the little cakes, which came in quite handy to nibble at occasionally, we all began to feel wonderfully at our ease, and quite sociable. The conversation did not flag much; but once when it showed a slight tendency to wobble, Nix set it in motion again by introducing the subject of optical illusions in connexion with the height of objects. After inform[Pg 26]ing us that a horse's head was exactly as long as a flour-barrel, and that a common stove-pipe hat was as broad across the crown as it was high from the brim to the top (both of which statements were argued pro and con), he drew our attention to the vast difference the position of the shoulders make in a man's height. This he illustrated by walking from the audience with his shoulders in their natural position, until, having traversed half the length of the room, he suddenly raised them, as represented in the accompanying sketches. The effect was quite startling, and very ludicrous. All the male part of the company tried [Pg 27]their shoulders at this experiment, even down to Freddy Nix, a little three-year-old, who, after ducking his head down on his chest, and toddling off across the room, returned swaggering, evidently under the impression that he had made a perfect giant of himself by the operation.

This was nominally a child's party, so we were to have some performances. The folding-doors into the adjoining parlor were closed, and one or two members of the company who were to be performers retired. In a few moments the doors opened and revealed an extempore stage. The kitchen clothes-horse, beautifully draped and decorated, formed the background; while on a line with the foot-lights were two heads, one at each side of the stage, intended to represent Tragedy and Comedy. They were simply two large pumpkins with grotesque faces marked on them with black and white paint. In less than no time a most remarkable-looking stranger stepped forward and began to address us. Every one stared, and wondered whence this singular-looking person could have come, for we hardly supposed that Nix could have had him secreted in the house all the evening for our special surprise. At last it dawned upon us, one by one, that the individual in question was no other than Mr. Graham, a very [Pg 28]staid gentleman, who had been with us a moment before. The annexed brace of sketches will show the appearance of Mr. Graham off and on the stage. But how was this change effected? We will explain. In the first place he had procured a narrow strip of black silk, which he had drawn round one of his front teeth, with the two ends inside his mouth, which, at a very short distance, looked exactly as though he had lost one of his teeth. (A little piece of court-plaster stuck on the tooth will answer the same purpose.) Then he had made a loop of horse-hair or grey thread, and securing two of the ends to the lining inside his hat, had hooked up the end of his nose with the other; in fact, he had put his nose in a sling. This altered the character of his whole face, so that his own[Pg 29] wife would not have known him had she not heard him speak. He now addressed the audience in a long, funny, showmanic rigmarole, of which we only remember the following:

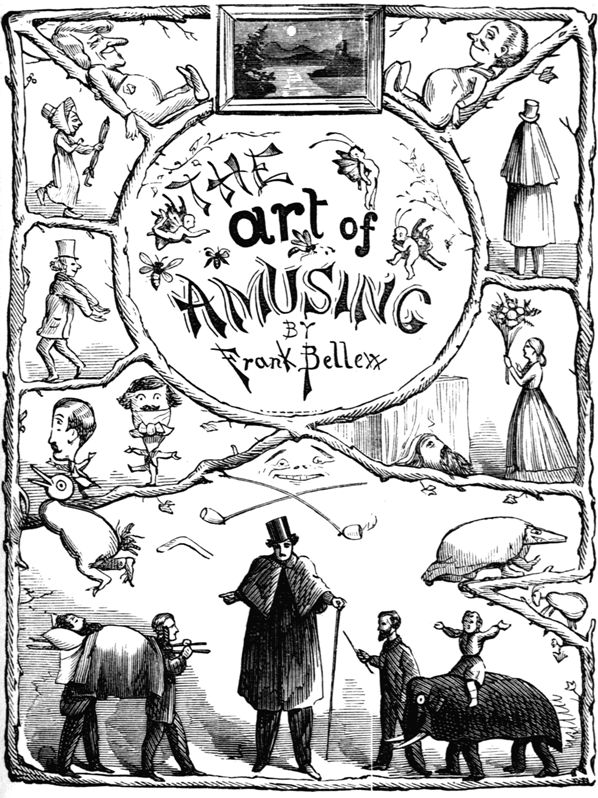

"Ladies and gentlemen, you have all heard of the Ornithorhyncus, which, as you are aware, is a species of duck-billed Platypus. You are familiar with the habits and appearance of the Ororo Wow; and you have listened to the sweet notes of the Catomonsterbung; but you are entirely ignorant of the newly-discovered creature known to scientific men as the Long-nosed Night-Howler, or Vulgaris Pueris cum Papyrus Capitus. This extraordinary animal is chiefly sugariverous in its diet, though it will eat almost everything when driven by hunger. It is perfectly tame, and will only attack human beings when it feels like it. I will now proceed to exhibit this extraordinary creature, requesting you only not to run pins into the animal, as it does not like that style of thing. Bring in the Night-Howler!!"

The last words were addressed in a loud voice to an assistant outside, who immediately appeared, leading an animal such as is represented in the annexed cut. This monster began immediately to emit the most hideous and unearthly noises, as became the Night-Howler. After walking round[Pg 30] among the audience once or twice, the Vulgaris Pueris retired behind the curtain. The accompanying sketch will explain how the Night-Howler is made. Beyond the boy and the boots and the brown-paper cap, all that is wanted is a rough shawl or large fur cape. The howl is produced by means of one or two instruments, into the construction of which we will in a future chapter initiate our readers. With one of these instruments the most varied tones may be produced, from the grunt of the hog to the most delicate notes of the canary.

The performance now proceeded: the second act[Pg 31] being some feats of strength by one of our party who had the necessary physical ability for that kind of display. These embraced the following programme, each feat being announced by Mr. Showman with some extravagantly pompous title:

Balancing chair on chin.

Holding child three years old at arm's length.

Lying with the head on one chair and the heels on another without any intermediate support, and in this position allowing an apparently heavy but really light trunk to be placed on his chest.

The whole wound up by his dancing a negro breakdown to imitation banjo[A] on the piano, the entire audience patting Juba.

Now another performer appeared on the stage, dressed in extravagant imitation of the one who had preceded him, and commenced parodying in a still more extravagant style all the motions of the professional acrobat. We expected something grand! After innumerable flourishes he brought forward a small three-pound dumb-bell, laid it on the floor, and, bowing meekly to the audience in different parts of the house, he stooped down as though about to make an immense muscular effort, grasped[Pg 32] the dumb-bell, slowly stretched it forth at arm's length, held it there a second or two, and then laid it down again, made a little flourish with his hands, and a low bow, just as they do in the circus after achieving something extra fine. In this way the performer went on burlesquing till we all roared with laughter. When he had retired, a conjuror appeared and exhibited numerous tricks, such as the ring trick, tricks with hat and dice, cup and ball, etc.; but as all these need machinery, we will not describe them at present. One or two, however, we may explain. No. 1. The performer presented a pack of cards to one of the audience and begged him to select a card; this the performer then took in his own hand, and carried it with its face downward, so that he could not see it, and placed in the middle of the floor of the stage; he then produced a large brown-paper cone, and placed it over the card, and commenced talking to the audience, telling them what he could do and what he could not do: finally he informed the audience that he could make that card pass to any place he or they chose to name. Where would they have it? One said one place, one another, till finally he pretended reluctantly to accede to one particularly importunate person's wishes, and declared that it should be found in the leaves of a[Pg 33] certain book on a certain table at the back of the audience—and there it was, sure enough. This was done by having a piece of waxed paper attached to a thread lying ready in the middle of the floor; on this waxed paper the conjuror pressed the card, the thread being carried out under the screen at the back, where stood a confederate, who quietly pulled the card out from under the cone, and while the conjuror was talking he walked round, entered by another door, and placed the card in the book, where it was subsequently found.

Another trick consisted in his allowing a person to draw a card which he was requested to examine carefully, and even to mark slightly with a pencil. While the spectator was doing this, the performer turned round the pack in his hand so as to have all the faces of the cards upwards except the top one, which showed its back; he then desired that the card might be slipped anywhere into the pack; he then shuffled them well. Of course, on inspecting the pack he soon detected the selected card, it being the only one with its face down, which, after various manipulations, putting under cones and what not, he returned to the audience much to their surprise.

These efforts at legerdemain were certainly not very brilliant, but they amused the audience and[Pg 34] were easy to do. We should like to give a few more of his simple tricks, but with one illusion-trick we will close the chapter, for which purpose it will serve, as it formed the finale to the conjuror's performance.

He stepped forward and said:

"I have shown you many wonderful things, but they are as nothing compared to what I can do. My supernatural power is such that I can lengthen or compress the human frame to any extent I please. You doubt it? Well, I will show you. You see Mr. Smith, yonder; he is a rather tall man; six feet two, I should judge? Well, I will throw him into a trance, and while he is in that state, I will squeeze him down to a length of about three feet, and I will have him carried to you in that condition. I must only insist upon one thing, and that is, that you do not say hokey pokey winkey fumm while he is in the trance; for if you do it might wake him up, and then he would be fixed at the height of three feet for the rest of his life; I could never stretch him out again."

Mr. Smith was requested to step behind the curtain. He walked forward, pale but firm and collected. Soon after he had disappeared we heard strange noises and fearful incantations, accompanied by a slight smell of brimstone and a strong smell[Pg 35] of peppermint. After a few minutes the tall Mr. Smith was carried in on the shoulders of two men a perfect dwarf, as promised by the conjuror, and as represented in the following cut.

How this is managed will become tolerably clear to the reader on examining the next diagram.

The tall Mr. S. had put a pair of boots on his hands, a roll of sheeting round his neck, so as to form something resembling a pillow, behind his head; then something on his arms under his chin to represent his chest (which is not shown in the diagram), and over that a baby's cradle-quilt, and then he rested his boots on another gentleman's[Pg 36] shoulders; two long sticks were provided and slung as represented, and the miracle was complete. We have seen the figure lengthened to an inordinate extent by the same process, the only difference being that the gentlemen were further apart.

Mr. Nix's party concluded, after several other games and amusements, with a neat but inexpensive entertainment, consisting of sandwiches, sardines, cold chicken, cakes, oranges, apples, nuts, candies, punch, negus, and lemonade. But everything was good of its kind; the sandwiches were sandwiches, and not merely two huge slices of bread plastered with butter, concealing an irregular piece of sinew and fat, which in vain you try to sever with your teeth, till you find yourself obliged[Pg 37] to drop the end out of your mouth, or else to pull the whole piece of meat out from between the bread, and allow it to hang on your chin till you cram it all into your mouth at once. His were not sandwiches of that kind, but, as we said before, sandwiches; the cakes had plenty of sugar in them, and so had the lemonade. But, above all, what made these little trifles the most enjoyable was the taste displayed by some one in the decoration of the table with a few evergreens, some white roses made out of turnip, and red roses out of beets, not to mention marigolds that once were carrots, nor the crisp frills of white paper which surrounded the large round cakes, nor the green leaves under the sandwiches, the abundance of snowy linen, shining knives and forks, and spoons. But we must conclude; what we wish particularly to impress upon the minds of our readers by thus dwelling on sandwiches and fine linen is, that you cannot afford to ignore one sense while you propose to gratify another; they are all intimately related and bound together like members of a fire company; if you offend one, all the others take it up.

[A] Should any of our friends not know how to produce an imitation of the banjo on a piano, we may as well inform them that it is done by simply laying a sheet of music over the strings during the performance.

In our last chapter we promised to explain the nature of the little instrument by which the Night-Howler produced those "hideous and unearthly noises" to which we alluded. We will now proceed to do so; and as this instrument is the same as that used by showmen in the play of Punch and Judy, we cannot do better, while we are about it, than instruct our readers how to get up a Punch and Judy show.

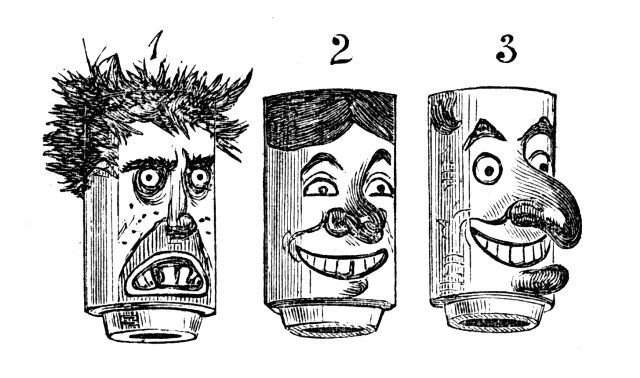

First, with regard to the instrument. It is a very simple affair: get two small pieces of clean white pine, and with a sharp knife cut them of the shape and size of the diagram marked 1. Then put these two pieces together as represented in Figure 2, having previously slipped between them a piece of common tape, also represented in the diagram (the tape must be just the same width as the[Pg 39] wood); then wind some thread round the whole thing lengthwise (to keep the bits of wood together and the tape taut), and the Punch-trumpet is made, as represented in figure 3. Place the instrument between your lips and blow; if you cannot produce noise enough to distract any well-regulated family in three-quarters of an hour, we are very much mistaken.

To produce variety of notes and tones, as well as to speak through it, after the manner of the Punch showmen, the instrument must be placed well back in the mouth near the root of the tongue, in such a position that you can blow through it and at the same time retain free use of your tongue. A little practice will enable you to do this, and to pronounce many words in a tolerably understand[Pg 40]able manner. To discover this last item in the use of the instrument, simple as it is, cost the writer of this an infinity of trouble and some money; and it was not until after two years' hunting and inquiry, and the employment of agents to hunt up professors of Punch and Judy, that we discovered an expert who, for a handsome fee, explained the matter; and then, of course, we were amazingly surprised that we had never thought of it before. From the same expert we learned how to make another instrument by means of which it is possible to imitate the note of almost every animal, from the hog to the canary-bird. We soon compassed the hog, the horse, the hen, the dog, the little pig, and something that might be called the horse-linnet, or the hog-canary; but ere long we found that considerable practice was necessary to enable us to accomplish the finer notes of the singing-birds. How to make this latter instrument we will explain in a future chapter; at present we must go on with the play of Punch and Judy.

We commence instructions with a view taken behind the scenes, which will help the description (see cut on page 40). We may state that the London showmen carry about with them a species of little theatre of simple construction, which is of course better than a mere door-way; but as the [Pg 41]latter will answer the purpose, and many people will not care to make a theatre, we will at present content ourselves with that which every house affords.

In the play of Punch and Judy there are many characters—indeed, you can introduce almost as great a variety as you please; but the leading ones are:

Mr. Punch, a merry gentleman, of violent and capricious temper.

Judy (wife of Punch).

Baby (offspring of Punch and Judy).

Ghost.

Constable.

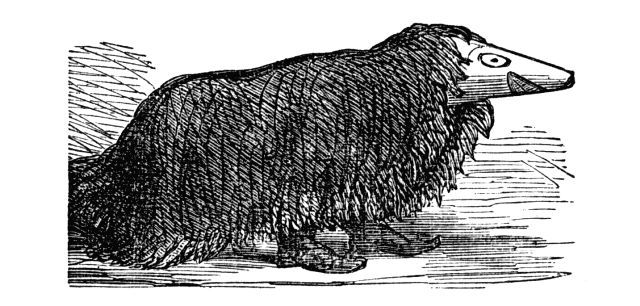

The heads of these characters can be made in several ways. The first is to get the necessary number of common round wooden lucifer match-boxes and some red putty. With the putty you make the noses and chins of the characters (all except the Ghost, who requires no nose). With a camel's-hair brush and a little India-ink or black paint you mark out the features strongly, taking care to make the eyes and eyeballs of a good size, so as to be seen at a distance. With a little red paint or red chalk you can color the cheeks, and with a little white paint or white chalk give brilliancy to the teeth and eyes. The annexed cut will show what the[Pg 42] style of countenance ought to be of each, No. 1 being the Constable, No. 2 Judy, and No. 3 Mr. Punch himself. The Ghost is not represented. In feature he is much like the Constable, only that his face must be made as white as possible, and the features simply marked out in blue or green or black. The Baby can be made out of an ordinary clothes-pin or stick of wood.

If the match-boxes cannot be easily obtained, just roll up a good-sized card, as represented in this figure, and paint on it the features. The nose and chin can be made of a bit of red rag or paper folded up of the desired shape, and either sewed or gummed on. Another and far better way of making these heads (though it takes more trouble), is to get a carpenter to cut out for you four or five pieces [Pg 43]of white pine or other fine wood of the shape of the sketch annexed, with a hole in each large enough to easily admit your fore-finger. From this block you can carve as elaborate a head as you please, and one of larger size than the match-box, which will be advantageous. The diagram marked O will show you how to set about making the carving. Having now made the bald heads, you must proceed to dress them. Punch must have a bright red cap with yellow tassel and binding, like the one in the accompanying sketch. Judy must have a white cap with broad frill and black ribbon. The Constable must have a wig made out of some scrap[Pg 44] of fur (the remains of a tippet or cuff), or if fur cannot be procured, a piece of rope unravelled will make a good wig. The Ghost only requires his winding-sheet drawn over his head. All these can be nailed on the heads of the actors with small tacks without hurting their feelings.

Having got the heads complete, we will proceed to construct their bodies. These merely consist of empty garments, the operator's hand supplying the bone and sinew. The dresses must be neatly fastened round the neck of the head, so that when the performer puts his hand inside the dress, he can thrust his fore-finger into the hole in the head. They must of course be sufficiently large to admit the hand of the showman, each sleeve to admit a thumb or finger, and the neck large enough for the passage of the fore-finger. Thus the thumb[Pg 45] represents one arm, the middle finger another arm, whilst the fore-finger, thrust into the head, supports and moves it about. The style of dress of Punch and Judy can be easily seen in the small sketch. The color of Punch's coat should be red, with yellow facings, with a hump sewed on his back and a paunch in front. Judy should have a spotted calico and white neck-handkerchief. The Constable had better be attired in black, and the Ghost and Baby in white. Each of the sleeves should have a hand fastened into it. The hands can be made of little slips of wood, with fingers and thumbs marked on them. They should be about two and a half or three inches long, only about three-quarters of an inch of which, however, will project beyond the sleeve; the rest, being inside, will serve to give stiffness to the arm when the performer's fingers are not long enough to reach the whole way.

Mr. Punch requires a club wherewith to beat his wife, and to perform his various other assaults and batteries. A gallows, too, should be provided, on the plan represented in the diagram, the use of which will be explained hereafter[Pg 46].

So much for the performers. Now for the theatre and the play. The theatre is easily made. A narrow board about three or four inches wide should be fixed across an open doorway just about one inch higher up than the top of the head of the exhibitor. From this board hangs a curtain long enough to reach the floor. Behind this curtain stands the operator, with his actors all ready on a chair or table at his side. He puts his Punch-trumpet in his mouth, gives one or two preliminary root-et-too-teet-toos, puts his hand fairly inside Mr. Punch's body, and hoists him up so that half his manly form may be seen above the screen. A glance at our picture, Behind the Scenes, will explain anything our words have failed to convey. The audience are of course on the opposite side of the curtain to which the performer stands.

Before we commence with the dialogue of the play, we must mention one very important part of the exhibition. As Mr. Punch's voice is, at the best of times, rather husky, it is necessary that the exhibitor should have a colleague or interpreter among the audience who knows the play by heart, and who, from practice, can understand what Mr. Punch says better than the audience. This person must repeat after Punch whatever he may say, only not to wound his feelings; he must do so in the[Pg 47] form of questions—for example, suppose Mr. Punch says, "Oh! I've got such a pretty baby!" the showman outside must repeat: "Oh! you've got a pretty baby, Mr. Punch, have you? Where is she?" The outside showman ought to have some instrument to play on—a tin tea-tray or tin pan will do—and if there is any one to accompany him on the piano when Mr. Punch sings a song or dances, so much the better. Now for the play.

Mr. Punch makes his début by dancing round his small stage in an extravagant and insane manner, singing some rollicking song in his own peculiar style. Having indulged himself in this way for a few seconds, he pulls up suddenly, and looking over the edge of the screen at the showman outside, exclaims:

Punch. "I say, old hoss!"

Showman. "I say, 'old hoss!' Mr. Punch, that's not a very polite way to address a gentleman. Well, what do you say?"

P. "I say!"

S. "Well, what do you say?"

P. "I say!"

S. "Well, you've said 'I say!' twice before. What is it you have to say?"

P. "I say!"

S. "What?"[Pg 48]

P. "Nothing particular!"

Mr. Punch dances off, hilariously singing.

S. "Nothing particular! Well, that is a valuable communication."

P. (Stopping again). "Oh, you April fool!"

S. "April fool? No, Mr. Punch, I'm not an April fool. This isn't the first of April."

P. "Isn't it? Well, salt it down till next year."

S. "Salt it down till next year? No, thankee, Mr. Punch. Guess you'll want it for your own use."

P. "Mr. Showman!"

S. "Well, Mr. Punch?"

P. "Have you seen my wife?"

S. "Seen your wife? No, Mr. Punch."

P. "She's such a pretty creature!"

S. "Such a pretty creature, eh? Well, I'd like to be introduced."

P. "She's such a beauty! She's got a nose just like mine" (touching his snout with his little hand).

S. "Got a nose just like yours, eh? Well, then, she must be a beauty."

P. "She's not quite so beautiful as me, though."

S. "Not so beautiful as you? No, of course not, Mr. Punch; we couldn't expect that."

P. "You're a very nice man. I like you."[Pg 49]

S. "Well, I'm glad you like me, Mr. Punch."

P. "Shall I call my wife?"

S. "Yes, by all means call your wife, Mr. Punch."

P. (Calling loudly). "Judy! Judy, my dear! Judy! come up-stairs!"

Judy now makes her appearance. Punch draws back and stands gazing at her for a few minutes in mute admiration. Without moving, he exclaims: "What a beauty!" then, turning to the audience, he asks earnestly: "Isn't she a beauty?" He now turns to Judy and asks her for a kiss; they approach and hug each other in a prolonged embrace, Mr. Punch all the time emitting a species of gurgling sound expressive of rapture. This is repeated several times, interspersed with the remarks of Mr. Punch on the beauty of his spouse; after which, at Mr. P.'s suggestion, the couple dance together to lively music and the enlivening tones of Mr. P.'s voice; the performance winding up by Mr. Punch's leaning up against the door of the theatre exhausted and delighted, and giving vent to a prolonged chuckle of gratification.

Punch now turns to the Showman and asks him if he has ever seen his Baby. The Showman replying in the negative, Punch extols the beauty of his offspring in the same extravagant strain as he[Pg 50] has already done that of his wife, makes the same comparison between his own and the Baby's nose, declares that the Baby never cries, and that she is "so fond of him."

The Baby is now ordered to be brought up-stairs, and Judy disappears to obey her lord's mandate. During her absence Punch favors the company with a song. When Judy returns, bearing the infant Punch in her arms, Mr. P. goes into raptures, calls it a pretty creature, pats its cheek, and goes through all the little endearing ceremonies common to fathers. After again informing the Showman that his Baby never cries, and is fondly attached to him, he takes the infant in his arms, whereupon she immediately sets up a continuous howl. Punch tries to hush and pacify it for some time, but at last, losing his temper, shakes it violently and throws it out of the window, or in other words, at the feet of the audience. Judy is of course distracted, weeps bitterly, and upbraids her husband, when the enraged Mr. Punch dives down-stairs and gets his club, and whilst Mrs. P. is still weeping, gives her three or four sound blows on the back of the head. This makes Mrs. P. cry still more, which, in turn, increases Mr. P.'s wrath, who ends by beating her to death and throwing her after the Baby. The Showman upbraids Punch[Pg 51] with his crime, but Punch defends himself by saying it served her right. However, he finally admits that he is naturally a little hasty, but then he adds, "It's over in a minute," and that's the kind of disposition he likes. He further adds:

P. "I'm a proud, sensitive nature."

S. "You're a proud, sensitive nature, are you, Mr. Punch? I don't see much pride in killing a baby."

P. "That's because you don't understand the feelings of a gentleman."

S. "Because I don't understand the feelings of a gentleman? Well, if those are the feelings of a gentleman, I don't want to understand them, Mr. Punch."

This dialogue can be carried on to suit the taste and invention of the exhibitor.

Presently, while Mr. P. is recklessly glorying in his crime, declaring that he is afraid of nothing, and laughing to scorn the Showman's admonition, the Ghost makes his appearance close to Mr. P.'s shoulder, and stands there for some time, listening unobserved to Punch's brag. After a while, however, turning round, Punch catches sight of him, and is rooted to the spot with horror for a few seconds; then he retreats backwards, his whole body trembling violently, till he reaches the side of the[Pg 52] theatre; here he turns round slowly to hide his face from the awful apparition. When, by turning away, he loses sight of the Ghost for a few seconds, he recovers his voice so far as to say to the Showman in trembling tones: "W-h-h-a-a-t a hor-r-r-rid creature! What an awful creature!" Then he turns round very slowly to see whether the "horrid creature" is gone, but finding it still there, suddenly jumps back—jambs himself up in the corner—pokes his head out of the window, and screams, "Murder! murder! murder!" shaking all the time violently. This he repeats several times, till at last the Ghost disappears. Then Mr. P. recovers his courage and swaggers about as before, vowing he is afraid of nothing, etc., etc.

Now appears on the stage the Constable, who twists himself about in a pompous style for some seconds, and then addressing Mr. Punch, says:

Constable. "I've come to take you up!"

P. "And I've come to knock you down!" (which he accordingly does with his club).

The Constable gets up, and is again knocked down several times in succession. Not relishing this style of thing, however, he disappears and returns with a club, and a battle royal ensues, part of which—that is to say, one round of the battle—shows the skill of the Constable in dodging Mr. P.'s[Pg 53] blows, and can be made immensely funny if properly performed. It is done in this way: The Constable stands perfectly still, and Punch takes deliberate aim; but when he strikes, the Constable bobs down quickly, and the blow passes harmlessly over his head. This is repeated frequently, the Constable every now and then retaliating on Mr. P.'s "nob" with effect. Not succeeding with the sabre-cut, Punch tries the straight or rapier thrust. He points the end of his baton straight at the Constable's nose, and after drawing back two or three times to be sure of his aim, makes a lunge; but the Constable is too quick, dodges on one side, and Punch's club passes innocently out of the window. This is repeated several times, till the Constable sails in and gives Punch a whack on the head, crying: "There's a topper!" Punch returns the compliment with the remark: "There's a whopper!" Now they have a regular rough and tumble, in which Punch is vanquished.

The Constable disappears and returns with the gallows, which he sticks up in a hole already made in the stage (four-inch board previously mentioned), and proceeds to prepare for the awful ceremony of hanging Mr. P. Punch, never having been hung before, cannot make out how the machine is intended to operate—at least he feigns profound[Pg 54] ignorance on the subject. When the Constable tells him to put his head into the noose, he puts it in the wrong place over and over again, inquiring each time, "That way?" till at last the executioner, losing all patience, puts his own head in the loop, in order to show Mr. P. how to do it, saying: "There! that's the way! Now do you understand?" To which Punch responds, "Oh! that's the way, is it?" at the same time pulling the end of the rope tight, and holding on to it till the struggling functionary is dead, crying all the time: "Oh! that's the way, is it? Now I understand!"

Punch dances a triumphant jig, and so ends the immoral drama of Punch and Judy.

Many more characters can be added at the option of the performer, besides which, jokes and riddles can be introduced to any extent. We have given the skeleton of the play, with all the necessary information for getting up the characters.

We will conclude this chapter with an excellent charade, the answer to which will be given in the next chapter:

CHARADE.

|

My whole is the name of the school-boy's dread, My first is the name of a quadruped; My first transposed a substance denotes, Which in carts or in coaches free motion promotes; [Pg 55] Transpose it again, and it gives you the key Which leads to the results of much industry. My second is that which deforms all the graces Which cluster around the fair maidens' fair faces; Transpose it, and it gives you the name of a creature Of no little notice in the history of nature. Now take my whole in transposition, And it will give you the dress of a Scotch musician. |

Heretofore the fireside amusements recorded by us have been rather masculine in their character. In this chapter we shall have the pleasure of describing an entertainment of more feminine qualities. It was a small party, of the description which the Scotch call a cookeyshine, the English a tea-fight, and we a sociable. A few young ladies in a country village had conspired together to pass a pleasant evening, and the head[Pg 57] conspirator wrote us a note, which consisted of several rows of very neat snake-rail fences (not "rail snake" fences, as the Irishman said), running across a pink field. We got over the fences easily, and found ourselves in a pretty parlor, with six pretty young ladies, one elderly ditto, and a kind of father. The ladies, as we entered, were engaged in making tasty little scent-bags. We had often seen the kind of thing before, but never so completely carried out.

The principal idea consisted in making miniature mice out of apple-seeds, nibbling at a miniature sack of flour. But in this case they had filled the sack with powdered orris-root, and the small bottles with otto of roses, making altogether a very fragrant little ornament. The subjoined sketch will convey the idea to any one wishing to try her hand at this kind of art.[Pg 58]

As to the process of manufacture, that is simple enough: you first make neat little bags of white muslin, and with some blue paint (water color) mark the name of the perfume, in imitation of the ordinary brands on flour-bags; then fill the bag with sachet-powder and tie it up. You then get some well-formed apple-seeds, and a needle filled with brown thread or silk with a knot at the end; after which pass the needle through one side of the small end of the seed, and out through the middle of the big end; then cut off your thread, leaving about half an inch projecting from the seed; this represents the tail of the mouse. After this you make another knot in your thread, and pass it through the opposite side of the small end of the seed, bringing it out, not where you did the other thread, but in the middle of the lower part, that part, in fact, which represents the stomach of the mouse. You can now sew your mouse on the flour-sack. It should be borne in mind that the two knots of thread, which represent the ears, must appear near the small end of the seed. We once saw some mice made of apple-seeds where the ears were placed at the big end, producing the most ridiculous effect. We annex enlarged diagrams of each style.

It will be seen that one looks like a mouse,[Pg 59] whilst the other resembles a pollywog, or a newly-hatched dragon.

You must now get a good-sized card, and if you wish to have it very nice, paint it to resemble the boards of a floor. On this you sew your sack, and one or two stray mice who are supposed to be running round loose. Then having provided yourself with a couple of those delicate little glass bottles of about an inch and a half in length, which are to be found in most toy-stores, you fill them with otto of roses or any other perfume; and with a little strong glue or gum, stick them to the card in the position represented. If glass bottles are not to be obtained, you may cut some out of wood, a small willow stick perhaps being the best for the purpose; blacken them with ink, and varnish them with weak gum-water, at the same time sticking on them little pieces of paper to represent the labels, and, if you please, a little lead-paper round the neck and mouth of the bottles, to give the flasks a champagney flavor. The boxes and jars are likewise cut out of wood,[Pg 60] and easily painted to produce the desired appearance.

After a time, while the young ladies were still at work on the mice like so many kittens at play, a practical young gentleman, in spectacles and livid hands, came in, and asked of what use were those articles. Upon which one of the young ladies very properly replied that they did not waste their time in making anything useful. This seemed to afford an opportunity to the young gentleman to say something agreeable in connection with beauty; but he put his foot in it, and we heard him late in the evening, as the party was breaking up, trying to explain his compliment, which, though well intended, had unfortunately taken the form of an insult, and had not been well received.

We had observed, on entering, that one of the young ladies present wore in her hair a very beautiful white rose, and that another held in her hand a small bunch of marigolds. As the season was mid-winter, this fact attracted our attention, and we very gracefully complimented said damsel on the beauty of her coiffure, at the same time expressing our ardent admiration for flowers generally, roses particularly, and white roses above all other roses. "We had made a study of them." We spoke rapturously of them as the poetry of vegetation, as ves[Pg 61]tals among flowers, as the emblems of purity, the incarnation of innocence. Then the young lady asked us how we liked them boiled, and taking the one from her head begged us to wear it next our heart for her sake. We received it reverentially at her hand—it was heavy as lead. Her somewhat ambiguous language immediately explained itself as she gaily stripped off the leaves and revealed a good-sized turnip-stock on a wooden skewer. We felt slightly embarrassed, but got over the difficulty by saying that when we spoke so poetically we had no idea what would turn-up.

"Ah!" sighed one of the young ladies, "it is the way of the world; the flower worshipped from afar, possessed, will ever turn out a turnip!"

"Or," added we, "as in the case of Cinderella's humble vegetable turn up, a turnout."

This inoffensive little joke, being rather far-fetched, perhaps, was immediately set upon and almost belabored to death by those who understood it; whilst for the enlightenment of those who did not, we had to travel all the way to fairy-land, so that it was some time before we got back to vegetable flowers—a subject on which we felt not a little anxious to be enlightened, as we saw therein something that might interest our friends who meet by the fireside and help us in our occupation of un[Pg 62]bending the bow. Marvellously simple were the means employed in producing such beautiful results. A white turnip neatly peeled, notched all round, stuck upon a skewer, and surrounded by a few green leaves, and behold a most exquisite white rose, perfect enough to deceive the eye in broad daylight at three feet distance. The above sketch will explain the whole mystery at once.

ROSE IN PROCESS OF MAKING.

ROSE IN PROCESS OF MAKING.

ROSE COMPLETED.

ROSE COMPLETED.

On the same principle a marigold may be cut out of a round of carrot with a little button of beet-root for the centre; a daisy can be made from a round[Pg 63] of parsnip with a small button of carrot for the centre; a dahlia from a beet; and several other flowers from pumpkins. It will be easily seen that a beautiful bouquet can be compiled of these flowers with the addition of a few sprigs of evergreen. Indeed, great taste and ingenuity may be displayed in managing these simple materials. When the process had been explained to us, as above described, we expressed our delight, at the same time saying carelessly that there were doubtless millions of ladies in the country who would find pleasure in learning so graceful an accomplishment. The gen[Pg 64]tleman with the gold spectacles was down upon us in a moment.

"Did we know what a million meant?"

To which we promptly replied that a million meant ten hundred thousand.

"Did we know what a billion meant?"

A billion, according to Webster, was a million million.

A light twinkled out of the gold spectacles, and a glow suffused the expansive forehead, as, with a certain playful severity, he propounded the following:

"How long would it take you to count a million million, supposing you counted at the rate of two hundred per minute for twenty-four hours per day?"

We replied, after a little reflection, that it would take a long time, probably over six months.

With a triumphant air, the gold spectacles turned to our friend Nix. Nix, who is a pretty good accountant, thought it would take nearer six years than six months. One young lady, who was not good at figures, felt sure she could do it in a week. Gold Spectacles exhibited that intense satisfaction which the mathematical mind experiences when it has completely obfuscated the ordinary understanding.[Pg 65]

"Why, sir," he said, turning to us, "had you been born on the same day as Adam, and had you been counting ever since, night and day, without stopping to eat, drink, or sleep, you would not have more than accomplished half your task."

This statement was received with a murmur of incredulous derision, whilst two or three financial gentlemen, immediately seizing pen and paper, began figuring it out, with the following result:

| 200 | Number counted per minute. |

| 60 | Minutes in an hour. |

| ——— | |

| 12000 | Number counted per hour. |

| 24 | Hours in a day. |

| ——— | |

| 48000 | |

| 24000 | |

| ——— | |

| 288000 | Number counted per day. |

| 365 | Days in the year. |

| ———— | |

| 1440000 | |

| 1728000 | |

| 864000 | |

| ————— | |

| 105120000 | Number counted per year. |

From this calculation we see that by counting steadily, night and day, at the rate of two hundred per minute, we should count something over one[Pg 66] hundred and five millions in a year. Now let us proceed with the calculation:

| 105,12(0,000) | 1,000,000,00(0,000(9,512 years. |

| 94,608 | |

| ———— | |

| 53,920 | |

| 52,550 | |

| ———— | |

| 13,600 | |

| 10,512 | |

| ———— | |

| 30,880 | |

| 21,024 | |

| ——— | |

| 9,856 |

So that it would take nine thousand five hundred and twelve years, not to mention several months, to count a billion. Gold Spectacles chuckled visibly, and for the rest of the evening gave himself airs more worthy of a conquered Southerner than a victorious mathematician. He afterwards swooped down upon and completely doubled up a pompous gentleman bearing the cheerful name of Peter Coffin, for making use of the very proper phrase, "As clear as a mathematical demonstration."

"That may not be very clear, after all, Mr. Coffin," said Gold Spectacles.

"How is that, Mr. Sprawl (Gold Specks' proper[Pg 67] name being Sprawl); can anything be clearer than a mathematical demonstration?"

"I think, sir," answered Mr. Sprawl, "I could mathematically demonstrate to you that one is equal to two. What would you think of that, sir?"

"I think you couldn't do it, sir."

Thereupon Mr. Sprawl took a sheet of paper and wrote down the following equation—the celebrated algebraic paradox:

a = x

a x = x2

a x - a2 = x2 - a2

(x - a) × a = (x - a) × (x + a)

a = x + a

a = 2 a

1 = 2

Mr. Coffin examined it carefully standing up, and examined it carefully sitting down, and then handed it back, saying that Mr. Sprawl had certainly proved one to be equal to two. The paper was passed round, and those learned enough scrutinized it carefully. The demonstration all allowed to be positive, yet no one could be made to admit the fact.

Here a certain married lady avowed her great delight in knowing that one had at last been proved equal to two. She had been for years, she said, try[Pg 68]ing to convince her husband of this fact, but he always obstinately refused to listen to the voice of reason. She now trusted he would not have the effrontery to fly in the face of an algebraic paradox.

Seeing the talk had taken an arithmetical turn, and was moreover getting fearfully abstruse, our friend Nix thought he would gently lead the tide of conversation into some shallower channel, wherein the young ladies might dabble their pretty feet without danger of being swept away in the scientific torrent. To this end he submitted the well known problem: "What is the difference between six dozen dozen and half a dozen dozen?" Strange to say, no one present had ever before heard of it, but the best part of the joke consisted in Mr. Sprawl being completely taken by it.

"Why, they are both the same," he answered promptly.

All the rest seemed to think so too, and some could not get into their heads, although poor Nix spent half an hour trying to convince them, that half a dozen dozen was the same thing as six dozen, or 72; whilst six dozen dozen must of course be seventy-two dozen, or 864.

While Nix still spoke, a handmaiden appeared, bearing tinkling cups and vessels of aromatic tea[Pg 69] (not the weak green kind, bear in mind), and plates of sweet cookies and toast, and then bread and butter, and steaming waffles, and divers and sundry other delicacies known to true housewives and good Christian women, who love their fellow-creatures and respect their organs of digestion.

As the tea is being served, we walk up to a young gentleman and ask him if he knows why the blind man was restored to sight when he drank tea. The young gentleman gave it up precipitately.

"Because he took his cup and saucer (saw sir)."

The gentleman in gold spectacles says something about our being a sorcerer, but we heed him not, fearing he may put us through another algebraic paradox. Then comes a general demand for the answer to the charade we published in our last chapter, which commenced:

"The answer to this, ladies, is Rattan; and you will find it," said we, "a most excellent charade for children."

Now commenced a grand festival of puzzles and riddles. Specimens of all kinds were trotted out for inspection, from the ponderous construction of our ancestors, commencing in some such style as, "All round the house, through the house, and never[Pg 70] touching the house," etc., to the neatly turned modern con.

Our friend Nix asked why Moses and the Jews were the best-bred people in the world?

Another wished to know why meat should always be served rare?

Both these individuals, however, refused to give the solution until the next meeting of the assembled company. Others were more obliging, but as their riddles were mostly old friends, somebody knew the answers and revealed them. It is a mistake to suppose that a good thing ought not to be repeated more than once. There are certain funny things that we remember for the last twenty years, and yet we never recall them without enjoying a hearty laugh. We have read Holmes's Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table once every six months, ever since it was published, and enjoy it better each time. We have been working away at the Sparrowgrass Papers for years, and yet we raise just as good a crop of laughter from them as ever. These books resemble some of our rich Western lands: they are inexhaustible. So when one of the company asked, "When does a sculptor die of a fit?" we waited quietly for the answer, "When he makes faces and busts," and laughed as heartily as though it were quite new, although we had been intimate with the[Pg 71] old con ever since it was made, some fifteen years ago. We even enjoyed the time-honored riddle: "What was Joan of Arc made of?" "Why, she was Maid of Orleans, of course." But then this was put by a seraph with amber eyes, and a very bewildering way of using them. The success attending this effort seemed to stimulate the gentleman in gold spectacles, who rushed into the arena with the inquiry: "What was Eve made for?" Most of us knew the answer well enough, but we waited politely to let him deliver it himself. Our surprise may be readily conceived when he informed us, with evident glee, that "she was made for Harnden's Express Company." Some looked blank, and others tittered, whilst Nix explained to the ladies the true solution. It was for Adam's Express Company that Eve was made. After this followed in quick succession a shower of riddles, some of them so abominably bad, that an old gentleman, who did not seem to take kindly to that sort of amusement, gave the finishing-stroke to the entertainment by the annexed:

Question. "Why is an apple-tart like a slipper?"

Answer. "Because you can put your foot in it—if you like."

After that we all went home.

A friend of ours, Dudley Wegger, who recently gave an extemporaneous entertainment, amongst other things, devised a new kind of play, of such exceedingly simple construction that we have judged it expedient to put it on record. It must be observed that it is his method especially which we applaud and recommend, and further be it observed, that we applaud and recommend it on account of no other excellence save that of simplicity.

Mr. Wegger possessed the power of imitating one or two popular actors. He had read our instructions on make-up—viz.: curled hair, turn-up nose, high shoulders, etc., and from these slender materials he made the body of his play. As soon as we arrived, he seized upon ourself, dragged us into a back room, put a hideous mask on our face[Pg 73] (which smelt painfully of glue and brown paper, by the way), and then commanded us to don sundry articles of female attire—to wit, a hat and gown. To our earnest appeals as to what we were to do, he only replied:

"Oh, nothing; just come on the stage, kick about, and answer my questions. You hold the stage and talk to the audience, whilst I go off and change my dress."

This we pledged ourself to do, and were nearly suffocated in the mask as a consequence.

When the curtain rose, Wegger marched on the stage attired in blue coat, brass buttons, striped pantaloons, yellow vest, and stylish hat stuck on one side. In his hand he held a small walking-cane, with which he frequently slapped his leg. This was the walking-gentleman part.

"Egad! here I am at last, after the fastest run across country on record. Slipped the Billies, took flying hollow at a leap, gave my admirable aunt the go-by, extracted the governor's lynch-pin, sent them all sprawling in the ditch, just in time to be picked up by old Hodge, the carrier, jogging along with his blind mare and rumbling old shandrydan. Gad, Mortimer, you are a sad rogue! I must turn over a new leaf, ecod! become steady, forget kissing and claret, go to church, read the Times, and in[Pg 74] fact, become a respectable member of society. Ah, ha, ha! What has brought me here? Gad, I deserve success. Heard from my valet last night that certain lady just come into immense fortune; lovely as she is wealthy, Venus and an heiress; total stranger, no means of procuring introduction; hired coach and four, gave post-boy guinea, told drive like devil, and here I am in a strange country, a strange house, and amongst strange people, to kill or conquer, veni, vidi, vici! Ha! ha! ha! first in the field—fair start and a free run; back myself at long odds to be in at the death. But gad! here she comes, the country Hebe, the pastoral Venus, the naiad of turnip-tops and mangel-wurzel.

Enter Heiress (ourself).

Gad! she is a devilish fine-looking woman. I must approach her (advances). Have I the honor to address the Lady Cicily de Rhino?"

Lady Cicily de Rhino. "You get eout!"

Mortimer (aside). "Charming! Gad! I am over head and ears in love already. Oh, bright divinity, why hide those radiant charms in sylvan shades, when charms of fashion and bon-ton beckon you away! With me your life shall be one live-long summer's day, and you and I two butterflies sipping sweet nectar from the ruby rims of endless brim[Pg 75]ming goblets. Say you'll be mine! A chaise awaits us, and on the wings of love we'll fly away! Say, charmer, say the word, and I am your slave for life."

Lady Cicily de Rhino. "Wal, slavery's bin abolished

even in New Jersey—guess you forgot that.

However, I don't keer if I do; jist hold on till I

git my things."

[Exit.

Mortimer. "Gad! I took the citadel by storm—but

some one approaches; I must withdraw for a moment."

[Withdraws.

Re-enter Lady C., with bundle and umbrella.

Lady C. "Wal, if the young man arn't gone; now that's mean."

Enter Reginald Spooneigh (Wegger, in a new dress).

Reginald. "Kynde fortune has thrown me in the angel's path. The belue skuye already smyles more beounteously on my poor fate. Fayer laydee, turn not away those gentle eyes, that e'en the turtle-dove might sigh, and dying, envy, envying, die of envy."

Lady C. "Oh, git eout!"

Reginald. "Say not so, fair laydee. A wanderer on this cruel earth, a lover of the sweet songs of birds, the murmuring of streams, the gay garb of nature, from mighty mountain-tops to rustling[Pg 76] glens. I bring an aching spirit seeking sympathy to thee."

Lady C. "Dew tell!"

Reginald. "A sympathetic heart within your bosom burns; say, let it beat in unison with mine?"

Lady C. "Well, I don't keer if I do; only hurry up, there's some one coming."

Reginald. "Coming? sayest though; then will

I retire for a brief space."

[Retires.

Lady C. "He seems a pretty nice kind or young man, tho' he ain't got so much style into him as tother feller. Wal, them folks didn't come this way arter all, so he'd no call to be so scart," etc., etc.

Enter General Hab-grabemall (Wegger again).

General. "Thunder and Mars! I thought I should never have got here. Road as dusty as a canteen of ashes; coach as slow as a commissary mule. Had half a mind to bivouac on the roadside—make a fire of the axletrees, and roast the postilion for dinner. But shells and rockets! I must beat up the quarters of this fair one, or some jackanapes civilian will be stealing a march upon me (sees Lady C.). Gad! there she is! I must make a charge on her left wing. Hey! my little[Pg 77] beauty, here's a battered old soldier, wounded everywhere except in his heart, crying surrender at your first fire. He yields himself prisoner-of-war, and gives up his untarnished sword to you and you alone."

Lady C. "Wal, I ain't no use for swords, and there are summeny solgers straggling round now with old weppins—"

General. "I have fought for my king and country through many a burning summer noon, and many an Arctic winter night, and now I would plant my laurels in the sunshine of your eyes, that they may bring forth bright blossoms."

Lady C. "Wal, if them's the case, they makes a difference."