GENEROSITY.

Andrew (preparing to divide the orange). "Will you choose the Big half, Georgie, or the Wee half?"

George. "'Course I'll choose the Big half."

Andrew (with resignation). "Then I'll just have to make 'em even."

August 1st.—Deer-shooting in Victoria Park commences.

2nd.—Distribution of venison to "Progressive" County Councillors and their families—especially to Aldermen.

3rd.—Stalking American bison in the Marylebone disused grave-yard is permitted from this day. A staff of competent surgeons will be outside the palings.

4th.—Chamois-coursing in Brockwell Park.

5th.—A few rogue elephants having been imported (at considerable expense to the rates), and located in the Regent's Park, the Chairman of the L. C. C., assisted by the Park-keepers, will give an exhibition of the method employed in snaring them. The elephants in the Zoological Gardens will be expected to assist.

6th.—Bank Holiday.—Popular festival on Hampstead Heath. Two herds of red deer will be turned on to the Heath at different points, and three or four specially procured man-eating Bengal tigers will be let loose at the Flag-staff to pursue them. Visitors may hunt the deer or the tigers, whichever they prefer. Express rifles recommended, also the use of bullet-proof coats. No dynamite to be employed against the tigers. Ambulances in the Vale of Health. The Council's Band, up some of the tallest trees, will perform musical selections.

7th.—Races at Wormwood Scrubbs between the Council's own ostriches and leading cyclists. A force of the A1 Division of the Metropolitan Police, mounted on some of the reindeer from the enclosure at Spring Gardens, will be stationed round the ground to prevent the ostriches escaping into the adjoining country.

8th.—Sale of ostrich feathers (dropped in the contests) to West-End bonnet-makers at Union prices.

9th.—Grand review of all the Council's animals on Clapham Common. Procession through streets (also at Union rate). Banquet on municipal venison, tiger chops, elephant steaks, and ostrich wings at Spring Gardens. Progressive fireworks.

Andrew (preparing to divide the orange). "Will you choose the Big half, Georgie, or the Wee half?"

George. "'Course I'll choose the Big half."

Andrew (with resignation). "Then I'll just have to make 'em even."

Rather a change—for the better.—They (the dockers) wouldn't listen to Ben Tillett. They cried out to him, "We keep you and starve ourselves." Hullo! the revolt of the sheep! are they beginning to think that their leaders and instigators are after all not their best friends? "O Tillett not in Gath!" And Little Ben may say to himself, "I'll wait Till-ett's over."

V.—School. "A Distant View."

"Distance lends enchantment"—kindly Distance!

Wiping out all troubles and disgraces,

How we seem to cast, with your assistance,

All our boyish lines in pleasant places!

Greek and Latin, struggles mathematic,

These were worries leaving slender traces;

Now we tell the boys (we wax emphatic)

How our lines fell all in pleasant places.

How we used to draw (immortal Wackford!)

Euclid's figures, more resembling faces,

Surreptitiously upon the black-board,

Crude yet telling lines in pleasant places.

Pleasant places! That was no misnomer.

Impositions?—little heed scape-graces;

Writing out a book or so of Homer,

Even those were lines in pleasant places!

How we scampered o'er the country, leading

Apoplectic farmers pretty chases,

Over crops, through fences all unheeding,

Stiff cross-country lines in pleasant places.

Yes, and how—too soon youth's early day flies—

In the purling brook which seaward races

How we used to poach with luscious May-flies,

Casting furtive lines in pleasant places.

Then the lickings! How we took them, scorning

Girlish outcry, though we made grimaces;

Only smiled to find ourselves next morning

Somewhat marked with lines in pleasant places!

Alma Mater, whether young or olden,

Thanks to you for hosts of friendly faces,

Treasured memories, days of boyhood golden,

Lines that fell in none but pleasant places!

["Mr. Asquith said that he was informed by the Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police that undoubtedly numerous accidents were caused by bicycles and tricycles, though he was not prepared to say from the cause of the machines passing on the near instead of the off side of the road. Bicycles and tricycles were carriages, and should conform to the rules of the road, and the police, as far as possible, enforced the law as to riding to the common danger."—Daily Graphic, July 25.]

Round the omnibus, past the van,

Rushing on with a reckless reel,

Darts that horrible nuisance, an

Ardent cyclist resolved that he'll

Ride past everything he can,

Heed not woman, or child, or man,

Beat some record, some ride from Dan

To Beersheba; that seems his plan.

Why does not the Home Office ban

London fiends of the whirling wheel?

Let them ride in the country so,

Dart from Duncansbay Head to Deal,

Shoot as straight as the flight of crow,

Sweep as swallow that seeks a meal,

We don't care how the deuce they go,

But in thoroughfares where we know

Cyclists, hurrying to and fro,

Make each peaceable man their foe,

Riders, walkers alike cry "Whoa!

Stop these fiends of the whirling wheel!"

Amid the glowing pageant of the year

There comes too soon th' inevitable shock,

That token of the season sere,

To the unthinking fair so cheaply dear,

Who, like to shipwreck'd seamen, do it hail,

And cry, "A Sale! a Sale!

A Sale! a Summer Sale of Surplus Stock!"

See, how, like busy-humming bees

Around the ineffable fragrance of the lime,

Woman, unsparing of the salesman's time,

Reviews the stock, and chaffers at her ease,

Nor yet, for all her talking, purchases,

But takes away, with copper-bulgèd purse,

The textile harvest of a quiet eye,

Great bargains still unbought, and power to buy.

Or she, her daylong, garrulous labour done,

Some victory o'er reluctant remnants won,

Fresh from the trophies of her skill,

Things that she needed not, nor ever will,

She takes the well-earned bun;

Ambrosial food, Demeter erst design'd

As the appropriate food of womankind,

Plain, or with comfits deck'd and spice;

Or, daintier, dallies with an ice.

Nor feels in heart the worse

Because the haberdashers thus disperse

Their surplus stock at an astounding sacrifice!

Yet Contemplation pauses to review

The destinies that meet the silkworm's care,

The fate of fabrics whose materials grew

In the same fields of cotton or of flax,

Or waved on fellow-flockmen's fleecy backs,

And the same mill, loom, case, emporium, shelf, did share.

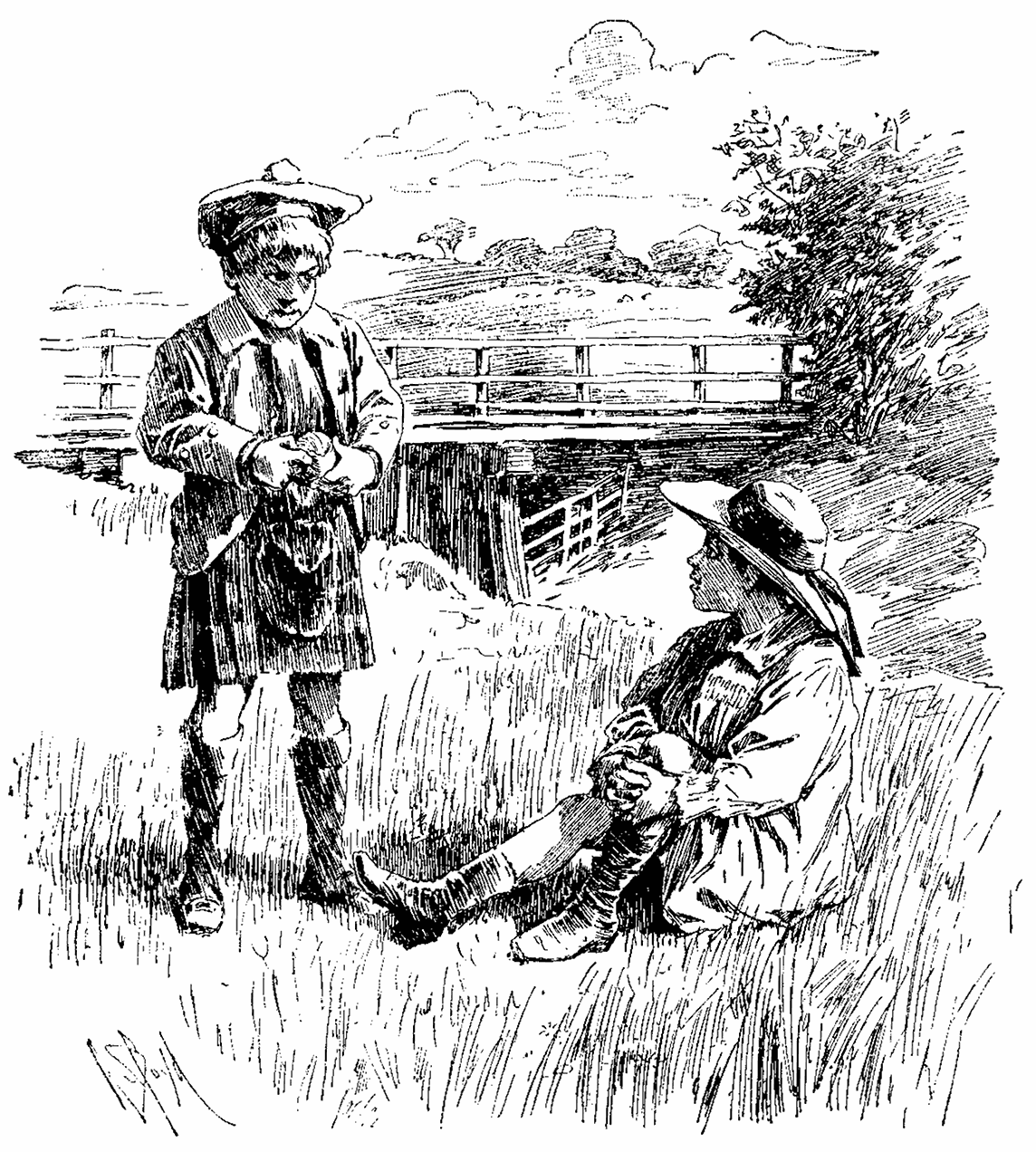

Scene—Hunters cantering round Show Ring.

Youth on hard-mouthed Grey (having just cannoned against old Twentystun). "'Scuse me, Sir,—'bliged to do it. Nothing less than a Haystack stops him!"

(For Use in Rotten Row.)

Question. What part of London do you consider the most dangerous for an equestrian?

Answer. That part of the Park known as Rotten Row.

Q. Why is it so dangerous?

A. Because it is overcrowded in the Season, and at all times imperfectly kept.

Q. What do you mean by "imperfectly kept"?

A. I mean that the soil is not free from bricks and other impediments to comfortable and safe riding.

Q. Why do you go to Rotten Row?

A. Because it is the most convenient place in London for the residents of the West End.

Q. But would not Battersea Park do as well?

A. It is farther afield, and at present, so far as the rides are concerned, given over to the charms of solitude.

Q. And is not the Regent's Park also available for equestrians?

A. To some extent; but the roads in that rather distant pleasaunce are not comparable for a moment with the ride within view of the Serpentine.

Q. Would a ride in Kensington Gardens be an advantage?

A. Yes, to some extent; still it would scarcely be as convenient as the present exercising ground.

Q. Then you admit that there are (and might be) pleasant rides other than Rotten Row?

A. Certainly; but that fact does not dispense with the necessity of reform in existing institutions.

Q. Then you consider the raising of other issues is merely a plan to confuse and obliterate the original contention?

A. Assuredly; and it is a policy that has been tried before with success to obstructors and failure to the grievance-mongers.

Q. So as two blacks do not make one white you and all believe that Rotten Row should be carefully inspected and the causes of the recent accidents ascertained and remedied?

A. I do; and, further, am convinced that such a course would be for the benefit of the public in general and riders in Rotten Row in particular.

'Tis a norrible tale I'm a-going to narrate;

It happened—vell, each vone can fill in the date!

It's a heartrending tale of three babbies so fine.

Whom to spifflicate promptly their foes did incline.

Ven they vos qvite infants they lost their mamma;

They vos left all alone in the vorld vith their pa.

But to vatch o'er his babbies vos always his plan—

(Chorus)—

'Cos their daddy he vos sich a keerful old man!

He took those three kiddies all into his charge,

And kep them together so they shouldn't "go large."

Two hung to his coat-tails along the hard track.

And the third one, he clung to his neck pick-a-back.

The foes of those kiddies they longed for their bleed,

And they swore that to carry 'em he shouldn't succeed,

But to save them poor babbies he hit on a plan—

(Chorus)—

'Cos their dadda he vos sich a artful old man!

Some hoped, from exposure, the kids would ketch cold,

And that croup or rheumatics would lay 'em in the mould;

But they seemed to survive every babbyish disease,

Vich their venomous enemies did not qvite please.

But, in course, sich hard lines did the kiddies no good;

They got vet in the storm, they got lost in the vood,

But their dad cried, "I'll yet save these kids if I can!"—

(Chorus)—

'Cos their feyther he vos sich a dogged old man!

Foes hoped he'd go out of his depth,—or his mind,—

Or, cutting his stick, leave his babbies behind,

Ven they came to the margin of a vide roaring stream.

And the kids, being frightened, began for to scream.

But he cries, cheery like, "Stash that hullabulloo!

Keep your eye on your father, and he'll pull you through!!"—

Vich some thinks he vill do—if any von can—

(Chorus)—

'Cos Sir Villyum he is sich a walliant old man!

(A Story in Scenes.)

PART V.—CROSS-PURPOSES.

Scene VI.—A First-Class Compartment.

Lady Maisie (to herself). Poets don't seem to have much self-possession. He seems perfectly overcome by hearing my name like that. If only he doesn't lose his head completely and say something about my wretched letter!

Spurrell (to himself). I'd better tell 'em before they find out for themselves. (Aloud; desperately.) My lady, I—I feel I ought to explain at once how I come to be going down to Wyvern like this.

[Lady Maisie only just suppresses a terrified protest.

Lady Cantire (benignly amused). My good Sir, there's not the slightest necessity, I am perfectly aware of who you are, and everything about you!

Spurr. (incredulously). But really I don't see how your ladyship——Why, I haven't said a word that——

Lady Cant. (with a solemn waggishness). Celebrities who mean to preserve their incognito shouldn't allow their friends to see them off. I happened to hear a certain Andromeda mentioned, and that was quite enough for Me!

Spurr. (to himself, relieved). She knows; seen the sketch of me in the Dog Fancier, I expect; goes in for breeding bulls herself, very likely. Well, that's a load off my mind! (Aloud.) You don't say so, my lady. I'd no idea your ladyship would have any taste that way; most agreeable surprise to me, I can assure you!

Lady Cant. I see no reason for surprise in the matter. I have always endeavoured to cultivate my taste in all directions; to keep in touch with every modern development. I make it a rule to read and see everything. Of course, I have no time to give more than a rapid glance at most things; but I hope some day to be able to have another look at your Andromeda. I hear the most glowing accounts from all the judges.

Spurr. (to himself). She knows all the judges! She must be in the fancy! (Aloud.) Any time your ladyship likes to name I shall be proud and happy to bring her round for your inspection.

Lady Cant. (with condescension). If you are kind enough to offer me a copy of Andromeda, I shall be most pleased to possess one.

Spurr. (to himself). Sharp old customer, this; trying to rush me for a pup. I never offered her one! (Aloud.) Well, as to that, my lady, I've promised so many already, that really I don't—but there—I'll see what I can do for you. I'll make a note of it; you mustn't mind having to wait a bit.

Lady Cant. (raising her eyebrows). I will make an effort to support existence in the meantime.

Lady Maisie (to herself). I couldn't have believed that the man who could write such lovely verses should be so—well, not exactly a gentleman! How petty of me to have such thoughts. Perhaps geniuses never are. And as if it mattered! And I'm sure he's very natural and simple, and I shall like him when I know him.

[The train slackens.

Lady Cant. What station is this? Oh, it is Shuntingbridge. (To Spurrell, as they get out.) Now, if you'll kindly take charge of these bags, and go and see whether there's anything from Wyvern to meet us—you will find us here when you come back.

Scene VII.—On the Platform at Shuntingbridge.

Lady Cant. Ah, there you are, Phillipson! Yes, you can take the jewel-case; and now you had better go and see after the trunks. (Phillipson hurries back to the luggage-van; Spurrell returns.) Well, Mr.—I always forget names, so shall call you "Andromeda"—have you found——The omnibus, is it? Very well, take us to it, and we'll get in.

[They go outside.

Undershell (at another part of the platform—to himself). Where has Miss Mull disappeared to? Oh, there she is, pointing out her luggage. What a quantity she travels with! Can't be such a very poor relation. How graceful and collected she is, and how she orders the porters about! I really believe I shall enjoy this visit. (To a porter.) That's mine—the brown one with a white star. I want it to go to Wyvern Court—Sir Rupert Culverin's.

Porter (shouldering it). Right, Sir. Follow me, if you please.

[He disappears with it.

Und. (to himself). I mustn't leave Miss Mull alone. (Advancing to her.) Can I be of any assistance?

Phillipson. It's all done now. But you might try and find out how we're to get to the Court.

[Undershell departs; is requested to produce his ticket, and spends several minutes in searching every pocket but the right one.

Scene VIII.—The Station Yard at Shuntingbridge.

Lady Cant. (from the interior of the Wyvern omnibus, testily, to Footman). What are we waiting for now? Is my maid coming with us—or how?

Footman. There's a fly ordered to take her, my lady.

Lady Cant. (to Spurrell, who is standing below). Then it's you who are keeping us!

Spurr. If your ladyship will excuse me, I'll just go and see if they've put out my bag.

Lady Cant. (impatiently). Never mind about your bag. (To Footman.) What have you done with this gentleman's luggage?

Footman. Everything for the Court is on top now, my lady.

[He opens the door for Spurrell.

Lady Cant. (to Spurrell, who is still irresolute). For goodness' sake don't hop about on that step! Come in, and let us start.

Lady Maisie. Please get in—there's plenty of room!

Spurr. (to himself). They are chummy, and no mistake! (Aloud, as he gets in.) I do hope it won't be considered any intrusion—my coming up along with your ladyships, I mean!

Lady Cant. (snappishly). Intrusion! I never heard such nonsense! Did you expect to be asked to run behind? You really mustn't be so ridiculously modest. As if your Andromeda hadn't procured you the entrée everywhere!

[The omnibus starts.

Spurr. (to himself). Good old Drummy! No idea I was such a [pg 053] swell. I'll keep my tail up. Shyness ain't one of my failings. (Aloud to an indistinct mass at the further end of the omnibus, which is unlighted.) Er—hum—pitch dark night, my lady, don't get much idea of the country! (The mass makes no response.) I was saying, my lady, it's too dark to—— (The mass snores peacefully.) Her ladyship seems to be taking a snooze on the quiet, my lady. (To Lady Maisie.) (To himself.) Not that that's the word for it!

Lady Maisie (distantly). My Mother gets tired rather easily. (To herself.) It's really too dreadful; he makes me hot all over! If he's going to do this kind of thing at Wyvern! And I'm more or less responsible for him, too! I must see if I can't——It will be only kind. (Aloud, nervously.) Mr.—Mr. Blair!

Spurr. Excuse me, my lady, not Blair—Spurrell.

Lady Maisie. Of course, how stupid of me. I knew it wasn't really your name. Mr. Spurrell, then, you—you won't mind if I give you just one little hint, will you?

Spurr. I shall take it kindly of your ladyship, whatever it is.

Lady Maisie (more nervously still). It's really such a trifle, but—but, in speaking to Mamma or me, it isn't at all necessary to say 'my lady' or 'your ladyship.' I—I mean, it sounds rather, well—formal, don't you know!

Spurr. (to himself). She's going to be chummy now! (Aloud.) I thought, on a first acquaintance, it was only manners.

Lady Maisie. Oh—manners? yes, I—I daresay—but still—but still—not at Wyvern, don't you know. If you like, you can call Mamma 'Lady Cantire,' and me 'Lady Maisie,' and, of course, my Aunt will be 'Lady Culverin,' but—but if there are other people staying in the house, you needn't call them anything, do you see?

Spurr. (to himself). I'm not likely to have the chance! (Aloud.) Well, if you're sure they won't mind it, because I'm not used to this sort of thing, so I put myself in your hands,—for, of course, you know what brought me down here?

Lady Maisie (to herself). He means my foolish letter! Oh, I must put a stop to that at once! (In a hurried undertone.) Yes—yes; I—I think I do. I mean, I do know—but—but please forget it—indeed you must!

Spurr. (to himself). Forget I've come down as a vet? The Culverins will take care I don't forget that! (Aloud.) But, I say, it's all very well; but how can I? Why, look here; I was told I was to come down here on purpose to——.

Lady Maisie (on thorns). I know—you needn't tell me! And don't speak so loud! Mamma might hear!

Spurr. (puzzled). What if she did? Why, I thought her la—your Mother knew!

Lady Maisie (to herself). He actually thinks I should tell Mamma! Oh, how dense he is! (Aloud.) Yes—yes—of course she knows—but—but you might wake her! And—and please don't allude to it again—to me or—or anyone. (To herself.) That I should have to beg him to be silent like this! But what can I do? Goodness only knows what he mightn't say, if I don't warn him!

Spurr. (nettled). I don't mind who knows. I'm not ashamed of it, Lady Maisie—whatever you may be!

Lady Maisie (to herself, exasperated). He dares to imply that I've done something to be ashamed of! (Aloud; haughtily.) I'm not ashamed—why should I be? Only—oh, can't you really understand that—that one may do things which one wouldn't care to be reminded of publicly? I don't wish it—isn't that enough?

Spurr. (to himself). I see what she's at now—doesn't want it to come out that she's travelled down here with a vet! (Aloud, stiffly.) A lady's wish is enough for me at anytime. If you're sorry for having gone out of your way to be friendly, why, I'm not the person to take advantage of it. I hope I know how to behave.

[He takes refuge in offended silence.

Lady Maisie (to herself). Why did I say anything at all! I've only made things worse—I've let him see that he has an advantage. And he's certain to use it sooner or later—unless I am civil to him. I've offended him now—and I shall have to make it up with him!

Spurr. (to himself). I thought all along she didn't seem as chummy as her mother—but to turn round on me like this!

Lady Cant. (waking up). Well, Mr. Andromeda, I should have thought you and my daughter might have found some subject in common; but I haven't heard a word from either of you since we left the station.

Lady Maisie (to herself). That's some comfort! (Aloud.) You must have had a nap, Mamma. We—we have been talking.

Spurr. Oh yes, we have been talking, I can assure you—er—Lady Cantire!

Lady Cant. Dear me. Well, Maisie, I hope the conversation was entertaining?

Lady Maisie. M-most entertaining, Mamma!

Lady Cant. I'm quite sorry I missed it. (The omnibus stops.) Wyvern at last! But what a journey it's been, to be sure!

Spurr. (to himself). I should just think it had. I've never been so taken up and put down in all my life! But it's over now; and, thank goodness, I'm not likely to see any more of 'em!

[He gets out with alacrity.

She (engaged to another). "We don't seem to be getting on very well; something seems to be weighing us down!"

He (gloomily). "It's that Diamond and Sapphire Ring on your left hand. We should be all right if it weren't for that!"

Mrs. R. has often had a cup of tea in a storm, but she cannot for the life of her see how there can possibly be a storm in a tea-cup. [pg 054]

Hostess. "You've eaten hardly anything, Mr. Simpkins!"

Mr. S. "My dear lady, I've Dined 'wisely, but not too well!'"

["Russia's love of peace is outweighed by her duty to safeguard her vital interests, which would seriously suffer were Japan or China to modify the present state of things in Corea."—Official Russian view of the Corean situation, given by "Daily Telegraph" Correspondent at St. Petersburg.]

Bruin, loquitur.

"Duty to safeguard my interests?" Quite so!

Nice way of putting it, yes, and so moral!

Yet I love Peace! Pity game-cocks will fight so!

Disfigures their plumes and their combs' healthy "coral."

Big Cochin-China and Bantam of Jap

Feel at each other they must have a slap.

Cock-a-doodle-do-o-o-o!!!

Humph! I must keep a sharp eye on the two!

Peace, now! She is such a loveable darling!

Goddess I worship in rapt contemplation.

Spurring and crowing, and snapping and snarling,

Wholly unworthy a bird—or a nation!

Still there is Duty! I have an idea

Mine lies in watching this fight in Corea.

Cock-a-doodle-do-o-o-o!!!

Bull yonder looks in a bit of a stew!

Some say my destiny pointeth due North,

Ice-caves are all very well—for a winter-rest.

But Bruin's fond of adventuring forth;

In the "Far East" he feels quite a warm interest;

Bull doesn't like it at all. But then Bull

Fancies that no one should feed when he's full!

Cock-a-doodle-do-o-o-o!!!

I am still hungry, and love chicken-stew!

To make the Corea a cock-pit, young Jappy,

May suit you, or even that huge Cochin-China;

But—fighting you know always makes me unhappy.

I feel, like poor Villikins robbed of his Dinah,

As if I could swallow a cup of "cold pison."—

But—still—these antagonists I must keep eyes on.

Cock-a-doodle-do-o-o-o!!!

Cockfighting is cruel,—but stirring fun, too!

Duty, dear boys! Ah! there's nothing like Duty.

Gives one "repose"—like that Blacksmith of Longfellow!

Go it, young Jap! That last drive was a beauty.

But—your opponent's an awfully strong fellow.

Little bit slow at first, sluggish and lumbering,

But when he makes a fair start there's no slumbering.

Cock-a-doodle-do-o-o-o!!!

Sakes! How his new steel spurs shone as he flew!

Now, should I stop it, or should I take sides?

Bull and the other onlookers seem fidgety!

Cochin strikes hard, but indulges in "wides";

Game-cock is game—though a little mite midgety.

Well, whate'er the end be, and whichever win,

I think the game's mine, when I choose to cut in.

Cock-a-doodle-do-o-o-o!!!

I'm safe for a dinner—off one of the two!

[Left considering and chortling.

(Dedicated (without permission) to the Pioneer Club)

Rouse ye, ye women, and flock to your banners!

War is declared on the enemy, Man!

If we can't teach him to better his manners,

We'll copy the creature as close as we can!

No longer the heel of the tyrant shall grind us.

Rouse ye and rally! The despot defy!

And the false craven shall tremble to find us

Resolved to a woman to do or to die.

Chorus.

Then hey! for the latchkey, sweet liberty's symbol!

Greet it, ye girls, with your lustiest cheer!

Away with the scissors! Away with the thimble!

And hey nonny no for the gay Pioneer!

Why should we writhe on a clumsy side-saddle

Designed on a most diabolical plan?

Women! submit ye no longer! Ride straddle,

And jump on the corns of your enemy, Man!

Storm the iniquitous haunts of his pleasure,

Leave him to nurse the dear babes when they fret,

Dine at St. James' in luxurious leisure,

And woo the delights of the sweet cigarette!

Look to your latchkeys! The whole situation

Upon the possession of these will depend.

Use them, ye women, without hesitation,

And dine when ye will with a gentleman friend.

Man's a concoction of sin and of knavery—

Women of India, China, Japan!

Rouse ye, and end this inglorious slavery!

Down with the tyrant! Down, down with the Man!

(Compiled by our Pet Pessimist.)

If you imagine that it will be fine, and consequently that you can don the lightest of attire, you may be sure that it will be cold and wet, and absolutely unsuitable to travelling.

If you fancy that you will enjoy a delightful visit to some intimate friends, you will find that you have had your journey to a spot "ten miles from anywhere" for nothing, as your intended hosts have gone abroad for the season.

If you believe that you are seeing a favourite piece being played admirably at a West End theatre, you will discover that the programme was altered four days ago, and that the temple of the drama will not reopen until the autumn.

If you arrange to go abroad with a friend, you will quarrel with your acquaintance on the following morning, and disarrange your plans for a lifetime.

Lastly, if you dream that you have decided to give up gadding about on a bank holiday to remain at home, you will see that it is better to follow your fancy, and avoid the risk of making a mistake by adventuring to strange places and pastures new.

"Well, good-bye for the present, Dearest! I hope you'll be quite well and strong when I can next come and see you."

"Oh, I hope I shall be well and strong enough to be away before that!"

(A Surrey Rondel.)

In sheer delight I sing the country's praise.

The town no longer takes me day or night.

'Mid scented roses one should loll and laze

In sheer delight.

The corn fields unto harvest glisten white,

In pastures lowing kine contented graze.

Per train (South-Eastern) now to wing his flight

No lover of the Surrey side delays.

My own case you suggest? Of course you're right.

Which p'r'aps explains why I to spend my days

In Shere delight!

"Sortes Aquaticæ"; or, Maxim for the Maidenhead Regatta.—After a rattling race with Kilby of Staines (who was worn to a standstill), and Cohen of Maidenhead (who pitched overboard), Verity of Weybridge easily retained the Upper Thames Single Punting Championship. Why, cert'n'ly! What says the old Latin saw? Magna est Veritas, et prævalebit! Which (obviously) means:—Great is Verity, and he shall prevail!

BY G***GE M*R*D*TH.

Volume II.

The die was now a-casting. Hurtled though devious windings far from ordered realms where the Syntax Queen holds sway, spinning this way and that like the whipped box-wood beloved of youth but deadly to the gout-ridden toes of the home-faring Alderman, now sinking to a fall, now impetuously whirled on a devil-dance, clamorous as Cocytus, the lost souls filling it to the brink, at last the meaning glimmered to the eye—not that wherein dead time hung just above the underlids, but the common reading eye a-thirst for meanings, baffled again and again and drooping a soporific lid slowly, nose a-snore, and indolent mind lapped in slumber. They discussed it.

"Am I a Literary Causerie?" breathed Aminta.

"No, but food for such."

"And if I am?" she said.

"Turgidity masquerading as depth. Was ever cavalry general so tortured into symbolism?"

"I remain," she insisted.

"I go to Paris," was his retort.

"My aunt stays with me."

"Thank Heaven!" he muttered.

The design was manifest. Who should mistake it? For a fencer plays you the acrobat, a measure he, poised on a plum-box with jargon-mouth agape for what shall come to it. Is the man unconscious? The worse his fate. For the fact is this. All are Meredithians in dialogue, tarred with one brush abysmally plunged in the hot and steaming tank, a general tarred, a tarred tutor, a tarred sister, aunt reeking of the tar and General's Doubtful Lady chin-deep in the compound, and no distinction.

Clatter, crash, bang. Helter-skelter comes dashing Lady Charlotte, a forest at her heels dragged in chains for all a neighbour may pout and fret and ride to hounds. She switched him a brat-face patter-down of an apology tamed to the net-ponds of a busk-madder, blue nose vermilion, mannish to the outside, breathing flames and scattering apish hop-poles like a parachute blown into space by the bellows of a hugger-mugger conformity. "I can mew," she said. "Old women can; it's a way they have. The person you call ... but no—I pass it. Was ever such folly in a man? And that man my brother Rowsley. But you have seen her you say—a Spaniard—Ay de mi; Señorita, and the rest of the gibberish. What is her colour?"

The question flicked him like a hansom's whip, that plucks you out an optic, policeman in helmet looking on, stolid on the mumchance. Out it goes at whip-end and no remedy, blue, green, brown or bloodshot. Glass can imitate or porcelain, and a pretty trade's a-doing in these, making a man like two light-houses, one fixed as fate, the other revolving like the earth on its axis.

"Brown," he answered, humbly.

"Morsfield's after her," said Lady Charlotte.

"Let him."

"But he's dangerous."

"I can trounce such. Did it at school, and can remember the trick."

A lady came moving onward. She had that in her gait which showed command, her bonnet puckered to the front, a fat aunt trailing behind. They came steadily. It was Aminta with her aunt.

Lord Ormont, his temper ablaze like his manuscript, thirty-four pages, neither more nor less, fortifications planned, advice given gratis to the loutish neglecting nation, stepped forward.

"You must remove her," he declared to Weyburn.

"But the aunt?" questioned Matey.

"She must go too. See to it quickly!" He fell back, the irrevocable quivering in his eyeball, destiny mocking with careless glee, while Morsfield and a bully-captain saw their chances and just missed the taking.

Away they clattered, Matey and Aminta, leaving the Pagnell to her passion-breathing Morsfield.

End of Vol. II.

Solo and Chorus.

The Opera time began in May,

And ended but last Saturday.

We hope it has been made to pay

Chorus. Augustus Druriolanus!

Solo. Not in the days of Mario

Was there an Impresario,

Arranger of scenario,

Who knew so "where he are!" he o-

peratical campaign can plan

With sure success! no better man

For operatic venture than

Chorus (in unison). Augustus Druriolanus!

All.

The Opera time, &c. (as above).

Maxim for Cyclists.—"Try-cycle before you Buy-cycle."

(A Seasonable Suggestion.)

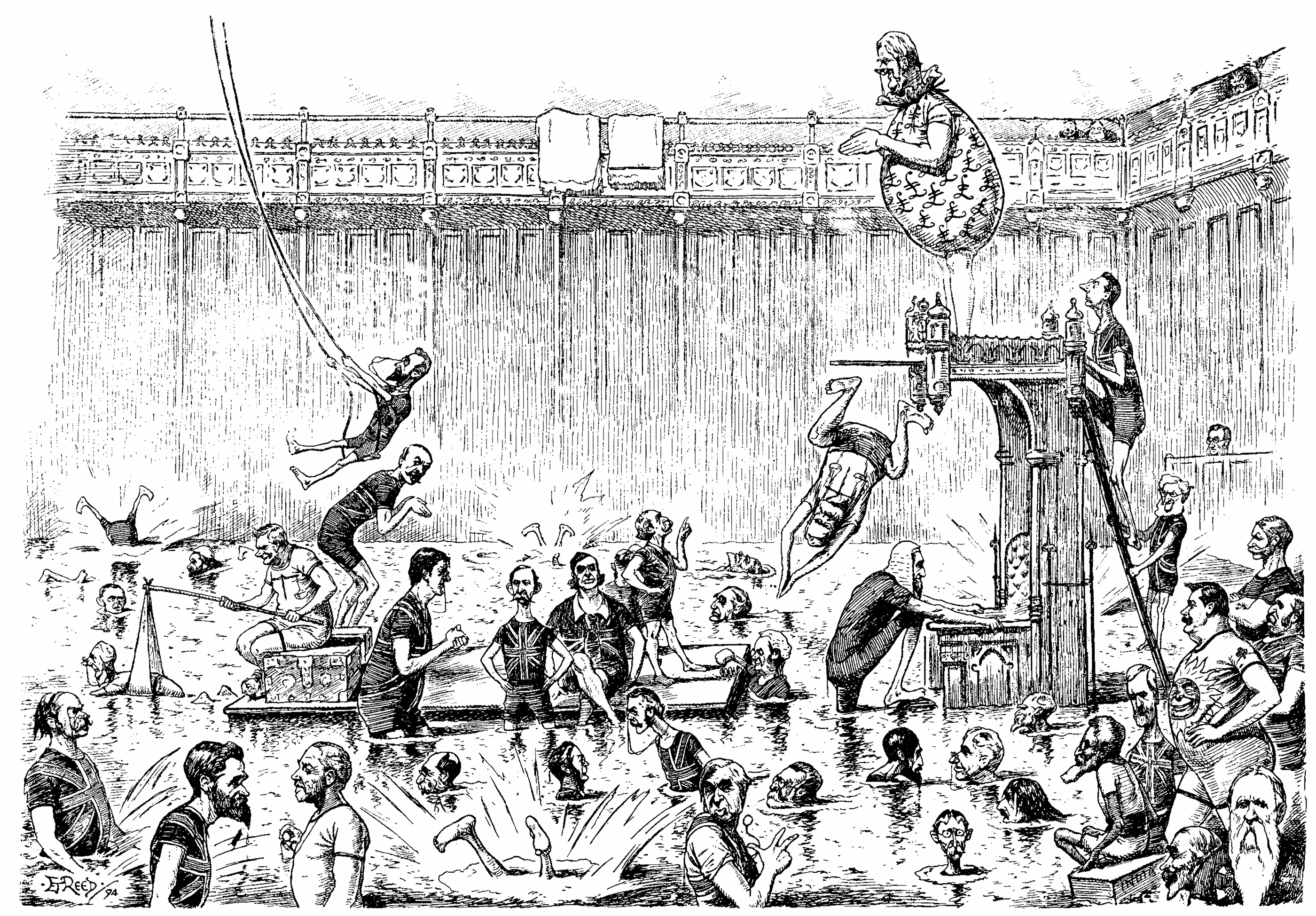

"It is proposed to establish Baths at the Houses of Parliament for the use of Members."—Daily Press.

Non-Golfer (middle-aged, rather stout, who would like to play, and has been recommended it as healthy and amusing). "Well, I cannot see where the Excitement comes in in this Game!"

Caddie. "Eh, mon, there's more Swearing used over Golf than any other Game! D'ye no ca' that Excitement?"

EXTRACTED FROM THE DIARY OF TOBY, M.P.

House of Commons, Monday, July 23.—Quite like old times to hear Tim Healy saying a few plain things about landlords; Prince Arthur replying; Tim growling out occasional contradiction; whilst O'Brien hotly interrupts. To make the reminiscence complete Joseph contributes a speech in which he heaps contumely and scorn on representatives of Irish nationality. Tim reminds him how different was his attitude, how varied his voice, at epoch of Kilmainham Treaty.

Tim has a rough but effective way of fastening upon a name or phrase, and even blatantly reiterating it. Thus, when Old Morality, in his kindly manner, once alluded to a visit paid to him at a critical time by his "old friend Mr. Walter," Tim leaped down upon it, and, characteristically leaving out the customary appellation, filled the air with scornful reference to "my old friend Walter." To-night, desiring to bring into sharp contrast Joseph's present attitude towards Ireland and the landlord party with that assumed by him twelve years ago, he insisted upon calling the Arrears Bill of 1882 "the Chamberlain Act." It wasn't Joseph's personal possession or invention any more than it was the Squire of Malwood's. But that way of putting it doubly suited Tim's purpose. It permitted him, without breach of order, to allude by name to the member for West Birmingham; there's a good deal in a name when the syllables are hissed forth with infinite hate and scorn. Also it accentuated the changed position vis-à-vis Ireland to which further reflection and honest conviction have brought the prime mover in the Kilmainham Treaty.

Irish Members, forgetting their own quarrels with Tim as he fustigated the common enemy, roared with delight. A broad smile lighted up the serried ranks of the Liberals. Prince Arthur wore a decorous look of sympathy with his wronged right hon. friend. The Duke of Devonshire,—"late the Leader of the Liberal Party,"—from the Peers' Gallery surveyed the scene with stolid countenance. Joseph, orchid-decked, sat in his corner seat below the gangway, staring straight before him as one who saw not neither did he hear.

Business done.—Tim Healy goes on the rampage. Evicted Tenants Bill read second time.

Tuesday.—As has been noted on an earlier occasion, Britannia has no bulwarks, no towers along her steep. It is, consequently, the more comforting to know that Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett (Knight) keeps his eye on things abroad as they affect the interests of British citizens. The Member for Sark tells me he has a faded copy of the Skibbereen Eagle containing its famous note of warning to Napoleon the Third. Was published at time of the irruption of Colonels. These gentlemen, sitting on boulevards sipping absinthe, used to twirl their moustache and—sacrrée!—growl hints of what they would do when they as conquerors walked down Piccadillee, and rioted in the riches of Leestar Square.

Napoleon the Third did not escape suspicion of fanning this flame. Howbeit the Skibbereen Eagle came out one Saturday morning with a leading article commencing: "We have our eye on Napoleon the Third, Emperor of the French."

Thus Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett (Knight) digs eagle claws into the aerie heights of the Clock Tower, and watches over the interests and cares of an Empire on which the sun rarely sets.

"All the kinder of him," Sark says, "since they cannot be said directly to concern him. In an effort to redress the balance between the Old World and the New, United States has lent us Ashmead. The temporary character of the arrangement makes only the more generous his concern for the interests of the Empire in which he lodges."

In the peculiar circumstances of the case those able young men, Edward Grey and Sydney Buxton, might be a little less openly contemptuous in their treatment of the Patriotic Emigrant. Hard to say at which office door, Foreign or Colonial, Ashmead bangs his head with more distressful result. He takes them in succession, with dogged courage that would in anyone else excite admiration. Of the two janitors, perhaps Edward Grey's touch is the lightest. He replies with a solemn gravity that puzzles Ashmead, and keeps him brooding till Speaker stays the merry laughter of the House by calling on the next question. Buxton is more openly contemptuous, more severely sarcastic, and sometimes, when Ashmead's prattling, of no consequence in the House, might possibly have serious effect when cabled to the Transvaal where they think all Members of Parliament are responsible men, he smartly raps out. Between the [pg 060] two the Patriot—made in Brooklyn, plated in Sheffield—has a bad time of it. Has long learned how much sharper than a serpent's tooth is the tongue of an Under Secretary of State.

Business done.—Second Reading of Equalisation of London Rates Bill moved.

Thursday.—Lords took Budget Bill in hand to-night. Markiss asked for week's interval. This looked like fighting. At least there would be a reconnaissance in force led by the Markiss. House full; peerless Peeresses looked down from side gallery; Markiss in his place; Devonshire in his—not Chatsworth; that going to be shut up; but corner seat below gangway; Rosebery hovering about, settled down at length in seat of Leader. Clerk read Orders of the Day. "Finance Bill second reading." "I move the Bill be read a second time," said Rosebery, politely taking his hat off to lady in gallery immediately opposite. Then he sat down.

Here was a pretty go! Expected Premier would make brilliant speech in support of Bill; the Markiss would reply; fireworks would fizz all round, and, though perhaps Budget Bill might be saved, Squire of Malwood would be pummelled. Rosebery takes oddest, most unparliamentary view of his duty. The Lords, he said, when last week subject was mooted, have nothing to do with Budget Bill, unless indeed they are prepared to throw it out. "Will you do that?" he asked. "No," said Markiss, looking as if he would much rather say "Yes." "Very well then," said Rosebery, "all speeches on the subject must be barren."

This to the Barons seemed lamentably personal.

Rosebery illustrated his point by declining for his own part to make a speech. Still there was talk; barren speeches for three hours; audience gradually dwindling: only a few left to witness spectacle of Halsbury's blue blood boiling over with indignation at sacrilegious assault on landed aristocracy.

"If you want to make your flesh creep," says Sark, "you should hear Halsbury, raising to full height his majestic figure, throwing the shadow of his proudly aquiline profile fiercely on the steps of the Throne where some minions of the Government cowered, exclaim, 'My Lords, I detect in this Bill a hostile spirit towards the landed aristocracy.'"

"A Halsbury! a Halsbury!" menacingly muttered Feversham and some other fiery crusaders.

For the moment, so deeply was the assembly stirred, a conflict between the two Houses seemed imminent. But Black Rod coming to take away the Mace the tumult subsided, and Lord Halsbury went home in a four-wheeler.

Business done.—Budget read second time in Lords.

Friday.—Scene in Commons quite changed; properties remain but leading characters altered. After unprecedented run, Budget Bill withdrawn; Irish Evicted Tenants Bill now underlined on bills. John Morley succeeds the Squire; Irish Members take up the buzzing of the no longer Busy B's.

As for the Squire, he takes well-earned, though only comparative rest; preparing for congratulatory feast spread for him next Wednesday. Like good boy whose work is done is now going to have his dinner. Also Rigby and Bob Reid, who bore with him the heat and burden of the day. It's a sort of Parliamentary Millennium. The Chancellor of the Exchequer sits down with the Attorney-General; the Solicitor-General puts his hand on the cockatrice's den (situate in the neighbourhood of Tommy Bowles); and Frank Lockwood has drawn them.

Business done.—In Committee on Evicted Tenants Bill.

Mrs. R. observes in a newspaper that a man was summoned for "illegal distress." She is much puzzled at this, as she thought England was a free country, where people might be as unhappy as they liked!

ell, my dear Mr. Punch, you, who hear everything, will be glad to receive from me the particulars of our Annual Farewell Charity Fête, given this year at the Grafton Gallery for the excellent object of providing the undeserving with pink carnations. It was a bazaar, a concert, and a fancy-dress ball, all in one; everyone who is anyone was there, and as they were all in costume, nobody could tell who was who. It was indeed a very brilliant scene.

I refused to hold a stall, for I had enough to do writing out autographs of celebrities (they sell splendidly), but it was hard work, and there was an absurd fuss just because I made the trifling mistake of signing "Yours truly, George Meredith" across a photograph of Arthur Roberts. What did it matter? I really cannot see that it made the slightest difference; the person had asked for an autograph of Meredith and he got it, and a portrait of Roberts into the bargain! so he ought to have been satisfied; but some people are strangely exacting! There was a great run on the autograph of Sarah Bernhardt and I grew quite tired of signing Yvette, Rosebery, and Cissie Loftus, however, it was all for the charity. I went as a Perfect Gentleman, and it was quite a good disguise—hardly anyone knew me! I saw Sir Bruce Skene dressed as a Temperance Lecturer; Gringoire was there as the Enemy of the People with a bunch of violets in his button-hole; the New Boy went as Becket, and Charley's Aunt as the Yellow Aster. The Gentleman of France looked well as The Prisoner of Zenda. I recognised our old friend Dorian Gray in a gorgeous costume of purple and pearls, with a crown on his head of crimson roses. He said he had come as a Prose Poem, and he was selling Prose Poem-granates for the good of the charity.

Here are some scraps of conversation I overheard in the crowd:—

Enemy of the People (to Sir Bruce Skene). Been having a good time lately?

Sir Bruce. Rather! Tremendous! I've been doing nothing but backing winners, and, what's more—(chuckling)—I've at last got that astronomer fellow to take my wife and child off my hands. Isn't that jolly?

Enemy of the People. Ah, really? She is coming to us in the autumn, you know.

Vivien, the Modern Eve (to the New Boy). I cannot stay here any longer. They never dust the drawing-room, the geraniums are planted all wrong, and I do not like the anti-macassars. Will you come with me?

New Boy. What a lark it would be! But I'm afraid I must stay and look after my white mice. You see, Bullock Major——

Lady Belton (after her marriage, to Charley's Aunt, tearfully). He doesn't understand me, Aunty.

Charley's Aunt. Never mind, my dear. Don't cry! You shall come with me to Brazil; you've heard me mention, perhaps, it's the place where the nuts come from; and we'll get up an amateur performance of the Pantomime Rehearsal!

We had all sorts of amusements. Under a palm, a palmist was prophesying long journeys, second marriages, and affairs of the heart to the white hand of giggling incredulity. Beautiful musicians, in blue uniforms, with gold Hungarian bands round their waists, were discoursing the sweetest strain that ever encouraged the conversation of the unmusical. A feature of the bazaar, that I invented, was a mechanical Sphinx behind a curtain. They asked it questions—chiefly, what would win the Leger—and put a penny in the slot. There never was any answer, and that was the great joke!

The whole thing was undoubtedly a wonderful success—and I knew it would be. I believed in my Fête, having always been rather a fatalist.

And, in the rush of a worldly, frivolous existence, how great a pleasure it is to think we should have aided—if ever so little—in brightening the lives of the poor young fellows, kept, perhaps, all the season through, in or near the hot pavement of Piccadilly, and with not so much as a buttercup to remind them of the green fields, the golden sunlight, the blue sky of the glorious country. To have helped in so noble a cause as ours is a privilege that made us leave the bazaar with tears of sympathy in our eyes, feeling better and purer men and women. Long, long may the button-hole of improvidence be filled by the wired carnation of judicious charity.

Believe me, dear Mr. Punch,

Yours very truly,

"Jemima the Penwoman."

P.S.—An absurd name they gave me on account of the autograph incident. You remember what "Jim the Penman" was? Of course, but there's no chance of my becoming the Pen-"Wiper" in the bosom of a family. Au revoir!

Throughout the dialogues, there were words used to mimic accents of the speakers. Those words were retained as-is.

The illustrations have been moved so that they do not break up paragraphs and so that they are next to the text they illustrate.

Errors in punctuations and inconsistent hyphenation were not corrected unless otherwise noted.