*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 40426 ***

This text uses UTF-8 (Unicode)

file encoding. If the apostrophes and quotation marks in this paragraph

appear as garbage, you may have an incompatible browser or unavailable

fonts. First, make sure that your browser’s “character set” or “file

encoding” is set to Unicode (UTF-8). You may also need to change the

default font.

Typographical errors are shown in the text with mouse-hover popups. French words

are shown as printed; misspellings were assumed to be intentional. The

same applies to proper names, except when the error was clearly

typographic. The publisher’s advertising section is shown as printed,

retaining all errors. Variation between “3d” and “3rd” is unchanged.

“Blue Wednesday”

· · ·

The Letters:

Freshman Year

Sophomore Year

Junior Year

Senior Year

Afterward

· · · · ·

Publisher’s Advertising

Alternative Cover

JUDY.

BY

JEAN WEBSTER

AUTHOR OF

WHEN PATTY WENT TO COLLEGE, ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BY THE AUTHOR

AND SCENES FROM THE PLAY

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1912, by

The Century Co.

Copyright, 1912,

by

The Curtis Publishing Company

Published October, 1912

DADDY-LONG-LEGS

3

“BLUE WEDNESDAY”

The first Wednesday

in every month was a Perfectly Awful Day—a day to be awaited with

dread, endured with courage and forgotten with haste. Every floor must

be spotless, every chair dustless, and every bed without a wrinkle.

Ninety-seven squirming little orphans must be scrubbed and combed and

buttoned into freshly starched ginghams; and all ninety-seven reminded

of their manners, and told to say, “Yes, sir,” “No, sir,” whenever a

Trustee spoke.

It was a distressing time; and poor Jerusha Abbott, being the oldest

orphan, had to bear the brunt of it. But this particular first

Wednesday, like its predecessors,

4

finally dragged itself to a close. Jerusha escaped from the pantry where

she had been making sandwiches for the asylum’s guests, and turned

upstairs to accomplish her regular work. Her special care was

room F, where eleven little tots, from four to seven, occupied

eleven little cots set in a row. Jerusha assembled her charges,

straightened their rumpled frocks, wiped their noses, and started them

in an orderly and willing line toward the dining-room to engage

themselves for a blessed half hour with bread and milk and prune

pudding.

Then she dropped down on the window seat and leaned throbbing temples

against the cool glass. She had been on her feet since five that

morning, doing everybody’s bidding, scolded and hurried by a nervous

matron. Mrs. Lippett, behind the scenes, did not always maintain that

calm and pompous dignity with which she faced an

5

audience of Trustees and lady visitors. Jerusha gazed out across a broad

stretch of frozen lawn, beyond the tall iron paling that marked the

confines of the asylum, down undulating ridges sprinkled with country

estates, to the spires of the village rising from the midst of bare

trees.

The day was ended—quite successfully, so far as she knew. The

Trustees and the visiting committee had made their rounds, and read

their reports, and drunk their tea, and now were hurrying home to their

own cheerful firesides, to forget their bothersome little charges for

another month. Jerusha leaned forward watching with curiosity—and

a touch of wistfulness—the stream of carriages and automobiles

that rolled out of the asylum gates. In imagination she followed first

one equipage then another to the big houses dotted along the hillside.

She pictured herself in a fur coat and a velvet hat trimmed with

feathers

6

leaning back in the seat and nonchalantly murmuring “Home” to the

driver. But on the door-sill of her home the picture grew blurred.

Jerusha had an imagination—an imagination, Mrs. Lippett told

her, that would get her into trouble if she did n’t take

care—but keen as it was, it could not carry her beyond the front

porch of the houses she would enter. Poor, eager, adventurous little

Jerusha, in all her seventeen years, had never stepped inside an

ordinary house; she could not picture the daily routine of those other

human beings who carried on their lives undiscommoded by orphans.

Je-ru-sha Ab-bott

You are wan-ted

In the of-fice,

And I think you ’d

Better hurry up!

Tommy Dillon who had joined the choir, came singing up the stairs and

down

7

the corridor, his chant growing louder as he approached room F. Jerusha

wrenched herself from the window and refaced the troubles of life.

“Who wants me?” she cut into Tommy’s chant with a note of sharp

anxiety.

Mrs. Lippett in the office,

And I think she ’s mad.

Ah-a-men!

Tommy piously intoned, but his accent was not entirely malicious.

Even the most hardened little orphan felt sympathy for an erring sister

who was summoned to the office to face an annoyed matron; and Tommy

liked Jerusha even if she did sometimes jerk him by the arm and nearly

scrub his nose off.

Jerusha went without comment, but with two parallel lines on her

brow. What could have gone wrong, she wondered. Were the sandwiches not

thin enough? Were there shells in the nut cakes? Had

8

a lady visitor seen the hole in Susie Hawthorn’s stocking?

Had—O horrors!—one of the cherubic little babes in her

own room F “sassed” a Trustee?

The long lower hall had not been lighted, and as she came downstairs,

a last Trustee stood, on the point of departure, in the open door

that led to the porte-cochère. Jerusha caught only a fleeting impression

of the man—and the impression consisted entirely of tallness. He

was waving his arm toward an automobile waiting in the curved drive. As

it sprang into motion and approached, head on for an instant, the

glaring headlights threw his shadow sharply against the wall inside. The

shadow pictured grotesquely elongated legs and arms that ran along the

floor and up the wall of the corridor. It looked, for all the world,

like a huge, wavering daddy-long-legs.

Jerusha’s anxious frown gave place to quick laughter. She was by

nature a sunny

9

soul, and had always snatched the tiniest excuse to be amused. If one

could derive any sort of entertainment out of the oppressive fact of a

Trustee, it was something unexpected to the good. She advanced to the

office quite cheered by the tiny episode, and presented a smiling face

to Mrs. Lippett. To her surprise the matron was also, if not exactly

smiling, at least appreciably affable; she wore an expression almost as

pleasant as the one she donned for visitors.

“Sit down, Jerusha, I have something to say to you.”

Jerusha dropped into the nearest chair and waited with a touch of

breathlessness. An automobile flashed past the window; Mrs. Lippett

glanced after it.

“Did you notice the gentleman who has just gone?”

“I saw his back.”

“He is one of our most affluential Trustees, and has given large sums

of money toward the asylum’s support. I am

10

not at liberty to mention his name; he expressly stipulated that he was

to remain unknown.”

Jerusha’s eyes widened slightly; she was not accustomed to being

summoned to the office to discuss the eccentricities of Trustees with

the matron.

“This gentleman has taken an interest in several of our boys. You

remember Charles Benton and Henry Freize? They were both sent through

college by Mr.—er—this Trustee, and both have repaid with

hard work and success the money that was so generously expended. Other

payment the gentleman does not wish. Heretofore his philanthropies have

been directed solely toward the boys; I have never been able to

interest him in the slightest degree in any of the girls in the

institution, no matter how deserving. He does not, I may tell you,

care for girls.”

“No, ma’am,” Jerusha murmured, since

11

some reply seemed to be expected at this point.

“To-day at the regular meeting, the question of your future was

brought up.”

Mrs. Lippett allowed a moment of silence to fall, then resumed in a

slow, placid manner extremely trying to her hearer’s suddenly tightened

nerves.

“Usually, as you know, the children are not kept after they are

sixteen, but an exception was made in your case. You had finished our

school at fourteen, and having done so well in your studies—not

always, I must say, in your conduct—it was determined to let

you go on in the village high school. Now you are finishing that, and of

course the asylum cannot be responsible any longer for your support. As

it is, you have had two years more than most.”

Mrs. Lippett overlooked the fact that Jerusha had worked hard for her

board

12

during those two years, that the convenience of the asylum had come

first and her education second; that on days like the present she was

kept at home to scrub.

“As I say, the question of your future was brought up and your record

was discussed—thoroughly discussed.”

Mrs. Lippett brought accusing eyes to bear upon the prisoner in the

dock, and the prisoner looked guilty because it seemed to be

expected—not because she could remember any strikingly black pages

in her record.

“Of course the usual disposition of one in your place would be to put

you in a position where you could begin to work, but you have done well

in school in certain branches; it seems that your work in English has

even been brilliant. Miss Pritchard who is on our visiting committee is

also on the school board; she has been talking with your rhetoric

teacher, and made a speech in your favor. She also read aloud an

13

essay that you had written entitled, ‘Blue Wednesday.’”

Jerusha’s guilty expression this time was not assumed.

“It seemed to me that you showed little gratitude in holding up to

ridicule the institution that has done so much for you. Had you not

managed to be funny I doubt if you would have been forgiven. But

fortunately for you, Mr. ——, that is, the gentleman who

has just gone—appears to have an immoderate sense of humor. On the

strength of that impertinent paper, he has offered to send you to

college.”

“To college?” Jerusha’s eyes grew big.

Mrs. Lippett nodded.

“He waited to discuss the terms with me. They are unusual. The

gentleman, I may say, is erratic. He believes that you have

originality, and he is planning to educate you to become a writer.”

“A writer?” Jerusha’s mind was

14

numbed. She could only repeat Mrs. Lippett’s words.

“That is his wish. Whether anything will come of it, the future will

show. He is giving you a very liberal allowance, almost, for a girl who

has never had any experience in taking care of money, too liberal. But

he planned the matter in detail, and I did not feel free to make any

suggestions. You are to remain here through the summer, and Miss

Pritchard has kindly offered to superintend your outfit. Your board and

tuition will be paid directly to the college, and you will receive in

addition during the four years you are there, an allowance of

thirty-five dollars a month. This will enable you to enter on the same

standing as the other students. The money will be sent to you by the

gentleman’s private secretary once a month, and in return, you will

write a letter of acknowledgment once a month. That is—you are not

to thank him for the money; he does n’t

15

care to have that mentioned, but you are to write a letter telling of

the progress in your studies and the details of your daily life. Just

such a letter as you would write to your parents if they were

living.

“These letters will be addressed to Mr. John Smith and will be sent

in care of the secretary. The gentleman’s name is not John Smith, but he

prefers to remain unknown. To you he will never be anything but John

Smith. His reason in requiring the letters is that he thinks nothing so

fosters facility in literary expression as letter-writing. Since you

have no family with whom to correspond, he desires you to write in this

way; also, he wishes to keep track of your progress. He will never

answer your letters, nor in the slightest particular take any notice of

them. He detests letter-writing, and does not wish you to become a

burden. If any point should ever arise where an answer would seem to be

imperative—such as in the event of your

16

being expelled, which I trust will not occur—you may correspond

with Mr. Griggs, his secretary. These monthly letters are absolutely

obligatory on your part; they are the only payment that Mr. Smith

requires, so you must be as punctilious in sending them as though it

were a bill that you were paying. I hope that they will always be

respectful in tone and will reflect credit on your training. You must

remember that you are writing to a Trustee of the John Grier Home.”

Jerusha’s eyes longingly sought the door. Her head was in a whirl of

excitement, and she wished only to escape from Mrs. Lippett’s

platitudes, and think. She rose and took a tentative step backwards.

Mrs. Lippett detained her with a gesture; it was an oratorical

opportunity not to be slighted.

“I trust that you are properly grateful for this very rare good

fortune that has befallen you? Not many girls in your position

17

ever have such an opportunity to rise in the world. You must always

remember—”

“I—yes, ma’am, thank you. I think, if that ’s all, I

must go and sew a patch on Freddie Perkins’s trousers.”

The door closed behind her, and Mrs. Lippett watched it with dropped

jaw, her peroration in mid-air.

19

THE LETTERS

OF MISS JERUSHA ABBOTT

to

MR. DADDY-LONG-LEGS SMITH

21

215 Fergussen Hall,

September 24th.

Dear Kind-Trustee-Who-Sends-Orphans-to-College,

Here I am! I traveled yesterday for four hours in a train.

It ’s a funny sensation is n’t it? I never rode in

one before.

College is the biggest, most bewildering place—I get lost

whenever I leave my room. I will write you a description later when

I ’m feeling less muddled; also I will tell you about my lessons.

Classes don’t begin until Monday morning, and this is Saturday night.

But I wanted to write a letter first just to get acquainted.

It seems queer to be writing letters to somebody you don’t know. It

seems queer

22

for me to be writing letters at all—I ’ve never written

more than three or four in my life, so please overlook it if these are

not a model kind.

Before leaving yesterday morning, Mrs. Lippett and I had a very

serious talk. She told me how to behave all the rest of my life, and

especially how to behave toward the kind gentleman who is doing so much

for me. I must take care to be Very Respectful.

But how can one be very respectful to a person who wishes to be

called John Smith? Why could n’t you have picked out a name with

a little personality? I might as well write letters to Dear

Hitching-Post or Dear Clothes-Pole.

I have been thinking about you a great deal this summer; having

somebody take an interest in me after all these years, makes me feel as

though I had found a sort of family. It seems as though I belonged to

23

somebody now, and it ’s a very comfortable sensation. I must say,

however, that when I think about you, my imagination has very little to

work upon. There are just three things that I know:

I. You are tall.

II. You are rich.

III. You hate girls.

I suppose I might call you Dear Mr. Girl-Hater. Only that ’s

sort of insulting to me. Or Dear Mr. Rich-Man, but that ’s

insulting to you, as though money were the only important thing about

you. Besides, being rich is such a very external quality. Maybe you

won’t stay rich all your life; lots of very clever men get smashed up in

Wall Street. But at least you will stay tall all your life! So

I ’ve decided to call you Dear Daddy-Long-Legs. I hope you

won’t mind. It ’s just a private pet name—we won’t tell

Mrs. Lippett.

24

The ten o’clock bell is going to ring in two minutes. Our day is

divided into sections by bells. We eat and sleep and study by bells.

It ’s very enlivening; I feel like a fire horse all of the

time. There it goes! Lights out. Good night.

Observe with what precision I obey rules—due to my training in

the John Grier Home.

Yours most respectfully,

Jerusha Abbott.

To Mr. Daddy-Long-Legs Smith.

25

October 1st.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

I love college and I love you for sending me—I ’m very,

very happy, and so excited every moment of the time that I can

scarcely sleep. You can’t imagine how different it is from the John

Grier Home. I never dreamed there was such a place in the world.

I ’m feeling sorry for everybody who is n’t a girl and who

can’t come here; I am sure the college you attended when you were a

boy could n’t have been so nice.

My room is up in a tower that used to be the contagious ward before

they built the new infirmary. There are three other girls on the same

floor of the tower—a Senior who wears spectacles and is always

asking us please to be a little more quiet,

26

and two Freshmen named Sallie McBride and Julia Rutledge Pendleton.

Sallie has red hair and a turn-up nose and is quite friendly; Julia

comes from one of the first families in New York and has n’t

noticed me yet. They room together and the Senior and I have singles.

Usually Freshmen can’t get singles; they are very scarce, but I got one

without even asking. I suppose the registrar did n’t think

it would be right to ask a properly brought-up girl to room with a

foundling. You see there are advantages!

My room is on the northwest corner with two windows and a view. After

you ’ve lived in a ward for eighteen years with twenty

room-mates, it is restful to be alone. This is the first chance

I ’ve ever had to get acquainted with Jerusha Abbott.

I think I ’m going to like her.

Do you think you are?

27

Tuesday.

They are organizing the Freshman basket-ball team and there ’s

just a chance that I shall make it. I ’m little of course, but

terribly quick and wiry and tough. While the others are hopping about in

the air, I can dodge under their feet and grab the ball.

It ’s loads of fun practising—out in the athletic field in

the afternoon with the trees all red and yellow and the air full of the

smell of burning leaves, and everybody laughing and shouting. These are

the happiest girls I ever saw—and I am the happiest of all!

I meant to write a long letter and tell you all the things

I ’m learning (Mrs. Lippett said you wanted to know) but 7th hour

has just rung, and in ten minutes I ’m due at the athletic field

in gymnasium clothes. Don’t you hope I ’ll make the team?

Yours always,

Jerusha Abbott.

28

P. S. (9 o’clock.)

Sallie McBride just poked her head in at my door. This is what she

said:

“I ’m so homesick that I simply can’t stand it. Do you feel

that way?”

I smiled a little and said no, I thought I could pull through. At

least homesickness is one disease that I ’ve escaped!

I never heard of anybody being asylumsick, did you?

29

October 10th.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

Did you ever hear of Michael Angelo?

He was a famous artist who lived in Italy in the Middle Ages.

Everybody in English Literature seemed to know about him and the whole

class laughed because I thought he was an archangel. He sounds like an

archangel, does n’t he? The trouble with college is that you are

expected to know such a lot of things you ’ve never learned.

It ’s very embarrassing at times. But now, when the girls talk

about things that I never heard of, I just keep still and look them

up in the encyclopedia.

I made an awful mistake the first day. Somebody mentioned Maurice

Maeterlinck, and I asked if she was a Freshman. That

30

joke has gone all over college. But anyway, I ’m just as bright

in class as any of the others—and brighter than some of them!

Do you care to know how I ’ve furnished my room? It ’s

a symphony in brown and yellow. The wall was tinted buff, and

I ’ve bought yellow denim curtains and cushions and a mahogany

desk (second hand for three dollars) and a rattan chair and a brown rug

with an ink spot in the middle. I stand the chair over the

spot.

The windows are up high; you can’t look out from an ordinary seat.

But I unscrewed the looking-glass from the back of the bureau,

upholstered the top, and moved it up against the window. It ’s

just the right height for a window seat. You pull out the drawers like

steps and walk up. Very comfortable!

Sallie McBride helped me choose the things at the Senior auction. She

has lived

31

in a house all her life and knows about furnishing. You can’t imagine

what fun it is to shop and pay with a real five-dollar bill and get some

change—when you ’ve never had more than a nickel in your

life. I assure you, Daddy dear, I do appreciate that

allowance.

Sallie is the most entertaining person in the world—and Julia

Rutledge Pendleton the least so. It ’s queer what a mixture the

registrar can make in the matter of room-mates. Sallie thinks everything

is funny—even flunking—and Julia is bored at everything. She

never makes the slightest effort to be amiable. She believes that if you

are a Pendleton, that fact alone admits you to heaven without any

further examination. Julia and I were born to be enemies.

And now I suppose you ’ve been waiting very impatiently to

hear what I am learning?

I. Latin: Second Punic war. Hannibal and his forces pitched

camp at Lake

32

Trasimenus last night. They prepared an ambuscade for the Romans, and a

battle took place at the fourth watch this morning. Romans in

retreat.

II. French: 24 pages of the “Three Musketeers” and third

conjugation, irregular verbs.

III. Geometry: Finished cylinders; now doing cones.

IV. English: Studying exposition. My style improves daily in

clearness and brevity.

V. Physiology: Reached the digestive system. Bile and the

pancreas next time. Yours, on the way to being educated,

Jerusha Abbott.

P. S. I hope you never touch alcohol, Daddy?

It does dreadful things to your liver.

33

Wednesday.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

I ’ve changed my name.

I ’m still “Jerusha” in the catalogue, but I ’m “Judy”

every place else. It ’s sort of too bad, is n’t it, to

have to give yourself the only pet name you ever had?

I did n’t quite make up the Judy though. That ’s what

Freddie Perkins used to call me before he could talk plain.

I wish Mrs. Lippett would use a little more ingenuity about choosing

babies’ names. She gets the last names out of the telephone

book—you ’ll find Abbott on the first page—and she

picks the Christian names up anywhere; she got Jerusha from a tombstone.

I ’ve always hated it; but I rather like Judy. It ’s such

a silly name. It belongs to the kind of girl I ’m not—a

sweet little blue-eyed thing, petted and spoiled by all the family, who

romps her way through life without any cares. Would n’t it be

nice to be like that? Whatever

34

faults I may have, no one can ever accuse me of having been spoiled by

my family! But it ’s sort of fun to pretend I ’ve been. In

the future please always address me as Judy.

Do you want to know something? I have three pairs of kid gloves.

I ’ve had kid mittens before from the Christmas tree, but never

real kid gloves with five fingers. I take them out and try them on

every little while. It ’s all I can do not to wear them to

classes.

(Dinner bell. Good-by.)

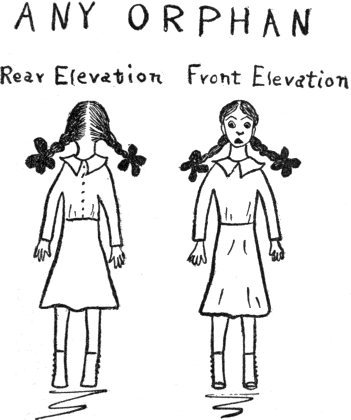

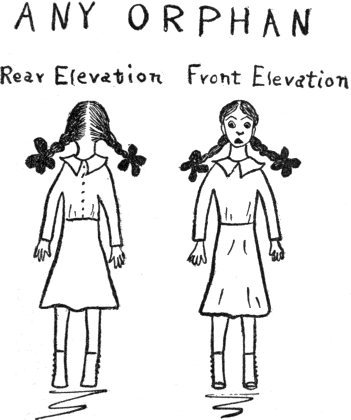

JUDY AND THE ORPHANS AT JOHN GRIER HOME.

35

Friday.

What do you think, Daddy? The English instructor said that my last

paper shows an unusual amount of originality. She did, truly. Those were

her words. It does n’t seem possible, does it, considering the

eighteen years of training that I ’ve had? The aim of the John

Grier Home (as you doubtless know and heartily approve of) is to turn

the ninety-seven orphans into ninety-seven twins.

The unusual artistic ability which I exhibit, was developed at an

early age through

36

drawing chalk pictures of Mrs. Lippett on the woodshed door.

I hope that I don’t hurt your feelings when I criticize the home of

my youth? But you have the upper hand, you know, for if I become too

impertinent, you can always stop payment on your checks. That

is n’t a very polite thing to say—but you can’t expect me

to have any manners; a foundling asylum is n’t a young

ladies’ finishing school.

You know, Daddy, it is n’t the work that is going to be hard

in college. It ’s the play. Half the time I don’t know what the

girls are talking about; their jokes seem to relate to a past that every

one but me has shared. I ’m a foreigner in the world and I don’t

understand the language. It ’s a miserable feeling. I ’ve

had it all my life. At the high school the girls would stand in groups

and just look at me. I was queer and different and everybody knew

it. I could feel “John Grier Home”

37

written on my face. And then a few charitable ones would make a point of

coming up and saying something polite. I hated every one of

them—the charitable ones most of all.

Nobody here knows that I was brought up in an asylum. I told Sallie

McBride that my mother and father were dead, and that a kind old

gentleman was sending me to college—which is entirely true so far

as it goes. I don’t want you to think I am a coward, but I do want

to be like the other girls, and that Dreadful Home looming over my

childhood is the one great big difference. If I can turn my back on that

and shut out the remembrance, I think I might be just as desirable

as any other girl. I don’t believe there ’s any real,

underneath difference, do you?

Anyway, Sallie McBride likes me!

Yours ever,

Judy Abbott.

(Née Jerusha.)

38

Saturday morning.

I ’ve just been reading this letter over and it sounds pretty

un-cheerful. But can’t you guess that I have a special topic due Monday

morning and a review in geometry and a very sneezy cold?

Sunday.

I forgot to mail this yesterday so I will add an indignant

postscript. We had a bishop this morning, and what do you think he

said?

“The most beneficent promise made us in the Bible is this, ‘The poor

ye have always with you.’ They were put here in order to keep us

charitable.”

The poor, please observe, being a sort of useful domestic animal. If

I had n’t grown into such a perfect lady, I should have gone

up after service and told him what I thought.

39

October 25th.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

I ’ve made the basket-ball team and you ought to see the

bruise on my left shoulder. It ’s blue and mahogany with little

streaks of orange. Julia Pendleton tried for the team, but she

did n’t make it. Hooray!

You see what a mean disposition I have.

College gets nicer and nicer. I like the girls and the teachers and

the classes and the campus and the things to eat. We have ice-cream

twice a week and we never have corn-meal mush.

You only wanted to hear from me once a month, did n’t you? And

I ’ve been peppering you with letters every few days! But

I ’ve been so excited about all these new adventures that I

must talk to somebody; and you ’re the only one I know.

40

Please excuse my exuberance; I ’ll settle pretty soon. If my

letters bore you, you can always toss them into the waste-basket.

I promise not to write another till the middle of November.

Yours most loquaciously,

Judy Abbott.

41

November 15th.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

Listen to what I ’ve learned to-day:

The area of the convex surface of the frustum of a regular pyramid is

half the product of the sum of the perimeters of its bases by the

altitude of either of its trapezoids.

It does n’t sound true, but it is—I can prove it!

You ’ve never heard about my clothes, have you, Daddy? Six

dresses, all new and beautiful and bought for me—not handed down

from somebody bigger. Perhaps you don’t realize what a climax that marks

in the career of an orphan? You gave them to me, and I am very, very,

very much obliged. It ’s a fine thing to be

42

educated—but nothing compared to the dizzying experience of owning

six new dresses. Miss Pritchard who is on the visiting committee picked

them out—not Mrs. Lippett, thank goodness. I have an evening

dress, pink mull over silk (I ’m perfectly beautiful in that),

and a blue church dress, and a dinner dress of red veiling with Oriental

trimming (makes me look like a Gipsy) and another of rose-colored

challis, and a gray street suit, and an every-day dress for classes.

That would n’t be an awfully big wardrobe for Julia Rutledge

Pendleton, perhaps, but for Jerusha Abbott—Oh, my!

I suppose you ’re thinking now what a frivolous, shallow,

little beast she is, and what a waste of money to educate a girl?

But Daddy, if you ’d been dressed in checked ginghams all your

life, you ’d appreciate how I feel. And when I started to the

high school, I entered upon another

43

period even worse than the checked ginghams.

The poor box.

You can’t know how I dreaded appearing in school in those miserable

poor-box dresses. I was perfectly sure to be put down in class next

to the girl who first owned my dress, and she would whisper and giggle

and point it out to the others. The bitterness of wearing your enemies’

cast-off clothes eats into your soul. If I wore silk stockings for the

rest of my life, I don’t believe I could obliterate the scar.

LATEST WAR BULLETIN!

News from the Scene of Action.

At the fourth watch on Thursday the 13th of November, Hannibal routed

the advance guard of the Romans and led the Carthaginian forces over the

mountains into the plains of Casilinum. A cohort of light armed

Numidians engaged the infantry of Quintus Fabius Maximus. Two battles

44

and light skirmishing. Romans repulsed with heavy losses.

I have the honor of being,

Your special correspondent from the front

J. Abbott.

P. S. I know I ’m not to expect any letters in return, and

I ’ve been warned not to bother you with questions, but tell me,

Daddy, just this once—are you awfully old or just a little old?

And are you perfectly bald or just a little bald? It is very difficult

thinking about you in the abstract like a theorem in geometry.

Given a tall rich man who hates girls, but is very generous to one

quite impertinent girl, what does he look like?

R.S.V.P.

45

December 19th.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

You never answered my question and it was very important.

ARE YOU BALD?

I have it planned exactly what you look like—very

satisfactorily—until I reach the top of your head, and then I

am stuck. I can’t decide whether you have white hair or

black hair or sort of sprinkly gray hair or maybe none at all.

Here is your portrait:

But the problem is, shall I add some hair?

Would you like to

46

know what color your eyes are? They ’re gray, and your eyebrows

stick out like a porch roof (beetling, they ’re called in novels)

and your mouth is a straight line with a tendency to turn down at the

corners. Oh, you see, I know! You ’re a snappy old thing

with a temper.

(Chapel bell.)

9.45 P. M.

I have a new unbreakable rule: never, never to study at night no

matter how many written reviews are coming in the morning. Instead,

I read just plain books—I have to, you know, because there

are eighteen blank years behind me. You would n’t believe, Daddy,

what an abyss of ignorance my mind is; I am just realizing the

depths myself. The things that most girls with a properly assorted

family and a home and friends and a library know by absorption,

I have never heard of. For example:

I never read “Mother Goose” or

47

“David Copperfield” or “Ivanhoe” or “Cinderella” or “Blue Beard” or

“Robinson Crusoe” or “Jane Eyre” or “Alice in Wonderland” or a word of

Rudyard Kipling. I did n’t know that Henry the Eighth was

married more than once or that Shelley was a poet. I did n’t

know that people used to be monkeys and that the Garden of Eden was a

beautiful myth. I did n’t know that R.L.S. stood for Robert

Louis Stevenson or that George Eliot was a lady. I had never seen a

picture of the “Mona Lisa” and (it ’s true but you won’t believe

it) I had never heard of Sherlock Holmes.

Now, I know all of these things and a lot of others besides, but you

can see how much I need to catch up. And oh, but it ’s fun!

I look forward all day to evening, and then I put an “engaged” on

the door and get into my nice red bath robe and furry slippers and pile

all the cushions behind me on the couch and light the brass

48

student lamp at my elbow, and read and read and read. One book

is n’t enough. I have four going at once. Just now,

they ’re Tennyson’s poems and “Vanity Fair” and Kipling’s “Plain

Tales” and—don’t laugh—“Little Women.” I find that I am

the only girl in college who was n’t brought up on “Little

Women.” I have n’t told anybody though (that would

stamp me as queer). I just quietly went and bought it with $1.12 of

my last month’s allowance; and the next time somebody mentions pickled

limes, I ’ll know what she is talking about!

(Ten o’clock bell. This is a very interrupted letter.)

Saturday.

Sir,

I have the honor to report fresh explorations in the field of

geometry. On Friday last we abandoned our former works in

parallelopipeds and proceeded to truncated

49

prisms. We are finding the road rough and very uphill.

Sunday.

The Christmas holidays begin next week and the trunks are up. The

corridors are so cluttered that you can hardly get through, and

everybody is so bubbling over with excitement that studying is getting

left out. I ’m going to have a beautiful time in vacation;

there ’s another Freshman who lives in Texas staying behind, and

we are planning to take long walks and—if there ’s any

ice—learn to skate. Then there is still the whole library to be

read—and three empty weeks to do it in!

Good-by, Daddy, I hope that you are feeling as happy as I am.

Yours ever,

Judy.

P. S. Don’t forget to answer my question. If you don’t want the trouble

of

50

writing, have your secretary telegraph. He can just say:

Mr. Smith is quite bald,

or

Mr. Smith is not bald,

or

Mr. Smith has white hair.

And you can deduct the twenty-five cents out of my allowance.

Good-by till January—and a merry Christmas!

51

Toward the end of

the Christmas vacation.

Exact date unknown.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

Is it snowing where you are? All the world that I see from my tower

is draped in white and the flakes are coming down as big as pop-corn.

It ’s late afternoon—the sun is just setting (a cold

yellow color) behind some colder violet hills, and I am up in my window

seat using the last light to write to you.

Your five gold pieces were a surprise! I ’m not used to

receiving Christmas presents. You have already given me such lots of

things—everything I have, you know—that I don’t quite feel

that I deserve extras. But I like them just the

52

same. Do you want to know what I bought with my money?

I. A silver watch in a leather case to wear on my wrist and get me to

recitations on time.

II. Matthew Arnold’s poems.

III. A hot water bottle.

IV. A steamer rug. (My tower is cold.)

V. Five hundred sheets of yellow manuscript paper. (I ’m going

to commence being an author pretty soon.)

VI. A dictionary of synonyms. (To enlarge the author’s

vocabulary.)

VII. (I don’t much like to confess this last item, but I will.)

A pair of silk stockings.

And now, Daddy, never say I don’t tell all!

It was a very low motive, if you must know it, that prompted the silk

stockings. Julia Pendleton comes into my room to do

53

geometry, and she sits cross legged on the couch and wears silk

stockings every night. But just wait—as soon as she gets back from

vacation I shall go in and sit on her couch in my silk stockings. You

see, Daddy, the miserable creature that I am—but at least

I ’m honest; and you knew already, from my asylum record, that I

was n’t perfect, did n’t you?

To recapitulate (that ’s the way the English instructor begins

every other sentence), I am very much obliged for my seven

presents. I ’m pretending to myself that they came in a box from

my family in California. The watch is from father, the rug from mother,

the hot water bottle from grandmother—who is always worrying for

fear I shall catch cold in this climate—and the yellow paper from

my little brother Harry. My sister Isobel gave me the silk stockings,

and Aunt Susan the Matthew Arnold poems; Uncle Harry (little

54

Harry is named for him) gave me the dictionary. He wanted to send

chocolates, but I insisted on synonyms.

You don’t object do you, to playing the part of a composite

family?

And now, shall I tell you about my vacation, or are you only

interested in my education as such? I hope you appreciate the

delicate shade of meaning in “as such.” It is the latest addition to my

vocabulary.

The girl from Texas is named Leonora Fenton. (Almost as funny as

Jerusha, is n’t it?) I like her, but not so much as Sallie

McBride; I shall never like any one so much as Sallie—except

you. I must always like you the best of all, because you ’re

my whole family rolled into one. Leonora and I and two Sophomores have

walked ’cross country every pleasant day and explored the whole

neighborhood, dressed in short skirts and knit jackets and caps, and

carrying shinny sticks to whack things with. Once we walked into

town—four

55

miles—and stopped at a restaurant where the college girls go for

dinner. Broiled lobster (35 cents) and for dessert, buckwheat cakes and

maple syrup (15 cents). Nourishing and cheap.

It was such a lark! Especially for me, because it was so awfully

different from the asylum—I feel like an escaped convict every

time I leave the campus. Before I thought, I started to tell the

others what an experience I was having. The cat was almost out of the

bag when I grabbed it by its tail and pulled it back. It ’s

awfully hard for me not to tell everything I know. I ’m a very

confiding soul by nature; if I did n’t have you to tell things

to, I ’d burst.

We had a molasses candy pull last Friday evening, given by the house

matron of Fergussen to the left-behinds in the other halls. There were

twenty-two of us altogether, Freshmen and Sophomores and Juniors and

Seniors all united in amicable accord. The kitchen is huge, with copper

pots and kettles

56

hanging in rows on the stone wall—the littlest casserole among

them about the size of a wash boiler. Four hundred girls live in

Fergussen. The chef, in a white cap and apron, fetched out twenty-two

other white caps and aprons—I can’t imagine where he got so

many—and we all turned ourselves into cooks.

It was great fun, though I have seen better candy. When it was

finally finished, and ourselves and the kitchen and the door-knobs all

thoroughly sticky, we organized a procession and still in our caps and

aprons, each carrying a big fork or spoon or frying pan, we marched

through the empty corridors to the officers’ parlor where half-a-dozen

professors and instructors were passing a tranquil evening. We serenaded

them with college songs and offered refreshments. They accepted politely

but dubiously. We left them sucking chunks of molasses candy, sticky and

speechless.

57

So you see, Daddy, my education progresses!

Don’t you really think that I ought to be an artist instead of an

author?

Vacation will be over in two days and I shall be glad to see the

girls again. My tower is just a trifle lonely; when nine people occupy a

house that was built for four hundred, they do rattle around a bit.

Eleven pages—poor Daddy, you must be tired! I meant this to be

just a short little thank-you note—but when I get started I seem

to have a ready pen.

Good-by, and thank you for thinking of me—I should be perfectly

happy except

58

for one little threatening cloud on the horizon. Examinations come in

February.

Yours with love,

Judy.

P. S. Maybe it is n’t proper to send love? If it is n’t,

please excuse. But I must love somebody and there ’s only you and

Mrs. Lippett to choose between, so you see—you ’ll

have to put up with it, Daddy dear, because I can’t love her.

On the Eve.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

You should see the way this college is studying! We ’ve

forgotten we ever had a vacation. Fifty-seven irregular verbs have I

introduced to my brain in the past four days—I ’m only

hoping they ’ll stay till after examinations.

Some of the girls sell their text-books when they ’re through

with them, but I intend to keep mine. Then after I ’ve graduated

59

I shall have my whole education in a row in the bookcase, and when I

need to use any detail, I can turn to it without the slightest

hesitation. So much easier and more accurate than trying to keep it in

your head.

Julia Pendleton dropped in this evening to pay a social call, and

stayed a solid hour. She got started on the subject of family, and I

could n’t switch her off. She wanted to know what my

mother’s maiden name was—did you ever hear such an impertinent

question to ask of a person from a foundling asylum?

I did n’t have the courage to say I did n’t know, so

I just miserably plumped on the first name I could think of, and that

was Montgomery. Then she wanted to know whether I belonged to the

Massachusetts Montgomerys or the Virginia Montgomerys.

Her mother was a Rutherford. The family came over in the ark, and

were connected by marriage with Henry the VIII.

60

On her father’s side they date back further than Adam. On the topmost

branches of her family tree there ’s a superior breed of monkeys,

with very fine silky hair and extra long tails.

I meant to write you a nice, cheerful, entertaining letter to-night,

but I ’m too sleepy—and scared. The Freshman’s lot is not a

happy one.

Yours, about to be examined,

Judy Abbott.

Sunday.

Dearest Daddy-Long-Legs,

I have some awful, awful, awful news to tell you, but I won’t begin

with it; I ’ll try to get you in a good humor first.

Jerusha Abbott has commenced to be an author. A poem entitled, “From

my Tower,” appears in the February Monthly—on the first

page, which is a very great honor for a Freshman. My English

61

instructor stopped me on the way out from chapel last night, and said it

was a charming piece of work except for the sixth line, which had too

many feet. I will send you a copy in case you care to read it.

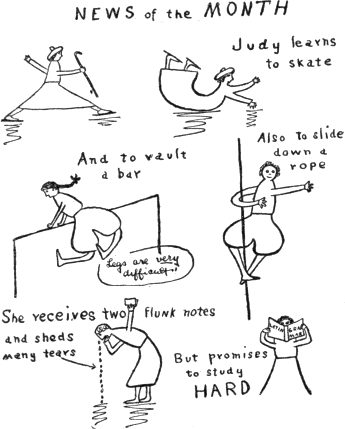

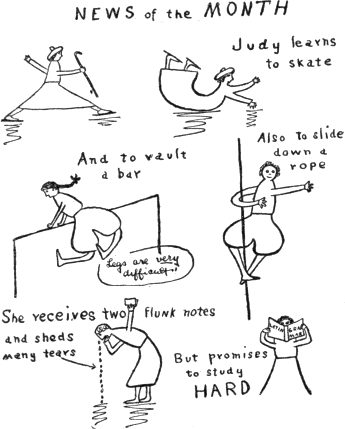

Let me see if I can’t think of something else pleasant—Oh, yes!

I ’m learning to skate, and can glide about quite respectably all

by myself. Also I ’ve learned how to slide down a rope from the

roof of the gymnasium, and I can vault a bar three feet and six inches

high—I hope shortly to pull up to four feet.

We had a very inspiring sermon this morning preached by the Bishop of

Alabama. His text was: “Judge not that ye be not judged.” It was about

the necessity of overlooking mistakes in others, and not discouraging

people by harsh judgments. I wish you might have heard it.

This is the sunniest, most blinding winter afternoon, with icicles

dripping from the fir trees and all the world bending under

62

a weight of snow—except me, and I ’m bending under a weight

of sorrow.

Now for the news—courage, Judy!—you must tell.

Are you surely in a good humor? I flunked mathematics and

Latin prose. I am tutoring in them, and will take another

examination next month. I ’m sorry if you ’re

disappointed, but otherwise I don’t care a bit because I ’ve

learned such a lot of things not mentioned in the catalogue.

I ’ve read seventeen novels and bushels of

poetry—really necessary novels like “Vanity Fair” and “Richard

Feverel” and “Alice in Wonderland.” Also Emerson’s “Essays” and

Lockhart’s “Life of Scott” and the first volume of Gibbon’s “Roman

Empire” and half of Benvenuto Cellini’s “Life”—was n’t he

entertaining? He used to saunter out and casually kill a man before

breakfast.

So you see, Daddy, I ’m much more intelligent than if

I ’d just stuck to Latin.

63

Will you forgive me this once if I promise never to flunk again?

Yours in sackcloth,

Judy.

64

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

This is an extra letter in the middle of the month because

I ’m sort of lonely to-night. It ’s awfully stormy; the

snow is beating against my tower. All the lights are out on the campus,

but I drank black coffee and I can’t go to sleep.

I had a supper party this evening consisting of Sallie and Julia and

Leonora Fenton—and sardines and toasted muffins and salad and

fudge and coffee. Julia said she ’d had a good time, but Sallie

stayed to help wash the dishes.

I might, very usefully, put some time on Latin to-night—but,

there ’s no doubt about it, I ’m a very languid Latin

scholar. We ’ve finished Livy and De Senectute and are now

engaged with De Amicitia (pronounced Damn Icitia).

Should you mind, just for a little while, pretending you are my

grandmother? Sallie has one and Julia and Leonora each two, and they

were all comparing them to-night.

65

I can’t think of anything I ’d rather have; it ’s such a

respectable relationship. So, if you really don’t object—When I

went into town yesterday, I saw the sweetest cap of Cluny lace

trimmed with lavender ribbon. I am going to make you a present of

it on your eighty-third birthday.

! ! ! ! ! ! ! !

! ! ! !

That ’s the clock in the chapel tower striking twelve. I

believe I am sleepy after all.

Good night, Granny.

I love you dearly.

Judy.

66

The Ides of March.

Dear D. L. L.,

I am studying Latin prose composition. I have been studying it.

I shall be studying it. I shall be about to have been studying

it. My reëxamination comes the 7th hour next Tuesday, and I am going to

pass or BUST. So you may expect to hear from me next, whole and happy

and free from conditions, or in fragments.

I will write a respectable letter when it ’s over. To-night I

have a pressing engagement with the Ablative Absolute.

Yours—in evident haste,

J. A.

67

March 26th.

Mr. D. L. L. Smith.

Sir: You never answer any questions;

you never show the slightest interest in anything I do. You are probably

the horridest one of all those horrid Trustees, and the reason you are

educating me is, not because you care a bit about me, but from a sense

of Duty.

I don’t know a single thing about you. I don’t even know your name.

It is very uninspiring writing to a Thing. I have n’t a

doubt but that you throw my letters into the waste-basket without

reading them. Hereafter I shall write only about work.

My reëxaminations in Latin and geometry came last week. I passed them

both and am now free from conditions.

Yours truly,

Jerusha Abbott.

68

April 2d.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

I am a BEAST.

Please forget about that dreadful letter I sent you last week—I

was feeling terribly lonely and miserable and sore-throaty the night I

wrote. I did n’t know it, but I was just coming down with

tonsilitis and grippe and lots of things mixed. I ’m in the

infirmary now, and have been here for six days; this is the first time

they would let me sit up and have a pen and paper. The head nurse is

very bossy. But I ’ve been thinking about it all the time

and I shan’t get well until you forgive me.

Here is a picture of the way I look, with a bandage tied around my

head in rabbit ’s ears.

69

Does n’t that arouse your sympathy? I am having sublingual

gland swelling. And I ’ve been studying physiology all the year

without ever hearing of sublingual glands. How futile a thing is

education!

I can’t write any more; I get sort of shaky when I sit up too long.

Please forgive me for being impertinent and ungrateful. I was badly

brought up.

Yours with love,

Judy Abbott.

70

The Infirmary.

April 4th.

Dearest Daddy-Long-Legs,

Yesterday evening just toward dark, when I was sitting up in bed

looking out at the rain and feeling awfully bored with life in a great

institution, the nurse appeared with a long white box addressed to me,

and filled with the loveliest pink rosebuds. And much nicer

still, it contained a card with a very polite message written in a funny

little uphill back hand (but one which shows a great deal of character).

Thank you, Daddy, a thousand times. Your flowers make the first

real, true present I ever received in my life. If you want to know what

a baby I am, I lay down and cried because I was so happy.

Now that I am sure you read my letters,

71

I ’ll make them much more interesting, so they ’ll be

worth keeping in a safe with red tape around them—only please take

out that dreadful one and burn it up. I ’d hate to think that you

ever read it over.

Thank you for making a very sick, cross, miserable Freshman cheerful.

Probably you have lots of loving family and friends, and you don’t know

what it feels like to be alone. But I do.

Good-by—I ’ll promise never to be horrid again, because

now I know you ’re a real person; also I ’ll promise never

to bother you with any more questions.

Do you still hate girls?

Yours forever,

Judy.

72

8th hour, Monday.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

I hope you are n’t the Trustee who sat on the toad? It went

off—I was told—with quite a pop, so probably he was a fatter

Trustee.

Do you remember the little dugout places with gratings over them by

the laundry windows in the John Grier Home? Every spring when the

hoptoad season opened we used to form a collection of toads and keep

them in those window holes; and occasionally they would spill over into

the laundry, causing a very pleasurable commotion on wash days. We were

severely punished for our activities in this direction, but in spite of

all discouragement the toads would collect.

And one day—well, I won’t bore you with particulars—but

somehow, one of the fattest, biggest, juiciest toads got into

73

one of those big leather arm chairs in the Trustees’ room, and that

afternoon at the Trustees’ meeting— But I dare say you were there

and recall the rest?

Looking back dispassionately after a period of time, I will say that

punishment was merited, and—if I remember

rightly—adequate.

I don’t know why I am in such a reminiscent mood except that spring

and the reappearance of toads always awakens the old acquisitive

instinct. The only thing that keeps me from starting a collection is the

fact that no rule exists against it.

After chapel, Thursday.

What do you think is my favorite book? Just now, I mean; I change

every three days. “Wuthering Heights.” Emily Bronté was quite young when

she wrote it,

74

and had never been outside of Haworth churchyard. She had never known

any men in her life; how could she imagine a man like

Heathcliffe?

I could n’t do it, and I ’m quite young and never

outside the John Grier Asylum—I ’ve had every chance in the

world. Sometimes a dreadful fear comes over me that I ’m not a

genius. Will you be awfully disappointed, Daddy, if I don’t turn out to

be a great author? In the spring when everything is so beautiful and

green and budding, I feel like turning my back on lessons, and

running away to play with the weather. There are such lots of adventures

out in the fields! It ’s much more entertaining to live books

than to write them.

Ow ! ! ! ! ! !

That was a shriek which brought Sallie and Julia and (for a disgusted

moment)

75

the Senior from across the hall. It was caused by a centipede like

this:

only worse. Just as I had finished the last sentence and was thinking

what to say next—plump!—it fell off the ceiling and landed

at my side. I tipped two cups off the tea table in trying to get

away. Sallie whacked it with the back of my hair brush—which I

shall never be able to use again—and killed the front end, but the

rear fifty feet ran under the bureau and escaped.

This dormitory, owing to its age and ivy-covered walls, is full of

centipedes. They are dreadful creatures. I ’d rather find a tiger

under the bed.

76

Friday, 9.30 P.

M.

Such a lot of troubles! I did n’t hear the rising bell this

morning, then I broke my shoe-string while I was hurrying to dress and

dropped my collar button down my neck. I was late for breakfast and

also for first-hour recitation. I forgot to take any blotting paper

and my fountain pen leaked. In trigonometry the Professor and I had a

disagreement touching a little matter of logarithms. On looking it up,

I find that she was right. We had mutton stew and pie-plant for

lunch—hate ’em both; they taste like the asylum. Nothing

but bills in my mail (though I must say that I never do get anything

else; my family are not the kind that write). In English class this

afternoon we had an unexpected written lesson. This was it:

I asked no other thing,

No other was denied.

I offered Being for it;

The mighty merchant smiled.

77

Brazil? He twirled a button

Without a glance my way:

But, madam, is there nothing else

That we can show to-day?

That is a poem. I don’t know who wrote it or what it means. It was

simply printed out on the blackboard when we arrived and we were ordered

to comment upon it. When I read the first verse I thought I had an

idea—The Mighty Merchant was a divinity who distributes blessings

in return for virtuous deeds—but when I got to the second verse

and found him twirling a button, it seemed a blasphemous supposition,

and I hastily changed my mind. The rest of the class was in the same

predicament; and there we sat for three quarters of an hour with blank

paper and equally blank minds. Getting an education is an awfully

wearing process!

But this did n’t end the day. There ’s worse to

come.

It rained so we could n’t play golf, but

78

had to go to gymnasium instead. The girl next to me banged my elbow with

an Indian club. I got home to find that the box with my new blue

spring dress had come, and the skirt was so tight that I

could n’t sit down. Friday is sweeping day, and the maid had

mixed all the papers on my desk. We had tombstone for dessert (milk and

gelatin flavored with vanilla). We were kept in chapel twenty minutes

later than usual to listen to a speech about womanly women. And

then—just as I was settling down with a sigh of well-earned relief

to “The Portrait of a Lady,” a girl named Ackerly,

a dough-faced, deadly, unintermittently stupid girl, who sits next

to me in Latin because her name begins with A (I wish Mrs. Lippett

had named me Zabriski), came to ask if Monday’s lesson commenced at

paragraph 69 or 70, and stayed ONE HOUR. She has just gone.

Did you ever hear of such a discouraging series of events? It

is n’t the big troubles

79

in life that require character. Anybody can rise to a crisis and face a

crushing tragedy with courage, but to meet the petty hazards of the day

with a laugh—I really think that requires spirit.

It ’s the kind of character that I am going to develop. I am

going to pretend that all life is just a game which I must play as

skilfully and fairly as I can. If I lose, I am going to shrug my

shoulders and laugh—also if I win.

Anyway, I am going to be a sport. You will never hear me complain

again, Daddy dear, because Julia wears silk stockings and centipedes

drop off the wall.

Yours ever,

Judy.

Answer soon.

80

May 27th.

Daddy-Long-Legs, Esq.

Dear Sir: I am in receipt of a

letter from Mrs. Lippett. She hopes that I am doing well in deportment

and studies. Since I probably have no place to go this summer, she will

let me come back to the asylum and work for my board until college

opens.

I HATE THE JOHN GRIER HOME.

I ’d rather die than go back.

Yours most truthfully,

Jerusha Abbott.

81

Cher Daddy-Jambes-Longes,

Vous etes un brick!

Je suis tres heureuse about the farm, parsque je n’ai

jamais been on a farm dans ma vie and I ’d hate

to retourner chez John Grier, et wash dishes tout

l’été. There would be danger of quelque chose affreuse

happening, parsque j’ai perdue ma humilité d’autre fois et j’ai

peur that I would just break out quelque jour et smash

every cup and saucer dans la maison.

Pardon brièveté et paper. Je ne peux pas send

des mes nouvelles parseque je suis dans French class et j’ai

peur que Monsieur le Professeur is going to call on me tout de

suite.

He did!

Au revoir,

Je vous aime beaucoup.

Judy.

82

May 30th.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

Did you ever see this campus? (That is merely a rhetorical question.

Don’t let it annoy you.) It is a heavenly spot in May. All the shrubs

are in blossom and the trees are the loveliest young green—even

the old pines look fresh and new. The grass is dotted with yellow

dandelions and hundreds of girls in blue and white and pink dresses.

Everybody is joyous and care-free, for vacation ’s coming, and

with that to look forward to, examinations don’t count.

Is n’t that a happy frame of mind to be in? And oh, Daddy!

I ’m the happiest of all! Because I ’m not in the asylum

any more; and I ’m not anybody’s nurse-maid or typewriter or

bookkeeper (I should have been, you know, except for you).

83

I ’m sorry now for all my past badnesses.

I ’m sorry I was ever impertinent to Mrs. Lippett.

I ’m sorry I ever slapped Freddie Perkins.

I ’m sorry I ever filled the sugar bowl with salt.

I ’m sorry I ever made faces behind the Trustees’ backs.

I ’m going to be good and sweet and kind to everybody because

I ’m so happy. And this summer I ’m going to write and

write and write and begin to be a great author. Is n’t that an

exalted stand to take? Oh, I ’m developing a beautiful character!

It droops a bit under cold and frost, but it does grow fast when the sun

shines.

That ’s the way with everybody. I don’t agree with the theory

that adversity and sorrow and disappointment develop moral strength. The

happy people are the ones who are bubbling over with kindliness.

I have no faith in misanthropes. (Fine

84

word! Just learned it.) You are not a misanthrope are you, Daddy?

I started to tell you about the campus. I wish you ’d come for

a little visit and let me walk you about and say:

“That is the library. This is the gas plant, Daddy dear. The Gothic

building on your left is the gymnasium, and the Tudor Romanesque beside

it is the new infirmary.”

Oh, I ’m fine at showing people about. I ’ve done it

all my life at the asylum, and I ’ve been doing it all day here.

I have honestly.

And a Man, too!

That ’s a great experience. I never talked to a man before

(except occasional Trustees, and they don’t count). Pardon, Daddy.

I don’t mean to hurt your feelings when I abuse Trustees.

I don’t consider that you really belong among them. You just

tumbled onto the Board by chance. The Trustee, as such, is fat and

pompous and

85

benevolent. He pats one on the head and wears a gold watch chain.

That looks like a June bug, but is meant to be a portrait of any

Trustee except you.

However—to resume:

I have been walking and talking and having tea with a man. And with a

very superior man—with Mr. Jervis Pendleton of the House of Julia;

her uncle, in short (in

86

long, perhaps I ought to say; he ’s as tall as you). Being in

town on business, he decided to run out to the college and call on his

niece. He ’s her father’s youngest brother, but she

does n’t know him very intimately. It seems he glanced at her

when she was a baby, decided he did n’t like her, and has never

noticed her since.

Anyway, there he was, sitting in the reception room very proper with

his hat and stick and gloves beside him; and Julia and Sallie with

seventh-hour recitations that they could n’t cut. So Julia dashed

into my room and begged me to walk him about the campus and then deliver

him to her when the seventh hour was over. I said I would,

obligingly but unenthusiastically, because I don’t care much for

Pendletons.

But he turned out to be a sweet lamb. He ’s a real human

being—not a Pendleton at all. We had a beautiful time;

I ’ve longed for an uncle ever since. Do you

87

mind pretending you ’re my uncle? I believe they ’re

superior to grandmothers.

Mr. Pendleton reminded me a little of you, Daddy, as you were twenty

years ago. You see I know you intimately, even if we have n’t

ever met!

He ’s tall and thinnish with a dark face all over lines, and

the funniest underneath smile that never quite comes through but just

wrinkles up the corners of his mouth. And he has a way of making you

feel right off as though you ’d known him a long time.

He ’s very companionable.

We walked all over the campus from the quadrangle to the athletic

grounds; then he said he felt weak and must have some tea. He proposed

that we go to College Inn—it ’s just off the campus by the

pine walk. I said we ought to go back for Julia and Sallie, but he

said he did n’t like to have his nieces drink too much tea; it

made them nervous. So we just ran away and had tea

88

and muffins and marmalade and ice-cream and cake at a nice little table

out on the balcony. The inn was quite conveniently empty, this being the

end of the month and allowances low.

We had the jolliest time! But he had to run for his train the minute

he got back and he barely saw Julia at all. She was furious with me for

taking him off; it seems he ’s an unusually rich and desirable

uncle. It relieved my mind to find he was rich, for the tea and things

cost sixty cents apiece.

This morning (it ’s Monday now) three boxes of chocolates came

by express for Julia and Sallie and me. What do you think of that? To be

getting candy from a man!

I begin to feel like a girl instead of a foundling.

I wish you ’d come and take tea some day and let me see if I

like you. But

89

would n’t it be dreadful if I did n’t? However, I know I

should.

Bien! I make you my compliments.

“Jamais je ne t’oublierai.”

Judy.

P. S. I looked in the glass this morning and found a perfectly new

dimple that I ’d never seen before. It ’s very curious.

Where do you suppose it came from?

90

June 9th.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

Happy day! I ’ve just finished my last

examination—Physiology. And now:

Three months on a farm!

I don’t know what kind of a thing a farm is. I ’ve never been

on one in my life. I ’ve never even looked at one (except from

the car window), but I know I ’m going to love it, and

I ’m going to love being free.

I am not used even yet to being outside the John Grier Home. Whenever

I think of it excited little thrills chase up and down my back.

I feel as though I must run faster and faster and keep looking over

my shoulder to make sure that Mrs. Lippett is n’t after me with

her arm stretched out to grab me back.

91

I don’t have to mind any one this summer, do I?

Your nominal authority does n’t annoy me in the least; you are

too far away to do any harm. Mrs. Lippett is dead forever, so far as I

am concerned, and the Semples are n’t expected to overlook my

moral welfare, are they? No, I am sure not. I am entirely

grown up. Hooray!

I leave you now to pack a trunk, and three boxes of teakettles and

dishes and sofa cushions and books.

Yours ever,

Judy.

P. S. Here is my physiology exam. Do you think you could have

passed?

92

Lock Willow Farm,

Saturday night.

Dearest Daddy-Long-Legs,

I ’ve only just come and I ’m not unpacked, but I can’t

wait to tell you how much I like farms. This is a heavenly, heavenly,

heavenly spot! The house is square like this:

And old. A hundred years or so. It has a veranda on the side

which I can’t draw and a sweet porch in front. The picture

93

really does n’t do it justice—those things that look like

feather dusters are maple trees, and the prickly ones that border the

drive are murmuring pines and hemlocks. It stands on the top of a hill

and looks way off over miles of green meadows to another line of

hills.

That is the way Connecticut goes, in a series of Marcelle waves; and

Lock Willow Farm is just on the crest of one wave. The barns used to be

across the road where they obstructed the view, but a kind flash of

lightning came from heaven and burnt them down.

The people are Mr. and Mrs. Semple and a hired girl and two hired

men. The hired people eat in the kitchen, and the Semples and Judy in

the dining-room. We had ham and eggs and biscuits and honey and

jelly-cake and pie and pickles and cheese

94

and tea for supper—and a great deal of conversation. I have never

been so entertaining in my life; everything I say appears to be funny.

I suppose it is, because I ’ve never been in the country

before, and my questions are backed by an all-inclusive ignorance.

The room marked with a cross is not where the murder was committed,

but the one that I occupy. It ’s big and square and empty, with

adorable old-fashioned furniture and windows that have to be propped up

on sticks and green shades trimmed with gold that fall down if you touch

them. And a big square mahogany table—I ’m going to spend

the summer with my elbows spread out on it, writing a novel.

Oh, Daddy, I ’m so excited! I can’t wait till daylight to

explore. It ’s 8.30 now, and I am about to blow out my candle and

try to go to sleep. We rise at five. Did you ever know such fun?

I can’t believe this is really Judy. You and the

95

Good Lord give me more than I deserve. I must be a very, very,

very good person to pay. I ’m going to be. You ’ll

see.

Good night,

Judy.

P. S. You should hear the frogs sing and the little pigs

squeal—and you should see the new moon! I saw it over my

right shoulder.

96

Lock Willow,

July 12th.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

How did your secretary come to know about Lock Willow? (That

is n’t a rhetorical question. I am awfully curious to know.)

For listen to this: Mr. Jervis Pendleton used to own this farm, but now

he has given it to Mrs. Semple who was his old nurse. Did you ever hear

of such a funny coincidence? She still calls him “Master Jervie” and

talks about what a sweet little boy he used to be. She has one of his

baby curls put away in a box, and it ’s red—or at least

reddish!

Since she discovered that I know him, I have risen very much in her

opinion. Knowing a member of the Pendleton family is the best

introduction one can have at

97

Lock Willow. And the cream of the whole family is Master Jervie—I

am pleased to say that Julia belongs to an inferior branch.

The farm gets more and more entertaining. I rode on a hay wagon

yesterday. We have three big pigs and nine little piglets, and you

should see them eat. They are pigs! We ’ve oceans of

little baby chickens and ducks and turkeys and guinea fowls. You must be

mad to live in a city when you might live on a farm.

It is my daily business to hunt the eggs. I fell off a beam in the

barn loft yesterday, while I was trying to crawl over to a nest that the

black hen has stolen. And when I came in with a scratched knee, Mrs.

Semple bound it up with witch-hazel, murmuring all the time, “Dear!

Dear! It seems only yesterday that Master Jervie fell off that very same

beam and scratched this very same knee.”

The scenery around here is perfectly beautiful. There ’s a

valley and a river

98

and a lot of wooded hills, and way in the distance, a tall blue mountain

that simply melts in your mouth.

We churn twice a week; and we keep the cream in the spring house

which is made of stone with the brook running underneath. Some of the

farmers around here have a separator, but we don’t care for these

new-fashioned ideas. It may be a little harder to take care of cream

raised in pans, but it ’s enough better to pay. We have six

calves; and I ’ve chosen the names for all of them.

1. Sylvia, because she was born in the woods.

2. Lesbia, after the Lesbia in Catullus.

3. Sallie.

4. Julia—a spotted, nondescript animal.

5. Judy, after me.

6. Daddy-Long-Legs. You don’t mind, do you, Daddy? He ’s pure

Jersey and has a sweet disposition. He looks like this—you can see

how appropriate the name is.

99

100

I have n’t had time yet to begin my immortal novel; the farm

keeps me too busy.

Yours always,

Judy.

P. S. I ’ve learned to make doughnuts.

P. S. (2) If you are thinking of raising chickens, let me recommend

Buff Orpingtons. They have n’t any pin feathers.

P. S. (3) I wish I could send you a pat of the nice, fresh butter I

churned yesterday. I ’m a fine dairy-maid!

P. S. (4) This is a picture of Miss Jerusha Abbott, the future great

author, driving home the cows.

101

Sunday.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

Is n’t it funny? I started to write to you yesterday

afternoon, but as far as I got was the heading, “Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,”

and then I remembered I ’d promised to pick some blackberries for

supper, so I went off and left the sheet lying on the table, and when I

came back to-day, what do you think I found sitting in the middle of the

page? A real true Daddy-Long-Legs!

I picked him up very gently by one leg, and dropped him out of the

window.

102

I would n’t hurt one of them for the world. They always

remind me of you.

We hitched up the spring wagon this morning and drove to the Center

to church. It ’s a sweet little white frame church with a spire

and three Doric columns in front (or maybe Ionic—I always get them

mixed).

A nice, sleepy sermon with everybody drowsily waving palm-leaf fans,

and the only sound aside from the minister, the buzzing of locusts in

the trees outside. I did n’t wake up till I found myself on

my feet singing the hymn, and then I was awfully sorry I had n’t

listened to the sermon; I should like to know more of the

psychology of a man who would pick out such a hymn. This was it:

Come, leave your sports and earthly toys

And join me in celestial joys.

Or else, dear friend, a long farewell.

I leave you now to sink to hell.

103

I find that it is n’t safe to discuss religion with the

Semples. Their God (whom they have inherited intact from their remote

Puritan ancestors) is a narrow, irrational, unjust, mean, revengeful,

bigoted Person. Thank heaven I don’t inherit any God from anybody!

I am free to make mine up as I wish Him. He ’s kind and

sympathetic and imaginative and forgiving and understanding—and He

has a sense of humor.

I like the Semples immensely; their practice is so superior to their

theory. They are better than their own God. I told them

so—and they are horribly troubled. They think I am

blasphemous—and I think they are! We ’ve dropped theology

from our conversation.

This is Sunday afternoon.

Amasai (hired man) in a purple tie and some bright yellow buckskin

gloves, very red and shaved, has just driven off with Carrie (hired

girl) in a big hat trimmed

104

with red roses and a blue muslin dress and her hair curled as tight as

it will curl. Amasai spent all the morning washing the buggy; and Carrie

stayed home from church ostensibly to cook the dinner, but really to

iron the muslin dress.

In two minutes more when this letter is finished I am going to settle

down to a book which I found in the attic. It ’s entitled,

“On the Trail,” and sprawled across the front page in a funny little-boy

hand:

Jervis Pendleton

If this book should ever roam,

Box its ears and send it home.

He spent the summer here once after he had been ill, when he was

about eleven years old; and he left “On the Trail” behind. It looks well

read—the marks of his grimy little hands are frequent! Also in a

corner of the attic there is a water wheel and a windmill and some bows

and

105

arrows. Mrs. Semple talks so constantly about him that I begin to

believe he really lives—not a grown man with a silk hat and

walking stick, but a nice, dirty, tousle-headed boy who clatters up the

stairs with an awful racket, and leaves the screen doors open, and is

always asking for cookies. (And getting them, too, if I know Mrs.

Semple!) He seems to have been an adventurous little soul—and

brave and truthful. I ’m sorry to think he is a Pendleton; he was

meant for something better.

We ’re going to begin threshing oats to-morrow; a steam engine

is coming and three extra men.

It grieves me to tell you that Buttercup (the spotted cow with one

horn, Mother of Lesbia) has done a disgraceful thing. She got into the

orchard Friday evening and ate apples under the trees, and ate and ate

until they went to her head. For two days she has been perfectly dead drunk!

106

That is the truth I am telling. Did you ever hear anything so

scandalous?

Sir,

I remain,