*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 40690 ***

WHG Kingston

"Roger Kyffin's Ward"

Chapter One.

A Panic in the City.

London was in commotion. On a certain afternoon in the early part of the year 1797, vast numbers of persons of all ranks of society, wealthy merchants, sober shopkeepers, eager barristers, country squires, men of pleasure, dandies, and beaus, and many others of even more doubtful position, might have been seen hurrying up through lanes and alleys towards the chief centre of British commerce—the Bank of England, that mighty heart, in and out of which the golden stream flows to and fro along its numberless arteries. Numerous carriages, also, some with coronets on their panels, and powdered footmen behind, rolled up from Cheapside. Among their occupants were ministers of state, foreign ambassadors, earls and barons of the realm, members of parliament, wealthy country gentlemen, and other persons of distinction. While in not a few were widows and spinster ladies, dowager duchesses and maids of honour, and other dames with money in the funds. On the countenances of the larger portion of the moving throng might be traced a word of uncomfortable import—“Panic.”

It was an eventful period. Seldom during that or the present century have English patriots had greater cause for anxiety. Never, certainly, from the day of the explosion of the South Sea Bubble up to that period, had the mercantile atmosphere been more agitated. The larger portion of the motley crowd turned on one side to the Bank of England, where the ladies, descending from their carriages, pressed eagerly forward amidst the people on foot, one behind the other, to reach the counters. Another portion entered the Royal Exchange, while a considerable number of the carriages proceeded along Cornhill.

The appearance of the surrounding edifices was, however, different from that of the present day. The old Mansion House was there, and the new Bank of England had been erected, but all else has been altered. The then existing Royal Exchange was greatly inferior to the fine structure at present to be seen between the Mansion House and the Bank. It stood in a confined space, surrounded by tall blocks of buildings, dark and dingy, though not altogether unpicturesque. Whatever were its defects, it served its purpose, and would have been serving it still, probably, had it not been burnt down.

Numerous excited groups of men now filled the greater part of the interior area; some were bending eagerly forward, either more forcibly to express an opinion, or to hear what was said by the speaker on the opposite side of the circle. Others were whispering into their neighbours’ ears, with hands lifted up, listening attentively to the remarks bestowed upon them, while others were hurrying to and fro gathering the opinion of their acquaintances, and then quickly again putting it forth as their own, or hastening away to act on the information they had received.

“Terrible news! The country will be ruined to a certainty! The French will be here within a week! Fearful disaster! The fleet has mutinied! The army will follow their example! Ireland is in open rebellion! The bank is drained of specie! Failures in every direction! The funds at fifty-seven!”

Such were some of the remarks flying about, and which formed the subject matter of the addresses delivered by the various speakers. Many persons then collected were sober-minded citizens, merchants of good repute, trading with the West Indian Sugar Islands, Africa, the Colonies of North America, or the Baltic, East India directors, or others, whose transactions compelled them to assemble, for the negotiation of their bills on ’change.

A considerable number, however, of those who came into the city from the West End did not stop at the Exchange, but continued their course a short distance farther, along Cornhill, where turning on one side they found themselves in the precincts of Change Alley. An old writer describes that region: “The limits are easily surrounded in a minute and a half. Step out of Jonathan’s into the alley, turn your face due east, move on a few paces to Garraway’s. From thence go out at the other door, and go on still east, into Birchin Lane, and then halting at the Sword-blade bank, and facing the north, you will enter Cornhill, and visit two or three petty provinces there to the west, and thus having boxed your compass, and sailed round the stock-jobbing globe, you turn into Jonathan’s again.”

In Jonathan’s well-known coffee-house, and in its immediate neighbourhood, was assembled a large number of persons, varying in rank and appearance far more than those who were inside the Exchange. To this point the coroneted carriages had been directing their course. The occupants of some had got out and entered the coffee-house. Others remained with their brokers at the door, eager to gain certain intelligence, which was to raise or depress the market. Here too were to be seen persons in Eastern costume, and others in English dress, both however with the unmistakable features of the Jew. There were courtiers and gentlemen from the fashionable parts of the metropolis, in silk stockings and diamond-buckled shoes, with powdered wigs, frilled shirts, and swords by their sides, or quakers in broad-brimmed hats and garments of sombre hue, such as were worn by our puritan ancestors of the previous century. Here too were portly citizens with gold-headed canes and well-brushed beavers, their countenances anxious, but honest and straightforward, though many other persons were there, some in shabby-genteel costume, others in threadbare and almost ragged coats, and again, many whose sharp eager eyes and pale features showed that they had been long accustomed to the transactions of the place. The two great parties in the State might in most cases have been distinguished by the difference of their costume. The Tories, the supporters of the war, determined foes of the men then in power in France, generally retained the gay and handsome costume of their fathers, while the Whigs and Jacobinical party affected a republican simplicity, and dressed in straight-cut coats and low-crowned hats, which had been introduced in France.

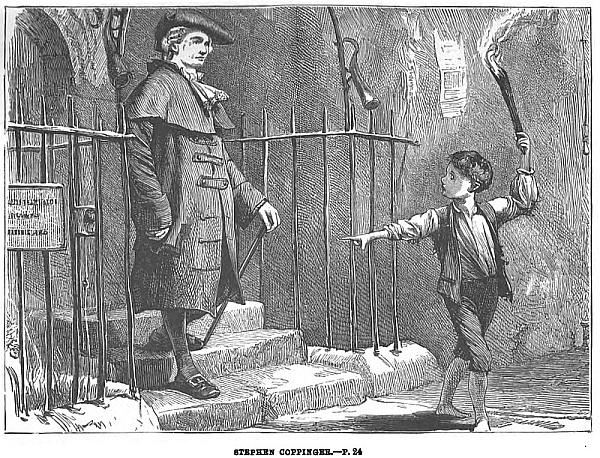

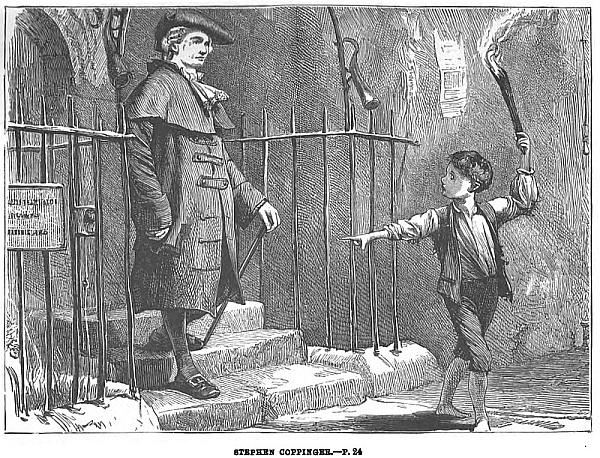

We shall have to return to Jonathan’s by-and-bye, and will in the meantime go back to the Royal Exchange. Among those who were making their way towards it from the lanes which led up from the banks of the river was a person not unworthy of notice. He was a man past the meridian of life, of tall and commanding figure. The leather-like skin of his colourless face, though free from spot or blemish, was slightly wrinkled, and his somewhat massive features wore a calm and unmoved expression, which might have surprised those who could have defined the feelings agitating his bosom. No wonder that his mind was troubled. Those were anxious times for men engaged even in very limited transactions. Stephen Coppinger’s were extensive and complex. There was scarcely a pie baked in those days in which he had not a finger. He walked at a dignified pace, with a smile on his lips, and his bright eyes calm, though watchful. His dark-coloured suit of fine cloth with brass buttons was carefully brushed, a small quantity of powder only shaken on his hair, which was fastened behind in a long queue, resting on his collar. The folds of his white neck-cloth, and the frill of fine lace which appeared beneath his waistcoat, were scrupulously clean and well arranged. Silk stockings with knee breeches, and shoes with steel buttons, encased his legs and feet. In his hand he carried a thick gold-headed walking-stick, though scarcely requiring it to support his steps, while a plain cocked hat, and a spencer, for the weather was cold, completed his costume. His step was firm, his head erect, as he walked along with a dignified air, bowing to one acquaintance, nodding to another, and returning with condescension the salutations of his inferiors. He observed many other persons proceeding in the same direction, several of whom he knew, the countenances of not a few wearing that expression of anxiety which he took care his own should not exhibit. Several of them did not notice him, as, lost in thought, with their heads cast down, they picked their way over the uneven pavement.

Stephen Coppinger had scarcely reached his accustomed “walk” in the Exchange, when his acquaintance, Alderman Bycroft, bustled up to him.

“Well, friend Coppinger, you look as calm as if nothing had happened!” exclaimed the alderman; “have you not heard the news?”

“Which news?” asked the merchant in a quiet voice, without the slightest change of countenance; “so many reports are flying about that I believe none of them.”

“You could not have heard the news, or you would not look so abominably unconcerned,” exclaimed the alderman, who was a somewhat fussy excitable gentleman. “Why, the news is positively fearful! A mutiny has broken out on board the channel fleet at Spithead! They have murdered Lord Bridport and most of their officers, and threatened, if they have not everything their own way, to carry the ships over to the French. The enemy’s fleets are mustering in great force, and may be across the Channel, for what we can tell, at this moment. The Irish are in rebellion, and are certain to join them and cut all our throats.”

“Terrible, if true,” answered Mr Coppinger, with a smile, which he could afford to bestow on his excitable friend; “but I think, my dear alderman, I can correct you. The crews of the Channel fleet have undoubtedly refused to proceed to sea unless their very reasonable demands are agreed to, and I know for certain that they have treated the admiral and their officers with every respect. They will, I have no fear, therefore, when their petition is granted, return to their duty. If the French come we will give them a warm reception. In the meantime, however, I acknowledge we are likely to suffer by having our merchantmen exposed to the depredations of the enemy’s ships, and this is about the worst danger I apprehend.”

“You take things too calmly, my friend!” exclaimed the alderman. “Suppose the fleet refuses to obey orders, what are we to do? There’s the question. I am of opinion that we should call out the train-bands, the volunteers, and the militia, and man every vessel in the Thames, and sail down and capture the mutineers.”

“I suspect, my friend, that your proposed flotilla would very soon be sent to the right-about, if not to the bottom. It would be wiser to inquire into the complaints of the seamen, and to redress their grievances. Their pay was small enough at first during Charles the Second’s reign, and since then all necessary articles of subsistence have advanced fully fifty per cent, and all the men require is, that their wages may be proportionably increased. They ask also that the naval pensions may be augmented, as have those of Chelsea, to 13 pounds a year. The Greenwich pensions still remain at 7 pounds. They also beg that while in harbour they may have more liberty to go on shore, and that when seamen are wounded they may receive their pay till cured or discharged. Their other requests are really as moderate, and though I, for one, would never countenance mutiny, from my heart I believe that their demands are just.”

“Can’t see that,” answered the alderman. “In my opinion the country is going to rack and ruin. What are we to do without gold? Then we are to have more loans. We have already lent Prussia, Sardinia, and the Emperor of Austria some seven or eight millions, and are now going to make a further loan to Portugal, and for all I know to the contrary we shall soon be subsidising all the rest of Europe.”

“If this war with France is to continue, I, for my part, shall be glad if we have so many friends on our side,” observed Mr Coppinger, whose great object at the moment was to tranquillise the minds of his City friends. “We are not likely to pay money away without getting something for it.”

“Not so sure of that,” replied the alderman; “John Bull is apt to throw his cash away with his eyes shut, and that is what we have been doing for some time past. Had Lord Malmesbury been successful in his negotiation for peace, things might have been different, but what can be worse with consols down to fifty-seven, a fearful run on the Bank of England, and now a suspension of payment in specie altogether, with this dangerous mutiny of the fleet as a climax! Then look at Ireland—half the country in a state of rebellion; the people shrieking out for the assistance of the French, and cutting each other’s throats in the meantime. Then these Jacobin clubs in London and throughout all our large towns, doing their utmost to bring about a republic in England. If they could imitate the French and cut off our king’s head, they would do it. And as to the army, I am not certain that we can put confidence in it. Ah! my dear sir, the sun of England’s glory has set; that is my opinion. I may be wrong—I hope so—but that is my opinion.”

“You take too gloomy a view of the state of affairs, alderman,” said Mr Coppinger. “Things are very bad, I’ll own, but they may improve. Lord Duncan’s late victory should give us confidence. The fate of the French who landed in Pembrokeshire the other day, shows that even though our enemies may set foot on our shores, they may not gain much by their impudence. No fear about our army, that is staunch, and the navy will soon return to its duty, and then Old England will be well able to hold her own against all her enemies.”

Stephen Coppinger was anxious to get rid of the alderman without rudeness, and that worthy finding he could not frighten his friend, soon bustled off to communicate his alarm to some more excitable listener.

The merchant, however, was very far from feeling the tranquillity he exhibited. He well knew the desperate state of affairs, but at the same time it was important that the public mind should be tranquillised. He had also several bills to negotiate and other business to transact, which required his own mind to be peculiarly calm and collected. Many other persons addressed him, most of them as agitated as Alderman Bycroft. He had to get rid of them one after the other, and having despatched his own business, maintaining his usual composed manner, he quitted the Exchange.

He proceeded along Cornhill to the narrow passage which led into Change Alley, and with deliberate steps entered Jonathan’s. Every room in that once celebrated coffee-house was full. Some persons were transacting private business in the smaller rooms, while in the larger, stood eager groups of brokers and dealers, with their books in their hands, noting the various transactions in which they were engaged.

The news flying about had caused the funds to fall yet lower than on the previous day, and brokers were hurrying to and fro, receiving orders from their various constituents, some to buy, others to sell forthwith. Stephen Coppinger gave certain directions to his broker in a subdued tone. It was even with greater difficulty than in the morning that he could command his voice, then bowing to his acquaintance as he passed, he took his way back to Idol Lane.

He preserved his calm and dignified air, during his walk to his counting-house. Passing through the public office to his private room, he closed the door, and throwing himself back into his arm-chair, pressed his hands on his brow for some minutes, lost in thought. At length turning round towards his large black writing-table, and referring to some letters and other papers, he seized a pen which he mechanically mended, almost in so doing cutting through his thumb nail, and made some rapid calculations. They were not apparently satisfactory. He rang sharply a hand-bell by his side. Scarcely had the silvery sounds died away when the heavy door of the oak-panelled room slowly opened, and a clerk, with a ponderous volume under his arm, entered. He was dressed as became the managing clerk of a large establishment, with great neatness and precision, his hair being carefully powdered, though his side curls were somewhat smaller than those of his employer. His complexion was clear, with a good colour on his cheeks, which betokened sound health, while his countenance wore a peculiarly calm expression, calculated to gain the confidence of those with whom he had dealings. Roger Kyffin was highly esteemed by his principal as well as by all his subordinates. His word was, in truth, as good as Stephen Coppinger’s bond. What Roger Kyffin said Stephen Coppinger would do, was done. On the day and hour Roger Kyffin promised that cash should be paid, it was paid without fail. Stephen Coppinger had no partner. He scorned to throw responsibility on an unknown company, while, with only one exception, to no other breast than his own would he confide the secrets of his transactions. That exception was the breast of Roger Kyffin. Roger Kyffin placed the open folio before his principal, and produced a paper with the remarks he had made respecting certain entries.

“Bad!” observed Stephen Coppinger, as he ran his eye over the book and paper; “but see, these letters bring worse news. The ‘Belmont Castle’ has been taken by the enemy. The ‘Tiger’ has foundered during a hurricane in the West Indies. Jecks Tarbett and Simmons have failed; their debt is a large one. Hunter and Dove’s affairs are in an unsatisfactory condition. I don’t like Joseph Hudson’s proceedings in Change Alley; he yesterday begged that I would renew his bill. In truth, Roger Kyffin, unless matters improve...” A groan escaped from Stephen Coppinger’s bosom.

“The amount you require must be raised,” observed Roger Kyffin, taking half a turn across the room. “Leave that to me. You have so often aided friends in need, that I anticipate no difficulty in obtaining help.”

“It will be from no want of exertion on your part if you fail,” said Stephen Coppinger, brightening up slightly.

“Keep up your spirits, sir,” said Roger Kyffin. “The credit of your firm will not suffer, depend on that. I will now set out and see what can be done. I hope to bring satisfactory intelligence before evening.”

Saying this, Roger Kyffin left the room, carefully closing the door behind him. While putting on his spencer and hat, he intimated to his principal subordinate, Mr Silas Sleech, that he should probably be absent for some hours. Mr Sleech glanced after him with a pair of meaningless eyes, set in an immovable countenance, and saying, “Oh, very well,” went on with his work.

More respecting Mr Silas Sleech and his doings may possibly be mentioned.

Chapter Two.

In which Several Personages are Introduced.

Roger Kyffin took his way westward. As soon as he had got out of the crowded thoroughfares, he called a coach, for in those days walking in London was a more fatiguing operation than at present. The progress of the vehicle, however, in which he took his seat was not very rapid. It was a large and lumbering affair, drawn by a pair of broken-down hacks, the asthmatic cough of one keeping in countenance the shattered knees of the other. At length he reached the door of a substantial mansion in the middle of Clifford Street. The bell was answered by a servant in sober livery.

“Is Mr Thornborough at home?” he asked, at the same time presenting a card with his name in a bold hand written on it. The servant was absent but a short time, when he returned, saying that his master would be glad to see Mr Roger Kyffin. The visitor was shown into a handsome parlour, where, seated before a fire with his buckled shoes on a footstool, was a venerable-looking gentleman, with his silvery locks slightly powdered hanging down over his shoulders. A richly-embroidered waistcoat, a plum-coloured coat with mother-of-pearl buttons, knee breeches, and black silk stockings with clocks, completed his costume. By his side sat a lady dressed in rich garments, though of somewhat sombre hue.

The white curls which appeared under her high cap showed that she was advanced in life, and the pleasant smile on her comely features betokened a kind and genial disposition. She rose from her seat, and kindly welcomed Roger Kyffin, directing the servant to place a chair for him before the fire. The old gentleman shook his hand, but pleaded age as an excuse for not rising.

“You have given us but little of your company for many a day, Mr Kyffin,” said the lady in a kind tone. “We thought you must have left London altogether.”

“No, Mrs Barbara, I have scarcely been beyond the sound of Bow Bells; but I must plead business as an excuse for my negligence. These are anxious times, and mercantile men must needs pay more than double attention to their affairs.”

“If they demand more time, undoubtedly we should give it; if not, we are robbing other matters of their due attention,” observed Mr Thornborough.

“I agree with you, sir,” answered Mr Kyffin; “I must confess, indeed, that a matter of business of great importance to a friend brought me to the west. I would ask you to allow me a few minutes that I may explain the matter to you clearly.”

“Speak on, friend, I keep no secrets from Barbara, and if she does not know all my affairs, it is through no wish on my part to hide them from her. My sister is a discreet woman, Mr Kyffin, and that’s more perhaps than can be said of all her sex.”

Mr Kyffin bowed his acquiescence in this opinion. He, then turning to the old gentleman, explained clearly the difficulties which surrounded his friend and principal, Mr Stephen Coppinger. Mr Thornborough uttered two or three exclamations as Roger Kyffin went on in his account.

“I thought that my friend Stephen had been a more prudent man,” he observed. “How could he enter into such a speculation? How could he trust such people as Hunter and Dove? Why, Roger Kyffin, you yourself should have been better informed about them. However, if we were only to undertake to assist the wise and prudent we might keep our money chests locked and our pockets buttoned up. Stephen Coppinger is an honest man, and has shown himself a kind and generous one, albeit he might not always have exhibited as much prudence, as was desirable. The amount you mention shall, however, be at his disposal. We must not let a breath of suspicion rest on his name. I have a regard for him, and his six fair daughters, and it would be cruel to allow the maidens to go out into the world without sufficient dowers or means of maintenance, whereas if Stephen Coppinger tides over the present crisis, he may leave them all well off.”

“That’s right, that’s right,” said Mrs Barbara, looking approvingly at her brother. “He gives good advice, and acts it, too, eh, Mr Kyffin? And now my brother has had his say I must have mine. What about the negro slave trade? We have not seen Mr Wilberforce nor any of his friends for several weeks, and my brother cannot help on the cause as he used to do.”

“It is a good cause, that will ultimately be successful,” answered Roger Kyffin; “but, my dear Mrs Barbara, like other good causes, we may have a long fight for it before we gain the day. Just now men’s minds are so engaged with our national affairs that the poor blacks are very little thought of.”

“Too true,” answered Mistress Barbara; “I wish, however, that Mr Wilberforce would call here. I want to tell him how delighted I am with his new book, which I got a few days ago—his ‘Practical View of Christianity.’ It will open the eyes, I hope, of some of the upper classes, to the hollow and unsatisfying nature of the forms to which they cling. I think, and my brother agrees with me, it’s one of the finest books on theology that has ever been written; that is to say, it is more likely to bring people to a knowledge of the truth than all the works of the greatest divines of the past and present age. Get the book and judge for yourself.”

Mr Kyffin promised to do so, and after some further conversation, he rose to take his departure. Mrs Barbara did not fail to press him to come again as soon as his occupations would allow.

“The money shall be ready for you before noon to-morrow,” said Mr Thornborough, shaking his hand. Roger Kyffin hastened back to Idol Lane. Mr Coppinger had not risen from his arm-chair since he quitted the house. The belief that his liabilities would be met without further difficulty, greatly relieved the merchant’s mind, and he thanked Roger Kyffin again and again for the important assistance afforded him.

“Say not a word about it,” answered the clerk; “if I have been useful to you, it was my duty. You found me in distress, and I shall never be able to repay the long-standing debt I owe you. Still I wish to place myself under a further obligation. I would rather have deferred speaking on the matter, but it will allow of no delay. I have to plead for a friend, ay, more than a friend—that unhappy young man—your nephew. You are mistaken as to his character. However appearances are against him. I am certain that Harry Tryon is not guilty of the crime imputed to him. Some day I shall be able to unravel the mystery. In the meantime I am ready to answer for his conduct, if you will reinstate him in the position which he so unwisely left. He has no natural love for business, I grant, but he is high-spirited and excessively sensitive, and I am therefore sure that he will not rest satisfied unless he is restored to his former position, and enabled to establish his innocence.”

“You press me hard, Kyffin,” answered Mr Coppinger. “Besides the fact that the lad is my great-nephew, although his grandmother and I have kept up very little intercourse for years, I have no prejudice against him, and I consider that I acted leniently in not sending after him, and compelling him to discover the authors of the fraud committed against my house. Even should he not be guilty, he must know who are guilty.”

“Granted, sir, and I speak it with all respect,” said Roger Kyffin, “but if he is innocent, and that he is I am ready to stake my existence, he would, had you examined him, have had an opportunity of vindicating himself. I know not now what has become of the lad, and I dread that he may be driven into some desperate course. I am, however, using every means to discover him, and I should be thankful if I could send him word that you are ready to look into his case.”

“No, no, Kyffin, I am resolved to wash my hands of the lad and his affairs, and I would advise you to do the same,” replied Mr Coppinger. “I find that he got into bad company, and was led into all sorts of extravagances, which of course would have made him try to supply himself with money. Had he been steady and industrious, I should have been less willing to believe him guilty.”

An expression of pain and sorrow passed over Roger Kyffin’s countenance when he heard these remarks.

“It is too true, I am afraid, that the lad was drawn into bad company, and I must confess that appearances are against him,” he answered. “I judge him, knowing his right principles, and, though in a certain sense, he wants firmness of character, I am sure that nothing would induce, him to commit the act of which he is suspected. I might tell you of many kind and generous things he has done. Since he has grown up he has shown himself to be a brave, high-minded young man.”

“I do not doubt his bravery or his generosity,” answered Mr Coppinger; “both are compatible with extravagance and dissipated conduct. But I am not prejudiced against the lad, and I would rather take your opinion of him than trust to my own. I would wish you, therefore, to follow your own course in this matter. If you think fit, get the lad up here. We will hear what he has to say for himself, and carefully go into his case. I wish that we had done so at first instead of letting him escape without further investigation.”

“Thank you, sir, thank you, Mr Coppinger; that is all I require,” exclaimed Roger Kyffin. “Where to find the lad, however, is the difficulty. He has gone through numerous adventures and dangers, and has been mercifully preserved. I had, indeed, given him up as lost, but I received a letter from him the other day, though, unfortunately, he neglected to date it. He spoke of others which he had written, but which I have not received. All I can hope now is that he will write again and let me know where he is to be found. Of one thing I am certain, that when he is found he will be well able to vindicate his character.”

Not till a late hour was the counting-house in Idol Lane closed that day. Further news of importance might arrive, and Stephen Coppinger was unwilling to risk not being present to receive it. A link boy was in waiting to light him to his handsome mansion in Broad Street. He had not yet retired, as was his custom later in the year, to his rural villa at Twickenham.

Clerks mostly lived in the city. Few, at that time, could enjoy a residence in the suburbs. Roger Kyffin, however, had a snug little abode of his own at Hampstead, from and to which he was accustomed to walk every day. In the winter season, however, when it was dark, several friends who lived in the same locality were in the habit of waiting for each other in order to afford mutual protection against footpads and highwaymen, to whose attacks single pedestrians were greatly exposed. At one time, indeed, they were accompanied by a regular guard of armed men, so audacious had become the banditti of London.

Roger Kyffin felt more than an ordinary interest in Mr Coppinger’s great-nephew—Harry Tryon—who has been spoken of. He loved him, in truth, as much as if he had been his own son.

When Roger Kyffin was a young man full of ardent aspirations, with no small amount of ambition, too, he became acquainted with a beautiful girl. He loved her, and the more he saw of her, the stronger grew his attachment. He had been trained for mercantile business, and had already attained a good situation in a counting-house. He had thus every reason to believe, that by perseverance and steadiness, he should be able to realise a competency. He hoped, indeed, to do more than this, and that wealth and honours such as others in his position had attained, he might be destined to enjoy. Fanny Ashton had, from the first, treated him as a friend. She could not help liking him. Indeed, possibly, had his modesty not prevented him at that time offering her his hand, she might have become his wife. At the same time, she probably had not asked herself the question as to how far her heart was his. She was all life and spirits, with capacity for enjoying existence. By degrees, as she mixed more and more with the gay world, her estimation of the humble clerk altered. She acknowledged his sterling qualities, but the fashionable and brilliant cavaliers she met in society were more according to her taste. An aunt, with whom she went to reside in London, mixed much in the world. Roger Kyffin, who had looked upon himself in the light of a permitted suitor, though not an accepted one, naturally called at her aunt’s house in the West End. His reception by Fanny was not as cordial as formerly. Her manner after this became colder and colder, till at last when he went to her aunt’s door he was no longer welcomed. Still his love for Fanny and his faith in her excellencies were not diminished.

“When she comes back to her quiet home she will be as she was before,” he thought to himself, and so, though somewhat sad and disappointed, he went on hoping that he might win her affection and become her husband.

At length Fanny Ashton returned home. Roger Kyffin, with the eye of love, observed a great change in her. She was no longer lively and animated as before. Her cheek was pale, and an anxious expression passed constantly over her countenance. She received him kindly, but with more formality than usual. Still Mr Kyffin ventured to speak to her. She appreciated his love and devotion, she said, and regretted she could not give her love in return.

Roger Kyffin did not further press his suit, yet went as frequently to the house as he could. Several times he had observed a gentleman in the neighbourhood. He was a fashionably-dressed, handsome man. There was something, however, in the expression of his countenance which Roger Kyffin did not like, for having seen him once, the second time they met he marked him narrowly. What brought him to that neighbourhood? One day as he was going towards Mrs Ashton’s house—Fanny’s mother was a widow, and she was her only child—he met the stranger coming out of the door. He would scarcely have been human had his jealousy not been aroused. He turned homeward, for he could not bring himself to call that day. The following evening, however, he went as usual, but great was his consternation to find that Fanny had gone to stay with her aunt. His worst fears were realised when, three weeks after this, he heard that Fanny Ashton had married Major Tryon. He could have borne his disappointment better if he could have thought that Fanny had married a man worthy of her.

To conquer his love he felt was impossible. His affection was true and loyal. He would now watch over her and be of service if he could. His inquiries as to the character of Major Tryon were thoroughly unsatisfactory. He was a gay man about town, well known on the turf, and a pretty constant frequenter of “hells” and gambling-houses. He was the son of an old general, Sir Harcourt Tryon, and so far of good family. Though a heartless and worthless roué, he seemed really to have fallen in love with Fanny Ashton, and having done his best to win her affections, he had at length resolved, as he called it, to “put his neck into the noose.” Roger Kyffin trembled for Fanny’s happiness, not without reason. Major Tryon had taken lodgings for her in London. Roger Kyffin discovered where he was residing. Unknown to her, he watched over her like a guardian angel, a fond father, or a devoted brother. In a short time her husband took her to the neighbourhood of Lynderton, in Hampshire, where Sir Harcourt and Lady Tryon resided, in the hopes, probably, that they would take notice of her. He engaged a small cottage with a pretty little garden in front of it, from which a view of the Solent and the Isle of Wight was obtained. Lady Tryon, however, and she ruled her husband, had greatly disapproved of her son’s marriage with the penniless Fanny Ashton, and consequently refused even to see his young wife.

In a short time Fanny was deserted by her worthless husband. Not many months had passed away before she received the announcement of his death in a duel. That very evening her child Harry was born. She never quite recovered from the shock she had received. Sad and dreary were the weeks she passed. No one called on her, for though it was known that Major Tryon was married, people were not aware that his young widow was residing at Sea View Cottage, which, standing at a distance from any high road, few of them ever passed. Her little boy was her great consolation. All her affections were centred in him. Her only visitor was good Dr Jessop, the chief medical practitioner at Lynderton. She called him in on one occasion when Harry was ill. There was not much the matter with the child, but he saw at once that the mother far more required his aid. There was a hectic flush on her cheek, a brightness in her eye, and a short cough which at once alarmed him, and he resolved to keep Master Harry on the sick list, that he might have a better excuse for going over to see the poor young widow.

Chapter Three.

The Hero’s Early Days, and a Description of a Lady of Quality.

Roger Kyffin heard of Major Tryon’s death soon after it occurred. He was afraid that Fanny might be left badly off, and he considered how he could with the greatest delicacy assist her. He would not intrude on her grief, but he thought that he might employ some person in the neighbourhood who would act as agent to take care that she was supplied with every comfort.

That evening he was travelling down in the mail coach to Lynderton. He knew his way to the cottage as well as anybody in the place.

Near it was a little inn, to which he had his carpet bag conveyed. Here he took up his abode. He felt a satisfaction in being near her, but was nervous lest by any means she should find out that he was in the neighbourhood. He soon discovered that Dr Jessop drove by every day and visited the cottage, and he resolved, therefore, to stop the doctor and introduce himself as a friend of Mrs Tryon’s family. If he found him a trustworthy and sensible person, he would employ him as his agent in affording the assistance he wished to render the widow. He saw him, and was satisfied that Dr Jessop was just the person he hoped to find.

“I have had a long round of visits,” said the worthy practitioner, “and would gladly put up my horse at the inn and talk the matter over with you.”

They were soon seated together in the little parlour allotted to Mr Kyffin. His wishes were easily explained. “My interesting patient will, I am sure, feel grateful for the sympathy and assistance of her unknown friend,” said the doctor; “but to be frank with you, Mr Kyffin, I fear she will not enjoy it for many years. I believe that her days are numbered—”

He stopped suddenly, observing Roger Kyffin’s countenance.

“My dear sir,” he exclaimed, “I was not aware how deeply I was wounding you, and yet, my friend, it is better to know the truth. You may yet prove a friend to her boy, and should she be taken away, the poor child will greatly need one.”

It would be difficult to describe the feelings which agitated Roger Kyffin’s kind heart. He had one consolation. He might, as the doctor suggested, prove a friend and guardian to the orphan boy. The kind doctor called every day to report on the health of his patient. He gladly undertook to do all in his power in carrying out Mr Kyffin’s wishes, and promised not to betray the donor of the money which was to be placed at Mrs Tryon’s disposal.

Roger Kyffin could with difficulty tear himself away from the neighbourhood. He received constant communications from Dr Jessop, who sent him rather more favourable reports of Mrs Tryon. Five years passed by—Mrs Tryon’s mother was dead. She had no wish to leave her little cottage. Where, indeed, could she go? Her only employment was that of watching over her little boy. During this time several changes had taken place in the neighbourhood. Sir Harcourt Tryon died. Though he must have been aware of his grandson’s existence, he had never expressed any wish to see him. At length the mother caught cold. The effect was serious. Dr Jessop became alarmed, and wrote an account of her state to Mr Kyffin. She could no longer take Harry out to walk, and had therefore to send him under charge of a nursemaid.

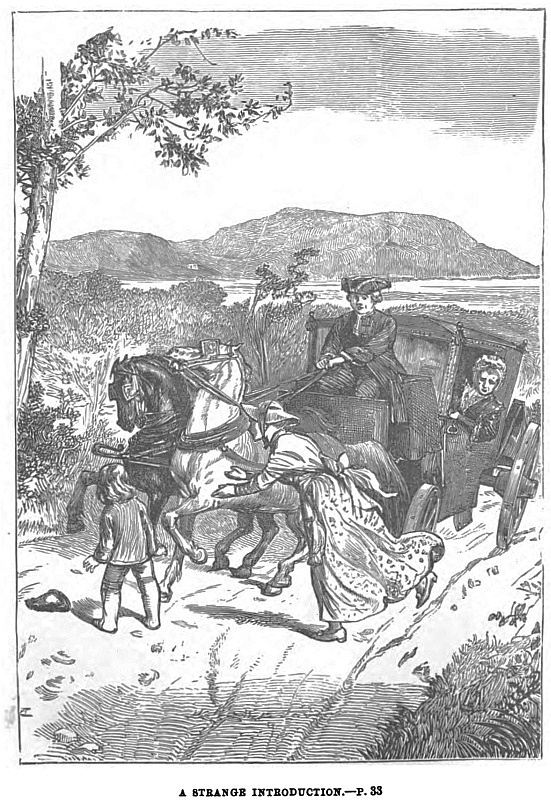

One day he and his nurse were longer absent than usual. What could have kept them? The young mother went to the garden-gate several times, and looked anxiously along the road. She felt the wind very cold. Again she entered the house. Could she have mistaken the hour? The next time she threw a shawl over her shoulders, but the cold made her cough fearfully. At last she saw a female figure in the distance. It was Susan the nurse, but Harry was not with her. Mrs Tryon had to support herself by the gate till the girl came up.

“Where is Harry? where is my child?” she exclaimed.

“I could not help it, ma’am, I did my best to prevent it,” answered the nurse, crying.

Poor Fanny’s heart sank within her; her knees trembled.

“Prevent what?” she exclaimed; “what has happened? where is my boy?”

“No harm has come to him, ma’am, though there might have been, but it is all right now,” answered Susan. “We were going on, Master Harry skipping and playing in front of me, when I saw a carriage coming along the road very fast. I ran on to catch hold of him, but he darted away just under the horses’ feet. I screamed out, and the coachman pulled up. An old lady was in the carriage, and putting her head out of the window she asked what was the matter? Seeing the little boy, she wanted to know whose child he was. When I told her, she ordered the footman to lift him into the carriage. She looked at his face as if she was reading a book, then she kissed him and sat him down by her side. I begged the lady to let me have him again, as I wanted to come home. ‘No,’ she said, ‘go and tell your mistress that his grandmother has taken him with her, that she is pleased with his looks, and must take him for a short time.’ I knew, ma’am, that you would be vexed, and I begged the lady again and again to let me have him, but she answered that he must go with her, and that it would be better for him in the end.”

Poor Mrs Tryon had been listening with breathless eagerness to this account of the nursemaid’s. Leaning on the girl’s arm, she tottered back to the house, scarcely knowing whether or not she ought to be thankful that the boy had been seen by his grandmother. One thing she knew, she longed to press him to her own bosom. She felt, however, weak and ill. While yet undecided how to act, Dr Jessop’s carriage drove up to the gate. As he entered the house, she was seized with a fit of coughing, followed by excessive weakness. As she was leaning back in the arm-chair, the doctor felt her pulse. As soon as she could speak she told him what had happened. He looked very grave.

“My dear madam,” he said, “I am sorry that her ladyship has carried off the little boy. If you will give me authority, I will drive on and bring him back to you. An old friend of yours has come down to this neighbourhood, and he wishes to see Harry. He has heard that you are ill, and desires to know from your own lips your wishes with regard to your boy.”

“What do you mean, doctor?” asked the dying lady, looking up with an inquiring glance at the doctor’s face. “The child is so young that I should not wish to part from him for some years to come.”

“My dear lady,” said Dr Jessop, solemnly, “the lives of all of us are in God’s hands. You are suffering from a serious complaint. It would be cruel in me not to warn you that you are in considerable danger.”

“Do you mean to say I’m going to die, doctor—that I must part from my boy?” gasped out poor Fanny, in a faint voice.

“I should wish you to be prepared, should it be God’s will to call you away,” answered the doctor, much moved. “If you will give authority to your devoted friend, Mr Roger Kyffin, I am sure he will act the part of a parent to your boy. I expect him here this evening, and as he wishes to see Harry, I will drive over to Lady Tryon and request her ladyship to allow me to bring your boy back to you. Certainly in most cases a child’s grandmother is a proper person to act as guardian, but though I attend Lady Tryon professionally when she is in the country, I am unable to express a satisfactory opinion as to her fitness for the task. I begged my friend Tom Wallis, the solicitor at Lynderton, to ride over here with Mr Kyffin; so that should you wish to place your boy under the legal protection of your old friend, you may be able to do so.”

“Surely his grandmother is a proper person to take charge of Harry; though I have no cause to regard her with affection,” said Fanny, in a faint voice, “yet I could with more confidence consign him to that kind and generous man, Mr Kyffin; I will do therefore as he wishes, only requesting that the boy may be allowed to remain as much as possible during his childhood with his grandmother.”

Poor Fanny! a lingering feeling of pride prompted this resolution. Far better would it have been, in all human probability, for the boy, had she committed him entirely to her faithful friend’s care, and not mentioned Lady Tryon. The doctor knew too well that his patient had not many hours to live. He hurried off to Aylestone Hall, the residence of Lady Tryon. The old lady expressed herself delighted with the child, and was very unwilling to part with him. Indeed, though she was told of her daughter-in-law’s dangerous state, she positively refused to give him up, unless the doctor promised to bring him back again. Harry was accordingly placed in the doctor’s carriage, which drove rapidly back to Mrs Tryon’s cottage.

“I can give you but little hopes,” said the doctor to Roger Kyffin, whom, in company with Mr Wallis, he met at the cottage gate.

Roger Kyffin sighed deeply. The little boy flew towards his mother. She had scarcely strength to bend forward to meet him. The doctor held him while she pressed him to her bosom.

“May he come in?” asked the doctor.

“Yes,” she whispered, “I should be glad to see him before I die; you were right, doctor, and kind to warn me.”

Roger Kyffin entered the room, but his knees trembled, and he could scarcely command his voice. Fanny thanked him for all his kindness; “continue it,” she said, “to this poor child.”

The doctor signed to Mr Wallis to come forward. He had brought writing materials. Fanny expressed her wish to place her child under Roger Kyffin’s guardianship. She signed the paper. She evidently wished to say more, but her voice failed her. It was with difficulty she could gasp out the last words she had uttered. In vain the doctor administered a restorative. With her one arm flung round her boy, while Roger Kyffin held her other hand, her spirit took its departure.

Roger Kyffin would gladly have carried Harry off to London, but no sooner did Lady Tryon hear of the death of her neglected daughter-in-law, than, driving over to the cottage, she took Harry with her back to Aylestone Hall. She directed also that a proper funeral should be prepared; and at her request several distant members and connections of the family attended it. Thus Mrs Tryon was laid to rest with as much pomp and ceremony as possible, in Lynderton churchyard.

With a sad heart Roger Kyffin returned to London and devoted himself with even more than his usual assiduity to his mercantile duties.

Aylestone Hall was a red brick building, surrounded by a limited extent of garden and shrubbery, within half a mile of the town of Lynderton. The interior, for a country house, had a somewhat gloomy and unpicturesque aspect. Young Harry felt depressed by the atmosphere, so different from the cheerful little cottage, with its flower-surrounded lawn, to which he had been accustomed. He was not drawn either to his grandmother, though she intended to be kind to him. She treated him indeed much as a child does a new plaything, constantly fondling it at first, and then casting it aside uncared for. Harry was also soon nauseated by the old lady’s caresses. He had, too, a natural antipathy to musk, of which her garments were redolent.

Lady Tryon was a small woman with strongly marked features, decidedly forbidding at first sight, though she possessed the art of smiling, and making herself very agreeable to her equals. She could smile especially very sweetly when she had an object to gain, or wished to be particularly agreeable; but her countenance could also assume a very different aspect when she was angry. She had bright grey eyes, which seemed to look through and through the person to whom she was speaking, while her countenance, utterly devoid of colour, was wrinkled and puckered in a curious way. She always wore rouge, and was dressed in the height of fashion. She very soon discarded her widow’s ugly cap, and the gayest, of colours decked her shrivelled form, the waist almost close up under the arms, and the dress very low, a shawl being flung over her shoulders. She could laugh and enjoy a joke, but her voice was discordant, and even when she wished to be most courteous there was a want of sincerity in its tone. Lady Tryon had been maid of honour in her youth to a royal personage, and possessed a fund of anecdote about the Court, which was listened to with respectful delight by her country neighbours. She was supposed to have very literary tastes, and to have read every book in existence. The fact was that she scarcely ever looked into one, but she picked up a semblance of knowledge, and having a retentive memory was able to make the most of any information she obtained. In the same way she had got by heart a large supply of poetry, which she was very clever in quoting, and as her audience was not often very critical, any mistakes of which she might have been guilty were rarely discovered. Her chief talent was in letter-writing, and she kept up a constant epistolary correspondence with aristocratic friends. No one could more elegantly turn a compliment or express sympathy with sorrow and disappointment. She occasionally, too, penned a copy of verses. If there was not much originality in the lines, the words were well chosen, and the metre correct. She described herself as being a warm friend and a bitter enemy. The latter she had undoubtedly proved herself on more than one occasion; but the warmth of her friendship depended rather upon the amount of advantage she was likely to gain by its exhibition than from any sensation of the heart. In fact, those who knew her best had reason to doubt whether she was possessed of that article. In reality, its temperature was, without variation, down at zero. Poor Sir Harcourt, a warmhearted man, had discovered this fact before he had been very long united to her. She, however, managed from the first to rule him with a rod of iron, and to gain her own way in everything. Most fatally had she gained it in the management of her son, whom she had utterly ruined by her pernicious system of education. Sir Harcourt endeavoured to make all the excuses for her in his power.

“She is all mind!” he used to observe. “A delightful woman—such powers of conversation! We must not expect too much from people! She has a wonderful command of her feelings: never saw her excited in my life! A wonderful mind, a wonderful mind has Lady Tryon!”

Lady Tryon had, however, one passion. It absorbed her sufficiently to make her forget any annoyances. She was fond of play. She would sit up half the night at cards, and, cool and calculating, she generally managed to come off winner. Of late years she had not been so successful. Her mind was not so strong as it was, and all her powers of calculation had decreased. Still she retained the passion as strong as ever. In London she had no difficulty in gratifying it, but during her forced visits to the country she found few people willing to play with her. At first, her country neighbours were highly flattered at being invited to her house, but they soon found that they had to pay somewhat dear for the honour. Still her ladyship, while winning their money, was so agreeable, and smiled so sweetly, and spoke so softly, that like flies round the candle, they could not resist the temptation of frequenting her house. For some years she managed to rule the neighbourhood with a pretty high hand. There was only one person who refused to succumb to her blandishments, and of her she consequently stood not a little in awe. This person was an authoress, not unknown to fame. She had more than once detected the piracies of which Lady Tryon had been guilty in her poetical effusions, and could not resist, when her ladyship spoke of books, asking her in which review she had seen such and such remarks. Miss Bertrand was young, not pretty, certainly, but very genuine and agreeable, and possessed of a large amount of talent. She drew admirably, and her prose and poetical works were delightful. Lady Tryon looked upon her as a rival, and hated her accordingly.

Such was the grand-dame under whose care Harry Tryon was to be brought up. Dr Jessop was not happy about the matter. He would far rather that the honest clerk had taken charge of the boy. He resolved, however, as far as he had the power, to counteract the injudicious system he discovered that Lady Tryon was pursuing. For this purpose he won the little fellow’s affection, and as he was a constant visitor at the house in his official capacity, he was able to maintain his influence. When her ladyship went to town he induced her to allow Harry to come and stay with him, and on these occasions he never failed to invite Roger Kyffin down to pay him a visit. The worthy clerk’s holidays were therefore always spent in the neighbourhood of Lynderton. The two kindly men on these occasions did their best to pluck out the ill weeds which had been growing up in Master Harry, while under his grandmother’s care. It was, however, no easy task to root them out, and to sow good seed in their stead. Still, by their means Harry did learn the difference between good and evil, which, if left to Lady Tryon’s instructions, he certainly would never have done. He also became very much attached to the old doctor and to his younger friend, and would take advice from them, which he would receive from no one else. He grew up a fine, manly boy, with many right and honourable feelings; and though his mental powers might not have been of a very high order, he had fair talents, and physically his development was very perfect. Lady Tryon herself began to teach him to read, and as he showed a considerable aptitude for acquiring instruction, and gave her no trouble, she continued the process till he was able to read without difficulty by himself. She put all sorts of books into his hands, from which his brain extracted a strange jumble of ideas. He certainly acquired very good manners from his grandmother, and to the surprise of the neighbourhood, when he was ten years old there was scarcely a better behaved boy in Lynderton. Dr Jessop then suggested that he should be sent to Winchester School, or some other place of public instruction. Lady Tryon would not hear of this, though she consented that he should attend the grammar school at Lynderton. For this the worthy doctor was not sorry.

“I can look after him the better,” he said to himself, “and go on with the process of pulling up the weeds during her ladyship’s absence.” Harry’s holidays were generally spent in the country. Twice, however, his grandmother had him up to London in the winter. On these occasions, Mr Kyffin got leave from her ladyship to have him to stay with him part of the time. Every spare moment of the day was devoted to the lad. He took him to all the sights of London, and in the evenings contrived for him variety of amusement. Harry became more and more attached to Mr Kyffin, and more ready to listen to his advice, and more anxious to please him. Thus the boy grew on, gaining mental and physical strength, though without forming many associates of his own rank in life. His manners were very good, and his tastes were refined, and this prevented him associating with the ordinary run of boys at the grammar school.

Chapter Four.

Harry Tryon’s First Adventure.—Lynderton and its Neighbourhood.

Harry Tryon in his new home had the sea constantly before his eyes. Sometimes he saw it blue and laughing, and dotted over with the white canvas of numerous vessels glistening in the sunshine. At other times the stout ships were tossed by tempests, or doing battle with the foaming waves. Often the boy longed for the life of a sailor, to go forth over that broad unknown ocean in search of adventure; but the old lady would not hear of it. It was the only wish in which she thwarted him: she usually spoiled him, and gave him everything he asked for, especially if he cried loud enough for it. But he was now getting too old to cry for what he wanted, and he must take some other means to obtain his wishes. Poor Harry! his nursery life had been a checkered one; sometimes shut up by himself in a dark room, sometimes almost starved and frightened to death; at others pampered, stuffed with rich food, exhibited in the drawing-room as a prodigy, his vanity excited, and allowed to do exactly as he listed. Perhaps one style of treatment checked the bad effects of the other.

Lynderton stood on the bank of a small river. Harry had no difficulty in obtaining a boat, in which he learned to row. Lady Tryon did not know how he was employed, or she would probably have sent for him, and kept him driving about in her musk-smelling carriage, which Harry hated. As he grew older he managed to get trips in fishing vessels, on board small traders which ran between the neighbouring ports, and sometimes he got a trip on board a revenue cruiser—the old “Rose,” well known on the coast. There were not many yachts in those days; but two or three of the people residing at Lynderton had small vessels, and Harry was always a welcome guest on board them. His love for the sea was thus partially gratified and fostered, and he became a first-rate hand in a boat or yacht. Still he yearned for something else.

One day he was standing on the quay at the foot of the town, when a stout sailor lad stopped near him, and putting out his hand exclaimed: “Well, Master Harry! I did not know you at first: you are grown so. You’re looking out for a sail down the river, I’ll warrant?”

“You are right, Jacob,” answered Harry, shaking the proffered hand. “I have not had a sniff of salt water for the last week. But where have you been all this time?”

“I have been to sea, Master Harry—to foreign lands—and if you are so minded I will help you to take a trip there, too.”

“You have not been away long enough to go to any foreign lands that I know of, except perhaps the coast of France or to Holland,” observed Harry.

“That’s just where I have been, Master Harry, and if you like to come down along the quay I will show you the craft I went in. She’s not one a seaman need be ashamed of, let me tell you.”

Harry accompanied his friend. Jacob Tuttle had been one of Harry’s first companions in a boat, and he indeed taught him to row. As he was six or eight years older than Harry, the latter looked at him with great respect, and considered him an accomplished seaman. He was, indeed, a good specimen of the British sailor of those days, brave, open-hearted, and generous, but with the smallest possible amount of judgment or discretion. Harry accompanied him along the bank of the river for some distance.

“There! what do you think of her?” asked Jacob, pointing to a wonderfully long, narrow lugger which lay alongside the wooden quay or jetty. “She measures 120 feet from the tip of her bowsprit to the end of her outrigger, and she sails like the wind. We pull forty oars, and there is no revenue cutter can come near us, blow high or blow low.” The vessel at which Harry and his companion were looking was indeed a beautiful craft. She had fore and aft cuddies for sleeping berths, and was open amid-ships “for the stowage of 2,000 kegs of spirits,” Jacob whispered in Harry’s ear. “Would you not like to take a trip in her, Master Harry?”

Harry confessed that he should like it very much.

Lady Tryon was on the point of starting for London. Probably the “Saucy Sally” would not sail for two or three days. He might make the trip and be back again without anybody knowing anything about it. Tuttle would introduce Harry to the skipper. He was a first-rate fellow, whether an Englishman or a foreigner he could not tell, but his equal was not easily to be found. It was a pleasure to be with him in a gale of wind, and to hear him issue his orders. Captain Falwasser was his name. The “Saucy Sally” carried fifty hands, officers and crew, all told, and had guns too, but they were kept stowed away below, unless wanted.

“But, Harry, come on board.”

Harry could not resist the temptation. He reflected little about the rights of the thing, and even if he had, to say the truth, Captain Falwasser’s occupation was at that time not much condemned by public opinion. He soon found himself visiting every part of the “Saucy Sally,” and being introduced to her daring skipper. Captain Falwasser was a strongly-built man, but in other respects refined and gentlemanly in appearance. The expression of his lips showed wonderful determination, and those who looked at his eye felt that they were in the presence of a man accustomed to command his fellows. His cheek was pale and sunken, and there was on his features a settled expression of melancholy. Harry was delighted with all he saw, and longed more than ever to take a trip on board the lugger. Captain Falwasser, however, did not seem inclined to indulge him in his wish. At last he had to go on shore, and return home. A few days after this he saw the “Saucy Sally” with her jovial crew, loudly cheering, while she dropped down the river, the Custom House officers looking on.

“We’ll catch them one of these days, in spite of all their cunning,” observed one. “They think we don’t know when they are coming back. We will show them their mistake.”

Harry kept thinking of the “Saucy Sally” and her bold skipper, and he still entertained the hopes of some day making a trip in her. Two or three weeks passed away, and once more she lay in Lynderton river, with her empty hold looking as innocent as if she had been merely out for a few hours’ pleasure trip. There were reports of a large cargo having been run somewhere on the Dorsetshire coast, not far from Yarmouth, but of course the crew of the “Saucy Sally” knew nothing of the matter. A body of yeomanry had met a large party of waggons, surrounded by two or three hundred men, each with pistols in their holsters, and carbines in their hands, proceeding northward; but the soldiers considered discretion, in this case, the better part of valour, being very sure, had they attempted to interfere with them, they would be cut down to a man. It was shrewdly suspected that this cavalcade was conveying to a place of safety the cargo landed from the “Saucy Sally.” Harry very naturally went down to have a look at the lugger. Jacob Tuttle told him how sorry he had felt that he could not come the last trip.

“If you have a mind for it still, come on board the night before, and I will stow you away. When we are fairly at sea, you can come out, and if the skipper is angry I will stand the blame.”

Harry managed to get away from Aylestone Hall, his grandmother being still absent, and was, unseen by any one, stowed on board the “Saucy Sally.” It is possible that more than once, while shut up in the close cuddy, he repented of his proposed exploit. However, he was in for it, as the crew, most of them half-seas over, kept coming on board. The next morning, if not as sober as judges, they were yet pretty well able to handle the lugger, and with their usual exulting shouts they manned their oars and pulled down the river. They were soon at sea, and getting a slant of wind, the smuggler’s enormous lug-sails were hoisted, and away she stood towards the French coast. Jacob, according to promise, released Harry. The skipper’s sharp eye soon singled him out, though he kept forward among the crew. He was summoned aft, and fully expected a severe scolding.

“What made you come with us, my boy?” asked Captain Falwasser, in a kind tone. “You are too young to run the dangers we have to go through. You will have enough of them by-and-bye. And so Jacob Tuttle brought you, did he? I will settle that business with him. You must be under my charge till I land you again at Lynderton.”

Jacob Tuttle not only got a severe scolding, but the captain threatened to dismiss him as soon as they got back to England. Meantime the appearance of the lugger was being changed. The crew, as they drew near the French coast, dressed as Frenchmen, and pieces of painted canvas were hung over the sides of the vessel, so that she no longer looked like the trim, dashing craft she really was. The “Saucy Sally” dropped her anchor close in with the coast, just as the shades of evening fell over the ocean. A boat was lowered. Harry had been made to change his dress like the rest. The skipper invited him to accompany him.

“Remember you are to be dumb,” said Captain Falwasser. “If you keep close to me no harm will come to you.”

A light was shown on board the vessel, and was immediately answered by another on shore. Soon afterwards a number of boats were heard approaching. The captain exchanged a signal with one of them, and then continued his course to the shore. After walking some distance they reached a town. The captain paid several visits, and as he spoke French, Harry could not make out what was said. The captain seemed greatly surprised and shocked at some disastrous news he heard. He transacted business with some people on whom he called, and Harry saw him pay away the contents of a large bag of gold. He was more silent than ever on his walk back to the beach. He sighed deeply. “Unhappy France, unhappy France!” he said to himself; “what is to become of you?”

When they got on board the lugger again, she was deeply laden with kegs and bales of goods. That instant her anchor was tripped, and sail being made, she stood back towards the English coast. Daylight soon afterwards broke. She made the land some time before dark, but waited till she could not be seen from the shore before she ran in. Sharp eyes kept looking out for the expected signal: it was made. She ran in till her bows almost touched the sand. Fully three hundred people were waiting on the beach; with wonderful rapidity her cargo was landed, and each cask or bale being put on the broad shoulders of a stout fellow, was carried away instantly up the cliff. Not a yard of silk, a bottle of brandy, nor a pound of tobacco remained on board. Instantly the oars were got out, and before daylight she was once more at the mouth of Lynderton river.

“I have only one request to make,” said the captain to Harry, “that you will promise me faithfully not to tell to any one what you have seen. You came on board the ‘Saucy Sally,’ were away a couple of nights, and were once again put safely on shore at Lynderton. That’s all you may tell, remember.”

Harry gave his promise; he felt grateful to. Captain Falwasser for the kind treatment he had received. Harry begged that Jacob Tuttle might be forgiven. The captain replied he would consider the matter; but Jacob did not seem inclined to trust to him, and soon afterwards entered on board a man-of-war.

This was Harry’s first adventure. He was somewhat disappointed in the result. It was some time before he engaged in another.

There were a good many country houses scattered about in the neighbourhood of Lynderton; and at most of them Harry, who was growing into a remarkably fine-looking young man, had become a great favourite. He danced well, could talk agreeably, and was always ready to make himself useful. He was a welcome guest, especially at Stanmore Park, the residence of Colonel Everard. The Colonel was one of the representatives of the oldest and most influential families in that part of the country. General Tryon had been an old friend of his, and he was very glad when Lady Tryon acknowledged her grandson, and took him under her protecting wing. Had the Colonel been a more acute observer than he was, he might not have so readily congratulated the boy on his good fortune. Colonel Everard had an only daughter, Lucy; and a niece, Mabel, who resided with him. The latter was the daughter of his brother, Captain Digby Everard, who was constantly at sea. When he came on shore for a short period he took up his residence at Stanmore Park. A maiden sister, always called Madam Everard, who superintended his household, was the only other constant member of his family. Stanmore Park was a fine old place of red brick, with spreading wings. A long drive under an avenue of noble trees led up to the front of the house, and looked out on a wide extent of park land. There was a beautiful view of the sea from the windows on the opposite side. There was a magnificent lawn of thick shrubberies, and lofty umbrageous trees, and extensive lakes, across which were bits of woodland scenery, the graceful trees of varied foliage being reflected in the calm water. Altogether, Stanmore Park was a very delightful place. Harry, however, although he was very fond of going there, liked the inhabitants even more than the place itself. Madam Everard was a good kind woman who, though advanced in life, had feelings almost as fresh as those of her young nieces, who were pretty, attractive girls. Harry thought so, and as he saw a good deal of them, he was well able to judge. His happiest days were spent in their society; sometimes attending them on horseback, sometimes fishing with them in the lake, sometimes rowing them in a boat on the largest piece of water. Captain Everard had had a miniature frigate placed on the lake; and Harry was present while it was being fitted out and rigged, so that he learnt the name of every rope and sail belonging to her. It was wonderful how much nautical knowledge he gained on that occasion.

Chapter Five.

Two Young Fire-Eaters Out-Generalled.

Lynderton was about that time made a depot of a foreign legion, and although the presence of a large body of military did not add much to the morality of the place, there was a considerable number of talented persons among the officers and their wives. Instruction could now be procured in abundance, in foreign languages, dancing, singing, in the use of all sorts of instruments, from pianos down to flageolets, and in drawing and painting. Counts and barons were glad to obtain remuneration for their talents, and many a butcher’s or grocer’s bill was liquidated by the instruction afforded to the female portions of the commercial families of the place in dancing and singing. Colonel Everard engaged a very charming countess to instruct his daughter and niece in dancing, and as it was convenient to have a third person, Harry was invited over to join the lessons. The name of the French lady who taught them dancing was Countess de Thaonville. She was a very handsome person, but there was a deep shade of melancholy on her countenance. No wonder. Her history was a sad one, as was that of many of her countrywomen and countrymen, now exiles in a foreign land. Harry benefited greatly by these lessons. They contributed to civilise and refine him. Had, however, Madam Everard known a little more of the world, as years rolled on, she would probably not have invited him so often to come to the house. In his young days he had looked on Lucy and Mabel very much in the light of sisters, but somehow or other he began to prefer one to the other. Mabel was certainly his favourite. How it came to pass he could not tell, but he was happier in her society than in that of her cousin, or in that of anybody else. He was only about two years her senior, while Lucy was several years older. This might have made some difference. Occasionally the Countess brought a young officer of the legion, Baron de Ruvigny, to the house to assist in the music, as he played the violin well. He was a mere youth, but very gentlemanly and pleasing, and he became a great favourite with Madam Everard. Harry did not quite like his coming; he thought he seemed rather too attentive to Mabel. However, he was a very good fellow, although he could not play cricket or row a boat, and as Mabel certainly gave him no encouragement, Harry began to like him.

By the time Harry was eighteen Mabel had become a lovely and an amiable girl. No wonder that being much in her society he should have loved her. Lady Tryon, who had always indulged him, was not long in discovering the state of his affections, and instead or attempting to check him, she encouraged him in his wish to obtain the hand of Mabel Everard.

Colonel Everard, like many old soldiers, was an early riser. He usually, in the summer, took a walk before breakfast through the grounds. His figure was tall and commanding. Although considerably more than seventy, he still walked with an upright carriage and soldier-like air. He carried a stick in his hand, but often placed it under his arm, as he was wont in his youth to carry his sword. The front part of his head was bald, and his silvery locks were secured behind in a queue, neatly tied with black ribbon. His features were remarkably fine, and age had failed to dim the brightness of his blue eye. His invariable morning costume was an undress military coat, which had seen some service, while no one could look at him without seeing that he was a man accustomed to courts as well as camps. One morning he was stopping to look at a flower-bed lately laid out by his daughter Lucy, when he heard footsteps approaching him. A turn of the walk concealed him from the house.

“Well, Paul, what is it?” he asked, looking up.

“I have something to communicate, Colonel.”

The speaker was a tall thin man, with a mark of a sword-cut on one of his well-bronzed and weather-beaten cheeks, which had not added to his beauty. There was, notwithstanding this, an honest, pleasant expression in his countenance which was sure to command confidence. His air was that of an old soldier; indeed, as he spoke, his hand went mechanically up to his hat, while as he halted, he drew himself as upright as one of the neighbouring fir-trees. Paul Gauntlett, the Colonel’s faithful follower and body servant, had left Lynderton with him upwards of fifty years before, and had been by his side in every battle in which he had been engaged.

“There’s mischief brewing, and if it is not put a stop to, harm will come of it,” he continued.

“What do you mean?” asked the Colonel.

“Just this, sir. I was lying down close to the lake to draw in a night line I set last night, when who should come by but young Master Harry Tryon with his fishing-rod in his hand, and his basket by his side. I was just going to get up and speak to him, for he did not see me, when I saw another person, who was no other than that young foreigner, the Baron de Ruvigny, as he calls himself. Master Harry asked him what he was doing, and he said that it was no business of his, as far as I could make out. Then Master Harry got very angry, and told him that he should not come to the park at all, and the other said that he was insulted. Then Master Harry asked him what business he had to write letters to young ladies, and the end of it was that they agreed to go into the town and get swords or pistols and settle the matter that way. If they fix on pistols it may be all very well; but if they fight with swords, Master Harry’s no hand with one, and the young Frenchman will pink him directly they cross blades.”

“I am glad you told me of this,” observed the Colonel. “It must be put a stop to, or the hot-headed lads will be doing each other a mischief. Who could the Frenchman have been writing to? Not my daughter or niece I hope. It will not do to have their names mixed up in a brawl.”

“I think we could manage it at once, sir; they have not yet left the grounds. They spoke as if they did not intend to fight till the evening, as each of them would have to look out for his seconds. When they parted, Master Harry walked on along the side of the lake and began to fish, looking as cool as a cucumber, while the young Frenchman went back into the summer-house, where he had been sitting when Master Harry found him, and went on writing away on a sheet of paper, he had spread on his hat. Now, sir, if you go down the walk you are pretty sure to find him there still, and I have no doubt that I shall be able to fall in with Master Harry, and I can tell him you want to see him at breakfast, and that he must come, and make no excuse.”

Great was Harry’s surprise to find the young Frenchman in the breakfast-room, where the Colonel and the rest of the party were already assembled. He was, as usual, cordially welcomed, and the butler shortly afterwards announced that the fish he had caught would be speedily ready.

“We are very glad you have come, Harry,” said Madam Everard, “you can help us in arranging an important matter. The Colonel has just heard that his Majesty intends honouring us with a visit in the course of a day or two. The King sends word that he shall ride over from Lyndhurst, and that we are to make no preparations for his reception; but he is always pleased when there is some little surprise and above all things he likes to see his subjects making themselves happy.”

“The Baron de Ruvigny says he is certain that Colonel Lejoille will lend the band of the regiment, and we must have the militia and volunteer bands. Will it not be delightful?” exclaimed Mabel.

“We must have two large tents put up on one side of the lawn, so as not to shut out the view from the windows.”

“There must be one for dancing,” said Lucy, who was especially fond of dancing. “There will be no want of partners, as there used to be before the foreign officers came here. How very kind of the King to say he will come.”

“Do you think that Cochut will have time to prepare a breakfast?” asked the Colonel, looking at his sister. “We must send for him at once to receive his orders. Baron, we must leave the bands of the regiments to you. Harry, you must arrange with Mr Savage, the sail-maker, for the tents.”

“Now, recollect you two young men are to devote all your time and energies to these objects,” said Madam Everard, looking at them with a meaning glance.

“I must see you both in my study before you leave,” said the Colonel, “and now, lads, go to breakfast.”

The two young men looked at each other, and possibly suspected that the Colonel might, by some wonderful means, have heard of their quarrel.

Chapter Six.

Royal Visitors.—The King and the Mace-Bearer.—The Foes reconciled.

The news of the good King’s intended visit to Stanmore Park was soon spread abroad. The mayor and burgesses of Lynderton resolved that they would request his Majesty to honour their borough by stopping on his way at their town-hall. The whole place was speedily in a state of the most intense commotion. While the Colonel and his womankind were making all the necessary preparations at the park, the lieges of Lynderton were engaged in the erection of triumphal arches, with a collection of banners of all sorts of devices, painting signboards and shop-fronts, and the polishing up of military accoutrements.

Lynderton was got into order for the reception of royalty even before Stanmore Park had been prepared. One chief reason was that there were many more hands in the town to undertake the work, and another was, there was less work to be done. The great difficulty was to have the band playing at both places at once.

Colonel Everard had already engaged them, and they could not on any account disappoint him. Still for the honour of Lynderton it was necessary that a musical welcome should be wafted to the King as he entered the precincts of the borough. At last it was arranged that a part of the foreign band should remain in the town to welcome the King, and then set off at a double-quick march to Stanmore, to be in readiness to receive him there.