TOM WALLIS

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: Tom Wallis

A Tale of the South Seas

Author: Louis Becke

Release Date: September 07, 2012 [EBook #40705]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TOM WALLIS ***

Produced by Al Haines.

TOM WALLIS

A TALE OF THE SOUTH SEAS

BY LOUIS BECKE

Author of 'Wild Life in Southern Seas'

'By Reef and Palm' 'Admiral Philip' etc.

WITH ELEVEN ILLUSTRATIONS BY

LANCELOT SPEED

SECOND IMPRESSION

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 BOUVERIE STREET AND

65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

1903

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

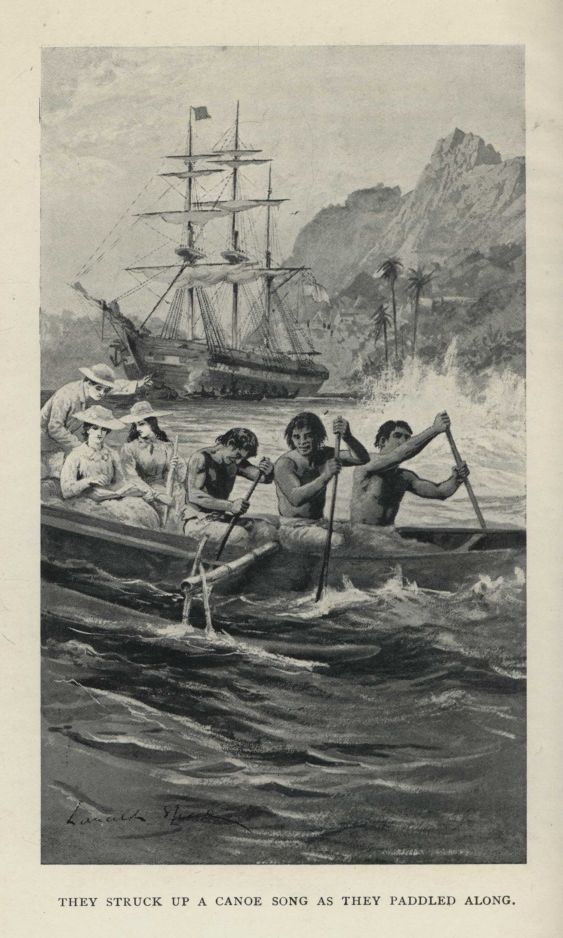

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

'She was running before the Wind' . . . Frontispiece

'She was soon run out of the Shed'

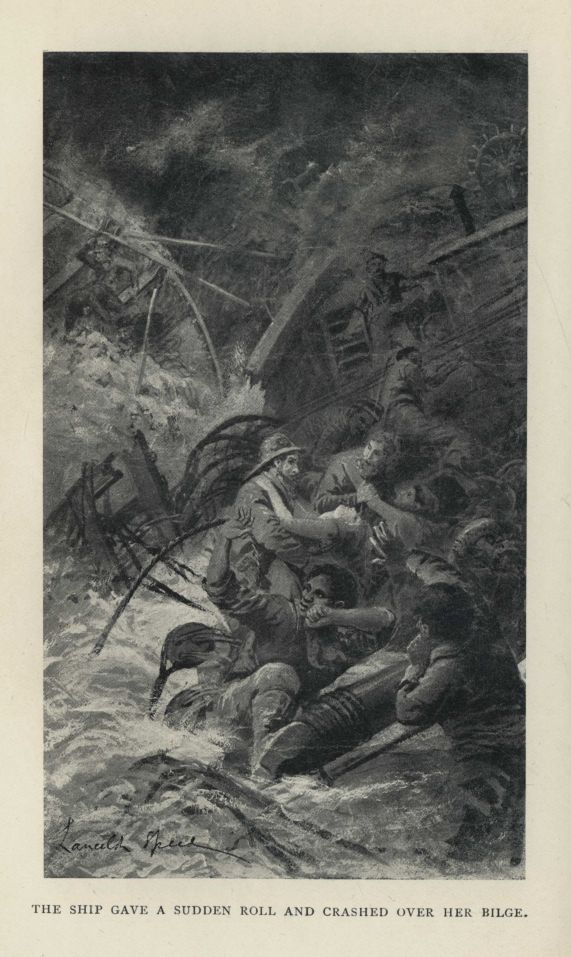

'A Black Wall of Sea towered high over the Rail'

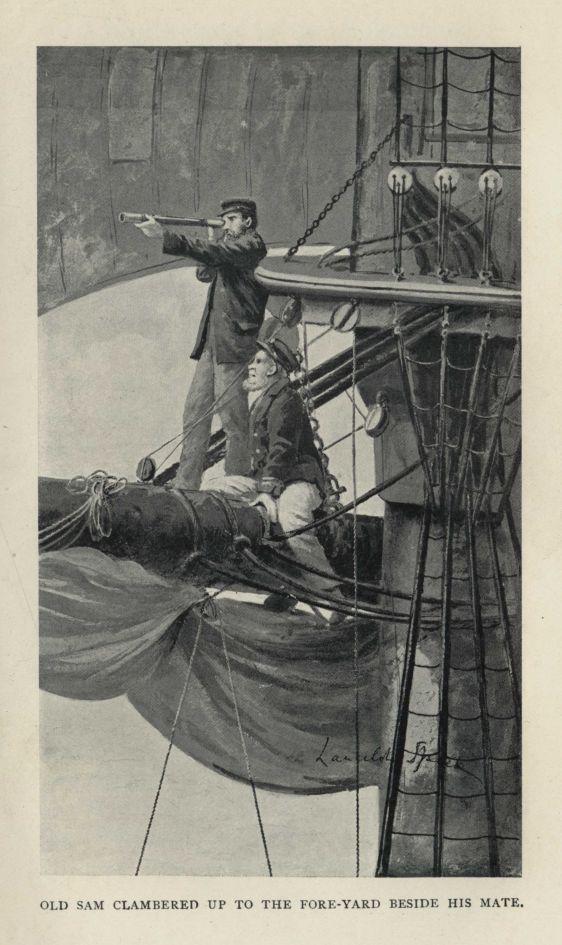

'Old Sam clambered up to the Fore-yard'

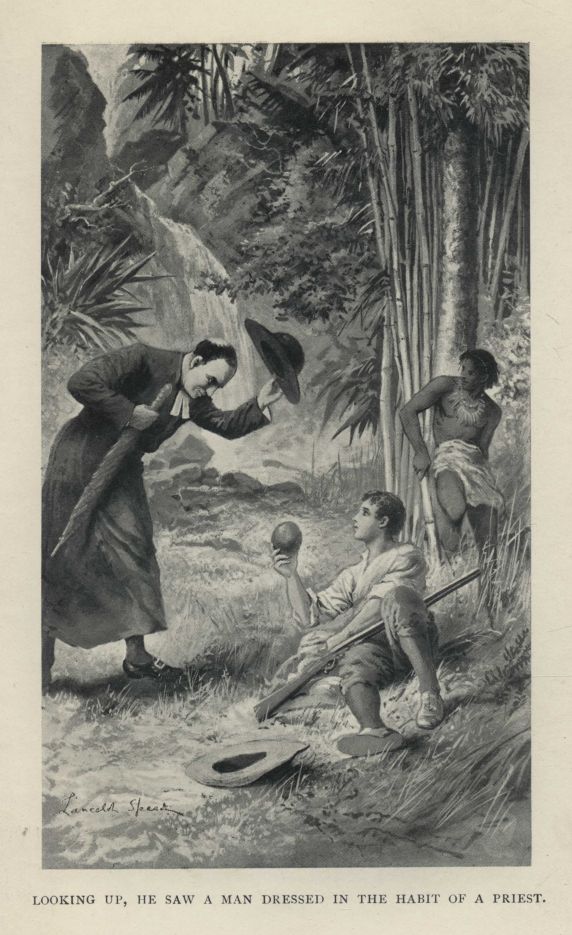

'He saw a Man in the Dress of a Priest'

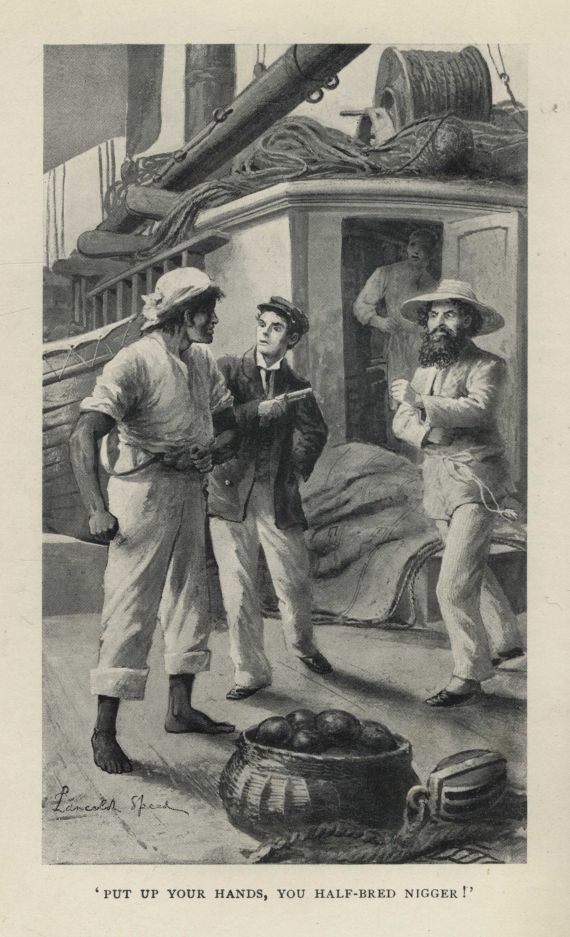

'I'll pound the Life out of you'

'I shall say "No," said the Girl'

TOM WALLIS

CHAPTER I

FATHER AND SONS

Northward from an Australian city, and hidden from seaward view by high wooded bluffs and green belts of dense wind-swept scrub, there lies one of the oldest and quaintest little seaport towns on the whole eastern sea-board, from the heat-smitten rocks of Cape York, in the far north of torrid Queensland, to where, three thousand miles to the south, the sweeping billows from the icy Antarctic leap high in air, and thunder against the grim and rugged walls of stark Cape Howe.

The house in which the Wallis family lived stood at the foot of one of these bluffs, within a stone's throw of the beach, and overlooking the bar; and at night time, when the swift outward rush of the river's current met the curling rollers from the open sea, the wild clamour and throbbing hum seemed to shake the walls of the old-fashioned building to its foundations. But to the two Wallis boys--who were born in that house--the noise of the beating surf, the hoarse shrieking notes of the myriad sea-birds, and the sough of the trade wind through the timbered slopes, were voices that they knew and understood, and were in a manner part and parcel of their own adventurous natures.

Let me try and attempt to draw, however rudely, an outline of a picture of their home, and of the sight that every morning the two lads saw from their bedroom window, before they clattered downstairs into the low-ceiled old-time dining-room, to each eat a breakfast that would have done credit to a hungry bullock-driver.

First, then, the wide, blue Pacific--would that I could see it now!--sparkling and shimmering in the yellow sunshine, unbroken in its expanse except for the great dome of Kooringa Rock, a mile from the shore, from which, when the wind blew east, came the unceasing croak and whistle of ten thousand gulls and divers, who made it their rendezvous and sleeping-place.

To the north, on the other side of the roaring, restless bar (the house was on the southern horn of the entrance to the harbour), there ran a long sweeping half-mooned beach, ten miles from point to point of headland, and backed at high-water mark by a thick fringe of low, scrubby timber, the haunt of the black wallaby, and the refuge from pursuit of mobs of wild cattle. Not a dozen people in the little township had ever been through this scrub on foot; but Tom and Jack Wallis knew and loved every foot of it, from the sandspit on the northern bank of the river to the purple loom of the furthest cape. Further back still from this narrow belt of littoral, the main coastal range rose, grey and blue in the distance, monotonous in its outlines, and its silence broken only by the axes of a few wandering parties of timber-getters, who worked on the banks of the many streams rising in the mountain gullies, whose waters joined those of the great tidal river on its way to the ocean.

Southward from the bar, the coast presented another aspect; high cliffs of black, iron-stone rock stood up steep-to from the sea, not in a continuous straight line, but in broken irregular masses, forming hundreds of small deep bays with lofty sides, and beaches of large rounded pebbles or snow-white sand. This part of the shore was so wild and desolate, that except themselves, a human being would seldom be seen about it from one year's end to the other, and the boys only went there during the crayfish season, or during an easterly gale, when from the grassy summit of one of the highest cliffs they loved to watch the maddened boil of surf far below, and catch the exhausted gulls and boobies, that sought refuge ashore from the violence of the wind amid the close-set, stunted herbage growing just beyond the reach of the flying spray. Iron-bound and grim-looking, it did not extend more than six or seven miles; and then came another long stretch of sandy beach for thrice that distance, banked up by lofty sand-dunes covered with a network of creepers, and a saline herb known as 'pig-face.'

Behind the sand-hills were a series of brackish lagoons, whose waters were covered with flocks of black swans, pelicans, and half a dozen varieties of wild duck and other waterfowl, which were seldom disturbed by any of the few settlers round about, who were too lazy to wade through water after a duck, although some of them would ride all night to steal a calf or a bullock. These lagoons had, here and there, narrow passages to the sea through the sand mounds, and where this was the case the waters were literally alive with fish--bream and whiting, and kingfish and trevally, and--but there, the memory of those happy, happy years of boyhood amid such rough and wild surroundings is strong with Tom Wallis still. For the lads, as their father sometimes said, were born in a civilized family by mistake--Nature having intended them to have black skins and woolly hair, and to hunt paddymelons and wallabies with boomerang and waddy, like the survivors of the tribe of blacks who still led a lingering existence along the shores and around the tidal lakes and inlets of that part of the country.

Of the town itself near which they lived little need be said, except that it was very quaint, and, for a new country like Australia, old-fashioned. Once, in the early days of the colony, it promised to become a thriving and prosperous place. Many retired military and civilian officers had been given very large grants of land in the vicinity of the port, upon which they had settled, and at one time many hundreds of convicts had been employed by them. Besides these, there was a large number of prisoners who toiled on the roads, or in the saw-pits, or up on the rivers felling timber, under the supervision of Government overseers. These wretched men were generally marched to their work every morning, returning to their barrack prison at night time. There had been at first a company of soldiers stationed at the port, but when it was discovered that the place was ill-chosen for a settlement--in consequence of the shifting nature of the bar--they were withdrawn to Sydney with all the prisoners, except those who were assigned to the settlers as servants or workmen. Then most of the principal settlers themselves followed, and left their houses untenanted, and their cleared lands to be overgrown, and become swallowed up by the ever-encroaching scrub, which in those humid coastal regions is more an Indian jungle than bush, as Australians understand the word 'bush.' With the soldiers went, of course, the leading civil officials, and the little seaport became semi-deserted, grass grew in the long, wide streets, and the great red-bricked barracks and Government storehouses were left to silence and decay.

Nearly twenty years after the breaking up of the settlement as a penal establishment, Lester Wallis and his young wife had settled in the place. He had formerly been in the service of the East India Company, where he had accumulated a small fortune. During a visit to Sydney, he had met and married the daughter of one of the Crown officials, an ex-naval officer, and, loth to return to the trying climate of India, decided to remain in Australia, and enter into pastoral pursuits. For a few thousand pounds he bought a small cattle-station at Port Kooringa, and, in a measure, became the mainstay of the place, for, in addition to cattle-raising, he revived the dying timber industry, and otherwise roused the remaining inhabitants of the little port out of their lethargic indifference. But fifteen years after he came to the place, and when his two boys were fourteen and thirteen years of age respectively, his wife died, after a few hours' illness. The blow was a heavy one, and for the time crushed him. He withdrew himself almost entirely from such society as the place afforded, dismissed most of his servants, and lived for more than a year in seclusion, in the lonely house facing the sea. His affection for his children, however, came to his aid, and did much to assuage his grief.

'Jack, my lad,' he said to the elder boy, one day, as they were riding along the northern beach, 'we must stick to each other always. You and Tom are all I have in the world to love. Had your mother lived, I should have liked to have returned to England and ended my days there. But she is gone, and now I have no desire to leave Australia. We shall stay here, Jack; and you and Tom shall help me till you are both old enough to choose your future.'

Jack, a sturdy, square-built youngster, with honest grey eyes, nodded his head.

'I shall never want to leave you and Kooringa, father. I promised mother that before she died. But Tom says he hopes you will let him go to sea when he is old enough.'

Mr. Wallis smiled, and then sighed somewhat sadly. 'Time enough to think of that, Jack. But I would rather he thought of something else. 'Tis a poor life and a hard one. But why do you not want to be a sailor?'

Jack shook his head. 'I should like to be an explorer--that is, I mean if you would let me. I should like to cross Australia; perhaps I might find Dr. Leichhardt'--and his eyes glistened; 'or else I should like to ride round it from Port Kooringa right up to Cape York, and along the Gulf of Carpentaria and the coast of Arnhem's Land and West Australia, and then along the Great Bight back to Kooringa. It would make me famous, father. Mother said it would be more than ten thousand miles.'

Mr. Wallis laughed. 'More than that, Jack. But who knows what may happen? Perhaps I may buy some cattle country in Queensland some day; then you shall have a chance of doing some exploring. But not for some years yet, my boy,' he added, placing his hand on his son's shoulder; 'I do not want to go away from Kooringa yet; and I want to come back here, so that when my time comes I may be laid beside her.'

'Yes, dad,' said the lad simply; 'I too want to be buried near poor mother when I die. Isn't it awful to think of dying at some place a long way from Kooringa, away from her? That's what I told Tom the other day. I said that if he goes to sea he might be drowned, or bitten in halves by a shark, like the two convicts who tried to cross the bar on a log when they ran away. Father, don't let Tom be a sailor. We might never see him again. Wouldn't it be awful if he never came back to us? And mother loved him so, didn't she? Don't you remember when she was dying how she made Tom lie down beside her on her bed, and cried, "Oh, my Benjamin, my Benjamin, my beloved"?'

'Yes, my lad,' answered the father, turning his face towards the sea, which shone and sparkled in the bright morning sunlight. Then the two rode on in silence, the man thinking of his dead wife, and the boy dreaming of that long, long ride of ten thousand miles, and of the strange sights he might yet see.

From the broad front verandah of the quiet house, young Tom had watched his father and brother ride off towards the town, on their way to the river crossing which was some miles distant from the bar. Once over the river, they would have to return seaward along its northern bank, till they emerged upon the ocean beach. They would not return till nightfall, or perhaps till the following day, as Mr. Wallis wished to look for some missing cattle in the scrubs around the base of rugged Cape Kooringa, and 'Wellington,' one of the aboriginal stockmen, had already preceded them with a pack-horse carrying their blankets and provisions, leaving Tom practically in charge, although old Foster, a somewhat rough and crusty ex-man-of-war's man, who had been Mrs. Wallis's attendant since her childhood, was nominally so. He with two or three women servants and the gardener were all that were employed in, and lived in the house itself, the rest of the hands having their quarters at the stockyards, which were nearly half a mile away.

Tom watched his brother and father till they disappeared in the misty haze which at that early hour still hung about the beach and the low foreshore, although the sun had now, as Foster said, a good hoist, and the calm sea lay clear and blue beneath. Then something like a sigh escaped him, as his unwilling eye lighted upon his lesson-books, which were lying upon the table of a little enclosure at one end of the verandah, which did duty as a schoolroom for his brother and himself.

'Well, it can't be helped,' he muttered; 'I promised dad to try and pull up a bit--and there's the tide going out fast. How can a fellow dig into school books when he knows it's going to be a dead low tide, and the crayfish will be sticking their feelers up everywhere out of the kelp? Dad said three hours this morning. Now, what does it matter whether it is this morning, or this afternoon, or this evening? And of course he didn't think it would be such a lovely morning--and he likes crayfish. I wonder if he will be angry when I tell him?' Then, stepping inside, he called out--

'Foster, where are you?' There was a rattle of knives in the pantry, and then the old man shuffled along the passage, and came into the dining-room.

'What now, Master Tom?' he grumbled; 'not at your lessons yet? 'Tis nine o'clock----'

'Yes, I know, Foster. But, Foster, just look at the tip of Flat Rock showing up already. It's going to be a dead low tide, and----'

'Don't you dare now! Ah, I know what you're going to say. No, I won't have it. Leastways I won't argy over it. And don't you disobey orders--not if all the crayfish in Australy was a runnin' up out o' the water, and climbin' trees.' Then, screwing his features up into an affectation of great wrath, he shuffled away again.

Tom's face fell, and again a heavy sigh escaped him, as he looked at the shimmering sea, and saw that beyond the bar it was as smooth as a mountain lake. Then he quietly opened the Venetian shutters of the dining-room, and let the bright sunlight stream in.

'It's no use,' he said to himself, 'I can't work this morning. I'll try and think a bit whether I shall go or not.'

Over the mantel in the dining-room was a marine picture. It was but rudely painted in water-colours--perhaps by some seaman's rough hand,--and the lapse of five and twenty years had dimmed it sadly; but to Tom's mind it was the finest painting in the world, and redolent of wild adventure and romance. It showed as a background the shore of a tropical island, the hills clothed with jungle, and the yellow beach lined with palm trees, while in the foreground the blue rollers of the ocean churned into froth against a long curve of coral reef, on which lay a man-of-war, with the surf leaping high over her decks, and with main and mizzen-masts gone. On the left of the picture was a beautiful white-painted brig, with old-fashioned rolling topsails and with her mainyard aback; and between her and the wreck were a number of boats crowded with men in uniform, escaping from the ship.

Often when the house was silent had Tom, even when a boy of ten, stolen into the room, and, sitting cross-legged on the rug, gazed longingly at the painting which, to his boyish imagination, seemed to live, ay, and speak to him in a wild symphony of crashing surf and swaying palm trees, mingling with the cries of the sailors and the shrill piping of the boatswain's whistles. Then, too, his eyes would linger over the inscription that, in two lines, ran along the whole length of the foot of the picture, and he would read it over and over again to himself gloatingly, and let his mind revel in visions of what he would yet see when he grew old enough to sail on foreign seas, as his father and his uncle Fred Hemsley had done. This is what the inscription said:--

'The Wreck of the Dutch warship Samarang on the coast of Timor Laut; and the Rescue of her Crew by the English brig Huntress, of Sydney, commanded by Mr. William Ford, and owned by Frederick Hemsley, Esquire, of Amboyna; on the morning of May 4, 1836.'

* * * * *

Half an hour later old Foster clattered suddenly along the verandah, peered into the schoolroom, and then into the dining-room, where Tom sat in a chair--still gazing at the picture.

'Rouse ye, rouse ye, Master Tom. Your eyes are better than mine. Here, look'--and he placed Mr. Wallis's telescope in the boy's hand--'look over there beyond Kooringa Rock. 'Tis a drifting boat, I believe. Kate tells me that it was in sight an hour ago, before your father and Master Jack went away, and yet the foolish creature never told me.'

Tom took the glass--an old-fashioned telescope, half a fathom long, and steadied it against a verandah post.

'Have you got her?' asked old Foster.

'Yes, yes,' answered the boy, quickly, his hand shaking with excitement; 'I can see her, Foster. There are people in her ... yes, yes, and they are pulling. I can see the oars dipping quite plainly. What boat can it be?'

'Shipwrecked people, o' course. What would any other boat be doin' out there, a comin' in from the eastward? Can you see which way she is heading?'

'Straight in for the bar, Foster.'

'And nothing but a steamer could stem the current now, with the tide runnin' out at six knots; an' more than that, they'll capsize as soon as they get abreast o' Flat Rock, and be aten up by the sharks. Master Tom, we must man our boat somehow, and go out to them. Then we can pilot them in to the bit o' beach under Pilot's Hill, if the current is too strong for us to get back here. But how we're going to launch the boat, let alone man her, is the trouble; there's not a man about the place but myself, and it will take the best part of an hour to send Kate or any other o' the women to the town and back.'

'Never mind that, Foster,' cried the boy; 'look down there on the rocks--there are Combo, and Fly, and some other black fellows spearing fish! They will help us to launch the boat, and come with us too.'

'Then run, lad; run as hard as ye can, and bring them up to the boatshed, an' I'll follow as soon as I get what I want.'

Seizing his cap, Tom darted away down the hill, across the beach, and then splashed through the shallow pools of water on the reef towards the party of aboriginals; whilst old Foster, calling out to Kate and the other women to get food ready against his return, in case it might be wanted for starving people, hurriedly seized some empty bottles and filled them with water; then, thrusting them into Jack's fishing-basket, which hung on the wall of the back verandah, he followed Tom down to the boatshed, where in a few minutes he was joined by the lad himself, and four stalwart, naked black fellows and their gins, all equally as excited as the old sailor.

The boat was a long, heavy whaleboat, but she was soon run out of the dark shed under the hill, and then into the water.

'Jump in, everybody,' said old Foster, seizing the steer oar, and swinging the boat's head round to the open sea.

CHAPTER II

CAPTAIN RAMON CASALLE AND HIS MEN

Under the five oars--Tom tugging manfully at the bow, though still panting with his previous exertions--the boat soon cleared the entrance to the little rocky cove, which, during the old convict days, had been made into a fairly safe boat harbour--the only one, except an unfrequented beach under Pilot's Hill, for many miles along the coast. Five minutes after the oars had touched the water she was fairly racing seaward, for she was in the full run of the ebbing tide as it swept through the sandbanks and reefs which lined the narrow bar. Then, as the water deepened, and the current lost its strength, Foster shielded his eyes with his hands from the blazing sun, and looking ahead, tried to discern the approaching boat.

'I can't see her anywhere!' he exclaimed presently; 'easy there, pulling. Perhaps she's in a line with Kooringa Rock, and we won't see her for another half-hour yet. Jump up, Combo, and take a look ahead.'

Combo, a huge, black-bearded fellow, with a broad much-scarred chest, showed his white teeth, drew his oar across, and sprung upon the after thwart. For two or three seconds he scanned the sea ahead, then he pointed a little to the northward of Kooringa Rock.

'I see um,' he said with a laugh; 'he long way yet--other side Kooringa--two fella mile yet, I think it;' then he added that the people in the boat had ceased pulling, and that she seemed to be drifting broadside to the southward with the current.

Old Foster nodded. 'That'll do, Combo, my boy. You've eyes like a needle. I can't see for the sun blaze right ahead. Give it to her, lads;' then he kept away a point or two to the southward, so as to pass close under Kooringa Rock, against the grim, weed-covered sides of which only the faintest swell rose and fell, to sway the hanging masses of green and yellow kelp to and fro. At any other time Tom's eyes would have revelled in the sight, and at the swarms of fish of all colours and shapes which swam to and fro in the clear water around the rock, or darted in and out amongst the moving kelp; but now his thoughts were centred solely on the boat's present mission--they were going to rescue what would most likely prove to be shipwrecked people--perhaps foreigners who could not speak English! Oh, how beautiful it was! And every nerve and fibre in his body thrilled with pleasure, as, with the perspiration streaming down his face, he watched his oar, and listened for the next word of command from the old sailor.

For a brief minute or two, as the boat passed along the base of the towering dome above, the fierce sun was lost, and Tom gave a sigh of relief, for although he had thrown off all but his shirt and trousers, his exertions were beginning to tell upon him, and he looked with something like envy at the smooth, naked backs of Combo and his sooty companions, who took no heed of the sun, but whose dark eyes gazed longingly at the white masses of breeding gulls and boobies which covered the grassy ledges near the summit of the rock. Then out again into the dazzling glare once more, and Foster gave a cry--'Avast pulling! There she is, close to, but pulling away from us!'

Tom jumped up and looked, and saw the strange boat. She was not more than half a mile away, and he could see the people in her quite plainly; she was again heading towards the entrance to the bar.

'Give way, lads,' said Foster; 'they're only pulling three oars to our five, and we'll soon be within hailing of 'em. They can't make any headway against the ebb, when they get in a bit further, and are bound to see us afore many minutes.'

The crew--black and white--needed no encouragement, and without a word bent to their oars again, and pulled steadily on for less than a quarter of an hour; then Foster stood up and hailed with all the strength of his lungs; but still the three oars of the strange boat were dipped steadily though slowly, and she still went on.

'They're not looking this way,' muttered the old man to Combo and his listening companions; then Combo himself, drawing in a deep breath, stood up and sent out a long, loud Coo-ee-ee!

As the strange weird cry travelled over the waters, Foster and his companions watched intently, and then gave a loud hurrah! as they saw the rowers cease, and figures stand up in the other boat; then presently there came back a faint answering cry, and they saw an oar was up-ended, as a sign that they were seen. It stood thus for a few seconds, then was lowered, and the strange boat slewed round, and began pulling towards them.

'Steady, now steady,' said Foster, warningly, to his crew, who began pulling with redoubled energy. 'Go easy; we'll be alongside in no time now. Master Tom, in with your oar, and come aft here. Take out a couple of those bottles of water, and keep 'em handy, but put the others out o' sight until I tell you. There's a power o' men in that boat, I can see, and I know what happens to a man perishin' o' thirst, when he gets his lips to water, and has no one to stand by him and take a turn in his swallow.'

Tom stumbled aft pantingly, and did as he was bid, and then, looking up, he saw the other boat was not a hundred yards away, and appeared crowded with men. Then followed a wild clamour of voices and cries, as the two boats touched gunwales, and a strange, rugged figure, who stood in the stern, cried out to Foster--

'Thank God, you are a white man! Have you any water?--ours was finished last night.'

'Enough to give you all a small drink,' replied Foster, quickly, as he handed the bottles over to him one by one, 'but we shall be ashore in another hour. Now, sir, tell some of your men to get into my boat as soon as they've had a drink.'

Although the castaways were the wildest-looking beings ever seen out of a picture-book, they still preserved discipline, and one of them at once began sharing out the water to the others, whilst the man who was steering, with his hands shaking with excitement, poured out a little into a tin mug, handed the rest back to Foster with an imploring look, and then sank on his knees in the bottom of the boat beside a small, crouched-up figure clothed in a dirty calico shirt. As Tom bent over to look, he saw that it was a child--a little girl about five or six years of age. She put her hand out to the mug, and with her eyes still closed drank it eagerly.

'No more, sir, just now!' cried Foster warningly to the man, who, with a great sob of joy, and the tears streaming from his haggard and sun-blackened face, had extended his hand for the bottle, 'no more just now for the little one. Pass her into my boat, and get in yourself; but first take some of this,' and he poured out a full drink.

The officer took it, drank half, and then returned it. 'Is that all that is left? Are you sure that we are safe? For God's sake keep what is left for my child!'

'Ay, ay, sir. Have no fear. In another hour we shall be ashore. But hand me the little one, sir--pass me a tow-line here, some o' you chaps; an' you, Combo, an' Fly, an' the other chap, put on all your beef, and pull with all your might.... Tom, you sit down there with the captain, an' hold the babby.... Never fear, sir, he'll hold her safe, God bless her, dear little mite! ... Cheer up, sir; food an' rest is all she wants, an' all you an' these other poor chaps want.... Pull, Combo, my hearty; pull, Fly; send her along as she never went before.'

Tom, unheeding the excitement of those around him, as a tow-line was passed from the other boat and made fast, and Combo and his two black companions, aided by one of the castaway sailors, bent to their oars and tautened it out, was gazing into the face of his charge, who lay quietly breathing in his arms, whilst her father, weak and exhausted as he was, was telling old Foster his story of disaster and death. It was the first time in Tom's life that he had ever held 'a baby'--as he mentally termed the little girl--in his arms, and under any other circumstances his youthful soul would have recoiled from such a position with horror. But presently, as she turned her face to his, and said in a thin, weak voice, 'Give me some water, please,' he began to shake at the knees, and feel frightened and intensely sympathetic at the same time.

'Only a little, Master Tom; only a mouthful at a time;' and old Foster, his face aglow with excitement, handed him the bottle of water and mug, and Tom carefully poured out about a wine-glassful, and put it to the lips of what, to his mind, seemed more like a dying monkey, with a wig of long black hair, than a real human child.

As the boats drew near the little boat harbour under Pilot's Hill, even the exhausted seamen in the one which was being towed gave a faint cheer, shipped their oars, and began to pull. The sea was still glassy smooth, for it was in November, when a calm would sometimes last for three days and more, only to be succeeded by a black north-easterly gale.

Standing on the shore awaiting the boats were nearly every one of Mr. Wallis's people, who were presently joined by some few of the townspeople, who had heard of something being afoot at the Beach House, as the Wallis's place was called.

'Jump out, Master Tom,' cried Foster, as the leading boat touched the soft, yielding sand, 'and give the baby to Kate. She'll know what to do.'

Tom, his chest swelling with a mighty dignity, surrendered his charge to its father for the moment, leaped out of the boat, and then held out his arms again for it, as if he had been used to carrying babies all his life; and Kate Gorman, a big-boned red-headed Irishwoman, splashed into the water with eyes aflame, and whipped the child away from him, and then, followed by the other women, and cuddling the now wondering child to her ample bosom, she pushed through the rest of the people, and strode up the grassy hill, leaving Tom bereft of his dignity and importance together.

Food and drink in plenty had been brought by the women, as Foster had ordered, and the famished seamen, after satisfying themselves, lay down upon the sweet-smelling grass above high water, to stretch and rest their cramped and aching limbs, before setting out to walk to Beach House along the edge of the cliffs, for there was no other way. And then there came to Tom the proudest moment of his life, when old Foster, who was sitting on the grass with the dark-faced, haggard man whom he had addressed as 'Sir,' beckoned him to come near, and, rising to his feet, said--

'An' this, captain, is Master Tom Wallis, sir, the master's son. I sarved with his mother's father, an'----'

The captain stretched out his hand to the boy, and grasped it warmly, as Tom hung his head and shuffled his feet, his face a deep red the while with delight.

'An' now, Master Tom,' resumed old Foster, throwing back his chest and trying to speak with great dignity, 'there's a great responsibility on us until your father comes home. Do you think you can find him at Cape Kooringa, and tell him to come back as quick as possible, inasmuch as there is a party of sufferin' and distressed seamen a-landed at his door, one of which is a infant, and needs medical aid at once?'

Tom's face beamed. 'I can saddle a horse an' be at the cattle camp at Cape Kooringa long before sunrise. Is there any other message, Mr. Foster?'

'Yes; tell your father that there are thirteen men, includin' the captain, and one infant child. Name of captain Raymon' Cashall, name of ship Bandolier. Ran ashore on the south end o' Middleton Reef, on a certain date, slipped off again and foundered in deep water. One boat, with chief mate and seven men, still a-missin'. Can you remember all them offishul details, Tom?'

'Yes, Mr. Foster,' said Tom, who had before this heard the old sailor use similarly impressive language when occasion demanded it.

'Then, as soon as you gets to the house, and before you saddles your horse and goes off in pursooance of your dooty, I rekwests that you will rekwest Kate Gorman to send some person (Mrs. Potter's boy will do) to meet me and the captain and his distressed and sufferin' seamen, with two or more bottles of brandy, and some water, the key of the lazarette being in my room. Please tell your father that these are sufferin' an' distressed seamen, with an infant as mentioned, with no clothes, the ship having gone down sudden soon after strikin', the second mate an' the captain's wife havin' died through bein' drownded when the ship struck an' washed overboard by a heavy sea, with two men, a Bengalee steward, another man name unknown, and a native nurse girl.'

With this rapidly delivered and puzzling message beating kink-bobs in his already excited brain, Tom started off, hot-foot. The 'lazarette' he knew to mean the cellar--Foster was fond of using the term. Kate Gorman had lived with them ever since Jack's birth.

Kate, red-fisted, red-haired, and honest-hearted, met the boy at the door, her rough freckled face beaming with smiles, though her red-hot tongue had a minute before been going unusually fast, as she rated and bullied the under-servants for being slow in bringing 'hot wather and flannels for the blessed child.'

'The brandy shall Misther Foster have widin twinty minutes by the grace av God, for I'll bust open the dure av his lazzyrett widout trapasin' about for his ould keys. But not a step shall ye move yoursilf till ye've aten and dhrunk somethin' afore ye go ridin' along to Kooringa, an' the black of the night a comin' on fast.'

And then the big Irishwoman, bustling and bristling with importance, yet speaking in a low voice on account of the 'swate blessed choild'--who lay slumbering on a bed that in Kate's eyes was for ever sacred--hurried first to the kitchen, and then to the stables, and, before he knew it, Tom's horse was ready saddled, and a huge dinner steaming and smoking placed before him.

'I can't eat, Kate,' he said; 'it is no use my trying. I want to get to Kooringa Cape to-night. I promised Foster.'

Kate bent down and clasped him in her arms.

'An' God go wid ye, Tom, me darlin'. Shure there's no danger, tho' 'tis a lonely ride along the beach. An', Tom, darlin', me swate, ask your father to hurry, hurry, hurry. For tho' I've niver borne a child meself, 'tis plain to me it is that the little one that lies a slapin' in your own mother's bed, will niver, niver wake in this world, unless some strathegy is done. An' there's no docther widin fifty mile av Port Kooringa; but the masther is full av docthorin' strathegy. So away ye go, Tom, an' all the blessin's av God go wid ye.'

So Tom, with a thrill of exultation and pride, led his horse down the hill to the shore, and springing into the saddle, set off at a steady trot along the long curving beach, towards the grey loom of Kooringa Cape, fifty miles away.

CHAPTER III

HOW TOM LIT A FIRE ON MISTY HEAD, AND WHAT CAME OF IT

Restraining his desire to put his horse into a gallop, Tom went steadily along for the first eight or ten miles, riding as near as possible to the water's edge, where the sand was hard, though by this time the tide was rising, and he knew that in another hour he would have to leave the beach entirely and pick up a cattle-track, which ran through the thick scrub, a few hundred yards back from high-water mark. Although the sun was still very hot, a south-easterly breeze had sprung up, and its cooling breath fanned the boy's heated face, and gave an added zest to the happiness of his spirits, for he was happy enough in all conscience. Here was he, he thought, only thirteen years of age, and the participator in the rescue of a shipwrecked crew, the full tale of whose disaster had yet to be told. Where, he wondered, did the Bandolier sail from, and whither was she bound, when she ran ashore at Middleton Reef? Oh, how heavenly it would be to-morrow, when he, and his father, and Jack were back at home, listening to the story of the wreck! And what strange-looking, tattooed sailors were those with the reddish-brown skins, and the straight jet-black hair like Red Indians? South Sea Islanders, of course! but of what Islands? And how long would they stay at Port Kooringa? Oh, how beautiful it would be if they could not get away for a long time, so that he might make friends with them all! Perhaps some of the brown men with the tattooed arms and legs would teach him to talk their language, and tell him about their island homes, where the palm trees grew thickly on the beaches, and the canoes floated upon the deep blue waters of the reef-encircled lagoons! Perhaps Captain Casalle might take a liking to him, and--he bent over his saddle and flushed with pleasure at the mere thought--and take him away when he got another ship. Oh, he did so hope that his father and the captain would become friends; then it would be so much easier (the 'it' being his father's consent to his becoming a sailor).

And so with such thoughts as these chasing quickly through his imagination, he was at last recalled to the present by the sound of splashing about his horse's feet, as the spent rollers sent every now and then thin, clear sheets of water swashing gently up the sand.

'Come, Peter, old chap,' he said, patting his willing horse on the neck, 'we must get up out of this on to the track, it's getting too soft;' and jumping off, he led the animal straight up over the loose, yielding sand which lay between the water's edge and the fringe of the scrub. Taking a drink from his canvas water-bag as he reached the end of the sand, he mounted again, and was soon riding along the track, which ran through a forest of native apple, whose thick umbrageous canopies of dark green shut out the sunlight so effectually, that the sudden transition made it appear as if he had moved from light to semi-darkness. From the leafy crowns of the trees, and stretching across or hanging in giant loops upon the ground, or swinging high above, was a network of great snaky vines, black, brown, and mottled, and so full of water that, as Tom well knew, he had but to cut off a four-foot length to obtain a full quart of the clear though astringent liquid. Now and then, as his horse's shoeless feet disturbed the loose carpet of fallen leaves, a frightened wallaby would bound away with heavy thumping leaps into the still gloomier shadows on the left, or down towards the ocean, whose softened and lulling murmur sounded as if the shore on which its waves curled and broke were miles and miles away, instead of scarce more than a stone's throw; though now and then, when the sea breeze rustled the dome of green above, it sang its never-ending song in louder tone. Sometimes there came a whirr of wings, as with harsh screaming notes a flock of green and golden parrakeets, intent upon feeding on the ripe wild apples, would flash by, and their cries perhaps be answered by the long-drawn-out note of a stock-whip bird.

The end of the first belt of scrub at last, and Tom emerged out into the open again--a wide stretch of dried-up swamp, along the seaward margin of which the track led in a waving line of white, hardened clay. Far back on the other side were clumps of tall, melancholy swamp gums, and beyond these the thickly timbered spurs of the coast range, standing out clearly and sharply in the blaze of the sinking sun.

'Come, Peter, my boy, it's getting cooler now, and you shall have a drink when we get to the Rocky Waterholes, behind Misty Head;' and Peter, tough old stock horse, to whom fifty miles, with such a light weight and easy-handed rider as was Tom, was a matter of no hardship, shook his clean-cut head, and giving an answering snort, set off at a steady swift canter, glad to be free of the curse of pestering flies, which in the sunlight hung about his nostrils, and crept into the corners of his big black eyes. An hour later, and just as the sun had sunk, a blazing ball of yellow, behind the purpling range, Tom drew rein at a spot known as the Rocky Waterholes--a series of small deep pools of limpid water at the back of a headland, whose high bold front rose stark from the sea. He had still five and twenty miles to ride before reaching the cattle-camp at Kooringa Cape, where he expected to find his father and Jack--unless, indeed, he met them returning driving the missing cattle, which was hardly likely, without they had met with them near a great fresh-water swamp at the back of Misty Head. Anyway, he thought, he would give Peter a bit of a spell for half an hour. If his father and Jack were already returning, they would be almost sure to stop at the Rocky Waterholes, and wait till the tide fell again--which would be towards dawn--instead of trying to drive the cattle along the track through the scrub in the darkness, and run the risk of some of them breaking away, and being lost.

Leading Peter up to one of the Waterholes, he let him drink his fill, and unbuckling the ends of the bridle, turned the animal adrift to feed upon the sweet grass and juicy 'pig-face' growing lower down. Then a sudden inspiration came to Tom. He would light a fire on the top of Misty Head; it would only take a few minutes, and if his father and Jack happened to be near, they would be sure to come and see who had lit it, and thus he could not possibly miss them.

The landward side of the head was mostly covered with a dense thicket, resembling the English privet, but as it did not reach higher than his waist, Tom forced his way through, and with some difficulty reached the summit--a little cleared space less than half an acre in extent, and free of scrub, but covered with coarse, dry grass about a foot high, swaying and rustling to the wind, which as the sun set had freshened. Lower down, on both sides, were a number of thick, stunted honeysuckles; and feeling his way very cautiously--for a slip meant a fall of two hundred feet or more into the sea below--Tom began to collect some of the dead branches, and then returned with them to the top. Once he had lit a fire, he would have light enough to show him where to find a thicker log or two, for there were many dead honeysuckles about, he knew, as the place was familiar to him. Pulling up some of the dried grass, and placing some twigs on the top, he struck a match and lit the heap. It blazed up crisply, and in a few minutes he could see his surroundings clearly.

'That's all right,' said Tom to himself; 'now for some big logs, and then I'll be off.'

Fifty feet away the gnarled and rugged branches of a dead and fallen honeysuckle stood revealed in the firelight, and he walked toward it. Taking hold of one of the largest branches, he began to drag it towards the fire, when he felt a smart puff of wind, and then heard an ominous crackle behind him, and then followed a sudden blaze of light--the long grass around the fire had caught, and a puff of wind had carried the flames to the scrub! Too late to avert the disaster, Tom dropped the log with a cry of terror, for he knew what a bush-fire at that dry time of the year meant; and, most of all, he dreaded the anger of his father for his carelessness. For a moment or two he stood gazing at the result of his folly; and then a cry of alarm broke from his lips as another eddying gust of wind came, and the flames answered with a roar as they swept through the scrub with a speed and fury that told Tom that in a few minutes they would be leaping and crashing into the timber on the other side of the Rocky Waterholes, and thence into the ranges beyond. And then, too, not only was his own retreat cut off, but the fire on the summit was eating its way to windward, and unless he could find some place of retreat on the sea-face or sides of the head, he stood a very good chance of becoming a victim to his own stupidity. As he looked about, undecided whether to try to get in advance of the flames by forcing his way through the dense jungle of the north side, down to the water, and then clambering along the rocks to where he had left his horse, or get over the edge of the cliff to a place of safety, there came another bursting roar, and a huge wall of flame sprang up and leapt and crashed through the gums and other lofty trees which grew close to the landward side of the Waterholes--the bush itself had caught. And as Tom gazed in guilty fear at the scene of devastation, he saw his horse break through the stunted herbage above the beach on the north side and gallop down to the water, where he stopped, terrified at the sudden rush of fire, and, no doubt, wondering what had become of his master.

The sight of the horse standing there on the beach in full glare of the flames, which now were lighting up the sea and hiding the land beyond in dense volumes of blood-red smoke, as the wind carried them inland, filled the boy's heart with a new fear--for his father and Jack. Perhaps at that moment they were between Misty Head and the range. If so, then they were in imminent danger, for he knew that, unless they were near the beach, they would be cut off and perish, for now the wind, as if to aid in the work of destruction, was blowing strongly. A prayer that they might be far away at Kooringa Cape rose to his lips, and then, as he saw Peter still standing and looking about in expectancy, he, like a brave lad, pulled himself together. He would climb down the north side of the head, before the fire, which was steadily working downward to the water, cut him off from the mainland altogether, and kept him there until morning. Force his way down through the close scrub he could not, for the rapidly creeping flames, feeding upon the dried leaves and undergrowth, would overtake him before he was halfway down; but there was, he knew, a break in the density of the scrub, caused by a zigzag and narrow cleft in the side of the head, reaching from near the summit to the boulders of blacktrap rock at the foot. A few minutes' search showed him the most suitable spot from where to begin the descent, and guided by the light of the fire--which revealed every leaf and stone as clearly as if it were broad daylight--he soon reached the top of the cleft, which for the first fifty or sixty feet ran eastwards towards the beach, and then made a sudden and downward turn to the sea. The sides, though terribly rugged, afforded him excellent facilities for descent, as, besides the jutting stones which protruded out of the soil, tough vines and short strong shrubs gave him good support.

'Easier than I imagined,' said Tom to himself, thinking of the pride he would have in relating his feat to Jack in the morning; 'now here's the beginning of the straight up-and-down part.' Grasping the thin stem of a small stumpy tree, with prickly leaves, known to the boys as 'bandy-leg,' he peered over. Suddenly he felt that the tree was yielding at the roots; he flung out his left hand for further support, and clutched a vine about as thick as a lead pencil. It broke, and, with a gasp of terror, poor Tom pitched headlong down, bounding from side to side, and crashing through the stunted herbage, till he struck the bottom, where he lay stunned and helpless, and bleeding from a jagged cut on the back of his head.

For some time he lay thus, and then, as returning consciousness came, he groaned in agony; for, besides the wound on his head, the fingers of his left hand were crushed, and he felt as if the arm were half torn from the socket. Wiping the dust and rubble, with which he was nearly blinded, from his face, he drew himself up into a sitting position, and began to feel his left arm from the shoulder down, fearing from the intense pain that one or more bones were broken; but in a few moments he found he could bend it. Groping about carefully--for the spot where he had fallen was in darkness, though he could discern the sea, not far below, still gleaming dully from the light of the fire--he found that the soil and rocks about him were quite dry and warm to the touch; evidently, therefore, he was some distance from the base of the head and above high-water mark. Slowly and painfully he crawled towards the opening, and discovered that he was about twenty feet over the water, just at the point where all vegetation ceased and bare rock began.

Already he was feeling thirst, and had he been able to use his left arm, he would have climbed down to the sea and swum round to the beach, where he felt sure that Peter was still awaiting him, with the water-bag hanging to the saddle dees. He leant his back against a rock, for now a deadly sickness came over him, and he went off into a long faint.

* * * * *

Ten miles away, and camped near a grassy headland known as the Green Bluff, was a party of eleven men, three of whom were watching the red glow of Misty Head; the rest were lying upon the grass, sleeping the sleep of exhausted nature. The three who watched were Mr. Wallis, Jack, and the black stockman, Wellington; those who slept were the first mate and seven of a boat's crew of the Bandolier. Only a few hours previously the latter had made the coast at the mouth of a small fresh-water creek, running into the sea at the Green Bluff, and were discovered there by Jack, who was tailing some cows and calves on the bank, whilst his father and Wellington were looking for the rest of the missing cattle further up the creek. The moment Jack heard the officer's story, he ran to the pack-horse, which was quietly standing under the shade of a mimosa, unshipped the packs (containing cooked beef, damper, and tea and sugar) and lit a fire, whilst one of the sailors filled the big six-quart billy with water from the creek. Then, picking up his father's shot-gun which was carried on the pack-horse, he loaded it with ball, jumped on his horse again, cut off a cow with a year-old calf from the rest of the mob, drove them a little apart from the others, and sent a bullet into the calf's head. Without wasting time to skin the animal, the half-famished seamen set about cutting up and cooking it (having first devoured the piece of cooked beef and damper). Then waving his hand to the officer, and telling him that he would be back with his father in an hour or less, Jack set of at a gallop in search of him. The officer, a tall, hatchet-faced New Englander, nodded his head--his mouth being too full to speak--and then turned his hollow eyes with a look of intense satisfaction and solicitude upon the frizzling and blood-stained masses of veal.

Towards sunset, Mr. Wallis, Jack, and Wellington came cantering down along the bank of the creek, and the genial, kind-hearted squatter, though the advent of the shipwrecked men meant the abandonment of his search for the rest of the cattle, and the loss of much valuable time, sprang from his horse, and shook hands warmly with the officer, as he congratulated him upon his safe arrival.

'You must camp here with us to-night,' he said, 'and perhaps to-morrow as well, or at least until such time as you and your men are sufficiently recovered to walk to Port Kooringa. In the morning, however, I shall send my black boy on in advance, and he will meet us with some more provisions. For the present we can manage--the creek is alive with fish, fresh beef is in plenty'--pointing to the grazing mob of cows and calves,--'and you and your men, above all things, need rest. Now, tell me, do you smoke?'

'Smoke, mister?' and the man's voice shook; 'ef I get a smoke I'll just be in heaven. But I can't do it here, with those poor men a-looking at me. Every one of them is as good a man as me, although I did hev ter belt the life out of them sometimes.'

Mr. Wallis slipped his pipe, tobacco pouch, and a box of matches into the officer's hand. 'Go down to the creek and lie down there and smoke,' he said with a smile; 'I wish I had more tobacco for your men.'

As the mate crept away like a criminal, clutching the precious pipe and tobacco in his gaunt, sun-baked hand, Wellington cried out, and pointed towards Misty Head--

'Hallo! look over there! Big feller fire alonga Misty Head.'

Mr. Wallis turned and watched, and as he saw the lurid flames and huge volumes of smoke rise, and then sweep quickly down the incline of the head, toward the dark line of bush beyond, he could not repress a groan of vexation and anger, for he knew that, with such a strong breeze, the whole coast would be aflame in a few hours, and hundreds of miles of country on Kooringa Run be swept in its devastating course, and cause him to lose some thousands of pounds. Then in addition to this, and of more importance to his generous mind--for money itself held no sway on a nature such as his--was the fact that he and the shipwrecked seamen would have to make their way to Port Kooringa along the beach as the tide served, for they could not for some days traverse the burnt-out country at the back of the many headlands and capes, as the ground would be a furnace covered with ashes.

Towards midnight, Wellington, who was on watch, roused his master, and reported that the fire was rapidly travelling towards the Green Bluff, and would be upon them in an hour. This was serious, for there was no beach to which they could retreat on either side of the bluff for many miles, and the country on the opposite side of the little creek was, though free from scrub, clothed in long grass, which a single flying spark would set ablaze.

Awakening the officer, he explained the situation to him, and suggested a way of escaping from the danger which menaced them by taking to the boat, putting to sea, and making direct for Port Kooringa at once.

Tired as were the mate and his men, they at once acquiesced. The cattle and horses were driven across the creek, and left to take care of themselves, the boat's water-breaker filled, and the saddles and other gear were placed in the boat, only just in time, for already the heat of the flames was getting oppressive. There was but little surf at the mouth of the creek, and the instant the boat had passed through it, the ragged sail was set, and she slipped through the water.

'Don't go too close to Misty Head,' said Mr. Wallis to the officer; 'there is always a strong tide-rip there.'

The officer altered the boat's course.

Poor Tom, just as the daylight broke, saw her sail pass about a mile off. He stood up and shouted till he was hoarse; and then, when he realized that she was too far off for him to be heard, or even seen in such a position, sat down and wept, forgetting his bodily pain in his anguish of spirit.

But, as the sun rose, his thirst became overpowering, and rising to his feet with a prayer for strength upon his lips, he began to make his way along the foot of the rocks. His arm was less painful now, but three of his fingers were black, swollen, and useless, and the wound in his head every now and then made him faint. When half-way to the beach, he saw that the water was sufficiently shallow for him to wade ashore on the clear, sandy bottom, instead of toiling over the rocks, so getting down at a spot where it was not over his knees, he first immersed his whole body and then bathed his head and face. The stinging, smarting sensation caused him fresh pain, but he set his teeth and bore it manfully, knowing that the salt water would do the cut on his head more good than harm, even though it made it bleed afresh.

With renewed courage--for the cool water had revived him wonderfully--he waded along cheerfully, his thoughts now turning to his father and Jack, for whom he was not at all alarmed, knowing that both of them were too good bushmen to be caught by a bush fire, no matter how suddenly it had come upon them. If they were camped at Kooringa Cape, there was no danger for them at all, as a few miles this side of it there was a wide tidal river, and if they had been anywhere near the Rocky Waterholes when the fire started they would have sought safety on one of the small islands in the Big Swamp. Anyway he would be home to-morrow, or the next day, if he had to keep to the beach--and no doubt would meet some one coming to look for him; for unless Peter had met his father's party, the animal was bound to make for home, and be seen by some person. Then that boat! Of course it must have been the missing boat from the Bandolier--no other boat would be coming down the coast, surely! Oh, if he were only home to know! But a drink first before he decided what to do.

Stepping out of the water on to the hard dry sand, Tom ascended the bank, and then a cry of dismay escaped from him--the Rocky Waterholes were surrounded by a belt of blazing logs, and it was impossible for him to approach within a hundred yards, and the holes themselves were not to be seen!

Tom returned to the beach to consider. He must get a drink, and there was none to be had on the way back home, except from the thick vines in the scrub through which he had ridden the previous morning. But was there any scrub left? As far as he could see to the southward, the coast was still burning, and even if the scrub where the vines grew had escaped, he could not cut one, for he had lost his knife when he fell. Well, he must try and get along the beach and round the cliffs, further on, to the creek at the Green Bluff. There was always deep running water there; and now he began to think of nothing else--he must get a drink, or he could never attempt to walk all the way to Port Kooringa. Oh, if he could but get to the creek quickly! he thought, as, taking off his boots and socks, which were filled with coarse gritty sand, he tied them together with the laces, and set out along the hard beach. If it were only five miles of such easy walking as the first two, he would soon reach there; but the remaining three were the trouble--three miles of rocky shore, under a blazing sun, and with his head making him feel strange and faint.

Never once halting, the lad kept steadily on, trying hard not to lose courage, for every minute he felt his strength failing him, and a strange buzzing noise was in his ears, and the yellow sand seemed to dance and twist about and sink away from his feet. Oh for a drink, a drink! A long drink would set him right again, he kept repeating to himself; there was nothing really much the matter with him except his head.

At last he came to the end of the beach, put on his boots, and began to climb over the first point of rocks. This took him much longer than he anticipated, and he slipped and fell heavily once or twice. Then came a succession of small deep bays, the shores of which were covered with smooth loose pebbles, giving way to every step, and terribly exhausting to walk over. Then again another point--a flat reef of rocks running out some distance into the sea, dangerous, slippery, and covered with a greasy green weed, and awash at high water. Tom had never before walked along this part of the coast, and at any other time its wild loneliness would have pleased his Nature-loving imagination--now it appalled and terrified the poor boy, who, though he did not know it, was rapidly becoming physically exhausted from the injury to his head, which was more serious than he imagined.

Once over the wide stretch of smooth rocks, he took heart again; Green Bluff, now black and smoking, seemed quite near. Another little bay, and then another, and panting and half frantic with excitement and thirst, Tom stumbled blindly over the loose stones and gravel, which were heaped up in ridges on the narrow foreshore. Surely, he asked himself, there could not be many more of these dreadful stony winding bays, backed up by steep walls of rock. Once more a high point obstructed him; and now an insensate rage took possession of him. With blazing eyes, and parched and cracking lips, he sprang at the great boulders, slipping and falling again and again, to rise with bleeding hands and face, a dazed determination in his whirling brain to get to the water at the Green Bluff in spite of everything. Trembling in every limb, he succeeded in getting round--and then stopped, his face white with horror: on the opposite side of the bay a long stretch of cliff rose sheer up from the deep blue water at its base. And then a sudden blackness shut out the world, and he sank down upon the shingle in despair.

CHAPTER IV

CAPTAIN SAM HAWKINS AND THE LADY ALICIA

Thirty miles to the eastward of Breaksea Spit, which lies off Sandy Cape, on the coast of Queensland, a little tubby and exceedingly disreputable-looking brig of about two hundred tons burden was floundering and splashing along before a fresh southerly breeze, and a short and jumpy head swell. By the noise she made when her bluff old bows plunged into a sea and brought her up shaking, and groaning, and rolling as she rose to it and tumbled recklessly down the other side, one would have thought that the Lady Alicia was a two thousand ton ship, close hauled under a press of canvas, and thrashing her way through the water at thirteen or fourteen knots. Sometimes, when she was a bit slow in rising, a thumping smack on her square old-fashioned stern would admonish her to get up and be doing, and with a protesting creak and grind from every timber in her sea-worn old frame, blending into what sounded like a heart-broken sigh, she would make another effort, and drop down into the trough again with a mighty splash of foam shooting out from her on every side, and a rattling of blocks, and flapping and slapping of her ancient, threadbare, and wondrously-patched canvas.

Aft, on the short, stumpy poop, a short stumpy man with a fiery-red face, keen blue eyes, and snow-white hair, was standing beside the helmsman, smoking, and watching the antics of the venerable craft--of which he was master and owner--with unconcealed pride. His age was about the same as the brig, a little over fifty years; and this was not the only point in which they resembled each other, for their appearance and characteristics bore a marked similarity in many respects.

In the first place, the Lady Alicia was a noisy, blustering old wave-puncher, especially when smashing her cumbrous way through a head sea, as she was doing at present. But despite her age and old-fashioned build, her hull was still as sound as a bell; and Captain Samuel Hawkins was a noisy, blustering old shell-back, especially when he met with any opposition; and despite his age and old-fashioned and fussy manner, his heart was not only as sound as a bell, but full to overflowing with every good and humane feeling, for all his forty years of life at sea.

Secondly, the Lady Alicia had antiquated single 'rolling' topsails (which were the skipper's especial pride, although they invariably jammed at critical moments during a heavy squall, and refused to lower, with all hands and the cook straining frantically with distended eyeballs at the down-hauls), and Captain Hawkins wore antiquated nether garments with a seamless bunt, and which fastened with large horn buttons at his port and starboard hips, and this part of his attire was the object of as much secret contempt with his crew as were the hated rolling topsails, though the old man was a firm believer in both.

Thirdly, the Lady Alicia carried stun sails (which was another source of pride to her master, and objects of bitter hatred to the mate, as useless and troublesome fallals); and Captain Hawkins wore a stove-pipe hat when on shore in Sydney, the which was much resented by many of his nautical cronies and acquaintances, who thought that he put on too many airs for the skipper of the Lazy Alice, as they derisively called the old brig. But no one of them would have dared to have said anything either about the brig's stunsails or sailing qualities, or her master's shore-going top-hat in his hearing; for the old man was mighty handy with his fists, and a disrespectful allusion to his own rig, or to that of his ship, would entail a quick challenge, and an almost certain black eye to the offender.

And, fourthly, the brig had been built for the Honourable East India Company, and in the Honourable East India Company's service old Samuel, then 'young Sam,' had served his apprenticeship to the sea; and, in fact, as he stood there on his own poop-deck, the most unnautical observer could not but think that he had been born for the Lady Alicia, and that the Lady Alicia had, so to speak, been built to match the personal appearance of her present commander, despite her previous thirty years of buffeting about, from the Persian Gulf to Macassar, under other skippers.

Presently, turning to the helmsman, a huge, brawny-limbed Maori half-caste, who had to stoop to handle the spokes of the quivering and jumping wheel, the master took his pipe from his mouth, knocked the ashes out upon the rail, and said--

'Well, William Henry, we're doing all right, hey?'

The Maori, deeply intent upon his steering, as his keen dark eye watched the lumping seas ahead, nodded, but said nothing, for he was a man of few words--except upon certain occasions, which shall be alluded to hereafter. Seated on the main hatch, the second mate and some of the crew were employed in sewing sails; for although the brig was jumping about so freely, and every now and then sending sheets of foam and spray flying away from her bows, the decks were as dry as a bone. Further for'ard the black cook was seated on an upturned mess-tub outside his galley door, peeling potatoes into a bucket by his side, and at intervals thrusting his great splay foot into the nose of Julia, the ship's pig, which, not satisfied with the peelings he threw her, kept trying to make a rush past through the narrow gangway, and get at the contents of the bucket.

Just before seven bells, the mate, who did such navigating work as was required, put his head up out of the companion, sextant in hand, and then laying the instrument down on the skylight, turned to the skipper.

'He says he feels bully this morning, and wants to come on deck.'

The little squat skipper nodded, hurried below, and in a few minutes reappeared with a bundle of rugs and rather dirty pillows, which he at once proceeded to arrange between the up-ended flaps of the skylight, then he hailed the black gentleman potato-peeler.

'Steward' (the term cook was never used by the worthy old captain), 'come aft here and lend a hand.'

'Ay, ay, sah,' replied the negro, in his rich, 'fruity' voice, 'I'se comin', sah;' and with a final and staggering kick with the ball of his foot on Julia's fat side, he put the bucket inside the galley, slid the door to, and followed the captain below, whilst the mate, a young, dark-faced, and grave-looking man, swiftly passed his sun-tanned hand over the couch made by the skipper, to see that there were no inequalities or discomforting lumps in the thick layer of rugs.

And then, curly wool and sooty black face first, and white head and red face beneath, up comes Tom Wallis, borne between them into life and sunshine again; but not the same Tom as he was ten days before--only an apology for him--with a shaven head, and an old, wan, and shrunken face, with black circles under the eyes, a bandaged foot, and left hand in a sling.

'Gently, there now, steward, gently does it. Hallo! youngster, you're laughing, are you? Right glad am I to see it, my lad. Steady now, steward, lower him away easy.... There! how's that, son?'

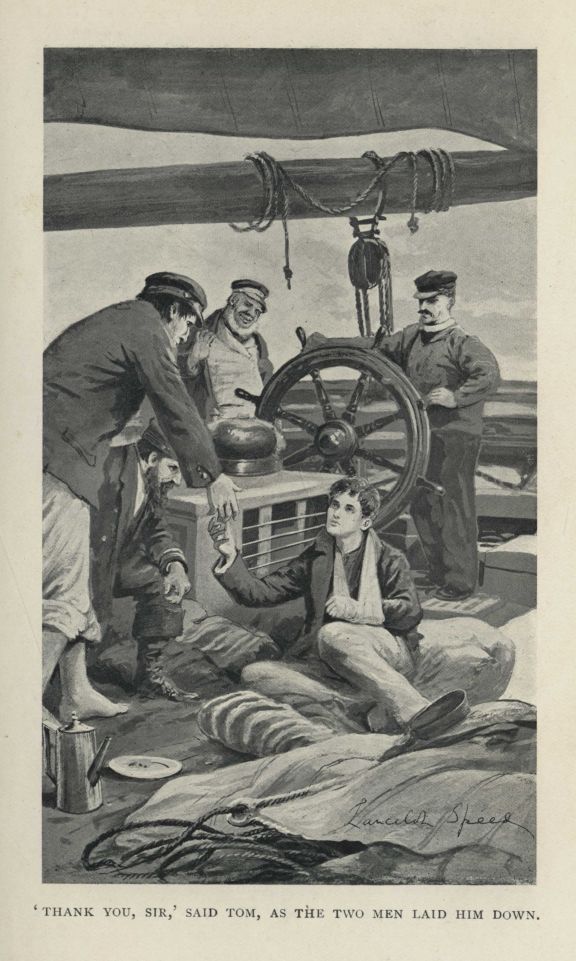

'Thank you, sir,' said Tom, as the two men laid him down upon the rugs. 'Oh, how lovely it is to see the sky again! Where are we now, sir?'

'Thirty mile or thereabout nor'-east o' Sandy Cape. How's the foot?'

'Much better, sir, thank you; but I think I might have the things off my hand now. I can move all my fingers quite easily.'

Hawkins turned to the mate. 'What do you think, Mr. Collier?'

The grave-faced young mate nodded, sat down beside the lad on the edge of the skylight, and taking Tom's hand out of the sling, began to unwind the bandages from his fingers, which he examined critically, and, pressing them carefully, asked the lad if he felt much pain.

'No, sir,' said Tom, lying manfully, as he looked into the officer's eyes--so calm, patient, and quiet, like those of his own father--'not much.'

'Then we'll have these off,' said Collier, as with a kindly smile he unfastened the bandages; 'but you won't be able to use that foot for another week or two.'

'I don't know how I managed to cut it,' said Tom, as he lay back with a sigh of relief, and watched the brig's royalmasts make a sweeping arc through the air as she rolled from side to side. 'I put on my boots when I came to the rocks beyond Misty Head.'

Captain Hawkins laughed. 'You was non compos mentis of the first class and stark naked in a state of noodity, and when we saw you spread-eagled as it were on the beach, and put ashore to see whether you were dead or alive we couldn't see a stitch of clothing anywhere, could we, William Henry?'

The Maori helmsman nodded his head affirmatively, and then, as eight bells were struck, and he was relieved at the wheel, he came and stood beside the master and mate, and a pleased expression came into his somewhat set and heavy features when Tom put out his hand to him.

'It was you who saw me first, and saved my life, wasn't it?' he said; and then with boyish awkwardness--'I am very much obliged to you, Mr. William Henry.'

The big half-caste took Tom's hand in his own for a moment, and shuffling his bare feet, muttered in an apologetic tone that 'it didn't matter much,' as he 'couldn't help a-seeing' him lying on the beach. Then he stood for'ard.

'Do you know who he is, young fellow?' said the skipper, impressively, to Tom, as soon as the big man was out of hearing.

Tom shook his head.

'That's Bill Chester, William Henry Chester is his full name he's the feller that won the heavy-weight championship in Sydney two years ago didn't you never hear of him?'

Tom again shook his head.

'Well you know him now and it'll be something for you to look back on when you comes to my age to say you've shook hands with a man like him. Why he's a man as could be ridin' in his own carriage and a hobnobbin' with dukes and duchesses in London if he'd a mind to; but no he ain't one of that sort a more modester man I never saw in my life. Why he stood his trial for killin' a water policeman once and only got twelve months for it the evidence showin' he only acted in self-defence being set upon by six of them Sydney water police every one of 'em being a bad lot and dangerous characters as I know; and the judge saying that he only stiffened the other man under serious provocation and a lenient sentence would meet the requirements of the case; seventeen pound ten me and some other men give the widow who said that she wished it had happened long before and saved her misery he being a man who when he wasn't ill-usin' sailor men was a-bootin' and beltin' his wife eleven years married to him although he was in the Government service I'll tell you the whole yarn some day and.... Now then where are you steerin' to? I don't want you a cockin' your ears to hear what I'm sayin'. Mind your steerin' you swab an' no eaves-droppin' or you'll get a lift under your donkey's lug.'

The man who had relieved 'William Henry'--a little, placid-faced old creature, who had sailed with Hawkins ever since that irascible person had bought the Lady Alicia when she was lying in Port Phillip, deserted by her crew, twenty years before, said, 'Ay, ay, sir,' and glued his eyes to the compass--although he had no more intention of listening to the skipper's remarks than he had of leading a mutiny and turning the brig into a pirate. He had been threatened with fearful physical damage so often during his score of years' service with the boisterous old captain, that had it been actually administered he would have died in a fit of astonishment, for 'old Sam' had never been known to strike one of his hands in his life, although he was by no means averse, as mentioned above, to displaying his pugilistic qualifications on shore, if any one had the temerity to make derogatory remarks about his wonderful old brig.

Swelling with importance, the old man, after glaring at the man at the wheel for a moment or two, turned to the mate--

'Mr. Collier this young person being an infant in the eyes of the law and this ship being on Government service and to-day being his convalescency as it were I shall require you to verify any or whatsoever statements as shall appear to be written in the log of this ship. I know my duty sir and I hereby notify you that I rely on you to assist and expiate me in every manner;' and the fussy little man waddled down the companion way with a kindly nod at Tom.

Tom began to laugh. 'He talks something like old Foster, Mr. Collier--the old man I was telling you about.'

The mate smiled. 'He's a good old fellow, my lad, good, and honest, and true; and now that he is out of hearing, I may tell you that, ever since you were brought on board he has studied your comfort, and has never ceased talking about you. Three days ago, when you were able to talk, and tell us how you came to be where we found you, he was so distressed that he told me that he was more than half inclined to turn the brig round and head for Sydney, so that you might be enabled from there to return to your father.'

Tom's eyes filled at once. 'My poor father! He will never expect to see me again;' and then, as his thoughts turned to home and all that was dear to him, he placed his hands over his face, and his tears flowed freely.

The officer laid his hand on his shoulder. 'Try and think of the joy that will be his when he sees you again, Tom. And, above all, my dear boy, try and think of the mercy of Him who has spared you. Try and think of Him and His goodness and----'

He rose to his feet, and strode to and fro on the poop, his dark, handsome features aglow with excitement. Then he stopped, and called out sharply to a couple of hands to loose the fore and main royals, for the wind was now lessening and the sea going down.

Ten minutes later he was again at Tom's side, his face as calm and quiet as when the lad had first seen it bending over him three days before, when he awoke to consciousness.

'I promised you I would tell you the whole yarn of your rescue. There is not much to tell. We were hugging the land closely that day, so as to get out of the southerly current, which at this time of the year is very strong. We saw the fire the previous night, when we were about thirty miles off the land, and abreast of Port Kooringa. Then the wind set in from the north-east with heavy rain-squalls, so the skipper, who knows every inch of the coast, and could work his way along it blindfolded, decided to keep in under the land, and escape from the current; for the Lady Alicia'--and here his eyes lit up--'is not renowned for beating to windward, though you must never mention such a heresy to Captain Hawkins. He would never forgive you. About four o'clock in the afternoon we went about, and fetched in two miles to the northward of Misty Head; and Maori Bill, the man who was here just now, and whom the skipper calls "William Henry," cried out, just as we were in stays again, that he could see a man lying on the beach. The captain brought his glasses to bear on you, and although you appeared to be dead, he sent a boat ashore. There was a bit of a surf running on the beach, but Harry took the boat in safely, and then jumped out, and ran up to where you were lying. He picked you up, and carried you down to the boat--you were as naked as when you first came into the world, Tom,--and then brought you, just hovering between life and death, aboard. Your left foot was badly cut, left hand swollen and helpless, and, worse than all, you had a terrible cut on the back of your head. And here you are now, Tom, safe, and although not sound, you will be so in a few days.'

Tom tried to smile, but the old house at Port Kooringa, and the sad face of his heart-broken father, came before his eyes, and again his tears flowed, as he thought of the anguish of those he loved.

'Oh, Mr. Collier, that day was the happiest day of my life! When I was riding along the beach, I felt as if I was moving in the air, and the sound of the surf and the cry of the sea-birds ... and the wavy, round bubbles that rose and floated before me in the sunshine over the sand ... and I was so glad to think that I could tell father and Jack about Foster and I going out in the boat to the shipwrecked sailors, and bringing them ashore. And I'm so sorry for being so foolish as to light a fire on Misty Head, when the country was so dry. Poor father, I wish I could tell him so now! Of course he will think I am dead;' and, in spite of himself, his eyes filled again, as he thought of his father's misery and worn and haggard face.

'Don't fret, my boy. It cannot be helped. And any day we may speak a ship bound to Sydney or Melbourne, in which case you will soon be back home; anyhow, the Lady Alicia should be in Sydney Harbour in four months from now.'

Then the mate gave Tom some particulars about the nature of the voyage. The brig was really, as the captain had said, on Government service, having been chartered by the New South Wales authorities to convey a boat to Wreck Reef--a dangerous shoal about two hundred miles north-east of Sandy Cape, and the scene of many disastrous wrecks. The boat, with an ample supply of provisions and water, charts and nautical instruments, and indeed every necessary for the relief of distressed seamen, was to be placed under a shed on an islet on the reef, where it would be safe and easily visible. During the past four or five years, so the mate said, several fine ships had run ashore, and the last disaster had resulted in terrible privations to an entire ship's company, who for many months had been compelled to remain there, owing to all the boats having been destroyed when the vessel crashed upon one of the vast network of reefs which extend east and west for a distance of twenty miles.

From Wreck Reef the brig was to proceed to Noumea, in New Caledonia, where she had to discharge about a hundred tons of coal destined for the use of an English gunboat, engaged in surveying work among the islands of the New Hebrides group.