|

Project Gutenberg's Poor Folk in Spain, by Jan Gordon and Cora Gordon

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Poor Folk in Spain

Author: Jan Gordon

Cora Gordon

Release Date: September 16, 2012 [EBook #40776]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POOR FOLK IN SPAIN ***

Produced by Bryan Ness, Matthias Grammel and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

|

BY THE SAME AUTHOR |

MODERN FRENCH PAINTERS With 20 Illustrations in colour and 24 in black and white. Crown 4to. 21s. net. MOTHER AND CHILD Drawings by Bernard Meninsky. With letterpress by Jan Gordon. Crown 4to. 15s. net. |

THE BODLEY HEAD |

|

| POOR FOLK IN SPAIN |

| BY JAN AND CORA GORDON |

| ILLUSTRATED BY THE AUTHORS |

| JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD LIMITED |

| VIGO ST. :: :: :: :: LONDON |

| First published 1922 |

| Printed in Great Britain by Richard Clay & Sons, Ltd., Bungay, Suffolk.

|

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | LONDON | 3 |

| II. | JESUS PEREZ | 7 |

| III. | THE FRONTIER | 17 |

| IV. | MEDINA DEL CAMPO | 29 |

| V. | AVILA | 40 |

| VI. | MADRID | 51 |

| VII. | A HOT NIGHT | 60 |

| VIII. | MURCIA—FIRST IMPRESSIONS | 70 |

| IX. | MURCIA—SETTLING DOWN | 81 |

| X. | MURCIA—BLAS | 90 |

| XI. | MURCIA—THE ALPAGATA SHOP | 95 |

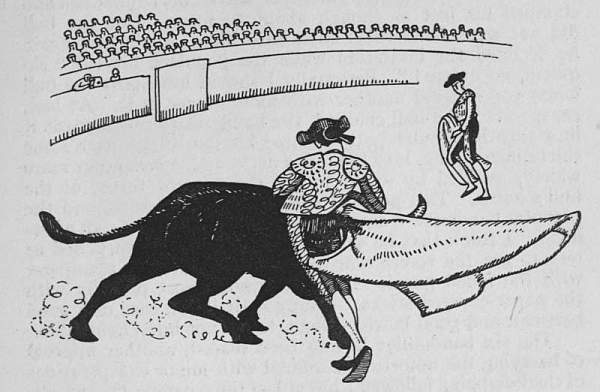

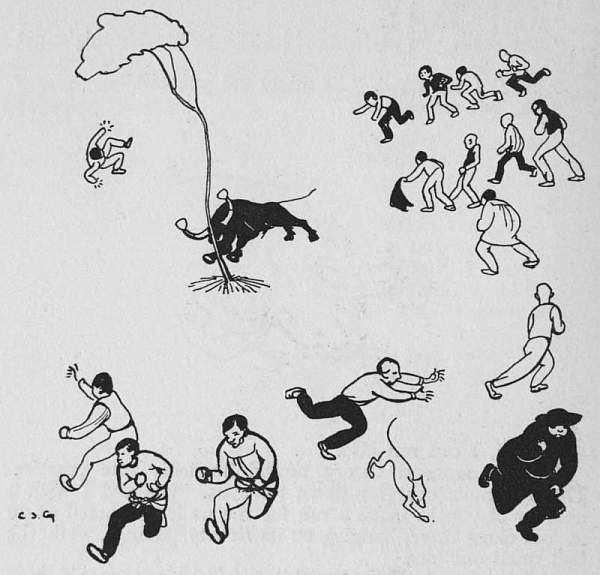

| XII. | MURCIA—BRAVO TORO | 98 |

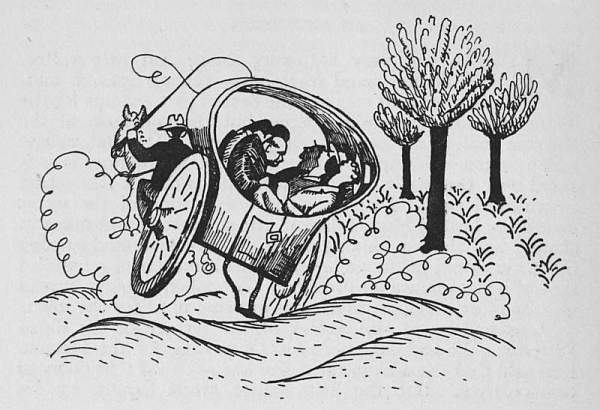

| XIVII. | AN EXCURSION | 109 |

| XIV. | VERDOLAY—HOUSEKEEPING | 123 |

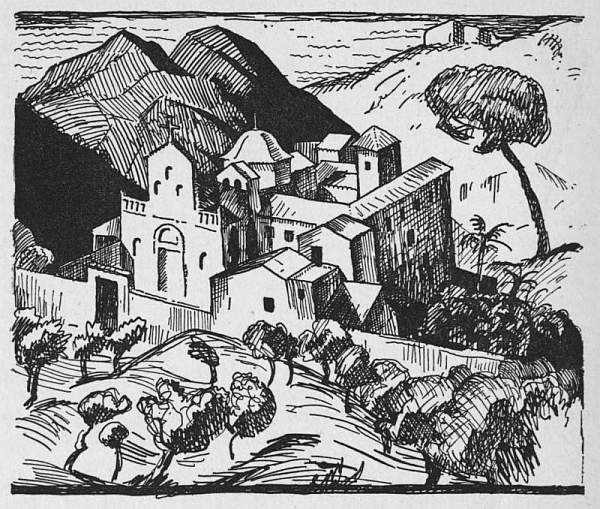

| XV. | VERDOLAY—SKETCHING IN SPAIN | 133 |

| XVi. | VERDOLAY—CONENI | 142 |

| XVII. | VERDOLAY—THE INHABITANTS | 147 |

| XVIII. | VERDOLAY—THE DANCE AT CONENI'S | 156 |

| XIX. | MURCIA—THE LAUD | 161 |

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| XX. | ALICANTE | 169 |

| XXI. | JIJONA—THE FIESTA | 185 |

| XXII. | JIJONA—TIA ROGER | 200 |

| XXIII. | JIJONA—A DAY'S WORK | 207 |

| XXIV. | JIJONA—THE GOATHERD | 218 |

| XXV. | MURCIA—AUTUMN IN THE PASEO DE CORVERAS | 226 |

| XXVI. | LORCA | 244 |

| XXVII. | MURCIA—LAST DAYS | 260 |

| XXVIII. | THE ROAD HOME | 268 |

| To face page | |

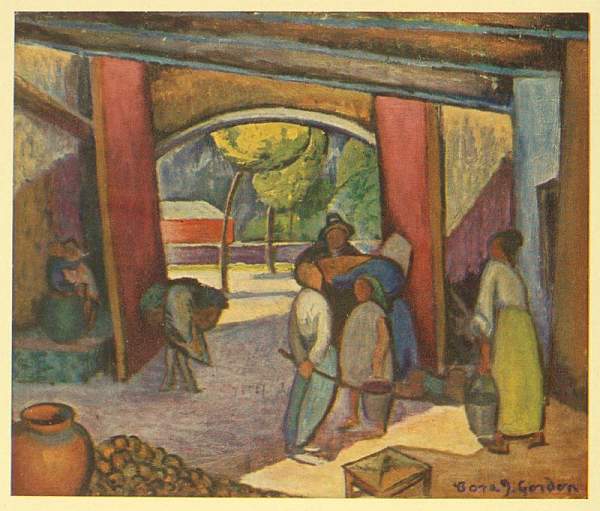

| SPANISH COURTYARD | Frontispiece |

| CARTERS IN THE POSADA | 70 |

| A MURCIAN BEGGAR WOMAN | 78 |

| GIRL SINGING A MALAGUEÑA | 220 |

| THE VALENCIAN JOTA DANCED BY THREE COUPLES | 222 |

We had tasted of Spain before ever we had crossed her frontiers. Indeed, perhaps Spain is the easiest country to obtain samples from without the fatigue of travelling. The Spaniard carries his atmosphere with him: wherever he goes he re-creates in his immediate surroundings more than a hint of his national existence. The Englishman abroad may be English—more brutally and uncompromisingly English than the Spaniard is Spanish—yet he does not carry England with him. He does not, that is, re-create England to the extent of making her seem quite real abroad; there she appears alien, remote, somewhat out of place. So, too, neither the Russian, the German, the Dane, the Portuguese, the Italian, nor the American can carry with him the flavour of his homeland in an essence sufficiently concentrated to withstand the insidious infiltration of a foreign atmosphere. To some extent the Scandinavian countries, Norway and Sweden, have this power; but Spain is thus gifted in the greatest measure. These three countries seem to possess a national unconsciousness which fends them off from too close a contact with lands which are foreign to them; perhaps one might almost accuse them of a lack of sensitiveness in certain aspects....

However, be the reason what it may, we had gathered some experience of Spain in Paris before, and in London during the war. What we had tasted we had liked, and so when in our low-ceilinged attic refuge in London we gazed out upon a sky covered with flat cloud, as though with a[Pg 4] dirty blanket, and wondered how we might escape in order to seek for our original selves—if they were not irretrievably lost—we thought of Spain. I think that we went to Spain to look for something that the war had taken from us. It was as though the low ceiling of our room, and the low-lying sky, shut us in with something which was not altogether true; indeed, we feel that many years must pass before the dissipation of this curious sensation of unreality which the war had stamped on to every one, except the most callous.

It is now clear that peace is the normal condition of the human race. In the olden days this was not the case, but the tendency has been changing, and to-day we increase our powers during times of peace, and our powers fall from us during the disorganizations of war. The artist, who is the barometer of social change, was attuned to peace. In peace he exercises important functions. But with the sudden outbreak of war the whole foundation of his being was suddenly torn away. When war broke out Art for the artist seemed almost meaningless. In the face of a human catastrophe who could paint pictures? Nero may have fiddled while Rome was burning, but it must have been a poor meaningless tune that he played, some popular jingle, a Roman variation of "Ta-ra-ra-Boom-de-Ay." We had come at last to a peace which still carried on its breezes all the poisons of war, and we, at least, felt an imperative need of escape to some place where the war had not been; to some place where perchance life had carried on a not too distorted existence since 1914.

Spain drew us to her more than did Scandinavia. Romance certainly had a finger in it; the sun perhaps two fingers—for we are undoubted sun-worshippers; the music of Spain, which had attracted us in Paris, causing Jan to abandon the banjo for the guitar, added an appeal; and I think an exhibition of Spanish landscapes by Wyndham[Pg 5] Tryon at the Twenty-One Galleries settled the matter. We had been in Majorca before the war, and this combined with our experience of Spaniards in Paris had fixed in our minds a belief in a simplicity and courtliness of the Spanish people which we hoped would be very soothing. Finally, two houses were offered by a friend rent free for the whole of the summer, together with introductions which would smooth the way. We then packed up painting materials, stamped clothes into a trunk, worried a strangely assorted collection of packages down our narrow and twisted staircase into a cab, and so—hey, for the Sun, southward!

Perhaps the reader should be warned that this is not properly a book about Spain in the true sense of the word; it is a book about ourselves. We are inclined to doubt if, in the true sense of the word, a book can ever be written about a country. Curiously enough the native scarcely perceives his country at all as long as he is living in it. When he travels he may come to a clearer vision, but then scarcely perceives with truth the country in which he is travelling. We might say that by travelling he makes out of the foreign land a sort of inverted image of his home. What he relishes abroad is probably what is lacking, what he dislikes abroad is perhaps more perfect in his own country. And thus his vision of abroad makes, as it were, a mould, and, if one could pour into it a substance which would reproduce the exact reverse as one makes a cast, one might procure a fairly faithful image of his unconscious judgment of his own land. So perhaps if this book could be turned inside out it might be found that, after all, stripped of its unessentials, we have been writing a book, not about Spain, but about England. Indeed, we have been writing about England already—romance, sun, an interesting national music, the guitar, and national unconsciousness are not assets to be found here in any overwhelming quantities. We must then deny that we are trying to write a book of any authority; we[Pg 6] do not even assert that our facts are correct, even though they are as we saw them; we admit a mental astigmatism which we cannot avoid and which may have twisted actual happenings or hearings as much as optical astigmatism may twist a straight line

Jesus Perez took us to Spain in spirit while we were still in Paris. We were off to Spain to paint, that being the normal course of our lives, but in addition Jan had formed a fixed resolution that happen what might he was not coming home without having bought a good Spanish guitar by the best guitar-maker he could find, while I wished to buy a Spanish lute. Arias and Ramirez, the two best modern luthiers in Madrid, both had recently died; we had, however, the address of the widow of Ramirez, who carried on her husband's business, but faintly in Jan's mind a cloud hung over the lady's name. He did not trust her. Not she, but Ramirez had made those superfine instruments. So we were overjoyed to meet Perez upon the Boulevard Montparnasse soon after our arrival in Paris. Perez was a friend of ours from the times before the war. He was almost a mystery man. Native of Malaga, self-styled painter—though he never showed his work—nobody could tell how he had managed to make a living during fifteen years of apparently unproductive existence. It is true that one summer he had disappeared from the quarter, returning late in November browned by the sun, and had explained that he had been smuggling in the Pyrenees; but that event was an exception, and for some months subsequently Perez was obviously well off as a result of his risky enterprises. Normally, he survived like so many others in the Quartier Montparnasse, drawing sufficient nourishment (supplemented very obviously by borrowing) from mysterious sources. But while most of[Pg 8] his confrères in penury had no talents, not even the talent for painting, Perez did know the guitar. Rumour said that he was one of the best amateur players of the Jota Arragonesa in Spain. Rumour may have exaggerated without detracting from the real quality of Perez's exquisite gift.

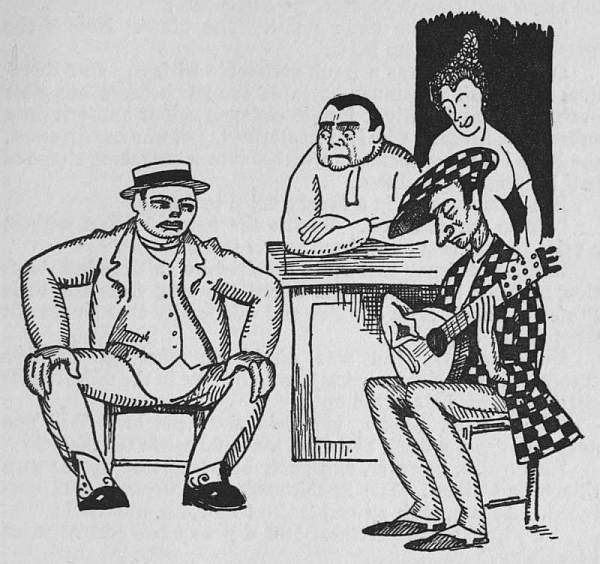

We saw a Perez very much polished up by so many years of war. He wore a clean straw hat, new clothes of the latest cut, a waistcoat of check with ornamental buttons, patent leather boots with a lacquer which flung back the rays of the June sun, and heavy owlish eyeglasses of tortoise-shell fastened with a broad black ribbon. Indeed, so transformed was he, that it was he who recognized us; and for some moments we stood trying to pierce through the new respectability, as though it were through a disguise.

Seated together at the "Rotonde" we exchanged some petty items of news. Perez had but recently returned from Spain; he had held a small exhibition, he said, which had provided funds; pictures were selling well in Spain.... He was delighted to hear of our plan, and thereupon wrote for us an introduction to a painter, a friend, who lived in Madrid. "Un homme très serviable," he said, manufacturing a French word out of one Spanish. Jan then asked his question. "A good guitar-maker in Spain," said Perez, pinching his lower lip between finger and thumb. He shook his head slowly.

"A good guitar-maker," repeated Perez. "In Madrid, eh? Frankly, no, I do not know of one at the moment. And you are going away at once. Tomorrow. Well, this afternoon I am free, that is good. The best guitar-maker at the moment lives here, here in Paris. His name is Ramirez. Yes, a relative of that other Ramirez. He has found a new form for the guitar. More fine, more powerful. Each one like a genuine Torres. You come with me. I will show you one or two that he made from an old piano which he pulled to pieces for the wood. Exquisite! And [Pg 9] if you like them, together we will seek out Ramirez and he will make you one. He is very busy, oh, excessively busy, but he will make you one because he is an old friend of mine."

So the hot afternoon found us sweating up the slopes of Montmartre.

"First," said Perez, "I will take you to the house of a friend who possesses two of Ramirez' guitars. One is one of those made from the old piano. It is marvellous!"

But when we reached the street he could not remember the number. It was four years, he explained, since last he had been there.

"However," he went on, "not far away is another possessor of such a guitar; possibly he will be in."

Up the hill we went into streets which became more narrow and more steep, until at length he led us through a courtyard with pinkwashed walls, up five flights of polished stairs, to a studio door upon which a visiting card was pinned:

The door, under Perez's knuckles, sounded hollow and forlorn. We waited for a while, and Perez was beginning to finger his lip when a faint shuffle on the other side of the door changed into the noise of locks. The door swung ajar revealing a small man, with a thin face and tousled head, clad in pyjamas and a Jaeger dressing-gown which trailed behind him on the floor. Failing to penetrate to the real Perez, as we also had failed, he blinked inquiringly at us. A moment of confused explanation ended with a warm hand-shake. Perez explained our presence and our purpose; with protestations of apology for his négligé M. La Branche led us into his studio.

[Pg 10] |

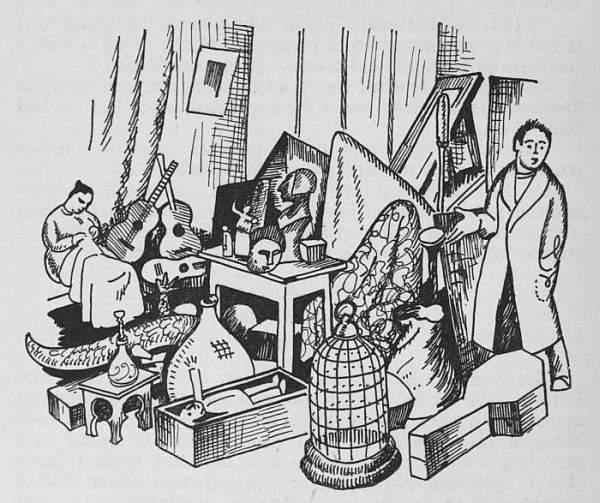

From the card upon his door we must presume that M. La Branche was both painter and etcher, and pictures hanging from the walls, and an etching press almost buried beneath a mound of tossed draperies, were evidences of the fact. But where he found space either to paint or to etch was a puzzle. The large studio was crammed with bric-à-brac. Indian tables, Chinese tables, wicker chairs, lacquer stools, screens, figures in armour, large vases, birdcages and innumerable articles strewed the floor, across which narrow lines of bare parquet showed like channels upon the chart of an estuary. Over the chairs were heaped draperies, on the [Pg 11] tables smaller bric-à-brac crowded together. Upon a sofa thrust to one side sat a woman methodically sewing at the hem of a long sheet. She took no notice of us, nor of M. La Branche, but continued her sewing, careful, however, not to swing her arm too wide for fear of banging into several guitars and other musical instruments, which almost disputed possession of the sofa with her.

Having cleared a table and sufficient chairs, M. La Branche gave us thé anglais, by the usual complex French method. Then from amongst his guitars he selected that made by Ramirez, and sitting down began to play. It is strange how a man's personality appears in everything he does. M. La Branche in his paintings was an expert painter rather than an artist; his etchings, large colour plates, showed a similar skill with the burin. His music was of the same nature. Everything that a practiced player should do, he did; his nimble fingers raced up and down the frets, his tempo and his modulations were impeccable, yet he did not make music. But we had not come with the intention of hearing music, but of hearing the qualities and power of the guitar, and this was, perhaps, more ably shown by the technicalities of M. La Branche than it might have been in the hands of a more artistic though less able musician.

The shop of Ramirez, the luthier, was down the hill, and to this, thoroughly satisfied about the excellence of his instruments, we went, Perez grumbling to us in undertones.

"That fellow La Branche—he does not play Spanish music. No—he comes from Toulouse. That explains it. It is the talent of the South of France, all on the top, all lively and excitable and showing off—that is how it is. Now I tell you, Monsieur and Madame Gordon, just because of that the Frenchman never will be able to understand our music. You English are nearer to us. You, when you have acquired ability, will play our music with much more insight and much more sensibility than that La Branche."

This comforted us exceedingly, for one day in wrath Modigliani, the Italian painter, had said that it was mere impertinence for an Englishman to think that he could understand the subtleties of the music of Spain.

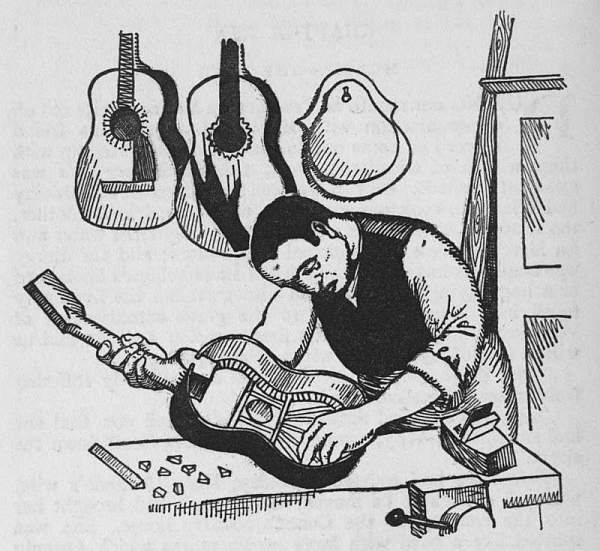

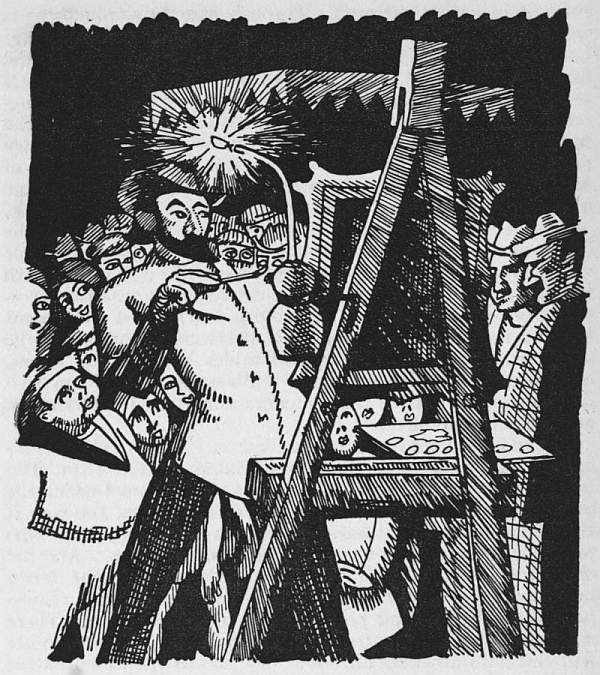

Ramirez almost makes his guitars out in the street. His workshop was about ten feet square with a door six feet wide. Here was a piece of pure Spain, though we could not recognize it (at the moment having no data), ten feet square, thrust bodily into the lower floor of a French house. The only light came in from the door, but the door was nearly as broad as the room. Almost blocking up the entrance, Ramirez, a burly, blue-jowled Spaniard, with something of the physical construction of a boxer, was working at delicate shavings of wood. Behind him the wall was hung with templates, cut from white wood, of the parts of the instruments he was making, guitars and lauds and bandurrias, strange instruments which Europe, outside of Spain, scarcely knows. On a shelf at the back of the small shop were heaped unfinished bandurrias bound with string, for the glue to become hardened in them. The workshop of Ramirez was not what we had expected. One is, I think, justified in expecting a neatness, a delicacy, about the place where fine musical instruments are made. Had Ramirez been a maker of chairs, or even of cartwheels, his workshop, though small, would have appeared appropriate; but that, from this rough place, could come out "the most difficult of musical instruments to make" disturbed one's sense of suitability.

The greeting which Ramirez gave us touched with doubt the picture which we had conceived of the amiability of the Spaniard. There was no cordiality in him. Some of his aloofness cleared away when he had penetrated through the disguise of a dandy to the real Perez beneath, but he continued his occupation, and to the statement that we wished him to make a guitar for Jan he shrugged his fat shoulders. He declared that he had already too much work.

"Those two instruments, for instance," he said, pointing to two unfinished guitars elaborately ornamented standing in a corner, "I have already been nine months over those, and have not had time to finish them. It is true they are exhibition instruments, for shops, and therefore have little if any interest for me."

Perez led him on with compliments, thawing away his frostiness gradually with Jan's admiration for the guitar of M. La Branche. Suddenly Ramirez put down his tools.

"Look here," he said, "I'll make the Señor a guitar. Three hundred francs is the price, and it will be finished in three months."

The bargain concluded, Ramirez picked up one of the unfinished instruments. He handed it to Jan, exhorting him to explore with a finger the exquisite workmanship of its interior. He rapped on the belly with his knuckle, and at the sound of its deep musical boom he smiled for the first time. Ramirez, having thawed, did not freeze up again. He began explaining the novel shape of his instrument, a shape which had been worked out for him by a mathematical philosopher. He said that the guitar was the most difficult of musical instruments to make, requiring a volume of tone which had to be produced from strings easy to pluck and finger. A problem very difficult to solve.

"And the guitar I made for you," he said, turning to Perez, "you gave it to S——?"

"Yes," said Perez.

"See here," said Ramirez, turning to us, "I make a guitar, an excellent one, one of my best. This fellow comes to see me, he hears the instrument. He says to me, 'Ramirez, keep that guitar for me, and I will at once go to work in a French munition factory, and I will work like a slave, and every week I will send you money until the guitar is paid for.' And I agree. And he goes and makes aeroplanes, and does honest work for the first time in his life, I believe, [Pg 14] and every week he sends money to me. And the week it is all paid up he stops work and goes off with the guitar. And he is crazy about the instrument. And he goes back to Spain and then he hears S—— playing. He is so enraptured by the wonderful playing of the man, that he runs home, fetches his guitar, and thrusts it into S—— 's hands, exclaiming: 'Here is an instrument worthy of you. It is too good for me, for I am a mere bungler beside you.' And so he gives away the guitar that he has laboured for. Ah yes, you villain, I have heard of you."

As we went down the hill, Perez tried to explain away this generosity so characteristic of his impulsive nature.

"It is not as though I would have played on the instrument again after having heard S—— touch it. Every time that I wished to play I would have thought, 'Ah yes, but if only he were playing it and not I.' And I had to give it to him, or perhaps I would never have been able to play again."

He asked us to come that evening to a certain small café in the Rue Campagne Premier; some other Spaniards were to come also and there was to be playing and singing. We were to come after the legal closing time, and we were to thump on the shutters.

In the night, in the dark, we rapped upon the rusty iron shutters, and one by one, like conspirators, were admitted into the dimly-lit café. It was a small place, characteristic of Paris, a combination of buvette with zinc bar, and cheap restaurant with marble-topped tables. Five years ago a good meal could be bought here for less than a franc. Behind the bar bottles and glass vats reached up to the ceiling; upon the dirty, green, oil-painted walls, cheap almanacs and trivial popular prints hung, together with excellent drawings and sketches, presented to Madame by her clients. One by one the invités slipped in. Madame and her two girl waitresses laughed and giggled at the kitchen door, while the patron, [Pg 15] grey-moustached, hollow-eyed and cadaverous, uncorked the bottles of wine behind the bar.

Here again for several hours the Spaniards re-created Spain. Perez is a player of temperament. Half of his skill and art he appears to suck from his audience. Thus at first he plays but indifferently well; but any music will rouse a crowd of Spaniards. To the growing excitement Perez responds, playing the better for it, thus creating more enthusiasm, and these interchanges continue, until he reaches the limit of his ability. But he is so sensitive to his audience that one indifferent person can take the edge off all his power. This night there was no one unresponsive. The playing of Perez became more and more brilliant. With his nails be rasped deep chords from his responsive instrument; to and fro he beat the strings in the remorseless rhythm of Jota Arragonesa. In the dimly lit café the dark figures and the sallow faces of the Spaniards were crowded about him in an irregular circle. "Olé! Olé!" they cried, and clapped their hands in time with the music. The air within the café throbbed and pulsated with the music. "Mais, c'est très bien," exclaimed Madame at intervals from her corner. "C'est très amusant, hein?" Two of the younger men were murmuring to the waitresses and were making them titter.

"Come," exclaimed Perez at last, "enough of this piece playing. Let us have a song. Vamos! who will sing?"

But something, possibly my presence, deterred the Spaniards from singing. They were shy as a group of schoolboys. One at last began to chant in a high quavering falsetto, but before the first half of his copla was ended he broke down into a laugh of hysterical shyness.

"Why then," cried Perez, "I'll have to sing myself, and Heaven knows I've got no voice."

The Spaniard believes that any singing is better than no singing. One of his chief pursuits in life is that of happiness—"allègre" he calls it. This allègre is produced not by [Pg 16] perfect results but by evidence of good intentions. He would rather have a bad player who plays from his heart than a good player who plays for his pocket. Any singing, then, so long as it is of the right nature, will suffice, no matter what its musical effect. Perez's singing had allègre, but no music. He lowed like a calf, rising up into strange throaty hoarseness like a barrow merchant who has been crying his goods all day, and descending into dim growls of deep notes. But even he at last tired; and after Madame had been yawning for some while, after the last bottle of wine had been drained of its last drops, we slipped out one by one into the moonlit streets of Paris and said our farewells on the Boulevard

I wonder what Charlemagne would have done if one had whisked him down from Paris to the Spanish Frontier in something under twenty hours? Probably the hero would have been paralysed with terror during the journey and would have revenged himself upon the magician by means of a little stake party.

But what would have been magic and miracle to Charlemagne remains in one's mind as a jumble—the interior of a second-class carriage; antimacassars; an adolescent who ate lusciously a basket of peaches, thereby reminding us that French peaches ripen early in June; intrusive knees and superfluous legs; an obese man who pinched my knee in his sleep, probably from habit; touches of indigestion which made one fidget, and in the dawn a little excitement roused by observing the turpentine tapping operations at work on the pine-trees by the side of the railroad—cemented together by the thick atmosphere of a summer's night enclosed between shut windows.

It is a strange fact that the more perfect do we make travelling, the more tedious does it become—I wonder whether the same may not apply to almost all progress in civilization.

The most primitive aspect of travel is that of walking, and even upon the most tedious of walks the exercise itself seldom degenerates into definite boredom, one is never far away from one's fellow men, yet even if one is quite alone the mere fact of walking is an occupation which cannot be despised; of riding similar things may be said. Coaching [Pg 18] may have had its inconveniences, yet a coach drive cannot have been lacking in definite interest. One was in very close contact with one's fellow passengers, coaching made as strange bedfellows as any adversity, and the journey was seldom so short that one could enjoy a sort of snuffy insulation from one's fellows—mutual discomforts, even mutual terrors of footpads made a definite bond of humanity.

It is true that in all these primitive processes the act of getting from here to there is prolonged—perhaps extremely prolonged—but mere duration is not tedium. If the act itself is interesting and vivid then the act itself is worth while. To-day the act of travelling by a fast train is scarcely worth while—the traveller can almost count it out as so much time lost out of life. I fear that when the aeroplane is perfected journeys will be performed in a tedium absolutely unrelieved, and those patients who have to undertake journeys would be advised to take a mild anæsthetic at the beginning.

What is missing to-day from the act of travelling—and what lacks from much modern civilization—is the expectation of the unexpected; the sense of adventure, the true sauce of life.

Now to have the true sense of adventure it is not necessary that one should always be expecting to meet a lion round the corner. Any little thing will do, anything not before experienced, anything that will give the imagination that extra fillip of interest which will convince it that the world will always remain a Fortunatus purse of new things to learn, anything that will make positive the fact that the act of living is also the act of growing,—anything of this nature will contribute to the sense of adventure.

But the trend of civilization to-day is that all these little interests are being quietly but very effectively crushed: we fling them beneath the wheels of railway trains and into the cogs of factories, with the result that only those experiences which are too large for us to fling thus are allowed to flourish. [Pg 19] We have, in fact, almost cleared away the little things and left only the big. Now, if we turn the corner, either there is nothing at all or, in one case out of a hundred, we find the lion. In our railway travelling to-day, either nothing happens or there is a railway accident; but we have turned so many corners in our lives which led to the mere blankness of more empty road, that the possibility of the lion has almost faded from our minds—and so the sense of adventure in little, the true sense of adventure, is in danger of atrophy.

Some day, I feel sure that this sense of adventure will take a revenge on the civilization which would destroy it. We kill off birds and caterpillars flourish. Some worm lies near the heart of things ready to gnaw at the right moment. I fear that never will they apply "preservation laws" to the sense of adventure, or we, as adventurers, properly appreciated, should be in receipt of a scholarship or of a civil list pension.

We were too dazed by the drug of twenty hours of tedium and sleeplessness to suck any adventure from the passage through the French Customs House at Hendaye. But this experience roused us so that we were quite mentally awake by the time that we reached Irun. Here a problem confronted us.

We had in our large leather trunk a good many yards of government canvas, several pounds' worth of paints, and ten pounds in weight of preparation for turning the government canvas into material for painting upon. We had heard that the Spanish customs were very strict; very strict in theory, that is.

"But if they worry you, bribe them a bit," had said a friend. Were these things contraband? If so, how much was one to bribe, and how was one to do it? There are plenty of men with nerve enough to try to tip Charon for his trip over the Styx, but Jan is not one of these.

Now for a man of Jan's kind to attempt a delicate piece of palmed bribing often results in things worse than if he [Pg 20] had left well alone. Ten to one there is a fumble and the coin drops to the floor beneath the nose of the chief bug-a-bug. So, fingering two unpleasantly warm five-peseta pieces in his pocket, he prayed fervently to kind Opportunity to step in.

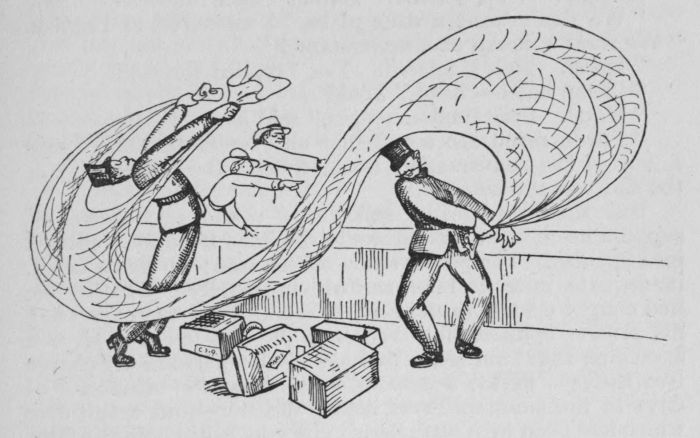

To his prayer the goddess answered. We had brought with us from our Paris studio a mosquito curtain which once before had been used in Majorca. As our baggage was packed in London we had, rather than undo straps and locks, tied this mosquito curtain, wrapped in clean brown paper, on to the outside of our suit-case. Upon this the authorities flung themselves.

"Hi!" they cried. "You will pay duty on this, it is new."

Two gendarmes and a clerk tore off the paper, pitched the mosquito curtain into a pair of scales, weighed it and wrote out the bill. All the while we had been clamouring, with a sudden memory from Hugo: "Antigua, antigua, antigua...."

This clamour became suddenly effective as soon as the officials had nothing to do than to collect the money. Instead of cash we gave them a chorus of "Antigua, antigua." The clerk and the two gendarmes then began what seemed to be an impromptu imitation of Miss Loie Fuller in her celebrated skirt dancing—mosquito curtain whirled this way and that in voluptuous curves. They were looking for evidence. Suddenly I pointed out a spot where perchance some full-blooded mosquito had come to a sudden death in 1913, when the world was yet at peace. The mosquito curtain was refolded, the bill torn up. They were quite peremptory with the rest of our luggage; so Jan dropped the two warm five-peseta pieces back into his pocket.

However much one may be in a country, one never feels that one is in the country until the door leading out of the customs house has been passed. So we never really thought of ourselves as being in Spain until we stepped on to the platform where the train for Madrid was standing. With a bitter shock, we realized that it was a chill day and raining. We [Pg 21] had come all the way from England, hunting the sun, to be greeted in June by a day which would fit, both in temperature and atmosphere, the tail-end of a March at home.

|

Of those minor adventures which make life so valuable, some of the finest flowers amongst them which may be picked are the delicate first impressions of a new country. These impressions have a flavour all their own; they are usually compressed within the space of one hour or so, and once experienced they never return. New impressions indeed one may gather by the score, but those first, fine savourings of the new can never be retasted.

We had expected so much from Spain. We had hoped at the first moment to open out our arms to her sun, to satiate our colour sense with the blueness of her skies—we were received instead with this grey, gloomy weather. How can one describe the revulsion? It would be an exaggeration to [Pg 22] say that it was as though we had touched a corpse where we had expected to find a living man, but the revulsion was of this nature though perhaps less poignant.

I left Jan to finish with the larger luggage and, securing the aid of a porter, set out to look for an hotel. At the exit of the station I was accosted by a sallow man with a large, peaked jockey cap pulled down over a thin face.

He said: "Hey, Señora! Hotel? Spik Engleesh. Yes."

"We don't want a dear place," I answered in English. "We want a cheap one, understand?"

"Hotel. Spik Engleesh. Yes," replied the tout.

"Cheap hotel—cheap," I said.

"Hotel. Spik Engleesh—yes," said he.

"Puede usted recomendarme una fonda barata?" said I, out of the conversation book, though the "barata"[1] at the end was my own.

But the tout turned sulky and would not answer—I suppose he thought his fee would diminish if he were enticed into Spanish. The porter stood on one side; he was a small, inadequate man and he sniffed continually. Whether he had caught cold from the rain, or whether he was expressing his private opinion of travellers, I did not learn. Jan was arranging about our trunk and a hold-all; I had in my charge two thermos flasks, a camera, two rucksacks—memories of days in the German Tyrol before the war—and a suit-case which had been with us in Serbia and which still bore the faint traces of a painted red cross, but the cat had for the last two years been sharpening her claws upon it and the leather now looked something like "Teddy Bear" material. These I distributed between the porter and the tout, and, trusting to Providence and my own powers of observation, we entered Irun.

Where was the queer magic which lies in the first impressions of a new land, the dreamlike quality, the unreality which [Pg 23] almost puts one's feet for a moment into Fairyland? Spain had played a nasty trick upon us; the grey sky and the low-lying cloud and the drizzling rain had nothing of Fairyland for us. With head held low against the drizzle one was conscious of nothing but a wall on the right hand and of dirty pavement beneath the feet.

The tout led me into the first house we reached. There, was a narrow passage which passed by a room of a dingy whiteness; but the tout showed me on, up some stumbly stairs and through a spring door. We came into a dark room in which, by means of the light filtering through the slats of the closed shutters, could be seen the dim outlines of a bed and of a tin wash-hand-stand.

"Ocho pesetas," said the tout.

"Por todo," I answered.

"Todo—todo—comida y toda," protested the tout. I had been waiting for this moment. In the conversation book which I had been studying was a phrase which had caught my fancy; it meant "no extras," but it was much more beautiful. The time had come.

"No hay extraordinario?" said I sternly.

"No, Señora, no," said the tout, spreading out his hands.

The matter having been thus settled, he took me downstairs again; and, in the dingy white diningroom, introduced me to a plump woman, the proprietress. I was ravenously hungry; the tables were laid. I asked:

"What time is lunch?"

"At two, Señora."

I was dismayed. It was now eleven o'clock—we had eaten little since the night before.

"But," I stammered, "I am hungry. Tengo hambre." My memory shuffled with conversation-book sentences and faint recollections of Majorca, but could find nothing about the minutiæ of food.

"Tengo hambre," I repeated desperately. Suddenly [Pg 24] inspiration came to me. I made motions of beating up an omelet and clucked like a hen that has laid an egg.

For a moment there was a silence, a positive kind of silence, which is much more still than mere absence of noise. Then a roar of laughter went up. The fat hostess shook like a jelly, the tout guffawed behind a restraining hand—he had not yet received his tip—while an old woman who had been sitting in one of the darker corners, went off:

"Ck! Ck! Ck! He! He! He! Ck! Ck! Ck! He! He! He!"

At this moment Jan arrived, having deposited the bigger luggage and having been informed that the train to Avila, our first stopping-place, went out at 8 a.m. I led him along the dark passage and upstairs. He flung wide the shutters. The window looked into a deep, triangular well at the bottom of which was a floor of stamped earth, a washtub and a hen-coop. Windows of all sizes pierced the walls at irregular intervals and across the well were stretched ropes, from some of which flapped pieces of damp linen or underclothes. In the light of the open window the room was dingy. We wondered if there were bugs in it, for we had been cautioned against these insects.

But the room did not smell buggy; it had a peculiar smell of its own. The strong characteristics of odours need more attention than novelists give them. For instance, I remember that German mistresses had a faint vinegary scent, but French governesses an odour like trunks which had been suddenly opened.

This room had an austere smell. It smelt, I don't know how, Roman Catholic: not of incense nor of censers, but of a flavour which, by some combination of circumstances, we have associated with Roman Catholicism in bulk. The bedroom door was largely panelled with tinted glass; it had a very flimsy lock, but we did not fear that we would be murdered or burgled in our bed.

The omelet was ready when we came down. The diningroom [Pg 25] had two doors, one leading to the kitchen, one up some steps and into the street. There was a broad stretch of window and almost all the other walls of the room were covered with big mirrors.

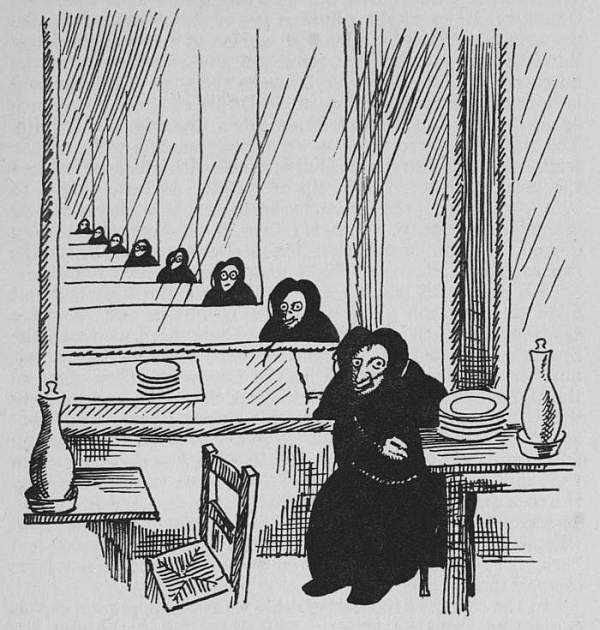

|

About five grim people, mostly clad in black—including the old lady—sat in the room and stared at us as we ate. We could not avoid this disconcerting gaze—look where we would we either caught a human eye or else, what was worse, we were fascinated by a long procession of eyes passing away into the dim mysteries of reflection and re-reflection of the mirrors. We had to choose between the gaze of one real old lady or of twenty-five reflected old ladies, of one callow youth or of twenty-five youths diminishing towards the infinite. The audience stared at us as we ate our omelet, watched the fruit—apricots, cherries and hard pears—with which we finished the meal, and noted each sip of coffee. At last, unable to bear any longer the embarrassment of this mechanically intensified curiosity, we took refuge in our bedroom and lay down. We then noted that the bed was too small, all the rest of the furniture, on the contrary, being much too big.

We rested till lunch. The omelet and the fruit had but filled some of the minor vacancies within us and we were ready again on the stroke of two. Once more we faced the Spanish stare and all the reflected repetitions of it. A fair number of persons lunched at the hotel. As they came in the women sat themselves directly at the table, but the men without exception went to the far corner where, suspended against the wall, was a small tin reservoir with a minute tap and beneath it a tiny basin. Each man rinsed his hands in the infinitesimal trickle, before he sat down to dinner. Why the men and women made this distinction we could not guess. It seemed to be a custom and not to be dependent upon whether the hands were dirty or not. Even if the hands had been dirty the small amount of water used would not have cleaned them.

In the centre of the dining table were white, porous vessels containing drinking water. The water oozes through the porous clay and appears on the outside of the vessel as a faint sweat. This layer of moisture evaporates and keeps all the [Pg 27] water in the vessel at several degrees cooler than the surrounding atmosphere.

Between mouthfuls of soup and wedges of beef the diners were watching us. As soon as the meal was over we fled into the streets of Irun. One cannot call Irun Spanish. It is abominably French, though France is pleasant in its own place. The café in the little plaza is French, with a French terrasse, French side screens of ugly ironwork and glass, and faces a square full of shady trees between which one sees modern fortifications of French appearance. So we sat sipping coffee and we said to ourselves: "Forget that you are in Spain. Put off your excitement. Don't waste your sensations with false sentiment"

Nor did the fact that all the wording on the shops was Spanish, nor even the sight of a building of pure modern Spanish architecture rouse us from our cloudy resignation. The building which towered into some six stories by the side of the railway was of a maroon brick. The lower story, including the entrance door, was decorated with appliqué in the design which the French used to call "l'art nouveau," and which now is confined almost exclusively to the iron work on boulevard cafés. It is marked by exaggerated curves. The whole bottom story of this building was sculptured in this fantastic fashion; in order to fit in with the decorations the front door was wider at the top than it was at the bottom, while the windows were of every variety of shape, squashed curves, dilated hearts, indented circles and so on. Above this story the building rose gravely brick save for the corners, which were decorated with bathroom tiles of bad glaze upon which flowers had been painted; roses, violets and pansies: the top story, however, was part Gothic, part Egyptian, with a unifying intermixture of more bathroom tiles.

A munition millionaire went to an art dealer saying he wanted a picture, but he didn't mind what sort of a picture it was provided it looked expensive. We imagined that the [Pg 28] architect of this house had received a similar order. Later on we were undeceived.

A yellow tram went by bearing the name "Fuentarabia." Having heard eulogies of this place, we decided to go. We reached the terminus of the tramway and the conductor told us we were there. Since then we have met so many people who were in ecstasies about the beauties of Fuentarabia, about its pure Spanish character, etc., etc., that we are still wondering if we went to Fuentarabia after all

[1] Cheap.

If civilization were without a flaw, the happy civilized traveller could pass through and circumambulate a foreign country yet never come into closer contact with the inhabitants than that transmitted through a Cook's interpreter. So that if you want to learn anything about a country, either you must put a sprag into the wheels of this civilization or you must let Opportunity do it for you. Opportunity is a very complaisant goddess: give her an inch and the ell at least is offered to you. She smiled upon us when we decided to stay the night at Irun; once more she smiled when the porter told us that the train to Avila left about eight o'clock, so we humped the two rucksacks and the suit-case from the inn to the station, got our trunk and hold-all from the baggage office and went to buy our tickets. Then we realized what Opportunity had been up to. The ticket clerk refused to give us tickets to Avila.

"Why not?

"The train does not go through Avila, it goes to Madrid by the other branch through Segovia. The train by Avila goes at four."

"Where, then, does it branch off?"

"At Medina del Campo."

"Then give us tickets to Avila and we will wait at Medina del Campo."

But the authorities did not approve of this novel idea. It seemed that the through-ticket system had not become the custom in Spain. We must then take tickets [Pg 30] to Medina or wait in Irun till the proper, respectable Avila train should go, so to the astonishment of the booking clerk we said:

"All right, give us tickets for Medina."

|

I do not believe that any pleasure traveller had stopped at Medina before we did. That is the impression we received, both from the behaviour of the porters at Irun and of those at Medina itself.

The scenery from the railway was, as scenery always is, fascinating because of one's elevation and the scope of one's view, tiring because of its continuous movement. We passed through mountains worthy of Scotland, very Scotch in colour, and at last came out upon the big plain of Valladolid.

While we were streaming across this and the mountains were fading slowly into a distant blue the luncheon-car waiter announced his joyful news. We had heard that living in Spain was going to be dear, so, with some trepidation, we decided to take that train luncheon—for our financial position did not encourage extravagance. The whole trip was, in theory, to come within the limits of Jan's war gratuity—about £120. We had calculated the railway travelling as £50 in all; this gave us £70 for all other expenses, including the purchase of the musical instruments upon which we had set our minds, and we hoped to stay for four or five months. Yet in spite of the need for economy luncheon called us if only as an experience.

The meal cost us about three and fourpence apiece: it was a complicated affair of many courses—even in a Soho restaurant the same would have come to about ten shillings, so that the spirit of economy in us was cheered and inspirited. Of our fellow passengers we remember nobody save a gigantic priest who waddled slowly along the corridors, carrying, suspended on a plump finger, a very small cage in which, like a mediæval captive in a "little ease," was a canary almost as large as its prison.

Medina station looked like an exaggerated cart-shed on a farm; two long walls and a roof of corrugated iron—there were no platforms, only one broad pavement along one of the walls. A small bookstall was against the wall and further along the pavement a booth of jewellery. This booth had glass windows and "Precio Fijo"[2]—"No bargaining," in other words—was painted across the glass in white letters.

Why Spaniards, en route, should have mad desires to purchase jewellery, we have not learned, but these jewellery booths are common on Spanish stations. The jewellers seem to detest bargaining, for these words always appear on the windows. I suppose the fact that the purchaser of jewellery

has got to catch a train may give him some occult advantage over the seller. One may imagine him slamming his last offer down on the counter and sprinting off with the coveted trinket to the train, while the defrauded merchant is struggling with the door-handle of his booth—so "No Bargaining" is painted up, very white and very positive.

As we had nine hours to wait, there was no need to hurry, so we allowed the crowd to drift out of the platform before we began to see about the disposal of our luggage. Stumbling about in Hugo Spanish we discovered that, owing to the receipt that had been given us at Irun, our big trunk would look after itself until claimed, but that there was no luggage office or other facility for getting rid of our smaller baggage. We, however, insinuated understanding into the head of a porter, who thereupon led us to a door amongst other doors in the wall labelled "Fonda." We came into a huge hall. Across one end stretched a majestic bar four feet high, of elaborately carved wood, upon the top of which were vases of fruits, tiers of bottles and glittering machines for the manufacture of drink. Three long tables were in the room, two spread simply with coffee-cups. The third table occupied the full length of the middle of the room. It seemed spread for some Lord Mayor's banquet. Snowy napery was covered along the centre with huge cut-glass dishes, stacked with fruit, alternated with palms flanked by champagne bottles and white and red wine bottles. Fully fifty places were laid, each place having seven or eight plates stacked upon it while the cutlery sparkled on either hand. A cadaverous, unshaven waiter lounged about amongst this magnificence and lazily flicked at the flies with his napkin.

This huge, deserted room, expectant of so many guests, made one think of the introduction to a fairy story: one could have sat the mad hatter, the dormouse and the March hare down there, but one could never imagine that fifty passengers could in sober earnestness crowd to have supper at Medina [Pg 33] del Campo upon the same day. No, rather here was one flutter of the dying pomp and majesty of Spain.

We placed our bags in a corner of the pretentious room and went from the station to look for the town. It was nowhere to be seen. A white road deep in dust gleamed beneath the afternoon sun and led away across the ochreous plain, but, of town, not a sign. Yet the white road was the only road; Medina must be somewhere, so off we walked. The plain was not quite flat, it flowed away in undulations which appeared shallow, but which proved sufficiently deep to swallow up all signs of Medina del Campo at the distance of a mile.

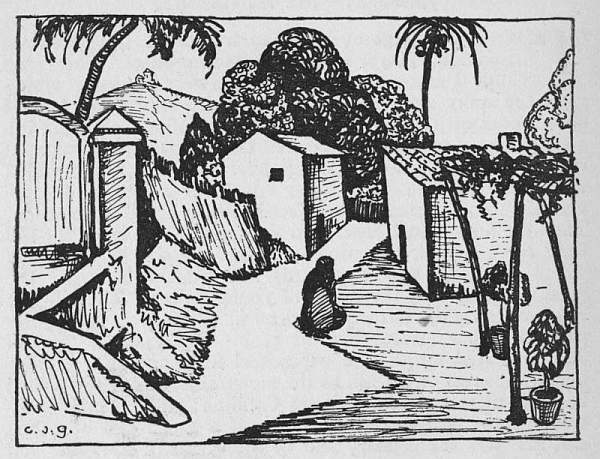

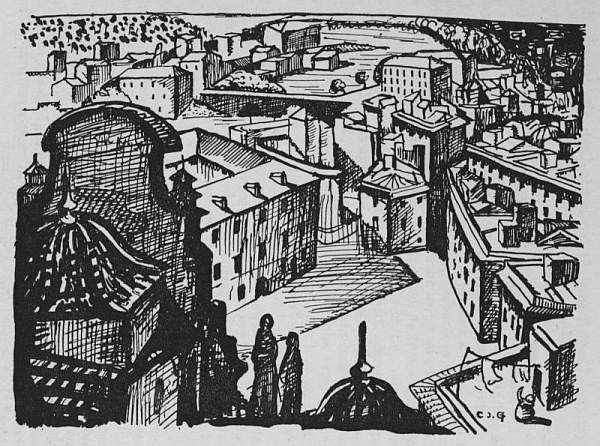

First we came to a line of little brightly coloured hovels, square boxes, many of only one room, then to a church, an ancient Spanish-Gothic church surrounded by gloomy trees. Suddenly the road turned a corner and we were almost in the middle of the town. Medina was Spanish enough. Here was the plaza at the end of which towered a high cathedral decorated with colour and with carving. The plaza lay broad and shining beneath the sunlight; loungers sprawled in the shadows beneath the small, vivid green trees, and in the deep stone arcades which edged the open square the afternoon coffee-drinkers, clad in cool white, lolled at the café tables.

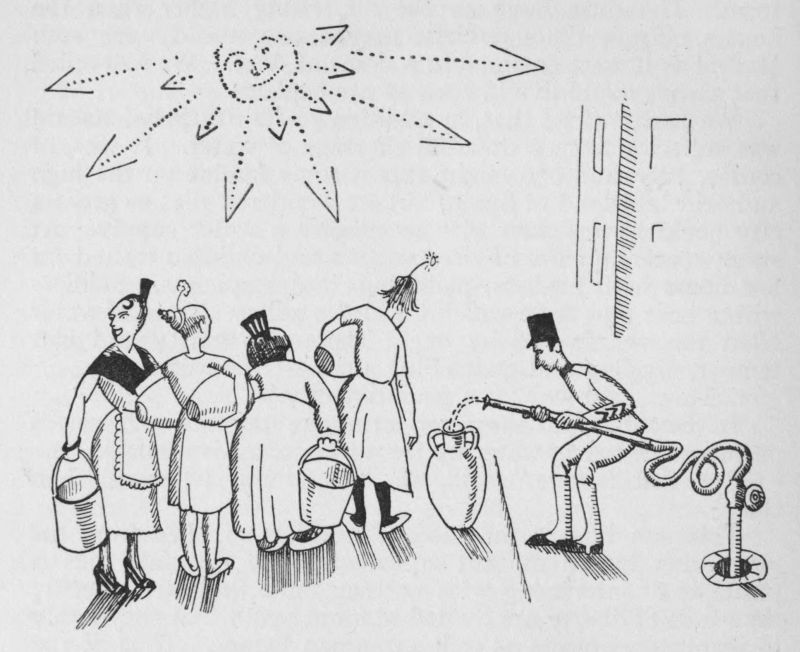

In the centre of the plaza was a fountain running with water, and about it came and went a continual procession of women bearing large, white amphoras upon their hips, children carrying smaller drinking vessels, and men wheeling long, barrow-like frameworks into which many amphoras were placed. The shops and cafés were painted in gay colours which were brilliant in the sun and which contrasted pleasantly with the crude—as though painted—green of the trees and the clear, soothing hue of the sky.

I know that historical things have happened at Medina del Campo, but we are not going to retail second-hand history. To us, as living beings, it is far more important that we bought our first oily, almondy Spanish cakes here than that Santa [Pg 34] Teresa (who started off at the age of ten years to be martyred by the Moors) founded a convent in the town.

Medina is a dead place and must be typical of Spain. It has a market, a plaza and a few ragged fringes of streets more than half full of collapsing houses, and in this gay-looking remnant of past glory are at least three enormous churches with monasteries in attendance. But even the churches are falling into ruin and the storks' nests are clustered flat on the belfries, while Hymen's debt collectors, clapping their beaks, gaze down from aloft into the empty roadways.

Sunset had played out a colour symphony in orange major by the time we had arrived back at the station where we asked for a meal; but the cadaverous, blue-jowled waiter had not laid covers for fifty in order that intrusive strangers might push in and demand food at whatever hour they chose.

"Supper," he said with some dignity and disgust at our ignorance, "is at eight."

So out we went on to the pavement platform, found a lattice seat and ate the cakes we had bought. They were like treacly macaroons, so oily that the paper in which they had been wrapped was soaked through, but it was with pure almond oil and the cakes were delicious. Lunch had been eaten at twelve and in trains one never eats quite at one's ease; hunger had gripped us when eight o'clock struck by the station clock. We took our seats at the long table before those piles of plates. A quarter-past eight went by, half-past eight was approaching. One by one about six or seven persons sauntered into the room and seated themselves, distant from each other in comparison with the size of the table as are the planets in the solar system. Nearest to us, our Mars, as it were, was a very fat commercial man, his face showing the hue of the ruddy planet. Our Venus was represented by a pale young priest, his long wrists projecting far from the sleeves of his cassock. Mercury looked appropriately enough like one who was always travelling; Saturn was [Pg 35] covered with rings—he must have been one of the customers of the "precio fijo" booths—the other planets were lost amongst cumulus of fruit and cirrus of palm.

The waiter became active. Balancing a large soup tureen, he ladled a thin, greenish soup into the upper plate. We then understood that we would have to eat our way down through the pile of plates, each plate a course. Mars rushed at his soup in such a wild manner that we felt it was a good thing indeed that the soup-plate was thus raised so near to his mouth or fully the half of the soup would have drenched his waistcoat.

Alice again was recalled to my mind. I remembered her dismay during her regal banquet when the dishes once introduced to her were whisked away from under her nose, for every time I laid down my knife and fork to speak to Jan my plate was seized and carried off by the cadaverous waiter. No sooner was I introduced to a new Spanish dish than it was wrested from me. Twice this had occurred. On the third occasion I lay in wait: as the waiter swooped for my plate I seized it. There was a momentary struggle, but I had two hands to his one; he retired with a look of astonishment on his face. Gradually I became aware of the fact that Mars never loosed his knife and fork until he had cleared his plate. He held both firmly in his two red hands. If he drank—which he did with gusto, throwing his head back, washing the wine, which had a queer tarry taste, about the inside of his mouth, almost cleaning his teeth with it—he held his fork sceptre-wise as if to say to the waiter, "Touch that last corner of beefsteak at your peril." When he had quite finished the course, when he had mopped up all the remnants with a piece of bread, then and then only did he lay down both knife and fork. Unconsciously I had been giving a signal to the waiter.

After the beefsteak we had a surprise. One has been so long accustomed to the French custom in gastronomy, that [Pg 36] one almost forgets that courses are not arranged in an immutable order. Once indeed I did make a bet in Paris that I would eat a meal in the inverse direction, beginning with the coffee and sweets and ending with the soup—which, by the way, proved very hard to swallow—but the mere fact that one could bet about it proves how fixed one imagines the laws of food progression to be. At Medina del Campo, after the beefsteak, which was about the third item on the menu, the waiter brought us fried fish, thereby proving that gastronomic progression is not so unalterable as is usually imagined. The fish looked like very small plaice, but they had a strange flavour which we had never before tasted. That the fish had been packed for several days in rotting hay seemed the nearest description and explanation, and we would have clung to this idea if the salad had not also had a perceptible tang of this unpleasant taste. We asked the waiter what the flavour was, but our Spanish broke down under the strain, and the waiter said "Claro"[3] and went away.

For some weeks afterwards the word "Claro" became our bugbear. The Spaniard gets little amusement from hearing his language spoken by foreigners. If the unfortunate foreigner does not get pronunciation, accent and intonation perfect the Spaniard says "Claro," in reality meaning "I can't make head or tail of what you are talking about." Both laziness and courtesy make the Spaniard say "Claro," and often the poor foreigner is quite delighted with his progress in the language—the people tell him that everything he says is perfectly clear, hooray; he thinks that he must have an unsuspected gift for languages—until one day he asks the way to somewhere and receives the usual answer, "Claro."

The Redonda Mesa,[4] which would I think be the Spanish for a "square meal," cost us again four pesetas, and it was an even better three and eightpenn'orth than we had been given on the train. The meal finished, the planets held a [Pg 37] public tooth-picking competition for a while, then one by one they resumed their normal orbits and passed from our sight.

We, with the processes of digestion heavy upon us, went back to the seat in the ill-lit station. Three more hours we had to wait for the train to Avila, so we sat in the mild night watching the only engine at Medina—an engine which looked like an immediate descendant of Stevenson's Rocket—push trucks very slowly to and fro. This engine, though it made a lot of spasmodic noise, did not destroy, it only interrupted, the intense silence which lay over the country-side. The platform was quite deserted. Presently two small boys came along. One had a red tin of tobacco which he offered to Jan; Jan shook his head but did not answer. They then tried to talk to us, but we knew better than to expose our imperfect Castilian to two small boys—so we kept silence. At last they said we were "misteriosos" and went away.

A luggage train steamed in. At the tail end of the train were three third-class carriages, and from these carriages, as well as from the waggons, poured out a mob of wild-looking men. They were dark brown, unshaven, covered with broad tattered straw hats, clothed in rough and ragged fustian and carried blankets of many coloured stripes. Huge bundles, sacks and strange implements were slung upon their backs. As they crowded in beneath the dim lamp at the station exit one could almost have sworn that all the figures from Millet's pictures had come to life. A smell of the soil and of labour and of sweat went up from them. These men were peasants from Galicia; they had come in third-class carriages, in goods waggons, travelling probably for two or three days, attached to luggage trains, across the country to the harvesting. One by one they passed out, their voices trailed away into the night towards Medina, and once more the silence came back.

Time wears itself out in the end. The train to Avila, [Pg 38] when it came, was fairly empty, so we could lay ourselves out at full length and rest, disturbed, however, by the continual fear that we might overshoot our destination.

It was pitchy night when we clambered down from the train at Avila. The large barn of a station was lit by but three minute lamps and the glow from the fonda door. In the semi-darkness the passengers moved about like ghosts, each intent on his own business. It was two o'clock in the morning, so before exploring we again put our baggage in a corner of the fonda; where also we found the one waiter presiding over a banquet laid for fifty non-existent guests. Speaking as little of the language as we did, it seemed impossible to go exploring a foreign town in the dead of night for a hotel which would probably be shut when we found it. So, feeling somewhat like Leon Berthelini and his wife in Stevenson's story, we sat down on a seat in the station to await the dawn.

The temperature of the night was almost perfect; there was a hint of chill in our faces which, however, did not penetrate through the clothing. For awhile porters moved about arranging luggage, then one by one the three lights were extinguished and the station was left to darkness. One porter clambered into a carriage which was standing on a siding; as he did not come out again nor pass down on the other side we imagine he went to bed in it. We were tempted to follow his example, but feared the train might move off unexpectedly and carry us to some remote part of Spain before we could wake up. One can tempt opportunity too far.

But the seat was hard. If, like Berthelini, we had had a guitar we might have performed miracles with it similar to his, but we had left our guitars in England. So Jan went exploring. Outside the station he found a small omnibus, its horses eating hay out of nose-bags. Hearing faint voices he discovered a sort of dimly lit underground bar annexed to the fonda, in which the driver of the omnibus and a friend [Pg 39] were drinking spirits, while the tired waiter lounged yawning behind the counter. Our ignorance of Spanish prevented us from thrusting ourselves into their company: but we waited for the driver to attend to his horses and in halting Hugo we asked him at what hour the omnibus went to the hotel. He replied "In the morning" and went back to his drinking.

The eau-de-nil of dawn found us on the edge of shivering, but the day warmed rapidly. A train thundered into the station pouring out its cascade of passengers. Gathering up our packages and tipping the waiter fifty centimes, we found a new omnibus which was labelled "Hotel Jardin" and took our seats inside. Dawn was over by the time we reached the hotel, though it was but four o'clock. We had a confused impression of great buff battlements overhanging the buildings, of a few stunted bushes, of one or two girls in black, of a huge room which was to be our bedroom and then—bed—sleep

Borrow has a description of an inn in Galicia in which a whole family occupies but one bedroom while the servant sleeps across the door. Our bedroom in the Hôtel del Jardin was quite large enough for any family other than, perhaps, a French Canadian, which sometimes runs, we have heard, into twenties and thirties. The walls were painted a pinky-mauve stucco, decorated with a broad olive-green ribbon of colour making a complete oblong or frame on each wall about eighteen inches within the edges of the wall, top, bottom and sides.

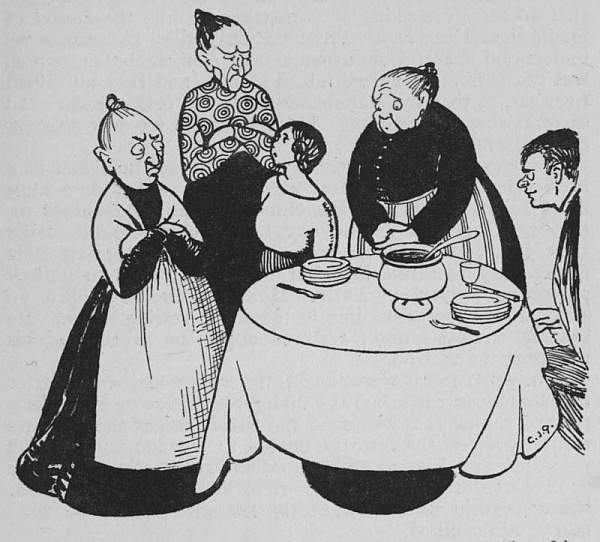

This method of making, as it were, a separate frame of each wall, was novel and rather pleasant. It is a common practice in Spanish wall decoration and is probably Moorish in origin. The hotel was full of dark corridors leading to huge bedrooms: it had a broad veranda upstairs full of large wicker chairs, bottoms up, while downstairs was a dining room with square tables and a small entrance hall in which sat the three old ladies.

With one of the old ladies we had bargained in a sleepy way upon our arrival. She had conceded us the room with full pension (no extraordinarios) for eight pesetas a day, but in general the three old ladies sat in the entrada together, giving a sense of black-frocked repose and of quiet dignity to the place. One was thin-faced, dried-up but energetically capable; one was large and motherly, while the third had no characteristics whatever and was ignored by every one.

[Pg 41] |

I do not think we realized that these three old ladies were the proprietresses until the second or third day at lunch-time. We had been given our seats at a table by the waiter; suddenly we found the three old ladies had surrounded us and were glowering down at us. We were rising to our feet but they peremptorily commanded us to stay where we were, breaking the rising tide of their wrath upon the waiter. Then, for the first time, we realized how completely we were married in Spain. In France, for instance, married people are "les époux," plural, separate; in England they are a "married [Pg 42] couple," which still recognizes a duality though perhaps less definitely than does France; but in Spain we were "un matrimonio," indissolubly wedded into one in the language, and into a masculine one at that. Somehow I always felt that we ought to be wheeled in on casters: it was improper that so stately a thing as a matrimonio like the Queen of Spain should use legs. From the old ladies' annoyance we understood that the matrimonio had done something which was not correct, but they talked so fast, and they all talked together, so that the matrimonio could not make head or tail of what they were saying. Nor indeed did we ever discover our misdemeanour.

For our six and eightpence a day we had breakfast in a little side room. This meal was of café au lait in a huge bowl, rolls and butter. Sometimes we had companions for this meal. On the second day I was some minutes earlier than Jan. At the table was a young peasant priest. He ignored my tentative bow but began muttering to himself protective prayers in Latin. However, once I looked up suddenly and surprised him in the act of staring at me. He quickly crossed himself and redoubled the urgency of his protestations to God.

The other meals were excellently cooked and with four or five courses to each, but the diningroom bore on its walls a placard saying that owing to the rise of prices the management regretted that it was unable to provide wine at the pension. So there was an extraordinario after all—and a very good extraordinario it was too—red Rioja wine with the faint, strange exotic taste in it of the tar with which the wine barrels are caulked.

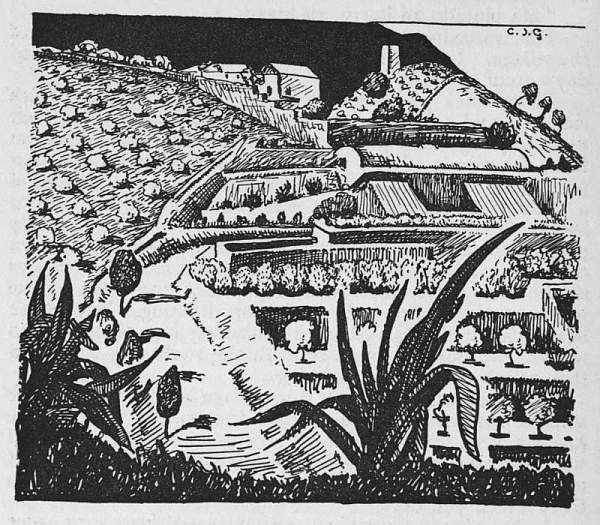

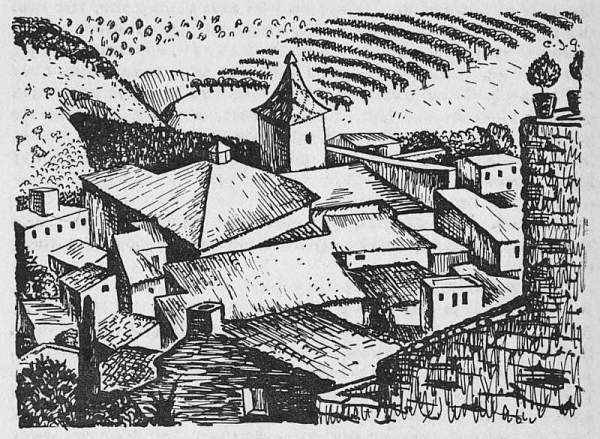

You know the queer old drawings one finds in ancient books: towns like bandboxes with the walls round a perfect circle, and peaked houses all comfortably packed inside, and soldiers' heads sticking out of the battlemented towers? Well, Avila is like that. You may stand on the opposite hillside [Pg 43] and see the full circle of her walls with never a breach in it, with towers at every two hundred yards or so, and you can gaze down into her houses, fitted neatly within the bandbox, and wonder if the old manuscripts were quite as exaggerated as one often supposed. From this hillside one might imagine that Avila has never changed from the days when the monks drew their primitive pictures. The walls top the hill-side and one sees nothing of the modern Avila which has spread beyond those great frowning gateways facing the plaza, but even the modern part of Avila which has oozed out beyond the walls is not overwhelmingly modern. There are none of the exquisite specimens of Spanish bad taste like that we found in Irun. The plaza is surrounded by coloured houses and arcades much as is that of Medina; the sun-blinds of the two large cafés are tattered and weather-beaten; the peasants stare at strangers with an unspoilt curiosity.

The habit of rushing about towns, of penetrating into every gloomy interior, ecclesiastical or otherwise, which seems to be decently penetrable, is a modern convention to which we do not subscribe. There are two aspects to every place, the living and the dead, and we prefer the former. There is this advantage in our attitude, that one does not have to seek out the living, it flows quite easily and naturally by, and one does not remain an open-mouthed spectator with a jackdaw brain, but incorporates oneself with it. We did not go into the cathedral, nor into any convent, nor did we climb up the towers or into the walls: we sat at the café drinking in both coffee and Spain.

Of costume, as Spain is so often painted, there was little; the peasant men wore tall, flat-brimmed hats and broad, blue sashes about their stomachs; the women shawls and woven leggings; the mules and donkeys had trappings of bright-coloured woolwork and often saddlebags with fine woven coloured patterns on them. String-soled sandals were the footwear of the men and of the soldiers: string-soled shoes, [Pg 44] alpagatas, were worn by the women and children. The town was moderately alive until eleven o'clock. Very early in the morning the peasants came into the market with their mules or donkeys, then gradually a quiet settled down, a quiet which lasted till the evening. After six o'clock Avila awoke, the business men left their shops, the officers their cantonments. The cadets and youths gathered in the plaza to flirt with the girls who, dressed in gay cottons, paraded to and fro in small giggling and swaying groups. Booths selling cool drinks and ices opened at the corners of the plaza, while wandering sweetmeat merchants sold fried almonds and sugared nuts. There was no woman with a lace mantilla and a high comb, nor any one with a flat hat, embroidered shawl and cigarette; so the cigar boxes are liars.

As one sits at the café table in Spain, life is, perhaps, presented to one in an aspect almost too crude. Lazarus lay at the rich man's gates exhibiting his sores, and the Spanish beggar follows his example. Spain needs no Charles Lamb to write of the decay of beggars. Decayed indeed they are, but not in that sense of which Lamb wrote: in tattered and unspeakable rags they pursue their trade from the Asturias to Cadiz. No dishonour attaches to beggary in Spain. A Spaniard was horrified when Jan told him that begging was not permitted in England.

"What, then, can those do who are unable or unwilling to work?" he asked.

A humble though probably verminous official refuge is provided for the beggar in each town, and, as he tells his clients, "God repays" his small extortions. The Spaniard is accustomed to his beggars, he does not nag at his conscience about them, but it harrows the unaccustomed heart of the Englishman who, taking his modest coffee or Blanco y negro after supper, finds a procession of misery thrusting importunate hands into his moment of quiet luxury. The Spanish beggar has no tenderness for one's sensibility. Each has the motto, [Pg 45] "If you have tears prepare to shed them now." Naturally we were their quarry. They presented us with a series of specimens worthy of a hospital museum. We hardened our hearts, as we were afraid of consequences, but after two days, when the beggars, disappointed with us, relaxed their exertions, we gave or withheld alms with the outward serenity of a Spaniard, but feeling inwardly brutal whenever we refused to give a dole.

Dirty, half-naked children dodged about the café pillars, hiding from the waiter's eyes. They stared wistfully at the small, square packets of beet sugar which the waiter brought with the coffee, and if a lump were left over they would creep up and in a cringing whine ask for it. Boys slightly older usually begged for a perra chica or for a cigarette. Their voices would be pathetic enough almost to break one's heart—they would say they had not eaten for three days—but if the refusal was decisive they would suddenly change their tones and shout out gaily to a comrade or run away whistling, or turn a few cartwheels down the gutter.

In Avila, too, we encountered the money problem. We had been told that the Spaniard calculates his cash in pesetas and centimos, the peseta being worth normally tenpence in English money and the ten-centimo piece about one penny. So far this had worked fairly well, we had been on the travellers' route and the peculiarity of travellers had been catered for; but here we found a new system of coinage.

"How much is that?" I asked a woman in the market, pointing to some object.

"That," she replied, "is worth six 'little bitches.'"

"Six what?" I exclaimed.

"Well, three 'fat dogs,' if you prefer."

"Three 'fat dogs'?"

"Yes, or one 'royal' and one 'little bitch.'"

"But I cannot understand. What is a 'royal'?"

"Oh, don't you know? Why, twenty 'royals' make a 'hard one.'"

At last we worried it out. The little bitch (perra chica) is five centimos, or one halfpenny. The fat dog (perro gordo) is the ten-centimo piece; these are both so called because of the lion on the back, though why the sex should be changed we do not know. The royal (real) is twenty-five centimos or twopence-halfpenny, the "hard one" (duro) is a five-peseta piece. The peseta is ignored. Nobody except an ignorant foreigner calculates in pesetas. The Spaniard, who often cannot write, does staggering sums in mental arithmetic, reducing thirty-two "little bitches" or seventeen "royals" almost instantly into the equivalent in minted coin.

We had come to Spain for the several reasons mentioned in Chapter I. We had found the freedom: it was as though some oppressing weight were lifted from off us, as though an attack of mental asthma had been relieved. But on the whole we felt that we had been defrauded in other respects. The weather, except for the afternoon at Medina, had been very cloudy and at times almost cold. We had heard no guitar during our week in Spain. One day a man with a primitive clarinet, accompanied by a man with a side drum, had wandered about the town making a queer music which had given us thrills of unexpected delight. But Jan does not play the clarinet. He had made up his mind about guitars, and guitars he would have. The last night which we were to spend in Avila, he said:

"See here, Jo, we'll go out and we'll walk up and down, through and round this town, till we hear a guitar playing. Then we will walk in and explain. I'm sure the people, whoever they may be, will not mind, but I am going to hear Spanish music."

After supper we set out again. We walked the town from the top to the bottom. Not a whisper of guitar or of any other music. We bisected the town from left to right—still silence except for the dim sounds of normal evening life. We went out into the little garden which was beyond the walls and, [Pg 47] leaning on the parapet, stretched our ears over the small suburb beneath. The cries of a wailing child or two, of a scolding woman and the shouts of an angry man answered us; of music not a note. We walked round the walls and were about to return in disappointment to the hotel, when Jan said "Hush!"

We listened. Barely audible, from below on the hill-side, came the faint tinkle of a guitar. We looked out across the dark country. The hill sloped steeply from our feet and rose again in planes of blue blackness to the distant mountains. Almost in the bottom of the valley we saw a square of light from an open door. The sound came from this direction. Cautiously we crept down the hill, which was steep, pebbly and without paths. As we came down, the noise grew louder.

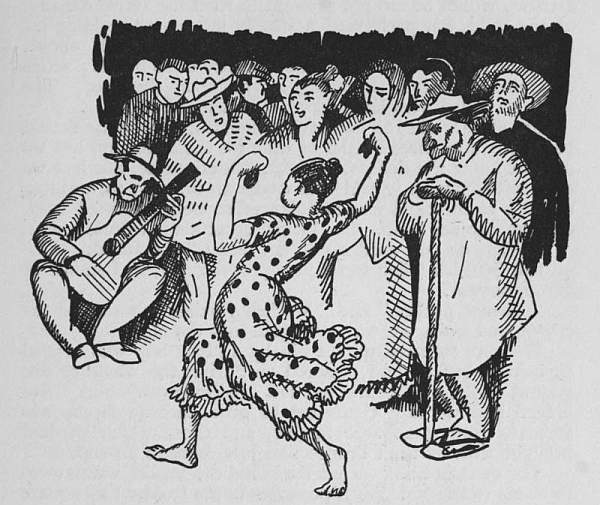

There was a small drinking house or venta by the roadside; near to it, drawn up on a grassy spot beneath some big trees, were gipsy caravans and booths, and as we passed by we could see, dimly white, the blanketed shapes of the gipsies as they lay on the grass asleep under the stars. From the venta came the sounds of music.

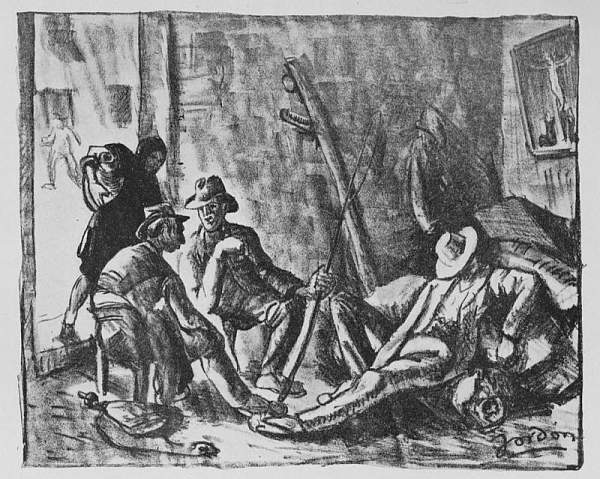

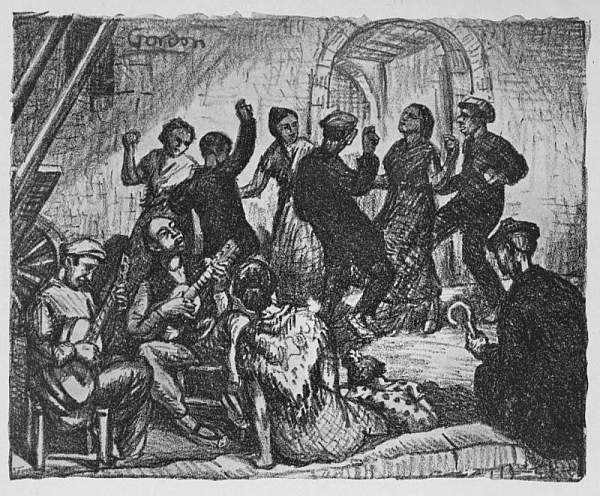

After a momentary hesitation we went in. The room, lit by one dim lamp, was crowded with gipsies and workmen. It was long in shape and an alcove almost opposite to the door was partitioned off as a bar. At one end was a table upon which three gipsies with dark, lined Spanish faces were sitting, and the audience had formed itself into rough, concentric semicircles spreading down the length of the room. Most of the men were swarthy with the sun, clad in the roughest of clothes, some with tall hats on, others with striped blankets flung over their shoulders. The inn looked like what the average traveller would describe as a nest of brigands.

We murmured a bashful "buenos noches," bowed to the company and crept into the background. A few returned our greeting, but with delicacy of feeling the majority took no overt notice of our presence.

The man on the table who held the guitar began to thrum on the instrument. A tall gipsy, whose face was drawn into clear, almost prismatic shapes, and who might have stepped out of an etching by Goya, put his stick into a corner, slipped off his blanket and, standing in the open space before the table, began a stamping dance, snapping his fingers in time with the rhythm. A workman standing near to us said:

"That man does not play the guitar very well, the other one plays better."

He went out and in a short while returned with his wife, a laughing woman whom he placed next to me. There was no drinking of wine. The alcarraza, an unglazed, bottle shaped drinking vessel, full of water, was handed about. It has a small spout, and from this the Spaniard pours a fine stream of water into his mouth. But beware, incautious traveller—ten to one you will drench yourself.

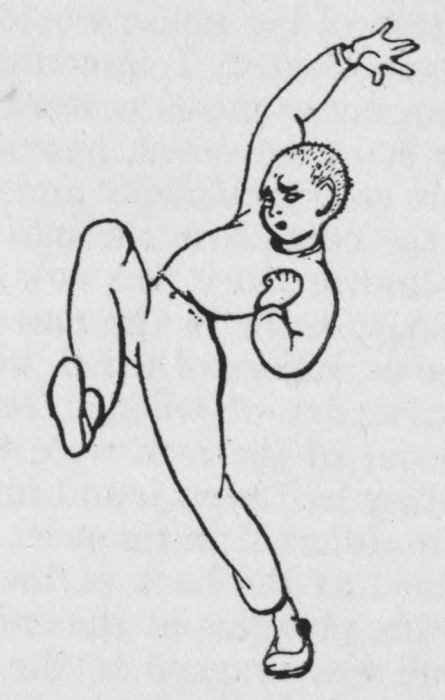

Though the audience apparently took no notice of our presence, in reality they were extremely conscious of us. One by one, as if by accident, gipsy women clad in red cottons came into the already crowded room. Soon a girl was urged to dance. She demurred, giggling. At last she was pushed into the open space, and with a gesture of resignation she began to dance. We are not judges of Spanish dancing: we had been looking for atmosphere, and had plunged into the thick of it. This was no café in Madrid or Seville got up for the entertainment of the traveller. This was the true, natural, romantic Spain. Opportunity again had blessed her disciples. One of the women pushed her way out of the door, and in a short while returned, dragging with her a child about nine years old. The little girl's face was frowning and angered, the sleep from which she had been roused still hung heavy on her eyelids.

"Aha!" exclaimed the audience. "She dances well."

The man who was reputed the better player roused himself from the table and sat down on a chair. They put castanets [Pg 49] into the child's hands. The man struck a few chords and slowly the music formed itself into the rhythm of a Spanish measure.

|

Relaxing none of her angry, sleepy expression, the child danced wonderfully. The castanets clashed and fluttered beneath her fingers, her skirts swirled this way and that, her feet beat the floor in time with the pulsation of the guitar. The audience shouted encouragement at her. With a wild series of movements, the dance at last came to an end.

"Brava! Brava!" cried the gipsies.

"One day that girl will be worth much money," said a man, with approval in his voice.

Then the best male dancer took the floor. With true artistic instinct he did not attempt to rival the active dancing of the child, but performed a stately movement, holding his arms above his head, and slowly turning himself about. When he sat down an old man of seventy or so began a series of senile caperings, thumping his stick on the floor. The audience rolled with laughter at the ancient buffoon.

For some while Jan had been wondering whether he should pay for two or three bottles of wine for the company, but we did not know the delicacies of Spanish etiquette, nor had we sufficient language in which to make an inquiry, so, pushing my way to the child who had danced so well, I pressed a few coppers into her hand. She looked up at me in astonishment.

"What do you want me to do, then?" she asked.