based upon the Third Prize ($15.00) Winning Plot of the Interplanetary Plot Contest won by Allen Glasser, 1610 University Ave., New York

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Wonder Stories Quarterly Winter 1932. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Many writers of science fiction, who have not given the matter much thought, assume that a man of intelligence from one planet would meet a cordial and sympathetic welcome on another world. It is assumed that people are everywhere educated, curious about other worlds and other cultures, and eager to help a visitor from an alien race.

Unfortunately there is no assurance that such is the case. Even were the members of another race, on another world possessed of education, there would be bound to be among them low and brutish elements. And if a stranger from another world, dazed by new conditions and unable to make his wants known, were to fall into their hands his fate might not be happy.

We have read no story that pictures with such clarity and insight the experiences of a man on another world than his own, than does this present story. With the basis of a splendid plot Mr. Hilliard has worked up a simply marvelous story.

The rolling, yellow sand reflected the heat of the sun in little, shimmering waves. It reflected the sun's light blindingly throughout all its visible expanse, with the exception of one spot where lay a circular shadow. In the great steely-blue dome of the sky there were no clouds.

The shadow, although not large, was very dark and distinct. The curved, even line of its circumference was precisely drawn.

In the air was a persistent rattle of sound—a series of closely spaced explosions, ever rising in intensity.

Suddenly a small, uneven shadow detached itself from the circular one; and floated swiftly across the sand. The rattling sound increased to a tremendous booming roar, and the large shadow began to fade. At the same time, the smaller one grew steadily darker.

High above the sand, a man was falling—much too swiftly.

The surface of the sand had been shaped into hills by the prevailing winds. These long, ridge-like hills, or dunes, were convex and gradual in slope on their windward sides, but on their lee sides they were concave, and very steep.

It was near the top of one of these steep slopes that the man landed. His frail legs and body crumpled under the weight of his head; he pitched forward, and half rolled, half slid to the bottom where he came to rest more gently, the target of a small avalanche of sand.

Immediately, he began to struggle; and, failing in his attempts to rise, stretched his slim arms skyward and uttered a sharp, squealing cry, painfully prolonged. Far above him a spherical object rapidly diminished in size. Fixedly he watched the sunlight glinting on its polished grey sides; watched it shrink to a tiny ball, a point, and then—nothing. He was alone.

The pressure was horrible. He buried his head in the hot sand, and clapped his ears in a vain attempt to ease the throbbing pain. They must have underestimated the weight of the Toonian atmosphere if they had expected him to live long here! It did not hurt his body, but his head was being crushed. He knew that he would soon die—and was glad. This wild, senseless punishment would be at an end.

He opened his eyes again, and stared in growing fascination and wonder at the great arched blue dome above him. Gradually the spectacle of this weirdly beautiful canopy occupied his whole attention. It was like a soft curtain of light blue material hiding the blackness of the sky and the gleaming stars;—yet the sun shone through. For a moment he forgot his loneliness, his pain, in rapt contemplation of the immense perfection above him—but only for a moment. Then the explanation came to him. That beautiful blue was the heavy atmosphere of Toon, which was slowly crushing him to death! He closed his eyes.

The heat was terrific, but not as intense as he had expected. Toon was nearer the Sun than was his own world—millions of miles nearer; yet he was not badly burnt, and this puzzled him. The explanation must again lie in the heavy atmosphere—serving as insulation, he finally decided.... He didn't care.

He felt strangely detached. What signifies life—or death—to a tiny being separated by fifty million miles from any of its kind? Deposited on this strange planet, he had no hopes of survival; his only emotion was astonishment that he had lived a moment.

He struggled to remove the parachute that had been so inadequate in easing his fall. Movement—even the raising of an arm was serious effort. He was glued to the ground by the tremendous gravitational pull of a planet so much greater in size than his own. He relaxed.

Why struggle? With the passing of hope, all incentive to effort passes also. He felt no distress at the thought of death. Life, not death, would be freakish in this great wasteland.

And he was past anger now. What they had done to him they had done through hate and fear. Only hate and fear could conceive of so fantastic a torture for a fellow being. There was no satisfaction now in the knowledge that they had feared him; nor did he care about their hate.... They had won. They would have their way, and all the people of the Loten would suffer in consequence....

Loten! A wave of sick loneliness swept over him.... A point in the sky, obscured by a weird curtain of blue—his home!

Certainly, no man had ever suffered thus! A surge of self-pity welled up within him. Certainly no being had ever been forced to long for the world—the globe which gave it birth! This horror was reserved for him alone....

He clenched his fists. Reason returned to rescue him from emotion. Loten did not exist for him. He was outside of the world—a tiny flame of consciousness in space. And what did that amount to, after all, he asked himself.... What, but Death?...

For a long time he lay there in the sand, quite motionless.

The sun was sinking. Its blazing heat was abating somewhat; its face was large, and red. For miles, across the surface of the sand, the shadows of the dunes were stretching out.... And out of the sunset a tiny speck of black appeared.

Where he lay the man heard the sound of it—a steady drone, or buzz. At first it did not catch his attention, its inception was so gradual; but soon it became a roar, and he opened his eyes with a start. He had heard no sound since the departure of the space ship—had expected none. An uneasy excitement gripped him. He strained his eyes upward....

Suddenly, over the dune against which he lay, there shot a something, roaring thunderously. He cowered down, stunned by the terrific sound of it; but he watched it with wide eyes, as it moved across the sky.

It was T-shaped; with the cross-piece going before. Beneath it hung two wheels. It gleamed metallically.

Without attempting to rise, he howled shrilly, time after time, catching his breath in gasps—while the thing moved steadily away.

Following an undeviating line, it left him far behind, diminished to a speck, and disappeared. The sound of it lingered when he could see it no longer.

His breath came quickly, spasmodically, through parted lips; his throat was tight, and his heart pounded. The staggering surprise of what he had seen and heard left him incapable of thought. His mind was a racing turmoil of questions. His contentment, his resignation were gone—destroyed in a moment; and in their place rose a great uneasiness.

The return of Hope, to a man who has definitely put it away from him, is a joy closely akin to pain in its intensity. His whole body shook as he struggled with the sand, attempting to rise.

He had seen a machine, he knew. It could not have been an animal. It was not alive, and it was made of metal.... A machine meant reasoning beings. There must be reasoning beings on Toon—where Loten's scientists had argued that they could not be! And machines that travelled through space! Perhaps....

As the new possibilities of his situation burst upon him, his homesickness returned a thousandfold; and he knew that he could rest no longer—could not wait in the sand for death. He must struggle—he must strive, until the end came—because there was a chance!

Immediately, his mind became purposeful, and he took stock of his position. He knew that the whole of Toon was not like this great stretch of sand. Thousands of years of observation of the bright planet had convinced the scientists of the Loten that it bore vegetation—and probably animal life of some sort....

But rational beings! His astonishment re-asserted itself. Five thousand years of systematic signalling had brought no response, and the project had lately been abandoned. Yet....

He shook his head, and returned to his problem. He must not waste time now.

He had food enough in his stomach to last three days at least, and he would not need water for even longer. He suddenly realized, with enormous satisfaction, that the pain in his head was considerably less than at first. Perhaps his system would be able to adjust itself to the atmospheric pressure....

The great question was where—and how—to go. He must go somewhere. Only motion would satisfy his craving for accomplishment of some sort. He would get no help on this great, sterile plain. He had no guarantee that another of the flying machines would come near him, and even if it did there was not much hope of attracting its attention. No, he must move....

He decided to follow in the direction the machine had taken. Its destination might be near-by—or it might be thousands of miles away. The probability seemed to be in favor of the former hypothesis, because the machine had been moving so very slowly.... Anyway, it was a chance!

Pulling his legs up under him, he made another determined attempt to rise; and finally succeeded in standing erect. But it made his legs ache terribly; and when he tried a step he slipped, falling back with a jarring thud.

He would have to crawl.

Ridding himself of the parachute, and with no further hesitation, he set out, crawling slowly and laboriously, keeping the sun at his back.

The heat was less oppressive now. The sun had sunk to a point where its rays were no hotter than at midday on his Loten; and he marvelled at the similarity of the two climates. He had seen none of the water vapors that astronomers described as almost constantly enveloping Toon. Toon—what he had seen of it—seemed to be as dry as the Loten, if not more so.

He climbed the long, gradual slope of a dune; and, after surveying the endless stretch of sand which met his view at the top, slid down the steep side, and crawled doggedly on.

Night was falling. The blue dome above him steadily darkened until it began to take on the appearance of his own native sky.

He was dead tired within an hour. He lay still for a time, breathing deeply—marshalling his strength. He was in excellent physical condition, but here his body was so heavy that the slightest motion was a strain. Soon, however, his eager spirit drove him onward.

At the end of another hour, happening to raise his head, he uttered an involuntary cry. Points of light glimmered in the sky.... So he was to see the stars after all!—though only at night, it seemed. He was relieved. In the back of his mind had been the ever-growing certainty that he would not be able to keep a direct course. He rested again, and picked out certain designs that would be helpful as guides.

He wondered if one of them were Loten. They were very dim and they blinked strangely; and their arrangement was meaningless to him. He fixed upon one of them—the brightest—and imagined that it might be his world—where his friends were, and his enemies; where his wives grieved for him perhaps; where his children laughed and played; where he might one day return....

He crawled along through the sand.

It was not really dark—only twilight. He wondered if this were night on Toon. It must be. Almost directly ahead of him—just a little to the right—was a radiance close to the horizon. It puzzled him. Soon it was spreading over the sky—a pale, ghostly light. Then a bright point appeared—a line; it grew. He stared in abject wonder while a great, white disk mounted into the sky, illuminating the scene around.

He rested a while, and watched it. It was Toon's satellite. It could be nothing else. But beside it the two luminaries of his own world were as pygmies. He was still watching it, fascinated, when he resumed his journey.

All through the night he travelled; and into the rising sun. The noonday heat forced him to take a prolonged rest, but he fought on as soon as possible; and sunset found him crawling weakly onward. The cool of night revived him somewhat. He knew that the strain under which he labored would hasten his time of sleep, and that worried him. Even now, he was often in a semi-conscious state. Still, he could not stop.

When the sun rose again, it shone through trees; and far across the yellow sand his tired eyes saw green hills. The sight invigorated him—spurred him on to stronger efforts. Soon after midday he lay panting in the shade of trees.

The trees astonished him. They towered above him, fully five times as high as any he had ever seen. Their stems were of enormous girth—rough and hard to the touch. There seemed to be something moving in their heavy foliage, far above him, and he heard faint, sharp whistling sounds. He looked around uneasily.

The size of the trees worried him. If there were animal life, it might be proportionately large. He shuddered. The desert, although uncomfortable, had had one advantage: he had been alone there.

Still, it was not loneliness that he was seeking, he thought grimly. Obviously, he....

He stiffened. He had been staring abstractedly at the coarse grass which grew thickly around him. Now his eyes became focussed upon a movement there—not three feet away. The grass was waving strangely, in a peculiar, uneven line; and he caught sight of something slim and green, that was not the grass. His throat contracted painfully. The thing did not seem to move, yet it was coming nearer. Whenever he caught sight of a part of its body, it appeared stationary; yet the waving of the grass was closer, and ever closer. It was very close now....

Suddenly his power of locomotion returned. He rolled over backward, and scrambled along the ground to a tree. Grasping the rough trunk, he pulled himself erect; and held himself in that position, panting.

He could see the thing more plainly now. It was like a long, green whip in the grass. Its forepart was raised in the air, and terminated in a triangular head, with two bright eyes whose steady, unwinking stare made him tremble weakly. With an effort he took his eyes from the creature; and, pushing himself away from the tree, ran desperately, as far as his legs would carry him. When he fell, he continued to crawl—farther, and ever farther into the green woods.

He wondered if all creatures crawled in this world of Toon. Perhaps the great gravitational pull made erect postures impossible.

For a long time he climbed steadily, threading his way through the underbrush, skirting fallen trees. He felt increasingly drowsy. His sleep period would come soon, he knew. He could not stave it off much longer. And when he had slept, he must eat....

He came to level ground. Ahead was an opening in the trees, where a wide ledge of stone was revealed. Out upon this he crawled, and gazed at the scene that opened out below. Miles of waving tree tops met his view; but what held his attention was a strip of silver cutting the green.

He felt a warm glow of satisfaction. Water, in his mind, was closely associated with organization, transportation facilities, reasoning beings....

Yet he must be wary. He had no idea what sort of beings they might be. This might be a canal, but it was strangely irregular in its course. At least he was making progress....

A peculiar, ringing sound came from the trees below. It was utterly unfamiliar to him. Nerving himself, he determined to discover what it was. He climbed down from the stone, and began the journey down the hill.

As he progressed the sound became louder, and others were added. He was puzzled by a low, intermittent muttering. It made him vaguely uneasy, and with every moment his agitation increased. The muttering was now very definitely spaced into irregular but continuous tones.

And he knew that he was listening to a conversation.

He was frightened. Now that he was so near to what he had been seeking, his courage left him; and he lay trembling, flat on the ground, awed by the booming voices of the creatures.

They must be very large, he thought, to utter such deep tones.

He had lain there for perhaps five minutes, when, suddenly, there came a rending crash; and, peering ahead, he saw the green top of a tree sway violently, sink, and disappear from sight. At the same time there came a louder cry, followed by the blending of two thunderous voices, speaking simultaneously.... Then a heavy thud, and another cry....

He crawled cautiously forward. He reached the fallen tree. Its trunk was suspended above the ground by the projection of a number of its large branches. He peered beneath it.

Directly before him, in a small clearing, two creatures were struggling together. They stood erect upon their huge legs, using their crudely bulky arms and hands to strike and tug at each other. They were tremendous in size—fully three times human stature; yet their heads were smaller than men's. Their erect posture gave them a weirdly half-human look, which was belied by the brutal savagery of their aspects. Their brows were low; their heads were covered with long hair; and in their gaping mouths he saw rows of sharp, white fangs. Their skin, instead of being golden, was a dirty grey in color, and was covered with short curling hair or fur.

But he could see very little of their bodies, because—and this sight seemed to him the strangest of all—they were almost entirely covered with cloth. This woven material was brown in color, and shaped to hang close to their bodies, even over the arms and legs. He lay very still, watching the titanic struggle with ever growing wonder.

They appeared to be evenly matched. Once, one of them was hurled heavily to the ground, but he leaped effortlessly to his feet. Both of them grunted and uttered sharp exclamations at intervals. They tramped back and forth, tearing up the grass, crushing down the small bushes.

They must greatly hate each other, he thought—or perhaps it was natural for them to fight like this. Now one of them was tiring—the smaller. Its movements were slower, and it stepped almost constantly backward. Suddenly from its bulbous nose spurted a red stream. He shuddered. The sight of these two strangely man-like creatures beating and tearing at one another sickened him.

The larger creature was pressing its advantage, advancing upon the other with cruel, flailing blows. Suddenly the smaller one crumpled to the ground, and lay still. The other turned away. It seemed satisfied. It grasped an object which was leaning against a tree—a cutting tool apparently, consisting of an edged block of metal attached to a long handle of wood; and without a backward glance at its fallen foe, made off through the trees.

The creature on the ground was alive. He could see the rise and fall of its breathing under the cloth covering of its breast. But the bright, red blood was still running out of the nose. It had lost an astonishing amount; and he feared that, unassisted, it would soon die. He must try to help.

With wildly beating heart, he crawled under the tree trunk and out into the clearing.

As he moved through the grass, he made a slight rustling sound, which the creature heard. It turned its head, and stared directly at him. He stopped fearfully....

The creature uttered a loud cry, and scrambled to its feet. He raised one hand, attempting a friendly gesture; but the creature, after watching him for a moment with wide eyes, bounded swiftly away into the woods. He heard the thumping and crashing of its passage through the underbrush long after it had disappeared from sight.

His first sensation was one of immense relief. He had been desperately afraid.

Evidently the thing had been afraid of him, too. And that was surprising.... Clearly, these could not be the reasoning things that had built the flying machine he had seen. His relief was quickly followed by disappointment. For a moment he had imagined that his first objective had been reached. Now he realized that he might be as far from it as ever. Toon was immense. Probably, now, he was in a country inhabited by inferior beings—beings that would be constantly hostile and dangerous to him. If that were so, his quest would end here, he knew. Sleep could not be warded off any longer. He could not protect himself. Soon he must eat—and there was no food.

He crawled into the bushes; and lay down, lonely and sick. He would stay here. This was failure—and the end. But he was not sorry for having tried....

Above him the sky was not blue, now; but a strange, dead grey. Nowhere could he see the sun. The wind sighed mournfully in the trees.

He slept.

He awakened in shivering terror. His entire body was wet. Water was falling on him. It was falling on the ground all around and on the trees—thousands, millions of drops. He choked, as he tried to breathe the damp, saturated air. Desperately he looked around for some protection, but there was none. He covered his face as best he could with his folded arms, and cried out in fear.

There came a shout; and he heard something moving toward him, but he did not care. Horror of the falling water crowded all other emotions from his mind.

One of the creatures was standing over him. He heard others approaching. They were shouting loudly back and forth to one another. In a moment, there was a circle of them, all around him.

He was too distressed to pay them any attention. After a time one of them bent down and grasped him under the armpits. He felt himself lifted into the air. He did not struggle, even when their faces were all around him—very close.

Now they were walking through the trees, one of them carrying him in its huge arms, quite gently. He was scarcely conscious of his surroundings. It was becoming more and more difficult to breathe.

Then he felt himself laid down on something soft and dry. The water was not falling on him now. He opened his eyes.

They had placed him under a shelter. He could hear the water on the black covering above him. There was one of them on each side of him, where he lay on what seemed to be a cushioned seat....

Suddenly there came a rumble, and the seat beneath him quivered and shook. He struggled to sit up. One of the creatures aided him, and wrapped a dry cloth about his body. He was grateful.

The seat was bumping up and down violently. On each side, he could see the trees moving slowly backward. He realized that he was in a vehicle. It jolted constantly, and he imagined that it must run directly on the rough ground. It made a continuous and tremendous noise. But it was a machine of transportation, however crude; and he quickly forgot his bodily discomfort, as the implications of this fact crowded through his mind.

He looked with a new interest at his captors. They were talking together excitedly—evidently about him, for they never removed their eyes from him. In spite of their strangeness and savagery, they must have reasoning minds. He could be pretty sure of that, now....

The vehicle came to rest, and to either side he saw structures, made, evidently, of cut trees. Then his heart leaped again, as he saw that they had glass. So they knew how to make that! There were only a few pieces of it let into the walls—but it was certainly glass, and his hopes rose a bit higher.

They carried him into one of the houses. It was quite dark. They set him down upon a large table. They were increasing rapidly in numbers, jostling in through the door and crowding around the table.

In the wall near him there was one of the pieces of glass. Abashed by the dozens of staring eyes, he looked through this, and saw a broad field, its soil turned up in long, straight rows—evidently for planting. Near the center of the field were two creatures, which immediately commanded his attention.

They were not alike. One was similar to those he had already seen, but the other was even larger and of a different shape. Four legs carried the great, bulky body, which rested in a horizontal position, as did the thick neck and long, tapering head. It was dragging the tool which turned up the furrows of soil, while the other followed behind, governing its directions.

Clearly, he thought, there were many types of creatures on Toon. He would have to try to understand their relations to one another....

Inside the room there was much noise, and the air was hot, damp, and very unpleasant to breathe. He was not afraid of the creatures now; and instinctively he realized that it was curiosity that brought them here, and that they meant him no harm. A few were trying to speak to him, looking directly into his eyes and making monosyllabic sounds. This amused him at first. They would not be quite so hopeful if they understood from where he had come.

But in another moment his amusement had vanished. One of the creatures, standing near, placed a finger close to where he sat, at the same time uttering a short disyllabic sound:

"Table!"

A thrill shot through him. He had expected no such intelligence on the part of his captors. A new wave of hope surged up within him.... Carefully, he repeated the gesture and the word.

His action was followed by a burst of excited conversation in the room. Several made sharp, guttural noises which he guessed meant gratification or amusement.

Immediately a number of them took up the game; and he eagerly did his part, repeating the sounds they made and identifying them with objects. With every possible gesture he tried to indicate to them his pleasure and gratification.

He was sorry when they began to go away.

It had been getting steadily darker for some time, when, suddenly, the room was brilliantly illuminated; and, looking quickly around, he saw a number of bright globes. This event brought him to a high pitch of elation. The character of the vehicle in which he had ridden had made him fear that they knew nothing of electricity, but here was tangible evidence that they did. His dream of a return to Loten seemed less like a wild imagining at every moment.

He was beginning to think of these creatures as people, almost human beings.

Now, only two of them remained. From their glances he knew that they were talking about him. Finally, one of them lifted him from the table; and, walking swiftly, carried him through the door, across a short stretch of open ground, and into a smaller and darker structure, there laying him down upon a bed of cloths and cushions in one corner of the single room. The other followed them in, carrying a china dish and cup. Setting these beside him, they both pointed with their fingers to their open mouths. He understood immediately, and was glad. He needed nourishment badly.

But when he looked into the dish his pleasure abated. It contained an assortment of what appeared to be parts of plants and—he tried to conceal his horror—animal flesh.

Looking up, he nodded—a gesture that he had quickly learned; and to his great relief they turned and left the room, closing the door. He heard a sharp click.

The flesh he immediately put aside. He did not like to think what its origin might be. He studied the plants. They had evidently been subjected to a heat process, but had not been chemically refined in any way. The percentage of nourishment in them must be very low, and it would be necessary for him to eat great quantities to sustain his strength. He wondered how long his stomach could stand it.

These people must eat almost daily to sustain themselves on such fare, he reasoned, marvelling.

With a pronged implement that they had given him, he set to work to mash the food into as soft a mass as possible. This process they accomplished easily with their fangs, he knew.

The taste was anything but pleasing, and he had great difficulty in swallowing; but he finally managed to assuage his hunger, and felt better. He drank a little water from the cup, which contained enough to supply him for at least five days.

This done, he stretched himself out upon the bed, and gave himself over to pleasant reflection. A far cry, he thought, from the man lying helpless in the desert, devoid of all hope, to the one who had established contact with a race of intelligent beings who would doubtless be willing to help him return to his own native world. He reflected that if the flying ship had hot happened to come near him, he would most certainly have perished by now—perished in a foreign world, far away from those he loved, never knowing there was a chance for his salvation. But now he had taken the first step.... Anything was possible now.

His attention returned to his surroundings. The bare room was lighted by a bulb hanging from wires in the center. From it dangled a cord, the purpose of which he quickly guessed. The walls and floor were bare wood, and rough. Along the whole length of one wall extended a low, narrow table, or bench, strewn with a miscellaneous collection of objects which aroused his curiosity.

He crawled to the bench, and pulled himself erect by grasping its edge. He was just tall enough to see along its surface. Near him rested a large roll of what he first thought was cord; but on closer examination he decided that it was metal wire covered with a fibre insulation. Obviously it was for the conduction of electricity. Scattered around it were a number of cylinders of varying sizes, which he saw were wound closely with very fine wires. Clearly, these people did more with electricity than make light, he thought, encouraged.

There was nothing else in the room except a pile of rusty metal in one corner. The whole place was depressingly dirty and dreary. He thought that he would feel better without the light. He made his way to the center of the room, and stretched upwards. Finding that he could just reach the cord, he jerked it; and returned in the darkness to his cot.

He lay there quietly, trying to calm his nerves. He wondered what they would do with him....

He was still wondering the same thing at the end of four days. They did not move him. They did nothing except come and look at him—a great many of them at first, but less and less as time went on. They came in the daytime—never at night. They fed him; and a few still tried to talk to him. This pleased him, and he strove eagerly to understand and imitate; but they soon got tired and stopped.

He learned to distinguish the males and females among the people that came, by differences in stature, length of hair, and clothing. He observed, with complete bewilderment, that the males often carried in their hands burning cylinders which they raised regularly to their mouths, blowing out smoke into the air. He guessed, finally, that this must be some sort of sanitary precaution.

Now, however, he was left alone most of the time. They brought him food, and then went away. He was uneasy. Physically, he felt far from well. The damp air made his throat and chest ache; and he feared that the long deprivation of sunlight was hurting him. He could not understand.

Gathering his courage one day, he attempted to open the door. He reached up and turned the knob the way he had seen the people do. But it would not move when he pushed. He remembered the clicking sound he had heard every time after they went out.

He became frightened. He did not understand this confinement. Why would they not let him out?

There passed another day, of mental torture. Would they let him die in this dark, dreary place? Had all his efforts merely led to a lonely, purposeless death?

He wondered what they would do if he went out of his own accord; and finally decided that he must do it, even at the risk of offending them. Further inactivity he could not bear.

Within five minutes he had formed a plan of action. It was night—the best time to work; for he must work undisturbed for a time.

He made his way to the bench, and collected three of the wound wire coils, which he dropped to the floor. With a cutting tool that he found he managed to get a length of wire from the large roll. The tool was very heavy.

Next, he crawled to the corner, and selected a number of small pieces of metal. He rested for a while, studying the light bulb which hung in the center of the room. From the light it gave and the size of the filament, he roughly estimated the power of the current.

Then, with a graphite writing instrument that he had found, he drew a diagram on the floor. He took a very long time doing this, and labeled it carefully. When he had finished, the little window at the end of the room showed that dawn was breaking outside.

Hurriedly then, he set to work with the metal, the coils, and the wire,—twisting, winding, connecting and cross-connecting—constantly glancing at his diagram and at the window. Finally, when it was broad daylight outside, he gave a sigh of satisfaction.

He had achieved an ugly, jumbled apparatus, vaguely cylindrical in shape with a point of metal at one end. He laid it on the floor; and making his way to the bench, secured two more lengths of wire. He crawled under the bench to where the power line for the light ran down the wall, and there connected them. Then, securing his cup of water, he dipped into it the ends of his two wires, and observed them for a moment. Satisfied, he carried them to his cylindrical apparatus, and connected one of them at the end opposite the metal point. The other he did not immediately connect.

He was breathing hard now, and his face was flushed. For a long time he sat very still and listened, but he heard no sound. At last, moving very slowly, he carried his cylinder to the door. He raised it, and placed the point against the metal lock, under the knob. He pressed his lips tightly together, and set his jaw.... With the end of the wire which he had not connected he touched a point on the cylinder.

There was no sound. There was no movement of the cylinder. Yet the metal lock dissolved, and daylight shot through the place where it had been. A cloud of light grey dust drifted lazily to the floor.

He disconnected the wires. Carefully he hid the thing under the cushions of his bed. Then he pushed open the door, and crawled out into the sunlight. The sun felt warm and pleasant on his back.

He heard a cry, and looked up fearfully. One of the men of Toon was running towards him carrying a dish. It was the man that brought his food.

His throat was tight, and he was trembling. He knew that this was the supreme moment. He nodded his head and smiled. He raised one hand, palm upward.

The man stopped directly in front of him, and growled—then raised an arm, pointing at the door of his prison.

He made a little murmuring sound to the man; and raising his face to the sun, smiled and nodded once more. The man pushed him backwards with one foot, always pointing at the door.

He turned, and crawled back into the shed. Dully he watched the man; who stood for a long time staring at the door where the lock had been—then strode to the pile of metal and picked up a chain.

He did not move when he felt the chain around his body. He closed his eyes, and did not open them until he heard the door shut. He did not move all that day. He only watched the little window. When, finally, the little window grew black, he drew his machine from under the cushions, and connected it again at the wall. The chain was fastened to a leg of the bench, and allowed him to do this. He destroyed a portion of the chain, and loosened it from his body. He crawled to the wall farthest from the house where the people lived. Moving the machine in a slow arc, he cut a hole in the wall. Disconnecting the wires, he used them to fasten the machine around his waist. Then he went out into the night.

He did not know where he was going—except that he was going away from these beings that held him prisoner without a reason. At first they had seemed kind—but they were kind no longer. Something had changed them, he thought; but he could not guess what....

He had progressed less than a hundred yards when a sudden tumult of sound froze him with terror. It was coming at him through the dark, a hoarse, senseless, animal cry. And bounding toward him he saw the dark shadow of a beast. He knew instinctively that here was an unreasoning creature—and all the strength went out of him. He lay flat and limp on his face. Now he heard its panting breath, and felt the heat of it on his body....

At the same time, but only semi-consciously, he heard the loud shouts of men. As in a dream, he felt himself grasped roughly and lifted from the ground. Soon he knew that he was back in the shed again. He saw a man standing above him holding his machine.

He felt strangely detached—as if he were not there at all. He saw the man look at the machine; look at the door; look at the chain; look at the hole in the wall; look at the light cord. He saw the man connecting his machine to the light cord; he felt powerless to warn the man that he might be connecting it wrong—that there were two ways: one right, one wrong....

An explosion threw the man heavily against the wall. He could see the man struggling slowly up—coming towards him—kicking him. But he could hardly feel the kick at all—and everything got dark....

When light came back it was just a small square above him. That puzzled him, until he reached out and found wooden walls all around him—very close. He was in a box. He became suddenly fully conscious of the fact. Looking down at him from above he saw the faces of two of the men of Toon.

He cried out involuntarily, struggling to escape. One of the creatures shook a heavy piece of metal threateningly over his head. He cowered down, shuddering, at sight of the merciless gleam in its eyes. The light was blotted out, as they placed a cover over him; and he was deafened by a long and thunderous pounding.

Then began a time of horror in the darkness. His active mind had nothing to feed upon but fear. Only too clearly was it brought to him that he did not know the ways of these creatures of Toon. What was deadly fear to him might be commonplace to them. He had hoped to find them friendly, merciful—yet friendship and mercy were qualities of his own experience in a world different from theirs. Why had he thought to find them here?

He had no measure of time. For endless hours he lay there in the dark, bracing himself against the sides to protect his head and body as much as possible; for the box seemed almost constantly in motion—jolting, tilting, and bumping until he was weak and breathless from the strain.

His mind, worn out by its relentless self-torture, sank at last to semi-consciousness.

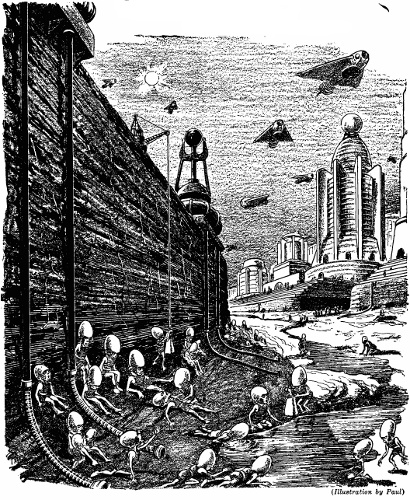

Suddenly light returned, and he was dragged roughly from his prison. He was in a large room where the combination of odor, heat, and noise was overpowering. Great numbers of the men of Toon were there, hurrying in all directions, seemingly very busy. He noted immediately that their clothing was different from that which he had seen, and wondered what the significance of that might be.... He felt strangely calm, now.

Before him was an immense, bulky man, who stood with legs apart and arms folded, staring at him with wide, unwinking eyes. This man had a face that was light red in color and rounded, almost swollen-looking in shape. He nodded, and his cheeks shook loosely. He nodded several times, and seemed very pleased. He spoke sharply; and others, standing around, sprang into action.

They brought a red cloth, and tied it around the captive's loins. They forced him to crawl back and forth on the floor, while the big man looked on, nodding and chuckling. Then the big man ran hot, cushion-like hands over his head and body; pried open his mouth; grasped his hand and shook it vigorously up and down; and, with a final nod, turned and walked away.

He understood none of this, and was very unhappy.

They placed him upon a high, draped platform, where there was a small chair and nothing else. There were a number of similar platforms in the room.

It was impossible for him to maintain his previous indifference to his surroundings. Around the walls of the room were long rows of barred enclosures, containing creatures of every conceivable size, shape, and color. Some were hideous; some were strangely beautiful; all were absorbingly interesting. For a time, he forgot everything else while he watched them and listened to the sounds that they made. Certainly, he thought, a scientist of the Loten would give twenty years of his life for the opportunity to see these creatures! Some of them were amazingly like reconstructions that had been made from fossilized bones found on the Loten.

They brought him food, which he judged must be the cooked seeds of grain. It was soft, and he forced himself to eat a little, although he was not hungry. He feared that he would have to learn to eat daily, for food concentrates seemed to be unknown here.

His mind was occupied trying to understand the meaning of this place. Great numbers of people were crowding into the room, now. Rows of them stood around his platform.

The other platforms were now occupied also. On them were beings resembling the people around them, but each one differing in some strange way from the normal. Some were enormously large, some small. And he saw one which was shaped like the men of Toon, yet was no taller than himself.

An endless stream of people surged through the room, circulating around the platforms and cages—gazing fixedly at their occupants.

He began to understand. These were exhibits—creatures strange to the crowds who came to look at them. Toon was very large; and transportation methods were poorly developed. Perhaps, therefore, these people had never seen many of the parts of their own globe.

Their staring eyes made him uncomfortable. Wherever he looked they were—staring eyes and gaping mouths. He felt suddenly ashamed. He wanted to hide himself—but they would not let him do that, he knew. How long would they keep him here, he wondered? There seemed to be no limit to the crowds. This must be a great center of population....

And in a flash he had forgotten the people, with their staring eyes, forgotten his shame, forgotten his bodily discomfort.... A center of population! Those words blazed in his mind. Once more, he knew the joy of hope.

With a sudden clear perception he realized that they could not have helped him more if they had done it consciously. He had arrived at a goal, which, a few days ago, had seemed impossible of attainment. Here, if anywhere, he would find help....

He must learn the language. That was imperative.... And again his good fortune amazed him. These people were constantly talking. His position was ideal for studying their speech. From what he already knew, it was quite simple; and it should not take long to learn enough to serve his purpose.

It took longer than he had expected, mainly because the people were not there all of the time. They came only at certain periods of the day; and he soon made a surprising discovery—that they slept during a great part of every night. In fact, almost one third of their time seemed to be spent in an unconscious state. The creatures in the cages slept even more. He could see no signs of intelligence in these caged creatures. They were dumb, and were completely dominated by the men.

He missed the sun badly. These people, in their dark houses and their draped bodies, did not seem to need it. Often he felt quite ill, but tried not to worry about his health.

At night, when alone, he practiced the sounds he had learned; and rehearsed the things he was going to say when his chance came.

He passed through a sleep period; and then, on the ninth day, decided that he was ready. To the attendant who brought his food he said:

"I talk."

The man started violently, and gaped at him.

"Talk?" he repeated blankly.

"Yes!"

The attendant looked at him uncertainly for a long time, and then walked slowly away.

He was disappointed. But he was not kept waiting long. Soon the man returned, accompanied by another.

"Blumberg wants to see you," they said. He did not understand that, and shook his head. However, they lifted him from his platform, and carried him out of the room. They took him up a long series of steps and through dark corridors, into a small room.

Here it was cool and light. In the center was a desk, and behind it sat the large man he had seen once before.

"Set him on the desk here," ordered the large man. "Now, little feller—they tell me you're talking!"

"I talk."

"Well, well, well!" said the large man jovially. "What'll we talk about?... I'm Blumberg, and I run this circus.... Who are you?"

He understood only the last words, but they were what he was waiting for.

"I am man of Loten," he said carefully. "Loten is world more far from heat star."

"What? Say that again!"

"I not live in your world—in this world...."

"The hell you don't."

Again he did not understand what the large man meant, and looked around helplessly. Then he saw a writing instrument on the desk, and picked it up. Blumberg pushed forward a piece of white paper. Quickly he drew, in its center, a large circle with lines extending from its circumference to indicate radiation. Outside it he drew four small circles at varying distances from the central one.

"Hey, Edgar—come here!" called Blumberg.

A pale young man who had been sitting in a corner approached the desk, saying, "Yes?"

He looked pleadingly at the pale young man. He placed his fingertip on the large circle, and said, "Heat star!"

"Sun," said the young man quickly.

"Sun!" he repeated gratefully. Next he indicated the third little circle from the center.

"This world?" he said.

"Earth," said the young man.

"Earth? This world is Earth?"

"Yes."

Blumberg grumbled: "What is this—a joke?"

He could not understand Blumberg. Eagerly he looked into the face of the pale young man, and indicated the fourth little circle.

"Mars," said Edgar.

"Mars!" he cried jubilantly. He pointed his finger at himself. "I am man of Mars," he said.

There was silence in the room, while they both stared at him. Then the big man began to laugh. His body shook, and his red cheeks jumped up and down.

"So you are a Martian—eh?"

"Yes—a Martian."

Blumberg was still laughing. "That oughta go big in the show—huh, Edgar?" he said.

"Yes, sir," said the young man.

"If you live on Mars, what're you doing here?"

The Martian had been expecting this question.

"They send me away to Earth."

"Why did they send you away to Earth?"

The Martian began to speak slowly, carefully. Through long days and nights he had rehearsed his story, knowing he would have to tell it. The pale young man helped him often, at points where he lacked words....

He told of the scarcity of water on Mars—of how there was only a little, that had to be preserved carefully.

Here Blumberg interrupted. "How much water has this chap been drinking?"

"Less than a cup, sir—in almost ten days," said Edgar. "The attendant was telling me ..."

Blumberg grunted. "Go on!" he said.

He told of the social order of Mars—of the three great classes: the Aristocrats, the Scientists, and the Workers. The Aristocrats, he explained, were the rulers, who utilized the knowledge of the Scientists and the energy of the Workers to build up a State for themselves.

He told how, once a year, the water rushed down the canals from the melting polar ice caps, spreading vegetation over the face of the planet, and of how quickly this precious water disappeared, evaporated by the ever-shining sun, until there was none left for the thirsty plants, and they died. Thus, every year the famine was worse on Mars, and more Workers died.

He told how he, and other Scientists, had wanted to spread oil on the canals to stop evaporation, and of how the Aristocrats had forbidden them to do it.

He told of the plan he had conceived to control the waters at the head of the canals when the ice melted in the spring, so as to force the Aristocrats to come to terms.

And finally, he told of their premature discovery of his plan; of their great anger and fear; of their determination to punish him as no man had ever been punished before; of his banishment from the very world in which he lived.

There was a long silence when he had finished. At last Blumberg coughed, and shook himself.

"That's a fine story," he grumbled, "but you left somethin' out.... What I wanta know is: how did you get here?"

"In a space traveller," said the Martian.

"What's that?"

Carefully, laboriously, he described the space ship. With the pencil he sketched diagram after diagram, while the pale young man helped him and labeled them as he directed. The young man was becoming visibly excited. When the Martian had finished, he burst out:

"By god, it would—it would do it!... Look—"

"Shut up!" said Blumberg. The perspiration was standing out in large beads on his forehead.

"Fellow," he said heavily, "if you're lying, you've got one hell of an imagination!"

"You not have space travellers?" asked the Martian tensely.

"No.... Just ships that travel in air," answered the pale young man. He heard the other's painful catch of breath, and continued quickly: "But with these diagrams it would be easy to—"

"Shut up, Edgar.... Shut up—an' get outta here!" barked the big man. The other turned, and left the room without a word.

"Now, look here, fellow," said Blumberg, "I'm goin' to take your word for it. I'm probably crazy to believe you; but I've seen most of the funny critters of this world in my time, an' I ain't ever seen one like you. So you may come from Mars, for all I know."

The other looked at him eagerly, trying to understand his words. "You think I am man of Lo—of Mars?"

"Yes—that's right."

The Martian quivered with excitement. He held out his arms in a gesture of appeal.

"You help me?..."

"Yes."

"You help me go to Mars?"

Blumberg looked down at the desktop, and was silent.

"Yes. I'll help you," said Blumberg suddenly. He stood up, and patted the other softly on the head.... "Sure ... you bet!"

The Martian lay upon his back on a leather couch in a small room where they had taken him. His eyes were wide and shining. His hands clenched and opened convulsively. It seemed to him that he had been waiting for days.

The door opened, and Blumberg entered, followed by a smaller man. As the Martian struggled to his knees to greet him, he spoke heartily.

"Hello there! Think I wasn't comin'? No use being in too much of a hurry, y'know.... Meet Dr. Smith. He's a scientist like you...."

The Martian nodded and smiled at them happily. Dr. Smith looked at him long and curiously, meanwhile automatically seating himself in a chair close to the couch. Blumberg, who was pacing the room, cleared his throat.

"Now, look here," he said, "I'm willing to help you, but you've got to help me do it ...—"

The Martian understood him immediately.

"Yes!" he replied quickly. "Yes."

"Good!... Now, Dr. Smith is going to ask you questions about things we need to know. You tell him all you can."

"Yes ... I tell him!"

Dr. Smith had many questions to ask, on many and diverse subjects. At first, communication between the two was very difficult; but both were highly intelligent and understanding men, and before long they became fairly successful in exchanging ideas. Blumberg paced constantly about the room. Occasionally he went out, but always returned quickly.

The catechism went on for hours; and ended only to be resumed early the next day.

And so it continued on the following day, and on the day after. The Martian was puzzled. They seemed to want to know so many things! Dr. Smith had questioned him on every subject—mechanics, electricity, magnetism, chemistry, colloids, catalysts, transmutation of metals—everything. He feared that they were wasting time, but did not think it proper to object when they were going to so much trouble on his account. Nevertheless, he could not help worrying; and that night, when the pale young man brought him his food, he asked timidly:

"Do they make the ship?..."

The pale young man looked at the floor, biting his lips. Then he went to the door, opened it, and looked out into the hall. He closed the door softly, and came near the couch. He looked straight into the Martian's eyes.

"There is no ship!"

"No ship?"

"No." The young man was flushed and angry. He spoke very fast: "That fat crook is not helping you.... But you are helping him—you bet!..."

"Does—does he not think—think I am the Martian?..."

"Oh, he thinks you're a Martian, all right! He knows you are. He's taking out patents already."

The other shook his head uncomprehendingly.

"Don't you see it? Where you come from they know things that they never even imagined here. You got knowledge in your head worth millions of dollars; I mean, you have facts which are of great value to Blumberg. Why, already you've told him to make gold out of lead—something very precious from something worthless. And a hundred other things besides.

"He does not care about you; he cares about your knowledge.... Do you see?"

"Yes."

The young man's anger suddenly abated, and he glanced fearfully at the door.

"I'm sorry," he said gruffly, "but somebody had to tell you. You won't get any help here!"

He turned, and almost ran from the room.

The Martian sat perfectly still for a long time. Then he climbed down from the couch, and crawled to the door. He reached up and grasped the knob. The young man had left it unlocked, and in a moment he was in the dim hallway. He crawled along, keeping close to the wall, until he came to the top of a stairway. He felt the cool night air on his face. Very slowly he lowered himself down the steps. He came to a wide door leading out into the open.

Seated in a chair by this doorway was a man, whistling. The Martian waited patiently in the shadows until the man stood up, yawned, and strolled away.

Outside, there were high, dark buildings all around him. He found himself in a narrow canyon running between them. He crawled down this canyon to the right, close against the buildings. The paving beneath him was hard, and hurt his knees. But he did not stop.

Someone was walking towards him. He could not escape being seen. He was near a large light on a pole. He raised his hand in a gesture of greeting....

It was a woman. Suddenly she saw him, and gasped. Then she screamed—piercingly. The sound echoed and re-echoed between the high walls of the buildings.

Windows and doors banged. Footsteps pounded on the pavement. Soon there were many people around him. Some of them were holding the woman. She hung limply in their arms.

A man strode into the group, swinging a club, and speaking authoritatively:

"Here! What's the trouble? Move on there!" He glanced at the woman. "Fainted? Take her to a drug store, somebody. She'll be all right.... What's this?" He grasped the Martian by the arm, and raised him to the light.... "Well, I'm damned!"

Followed by the curious crowd, he half carried, half dragged his captive along the street, around a corner, and through a lighted doorway. He slammed the door shut.

"Found a freak, Yer Honor.... Scared a woman half to death! It musta got outa the 'Garden'; I found it on Forty-ninth Street...."

The man seated behind the high desk nodded, and picked up a telephone. Into this he spoke in a low voice, waited, and then spoke again. Finally he laid it down, and said, "He is coming over. Hold on to it." He resumed his writing.

The Martian watched the man writing on the high desk. He thought that this man must be some person of authority—some ruler of the people, perhaps. After long and painful uncertainty, he nerved himself to speak:

"Please help me...."

The man behind the desk looked up and smiled. "Yes. That is what we are here for.... Only be patient," he said, and returned to his writing.

The Martian remained quiet. He would not dare disturb the man again, but he kept watching him....

"Good morning, Your Honor!"

At the sound of the voice, he gave a start of surprise and fear. Blumberg walked towards him, smiling. He struggled, and averted his eyes. But his captor held him tightly. Blumberg patted him on the head with his large, soft hand. He trembled.

"One of yours?" said the man behind the high desk. "What is the trouble with him? He seems distressed."

Blumberg smiled at the other, and tapped his own head three times with his fingertip. The other raised his eyebrows.

"Tell the Judge about yourself," said Blumberg softly. "He is a great man, and he can help you."

The Martian was surprised that Blumberg would allow him to speak. He made a desperate effort:

"I am a native of Mars. Please, I must return home. Please help me.... I—"

"See!" said Blumberg. He was laughing.

The Judge nodded. "Can you handle him?" he asked.

"Sure! They get along better with me than in—other places. I know how to treat 'em; and they make a good living."

"All right," said the Judge. "Take him along. But don't let me catch him running around the streets again, or you might rate a fine."

"Don't worry! We're going on the road in a couple of days now. You won't see him again.... Well, good morning to you!"

"Good morning!" said the Judge.

The Martian lay, face down, on the leather couch. Over him stood Blumberg, breathing hard. With a light cane that he carried he struck the Martian sharply on his frail back.

"Don't try it again, or you'll get more of that!" he said softly.

The Martian did not move or utter a sound until he heard the door slam. Then he made his way to the table; and, grasping the edge, pulled himself erect. There was something on the table that he wanted....

The door opened softly, and the pale young man came in.

"You should not have tried it," he whispered.

The Martian pointed to the window. Over the top of a building lower than its neighbors a small, square patch of sky was visible, and in this patch a few stars twinkled faintly.

"Is Mars there?" he asked.

The young man was silent for a moment, looking at the floor and biting his lips. Then:

"Yes," he said. "As it happens, it is. Mars is the brightest of those stars, and the topmost."

"Thank you," said the Martian. "You have been very kind to me!"

The pale young man looked at him, and at the table. Then he turned, without a word, and left the room.

The Martian did not take his eyes from the little point of light. But one of his hands reached over the table, and grasped a knife which lay there. His eyes still on Loten—his home, he plunged the knife into his heart. And the little point of light, while he fixedly watched it, flickered—and died.