| Maj. F. S. Maude | Maj. Hon. A. H. Hamilton | Lord Methuen | Col. Mackinnon, C.I.V. | Capt. C. F. Vandeleur |

Photo by Gregory & Co., London

| Maj. F. S. Maude | Maj. Hon. A. H. Hamilton | Lord Methuen | Col. Mackinnon, C.I.V. | Capt. C. F. Vandeleur |

South Africa

and the

Transvaal War

BY

LOUIS CRESWICKE

AUTHOR OF “ROXANE,” ETC.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

IN SIX VOLUMES

VOL. V.—FROM THE DISASTER AT KOORN SPRUIT TO LORD ROBERTS’S ENTRY INTO PRETORIA

EDINBURGH: T. C. & E. C. JACK

MANCHESTER: KENNETH MACLENNAN, 75 PICCADILLY

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

| PAGE | |

| CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE | vii |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Disaster at Koorn Spruit | 1 |

| The Reddersburg Mishap | 16 |

| Escape of Prisoners from Pretoria | 21 |

| Preparations for Action | 32 |

| The Battle of Boshop, April 5 | 38 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Mafeking, April | 46 |

| Affairs in Rhodesia | 53 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Siege of Wepener | 54 |

| Operations for Relief | 68 |

| The Tentacles at Work | 82 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Great Advance— | |

| From Bloemfontein, Brandfort, and the Vet to Welgelegen, May 9 | 87 |

| From Thabanchu to Winburg and Welgelegen (General Ian Hamilton), May 9 | 95 |

| Towards the Zand River to Kroonstad, May 12 | 101 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Mafeking, May | 108 |

| With Colonel Mahon’s Force | 117 |

| On the Western Frontier | 132 |

| The Relief | 134 |

| How the News was Received by the British Empire | 140 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| From Kroonstad to Johannesburg | 144 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| General Rundle’s March to Senekal | 154 |

| The Highland Brigade | 156 |

| Lord Methuen’s March from Boshop to Kroonstad, May 29 | 159 |

| The Battle of Biddulph’s Berg, May 28, 29 | 161 |

| Fighting on the Western Border, May 30 | 169 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| General Buller’s Advance to Newcastle | 171 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| The Interregnum at Pretoria | 179 |

| From Johannesburg to Pretoria | 184 |

| APPENDIX | |

| Rearrangement of Staff | 193 |

| Deaths in Action and from Disease | 195 |

| PAGE | |

| Map showing the Lines of Advance from Bloemfontein to Pretoria | At Front |

| 1. COLOURED PLATES | |

| General and Staff | Frontispiece |

| Sergeant—18th Hussars | 48 |

| Mounted Infantry | 56 |

| Scout—6th Dragoon Guards | 68 |

| The Royal Marines | 76 |

| Northumberland Fusiliers and Durham Light Infantry | 80 |

| West Surrey and East Surrey | 96 |

| Officers of the Seaforth Highlanders | 160 |

| 2. FULL-PAGE PLATES | |

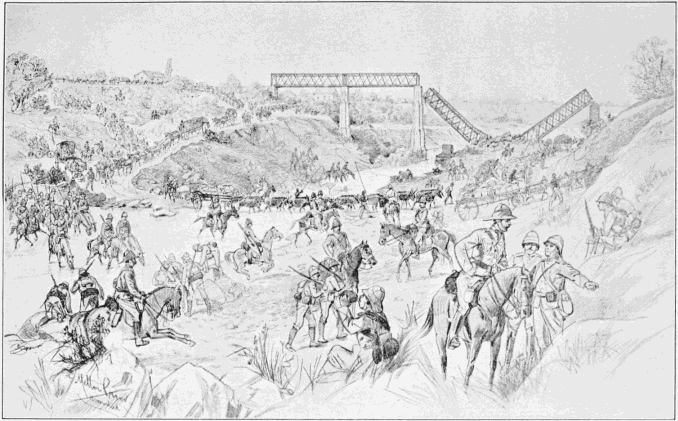

| The Disaster at Koornspruit | 8 |

| The Reddersburg Mishap | 16 |

| British Prisoners on their way to Pretoria | 24 |

| Lord Roberts’s Column Crossing the Sand River Drift | 100 |

| The Surrender of Kroonstadt | 104 |

| Mafeking: “The Wolf that Never Sleeps” | 108 |

| The Last Attack on Mafeking | 136 |

| Lord Roberts and his Army Crossing the Vaal River | 140 |

| Royal Horse Artillery Crossing the Vaal | 144 |

| General Ian Hamilton thanking the Gordons for their Attack at the Battle of Doornkop | 148 |

| The City of London Imperial Volunteers Supporting General Hamilton’s Left Flank in the Action at Doornkop | 152 |

| Hauling down the Transvaal Flag at Johannesburg | 156 |

| The Grenadier Guards at the Battle of Biddulph’s Berg | 168 |

| Pursuing the Boers after the Fight on Helpmakaar Heights | 176 |

| Scene in Pretoria Square, June 5 | 184 |

| The Entry of Lord Roberts and Staff into Pretoria | 192 |

| 3. FULL-PAGE PORTRAITS | |

| Lieut.-General Sir Archibald Hunter, K.C.B. | 32 |

| Colonel Lord Chesham | 40 |

| Lieut.-General Sir H. M. Leslie-Rundle, K.C.B. | 64 |

| Major-General Pole-Carew | 72 |

| Major-General Ian Hamilton | 88 |

| Lieut.-General Sir Frederick Carrington, K.C.M.G. | 112 |

| Lieut.-Colonel Bryan T. Mahon, D.S.O. | 120 |

| Lieut.-Colonel Plumer | 128 |

| 4. MAPS AND ENGRAVINGS IN THE TEXT | |

| Plan—Koorn Spruit Disaster | 5 |

| Map—District S. and E. of Bloemfontein | 15 |

| The Model School, Pretoria | 22 |

| New Camp for British Prisoners at Pretoria | 29 |

| Field Gun—Elswick Battery | 39 |

| The Native Village of Mafeking | 47 |

| Mafeking Postage Stamps | 52 |

| The Defence of Wepener | 58 |

| Wepener | 66 |

| Operations at Dewetsdorp | 76 |

| Map of Movements S. and E. of Bloemfontein | 82 |

| Kent Cottage, St. Helena | 86 |

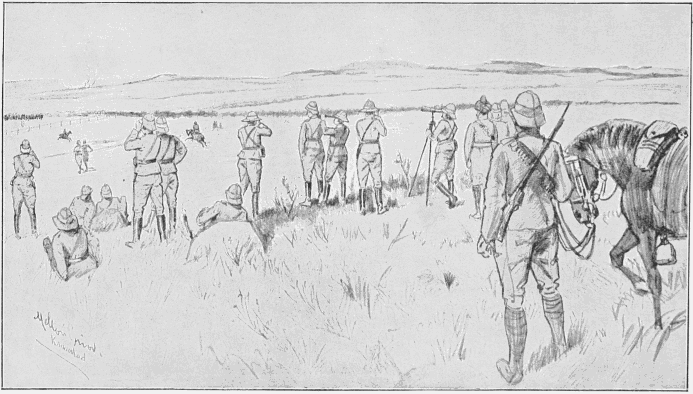

| Lord Roberts and Staff Watching the Boers’ Retreat from Zand River | 103 |

| Kroonstadt | 107 |

| General Baden-Powell and Officers at Mafeking | 114 |

| Map and Itinerary, Colonel Mahon’s March | 118 |

| Map of Route from N. for Relief of Mafeking | 127 |

| Mafeking Railway Station | 139 |

| Deviation Bridge at Vereeniging | 153 |

| Highlanders at the End of a Forced March | 160 |

| Map of Portion of Natal | 175 |

| Map—Johannesburg to Pretoria, &c. | 186 |

MARCH 1900.

31.—Loss of British convoy and seven guns at Koorn Spruit.

APRIL 1900.

4.—Capture of British troops by the Boers near Reddersburg.

5.—General Villebois killed near Boshop, and party of Boer mercenaries captured by Lord Methuen.

General Clements received the submission of 4000 rebels.

British occupation of Reddersburg.

7.—Skirmish near Warrenton.

9.—Colonial Division attacked at Wepener.

11.—General Chermside promoted to command Third Division, vice General Gatacre, ordered home.

20.—Boer positions attacked at Dewetsdorp.

23.—General Carrington arrived at Beira.

25.—Wepener siege raised.

General Chermside occupied Dewetsdorp.

Bloemfontein Waterworks recaptured.

26.—Sir C. Warren appointed Governor of Griqualand West.

27.—Thabanchu occupied.

28.—Fighting near Thabanchu Mountain.

MAY 1900.

1.—General Hamilton captured Houtnek.

5.—British occupation of Brandfort.

Lord Roberts’s further advance to the Vet River.

6.—The Vet River passed and Smaldeel occupied.

7.—General Hunter occupied Fourteen Streams.

8.—Ladybrand deserted by the Boers.

9.—Capture of Welgelegen.

Mafeking Relief Force reached Vryburg.

10.—Battle of Zand River.

Occupation of Ventersburg.

12.—Lord Roberts occupied Kroonstad without resistance.

Commandant Eloff attacked Mafeking, and was captured by Col. Baden-Powell.

13.—General Buller advanced towards the Biggarsberg.

14.—Occupation of Dundee.

15.—Occupation of Glencoe.

Mafeking Relief Force defeated the Boers at Kraaipan.

16.—Christiana occupied.

17.—General Ian Hamilton occupied Lindley.

Colonel Mahon, at the head of the relief force, entered Mafeking.

Lord Methuen entered Hoopstad.

18.—Occupation of Newcastle.

20.—Colonel Bethune’s Mounted Infantry ambushed near Vryheid.

22.—General Ian Hamilton occupied Heilbron after a series of engagements. The main army, under Lord Roberts, pitched its tents at Honing Spruit, and General French crossed the Rhenoster to the north-west of the latter place.

23.—Rhenoster position turned.

24.—British Army entered the Transvaal, crossing the Vaal near Parys, unopposed.

27.—The passage of the Vaal was completed by the British Army.[Pg viii]

28.—Orange Free State formally annexed under the title of Orange River Colony.

The Battle of Biddulph’s Berg.

29.—Battle of Doornkop: Boers defeated.

Lord Roberts arrived at Germiston.

Kruger fled his capital at midnight amid the lamentations of the populace.

30.—Occupation of Utrecht by General Hildyard.

Sir Charles Warren defeated the enemy near Douglas.

31.—Battalion of Irish Yeomanry captured at Lindley.

The British flag hoisted at Johannesburg.

JUNE 1900.

5.—The British flag hoisted in Pretoria.

SOUTH AFRICA AND THE TRANSVAAL WAR

MAFEKING, 18TH MAY 1900

The last volume closed with an account of Colonel Plumer’s desperate effort to relieve Mafeking on the 31st of March. On that unlucky day events of a tragic, if heroical, nature were taking place elsewhere. These have now to be chronicled. On the 18th of March a force was moved out under the command of Colonel Broadwood to the east of Bloemfontein. The troops were sent to garrison Thabanchu, to issue proclamations, and to contribute to the pacification of the outlying districts. They were also to secure a valuable consignment of flour from the Leeuw Mills. The enemy was prowling about, and two commandos hovered[Pg 2] north of the small detached post at the mills. Reinforcements were prayed for, and a strong patrol was sent off for the protection of the post, or to cover its withdrawal in the event of attack. Meanwhile the enemy was “lying low,” as the phrase is. Whereupon Colonel Pilcher pushed on to Ladybrand, made a prisoner of the Landdrost, but, hearing of the advance of an overwhelming number of the foe, retired with all promptness to Thabanchu. The Boers, with the mobility characteristic of them, were gathering together their numbers, determining if possible to prevent any onward move of the forces, and bent at all costs on securing for their own comfort and convenience the southern corner of the Free State, whence the provender and forage of the future might be expected to come. Without this portion of the grain country to fall back on, they knew their activities would be crippled indeed.

In consequence, therefore, of the close proximity of these Federal hordes, Colonel Broadwood made an application to head-quarters for reinforcements, and decided to remove from Thabanchu. On Friday the 30th he marched to Bloemfontein Waterworks, south of the Modder. His force consisted of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade (10th Hussars and the composite regiment of Household Cavalry), “Q,” “T,” and “U” Batteries R.H.A. (formed into two six-gun batteries, “Q” and “U”), Rimington’s Scouts, Roberts’s Horse, Queensland and Burma Mounted Infantry. The baggage crossed the river, and outspanned the same evening. On the following morning at 2 A.M. the force, having fought a rearguard action throughout the night, arrived in safety at Sanna’s Post. Here for a short time they bivouacked, and here for a moment let us leave them.

At this time a mounted infantry patrol was scouring the country. They were seen by some Boers who were scuttling across country from the Ladybrand region, and these promptly hid in a convenient spruit, whence, in the time that remained to them, they planned the ambush that was so disastrous to our forces and so exhilarating to themselves. There are differences of opinion regarding this story. Some believe that the ambush was planned earlier by a skilful arrangement in concert with the Boer hordes—the hornets of Ladybrand, whose nest had been disturbed by the invasion of Colonel Pilcher—who owed Colonel Broadwood a debt. They declare that the hiding-place was carefully sought out, so that those sheltered therein should, on a given signal from De Wet, act in accord with others of their tribe, and blockade the passage of the British, who were known—everything was known—to be returning to Bloemfontein.

According to Boer reports, the plans for the cutting off and surrounding of Colonel Broadwood were carefully made out, but only at the last moment, and if, for once, Boer reports can be believed, the successful scheme may be looked upon as one of the finest pieces of[Pg 3] strategy with which De Wet may be accredited. The Boer tale runs thus: The Dutchman on the 28th, with a commando of 1400 and four guns and a Maxim-Nordenfeldt, was moving towards Thabanchu for the purpose of attacking Sanna’s Post, where he believed a force of 200 of the British to be. He did all his travelling by night, and found himself on the evening of the 30th at Jan Staal’s farm, on the Modder River, to the north of Sanna’s Post. Then, in the very nick of time, he was informed by a Boer runner that Colonel Broadwood’s convoy was moving from Thabanchu. Quickly a council of war was gathered together. It was a matter of life or death. De Wet, with Piet de Wet, Piet Cronje, Wessel, Nell, and Fourie, put their heads together and schemed. They were doubtless assisted by the foreign attachés who were present. The result of the hurried meeting was the division of the Boer force into three commandos. The General himself, with 400 men, decided to strain every nerve to reach Koorn Spruit and ensconce himself before the arrival of the convoy. Being well acquainted with the topography of the country, the race was possible—400 picked horsemen against slow-moving, drowsy cattle! The thing was inviting. Success rides but on the wings of opportunity, and De Wet saw the opportunity and grabbed it! The rest of the Boers were to dispose themselves in two batches—500 of them, with the artillery, to plant themselves N.N.E. of Sanna’s Post, while the remainder took up a position on the left of their comrades, and extended in the direction of the Thabanchu road.

It was wisely argued that Broadwood’s transport must cross Koorn Spruit, and that if the Boers were posted so as to shell the British camp at daybreak, the convoy would be hurried on, while the bulk of the force remained to guard the rear.

Accordingly, the conspirators, with amazing promptitude, got under way, the four guns with the commando being double-horsed and despatched to the point arranged on the N.N.E. of Sanna’s Post, while the other galloped as designed. Fortune favoured them, for they reached their destinations undiscovered; and the scheme, admirable in conception, was executed with signal success.

Day had scarcely dawned before the Boers near the region of the waterworks apprised the convoy of their existence. The British kettles were boiling, preparations for breakfast were briskly going forward, when, plump!—a shell dropped in their midst. Consternation prevailed. Something must be done. The artillery? No; the British guns were useless at so long a range. As well have directed a penny squirt at a garden hose! All that was to be thought of was removal—and that with all possible despatch. Scurry and turmoil followed. Mules fought and squealed and kicked, horses careered and plunged, but at last the convoy and two[Pg 4] horse batteries were got under way, while the mounted infantry sprayed out to screen the retreat. All this time shells continued to burst and bang with alarming persistency. They came from across the river, and consequently it was imagined that every mile gained brought the convoy nearer to Bloemfontein and farther from the enemy. They had some twenty miles to go. Still, the officers who had charge of the party believed the coast to be clear. After moving on about a mile they approached a deep spruit—a branch of the Modder, more morass than stream. It was there that De Wet and his smart 400 had artfully concealed themselves.

The spruit offered every facility for the formation of an ingenious trap. The ground rose on one side toward a grassy knoll, on the slopes of which was a stony cave from which a hidden foe could command the drifts. So admirably concealed was this enclosure and all that it enclosed, that the leading scouts passed over the drift without suspecting the presence of the enemy. These latter, true to their talent of slimness, made no sign till waggons and guns had safely entered the drift, and were, so to speak, inextricably in their clutches.

Their manœuvre was entirely successful. Some one said the waggons were driven into the drift exactly as partridges are driven to the gun. Another gave a version of very much the same kind. He said, “It was just like walking into a cloak-room—the Boers politely took your rifle and asked you kindly to step on one side, and there was nothing else you could do!”

The nicety of the situation from the Boer point of view was described by a correspondent of The Times:—

“The camp was about three miles from the drift, which lay in the point of a rough angle made by an embankment under construction and the bush-grown sluit which converged towards it. Thus when the Boers were in position, lining the sluit and the embankment, the position became like the base of a horse’s foot. The Boers were the metal shoe, our own troops the frog. At the point where the drift cuts the sluit the nullah is broad and extensive. The Boers stationed at this spot realised that the baggage was moving without an advanced guard. They were equal to the situation. As each waggon dropped below the sky-line into the drift the teamsters were directed to take their teams to right or left as the case might be, and the guards were disarmed under threat of violence. No shot was fired. Each waggon in turn was captured and placed along the sluit, so that those in rear had no knowledge of what was taking place to their front until it became their turn to surrender. To all intents and purposes the convoy was proceeding forward. The scrub and high ground beyond the drift was sufficient to mask the clever contrivance of the enemy. Thus all the waggons except nine passed into the hands of the enemy.[Pg 5]”

The waggons, numbering some hundred, had no sooner descended to the spruit and got bogged there than, from all sides sprung up as from the earth, Boers with rifles at the present, shouting—“Hands up. Give up your bandoliers.” A scene of appalling confusion followed. Some cocked their revolvers. Others were weaponless. So unsuspecting of danger had they been that their rifles, for comfort’s sake, had been stowed on the waggons, the better to allow of freedom to assist in other operations of transport. Some men of the baggage guard shouldered their rifles; others, from under the medley of waggons, still strove ineffectually to show fight. The Boers were unavoidably in the ascendant. The hour and the opportunity were theirs.

At this time up came U Battery, with Roberts’s Horse on their left. The battery was surrounded, armed Boers roared—“You must surrender!” and then, sharp and clear, the first shot rang through the air. This was said to have been fired by Sergeant Green, Army Service Corps, who, refusing to surrender, had shot his antagonist, and had instantly fallen victim to his grand temerity. The drivers of the batteries were ordered to dismount, but as gunners don’t dismount graciously to order of the foe, the tragedy pursued its course. Major Taylor, commanding the battery, however, succeeded in galloping off to warn the officer commanding Q Battery of the catastrophe. Meanwhile, in that serene and pastoral spruit reigned fire and fury and the clash of frenzied men. Down went a horse—another, another. Then man after man—groaning and reeling in their agony. Many in the spruit lay dead. At this[Pg 6] time the troop of Roberts’s Horse had appeared on the scene, and were called on to surrender. Realising the disaster, they wheeled about, and galloped to report and bring assistance. This was the signal for more volleys from the enemy in the spruit, and the horsemen thus sped between two fires—that of the Mausers below them and of the shells which had continued to harry the troops. Nevertheless the gallant fellows rode furiously for dear life on their journey. Men dropped from their saddles like ripe fruit from a shaken tree. Still they sped on. They must bring help at any price. Meanwhile the scene in the spruit was one of horror, for the Boers were sweeping every nook and corner with their Mausers. Cascades of fire played on the unfortunate mass therein entangled, on waggons overturned and squealing mules, on guns and horses hopelessly heaped together, on men and oxen sweating and plunging in death-agony. The heaving, struggling, horrific picture was too grievous for description. Only a part of their terrible experience was known by even the actors themselves. Luckily, a merciful Providence allows each human intelligence to gauge only a certain amount of the awful in tragic experience. There are some who told of wounded men lying blood-bathed and helpless beneath baggage that weighed like the stone of Sisyphus; of horses that uttered weird screams of agonised despair, which petrified the veins of hearers and sent the current of blood to their hearts; of oxen and mules that stamped and kicked, dealing ugly wounds, so that those who might have crawled out from under them could crawl no more. Some guns were overturned—a hopeless bulk of iron, that resisted all efforts at removal; others, bereft of their drivers, were dragged wildly into space by maddened teams, whose happy instinct had caused them to stampede. Seeing the disaster, they had pulled out to left and struggled to get back to camp, yet even as they struggled they were disabled and thus left at the mercy of the foe.

Major Burnham, the famous scout, who having been taken a prisoner earlier and at this juncture remained powerless in the hands of the Boers, thus described the terrible sight which he was forced to witness:—

“One of the batteries (Q), which was upon the outside of the three-banked rows of waggons, halted at the spruit, dashed off, following Roberts’s Horse to the rear and south. Yet most of them got clear, although horses and men fell at every step, and the guns were being dragged off with only part of their teams, animals falling wounded by the way. Then I saw the battery, when but 1200 yards from the spruit, wheel round into firing position, unlimber, and go into action at that range, so as to save comrades and waggons from capture. Who gave the order for that deed of self-sacrifice I don’t know. It may have been a sergeant or lieutenant,[Pg 7] for their commanding officer had been left behind at the time. One of the guns upset in wheeling, caused by the downfall of wounded horses. There it lay afterwards, whilst three steeds for a long time fought madly to free themselves from the traces and the presence of their dead stable companions.”

Those of the unfortunate men who were uninjured struggled grandly to save the guns, to drag them free from the scene of destruction, but several of the guns whose teams were shot fell into the hands of the enemy. Some gallant fellows of Rimington’s Scouts made a superb effort to rush through the fire of the Federals and save them, but five guns only were rescued. These were all guns of Q Battery, which, when the first alarm was given, were within 300 yards of the spruit. When the officer who commanded the battery strove to wheel about, though the Boers took up a second position and poured a heavy fire on the galloping teams, a wheel horse was shot, over went a gun, more beasts dropped, a waggon was rendered useless, but still the teams that remained were galloped through the confusion to the shelter of some tin buildings, part of an unfinished railway station, some 1150 yards from the disastrous scene. Here a new era began. Much to the amazement of the Boers, the guns came into action, and continued, in the face of horrible carnage, to make heroic efforts at retaliation, the officers themselves assisting in serving the guns till ordered to retire. At this time Q Battery was assailed by a terrific cross fire, and gradually the numbers of the gunners and horses became thinned, till the ground, covered with riderless steeds and dismounted and disabled men, presented a picture of writhing agony and stern heroism that has seldom been equalled. But the splendid effort had grand results.

No sooner were the British guns in action than the whole force rallied: the situation was saved. The Household Cavalry and the 10th Hussars were off in one direction, Rimington’s Scouts and the mounted infantry in another, making for some rising ground on the left where their position would be defensible and a line of retreat found. Meanwhile Q Battery from six till noon pounded away at the Dutchmen, while Lieutenant Chester-Master, K.R.R., found a passage farther down the spruit unoccupied by the enemy, by which it was possible to effect a crossing. Major Burnham’s account of the artillery duelling at this time is inspiriting:—

“As soon as the gunners manning the five guns opened with shrapnel, the Boers hiding in Koorn Spruit slackened their fire, preferring to keep under cover as much as possible. In that way many others escaped. The mounted infantry deployed and engaged the Boer gunners and skirmishers to the east, and the cavalry with Roberts’s Horse dismounted and rallied to cover the guns from the fire. A small body was also despatched to strike south and fight north. My captors directed their attention to Q Battery. They got the range,[Pg 8] 1700 yards, by one of the Boers firing at contiguous bare ground, until he saw by the dust puffs he had got the distance, whereupon he gave the others the exact range, which they at once adopted. The gunners gave us nearly forty-eight shrapnel, for they were firing very rapidly, but although they had the range of our kraal, they only managed to kill one horse. I noticed that the Boers, though they dodged and took every advantage of cover, fired most carefully, and yet rapidly. It was the same with those in the spruit as inside the kraal where I sat. That day the Boers said to me they had but three men killed in the spruit, and only a half-dozen or so wounded. Those artillerymen, how I admired and felt proud of them! and the Boers, too, were astonished at their courage and endurance. Fired at from three sides, they never betrayed the least alarm or haste, but coolly laid their guns and went through their drill as if it had been a sham-fight, and men and horses were not dropping on all sides. There was a little bit of cover a hundred yards or so behind the battery, around the siding and station buildings of the projected railway and embankment. Thither the living horses from the limbers and guns were taken, and the wounded were conveyed. When, three hours later, their ammunition for the 12-pounders was scarce, and the Boer rifle fire from the gulch, the waggons, and ridge opened heavy and deadly, the gunners would crawl back and forward for powder and shell. Had it not been for those terrible cannon, the Boers told me that they would have charged, closing in on all sides upon Broadwood’s men.”

When the order to retire was received, Major Phipps Hornby ordered the guns and their limbers to be run back by hand to where the teams of uninjured horses stood behind the station buildings. Then such gunners as remained, assisted by the officers and men of the Burma Mounted Infantry, and directed by Major Phipps Hornby and Captain Humphreys (the sole remaining officers of the battery), succeeded in running back four of the guns under shelter. It is said the guns would never have been saved but for the gallant action of the officers and men of the Burma Mounted Infantry, who, when nearly every gunner was killed, volunteered, and succeeded, under the heaviest fire, in dragging the guns back by hand to a place of safety. It was while doing this that Lieutenant P. C. Grover, of the Burma Mounted Infantry, was killed. Though one or two of the limbers were thus valiantly withdrawn under a perfect cyclone of shot and shell, the exhausted men found it impossible to drag in the remaining limbers or the fifth gun. Human beings failing, the horses had also to be risked, and presently several gallant drivers volunteered to plunge straight into the hellish vortex. They got to work grandly, though horses dropped in death agony and man after man, hero after hero, was picked off by the unerring and copious fire of the Dutchmen. It is difficult to get the names of all the glorious fellows who carried their lives in their hands on that great but dreadful day, but Gunner Lodge and Driver Glasock were chosen as the representatives of those who immortalised themselves and earned the Victoria Cross. Of[Pg 9] Bombardier Gudgeon’s magnificent energy enough cannot be said. One after another teams were shot, but he persisted in his work of getting fresh teams. Three times he strove to roll a gun to a place of safety, and on the third occasion was wounded. The splendid discipline of the gunners was extolled by every eye-witness, and the way the noble fellows, surrounded with Boer sharpshooters, stood to the guns was so marvellous, so inspiriting, that even the men who were covering the retirement, at risk of their lives were impelled to rise and cheer the splendid action of the glorious remnant. The correspondent of The Times declared that “When the order came for the guns to retire, ten men and one officer alone remained upon their feet, and they were not all unwounded. The teams were as shattered as the gun groups. Solitary drivers brought up teams of four—in one case a solitary pair of wheelers was all that could be found to take a piece away. The last gun was dragged away by hand until a team could be patched up from the horses that remained. As the mutilated remnant of two batteries of Horse Artillery tottered through the line of prone mounted infantry covering its withdrawal, the men could not restrain their admiration. Though it was to court death to show a hand, men leaped to their feet and cheered the gunners as they passed. Seven guns and a baggage train were lost, but the prestige and honour of the country were saved. Five guns had been extricated. The mounted infantry had found a line of retreat, and total disaster was avoided. But the fighting was not over. The extrication of a rearguard in the front of a victorious and exultant enemy has been a difficult and a delicate task in the history of all war. In the face of modern weapons it is fraught with increased difficulties. For two hours Rimington’s Scouts, the New Zealand Mounted Infantry, Roberts’s Horse, and the 3rd Regiment of Mounted Infantry covered each other in retreat, while the enemy galloped forward and, dismounting, engaged them, often at ranges up to 300 yards.”

The force was surrounded by the enemy on all sides, and there was no resource but to fight through—the cavalry and mounted infantry taking a line towards a drift on the south. Roberts’s Horse made a gallant and desperate effort to outflank the Dutchmen, and lost heavily; and Aldersen’s Brigade, with magnificent dash and considerable skill, succeeded in holding back the hostile horde. This retirement was no easy matter, for the position taken up by the Federals was exceptionally favourable to them. To the north the spruit twisted in a convenient hoop, which sheltered them; to the south was the embankment of the railway in course of construction; from these points and from front and rear the enemy was able, in comparative security, to batter and harass the discomfited troops.

Fortunately, in the end, Colvile’s Division, which had been[Pg 10] making its way from Bloemfontein, arrived in time to check the Boers in their jubilant advance, though some hours too late to prevent the enemy from capturing and removing the waggons and guns.

While the retreat was being effected more valorous work was going on elsewhere. The members of the Army Medical Corps, with the coolness peculiar to them, were exposing themselves and rushing to the assistance of the wounded, many being stricken down in the midst of their splendid labours. Roberts’s Horse made themselves worthy of the noble soldier who godfathered them, and one—a trooper of the name of Tod—a prodigy of valour, rode deliberately into the mêlée in search of the wounded, and returned with the dead weight of a helpless man in his arms, under the fierce fire of the foe. If disaster does nothing more, it breeds heroes. The melancholy affair of Koorn Spruit brought to light the superb qualities that lie dormant in many who live their lives in the matter of fact way and give no sign.

Splendid actions followed one another with amazing persistence, man after man and officer after officer attempting deeds of daring, each of which in themselves would form the foundation of an heroic tale. Lieutenant Maxwell of Roberts’s Horse, from the very teeth of the enemy dragged off a wounded man—a lad who, by the time he was rescued, had fainted. But the young subaltern promptly got him in the saddle, and the pair sped forth from the fiery zone alive. The Duke of Teck also rushed to the succour of Lieutenant Meade, who was wounded (a bullet cutting off his finger and piercing his thigh), gave up to him his horse and removed him from the scene of danger. At the same time Colonel Pilcher was gallantly rescuing Corporal Packer of the 1st Life Guards. Major Booth (Northumberland Fusiliers) lost his life through doggedly holding a position with four others, in order to cover the retreat.

When the Queenslanders arrived they too showed the stuff they were made of, the best British thews combined with the doughtiest British hearts. They plunged into action—so dashingly indeed that the Boers very nearly mopped them up. But Colonel Henry was equal even to the skittish foe, and contrived to entertain the Dutchmen by leading them so active a dance that eventually the Colonials were able to fight out their own salvation.

At last the guns got away and followed the line of retreat taken by the cavalry. The troops then conducted their retirement by alternate companies, each company taking up its duties without fluster, and covering the other company’s retirement with great steadiness until they reached Bushman’s Kop. The marvellous coolness of the force was particularly amazing, as every man, with the Boers still at his heels, believed himself to be cut off, yet in spite of[Pg 11] this belief showed no signs of concern. In one regiment, consisting of 11 officers and 200 men, two officers were killed, four wounded, and sixty-six men killed and wounded.

Strange scenes took place during those awful hours in the donga, and wonderful escapes were made. One trooper was seized on by a Boer. “Surrender,” cried the Dutchman, but before another word could be uttered, the trooper’s sabre whistled from its sheath and the Boer was dead. Another who was wounded got off, as he said, “by the skin of his teeth.” He had become jammed under a waggon in company with a Boer—who had crept there for cover—and the hindquarters of a dying mule. Over the cart poured a rattling rain of bullets, to which he longed to respond. The Boer, believing the wounded man to be his prisoner, made himself known. “Hot work this,” he said. The next instant the Boer was caught by the throat and knocked insensible, while the Briton promptly extricated himself and vanished from the seething, fighting mass. Another of the Household Cavalry, when summoned to surrender his rifle, threw it with such force at the head of his would-be captor that he was able to make good his escape.

The following interesting account was given from the point of view of an officer of the Life Guards who was present:—

“We heard firing at 6.30, and while we were saddling bang came two shells a little short, followed by three others. The firing went on for half-an-hour incessantly. The convoys got under way very quickly, followed by Mounted Infantry and Life Guards. Luckily only two shells burst, and only one mule was killed. We moved on to the spruit and were shot at by Mausers from our right flank. The convoys were on the brink of the drift. Some of the waggons were actually crossing, and our artillery close on to them, when a terrific fire came from the spruit. The U Battery was captured—the men and officers being killed, wounded, or prisoners. We went about and retired in good order in a hail of shot, being within 120 yards of the enemy. It is wonderful how we escaped. Two of our men were shot—one in the thigh and the other in the shoulder—and we had altogether 32 missing. Our leading horses and baggage were within nine feet of the fire; yet many of them got off, including my servant and horse. I lost, however, my saddlebags, with change of clothes, trousers, shoes, iron kettle, and letters which I grudge the Boers reading. We got out of fire and lined the river banks, firing shots at the Boers, who were, however, too distant. We were well hid in a position like what the Boers had held themselves, and we hoped to enfilade them, but the river twisted too much, and it is impossible to locate fire with smokeless powder. We then followed the 10th Hussars for four miles towards Bushman’s Kopje. The Ninth Division[Pg 12] Infantry, under Colvile, came over the ridge with eighteen guns, and we heard a lot of heavy firing.”

He went on to say: “Why we are alive I can’t say. Many of the bullets were explosive, as I heard them burst when they hit the ground. The shelling was most trying, as we had to stand quite still for twenty minutes a living target.”

A laughing philosopher, a Democritus of the nineteenth century, gave to the world, viâ the Pall Mall Gazette, his curious experiences. Among other things he said:—

“Roberts’s Horse was ordered to trot off to the right of the convoy. ‘Oh! those are our men, you fool,’ said everybody. Two men came up to the Colonel. ‘We’ve got you surrounded, you’d better surrender,’ say they; and heads popped up in the grass forty yards from us. Boers appeared all along the ridge a hundred yards ahead. ‘Files about, gallop!’ yells the adjutant. (They dropped him immediately.)

“I was carrying a fence-post to cook the breakfast of my section (of four men). I turned my horse; there came a crackling in the air, on the ground, everywhere; the whole world was crackling, a noise as of thorns crackling or the cracks of a heavy whip. My gee-gee (usually slow) went well, stimulated by the horses round it, and actually took a water-jump; I had to hold my helmet on with my right hand, which still held the fence-post, and I thought my knuckles would surely get grazed by a bullet. They were pouring in a cross-fire now as well, and once or twice I heard the s-s-s-s-s of the Mauser bullet (the crackle is explosives, you know). It was very exhilarating; the gallop and the fire made me shout and sing and whistle. I jumped a dead man, and almost immediately caught up B., who is one of my section.

“The fire was slackening, and we were half a mile away by then, and we looked round to see whether anybody was forming up. The plain was dotted with men and many riderless horses. Everybody was yelling, ‘When do we form up?’ You feel rather foolish when running away. At about one mile we formed up again. From the rear, and from the place we had come from, and from the river bed, there came a noise as of thousands of shipwrights hammering. Nine (?) of our guns were captured; the remaining three fired at intervals. My squadron was sent into a depression on the left of the New Zealanders. Here we dismounted (No. 3 of each section holding the horses), and went up as a firing line, range 1200, 1400, and 1600 yards. The General passed. ‘Ever been in such a warm corner?’ says he to the bugler. ‘Oh yes,’ says the little chap, quite cheerfully and untruthfully. The General remarked, laughing, that he hadn’t. I felt sorry for him, and heard the newsboys shouting, ‘Another British disaster!’ and the Continental[Pg 13] papers, ‘Nouvelle défaite des Anglais! Yah!’ It was the greatest fun out, barring the loss of the guns and men. For we were not losing a situation of strategic importance or anything of that kind. The Boers had collared our blankets and things, but we chuckled at the thought of what they would suffer if they ever slept in ’em.”

Sergeant-Major Martin, who, with Major Taylor (commanding U Battery), was incidental in warning Colonel Rochfort and Major Phipps Hornby of their danger, and thus assisting to save Q Battery, described his experiences:—

“A Boer commander stepped out and confronted the Major with fixed bayonet; all his (the Boer’s) men stood up in the spruit ready to shoot us down if we had attempted to fight, ordered the Major to surrender, and also the battery. The battery had no chance whatever to do anything. As the trap was laid, so we fell into it. Now, as the Major was talking to the Boer commander, I turned my horse round (I was then three yards from him) and walked quietly to the rear of our battery. When I got there, putting spurs to my horse, I galloped for all I was worth to tell the Colonel to stop the other battery, as U Battery were all prisoners. I then looked towards the battery; the Boers were busy disarming them. I went a little distance in that direction to have a last look. By this time the Household Cavalry had come up, and the 14th Hussars; they halted, soon found out what had happened, and turned round to retire. As they did so the Boers opened fire on us. The bullets came like hailstones. It was a terrible sight. One gun and its team of horses galloped away; by some means or other it was pulled up. I took possession of it, still under this heavy fire, and, finding one of our drivers, I put him in the wheel, and drove the leaders myself. We had between us 14 horses. I drove in the lead for about six miles, following the cavalry, who had gone on to see if we could get through. Eventually, after several hours, I got into safe quarters.”

The list of loss was terrible:—

Brevet-Major A. W. C. Booth, Northumberland Fusiliers; Lieutenant P. Crowle, Roberts’s Horse; Lieutenant Irvine, Army Medical Service (attached to Royal Horse Artillery), were killed. Among the wounded were: Brevet-Colonel A. N. Rochfort, Royal Horse Artillery, Staff. Q Battery Royal Horse Artillery.—Captain G. Humphreys, Lieutenant E. B. Ashmore, Lieutenant H. R. Peck, Lieutenant D. J. Murch, Lieutenant J. K. Walch, Tasmanian Artillery (attached). Royal Horse Guards.—Lieutenant the Hon. A. V. Meade. Roberts’s Horse.—Major A. W. Pack Beresford, Captain Carrington Smith, Lieutenant H. A. A. Darley, Lieutenant W. H. M. Kirkwood. Mounted Infantry.—Major D. T. Cruickshank, 2nd Essex Regiment; Lieutenant F. Russell-Brown, Royal Munster Fusiliers; Lieutenant P. C. Grover, Shropshire Light Infantry (since dead); Lieutenant H. C. Hall, Northumberland Fusiliers. Wounded and Missing.—Captain P. D. Dray, Lieutenant and Quartermaster Hawkins. Missing.—Lieutenant H. R. Horne. Royal Horse Artillery.[Pg 14]—Captain H. Rouse, Lieutenant G. H. A. White, Lieutenant F. H. G. Stanton, Lieutenant F. L. C. Livingstone-Learmonth. 1st Northumberland Fusiliers.—Lieutenant H. S. Toppin. 2nd Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry.—Lieutenant H. T. Cantan. 1st Yorkshire Light Infantry.—Captain G. G. Ottley. Royal West Kent Regiment.—Lieutenant R. J. T. Hildyard. Captain Wray, Royal Horse Artillery, Staff; Captain Dray, Roberts’s Horse; Lieutenant the Hon. D. R. H. Anderson-Pelham, 10th Hussars; Lieutenant C. W. H. Crichton, 10th Hussars.

The casualties all told numbered some 350, including 200 missing. Reports differ regarding the strength of the enemy. Lord Roberts estimated it at 8000 to 10,000, while De Wet declared he had only about 1400 men.

All that remained of U Battery was one gun, Major Taylor, a sergeant-major, a shoeing-smith, and a driver!

In Q Battery, Captain Humphreys, Lieutenants Peck, Ashmore, Murch were wounded, and the latter two reported missing.

The whole of the grievous Saturday afternoon was spent by the gallant doctors in tending the ninety or more of our brave wounded who lay helpless in the spruit. They were carried to the shelter of the tin houses, and the work of bandaging and extracting bullets was pursued without a moment’s relaxation. The removal of the sufferers from the neighbourhood of the spruit on the day following was a sorry task, and the sight that presented itself to the ambulance party was one which was too shocking to be ever forgotten. In the spruit itself the wreckage of waggons which had been looted by the Boers covered most of the scene, and, interspersed with them were horses and cattle, maimed, mutilated, and dead. With these, in ghastly companionship, were the bodies of slain soldiers and black waggon-drivers. The living wounded were conveyed from the disastrous vicinity in ambulances and waggons brought for them under the covering fire of the guns, which swept the length of the river and deterred the enemy from attempting to block the passage of the melancholy party. The Republicans, however, fired viciously from adjacent kopjes, but without disturbing the progress of the operations.

At noon General French’s cavalry, with Wavell’s Brigade, had left Bloemfontein to occupy a position on the Modder between Glen and Sanna’s Post, and keep an eye on further encroachments of the Boers. The enemy, on the fatal Saturday night, had destroyed the waterworks, thus forcing the inhabitants of Bloemfontein to fall back on some insanitary wells, as a substitute for which the waterworks had been erected. Here, on their departure for Ladybrand, they left 12 officers and 70 men, who had been wounded in the fray, and whom they doubtless considered might be an encumbrance to their future movements. These were conveyed by ambulance to Bloemfontein.[Pg 15]

As an instance of Boer treachery, it was stated that the Free State commandant Pretorius, whose farm overlooked the spruit wherein the ambuscade was arranged, had given up arms and taken the oath to retire to his farm. Yet on the day of the disaster he led the Boers to the attack, while the members of his family were prominent among the looters of the wrecked waggons. Other tales of cruelty and ill-treatment and treachery on the part of the Boers were well authenticated. It is useless to repeat them, but the circumstances are merely noted to give an explanation for a change of policy which was necessitated by the actions of the enemy—a change which was, unfortunately, adopted only when many martyrs had been made in the cause of forbearance.

The Boers, triumphant with their success at Koorn Spruit, scurried to Dewetsdorp, drove out the British detachment which had been posted there by General Gatacre, and on the 4th of April came in for another piece of luck, for which we had to pay by the loss of three companies of Royal Irish Rifles and two companies of the Northumberland Fusiliers.

The unfortunate occurrence took place near Reddersburg, somewhat to the east of Bethanie Railway Station. A party of infantry, consisting of three companies of Royal Irish Rifles and two companies of the Northumberland Fusiliers, who had been in occupation of Dewetsdorp, and engaged on a pacification mission on the east of the Free State, were ordered on the 3rd to retire to Reddersburg, a place situated some thirty-seven miles from Bloemfontein and fifty miles from Springfontein, where General Gatacre had taken up his head-quarters. In their retirement the troops, it is said, took a somewhat unusual detour, and thus, if they did not court, ran risk of disaster. Anyway, they had travelled about four miles to the east of their destination when, at Mosterts Hok, they were surprised to discover a strong force of some 2500 Boers. They were still more surprised to find that, while they themselves were unaccompanied by artillery, and were possessed of little reserve ammunition, the Dutchmen were provided with three or four formidable guns. Thus, the situation from the first was alarming. Our men, comparatively defenceless, saw themselves hedged in by an overmastering horde. They quickly occupied a position on a peaked hill rising in the centre of ground sliced and seamed with dry nullahs. These popular havens of refuge were at once seized by the Boers and deftly made use of. The Dutchmen, under cover of the dongas, crept cautiously up on all sides of the kopje, surrounding it and pouring cascades of rifle-fire on the small exposed force. In no time the chance of retreat was barred on all sides, and there was no resource but to fight through. But unfortunately, as British ammunition was limited and the Boers warily kept well out of range, all that could be done was to prolong hostilities in the hope that delay would enable reinforcements from Bethanie to come to the rescue. But these did not arrive. The Boers, grasping the situation, gathered courage and approached nearer and nearer. With the dusk coming on and some 2500 of the foe enfilading them from three sides, the British position, as may be imagined, was not a hopeful one. Nevertheless, the Royal Irish Rifles displayed the national spirit of dare-devilry—“fought like bricks,” some one said—never losing heart under the persistent attacks of shot and shell that continued till nightfall.

Hoping and waiting and fighting; so passed the dreadful hours of dark. Then, with the dawn, the enemy, flushed with triumph, commenced to pound their prey with redoubled vigour, while our parched and almost ammunitionless troops, in a ghastly quandary, alternately fought and prayed for relief!

Meanwhile the news of the affair having reached Lord Roberts, General Gatacre, on the afternoon of the 3rd, was ordered to proceed from Springfontein to the spot, while the Cameron Highlanders were despatched from Bloemfontein to Bethanie.

General Gatacre, with his main body and an advance guard of mounted infantry under Colonel Sitwell, then marched viâ Edenburg to the succour of the detachment. On the morning of the 4th, Colonel Sitwell having arrived at Bethanie, some fifteen miles from Mosterts Hok, heard sounds of artillery in the distance, and believing that the engagement was going on, prepared to rush to the rescue. But with the small force at his disposal, he deemed it impossible to try a frontal attack, and decided to make an attempt to get round the enemy’s right flank. The manœuvre was unsuccessful, for a party of hidden Boers, from a kopje north-west of Reddersburg, assailed him and forced him to retire and wait till the main column should come to his assistance. But by the time General Gatacre had reached the scene (10.30 A.M. on the 4th) the drama had been enacted, the curtain had descended on the tragedy. The small and valorous party on Mosterts Hok, which for thirty hours had been fighting and were at last sans water, sans ammunition, sans everything in fact, had been forced to surrender. No sign of them was to be seen. The unfortunate band—many of them the survivors of the fatal exploit at Stormberg—were now on their way to that aristocratical prison-house—the Model School at Pretoria.

General Gatacre, finding further effort useless, then occupied the town of Reddersburg. There, the Boers had hoisted the Free State flag, and were making themselves generally objectionable. Quickly the Boer banner was torn down and the Union Jack run up, though during the operations the General narrowly escaped assassination. He was fired at from a house, but fortunately escaped with only a scratch on the shoulder.

By evening, acting on instructions from Bloemfontein, and owing to the fact that the enemy was massed in all directions and surrounding the town, the force and its prisoners returned to Bethanie, and there encamped to mount guard over the rail. Details regarding the movements of the troops on this grievous day were given by a correspondent, in the Daily Telegraph, whose version throws a somewhat depressing light on the sufficiently depressing affair. The writer declared that:—

“A large British force, with a brigade division of artillery[Pg 18] (eighteen guns), on the march to Bloemfontein, was at Bethanie, about eleven miles from Reddersburg, on the night of April 3, and got the news of the above-mentioned infantry being surrounded about 11 P.M. The men immediately saddled up, got under arms, and remained all night ready to move off in relief, but did not receive orders to do so until 8 A.M. on April 4, and then were only permitted to proceed at a walk, constantly halting to water the horses. The result of the delay was that the column arrived just too late, and was then not even allowed to pursue the enemy and release the prisoners, who were dead beat and could not possibly have been hurried along. The relief column was manœuvred outside the town of Reddersburg during most of the day, and then was ordered to return to Bethanie, but, when within a few miles of camp, with the horses and men tired out, a complete change of instructions were issued, and the column was wheeled about and told to march back and take the town of Reddersburg. The Cameron Highlanders, who had just come off a troopship from Egypt, and were, consequently, quite unfit, could hardly move, but all had to turn, for no apparent reason, and march to the ground they had left. The mounted infantry and artillery trotted back and occupied Reddersburg about dusk, with only one casualty, viz. an officer of mounted infantry, and the force bivouacked, with very little food, just outside the town.

“About midnight, the order was given to return to Bethanie again, and the men, who could hardly crawl, were awakened, the march resumed, and Bethanie was reached about 7 A.M. on April 5, after great and unnecessary distress both to men and animals, while no object was gained, the whole expedition being a miserable fiasco, disheartening and humiliating to every one present.

“To whom blame is attributable it is difficult to say, as the officer in command seemed not to have a free hand, but to be directed by wires received at intervals, which must have taken five or six hours to reach him. Either the relief ought never to have been attempted, or it ought to have been carried out expeditiously and with determination.”

Mr. Purves, who, as a lance-corporal with one of the Ambulance Corps, was in the thick of the fray, gave a graphic description of the unhappy affair:—

“Reaching Dewetsdorp on the morning of Sunday, April 1st, we first became aware that our progress was being watched by the Boers. Just as we were about to camp outside the dorp, our scouts exchanged a few shots with those of the enemy. Beyond a temporary disarrangement of our plans, nothing happened, as the main body of the enemy did not show at all, and things quieted down till nightfall, when another alarm was caused by the arrival of the Mounted Infantry (Royal Irish Rifles and Northumberland Fusiliers), who were mistaken by our people for Boers, as their arrival was unexpected, and our presence in[Pg 19] the position occupied by us was a surprise to them. The Mounted Infantry actually dismounted to prepare for business, when fortunately a mutual recognition took place, and a hearty greeting to the brave fellows who were to bear the brunt of the coming action was extended by our force. Captain Casson (one of the first to fall at Mosterts Hock) commanded the new-comers. After a night’s rest, we started again on the march, which continued without event till Tuesday, 3rd, when our scouts at 11.30 came back with the news that the enemy were upon us, making for two kopjes in front of us. Both of these were immediately crowned by our little force of 440—the above-mentioned Mounted Infantry, with some of the Royal Irish Rifles taking the northern kopje, and the remainder of the Royal Irish Rifles that to the south. Rifle firing opened at once, and gradually grew hotter till about 2 P.M., when the Boers opened with artillery, four guns being brought into play in positions that enabled them to sweep our two lines. Fortunately, the firing was most erratic, and little or no damage was done by the shells. Volley fire from the Royal Irish Rifles soon put one of the guns out of action. We had no artillery, and the wonder is that we held the position, extended as it was far beyond what seemed tenable to so small a force, for the long time we did. The bearers of C Company, Cape Medical Staff Corps, had a particularly warm time of it. Sent as they were at the commencement of the action right on to the fighting line, they stuck to their posts till the very last without any cover, and only retired with the last line of straggling defenders, who worked their way back through a deadly hail of bullets, explosive and otherwise, to their own camp, after the Boers had won the day. The first day’s fight lasted till darkness, when we tried to snatch some rest—a luxury that came to few. Next morning at 5.30 found us sniping at one another prior to the forenoon fire that soon kept every one busy at all points. At 8 the artillery commenced firing, and the fight became fiercer till about 9, when our men on the north kopje, unable to contend against the fearful odds, hoisted the white flag, and the Boers on that side rushed the position, and were thus able to pour a murderous fire into the unfortunate Royal Irish Rifles on the southern height, who, while their attention was riveted on the enemy on their front, were in ignorance of what was going on in their rear for a while. When they turned to reply to the rear attack, their position was taken, and the poor fellows, accompanied by nine of the stretcher-bearers, had to run for the hospital, distant 600 yards, under a fearful cross-fire. Several of the Rifles were killed, but the bearers escaped marvellously. The hospital, which was pitched between the two kopjes, suffered from the shelling, and was in itself dangerous; while, to add to the risk, a trench thrown up to protect the sick was mistaken by the Boers for a rifle-trench, and became a mark for their special attention. One shell burst near the operating-tent while the surgeons were at work on a wounded man, and riddled the tent, fortunately hitting no one. Another banged into a buck waggon. A third cut a mule in halves. A slight bruise on the knee was the only hurt suffered by any of the Hospital Corps. Our dead numbered ten, whom we buried on the battle-field, placing over the grave a neatly dressed and lettered stone, executed by Private Buckland, C Medical Staff Corps. Two of the wounded died afterwards in the temporary hospital at Reddersburg, and are buried in the cemetery there. The wounded, thirty-two in number, were sent down from Bethanie to one of the base hospitals, for treatment in the convalescent stage. Enough praise cannot be given to the warm-hearted people of the Dutch village of Reddersburg. It mattered not that we were British. Their all was placed at our disposal, and to their generosity much of our success with the wounded is to be attributed.”

The casualties were as follows:—

Killed—Captain F. G. Casson, Northumberland Fusiliers; 2nd Lieut. C. R. Barclay, Northumberland Fusiliers. Dangerously Wounded—Captain W. P. Dimsdale, Royal Irish Rifles. Slightly Wounded—Lieut. E. C. Bradford, Royal Irish Rifles. Captured—Captain Tennant, Royal Artillery; 2nd Lieut. Butler, Durham Light Infantry, attached to Northumberland Fusiliers; Captain W. J. McWhinnie, Royal Irish Rifles; Captain A. C. D. Spencer, Royal Irish Rifles; Captain Kelly, Royal Irish Rifles; 2nd Lieut. E. H. Saunders, Royal Irish Rifles; 2nd Lieut. Bowen-Colthurst, Royal Irish Rifles; 2nd Lieut. Soutry, Royal Irish Rifles, and all remaining rank and file.

Lieut. Stacpole (Northumberland Fusiliers) was also wounded on the 4th. He was riding for reinforcements, and as he approached Reddersburg, unknowing the place was in the hands of the Boers, he was greeted with shots which killed his horse, wounded him, and placed him at the mercy of the enemy, by whom he was captured. The Boers in their retreat, however, left their prisoners behind. The total of killed and wounded numbered between 50 and 150. The strength of the British was 167 mounted infantry, 424 infantry. The enemy were said to be 3200 strong.

The unlucky termination of the affair completed the eastern flanking movement of the Boers, who were now trickling over the country from Sanna’s Post on the south to a point east of Jagersfontein road. They soon held the Free State east of the railway beyond Bethulie, and considerable numbers went south towards Smithfield and Rouxville, their determination, after their recent successes, being to harass the British force as much as possible. It was now becoming evident that all the present trouble was due to over-leniency, and it began to be urged that some measures must be adopted which would ensure for the conquerors of the enemy’s country the respect that was due to them. The humanitarian attitude of Lord Roberts had produced an unlooked-for result. The Commander-in-Chief had attempted to administer justice for a seventeenth-century people on the ethics of those of the nineteenth, and the experiment had proved disastrous. The enemy, far from being impressed by the show of magnanimity, was laughing in his sleeve at his immunity from pains and penalties. Our troops were forced now to move in a country where nearly every man was a foe or a spy, and one who, moreover, thought meanly of us for the concessions which had been made. As an instance of contrast between our own and the Dutchman’s mode of dealing with those considered as rebels, an instructive story was told. A Free State burgher at the outset of hostilities entered the Imperial service as a conductor of transport. It was a non-combatant’s occupation, and one for which he was fitted, owing to his knowledge of the Kaffir and Dutch languages. This man was captured by the Boers, who, declaring him to be a rebel,[Pg 21] instantly shot him dead. We, on the other hand, accepted an obsolete rifle, a flint-lock elephant gun belonging to the days of the Great Trek perhaps, as a peace-offering and then told the rebel to go away and turn over a new leaf. His new leaf resolved itself into unearthing Mausers and Martinis, and popping at us from the first convenient kopje—if not from the windows of his farm!

To this cause may be attributed the sudden return of so-called ill-luck, which seemed epidemic. April had brought with it an alarming list of losses at Sanna’s Post, which was followed by a grievous total of killed, wounded, and missing—five companies lost to us—at Reddersburg. We had, moreover, disquieting days around Thabanchu, Ladybrand, and Rouxville, and were being forced gradually, and not always gracefully, to retreat. For instance, in the retirement from Rouxville, four companies of the Royal Irish, some Queenstown and Kaffrarian Rifles, had merely escaped by what in vulgar phrase we term “the skin of their teeth.” It was merely owing to the smartness of General Brabant, who sent two squadrons of Border Horse from Aliwal North to the rescue, that the small force escaped being cut off. This officer’s little band garrisoning Wepener was meanwhile beginning to test the Boer force in earnest.

At this time great excitement prevailed owing to the escape from Pretoria of Captain Haldane, D.S.O. (Gordon Highlanders), who was captured after the disaster to the armoured train at Chieveley; of Lieutenant Le Mesurier (Dublin Fusiliers), who was taken prisoner with Colonel Moeller’s force after the battle of Glencoe; and of Sergeant Brockie, a Colonial volunteer. These officers had a more adventurous task than even that of Mr. Churchill, for since the war correspondent’s escape the Boers had naturally taken additional precautions, and had mounted extra guard over their prisoners. The officers most ingeniously contrived to dig a trench underneath the floor of the prison, and here they hid themselves. For eighteen long days they remained cramped in this small underground hole, in the daily expectation that the other officers and their guards were about to be transferred to new quarters, when a chance of escape would be offered.

Captain Haldane gave exciting details of his adventures in Blackwood’s Magazine; but, before dealing with them, it is interesting to consider the position of the vast congregation of British officers that had gradually been collected within the confines of the Model School. Curiously enough, after all the fighting, the sum total of prisoners of war on both sides was now nearly equal. By[Pg 22] the 23rd of March the Boer prisoners in our hands were 5000, while the British prisoners in Pretoria numbered some 3466. Since that date, through various unlucky accidents, the Boers had captured some 1000 more of our troops, and thus early in April the enemy almost equalled us in the matter of capture!

The Model School stands in the centre of the town. It is commodious, though devoid of privacy (on the principle of a boys’ dormitory) well ventilated, lighted with electricity, and roofed with corrugated iron. At the time of the escape there was a gymnasium, and also a scaling-ladder against the wall, which suggested infinite possibilities to such men as Captain Haldane, who had all the exciting histories of “Latude,” “Jack Sheppard,” and “Monte Christo” at his fingers’ ends. There were rough screens to enclose some of the cubicles, and the walls in some cases were decorated with cuttings from the illustrated papers, or with humorous sketches made by talented amateurs. Two of these were especially admired, a chase after President Steyn personally conducted by Lord Roberts, and a caricature of President[Pg 23] Kruger, which latter was highly appreciated even by the Boers when it came under their notice.

The special nook of the Rev. Adrian Hofmeyer, who had made himself into a general favourite, and was laconically declared to be a “regular brick,” was the most decorative of all, being made gay with various scraps of colour and design to cheer the weary eye. By this time the reverend gentleman, having had a more trying experience of incarceration than most, had got to look upon the Model School in the light of residential chambers, and consoled others with the account of his own experiences. His story was not an enlivening one:—

“I was lodged in the common jail, Cronje’s law adviser having informed him it would not be legal to shoot me. Cronje consequently thought the best thing to do would be another illegality, namely, imprison a non-combatant and correspondent. Mr. Cronje has ample time to-day in St. Helena to meditate upon this and other illegal acts of his. I was locked up in a cell eighteen feet by nine feet, and for the first few days was allowed to have my meals at the hotel. Soon, however, this liberty was taken away, for it proved too much for the Christian charity of the Zeerust burghers to see a despised prisoner of war marched up and down from the hotel to the jail under police escort. Other restrictions were soon imposed also, and after a little while I was locked up day and night, the door of the unventilated cell being open only three times a day for fifteen minutes at a time. No books nor papers were allowed me, no visitors, and the few loyal friends who tried to supply me with luxuries were cruelly forbidden to do so by the authorities. I cannot help thinking to-day of the strange irony of fate. The commanders who practised this cruelty upon me were Cronje and Snyman. The one is to-day a prisoner of war, and can, perhaps, put himself in my place. He is an old personal acquaintance, too.”

The worthy padre was afterwards removed, and gave a further description of his experiences.

“After eight weeks of such life I was taken to Pretoria, and there quartered in the Staats Model School with the British officers. Here everything was better, and I quickly recovered my health and strength. The building was a magnificent one, and the surroundings very pleasant, but our jailer, a Landdrost, and our guards, the Zarps, never forgot to remind us of the fact that we were prisoners. The food we got from Government sufficed for one meal; the rest we had to buy, being charged most exorbitant prices. When I left, the officers’ mess amounted to £1600 per month for 144 officers. On my arrival, I was asked by the officers to conduct service for them every Sunday, in addition to that held by an Anglican clergyman. For two Sundays, therefore, we had two services a day, and then Winston Churchill escaped, and the following extraordinary letter was sent the officers by the Anglican clergyman:—

“‘Gentlemen,—By the kind courtesy of the Government, I have been permitted to hold services for you in connection with the Church of England, which services I have felt it a privilege on my part to conduct. After what has recently occurred—viz. the escape of Mr. Churchill from confinement—I ex[Pg 24]ceedingly regret that, in consideration of my duty to the Government, I must discontinue such regular ministrations, as I desire to maintain the honour due to my position. Of course I shall always be glad to minister to you in any emergency, with the special permission of the authorities, who will, with their usual kindness, duly inform me.—With my best wishes, I am, gentlemen, yours sincerely, ——.’

“Out of charity, I do not publish the reverend gentleman’s name,[2] but I can add that ‘the emergency’ referred to never presented itself. Since that time, I had the pleasure and honour of conducting the services every Sunday, and they were the pleasantest hours I spent in prison. Our singing was so hearty and good, that many of the townsfolk strolled up of a Sunday morning to hear us.”

As may be imagined, all manner of devices were invented for the purpose of securing news, the only intelligence of outside events coming to the unhappy prisoners through the Standard and Diggers’ News, which journal, of course, dwelt gloatingly on British disasters. But the authorities were suspicious. One day a harmonium was removed, owing to the treasonable practice of performing “God save the Queen”; on another, a cherished terrier was banished, as he was declared to be a smuggler, and charged with the crime of carrying notes in his tail! But at last, an ingenious ruse was successfully perpetrated. A man, accompanied by a dog, came to the railings and there engaged in a private dialogue, which savoured of the maniacal, till the eagerly listening officers discovered that there might be method in the strange man’s madness. A sample of the scene was given by the correspondent of the Standard:—

“‘Would you like a swim?’ asked the master, and the dog, with a wag of his tail, answered ‘Yes.’ ‘Ladysmith is all right,’ continued the man, and the tail wagged assent. ‘We will come again,’ said the master, and the dog agreed. For a time the prisoners thought him mad, this man with the dog who talked in his beard, and mixed his dog talk with such names as ‘Ladysmith,’ ‘Mafeking,’ ‘Cronje,’ ‘Roberts.’ Then the truth dawned on them, and the ‘Dog Man’ became a hero, whose coming was watched with longing, and whose mutterings in his beard were ‘as cool waters to the thirsty soul,’ or as ‘good news from a far country.’ One day the ‘Dog Man’ was missing, and there was lamentation, until, looking towards the house opposite, the prisoners saw him standing well back in the passage, at the entrance to which two girls kept watch. The ‘Dog Man’ was waving his hat in eccentric fashion, and the waving was found to be legible to those who understand signalling. Next morning a tiny flag was substituted for the hat, and communication between the officers and the Director of Telegraphs was established by flag signal.”

The prisoners endeavoured to keep up an air of jocosity, though,[Pg 25] as one confessed, their tempers were “very short and inclined to be captious.” Naturally their occupations were limited, and it was not unusual to see gallant commanders engaged in darning their socks, or washing their clothes under the pump. Their attire, too, was not of the choicest, some of them having been accommodated when sick with suits technically known as “slops,” purchased for a low price in Johannesburg. Hence one officer disported himself in choice pea-green, while another figured in rich yellow. These prison suits were scarcely becoming, particularly as many of the smartest of the smart were growing beards, or, if not beards, the ungainly chin tuft or “Charley,” which destroyed their martial aspect. Sometimes they engaged in games, bumble puppy and the like, and occasionally expanded to other sports. A letter from a sprightly member of the band to the Eton College Chronicle described the humorous side of their daily life:—

“Model School, Pretoria.

“Dear Mr. Editor,—Whilst following the fortunes of old Etonians in South Africa, perhaps it may have escaped your notice that a small and unhappy band has already reached Pretoria. Mr. Rawlins’s House is represented by Captain Ricardo (Royal Horse Guards), and H. A. Chandos-Pole-Gell (Coldstream Guards); Mr. Carter’s by Major Foster (Royal Artillery); the late Mr. Dalton’s, Mr. Ainger’s, and Mr. Luxmore’s respectively by M. Tristram (12th Lancers), G. Smyth-Osbourne (Devonshire Regiment), and G. L. Butler (Royal Artillery); and Mr. Cornish’s by G. R. Wake (Northumberland Fusiliers). The histories of their separate captures would take up too much of your valuable space. Some have been here but a short time, some many weeks; and during their captivity their thoughts turned to old Eton days, and the game of fives recommended itself to them as a means of passing some of the many weary hours. There was no “pepper-box,” or “dead man’s hole”; but a room, two of whose walls mainly consisted of windows, with the aid of three cupboards and a piece of chalk, was quickly converted into a fives court. Entries for a Public Schools’ tournament were numerous, Eton sending three pairs. Tristram and Gell unanimously elected themselves to represent Eton’s first pair, closely followed by Eton II., Ricardo and Osbourne, Eton III. being Wake and Butler. The facts that Tristram had recently been perforated with Mauser bullets, and Gell had spent Christmas and the three preceding weeks in the various jails between Modder River and Bloemfontein, were no doubt responsible for their not carrying off the coveted trophy. Alas! they were badly beaten in the first round by Marlborough. Not so Eton II. and III., who carried the Light Blue successfully into the second round, both having drawn byes. This good fortune could not last, and they fell heavily at the second venture, being beaten by Wellington and Rugby respectively. The ultimate winners proved to be Wellington, after a desperate encounter with Charterhouse.

“So much for our pleasures; our troubles are legion, but we will not burden you with them. We daily expect to hear of the E.C.R.V. sharing the hardships of the campaign, and covering themselves with glory to the tune of

“Floreat Etona.

“P.S.—We all hope to be at Eton on the 4th of June.

“Feb. 14, 1900.”

(Curiously enough, the 4th of June brought to a close the deadly period of durance vile. On that date the gallant crew spent their last night as prisoners!)

To return to Captain Haldane and his partners in adventure. Ever since Mr. Churchill’s escape he had racked his brains to discover a means of escape, and had made multifarious plans, many of which were rejected as absolutely hopeless, while many others failed after efforts which testified to the perseverance and ingenuity of their inventors. It was no easy matter after Mr. Churchill’s exploit to hit on a means of evading the wily and now alert Boer.

The guard were armed with rifles, revolvers, and whistles, and as these consisted of some thirty men, who furnished nine sentries in reliefs of four hours, there was little hope of escaping their vigilance. Fortunately the prisoners, such as had plain clothes in their possession, were permitted to wear them, otherwise the dream of freedom could scarcely have been indulged in. Bribery was not to be thought of, and a repetition of Mr. Churchill’s desperate dash for freedom was impossible. It remained, therefore, for Captain Haldane and his colleagues to invent a new and ingenious method of bursting their bonds. An effort to cut the electric wires to throw the place in darkness while they scaled the walls, proved a sorry failure, and at last, having tried the roof and other points of egress and found them wanting, the companions hit on the happy idea of burrowing a subterranean place of concealment. Here they thought to scrape on and on till they bored a tunnel into the open! The discovery of a trap-door in the planks under one of the beds lent impetus to their designs, and they arranged to excavate a route diagonally under the street, and so pass into the gardens of the neighbouring houses. Marvellous was the patience and perseverance with which they, almost toolless—with only scraps of biscuit tins and screwdrivers—toiled daily in the accomplishment of their plan, and pathetic their dismay when their tunnel finished up by landing them in several feet of water with a promise of more to come. But they were indefatigable. Captain Haldane, like the great Napoleon, argued that the word impossible was only to be found in the dictionary of fools. Rumours that the prisoners were to be removed to a new building in two or three days only contrived to render the conspirators more desperate in their craving to be at large, and again the trap-door system was discussed. The young men determined on revised operations, and hit on the plan of living underground in the cave they should dig, thus disappearing from Boer ken and conveying the idea that they had already bolted, leaving as evidence of flight their three empty beds! Here they proposed to wait till, the hue-and-cry after them having ceased, and the prison doors having been opened for the removal of the other officers, they could[Pg 27] slink forth at their leisure. But the change of prison did not come to pass as soon as expected. The empty beds told their tale; the place was searched, the crouching creatures in their burrow heard the tramp of armed men above them, voices in close conference, and afterwards the departing footsteps of the discomfited Boer detectives. It was decided that the prisoners were gone, and further report, amplified by Kaffir imagination, declared that they were already on their way to Mafeking! Still, though safe from discovery, the plotters were far from comfortable. Food in very meagre quantities was smuggled through the trap-door, till at last, famine being the mother of resource, by a process of what they called “signalgrams,” their wants and intentions were conveyed to those above. Then when the appointed raps gave notice of the opening of the mysterious portal, potted meats and other luxuries were liberally passed down. And here, in this ventilationless, miry hole, in darkness and dank-smelling atmosphere, they groped a weary existence, daring neither to cough, nor sneeze, nor whisper, lest discovery should rob them of success. They were unwashed—so grimy as to be unrecognisable even to themselves—they were cramped and covered with bruises, brought about by bumping their heads against the dome of their low dwelling; they were often hungry and sleepless, but they were buoyed up with a vast amount of hope and pluck.