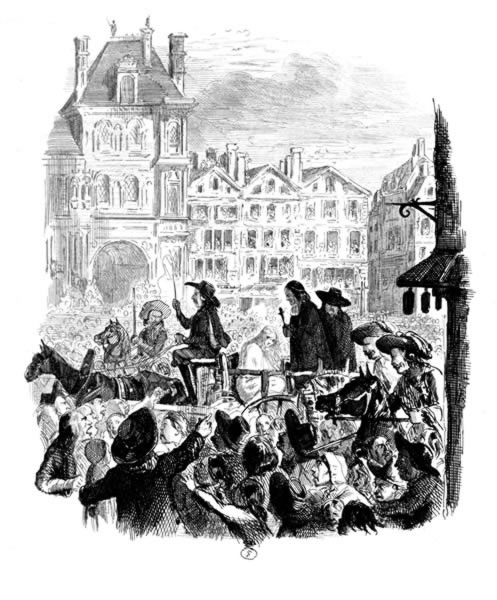

The Marchioness going to Execution.

The Marchioness going to Execution.  The Marchioness going to Execution.

The Marchioness going to Execution.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | "PUNCH" | 1 |

| II. | CARTOONS | 15 |

| III. | THE LAWYER'S STORY | 35 |

| IV. | LOVE OF FIELD SPORTS | 40 |

| V. | INVENTORS AND ILLUSTRATORS | 54 |

| VI. | "INGOLDSBY LEGENDS" | 59 |

| VII. | DICKENS AND THACKERAY ON LEECH | 66 |

| VIII. | DEAN HOLE | 80 |

| IX. | TYPES | 89 |

| X. | LEECH AND HIS PREDECESSORS | 96 |

| XI. | KENNY MEADOWS | 103 |

| XII. | "COMIC HISTORY OF ROME" | 106 |

| XIII. | PERSONAL ANECDOTES | 113 |

| XIV. | PERSONAL ANECDOTES—CONTINUED | 119 |

| XV. | SPORTING NOVELS | 130 |

| XVI. | THE "BON GAULTIER BALLADS" | 137 |

| XVII. | SPORTING NOVELS—CONTINUED | 152 |

| [Pg vi]XVIII. | MICHAEL HALLIDAY AND LEECH | 163 |

| XIX. | THOMAS HOOD AND LEECH | 182 |

| XX. | DR. JOHN BROWN AND LEECH | 218 |

| XXI. | AUTOGRAPH-HUNTERS AND OTHERS | 229 |

| XXII. | ARTISTS' LIVES | 239 |

| XXIII. | LEECH EXHIBITION | 247 |

| XXIV. | MILLAIS AND LEECH | 275 |

| XXV. | MR. H. O. NETHERCOTE AND JOHN LEECH | 283 |

| PAGE | |

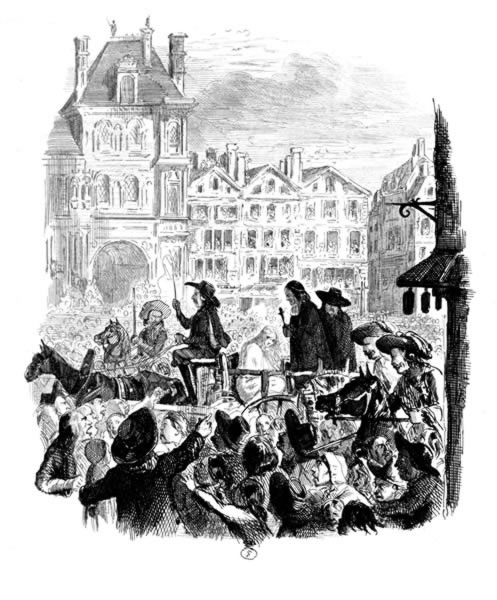

| The Marchioness going to Execution | Frontispiece |

| The Drunken Post-boy | 11 |

| "They may be Officers, but they are not Gentlemen" | 13 |

| Jack Armstrong | 17 |

| The Jew and Skeleton Tailors | 29 |

| "I'll thin your Top!" | 37 |

| "Give her her Head, Jack" | 42 |

| "Oh, if this is one of the Places Charley spoke of, I shall go back!" | 44 |

| Jack Johnson attempts to rescue Derval To face p. | 57 |

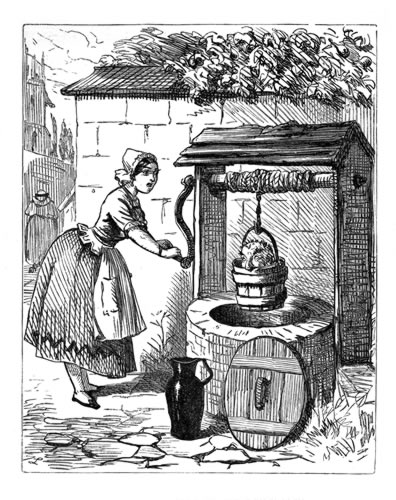

| The Maid and the Head of Gengulphus | 62 |

| Elopement of Roman Youth with Sabine Ladies | 109 |

| Rome saved from the Gauls by Geese | 111 |

| Little John and Red Friar | 140 |

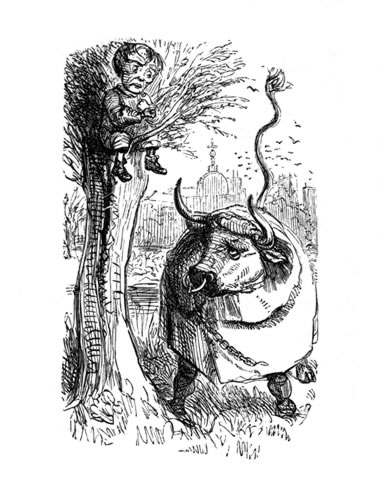

| Little John and the Popish Bull | 142 |

| George of Gorbals | 149 |

| [Pg viii]The Lover's Friend and the Lover | 150 |

| After aiming for a Quarter of an Hour, Mr. B. fires both his Barrels, and misses! | 173 |

| What wide Reverses of Fate are there! | 188 |

| Miss Kilmansegg | 191 |

| The Foreign Count | 197 |

| The Wedding—"Wilt thou have this Woman?" | 202 |

| Love at the Board | 204 |

| He brought strange Gentlemen home to Dine | 208 |

| The Torn Will | 212 |

| Bedtime | 216 |

| "He blows his own Nose!" | 228 |

| The Seal | 235 |

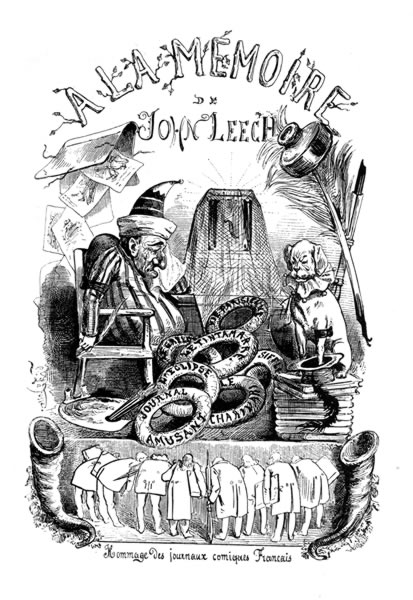

| A Cypress Branch for the Tomb of John Leech | 301 |

In the year 1841 I exhibited a picture at the Suffolk Street Gallery, and I recollect accidentally overhearing fragments of a conversation between a certain Joe Allen and a brother member of the Society of British Artists in Suffolk Street. Allen's picture happened to hang near mine, and we were both "touching up" our productions. Joe Allen was the funny man of the society, and, though he startled me a little, he did not surprise me by a loud and really good imitation of the peculiar squeak of Punch.

"Look out, my boy," he said to his friend, "for the first number. We" (I suppose he was a member of the first staff) "shall take the town by storm.[Pg 2] There is no mistake about it. We have so-and-so"—naming some well-known men—"for writers; Hine, Kenny Meadows, young Leech, and a lot more first-rate illustrators," etc.

Whether Allen's friend took his advice and bought the first number of Punch, which appeared in the following July, I know not; but I bought a copy, and remember my disappointment at finding Leech conspicuous by his absence from the pages. In the hope of finding him in the second issue, I went to the shop where I had bought the first. The shopman met my request for the second number of Punch, as well as I can recollect, in the following words:

"What paper, sir? Oh, Punch! Yes, I took a few of the first; but it's no go. You see, they billed it about a good deal" (how well I recollect that expression!), "so I wanted to see what it was like. It won't do; it's no go."

I have been told that, like most newspapers, Punch had some difficulty in keeping upon his legs in his first efforts to move; but as those elegant members, so exquisitely drawn by Tenniel, have supported the famous hunchback for nearly half a century, there is no need for his friends' anxiety as to his future movements.

Though Leech had engaged himself to the then proprietors of Punch as one of the illustrators of the paper, it seems strange that his first contribution did not appear till the 7th of August, and in the fourth number, and stranger still that its appearance should have damaged the paper. Under the heading of "Foreign Affairs," the artist represents groups of foreigners such as may be seen any day in the neighbourhood of Leicester Square. The reader is told in a footnote that the plate does not represent foreign gentlemen, an unnecessary intimation to anyone who knows a foreign gentleman.

It is said that this engraving sent down the circulation of Punch to an alarming point. I confess my inability to understand this, and would rather attribute the decadence to some other cause, contemporary with the production of "Foreign Affairs." The drawing is somewhat hard upon the foreign frequenters of the purlieus of Leicester Square, and would only have been more acceptable to John Bull on that account. By Leech's non-appearance in Punch for many months after "Foreign Affairs" was published, one is driven to the conclusion that the managers had little faith in him as an attraction. The second volume contains very few of Leech's designs, while it bristles with inferior work.

My own admiration for Leech's genius, so constantly roused by his works, with which I was familiar, created a great desire for his acquaintance; but being perfectly unknown at that time as an artist, and knowing none of Leech's friends, I began to despair of the realization of my wishes, when accident helped me.

A Scottish painter—a Highlander and fierce Jacobite—named McIan, who was also an actor and friend of Macready, to whose theatrical company he was attached, lived with his wife, an accomplished artist, somewhere in the neighbourhood of Gordon Square. Calling one morning to see Mrs. McIan, I found her in her studio, not, as usual, hard at work at her own easel, but superintending the labours of a pupil, who was hard at work at another; and the pupil, a tall, slim, and remarkably handsome young man, was John Leech.

I made some remark about the different method in which he was employed to that with which he was familiar. I forget what he was copying—some still life, I think.

"I like painting much better than what I have to grind at day after day, if I could only do it," said Leech; "but it's so confoundedly difficult, you know, and requires such a lot of patience."

I fancy I thought his efforts in oil-painting on that occasion very promising; but the exigencies of his position quite prevented the unceasing devotion to the study of painting which is required before any success can be assured.

Leech was once heard to say that he would rather be the painter of a really good picture than the producer of any number of the "kind of things" he did. I, for one, am very thankful that he never did produce a good picture, for he would have been tempted to repeat the success, to the loss of numbers of delightful sketches.

Mrs. McIan appeared to think that Leech would soon cease to draw for Punch; indeed, she doubted, as did many others, that Punch would long succeed in attracting the public; and I joined her in the hope—rather hypocritically, I fear—that her young friend would persevere in mastering the difficulty of the technicalities of oil-painting, and thus place himself amongst the best painters of the country. Leech had taken many lessons from Mrs. McIan, and that lady seemed convinced that he had but to persevere and the difficulties would fall before him, as, to use her own figure, the walls of Jericho fell before the sound of the trumpet. Ah, perseverance! "there's the rub."

From the time of my introduction to Leech I became gradually very intimate with him, and the more I knew of his nature, the more I became convinced that he totally lacked the disposition for continuous, steady, mechanical industry necessary for success in painting. He constantly ridiculed the care spent on the details in pictures; finish, in his opinion, was so much waste of time. "When you can see what a man intends to convey in his picture, you have got all he wants, and all you ought to wish for; all elaboration of an idea after the idea is comprehensible is so much waste of time"—this was his constant cry, a little contradicted by the fact that he as constantly tried to paint his ideas, but in a fitful and perfunctory manner.

I can imagine the enthusiasm that was lighted up in Leech upon his first sight of one of our annual exhibitions. After a visit to one of them he was known to have gone home, and getting out easel, canvas, and colours, he would set to work in a fury of enthusiasm, which evaporated at the encounter of the first technical difficulty. He used to take pleasure in watching my own attempts at painting, and I remember on one occasion, when I was finishing a rather elaborate piece of work, he said:

"Ah, my Frith, I wasn't created to do that sort of thing! I should never have patience for it."

He was right, and, happily for the world, he became convinced that, even if he had the power to fully "carry out"—as we call it—one of his drawings into a completed oil picture, the time required would have deprived us of immortal sketches; and though he undoubtedly "left off where difficulties begin"—as I once heard a painter, who was exasperated at Leech's sneers at his manipulation, say to him—he has left behind him work which will continue to delight succeeding generations so long as wit, humour, character and beauty are appreciated—that is to say, so long as human nature endures.

I feel I ought to apologize for what I am about to tell, because it has nothing to do with my hero beyond the fact of its occurrence having taken place on the memorable morning when I first had the happiness of meeting him.

I have said that McIan was a Scotchman, a Highlander of the clan McIan, and a worshipper of Charles Stuart, whose usual cognomen, the Pretender, I should have been sorry to have used in the presence of my Jacobite friend. As Leech left the room to go to his "grind," as he called his woodwork, McIan entered, and we were discussing Leech's[Pg 8] prospects when McIan's servant—an old, hard-featured Scotchwoman—hurried into the room, and, in an awe-stricken voice, said:

"Sir—sir, here's the Preences!"

The words were scarcely out of her mouth, when two gentlemen entered—tall, rather distinguished but melancholy, looking young men. No sooner did McIan and his wife catch sight of them, than, without a word, they both dropped upon their knees, and while the lady kissed the hands of one of the gentlemen, her husband paid a similar attention to the hands of the other. I was holding my hat, and I remember I dropped it in my astonishment, for I was not aware that I was in the presence of the last of the Stuarts; or that these two young men claimed to be the great-grandsons of the hero of Culloden, and amongst a large section of Scotchmen, and not a few Englishmen, had their claim allowed. Anyone curious about this delusion can read for himself how it was dispelled, but the men themselves implicitly believed in their royal descent. They are both dead now. I once saw one of them again at a garden-party at Chelsea Hospital, where his likeness to the Stuarts was the talk of the company. It was certainly striking.

It is a melancholy task to me to try to recall the[Pg 9] social scenes in which Leech so often figured—sad indeed to think how few of his friends, more intimate with him than I, now remain amongst us! Though Leech very seldom illustrated any ideas but his own, I can recall an example or two to the contrary; and still oftener have I seen, by the sparkle of his eye, that something occurring in conversation had suggested a "cut."

I think it was Dickens who said that a big cock-pheasant rising in covert under one's nose was like a firework let off in that locality. Elsewhere we have Leech's rendering of the idea.

When cards, or some other way of getting rid of time after dinner, had been proposed, I have heard Leech say:

"Oh, bother cards! Let us have conversation."

And talk it was, often good talk; but Leech was more a listener than a partaker. Not that he could not talk, and admirably; but he was always on the watch for subjects which he hoped something in conversation might suggest.

Leech's mental condition was certainly deeply tinged with the sadness so common to men who possess wit and humour to a high degree. He sang well, but his songs were all of a melancholy character, and very difficult to get from him. Indeed,[Pg 10] the only one I can remember, and that but partially, was something about "King Death," with allusions to a beverage called "coal-black wine," which that potentate was supposed to drink. As I write I can see the dear fellow's melancholy face, with his eyes cast up to the ceiling, where Dickens said the song was written in ghostly characters which none but Leech could read.

I may give another example—rare, no doubt—of Leech's having used a suggested subject. Many years ago my brother-in-law, long since dead, took a party of friends to the Derby. They drove, or, rather, were driven, down to Epsom, the usual post-boy being recommended as a careful, steady driver—a character very desirable, considering the crowded state of the road, more especially on the return journey. The post-boy quite realized all that was said of him as the party went to the course, but when the time came for departure he was found, after considerable searching, to be as nearly dead-drunk as possible. What was to be done? The man could scarcely stand; his driving was, of course, out of the question.

"Well," said my brother-in-law to his friends, "if you will trust yourselves to me, I will ride and drive you back;" and, after tying the post-boy on to the [Pg 12] carriage, where he soon fell fast asleep, my brother mounted and drove his party safely home.

This I thought a good subject for Leech, and I suggested it to him. He smiled faintly, and said not a word. Very nearly a year after I had told him of the incident, as I was walking with him one day, he said:

"By the way, Frith, are you going to use the subject you mentioned to me of the drunken post-boy and your brother-in-law?"

"I? No," said I; "it's more in your way than mine."

"Then I'll do it next week."

He was as good as his word.

Nothing could be less like my brother-in-law than the delightful "swell" who is driving home some charming women, who are, however, left to our imagination; and as to the post-boy, the artist has awoke him to some purpose. What could surpass that drunken smile?

Long, long ago there might have been seen on the sands at Ramsgate two stuffed figures, the size of life, intended to represent soldiers; for they were bedecked with the red coat, cap, and trousers of the ordinary private. The clothes were simply stuffed out into something resembling human forms, but the [Pg 14] effect, as may be supposed, was ludicrous in the extreme. They were the work of a professor of archery, who supplied his customers with bows and arrows, with which the archer showed how seldom he could hit the target made by the two soldiers. Leech and I watched the shooting for some time, till the little sketch-book was produced, and Leech made a rapid drawing of the two soldiers, afterwards to figure in an inimitable cut in Punch.

A young lady is seen bathing with her aunt, whose attention she is directing to the two stuffed figures. The aunt is short-sighted, and the girl is wickedly pretending that the figures are live officers, watching the bathers. The aunt says, "They may be officers, but they are not gentlemen," etc.

I am sure that Leech never used a model, in the sense that the model is commonly used by artists, for the thousands of human beings made immortal by his genius; but that he made numberless sketches for backgrounds, detail of dresses, landscapes, foregrounds, and bits of character caught from unconscious sitters, there can be no doubt. How wonderful was the memory, how sensitive the mental organization, that could retain and reproduce every variety of type, every variety of beauty and character!

As I fancy I am one of the few of Leech's friends who have figured personally in Punch, I may be excused for the egotism of the following:

About the year 1852 I began the first of a series of pictures from modern life, then quite a novelty in the hands of anyone who could paint tolerably. When the picture which was called "Many Happy Returns of the Day" (a birthday subject, in which the health of the little heroine of the day is being drunk) was finished, Leech came to see it, and expressed his satisfaction on finding an artist who could leave what he called "mouldy costumes" for the habits and manners of everyday life. As he was speaking, two of my brother artists, whose practice was on different lines to mine, called, and saw my picture for the first time. They both looked attentively at it, and the longer they looked—judging from their[Pg 16] faces—the less they liked it. I shall not forget Leech's expression when I gave him a sort of questioning look as to the correctness of his judgment.

"Well, what do you think of the picture?" said Leech to one of the painters.

"Well, really I don't know what to think," was the reply.

It never occurred to me that the incident was one likely to serve my friend for a drawing; lively was my surprise, and great was my pleasure, therefore, when I saw myself "immortalized for ever," as my old master used to say, in the pages of Punch.

In this drawing may be seen a striking proof of the avoidance of personality which always distinguished Leech. I cannot see my own back, but I have been assured by those who have had that privilege that there is a dashing, not to say aristocratic, character about Jack Armstrong to which I have no claim. While Messrs. Potter and Feeble are quite curiously unlike the persons they are supposed to represent—neither of my high art friends wore beards—yet the attitudes of the men were exactly reproduced; while the background, with armour, oak-cabinet, etc., for which no sketch was taken, was a perfectly correct representation of my old painting-room.

In one of my autumnal holidays Leech stayed a few days with me. He had not been well; picking up "a thousand stones in a thousand hours," to which he likened his unceasing work, had begun to tell upon him; and in reply to my warning, that, for his own sake, to say nothing of the interests of Punch, he should husband his strength—for, I added, "If anything happened to you, who are 'the backbone of Punch,' what would become of the paper?"—I can see his smile as I hear him say, "Don't talk such rubbish! backbone of Punch, indeed! Why, bless your heart! there isn't a fellow at work upon the paper that doesn't think that of himself, and with about as much right and reason as I should. Punch would get on well enough without me, or any of those who think themselves of such importance."

Among the many admirable qualities that adorned the character of John Leech his modesty was remarkable; he thought little or nothing of his own work. "Talk of drawing, my dear fellow," he once said to me, "what is my drawing compared to Tenniel's? Look at the way that chap can draw a boot; why, I couldn't do it to save my life."

Though Leech in his modesty chose to ignore the fact, it was no less a fact that for nearly a quarter of a century he was the leading spirit of Punch.[Pg 19] "Think," said Thackeray, "what a number of Punch would be without a drawing by Leech in it!"

In addition to the wonderful political cartoons, Leech contributed more than three thousand illustrations of life and manners to the paper; and it is said—I know not how truly—that he received from first to last more than £40,000 for his contributions to Punch alone. If he did, what did he do with the money? That he was in no way extravagant I know, and that he was frequently in dire straits after his connection with Punch I also know. Let my reader imagine what pecuniary trouble must have been to this man, whose mind was racked by the constantly recurring demands for intellectual work such as Leech supplied week after week, and often day after day! Did he lend or give away his hardly-earned money? Did he accept bills for so-called friends, and find that he had to meet them? Leech was one of the most open-hearted and generous of men, an easy victim to a plausible tale of real or fictitious distress. I suppose we shall never know why a man who made so large an income, who had not a large family to absorb much of it, and who never lived expensively, should have died comparatively poor. Let me leave these painful considerations[Pg 20] and "pursue the triumph and partake the gale" of the artist's glorious career.

Between Cruikshank and Leech there existed little sympathy and less intimacy. The extravagant caricature that pervades so much of Cruikshank's work, and from which Leech was entirely free, blinded him a little to the great merit of Cruikshank's serious work. I was very intimate with "Immortal George," as he was familiarly called, and I was much surprised by the coolness with which he received my enthusiastic praise of Leech.

"Yes, yes," said George, "very clever. The new school, you see. Public always taken with novelty."

For the larger part of fifty-seven years Cruikshank told me he had been in the habit of drinking wine and spirits, often a great deal too much of both; but from his fifty-seventh birthday to his seventy-fifth, when he lectured me for taking a single glass of sherry, he had devoted himself to strict teetotalism, the interests of which he advocated by tongue, brush, and etching-needle.

Unlike Leech, Cruikshank was a painter, and the last years of his life were spent in painting a huge picture, or, rather, a series of pictures upon one canvas, which he called "The Worship of Bacchus." From this work he executed a large engraving, a[Pg 21] proof of which he presented to me, telling me to study it well and I should see what dire results might arise from drinking a glass of sherry. Like most proselytes, Cruikshank carried his faith in his creed to the verge of absurdity, and sometimes beyond it; but in the "Worship of Bacchus," and more powerfully still in a series of etchings called "The Bottle," he gave his tragic power full play, and produced scenes and incidents in which the consequences of "drink" are portrayed—now with pathos, now with the terrible retribution that often ends the drunkard's career in madness.

In one of the large cartoons in Punch Leech used the awful figure of "Fagin in the Condemned Cell" (one of Cruikshank's finest illustrations to "Oliver Twist"), changing him into King Louis Philippe. That sovereign was always somewhat of a red rag to Leech, as many cuts, in which the king is turned into ridicule, prove; and when the crash of 1848 came, Leech received the fugitive with a shower of drawings, culminating in the tragic figure exiled and in the condemned cell. The student of Leech does not require to be told that the artist was as great in the tragedies of life as he was when he shot the follies as they flew about him, or when he touched so caressingly the beauty of childhood and of women.

During the Crimean War, when such fearful news came to us of the sufferings of our soldiers during the inclement winter of 1854-55, the Emperor of Russia is said to have invoked the aid of Generals January and February in our ruin. Those officers certainly destroyed many of our men, but one of them laid his icy hand upon the man who had called him for so different a purpose. Never can I forget the impression that Leech's drawing of the Emperor's death-bed made upon me! There lay the Czar, a noble figure in death, as he was in life, and by his side a stronger King than he—a bony figure, in General's uniform, snow-besprinkled, who "beckons him away." Of all Leech's serious work, this seems to me the finest example. Think how savage Gillray or vulgar Rowlandson would have handled such a theme!—the Emperor would have been caricatured into a repulsive monster, and Death would have lost his terrors. Moreover, neither of those artists was capable of conceiving the subject.

To show the infinite variety of Leech's powers, I may draw attention in this place to another of the political cartoons.

The uneasiness created in this country by what was called the "Papal Aggression" always seemed to me as absurd and unfounded as it has since proved[Pg 23] to have been. I remember asking Cardinal Manning, then Archbishop of Westminster by order of the Pope, for his autograph. He wrote his name for me, but when I asked him to add his title, he smiled and said, "I dare not do that; I might be sent to prison if I wrote my Popish title."

Lord John Russell was in power at that time, and was of course very active in the crusade against the Catholics. The Cardinal in England was Wiseman; and Leech drew Lord John as a street boy, running away from the Cardinal's door, after chalking "No Popery" upon it. Perfect in workmanship, and perfect in idea, is this admirable drawing.

I may note here one very bad consequence of the "Papal Aggression"—namely, the secession of Richard Doyle from the Punch staff. Doyle was a Catholic; it was therefore impossible for him to remain amongst men who, by pen and pencil, opposed what was called the audacious attempt to "tithe and toll in our dominions." It was a pity, for Doyle was, next to Leech, by far the strongest man on the staff of Punch artists—quaintly humorous, and full of a delicate fancy, but without the broad views of life or the grasp of character that distinguished Leech. Of course, as personality was the essence of the political cartoons, the use of it was[Pg 24] unavoidable; but Leech managed to be personal without being offensive to the chief actor, unless, as in the case of Louis Philippe and a few others, he considered that their escapades deserved severe castigation; he then took good care to apply the whip with a will. Lord Russell, in his "Recollections," speaks of the "No Popery" satire as "a fair hit."

In many of the political cartoons official personages are represented as boys, well-behaved or ill-behaved, obstinate or stupid, or both, in the work appointed for them. For example, when Sir Robert Peel resigned, in 1846, Lord John Russell figures as page-boy applying for the vacant place. The Queen looks the button boy up and down, and then says, "I fear, John, you are not strong enough for the situation."

Then we have Disraeli, also as a boy, in whose figure that statesman's curious foppery in dress is felicitously noted, confronted with a majestic figure of Sir Robert Peel, who says:

"Well, my little man, what are you going to do this Session, eh?"

"Why—aw—aw—I've made arrangements—aw—to smash everything."

Events of the past, looked at by the light of the[Pg 25] present, assume sometimes very strange, almost incredible aspects. Can there have been a time, one is inclined to ask, when a man's religion could prove a bar to college, Bench, and Parliament? Assuredly there was such a time, and not long ago—say forty years or so—when no Jew could be a judge or a member of Parliament; and it was only after severe battles and many defeats that victory at last attended the Jewish banner. One of the most violent opponents of the Jews was Sir Robert Harry Inglis, a very conscientious and worthy gentleman. By a happy thought of Leech's, Sir Robert is made to figure in one of the most humorous of the political cartoons.

About this time my old friend Frank Stone had painted two pictures in illustration of his favourite theme—love. They were called "The First Appeal" and "The Last Appeal." In the first a kind of peasant lover is beseeching his "flame" to listen to his vows. She listens, but without encouraging a hope in the swain that he will prevail. Time is supposed to pass, leaving terrible traces of suffering—apparently to the verge of consumption—in the young man, who, on finding the girl at a well, makes his last, almost dying, appeal. He seizes her hand; but she turns away, deaf to his passionate beseeching.

In the Leech drawing the composition of Stone's picture is exactly preserved; but in place of the lady we have Sir Robert Inglis, who turns away in horror from a young gentleman of a very marked Jewish type indeed.

The present Punch artists have greatly the advantage of Leech, in respect of the aid derivable from photography. In these days, there is scarcely a statesman whose photograph cannot be seen in the London shop-windows, to the great advantage of the political caricaturists of to-day. It was only at the latter part of Leech's time that photography became so generally used to familiarize us with the features of our legislators, and even then I doubt if Leech took much advantage of it. He had seen all these men, and a rough sketch in his note-book, aided by his marvellous memory, was sufficient to enable him to produce unmistakable likenesses.

It remains for me to note some of the instances in which Leech's powers were brought to bear upon the social questions of the time—questions admitting of a humorous or a pathetic treatment, apart from those of a merely political character.

In 1850 a motion by Lord Ashley, afterwards Shaftesbury, was carried against the Government by a majority of ninety-three to sixty-eight, ordering[Pg 27] that the transmission and delivery of letters on Sunday should cease in all parts of the kingdom. The new law was acted upon for some weeks, and caused so much public inconvenience, and so great and indignant a popular outcry, that the obnoxious rules were rescinded. Leech took full advantage of the opportunity thus afforded him. His ready imagination supplied him with instances in which the operation of the new law would cause loss and suffering. This was shown in a drawing which, amongst other proofs, depicts a mother in great distress because she can have no news of her sick child. And when, in September, 1850, the obnoxious regulation was withdrawn, Leech celebrated the event in an admirable cartoon, in which the promoters, Lords Russell and Ashley, dressed as Puritans, are ruefully contemplating each other, Russell addressing his fellow-Puritan with, "Verily, Brother Ashley, between you and me and the post we have made a nice mess of it!"

The neglect of our troops during the Crimean campaign afforded the artist many humorous and tragic subjects. The Government was accused, rightly or wrongly, of many sins of omission and commission; amongst the rest, of not providing the army with clothing suitable to the terrible winter[Pg 28] which it was sure to have to pass in front of Sebastopol. And one of Leech's most telling drawings represents two ragged soldiers shivering in the snow. One tells the other that news has arrived of a medal that is to be awarded. "Yes," says his comrade; "but they had much better send us a coat to put it on."

Two pictures may be noted—one by Tenniel, which is infinitely pathetic, the other by Leech, ghastly in its contrast to the humorous side of the author's powers. The first represents a fashionable lady, whose magnificent ball-dress has just been fitted upon her by the dressmaker, who says:

"We would not have disappointed your ladyship at any sacrifice, and the robe is finished À MERVEILLE."

But the sacrifice! The lady turns to the looking-glass, wherein she sees the dress, and part of the cost of making it, in the appalling figure of the workwoman, whose haggard form leans back exhausted, dully lighted by a dying lamp, by the help of which all night long the lady has not been "disappointed."

The sufferings of the workers, through which their employers so often became rich, touched the tender heart of Leech, and he never lost an opportunity[Pg 30] of pointing out the selfish tyranny of both the men and women traders who almost ground the life out of their unhappy assistants.

If John Leech could have entertained a prejudice against any human beings, it must have been against the Jewish race, for there is scarcely an instance in which he deals with the Jews that they do not suffer under his hand. The points of their physiognomy are rather cruelly prominent sometimes, even almost to caricature, and they are constantly placed in ludicrous positions. There can be no doubt that in some instances the tailor is no less a bloodsucker than the dressmaker, but I think there are as many, or more, Christian—or, rather, unchristian—tailors who "sweat" their workpeople as there are Jewish. However, in one of Leech's most powerful prints, he gives the pas to the Jew, who watches a group of skeleton tailors as they labour in their bones for his benefit. It is a gruesome drawing, which, once seen, can never be forgotten.

Leech was happily left to his own devices as regards the contributions to Punch, with the sole exception of the large cartoons, the subjects of which were always settled by the whole staff at a dinner, which took place every Wednesday. At this dinner no strangers were present. This was, and is still,[Pg 31] the rule. Exceptions, however, were made on one or two occasions in favour of Charles Dickens, Sir Joseph Paxton, and some others.

It was, of course, open to any member to suggest a subject, and in the early Leech days it is said that the discussions on a proposed theme waxed fast and furious, Thackeray and Douglas Jerrold generally taking opposite sides. The dinners were usually held in the front room of the first-floor of No. 11, Bouverie Street—the business-place of the proprietors of the paper—and the Bedford Hotel, Covent Garden, was sometimes honoured by the presence of the staff. During the summer months the dinners took place at Greenwich, Richmond, or Blackwall; and once a year there was a more comprehensive banquet, at which compositors, readers, printers, clerks, etc., assisted. This dinner was called the "Way-goose." I am speaking of long ago. Whether these details would apply to the present time I know not.

I never knew Jerrold. I have frequently seen him, but always avoided an introduction; for, to speak the truth, I was afraid of him. I had heard so many stories of his making "dead sets" at new acquaintances as to disincline me to become one. By anybody quick at repartee I was told he was[Pg 32] easily silenced, and an example was mentioned when a barmaid succeeded in stopping a torrent of "chaff" of which she was the victim. It appears that Jerrold went with some friends to a supper-room one night after the theatre. The supper was "topped up" with hot grog, which was served to the guests in large, old-fashioned rummers.

"There," said the girl, as she placed the big glass before Jerrold, "there's your grog, and mind you don't fall into it."

Jerrold was a very little man, and the hit told to the extent of dulling him for the rest of the evening.

At the Wednesday dinner the whole of the contents of the forthcoming number of Punch were discussed. When the cloth was removed and dessert laid upon the table, the first question put by the editor was:

"What shall the cartoon be?"

It is said of Tenniel that he rarely suggested a subject for the cartoon, but that the readiness with which he saw and explained the possibilities of a subject was remarkable. During the Indian Mutiny, Shirley Brooks proposed that the picture should represent the British Lion in the act of springing upon the native soldiers in revenge for the cruelties[Pg 33] at Cawnpore. Tenniel rose to the occasion, and, as Brooks told me, he exclaimed, "By Jove, that will do for a double-page cut!" and a magnificent double-page drawing was made of it by him.

In the inevitable difference of opinion that arose on the occasion of these dinners—the chief disputants being, as I have just observed, Thackeray and Jerrold—Jerrold, being the oldest as well as the noisiest, generally came off victorious. In these rows it is said to have required all the suavity of Mark Lemon to calm the storm, his award always being final. Jerrold used to say:

"It's no use our quarrelling, for we must meet again and shake hands next Wednesday."

The last editions of the evening papers were always brought in, so that the cartoon might apply to the latest date. On the Thursday morning following the editor called at the houses of the artists to see what was being done. On Friday night all copy was delivered and put into type, and at two o'clock on Saturday proofs were revised, the forms made up, and with the last movement of the engine the whole of the type was placed under the press, which could not be moved till the Monday morning.

By means of the Wednesday meetings, the discussions[Pg 34] arising on all questions helped both caricaturist and wit to take a broad view of things, as well as enabled the editor to get his team to draw well together and give uniformity of tone to all the contributions.

By the courtesy of the proprietors of Punch, I am allowed to reproduce in this place a delightfully humorous drawing, the scene of which is laid in a barber's shop.

This picture explains itself, but there is a circumstance connected with it which is, I think, well worth relating; and as I heard it from Leech's own lips at one of the pleasant Egg dinners, I will give it in Leech's own words, the strangeness of the incident having left a very vivid impression on my memory. The usual company—Dickens, Forster, Lemon, etc.—was present; Leech was singing. We had listened for some time to the inevitable "King Death," when Dickens exclaimed:

"There, that will do; if you go on any longer, you will make me cry. Tell them about the lawyer who lost his client. Yes, I know the story, but[Pg 36] they don't; and I would much rather hear it again than listen to any more of that lugubrious song."

"Well, here goes," said Leech. "I suppose there is no one at this table who neglects to improve his mind by the weekly study of Punch; at any rate, all civilized people are familiar with the illustrations which adorn that famous periodical. Amongst those classical works the other day was a high-art drawing by me, representing a gentleman in a barber's shop, having his hair cut. In the course of talk peculiar to his fraternity, the little hairdresser remarks that his customer's hair is very thin on the top. This mild observation moved the object of it, a person of irascible temper, into ungovernable fury. He springs from his chair, which he upsets in the action, and flying at the terrified barber, he exclaims, 'Confound you, you puppy! Do you think I came here to be insulted and told of my imperfections? I'll thin your top!'

"Well, I don't see anything particularly facetious in the drawing, but a friend of mine, a lawyer in Bedford Row, did, and laughed whenever he thought of it. Unfortunately, the day on which the drawing was published had been fixed for a consultation upon a matter in which an old and respected client's interests were seriously involved. Legal points of [Pg 38] extreme intricacy and difficulty were to be examined and discussed; hopes were to be encouraged, and anxiety appeased. In his information to his legal adviser, the client had arrived at a point of extreme gravity, when my unfortunate drawing obtruded itself upon the legal mind, and so disturbed it as to cause the lawyer to repress a laugh with much difficulty.

"'I see you smile,' said the client. 'Surely the very serious character of the evidence which I put before you should strike you as convin——'

"'Oh, I beg your pardon; I was not smiling.'

"'Well, you did something very like it. I really must ask for your strictest attention to facts which are capable of such absolute—— There you go again! My dear sir, what can there be in my statement to cause a smile? Pray think of the gravity of the case—how deeply my interests are at stake—and give me your most serious attention.'

"'I will—indeed I will,' said the lawyer, mentally devoting me and my drawing to the devil.

"For some minutes the legal gentleman succeeded in banishing the little barber and his enraged victim; but suddenly they again ruthlessly seized upon his imagination, and he laughed aloud.

"'Good God!' said the client; 'what is there to laugh at in that?'

"'I assure you, sir, I was not laughing at what you told me, which is important indeed, but at a ludicrous idea that crossed my mind.'

"'What business have ludicrous ideas in your mind when you require all its attention for business which—excuse my saying so—you are well paid for listening to?'

"The consultation proceeded; graver and graver grew the details; when, at a moment of extreme importance, the barber came again upon the scene, and the lawyer laughed loud and long.

"'It's no use; I can't get rid of it,' he said to his astonished and indignant visitor. 'There is a drawing in Punch to-day that is so irresistibly funny that I can't get it out of my head, and I can't help laughing whenever I think of it.'

"'I don't believe a single word you say!' said the angry client; 'and as you persist in treating my case with such insulting levity, I will go elsewhere, and endeavour to find someone who will attend to me. And as for you, sir, I will never trouble you again on this or any other matter.'

"That," said Leech, "is how my friend lost his client."

Leech had long passed his boyish days before his love for field sports showed itself in his works. I recollect his saying how fruitful of subject the hunting-field, the stubble, and the stream would prove to the artist who was also a sportsman. In his early works, dealing as they did chiefly with the London life of the street or the home, we find the horse playing an inferior part; and it was not till he felt the importance of varying his subjects, and of supplying the public with the sporting scenes they love so much, that, mounted by his friend Adams, he joined the "Puckeridge" and became one of the "field."

Leech was a timid rider. He much preferred an open gate to a thickset hedge, and the highroad to either. He must, however, have frequently been in[Pg 41] full career with the "field"; how otherwise could he have acquired his knowledge of the thorough sportsman's seat on horseback, the cut of his clothes—correct even to the number of buttons—and, above all, display that Heaven-gifted power of showing the horse in repose, as well as in all the varieties of action? Landseer and all the animal-painters within my knowledge studied the horse from casts, often from the Elgin marbles, before they attempted drawing from the living animal. Landseer made himself acquainted with the superficial structure by dissection; but Leech, without any preparatory study whatever, drew the hunter, the cab-horse, the hackney, the rough pony, the cob—no matter which—in absolute perfection.

In the autograph letters which, through Mr. Adams' kindness, I am permitted to publish, Leech's constant charge to his friend to get him a horse suitable to a "timid, elderly gentleman," or to give the animal some preliminary gallops himself so as to take the freshness out of him, prove, as I said before, that Leech was anything but a daring rider. In spite of his care, however, he had some ugly falls, in which, happily, his hat was the greatest sufferer. Numbers of the hunting scenes were facts, and the persons represented were Leech and his friend—notably [Pg 43] one in which the artist is riding a mare afflicted with the "freshness" he dreaded, which his friend observing, shouts, "Give her her head, Jack! give her her head!" while it is pretty evident that more "head" will lead to the rider being swept from the saddle by the branches through which the mare is plunging.

"Barlow, Derbyshire,

"July, 1852."My dear Charley,

"You will see from the above address that I am still rusticating. I expect to be in town soon after the 12th of August, and then, after I have done my month's work, I am your man. You say when, and, if you are quite sure it will not distress Mrs. Adams, I will bring my wife with me. Charles Eaton [Mrs. Leech's brother] says he will come too. I am sure nothing would please him more than to run down to Barkway. Don't make yourself uncomfortable about the quantity of sport. I shall be quite satisfied with what you offer me. I rejoice to hear such good accounts of your wife and little ones. Pray give our united regards to her and them, and believe me ever,

"Yours faithfully,

"John Leech."

Yet another fact. Somewhere in the Puckeridge country there is a deep gully, or dried-up watercourse, with precipitous sides, with which Leech, one hunting-morning, found himself face to face. Some of the "field" had crossed, and were climbing the opposite bank. Leech pulled up, and said to his friend:

"Oh, if this is one of the places Charley spoke of, I shall go back!"

I am able here to give the rough sketch, now in Mr. Adams' possession, from which the drawing was taken that afterwards appeared in Punch.

Some years ago I took my exercise chiefly on horseback, and, after risking my neck several times from the "freshness" of a thoroughbred mare, I thought it best to get rid of her. Amongst the rest of my horsey friends, I thought Leech would be likely to know of an animal that might suit me, and I spoke to him on the subject. Leech soon succeeded, and sent the horse for my inspection. The man who brought the animal for approval assured me that a child could ride him with perfect safety. I liked his looks, and bought him. My first and last ride upon my new purchase was to Rotten Row in the height of the season. Whether he was a horse of Radical or Socialistic principles, or not, I[Pg 46] cannot say; but what I soon discovered was a determined dislike to the aristocratic company in which he found himself; he shied at the ladies and kicked at the gentlemen, and finally took to what is called "buck-jumping," an amusement which would speedily have relieved him of my company if I had not taken advantage of a momentary cessation of his antics and safely descended from his detestable back. Leech soon heard of "the dangers I had passed," when he wrote to me as follows:

"6, The Terrace, Kensington,

"Sunday."My dear Frith,

"I was shocked last night at the Garrick to hear from Elmore that I had nearly killed you through recommending a horse which had misbehaved himself in the Park. To be sure, I told you that I had been to look at an animal for my little girl, and that it did not suit, and I told you that it might be worth your looking at, as I had heard that it was young, sound, and steady; but if you ride a beast that you know nothing about in Rotten Row, and if that beast has not been out for a week, or probably a fortnight, I must protest against being made answerable for the consequences. I most[Pg 47] sincerely hope, however, that you are not hurt or come to grief in any way.

"Believe me,

"Yours always,

"John Leech."

It goes without saying that so true-hearted a man as John Leech, would be—as indeed he was—a model of the domestic virtues—the best of husbands and fathers, and a most dutiful and affectionate son. In evidence of the latter, I put before my readers some letters written to his parents in his maturer years, which will amply justify what I say of him.

"32, Brunswick Square,

"February 25, 1854."My dear Papa,

"I am sure you will be glad to hear that you have a little granddaughter.

"She came into the world at a quarter-past eleven o'clock—just now—and she is, with dear Annie (to me a novel phrase), 'as well as can be expected.'

"Kind love to all.

"Your affectionate son

"John.

"Tell Polly that the flag will be hoisted!"

"8, St. Nicholas Cliff, Scarboro',

"August 30, 1858."My dear Mamma,

"Thank you with my best love for thinking of my birthday. I hope you will be able to wish me happy returns of the day for many and many a year to come. The children gave your kisses very heartily, I assure you. You will be glad to hear, I am sure, that they were never better.

"Thank God they are thriving beautifully, which is a great happiness to me. I wish you could see them making dirt pies and gardens on the sands. A great many people notice them—indeed, although I say it, between you and me, I don't see any nicer little folks down here. If either you or papa could come here for a time we would endeavour to take the best care of you. I am no great hand at pen-and-inking, as you know, so you will excuse a very short note. I thought, however, that you would like to know that I got from Ireland safe and sound, and always believe me,

"My dear mamma,

"Your affectionate son,

"John."

"1, Crescent, Scarboro',

"August 29, 1859."My dear Mamma,

"It would be a great comfort to me, and I think it would be pleasant for you, if you would come here and see us for as long as you can spare the time. I want very much to go into the north, but I do not like leaving Annie quite alone with the chicks. We can give you a bed in, I think you will say, a tolerably comfortable house. Come as soon as you can, and stay as long as you can. I think it would do you good; only bring warm things, as when it is cold here, it is very cold. By the way, it is my birthday. What shall I say? Well, I wish you many happy returns of the day, and believe me, with best love from all to all,

"Your affectionate son,

"John."

"5, Pleydell Gardens,

"Sandgate Road, Folkestone,

"August 29, 1862."My dear Mamma,

"Many thanks for your note this morning. You will be glad to know, I am sure, that it found us all very well. May you be able to send me such a congratulation for many a year to come. And[Pg 50] with best love to you, and to all at home, believe me ever,

"Your affectionate son,

"John.

"Tell papa that if he would like to run down here, we can give him a bed. He would like to see a couple of little brown faces. I am going away for a few days (on Monday, I think); so if any of you could keep Annie with the chicks, and keep her company while I am absent, it would be very nice, I think."

A great deal has been said—and with a certain amount of truth, no doubt—about the difference between a drawing on wood as it leaves the hands of the artist, and as it appears after its sufferings at the hands of the wood-engraver. Leech is reported to have replied to an admiring friend, who was extolling one of his drawings:

"Ah, wait till you see what it looks like in Punch next week."

I once saw one of Leech's drawings on the wood, and I afterwards saw it in Punch, and I remember wondering at the fidelity with which it was rendered. Some of the lines, finer than the finest hair, had been cut away or thickened, but the character, the[Pg 51] vigour, and the beauty were scarcely damaged. To Mr. Swain, who for many years cut all Leech's drawings, the artist owed and acknowledged obligation; he thought himself fortunate in avoiding certain other wood-cutters, who were somewhat remorseless in their operations.

Mr. Swain, the wood-engraver, writes:

"For twenty-five years I engraved nearly all Mr. Leech's drawings. I always found him kind, and willing to forgive any of my shortcomings in not rendering his touches in all things. My work was always against time. I seldom had more time than two days to engrave one of his drawings in.

"Photographing drawings on wood was not known in his time, or it would have been a great advantage to him; instead of drawing on the block, he would then have drawn on paper, as most artists do in the present day, and had his drawings photographed on the wood, thus preserving the finished drawings, which would have been of great value now; besides, it would have been a great help to the engraver, always to have the original drawing to refer to in engraving the blocks.

"He never had any models, and rarely ever made[Pg 52] any sketches. He showed me a little note-book once with a few thumb-nail sketches of bits of background, but he seemed never to forget anything he saw, and could always go back in his memory for any little bit of country street he might want for background, etc.

"It was generally very late in the week before he could get his drawings ready, which gave very little time to the engraver to do justice to his work.

"His first introduction to Punch was through Mr. Percival Leigh.

"Mr. Leech was a man of very nervous temperament. I will give you an instance of this. Mr. Mark Lemon told me one day that Leech had been invited to a gentleman's house in the country for a few days' hunting. He arrived there in the evening. He was awakened early in the morning by a grating noise made by the gardener rolling the gravel under his window—noise he could never endure. This had such an effect upon his nerves, that he got up, packed his things, and was off to town before any of the family were aware of it. A barrel-organ was to him an instrument of torture.

"He had lived in Russell Square for many years,[Pg 53] but for some time before his death he took a large house—6, The Terrace, Kensington.

"I remember going to see him at his new house. He took great delight in showing me over it, and pointing out that he had had double windows put in all over the house to keep all noises out."

In looking at the plethora of lovely women's faces in the "Pictures of Life and Character," the spectator may fairly ask himself to realize, if he can, anything more exquisite; and if he fail, he will also fail to imagine that the charming creatures could have suffered much in their passage from the wood to the paper.

I have said elsewhere that Charles Dickens was an occasional guest at the Punch Wednesday dinners; he was also an intimate friend of several of the writers, notably of Leech, Lemon, and Douglas Jerrold. Dickens was, of course, one of Thackeray's warmest admirers, but I am pretty sure that the friendship between those great men could never have reached intimacy. Though Leech failed in his application for the post of illustrator of the "Pickwick Papers," he showed himself to be at one with[Pg 55] the great writer in the etchings and woodcuts with which he ornamented Dickens' Christmas books, in conjunction with Stanfield, Maclise, Cattermole, and others. Though Leech's etchings are inferior as works of art to his wood-drawings, they still show the same beauty, and perfect realization of character; in this assertion I am borne out by the illustrations in the "Christmas Carol," and by those in the "Haunted Man and the Battle of Life."

In my own profession I have observed, almost as a rule, that the artist who habitually invents his own subjects—in other words, draws upon himself for original ideas—generally fails, comparatively, in his attempts to realize the ideas of others. May I not say the same of many writers? Dickens, for instance, wrote of the life about him; but if, like Scott, he had attempted to revive the past, would he have produced work worthy to rank with "David Copperfield"? Scott seems to me a still more conspicuous supporter of my theory, for he tried modern life in "St. Ronan's Well," and produced a book incontestably inferior to "Kenilworth."

Our historical painters have almost invariably failed in their attempts upon everyday life; this extends even to the painters of genre. Witness the works of the elder Leslie, who painted scenes from[Pg 56] Shakespeare, Molière, and the poets of the last century, with a success that would have delighted the authors; but when he sought inspiration from the life about him, the result was far from satisfactory—conspicuous, indeed, in its contrast with his perfect rendering, of "Sir Roger de Coverley" or "Uncle Toby," and the alluring "Widow Wadman."

But the greatest of English painters is the greatest help to me in the contention into which I venture to enter. Hogarth was beguiled by a spirit, which must have been evil, into painting huge Scripture subjects. The size of these pictures, always of the proportion of full life, was unsuited to his hand, while the themes became ludicrous under his treatment. He failed completely also as an illustrator, witness his designs from "Hudibras." In the Bristol Gallery, and in the Foundling Hospital, these specimens of perverted genius may be seen; and no one can look at them without regret that time should have been so misspent—time which might have given us another immortal series like the "Marriage à la Mode."

I fancy I can hear my readers say—And what has all this to do with John Leech? Well, this: Leech is now about to pose as the destroyer, in his own person, of my theory—he is, in fact, the exception to my rule; for though the incidents in Albert Smith's "Ledbury" and "Brinvilliers" bear no comparison in human interest with the delightful transcripts of real life to be found in such profusion in the pictures of "Life and Character," Leech's rendering of them could not be surpassed.

The tragic and humorous powers of the artist are fully displayed in the examples which follow. In the first, from "Ledbury," "Jack Johnson attempts to rescue Derval": the awful swirl of the river as it engulfs the drowning man, while his would-be rescuer, finding the stream too strong for him, clings frantically to a ring in the stonework of the bridge, a full moon lightning up the scene, and throwing the Pont Neuf which spans the Seine in the distance into deep shadow—all are combined with admirable skill into, perhaps, the most powerful etching and the most perfect illustration in the book.

In the second example the artist is in full sympathy with his author—"Mrs. De Robinson holds a Conversazione of Talented People;" and amongst them is "the foreign gentleman who executes an air upon the grand piano." Here we have Leech using the scene as a peg upon which he can hang the humorous character in which he takes such hearty,[Pg 58] healthy delight. The performer himself is scarcely a caricature of the foreign pianist; while his audience, not forgetting the deaf old lady in the corner—includes the affected gentleman, whose soul is in Elysium; together with a variety of types, in which "lovely woman" is not forgotten.

In the "Ingoldsby Legends" Leech found a very congenial field for the exercise of his powers. Though I will not presume to prophesy respecting literary merit, I venture to think that, during the course of his practice, Leech's illustrations have occasionally appeared attached to literature scarcely worthy of them; they will, doubtless, in some cases, act as the salt, which will preserve for posterity certain books of an ephemeral character. This remark cannot apply to the "Ingoldsby Legends," which is a work that "the world will not willingly let die," until delightful wit and humour, wedded to no less delightful verse, cease to charm. The burden of the illustrations of the "Legends" falls upon the worthy shoulders of John Tenniel, and they show some of the strongest work of that admirable artist. Leech appears in[Pg 60] diminished force as to numbers, but in the examples I give he leaves nothing to wish for.

"16, Lansdowne Place, Brighton,

"September 3, 1863."My dear Sir,

"I have been obliged to make the 'Auto da Fé' this size, as I found I could not possibly get the subject on to a small block. You will see, too, that I have altered the appearance of the victims. It occurred to me that a real human being burning alive was hardly fun, so I have made them a set of Guy Fawkeses, and added, I hope, to the humour while getting rid of the horror.

"Believe me, my dear Sir,

"Yours faithfully,

"John Leech."Richard Bentley, Esq."

In the second example we have the figure of a maid at a well, which Leech has given us with the charm that never fails him. Her astonishment at the head in the bucket might have been indicated more forcibly, but there, I fancy, the engraver must have been to blame; yet he gives the head of Gengulphus with such perfection of expression and character as to make one feel that the original drawing of it could scarcely have been better.

The Maid and the Head of Gengulphus.

The Maid and the Head of Gengulphus.As this memoir progresses I propose to submit further illustrations from some of the many serials, novels, tales, poems, etc., with which Leech was connected. I also propose, in the course of my narrative, to quote opinions of Leech's powers from men better qualified to judge of them, and able to express their opinions in far more felicitous language than mine. Amongst those Dickens takes a foremost place. I think the friendship between Leech and Dickens began very early in the life of the former; the nature of Leech's work, and the modest and gentle character of the man, were especially attractive to Dickens.

In the amateur company of actors formed by Dickens, Leech was a conspicuous figure; but his heart was not in the work, though he entirely sympathized with the object of it, which was of a charitable nature, resulting in many performances—very successful in a pecuniary sense—for the benefit of poor and deserving literary men. The company consisted of Dickens, Mark Lemon, John Forster, G. H. Lewis, Douglas Jerrold, Leech, Egg, Wilkie Collins, Frank Stone, and others, who christened themselves "The Guild of Literature and Art." The late Lord Lytton took great interest in the Guild, for which he wrote a play called "Not so Bad as We Seem; or, Many Sides to a Character,"[Pg 64] and to this he added a gift of land on his estate in Hertfordshire, where some houses of a superior cottage form were built, in which decayed artists and authors were to end their days; but these gentlemen declined to begin any days there under the conditions prescribed; and when the houses were built, tenants for them could not be found. The Guild, therefore, was something of a fiasco, with the exception of the relief it afforded in several instances to worthy objects.

Leech acted in the first play that the amateurs ventured upon, no less than Ben Jonson's "Every Man in his Humour," in which Dickens played Bobadil and Leech Master Matthew. This occurred about 1847, I think, and I was honoured by an invitation to the first or second performance. Par parenthèse, I may add that I had the honour of being asked to join the company, but feeling that I could not learn a part, or, if I did get over that difficulty, the footlights would paralyze my memory, and also having neither face nor figure for the stage, I thought it best to "stick to my last."

Though Leech had a good part in "Every Man," strange to say, I have no recollection of his performance; though that of Dickens, Jerrold, Egg, and others remains vividly in my memory. Dickens[Pg 65] gave proofs in Bobadil, and in many other characters, that he might have been a great actor. The same, nor anything like it, could not be said with truth of Leech, if he played his other parts no better than he did that of Slender in the "Merry Wives of Windsor." It is only in that character that I can remember him, though I must have seen him in others. The tone in which he said "Oh, sweet Anne Page!" can I ever forget? There was a ring of impatience in his performance, a kind of "Oh, I wish this was all over!" that was plainly perceptible to those who knew him intimately. Leech's tall figure and handsome face told well upon the stage, but with those his attractions as an actor ceased. In Lord Lytton's play Leech had no part, I think, but my old friend Egg played that of a poor poet, who is discovered in a miserable attic when the curtain rises, and the poet soliloquizes to the effect that "Years ago, when under happier circumstances"—something or other. Egg always begun, "Here's a go, when under," etc. Unlike Leech, Egg was fond of acting, but, like Leech, he displayed no capacity for the art.

Perhaps the most striking difference between Leech and the caricaturists who preceded him, as well as those who were his contemporaries, was shown in the part that beauty played in every drawing in which it could be appropriately introduced; he may be credited with the creation of many of the loveliest creatures that ever fell from the pencil of an artist. Leech revelled in beauty as Gillray and Rowlandson revelled in ugliness.

In 1841 a work appeared, in book-form, of sketches by Leech, entitled "The Rising Generation," in which the rising youth, with their mannish manners, were satirized. Of this book Dickens wrote:

"We enter our protest against those of the rising generation who are precociously in love being made the subject of merriment by a pitiless and[Pg 67] unsympathizing world. We never saw a boy more distinctly in the right than the young gentleman kneeling in the chair to beg a lock of hair from his pretty cousin to take back to school. Madness is in her apron, and Virgil, dog-eared and defaced, is in her ringlets. Doubts may suggest themselves of the perfect disinterestedness of the other young gentleman contemplating the fair girl at the piano—doubts engendered by his worldly allusion to 'tin,' although that may have arisen in his modest consciousness of his own inability to support an establishment; but that he should be 'deucedly inclined to go and cut that fellow out' appears to us one of the most natural emotions of the human breast. The young gentleman with the dishevelled hair and clasped hands, who loves the transcendent beauty with the bouquet and can't be happy without her, is to us a withering and desolate spectacle. Who could be happy without her? The growing youths are not less happily observed and depicted than the grown women. The languid little creature, who 'hasn't danced since he was quite a boy,' is perfect; and the eagerness of the small dancer, whom he declines to receive for a partner at the hands of the glorious old lady of the house (the little feet quite ready for the first position, the whole heart projected into the[Pg 68] quadrille, and the glance peeping timidly at the desired one out of a flutter of hope and doubt), is quite delightful to look at. The intellectual youth, who awakens the tremendous wrath of a Norma of private life by considering woman an inferior animal, is lecturing at the present moment, we understand, on the Concrete in connection with the Will. The legs of the young philosopher who considers Shakespeare an overrated man were seen by us dangling over the side of an omnibus last Tuesday. We have no acquaintance with the scowling young gentleman, who is clear that 'if his governor don't like the way he is going on, why, he must have chambers and so much a week;' but, if he is not by this time in Van Diemen's Land, he will certainly go to it through Newgate. We should exceedingly dislike to have personal property in a strong-box, to live in the quiet suburb of Camberwell, and to be in the relation of bachelor uncle to that youth. In all his designs, whatever Mr. Leech desires to do he does. His drawing seems to us charming, and the expression, indicated by the simplest means, is exactly the natural expression, and is recognised as such at once. Some forms of our existing life will never have a better chronicler. His wit is good-natured, and always the wit of a gentleman.[Pg 69] He has a becoming sense of responsibility and restraint; he delights in agreeable things, and he imparts some pleasant air of his own to things not pleasant in themselves; he is suggestive and full of matter, and he is always improving. Into the tone as well as into the execution of what he does, he has brought a certain elegance which is altogether new, without involving any compromise of what is true. Popular art in England has not had so rich an acquisition."

In the endeavour to satisfy Dickens with the type required for the characters in his stories, Leech encountered the difficulty that all the author's illustrators had to master. "Phiz" made many drawings in Dickens' presence before he could realize the author's idea of Mr. Dombey; Cruikshank was more than once required to redraw a whole scene from "Oliver Twist"; and Leech has often been heard to speak of the minute details as to feature, height, thinness or fatness—in fact, every physical and, so far as it could be shown by appearance, mental quality—that Dickens insisted upon before he could be satisfied with the vera effigies of one of his characters. The feelings of the great author, then, may be imagined when he found—too late for correction—a terrible error into which Leech had fallen[Pg 70] in the drawing of a scene from "The Battle of Life," by introducing a personage into a scene which closes the second part of the tale, who was not intended to have been present.

It was in December, 1846, that "The Battle of Life" made one of the series of Christmas stories. In Leech's unfortunate illustration, which represented the flight of the bride, he made the mistake of supposing that Michael Warden had taken part in the elopement, and introduced his figure with that of Marian. Leech's error was not discovered until too late for remedy, the publication of the book having been delayed to the utmost limit expressly for those drawings; and it is highly characteristic of Dickens, and of the true regard he had for the artist, that, knowing the pain he must inflict, under the circumstances, by complaining, he never reproached Leech; excusing him, no doubt, on the ground of the hurry and confusion under which so much of his work was produced; but anyone who reads the story carefully will see what havoc the mistake makes of one of the most delicate turns in it.

Dickens wrote thus to Forster in reference to the grievous error: "When I first saw it, it was with a horror and agony not to be expressed. Of course, I need not tell you, my dear fellow, that Warden had[Pg 71] no business in the elopement scene; he was never there. In the first hot sweat of this surprise and novelty, I was going to implore that the printing of that sheet might be stopped, and the figure taken out of the block; but when I thought of the pain this might give to our kind-hearted Leech, and that what is such a monstrous enormity to me as never entered my brain, may not so present itself to others, I became more composed, though the fact is wonderful to me. No doubt a great number of copies will be printed by the time this reaches you, and therefore I shall take it for granted that it stands as it is. Leech otherwise is very good, and the illustrations altogether are by far the best that have been done for any of my Christmas books."

It may appear presumptuous in me to differ from Dickens in respect to the illustrations to "The Battle of Life"; but, in my opinion, these are not to be compared favourably with those of the "Christmas Carol." With the well-known readiness of people to ferret out mistakes, it seems strange that the illustrator's mistake was never publicly noticed.

The first series of "The Pictures of Life and Character," reprinted from Punch, appeared in 1854. They were heartily welcomed by the public; and it is as follows that Thackeray, Leech's intimate friend,[Pg 72] speaks of them in the Quarterly Review, in an article published at that time:

"This book is better than plum-cake at Christmas. It is one enduring plum-cake, which you may eat, and which you may slice and deliver to your friends, and to which, having cut it, you may come again, and welcome, from year's end to year's end. In the frontispiece you see Mr. Punch examining the pictures in his gallery—a portly, well-dressed, middle-aged, respectable gentleman, in a white neck-cloth and a polite evening costume, smiling in a very bland and agreeable manner upon one of his pleasant drawings, taken out of one of his handsome portfolios. Mr. Punch has very good reason to smile at the work and be satisfied with the artist. Mr. Leech, his chief contributor, and some hundred humorists, with pencil and pen, have served Mr. Punch admirably. There is no blinking the fact that in Mr. Punch's cabinet John Leech is the right-hand man.

"Fancy a number of Punch without John Leech's pictures! What would you give for it? The learned gentlemen who wrote the book must feel that without him it were as well left alone. Look at the rivals whom the popularity of Punch has brought into the field—the direct imitators of Mr.[Pg 73] Leech's manner—the artists with a manner of their own. How inferior their pencils are to his humour in depicting the public manners, in arresting and amusing the nation! The truth, the strength, the free vigour, the kind humour, the John Bull pluck and spirit of that hand are approached by no competitor. With what dexterity he draws a horse, a woman, a child! He feels them all, so to speak, like a man. What plump young beauties those are with which Mr. Punch's chief contributor supplies the old gentleman's pictorial harem! What famous thews and sinews Mr. Punch's horses have, and how Briggs on the back of them scampers across the country! You see youth, strength, enjoyment, manliness, in those drawings, and in none more so, to our thinking, than in the hundred pictures of children which this artist loves to design. Like a brave, hearty, good-natured Briton, he becomes quite soft and tender with the little creatures, pats gently their little golden heads, and watches with unfailing pleasure their ways, their jokes, laughter, caresses. Enfants terribles come home from Eton, young miss practising her first flirtation, poor little ragged Polly making dirt-pies in the gutter, or staggering under the weight of her nurse-child, who is as big as herself—all these little ones, patrician and[Pg 74] plebeian, meet with kindness from this kind heart, and are watched with curious anxiety by this amiable observer.

"Now, anyone who looks over Mr. Leech's portfolio must see that the social pictures which he gives us are authentic. What comfortable little drawing-rooms and dining-rooms, what snug libraries, we enter! What fine young gentlemanly wags they are, those beautiful little dandies, who wake up gouty old grandpapa to ring the bell; who decline aunt's pudding and custards, saying that they will reserve themselves for anchovy-toast with the claret; who talk together behind ball-room doors, where Fred whispers Charley, pointing to a dear little partner seven years old, 'My dear Charley, she has very much gone off; you should have seen that girl last season!'

"Look well at the economy of the famous Mr. Briggs. How snug, quiet, and appropriate all the appointments are! What a comfortable, neat, clean, middle-class house Briggs' is (in the Bayswater suburb of London, we should guess from the sketches of the surrounding scenery)! What a good stable he has, with a loose-box for those celebrated hunters which he rides! How pleasant, clean, and warm his breakfast-table looks! What[Pg 75] a trim maid brings in the boots that horrify Mrs. B.! What a snug dressing-room he has, complete in all its appointments, and in which he appears trying on that delightful hunting-cap which Mrs. Briggs flings into the fire! How cosy all the Briggs party seem in their drawing-room, Briggs reading a treatise on dog-breaking by a lamp, mamma and grannie with their respective needlework, the children clustering round a big book of prints—a great book of prints such as this before us, at this season, must make thousands of children happy by as many firesides! The inner life of all these people is represented. Leech draws them as naturally as Teniers depicts Dutch boors, or Morland pigs and stables. It is your house and mine; we are looking at everybody's family circle. Our boys, coming from school, give themselves such airs, the young scapegraces! Our girls, going to parties, are so tricked out by fond mammas—a social history of London in the middle of the nineteenth century. As such future students—lucky they to have a book so pleasant!—will regard these pages; even the mutations of fashion they may follow here, if they be so inclined. Mr. Leech has as fine an eye for tailory and millinery as for horseflesh. How they change, these cloaks and bonnets! How we have to[Pg 76] pay milliners' bills from year to year! Where are those prodigious chatelaines of 1850, which no lady could be without? Where are those charming waistcoats, those stunning waistcoats, which our young girls used to wear a few seasons back, and which caused 'Gus, in the sweet little sketch of 'La Mode,' to ask Ellen for her tailor's address? 'Gus is a young warrior by this time, very likely facing the enemy at Inkerman; and pretty Ellen, and that love of a sister of hers, are married and happy, let us hope, superintending one of those delightful nursery scenes which our artist depicts with such tender humour. Fortunate artist, indeed! You see he must have been bred at a good public school, and that he has ridden many a good horse in his day; paid, no doubt out of his own pocket, for the originals of those lovely caps and bonnets; and watched paternally the ways, smiles, frolics, and slumbers of his favourite little people.

"As you look at the drawings, secrets come out of them—private jokes, as it were, imparted to you by the author for your special delectation. How remarkably, for instance, has Mr. Leech observed the hairdressers of the present age! Mr. Tongs, whom that hideous old bald woman who ties on her bonnet at the glass informs that 'she has used the whole[Pg 77] bottle of Balm of California, but her hair comes off yet'—you can see the bears' grease not only on Tongs' head, but on his hands, which he is clapping clammily together. Remark him who is telling his client 'there is cholera in the hair,' and that lucky rogue whom that young lady bids to cut off a long thick piece—for somebody, doubtless. All these men are different and delightfully natural and absurd. Why should hairdressing be an absurd profession?

"The amateur will remark what an excellent part hands play in Mr. Leech's pieces; his admirable actors use them with perfect naturalness. Look at Betty putting down the urn; at cook laying her hands upon the kitchen-table, whilst the policeman grumbles at the cold meat. They are cooks' and housemaids' hands without mistake, and not without a certain beauty, too. That bald old lady tying on her bonnet at Tongs' has hands which you see are trembling. Watch the fingers of the two old harridans who are talking scandal; for what long years they have pointed out holes in their neighbours' dresses and mud on their flounces!

"'Here's a go! I've lost my diamond ring!'