THE MARINES HAVE LANDED

THE MARINES

HAVE LANDED

By

LIEUT.-COL. GILES BISHOP, JR.

United States Marine Corps

Illustrations by

Donald S. Humphreys

THE PENN PUBLISHING COMPANY

PHILADELPHIA

1920

Copyright 1920

by The Penn Publishing Company

The Marines Have Landed

To

MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE BARNETT,

Commandant, United States Marine Corps,

who, while holding the chief position of honor in that organisation since nineteen hundred and fourteen, has accomplished so much in furthering its efficiency and its prestige, and who has at all times and in all ways endeared himself to his officers and men, this volume is respectfully dedicated

Introduction

How many of our boys, in times past, while glancing through the morning paper have read the following statement: "The United States Marines have landed and have the situation well in hand." The cable message may have come at any date, and from any part of the world. If those words caused any comment on the part of the young American, it was probably a mild wonder as to just who the marines were. Sometimes he may have asked his father for enlightenment, and the parent, being no better informed than the son but feeling a reply was necessary, would say in an off-hand manner, "Oh, they are just a lot of sailors from one of our battleships, that's all," and there the subject rested.

It is the author's desire in this volume to explain just who the marines are, what they do, where they go, so as to make every red-blooded American boy familiar with the services rendered by the United States Marine Corps to the nation in peace and war. And if in this endeavor you suspect me of exaggeration I ask that you will get the first real marine you meet to tell you where he has been and what he has done. Then, if at the end of a half hour you are not convinced that the adventures of Dick Comstock, in this and the books to follow, are modest in comparison, I shall most humbly apologize.

THE AUTHOR.

Contents

Illustrations

The Thin Brown Line of Marines . . . . . . Frontispiece

The Marine Orderly Answered the Summons

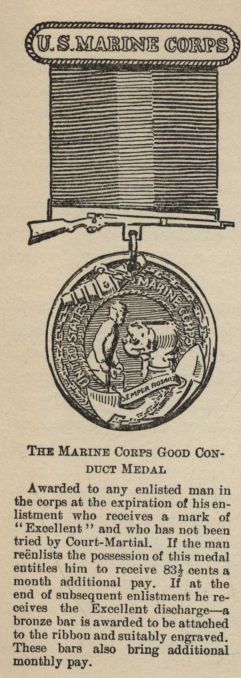

The Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal

"Look, There is Your Horseman!"

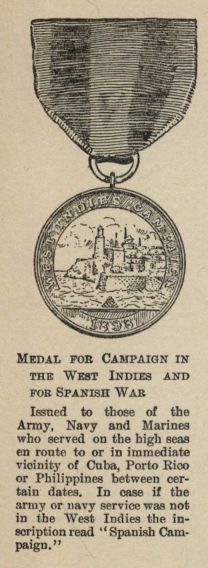

Medal for Campaign in the West Indies and for Spanish War

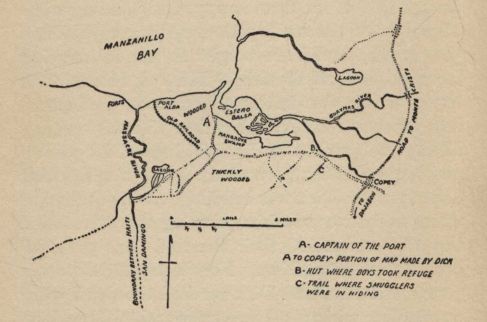

Map Showing Position of Hut in Which Boys Took Refuge

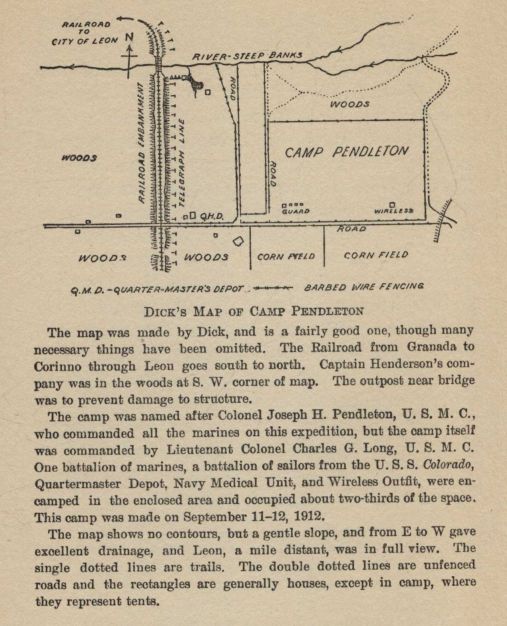

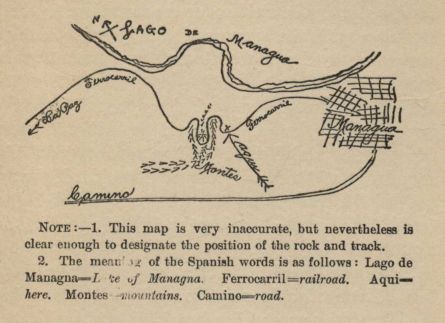

Map Showing Position of Rock and Track

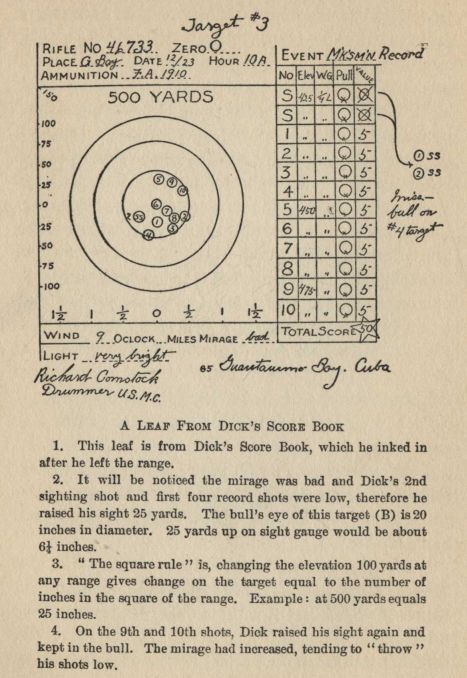

The Marines Have Landed

CHAPTER I

A BITTER DISAPPOINTMENT

"Dick Comstock, you've been fighting! What will Mother and Father say when they see your black eye?" and Ursula Comstock looked with mingled pity and consternation at her brother, who, at the moment, cautiously entered the cheery living-room.

"And to-day of all days in the year to have such a thing happen," she continued. "Everyone in town will see it to-night when you deliver your oration. I do think, Dick, if you had to fight, you might have waited until to-morrow, at least."

"It couldn't be helped, Sister, so stop scolding, and get me a raw steak or something to put on my eye," answered her brother, ruefully. "I know it's going to mortify Mother fearfully that her 'handsome son' is so badly banged up, but necessity knows no law, in war anyway. Now be a good sister and help me. Maybe by to-night it won't look so bad, and if you are as clever painting my face as you are your canvases it may not even be noticed."

"How did it happen?" inquired Ursula a little later, after first aid had been applied to the injured eye.

"Oh! It wasn't anything really of any account. I had to teach 'Reddy' Doyle a lesson he has been needing for a long time, that's all," answered Dick, bending over a basin of hot water while the tall, lithe girl, one year his junior, handed him steaming hot compresses.

"Tell me about it," demanded the girl, for between Richard and herself there were few secrets, and a more devoted brother and sister would be hard to find in all New England.

"Well, you see, Doyle and I never have been good friends in all the years we've been classmates at school. He goes with a gang I never cared for and he has always been inclined to bully. We've often had little tussles, but nothing that amounted to a great deal. You know he's a dandy athlete and I couldn't afford, half of the time, to have trouble with him. He is just cranky enough to have resigned from the school teams, and he's really too valuable a fellow to lose, consequently I've so often swallowed my pride in order to humor him that he began to believe I was afraid of him, I guess.

"But he has one mean trait I simply can't endure, and that is the torturing of dumb animals. I often heard from the other fellows of his tricks in that line. To-day I witnessed one, and--well--I've a black eye to pay for my meddling."

"That is not all the story, and you know it, Dick, so you may as well tell me now, for I shall get it sooner or later. What did he do that caused you to take such chances on this day of all days?"

"I didn't happen to think much about the day," grinned Dick, "but I do guess I'm a sight. Dad won't care; yet, as I said, I do feel sorry on Mother's account."

"Richard Comstock, if you do not stop this evasion and tell me at once what occurred, fully and finally, I'll refuse to help you another single bit. Now talk."

While Ursula was speaking she unconsciously shook a piece of very raw, red beef at her brother in such an energetic manner that he feared it might land in any but the place for which it was intended unless he obeyed without further delay.

A final rehearsal for the high school graduating exercises which was scheduled to take place in the evening had been held in the theatre, and after dismissal, as a number of the boys were going along Broad Street, a poor, emaciated cat ran frantically across the road towards them and climbed a small tree just in time to escape the lathering jaws of a closely pursuing bulldog. Percy Doyle, the red-haired owner of the dog, not satisfied with witnessing the poor feline barely escape his pet, ran quickly to the tree, grasped the cat by the neck and threw it to the eager brute. Almost instantly the powerful animal had shaken the cat to death.

This cold-blooded act was more than the good-natured Dick could stand and with a warning cry of anger and indignation he called upon Doyle to defend himself. Then there followed a royal combat, for these two lads were strong for their age and their years of activity in all kinds of sports had made them no mean antagonists.

In the end Doyle was beaten, but the victor had by no means escaped unscathed.

By the time Dick finished his recital the raw beef was properly bound over his eye and the grime of battle washed from his face by his gentle nurse, who completed her task by kissing him as she exclaimed with enthusiasm:

"Good for you, Dick, I hope you thrashed him well while you were about it, for he certainly deserved a beating. Now run along and get a bath and clean up properly before Mother comes home. She has gone to the station to meet Father. You have no time to spare; the New York express is about due," and with the words she shoved him towards the doorway leading to the hall.

"Call me when you are ready, and I'll come and paint you up like an Indian," she added as he disappeared up the stairs.

A half hour later when Dick appeared in the living-room and greeted his parents, Ursula's efforts at facial decoration proved so successful that no one other than his fond and adoring mother discovered the deception. Her searching eye was not to be deceived, however, and once again Dick was obliged to recount the details of his afternoon's experience.

"No one will notice my black eye, Mother, and if so half of the audience will have heard how I got it, so you need not worry."

Dick's father said nothing, but the look of pride and approbation in his eyes was enough to quiet any qualms as to his father's attitude.

John Comstock, having laid aside the evening paper he was reading when his son entered, now began searching through its pages, speaking as he did so:

"Have you seen to-night's paper, Dick?"

"No, Dad. Why, is there anything of particular interest in it--that is aside from the announcements of the big event being staged at the theatre?" inquired Dick.

"Unfortunately, yes," replied his father. "When I left home last week I told you I would see Senator Kenyon while in Washington and try to get him to give you that appointment to the Naval Academy we all have been hoping for and which we believed as good as settled in your favor until a few weeks ago."

"Did you see him? What did he say?" asked Dick in one breath, his face lighting up with excitement.

"Yes, I saw him, but my visit was fruitless. He politely but firmly told me he could not give it to you; and he would not tell me at the time who was to be the lucky boy. In to-night's paper I have just read that the selection has been made."

The look of disappointment which came over Dick's countenance was reflected in the faces of both his mother and sister. He gulped once or twice before he finally mustered up courage to reach out his hand for the paper, and the tears blinded his eyes while he read the brief article which so certainly delayed if it did not entirely destroy his boyhood's dream.

For a few moments silence reigned in the little group, and Ursula, rising quietly, walked to her brother and placed an affectionate, consoling arm over his dejectedly drooping shoulders.

"Never mind, Dick, the appointee may not pass the exams, and then possibly you will get your chance after all," she said consolingly.

"There's no hope he won't pass," answered Dick dolefully, and then more bravely, "neither would you nor I wish him such bad luck."

"Is it anyone we know?" now inquired Mrs. Comstock.

"I should say we do. It's one of my best friends;--it's Gordon Graham, our class valedictorian."

"Gordon Graham!" exclaimed Ursula, a slight flush tinging the peachy contour of her cheek, "Gordon Graham! Why, I never knew he even wanted to go to Annapolis!"

"He doesn't," answered Dick ruefully, "but his father does want him to go, and now Gordon has no choice."

"Mr. Graham is a rich man, and a politician. I suppose he wields such an influence in this district that Senator Kenyon could not afford to go against his wishes in the matter," said Dick's father, "and unfortunately I am not wealthy, and have always kept out of politics. Consequently, my boy, you may blame your father for this miscarriage of our plans. With the election so near, a senator has to look to his fences," he added as they arose to answer the summons to the evening repast.

"Our Policy in the West Indies and the Caribbean," was the subject of Richard's salutatory address in the crowded theatre that evening at the graduation exercises of the Bankley High School. To his friends it seemed something more than the average boyish ebullition. At any rate, Dick was a thoughtful lad and had expended his best efforts in the preparation of his oration. During its composition he had even looked into the future and in the measures he advanced as necessary for the military, naval and commercial integrity of the nation, he had always liked to think of himself as a possible factor.

To-night he experienced his first bitter disappointment, and instead of "Admiral Richard Comstock" being an actor in the stirring events that some day indubitably would occur, he saw his more fortunate chum, Gordon Graham, writing history on the pages of his country's record.

After the exercises he met Gordon, and the two boys walked home together along the lofty, elm-arched streets.

"Naturally I'm fearfully disappointed," said Dick, having first congratulated Gordon on his good fortune, "but I'm not churlish about the matter, and I guess the chief reason is because you got it. I'm mighty glad for you, Gordon."

"It is too bad, old man," Gordon replied feelingly, "because I know how you have looked forward to being appointed, and you know, Dick, I never was anxious for it. If it was not for frustrating my father's wishes, I should almost be inclined to flunk the examinations. In fact I may be unable to get by anyway, for they are very difficult."

"You'd never do that, Gordon! You couldn't afford to do such a thing--humble your pride in that manner. That wouldn't be helping me and you'd only injure yourself and hurt your father beyond measure," said Dick bravely.

"Oh, I suppose I shall have to go, and I will do my best, Dick; only I do wish we both were going. It is beastly to think of separating after all these years we have been together."

"We have a few days left yet before you leave, so cheer up," answered Dick, "and suppose we make the best of them. What do you say to a swim and row to Black Ledge to-morrow morning?"

"Good! I will meet you at eight o'clock. Bring along your tackle, for we may get some bass or black-fish, and we will make a day of it," responded Gordon enthusiastically, as they parted at the corner.

On entering the house Dick immediately sought his father.

"Father," he said, "what do you propose for me now that the Annapolis appointment is closed?"

"I have been thinking over the question for weeks," answered Mr. Comstock, leaning back wearily in his chair. "I counted on the Naval Academy more than you did, I might say; for, Dick, things have not been going well in the business, and the family exchequer is at a very low point, so low in fact I hardly know just how things will end."

Dick, immersed in his own selfish thoughts, for the first time realized how worried and care-worn his father appeared.

"What is the trouble, Dad?" he asked with a world of solicitude and tenderness in his voice.

"To tell you the truth, Dick, I cannot afford to send you to college. I am afraid that unless I can recoup my recent losses I shall be unable even to allow your sister to finish her art studies after her graduation next year, as we had planned. My boy, I have very little left."

He stopped for a moment and his hand visibly shook as he passed it over his troubled brow.

"I broke the news to your mother some time ago, and my visit to Washington was in the hope of recovering something from the wreck, but it looks dark. Also while there, beside seeing Senator Kenyon, I tried my best to get you into West Point. But that, too, was a failure."

"Dad, don't worry about me," said the boy, rising and going to stand by his father's side; "I'll get along all right, and between us we will fasten on something I can turn my hand to. I have had a mighty easy time of it for seventeen years, nearly, and I'm only too glad to pitch in and help out."

"The situation is not so bad as all that, Richard," answered Mr. Comstock, gazing at his manly boy with a proud look. "You do not have to strike out for yourself for a good while yet. I even thought another year at Bankley, taking the post-graduate course, would be the best plan for the present. In the meantime you have a whole summer's vacation ahead of you, which your good work at school richly deserves."

"No, I've finished with Bankley," said Dick with finality in his tone.

"Well! Well! We must talk about the matter some other time, my son, and if you intend to go to Black Ledge to-morrow morning with Gordon, you had best be getting under the covers."

Whereupon Dick said "Good-night" and slowly climbed the stairs to his bedroom.

Before Dick succeeded in getting to sleep he firmly resolved to relieve his father's shoulders of some of the burden by shifting for himself, but just how he proposed to go about it was even to his own active mind an enigma.

CHAPTER II

"THE OLDEST BRANCH OF THE SERVICE"

When Dick ran down the wharf the next morning he found Gordon and several other boys there already. He was later than he had intended; unless an early start was made their sport would be spoiled. Black-fish bite well only on the flood tide, and the row to Black Ledge, situated at the mouth of the broad river, near the entrance to the spacious harbor, was a distance of at least four miles.

In order to better their time Dick and Gordon invited Donald Barry and Robert Meade, two boys of their own age, to join them and help man the oars, while Tommy Turner, a freshman at Bankley, was impressed as coxswain of the crew.

Lusty strokes soon carried them away from the landing out into the sparkling waters of the river. Tommy Turner, though not a "big boy," knew his duties as coxswain, so he set his course diagonally for the opposite bank. Already the tide had turned, and to go directly down-stream would have meant loss of more time, while under the shelter of the left bank of the river the current and wind were not so strong as out in mid-channel.

With expertness born of much experience he guided the little round-bottomed craft in and out amidst the river traffic. The swell from an outward-bound excursion steamer caused the rowboat to rock and toss, but not a single "crab" or unnecessary splash did the rowers make as they bent their backs gladly to their task.

"Those farmers from up state on board the Sunshine thought we would all be swamped sure," remarked Tommy, laughingly. "I'd like to bet that half of them never saw blue water before in their lives."

Dick, stroking the crew, only grinned appreciatively at Tommy's sally, but Donald Barry called out from his place as bow oar:

"Don't get too cocky, Tommy, for if they knew you had never learned to swim, they might well have felt uneasy about you."

"I'll learn some day, fast enough," answered Tommy, slightly chagrined at Donald's remark, "but in the meantime, Don, if you would feather your oar better maybe the wind against it wouldn't be holding us back so much."

Tommy Turner was always ready with a "come back," as the boys expressed it, and for a while nothing more was said. Suddenly the coxswain, who had been gazing fixedly ahead for some time, gave a loud shout.

"Say, fellows, the fleet is coming in! I thought I couldn't be mistaken when I saw all that smoke way out there, and now it's a sure thing."

By common consent the rowers ceased their exertions and looked in the direction indicated by Tommy. Far out over the white-capped waves of the Sound could be seen against the deep blue sky, dark, low-lying clouds of black smoke, while just becoming distinguishable to the naked eye the huge hulks of several battleships could be discerned.

"This sure is luck," exclaimed Robert Meade. "I've often wanted to see a lot of battleships come to anchor together, but never have been on the spot at the right moment."

"Let's call off the fishing and row out to their anchorage; it's only a little over a mile farther out. What do you all say?" asked Donald, appealing to the others.

"Yes,--let's!" spoke up the ubiquitous Tommy. "We can go after the fish later if we like."

"You would not be so much in favor of that extra mile or two if you were pulling on an oar, kid," vouchsafed Gordon rather grimly, for the sight of the ships brought to his mind that sooner or later he might be passing his days on one of those very vessels.

"Right you are, sir, Admiral Graham, sir," quickly retorted the coxswain, and even Dick joined in the laughter now turned on Gordon.

How differently he gazed at the ships to-day from what he would have done a few days since. Then they would have meant so much to him, while now he seemed to resent their very presence in the harbor.

The rowers had resumed their work and without further words Tommy changed the boat's course.

By the time the five boys in their tiny craft reached the vicinity the great vessels were steaming in column towards the harbor entrance. On the fresh morning breeze was borne the sound of many bugles, the shrill notes of the boatswain's pipes calling the crew on deck, and the crashings of many bands.

The boys resting on their oars drank in the beauty and majesty of the scene with sighs of complete satisfaction while they interestedly watched every maneuver of the approaching ships. The powerful dreadnaught in the lead flew the blue flag with two white stars of a rear admiral. From the caged mainmast and from the signal yard on the foremast strings of gaily-colored flags were continually being run up or down, and sailors standing in the rigging were waving small hand flags to and fro with lightning rapidity.

"Those colored and fancy flags make the outfit look like a circus parade," remarked Tommy, lolling back in the stern sheets with the tiller ropes lying idly in his hands.

"That's the way the Admiral gives his orders to the other ships," volunteered Dick. "You'll notice they run up every set of flags first on the flagship, then the ships behind follow suit, finally when the order is understood by them all and it comes time to do that which the Admiral wants done, down they all go together."

"Jinks! I'd think it a pretty tedious way of sending messages," remarked Donald Barry, watching the gay flags go fluttering upwards in the breeze; "just imagine spelling out all those words. I'd think that sometimes they'd all go ashore or run into each other or something before they half finished what they wanted to say."

Dick, having spent considerable of his spare moments in reading up about naval matters, smiled at Donald and continued his explanation.

"It isn't necessary to spell out the words. Each group of flags means some special command, and all you have to do is to look it up in the signal book as you would a word in the dictionary. Most of the commoner signals become so well known after a little experience that it is only a matter of seconds to catch the meaning."

"I wish we could go on board one of the ships, don't you, fellows?" mused Robert rather irrelevantly. He was generally the silent one of the party, but the lads agreed with him that his wish was a good one. Yet such luck was hardly to be expected.

The flagship was passing but a few yards away, and the watchers could readily see the sailors on her decks all dressed in white working clothes, while on the broad quarter-deck a line of men, uniformed in khaki and armed with rifles, were drawn up in two straight military rows. Near these men glistened the instruments of the ship's band as they stood playing a lively march.

Suddenly the boys heard a sharp command wafted to them over the water. "Haul down!" were the words, and simultaneously from every ship in the column the lines of flags were hauled down to the signal bridges. Then came the splash of anchors, the churning of reversed propellers, the smoke and dust of anchor chains paying out through hawse pipes, and the fleet had come to anchor. Hardly had the great anchors touched the water when long booms swung out from the ships' sides, gangways were lowered, and from their cradles swift launches with steam already up were dropped into the water by huge electric cranes.

"What is the blue flag with all the stars they hoisted at their bows when they stopped?" questioned Donald, turning to Dick as being the best informed member of the party.

"That is the Union Jack," Dick replied, "and they fly that from the jack staff only when a ship is in dock, tied up to a wharf or at anchor; and also, if you noticed, they pulled down the National Ensign from the gaff on the mainmast and hauled another up on the flagstaff astern at the same time. When the flag flies from the gaff it means the ship is under way."

"It certainly is a shame, Dick, you cannot go to Annapolis in my place," remarked Gordon, regretfully; "you already know more than all of us combined about the Navy. But do you know, seeing these ships to-day and the businesslike way they do things has stirred my blood. It is just wonderful! But for the life of me I cannot see how a chap can learn all there is to know about them in only four years. I rather think I shall have to do some pretty hard digging if I ever expect to be a naval officer."

"Keep your ship afloat, Admiral Graham, and hard digging won't be necessary," interposed Tommy, and a roar of laughter followed his quip, as was usually the case.

The boys now began rowing towards the flagship, which in anchoring had gone several hundred yards beyond them. Nearing her, the strains of a lively march were heard, and an officer in cocked hat, gold lace and epaulettes, went down the gangway into a waiting motor boat. No sooner had the officer stepped into the boat than she scurried away for the shore landing. Again the boys stopped to watch proceedings. When the motor boat started from the gangway one of the sailors on deck blew a shrill call on a pipe and the khaki-clad line of men, who had been standing immovably with their rifles at the position of "present arms," brought them to the deck as if actuated by a single lever, and a moment later they were marched away.

"Those soldiers are marines, aren't they?" asked Robert. "Anyway, they are dressed the same as the marines up at the Navy Yard."

"Sure they are marines," answered Tommy; "I know all about 'em, for my Uncle Fred was a marine officer once. He swears by 'em, and says they are the best fighters in the world."

This was Robert Meade's first year at Bankley High School, having spent all his life previously in an up-state town, and the soldier element on board ship was not clear in his mind.

"I always used to think that the marine was a sailor," said he. "At least, most of the papers half the time must be wrong, for you see pictures supposed to be marines landing at this or that place and they are almost always dressed as sailors."

"That's because the papers don't know anything," commented Tommy indignantly. "Why, the marines are the oldest branch of the service; older than the Navy or the Army. Aren't they, Dick?"

"Well, to tell the truth," Dick answered, "I'm a bit hazy about marines myself. Of course I've seen them around town and on the ships all my life, off and on, but I've been so much more interested in the work of a sailor that I haven't paid much attention to the military end of it."

"The marine is 'soldier and sailor too,'" said Tommy, sententiously. "That English poet, Kipling, says he can do any darned thing under the sun; and if all my uncle tells me is true, it must be so. He was a volunteer officer of marines in the war with Spain and fought in Cuba with them."

"Well, if they are soldiers also, why don't they stay ashore with the army?" persevered Robert, wishing to understand more about the men who had excited his interest.

"It's a pretty long story to tell you in a minute," answered Tommy; "besides, I may not get it all straight."

"That will be all right, Tommy," Gordon called out. "I do not know anything about them, either, and I suppose I had better learn everything I can about the Navy now. I've made up my mind, boys, that I do want to be an officer on one of these ships, and I am going to tell my father so to-night, as I know it will please him. So, Tommy, I propose that when we start for the boat-house, as you will have nothing else to do but steer, you tell us all you know about these 'Sea Soldiers.' Is my motion seconded?"

As Gordon finished speaking they were lying a little off the starboard quarter of the flagship, idly tossing in the short choppy sea that the breeze from the Sound had stirred up. A whistle from the deck now attracting their attention, the boys looked up in time to see a small marine with a bugle in his hand run along the deck and, after saluting the naval officer who had summoned him by the shrill blast, receive some instructions from the officer. After giving another salute to the officer, a second or two later the little trumpeter blew a call, the meaning of which was unknown to the silently attentive lads in the rowboat.

All the boys had some remark to make at this.

"Hello, look at Tom Thumb blowing the bugle," called Tommy, and he added, "If all the marines are his size, I should think someone had been robbing a nursery."

"Wonder what all the excitement means, anyway?" inquired Donald, as he saw various persons on the ship running about, evidently in answer to the summons of the bugle.

"You know all the bugle calls, Dick, because you were the best bugler in the Boy Scouts when we belonged; what was the call?" Gordon asked.

"You've sure got me buffaloed," answered Dick. "I learned every call in the Instruction Book for Boy Scouts, and I know every army call, but that one wasn't among them."

During this time their little boat was drifting slowly astern again when suddenly a long heavy motor boat rounded the battleship, just clearing her, and at terrific speed bore down on the drifting rowboat.

Instinctively the occupants of the rowboat sprang into action.

A warning cry was shouted to them through a megaphone from the deck of the battleship, the coxswain of the fast flying motor boat sounded two short blasts on his whistle, threw his helm hard over, and the crew shouted loudly. Tommy Turner in the excitement of the moment mixed his tiller ropes and sent his frail craft directly across the sharp bow of the approaching vessel.

With a smashing and crashing of wood the heavy motor boat practically cut the rowboat in two, forcing it beneath the surface and passing over it, and more quickly than it has taken to relate it the five boys were thrown into the sea.

* * * * * * * * *

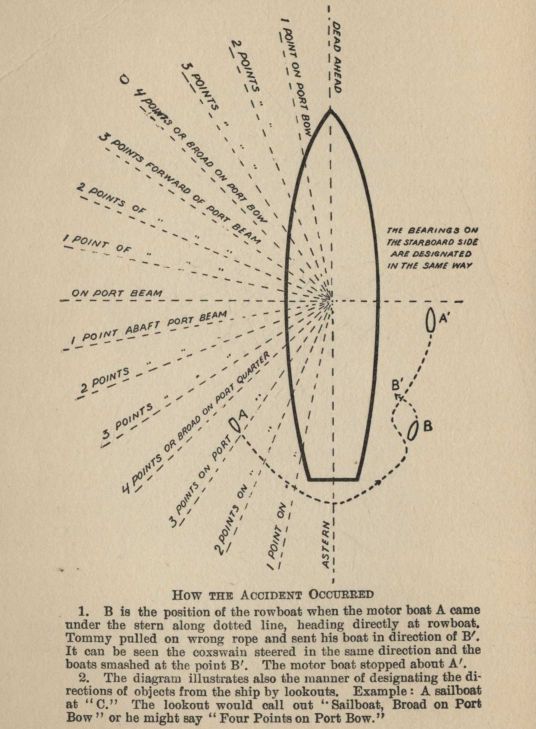

How the accident occurred

1. B is the position of the rowboat when the motor boat A came under the stern along dotted line, heading directly at rowboat. Tommy pulled on wrong rope and sent his boat in direction of B'. It can be seen the coxswain steered in the same direction and the boats smashed at the point B'. The motor boat stopped about A'.

2. The diagram illustrates also the manner of designating the directions of objects from the ship by lookouts. Example: A sailboat at "C." The lookout would call out "Sailboat, Broad on Port Bow" or he might say "Four Points on Port Bow."

* * * * * * * * *

Dick Comstock, coming first to the surface, looked about him for his companions. The motor boat was now about fifty yards away; her engine had stopped and her crew were looking anxiously towards the spot where the accident had taken place.

As Dick shook the water from his eyes and ears, he heard the voice of the coxswain answering a question apparently addressed him by someone from the deck of the flagship.

"I can't reverse my engines, sir. Something fouling the propellor," he called out.

By this time Dick saw the bobbing heads of Robert, Donald and Gordon not far from him.

"Where's Tommy?" called Dick, anxiously, trying to rise from the water as far as possible in his endeavor to sight the missing boy.

To these four lads the choppy sea meant nothing, in spite of the fact they were fully clothed when so suddenly upset. But in Tommy's case it was a far different matter, for, as has been stated, Tommy, though a plucky little fellow, was unable to swim.

The wrecked rowboat had floated some distance away and with one accord the four boys swam rapidly towards it in the hope that Tommy might be found clinging to the débris.

Meanwhile on the deck of the battleship there was great excitement. A life-boat was being quickly lowered from its davits and active sailors were piling into it. The starboard life-lines of the quarter-deck were lined with men in white uniforms and dungarees, for many of the engine room force had been attracted to the deck to witness the episode though they were not allowed there on ordinary occasions in that attire, and also there was a sprinkling of marines in khaki. Shouts, signals and directions were coming from all sides, while two of the motor boat's crew were already in the water swimming back towards the boys to lend them aid if necessary.

On reaching the wreck, Dick, who was first to arrive, half pulled himself out on the upturned bottom in order to search to better advantage. Discovering with sinking heart that Tommy was not there, without a moment's hesitation he disappeared beneath the boat searching with wide open eyes for his little friend, nor was he alone in his quest, for each of the boys in turn dove under the boat on arrival. Staying as long under water as he possibly could Dick came to the surface to free his lungs of the foul air with which they were now filled. Again his anxious eyes swept the roughened water in eager survey and then with a loud cry of gladness he was going hand over hand in the famous Australian crawl, but this time away from the boat and towards the ship.

In that momentary glance he saw an arm and hand emerge from the waves, the clenched fist still holding fast to a piece of tiller rope. It had shown but an instant above the surface and then disappeared. Could he reach the spot in time? Could he? He would--he must, and with head and face down his arms flew like flails beating the water past him as he surged forward.

On board the flagship, Sergeant Michael Dorlan, of the Marines, had been an eye-witness of the whole occurrence. For some time previous he had been watching the boys in the boat. The manner in which they handled their oars showed him they were no novices. He noted also that there were five occupants in the unlucky craft when she was struck. Calmly he counted the heads appearing in the water beneath.

"One," counted Dorlan aloud to himself as Dick's drenched head almost instantaneously bobbed up, "two, three," he continued in rapid succession, "four----," and then he waited, holding his breath, while his honest Irish heart beat faster beneath his woolen shirt.

"They kin all shwim," he muttered aloud as the four lads struck out vigorously in the water, "but, bedad, the fifth kid ain't up yet."

During all this time Dorlan was unlacing his shoes with rapidly moving fingers. His coat he unconsciously took off and threw to the deck and then he climbed to the top rail of the life-lines, steadying himself by holding to an awning stanchion. Never once did his sharp, gray-blue eyes leave the surface of the water. As Dick cried out and dashed through the waves towards the spot where he momentarily glimpsed the tightly clenched hand of Tom Turner, a brown streak appeared to shoot from the rail of the dreadnaught and with hardly a splash was lost and swallowed up in the sea.

Sergeant Michael Dorlan had also seen that for which he was looking and like a flash he had gone to the rescue. From the height of over twenty feet his body shot like a meteor in the direction of the drowning boy. To the officers and crew on board the flagship it seemed an eternity before a commotion below them and a spurning and churning of the water announced his reappearance. And Dorlan did not come to the surface alone, for it was seen that he was supporting the form of the boy he had gone to rescue.

A great cheer filled the air as the crew of the ship spontaneously gave vent to their relief, and a few seconds later the unconscious lad was hurried up the gangway by willing hands, followed unassisted by his four drenched and solicitous comrades.

CHAPTER III

UNCLE SAM'S UNINVITED GUESTS

"Right down to the sick bay[#] with him," ordered an officer as Tommy was carried over the side in the strong arms of Sergeant Dorlan, who, on climbing up the gangway, had tenderly taken the boy from the sailor holding him. "Hurry along, Sergeant, the surgeon is already there waiting."

[#] Sick bay--The ship's hospital.

After giving these directions the officer turned to the four dripping lads and said:

"Are you boys injured in any way?"

"No," they replied as if with one breath.

"You look as though you had been struck in the eye pretty badly," said the officer, giving Dick's bruised cheek a close scrutiny, and for a moment the boy blushed as if caught in a misdemeanor.

"I was hit in the eye yesterday," he finally managed to stammer; "it wasn't caused by anything that happened to-day," and then to change the subject if possible, he inquired:

"May we have permission to go down where they have taken Tommy Turner? We are all mighty anxious about him."

"Don't you all want to get on some dry clothes first?" inquired the officer.

The boys preferred, however, to hear first the news as to their friend's condition; consequently they were taken below, where already the ship's surgeon and his assistants were working hard to restore life to the still unconscious Tommy.

Sitting on a mess bench which some men had placed for them, each boy wrapped in blankets furnished by other thoughtful members of the crew, they waited silently and with palpitating hearts while a long half hour slowly ticked away. Though many sailors were continually passing to and fro they were all careful not to disturb the four shipwrecked boys who sat there with eyes fastened in anxious hopefulness on the door to the "sick bay," as the hospital is called on shipboard.

After what seemed an eternity, the door opened and Sergeant Dorlan came out quietly, closing it behind him. Immediately the watchers jumped to their feet.

"Is he all right?" whispered Dick, plucking at Dorlan's wet sleeve. "Is he----"

"Lord love ye, me lads, he's as fit as a fiddle and will live to laugh at ye in yer old age," replied Dorlan, cheerfully, and it was with a mutual sigh of relief they heard the announcement. A messenger approaching at this moment, called to the boys:

"The Officer of the Deck says, seeing your friend's all right, that you are to follow me to the Junior Officers' Quarters, where you can get a bath and your clothes will be dried out for you."

"We'd like to see our friend first, if we might," suggested Dick.

"The little lad's asleep and old 'Saw Bones' wouldn't let ye in to disturb him for love nor money. Go ahead and get policed up," suggested the sergeant, turning aft towards the marines' compartment as he spoke.

"We do not know your name, Sergeant," spoke up Gordon, placing a detaining hand on the marine's arm, "but we all want to thank you for saving Tommy Turner's life. It was just too fine for words, and I for one should like to shake hands with you."

"It's all in the day's wurruk, me lad," said Dorlan, confused by this frank praise, "but it's happy I am to shake the hands of such plucky lads as ye are yersel's, so put her there," and he extended a brown horny hand which they all grasped simultaneously.

"When ye git all fixed up and dhried out, come on back here and it's proud I'll be to show ye about the old tub," with which remark he left them at liberty to follow the Officer of the Deck's messenger to the Junior Officers' Quarters.

Divesting themselves of their soaked garments on arrival there they were supplied with soap, towels and bath robes and were soon enjoying the bath. With spirits no longer depressed for fear of danger to their friend, the four lads were now beginning thoroughly to enjoy their novel experience.

"Which fellow said he wished he could visit a man-of-war?" questioned Donald from the confines of a little enclosure where the sound of splashing water announced he was already under the shower.

"It was the Sphinx," laughingly answered Gordon from his own particular cubby hole.

"I didn't want to come on board in quite the manner I did, though," called out Robert, "and furthermore, don't call me Sphinx in the future. If I'd had the sense of that old hunk of stone, I could have foreseen the danger and been able to avoid it."

"Hurry up, you fellows, and don't talk so much. Let me have a whack at one of those showers," called Dick, who had been forced to wait, there being not enough bathing places to allow all to indulge at the same time. "I want to hurry out of this and take a look around this ship before I go ashore."

"Speaking of leaving," remarked Gordon as he emerged for a rub down, "how do you suppose we are going to leave?"

"To tell the truth, I hadn't thought of that," Dick replied, "and how about your boat? It's all smashed up."

"She was about ready for the junk pile, anyway," said Gordon, "and I was going to give her to the boat club before I left for Annapolis next week."

"I wonder what Uncle Sam does when he smashes up your boats like that?" questioned Donald.

"In this case," Dick vouchsafed, "I rather guess 'Uncle Sam' will say it is altogether our own fault. Poor Tommy was so rattled that he pulled on the wrong rope and steered us right in front of the motor boat even after they had veered off to avoid hitting us."

"Well, if they permit us to take a look around the ship, I am willing to call it square," Gordon remarked philosophically.

A little later the boys were escorted to a vacant stateroom or cabin where they found their underwear already dry and waiting to be donned.

"I call that quick work," exclaimed Gordon, and while he was speaking a knock sounded at the door.

"Come in!" he called out, and a colored mess boy stuck his woolly head into the room.

"Yoh clo'es will be ready foh yoh all in jest a jiffy, sah. Here am yoh rubber shoes dry a'ready an' de tailor am a-pressing yoh pants and yoh coats, sah."

"Where did you find our coats?" inquired Dick. "They were in the rowboat the last I knew."

The colored boy grinned broadly, showing an expansive row of shining white teeth.

"Ah don't rightly know foh shu, boss, but Ah reckon dey foun' 'em floatin' on de water an' fetched 'em aboahd wid yoh boat, sah."

"You mean to say they have rescued the rowboat too and have it on board this ship?" asked Gordon incredulously.

"Shu as shootin', sah, an' Chips wid his little Chips is fixin' of her up good as new. Dey ain't nuthin' we cain't do on one ob Unc' Sam's ships, sah."

With which closing encomium the black face was withdrawn and the door closed.

"Wonder what he meant by his 'Chips wid his little Chips'?" laughingly questioned Robert Meade.

"You will have to ask Dick," answered Gordon rather enviously. For now that he had become so enthusiastic over his determination to follow his father's wishes and become a naval officer he felt he had neglected many past opportunities for learning about the service.

"He meant the Chief Carpenter and his helpers, I 'reckon. 'You see, 'Chips' is a nickname in the Navy for the man who handles the saw and hammer," Dick announced.

"When you boys are dressed come out into the mess room. Put on your bath robes till your clothes are ready for you," called a voice from the passageway outside their door and needing no second bidding they all walked out into the comfortable room where a number of junior officers were standing about.

"I am Ensign Whiting, and these are the junior officers of the ship," announced the officer who had previously called to them, and he introduced the lads to the others with an easy wave of his hand. "Sit down and tell us all about the accident. By the way, your friend Tommy is still sleeping, and as it is noon we should be very glad if you would accept our invitation to lunch. The Captain sent word he wishes to see you, but I told him you probably would eat with us, so, unless you are in a hurry to get away, you need not go up to see him till later."

The boys gladly accepted the kind invitation and as the meal was immediately announced they sat down in the places already provided and proceeded to enjoy thoroughly their first meal on board a battleship.

During the repast they related how the accident occurred, and all were high in praise of the marine sergeant who so promptly came to their rescue. They learned that their wrecked boat had been towed back to the ship and hauled out on board, and the damage to it was not so great but that the ship's carpenters could easily repair it.

"Mike Dorlan is a bit too fond of the firewater," volunteered one of the officers, "but when it comes to being the right man in the right place at the right time, it would be hard to find his equal."

"We tried to thank him for rescuing Tommy," said Gordon, "but we could not make him understand what a noble thing it was."

"That's Mike all over. He's a gruff old chap as a rule, and I suppose saving anyone in such an easy manner, as he would call it, doesn't seem much to him," remarked Ensign Whiting. "Mike already owns gold and silver life-saving medals presented to him by the Navy Department."

"I never knew that," said an officer who had been introduced to the boys as a Lieutenant of Marines. "He never wears them at inspection nor the ribbons for them at other times."

"Dorlan? Wear medals? Not that old leatherneck!"[#] exclaimed Whiting. "Yet I happen to know that he has several in his ditty box[#] and if you tackle him just right he will spin you some mighty interesting yarns. Why, he was all through the Spanish War, first on a ship and then ashore at Guantanamo; he fought in the Philippine Insurrection and was one of the first marines to enter Pekin during its relief at the Boxer uprising in 1900, and later he was in Cuba during the insurrection there in 1906, and I believe he has landed for one reason or another in about every place there ever was trouble brewing in the last fifteen years. To cap the climax he even has a medal of honor which he received for some wonderfully impossible stunt he did out in China. Ah! Old Mike is a wonder, all right!"

[#] Leatherneck--A sobriquet often applied to marines. Supposed to have originated from the leather collar which formed part of the uniform of marines in the early days of the last century.

[#] A small wooden box issued to the men in which they keep writing paper, ink, and odds and ends. It is fitted with a lock.

"Do you suppose we can see Sergeant Dorlan later?" asked Dick eagerly. "You see, he promised to show us over the ship, and this being the first time that any of us has ever been lucky enough to get on board a United States ship, we all want to make the best of fortunate misfortune, as you might say."

"Why, certainly: right after you see the Captain," replied Ensign Whiting, "and as your clothes are now ready, suppose you get into them at once and I will take you up above for your interview."

Captain Cameron, of the U.S.S. Nantucket, flagship of the Battleship Division of the Atlantic Fleet, was a big jovial man of ruddy complexion and his greeting of the shipwrecked boys who were ushered into his cabin by the marine orderly was hearty, and complimentary.

"It is a pleasure to meet you, young gentlemen," he said, shaking each of them by the hand. "I only regret your introduction on board my ship was attended by such an unhappy incident. However, it is to be hoped that you won't bear the Navy any grudge after I explain to you that we are doing our best to make full amend for the accident. Mr. Ennis, the ship's carpenter, reports that his men will soon have your boat in nearly perfect condition, and the surgeon states your young friend will have no ill effects from his experience. Please be seated and make yourselves at home, for I have a few questions to ask you."

It was indeed an interesting place to sit, being filled with curios which the Captain during his many years of service in the Navy had collected in nearly every corner of the world, and while he talked they found it difficult to keep their eyes from wandering about the room on cursory inspection of the idols, weapons, pictures and objects of art, attractively arranged on walls and tables.

"Now that we are all comfortable, suppose you tell me how the accident occurred," said their host, turning first to Dick, who was seated nearest him. Whereupon the boy told him the entire story and each of the others added the details that came to their minds.

"It is needless to say that I wish it had not happened," said he; "my coxswain was at fault for coming around so close under the stern of the ship, but I can see that you are inclined to place the blame on your own coxswain, who steered you across the bow of the motor boat after she had blown the proper whistles. However, I have endeavored to do the best I can by you. Your boat is nearly repaired; your oars and stretchers replaced, your clothes recovered, and though they may have suffered a little from their wetting I do not imagine any great harm has resulted. It is true you lost your lunches but I am inclined to believe you have not suffered on that account either, and even the box of fish lines was picked up. The only thing really worrying me is your friend Tommy, but even in his case nothing more than a slight bruise on the forehead has resulted. Now I want to know if there is anything else I can do to even up our account?"

"Well, sir," Richard answered, looking a little embarrassed while he turned the edge of a rug with the toe of his shoe, "there is one more thing you may do for us if you will."

Captain Cameron, believing he had already done more than he was called upon to do under the circumstances, was surprised at this reply.

"And what may that be?" he inquired rather sharply.

"If you would permit all of us to have a good look around your ship, sir, before we leave, it would be greatly appreciated and also, sir, we should like it very much if Sergeant Dorlan could act as the guide. You see, he offered to do it," and Richard ended his request by looking directly at his host.

"If that is all, my boys," said the Captain, once again his genial self, "I gladly grant it, and furthermore, during our stay in port I shall be happy to see you on board at any time outside of working hours."

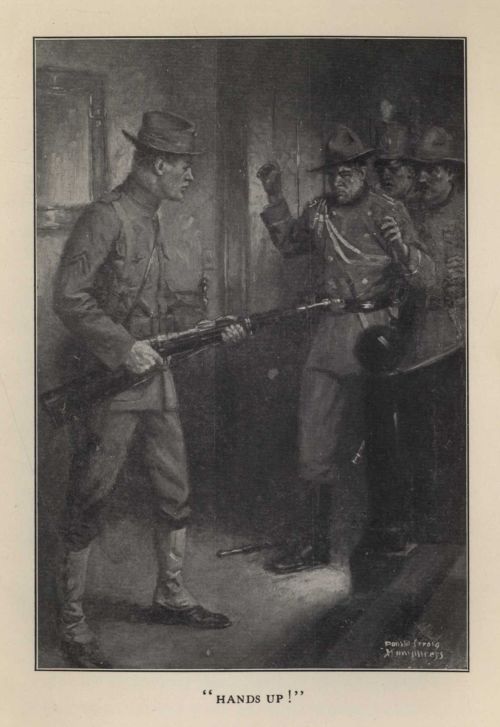

Ringing a bell, the marine orderly answered the summons.

"Orderly, present my compliments to Captain Henderson and ask him to detail Sergeant Dorlan to accompany these young gentlemen on an inspection tour of the ship."

The marine snapped his hand to his cap in salute, and after his "Aye, aye, sir," which is the naval way of replying to an order, he turned and left the cabin, followed by the delighted youngsters.

Captain Kenneth Henderson, United States Marine Corps, was holding five-inch gun drill when the orderly found him. After receiving the message from his Commanding Officer he immediately called Sergeant Dorlan and gave him his instructions.

"Before you start out, Sergeant, you had better stop in the sick bay and pick up the other member of the party. When I came by there a while ago he was feeling fine and getting ready to dress. He of course will wish to go around with you."

Tommy was feeling perfectly well. A small blue mark still remained on his forehead showing where he had been hit by some part of the wreckage in the accident and knocked insensible. Being fully dressed when the others arrived, they all were soon investigating the wonderful battleship. For two full hours they pestered the patient Dorlan with more questions and inquiries than he could have answered in a lifetime. In the course of their personally conducted trip they were on a visit to the bridge when their attention was again attracted to the small bugler of marines who had been the innocent cause of their presence on board the flagship. He was again sounding the call which they had been discussing when the motor boat dashed under the stern of the vessel and crashed into them.

"What is the meaning of that call?" asked Dick of their guide.

"He's callin' away the motor sailer," replied Dorlan.

"Is he a marine--the little fellow blowing the bugle?" inquired Tommy.

"Surest thing ye know," was the answer.

"Why! He can't be as old as we are," remarked Dick; "how old do you have to be to enlist in the Marines?"

"Those kids sometimes come in at the age of fifteen," answered Dorlan; "they enlist as drummers and trumpeters and serve till they're twenty-one years old."

"May anyone enlist?" Dick asked.

"Sure, if yer old enough."

"And work your way up to a commission, as they do in the army?"

"Indeed ye can, if ye've got it in ye," replied the Sergeant; "Captain Henderson come up from the ranks, and a mighty good officer he is, too," he added.

After this talk Richard Comstock remained very thoughtful. A sudden idea had come to his mind, and he wanted to think it over. The sight of the neat-looking marines, their military bearing, smart uniforms and soldierly demeanor attracted him powerfully, and when he learned that enlisted men were afforded the opportunity to rise in rank to that of commissioned officer, he saw in this a means of following a career which, if not exactly the one he had always desired to pursue, was similar in many respects, at least.

A little later the boys were taken ashore in one of the flagship's steamers, first being assured that their own boat would be sent to the boat club in the morning.

CHAPTER IV

SEMPER FIDELIS--ALWAYS FAITHFUL

The actions of Dick Comstock for the next few days were clothed in mystery so far as his own immediate family was concerned, for he kept his own counsel as to his movements when away from home. Even his sister Ursula was not taken into his confidence. In the meantime the day of Gordon Graham's departure for Annapolis arrived, and his friends went to the station to give him a proper send-off.

Ursula and Dick were there, also Donald, Robert and Tommy Turner and many of Gordon's classmates, of whom Dick was the closest friend.

"I still wish you were going, Dick," said Gordon sadly when the express pulled in under the train shed. "It will be fearfully strange down there with none of the old crowd around. Have you made any plans yet regarding what you are going to do?"

"Not fully," answered Richard. "I expect to be leaving town in a day or two, though."

"Where are you going?" inquired Gordon in surprise. But Ursula approached them at that moment, and Dick gave a warning signal for silence which Gordon saw and understood.

"Good-bye, Gordon," she said prettily, and Gordon suddenly regretted that so many of the boys and girls were there to bid him farewell. He would have much preferred to say his adieus to Ursula with no others present. Strange he never before realized what a beautiful girl she had become, with her blue eyes looking straight out at one from under the black eyebrows and the hair blowing about her delicately tinted cheeks.

"A-l-l A-b-o-a-r-d!" rang the voice of the conductor, standing watch in hand ready to give the starting signal to the engineer. The porters were picking up their little steps and getting ready to depart.

"Good-bye, Ursula," said the lad simply, wringing her hand with a heavier clasp than he knew, and though he nearly crushed the bones, she never gave the least sign of the pain he was causing her; perhaps she did not really feel it.

"Kiss me, Gordon," cried his mother, as she threw her arms around him. "Don't forget to write immediately on arriving."

"Come on, my son, time to jump aboard," cautioned his father in a suspiciously gruff tone, and in a moment more Gordon mounted the steps where from the platform of the moving train he stood waving his hat in farewell.

"Give him the school yell, fellows," shouted Tommy Turner at the top of his lungs, and with that rousing cry ringing in his ears Gordon Graham started on life's real journey.

That same evening while Dick's father was engaged with some business papers, the boy came quietly into the room.

"Father, may I interrupt your work for a little while?" he inquired.

"Nothing important, Dick, my boy," answered Mr. Comstock, laying aside the document he was reading; "what can I do for you?"

"Mother has just told me you are going to New York to-morrow; is that so?"

"Yes, I have business there for the firm. Why?"

"I was hoping I might go along with you," returned the boy.

Dick's father scrutinized his son's face for a moment, wondering what was behind the quiet glance and serious manner of the lad.

"What is the big idea?" questioned Mr. Comstock. "Want to spend a week or two with Cousin Ella Harris?"

"No," replied Dick slowly, "I have something else in mind, but I don't want to tell you what it is until we get on the train. It's a matter I have been thinking over for some time and--well, you will know all about it to-morrow, if I may go with you."

"Very well," replied his father, turning again to his work; "pack up and be ready to leave in the morning. We'll take the ten o'clock express."

"Good-night, Dad, and thank you," said Dick simply.

"Good-night, Dick," answered Mr. Comstock, without looking up, consequently he failed to see the lingering look the boy gave the familiar scene before him, as if bidding it a silent last "good-night." For Dick was drinking in each detail of the room as if trying to fix its every feature indelibly in his memory.

At breakfast next morning he was more quiet than his mother had ever known him, and both she and his sister Ursula were surprised to see the tears fill his eyes when he kissed them.

"I never knew you to be such a big baby, Dick," said Ursula. "If you feel so bad about leaving us why did you ask Father to take you on for a visit with Cousin Ella?" Although Dick had not said that this was his object in going away, it was a natural inference on Ursula's part, and as he vouchsafed no reply to the contrary she consequently watched him depart with a light heart.

In the crowded train Mr. Comstock and Richard succeeded finally in getting a seat to themselves, and while his father finished reading the morning paper, Dick spent his time in looking out the car window at the familiar sights along the road. But before long he was talking earnestly.

"Dad, I've decided what I want to do," he began, "but I can't do it unless I get your consent."

"What's on your mind, son?" said Mr. Comstock, folding his paper and smiling at the boy beside him. "Go ahead and I will pay close attention."

"If I went to Annapolis," Dick observed, "I'd finish my course there at the age of twenty-one, shouldn't I?"

"Yes, the course is four years at the Naval Academy."

"It would be the same if I went to West Point. In other words, by the time I was twenty-one years old I would, if successful at either institution, be either an ensign or a second lieutenant, as the case might be!"

"Quite true," remarked Mr. Comstock, still unable to comprehend where this preliminary fencing was leading.

"Have you ever heard of the United States Marine Corps?" asked Dick after the silence of a second or two.

"Most certainly I have," was the reply. "The marines figure in nearly every move our country makes in one way or another. They are always busy somewhere, though they get but little credit from the general public for their excellent work. I am not as familiar with their history as I should be--as every good American who has his country's welfare at heart should be, I might add, though perhaps I know a little more about them than a vast majority. Were it not for the marines our firm would have lost thousands of dollars some years ago when the revolutionists started burning up the sugar mills and the cane fields in Cuba. Our government sent a few hundred marines down there in a rush and they put a stop to all the depredations in a most efficient manner. The presence on the premises saved our mill beyond a doubt. But, how do the marines figure in this discussion? You don't mean----"

"Well, you see, it's this way," said the boy, and now his words no longer came slowly and haltingly, "I've made up my mind to become a Marine Officer, and if I can't do it by the time I'm twenty-one, then my name isn't Richard Comstock."

"Bless me! How do you propose going about it, Dick? As I have told you, there is no chance of going to the Naval Academy this year, and I understand that all marine officers are appointed to the Corps from among Annapolis graduates. For that reason I do not believe you have----"

"Excuse me, Dad, but that's just where you are mistaken. All the marine officers don't go through the Naval Academy. Some of them enlist and go up from the ranks. They win their shoulder straps on their own merit. That's what I expect to do if you will only give me the chance. And you will, won't you, Dad?" Dick's voice trembled with eagerness as he put the momentous question.

A few moments elapsed before his father answered and when he began speaking he reached out and gently placed his hand over that of his son.

"Evidently you have been looking into this matter thoroughly. I know now what has been keeping you so silent these last few days. I suspected you were grieving over your disappointment at my inability to send you to the Naval School or possibly over the departure of your chum, Graham, but I might have known my boy was using his time to better advantage than 'crying over spilled milk.'"

Mr. Comstock paused a moment and then continued:

"I know how your mind is wrapped up in a military career, Dick. Ever since you were a little shaver you have played at military and naval mimic warfare. You love it, and I believe you would become a good officer some day with proper training. Anything I may honorably do for the attainment of your desires and your advancement I am but too willing to undertake. But, my boy, I am not sure of the advisability of permitting you to become an ordinary enlisted man with that uncertainty of ever gaining your point--I imagine it is a more or less uncertain proposition. Besides, Dick, you are pretty young to be allowed to start out on such a hard life. The career of an enlisted man is not a bed of roses--full of trials and temptations of all kinds. At West Point or Annapolis you will be given kind treatment and be under careful surveillance for four years and not subjected to the roughness and uncouthness which must attend a start in the ranks. In another year there may be an opening for you at either place. However, I will not deny your request until I have looked further into the case. I am afraid your mother would never hear of such a thing for her only boy. Why not wait and consult her regarding it?"

"I'll tell you why, Dad," began Dick, launching again into his subject at once so as to press home the slight advantage he believed he had gained, "on the Fourth of July I'll be seventeen years of age. Mother didn't happen to think of that, or she would have made me wait a few days before going to Cousin Ella's, where she believes I have gone. You know, Dad, that for years I've been able to blow a bugle and handle the drumsticks better than any other boy in town. Well, last week, when we were on board the Nantucket, I saw some young boys belonging to the Marine guard of the ship, and I found out all about them. Why, they were smaller than Tommy Turner!

"It appears that there is a school for musics[#] at the Marine Barracks in Washington, D.C., where boys between the ages of fifteen and seventeen are given training. They enlist to serve until majority, but often after they have served a short time as drummer or trumpeter they get permission to change their rank and become privates. This puts them in line for promotion to the rank of corporal and sergeant. I've been talking with Tommy's uncle, and he was kind enough to have me meet an officer of Marines stationed at the Navy Yard back home, who recently came from recruiting duty. That officer, Lieutenant Stanton is his name, told me that the Corps is filled up just now, and all enlisting stopped, so that my only chance to get in right away would be in this school for musics. In two days more I'll be too old to get in. I knew if I proposed the subject at home, Mother would offer such objections that I just couldn't refuse to do as she wished. Therefore I've packed up and left home for good. Dad, you--you won't stop me, will you? You'll give me this chance? I've set my heart on it so much!"

[#] In the Army and Marine Corps drummers and trumpeters are generally called "musics." On board ship the sailor man who blows the trumpet is called a "bugler." The school for Marine Corps musics is now located at Paris Island, S.C. (1919)

Dick stopped talking. It was the longest extemporaneous speech he ever had made in his life, and as he watched his father's face, he wondered if he had said too much or not enough!

Once again a long silence ensued, while Mr. Comstock reviewed all the boy had said. What should he do? To deny Dick's request might be the very worst step he possibly could take, for he knew the process of reasoning by which this purposeful, upright son of his arrived at his conclusions. He believed thoroughly in his son, and wanted to make no mistake in his decision.

"Let us go in to luncheon, Dick, and give me a little time to think this over. It is a little sudden, you know, and should not be gone into unwisely."

During the meal John Comstock questioned Dick closely regarding this subject uppermost in the minds of both. He saw that the lad was bent upon carrying out his project; that the boy had given it careful thought; that he had weighed its advantages and disadvantages with more acumen than most boys of his age.

Richard was a good student, and not for a moment did the father doubt that his son if given the opportunity would win his commission.

"Was it your idea to go to the New York recruiting station to-day on our arrival?" asked Mr. Comstock, when they resumed their seat in the day coach.

"Yes, Dad, for if I enlist in New York the government sends me to Washington and pays my way there."

"I have a better plan than that," said his father. "I will let my business in New York wait on my return, and we will both go to Washington this afternoon, and spend the night in a comfortable hotel. To-morrow I will go to the Commandant of the Marine Corps with you, armed with a letter of introduction, and we will talk it over with him. In this way I shall have a much clearer and more authoritative view of your prospects. Then if you get by the physical examination and are accepted I shall be able to see for myself how and where you will be fixed."

"Then I may go? You will allow me?" cried Richard, almost jumping out of his seat in his enthusiasm. "You are just the finest Dad in the world! And what is best of all about your plan is that Mother will be less worried if you are able to tell her everything as you see it."

"That is one of my chief reasons for going about it in this way," quietly remarked his father. "I know she will be heart-broken at first, and probably will accuse me of being an unworthy parent; so, my boy, it is a case of how you manage your future, which must prove to her that we both acted for your best interests."

"I'll work hard; I don't need to tell you that, Father," Dick replied.

On arriving in New York they hastened across the city, luckily making good connections for Washington, and the following morning the schedule as planned was begun.

It was Richard's first visit to the capital, and consequently everything he saw interested him. The wonderful dome of the Capitol building; the tall white shaft of Washington Monument, the imposing architecture of the State, War and Navy Departments, the broad streets, the beautiful parks and circles with their many statues, all claimed his attention.

After securing the letter of introduction, Mr. Comstock first took Richard to the Navy Department where, on inquiry, they found that Marine Corps Headquarters was in a near-by office building. The original structure built for the Navy was even then getting too small for the business of its many bureaus. The building they sought was but a few steps away, and their route led them directly past the White House, the official residence of the President of the United States.

While on their journey they saw but few persons in uniform. Even in the Navy Building there was a decided absence of officers or men in the dress of their calling. This seemed very odd to the boy, as he always pictured in his imagination the "seat of the nation" was gay with uniformed officials of his own and other countries.

"Why is it, Father, you see so few uniforms in the capital?" he inquired.

"I am not positive I am right," replied Mr. Comstock, "but the American officers, soldiers and sailors object to wearing their military clothes except when they are actually required to do so.[#] Our nation is so democratic that they believe it makes them appear conspicuous. Furthermore, in uniform they are often discriminated against, particularly in the case of enlisted men. This is one of the reasons why a better class of men do not go into the service--they consider the wearing of a uniform belittles them in the eyes of the public."

[#] Previous to the war with Germany officers of the United States services were not required to wear uniforms when off duty and outside their ship or station. Enlisted men were also permitted to wear civilian clothing while on liberty, under certain restrictions. Civilian clothing was generally called "cits" by those in service.

"I think a uniform is the best kind of clothing a fellow can wear. I'll be mighty proud of mine, and never will be ashamed of it."

"In Europe," continued Dick's father, "a soldier is looked upon in a different light, depending to a great extent in what country he serves. They are honored and usually given every consideration, or at least the officers are, and particularly in Germany, where militarism is the first word in culture. The United States, on the other hand, maintains such a small and inadequate army and navy that our men in uniform are really more like curiosities to the people than anything else."

"But there are a lot of men in uniform back home," Dick remarked.

"Yes, enlisted men, seldom officers. The reason is, the proximity of several army forts, a navy yard and the frequent visits of the men-of-war in our harbor. So we at home are familiar with the different branches of the service; but it is far from being the case in most cities of our republic," answered Mr. Comstock.

They were now approaching the building wherein the headquarters of the Marine Corps were located, when Dick exclaimed:

"Look, Father! There are some marines now; aren't they simply great?"

Two stalwart men in uniform were crossing the street just ahead of the speaker. In their dark blue coats piped in red, with the five shiny brass buttons down the front and yellow and red chevrons on the arms, trousers adorned with bright red stripes and blue caps surmounted by the Corps insignia over the black enameled vizors, they were indeed a most attractive sample of the Marine Corps non-commissioned officer at his best.

"It's their regular dress uniform," Dick announced, "and I think it's the best looking outfit I have ever seen, but, Dad, you should see the officers when they get into their full dress!"

"Where did you pick up all your knowledge of their uniforms, Dick?" asked his father curiously.

"Oh, Tommy Turner made his uncle show them all to us. You see, he stayed in the Corps for some years after the Spanish War, and he has always kept his uniforms. He believes that some day he may need them again if ever the United States gets into a big fight, and if that time comes he is going back into the marines."

Following the two non-commissioned officers into a tall structure, Mr. Comstock and Richard were whisked up several stories in an elevator and found themselves before an opened door upon which were the words, "Aide to the Commandant."

A young man in civilian dress rose as they entered and inquired their business, which Mr. Comstock quickly explained.

"Sit down, sir, if you please, and I will see if the General can talk with you," he said.

They did as directed, while the young man disappeared into an adjoining room. A few moments later he returned and motioned for them to follow him.

"What may I do for you, Mr. Comstock?" inquired a large, handsome, gray-haired gentleman standing behind the desk when they entered. He too was in civilian clothes, but despite the fact, looked every inch the soldier he was known to be.

Mr. Comstock introduced Richard to the General and then told him the reason of his visit.

"My boy is anxious to become a marine, and I have promised to look into the necessary preliminary steps. I understand that you are not recruiting just at present, but we were told that possibly my son would be taken into the Corps as a bugler or drummer."

"Yes, we do take boys in for training as field musics," said the General, glancing at Dick for a moment, "but your son, I fear, is too old; the ages for this class of enlistment are from fifteen to seventeen years, and judging by the lad's size he already passed the age limit."

"He is very nearly, but has yet a few hours of grace," replied Mr. Comstock. "He will be seventeen to-morrow, and I was hoping that you might enlist him to-day. My son's object in going into the Corps is to work for a commission. That is one of the inducements which I understand the Corps offers its enlisted personnel, is it not?"

"You are right, Mr. Comstock; at the present time our officers are taken from graduates of the Naval Academy or from the ranks. There have been times when civilian appointments were allowed, but the law has now been changed."

"In that case then, could you take my boy into your organization? He understands that his advancement depends entirely on his own merit, and he has taken a decided stand as to what he intends to do and has my full consent to try it."

"Does he also understand that the number of officers appointed from the ranks are few, and picked for their exceptionally good records and ability, and that he serves an apprenticeship until he is twenty-one years of age?" inquired the Commandant.

"Yes, sir," answered Richard, speaking for the first time.

"Why do you not enter the Naval Academy, young man, and after graduation come into the Corps?" asked the General, looking at Dick with his stern eyes.

"Well, sir, I failed to get the appointment at the last minute."

"Do you also realize there are many unpleasant things connected with the life of an enlisted man, and are you prepared to meet them?"

"Yes, sir, and I believe I can make good."

"I like your spirit, young man," said the General approvingly; "the motto of the Marine Corps is 'Semper Fidelis--Always Faithful,' and to be a true marine you must bear that motto in mind at all times and under all conditions, if it is your hope to succeed in the service."

He now turned to Dick's father:

"Ordinarily, Mr. Comstock, our young men are held at the school for a few days before we complete their enlistment in order that they may get an idea of the life and duties to which they are about to bind themselves when taking the oath of allegiance. In your son's case, I believe he knows what he wants, and he is the kind of young man we wish to get. Were he compelled to wait according to our usual custom he would be past the age limit, consequently I will further your desires and arrange to have him sworn into service immediately, providing he passes the surgeon's examination. I will give you an order to the Commanding Officer of the Marine Barracks which will answer your purpose."

Saying this he gave the necessary directions to the aide, who had remained standing near by, and a little later Dick and his father were on a street car bound for the barracks, where the School for Musics was located. Arriving there they soon found themselves in the presence of the colonel commanding the post, who, on reading the instructions of the Commandant, looked the boy over with an approving eye.

"I reckon you will be about the tallest apprentice we have here," he said, and calling an orderly directed him to escort Dick to the examining surgeon, and invited Mr. Comstock to sit and await the result.

The Marine Corps is primarily organized for service with the Navy, though this has by no means been its only function in the past, nor likely to be in the future. On many occasions the Corps has acted independently and also with the Army, which is provided for in the statutes. Being attached to the Navy and operating with it at Navy Yards, Naval Stations and on board ship its medical officers are supplied by the Navy, for the Corps maintains no sanitary service of its own.

The Navy surgeon gave the lad a very thorough examination, one even more thorough than usual, and after Dick had been passed and departed he remarked to his assistant:

"That boy is one of the finest specimens of the American youth I have ever examined. He is so clean limbed and perfectly muscled that it was a joy to look at him."

After this visit, Dick, with the attendant orderly, returned to the office of the Commanding Officer.

"Well, the surgeon states you are all right," said Colonel Waverly, having glanced at the slip of paper the orderly handed him; "you are quite positive that you wish to undertake the obligation, young man?"

"Quite, sir," was Dick's laconic response.

"Very well," and the Colonel then called loudly for the Sergeant Major. "Sergeant Major, this young man is to be enlisted as an apprentice at once. Make out the necessary papers."

Fifteen minutes later, with his right hand held high, his head proudly erect, Richard Comstock took the solemn oath of allegiance to his country, which so few young men seriously consider as they repeat its impressive vows, and with the final words he graduated to man's estate.

CHAPTER V

A DRUMMER IN THE U. S. MARINES

"Rise and shine! Come on, you kids, shake a leg and get up out of this!"

Dick Comstock sleepily rubbed his eyes for the fraction of a second and then sprang out of his comfortable bunk as the sergeant's voice bellowed through the room. In the long dormitory thirty-odd boys, their ages ranging from fifteen to Dick's own, were hurrying their preparations to get into uniform and down on the parade ground in time for reveille roll call. Another day in a marine's life had begun.

Out the doors and down the stairs clattered the noisy, boisterous throng, fastening last buttons as they emerged into the light of the midsummer rising sun.