The Spell of Switzerland

by

Nathan Haskell Dole

The Spell of Switzerland

by

Nathan Haskell Dole

THE SPELL SERIES

Each volume with many illustrations from original drawings or special photographs. Octavo, with decorative cover, gilt top, boxed.

Per volume $2.50 net, postpaid $2.70

THE SPELL OF ITALY

By Caroline Atwater Mason

THE SPELL OF FRANCE

By Caroline Atwater Mason

THE SPELL OF ENGLAND

By Julia de W. Addison

THE SPELL OF HOLLAND

By Burton E. Stevenson

THE SPELL OF SWITZERLAND

By Nathan Haskell Dole

THE SPELL OF THE ITALIAN LAKES

By William D. McCrackan

In Preparation

THE SPELL OF THE RHINE

By Frank Roy Fraprie

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

53 BEACON STREET, BOSTON, MASS.

ILLUSTRATED

from photographs and original paintings by

Woldemar Ritter

Publishers

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

BOSTON MDCCCCXIII

Copyright, 1913, by

L. C. Page & Company

(INCORPORATED)

Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London

All rights reserved

First Impression, October, 1913

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. SIMONDS & CO., BOSTON, U. S. A.

The present book is cast in the guise of fiction. The vague and flitting forms of my niece and her three children are wholly figments of the imagination. No such person as “Will Allerton” enters my doorway. The “Moto,” which does such magical service in transporting “Emile” and his admirers from place to place is as unreal as Solomon’s Carpet.

After Lord Sheffield and his family had started back from a visit to Gibbon at Lausanne, his daughter, Maria T. Holroyd, wrote the historian: “I do not know what strange charm there is in Switzerland that makes everybody desirous of returning there.” It is the aim of this book to express that charm. It lies not merely in heaped-up masses of mountains, in wonderfully beautiful lakes, in mysterious glaciers, in rainbow-adorned waterfalls; it is largely due to the association with human beings.

The spell of Switzerland can be best expressed not in the limited observations of a single person but rather by a concensus of descriptions. The casual traveller plans, perhaps,[Pg vi] to ascend the Matterhorn or Mount Pilatus; but day after day may prove unpropitious; clouds and storms are the enemy of vision. One must therefore take the word of those more fortunate. Poets and other keen-eyed observers help to intensify the spell. These few words will explain the author’s plan. It is purposely desultory; it is not meant for a guide-book; it is not intended to be taken as a perfectly balanced treatise covering the history in part or in whole of the twenty-four cantons; it has biographical episodes but they are merely hints at the richness of possibilities, and if Gibbon and Tissot and Rousseau stand forth prominently, it is not because Voltaire, Juste Olivier, Hebel, Töpfer, Amiel, Frau Spyri, and a dozen others are not just as worthy of selection. One might write a quarto volume on the charms of the Lake of Constance or the Lake of Zürich or the Lake of Lucerne. Scores of castles teem with historic and romantic associations. It is all a matter of selection, a matter of taste. It is not for the author to claim that he has succeeded in conveying his ideas, but whatever effect his work may produce on the reader, he, himself, may, without boasting, claim that he is completely under the spell of Switzerland.

Boston, October 1, 1913.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Preface | v | |

| I. | Uncle and Niece | 1 |

| II. | Just a Common Voyage | 8 |

| III. | A Roundabout Tour | 25 |

| IV. | Home at Lausanne | 37 |

| V. | Gibbon at Lausanne | 74 |

| VI. | Around the Lake Leman | 101 |

| VII. | A Digression at Chillon | 122 |

| VIII. | Lord Byron and the Lake | 136 |

| IX. | A Princess and the Spell of the Lake | 149 |

| X. | The Alps and the Jura | 160 |

| XI. | The Southern Shore | 173 |

| XII. | Geneva | 197 |

| XIII. | Sunrise and Rousseau | 216 |

| XIV. | The City of Rousseau and Calvin | 232 |

| XV. | Famous Folk | 269 |

| XVI. | The Ascent of the Dôle | 290 |

| XVII. | A Former Worker of Spells | 311 |

| XVIII. | To Chamonix | 322 |

| XIX. | A Detour to Zermatt | 350 |

| XX. | The Vale of Chamonix | 364 |

| XXI. | Hannibal in Switzerland | 382 |

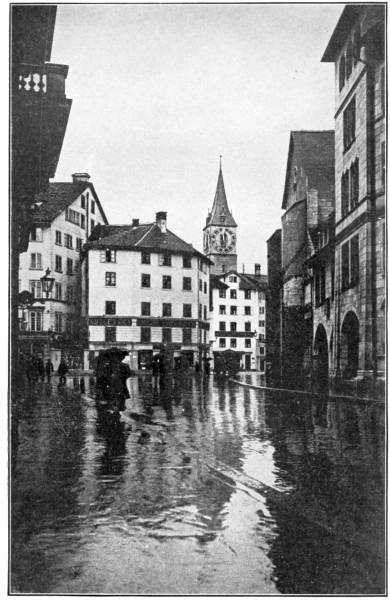

| XXII. | Zürich | 400 |

| XXIII. | At Zürich with the Professor | 414 |

| XXIV. | On the Shores of Lake Lucerne | 445 |

| XXV. | Lausanne Again | 454 |

| Bibliography | 469 | |

| Index | 471 |

THE SPELL OF SWITZERLAND

I MUST confess, I did not approve of my niece and her husband’s plan

of expatriating themselves for the sake of giving their only son and

heir, and their twin girls, a correct accent in speaking French. But I

had the grace to hold my tongue. I wonder if my wife would have been

equally discreet—supposing I possessed such a helpmeet. Probably she

would not have done so, even if I had; and probably also I should not,

if she had. For the very fact of my having a wife would prove that I

should be different from what I am.

There is an implication in this slight exhibition of boastfulness; but it is not subtle. Any[Pg 2] one would see it instantly—namely, that I am a bachelor. A bachelor uncle whose niece takes it into her head to marry and raise a family, is as deeply bereaved as he would be were he her father. More so, indeed, for a father has his wife left to him....

The relationship between uncle and niece has never been sufficiently celebrated in poetry. It deserves to be sung. Besides the high, noble friendship which it implies, there is also about it a touch of almost lover-like sentiment. The right-hearted uncle loves to lavish all kinds of luxuries on his niece and feels sufficiently repaid by the look of frank affection in her eyes, the unabashed kiss which is the envy of young men who happen to witness it.

Here are the facts in my case. After my brother’s wife died, he urged me to make my home at his house. I suppose I might have done so long before; but I had been afraid of my sister-in-law. She was a tall imperious woman; she did not approve of me at all. She could not see my jokes, or, if she did, she frowned on them. I suppose she thought me frivolous. She was one of those women who make you appear at your worst. She was sincere and genuine and good, but our wireless apparatus was not tuned in harmony. As long[Pg 3] as she was at the helm of my brother’s establishment I preferred to enjoy less comfortable quarters elsewhere.

But when, as the Wordsworth line has it, “Ruth was left half desolate” (though her father did not “take another mate”), and they showed me how delightfully I could dispose of my library and have an open fire on cold winter evenings, and what a perfect position was, as it were, destined for my baby grand—for I am devoted to music—en amateur, of course,—I yielded, and for ten happy years, saw Ruth grow from a young girl into the woman “nobly planned, to warn, to comfort and command.”

Command? What woman does not?

At my advice she took up the violin, and I shall never forget the hours and hours when we practised and really played mighty well—if I do say it, who shouldn’t—through the whole range of duets, beginning with simple pieces for her immature fingers and ending with the strange and sometimes—to me—incomprehensible fantaisies of the super-modernists.

But all these simple home-joys came to their inevitable end. The right man appeared and did as the right men always have done and will do. Uncles are as prone to jealousy as any[Pg 4] other class of bipeds; but here again the philosophy of life which I trust I have made evident I cherish, and which, as one good turn deserves another, cherishes me, enabled me to preserve a front of discreet neutrality. I may have been over-zealous to look up the young man’s record; but there was nothing to which the most scrupulous could take exception. He was a clean, straight, manly youth with excellent prospects.

Will Allerton lived in Chicago; that was a second count against him, but equally futile as a valid argument for dissuasion. After their wedding-journey, they went to a delightful little house in East Elm Street in Chicago. Business called me to that city two or three times, and I visited them. So many of my friends had been unhappily married that I was more or less pessimistic about that kind of life-partnership; but my niece’s happy home was an excellent cure for my bachelor cynicism. The coming of their first child,—they did me the honour of making me his godfather, though I do not much believe in such formalities; and they also named him for me,—the coming of this little mortal made no change other than a decided increase in the bliss of that loving home.

When little Lawrence was four years old, and the twins were two, his grandfather died suddenly. It was a tremendous change to have my good brother removed from my side. My niece and her husband came on from Chicago. They were pathetically solicitous for my welfare. Most insistently they urged me to come and live with them. There was plenty of room in the house, they said.

I was greatly touched by their generous kindness, but I set my face sternly against any uprooting of the sort. I said I much preferred to stay on where I was. I had consulted with my Lares and Penates and found that they opposed any such bouleversement. The old housekeeper who had looked after our comfort was still capable of doing all that was necessary for me. My wants were few; I lived the simple life and its cares and pleasures amply satisfied my ambition. I had a small circle of congenial friends, particularly among my books. I did not know what it meant to be lonely. If I needed company, I could always fortify myself with the presence of college classmates. I had organized a quartet of fairly capable musicians who came once or twice a week to play chamber-music with me, and for me. I had several protégés studying music at[Pg 6] the conservatory and my Sunday afternoon musicales were a factor in my satisfaction. So it was arranged that I should make no radical change for the present, at least. I would spend my vacations with them at the seashore, where we had a comfortable little datcha, and at least once during the winter I would make them a visit in Chicago.

Thus passed two more years. Then out of a clear sky came the report that my niece and her husband were going to take their young hopeful and his sisters to Switzerland, so that he might learn to speak French with a perfect accent! Will had a rich old aunt—a queer, misanthropic personage, who lived the life of a hermit. She, too, took the long journey into the Unknown and, as she could not carry her possessions with her, they fell to her nephew.

I saw them off, and the last word my niece said, as we parted tenderly, was, “You must run over and make us a visit.”

I shook my head: “I am afflicted with a fatal illness. I am afraid of the voyage.”

Her sweet face expressed such concern that I quickly added: “It is nothing serious; but there is no hope for it—it is only old age.”

“That’s just like you,” she exclaimed, “and I know you do not dread the ocean.”

“Well, we’ll see,” I tergiversated. “I don’t believe you’ll stay. You’ll miss all the American conveniences and you’ll get so tired of hearing nothing but French.”

“Nonsense!” she exclaimed. “Of course we shall stay, and of course you’ll come.”

IT was inevitable. I, who had always jestingly compared myself to a

brachypod, fastened by Fate to my native reef, and getting contact

with visitors from abroad only as they were brought by tides and

currents, began to feel the irresistible impulse to grow wings and fly

away. How could I detach my clinging tentacles?

Every letter from Lausanne, where my dear ones had established themselves, urged me to “run over” and make them a long visit. My room was waiting for me. They depicted the view from its windows; splendid sweeps of mountains, snow-clad, tinged rose-flesh tints by the marvellous, magical kiss of the hidden sun; the lake glittering in the breeze, or dazzlingly azure in the afternoon calm; the desk; the comfortable, old, carved bedstead; the quaint, tiled stove which any museum would be glad to possess. There were excursions on foot or by [Pg 9]automobile; mountains to climb; the Dolomites to visit. Each time new drawings, new seductions. With each week’s mail I felt the insidious, impalpable lure.

I have many friends who put faith in astrology. One of my acquaintances is making a large income from constructing horoscopes. She is sincere; she has a real faith. She acts on the hypothesis that from even the most distant of the planets radiate baleful or beneficent influences which move those mortals who are, as it were, keyed or tuned to them. Saturn, whose density is less than alcohol, a billion miles away; Neptune, almost three billion miles away, infinitesimal specks in the ocean of space, make men and women happy or miserable. How much more then is it possible that the heaped-up masses of mighty mountains may work their spell on men half-way around this globe of ours? I began to be conscious of the Spell of Switzerland.

A half-crazy friend of mine, a painter, who loved mountains and depicted them on his canvases, once broached a theory of his, as we stood on top of Mount Adams:—

“The time will come,” he said with the conviction of a prophet, “when we shall be able to take advantage of the electric current flowing[Pg 10] from this mountain-mass to Mount Washington, yonder, and commit ourselves safely and boldly to its control. Then we shall be able to practise levitation. It will be perfectly easy, perfectly feasible to leap from one peak to another.”

I am sure I felt stirring within me the impulse to leap into the air with the certainty that I should land on top of the Jungfrau or of Mont Blanc. It was a cumulative attraction. Every day it grew more intense. I got from the library every book I could find about Switzerland. I soaked myself in Swiss history. I began to know Switzerland as familiarly as if I had already been there.

Then came the decisive letter. My niece absolutely took it for granted that I was coming. She said: “We will meet you at Cherbourg with the motor. Cable.”

This time I was obedient. I wound up my affairs for an indefinite absence.

I took passage on a slow steamer, for I was in no hurry, and I wanted to have time enough to finish some more reading. I wanted to know Switzerland before I actually met her. I knew that I was destined to love her.

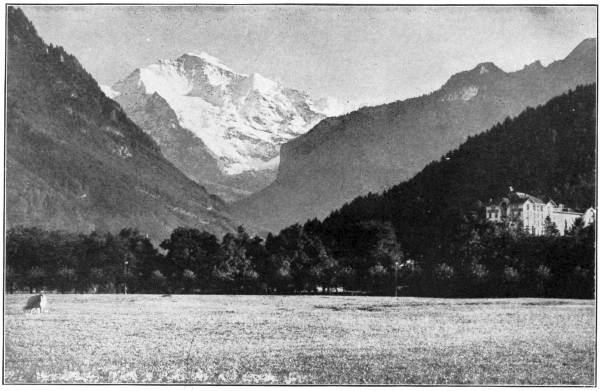

THE ALPENGLOW ON THE JUNGFRAU.

Theoretically one may understand psychology, even the psychology of woman—may, I say, not insisting too categorically upon this point, especially since the recent discovery that woman has, to her advantage over man, a superfluous and accessory chromosome to every cell in her dear body—one may know anatomy and physiology; but, when one falls in love with her, all this knowledge is as nought; she becomes, in the words of Heine, die eine, die feine, die reine. In this spirit, I studied the geology of Switzerland, realizing in advance that, as soon as I saw the Alpenglow on the peak of the Wetterhorn or of Die Jungfrau, I should not care a snap of my finger for the scientific constitution of the vast rock-masses, or for the theories that explain how they are doubled over on themselves and piled up like the folds of a rubber blanket.

On the first day out, as I sat on the deck as far forward as possible,

I became in imagination the prehistoric ancestor of the frigate-bird,

spreading my broad wings, tireless, above the waste of that Jurassic

Sea which, only a brief geologic age ago, swept above what is now the

highest land of Europe, with its south-most boundary far away in

Africa. By the same power of the imagination I saw mighty islands

emerge from the face of those raging waters. To the imagination a

thousand or a[Pg 11]

[Pg 12] million years is but as a wink; it can see in the

corrugated skin of a parched apple all the vast cataclysms of a

continent. Through the ages these seas deposited their strata to be

pressed into rock; those strata were upheaved and, as they became dry

land, the torrential rains, the mighty rivers, gnawed them away and

spread them out over the central plain of what is now Switzerland, and

filled the valleys of the Rhine and the Rhône and the Reuss, the Po

and the Inn and the Danube, making the plains of Lombardy and Germany,

of Belgium, of Holland and southeastern France. Almost three solid

miles, it is estimated, have been eroded and carried away from the

mountain-tops—sedimentary rocks and crystalline schists and even the

tough granite.

As Sir John Lubbock well says, “true mountain ranges, that is to say, the elevated portions of the earth’s surface, are the continents themselves, on which most mountain-chains are mere wrinkles.” Under enormous pressure, and as the interior of the earth gradually cooled and shrank, the crust remaining at the same temperature, through the force of gravity great plaques of the crust sank in and perhaps, as in the case of mesas, left great mountain-masses, which the streams and rivers immediately[Pg 13] began to carve into secondary hills and valleys. Sometimes these mountain-masses resisted pressure; “these,” says Sir John, “form buttresses, as it were, against which surrounding areas have been pressed by later movements. Such areas have been named by Suess ‘Horsts,’ a term which it may be useful to adopt, as we have no English equivalent. In some cases where compressed rocks have encountered the resistance of such a ‘Horst,’ as in the northwest of Scotland and in Switzerland, they have been thrown into the most extraordinary folds, and even thrust over one another for several miles.”

Sir John, whose book, “The Scenery of Switzerland,” I had with me as I sat in my cozy nook in the bow, asserts boldly that Switzerland was not formed, as people used to think, by upheaving forces acting vertically from below. “The Alps,” he says, “have been thrown into folds by lateral pressure, giving every gradation from the simple undulations of the Jura to the complicated folds of the Alps.”

Thus the strata between Bâle and Milan, a distance of one hundred and thirty miles, would, if horizontal, occupy two hundred miles. In some cases the most ancient portions are[Pg 14] thrown up over more recent ones. The higher the mountain is, however, the more likely it is to be young; whereas low ranges are like the worn-out teeth of some ancient dame. “The hills of Wales,” says Sir John, “though comparatively so small, are venerable from their immense antiquity, being far older, for instance, than the Vosges themselves, which, however, were in existence while the strata now forming the Alps were still being deposited at the bottom of the ocean. But though the Alps are from this point of view so recent, it is probable that the amount which has been removed is almost as great as that which still remains. They will, however, if no fresh elevation takes place, be still further reduced, until nothing but the mere stumps remain.”

Now I read geology as if I understood all about it; but, five minutes after I have put the book down, I get the ages inextricably mixed; Eocene and Pleiocene and pre-Carboniferous and Cambrian and Silurian are all one to me. Jurassic sounds as if it were an acid and I can not possibly remember in which era fossils lived and impressed themselves into the soft clay like seals on wax.

It is tremendously interesting. When I am reading about those old days, I have no difficulty[Pg 15] in picturing before my mental vision a great jungle filled with eohippuses and megatheriums and ichthyosauruses and other monstrous creatures. When I get to Oeningen I mean to make a study of fossils: I am told it has the richest collection in the world.

That night I dreamed that I stood on the highest peak of the primitive Alps and a great earthquake shook off colossal blocks of gneiss; vast rivers went rushing down the valleys. I awoke suddenly with a sort of involuntary terror. It was nothing but the tail-end of a gale which tossed the ship like a cockle-shell. The rivers were the streams of water rushing down the deck as the ship plunged her nose into the smothering spume of the angry sea. I slipped on my storm-coat and, clinging to the jamb of my stateroom, gazed out on the wild scene. The sky was clearing, and a moon, which must have been in its second childhood—it looked so slim and young—was riding low in what I supposed was the east; the morning star was darting among scurrying clouds; great phosphorescent splashes of foam were flying high; the ship was staggering like the conventional, or perhaps I should say unconventional, drunken man. A splash of spray in my face counselled me to retire behind my door, and I[Pg 16] made a frantic dash for my berth, and slept the sleep of the just the rest of the night.

To a man free of care, without any reason for worry, in excellent health, capable of long hours of invigorating sleep, an ocean voyage is an excellent preparation for a season of sightseeing, of mountain-climbing, of new experiences.

I considered myself quite fortunate to discover on board two Swiss gentlemen. One was a professor from the University of Zürich; the other was an electrical engineer from Geneva. I had many interesting talks with them about Helvetic politics and history.

Professor Heinrich Landoldt was a tall, blond-haired, middle-aged man, with bright blue eyes and a vivid eloquence of gesticulation. He was greatly interested in archaeology and had been down to Venezuela to study the lake dwellings, still inhabited, on the shores of Lake Maracaibo. Here, in our own day, are primitive tribes living exactly as lived the unknown inhabitants of the Swiss lakes, whose remains still pique the curiosity of students. Painters, like M. H. Coutau, have drawn upon their imagination to depict the kind of huts once occupied on the innumerable piles found, for instance, at Auvergnier. But Dr. Landoldt had[Pg 17] actually seen half-naked savages conducting all the affairs of life on platforms built out over the shallow waters of their lake. Their pottery, their ornaments, their weapons, their weavings of coarse cloth, belong to the same relative age, which, in Switzerland, antedated history. Probably Venice began in the same way; not without reason did the discoverer, Alonzo de Ojeda, in 1499, call the region of Lake Maracaibo Venezuela—Little Venice.

The same conditions bring about the same results since human nature is everywhere the same. One need not follow the worthy Brasseur de Bourbourg and try to make out that the Aztecs of Mexico were the same as the ancient Egyptians simply because they built pyramids and laid out their towns in the same hieroglyphic way.

The presence of enemies, and the abundance of growing timber along the shores, sufficed to suggest the plan of sinking piles into the mud and covering them over with a flooring on which to construct the thatched hovels. The danger of fire must have been a perpetual nightmare to these primitive peoples, the abundance of water right at hand only being a mockery to them. The unremitting, patient energy of those savages, whether then or now, in working with[Pg 18] stone implements, fills one with admiration. Professor Landoldt had many specimens which he intended to compare with the workmanship of the lacustrians of Neuchâtel, Bienne and Pfäffikersee, antedating his by thousands of years.

He has invited me to make him a visit in Zürich and I mean to do so. He tells me that the museum there is exceedingly rich in relics of prehistoric peoples. Perhaps we can go together and pay our respects to the shades of the lake-dwellers. I always like to pay these delicate attentions to the departed. So I would gladly burn some incense to Etruscan or Kelt, whoever first ventured out into the placid waters of the lake—any lake, it matters not which—there are dozens of them—and pray for the repose of their souls; they must have had souls and who knows, possibly some such pious act might give pleasure to them, if perchance they are cognizant of things terrestrial.

My electrical friend, M. Pierre Criant, was also very polite and, when he learned that I was bound for Switzerland to spend some months—Heaven alone knows how many—he urged me to look him up, whenever I should reach Geneva. He would be glad to show me the great plans that were formulating for utilizing[Pg 19] the tremendous energy of the Rhône. This was particularly alluring to my imagination for I have a high respect for electrical energy. M. Criant seemed to carry it around with him in his compact, muscular form.

We three happened to be together one morning and I had the curiosity to ask them, as intelligent men, what they thought of the “initiative and referendum,” which I understood was a characteristic Swiss institution, and which a good many Americans believed ought to be introduced into our American system of conducting affairs, as being more truly democratic than entrusting the settlement of great questions to our Representatives in Congress or in Legislature assembled. I remarked that some good Americans looked to it as a cure for all existing political evils. We adopted the Australian ballot and it immediately worked like a charm; undoubtedly its success prepared the way for receiving with greater alacrity a novelty which promised to be a universal panacea. “How does it really work in Switzerland?” I demanded.

“In our country,” replied M. Criant, “a certain number of persons have the right to require the legislature to consider any given question and to formulate a bill concerning it;[Pg 20] this must be submitted to the whole people; it is called the indirect initiative. They may also draft their own bill and have this submitted to the whole people. This is of course the direct initiative. Some laws cannot become enforceable without receiving the popular sanction. This is called the compulsory referendum. Other bills are submitted to the people only when the petition of a certain number of citizens demand it. This is the optional referendum. This right may apply to the whole country, or to a Canton, or only to a municipality: the principle is everywhere the same. Suppose an amendment to the Federal Constitution is desired. At least fifty thousand voters must express their desire; then the question is submitted to all the people. Again, if thirty thousand voters, or eight of the Cantons, consider it advisable to support any federal law or federal resolution, they must be submitted to the popular vote; but this demand must be made within three months after the Federal Assembly has passed upon them. Of course this does not apply to special legislation or to acts which are urgent.”

“Has the initiative proved a working success?” I asked.

“Well,” replied Professor Landoldt, “in[Pg 21] 1908, more than two hundred and forty-one thousand voters carried the initiative, proposed by almost one hundred and sixty-eight thousand signatures, against the sale of absinthe. In the same way, locally, vivisection was partially prohibited in my Canton in 1895. In Zürich there was a strong feeling in the community that the public service corporations and the large moneyed interests had altogether too much influence in the government; even the justice of the courts was called in question, and, under the leadership of Karl Bürkli, who was a follower of Fourier, the initiative and referendum were adopted especially as a protest against the high-handed autocracy of such men as Alfred Escher. It has been principally used as a weapon against the party in power; but not always successfully. Sometimes it has worked disastrously, as for instance when, in November, the unjust prejudice against the Jews was sufficiently strong to introduce into the Constitution an amendment prohibiting the butchering of cattle according to the old Bible rite. They professed to believe in the Bible, but not in what it says! In this case the societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals combined with the Jew-baiters.”

“A measure which affects me personally,”[Pg 22] said M. Criant, taking up the theme, “but which is really in the line of progress, was passed in 1908, when by an overwhelming majority—some three hundred and five thousand against about fifty-six thousand—the Federal Government took over from the individual cantons the right to legislate concerning the water resources when any national interest might be at stake. There are such tremendous hydraulic possibilities in Switzerland that it would be a national misfortune to have them controlled by local or by private corporations.”

“We have the same problem in America,” I remarked. “One of the greatest and most insidious dangers threatening our people is the Water Trust, which is already strongly intrenched behind special privileges and protected by enormous moneyed interests. I believe the people ought to control the natural monopolies.”

“So do I,” exclaimed Professor Landoldt fervently. And he went on: “We have recently stood fast by those principles by taking over the railways, the last item in this tremendous business being the acquisition, a few months ago, of the St. Gothard line which, with its debt, has cost, or will cost, some fifty millions. It took us about seven years to get[Pg 23] worked up to the pitch of government ownership. The price seemed extravagant in 1891, and the measure was defeated more than two to one; in 1898 there was a majority of more than two hundred thousand in favour of it; the vote brought out almost the whole voting strength of the country.

“The citizens of Zürich, a few years ago, refused to spend their money in building an art-museum; but thought better of it in 1906. The truth of the matter is, the people like to show their power; they like to discipline their representatives, often at the expense of their own best interests. In 1900 they turned down by a majority of nearly two hundred thousand a Workmen’s Compulsory Insurance bill which both houses had carried with only one opposing vote.

“The interference of the people with the finances of the cantons, or of the cities, often works mischief. How, indeed, could they be expected to show much wisdom in deciding on questions which even an expert would find difficult? They are willing to reduce water-rates, but they object to increase taxes, except on large fortunes. They will readily authorize incurring a good big debt, but they do not like to face the necessity of paying it, or providing[Pg 24] for the payment of it. As a people we are a little near-sighted; we are not gifted with imagination.”

“I should think this popular interest in government would tend to educate the masses,” I suggested.

“It certainly does,” replied M. Criant. “Questions are discussed on their merits and though, of course, a tricky orator may mislead, it will not be for long.”

At this point we were interrupted, so that nothing more was said at the time about Swiss politics. Both my friends, however, renewed their invitations for me to be sure to look them up. It is one of the great pleasures and advantages of travelling that one may make delightful acquaintances. I had no intention of letting slip the opportunity of further intercourse with men so genial and well informed as Professor Landoldt and M. Criant.

The voyage came to an end, as do all things earthly. Nothing untoward happened; and we reached Cherbourg on schedule time.

RUTH and her husband were waiting for me. Will took charge of my

luggage. He sent my trunk by express to Lausanne. He even insisted on

paying the duties on my cigars—several boxes of Havanas. I always

smoke the best cigars, though, thank the Heavenly Powers, I am not a

slave to the habit. I suppose every man says that, if for no other

reason than to contradict his wife.

When everything was arranged, we took our places in the handsome French touring-car, which, like a living thing instinct with life, proud of its shiny sides, of its rich upholstery, of its wide, swift tires, of its perfectly adjusted machinery, was to bear us across France.

Emile, in green livery, managed her with the skill of a Bengali mahout in charge of an obedient and well-trained elephant. Emile was a character. Born in French Switzerland, he spoke French, German and Italian with equal fluency, and he had a smattering of English[Pg 26] which he invested with a picturesque quality due to transplanted idioms and a variegated accent. Had he worn an upward-curling mustache and a pointed Napoleonic beard, one might have taken him for at least a vicomte. He knew every nook and corner of the twenty-two cantons and he had a sense of locality worthy of a North American Indian.

I could write a book about that trip from Cherbourg to Lausanne. Time meant nothing to us. We could follow any whim, delay anywhere, without serious fillip of conscience. The children were in trustworthy hands; the weather was fine. If there is anything in astrology, the stars may be said to have been propitious. We stopped for a day at the little town of Dol in Bretagne. In honour of some problematic ancestor I had the portal of the cathedral decorating my book-plate, and it was an act which a Chinese mandarin would approve—to pay our respects to the dim shades of Sir Raoul, or Duc Raoul, who is said to have accompanied William the Conqueror to England and to have killed Hereward the Wake in a hand-to-hand contest among the fens. Fortunate little town to have such a cathedral, though why Samson should be its patron saint I do not pretend to understand. His conduct[Pg 27] with Delilah was hardly saint-like, as we are accustomed to regard conduct in these days.

We climbed Mont Dol and saw the footprints made by the agile archangel Michael when he crouched to spring over to the rock that bears his name. Generally such marks are attributed to the fallen angel who switches the forked tail. That unpleasant personage must have been in ancient days as diligent in travel as the Wandering Jew. The book of Job contains his confession to the Lord that he was even then in the habit of going to and fro in the earth and walking up and down in it.

We saw Mont Michel, too, and wandered all over its wonderful castle. We did not think it best to make a long sojourn in Paris. No longer is it said that good Americans go there when they die. They had been having rain and the Seine was on a rampage. What a strange idea to build a big city on a marsh! it is certain to be deluged every little while; and house-cleaning must be a terrible nuisance after the muddy waters have swept through the second story floors, even if the foundations do not settle or the house itself go floating down stream. The river was threatening to pour over the quais; the arches of the bridges were almost hidden and men were working like[Pg 28] beavers to protect the adjoining streets from inundation.

When human beings put themselves in the way of the forces of nature they are likely to be relentlessly wiped out of existence. Mountains have a way of nervously shaking their shoulders as if they felt annoyed at the temples or huts put there by men, just as a horse scares away the flies on his flank, and, as the flies come back, so do men return to the fascinating heights. It has been remarked that large rivers always run by large cities, but the intervales through which the rivers run, the flat lands which offer such opportunities for laying out streets at small expense, are the creations of the busy waters, and they seem to resent the trespassing of bipeds, and they sometimes rise in their wrath and sweep the puny insects away.

I ought not to speak disparagingly of Paris: it was in my plan to return later and stay as long as I pleased. How can one judge of a person or of a city in a moment’s acquaintance? We left by the Porte de Clarenton; we sped through the famous forest of Fontainebleau—Call it a forest! It is about as much of a forest as a golf links are a mountain lynx. We stayed long enough to look into the famous[Pg 29] palace, and evoke the memories of king and emperor.

We spent a night at Orléans. I dreamed that night that Julius Cæsar was kind enough to show me about. He pointed out the spot where his camp was established and he told me how he burnt the town of Genabum, the capital of the Carnutes. I had not long before read Napoleon’s “Life of Cæsar.”

To think of two thousand years of continuous existence; the same river flowing gently by. If only rivers could remember and relate! It would have reflected Attila in its gleaming waters. It would also have its memories of the Maid whose courage freed the former city of the Aurelians from its English foes.

When we reached Tours the question arose whether we should not take the roundabout route through Poitier, Angoulême and Biarritz, thence zigzagging over to Pau, with its memories of Marguerite de Valois, and the birthplace of Bernadotte, pausing at Carcassonne—if for nothing else to justify one’s memory of Gustave Nadaud’s famous poem:—

getting wonderful views of the Pyrenees—only three hundred and fifty-two miles from Tours to Biarritz, less than three hundred miles to Carcassonne.

One hundred and thirty miles farther is Montpellier, once famous for its school of medicine and law. Here Petrarca studied almost six hundred years ago and here, in 1798, Auguste Comte, the prophet of humanity, was born.

At Nîmes, thirty miles farther on, beckoned us the wonderful remains of the old Roman civilization—the beautiful Maison Carrée, its almost perfect amphitheatre, where once as many as twenty thousand spectators could watch naval contests on its flooded arena, where Visigoths and Saracens engaged in combats which made the sluices run with blood. Here were born Alphonse Daudet and the historian Guizot. Was it not worth while to make a pilgrimage to such birthplaces? I would walk many miles to meet Tartarin.

Only twenty-five miles farther lies Avignon, on the Rhône, once the abiding-place of seven Popes, and from there a run of one hundred and eighty-five miles takes one to Grenoble, whence, by way of Aix-les-Bains, it is an easy and delightful way to reach Geneva. Then[Pg 31] Lausanne—home, so to speak!—a lakeside drive of a couple of hours!

The other choice led from Tours, through Bourges, Nevers, Lyons, tapping the longer route at Chambéry.

“We will leave it to you to decide,” said my niece. “It makes not the slightest difference to us. We have plenty of time. Emile says the roads are equally good in either itinerary. I myself think the route skirting the Pyrenees would be much more interesting.”

“So do I! I vote for the longer route.”

Now there is nothing that I should better like than to write a rhapsody about that marvellous journey—not a mere prose “log,” giving statistics and occasionally kindling into enthusiasm over historic château or medieval cathedral or glimpse of enchanting scenery; but the “journal” of a new Childe Harold borne along through delectable regions and meeting with poetic adventures, having at his beck and call a winged steed tamer than Pegasus and more reliable. But I conscientiously refrain. My eyes are fixed on an ultimate goal, and what comes between, though never forgotten, is only, as it were, the vestibule. So I pass it lightly over, only exclaiming: “Blessed be the man who first invented the[Pg 32] motor-car and thrice blessed he who put its crowning perfections at the service of mankind!” In the old days the diligence lumbered with slow solemnity and exasperating tranquillity through landscapes, even though they were devoid of special interest. The automobile darts, almost with the speed of thought, over the long, uninteresting stretches of white road. There is no need to expend pity on panting steeds dragging their heavy load up endless slopes. And when one wants to go deliberately, or stop for half an hour and drink in some glorious view, the pause is money saved and joy intensified. There is no sense of weariness such as results from a long drive behind even the best of horses. Not that I love horses less but motos more!

Twenty days we were on the road and favoured most of the time with ideal weather. It was one long dream of delight. We had so much to talk about; so much we learned! So many wonderful sights we saw!

How could I possibly describe the first distant view of the Alps? It is one of those sensations that only music can approximately represent in symbols. Olyenin, the hero of Count Tolstoï’s famous novel, “The Cossacks,” catches his first glimpse of the Caucasus and[Pg 33] they occupy his mind, for a time at least, to the exclusion of everything else. “Little by little he began to appreciate the spirit of their beauty and he felt the mountains.”

I have seen, on August days, lofty mountains of cloud piled up on the horizon, vast pearly cliffs, keenly outlined pinnacles, and I have imagined that they were the Himalayas—Kunchinjunga or Everest—or the Caucasus topped by Elbruz—or the Andes lifting on high Huascarán or Coropuna—or more frequently the Alps crowned by Mont Blanc or the Jungfrau. For a moment the illusion is perfect, but alas! they change before your very eyes—perhaps not more rapidly than our earthly ranges in the eyes of the Deity to whom a thousand years is but a day. They, too, are changing, changing. Only a few millions of years ago Mont Blanc was higher than Everest; in the yesterday of the mind the little Welsh hills, or our own Appalachians, were higher than the Alps.

Like summer clouds, then, on the horizon are piled up the mighty wrinkles of our old Mother Earth. We cannot see them change, but they are dissolving, disintegrating. Only a day or two ago I read in the newspaper of a great peak which rolled down into the valley,[Pg 34] sweeping away and burying vineyards and orchards and forests and the habitations of men. The term everlasting hills is therefore only relative and their resemblance to clouds is a really poetic symbol.

Oh, but the enchantment of mountains seen across a beautiful sheet of water! It is a curious circumstance that the colour of one lake is an exquisite blue, while another, not so far away, may be as green as an emerald. So it is with the tiny Lake of Nemi, which is like a blue eye, and the Lake of Albano, which is an intense green. Here now before our eyes, as we drove up from Geneva to Lausanne, lay a sheet of the most delicate azure, and we could distinctly see the fringe of grey or greenish grey bottom, the so-called beine or blancfond, which the ancient lake-dwellers utilized as the foundation for their aerial homes. My nephew told me how a scientist, named Forel, took a block of peat and soaked it in filtered water, which soon became yellow. Then he poured some of this solution into Lake Geneva water, and the colour instantly became a beautiful green like that of Lake Lucerne.

I found that Will Allerton is greatly interested in the geology of Switzerland. Indeed, one cannot approach its confines without marvelling[Pg 35] at the forces which have here been in conflict—the prodigious energy employed in sweeping up vast masses of granite and protogine and gneiss as if they were paste in the hands of a baby; the explosive powers of the frost, the mighty diligence of the waters. Here has gone on for ages the drama of heat and cold. The snow has fallen in thick blankets, it has changed by pressure into firn, and then becomes a river of ice, flowing down into the valleys, gouging out deep ruts and, when they come into the influence of the summer sun, melting into torrents and rushing down, heaping up against obstacles, forming lakes, and then again finding a passage down, ever down, until they mingle with the sea.

As we mounted up toward Lausanne, the ancient terrace about two hundred and fifty feet above the present level of the lake is very noticeable. In fact the low tract between Lausanne and Yverdun, on the Lake of Neuchâtel, which corresponds to that level, gives colour to the theory that the Lake of Geneva once emptied in that direction and communicated with the North Sea instead of with the Mediterranean as now. How small an obstacle it takes entirely to change the course of a river or of a man’s life!

These practical remarks were only a foil to the exclamations of delight elicited by every vista. I mean to know the lake well, and shall traverse it in every direction. It takes only eight or ten minutes from my niece’s house by the funicular, or, as it is familiarly called, la ficelle, down to Ouchy, the port of Lausanne. I parodied the lines of Emerson—

But I must confess I was not sorry to dismount from the motor-car in front of the charming house that was destined to be my abode for so many months.

THE house stands by itself in a commanding situation on the Avenue de

Collanges. It is of dark stone, with bay windows. The front door

seemed to me, architecturally, unusually well-proportioned. It was

reached by a long flight of steps. It belonged to an old Lausanne

family who were good enough to rent it completely furnished. I

noticed, in the library, shelves full of interesting books bound in

vellum. Interesting? Well, I doubt if I should care to read many of

them—they are in Latin for the most part. How in the world could men

in those old days induce printers to manufacture such stately tomes

filled with so much wasted learning, on hand-made paper?

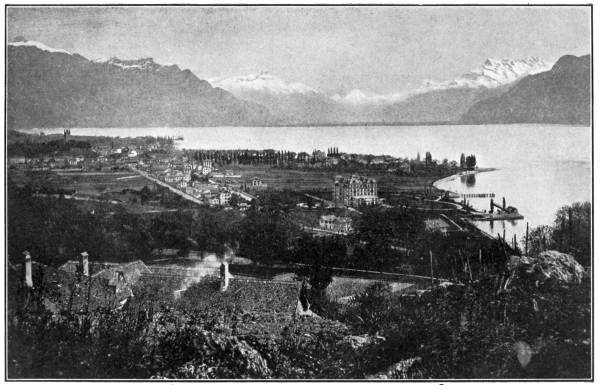

I suppose it was characteristic of me to be attracted first of all by the library, but, as soon as I got to my own room, I went to the window—I confess it, the tears came to my eyes! It[Pg 38] must be a dream. I recognize the cathedral with its massive Gothic tower and its slender spire and over the house-tops, far below, four hundred feet below, gleams the azure lake, and beyond rise the mountains. A steamboat cuts a silvery furrow through the blue, and a pearly cloud clings to the side of—yes, it must be La Dent du Midi! Below me, for the most part, lies Lausanne. I shall have plenty of time to know it thoroughly, and never, never shall I tire of that view from my chamber-window, looking off across the azure lake.

So absorbed was I in my contemplation that I had not realized how near luncheon-time it was. My trunk was at hand, unstrapped, and I quickly changed from ship and automobile costume into somewhat more formal dress. I was still looking out of the window with my collar in my hand when a miniature cyclone burst open the door. Yes, it was my nephew and namesake with the twin girls, blue-eyed Ethel and blue-eyed Barbara, who came to sweep me down with them to luncheon. How friendly, how gay, how excited, they were to see their Oncle Américain! We became great friends on the spot!

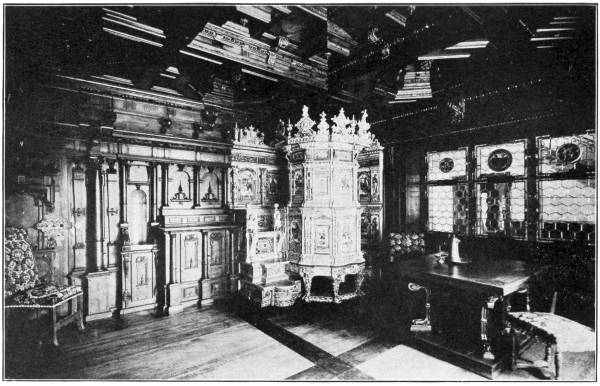

How delightful it is, after weeks of desultory meals at restaurants and hotels, to sit once [Pg 39]more at a well-ordered home table! The dining-room was a large, stately apartment, with wide window-recesses. There was fine stained glass in the windows. A number of admirable chamois heads with symmetrical horns were attached to the walls. In one corner stood a superb example of the ancient pottery stoves. It was of white and blue faïence à émail stannifère with gaily painted flowers in the four corner vases. An inscription informed those that could read the quaint lettering that it was made at Winterthür in 1647. How many generations of men it had warmed and comforted! How many happy families had gathered about its huge flanks! What stories it might relate of the days of yore! In spite of its artistic and antiquarian charm, however, it does not compare to the old New England or English open fireplace with fire-dogs supporting great logs of flaming wood which, as they burn down, turn into visions of rose-red palaces. I wonder how many of these old stoves are to be found in Switzerland. The art of making them is said to have been brought from Germany, but it soon acquired an individuality of its own. I am told that there are superb specimens of them in the various museums. The stannifer enamel is made by including some of[Pg 40] the oxide of tin in the biscuit. It makes the enamel opaque.

A WINTERTHUR STOVE.

After luncheon Will asked me if I would like to go over to the University, where he said he had a little business. I was very glad to do so. The Avenue de Collanges passes by the Free Theological Institute, the Ecole de Saint Roche, and, after joining with the Rue Neuve, leads into the Place de la Riponne, facing which stands the Palais de Rumine in which are the offices of the University.

After the Reformed Church was established in Lausanne there was a great demand for ministers, and a sort of theological school was founded in 1536. Pierre Viret, a tailor’s son, was active in this work. The famous Konrad von Gesner, the following year, became professor of Greek there, though he was only twenty-one. He won his great reputation as a zoölogist and botanist. An indefatigable investigator, he published no less than seventy-two works and left eighteen partly completed. They covered medicine, mineralogy and philology, as well as botany. He collected more than five hundred different plants which the ancients knew nothing about.

Another of the early professors was Theodore de Bèze. I remembered seeing his name on[Pg 41] my Greek Testament but I had forgotten what an interesting character he was. It is a tremendous change from being a dissipated cavalier at the court of François I, writing witty and improper verses, to teaching Greek and morals at Lausanne; but it was brought about by an illness which made him see a great light. While teaching at Lausanne he wrote a Biblical drama, entitled, “Abraham’s Sacrifice.” I am sorry to say he approved of the sacrifice of Servetus. He was at Lausanne for ten years and then was called to Geneva, where he became Calvin’s right-hand man and ultimately succeeded him. I wonder if he kept a copy of his early verses and read them over with mingled feelings.

It is rather odd that one of Bèze’s successors, Alexandre Rodolphe Vinet, who is regarded in Lausanne as the greatest of all her professors, had a somewhat similar experience. He, too, was gay and dissipated and wrote rollicking verses when he was a young man; he, like old Omar, urged his friends to empty the wine-cup (or rather the bottle, as it rhymed better) and let destiny go hang: “The god that watches o’er the trellis is now our only reigning king.” Perhaps, later, he may have found a hidden spiritual meaning in his references.[Pg 42] Ascetics converted from rather free living have been known thus to argue. Vinet, Will told me, began by teaching theology; but he demanded greater freedom of utterance than the directors of the Academy were prepared to allow. He detested the Revivalists and called them lunatics. He opposed any established church. He was simply ahead of his day. He was a brilliant preacher, and his lectures on literature were highly enjoyed; but, after the Revolution of 1845, he was obliged to resign. Two years later he died. He, too, wrote many valuable books, mostly theological works, half a dozen of which have been translated into English.

Talking about these early days, we had reached the Palais Rumine, that monument of Russian generosity—a new building—one might call it almost a parvenu building—compared with the old Gothic cathedral, only a few steps farther on.

In a way, however, the cathedral is even later than the palace, because its restoration, in accordance with plans designed by the famous French architect, Viollet-le-Duc, was not completed until 1906, two years after the other building was dedicated to its present uses. The palace, which was built from the fifteen hundred[Pg 43] thousand francs left by Gavriil Riumin (to spell the name in the Russian way), contains the various offices of the University, as well as picture galleries and museums.

“So this is the famous University of Lausanne,” I exclaimed, as we entered the learned portal.

“It has been a University for only about a quarter of a century,” remarked Will. “Gibbon and others wanted the Academy raised to a University more than a hundred years ago; but there seemed to be some prejudice against it. Its various schools were added at intervals. There has been a Special Industrial School ‘of Public Works and Constructions’ for about sixty years. In 1873 a school of pharmacy was started, and in 1888, when the Academy became a full-fledged University, it established a medical school. Theology still stands first; then come the schools of letters, of law, of science, of pedagogy, and of chemistry. Instruction is given in design, fencing, riding and gymnastics, and the University grants three degrees, the baccalaureate, the licentiate and the doctorate. It has an excellent library.”

“My errand will take me only a moment,” he added. “It is too fine a day to waste indoors; we shall have plenty of times when the[Pg 44] atmosphere is not so clear, for the museums and the cathedral. I propose we stretch our legs by walking up to the Signal. Are you fit for such a climb?”

“What do you take me for?” I asked, with a fine show of indignation. “It is only about four hundred feet above where we are now.”

I had not studied the guide-book for nothing.

There may be a great exhilaration and excitement and delight in climbing to the top of lofty mountains, but, when one has achieved the summit, even if the view be not cut off by clouds, the distances are so enormous that for poor mortal eyes the result is most unsatisfactory. Huddled together, peak with peak, an indistinguishable mass, lie other mountains and ranges of mountains, with bottomless valleys; the effect is as unsatisfactory as the air is rare. One can see nothing clearly; one is out of one’s element, so to speak; one can hardly breathe.

But from a height of a thousand feet, or so, one gets a comprehensive view of the world; one can distinguish the habitations of men; their farms and fields are marked off with fences; the rivers and brooks are not voiceless. It is a satisfying experience. Such is the impression that I got from the top of the Signal.[Pg 45] The city is fascinating, seen from above. There is the great bulk of the cathedral with its massive tower and the tall slender spire; the red roofs of innumerable houses; chimneys of factories in the lower town; then the exquisite lake; and, beyond it, the singularly silent and solemn masses of Les Diablerets, Le Grand Muveran and the jagged teeth of the Savoy Mountains, biting into the sky. They are so high that they shut off the grand bulk of Mont Blanc. It was certainly most thoughtful of my Lord Rhône to pause in the great valley and make a sky-blue lake for the delectation of mortals! Like swans with raised wings are the sail-boats. How far the wake made by that excursion steamboat extends across the placid water; it is curved like a scimetar of damascened steel!

“What a host of hotels!” I exclaimed. “I wonder how many foreigners are staying at Lausanne.”

“There must be five or six thousand regular residents from other parts of the world, besides the multitude of transients; Lausanne is a convenient stopping-place for several routes, to say nothing of the Simplon Tunnel line to Italy. There are probably fourteen hundred students at the University, and half of that number are[Pg 46] Germans, Russians and Poles. The German Minister of Public Instruction permits students of the Empire to spend the first three semesters at certain of the Swiss universities. But a suspicion arose in some Vaterland circles that these young men were being corrupted by Russian radicalism and Vaudois democracy—undermining their monarchical principles. There was also some jealousy, especially in the Law School. Herr Kuhlenbeck and Herr Vleuten were the so-called treaty professors, and the fees were not equally distributed. The Rundschau charged that young men learned socialism.

“It has always seemed to me an excellent notion to exchange students, just as we are beginning to exchange professors. It might serve to undermine narrow, sectional patriotism, but it would teach a broader, world patriotism.”

The view back of Lausanne also claimed my attention.

“These heights of Jorat,” said Will, “are rather interesting geologically. It seems to be a sort of subsidiary wave, filling the space between the Jura and the Alps; but it has an individuality of its own. It was always covered with great sombre forests which gave it a melancholy aspect. The basis of the soil is sandstone,[Pg 47] covered with pudding-stone. The ridge is all cut up with deep valleys. I have heard it said that the inhabitants had quite distinguishing characteristics and I don’t know why the people who live on some particular soil should not develop in their own way, just as the trees and plants and even the animals do. The stature diminishes as men inhabit higher and higher altitudes. The Swiss of the plains are generally rather heavy and slow, serious and solid. In the same way the people who live along the Jorat ought to be self-contained, close-mouthed, rather sad in temperament, perhaps uncertain in their movements, like the brook, the Nozon, which can’t quite make up its mind whether to flow to the Mediterranean by way of the Rhône or to the German Ocean by way of the Rhine.”

“It used to be a pretty important region, I should judge,” said I, “from all I have read of Swiss history. One flood of invasion after another dashed up against its walls and poured through its valleys.”

“It was, indeed. Some day I will show you the old tower which was called the Eye of Helvetia because it looked down and guarded the chief routes south and north, which crossed at its feet. It can be seen on a clear day from the[Pg 48] top of Mont Pélerin. Then there is the tower of Gourze, where Queen Berthe took refuge when the Huns came sweeping over this land. Lausanne itself, as it is now, is a proof of the old invasions; it used to stand on the very shores of the lake, but, when the Allemanni came, the inhabitants took refuge in the heights.”

“I think this is a charming view, but, do you know, to me its greatest charm is in the signs of a flourishing population. See the church spires picturesquely rising above clumps of trees, and, here and there, the tiled roofs of some old château—of course I do not know them from one another, but I know the names of several—Moléson, Corcelles, Ropraz, Ussières, Chatélard, Hermenches.”

Several of these my nephew and I afterwards visited. I recall with delight our trip to the Château de Ropraz, where once lived the wonderfully gifted Renée de Marsens. It now belongs to the family of Desmeules. Near it, on a hill, lies the little village, the church of which was reconstructed in 1761, though its interior still preserves its venerable, archaic appearance. A grille surmounted by the Clavel arms separates the nave from the choir. There are tombs with Latin inscriptions, and on the walls[Pg 49] are escutcheons painted with the arms of the old seigneurs. They still show the benches reserved for the masters of the château, flanked by two chairs with copper plates signifying that they are the “Place du Commandant” and the “Place du Chef de la Justice.” Seats were provided for visiting strangers and also for the domestics of the château. On the front of the pulpit is a panneau of carved wood bearing the words Soli Deo Gloria.

Renée, after her father’s fortune was lost, failed to make a suitable marriage, but she lived in Lausanne until 1848, and people used to go to call on her. They loved her for the brilliancy of her mind and her exquisite old-fashioned politeness. She knew Voltaire and all the great men of his time.

Another of the châteaux which we mentioned but were not certain that we could see was that of l’Isle, situated at the base of Mont Tendre in the valley of the Venoge. To this, also, we made an excursion one afternoon. It must have been splendid in its first equipment. It was built for Lieutenant Charles de Chandieu on plans furnished by the great French architect, François Mansard, whose memory is preserved in thousands of American roofs. In its day it was surrounded by a fine park. One[Pg 50] room was furnished with Gobelin tapestries, brilliant with classic designs. Other rooms had tapestries with panels of verdure in the style of the Seventeenth Century. The salon was floored with marble (“the marble halls” which one might dream of dwelling in) and hung with crimson damask, setting forth the family portraits and the painted panels. On the mantels were round clocks of gilt bronze, while huge mirrors, resting on carved consoles, reflected the brilliant companies that gathered there to dance or play. There was an abundance of high-backed armchairs and sofas, or as they called them, canapés, upholstered in velvet, commodes in ebony adorned with copper, and marquetry secretaries.

On the ground floor there was a great ballroom hung with splendid Cordovan leather. As it had a large organ it was probably used as a chapel, for the family was musical and several of the ladies of the Chandieu family composed psalms—Will called them chants-Dieu, which was not bad.

From the entrance-hall a splendid stairway, still well-preserved, with its wrought-iron railing led up to the sleeping-rooms, which were furnished with great beds à la duchesse with satin baldaquins. Among the treasures was a[Pg 51] beautiful chest of marquetry bearing the coat-of-arms quartered; it was a marriage-gift. Another, dated 1622, came from the Seigneur de Bretigny.

In front was a terrace with steps at the left leading down to the water. On each side of the stately main entrance, which reached to the roof, well adorned with chimneys, were three generous windows on each floor. In front there was a wide and beautifully kept lawn. The property was sold in 1810 for one hundred and seventy thousand francs. It came into the hands of Jacques-Daniel Cornaz, who, in 1877, sold it again for two hundred thousand. It now belongs to the Commune and is used for the écoles séculaires. The wall that once surrounded it has disappeared and the prosperous farms once attached to it were sold.

There is nothing in the literature of domestic life more fascinating than the diary and letters of Catherine de Chandieu, who married Salomon de Charrière de Sévery. They inherited the charming estate of Mex with its châteaux, and one of them, with a queer-shaped apex at each corner and a fascinating piazza, became their summer home. Another of these fine old places was the Château de Saint-Barthélemy, which belonged to the Lessert family[Pg 52] for three or four generations; then came into the possession of the famous Karl Viktor von Bonstetten, the author and diplomat, and was bought in 1909 by M. Gaston de Cerjat. In the hall hung pictures of several French kings, probably presented because of diplomatic services. Many of these old manor-houses on the shores of the Lakes of Geneva and of Neuchâtel have come into the possession of wealthy foreigners who have modernized them; others are now asylums, or schools, or boarding-houses.

But in those days they were filled with a cultivated and hospitable gentry who were always paying and receiving visits.

Really there is no end to the romance of these old houses; yet, curiously enough, most of them were carefully set down in little valleys which protected them from cold winds, but also from the magnificent views which they might have had. Even when they were on hills, trees were so planted as to hide the enchanting landscape, the lake and the gleaming mountains. Albrecht von Haller, the Bernese poet and novelist, Charles de Bonnet of Geneva, and Rousseau at Paris, “lifted the veil from the mountains” and made the world realize that the lake was something else than a trout-pond.

A SWISS CHÂTEAU.

It was time for us to be getting back. While we were on Le Signal some aerial Penelope had woven a web of delicate cloud and spread it out half-way up the Savoy Mountains across the lake; everything had changed as everything will in a brief half-hour. There were different gorges catching sunbeams, and tossing out shadows; there was another tint of violet over the waters. I suggested a plan for describing mountain views. It was to gather together all the adjectives that would be appropriate—high, lofty, massive, portentous, frowning, cloud-capped, craggy, granitic, basaltic, snow-crowned, delectable and so on, just as Lord Timothy Dexter did with his punctuation-marks, delegating them to the end of his “Pickle for the Knowing Ones,” so that people might “pepper and salt” it as they pleased. If I wrote a book about Switzerland—that is, if I find that my impressions, jotted down like a diary, are worth publishing, I mean to add an appendix to contain a sort of armory of well-fitting adjectives and epithets for the use of travellers and sentimental young persons. In this way I may be recognized as a benefactor and philanthropist.

“Do you know what is the origin of the name, Lausanne?” asked Will,

arousing me[Pg 53]

[Pg 54] from a revery caused by the compelling beauty of those

gem-like peaks, that rippling ridge of violet-edged magnificences that

loomed above the glorious carpet of the lake. The pedigree of names is

always interesting to me. Philology has always been a hobby of mine.

“Why, yes,” said I, “that is an easy one. It comes from the former name of the river, Flon. The Romans used to call the settlement here Lousonna. Almost all names of rivers have the primitive word meaning water, or flow, hidden in them. The Aa, the Awe, the Au, the Ouse, the Oise, the Aach and the English Avon, and a lot more, come from the Old High German aha, and that is nothing but the Latin aqua. The Greek hudor is seen in the Oder, the Adour, the Thur, the Dranse and even in the Portuguese Douro; and the Greek rheo, ‘I flow,’ is in the Rhine and the Rhône and the Reuss and in the Rye.”

“So I suppose you derive Lausanne from the French l’eau.”

As I passed in silent contempt such an atrocious joke as that, he seized the opportunity to tell me about the Frenchman who had some unpleasant associations with the inhabitants and declared it was derived from les ânes—the asses.

“From all I have read about them,” I replied, “they must have been a pretty narrow-minded, bigoted set of people here. Way back in 1361 an old sow was tried and condemned to be hanged for killing a child; and about the middle of the next century a cock was publicly burned for having laid a basilisk’s egg. One of the worthy bishops of Lausanne,—did you ever hear?—went down to the shores of the lake and recited prayers against the bloodsuckers that were killing the salmon.”

“Was that any more superstitious than for present-day ministers to pray for rain?”

“I suppose not; only it seems more trivial,” I replied absently, as I gazed down upon the housetops. “I did not realize Lausanne was so large.”

“The city is growing, Uncle. Toward the south and the west you can see how it is spreading out. There is something tragic to me in the outstretch of a city. It is like the conquest of a lava-flow, such as I once saw on the side of Kilauea, in the Hawaiian Islands; it cuts off the trees, it sweeps away the natural beauties. Lausanne has trebled its population in fifty years. It must have been much more picturesque when Gibbon lived here. For almost[Pg 56] eighty years they have been levelling off the hills. It took five years to build the big bridge which Adrien Pichard began, but did not live to finish. The bridge of Chauderon has been built less than ten years.”

“They must have had a tremendous lot of filling to do.”

“They certainly have, and they have given us fine streets and squares—especially those of La Riponne and Saint-François. It was too bad they destroyed the house of the good Deyverdun, where Gibbon spent the happiest days of his life. It had too many associations with the historic past of Lausanne. They ought to have kept the whole five acres as a city park. What is a post office or a hotel, even if it is named after a man, compared to the rooms in which he worked, the very roof that sheltered him?”

“We have still time enough,” said I, consulting the elevation of the sun; “let us go down by way of the cathedral. I should like to see it in the afternoon light.”

“We can take the funiculaire down; that will get us there quicker.”

We did so, and then the Rue l’Industrie brought us, by way of the Rue Menthon, to the edifice itself.

“I want you to notice the stone of which the cathedral is built,” said Will.

“Yes, it’s sandstone.”

“It is called Lausanne stone. A good many of the old houses are built of it, and it came from just one quarry, now exhausted, I believe. It seems to have run very unevenly. Some of the big columns are badly eaten by the tooth of time; in others the details are just as fresh as if they had been done yesterday. Notice those quaint little figures kneeling and flying in the ogives of the portal; some are intact, others look as if mice had gnawed them. It is just the same with some of the fine old houses; one will be shabby and dilapidated; the very next will be well-preserved.”

“I think it is a rather attractive colour—that greyish-green with the bluish shadows.”

We stood for a while outside and looked up at the mighty walls and the noble portal. We walked round on the terrace from which one gets such a glorious view.

There is something solemn and almost disquieting in a religious edifice which has witnessed so many changes during a thousand years. Its very existence is a curious and pathetic commentary on the superstitions of men. Westerners, interpreting literally the symbolism[Pg 58] of the Orient, believed that the world would come to an end at the end of the first millennium. It was a terrible, crushing fear in many men’s minds. When the dreaded climacteric had passed and nothing happened, and the steady old world went on turning just as it had, the pious resolved to express their gratitude by erecting a shrine to the Virgin Mother of God. Before it was completed its founder was assassinated. In the thirteenth century it was thrice devastated by fires which were attributed by the superstitious to the anger of God at the sins of the clergy and of the people. The statue of the Virgin escaped destruction and the church was rebuilt between 1235 and 1275. When it was consecrated, in October, 1275, Pope Gregory X, with the Emperor, Rudolf of Hapsburg, his wife and their eight children, and a brilliant crowd of notables, cardinals, dukes, princes and vassals of every degree, were present. The great entrance on the west was completed in the fifteenth century. The nave is three hundred and fifty-two feet long; its width is one hundred and fifty feet and it is divided into eight aisles. There are seventy windows and about a thousand columns, many of them curiously carved.

The well-known Gate of the Apostles is in[Pg 59] the south transept. It commemorates only seven of them, though why that invidious distinction should have been made no one knows. Old Testament characters fill up the quota. These worthies stand on bowed and cowed demons or other enemies of the Faith.

In the south wall is the famous rose-window, containing representations of the sun and the moon, the seasons and the months, the signs of the zodiac and the sacred rivers of Paradise, and quaint and curious wild beasts which probably are visual traditions of the antidiluvian monsters that once inhabited the earth, and were still supposed to dwell in unexplored places.

The vaulting of the nave is sixty-two feet high. It gave plenty of room for the two galleries which once surmounted the elaborately carved façade. One of them was called the Monks’ Garden, because it was covered with soil and filled with brilliant flowers.

Back of the choir is a semicircular colonnade. The amount of detail lavished on the various columns is a silent witness of the cheapness of skilled labour and of the time people had to spend. The carved choir stalls, completed in 1506, were somehow spared by the vandal iconoclasts of the Reformation; but thirty years[Pg 60] later Bern, when taking possession of Lausanne, carried off eighteen wagon-loads of paintings, solid gold and silver statues, rich vestments, tapestries, and all the enormous wealth contributed to the treasures of the church.

We were fortunate to find the cathedral still open, and in the golden afternoon light we slowly strolled through the silent fane—the word fane always sounds well. We paused in front of the various historic tombs. Especially interesting was that dedicated to the memory of Otho de Grandson, who, having been charged with having instigated the murder of Amadée VII, was obliged to enter into a judicial duel with Gérard d’Estavayer, the brother of the fair Catherine d’Estavayer whom he expected to marry.

Gérard apparently stirred up great hatred against him. Otho had in his favour the Colombiers, the Lasarraz, the Corsonex, and the Rougemonts; while with Gérard were the Barons de Bussy, de Bonvillar, de Bellens, de Wuisternens, de Blonay and, especially, representatives of the powerful family of d’Illens whose great, square castle is still pointed out, beetling over the Sarine opposite Arconciel. These men were probably jealous of Otho. His[Pg 61] friends wore a knot of ribbons on the tip of their pointed shoes, while his enemies carried a little rake over their shoulders.

Otho shouted out his challenge to Gérard: “You lie and have lied every time you have accused me. I swear it by God, by Saint Anne and by the Holy Rood. But come on! I will defend myself and I will so press forward that my honour will be splendidly preserved. But you shall be esteemed as a liar.”

So Otho made the sign of the Cross and threw down the battle-gage. But, although he was undoubtedly innocent, the battle went against him. His effigy is still to be seen in the cathedral. The hands resting on a stone cushion are missing but this probably was due to some accident and not to any symbolism. This all happened about a hundred years before Columbus discovered America—in 1398.

Here, too, lies buried, under a monument by Bartolini, Henrietta, the first wife of Lord Stratford de Redcliffe, minister from England to Switzerland. She died in 1818.

There are monuments also commemorating the Princess Orlova, who was poisoned by Catharine II of Russia, and Duc Amadée VIII, who caused Savoy to be erected into a duchy and became Pope Felix V in 1439, after he had[Pg 62] lived for a while in a hermitage on the other shore of the lake. He is not buried in the cathedral but his intimate connection with the history of Lausanne is properly memorialized by his monument.

A city is like an iceberg. Its pinnacles and buttresses tower aloft and glitter in the sun; it seems built to last for ever. But it is not so; its walls melt and flow away and are put to other uses. A temple changes into a palace, and a fortification is torn down to make a park. Where are the fifty chapels that once flanked Notre Dame de Lausanne? Where is the fortified monastery of Saint Francis? Where is the lofty tower of La Grotte, and the moat in which it was reflected?

A great pageant took place in the cathedral in 1476. After Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, had been defeated at Grandson, he collected what remained of his army of 50,000 men, and encamped in the plains of Le Loup. Then on Easter Sunday, he attended high mass. The cathedral was lavishly decorated and a brilliant throng “assisted” at the ceremonies. The Duchess Yolande of Savoy came from Geneva, bringing her whole court and an escort of three thousand horsemen. The Pope’s legate and the emperor’s ambassadors[Pg 63] brought their followers, while representatives of other courts were on hand, for the occasion was made memorable by the proclamation of peace between the duke and the emperor. There was a great clanging of bells and fanfare of trumpets and the whole city was overrun with soldiers. The commissary department was strained to feed such multitudes. It is said that an English knight, serving in the duke’s army, was reduced to eating gold; at any rate his skull was found some years ago with a rose noble tightly clenched between its teeth!

A few months later the battle of Morat was fought; the duke was defeated and Lausanne was doubly sacked, first by the Comte de Gruyère and, a few hours later, by his allies, the Bernese troops, who spared neither public nor private edifices.

Just sixty years later Lausanne fell definitely into the hands of the Bernese, and they, by what seems an almost incredible revival of the judicial duel—only with spiritual instead of carnal weapons—ordered a public dispute on religion to decide whether Catholicism or Protestantism should be the religion of the city.

The comedian of the occasion seems to have[Pg 64] been the lively Dr. Blancherose, who was constantly interrupting and interpolating irrelevant remarks, to the annoyance of the other disputants and to the amusement of the audience which packed the cathedral. On one occasion he declared that the word cephas was Greek and meant head; Viret replied that it was a Syriac word and meant stone. The Pope could have well dispensed with such an advocate.

The superiority of the Protestant debaters resulted in converting some of the opposite party, and the establishment of the Academy of Lausanne was the direct outcome of this debate, which was declared in all respects favourable to the Reformers.

The day after the decision was rendered, a crowd of bigots broke into the cathedral, overturned the altars and the crucifix, and desecrated the image of the Virgin. Workmen were paid for fifteen days at the rate of four and one sixth sous a day to clear Notre Dame of its altar-stones. And yet Jean François Naegueli (or Nägeli), when he took possession of Lausanne, had promised to protect the two Christian faiths.

It is a question whether one would rather live in those days under the easy-going régime[Pg 65] of the superstitious Catholics or under that of the stern, forbidding bigotry of the Protestants. Geneva could not endure the latter and banished Farel and Calvin two years later; but back they came and established the tyranny more solidly than ever. Calvin drove Castellio out of Geneva, caused Jacques Gruet to be tortured and put to death, mainly because he danced at a wedding and wore new-fangled breeches, and had Servetus burned at the stake. It was a cruel age.