ARLO BATES

BOSTON

ROBERTS BROTHERS

1891

| PAGE | ||

| Tale the First: | A Strange Idyl | 7 |

| Interlude First: | An Episode in Mask | 55 |

| Tale the Second: | The Tuberose | 67 |

| Interlude Second: | An Evening at Whist | 89 |

| Tale the Third: | Saucy Betty Mork | 101 |

| Interlude Third: | Mrs. Fruffles is at Home | 131 |

| Tale the Fourth: | John Vantine | 141 |

| Interlude Fourth: | The Radiator | 155 |

| Tale the Fifth: | Mère Marchette | 163 |

| Interlude Fifth: | “Such Sweet Sorrow” | 189 |

| Tale the Sixth: | Barum West’s Extravaganza | 201 |

| Interlude Sixth: | A Business Meeting | 221 |

| Tale the Seventh: | A Sketch in Umber | 233 |

| Interlude Seventh: | Thirteen | 253 |

| Tale the Eighth: | April’s Lady | 263 |

| Interlude Eighth: | A Cuban Morning | 285 |

| Tale the Ninth: | Delia Grimwet | 301 |

He lay upon an old-fashioned bedstead whose carved quaintness would once have pleased him, but to which he was now indifferent. He rested upon his back, staring at the ceiling, on whose white surface were twinkling golden dots and lines in a network which even his broken mind knew must be the sunlight reflected from off the water somewhere. The windows of the chamber were open, and the sweet summer air came in laden with the perfume of flowers piquantly mingled with pungent sea odors. Now and then a bee buzzed by the casement, or a butterfly seemed tempted to enter the sick-room—apparently thought better of it, and went on its careless way.

Of all these things the sick man who lay there was unconscious, and the sweet young[10] girl sitting by his bed was too deeply buried in her book to notice them. For some time there was no movement in the chamber, until, the close of a chapter releasing for an instant the reader’s attention, she looked to discover that the patient’s eyes were open. Seeing him awake, she rose and came a step nearer, thereby making the second discovery, more startling than the first, that the light of reason had replaced in those eyes the stare of delirium.

“Ah,” she said, softly, “you are awake!”

The invalid turned his gaze toward her, far too feeble to make any other movement; but he made no attempt to speak.

“No,” she continued, with that little purring intonation which betrays the feminine satisfaction at having a man helpless and unable to resist coddling; “don’t speak. Take your medicine, and go to sleep again.”

She put a firm, round arm beneath his head, and bestowed upon him a spoonful of a colorless liquid, afterward smoothing his pillows with deft, swift touches. He submitted with utter passiveness of mind and body, ignorant who this maiden might be, where he was, or, indeed, who he was. Painfully he endeavored to think, to remember, to understand; but with no result save confusing[11] himself and bringing on an ache in his head. His nurse, at the convenient end of another chapter, observed a look of pain and trouble upon the thin face, scarcely less white than the pillow against which it rested.

“You are worrying,” she observed with authority. “Go to sleep. You are not to think yet.”

And, staying himself upon the resolution and confidence in her tone, he abandoned himself again to the current of circumstances, and drifted away into dreams.

The girl, watching closely now, with mind distracted from her story to the more tangible mystery involved in the presence of the sick man, gave a little sigh of relief when his even breathing indicated that he had fallen asleep. She removed softly to a seat near the window, and looked out upon the tranquil beauty of the afternoon. Long Island Sound lay before her, dimpling and twinkling in the sunshine, while nearer a sloping lawn stretched from the house to the shore. Glancing backward and forward between the sunny landscape and the bed where her patient slept, the maiden fell to wondering about him, recalling the little she knew, and straining her fancy to construct the story of his life.

Three weeks before a Sound steamer had been wrecked so near this spot that through the stormy night she had seen the glare of the fire which broke out before the hull sank, and the next morning’s tide had brought to shore this man, a floating waif, saved by a life-preserver and some propitious current. A terrible wound upon his head showed where he had experienced some blow, and left him hesitating with distraught brain between life and death. In his delirium he had muttered of varied scenes. He must, the watcher reflected, have travelled extensively. Now there were words which showed that he was sharing in wild escapades; cries of defiance or of encouragement to comrades whose shadowy forms his disordered brain summoned from the mysterious past; strange names, and words in unknown tongues mingled themselves with incoherent appeals or bitter reproaches.

To the girl who had been scarcely less at his bedside than the old woman who nominally nursed him, these broken fragments of wild talk had been like bits of jewels from which her mind had fashioned a fantastic mosaic. The mystery surrounding the stranger would, in any case, have appealed strongly to her quick fancy, but when[13] to this was added the brilliancy of his delirious ravings, it is small wonder that her imagination took fire, and she wove endless romances, in all of which the unconscious sick man figured as the hero. Scraps of talk in an unknown tongue, a few sonorous foreign words, a little ignorance concerning matters in reality commonplace enough, have, in many a case before, been the sufficient foundations for a gorgeous fata morgana of fancy.

The stranger had been thrown ashore only partially dressed, and with nothing upon him which bore a name. A belt around his waist contained about fifteen hundred dollars in bills and a small quantity of gold-dust. From the presence of this latter they had speculated that the wounded man might be a returning Californian, yet his clothing was of too fine texture and manufacture for this supposition. Several persons, seeking for friends lost in the disaster from which he came, had vainly endeavored to identify him, and his description had been given in the New York papers; but without result. There seemed, upon the whole, to be no especial hope of obtaining any satisfactory information regarding the sick man until he was able to furnish it himself; and to-day for the first time the watcher found in his eyes the light of returning[14] reason. She felt as if upon the threshold of a great discovery. She smiled softly to herself to think how eager she had become over this mystery; to recognize how large a place the stranger occupied in her thoughts; yet she could but acknowledge to herself that this was an inevitable consequence of the existence which surrounded her.

The life into which the wounded man had been driven by the currents of the sea and those stronger currents of the universe which we call Fate was a sufficiently monotonous one. The household into which he had been received consisted of an old gentleman, broken alike in health and fortune, so that while the establishment over which presided his only child was not one of absolute want, it was often straitened by the necessity of uncomfortable economies. Alone with an old family servant, the father and daughter lived on in the homestead which the wealth of their ancestors had improved, but which their present revenues were inadequate to preserve in proper state. One day with them was so like every other day that the differences of the calendar seemed purely empirical, even when assisted by such diversity as old Sarah, the faithful retainer, was able to compass in the matter of the viands which,[15] at stated periods in the week, appeared upon their frugal table.

Old Mr. Dysart would have failed to perceive the justice of the epithet “selfish” as applied to himself; yet no word so perfectly described him. He was absorbed in the compilation of a complete genealogy of the entire Dysart family, with all its ramifications and allied branches. What became of his daughter while he delved among musty parchments in his stately old library; how the burdens of the household were borne; and how a narrow income was made to cover expenses, were plainly matters upon which he could not be expected to waste his valuable time. The maiden could scarcely have been more alone upon a desert island, or in a magic tower. Her days followed each other with slow, monotonous flow, like the sands in an hour-glass,—each like the one before, and each, too, like the one to follow.

Amid such a colorless waste of existence the rich mystery of the wounded stranger appeared doubly brilliant by contrast; and it is small wonder that to the watcher the first gleam of returning intelligence in the sick man’s eyes was as the promise of the opening of a door behind which lay an enchanted palace.

It was yet a day or two before the sick man spoke. He was very weak, and lay for the most part in a deathlike but health-giving sleep. At length the day came when he said feebly:—

“Where am I?”

“Here,” his nurse answered, with truly feminine irrelevancy.

“Where?”

“At Glencarleon.”

He lay silent for some moments, evidently struggling to attach some meaning to the name, and to collect his strength for further inquiries.

His eyes expressed his mental confusion.

“You were hurt in the steamer accident,” she explained. “You came ashore here, and are with friends. Don’t try to talk. It is all right.”

He was too feeble to remonstrate,—too feeble even to reason, and he obeyed her injunction of silence without protest. She retreated to her favorite seat by the window, and took up her sewing; but her revery progressed more rapidly than her stitches,[17] and when she was relieved from her post by old Sarah, she stole softly out of the room to continue her dreaming in an arbor overlooking the water, where, in pleasant weather, she was wont to spend her leisure hours.

The next day, when she gave her patient his morning gruel, he watched her with questioning eyes, as if endeavoring to identify her, and at last framed another inquiry.

“Who are you?” he asked.

“I am Columbine.”

“Columbine?”

“Columbine Dysart.”

That he knew little more than before was a consequence of the situation, and Mistress Columbine was wise enough to spare him the necessity of saying so.

“You do not know us,” she said; “but we will take good care of you until you are well enough to hear all about it.”

“But—” he began, the puzzled look upon his wan face not at all dissipated.

“No,” she returned, “there is no ‘but’ about it. It is all right.”

“But,” he repeated with an insistence that would not be denied, “but—”

“Well?” queried she, seeing that something troubled him too much to be evaded.

“But who am I?” he demanded, so earnestly[18] that the absurdity of such a question was lost in its pathos.

“Who are you?” she echoed, in bewilderment. Then, with the instant reflection that he was still too near delirium and brain-fever to be allowed to trouble himself with speculations, she added, brightly, and with the air of one who settles all possible doubts, “Why, you are yourself, of course.”

She smiled so dazzlingly as she spoke that a complete faith in her assurances mingled itself with some dimly felt sense of the ludicrous in the sick man’s mind, and although the baffled look did not at once disappear from his face, yet he said nothing further, and not long after he fell asleep, leaving Columbine free to seek her arbor again and ponder on this new phase of her interesting case. She attached no serious importance then to the fact that her patient seemed so uncertain concerning his identity; but, as the days went by, and he was as completely unable to answer his own query as ever, a strange, baffled feeling stole over her; a teasing sense of being brought helplessly face to face with a mystery to which she had no key.

His convalescence was somewhat slow, the hurts he had received having been of a very serious nature; but when he was able to leave[19] his room, and even to accompany Columbine to her favorite arbor, he was still grappling vainly with the problem of who and what he was.

This first visit to the arbor, it should be noted, was an event in the quiet life at the old house. Columbine was full of petty excitement over it, her fair cheeks flushed and her hair disordered with running to and fro to see that the cushions were in place, the sun shining at the right angle, and the breeze not too fresh. She insisted upon supporting the sick man on one side, while faithful old Sarah, her nurse in childhood, and since promoted to fill at once the place of housekeeper and all the departed servants, took his arm upon the other to help him along the smoothly trodden path through the neglected garden. Mr. Dysart was as usual in his library, and to disturb him there was a venture requiring more daring than either of the women possessed. They got on very tolerably without him, however, and the patient was soon installed amid a pile of wraps and shawls in the summer-house, where he was left in charge of Miss Dysart, while Sarah returned to her household avocations.

It was a beautiful day in the beginning of September, warm and golden, with all the[20] mellowness of autumn in the air, while yet the glow of summer was not wholly lost. The soft sound of water on the shore was heard through the chirping of innumerable insects, shrilling out their delight in the heat; while now and then the notes of a bird mingled pleasantly in the harmony. The convalescent drew in full breaths of the sweet air with a sigh of satisfaction, leaning back among his cushions to look, with the pleasure of returning life, over the fair scene before him.

For some time nurse and patient sat silent, but the girl, watching him intently, was in no wise dissatisfied with the other’s evident appreciation of her favorite spot. Indeed, she had dreamed here of him so often that some subtle clairvoyancy may have secretly put him in harmony with the place before he saw it. Columbine liked him for the pleasure so evident upon his handsome, wasted face, while inly she was aware how great would have been her disappointment had he been less alive to the charms of the view.

“How lovely it is!” he said, at length. “It is, perhaps, because you live in so lovely a place,” he added, after a trifling pause, and with a faint smile, “that you are so kind to a waif like myself.”

“Perhaps,” she answered, returning his smile. “But, really, we only did what any one would have done in our place.”

“Oh, no; and besides, few could have done it so well. It is so pleasant, I seem to have lived here always.”

“It may be,” Columbine suggested, with deliberation, “that it recalls some place you have known.”

A shadow came over his face.

“It is a pity,” he said, “that if that unlucky disaster could spare me nothing of my baggage, it could not at least have left me my few poor wits. I might make an interesting case for psychologists. They might discover from me in what part of the brain the faculty of memory is located, for that wretched wound seems to have let mine all ooze out of my cranium. I do not feel, Miss Dysart, like an idiot in all respects, since I certainly know my right hand from my left; and I have found, by experiment in the night-watches, that I could still make myself understood in two or three languages.”

“You had much better have slept,” interpolated his listener.

“But as far as my personal history goes,” he continued, replying to her words by a smile, “my mind is an absolute blank. I[22] can give you several interesting pieces of information concerning ancient history and chronology; but I haven’t the faintest idea what my name is; and you must acknowledge that it is a little hard for a man to be ignorant of his own name.”

“Yes,” Columbine assented, bending forward and clasping her hands in front of her knees. “Yes; and it is so strange! Try and remember; you must surely recollect something.”

“I have tried; I do try; but I can only conjure up a confused mass of shifting images; things I seem to have been and to have done, all indistinguishably mixed with what I have only dreamed or hoped to do and be.”

“How strange!” she said again, fixing her wide-open dark eyes upon him, and then turning her gaze to the sea beyond; “but it will come to you in time.”

“Heavens!” he exclaimed, energetically, “I hope so, else I shall regret that you pulled me out of the water. To-day I do seem to have a glimpse of something more tangible. Since I sat here I almost thought I remembered—”

He broke off suddenly, his bright look fading into an expression of helpless annoyance.

“What?” cried Columbine, eagerly.

“I cannot tell,” he groaned. “It is all gone.”

“Oh, what a pity!” exclaimed she, springing to her feet in a flush of sympathy and baffled curiosity. “Oh, how cruel!”

Then she remembered that she was absolutely disobeying the doctor’s orders, and was allowing her patient to become excited.

“There, there,” she said, “how wrong of me to let you worry! Everything will come back to you when you are stronger. Now it is time for your luncheon. It is so warm and bright you may have it here if you will promise not to bother your head. For I really think,” she added, wisely, giving his wraps a deft touch or two, “that the best way to remember is not to try.”

“I dare say you are right,” he agreed. “At least trying doesn’t seem to accomplish much.”

She flitted away, to return a moment or two later with an old-fashioned salver, upon which, in dainty china two or three generations old, Sarah had arranged the invalid’s luncheon. She drew the rustic table up to his side and served him, while he ate with that mixture of eagerness and disinclination which marks the appetite of one in the early stages of a convalescence.

“That pitcher,” he observed, carelessly, as she poured out the cream, “ought to belong to my past. It has a familiar look, as if it could claim acquaintance if it would only deign.”

“It was my grandmother’s,” Columbine said. “When we were little, Cousin Tom used to tease me by saying my cheeks looked like those of that fat face on the handle. I was more buxom then than now.”

Instead of replying, her companion laid down his spoon and looked at her in delighted amaze. Then he struck his hands together with sudden vigor.

“Tom!” he cried. “Tom!”

“Well?” queried she, looking at him as if he had gone distraught. “It isn’t so strange a name, is it?”

“But, don’t you see?” he exclaimed, joyously,—“I’m Tom! I have found my name!”

The rest of Tom’s name, however, remained as profoundly and as provokingly concealed in the wounded convolutions of his brain as ever. Columbine called him Mr. Tom, and it is not unlikely that the familiarity[25] of the monosyllable, which seemed to place them at once upon an intimate footing, had a strong influence upon their relations. The maiden had a crisp way of pronouncing the name, as if she were half conscious of a spice of impropriety in a term so familiar, and felt it, too, to be something of a joke, which was so wholly fascinating that the patient did not have to be very far advanced toward his normal condition of health and spirits to enjoy it so well as to reflect that the name so rendered ought to be enough for any man.

Mr. Tom soon began to gather up a few stray bits from his childhood, his memory apparently returning to its former state by the same slow road it had travelled from his birth to reach it.

“I remember a few beginnings,” he had said, hopefully, on the day following that of his first visit to the arbor. “I had a carved coral of a most luscious pink color. It is even now vaguely connected in my mind with the idea of eating; so I infer that I must have cherished a fond delusion that it was good to eat.”

“It is at least good to remember,” Columbine returned, laughing. “It wouldn’t be a bad idea to open an account of things recovered[26] from the sea of the past. You can begin by putting down: Item, one coral.”

“Yes; and one nurse. I distinctly recall the nurse. She had a large mole on her chin. Yes; I can certainly swear to the nurse.”

He was in excellent spirits to-day. The dawning of recollection gave promise of the restoration of complete remembrance; the day was enchanting; his appetite and his luncheon came to a wonderfully good agreement, while a prettier serving-maid than Miss Dysart could hardly be found.

“It must be very like being a child again,” she observed, thoughtfully; “and that is a thing, you know, for which the poets are always sighing.”

“You will have the advantage of growing up with me,” was his gay retort, “if this process continues. Only you’ll have the advantage of superior age.”

After that he told her each morning what he had been able to recover from forgetfulness since the previous day. It is difficult to imagine the strangeness of this relation. It possessed all the piquancy of fiction to which its ingenious author added new incidents from day to day; yet it had, too, the strong attractiveness of truth and personal[27] interest. Columbine listened and commented, deeply engrossed and fascinated by the novel experience which gave her an acquaintance with the entire past life of her stranger guest, yet an acquaintance which was etherealized and marked by a certain charm not to be found in actual companionship. Had she really shared the childhood thus narrated to her it would have been in no way remarkable; but now she seemed to live it herself, with a vitality and interest more vivid each day. Often the freakish faculty, upon whose vigor depended the continuity of Mr. Tom’s narration, would for days concern itself with the veriest trifles, advancing the essentials of the story not a whit; or, again, it would seem to turn perversely backward, although no efforts availed to speed it forward.

The main facts of Mr. Tom’s story, so far as they were gathered up in the first week of this odd story-telling, were as follows: He made his acquaintance with the world doubly orphaned, his father being lost at sea upon a return voyage from India before the boy’s birth, and his mother dying in childbed. Reflecting upon what he was able to recall, Tom concluded that his parents were persons of wealth. His surroundings had at least been luxurious. The truth was, as he came,[28] in time, to remember, that, being left without near relatives, he had been, by his guardian, confided to the care of trusty people, who spoiled and adored him until he was transferred to boarding-school.

“I have grown to be a dozen years old,” Tom remarked to Miss Dysart one afternoon as they sat in the arbor, she sewing, and he idly pulling to pieces a purple aster. “I have even conducted myself to boarding-school, and I cannot conceive why I can’t get hold of my family name. I must have been called by it sometimes. I remember being dubbed Tom, Tommy, Thomas,—that was when I was stubborn; Tom Titmouse—that was by nurse; Tom Tattamus—that by the particularly odious small boy next door; but beyond that I might as well never have had a name at all. My trunks, I know, were marked with a big W, but all the names beginning with that letter that I can hit upon seem equally strange to me. I do not see why, of all things, it is precisely that which I cannot remember.”

“It is because you worry about it,” his companion suggested; “probably that particular spot in your brain where your name is lodged is kept irritated by your impatience.”

“Heavens!” laughed he. “How psychologic and physiological you are! Well, if I’ve no name, I can invent one, I suppose.”

“Or make one. Do you realize what a fascinating position you are in? Common mortals have only the consolation of speculating about their future; but you can also amuse yourself with boundless speculations concerning your past. You are relieved from all responsibility—”

“Oh, no,” he interrupted; “that is the worst of it. I have responsibilities without knowing what they are. The past holds me like a giant from behind, and I cannot even see my captor.”

“Oh, you look at it all too seriously!” Columbine returned. “You can fashion your past, as we all do our futures, just as you like. I think you are decidedly to be envied.”

“Envied!”

The bitterness of the exclamation brought to her a sudden realization of the difference of their points of view, and revealed how deep was the man’s humiliation at his helpless position. A quick flush of pity and sympathy mantled her cheek.

“Forgive me,” she exclaimed, impulsively. “I had no right to be so thoughtless. I beg your pardon.”

“There is no occasion. You are right. It is certainly better to laugh than to cry over the inevitable, especially as things are righting themselves. But we, or, rather, I, must go into the house. It is growing cool.”

Life at the old Dysart place went forward in a slow and decorous fashion, little allied to the bustling manners of the present day. Mr. Dysart was getting now to be an old man, albeit it is doubtful if in any abundant sense he can ever have been a young one. In any case he had, by long burrowing among musty records and genealogical parchments, acquired a dry and antique appearance, as, to use a somewhat presumptuous yet not inexact metaphor, certain scholarly worms had taken on a brown hue from continued dining on the bindings of his venerable folios. He inhabited a remote and essentially unworldly sphere, from which the existence of his daughter was wholly separate. He was conscious of her presence in an unrealizing way; was even aware that just now she had in the house a guest who had come ashore from a wreck. But that was the affair of[31] Columbine and old Sarah; he could not of course be expected to loosen his hold upon the clew which he hoped would lead him to the exact connection between the Dysarts and the Van Rensselaers of two generations back, to pay attention to a chance waif from that outer world with which he had never considered it worth his while to concern himself.

As far as Mr. Tom was concerned, Mr. Dysart might as well not have existed. They did once meet in the passage before the study door when the invalid in his first days of walking was one rainy morning wandering restlessly about the halls; but the owner of the house hurried furtively past, as if he were the interloper and the other lord of the manor; and even when the convalescent was well enough to join the family at table, Mr. Dysart was very seldom there, so that the meals were for the most part taken tête-à-tête by Columbine and her patient.

The result of such a situation is evident from the beginning. Exceptional natures might be imagined, perhaps, that would not have grown dangerously interested in each other under such circumstances; but at least these two drew every day closer together. Neither had any tie belonging to the past;[32] or, more exactly, Columbine had none, and he, for the time being, at least, had no past. His helplessness and the mystery enshrouding him would have appealed to the heart of any woman, and Columbine had no distractions to fill her life and crowd out this ever-deepening interest. Of Mr. Tom, her beauty and freshness, her simplicity, which was so far removed from insipidity, her innocence, which never suggested ignorance, won the respect and admiration long before he was conscious that love, too, was growing in his heart.

There came a day, however, when he could no longer be ignorant of the nature of his feelings.

The two had gone past the arbor and down to the shore. Columbine was seated upon a rock, while Tom lay at her feet, idly tossing pebbles into a pool left among the sea-weed by the ebbing tide. The maiden wore that day a dress of gray flannel, almost the color of the stone upon which she sat, trimmed with a velvet of orange which no complexion less brilliant than hers could have endured. She twisted in her fingers a spray of goldenrod, yellow-coated harbinger of autumn.

“The summer is gone,” Columbine remarked, pensively. “It is getting late even for goldenrod.”

“Yes,” he echoed, “the summer is gone. I lost so much of it I hardly realize—”

He broke off suddenly, a new thought seizing him.

“Why!” he exclaimed, “how long I have been here! I ought to have taken myself off your hands long ago. How you must think I abuse your hospitality!”

“Nonsense!” she returned, brightly; “you of course cannot go until you are well. It is necessary that you at least conjure from the past the rest of your name before you start out into the world again. Make yourself as comfortable as you can, Mr. Tom; you won’t be let loose for a long time to come yet.”

Despite the lightness of her manner her companion fancied he detected a shade of some hitherto unnoted feeling in her words; but whether dread of his departure or desire to be rid of him he could not divine. The latter thought struck him with a sudden chill. The love which had been fostered in his mind by this close and intimate companionship was not unmixed at this moment with a fear of being thrown upon his own resources while ignorant alike of his place and his name. He clung strongly to Columbine as to one who understood and sympathized with his strange[34] mental weakness. The color flamed into his pale cheeks with a sudden throb of intense emotion; then faded, to leave him whiter than ever.

“Besides,” Columbine continued, after a moment’s pause, her glance still downcast, “why shouldn’t you stay? Your being here makes no difference to papa; he smokes and grubs after the roots of his ancestral tree the same as ever; and as for me,” lifting her eyes with a sudden smile that showed all her dimples, “you know how much you amuse me. You are as good as a continued story, and are alive, too, the last being a good deal in this desert.”

He returned her smile with effort. His moment of intense feeling had so overpowered him that he felt weak and faint.

“How white you are!” she exclaimed, noting the wanness of his face; “you should have had your bouillon long ago. A pretty condition you are in to go roaming off by yourself!”

She tripped lightly off towards the house for the forgotten nourishment, and Mr. Tom was left to his reflections. He raised himself, as her graceful figure vanished, then sank back upon his rug with something like a groan. All in an instant the knowledge had[35] come to him that he loved her. He had gone on from day to day conscious only of thinking of his own history, which, bit by bit, he was disinterring from the past, as men bring to light some buried city, and insensibly Columbine had become dear to him before he was aware.

He buried his face in his hands in a despair which was in part the result of his strange mental confusion; in part arose from his physical weakness. He did not reflect then that his case was not necessarily hopeless; that nothing in his life which remembrance had recovered need raise a barrier between himself and Columbine. Afterward this thought came to him and brought comfort; now he was overwhelmed by a sense of impotent misery. Helpless in the hand of fate, it seemed to him that this love, of which he was newly aware, was but a fresh device of malignant destiny. He did not even consider whether his affection might be returned; he only felt the impossibility of offering his broken life to Columbine,—of binding her to a past that was uncertain and a future that was insecure.

Tears of weakness, and scorn of that weakness, came into his eyes. Their traces were still visible when Columbine returned.

“Come,” she said, ignoring the signs of[36] his agitation, “you have told me nothing on the story to-day. Just down there,” indicating by a pretty sweep of the hand a little pebbly cove lying just below them, “is where Sarah and I found you.”

“And I would to God,” cried poor Tom with sudden fierceness, “that you had left me there.”

Columbine made, for the moment, no reply to this outburst. She insisted upon his drinking his bouillon, despite his protests of disinclination, and then brought him back to the tale of his life.

“There is an air of improbability about my story,” he said, after a little musing. “Indeed, so much so that I myself begin to doubt the truth of it. In the first place it seems particularly arranged to baffle inquiry. Whenever I recall a person to whom I might send for verification or information, I straightway remember that he is dead, or that my wanderings have carried me beyond his knowledge. I am apparently as far as ever from knowing who I am or what I am. And, besides, suppose your beautiful theory, that my memory acts as it does because the impressions of youth are strongest, is not true? You put me in the same category with those whose memory is weakened by age; but this[37] may be all moonshine. Perhaps this history, to which I am painfully adding every day, is something I have read, and only a fiction after all.”

“But why suppose so many tormenting things?” returned Columbine, brightly. “The fault of the age, they say,—we know very little of it here, but cousin Tom sends me a paper occasionally,—is unrest; and whoever you are, a little tranquillity will scarcely be likely to harm you. Go on with the life and adventures, and never mind now whether they are true or not. At least they are interesting. You broke off yesterday in a most exciting account of a tiger hunt.”

“Ah, yes; I got the rest of it together this morning. Where did I leave off? Had we reached the second jungle?”

The salt meadows were on fire. The pungent odor of burning peat and saline grasses floated over the Dysart place and about the arbor one October morning when Tom sat there meditating. He was thinking of Columbine, and of his passion for her. His health now seemed firmly re-establishing itself, and his memory had gone on over the[38] old track of his life in its singular method of progression until he felt confident that he should ultimately be in possession of all his past. He reviewed what he remembered, as he sat this morning inhaling the aromatic scent of the burning lowlands, and the result was not unsatisfactory. He had recovered from oblivion his life up to the time, three years before, when he took passage home from India, and his financial affairs at that period were in an eminently satisfactory position. He recalled that he had been regarded on shipboard as a person of more consequence than the British officer who, with his daughter, occupied the cabin of the Indiaman with him; and he trusted that no untoward circumstances of the interval had placed him in a condition less desirable.

He had reconciled himself to remaining at the Dysart mansion by turning over to old Sarah a goodly portion of the money contained in his travelling-belt, and blessed himself that his wandering life had led him to form the habit of always going thus provided. He sat now waiting for Columbine to appear, and fondly picturing to himself the delight of telling his love when the time came that he dare speak. Each day increased his attachment, and he believed, as every lover will,[39] that his love was returned. A smile of brooding contentment, so deep that even the impatience of his passion could not disturb it, dwelt upon his face as he inhaled the fragrant odors from the burning marshes, and listened for the step of the maiden he loved.

She came at last, moving along the garden paths between the faded shrubs, a gracious and winning figure. She was dressed that morning in a gown of russet wool, with a bunch of gold and crimson leaves at her throat, and never, in Tom’s eyes, had she looked so lovely.

“I shouldn’t have been so late in getting here,” she said, as she took her accustomed seat, “but Sarah is greatly concerned about the fire in the salt marshes. She says it is thirty years since they burnt over, and she presages all sorts of dire calamities from that fact.”

“That they haven’t burnt over for thirty years?”

“Well,” Columbine returned with a pout, “she is not at all clear what she does mean, so it isn’t to be expected that I shall be. We will go on with the life and adventures, if you please.”

“But suppose I haven’t remembered anything more?”

“Nonsense,” retorted pretty Columbine; “you never really remember. I am convinced that you make it all up as you go along; but you tell it so seriously that it might as well be true. And in any case it does credit to your powers of imagination.”

His story now was of his voyage from Calcutta. He told of moonlight nights in the Indian ocean, of long days of sunny idling on deck, and all the pleasant details of a prosperous voyage over Southern seas.

“Miss Grant wasn’t very pretty,” he observed, lying lazily back and looking up into the blue October sky, “at least not as I remember her; but she was very good company, only a little given to sentimentalizing. She had a guitar, and I will confess I did hate to see that guitar come out.”

“She would be pleased if she could hear you,” laughed Columbine. “What was there so frightful about her guitar?”

“Oh, when she had that she always sang moony songs, and after that—”

“Well?” demanded Miss Dysart, mischievously.

“Oh, after that,” he returned, with an impatient shake of his shoulders, “she was sure to talk sentiment.”

His companion laughed merrily. The[41] faint, almost unconscious feeling of jealousy which had risen at the mention of this engaging young lady had vanished entirely in the indifference with which Mr. Tom spoke of her. She moved her head with a happy little motion not unlike that with which a bird plumes itself. Her soft, low laugh did not really end, but lost itself among the dimples of her cheeks.

Tom regarded her with shining eyes.

“Not that I should mind some people’s talking sentiment,” he said with a smile.

She raised her laughing gaze to his, and, as their eyes met, the meaning of the look in his was too plain to be mistaken. She flushed and paled, dropping her gaze from his.

“And did nothing especial happen on the voyage?” she asked, with a strong effort to regain her careless manner.

“Not that I recall,” he answered, putting his hand beside hers upon the rustic table so that their fingers almost touched.

A moment of silence followed, broken only by the chirping of a few belated crickets, that, despite the advancement of the season, had not yet discontinued their autumnal concerts. The two, so quiet outwardly, sat with beating hearts, when suddenly a wandering[42] breeze brought into the summer-house a puff of smoke from the burning salt meadows. It was laden with the fetid odor of consuming animal matter, and so powerful was it that both involuntarily turned away their heads.

“Bah!” Columbine cried. “How horrible! There must be a dead animal of some sort there that the fire has reached.”

She stopped speaking and gazed with surprise at Tom, who had buried his face in his hands with a groan.

“What is it? Has it made you ill? It is gone now.”

He lifted a face white with emotion.

“No,” he said, “it has not made me ill,—physically, that is; but it has done worse, it has made me remember.”

“Ah!” she exclaimed. “What is it? is it so terrible?”

She leaned toward him, and to poor Tom she looked the incarnation of enticing loveliness. Sympathy and interest—not unmixed, she being a woman, with curiosity—sparkled in her eyes, yet he nerved himself to tell her all that had come back to him.

“That smell of burning hide,” he began, “brought it all up in a flash. The ship got on fire; Miss Grant clung to me; there was just such an odor leaking out around the[43] hatches from the hold where the flames were at the cargo; she—I—when everything else was right, when the fire was out, I was all wrong.”

“I do not understand,” Columbine said.

She drew away from him, her cheeks pale, her very lips wan. She did not meet his gaze, but sat with downcast eyes.

“I was engaged to Miss Grant. I did not pretend to love her, but I thought we were all bound for the bottom, and”—

He stopped helplessly; her eyes flashed upon him.

“And if a lie would soothe her last moments,” she said, bitterly, “you— No, no; I beg your pardon.”

“I remember more,” he went on, wrenching each word out as if by a strong effort of will. “The shock, and, perhaps, previous seeds of disease, were too much for her father; he died the day before we landed. She was alone in the world, she had no protector, and I—I married her at once, to protect her.”

A sparrow flew up into the lattice outside the arbor without noticing the pair within, so dead was the stillness which now fell upon them. At length Columbine rose and stood an instant by the table which had been between[44] them. She wavered an instant, then stooped and kissed him upon the forehead. Then without a word she turned from the arbor and fled swiftly to the house.

Left alone in the summer-house Tom’s first feeling was a great throb of joy; but it gave place almost instantly to an aching pang of misery. To be assured of Columbine’s love would have been intense happiness an hour before; now it could only add to his pain. He raged against the toils in which fate had entangled him, yet defiance to helplessness and every paroxysm of rage at destiny ended in a new and humiliating consciousness of his own impotence. He felt like one who walked blindfolded, with light granted him, not to avoid missteps, but merely to see them after they were taken.

One thing at least was clear to Tom,—that he must leave the Dysart mansion. To go on seeing Columbine day after day, with the knowledge at once of their love and of the barrier that stood between them, was a position too painful and too anomalous to be endured. Both for his own sake and for Miss[45] Dysart’s it was necessary that he delay no longer. Where he was going he was not at all clear; that he left to circumstances to decide. He quitted the arbor and walked toward the house, so intent upon his painful thoughts that at a turning of the path he ran plump against old Sarah, who was hurrying along with a face full of anxiety.

“Oh, mercy gracious, Mr. Thomas!” the faithful creature cried; “I’m sure I beg your pardon! But you look as if you’d seen a ghost!”

“So I have,” he answered. “Where are you going with that spade?”

“To the salt meadows,” she answered. “The fire’s sure to come into the lower garden if we don’t ditch it, and if it does, there’ll be no stopping it from the house.”

“What!” exclaimed Tom. “Where are the men?”

“There ain’t no men,” old Sarah returned, philosophically. “Why should there be?”

“But you are not going down to ditch alone?”

“’D I be likely to stop in-doors and let the house where I’ve lived fifty years burn over my head?” demanded she, grimly.

“Give me the spade,” was his reply. “A little work will do me good.”

Old Sarah remonstrated, but it ended in the strangely matched pair going together to the meadows below.

The dry sphagnum was readily cut through with the spade, and it was not a difficult, although a slow task, to dig a wide, shallow trench between the stretch of burning moss and the gardens. Once the ditch was complete, it would be easy to fight the fire on the home side, since there was nothing swift or fierce about the conflagration, it being rather a sullen, relentless smouldering of the moss and grass-roots, dry from the long drought.

Zealously as the two labored, the fire gained upon them, and as they worked, they could not but cast despairing glances at the long stretch of garden which lay still unprotected.

Meanwhile Columbine from her window had seen the laborers, and, in a moment realizing the danger, she flew to the library.

“Father,” she cried, “the salt marshes have been burning all day, and the fire is almost up to the garden.”

“Good heavens, Columbine, how impetuous you are! You have quite driven out of my head what became of the second son of—”

“But, father,” she interrupted, impatiently, “do you realize that if you sit here pothering[47] about second sons the house may be burned over our heads?”

“Burned!” exclaimed the genealogist, in dismay; “and all my papers scattered about! Oh, help me, Columbine, to pack up my notes; but don’t take up anything without asking me where it goes. Do you think that iron-bound trunk will hold them all?”

Fearing to trust herself to reply, Columbine darted from the library, leaving her father to the half-frenzied collection of his papers, and betook herself to the salt meadows, where, grimed with smoke, Tom and the old serving woman were sturdily laboring. The pungent smoke eddied about them, and already old Sarah’s gown showed marks of having been on fire in a dozen places. Columbine stood upon the descending path a moment and regarded them; then, with a step which bespoke determination, she went on and joined them.

“Go back!” shouted Tom, hoarsely, as she approached; “don’t you see how the sparks are flying about? You’ll be a-fire before you know it.”

And, indeed, the fire was becoming more active as it crept nearer to the edges of the meadows, where the grass was taller. The word of warning had hardly left Tom’s lips[48] before she found her dress burning, and while, being of wool, it was easily extinguished, Tom found in it an excuse for taking her in his arms to smother the flame.

“Go back to the house,” he said, in a voice which was full of feeling, yet which it would have been impossible to disobey. “We shall save the place; but I cannot work while you are in danger.”

“And you?” she demanded, clasping her hands upon his arm.

“Nonsense! there is no danger for me,” he returned, smiling tenderly. “Don’t think of me.”

It was not until late in the night that the contest against the fire was concluded. Tom worked with an energy in which desperation had a large place, while old Sarah, with the pathetic fidelity of an animal, labored by his side, indefatigable and unmurmuring. Faint streaks of light had begun to show in the east when Tom flung down the spade, upon which he had been leaning, for a last close scrutiny.

“It is all right now,” he said; “there can’t possibly be any fire left on this side of the marshes. It was lucky for us that the tide rose into the lower part of the trench.”

Undemonstratively, as she had worked, old[49] Sarah gathered herself together, grimy, stooping, quivering with weariness and hunger, and crept back to the house they had saved; while Tom, with tired step, climbed the path and took his way past the summer-house toward the other side of the mansion. As he passed the arbor something stirred within.

“Columbine!” he said, in surprise, recognizing by some instinct that it was she. “Why, Columbine, what are you here for? You will be chilled to death.”

“You sent me away,” returned the girl, with a trace of dogged protest in her voice. “You wouldn’t let me help.”

“I should hope not,” laughed Tom, nervously, taking off his hat and passing his hand through his hair, from which odors of smoke flowed as he stirred it. “You were hardly made to fight fire.”

“No,” she answered, with sudden and significant vehemence, “I was not made to fight fire.”

He moved uneasily where he stood in the darkness; then he took a stride forward and sat down beside her. They were silent a moment, his eyes fixed upon the first far sign of dawn, while hers searched the gloom for his features.

“Columbine,” he began, at length, in a[50] voice of strange softness, “it would have been better for us both if I had never come here.”

“No, no,” was her eager reply; “I cannot have you say that. You have put savor into my life that was so vapid before.”

“But a bitter savor,” he said.

“Bitter, yes,” Columbine returned in a voice which, though low and restrained, betrayed the fierceness of her excitement. “Bitter as death; but sweet too, sweet as—”

She left the sentence unfinished. Below on the shore the full tide was lapping the stones with monotonous melody. Save for their iterance, the stillness was almost as deep as the marvellous silence of a winter night which no sound of living thing breaks.

“Whatever comes,” Columbine murmured a moment later, her voice changed and softened so that he had to bend to catch her words, “I am glad of all that has happened; glad of you; glad, always glad.”

He caught her passionately in his arms and covered her downcast head with kisses, while she yielded unresistingly to his embrace, although she sobbed as if her heart would break. In the east the promise of the dawn shone steadily, increasing slowly but surely. It became at last so strong that Columbine, opening her swollen lids, was[51] able to distinguish objects a little. At that moment she became conscious that the arms of her lover had loosened their hold upon her. She looked into his face with sudden alarm. Mr. Tom had fallen into a dead faint.

The afternoon sun was shining into Tom’s chamber windows when he awoke. Ten hours of heavy sleep had had a wonderfully revigorating effect upon him, and despite some stiffness he awoke with a sense of renewed power. His repose had, too, a far more remarkable effect than this. Before his eyes were open he said aloud, as if he were solemnly summoning some culprit before the bar of an awful tribunal:—

“Thomas Wainwright!”

The sound of his own words acted upon him like an electric shock. He started up in bed, wide awake, his eyes shining, his whole manner alert, joyous, and confident. He was nameless no longer. Treacherous memory had yielded up its tenaciously kept secret, and at last he emerged from the shadowy company of the nameless to be again a man among men.

He sprang from his couch and made his toilet with impatient eagerness. As he dressed he remembered everything in an instant. That baffling mystery of his family name seemed the key to all the secrets of his past, and, having yielded up this prime fact, his memory made no further resistance. His whole life lay before him, no longer laboriously traced out, bit by bit, but unrolled as a map, visible at a single coup d’œil.

Little that he recalled was of a nature to change the conclusions he had formed of his circumstances, except the single fact that his wife had not outlived her honeymoon. The shock of her father’s death, and, perhaps, some seeds of malaria contracted in India, had proved too much for her delicate constitution, and Tom, eagerly reviewing his newly recovered past, felt a pang of unselfish sorrow for the unloved bride who had for so short a time borne his name, that name which he now kept saying over to himself, as if he feared he might again forget it.

He hurried downstairs, and in the old-fashioned hall, stately with its wainscoting and antique carved furniture, he met Columbine coming towards him. Like his, her eyes shone with a new light, her lips were parted with excitement, and her step was eager.

“Good-morning, Mr. Wainwright,” she fluted in a voice high with excitement and joyousness. “I heard your step, and could not wait for you to get to the parlor.”

“Good heavens!” cried he, stopping short in amazement. “How did you know? Are you a witch?”

“No,” she laughed, pleasure and excitement mingling rather dangerously in her mood. “Nothing of the sort, I assure you; though one of my ancestors was tried for witchcraft at Salem. Cousin Tom sent me this advertisement, and I knew at once that it must be you.”

The advertisement she showed him was cut from a New York paper, and called, with a detailed description of the personal appearance of the missing man, for tidings of one Thomas Wainwright, of Baltimore, supposed to have perished in the wreck of the Sound steamer, and whose large estate was unsettled. Tom read it over with mingled feelings.

“Bah!” he said. “When I get home I shall only have to look over a file of the daily papers to read my obituary. Fortunately I have been back from India so few years that they cannot say a great deal about me.”

“De mortuis,” returned Columbine, smiling. “They will only say good of you. I congratulate you on having found your name.”

“I had it before you told me,” he said.

He took her hands in his and looked at her tenderly.

“I have all my past, too,” he went on. “I am free; I have nothing to hide; nothing stands between us. Will you be my wife, Columbine?”

She grew pale as ashes; then flushed celestial red; but her eyes did not flinch.

“I trust you utterly,” she answered him. “And I love you no less.”

[Scene:—A balcony opening by a wide, curtained window from a ball-room in which a masquerade is in progress. Two maskers, the lady dressed as a peasant girl of Britany and her companion as a brigand, come out. The curtains fall behind them so that they are hidden from those within.]

He. You waltz divinely, mademoiselle.

She. Thank you. So I have been told before, but I find that it depends entirely upon my partner.

He. You flatter me. Will you sit down?

She. Thank you. How glad one is when a ball is over. It is almost worth enduring it all, just to experience the relief of getting through with it.

He. What a world-weary sentiment for one so young and doubtless so fair.

She. Oh, everybody is young in a mask, and by benefit of the same doubt, I suppose, everybody is fair as well.

He. It were easy in the present case to settle all doubts by dropping the mask.

She. No, thank you. The doubt does not trouble me, so why should I take pains to dispel it? Say I am five hundred; I feel it.

He. What indifference; and in one who waltzes so well, too. Will you not give me another turn?

She. Pardon me. I am tired.

He. And you can resist music with such a sound of the sea in it?

She. It is not melancholy enough for the sea.

He. Is the sea so solemn to you, then?

She. Inexpressibly. It is just that—solemn. It is too sad for anger, and too great and grave for repining; it is as awful as fate.

He. I confess it never struck me so.

She. It did not me always. It was while I was in Britany—where I got this peasant dress; isn’t it quaint?—that I learned to know the sea. It judged me; it reiterated one burden over and over until it seemed to me that I should go mad; yet at the same time its calmness gave me self-control. If there had been the slightest trace of anger or relenting in its accusations, I could have turned away easily enough, and shaken its influence all off. But it was like an awful tribunal before which I had to stand silent, and review my past as interpreted by inexorable justice,—with no palliations, no shams, nothing but honest truth. But why should I say all this rigmarole to you? You must be amused,—if you are not too much bored, that is.

He. On the contrary, I thank you very much.

She. For what?

He. First, for your confidence in me; and second, for telling me an experience so like my own.[59] It was not the sea, but circumstances that delivered me over to myself,—a long, slow convalescence, in which I, too, had an interview with the Nemesis of truth, and found a carefully built structure of shams and self-deception go down as mist before the sun. The most frightful being in the world to encounter is one’s estranged better self.

She. That is true. No one but myself could have persuaded me that it was I who was to blame. The more I was argued with, the more I believed myself a martyr, and my husband—

He. Your husband?

She. I have betrayed myself. I am not mademoiselle, but madame.

He. But I see no—

She. No ring? True; I returned that to my husband before I went to Britany.

He. And in Britany?

She. In Britany I would have given the world to have it back again.

He. But your husband? Did he accept it so easily?

She. What else can a man do when his wife casts him off?

He. Do? Oh, it is considered proper in such cases, I believe, for him to make a violent pretence of not accepting his freedom.

She. You seem to be sure he considered it freedom!

He. Pardon me. I forgot for the moment that you were his wife.

She. Compliments do not please me.

He. Then you are not a woman.

She. Will you be serious?

He. Why should I be—at a ball?

She. Because I choose.

He. Oh, good and sufficient reason!

She. But tell me soberly,—you are a man,—what could my husband have done?

He. Do you mean to make my ideas standards by which to try him?

She. Perhaps yes; perhaps no. At least tell me what you think.

He. A man need not accept a dismissal too easily.

She. But what then?

He. He might have followed; he might have argued. It is scarcely possible that you alone were to blame. Was there nothing in which he might have acknowledged himself wrong,—nothing with which he should reproach himself?

She. How can I tell what took place in his heart? I only know my own. He may have repented somewhat, or he may not. As for following— You do not know my husband. He is just, just, just. It was his one fault, I thought then. It took time for me to appreciate the worth of such a virtue.

He. But what has that to do with following you?

She. ‘She has chosen,’ he would reason. ‘Let the event punish her; it is only right that she should suffer for her own act.’

He. But is his justice never tempered by mercy?

She. The highest mercy is to be just. To palliate is merely to postpone sentence.

He. You are the first woman I ever met who would acknowledge that.

She. Few women, I hope, have been taught by an experience so hard as mine. But how dolefully we are talking. Do say something amusing; we are at a ball.

He. I might give you an epigram for the one with which you served me a moment ago, and retort that to be amusing is to be insincere.

She. Then—for we came to be amused—why are we here?

He. Manifestly because we prize insincerity.

She. You are right. I came to get away from myself. One must do something, and even the dissipations of charity pall after a time.

He. We seem to be in much the same frame of mind, and perhaps cannot do better than to stay where we are, consorting darkly, while the others take pains to amuse themselves. So we get through the evening, that is the main thing.

She. You have forgotten to be as complimentary as you were half an hour since.

He. Have I? And yet the greatest compliment a man can pay a woman is sincerity.

She. If he does not love her, yes.

He. Ah, then you agree with Tom Moore:

She. Perhaps; but it is no matter, since we were not talking of love.

He. But if we were?

She. If we were we should undoubtedly say a great many foolish things and quite as many false ones.

He. You are cynical.

She. Oh, no. Cynicism is like a cravat, very becoming to a man if properly worn, but always setting ill upon a lady.

He. Did you learn that, also, in Britany? It is a country of enlightenment. Would that my wife had gone there.

She. Or her husband!

He. You are keen. Her husband learned bitter truths enough by staying at home. I am evidently your complement; for I had a wedding-ring sent back to me.

She. And why?

He. Why? Why? Who ever knows a woman’s reason! Because I refused, perhaps, to call black white, to say I was pleased by what made me angry; because— No; on the whole, since I am not making love to her, it is hardly worth while to lie to a peasant from Britany, though it is of course[63] necessary to sustain the social fictions with people nearer home. It was because the wedding-ring was a fetter that constrained my wife, body and soul; because I was as inflexible as steel. My purposes, my views, my beliefs were the Procrustean bed upon which every act of hers was measured. Voila tout!

She. I understand, I think.

He. Oh, I have learned well enough where the blame lay in the three years since she left me.

She. Three years!

He. Why do you start?

She. It is three years, too, since I—

He. Who are you?

She. It is no matter; my husband is far from here.

He. That is more than I can say of my wife.

She. Where is she, then?

He. Heaven knows; not I. But let that go. Why may we not be useful to each other? Our cases are similar; we are both lonely.

She. And strangers.

He. Acquaintance is not a matter of time, but of temperament. Should we have found it possible to be so frank with one another had we been merely strangers?

She. You are specious.

He. No; only honest.

She. But what—

He. What? Why, friendship. We have found[64] it possible to be frank in masks; why not out of them?

She. Then you propose a platonic friendship?

He. I want a woman who will be my friend, to whom I can talk freely. There are words a man has no power or wish to say to a man, yet which must be spoken or they fester in his mind.

She. I am, then, to be a safety-valve.

He. Every man must have a woman as a lodestar; you are to be that to me.

She. And your wife?

He. My wife? She voluntarily abandoned me. I haven’t seen her for three years; and surely she ought to cease to count by this time.

She. You are heartless.

He. Heartless?

She. You should be faithful to your lost—

He. Lost fiddlestick!

She. You are very rude!

He. I don’t see—

She. And very disagreeable.

He. But—

She. If you had really loved your wife, you’d always mourn for her, whatever she did.

He. Good Heavens! That is like a woman. A man is expected to bear anything, everything, and if at last he does not come weeping to kiss the hand that smites him, he is heartless, forsooth! Bah! I am not a whipped puppy, thank you.

She. Your love was, perhaps, never distinguished by meekness?

He. I’m afraid not.

She. It might be none the worst for that. The ideal man for whom I am looking will not be too lamblike, even in love.

He. You look for an ideal man, then?

She. As closely as did Diogenes.

He. And your husband?

She. Oh, like your wife, he should, perhaps, begin not to count.

He. Good. We are sworn friends, then, until you find your ideal man.

She. If you will.

He. Then unmask.

She. Is that in the bargain?

He. Of course. Else how should we know each other again?

She. But—

He. Unmask!

She. Very well,—when you do.

He. Now, then. [They unmask.]

She. Philip!

He. Agnes!

She. You knew all the time!

He. Who told you I was here?

She. I didn’t know it.

He. I thought you went to Russia.

She. Well, I didn’t. I hope you feel better! Good night.

He. Wait, Agnes. I—

[There is a moment’s silence, in which they look at each other intently. He takes her hand in both his.]

He. Agnes, I am not your ideal man, but—

She. Nor I your ideal woman, apparently. Your wife does not count, you say.

He. No more than your husband; so we are quits there.

She. It’s very horrid of you to remind me of that.

He. I acknowledge that I was always very horrid in everything.

She. Oh, if you acknowledge that, Phil, it is hardly worth while to spend any more time in explanations while this divine waltz is running to waste.

He. But you were tired and out of sorts.

She. You old goose, don’t you see that I’m neither!

He. And you do waltz divinely.

[They attempt to adjust their masks, but somehow get into each other’s arms. In a few moments more, however, they are seen among the dancers within.]

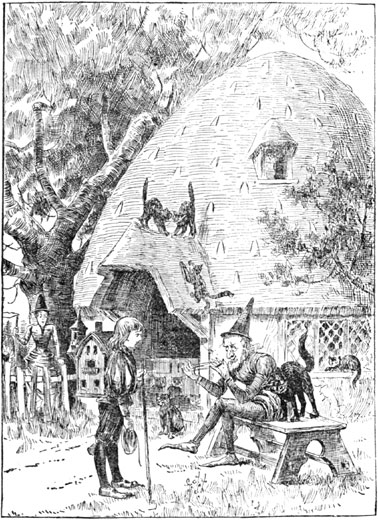

“I shall feel honored, Mistress Henshaw, if you will accept this posie as a token which may perchance serve to keep me in remembrance while I am over the sea.”

“I am extremely beholden to you,” replied the old dame addressed, her wrinkled face illuminated with a smile of pleasure. “But for keeping you in remembrance it needs not this posie or other token. I do not hold my friends so lightly.”

“I thank you for counting me one of your friends,” John Friendleton said frankly. “I have no kindlier memories of Boston than of the home under your roof.”

He had placed upon the many-legged table a flower-pot containing a thrifty tuberose, and with a kindly smile upon his handsome and winning face, he stood regarding the old dame into whose custody he had just given the plant. The dress of the period,—the days of the end of the seventeenth century,—plain[70] though it was, accorded well with the sturdy honesty and kindness of his face and the compact and strong build of his figure. The wrinkled crone returned his smile with one of frosty but genuine warmth.

“This plant is none the less pleasing to me,” she said, “though I by no means need it as a reminder. I shall be very careful in its nourishing.”

“It is by no means an ordinary herb,” Friendleton returned lightly. “There may be magic in it for aught I can tell. My uncle, who sent me the bulbs from even so far away as Spain, hath a shrewd name as a wise man; and to say sooth he belike doth know far more than altogether becometh a good Christian. I give you fair warning that there may be mischief in the herb; though to be sure,” he added laughing, “the earth in which it grows is consecrated, for I filled the pot from Copp’s Hill graveyard hard by here.”

A momentary gleam shot with a sinister light its fiery sparkle across the black eyes of Mistress Henshaw.

“To one who feareth no harm,” she answered, “it seldom haps. I trust the wind may hold fair for your sailing,” she added,[71] glancing from the small-paned window, “and that you may safely return to Boston as you are minded.”

“Thank you, I have hitherto been much favored by Providence in my journeyings. Farewell, Mistress Henshaw.”

The old dame received his adieu, and a moment later she watched from the window his active young figure as he walked briskly away. She regarded it intently until a corner hid him from sight. Then she turned back to her room and her occupations.

“Providence, indeed!” she muttered half aloud, with a world of contempt in her tone.

Then she turned to the thrifty, healthy tuberose and caressed its leaves with her thin old fingers as if it were alive and could understand her attentions.

The house in which this conversation took place was still standing a few years since, the oldest in Boston, at the corner of Moon and Sun Court streets. It was erected in 1669; its timber, tradition says, being cut in the neighborhood. The upper story projected over the lower like a frowning brow, from beneath which the windows shone at night like the glowing eye-balls of a wild beast. It was a stout and almost warlike-looking edifice, which preserved even up to the[72] day when, in 1878, it was at length pulled down by the hand of progress, a certain strongly individual appearance, which if less marked at the time when John Friendleton bade Mistress Henshaw good-by, and the building was thirty years old, must always have distinguished the dwelling from those about it.

Dwellings, however, take much of their air from dwellers, and Mistress Henshaw was likely to impart to any house she inhabited a bearing unlike that of its neighbors. She was a dame to all appearances of some three score winters, each frosty season having left its snow upon her hair. Her figure was still erect, while her eyes were piercing and black and capable of a glance of such strength and directness as almost to seem supernatural.

It may have been from the power and fervor of this glance that Mistress Henshaw acquired the uncanny reputation which she enjoyed in Boston. As she moved with surprising energy about the house, overseeing and directing her dumb negro servant Dinah, the eyes of passers-by who saw her erect figure flit by the windows were half averted as if from some deadly thing which yet held them with a weird fascination; and at nightfall the children whom chance belated in the[73] neighborhood went skurrying past Dame Henshaw’s house like frightened hares.

It is not perhaps to be told why Satan should have been able to establish his kingdom among a people so devout and pious as the godly inhabitants of the Massachusetts colony; yet we have it upon the testimony of no less a man than the sage and reverend Cotton Mather, whose sepulchre is with us unto this day, and upon the word of many another scarcely less wise and devout, that the Father of Evil did establish a peculiar and covenant people of his own in the midst of the very elect of New England. It may be that it is always as it was in the days of Job, and that the sons of God never assemble without finding in their midst the dark form of Lucifer; for certain it is that the devil, to quote the Rev. Cotton Mather’s own words, “broke in upon the country after as astonishing a manner as was ever heard of.”

“Flashy people,” quaintly and solemnly remarks the learned divine, “may burlesque these things, but when hundreds of the most sober people in a country where they have as much mother-wit certainly as the rest of mankind, know them to be true, nothing but the absurd and forward spirit of Sadducism can question them.” From all of which,[74] and from much more which might be cited, it is evident that there was plenty of witchcraft abroad in those days, whether Mistress Henshaw was concerned therein or not.

It is sufficient to note that certain gossips scrupled not to declare that Dame Henshaw was one of the accursed who bore the mark of the beast and kept tryst at the orgies of the witches’ sabbath, and the report once started the facts in the case made little difference. Some of her neighbors went so far as to declare that if the dame’s residence were forcibly changed from Sun Court street to Prison lane, the community would be the better off.

Governor Belamont, however, in this last year of the century, was far more exercised about pirates than concerning witches; and better pleased at the capture of Captain Kidd, who had just fallen into his hands, than if he had discovered all the wise women in the colonies. Public feeling, moreover, was still in a reactionary state from the horrors of the Salem delusion of 1692; and thus it came about that Mistress Henshaw was left unmolested.

The second person in the dialogue given above, John Friendleton, was an Englishman, and, if tradition be true, the son of an old[75] lover of Mistress Henshaw. He had taken up his abode with that lady upon his arrival in the New World, whither he had been led, like many another stout young blade of his day, by the hope of finding fair fortunes in the growing colonies, and from the first he had been a favorite with the old lady. It was whispered over certain of those tea-cups which we now tenderly cherish from a respect for the memory of very great grandmothers and an æsthetic enjoyment of the beauties of old china, that it was by the aid of unhallowed power exercised in his behalf that the young man was always so fortunate in his undertakings. There were sinister tales of singular coincidences which had worked for his good, and behind which the gossips believed to lie the instigating will of his powerful landlady. Whether he himself was aware of this supernatural aid, opinion was divided, but he was so frank and handsome withal that the weight of opinion leaned toward acquitting him. The habit of New England thought, moreover, was so opposed to imagining a witch as exercising her power for anything but evil, that these rumors after all gained no great or general credence.

The friendship between the dame and her lodger was perhaps based upon mutual need.[76] The young man gave her that full confidence which a pure-minded youth enjoys bestowing upon an elderly female friend; while in turn the childless old lady, alone and otherwise friendless, regarded him with tender affection. She cherished any chance token from him, and especially did she seem touched by this gift of a tuberose which he had given her at parting. She knew how carefully he had tended and cherished the plant, more rare then than now, and long after the sails of the ship which conveyed him to England, whither he had been summoned by the serious illness of a relative, had dipped under the horizon, the old witch—if witch she were—sat regarding the flower with eyes in which the tears glistened.

It was early springtime when John Friendleton once more caught sight of the beacon upon Trimountain, and the walls of the fort standing upon a hill which has itself been removed by the enterprise of Boston. The few months of the young man’s absence, and the progress of time from one century to another—for it was now 1700—had brought no[77] great changes to the town; but to him it seemed far from being the same he had left.

The first tidings he had received from Boston, after landing in England, had been a letter telling of the death of Mistress Henshaw. She had set out from Boston, so the letter informed him, to visit a sister living somewhere in the wilds toward far Pemaquid, and had never returned. The letter was written by one Rose Dalton, who claimed to be a niece of the deceased, and who had come into possession of the small property of Mistress Henshaw by virtue of a will made before the adventurous and fatal journey. The writer added to her letter the information that she should live on with dumb Dinah, holding as nearly as possible to the fashion of her aunt’s housekeeping.

When John stood once more upon the well-remembered threshold, he felt half disposed to turn away and enter no more a place in which every familiar sight could but call up sad memories. Then, endeavoring to shake off his melancholy, he knocked.

A light, brisk step approached from within, and the door opened quickly.

John stood in amazement, unable to utter a word, so bewildered was he by the beauty of the maiden who stood before him; a[78] beauty which now, after nearly two centuries, is still a tradition of marvel. Something unreal and almost supernatural there might seem in the wonderful loveliness of this exquisite creature, were it not that she seemed so to overflow with life and vitality. Her soft and dove like eyes were full of gleams of human energy, of joy, of passion; she had all the beauty of a perfect dream without its unreality; and then and there the young Englishman’s heart fell down and worshipped her, never after to swerve from its allegiance.

“You must be Mr. Friendleton,” the maiden said, courtesying bewitchingly. “I knew your ship was in.”

“I—I have been minding my luggage,” he stammered, rather irrelevantly, his eyes fastened upon her face.

“Be pleased to enter,” said she, smiling a little at the boldness and unconsciousness of his stare. “Your room has been preserved as you left it at your departure. My aunt, good Mistress Henshaw, as I wrote you, straitly enjoined in her will that everything should be kept for you as you had left it. Her affections were marvellously set upon you.”

That he should be allowed to enter under[79] the same roof with this beautiful creature seemed to John Friendleton the height of bliss, and he had no words to express his delight when he learned that Mistress Rose expected him to take up his abode there as in former times. Her aunt had wished it; had especially spoken of it in her will, and so it was to be.

It would be impossible to pretend that Friendleton struggled much against this proposition, when inclination so strongly pleaded for the carrying out of the wishes of his dead friend; and in this way he became the lodger of young Mistress Rose.

It did not long escape the eye of the young man that his new landlady wore always at her throat a cluster of the white, waxy blossoms of the tuberose. The circumstance was in itself sufficiently curious and unusual to excite his attention, and it recalled to his mind the plant he had given to Mistress Henshaw. He wondered what had been the fate of his gift, and one day he ventured to ask Mistress Rose about it. For reply she led him to the room formerly occupied[80] by her aunt, and showed him the tuberose in a quaint pot. It had grown tall and thrifty, and half a dozen slim stalks upon it stood up stoutly, covered with buds, which showed here and there touches of dull red evolved in their transformation from green to white.

“I marvel how it hath increased,” John said.

“It hath thriven marvellously,” she replied. “Never before hath it been known that the plant would bloom throughout all the year, but this sends out buds continually. I daily wear a blossom, as you may see, and I find its odor wonderfully cheering, although for most it is too powerfully sweet.”

“It is an ornament which becometh you exceedingly well,” he responded, flushing.

“My neighbors,” returned she smiling, “regard it as exceeding frivolous.”

The fragrance of the flower which Mistress Rose wore at her throat floated about John wherever his daily occupations led him, and doubly did the delicious perfume steal through his dreams. He never thought of the maiden without feeling in the air that divinely sweet odor; and a thousand times he secretly compared her to the flower she wore. Nor was the comparison inapt; since her beauty was[81] rendered somewhat unearthly by the strange pallor of her face, while the intense and passionate intoxication it produced might, without great straining of the simile, be directly compared to the exaltation which the delicious and powerful fragrance produces in sensuous and sensitive natures.

The intimacy between the young people was at first hindered by the shyness of Friendleton, who was only too conscious of the fervor and depth of his passion; but as Rose had many of the well-remembered ways of her aunt, and, stranger yet, appeared well versed in his own past history, he soon became more at his ease. In defiance of the proverb which condemns all true lovers to uneven ways and obstructed paths, the wooing of lovely Mistress Rose by John Friendleton ran smoothly and happily on, seeming to have begun with the young man’s first meeting with his lovely landlady. The gossips of Boston town, strangely enough, left the relations of the lovers untouched by any but friendly comment; and in a fashion as natural as the ripening of the year, their love ripened into completeness.