CHARLES I. IN PRISON

Photogravure after De La Roche

CHARLES I. IN PRISON

Photogravure after De La Roche

| Charles I. in Prison | Frontispiece | ||

| Photogravure after De La Roche. | |||

| Lord William Russell Taking Leave of His Children, 1683 | 180 | ||

| Photogravure after a painting by Bridges. | |||

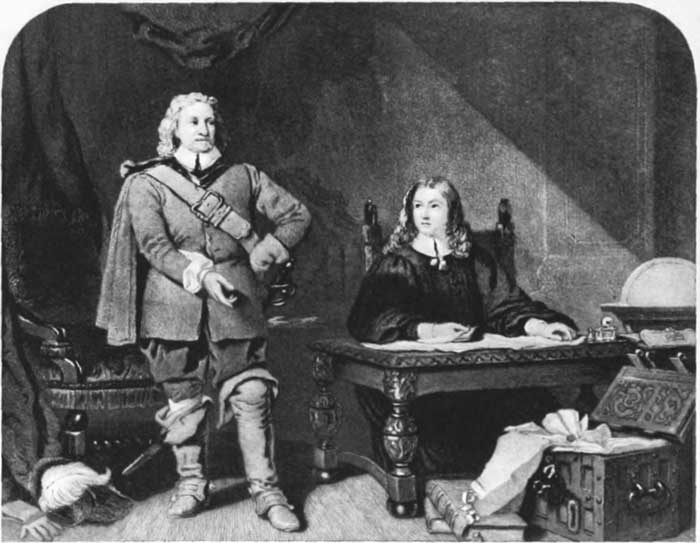

| Oliver Cromwell Dictating to John Milton | 284 | ||

|

The letter to the Duke of Savoy to stop the persecution of the Protestants of Piedmont, 1655. Photogravure from an engraving by Sartain after Newenham. |

|||

| The Duke of Buckingham | Frontispiece | ||

| From an old painting. | |||

| Nell Gwynne | 64 | ||

| Photogravure after Sir Peter Lely. | |||

The two chief diarists of the age of Charles the Second are, mutatis mutandis, not ill characterized by the remark of a wicked wit upon the brothers Austin. "John Austin," it was said, "served God and died poor: Charles Austin served the devil, and died rich. Both were clever fellows. Charles was much the cleverer of the two." Thus John Evelyn and Samuel Pepys, the former a perfect model of decorum, the latter a grievous example of indecorum, have respectively left us diaries, of which the indecorous is to the decorous as a zoölogical garden is to a museum: while the disparity between the testamentary bequests of the two Austins but imperfectly represents the reputation standing to Pepys's account with posterity in comparison with that accruing to his sedate and dignified contemporary.

Museums, nevertheless, have their uses, and Evelyn's comparatively jejune record has laid us under no small obligation. But for Pepys's amazing indiscretion and garrulity, qualities of which one cannot have too little in life, or too much in the record of it, Evelyn would have been esteemed the first diarist of his age. Unable for want of these qualifications to draw any adequate picture of the stirring life around him, he has executed at least one portrait admirably, his own. The likeness is, moreover, valuable, as there is every reason to suppose it typical, and representative of a very important class of society, the well-bred and well-conducted section of the untitled aristocracy of England. We may well believe that these men were not only the salt but the substance of their order. There was an ill-bred section exclusively devoted to festivity and sport. There was an ill-conducted section, plunged into the dissipations of court life. But the majority were men like Evelyn: not, perhaps, equally refined by culture and travel, or equally interested in literary research and scientific experiment, but well informed and polite; no strangers to the Court, yet hardly[Pg x] to be called courtiers, and preferring country to town; loyal to Church and King but not fanatical or rancorous; as yet but slightly imbued with the principles of civil and religious liberty, yet adverse to carry the dogma of divine right further than the right of succession; fortunate in having survived all ideas of serfdom or vassalage, and in having few private interests not fairly reconcilable with the general good. Evelyn was made to be the spokesman of such a class, and, meaning to speak only for himself, he delivers its mind concerning the Commonwealth and the Restoration, the conduct of the later Stuart Kings and the Revolution.

Evelyn's Diary practically begins where many think he had no business to be diarising, beyond the seas. The position of a loyalist who solaces himself in Italy while his King is fighting for his crown certainly requires explanation: it may be sufficient apology for Evelyn that without the family estates he could be of no great service to the King, and that these, lying near London, were actually in the grasp of the Parliament. He was also but one of a large family and it was doubtless convenient that one member should be out of harm's way. His three years' absence (1643-6) has certainly proved advantageous to posterity. Evelyn is, indeed, a mere sight-seer, but this renders his tour a precise record of the objects which the sight-seer of the seventeenth century was expected to note, and a mirror not only of the taste but of the feeling of the time. There is no cult of anything, but there is curiosity about everything; there is no perception of the sentiment of a landscape, but real enjoyment of the landscape itself; antiquity is not unappreciated, but modern works impart more real pleasure. Of the philosophical reflections which afterward rose to the mind of Gibbon there is hardly a vestige, and of course Evelyn is at an immeasurable distance from Byron and De Staël. But he gives us exactly what we want, the actual attitude of a cultivated young Englishman in presence of classic and renaissance art with its background of Southern nature. We may register without undue self-complacency a great development of the modern world in the æsthetical region of the intellect, which implies many other kinds of progress. It is interesting to compare with Evelyn's nar[Pg xi]rative the chapters recording the visit to Italy supposed to have been made at this very period by John Inglesant, who inevitably sees with the eyes of the nineteenth century. Evelyn's casual remarks on foreign manners and institutions display good sense, without extraordinary insight; in description he is frequently observant and graphic, as in his account of the galley slaves, and of Venetian female costumes. He naturally regards Alpine scenery as "melancholy and troublesome."

Returned to England, Evelyn strictly follows the line of the average English country gentleman, execrating the execution of Charles I., disgusted beyond measure with the suppression of the Church of England service, but submissive to the powers that be until there are evident indications of a change, which he promotes in anything but a Quixotic spirit. Although he is sincerely attached to the monarchy, the condition of the Church is evidently a matter of greater concern to him: Cromwell would have done much to reconcile the royalists to his government, had it been possible for him to have restored the liturgy and episcopacy. The same lesson is to be derived from his demeanor during the reigns of Charles and James. The exultation with which the Restoration is at first hailed soon evaporates. The scandals of the Court are an offense, notwithstanding Evelyn's personal attachment to the King. But the chief point is not vice or favoritism or mismanagement, but alliances with Roman Catholic powers against Protestant nations. Evelyn is enraged to see Charles missing the part so clearly pointed out to him by Providence as the protector of the Protestant religion all over Europe. The conversion of the Duke of York is a fearful blow, James's ecclesiastical policy after his accession adds to Evelyn's discontent day by day, while political tyranny passes almost without remark. At last the old cavalier is glad to welcome the Prince of Orange as deliverer, and though he has no enthusiasm for William in his character as King, he remains his dutiful subject. Just because Evelyn was by no means an extraordinary person, he represents the plain straightforward sense of the English gentry. The questions of the seventeenth century were far more religious than political. The synthesis "Church and King" expressed the dearest convictions of the great[Pg xii] majority of English country families, but when the two became incompatible they left no doubt which held the first place in their hearts. They acted instinctively on the principle of the Persian lady who preferred her brother to her husband. It was not impossible to find a new King, but there was no alternative to the English Church.

Evelyn's memoirs thus possess a value far exceeding the modest measure of worth allowed them by De Quincey: "They are useful as now and then enabling one to fix the date of a particular event, but for little besides." The Diary's direct contribution to historical accuracy is insignificant; it is an index, not to chronological minutiæ, but to the general progress of moral and political improvement. The editor of 1857 certainly goes too far in asserting that "All that might have been excluded from the range of his opinions, his feelings and sympathies embraced"; but it is interesting to observe the gradual widening of Evelyn's sympathies with good men of all parties, and to find him in his latter days criticising the evidence produced in support of the Popish Plot on the one hand, and deploring the just condemnation of Algernon Sydney on the other. It is true that, so far as the sufferings of his country are concerned, his attitude is rather that of the Levite than of the Samaritan; but more lively popular sympathies would have destroyed the peculiar value attaching to the testimony of the reluctant witness. We should, for example, have thought little of such a passage as the following from the pen of Burnet, from Evelyn it is significant indeed:—

October 14, 1688.—The King's birthday. No guns from the Tower as usual. The sun eclipsed at its rising. This day signal for the victory of William the Conqueror against Harold, near Battel in Sussex. The wind, which had been hitherto west, was east all this day. Wonderful expectation of the Dutch fleet. Public prayers ordered to be read in the churches against invasion.

It might be difficult to produce a nearer approximation in secular literature to Daniel's "Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin."

There is little else in the Diary equally striking, though Evelyn's description of Whitehall on the eve of the death of Charles the Second ranks among the memorable passages of the language. It is nevertheless full of interesting anecdotes and curious notices, especially of the[Pg xiii] scientific research which, in default of any adequate public organization, was in that age more efficaciously promoted by students than by professors. De Quincey censures Evelyn for omitting to record the conversation of the men with whom he associated, but he does not consider that the Diary in its present shape is a digest of memoranda made long previously, and that time failed at one period and memory at the other. De Quincey, whose extreme acuteness was commonly evinced on the negative side of a question, saw the weak points of the Diary upon its first publication much more clearly than his contemporaries did, and was betrayed into illiberality by resentment at what he thought its undeserved vogue. Evelyn has in truth been fortunate; his record, which his contemporaries would have neglected, appeared (1818) just in time to be a precursor of the Anglican movement, a tendency evinced in a similar fashion by the vindication, no doubt mistaken, of the Caroline authorship of the "Icon Basilike." Evelyn was a welcome encounter to men of this cast of thought, and was hailed as a model of piety, culture, and urbanity, without sufficient consideration of his deficiencies as a loyalist and a patriot. It also conduced to his reputation that all his other writings should have virtually perished except his "Sylva," like his Diary a landmark in the history of improvement, though in a widely different department. But for his lack of diplomatic talent, he might be compared with an eminent and much applauded, but in our times somewhat decrescent, contemporary, Sir William Temple. Both these eminent persons would have aroused a warmer feeling in posterity, and have effected more for its instruction and entertainment, if they could occasionally have dashed their dignity with an infusion of the grotesqueness, we will not say of Pepys, but of Roger North. To them, however, their dignity was their character, and although we could have wished them a larger measure of geniality, we must feel indebted to them for their preservation of a refined social type.

Evelyn lived in the busy and important times of King Charles I., Oliver Cromwell, King Charles II., King James II., and King William, and early accustomed himself to note such things as occurred, which he thought worthy of remembrance. He was known to, and had much personal intercourse with, the Kings Charles II. and James II.; and he was in habits of great intimacy with many of the ministers of these two monarchs, and with many of the eminent men of those days, as well among the clergy as the laity. Foreigners distinguished for learning, or arts, who came to England, did not leave it without visiting him.

The following pages contribute extensive and important particulars of this eminent man. They show that he did not travel merely to count steeples, as he expresses himself in one of his Letters: they develop his private character as one of the most amiable kind. With a strong predilection for monarchy, with a personal attachment to Kings Charles II. and James II., formed when they resided at Paris, he was yet utterly averse to the arbitrary measures of these monarchs.

Strongly and steadily attached to the doctrine and practice of the Church of England, he yet felt the most liberal sentiments for those who differed from him in opinion. He lived in intimacy with men of all persuasions; nor did he think it necessary to break connection with anyone who had ever been induced to desert the Church of England, and embrace the doctrines of that of Rome. In writing to the brother of a gentleman thus circumstanced, in 1659, he expresses himself in this admirable manner: "For the rest, we must commit to Providence the success of times and mitigation of proselytical fervors; having for my own particular a very great charity for all who sincerely adore the Blessed Jesus, our common and dear Saviour, as being full of hope that God (however the present zeal of some, and the[Pg xvi] scandals taken by others at the instant [present] affliction of the Church of England may transport them) will at last compassionate our infirmities, clarify our judgments, and make abatement for our ignorances, superstructures, passions, and errors of corrupt times and interests, of which the Romish persuasion can no way acquit herself, whatever the present prosperity and secular polity may pretend. But God will make all things manifest in his own time, only let us possess ourselves in patience and charity. This will cover a multitude of imperfections."

He speaks with great moderation of the Roman Catholics in general, admitting that some of the laws enacted against them might be mitigated; but of the Jesuits he had the very worst opinion, considering them as a most dangerous Society, and the principal authors of the misfortunes which befell King James II., and of the horrible persecutions of the Protestants in France and Savoy.

He must have conducted himself with uncommon prudence and address, for he had personal friends in the Court of Cromwell, at the same time that he was corresponding with his father-in-law, Sir Richard Browne, the Ambassador of King Charles II. at Paris; and at the same period that he paid his court to the King, he maintained his intimacy with a disgraced minister.

In his travels, he made acquaintance not only with men eminent for learning, but with men ingenious in every art and profession.

His manners we may presume to have been most agreeable; for his company was sought by the greatest men, not merely by inviting him to their own tables, but by their repeated visits to him at his own house; and this was equally the case with regard to ladies, of many of whom he speaks in the highest style of admiration, affection, and respect. He was master of the French, Italian, and Spanish languages. That he had read a great deal is manifest; but at what time he found opportunities for study, it is not easy to say. He acknowledges himself to have been idle, while at Oxford; and, when on his travels, he had little time for reading, except when he stayed about nineteen weeks in France, and at Padua, where he was likewise stationary for several months. At Rome, he remained a considerable time,[Pg xvii] but, while there, he was so continually engaged in viewing the great variety of interesting objects to be seen in that city, that he could have found little leisure for reading. When resident in England, he was so much occupied in the business of his numerous offices, in paying visits, in receiving company at home, and in examining whatever was deemed worthy of curiosity, or of scientific observation, that it is astonishing how he found the opportunity to compose the numerous books which he published, and the much greater number of Papers, on almost every subject, which still remain in manuscript; to say nothing of the very extensive and voluminous correspondence which he appears to have carried on during his long life, with men of the greatest eminence in Church and State, and the most distinguished for learning, both Englishmen and foreigners. In this correspondence he does not seem to have made use of an amanuensis; and he has left transcripts in his own hand of great numbers of letters both received and sent. He observes, indeed, in one of these, that he seldom went to bed before twelve, or closed his eyes before one o'clock.

He was happy in a wife of congenial dispositions with his own, of an enlightened mind, who had read much, and was skilled in etching and painting, yet attentive to the domestic concerns of her household, and a most affectionate mother.

His grandfather, George, was not the first of the family who settled in Surrey. John, father of this George, was of Kingston, in 1520, and married a daughter of David Vincent, Esq., Lord of the Manor of Long Ditton, near Kingston, which afterward came in the hands of George, who there carried on the manufacture of gunpowder. He purchased very considerable estates in Surrey, and three of his sons became heads of three families, viz, Thomas, his eldest son, at Long Ditton; John, at Godstone, and Richard at Wotton. Each of these three families had the title of Baronet conferred on them at different times, viz, at Godstone, in 1660; Long Ditton, in 1683; and Wotton, in 1713.

The manufacture of gunpowder was carried on at Godstone as well as at Long Ditton; but it does not appear that there ever was any mill at Wotton, or that the purchase of that place was made with such a view.[Pg xviii]

It may be not altogether incurious to observe, that though Mr. Evelyn's father was a man of very considerable fortune, the first rudiments of this son's learning were acquired from the village schoolmaster over the porch of Wotton Church. Of his progress at another school, and at college, he himself speaks with great humility; nor did he add much to his stock of knowledge, while he resided in the Middle Temple, to which his father sent him, with the intention that he should apply to what he calls "an impolished study," which he says he never liked.

The "Biographia" does not notice his tour in France, Flanders, and Holland, in 1641, when he made a short campaign as a volunteer in an English regiment then in service in Flanders.1 Nor does it notice his having set out, with intent to join King Charles I. at Brentford; and subsequently desisting when the result of that battle became known, on the ground that his brother's as well as his own estates were so near London as to be fully in power of the Parliament, and that their continued adherence would have been certain ruin to themselves without any advantage to his Majesty. In this dangerous conjuncture he asked and obtained the King's leave to travel. Of these travels, and the observations he made therein, an ample account is given in this Diary.

The national troubles coming on before he had engaged in any settled plan for his future life, it appears that he had thoughts of living in the most private manner, and that, with his brother's permission, he had even begun to prepare a place for retirement at Wotton. Nor did he afterward wholly abandon his intention, if the plan of a college, which he sent to Mr. Boyle in 1659, was really formed on a serious idea. This scheme is given at length in the "Biographia," and in Dr. Hunter's edition of the "Sylva" in 1776; but it may be observed that he proposes it should not be more than twenty-five miles from London.

As to his answer to Sir George Mackenzie's panegyric on Solitude, in which Mr. Evelyn takes the opposite part[Pg xix] and urges the preference to which public employment and an active life is entitled,—it may be considered as the playful essay of one who, for the sake of argument, would controvert another's position, though in reality agreeing with his own opinion; if we think him serious in two letters to Mr. Abraham Cowley, dated 12th March and 24th August, 1666, in the former of which he writes: "You had reason to be astonished at the presumption, not to name it affront, that I, who have so highly celebrated recess, and envied it in others, should become an advocate for the enemy, which of all others it abhors and flies from. I conjure you to believe that I am still of the same mind, and that there is no person alive who does more honor and breathe after the life and repose you so happily cultivate and advance by your example; but, as those who praised dirt, a flea, and the gout, so have I public employment in that trifling Essay, and that in so weak a style compared with my antagonist's, as by that alone it will appear I neither was nor could be serious, and I hope you believe I speak my very soul to you.

In the other, he says, "I pronounce it to you from my heart as oft as I consider it, that I look on your fruitions with inexpressible emulation, and should think myself more happy than crowned heads, were I, as you, the arbiter of mine own life, and could break from those gilded toys to taste your well-described joys with such a wife and such a friend, whose conversation exceeds all that the mistaken world calls happiness." But, in truth, Mr. Evelyn's mind was too active to admit of solitude at all times, however desirable it might appear to him in theory.

After he had settled at Deptford, which was in the time of Cromwell, he kept up a constant correspondence with Sir Richard Browne (his father-in-law), the King's Ambassador at Paris; and though his connection must have been known, it does not appear that he met with any interruption from the government here. Indeed, though he remained a decided Royalist, he managed so well as to have intimate friends even among those nearly connected with Cromwell; and to this we may attribute[Pg xx] his being able to avoid taking the Covenant, which he says he never did take. In 1659, he published "An Apology for the Royal Party"; and soon after printed a paper which was of great service to the King, entitled "The Late News, or Message from Brussels Unmasked," which was an answer to a pamphlet designed to represent the King in the worst light.

On the Restoration, we find him very frequently at Court; and he became engaged in many public employments, still attending to his studies and literary pursuits. Among these, is particularly to be mentioned the Royal Society, in the establishment and conduct of which he took a very active part. He procured Mr. Howard's library to be given to them; and by his influence, in 1667, the Arundelian Marbles were obtained for the University of Oxford.

His first appointment to a public office was in 1662, as a Commissioner for reforming the buildings, ways, streets, and incumbrances, and regulating hackney coaches in London. In the same year he sat as a Commissioner on an inquiry into the conduct of the Lord Mayor, etc., concerning Sir Thomas Gresham's charities. In 1664 he was in a commission for regulating the Mint; in the same year was appointed one of the Commissioners for the care of the Sick and Wounded in the Dutch war; and he was continued in the same employment in the second war with that country.

He was one of the Commissioners for the repair of St. Paul's Cathedral, shortly before it was burned in 1666. In that year he was also in a commission for regulating the farming and making saltpetre; and in 1671 we find him a Commissioner of Plantations on the establishment of the board, to which the Council of Trade was added in 1672.

In 1685 he was one of the Commissioners of the Privy Seal, during the absence of the Earl of Clarendon (who held that office), on his going Lord Lieutenant to Ireland. On the foundation of Greenwich Hospital, in 1695, he was one of the Commissioners; and, on the 30th of June, 1696, laid the first stone of that building. He was also appointed Treasurer, with a salary of £200 a year; but he says that it was a long time before he received any part of it.[Pg xxi]

When the Czar of Muscovy came to England, in 1698, proposing to instruct himself in the art of shipbuilding, he was desirous of having the use of Sayes Court, in consequence of its vicinity to the King's dockyard at Deptford. This was conceded; but during his stay he did so much damage that Mr. Evelyn had an allowance of £150 for it. He especially regrets the mischief done to his famous holly hedge, which might have been thought beyond the reach of damage. But one of Czar Peter's favorite recreations had been to demolish the hedges by riding through them in a wheelbarrow.

October, 1699, his elder brother, George Evelyn, dying without male issue, aged eighty-three, he succeeded to the paternal estate; and in May following, he quitted Sayes Court and went to Wotton, where he passed the remainder of his life, with the exception of occasional visits to London, where he retained a house. In the great storm of 1703, he mentions in his last edition of the "Sylva," above one thousand trees were blown down in sight of his residence.

He died at his house in London, 27th February, 1705-6, in the eighty-sixth year of his age, and was buried at Wotton. His lady survived him nearly three years, dying 9th February, 1708-9, in her seventy-fourth year, and was buried near him at Wotton.

Of Evelyn's children, a son, who died at the age of five, and a daughter, who died at the age of nineteen, were almost prodigies. The particulars of their extraordinary endowments, and the profound manner in which he was affected at their deaths, may be seen in these volumes.

One daughter was well and happily settled; another less so; but she did not survive her marriage more than a few months. The only son who lived to the age of manhood, inherited his father's love of learning, and distinguished himself by several publications.

Mr. Evelyn's employment as a Commissioner for the care of the Sick and Wounded was very laborious; and, from the nature of it, must have been extremely unpleasant. Almost the whole labor was in his department, which included all the ports between the river Thames and Portsmouth; and he had to travel in all seasons and weathers, by land and by water, in the execution of his[Pg xxii] office, to which he gave the strictest attention. It was rendered still more disagreeable by the great difficulty which he found in procuring money for support of the prisoners. In the library at Wotton, are copies of numerous letters to the Lord Treasurer and Officers of State, representing, in the strongest terms, the great distress of the poor men, and of those who had furnished lodging and necessaries for them. At one time, there were such arrears of payment to the victuallers, that, on landing additional sick and wounded, they lay some time in the streets, the publicans refusing to receive them, and shutting up their houses. After all this trouble and fatigue, he found as great difficulty in getting his accounts settled.2 In January, 1665-6, he formed a plan for an Infirmary at Chatham, which he sent to Mr. Pepys, to be laid before the Admiralty, with his reasons for recommending it; but it does not appear that it was carried into execution.

His employments, in connection with the repair of St. Paul's (which, however, occupied him but a brief time), as in the Commission of Trade and Plantations, and in the building of Greenwich Hospital, were much better adapted to his inclinations and pursuits.

As a Commissioner of the Privy Seal in the reign of King James II., he had a difficult task to perform. He was most steadily attached to the Church of England, and the King required the Seal to be affixed to many things incompatible with the welfare of that Church. This, on some occasions, he refused to do, particularly to a license to Dr. Obadiah Walker to print Popish books;3 and on other occasions he absented himself, leaving it to[Pg xxiii] his brother Commissioners to act as they thought fit. Such, however, was the King's estimation of him, that no displeasure was evinced on this account.

Of Evelyn's attempt to bring Colonel Morley (Cromwell's Lieutenant of the Tower, immediately preceding the Restoration) over to the King's interest, an imperfect account is given in the "Biographia." The fact is, that there was great friendship between these gentlemen, and Evelyn did endeavor to engage the Colonel in the King's interest. He saw him several times, and put his life into his hands by writing to him on 12th January, 1659-60; he did not succeed, and Colonel Morley was too much his friend to betray him; but so far from the Colonel having settled matters privately with Sir Anthony Ashley Cooper, or General Monk, as there described, he was obliged, when the Restoration took place, actually to apply to Evelyn to procure his pardon; who obtained it accordingly, though, as he states, the Colonel was obliged to pay a large sum of money for it. This could not have happened, if there had been any previous negotiation with General Monk.

Dr. Campbell took some pains to vindicate Mr. Evelyn's book, entitled, "Navigation and Commerce, their Origin and Progress," from the charge of being an imperfect work, unequal to the expectation excited by the title. But the Doctor, who had not the information which this Journal so amply affords on this subject, was not aware that what was so printed was nothing more than an Introduction to the History of the Dutch War; a work undertaken by Evelyn at the express command of King Charles II., and the materials for which were furnished by the Officers of State. The completion of this work, after considerable progress had been made in it, was put a stop to by the King himself, for what reason does not appear; but perhaps it was found that Evelyn was inclined to tell too much of the truth concerning a transaction, which it will be seen by his Journal that he utterly reprobated. His copy of the History, as far as he had proceeded, he put into the hands of his friend, Mr. Pepys, of the Admiralty, who did not return it; but the books and manuscripts belonging to Mr. Pepys passed into the possession of Magdalen College, Cambridge.[Pg xxiv]

From the numerous authors who have spoken in high terms of Mr. Evelyn, we will select the two following notices of him.

In the "Biographia Britannica" Dr. Campbell says, "It is certain that very few authors who have written in our language deserve the character of able and agreeable writers so well as Mr. Evelyn, who, though he was acquainted with most sciences, and wrote upon many different subjects, yet was very far, indeed the farthest of most men of his time, from being a superficial writer. He had genius, he had taste, he had learning; and he knew how to give all these a proper place in his works, so as never to pass for a pedant, even with such as were least in love with literature, and to be justly esteemed a polite author by those who knew it best."

Horace Walpole (afterward Earl of Orford), in his Catalogue of Engravers, gives us the following admirably drawn character: "If Mr. Evelyn had not been an artist himself, as I think I can prove he was, I should yet have found it difficult to deny myself the pleasure of allotting him a place among the arts he loved, promoted, patronized; and it would be but justice to inscribe his name with due panegyric in these records, as I have once or twice taken the liberty to criticise him. But they are trifling blemishes compared with his amiable virtues and beneficence; and it may be remarked that the worst I have said of him is, that he knew more than he always communicated. It is no unwelcome satire to say, that a man's intelligence and philosophy is inexhaustible. I mean not to write his biography, but I must observe, that his life, which was extended to eighty-six years, was a course of inquiry, study, curiosity, instruction, and benevolence. The works of the Creator, and the minute labors of the creature, were all objects of his pursuit. He unfolded the perfection of the one, and assisted the imperfection of the other. He adored from examination; was a courtier that flattered only by informing his Prince, and by pointing out what was worthy of him to countenance; and really was the neighbor of the Gospel, for there was no man that might not have been the better for him. Whoever peruses a list of his works will subscribe to my assertion. He was one of the first promoters of the Royal Society; a patron of the ingenious and the indigent; and[Pg xxv] peculiarly serviceable to the lettered world; for, besides his writings and discoveries, he obtained the Arundelian Marbles for the University of Oxford, and the Arundelian Library for the Royal Society. Nor is it the least part of his praise, that he who proposed to Mr. Boyle the erection of a Philosophical College for retired and speculative persons, had the honesty to write in defense of active life against Sir George Mackenzie's 'Essay on Solitude.' He knew that retirement, in his own hands, was industry and benefit to mankind; but in those of others, laziness and inutility."

Evelyn was buried in the Dormitory adjoining Wotton Church.

On a white marble, covering a tomb shaped like a coffin, raised about three feet above the floor, is inscribed:

Here lies the Body

of John Evelyn, Esq.,

of this place, second son

of Richard Evelyn, Esq.;

who having serv'd the Publick

in several employments, of which that

of Commissioner of the Privy-Seal in the

Reign of King James the 2d was most

honourable, and perpetuated his fame

by far more lasting monuments than

those of Stone or Brass, his learned

and usefull Works, fell asleep the 27 day

of February 1705-6, being the 86 year

of his age, in full hope of a glorious

Resurrection, thro' Faith in Jesus Christ.

Living in an age of extraordinary

Events and Revolutions, he learnt

(as himself asserted) this Truth,

which pursuant to his intention

is here declared—

That all is vanity which is not honest,

and that there is no solid wisdom

but in real Piety.

Of five Sons and three Daughters

born to him from his most

vertuous and excellent Wife,

Mary, sole daughter and heiress

of Sir Rich. Browne of Sayes

Court near Deptford in Kent,

onely one daughter, Susanna,

married to William Draper

Esq., of Adscomb in this[Pg xxvi]

County, survived him; the

two others dying in the

flower of their age, and

all the Sons very young, except

one named John, who

deceased 24 March, 1698-9,

in the 45 year of his age,

leaving one son, John, and

one daughter, Elizabeth.

I was born at Wotton, in the County of Surrey, about twenty minutes past two in the morning, being on Tuesday the 31st and last of October, 1620, after my father had been married about seven years,4 and that my mother had borne him three children; viz, two daughters and one son, about the 33d year of his age, and the 23d of my mother's.

My father, named Richard, was of a sanguine complexion, mixed with a dash of choler: his hair inclining to light, which, though exceedingly thick, became hoary by the time he had attained to thirty years of age; it was somewhat curled toward the extremities; his beard, which he wore a little peaked, as the mode was, of a brownish color, and so continued to the last, save that it was somewhat mingled with gray hairs about his cheeks, which, with his countenance, were clear and fresh-colored; his eyes extraordinary quick and piercing; an ample forehead,—in sum, a very well-composed visage and manly aspect: for the rest, he was but low of stature, yet very strong. He was, for his life, so exact and temperate, that I have heard he had never been surprised by excess, being ascetic and sparing. His wisdom was great, and his judgment most acute; of solid discourse, affable, humble, and in nothing affected; of a thriving, neat, silent, and methodical genius, discreetly severe, yet liberal upon all just occasions, both to his children, to strangers, and servants; a lover of hospitality; and, in brief, of a singular and Christian moderation in all his actions; not illiterate, nor obscure, as, having continued Justice of the Peace and of the Quorum, he served his country as High Sheriff, being, as I take it,[Pg 2] the last dignified with that office for Sussex and Surrey together, the same year, before their separation. He was yet a studious decliner of honors and titles; being already in that esteem with his country, that they could have added little to him besides their burden. He was a person of that rare conversation that, upon frequent recollection, and calling to mind passages of his life and discourse, I could never charge him with the least passion, or inadvertency. His estate was esteemed about £4000 per annum, well wooded, and full of timber.

My mother's name was Eleanor, sole daughter and heiress of John Standsfield, Esq., of an ancient and honorable family (though now extinct) in Shropshire, by his wife Eleanor Comber, of a good and well-known house in Sussex. She was of proper personage; of a brown complexion; her eyes and hair of a lovely black; of constitution more inclined to a religious melancholy, or pious sadness; of a rare memory, and most exemplary life; for economy and prudence, esteemed one of the most conspicuous in her country: which rendered her loss much deplored, both by those who knew, and such as only heard of her.

Thus much, in brief, touching my parents; nor was it reasonable I should speak less of them to whom I owe so much.

The place of my birth was Wotton, in the parish of Wotton, or Blackheath, in the county of Surrey, the then mansion-house of my father, left him by my grandfather, afterward and now my eldest brother's. It is situated in the most southern part of the shire; and, though in a valley, yet really upon part of Leith Hill, one of the most eminent in England for the prodigious prospect to be seen from its summit, though by few observed. From it may be discerned twelve or thirteen counties, with part of the sea on the coast of Sussex, in a serene day. The house is large and ancient, suitable to those hospitable times, and so sweetly environed with those delicious streams and venerable woods, as in the judgment of strangers as well as Englishmen it may be compared to one of the most pleasant seats in the nation, and most tempting for a great person and a wanton purse to render it conspicuous. It has rising grounds, meadows, woods, and water, in abundance.[Pg 3]

The distance from London little more than twenty miles, and yet so securely placed, as if it were one hundred; three miles from Dorking, which serves it abundantly with provision as well of land as sea; six from Guildford, twelve from Kingston. I will say nothing of the air, because the pre-eminence is universally given to Surrey, the soil being dry and sandy; but I should speak much of the gardens, fountains, and groves that adorn it, were they not as generally known to be among the most natural, and (till this later and universal luxury of the whole nation, since abounding in such expenses) the most magnificent that England afforded; and which indeed gave one of the first examples to that elegancy, since so much in vogue, and followed in the managing of their waters, and other elegancies of that nature. Let me add, the contiguity of five or six manors, the patronage of the livings about it, and what Themistocles pronounced for none of the least advantages—the good neighborhood. All which conspire here to render it an honorable and handsome royalty, fit for the present possessor, my worthy brother, and his noble lady, whose constant liberality gives them title both to the place and the affections of all that know them. Thus, with the poet:

I had given me the name of my grandfather, my mother's father, who, together with a sister of Sir Thomas Evelyn, of Long Ditton, and Mr. Comber, a near relation of my mother, were my susceptors. The solemnity (yet upon what accident I know not, unless some indisposition in me) was performed in the dining-room by Parson Higham, the present incumbent of the parish, according to the forms prescribed by the then glorious Church of England.

I was now (in regard to my mother's weakness, or rather custom of persons of quality) put to nurse to one Peter, a neighbor's wife and tenant, of a good, comely, brown, wholesome complexion, and in a most sweet place toward the hills, flanked with wood and refreshed with streams; the affection to which kind of solitude I sucked in with my very milk. It appears, by a note of my[Pg 4] father's, that I sucked till 17th of January, 1622, or at least I came not home before.5

1623. The very first thing that I can call to memory, and from which time forward I began to observe, was this year (1623) my youngest brother, being in his nurse's arms, who, being then two days and nine months younger than myself, was the last child of my dear parents.

1624. I was not initiated into any rudiments until near four years of age, and then one Frier taught us at the church-porch of Wotton; and I do perfectly remember the great talk and stir about Il Conde Gondomar, now Ambassador from Spain (for near about this time was the match of our Prince with the Infanta proposed); and the effects of that comet, 1618, still working in the prodigious revolutions now beginning in Europe, especially in Germany, whose sad commotions sprang from the Bohemians' defection from the Emperor Matthias; upon which quarrel the Swedes broke in, giving umbrage to the rest of the princes, and the whole Christian world cause to deplore it, as never since enjoying perfect tranquillity.

1625. I was this year (being the first of the reign of King Charles) sent by my father to Lewes, in Sussex, to be with my grandfather, Standsfield, with whom I passed my childhood. This was the year in which the pestilence was so epidemical, that there died in London 5,000 a week, and I well remember the strict watches and examinations upon the ways as we passed; and I was shortly after so dangerously sick of a fever that (as I have heard) the physicians despaired of me.

1626. My picture was drawn in oil by one Chanterell, no ill painter.

1627. My grandfather, Standsfield, died this year, on the 5th of February: I remember perfectly the solemnity at his funeral. He was buried in the parish church of All Souls, where my grandmother, his second wife, erected him a pious monument. About this time, was the con[Pg 5]secration of the Church of South Malling, near Lewes, by Dr. Field, Bishop of Oxford (one Mr. Coxhall preached, who was afterward minister); the building whereof was chiefly procured by my grandfather, who having the impropriation, gave £20 a year out of it to this church. I afterward sold the impropriation. I laid one of the first stones at the building of the church.

1628-30. It was not till the year 1628, that I was put to learn my Latin rudiments, and to write, of one Citolin, a Frenchman, in Lewes. I very well remember that general muster previous to the Isle of Rhè's expedition, and that I was one day awakened in the morning with the news of the Duke of Buckingham being slain by that wretch, Felton, after our disgrace before La Rochelle. And I now took so extraordinary a fancy to drawing and designing, that I could never after wean my inclinations from it, to the expense of much precious time, which might have been more advantageously employed. I was now put to school to one Mr. Potts, in the Cliff at Lewes, from whom, on the 7th of January, 1630, being the day after Epiphany, I went to the free-school at Southover, near the town, of which one Agnes Morley had been the foundress, and now Edward Snatt was the master, under whom I remained till I was sent to the University.6 This year, my grandmother (with whom I sojourned) being married to one Mr. Newton, a learned and most religious gentleman, we went from the Cliff to dwell at his house in Southover. I do most perfectly remember the jubilee which was universally expressed for the happy birth of the Prince of Wales, 29th of May, now Charles II., our most gracious Sovereign.

1631. There happened now an extraordinary dearth in England, corn bearing an excessive price; and, in imitation of what I had seen my father do, I began to observe matters more punctually, which I did use to set down in a blank almanac. The Lord of Castlehaven's arraignment for many shameful exorbitances was now all the talk, and the birth of the Princess Mary, afterward Princess of Orange.

21st October, 1632. My eldest sister was married to Edward Darcy, Esq., who little deserved so excellent a[Pg 6] person, a woman of so rare virtue. I was not present at the nuptials; but I was soon afterward sent for into Surrey, and my father would willingly have weaned me from my fondness of my too indulgent grandmother, intending to have placed me at Eton; but, not being so provident for my own benefit, and unreasonably terrified with the report of the severe discipline there, I was sent back to Lewes; which perverseness of mine I have since a thousand times deplored. This was the first time that ever my parents had seen all their children together in prosperity. While I was now trifling at home, I saw London, where I lay one night only. The next day, I dined at Beddington, where I was much delighted with the gardens and curiosities. Thence, we returned to the Lady Darcy's, at Sutton; thence to Wotton; and, on the 16th of August following, 1633, back to Lewes.

3d November, 1633. This year my father was appointed Sheriff, the last, as I think, who served in that honorable office for Surrey and Sussex, before they were disjoined. He had 116 servants in liveries, every one liveried in green satin doublets; divers gentlemen and persons of quality waited on him in the same garb and habit, which at that time (when thirty or forty was the usual retinue of the High Sheriff) was esteemed a great matter. Nor was this out of the least vanity that my father exceeded (who was one of the greatest decliners of it); but because he could not refuse the civility of his friends and relations, who voluntarily came themselves, or sent in their servants. But my father was afterward most unjustly and spitefully molested by that jeering judge, Richardson, for reprieving the execution of a woman, to gratify my Lord of Lindsey, then Admiral: but out of this he emerged with as much honor as trouble. The king made this year his progress into Scotland, and Duke James was born.

15th December, 1634: My dear sister, Darcy, departed this life, being arrived to her 20th year of age; in virtue advanced beyond her years, or the merit of her husband, the worst of men. She had been brought to bed the 2d of June before, but the infant died soon after her, the 24th of December. I was therefore sent for home the second time, to celebrate the obsequies of my sister; who was interred in a very honorable manner in our[Pg 7] dormitory joining to the parish church, where now her monument stands.

1635. But my dear mother being now dangerously sick, I was, on the 3d of September following, sent for to Wotton. Whom I found so far spent, that, all human assistance failing, she in a most heavenly manner departed this life upon the 29th of the same month, about eight in the evening of Michaelmas-day. It was a malignant fever which took her away, about the 37th of her age, and 22d of her marriage, to our irreparable loss and the regret of all that knew her. Certain it is, that the visible cause of her indisposition proceeded from grief upon the loss of her daughter, and the infant that followed it; and it is as certain, that when she perceived the peril whereto its excess had engaged her, she strove to compose herself and allay it; but it was too late, and she was forced to succumb. Therefore summoning all her children then living (I shall never forget it), she expressed herself in a manner so heavenly, with instructions so pious and Christian, as made us strangely sensible of the extraordinary loss then imminent; after which, embracing every one of us she gave to each a ring with her blessing and dismissed us. Then, taking my father by the hand, she recommended us to his care; and, because she was extremely zealous for the education of my younger brother, she requested my father that he might be sent with me to Lewes; and so having importuned him that what he designed to bestow on her funeral, he would rather dispose among the poor, she labored to compose herself for the blessed change which she now expected. There was not a servant in the house whom she did not expressly send for, advise, and infinitely affect with her counsel. Thus she continued to employ her intervals, either instructing her relations, or preparing of herself.

Though her physicians, Dr. Meverell, Dr. Clement, and Dr. Rand, had given over all hopes of her recovery, and Sir Sanders Duncombe had tried his celebrated and famous powder, yet she was many days impairing, and endured the sharpest conflicts of her sickness with admirable patience and most Christian resignation, retaining both her intellectuals and ardent affections for her dissolution, to the very article of her departure. When[Pg 8] near her dissolution, she laid her hand on every one of her children; and taking solemn leave of my father, with elevated heart and eyes, she quietly expired, and resigned her soul to God. Thus ended that prudent and pious woman, in the flower of her age, to the inconsolable affliction of her husband, irreparable loss of her children, and universal regret of all that knew her. She was interred, as near as might be, to her daughter Darcy, the 3d of October, at night, but with no mean ceremony.

It was the 3d of the ensuing November, after my brother George was gone back to Oxford, ere I returned to Lewes, when I made way, according to instructions received of my father, for my brother Richard, who was sent the 12th after.

1636. This year being extremely dry, the pestilence much increased in London, and divers parts of England.

13th February, 1637: I was especially admitted (and, as I remember, my other brother) into the Middle Temple, London, though absent, and as yet at school. There were now large contributions to the distressed Palatinates.

The 10th of December my father sent a servant to bring us necessaries, and the plague beginning now to cease, on the 3d of April, 1637, I left school, where, till about the last year, I have been extremely remiss in my studies; so as I went to the University rather out of shame of abiding longer at school, than for any fitness, as by sad experience I found: which put me to re-learn all that I had neglected, or but perfunctorily gained.

10th May, 1637. I was admitted a Fellow-commoner of Baliol College, Oxford; and, on the 29th, I was matriculated in the vestry of St. Mary's, where I subscribed the Articles, and took the oaths: Dr. Baily, head of St. John's, being vice-chancellor, afterward bishop. It appears by a letter of my father's, that he was upon treaty with one Mr. Bathurst (afterward Doctor and President), of Trinity College, who should have been my tutor; but, lest my brother's tutor, Dr. Hobbs, more zealous in his life than industrious to his pupils, should receive it as an affront, and especially for that Fellow-commoners in Baliol were no more exempt from exercise than the meanest scholars there, my father sent me thither to one Mr. George Bradshaw (nomen invisum! yet the son of an[Pg 9] excellent father, beneficed in Surrey). I ever thought my tutor had parts enough; but as his ambition made him much suspected of the College, so his grudge to Dr. Lawrence, the governor of it (whom he afterward supplanted), took up so much of his time, that he seldom or never had the opportunity to discharge his duty to his scholars. This I perceiving, associated myself with one Mr. James Thicknesse (then a young man of the foundation, afterward a Fellow of the house), by whose learned and friendly conversation I received great advantage. At my first arrival, Dr. Parkhurst was master: and after his decease, Dr. Lawrence, a chaplain of his Majesty's and Margaret Professor, succeeded, an acute and learned person; nor do I much reproach his severity, considering that the extraordinary remissness of discipline had (till his coming) much detracted from the reputation of that College.

There came in my time to the College one Nathaniel Conopios, out of Greece, from Cyrill, the patriarch of Constantinople, who, returning many years after, was made (as I understand) Bishop of Smyrna. He was the first I ever saw drink coffee; which custom came not into England till thirty years after.7

After I was somewhat settled there in my formalities (for then was the University exceedingly regular, under the exact discipline of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, then Chancellor), I added, as benefactor to the library of the College, these books—"ex dono Johannis Evelyni, hujus Coll. Socio-Commensalis, filii Richardi Evelyni, è com. Surriæ, armigr."—

"Zanchii Opera," vols. 1, 2, 3.

"Granado in Thomam Aquinatem," vols. 1, 2, 3.

"Novarini Electa Sacra" and "Cresolii Anthologia Sacra"; authors, it seems, much desired by the students of divinity there.

Upon the 2d of July, being the first Sunday of the month, I first received the blessed Sacrament of the Lord's Supper in the college chapel, one Mr. Cooper, a Fellow of the house, preaching; and at this time was the Church of England in her greatest splendor, all things decent, and becoming the Peace, and the persons that governed.[Pg 10] The most of the following week I spent in visiting the Colleges, and several rarities of the University, which do very much affect young comers.

18th July, 1637. I accompanied my eldest brother, who then quitted Oxford, into the country; and, on the 9th of August, went to visit my friends at Lewes, whence I returned the 12th to Wotton. On the 17th of September, I received the blessed Sacrament at Wotton church, and 23d of October went back to Oxford.

5th November, 1637. I received again the Holy Communion in our college chapel, one Prouse, a Fellow (but a mad one), preaching.

9th December, 1637. I offered at my first exercise in the Hall, and answered my opponent; and, upon the 11th following, declaimed in the chapel before the Master, Fellows, and Scholars, according to the custom. The 15th after, I first of all opposed in the Hall.

The Christmas ensuing, being at a Comedy which the gentlemen of Exeter College presented to the University, and standing, for the better advantage of seeing, upon a table in the Hall, which was near to another, in the dark, being constrained by the extraordinary press to quit my station, in leaping down to save myself I dashed my right leg with such violence against the sharp edge of the other board, as gave me a hurt which held me in cure till almost Easter, and confined me to my study.

22d January, 1638. I would needs be admitted into the dancing and vaulting schools; of which late activity one Stokes, the master, did afterward set forth a pretty book, which was published, with many witty elogies before it.

4th February, 1638. One Mr. Wariner preached in our chapel; and, on the 25th, Mr. Wentworth, a kinsman of the Earl of Strafford; after which followed the blessed Sacrament.

13th April, 1638. My father ordered that I should begin to manage my own expenses, which till then my tutor had done; at which I was much satisfied.

9th July, 1638. I went home to visit my friends, and, on the 26th, with my brother and sister to Lewes, where we abode till the 31st; and thence to one Mr. Michael's, of Houghton, near Arundel, where we were very well treated; and, on the 2d of August, to Portsmouth, and thence,[Pg 11] having surveyed the fortifications (a great rarity in that blessed halcyon time in England), we passed into the Isle of Wight, to the house of my Lady Richards, in a place called Yaverland; but were turned the following day to Chichester, where, having viewed the city and fair cathedral, we returned home.

About the beginning of September, I was so afflicted with a quartan ague, that I could by no means get rid of it till the December following. This was the fatal year wherein the rebellious Scots opposed the King, upon the pretense of the introduction of some new ceremonies and the Book of Common Prayer, and madly began our confusions, and their own destruction, too, as it proved in event.

14th January, 1639. I came back to Oxford, after my tedious indisposition, and to the infinite loss of my time; and now I began to look upon the rudiments of music, in which I afterward arrived to some formal knowledge, though to small perfection of hand, because I was so frequently diverted with inclinations to newer trifles.

20th May, 1639. Accompanied with one Mr. J. Crafford (who afterward being my fellow-traveler in Italy, there changed his religion), I took a journey of pleasure to see the Somersetshire baths, Bristol, Cirencester, Malmesbury, Abington, and divers other towns of lesser note; and returned the 25th.

8th October, 1639. I went back to Oxford.

14th December, 1639. According to injunctions from the Heads of Colleges, I went (among the rest) to the Confirmation at St. Mary's, where, after sermon, the Bishop of Oxford laid his hands upon us, with the usual form of benediction prescribed: but this received (I fear) for the more part out of curiosity, rather than with that due preparation and advice which had been requisite, could not be so effectual as otherwise that admirable and useful institution might have been, and as I have since deplored it.

21st January, 1640. Came my brother, Richard, from school, to be my chamber-fellow at the University. He was admitted the next day and matriculated the 31st.

11th April, 1640. I went to London to see the solemnity of his Majesty's riding through the city in state to the Short Parliament, which began the 13th following,—a very[Pg 12] glorious and magnificent sight, the King circled with his royal diadem and the affections of his people: but the day after I returned to Wotton again, where I stayed, my father's indisposition suffering great intervals, till April 27th, when I was sent to London to be first resident at the Middle Temple: so as my being at the University, in regard of these avocations, was of very small benefit to me. Upon May the 5th following, was the Parliament unhappily dissolved; and, on the 20th I returned with my brother George to Wotton, who, on the 28th of the same month, was married at Albury to Mrs. Caldwell (an heiress of an ancient Leicestershire family, where part of the nuptials were celebrated).

10th June, 1640. I repaired with my brother to the term, to go into our new lodgings (that were formerly in Essex-court), being a very handsome apartment just over against the Hall-court, but four pair of stairs high, which gave us the advantage of the fairer prospect; but did not much contribute to the love of that impolished study, to which (I suppose) my father had designed me, when he paid £145 to purchase our present lives, and assignments afterward.

London, and especially the Court, were at this period in frequent disorders, and great insolences were committed by the abused and too happy City: in particular, the Bishop of Canterbury's Palace at Lambeth was assaulted by a rude rabble from Southwark, my Lord Chamberlain imprisoned and many scandalous libels and invectives scattered about the streets, to the reproach of Government, and the fermentation of our since distractions: so that, upon the 25th of June, I was sent for to Wotton, and the 27th after, my father's indisposition augmenting, by advice of the physicians he repaired to the Bath.

7th July, 1640. My brother George and I, understanding the peril my father was in upon a sudden attack of his infirmity, rode post from Guildford toward him, and found him extraordinary weak; yet so as that, continuing his course, he held out till the 8th of September, when I returned home with him in his litter.

15th October, 1640. I went to the Temple, it being Michaelmas Term.

30th December, 1640. I saw his Majesty (coming from[Pg 13] his Northern Expedition) ride in pomp and a kind of ovation, with all the marks of a happy peace, restored to the affections of his people, being conducted through London with a most splendid cavalcade; and on the 3d of November following (a day never to be mentioned without a curse), to that long ungrateful, foolish, and fatal Parliament, the beginning of all our sorrows for twenty years after, and the period of the most happy monarch in the world: Quis talia fando!

But my father being by this time entered into a dropsy, an indisposition the most unsuspected, being a person so exemplarily temperate, and of admirable regimen, hastened me back to Wotton, December the 12th; where, the 24th following, between twelve and one o'clock at noon, departed this life that excellent man and indulgent parent, retaining his senses and piety to the last, which he most tenderly expressed in blessing us, whom he now left to the world and the worst of times, while he was taken from the evil to come.

1641. It was a sad and lugubrious beginning of the year, when on the 2d of January, 1640-1, we at night followed the mourning hearse to the church at Wotton; when, after a sermon and funeral oration by the minister, my father was interred near his formerly erected monument, and mingled with the ashes of our mother, his dear wife. Thus we were bereft of both our parents in a period when we most of all stood in need of their counsel and assistance, especially myself, of a raw, vain, uncertain, and very unwary inclination: but so it pleased God to make trial of my conduct in a conjuncture of the greatest and most prodigious hazard that ever the youth of England saw; and, if I did not amidst all this impeach my liberty nor my virtue with the rest who made shipwreck of both, it was more the infinite goodness and mercy of God than the least providence or discretion of mine own, who now thought of nothing but the pursuit of vanity, and the confused imaginations of young men.

15th April, 1641. I repaired to London to hear and see the famous trial of the Earl of Strafford, Lord-Deputy of Ireland, who, on the 22d of March, had been summoned before both Houses of Parliament, and now appeared in[Pg 14] Westminster-hall,8 which was prepared with scaffolds for the Lords and Commons, who, together with the King, Queen, Prince, and flower of the noblesse, were spectators and auditors of the greatest malice and the greatest innocency that ever met before so illustrous an assembly. It was Thomas, Earl of Arundel and Surrey, Earl Marshal of England, who was made High Steward upon this occasion; and the sequel is too well known to need any notice of the event.

On the 27th of April, came over out of Holland the young Prince of Orange, with a splendid equipage, to make love to his Majesty's eldest daughter, the now Princess Royal.

That evening, was celebrated the pompous funeral of the Duke of Richmond, who was carried in effigy, with all the ensigns of that illustrious family, in an open chariot, in great solemnity, through London to Westminster Abbey.

On the 12th of May, I beheld on Tower-hill the fatal stroke which severed the wisest head in England from the shoulders of the Earl of Strafford, whose crime coming under the cognizance of no human law or statute, a new one was made, not to be a precedent, but his destruction. With what reluctancy the King signed the execution, he has sufficiently expressed; to which he imputes his own unjust suffering—to such exorbitancy were things arrived.

On the 24th of May, I returned to Wotton; and, on the 28th of June, I went to London with my sister, Jane, and the day after sat to one Vanderborcht for my picture in oil, at Arundel-house, whose servant that excellent painter was, brought out of Germany when the Earl returned from Vienna (whither he was sent Ambassador-extraordinary, with great pomp and charge, though with[Pg 15]out any effect, through the artifice of the Jesuited Spaniard who governed all in that conjuncture). With Vanderborcht, the painter, he brought over Winceslaus Hollar, the sculptor, who engraved not only the unhappy Deputy's trial in Westminster-hall, but his decapitation; as he did several other historical things, then relating to the accidents happening during the Rebellion in England, with great skill; besides many cities, towns, and landscapes, not only of this nation, but of foreign parts, and divers portraits of famous persons then in being; and things designed from the best pieces of the rare paintings and masters of which the Earl of Arundel was possessor, purchased and collected in his travels with incredible expense: so as, though Hollar's were but etched in aquafortis, I account the collection to be the most authentic and useful extant. Hollar was the son of a gentleman near Prague, in Bohemia, and my very good friend, perverted at last by the Jesuits at Antwerp to change his religion; a very honest, simple, well-meaning man, who at last came over again into England, where he died. We have the whole history of the king's reign, from his trial in Westminster-hall and before, to the restoration of King Charles II., represented in several sculptures, with that also of Archbishop Laud, by this indefatigable artist; besides innumerable sculptures in the works of Dugdale, Ashmole, and other historical and useful works. I am the more particular upon this for the fruit of that collection, which I wish I had entire.

This picture9 I presented to my sister, being at her request, on my resolution to absent myself from this ill face of things at home, which gave umbrage to wiser than myself that the medal was reversing, and our calamities but yet in their infancy: so that, on the 15th of July, having procured a pass at the Custom-house, where I repeated my oath of allegiance, I went from London to Gravesend, accompanied with one Mr. Caryll, a Surrey gentleman, and our servants, where we arrived by six o'clock that evening, with a purpose to take the first opportunity of a passage for Holland. But the wind as yet not favorable, we had time to view the Block-house of that town, which answered to another over against it[Pg 16] at Tilbury, famous for the rendezvous of Queen Elizabeth, in the year 1588, which we found stored with twenty pieces of cannon, and other ammunition proportionable. On the 19th of July, we made a short excursion to Rochester, and having seen the cathedral went to Chatham to see the Royal Sovereign, a glorious vessel of burden lately built there, being for defense and ornament, the richest that ever spread cloth before the wind. She carried an hundred brass cannon, and was 1,200 tons; a rare sailer, the work of the famous Phineas Pett, inventor of the frigate-fashion of building, to this day practiced. But what is to be deplored as to this vessel is, that it cost his Majesty the affections of his subjects, perverted by the malcontent of great ones, who took occasion to quarrel for his having raised a very slight tax for the building of this, and equipping the rest of the navy, without an act of Parliament; though, by the suffrages of the major part of the Judges the King might legally do in times of imminent danger, of which his Majesty was best apprised. But this not satisfying a jealous party, it was condemned as unprecedented, and not justifiable as to the Royal prerogative; and, accordingly, the Judges were removed out of their places, fined, and imprisoned.10

We returned again this evening, and on the 21st of July embarked in a Dutch frigate, bound for Flushing, convoyed and accompanied by five other stout vessels, whereof one was a man-of-war. The next day at noon, we landed at Flushing.

Being desirous to overtake the Leagure,11 which was then before Genep, ere the summer should be too far spent, we went this evening from Flushing to Middleburg, another fine town in this island, to De Vere, whence the most ancient and illustrious Earls of Oxford derive their family, who have spent so much blood in assisting the state during their wars. From De Vere we passed[Pg 17] over many towns, houses, and ruins of demolished suburbs, etc., which have formerly been swallowed up by the sea; at what time no less than eight of those islands had been irrecoverably lost.

The next day we arrived at Dort, the first town of Holland, furnished with all German commodities, and especially Rhenish wines and timber. It hath almost at the extremity a very spacious and venerable church; a stately senate house, wherein was holden that famous synod against the Arminians in 1618; and in that hall hangeth a picture of "The Passion," an exceeding rare and much-esteemed piece.

From Dort, being desirous to hasten toward the army, I took wagon this afternoon to Rotterdam, whither we were hurried in less than an hour, though it be ten miles distant; so furiously do those Foremen drive. I went first to visit the great church, the Doole, the Bourse, and the public statue of the learned Erasmus, of brass. They showed us his house, or rather the mean cottage, wherein he was born, over which there are extant these lines, in capital letters:

ÆDIBUS HIS ORTUS, MUNDUM DECORAVIT ERASMUS

ARTIBUS INGENIO, RELIGIONE, FIDE.

The 26th of July I passed by a straight and commodious river through Delft to the Hague; in which journey I observed divers leprous poor creatures dwelling in solitary huts on the brink of the water, and permitted to ask the charity of passengers, which is conveyed to them in a floating box that they cast out.

Arrived at the Hague, I went first to the Queen of Bohemia's court, where I had the honor to kiss her Majesty's hand, and several of the Princesses', her daughters. Prince Maurice was also there, newly come out of Germany; and my Lord Finch, not long before fled out of England from the fury of the Parliament. It was a fasting day with the Queen for the unfortunate death of her husband, and the presence chamber had been hung with black velvet ever since his decease.

The 28th of July I went to Leyden; and the 29th to Utrecht, being thirty English miles distant (as they reckon by hours). It was now Kermas, or a fair, in this[Pg 18] town, the streets swarming with boors and rudeness, so that early the next morning, having visited the ancient Bishop's court, and the two famous churches, I satisfied my curiosity till my return, and better leisure. We then came to Rynen, where the Queen of Bohemia hath a neat and well built palace, or country house, after the Italian manner, as I remember; and so, crossing the Rhine, upon which this villa is situated, lodged that night in a countryman's house. The 31st to Nimeguen; and on the 2d of August we arrived at the Leagure, where was then the whole army encamped about Genep, a very strong castle situated on the river Waal; but, being taken four or five days before, we had only a sight of the demolitions. The next Sunday was the thanksgiving sermons performed in Colonel Goring's regiment (eldest son of the since Earl of Norwich) by Mr. Goffe, his chaplain (now turned Roman, and father-confessor to the Queen-mother). The evening was spent in firing cannon and other expressions of military triumphs.

Now, according to the compliment, I was received a volunteer in the company of Captain Apsley, of whose Captain-lieutenant, Honywood (Apsley being absent), I received many civilities.

The 3d of August, at night, we rode about the lines of circumvallation, the general being then in the field. The next day I was accommodated with a very spacious and commodious tent for my lodging; as before I was with a horse, which I had at command, and a hut which during the excessive heats was a great convenience; for the sun piercing the canvas of the tent, it was during the day unsufferable, and at night not seldom infested with mists and fogs, which ascended from the river.

6th August, 1641. As the turn came about, we were ordered to watch on a horn-work near our quarters, and trail a pike, being the next morning relieved by a company of French. This was our continual duty till the castle was refortified, and all danger of quitting that station secured; whence I went to see a Convent of Franciscan Friars, not far from our quarters, where we found both the chapel and refectory full, crowded with the goods of such poor people as at the approach of the army had fled with them thither for sanctuary. On the day following, I went to view all the trenches, approaches, and mines, etc. of the[Pg 19] besiegers; and, in particular, I took special notice of the wheel-bridge, which engine his Excellency had made to run over the moat when they stormed the castle; as it is since described (with all the other particulars of this siege) by the author of that incomparable work, "Hollandia Illustrata." The walls and ramparts of earth, which a mine had broken and crumbled, were of prodigious thickness.

Upon the 8th of August, I dined in the horse-quarters with Sir Robert Stone and his lady, Sir William Stradling, and divers Cavaliers; where there was very good cheer, but hot service for a young drinker, as then I was; so that, being pretty well satisfied with the confusion of armies and sieges (if such that of the United Provinces may be called, where their quarters and encampments are so admirably regular, and orders so exactly observed, as few cities, the best governed in time of peace, exceed it for all conveniences), I took my leave of the Leagure and Camerades; and, on the 12th of August, I embarked on the "Waal," in company with three grave divines, who entertained us a great part of our passage with a long dispute concerning the lawfulness of church-music. We now sailed by Teil, where we landed some of our freight; and about five o'clock we touched at a pretty town named Bommell, that had divers English in garrison. It stands upon Contribution-land, which subjects the environs to the Spanish incursions. We sailed also by an exceeding strong fort called Lovestein, famous for the escape of the learned Hugo Grotius, who, being in durance as a capital offender, as was the unhappy Barneveldt, by the stratagem of his lady, was conveyed in a trunk supposed to be filled with books only. We lay at Gorcum, a very strong and considerable frontier.

13th August, 1641. We arrived late at Rotterdam, where was their annual mart or fair, so furnished with pictures (especially landscapes and drolleries, as they call those clownish representations), that I was amazed. Some of these I bought and sent into England. The reason of this store of pictures, and their cheapness, proceeds from their want of land to employ their stock, so that it is an ordinary thing to find a common farmer lay out two or three thousand pounds in this commodity. Their houses are full of them, and they vend them at their fairs to very great gains. Here I first saw an elephant, who was[Pg 20] extremely well disciplined and obedient. It was a beast of a monstrous size, yet as flexible and nimble in the joints, contrary to the vulgar tradition, as could be imagined from so prodigious a bulk and strange fabric; but I most of all admired the dexterity and strength of its proboscis, on which it was able to support two or three men, and by which it took and reached whatever was offered to it; its teeth were but short, being a female, and not old. I was also shown a pelican, or onocratulas of Pliny, with its large gullets, in which he kept his reserve of fish; the plumage was white, legs red, flat, and film-footed, likewise a cock with four legs, two rumps and vents: also a hen which had two large spurs growing out of her sides, penetrating the feathers of her wings.

17th August, 1641. I passed again through Delft, and visited the church in which was the monument of Prince William of Nassau,—the first of the Williams, and savior (as they call him) of their liberty, which cost him his life by a vile assassination. It is a piece of rare art, consisting of several figures, as big as the life, in copper. There is in the same place a magnificent tomb of his son and successor, Maurice. The senate-house hath a very stately portico, supported with choice columns of black marble, as I remember, of one entire stone. Within, there hangs a weighty vessel of wood, not unlike a butter-churn, which the adventurous woman that hath two husbands at one time is to wear on her shoulders, her head peeping out at the top only, and so led about the town, as a penance for her incontinence. From hence, we went the next day to Ryswick, a stately country-house of the Prince of Orange, for nothing more remarkable than the delicious walks planted with lime trees, and the modern paintings within.