“THE YOUNGEST SOLDIER OF THE REVOLUTION”

Carolyn Sherwin Bailey

“THE YOUNGEST SOLDIER OF THE REVOLUTION”

BOYS AND GIRLS OF COLONIAL DAYS

BY

CAROLYN SHERWIN BAILEY

Author of

“What To Do for Uncle Sam,” “Boys and Girls

Of Pioneer Days” and other stories

Illustrated By

ULDENE SHRIVER

1925

A. FLANAGAN COMPANY

CHICAGO

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY A. FLANAGAN COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Boys and Girls of Colonial Days

Peering over the edge of the boat rail, Love strained her weary, blue eyes for a glimpse of land. The sun, a ball of soft, gold light, showed now through the haze, and suddenly, like a fairy place the city appeared. There were tall, shining towers, gold church spires, pointed roofs with wide, red chimneys where the storks stood in one-legged fashion, and great windmills with their long arms stretched out to catch the four winds. Amsterdam, in Holland, it was, the haven of this little boat load of Pilgrims.

Love Bradford, ten years old, flaxen haired, and as winsome as an English rose in June, wrapped her long, gray cloak more closely about her and turned to one of the women.

“Do you think that my father may have taken another boat that sailed faster than this and is waiting for me on the shore, Mistress Brewster? The last words that he said to me when he left me on the ship were ‘Bide patiently until I come, Love; I will not be long.’ That was many days ago.”

Mistress Brewster turned away that the little girl might not see the tears that filled her eyes. Love’s father, just before the ship that bore the Pilgrims from England had sailed, had been cast into prison by the King, because of his faith. Love was all alone, but Mistress Brewster did not want her to know of her father’s fate.

“Perhaps your father will meet you some day soon in Holland. Surely, if he said that he would not be long, he will keep his word. See, Love, see the little boy of your own age down there in the fishing boat.”

Love looked in the direction in which the woman pointed. A plump, rosy little boy with eyes as blue as Love’s own and dressed in full brown trousers and clumsy wooden shoes sat on a big net in one end of the boat. He looked up as the sails of the little fishing craft brought it alongside the boat that bore the wanderers from England. At first he dropped his eyes in shyness at sight of the little girl. Then he lifted them again and, as his eyes met hers, the two children smiled at each other. It was like a flash of sunshine piercing the gray haze that hung over the sea.

There were friends waiting on the shore for all save Love. Older brothers these were, fathers and other relatives who had made the pilgrimage from England a few months before and had homes ready for them all. They climbed a long hill, very flat on the top, and reached by a flight of steps. Then they were as high as the trees that lined the beach and could look over the narrow streets, the tidy cottages with their red roofs, and the pretty gardens. There were many little canals, like blue ribbons, cutting the green fields.

“Welcome to Amsterdam!” said a Dutch housewife, in wide white cap and apron, who met them. She put her hand on Love’s yellow hair. “And in which house are you going to live, little English blossom?” she asked kindly.

Love looked up wonderingly into her face and there was a whispered consultation between Mistress Brewster and the Amsterdam woman. “Poor little blossom! She shall come home with me. There is always room for one more in the stork’s nest,” the Dutch woman said kindly. She took Love’s hand and led her away from the others, and along the canal.

The house where they stopped was very odd indeed. It was made of red and yellow bricks and it stood on great posts sunk deep into the ground. Opening the white door that fairly shone, it was so clean, they were in the kitchen. Such a kitchen it was, so cosy and so quaint! The floor was made of white tiles and there was a queer little fireplace. It looked like a big brass pan filled with coals, and there was a shining copper kettle hung over it by a chain from the ceiling. The kettle bubbled and sang a cheerful welcome to Love. There were stiff white curtains at the windows and, on the sill of one, was a row of blossoming plants. Blue and white dishes and a pair of tall candlesticks stood on a shelf. Love could see a bright sitting room beyond and another room where there was a strange bed built in the wall, and stretching almost from the floor to the ceiling.

“Jan, Jan,” the woman called. “Come in from the garden and offer your new little English sister a seed cake. You may have one yourself, too. You have long wished for a playmate and here is one come to live in the house with you.”

The door opened slowly and in came Jan. He did not look up at first. Then his eyes caught Love’s. It was the little boy of the fishing boat. His dear mother it was who had offered to take care of lonely little Love.

“THE KETTLE BUBBLED AND SANG A CHEERFUL WELCOME TO LOVE”

“You may help me drive the dogs that draw the milk wagon,” Jan said to Love the next morning after they had become very well acquainted over their breakfast of milk and oatmeal cakes.

“And so I can help to earn money for your kind mother,” Love said with shining eyes.

Jan had two dogs and a little two-wheeled cart to which he harnessed them every morning. Into the cart his mother put two shining pails of milk and a long handled dipper for measuring. To-day she put in some round, white cheeses and golden balls of butter. Off started the cart along the narrow street with Love running gaily along one side and Jan clattering along in his wooden shoes on the other side. The dogs knew where to stop almost as well as Jan did for they had made the trip so many times. The cheese and butter were soon gone, and every one had a pleasant smile for the little English lass. At one cottage, a Dutch housewife brought out a strange, earth-colored bulb that she put in Love’s hands. Then, smiling down into the little girl’s wondering face, she said:

“It is a rare one indeed. I give it to you that you may plant it and tend it all winter. When the spring comes, you will have a finer one than any child in all Amsterdam.”

Love thanked the woman but she puzzled over the hard, dry bulb as she and Jan walked home beside the empty milk cart. “It looks like nothing but an onion. What good is it, Jan?”

Jan’s eyes twinkled. “I know, but I won’t tell,” he said. “I want you to be surprised next spring. Come, Love, we will plant it in the corner of the garden that the sun shines on first in the spring. Then we will wait.”

As Jan dug a hole and Love planted the bulb, his words repeated themselves in the little girl’s lonely heart. She remembered, too, what her dear father had said last to her, “Wait patiently until I come, Love.” Would her patience bring the hard bulb to life or her father back, Love wondered sorrowfully.

The days passed, with blue skies and the bright sun shining down upon the canal, and then grew shorter. The storks flew south, and Love was very happy. Her days with Jan were busy, merry ones. She, too, had wooden shoes now; and Jan’s mother had made her a warm red skirt and a velvet girdle and a little, green, quilted coat. Love looked like a real little Dutch girl as she skated to school, with her knitting in her school bag to busy her fingers with when it was recess time.

There was never any place in England, Love thought, so merry and gay as the frozen canal in front of her new home in Holland. Everybody was on skates; the market women with wooden yokes over their shoulders, from which hung baskets of vegetables; and even a mother skating and holding her baby in a snug nest made of a shawl on her back. The old doctor skated, with his pill bag on one arm, to see a sick patient at the other end of the town; and long rows of happy children glided by, holding each other’s coats and twisting and twining about like a gay ribbon.

“Are you not glad, Love, that you came here to Holland to be my sister?” Jan asked as, holding her hand in his, he skated with Love to school.

“I am glad, Jan,” Love laughed back. “I feel as if it were a story book that I am living in, and you and your dear mother and our house and the canal were the pictures in it. But, oh, Jan, I wish very much that I could see my father—so tall and brave and strong!” Then she stopped. “We must be hastening, Jan,” she said, “or we shall be late for school.” But to herself, Love was saying, “Be patient.”

Spring came early that year in Amsterdam. The ice melted and the canals were once more blue ribbons of water. The sails of the windmills whirred, and the housewives scrubbed their sidewalks until the stones were clean enough to eat from. The storks built again in the red chimneys and, everywhere, the tulips burst into bloom. Love had never seen such beautiful flowers in all her life. There was no garden in all Amsterdam so small or so poor as not to have a bed of bright red and yellow tulips.

With the first sunshine, Love went out to the garden where she and Jan had planted the ugly, hard bulb. How wonderful; her patience had been rewarded! There were two tall, straight green leaves and between them, like a wonderful cup upon its green stem, a great, beautiful tulip. It was larger than any of the others. It was not red or yellow like the others, but pink, like a rose, or a sunrise cloud, or a baby’s cheek.

“Come, Jan; come, mother,” cried Love, and then the three stood about the pink tulip in admiration.

“It is the most beautiful tulip in all Amsterdam,” said Jan.

“It is worth money,” said his mother. “Some one would pay a good price for the bulb.”

Love remembered what Jan’s mother had said. As the days passed and the pink tulip opened wider and showed a deeper tint each day, a plan began to form in the little girl’s mind. She knew that there was not very much money in Jan’s home to which she had been so kindly welcomed. She knew, too, that nothing was so dear to the people of Holland as their tulips. Strange tales were told; how they sold houses, cattle, land, everything to buy tulip bulbs.

JAN AND HIS DOG CART

One Saturday when Jan was away doing an errand for his mother, Love dug up her precious pink tulip and planted it carefully in a large flower pot. With the pot hugged close to her heart, she went swiftly away from the house, down the long steps, and as far as the road that led along the coast of the sea below the dike. Here, where great merchant ships from all over the world anchored almost every day, Love felt sure that some one would see her tulip and want to buy it.

There was such a crowd,—folk of many nations busy unloading cargoes,—that at first no one saw the little girl with the flower in her arms. Up and down the shore she walked, a little frightened but brave. She held the flower high, and called in her sweet voice, “A rare pink tulip. Who will buy my pink tulip?”

Intent on holding the flower carefully, she came suddenly in front of a man who had been walking in lonely fashion up and down the shore. She heard him call her name eagerly.

“Love! Love! Oh, my little Love!”

Looking up, Love almost dropped the tulip in her joy. Then she set it down and rushed into his arms.

“Father, dear father! Oh, where have you been so long?” she cried.

It was a story told between laughter and tears. Goodman Bradford, only a short time since released from prison, had come straight to Amsterdam, but he had been able to find no trace of Love. Mistress Brewster had gone on with the Pilgrims to America, and there was no one to tell Goodman Bradford where his little daughter was. Now, he could make a home for her and reward Jan’s mother.

“I was patient,” Love said, “as you bade me be, and see,” she cried as, hand in hand, they reached the quaint little cottage where Jan and his mother stood at the door to greet them, “in good time they both came to me—the pink tulip, and my father.”

“See to it, Preserve, that you win a colored ribbon from the schoolmaster to-day,” Mistress Edwards said as she turned from her task of polishing the pewter platter to look at the boy who stood in the doorway of the log cabin.

“THE LOG CABIN WAS BUT A ROUGH HOME”

“This is the day, I hear, on which the good-conduct ribbons are given out for the month, brightly dyed ones for the boys and girls whose lessons have been well learned, and black for the dunces. There is no chance of your coming home to me to-night without a ribbon of merit, is there?” The Colonial mother crossed the room and put her hands on her lad’s shoulder, looking anxiously into his honest brown eyes.

“No, mother,” Preserve answered. “At least I have hopes of winning a ribbon. Not once this month have I failed in my sums, and I can read my chapters in the Bible as well as any child in school.”

“That is good!” Mistress Edwards said, pulling the boy’s long, dark cloak more closely about him and smoothing the cloth of his tall hat.

Preserve Edwards was a Puritan lad of many years ago. The log cabin that he was leaving to walk two miles through the clearing and across the woods to school was but a rough home. A few straight chairs and a hard settle, made of logs and standing by the fireplace, a deal table and the few pewter utensils, were almost the only furnishings of the living room. In one corner stood an old musket. Mistress Edwards looked toward it now in fear.

“Do you come home as soon as school is out, Preserve. I pray you do not linger on the way to play hare and hounds with the other boys and girls of the village. Remember, my boy, that your father is away with the horse these two days to fetch back a piece of linsey-woolsey cloth and some flour from Boston for me. He is not likely to come home for some days yet, and I am full of strange dread at what I saw in the cornfield this morning.”

“What did you see, mother?” Preserve’s eyes opened wide with wonder.

“It was not so much what I saw, but what it portended for us,” Mistress Edwards said. “It was only a flash of color, like painted feathers, among the withered stalks of corn. It minded me of Big Hawk’s headdress. If he were to find out that we were alone, one helpless woman and a boy of twelve here, I think it would go badly with us.”

Preserve laughed bravely. Then he reached up to kiss his mother good-bye.

“It was no more than a red-winged blackbird that you saw,” he said, “or perhaps it was a bright tanager. The birds are getting ready to flock, now, for they feel the autumn chill in the air. But I will hurry home—with my ribbon,” Preserve added.

Then he ran down the little path to the gate in the paling that surrounded the cabin, his speller under his arm, and his high-heeled, buckled shoes making the dry leaves scatter as he went.

It was a long road and a lonely one to the log schoolhouse. Preserve took his way through the cornfield where the dried stalks, rattling in the cold wind, made him think of the songs that he had heard Big Hawk and his tribe sing the last time they attacked the little Colonial settlement. That had been some months since, now, and Preserve could find no traces of footprints or any other marks of Indians in the cornfield.

“My mother had a fear for nothing,” Preserve said to himself. He went through a bit of woods, next, and pulled a small square of bark from one of the many birch trees that stood there, so white and still. It was for Preserve to write his sums upon in school, and as he hurried on he repeated his tables over and over to be sure that he knew them well.

There were log cabins scattered here and there, and from these came other boys and girls who followed Preserve on the way to school. Deliverance Baxter joined Preserve. She wore a long, scant, gray frock, and her yellow hair was tucked tightly inside a close, white cap. A white kerchief was folded neatly around her neck, and she, also, wore big buckles on her black slippers. Her eyes twinkled roguishly, though, as she chatted to Preserve.

“There is no doubt at all, Preserve, but that you will wear home the long streamers of red ribbon on your cape this afternoon. I have been quite as perfect as you in my lessons for the month, but, woe is me, I did a great wrong yesterday. You know that Master Biddle, our schoolmaster, has just purchased a new wig from Boston town. The queue in the back is so unusually long and tied with such a large bow that it caught my eye when I was getting the pile of copy books from behind his desk. I know not, Preserve, what witchery was in my fingers, but I tied Master Biddle’s queue to his chair. When he stood up, why, his wig was greatly disarranged; and I must needs stay after school until dusk, sitting on the dunce’s stool. I am most sorry, and will never be so witch-like again. You see I stand small chance of the ribbon, now, Preserve.”

“‘I TIED MASTER BIDDLE’S QUEUE TO HIS CHAIR’”

The boy laughed, but he took the little girl’s hand comfortingly in his. Reaching in his lunch bag, he took out a red apple and slipped it into the big pocket that hung at her side.

“You were always a bit roguish in spite of your Puritan dress and sober living, Deliverance,” he said. “Never mind about the ribbon. If I should win it, why, there is all the more chance of its being yours the next time. Here we are! See to it, Deliverance, that you tie no more queues to-day. Oh, see how finely Master Biddle is dressed for giving out the prizes!” Preserve said as they reached the schoolhouse door and took their places behind the rude desks, built of boards and resting on pegs in the floor.

Other children were quietly taking their places in the little schoolroom, the smaller ones perched on hard benches made of logs. They all looked in awe at the schoolmaster, who stood on a platform, facing them. He wore a smart velvet coat with long tails, and inside it could be seen a waist coat which was very long and a fine white shirt with stiffly-starched ruffles. His knee breeches were of velvet like his coat, and there were silver buckles at the knees as well as on his shoes. A stiffly-ironed stock was wound about his neck, and worn to keep his head stiff and straight as became the dignity of the times. Above all was his white powdered wig, neatly braided in the back.

Looking at Master Biddle alone was enough to make the children of the Colonies sit up very straight and recite their lessons as well as they could. There was a prayer first, and then the boys and girls recited their reading, spelling, and arithmetic. Their pencils were thick plummets of lead and their copy books were made of foolscap paper, sewed in the shape of books and carefully ruled by hand. At eleven o’clock came recess, and at the end of the afternoon the awarding of the good-conduct ribbons.

“For perfect deportment,” Master Biddle announced as he pinned a bow of blue ribbon to one boy’s cape.

“For poor lessons!” he said, sadly, as he fastened a black bow to another. Then he held up a red bow with especially long, streaming ends.

“For perfect deportment, and for perfect lessons,” he said, as he fastened the red ribbon bow to Preserve Edward’s cape.

To-day it would seem but a small prize, but in the eyes of these Puritan boys and girls of so many years ago, the bow of ribbon, its streamers of red gayly flying over the long cape of a boy or the dull linsey-woolsey frock of a little girl, was a mark of great honor indeed. Ribbons were scarce and high in price in those days. Colors for children were almost forbidden, and for their elders as well. So Preserve walked out of the school door at the end of the day with his head very high and started home as proudly as any soldier wearing a decoration for bravery.

He did not notice how the dusk was settling down all about him. The trees on either side, made dark shadows and there was no sound except the whir of a partridge’s wing or the rattle of a falling nut. He did not hear the soft footfall behind him until Deliverance, breathless and her face white with fear, was upon him. She laid a soft hand on his shoulder and whispered in his ear:

“I beg you, Preserve, to let me walk with you. I know that it is not far to my cabin, but all the way through these woods I have heard strange sounds and I fancy, even now, that I see shapes behind the trees and bushes.”

Preserve took the timid little girl’s hand and tried to laugh away her fears.

“So was my mother afraid this morning, at nothing,” he said. “She was of a mind that she saw Indians—Oh!” the boy’s voice was suddenly hushed.

Towering in the path in front of the children, like a great forest tree dressed in its gorgeous cloak of gaudy autumn leaves, stood the Indian chief, Big Hawk. He wore his war paint and his festival headdress of hawk’s feathers. Slung over his blanket were his bow and a quiver full of new arrows. It seemed little more than a second before the edges of the path and the deep places among the trees on either side were alive with the Indians of Big Hawk’s tribe.

“HE POINTED TOWARD HIS TRIBE’S CAMPING PLACE”

Big Hawk looked at the frightened children, indicating with gestures what was his plan. He pushed back the white cap from Deliverance’s pale forehead and laid his hand on the little girl’s sunny hair. Then he pointed toward his tribe’s camping place in the west. He wanted to take Deliverance there and hold her for a ransom. To Preserve he made gestures showing that he wished him to lead the way to the Edwards’ cabin that they might plunder it before going back that night.

Deliverance clung, crying, to Preserve. He tried to be brave, but it was a test for a man’s courage, and he was only a boy.

It was a second’s thought and a strange whim of a savage that saved the two. The wind of the fall blowing through the trees caught the ends of Preserve’s ribbon of honor and sent them, fluttering like tongues of flame, against the dark of the tree trunks. The color caught Big Hawk’s eye, and he touched the bow on Preserve’s cloak with one hand.

Quick as a flash a thought came to Preserve. He drew back from Big Hawk’s touch and put his own hands over the ribbon as if to guard it.

“Heap big chief!” Preserve’s voice rang out, brave and clear. Then, after waiting a second, he unpinned the red bow and held it, high, before Big Hawk’s face.

“Big Hawk, heap bigger chief!” he said, as he went boldly up to the Indian and fastened the ribbon on his blanket. Then he motioned to Big Hawk to return to his camp and show the rest of the tribe his new decoration. A slow smile overspread Big Hawk’s painted face. Then he turned and, motioning to his braves to follow him, went silently back through the woods, leaving Preserve and Deliverance alone, and safe.

Deliverance was the first to speak.

“My heart does beat so fast I can scarcely breathe, Preserve. Oh, but you are a brave boy! What shall we do now?” the little girl asked.

“Run!” said Preserve, without a moment’s hesitation. “We had best run like rabbits, Deliverance!”

Hand in hand, the two scampered along, Preserve helping the little girl over the rough places, until the light from a candle in Deliverance’s cabin was in sight. Her father had come home early, and when the children told him of their adventure, he set out to warn the rest of the settlers of the danger so bravely averted, and put them on guard against the Indians.

Preserve went on home, alone. His mother stood in the cabin door, anxious because he was so late.

“No ribbon? Oh, my lad, why have you disappointed me!” she said when she saw him.

“Big Hawk wears my decoration,” Preserve said, as he told his story. “But I think that Master Biddle would have rather that little Mistress Deliverance, for all her witching ways, had his red bow,” he finished, laughing.

“It may chance that you will not be able to return by Thanksgiving Day?” Remember Biddle asked with almost a sob in her voice.

A little Puritan girl of long ago was Remember, dressed in a long straight gown of gray stuff, heavy hobnailed shoes and wearing a white kerchief crossed about her neck. She stood in the door of the little log farm-house that looked out upon the dreary stretch of the Atlantic coast with Plymouth Rock raising its gray head not so very far away.

No wonder Remember felt unhappy. Her mother was at the door, mounted upon their horse, and ready to start away for quite a long journey as journeys were counted in those days. She was going with a bundle of herbs to care for a sick neighbor who lived a distance of ten miles away. It had been an urgent summons, brought by the post carrier that morning. The neighbor was ill, indeed, and the fame of Mistress Biddle’s herb brewing was well known through the countryside.

She leaned down from the saddle to touch Remember’s dark braids. The little girl had run out beside the horse and laid her cheek against his soft side. Her father was far away in Boston, attending to some important matters of shipping. Her mother’s going left Remember all alone. She repeated her question, “Shall I be alone for Thanksgiving Day, mother, dear?” she asked.

“‘SHALL I BE ALONE FOR THANKSGIVING DAY, MOTHER, DEAR?’”

Her mother turned away that the little daughter might not see that her eyes, as well, were full of sorrow.

“I know not, Remember. I sent a letter this morning by the post carrier to Boston telling your father that I should wait for him at Neighbor Allison’s, and if I could leave the poor woman he could come home with me. I hope that we shall be here in time for Thanksgiving Day, but if it should happen, Remember, that you must be alone; take no thought of your loneliness. Think only of how much cause we have for being thankful in this free, fertile land of New England. And keep busy, dear child. You will find plenty to do in the house until my return.”

Throwing the girl a good-bye kiss, Mistress Biddle gave the horse a light touch with her riding whip and was off down the road, her long, dark cloak blowing like a gray cloud on the horizon in the chill November wind.

For a few moments Remember leaned against the beams of the door listening to the call of a flock of flying crows and the crackling of the dried cornstalks in the field back of the house. Beyond the cornfield lay the brown and green woods, uncut, save by an occasional winding Indian trail. The neighboring cabins were so far away that they looked like toy houses set on the edge of other fields of dried cornstalks. Looking again toward the woods Remember shivered a little. She saw in imagination, a tall, dark figure in gay blanket and trailing feather headdress stalk out from the depths of the thicket of pines and oaks. Then she laughed.

“There hasn’t an Indian passed here since early in the summer,” she said to herself. “Mother would not have left me here alone if she had not known that I should be quite safe. I will go in now and play that I am the mistress of this house, and I am getting it ready for company on Thanksgiving Day. It will be so much fun that I shall forget all about being a lonely little girl.”

It was a happy play. Remember tied one of her mother’s long aprons over her dress to keep it clean, and began her busy work of cleaning the house and making it shine from cellar to ceiling. She sorted the piles of ruddy apples and winter squashes and pumpkins in the cellar, and rehung the slabs of rich bacon and the strings of onions. As she touched the bundles of savory herbs that hung about the cellar walls, Remember gave a little sigh.

“I see no chance of these being used in the stuffing of a fat turkey for Thanksgiving,” she said to herself. “It may be that I shall have to eat nothing but mush and apple sauce for my dinner, and all alone. Ah, well-a-day!” She began to sing in her sweet, child voice one of the hymns that she had learned at the big white meeting-house:

“The Lord is both my health and light;

Shall men make me dismayed?

Since God doth give me strength and might,

Why should I be afraid?”As she sang, Remember lifted a bucket of soft soap that stood on the cellar floor and tugged it up to the kitchen. Then she went to work with a will.

Several days passed before Remember had cleaned the house to her satisfaction. On her hands and knees she scoured the floors, her rosy hands and arms drenched with the foaming soapsuds. Afterward she sprinkled sand upon the spotless boards in pretty patterns as was the fashion in those days. She swept the brick hearth with a broom made of twigs, and she scoured the pewter and copper utensils until they were as bright as so many mirrors. She washed the wooden chairs until the bunch of cherries painted upon the back of each looked bright enough to pick and eat. She dusted the straight rush-bottomed chairs and the settle that stood by the side of the fireplace. Even the tall clock in the corner had its round glass face washed. Then Remember stood in the center of the kitchen looking at the good result of her work.

“My mother, herself, could have done no better!” she thought. Then she looked at the keg that had held their precious store of soft soap. There was no soap to be bought in those long-ago days; the Puritans were obliged to make their own.

“I have used up all the soap. Oh, what will my mother say at such waste? What shall I do?” Remember said, in dismay.

She sat down by the fire and thought. Suddenly she jumped up. A happy plan had come to her.

“I will make a mess of soap,” Remember said to herself. “I have helped mother to make soap many a time and I can do no more than try. It is yet some days until Thanksgiving and I should be sadly idle with nothing more to do, now that the house is put so well in order.”

The soap-making barrel, a hole bored in the bottom, stood in a corner of the cellar; it was light enough so that Remember could easily handle it and she was strong for her twelve summers and winters. In the bottom of the barrel she put a layer of clean, fresh straw from the shed and over this she filled the barrel as far as she could with wood ashes. Then she rolled, and tugged, and lifted the barrel to a high bench that stood by the kitchen door, taking care that the hole was just above a large, empty bucket. Then Remember brought pails of water and, standing on a stool, poured the water into the barrel until it began to drip down through the ashes and the straw into the bucket below. It looked rather dirty as it filtered down into the bucket but Remember took good care not to touch it with her fingers for she knew that it had turned into lye. Late in the afternoon Remember took out a hen’s egg and dropped it into the bucket to see what would happen.

“REMEMBER BROUGHT PAILS OF WATER”

“It floats!” she said. “Now I am sure that I made the lye right and I can attend to the grease to-morrow.”

Remember had to start a huge fire the next day and she got out the great black soap kettle, filled it with the lye and hung it over the fire. Into this she put many scraps of meat fat and waste grease that her mother had been saving for just such a soap-making emergency as this. It bubbled and boiled and Remember carefully skimmed from the top all the bones and skin and pieces of candle wicking that rose, as the lye absorbed the grease, and cooked it into a thick, ropy mixture. It looked very much like molasses candy as it boiled and after a while Remember knew that it was done. She lifted the kettle off the fire and poured the thick, brown jelly, that was now good soft soap, into big earthenware crocks to cool.

“I made the soap quite as well as my mother could,” Remember said to herself with a great deal of satisfaction as she put the crocks, all save one, in the cellar. This one she kept for use in the kitchen.

“There’s not another thing that I can think of to do,” Remember said now. She looked out of the window at the bleak, bare fields behind which the November sun was just preparing to set in a flame-colored ball. “Here it is the afternoon before Thanksgiving Day and mother and father are not home yet, and we haven’t anything in the house for a Thanksgiving dinner!” She looked toward the woods now. What was that?

A speck of color that she could see in the narrow footpath between the trees suddenly came nearer, growing larger and brighter all the time. Remember could distinguish the gaudy blanket, bright moccasins, and feather headdress of an Indian. Stalking across the field, he was fast approaching their little log house which he could easily see from the woods and which seemed to offer him an easy goal. Remember covered her face with her hands, trying in her terror to think what to do.

The bolt on the kitchen door was but a flimsy protection at best. Remember knew that the Indian would be able to wrench it off with one tug of his brawny arm. She knew, too, that it had been the custom of the Indians who were encamped not far off to take the children of the colonists and hold them for a high ransom.

“The white face takes our lands; we take the papoose of the white face,” they had threatened, and they were cruel indeed to the children whom they held, especially if their parents were a long time supplying the necessary ransom. But it had been so long now since an Indian had been seen in their little settlement, that Remember’s mother had felt quite safe in leaving her.

Remember looked now for a place to hide. There was none. The cellar would be the first place, she knew, where the Indian would look for her. The tall clock was too small a space into which to squeeze her fat little body; and there was no use hiding under the bed for she would be dragged out at once. Remember turned, now, hearing a footstep. The Indian, big, brown, and frowning had crossed the threshold and stood in the center of the room. His blanket trailed the floor; over his shoulder was slung a pair of wild turkeys he had killed.

Remember trembled, but she faced him bravely.

“How!” she said, reaching out a kind little hand to him. The Indian shook his head, and did not offer to shake hands with the little girl. Instead, he pointed to the door, motioning to her that she was to follow him.

Remember’s mind worked quickly. She knew that Indians were fond of trinkets and could sometimes be turned away from their cruel designs by means of very small gifts. She ran to her mother’s work basket and offered him in succession a pair of scissors, a case of bright, new needles, a scarlet pincushion, and a silver thimble. Each, in turn, the Indian refused, shaking his head and still indicating by his gestures that Remember was to follow him.

Now he grasped the little girl’s hand and tried to pull her. There was no use resisting. But just as they reached the door the Indian caught sight of the crock of soft soap—dark, sticky, and strangely fascinating to him. He stuck one long brown finger in it and started to put it in his mouth, but Remember reached up and pulled his hand away. She shook her head and made a wry face to show him that it was not good to eat.

“How?” he questioned, pointing to the soap.

Remember pulled from his grasp. Pouring a dipperful of water in a basin, she took a handful of the soap and showed the Indian how she could wash her hands. As he watched a look, first of wonder, and then of pleasure, crept into his face. He smiled and looked at his own hands. They were stained with earth and sadly in need of washing. Remember refilled the basin with water and the Indian, helping himself to a huge handful of the soap, washed his hands solemnly as if it were a kind of ceremony.

“THE INDIAN, HELPING HIMSELF TO A HUGE HANDFUL OF THE SOAP, WASHED HIS HANDS SOLEMNLY”

As Remember watched him, her heart beat fast indeed. “As soon as he finishes he will take me away,” she thought.

Slowly the Indian dried his hands on the towel she gave him. Then he picked up the crock of soft soap. He set it on his shoulder. Pointing to the pair of turkeys that he had laid on the table to show that he was giving them to Remember in exchange for the soap, he strode out of the door and was soon lost to sight in the wood’s path.

Remember dropped down in a chair and could scarcely believe she was really safe. A quick clatter of hoofs roused her. She darted to the door.

“Father, mother!” she cried.

Yes, it was indeed they; her father riding in front with her mother in the saddle behind.

“Just in time for Thanksgiving!” they cried as they jumped down and embraced Remember.

“And I’m here, too, and we have a pair of turkeys for dinner,” Remember said, half smiles and half tears, as she told them her strange adventure.

“If you will but help me, Hannah, as a little girl of ten should, with the candle dipping you will forget to fret all the day long about the home coming of father and Nathaniel,” Mistress Wadsworth said, laying a kind hand on the bent head of the little daughter.

All through the long, gray afternoon Hannah had looked out of the diamond-shaped panes of the window, past the fields of dried cornstalks that looked as if they were peopled with ghosts in their garments of snow, and toward the forest of pointed, green firs beyond. She turned from the window now, as her mother spoke to her, and looked up bravely, trying to smile.

“You are quite as anxious about dear brother Nathaniel and father as I am,” she said. “It is now two weeks since they started away with the sledge to bring us back the wood for the winter. Father said that it would take him no longer than ten days at the utmost. Brother Nathaniel is only twelve, and young for so hard a journey. There have been storms, and there are Indians—” a sob caught the little girl’s voice.

It was Mistress Wadsworth’s turn to look out now with saddened eyes through the window and into the falling twilight of the New England winter.

“Your father said that he would be home for Christmas Day,” she said, “and he will keep his word unless some ill befalls them. In the meantime, we will make the candles. Then the house will be brighter to welcome them than when we burn only pine knots. To-night, Hannah, we will measure the candle wicking for we shall be busy the greater part of to-morrow with the dipping.”

As the two, both mother and little daughter dressed in the long, straight frocks of dark homespun and the white caps that were worn in those long-ago days, bent over the pine table after supper, they looked very much alike. The fire in the great brick fireplace had a sticky, pitchy lump of fire wood upon the top. It was a pine knot, and the only light in the room. It flickered upon the bright rag rugs of the floor and the painted chairs with their scoured rush seats and on the green settle, making a pleasant, cheerful glow. They tried not to hear the wind that howled down the chimney, or think of the beloved father and little brother who were so far away in a bleak lumber clearing.

Measuring the wicks for the tallow candles was so painstaking a task that Mistress Wadsworth did it herself; Hannah, standing beside her, only watched. She stuck an old iron fork straight up in the soft wood of the table some eight inches from the edge. Around it she threw half a dozen loops of the soft candle wicking. She cut these loops off evenly at the edge of the table. Then she measured and cut more until she had made several dozen, all exactly the same length. As she worked, they talked together of what Hannah most loved to hear about, Christmas in her dear mother’s girlhood home, merry England.

“They had polished brass sconces fastened everywhere to the walls,” Mistress Wadsworth said. She could almost see the bright scene in the dim shadows cast by the pine knots. “In every sconce there would be tall white candles. We burned more candles in a night then than we can afford to burn in a month now,” she sighed.

“And there was a fir tree from the forest brought into the hall for the children,” Hannah continued, for she knew the story well. “There were candles on the tree, lighted and shining. Oh, it must have been a pretty sight to see the children dance about the Christmas tree and sing their carols! We never have Christmas trees with candles in this new land, do we mother? Why?” she asked.

“The Governor decrees that we shall not continue the customs of the land that we have left so far behind,” Mistress Wadsworth replied, but with another sigh. “And now to bed, little daughter, for we shall be busy indeed on the morrow.”

When morning came, Hannah found that her mother had worked after she had gone to bed, twisting and doubling each candle wick and slipping through the loop a candle rod. This rod was a stick like a lead pencil but over three times as long. Six wicks hung from each rod. They looked, Hannah thought, as if they were so many little clothes lines. Then the big iron kettle filled with clean white tallow was swung on a heavy iron hook in the fireplace. As the tallow melted, Mistress Wadsworth directed Hannah as she tipped down two straight backed chairs and placed two long poles across them like the sides of a ladder with no rungs. Across these were laid the candle rods with their hanging wicks. Then the kettle was taken from the fire and set on the wide hearth, and the pleasant task of the candle dipping was begun.

One at a time, Hannah took the candle rods carefully by their ends and dipped the wicks for a second in the melted tallow. Then she put it back between the chairs to dry and took up another rod, dipping the wicks in the same way. When the last wicks had been dipped, the first ones were dry enough to dip again. With each dipping, the candles grew plump and straight and white. One candle rod, though, Hannah dipped only once in every three times. When her mother noticed this she said, “Little daughter, you are neglecting six of the candles. See how small they are!”

“HANNAH DIPPED THE WICKS FOR A SECOND IN THE MELTED TALLOW”

Hannah ran over, threw her arms about her mother’s neck and whispered something in her ear. Mistress Wadsworth shook her head at first; then she smiled.

“It can do no harm that I see,” she said. “It will be only a child’s play before Christmas and no cause for the Governor’s displeasure. Yes, little daughter, if you wish. If it brings joy to your sorrowful heart, I shall be glad.”

When the candle dipping was over and the precious candles were laid away to be burned only if the father and little Nathaniel came home, Hannah slipped six, as small as Christmas tree candles, from one rod and wrapped them carefully in a bit of fair white linen. They were her little candles, to be used as she wished.

The days, white with snow and very cold, wore on until it was only a week before the blessed Christmas day. There were slight preparations for it in the little New England settlement where Hannah lived for it was not thought fitting to be merry and gay at Christmas time these centuries ago. But at the small white meeting-house Hannah and the other little colonist children practised a carol to be sung on Christmas Day.

“Shout to Jehovah, all the earth,

Serve ye Jehovah, with gladness;

Before him bow, singing with mirth.”The children sang it as it was pitched by the elder’s tuning fork, and the tune was slow and dirge like. The tears came again to Hannah’s eyes as she tried to sing, for no word had come as yet of father and Nathaniel. A runner to the village brought word a few days before of attacks by the Indians on near-by parties of wood cutters. Could they have encountered the party with whom were father and Nathaniel, she thought?

THE TOWN CRIER

But Hannah’s secret kept her happy! A few days before Christmas she went to a near-by bit of woodland. She carried the old hatchet that Nathaniel had left at home, and she looked over the young fir trees until she found one that was well shaped, tiny, and as green as green could be. She chopped and hacked at the roots until she cut down the little tree. Then she tugged it home. As she held its prickly needles close to her warm cloak she whispered, “You are not to bear gifts, little Christmas tree, because that would not be right; only candles to light the way home for dear father and brother Nathaniel.”

At last it was three days before Christmas and evening in the little New England village. The town crier had taken his way through the narrow main street early in the afternoon,—a dismal enough looking figure in his long, black cloak and tall, black hat, and ringing his bell.

“Lost, in all probability, lost,” he called. “This Christmas time,” and then he gave the toll of names of the men and boys who had started out so many weeks before on the ill-fated lumber trip and from whom no word had come. As he reached the names, “Goodman Wadsworth, little Nathaniel Wadsworth,” Mistress Wadsworth cowered in front of the fire, her bowed head in her hands. But Hannah kissed her gently for comfort, and took out the little tallow candles that she had dipped. Then she set up the tiny fir tree, with the lighted Christmas candles, in front of the window that looked out upon the main street.

Now the village was black with the night. The fires were low, and the barred doors and windows shut in Hannah’s and her mother’s sadness. The long street was white with snow. A few glimmering stars shed a fitful path of light down it, but the houses were like so many tightly-closed eyes. They could hardly be seen at all.

“THE LITTLE WHITE BOY ... HAD PRINTED STRANGE CHARACTERS”

It was almost ten o’clock when an Indian boy, little Fleet-as-an-Arrow, like a flash of color in the dark of the night, darted down the street. He was wrapped from head to foot in his scarlet blanket. He was panting. His bare limbs were cold. He had come a long, long way without food since morning, but he did not stop running now that he was nearing his goal. The dim little town frightened him, though. He had never been in so strange a place before. The home that little Fleet-as-an-Arrow knew was a wide plain with a background of forests; his house was a painted wigwam; and his light was a camp fire. But he pressed against his heart a bit of white birch bark upon which a little white boy of his own age, brought to the camp a captive with a band of prisoners, had printed strange characters. It was not like the picture writing of the tribe, but it must be important for all that, Fleet-as-an-Arrow knew. The little white boy, whom this little Indian boy had grown to love like his own brother, had begged him to carry the writing to his mother.

“Go to the North,” he had said. So Fleet-as-an-Arrow had watched the moss on the trees and followed the north star. Here he was, but how could he tell in which of all these strange wigwams the mother of his little white friend lived?

Suddenly Fleet-as-an-Arrow’s dark eyes flashed into a smile. At the end of the street a bright light attracted him. He ran on, bravely following it. Of all the windows in the whole village this was the only one that was unbarred, and where the curtains were parted. As he came nearer the light, Fleet-as-an-Arrow’s heart almost stopped beating for admiration and wonder. Never in all his twelve years had the little Indian boy seen a sight like this. It was an evergreen tree such as he knew and loved in his own home forest, but it was covered with glimmering, sparkling, starry lights. There it stood, Hannah’s Christmas tree, the little tallow candles drawing Fleet-as-an-Arrow with Nathaniel’s message like a magnet.

“HE BEAT THE HEAVY OAK PANELS WITH HIS HALF-FROZEN, BROWN LITTLE HANDS”

He stopped at the door and beat the heavy oak panels with his half-frozen, brown little hands. When Mistress Wadsworth, followed closely by Hannah, opened it, frightened and dazed at the strange visit in the night, Fleet-as-an-Arrow looked at them a minute on the threshold. In the light of the little Christmas tree he could see Hannah’s pink cheeks and wide-open, blue eyes and the pale gold braids of her hair. Why, she looked like the boy that he had left in the Indian’s camp, Fleet-as-an-Arrow saw. He knew now that he had found the right place. He went inside and pulled the message, written with a bit of charcoal in scrawling letters on the square of birch bark, from beneath his blanket. Then he thrust it into Mistress Wadsworth’s hands. She read it in the glow of the fire.

“We are safe, but the Indians will not let us go without gifts of beads and corn. Send some men to fetch us.

Your son,

Nathaniel.”

With a glad cry, Mistress Wadsworth put her arms about the little Indian boy. Then, while she put on her bonnet and cloak and lighted the big, brass lantern, Hannah drew Fleet-as-an-Arrow up to the fire and brought him food. Running with her lantern from one sleeping house to another, Mistress Wadsworth soon roused the men of the village who organized themselves into a rescuing party.

When the first pale pink of the morning sun tinged the sky, the party, with the gifts which the Indians demanded as a ransom for their captives, was on its way. They carried Little Fleet-as-an-Arrow in front as their guide.

Such a Christmas Eve as it was. Father and Nathaniel, ragged and hungry, but safe, were home in time! Two of the large tallow candles in the polished brass candlesticks shone on the mantelpiece over the fireplace, and Hannah lighted the little Christmas tree again. She and brother Nathaniel, hands clasped happily together, sat in its light, so glad to be together again that they needed neither gifts nor sweets to make their Christmas joy.

The grim iron doors of the prison clanged shut and the turnkey fastened them. Hearing the sound, Desire touched the homespun sleeve of the little boy with whom she was walking home from market down the narrow street of the musty old town of Salem.

“Did you hear that sound of the locking of the doors, Jonathan? It means that they’ve caught and imprisoned another witch.”

The boy, a quaint little figure in his long trousers, short jacket, and ruffled shirt looked, wide-eyed, at the little girl. Quite as strangely dressed a child as Jonathan was small Desire, the only daughter of Elder Baxter who was high in authority in old Salem in those far-away days. Although not quite twelve summers and winters of the New England of a stern long-ago had painted Desire’s plump cheeks the pink of a rose and burned the shining gold of her hair, her gray frock with its short waist and long skirt nearly trailed the gray cobble stones of the street. Her soft brown hair was braided close to her head and pulled back tightly in front from her white brow and tucked out of sight beneath her stiff cap. A white kerchief was folded closely about her primly held shoulders and over her frock she wore a long, dark cape for the fall day was chill.

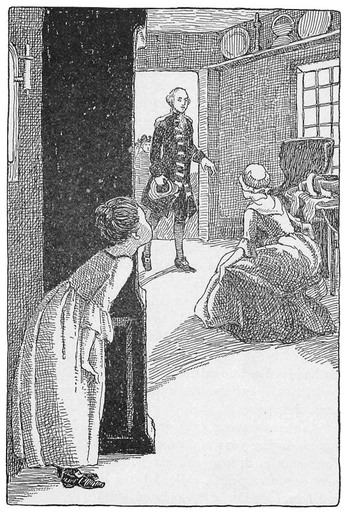

“‘DO YOU KNOW WHO THE WITCH IS, DESIRE?’ HE ASKED”

Jonathan set down the rush basket of food supplies that he was carrying for Desire, and he touched the iron paling that shut in the prison.

“Do you know who the witch is, Desire?” he asked, his voice low with awe.

“Not I,” the little maid answered, “but they do say that she has been brewing her spells for six months’ time before the elders caught her. I heard my father and mother talking about it only this morning. They said that before the day was over the witch that was the cause of all our recent troubles in Salem would be caught and safely imprisoned.”

“What troubles?” Jonathan asked.

“Have you not heard, Jonathan?” Desire lowered her voice and looked up and down the street to see that no one was listening to her.

“Abigail Williams was ill of the whooping cough and she had three fits which, as every one knows, is a sign that a witch had cast a spell over her. And Mercy Talcott’s teakettle boiled over and nearly scalded Mercy’s mother. On the way for some ointment at the doctor’s to put on her mother’s hand, Mercy saw the witch herself flying over the tops of the trees on Gallows Hill and,” Desire’s voice was a whisper now, “she was riding on a broomstick.”

“How did Mercy know that it was a witch, and how could she be riding on a broomstick?” asked the practical Jonathan.

Desire tossed her head. “I can’t explain that to you, Jonathan. It was toward evening and Mercy says that she saw a long, dark form in the trees and she heard the dry leaves rustle.”

“Crows!” said Jonathan.

“For shame, Jonathan,” said Desire. “Do you not know that the eyes of Mercy Talcott are keen for seeing witches. She is to be at the trial to-morrow, and identify the evil creature.” Desire repeated the words of her elders in those far-away Colonial days of ignorance and superstition. “When shall we rid ourselves of this pest of witchcraft in Salem?” she said.

“Well,” Jonathan said, swinging the basket upon his shoulder and leading the way along the street again, “There’ll probably be one less witch to-morrow for she won’t have a chance to escape if that tale-bearing Mercy Talcott is at the trial. Let us go on by the side street and see if Jack is safe at Granny Hewitt’s, Desire.”

The two children hastened their steps and passed the scattering little brown houses of old Salem. Their quaintly gabled roofs made them look like dolls’ cottages. The windows with their tiny diamond-shaped panes were neatly curtained with white. At one house, a little larger than the others and having no garden, they drew their breath.

“The Witches’ House,” said Desire.

It was here that so many of these unfortunate creatures of the dark days of Salem had been kept in confinement before they met their punishment in prison, on the ducking stool, or on Gallows Hill. A little farther along they passed a great white meetinghouse where a gilded weathercock pointed bravely to the sky and high, white pillars stood at either side of the doorway.

“The witch will be tried here in the morning,” Jonathan said, and the two children walked a little faster toward a pleasanter stopping place, Governor Endicott’s big white house, set in the midst of his fair English garden.

Even now, when the wind blew cold from the water front and rustled the cornstalks and rattled the red pods of the rose hips, the Governor’s garden was a pleasant place for a child to see. Bright little marigolds, defying the frost, lifted their orange blossoms along the path. Great beds of scarlet dahlias and purple asters made a mass of color. The late sun marked for itself a long, golden shaft across the sundial, and at the back of the house could be seen a patch of winter squashes and pumpkins mellowing in a sunny spot.

“Was not the Governor kind to give us the pumpkin?” said Jonathan.

“And wasn’t Granny kind to show us how to make it into so strange a hobgoblin of a creature as is our Jack?” added Desire. “She said that almost no other granny in old Salem was old enough to remember about carving a pumpkin into a face as they did long ago in England. She told me that we must keep it a secret until All Hallow E’en, and then take the pumpkin with a tallow drip shining inside him, lighting his funny face, down through the street to show the other children.”

“I lighted it last night,” Jonathan confessed. “I went to Granny’s house with a cheese ball that was a gift from my mother to Granny.”

“How did the pumpkin look?” asked Desire eagerly.

“Fearsome!” said Jonathan. “We put it in the window and I went outside in the dark to look at it. It had the appearance of a grinning monster,” the boy laughed at his memory of the Jack-o’-Lantern.

“Here we are at Granny’s. Let us go in a moment,” Desire said as the two stopped before a tumble-down cottage at the end of a tiny lane. Granny Hewitt lived alone there, a little wrinkled crone with a face like a brown walnut and eyes that shone like two stars. But her mouth, oh, that was the best part of Granny; all the children said that it made them think of their own dear mother’s when she smiled. How could a smile be lovelier than that?

Having no kin of her own, Granny Hewitt loved the boys and girls who passed her cottage every day on their way to and from school. She made molasses cookies and vinegar taffy for them. She put balm on their scratches, and covered their primers and spellers with pieces of bright calico. No wonder Desire and Jonathan wanted to stop a moment at Granny Hewitt’s house. They went up the white gravel path with its neat border of clam shells. Desire lifted the big brass knocker on the door, letting it drop with a clang.

“GRANNY HEWITT LOVED THE BOYS AND GIRLS”

There was no sound inside.

“She has gone to market,” Jonathan said.

“Well, good-bye, Jonathan,” Desire said, taking her basket from the boy’s hands. “I probably shall not see you to-morrow. It may be that my father will let me sit in our pew in the meeting-house during the witch’s trial.”

Jonathan’s eyes almost popped out of his head in surprise. “Could I go, too?” he asked.

“I’ll see if I can get you in,” Desire promised as the two friends parted.

The morning of the witch’s trial was as bright and peaceful as the fall sun lighting field and dingy streets and roofs could make it. By half-after seven, although the trial was not to begin until ten, the green common that surrounded the Second Meeting-house was a moving black and gray mass of stern men in their dark capes, buckled shoes, and tall hats, and gray-gowned women.

Inside the meeting-house every pew was filled. The platform was lined with the black-gowned elders, and the Governor himself, a dignified figure in his flowing cloak and powdered wig, occupied the pulpit. Desire sat, prim and quiet beside her mother, her little round head not much above the high back of the pew. On the other side sat Jonathan whose urgent request to come had been granted.

It was rumored that the witch who was about to be tried was of some repute in the practice of magic, and that she was to be made an example for any followers whom she might have.

Jonathan nudged Desire’s elbow. “Where is she?” he asked.

“Ssh,” the little girl put a warning finger to her lips. “They’ll bring her out in a minute.” As she finished her whispered warning, her father, Elder Baxter, rose and began to speak.

“We are met together to pass judgment upon a woman of Salem town who has wrought her magic arts to the undoing of its citizens. She has cast her spell over a child and thrown it into dire sickness. She has bewitched the kitchen of our neighbor, Elder Talcott. A child of twelve years and well versed in the art of discovering witchcraft saw this same witch after she had practised her arts. Mercy Talcott will please come to the platform. Bring in the witch.”

Desire and Jonathan craned their necks to see better as the black row of the elders parted to let in a bent, trembling little old lady. Two jailers guarded her, one on each side. She still wore her tidy white apron with its knitting pocket, and her white cap was tied neatly under her chin. She was shaking from head to foot with her fright. Her head was bent low so that no one could see her face. She held her Bible clasped closely to her heart.

At the same time Mercy Talcott, a little girl dressed like Desire but with a less winning face, stepped up, also, to the platform. It was the custom of those strange days to believe that certain children could identify witches, and Mercy was one of these children.

The elder spoke again, “I have not made one most important charge of all as I wish to make it in the presence of the prisoner, herself. She has a creature of some other kind than human with whom she consults on matters of witchery. It has been seen at night looking out of her window with glaring eyes and wide-open mouth set in its huge head.

“Look up, witch. Mercy Talcott, is this the witch that you saw leaving your house the day that your mother was burned?”

Slowly, and in terror the little old lady lifted her head. At the same time and in the same sobbing breaths Jonathan and Desire said, “It is Granny Hewitt!”

Mercy saw, too, who it was. She remembered the little rag doll that Granny had made her when she was a very little girl. It wore a gay pink calico dress, and its cheeks were stained red with pokeberry juice. Mercy caught her breath and hesitated. She knew that it was only in fancy that she had seen the broomstick and its wild rider. As she waited, Desire pulled Jonathan from his seat. Before her mother could question or stop them, the two children were at the front of the pulpit, facing the Governor.

Desire clasped her hands and raised them in pleading toward the great man who bent down toward her in surprise. The whole meeting-house was still as Desire spoke in her sweet, high voice.

“Your Excellency, I beg your mercy for our dear Granny. She is not a witch but a kind friend to all the children of Salem. It is I who should be punished in her place. If your Excellency will but think back to the last tithing day, you will remember that you gave two children, Jonathan and me, a pumpkin for our play. We took it to Granny Hewitt’s house and she helped us to make it into a Jack whose tallow drip, lighted, in Granny’s window some one saw and spoke of to you. My father did not know that it was my fault, else he would not have accused Granny. Oh, speak, Jonathan, and attest to the truth of what I am saying!”

She turned to the little boy but Jonathan, made courageous by Desire’s bravery, had gone to Mercy’s side.

“It was crows you saw on Gallows Hill,” he said in her ear. “You never, never saw Granny Hewitt riding on a broomstick. Say so.”

Mercy looked into Granny’s tear-stained face. Then, with a rush of love she threw herself into her arms. “I never saw Granny riding on a broomstick. She isn’t a witch,” Mercy declared.

The white doors of the meeting-house opened wide and the people waited with heads bowed, half in shame and half in joy, as Granny, surrounded by the children, passed into the sunshine and the freedom outside. Then they followed, making a kind of triumphal procession to the cottage at the end of the street. Kind hands led Granny all the way and kind hearts made her forget all about her experiences. In her window there still stood the grinning Jack-o’-lantern, and at sight of it bursts of laughter took away all thought of tears. One of the elders set it upon one of Granny’s fence posts and then held Desire up beside it.

“Hurrah for the Jack-o’-lantern witch,” some one said, and the crowd shouted their happiness and relief.

“THE JACK-O’-LANTERN WITCH”

“Did you see him to-day?” asked a little girl in gray, all excitement, as she opened the door to admit her brother.

The boy, shaking with the cold—for it was winter and his jacket was none too thick—set down his basket on the rough deal table, and leaned over the tiny fire that burned on the hearth. His eyes shone, though, as he turned to answer his sister.

“Yes, Beth, I saw him down at the wharf and he gave me this.” As he spoke, William drew from underneath his coat, where he had tucked it to surprise Beth, a crude little brush made of rushes bound together with narrow strips of willow.

“What is it?” Beth took the brush in her hands and held it up to the light, looking at it curiously. She made a quaint picture in the shifting light of the fire, a little Quaker girl of old Philadelphia, her yellow curls tucked inside a close-fitting gray cap, and her straight gray frock reaching almost to the heels of her heavy shoes.

“It is something new for cleaning,” William explained. He took the brush and began sweeping up the ashes on the hearth, as Beth watched him curiously. “Mr. Franklin brought a whole bunch of them down to the wharf to show to people, and he gave me one.”

“How did he make it?” Beth asked curiously.

“It took him a whole year, for it had to grow first,” William explained. “He saw some brush baskets last year that the sea captains had brought fruit in, lying in the wet on the wharf. They had sprouted and sent out shoots, so what did Mr. Franklin do but plant the shoots in his garden. They grew and this year he had a fine crop of broom corn, as he called it. He dried it, and bound it into these brushes. He has some with long handles, and he calls them brooms.”

The children’s mother had come in now from the next room and she grasped the hearth brush with eagerness.

“It is just what Philadelphia, the city of cleanliness, needs,” she said, as she went to work brushing the corners of the window sills and the mantle piece. “If we were to take more thought of our houses and less of these street brawls as to who is for, and who is against the king, it would be better.”

“That is what Mr. Franklin does,” William said. “Do you remember how the streets were full of quarreling folk last summer, and a hard thunder storm came up that every one thought was sent directly from the skies as a punishment for our wickedness? The women and children were crying, and the men praying when Mr. Franklin came in their midst. I can see him now, looking like a prophet with his long hair flowing over his shoulders and his long cloak streaming out behind him. As the skies flashed with lightning and the thunder crashed he told them not to be afraid. He said that he would give them lightning rods to put on their houses that would keep them from burning down.”

“Yes,” their mother said. “He helps us all very much. Mr. Franklin is truly our good neighbor in Philadelphia.”

As her mother finished speaking, Beth emptied the basket that William had brought in. There was not a great deal in it—a little flour, some tea, a very tiny package of sugar, and some potatoes. She arranged them on the shelves in the kitchen, shivering a little as she moved about the cold room.

Chill comfort it would seem to a child to-day. Philadelphia was a new city, and these settlers from across the sea had brought little with them to make their lives cheerful. Outside, huge piles of snow drifted the narrow streets and were banked on the low stone doorsteps of the small red brick houses. A chill wind blew up from the wharves and such of the Friends as were out hurried along with bent heads, against which the cold beat, and they wrapped their long cloaks closely around them.

It was almost as cold in the Arnold’s house as it was outside. The children’s father had not been able to stand the hardships of the new country, and there were only Beth, and William, and their mother left to face this winter. Mrs. Arnold did fine sewing, and William ran errands for the sailors and merchantmen down at the wharves, having his basket filled with provisions in return for his work. It was a hard winter for them, though; no one could deny that.

Mrs. Arnold drew her chair up to the fireplace now and opened her bag of sewing. Beth leaned over her shoulder as she watched the thin, white fingers trying to fly in and out of white cloth.

“Your fingers are stiff with the cold,” Beth exclaimed as she blew the coals with the bellows and then rubbed her mother’s hands.

“Not very,” she tried to smile.

“Yes, very,” William said as he swung his arms and blew on his finger tips. “We’re all of us cold. It would be easier to work if we could only keep warm.”

Just then they heard a rap at the brass knocker of their door. Beth ran to open it, and both children shouted with delight as a strange, slightly stooping figure entered. His long white hair made him look like some old patriarch. His forehead was high, and his eyes deep set in his long, thin face. His long cloak folded him like a mantle. He reached out two toil-hardened hands to greet the family.

“Mr. Franklin!” their mother exclaimed. “We are most glad to see you. You are our very welcome guest always, but it is poor hospitality we are able to offer you. Our fire is very small and the house cold.”

“A small fire is better than none,” their guest said, “and the welcome in Friend Arnold’s house is always so warm that it makes a fire unnecessary. Still,” he looked at the children’s blue lips and pinched cheeks, “I wish that your hearth were wider.”

He crossed to the fireplace, feeling of the bricks and measuring with his eye the breadth and depth of the opening in the chimney. He seemed lost in thought for a moment, and then his face suddenly shone with a smile like the one it had worn when he had seen the first green shoots of the broom corn pushing their way up through the ground of his garden.

“What is it, Mr. Franklin?” Beth asked. “What do you see up in our chimney?”

“A surprise,” the good neighbor of Philadelphia replied. “If I make no mistake in my plans, you will see that surprise before long. In the meantime, be of good cheer.”

He was gone as quickly as he had come, but he had left a glow of cheer and neighborliness behind him. All Philadelphia was warmed in this way by Benjamin Franklin. Whenever he crossed a threshold, he brought the spirit of comfort and helpfulness to the house.

“What do you suppose he meant?” Beth asked as the door closed behind the quaint figure of the man.

“I wonder,” William said. Then he took out his speller and copy book and the words of their visitor were soon forgotten.

But all Philadelphia began to wonder soon at the doings at the big white house where Benjamin Franklin lived. The neighbors were used to hearing busy sounds of hammering and tinkering coming from the back where Mr. Franklin had built himself a workshop. Now, however, he sent away for a small forge and its flying sparks could be seen and the sound of its bellows heard in the stillness of the long, cold winter nights. Great slabs of iron were unloaded for him at the wharf, and for days no one saw him. He was shut up in his workshop and from morning until night passers-by heard ringing blows on iron coming from it as if it were the shop of some country blacksmith.

“Benjamin Franklin wastes his time,” said some of the Philadelphians. “He should be in the town hall, helping us to settle some of our land disputes.”

But others spoke more kindly of the man of helpful hands.

“Mr. Franklin is making Philadelphia truly a City of Friends by being the best Friend of us all,” they said.

None could explain Benjamin Franklin’s present occupation, though.

In the middle of the winter Beth and William and their mother went to a friend’s house to stay for a week. Mrs. Arnold was not well, and the house was very cold. The week for which they were invited lengthened into two, then three.

“We must go home,” Mrs. Arnold said at last. “Mr. Franklin said that he would stop this afternoon and help William carry the carpet bag. It is time that we began our work again.”

“THEY TOOK THEIR HOMEWARD WAY THROUGH THE SNOW”

As they took their homeward way through the snow, they noticed, again, the happy smile on Mr. Franklin’s kind face. He held the handle of the bag with one hand and Beth’s chilly little fingers with the other. He was the spryest of them all as they hurried on. They understood why, as they opened the door of their home.

They started, at first, wondering if, by any chance they had come to the wrong house. No, there were the familiar things just as they had left them; the row of shining copper pans on the wall, the polished candlesticks on the mantel piece, the warming pan in the corner and the braided rag rugs on the floor. But the house was as warm as summer. They had never felt such comforting heat in the winter time before. The fireplace, that had been all too tiny, was gone. In its place, against the chimney, was a crude iron stove, partly like a fireplace in shape, but with a top and sides that held and spread the heat of the glowing fire inside until the whole room glowed with it.

THE FIRST STOVE

“That is my surprise,” Mr. Franklin explained, rubbing his hands with pleasure as he saw the wonder and delight in the faces of the others, “an iron genie to drive out the cold and frighten away the frosts. You can cook on it, or hang the kettle over the coals. It will keep the coals alive all night and not eat up as much fuel as your draughty fireplace did. This is my winter gift to my dear Friend Arnolds.”

“Oh, how wonderful! How can we thank you for it? We, who were so poor, are the richest family in all Philadelphia now. Now I shall be able to work!” the children’s mother said.

Beth and William put out their hands to catch the friendly warmth of the fire in this, the first stove, in the City of Friends. It warmed them through and through. Then William examined its rough mechanism so that he would be able to tend it, and Beth bustled about the room, filling the shining brass teakettle and putting a spoonful of tea in the pot to draw a cup for their mother and Mr. Franklin. At last she turned to him, her blue eyes looking deep in his.

“You are so good to us,” Beth said. “Why did you work so hard to invent and make this iron stove for us?”

The kindest Friend that old Philadelphia ever had stopped a second to think. He never knew the reason for his good deeds. They were as natural as the flowering of the broom corn in his garden. At last he spoke:

“Because of your warm hearts, little Friend,” he said. “Not that they needed any more heat, but that you may see their glow reflected in the fires you kindle in my stove.”

And so may we feel the kindly warmth of Benjamin Franklin’s heart in our stoves, which are so much better, but all modelled after the one he made for his neighbors in the Quaker City of long ago.

“Is it, think you, because her father is the President of the Continental Congress that Susan Boudinot behaves so?” Abigail whispered the question across the aisle of the Dame’s school in old Boston to one of the other little old-time lassies.

“Perhaps that is it. Look at her now. She minds it not in the least that she must sit in the dunce’s corner. She is smiling with those red lips and big blue eyes of hers as though she were not in disgrace,” the other little girl whispered back.

From other corners of the schoolroom came whispered comments about the wilful little Susan.

“What did Susan do that she was put in the dunce’s corner?”

“Indeed she did a great deal to try the good Dame’s patience. She tied the braids of Mercy Wentworth and Prudence Talbot together so tightly that when the Dame called upon Mercy to bring her copy book to her to show its pothooks, Prudence was well nigh dragged too. As if this were not enough, Susan put sand in the ink and made it so thick as to spoil the good Dame’s copperplate writing.”

The school was hushed, though, as the Dame who taught it entered and took her seat behind the desk, a quaint figure in her black gown, white apron, great spectacles and smoothly-parted back hair. All the children of these old Colony days, seated in front of her on the hard benches, bent their heads low again over their spellers or slates. Their hair was smoothly cropped or tightly braided. Only the wayward little girl, perched high upon the dunce’s stool, wore her hair in a mass of tangled curls. They gleamed like gold in the sunshine that filtered in through the window. Susan’s hair was like her own wilful little self, impatient of bounds and training.

As the Dame had returned to the room Susan’s lips had drooped a little and lost their smile. She cast her eyes toward the toes of her buckled shoes just above which ruffled the dainty white frills of her pantalettes. She crossed her hands demurely in the lap of her short-waisted, rose-sprigged gown. Presently, though, Susan looked up and glanced out of the school window. There was the green Boston Common, and the white meeting-house, and the brick mansions with their wide white doorways and brass knockers. Susan could see in fancy as far as the sea front, where she knew there were British ships at anchor with the fishing smacks and the merchant vessels of the Colonies.

“THE WAYWARD LITTLE GIRL, PERCHED HIGH UPON THE DUNCE’S STOOL”

These were troubled times, as Susan well knew, for the settlers in the new land. She heard her father speak of the growing discontent of the Colonies against the stern rule of the English King, and their disinclination to pay taxes on goods when they were allowed no representation in Parliament.

Only that morning, as Susan had pouted and frowned when her mother tried to comb out her twisting, tangling curls, there had been the sound of loud voices in the next room where her father received his business callers. Susan’s sweet-faced mother had sighed.

“Ah, Susan dear, why do you add to our troubles by being such a wilful little lass. Hear you not the voices in the other room? It is the King’s collector, and your father is trying to explain to him that the Congress feels it especially unjust to be obliged to pay a tax on tea—that pleasant beverage that is so much drunk at the Boston parties. I know not how it will all come out, and my heart is aching for the trouble that I feel will come. Be good, dear child. This will help us as you can in no other way.”

Susan had thrown her arms about her mother’s neck in a burst of love.

“I will be good, dear mother. I will be good,” she had exclaimed, for at heart there was no kinder child in all Boston than little Mistress Susan Boudinot. The scene came back to her now and she turned toward her teacher, the Dame, reaching out her slim little arms imploringly. What right had she, a little girl, to be naughty when her country was in such dire peril, she thought?

“I will be good,” she said in a burst of penitent tears as the Dame motioned kindly to her to leave the dunce’s corner. “I do not know why I was moved to tie Mercy and Prudence together by their hair except it was what the elder speaks of in meeting as the old Adam coming out of one. And I am sorry indeed about the ink.”

“That will do,” the Dame said, trying not to smile. “Take your seat, Susan, and write at least ten times, ‘Be ye kind to one another,’ in your copy book, and remember to keep it treasured in your mind as well as on the white pages.”

Susan slipped gladly into her place beside Abigail and was soon scratching away with her quill pen as industriously as any of the others.

School was not out until late in the afternoon, and Susan, surrounded by Abigail and Mercy and Prudence and many of the other little Colonial maidens, took their merry way through the narrow, brick-paved streets of old Boston. In their flowered poke bonnets, round silk capes, and full skirts they looked like a host of blossoms of as many different colors—lavender, green, pink, and blue. At the gate of one of the old mansions not far from the Common, Susan, her curls flying and her cheeks rosy from the warm sea air, waved her hand in good-bye.