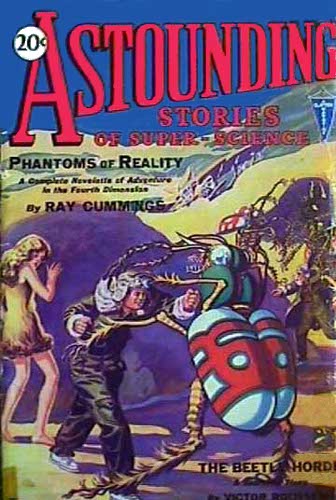

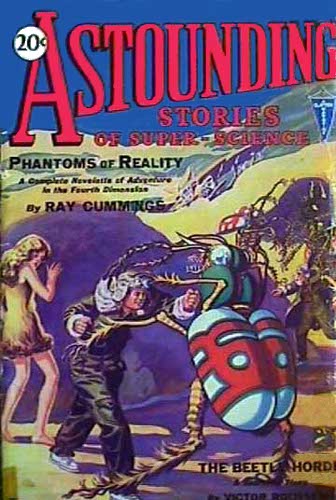

Painted in Water-colors from a Scene in "The Beetle Horde."

On Sale the First Thursday of Each Month

The Clayton Standard on a Magazine Guarantees:

That the stories therein are clean, interesting, vivid; by leading writers of the day and purchased under conditions approved by the Authors' League of America;

That such magazines are manufactured in Union shops by American workmen;

That each newsdealer and agent is insured a fair profit;

That an intelligent censorship guards their advertising pages.

The other Clayton magazines are:

ACE-HIGH MAGAZINE, RANCH ROMANCES, COWBOY STORIES, CLUES, FIVE-NOVELS MONTHLY, WIDE WORLD ADVENTURES, ALL STAR DETECTIVE STORIES, FLYERS, RANGELAND LOVE STORY MAGAZINE, WESTERN NOVEL MAGAZINE, BIG STORY MAGAZINE, MISS 1930, and FOREST AND STREAM

More Than Two Million Copies Required to Supply the Monthly Demand for Clayton Magazines.

Issued monthly by Publishers' Fiscal Corporation, 80 Lafayette St., New York, N. Y. W. M. Clayton, President; Nathan Goldmann, Secretary. Application for entry as second-class mail pending at the Post Office at New York, under Act of March 3, 1879. Application for registration of title as Trade Mark pending in the U.S. Patent Office. Member Newsstand Group—Men's List. For advertising rates address E. R. Crowe & Co., Inc., 25 Vanderbilt Ave., New York; or 225 North Michigan Ave., Chicago.

| EDITORIAL | THE EDITOR | 7 |

An Introduction to a New and Unique Magazine.

| THE BEETLE HORDE | VICTOR ROUSSEAU | 8 |

Only Two Young Explorers Stand in the Way of the Mad Bram's Horrible Revenge—the Releasing of His Trillions of Man-sized Beetles upon an Utterly Defenseless World. (Part One of a Two-part Novel.)

| THE CAVE OF HORROR | CAPTAIN S. P. MEEK | 32 |

Screaming, the Guardsman Was Jerked Through the Air. An Unearthly Screech Rang Through the Cavern. The Unseen Horror of Mammoth Cave Had Struck Again!

| PHANTOMS OF REALITY | RAY CUMMINGS | 46 |

Red Sensua's Knife Came up Dripping—and the Two Adventurers Knew that Chaos and Bloody Revolution Had Been Unleashed in that Shadowy Kingdom of the Fourth Dimension. (A Complete Novel.)

| THE STOLEN MIND | M. L. STALEY | 75 |

What Would You Do, If, Like Quest, You Were Tricked, and Your Very Mind and Will Stolen from Your Body?

| COMPENSATION | C. V. TENCH | 92 |

Professor Wroxton Had Disappeared—But in the Bottom of the Mysterious Crystal Cage Lay the Diamond from His Ring!

| TANKS | MURRAY LEINSTER | 100 |

Two Miles of American Front Had Gone Dead. And on Two Lone Infantrymen, Lost in the Menace of the Fog-gas and the Tanks, Depended the Outcome of the War of 1932.

| INVISIBLE DEATH | ANTHONY PELCHER | 118 |

On Lees' Quick and Clever Action Depended the Life of "Old Perk" Ferguson, the Millionaire Manufacturer Threatened by the Uncanny, Invisible Killer.

What are "astounding" stories?

Well, if you lived in Europe in 1490, and someone told you the earth was round and moved around the sun—that would have been an "astounding" story.

Or if you lived in 1840, and were told that some day men a thousand miles apart would be able to talk to each other through a little wire—or without any wire at all—that would have been another.

Or if, in 1900, they predicted ocean-crossing airplanes and submarines, world-girdling Zeppelins, sixty-story buildings, radio, metal that can be made to resist gravity and float in the air—these would have been other "astounding" stories.

To-day, time has gone by, and all these things are commonplace. That is the only real difference between the astounding and the commonplace—Time.

To-morrow, more astounding things are going to happen. Your children—or their children—are going to take a trip to the moon. They will be able to render themselves invisible—a problem that has already been partly solved. They will be able to disintegrate their bodies in New York and reintegrate them in China—and in a matter of seconds.

Astounding? Indeed, yes.

Impossible? Well—television would have been impossible, almost unthinkable, ten years ago.

Now you will see the kind of magazine that it is our pleasure to offer you beginning with this, the first number of Astounding Stories.

It is a magazine whose stories will anticipate the super-scientific achievements of To-morrow—whose stories will not only be strictly accurate in their science but will be vividly, dramatically and thrillingly told.

Already we have secured stories by some of the finest writers of fantasy in the world—men such as Ray Cummings, Murray Leinster, Captain S. P. Meek, Harl Vincent, R. F. Starzl and Victor Rousseau.

So—order your next month's copy of Astounding Stories in advance!—The Editor.

Out of the south the biplane came winging back toward the camp, a black speck against the dazzling white of the vast ice-fields that extended unbroken to the horizon on every side.

It came out of the south, and yet, a hundred miles further back along the course on which it flew, it could not have proceeded in any direction except northward. For a hundred miles south lay the south pole, the goal toward which the Travers Expeditions had been pressing for the better part of that year.

Not that they could not have reached it sooner. As a matter of fact, the pole had been crossed and re-crossed, according to the estimate of Tommy Travers, aviator, and nephew of the old millionaire who stood fairy uncle to the expedition. But one of the things that was being sought was the exact site of the pole. Not within a couple of miles or so, but within the fraction of an inch.

It had something to do with Einstein, and something to do with terrestrial magnetism, and the variations of the south magnetic pole, and the reason therefore, and something to do with parallaxes and the precession of the equinoxes and other things, this search for the pole's exact location. But all that was principally the affair of the astronomer of the party. Tommy Travers, who was now evidently on his way back, didn't give a whoop for Einstein, or any of the rest of the stuff. He had been enjoying himself after his fashion during a year of frostbites and hard rations, and he was beginning to anticipate the delights of the return to Broadway.

Captain Storm, in charge of the expedition, together with the five others of the advance camp, watched the plane maneuver up to the tents. She came down neatly on the smooth snow, skidded on her runners like an expert skater, and came to a stop almost immediately in front of the marquee.

Tommy Travers leaped out of the enclosed cockpit, which, shut off by glass from the cabin, was something like the front seat of a limousine.

"Well, Captain, we followed that break for a hundred miles, and there's no ground cleft, as you expected," he said. "But Jim Dodd and I picked up something, and Jim seems to have gone crazy."

Through the windows of the cabin, Jim Dodd, the young archaeologist of the party, could be seen apparently wrestling with something that looked like a suit of armor. By the time Captain Storm, Jimmy, and the other members of the party had reached the cabin door, Dodd had got it open and flung himself out backward, still hugging what he had found, and maneuvering so that he managed to fall on his back and sustain its weight.

"Say, what the—what—what's that?" gasped Storm.

Even the least scientific minded of the party gasped in amazement at what Dodd had. It resembled nothing so much as an enormous beetle. As a matter of fact, it was an insect, for it had the three sections that characterize this class, but it was merely the shell of one. Between four and five feet in height, when Dodd stood it on end, it could now be seen to consist of the hard exterior substance of some huge, unknown coleopter.

This substance, which was fully three inches thick over the thorax, looked as hard as plate armor.

"What is it?" gasped Storm again.

Tommy Travers made answer, for James Dodd was evidently incapable of speech, more from emotion than from the force with which he had landed backward in the snow.

"We found it at the pole, Captain," he said. "At least, pretty near where the pole ought to be. We ran into a current of warm air or something. The snow had melted in places, and there were patches of bare rock. This thing was lying in a hollow among them."

"If I didn't see it before my eyes, I'd think you crazy, Tommy," said Storm with some asperity. "What is it, a crab?"

"Crab be damned!" shouted Jim Dodd, suddenly recovering his faculties. "My God, Captain Storm, don't you know the difference between an insect and a crustacean? This is a fossil beetle. Don't you see the distinguishing mark of the coleoptera, those two elytra, or wing-covers, which meet in the median dorsal line? A beetle, but with the shell of a crustacean instead of mere chitin. That's what led you astray, I expect. God, what a tale we'll have to tell when we get back to New York! We'll drop everything else, and spend years, if need be, looking for other specimens."

"Like fun you will!" shouted Higby, the astronomer of the party. "Lemme tell you right here, Dodd, nobody outside the Museum of Natural History is going to care a damn about your old fossils. What we're going to do is to march straight to the true pole, and spend a year taking observations and parallaxes. If Einstein's brochure, in which he links up gravitation with magnetism, is correct—"

"Fossil beetles!" Jim Dodd burst out, ignoring the astronomer. "That means that in the Tertiary Era, probably, there existed forms of life in the antarctic continent that have never been found elsewhere. Imagine a world in which the insect reached a size proportionate to the great saurians, Captain Storm! I'll wager poor Bram discovered this. That's why he stayed behind when the Greystoke Expedition came within a hundred miles of the pole. I'll wager he's left a cairn somewhere with full details inside it. We've got to find it. We—"

But Jim Dodd, suddenly realizing that the rest of the party could hardly be said to share his enthusiasm in any marked degree, broke off and looked sulky.

"You say you found this thing pretty nearly upon the site of the true pole?" Captain Storm asked Tommy.

"Within five miles, I'd say, Captain. The fog was so bad that we couldn't get our directions very well."

"Well, then, there's going to be no difficulty," answered Storm. "If this fair weather lasts, we'll be at the pole in another week, and we'll start making our permanent camp. Plenty of opportunity for all you gentlemen. As for me, I'm merely a sailor, and I'm trying to be impartial.

"And please remember, gentlemen, that we're well into March now, and likely to have the first storms of autumn on us any day. So let's drop the argument and remember that we've got to pull together!"

Tommy Travers was the only skilled aviator of the expedition, which had brought two planes with it. It was a queer friendship that had sprung up between him and Jim Dodd. Tommy, the blasé ex-Harvard man, who was known along Broadway, and had never been able to settle down, seemed as different as possible from the spectacled, scholarly Dodd, ten years his senior, red-haired, irascible, and living, as Tommy put it, in the Age of Old Red Sandstone, instead of in the year 1930 A. D.

It was generally known—though the story had been officially denied—that there had been trouble in the Greystoke Expedition of three years before. Captain Greystoke had taken the brilliant, erratic Bram, of the Carnegie Archaeological Institute, with him, and Bram's history was a long record of trouble.

It was Bram who had exploded the faked neolithic finds at Mannheim, thereby earning the undying enmity of certain European savants, but brilliantly demolishing them when he smashed the so-called Mannheim stone pitcher (valued at a hundred thousand dollars) with a pocket-axe, and caustically inquired whether neolithic man used babbit metal rivets to fasten on his jug handles.

Bram's brilliant work in the investigation of the origin of the negrito Asiatic races had been awarded one of the Nobel prizes, and Bram had declined it in an insulting letter because he disapproved of the year's prize award for literature.

He had been a storm center for years, embittered by long opposition, when he joined the Greystoke Expedition for the purpose of investigating the marine fauna of the antarctic continent.

And it was known that his presence had nearly brought the Greystoke Expedition to the point of civil war. Rumor said he had been deliberately abandoned. His enemies hoped he had. The facts seemed to be, however, that in an outburst of temper he had walked out of camp in a furious snowstorm and perished. For days his body had been sought in vain.

Jimmy Dodd had run foul of Bram some years before, when Bram had published a criticism of one of Dodd's addresses dealing with fossil monotremes, or egg-laying mammals. In his inimitable way, Bram had suggested that the problem which came first, the egg or the chicken, was now seen to be linked up with the Darwinian theory, and solved in the person of Dodd.

Nevertheless, Jimmy Dodd entertained a devoted admiration for the memory of the dead scientist. He believed that Bram must have left records of inestimable importance in a cairn before he died. He wanted to find that cairn.

And he knew, what a number of Bram's enemies knew, that the dead scientist had been a morphine addict. He believed that he had wandered out into the snow under the influence of the drug.

Dodd, who shared a tent with Tommy, had raved the greater part of the night about the find.

"Well, but see here, Jimmy, suppose these beetles did inhabit the antarctic continent a few million years ago, why get excited?" Tommy had asked.

"Excited?" bellowed Dodd. "It opens one of the biggest problems that science has to face. Why haven't they survived into historic times? Why didn't they cross into Australia, like the opossum, by the land bridge then existent between that continent and South America? Beetles five feet in length, and practically invulnerable! What killed them off? Why didn't they win the supremacy over man?"

Jimmy Dodd had muttered till he went to sleep, and he had muttered worse in his dreams. Tommy was glad that Captain Storm had given them permission to return to the same spot next morning and look for further fossils, though his own interest in them was of the slightest.

The dogs were being harnessed next morning when the two men hopped into the plane. The thermometer was unusually high for the season, for in the south polar regions the short summer is usually at an end by March. Tommy was sweating in his furs in a temperature well above the freezing point. The snow was crusted hard, the sky overcast with clouds, and a wind was blowing hard out of the south, and increasing in velocity hourly.

"A bad day for starting," said Captain Storm. "Looks like one of the autumn storms was blowing up. If I were you, I'd watch the weather, Tommy."

Tommy glanced at Dodd, who was huddled in the rear cockpit, fuming at the delay, and grinned whimsically. "I guess I can handle her, Captain," he answered. "It's only an hour's flight to where he found that fossil."

"Just as you please," said Storm curtly. He knew that Tommy's judgment as a pilot could always be relied upon. "You'll find us here when you return," he added. "I've counter-manded the order to march. I don't like the look of the weather at all."

Tommy grinned again and pressed the starter. The engine caught and warmed up. One of the men kicked away the blocks of ice that had been placed under the skids to serve as chocks. The plane taxied over the crusted snow, and took off into the south.

The camp was situated in a hollow among the ice-mountains that rose to a height of two or three thousand feet all around. Tommy had not dreamed how strongly the gale was blowing until he was over the top of them. Then he realized that he was facing a tougher proposition than he had calculated on. The storm struck the biplane with full force.

A snowstorm was driving up rapidly, blackening the sky. The sun, which only appeared for a brief interval every day, was practically touching the horizon as it rose to make its minute arc in the sky. A star was visible through a rift in the clouds overhead, and the pale daylight in which they had started had already become twilight.

Tommy was tempted to turn back, but it was only a hundred miles, and Jimmy Dodd would give him no peace if he did so. So he put the plane's nose resolutely into the wind, watching his speed indicator drop from a hundred miles per hour to eighty, sixty, forty—less.

The storm was beating up furiously. Of a sudden the clouds broke into a deluge of whirling snow.

In a moment the windshield was a frozen, opaque mass. Tommy opened it, and peered out into the biting air. He could see nothing.... The plane, caught in the fearful cross-currents that swirl about the southern roof of the world, was fluttering like a leaf in the wind. The altimeter was dropping dangerously.

Tommy opened the throttle to the limit, zooming, and, like a spurred horse, the biplane shot forward and upward. She touched five thousand, six, seven—and that, for her, was ceiling under those conditions, for a sudden tremendous shock of wind, coming in a fierce cross-current, swung her round, tossed her to and fro in the enveloping white cloud. And Tommy knew that he had the fight of his life upon his hands.

The compasses, which required considerable daily adjusting to be of use so near to the pole, had now gone out of use altogether. The air speed indicator had apparently gone west, for it was oscillating between zero and twenty. The turn and bank indicator was performing a kind of tango round the dial. Even the eight-day clock had ceased to function, but that might have been due to the fact that Tommy had neglected to wind it. And the oil pressure gauge presented a still more startling sight, for a glance showed that either there was a leak or else the oil had frozen.

Tommy looked around at Dodd and pointed downward. Dodd responded with a vicious forward wave of his hand.

Tommy shook his head, and Dodd started forward along the cabin, apparently with the intention of committing assault and battery upon him. Instead, the archaeologist collapsed upon the floor as the plane spun completely around under the impact of a blast that was like a giant's slap.

The plane was no longer controllable. True, she responded in some sort to the controls, but all Tommy was able to do was to keep her from going into a crazy sideslip or nose dive as he fought with the elements. And those elements were like a devil unchained. One moment he was dropping like a plummet, the next he was shooting up like a rocket as a vertical blast of air caught the plane and tossed her like a cork into the invisible heavens. Then she was revolving, as if in a maelstrom, and by degrees this rotary movement began to predominate.

Round and round went the plane, in circles that gradually narrowed, and it was all Tommy could do to swing the stick so as to keep her from skidding or sideslipping. And as he worked desperately at his task Tommy began to realize something that made him wonder if he was not dreaming.

The snow was no longer snow, but rain—mist, rather, warm mist that had already cleared the windshield and covered it with tiny drops.

And that white, opaque world into which he was looking was no longer snow but fog—the densest fog that Tommy had ever encountered.

Fog like white wool, drifting past him in fleecy flakes that looked as if they had solid substance. Warm fog that was like balm upon his frozen skin, but of a warmth that was impossible within a few miles of the frozen pole.

Then there came a momentary break in it, and Tommy looked down and uttered a cry of fear. Fear, because he knew that he must be dreaming.

Not more than a thousand feet beneath him he saw patches of snow, and patches of—green grass, the brightest and most verdant green that he had ever seen in his life.

He turned round at a touch on his shoulder. Dodd was leaning over him, one hand pointing menacingly upward and onward.

"You fool," Tommy bellowed in his ear, "d'you think the south pole lies over there? It's here! Yeah, don't you get it, Jimmy? Look down! This valley—God, Jimmy, the south pole's a hole in the ground!"

And as he spoke he remembered vaguely some crank who had once insisted that the two poles were hollow because—what was the fellow's reasoning? Tommy could not remember it.

But there was no longer any doubt but that they were dropping into a hole. Not more than a mile around, which explained why neither Scott nor Amundsen had found it when they approximated to the site of the pole. A hole—a warm hole, up which a current of warm air was rushing, forming the white mist that now gradually thinned as the plane descended. The plateau with its covering of eternal snows loomed in a white circle high overhead. Underneath was green grass now—grass and trees!

The fog was nearly gone. The plane responded to the controls again. Tommy pushed the stick forward and came round in a tighter circle.

And then something happened that he had not in the least expected. One moment he seemed to be traveling in a complete calm, a sort of clear funnel with a ring of swirling fog outside it—the next he was dropping into a void!

There was no air resistance—there seemed hardly any air, for he felt a choking in his throat, and a tearing at his lungs as he strove to breathe. He heard a strangled cry from Dodd, and saw that he was clutching with both hands at his throat, and his face was turning purple.

The controls went limp in Tommy's hands. The plane, gyrating more slowly, suddenly nosed down, hung for a moment in that void, and then plunged toward the green earth, two hundred feet below, with appalling swiftness.

Tommy realized that a crash was inevitable. He threw his goggles up over his forehead, turned and waved to Dodd in ironic farewell. He saw the earth rush up at him—then came the shattering crash, and then oblivion!

How long he had remained unconscious, Tommy had no means of determining. Of a sudden he found himself lying on the ground beside the shattered plane, with his eyes wide open.

He stared at it, and stared about him, without understanding where he was, or what had happened to him. His first idea was that he had crashed on the golf links near Mitchell Field, Long Island, for all about him were stretches of verdant grass and small shrubby plants. Then, when he remembered the expedition, he was convinced that he had been dreaming.

What brought him to a saner view was the discovery that he was enveloped in furs which were insufferably hot. He half raised himself and succeeded in unfastening his fur coat, and thus discovered that apparently none of his bones was broken.

But the plane must have fallen from a considerable height to have been smashed so badly. Then Tommy discovered that he was lying upon an extensive mound of sand, thrown up as by some gigantic mole, for burrow tracks ran through it in every direction. It was this that had saved his life.

Something was moving at his side. It was half-submerged in the sand-pile, and it was moving parallel to him with great rapidity.

A grayish body, half-covered with grains of sand emerged, waving two enormously long tentacles. It was a shrimp, but fully three feet in length, and Tommy had never before had any idea what an unpleasant object a shrimp is.

Tommy staggered to his feet and dropped nearer the plane, eyeing the shrimp with horror. But he was soon relieved as he discovered that it was apparently harmless. It slithered away and once more buried itself in the pile of sand.

Now Tommy was beginning to remember. He looked into the wreckage of the plane. Jim Dodd was not there. He called his name repeatedly, and there was no response, except a dull echo from the ice-mountains behind the veil of fog.

He went to the other side of the plane, he scanned the ground all about him. Jimmy had disappeared. It was evident that he was nowhere near, for Tommy could see the whole of the lower scope of the bowl on every side of him. He had walked away—or he had been carried away! Tommy thought of the shrimp, and shuddered. What other fearsome monsters might inhabit that extraordinary valley?

He sat down, leaning against the wreck of the fuselage, and tried to adjust his mind, tried to keep himself from going mad. He knew now that the flight had been no dream, that he was a member of his uncle's expedition, that he had flown with Jim toward the pole, had crashed in a vacuum. But where was Jim? And how were they going to get out of the damn place?

Something like a heap of stones not far away attracted Tommy's attention. Perhaps Jim Dodd was lying behind that. Once more Tommy got upon his feet and began walking toward it. On the way, he stumbled against the sharp edge of something that protruded from the ground.

It cut his leg sharply, and, with a curse, he began rubbing his shin and looking at the thing. Then he saw that it was another of the fossil shells, half-buried in the marshy ooze on which he was treading. The ground in this lower part of the valley was a swamp, on account of the very fine mist falling from the fog clouds that surrounded it impenetrably on every side.

Then Tommy came upon another shell, and then another. And now he saw that there were piles of what he had taken to be rock everywhere, and that this was not rock but great heaps of the shells, all equally intact.

Hundreds of thousands of the prehistoric beetles must have died in that valley, perhaps overcome by some cataclysm.

Tommy examined the heap near which he stood; he yelled Dodd's name, but again no answer came.

Instead, something began to stir among the heaps of shells. For a moment Tommy hoped against hope that it was Dodd, but it wasn't Dodd.

It was a living beetle!

A beetle fully five feet high as it stood erect, a pair of enormous wings outspread. And the head, which was larger than a man's, was the most frightful object Tommy had ever seen.

Jim Dodd would have said at once that this was one of the Curculionidae, or snout beetles, for a prolongation of the head between the eyes formed a sort of beak a foot in length. The mouth, which opened downward, was armed with terrific mandibles, while the huge, compound eyes looked like enormous crystals of cut glass. Immediately in front of the eyes were two mandibles as long as a man's arms, with feathery processes at the ends. In addition to these there were three pairs of legs, the front pair as long as a man's, the hind pair almost as long as a horse's.

Paralyzed with horror, Tommy watched the monster, which had apparently been disturbed by the vibrations of his voice, extract itself from among the shells. Then, with a bound that covered fifteen feet, it had lessened the distance between them by half.

And then a still more amazing thing happened. For of a sudden the hard shell slipped from the thorax, the wing-cases dropped off, the whole of the bony parts slipped to the ground with a clang, and a soft, defenseless thing went slithering away among the rocks.

The beetle had moulted!

Tommy dropped to the ground in the throes of violent nausea.

Then, looking up again, he saw the girl!

She was about a hundred yards away from him, very close to the fallen plane, and she must have emerged from a large hole in the ground which Tommy could now see under a ledge of overhanging rock.

She seemed to be dressed in a single garment which fell to her knees, and appeared to fit tightly about her body, but as she came nearer, Tommy, watching her, petrified by this latest apparition, discovered that it was woven of her own hair, which must have been of immense length, for it fell naturally to her shoulders, and thence was woven into this close-fitting material, a fringe an inch or two in length extending beneath the selvage.

She was about six feet tall, and apparently made after the normal human pattern. She moved with a slow, majestic swing, and if ever any female had seemed to Tommy to have the appearance of an angel, this unknown woman did.

She was so fair, in that flossy, flaxen covering, she moved with such easy grace, that Tommy, gaping, gradually crept nearer to her. She did not seem to see him. She was stooping over the very sand heap into which he had fallen. Suddenly, with lightning-like rapidity, her arms shot out, her hands began tunneling in the sand. With a cry of triumph she pulled out the shrimp Tommy had seen, or another like it, and, stripping it off the shell, began devouring it with evident relish.

In the midst of her meal the girl raised her head and looked at Tommy. He saw that her eyes were filmed, vacant, dead. Then of a sudden a third membrane was drawn back across the pupils, and she saw him.

She let the shrimp drop to the ground, uttered a cry, and moved toward him with a tottering gait. She groped toward him with outstretched arms. And then she was blind again, for the membrane once more covered her pupils. It was as if her eyes were unable to endure even the dim light of the valley, through whose surrounding mists the low sun, setting just above the horizon, was unable to diffuse itself save as a brightening of the fog curtain.

Tommy stepped toward the girl. His outstretched hand touched hers. It was unquestionably a woman's hand he held, delicately warm, with exquisitely moulded fingers, in whose touch there seemed to be, for the girl, some tactile impression of him.

Again that membrane was drawn back from the girl's pupils for a fleeting flash. Tommy saw two eyes of intense black, their color contrasting curiously with the flaxen color of her hair and her white skin, almost the tint of an albino's. Those eyes had surveyed him, and appeared satisfied that he was one of her kind. She could not have seen very much in that almost instantaneous flash of vision. Queer, that membrane—as if she had been used to living in the dark, as if the full light of the day was unbearable!

She drew her hand away. Soft vocals came from her lips. Suddenly she turned swiftly. She could not have seen, but before Tommy had seen, she had sensed the presence of the old man who was creeping out of the hole in the mountainside.

He moved forward craftily, and then pounced upon the sand pile, and in a moment had pulled out another of the big shrimps, which he proceeded to devour with greedy relish. The girl, leaving Tommy's side, joined him in that unpleasant feast.

And in the midst of it a flood came pouring from the hole—a flood of living beetles, covering the ground in fifteen-foot leaps as they dashed at the two.

To his horror, Tommy saw Jimmy Dodd among them, wrapped in his fur coat like a mummy, and being pushed and rolled forward like a football.

For a moment Tommy hesitated, torn between his solicitude for Jim Dodd and that for the girl. Then, as the foremost of the monsters bounded to her side, he ran between them. The vicious jaws snapped within six inches of Tommy's face, with a force that would have carried away an ear, or shredded the cheek, if they had met.

Tommy struck out with all his might, and his fist clanged on the resounding shell so that the blood spurted from his bruised knuckles. He had struck the monster squarely upon the thorax, and he had not discommoded it in the least. It turned on him, its glassy, many-faceted eyes glaring with a cold, infernal light. Tommy struck out again with his left hand, this time upon the pulpy flesh of the downward-opening mouth.

An inch higher, and he would have impaled his hand upon the beak, with a point like a needle, and evidently used for purposes of attack, since it was not connected with the mandibles. The blow appeared to fall in the only vulnerable place. The monster dropped upon its back and lay there, unable to reverse itself, its antenna and forelegs waving in the air, and the rear legs rasping together in a shrill, strident shriek.

Instantly, as Tommy darted out of the way, the swarm fell upon the helpless monster and began devouring it, tearing strips of flesh from the lower shell, which in the space of a half-minute was reduced simply to bone. The most horrible feature of this act of cannibalism was the complete silence with which it was performed, except for the rasping of the dying monster's legs. It was evident that the huge beetles had no vocal apparatus.

For the moment left unguarded, Jim Dodd flung down the collar of his fur coat, stared about him, and recognized Tommy.

"My God, it's you!" he yelled. "Well, can you—?"

He had no time to finish his sentence. A pair of antenna went round his neck from behind. At the same instant Tommy, the old man, and the girl were gripped by the monsters, which, forming a solid phalanx about them, began hustling them in the direction of the hole. Resistance was utterly impossible. Tommy felt as if he was being pushed along by a moving wall of stone.

Inside the opening it was completely dark. Tommy shouted to Dodd, but the strident sounds of the moving legs drowned his cries. He was being pushed forward into the unknown.

Suddenly the ground seemed to fall away beneath his feet. He struggled, cried out, and felt himself descending through the air.

For a full half-minute he went downward at a speed that constricted his throat so that he could hardly draw breath. Then, just as he had nerved himself for the imminent crash, the speed of his descent was checked. In another moment he found that he was slowing to a standstill in mid-air.

He was beginning to float backward—upward. But the wall of moving shells, pushing against him, forced him on, downward, and yet apparently against the force of gravitation.

Then of a sudden Tommy was aware of a dim light all about him. His feet touched earth and grass as softly as a thistledown alighting.

He found himself seated in the same dim light upon red grass, and staring into Jimmy's face.

"What I was going to say when we were interrupted, was, 'Can you beat it?'" Jimmy Dodd observed, with admirable sang-froid.

They were still seated on the red grass, gazing about them at what looked like an illimitable plain, and upward into depths of darkness. It was warm, and the light, furnished by what appeared to be luminous vegetation, was about that of twilight.

On every side were clumps of trees and shrubs, which formed centers of phosphorescent illumination, but for the most part the land was open, and here and there human figures appeared, moving with head down and arms hanging earthward.

"No, I'm damned if I can," said Tommy. "What happened to you after we crashed?"

"Why, first thing I knew, I found myself riding on the back of a fossil beetle, apparently one of the curculionidae," said Dodd.

"Never, mind being so precise, Jimmy. Let's call it a beetle. Go on."

"They set me down inside the hole and seemed to be investigating me, the whole swarm of them. Of course, I thought I was dead, and come to my just reward, especially when I saw those beaks. Then one of them began tickling my face with its antenna, and I drew up my fur collar. They didn't seem to like the feel of the fur, and after a while the whole gang started hustling me back again, like a nest of ants carrying something they don't want outside their hill. And then you bobbed up."

"Well, my opinion is you saved your life by pulling up your collar," said Tommy. "Looks to me as if it's a case of the survival of the fittest, said fittest being the insect, and the human race taking second place. You know what the humans here live on, don't you?"

"No, what?"

"Shrimps as big as poodles. If you'd seen that girl and the old man getting outside them, you'd realize that there seems to be a food shortage in this part of the world. Say, where in thunder are we, Jimmy?"

"Haven't you guessed yet, Travers?" asked Dodd, a spice of malice in his voice.

"I suppose this is some sort of big hole on the site of the south pole, with warm vapors coming up. Maybe a great fissure in the earth, or something."

Jimmy Dodd's grin, seen in the half-light, was rather disconcerting. "How far do you think we dropped just now?" Dodd asked.

"Why, I'd say several hundred yards," replied Tommy. "What's your estimate?"

"Just about ten miles," answered Dodd.

"What? You're still crazy! Why, we slowed up!"

"Yeah," grinned Dodd, "we slowed up. We're inside the crust of the world. That's the long and short of it. The earth we've known is just a shell over our heads."

"Yeah? Walking head downward, are we? Then why don't we drop to the center of the earth, you damn fool?"

"Because, my dear fellow, you can swing a pailful of water round your head without spilling any of it. In other words, our old friend, centrifugal force. The speed with which the earth is rotating, keeps us on our feet, head downward. To be precise, the center of the earth's gravity lies in the middle of the hollow sphere, of course, but the counteraction of centrifugal force throws it outward to the middle of the ten-mile crust. That's why we slowed down after we were half-way through. We were moving against gravity."

"And what's up there, or down there, or whatever you call it?" asked Tommy, pointing to what ought to have been the sky.

"Nothing. It's the center of the tennis ball, though I imagine it's pretty near a vacuum when you get up a mile or so, owing to the speed of the earth's rotation, which forces the heat into the shell."

"You mean to say you actually believe that stuff you've been handing me?" asked Tommy, after a pause. "Then how did human beings get here, and those damn beetles? And why's the grass red?"

"The grass is red because there's no sunlight to produce chlorophyll. The inhabitants of the deep sea are red or black, almost invariably. In the case of the humans, they've become bleached. My belief is that that man and woman we saw, and those"—he pointed to the vague forms of human beings, who moved across the grass, gathering something—"are survivors of the primitive race that still exists as the Australians. Undoubtedly one of the branches of the human stock originated in antarctica at a time when it enjoyed a tropical temperature, and was the land bridge between Australia and South America."

"And the—beetles?" asked Tommy.

"Ah, they go back to the days when nature was in a more grandiose mood!" replied the archaeologist enthusiastically. "That's the most wonderful discovery of the ages. The world will go crazy over them when we bring back the first living specimens to the zoological parks of the great cities.

"But," Dodd went on, speaking with still more enthusiasm, "of course, this is only the beginning, Tommy. There are ten million species of insects, according to Riley, and it is inevitable that there must be hundreds of thousands of other survivals from the age of the great saurians, perhaps even some of the saurians themselves. Who knows but that we may discover the ancestor of the extinct monotremes, the rhynchocephalia, the pterodactyls, hatch a brood of aepyornis eggs—"

"And," said Tommy tartly, "how are we going to get them back, apart from the little problem of getting out of here ourselves?"

"Don't let's worry about that now," answered Dodd. "It will take ten years of the hardest kind of labor even to begin a classification of the inhabitants of this inner world. I could sit down for ever, and—"

But Jimmy Dodd rose to his feet as a pair of antenna whipped round his neck and jerked him bodily upward.

One of the monster beetles was standing upright behind them, and by its gestures it evidently meant that Dodd and Tommy were to join the crowd of humans in the offing. As Dodd turned upon it with an indignant show of fists, one of the antennae whipped off his fur coat and stung him painfully with the bristle-like attachment at the end.

It was a painful moment when Dodd and Tommy realized that they were powerless against the monstrous beetles. Tommy tried the uppercut with which he had knocked out the deceased monster, but the quick jerks of the present beetle's head were infinitely faster than the movements of his fists, while the antenna had a whiplike quality about them that speedily convinced him that discretion was the card to play.

Under the threat of the curling antenna, Tommy and Dodd moved in the direction of the slowly circulating humans. Numerous tiny rodents, which evidently kept the red grass short, scampered away under their feet. The beetles made no further effort to force them on, but now they could see that a number of the monsters were stationed at intervals around a wide circle, keeping the humans in a single body.

"Good Lord!" ejaculated Tommy, stopping. "See what they're doing, Dodd? They're herding us, like cowboys herd steers. Look at that!"

One of the herd, a male with a long beard, suddenly broke from the herd, bawling, and flung himself upon a beetle guard. The antenna shot forth, coiled around his neck, and hurled him a dozen feet to the ground, where he lay stunned for a moment before arising and rejoining his companions.

"But what are they looking for?" demanded Dodd.

Tommy had not heard him. He had stopped in front of one of the luminous trees and was plucking a fruit from it.

"Jimmy, ever see an apple before?" he asked. "If this isn't an apple, I'll eat my head."

It certainly was an apple, and one of the largest and juiciest that Tommy had ever tasted. It was the reddest apple he had ever seen, and would have won the first prize at any agricultural fair.

"And look at this!" shouted Tommy, plucking an enormous luminous peach from another tree.

They began munching slowly, then, seeing one of the beetle guards approaching them, they moved into the midst of the crowd.

"Did you notice anything strange about those fruit trees?" inquired Dodd, as he munched. "I'll swear they were monocotyledonous, which, after all, is what one would expect. Still, to think that the monocotyledons evolved the familiar drupes, or stone fruits, on a parallel line to the dicotyledons is—amazing!"

A box on the ear like the kick of a mule's hoof jerked the last word from his lips as he went sprawling. He got up, to see the girl standing before him, intense disgust and anger on her face.

She snatched the fruits from the hands of the two Americans and hurled them away. It was evident from her manner that she considered such diet in the highest degree unclean and disgusting; also that she considered herself charged with the duty of superintending Tommy's and Dodd's education, but especially Dodd's.

Taking him by the arm, she propelled him into the midst of the groping humans. She released him, stooped, and suddenly stood up, a shrimp about eighteen inches long in her hand.

Towering over Dodd by six inches, she took his face in her hands and began caressing him; then, seizing his jaws in her strong fingers, she pried them apart, and popped the tail end of the shrimp into his mouth.

Dodd let out a yelp, and spat out the love-gift, to be rewarded with another box on the ear by the young Amazon, while Tommy stood by, convulsed with laughter, and yet in considerable trepidation, for fear of being forced to share Dodd's fate.

For the girl was again holding out the tail end of the crustacean, and Jim Dodd's jaws were slowly and reluctantly approaching it.

But suddenly there came an intervention as the strident rasping of beetle legs was heard in the distance. Panic seized the human herd, grovelling for shrimps in the sandy soil with its tufts of red grasses. Milling in an uneasy mob, they cowered under the lashes of the antenna of the beetle guards, which sacrificed their backs through their hair garments whenever any of them tried to bolt.

Nearer and nearer came the beetles, louder and more penetrating the shriek of their rasping legs. Now the swarm came into sight, rank after rank of the shell-clad monsters, leaping fifteen feet at a bound with perfect precision, until they had formed a solid phalanx all around the humans.

Tommy heard sighs of despair, he heard muttering, and then he realized, with deep thankfulness, that these human beings, degraded though they were, had a speech of their own.

In the middle of the front line appeared a beetle a foot taller than the rest. That it was either a king or queen was evident from the respect paid it by the rest of the swarm. At its every movement a bodyguard of beetles moved in unison, forming themselves in a group before it and on either side.

There would have been something ludicrous about these movements, but for the impression of horror that the swarm made upon Tommy and Jim Dodd. Hitherto both had supposed that the hideous insects acted by blind instinct, but now there could no longer be any doubt that they were possessed of an organized intelligence.

The strident sounds grew louder. Already Tommy was beginning to discover certain variations in them. It was dawning upon him that they formed a language—and a perfectly intelligible one. For, as the note changed about a half-semitone, two of the monsters left the side of their ruler and reached the two men with three successive leaps.

Their movements left no doubt in either Tommy's or Dodd's mind what was required. The two strode hastily toward the assemblage, and stopped as the antenna of their guards came down in menacing fashion.

It was light enough for Tommy to see the face of the ruler of the hellish swarm. And it required all his powers of will to keep from collapsing from sheer horror at what he saw.

For, despite the close-fitting shell, the face of the beetle king was the face of a man—a white man!

Jim Dodd's shriek rang out above the shrilling of the beetle-legs, "Bram! It's you, it's you! My God, it's you, Bram!"

A sneering chuckle broke from Bram's lips. "Yes, it's me, James Dodd," he answered. "I'm a little surprised to see you here, Dodd, but I'm mighty glad. Still insane upon the subject of fossil monotremes, I suppose?"

The words came haltingly from Bram's lips, as from those of a man who had lost the habit of easy speech. And Tommy, looking on, and trying to keep in possession of his faculties, had already come to the conclusion that the sounds were inaudible to the beetles. Probably their hearing apparatus was not attuned to such slow vibrations of the human voice.

Also he had discovered that Bram was wearing the discarded shell of one of the monsters: he had not grown the shell himself. It was fastened about his body by a band of the hair-cloth, fastened to the two protuberances of the elytra, or wing-cases, on either side of the dorsal surface.

The discovery at least robbed the situation of one aspect of terror. Bram, however he had obtained control of the swarm, was still only a man.

"Yes, still insane," answered Dodd bitterly. "Insane enough to go on believing that the polyprotodontia and the dasyuridae, which includes the peramelidae, or bandicoots, and the banded ant-eaters, or myrmecobidae, are not to be found in fossil form, for the excellent reason that they were not represented before the Upper Cretaceous period."

"You lie! You lie!" screamed Bram. "I have shown to all the world that phascalotherium, amphitherium, amblotherium, spalacotherium, and many other orders are to be found in the Upper Jurassic rocks of England, Wyoming, and other places. You—you are the man who denied the existence of the nototherium, of the marsupial lion, in pleistocene deposits! You denied that the dasyuridae can be traced back beyond the pleistocene. And you stand there and lie to me, when you are at my mercy!"

"For God's sake don't aggravate him," whispered Tommy to Dodd. "Don't you see that he's insane? Humor him, or we'll be dead men. Think what the world will lose, if you are never able to go back with your specimens," he added craftily.

But Dodd, whose eyes were glaring, said a sublime thing: "I have given my life to science, and I will never deny my master!"

With a screech, which, however, was evidently inaudible to the beetles, Bram leaped at Dodd and seized him by the throat. The two men fell to the ground, the ponderous beetle-shell completely covering them. Underneath it they could be seen to be struggling desperately. All the while the beetle horde remained perfectly motionless. Tommy thought afterward that in this fact lay their brightest chances of escape, if Bram's immediate vengeance did not fall on them.

Either because Bram was not himself a beetle, or because in some other way the swarm instinct was not stirred, the monsters watched the struggle with complete indifference.

At the moment, however, Tommy was only concerned with saving Dodd from the madman. He got his foot beneath the shell, then inserted his leg; using his whole body as a lever, he succeeded in turning Bram over on his back.

Then, and only then, the swarm rushed in upon them. Then Tommy realized that he had touched one of the triggers that regulated the beetle's automatism. In another instant Bram would have been torn to pieces. The needle-beaks were darting through the air, the hideous jaws were snapping. Bram's yells rang through the cavern.

Dodging beneath the avalanche of the monsters, Tommy got Bram upon his feet again. The beetles stopped, every movement arrested. Bram's hand went to the pocket of his tattered coat, there came a snap, a flash. Bram had ignited an automatic cigarette-lighter!

Instantly the monsters went scurrying away into the distance. And Tommy had another clue. The beetles, living in the dimness of the underworld, could not stand light or fire!

He ran to where Jimmy was lying, face upward, on the ground. His face was badly scarred by Bram's nails, and the blood was spurting from a long gash in his throat, made by the sharp flint that was lying beside him.

He had some time before discarded his fur coat. Now he pulled off his coat, and, tearing off the tail of his shirt, he made a pad and a bandage, with which he attempted to staunch the blood and bind the wound. It must have taken ten minutes before the failing heart force enabled him to get the bleeding under control. Dodd had nearly bled to death, his face was drawn and waxen, but, because the pulsation was so feeble, the artery had ceased to spurt.

Then only did Tommy take notice of Bram. He had been squatting near, and Tommy realized that he had unconsciously observed Bram put some sort of pellets into his mouth. Now he realized that Bram was a drug fiend. That was what had made him walk out of the Greystoke camp in the storm.

Bram got up and came toward them. "Is he dead?" he whispered hoarsely. "I—I lost my temper. You two—I don't intend to kill you. There—there's room for the three of us. I've got—plans of the utmost importance to humanity."

"I don't think much of the way you've started to carry them out," answered Tommy bitterly. "No, he's not dead yet, but I wouldn't give much for his chances, even in the best hospital. The best thing you can do now is to go to hell, and take your beetles with you," he added.

Bram, without replying, raised his head and emitted from his throat the shrillest whistle that Tommy had ever heard. The response was amazing.

Rasping out of the darkness came eight beetles in pairs. Instead of leaping from an upright position, they trotted in the manner of horses, on all fours, their shells, which touched at the edges, forming a solid surface, gently rounded in the center so that a man's body could lie there and fit snugly into the groove.

"Help me get him up," said Bram. "Trust me! I'll do my best for him. If we leave him here they may kill and eat him. I can't trust all those beetle guards."

Tommy hesitated a moment, then decided to follow Bram's suggestion. Together they raised the unconscious man to the beetle-shell couch. Bram seated himself upon the boss of one of the beetle-shells in front, and Tommy jumped up behind.

Next moment, to his amazement, the trained steeds were flying smoothly through the air, at a rate that could not have been less than seventy-five to eighty miles an hour.

Tommy's shell seat was not a bed of roses, but he hardly noticed that. He was thinking that if Dodd lived they should be able to turn the tables.

For, unknown to Bram, he was in possession of the cigarette-lighter which he had picked up, and which Bram, in his agitation, had forgotten. It was full of petrol, or some other fluid of a similar nature, which Bram must have obtained from some natural source within the earth. And, in an emergency, Tommy knew that he had the means of keeping the beetles at bay.

They had traveled for perhaps an hour when a faint light began to glow in the distance. It grew brighter, and a roaring sound became audible. A turn of the track that they were traversing, and the light became a glare. A terrific sight met Tommy's eyes.

Out of the bowels of the earth—actually out of the crust beneath their feet—there shot a pillar of roaring flame, of intense white color, and radiating a heat that was perceptible even at a distance of several hundred yards. The beetle steeds dropped gently to the ground; they halted. Bram got down, grinning.

"Nicely trained horses, what?" he asked. "By the way, you have the advantage of me in names. Who and what are you?"

Tommy told him.

"Well, Travers, it looks as if we're going to be companions for some time to come, and I quite admit you saved my life back there. So we don't want to start with secrets. This is a natural petrol spring, which has probably been burning undiminished for ages. My trained beetles are blind—you didn't happen to notice I'd cut off their antenna? But the rest of the swarm daren't come near it. So that makes me their master.

"Pretty trick, what, Travers? I'm the Lord of the Flame down here, and I'm using my advantage. But don't get the idea of supplanting me. There are lots of other tricks you don't know anything about, and I'll have to trust you better before—"

He broke off and slipped another pellet into his mouth.

"Help me get Dodd down, if this is our destination," answered Tommy.

They lifted Dodd to the ground. He was conscious now, and moaning for water. The two men carried him into a sort of large cavern, at the farther end of which the fire was roaring. Bram went to a spring that trickled down one side, filled something that looked like a petrified lily calyx, and brought it to Dodd, who drained it.

Tommy looked about him. He was astonished to see that the place was, in a way, furnished. Bram had carved out a very creditable couch, and several low chairs, evidently with a stone ax, for by the light of the fire, which cast a fair illumination even at that distance, Tommy could see the marks of the implement, rough and irregular, in the wood.

On the ground were thick rugs, woven of hair, and two or three more rugs of the same material lay on the couch. It was evident that the human herd was expected to furnish textile materials as well as meat.

"Sit down, and make yourself comfortable," said Bram, when they had raised Dodd to the couch. "We'll have dinner, and then we'll talk. I can give you a fine vegetarian meal. Those dirty shrimp-eating savages look on me as a cannibal because I eat the fruits of the trees." He grinned. "There's a bad shortage of food in Submundia, as I've named this part of the world," he went on, "for until I came the beetles simply devoured the humans wholesale, instead of breeding them, like I taught them. And there's another of the hundred-and-fifty year swarms due to hatch out soon. However, we'll talk about that later. And all those fine fruits going to waste! Excuse me, Travers."

He disappeared, and returned in a minute or two with a small table, piled high with luscious fruits unknown to Tommy, though among them were some that looked like loaves of natural bread.

Tommy, whose appetite never failed him even in the worst circumstances, fell to with a will. He was enjoying his meal when he happened to look up, and saw that the penumbra at the edge of the lighted zone was dense with beetles.

Thousands—perhaps millions, for they stretched away as far as the eye could see, were packed together, their antenna waving in unison, their heads, beneath the shells, directed toward the fire.

Bram saw Tommy's look of disgust, and laughed. "The fire seems to intoxicate them, Travers," he said. "They always throng the entrance when I'm here. It's as far as they dare go. They're quite blind in the least light. Care to smoke? I've learned the art of making some quite decent cigars." He produced a handful. "Oh, by the way, you didn't see my lighter anywhere, did you?" he went on, with a pretense of carelessness.

"No," lied Tommy. "I was surprised you—"

"Oh, there's a supply of petrol in the rocks. No matter," answered Bram carelessly. "Your friend looks bad," he added, glancing at Dodd, who had fallen asleep. "Travers, I'm sorry I lost my temper. The—the shock of meeting men from the upper world, you know."

Dodd opened his eyes and tried to whisper. Tommy bent over him and listened.

"He wants to know whether he can have that girl to take care of him," he said.

"What, the one I saw you with? Why, she's a cull, Travers."

"What d'you mean?" asked Tommy.

"Why—useless, you know. There's several of them running loose, and waiting to be rounded up. We raise two breeds, one for replenishing the stock, and one for meat. She's just a cull, a reversion, no use for either purpose. I'll have her brought by all means. I—I like Dodd. I want to get him to like me," Bram went on, with a sort of penitence that had a pathetic touch. "Our little differences—quite absurd, and I can prove he's wrong in his ideas.

"Make yourself comfortable as long as you're here, Travers, and don't mind me. Only, don't try to escape. The beetles will get you if you do, and there's no way out of here—none that you'll find. And don't try to follow me. But you're a sensible man, and we'll all get along famously, I'm sure, as soon as Dodd recovers."

There were no means known to Tommy of reckoning time in that strange place of twilight. His watch had been broken in the airplane fall; and Dodd never remembered to wind his, but they estimated that about two weeks had passed, judging from the number of times they had slept and eaten.

In those two weeks they had gradually begun to grow accustomed to their surroundings. Haidia, the girl, had arrived on beetle-back within an hour after Bram's departure, apparently into a cleft of the rocks—how he had communicated his order to the beetle steeds Tommy had no idea. And under the girl's ministrations Dodd was making good progress toward recovery.

That Haidia was in love with Dodd in quite a human way was evident. To please the girl, both Dodd and Tommy had learned to eat the raw shrimps, which, being bloodless, were really no worse than oysters, and had a flavor half-way between shrimp and crawfish. To please the men, Haidia tried not to shudder when she saw them devouring the breadfruit and nectarines of which Bram always had a plentiful supply. Bram was solicitous in his inquiries for Dodd's health.

"Jim, I've been thinking about our chances of getting away," said Tommy one morning. "It's evident Bram's only waiting for your recovery to put some proposition up to us. Suppose you were to feign paralysis."

"How d'you mean? What for?" demanded Dodd.

"If he thinks you're helpless, he'll be less on his guard. You haven't walked about in his presence." That was true, for the activities of the two had been nocturnal, when Bram had vanished. "Let him think a nerve's been severed in your neck, or something of the sort. If it doesn't work, you can always get better."

Dodd's realistic portrayal of a man with a partly paralyzed right side brought cries of horror from Bram next morning. Solicitously he helped Dodd back to the couch. Bram, when not under the influence of his drug, had moments of human feeling.

"Can't you move that arm and leg at all, Dodd?" he asked. "No feeling in them?"

"There's plenty of feeling," growled Dodd, "but they don't seem to work, that's all."

"You'll get better," said Bram eagerly. "You must get better. I need you, Dodd, in spite of our differences. There's work for all of us, wonderful work. A new humanity, waiting to be born, Dodd, not of the miserable ape race, but of—of—"

He checked himself, and a cunning look came over his face. He turned away abruptly.

At the end of two weeks or so, an amazing thing happened. One day Haidia, with a look of triumph in her eyes, addressed Dodd with a few English words!

Her brain, which had probably developed certain faculties in different proportions from those of the upper human race, had registered every word that either of the two men had ever spoken, and remembered it. As soon as Dodd ascertained this, he began to instruct her, and, with her abnormal faculties of memory, it was not long before she could talk quite intelligently. The obstacle that had stood between them was swept away. She became one of themselves.

In the days that followed the girl told them brokenly something of the history of her race, of the legend of the universal flood that had driven them down into the bowels of the earth, of the centuries-long struggle with the beetles, and of the insects' gradual conquest of humanity, and the final reduction of the human race to a miserable, helpless remnant.

Everywhere, Haidia told them, were beetle swarms, everywhere humanity had been reduced to a few handfuls. Bram, by breeding mankind from prolific strains, and using the new-born progeny for food, had temporarily averted universal starvation. But a new swarm of beetles was due to hatch out shortly, and then—

The girl, with a shudder, put her hand to her bosom, and brought out a little bright-eyed lizard.

"The old man you saw with me, who is one of our wise elders, has told our people that these things feed upon the beetle larvae," she said. "We are putting them secretly into the nests. But what can a few lizards do against millions." She looked up. "In the earth above us, the beetle larvae extend for miles, in a solid mass," she said. "When they come out as beetles, it will be the end of all of us."

Bram had grown less suspicious as the time passed. His sudden visits to the cavern had ceased. Dodd and Tommy knew that he spent the nights—if they could be termed nights—lying in a drugged slumber somewhere among the rocks. They had asked Haidia whether there was any way of escape into the upper world.

"There are two ways from here," answered the girl. "One is the way you came, but it is impossible to pass the beetle guards without being torn to pieces. The other—"

She shuddered, and for an instant drew back the film from across her pupils, then uttered a little cry of pain at the light, dim though it was.

"There is a bridge across that terrible monster that devours all it touches," she said, shuddering, meaning the fire.

Suddenly Dodd had an inspiration. He still had the fur coat that he had worn, and, reaching into a pocket he drew out a pair of snow goggles, which he adjusted over Haidia's nose.

"Now look!" he said.

Haidia looked, blinked and, with an effort kept her eyes open. She gazed at Dodd in amazement. Dodd laughed, and pulled her toward him. He kissed her, and Haidia's eyes closed.

"What is this?" she murmured. "First you give me medicine that opens my eyes, and then you give me medicine that closes them."

"That's nothing," grinned Dodd. "Wait till you understand me better."

Bram's eyes were preternaturally bright. It was evident that he had been increasing his dose of late, and that he was fully under the influence of it now.

"Well, gentlemen, the time has come for us to be frank with one another," he said, as the three were gathered about the little table, while Haidia crouched in a far corner of the cave. "I want you to work for me in my plans for the regeneration of humanity. The time for which I have long labored is almost at hand. Any day now the new swarm of beetles may emerge from the pupal stage. But before I speak further, come and see them, gentlemen!"

He rose, and Dodd and Tommy rose too, Tommy supporting Dodd, who let his arm and leg trail awkwardly as he moved.

Bram led the way into the cleft among the rocks into which he had been in the habit of passing. Beyond this opening the two men saw another smaller cavern, with a beetle guard standing on either side, antenna waving.

Bram shrilled a sound, and the antenna dropped. The three passed through. Tommy saw a hair-cloth pallet set against the rocks, a table, and a chair. Beyond was a sloping ramp of earth. Overhead was a rock ceiling.

Bram led the way up the ramp, and the three stepped through a gap in the rocks and found themselves on an extensive prairie. But in place of the red grass there was a vast sea of mud.

By the light cast by the petrol fire, which roared up in the distance, a veritable fiery fountain, the two Americans could see that the mud was filled with huge encysted forms, grubs three or four feet long, motionless in the soil.

Bram scooped up one of them and tossed it into the air. It thudded to their feet and remained motionless.

"As far as you can see, and for miles beyond, these pupae of the beetles lie buried in the decaying vegetation in which the eggs were hatched," said Bram. "Every century and a half, so far as I have been able to judge from comparative anatomy, a fresh swarm emerges. See!"

He pointed to the pupa he had unearthed, which, as if stirred into activity by his handling, was now beginning to move. Or, rather, something was moving inside the cocoon.

The shell broke, and the hideous head and folded antenna of a beetle appeared. With a convulsive writhing, the monster threw off the covering and stepped out. It extended its wings, glistening, with moisture, from the still soft and pliant carapace, or shell, and suddenly zoomed off into the distance.

Tommy shuddered as the boom of its flight grew softer and subsided.

"Any day now the entire swarm will emerge," cried Bram. "How many moultings they undergo before they undergo the finished state, I do not know, but already, as you see, they are prepared for the battle of life. They emerge ravenous. That beetle will fall upon the man-herds and devour a full grown man, unless the guards destroy it."

He raised his arms with the gesture of an ancient prophet. "Woe to the human race," he cried, "the wretched ape spawn that has cast out its teachers and persecuted those who sought to raise it to higher things!"

Tommy knew that Bram was referring to himself. Bram turned fiercely upon Dodd.

"When I joined the Greystoke expedition," he cried, "it was with the express intention of refuting your miserable theories as to the fossil monotremes. I could not sleep or eat, so deeply was I affronted by them. For, if they were true, the dasyuridae are an innovation in the great scheme of nature, and man, instead of being a mere afterthought, a jest of the Creative Force, came to earth with a purpose.

"That I deny," he yelled. "Man is a joke. Nature made him when she was tired, as the architect of a cathedral fashions a gargoyle in a sportive moment. It is the insect, not man, who is the predestined lord of the ages!"

And for once in his life, perhaps because at this point Tommy dug him violently in the ribs, Dodd had the sense to remain silent. Bram led the way swiftly back into the larger cave.

"When this swarm hatches out," he said, "I calculate that there will be a trillion beetles seeking food. There is no food for a tithe of them here underneath the earth. What then? Do you realize their stupendous power, their invincibility?

"No, you don't realize it, because your minds, through long habit, are only attuned to think in terms of man. All man's long history of slaughter of the so-called lower creatures obsesses you, blinds your understanding. A beetle? Something to be trodden underfoot, crushed in sport! But I tell you, gentlemen, that nature—God, if you will—has designed to supplant the man-ape by the beetle.

"He has resolved to throw down the wretched so-called intelligence of your kind and mine, and supplant it by the divine instinct of the beetle, an instinct that is infinitely superior, because it arrives at results instantaneously. It knows where man infers. Attuned closely to nature, it alone is able to fulfil the divine plan of Creation."

Bram was certainly under the influence of his drug; nevertheless, so violent were his gestures, so inspired was his utterance, that Tommy and Dodd listened almost in awe.

"They are invincible," Bram went on. "Their fecundity is such that when the new swarm is hatched out their numbers alone will make them irresistible. They do not know fear. They shrink from nothing. And they will follow me, their leader—I, who know the means of controlling them. How, then, can puny man hope to stand against them?

"Join me, gentlemen," Bram went on. "And beware how you decide rashly. For this is the supreme moment, not only of your own lives, but for all humanity and beetledom. Upon your decision hangs the future of the world.

"For, irresistible as the beetles are, there is one thing they lack. That is the sense of historic continuity. If they destroy man, they will know nothing of man's achievements, poor though these are. My own work on the fossil monotremes—"

"Which is a tissue of inaccuracies and half-baked deductions!" shouted Dodd.

Bram started as if a whip had lashed him. "Liar!" he bawled. "Do you think that I, who left the Greystoke expedition in a howling blizzard because I knew that here, in the inner earth, I could refute your miserable impostures—do you think that I am in the mood to listen to your wretched farrago of impossibilities?"

"Listen to me," bawled Dodd, advancing with waving arms. "Once and for all, let me tell you that your deductions are all based upon fallacious premises. No, I will not shut up, Tom Travers! You want me to aid your damned beetles in the destruction of humanity! I tell you that your phascalotherium, amphitherium, and all the rest of them, including the marsupial lion, are degenerate developments of the age following the pleistocene. I say the whole insect world was made to fertilize the plant world, so that it should bear fruit for human food. Man is the summit of the scale of evolution, and I will never join in any infamous scheme for his destruction."

Bram glared at Dodd like a madman. Three times he opened his mouth to speak, but only inarticulate sounds came from his throat. And when at last he did speak, he said something that neither Dodd nor Tommy had anticipated.

"It looks as if you're not so paralysed as you made out," he sneered. "You'll change your mind within what used to be called a day, Dodd. You'll crawl to my feet and beg for pardon. And you'll recant your lying theories about the fossil monotremes, or you die—the pair of you—you die!"

"I heard what he said. You shall not die. We shall go away to your place, where there are no beetles to eat us, even if"—Haidia shuddered—"even if we have to cross the bridge of fire, beyond which, they tell me, lies freedom."

High over and a little to one side of the petrol flame Dodd and Tommy had seen the slender arch of rock leading into another cleft in the rocks. They had investigated it several times, but always the fierce heat had driven them back.

Both Dodd and Tommy had noticed, however, that at times the fire seemed to shrink in volume and intensity. Observation had shown them that these times were periodical, recurring about every twelve hours.

"I think I've got the clue, Tommy," said Dodd, as the three watched the fiery fountain and speculated on the possibility of escape. "That flow of petrol is controlled, like the tides on earth, by the pull of the moon. Just now it is at its height. I've noticed that it loses pretty nearly half its volume at its alternating phase. If I'm right, we'll make the attempt in about twelve hours."

"Bram's given us twenty-four," said Tommy. "But how about getting Haidia across?"

"I go where you go," said Haidia, sidling up to Dodd and looking down upon him lovingly. "I do not afraid of the fire. If it burn me up, I go to the good place."

"Where's that, Haidia?" asked Dodd.

"When we die, we go to a place where it is always dark and there are no beetles, and the ground is full of shrimps. We leave our bodies behind, like the beetles, and fly about happy for ever."

"Not a bad sort of place," said Dodd, squeezing Haidia's arm. "If you think you're ready to try to cross the bridge, we'll start as soon as the fire gets lower."

"I'll be on the job," answered Haidia, unconsciously reproducing a phrase of Tommy's.

The girl glided away, and disappeared through the thick of the beetle crowd clustered about the entrance to the cavern. Tommy and Dodd had already discovered that it was through her ability to reproduce a certain beetle sound meaning "not good to eat" that the girl could come and go. They had once tried it on their own account, and had narrowly escaped the lashing tentacles.

After that there was nothing to do but wait. Three or four hours must have passed when Bram returned from his inner cave.

"Well, Dodd, have you experienced a change of heart?" he sneered. "If you knew what's in store for you, maybe you'd come to the conclusion that you've been too cocksure about the monotremes. We're slaughtering in the morning."

"That so?" asked Dodd.

"That's so," shouted Bram. "The beetles are beginning to emerge from the pupae, and they'll need food if they're to be kept quiet. We're rounding up about threescore of the culls—your friend Haidia will be among them. We've got some caged ichneumon flies, pretty little things only a foot long, which will sting them in certain nerve centers, rendering them powerless to move. Then we shall bury them, standing up, in the vegetable mould, for the beetles to devour alive, as soon as they come out of the shells. You'll feel pretty, Dodd, standing there unable to move, with the new born beetles biting chunks out of you."

Tommy shuddered, despite his hopes of their escaping. Bram, for a scientist, had a grim and picturesque imagination.

"Dodd, there is no personal quarrel between us," Bram went on. Again that note of pathetic pleading came into his voice. "Give up your mad ideas. Admit that the banded ant-eater, at least, existed before the pleistocene epoch, and everything can be settled. When you see what my beetles are going to do to humanity, you'll be proud to join us. Only make a beginning. You remember the point I made in my paper, about spalacotherium in the Upper Jurassic rocks. It would convince anybody but a hardened fanatic."

"I read your paper, and I saw your so-called spalacotherium, reconstructed from what you called a jaw-bone," shouted Dodd. "That so-called jaw-bone was a lump of chalk, made porous by water, and the rest was in your imagination. Do your worst, Bram, I'll never crucify truth to save my life. And I'll laugh at your spalacotherium when your beetles are eating me."

Bram yelled and shrieked, he stamped up and down the cavern, shaking his fists at Dodd. At last, with a final torrent of objurgation, he disappeared.

"A pleasant customer," said Tommy. "We'll have to make that bridge, Jim, no question about it, even if it means death in the petrol fire."

"Fire's dying down fast," answered Dodd. "Haidia ought to be here soon."

"If Bram hasn't got her."

"Bram got—that girl? If Bram harms a hair of her head I'll kill him with worse tortures than he's ever dreamed of," answered Dodd, leaping up, white with rage.

"You mean you—?" Tommy began.

"Love her? Yes, I love her," shouted Dodd. "She's a girl in a million. Just the sort of helpmate I need to assist me in my work when we get back. I tell you, Tommy, I didn't know what love meant before I saw Haidia. I laughed at it as a romantic notion. 'Oh lyric love, half angel and half bird!'" he quoted, beginning to stride up and down the cavern, while Tommy watched him in amazement.

And at this moment a complete beetle entered the cave. Complete, because it had a plastron, or breast-shell, as well as a back-shell, or carapace.

A double breast-shell! A new species of beetle? An executioner beetle, sent by Bram to summon them to the torture? Tommy shuddered, but Dodd, lost in his love ecstasy, was ignorant of the creature's advent.

"'Oh lyric love—'" he shouted again, as he twirled on his heel, to run smack into the monster. The crack of Dodd's head against the beetle-shell re-echoed through the cave.

The double plastron dropped, the carapace fell down: Haidia stood revealed. The lovers, folded in each other's arms, passed momentarily into a trance.

It was Tommy who separated them. "We'll have to make a move," he said. "I think the fire's as low as it ever gets. Why did you bring the shells, Haidia?"

"To save us all from the beetles," answered the girl. "When they see us in the shells, they will not know we are human. That is what makes it so hard to have to be eaten by those beetles, when they are such dumb-bells," she added, reproducing another of Tommy's words.

"Come," she continued bravely, "let us see if we can pass the fire."

The roaring fountain made the air a veritable inferno. Overhead the rocks were red-hot. A cascade of sparks tumbled in a fiery shower from the rock roof. Dodd, holding Haidia in his arms, to protect her, staggered ahead, with Tommy in the rear. Only the beetle-shells, which acted as non-conductors of the heat, made that fiery passage possible.

There was one moment when it seemed to Tommy as if he must let go, and drop into that raging furnace underneath. He heard Dodd bawling hoarsely in front of him, he nerved himself to a last effort, beating fiercely at his blazing hair—and then the heat was past, and he had dropped unconscious upon a bed of cool earth beside a rushing river.

He was vaguely aware of being carried in Dodd's arms, but a long time seemed to have passed before he grew conscious again. He opened his eyes in utter darkness. Dodd was whispering in his ear.