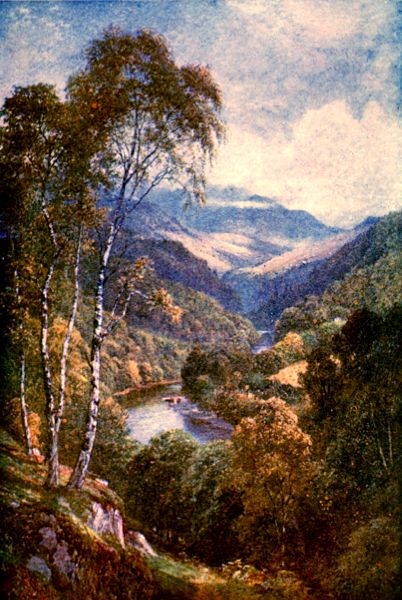

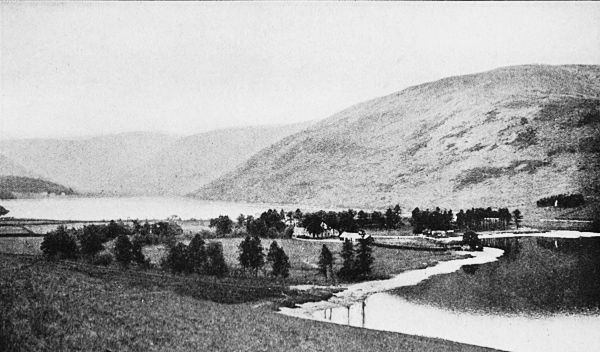

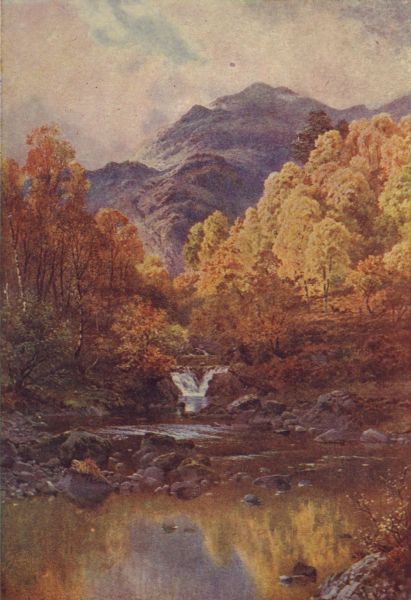

The Pass of Killiecrankie

The Pass of Killiecrankie

(See page 195)

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Spell of Scotland

The Spell Series

Author: Keith Clark

Release Date: December 14, 2012 [eBook #41623]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SPELL OF SCOTLAND***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/spellofscotland00claruoft |

THE SPELL OF SCOTLAND

THE SPELL SERIES

Each volume with one or more colored plates and many illustrations from original drawings or special photographs. Octavo, decorative cover, gilt top, boxed.

Per volume, net $2.50; carriage paid $2.70

By Isabel Anderson

THE SPELL OF BELGIUM

THE SPELL OF JAPAN

THE SPELL OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS AND THE PHILIPPINES

By Caroline Atwater Mason

THE SPELL OF ITALY

THE SPELL OF SOUTHERN SHORES

THE SPELL OF FRANCE

By Archie Bell

THE SPELL OF EGYPT

THE SPELL OF THE HOLY LAND

By Keith Clark

THE SPELL OF SPAIN

THE SPELL OF SCOTLAND

By W. D. McCrackan

THE SPELL OF TYROL

THE SPELL OF THE ITALIAN LAKES

By Edward Neville Vose

THE SPELL OF FLANDERS

By Burton E. Stevenson

THE SPELL OF HOLLAND

By Julia De W. Addison

THE SPELL OF ENGLAND

By Nathan Haskell Dole

THE SPELL OF SWITZERLAND

THE PAGE COMPANY

53 Beacon Street Boston, Mass.

"A Traveller may lee wi authority." (Scotch Proverb)

ILLUSTRATED

BOSTON

THE PAGE COMPANY

MDCCCCXVI

Copyright, 1916, by

The Page Company

All rights reserved

First Impression, November, 1916

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. SIMONDS COMPANY, BOSTON, U. S. A.

TO

THE LORD MARISCHAL

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Hame, Hame, Hame! | 1 |

| II. | Scotts-Land | 24 |

| III. | Border Towns | 53 |

| IV. | The Empress of the North | 82 |

| V. | The Kingdom of Fife | 149 |

| VI. | To the North | 171 |

| VII. | Highland and Lowland | 194 |

| VIII. | The Circle Round | 220 |

| IX. | The Western Isles | 252 |

| X. | The Lakes | 277 |

| XI. | The West Country | 314 |

| Bibliography | 335 | |

| Index | 339 | |

| PAGE | |

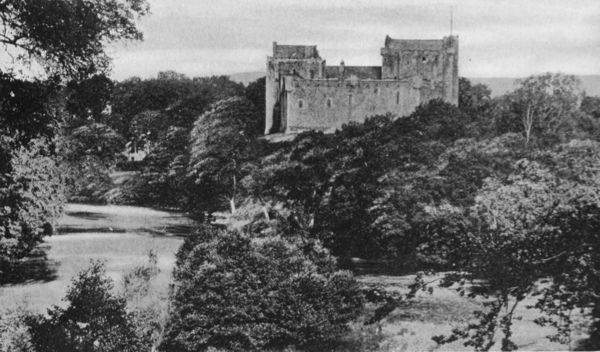

| The Pass of Killiecrankie (in full colour) (See page 195) | Frontispiece |

| MAP OF SCOTLAND | 1 |

| James VI | 6 |

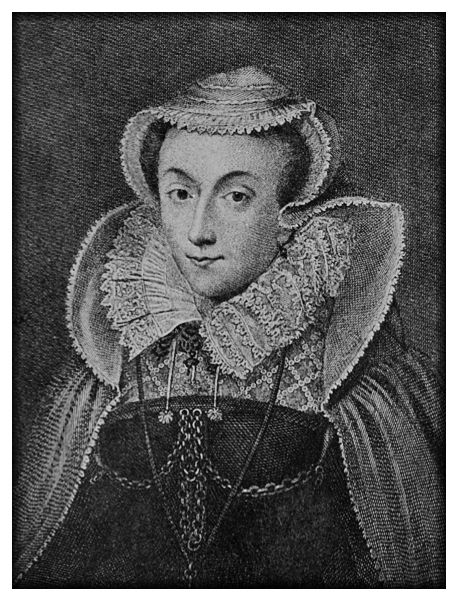

| Queen Mary | 15 |

| James II | 25 |

| Melrose Abbey | 34 |

| Abbotsford (in full colour) | 41 |

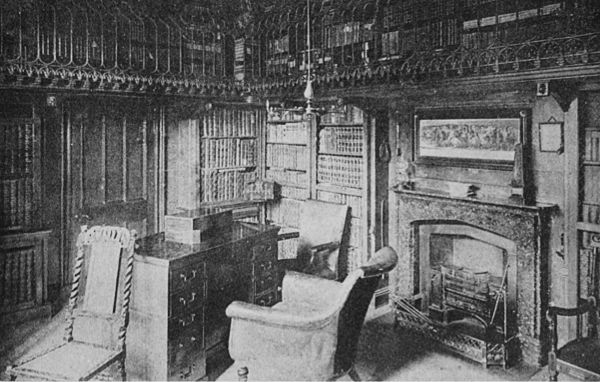

| The Study, Abbotsford | 45 |

| St. Mary's Aisle and Tomb of Sir Walter Scott, Dryburgh Abbey | 51 |

| Jedburgh Abbey | 63 |

| Hermitage Castle | 66 |

| Newark Castle | 74 |

| Interior View, Tibbie Shiel's Inn | 77 |

| St. Mary's Lake | 80 |

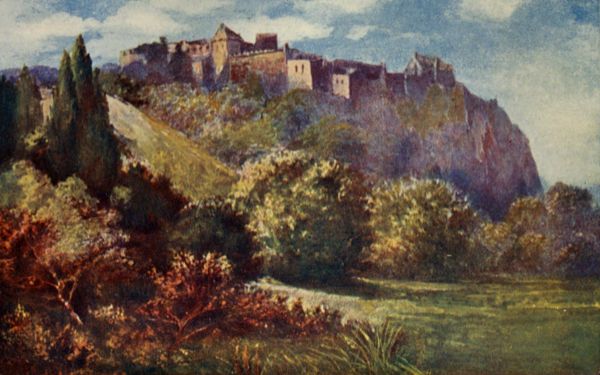

| Edinburgh Castle (in full colour) | 86 |

| Mons Meg | 90 |

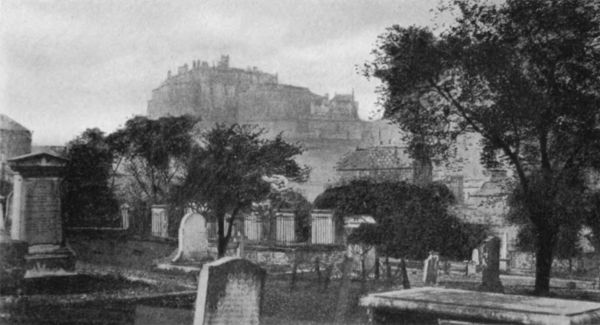

| Greyfriars' Churchyard | 96 |

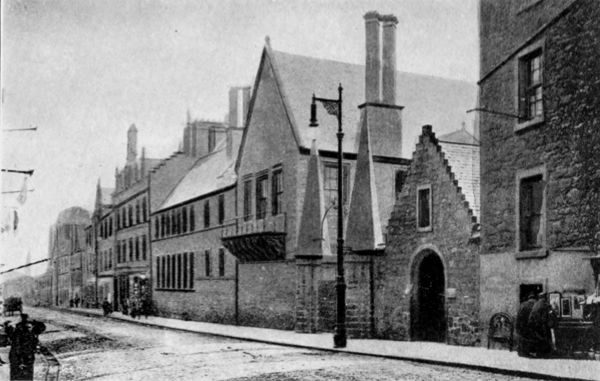

| Moray House | 102 |

| Interior of St. Giles | 104 |

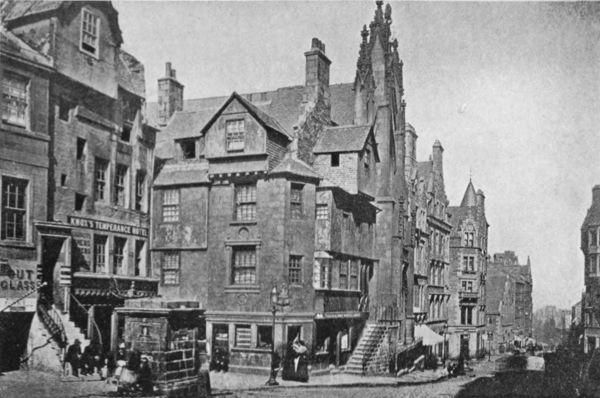

| John Knox's House | 106 |

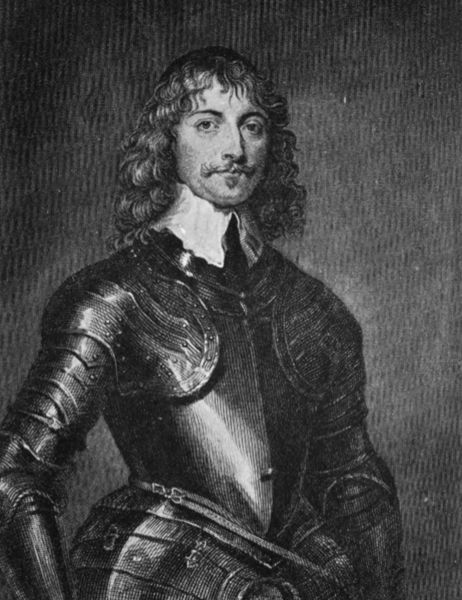

| James Graham, Marquis of Montrose | 108 |

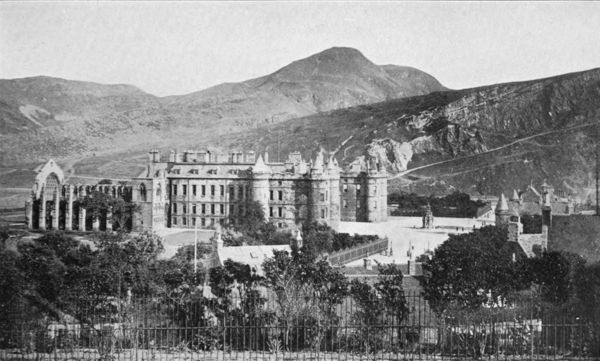

| Holyrood Palace | 111 |

| James IV | 115 |

| Margaret Tudor, Queen of James IV | 124 |

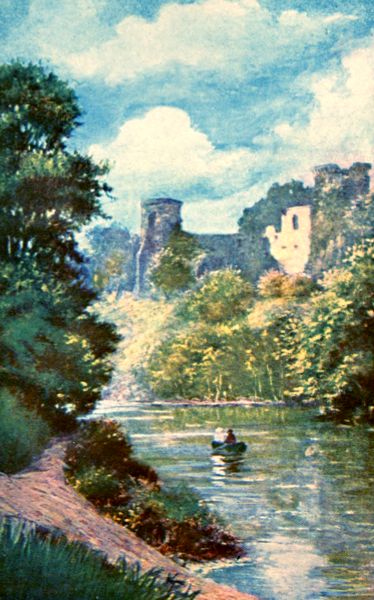

| Bothwell Castle (in full colour) | 131 |

| Princes Street | 134 |

| John Graham of Claverhouse, Viscount Dundee | 142 |

| Tantallon Castle | 157 |

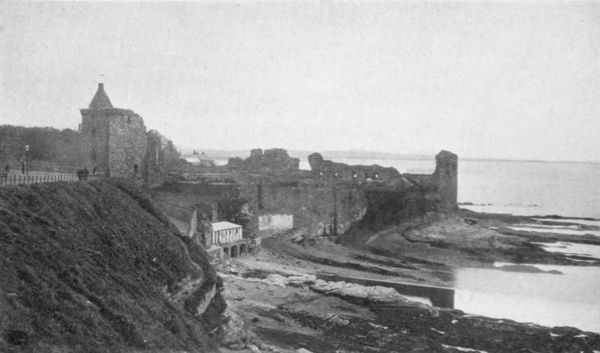

| St. Andrews Castle | 165 |

| Drawing-room, Linlithgow Palace, where Queen Mary was Born | 184 |

| Huntington Tower | 190 |

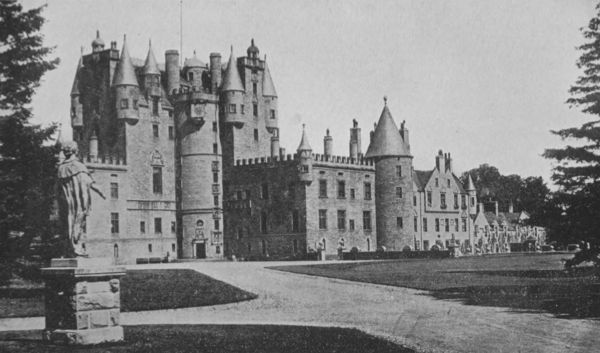

| Glamis Castle | 194 |

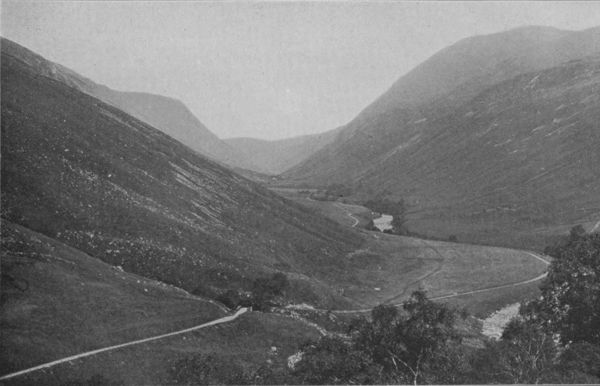

| Glen Tilt | 197 |

| Invercauld House | 200 |

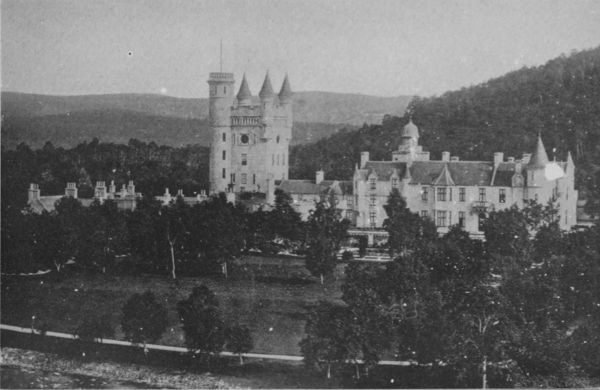

| Balmoral Castle | 205 |

| Marischal College | 207 |

| Dunnottar Castle | 212 |

| Spynie Castle | 224 |

| Cawdor Castle (in full colour) | 227 |

| Battlefield of Culloden | 232 |

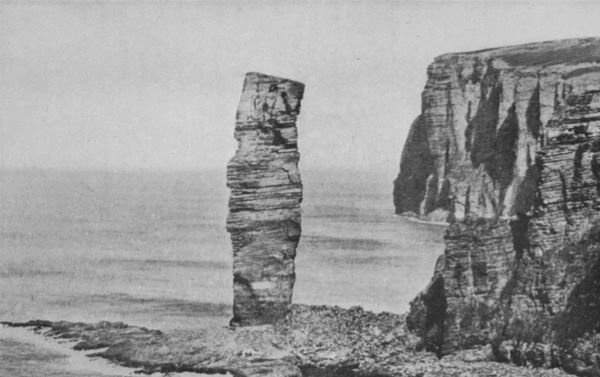

| The Old Man of Hoy | 237 |

| Earl's Palace, Kirkwall | 240 |

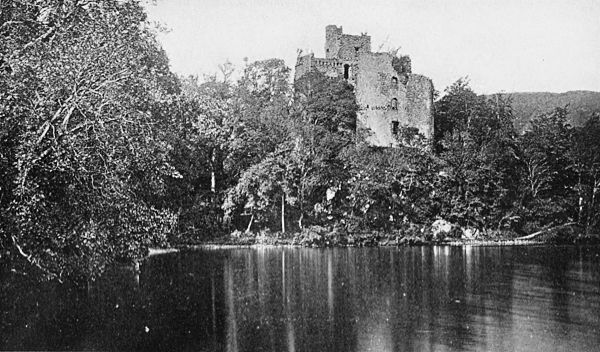

| Invergarry Castle | 248 |

| Kilchurn Castle | 258 |

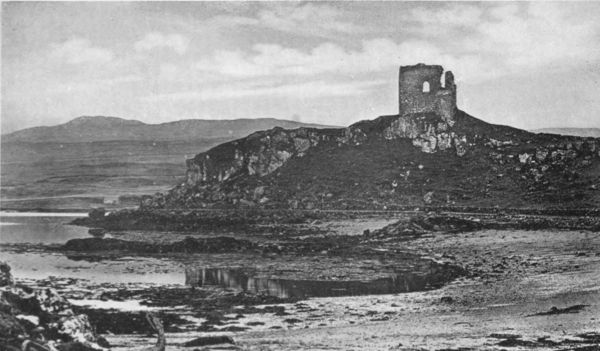

| Aros Castle | 265 |

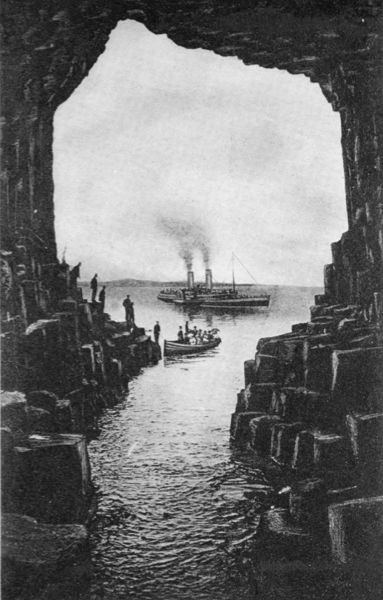

| Entrance to Fingal's Cave | 267 |

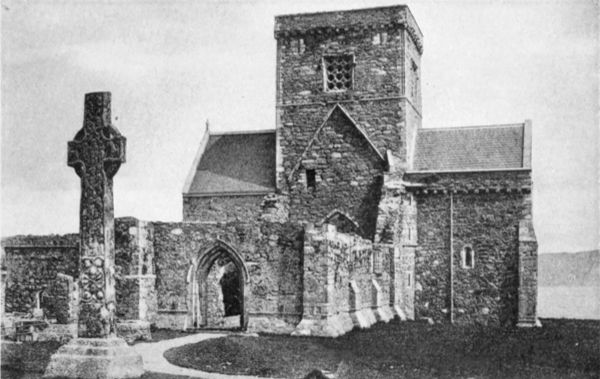

| Cathedral of Iona and St. Martin's Cross | 273 |

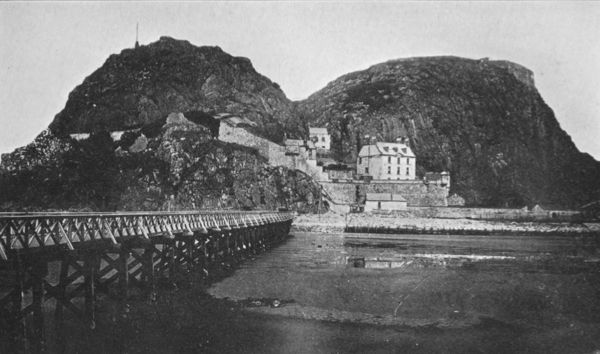

| Dumbarton Castle | 282 |

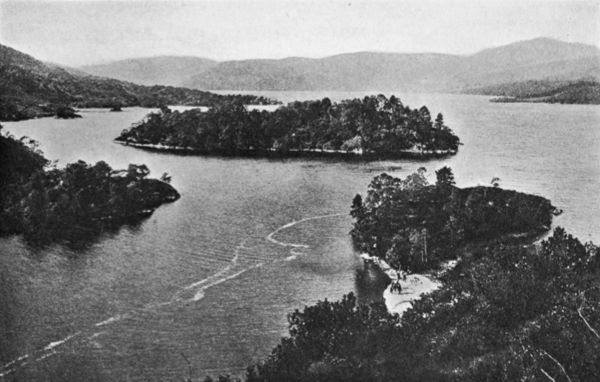

| Loch Katrine | 289 |

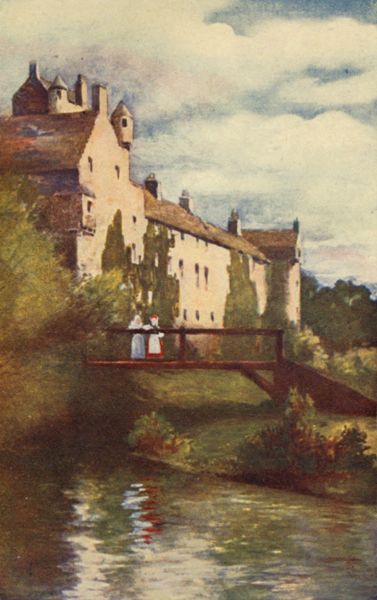

| The Brig o' Turk | 294 |

| The Trossachs (in full colour) | 296 |

| Stirling Castle (in full colour) | 304 |

| Doune Castle | 310 |

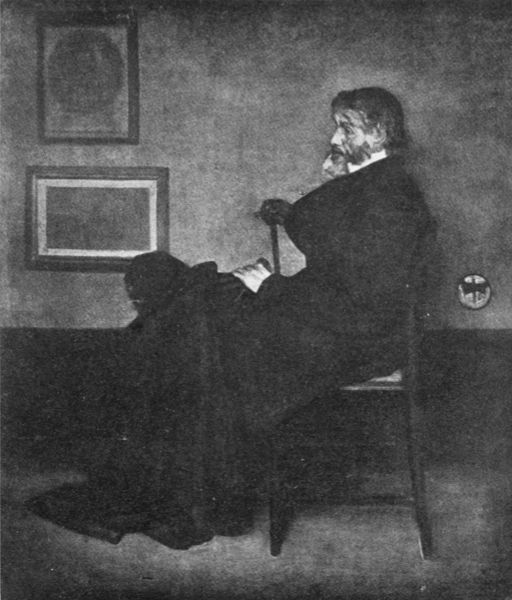

| Portrait of Thomas Carlyle, by Whistler | 317 |

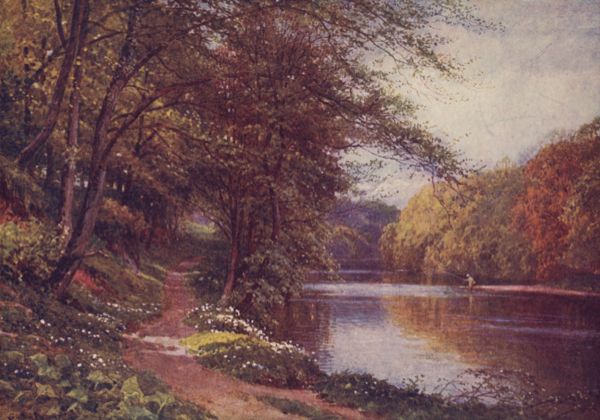

| Ayr River (in full colour) | 322 |

| Burns' Cottage, Birth-place of Robert Burns, Ayr | 328 |

| Caerlaverock Castle | 333 |

THE

SPELL OF SCOTLAND

"It's hame, and it's hame, hame fain wad I be,

And it's hame, hame, hame, to my ain countree!"

ime was when half a hundred ports ringing round the semi-island of Scotland invited your boat to make harbour; you could "return" at almost any point of entry you chose, or chance chose for you.

To-day, if you have been gone for two hundred and fifty years, or if you never were "of Scotia dear," except as a mere reading person with an inclination toward romance, you can make harbour after a transatlantic voyage at but one sea-city, and that many miles up a broad in-reach[Pg 2]ing river. Or, you can come up the English roads by Carlisle or by Newcastle, and cross the Border in the conquering way, which never yet was all-conquering. There is shipping, of course, out of the half hundred old harbours. But it is largely the shipping that goes and comes, fishing boats and coast pliers and the pleasure boats of the western isles.

You cannot come back from the far corners of the earth—to which Scotland has sent such majorities of her sons, since the old days when she squandered them in battle on the Border or on the Continent, to the new days when she squanders them in colonization so that half a dozen of her counties show decline in population—but you must come to Glasgow. The steamers are second-class compared with those which make port farther south. They are slower. But their very lack of modern splendour and their slow speed give time in which to reconstruct your Scotland, out of which perhaps you have been banished since the Covenant, or the Fifteen, or the Forty Five; or perhaps out of which you have never taken the strain which makes you romantic and Cavalier, or Presbyterian and canny. We who have it think that you who have it not lose something very precious for which there is no substitute. We pity you.[Pg 3] More clannish than most national tribesmen, we cannot understand how you can endure existence without a drop of Scotch.

Always when I go to Scotland I feel myself returning "home." Notwithstanding that it is two centuries and a bittock since my clerical ancestor left his home, driven out no doubt by the fluctuant fortunes of Covenanter and Cavalier, or, it may be, because he believed he carried the only true faith in his chalice—only he did not carry a chalice—and, either he would keep it undefiled in the New World, or he would share it with the benighted in the New World; I know not.

All that I know is that in spite of the fact that the Scotch in me has not been replenished since those two centuries and odd, I still feel that it is a search after ancestors when I go back to Scotland. And, if a decree of banishment was passed by the unspeakable Hanoverians after the first Rising, and lands and treasure were forfeited, still I look on entire Scotland as my demesne. I surrender not one least portion of it. Not any castle, ruined or restored, is alien to me. Highlander and Lowlander are my undivisive kin. However empty may seem the moorlands and the woodlands except of grouse and deer, there is not a square foot of the[Pg 4] twenty-nine thousand seven hundred eighty-five square miles but is filled for me with a longer procession, if not all of them royal, than moved ghostly across the vision of Macbeth.

Nothing happens any longer in Scotland. Everything has happened. Quite true, Scotland may some time reassert itself, demand its independence, cease from its romantic reliance on the fact that it did furnish to England, to the British Empire, the royal line, the Stewarts. Even Queen Victoria, who was so little a Stewart, much more a Hanoverian and a Puritan, was most proud of her Stewart blood, and regarded her summers in the Highlands as the most ancestral thing in her experience.

Scotland may at sometime dissolve the Union, which has been a union of equality, accept the lower estate of a province, an American "state," among the possible four of "Great Britain and Ireland," and enter on a more vigorous provincial life, live her own life, instead of exporting vigour to the colonies—and her exportation is almost done. She may fill this great silence which lies over the land, and is fairly audible in the deserted Highlands, with something of the human note instead of the call of the plover.

But, for us, for the traveler of to-day, and[Pg 5] at least for another generation, Scotland is a land where nothing happens, where everything has happened. It has happened abundantly, multitudinously, splendidly. No one can regret—except he is a reformer and a socialist—the absence of the doings of to-day; they would be so realistic, so actual, so small, so of the province and the parish. Whereas in the Golden Age, which is the true age of Scotland, men did everything—loving and fighting, murdering and marauding, with a splendour which makes it seem fairly not of our kind, of another time and of another world.

You must know your Scottish history, you must be filled with Scottish romance, above all, you must know your poetry and ballads, if you would rebuild and refill the country as you go. Not only over fair Melrose lies the moonlight of romance, making the ruin more lovely and more complete than the abbey could ever have been in its most established days, but over the entire land there lies the silver pall of moonlight, making, I doubt not, all things lovelier than in reality.

We truly felt that we should have arranged for "a hundred pipers an' a' an' a'." But we left King's Cross station in something of disguise. The cockneys did not know that we were[Pg 6] returning to Scotland. Our landing was to be made as quietly, without pibroch, as when the Old Pretender landed at Peterhead on the far northeastern corner, or when the Young Pretender landed at Moidart on the far western rim of the islands. And neither they nor we pretenders.

JAMES VI.

JAMES VI.

The East Coast route is a pleasant way, and I am certain the hundred pipers, or whoever were the merry musicmakers who led the English troops up that way when Edward First was king, and all the Edwards who followed him, and the Richards and the Henrys—they all measured ambition with Scotland and failed—I am certain they made vastly more noise than this excellently managed railway which moves across the English landscape with due English decorum.

We were to stop at Peterborough, and walk out to where, "on that ensanguined block at Fotheringay," the queenliest queen of them all laid her head and died that her son, James Sixth of Scotland, might become First of England. We stopped at York for the minster, and because Alexander III was here married to Margaret, daughter of Henry III; and their daughter being married to Eric of Norway in those old days when Scotland and Norway were [Pg 7] kin, became mother to the Maid of Norway, one of the most pathetic and outstanding figures in Scottish history, simply because she died—and from her death came divisions to the kingdom.

We paused at Durham, where in that gorgeous tomb St. Cuthbert lies buried after a brave and Scottish life. We only looked across the purpling sea where already the day was fading, where the slant rays of the sun shone on Lindisfarne, which the spirit of St. Cuthbert must prefer to Durham.

All unconsciously an old song came to sing itself as I looked across that wide water—

"My love's in Germanie,

Send him hame, send him hame,

My love's in Germanie,

Fighting for royalty,

He's as brave as brave can be,

Send him hame, send him hame!"

Full many a lass has looked across this sea and sung this lay—and shall again.

The way is filled with ghosts, long, long processions, moving up and down the land. A boundary is always a lodestone, a lodeline. Why do men establish it except that other men dispute it? In the old days England called it treason for a Borderer, man or woman, to intermarry with Scotch Borderer. The lure, you[Pg 8] see, went far. Even so that kings and ladies, David and Matilda, in the opposing edges of the Border, married each other. And always there was Gretna Green.

Agricola came this way, and the Emperor Severus. There is that interesting, far-journeying Æneas Sylvius Piccolomini, the "Gil Blas of the Middle Ages," who later became Pius II. He came to this country by boat, but becoming afraid of the sea, returned by land, even opposite to the way we are going. Froissart came, but reports little. Perhaps Chaucer, but not certainly. George Fox came and called the Scots "a dark carnal people."

With the Act of Union the stream grows steady and full. There is Ben Jonson, trudging along the green roadway out yonder; for on foot, and all the way from London, he came northward to visit William Drummond of Hawthornden. Who would not journey to such a name? But, alas, a fire destroyed "my journey into Scotland sung with all the adventures." All that I know of Ben is that he was impressed with Lomond—two hundred years before Scott.

And there trails Taylor, "water poet," hoping to rival Rare Ben, on his "Pennyless Pilgrimage," when he actually went into Scotland without a penny, and succeeded in getting gold[Pg 9] to further him on his way—"Marr, Murraye, Elgin, Bughan, and the Lord of Erskine, all of these I thank them, gave me gold to defray my charges in my journey."

James Howell, carries a thin portfolio as he travels the highway. But we must remember that he wrote his "Perfect Description of the People and Country of Scotland" in the Fleet.

Here is Doctor Johnson, in a post chaise. Of course, Sir! "Mr. Boswell, an active lively fellow is to conduct me round the country." And he's still a lively conductor. Surely you can see the Doctor, in his high boots, and his very wide brown cloth great coat with pockets which might be carrying two volumes of his folio dictionary, and in his hand a large oak staff. One tries to forget that years before this journey he had said to Boswell, "Sir, the noblest prospect that a Scotchman ever sees is the highroad that leads him to London." And, was there any malice in Boswell's final record—"My illustrious friend, being now desirous to be again in the great theater of life and animated existence"?

The poet Gray preceded him a little, and even John Wesley moves along the highroad seeking to save Scottish souls as well as English. A few years afterward James Hogg comes down[Pg 10] this way to visit his countryman, Tammas Carlyle in London; who saw Hogg as "a little red-skinned stiff rock of a body with quite the common air of an Ettrick shepherd."

There is Scott, many times, from the age of five when he went to Bath, till that last journey back from Italy—to Dryburgh! And Shadowy Jeanie Deans comes downward, walking her "twenty-five miles and a bittock a day," to save her sister from death.

Disraeli comes up this way when he was young and the world was his oyster. Stevenson passes up and down, sending his merry men up and down. And one of the most native is William Winter—"With a quick sense of freedom and of home, I dashed across the Border and was in Scotland."

There is a barricade of the Cheviots stretching across between the two countries, but the Romans built a Wall to make the division more apparent. In the dawn of the centuries the Romans came hither, and attempting to come to Ultima Thule, Picts and Scots—whatever they were, at least they were brave—met the Romans on the Border, as yet unreported in the world's history and undefined in the world's geography, and sent them back into what is England. The Romans in single journeys, and[Pg 11] in certain imperial attempts, did penetrate as far as Inverness. But they never conquered Scotland. Only Scotland of all the world held them back. And in order to define their defeat and to place limits to the unlimited Roman Empire, the Great Wall was built, built by Hadrian, that men might know where civilization, that splendid thing called Roman civilization, and barbarism did meet. Scotland was barbarism. And I think, not in apology but in all pride, she has remained something of this ever since. Never conquered, never subdued.

The Wall was, in truth, a very palpable thing, stretching from the Solway to the North Sea at the Tyne, with ample width for the constant patrol, with lookout towers at regular and frequent intervals, with soldiers gathered from every corner of the Empire, often the spawn of it, and with much traffic and with even permanent villas built the secure side of the barrier. If you meet Puck on Pook's hill, he will tell you all about it.

Our fast express moves swiftly northward, through the littoral of Northumberland, as the ship bearing Sister Clare moved through the sea—

"And now the vessel skirts the strand

[Pg 12]Of mountainous Northumberland;

Towns, towers, and hills successive rise,

And catch the nun's delighted eyes."

The voyager enters Berwick with a curious feeling. It is because of the voyagers who have preceded him that this town is singular among all the towns of the Empire. It is of the Empire, it is of Britain; but battled round about, and battled for as it has been since ambitious time began, it is of neither England nor Scotland. "Our town of Berwick-upon-Tweed," as the phrase still runs in the acts of Parliament, and in the royal proclamations; not England's, not Scotland's. Our town, the King's town.

For it is an independent borough (1551) since the men who fared before us could not determine which should possess it, and so our very own time records that history in an actual fact. I do not suppose the present serious-looking, trades-minded people of the city, with their dash of fair Danish, remember their singular situation day by day. The tumult and the shouting have died which made "the Border" the most embattled place in the empire, and Berwick[Pg 13]-upon-Tweed the shuttlecock in this international game of badminton.

It is a dual town at the best. But what has it not witnessed, what refuge, what pawn, has it not been, this capital of the Debatable Land, this Key of the Border.

The Tweed is here spanned by the Royal Border Bridge, opened in 1850, and called "the last Act of Union." But there is another bridge, a Roman bridge of many spans, antique looking as the Roman-Moorish-Spanish bridge at Cordova, and as antique as 1609, an Act of Union following swiftly on the footsteps of King James VI—who joyously paused here to fire a salute to himself, on his way to the imperial throne.

The walls of Berwick, dismantled in 1820 and become a promenade for peaceful townsfolk and curious sightseers, date no farther back than Elizabeth's time. But she had sore need of them; for this "our town," was the refuge for her harriers on retaliatory Border raids, particularly that most terrible Monday-to-Saturday foray of 1570, that answer to an attempt to reassert the rights of Mary, when fifty castles and peels and three hundred villages were laid waste in order that Scotland might know that Elizabeth was king.[Pg 14]

It was her kingly father, the Eighth Henry, who ordered Hertford into Scotland—"There to put all to fire and sword, to burn Edinburgh town, and to raze and deface it, when you have sacked it and gotten what you can of it, as there may remain forever a perpetual memory of the vengeance of God lighted upon it for their falsehood and disloyalty. Sack Holyrood House and as many towns and villages about Edinburgh as ye conveniently can. Sack Leith and burn it and subvert it, and all the rest, putting man, woman and child to fire and sword without exception, when any resistance is made against you. And this done, pass over to the Fife land, and extend like extremities and destructions in all towns and villages whereunto ye may reach conveniently, not forgetting among the rest, so to spoil and turn upside down the Cardinal's town of St. Andrews, as the upper stone may be the nether, and not one stick stand by another, sparing no creature alive within the same, especially such as either in friendship or blood be allied to the Cardinal. The accomplishment of all this shall be most acceptable to the Majesty and Honour of the King."

Berwick has known gentler moments, even marrying and giving in marriage. It was at this Border town that David, son of the Bruce, [Pg 15] and Joanna, sister of Edward III, were united in marriage. Even then did the kingdoms seek an Act of Union. And Prince David was four, and Princess Joanna was six. There was much feasting by day and much revelry by night, among the nobles of the two realms, while, no doubt, the babies nodded drowsily.

QUEEN MARY.

QUEEN MARY.

At Berwick John Knox united himself in marriage with Margaret Stewart, member of the royal house of Stewart, cousin, if at some remove, from that Stewart queen who belonged to "the monstrous regiment of women," and to whose charms even the Calvinist John was sensitive. One remembers that at Berwick John was fifty, and Margaret was sixteen.

There is not much in Berwick to hold the attention, unless one would dine direct on salmon trout just drawn frae the Tweed. There are memories, and modern content with what is modern.

Perhaps the saddest eyes that ever looked on the old town were those of Queen Mary, as she left Jedburgh, after her almost fatal illness, and after her hurried ride to the Hermitage to see Bothwell, and just before the fatal affair in Kirk o' Field. Even then, and even with her spirit still unbroken, she felt the coming of the end. "I am tired of my life," she said more[Pg 16] than once to Le Croc, French ambassador, on this journey as she circled about the coast and back to Edinburgh.

She rode toward Berwick with an escort of a thousand men, and looked down on the town from Halidon Hill, on the west, where two hundred years before (1333) the Scots under the regent Douglass had suffered defeat by the English.

It was an old town then, and belonged to Elizabeth. But it looked much as it does to-day; the gray walls, so recently built; the red roofs, many of them sheltering Berwickians to-day; the church spires, for men worshiped God in those days in churches, and according to the creeds that warred as bitterly as crowns; masts in the offing, whence this last time one might take ship to France, that pleasant smiling land so different from this dour realm. At all these Mary must have looked wistfully and weariedly, as the royal salute was fired for this errant queen. She looked also, over the Border, then becoming a hard-and-fast boundary, and down the long, long road to Fotheringay, and to peace at last and honour, in the Abbey.

It is well to stand upon this hill, before you go on to the West and the Border, or on to the North and the gray metropolis, that you may[Pg 17] appreciate both the tragedy and the triumph that is Scotland's and was Mary's. The North Sea is turning purple far out on the horizon, and white sea birds are flying across beyond sound. The long level light of the late afternoon is coming up over England. In the backward of the Border a plaintive curlew is crying in the West, as he has cried since the days of Mary, and æons before.

You may go westward from here, by train and coach, and carriage and on foot, to visit this country where every field has been a battlefield, where ruined peel towers finally keep the peace, where castles are in ruins, and a few stately modern homes proclaim the permanence of Scottish nobility; and where there is no bird and no flower unsung by Scottish minstrelsy, or by Scott. Scott is, of course, the poet and prose laureate of the Border. "Marmion" is the lay, almost the guide-book. It should be carried with you, either in memory or in pocket.

If the day is not too far spent, the afternoon sun too low, you can make Norham Castle before[Pg 18] twilight, even as Marmion made it when he opened the first canon of Scott's poem—

"Day set on Norham's castle steep

And Tweed's fair river, broad and deep,

And Cheviot's mountains lone;

The battled towers, the donjon keep,

The loophole grates, where captives weep,

The flanking walls that round it sweep,

In yellow luster shone."

There is but a fragment of that castle remaining, and this, familiar to those who study Turner in the National Gallery. A little village with one broad street and curiously receding houses attempts to live in the shadow of this memory. The very red-stone tower has stood there at the top of the steep bank since the middle Eleven Hundreds. Henry II held it as a royal castle, while his craven son John—not so craven in battle—regarded it as the first of his fortresses. Edward I made it his headquarters while he pretended to arbitrate the rival claims of the Scottish succession, and to establish himself as the Lord Superior. On the green hill of Holywell nearby he received the submission of Scotland in 1291—the submission of Scotland!

Ford castle is a little higher up the river, where lodged the dubious lady with whom the[Pg 19] king had dalliance in those slack days preceding Flodden—the lady who had sung to him in Holyrood the challenging ballad of "Young Lochinvar!" James was ever a Stewart, and regardful of the ladies.

"What checks the fiery soul of James,

Why sits the champion of dames

Inactive on his steed?"

The Norman tower of Ford (the castle has been restored), called the King's tower, looks down on the battlefield, and in the upper room, called the King's room, there is a carved fireplace carrying the historic footnote—

"King James ye 4th of Scotland did lye

here at Ford castle, A. D. 1513."

Somehow one hopes that the lady was not sparring for time and Surrey, and sending messages to the advancing Earl, but truly loved this Fourth of the Jameses, grandfather to his inheriting granddaughter.

Coldstream is the station for Flodden. But the village, lying a mile away on the Scotch side of the Tweed, has memories of its own. It was here that the most famous ford was found between the two countries, witness and way to so many acts of disunion; from the time when Edward I, in 1296, led his forces through it into[Pg 20] Scotland, to the time when Montrose, in 1640, led his forces through it into England.

"There on this dangerous ford and deep

Where to the Tweed Leet's eddies creep

He ventured desperately."

The river was spanned by a five-arch bridge in 1763, and it was over this bridge that Robert Burns crossed into England. He entered the day in his diary, May 7, 1787. "Coldstream—went over to England—Cornhill—glorious river Tweed—clear and majestic—fine bridge."

It was the only time Burns ever left Scotland, ever came into England. And here he knelt down, on the green lawn, and prayed the prayer that closes "The Cotter's Saturday Night"—

"O Thou who pour'd the patriot tide

That streamed through Wallace's undaunted heart,

Who dared to nobly stem tyrannic pride

Or nobly die, the second glorious part,

(The patriot's God, peculiarly Thou art,

His friend, inspirer, guardian and reward!)

O never, never, Scotia's realm desert;

But still the patriot and the patriot bard,

In bright succession raise, her ornament and guard!"

Surely a consecration of this crossing after its centuries of unrest.

General Monk spent the winter of 1659 in Coldstream, lodging in a house east of the mar[Pg 21]ket-place, marked with its tablet. And here he raised the first of the still famous Coldstream Guards, to bring King Charles "o'er the water" back to the throne. Coldstream is the Gretna Green of this end of the Border, and many a runaway couple, noble and simple, has been married in the inn.

Four miles south of Coldstream in a lonely part of this lonely Border—almost the echoes are stilled, and you hear nothing but remembered bits of Marmion as you walk the highway—lies Flodden Field. It was the greatest of Scotch battles, not even excepting Bannockburn; greatest because the Scotch are greatest in defeat.

It was, or so it seemed to James, because his royal brother-in-law Henry VIII was fighting in France, an admirable time wherein to advance into England. James had received a ring and a glove and a message, from Anne of Brittany, bidding him

"Strike three strokes with Scottish brand

And march three miles on Scottish land

And bid the banners of his band

In English breezes dance."

James was not the one to win at Flodden, notwithstanding that he had brought a hundred[Pg 22] thousand men to his standard. They were content to raid the Border, and he to dally at Ford.

"O for one hour of Wallace wight,

Or well skill'd Bruce to rule the fight,

And cry—'Saint Andrew and our right!'

Another sight had seen that morn

From Fate's dark book a leaf been torn,

And Flodden had been Bannockburn!"

The very thud of the lines carries you along, if you have elected to walk through the countryside, green now and smiling faintly if deserted, where it was brown and sere in September, 1513. One should be repeating his "Marmion," as Scott thought out so many of its lines riding over this same countryside. It is a splendid, a lingering battle picture—

"And first the ridge of mingled spears

Above the brightening cloud appears;

And in the smoke the pennon flew,

As in the storm the white sea mew,

Then mark'd they, dashing broad and far,

The broken billows of the war;

And plumed crests of chieftains brave,

Floating like foam upon the wave,

But nought distinct they see.

Wide ranged the battle on the plain;

Spears shook, and falchions flash'd amain,

Fell England's arrow flight like rain,

Crests rose and stooped and rose again

Wild and disorderly."

[Pg 23]

Thousands were lost on both sides. But the flower of England was in France, while the flower of Scotland was here; and slain—the king, twelve earls, fifteen lords and chiefs, an archbishop, the French ambassador, and many French captains.

You walk back from the Field, and all the world is changed. The green haughs, the green woodlands, seem even in the summer sun to be dun and sere, and those burns which made merry on the outward way—can it be that there are red shadows in their waters? It is not "Marmion" but Jean Elliott's "Flower of the Forest" that lilts through the memory—

"Dule and wae was the order sent our lads to the Border,

The English for once by guile won the day;

The Flowers of the Forest that foucht aye the foremost,

The pride of our land are cauld in the clay.

"We'll hear nae mair liltin' at the eve milkin',

Women and bairns are heartless and wae;

Sighin' and moanin' on ilka green loanin'—

The Flowers of the Forest are a' wede away."

I know not by what alchemy the Scots are always able to win our sympathy to their historic tragedies, or why upon such a field as Flodden, and many another, the tragedy seems but to have just happened, the loss is as though of yesterday.

t is possible to enter the Middle Marches from Berwick; in truth, Kelso lies scarcely farther from Flodden than does Berwick. But Flodden is on English soil to-day, and memory is content to let it lie there. These Middle Marches however are so essentially Scottish, the splendour and the romance, the history and the tragedy, that one would fain keep them so, and come upon them as did the kings from David I, or even the Celtic kings before him, who sought refuge from the bleak Scottish north in this smiling land of dales and haughs, of burns and lochs. Not at any moment could life become monotonous even in this realm of romance, since the Border was near, and danger and dispute so imminent, so incessant.

Preferably then one goes from Edinburgh (even though never does one go from that city, "mine own romantic town," but with regret; not even finally when one leaves it and knows [Pg 25] one will not return till next time) to Melrose; as Scottish kings of history and story have passed before. There was James II going to the siege of Roxburgh, and not returning; there was James IV going to the field of Flodden and not returning; there was James V going to hunt the deer; there was James VI going up to London to be king; Mary Queen on that last journey to the South Countrie; Charles I and Charles II losing and getting a crown; Charles III—let us defy history and call the Bonnie Prince by his title—when he went so splendidly after Prestonpans.

JAMES II.

JAMES II.

It is a royal progress, out of Edinburgh into the Middle Marches; past Dalkeith where James IV rode to meet and marry Margaret of England; past Borthwick, where Queen Mary spent that strange hot-trod honeymoon with Bothwell—of all place of emotion this is the most difficult to realize, and I can but think Mary's heart was broken here, and the heartbreak at Carberry Hill was but an echo of this; past Lauder, where the nobles of ignoble James III hung his un-noble favourite from the stone arch of the bridge; into the level rays of a setting sun—always the setting sun throws a more revealing light than that of noonday over this Scotland.

I remember on my first visit to Melrose, of course during my first visit to Scotland, I scheduled my going so as to arrive there in the evening of a night when the moon would be at the full. I had seen it shine gloriously on the front of York, splendidly on the towers of Durham. What would it not be on fair Melrose, viewed aright?

I hurried northward, entered Edinburgh only to convey my baggage, and then closing my eyes resolutely to all the glory and the memory that lay about, I went southward through the early twilight. I could see, would see, nothing before Melrose.

The gates of the Abbey were, of course, closed. But I did not wish to enter there until the magic hour should strike. The country round about was ineffably lovely in the rose light of the vanishing day.

"Where fair Tweed flows round holy Melrose

And Eildon slopes to the plain."

The Abbey was, of course, the center of thought continually, and its red-gray walls[Pg 27] caught the light of day and the coming shadows of night in a curious effect which no picture can report; time has dealt wondrously with this stone, leaving the rose for the day, the gray for the night.

I wandered about, stopping in the empty sloping market-place to look at the Cross, which is as old as the Abbey; looking at the graveyard which surrounds the Abbey, where men lie, common men unsung in Scottish minstrelsy, except as part of the great hosts, men who heard the news when it was swift and fresh from Bannockburn, and Flodden, and Culloden; and where men and women still insert their mortality into this immortality—Elizabeth Clephane who wrote the "Ninety and Nine" lies there; and out into the country and down by the Tweed toward the Holy Pool, the Haly Wheel, to wonder if when I came again in the middle night, I, too, should see the white lady rise in mist from the waters, this lady of Bemersyde who had loved a monk of Melrose not wisely but very well, and who drowned herself in this water where the monk in penance took daily plunges, come summer, come winter. How often this is the Middle-Age penalty!

Far across the shimmering green meadows and through the fragrant orchards came the[Pg 28] sound of bagpipes—on this my first evening in Scotland! And whether or not you care for the pipes, there is nothing like them in a Scottish twilight, a first Scottish twilight, to reconstruct all the Scotland that has been.

The multitudes and the individuals came trooping back. At a time of famine these very fields were filled with huts, four thousand of them, for always the monks had food, and always they could perform miracles and obtain food; which they did. That for the early time. And for the late, the encampment of Leslie's men in these fields before the day when they slaughtered Montrose's scant band of royalists at Philipshaugh, and sent that most splendid figure in late Scottish history as a fugitive to the north, and to the scaffold.

I knew that in the Abbey before the high altar lay the high heart of The Bruce, which had been carried to Spain and to the Holy Land, by order of Bruce, since death overtook him before he could make the pilgrimage. Lord James Douglass did battle on the way against the Moslems in southern Spain, where "a Douglass! a Douglass!" rang in battle clash against "Allah, illah, allah," and the Douglass himself was slain. The heart of The Bruce flung against the infidel, was recovered and sent on[Pg 29] to Jerusalem, and then back to Melrose. The body of Douglass was brought back to Scotland, to St. Bride's church in Douglass, and his heart also lies before the high altar of Melrose. "In their death they were not divided."

There lies also buried Michael Scot

"Buried on St. Michael's night,

When the bell toll'd one and the moon was bright."

On such a night as this, I hoped. And Scot is fit companion for the twilight. This strange wizard of a strange time was born in Upper Tweedale, which is the district of Merlin—the older wizard lies buried in a green mound near Drummelzier. Michael traveled the world over, Oxford, Paris, Bologna, Palermo, Toledo, and finally, perhaps because his wizardry had sent him like a wandering Jew from place to place, back to the Border, his home country, where he came and served the Evil One. Dante places him in the Purgatory of those who attempt blasphemously to tear the veil of the future. The thirteenth century was not the time in which to increase knowledge, whether of this world or the next. Even to-day perhaps we save a remnant of superstition, and we would not boast

"I could say to thee

The words that cleft the Eildon hills in three."

[Pg 30]

Very dark against the gathering dark of the night sky rose the Eildon hills above, cleft in three by the wizardry of Scot. To that height on the morrow I should climb, for it is there that Sir Walter Scott, a later wizard, had carried our Washington Irving, just a century ago, and shown him all this Borderland—which lay about me under the increasing cover of night.

"I can stand on the Eildon Hill and point out forty-three places famous in war and verse," Sir Walter said to our Irving. "I have brought you, like a pilgrim in the Pilgrim's Progress, to the top of the Delectable Mountains, that I may show you all the goodly regions hereabouts. Yonder is Lammermuir and Smailholm; and there you have Galashiels and Torwoodelee and Gala Water; and in that direction you see Teviotdale and the Braes of Yarrow; and Ettrick stream winding along like a silver thread to throw itself into the Tweed. It may be pertinacity, but to my eye, these gray hills and all this wild Border country have beauties peculiar to themselves. When I have been for some time in the rich scenery about Edinburgh, which is like an ornamented garden land, I begin to wish myself back again among my own honest gray hills; and if I did not see the heather at least once a year, I think I should die."[Pg 31]

On the morrow. But for to-night it was enough to remember that perfect picture as imagination painted it in Andrew Lang's verse—

"Three crests against the saffron sky,

Beyond the purple plain,

The kind remembered melody

Of Tweed once more again.

"Wan water from the Border hills,

Dear voice from the old years,

Thy distant music lulls and stills,

And moves to quiet tears.

"Like a loved ghost thy fabled flood

Fleets through the dusky land;

Where Scott, come home to die, has stood,

My feet returning, stand.

"A mist of memory broods and floats,

The Border waters flow;

The air is full of ballad notes

Borne out of long ago.

"Old songs that sung themselves to me,

Sweet through a boy's day dream,

While trout below the blossom'd tree

Plashed in the golden stream.

"Twilight, and Tweed, and Eildon Hill,

Fair and too fair you be;

You tell me that the voice is still

That should have welcomed me."

[Pg 32]

I did not miss the voice, any of the voices. They whispered, they sang, they crooned, they keened, about me. For this was Melrose, mael ros, so the old Celtic goes, "the naked headland in the wood." And I was seeing, was hearing, what I have come to see and hear; I, a Scot, if far removed, if in diluted element, and Scott's from the reading days of Auld Lang Syne.

And should I not within the moonlight see the white lady rise from the Haly Wheel? And should I not see the moonlight flooding the Abbey, Melrose Abbey? Out of a remembered yesterday, out of a confident midnight—surely there was a budding morrow in this midnight—I remembered the lines—

"If thou would'st view fair Melrose aright,

Go visit it by the pale moonlight;

For the gay beams of lightsome day

Gild but to flout the ruins gray.

When the broken arches are black in night,

And each shafted oriel glimmers white,

When the cold light's uncertain shower

Streams on the ruined central tower;

When buttress and buttress alternately

Seem framed of ebon and ivory;

When silver edges the imagery,

And the scrolls that teach thee to live and die;

When distant Tweed is heard to rave,

[Pg 33]And the owlet to hoot o'er the dead man's grave,

Then go—but go alone the while—

Then view St. David's ruined pile;

And, home returning, soothly swear

Was never scene so sad and fair."

The moon did not rise that night.

I walked about the fields, lingered about the Cross in the market, looked expectantly at the Abbey, until two in the morning.

"It was near the ringing of matin bell,

The night was well nigh done."

The moon did not rise, and neither did the white lady. It was not because there was a mist, a Scottish mist, over the heavens; they were clear, the stars were shining, and the pole star held true, Charles' wain—as Charles should in Bonnie Scotland—held true to the pole. But it was a late July moon, and those Eildon hills and their circling kin rose so high against the night sky—daytime they seemed modest enough—that the moon in this latitude as far north as Sitka did not circle up the sky. Neither does the sun in winter, so the guardian explained to me next day.

Fair Melrose is fairest, o' nights, at some later or earlier time of the year. It was then that I resolved to return in December, on December 27, when the festival of St. John's is celebrated with torch lights in the ruins of the[Pg 34] Abbey—and Michael Scot comes back to his own! But then I reflected that the moon is not always full on the Eve of St. John's.

"I cannot come, I must not come,

I dare not come to thee,

On the Eve of St. John's, I must walk alone,

In thy bower I may not be."

I chose, years later, an October moon, in which to see it "aright."

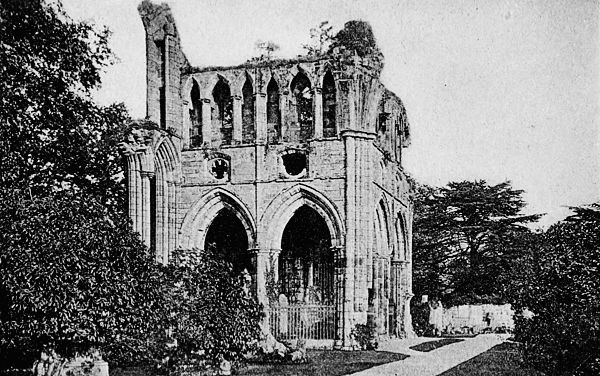

MELROSE ABBEY.

MELROSE ABBEY.

Viewed by day, Melrose is surely fair; fair enough to enchant mortal vision. It is the loveliest ruin in the land where reform has meant ruin, and where from Kelso to Elgin, shattered fanes of the faith proclaim how variable is the mind of man through the generations, and how hostile when it forsakes.

Melrose is an old foundation. In truth the monastery was established at old Melrose, two miles farther down the Tweed, and is so lovely, so dramatic a corner of the Tweed, that Dorothy Woodsworth declared, "we wished we could have brought the ruins of Melrose to this spot." She missed the nearby murmur of the river as we do.

This oldest harbour of Christianity was founded in the pagan world by monks from Iona. Therefore by way of Ireland and not from Rome, blessed by Saint Columba sixty [Pg 35] years before Saint Augustine came to Canterbury. It was the chief "island" between Iona and Lindisfarne. Very haughty were these monks of the West. "Rome errs, Alexandria errs, all the world errs; only the Scots and the Britons are in the right." There is surely something still left of the old spirit in Scotia, particularly in spiritual Scotia.

Near Melrose was born that Cuthbert who is the great saint of the North, either side the Border, and who lies in the midst of the splendour of Durham. A shepherd, he watched his sheep on these very hills round about us, and saw, when abiding in the fields, angels ascending and descending on golden ladders. Entering Melrose as a novice he became prior in 664, and later prior at Lindisfarne. When the monks were driven from the Holy Island by the Danes they carried the body of St. Cuthbert with them for seven years, and once it rested at Melrose—

"O'er northern mountain, march and moor,

From sea to sea, from shore to shore,

Seven years St. Cuthbert's corpse they bore,

They rested them in fair Melrose;

But though alive he loved it well,

Not there his relics might repose."

When King David came to the making of[Pg 36] Scotland, he came into the Middle Marches, and finding them very lovely—even as you and I—this "sair sanct to the Croon," as his Scottish royal descendant, James VI saw him—and James would have fell liked to be a saint, but he could accomplish neither sinner nor saint, because Darnley crossed Mary in his veins—David determined to build him fair Abbeys. Of which, Melrose, "St. David's ruined pile," is the fairest. He brought Cistercians from Rievaulx in Yorkshire, to supplant the Culdees of Iona, and they builded them a beautiful stone Melrose to supplant the wooden huts of old Melrose. It centered a very active monastic life, where pavements were once smooth and lawns were close-clipped, and cowled monks in long robes served God, and their Abbot lorded it over lords, even equally with kings.

But it stood on the highway between Dunfermline and London, between English and Scottish ambitions. And it fell before them. Edward I spared it because the Abbots gave him fealty. But Edward II, less royal in power and in taste, destroyed it. The Bruce rebuilded it again, greater splendour rising out of complete ruin. When Richard II came to Scotland he caused the Abbey to be pillaged and burned. And when Hertford came for Henry VIII, after the Thirty[Pg 37] Nine Articles had annulled respect for buildings under the protection of Rome, the final ruin came to St. David's church-palace. Yet, late as 1810, church service, reformed, of course, was held in a roofed-over part of the Abbey ruin. To-day it is under the protection of the Dukes of Buccleuch. And, we remember as we stand here, while the beams of lightsome day gild the ruin, the mottoes of the great family of the Border, Luna Cornua Reparabit, which being interpreted is, "There'll be moonlight again." Then to light the raids, the reiving that refilled the larder. But to-morrow for scenic effect.

Examined in this daylight, the beauty of Melrose surely loses very little. It is one of the most exquisite ruins in the United Kingdom, perhaps second to Tintern, but why compare? It is of finest Gothic, out of France, not out of England. In its general aspect it is nobly magnificent—

"The darken'd roof rose high aloof

On pillars, lofty, light and small;

The keystone that locked each ribbed aisle

Was a fleur de lys or a quatre feuille,

The corbels were carved grotesque and grim;

And the pillars with clustered shafts so trim,

With base and with capital flourish'd around

Seem'd bundles of lances which garlands had bound."

[Pg 38]

And, as a chief detail which yields not to Tintern or any other, is the east window over the high altar, through which the moon and sun shines on those buried hearts—

"The moon on the east oriel shone

Through slender shafts of shapely stone,

By foliaged tracery combined.

Thou would'st have thought some fairy'd hand

'Twixt poplars straight the osier wand

In many a freakish knot had twined,

Then framed a spell when the work was done,

And changed the willow wreaths to stone.

The silver light, so pale and faint,

Showed many a prophet and many a saint,

Whose image on the glass was dyed,

Full in the midst his cross of red

Triumphant Michael brandish'd,

And trampled on the Apostate's pride;

The moonbeams kissed the holy pane,

And threw on the pavement a bloody stain."

If "Scott restored Scotland," he built the "keep" which centers all the Scott-land of the Border side.

Two miles above Melrose, a charming walk leads to Abbotsford; redeemed out of a swamp into at least the most memory-filled mansion of all the land. Scott, like the monks, could[Pg 39] not leave the silver wash of the Tweed; and, more loving than those who dwelt at Melrose and Dryburgh, he placed his Abbot's House where the rippling sound was within a stone's throw.

The Tweed is such a storied stream that as you walk along, sometimes across sheep-cropped meadows, sometimes under the fragant rustling bough and athwart the shifting shadows of oak, ash, and thorn—Puck of Pook's hill must have known the Border country in its most embroidered days—you cannot tell whether or not the deep quiet river is the noblest you have seen, or the storied hills about are less than the Delectable mountains.

The name "Tweed" suggests romance—unless instead of having read your Scott you have come to its consciousness through the homespun, alas, to-day too often the factory-spun woolens, which are made throughout all Scotland, but still in greatest length on Tweedside.

Dorothy Wordsworth, winsome marrow, who loved the country even better than William, I trow—only why remark it when he himself recognized how his vision was quickened through her companionship?—has spoke the word Tweed—"a name which has been sweet in[Pg 40] my ears almost as far back as I can remember anything."

The river comes from high in the Cheviot hills, where East and West Marches merge and where—

"Annan, Tweed, and Clyde

Rise a' out o' ae hillside."

And down to the sea it runs, its short hundred miles of story—

"All through the stretch of the stream,

To the lap of Berwick Bay."

As you walk along Tweedside, you feel its enchantment, you feel the sorrow of the thousands who through the centuries have exiled themselves from its banks, because of war, or because of poverty, or because of love—

"Therefore I maun wander abroad,

And lay my banes far frae the Tweed."

But now, you are returned, you are on your way to Abbotsford, there are the Eildons, across the river you get a glimpse of the Catrail, that sunken way that runs along the boundary for one-half its length, and may have been a fosse, or may have been a concealed road of the Romans or what not. Scott once leaped his horse across it, nearly lost his life, and did lose his confidence in his horsemanship.

"And all through the summer morning

I felt it a joy indeed

To whisper again and again to myself,

This is the voice of the Tweed."

Abbotsford

Abbotsford

It is not possible to approach Abbotsford, as it should be approached, from the riverside, the view with which one is familiar, the view the pictures carry. Or, it can be done if one would forego the walk, take it in the opposite direction, and come hither by rail from Galashiels—that noisy modern factory town, once the housing place for Melrose pilgrims, which to-day speaks nothing of the romance of Gala water, and surely not these factory folk "can match the lads o' Gala Water." It is a short journey, and railway journeys are to be avoided in this land of by-paths. But there, across the water, looking as the pictures have it, and as Scott would have it, rises Abbotsford, turreted and towered, engardened and exclusive.

It stands on low level ground, for it is redeemed out of a duckpond, out of Clarty hole. Sir Walter wished to possess the Border, or as much of it as might be, so he made this first purchase of a hundred acres in 1811. As he wrote to James Ballantyne—

"I have resolved to purchase a piece of ground sufficient for a cottage and a few fields.[Pg 42] There are two pieces, either of which would suit me, but both would make a very desirable property indeed, and could be had for between 7,000 and 8,000 pounds, or either separate for about half that sum. I have serious thoughts of one or both."

He began with one, and fourteen years later, when the estate had extended to a thousand acres, to the inclusion of many fields, sheep-cropped and story-haunted, he entered in his diary—

"Abbotsford is all I can make it, so I am resolved on no more building, and no purchases of land till times are more safe."

By that time the people of the countryside called him "the Duke," he had at least been knighted, and was, in truth, the Chief of the Border; a royal ambition which I doubt not he cherished from those first days when he read Percy under a platanus.

He paid fabulous prices for romantic spots, and I think would have bought the entire Border if the times had become safer, in those scant seven years that were left to him. Even Scott could be mistaken, for he bought what he believed was Huntlie Bank, where True Thomas had his love affair with the fair ladye[Pg 43]—

"True Thomas lay on Huntlie Bank;

A ferlie he spied wi' his e'e;

And there he saw a ladye bright

Come riding down by the Eildon tree.

"Her skirt was o' the grass-green silk,

Her mantle o' the velvet fyne;

At ilka tett o' her horse's mane

Hung fifty siller bells and nine."

And now the experts tell us that it is not Huntlie Bank at all, but that is in an entirely different direction, over toward Ercildoune and the Rhymer's Tower.

There is a satisfaction in this to those of us who believe in fairies and in Scott. For fairies have no sense of place or of time. And of course if they knew that Scott wished them to have lived at his Huntlie Bank, they straightway would have managed to have lived there. Always, as you go through this land of romance, or any romance land, and wise dull folk dispute, you can console yourself that Scott also was mistaken(?).

The castle began with a small cottage, not this great pile of gray stone we can see from the railway carriage across the Tweed, into which we make our humble way through a wicket gate, a restrained walk, and a basement doorway. "My dreams about my cottage go[Pg 44] on," he wrote to Joanna Baillie, as we all dream of building cottages into castles. "My present intention is to have only two spare bedrooms," but "I cannot relinquish my Border principles of accommodating all the cousins and duniwastles, who will rather sleep on chairs, and on the floor, and in the hay-loft, than be absent when folks are gathered together."

So we content ourselves with being duniwastles, whatever that may be, and are confident that Sir Walter if he were alive would give us the freedom of the castle.

In any event, if we feel somewhat robbed of any familiar intercourse, we can remember that Ruskin called this "perhaps the most incongruous pile that gentlemanly modernism ever designed." This may content the over-sensitive who are prevented ever hearing the ripple of the Tweed through the windows.

Scott was a zealous relic hunter, and if you like relics, if you can better conjure up persons through a sort of transubstantiation of personality that comes by looking on what the great have possessed, there can be few private collections more compelling than this of Abbotsford.

In the library are such significant hints for reconstruction as the blotting book wherewith Napoleon cleared his record, the crucifix on [Pg 45] which Queen Mary prayed, the quaigh of her great great and last grandson, the tumbler from which Bobbie Burns drank—one of them—the purse into which Rob Roy thrust his plunder, the pocket book of Flora MacDonald, which held nothing I fear from the generosity of the Bonnie Prince.

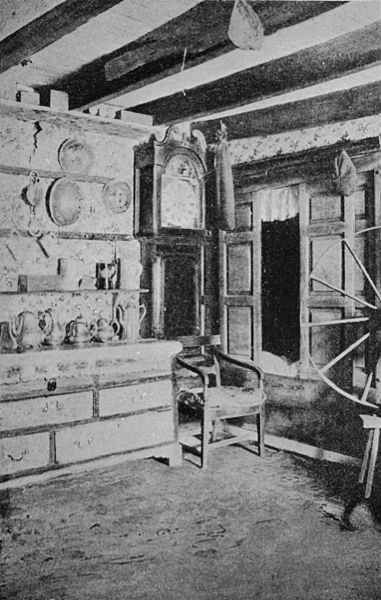

THE STUDY, ABBOTSFORD.

THE STUDY, ABBOTSFORD.

In the armoury are Scott's own gun, Rob Roy's gun, dirk and skene dhu, the sword of Montrose, given to that last of the great Cavaliers by his last king, Charles I, the pistol of Claverhouse, the pistol of Napoleon, a hunting flask of James III; and here are the keys of Loch Leven castle, dropped in the lake by Mary Queen's boatman; and the keys of the Edinburgh Tolbooth turned on so many brave men, yes, and fair women, in the old dividing days, of Jacobite and Covenanter.

The library of Scott, twenty thousand volumes, still lines the shelves, and one takes particular interest in this place, and its little stairway whereby ascent is made to the balcony, also book-lined, and escape through a little doorway. When Scott first came to the cottage of Abbotsford he wrote, furiously, in a little window embrasure with only a curtain between him and the domestic world. Here he had not only a library, but a study, where still stands the desk[Pg 46] at which the Waverleys were written, and the well-worn desk chair.

After he had returned from Italy, whither he went in search of health and did not find it, he felt, one day, a return of the old desire to write, the ruling passion. He was wheeled to the desk, he took the pen,—nothing came. He sank back and burst into tears. As Lockhart reports it—"It was like Napoleon resigning his empire. The scepter had departed from Judah; Scott was to write no more."

Scott has always seemed like a contemporary. Not because of his novels; I fear the Waverleys begin to read a little stilted to the young generation, and there are none left to lament with Lowell that he had read all of Scott and now he could never read him all over again for the first time. It is rather because Scott the man is so immortal that he seems like a man still living; or at least like one who died but yesterday. Into the dining-room where we cannot go—and perhaps now that we think it over it is as well—he was carried in order that out of it he might look his last on "twilight and Tweed and Eildon hill." And there he died, even so long ago as September, 1832.

"It was a beautiful day," that day we seem almost to remember as we stand here in the[Pg 47] vivid after glow, "so warm that every window was wide open, and so peacefully still that the sound of all others most delicious to his ear, the gentle ripple of the Tweed, was distinctly audible."

Five days after they carried him to rest in the Abbey—rival certainly in this instance of The Abbey of England, where is stored so much precious personal dust. The time had become thrawn; dark skies hung over the Cheviots and the Eildon, and over the haughs of Ettrick and Yarrow; the silver Tweed ran leaden, and moaned in its going; there was a keening in the wind.

The road from Abbotsford past Melrose to Dryburgh is—perhaps—the loveliest walk in the United Kingdom; unless it be the road from Coventry past Kenilworth to Stratford. It was by this very way that there passed the funeral train of Scott, the chief carriage drawn by Scott's own horses. Thousands and thousands of pilgrims have followed that funeral train; one goes to Holy Trinity in Stratford, to the Invalides in Paris, but one walks to Dryburgh[Pg 48] through the beautiful Tweedside which is all a shrine to Sir Walter.

The road runs away from the river to the little village of Darnick, with its ivy-shrouded tower, across the meadows to the bridge across the river, with the ringing of bells in the ear. For it was ordered on that September day of 1832, by the Provost, "that the church bell shall toll from the time the funeral procession reaches Melrose Bridge till it passes the village of Newstead."

I do not suppose the people of this countryside, who look at modern pilgrims so sympathetically, so understandingly, have ever had time to forget; the stream of pilgrims has been so uninterrupted for nearly a century. Through the market-place of Melrose it passed, the sloping stony square, where people of the village pass and repass on their little village errands. And it did not stop at the Abbey.

The day was thickening into dusk then; it is ripening into sunset glory to-day. And the Abbey looks very lovely, and very lonely. And one wonders if Michael Scot did not call to Walter Scott to come and join the quiet there, and if the dust that once was the heart of Bruce did not stir a little as the recreator of Scotland was carried by.[Pg 49]

To the village of Newstead you move on; with the sound of immemorial bells falling on the ear, and pass through the little winding street—and wonder if the early Roman name of Trimontium, triple mountains, triple Eildon, was its first call name out of far antiquity as Scott believed.

Then the road ascends between hedgerows, and begins to follow the Tweed closely—and perhaps you meet pilgrims on Leaderfoot bridge who have come the wrong way. There is a steep climb to the heights of Bemersyde, where on the crest all Melrose Glen lies beautifully storied before you. And here you pause—as did those horses of Scott's, believing their master would fain take one last look at his favourite view.

There is no lovelier landscape in the world, or in Scotland. The blue line of the Cheviots bars back the world, the Dunion, the Ruberslaw, the Eildon rise, and in the great bend of the river with richly wooded braes about is the site of Old Melrose. Small wonder he paused to take farewell of all the country he had loved so well.

The road leads on past Bemersyde village with woodlands on either side, and to the east, near a little loch, stands Sandyknowe Tower.[Pg 50]

Near the tower lies the remnant of the village of Smailholm, where Scott was sent out of Edinburgh when only three years old. It is in truth his birthplace, for without the clear air of the Border he would have followed the other Scott children; and without the romance of the Border he might have been merely a barrister.

Sandyknowe is brave in spite of its ruin, for it is built of the very stone of the eternal hills, and has become part of the hills. From its balcony, sixty feet high, a beautiful Scottish panorama may be glimpsed, and here Scott brought Turner to make his sketch of the Border. And here, because a kinsman agreed to save Sandyknowe Tower from the mortality that comes even to stone if Scott would write a ballad and make it immortal, is laid the scene of "Eve of St. John's"—with these last haunting intangible lines—

"There is a nun in Dryburgh bower

Ne'er looks upon the sun;

There is a monk in Melrose tower

He speaketh a word to none."

Then, back to the Tweed, where the river sweeps out in a great circle, and leaves a peninsula for Dryburgh. The gray walls of the ruin lift above the thick green of the trees; yew and oak and sycamore close in the fane.

ST. MARY'S AISLE AND TOMB OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, DRYBURGH ABBEY.

ST. MARY'S AISLE AND TOMB OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, DRYBURGH ABBEY.

Druid and Culdee and Roman have built shrines in this lovely spot, but to-day pilgrimage is made chiefly because in the quiet sheltered ruined St. Mary's aisle sleeps Sir Walter. It would make one-half in love with death to think of being buried in so sweet a place.

Dryburgh is also one of St. David's foundations, in the "sacred grove of oaks," the Darach Bruach of the worship that is older than Augustus or Columba. These were white monks that David brought up from Alnwick where his queen had been a Northumbrian princess, and their white cloaks must have seemed, among these old old oaks, but the white robes of the Druids come back again.

It is a well-kept place, vines covering over the crumbling gray stone, kept by the Lords of Buchan. And, perhaps too orderly, too fanciful, too "improved"; one likes better the acknowledged ruin of Melrose, and one would prefer that Sir Walter were there with his kin, instead of here with his kindred. But this is a sweet place, a historic place, begun by Hugh de Moreville, who was a slayer of Thomas à Becket, and was Constable of Scotland. His tomb is marked by a double circle on the floor of the Chapter House, and there is nothing of the Chapter House; it is open to beating rain and[Pg 52] scorching sun—fit retribution for his most foul deed.

It is not this remembrance you carry away, but that of St. Mary's aisle, in

"Dryburgh where with chiming Tweed

The lintwhites sing in chorus."

t is a very great little country which lies all about Melrose, with never a bend of the river or a turn of the highway or a shoulder of the hill, nay, scarce the shadow of any hazel bush or the piping of any wee bird but has its history, but serves to recall what once was; and because the countryside is so teeming seems to make yesterday one with to-day. The distances are very short, even between the places the well-read traveler knows; with many places that are new along the way, each haunted with its tradition, soon to haunt the traveler, while the people he meets would seem to have been here since the days of the Winged Hats.

Perhaps in order to get into the center of the ecclesiastical country—for after this being a Borderland, and a Scott-land, it is decidedly Abbots-land, even before Abbotsford came into[Pg 54] being with its new choice of old title—the traveler will take train to Kelso, or walk there, a scant dozen miles from Melrose.

The journey is down the Tweed, which opens ever wider between the gentle hills that are more and more rounding as the flow goes on to the sea. There is not such intense loneliness; here is the humanest part of the Scottish landscape, and while even on this highway the cottages are not frequent, and one eyes the journeymen with as close inspection as one is eyed, still it is a friendly land. The southern burr—we deliberately made excuse of drinking water or asking direction in order to hear it—is softer than in the North; yet, you would not mistake it for Northumberland. We wondered if this was the accent Scott spoke with; but to him must have belonged all the dialect-voices.

It was at Roxburgh Castle that King David lived when he determined to build these abbeys of the Middle Marches, of which the chief four are Melrose, Dryburgh, Jedburgh and Kelso, with Holyrood as their royal keystone.

Roxburgh was a stronghold of the Border, and therefore met the fate of those strongholds, when one party was stronger than the other; usually the destruction was by the English because they were farther away and could hold[Pg 55] the country only through making it desolate.

Who would not desire loveliness and desire to fix it in stone, if he lived in such a lovely spot as this where the Tweed and Teviot meet? David had been in England. He was brother to the English queen Maude, wife of Henry I, and had come in contact with the Norman culture. Or, as William of Malmesbury put it, with that serene assurance of the Englishman over the Scot, he "had been freed from the rust of Scottish barbarity, and polished from a boy from his intercourse and familiarity with us." Ah, welladay! if residence at the English court and Norman culture resulted in these lovely abbeys, let us be lenient with William of Malmesbury. Incidentally David added to the Scotland of that time certain English counties, Northumberland and Cumberland and Westmoreland—as well as English culture!

David was son to Saxon Margaret, St. Margaret, and from her perhaps the "sair sanct" inherited some of his gentleness. But also he had married Matilda of Northumberland, wealthy and a widow, and he preferred to remain on the highway to London rather than at Dunfermline. So he was much at Roxburgh.

But the castle did not remain in Scottish or English hands. It was while curiously inter[Pg 56]ested in a great Flemish gun that James II was killed by the explosion—and the siege of Roxburgh went on more hotly, and the castle was razed to its present low estate.

To-day the silly sheep are cropping grass about the scant stones that once sheltered kings and defied them; and ash trees are the sole occupants of the once royal dwelling. To the American there is something of passing interest in the present seat of the Duke of Roxburgh, Floors castle across the Teviot. For the house, like many another Scottish house, still carries direct descent. And an heiress from America, like the heiress from Northumberland, unites her fortune with this modern splendour—and admits Americans and others on Wednesdays!

The town of Kelso is charming, like many Tweed towns. It lies among the wooded hills; there is a greater note of luxury here. Scott called it "the most beautiful if not the most romantic village in Scotland." Seen from the bridge which arches the flood, that placid flood of Tweed, and a five-arched bridge ambitiously and successfully like the Waterloo bridge of London, one wonders if after all perhaps Wordsworth wrote his Bridge sonnet here—"Earth hath not anything to show more fair." Surely this bridge, these spires and the great[Pg 57] tower of the Abbey, "wear the beauty of the morning," the morning of the world. The hills, luxuriously wooded, rise gently behind, the persistent Eildons hang over, green meadows are about, the silver river runs—and the skies are Scottish skies, whether blue or gray.

The Abbey, of course, is the crown of the place, bolder in design and standing more boldly in spite of the havoc wrought by men and time, and Hertford and Henry VIII; calmer than Melrose, less ornamental, with its north portal very exquisite in proportion.

The Abbot of Kelso was in the palmy early days chief ecclesiastic of Scotland, a spiritual lord, receiving his miter from the Pope, and armoured with the right to excommunicate.

There have been other kings here than David and the Abbot. The latter days of the Stewarts are especially connected with Kelso, so near the Border. Baby James was hurried hither and crowned in the cathedral as the III after Roxburgh. Mary Queen lodged here for two nights before she rode on to Berwick. Here in the ancient market-place, looking like the square of a continental town, the Old Chevalier was proclaimed King James VIII on an October Monday in 1715, and the day preceding the English chaplain had preached to the troops from[Pg 58] the text—"The right of the first born is his." Quite differently minded from that Whig minister farther north, who later prayed "as for this young man who has come among us seeking an earthly crown, may it please Thee to bestow upon him a heavenly one."

When this Rising of the Forty Five came, and he who should have been Charles III (according to those of us who are Scottish, and royalist, and have been exiled because of our allegiance) attempted to secure the throne for his father, he established his headquarters at Sunilaw just outside Kelso; the house is in ruins, but a white rose that he planted still bears flowers. To the citizens of Kelso who drank to him, the Prince, keeping his head, and having something of his royal great uncle's gift of direct speech, replied, "I believe you, gentlemen, I believe you. I have drinking friends, but few fighting ones in Kelso."

Scott knew Kelso from having lived here, from going to school here, and it was in out of the Kelso library—where they will show you the very copy—that he first read Percy's Reliques.

"I remember well the spot ... it was beneath a huge platanus, in the ruins of what had been intended for an old fashioned arbour[Pg 59] in the garden.... The summer day had sped onward so fast that notwithstanding the sharp appetite of thirteen, I forgot the dinner hour. The first time I could scrape together a few shillings I bought unto myself a copy of the beloved volumes; nor do I believe I ever read a book half so frequently or with half the enthusiasm."

Was it not a nearer contemporary to Percy, and a knight of romance, Sir Philip Sidney, who said, "I never read the old song of Percie and Douglas that I found not my heart moved more than with a trumpet"?

For myself I have resolutely refused to identify the word, Platanus, lest it should not be identical with the spot where I first read my Percy.

Scott also knew Kelso as the place of his first law practice, and of his honeymoon. Here flowered into maturity that long lavish life, so enriched and so enriching of the Border.

Horatio Bonar was minister here for thirty years—I wondered if he wrote here, "I was a wandering sheep."

While James Thomson, who wrote "The Seasons," but also "Rule, Britannia"—if he was a Scotsman; perhaps this was an Act of Union[Pg 60]—

"Rule, Britannia, rule the waves;

Britons never will be slaves!"

was born at a little village nearby, back in the low hills of Tweed, in 1700, seven years before the Union.

From Kelso I took train to the Border town which even the Baedeker admits has had "a stormy past," and where the past still lingers; nay, not lingers, but is; there is no present in Jedburgh. It is but ten miles to the Border; more I think that at any other point in all the blue line of the Cheviot, is one conscious of the Border; consciousness of antiquity and of geography hangs over Jedburgh.

It lies, a hill town, on the banks of the Jed; "sylvan Jed" said Thomson, "crystal Jed" said Burns; a smaller stream than the Tweed, more tortuous, swifter, rushing through wilder scenery, tumultuous, vocative, before Border times began—if ever there were such a time before—and disputatious still to remind us that this is still a division in the kingdom.

One of the most charming walks in all Scotland—and I do not know of any country where[Pg 61] foot-traveler's interest is so continuous (I wrote this before I had read the disastrous walking trip of the Pennell's)—is up this valley of the Jed a half dozen miles, where remnants of old forest, or its descendants, still stand, where the bracken is thick enough to conceal an army crouching in ambush, where the hills move swiftly up from the river, and break sharply into precipices, with crumbling peel towers, watch towers, to guard the heights, and where outcropping red scars against the hill mark sometimes the entrance to caves that must have often been a refuge when Border warfare tramped down the valley.

In Jedburgh we lodged not at the inn; although the name of Spread Eagle much attracted us; but because every one who had come before us had sought lodging, we, too, would "lodge," if it be but for a night.

Mary Queen had stayed at an old house, still standing in Queenstreet, Prince Charles at a house in Castlegate, Burns in the Canongate, the Wordsworths, William and Dorothy, in Abbey Close, because there was no room in the inn. I do not know if it were the Spread Eagle then, but the assizes were being held, Jethart justice was being administered, or, juster justice, since these were more parlous[Pg 62] times, and parley went before sentence. Scott as a sheriff and the other officials of the country were filling the hostelry. But Sir Walter, then the Sheriff of Selkirk, sheriff being a position of more "legality" than with us, and no doubt remembering his first law case which he had pled at Jedburgh years before, came over to Abbey Close after dinner, and according to Dorothy Wordsworth "sate with us an hour or two, and repeated a part of the 'Lay of the Last Minstrel.'"

Think of not knowing whether it was an hour or two hours, with Scott repeating the "Lay," and in Jedburgh.

We lodged in a little narrow lane, near the Queen in the Backgate, with a small quaint garden plot behind; there would be pears in season, and many of them, ripening against these stone walls. The pears of the Border are famous. Our landlady was removed from Yetholm only a generation. Yetholm is the gipsy capital of this countryside. And we wondered whether Meg Faa, for so she ambitiously called herself, by the royal name of Scottish Romany, was descended from Meg Merrilies. Mrs. Faa had dark flashing eyes in a thin dark face, and they flashed like a two-edged dagger. She was a small woman, scarce taller than [Pg 63] a Jethart ax as we had seen them in the museum at Kelso. I should never have dared to ask her about anything, not even the time of day, and, in truth, like many of the Scotch women, she had a gift of impressive silence. All the night I had a self-conscious feeling that something was going to happen in this town of Jed, and in the morning when I met Mrs. Faa again and her eyes rather than her voice challenged me as to how I had slept, I should not have dared admit that I slept with one eye open lest I become one more of the permanent ghosts of Jed.

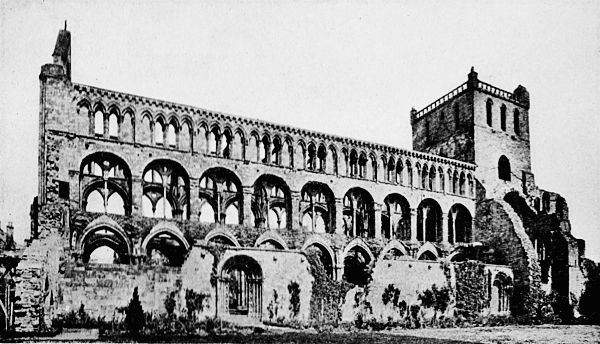

JEDBURGH ABBEY.

JEDBURGH ABBEY.

The Abbey is, in its way, its individual way, most interesting of the chief four of "St. David's piles." It is beautifully lodged, beside the Jed, near the stream, and the stream more a part of its landscape; smooth-shaven English lawns lie all about, a veritable ecclesiastical close. It is simpler than Melrose, if the detail is not so marvelous, and there is substantially more of it. The Norman tower stands square; if witches still dance on it they choose their place for security. The long walls of the nave suggest almost a restoration—almost.

When the Abbey flourished, and when Alexander III was king, he was wedded here (1285)[Pg 64] to Joleta, daughter of the French Count de Dreux. Always French and Scotch have felt a kinship, and often expressed it in royal marriage. The gray abbey walls, then a century and a half old, must have looked curiously down on this gay wedding throng which so possessed the place, so dispossessed the monks, Austin friars come from the abbey of St. Quentin at Beauvais.

Suddenly, in the midst of the dance, the King reached out his hand to the maiden queen—and Death, the specter, met him with skeleton fingers. It may have been a pageant trick, it may have been a too thoughtful monk; but the thirteenth century was rich with superstition. Six months later Alexander fell from his horse on a stormy night on the Fife coast—and the prophetic omen was remembered, or constructed.