James Robinson & Sons Dublin, Photo.

Walker & Boutall Ph. Sc.

Charles E Ryan

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: With an Ambulance During the Franco-German War

Personal Experiences and Adventures with Both Armies 1870-1871

Author: Charles Edward Ryan

Release Date: December 22, 2012 [eBook #41689]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WITH AN AMBULANCE DURING THE FRANCO-GERMAN WAR***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/withambulancedur00ryan |

Click on the images to obtain enlarged high-resolution versions.

By CHARLES E. RYAN, F.R.C.S.I., M.R.C.P.I.

KNIGHT OF THE ORDER OF LOUIS II, OF BAVARIA

WITH PORTRAIT AND MAPS

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

153-157 FIFTH AVENUE

1896

ABERDEEN UNIVERSITY PRESS.

TO

JAMES TALBOT POWER,

MY OLD FRIEND AND SCHOOLFELLOW,

I DEDICATE

THE FOLLOWING PAGES.

Ere I attempt to set before the public this slight record of my experiences during the Franco-German War, I must first disclaim all pretence to literary merit.

It was written in 1873, and is simply an embodiment of a series of notes or jottings, taken during the war in my spare moments, together with the contents of a number of descriptive letters to my friends. They were written solely for them, and nothing was farther from my mind at the time than the idea of publication.

Thus, they remained in a recess of my study for nearly a quarter of a century, until a new generation had grown up around me; and doubtless, but for their friendly importunity, there they would have lain until the memory of their author, like the ink in which they were written, had faded to a blank.

I would ask my readers to bear in their kindly recollection that the scope of such a work as the following must of necessity be limited.

As a medical man, I had at all times and in[vi] all places my duties to perform; hence I have been unable to be as elaborate as other circumstances might warrant.

I would also remind them (and every one who has been through a campaign will know) how vague and uncertain is the information which subordinates possess of the general movements of the army with which they are serving.

It happens occasionally that they are wholly ignorant of events occurring around them, the news of which may have already reached the other side of the world.

Again, I am greatly impressed with the difficulty of representing, in anything like adequate language, those scenes—some of which have already been delineated by the marvellous pen of M. Zola in La Débâcle—which the general public could never have fancied, still less have realised, except by the aid of a masterly exposition of facts such as that stirring chronicle of the war has given. In it the writer has dealt rather with history as it occurred, than invented an imaginary tale; and those who were eye-witnesses of Sedan can add little to his description.

For many reasons, therefore, I am filled with the sense of my own incompetence to do justice to my subject. But I console myself with the reflection that my theme is full of interest to the present generation. Nor does it appear a vain undertaking if one who was permitted to see much[vii] of both sides should give his impressions as they occurred, and in the language he would have used at the time. My feeling throughout has been that of a witness under examination. I have endeavoured to narrate the incidents which I saw, certainly with as close an approach to the reality as I could command, and, if in a somewhat unvarnished tale, yet, as I trust, have set down nought in malice. I have added no colour which the original sketch did not contain; and have been careful not to darken the shading.

Glenlara, Tipperary,

January, 1896.

The first question friends will naturally ask is, how I came to think of going abroad to take part in the struggle between France and Germany, what prompted me to do so, and by what combination of circumstances my hastily arranged plans were realised.

These points I will endeavour to explain. From the outset of the war I took a deep interest in the destinies of France, and warmly sympathised with her in her affliction. I longed earnestly to be of some service to her; indeed, my enthusiasm was so great at the time that I would even have fought for her could I have done so. I was then studying medicine in Dublin, and was in my twenty-first year. Just about the time of the battles of Weissenburg and Wörth nearly every one in Dublin was collecting old linen to make charpie for the French wounded; and, as I could do nothing else, I exerted myself in getting together from my friends all the material I could procure for the purpose. Day by day news[2] poured in of French defeats following one another in close succession, with long lists of killed and wounded; while among other details I learnt that the French were very short of medical men and skilled dressers, and that the sufferings of the wounded were, in consequence, beyond description. I thought to myself, "Now is my opportunity. If I could but get out to those poor fellows I might render them some substantial assistance; and what an amount of suffering might one not alleviate did one but give them a draught of cold water to appease their agonising thirst!"

For a few days these thoughts occupied my mind almost to the exclusion of every other. It happened one evening, when I was returning by train from Kingstown, that I met Dr. Walshe, surgeon to Jervis Street Hospital. During the course of our conversation, which was upon the then universal topic of the Franco-German War, he remarked that if he were unmarried and as young and active as I was, he would at once go over to France, and seek a place either in a military field hospital or in an ambulance, or endeavour to get into the Foreign Legion, which was then being enrolled, adding, that he greatly wondered no one as yet had left Dublin with this object. I replied, "I shall be the first, then, to lead the way"; and there and then made up my mind to set out.

It was the 12th of August, 1870.

I endeavoured to discover some kindred spirit who would come out with me and share my adventures, but not one could I find. Those who had not very plausible reasons at hand, to disguise those which perhaps they had, laughed at my proposal, and appeared to look upon me as little better than a mad fellow. How could I dream of going out alone to a foreign country, where the fiercest war of the century was raging? Even some of my professors joined in the laugh, and good-humouredly wished me God-speed and a pleasant trip, adding that they were sure I should be back again in a few days. Two of them had, in fact, just returned from Paris, where they could find nothing to do; and they reported that it was dangerous to remain longer, as the populace were marching up and down the streets in the most disorderly fashion, and strangers ran no small risk of being treated as Prussian spies.

All this was unpleasant to hear; but I was determined not to be thwarted; and so, portmanteau in hand, I stepped on board the Kingstown boat. It was the 15th August, a most glorious autumn evening, and the sea was beautifully calm. I now felt that my enterprise had begun, and as I stood on deck watching the beautiful scenery of Dublin Bay receding from my view, the natural reflection occurred that this might be the last time I should see my native land. I was leaving the[4] cherished inmates of that bright little spot, which I now more than ever felt was my home. It would be my first real experience of the world, and I was about to enter upon the battle of life alone.

Arriving in London on the morning of the 16th, and having spent the day with some of my school friends, in the evening I went on board the Ostend boat at St. Katharine's wharf. We were to start at four o'clock next morning. I slept until I was awakened by the rolling of the vessel out at sea. The boat was a villainous little tub, and appeared to me to go round like a teetotum. We had an unusually long and rough passage of sixteen hours, and I was fearfully ill the whole time. When we arrived at Ostend, so bad was I that I could not leave my cabin until long after everybody else. Hence a friend of mine, Monsieur le Chevalier de Sauvage Vercourt, who had come up from Liège to meet me, made certain when he failed to perceive me among the passengers that I had missed the boat. On inquiring, however, of the steward if any one had remained below he discovered me.

My friend gave me two letters of introduction, one to M. le Vicomte de Melun, which subsequently got me admitted into "La Société Française pour le secours aux blessés de terre et de mer"; the other to the Mayor, M. Lévy, asking him whether he could find a way for me into the[5] Army as an assistant. When I had pulled myself together a bit, Vercourt and I dined together in the open air, at a Café on the Grande Promenade.

It was the fashionable hour, and every one seemed to be in gala dress. Half, at least, of those we saw were English, the remainder French and Belgians. It is a curious sensation, that of being for the first time in a foreign country, where one's whole surroundings differ from all one has been accustomed to see and hear in one's native land. My boyish experience made everything, however trivial, a subject of interest. As I walked through the town with Vercourt, I was greatly struck by the civility of the people, their cleanliness and the neatness of their persons and dress, and above all by the absence of any visible wretchedness even among the poor.

These points occupied our attention and conversation until we found ourselves on our way to Brussels. The country through which we passed, though really most unattractive, had for me many points of interest, and gave me an agreeable picture of what was meant by "foreign climes".

The bright clean cottages and farmsteads, with their gardens and flowers, contrasted lamentably to my mind with the tumble-down dilapidated hovels of mud, surrounded by slush and water, which I had been accustomed to see from my childhood. Everything bespoke the comfort,[6] happiness, and prosperity of these people. The neatly trimmed hedges with which every field is fenced, the lines of poplars skirting the roadways and canals give a surprisingly smart and cultivated aspect to the whole face of the country. I was greatly struck by the blue smocks and wooden sabots of the men and women. Even the children in the rural parts of Belgium wear these wooden shoes. During our stoppages at the different stations the Flemish jargon, as in my untravelled ignorance I called it, of the rustics amused me. I noticed in one part of the country that all the pumps had their handles at the top, and that these moved up and down like the ramrod of a gun. It was novel to see the people on stools working them. At ten o'clock that night we arrived in Brussels, and put up at the Hôtel de Suède.

My friend and I rose early next morning, and went sight-seeing. He was an habitué of the place, so our time was spent to the best advantage. That Brussels is a most charming town was my first impression; and I think so still. My delight at seeing the Rue de la Reine and the Boulevards leading from it I shall not easily forget. A city beautifully timbered and abounding in fountains, grass, and flowers, was indeed a novelty to one whose experience of cities had been gained in smoky London and dear dirty Dublin. In the Rue de la Reine I remarked the[7] two carriage-ways, divided by a grove of trees. This plantation consisted of full-grown limes, elms, sycamores, arbutus, and acacias. There was yet another row on the footpath, next the houses. The breadth of this long Boulevard may be about that of Sackville Street. It was a beautiful sunny day, and as I sauntered along beneath the trees something new met my eye at every turn. I was struck by such a simple matter as seeing the carriages dash into the courtyards through the open gates, instead of stopping in the street, whilst the occupants were making a morning call. Then the high-stepping horses and the gaudy equipages were enough, as I thought, to dazzle the youthful mind. One could live here a lifetime and never know that such a thing as dirt existed,—at all events, in the sense with which we were only too conversant in some parts of my native land twenty-five years ago.

These simple observations of the boy at his first start in life make me smile as I read them over. Yet I do not think that I ought to suppress them; for who is there that has not felt the indescribable charm of those early days, when the commonest things in our journeying fill the mind as if they were a wonder in themselves? And what is there in the grown man's travels to equal that opening glimpse of a world we have so often heard talked about, yet never have seen with our eyes until now?

But to return. It was in the Rue du Pont that I first saw the tramways. I went in one of the cars to the superb Park, which is as fine as any in Europe, and of which Brussels is so justly proud. It amused me beyond measure to see the butchers', bakers', and grocers' boys driving about their carts drawn by teams of huge dogs, varying in number from one to four. While the drivers were delivering their goods the poor animals would lie down in their harness with their tongues out, until a short chirp brought them on their feet again, ready to start. This seemed for them the most difficult part, since once set going, they went at a great rate, apparently without much trouble, and rather enjoying their task than otherwise. I have seen teams of dogs so fresh that they were all barking whilst they tore along the street at full speed. In the evening the cafés were beautifully illuminated; and seated beneath the trees hundreds of people enjoyed their cigarettes and café noir, while they discussed, with many and vigorous gesticulations, the affairs of Europe. In the afternoon of the 18th I bade good-bye to my kind friend Vercourt, who had been so admirable a cicerone to me, and took my seat in the train for Paris.

During our journey I was rudely awakened from a sound sleep at one station by every one suddenly jumping on their legs and crying out, "La douane!" while they seized their luggage, and[9] rushed out of the train as if it were on fire. If you did not do the same you were unceremoniously bundled out by the officials. To every inquiry I got the same answer, "C'est la douane". Now this word was not in my vocabulary. I may observe that at my school French was taught on the good old plan, out of Racine and "Télémaque," in which commercial terms are not abundant, and hence I did not know in the least the meaning of "la douane"; it might have signified fire, blood or murder; and I was for a long time sorely puzzled. I thought in my drowsy confusion that some part of the train had broken down, and that all the passengers and luggage had to be removed with as much haste as possible. But when I, a passenger to Paris, saw a fellow seize my portmanteau and disappear with it through one of the doors, it was too much for me; I went after my effects, collared him, and asked him, in the best French I could muster, where he was going with my property. A big gendarme explained the situation, and pointed to a large room, where the rattling of keys and opening of boxes soon made his interpretation unnecessary.

On returning to my carriage I found myself next a middle-aged gentleman, who, though he spoke French fluently to his neighbours, was evidently an Englishman. We joined in conversation, and he seemed to know more about[10] Ireland and Irish affairs than I did myself, which, in truth, might easily have been. He had such a frank, genial manner, and appeared to feel so genuine a sympathy, not only with my own countrymen, but with poor suffering France, that I confided to him my story and mission, which evidently pleased him; and he told me that he would get me a cheap billet from his landlady in the Hôtel de l'Opéra, a comfortable hotel centrally situated opposite the new Opera House. He had told me his name was Steel, but vouchsafed no further information about himself. When we arrived in Paris he was accosted by several of the officials as Monsieur le Général; and he bade me stay with him, and said that he would accompany me to my hotel. Having, after much tiresome waiting, got possession of our luggage, we passed out of the station between two lines of soldiers, and were carefully and closely inspected before being allowed to proceed. A whisper from my new friend the General appeared to be a magic pass, for every one seemed to know him. A stalwart gendarme demanded my passport, took down my name and address, where I last came from, and what was my business in Paris, and then let me go. When we arrived at the Hôtel de l'Opéra, again the concierge greeted my mysterious friend with the title of M. le Général, when he hurried upstairs, bidding me wait until he came[11] down, and he would go out with me to dine at a restaurant.

As I stepped outside the door and looked up and down the Boulevards, I knew at once that what I had heard and read of the beauties of Paris as seen by night was no fiction, but a bright reality. What added to the novelty of the scene was that the whole populace seemed to be in a fever of excitement. I asked my friend what was it all about. He told me that they were rejoicing because a proclamation had just been made from the Mairie of three glorious victories won by their arms. This accounted for the bands of civilians, thousands in each, composed of labourers and artisans, who were marching boisterously up and down the streets, cheering and singing the "Marseillaise," with flags and banners flying of every colour and description. The sight was at first appalling, as that momentary glance recalled to my mind so vividly what I had read about the scenes enacted in the streets of Paris during the first Revolution, by a similar communistic and ungovernable mob. Yet I thought the whole thing good fun; but my friend warned me not to speak, and told me to keep out of the streets at night. It was dangerous for a stranger to go out after dark, since the populace were apt to take him for a spy, or as being there in the interest of the enemy, and this might mean instantaneous death. Such[12] things had occurred lately. We now turned into the Café Anglais, and dined very well, after which my mysterious friend took leave of me and disappeared. I only saw him again for five minutes a few days subsequently, and have never set eyes on him since, nor could I get any satisfactory information at the hotel, although they informed me that he was a resident in Paris, and was often at the Hôtel de l'Opéra. Perhaps some reader of these pages may know more concerning M. le Général Steel than I ever did. Who and what was he? But conjecture is idle work, and I must get on with my story.

Having seen Brussels before Paris, the latter did not make that impression which it generally does on one who views it for the first time, before he has visited any other of the capital cities on the Continent,—for Brussels is a miniature Paris. I walked up and down the Boulevards, observing everything and everybody, until, feeling somewhat tired, I looked at my watch, and found to my astonishment that it was nearly one o'clock, so I returned to my hotel and went to bed, and dreamed of the glories of the city of pleasure.

Next morning, the 19th, I sallied out in quest of the Mansion House to which I had been directed. For some time I walked up and down the Boulevards in order to make observations as to my whereabouts, and to note my surroundings. My first great landmark was[13] the beautiful new Opera House, which is one of the sights of Paris. Its massive pillars and wonderful display of allegorical figures, all in white marble, delighted me—as also did the wooded Boulevards with their gorgeous shops and all the pleasing sights which met my gaze at every turn.

Having been only a few days in the country, I naturally felt a little shy at venturing into anything like a long conversation with the natives. Soon, however, I mustered up sufficient courage (to be wanting in which was to fail in my errand) to ask my way of one of those gaily dressed officers of the peace, who, from their gorgeous uniform and the dignity of their manners, I had made up my mind could be nothing less than majors-general of the reserve out for a stroll.

My bad French elicited from this worthy only the most courteous civility, and he took the greatest pains to explain to me my route. As I went on I felt elated at this first experience of the proverbial civility of Frenchmen, and was sure that I should find it easy to get on with them.

After some two miles of pleasant rambling, I arrived at the Mairie in the Place du Prince Eugène; but found that M. le Maire was out, so returned and dined at the Café Royale, opposite the Madeleine and afterwards visited the church, and walked outside it several times. It was[14] from all sides alike massive and beautiful, nor was I disappointed at its interior, though I confess it did not impress me so much as the façade. Having spent an hour inspecting its details I took a cabriolet to the Mansion House, where, having sent in Vercourt's letter, I was ushered into the presence of M. le Maire, after about ten minutes waiting.

This polished gentleman received me with the greatest kindness and civility, but explained that he could not procure me a place in the Army Medical Department. He referred me to l'Intendance Militaire, Rue St. Dominique, which was the Foreign Legion Office. I at once started afresh, and, having found out the officials to whom I was directed, they informed me that they had not the power of giving appointments, but that M. Michel Lévy, Medicine Inspecteur, Val de Grace, was the person to whom I should apply, at the same time assuring me that there was not the least use in my doing so, as the Foreign Legion was fully equipped and all the vacancies filled up. Believing this information to be correct, I set this last proposition aside and kept it in my sleeve as a dernier ressort. Although defeated in my object I was not in the least discouraged, for I had determined to make every effort before confessing myself beaten.

As I was much fatigued, and it was too late to prosecute my plans any further that day, I[15] went out for a stroll on the Boulevards. Presently I heard the trampling of horses coming down the street, mingled with the loud cheering of the populace. It was a troop of Cuirassiers, and in another minute I was in the midst of a seething crowd, and could perceive nothing around me but a sea of hands, hats, and heads in commotion. The civilians, who were in a wild state of excitement, cheered the troops, "Vive les Cuirassiers!" while the dragoons in return shouted "A Berlin!" and "Vive la France!"—not "Vive l'Empereur!" When they had passed, the excitement continued in another form, for a desperate-looking mob marched up and down in detachments as they had done upon the previous night, with flags flying, and banners waving, singing all the while "La Marseillaise" and the "Champs de la Patrie," with intervening shouts of "A Berlin". All this was of great interest to me, especially the singing. When the crowd joined in the chorus of their National Anthem the effect was something never to be forgotten.

I now went to bed, feeling sleepy and done up from sheer excitement. Next day, the 20th August, a lovely morning, I found my way to the Palais de l'Industrie, where, after waiting three hours in a crowded ante-room, I presented my letter to M. le Vicomte de Melun, who came out to see me. This kind old gentleman spoke graciously, and desired me to come next day,[16] when he would give me a place in an Ambulance. Fully satisfied this time with the result of my efforts I returned with a light heart, and having dined in the Rue Royale went out sight-seeing. A few hundred paces brought me into the Place de la Concorde, and, oh, what an incredibly magnificent sight presented itself from the centre of that beautiful square! I passed the rest of the evening in the Bois de Boulogne, and rising early next morning, full of hope, hastened to the Palais de l'Industrie, where, without much delay, I saw M. de Melun. He informed me with regret that every place in the Ambulances about to start had been filled up previous to my application. However, if I left my letters and certificates and came again on Tuesday morning, he would let me know, should there be a vacancy for me in any of those which were starting at the end of the week.

This second disappointment greatly annoyed me, but I did not give in. As it was Sunday I hastened back to High Mass at the Madeleine, a grand choral and musical display. The constant clink of the money and the click of the beadle's staff as he strode along bespangled with gold lace and gaudy trappings, made prayer and recollection well nigh an impossibility. Coming out of church, I met an old schoolfellow of mine, a Parisian, with whom I had a long chat and pleasant walk in the Tuileries. He pointed out to me the Empress[17] leaving the Palace by a private way, accompanied by some of her ladies-in-waiting. I may remark that she wore a dress of grey silk, trimmed with black crape.

During the whole of this day troops continued to march through the city, some mere regiments of beardless boys, awkward and unsoldierlike, but with a true martial spirit, if one might judge by the hearty way in which they sang as they went along, and joined in the choruses.

These were the latest levies, and were going to the front. Next day, Monday the 22nd, after many circuitous wanderings, I made my way to the Irish College; and left my letter of introduction to Father M——, who was not at home, but was expected the following day. When I got back I found that the Boulevards and Champs Elysées were thronged with noisy workmen singing the "Marseillaise" on their way home from the fortifications, where they had been employed in great numbers on the extensive works which were being now pushed forward night and day. To avoid being jostled by the mob I took a place on the top of an omnibus. It was dusk, and as we came down the Champs Elysées, the beautifully illuminated gardens, with their cafés chantants, merry-go-rounds and bowers,—surrounded by the most fanciful and pretty devices imaginable, and lighted up with miniature lamps,—together with the lively din of music and singing followed by[18] rounds of applause, made me feel transported for the moment to fairyland. But it was a short-lived delusion; and who would imagine, with all this folly, at once so frivolous and so French, that the great tragedy of war was being enacted around us? However, that such was the case even here was abundantly evident, for it was the sole topic of conversation. Soldiers were everywhere in the streets; the public vehicles and omnibuses were crammed with them; their officers seemed to monopolise half the private carriages; they crowded the public buildings, and soldiers' heads appeared out of half the street windows. I had always heard that Frenchmen were a highly excitable people, and the truth of that saying was never so clearly demonstrated. Here they were in their thousands, moving about in a state of restless, purposeless commotion, singing songs from noon to midnight, and, as it appeared to me, most of them quite out of their senses.

Tuesday, the 23rd August, I went once more to try my luck at the Palais de l'Industrie; and M. le Vicomte de Melun again told me that there was no vacancy, but my name had been placed on the Society's books for an appointment, and when the vacancy occurred he would communicate with me at the Hôtel de l'Opéra. I felt disappointed that every effort up to this had been a failure, but consoled myself at having gained one point, viz., that of having[19] been registered as a member of the Red Cross Society.

I now determined to try some of the working staff, who, though perhaps less influential than the Vicomte, might be able to help me quite as well. Not to be daunted, I went to another part of the Palais, where I informed a gentleman, who, I perceived, was a superintendent and active manager, that my name had been placed on the Society's books by M. de Melun. This made him all attention. He spoke English well, and was very civil to me. His name was M. Labouchère, 77 Rue Malesherbes. In few words I told him the object of my mission, how I wanted to work, and was willing to accept a place in any capacity whatever, in the service of the wounded. He now informed me that there was one vacancy as aide in a Belgian Ambulance, and as I was most anxious to fill it he had my name put down. He gave me the casquet and badge of the Society, and told me to come to-morrow for my outfit and all necessaries.

In the meantime I was sent out with eight or ten others of the Swiss Ambulance, to collect money in the streets through which we passed. We went in a body, and had each a little net bag at the end of a long pole, very like a landing net, but with a longer handle and a smaller net. As we passed along we cried out, "Pour les blessés," and as the omnibuses and carriages[20] drew up while we were passing, we availed ourselves of this opportunity by putting our bags up to and sometimes through the windows, and landing them in the laps of those within. By this means we got heaps of silver pieces, and even gold from some of the best dressed personages. We also put our nets up to the windows, wherever we saw them occupied, and into the shops. Large crowds gathered along the route, and everybody gave something,—a great many two and five franc pieces. It was several hours before we reached the railway station, as we went very slowly. All knew by my accent that I was a foreigner, and perhaps British; and they seemed to like the idea, for they pressed forward to throw their coins to me, when there were other nets nearer them. When the time of reckoning came I found that I had collected more than my comrades. I saw ladies in the carriages that passed us crying bitterly, and the weeping and evident grief of the ambulance men on parting with their friends at the railway terminus were very touching. Having placed my money in the van I returned to the Palais de l'Industrie, where I was introduced to M. le Verdière, second in command in the Belgian Ambulance. He desired me to come at nine o'clock next day to get into my uniform and prepare for starting.

Highly pleased at what I considered at last a success, I went, as I had previously arranged,[21] to see Dr. M—— at the Irish College. He received me very warmly, and introduced me to a Chinese bishop with a pigtail, whom I found a most intelligent and agreeable man.

That evening I saw troops going to the front in heavy marching order; and although they were four abreast, they reached from the Arc de Triomphe to within some little distance of the Place de la Concorde. On my way home I met a man who told me sorrowfully that before the war he had been a successful teacher with a large class, but that all his pupils were drawn in the conscription, and his occupation was gone.

Next morning, the 24th, I was all excitement, as I fully expected that this day might see me on my way to the front. I hastened to the Palais de l'Industrie, where M. Labouchère informed me of the nature of my appointment in the Belgian Ambulance. What was my astonishment when I found that I should have ten infirmiers under me, for whom I was to be responsible, and to whom I must issue orders! Much as I desired to accept this most tempting offer, common sense got the better of my ambition; and I declined, feeling conscious that my imperfect knowledge of French would prevent my being able to discharge my duties with efficiency.

All this was a disappointment and a humiliation, but I had now become used to reverses.[22] My friends, of whom I had already quite a number, comforted me by saying that I should be most likely sent to Metz, which was full of wounded with but few attendants, numbers of the latter having been carried off by typhus fever, which was making great havoc in the town. I stated that I had not the least objection to going if the Society wished me to do so; but I felt that I should prefer some other mission. Later on in the day, as I was searching for M. Labouchère in the Palais de l'Industrie, I was astonished to perceive that one of the large open spaces of the Palais, which was used but yesterday for drilling the recruits, now contained rows of mounted cannon placed close beside each other, while the unmounted guns were piled in lines one above another; great heaps of cannon balls were also stacked in the centre, like ricks of turf. This change, wrought since the evening before, will give an idea of the rapidity and energy with which the Government plans were being executed. Emerging by one of the upper doors of the building, I was startled at seeing the whole Champs Elysées occupied by masses of soldiers, flanked at each side by double rows of cavalry. They were being inspected before going to the front. It was a splendid sight. I went out afterwards to the Bois de Boulogne, where the timber next the ramparts was already being cut down. There were crowds of men at work on[23] the fortifications as I passed through, making ready for the siege.

As it was growing dusk I moved towards home, and met on my way a stream of soldiers dressed in a most elaborate uniform, differing in every way from that of the Line. From the enthusiastic reception they met with on all sides, and the familiar smiles and nods which they exchanged with the admiring citizens, I knew that they were the Garde Nationale, the pride of the Parisians.

August 25th I went to my official quarters full of hope, but found that nothing further had been decided. M. Labouchère told me that I was certain of a place in a French Ambulance, and presented my testimonials and papers to the chief of the 8th Ambulance, who disappeared with them into the committee room, promising to send me an answer at once. This he never did, though I waited his reply for some hours, until hunger compelled me to go in search of dinner, which I found in the Boulevard St. Michel, No. 43, Café-Brasserie du Bas Rhin, where I had as much beef as I could wish for. (I was afterwards told that nothing but horse flesh was sold at this restaurant.)

I then returned to the Palais de l'Industrie, where I was offered a post in the Medical Staff in charge of a train between Paris and Metz. I declined, upon the ground of my expecting to hear every minute of my having been appointed to an Ambulance. Hours passed without a syllable[25] from the Chief of the 8th Ambulance; and now for the first time I felt discouraged, but pulled myself together, and again threw myself with energy into the struggle.

I still had forces in reserve; for my friend, Madame A——, lady-in-waiting to the Empress, had promised me letters of introduction, which I daily expected, but which had not yet arrived. As I was whiling away the time conversing with one of the understrappers of the Palais, he told me that the siege of Paris by the Prussians was confidently expected by most Parisians; they talked of cutting down all the trees around Paris, and demolishing the farmsteads and farm produce in the vicinity, and my informant observed, "Déjà on cherche la démolition du Bois de Boulogne".

I walked out to the fortifications and saw batches of men throwing up mounds, whilst others were making excavations beneath the mason-work of the permanent bridges, to facilitate their being blown up on the approach of the enemy. Upon my return the garçon at the Hotel showed me with much pride his uniform and accoutrements, with which he had been presented that day on being made a member of the National Guard.

The loud beating of drums and the clatter and din of horses and men as they passed along the Boulevards before dawn, made it easy to be up at an early hour next morning, the 26th of August.

I set out for the Palais de l'Industrie, where[26] an order was handed me to hold myself in readiness to start that night for the front, so I returned quickly to my hotel, paid my bill and packed up my traps. I found two letters awaiting me: one from Madame A——, with an introduction to Professor Ricord, the Emperor's surgeon; and another from the Princess Poniatowsky, enclosing a note to the Count de Flavigny, President of the Society. They were now of no use, as I had been appointed to an Ambulance; but had I got them at first I should have been saved many days of anxious waiting. As it afterwards turned out, it was my good luck that they did not arrive sooner. An order was now issued that all strangers should quit Paris; and a heavy gloom seemed to be settling down rapidly over every one and everything. The conviction was daily growing that the Prussians were approaching Paris; but no one really knew, as every day's intelligence contradicted that of the day before. There seemed to be a great national competition in lying, in which every one manfully struggled for the prize.

At this juncture I was introduced to Dr. Frank, second in command of an Ambulance which had lately been organised in Paris by a number of English and American surgeons, and which was known as the Anglo-American. Dr. Frank received me courteously, and appointed me one of his sous-aides or dressers. Having given me[27] directions as to my outfit, he sent me off with another young member of the Ambulance, John Scott of Belfast, to procure all necessary supplies. The pleasure I experienced at finding myself in harness at last was beyond expression; and it was not lessened by discovering in my new mate a bright, jovial, and witty companion and a fellow-countryman to boot. We hurried off to the Palais Royal, where we ordered our uniforms, knapsacks and kits, and then went out and had a chat and a stroll.

Saturday morning, the 27th, Dr. Frank introduced me to Dr. Marion Sims, now chef or surgeon-in-chief, and also to his staff, which was composed of Drs. MacCormac, Webb, Blewitt, May, Tilghman, Nicholl, Hayden, and Hewitt, and Drs. Wyman and Pratt, as also to Mr. Fred Wallace and Harry Sims. Hewitt and I worked away for some hours getting the stores ready. Having finished this task we went to be photographed at Nader's, in full marching kit. I now packed up everything I did not want and sent them to M. de B——'s house (where they remained until after the war was over), and made my final preparations for starting. I received a month's pay in advance from Dr. Frank, so there was but little chance of my being hard up for money, as we were to be found in everything. Colonel Loyd Lindsay's English branch of the "Société pour le Secours aux Blessés" furnished[28] the English contingent of the ambulance with the sinews of war; and of this Dr. Frank was the representative.

On the 28th August I went in full uniform to the Madeleine, after which I took all my traps to the Palais de l'Industrie, where I met Marion Sims and had a chat with him. He addressed me kindly as "my dear boy"; and from the gentleness of his manner and his sympathetic nature, I felt that I should like him very much; and so it afterwards came to pass. We all now worked with a will, getting together our stores, provisions, horses and waggons, and making all ready for the procession, which, after a scene of confusion, noise, and excitement, left the Palais de l'Industrie about three o'clock, in the following order:—In front, carried by Dr. Sims' three charming daughters, the flags of England, France, and America; then the surgeons and the assistant surgeons; after these the dressers or sous-aides, of which I was one; then the infirmiers, all fully equipped, with the waggons for stores and wounded bringing up the rear.

While we were standing in our places, in the Champs Elysées, waiting for the final start, a young girl, pretty, and elegantly dressed in deep mourning, stepped up and tried to address me, but she sobbed so much that I could with difficulty understand what she said. After a little time she made her wish intelligible. Should[29] her husband ever come across my path in a wounded condition, she charged me to be kind to him, and to bestow upon him particular care for her sake. The earnestness with which she confided her sorrow to me, a stranger who had nothing to recommend him but his youth, well nigh overcame me, so that the poor thing very nearly had a companion in tears. She gave me her card, which I still possess. The girl could not have been more than twenty. I tried to say something to her that was kind; but so confused and upset was I that I could hardly utter a word. Presently the Count de Flavigny came forward and addressed us in a long and eloquent speech, flattering alike to our nationalities and to our cause.

A death-like silence reigned throughout the crowd as he reminded us of the scenes upon which we were about to enter; the cause we were to vindicate; the hardships we were likely to undergo; the good that each of us was bound in duty to perform; the sacrifice of every personal consideration, and even of our lives if necessary, in the grand and holy cause of the service of the wounded.

There were tears in many eyes, for not a few of the bystanders had at that moment friends near and dear, in dread suffering and perhaps in the agony of death. These few minutes made a deep impression upon me.

I now realised that I was entering upon a hazardous campaign, and felt the weight of the task that I had undertaken; and as the word "Marchez" was given I stepped out strong in mind and body, proud of the privilege which it had pleased Providence to bestow upon me, and yearning to fulfil that mission of charity which we had that day inaugurated.

As we passed through the streets in the order I have already given, the dense crowds cheered us along the way to the railway station (de l'Est), crying, "Vive les Americains!" "Vive l'Angleterre!" while the handkerchiefs of the ladies waved from all windows. Tears flowed abundantly on every side, as they readily do in France for less reason than the present one. All were delighted at the practical sympathy of the foreigners, on behalf of their wounded and suffering fellow-countrymen.

The crowds were so great that we found it difficult to make anything like rapid progress, and were several hours reaching the station.

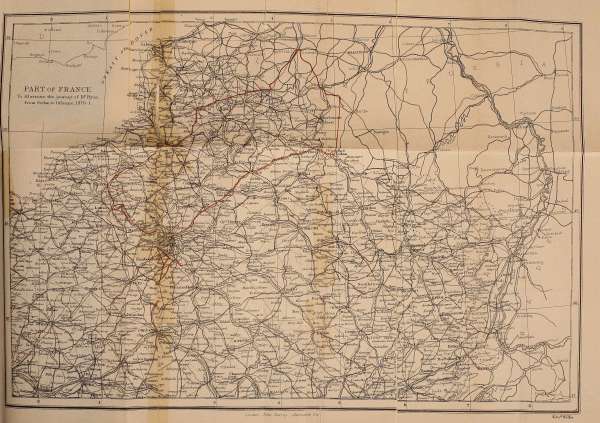

Having arrived at our destination, we took our seats in the waiting-room, not knowing in the least where we were going, as no one did but the chief and Dr. Frank. After waiting a couple of hours we got into a train in which we started off into the darkness, for it was ten o'clock. We travelled all night, and as morning dawned arrived at Soissons. Here we learned that we[31] were under orders to join MacMahon's army at once. As from information received, Dr. Sims supposed him to be somewhere in the vicinity of Sedan, it was his intention to make for Mézières, a small town in that neighbourhood, which we reached on Monday night, 29th August, arriving at Sedan the following morning, Tuesday, 30th, and remaining there to await further orders.

As we entered the town I was astonished to perceive that not a single soldier was visible, and that the sentinels on duty at the gates were peasants dressed in blue blouses, bearing guns upon their shoulders, a military képi being the only attempt at uniform.

All was still as we hastened through the streets to our quarters, at the Croix d'Or in the Rue Napoléon.

On the 30th of August we got orders through the Courrier des Ambulances, the Vicomte de Chizelles, to proceed at once to Carignan, where hard fighting had been going on, and where, we were told, the field had been won by the French. Accordingly at noon the whole ambulance moved out of the town, by the Torcy gate to the railway station, a few hundred yards outside the ramparts, whence a special train was to have carried us on to the field of our labours. Through some mismanagement on the part of the French authorities, and through a combination of adverse circumstances, our transport was delayed so long that we were unable to leave that evening. The railway officials contended that the cause of the delay was neglect, on the part of our comptable, to specify the exact amount of accommodation required for the transport of our waggons, stores, and horses, without which we could not work efficiently on the field of battle; but the real cause of the delay,[33] we subsequently discovered, was the capturing and blocking of the line by the Prussians, which fact was, in French fashion, studiously concealed from us. All this was very annoying to our chiefs, who were most anxious to get to the front. In order, therefore, that we might be able to start at daybreak next morning, we took up our quarters for that night in the station house. Being much fatigued after the excitement of the day we went to the bureau, where all our luggage was, and, after much ado, got hold of our wraps. There was one large waiting-room through which every one was obliged to pass in order to enter or leave the station, and here I and a number of my comrades stretched ourselves upon the bare boards, covered up in our rugs and overcoats.

Shortly after eleven o'clock, the arrival of a train caused us to start to our feet. The Germans, we knew, were in the neighbourhood, and the thought of a surprise flashed simultaneously through the mind of each one, when, to our intense astonishment, the door opened, and Napoléon, with his entire état major, marshals, and generals, walked into the room.

The Emperor wore a long dark blue cloak and a scarlet gold-braided képi. At first he seemed rather surprised at our presence, and for a moment or two delayed returning our salute, which he eventually acknowledged by a slight inclination of the head. He had a tired, scared, and haggard[34] appearance, and, besides looking thoroughly ill, seemed anxious and impatient. After a few moments' delay he hurried off on foot, in the midst of his entourage, through the station house, and along the road leading to the town of Sedan.

I and two of my comrades followed until we saw the Emperor and his attendants arrive at the gate, through which, after some parley with a blue-bloused sentry (for there was not a regular soldier in the town), they gained admittance. As we were about returning to our temporary quarters, speculating on the probable future as suggested by the scene I have described, we met a party of soldiers straggling along, composed of men of different regiments, both line and cavalry. We addressed one of them, who seemed more tired and worn out than the rest. He told us they belonged to the 5th and 12th Army Corps, and that they had escaped from the affair at Beaumont, where, having been several days short of provisions and exhausted with hunger and fatigue, the French were thoroughly routed. He said that they numbered about eighty, and were accompanied by an officer whom I afterwards heard give the name of De Failly, when challenged by the sentry. This was no other than the General de Failly who, on that very day at Beaumont, was deprived of his command for bad leadership, and superseded by De Wimpffen. In the rear of this party of fugitives was a cartload[35] of women and children. One of the women told most pitifully how the Prussian shells had that morning devastated their homes in the vicinity of Beaumont and Raucourt, and how several parts of those villages were then in flames. These poor creatures, numbed with cold and fright, gladly partook of the contents of some of our flasks; and we were all pleased when, after half an hour's parley with the peasant sentry, the drawbridge was let down and they were admitted into the town.

I now returned to my quarters in the station, where I slept soundly until I was awakened at break of day by Dr. Frank, who enjoined us to get ready at once, so as to push on to the front. This was the morning of the 31st August. At early dawn there was a thick fog, which, however, soon cleared away, revealing to us the fact that we were not far from the Prussian lines, and that they had actually during the night got full possession of the range of hills commanding the station and the whole town of Sedan. At times we could see distinctly numbers of Prussian Uhlans appearing now and then, from behind woods and plantations, on the heights of Marfée opposite us, and again disappearing, leaving us fully convinced that there were more where those came from. A little later, when the fog cleared off, we perceived in the opposite direction, at the north-east side of the town, numbers of troops moving about. These we found to be MacMahon's forces. Now we[36] became conscious of how we really stood. Our chief called us together, and with the stern manner and firm voice of an old veteran said, "Gentlemen, by a combination of unforeseen circumstances over which I had no control, we are now in the awkward position of finding ourselves placed between the line of fire of two armies. If they commence hostilities we are lost. It is therefore my intention as promptly as possible to retreat behind the French lines." Having said so much, he gave the order to move on. This we did across some fields, which we traversed with ease; but presently we came upon some heavy potato and turnip plots. Here our progress was necessarily very slow, heavily-laden as we were, with our three waggons ploughing through the soft furrows; and as we were not quite sure of the country that lay between us and the army, our position was most unenviable.

Two of our party, Drs. May and Tilghman, went ahead upon horseback, one of them carrying an ambulance flag. These two galloped along rather too impetuously as it appeared, for they came unexpectedly upon the French outposts, who, not knowing them to be friends, quickly fired a volley at them. Having discovered who they were they did not repeat this salute. It was just as our waggon horses had come to a standstill, being completely exhausted from pulling and floundering in the soft ground, that[37] Drs. May and Tilghman returned at a gallop to inform us that the Meuse lay between us and the main body of the army, and that there was no bridge, or other means of crossing, without going round through the town.

Just at this moment a courier came up in hot haste to say that, as the Prussians had just been seen in the immediate vicinity, the gate of the town would be immediately closed, and that the Military Commandant required us at once to make good our retreat, and get in the rear of the French army. We now saw that there was no alternative but to leave our baggage, stores, and waggons just where they were, and to fly into the town, which we did with all possible expedition, as from the position of the enemy we expected every minute that an engagement would take place. When we got inside the gates, two civilians volunteered, for a reward, to recover the baggage and waggons, with May and Tilghman as their leaders. These two gentlemen were veteran campaigners of the American Confederate Army, as were also all the other Americans of our ambulance, save Frank Hayden, who hailed from the North.

These not only brought back all our effects, but also a quantity of potatoes which were found in the field where the waggons had been left, and upon which we largely subsisted during the week following.

We now reported ourselves to the Intendant Militaire, who told us that he had the night before received an order to have in readiness 1800 beds for the use of the wounded. There was not a military surgeon in the town, nor any medical stores or appliances save our own; and of civilian doctors we never heard, nor were they en évidence.

The Intendant Militaire put all the beds which he had provided at our disposal, and gave us full control over their disposition and management.

Accordingly we took possession of the Caserne D'Asfeld, and made ready for receiving the wounded. We also had our stores arranged so that everything might be at hand when required.

It was while thus busily engaged, transporting our stores, and putting things in their place ready for use, that I saw the Emperor Napoléon slowly pacing up and down in front of the Sous-Préfecture, cigar in mouth, with his hands behind his back and head bent, gazing vacantly at the ground.

All that morning we had heard the distant booming of cannon, in the southward direction of Carignan and Mouzon. As the day advanced the cannonading came nearer, and grew more distinct, until it seemed to be in the immediate neighbourhood of the town. At nightfall the firing ceased, and we could perceive the glare of a distant village, in the direction of Douzy, lighting up the darkness.

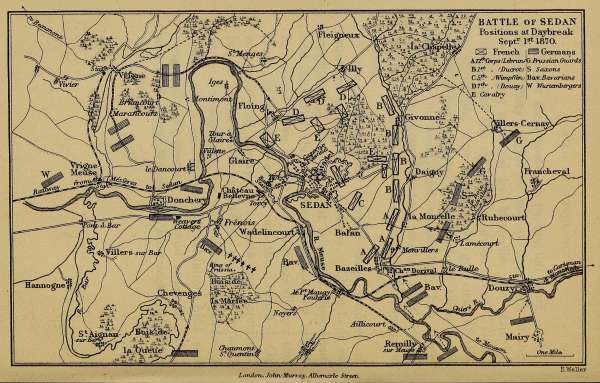

A brief sketch of the defences of Sedan, as well as an explanation of the position in which our hospital stood with regard to the fortifications, will not be out of place. The river Meuse, on the right bank of which Sedan is situated, communicates by sluice-gates with two deep trenches about thirty feet wide, separated from one another by a high embankment. On opening these gates, the trenches and a vast expanse of meadow land, extending nearly to Bazeilles and along the river beyond it, had been flooded, and the city was thus defended by a double wet ditch for about three-fourths of its circumference. All this lay external to the stone-faced ramparts, upon which stood heavy siege-guns, ostensibly to protect the town. They were, in fact, obsolete dummies. Outside these, again, were high earthworks, faced by strong palisades of spiked timber. At the summit of the north-east corner of the fortifications, towering above the plateau of Floing, rose the Citadel,—a huge, dark mass of mason-work and grassy slopes, which seemed to frown over a series of steep cliffs upon the town beneath. Above this stood our hospital of the Caserne D'Asfeld, called after a French Marshal of Louis XIV.'s time. The Prussians afterwards knew it as the "Kronwerk D'Asfeld". It was a fortress which had a drawbridge and defences of its own. From these details we may judge what a stronghold Sedan would prove, were it not for the range[40] of hills opposite, called the Heights of Marfée. But these command the town; and the Prussians had been permitted to occupy them.

Now, as to the Caserne itself. Standing on the highest point of the fortifications, about 100 feet above the Meuse, it might have seemed the very position for a hospital. It was a two-storied bomb-proof building, with a flat roof, 240 feet long, and contained nine large wards, fifty-three feet by seventeen, and ten feet high, as well as four small ones with twenty beds in each. There were two spacious windows in every ward. The floors were concrete. On the fortifications outside were rows of magnificent trees, which gave the grounds a picturesque appearance. But in front, facing the town, there were no trees; and from this point we had an unbroken view of Sedan and the valley of the Meuse, with the hills opposite. The villages of Donchery, Frénois, and Wadelincourt were all visible.

Six cannon commanded the outer breastworks, behind the buildings, and two sallyports led out beneath the fortifications, on to the plains of Floing. We heard from the wounded, as well as from other sources, that the French were retreating on Sedan, and that the Prussians held the left bank of the Meuse, and the valley and hills about it. The French, on their side, occupied the Illy heights to the north of the town above the plateau of Floing,[41] the Bois de Garenne, and the east and south-east plains, from Daigny and the valley of Givonne to Bazeilles. Hence, it was evident, even at so early a date, that the French army had only the strip of small country to the north and east of Sedan, between the right bank of the Meuse and the Ardennes, by which to make good their retreat on Mézières. And of this narrow space, the defile of St. Albert alone was available for the passage of large bodies of soldiers.

The Prussian outposts were already in Vendresse and Donchery. Could they succeed in moving further north before the French started, they might cut off the retreat of the whole army.

The movements of the French in these straits had been extremely perplexing to us. They must have known their situation, if not on the 29th, certainly on the 30th and 31st. Why, then, did they not keep to the left bank of the Meuse, and seize the only available strong position visible on that side—the Heights of Marfée, which they could have held, and the possession of which would have covered their retreat along the defile of St. Albert? Instead of doing so, they chose to fall back on Sedan; a trap out of which no sane man, military or civilian, could, under the circumstances, expect an army to free itself. These positions were occupied by the Prussians at the earliest possible moment. But even if the French could not have come up by the left bank of the Meuse, they might, as late as the night of the 31st, have retreated by Moncelle, the plain of Floing, and the right bank of the river. Thus, at all events, they would have got clear of the enemy's heavy guns, which assailed them from the hills in front; and would have had some chance of meeting their foes on more equal terms. But they went to their destruction like men in a dream.

Late that evening, several large batches of wounded came into the Caserne. These kept us employed till after midnight, when we slipped out and ascended the fortifications, that we might look once more at the still blazing village, the name of which we had not then heard. Of course it was Douzy. And now we perceived, by the innumerable camp-fires gleaming around us on all sides, that we were close to the ill-fated army, of which Marshal MacMahon held the command. To-morrow it would cease to exist, and with it the Napoleonic Empire would come to an end.

| French | Germans |

| A 12th Corps (Lebrun) | G Prussian Guards |

| B 1st " (Ducrot) | S Saxons |

| C 5th " (Wimpffen) | Bav. Bavarians |

| D 7th " (Doucey) | W Wurtembergers |

| E Cavalry |

Full of strange forebodings, I retired to the guard-room at the end of the building which overlooked the town, where Père Bayonne, our Dominican chaplain, Hewitt, and myself had our stretchers. Tired out, I slept as soundly as if nothing had happened, or was to happen. But about a quarter to five on the following morning,—that historic Thursday, the 1st of September,—Père Bayonne and I were aroused by the strange and terrible sound of roaring cannon. We heard the shells whizzing continually, and by-and-by the prolonged peals of the mitrailleuse. On looking out, we saw a thick mist lying along the valley, and clinging about the slopes of the hills in front of us. Presently it cleared away; the morning became beautifully fine, and the sun shone forth with genial warmth.

Immediately beneath us lay the town, with its double fortifications, and its trenches filled by the[44] Meuse, which seemed a silver thread winding through a charmingly wooded and delightful country. The whole range of hills which commanded the town was occupied by the Prussians; and we could see their artillery and battalions in dark blue, with their spiked helmets and their bayonets flashing in the sunlight.

Neither had we long to wait before 150 guns were, each in its turn, belching out fire and smoke. For the first couple of hours the heaviest part of the fighting was kept up from the left and further extremity of this range of hills. But as the morning wore on, the guns immediately opposite us opened fire, although the main body of the Prussians had not yet come up the valley into view. The plains and hills to the north and north-east of the town and immediately behind us were covered with French troops, the nearest being a regiment of the Line, a Zouave regiment, and a force of cuirassiers. It was magnificent to see the bright helmets and breast-plates of the latter gleaming in the sun, as they swept along from time to time, and took up fresh positions. I watched them suddenly wheel and gallop at a headlong pace for some hundred yards, then stop as they were making a second wheel, and tear up to the edge of a wood on a piece of high ground, where they remained motionless. A regiment of the Line then advanced, and opened fire across them, down into the valley beneath the[45] wood; while for twenty minutes a hot counter-fire was kept up by a force of advancing Prussians, the French still moving forward, and leaving plenty of work for us in their rear. As the firing ceased, the cuirassiers, who had been up till then motionless spectators of the scene, suddenly began to move, first at a walk, then breaking into a trot, and, finally, having cleared the corner of the wood, into full gallop. They dashed down the valley of Floing and were quickly lost to our view. This was the beginning, as I afterwards learned, of one of the most brilliant feats of the French arms during that day. It has been graphically described by Dr. Russell, the war correspondent of the Times. Beyond doubt, until noon, when all chance of success vanished, the French fought bravely. I shall here instance one out of many personal feats of valour, which came under our notice.

While I was assisting in dressing a wounded soldier, he told me the following story, which was subsequently corroborated by one of his officers who came to see him. This soldier was St. Aubin, of the Third Chasseurs d'Afrique, concerning whom I shall have more to say by-and-by. He was only twenty-three, and a tall, fair, handsome fellow. He had been in action for seven hours, and had received a bayonet thrust through the cheek. His horse was shot under him during the flight of the French towards Sedan. Still[46] undismayed, he provided himself with one of the chassepots lying about, and falling in with a body of Marines, the best men in the French army, he, in company with this gallant band, faced the enemy again. Numbers of his companions fell; he himself got a bullet through the right elbow. Promptly tearing his pocket handkerchief into strips with his teeth, he tied up his wounds, and securing his wrist to his belt, seized his sword, determined to fight on. Unfortunately, the fragment of a shell struck him again, shattering the right shoulder. In this plight he mounted a stray horse, and, as he told me, holding his sword in his teeth, put spurs to his steed, and joined his companions at Sedan, where he sank out of the saddle through sheer exhaustion and loss of blood.

Early in the day vigorous fighting was going on outside the town, about Balan and Bazeilles, and between us and the Belgian frontier. As early as ten o'clock, it was evident that the Prussians were extending their line of fire on both sides, with the ultimate object of hemming in the French army, now being slowly forced back upon the town. By eleven o'clock, the plains to the north and east between us and the Belgian frontier were occupied by dense masses of the French; and at noon, the Prussian artillery on the hills in front turned their fire over our heads, on the French troops behind us. From this[47] moment, we found ourselves in the thick of the fight. Around us on every side raged a fierce and bloody conflict. The Prussian guns in front, which had kept up an intermittent fire since early morning, now seemed to act in concert, and the roaring of cannon and whizzing of shells became continuous. It was an appalling medley of sounds; and we could scarcely hear one another speak.

During this murderous fire, we received into our hospital twenty-eight officers of all grades (among them two colonels), and nearly 400 men of all arms. Occasionally, one of the shells which were passing over us in quick succession would fall short, striking, at one time, the roof of our Hospital or the stone battlements in front, at another the earthworks or a tree within the fort. One of these shells burst at the main entrance, close to where I was at work, killing two infirmiers and wounding a third,—the first two were, indeed, reduced to a mass of charred flesh, a sight of unspeakable horror. A second shell burst close to the window of the ward, in which Drs. MacCormac, Nicholl, Tilghman, and May were operating, chipping off a fragment of the corner stone; a third struck the coping wall of the fortification overhanging the town, about twenty feet from our mess-room window; and a fragment entered, and made a hole in the ceiling. The bomb-proof over our[48] heads came in for a shower of French mitrailleuse bullets, which so frightened our cook that he upset a can of savoury horseflesh soup, which he had prepared for us. But, to add to the danger, about half-past two a detachment of artillery, bringing with them three brass nine-pounders, came into our enclosure (for, as I have said, the guns supposed to be guarding our fort were absolute dummies), and opened a hot fire on the enemy, in the vain attempt to enable Ducrot's contingent to join De Wimpffen at Balan. It was a brave and determined effort, but as futile as it was rash, for it brought the Prussian fire down upon us; and in less than half an hour, the French had to abandon their guns, which were soon dismantled, while the trenches about them were filled with dead and wounded. At one time, Dr. May and I counted on the plain a rank of eighty-five dead horses, exclusive of the maimed. The sufferings of these poor brutes, which were as a rule frightfully mutilated, seemed to call for pity almost as much as those of the men themselves. For the men, if wounded very badly, lay still, and their wants were quickly attended to; but the horses, sometimes disembowelled, their limbs shattered, kept wildly struggling and snorting beneath dismounted gun-carriages and upturned ammunition waggons, until either a friendly revolver or death from exhaustion put an end to their torment.

Everywhere on this plain, to the north of the[49] town, there was now the most hopeless confusion. The soldiers, utterly demoralised—more than half of them without arms—were hugging the ramparts in dense masses, seeking thus to escape the deadly fire directed on them by the advancing Prussians. It was clear that the fortunes of the day were going against the French; and if we ask the reason, some reply may be found in the testimony of a Colonel, who told us, with sobs and tears, that for six hours he had been under fire, and had received no orders from his General. A little later on, about half-past three, an officer, carrying the colours of his regiment, rushed into our Hospital in a state of the wildest excitement, crying out that the French had lost, and entreating Dr. May to hide his flag in one of our beds,—a request with which the latter indignantly refused to comply.

About a quarter to four, although the din of battle was still raging, we could see the white flag flying, and rumours of a truce were current. The space round the Caserne D'Asfeld was at this time crowded with troops; and a knot of them were wrangling for water about our well, which, being worked only by a windlass and bucket, gave but a scanty supply. The events that now followed have been described by the French as an attempt on the part of Ducrot to get his forces through the town, and out by the Balan gate, there to reinforce General Wimpffen, and sustain his final[50] attempt to break through the German lines. But what really happened was this: The French, aware that the battle was lost, had become panic-stricken, and getting completely out of the control of their officers, their retreat on Sedan was, in plain truth, the stampede of a thoroughly disorganised and routed army. It was a strange sight, and by no means easy to picture. A huge and miscellaneous collection of men, horses, and materials were jammed into a comparatively small space, all in the utmost disorder and confusion. Soldiers of every branch—cavalry, infantry, artillery—flung away their arms, or left them at different places, in stacks four or five feet high. Heedless of command, they made for the town by every available entrance. And I saw French officers shedding tears at a spectacle, which no one who was not in arms against them could witness without grief and shame.

A Colonel, who had carried his eagles with honour through the battles of Wörth and Weissenburg, related how he had buried the standard of his regiment, together with his own decorations, and burned his colours, to save them from falling into the hands of the enemy. All these officers had but one cry: "Nous sommes trahis!" openly declaring that the loss of their country, and the dishonour of its arms, were due to the perfidy and incompetence of their statesmen and generals. That some of these allegations of treason were[51] well founded is beyond question: the universal incompetency we saw with our own eyes.

I observed one remarkable incident during this state of general disorder. A regiment of Turcos came into our enclosure with their officers, in perfect order, fully armed and accoutred. These gaunt-looking fellows, fierce, bronzed, and of splendid physique, stood stolid and silent, with their cloaks, hoods, and gaiters still beautifully white. Watching for some minutes, I noticed a movement among them, and they commenced a passionate discussion in their own tongue, evidently on a subject of interest to them all. In another minute the conclusion was manifest. Approaching the parapet in small parties, and clubbing their rifles, they smashed off the stocks against the stonework, and flung the pieces into the ditch beneath. In like manner they disposed of their heavy pistols and side-arms. Then, having lighted their cigarettes, they relapsed into a state of silent and dreamy inactivity, in which not a word was spoken.

Along the roads leading to the gates of the town, more particularly along the one beneath us, streamed a dense mass of soldiers belonging to various regiments, with numbers of horses ridden chiefly by officers, and some waggons, all bearing headlong down on the gates. As they passed over the narrow bridges, literally in tens of thousands, packed close together, some horses[52] and a few men were pushed over the low parapet into the river, and many of the fugitives were trodden under foot. At length, between four and five P.M., the firing gradually slackened. For some time it was still kept up, but in a desultory manner, towards Balan. At half-past five it ceased altogether; and the sensation of relief was indescribable.

The grounds about the Caserne D'Asfeld had, in the meanwhile, become packed with runaway soldiers, whose first exploit was forcibly to enter our kitchen and store-rooms, and plunder all they could lay hands on. Of course, they were driven to these acts by the exigencies of the situation. The blame for such excesses cannot but attach to that centre of all corruption, the French Commissariat, which broke down that day as it had done at every turn during the whole campaign. We had some wounded men in the theatre, Place de Turenne, down in Sedan; but the streets and squares were so densely crowded that it was with difficulty some of our staff could make their way to them. All were now burning with anxiety to know whether the French would surrender, or hostilities be resumed on the morrow. A continuance of the struggle, as we felt, would mean that some hundred and twenty thousand soldiers, and ourselves along with them, were to be buried in the ruins of Sedan.

Our fears, however, were soon allayed. Before nightfall we heard that the Emperor had opened[53] negotiations with the German King, and that the capitulation was certain.

At last darkness set in. The stillness of the night was unbroken, save for a musical humming sound as if from a mighty hive of bees;—it was the murmur of voices resounding from the hundred thousand men caged within the beleaguered city. As we stood for a moment on the battlements, sniffing the cool air, with which was still intermingled the gruesome odour of the battlefield, how impressive a sight met our gaze! Bazeilles was burning; its flames lit up the sky brilliantly, and brought out into clear relief the hills and valleys for miles around; they even threw a red glare over Sedan itself; while above the site of the burning village there seemed to dance one great pillar of fire, from which tongues shot out quivering and rocketing into the atmosphere, as house after house burst into flames.

The number of Frenchmen wounded during those few hours of which I write, is said to have been 12,500. Probably a third of that figure would represent the number of Prussian casualties. As for our own ambulance, during that day it afforded surgical aid to 100 officers and 524 men. The number of those killed will never be known; all I can state is, that in places the French were mown down before our eyes like grass. There is a thicket on a lonely hill side, skirting the Bois de Garenne, within rifleshot of the Caserne D'Asfeld,[54] where six and thirty men fell close together. There they were buried in one common grave; and few besides myself remain to tell the tale.

Such is the story of Sedan as I beheld it, and as faithful a record as I can give from my own experience, of that never-to-be-forgotten 1st of September, 1870.

To our labours in the Hospitals I shall presently return. On the 31st, Drs. Frank and Blewitt had established a branch hospital at Balan, and during that day and 1st September, had rendered assistance, both there and at Bazeilles, to those who were wounded in the street-fighting or injured by the flames. Dr. Blewitt informed me that at one time, the house in which they were treating a large number of wounded had its windows and doors so riddled with bullets, that, in order to escape with their lives, they had to lie down on the floor, and remain there until the leaden shower was over. The French inhabitants also, he said, had fired upon the Bavarians; they had set their bedding and furniture alight, and thrown them out on the heads of the Germans, who were packed close in the streets; and after the first repulse of the invaders, several wounded Prussians had been barbarously butchered, some even (horrible to relate) had had their throats cut with[56] razors. This, it was reported, had been the work of French women. On the other hand, several of the native soldiers had been found propped up against the walls in a sitting posture, with pipes and flowers in their mouths. Upon retaking the village, when the Germans discovered what had been done, they retaliated by shooting down and bayoneting all before them, nor in some instances did the women and children escape this cruel fate. So exasperated, indeed, were the Germans by the events of those two dreadful hours on the 1st, that not a life did they spare, nor a house did they leave intact, in that miserable town.

Such, in brief, was the history of Bazeilles. It is not a subject which one can dwell upon. When, within a day or two later, I had occasion to pass through it, and saw the still burning ruins which bore witness to the awful deeds done on both sides, my heart sank. All that fire and sword could wreak upon any town and its inhabitants was visible here; and it is not too much to affirm that, so long as the name of Bazeilles is remembered, a stain will rest on the memory of French and Germans, both of whom contributed to its ruin.

On the 5th September Dr. Frank took possession of the Château Mouville, which belonged to the Count de Fienne. It is situated between Balan and Bazeilles, and was quickly filled with[57] wounded from both places. But for some time our ambulance was unable to get its waggons through the streets, so impeded were they with the charred remains of the dead and dying.

I have now described what I can vouch for, on the testimony of some of my companions, as having occurred at these two places; and I will leave my own account of what I saw myself in Bazeilles until a later occasion.

To go back to Sedan. As night drew near, the refugees outside the Caserne lighted their fires, and put up their tents. Those who had no tents rolled themselves in their cloaks, and lay down just where they happened to be. All were overcome by fatigue, long marches, and want of food and sleep; they seemed only too glad to rest anywhere, and to enjoy a respite from the sufferings and hardships which during so many days had weighed upon them.

The true story of these unhappy soldiers will never become known in detail; and if it did, the public would hardly believe it. Many of them started, as I heard from their own lips, with only two-thirds of the kit they were booked as having received. In some instances their second pair of boots were wanting; or, if not, the pair supplied had thick brown paper soles covered with leather, and were often a misfit. The men, as we read with perfect accuracy in La Débâcle, were marched and countermarched to no purpose; they[58] received contradictory orders; and I learned from their statements, that neither general officers nor subalterns knew whither they were going; and that one corps was constantly getting foul of the other, simply from not being acquainted with the map of the district in which they found themselves. More than one declared to me that their officers were officiers de salon; they were canaille, said the men, who when under fire were the first to seek shelter, and from their position of security to cry "En avant, mes braves!" In fact, the common soldiers felt and expressed the heartiest contempt for them. Of this I had abundant evidence. It was enough to see how the rank and file came into the cafés and sat down beside the officers of their own regiment, as I have seen them do, taking hardly any notice of them, or deigning them only the lamest of salutes. On the other hand, when officers came into a café (which they did upon every possible occasion), the men would pretend not to see them. I have observed, not once, but scores of times, captains of the Line, wearing decorations, seated in taverns drinking beer and absinthe with the common soldiers. They were as despicable in their familiarities as in their want of courage; and who can be surprised if their men did not respect them, or wonder that such leaders had no control over the privates when in action?