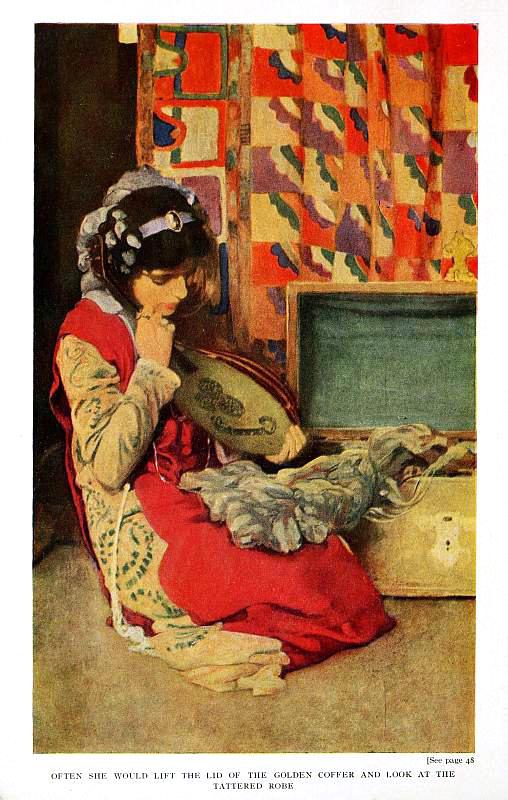

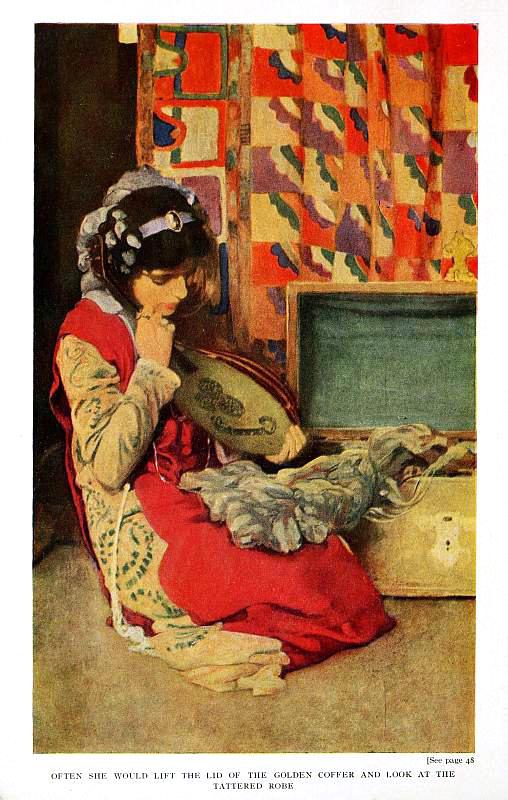

[See page 48

OFTEN SHE WOULD LIFT THE LID OF THE GOLDEN COFFER AND LOOK AT THE

TATTERED ROBE

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Maker of Rainbows, by Richard Le Gallienne

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Maker of Rainbows

And other Fairy-tales and Fables

Author: Richard Le Gallienne

Illustrator: Elizabeth Shippen Green

Release Date: January 26, 2013 [EBook #41921]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAKER OF RAINBOWS ***

Produced by Anna Hall and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

[See page 48

OFTEN SHE WOULD LIFT THE LID OF THE GOLDEN COFFER AND LOOK AT THE

TATTERED ROBE

BY

RICHARD LE GALLIENNE

AUTHOR OF

"AN OLD COUNTRY HOUSE"

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

ELIZABETH SHIPPEN GREEN

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

MCMXII

COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY HARPER & BROTHERS

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

PUBLISHED OCTOBER, 1912

I · M

THAT THIS VOLUME SHALL BE ENTIRELY IN KEEPING WITH ITS FAIRY-TALE CONTENTS, I DEDICATE IT TO MY GOOD FRIENDS, ITS PUBLISHERS, MESSRS. HARPER & BROTHERS IN REMEMBRANCE OF KINDLY RELATIONS BETWEEN THEM AND ITS WRITER SELDOM FOUND OUT OF A FAIRY-TALE

THE MAKER OF

RAINBOWS

A PROLOGUE

eople in London—not merely literary

folk, but even those "higher social

circles" to which a certain publisher,

whose name—or race—it is hardly

fair to mention, had so obsequiously

climbed—often wondered whence had come the

wealth that enabled him to maintain such an establishment,

give such elaborate "parties," have

so many automobiles, and generally make all that

display which is so convincing to the modern

mind.

eople in London—not merely literary

folk, but even those "higher social

circles" to which a certain publisher,

whose name—or race—it is hardly

fair to mention, had so obsequiously

climbed—often wondered whence had come the

wealth that enabled him to maintain such an establishment,

give such elaborate "parties," have

so many automobiles, and generally make all that

display which is so convincing to the modern

mind.

Of course they were not seriously concerned, because, so long as it is a party, and the chef is paid so much, and the wines are as old as they should be, not even the rarest blossom on the most ancient and distinguished genealogical tree cares whose party it is, or, indeed, with whom she dances. There is only one democracy, and that is controlled by gentlemen with names that[Pg 2] hardly sound beautiful enough to mention in fairy tales—that democracy of money to which the fairest flower of our aristocracy now bows her coroneted head.

Strange—but we all know that so it is. Therefore, all sorts of distinguished and beautiful people came to the publisher's "parties."

It would have made no difference, really, to their hard hearts, could they have known where all the champagne and conservatories and music came from—they would have gone on dancing all the same, and eating pâté de foie gras and sherbets; yet it may interest a sad heart here and there to know how it was that that publisher—whose name I forget, but whose nose I can never forget—was able to pay for all that music and dancing, strange flowers, and enchanted food, none of which he, of course, understood.

Aristocrats in London, of course, know nothing of a northern district of New York City called Harlem, with so many streets that a learned arithmetician would be needed to number them: a district which, at the first call of spring, becomes vocal with children on door-steps and venders of every vegetable in every language. In this district, too, you hear strange trumpets blow, announcing[Pg 3] knife and scissors grinders, and strange bells ringing from strings suspended across carts, whose merchandise is bottles and old newspapers. You will hear, too, just when the indomitable sweet smells from the terrible eternal spring are blowing in at your window, and the murmur of rich happy people going away is heard in the land, a raucous cry in the hot street—a cry full of melancholy, even despair: it goes something like this—"Cash clo'! Cash clo'!"

Well, it was just then that a young poet, living in one of those highly arithmetical streets, was wondering, as all the sad spring murmur came to his ears, how he could possibly buy a rose for the bosom of his sweetheart, with whom he was to dance that night at a local ball. Everything he had in the world had gone. He had sold everything—except his poems. All his precious books had gone, sad one by one. Little paintings that once made his walls seem like the Louvre had gone. All his old silver spoons and all the little intaglios he loved so well, and yes! he had even sold the old copper chest of the Renaissance, all studded nails, with three locks, in which ... well, all had gone. Only, where was that rose for the bosom of his sweetheart—where was it growing? Where and how was it to be bought?

Just as he was at his wit's end, he heard a cry through the window. It had meant nothing to him before. Now—strange as it may sound—it meant a rose!

"Cash clo'! Cash clo'!"

He had an old dress-suit in his wardrobe. Perhaps that would buy a rose! So, leaning through the window, he called down to the voice to "come up."

The gentleman from Palestine came up.

It would be easy to describe the contempt with which he surveyed the distinguished though somewhat ancient garments thus offered to him—in exchange for a rose!—how he affected to examine linings and seams, knowing all the time the distinguished tailor that had made them, and what a bargain he was about to drive.

Of course, they weren't, well ... really ... practically ... they weren't worth buying....

The poet wondered a moment about the cost of a rose.

"Are they worth the price of a rose?" he asked.

The gentleman from Palestine didn't, of course, understand.

"You see," said he, finally; "I'd like to give you more, but you know how it is ... look at these linings and buttonholes! Honestly, I don't[Pg 5] really care about them at all—but—really a dollar and a half is the best I can do on them...." And he eyed the poet's clothes with contempt.

"A dollar seventy-five," said the poet, standing firm.

"All right," at last said the gentleman from Palestine, "but I don't see where I am to make any profit; however—" And he handed out the small, dirty money.

Then the poet bowed him out gently, saying in his heart:

"Now I can buy my rose!"

When the Palestinian dealer in old dress-suits went home—after sadly leaving behind him that dollar seventy-five—he made an astonishing discovery.

In the necessary process of re-examining the "goods," something fell out of one of the pockets, something the poet, after his nature, had quite forgotten. The old-clothes man, now a publisher, picked them up from the floor and gazed at them in delight. The poet, in his grandiose carelessness, had forgotten to empty his pockets of various old dreams!

Now, to be fair to the gentleman from Palestine, he belonged to a race that loves dreams, and, to do him justice, he forgot all about the profit he was[Pg 6] to make of the poor poet's clothes, as he sat, cross-legged, on the floor, and read the dreams that had fallen from the pocket of the poet's old dress-suit. He read on and read on, and laughed and cried—such a curious treasure-trove, such an odd medley of fairy tales and fables and poems had fallen out of the poet's pocket—and it was only later that the thought came to him that he might change from an old-clothes man into a publisher of dreams.

Now, these are some of the dreams that fell out of the poet's pocket.

t was a bleak November morning in

the dreary little village of Twelve-trees.

Nature herself seemed hopeless

and disgusted with the universe,

as the chill mists stole wearily among

the bare trees, and the boughs dripped with a

clammy moisture that had nothing of the energy

of tears.

t was a bleak November morning in

the dreary little village of Twelve-trees.

Nature herself seemed hopeless

and disgusted with the universe,

as the chill mists stole wearily among

the bare trees, and the boughs dripped with a

clammy moisture that had nothing of the energy

of tears.

Twelve-trees was a poor little village at the best of times, but the past summer had been more than usually unkind to it, and the lean wheat-fields and the ragged orchards had been leaner and more ragged than ever before—so said the memory of the oldest villagers.

There was very little to eat in the village of Twelve-trees, and practically no money at all. Some of the inhabitants found consolation in the fact that at the Inn of the Blessed Rood the cider-kegs still held out against despair.

But this was no comfort to the gaunt and shivering[Pg 8] children left to themselves on the chill door-steps, half-heartedly trying to play their innocent little games. Even the heart of childhood felt the shadows that November morning in the dreary little village of Twelve-trees, and even the dogs and the cats of the village seemed to be under the same spell of gloom, and moved about with a dank hopelessness, evidently expecting nothing in the shape of discarded fish or transfiguring smells.

There was no life in the long, disheveled High Street. No one seemed to think it worth while to get up and work. There was nothing to get up for, and no work worth doing. So, naturally, in all this echoing emptiness, this lack of excitement, anything that happened attracted a gratefully alert attention—even from those cats and dogs so sadly prowling amid the dejected refuse of the village.

Presently, amid all the November numbness, the blank nothingness of the damp, deserted street, there was to be seen approaching from the south a curious little figure of an old man, trundling at his side a strange apparatus resembling a knife-grinder's wheel, and he carried some forlorn old umbrellas under one arm. Evidently he was an itinerant knife-grinder and umbrella-mender. As[Pg 9] he proceeded up the street, he called out some strange sing-song, the words of which it was impossible to distinguish.

But, though his cry was melancholy, his old puckered and wizened face seemed to be alight with some inner and inextinguishable gladness, and his electrical blue eyes, startlingly set in a network of wrinkles, were as full of laughter as a boy's. His cry attracted a weary face here and there at window and door; but, seeing nothing but an old knife-grinder, the faces lost interest and immediately disappeared. The children, however, being less sophisticated, were filled with a grateful curiosity toward the stranger, and left the chill door-steps and trooped about him in wonder.

A little girl, with tears making channels down her pale, unwashed face, caught the old man's eye.

"Little one," he said, with a magical smile, and a voice all reassuring love, "give me one of those tears, and I will show you what I can make of it."

And he touched the child's face with his hand, and caught one of her tears on his finger, and placed it, glittering, on his wheel. Then, working a pedal with his foot, the wheel began to move so swiftly that one could see nothing but its whirling; and as it whirled, wonderful colored rays[Pg 10] began to rise from it, so that presently the dreary street seemed full of rainbows. The sad houses were lit up with a fairy radiance, and the faces of the children were all laughter again.

"Well, little one," he said, when the wheel stopped whirling, "did you like what I made out of that sad little tear?"

And the children laughed, and begged him to do some other trick for them.

At that moment there came down the street a poor old half-witted woman, indescribably dirty and bedraggled, talking to herself and laughing in a creepy way. The village knew her as Crazy Sal, and the children were accustomed to make cruel sport of her. As she came near they began to jeer at her, with the heartlessness of young, unknowing things.

But the strange old man who had made rainbows out of the little girl's tear suddenly stopped them.

"Stay, children," he said, "and watch."

And, as he said this, his wheel went whirling again; and as it whirled a light shot out from it, so that it illuminated the poor old woman, and in its radiance she became strangely transfigured. In place of Crazy Sal, whom they had been accustomed to mock, the children saw a beautiful[Pg 11] young girl, all blushes and bright eyes and pretty ribbons; and so great was the murmur of their surprise that it drew to the door-steps their fathers and mothers, who also saw Crazy Sal as none of them had ever seen her before—except a very old man who remembered her as a beautiful young girl, and remembered, too, how her mind had gone from her as the news came one day that her sweetheart, a sailor, had been drowned in the North Sea.

"Who and what are you?" said this old man, stepping out a little in front of the gathering crowd. "Are you a wizard, that you change a child's tears into laughter, and turn an old half-witted woman back to a young girl? You must be of the devil...."

"Give me an ear of corn from your last harvest," answered the old knife-grinder, "and let me put it on my wheel."

An ear of corn was brought to him, and once more his wheel went whirring, and again that strange light shot out from it, and spread far past the houses over the fields beyond; and, lo! to the astonished sad eyes of the weary farmers, they appeared waving with golden grain, waiting for the scythe.

And again, as the wheel stopped whirring, the[Pg 12] old man who had remembered Crazy Sal as a young girl spoke to the knife-grinder; again he asked:

"What and who are you? Are you a wizard that you change a child's tears into laughter, and turn an old half-witted woman back to a young girl, and make of a barren glebe a waving corn-field?"

And the man with the strange wheel answered:

"I am the maker of rainbows. I am the alchemist of hope. To me November is always May, tears are always laughter that is going to be, and darkness is light misunderstood. The sad heart makes its own sorrow, the happy heart makes its own joy. The harvest is made by the harvestman—and there is nothing hard or black or weary that is not waiting for the magic touch of hope to become soft as a spring flower, bright as the morning star, and valiant as a young runner in the dawn."

But the village of Twelve-trees was not to be convinced by such words made out of moonshine. Only the children believed in the laughing old man with the strange wheel.

"Rainbows!" mocked their fathers and mothers—"rainbows! Much good are rainbows to a starving village."

The old maker of rainbows took their taunts in silence, and made ready to go his way; but as he started once more along the road he said, with a cynical smile:

"Have you never heard that there is a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow?..."

"A pot of gold?" cried out the whole village of Twelve-trees.

"Yes," he answered, "a pot of gold! I know where it is, and I am going to find it."

And he moved on his way.

Then the villagers looked at one another, and said over and over again, "A pot of gold!"

And they took cloaks and walking-staves and set out to accompany the old visitor; but when they reached the outskirts of the village there was no sign of him. He had mysteriously disappeared.

But the children never forgot the rainbows.

nce on a time toward the end of

February, when the snow still festered

in the New York streets, and

the wind blew cruelly from river to

river, a strange figure made a somewhat

storm-tossed progress along Forty-second

Street, walking toward the East Side. He was a

tall, distinguished, curiously sad-looking man,

with longish hair growing gray, and clothes which,

though they had been brushed many times, still

proclaimed aloud a Bond Street tailor. As he

walked along he had evidently some trouble with

one of his eyes, which he rubbed from time to

time, as though a cinder, perhaps, from the Elevated

Railroad had lodged there, and at last he held

a handkerchief to it as he walked along. But

whatever the trouble was, it did not seem to

interfere with a keen and kindly vision that noted

every object and character of the thronged street.

Now and again, strangers in that noisy and bewildering[Pg 15]

quarter would ask direction from him,

and he never failed to stop with an aristocratic

painstaking courtesy and set them on their way.

Nervous old women with bundles at perilous crossings

found his arm ready to pilot them safely to

the other side. There was about him a curious

gentleness which, after a while, did not fail to

attract the attention of enterprising boys and

observing beggars, for whom, as he walked along,

evidently sorely troubled with his eye, he did not

fail to find pennies and kind words.

nce on a time toward the end of

February, when the snow still festered

in the New York streets, and

the wind blew cruelly from river to

river, a strange figure made a somewhat

storm-tossed progress along Forty-second

Street, walking toward the East Side. He was a

tall, distinguished, curiously sad-looking man,

with longish hair growing gray, and clothes which,

though they had been brushed many times, still

proclaimed aloud a Bond Street tailor. As he

walked along he had evidently some trouble with

one of his eyes, which he rubbed from time to

time, as though a cinder, perhaps, from the Elevated

Railroad had lodged there, and at last he held

a handkerchief to it as he walked along. But

whatever the trouble was, it did not seem to

interfere with a keen and kindly vision that noted

every object and character of the thronged street.

Now and again, strangers in that noisy and bewildering[Pg 15]

quarter would ask direction from him,

and he never failed to stop with an aristocratic

painstaking courtesy and set them on their way.

Nervous old women with bundles at perilous crossings

found his arm ready to pilot them safely to

the other side. There was about him a curious

gentleness which, after a while, did not fail to

attract the attention of enterprising boys and

observing beggars, for whom, as he walked along,

evidently sorely troubled with his eye, he did not

fail to find pennies and kind words.

At last he had become so noticeable for these oddities of behavior that, as he went along, he had collected quite an escort of miscellaneous individuals, ragged children with pale, precocious faces, voluble old Irishwomen with bedraggled petticoats, sturdy beggars on crutches, and a sprinkling of so-called "respectable" people, curiously hovering on the skirts of the strange crowd. From some of these last came at length unkindly comments. The man was evidently crazy—more probably he was drunk. But it was plainly evident that he had something the matter with his eye.

At last a kindly individual suggested that he should go to a drug-store and get the drug clerk to look at his eye. To this the stranger assented,[Pg 16] and, accompanied by his motley escort, he entered a drug-store and put himself into the hands of the clerk, while the crowd thronged the door and glared through the windows, wondering what was the matter with the eccentric gentleman, who, after all, was very free with his pence and had so kind a tongue. A policeman did not, of course, fail to elbow himself into the store, to inquire what was the matter.

Meanwhile the drug clerk proceeded to lift up the stranger's eyelid in a professional manner, searching for the extraneous particle of pain.

At last he found something, and made a strange announcement. The something in the stranger's eye was—Pity.

No wonder it had caused such a sensation in the most pitiless city in the world.

here was once a poet who lived all

alone by the sea. He had built for

himself a little house of boulders mortised

in among the rocks, so hidden

that it was seldom that any wayfarer

stumbled upon his retreat. Wayfarers indeed

were few in that solitary island, which was for the

most part covered with thick beech woods, and

had for its inhabitants only the wild creatures of

wood and water and the strange unearthly shapes

that none but the poet's eyes could see. The

nearest village was miles away on the mainland,

and for months at a time the solitude would be

undisturbed by sound of human voice or footstep—which

was the poet's idea of happiness. The

world of men had seemed to him a world of sorrow

and foolishness and lies, and so he had forsaken it

to dwell with silence and beauty and the sound of

the sea.

here was once a poet who lived all

alone by the sea. He had built for

himself a little house of boulders mortised

in among the rocks, so hidden

that it was seldom that any wayfarer

stumbled upon his retreat. Wayfarers indeed

were few in that solitary island, which was for the

most part covered with thick beech woods, and

had for its inhabitants only the wild creatures of

wood and water and the strange unearthly shapes

that none but the poet's eyes could see. The

nearest village was miles away on the mainland,

and for months at a time the solitude would be

undisturbed by sound of human voice or footstep—which

was the poet's idea of happiness. The

world of men had seemed to him a world of sorrow

and foolishness and lies, and so he had forsaken it

to dwell with silence and beauty and the sound of

the sea.

For him the world had been an uncompanioned wilderness. Here at last his spirit had found its[Pg 18] home and its kindred. The speech of men had been to him a vain confusion, but here were the voices he had been born to understand, the elemental voices of earth and sea and sky, the secret wisdom of the eternal. From morning till night his days were passed in listening to these voices, and in writing down in beautiful words the messages of wonder they brought him. So his little house grew to be filled with the lovely songs that had come to him out of the sky and the sea and the haunted beeches. He had written them in a great book with silver clasps, and often at evening, when the moon was rising over the sea, he would sing them to himself, for joy in the treasure which he had thus hoarded out of the air, as a man might weigh the grains of gold sifted from some flowing river.

One night, as he thus sat singing to himself in the solitude, he was startled by a deep sigh, as of some human creature near at hand, and looking around he was aware of a lovely form, half in and half out of the water, gazing at him with great moonlit eyes from beneath masses of golden hair. In awe and delight he gazed back spellbound at the unearthly vision. It was a fairy woman of the sea, more beautiful than tongue can tell. Over her was the supernatural beauty of dreams and as[Pg 19] he looked at her the poet's heart filled with that more than mortal happiness that only comes to us in dreams.

"Beautiful spirit," at length he cried, stretching out his arms to the vision; but as he did so she was gone, and in the place where she had been there was nought but the lonely moonlight falling on the rocks.

"It was all a trick of the moonlight," said the poet to himself, but, even as he said it, there seemed to come floating to him the cadences of an unearthly music of farewell.

In his heart the poet knew that it had not been the moonlight, but that nature had granted him one of those mystic visitations which come only to those whose loving meditation upon her secrets have opened the hidden doors. She had drawn aside for a moment the veil of her visible beauty, and vouchsafed him a glimpse of her invisible mystery. But the veil had been drawn again almost instantly, and the poet's eyes were left empty and hungered for the face that had thus momentarily looked at him through the veil. Yet his heart was filled with a high happiness, for, the vision once his, would it not be his again? Did it not mean that through the long initiation of his solitary contemplation he had come at length to[Pg 20] that aery boundary where the wall between the seen and the unseen grows transparent and the human meets the immortal face to face?

Still, days passed, and the poet watched in vain for the beautiful woman of the sea. She came not again for all his singing, and his heart grew heavy within him; but one day, as he walked the seashore at dawn, it gave a great bound of joy, for there in mystical writing upon the silver sand was a message which no eyes but his could have read. But the poet was skilled in the secret script of the elements. To him the patterns of leaves and flowers, the traceries of moss and lichen, the markings on rocks and trees, which to others were but meaningless decorations, were the letters of nature's hidden language, the spell-words of her runic wisdom. To other eyes the message he had found written on the sand would have seemed but a tangle of delicate weeds and shells cast up by the sea. To him, as he turned it into our coarser human speech, it said:

And that night, when the poet sat and sang, with full heart, in the moonlight—lo! the vision was there once more.... But again, as he stretched out his arms, she was gone. But this time the poet did not grieve as before, for he knew that she would come again, as indeed it befell. When she appeared to him the third time she had stolen so near to his side that he could gaze deep into her strange eyes, as into the fathomless, moonlit sea, and at the ending of his song she did not fade away as before, but her long hair fell all about him like a net of moonbeams, and she lay like the moon herself in his enraptured arms.

To the passionate lover of nature, the anchorite of her solitudes, there often comes, in the very hour of his closest approach to her, an aching sense of incomplete oneness with her, a human desire for some responsive embodiment of her mysterious beauty; and there are ecstatic moments in which nature seems on the tremulous verge of sending us a magic answer—moments of intense reverie when the woods seem about to reveal to us the inner heart of their silence, in some sudden shape of unimaginable enchantment, or the infinite of the starry night take form at our side in some companionable radiance. We[Pg 22] long, as it were, to press our lips to the forehead of the dawn, to crush the leafy abundance of summer to our breast, and to fold the infinite ocean in our embrace.

To the poet, reward of his lonely vigils and endless longing, nature had granted this marvel. How often, as he had gazed at the moon rising out of the sea, had he dreamed of a shining shape that came to him along her silver pathway. And to-night the mystery of the moonlit sea was in his arms. No longer a lovely vision calling him from afar—an unapproachable wonder, a voice, a gleam—but a miraculously embodied spirit of the elements, supernaturally fair.

The poet was, more than all men, learned in beautiful words, but he could find no words for this strange happiness that had befallen him; indeed, he had now passed beyond the world of words, and as he gazed into those magic eyes, that seemed like sea-flowers growing out of the air, they spoke to each other as wave talks to wave, or the leaves whisper together on the trees.

So it was that the poet ceased to be alone in his solitude, and the fairy woman from the sea became his wife, and very wonderful was their happiness. But, as with all happiness, theirs, too, was not without its touch of sorrow. For, marvelously[Pg 23] wedded though they were, so closely united that they seemed veritably one rather than two beings, there had been a deep meaning to that little song which the poet had found written in seaweed upon the sand:

it had said,

For not even their love could cast down for them one eternal barrier. They could meet and love across it, but it was still there. They were children of two diverse elements, and neither could cross from one into the other—she a child of the blue sea, he a child of the green earth. She must always leave him at the edge of the mysterious woods in which her heart ached to wander, and, however far out into the wide waters he would swim at her side, there would always be those deep-sea grottoes and flower-gardens whither he could never follow. Down into these enchanted depths he would watch her glide her shimmering way, but never might he follow her to the hidden kingdoms of the sea. He must await her out there, an alien, in the upper sunshine, and watch her glittering kindred[Pg 24] stream in and out the rainbowed portals—till again she was at his side, her hands filled for his consolation with the secret treasures of the sea.

So would she, from the shore, with despair in her eyes, watch him disappear among the beech-trees to gather for her the waxen flowers and the sweet-smelling green leaves and grasses she loved more than any that grew in the sea. Thus across their barrier would they make exchange of the marvels that grew on either side, and thus, indeed, the barrier grew less and less by reason of their love. Sometimes they asked each other if that other mystery, Death, would remove the barrier altogether....

But at the heart of the woman Life was already whispering another answer.

"What," said she, as they watched the solemn stars in the still water one summer night, "what if a little being were born to us that should belong to both our worlds, to your green earth and to my blue sea? Would you seem so lonely then? A little being that could run by your side in the meadows, and swim with me into the depths of the sea!..."

"Would you be so lonely then?" he echoed.

And lo! after a season, it was this very marvel that came to pass; for one night, as she came[Pg 25] along the moon-path to his side, she was not alone, but a tiny fairy woman was with her—a little radiant creature that, as her mother had dreamed, could gather with one hand the flowers that grow in the deeps of the wood and with the other the flowers that grow in the deeps of the sea.

Like any other mortal babe she was, save for this: around her waist ran a shimmering girdle—of mother-of-pearl.

So the poet and his wife called her Mother-of-Pearl; and she became for them, as it were, a baby-bridge between two elements. In her mysterious life their two lives became one, as never before. So near she brought them to each other that often there seemed no barrier at all. And thus days and years passed, and very wonderful was their happiness.

But by this the world which the poet had forgotten had grown curious regarding the life which he lived alone among the rocks. Many of his songs, as songs will, had escaped from his solitude, and floated singing among men; and weird rumors grew of the strange happiness that had come to him. Some of the more curious had spied upon him in his seclusion, and had brought back to the town marvelous accounts of having seen him in the moonlight with his fairy wife and child[Pg 26] at his side. And, after its fashion, the world had decided that here was plainly the work of the devil, and that the poet was a wizard in league with the powers of darkness. So the ignorant world has ever interpreted the beauty it could not understand, and the happiness it could not give.

Thus a cloud began to gather of which the poet and his mer-wife and little Mother-of-Pearl knew nothing, and one evening at moonrise, as they were disporting themselves in their innocent happiness by the sea, it burst upon them from the beech-trees with a gathering murmur and a sudden roar.

A great mob, uttering cries and waving torches, broke from the wood and ran toward them.

"Death to the wizard!" they cried. "Death! Death!"

As the poet heard them, he turned to his wife and little Mother-of-Pearl. "Fear not," he cried, "they cannot hurt us."

Then, as again the cry went up, "Death to the wizard!" a sudden light shone in his face.

"Death ... yes! That is the last door of the barrier...." and he plunged into the moonlit water.

And when the rabble at length reached the shore with their torches, the poet and his loved ones were already lost in the silver pathway that leads to the hidden kingdoms of the sea.

ne day, walking by the sea,

ne day, walking by the sea,

here was once a great lord. He

was lord of seven castles, and there

were seven coronets upon his head.

He was richer than he ever gave

himself the trouble to think of, for,

north, south, east, and west, the horizon even set

no bounds to his estates. A thousand villages

and ten thousand farms were in the hollow of his

hand, and into his coffers flowed the fruitfulness

and labor of all these. Therefore, as you can

imagine, he was a very rich lord. He had more

beautiful titles, denoting the various principalities

over which he was lord, than the deepest-lunged

herald could proclaim without taking breath at

least three times. In person he was most noble

and beautiful to look upon, and his voice was

like the rippling of waters under the moon, save

when it was like the call of a golden trumpet.

He stood foremost in the counsels of his realm,

not only for his eloquence, but for his wisdom.

Also, God had given him a good heart.

here was once a great lord. He

was lord of seven castles, and there

were seven coronets upon his head.

He was richer than he ever gave

himself the trouble to think of, for,

north, south, east, and west, the horizon even set

no bounds to his estates. A thousand villages

and ten thousand farms were in the hollow of his

hand, and into his coffers flowed the fruitfulness

and labor of all these. Therefore, as you can

imagine, he was a very rich lord. He had more

beautiful titles, denoting the various principalities

over which he was lord, than the deepest-lunged

herald could proclaim without taking breath at

least three times. In person he was most noble

and beautiful to look upon, and his voice was

like the rippling of waters under the moon, save

when it was like the call of a golden trumpet.

He stood foremost in the counsels of his realm,

not only for his eloquence, but for his wisdom.

Also, God had given him a good heart.

Only one gift had been denied him—the gift of sleep. By whatever means he might weary himself in the day—in study, in sport, in recreation, or in the business of the realm—night found him sleepless, and all the dark hours the lights burned in his bedchamber and in his library, as he would pace from one to the other, with eyes tragically awake and brain torturingly alert and clear.

Every means known to science by which to bring sleep to the eyes of sleepless men had been tried in vain. Learned physicians from all parts of the world had come to my lord's castle, and had gone thence, confessing that their skill had availed nothing. All strange and terrible drugs that have power over the spirit of man had failed to conquer those stubborn eyelids. My lord still paced from his bedchamber to his library, from his library to his bedchamber—sleepless.

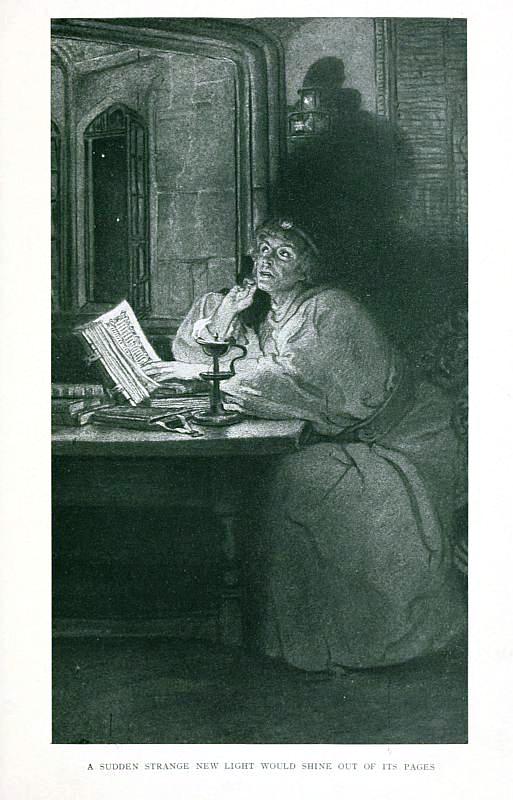

A SUDDEN STRANGE NEW LIGHT WOULD SHINE OUT OF ITS PAGES

A SUDDEN STRANGE NEW LIGHT WOULD SHINE OUT OF ITS PAGES

Sometimes in his anguish he had thrown himself on his knees in prayer before a God whom he had not always remembered—the God who giveth His beloved sleep—but his prayers had remained unanswered; and in his darkest moments he had dreamed of snatching by his own hands that sleep perpetual of which a great Latin poet he loved had sung. Often, as he paced his library, he [Pg 31]would say over and over to himself, Nox est perpetua una dormienda—and in the still night the old words would often sound like soft dark voices calling him away into the endless night of the endless sleep. But he was not the man to take that way of escape. No; whatever the suffering might be, he would fight it out to the end, and so he continued sleepless, trying this resource and that, but, most of all, that first and last resource—courage. It is seldom that courage fails to wrest for us some recompense from the hardest situation, and the sleepless man, as night after night he fought with his fate, did not miss such hard-wrung rewards. Often, as in the deepest hush of the night he wearily took up some great old book of philosopher or poet familiar to him from his youth, a sudden strange new light would shine out of its pages, as of some inner radiance of truth which he had missed in his daylight reading. At such times an exaltation would come over him, and it would almost seem as though the curse upon him was really a blessing of initiation into the world of a deeper wisdom, the gate of which is hidden by the glare of the sun. In the daylight the eternal voices are lost in the transitory clamor of human business; it is only when the night falls, and the stars rise, and the noise[Pg 32] of men dies down like the drone of some sleeping insect, that the solemn thoughts of God may be heard.

Other compensations he found when, weary of his books and despairing of sleep, he would leave his house and wander through the silent city, where the roaring thoroughfares of the daytime were silent as the pyramids, and the great warehouses seemed like deserted palaces haunted by the moon. Night-walkers like himself grew to find his figure familiar, and would say to themselves, or to each other, "There goes the lord who never sleeps"; and the watchmen on their rounds all knew and saluted the man whose eyelids never closed. Enforced as these nocturnal rambles were, they revealed to him much beautiful knowledge which those more fortunate ones asleep in their beds must ever miss. Thus he came in contact with all the vast nocturnal labor of the world, the toil of sleepless men who keep watch over the sleeping earth, and work through the night to make it ready for the new-born day; all that labor which is put away and forgotten with the rising of the sun, and of which the day asks no questions, so that the result be there. This brought him very near to humanity and taught him a deep pity for the grinding lot of man.

Then—was it no compensation for this sleepless one that he thus became a companion of all the ensorceled beauty of Night, walking by her side, a confidant of her mystic talk, as he gazed into her everlasting eyes? Was it nothing to be the intimate of all her sibylline moods, learned in every haunted murmur of her voice, intrusted with her lunar secrets, and a friend of all her stars?

Yes! it was much indeed, he often said to himself, as he turned homeward with the first flush of morning, and met the great sweet-smelling wains coming from the country, laden with fruits and flowers, and making their way like moving orchards and meadows through the city streets.

The big wagoners, too, were well acquainted with the great lord who never slept, and would always stop when they saw him, for it was his custom to buy from them a bunch of country flowers.

"The country dew is still on them," he would say; "it will have dried long since when the people sleeping yonder come to buy them," and, as he slipped back into his house, he would often feel a sort of pity for those who slept so well that they never saw the stars set and the sun rise.

Such were some of the compensations with[Pg 34] which he strove to strengthen his soul—not all in vain. So time passed; but at length the strain of those interminable nights began to tell upon the sleepless man, and strange fancies began to take possession of him. His vigils were no longer lonely, but inhabited by spectral voices and shadowy faces. Rebellion against his fate began to take the place of courage; and one night, in anger against his unending ordeal, he said to himself: "Am I not a great lord? It is intolerable that I should be denied that simple thing which the humblest and poorest possess so abundantly. Am I not rich? I will go forth and buy sleep."

So saying, he took from a cabinet a great jewel of priceless value. "It is worth half my estate," he said. "Surely with this I can buy sleep." And he went out into the night.

As if in irony, the night was unusually wide-awake with stars, and the moon was almost at its full. As the sleepless one looked up into the firmament, it almost seemed as though it mocked him with his brilliant wakefulness. From horizon to horizon, in all the heaven, there was to be seen no downiest feather of the wings of sleep. To his upturned eyes, pleading for the mercy of sleep, the stars sent down an answer of polished steel. And so he turned his eyes again upon the earth.[Pg 35] Everything there also, even the keenly cut shadows, seemed pitilessly awake. It almost seemed as though God had withdrawn the blessing of sleep from His universe.

But no! Suddenly he gave a cry of joy, as presently, by the riverside, stretched in an angle of its granite embankment, as though it had been a bed of down, he came upon a great workman fast asleep, with his arms over his head and his face full in the light of the moon. His breath came and went with the regularity of a man who has done his days work and is healthily tired out. He seemed to be drinking great draughts of sleep out of the sky, as one drinks water from a spring. He was poorly clad, and evidently a wanderer on the earth; but, houseless as he was, to him had been granted that healing gift which the great lord who gazed at him had prayed for in vain for months and years, and for which this night he was willing to surrender half—nay, the whole—of his wealth, if needs be—

The sleepless one gazed at the sleeper a long time, fascinated by the mystery and beauty of that strange gift that had been denied him. Then he took the jewel in his hand and looked at it, picturing to himself the sleeping man's surprise when he awoke in the morning and found so unexpected a treasure in his possession, and all that the sudden acquisition of such wealth would mean to him. But, as I said at the beginning, God had given him a good heart, and, as he gazed on the man's sleep again, a pang of misgiving shot through him. After all, what were worldly possessions compared with this natural boon of which he was about to rob the sleeping man? Would all his castles be a fair exchange for that? And was he about to subject a fellow human being to the torture which he had endured to the verge of madness?

For a long time he stood over the sleeper struggling with himself.

"No!" at last he said. "I cannot rob him of his sleep," and turned and passed on his way.

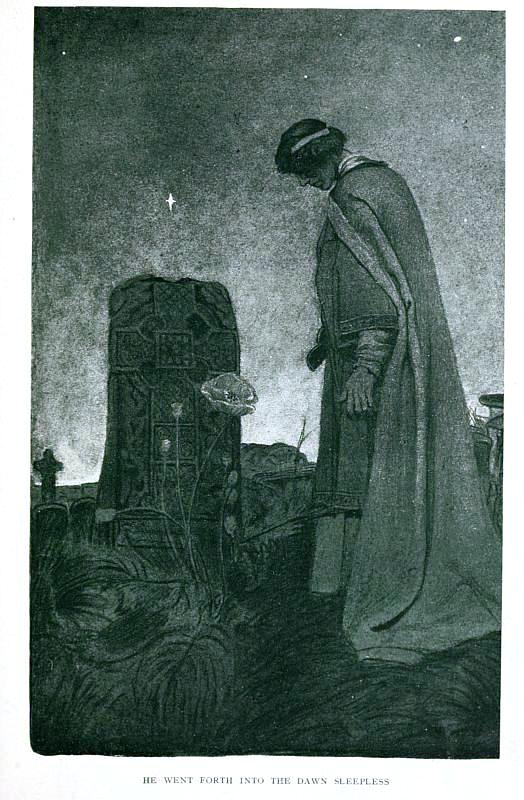

HE WENT FORTH INTO THE DAWN SLEEPLESS

HE WENT FORTH INTO THE DAWN SLEEPLESS

Presently he came to where a beautiful woman lay asleep with a little child in her arms. They were evidently poor outcasts, yet how tranquilly they lay there, as if all the riches of the earth were theirs, and as if there was no hard world [Pg 37]to fight on the morrow. If sleep had seemed beautiful on the face of the sleeping workman, how much more beautiful it seemed here, laying its benediction upon this poor mother and child. How trustfully they lay in its arms out there in the shelterless night, as though relying on the protection of the ever-watchful stars. Surely he could not violate this sanctuary of sleep, and think to make amends by exchange of his poor worldly possessions. No! he must go on his way again. But first he took a ring from his finger and slipped it gently into the baby's hand. The tiny hand closed over it with the firmness of a baby's clutch. "It will be safe there till morning," he said to himself, and left them to their slumbers.

So he passed along through the city, and everywhere were sleeping forms and houses filled with sleepers, but he could not bring himself to carry out his plan and buy sleep. Sleep was too beautiful and sacred a thing to be bought with the most precious stone, and man was so piteously in need of it at each long day's end.

Thus he went on his way, and at last, as the dawn was showing faint in the sky, he found himself in a churchyard, and above one of the graves was growing a shining silver flower.

"It is the flower of sleep," said the sleepless one, and he bent over eagerly to gather it; but as he did so his eyes fell upon an inscription on the stone. It was the grave of a beautiful girl who had died of heart-break for her lover.

"I may not pluck it," he said. "She needs her sleep as well."

And he went forth into the dawn sleepless.

A FABLE FOR CAPITALISTS

nce upon a time there was a man

who found himself, suddenly and

sadly, without any money. I am

aware that in these days it is hard

to believe such a story. Nowadays,

everybody has money, and it may seem like a

stretch of the imagination to suggest a time when

a man should search his pockets and find them

empty. But this is merely a fairy tale; so, I

trust that the reader will help me out by taking

so apparently preposterous a statement for

granted.

nce upon a time there was a man

who found himself, suddenly and

sadly, without any money. I am

aware that in these days it is hard

to believe such a story. Nowadays,

everybody has money, and it may seem like a

stretch of the imagination to suggest a time when

a man should search his pockets and find them

empty. But this is merely a fairy tale; so, I

trust that the reader will help me out by taking

so apparently preposterous a statement for

granted.

The man had been a merchant of butterflies in Ispahan, and, though his butterflies had flitted all about the flowered world, the delight of many-tongued and many-colored nations, he found himself at the close of the day a very poor and weary man.

He had but one consolation and companion[Pg 40] left—a strange, black butterfly, which he kept in a silver cage, and only looked at now and again, when he was quite sure that he was alone. He had sold all his other butterflies—all the rainbow wings—but this dark butterfly he would keep till the end.

Kings and queens, in sore sorrow and need, had offered him great sums for his black butterfly, but it was the only beautiful thing he had left—so, selfishly, he kept it to himself. Meanwhile, he starved and wandered the country roads, homeless and foodless: his breakfast the morning star, his supper the rising moon. But, sad as was his heart, and empty as was his stomach, laughter still flickered in his tired eyes; and he possessed, too, a very shrewd mind, as a man who sells butterflies must. Making his breakfast of blackberries one September morning, in the middle of an old wood, with the great cages of bramble overladen with the fruit of the solitude, an idea came to him. Thereupon he sought out some simple peasants and said: "Why do you leave these berries to fall and wither in the solitude, when in the markets of the world much money may be made of them for you and for your household? Gather them for me, and I will sell them and give you a fair return for your labor."

Now, of course, the blackberries did not belong to the dealer in butterflies. They were the free gift of God to men and birds. But the simple peasants never thought of that. Instead, they gathered them, east and west, into bushel and hogshead, and the man that had no money, that September morning, smiled to himself as he paid them their little wage, and filled his pockets, that before had been so empty, with the money that God and the blackberries and the peasants had made for him.

Thus he grew so rich that he seldom looked at the dark butterfly in the silver cage—but sometimes, in the night, he heard the beating of its wings.

hen the first dazzle of bewildered

happiness in her new estate had

faded from her eyes, and the miracle

of her startling metamorphosis

from a wandering beggar-maid to

a great Queen on a throne was beginning to lose

a little of its wonder and to take its place among

the accepted realities of life, Queen Cophetua became

growingly conscious of some dim dissatisfaction

and unrest in her heart.

hen the first dazzle of bewildered

happiness in her new estate had

faded from her eyes, and the miracle

of her startling metamorphosis

from a wandering beggar-maid to

a great Queen on a throne was beginning to lose

a little of its wonder and to take its place among

the accepted realities of life, Queen Cophetua became

growingly conscious of some dim dissatisfaction

and unrest in her heart.

Indeed, she had all that the world could give, and surely all that a woman's heart is supposed to desire. The King's love was still hers as when he found her at dawn by the pool in the forest; and, in exchange for the tattered rags which had barely concealed the water-lily whiteness of her body, countless wardrobes were filled with garments of every variety of subtle design and exquisite fabric, textures light as the golden sun, purple as the wine-dark sea, iridescent as the rainbow, and soft as summer clouds—the better[Pg 43] to set off her strange beauty for the eyes of the King.

And, every day of the year, the King brought her a new and priceless jewel to hang about her neck, or wear upon her moonbeam hands, or to shine in the fragrant night of her hair.

Ah! what a magical wooing that had been in the depths of the forest, that strange morning! The sun was hardly above the tops of the trees when she had awakened from sleep at the mossy foot of a giant beech, and its first beams were casting a solemn enchantment across a great pool of water-lilies and filling their ivory cups with strange gold. She had lain still a while, watching through her sleepy eyelids the unfolding marvel of the dawn; and then rousing herself, she had knelt by the pool, and letting down her long hair that fell almost to her feet had combed and braided it, with the pool for her mirror—a mirror with water-lilies for its frame. And, as she gazed at herself in the clear water, with a girlish happiness in her own beauty, a shadow fell over the pond; and, startled, she saw beside her own face in the mirror the face of a beautiful young knight, so it seemed, bending over her shoulder. In fear and maiden modesty—for her hair was only half braided, and, whiter than any water-lily in the[Pg 44] pond, her bosom glowed bare in the morning sunlight—she turned around, and met the eyes of the King.

Without moving, each gazed at the other as in a dream—eyes lost fathom-deep in eyes.

At last the King found voice to speak.

"You must be a fairy," he had said, "for surely you are too beautiful to be human!"

"Nay, my lord," she had answered, "I am but a poor girl that wanders with my lute yonder from village to village and town to town, singing my little songs."

"You shall wander no more," said the King. "Come with me, and you shall sit upon a throne and be my Queen, and I will love you forever."

But she could not answer a word, for fear and joy.

And therewith the King took her by the hand, and set her upon his horse that was grazing hard by; and, mounting behind her, he rode with her in his arms to the city, and all the while her eyes looked up into his eyes, as she leaned upon his shoulder, and his eyes looked deep down into hers—but they spake not a word. Only once, at the edge of the forest, he had bent down and kissed her on the lips, and it seemed to both[Pg 45] as if heaven with all its stars was falling into their hearts.

As they rode through the city to the palace, surrounded by wondering crowds, she nestled closer to his side, like a frightened bird, and like a wild birds were her great eyes gazing up into his in a terror of joy. Not once did she move them to right or left, for all the murmur of the people about them. Nor did the King see aught but her water-lily face as they wended thus in a dream through the crowded streets, and at length came to the marble steps of the palace.

Then the King, leaping from his horse, took her tenderly in his arms and carried her lightly up the marble steps. Upon the topmost step he set her down, and taking her hand in his, as she stood timidly by his side, he turned his face to the multitude and spake.

"Lo! my people," he said, "this is your Queen, whom God has sent to me by a divine miracle, to rule over your hearts from this day forth, as she holds rule over mine. My people, salute your Queen!"

And therewith the King knelt on one knee to his beggar-maid and kissed her hand; and all the people knelt likewise, with bowed heads, and a great cry went up.

"Our Queen! Our Queen!"

Then the King and Queen passed into the palace, and the tiring-maids led the little beggar-maid into a great chamber hung with tapestries and furnished with many mirrors, and they took from off her white body the tattered gown she had worn in the forest, and robed her in perfumed linen and cloth of gold, and set jewels at her throat and in her hair; and at evening in the cathedral, before the high altar, in the presence of all the people, the King placed a sapphire beautiful as the evening star upon her finger, and the twain became man and wife; and the moon rose and the little beggar-maid was a Queen and lay in a great King's arms.

On the morrow the King summoned a famous worker in metals attached to his court, and commanded him to make a beautiful coffer of beaten gold, in which to place the little ragged robe of his beggar-maid; for it was very sacred to him because of his great love. After due time the coffer was finished, and it was acclaimed the masterpiece of the great artificer who had made it. About its sides was embossed the story of the King's love. On one side was the pool with the water-lilies and the beggar-maid braiding her hair on its brink. And on another she was riding[Pg 47] on horseback with the King through the forest. And on another she was standing by his side on the steps of the palace before all the people. And on the fourth side she was kneeling by the King's side before the high altar in the cathedral.

The King placed the coffer in a secret gallery attached to the royal apartments, and very tenderly he placed therein the little tattered gown and the lute with which his Queen was wont to wander from village to village and town to town, singing her little songs.

Often at evening, when his heart brimmed over with the tenderness of his love, he would persuade his Queen to doff her beautiful royal garments and clothe herself again in that little tattered gown, through the rents of which her white body showed whiter than any water-lilies. And, however rich or exquisite the other garments she wore, it was in those beloved rags, the King declared, that she looked most beautiful. In them he loved her best.

But this had been a while ago, and though, as has been said, the King's love was still hers as when he had met her that strange morning in the forest, and though every day he brought her a new and priceless jewel to hang about her neck, or wear upon her moonbeam hands, or to shine[Pg 48] in the fragrant night of her hair, it was many months since he had asked her to wear for him the little tattered gown.

Was the miracle of their love beginning to lose a little of its wonder for him, too; was it beginning to take its place among the accepted realities of life?

Sometimes the Queen fancied that he seemed a little impatient with her elfin bird-like ways, as though, in his heart, he was beginning to wish that she was more in harmony with the folk around her, more like the worldly court ladies, with their great manners and artificial smiles. For, though she had now been a Queen a long while, she had never changed. She was still the wild gipsy-hearted child the King had found braiding her hair that morning by the lilied pool.

Often she would steal away by herself and enter that secret gallery, and lift the lid of the golden coffer, and look wistfully at the little tattered robe, and run her hands over the cracked strings of her little lute.

There was a long window in the gallery, from which, far away, she could see the great green cloud of the forest; and as the days went by she often found herself seated at this window, gazing in its direction, with vague unformed feelings of sadness in her heart.

One day, as she sat there at the window, an impulse came over her that she could not resist, and swiftly she slipped off her beautiful garments, and taking the little robe from the coffer, clothed herself in the rags that the King had loved. And she took the old lute in her hands, and sang low to herself her old wandering songs. And she danced, too, an elfin dance, all alone there in the still gallery, danced as the apple-blossoms dance on the spring winds, or the autumn leaves dance in the depths of the forest.

Suddenly she ceased in alarm. The King had entered the gallery unperceived, and was watching her with sad eyes.

"Are you weary of being a Queen?" said he, sadly.

For answer she threw herself on his breast and wept bitterly, she knew not why.

"Oh, I love you! I love you," she sobbed, "but this life is not real."

And the King went from her with a heavy heart.

And from day to day an unspoken sorrow lay between them; and from day to day the King's words haunted the Queen with a more insistent refrain:

"Are you weary of being a Queen?"

Was she weary of being a Queen?

And so the days went by.

One day as the Queen passed down the palace steps she came upon a beautiful girl, clothed in tatters as she had once been, seated on the lowest step, selling flowers—water-lilies.

The Queen stopped.

"Where did you gather your water-lilies, child?" she asked.

"I gathered them from a pool in the great forest yonder," answered the girl, with a curtsey.

"Give me one of them," said the Queen, with a sob in her voice, and she slipped a piece of gold into the girl's hand, and fled back into the palace.

That night, as she lay awake by her sleeping King, she rose silently and stole into the secret gallery. There, with tears running down her cheeks, she dressed herself in the little tattered gown and took the lute in her hand, and then stole back and pressed a last kiss on the brow of her sleeping King, who still slept on.

But at sunrise the King awoke, with a sudden fear in his heart, and lo! where his Queen had lain was only a white water-lily.

And at that moment, in the depths of the forest, a beggar-maid was braiding her hair, with a pool of water-lilies for her mirror.

er talk was of all woodland things,

er talk was of all woodland things,

n an evening of singular sunset,

about the rich beginning of May,

the little market-town of Beethorpe

was startled by the sound of a

trumpet.

n an evening of singular sunset,

about the rich beginning of May,

the little market-town of Beethorpe

was startled by the sound of a

trumpet.

Beethorpe was an ancient town, mysteriously sown, centuries ago, like a wandering thistle-down of human life, amid the silence and the nibbling sheep of the great chalk downs. It stood in a hollow of the long smooth billows of pale pasture that suavely melted into the sky on every side. The evening was so still that the little river running across the threshold of the town, and encircling what remained of its old walls, was the noisiest thing to be heard, dominating with its talkative murmur the bedtime hum of the High Street.

Suddenly, as the flamboyance of the sky was on the edge of fading, and the world beginning to wear a forlorn, forgotten look, a trumpet sounded from the western heights above the town,[Pg 55] as though the sunset itself had spoken; and the people in Beethorpe, looking up, saw three horsemen against the lurid sky.

Three times the trumpet blew.

And the simple folk of Beethorpe, tumbling out into the street at the summons, and looking to the west with sleepy bewilderment, asked themselves: Was it the last trumpet? Or was it the long-threatened invasion of the King of France?

Again the trumpet blew, and then the braver of the young men of the town hastened up the hill to learn its meaning.

As they approached the horsemen, they perceived that the center of the three was a young man of great nobility of bearing, richly but somberly dressed, and with a dark, beautiful face filled with a proud melancholy. He kept his eyes on the fading sunset, sitting motionless upon his horse, apparently oblivious of the commotion his arrival had caused. The horseman on his right hand was clad after the manner of a herald, and the horseman on his left hand was clad after the manner of a steward. And the three horsemen sat motionless, awaiting the bewildered ambassadors of Beethorpe.

When these had approached near enough the[Pg 56] herald once more set the trumpet to his lips and blew; and then, unfolding a parchment scroll, read in a loud voice:

"To the Folk of Beethorpe—Greeting from the High and Mighty Lord, Mortimer of the Marches:

"Whereas our heart had gone out toward the sorrows of our people in the counties and towns and villages of our domain, we hereby issue proclamation that whosoever hath a sorrow, let him or her bring it forth; and we, out of our private purse, will purchase the said sorrow, according to its value—that the hearts of our people be lightened of their burdens."

And when the herald had finished reading he blew again upon the trumpet three times; and the villagers looked at one another in bewilderment—but some ran down the hill to tell their neighbors of the strange proposal of their lord. Thus, presently, nearly all the village of Beethorpe was making its way up the hill to where those three horsemen loomed against the evening sky.

Never was such a sorrowful company. Up the hill they came, carrying their sorrows in their hands—sorrows for which, in excited haste, they had rummaged old drawers and forgotten cupboards, and even ran hurriedly into the churchyard.

THE HERALD ONCE MORE SET THE TRUMPET TO HIS LIPS AND BLEW

THE HERALD ONCE MORE SET THE TRUMPET TO HIS LIPS AND BLEW

Lord Mortimer of the Marches sat his horse with the same austere indifference, his melancholy profile against the fading sky. Only those who stood near to him noted a kindly ironic flicker of a smile in his eyes, as he saw, apparently seeing nothing, the poor little raked-up sorrows of his village of Beethorpe.

He was a fantastic young lord of many sorrows. His heart had been broken in a very strange way. Death and Pity were his closest friends. He was so sad himself that he had come to realize that sorrow is the only sincerity of life. Thus sorrow had become a kind of passion with him, even a kind of connoisseurship; and he had come, so to say, to be a collector of sorrows. It was partly pity and partly an odd form of dilettanteism—for his own sad heart made him pitiful for and companionable with any other sad heart; but the sincerity of his sorrow made him jealous of the sanctity of sorrow, and at the same time sternly critical of, and sadly amused by, the hypocrisies of sorrow.

So, as he sat his horse and gazed at the sunset, he smiled sadly to himself as he heard, without seeming to hear, the small, insincere sorrows of[Pg 58] his village of Beethorpe—sorrows forgotten long ago, but suddenly rediscovered in old drawers and unopened cupboards, at the sound of his lordship's trumpet and the promise of his strange proclamation.

Was there a sorrow in the world that no money could buy?

It was to find such a sorrow that Lord Mortimer thus fantastically rode from village to village of his estates, with herald and steward.

The unpurchasable sorrow—the sorrow no gold can gild, no jewel can buy!

Far and wide he had ridden over his estates, seeking so rare a sorrow; but as yet he had found no sorrow that could not be bought with a little bag of gold and silver coins.

So he sat his horse, while the villagers of Beethorpe were paid out of a great leathern bag by the steward—for the steward understood the mind of his master, and, without troubling him, paid each weeping and whimpering peasant as he thought fit.

In another great bag the steward had collected the sorrows of the Village of Beethorpe; and, by this, the moon was rising, and, with another blast of trumpet by way of farewell, the three horsemen took the road again to Lord Mortimer's castle.

When, out of the great leathern bag, in Lord Mortimer's cabinet they poured upon the table the sorrows of Beethorpe, the young lord smiled to himself, turning over one sorrow after the other, as though they had been precious stones—for there was not one genuine sorrow among them.

But, later, there came news to him that there was one real sorrow in Beethorpe; and he rode alone on horseback to the village, and found a beautiful girl laying flowers on a grave. She was so beautiful that he forgot his ancient grief, and he thought that all his castles would be but a poor exchange for her face.

"Maiden," said he, "let me buy your sorrow—with three counties and seven castles."

And the girl looked up at him from the grave, with eyes of forget-me-not, and said: "My lord, you mistake. This is not sorrow. It is my only joy."

he sun was scarcely risen, but the

young princess was already seated

by her window. Never did window

open upon a scene of such enchantment.

Never has the dawn risen

over so fair a land. Meadows so fresh and grass

so green, rivers of such mystic silver and far

mountains so majestically purple, no eye has seen

outside of Paradise; and over all was now outspread

the fairy-land of the morning sky.

he sun was scarcely risen, but the

young princess was already seated

by her window. Never did window

open upon a scene of such enchantment.

Never has the dawn risen

over so fair a land. Meadows so fresh and grass

so green, rivers of such mystic silver and far

mountains so majestically purple, no eye has seen

outside of Paradise; and over all was now outspread

the fairy-land of the morning sky.

Even a princess might rise early to behold so magic a spectacle.

Yet, strangely enough, it was not upon this miracle that the eyes of the princess were gazing. In fact, she seemed entirely oblivious of it all—oblivious of all that was passing in the sky, and of all the dewy awakening of the earth.

Her eyes were lost in a trance over what she deemed a rarer beauty, a stranger marvel. The princess was gazing at her own face in a golden mirror.

HER ONLY CARE WAS TO GAZE ALL DAY AT HER OWN FACE

HER ONLY CARE WAS TO GAZE ALL DAY AT HER OWN FACE

And indeed it was a beautiful face that she saw there, so beautiful that the princess might well be pardoned for thinking it the most beautiful face in the world. So fascinated had she become by her own beauty that she carried her mirror ever at her girdle, and gazed at it night and day. Whenever she saw another beautiful thing she looked in her mirror and smiled to herself.

She had looked at the most beautiful rose in the world, and then she had looked in her mirror and said, "I am more beautiful."

She had looked at the morning star, and then she had looked in her mirror and said, "I am more beautiful."

She had looked at the rising moon, and then she had looked in her mirror and still she said, "I am more beautiful."

Whenever she heard of a beautiful face in her kingdom she caused it to be brought before her, and then she looked in her mirror, and always she smiled to herself and said, "I am more beautiful."

Thus it had come about that her only care was to gaze all day at her own face. So enamored had she become of it, that she hated even to sleep; but not even in sleep did she lose the beautiful face she loved, for it was still there in[Pg 64] the mirror of dreams. Yet often she would wake in the night to gaze at it, and always she arose at dawn that, with the first rays of the sun, she might look into her mirror. Thus, from the rising sun to the setting moon, she would sit at her window, and never take her eyes from those beautiful eyes that looked back at her, and the longest day in the year was not long enough to return their gaze.

This particular morning was a morning in May—all bloom and song, and crowding leaves and thickening grass. The valley was a mist of blossom, and the air thrilled with the warbling of innumerable birds. Soft dewy scents floated hither and thither on the wandering breeze. But the princess took no note of these things, lost in the dream of her face, and saw the changes of the dawn only as they were reflected in her mirror and suffused her beauty with their rainbow tints. So rapt in her dream was she that, when a bird alighted near at hand and broke into sudden song, she was so startled that—the mirror slipped from her hand.

Now the princess's window was in the wall of an old castle built high above the valley, and beneath it the ground sloped precipitately, covered with underbrush and thick grasses, to a[Pg 65] highroad winding far beneath. As the mirror slipped from the hand of the princess it fell among this underbrush and rolled, glittering, down the slope, till the princess finally lost sight of it in a belt of wild flowers overhanging the highroad.

As it finally disappeared, she screamed so loudly that the ladies-in-waiting ran to her in alarm, and servants were instantly sent forth to search for the lost mirror. It was a very beautiful mirror, the work of a goldsmith famous for his fantastic masterpieces in the precious metals. The fancy he had skilfully embodied was that of beauty as the candle attracting the moths. The handle of the mirror, which was of ivory, represented the candle, the golden flame of which swept round in a circle to hold the crystal. Wrought here and there, on the golden back of the mirror, were moths with wings of enamel and precious stones. It was a marvel of the goldsmith's art, and as such was beyond price. Yet it was not merely for this, as we know, that the princess loved it, but because it had been so long the intimate of her beauty. For this reason it had become sacred in her eyes, and, as she watched it roll down the hillside, she realized that it had gained for her also a superstitious value. It almost seemed as if to lose it would be to lose[Pg 66] her beauty too. She ran to another mirror in panic. No! her beauty still remained. But no other mirror could ever be to her like the mirror she had lost. So, forgetting her beauty for a moment, she wept and tore her hair and beat her tiring-maids in her misery; and when the men returned from their searching without the mirror, she gave orders to have them soundly flogged for their failure.

Meanwhile the mirror rested peacefully among the wild flowers and the humming of bees.

A short while after the serving-men had been flogged and the tiring-maids had been beaten, there came along the white road at the foot of the castle a tired minstrel. He was singing to himself out of the sadness of his heart. He was forty years old, and the exchange that life had given him for his dreams had not seemed to him a fair equivalent. He had even grown weary of his own songs.

He sat, dejected, amid the green grasses, and looked up at the ancient heaven—and thought to himself. Then suddenly he turned his tired eyes again to earth, and saw the daisies growing there, and the butterflies flitting from flower to flower. And the road, as he looked at it, seemed long—longer than ever. He took his old lute[Pg 67] in his hand—wondering to himself if they could play another tune. They were so in love with each other—and so tired of each other.

He played one of his old songs, of which he was heartily weary, and, as he played, the butterflies flitted about him and filled his old hair with blue wings.

He was forty years old and very weary. He was alone. His last nightingale had ceased singing. The time had come for him when one thinks, and even dreams, of the fireside, the hearth, and the beautiful old memories.

He had, in short, arrived at that period of life when one begins to perceive the beauty of money.

As a boy he had never given a thought to gold or silver. A butterfly had seemed more valuable to him than a gold piece. But he was growing old, and, as I have said, he was beginning to perceive the beauty of money.

The daisies were all around him, and the lark was singing up there in the sky. But how could he cash a daisy or negotiate a lark?

Dreams, after all, were dreams.... He was saying this to himself, when suddenly his eye fell upon the princess's mirror, lying there in the grass—so covered with butterflies, looking[Pg 68] at themselves, that no wonder the serving-men had been unable to find it.

The mirror of the princess, as I have said, was made of gold and ivory, and wonderful crystal and many precious stones.

So, when the minstrel took it in his hands out of the grass, he thought—well, that he might at least buy a breakfast at the next town. For he was very hungry.

Well, he caught up the mirror and hid it in his faded doublet, and took his way to a wood of living green, and when he was alone—that is, alone with a few flowers and a bird or two, and a million leaves, and the soft singing of a little river hiding its music under many boughs—he took out the mirror from his doublet.

Shame upon him! he, a poet of the rainbow, had only one thought as he took up the mirror—the gold and ivory and the precious stones. He was merely thinking of them and his breakfast.

But when he looked into the mirror, expecting to see his own ancient face—what did he see? He saw something so beautiful that, just like the princess, he dropped the mirror. Have you ever seen the wild rose as it opens its heart to the morning sky; have you ever seen the hawthorn holding in its fragrant arms its innumerable[Pg 69] blooms; have you seen the rising of the moon, or looked in the face of the morning star?

The minstrel looked in the mirror and saw something far more wonderful than all these wonderful things.

He saw the face of the princess—eternally reflected there; for her love of her own beautiful face had turned the mirror into a magic glass. To worship oneself is the only way to make a beautiful face.

And as the minstrel looked into the mirror he sadly realized that he could never bring himself to sell it—and that he must go without his breakfast. The moon had fallen into his hand out of the sky. Could he, a poet, exchange this celestial windfall for a meal and a new doublet? As the minstrel gazed and gazed at the beautiful face, he understood that he could no more sell the mirror than he could sell his own soul—and, in his pilgrimage through the world, he had received many offers for his soul. Also, many kings and captains had vainly tried to buy from him his gift of courage.

But the minstrel had sold neither. And now had fallen out of the sky one more precious thing to guard—the most beautiful face in the world. So, as he gazed in the mirror, he forgot his hunger,[Pg 70] forgot his faded doublet, forgot the long sorrow of his days—and at length there came the setting sun. Suddenly the minstrel awoke from his dream at the sound of horsemen in the valley. The princess was sending heralds into every corner of her dominions to proclaim the loss of the mirror, and for its return a beautiful reward—a lock of her strange hair.

The minstrel hid himself, with his treasure, amid the fern, and, when the trumpets had faded in the distance, found the highroad again and went upon his way.

Now it chanced that a scullery-maid of the castle, as she was polishing a copper saucepan, had lifted her eyes from her work, and, looking down toward the highroad, had seen the minstrel pick up the mirror. He was a very well known minstrel. All the scullery-maids and all the princesses had his songs by heart.

Even the birds were fabled to sing his songs, as they flitted to and fro on their airy business.

Thus, through the little scullery-maid, it became known to the princess that the mirror had been found by the wandering minstrel, and so his life became a life of peril. Bandits, hoping for the reward of that lock of strange hair, hunted[Pg 71] him through the woodland, across the marshes, and over the moors.

Jews with great money-bags came to buy from him—the beautiful face. Sometimes he had to climb up into trees to look at it in the sunrise, the woods were so filled with the voices of his pursuers.

But neither hunger, nor poverty, nor small ferocious enemies were able to take from him the beautiful face. It never left his heart. All night long and all the watching day it was pressed close to his side.

Meanwhile the princess was in despair. More and more the fancy possessed her that with the lost mirror her beauty too was lost. In her unhappiness, like all sad people, she took strange ways of escape. She consulted the stars, and empirics from the four winds settled down upon her castle. Each, of course, had his own invaluable nostrum; and all went their way. For not one of these understood the heart of a poet.

However, at last there came to the aid of the princess a reverend old man of ninety years, a famous seer, deeply and gently and pitifully learned in the hearts of men. His was that wisdom which comes of great goodness. He understood the princess, and he understood the minstrel; for,[Pg 72] having lived so long alone with the Infinite, he understood the Finite.