ROSA BONHEUR

MASTERPIECES IN COLOR

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/rosabonheur00cras |

ROSA BONHEUR

MASTERPIECES IN COLOR

MASTERPIECES

IN COLOUR

EDITED BY - -

M. HENRY ROUJON

ROSA BONHEUR

(1822-1899)

| IN THE SAME SERIES | |

| REYNOLDS | LE BRUN |

| VELASQUEZ | CHARDIN |

| GREUZE | MILLET |

| TURNER | RAEBURN |

| BOTTICELLI | SARGENT |

| ROMNEY | CONSTABLE |

| REMBRANDT | MEMLING |

| BELLINI | FRAGONARD |

| FRA ANGELICO | DÜRER |

| ROSSETTI | LAWRENCE |

| RAPHAEL | HOGARTH |

| LEIGHTON | WATTEAU |

| HOLMAN HUNT | MURILLO |

| TITIAN | WATTS |

| MILLAIS | INGRES |

| LUINI | COROT |

| FRANZ HALS | DELACROIX |

| CARLO DOLCI | FRA LIPPO LIPPI |

| GAINSBOROUGH | PUVIS DE CHAVANNES |

| TINTORETTO | MEISSONIER |

| VAN DYCK | GÉRÔME |

| DA VINCI | VERONESE |

| WHISTLER | VAN EYCK |

| RUBENS | FROMENTIN |

| BOUCHER | MANTEGNA |

| HOLBEIN | PERUGINO |

| BURNE-JONES | HENNER |

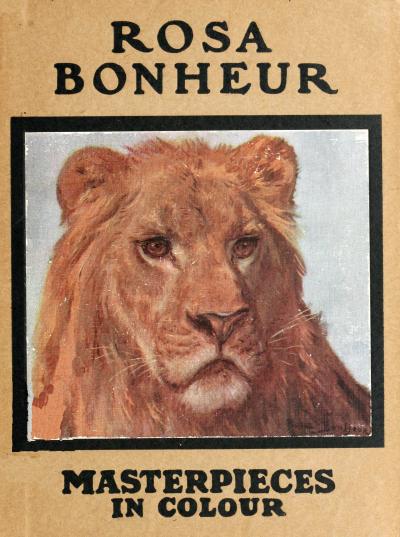

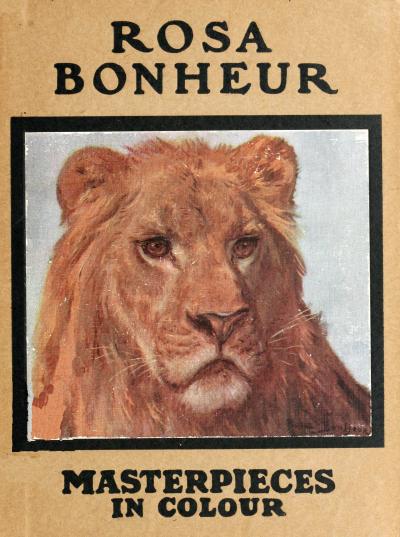

PLATE I.—THE LION MEDITATING

(Rosa Bonheur Museum)

According to artists, the lion is the most difficult of all animals to paint, on account of the prodigious mobility of his physiognomy. Rosa Bonheur was able, thanks to her inimitable art, to catch and reproduce the fugitive facial expressions of the kingly beast,—expressions that the artist succeeded in securing during a visit to a certain menagerie, and which she managed to record with a most surprising vigour and fidelity.

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH

BY FREDERIC TABER COOPER

ILLUSTRATED WITH EIGHT

REPRODUCTIONS IN COLOUR

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

NEW YORK—PUBLISHERS

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

August, 1913

THE·PLIMPTON·PRESS

NORWOOD·MASS·U·S·A

| Page | |

| Childhood and Youth | 11 |

| The First Successes | 22 |

| The Years of Glory | 45 |

| Plate | ||

| I. | The Lion Meditating | Frontispiece |

| Rosa Bonheur Museum | ||

| II. | The Ass | 14 |

| Rosa Bonheur Studio, at By | ||

| III. | The Horse Fair | 24 |

| National Gallery, London | ||

| IV. | Ploughing in the Nivernais | 34 |

| Luxembourg Museum, Paris | ||

| V. | Ossian’s Dream | 40 |

| Rosa Bonheur Studio, Peyrol Collection | ||

| VI. | The Duel | 50 |

| Collection of Messrs. Lefèvre, London | ||

| VII. | Tigers | 60 |

| Rosa Bonheur Studio, at By | ||

| VIII. | Trampling the Grain | 70 |

| Rosa Bonheur Studio, at By |

In 1821, a young painter of brilliant promise was living in Bordeaux. His name was Raymond Bonheur. But the fairies who presided at his birth omitted to endow him with riches, in addition to talent. The hardships of existence compelled him to relinquish his dreams of glory and to pursue the irksome task of earning his daily bread. The artist[Pg 12] became a drawing master and went the rounds of private lessons. Among his pupils he made the acquaintance of a young girl, Mlle. Sophie Marquis, as penniless as himself, but attractive and gentle, full of courage, and displaying exceptional ability in music. A similarity of tastes and opinions drew these two artistic natures toward each other. They fell in love, and the marriage service united their destinies.

The young couple started upon married life with no other fortune than their mutual attachment and equal courage. He continued to teach drawing and she gave lessons in music. But before long she was forced to put an end to these lessons in order to devote herself to new duties. Indeed, it was less than a year after their marriage, namely on the 16th of March, 1822, that a little girl was born into the world: this little girl was Rosalie Bonheur, better known under the name of Rosa Bonheur.

It is not surprising in such an artistic environment, that the child’s taste should have undergone a sort of obscure, yet undoubted impregnation. From the time that she began to understand, she heard art and nothing else discussed around her; her first uncertain steps were taken in her father’s studio, and her first playthings were a brush and a palette laden with colours.

PLATE II.—THE ASS

(Rosa Bonheur Studio, at By)

Rosa Bonheur was inimitable in the art of seizing the expression on the face of an animal. Here, for instance, is a study of an ass which makes quite a charming picture. Note the admirable rendering of the animal’s attitude, which is half obstinacy and half resignation, while the worn-out body weighs so heavily on the shrunken legs!

Rosalie could hardly walk before she was drawing and painting everywhere. Later on, she gave a spirited account of this:

“I was not yet four years old when I conceived a veritable passion for drawing, and I bespattered the white walls as high as I could reach with my shapeless daubs: another great source of amusement was to cut objects out of paper. They were always the same, however: I would begin by making long paper ribbons, then with my scissors, I would cut out, in the first place, a shepherd, and after him a dog, and next a cow, and next a ship, and next a tree, invariably in the same order. I have spent many a long day at this pastime.”

The Bonheurs had, at this time, formed a close friendship with a family by the name of Silvela, but the latter left Bordeaux in 1828 in order to assume the direction of an institute for boys in Paris. The separation did not break off their intercourse. They corresponded frequently and in every letter the Silvelas urged Raymond Bonheur to come and join them in Paris where, they said, he would find an easier and more remunerative way of employing his talent. These repeated appeals strongly tempted the man, but a journey to Paris, at this epoch, was not an easy matter. Besides, his family had increased to the extent of two more children: Auguste Bonheur, born in 1824, and Isidore Bonheur, born in 1827. At last, after much hesitation, he made up his mind to set forth alone to try his luck, prepared to return home if he did not succeed.

He went directly to the Silvelas’ in the capacity of instructor of drawing; the families of some of the pupils took an interest in him and obtained him[Pg 17] opportunities. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, the great naturalist, entrusted him with the execution of a large number of plates for a natural history. If not a fortune, this was at least an assured living. Accordingly, Bonheur decided to transfer his entire household to Paris.

They joined him in 1829 and were installed in the Rue Saint-Antoine.

Little Rosa, who was then seven years old, was no sooner settled in Paris, than she was placed together with her brothers in a boys’ school which happened to be located in the same house where the Bonheurs lived.

Being brought up with young boys of her own age, she acquired those boyish manners that she retained throughout life, and to which she owes, without the slightest doubt, that virile mark which was destined to characterize her painting. She used to go with her comrades, during recess, to play in the Place Royale. “I was the ring-leader in all[Pg 18] the games and I did not hesitate, when necessary, to use my fists.”

The revolution of 1830 ensued and Rosa witnessed it develop beneath the windows of her father’s dwelling. These were evil hours and the Bonheur family suffered in consequence. Lessons became rarer and the pinch of poverty was felt within the household, which was forced to migrate again to No. 30 Rue des Tournelles, a large seventeenth century mansion, solemn and gloomy, of which Rosa must have retained the worst possible memories had it not chanced that it was here she acquired a little comrade, Mlle. Micas, who was destined to become, subsequently, her best friend.

The years which followed were equally unfortunate for Raymond Bonheur: Paris had hardly recovered from the shock of the Revolution, when in 1832 the cholera made its appearance. There was no further question of lessons, for everyone[Pg 19] thought solely of his own safety; the rich fled from the city, the others remained closely housed in order to avoid the fatal contagion. To escape the scourge, Raymond Bonheur once more changed his dwelling and established himself in the Rue du Helder. Variable and impulsive by nature, the painter delighted in change. He was barely installed in the Rue du Helder when he left the new abode in order to move to Ménilmontant in the centre of a hotbed of Saint-Simonism, the doctrines of which he had enthusiastically espoused. In 1833, we find him installed on the Quai des Écoles. This year a great misfortune befell the family: Mme. Bonheur died and the painter found himself alone and burdened with the responsibility of feeding, tending, and bringing up four children, one of whom, Isabelle Bonheur, born in 1830, was only three years old.

It was at this time that Raymond Bonheur became anxious to have Rosa, who was now eleven[Pg 20] years of age, acquire some vocation. Inasmuch as she had shown the most violent aversion to study in every school she had attended, her father fancied that perhaps business would be more to her taste. Accordingly he apprenticed her to a dressmaker. But the young girl showed no more inclination for sewing than for arithmetic and grammar. At the end of two weeks it became necessary to give up the experiment.

Raymond Bonheur, who was absent all day long giving lessons, was absolutely bent upon finding some occupation for Rosa. He made one last attempt to send her to school; so he placed her with Mme. Gibert in the Rue de Reuilly. Rosa with her boyish manners and her incorrigible turbulence brought revolution into the peaceful precincts of the pension. She engaged her new comrades in games of mimic warfare, combats, cavalry charges across the flower-beds of the garden which was reduced to ruins before the end of the second day.[Pg 21] The principal in consternation returned the irrepressible amazon to her father.

The latter, in very natural despair, allowed Rosa to stay at home, in the Rue des Tournelles, where he was newly established and where he had fitted up a studio. He even allowed the young girl free entry to the studio and gave her permission to sketch. She asked for nothing better. While her father scoured the city on his round of lessons, she would shut herself into the studio and work with desperate energy, taking in turn every object hanging on the walls for her models.

One day on returning home, at the end of his day’s work, Raymond Bonheur discovered on the easel a little canvas representing a bunch of cherries, a well drawn canvas and excellently painted from nature. This was Rosa Bonheur’s first painting; it bore witness to a genuine artistic temperament. Her father was delighted, but he hid his pleasure.

“That is not so bad,” he allowed to Rosa. “Work seriously, and you may become an artist.”

This word of encouragement set the young girl’s heart to pulsing with emotion. Then it needed only application and courage? She felt within her an energy that nothing could rebuff and an ambition that nothing could quench.

Rosa Bonheur had found her path.

Not long after this, a serious and determined young girl might be seen

in the halls of the Louvre, copying with desperate energy the works of

the great masters. She wore an eccentric costume, consisting of a sort

of dolman with military frogs. It was young Rosa Bonheur serving her

apprenticeship to art. The students and copyists who regularly

frequented the museum, not knowing her name, had christened her “the

little hussard.” But the jests and criticisms flung out by passing

strangers in [Pg 23]

[Pg 24]

[Pg 25]regard to her work, far from discouraging her, only

drove her to still more obstinate and persistent study. The hours

which she did not consecrate to the Louvre, she spent in her father’s

studio, multiplying her sketches and anatomical studies. Even at this

period she had already grasped instinctively the truth formulated by

Ingres, that “honesty in art depends upon line-work.” Few painters

have so far insisted upon this honesty, this conscientiousness,

without which the most gifted artist remains incomplete. Whatever

gifts he may be endowed with by nature, talent cannot be improvised;

it is the fruit of independent and sustained toil. Later on, when she

in her turn became a teacher, Rosa Bonheur was able to proclaim the

necessity of line-work with all the more authority because it had

always been the fundamental basis, the very scaffolding of all her

works. “It is the true grammar of art,” she would affirm, “and the

time thus spent cannot fail to be profitable in the future.”

PLATE III.—THE HORSE FAIR

(National Gallery, London)

This painting is considered by some critics to be Rosa Bonheur’s masterpiece. There is no other painting of hers in which she attained the same degree of power, or the same degree of truth in individual expression. What naturalness, and what vigour in this drove of prancing horses, and what movement of those haunches straining under the effort of the muscles!

During this period of study, she was living in the Rue de la Bienfaisance; her father’s mania for changing his residence dragged her successively to the Rue du Roule, and then to the Rue Rumford, in the level stretch of the Monceau quarter, where Raymond Bonheur, who had just remarried, installed his new household.

At that time the Rue Rumford was practically in the open country. On all sides there were farms abundantly stocked with cows, sheep, pigs, and poultry. This was an unforeseen piece of good fortune for young Rosa, and she felt her passionate love for animals reawaken. Equipped with her pencils, she installed herself at a farm at Villiers, near to the park of Neuilly, and there she would spend the entire day, striving to catch and record the different attitudes of her favourite models. For the sake of greater accuracy, she made a study of the anatomy of animals, and even did some work in dissection. Not content with this, she applied herself[Pg 27] to sculpture, and made models of the animals in clay or wax before drawing them. This is how she came to acquire her clever talent for sculpture which would have sufficed to establish a reputation if she had not become the admirable painter that we know her to have been.

Her special path was now determined: she would be a painter of animals. She understood them, she knew them, and loved them. But it did not satisfy her to study them out-of-doors; she wanted them in her own home. She persuaded her father to admit a sheep into the apartment; then, little by little, the menagerie was increased by a goat, a dog, a squirrel, some caged birds, and a number of quails that roamed at liberty about her room.

At last, in 1841, after years of devoted toil, Rosa ventured to offer to the Salon a little painting representing Two Rabbits and a drawing depicting some Dogs and Sheep. Both the drawing and the painting were accepted. It was an occasion of great[Pg 28] rejoicing both for Rosa Bonheur and for her father. The young artist was at this time only nineteen years of age.

From this time forward, she sent pictures to the Salon annually. During the first years her exhibits passed unnoticed; but little by little her sincerity and the vigour of her talent made an impression upon the critics. The latter were soon forced to admire the intense relief of her method of painting, living animals transcribed in full action, and their different physiognomies rendered with admirable fidelity and art. But what labour it cost to arrive at this degree of perfection! Every morning, the young artist made the rounds of slaughter-houses, markets, the Museum, anywhere and everywhere that she might see and study animals. And this was destined to continue throughout her entire life.

In 1842 she sent three paintings to the Salon: namely, an Evening Effect in a Pasture, a Cow lying in a Pasture, and a Horse for Sale; and in addition[Pg 29] to these, a terra-cotta, the Shorn Sheep, which received the approval of the critics. And no less praise was bestowed upon her paintings, which showed a talent for landscape fully equal to her mastery of animal portraiture.

Her success was progressive. Her pictures in the Salon of 1843 sold to advantage and Rosa Bonheur was able to travel. She brought home from her trip five works that found a place in the Salon of 1845. The following year her exhibits produced a sensation. Anatole de la Forge devoted an enthusiastic article to her, and the jury awarded her a third-class medal.

“In 1845,” Rosa Bonheur herself relates, “the recipients had to go in person to obtain their medals at the director’s office. I went, armed with all the courage of my twenty-three years. The director of fine-arts complimented me and presented the medal in the name of the king. Imagine his stupefaction when I replied: ‘I beg of you, Monsieur, to thank[Pg 30] the king on my behalf, and be so kind as to add that I shall try to do better another time.’”

Rosa Bonheur kept her word: her whole life was a long and sustained effort to “do better.” After the Salon of 1846, where she was represented by five remarkable exhibits, she paid a visit to Auvergne, where she was able to study a breed of cattle very different from any that she had hitherto seen and painted: superb animals of massive build, with compact bodies, short and powerful legs, and wide-spread nostrils. The sheep and horses also had a characteristic physiognomy that was strongly marked and noted with scrupulous care, and enabled her to reappear in the Salon of 1847 with new types that gathered crowds around her canvases, to stare in wonderment at these animals which were so obviously different from those which academic convention was in the habit of showing them.

The general public admired, and so did the critics. It was only the jury that remained hostile towards[Pg 31] this independent and personal manner of painting, which ignored the established procedure of the schools and based itself wholly upon inspiration and sincerity; accordingly, they always took pains to place her pictures in obscure corners or at inaccessible heights. The public, however, which always finds its way to what it likes, took pains on its part to discover and enjoy them.

In 1848 Rosa Bonheur had her revenge. The recently proclaimed Republic, wishing to show its generosity towards artists, decreed that all works offered that year to the Salon should without exception be received. As to the awards, they were to be determined by a jury from which the official and administrative element was to be henceforth banished. The judges were Léon Cogniet, Ingres, Delacroix, Horace Vernet, Decamps, Robert-Fleury, Ary Scheffer, Meissonier, Corot, Paul Delaroche, Jules Dupré, Isabey, Drolling, Flandrin, and Roqueplan.

Rosa Bonheur exhibited six paintings and two[Pg 32] pieces of sculpture. The paintings comprised: Oxen and Bulls (Cantal Breed), Sheep in a Pasture, Salers Oxen Grazing, a Running Dog (Vendée breed), The Miller Walking, An Ox. The two bronzes represented a Bull and a Sheep.

Her success was complete. Judged by her peers, in the absence of academic prejudice, she obtained a medal of the first class.

This year an event took place in her domestic life. As a result of

recent remarriage, her father had a son, Germain Bonheur. The house

had become too small for the now enlarged family; besides, the crying

of the child, and the constant coming and going necessitated by the

care that it required seriously interfered with Rosa’s work.

Accordingly she left her home in the Rue Rumford and took a studio in

the Rue de l’Ouest. She was accompanied by Mlle. Micas, the old-time

friend of her childhood, whom she had rediscovered, and who from this

time forth attached herself to Rosa with a devotion sur[Pg 33]

[Pg 34]

[Pg 35]passing

that of a sister, and almost like that of a mother. She also was an

artist and took a studio adjoining that of her friend; several times

she collaborated on Rosa’s canvases, when the latter was over-burdened

with work. After Rosa had sketched her landscape and blocked in her

animals, Mlle. Micas would carry the work forward, and Rosa, coming

after her, would add the finishing touch of her vigorous and

unfaltering brush. But to Rosa Bonheur Mlle. Micas meant far more as a

friend than as a collaborator. With a devoted and touching tenderness

she watched over the material welfare of the great artist, who was by

nature quite indifferent to the material things of life. It was the

good and faithful Nathalie who supervised Rosa’s meals and repaired

her garments. She was also a good counsellor, and on many different

occasions Rosa Bonheur paid tribute to the intelligence and devotion

of her friend.

PLATE IV.—PLOUGHING IN THE NIVERNAIS

(Luxembourg Museum)

This painting shows the artist in the full possession of her vigorous and unfaltering talent. The Luxembourg is to-day proud of the possession of such a masterpiece. It testifies to Rosa Bonheur’s equal eminence as an animal painter and a painter of landscapes.

The resplendent successes of recent Salons had[Pg 36] in no wise diminished Rosa Bonheur’s ardent passion for study. In contrast to many another artist, who think that there is nothing more to learn, as soon as they become known, she persevered without respite in her painful drudgery of research and documentation.

Every day she covered the distance from the Rue de l’Ouest to the slaughter-houses in order to catch some hitherto unknown aspect of animal life, and to note the quivering of the wretched beast that scents the blood and foresees its approaching death.

There was much that was disagreeable for a young woman in this daily promiscuous contact with butchers, heavy, tactless brutes, who frequently insulted her with their vulgar and suggestive jokes. She pretended not to understand, but nothing short of her unconquerable passion for study would have sustained her courage.

Together with the success of recognition came the success of prosperity. Rosa began to sell her[Pg 37] paintings profitably. A certain shirt-manufacturer, M. Bourges, who was also an art collector, acquired a goodly number of her works; and after him came M. Tedesco, the celebrated picture dealer, who was a keen admirer of her talent. In 1849, the far reaching renown of her Ploughing in the Nivernais brought her the honour of making a sale to the State, which acquired the celebrated painting for the Museum of the Luxembourg, where it still remains.

The subject of the picture is well known: in a pleasant stretch of rolling country, bounded by a wooded slope, two teams of oxen are dragging their heavy ploughs and turning up a field in which we see the furrows that have already been laid open. The whole interest centres in the team in the foreground. The six oxen which compose it, ponderous and slow, convey a striking impression of tranquil force: and from the different attitudes of the six, we perceive a progression in the degree of effort put[Pg 38] forth to drag the plough. The first two move with a heavy nonchalance that bears witness to the slight contribution that they make to the task; the next two, being nearer the plough, are doing more real work; their straining limbs sink deeper into the earth and their lowered heads indicate the greater tension of their muscles. As to the last two, they are sustaining the heaviest part of the toil, as is apparent from the way in which their muscles visibly stand out, and from the contraction of their limbs gathered under them in the effort to drag free the weight of the ploughshare buried in the soil. It is only those who never have witnessed the tilling of the soil who could remain unmoved in the presence of such a work. The oxen are admirable in composition, in action, in modelling, and in strength. And what is to be said of the landscape which is bathed in a clear, bright light, flecked here and there with trails of fleecy cloud?

It seemed that after such a picture, it would be [Pg 39]

[Pg 40]

[Pg 41]impossible for

Rosa Bonheur to rise to a greater height of perfection. Nevertheless,

three years later she exhibited her Horse Fair, a remarkable

achievement which raised her while still living to the pinnacle of

glory. The Horse Fair is not only the artist’s masterpiece, but it

is one of those productions which do the greatest honour to French

painting. Celebrated from the day of its first appearance, this canvas

has steadily gained in the esteem of the world of art and was destined

to bring, even in our own times, the fabulous price attained by

certain paintings by Rembrandt, Raphael, and Holbein.

PLATE V.—OSSIAN’S DREAM

(Rosa Bonheur Studio, Peyrol Collection)

A fantasy by the great artist. During her visit to Scotland her soul had thrilled at the recital of poetic legends; and this is one of these dreams that she has rendered in an inspired page, in which she reveals her mastery of a type of subject which she undertook only accidentally.

In preparation for her Horse Fair, Rosa Bonheur betook herself daily to the spot where the fair was held. But having learned wisdom through the embarrassment of her experiences at the slaughter-house, she assumed masculine garments, in order to attract less attention. She formed the habit of assuming them frequently from that time onward, especially in her studio.

In spite of its triumphal success, the Horse Fair did not immediately find a purchaser and was returned to the artist’s studio. It was acquired later on by Mr. Gambard, the great London picture dealer, for the sum of 40,000 francs.

This celebrated canvas has a lengthy history which deserves to be related.

In coming to terms with Mr. Gambard, Rosa Bonheur, who was never avaricious, feared that she had exacted too large a sum in demanding 40,000 francs. Since the purchaser desired to reproduce the picture in the form of an engraving, and its dimensions were so great as to hamper considerably the work of the engraver, she offered to make Mr. Gambard, without extra charge, a reduced replica of the Horse Fair, one-quarter the original size.

Mr. Gambard, who was making an excellent bargain, accepted with an eagerness that it is easy to imagine. The reduced copy was delivered and was immediately purchased by an English art fancier,[Pg 43] Mr. Jacob Bell, for the sum of 25,000 francs. As for the original, it was exhibited in the Pall Mall gallery, but its vast dimensions discouraged purchasers. It was at last acquired by an American, Mr. Wright, at the cost of 30,000 francs, on condition that Mr. Gambard might retain possession for two or three years longer, in order to exhibit it in England and the United States. When the moment for delivery arrived, the American claimed that he was entitled to a share of the profits resulting from the exhibition of the work. As a consequence, the picture which was originally purchased by Mr. Gambard for 40,000 francs, eventually brought him in only 23,000, while the reduced replica, which cost him nothing, brought him in 25,000 francs. Considerably later, the American owner having met with reverses, the Horse Fair was sold at public auction and was knocked down at $53,000 (265,000 francs) to Mr. Vanderbilt, who presented it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As to the reduced copy, the property of Mr. Jacob Bell, the latter bequeathed it, together with his other paintings, to the National Gallery, where it now is. The reproduction which we give in the present volume was made from this smaller copy.

When Rosa Bonheur learned that this reduced replica was to find a place in the National Gallery, she exhibited a scrupulousness that well illustrates her honesty and disinterestedness. Since it was originally painted merely to serve as a model for the engraver, the artist had not given it the finish that she was accustomed to give to her pictures. Accordingly, she set to work for the third time to paint the Horse Fair, and bestowed upon it such conscientious work and mature talent that in the opinion of some judges this second replica is superior to the original. When the canvas was finished, she offered it to the London Gallery. The English authorities were deeply touched by the scrupulousness of the famous artist, and thanked her cordially, but explained[Pg 45] that they felt themselves bound by the terms of the Jacob Bell bequest, and consequently could not take advantage of her generous offer. The work, nevertheless, remained in England, having been purchased by a Mr. MacConnel for 2,500 francs.

After her immense success at the Salon of 1854, Rosa Bonheur gave up her studio in the Rue de l’Ouest, and installed herself in the Rue d’Assas, in a studio which she had had built expressly to suit her needs.

The new studio in the Rue d’Assas was very far from being a commonplace studio. It was situated in the rear of a large court, and occupied the entire rear building. It was an immense room, with a broad, high window, through which a superb flood of daylight streamed in; and from floor to ceiling the walls were lined with studies, drawings, sketches, rough essays in colour, that the great artist had[Pg 46] brought back from her travels. So far, nothing the least out of the ordinary. But what gave the establishment its picturesque and curious character was the court-yard, transformed by Rosa Bonheur into a veritable farm. Under shelters arranged along the walls a variety of animals roamed at will: goats, heifers of pure Berri breed, a ram, an otter, a monkey, a pack of dogs, and her favourite mare, Margot. Mingled with the divers cries of this heterogeneous menagerie, were the bewildering twitterings of an assortment of birds, the clucking of hens, the sonorous quack-quack of ducks, and dominating all the rest, the strident screams of numerous parrakeets.

And all this was only one part of her menagerie; the rest was domiciled at her country place at Chevilly, where she also had another studio. Even in the country Rosa Bonheur had no chance to rest. She had now become celebrated, and the patrons of art fought among themselves for her productions. The two art firms of Tedesco in Paris and Gambard[Pg 47] in London deluged her with orders; and, in spite of her courage, she could hardly keep pace with them.

Her reputation had overleaped frontiers; she was as celebrated abroad as she was in France. The city of Ghent, to which she had loaned the Horse Fair for its exposition, demonstrated its gratitude by sending her an official delegation headed by the burgomaster himself, to present her with a jewel of much value.

Her talent was no longer open to question; everyone agreed in

recognizing it. The critics saw in her far more than a conscientious

and gifted artist; they regarded her as the inspired interpreter of

rural life. “The work of Rosa Bonheur,” wrote Anatole de la Forge in

1855, “might be entitled the Hymn to Labour. Here she shows us the

tillage of the soil; there, the sowing; further on, the reaping of the

hay, and then that of the grain; elsewhere the vintage; always and

everywhere, the labour of the field. Man, under her inspired touch,

appears only as a[Pg 48] docile instrument, placed here by the hand of God

in order to extract from the bowels of the earth the eternal riches

that it contains. Also, in depicting him as associated with the toil

of animals, she shows him to us only under a useful and noble aspect;

now at the head of his oxen, bringing home the wagons heavily laden

with the fruit of the harvest; or again, with his hand gripping the

plough, cleaving the soil to render it more productive.” And Mazure,

writing at the same period, declared: “Next to the old Dutch painters,

and better than the early landscape artists in France, we have in our

own day some very clever painters of cattle. They are Messieurs

Brascassat, Coignard, Palizzi, and Troyon, and more especially a

woman, Mlle. Rosa Bonheur, who carries this order of talent to the

point of genius. Several of them must be praised for the art with

which they work their animals into the setting of the landscape; but

if we consider the painting of the animals themselves, regardless of

the landscape, and if what we [Pg 49]

[Pg 50]

[Pg 51]

[Pg 52]are seeking is a monograph on the

labour of the fields, nothing can compare with the artist whose name

stands last in the above list.”

PLATE VI.—THE DUEL

(Collection of Messrs. Lefêvre, London)

This picture is one of the last that Rosa Bonheur painted. It is celebrated in England because of the reputation of the two horses who are engaged in this passionate duel, on which the artist has expended all the resources of her marvellous talent.

Equally enthusiastic over her paintings was Mr. Gambard, who supplemented his enthusiasm with a very warm personal friendship for the great artist. He had several times invited her to visit England; in 1854 Rosa Bonheur made up her mind to take the journey, accompanied by Mlle. Micas. It proved to be a triumphal journey. After a sojourn at the Rectory at Wexham, with Mr. Gambard as host,—a sojourn marked by official invitations and delicate attentions,—Rosa Bonheur made a long excursion into Scotland, accompanied by friends across the Channel.

This cattle-raising land stirred her to a passionate interest. In the fields through which her route lay cattle came into view from time to time; and hereupon the artist would have the carriage halted, and take notes upon her drawing tablets. Each herd[Pg 53] that was encountered meant a new halt and new sketches. The great fair at Falkirk, to which herds were brought from every corner of Scotland, afforded her a unique opportunity for observations and studies. From morning until evening she plied her pencil feverishly, accumulating material for future paintings. At this same fair she purchased a young bull and five superb oxen, to help complete her menagerie. From this journey she brought back a number of pictures of remarkable vigour and beauty. They include a Morning in the Highlands, Denizens of the Highlands, Changing Pasture, After a Storm in the Highlands, etc., etc.

Rosa Bonheur returned to her studio in the Rue d’Assas and immediately prepared her exhibits for the Universal Exposition of 1855. She was represented there by a Hay Harvest in Auvergne, which brought her the grand medal of honour.

From this time forward Rosa Bonheur ceased to exhibit at the Salons. She believed, and not without[Pg 54] reason, that her reputation had nothing more to gain by these annual offerings, which interrupted her more productive work. She had given herself freely to the public; henceforth she sought only to satisfy the demands of the patrons of art, who, in daily increasing numbers, besieged her with their orders. She worked chiefly for the English, who had given her so warm a welcome, and who, perhaps, had a better sense than the French have, of the beauty of the life of the soil. The Frenchman, good judge that he is in matters of art, duly admires a beautiful work, regardless of its subject; he is able to appreciate the composition of an agricultural scene, but, being little inclined by nature to the work of the fields, he will rarely feel a desire to adorn the walls of his apartment with a Harvest Scene or Grazing Cattle; he assumes that it is the business of the museums to acquire pictures of this order. The Englishman is quite different. As a landed proprietor deeply attached to his ancestral acres, he appreciates paintings of rural life, less as an artist than professionally, as a gentleman-farmer who knows all the breeds of cattle and sheep and to whom Rosa Bonheur’s paintings were at this epoch veritable documents, quite as much as they were works of art.

In 1860, she gave up her studio in the Rue d’Assas, as well as the one at Chevilly, in order to install herself at By, in the chateau of By which she had purchased for 50,000 francs and in which she had a vast studio constructed. Hither she transferred her imposing menagerie which had grown year by year through new acquisitions. It included sheep, gazelles, stags, does, kids, an eagle, various other birds, horses, goats, watch dogs, hunting dogs, greyhounds, wild boars, lions, a yak (an animal known by the name of the grunting ox of Tartary), monkeys, parrakeets, marmosets, squirrels, ferrets, turtles, green lizards, Iceland ponies, moufflons, lizards, wild American mustangs, bulls, cows, etc.

Rosa Bonheur worked with desperate energy in the midst of her models and delighted in portraying them in a setting of some one of those picturesque and impressive vistas of the forest of Fontainebleau, adjacent to her own residence. She was unremittingly productive; yet France hardly heard her name mentioned save as an echo of her triumphs abroad. England has gone wild over her paintings; and America was not slow in following suit.

But the echo was so loud, especially after the Universal Exposition at London in 1862, that the government three years later made her Chevalier of the Legion of Honour. Rosa Bonheur has given her own account of the event:

“In 1865,” she writes, “I was busily engaged one afternoon over my pictures (I had the Stags at Long-Rocher on my easel), when I heard the cracking of a postillion’s whip and the rumble of a carriage. My little maid Félicité entered the studio in great excitement:

“‘Mademoiselle, mademoiselle! Her Majesty the Empress!’

“I had barely time to slip on a linen skirt and exchange my long blue blouse for a velvet jacket.

“‘I have here,’ the empress told me, ‘a little gift which I have brought you on behalf of the Emperor. He has authorized me to take advantage of the last day of my regency to announce your appointment to the Legion of Honour.’

“And in conferring the title, she kissed the newly made Chevalier and pinned the cross upon my velvet jacket. A few days later I received an invitation to take breakfast at Fontainebleau where the Imperial Court was installed. On the appointed day, they sent to fetch me in gala equipage. On arriving, I mistook the door and was about to lose my way, when M. Mocquard came to my rescue and offered his arm to escort me. At breakfast, I was placed beside the Emperor and throughout the whole repast he talked to me regarding the intelligence of animals.[Pg 57] The Empress afterwards took me for an excursion on the lake in a gondola. The Prince Imperial, who had previously called upon me at By, accompanied us. This visit to the Court greatly interested me, but I think that I must have been a disappointment to Princess Metternich who amused herself with watching my every movement, expecting no doubt to see me commit some breach of etiquette.”

In acknowledgment of the distinguished honour she had received from the Emperor, Rosa Bonheur felt that she was in duty bound to be represented at the Universal Exposition of 1867. Accordingly, she sent no less than ten remarkable works: Donkey Drivers of Aragon, Ponies From the Isle of Skye, Sheep on the Seashore, A Ship, Oxen and Cows, Kids Resting, A Shepherd in Béarn, The Razzia, etc.

All that she obtained was a medal of the second class. The judges owed her a grudge because of her long neglect of twelve years. There could be no question of disputing her talent, but they resented[Pg 58] her having employed it solely for the benefit of England. The critics showed her the same coldness, courteous but unmistakable. In some of the articles, she was referred to as Miss Rosa Bonheur. Some little injustice was intermingled with this show of hostility; Troyon was exalted at her expense; and her animals were criticized as being “purplish and cottony.” Furthermore, they reproached her with the fact that all the pictures exhibited were owned by Englishmen, with the single exception of the Sheep on the Seashore, which was the property of the Empress.

It is necessary here to open a parenthesis and refer to a period in the life of the great artist which should not be passed over in silence: the period of her art school. For this purpose we must turn back to the year 1849. At that time Raymond Bonheur who, as we know, gave drawing lessons, was directing a school of design for young girls, situated in the Rue Dupuytren. One year after his appointment as director, Raymond Bonheur died and the direction of the school was instructed to Rosa, who enlisted the aid of her sister, also a painter of some talent, who was subsequently married to M. Peyrol.

PLATE VII.—TIGERS

(Rosa Bonheur Studio, at By)

Rosa Bonheur spent entire days in the Jardin des Plantes, or in menageries in order to catch the attitudes and the mobile physiognomies of the beasts of prey. Accordingly no other artist has attained such perfect truth, as is shown in the tigers here portrayed.

Rosa Bonheur fulfilled her duties with much devotion and intelligence. She herself had too high a regard for line-work to fail to bring to her task as teacher all of her ardent faith as an artist. She divided the scheme of instruction into two series, one of the great studies of animals and the other of little studies. Rosa Bonheur was not always an agreeable teacher; she made a show of authority, not to say severity. She would not excuse laziness or negligence, and when a pupil showed her a drawing that was obviously done in a hurry she would grow indignant:

“Go back to your mother,” she would say, “and mend your stockings or do embroidery work.”

But this pedagogical rigour was promptly offset by a return of her

natural kindliness, a jesting word,[Pg 59]

[Pg 60]

[Pg 61]

[Pg 62] a pleasantry, an affectionate

term intended to prevent the discouragement of a pupil who often was

guilty of nothing worse than thoughtlessness.

Under her firm and able guidance, the school achieved success. Many of her graduate pupils attained an honourable career in painting, and if no name worthy of being remembered is included among the whole number, the reason is that genius cannot be manufactured and that it was not within the power of Rosa Bonheur to give to her young pupils something of herself.

In 1860, the great artist, being overburdened with work and unable to carry on simultaneously the instruction and practice of her art, resigned her position as director. The school passed into the hands of Mlle. Maraudon de Monthycle, who won distinction as a director, but did not succeed in making the name of Rosa Bonheur forgotten.

The time of her retirement as professor of the school of design coincides with that of her installation[Pg 63] at By. After having in a measure obeyed the paternal tradition of repeated removals, she was this time definitely established. It was destined to be her last residence; and it certainly was an attractive place, that great chateau of By, with its broad windows and its original style, which called to mind certain dwellings in Holland. And what a delightful setting it had in the shape of the forest of Fontainebleau, so varied in aspect, so rich in picturesque corners, so alluring with the beauty of its dense woodlands, and the poetry of its open glades!

Rosa Bonheur was always passionately enamoured of nature, of the entire work of creation. She adored animals neither more nor less than she loved beautiful trees and broad horizons; she went into ecstacies before the splendour of the rising sun which day by day brings a renewed thrill of life to all things and creatures; and it was equally one of her joys to watch the diffused light spreading softly through a misty haze over the slumbering earth.

Rosa Bonheur had no sooner withdrawn to the solitude of By than she sought, as we have already seen, to become forgotten, in order to devote herself exclusively to the innumerable tasks which incessant orders from England and America demanded of her. She planned for herself a laborious and tranquil existence, rendered all the pleasanter through the devoted and watchful affection of her old friend, Mlle. Nathalie Micas, who lived with her. We have seen that she came out of her voluntary obscurity in 1867 to the extent of sending a few pictures to the Universal Exposition. From this date onward she ceased to exhibit, and no other canvas bearing her signature was seen in public until the Salon of 1899, which was the year of her death.

Relieved of all outside interruption, Rosa Bonheur worked with indefatigable energy. Yet she could hardly keep pace with the demands of her purchasers, who were constantly increasing in number and constantly more urgent. Her paintings had[Pg 65] acquired a vogue abroad and brought their weight in gold. Certain pictures brought speculative prices in America even before they were finished and while they were still on the easel at By. At this period, it may be added, everything which came from the artist’s brush possessed an incomparable and masterly finish. Never a suggestion of weakness in design even in her most hastily executed canvases. I must at once add that hasty canvases are extremely rare in the life work of Rosa Bonheur; she had too high a sense of duty to her art and too great a respect for her own name to slight any necessary work on a canvas. Certain pictures appear to have been done rapidly solely because the artist possessed among her portfolios fragmentary studies made from nature and drawn with scrupulous care, and all that she needed to do was to transfer them to her canvas.

From the host of works that the artist put forth at this period, we may cite: 1865, Changing Pasture, A Family of Roebuck; 1867, Kids Resting; 1868,[Pg 66] Shetland Ponies; 1869, Sheep in Brittany; 1870, The Cartload of Stones.

The war of 1870 brought consternation to her patriotic soul. She suffered cruelly from the ills which had befallen her country. Generous by nature and a French woman to her inmost fibre, she did her utmost to relieve the suffering that she saw around her as a result of the Prussian invasion. She spoke words of comfort to the peasants and aided them with donations, distributing bags of grain that were sent to her by her friend Gambard, at this time consul at Odessa.

One day a Prussian officer of high rank presented himself at her home in the name of Prince Karl-Frederick. The latter, who was a confirmed admirer of the artist, whom he had met in former years, sent her an order of safe-conduct which would place her and her belongings beyond the danger of any annoyance. Rosa Bonheur ran her eye over the paper and in the presence of the officer tore it into tiny[Pg 67] pieces. Nobly and simply the great artist refused to accept any favours, feeling, in view of the existing painful circumstances, that it would be a shameful thing for her to do. A French woman before all else, she submitted in advance to all the abuses and exigencies of the conquerors. On another occasion, a German prince came to By, to pay his respects. She refused to receive him. We should add that the Prussians, whose excesses and brutalities were so frequent during that campaign, had the wisdom not to meddle with Rosa Bonheur.

After the treaty of peace was signed, she set herself eagerly to work once more. “I was occupied at that time,” she wrote, “in studying the big cats; I made sketches at the Jardin des Plantes, in the circuses, in the menageries, anywhere and everywhere that I could find lions and panthers.”

This is the epoch from which dates that admirable series of wild

beasts in which Rosa Bonheur manifests a power of expression and

virility of execution that[Pg 68] she never before had occasion to display,

and that seem absolutely incredible as coming from the brush of a

woman. No other painter has rendered with greater truth and force the

undulous and elastic movements of the panther or the tiger; Barye

himself, in his admirable bronzes, has never endowed his lions with

greater life or more majestic grandeur than Rosa Bonheur has done. The

latter, with her astounding memory and with an eye as profound and

luminous as a photographic lens, caught and retained the most fugitive

expressions on the mobile physiognomy of the great cats. She noted

them down with rapid and unfaltering pencil; the painting of the

picture after this was a mere matter of execution. Is there any finer

presentment of the tranquil beauty of a lion in repose than The Lion

Meditating? Beneath the royal mane, his features have a haughty

placidity and his eyes a serene intentness that are admirably

rendered. The Lion Roaring is possibly even more beautiful, because

of the [Pg 69]

[Pg 70]

[Pg 71]difficulty which the artist had to overcome in catching the

peculiarly rapid and mobile expression which accompanies the act of

roaring. Under the effort of his tense muscles, the mane rises,

bristling, around the powerful neck and above the straining head.

There is nothing cruel in the physiognomy of this lion: his roaring is

not the cry of the beast of prey scenting his victim, but the call of

the desert king, saluting the rising orb of day or the descending

night. The artist has admirably expressed this difference in a

foreshortening of the head which Correggio or Veronese might have

envied her.

PLATE VIII.—TRAMPLING THE GRAIN

(Rosa Bonheur Studio, at By)

This work, which was her last, is one of the most beautiful of all that Rosa Bonheur painted because of the intensity of the movement which sweeps the horses in a superb headlong rush, over the heaped-up grain which they trample under foot. This splendid canvas remains unfinished, death having overtaken the noble artist before the final touches had been added.

In all the animals that she painted,—and she painted nearly all the animals there are,—Rosa Bonheur succeeded in reproducing their separate characteristic expressions, “the amount of soul which nature has bestowed upon them.” M. Roger Milès, the excellent art critic, from whom we have frequently borrowed in the course of this biography, expresses it in the following admirable manner:

“Through the infinite study that she made of animals, Rosa Bonheur reached the conviction that their expression must be the interpretation of a soul, and since she understood the types and the species that her brush reproduced, she was able, through an instinct of extraordinary precision, to endow them, one and all, with precisely the glance and the psychic intensity that belongs to them. She takes the animals in the environment in which they live, in the setting with which their form harmonizes, in short, in the conditions that have played an essential part in their evolution, and she records with inflexible sincerity what nature places beneath her eyes and what her patient study has permitted her to understand. It is more especially for this reason, among many others, that the work of Rosa Bonheur deserves to live, and that the eminent artist stands to-day as one of the most finished animal painters with which the history of our national art is honoured.”

In the peaceful and laborious atmosphere of By, the years slipped happily away. But before long a cloud came to darken this serenity. The health of her tenderly loved friend, Mlle. Micas, began to decline; the doctor ordered a southern climate. Rosa Bonheur did not hesitate; she had a villa built at Nice, and every year, during the winter, the artist accompanied her beloved invalid to the land of sunshine. These annual changes of climate and the care with which Rosa Bonheur surrounded her friend certainly delayed the fatal issue. But the disease had taken too deep a hold. Mlle. Micas passed away on the 24th of June, 1889. “This loss broke my heart,” wrote the artist. “It was a long time before I could find in my work any relief from my bitter pain. I think of her every day and I bless the memory of that soul which was so closely in touch with my own.”

From that day onward, Rosa Bonheur became a prey to melancholy, and her thoughts turned ceaselessly[Pg 74] to the tender friend whom she had lost forever. None the less, she continued to work with dogged energy, quite as much to deaden her pain as to satisfy the ever increasing orders.

A great joy, however, came to her in the midst of her sorrow. President Carnot, imitating the Emperor, came in person to bring her the Cross of Officer of the Legion of Honour. She was keenly appreciative of such a mark of high courtesy, which was at the same time a well deserved recompense for an entire life consecrated to art. Rosa Bonheur possessed a number of decorations, notably the Cross of San Carlos of Mexico which was given her by the Empress Charlotte, the Cross of Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic, the Belgian Cross of Leopold, the Cross of Saint James of Portugal, etc. The noble artist accepted these distinctions gratefully, but was in no way vain of them, for no woman was ever more simple or more modest than she.

At about this epoch, she devoted herself for a time to pastel work, and in 1897 exhibited four examples of ample dimensions and representing various animals. The whole city of Paris flocked to this exhibition and unanimously proclaimed her talent as a pastel painter.

It was also about this time that she gained a new friend whose devotion, although it did not make her forget her beloved Nathalie Micas, at least in a measure softened the bitterness of her loss. A young American, Miss Anna Klumpke, who was an enthusiastic admirer of Rosa Bonheur, and who herself had some talent for painting, presented herself one day at By and begged the favour of an interview with the artist. The latter received her with her wonted graciousness. The conversation turned upon art. The young girl emboldened, by her hostess’s kindness, ventured to ask if she might come to take a few lessons, and at the same time showed a few sketches. Rosa Bonheur examined[Pg 76] them and discovered not merely promise, but what was better, an unmistakable talent. She not only acquiesced to Miss Klumpke’s desire; she did even better, she offered the hospitality of her own home. Miss Klumpke’s visit, which was to have been for only a short time, became permanent; a substantial friendship was formed between the two women; it was Miss Anna Klumpke who closed the eyes of Rosa Bonheur and who was her sole testamentary legatee. She has piously preserved the memory of her benefactress and she has converted the Chateau of By, which she still occupies, into a museum filled with relics of the great artist. She has also published an admirable volume upon the life and work of her eminent friend, that forms a veritable monument of affectionate admiration.

Rosa Bonheur was not slow in reverting again to painting and produced her famous picture: The Duel, the celebrity of which was almost as great as that of the Horse Fair and Ploughing in the Niver[Pg 77]nais. The duel in question is between two stallions, and what adds to the interest of the scene is that it is historic and perfectly familiar to all the sporting men of England. It was a struggle in which an Arabian thoroughbred, Godolphin-Arabian, overpowered Hobgoblin, another thoroughbred of English breed. The mettle of these horses, fired by the heat of battle, is interpreted in a masterly fashion.

No less perfect is the canvas representing The Threshing of the Grain, which it took Rosa Bonheur twenty years to bring to completion. Over a field in which the sheaves of grain have been strewn, eleven horses, drawn life-size, are driven at full gallop, trampling the golden tassels under their powerful hoofs. The artist has rarely attained the height of perfection to which this picture bears witness.

But at last we come to the close of her career. Rosa Bonheur was seventy-seven years of age, but in the enjoyment of robust health; her talent still[Pg 78] retained its unvarying power and her hand was still firm. Her age was not betrayed in any of her works, which had the appearance of having been painted in the flood-tide of youth. Such is the impression of critics before her painting, A Cow and Bull in Auvergne, Cantal Breed, which, contrary to her habit, she sent to the Salon. The praise was unanimous; they even talked of awarding her the medal of honour which she refused in a letter of great beauty and dignity. It seemed at that time that the artist would enjoy her robust old age for a long time to come, when a congestion of the lungs prostrated her suddenly and the end came in a few days. She died on the 25th of May, 1899.

The concert of regrets which greeted her death was touching in its unanimity. Without a dissenting note, without reserve, the entire press paid tribute to the dignity of her life, the nobility of her character, the greatness of her talent. According to her desire, she was interred in the cemetery of Père-Lachaise;[Pg 79] and the cortège which followed her coffin was made up of every eminent figure known to the Parisian world of art and letters. Strangers came in throngs, especially from England. And this innumerable cortège that followed her bier testified more eloquently than any panegyric to the goodness of this admirable artist who had been able to lead a long and glorious career without creating a single enemy.