FOURTH EDITION.

LONDON.

PRINTED FOR J. HARRIS, SUCCESSOR TO E. NEWBERY, AT

THE ORIGINAL JUVENILE LIBRARY, THE CORNER OF

ST. PAUL'S CHURCH YARD.

1810.

E. Hemsted, Printer, Great New-street, Gough-square.

Published Nov. 1st. 1803, by J. Harris corner of St.Pauls Church Yard.

| Page | |

| Curiosity | 1 |

| The Unsettled Boy | 11 |

| Cecilia and Fanny | 21 |

| Henry | 33 |

| Maria; or, the Little Slattern | 40 |

| Frederick's Holidays | 51 |

| The Little Quarrellers | 60 |

| The Vain Girl | 68 |

| The Young Gardeners | 78 |

| The Whimsical Child | 85 |

| Edward and Charles | 94 |

| The Truant | 104 |

| Jealousy | 115 |

| Edmond | 121 |

| The Ghost and the Dominos | 129 |

| Fido | 143 |

| The Reward of Benevolence | 150 |

| Jemima | 162 |

| The Trifler | 171 |

| The Cousins | 177 |

| The Travellers | 189 |

| The Strawberries | 200 |

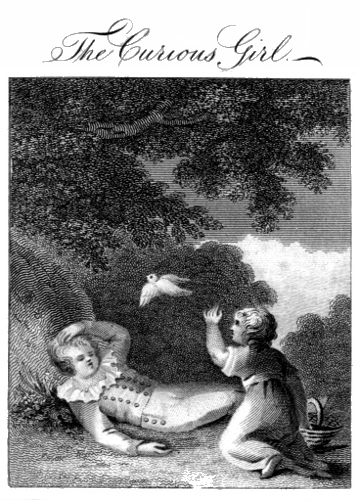

Arabella fancied there could be no pleasure in the world equal to that of listening to conversations in which she had no concern, peeping into her mamma's drawers and boxes, and asking impertinent questions. If a parcel was brought to the house, she had no rest till she had found out what was in it; and if her papa rung the bell, she would never quit the room till the servant came up, that she might hear what he wanted.

She had been often desired to be less curious, and more attentive to her lessons; to play with her doll and her baby-house, and not trouble herself with other people's affairs: but she never minded what was said to her, and when she was sitting by her mamma, with a book in her hand, instead of reading it, and endeavouring to improve herself, she was always looking round her, to observe what her brothers and sisters were doing, and to watch every one who went out or came into the room.

She desired extremely to have a writing-master, because she hoped, that, after she had learnt a short time, she should be able to read writing, and then she should have the pleasure of finding out who all the letters were for, which the servant carried to the post-office; and might sometimes peep over her papa's shoulder, and read those which he received. One day perceiving her mamma whisper to her brother William, and that they soon after left the room together, she immediately concluded there must be something going forward, some secret which was to be hid from her, and which, perhaps, if she lost the present moment, she never should be able to discover. Poor Arabella could sit still no longer; she watched them from the window, and seeing that they went towards a gate in the garden, which opened into the wood, she determined to be there before them, and to hide herself in the bushes near the path, that she might overhear their conversation as they passed by. This she soon accomplished, by taking a shorter way; but it was not very long before she had reason to wish she had not been so prying; for the gardener passing through the wood with an ill-natured cur which always followed him, seeing her move among the bushes, it began to bark violently, and in an instant jumped into her lap.

She was very much frightened, and, in trying to get away, without intending it, gave him a great blow on the head; in return for which he bit her finger, and it was so very much hurt, and was so long before it was quite well again, that her friends hoped it would have cured her of being so curious; but they were much mistaken. Arabella's finger was no sooner well, than the pain she had suffered, her fright, and the gardener's cur, were all forgotten; and whenever any thing happened, let the circumstance be ever so trifling, if she did not perfectly understand the whole matter, she could not rest or attend to any thing she had to do, till she had discovered the mystery; for she imagined mysteries and secrets in every thing she saw and heard, unless she had been informed of what was going to be done.

Some time after her adventure in the wood, she one morning missed her brother William, and not finding him at work in his little garden, began directly to imagine her mamma had sent him on some secret expedition; she resolved, however, on visiting the whole house, in the hope of finding him, before she made any inquiry, and accordingly hunted every room and every closet, but to no purpose. From the house she went to the poultry-yard, and from thence to the lawn, but William was no where to be found. What should she do!—"I will hunt round the garden once more," said she; "I must and will find him, and know where he has been all this time; why he went without telling me, and why I might not have been intrusted with the secret. I will not eat my dinner till I find him, even if he does not return till night."

Arabella returned once more to the garden, where at length, in a retired corner which she had not thought of visiting, she found her brother sleeping under a large tree. He had a little covered basket by his side, and slept so soundly, that he did not move when she came near the place, though she was talking to herself as she walked along, and not in a very low voice.

"Now," thought the curious girl, "I have caught him: he must have been a long way, for he appears to be very warm and tired; and he has certainly got something in that basket which I am not to see, and I suppose mamma is to come here and take it from him, that I may know nothing of it. Mamma and William have always secrets, but I will discover this, however—I am determined I will."

She then crept softly up to the basket, and stopped down to lift up the cover, afraid almost to breathe, lest she should be caught; and looking around to see if her mamma was coming, and then once more at her brother, that she might be certain he was still asleep, gently she put her hand upon the basket, and, without the least noise, drew out a little wooden peg, which fastened down the cover. "Now," thought she, "Master William, I shall see what you have got here." Away she threw the peg, up went the cover of the basket, and whizz—out flew a beautiful white pigeon.

A violent scream from Arabella awoke William, who, seeing the basket open, the pigeon mounted into the air, and his sister's consternation, immediately guessed what had happened, and addressed her in the following manner:

"You see, my dear Arabella, the consequence of your curious and suspicious temper: I wished to make you a present to-day, because it is your birthday, but you will not allow your friends to procure you an agreeable surprise; for nobody in the house can take a single step, or do the least thing, without your watching and following them. I know you have long wished to have a white pigeon, and I have walked two long miles in all this heat, to get one for you. I sat down here, that I might have time to contrive how I should get it into the house without your seeing it, because I did not wish to give you my present till after dinner, when papa and mamma will give you theirs; and whilst I was endeavouring to think on some way to escape your prying eyes, I was so over-powered with fatigue and heat, that I fell fast asleep; and I see you have taken that time to peep into my basket, and save me any farther trouble. You have let my present fly away: I am sorry for it, my dear sister, but you have no one to blame but yourself; and I must confess that I am not half so sorry for your loss, as I am for the fate which attends two poor little young ones which are left in the basket, and who, far from being able to take wing, and follow their mother, are not old enough even to feed themselves, and must soon perish for want of food."

William's words were but too true; the poor things died the next morning, and Arabella passed the whole day in unavailing tears, regret, and sorrow.

"I do not think, at last, that I shall like to be a surgeon," said Gustavus to his papa, as he trotted by his side on his little poney. "Edward Somerville is to be a clergyman: and he has been telling me that he is to go to Oxford, and then he is to have a living, and will have a nice snug parsonage-house, and can keep a horse, and some dogs, and have a pretty garden; whilst I shall be moped up in a town, curing wounds, and mending broken bones—I shall not like it at all."

"It was your own choice," answered his papa; "but if you think you should like better to take orders, I am sure I have no objection."

Three months after this conversation, Gustavus being invited to accompany some friends to see a review, he returned home with his little head so filled with military ideas, that he was certain, he said, nothing could be so delightful and so happy as the life of an officer; and that travelling about and seeing different places was better than all the snug parsonage-houses in England. But, not many months from that time, going with his papa to Portsmouth, to visit his elder brother, who belonged to the navy, he was so struck with the novelty of the scene (having never seen a man of war before), thought there was so much bustle and gaiety in it, that it must be the pleasantest life in the world, and earnestly requested that he might be allowed to go to sea.

His papa now thought it time to represent to him the folly and imprudence of being so unsettled. "My dear boy," said he, taking him affectionately by the hand, "if you continue thus changing your mind every three months, you will never be any thing but an idle fellow, and your youth will be lost in preparations for different professions; or, should you remain long enough fixed to have entered into any line of life, you will not be long before you will desire to quit it for another, of which you will probably be entirely ignorant, and by that means ruin your fortune, and expose yourself to ridicule.

"You make me recollect two boys I once knew, and whose story has often been the subject of conversation, in a winter's evening, at the house of an old clergyman, from whom I received the first principles of the virtuous education my father had the goodness to bestow upon me.

"Robin was the son of a farmer who lived in the village; his uncle kept a grocer's shop in the next market town, and had a son named Richard. They were very clever boys, both understood the business they had been bred to extremely well, and, at the age of sixteen, were become very useful to their parents; but about that time they took it into their heads to grow tired of the employment they were engaged in, and to wish to change places with each other; Robin fancying that he should like extremely to be a grocer, and Richard, that nothing could possibly be so pleasant and agreeable as working in the fields.

"The two fathers, who wished for nothing so much as the happiness of their children, were much grieved at this whim; for they very well knew, that all they had been learning could be of no use to them, if they were now to change their situations, and would be exactly so much time and labour lost, and every thing was to begin again; but Robin and Richard thought differently, and said they could not see that there was any thing to learn.

"Their fathers desired they might change places for one month, and agreed that if in that time they saw no reason why they should not remain, the one to learn the business of a farmer, and the other to serve in a grocer's shop, they would willingly consent to indulge them in their inclination; and accordingly, on the day on which Richard was sent out to work in a large turnip field, Robin, decorated with a pair of white sleeves, and an apron before him, was placed behind his uncle's counter.

"The first day he did nothing but grin and stare about him, dip his fingers in the jars of honey, and fill his pockets with currants, raisins, and figs, and he thought it pleasant enough; but the moment he was set at work, he found himself so aukward, that, if he had not been ashamed, he would have begged to return immediately to his plough and his spade. Notwithstanding his earnest endeavours, he could not by any means contrive to tie up a pound of rice, for when he had folded the paper at one end, and, as he thought, secured it, he let it run out at the other; and something of the same kind happening to every thing he undertook, the shop was strewed from one end to the other with rice, tea, and sugar; and his uncle told him he was only wasting his goods, and doing mischief, without being of the smallest use. If he was sent out with any parcels, he was sure to lose his way, and ramble about whole hours together, till somebody was sent in search of him. No one pitied him; he was the jest of the whole family; and, before half the month was expired, he begged in the most earnest manner, that he might return to the farm.

"Richard, who had never been much exposed either to heat or cold, desired his uncle would excuse his working till the cool of the evening; but the farmer laughed at him, and asked him if he thought that would be the way to get his work done. He was therefore obliged to go out and attempt something, but his whole day's work might have been done in a couple of hours by a country boy of twelve years of age, and would also have been much better done, for poor Richard did not know what he was about.

"At five o'clock he said he must go and get his tea; but his uncle told him they never drank any such slops, and promised him a good mess of porridge for his supper, if he made haste to finish his work.

"Richard could not work; he had done nothing right, and the next day he found it worse and worse; he did not know even how to handle a spade, much less how to make use of it. He sauntered about, with his arms across, the whole long summer's day, doing nothing, yet tired and uncomfortable: he had nobody to speak to—he could not find one idle person; even his aunt, when he went to seek her, was busy in her dairy, and told him to go and mind his business, and not lounge about and disturb those who were inclined to work.

"Every creature he saw had some employment which they understood, and appeared to take pleasure in, whilst he, unable to do the same, and weary of wandering alone, from the garden to the field, and from the field to the garden, wished a thousand times he had never quitted his father's shop, where, being able to act his part as well as other people, he felt himself of some consequence: now he was nobody, he was in every one's way, and all were tired of him.

"Robin and Richard were glad to return to their own homes, and re-assume their former employments, in which they prospered so well, that they never after felt the least inclination to quit them, and are at this time living in ease and plenty, respected and esteemed by their friends and neighbours."

Cecilia went to spend a month with her aunt in the country. She was very much pleased at being in a place where she could run in the garden and in the fields as much as she liked, but she would have been much happier if her sister had been with her; and Fanny, who fancied she should have no pleasure in any thing without the company of her dear Cecilia, was tired of her absence, and longed for her return, before she had been two days gone.

They could both write tolerably well, and Cecilia, the week after her arrival at her aunt's, addressed the following letter to her sister:

"MY DEAR FANNY,

"I wish mamma could have parted with us both at the same time, that we might have rambled about together in my aunt's beautiful gardens, and in the fields and meadows which surround the house: but I believe I am wrong in forming such a wish, for she would then be left quite alone, and that I do not desire on any account; if I did, I should appear very selfish, and as if I thought of nobody's pleasure except my own, and that I should be extremely sorry for.

"I am sure you will like to know that I am very happy at my aunt's, and how good and kind she is to me. All the long border behind the summer-house is to be called our garden, and it is now putting in order for us; and when neither of us are here, my aunt says the gardener shall take care of it: it is full of beautiful rose-trees and flowering shrubs; and Thomas is planting many more, and sowing mignonette, and other seeds, so that when you come here, you will find it quite flourishing.

"My aunt sends me very often with Biddy to walk by the sea-side, and I have found a number of very pretty shells and sea-weeds, which I shall bring you, and a great many curiosities which I have picked up on the beach. I never saw such things before, and I am sure you never did. We never see any thing where we live but houses and pavement—here I have seen the mowers and the haymakers, and I know how to make hay, and how butter is made, and many other things.

"Good night, my dear Fanny! Pray give my duty to dear mamma, and believe me,

"Your most affectionate sister,

"Cecilia."

Fanny was delighted at receiving this letter, and wrote the following answer to her sister:

"MY DEAR CECILIA,

"How glad I am to hear that you are so happy in the country! I should certainly like very much to be with you, but not to leave mamma alone; and she is so good, that I am not half so lonely as I thought I should be in your absence. Only think, my dear sister! she has bought me the sweetest little goldfinch you ever saw, and it is so tame, that the moment I come near the cage, it jumps down from its perch to see what I have got for it.

"But this is not all: she has taken me to a shop, and bought me a great many pretty prints, which I am sure you will have great pleasure in looking at when you come home. We have been twice at M—— to spend the day; and indeed, my dear Cecilia, I have had a great deal of pleasure, though perhaps not quite so much as you have had in your fields and meadows, and among your haymakers; but mamma says we may be happy in any place if we choose it, and will determine to make ourselves contented, instead of spending our time in wishing ourselves in other places than where we are: and I am sure she is very right, for if I were to fret and vex myself because I am not in the country, and you do the same because you are not in town, my goldfinch and my prints, my pleasant walks in the gardens at M——, and all mamma's kindness, would be lost upon me, and you would have no pleasure in your little garden, or in looking at the haymakers, your shells, your sea-weeds, or any of the curiosities you meet with.

"Pray, dear Cecilia, let me have one more letter from you before you come home, and do not burn mine, for I shall like to see how much better I write next year; and so will you, I dare say, so I shall lock up your letters in my little work-trunk.

"Mamma desires her best love to you. Give my duty to my aunt, and believe me

"Your affectionate sister,

"Fanny."

It was almost a fortnight before Fanny heard again from her sister, when one morning a basket, covered very closely, and a small parcel, with a letter tied upon it, were brought up stairs, and placed upon the table before her. The letter was from her sister, and contained the following words:

"MY DEAR FANNY,

"You would have heard from me much sooner, but I waited to write by George, whom my aunt told me she should be obliged to send to town on business. He brings you a basket of strawberries from her, with her love to you: fourteen of them are from our garden, and I assure you I had a pleasure in picking them, which I cannot describe: they are in a leaf by themselves, and I beg you will let me know if they are ripe and sweet, for I did not taste them; I was determined to send you all the first. I send you also a little parcel of shells and sea-weeds, and when I am with you, I will teach you how to make very pretty pictures of them, as my aunt has had the goodness to teach me.

"I have been very happy here, though I could not persuade myself to believe it possible when I first came, because I could not have mamma and you with me; but I shall remember her advice, and always endeavour to be pleased, and find amusement where I am, and with what I have, instead of fretting, like our cousin Emily, because she had not a blue work-bag instead of a pink one, or because see had an ivory toothpick-case given to her when she was wishing for a tortoise-shell one.

"My aunt says, that children who do so are so very tiresome, that they make themselves disliked by every body, and that they are never invited a second time to a house, because people are generally tired of their company on the first visit.

"I hope I shall see you and my dearest mamma next week; but you may write to me by George, for I shall be very much disappointed if he returns without a letter from you.—Adieu! dear Fanny.

"I am affectionately yours,

"Cecilia."

Fanny had only time to write a short note to her sister, which George called for soon after dinner; and Cecilia's return the following week, put an end to the correspondence for that time. The two sisters were extremely happy to meet, though they had not made themselves disagreeable, and teased people with their ill humour when they were separated; and they were very well convinced, that if they had done so, they should have suffered by it, and have been very uncomfortable.

The following summer Fanny paid a visit to her aunt, and had the pleasure of finding their little garden in such good order, and so many strawberries in it, that she could send her sister a basket-full. She could work very neatly; and her aunt having given her a large parcel of silks, riband, twist, and gold cord, she made the prettiest pincushions that ever were seen, to send to her mamma, her sister, and her cousins.

Cecilia was extremely fond of drawing, and was so attentive to her lessons during her sister's absence, that she had a portfolio full of pretty things to shew her on her return.

No little girls in the world could be happier than Cecilia and Fanny, and the reason of it is very plain: they were always obedient to their mamma's commands, kind to the servants, and obliging to every body; always contented with what they had, and in whatever place they happened to be; and never fretful and out of humour for want of something to do, for they had endeavoured to learn every thing when they had an opportunity of doing so, that they might never be at a loss for employment and amusement.

Henry was the son of a merchant of Bristol: he was a very good-natured, obliging boy, and loved his papa and mamma, and his brothers and sisters, most affectionately; but he had one very disagreeable fault, which was, that he did not like to be directed or advised, but always appeared displeased when any body only hinted to him what he might, or what he ought not to do; he fancied he knew right from wrong perfectly well, and that he did not require any one to direct him.

He was the most amiable boy in the world, if you would let him have his own way: he never heard any body say they wished for a thing, that he did not run to get it for them, if it was in his power; and no one could be more ready to lend his toys to his brothers and sisters, whenever they appeared to desire them: but the moment he was told not to stand so near the fire, or not to jump down two or three stairs at a time, not to climb upon the tables, or to take care he did not fall out of the window, he grew directly angry, and asked if they thought he did not know what he was about—said he was no longer a baby, and that he was certainly big enough to take care of himself.

His friends were extremely sorry to perceive this fault in his disposition, for every body loved him, and wished to convince him, that, though he was not a baby, he was but a child; and that if he would avoid getting into mischief, he must, for some years, submit to be directed by his papa and mamma, and, in their absence by some other person who knew better than he did: but he never minded their advice, till he had one day nearly lost his life by not attending to it.

A lady, who visited his mamma, and who was extremely fond of him, met him in the hall on new year's day, and gave him a seven shilling piece to purchase something to amuse himself.—Henry was delighted at having so much money; but instead of informing his parents of the present he had received, and asking them to advise him how to spend it, he determined to do as he liked with it, without consulting any body; and having long had a great desire to amuse himself with some gunpowder, he began to think (now he was so rich) whether it might not be possible to contrive to get some. He had been often told of the dreadful accidents which have happened by playing with this dangerous thing, but he fancied he could take care, he was old enough to amuse himself with it, without any risk of hurting himself; and meeting with a boy who was employed about the house by the servants, he offered to give him a shilling for his trouble, if he would get him what he desired; and as the boy cared very little for the danger to which he exposed Henry, of blowing himself up, so as he got but the shilling, he was soon in possession of what he wished for.

A dreadful noise was, some time afterwards, heard in the nursery. The cries of children, and the screams of their maid, brought the whole family up stairs: but oh! what a shocking sight was presented to their view on opening the door! There lay Henry by the fireside, his face black, and smeared with blood; his hair burnt, and his eyes closed: one of his little sisters lay by him, nearly in the same deplorable condition; the others, some hurt, but all frightened almost to death, were got together in a corner, and the maid was fallen on the floor in a fit.

It was very long before either Henry or his sister could speak, and many months before they were quite restored to health, and even then with the loss of one of poor Henry's eyes. He had been many weeks confined to his bed in a dark room, and it was during that time that he had reflected upon his past conduct: he now saw that he had been a very conceited, wrong-headed boy, and that children would avoid a great many accidents which happen to themselves, and the mischiefs they frequently lead others into, if they would listen to the advice of their elders, and not fancy they are capable of conducting themselves without being directed; and he was so sorry for what he had done, and particularly for what he had made his dear little Emma suffer, that he never afterwards did the least thing without consulting his friends; and whenever he was told not to do a thing, though he had wished it ever so much, instead of being angry, as he used to be, he immediately gave up all desire of doing it, and never after that time got into any mischief.

Little Maria B—— was so slatternly, and so careless of her clothes, that she never was fit to appear before any body, without being first sent to her maid to be new dressed. If she came to breakfast quite nice and clean, before twelve o'clock you could scarcely perceive that her frock had ever been white: her face and hands were always dirty, her hair in disorder, and her shoes trodden down at the heels, because she was continually kicking them off.

At dinner no one liked to sit near her, for she was sure to throw her meat into their laps, pull about their bread with her greasy fingers, and never failed to overset her drink upon the table-cloth.

One day her brother ran into the nursery in great haste, desiring she would go down with him immediately into the parlour, and telling her, that a gentleman had brought a large portfolio, full of beautiful prints of all kinds of birds and animals, which he was going to shew to them, if they were ready to come to him directly, for he could not stay with them, he said, more than half an hour.

Poor Maria was in no condition to shew herself; she had been washing her doll's clothes (though her maid had desired her not to do it, and had promised to wash them for her, if she would have patience till the afternoon), and had thrown a large basin of water all over her; after which, wet as she was, she had been rummaging in a dirty closet, where she had no kind of business, and was, when her brother came into the nursery, covered with dust and cobwebs.

Susan was called in haste to new-dress her; but she was so extremely careless of her clothes, and tore them so much every day, that one person was scarcely sufficient to keep them in order for her. Not a frock was to be found, which had not the tucks ripped, and the strings broken, nor a pair of shoes fit to put on; her face and hands could not be got clean without warm water, and that must be fetched from the kitchen; then she had to look for a comb, Maria had poked hers into a mouse-hole, and had been rubbing the grate with her brush: in short, by the time all was ready, and she was dressed, a full hour had slipped away without her perceiving it.

Down stairs, however, she went, opened the parlour-door, and was just going to make a fine courtesy to the gentleman and his portfolio, when to her very great surprise and mortification, she perceived her mamma sitting alone, at work by the fire. The gentleman had shewn his prints to her brothers and sisters, made each of them a present of a very pretty one, and had been gone some time.

When her aunt came from Bath, she brought her a nice green silk bonnet, and a cambric tippet, tied with green riband. Maria was very much delighted with it, and fancied she looked so well in it, that she could not be prevailed upon to pull it off; but she soon forgot that it was new and very pretty, and ought to be taken care of; she thought of nothing, when she could escape from her maid, but of getting into holes and corners; and having rambled into an old back kitchen, and finding herself too warm, she took off her pretty green bonnet, and threw it down on the ground, but recollecting something she had now an opportunity of doing, ran away in great haste, and left it there.

When she was asked what she had done with her bonnet, she said she did not know, and the servants lost their time in seeking for it; for who would have thought of looking for a young lady's bonnet in a dirty back kitchen?

There, however, it was found, with a black cat and four kittens lying asleep in it, and so entirely spoiled, that it could never be worn any more; and she was obliged to wear her old bonnet a great many months longer, for her mamma was extremely angry with her, and would not buy her a new one; nor did she deserve to have one, till she could learn to take more care of it, and not leave it about in such dirty places.

It is not very usual to see young ladies wandering about by themselves in stables and outhouses, but Maria had very great pleasure in it, and never lost the opportunity when she could get away without being seen; and she was so dirty, and had so often her clothes torn, that she was frequently taken by strangers for some poor child sent on an errand to the servants.

One day, when she was passing through the gate to see who was coming down the lane, a little boy upon an ass, who came up from the sea-side every week with fish, seeing her there doing nothing, called out, "Here, hark! you little girl, open the gate, I say—come, make haste, do not stand there like a post. What! are you asleep?"

Maria was so much ashamed, that she could not move, but hung down her head, and the boy (who had a mind to make her save him the trouble of getting off from his ass) continued to talk to her in the polite manner in which he had begun: "Why, you little dirty thing! open the gate I say—if you do not, I will tell the cook of you, and she will tell Madam, and I shall get you turned out of the house."

Thus was Maria B—— continually mortified by one person or another, and losing every pleasure and amusement which her brothers and sisters were indulged in, because she was never ready to join in them. They often went to walk in the charming woods and meadows which surrounded the house, and were sometimes sent with their maid to carry comfortable things to their poor sick neighbours, from whom they received in return a thousand thanks and prayers to God for their happiness; but Maria could have no share in either, for she was never with them, and they knew nothing of her.

Once, when their grandpapa sent his coach to fetch them to dine with him, Maria was not to be found; and, after seeking her all over the house to no purpose, they at length caught her in the garden with a watering pot, which she could hardly lift from the ground, her shoes wet and covered with mould, her frock in the same condition, and her hands and arms dirty quite up to the elbows. Her mamma positively declared that the horses should not be kept a moment longer, the coachman was desired to drive on, and Maria was left to spend the day in the nursery from whence she was ordered not to stir.

There she spent a melancholy day indeed, for she had no means of amusing herself to make time pass lightly on: she had no pleasure in reading, so that all the pretty books which had been bought for her were of no use; she could not play with her doll, for it had no clothes, they were all lost or burnt; and she had suffered a little puppy to play with her work-bag, till both that and the work which was in it, thread-case, cotton, and every thing else were all torn to pieces. The only thing she found to do, was to sit down by the window, look at the road and cry, till her brothers and sisters returned, and then she had the mortification of hearing them recount the pleasure they had enjoyed, talk of the curiosities their grandpapa had shewn them in the great closet at the end of the gallery, and of seeing all the pretty things they had brought home with them, and of which she might have had her share if she had been of their party.

"I wish," said Frederick to Mr. Peterson, "I could be with my aunt in town to spend the holidays; I shall be so tired here in the country, I shall not know what to do with myself. Two of my schoolfellows live in the next street to my aunt, and they will be going with their papa to the play, and to Astley's, and to walk in the Park, and will have so much more pleasure than I shall have—why, I might as well be at school, as here sauntering about the fields."

"You are not very civil," answered Mr. Peterson. "When you came from Barbadoes last year, and had no other acquaintance, you liked very well to be with me in the holidays: however, if you desire it, my dear Frederick, you shall go to your aunt's, that you may be near your little friends, and I will write to their papa, to request that he will give you leave to be with them as much as possible, that you may partake of all their pleasures, for I do not think you will have a great deal in your aunt's house; you know she is always ill, and cannot have it in her power to procure you much amusement."

Frederick was accordingly sent to town, and his first wish was to pay a visit to his two friends in the next street. His aunt's servant was ordered to conduct him to the house, and he was shewn immediately up stairs; but, instead of meeting with those he expected, he found their papa alone in the drawing-room, sitting at a table covered with papers, and apparently very busy.

On inquiring for his schoolfellows, he was very much surprised at being informed that they were gone into the country: "for," said their papa, "they would not have liked to be confined at home all their holidays, and I should have had no time to run about with them; they might as well have remained at school as have been here; but where they are gone they will enjoy themselves; they will spend a week at their grandfather's, and from thence go to my good friend, Mr. Peterson's, where they will have all the pleasure and amusement they can possibly wish for."

Frederick was so vexed and disappointed that he could not open his lips, but made a low bow, and returned to his aunt, whom he found just risen to breakfast. She was quite crippled with rheumatism, and had so great a weakness in her eyes, that she could not bear the light, and would only allow one of the windows to have a little bit of the shutter open.

In this dismal room, without any thing to amuse himself with, was poor Frederick condemned to spend his holidays: his aunt made him read to her whenever she was awake, and it was only when she dropped asleep for half an hour in her easy chair, that he could creep softly to the other end of the room, and peep with one eye into the street, through the little opening between the shutters.

Poor Frederick now sincerely repented having been so rude and ungrateful to Mr. Peterson, and wished a thousand times a day he had been contented to stay at his house; he would have been very happy to have had it in his power to return, but dared not propose it to his aunt, and would also have been ashamed to appear before Mr. Peterson.

After many melancholy days, and tedious evenings, spent in lonely solitude, he at length saw the happy morning which was to end his captivity. "What a foolish boy I have been!" thought he, as he was putting his things together. "The day of my return to school is my first holiday, and the preparations I am making for it the only pleasure I have felt since I left it. In the country, where I might have enjoyed the liberty of running in the fields in the open air, I was discontented and restless; and I left it, to shut myself up in a sick room. I am now going back to school, to have the pleasure of hearing how agreeably all my schoolfellows have been spending their time, whilst I shall have nothing to recount to them, but how many phials were ranged on my aunt's chimney-piece, and how many hackney-coaches I could see with one eye pass through the street."

Frederick was very right; he found his two little friends just arrived, and who, for a whole week, could speak of nothing but the pleasure they had enjoyed at Mr. Peterson's. They told him of their having being several times on the river on fishing-parties, of two nice little ponies which had been procured for them, that they might ride about in the shady lanes, and round the park, and of the beautiful houses and gardens they had been taken to see in the neighbourhood.

They had a great many very pretty presents, which they shewed to Frederick, and which they had received from their friends, who had been pleased with their behaviour, and had desired they might be allowed to pay them a visit at the next vacation.

Frederick could never forget how much he had lost by his folly; he knew he had been wrong, and, as he was not a bad boy, he was not ashamed to acknowledge it, but wrote a very pretty letter to Mr. Peterson, begging him to forgive the rudeness he had been guilty of, and telling him how much he had suffered by it; assuring him that he would never again desire to quit his house to go to any other, and saying, that he never should have done it, if he had not been a foolish restless boy; that he had been severely punished for his fault, and hoped he would think it enough, and grant him his pardon as soon as possible.

Mr. Peterson readily complied with his request, and invited him, the next time he left school, to accompany his two little friends to his house, where they spent a month in the midst of pleasure and amusement; sometimes riding the ponies to the top of a hill, from whence they could see the hounds followed by the huntsman, and several gentlemen on horseback; at other times assisting their good friend to entertain his tenants with their wives and children round a Christmas fire in the great hall: in short, Frederick was so happy, that he never once thought of Astley, the Park, or the play, or had any desire to quit Mr. Peterson in search of other amusements.

Margaret and Frances lived with their papa and mamma in a pretty white house on the side of a hill; they had a very large garden which led into a meadow, at the bottom of which ran a beautiful river.

Every body thought them the happiest children in the world, and certainly they might have been so, if their dispositions had been more amiable; for their papa and mamma were very fond of them, and indulged them in every thing proper for their age, and their friends were continually bringing them presents of toys and dolls, or some pretty thing or other.

They had each a little garden of their own, full of sweet flowers and shrubs, currants, gooseberries, and strawberries. Margaret had a squirrel, in which she took great delight, for it would jump joyfully about its cage whenever she came near it, and would eat nuts and biscuit out of her hand; and Frances had a beautiful canary-bird in a nice gilt cage, which awoke her every morning with a song, and told her it was time to rise. Margaret's nurse had brought her a white hen with eight little chickens, and Frances had the prettiest bantams that ever were seen.

Their mamma sent them to walk with their maid every evening, either over the hill where the sheep and cows were feeding, or along the side of the clear river, to pick up pebbles, to hear the merry songs of the fishermen, and see the boats pass with the market-people, going to the town with their fruit and their vegetables. Sometimes their papa took them in his pleasure-boat across the river, to eat strawberries and cream at a farm-house; and sometimes they were permitted to accompany their mamma when she went to dine with her friends in the neighbourhood.

It is scarcely to be believed, that two children who might have lived so happily, should have found their greatest pleasure in tormenting each other; and though, before their parents and strangers, they appeared to be all sweetness and good-humour, that they should have been continually contriving how to vex and teaze each other. The moment they were alone, they did nothing but fight and quarrel, and dispute about trifles.

Not contented with this, whenever they were displeased, they did not care what mischief they did, but tried, by every means in their power, to vex each other, by spoiling and destroying every thing which came in their way. Margaret was quite delighted when she had been running over all Frances's garden, and treading down every thing which was growing in it; and Frances, to be revenged on her sister, never failed to go directly and pull up all her flowers by the roots, throw stones at her little chickens, and tear her doll's clothes to pieces.

One day when they had had a great quarrel about some foolish thing not worth mentioning, Margaret was so extremely angry, that she got her mamma's ink-stand, and threw the ink all over her sister's work, and then walked out of the room, leaving it on the table, Frances, who was gone to ask her mamma for some thread, no sooner returned to the parlour, and found her work in so sad a condition, but guessing immediately how it came so, instead of seeking for her sister, and telling her in a gentle manner how wrong she had acted, and begging that all their quarrels might be ended, and that they might live together as sisters should do, and endeavour to make each other happy, instead of spending their time in vexing and teazing each other—instead of doing this, the malicious girl thought of nothing but how she might be revenged; and watching for a favourable opportunity, she seized on a fine damask napkin which had been given to Margaret to hem and mark, threw it down on the hearth, contriving to let one end of it lie over the fender, and then began to poke the fire as violently as she could, hoping some of the cinders would fall upon it, and burn a few holes in it. Her wish was soon accomplished, and even beyond what she desired, for the napkin was in an instant in a blaze, and the house in danger of being burnt to the ground. Terrified almost to death, she began to scream for help, and the whole family were immediately assembled in the parlour; Margaret among the rest, with the bottom of her frock covered with ink, though she had not perceived it, and which too plainly shewed who had done the first mischievous exploit.

They were now both strictly examined, and their tricks soon discovered: their papa and mamma watched them very narrowly, and found that they were quite different when alone, to what they appeared when in their presence; and they no longer treated them with the kindness and indulgence they had hitherto done. Their gardens were taken from them, the squirrel and the canary-bird given away, and the white hen, with her little brood of chickens, sent back to the nurse: they were deprived of all their amusements, and they had lost the good opinion of their parents and friends, for the servants had told their story to every body they met with, and they were never mentioned without being called the Sly Girls, or the Little Quarrellers.

Caroline was trifling away her time in the garden with a little favourite spaniel, her constant companion, when she was sent for to her music-master; and the servant had called her no less than three different times before she thought proper to go into the house.

When the lesson was finished, and the master gone, she turned to her mamma, and asked her, in a fretful and impatient tone of voice, how much longer she was to be plagued with masters—said she had had them a very long time, and that she really thought she now knew quite enough of every thing.

"That you have had them a very long while," answered her mamma, "I perfectly agree with you; but that you have profited so much by their instruction, as you seem to imagine, I am not so certain. I must, however, acquaint you, my dear Caroline, that you will not be plagued with them much longer, for your papa says he has expended such large sums upon your education, that he is quite vexed and angry with himself for having done so, because he finds it impossible to be at an equal expense for your two little sisters; I would therefore advise you, whilst he is so good as to allow you to continue your lessons, to make the most of your time, that it may not be said you have been learning so long to no purpose."

Caroline appeared quite astonished at her mamma's manner of speaking, assured her she knew every thing perfectly, and said, that if her papa wished to save the expense of masters for her sisters, she would undertake to make them quite as accomplished as she herself was.

Some time after this conversation, she accompanied her mamma on a visit to a particular friend who resided in the country; and as there were several gentlemen and ladies at the same time in the house, Caroline was extremely happy in the opportunity she thought it would give her of surprising so large a party by her drawing, music, & and she was not very long before she gave them so many samples of her vanity and self-conceit, as rendered her quite ridiculous and disgusting.

She was never in the least ashamed to contradict those who were older and better instructed than herself, and would sit down to the piano with the utmost unconcern, and attempt to play a sonata which she had never seen before, though at the same time she could not get through a little simple song, which she had been three months learning, without blundering half a dozen times.

There lived, at about the distance of a mile from Mrs. Melvin's house, a widow lady, with her daughter, a charming little girl of thirteen years of age, on whose education (so very limited was her fortune) she had never had it in her power to be at the smallest expense: indeed, her income was so narrow, that, without the strictest economy in every respect, she could not have made it suffice to procure them the necessaries of life; and was obliged to content herself with the little instruction she could give to her child, and with encouraging her as much as possible to exert herself, and endeavour to supply, by attention and perseverance, the want of a more able instructor, and to surmount the obstacles she would have to meet with.

When Caroline heard this talked of, she concluded immediately that Laura must be a poor little ignorant thing, whom she should astonish by a display of her accomplishments, and enjoyed in idea the wonder she would shew, when she beheld her beautiful drawings, heard her touch the keys of the piano, and speak French and Italian as well as her own language; which she wished to persuade herself was the case, though she knew no more of either than she did of all the other things of which she was so vain and conceited.

She told Mrs. Melvin that she really pitied extremely the situation of the poor unfortunate Laura, and wished, whilst she was so near, she could have an opportunity of seeing her frequently, as she might give her some instruction which would be of service to her. Mrs. Melvin was extremely disgusted with the vanity of her friend's daughter, and wishing to give her a severe mortification, which she thought would be of more use to her than any lesson she had ever received, told her she should pay a visit the next morning.

The weather was extremely fine, and the whole company set forward immediately after breakfast, and were soon in sight of a very neat but small house, which they were informed belonged to the mother of Laura. A little white gate opened into a garden in the front of it, which was so neat, and laid out with so much taste, that they all stopped to admire it, for the flowers and shrubs were tied up with the utmost nicety, and not a weed was to be seen in any part of it.

"This is Laura's care," said Mrs. Melvin; "her mamma cannot afford to pay a gardener, but hires a labourer now and then to turn up the ground, and, with the help of their maid, she keeps this little flower garden in the order in which you see it; for by having inquired of those who understand it (instead of fancying herself perfect in all things), she has gained so much information, that she has become a complete florist."

They were shewn into a very neat parlour, which was ornamented with a number of drawings. "Here," says Mrs. Melvin, "you may again see the fruits of Laura's industry and perseverance; she has had no instruction, except the little her mamma could give her, but she was determined to succeed, and has done so, as you may perceive; for these drawings are executed with as much taste and judgment as could possibly be expected of so young a person, even if she had had the advantage of having a master to instruct her. The fringe on the window curtains is entirely of her making, and the pretty border and landscape on that fire-screen is of her cutting."

Caroline began to fear she should not shine quite so much as she had expected to do, and was extremely mortified when Laura came into the room, and was desired to sit down to the piano, at hearing her play and sing two or three pretty little songs, so well and so sweetly, that every one present was delighted with her.

She scarcely ever dared, after this visit, to boast of her knowledge; and if she did, Mrs. Melvin, who was her real friend, and wished to cure her of her vanity, never failed to remind her of the little she knew, notwithstanding all the money which had been expended upon her education, in comparison to Laura, who had never cost her mamma a single shilling.

Charles, William, and Henry, had a large piece of ground given to them to make a garden of. Their papa gave them leave to apply to the gardener for instruction as often as they pleased, but not to expect any assistance from him or any other person: they were to put it in order, and keep it so by their own labour.

"I know," said Charles to William, "that we shall never agree with Henry; he is such an odd boy, that I really believe when once the garden is put in order, he will be contented to walk about and look at it, without ever touching any thing, for he is always quarrelling with us because we have no patience, as he calls it."—"Yes," replied William, "it is very true. Do you remember how angry he was when his bantam hen was hatching her chickens, and we helped to pull them out of the eggs! Who would have thought we should have killed any of them! I am sure I did not; but they were so long, I could not bear to sit there all day waiting for them. I think, Charles, we had better give him his share of the ground, and let him do as he will with it, and you and I will make a pretty garden of the rest, and manage it as we think proper."

This being settled, and the ground fairly divided, they all three went to work with the utmost alacrity. They rose with the lark in the morning, turning up the earth, and clearing it of stones and rubbish; but Henry by himself had got his garden laid out in beds and borders, ready for planting, before Charles and William together had half done theirs: they could not determine how to do it; the borders were too narrow, and must be made broader; this bed must be longer, and that shorter; so that what they did in the morning, they undid in the evening, and their piece of ground lay in confusion and disorder, long after Henry had planted his borders with strawberries, and his beds were sown with annuals, and filled with pretty flowers and bulbous roots.

Charles and William had at length got their garden laid out in tolerable order, and, in other hands, it might soon have been in a very flourishing state; for their papa had given them leave to remove several pretty shrubs from his into their garden, and consequently it already wore a pleasant appearance. Two days had, however, scarcely elapsed, before these whimsical boys were tired of the manner in which their tree, &c. were planted, and longed to remove them.

"This little cherry-tree," said William, "will surely look better at the corner of the wall."

"That it will," answered Charles, "and will grow better there, I dare say; and the rose-trees, do observe how ill they appear at the end of that border—who would ever have thought of planting rose-trees in such a place?"

"Nobody," said Charles, "and we had better change them directly, or it will be supposed we know nothing of gardening, and we shall be laughed at for pretending to it."

No sooner said than done; the plants and flowers were removed, and, in about a week from that day, were all put back into their former places.

When their seeds were just beginning to appear above the ground, they fancied that bed would do better for something else, and in less than five minutes the spade was brought, the bed turned up, and all the little flowers, which were springing up so strong and promising, were destroyed without pity.

What a different appearance did the two gardens make in the month of June! Charles and William saw, with sorrow and regret, that theirs was nothing more than a piece of waste ground; they had removed their trees and shrubs so often, that they had all perished; and not having patience to let their seeds come up and grow into blossom, their beds had nothing in them.

Henry's garden was beautiful; there was not the smallest bit of it but had some pretty flower or fruit-tree growing in it: every part was blooming and sweet; and his two brothers discovered, when too late, that without perseverance and steadiness, nothing can be accomplished, and that unless they came to a determination to follow the good example their brother Henry set before them on this occasion, as on all others, their minds would, like their garden, be uncultivated and waste.

Mr. and Mrs. Clermont invited their little niece, Elizabeth Sinclair, to spend a month with them in the country. Mr. Clermont was extremely fond of children, but his partiality to their company never extended to any who had been improperly and foolishly indulged, and were whimsical and discontented; and had he known that his sister had suffered her little girl to have those disagreeable qualities, he never would have asked her to his house; but he had been two years abroad, and knew nothing of her.

The day on which she was expected, her uncle and aunt went to meet her, and were very much pleased with her appearance, as well as the affectionate manner in which she returned the caresses they bestowed upon her. She was extremely pretty, had fine teeth, fine hair, and a beautiful complexion; and Mr. Clermont said to his wife, "I shall be delighted to have this sweet little creature with me, and to shew all my friends what a charming niece I have." But he was not long in changing his opinion, and very soon discovered that her beauty, much as he had thought of it, did not prevent her being the most disagreeable girl he had ever met with.

She was no sooner in the house than she complained of being too warm, then too cold, and a minute after, too warm again—too tired to sit up, yet not choosing to go to bed—wishing for some tea, and then not liking any thing but milk and water—now drinking it without sugar, then desiring to have some, and, after saying she never supped, bursting into tears because she was going to be sent to bed without supper.

"I perceive I was mistaken," said Mr. Clermont; "this sweet little creature will be a pretty torment to us, if we permit her to have her own way; but I shall put a stop to it immediately."

Accordingly, the next day at dinner, he asked her if she would be helped to some mutton, but she refused it, saying she never could eat any thing roasted. "Then, my dear," replied Mr. Clermont, "here is a boiled potatoe for you; eat that, for you will have nothing else."

Elizabeth was extremely disconcerted, and thought, if she had been at home, her mamma would have ordered half a dozen different things for her, rather than suffer her to eat any thing she disliked, or to dine upon potatoes. She made a very bad dinner, and was cross and out of humour the whole evening.

The next day at table Mr. Clermont offered to help her to some boiled lamb; but Elizabeth, according to her usual custom of never liking what was offered to her, said she could not eat lamb when it was boiled. "So I expected," said Mr. Clermont, "and (taking off the cover from a small dish which was placed next to him) here are some roasted potatoes, which I have provided on purpose, fearing you might not happen to like the rest of the dinner."

Elizabeth began to cry bitterly, but her uncle paid no kind of attention to her tears, only saying that if she preferred a basin of water-gruel, she should have some made in an instant. She was extremely hungry (having quarrelled with her breakfast, and had nothing since), and perceiving that her tears were not likely to produce any good effect, was glad to dine very heartily on lamb and spinage, and to eat some currant tart, which she had said she could not bear even the smell of. She insisted, however, on returning to her mamma immediately, saying she would not stay any longer in a house where she was in danger of being starved, and was sure her mamma would be very angry if she knew how she was treated.

"I am sorry to inform you, my dear niece," said Mr. Clermont, "that you must endeavour to put up with it at least a month or six weeks, for your mamma is gone into Wales on business of consequence, and will not be at home to receive you till that time is expired."

This was sad news for Elizabeth; she was extremely unhappy, and wished a thousand times she had never quitted her own home, where she was indulged in all her whims, and where every one's time was employed in trying to please and amuse her; "And now," thought she, "on the contrary, I never have any thing I like, and my uncle appears to take pleasure in teazing and vexing me from morning to night." Finding, however, that she must either eat what was provided for her, or suffer hunger, and conscious that she had no real dislike to any thing in particular, though she had a great pleasure in plaguing every body about her, she thought it advisable to submit, and consequently dined extremely well every day, whether the meat was roasted or boiled, stewed or fried.

One day, when she was going with her uncle and aunt to take a walk to the next village, a poor miserable woman, with a child in her arms, and followed by two others, met them at the gate, and begged, for God's sake, they would take pity upon her and her helpless infants, who she said had not tasted food since the foregoing day.

Cold meat and bread being immediately brought out to them, both the woman and her children seized upon it with so much eagerness, that they might really be believed to be almost famished.

Mr. Clermont desired Elizabeth would observe them attentively, and, after making her take particular notice of the joy with which the poor people were feasting on the scraps that came from their table, asked her if she thought she ever again could, without being guilty of a dreadful sin, despise, as she frequently had done, and refuse to eat of the wholesome and plentiful food which, through the great goodness of God, her friends were enabled to provide for her.

Elizabeth was struck with her uncle's words, and with the sight before her; she felt that she had, by her ingratitude and unthankfulness to God, rendered herself very undeserving of the comforts he had bestowed upon her, and of which the poor children she was then looking at stood so much in need; and she never, from that day, was heard to find fault with any thing, but prayed that she might in future deserve a continuance of such blessings.

Mr. Spencer sent for his two sons, Edward and Charles, into his closet; he took each of them by the hand, and drawing them affectionately towards him, told them he was going to undertake a long journey, that he hoped they would be very good boys during his absence, obedient and dutiful to their mamma, and never vex or teaze her, but do every thing she wished them to do; he also desired them to be kind to poor Ben, and to recollect, that, though his face was black, he was a very good boy, and that God would love him, whilst he continued to behave well, just as much as if his skin were as white as theirs, and much more than he would either of them, unless they were equally deserving of his love, as black Ben had rendered himself by his good-natured and amiable disposition.

Edward and Charles both promised their papa that they would do every thing he desired, but they were not both equally sincere: Edward could with difficulty hide his joy, when his papa told him he was going from home, for he was a very naughty boy, and had no inclination to obey any body, but to be his own master, and do as he liked, to get into all kinds of mischief, and kick and cuff poor Ben whenever he pleased.

Thinking, however, it would be proper to appear sorry for what he was, in reality, extremely glad of, and seeing poor Charles take out his handkerchief to wipe away his tears, when he was taking leave of his papa, he pulled out his also; but it was not to wipe his eyes, but to hide his smiles, for he was so happy at the thought of all the tricks he could play, without having any one to control him, that he was afraid his joy would be perceived, and his hypocrisy detected.

Mrs. Spencer's health was so indifferent, that she seldom quitted her apartment, so that she knew very little of the behaviour of her sons. Edward, as soon as he had breakfasted, usually took his hat, and went out without telling any one where he was going, or when he should return.

One day, when he was gone away in this manner, and Charles was left quite alone, he went up stairs to his mamma, and asked her leave to take a walk in the fields; and away he went with his favourite dog, for he had no other company, and he said, "Come along, Trimbush, let us take a ramble together; my brother always quarrels and fights with me, but I know you will not, my poor Trimbush: here, my poor old fellow, here is a piece of bread which I saved from my breakfast on purpose for you."

Charles had not walked very far, before he thought he heard Ben crying; and thinking it very probable that his brother was beating him, he went as fast as he possibly could towards the place whence the sound came. There he found poor black Ben with a load of faggots upon his back, almost enough to break it, and Edward whipping him because he cried, and said they were too heavy.

Charles began immediately to unload the poor boy; but Edward said, if he attempted to do so, he would break every bone in his skin: he was, however, not to be frightened from his good-natured and humane intention, and therefore continued to take off the faggots, telling his brother, that if he came near to prevent him, he would try which had most strength; and as Edward was a great coward, and never attempted to strike any body but the poor black boy, who dared not return the blow, he thought it proper to walk away, and leave his brother to do as he liked. When they met afterwards, and Charles offered to shake hands with him, saying he was sorry for what he had said to him, and begged they might be good friends, he appeared very willing to forget what had passed, and assured him he forgave him with all his heart; but his whole thoughts were employed in finding out some way to be revenged on his brother, and he had soon an opportunity of doing what might have cost him his life, though it is to be hoped he was not quite wicked enough to desire it.

Walking one morning by the side of the river, he begged Charles to get into a little boat which lay close to the shore, to look for a sixpence which he pretended to have left in it, and began to sob and cry, because he was afraid he had lost his money. Charles, who was always glad to oblige his brother, jumped into the boat with the utmost readiness, but in an instant the wicked Edward, having cut the rope by which it was fastened, away it went into the middle of the river, and no one can tell whither it might have been driven, or what terrible accident might have happened, if the wind had been high, and had not the good affectionate Ben stripped off his clothes, and plunged into the river to go to Charles's assistance.

Ben could swim like a fish, and was soon within reach of the boat, which, by getting hold of the end of the rope, he brought near enough to the shore for Charles to jump out on a bank.

Edward fancied, that, as his mamma knew nothing of his tricks, and as he was certain Charles was too good-natured to tell tales, his papa would never hear of them: but he was very much mistaken. Old Nicholls, the butler, had observed his behaviour, and as soon as his master returned, took the first opportunity of telling him of every thing which had passed in his absence.

Mr. Spencer now recollected that he had been much to blame in keeping his sons at home, and determined to send them both to school immediately: he observed, however, that they were not equally deserving of kindness and indulgence, and that it would be proper and just to make Edward feel how much he was displeased by the accounts he had received of his conduct: he was therefore sent to a school at a considerable distance from home, so far off, that he neither came home at Christmas nor Whitsuntide, nor saw any of his friends from one year to the other; he was not allowed to have any pocket money, for his papa said he would only make an ill use of it; nor had he ever any presents sent him of any kind.

Charles was only twenty miles from his father's house, and was always at home in the holidays: he had a great many things given to him on new year's day, and his papa brought him a little poney that he might ride about the park; and he always let poor Ben have a ride with him, for he loved him very much; and Ben, who was a grateful, kind-hearted boy, did not forget how many times Charles had saved him from his wicked brother, and would have done any thing in the world to give him pleasure.

"What will become of us to-morrow?" exclaimed a boy at M—— school, to little George Clifton, as they were undressing to go to bed. "I am so frightened, that I shall not be able to close my eyes."

George, who was very sleepy, and had no inclination to be disturbed, scarcely attended to what he was saying; but, on being asked how he thought to get off, and how he should relish a good sound flogging, if he could not excuse himself, he thought it time to inquire into his meaning, and was informed that some of the boys had that evening been robbing the master's garden, that they had taken away all the fruit, both ripe and unripe, and had trodden down and destroyed every thing.

George said he was very sorry for it, but he had no fears on his own account, for he could prove that he had drank tea and spent the whole evening at his aunt's, and was but just returned before their hour of going to bed; but Robert assured him, that all he could say would avail him nothing, and that he was very certain he would not be believed; and moreover, that the master had declared, as he could not discover the offenders he would punish the whole school: "And for my part," said Robert, "I am determined not to stay here, to suffer for what I do not deserve. I can easily slip out of this window into the yard, and at the dawn of day I intend to set off; and shall be many miles from M——, when you are begging in vain for forgiveness of your hard-hearted master."

George, who, though a good boy in other respects, had a very great dislike to the trouble of learning any thing, and had been sent to school much against his inclination, thought this an excellent opportunity of leaving it, and had no doubt, but having such a melancholy story to recount of the injustice of his master, added to the many hardships he fancied he had already endured on different occasions, he should be able to prevail upon his papa to keep him at home; and imagined, that, when he grew up to be a man, he should, by some means or other, have as much learning and knowledge as other people, without plaguing himself with so many books and lessons. Robert had therefore very little difficulty in persuading him to accompany him, which he had no reason to wish for, but that he knew he had always a good deal of pocket-money, which he hoped to get possession of, and cared very little, if once he could carry that point, what became of poor George. He knew him to be quite innocent, and also that the master was well acquainted with the names of the boys who had done the mischief, and consequently had no thought of punishing the whole school; but he was a wicked boy, had been the chief promoter of the robbery, long tired of confinement, and determined to run away. At four o'clock in the morning they got out of the window into the yard, jumped over a low wall, and were soon several miles from the school.

Poor little George began, before it was long, to grow very tired; he was hungry also, and had nothing to eat. Robert asked him if he had any money, and said he would soon procure him something to eat, if he would give him the means of paying for it; but the moment he had got his little purse in his hand, he told him that he must now wish him a good morning; that he was not such a fool as to go home to get a horsewhipping for having run away from school, but should go immediately to Portsmouth, where he should find ships enough ready to sail for different parts of the world, and would go to sea, which was, he said, the pleasantest life in the world; and making him a very low bow, he set off immediately across the fields towards the high road, and was out of sight in an instant.

George began to cry bitterly; he now repented having listened to this wicked boy's advice, and would have returned to school if he could; but he did not know the way back again, and, if he had known it, would have been afraid to see his master. He wandered on the whole long day, without seeing any body who thought it worth their while to stop to listen to his tale; and at length, towards the close of evening, quite ill for want of eating, and so tired that he could no longer stand, he seated himself by the side of a brook, and leaning his head upon his hand, sobbed aloud.

An old peasant returning from his labour, and passing that way, stopped to look at him, and perceiving that he was in much distress, went up to the place where he was sitting, and inquired kindly what ailed him.

"I am a naughty boy," said George, "and do not deserve that you should take notice of me."—"When naughty boys confess their faults, they are more than half cured of them," replied the old peasant. "Whatever you have done, I am sure you repent of it, and I will take care of you."

He then took him by the hand, and led him to his cottage, which was very near, and where he found an old woman spinning near the window, and a young one sitting with two pretty little girls and a boy, whom she was teaching to read: they had each a book in their hand, and were so attentive to their lessons, that they scarcely looked up when the door was opened.

"There," said the old peasant, "sits my good wife, this is my daughter, and these are her children: we are poor people, and cannot afford to spend much money on their education, but they are very good, and endeavour to learn what they can from their mother, and get their lessons ready against the hour they go to school in the morning, that they may make the most of their time, and not rob their parents by being idle."

"Rob their parents!" exclaimed George. "Yes, rob them," replied the old man. "Would it not be robbing their father and mother, if they allowed them to squander their money upon them in paying for their schooling to no purpose?"

George wiped the tears from his eyes, and said he was afraid he was a very bad boy; but he was sorry for it, and would endeavour to mend, if his papa could be prevailed on to pardon what was past. He then told the old man all that had happened, and how the wicked Robert had enticed him to run away from school; but he was so hungry, and so fatigued, that he could hardly speak or hold up his head. The young woman gave him a large bowl of milk and bread, and put him into a neat, clean bed, where he slept soundly till eight o'clock the next morning, when, after a comfortable breakfast, the good peasant accompanied him to his father's house, and said so much in his favour, and of the sorrow he had shewn for his ill behaviour, that he was immediately forgiven.

He was, at his own desire, taken back to school, where he entreated his master to pardon the little attention he had paid to his books, and the instruction he had been so good as to give him; as also his elopement, a fault he had, he said, repented of almost as soon as he had committed it.

The master readily forgave him upon his acknowledging his error, and assured him, that, though he always punished those who deserved it, he knew very well how to distinguish the innocent from the guilty, and that, whilst he behaved like a good boy, he would have no reason to fear his anger.

Rose was eight years of age when her sister Harriet was born: she was extremely fond of the baby, watched its cradle whilst it slept, and was never tired of looking at it, and admiring its little features; but she could not, without pain, observe, that she was no longer, as she had been accustomed to be, the sole object of her mamma's care and attention.

Harriet must not be left a moment! Harriet must not be disturbed! And even if her mamma had the head-ach, and Rose was not suffered to go into her room, the little stranger was admitted. She concluded that she was no longer loved by any body, for even the servants were, she fancied, more occupied with her little sister than with her, or any thing which concerned her; and before she was ten years of age, she was become so very jealous and fretful, that she took no pleasure in any thing, nor was it in the power of any one to please or amuse her.

One day walking in the garden with her mamma, who carried the little Harriet in her arms, and coming to a part of it where several tall and far-spreading trees afforded them a pleasant shade from the heat of the sun, they stopped to enjoy its coolness. The gardener was ordered to bring them some cherries, and they sat down on the grass to await his coming: the little one, however, had no inclination to be so long still, and her mamma, to please and keep her quiet, lifted her up, and seated her on the bough of a tree which spread above their heads.

Rose immediately changed colour; her countenance, which a moment before was tolerably cheerful, now became gloomy and sullen; she leaned her cheek upon her hand, and her eyes followed them, expressing nothing but discontent and jealousy.

Her mamma was not long before she perceived the angry glances thrown upon her, and asked her, in a tone of displeasure, what they signified? "I cannot help fearing," said Rose, "that you no longer love me, now that you have another little girl. I remember, when you played with me all day; I was then continually on your knee, and every thing you had was brought out to amuse me; the servants also thought of nothing but how to give me pleasure; but now I go neglected about the house, and nobody minds me: it is true, I have every thing I want, and my papa and you are always buying me toys and pretty things of one kind or another; and I have often some of my little friends, whom you allow me to invite to drink tea, and spend the afternoon with me; but——"

"But," interrupted her mamma, "I no longer take you upon my knee like a baby, or carry you in my arms; nor have I strength sufficient to lift you up, and place you upon the bough of a tree, to please and make you quiet, as I have done by your little sister. You forget, I imagine, that you are ten years old, and that if I were to treat you in the same manner as I do a child of two, we should both be laughed at by every creature who might happen to see us. Reflect, my dear Rose, and do not suppose, that, because the helpless age of this little darling demands more care and attention than is necessary to you—because, being her nurse, I am obliged to have her often with me, when the company of another would be troublesome and inconvenient to me—do not fancy, my love, from these circumstances, that you are less beloved by either your papa or myself; but that as you increase in years, we shall shew our affection to you in a very different way to that in which we now do; as at present we treat you much otherwise than we did when you were of the age of your sister Harriet.