SUMMER

DALLAS LORE SHARP

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Summer, by Dallas Lore Sharp This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Summer Author: Dallas Lore Sharp Release Date: February 23, 2013 [EBook #42170] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SUMMER *** Produced by Greg Bergquist, Matthew Wheaton and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

SUMMER

DALLAS LORE SHARP

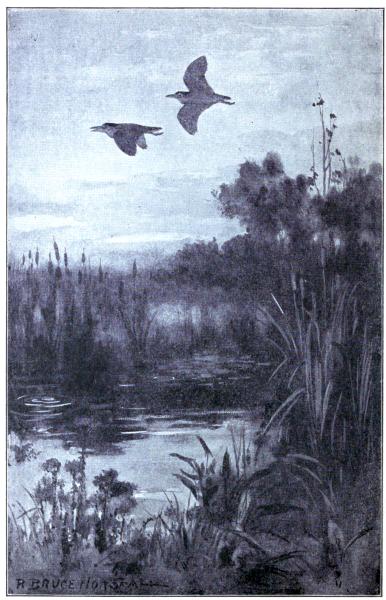

A SUMMER EVENING—NIGHT HERONS

(page 54)

The Dallas Lore Sharp Nature Series

ILLUSTRATED BY

ROBERT BRUCE HORSFALL

BOSTON NEW YORK CHICAGO

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY PERRY MASON COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1913 AND 1914, BY THE ATLANTIC MONTHLY COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY THE CENTURY COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & CO.

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY DALLAS LORE SHARP

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Riverside Press

CAMBRIDGE . MASSACHUSETTS

U . S . A

TO

ROBERT BRUCE HORSFALL

THE FRIEND AND ARTIST

OF THESE FOUR BOOKS

| Introduction | ix | |

| I. | The Summer Afield | 1 |

| II. | The Wild Animals at Play | 9 |

| III. | A Chapter of Things to See this Summer | 18 |

| IV. | The Coyote of Pelican Point | 27 |

| V. | From T Wharf to Franklin Field | 39 |

| VI. | A Chapter of Things to Hear this Summer | 46 |

| VII. | The Sea-Birds’ Home | 57 |

| VIII. | The Mother Murre | 65 |

| IX. | Mother Carey’s Chickens | 79 |

| X. | Riding the Rim Rock | 88 |

| XI. | A Chapter of Things to Do this Summer | 100 |

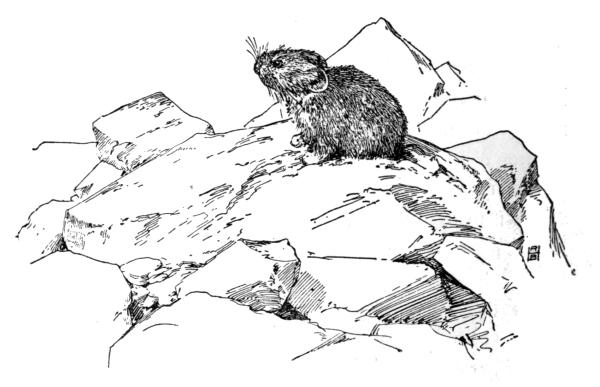

| XII. | The “Cony” | 112 |

| Notes and Suggestions | 123 |

In this fourth and last volume of these outdoor books I have taken you into the summer fields and, shall I hope? left you there. After all, what better thing could I do? And as I leave you there, let me say one last serious word concerning the purpose of such books as these and the large subject of nature-study in general.

I believe that a child’s interest in outdoor life is a kind of hunger, as natural as his interest in bread and butter. He cannot live on bread and butter alone, but he ought not to try to live without them. He cannot be educated on nature-study alone, but he ought not to be educated without it. To learn to obey and reason and feel—these are the triple ends of education, and the greatest of these is to learn to feel. The teacher’s word for obedience; the arithmetic for reasoning; and for feeling, for the cultivation of the imagination, for the power to respond quickly and deeply, give the child the out-of-doors.

“If I could teach my Rugby boys but one thing,” said Dr. Arnold, “that one thing should be poetry.” Why? Because poetry draws out the imagination, quickens and refines and deepens the emotions. The first great source of poetry is Nature. Give the child poetry; and give him the inspiration of the poem, the teacher of the poet—give him Nature. Make a poet of the child, who is already a poet born.

How can so essential, so fundamental a need become a mere fad of education? A child wants first to eat, then to play, then he wants to know—particularly he wants to know the animals. And he does know an elephant from a kangaroo long before he knows a Lincoln from a Napoleon; just so he wants to go to the woods long before he asks to visit a library.

The study of the ant in the school-yard walk, the leaves on the school-yard trees, the clouds over the school-house roof, the sights, sounds, odors coming in at the school-room windows, these are essential studies for art and letters, to say nothing of life.

And this is the way serious men and women think about it. Captain Scott, dying in the Antarctic snows, wrote in his last letter to his wife: “Make our boy interested in natural history if you can. It is better than games. Keep him in the open air.”

I hope that these four volumes may help to interest you in natural history, that they may be the means of taking you into the open air of the fields many times the seasons through.

Mullein Hill, February, 1914.

SUMMER

The word summer, being interpreted, means vacation; and vacation, being interpreted, means—so many things that I have not space in this book to name them. Yet how can there be a vacation without mountains, or seashore, or the fields, or the forests—days out of doors? My ideal vacation would have to be spent in the open; and this book, the larger part of it, is the record of one of my summer vacations—the vacation of the summer of 1912. That was an ideal vacation, and along with my account of it I wish to give you some hints on how to make the most of your summer chance to tramp the fields and woods.

For the real lover of nature is a tramp; not the kind of tramp that walks the railroad-ties and carries his possessions in a tomato-can, but one who follows the cow-paths to the fields, who treads the rabbit-roads in the woods, watching the ways of the wild things that dwell in the tree-tops, and in the deepest burrows under ground.

Do not tell anybody, least of all yourself, that you love the out-of-doors, unless you have your own path to the woods, your own cross-cut to the pond, your own particular huckleberry-patch and fishing-holes and friendships in the fields. The winds, the rain, the stars, the green grass, even the birds and a multitude of other wild folk try to meet you more than halfway, try to seek you out even in the heart of the great city; but the great out-of-doors you must seek, for it is not in books, nor in houses, nor in cities. It is out at the end of the car-line or just beyond the back-yard fence, maybe—far enough away, anyhow, to make it necessary for you to put on your tramping shoes and with your good stout stick go forth.

You must learn to be a good tramper. You thought you learned how to walk soon after you got out of the cradle, and perhaps you did, but most persons only know how to hobble when they get into the unpaved paths of the woods.

With stout, well-fitting shoes, broad in the toe and heel; light, stout clothes that will not catch the briers, good bird-glasses, and a bite of lunch against the noon, swing out on your legs; breathe to the bottom of your lungs; balance your body on your hips, not on your collar-bones, and, going leisurely, but not slowly (for crawling is deadly dull), do ten miles up a mountain-side or through the brush; and if at the end you feel like eating up ten miles more,[Pg 3] then you may know that you can walk, can tramp, and are in good shape for the summer.

In your tramping-kit you need: a pocket-knife; some string; a pair of field-glasses; a botany-can or fish-basket on your back; and perhaps a notebook. This is all and more than you need for every tramp. To these things might be added a light camera. It depends upon what you go for. I have been afield all my life and have never owned or used a camera. But there are a good many things that I have never done. A camera may add a world of interest to your summer, so if you find use for a camera, don’t fail to make one a part of your tramping outfit.

After all, what you carry on your back or on your feet or in your hands does not matter half so much as what you carry in your head and heart—your eye, and spirit, and purpose. For instance, when you go into the fields have some purpose in your going besides the indefinite desire to get out of doors.

If you long for the wide sky and the wide winds and the wide slopes of green, then that is a real and a definite desire. You want to get out, OUT, OUT, because you have been shut in. Very good; for you will get what you wish, what you go out to get. The point is this: always go out for something. Never yawn and slouch out to the woods as you might to the corner grocery store, because you don’t know how else to kill time.

Go with some purpose; because you wish to visit some particular spot, see some bird, find some flower, catch some—fish! Anything that takes you into the open is good—ploughing, hoeing, chopping, fishing, berrying, botanizing, tramping. The aimless person anywhere is a failure, and he is sure to get lost in the woods!

It is a good plan to go frequently over the same fields, taking the beaten path, watching for the familiar things, until you come to know your haunt as thoroughly as the fox or the rabbit knows his. Don’t be afraid of using up a particular spot. The more often you visit a place the richer you will find it to be in interest for you.

Now, do not limit your interest and curiosity to any one kind of life or to any set of things out of doors. Do not let your likes or your prejudices interfere with your seeing the whole out-of-doors with all its manifold life, for it is all interrelated, all related to you, all of interest and meaning. The clover blossom[Pg 5] and the bumblebee that carries the fertilizing pollen are related; the bumblebee and the mouse that eats up its grubs are related; and every one knows that mice and cats are related; thus the clover, the bumblebee, the mouse, the cat, and, finally, the farmer, are all so interrelated that if the farmer keeps a cat, the cat will catch the mice, the mice cannot eat the young bumblebees, the bumblebees can fertilize the clover, and the clover can make seed. So if the farmer wants clover seed to sow down a new field with, he must keep a cat.

I think it is well for you to have some one thing in which you are particularly interested. It may be flowers or birds or shells or minerals. But as the whole is greater than any of its parts, so a love and knowledge of nature, of the earth and the sky over your head and under your feet, with all that lives with you there, is more than a knowledge of its birds or trees or reptiles.

But be on your guard against the purpose to spread yourselves over too much. Don’t be thin and superficial. Don’t be satisfied with learning the long Latin names of things while never watching the ways of the things that have the names. As they sat on the porch, so the story goes, the school trustee called attention to a familiar little orange-colored bug, with black spots on his back, that was crawling on the floor.

“I s’pose you know what that is?” he said.

“Yes,” replied the applicant, with conviction; “that is a Coccinella septempunctata.”

“Young man,” was the rejoinder, “a feller as don’t know a ladybug when he sees it can’t get my vote for teacher in this deestrict.”

The “trustee” was right; for what is the use of knowing that the little ladybug is Coc-ci-nel’-la sep-tem-punc-ta’-ta when you do not know that she is a ladybug, and that you ought to say to her:—

Let us say, now, that you are spending your vacation in the edge of the country within twenty miles of a great city such as Boston. That might bring you out at Hingham, where I am spending mine. In such an ordinary place (if any place is ordinary,) what might you expect to see and watch during the summer?

Sixty species of birds, to begin with! They will keep you busy all summer. The wild animals, beasts, that you will find depend so very much upon your locality—woods, waters, rocks, etc.—that it is hard to say how many they will be. Here in my woods you might come upon three or four species of mice, three species of squirrels, the mink, the muskrat, the weasel, the mole, the shrew, the fox, the skunk, the rabbit, and even a wild deer. Of reptiles and amphibians you would see several more species than of fur-bearing animals,—six snakes, four common turtles, two salamanders,[Pg 7] frogs, toads, newts,—a wonderfully interesting group, with a real live rattler among them if you should go over to the Blue Hills, fifteen miles away.

RED SALAMANDERS, OLD AND YOUNG

You will go many times into the fields before you can make of the reptiles your friends and neighbors. But by and by you will watch them and note their ways with as much interest as you watch the other wild folk about you. It is a pretty shallow lover of nature who jumps upon a little snake with both feet, or who shivers when a little salamander drops out of the leaf-mould at his feet.

NEWTS

And what shall I say of the fishes? There are a dozen of them in the stream and ponds within the compass of my haunt. They are a fascinating family, and one very little watched by the ordinary tramper. But you are not ordinary. Quiet and patience and much putting together of scraps of observations will be necessary if you are to get at the whole story of any fish’s life. The story will be worth it, however.

No, I shall not even try to number the insects—the butterflies, beetles, moths, wasps, bees, bugs, ticks, mites, and such small “deer” as you will find in the round of your summer’s tramp. Nor shall I try to name the flowers and trees, the ferns and mosses. It is with the common things that you ought now to become familiar, and one summer is all too short for the things you ought to see and hear and do in your vacation out of doors.

The watcher of wild animals never gets used to the sight of their mirthless sport. In all other respects animal play is entirely human.

A great deal of human play is serious—desperately serious on the football-field, and at the card-table, as when a lonely player is trying to kill time with solitaire.

I have watched a great ungainly hippopotamus for hours trying to do the same solemn thing by cuffing a croquet-ball back and forth from one end of his cage to the other. His keepers told me that without the plaything the poor caged giant would fret and worry himself to death. It was his game of solitaire.

In all their games of rivalry the animals are serious as humans, and, forgetting the fun, often fall to fighting—a sad case, indeed. But brutes are brutes. We cannot expect anything better of the animals. Only this morning the whole flock of chickens in the hen-yard started suddenly on the wild flap to see which would beat to the back fence and wound up on the “line” in a free fight, two of the cockerels tearing the feathers from each other in a desperate set-to.

You have seen puppies fall out in the same human fashion, and kittens also, and older folk as well. I have seen a game of wood-tag among friendly gray squirrels come to a finish in a fight. As the crows pass over during the winter afternoon, you will notice their play—racing each other through the air, diving, swooping, cawing in their fun, when suddenly some one’s temper snaps, and there is a mix-up in the air.

They can get angry, but they cannot laugh. I once saw what I thought was a twinkle of merriment, however, in an elephant’s eye. It was at the circus several years ago. The keeper had just set down for one of the elephants a bucket of water which a perspiring youth had brought in. The big beast sucked it quietly up,—the whole of it,—swung gently around as if to thank the perspiring boy, then soused him, the whole bucketful! Everybody roared, and one of the other elephants joined in with trumpetings, so huge and jolly was the joke.

The elephant who played the trick looked solemn[Pg 11] enough, except for a twitch at the lips and a glint in the eye. There is something of a smile about every elephant’s lips, to be sure, and fun is so contagious that one should hesitate to say that he saw an elephant laugh. But if that elephant didn’t laugh, it was not his fault.

From the elephant to the infusorian, the microscopic animal of a single cell known as the paramœcium, is a far cry—to the extreme opposite end of the animal kingdom, worlds apart. Yet I have seen Paramœcium caudatum at play in a drop of water under a compound microscope, as I have seen elephants at play in their big bath-tub at the zoölogical gardens.

Place a drop of stagnant water under your microscope and watch these atoms of life for yourself. Invisible to the naked eye, they are easily followed on the slide as they skate and whirl and chase one another to the boundaries of their playground and back again, first one of them “it,” then another. They stop to eat, they slow up to divide their single-celled bodies into two cells, the two cells now two living creatures where a moment before they were but one, both of them swimming off immediately to feed and multiply and play.

Play seems to be as natural and as necessary to the wild animals as it is to human beings. Like us the animals play hardest while young, but as some human children never outgrow their youth and love[Pg 12] of play, so there are old animals that never grow too fat nor too stiff nor too stupid to play.

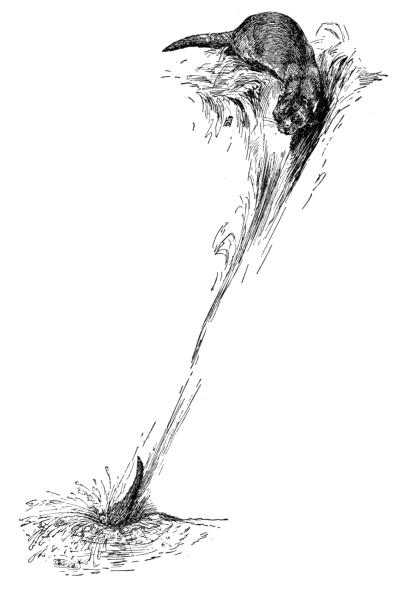

The condition of the body has a great deal to do with the state of the spirit. The sleek, lithe otter could not possibly grow fat. He keeps in trim because he cannot help it, perhaps, but however that may be, he is a very boy for play, and even goes so far as to build himself a slide or chute for the fun of diving down it into the water. A writer in one of the magazines tells of an otter in the New York Zoölogical Park that swam and dived with a round stone balanced on his head.

Building a slide is more than we children used to do, for we had ready-made for us grandfather’s two big slanting cellar-doors, down which we slid and slid and slid till the wood was scoured white and slippery with the sliding. The otter loves to slide. Up he climbs on the[Pg 13] bank, then down he goes—splash—into the stream. Up he climbs and down he goes—time after time, day after day. There is nothing like a slide, unless it is a cellar-door.

How much of a necessity to the otter is his play, one would like to know—what he would give up for it, and how he would do deprived of it. In the case of Pups, my neighbor’s beautiful young collie, play seems more needful than food. There are no children, no one, to play with him there, so that the sight of my small boys sets him almost frantic.

His efforts to induce a hen or a rooster to play with him are pathetic. The hen cannot understand. She hasn’t a particle of play in her anyhow, but Pups cannot get that through his head. He runs rapidly around her, drops on all fours flat, swings his tail, cocks his ears, looks appealingly and barks a few little cackle-barks, as nearly hen-like as he can bark them, then dashes off and whirls back—while the hen picks up another bug. She never sees Pups. The old white coon cat is better; but she is usually up the miff-tree. Pups steps on her, knocks her over, or otherwise offends, especially when he tags her out into the fields and spoils her hunting. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals ought to send some child or puppy out to play with Pups of a Saturday.

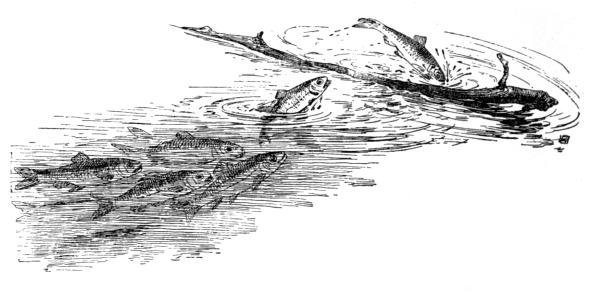

I doubt if among the lower forms of animals play[Pg 14] holds any such prominent place as with the dog and the keen-witted, intelligent otter. To catch these lower animals at play is a rare experience. One of our naturalists describes the game of “follow my leader,” as he watched it played by a school of minnows—a most unusual record, but not at all hard to believe, for I saw recently, from the bridge in the Boston Public Garden, a school of goldfish playing at something very much like it.

This naturalist was lying stretched out upon an old bridge, watching the minnows through a large crack between the planks, when he saw one leap out of the water over a small twig floating at the surface. Instantly another minnow broke the water and flipped over the twig, followed by another and another, the whole school, as so many sheep, or so many children, following the leader over the twig.

The love of play seems to be one of the elemental needs of all life above the plants, and the games of[Pg 15] us human children seem to have been played before the dry land was, when there were only water babies in the world, for certainly the fish never learned “follow my leader” from us. Nor did my young bees learn from us their game of “prisoners’ base” which they play almost every summer noontime in front of the hives. And what is the game the flies play about the cord of the drop-light in the centre of the kitchen ceiling?

One of the most interesting animal games that I ever saw was played by a flock of butterflies on the very top of Mount Hood, whose pointed snow-piled peak looks down from the clouds over the whole vast State of Oregon.

Mount Hood is an ancient volcano, eleven thousand two hundred twenty-five feet high. Some seven thousand feet or more up, we came to “Tie-up Rock”—the place on the climb where the glacier snows lay before us and we were tied up to one another and all of us fastened by rope to the guide.

From this point to the peak, it was sheer deep snow. For the last eighteen hundred feet we clung to a rope that was anchored on the edge of the crater at the summit, and cut our steps as we climbed.

Once we had gained the peak, we lay down behind a pile of sulphurous rock, out of the way of the cutting wind, and watched the steam float up from the crater, with the widest world in view that I ever turned my eyes upon.

The draft pulled hard about the openings among the rock-piles, but hardest up a flue, or chimney, that was left in the edge of the crater-rim where parts of the rock had fallen away.

As we lay at the side of this flue, we soon discovered that butterflies were hovering about us; no, not hovering, but flying swiftly up between the rocks from somewhere down the flue. I could scarcely believe my eyes. What could any living thing be doing here?—and of all things, butterflies? This was three or four thousand feet above the last vestige of vegetation, a mere point of volcanic rock (the jagged edge-piece of an old crater) wrapped in eternal ice and snow, with sulphurous gases pouring over it, and across it blowing[Pg 17] a wind that would freeze as soon as the sun was out of the sky.

But here were real butterflies. I caught two or three of them and found them to be vanessas (Vanessa californica), a close relative of our mourning-cloak butterfly. They were all of one species, apparently, but what were they doing here?

Scrambling to the top of the piece of rock behind which I had been resting, I saw that the peak was alive with butterflies, and that they were flying—over my head, out down over the crater, and out of sight behind the peak, whence they reappeared, whirling up the flue past me on the wings of the draft that pulled hard through it, to sail down over the crater again, and again to be caught by the draft and pulled up the flue, to their evident delight, up and out over the peak, where they could again take wings, as boys take their sleds, and so down again for the fierce upward draft that bore them whirling over Mount Hood’s pointed peak.

Here they were, thousands of feet above the snow-line, where there was no sign of vegetation, where the heavy vapors made the air to smell, where the very next day a wild snowstorm wrapped its frozen folds about the peak—here they were, butterflies, playing, a host of them, like so many schoolboys on the first coasting snow!

The dawn, the breaking dawn! I know nothing lovelier, nothing fresher, nothing newer, purer, sweeter than a summer dawn. I am just back from one—from the woods and cornfields wet with dew, the meadows and streams white with mist, and all the world of paths and fences running off into luring spaces of wavering, lifting, beckoning horizons where shrouded forms were moving and hidden voices calling. By noontime the buzz-saw of the cicada will be ripping the dried old stick of this August day into splinters and sawdust. No one could imagine that this midsummer noon at 90° in the shade could have had so Maylike a beginning.

I said in “The Spring of the Year” that you should see a farmer ploughing, then a few weeks later the field of sprouting corn. Now in July or August you must see that field in silk and tassel, blade and stalk standing high over your head.

You might catch the same sight of wealth in a cotton-field, if cotton is “king” in your section; or in a[Pg 19] vast wheat-field, if wheat is your king; or in a potato-field if you live in Maine—but no, not in a potato-field. It is all underground in a potato-field. Nor can cotton in the South, or wheat in the Northwest, give you quite the depth and the ranked and ordered wealth of long, straight lines of tall corn.

Then to hear a summer rain sweep down upon it and the summer wind run swiftly through it! You must see a great field of standing corn.

Keep out from under all trees, stand away from all tall poles, but get somewhere in the open and watch a blue-black thunderstorm come up. It is one of the wonders of summer, one of the shows of the sky, a thing of terrible beauty that I must confess I cannot look at without dread and a feeling of awe that rests like a load upon me.

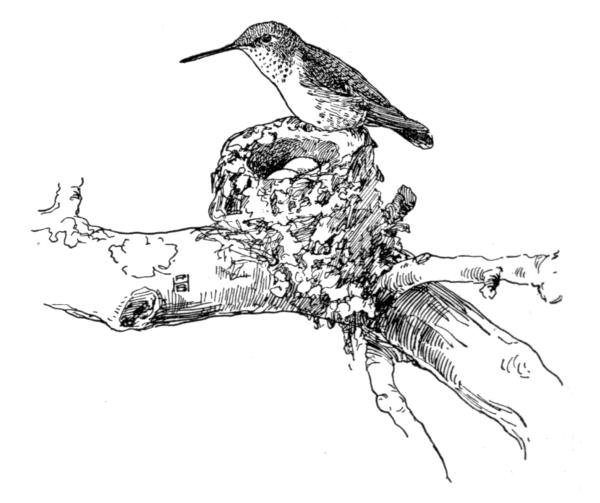

But there are many smaller, individual things to be seen this summer, and among them, notable for many reasons, is a hummingbird’s nest. “When completed it is scarcely larger than an English walnut and is usually saddled on a small horizontal limb of a tree or shrub frequently many feet from the ground. It is composed almost entirely of soft plant fibers, fragments of spiders’ webs sometimes being used to hold them in shape. The sides are thickly studded with bits of lichen, and practiced, indeed, is the eye of the man who can distinguish it from a knot on the limb.”

This is the smallest of birds’ nests and quite as rare and difficult to find as any single thing that you can go out to look for. You will stumble upon one now and then; but not many in a whole lifetime. Let it be a test of your keen eye—this finding of a little hummer’s nest with its two white eggs[Pg 21] the size of small pea-beans or its two tiny young that are up and off on their marvelous wings within three weeks from the time the eggs are laid!

Have you read Mr. William L. Finley’s story of the California condor’s nest? The hummingbird young is out and gone within three weeks; but the condor young is still in the care of its watchful parents three months after it is hatched. You ought to watch the slow, guarded youth of one of the larger hawks or owls during the summer. Such birds build very early,—before the snow is gone sometimes,—but they are to be seen feeding their young far into the summer. The wide variety in bird-life, both in size and habits, will be made very plain to you if you will watch the nests of two such birds as the hummer and the vulture or the eagle.

This is the season of flowers. But what among them should you especially see? Some time ago one of the school-teachers near me brought in a list of a dozen species of wild orchids, gathered out of the meadows, bogs, and woods about the neighborhood. Can you do as well?

Suppose, then, that you try to find as many. They were the pink lady’s-slipper; the yellow lady’s-slipper; the yellow fringed-orchis (Habenaria ciliaris);[Pg 22] the ladies’-tresses, two species; the rattlesnake-plantain; arethusa, or Indian pink; calopogon, or grass pink; pogonia, or snake-mouth (ophioglossoides and verticillata); the ragged fringed-orchis; and the showy or spring orchis. Arethusa and the showy orchis really belong to the spring but the others will be task enough for you, and one that will give point and purpose to your wanderings afield this summer.

ORCHIDS

1. Arethusa bulbosa

2. Pogonia ophioglossoides

3. Pink Lady’s-Slipper

4. Yellow Lady’s-Slipper

5. Showy Orchis

There are a certain number of moths and butterflies that you should see and know also. If one could come to know, say, one hundred and fifty flowers and the moths and butterflies that visit them (for the flower and its[Pg 23] insect pollen-carrier are to be thought of and studied together), one would have an excellent speaking acquaintance with the blossoming out-of-doors.

Now, among the butterflies you ought to know the mourning-cloak, or vanessa; the big red-brown milkweed butterfly; the big yellow tiger swallowtail; the small yellow cabbage butterfly; the painted beauty; the red admiral; the common fritillary; the common wood-nymph—but I have named enough for this summer, in spite of the fact that I have not named the green-clouded or Troilus butterfly, and Asterias, the black swallowtail, and the red-spotted purple, and the viceroy.

Among the moths to see are the splendid Promethea, Cecropia, bullseye, Polyphemus, and Luna, to say nothing of the hummingbird moth, and the sphinx, or hawk, moths, especially the large one that feeds as a caterpillar upon the tomato-vines, Ma-cros’-i-la-quin-que-mac-u-la’-ta.

There is a like list of interesting beetles and other insects, that play a large part in even your affairs, which you ought to watch during the summer: the honeybee, the big droning golden bumblebee, the large white-faced hornet that builds the paper nests in the bushes and trees, the gall-flies, the ichneumon-flies, the burying beetle, the tumble-bug beetle, the dragon-fly, the caddis-fly—these are only a few of[Pg 24] a whole world of insect folk about you, whose habits and life-histories are of utmost importance and of tremendous interest. You will certainly believe it if you will read the Peckhams’ book called “Wasps, Social and Solitary,” or the beautiful and fascinating insect stories by the great French entomologist Fabre. Get also “Every-day Butterflies,” by Scudder; and “Moths and Butterflies,” by Miss Dickerson, and “Insect Life,” by Kellogg.

You see I cannot stop with this list of the things. That is the trouble with summer—there is too much of it while it lasts, too much variety and abundance of life. One is simply compelled to limit one’s self to some particular study, and to pick up mere scraps from other fields.

But, to come back to the larger things of the out-of-doors, you should see the mist some summer morning very early or some summer evening, sheeted and still over a winding stream or pond, especially in the evening when the sun has gone down behind the hill, the flame has faded from the sky, and over the rim of the circling slopes pours the soft, cool twilight, with a breeze as soft and cool, and a spirit that is prayer. For then from out the deep shadows of the wooded shore, out over the pond, a thin white veil will come creeping—the mist, the breath of the sleeping water, the soul of the pond!

You should see it rain down little toads this summer—if you can! There are persons who claim to have seen it. But I never have. I have stood on Maurice River Bridge, however, and apparently had them pelting down upon my feet as the big drops of the July shower struck the planks—myriads of tiny toads covering the bridge across the river! Did they rain down? No, they had been hiding in the dirt between the planks and hopped out to meet the sweet rain and to soak their little thirsty skins full.

You should see a cowbird’s young in a vireo’s nest and the efforts of the poor deceived parents to satisfy its insatiable appetite at the expense of their own young ones’ lives! Such a sight will set you to thinking.

I shall not tell you what else you should see, for the whole book could be filled with this one chapter, and then you might lose your forest in your trees. The individual tree is good to look at—the mighty wide-limbed hemlock[Pg 26] or pine; but so is a whole dark, solemn forest of hemlocks and pines good to look at. Let us come to the out-of-doors with our study of the separate, individual plant or thing; but let us go on to Nature, and not stop with the individual thing.

“We have stopped the plumers,” said the game-warden, “and we are holding the market-hunters to something like decency; but there’s a pot-hunter yonder on Pelican Point that I’ve got to do up or lose my job.”

Pelican Point was the end of a long, narrow peninsula that ran out into the lake, from the opposite shore, twelve miles across from us. We were in the Klamath Lake Reservation in southern Oregon, one of the greatest wild-bird preserves in the world.

Over the point, as we drew near, the big white pelicans were winging, and among them, as our boat came up to the rocks, rose a colony of black cormorants. The peninsula is chiefly of volcanic origin, composed of crumbling rock and lava, and ends in well-stratified cliffs at the point. Patches of scraggly sagebrush grew here and there, and out near the cliffs on the sloping lava sides was a field of golden California poppies.

The gray, dusty ridge in the hot sun, with cliff swallows and cormorants and the great pouched pelicans[Pg 28] as inhabitants, seemed the last place that a pot-hunter would frequent. What could a pot-hunter find here? I wondered.

We were pulling the boat up on the sand at a narrow neck in the peninsula, when the warden touched my arm. “Up there near the sky-line among the sage! What a shot!”

I was some seconds in making out the head and shoulders of a coyote that was watching us from the top of the ridge.

“The rascal knows,” went on the warden, “I have no gun; he can smell a gun clear across the lake. I have tried for three years to get that fellow. He’s the terror of the whole region, and especially of the Point; if I don’t get him soon, he’ll clean out the pelican colony.

“Why don’t I shoot him? Poison him? Trap him? I have offered fifty dollars for his hide. Why don’t I? I’ll show you. Now you watch the critter as I lead you up the slope toward him.”

We had not taken a dozen steps when I found myself staring hard at the place where the coyote had been, but not at the coyote, for he was gone.[Pg 29] He had vanished before my eyes. I had not seen him move, although I had been watching him steadily.

“Queer, isn’t it?” said the warden. “It’s not his particular dodge, for every old coyote that has been hunted learns to work it; but I never knew one that had it down so fine as this sinner. There’s next to nothing here for him to skulk behind. Why, he has given my dog the slip right here on the bare rock! But I’ll fix him yet.”

I did not have to be persuaded to stay overnight with the warden for the coyote-hunt the next day. The warden, I found, had fallen in with a Mr. Harris, a homesteader, who had been something of a professional coyote-hunter. Harris had just arrived in southern Oregon, and had brought with him his dogs, a long, graceful greyhound, and his fighting mate, a powerful Russian wolfhound; both were crack coyote dogs from down Saskatchewan. He had accepted the warden’s offer of fifty dollars for the hide of the coyote of Pelican Point, and was now on his way round the lake.

The outfit appeared late the next day, and consisted of the two dogs, a horse and buckboard, and a big, empty dry-goods box.

I had hunted possums in the gum swamps of the South with a stick and a gunny-sack, but this rig, on the rocky, roadless shores of the lake—a dry-goods box for coyotes!—beat any hunting combination I had ever seen.

We had pitched the tent on the south shore of the point where the peninsula joined the mainland, and were finishing our supper, when not far from us, back on shore, we heard the doleful yowl of the coyote.

We were on our feet in an instant.

“There he is,” said the warden, “lonesome for a little play with your dogs, Mr. Harris.”

There was still an hour and a half of good light, and Harris untied his dogs. I had never seen the coyote hunted, and was greatly interested. Harris, with his dogs close in hand, led us directly away from where we had heard the coyote bark. Then we stopped and sat down. At my look of inquiry, Harris smiled.

“Oh, no, we’re not after coyotes to-night, not that coyote, anyhow,” he said. “You know a coyote is made up of equal parts of curiosity, cowardice, and craft; and it’s a long hunt unless you can get a lead on his curiosity. We are not out for him. He sees that. In fact, we’ll amble back now—but we’ll manage to get up along the crest of that little ridge where he is sitting, so that the dogs can follow him whichever way he runs. You hunt coyotes wholly by sight, you know.”

The little trick worked perfectly. The coyote, curious to see what we were doing, had risen to his feet, and stood, plainly outlined against the sky. He was entirely unsuspecting, and as we approached,[Pg 31] only edged and backed, more apparently to get a sight of the dogs behind us than through any fear.

Suddenly Harris stepped from before the dogs, pointed them toward the coyote, and slipped their leashes. The hounds were trained to the work. There was just an instant’s pause, a quick yelp, then two doubling, reaching forms ahead of us, with a little line of dust between.

The coyote saw them coming, and started to run, not hurriedly, however, for he had had many a run before. He was not afraid, and kept looking behind to see what manner of dog was after him this time.

But he was not long in making up his mind that this was an entirely new kind, for in less than three minutes the hounds had halved the distance that separated him from them. At first, the big wolfhound was in the lead. Then, as if it had taken him till this time to find all four of his long legs, the greyhound pulled himself together, and in a burst of speed that was astonishing, passed his heavier companion.

We raced along the ridge to see the finish. But the coyote ahead of the dogs was no novice. He knew the game perfectly. He saw the gap closing behind him. Had he been young, he would have been seized by fear; would have darted right and left, mouthing and snapping in abject terror. Instead of that, he dug his nails into the shore, and with all his wits about him, sped for the desert. The greyhound was close behind him.

I held my breath. Harris, I think, would have taken his fifty dollars then and there! And the warden would have handed it to him, despite his past experience with the beast; but suddenly the coyote headed straight off for a low manzanita bush that stood up amid the scraggly sagebrush back from the shore.

The hunt was now going directly from us, with the dust and the wolfhound behind, following the line in front. The gap between the greyhound and the coyote seemed to have closed, and when the hound took the low manzanita with a bound that was half-somersault, Harris exclaimed, “He’s nailed him!” and we ran ahead to see the wolfhound complete the job.

The wolfhound, however, kept right on across the desert; the greyhound lagged uncertainly far behind; in the lead, ahead of the big grizzled wolfhound, bobbed the form of a fleeing jack-rabbit!

The look of astonishment and then of disgust on Harris’s face was amusing to see. The warden may have been disappointed, but he did not take any pains to repress a chuckle.

Harris said nothing. He was searching the stunted sagebrush off to the left of us. We followed his eyes, and he and the warden, both experienced plainsmen, picked out the skulking, shadowy shape of the coyote, as the creature, with belly to the ground, slunk off out of sight.

It was too late for any further attempt that night.

“An old stager, sure,” Harris commented, as we[Pg 33] returned to camp. “Knows a trick or two for every one of mine. But I’ll fix him.”

Nothing was seen of the coyote all the early part of the next day, and no effort was made to find him; but toward the middle of the afternoon, Harris hitched up the bronco, and, unpacking a flat package in the bottom of the buckboard, showed us a large glass window, which he fitted as a door into one end of the big dry-goods box. Then into the glass-ended box he put the two hounds.

“Now, gentlemen,” he said, “I’m going to invite you to take a sight-seeing trip on this auto out into the sagebrush. Incidentally, if you chance to see a coyote, don’t mention it.”

If all the coyotes, jack-rabbits, gophers, and pelicans of the territory had come out to see us thump and bump over the dry, uneven desert, I should not have been surprised; and so, on coming back to camp, it was with no wonder at all that I discovered the coyote, out on the point, staring at us from across the neck of the peninsula. Nothing like this had happened on his side of the lake before.

Harris saw him instantly, and was quick to recognize our advantage. We had the coyote cornered—out on the long, narrow peninsula, where the dogs must run him down. The wily creature had so far forgotten himself as to get caught between us and the ridge along shore, and, partly in curiosity, had kept running ahead and stopping to look at us, until[Pg 34] now he was past the place where he could skulk back without our seeing him, into the open plain.

Even yet all depended upon our getting so close to him that the dogs could keep him constantly in sight. The crumbling ledges at the end of the point were full of holes and crevices into which the beast could dodge.

We were not close enough, however. With one of us watching the coyote, should he happen to run, Harris turned the bronco slowly round until the glass end of the box in the back of the buckboard was pointing directly at the creature. There was a scramble of feet inside the box. The dogs had sighted the beast. Then Harris started as if to drive away, the coyote watching us all the time.

Instead of driving off, he made a circle, and coming back slowly toward the coyote, gained the top of a little knoll. Had the coyote seen the dogs in the box, he would have vanished instantly; but the box interested and puzzled him.

He stood looking with all his eyes as the procession turned, and once more the glass end of the box was pointed directly toward him. The dogs evidently knew what was expected of them. They were silent, but ready. Suddenly, without stopping the pony, Harris pulled open the glass door, and yelled, “Go!”

And go they did. I never saw hundred-yard runners leap from the mark as those two hounds leaped from that box. The coyote, in his astonishment, actually[Pg 35] turned a back handspring and started for the point.

The dogs were hardly two hundred yards behind him, and were making short work of the space between. It seemed hardly fair, and I must say that I felt something like sympathy for the under dog, wild dog though he was; the odds against him were so great.

But the coyote knew his track thoroughly, and was taking advantage of the rough, loose, shelving ground. For the farther out toward the end of the point they ran, the narrower, rockier, and steeper grew the peninsula, the more difficult and dangerous the footing.

The coyote slanted along the side of the ridge, and took a sloping slab of rock ahead of him with a slow side-step and a climb that brought the dogs close up behind him. They took the rock at a leap, slid halfway across, and scrambling, rolled several yards down the slope—and lost all the gain they had made.

Things began to even up. The chase began to be interesting. Here judgment was called for, as well as speed. The cliff swallows swarmed out of their nests under the overhanging rocks; the black cormorants and great-winged pelicans saw their old enemy coming, and rose, flapping, over the water; the circling gulls dropped low between the runners; their strange clangor and the stranger tropical shapes thick in[Pg 36] the air gave the scene a wildness altogether new to me.

On fled the coyote; on bounded the dogs. He would never escape! Nothing without wings could ever do it! Mere feet could never stand such a test! The chances that pursued and pursuers took—the leaps—the landings! The whole slope seemed rolling with stones, started by the feet of the runners.

They were nearing the high, rough rocks of the tip of the point. Between them and the ledges of the point, and reaching from the edge of the water nearly to the top of the ridge, lay the steep golden garden of California poppies, blooming in the dry lava soil that had crumbled and drifted down on the rocky side.

The coyote veered, and dashed down toward the middle of the poppies; the hounds hit the bed two jumps behind. There was a cloud of dust, and in it we saw an avalanche of dogs ploughing a wide furrow through the flowers nearly down to the water. Climbing slowly out near the upper edge of the bed was the coyote, again with a good margin of lead.

But the beast was at the end of the point, and nearing the end of his race. Had we been out of the way, he might have turned and yet given the dogs the slip—for behind us lay the open desert.

Straight toward the rocks he headed, with the hounds laboring up the slope after him. He was[Pg 37] running to the very edge of the point, as if he were intending to leap off the cliff to death in the lake below, and I saw Harris’s face tighten as his hounds topped the ridge, and senselessly tore on toward the same fearful edge. But the race was not done yet. The coyote hesitated, turned down the ledges on the south slope, and leaping in among the cormorant nests, started back toward us.

He was surer on his feet than were the hounds, but this hesitation on the point had cost him several yards. The hounds would pick him up in the little cove of smooth, hard sand that lay, encircled by rough rocks, just ahead, unless—no, he must cross the cove, he must take the stretch. He was taking it—knowingly, too, and with a burst of power that he had not shown upon the slopes. He was flinging away his last reserve.

The hounds were nearly across; the coyote was within fifty feet of the boulders, when the greyhound, lowering his long, flat head, lunged for the spine of his quarry.

The coyote heard him coming, spun on his fore feet, offering his fangs to those of his foe, and threw himself backward just as the jaws of the wolfhound clashed at him and flecked his throat with foam.

The two great dogs collided and bounded wide apart, startling a jack rabbit that dived between them into a hole among the rocks. The coyote, on his feet in an instant, caught the motion of the rabbit, and[Pg 38] like his shadow, leaped into the air after him for the hole.

He was as quick as thought, quicker than either of the hounds. He sprang high over them,—safely over them, we thought,—when, in mid-air, at the turn of the dive, he twisted, heeled half-over, and landed hard against the side of the hole; and the wolfhound pulled him down.

It was over; but there was something strange, almost unfair, it seemed, about the finish.

Before we got down to the cove both of the dogs had slunk back, cowering from the dead coyote. Then there came to us the buzz of a rattlesnake—a huge, angry reptile that lay coiled in the mouth of the hole. The rabbit had struck and roused the snake. The coyote in his leap had caught the warning whir, but caught it too late to clear both snake and hounds. His twist in the air to clear the snake had cost him his life. So close is the race in the desert world.

Over and over I read the list of saints and martyrs on the wall across the street, thinking dully how men used to suffer for their religion, and how, nowadays, they suffer for their teeth. For I was reclining in a dentist’s chair, blinking through the window at the Boston Public Library, seeing nothing, however, nothing but the tiles on the roof, and the names of Luther, Wesley, Wycliffe, graven on the granite wall, while the dentist burred inside of my cranium and bored down to my toes for nerves. So, at least, it seemed.

By and by my gaze wandered blankly off to the square patch of sky in sight above the roof. A black cloud was driving past in the wind away up there. Suddenly a white fleck swept into the cloud, careened, spread two wide wings against it, and rounded a circle. Then another and another, until eight herring gulls were soaring white against the sullen cloud in that little square of sky high over the roofs of Boston.

Was this the heart of a vast city? Could I be in a dentist’s chair? There was no doubt about the chair; but how quickly the red-green roof of the Library[Pg 40] became the top of some great cliff; the droning noise of traffic in the streets, the wash of waves against the rocks; and yonder on the storm-stained sky those wheeling wings, how like the winds of the ocean, and the raucous voices, how they seemed to fill all the city with the sweep and the sound of the sea!

Boston, Baltimore, New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco—do you live in any one of them or in any other city? If you do, then you have a surprisingly good chance to watch the ways of wild things and even to come near to the heart of Nature. Not so good a chance, to be sure, as in the country; but the city is by no means so lacking in wild life or so shunned by the face of Nature as we commonly believe.

All great cities are alike, all of them very different, too, in details; Boston’s streets, for instance, being crookeder than most, but like them all, reaching out for many a mile before they turn into country roads and lanes with borders of quiet and wide green fields.

But Boston has the wide waters of the Harbor and the Charles River Basin. And it also has T Wharf! They did not throw the tea overboard there, back in Revolutionary days, as you may be told, but T Wharf is famous, nevertheless, famous for fish!

Fish? Swordfish and red snappers, scup, shad,[Pg 41] squid, squeteague, sharks, skates, smelts, sculpins, sturgeon, scallops, halibut, haddock, hake—to say nothing of mackerel, cod, and countless freak things caught by trawl and seine all the way from Boston Harbor to the Grand Banks! I have many a time sat on T Wharf and caught short, flat flounders with my line. It is almost as good as a trip to the Georges in the “We’re Here” to visit T Wharf; and then to walk slowly up through Quincy Market. Surely no single walk in the woods will yield a tithe of the life to be found here, and found only here for us, brought as the fish and game and fruits have been from the ends of the earth and the depths of the sea.

There is no reason why city children should not know a great deal about animal life, nor why the teachers in city schools should feel that nature study is impossible for them. For, leaving the wharf with its fish and gulls and fleet of schooners, you come up four or five blocks to old King’s Chapel Burying-Ground where the Boston sparrows roost. Boston is full of interesting sights, but none more interesting to the bird-lover than this sparrow-roost. The great bird rocks in the Pacific, described in another chapter of this book, are larger, to be sure, yet hardly more clamorous when, in the dusk, the sparrow clans begin to gather; nor hardly wilder than this city roost when the night lengthens, and the quiet creeps down the alleys and along the empty streets, and the sea winds stop on the corners, and the lamps,[Pg 42] like low-hung stars, light up the sleeping birds till their shadows waver large upon the stark walls about the old graveyard that break far overhead as rim rock breaks on the desert sky.

Now shift the scene to an early summer morning on Boston Common, two blocks farther up, and on to the Public Garden across Charles Street. There are more wild birds to be seen in the Garden on a May morning than there are here in the woods of Hingham, and the summer still finds some of them about the shrubs and pond. And it is an easy place in which to watch them. One of our bird-students has found over a hundred species in the Garden. Can any one say that the city offers a poor chance for nature-study?

This is the story of every great city park. My friend Professor Herbert E. Walter found nearly one hundred and fifty species of birds in Lincoln Park, Chicago. And have you ever read Mr. Bradford Torrey’s delightful essay called “Birds on Boston Common”?

Then there are the squirrels and the trees on the Common; the flowers, bees, butterflies, and even the schools of goldfish, in the pond of the Garden—enough of life, insect-life, plant-life, bird-life, fish-life, for more than a summer of lessons.

Nor is this all. One block beyond the Garden stands the Natural History Museum, crowded with mounted specimens of birds and beasts, reptiles,[Pg 43] fishes, and shells beyond number—more than you can study, perhaps. You city folk, instead of having too little, have altogether too much of too many things. But such a museum is always a suggestive place for one who loves the out-of-doors. And the more one knows of nature, the more one gets out of the museum. You can carry there, and often answer, the questions that come to you in your tramps afield, in your visits to the Garden, and in your reading of books. Then add to this the great Agassiz Museum at Harvard University, and the Aquarium at South Boston, and the Zoölogical Gardens at Franklin Park, and the Arnold Arboretum—all of these with their multitude of mounted specimens and their living forms for you! For me also; and in from the country I come, very often, to study natural history in the city.

What is true of Boston is true of every city in some degree. The sun and the moon and stars shine upon the city as upon the country, and during my years of city life (I lived in the very heart of Boston) it was my habit to climb to my roof, above the din and glare of the crowded street, and here among the chimney-pots to lie down upon my back, the city far below me, and overhead the blue sky, the Milky Way, the constellations, or the moon, swinging—

Here, too, I have watched the gulls that sail over the Harbor, especially in the winter. From this outlook I have seen the winging geese pass over, and heard the faint calls of other migrating flocks, voices that were all the more mysterious for their falling through the muffling hum that rises from the streets and spreads over the wide roof of the city as a soft night wind over the peaked roofs of a forest of firs.

ARGIOPE, THE MEADOW SPIDER

Strangely enough here on the roof I have watched the only nighthawks that I have ever found in Massachusetts. This is surely the last place you would expect to find such wild, spooky, dusk-loving creatures as nighthawks. Yet here, on the tarred and pebbled roofs, here among the whirling, squeaking, smoking chimney-pots, here above the crowded, noisy streets, these birds built their nests,—laid their eggs, rather, for they build no nests,—reared their young, and in[Pg 45] the long summer twilight rose and fell through the smoky air, uttering their peevish cries and making their ghostly booming sounds with their high-diving, just as if they were out over the darkening swales along some gloomy swamp-edge.

For many weeks I had a big tame spider in the corner of my study there in that city flat, and I have yet to read an account of all the species of spiders to be found dwelling within the walls of any great city. Even Argiope of the meadows is doubtless found in the Fens. Not far away from my flat, down near the North Station, one of my friends on the roof of his flat kept several hives of bees. They fed on the flowers of the Garden, on those in dooryards, and on the honey-yielding lindens which stand here and there throughout the city. Pigeons and sparrows built their nests within sight of my windows; and by going early to the roof I could see the sun rise, and in the evening I could watch it go down behind the hills of Belmont as now I watch it from my lookout here on Mullein Hill.

One is never far from the sky, nor from the earth, nor from the free, wild winds, nor from the wilder night that covers city and sea and forest with its quiet, and fills them all with lurking shadows that never shall be tamed.

The fullness, the flood, of life has come, and, contrary to one’s expectations, a marked silence has settled down over the waving fields and the cool deep woods. I am writing these lines in the lamplight, with all the windows and doors open to the dark July night. The summer winds are moving in the trees. A cricket and a few small green grasshoppers are chirping in the grass; but nothing louder is near at hand. And nothing louder is far off, except the cry of the whip-poor-will in the wood road. But him you hear in the spring and autumn as well as in the summer. Ah, listen! My tree-toad in the grapevine over the bulkhead door!

This is a voice you must hear—on cloudy summer days, toward twilight, and well into the evening. Do you know what it is to feel lonely? If you do, I think, then, that you know how the soft, far-off, eerie cry of the tree-toad sounds. He is prophesying rain, the almanac people think, but I think it is only the sound of rain in his voice, summer rain after a long drouth, cooling, reviving, soothing rain, with just a[Pg 47] patter of something in it that I cannot describe, something that I used to hear on the shingles of the garret over the rafters where the bunches of horehound and catnip and pennyroyal hung.

You ought to hear the lively clatter of a mowing-machine. It is hot out of doors; the roads are beginning to look dusty; the insects are tuning up in the grass, and, like their chorus all together, and marching round and round the meadow, moves the mower’s whirring blade. I love the sound. Haying is hard, sweet work. The farmer who does not love his haying ought to be made to keep a country store and sell kerosene oil and lumps of dead salt pork out of a barrel. He could not appreciate a live, friendly pig.

Down the long swath sing the knives, the cogs click above the square corners, and the big, loud thing sings on again,—the song of “first-fruits,” the first great ingathering of the season,—a song to touch the heart with joy and sweet solemnity.

You ought to hear the Katydids—two of them on the trees outside your window. They are not saying “Katy did,” nor singing “Katy did”; they are fiddling “Katy did,” “Katy didn’t”—by rasping the fore wings.

Is the sound “Katy” or “Katy did”? or what is said? Count the notes. Are they at the rate of two hundred per minute? Watch the instrumentalist—till you make sure it is the male who is wooing Katy with his persistent guitar. The male has no long ovipositors.

Another instrumentalist to hear is the big cicada or “harvest-fly.” There is no more characteristic sound of all the summer than his big, quick, startling whirr—a minute mowing-machine up on the limb overhead! Not so minute either, for the creature is fully two inches long, with bulging eyes and a click to his wings when he flies that can be heard a hundred feet away! “Dog-days-z-z-z-z-z-z-z” is the song he sings to me.

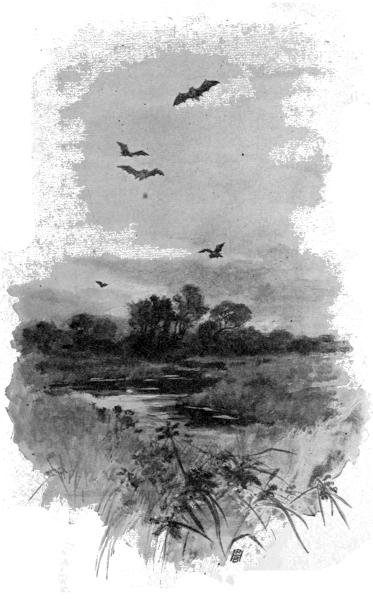

“FLITTING AND WAVERING ABOUT”

This is the season of small sounds. As a test of the keenness of your ears go out at night into some open glade in the woods or by the side of some pond and listen for the squeaking of the bats flitting and wavering above in the uncertain light over your head. You will need a stirless midsummer dusk; and if you can hear the thin, fine squeak as the creature dives near your head, you may be sure your ears are almost as keen as those of the fox. The sound is not audible to most human ears.

Another set of small sounds characteristic of midsummer is the twittering of the flocking swallows in the cornfields and upon the telegraph-wires. This summer I have had long lines of the young birds and their parents from the old barn below the hill strung on the wires from the house across the lawn. Here they preen while some of the old birds hawk for flies, the whole line of them breaking into a soft little twitter each time a newcomer alights among them. One swallow does not make a summer, but your electric light wires sagging with them is the very soul of the summer.

In the deep, still woods you will hear the soft call of the robin—a low, pensive, plaintive note unlike[Pg 52] its spring cry or the after-shower song. It is as if the voice of the slumberous woods were speaking—without alarm, reproach, or welcome either. It is an invitation to stretch yourself on the deep moss and let the warm shadows of the summer woods steal over you with sleep.

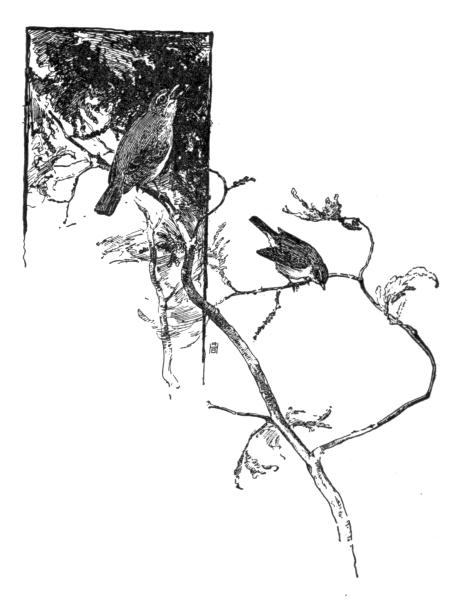

THE RED-EYED VIREO

And this, too, is a thing to learn. Doing something, hearing something, seeing something by no means exhausts our whole business with the out-of-doors. To lie down and do nothing, to be able to keep silence and to rest on the great whirling globe is as needful as to know everything going on about us.

There is one bird-song so characteristic of midsummer that I think every lover of the woods must know it: the oft-repeated, the constant notes of the red-eyed vireo or “preacher.” Wilson Flagg says of him: “He takes the part of a deliberative orator who explains his subject in a few words and then makes a pause for his hearers to reflect upon it. We might suppose him to be repeating moderately with a pause between each sentence, ‘You see it—you know it—do you hear me?—do you believe it?’ All these strains are delivered with a rising inflection at the close, and with a pause, as if waiting for an answer.”

A few other bird-notes that are associated with hot days and stirless woods, and that will be worth your hearing are the tree-top song of the scarlet tanager. He is one of the summer sights, a dash of the burning tropics is his brilliant scarlet and jet black, and his song is a loud, hoarse, rhythmical carol that has the flame of his feathers in it and the blaze of the sun. You will know it from the cool, liquid song of the robin both by its peculiar quality and because it is a short song, and soon ended, not of indefinite length like the robin’s.

Then the peculiar, coppery, reverberating, or[Pg 54] confined song of the indigo bunting—as if the bird were singing inside some great kettle.

One more—among a few others—the softly falling, round, small, upward-swinging call of the wood pewee. Is it sad? Yes, sad. But sweeter than sad,—restful, cooling, and inexpressibly gentle. All day long from high above your head and usually quite out of view, the voice—it seems hardly a voice—breaks the long silence of the summer woods.

When night comes down with the long twilight there sounds a strange, almost awesome quawk in the dusk over the fields. It sends a thrill through me, notwithstanding its nightly occurrence all through July and August. It is the passing of a pair of night herons—the black-crowned, I am sure, although this single pair only fly over. Where the birds are numerous they nest in great colonies.

It is the wild, eerie quawk that you should hear, a far-off, mysterious, almost uncanny sound that fills the twilight with a vague, untamed something, no matter how bright and civilized the day may have been.

From the harvest fields comes the sweet whistle of Bob White, the clear, round notes rolling far through the hushed summer noon; in the wood-lot the[Pg 55] crows and jays have already begun their cawings and screamings that later on become the dominant notes of the golden autumn. They are not so loud and characteristic now because of the insect orchestra throbbing with a rhythmic beat through the air. So wide, constant, and long-continued is this throbbing note of the insects that by midsummer you almost cease to notice it. But stop and listen—field crickets, katydids, long-horned grasshoppers, snowy tree-crickets: chwĭ-chwĭ-chwĭ-chwĭ—thrr-r-r-r-r-r-r —crrri-crrri-crrri-crrri—gru-gru-gru-gru— retreat-retreat-retreat-treat-treat—like the throbbing of the pulse.

One can do no more than suggest in a short chapter like this; and all that I am doing here is catching for you some of the still, small voices of my summer. How unlike those of your summer they may be I can easily imagine, for you are in the Pacific Coast, or off on the vast prairies of Canada, or down in the sunny fields and hill-country of the South.

I have done enough if I have suggested that you stop and listen; for after all it is having ears which hear not that causes the trouble. Hear the voices that make your summer vocal—the loud and still voices which alike pass unheeded unless we pause to hear.

As a lesson in listening, go out some quiet evening, and as the shadows slip softly over the surface of the wood-walled pond, listen to the breathing of the fish as they come to the top, and the splash of the muskrats, or the swirl of the pickerel as he ploughs a furrow through the silence.

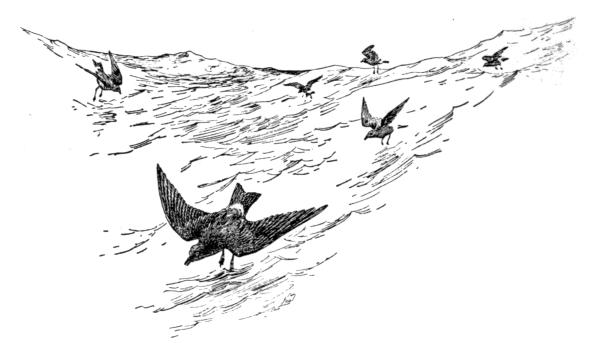

After my wandering for years among the quiet lanes and along the winding cow-paths of the home fields, my trip to the wild-bird rocks in the Pacific Ocean, as you can imagine, was a thrilling experience. We chartered a little launch at Tillamook, and, after a fight of hours and hours to cross Tillamook Bar at the mouth of the bay, we got out upon the wide Pacific, and steamed down the coast for Three-Arch Rocks, which soon began to show far ahead of us just off the rocky shore.

I had never been on the Pacific before, nor had I ever before seen the birds that were even now beginning to dot the sea and to sail over and about us as we steamed along. It was all new, so new that the very water of the Pacific looked unlike the familiar water of the Atlantic. And surely the waves were different,—longer, grayer, smoother, with an immensely mightier heave. At least they seemed so, for every time we rose on the swell, it was as if our boat were in the hand of Old Ocean, and his mighty arm were “putting” us, as the athlete “puts” the shot. It was all new and strange and very wild to me, with the wild cries of the sea-birds already[Pg 58] beginning to reach us as flocks of the birds passed around and over our heads.

The fog was lifting. The thick, wet drift that had threatened our little launch on Tillamook Bar stood clear of the shouldering sea to the westward, and in over the shore, like an upper sea, hung at the fir-girt middles of the mountains, as level and as gray as the sea below. There was no breeze. The long, smooth swell of the Pacific swung under us and in, until it whitened at the base of the three rocks that rose out of the sea in our course, and that now began to take on form in the foggy distance. Gulls were flying over us, lines of black cormorants and crowds of murres were winging past, but we were still too far away from the looming rocks to see that the gray of their walls was the gray of uncounted colonies of nesting birds, colonies that covered their craggy steeps as, on shore, the green firs clothed the slopes of the Coast Range Mountains up to the hanging fog.

As we ran on nearer, the sound of the surf about the rocks became audible, the birds in the air grew more numerous, their cries now faintly mingling with the sound of the sea. A hole in the side of the middle Rock, a mere fleck of foam it seemed at first, widened rapidly into an arching tunnel through which our boat might run; the swell of the sea began to break over half-sunken ledges; and soon upon us fell the damp shadows of the three great rocks, for now we were looking far up at their sides, where we could[Pg 59] see the birds in their guano-gray rookeries, rookery over rookery,—gulls, cormorants, guillemots, puffins, murres,—encrusting the sides from tide-line to pinnacles, as the crowding barnacles encrusted the bases from the tide-line down.

TUFTED PUFFINS

We had not approached without protest, for the birds were coming off to meet us, wheeling and clacking overhead, the nearer we drew, in a constantly thickening cloud of lowering wings and tongues. The clamor was indescribable, the tossing flight enough to make one mad with the motion of wings. The air was filled, thick, with the whirling and the screaming, the clacking, the honking, close to our ears, and high up in the peaks, and far out over the waves. Never had I been in this world before. Was I on my earth? or had I suddenly wakened up in some old sea world where there was no dry land, no life but this?

We rounded the outer or Shag Rock and headed slowly in opposite the yawning hole of the middle Rock as into some mighty cave, so sheer and shadowy rose the walls above us,—so like to cavern thunder was the throbbing of the surf through the hollow arches, was the flapping and screaming of the birds[Pg 60] against the high circling walls, was the deep, menacing grumble of the bellowing sea-lions, as, through the muffle of surf and sea-fowl, herd after herd lumbered headlong into the foam.

It was a strange, wild scene. Hardly a mile from the Oregon coast, but cut off by breaker and bar from the abrupt, uninhabited shore, the three rocks of the Reservation, each pierced with its resounding arch, heaved their huge shoulders from the waves straight up, high, towering, till our little steamer coasted their dripping sides like some puffing pygmy.

Each rock was perhaps as large as a solid city square and as high as the tallest of sky-scrapers; immense, monstrous piles, each of them, and run through by these great caverns or arches, dim, dripping, filled with the noise of the waves and the beat of thousands of wings.

They were of no part or lot with the dry land. Their wave-scooped basins were set with purple starfish and filled with green and pink anemones, and beaded many deep with mussels of amethyst and jet that glittered in the clear beryl waters; and, above the jeweled basins, like fabled beasts of old, lay the sea-lions, uncouth forms, flippered, reversed in shape, with throats like the caves of Æolus, hollow, hoarse, discordant; and higher up, on every jutting bench and shelf, in every weathered rift, over every jog of the ragged cliffs, to their bladed backs and pointed peaks, swarmed the sea-birds, webfooted, amphibious,[Pg 61] shaped of the waves, with stormy voices given them by the winds that sweep in from the sea.

As I looked up at the amazing scene, at the mighty rocks and the multitude of winging forms, I seemed to see three swirling piles of life, three cones that rose like volcanoes from the ocean, their sides covered with living lava, their craters clouded with the smoke of wings, while their bases seemed belted by the rumble of a multi-throated thunder. The very air was dank with the smell of strange, strong volcanic gases,—no breath of the land, no odor of herb, no scent of fresh soil; but the raw, rank smells of rookery and den, saline, kelpy, fetid; the stench of fish and bedded guano, and of the reeking pools where the sea-lion herds lay sleeping on the lower rocks in the sun.

A boat’s keel was beneath me, but as I stood out on the pointed prow, barely above the water, and found myself thrust forward without will or effort among the crags and caverns, among the shadowy walls, the damps, the smells, the sounds, among the bellowing beasts in the churning waters about me, and into the storm of wings and tongues in the whirling air above me, I passed from the things I had known, and the time and the earth of man, into a monstrous period of the past.

This was the home of the sea-birds. Amid all the din we landed from a yawl and began our climb toward the top of Shag Rock, the outermost of the[Pg 62] three. And here we had another and a different sight of the wild life. It covered every crag. I clutched it in my hands; I crushed it under my feet; it was thick in the air about me. My narrow path up the face of the rock was a succession of sea-bird rookeries, of crowded eggs, and huddled young, hairy or naked or wet from the shell. Every time my fingers felt for a crack overhead they touched something warm that rolled or squirmed; every time my feet moved under me, for a hold, they pushed in among top-shaped eggs that turned on the shelf or went over far below; and whenever I hugged the pushing wall I must bear off from a mass of squealing, struggling, shapeless things, just hatched. And down upon me, as rookery after rookery of old birds whirred in fright from their ledges, fell crashing eggs and unfledged young, that the greedy gulls devoured ere they touched the sea.

I was midway in the climb, at a bad turn round a point, edging inch by inch along, my face pressed against the hard face of the rock, my feet and fingers gripping any crack or seam they could feel, when out of the deep space behind me I caught the swash of waves. Instantly a cold hand seemed to clasp me from behind.

I flattened against the rock, my whole body, my very mind clinging desperately for a hold,—a falling fragment of shale, a gust of wind, the wing-stroke of a frightened bird, enough to break the hold and[Pg 63] swing me out over the water, washing faint and far below. A long breath, and I was climbing again.

BRANDT’S CORMORANT

We were on the outer Rock, our only possible ascent taking us up the sheer south face. With the exception of an occasional Western gull’s and pigeon guillemot’s nest, these steep sides were occupied entirely by the California murres,—penguin-shaped birds about the size of a small wild duck, chocolate-brown above, with white breasts,—which literally covered the sides of the three great rocks wherever they could find a hold. If a million meant anything, I should say there were a million murres nesting on this outer Rock; not nesting either, for the egg is laid upon the bare ledge, as you might place it upon a mantel,—a single sharp-pointed egg, as large as a turkey’s, and just as many of them on the ledge as there is standing-room for the birds. The murre broods her very large egg by standing straight up over it, her short legs, by dint of stretching, allowing her to straddle it, her short tail propping her securely from behind.

On, up along the narrow back, or blade, of the rock, and over the peak, were the well-spaced nests of the Brandt’s cormorants, nests the size of an ordinary straw hat, made of sea-grass and the yellow-flowered sulphur-weed that grew in a dense mat over the north slope of the top, each nest holding four long, dirty blue eggs or as many black, shivering young; and in the low sulphur-weed, all along the roof-like slope of the top, built the gulls and the tufted puffins; and, with the burrowing puffins, often in the same holes, were found the Kaeding’s petrels; while down below them, as up above them,—all around the rock-rim that dropped sheer to the sea,—stood the cormorants, black, silent, statuesque; and everywhere were nests and eggs and young, and everywhere were flying, crying birds—above, about, and far below me, a whirling, whirring vortex of wings that had caught me in its funnel.

I hear the bawling of my neighbor’s cow. Her calf was carried off yesterday, and since then, during the long night, and all day long, her insistent woe has made our hillside melancholy. But I shall not hear her to-night, not from this distance. She will lie down to-night with the others of the herd, and munch her cud. Yet, when the rattling stanchions grow quiet and sleep steals along the stalls, she will turn her ears at every small stirring; she will raise her head to listen and utter a low, tender moo. Her full udder hurts; but her cud is sweet. She is only a cow.

Had she been a wild cow, or had she been out with her calf in a wild pasture, the mother-love in her would have lived for six months. Here in the barn she will be forced to forget her calf in a few hours, and by morning her mother-love shall utterly have died.

There is a mother-principle alive in all nature that never dies. This is different from mother-love. The oak tree responds to the mother-principle, and bears acorns. It is a law of life. The mother-love or passion, on the other hand, occurs only among the higher[Pg 66] animals. It is very common; and yet, while it is one of the strongest, most interesting, most beautiful of animal traits, it is at the same time the most individual and variable of all animal traits.

This particular cow of my neighbor’s that I hear lowing, is an entirely gentle creature ordinarily, but with a calf at her side she will pitch at any one who approaches her. And there is no other cow in the herd that mourns so long after her calf. The mother in her is stronger, more enduring, than in any of the other nineteen cows in the barn. My own cow hardly mourns at all when her calf is taken away. She might be an oak tree losing its acorns, or a crab losing her hatching eggs, so far as any show of love is concerned.

The female crab attaches her eggs to her swimmerets and carries them about with her for their protection as the most devoted of mothers; yet she is no more conscious of them, and feels no more for them, than the frond of a cinnamon fern feels for its spores. She is a mother, without the love of the mother.

In the spider, however, just one step up the animal scale from the crab, you find the mother-love or passion. Crossing a field the other day, I came upon a large female spider of the hunter family, carrying a round white sack of eggs, half the size of a cherry, attached to her spinnerets. Plucking a long stem of grass, I detached the sack of eggs without bursting it. Instantly the mother turned and sprang at the[Pg 67] grass-stem, fighting and biting until she got to the sack, which she seized in her strong jaws and made off with as fast as her long, rapid legs would carry her.

I laid the stem across her back and again took the sack away. She came on for it, fighting more fiercely than before. Once more she seized it; once more I forced it from her jaws, while she sprang at the grass-stem and tried to tear it to pieces. She must have been fighting for two minutes when, by a regrettable move on my part, one of her legs was injured. She did not falter in her fight. On she rushed for the sack as fast as I pulled it away. She would have fought for that sack, I believe, until she had not one of her eight legs to stand on, had I been cruel enough to compel her. It did not come to this, for suddenly the sack burst, and out poured, to my amazement, a myriad of tiny brown spiderlings. Before I could think what to do that mother spider had rushed among them and caused them to swarm upon her, covering her, many deep, even to[Pg 68] the outer joints of her long legs. I did not disturb her again, but stood by and watched her slowly move off with her encrusting family to a place of safety.

I had seen these spiders try hard to escape with their egg-sacks before, but had never tested the strength of their purpose. For a time after this experience I made a point of taking the sacks away from every spider I found. Most of them scurried off to seek their own safety; one of them dropped her sack of her own accord; some of them showed reluctance to leave it; some of them a disposition to fight; but none of them the fierce, consuming mother-fire of the one with the hurt leg.