OR

BY

BY

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1874, by

CHARLES HEBER CLARK,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C.

I have resolved to dedicate this book to a humorist who has had too little fame, to the most delicious, because the most unconscious, humorist, to that widely-scattered and multitudinous comedian who may be expressed in the concrete as

To his habit of perpetrating felicitous absurdities I am indebted for "laughter that is worth a hundred groans." It was he who put into type an article of mine which contained the remark, "Filtration is sometimes accomplished with the assistance of albumen," and transformed it into "Flirtation is sometimes accomplished with the resistance of aldermen." It was he who caused me to misquote the poet's inquiry, so that I propounded to the world the appalling conundrum, "Where are the dead, the varnished dead?" And it was his glorious tendency to make the sublime convulsively ridiculous that rejected the line in a poem of mine, which declared that a "comet swept o'er the heavens with its trailing skirt," and substituted the idea that a "count slept in the haymow in a traveling shirt." The kind of talent that is here displayed deserves profound reverence. It is wonderful and awful; and thus I offer it a token of my marveling respect.

"Fun is the most conservative element of society, and it ought to be cherished and encouraged by all lawful means. People never plot mischief when they are merry. Laughter is an enemy to malice, a foe to scandal and a friend to every virtue. It promotes good temper, enlivens the heart and brightens the intellect."

It seems to be necessary to say a few words in reference to the contents of this volume as I offer it to the public. Several of the incidents related in the story have already appeared in print, and have been copied in various newspapers throughout the country. Sometimes they have been attributed to the author; but more frequently they have been given either without any name attached to them, or they have been credited to persons who probably never saw them. The best of the anecdotes have been imitated, but none of them, I believe, are imitations. I make this statement, so that if the reader should happen to encounter anything that has a familiar appearance, he may understand that he has the original and not a copy before him. But a very large portion of the matter contained in the book is entirely new, and is now published for the first time; while all the rest of it has been rewritten and improved, so that it is as good as new.

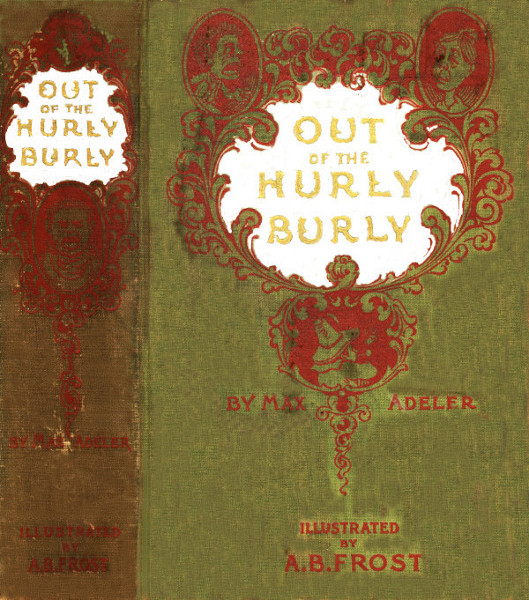

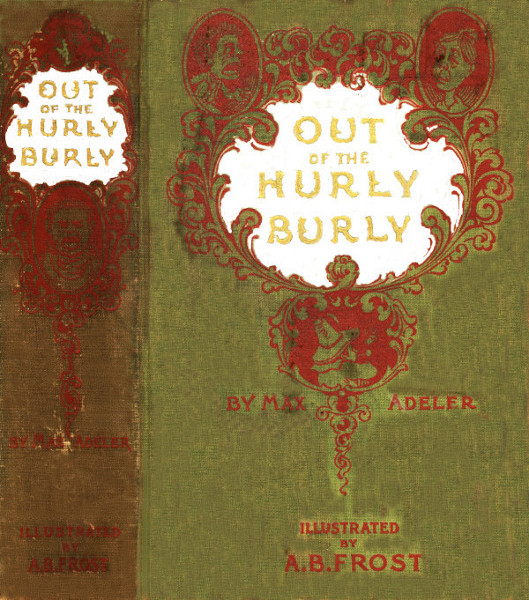

If this little venture shall achieve popularity, I must attribute the fact largely to the admirable pictures with which it has been adorned by the artists whose names appear upon the title page. All of these gentlemen have my hearty thanks for the efforts they have made to accomplish the best results; but while I express my appreciation of the beautiful landscapes of Mr. Schell, the admirable drawings of Mr. Sheppard and the excellent designs of Mr. Bensell, I wish to direct attention especially to the humorous pictures of Mr. Arthur B. [Pg 6] Frost. This artist makes his first appearance before the public in these pages. These are the only drawings upon wood that he has ever executed, and they are so nicely illustrative of the text, they display so much originality and versatility, and they have such genial humor, with so little extravagance and exaggeration, that they seem to me surely to give promise of a prosperous career for the artist.

It is customary upon these occasions to say something of an apologetic nature for the purpose of inducing the public to believe that the author regards with humility the work of which he is really exceedingly proud—something that will tend to soften the blows which are expected from ferocious and cruel critics. But I believe I have nothing of this kind to offer. If I thought the book required an apology, I would not publish it. Any reviewer who does not like it is at liberty to say so; and I am the more ready to accord him this permission because I am impressed with the conviction that he will hit as hard as he wants to whether I give him leave or withhold it. All I ask is that the volume shall have fair play. If it is successful as an attempt to construct a book of humor which will contribute to innocent popular amusement without violating the laws that govern the construction and orthography of the English language, and as an effort to give pleasure to sensible grown people without offering entertainment to children and idiots, it deserves commendation. If it is a failure in these respects, then it ought to be suppressed, for it certainly has no mighty moral purpose, and it is not designed to reform anything on earth but the personal fortunes of the author.

| CHAPTER I. | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| The founder of New Castle—A search for quietness—Life in the city and in the village—Why the latter is preferable—Peculiarities of the village—A sleepy old town—We erect our family altar | 25 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| A very dangerous invention—The patent combination step-ladder—Domestic servants—Advertising for a girl—The peasant-girl of fact and fiction—A contrast | 36 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The view upon the river—A magnificent panorama—Mr. and Mrs. Cooley—Matrimonial infelicities—The case of Mrs. Sawyer—A blighted life—A present—Our century plant and its peculiarities | 47 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Judge Pitman—His experiment in the barn—A lesson in natural history—Catching the early train—One of the miseries of living in the village—Ball's lung exercise—Mr. Cooley's impertinence | 56 |

| [Pg 8] | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| A little love affair—Cowardice of Mr. Parker—Popular interest in amatory matters—The Magruder family—An event in its history—Remarkable experiments by Mrs. Magruder—An indignant husband—A question answered | 68 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The editor of our daily paper—The appearance and personal characteristics of Colonel Bangs—The affair with the tombstone—Art news—Colonel Bangs in the heat of a political campaign—Peculiar troubles of public singers—The phenomena of menageries—Extraordinary sagacity of the animals—The Wild Man of Afghanistan | 84 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Battery and its peculiarities—A lovely scene—Swede and Dutchman two hundred years ago—Old names of the river—Indian names generally—Cooley's boy—His adventure in church—The long and the short of it—Mr. Cooley's dog and our troubles with it | 99 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Morning Argus creates a sensation—A new editor—Mr. Slimmer the poet—An obituary department—Mr. Slimmer on death—Extraordinary scene in the sanctum of Colonel Bangs—Indignant advertisers—The colonel violently assaulted—Observations of the poet—The final catastrophe—Mysterious conduct of Bob Parker—The accident on Magruder's porch—Mrs. Adeler on the subject of obituary poetry in general | 113 |

| [Pg 9] | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The reason why I purchased a horse—A peculiar characteristic—Driving by the river—Our horse as a persecutor—He becomes a genuine nightmare—Experimenting with his tail—How our horse died—In relation to pirates—Mrs. Jones's bold corsair—A lamentable tale | 134 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| A picturesque church—Some reflections upon church music—Bob Parker in the choir—Our undertaker—A gloomy man—Our experience with the hot-air furnaces—A series of accidents—Mr. Collamer's vocalism—An extraordinary mistake | 152 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| A fishing excursion down the river—Difficulties of the voyage—A series of unfortunate incidents—Our return home, and how we were received—A letter upon the general subject of angling—The sorrows of the fishermen—Lieutenant Smiley—His recollections of Rev. Mr. Blodgett—A very remarkable missionary | 164 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| How the plumber fixed my boiler—A vexatious business—How he didn't come to time, and what the ultimate result was—An accident; and the pathetic story of young Chubb—Reminiscences of General Chubb—The eccentricities of an absent-minded man—The rivals—Parker versus Smiley | 183 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| An evil day—Flogging-time in New Castle—How the punishment is inflicted—A few remarks upon the general merits of the system—A singular judge—How George Washington Busby was sentenced—Emotions of the prisoner—A cruel infliction, and a code that ought to be reformed | 200 |

| [Pg 10] | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| A Delaware legend—A story of the old time—The Christmas play—A cruel accusation—The flight in the darkness along the river shore—The trial and the condemnation—St. Pillory's day seventy years ago—Flogging a woman—The deliverance | 211 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| A very disagreeable predicament—Wild exultation of Parker—He makes an important announcement—An interview with the old man—The embarrassment of Mr. Sparks, and how he overcame it—A story of Bishop Potts—The miseries of too much consolidation—How Potts suffered, and what his end was | 237 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Old Fort Kasimir—Two centuries ago—The goblins of the lane—An outrage upon Pitman's cow—The judge discusses the subject of bitters—How Cooley came home—Turning off the gas—A frightful accident in the Argus office—The terrible fate of Archibald Watson—How Mr. Bergner taught Sunday-school | 255 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| A dismal sort of day—A few able remarks about umbrellas—The umbrella in a humorous aspect—The calamity that befell Colonel Coombs—An ambitious but miserable monarch—The influence of umbrellas on the weather—An improved weather system—A little nonsense—Judge Pitman's views of weather of various kinds | 278 |

| [Pg 11] | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Trouble for the hero and heroine—A broken engagement and a forlorn damsel—Bob Parker's suffering—A formidable encounter—The peculiar conduct of a dumb animal—Cooley's boy and his home discipline—A story of an echo | 293 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| A certificate concerning Pitman's hair—Unendurable persecution—A warning to men with bald-headed friends—An explanation—The slanderer discovered—Benjamin P. Gunn—A model life-insurance agent | 306 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| A certain remarkable book—A few suggestions respecting Boston—Delusions of childhood—Bullying General Gage—Judge Pitman and the catechism—An extraordinary blunder—The facts in the case of Hillegass—A false alarm | 324 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Settling the business—Vindication of Mr. Bob Parker—A complete reconciliation—The great Cooley inquest—The uncertainty in regard to Thomas Cooley—A phenomenal coroner—The solution of the mystery | 334 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| An arrival—A present from a Congressman—Meditation upon his purpose—The patent-office report of the future—A plan for revolutionizing public documents and opening a new department in literature—Our trip to Salem—A tragical event—The last of Lieutenant Smiley | 350 |

| [Pg 12] | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Pitman as a politician—He is nominated for the Legislature—How he was serenaded, and what the result was—I take a hand at politics—The story of my first political speech—y reception at Dover—Misery of a man with only one speech—The scene at the mass meeting—A frightful discomfiture | 363 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| The wedding-day—Enormous excitement in the village—Preparations for the event—The conduct of Bob Parker—The ceremony at the church, and the company at Magruder's—A last look at some old friends—Departure of the bride and groom—Some uncommonly solemn reflections, and then—The end | 387 |

| No. | Page | |

| 1.— | Book Cover. | Frontispiece. |

| 2.— | Title Page | 1 |

| 3.— | The Founder of the Village (Initial Letter) | 25 |

| 4.— | A Professor of Music | 26 |

| 5.— | A Disgusted Agriculturist | 28 |

| 6.— | New Castle from the River (Full Page) | 32 |

| 7.— | The Real Peasant-Girl (Initial Letter) | 36 |

| 8.— | A Dangerous Invention | 37 |

| 9.— | The Early Morning Fire | 39 |

| 10.— | The Ideal Peasant-Girl | 42 |

| 11.— | Unsymmetrical Cold Beef | 43 |

| 12.— | The View down the River (Full Page) | 46 |

| 13.— | A Family Jar (Initial Letter) | 47 |

| 14.— | A Musical Navigator | 48 |

| 15.— | The Nocturnal Dog | 49 |

| 16.— | Mr. Sawyer's Nose | 52 |

| 17.— | The Man with the Century Plant | 53 |

| 18.— | A Lively Vegetable | 54 |

| 19.— | Judge Pitman's Bag (Initial Letter) | 56 |

| 20.— | The Judge introduces Himself | 57 |

| 21.— | Pitman's Musical Experiment | 59 |

| 22.— | That Infamous Egg | 60 |

| 23.— | The Dog by the Wayside | 61 |

| 24.— | Catching the Train | 61 |

| 25.— | Hauled In | 62 |

| [Pg 14] | ||

| 26.— | An Altercation with Cooley | 64 |

| 27.— | My Lung Exercise | 66 |

| 28.— | A Female Professor (Initial Letter) | 68 |

| 29.— | The Lamp Turned Low | 68 |

| 30.— | Studying Up | 69 |

| 31.— | Parker Relating his Woes | 69 |

| 32.— | Magruder's Wooing | 72 |

| 33.— | A Queer Feeling in his Head | 72 |

| 34.— | Magruder Tells his Brother | 73 |

| 35.— | The Class Going Up | 74 |

| 36.— | A Secreted Observer | 74 |

| 37.— | A General Attack on the Subject (Full Page) | 78 |

| 38.— | Peeping Through the Crack | 79 |

| 39.— | A Furious Husband | 80 |

| 40.— | An Asinine Being (Initial Letter) | 84 |

| 41.— | The Colonel's Bravery | 85 |

| 42.— | An Interview with Cooley | 86 |

| 43.— | That Tombstone | 87 |

| 44.— | Mr. Mullins Explains | 88 |

| 45.— | Exit Murphy | 89 |

| 46.— | A Late Call | 91 |

| 47.— | A Captive Maiden | 91 |

| 48.— | Excavating Her | 92 |

| 49.— | Her Feet | 92 |

| 50.— | That Antiquarian | 92 |

| 51.— | The Raging Rhinoceros | 94 |

| 52.— | The King of Beasts | 94 |

| 53.— | The Rival Lovers | 96 |

| 54.— | On the Settee | 96 |

| 55.— | She Sat on Him | 97 |

| 56.— | Too Thin | 97 |

| 57.— | The Wild Man | 98 |

| 58.— | The Fat Woman | 98 |

| 59.— | The Boy of the Period (Initial Letter) | 99 |

| [Pg 15] | ||

| 60.— | The Battery (Full Page) | 102 |

| 61.— | An Ancient Warrior | 103 |

| 62.— | A Raid on the Melon-Patch | 105 |

| 63.— | Communing with Jones's Boy | 106 |

| 64.— | Held Fast | 107 |

| 65.— | The Solemnity of Jones | 107 |

| 66.— | Taking him Out | 108 |

| 67.— | Not Matched | 109 |

| 68.— | Dosing a Cur | 110 |

| 69.— | Over the Fence and Back Again | 110 |

| 70.— | Much too Faithful | 111 |

| 71.— | Cruelty to an Animal | 112 |

| 72.— | Removing a Mouthful | 112 |

| 73.— | A Patron of the "Argus" (Initial Letter) | 113 |

| 74.— | The Poet | 114 |

| 75.— | The Editor Explaining his Views | 115 |

| 76.— | The Throes of Composition | 116 |

| 77.— | A Row of Readers | 117 |

| 78.— | Taking a Peep | 117 |

| 79.— | The Scene in the Sanctum | 118 |

| 80.— | That Monkey | 119 |

| 81.— | Mrs. Smith's Woe | 120 |

| 82.— | Bartholomew's Indignant Father | 122 |

| 83.— | Mr. Mcfadden | 124 |

| 84.— | The Editor meets the Poet | 126 |

| 85.— | The Colonel in a Tight Place | 127 |

| 86.— | Going up Stairs | 128 |

| 87.— | In Highland Costume | 130 |

| 88.— | Why Bob Stayed | 130 |

| 89.— | Sawing him Out | 131 |

| 90.— | Mrs. Adeler's Views | 132 |

| 91.— | Bob's Trousers | 133 |

| 92.— | The New Mazeppa (Initial Letter) | 134 |

| 93.— | Cooley at an Auction | 135 |

| [Pg 16] | ||

| 94.— | Our Urbane Horse | 136 |

| 95.— | Trying to Catch Up | 138 |

| 96.— | Kicking | 139 |

| 97.— | A Nightmare | 140 |

| 98.— | Haunted | 141 |

| 99.— | An Artificial Tail | 142 |

| 100.— | A Demoralized Horse | 142 |

| 101.— | It Came Off! | 143 |

| 102.— | The Melodramatic Freebooter | 144 |

| 103.— | Mrs. Jones's Pirate | 145 |

| 104.— | Sweeping the Horizon | 146 |

| 105.— | The Weekly Wash | 146 |

| 106.— | Hailing the "Mary Jane" | 147 |

| 107.— | A General Massacre | 147 |

| 108.— | The Paternal Jones | 148 |

| 109.— | She Puts on her Things | 148 |

| 110.— | Slaying the Captain | 149 |

| 111.— | "False! False!" | 150 |

| 112.— | More Butchery | 150 |

| 113.— | Suicide of the Widow | 150 |

| 114.— | The Wreck of Mrs. Jones | 151 |

| 115.— | A Chorister (Initial Letter) | 152 |

| 116.— | The Spire | 153 |

| 117.— | Sinful Games | 154 |

| 118.— | The Old Church (Full Page) | 156 |

| 119.— | A Chinese Prayer | 157 |

| 120.— | The Minister and I | 157 |

| 121.— | In the Pipe | 158 |

| 122.— | Bob in the Choir | 158 |

| 123.— | The Undertaker's Sign | 159 |

| 124.— | A Gloomy Man | 160 |

| 125.— | Very Warm Work | 161 |

| 126.— | Collamer Falls In | 161 |

| 127.— | The Clergyman | 162 |

| [Pg 17] | ||

| 128.— | Collamer Sings | 162 |

| 129.— | He Asks a Question | 163 |

| 130.— | A Ribald Boy | 163 |

| 131.— | A Fisherman (Initial Letter) | 164 |

| 132.— | Bringing 'em Home | 164 |

| 133.— | Pushing Off | 165 |

| 134.— | We Change Places | 165 |

| 135.— | Cooling Off | 166 |

| 136.— | Waiting for Bites | 166 |

| 137.— | Anchor Gone | 166 |

| 138.— | Fixing an Oar | 167 |

| 139.— | Lost Him | 167 |

| 140.— | Saved | 167 |

| 141.— | A Tangle | 168 |

| 142.— | The Man who Owned the Boat | 168 |

| 143.— | A Successor of Izaak Walton | 169 |

| 144.— | A Disheartened Digger | 170 |

| 145.— | Tears | 171 |

| 146.— | Watching the Cork | 171 |

| 147.— | A Naked Hook | 171 |

| 148.— | The Last Match | 172 |

| 149.— | Caught on a Limb | 173 |

| 150.— | A Playful Eel | 174 |

| 151.— | Wriggling | 174 |

| 152.— | Pulling In | 175 |

| 153.— | That Infamous Boy | 175 |

| 154.— | A South Sea Islander | 177 |

| 155.— | Mr. Blodgett, Missionary | 177 |

| 156.— | Going to the Picnic | 177 |

| 157.— | The Vestry Meeting | 178 |

| 158.— | Putting them to Sleep | 178 |

| 159.— | The Funeral Service | 179 |

| 160.— | The Remaining Warden | 179 |

| 161.— | Going Home | 180 |

| [Pg 18] | ||

| 162.— | He Paddled his own Canoe | 180 |

| 163.— | Smashing poor Mott | 181 |

| 164.— | A Fijian | 182 |

| 165.— | Our Plumber (Initial Letter) | 183 |

| 166.— | He Examines the Range | 184 |

| 167.— | I Meet Him | 184 |

| 168.— | How he Goes to Wilmington | 184 |

| 169.— | An Indignant Artisan | 185 |

| 170.— | On the Asparagus Bed | 185 |

| 171.— | The Condition of my Grass-plot | 186 |

| 172.— | At the Front Gate | 186 |

| 173.— | A View of the Ruins | 187 |

| 174.— | Watching | 188 |

| 175.— | One of the Robbers | 188 |

| 176.— | Mr. Nippers Enters | 188 |

| 177.— | I Expostulate with Nippers | 189 |

| 178.— | Mrs. Cooley's Servant | 190 |

| 179.— | She Shakes Henry | 190 |

| 180.— | Bob as an Author | 191 |

| 181.— | Young Chubb | 191 |

| 182.— | Mysterious Music | 192 |

| 183.— | "What does this Mean?" | 193 |

| 184.— | Trying to Make him Disgorge | 193 |

| 185.— | HEnry's Brother tries Pressure | 194 |

| 186.— | Exit with the Sexton | 194 |

| 187.— | The Tomb of Chubb | 195 |

| 188.— | General Chubb's Legs | 196 |

| 189.— | The Influence of Art | 197 |

| 190.— | The General Dives In | 197 |

| 191.— | Through the Canvas | 197 |

| 192.— | Pilloried (Initial Letter) | 200 |

| 193.— | Infant Spectators | 201 |

| 194.— | The Whipping-post | 201 |

| 195.— | An Ancient Custom | 202 |

| [Pg 19] | ||

| 196.— | That Remarkable Judge | 204 |

| 197.— | George Washington Busby | 205 |

| 198.— | The Jury | 205 |

| 199.— | Maternal Love | 206 |

| 200.— | Manhood's Toil | 206 |

| 201.— | Busby Whispers to the Tipstaff | 207 |

| 202.— | More Hopeful Still | 207 |

| 203.— | His Infant Steps | 208 |

| 204.— | Busby's Heart grows Lighter | 209 |

| 205.— | The Thunderbolt Falls | 209 |

| 206.— | Leading him Out | 210 |

| 207.— | Wielding the Lash (Initial Letter) | 211 |

| 208.— | Hob-nobbing | 212 |

| 209.— | The Major in a Sulk | 213 |

| 210.— | The Lovers | 215 |

| 211.— | "Where did You get That?" | 217 |

| 212.— | The Flight by the River | 219 |

| 213.— | Dick Confesses | 226 |

| 214.— | Wearing the Wooden Collar | 228 |

| 215.— | A Flogging Seventy Years Ago (Full Page) | 230 |

| 216.— | Pardoned | 233 |

| 217.— | A Broken Man | 235 |

| 218.— | The Market Green and the Old Church | 236 |

| 219.— | A Juvenile Musician (Initial Letter) | 237 |

| 220.— | Caught | 238 |

| 221.— | Can't Reach It | 238 |

| 222.— | Creeping Out | 239 |

| 223.— | Back Again in a Hurry | 239 |

| 224.— | A Mighty Ugly Situation | 240 |

| 225.— | Listening | 240 |

| 226.— | Parker Exults | 241 |

| 227.— | The Second Hornpipe | 241 |

| 228.— | He Surveys her Dwelling | 241 |

| 229.— | Old Sparks's Sacred Dust | 244 |

| [Pg 20] | ||

| 230.— | A Conscientious Tombstone | 244 |

| 231.— | Bishop Potts | 246 |

| 232.— | A Warm Welcome | 246 |

| 233.— | A Surprise for the Bishop | 247 |

| 234.— | The Bride goes Home in a Row | 248 |

| 235.— | Potts Meditates | 249 |

| 236.— | Waving Farewell | 249 |

| 237.— | The Bishop is Confounded | 250 |

| 238.— | Starting the Third Time | 252 |

| 239.— | Potts Becomes Hysterical | 253 |

| 240.— | The Peruvian Monk | 253 |

| 241.— | The Maniac Doctor | 253 |

| 242.— | Bob gives an Opinion | 254 |

| 243.— | Potts's Child | 254 |

| 244.— | On the Ramparts (Initial Letter) | 255 |

| 245.— | The Site of Fort Kasimir (Full Page) | 258 |

| 246.— | Modern Warriors | 259 |

| 247.— | A Dutch Goblin | 260 |

| 248.— | Pitman tells of his Griefs | 260 |

| 249.— | A Troublesome Cow | 261 |

| 250.— | That Scandalous Blind-board | 261 |

| 251.— | The Temperance Society makes an Inspection | 262 |

| 252.— | "I'll Knock the Stuffin' out o' him" | 262 |

| 253.— | The Judge's Bitters Advertisements | 263 |

| 254.— | He Takes a Tonic | 263 |

| 255.— | Another Dozen | 264 |

| 256.— | Cooley's Illuminated Nose | 265 |

| 257.— | "Out, Brief Candle" | 266 |

| 258.— | "There was Mrs. Cooley a-Watchin'" | 266 |

| 259.— | Dr. Hopkins is Amazed | 267 |

| 260.— | Appalling Intelligence | 268 |

| 261.— | The Commodore's Tomb | 269 |

| 262.— | The Fall of Simms | 270 |

| 263.— | "Knock 'em with a Pole" | 270 |

| [Pg 21] | ||

| 264.— | Hit by an Apple | 271 |

| 265.— | Tim Keyser's Nose | 272 |

| 266.— | "He Slid Around so Quick" | 272 |

| 267.— | "He Cut an Opening in the Ice" | 273 |

| 268.— | The Pickerel Bites | 273 |

| 269.— | "The Better of the Fight" | 274 |

| 270.— | "And Pulled Tim Keyser Through" | 274 |

| 271.— | Under Water | 275 |

| 272.— | An Awful Sneeze | 275 |

| 273.— | He Floats Ashore | 276 |

| 274.— | "He Very Roundly Swore" | 276 |

| 275.— | At Dinner | 277 |

| 276.— | A Very Wet Time (Initial Letter) | 278 |

| 277.— | A Damp Fisherman | 279 |

| 278.— | Forlorn | 279 |

| 279.— | The Comic Umbrella | 280 |

| 280.— | Delicate Warriors | 281 |

| 281.— | The Experiment of Coombs | 281 |

| 282.— | An Embarrassed Panther | 282 |

| 283.— | Bringing Home the Monster | 282 |

| 284.— | Getting Ready for Action | 283 |

| 285.— | The Medicine Man Dies | 283 |

| 286.— | Cooley Awaits the Simoom | 286 |

| 287.— | The Judge Enjoys the Weather | 290 |

| 288.— | Perfectly Satisfied | 291 |

| 289.— | The Genuine Weather-Gauge | 292 |

| 290.— | "A Friend of Man" (Initial Letter) | 293 |

| 291.— | The Impetuosity of Bob | 296 |

| 292.— | A Somnambulist | 297 |

| 293.— | A Precautionary Measure | 297 |

| 294.— | Dreaming of Magruder | 297 |

| 295.— | Under the Bed | 298 |

| 296.— | Bob is Amazed | 298 |

| 297.— | Hunting for Henry | 298 |

| [Pg 22] | ||

| 298.— | The Mystery Unraveled | 299 |

| 299.— | "Perfectly Still" | 300 |

| 300.— | The Consequences of a Sneeze | 301 |

| 301.— | The Dog Leaves | 301 |

| 302.— | I Suddenly Climb the Fence | 301 |

| 303.— | Sold | 302 |

| 304.— | "Commere To Me" | 302 |

| 305.— | A Victim | 303 |

| 306.— | A Human Echo | 304 |

| 307.— | It Won't Answer | 304 |

| 308.— | After That Boy | 305 |

| 309.— | A Bald-headed Party (Initial Letter) | 306 |

| 310.— | A Deluge of Letters | 308 |

| 311.— | Mrs. Singerly's Poodle | 309 |

| 312.— | The Rally of the Baldheaded | 309 |

| 313.— | A Microscopic Examination | 310 |

| 314.— | Benjamin P. Gunn | 313 |

| 315.— | A Visit to Mrs. Kemper | 315 |

| 316.— | Gunn Waits with the Doctor | 317 |

| 317.— | Pounding on the Partition | 317 |

| 318.— | Up the Steeple | 318 |

| 319.— | Into the Crater | 318 |

| 320.— | Benjamin is Ejected | 319 |

| 321.— | Portrait of Gunn | 319 |

| 322.— | On the War Path | 323 |

| 323.— | General Gage and the Boy (Initial Letter) | 324 |

| 324.— | The Judge is Puzzled | 329 |

| 325.— | Catechizing Him | 329 |

| 326.— | The Doctors at Hillegass's House | 330 |

| 327.— | Hillegass Recovers | 331 |

| 328.— | The Joke on the Chief | 332 |

| 329.— | A Deluge | 332 |

| 330.— | The Combat on the Stairs | 333 |

| 331.— | A Fireman | 333 |

| [Pg 23] | ||

| 332.— | The Bone Controversy (Initial Letter) | 334 |

| 333.— | Examining the Premises | 335 |

| 334.— | We Proceed Carefully | 336 |

| 335.— | An Explosion at Cooley's | 339 |

| 336.— | The Remains Scatter | 340 |

| 337.— | "Fooling with a Gun" | 341 |

| 338.— | Selfridge Argues with Smith | 342 |

| 339.— | The Rival Juries | 343 |

| 340.— | Cooley Turns Up | 344 |

| 341.— | "Tossed the Little Baby" | 348 |

| 342.— | That Mummy | 349 |

| 343.— | A Patent-Office Report (Initial Letter) | 350 |

| 344.— | Pub. Docs | 351 |

| 345.— | Alphonso Lies in Wait | 353 |

| 346.— | Lucullus, the Serenader | 353 |

| 347.— | Death of Alphonso | 354 |

| 348.— | Lucullus Breaks Jail | 354 |

| 349.— | Smith Bombards the Artists | 355 |

| 350.— | The Lovers Float Ashore | 356 |

| 351.— | A Parting Scene | 357 |

| 352.— | Smiley is Intoxicated | 358 |

| 353.— | "He Leaped into the Sea" | 360 |

| 354.— | Bob is Rescued | 361 |

| 355.— | Nursing the Invalid | 362 |

| 356.— | Tail-piece | 362 |

| 357.— | Before the Mass Meeting (Initial Letter) | 363 |

| 358.— | The Serenaders at Pitman's | 365 |

| 359.— | Cooley Argues with Daniel Webster | 366 |

| 360.— | The Discomfited Drummer | 367 |

| 361.— | The Kickapoo's Mistake | 369 |

| 362.— | A Patriotic Dutchman | 370 |

| 363.— | Collapsed | 370 |

| 364.— | Commodore Scudder's Dog | 371 |

| 365.— | The Committee Welcomes Me | 373 |

| [Pg 24] | ||

| 366.— | The Cold-eyed Drummer | 375 |

| 367.— | "Go, Mark him Well" | 376 |

| 368.— | Mr. Hotchkiss's Joke | 379 |

| 369.— | The Drummer Glares at Me | 381 |

| 370.— | I Retreat in Despair | 386 |

| 371.— | A Solemn Vow | 386 |

| 372.— | The Waiter (Initial Letter) | 387 |

| 373.— | The Collars in his Trunk | 389 |

| 374.— | A Shirt-button Lost | 390 |

| 375.— | Waiting for the Bride | 390 |

| 376.— | At the Reception | 392 |

| 377.— | Pitman Expresses his Views | 394 |

| 378.— | "We Flung a Shoe after Them" | 394 |

| 379.— | The Final Bow | 398 |

The Founder of New Castle— Search for Quietness—Life in the City and the Village—Why the Latter is Preferable—Peculiarities of the Village—A Sleepy Old Town—We Erect our Family Altar.

If Peter Menuit had never been born, it is extremely probable that this book would not have been written. Mr. Menuit, however, had nothing to do with the construction of the volume, and his controlling purpose perhaps was not to prepare the way for it. Peter Menuit was a Swede who in 1631 came sailing up the Delaware River in a queer old craft with bulging sides and with stem and stern high in the air. Moved by some mysterious impulse, he dropped his anchor near a certain verdant shore and landed. Standing there, he surveyed the lovely scene that lay before him in the woodland and the river, and then announced to his companions his determination to remain upon [Pg 26] that spot. He began to erect a town upon the bank that went sloping downward to the sandy beach, and his only claim to the immortality that has been allotted to him is that he created what is now New Castle.

It would be pleasant, if it did not seem vain, to hope that New Castle will base its aspirations to enduring fame upon the circumstance that another humble personage came, two hundred years and more after Menuit's arrival, to live in it and to tell, in a homely but amiable fashion, the story of some of its good people, and to say something of a few of their peculiarities, perplexities and adventures.

We were in search of quietness. The city has many charms and many conveniences as a place of residence; and there are those who, having accustomed themselves to the methods of life that prevail among the dense populations of the great towns, can hardly find happiness and comfort elsewhere. But although the gregarious instinct is strong in me, I cannot endure to be crowded. I love my fellow-man with inexpressible affection, but oftentimes he seems more lovable when I behold him at a distance. I yearn occasionally for human society, but I prefer to have it only when I choose, not at all times and seasons without intermission. In the city, however, it is impossible to secure solitude when it is desired. If I live, as I must, in one of a row of houses, the partition walls upon both sides are likely to be thin. It is possible that I may have upon the one hand a professor of music who gives, throughout the day, maddening lessons to muscular pupils and practices scales himself with energetic persistency during the night. Upon the other [Pg 27] side there may be a family which cherishes two or three infants and sustains a dog. As a faint whisper will penetrate the almost diaphanous wall, the mildest as well as the most violent of the nocturnal demonstrations of the children disturb my sleep; and when these have ceased, the dog will probably become boisterous in the yard.

If there is not a boiler-making establishment in the street at the rear of the house, there will be a saw-mill with a steam whistle, and it is tolerably certain that my neighbor over the way will either have a vociferous daughter who keeps the window open while she sings, or will permit his boy to perform upon a drum. There is incessant noise in street and yard and dwelling. There is perpetual, audible evidence of the active existence of human beings. There is too much crowding and too little opportunity for absolute withdrawal from the confusion and from contact with the restless energy of human life.

It has always seemed to me that village life is the happiest and the most comfortable, and that the busy city man who would establish his home where he can have repose without inconvenience and discomfort should place it amid the trees and flowers and by the grassy highway of some pretty hamlet, where the noise of the world's greater commerce never comes, and where isolation and companionship are both possible without an effort. Such a home, planted judiciously in a half acre, where children can romp and play and where one can cultivate a few flowers and vegetables, mingling the sentimental heliotrope with the practical cabbage, and the ornamental verbena with the useful onion, may be made an earthly Paradise.

There must not be too much ground, for then it becomes a burden and a care. There are few city men who have the agricultural impulse so strong in them that they will find delight, after a day of mental labor and excitement, in rasping [Pg 28] a garden with a hoe in the hope of securing a vegetable harvest. A very little exercise of that kind, in most cases, suffices to moderate the horticultural enthusiasm of the inexperienced citizen. It is pleasant enough to weed a few flowers or to toss a spadeful or two of earth about the roots of the grapevine when you feel disposed to such mild indulgence in exercise; but when the garden presents tasks which must be performed no matter what the frame of mind or the condition of the body, you are apt, for the first time, to have a thorough comprehension of the meaning of the curse uttered against the ground when Adam went forth from Eden. It is far better and cheaper to hire a competent man to cultivate the little field; then in your leisure moments you may set out the cabbage plants upside down and place poles for the strawberry vines to clamber upon, knowing well that if evil is done, it will be corrected on the morrow when the offender is far away, and when the maledictions of the agricultural expert, muttered as he relieves the vegetables from the jeopardy in which ignorance has placed them, cannot reach your ears.

I like a house not too old, but having outward comeliness, with judicious arrangement of the interior, and all of those convenient contrivances of the plumber, the furnace-maker and the bell-hanger which make the merest mite of a modern dwelling incomparably superior in comfort to the most stupendous of marble palaces in the ancient times. I would have no neighbor's house within twenty yards upon either side; I would have noble [Pg 29] shade trees about the place, and I would esteem it a most fortunate thing if through the foliage I could obtain constant glimpses of some shining stream upon whose bosom ships come to and fro, and on which I could sometimes find solace and exercise in rowing, fishing and sailing.

Village life is the best. It has all the advantages of residence in the country without the unpleasant things which attend existence in a wholly rural home. There is not the oftentimes oppressive solitude of the country, nor is there the embarrassment that comes from the distance to the station, to the shops and to the post-office. There are the city blessings of the presence of other human beings, and of access to the places where wants may be supplied, without the crowds, without the mixed and villainous perfumes of the streets and without the immoderate taxes. With the conveniences of a civilized community, a village may have pure and healthful air, opportunity for parents and children to amuse themselves out of doors, cheap fare, moderate rent, milk which knows not the wiles of the city dealer, and a moral atmosphere in which a family may grow up away from the temptations and the evil associations which tend to corrupt the young in the great cities.

More than this, I like life in the village because it brings a man into kindlier relations with his fellows than can be obtained elsewhere. In the city I am jostled at every step by those who are strangers to me, who know nothing of me, and who care nothing. In the village I am known by every one, and I know all. If I have any title to respect, it is admitted by the entire society of the place, and perhaps I may even win something of affection if I am worthy of it.

In the country town, too, you may have your morals carefully looked after. There are prying eyes and busy tongues, and you are so conspicuous that unless you walk straightly, [Pg 30] the little world around you shall know of your slips and falls. You may quarrel with your wife for ever in the city and few care to hear the miserable story; but in the village the details of the conjugal contest are heralded about before the day is spent.

The interest that is felt in you is amazing. The cost of your establishment is as well known as if it were blazoned upon the walls. You cannot impose upon the people with a pretence of splendor if you have not the reality; one gossiping old woman who has discovered the sham will make you an object of public scorn in an hour. The village knows how your children are dressed and trained; how often you have mutton and the extent of your indulgence in beef. The cost of your carpets is a matter of common notoriety; your differences with your servants are discussed at the sewing-circle, and the purchase of new clothing for your family is a concern of public interest. The arrival of your wife's winter bonnet actually creates excitement in the village society, and you are certain, therefore, to get the full worth of your investment in that article of dress, while the owner obtains unlimited satisfaction; for winter bonnets are purchased for the benefit of other people chiefly, not for the convenience and happiness of the wearers.

Every man is something of a hero-worshiper; and if in the city I find it difficult to select an idol from among the many who thrust their greatness upon me, I am not so embarrassed in the village. Here I will probably find but one man who is revered as the embodiment of the worshipful virtues. He has larger wealth than any of his fellow-villagers; he lives in the most sumptuous house in the place; he belongs to the oldest family, and his claim to superiority is admitted almost without question by his reverent townsmen. It gives me joy to add my voice to the chorus of admiration, and to feel humble in that presence [Pg 33] wherein my neighbors have humility. Sometimes, of course, I cannot help perceiving that the object of this adoration is, after all, a very pigmy of his kind. I am compelled to admit that his fortune seems large only because mine and Jones's are small; that his house is a palace only for the reason that it dwarfs my little cottage; that if unassisted brains carried the day, and strutting was felonious, he would certainly occupy a much less magnificent position. I know that in a greater community he would be wholly insignificant. And yet I admit his claim to profound respect. It pleases me to see him play his little part, and to observe with what calm, luxurious confidence in his own right and title to homage he passes through life. And I know, after all, that the greater men, out in the busy hurly-burly of the world, are not so very much greater. A good deal of their claim to superiority, too, is a miserable sham; and doubtless, if we could see them as closely as we see our village grandee, we should find that they also depend much upon popular credulity for the stability of their reputations.

My pompous village nabob, too, is honest. I am sure of this. He helps to conduct the government of the community, but he does his duty fairly and he is a gentleman. I could love him for that alone, and for that feel a deeper affection for life in his village. When I go to the city and perceive what creatures wield the power there, when I watch the trickery, the iniquity, the audacious infamy, of the cliques that control the machinery of that great government, and when I look, as I do sometimes, into the faces of those who are thus leagued for plunder and power, only to see there vulgarity, ignorance, vice and general moral filthiness, my soul is made sick. I can turn then with pleasure to the simple methods with which our village is governed, and honestly give my respect to the guileless old gentleman who presides over its destinies.

We wish for quietness, and in New Castle it can be obtained, I think, in a particularly concentrated form. When Swede and Dutchman and Englishman had done contending for possession of the place, there was peace until the Revolution came, and with it ships of war and privateers, and such hurrying of troops and supplies across from New Castle to Frenchtown, from the Delaware to the Chesapeake, as kept the old town in a stir. There was then an interval of repose until the second war with England, when these busy scenes were re-enacted. Later in the century a mighty stir was made by the construction of a railroad, one of the earliest in the country, to Chesapeake Bay; then, as the excitement died away, the old town gradually went to sleep, and for nearly forty years it slumbered so soundly that there seemed to be a chance that it would never wake again. But time achieves wonderful things, and perhaps the day will come when the vicinity of the old town to the bay, the depth of water at its shores and the facilities offered for manufacturing and easy transportation, may make the village a great industrial centre, with hundreds of mills and multitudes of working-people. But as we join ourselves to the community there is no promise of such an awakening. We have still the profound repose and the absence of change that make the place so dear to those who have known it in their childhood. There are the paved streets where the grass grows thickly; the ancient wharves protruding into the stream, deserted but by the anglers and the naked and wicked little boys who go in to swim; the tumbling stone ice-piers, a little way out in the river; the old court-house, whose steeple is the point upon which moves the twelve-mile radial line whose northern end describes the semi-circular boundary of Delaware; the rickety town-hall, the ancient churches and the grim old houses with moss-covered roofs, the Battery, with its drooping willows [Pg 35] and its glorious vista of river and shore beyond, and the dense masses of foliage, shutting out the sky here and there as one passes along the streets.

Into such a house as I have described, not far from the river, and with our neighbors at a little more than arm's length, I have come with wife and family, with household gods and domestic paraphernalia generally, to begin the life which will supply the material wherewith to construct the ensuing pages. It may perhaps turn out that the better part of that existence will not be told, but perchance it may be that the events related will be those which will possess for the reader greatest interest and amusement.

A Very Dangerous Invention—The Patent Combination Step-ladder—Domestic Servants—Advertising for a Girl—The Peasant-girl of Fact and Fiction— Contrast.

A step-ladder is an almost indispensable article to persons who are moving into a new house. Not only do the domestics find it extremely convenient when they undertake to wash the windows, to remove the dust from the door and window-frames, and to perform sundry other household duties, but the lord of the castle will require it when he hangs his pictures, when he fixes the curtains and when he yields to his wife's entreaty for a hanging shelf or two in the cellar. I would, however, warn my fellow-countrymen against the contrivance which is offered to them under the name of the "Patent Combination Step-ladder." I purchased one in the city just before we moved, because the dealer showed me how, by the simple operation of a set of springs, the ladder could be transformed into an ironing-table, and from that into a comfortable settee for the kitchen, and finally back again into a step-ladder, just as the owner desired. It seemed like getting [Pg 37] the full worth of the money expended to obtain a trio of such useful articles for a single price, and the temptation to purchase was simply irresistible. But the knowledge gained by a practical experience of the operation of the machine enables me to affirm that there is no genuine economical advantage in the use of this ingenious article.

Upon the day of its arrival, the servant-girl mounted the ladder for the purpose of removing the globes from the chandelier in the parlor, and while she was engaged in the work the weight of her body unexpectedly put the springs in motion, and the machine was suddenly converted into an ironing-table, while the maid-servant was prostrated upon the floor with a sprained ankle and amid the fragments of two shattered globes.

Then we decided that the apparatus should be used exclusively as an ironing-table, and to this purpose it would probably have been devoted permanently if it had suited. On the following Tuesday, however, while half a dozen [Pg 38] shirts were lying upon it ready to be ironed, some one knocked against it accidentally. It gave two or three ominous preliminary jerks, ground two shirts into rags, hurled the flat-iron out into the yard, and after a few convulsive movements of the springs, settled into repose in the shape of a step-ladder.

It became evident then that it could be used with greatest safety as a settee, and it was placed in the kitchen in that shape. For a few days it gave much satisfaction. But one night when the servant had company the bench was perhaps overloaded, for it had another and most alarming paroxysm; there was a trembling of the legs, a violent agitation of the back, then a tremendous jump, and one of the visitors was hurled against the range, while the machine turned several somersaults, jammed itself halfway through the window-sash, and appeared once more in the similitude of an ironing-table.

It has now attained to such a degree of sensitiveness that it goes through the entire drill promptly and with celerity if any one comes near it or coughs or sneezes close at hand. We have it stored away in the garret, and sometimes in the middle of the night a rat will jar it, or a current of air will pass through the room, and we can hear it dancing over the floor and getting into service as a ladder, a bench and a table fifteen or twenty times in quick succession.

The machine will be disposed of for a small fraction of the original cost. It might be a valuable addition to the collection of some good museum. I am convinced that it will shine with greater lustre as a curiosity than as a household utensil.

Perhaps we may attribute to the fantastic capers of this step-ladder the dissatisfaction expressed by the servant who came with us from the city; at any rate, she gave us notice at the end of the first week that she would not remain. She is the ninth that we have had within four months. Mrs. [Pg 39] Adeler said she was not sorry the woman intended to go, for she was absolutely good for nothing; but I think a poor servant is better than none at all. Life is gloomy enough without the misery which comes from rising before daylight to fumble among the fires, and without living upon short rations because one's wife has no time to attend to the cooking.

I am not sure, at any rate, that it would be a very great advantage to have thoroughly good servants, for then women would be deprived of the very evident pleasure they now take in discussing the shortcomings of their domestics. The practice is so common that there must be supreme consolation in the sympathy and in the relief to the overcharged feelings that are permitted by such communion.

Place two women together under any circumstances, and it makes no difference where the conversation starts from, for it will be perfectly certain to work around to the hired-girl question before many minutes have elapsed. I have seen an elderly housekeeper, with experience in conducting the talk in the desired direction, break in upon a discussion of Pythagoras and the doctrine of the transmigration of souls, and switch off the entire debate with such expedition that a careless listener would for some moments have an indistinct impression that the conversation referred to the inefficiency of Pythagoras as a washer and ironer, and to the tendency of that heathen philosopher to take two Thursdays out every week.

And when a woman has an unusually villainous servant, is it not interesting to observe how she glories in the superior intensity of her sufferings as compared with those of [Pg 40] her neighbors, and to perceive how she rejoices in her misery? A housewife who possesses a really good girl is always in a condition of wretchedness upon such occasions, and is apt to listen in envious silence while her companions unburden their souls to each other.

Mrs. Adeler intimated that these accusations were slanderous, but she ventured to observe that the practical question which required immediate consideration was, How shall we get another girl?

"There is but one method, Mrs. A.: it is to advertise. Do not patronize the establishments which, in bitter irony, are styled 'intelligence offices.' An intelligence office is always remarkable for the dense stupidity of everybody connected with it. But a single manifestation of intelligence gleams through the intellectual darkness that enshrines the souls of the beings who maintain such places. I refer to the singular ability displayed in extracting two-dollar bills from persons who know that they will get nothing for their money."

Mrs. Adeler admitted that it would perhaps be better to advertise.

"How would it answer to insert in the daily paper an advertisement in which sarcasm is mingled with exaggeration in such a way that it shall secure an unlimited number of applications, while we shall give expression to the feeling of bitterness that is supposed to exist in the bosom of every housekeeper?"

She said she thought she hardly caught the idea precisely.

"Suppose, for instance, we should publish something like this: 'Wanted: a competent girl for general housework.' The most strenuous effort will be made to give such a person complete satisfaction. If she is not pleased with the furniture already in the kitchen, we are willing to have the [Pg 41] range silver plated, the floor laid in mosaic and the dresser covered with pink plush. No objection will be made to breakage. The domestic will be permitted at any time to disport in the china closet with the axe. We consider hair in the breakfast-rolls an improvement; and the more silver forks that are dropped into the drain, the more serene is the happiness which reigns in the household. Our girl cannot have Sunday out. She can go out every day but Sunday, and remain out until midnight if she wishes to. If her relations suffer for want of sugar, she can supply them with ours. We rather prefer a girl who habitually blows out the gas, and who is impudent when complaint is made because she soaks the mackerel in the tea-kettle. If she can sprinkle hot coals over the floor now and then, and set the house afire, we will rejoice the more, because it will give the fire-department healthful and necessary exercise. Nobody will interfere if she woos the milkman, and she will confer a favor if she will discuss family matters across the fence with the girl who lives next door. Such a servant as this can have a good home, the second-story front room and the whole of our income with the exception of three dollars a week, which we must insist, reluctantly, upon reserving for our own use.'

"How does that strike you, Mrs. Adeler?"

She said that it struck her as being particularly nonsensical. She hoped I wouldn't put such stuff as that in the paper.

"Certainly not, Mrs. A. If I did, we should cause a general immigration of the domestics of the country to New Castle. We will not precipitate such a disaster."

The insertion of a less extended advertisement, couched in the usual terms, secured a reply from a young woman named Catherine. And when Catherine's objections to the size of the family, to the style of the cooking-range, to the [Pg 42] dimensions of the weekly wash and to sundry other things had been overcome, she consented to accept the position.

"I hope she will suit," exclaimed Mrs. Adeler, with a sigh and an intonation which implied doubt. "I do hope she will answer, but I am afraid she won't, for according to her own confession she doesn't know how to make bread or to iron shirts or to do anything."

"That is the reason why she demanded such exorbitant wages. Those servants who are entirely ignorant always want the largest pay. If we ever obtain a girl who understands her business in all its departments, I cherish the conviction that she will work for us for nothing. The wages of domestics are usually in inverse ratio to the merit of the recipients. Did you ever reflect upon the difference between the real and the ideal Irish maiden?"

Mrs. A. admitted that she had not considered the subject with any degree of attention.

"The ideal peasant-girl lives only in fiction and upon the stage. We are largely indebted to Mr. Boucicault for her existence, just as we are under obligations to Mr. Fennimore Cooper for a purely sentimental conception of the North American Indian. Have you ever seen the Colleen Bawn?"

"What is that?" inquired Mrs. Adeler, as she bit off a piece of thread from a spool.

"It is a play, a drama, my dear, by Mr. Dion Boucicault."

"You know I never go to theatres."

"Well, in that and in many other of his dramas Mr. Boucicault has drawn a particularly affecting portrait of the imaginary peasant-girl of Ireland. She is, as depicted by [Pg 43] him, a lovely young creature, filled with tenderest sensibility, animated by loftiest impulses and inspired perpetually by poetic enthusiasm. The conversation of this fascinating being sparkles with wit; she overflows with generosity; she has unutterable longings for a higher and nobler life; she loves with intense and overpowering passion; she is capable of supreme self-sacrifice; and she always wears clean clothing. If such charming girls really existed in Ireland in large numbers, it would be the most attractive spot in the world. It would be a particularly profitable place for young bachelors to emigrate to. I think I should even go there myself."

Mrs. Adeler said she would certainly accompany me if I did.

"But these persons have no actual existence. We know, from a painful experience, what the peasant-girl of real life is, do we not? We know that her appearance is not prepossessing; we are aware that her lofty impulses do not lift her high enough to enable her to avoid impertinence and to conquer her unnatural fondness for cooking wine. She will withhold starch from the shirt collars and put it in the underclothing; she will hold the baby by the leg, so that it is in perpetual peril of apoplexy, and she will drink the milk. All of her visitors are her cousins; and when they have spent a festive evening with her in the kitchen, is it not curious to remark with what certainty we find low tide in the sugar-box and an absence of symmetry about the cold beef? The only evidence that I can discover of the existence in her soul of a yearning for a higher life is that she nearly always wants Brussels carpet in the kitchen, and this longing is peculiarly intense if, when at the home of her childhood, she was accustomed to live in a mud-cabin and to sleep with a pig."

But I do not regret that Mr. Boucicault has not placed this person upon the stage. It is, indeed, a matter for rejoicing that she is not there. She plays such a part in the drama of domestic life that in contemplation of the virtues of the fabulous being we find intense relief.

The View Upon the River; a Magnificent Panorama—Mr. and Mrs. Cooley—Matrimonial Infelicities—The Case of Mrs. Sawyer; a Blighted Life—A Present: our Century Plant and its Peculiarities.

We have a full view of the river from our chamber window, and it is a magnificent spectacle that greets us as we rise in the morning and fling the shutters wide open. The sun, in this early summer-time, has already crept high above the horizon of the pine-covered shore opposite, and has flooded the unruffled waters with its golden light until they are transformed for us into a sea of flame. There comes a fleet of grimy coal schooners moving upward with the tide, their dingy sails hanging almost listless in the air; now they float, one by one, into the yellow glory of the sunshine which bars the river from shore to shore. Yonder is a tiny tug puffing valorously as it tows the great merchantman—home from what distant land of wonders?—up to the wharves of the great city. And look! there is another tug-boat going down stream, with a score of canal-boats moving in huge mass slowly behind it. They come from far up among the mountains of the Lehigh [Pg 48] and the Schuylkill with their burdens of coal, and they are bound for the Chesapeake. Those men lounging lazily about upon the decks while the women are getting breakfast ready spend their lives amid some of the wildest and noblest scenery in the world. I would rather be a canal-boat captain, Mrs. Adeler, and through all my existence float calmly and serenely amid those regions of beauty and delight, without ever knowing what hurry is, than to be the greatest and busiest of statesmen—that is, if one calling were as respectable and lucrative as the other.

That fellow upon the boat at the rear is playing upon his bugle. The canal-boat bugler is not an artist, but he makes wonderful music sometimes when he blows a blast up yonder in the heart of Pennsylvania, and sets the wild echoes flying among the cañons of those mighty hills. And even now it is not indifferent. Listen! The tones come to us mellowed by the distance, and so indistinct that they have lost all but the sweetness which makes them seem so like the sound of

"Horns of Elfland, faintly blowing."

That prosaic tooter floating there upon the river doubtless would be surprised to learn that he is capable of such a suggestion; but he is.

Off there in the distance, emerging from the shadowy mantle of mist that rests still upon the bosom of the stream to the south, comes the steamboat from Salem, with its decks loaded down with rosy and fragrant peaches, and with baskets of tomatoes and apples and potatoes and berries, ready for the hungry thousands of the Quaker City. The schooner [Pg 49] lying there at the wharf is getting ready to move away, so that the steamer may come in. You can hear the screech made by the block as the tackle of the sail is drawn swiftly through it. Now she swings out into the stream, and there, right athwart her bows, see that fisherman rowing homeward with his net piled high in tangled meshes in the bow of his boat. He has a hundred or two silver-scaled shiners at his feet, I'll warrant you, and he is thinking rather of the price they will bring than of the fact that his appearance in his rough batteau gives an especially picturesque air to the beauty of that matchless scene. I wish I was a painter. I would pay any price if I could fling upon canvas that background of hazy gray, and place against it the fiery splendor of the sunlit river, with steamer and ship and weather-beaten sloop and fishing-boat drifting to and fro upon the golden tide.

There, too, is old Cooley, our next-door neighbor on the east. He is out early this morning, walking about his garden, pulling up a weed here and there, prowling among his strawberry vines and investigating the condition of his early raspberries. That dog which trots behind him, my dear, is the one that barked all night. I shall have to ask Cooley to take him in the house after this. We had enough of that kind of disturbance in the city; we do not want it here.

"I don't like the Cooleys," remarked Mrs. A.

"Why not?"

"Because they quarrel with each other. Their girl told our girl that 'him and her don't hit it,' and that Mr. Cooley is continually having angry disputes with his wife. She says that sometimes they even come to blows. It is dreadful."

"It is indeed dreadful. Somebody ought to speak to [Pg 50] Cooley about it. He needs overhauling. Perhaps he is too ignorant a man to have perceived the true road to happiness. Of course, Mrs. A., you know the secret of real happiness in married life?"

She said she had never thought much about it. She was happy, and it seemed natural to be so. She thought it very strange that there should ever be any other condition of things between man and wife.

"Mrs. Adeler, the secret of conjugal felicity is contained in this formula: demonstrative affection and self-sacrifice. A man should not only love his wife dearly, but he should tell her he loves her, and tell her very often. And each should be willing to yield, not once or twice, but constantly and as a practice, to the other. The man who never takes the baby from his wife, who never offers to help her in her domestic duties, who will sit idly by, indulging himself with repose while she is overwhelmed with care and work among the children, or with other matters, is a mean wretch who does not deserve to have a happy home. And a wife who never holds up her husband's hands in his struggle with the world, who displays no interest in his perplexities and trials, who has never a word of cheer for him when he staggers under his heavy burden, is not worthy the name of a wife. Selfishness, my dear, crushes out love, and most of the couples who are living without affection for each other, with cold and dead hearts, with ashes where there should be a bright and holy flame, have destroyed themselves by caring too much for themselves and too little for each other."

"To me," said Mrs. Adeler, "the saddest thing about such coldness and indifference is that both the man and the woman must sometimes think of the years when they loved each other."

"Yes, and can you imagine anything that would be more likely to give a woman the heartache than such a recollection? [Pg 51] When her husband comes home and enters the house without a smile or a word of welcome; when he growls at his meals, and finds fault with this and that domestic arrangement; when he buries his nose in his newspaper after supper, and never resurrects it excepting when he has a savage word of reproof for one of his children, or when he goes out again to spend the evening and leaves his wife alone, the picture which she brings up from the past cannot be a very pleasant one.

"Indeed, my dear, the man's present conduct must fill the woman's soul with bitter pain when she contrasts it with that which won her affection. For there must have been a time when she looked forward with joy to his coming, when he caressed her and covered her with endearments, when he looked deep into her eyes and said that he loved her, and when he said that he could have no happiness in this world unless she loved him wholly and truly. When a man makes such a declaration as that to a woman, he is a villain if he ever treats her with anything but loving-kindness. And I take the liberty of doubting whether he who leads a young girl into wedlock with such pledges, and then acts in direct violation of them, ought not to be prosecuted for obtaining valuable consideration upon false pretences. It is infinitely worse, in my opinion, than stealing ordinary property."

Mrs. Adeler expressed the opinion that death at the stake might be regarded as an appropriate punishment for criminals of this class.

"But there is a humorous side even to this melancholy business. Do you remember the Sawyers, who used to live near us in the city? Well, before Sawyer's marriage I was his most intimate friend; and when they returned from their wedding-trip, of course I called upon them. Mrs. Sawyer alone was at home, and after a brief discussion of the weather, the conversation turned upon Sawyer. I had [Pg 52] known him for many years, and I took pleasure in making Mrs. Sawyer believe that he had as much virtue as an omnibus load of patriarchs. Mrs. Sawyer assented joyously to it all, but I thought I detected a shade of sadness on her face while she spoke. I asked her if anything was the matter—if Sawyer's health was not good.

"'Oh yes,' she said, 'very good indeed, and I love him dearly. He is the best man in the world; but—but—'

"Then I assured Mrs. Sawyer that she might speak frankly to me, as I was Sawyer's friend, and could probably smooth away any little unpleasantness that might mar their happiness. She then said it was nothing. It might seem foolish to speak of it; she knew it was not her dear husband's fault, and she ought not to complain; but it was hard, hard to submit when she reflected that there was but one thing to prevent her being perfectly happy; yes, but one thing, 'for oh, Mr. Adeler, I would ask for nothing more in this world if Ezekiel only had a Roman nose!'

"It is an awful thing, Mrs. Adeler, to think of two young lives being made miserable for want of one Roman nose, isn't it?"

Mrs. A. gently intimated that she entertained a suspicion that I had made up the story; and if I had not, why, then Mrs. Sawyer certainly was a very foolish woman.

My wife's cousin, Bob Parker, came down a fortnight ago to stay a day or two on his way to Cape May, with the intent to tarry at that watering-place for a week or ten days, and then to return here to remain with us for some time. Bob is a bright youth, witty in his own small way, fond of [Pg 53] using his tongue, and always overflowing with animal spirits. He came partly to see us, but chiefly, I think, because he cherishes a secret passion for a certain fair maid who abides here.

He brought me a splendid present in the shape of an American agave, or century plant. It was offered to him in Philadelphia by a man who brought it to the store and wanted to sell it. The man said it had belonged to his grandfather, and he consented to part with it only because he was in extreme poverty. The man informed Bob that the plant grew but half an inch in twenty years, and blossomed but once in a century. The last time it bloomed, according to the information obtained from the gray-haired grandsire of the man, was in 1776, and it would therefore certainly burst out again in 1876. Patriotism and a desire to have such a curiosity in the family combined to induce Mr. Parker to purchase it at the price of fifty dollars.

I planted the phenomenon on the south side of the house, [Pg 54] against the wall. Two days afterward I called Bob's attention to the circumstance that the agave had grown nearly three feet since it was placed in the ground. This seemed somewhat strange after what the man said about the growth of half an inch in two decades. But we concluded that the surprising development must be due to the extraordinary fertility of the soil, and Bob exulted as he thought how he had beaten the man by getting a century plant so much larger and so much more valuable than he had supposed. Bob said that the man would be wofully mad if he should call and see that century plant of his grandfather's getting up out of the ground so splendidly.

That afternoon we all went down to Cape May, and for two weeks we remained there. Upon our return, Bob remarked, as we stepped from the boat, that he wanted to go around the first thing and see how the plant was coming on. He suggested gloomily that he should be bitterly disappointed if it had perished from neglect during our absence.

But it was not dead. We saw it as soon as we came near the house. It had grown since our departure. It had a trunk as thick as my leg, and the branches ran completely over three sides of the house; over the window shutters, [Pg 55] which were closed so tightly that we had to chop the century plant away with a hatchet; over the roof, down the chimneys, which were so filled with foliage that they wouldn't draw; and over the grapevine arbor, in such a fashion that we had to cut away vines and all to get rid of the intruder.

The roots, also, had thrown out shoots over every available square foot of the yard, so that I had eight or ten thousand century plants in an exceedingly thriving condition, while a branch had grown through the open cellar window, and was getting along so finely that we could only reach the coal-bin by tramping through a kind of an East Indian jungle.

Mr. Parker, after examining the vegetable carefully, observed:

"I'm kind of sorry I bought that century plant, Max. I have half an idea that the man who sold it to me was a humorist, and that his Revolutionary grandfather was an octogenarian fraud."

If anybody wants a good, strong, healthy century plant that will stand any climate, and that is warranted to bloom in 1876, mine can be had for a very reasonable price. This may be regarded as an unparalleled opportunity for any young agriculturist who does not want to wait long for his vegetables to grow.

Judge Pitman—His Experiment in the Barn—A Lesson in Natural History—Catching the Early Train—One of the Miseries of Living in a Village—Ball's Lung Exercise—Mr. Cooley's Impertinence.

My next-door neighbor upon the west is Judge Pitman. I heard his name mentioned before I became acquainted with him, and I fancied that he was either a present occupant of the bench, or else that he had gone into retirement after spending his active life in dispensing justice and unraveling the tangles of the law. But it appears that he has never occupied a judicial position, and that his title is purely complimentary, having no relation whatever to the nature of his pursuits either in the past or in the present. The judge, indeed, is merely the owner of a couple of steam-tugs and one or two wood sloops which ply upon the river and upon Chesapeake Bay. He spends most of his time at home, living comfortably upon the receipts of a business which is conducted by his hired men, and perhaps also upon the interest of a few good investments in this and other places.

A very brief acquaintance with the judge suffices to convince any one that he has never presided in court. He is a rough, uneducated man, with small respect for grammar, an [Pg 57] irrepressible tendency to distort the language, and very little information concerning subjects which are not made familiar by the occurrences of every-day life. But he is hearty, genial, sincere and honest, and I very soon learned to like him and to find amusement in his quaint simplicity.

My first interview with the judge was somewhat remarkable. I came home early one afternoon for the purpose of training some roses and clematis against my fence. While I was busily engaged with the work, the judge, who had been digging potatoes in his garden, stuck his spade in the earth and came to the fence. After looking at me in silence for a few moments, he observed,

"Fine day, cap!"

The judge has the habit of conferring titles promiscuously and without provocation, particularly upon strangers. To call me "cap." was his method of expressing a desire for sociability.

"It is a beautiful day," I observed, "but the country needs rain."

"It never makes no difference to me," replied the judge, "what kinder weather there is; I'm allers satisfied. 'Twon't rain no sooner for wishin' for it."

As there was no possibility of our having a controversy upon this point, I merely replied, "That is true."

"How's yer pertaters comin' on?" inquired the judge.

"Very well, I believe. They're a little late, but they appear to be thriving."

"Mine's doin' first rate," returned the judge. "I guannered them in the spring, and I've bin a-hoein' at 'em and keepin' the weeds down putty stiddy ever since. Mons'ous sight o' labor growin' good pertaters, cap."

"I should think so," I rejoined, "although I haven't had much practical experience in that direction thus far."

"Cap.," observed the judge, after a brief interval of silence, "you're one of them fellers that writes for the papers and magazines, a'n't you?"

"Yes, I sometimes do work of that kind."

"Well, see here: I've got somethin' on my mind that's bin a-botherin' me the wust kind for a week and more. You've read the 'Atlantic Monthly,' haven't you?"

"Yes."

"Well, my daughter bought one of 'em, and I was a-readin' it the other night, when I saw it stated that guanner could be influenced by music, and that Professor Brown had made some git up and come to him when he played a tune on the pianner."

I remembered, as the judge spoke, that the magazine in question did contain a paragraph to the effect that the iguana was susceptible of such influence, and that Mrs. Brown had succeeded in taming one of these animals, so that it would run to her at the sound of music. But I permitted Mr. Pitman to continue without interruption.

"Of course," said he, "I never really believed no such nonsense as that, but it struck me as kinder sing'lar, and I thought I'd give the old thing a trial, anyhow. So I got down my fiddle and went to the barn, and put a bag of guanner in the middle of the floor and begun to rake out a tune. First I played 'A Life on the Ocean Wave and a Home on the Rollin' Deep' three or four times; and there that guanner sot, just as I expected 'twould. Then I begun agin and sawed out a lot o' variations, but still she didn't budge. Then I put on a fresh spurt and jammed in a passel o' extra sharps and flats and exercises; and I played that tune backward and sideways and cat-a-cornered. And I stirred in some scales, and mixed the tune up with Old Hundred and Mary Blaine and some Sunday-school songs, until I nearly fiddled my shirt off, and nary time did that guanner bag git up off o' that floor. I knowed it wouldn't. I knowed that feller wa'n't tellin' the truth. But, cap., don't it strike you that a man who'd lie like that ought to have [Pg 60] somethin' done to him? It 'pears to me 's if a month or two in jail'd do that feller good."

The lesson in natural history which I proceeded to give to the judge need not be repeated here. He acknowledged that the laugh was fairly against him, and ended his affirmation of his new-born faith in the integrity of the Atlantic Monthly by inviting me to climb over the fence and taste some of his Bartlett pears. The judge and I have been steady friends ever since.

I find that one of the most serious objections to living out of town lies in the difficulty experienced in catching the early morning train by which I must reach the city and my business. It is by no means a pleasant matter, under any circumstances, to have one's movements regulated by a timetable and to be obliged to rise to breakfast and to leave home at a certain hour, no matter how strong the temptation to delay may be. But sometimes the horrible punctuality of the train is productive of absolute suffering. For instance: I look at my watch when I get out of bed and find that I have apparently plenty of time, so I dress leisurely, and sit down to the morning meal in a frame of mind which is calm and serene. Just as I crack my first egg I hear the down train from Wilmington. I start in alarm; and taking out my watch, I compare it with the clock and find that it is eleven minutes slow, and that I have only five minutes left in which to get to the dépôt.

I endeavor to scoop the egg from the shell, but it burns my fingers, the skin is tough, and after struggling with it for a moment, it mashes into a hopeless mess. I drop it in disgust and seize a roll, while I scald my tongue with a quick mouthful of coffee. Then I place the roll in my mouth while my wife hands me my satchel and tells me she thinks she hears the whistle. I plunge madly around [Pg 61] looking for my umbrella, then I kiss the family good-bye as well as I can with a mouth full of roll, and dash toward the door.

Just as I get to the gate, I find that I have forgotten my duster and the bundle my wife wanted me to take up to the city to her aunt. Charging back, I snatch them up and tear down the gravel-walk in a frenzy. I do not like to run through the village: it is undignified and it attracts attention; but I walk furiously. I go faster and faster as I get away from the main street. When half the distance is accomplished, I actually do hear the whistle; there can be no doubt about it this time. I long to run, but I know that if I do I will excite that abominable speckled dog sitting by the sidewalk a little distance ahead of me. Then I really see the train coming around the curve close by the dépôt, and I feel that I must make better time; and I do. The dog immediately manifests an interest in my [Pg 62] movements. He tears after me, and is speedily joined by five or six other dogs, which frolic about my legs and bark furiously. Sundry small boys, as I go plunging past, contribute to the excitement by whistling with their fingers, and the men who are at work upon the new meeting-house stop to look at me and exchange jocular remarks with each other. I do feel ridiculous; but I must catch that train at all hazards.

I become desperate when I have to slacken my pace until two or three women who are standing upon the sidewalk, discussing the infamous price of butter, scatter to let me pass. I arrive within a few yards of the station with my duster flying in the wind, with my coat tails in a horizontal position, and with the speckled dog nipping my heels, just as the train begins to move. I put on extra pressure, resolving to get the train or perish, and I reach it just as the last car is going by. I seize the hand-rail; I am jerked violently around, but finally, after a desperate effort, I get upon the [Pg 63] step with my knees, and am hauled in by the brakeman, hot, dusty and mad, with my trousers torn across the knees, my legs bruised and three ribs of my umbrella broken.

Just as I reach a comfortable seat in the car, the train stops, and then backs up on the siding, where it remains for half an hour while the engineer repairs a dislocated valve. The anger which burns in my bosom as I reflect upon what now is proved to have been the folly of that race is increased as I look out of the window and observe the speckled dog engaged with his companions in an altercation over a bone. A man who permits his dog to roam about the streets nipping the legs of every one who happens to go at a more rapid gait than a walk, is unfit for association with civilized beings. He ought to be placed on a desert island in mid-ocean, and be compelled to stay there.

This will do as a picture of the experience of one morning—one melancholy morning. Of course it is exceptional. Rather than endure such agony of mind and discomfort of body frequently, I would move back to the city, and abandon for ever my little paradise by the Delaware.