*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 42224 ***

"COPYRIGHT BY THE DELPHIAN SOCIETY, CHICAGO"

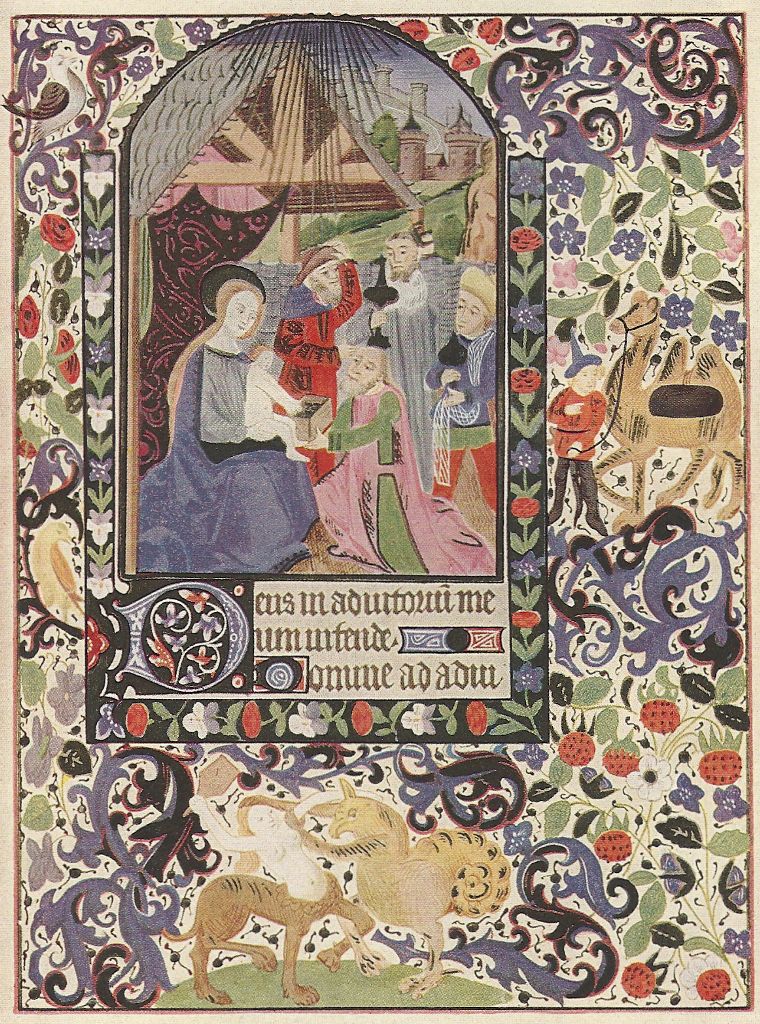

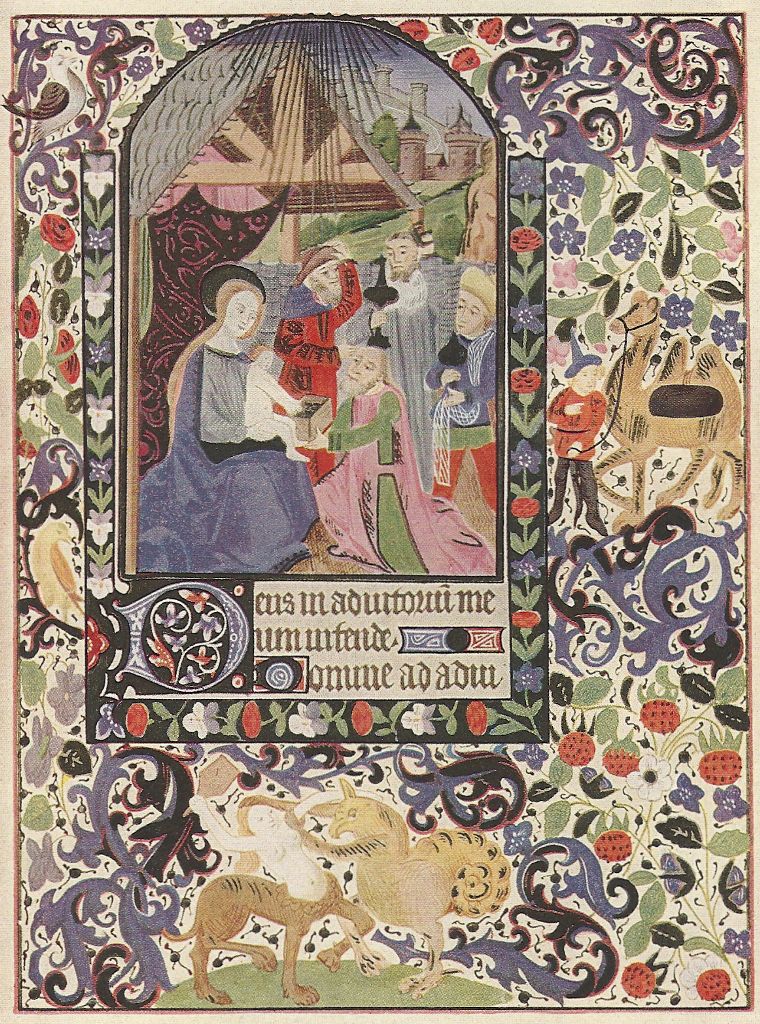

THE ADORATION OF THE MAGI.

Reproduced for our Members through the courtesy of

The Newberry Library, Chicago

This illuminated manuscript represents the work done by

French monks in the early part of the fourteenth century.

The border, containing as it does many grotesque

figures scattered through its foliage, indicates this, as also the

style of the faces in the miniature work. This is taken from one

of the many "Book of Hours" and was the page used for the

"Sext Hour," a full description of illuminated manuscript will

be found Part IX, page 101.

[I]

THE WORLD'S

PROGRESS

WITH

ILLUSTRATIVE TEXTS

FROM MASTERPIECES OF

EGYPTIAN, HEBREW, GREEK,

LATIN, MODERN EUROPEAN

AND AMERICAN

LITERATURE

FULLY ILLUSTRATED

EDITORIAL STAFF

| Very Rev. J. K. Brennan | Missouri |

| Gisle Bothme, M.A. | University of Minnesota |

| Chas. H. Caffin | New York |

| James A. Craig, M.A., B.D., Ph.D. | University of Michigan |

| Mrs. Sarah Platt Decker | Colorado |

| Alcée Fortier, D.Lt. | Tulane University |

| Roswell Field | Chicago |

| Bruce G. Kingsley | Royal College of Organists, England |

| D. D. Luckenbill, A.B., Ph.D. | University of Chicago |

| Kenneth McKenzie, Ph.D. | Yale University |

| Frank B. Marsh, Ph.D. | University of Texas |

| Dr. Hamilton Wright Mabie | New York |

| W. A. Merrill, Ph.D., L.H.D. | University of California |

| T. M. Parrott, Ph.D. | Princeton University |

| Grant Showerman, Ph.D. | University of Wisconsin |

| H. C. Tolman, Ph.D., D.D. | Vanderbilt University |

| I. E. Wing, M.A. | Michigan |

VOL. I

THE DELPHIAN SOCIETY

[II]

Copyright 1913

by

THE DELPHIAN SOCIETY

Chicago

COMPOSITION, ELECTROTYPING, PRINTING

AND BINDING BY THE

W. B. CONKEY COMPANY

Hammond, Indiana

[III]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART I.

| Page |

| The Delphian Course of Reading | VIII |

| Prehistoric Man; Customs and Occupations. Dawn of Civilization | XIV |

| EGYPT. |

| Prefatory Chapter | 13 |

| Chapter I. |

| Its Antiquity; Story of Joseph, Physical Geography, Prehistoric Egypt | 20 |

| Chapter II. |

| Sources of Egyptian History; Herodotus' Account of Egypt | 31 |

| Chapter III. |

| Pyramid Age; Early Egyptian Kings; Construction of Pyramids | 37 |

| Chapter IV. |

| Age of Darkness; Middle Empire; Reigns of Amenemhet I. and III.; Description of Labyrinth | 43 |

| Chapter V. |

| Egypt under the Shepherd Kings; Beginning of the New Empire; Conquests of Thutmose I. | 51 |

| Chapter VI. |

| First Egyptian Queen; Temple of Hatshepsut; Expedition to Punt | 57 |

| Chapter VII. |

| Military Kings; Hymn of Victory; Worship of the Solar Disk; Temple of Karnak | 64 |

| Chapter VIII. |

| Nineteenth Dynasty; Egypt under Ramses the Great; Twentieth Dynasty; Priest Rule; Ethiopian Kings | 72 |

| Chapter IX. |

| Social Life in Egypt; Houses, Dress, Family Life | 85 |

| Chapter X. |

| Sports and Recreations | 96 |

| Chapter XI. |

| Agriculture and Cattle Raising; Arts and Crafts; Egyptian Markets; Military Affairs | 100 |

| Chapter XII.[IV] |

| Schools and Education; Egyptian Literature | 112 |

| Chapter XIII. |

| Religion of Ancient Egypt; Hymn to the Nile; Egyptian Temples and Ceremonies | 119 |

| Chapter XIV. |

| Art and Decoration | 133 |

| Chapter XV. |

| Tombs and Burial Customs | 138 |

| Chapter XVI. |

| Excavations in Egypt; Discoveries of W. M. Flinders Petrie | 144 |

| Descriptions of Egypt. |

| Description of the Nile | 153 |

| Feast of Neith | 155 |

| Karnak | 159 |

| Memphis | 161 |

| Hymn to the God Ra | 163 |

| Egyptian Literature. |

| An Old Kingdom Book of Proverbs | 164 |

| The Voyage of the Soul | 168 |

| The Adventures of the Exile Sanehat | 171 |

| The Song of the Harper | 179 |

| Present Day Egypt. |

| Alexandria | 181 |

| Cairo | 182 |

| Egyptian Museum | 185 |

| Suez Canal | 187 |

| BABYLONIA AND ASSYRIA. |

| Prefatory Chapter | 193 |

| Chapter I. |

| Early Civilization of Asia; Recovery of Forgotten Cities | 201 |

| Chapter II. |

| Sources of Babylonian and Assyrian History; Physical Geography | 211 |

| Chapter III. |

| Prehistoric Chaldea; Charms and Talismans; Semitic Invasion | 218 |

| Chapter IV. |

| City-States Before the Rise of Babylon; Hymn to the Moon-God | 227 |

| Chapter V. |

| Dominance of Babylon | 232 |

| Chapter VI.[V] |

| Beginnings of Assyrian Empire; Conquest of Asshurnatsirpal | 237 |

| Chapter VII. |

| Assyria a Powerful Empire; Hebrew Account of the War with Assyria | 245 |

| Chapter VIII. |

| Last Years of Assyrian Dominance | 256 |

| Chapter IX. |

| Chaldean Empire in Babylonia | 264 |

| Chapter X. |

| Social Life in Mesopotamia. The Babylonian and Assyrian Compared; Their Houses and Family Life | 270 |

| Chapter XI. |

| Morality of the Ancient Babylonians | 276 |

| Chapter XII. |

| Literature and Learning; Deluge Story | 283 |

| Chapter XIII. |

| Clothing Worn by Assyrians and Babylonians; Their Food | 293 |

| Chapter XIV. |

| Architecture and Decoration | 300 |

| Chapter XV. |

| Religious Customs | 307 |

| Chapter XVI. |

| The Laboring Classes; Professions | 317 |

| Chapter XVII. |

| The Medes | 328 |

| Chapter XVIII. |

| Condition of Persia Before the Age of Cyrus; Cyrus the Great and the Persian Empire | 332 |

| Chapter XIX. |

| War with Greece | 340 |

| Chapter XX. |

| Manners and Customs of the Persians; Their Religion | 346 |

| Chapter XXI. |

| Contributions of Babylonia, Assyria and Persia to Modern Civilization | 357 |

| Assyrian Literature.[VI] |

| Chaldean Account of the Deluge | 361 |

| Descent of Ishtar to Hades | 367 |

| Gyges and Assurbanipal | 371a |

| Purity | 371c |

| Zoroaster's Prayer | 371d |

| THE HEBREWS AND THEIR NEIGHBORS. |

| Chapter I. |

| Syria | 372 |

| Chapter II. |

| The Land of Phoenicia; Reign of Hiram; Invasion of Asshurbanipal | 378 |

| Chapter III. |

| Phoenician Colonies and Commerce | 390 |

| Chapter IV. |

| Occupations and Industries; Literature and Learning; Religion | 399 |

| Chapter V. |

| Physical Geography of Palestine; Climate and Productivity | 408 |

| Chapter VI. |

| Effects of Geographical Conditions upon the Hebrews | 418 |

| Chapter VII. |

| Sources of Hebrew History | 426 |

| Chapter VIII. |

| Condition of the Hebrews Prior to Their Occupation of Canaan | 434 |

| Chapter IX. |

| Era of the Judges | 441 |

| Chapter X. |

| Morality of the Early Hebrews | 448 |

| Chapter XI. |

| Causes Leading to the Establishment of the Kingdom. David's Lament; His Reign. Solomon Rules; King Solomon and the Bees | 453 |

| Chapter XII. |

| After the Division of the Kingdom; End of Israel | 469 |

| Description of Illustrations | 483 |

[VII]

FULL PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

PART I.

| Page |

| Illuminated Missal | Frontispiece |

| Distant View of the Pyramids | 44 |

| Near View of Pyramids and Sphinx | 68 |

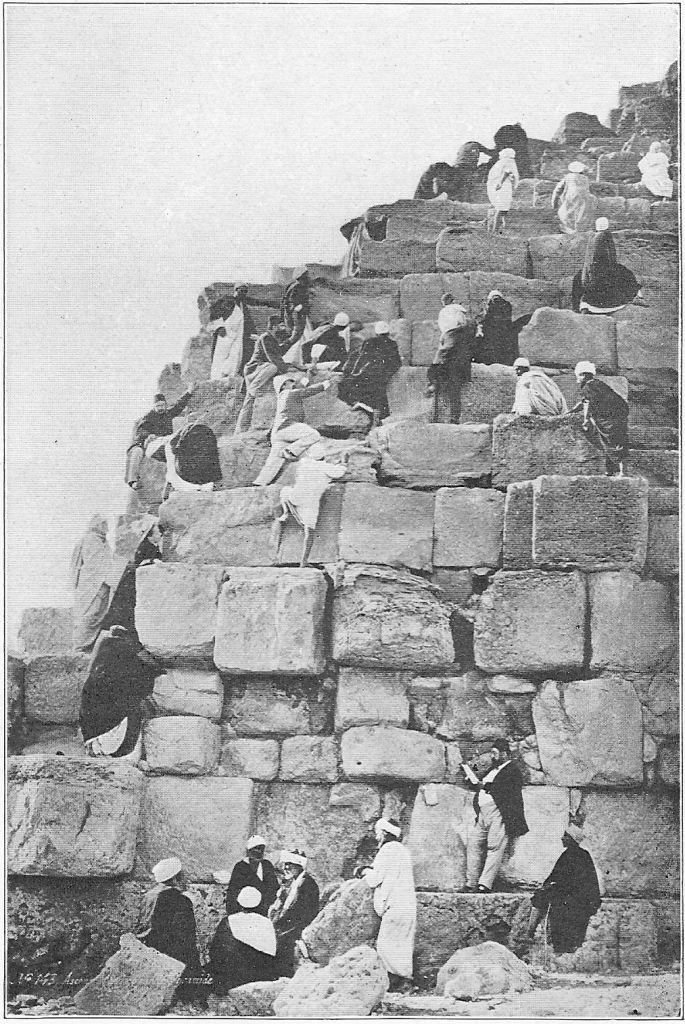

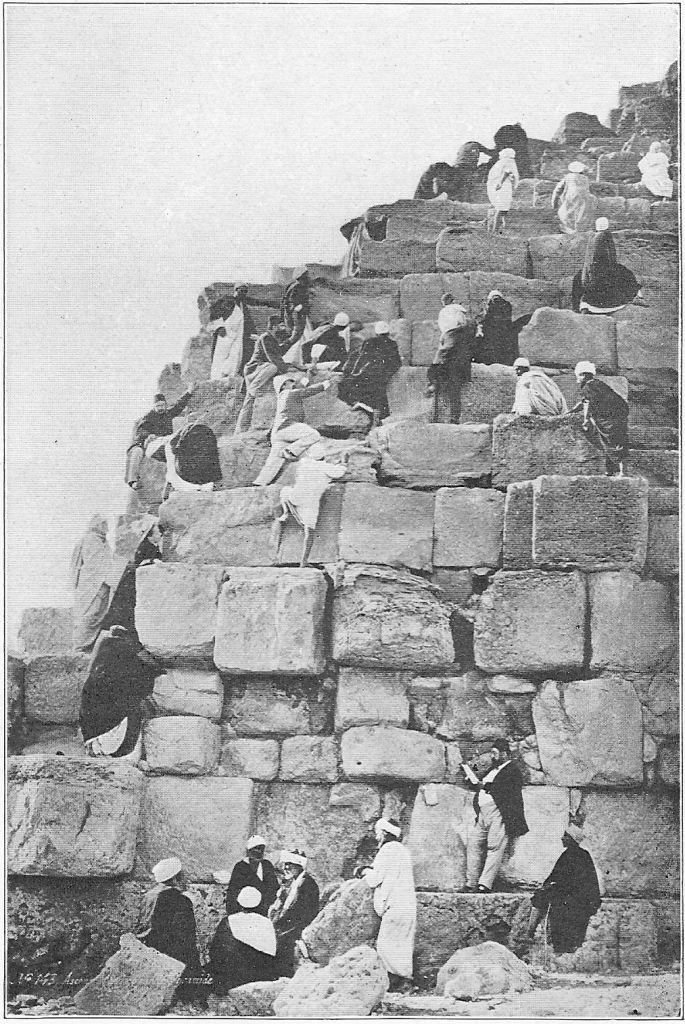

| Tourists Scaling the Great Pyramid | 92 |

| Column and Pylon of Karnak | 124 |

| Beautiful Island of Philea | 148 |

| Windows of a Harem | 172 |

| Ship of the Desert (Photogravure) | 192 |

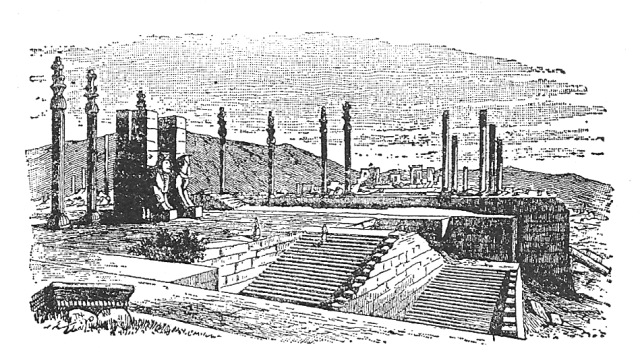

| Winged Lion | 236 |

| Musicians and Attendants in the Garden of Asshurbanipal | 284 |

| Sword-Maker of Damascus | 348 |

| The River Jordan | 392 |

| Jappa Harbor | 432 |

| Roses of Sharon | 464 |

| Map of Ancient Egypt | VI |

[VIII]

THE DELPHIAN COURSE

OF READING

wo thousand years before the sight of a

new world burst upon the view of the Genoese

mariner, there existed in north-central Greece a

sanctuary famous in three continents. Located

in mountainous Phocis, in a natural amphitheater,

overhung by frowning rocks and reached only through

mysterious caves, was the Oracle of Delphi. Here in remote

times Apollo was believed to reveal his wishes to men

through the medium of a priestess, speaking under the influence

of vaporous breath which rose from a yawning fissure.

Her utterances were not always coherent and were

interpreted to those seeking guidance by Apollo's priests.

As its fame spread, the number of visitors to Delphi increased.

More priests were needed to counsel and advise.

Although the first blind faith in earlier deities lessened, the

prestige of Delphi was nevertheless preserved. Apollo's

priests became better versed in the affairs of Greece and the

surrounding countries; their assistants became familiar with

all vital issues, and thus intelligent replies were given to unceasing

inquiries. In time the Greek divinities were almost

forgotten and Christianity became the state religion, yet the

Oracle of Delphi continued to draw men unto it until the

fifth Christian century.

Ancient writers have left us abundant accounts of journeyings

made thither by potentates and kings, and have described

at length the rich offerings left by them in gratitude.

The humble were seldom mentioned by early writers and it

remained for the last few years to bring to light little leaden

tablets—valueless from the standpoint of plunderers, earth-covered

and revealed only by the excavator's spade—silent

testimonials of appeals made to the oracle by the common

people.

[IX]

It is difficult for us today to understand the powerful

influence which the Delphian Oracle exercised for a thousand

years in Greece. This might fittingly be compared to

that wielded by the Church in the Middle Ages. Here questions

of international importance were brought, policies determined,

and the balance delicately turned for peace or war.

Nor were questions of the humblest slighted. Any interference

on the part of one state designed to deny citizens of

another free access to Delphi precipitated serious trouble.

There is no doubt but that implicit faith directed the first

visitors to Delphi and beyond question this faith to some extent

survived. The peasant accepted literally the presence of

deity as many a worshipper today regards the statue, not as

a symbol, but as the very Christ. However, there have been

in all ages the discerning who have distinguished between the

symbol and that symbolized, and certainly the keen, alert

Greeks did not remain blind adherents of antiquated conceptions.

The wisdom of the Delphian priests was revered and

their judgments accepted much in the same way as were

those of the seers who taught the children of Israel at the

city gates. The Oracle of Delphi became potent—a name

with which to conjure.

We know full well today that no priestess upon a tripod

can reveal to us the secrets of the future. A thorough understanding

of the past must be the safest guide for coming

years. No vapor can inspire sudden revelations—the result

only of faithful effort and earnest thought. Yet the story of

the ancient oracle charms us still and when a name was

sought for a national organization, that had for its avowed

purpose the promotion of educational interests in a continent,

none was deemed more suitable than that which for so many

years cast its gracious spell from one sea to another.

Each new decade brings new needs, and the conditions of

fifty years ago were wholly different from those confronting

us today. Ours is an age characterized by intensity, strenuous

effort and tireless exertion. Leisure seems to have disappeared

from our national life and to be remembered only

when reviewing pleasant stories of other times. Educators

complain that we are neglecting the wisdom of the past—that

the enduring thoughts of men as preserved to us in their[X]

writings have ceased to be familiar. The thoughtful deplore

the loss of culture, courtesy and old-time chivalry. Frequently

the critics fail to look beneath the surface for reasons

leading to the very evident result. The truth is that in no

previous age have the hearts of people been more sensitive

to injustice, more united for fair dealing between man and

man, more eager for the best the world can offer. But we

are living in a transition period; social and industrial conditions

have not yet crystallized in their new forms sufficiently

to permit the wider opportunity for cultivation and reflection

which must necessarily overtake us in time.

At present people accumulate fine libraries and rarely

read them; for their shelves they seek the best—for their diversion

the lightest and most transient literature. Few are

there who do not dream of a happy time when it shall be

their delight to browse among their books and find companionship

in them. Still the years fly by relentlessly and

many who are not mere theorists are sounding a warning:

This time so fondly anticipated will never come to many of

the present generation; seize today; snatch a brief moment

for the consideration of enduring thoughts; do not merely

provide for the temporal wants and leave the soul famishing.

Dr. Eliot, late president of Harvard, in repeated lectures and

addresses has voiced this crying need.

"From the total training during childhood there should

result in the child a taste for interesting and improving reading,

which should direct and inspire its subsequent intellectual

life. That schooling which results in this taste for good

reading, however unsystematic or eccentric the schooling may

have been, has achieved a main end of elementary education;

and that schooling which does not result in implanting this

permanent taste has failed. Guided and animated by this

impulse to acquire knowledge, and exercise his imagination

through reading, the individual will continue to educate himself

all through life. Without that deep-rooted impulsion he

will soon cease to draw on the accumulated wisdom of the

past and the new resources of the present, and, as he grows

older, he will live in a mental atmosphere which is always

growing thinner and emptier. Do we not all know many

people who seem to live in a mental vacuum—to whom, in[XI]deed,

we have great difficulty in attributing immortality, because

they apparently have so little life except that of the

body? Fifteen minutes a day of good reading would have

given any one of this multitude a really human life."[1]

To meet this condition, which prevails throughout the

length and breadth of our land, to stimulate a deeper interest,

quicken a latent appreciation and facilitate the use of brief

periods of freedom for self-improvement, the Delphian Society

was organized and the Delphian Course of Reading

made possible.

Believing that only a comprehensive course could meet

the requirements of the day and prove acceptable to a large

number of people, the Delphian Society has included those

subjects which are now offered in the curriculums of our

leading colleges and universities—history, literature, philosophy,

poetry, fiction, drama, art, ethics, music. Mathematics,

being in its higher forms essential to few, has been

omitted; languages, requiring the aid of a teacher, and such

sciences as make laboratories necessary, are not included.

None of these subjects possess purely cultural qualities. Technical

information has no place whatever in such a scheme.

The branches of human interest which remain are those of

vital importance to everyone.

Not only is the list of subjects widely inclusive, but the

method of treatment has been carefully considered. Finding

the beginnings of most modern activities in antiquity, the

Delphian Course presents the gradual unfoldment of each

subject from earliest times to our own. The distance between

an imitation of the hunt, as found among the diversions

of primitive people, and a modern play is great, and

yet no complete idea of the latter can be acquired without

some conception of dramatic origins. The crude picture

drawn upon the sooty hide which formed a hut in early times

and the crowning masterpiece of a Raphael present extremes,

and yet he who would follow the gradual growth of painting

realizes that each has its place in the progress of art. Only

in comparatively recent times has the value of each link

which form the long chain of development been understood.

No amount of heterogenous reading can compare with the[XII]

systematic tracing of one subject from its early manifestations

to its present forms.

Correlation of topics presents wonderful possibilities. If

we become interested, for example, in society as portrayed in

the earliest English novels, how much more shall we then

appreciate the canvases of Hogarth, which depict the same

social conditions. If the age of idealism in literature be

under consideration, the productions of contemporaneous

artists grow to have for us a new significance.

It is a mistake to imagine that relaxation and diversion

are obtainable only from reading matter of the day. Oscar

Kuhms calls attention to the fact that "to spend hours over

illustrated magazines, Sunday newspapers, and the majority

of popular novels, has very little to do with the art of reading

in its larger sense." To a far greater extent than is generally

imagined, the inordinate reading of magazines accounts

for the host of superficial readers of our generation. To see

how temporary is their interest one needs only to examine

journals three or four years old.

The pleasures of travel may be greatly enhanced by definite

knowledge of countries visited—their recorded past, the

manner of life of those who dwelt within them and those

now populating them; ruins, old temples, surviving art, make

slight appeal to those wholly unfamiliar with the ages that

produced them. The enjoyment of a play is more poignant

for the one who has in mind the changes which plays and

playhouses have witnessed. There is something impressive

in the thought that for ages audiences have been thus held

spellbound. Four centuries before the Christian era imposing

dramas and keenly satirical comedies were given before

larger assemblies than modern theatres could accommodate.

Only in modern times has a curtain separated the players

and spectators. Formerly the favored sat upon the stage itself;

in the Elizabethan playhouse the majority stood

throughout an entire performance. Sentences in Shakespeare's

plays are meaningless without taking these facts into

account. Some extended acquaintance with pictures would

put an end to comments made not infrequently by critics that

the spectacle of groups of people today in attendance upon an

art exhibit supplies an astonishing sight. The majority[XIII]—so

it has been stated—find a number in their catalogues,

search frantically about for a picture so designated, and when

they discover it, sigh with satisfaction and begin the search

for another—"for all the world as though they were indulging

in a simple hunting game!" Why Raphael painted so

many Madonnas, why Watteau seems to have known only

the gay and carefree—these are simple questions which many

might find perplexing to adequately explain.

The traveler whose time in a foreign land is limited does

not seek the commonplace and unattractive; he does not try

to compass all a city might have to show in the brief period

he can spend there; rather, he obtains the guidance of those

more familiar with the locality, and gives his attention to the

best it has to offer. So if our time for reading and self-improvement

must be brief, we shall find small satisfaction in

wasting it blindly searching for what may satisfy. Educators

are usually less pressed by insidious cares and more free

to give their devotion to favorite subjects.

It is a mistake to suppose one reads chiefly for information.

We read to develop our insight into the mystery of

life; to gain an individual viewpoint; to establish our standards

of conduct and modify our standard of judgment. Reading

which is mere diversion can never bestow this power.

If those adopting the Delphian Course as the basis of

their reading find that with its aid they are enabled to accomplish

more satisfying results; if they finally discover that

with its guidance one can make more intelligent use of his own

library; if a love for things worth while—the lasting and enduring

thoughts and sentiments of men—increases, and the

desire for wider knowledge is aroused—the hopes and ambitions

of the Delphian Society shall have been largely realized.

[XIV]

PRIMITIVE DRAWING OF MAN.

PRIMITIVE DRAWING OF MAN.

PREHISTORIC MAN

he word prehistoric means, literally, before history

begins, and by prehistoric man we mean

those human beings who lived upon the earth

before records were kept. History, properly so

called, does not begin until civilization is

reached. The roaming of savage people over land in

search of food has little or no importance for the student of

history, although knowledge of a people in its savage state may

throw some light upon its future development. While prehistoric

ages are the concern of the archaeologist rather than the

historian, we shall find that historic ages owe a great debt to

prehistoric ages, and with this aspect of the matter the historian

has deep interest.

The science of geology teaches us that the earth has not

always possessed its present familiar appearance. On the contrary,

countless years were consumed in molding it to its present

shape, and even yet it is undergoing constant change. It

is supposed that in the beginning all was a chaotic heap of Matter.

In the words of a familiar story: "The earth was not

solid, the sea was not liquid, nor the air transparent. All lay

in confusion."

In some mysterious way,—that nobody understands—Motion

was started in this chaotic whole. Gradually the

mass became more and more compact; at the same time it

became very hot. Revolving on an imaginary axis, the mass

grew rounder and rounder, flattening slightly at the poles, or

the ends of the axis. Gradually the surface of the mass cooled,

and cooling, formed the earth's crust. Because it did not cool

evenly, but shrunk to fit the still molten mass, this surface

or crust was left with deep crevasses and high ridges. This

marked irregularity was further increased by mighty upheavals

caused by pressure of heat from within. Thus were many of

the mountains formed.[XV]

This process, so slightly indicated here, extended over a

vast period of time. It is supposed that later, for a protracted

period, rain fell. When the age of rain had passed, the deep

depressions in the earth's surface were left filled with water—our

present oceans and some of the seas. It would be impossible

for us to review rapidly all the stages through which

the earth passed in its making. Suffice it to say that conditions

upon it were not always favorable to life as we know it. In

course of long geological ages—perhaps millions and millions

of years—forests of trees, plants, shrubs and flowers sprang

up and covered the bare earth. Last of all, probably, man

appeared. How all these things came about no one understands,

but it is generally accepted that they occurred in an order

similar to that just given. It would be useless for us to inquire

into all the reasons that have led to these conclusions, but the

most important one has been evidences within the earth itself.

Men who work deep down in mines know that as they

descend lower and lower, the temperature rises, until there is

a noticeable difference between the temperature at the entrance

of a mine and at its lowest point. Moreover, not infrequently

volcanoes pour forth streaming lava, smoke and fire accompanying

the eruption. While such evidences lead to the conclusion

that the temperature of its interior is very high, still

there are many reasons for believing that the earth is a solid

mass. From the examination of the various earth strata, their

composition and the evidences each bears of the conditions under

which it was formed, we learn of periods of rain, heat and cold

prevailing. All these facts belong to the realm of geology however,

and concern us here only as they have concerned the progress

of mankind. These same earth layers or strata which preserve

eloquent testimony regarding the earth's development, contain

also remains of prehistoric men—men who lived in the far

away time before records were made and of which the rocks

alone give testimony.

Of the beginnings of the human race we know nothing.

Many scientists, notably Darwin and his followers, have sought

to show that man evolved from some lower animal life, in a way

similar to that in which we find some plant or flower perfected

from inferior origin. Whether the theory of man's evolution

from some lower animal will ever be shown to be true the future[XVI]

alone can tell. Nevertheless the scholarly world today has generally

accepted the evolutionary view of life and the world.

Buried within the earth along river-beds, around cliffs,

in mounds and many other places, have been found remains

of primitive man. While the beginnings of the human race,

as has been said, are utterly unknown, the earliest stage of

which we have knowledge has been called the Paleolithic Age,—the

age of the River-drift Man.

Whether we accept the theory of man's evolution from the

lower animal kingdom or not, we must admit that the earliest

Paleolithic people of whom we have knowledge differed but

little from the wild beasts. They lived in caves along rivers,—natural

retreats where wild animals might have taken refuge.

They lived on berries, roots, fish and such small game as they

could kill by blows. They did not cook their food, but devoured

raw meat much as did the wild beasts. They did not even bury

their dead. From the stones accessible to them they selected

their weapons, chipping them roughly. The crude weapons

of this period have given it the name of the Rough Stone Age.

The Paleolithic man, or man of the Rough Stone age, did

not try to tame the beasts he encountered. He stood in great

fear of those with whose strength he was not able to combat.

He feared especially strange beings like himself, and with his

family dwelt apart from others so far as possible. He did

not plant nor gather stores for the future; thus when food failed

in his vicinity, he was obliged to roam on until he came upon

a fresh supply of acorns, berries, roots and small animals. Any

cave served for his dwelling. He protected himself from

cold by a covering made from the skin of the beast he had

slain. He had few belongings and these were scarcely valued,

being easily replaced.

It is not difficult to see why the man of the Rough Stone

Age preferred to live by the side of some river. In early times,

before paths were worn through the forests, travel was easiest

along the river bed. Food was more abundant here, for fish

inhabited the streams and thither also animals came to drink,

and in the reeds by the river's side, birds and wild fowl breeded.

Moreover, man was a timid creature and feared to venture far

inland.

From all this we see that man in his primitive state gave[XVII]

little promise of his future development. For how long a time

he continued in this stage, we cannot estimate. Yet we find

a decided improvement in the latter part of this Paleolithic Age,

for fire and its uses became known. This brought about a

wonderful change.

The man of the Paleolithic or Rough Stone Age was followed

by the man of the Neolithic Age—the cliff dweller. He

exchanged a home by the river for one higher up; secure in

some elevated cliff, the Neolithic man lived, away from molesting

beasts. Again, the stone weapons were greatly improved.

No longer were they rough; on the contrary, they were now

polished smooth. Ingenious from the beginning, man found

that sharp edges of stone were more useful than blunt ones,

that smooth handles were more convenient than irregular stones

with no handles at all. For this reason, this period has been

called the Smooth Stone Age. Other improvements no less

momentous had been wrought. Food was now cooked, and as

a result, man grew a little less ferocious. He had less fear of

the wild beasts than before, and domesticated some of them.

No longer was he wholly dependent upon such food as nature

provided, for he had learned how to sow grain and gather it.

He had learned how to fashion bowls and other receptacles of

clay. He now buried his dead with weapons and other useful

articles, proving that he believed that the dead still had need of

such things. We must not, however, suppose that he believed

in immortality, for the evidence shows that his conception of

a hereafter was very vague. In most cases the care for and fear

of the dead ceased a few years after their burial. Before the

close of this period men had journeyed far from abject savagery.

Finally we come to the Metal—sometimes called the Bronze—Age.

The discovery of metal proved the greatest boon,

for now it was possible to make sharp tools and weapons.

Hitherto the mere cutting down of a tree had taken a prodigious

time. With a bronze ax, it could be quickly accomplished.

Progress made rapid strides after this invaluable discovery.

Nor this alone. Having learned to domesticate the beasts,

men passed from a purely hunting into a pastoral stage. Having

learned to reap and sow, it became convenient to have a fixed

habitation. Instead of dwelling apart, it proved safest to settle

in hamlets or villages. In other words, man had become

civilized, and with the dawn of civilization we find the dawn

of history.[XVIII]

From this cursory view of the three important stages in

prehistoric times, it is possible to derive mistaken notions.

For example, there was never a time when stone was the

only material available to man. Wood, ivory and shell were

probably always known and frequently procurable. Neither is

it to be supposed that each of these periods broke off abruptly

or that they extended over all lands simultaneously. Quite on

the contrary, stages in human development are never abrupt,

and changes come about unnoticed. In nature results are

slowly attained and there are no sharp distinctions between

them. The three divisions of Rough and Smooth Stone and

Metal Ages refer to conditions of progress—not to periods

of time. The Egyptians had passed through all three stages

before the dawn of history; the American Indians were in

the Smooth Stone Age when Columbus discovered America;

and in Central Australia there are tribes today just emerging

from the Smooth Stone period. The rapidity with which a

tribe passes from one to another of these stages depends upon

the natural conditions of the country, contact with outside

peoples and many other factors.

When written records enable us to weigh the true and

the false, to sift out fact from fiction and legend from verified

event, several nations had come into possession of a very fair

degree of civilization. They had settled homes in towns and

villages, recognized some form of government, understood the

uses of fire, planted crops and garnered them, spun, wove

and made pottery; they had attained considerable skill in the

working of metals, had domestic animals and cultivated plants;

they possessed a spoken, and sometimes a written, language

and had attained no little skill in decorative art. A rich legacy

was this for historic ages. Surely there is interest for the historian

in this remote time that lies clouded still by much

uncertainty. Let us consider some of these more important

attainments and try to see how naturally men grew to master

them and how in obscure ages the human race travelled so far

on the high road to progress.

Discovery of Fire.

We have already noted that there was a time when fire was

unknown. How then could the Paleolithic man, thrown wholly[XIX]

upon his own observation and resources, come upon this discovery,

which was to work such changes for the future? Only

from his observance of natural phenomena. When storms

swept over desert and plain, vivid lightning flashed, and occasionally

some tree was struck by the bolt and flamed up,

greatly to the astonishment and alarm of the unknowing mind.

At other times, volcanic eruptions occurred, and dry leaves and

forests caught on fire from flying cinders. In the natural

course of events, men soon found that the warmth of burning

wood was agreeable, that fire at night allowed them to keep

watch over possible invaders—whether man or wild beasts—and

that the interior of a tree's trunk could be more easily

removed by burning than by laborious scraping out with stone

implements. Having once tasted roasted flesh, a desire for

cooked food was probably developed. Such a valued possession

as fire proved, needed to be carefully tended, and when it was

exhausted, human ingenuity set to work to create it anew.

It is not unlikely that sparks occasionally struck out from flint

when it was being chipped into shape for a weapon or implement.

Necessity and desire have always worked wonders, and

primitive man learned shortly to produce the vital spark, both

by friction and by drilling.

Having mastered the art of fire-making, many innovations

were consequent upon it. Some fixed habitation was necessary

if the coals were to be kept covered from day to day, and from

meal to meal. Cooked foods gradually took the place of raw

ones; in cold weather the family grew to gather around the

fire, where meals were prepared and warmth was to be found.

When the family, clan or tribe removed to a new home, coals

were carried to kindle the fire upon the new hearth. When

men journeyed abroad in the night, they carried torches to guide

them; when they labored at home, fire grew indispensable

for baking their clay pottery, smelting their ore, and manifold

purposes.

While fire became one of man's aids, it wrought a decided

change in the position of woman. Before its discovery, man

and woman had probably gone side by side, sharing alike dangers

and hardships. With its acquisition, some one was required

to stay to watch lest it go out, and thus was developed

the fireside and the home. "The fire has made the home. We[XX]

have heard much in these later days about woman's position.

We are assured that she has not all her rights. Now, there

can be little doubt that the primitive woman had all her rights.

It is probable that she was as free as her husband to kill the

wild beasts, catch fish, fight her savage neighbors, eat the raw

meat which she tore by main strength from the carcass of the

lately slain beast. The beginning of woman's slavery was the

discovery of the fire. The value of fire known and the need

of feeding it recognized, it became necessary that someone

should stay by it to tend it. Notwithstanding the fact that

woman had all her rights and was free to come and go as

she would, it was still true that, on account of children and

certain physical peculiarities, the woman was more naturally

the one who would remain behind to care for the feeding of

the flame. Before that, men and women wandered from place

to place, thoughtless of the night. After that, a place was fixed

to which man returned after the day's hunt. It was the

beginning of the home."[1]

The House.

The man of the Paleolithic Age crept into any cave that

offered shelter from the storm and molesting beasts. Such

caves were plentiful along the river's bank. Here today, elsewhere

tomorrow, little heed was given to the particular shelter

in which he took refuge. With the possession of fire, a fixed

home became desirable. Even so, caves still remain the homes

of men for a long period of time.

The Neolithic man sought an abode farther away from the

main highway—the river. In cliffs towering above the river

bed—sometimes away from streams altogether, he scooped out

a cave similar to the ones occupied by his ancestors. Thus in

many countries remains are found of a race of cliff-dwellers.

In ancient Greece, for example, have been found evidences of

people living thus, and Indians in Mexico and Arizona three

thousand years later were discovered in similar dwellings.

With a settled life, and cultivation of the soil, man frequently

was forced to provide a home for himself. The

material from which he made it depended upon the resources

of the locality. In Egypt and Babylonia, sun-baked[XXI]

mud huts afforded the simplest, least expensive structures, both

in point of time and labor. Among pastoral tribes, tents

formed of animal skins sewed together were easiest to provide.

This was the usual shelter also of the American Indians and

other hunting tribes. The Laplander found cakes of ice suited

for his home, while man in the tropics quickly constructed a

shelter from the huge palm leaves, available on every hand.

"Of all places for studying construction of huts, Africa

is the very best. There one may see samples of everything

that can be thought of in the way of circular houses; built

of straw, sticks, leaves, matting; of one room or of many;

large or small; crude or wonderfully artistic and carefully

made. They may be permanent constructions to be occupied

for years or temporary shelter for a single night; they may

consist of frameworks made of light poles over which are

thrown mats or sheets of various materials and which after

using can be taken apart, packed away, and transported."[2]

From lightly built, temporary dwellings, it was but a short

step to the more substantial, more enduring ones. Stone

houses, dwellings made of timber and of brick, as the country

afforded, replaced the earlier homes, and when written records

bring the full light of knowledge upon the life of nations, in

the matters of constructing dwelling places, several peoples

had become proficient.

Food.

It would be difficult to discover any plant or animal life

which had not served at some period for food. Primitive

man knew nothing about harmful plants, and only by long

experience did he learn to avoid such as worked him woe.

No insect or animal is so repulsive but that it has been appropriated

by the food-hunter in some age and country, and things

today which we would refuse in time of distress were used

as a matter of course by earlier people.

Nature supplied acorns, berries, roots, fruits, fish and plenty

of game. All these articles were at first eaten in their native

state. When fire became well known, cooked foods grew in

favor. It is supposed that these were at first roasted. To suspend

meat over a fire or make a large opening in the ground,[XXII]

cover the floor with stones, heat these very hot, then remove the

fire and bake the food, these are the most primitive—as well,

perhaps, as the most satisfactory—ways known to us. Boiling

was probably a later method, and this was not done as we

boil food today. Rather, stones were heated very hot and

tossed into kettles of water. In this way the water was

brought to a boiling point and the food cooked.

Cultivated Plants.

Before men learned to cultivate plants and to domesticate

animals, subsistence was always an uncertain matter. They

roamed about in one vicinity until nature could no longer supply

their needs, then left the exhausted land to recover itself

while new territory afforded means for satisfying hunger.

After fire became such a potent factor, as we have seen, a

fixed abode was desirable. It fell to the lot of women to stay

and tend the hearth. Shut off from the long expeditions

undertaken by men, they soon learned to make as much as

possible of the space around about their homes. Sticks were

sometimes placed around plants or bushes to protect them from

the careless step until their fruits matured. Occasionally plants

were dug up and replanted nearer the hut. The garden and

grain field were but natural results of this spirit of husbanding

the stores provided by mother earth.

While women were the first to domesticate plants in the

simple way just indicated, not much came of it until men

adopted the idea and carried it further. With sharp sticks

they scratched the soil and with the help of animals they trod

in the seeds. Irrigation was sometimes needed—as in Egypt—to

insure good crops. Thus from slight beginnings developed

the agriculture of the world. With reasonable labor

and painstaking, the tiller of the soil could be sure of a living

for himself and his family, and before historic records illumine

the life of several nations, farming was well understood.

Indeed it is safe to say that until very recent times methods

followed by tillers of the soil in quite a number of countries

advanced very little upon those of the prehistoric man.

It is interesting to trace the history of present day foods,

grains, vegetables and fruits, with the attempt to ascertain

where each was native. All have been greatly improved by[XXIII]

cultivation and not alone our varieties, but even distinct fruits

and plants have resulted from man's propagation. Often the

original species have been vastly improved. For example,

the potato was a native of Chili. Found there in the sixteenth

century of our era, it was described as "watery, insipid, but

with no bad taste when cooked." It is supposed that it was

taken from some Spanish ship to Virginia, and in the latter

part of the same century carried to Europe. Its cultivation

has spread over many countries, and from a small, watery

tuber it has been brought to large size, mealiness and taste

agreeable to the palate. Even today it flourishes in its wild

state in Chili and Peru.

The cabbage was once a weed, growing on rocks by the

seashore. By man's care it has been developed to the vegetable

widely used today; moreover, its blossom has been exaggerated

until a wholly new vegetable in the form of the cauliflower

is the result.

"When we visit a vegetable garden or see fresh, attractive

fruits offered in market or inspect the wonders shown upon the

tables of county fairs and agricultural shows, we seldom

realize how truly they are all the work of man....

"One of the most wonderful illustrations of what man

can do in changing nature is seen in the case of the peach.

Some time, long ago, perhaps in Western Asia, grew a wild

tree which bore fruits, at the center of which were the hardest

of hard pits, containing the bitterest of kernels; over this hard

stone was a thin layer of flesh—bitter, stringy, with almost

no juice, and which, as it ripened, separated, exposing to view

the contained seed; such was nature's gift. Man taking it

found that it contained two parts which might by proper

treatment be made of use for food—the thin external pulp

and the bitter inner pit. He has improved both. Today we

eat the luscious peaches with their thick, soft, richly-flavored

juicy flesh—they are one product of man's patient ingenuity.

Or we take the soft shelled almond with its sweet kernel; it

is the old pit improved and changed by man: in the almond,

as it is raised at present, we care nothing for the pulp and it

has almost vanished. The peach and almond are the same

in nature; the differences they now betray are due to man."[3]

[XXIV]

Many of the grains were known and grown by prehistoric

man. Millet, wheat and barley were known in earliest recorded

times in Egypt; these grains were also cultivated before historic

times. Oats and rye were early plant products. Corn

was native to America and unknown to the antiquity of the Old

World. Several of our vegetables, such as the radish, carrot,

turnip, beet and onion, were early grown for food. The lemon,

orange, fig and olive were all native to Asia. Many flowers are

mentioned by early writers and they too were unquestionably

carefully tended in remote times. It is a subject for pleasant

investigation to find out where flowers, cultivated in some

countries, grow wild in others.

Domestication of Animals.

Desiring to provide food for time of want, primitive man

learned to keep a wounded animal instead of at once killing

it. Quite naturally it might come about that such a creature

would grow less wild and become a pet. Realizing the advantage

of confining animals, enclosures were probably thrown

around herds of goats, deer or sheep. Ingenious man soon

seized upon these half tamed beasts to help him in his work.

Their use being proven, he would not rest until he had tamed

them to his hand. The dog was the first dumb friend of men,

accompanying them upon the hunt and aiding in bringing

game to bay. The oldest friend, the dog, has also proven the

most faithful of the animal kingdom. When history dawned,

the dog, cow, sheep, goat, donkey, and pig were already

domesticated. The horse was less commonly known in remote

times. All these animals were originally small and not to

be compared with their present day descendants.

Dress in Prehistoric Times.

Among primitive people dress is invariably a simple matter.

In warm countries little clothing is needed, and even in colder

lands, ornaments are valued above mere protection from the

elements. It has been well established that love of decoration

has been a powerful factor with primitive tribes, and that to

this passion the habit of wearing clothing can largely be

traced. Skins of wild beasts were often used by early men as

protection from the cold, but it will be remembered that the[XXV]

Indians found by early discoverers in America were very scantily

clad, although furs were available on every hand. Yet

the Indian, who braved the winter's blast unclad, was eager

to barter his all for glass beads, scarlet cloth, or little trinkets

with which he could ornament himself. The habits of different

tribes and peoples have differed considerably; some

have adopted clothing earlier than others; some still go unclad.

Generally speaking, we may note that during the hunting

stage, if men have worn clothing except for ornamentation,

it has been the skins of animals; as spinning and weaving

have become known, coarse, home-made stuffs have come

into use. In Egypt, linens were early woven; in northern

countries, woolen stuffs were made. Feathers, furs, fabrics

woven of grasses or reeds, leaves, shells, teeth, tusks and

metal ornaments have held varying favor for decorative purposes.

Art.

At first thought it seems surprising that art can be ultimately

traced back to the self-ornamentation of the savage;

yet this is probably true. The earliest people of whom we

know loved to paint their bodies; the American Indians made

ready for feast or war by painting their bodies in startling

colors, and the tribes lowest today in the social scale—tribes

of Central Australia—have a similar practice. Dark skinned

tribes have frequently painted themselves with white; fair

skinned tribes with dark colors. The use of colors among

primitive peoples is an interesting study, and it is significant

to note that red has always been a favorite.

"Red—and particularly yellowish red—is the favorite

color of the primitive as it is the favorite color of nearly all

peoples. We need only observe our children to satisfy ourselves

how little taste on this point has changed. In every

box of water colors the saucer that contains the cinnabar red

is the first one emptied; and 'if a child expresses a particular

liking for a color, it is nearly always a bright dazzling red.

Even adults, notwithstanding the modern impoverishment and

blunting of the color sense, still, as a rule, feel the charm of

red.'... It may be questioned whether the strong effect

of red is called out by the direct impression of the color, or[XXVI]

by certain associations. Many animals have a feeling for

red similar to that of man. Every child knows that the sight

of a red cloth drives oxen and turkeys into the most passionate

excitement.... As to the primitive peoples, one

circumstance is here significant above all others. Red is the

color of blood, and men see it, as a rule, precisely when their

emotional excitement is greatest—in the heat of the chase and

of the battle. In the second place, all the ideas that are

associated with the use of the red color come strongly into

play—recollections of the excitement of the dance and combat.

Notwithstanding all these considerations, painting with red

would hardly have been so generally diffused in the lowest

stages of civilization if the red coloring material had not been

everywhere so easily and so abundantly procurable. Probably

the first red with which the primitive man painted himself

was nothing else than the blood of the wild beast or the enemy

he had slain. At present most of the decoration is done with

a red ochre, which is very abundant nearly everywhere, and

is commonly obtained through exchange by those tribes in

whose territory it is wanting."[4]

The difficulty found in this means of decoration is that it

is not lasting. However skillfully the savage covers himself

with solid coloring or design, a short time only and his labor

is effaced. To overcome this trouble, tattooing was devised.

By this means the color was placed beneath the skin and thus

not subject to change. Very elaborate patterns were sometimes

worked out and the man so ornamented was far more

attractive in the eyes of his fellowmen.

Next to the personal adornment of primitive peoples comes

the decoration of their weapons and implements and the patterns

in their handicrafts, such as basketry and mattings. Generally

speaking those are in imitation of nature, and more, imitation

of human and animal forms. Heretofore it has not been

unusual to dismiss these as merely geometrical designs. Surely

they were never such in the mind of the ancient worker. He

copied things that he saw around him—copied them awkwardly

no doubt, but nevertheless certainly. Some of these patterns

we can recognize; others defy us. For example, the waving

line has been interpreted to represent the course of the serpent;

[XXVII]the herring bone pattern originated as a copy of the feather.

Sometimes the patterns copy the skin markings of some animal

or serpent; sometimes they imitate the scales of a fish. Very

seldom have these early artists attempted to copy plants or

flowers. Sometimes the bone knife bears an excellent drawing

of a bird or fish; occasionally the whole object has been

given the form of some living creature, as, for example, bone

needle cases have come to us which have the form of fish or

birds. Shields, knives, bows and arrows, and weapons of

whatever sort often bore some picture, more or less decorative.

Such a picture upon an arrow enabled the savage to identify

as his game some animal that died some distance from where

it was wounded. Clubs and throw-sticks remain whereupon

is scratched the picture of some familiar animal—a kangaroo,

a snake, or a fish. But the pictures painted by primeval man

were not limited to those which adorned their weapons and

implements. The hide pictures, or pictures painted or scratched

upon hides are very interesting. Generally the hide used for

this purpose was a portion of the hut. During times when

inclement weather forced the early tribesman to remain inside

for shelter, it may be, merely for diversion he occupied himself

by scratching some picture upon the soot-covered skin

that formed his hut. A tooth or bit of flint furnished him

with a tool. Or again, a piece of charcoal, snatched from the

hearth, furnished him means of picturing some scene upon a

fresh skin. Figures of men and animals, drawn in outline,

make up the picture. Now a battle, now a hunting scene may

be delineated. The Eskimo brings into his picture some of

the round snow huts, with the animals which he hunts—bears,

walruses, and the like. In detail and accuracy of outline

the tribes still in the hunting stage greatly excel those which

have developed into a settled farming people. Nor is this

difficult to understand. The success of the hunter depends in

no small degree upon his ability to follow the faint foot-prints

of the game. He must be susceptible to many indications

wholly unseen by the casual eye. The keen vision of the

uncivilized hunter is well recognized. When he no longer

needs this wonderful sight to accomplish his daily tasks, it

disappears. For this reason we find a fidelity to nature in

the pictures of the early hunting peoples which is missed in

the productions of more highly developed peoples.[XXVIII]

Finally we may gather these conclusions from the facts

known of primitive art—or of art among primitive peoples.

While no great masterpieces remain as models for future

generations, it is among prehistoric men that art had its beginnings.

Nor is it possible to sweep aside the art of this

remote period, relegating it to the realm of the curious alone.

Recent scholarly investigators in this field have reached far

different conclusions, finding here the indications of man's

artistic possibilities and the promise for the future.

"The agreement between the artistic works of the rudest

and of the most cultivated peoples is not only in breadth but

also in depth. Strange and inartistic as the primitive forms

of art sometimes appear at the first sight, as soon as we examine

them more closely, we find that they are formed according to

the same laws as govern the highest creations of art....

The emotions represented in primitive art are narrow and

rude, its materials are scanty, its forms are poor and coarse,

but in its essential motives, means, and aims, the art of the

earliest times is at one with the art of all times."[5]

Religion of Prehistoric Men.

We have found that men of earliest times had no belief

in a future life. They did not even bury their dead. The

man of the Smooth Stone Age had advanced greatly in this

respect. He buried his dead with weapons and implements

which he imagined would be as useful in the next world as

they had proven during the earthly life. The question arises

consequently, how did the idea of a future existence, of a

soul apart from the body, have its origin among men? The

answer is, through dreams and visions. We understand today

that dreams frequently result from physical derangement. In

early times, under the unwholesome conditions that prevailed,

men dreamed more constantly and vividly than they do now.

Having feasted immoderately, the man lay down to sleep.

While he slept, he dreamed—dreamed perchance of a hunt

that seemed very real to him. When he awakened, he related

his experiences, but his companions insisted that he had not

been absent. He had to explain the matter in some way,

so he fancied that he was not one, but two, and that it was[XXIX]

his other self that had been fortunate in the chase. Again,

he would dream of one of his dead relatives. Not understanding

the stuff that dreams are made of, or that dreams

were less real than life, he inferred that his dead relative had

returned to him for the time being, and that he still lived in

some way. We can understand his condition the better if

we think of the child who has dreamed and has been either

pleased or terrified with his dream. The idea of another

existence awakened, ancestor worship was a natural result.

The early man who had developed a religious sense, worshipped

two different kinds of forces; the forces of nature,

and his ancestors. The savage bowed down to the stick that

tripped him in the forest. He could not understand how such

a small object could possess power to throw him and since

it apparently did possess it, he worshipped it. The sun brought

light and warmth. By its presence man was benefited. Therefore,

primeval man worshipped the sun.

Ancestor worship was inspired by quite different motives.

If it were true that the dead lived on, then it must be possible

for them to work one's weal or woe. If the dead were cared

for and ministered unto, they would be appeased and would

have no desire to bring trouble or misfortune upon the survivor.

The taboo held an important place in early religious beliefs

and practices. A taboo is a prohibition laid upon some

object or some performance, with the superstitious idea that

injury will follow if the object be used or the performance

done. Some of the tribes of Central Australia, today in the

Smooth Stone stage of development, hold the idea that the

meat of the emu may be eaten only by the elders of the tribe.

For women, therefore, there is a taboo on this meat, and its

use by them would be regarded as a great sacrilege. The

early Hebrews had a similar taboo, recorded in the earliest

set of commandments preserved by them. It was "Thou shalt

not seethe the kid in its mother's milk." This does not mean

one of many foolish meanings worked into it, but rather that

the early Hebrews for some reason had placed this taboo on

kid cooked in milk. The use of beans was similarly tabooed

by Pythagoras and forbidden to his followers. A study of

the taboo is interesting indeed.[XXX]

The totem was important to the primitive man. A totem

is an animal or species of animal from which a social circle

derives its origin. One clan owed its being to a black hawk,

another to an eagle, and so on. No one of a clan would kill

its totem, or in other words, there was a taboo placed upon

the totem. Of course this taboo affected only the one clan.

Early religion consisted for the most part in certain observances—not

so much in formulated beliefs. To be sure,

the primeval man believed that harm would overtake him if

he failed to perform certain ceremonies, but it was the performance

or the refraining from the performance that was important.

Among the earliest people associated into tribes there were

distinct moral requirements. There were some people who were

not to be killed, except upon due provocation, while to kill those

of other tribes brought great glory. Again, it was not right

to lie to those of one's own tribe, but to others one might

lie at all times. "An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth,"

was the primitive way of viewing injury, and yet when history

sheds its light upon certain nations of antiquity, some of them

had already come into the transition state, where damages

might be given if satisfactory to the injured. The Babylonians

afford an excellent example of this condition.

Conclusion.

Each individual passes through many of the stages through

which the race has come. A child may pass in a week or a

month through a stage covering centuries in the development of

the race, but nevertheless he experiences it clearly for the time

being. The savage personified everything around him. If he

struck himself against a tree, he was angry with the tree that

had hurt him, and he tried to hurt the tree in revenge. The

child today falls against a chair and hits the chair that hurt

him. Now just as the child by such experiences, scarcely noted

by others, realized far less by himself, comes into the clear

vision of manhood, so by similar experiences the whole race has

come to its present development. We are too prone to smile at

the conceptions of the primitive world, and, grown wise with

the flight of centuries, cast aside the beliefs of early ages

when men adjusted themselves to life. Let us reflect then[XXXI]

upon the attainments of prehistoric man and attempt to fathom

how great a debt historic peoples owe him. In view of his

achievements, we must grant that by his efforts civilization

was greatly aided. The stepping stones on which he rose

from abject savagery to higher things stand out sharply in

spite of absence of records and scant remains. The rough

pioneering had been done, in a great measure, and not alone

the rudiments of civilization but evidences of culture were

plainly visible at the dawn of history, properly so-called.

ABORIGINAL ROCK-CARVINGS.

ABORIGINAL ROCK-CARVINGS.

[Pg 12]

EGYPTIAN AFTERGLOW.

"'Tis sunset hour on Egypt's arid plains.

Each mighty pyramid, with purpling crest,

Looms dark against the glory in the west.

Swiftly the heaven's beauty dies and wanes,

Till sudden darkness its rich splendor stains.

Then slowly, dawn-like, on the shadows rest

Faint crimsons, violets, tint to tint soft pressed;

They brighten, glow, then fade and darkness reigns."

P. F. Camp.

[Pg 13]

EGYPT

PREFATORY CHAPTER

here never was a time when men were so intensely

interested in origins and development as

they are today. Our biologists are studying life

in all its forms, from the single cell to the highest

mammal. Our psychologists are studying mind—what

consciousness is; how attention, habit, memory are

formed. Our physicists, not content with studying gravitation,

heat, light, electricity, etc., are inquiring into the very nature

of matter itself, and, together with the astronomers and geologists,

are telling us not only how the earth, but also how the

universe came to be. Our anthropologists, ethnologists and

sociologists are just as actively and patiently inquiring into

the origins of customs, institutions, law, religion, society. The

historian is no longer content to rehearse a story because it is

interesting; he insists upon getting at the original documents,

at the facts in the case, not at theories. The savage, when

asked why he observes a certain custom or performs some ceremony

whose meaning he does not know, replies that his ancestors

did the same. To inquire beyond this seems to him

more than useless. Until the beginning of our modern scientific

age the answer to similar questions among ourselves—as it still

is among the Chinese, would have been, "it is written," "thus

saith the Lord," "Aristotle, Plato or St. Augustine thought so

and so about the matter." But today all is different. We are no

longer content to know what is written, or what somebody thinks

about a subject, we insist upon demonstrating or having some

one demonstrate for us, the proposition put forward. We want

the "facts." Our whole system of education encourages pupils

to perform experiments and thus verify the statements they may

find in their text-books on chemistry, physics and other subjects.[Pg 14]

It is the inductive method which gives the pupil the facts and

encourages him to draw his own conclusions.

But what has Egypt to offer the modern man? Does it interest

any but specialists and archaeologists? Apparently it does,

for every year sees an increase of tourists in the Nile valley.

It is true many go there because of the ideal climate or because

it has become the fashion to do so. But if we look at the matter

more closely, do we not see other, deeper reasons? Is it

not true that many go because in their youth they had read

about the pyramids and the wonderful temples of Egypt, and

because now when they have the opportunity they desire to

see these for themselves? The architect, the engineer, the contractor,

all are interested in these masses of masonry. Again,

when we are beginning to reclaim the desert areas in our western

states, Egypt with its system of irrigation, older than history,

arouses a new interest. The fact is that in spite of our

practical nature, as some would put it, or rather, as we prefer

to have it, because of our intensely practical nature, we are

beginning to feel the necessity of inquiring into the activities

of other peoples, be they past or present, not only because such

inquiry will satisfy our curiosity or enliven our dull moments,

but because of the lasting benefit we derive from it. We insist

upon knowing the people who have achieved, who have accomplished

things, and surely the pyramids alone would demonstrate

that the ancient Egyptians belonged to this class.

Man attained to civilization for the first time in the Nile

valley. We study the natives of Australia and Africa for social

origins. It is here we can gather most information about the

primitive forms of marriage and the growth of the family; about

the beginnings of dress and ornament; about primitive warfare,

magic, religion and early forms of tribal government. Just

as we pay special attention to the development of the mind of

the child in the study of psychology, so we feel that the best

way to study the complex features of our civilization is to

observe the simpler life of the savage. But the child becomes a

man while the savage has not yet developed a civilization before

our eyes. The growth of the race is slow. It is only when we

are able to observe a race through a period of thousands of years

that it is possible to see it grow from infancy to manhood. We

can follow our own ancestors from the time they had advanced[Pg 15]

little beyond the stage of savagery, but it is to be observed that

they did not develop but borrowed their civilization. Of the

beginnings of the Greeks and Romans, whose civilization our

ancestors took over, we know but little, but in the case of the

Egyptians matters are different. We are able, by means of

archaeological, monumental and inscriptional remains to follow

them as they developed in the Nile valley, unassisted by any

outside civilization—for none existed, the world's first great

civilized state.

"It may appear paradoxical to affirm that it is in arid districts,

where agriculture is most arduous, that agriculture began; yet

the affirmation is not to be gainsaid but rather supported by

history, and is established beyond reasonable doubt by the evidence

of desert organisms and organizations."[1] This lesson

drawn from the life of the Papago Indians might just as well

have been drawn from Egyptian life. Egypt is practically

rainless, but the soil of the Nile valley, ever renewed by the silt

deposited by the yearly inundation, yields enormous returns

provided only man uses his energy and ingenuity. Long before

our written records begin the Egyptians had developed

an extensive system of irrigation. Thus by arduous toil, organized

and watched over by the growing state, Egypt developed

an enormous agricultural wealth—the foundation upon which

her civilization was built. With Egypt it was not a question of

the "conservation" but of the development of her natural resources.

The Egyptian was forced to keep up a continuous

struggle with nature and as a result he was always practical.

Egypt has been called the mother of the mechanical arts. It

is not surprising that the imaginative Greeks, when they became

acquainted with the material civilization of Egypt, her pyramids

and temples, her system of irrigation, her craftsmanship,

conceived an exaggerated opinion of the wisdom of the Egyptians.

Even today we hear surmises of "lost arts" which were

used in the construction of the pyramids. But we know better.

The pyramids were built by the brawn of tens of thousands of

serfs, without the use, it would seem, of even a pulley; not even

the roller seems to have been known. On the other hand, we

have only to visit the museums here and abroad—especially[Pg 16]

the one in Cairo, to realize the marvellous skill the Egyptian

workman acquired in the carving of wood, ivory and stone, and

in the working of metals. Our architects are studying the products

of the greatest geniuses Egyptian culture produced, and

our students of design may learn many a lesson from the workmanship

of her artisans.

Not long since it was not unusual to see ridicule heaped

upon the theories of the "high-brows" by our farmers, manufacturers

and other "practical" men. Probably our system of

education was at fault. Nevertheless, these same farmers,

manufacturers and other practical men are beginning to realize

the importance of the researches and investigations of the

specialists. We cannot hope to compete with the industries

of the Germans which rest upon a scientific basis, as long as

ours are conducted by "rule-of-thumb" methods. There is no

better opportunity offered anywhere for observing the limitations

of an exclusively practical system of education than the

study of Egyptian learning.

The Egyptian regarded learning as a means to an end, and

that end was never the increase of the sum of human knowledge

or the advancement of humankind, but always freedom from

manual labor. Next to a few folk songs, preserved in the decorations

of Fifth Dynasty tombs—by mere accident, for a scribe

would never have thought of preserving them, the oldest literature

of the Egyptians which has come down to us consists of the

precepts of Kagemni and Ptah-hotep.[2] This wisdom of the

viziers of the Pharaohs of the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties, is

similar to that of the books of instruction from all periods of

Egyptian history, and consists largely of rules of conduct. The

sole object of an education was to obtain a position as scribe

or secretary of higher or lower rank in the government service,

and this could only be done by gaining and keeping the favor

of the Pharaoh or of one of his officials. These scribes never

weary of telling of the superiority of their calling over that of

the man who must labor with his hands, who is like a heavily

laden ass driven by the scribes. Of course we too recognize

the gulf fixed between the educated and the unlettered, but we

try to bridge it. It is not probable that many of the laboring

classes knew more than the barest elements of reading and[Pg 17]

writing. The Egyptian script was exceedingly cumbrous, and

probably few would have seen any use in mastering it, even if

they had had the time, unless they intended to enter upon a scribal

career. Of course many such careers were open, for the elaborate

bureaucratic system of administration demanded the services

of a host of secretaries and overseers. In time these constituted

a distinct middle class, largely recruited, we may be sure, from

the laboring class below. The Egyptian was always ready to

recognize and reward ability, no matter where it was found.

Now a word about the limitations of such a view of education.

As already indicated, the object of an education was to gain

a government position. In Egypt, as elsewhere, the chief end

of government, in the eyes of the officials at least, was the collection

of revenues. Taxes were in kind and as a result the

work of the scribe consisted in finding out the amount of the

harvest and deducting the king's share. The extensive mining

and building operations conducted by the Pharaohs required

the services of hundreds of scribes and overseers to superintend

the work and distribute the rations of the armies of workmen

employed in these projects. In this work the scribe

developed a remarkable facility with figures. But he never

advanced beyond concrete examples. Multiplication and division

in our sense of the terms were unknown to him, their places

were taken by addition and subtraction. For example: to multiply

seven by nine, the Egyptian scribe would proceed, 1·7=7,

2·7=14, 2·14=28, 2·28=56, etc. That is he always

doubled the last figure. It was nothing but addition. He

wrote his results as follows:

and then found which of the numbers of the first column added

together would give the sum 9. These were 8 and 1. He

then added the corresponding numbers in the second column

and got the result, 56+7=63. So 50÷7 would have

looked like this: 50-28=22; 22-14=8; 8-7=1.

The result was (4+2+1) sevens with 1 as remainder. The[Pg 18]

Egyptian scribe could not handle fractions other than those with

one as numerator. Two-thirds was the only exception. The

Egyptian knew that the area of a rectangle was to be found by

multiplying the two adjacent sides together, and that the area

of a right angled triangle was equal to half the area of a rectangle

whose base and altitude were equal respectively to the

sides adjacent to the right angle. When his problem was to

find the area of an isosceles triangle he applied the same

rule, that is, multiplied the base by one of the sides and divided

by two. Here theory might have helped him, had he been able

to develop it. He never reached the conception of base and

altitude. His rule for finding the area of a circle is worth mentioning.

He took the diameter, subtracted one-ninth of it

therefrom, and squared the result. In a word, he had not come

far from the correct value of π. But the Egyptian always dealt

with concrete examples, he never was able to generalize and

carry his mathematics into the theoretical. As a result he

never attained scientific accuracy. Not that he did not set

himself difficult problems. Indeed many of them are so complicated

that they required an immense amount of reckoning, by

his methods, to solve. Without giving his solution, let me add

one more of his problems: "A man owns 7 cats; each cat eats

7 mice daily; each mouse eats 7 ears of grain; each ear contains

7 grains; each grain gives a sevenfold return in the harvest.

What is the sum of the cats, mice, ears and grains?"

The Egyptians observed the stars. They had names for all

of the principal constellations; knew the circumpolar stars