CONTENTS

1837–1838.

Death of William IV.—Princess Alexandrina Victoria summoned to the Throne—Ignorance of the Public about the young Queen—Her early training—Severance of the Crown of Great Britain and Hanover—Prorogation of Parliament—Early Railways—Electric Telegraph—The Coronation—Popular Reception of Wellington and Soult—State of Parties—Result of General Election—Rebellion in Canada—The Earl of Durham—Debate on Vote by Ballot.

1837–1842.

Lord Melbourne’s services and character—Prevailing discontent of the Working Classes—Its Causes—The Chartists—Riots at Newport and elsewhere—Fall of the Ministry—Sir Robert Peel sent for—The “Bedchamber Question”—Melbourne recalled to Office—The Penny Post—Its remarkable Success—Betrothal of the Queen—Character of Prince Albert—Announcement to Parliament—Debates—Marriage of the Queen and Prince Albert—War declared with China—Capture of Chusan—Bombardment of the Bogue Forts—Peace concluded under the Walls of Nankin.

1841–1846.

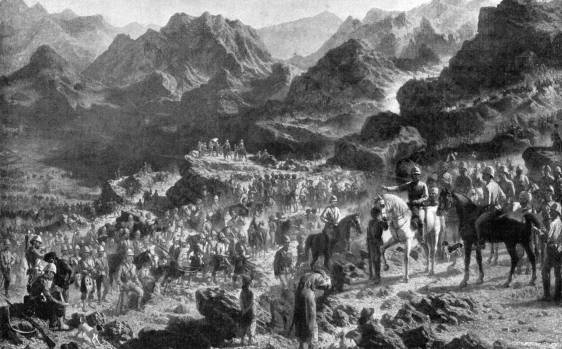

Unpopularity of the Whigs—Fall of the Melbourne Ministry—Peel’s Cabinet—The Afghan War—Murder of Sir A. Burnes and Sir W. Macnaghten—The Retreat from Cabul—Annihilation of the British Force—The Corn Duties—The Pioneers of Free Trade—Failure of Potato Crop in Ireland—Lord John Russell’s conversion to Free Trade—Peel and Repeal—Rupture of the Tory Party—The Corn Duties repealed—Defeat and Resignation of the Government—Review of Peel’s Administration.

1833–1849.

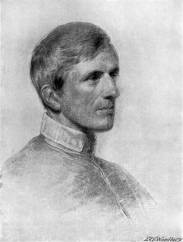

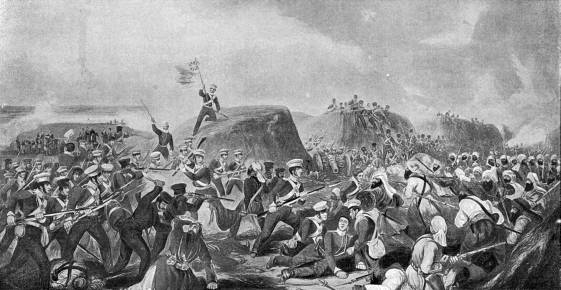

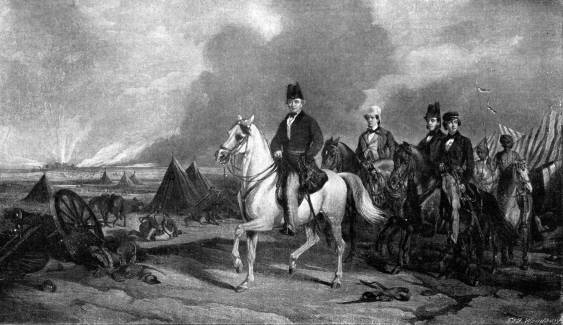

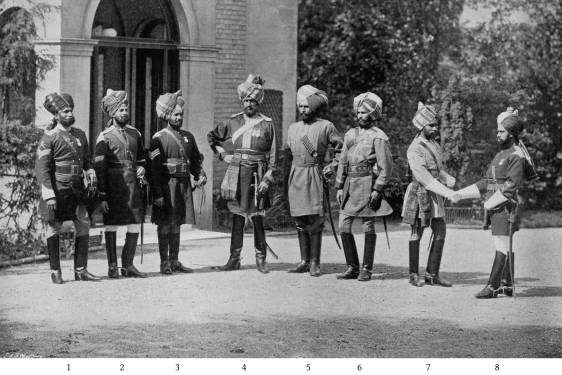

The Churches of England and Scotland—“Tracts for the Times”—Newman, Keble, and Pusey—“Ten Years’ Conflict” in Scotland—Disruption of the Church—Dr. Chalmers—Rise of the Free Church—Affairs of British India—First Sikh War—Battles of Meeanee, Moodkee, Ferozeshah, Aliwal and Sobraon—Second Sikh War—Murder of Vans Agnew and Anderson—Battle of Ramnuggur—Siege and Fall of Mooltan—Battles of Chilianwalla and Goojerat—Annexation of the Punjab.

1846–1850.

The Irish Famine—Smith O’Brien’s Rebellion—Widow Cormack’s Cabbages—The Special Commission—Revival of the Chartist Movement—The Monster Petition—Its Exposure and Collapse of the Movement—Revolutionary Movements in Britain compared with those in other Countries—Growing Affection for the Queen—Its Causes—Royal Visit to Ireland—The Pacifico Imbroglio—Rupture with France Imminent—Civis Romanus Sum—Lord Palmerston’s Rise—Sir Robert Peel’s Death—The Invention of Chloroform.

1849–1851.

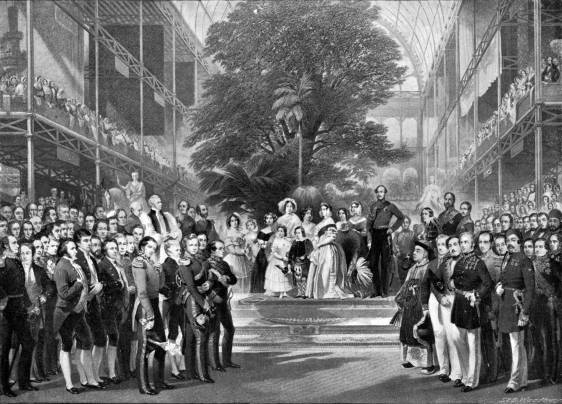

Prince Albert’s Industry—His proposal for a Great Exhibition—Adoption of the Scheme—Competing Designs—Mr. Paxton’s selected—Erection of the Crystal Palace—Colonel Sibthorp denounces the Scheme—Papal Titles in Great Britain—Popular Indignation—The Ecclesiastical Titles Bill—Defeat of Ministers on the Question of the Franchise—Difficulty in finding a Successor to Russell—He resumes Office—Opening of the Great Exhibition—Its success and close.

1851–1853.

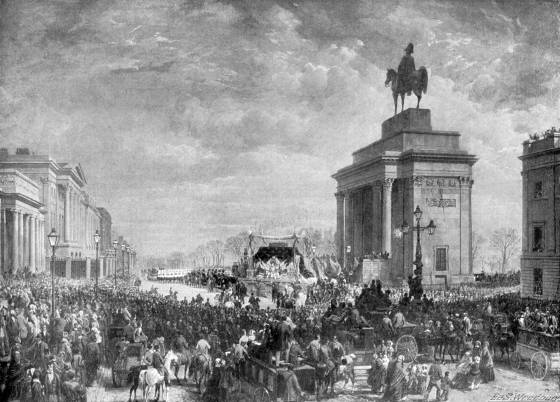

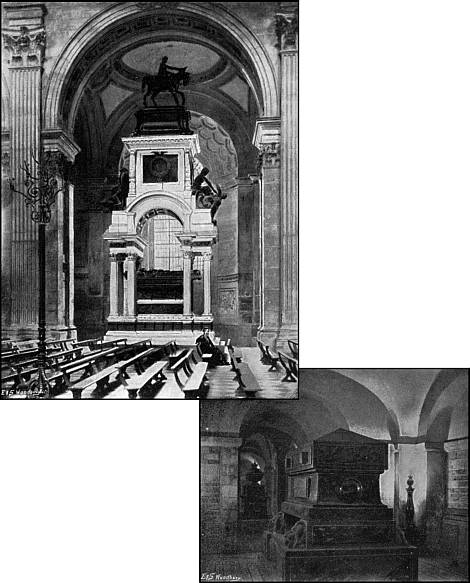

Louis Napoleon’s Coup d’État—Condemned in the English Press—Lord Palmerston’s Indiscretion Rebuked by the Queen—He Repeats it and is Removed from Office—Opening of the New Houses of Parliament—French Invasion Apprehended—Russell’s Militia Bill—Defeat and Resignation of Ministers—The “Who? Who?” Cabinet—Death of the Duke of Wellington—His Funeral—The Haynau Incident—General Election—Disraeli’s First Budget—Defeat and Resignation of Ministers—The Coalition Cabinet—Expansion of the British Colonies—Repeal of the Transportation Act.

1853–1854.

The “Sick Man”—Position of the Eastern Question—Projects of the Emperor Nicholas—The Custody of the Holy Places—Prince Menschikoff’s Demand—Russian Invasion of Moldo-Wallachia—The Vienna Note—Declaration of War by the Porte—Destruction of the Turkish Fleet—Resignation of Lord Palmerston—Great Britain and France Declare War with Russia—State of the British Armaments.

1854–1856.

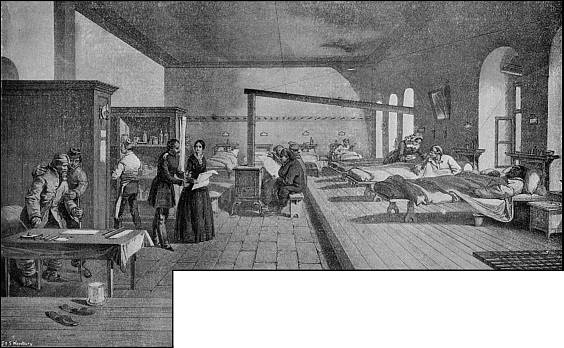

Mr. Gladstone’s War Budget—Humiliation and Prayer—The Invasion of the Crimea—The Battle of Alma—A Fruitless Victory—Effect in England—War Correspondents—Balaklava—Cavalry Charges by the Heavy and Light Brigades—“Our’s Not to Reason Why”—Russian Sortie—Battle of Inkermann—Breakdown of Transport and Commissariat—Hurricane in the Black Sea—Florence Nightingale—Fall of the Coalition Cabinet—Lord Palmerston Forms a Ministry—Victory of the Turks at Eupatoria—Unsuccessful Attack by the Allies—Death of Lord Raglan—His Character—Battle of Tchernaya—Evacuation of Sebastopol—Surrender of Kars—Conclusion of Peace.

1857–1858.

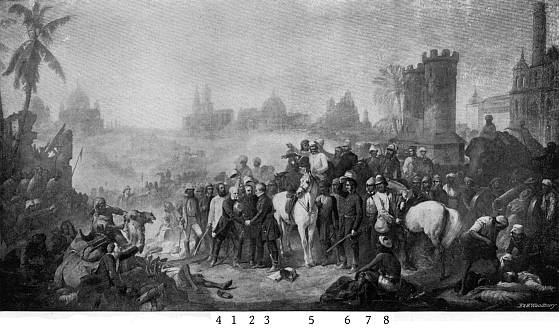

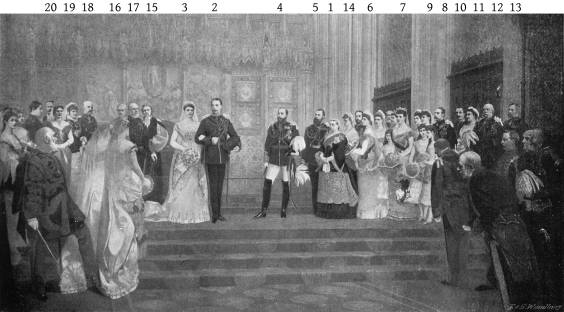

The Lorcha Arrow—War with China—Defeat of the Government—Dissolution of Parliament—Palmerston returns to Office—Startling News from India—Mutiny at Meerut—The Chupatties—Loyalty of the Sikhs—Lord Canning’s Presence of Mind—Disarmament of Sepoys at Meean Meer—The Rising at Cawnpore—Nana Sahib’s Treachery—The Massacre—Siege of Delhi—The Relief of Lucknow—Death of Havelock—Sir Hugh Rose’s Campaign—The Ranee of Jhansi—Capture and Execution of Tantia Topee—End of the East India Company’s Rule—Marriage of the Princess Royal.

1858–1860.

Commercial Panic in London—Suspension of the Bank Charter Act—The Orsini Plot—The Conspiracy to Murder Bill—Defeat and Resignation of the Government—Lord Derby’s Second Administration—Disraeli’s Reform Bill—Vote of No Confidence—Defeat and Resignation of the Government—Lord Palmerston’s Second Administration—Threatened French Invasion—The Volunteers—The Paper Duty Repealed by the Commons and Restored by the Lords—A Constitutional Problem—Its Solution—War with China—British and French Defeat at Pei-ho—Return of Lord Elgin to China—Wreck of the Malabar—Capture of the Tangku and Taku Forts—Occupation of Tien-tsin—Murder of British Officers and others—Capitulation of Pekin—Destruction of the Summer Palace—Treaty with China.

1861–1865.

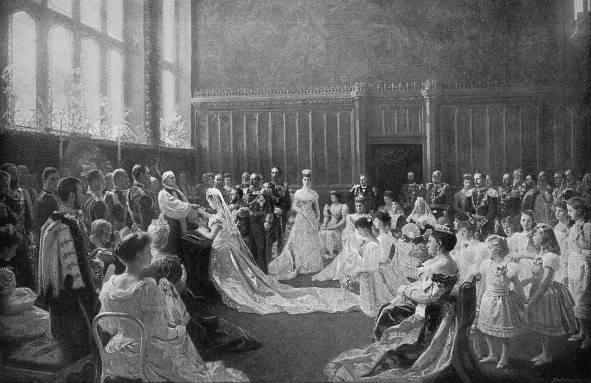

The American Civil War—Recognition of Confederate States as Belligerents—English Opinion in Favour of the Confederates—The Trent Affair—Dispatch of Troops to Canada—Death of the Prince Consort—His Last Memorandum—The Cruiser Alabama—Claims against Great Britain—Arbitration—Award Unfavourable to Great Britain—Public Indignation—Marriage of the Prince of Wales—The Schleswig-Holstein Difficulty—Neutrality Observed by Great Britain—Popular Sympathy with Denmark—Dissolution of Parliament—Result of the Elections—Death of Lord Palmerston.

1866–1872.

Mr. Gladstone’s Reform Bill—The Cave of Adullam—Defeat and Resignation of the Ministry—Retirement of Earl Russell—Lord Derby’s Last Administration—Disturbance in Hyde Park—Commercial Panic—Completion of the Atlantic Cable—Mr. Disraeli’s Reform Bill—Secessions from the Cabinet—The Fenians—War with Abyssinia—Retirement of Lord Derby—The Irish State Church—Dissolution of Parliament—Liberal Triumph—Mr. Gladstone’s Cabinet—Disestablishment of the Irish Church—Death of Lord Derby—Irish Land Legislation—National Education—Army Purchase—The Ballot Bill—Adoption of Secret Voting.

1870–1880.

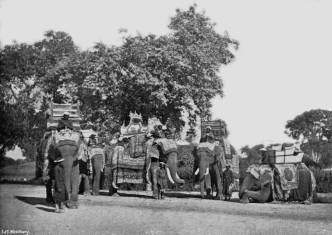

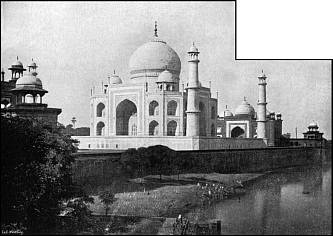

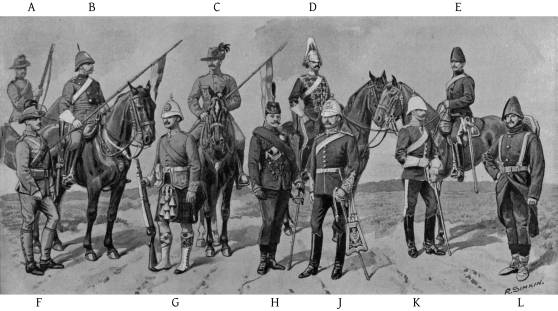

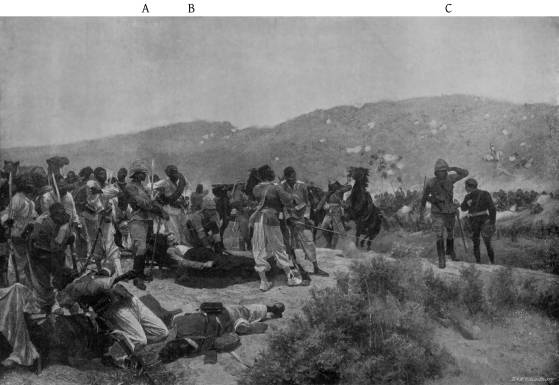

The Franco-German War—Russia seizes her Opportunity—The Irish University Bill—Defeat and Resignation of Ministers—Mr. Gladstone resumes Office—Dissolution of Parliament—Conservative Victory—The Ashanti War—Mr. Disraeli’s Third Administration—Mr. Gladstone Retires from the Leadership—Annexation of the Fiji Islands—Purchase of Suez Canal Shares—Visit of the Prince of Wales to India—The Queen’s New Title—Threatening Action of Russia—The Bulgarian Massacres—Disraeli becomes Earl of Beaconsfield—The Russo-Turkish War—Great Britain Prepares to Defend Constantinople—Secession of Lord Carnarvon and Lord Derby—The “Jingo” Party—The Berlin Congress and Treaty—“Peace with Honour”—Massacre at Cabul—War with Afghanistan—The Zulu War—Disaster of Isandhlana.

1879–1881.

The Condition of Egypt—Mr. Goschen’s Commission—Ismail’s Coup d’état—His Deposition by the Sultan—Establishment of the Dual Control—The First Midlothian Campaign—Commercial and Agricultural Depression—Sudden Dissolution of Parliament—Lord Derby joins the Liberals—Second Midlothian Campaign—Great Liberal Victory—Mr. Gladstone’s Second Administration—Charles Stuart Parnell and the Irish Home Rule Party—War with Afghanistan—Battle of Maiwand—General Roberts’s March—Defeat of Ayub Khan and Evacuation of Cabul and Candahar—Revolt of the Transvaal—Battles of Laing’s Nek and Majuba Hill—Establishment of the Boer Republic—Weakness of the Conservative Opposition—The Fourth Party—Irish Affairs—Boycotting—A New Coercion Bill—The Irish Land Bill—Resignation of the Duke of Argyll—Death of Lord Beaconsfield—Military Revolt in Egypt—Bombardment of Alexandria—Expedition against Arabi—Battles of Kassassin and Tel-el-Kebir—Overthrow of Arabi.

1881–1887.

Imprisonment of Irish Members of Parliament—Assassination of Lord Frederick Cavendish and Mr. Burke—Prevalence of Outrages in Ireland—A New Coercion Bill—Trial and Execution of the Phœnix Park Murderers—The Dynamite Conspiracy—Corrupt Practices Act—The Affairs of Egypt—General Gordon sent to Khartoum—Gordon Besieged—Inaction of the Government—Relief of Khartoum Undertaken—Too Late!—Death of Gordon—Lord Wolseley’s Campaign—Abandonment of the Soudan—Mr. Gladstone’s Reform Bill—The Question of Redistribution of Seats—The Frontier Question in Afghanistan—Defeat of Ministers on the Budget and their Resignation—Lord Salisbury’s First Administration—Dissolution of Parliament—The Irish Party and the Balance of Power—Mr. Gladstone’s Third Administration—His Conversion to Home Rule—Rupture of the Liberal Party—The Home Rule Bill Rejected—Dissolution of Parliament—Unionist Victory—Lord Salisbury’s Second Administration—Lord Randolph Churchill Resigns—The Round Table Conference.

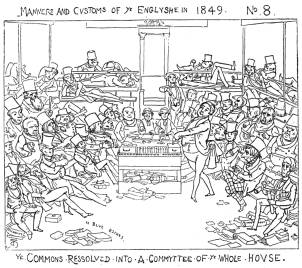

1887–1897.

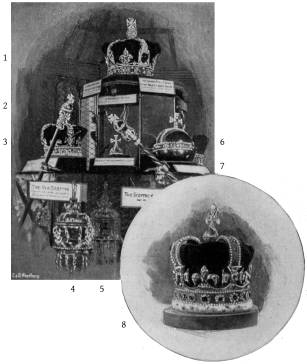

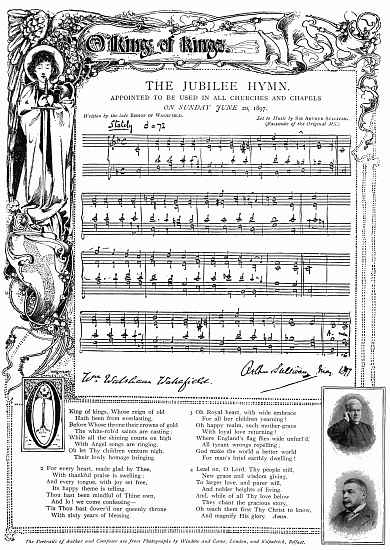

Adoption of the Closure by the House of Commons—The Queen’s Jubilee—Thanksgiving Service in Westminster Abbey—The Imperial Institute—“Parnellism and Crime”—Appointment of Special Commission of Judges—Their Report—Fall of Parnell—Disruption of the Irish Party—Deaths of Parnell and W. H. Smith—The Baring Crisis—The Local Government Bill—Establishment of County Councils—Free Education—Death of the Duke of Clarence—General Election—Mr. Gladstone’s Fourth Midlothian Campaign—The Newcastle Programme—Victory of Home Rulers—The Second Home Rule Bill—Its Rejection by the Lords—Parish Councils and Employers’ Liability Acts—Mr. Gladstone Resigns the Leadership—Lord Rosebery becomes Prime Minister—Disunion of Ministerialists—Defeat and Resignation of the Government—Lord Salisbury’s Third Administration—General Election—Unionist Triumph—The Eastern Question—Massacres in Armenia—Lord Rosebery Resigns the Leadership—Trouble in the Transvaal—Dr. Jameson’s Raid—The German Emperor’s Message—The Venezuelan Dispute—President Cleveland’s Message.

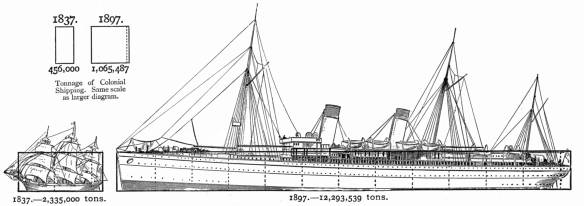

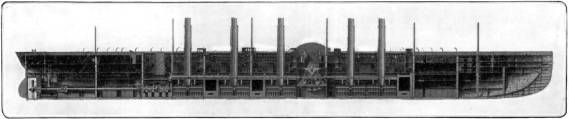

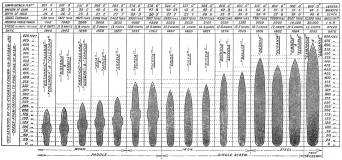

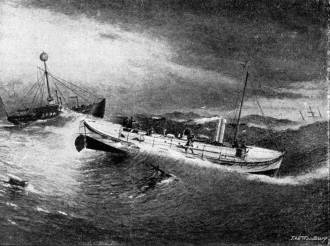

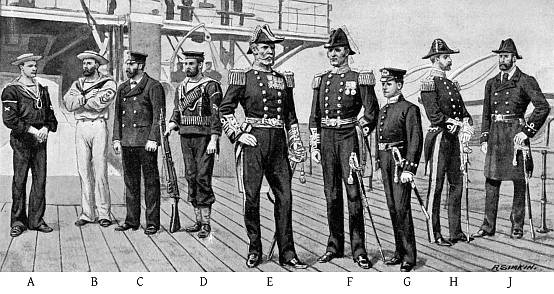

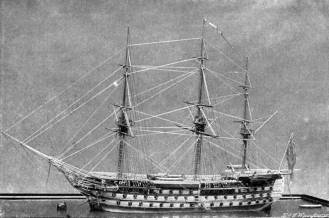

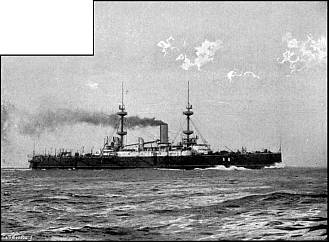

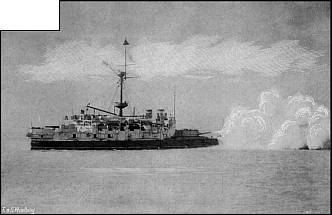

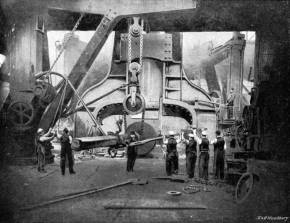

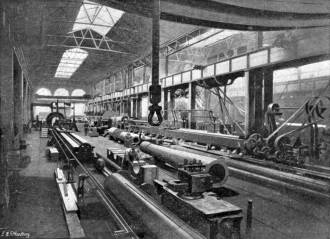

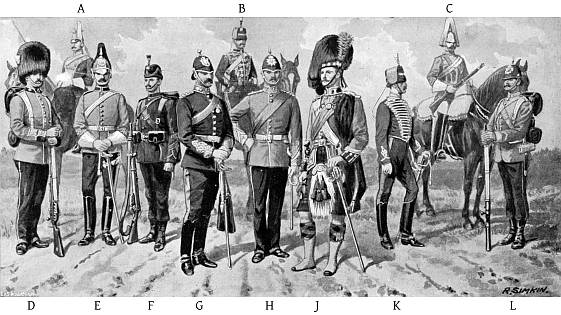

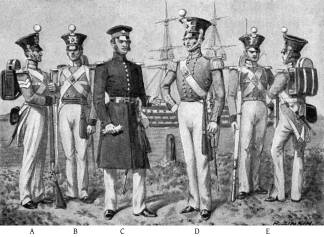

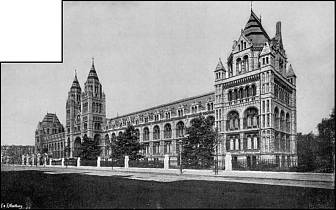

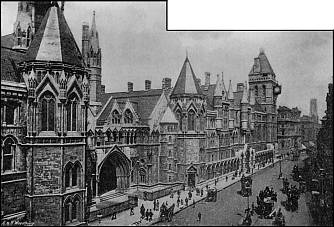

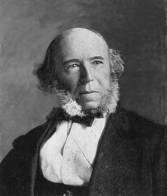

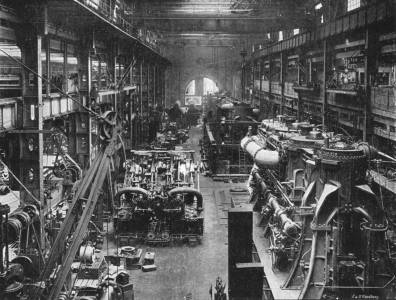

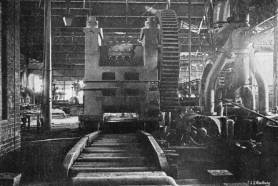

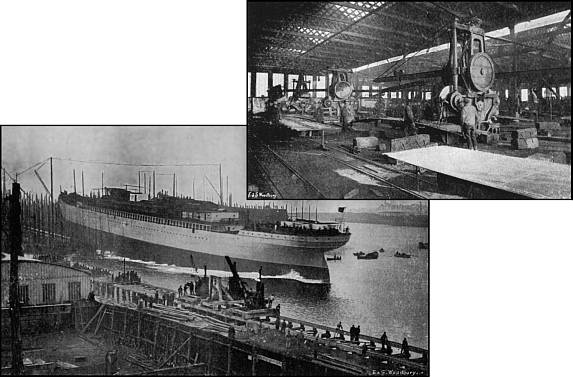

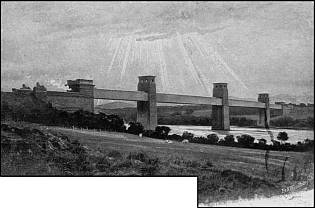

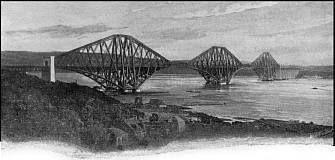

Material Progress during the Reign—Modern Locomotion—The Bicycle—Motor Carriages—The Proposed Channel Tunnel—Steam Navigation—Ironclads—The Telephone—The Phonograph—Electricity as an Illuminant—Photography—Its Effect on Painting and Engraving—Victorian Architecture—Absence of Principle in Design—Universal Education—Its Effect on Moral Character and Literary Habits—The Predominance of Fiction—The Growth and Character of British Journalism—The Advance of Natural Science—Surgery and Medicine—Vaccination—Antiseptic and Aseptic Treatment—Bacteriology—The Röntgen Rays—Sanitary Legislation—Conclusion.

PART TWO: THE DIAMOND JUBILEE CELEBRATIONS

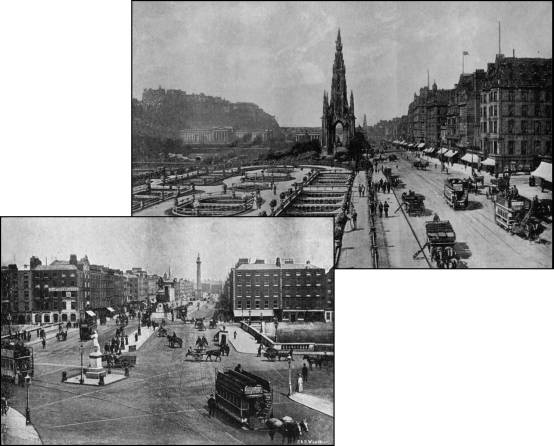

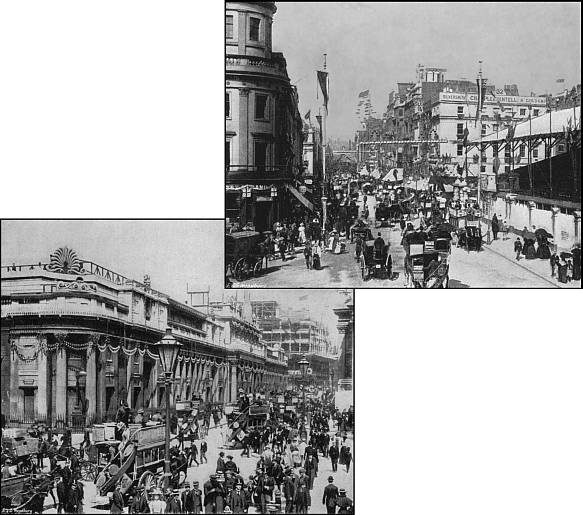

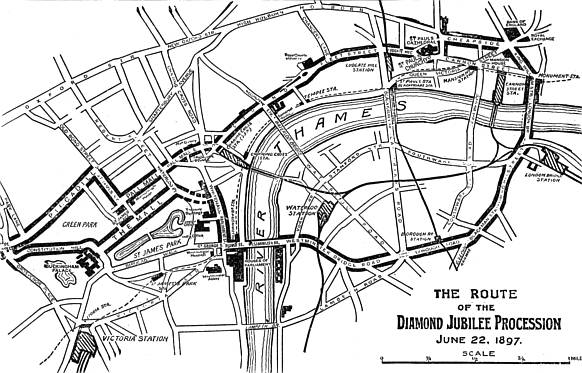

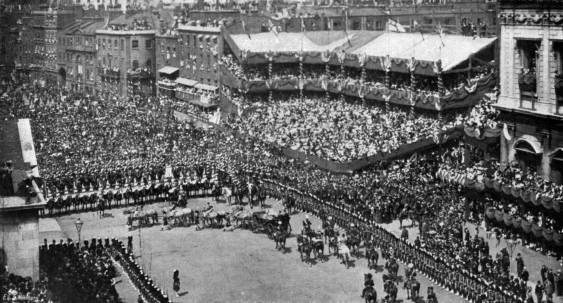

The Central Idea of the Celebrations—The Imperial Character of the Pageant—The Colonial Premiers Invited—The Decorations—Influx of Visitors—Grand Stands—Precautions against Accidents—Thanksgiving Services on Accession Day—The Queen’s Arrival in London—Night in the Streets.

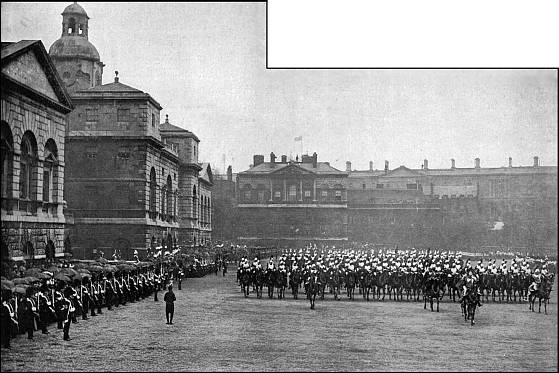

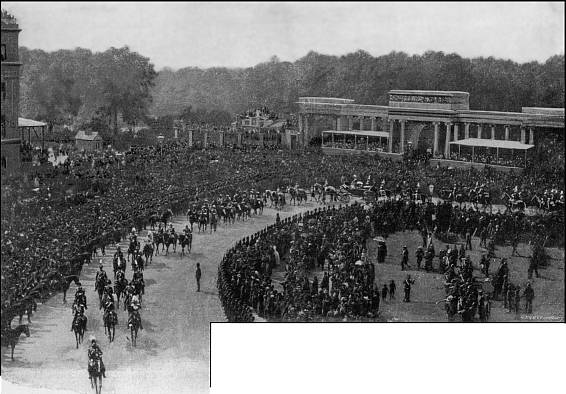

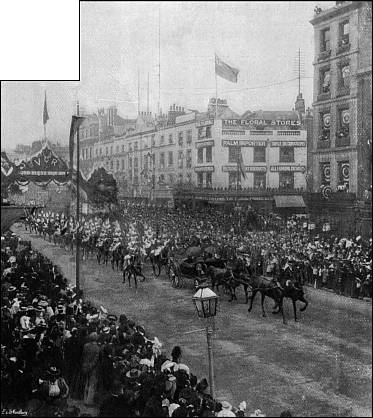

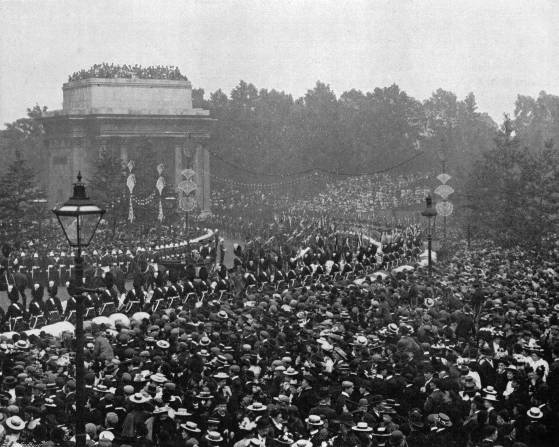

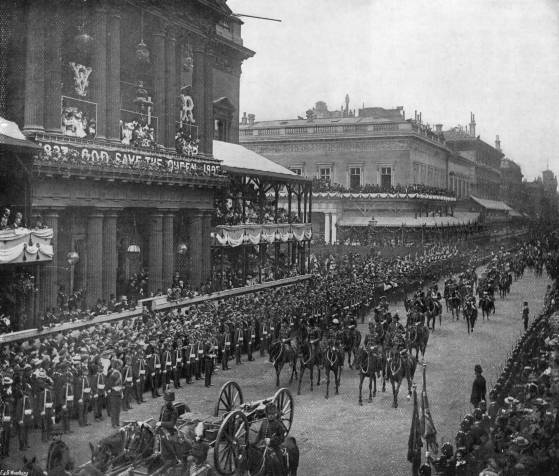

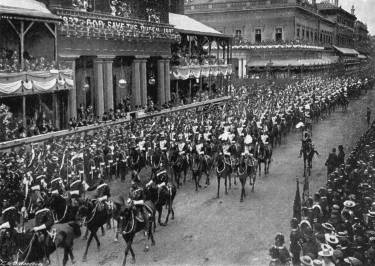

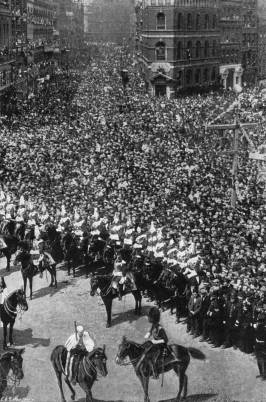

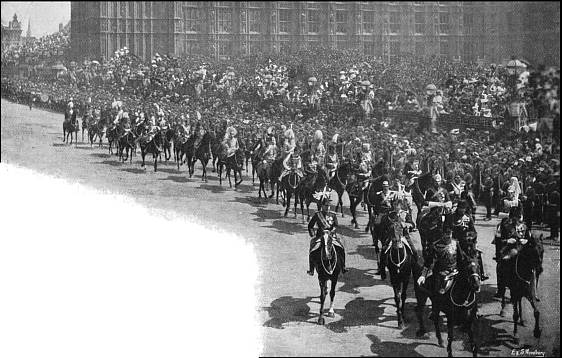

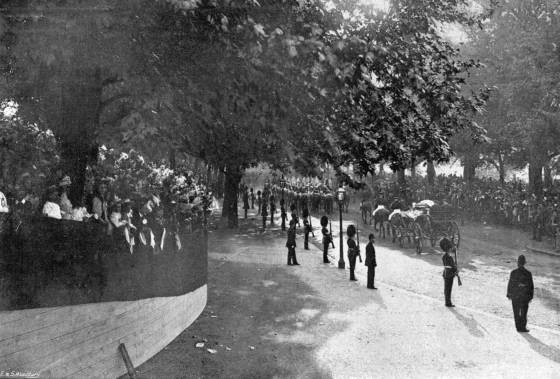

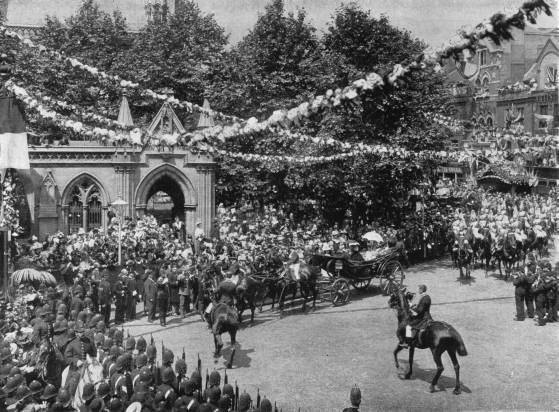

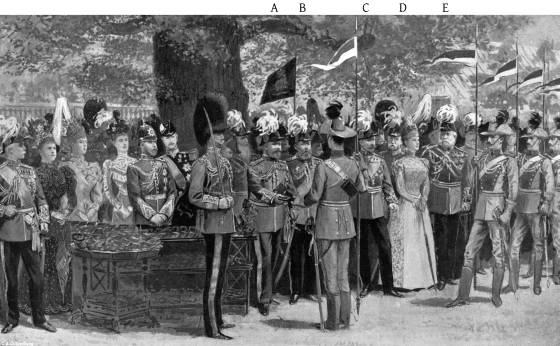

The Weather—A brilliant day for a brilliant pageant—The Queen’s Message to her people—The Colonial Procession—The Royal Procession—Loyal enthusiasm—The Queen’s reception at the City boundary—The Service at the steps of St. Paul’s—The halt at the Mansion House—In the Borough—Return to the Palace—Presents to the Queen—Congratulations from abroad—The Royal Dinner.

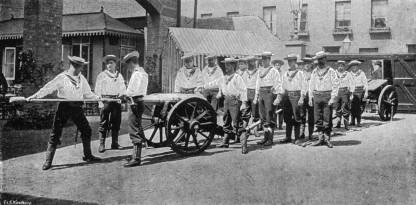

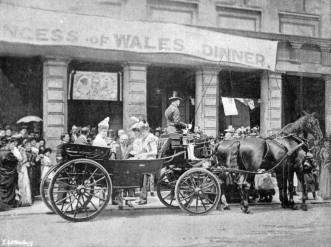

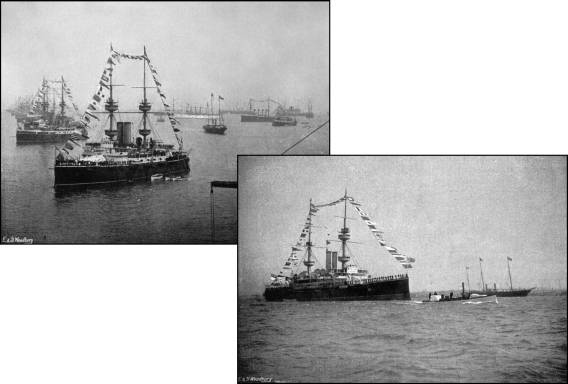

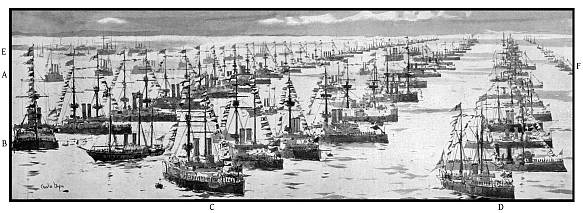

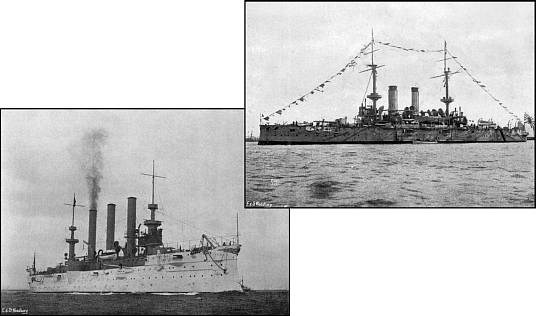

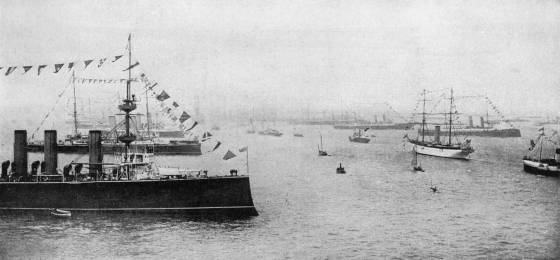

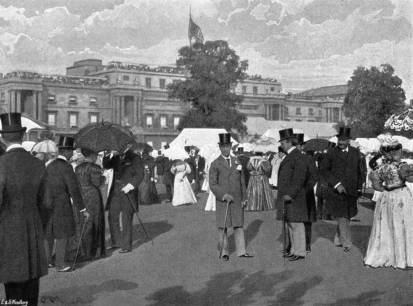

Illuminations in London—Festivities in the Provinces and the Colonies—Addresses of Congratulation from the Lords and Commons—Gathering of School Children on Constitution Hill—State Performance at the Opera—The Princess of Wales’s Dinners to the Poor—State Reception—Special Performance at the Lyceum—Torchlight Evolutions by Etonians at Windsor—Naval Review at Spithead—The Fleet Illuminated—The Colonial Troops at the Naval Review.

The Queen’s Visit to Kensington—Garden Party at Buckingham Palace—Review at Aldershot—Gift of a Battleship—The Prince of Wales’s Hospital Fund—The Jubilee Medals—Conclusion.

SIXTY YEARS A QUEEN.

From the

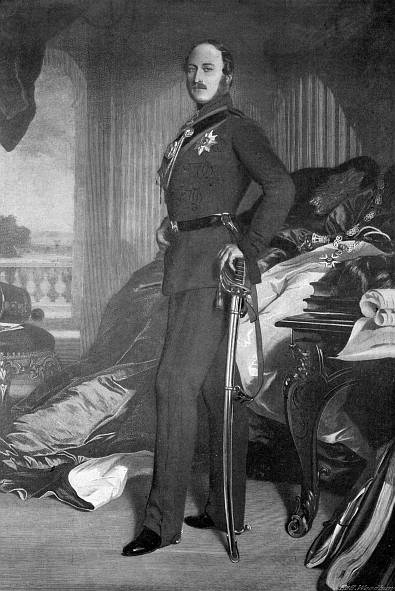

Painting by F. WINTERHALTER

Graciously lent by Her Majesty specially for “Sixty Years a Queen.”

a Queen

SIR HERBERT MAXWELL, BART, M.P.

BY SPECIAL PERMISSION.

HER MAJESTY’S PRINTERS, LONDON.

PUBLISHED BY HARMSWORTH BROS. LIMITED,

24, TUDOR STREET, E.C.

PREFACE

AN attempt has been made in the following pages to give a general view of the principal events in the reign of Queen Victoria and the changes resulting from the development of the means of travel and communication, the accumulation of wealth, the acquirement of political power by the people, and the spread of education among them. In making this attempt the author had to choose between compiling a dry chronicle, and placing before his readers the salient points in a period of rapid and successful progress. He chose the latter; but, in order to carry his purpose into effect within the limits assigned to him, he had to pass in silence over the names of many persons distinguished in politics, science, literature, art, and warfare. Those, or the descendants of them, whose achievements entitle them to an honoured place in the annals of their age, will understand that it was possible only to find room for mention of a few of the illustrious band who have contributed to the great work of empire and civilisation.

Especially in regard to literature, it may be felt that the reference to that department is out of all proportion to its importance. But the subject is so vast that it is almost hopeless to deal with, to any good purpose, in two or three pages. Attention has, however, been drawn in the concluding chapter to the effects of universal compulsory education on our national prosperity, moral character, and intellectual life. In respect of its action on the material well-being of the population, it is not unreasonable to attribute to its influence part of the marked decrease in pauperism in the last quarter of a century, even if the more equable diffusion of wealth be reckoned the principal factor in that process. If the results quoted cannot be proved to be the direct outcome of universal education, at all events they synchronise in a remarkable manner with the period of its existence.

Turning next to the literary habits of the people, it is not possible to doubt the important bearing which recreative reading has upon the national character. We are not, and probably never shall be, a nation of students, but we have become within the limits of the present reign a nation of readers. The press of the country is free—free in a sense that has never been tolerated in any other State. Public men and measures are submitted to searching criticism in a degree that would be wholly intolerable but for the general high tone maintained in British journalism. There are few things more remarkable in our civilisation than the abundance of excellent writing supplied to the daily and weekly press, and the sound morality which pervades it.

Next to the newspaper press, and hardly inferior to it in influence, is the mass of fiction produced year after year in ever-increasing volume. To ascertain how vastly its attractions prevail over those of historical, poetic, philosophic, or scientific works, it is only necessary to consult the returns of any free library. For good or for ill, the thoughts of countless readers, old and young, are continually engaged on the fictitious fortunes, dilemmas, and vicissitudes of imaginary individuals. On the whole, the influence of this literature is harmless and in some degree salutary, though it is true that within recent years a school of novelists has arisen, containing some skilful and attractive writers, who rely on winning popularity by going as near as they dare to the worst kind of realism pursued by certainiv French authors. It will do incalculable damage, not only to English literature, but to the English character, if the public, in whose hands is the verdict, encourage perseverance in this line. Hitherto, in the present century, fiction has been maintained in Great Britain at a higher level than it has ever touched before. The most popular writers of romance—Scott, Marryat, Thackeray, Dickens (not to mention any living authors)—dealt, indeed, with the foibles, crimes, and misfortunes of men and women, but they never failed to keep a high ideal before their readers. Their favourite characters were depicted as at war with evil: not always successful, not without frailty, and even folly; but no religion ever preached a purer morality than did these masters in the story-teller’s craft. It will be deplorable if people learn to employ their leisure, not in narratives of heroism, self-denial, and innocent love, but in studies of degradation and despair, and restless stirring of sexual problems.

Some of the most striking and valuable discoveries in physical science receive mention in the course of this narrative, as being among the more memorable features of the reign, but it has been impossible even to allude to countless others, almost as important to the welfare and progress of humanity. Less obvious to the general public, but not less remarkable, has been the application of the exact and comparative method to intellectual research, so that, although students still differ, and are likely to continue to the end of time to differ on some of the conclusions at which they arrive, for the first time in the world’s history they are of one mind about the right system of enquiry.

There are still to be witnessed in the Queen’s realm those violent contrasts between vast wealth and grinding poverty, which must ever arise in every civilised State in periods of great commercial and productive activity. They are a standing perplexity and distress to philanthropists; but one of the brightest features in the reign of Queen Victoria, of infinitely deeper significance than the accumulation of riches by the nation and by individuals, is the degree to which that wealth has penetrated the middle and industrial classes.

The effect of the application of steam to machinery, which coincided so nearly with the beginning of the present reign, was, indeed, injurious to certain limited industries, but the general result has been a continuous rise in the wages paid to artisans. The first few years of the factory system, coupled with a lamentable ignorance of, and indifference to, sanitary principles, brought a terrible increase of disease, squalor, and suffering in their train. This soon attracted the attention of philanthropists, among whom the leading place must be assigned to the Earl of Shaftesbury; and year by year the two rival political parties have vied with each other in applying remedial and protective legislation to the evils of overcrowding, insanitary dwellings, and other dangers besetting extraordinary industrial activity. There are slums still, but they must be hunted for, instead of forcing themselves on attention as was the case not long ago in almost every large town. Artisans’ dwellings, far exceeding in comfort, in solidity, and in sanitation anything that our forefathers may have dreamt of, are now the rule and not the exception.

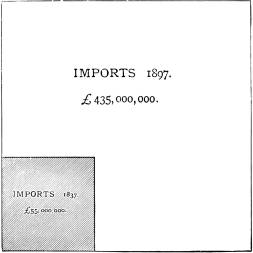

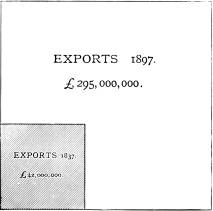

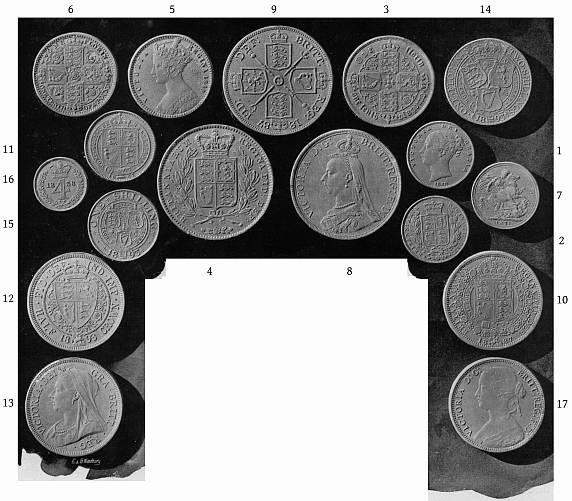

Mere quotation of figures will not make clear the increased share of the national wealth which now finds its way into the pockets of the working classes, because the unprecedented cheapness of all the necessaries and many of the luxuries of life (intoxicants alone excepted) has raised the buying power of wages in a degree which cannot be estimated. Mr. W. H. Mallock, a well-known writer on this subject, has recently devoted some close enquiry to it, and has brought out some remarkable results. He quotes the calculation of statisticians upon the income of the nation in 1851, when it was estimated at £600,000,000, and in 1881, when it was reckoned at £1,200,000,000, having doubled itself in thirty years. He then deducts from these totals the amounts assessed to income-tax, arriving by this process at the total paid in wages (or the total of all incomes under £150), which was £340,000,000 in 1851, and £660,000,000 in 1881. In those thirty years the wage-earning class had increased in number from 26,000,000 to 30,000,000, or 16 per cent., while the wages paid to them had increased by nearly 100 per cent. In fact the income of the working classes in 1881 was about equal to that of the whole nation in 1851, with largely increased purchasing power, owing to reduction in prices.

v But this does not exhaust the evidence of the diffusion of wealth which has been going on, a process which is apt to be overlooked in the attention attracted to the building up of a few colossal fortunes. Mr. Mallock shows, by taking the increase in the number of incomes between £150 and £1,000 a year, how greatly the middle classes have increased in numbers. Persons assessed for taxation on incomes between these limits have increased in number during the period under consideration from 300,000 to 990,000, that is, in a ratio of nearly 250 per cent. It is hardly possible to over-estimate the importance of these figures in their bearing on the prospects of the stability of the present social system in Great Britain. Had this enormous increase in wealth been accumulated in a few hands, it must have given a great impetus to the revolutionary agencies always present under settled governments. But its dispersal among a multitude of owners broadens the foundations of authority, and at the same time acts as a powerful check upon legislation for a limited class.

It must be admitted that, side by side with the advance in general welfare, certain less desirable incidents of our civilisation claim attention. One of these is the recurrence of disputes on a large scale between employers and workmen, resulting in industrial strikes far exceeding in extent and intensity anything of the sort that could be organised before the legislature relaxed the laws against conspiracy and combination. Although labour disputes are conducted now with a general absence of the violence which almost invariably accompanied them in earlier days, they are not without deplorable results in the losses entailed on the working classes during their continuance, and in the damaging effect they sometimes bring upon the industries affected. But the principle of arbitration is gradually winning its way, and the fact that on several recent occasions recourse to this reasonable method has proved successful in averting a prolonged struggle, encourages the hope that employers and employed are beginning to recognise their common advantage in conciliation.

It is less easy to prescribe a remedy for the admitted evil of the excessive aggregation of the people in centres of industry, and the corresponding depletion of the rural districts. This tendency has been at work ever since Virgil wrote his—

and perhaps from long before. Increased facilities of locomotion, and the stimulus lent by education to intellectual energy, have intensified the movement; but at all events the worst effects of it on the national physique are being mitigated by the attention directed to sanitary engineering.

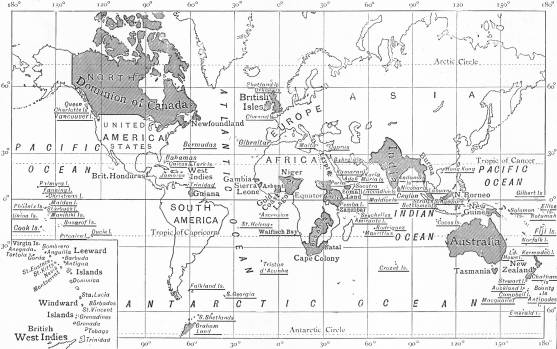

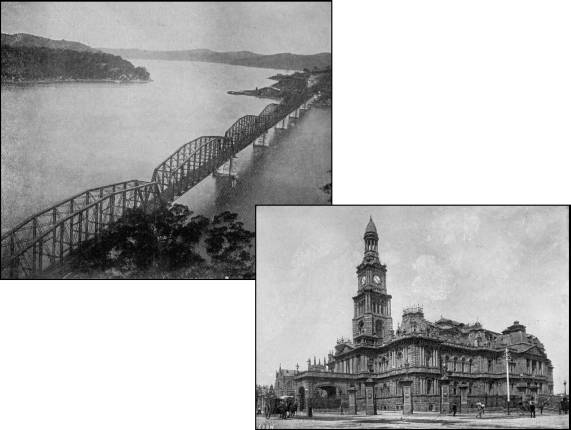

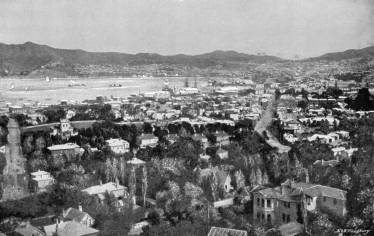

One of the results of general education has been to give greater breadth and accuracy to the popular aspirations for the Empire. Five and twenty years ago the British Colonies were regarded, even by experienced statesmen, with a degree of indifference, which it is difficult for the present generation to realize. It seemed to be assumed that, sooner or later, each of them would throw off the bond attaching it to the Mother country, and that nothing was to be gained by maintaining a union of which the value could not be shown in a profit and loss account. A complete change has come over public opinion in this respect. Imperial federation is in the air; the precise means by which it is to be secured have not been formulated, but the sentiment is as strong in the general mind of the natives of these islands as it seems to be in that of the Queen’s subjects in India, in Canada, and in Australasia. Although the presence of a large proportion of the Dutch race in our South African Colonies renders the feeling in that land less pronounced, it is not unreasonable to hope that even there just laws, wise administration, and the prestige of a mighty empire will prevail to dispel suspicion and establish a lasting harmony.

The example of good government, which has been set forth at home during the present reign, is one in which every Briton may take a just pride. Party politics are as vehement as ever, and sometimes descend into acrimony; but the last traces of corruption have disappeared from public life, and all the acts of administration are open to the most searching scrutiny.

vi Not less remarkable is the change which has come over the habits of all classes in regard to alcoholic indulgence, which, throughout the last century and a considerable portion of the present one, remained as a reproach on our social life. Formerly, though intemperance was looked on as undesirable, it was not thought discreditable, or, at least, not incompatible with the discharge of the most important offices. But at the present time indulgence in drink is regarded as a bar to all except ordinary manual labour, and even in that department the working man is steadily emancipating himself from the thraldom which, at no distant date, lay so heavily upon all classes.

These, and many others such as these, are some of the features which distinguish the longest reign in our annals. So important are they, regarded as affecting the happiness of millions of human beings, that the remarkable length of the reign sinks into secondary moment compared with its character. It has been an age of material progress more swift and political change more permanent than any which preceded it, and there have not been wanting those who viewed each successive step in the movement with apprehension, predicting disaster to cherished institutions—to the monarchy itself. The result, so far, has been to falsify those predictions. The British monarchy reposes at present on surer foundations than military prowess or legislative sagacity can supply; it rests on the genuine affection of the people. Power has been committed to them during these sixty years in no illiberal measure; in a very practical sense they are masters, under the Almighty, of the destiny of the empire, for they can, by their votes, put those Ministers in power who shall do their pleasure. How comes it that this power has been exercised with a moderation very different from that which there is plenty of historical precedent for anticipating? There are doubtless many contributory causes—an abundant employment owing to the expansion of industry, cheap food, the diffusion of wealth, the readiness of the British people to avail themselves of new lands, the hold which religious principles keep upon them, and the instinctive conservatism which affects, often unconsciously to themselves, all but those who adopt extreme views in politics. All these, and many more, must be taken into account in considering what has taken place; but there is one which a watchful observer will reckon more direct in its effect than any of them—namely, the personal character of the Monarch. Vigilant as she is known to have been in attention to public affairs, conscientious as she has shown herself in complying with the limitations of our Constitution, Queen Victoria has set before her people a perfect Court and a model home. Not by design has this been done, not by laborious compliance with irksome rules or straining for public approval, but by the action of a true nature, guided by a vigorous intellect and resolute will.

What might have been the result of the enormous development of popular power if the Monarch had been one whose character had attracted no affection or respect, it is idle to speculate. It is enough that every true Briton is able to say, with heartfelt gratitude: “Thank Heaven that throughout this critical period of change we have remained the subjects of Victoria the Great and Good!”

SIXTY YEARS A QUEEN:

TOLD BY

SIR HERBERT MAXWELL, Bart., M.P.

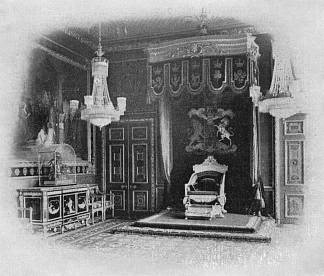

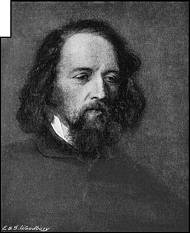

HER MAJESTY QUEEN VICTORIA IN CORONATION ROBES.

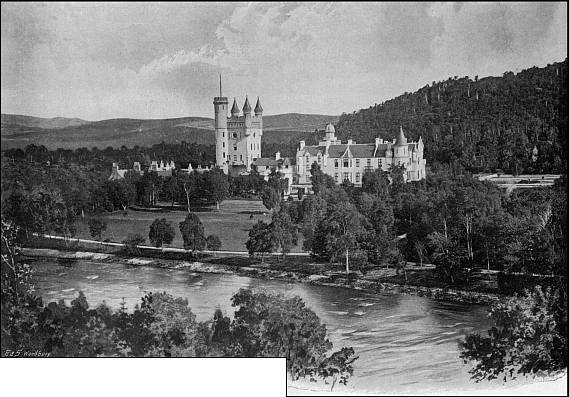

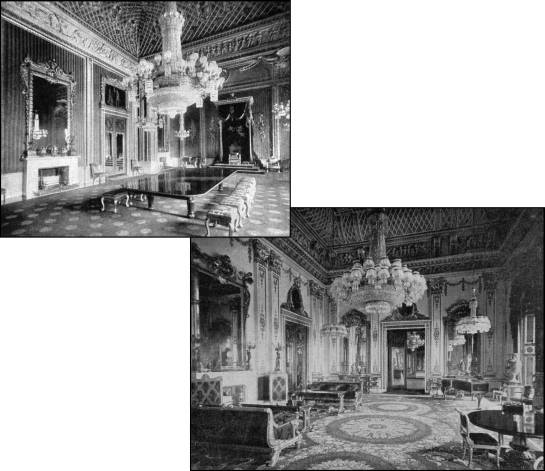

WINDSOR CASTLE.

SIXTY YEARS A QUEEN

CHAPTER I.

1837–1838.

Death of William IV.—Princess Alexandrina Victoria summoned to the Throne—Ignorance of the Public about the young Queen—Her early training—Severance of the Crown of Great Britain and Hanover—Prorogation of Parliament—Early Railways—Electric Telegraph—The Coronation—Popular Reception of Wellington and Soult—State of Parties—Result of General Election—Rebellion in Canada—The Earl of Durham—Debate on Vote by Ballot.

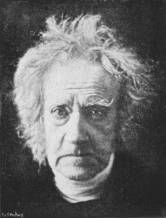

AT the present day, tidings, however fateful or momentous, flash silently over unconscious fells and floods to the uttermost limits of Empire; but it was otherwise sixty years ago. Throughout the brief night of June 19, 1837, the land echoed to the furious galloping of horses and the ceaseless rattle of flying wheels; for William the King lay dying at Windsor Castle.

He drew his last breath before dawn on the 20th, and mounted messengers thronged the highways yet more thickly than before in the early hours of morning. |Death of William IV.| Among them were two of very high degree—Dr. Howley, Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Marquis of Conyngham, Lord Chamberlain—charged to proceed post haste to Kensington Palace in order to summon the Princess Victoria to the throne of Great Britain and Ireland. Leaving Windsor shortly after two in the morning, they did not reach Kensington till five o’clock. The Palace was wrapped in silence; it was with great difficulty that even the gate-porter could be roused, and there was further delay inside the courtyard. At last the Archbishop and the Lord Chamberlain obtained admission, were shown into a room, and left to themselves. |Princess Alexandrina Victoria summoned to Throne.| After waiting some time they rang the bell, and desired the sleepy servant who answered it to convey to the Princess their request for an immediate audience, on business of extreme urgency. Again the impatient dignitaries were left alone, and once more they pealed the bell. This time they were informed by the Princess’s attendant that Her Royal Highness was asleep, and must on no account be disturbed.

“We are come,” was their reply, “on business of State to the Queen, and even her sleep must give way to that.”

The attendant yielded, and then, to quote the simple but vivid description by Miss Wynn, “in a few minutes she (the Queen) came into the room in a loose white nightgown and shawl, her4 nightcap thrown off, and her hair falling on her shoulders, her feet in slippers, tears in her eyes, but perfectly collected and dignified.”

H.R.H. VICTORIA MARIA LOUISA, DUCHESS OF KENT, AND HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN AT THE AGE OF THREE.

Next, the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, was summoned, and Charles Greville has described in his diary how the young Queen met the Privy Council at eleven o’clock.

“Never was anything like the first impression she produced, or the chorus of praise and admiration which is raised about her manner and behaviour, and certainly not without justice. It was very extraordinary, and something far beyond what was looked for. |Ignorance of Public about the young Queen.| Her extreme youth and inexperience, and the ignorance of the world concerning her, naturally excited great curiosity to see how she would act on this trying occasion, and there was a considerable assemblage at the palace, notwithstanding the short notice that was given.”

HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN AT THE AGE OF ELEVEN.

Bowing to the lords present, Queen Victoria, quite simply dressed in black, took her seat, and proceeded to read her speech in clear, calm accents. Then, having taken the oath for the security of the Church of Scotland, she received the allegiance of the Privy Councillors present, the two Royal Dukes having precedence of the others.

“As these two old men,” wrote Greville, “her uncles, knelt before her ... I saw her blush up to the eyes, as if she felt the contrast between their civil and natural relations.”

At noon the Queen held a Council, at which the excellent impression she had made already was confirmed. Throughout the trying ceremonies of the first day of her reign she bore herself with a dignity and composure which amazed, as much as it delighted, her Ministers.

Princess Alexandrina Victoria, upon whose young shoulders the weight of the Empire had been laid so suddenly, was the only child of Edward, Duke of Kent, fourth son of George III., by her Serene Highness Victoria Maria Louisa, daughter of the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and widow of the Prince of Leiningen. William IV., third son of George III., had left no children born in wedlock; on his death, therefore, the succession devolved on his niece, who was born on May 24, 1819, and was therefore just over eighteen at her accession. Nothing would have5 been more natural than that the character of the Princess, as heiress to the Crown, and the qualifications for rule of which she might have given promise even at that tender age, should have been widely and eagerly discussed, or, at least, that the late King’s Ministers should have formed some opinion of them; but this was not the case. The gossiping Greville repeatedly lays stress on the seclusion in which Her Royal Highness had been brought up, her inexperience, and the complete ignorance of the public about her character and even her appearance; so much so, that “not one of her acquaintance, none of the attendants at Kensington, not even the Duchess of Northumberland, her governess, have any idea of what she is or promises to be.” It may easily be imagined, therefore, how greatly the severity of the sudden ordeal to which the girl-Queen was exposed was intensified by the anxious and curious interest of those who were present at her first Council.

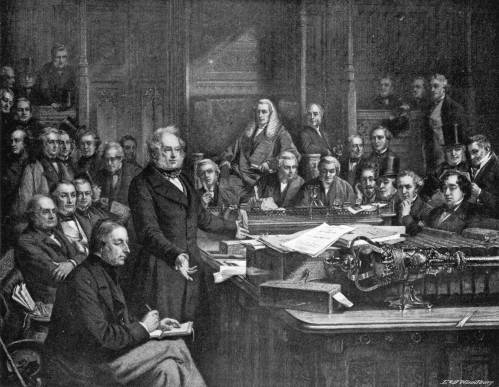

HER MAJESTY’S FIRST COUNCIL, AT KENSINGTON PALACE, June 20, 1837.

- Her Majesty.

- Duke of Argyll, Lord Steward.

- Earl of Albemarle, Master of the Horse.

- The Right Honourable G. Byng, Comptroller.

- C. C. Greville, Esq., Clerk of the Council.

- Marquess of Anglesea.

- Marquess of Lansdowne, President of the Council.

- Lord Cottenham, Lord High Chancellor.

- Lord Howick, Secretary at War.

- Lord John Russell, Secretary of State for the Home Department.

- The Right Honourable T. Spring Rice, Chancellor of the Exchequer.

- Viscount Melbourne, First Lord of the Treasury.

- Lord Palmerston, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs.

- The Right Honourable J. Abercrombey, Speaker of the House of Commons.

- Earl Grey.

- The Earl of Carlisle.

- Lord Denman, Lord Chief Justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench.

- The Right Honourable F. Erskine, Chief Judge of the Bankruptcy Court.

- Lord Morpeth, Chief Secretary for Ireland.

- The Earl of Aberdeen.

- Lord Lyndhurst.

- The Archbishop of Canterbury.

- His Majesty the King of Hanover.

- The Duke of Wellington.

- The Earl of Jersey.

- The Right Honourable J. W. Croker.

- The Right Honourable Sir R. Peel, Bart.

- H.R.H. the Duke of Sussex.

- Lord Holland, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.

- Sir J. Campbell, Her Majesty’s Attorney-General.

- Marquess of Salisbury.

- Lord Burghersh.

- The Right Honourable T. Kelly, Lord Mayor of London.

Of all the illustrious personages here represented, Her Majesty is now the sole survivor.

For the seclusion in which the Princess Victoria had been brought up, sufficient cause will be apparent to those who have studied the domestic annals of the Court during the reigns of her6 uncles George IV. and William IV., which were, in truth, in accord with the worst traditions of Royalty. |Her early training.| The Duke of Kent had died shortly after the birth of his daughter, and his widow, over-anxious, perhaps, to screen the young life from contagion of evil, sought to protect the Princess Victoria by a training which, in most modern families, would be regarded as unnecessarily severe. But deep-rooted custom requires drastic treatment to remove it. On weak or light natures such discipline is too often seen to work disastrous reaction; happily, the young Queen was inspired by an intellect of such fibre, and a spirit of such temper, that she responded to her early training by establishing and maintaining in her Court such a high moral ideal as has never been known since the days of the mythical Round Table.

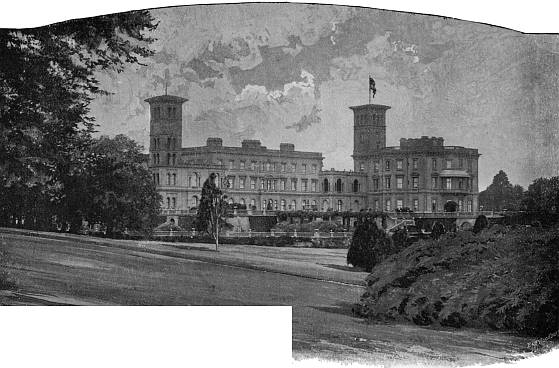

Her Majesty the Queen was born in the ground-floor room occupying the farthest angle of the building on the extreme right of the picture. A tablet within the room records the fact.

HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN AT THE AGE OF FOUR.

Queen Victoria’s accession was the cause of the departure from England of a Prince deservedly unpopular, whose signature stands first among those appended to the Act of Allegiance executed at Kensington Palace. |Severance of the Crown of Great Britain and Hanover.| Hitherto, for more than one hundred and twenty years, succession to the throne of Great Britain had carried with it the crown of Hanover; but, inasmuch as that crown was limited to the male line, it passed, on the death of King William, to his eldest surviving brother, the Duke of Cumberland. It is not necessary to discuss here the character of that Prince—it is enough to say that his departure to take up his inheritance in Hanover was probably cause of regret to very few persons in this country and reason for rejoicing to a great many. Nor, in looking back over the history of the past sixty years, can any thoughtful person fail to recognise advantage in the severance of the monarchies of Great Britain and Hanover. Any loss of prestige or dignity which might have been anticipated has been amply outweighed by the freedom enjoyed by this country from continental complications. England, while she has forfeited no weight in the Councils of Europe, is in a far stronger position to enforce her will when necessary, and the development of rapid and easy transit have protected Englishmen from any disadvantage that might have been apprehended from an exclusively insular Court.

HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN AS PRINCESS VICTORIA.

One of the incidents of the ceremony of accession commented on with most interest was the fact that, in signing the Oath for the security of the Church of Scotland, the Queen wrote only “Victoria,” instead of her full name “Alexandrina Victoria.” Surely it was a happy inspiration which prompted the choice of the single name—prophetic, as it has turned out, of the character of the coming reign. Probably not one in a thousand of her subjects are aware that Her Majesty has two baptismal names, though there is historic interest attached to their origin. The Duke of Kent gave his daughter the name of Alexandrina in compliment to the Empress of Russia, intending her second name should be Georgiana. The Regent, however, objected to the name Georgiana being second to any other in this country; so, as the Princess’s father was determined that Alexandrina should be the first name, it was decided she should not bear the other one at all.

On July 17 the Queen went in State to the House of Lords to prorogue Parliament. |Prorogation of Parliament.| After listening to an Address made by the Speaker on behalf of the House of Commons, and giving her consent to certain bills, Her Majesty proceeded to read her speech to Parliament in clear and unfaltering accents. The concluding paragraph, viewed in the light of subsequent events, must be admitted to have been more amply fulfilled than most human promises, however sincerely spoken:—

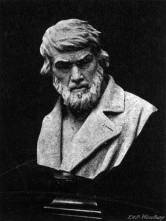

BUST OF HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN AS PRINCESS VICTORIA.

“I ascend the throne with a deep sense of the responsibility imposed on me; but I am supported by the consciousness of my own right intentions, and by my dependence on the protection of Almighty God. It will be my care to strengthen our institutions, civil and ecclesiastical, by discreet improvement wherever improvement is required, and to do all in my power to compose and allay animosity and discord. Acting upon these principles, I shall, upon all occasions, look with confidence to the wisdom of Parliament and the affection of my people, which form the true support of the dignity of the Crown and ensure the stability of the Constitution.”

Every opportunity which was afforded to Parliament and the public of passing judgment on the Queen’s demeanour tended to deepen the favourable impression already created. Greville—the “Man in the Street” of those days—he of whom Lowe afterwards wrote—

is not an authority on which too much reliance should be placed, yet his diary is useful as a reflection of passing events. It is full of enthusiastic praise of the new Monarch.

“All that I hear of the young Queen leads to the conclusion that she will some day play a conspicuous part, and that she has a great deal of character.... Melbourne thinks highly of her sense, discretion, and good feeling; but what seems to distinguish her above everything are caution and prudence, the former in a degree which is almost unnatural in one so young, and unpleasing because it suppresses the youthful impulses which are so graceful and attractive.... With all her prudence and discretion she has great animal spirits, and enters into the magnificent novelties of her position with the zest and curiosity of a child.... The smallness of her stature is quite forgotten in the majesty and gracefulness of her demeanour.”

HER MAJESTY TAKING THE OATH ON HER ACCESSION.

Sixty years ago! It is the second and third generation from that time which now cries “God save the Queen! Long live Victoria!” Never before in the history of our nation has it fallen to the lot of any historian to tell the story of such a long reign, to chronicle such unbroken national progress, to trace such a series of peaceful changes, to record such accumulation of wealth and diffusion of comfort in a like period.

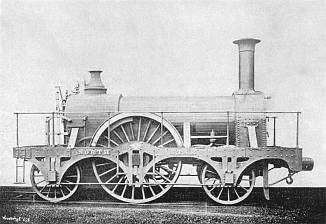

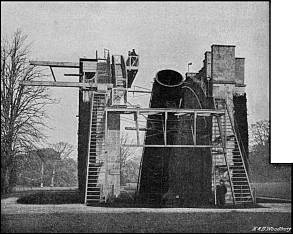

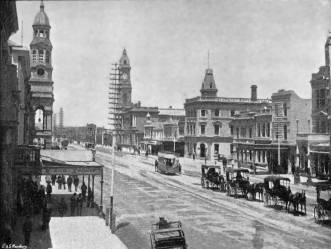

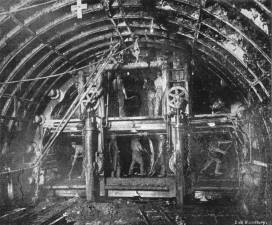

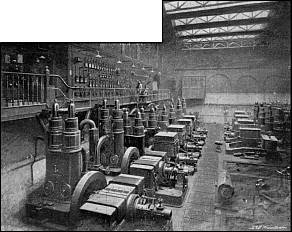

Sixty years ago! The population of these islands was then some twenty-five millions; it amounts now to upwards of thirty-eight millions. |Early Railways.| The Liverpool and Manchester Railway, about thirty miles long, had been open for eight years, causing far-sighted folk to predict an important change in the mode of travelling. The Liverpool and Birmingham Railway was opened in the year of the Queen’s accession. In 1838 the line between London and Birmingham was finished, and trains were timed to do the distance—112¼ miles—at the average speed of twenty miles an hour. The London and Croydon Railway began running in 1839, and in 1840 there were 838 miles of railway open in the United Kingdom. At the present time there are 20,000 miles open, owned by companies which in 1894 had an authorised capital of £1,099,013,785, earning a gross revenue of £84,310,831, and a net profit of £37,102,518.

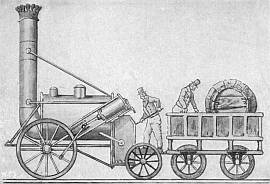

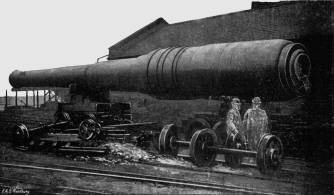

This engine was constructed by Messrs. Stephenson & Co. in 1829, to compete in the trial of locomotive engines held at Rainhill, on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in October of that year, where it gained the prize of £500. The “Rocket” worked on the Liverpool and Manchester line till 1837, when it was removed to the Midgeholm Railway, near Carlisle. It ceased running in 1843–4, and was presented to the South Kensington Museum in 1862.

In order to convey the impressions of an educated traveller by the new mode of transit, the temptation to quote once more from the lively Greville is irresistible. In July 1837 he became tired of hearing nothing in London except about the Queen and the coming elections, so he resolved to see the new Birmingham and Liverpool Railway. Reaching Birmingham in 12½ hours by coach, he “got upon the railroad at half-past seven in the morning. Nothing can be more comfortable than the vehicle in which I was put, a sort of chariot with two places, and there is nothing disagreeable about it but the occasional whiffs of stinking air which it is impossible to exclude altogether. The first9 sensation is a slight degree of nervousness and a feeling of being run away with, but a sense of security soon supervenes, and the velocity is delightful.”

The “velocity” referred to was regulated to an average of about twenty miles an hour; but the diarist makes mention of a foolhardy driver who ventured to run forty miles an hour, and was promptly dismissed by the directors.

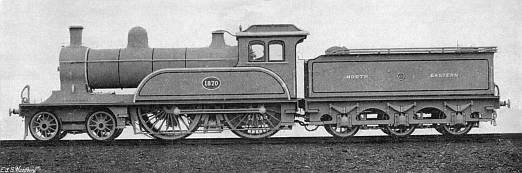

This engine, No. 1870 of the North Eastern Railway, was built in 1896 by the Gateshead works. It is a “non-compound” engine, with the largest coupled driving wheels hitherto known, viz., 7 ft. 7 in. The diameter of the cylinders inside is 20 in. A sister engine (No. 1869) was constructed at the same time, and the weight of each of them with tender fully loaded is over 90 tons.

This engine was designed by Sir Daniel Gooch in 1836 and built by Robert Stephenson & Co. in 1837. It was one of the first engines belonging to the Great Western Railway Company, and continued at work until 1870, running a total distance of 429,000 miles.

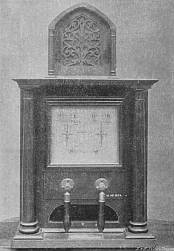

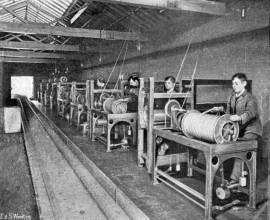

The application of another of the forces of Nature to the service of human intercourse has brought about a change in political, military, social, and commercial relations even more complete than that wrought by steam. |Electric Telegraph.| The invention of the electric telegraph coincided very nearly with the beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign. In 1835 Mr. Morse, an American citizen, produced a working model of an instrument designed to communicate alphabetical symbols by the interruption of the electric current, but he failed to persuade Congress to furnish him with the funds necessary to the practical application of his discovery. Next year he tried to take out a patent for it in this country; but, meanwhile, Cooke and Wheatstone had anticipated him with one instrument, and the brothers Highton with another, both of which were soon in use on railways. The growth of this means of communication may be seen in the “Post Office Annual,” which shows that in the year 1895–96 about seventy-nine million telegrams were delivered through the Post Office, besides those dealt with by certain public companies.

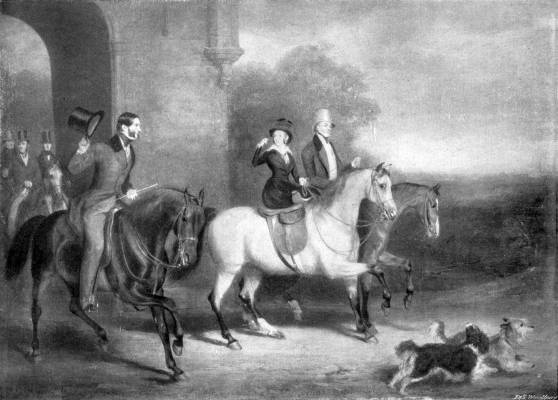

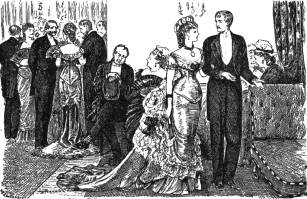

LA BELLE ALLIANCE.

This sketch represents Marshal Soult meeting his old antagonist, Lord Hill, at the Duke of Wellington’s. “At last,” he says, “I meet you, I, who have run after you so long!” “La Belle Alliance” is well known as the name of a particular spot, which was one of the points of attack at the Battle of Waterloo.

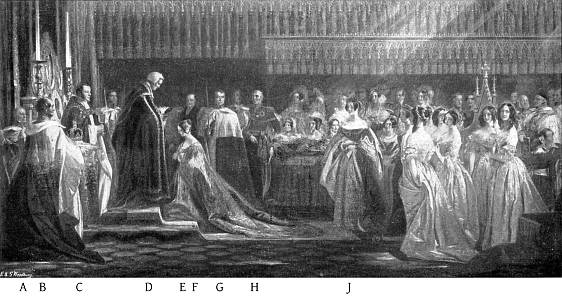

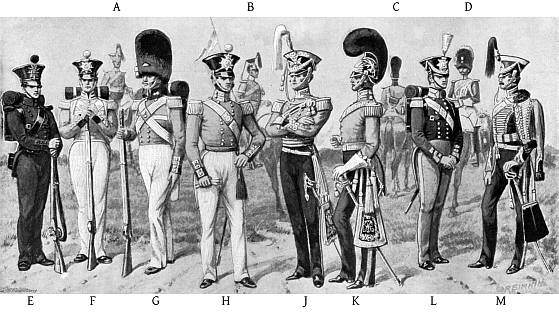

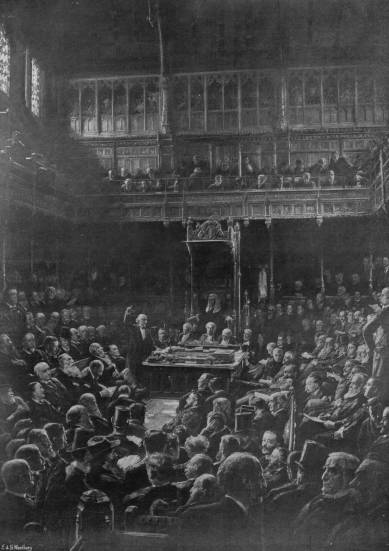

The Queen’s Coronation was deferred till June 1838. It would be tedious to dwell on the splendour of the ceremonial. |The Coronation.| Perhaps the most readable, and not the least truthful, account has been preserved in one of Barham’s Ingoldsby Legends—Mr. Barney Maguire’s Account of the Coronation, set to the tune of The Groves of Blarney, and beginning—

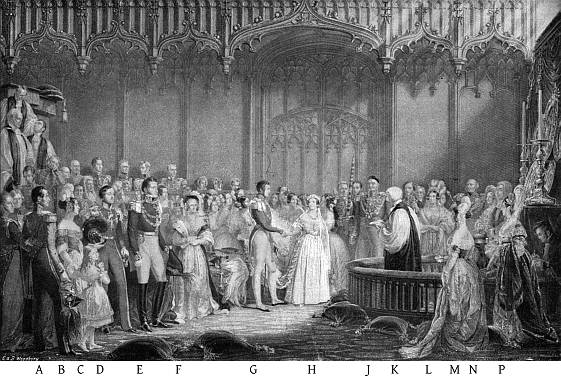

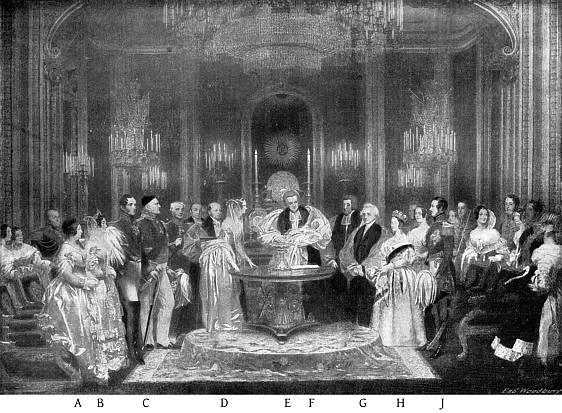

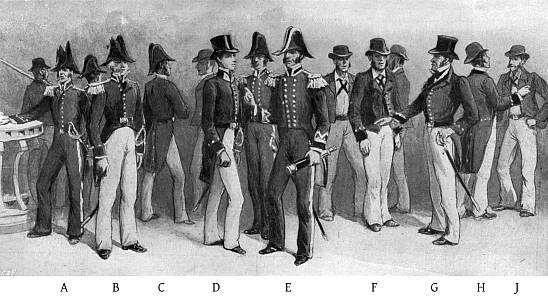

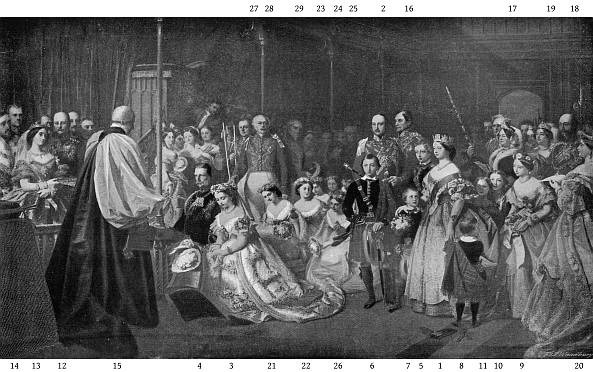

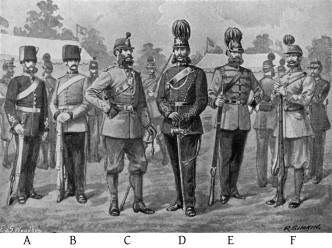

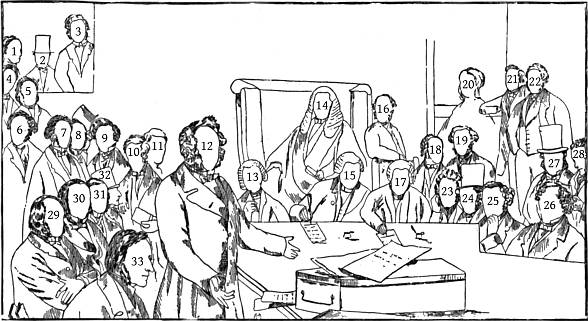

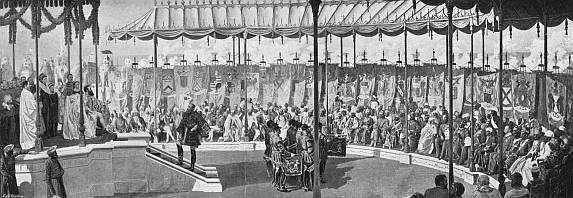

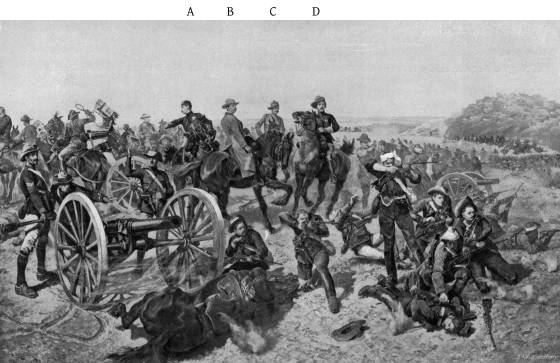

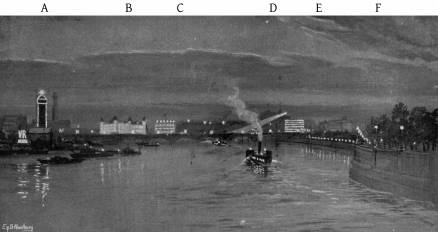

A. Lord Willoughby de Eresby. B. The Duke of Norfolk. C. The Marquis of Conyngham. D. The Archbishop of Canterbury. E. Her Majesty the Queen. F. Lord Melbourne. G. The Bishop of London. H. The Duke of Wellington. J. The Duchess of Sutherland.

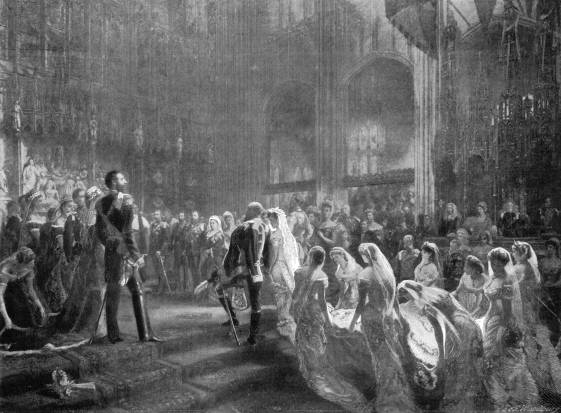

HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN RECEIVING THE SACRAMENT AFTER HER CORONATION IN WESTMINSTER ABBEY,

June 28, 1838.

Lord Willoughby de Eresby, as Hereditary Lord High Chamberlain, held the Crown, and Lord Melbourne as First Lord of the Treasury, the Sword of State. The Duke of Norfolk was Earl Marshal, the Marquis of Conyngham Lord Chamberlain, the Duke of Wellington Lord High Constable of England, and the Duchess of Sutherland Mistress of the Robes.

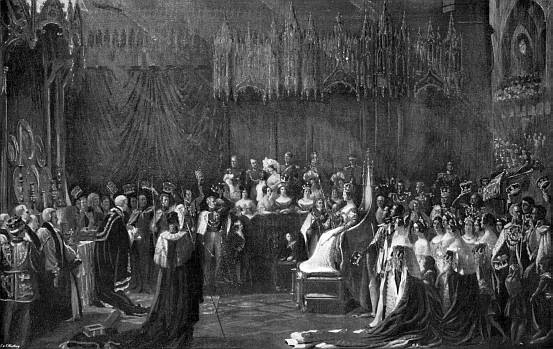

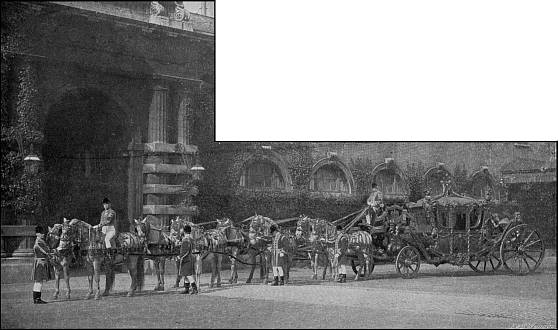

THE CORONATION OF HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN WESTMINSTER ABBEY, June 28, 1838.

The moment depicted is when the Archbishop, having placed the Crown on the head of the Queen, and the emblems of sovereignty in her hands, has returned to the altar. It was at this time that the members of the Royal Family, the peers and the peeresses assumed their coronets. The whole Abbey rang with cheers and cries of “God save the Queen,” and the animation of the scene reached its climax.

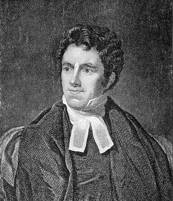

Sat in the House of Commons for forty-seven years. He introduced the great Reform Bill in 1831 and was twice Prime Minister (1846–52, and 1865–6). He was raised to the Peerage in 1861.

Two personages in the procession, who had met under far different circumstances in earlier years, met with a tremendous ovation wherever they moved. One of these was the Duke of Wellington—our Great Duke—and the other was the veteran Duke of Dalmatia—the puissant Maréchal Soult of the Peninsula and Waterloo—once the redoubtable foe of England. Mr. Justin McCarthy has suggested that “the cheers of a London crowd on the day of the Queen’s coronation did something genuine and substantial to restore the good feeling between this country and France, and efface the bitter memories of12 Waterloo.” On the other hand, the anti-monarchical party in France attributed the popular reception of Soult in London to the prevalence of sympathy with Republican views. |Popular Reception of Wellington and Soult.| Certain it is that when, in later years, Soult championed the English alliance in the French Assembly he referred with feeling to his reception at Queen Victoria’s coronation: “I fought the English,” he said, “down to Toulouse, when I fired the last shot in defence of national independence; in the meantime I have been in London, and France knows how I was received. The English themselves cried ‘Vive Soult!’ They cried ‘Soult for ever!’” One may formulate rules of diplomacy and international courtesy, but who shall weigh the effect of sympathy between a generous people and a former gallant foe?

Parliament had voted £243,000 for the expenses of George IV.’s coronation—perhaps the effect of a newly-extended franchise may be traced in the more economical figure of £70,000, which sufficed for that of our present Queen.

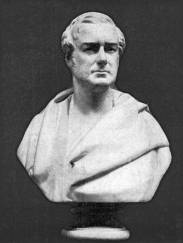

SIR ROBERT PEEL

(1788–1850).

Was appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland in 1812, Home Secretary in 1822, and again in 1828–30 under the Duke of Wellington. In 1830 he reconstructed the Metropolitan Police. He was Prime Minister in 1834–5, and again from 1841 to 1846. His second Administration was distinguished by the total abolition of the Duty on Corn.

The battle of Reform had been fought out in the country and in Parliament five years before the accession, and there were, as yet, no signs—to quote Sir Robert Peel’s famous expression at Tamworth—of the Constitution being “trampled under the hoof of a ruthless democracy.” On the whole, life—its business and pleasures—seemed to be going forward on much the same lines as before the great Act, dreaded, as it had been, as intensely by one party, as it had been pressed forward and welcomed by the other. Lord Melbourne was the head of a Whig Administration, of which, as everybody knows, the late King had waited impatiently for the first decent opportunity to get rid. But Melbourne and Lord John Russell (who, with the office of Home Secretary, was leader of the House of Commons) had to reckon with an advance wing of their own party, already known as Radicals, and were at least as profoundly averse from their projects as they were from the Tory policy. |State of Parties.| Melbourne and Russell desired to put down Radicalism and proceed with moderate and safe reforms, above all in Ireland, where the chronic discontent was being fanned to eruption by the exertions of Daniel O’Connell. The King’s death had relieved the Whig Cabinet from the adverse influence of the Court; moreover, the reliance placed from the first by the young Queen upon Lord Melbourne, and the intimate relations between them, brought about by the circumstances of the case, enabled the Whigs to assume the peculiar rôle of their opponents—that of the special supporters of the throne.

The Tories,B on the other hand, approached with much misgiving the General Election, which, according to the law as it then stood, followed of necessity on the demise of the monarch. They knew that the Duchess of Kent had favoured Whig principles in the education of the Queen; they saw that13 Melbourne’s personal charm had secured for him complete ascendancy in the councils of the new Sovereign, and they had nothing to expect in the country but reverse.

However, the unpopularity of the new Poor Law told against Ministers in the rural constituencies, and the elections left parties almost unchanged. |Result of General Election.| When the first Parliament of Queen Victoria assembled on November 20, 1837, the Whig Government reckoned a majority of about thirty in the House of Commons. “Of power,” wrote the contemporary compiler of the Annual Register, “in a political sense, they had none. They could carry no measure of any kind but by the sufferance of Sir Robert Peel.”

One incident in the short winter session of 1837, often as it has been recorded, retains a lasting interest because of the subsequent celebrity of the individual who gave rise to it. Mr. Benjamin Disraeli, the son of a distinguished man of letters, had just entered Parliament for the first time as Member for Maidstone. He chose a debate on Irish Election Petitions as the opportunity for his maiden speech. “A bottle-green frock coat,” writes an eye-witness, “and a waistcoat of white, of the Dick Swiveller pattern, the front of which exhibited a network of glittering chains; large, fancy pattern pantaloons, and a black tie, above which no shirt-collar was visible, completed the outward man. A countenance lividly pale, set out by a pair of intensely black eyes, and a broad but not very high forehead, overhung by clustering ringlets of coal-black hair, which, combed away from the right temple, fell in bunches of well-oiled ringlets over his left cheek.”

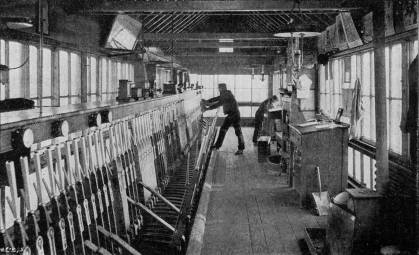

The Cabin here represented is that at Crow West Junction, Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway.

Not a prepossessing personality in the eyes of the British House of Commons, and when the young orator proceeded to launch into profuse and florid metaphor, accompanied by exaggerated theatrical gestures, the forbearance usually shown towards a new member’s first appearance was overborne by impatience at Disraeli’s ludicrous affectation. He spoke amid incessant interruption and laughter. “At last, losing his temper, which until now he had preserved in a wonderful manner, he paused in the midst of a sentence, and looking the Liberals indignantly in the face, raised his hands, and opening his mouth as widely as its dimensions would admit, said in a remarkably loud and almost terrific tone, ‘I have begun several times many things, and I have often succeeded at last; ay, sir, and though I sit down now, the time will come when you will hear me.’” The contrast between the early manner of this statesman, and his peculiarly quiet and leisurely bearing in the debates of later years, betrays the close study which he devoted to outward effect.

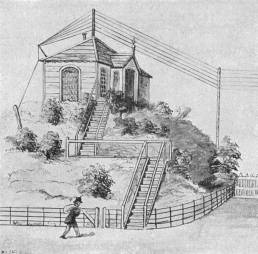

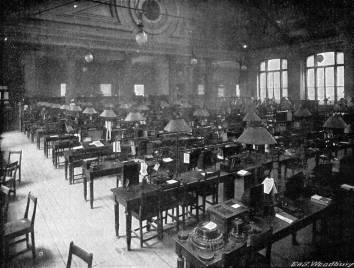

THE FIRST TELEGRAPH STATION (SLOUGH STATION, G.W.R., 1844).

14 The Prime Minister, William Lamb, second Viscount Melbourne, was a typical Whig, genuinely disposed to moderate reform, but in the habit of meeting Radical suggestions with the discouraging question, “Why not leave it alone?” Of similar political temperament was his lieutenant in the Commons, Lord John Russell. It very soon became evident that the Radicals, though diminished in numbers by the result of the elections, were likely to give Ministers trouble in the new Parliament. In the Upper Chamber, Lord Brougham, who had conceived a violent dislike to Melbourne, began to employ his fiery energy and power of acrid invective against the Government, and showed himself ready to place himself at the head of the Radicals. In his first serious attack on Ministers he allied himself with the Tory Lord Lyndhurst. The opportunity arose out of events in Canada, to which it is necessary briefly to refer.

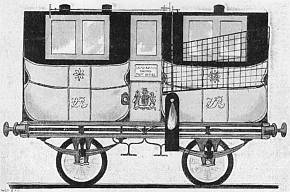

This Coach, used at Her Majesty’s Coronation, was designed by Sir William Chambers, and finished in the year 1761. The paintings, of which the following are the most important, were executed by Cipriani. The Front Panel:—Britannia seated on a throne holding a Staff of Liberty, attended by Religion, Justice, Wisdom, Valour, Fortitude, Commerce, Plenty, and Victory, presenting her with a Garland of Laurel; in the background a view of St. Paul’s and the River Thames. The Right Door:—Industry and Ingenuity giving a Cornucopia to the Genius of England, and on each side History recording the Reports of Fame, and Peace burning the Implements of War. The Back Panel:—Neptune and Amphitrite issuing from their palace in a triumphant car, drawn by sea-horses, attended by the Winds, Rivers, Tritons, and Naiads, bringing the tribute of the world to the British shore. Upper part of Back Panel:—The Royal Arms, ornamented with the Order of St. George; the Rose, Shamrock, and Thistle entwined. The Left Door:—Mars, Minerva, and Mercury supporting the Imperial Crown of Great Britain, and on each side the Liberal Arts and Sciences protected. The design of the Coach itself is in keeping with the above ideas. The length of the Carriage is 24 feet; width, 8 feet 3 inches; height, 12 feet; length of pole, 12 feet 4 inches; weight, 4 tons. The harness is made of red morocco leather. On State occasions eight cream-coloured horses, as here represented, are used.

On January 1, 1844, the following message was received from Slough by this instrument:—“A murder has just been committed at Salt Hill, and the suspected murderer was seen to take a first-class ticket for London by the train which left Slough at 7.42 p.m. He is in the garb of a Quaker, with a brown great coat on, which reaches nearly down to his feet. He is in the last compartment of the second first-class carriage.” The murderer, Tawell, was identified, apprehended, and convicted. This was the first occasion on which a telegraphic message overtaking a criminal led to his arrest.

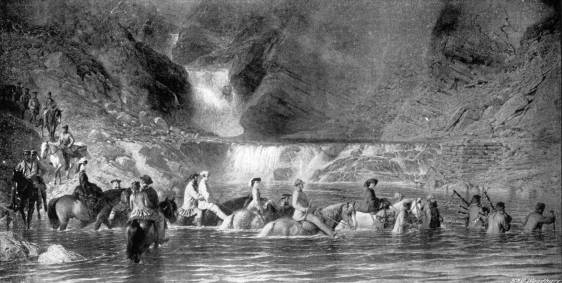

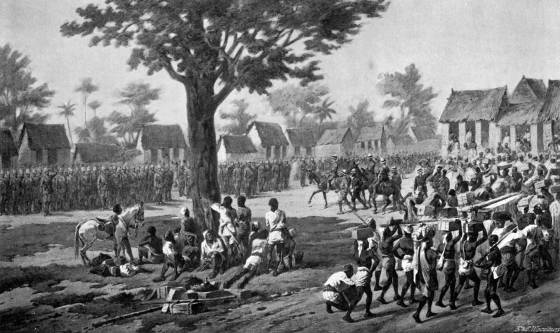

By the Constitution of 1791 Canada had been divided into two Provinces, Upper and Lower Canada, each with its separate Governor, Executive Council (corresponding to a Privy Council), Legislative Council, appointed by the Crown for life, and Representative Assembly. The bulk of the people of Lower Canada were of French descent, Catholics, and intensely conservative of the mode of life and habits of France before the Revolution. English law had been established there by proclamation in 1763, but by the wise Act of 1774 French civil law was restored, and free exercise of the Roman Catholic religion guaranteed. Probably all would have gone tranquilly with the Province had its French population been left to themselves. But they had restless neighbours in Upper Canada. Englishmen, and especially Scots and Ulstermen, had settled there in large numbers, busy, pushing15 men of business, traders, and farmers, developing their land with energy, overflowing, as their children multiplied, into the territory of their French fellow-subjects, and there forming a British party, impatient of the antique legal procedure, the foreign law of land tenure, and the sleepy, unbusiness-like ways of the Lower Province. Hence arose friction which soon became chronic. |Rebellion in Canada.| The Legislative Council, nominees of the Crown, naturally favoured the British section, thereby finding themselves at issue with the Representative Assembly. Discontent had been smouldering for many years, and at last matters came to a crisis. The Representative Assembly resolved to resist further encroachment. Headed by Louis Papineau, a militia officer and Member for Montreal, they drew up a protest and laid their grievances before the Governor, Lord Gosford. They complained of arbitrary infringement of the Constitution and other matters, demanded that the Legislative Council should be made elective, and ended by refusing to vote supplies. Public meetings were held, and addressed in inflammatory language by Papineau, who dwelt on the example set by the United States in resisting tyranny. Lord Gosford met matters with a high hand. Warrants were issued for the arrest of certain representatives; resistance to their execution resulted in violence, and the transition to rebellion was as speedy as probably it was involuntary. Proximus ardet—the flame spread to Upper Canada, of which the people had grievances of their own, though of a different kind from those of their French neighbours, and a rising took place under the leadership of one McKenzie, a revolutionary journalist. But the chief danger arose from the sympathetic action of certain American citizens, who, to the number of several hundreds, assembled under a person named Van Rensselaer, and took possession of Navy16 Island in the Niagara River, forming part of Canadian territory. At the present day, with the dense population of the United States and rapid means of transit, such a position of affairs would undoubtedly prove extremely critical; happily the British authorities proved able to deal with it successfully. The rebels being ill-prepared for impromptu war, Lord Gosford put down the rising in Lower Canada, though not without considerable bloodshed. In Upper Canada, the Governor, Major Head, better known afterwards as Sir Francis Head, an amusing writer, sent every regular soldier at his command to the assistance of Lord Gosford, and, declaring he would rely on the loyal Canadians to suppress the rebellion, handed over 6,000 stand of arms to the Mayor of Toronto. The people responded gallantly, delighted by this mark of confidence; ten or twelve thousand men assembled under arms, and a single encounter with McKenzie’s force was enough to decide the fate of the revolt. Desultory skirmishing took place with bodies of American “sympathisers” at various points along the frontier before the affair could be said to be over, and there can be no doubt that, had the United States Government adopted a less friendly attitude, British rule in Canada might have stood in very great jeopardy.

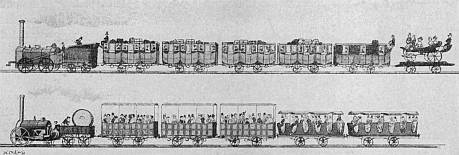

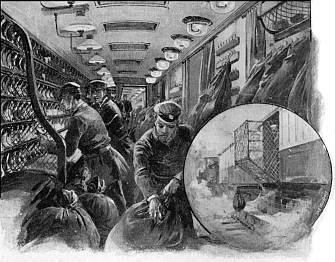

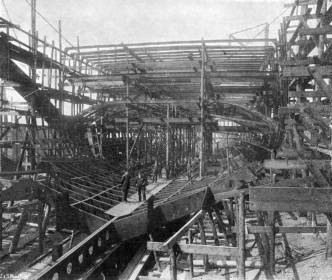

TRAINS ON THE LIVERPOOL AND MANCHESTER RAILWAY, RUNNING AT THE TIME OF HER MAJESTY’S ACCESSION.

The upper figure represents a first-class train, carrying Her Majesty’s Mails, and the lower one a second-class train with open carriages.

The Imperial Parliament was summoned to meet on January 16, 1838, to consider the Canadian situation. A Bill was introduced suspending the Constitution of Lower Canada, and empowering the Queen to appoint a Governor and Special Council, who should assume for the time all the functions of the legislature in that Province. The Duke of Wellington, as leader of the Opposition in the Lords, and Sir Robert Peel in the Commons, supported the Government, and the only opposition was offered by the Radicals. Brougham attacked the Bill in a speech of which Melbourne complained as “a most laboured and extreme concentration of bitterness.” In the other House the chief point of interest to readers of the debate at this day lies in a speech by Mr. W. E. Gladstone, the Tory Member for Newark, who taunted Mr. Joseph Hume and the Radicals with their failure to perform in session their boastful promises during the recess.

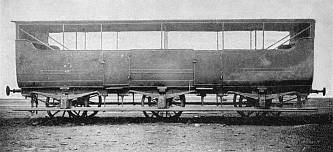

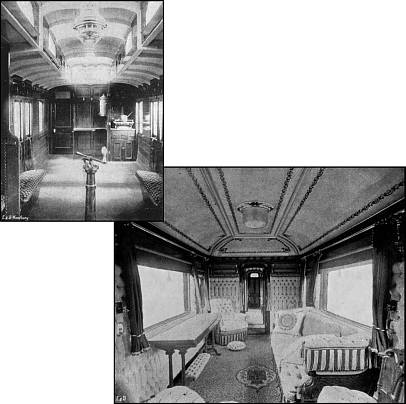

This is the carriage which has been used by Her Majesty for many years on her journeys to and from Scotland. It contains sitting and sleeping compartments (the former having padded walls and ceiling, lined with watered silk), and accommodation for Her Majesty’s personal attendants. It is about 60 feet long.

The Governor appointed under the Act was the Earl of Durham, a man of remarkable ability, who had embraced Radical principles with great ardour. This, however, did not prevent him interpreting his office as that of a practical dictator—he far exceeded the powers vested in him by the Act.|The Earl of Durham.| In dealing with offenders he would not stoop to the only way of obtaining convictions—that of packing juries—and adopted the arbitrary course of ordering into exile those connected with the late rebellion, on pain of death if they returned. Looking back to the existing state of things, it is impossible to question the real clemency and wisdom of the new Governor’s ordinances; nevertheless, they were at once attacked in the Imperial Parliament, and vigorously denounced as tyrannical and unconstitutional. Lord Durham had made many enemies in both17 Houses. Lord Lyndhurst and the Tories joined forces with Lord Brougham and the Radicals in pressing Ministers to disallow the ordinances of which they had already approved. Brougham perceived the opportunity of discomfiting the hated Melbourne, and he pressed it. The Ministry were not strong enough to resist. Lord Durham was recalled, and, though his recommendations were ultimately carried into effect by making Canada a self-governing colony, he never recovered the unmerited disgrace he had suffered. Proud, impetuous, and sensitive, he fell into ill-health, and died in 1840 at the age of forty-eight. His end must ever be regarded as one of those misfortunes arising out of Party government, for his policy has been amply vindicated since, lying as it does at the foundation of the whole modern scheme of Colonial government.

THE RIGHT HON. CHARLES PELHAM VILLIERS.

Born 1802. Is a grandson of the First Earl of Clarendon, and has represented Wolverhampton in Parliament continuously from 1835 to the present day. He took part, with Cobden and Bright, in the Free Trade movement, and in the passing of the Ballot Act. He and Mr. Gladstone are the only survivors of those who sat in Queen Victoria’s first Parliament.

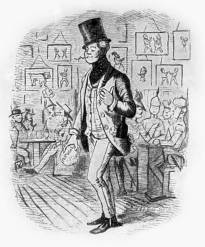

THE THREE SINGLES.

Lord Brougham in 1837 had opposed the Government measures relating to Canada. For some time he stood alone, and it was not until the Bill for Abolishing the Canadian Legislature had made considerable progress, that he found himself supported by the Earl of Mansfield and Lord Ellenborough. But though acting together on this occasion, each had his own separate motive and argument, and perhaps there were not three members of the House of Peers who better deserved to be acting singly and without party connection. Lord Brougham is here represented with the Earl of Mansfield on his right arm and Lord Ellenborough on his left.

One other debate in the Commons during this session must be referred to, if it be only to mark the wide interval which separates the Liberal Party of the present day from the Whig leaders at the beginning of the reign. On February 15 Mr. Grote brought forward his annual motion in favour of the Ballot in Parliamentary elections. |Debate on Vote by Ballot.| Hitherto little interest had been attached to the project, owing to the disfavour with which it was regarded by all but extreme Radicals. On this occasion, however, several Ministers and many supporters of the Government were known to have pledged themselves at the polls to the principle of secret voting. Lord John Russell had declared that to carry such a measure would be tantamount to a repeal of the Reform Act of 1832; that for the Government to promote it would be a breach of faith to those who had supported the extension of the franchise, and he refused to be any party to “what neither his sense of prudence nor of honour would justify.” Sir Robert Peel supported the Government in resisting the motion, and it was rejected by a majority of 117 in a House of 513 Members. This was hailed as a moral victory by the supporters of the Ballot. Brougham was jubilant, and told the Lords they must make up their minds to this fresh reform. A few days later he declared in Greville’s room that it would become law in five years from that time, and many people regarded it as paving the way to Republican government. On the other hand Greville quotes Charles Villiers, “one of the Radicals with whom I sometimes converse,” as declaring that it would prove a Conservative measure, and that better men would be chosen. In effect, it took, not five years, but thirty-four, to reconcile Englishmen to the practice of secret voting; and Mr. Villiers has lived to see that the protection thereby afforded to the voter has certainly not operated to the exclusion of Conservatives from office. But it would be unphilosophic to argue that what was conceded in 1872 to an experienced and educated electorate, without evil consequences, might have been bestowed with equal safety in 1838, only five years after the great measure of enfranchisement.

HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN 1839,

Attended by Viscount Melbourne, the Marquis of Conyngham, who raises his hat, the Hon. George S. Byng, the Earl of Uxbridge, and Sir George Quinton.

CHAPTER II.

1837–1842

Lord Melbourne’s services and character—Prevailing discontent of the Working Classes—Its Causes—The Chartists—Riots at Newport and elsewhere—Fall of the Ministry—Sir Robert Peel sent for—The “Bedchamber Question”—Melbourne recalled to Office—The Penny Post—Its remarkable Success—Betrothal of the Queen—Character of Prince Albert—Announcement to Parliament—Debates—Marriage of the Queen and Prince Albert—War declared with China—Capture of Chusan—Bombardment of the Bogue Forts—Peace concluded under the Walls of Nankin.

THE ardour and intelligence with which the Queen applied herself to master the details of ceremony and business incident to her position at the head of a great Empire, did not protect her from censorious and even malicious criticism. It was natural, perhaps, that the exclusive confidence reposed by Her Majesty in Lord Melbourne should excite the jealousy of others, whose exalted rank gave them what they considered a superior claim to access to the presence.

Lord Melbourne’s constant attendance at Court had compelled him to change his demeanour in a very remarkable degree. |Lord Melbourne’s services and character.| Hitherto, his affectation had been to conceal all traces of seriousness in transacting business; he would sprawl on a sofa, blow a feather about the room, balance a chair, or dandle a cushion while receiving deputations—the very incarnation of indolence—to the despair of those who anxiously desired to engage his attention, and who could scarcely be persuaded by those who knew him best that he had spent strenuous hours in getting up the subject under discussion, was perfectly acquainted with all its details, and was, besides, listening most attentively to all that was said. His physician, Dr. Copeland, knew how really hard the Prime Minister worked, and told Bishop Wilberforce that he (Melbourne) used to transact business all day in his bedroom with his secretaries in order that bores might be dismissed with the information that “my lord had not yet left his bedroom.”

But besides this tiresome frivolity of manner, there was another habit in regard to which Melbourne had to put severe restraint on himself in the Royal presence. It had been his custom to season his conversation with a multitude of indecorous oaths. Mr. Denison (afterwards Speaker, and subsequently Viscount Ossington) spoke to him one day about some points in the Poor Law Bill, then under consideration. Melbourne was just going out for a ride, and referred Denison to his brother George. “I have been with him,” replied Denison, “but he damned me, and damned the Bill, and damned the paupers.” “Well, damn it! what more could he do?” quoth Melbourne, and rode off.

In spite of all his affectation and a degree of underlying weakness, this Minister performed a singularly valuable public service to his country in the support and advice he afforded the Queen at the most critical time of her life; a service that was explicitly and handsomely acknowledged in the House of Lords by his chief opponent there, the Duke of Wellington, in 1841.

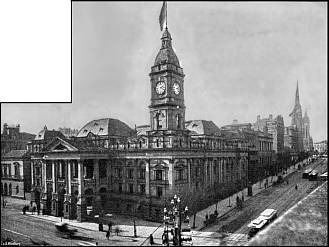

Corporation of Glasgow.

HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN 1839.

There was a great deal of brooding discontent in the country at the opening of Queen Victoria’s reign, which soon passed into a phase calling for active measures of repression. Some have recognised in the Chartist movement the chagrin of the working classes, who having imparted to the mills of State the impetus necessary to grind out political rights for their employers—the merchants, farmers, and middle class generally—found themselves no better equipped for political action than they were before. |Prevailing discontent of the Working Classes.| But such a suggestion finds no reflection in actual experience of popular movements. Agitators might declaim in vain against the injustice of a restricted franchise if their hearers had no other cause for discontent. The real root of bitterness lay in the suffering and distress caused by the severe winter of 1837–8, the high price of bread,C and, on the top of all, detestation of the new Poor Law. |Its causes.| It is genuine grievances such as these which, from time to time, force on the attention of those who suffer from them the glaring contrast between the privations of the many and the superfluities of the few. So, in 1838, hungry crowds were easily persuaded to listen to denunciations of the privileged classes; to believe that the Queen and a dilettante Prime Minister were insensible to their sufferings so long as their own tables were abundantly supplied;20 and that Government was no more than a machine for enriching the classes at the expense of the masses.

Sketches, 1837.

DANIEL O’CONNELL, M.P.,

1775–1847.

Known as “The Liberator.” Was an Irish barrister. Elected to the House of Commons in 1828, he was the principal advocate of Catholic Emancipation, and founder of the “Loyal National Repeal Association.” The sketch represents him on the watch for an opportunity to attack the Government with the weapon of “Repeal.”

It has to be remembered, also, that during the development of crowded centres of population, consequent on the rapid increase in various industries, the artizan and mining classes found themselves at a great disadvantage in negotiating with their employers, owing to the stringent laws regulating trades unions. A whole generation was to pass away before, in 1875, Mr. (now Viscount) Cross should pass a measure abolishing criminal proceedings in cases of breach of engagement, placing employer and workman on equal terms before the law, and enacting that nothing which it was legal for a single workman to do should be illegal when done by a combination of workmen or a trades union.

The Whig leaders having declined to re-open the question of electoral reform, a document was drawn up at a conference between a few Radical members of Parliament and the representatives of the Working Men’s Association, formulating the demands made on behalf of the proletariate. Universal male suffrage, annual Parliaments, vote by ballot, abolition of the property qualification required at that time from a member of Parliament, payment of members, and equal electoral districts, were the six points insisted on; of which three, it will be seen, have since been practically carried into effect. |The Chartists.| “There is your Charter!” exclaimed O’Connell, handing it to the secretary of the Working Men’s Association; “agitate for it, and never be content with anything less.” The term took the popular fancy; the programme became known as the Charter, and those who supported it were hereafter known as Chartists.

Not a very formidable programme after all, nor one that might not be advanced by constitutional means, but one that, like many other popular agitations, fell into dangerous paths by the imprudent zeal of some of its advocates, and still more, by the violence of the discontented, unfortunate, or predatory waifs of civilisation, ever ready to promote any social change for the sake of what plunder it may bring within their reach.

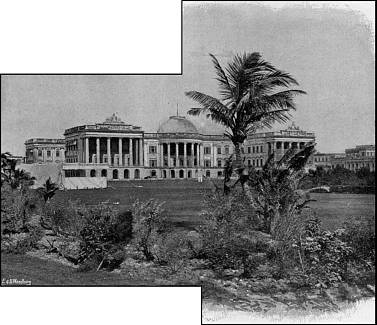

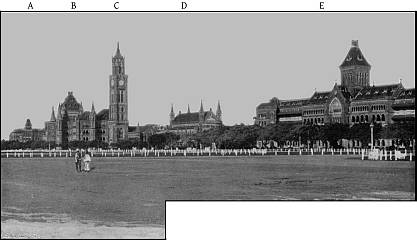

The Peninsula of Aden was added to Her Majesty’s dominions by conquest in 1839. Its situation at the mouth of the Red Sea, on the direct route to India and the East, makes it invaluable as a coaling-station both for naval and mercantile purposes. In this district rain falls only about once in three years. The town is supplied with wells and storage tanks cut in the solid rock, the construction of which cost over £1,000,000.

In November 1839 the miners of the Newport district of Monmouthshire assembled to the number of 10,000 under a tradesman called Frost and attempted to release from gaol one Vincent, who had been imprisoned for using seditious language. |Riots at Newport and elsewhere.| The mayor and magistrates of Newport, with a handful of soldiers, offered a gallant resistance; the rioters were dispersed with a loss of ten killed and fifty wounded, the mayor, Mr. Phillips, receiving two gunshot wounds. Frost and two others were afterwards convicted of high treason and sentenced to death. But the dawn of milder methods of government had begun: the death sentence was commuted by the Royal mercy to one of transportation for life: even that was subsequently relaxed, and Frost was allowed to return to England some years later to find himself and the Chartists an unquiet memory of the past.

But in spite of the punishment of the Newport rioters, and hundreds of others in different places,21 Chartism continued to spread until it became merged in the more intelligent and fruitful agitation for the repeal of the Corn Laws.

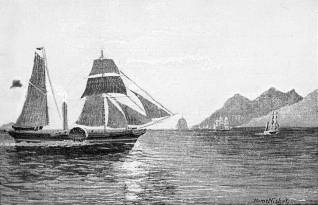

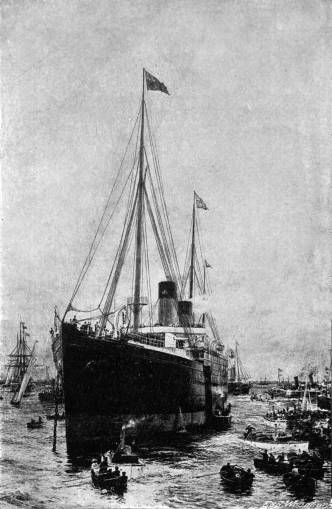

“WILLIAM FAWCETT,” THE FIRST P. & O. STEAMSHIP, IN THE GUT OF GIBRALTAR, 1837.

This was the first steamer employed in carrying mails to the Peninsular ports in 1837. Tonnage, 206; horse-power, 60.

This great question was brought under the consideration of Parliament, in the session of 1839, by Lord Brougham in the Lords on February 18, and the following day by Mr. Charles Villiers in the Commons; but the motion for inquiry was negatived without a division in the former and by a majority of 189 in the latter. Both Parliament and country, however, were to hear plenty about the Corn Duties in the next few years.

The Whig Ministry were now approaching the end of their second year of office, and steadily losing favour in the country. They had earned the enmity of the Chartists by their apathy to further reform; and the novel advantage of Royal confidence in and affection for a Whig Prime Minister did not affect the general drift of middle-class opinion. Meanwhile, Peel was indefatigable on the platform securing popular support for the new Conservatism.