The Project Gutenberg EBook of Fables and Fabulists: Ancient and Modern, by Thomas Newbigging This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Fables and Fabulists: Ancient and Modern Author: Thomas Newbigging Release Date: May 21, 2013 [EBook #42761] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FABLES, FABULISTS: ANCIENT, MODERN *** Produced by David Edwards, Stephen Blundell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

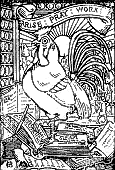

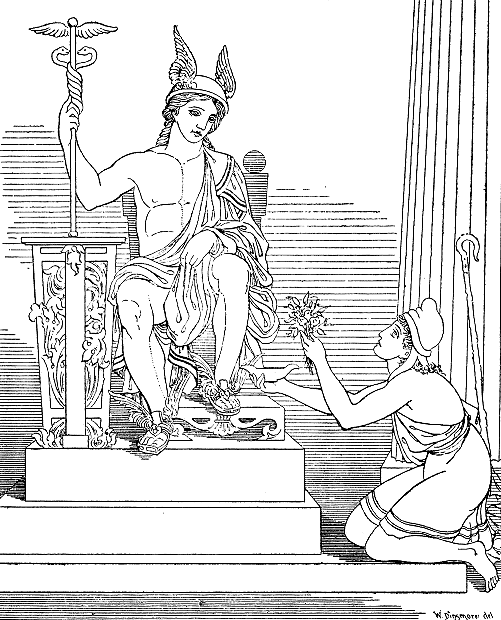

MERCURY BESTOWING ON THE YOUTHFUL ÆSOP THE INVENTION OF THE APOLOGUE. (See page 43.)

MERCURY BESTOWING ON THE YOUTHFUL ÆSOP THE INVENTION OF THE APOLOGUE. (See page 43.)CHEAP EDITION.

LONDON:

ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

1896.

[All rights reserved.]

Shakespeare: Coriolanus.

Andrew Lang.

'The fables which appeal to our higher moral sympathies may sometimes do as much for us as the truths of science.'

Mrs. Jameson.

'The years of infancy constitute, in the memory of each of us, the fabulous season of existence; just as in the memory of nations, the fabulous period was the period of their infancy.'—Giacomo Leopardi.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | DEFINITION OF FABLE | 1 |

| II. | CHARACTERISTICS OF FABLES | 7 |

| III. | THE MORAL AND APPLICATION OF FABLES | 13 |

| IV. | FABULISTS AS CENSORS | 19 |

| V. | LESSONS TAUGHT BY FABLES | 25 |

| VI. | ÆSOP | 33 |

| VII. | STORIES RELATED OF ÆSOP | 42 |

| VIII. | THE ÆSOPIAN FABLES | 52 |

| IX. | PHÆDRUS AND BABRIUS | 63 |

| X. | THE FABLE IN HISTORY AND MYTH | 68 |

| XI. | HINDOO, ARABIAN, AND PERSIAN FABLES.—PILPAY, LOCMAN.—'THE GESTA ROMANORUM' | 80 |

| XII. | MODERN FABULISTS: LA FONTAINE, GAY | 96 |

| XIII. | MODERN FABULISTS: DODSLEY, NORTHCOTE | 108 |

| XIV. | MODERN FABULISTS: LESSING, YRIARTE, KRILOF | 115 |

| XV. | OTHER AND OCCASIONAL FABULISTS | 125 |

| XVI. | CONCLUSION | 143 |

| INDEX | 147 | |

Tennyson: The Flower.

Byron: The Astrologer.

The term 'fable' is used in two senses, with two distinctive meanings.

First, as fabulæ, it is employed to denote the myths or fictions which, by the aid of imagination and superstition, have clouded, or have become blended with, the history of the remote past. Such are the stories related of Scandinavian and Grecian heroes and gods; beings, some of whom doubtless had an actual human existence, and were wise and valiant and powerful, or the reverse,[2] in their day, but around whose names and persons have clustered all the marvellous legends that are to be found in mythological lore. The better name for these is 'romance.'

Secondly, as fabellæ, it is used to signify a special branch of literature, in which the imagination has full play, altogether unassisted by superstition in any shape or form. The fabulist confers the powers or gifts of reason and speech on the humbler subjects over whom he exercises sway, and so has ample scope for his imaginative faculty; but there is no attempt on his part at any serious make-believe in his inventions. On the contrary, there is a tacit understanding between him and his hearers and readers, that what he narrates is only true in the sense of its application to corresponding circumstances in human life and conduct.

It is with fable as understood in this latter sense that we propose to deal.

The Fable or Apologue has been variously defined by different writers. Mr. Walter Pater, paraphrasing Plato's definition, says that 'fables are medicinable lies or fictions, with a provisional or economized truth in them, set forth under such terms as simple souls can best receive.'[1] The sophist Aphthonius, taking the same view, defines[3] the fable as 'a false discourse resembling truth.'[2] The harshness of both these definitions is scarcely relieved by their quaintness. To assert that the fable is a lie or a falsehood does not fairly represent the fact. A lie is spoken with intent to deceive. A fable, in its relation, can bear no such construction, however exaggerated in its terms or fictitious in its characters. The meanest comprehension is capable of grasping the humour of the situation it creates. Even the moral that lurks in the narration is often clear to minds the most obtuse. This is at least true of the best fables.

Dr. Johnson, in his 'Life of Gay,' remarks that 'A fable or epilogue seems to be, in its genuine state, a narrative in which beings irrational, and sometimes inanimate—quod arbores loquantur, non tantum feræ[3]—are, for the purpose of moral instruction, feigned to act and speak with human interests and passions.'

Dodsley says that ''tis the very essence of a fable to convey some moral or useful truth beneath the shadow of an allegory.'[4] Boothby defines the[4] fable as 'a maxim for the use of common life, exemplified in a short action, in which the inhabitants of the visible world are made the moral agents.' G. Moir Bussey states that 'the object of the author is to convey some moral truth to the reader or auditor, without usurping the province of the professed lecturer or pedant. The lesson must therefore be conveyed in an agreeable form, and so that the moralist himself may be as little prominent as possible.'[5] Mr. Joseph Jacobs says that 'the beast fable may be defined as a short humorous allegorical tale, in which animals act in such a way as to illustrate a simple moral truth or inculcate a wise maxim.'[6]

These various definitions or descriptions apply more especially to the Æsopian fable (and it is with this that we are dealing at present), which is par excellence the model of this class of composition. Steele declares that 'the virtue which we gather from a fable or an allegory is like the health we get by hunting, as we are engaged in an agreeable pursuit that draws us on with pleasure, and makes us insensible of the fatigues that accompany it.'[7] This is applied to the longer fable or epic, such as the 'Iliad' and 'Odyssey' of Homer, or the[5] 'Faerie Queen' of Spenser, rather than to the fable as the term is generally understood, otherwise the simile is somewhat inflated.

One more definition may be attempted:

The Æsopian fable or apologue is a short story, either fictitious or true, generally fictitious, calculated to convey instruction, advice or reproof, in an interesting form, impressing its lesson on the mind more deeply than a mere didactic piece of counsel or admonition is capable of doing. We say a short story, because if the narration is spun out to a considerable length it ceases to be a true fable in the ordinary acceptation of the term, and becomes a tale, such, for example, as a fairy tale. Now, a fairy or other fanciful tale usually or invariably contains some romance and much improbability; it often deals largely in the superstitious, and it is not necessarily the vehicle for conveying a moral. The very opposite holds good of a fable. Although animals are usually the actors in the fable, there is an air of naturalness in their assumed speech and actions. The story may be either highly imaginative or baldly matter-of-fact, but it never wanders beyond the range of intuitive (as opposed to actual or natural) experience, and it always contains a moral. In a word, a fable is, or ought to be, the very quintessence of common sense and wise counsel couched in brief narrative form. It partakes somewhat of the[6] character of a parable, though it can hardly be described as a parable, because this is more sedate in character, has human beings as its actors, and is usually based on an actual occurrence.

Though parables are not fables in the strict and limited meaning of the term, they bear a close family relationship to them. Parables may be defined as stories in allegorical dress. The Scriptures, both old and new, abound with them. The most beautiful example in the Old Testament is that of Nathan and the ewe lamb,[8] in which David the King is made his own accuser. This was a favourite mode of conveying instruction and reproof employed by our Lord. Christ often 'spake in parables'; and with what feelings of reverential awe must we regard the parables of the Gospels, coming as they did from the lips of our Saviour!

[1] 'Plato and Platonism,' by Walter Pater. London: Macmillan and Co., 1893, p. 225.

[2] Aphthonius flourished at Antioch, at what time is uncertain. Forty of his Æsopian fables, with a Latin version by Kimedoncius, were printed from a MS. in the Palatine Library at the beginning of the seventeenth century. 'The Æsopian Fable,' by Sir Brooke Boothby, Bart. Edinburgh: Constable and Co., 1809. Preface, p. xxxi.

[3] 'Even trees speak, not only wild beasts.'—Phædrus, Book i., Prologue.

[4] 'Essay on Fable.'

[5] 'Fables Original and Selected,' by G. Moir Bussey. London: Willoughby and Co., 1842.

[6] 'The Fables of Æsop,' as first printed by William Caxton in 1484. London: David Nutt, 1889, vol. i., p. 204.

[7] 'The Tatler,' No. 147, vol. iii., p. 205.

[8] 2 Samuel xii. 1-7.

Shakespeare: Hamlet.

There is an archness about the best fables that creates interest and awakens curiosity; and it is the quality of such that, whilst simple enough as stories to be understood and enjoyed by the young, they are at the same time calculated to interest, amuse, instruct and admonish those more advanced in years.

A fable should carry its moral without the telling; nevertheless the application is often worth supplying, because it puts, or should put, the lesson taught by the fable in a terse and impressive form. Above and beyond all, a fable should possess the quality of simplicity, and whilst easy to be understood, it should have force and appropriateness.

Fables treat of the follies and weaknesses, and also of the nobler qualities, of humankind, generally[8] through the medium of the lower animals and the members of the vegetable and natural kingdom. These are made to represent the characters we find in human life. Curious, that although it is chiefly the lower animals and inanimate things that are made the vehicle of the instruction or reproof contained in the story, we do not feel that there is any incongruity in these having the power of speech. We willingly accept the circumstance of their faculty of speech and reasoning as Gospel truth for the time being. It is natural that they in the fable should speak as the heroes or actors, and we listen to their words, whether wise or foolish, with deference or contempt as the case may be.

It is a question in casuistry how far justice and injustice are done to the inferior animals and the members of the vegetable kingdom by this liberty that is taken with them in the fable. If they had the knowledge of the fact, and the power of remonstrance, it may be conceived that some of them, at least, would repudiate the characters and propensities which we in our superior conceit so glibly ascribe to them in the fable. And, indeed, there is doubtless a good deal of unfairness in our habit of stigmatizing this one with cunning, that one with cowardice, and the other with cruelty, or stupidity, or dishonesty, as suits our purpose. Possibly if some[9] of the humbler creatures thus branded were gifted with the power of writing fables for the benefit of their fellow creatures and associates, they might be able to point to characteristics in the higher order of beings which it is desirable to hold in reprobation, and this, too, with as much or more reason and justice on their side than we have on ours. But, in truth, the fabulists themselves tacitly admit the force of this argument, inasmuch as the failings and defects and general qualities which they ascribe to the characters in the fable are, of course, those of the human species. A fable of Æsop, The Man and the Lion,[9] is very much to the point here:

'Once upon a time a man and a lion were journeying together, and came at length to high words which was the braver and stronger of the two. As the dispute waxed warmer they happened to pass by, on the road-side, a statue of a man strangling a lion. "See there," said the man; "what more undeniable proof can you have of our superiority than that?" "That," said the lion, "is your version of the story; let us be the sculptors, and for one lion under the feet of a man, you shall have twenty men under the paw of a lion!" Men are but sorry witnesses in their own cause.'

A fable is generally a fiction, as has already been said. It is a singular paradox, however, that nothing is truer than a good fable. True to intuition, true to nature, true to fact. The great virtue of fables consists in this quality of truthfulness, and their enduring life and popularity are corroboration of it. If not true in the sense of being reasonable, they are nothing, or foolish, and therefore intolerable. We instinctively feel their truth, and are encouraged, or amused, or conscience-smitten by the narration, for they deal with principles which lie at the very root of our human nature.

It is a remarkable feature of this species of composition that a departure from the natural order of things loses its incongruity in the fable; and although this view has been controverted, the argument against it fails to carry conviction in face of the excellent examples that can be adduced. By way of illustration, take the fable of the man and his goose that laid the golden eggs. We don't remember ever meeting with a goose of this particular breed out of the fable. There are numberless geese in the world—human and other. But the goose that lays a golden egg every morning is a rara avis. Nevertheless, she has a veritable existence in the fable, and we would as soon think of casting a doubt on our own identity as on that of the fabled bird. The[11] story has always been, and will continue to be, Gospel truth to us, and we never recall it without commiserating the untimely end of the poor obliging goose, and thinking, at the same time, what a goose its owner must have been to kill it and cut it up, in expectation of finding in its inside the inexhaustible treasure his impatient greed had pictured as existing there. Semper avarus eget. Had we been the fortunate owner of such an uncommon fowl, one golden egg each day would have contented us!

Certain early authors, with the formalism which characterizes their writings, have attempted an arrangement of fables under three distinct heads or classes, designating them, respectively, Rational, Emblematical, and Mixed. The Rational fable is held to be that in which the actors are either human beings or the gods of mythology; or, if beasts, birds, trees, and inanimate objects are introduced, the former only are the speakers. The Emblematical fable has animals, members of the vegetable kingdom, and even inanimate things for its heroes, and these are accordingly gifted with the power of speech. The Mixed fable, as the name implies, is that in which an association of the two former kinds is to be found. The distinction, though perfectly accurate, serves no useful purpose and need not be observed. As a matter of fact, all fables are[12] rational or reasonable from the fabulist's stand-point; and all are emblematical or typical of moods, conditions, and possible or actual occurrences in daily life, whoever and whatever be the actors and speakers introduced.

[9] Quoted from James's 'Fables of Æsop.' Murray, 1848.

Ben Jonson: Love Freed.

Thus La Fontaine:[10] 'The fable proper is composed of two parts, of which one may be termed the body and the other the soul. The body is the subject-matter of the fable and the soul is the moral.'

On the origin of the added morals to fables, Mr. Joseph Jacobs[11] has the following appropriate remarks: 'The fable is a species of the allegory, and it seems absurd to give your allegory, and then give in addition the truth which you wish to convey. Either your fable makes its point or it does not. If it does, you need not repeat your point: if it does not, you need not give your fable. To add your point is practically to confess the fear that your fable has not put it with sufficient[14] force. Yet this is practically what the moral does, which has now become part and parcel of a fable. It was not always so; it does not occur in the ancient classical fables. That it is not an organic part of the fable is shown by the curious fact that so many morals miss the point of the fables. How then did this artificial product come to be regarded as an essential part of the fable? Now, we have seen in the Jātakas what an important rôle is played by the gāthas or moral verses which sum up the whole teaching of the Jātakas. In most cases I have been able to give the pith of the Birth-stories by merely giving the gāthas, which are besides the only relics which are now left to us of the original form of the Jātakas. Is it too bold to suggest that any set of fables taken from the Jātakas or their source would adopt the gātha feature, and that the moral would naturally arise in this way? We find the moral fully developed in Babrius and Avian, whom we have seen strong reason for connecting with Kybises' Libyan fables. We may conclude the series of conjectures by suggesting that the morals of fables are an imitation of the gāthas of Jātakas as they passed into the Libyan collection of Kybises.'

Montaigne remarks that 'most of the fables of Æsop have diverse senses and meanings, of which the mythologists chose some one that quadrates[15] well to the fable; but for the most part 'tis but the first face that presents itself and is superficial only; there yet remain others more vivid, essential and profound into which they have not been able to penetrate.'[12]

If this be so, it is an argument against the common practice of limiting their significance to the one moral that is often given as an appendage to the fable. It is worthy of note that Æsop did not supply, either orally or in writing, the separate moral to any of his fables. They were left to speak for themselves and produce their unaided effect. The moral or application appended to or introducing a fable (for both practices are followed), is an innovation, as appears from what has already been advanced, probably intended to make clear what was obscure in the apologue.

The true moral is contained in the fable itself. The application may, and often does, vary with the idiosyncrasies of the commentator. Besides the moral and application there is in some collections of fables what is designated 'The Remark,' and 'The Reflection,' in which the commentator tries, as it were, to drive home the application of the story with an additional blow. Our own experience as a youth was that all these appendages to the fable were invariably skipped.

From all which it would appear that the moral and the so-called application of a fable are not one and the same thing. In point of fact, the latter may and does vary according to the peculiar views of the commentator. An exemplification of this may be found in the applications of Sir Roger L'Estrange and Dr. Samuel Croxall, the latter taking it upon him to stigmatize in strong language the twist which he asserted the former gave to the morals of the fables in his collection. L'Estrange, who was a Catholic, concerned himself in helping the restoration of Charles II., and was a devoted adherent of his successor, James, from whom he received place and emoluments. In publishing his version of Æsop, his object, as he affirms in his preface, was to influence the minds of the rising generation, 'who being as it were mere blank paper, are ready indifferently for any opinion, good or bad, taking all upon credit.' Whereupon Croxall observes: 'What poor devils would L'Estrange make of the children who should be so unfortunate as to read his book and imbibe his pernicious principles—principles coined and suited to promote the growth and serve the ends of Popery and arbitrary power,' and more to the same purpose.

The question as to whether the moral or application, if any is supplied, should be placed at the beginning or end of a fable has sometimes been[17] discussed. On this head Dodsley has some pertinent remarks that may be quoted. He says: 'It has been matter of dispute whether the moral is better introduced at the end or beginning of a fable. Æsop universally rejected any separate moral. Those we now find at the close of his fables were placed there by other hands. Among the ancients Phædrus, and Gay among the moderns, inserted theirs at the beginning; La Motte prefers them at the conclusion, and La Fontaine disposes them indifferently at the beginning or end, as he sees convenient. If,' he adds, 'amidst the authority of such great names I might venture to mention my own opinion, I should rather prefer them as an introduction than add them as an appendage. For I would neither pay my reader nor myself so bad a compliment as to suppose, after he had read the fable, that he was not able to discover its meaning. Besides, when the moral of a fable is not very prominent and striking, a leading thought at the beginning puts the reader in a proper track. He knows the game which he pursues; and, like a beagle on a warm scent, he follows the sport with alacrity in proportion to his intelligence. On the other hand, if he have no previous intimation of the design, he is puzzled throughout the fable, and cannot determine upon its merit without the trouble of a fresh perusal. A ray of light imparted at first may[18] show him the tendency and propriety of every expression as he goes along; but while he travels in the dark, no wonder if he stumble or mistake his way.' If it be considered necessary or desirable to give the moral separately, or to apply the fable, Dodsley's argument here seems to us to be incontrovertible.

[10] Preface, 'Fables,' 1668.

[11] 'History of the Æsopic Fable,' p. 148.

[12] Essay: 'Of Books.'

Shakespeare: King Henry IV.

Fabulists as censors have always been not only tolerated, but patronized and encouraged, even in the most despotic countries, and when they have exposed wickedness and folly in high places with an unsparing hand. Æsop among the ancients, and Krilof amongst the moderns, are both striking examples of this. The fables of antiquity may indeed be truly said to have been a natural product of the times in which they were invented. In the early days, when free speech was a perilous exercise, and when to declaim against vice and folly was to court personal risk, the fable was invented, or resorted to, by the moralist as a circuitous method of achieving the end he desired to reach—the lesson he wished to enforce. The entertainment afforded by the fable or apologue took off the[20] keen edge of the reproof; and, whilst the censure conveyed was not less pointed and severe, the device of making the humbler creatures the scapegoat of human weakness or vice mollified its bitterness. The very indirectness of the fable had the effect of making the sinner his own accuser. Whom the cap fitted was at liberty to don it.

Phædrus, in the prologue to his third book, thus gives his view of the origin and purpose of fables:

The fable saves the self-love of the person to whom it is applicable. It enables him to stand aside, as it were, and become a spectator of the effect produced by his own conduct. In this way he is impressed and humbled without being affronted. When one, even though guilty, is openly and directly reproved for a misdeed, the stigma often raises a rebellious spirit, which either suggests a hundred justifiable reasons for his[21] action or begets a defiant mood, driving him to persist in his evil courses.

Listening to the fable, 'we see nothing of the satirist, who probes only to heal us, and who does not exhibit any of the personal spleen and ill-humour which meet and put us out of countenance with ourselves and each other in the invectives of those who sometimes set up for moralists without the essential qualification of good nature. The fable gives an agreeable hint of the duties and relations of life, not a harangue on our want of sense or decorum. We feel none of the superiority of the fabulist, who, indeed, generally leaves us to make the application of his instructive story in our own way; and if we do sometimes prefer to apply it to our neighbour's case instead of our own, we are still improved and amended, inasmuch as we have learned to despise some vice or folly which our unassisted judgment might have regarded more leniently.'[14] Dodsley, again, puts the matter finely when he says:[15] 'The reason why fable has been so much esteemed in all ages and in all countries, is perhaps owing to the polite manner in which its maxims are conveyed. The very article of giving instruction supposes at least a superiority of wisdom in the adviser—a circumstance by no means favourable to the ready[22] admission of advice. 'Tis the peculiar excellence of fable to waive this air of superiority; it leaves the reader to collect the moral, who, by thus discovering more than is shown him, finds his principle of self-love gratified, instead of being disgusted. The attention is either taken off from the adviser, or, if otherwise, we are at least flattered by his humility and address. Besides, instruction, as conveyed by fable, does not only lay aside its lofty mien and supercilious aspect, but appears dressed in all the smiles and graces which can strike the imagination or engage the passions. It pleases in order to convince, and it imprints its moral so much the deeper in proportion that it entertains; so that we may be said to feel our duties at the very instant we comprehend them.'

The humour of a good fable is a fine lubricant to the temper. Sarcasm, irony, even direct criticism, are in place in the fable, but humour is its saving grace. Without this it cannot be classed in the first order. Wanting in this quality, the fables of some writers who have attempted them are flat, stale and unprofitable. Humour in the fable is the gilding of the pill. It is like the effervescing quality in champagne, the subtle flavour in old port.

It may be questioned whether a fable has ever the full immediate effect intended. Men are loath[23] to apply the moral to their own case, though they have no difficulty in applying it to the case of others—even to their best acquaintances and friends. For example, take the present company, the present company of my readers—it is usual, by the way, to except 'the present company,' but we will be rash enough, even at the risk of castigation, to break the rule—take, then, the present company in illustration of our point. Who among us would admit for a moment that we are the counterpart or human representative of the fox with its low cunning, the loquacious jackdaw, the silly goose, the ungrateful viper, the crow to be cajoled by flattery, not to mention the egregious donkey? 'Satire,' says an acute writer,[16] 'is a sort of glass wherein beholders do generally discover everybody's face but their own.' Or, to parody a line of Young, 'All men think all men peccable but themselves.' To be sure, we might be willing, modestly perhaps, to admit that we who are singers can emulate the nightingale; that we even possess some of the—call it shrewdness, of the fox; the faithful character of the honest dog; vie in dignity of manners and bearing with the stately lion. But all that is a matter of course; the noble traits we possess are so self-evident that none excepting the incorrigibly blind or prejudiced will be found to dispute them! So that[24] the admonishing fable contains no lesson for any of us, but should be seriously taken to heart, with a view to their reformation, by certain persons whom we all know. That view of the question, however, need not be further pursued.

[13] Boothby's translation.

[14] G. Moir Bussey: Introduction to 'Fables.'

[15] 'Essay on Fable.'

[16] Swift: Preface to 'The Battle of the Books.'

Cowper: Pairing Time Anticipated.

In the earlier ages of the world's history fables were invented for the edification of men and women. This was so in the palmiest days of Greek, Roman and Arabian or Saracenic civilization. In these later days fables are generally assumed to be more for the delectation of children than adults. This change of auditory need not be regretted; it has its marked advantages. The lesson which the fable inculcates is indelibly stamped on the mind of the child, and has an influence, less or more, on his or her career during life.

Jean Jacques Rousseau is the only writer of eminence who has inveighed against this use of the fable, but his remarks are by no means convincing. He accounted them lies without the[26] 'medicinable quality,' and reprobated their employment in the instruction of youth. 'Fables,' says Rousseau, 'may amuse men, but the truth must be told to children.' His animadversion had special reference to the fables of La Fontaine, and doubtless some of these, and the morals deduced from them, are open to objection; but to condemn fables in general on this account is surely the height of unreason.

A greater than Rousseau had, long before, given expression in cogent language to the worth of the fable as a vehicle of instruction for youth. Plato, whilst excluding the mythical stories of Hesiod and Homer from the curriculum of his 'Republic'—that perfect commonwealth, in depicting which he lavished all the resources of his wisdom and genius—advised mothers and nurses to repeat selected fables to their children, so as to mould and give direction to their young and tender minds.

Phædrus, again, in the prologue to his fables, says—

so that his view of the question also was just the very antipodes of that of the French philosopher.

Quintilian urges[17] that 'boys should learn to[27] relate orally the fables of Æsop, which follow next after the nurse's stories.' True, he recommends this with a view to initiating them in the rudiments of the art of speaking; but he would not have inculcated the use of fables for children for even this secondary purpose, if he had dreamt for a moment they would have had a bad effect on their minds.

Rousseau, with all his knowledge of human character and his power of imagination, had a matter-of-fact vein running through his mind, which led him to entertain the mistaken view that the influence of fables on the juvenile mind was objectionable. Cowper, who was no mean writer of fables himself, with his clear common sense, broad natural instincts, and mother wit—in which Rousseau was lacking—saw the unwisdom of the philosopher's conclusions, and satirized his views in the well-known lines:

It is no exaggeration to assert that the effect which fables and their lessons have had on the[28] people is incalculable. They have been read and rehearsed and pondered in all ages, and by thousands whom no other class of literature could attract. The story and its moral (in the Æsopian fable at least) are obvious to the dullest comprehension, and they cling to the memory like the limpet to the rock, and find their application in all the concerns of daily life.

But it is not the illiterate alone that have profited by the fable; all classes have been affected by its lesson. We are all apt scholars when the fable is the schoolmaster. There is no class of the community that has not come under its sway. It has penetrated to the highest stratum of society equally with the humblest, and may be credited with an influence as wide and far-reaching as the sublimest moral treatise which the human intellect has produced.

The epic and the novel (fables of a kind), like some paintings, cover a wide canvas, and the details are not always easily grasped and remembered; but the true fable is a story in miniature which we take in at a glance, and stow away for after use in a small corner of our memory.

We have the 'successful villain' in the fable as sometimes on the stage; and it may be a question whether the tendency of this is not rather to encourage dissimulation in certain ill-constituted minds, than to inculcate virtue. One of Northcote's[29] fables, The Elephant and the Fox, will exemplify what we mean.

'A grave and judicious elephant entering into argument with a pert fox, who insisted upon his superior powers of persuasion, which the elephant would not allow, it was at length agreed between them that whichever attracted the most attention from his auditors by his eloquence should be deemed the victor. At a certain appointed time a great assembly of animals attended the trial, and the elephant was allowed to speak first. He with eloquence spoke of the high importance of ever adhering with strictness to justice and to truth; also of the happiness which resulted from controlling the passions, of the dignity of patience, the inhospitable and hateful nature of selfishness, and the odiousness of cruelty and carnage.

'The pert fox, perceiving the audience not to be much amused by the discourse of the elephant, made no ceremony, but interrupted the oration by giving a farcical account of all his mischievous tricks and hairbreadth escapes, the success of his cunning, and his adroit contrivances to extricate himself from harm—all which so delighted the assembly, that the elephant was soon left, in the midst of his wise advice, without a single auditor near him; for they one and all with eagerness thronged to hear the diverting follies and knaveries[30] of the fox, who, of course, was in the end declared the victor.'

It might almost appear that a fable of this kind is an error of judgment, and that it is calculated to do harm rather than good, inasmuch as it exhibits the triumph of duplicity and the defeat of wisdom. True, the author of the fable tries to recover the lost ground in the application, by mildly holding up the fox to reprobation, thus:

'Application: The effect these two orators had on the perceptions of their audience was exactly the reverse one to the other. That of the elephant touched the guilty, like satire, with pain and reproach; even the most innocent was humbled, as none were wholly free from vice, and all felt themselves lowered even in their own opinion, and heard the admonition as an irksome duty, but still with little inclination to undergo the difficult task of amendment. But when the fox began, all was joy; the innocent felt all the gratification which proceeds from the consciousness of superiority, and the guilty to find their vices and follies treated only as a jest; for we all have felt how much more pleasure we enjoy laughing at a fool than in being scrutinized by the sage. From this cause it is that farce of the most grotesque and absurd kind is tolerated and received, and not without some degree of relish, even by the good and the wise, as we all want comfort.'

In spite of the application—nay, rather to some extent by reason of it, for the anti-climax is extraordinary in a fable—it may be doubted whether our sympathies are not with the fox rather than with the elephant. We feel that the latter, with all his wisdom and good advice, is somewhat of a bore; whilst the fox, rake and wastrel though he be, has that touch of nature that makes him kin.

Æsop's well-known fable of The Fox and the Crow is also an example of the success of the scoundrel, but mark the difference: here there is the obvious reproof of the vain and silly bird, deceived by flattering words, till, in attempting to sing, she drops into the mouth of the fox the savoury morsel she held in her beak! Here our verdict is: 'Served her right!' In Northcote's fable, clever though it is as a narration, this climax is altogether wanting.

It has been suggested that there is a closer natural affinity than at first sight appears between man and the lower animals, and that the recognition of this contact at many points would suggest the idea of conferring the power of speech upon the latter in the fable. In the higher reason and its resultant effects they differ fundamentally; mere animals are wanting discourse of reason, but the purely animal passions of cunning, anger, hatred, and even revenge and love of kind, and[32] the nobler characteristics of faithfulness and gratitude prevail in the dispositions of both. These similarities would strike observers in the pastoral ages of the world with even greater force than in later times.

The ineradicable impression which certain fables have made upon the mind through uncounted generations by their self-evident appropriateness and truth, is well exemplified in The Wolf and the Lamb; The Fox and the Grapes; The Hare and the Tortoise; The Dog and the Shadow; The Mountain in Labour; The Fox without a Tail; The Satyr and the Man, who blew hot and cold with the same breath, and others. It is safe to assert that nothing in literature has been more quoted than the fables named. We could not afford to lose them; their absence would be a distinct loss—literature and life would be the poorer without them; and, such being the fact, we are justified in holding those writers in esteem who have contributed to the instruction and entertainment of mankind in the fables they have invented.

Byron.

Pope.

Æsop is justly regarded as the foremost inventor of fables that the world has seen. He flourished in the sixth century before Christ. Several places, as in the case of Homer, are claimed as his birthplace—Sardis in Lydia, Ammorius, the island of Samos, and Mesembra, a city of Thrace; but the weight of authority is in favour of Cotiæum, a city of Phrygia in the Lesser Asia,[19] hence his sobriquet of 'the Phrygian.'

Whether he was a slave from birth is uncertain, but if not, he became such, and served three masters in succession. Demarchus or Caresias of Athens was his first master; the next, Zanthus[34] or Xanthus, a philosopher, of the island of Samos; and the third, Idmon or Jadmon, also of Samos. His faithful service and wisdom so pleased Idmon that he gave Æsop his freedom.

Growing in reputation both as a sage and a wit, he associated with the wisest men of his age. Amongst his contemporaries were the seven sages of Greece: Periander, Thales, Solon, Cleobulus, Chilo, Bias and Pittacus; but he was eventually esteemed wiser than any of them. The humour with which his sage counsels were spiced made these more acceptable (both in his own and later times) than the dull, if weighty, wisdom of his compeers.

He became attached by invitation of Crœsus, the rich King of Lydia, to the court at Sardis, the capital, and continued under the patronage of that monarch for the remainder of his life. Crœsus employed him in various embassies which he carried to a successful issue. The last he undertook was a mission to Delphi to offer sacrifices to Apollo, and to distribute four minæ[20] of silver to each citizen. To the character of the Delphians might with justice be applied the saying of a later time: 'The nearer the temple and the farther from God.' Familiarity with the Oracle, as is the case in smaller matters, bred[35] contempt, for the meanness of their lives was due to the circumstance that the offerings of strangers coming to the temple of the god enabled them to live a life of idleness, to the neglect of the cultivation of their lands.

Æsop upbraided them for this conduct, and, scorning to encourage them in their evil habits, instead of distributing amongst them the money which Crœsus had sent, he returned it to Sardis. This, as was natural with persons of their mean character, so inflamed them against him that they conspired to compass his destruction. Accordingly (as the story goes), they hid away amongst his baggage, as he was leaving the city, a golden goblet taken from the temple and consecrated to Apollo. Search being made, and the vessel discovered, the charge of sacrilege was brought against him. His judges pronounced him guilty, and he was sentenced to be precipitated from the rock Hyampia. Immediately before his execution he delivered to his persecutors the fable of The Eagle and the Beetle,[21] by which he warned them that even the weak may procure vengeance against the strong for injuries inflicted. The warning was unheeded by his murderers. The shameful sentence was carried out, and so Æsop died, according to Eusebius, in the fourth year of the fifty-fourth Olympiad, or[36] 561 years before the Christian era. The fate of poor Æsop was like that of a good many other world-menders!

According to ancient chroniclers, the death of Æsop did not go unavenged. Misfortunes of many kinds overtook the Delphians; pestilence decimated them; such of their lands as they tried to cultivate were rendered barren, with famine as the result, and these miseries continued to afflict them for many years. At length, having consulted the Oracle, they received as answer that which their secret conscience affirmed to be true, that their calamities were due to the death of Æsop, whom they had so unjustly condemned. Thereupon they caused proclamation to be made in all public places throughout the country, offering reparation to any of Æsop's representatives who should appear. The only claimant that responded was a grandson of Idmon, Æsop's former master; and having made such expiation as he demanded, the Delphians were delivered from their troubles.

Not only was Æsop unfortunate in his death: his personal appearance has suffered disparagement. The most trustworthy chroniclers in ancient times describe him as a man of good appearance, and even of a pleasing cast of countenance; whereas in later years he has been portrayed both by writers and in pictures[37] as deformed in body and repellent in features. Stobæus, it is true, who lived in the fifth century A.D., had written disparagingly of 'the air of Æsop's countenance,' representing the fabulist as a man of sour visage, and intractable, but he goes no farther than that.

It is to Maximus Planudes, a Constantinople monk of the fourteenth century, nearly two thousand years after the time of Æsop, that the burlesque of the great fabulist is due. Planudes appears to have collected all the stories regarding Æsop current during the Middle Ages, and strung them together as an authentic history. Through ignorance, or by intention, he also confounded the Oriental fabulist, Locman,[22] with Æsop, and clothed the latter in all the admitted deformities of the other. He affirmed him as having been flat-faced, hunch-backed, jolt-headed, blubber-lipped, big-bellied, baker-legged, his body crooked all over, and his complexion of a swarthy hue. Even in recent years, accepting the description of the monk, Æsop has been thus depicted in the frontispiece to his fables. This writer is untrustworthy in other respects, for in his pretended life of the sage he makes him speak of persons who did not exist, and of events that did not occur for eighty to two hundred years after his death.

That the story of Æsop's hideous deformity is untrue is clear from evidence that is on record. Admitted that this evidence is chiefly of a negative kind, it is sufficiently strong to refute the statements of the monk. In the first place, Planudes, as we have seen, is an untrustworthy chronicler in other respects, and an account of Æsop, written after the lapse of two thousand years, could only be worthy of credence issuing from a truthful pen, and based on documentary or other unquestionable evidence. Of such evidence the Constantinople monk had probably none.

Again, it is related that during the years of his slavery Æsop had as mate, or wife, the beautiful Rhodope,[23] also a slave—an unlikely circumstance, assuming him to have been as repulsive in bodily appearance as has been asserted. At all events, any incongruous association of this kind would have been remarked and commented on by earlier writers.

Further, none of Æsop's contemporaries, nor any writers that immediately followed him, make[39] mention of his alleged deformities. On the contrary, the Athenians, about two hundred years after his death, in order to perpetuate his memory and appearance, commissioned the celebrated sculptor Lysippus to produce a statue of Æsop, and this they erected in a prominent position in front of those of the seven sages, 'because,' says Phædrus,[24] 'their severe manner did not persuade, while the jesting of Æsop pleased and instructed at the same time.' It is improbable that the figure of a man monstrously deformed as Æsop is said to have been would have proved acceptable to the severe taste of the Greek mind. An epigram of Agathia, of which the following is a translation,[25] celebrates the erection of this statue:

Philostratus, in an account of certain pictures in existence in the time of the Antonines, describes one as representing Æsop with a pleasing cast of countenance, in the midst of a circle of the various animals, and the Geniuses of Fable adorning him with wreaths of flowers and branches of the olive.

Dr. Bentley, in his 'Dissertation,' ridicules the account of Æsop's deformity as given by Planudes in face of all the evidence to the contrary. 'I wish,' says he, 'I could do that justice to the memory of our Phrygian, to oblige the painters to change their pencil. For 'tis certain he was no deformed person; and 'tis probable he was very handsome. For whether he was a Phrygian or, as others say, a Thracian, he must have been sold into Samos by a trader in slaves; and 'tis well known that that sort of people commonly bought up the most beautiful they could light on, because they would yield the most profit.'

Bentley's conjecture that Æsop was 'very handsome' does not find general acceptance; it has, nevertheless, a solid foundation in the fact that the Greeks confined art to the imitation of the beautiful only, reprobating the portrayal of ugly forms, whether human or other. It is not to be believed, therefore, that the chisel of Lysippus was employed in the production of a[41] statue to a deformed person, which not even the gift of wisdom would have rendered acceptable to the severe taste of his countrymen. Without going so far, however, as to accept the view of the learned Master of Trinity, that Æsop was probably very handsome, we may with safety conclude that the objectionable portrait of the sage as drawn by the Byzantine is without justification.

[19] Suidas.

[20] The mina was twelve ounces, or a sum estimated as equal to £3 15s. English.

[22] Spelt variously Locman, Lôqman, Lokman.

[23] This woman is notorious in history as a courtesan who essayed to compound for her sins by votive offerings to the temple at Delphi. She is also said to have built the Lesser Pyramid out of her accumulated riches, but this is denied by Herodotus, who claims for the structure a more ancient and less discreditable foundation, being the work, as he asserts, of Mycerinus, King of Egypt (Herod., ii. 134).

[24] Phædrus, Epilogue, book ii.

[25] Boothby, Preface, p. xxxiv.

Scott: The Lay of the Last Minstrel.

James Clerk Maxwell.

There are numerous tales told of Æsop, some of which are obviously mythical; others, though their actual parentage may be doubtful, are entirely in keeping with his reputation for common, or uncommon, sense and ready wit. Phædrus has several of these, and Planudes, an untrustworthy chronicler, as we have seen, has many more. Some of the stories of the latter are absurd enough, and bordering perhaps on the foolish; but, on the other hand,[43] he tells several that may be pronounced excellent in every sense, and whatever the shortcomings of the monk in other respects, he deserves credit for having rescued these from the oblivion which otherwise might have been their fate.

Most writers, especially modern writers, on Æsop, have scouted with an unnecessary display of eclecticism the whole of the stories collected by Planudes regarding his hero; but in this they show a want of discrimination. Whether the stories are true of Æsop or not, and I know of no character on whom they may be more aptly fathered, they are as ripe in wisdom as are many of the best of the fables, and their pedigree is quite as authentic.

Philostratus, in his life of Apollonius Tyaneus, gives the following mythical account of the youthful Æsop: When a shepherd's boy, he fed his flock near a temple of Mercury, and frequently prayed to the god for mental endowments. Many other supplicants also came and laid rich presents upon the altar, but Æsop's only offering was a little milk and honey, and a few flowers, which the care of his sheep did not allow him to arrange with much art. The mercenary god disposed of his gifts in proportion to the value of the offerings. To one he gave philosophy, to another eloquence, to a third[44] astronomy, and to a fourth the poetical art. When all these were given away he perceived Æsop, and recollecting a fable which the Hours had related to him in his infancy, he bestowed upon him the invention of the Apologue.

Even when a slave, readiness of resource was a characteristic of Æsop, and often stood him in good stead. His first master, Demarchus, one day brought home some choice figs, which he handed to his butler, telling him that he would partake of them after his bath. The butler had a friend paying him a visit, and by way of entertainment placed the figs before him, and both heartily partook of them. Fearing the displeasure of Demarchus, he resolved to charge Æsop with the theft. Having finished his ablutions, Demarchus ordered the fruit to be brought; but the butler had none to bring, and charged Æsop with having stolen and eaten them. The slave, being summoned, denied the charge. It was a serious matter for one in his position. To be guilty meant many stripes, if not death. He begged to have some warm water, and he would prove his innocence. The water being brought, he took a deep drink; then, putting his finger down his gullet, the water—the sole contents of his stomach—was belched. Demarchus now ordered the butler to do the same, with the result that he was proved to be[45] both thief and liar, and was punished accordingly.

Æsop going on a journey for his master, along with other slaves of the household, and there being many burdens to carry, he begged they would not overload him. Looking upon him as weak in body, his fellow-slaves gave him his choice of a load. On this, Æsop selected the pannier of bread, which was the heaviest burden of all, at which his companions were amazed, and thought him a fool. Noon came, however, and when they had each partaken of its contents, Æsop's burden was lightened by one half. At the next meal all the bread was cleared out, leaving Æsop with only the empty basket to carry. At this their eyes were opened, and instead of the fool they at first thought him, he was seen to be the wisest of them all.

The second master who owned Æsop as a slave was Zanthus, the philosopher. Their meeting was in this wise: Æsop being in the marketplace for sale along with two other slaves, Zanthus, who was looking round with a view to making a purchase, asked them what they could do. Æsop's companions hastened to reply, and between them professed that they could do 'everything.' On Æsop being similarly questioned, he laughingly answered, 'Nothing.' His two fellow-slaves had forestalled him in all[46] possible work, and left him with nothing to do. This reply so amused Zanthus that he selected Æsop in preference to the others who were so boastful of their abilities.

Zanthus once, when in his cups, had foolishly wagered his land and houses that he would drink the sea dry. Recovering his senses, he besought Æsop his slave to find him a way out of his difficulty. This Æsop engaged to do. At the appointed time, when the foolish feat was to be performed, or his houses and lands forfeited, Zanthus, previously instructed by Æsop, appeared at the seaside before the multitude which had assembled to witness his expected discomfiture. 'I am ready,' cried he, 'to drain the waters of the sea to the last drop; but first of all you must stop the rivers from running into it: to drink these also is not in the contract.' The request was admitted to be a reasonable one, and as his opponents were powerless to perform their part, they were covered with derision by the populace, who were loud in their praises of the wisdom of Zanthus.

Philosopher notwithstanding, Zanthus appears to have been often in hot water. On another occasion his wife left him, whether on account of her bad temper (as the report goes), or from his too frequent indulgence in liquor (as is not[47] unlikely), matters little. He was anxious that she should return, but how to induce her was a difficulty hard to compass. Æsop, as usual, was equal to it. 'Leave it to me, master!' said he. Going to market, he gave orders to this dealer and that and the other, to send of their best to the residence of Zanthus, as, being about to take unto himself another wife, he intended to celebrate the happy occasion by a feast. The report spread like wildfire, and coming to the ears of his spouse, she quickly gathered up her belongings in the place where she had taken up her abode, and returned to the house of her lord and master. 'Take another wife, say you, Zanthus! Not whilst I am alive, my dear!' And so the ruse was successful, for, as the story affirms, she settled down to her duties, and no further cause for separation occurred between them ever after.

Phædrus relates several stories showing the characteristic readiness of the sage. A mean fellow, seeing Æsop in the street, threw a stone at him. 'Well done!' was his response to the unmannerly action. 'See! here is a penny for you; on my faith it is all I have, but I will tell you how you may get something more. See, yonder comes a rich and influential man. Throw a stone at him in the same way, and you will receive a due reward.' The rude fool, being[48] persuaded, did as he was advised. His daring impudence, however, brought him a requital he did not hope for, though it was what he deserved, for, being seized, he paid the penalty. Æsop in this incident exhibited not only his ready wit, but his deep craft, inasmuch as he brought condign punishment upon his persecutor by the hand of another, though he himself, being only a slave, might be insulted with impunity.

An Athenian, seeing Æsop at play in the midst of a crowd of boys, stopped and laughed and jeered at him for a madman. The sage, a laugher at others rather than one to be laughed at, perceiving this, placed an unstrung bow in the middle of the road. 'Hark you, wise man,' said he; 'unriddle what this means.' The people gathered round, whilst the man tormented his invention for a long time, trying to frame an answer to the riddle; but at last he gave it up. Upon this the victorious philosopher said: 'The bow will soon break if you always keep it bent, but relax it occasionally, and it will be fit for use, and strong, when it is wanted'—a piece of sound advice which others than the wiseacre chiefly concerned would find it advantageous to practise.

A would-be author had recited some worthless composition to Æsop, in which was contained an inordinate eulogy of himself and his own[49] powers, and, desiring to know what the sage thought about it, asked: 'Does it appear to you that I have been too conceited? I have no empty confidence in my own capacity.' Worried to death with the execrable production, Æsop replied: 'I greatly approve of your bestowing praise on yourself, for it will never be your lot to receive it from another.'

In the course of a conversation, being asked by Chilo (one of the wise men of Greece), 'What is the employment of the gods?' Æsop's answer was: 'To depress the proud and exalt the humble.' And in allusion to the sorrows inseparable from the human lot, his explanation, at once striking and poetical, was that 'Prometheus having taken earth to form mankind, moistened and tempered it, not with water, but with tears.'

Apart from wisdom in the highest sense, Æsop possessed no little share of worldly wisdom, or political wisdom—often only another name for chicane—and exercised it as occasion served. It is related by Plutarch, in the 'Life of Solon,' that 'Æsop being at the Court of Crœsus at a time when the seven sages of Greece were also present, the King, having shown them the magnificence of his Court and the vastness of his riches, asked them, "Whom do you think the happiest man?" Some of them named one, and some another. Solon (whom without injury we may look upon[50] as superior to all the rest) in his answer gave two instances. The first was that of one Tellus, a poor Athenian, but of great virtues, who had eminently distinguished himself by his care and education of his family, and at last lost his life in fighting for his country. The other was of two brothers who had given a very remarkable proof of their filial piety, and were in reward for it taken out of this life by the gods the very night after they had performed so dutiful an action. He concluded by adding that he had given such instances because no one could be pronounced happy before his death. Æsop perceived that the King was not well satisfied with any of their answers, and being asked the same question, replied "that for his part he was persuaded that Crœsus had as much pre-eminence in happiness over all other men as the sea has over all the rivers."

'The King was so much pleased with this compliment that he eagerly pronounced that sentence which afterwards became a common proverb, "The Phrygian has hit the mark." Soon after this happened, Solon took his leave of Crœsus, and was dismissed very coolly. Æsop, on his departure, accompanied him part of his journey, and as they were on the road took an opportunity of saying to him, "Oh, Solon, either we must not speak to kings, or we must say what will please[51] them." "On the contrary," replied Solon, "we should either not speak to kings at all, or we should give them good and useful advice." So great was the steadiness of the chief of the sages, and such the courtliness of Æsop.'[28]

It will be noticed that this reply of Æsop to the question of the King was evasive, though the vanity of the latter probably prevented his remarking it. He does not declare the King to be the happiest man, but leaves it to be inferred that, assuming happiness to be attained by men during life (which Solon denied), then was Crœsus pre-eminent over all others in that respect. It must be admitted that the answer does not display the character of Æsop in the best light as a moralist, however much it may exalt his reputation as a courtier. There probably was a good deal of the fox in his nature, and this, not less than his wisdom, enabled him to maintain his position at the Court of this vain and wealthy potentate.

[26] Solon.

[27] Crœsus.

[28] Quoted from the 'Life of Æsop' in the introduction to Dodsley's 'Select Fables.'

Shakespeare: Hamlet.

It has been asserted that this same Æsop, if not a mythical personage, is at least credited with much more than is his due, and that it is only around his name that have clustered the various fables attributed to him, like rich juicy grapes round their central stalk, or, to use a more appropriate image, like swarming bees round a pendent branch. Others have endeavoured, with less or more feasibility, to prove that most of what are called Æsopian fables had their origin in the far East—'The inquisitive amongst the Greeks,' say they, 'travelled into the East to ripen their own imperfect conceptions, and on their return taught them at home, with the mixture of fables and ornaments of fancy'[29]—that the ideas first propounded in India and[53] Arabia were thus carried westward; that Æsop appropriated them and gave them forth in a modified form and in a new dress. Scholars and investigators differ in their views regarding the truth, or the extent of the truth, of these allegations, and display much erudition in their attempts to settle the question. It would appear that Æsop has indubitably the credit of certain fables of which he was not the inventor, as they were in vogue at a period anterior to the era in which he flourished. It is equally proved, on the other hand, that genuine Æsopian or Grecian fables have been attributed to Eastern sources, and are found included in collections of Eastern fables compiled in the earlier years of the Christian era. All this is only what might be expected, and does not affect to any serious extent the credit for ingenuity and originality of either Æsop or other early fabulists. Doubtless Æsop did get some of the subjects of his fables from foreign sources, but he melted them in the crucible of his mind—he distilled their very essence, and handed us the precious concentrated spirit. If he had done nothing more, that was good.

It is well known, of course, that there were fables of a very excellent kind before the time of Æsop. Amongst the Æsopian fables supposed to be borrowed from the Jātakas are The Wolf and the Crane, The Ass in the Lion's Skin, The Lion and[54] Mouse, and The Countryman, his Son and the Snake. And Plutarch[30] asserts that the language of Hesiod's nightingale to the hawk (spoken three hundred years before the era of Æsop) is the origin of the beautiful and instructive wisdom in which Æsop has employed so many tongues. Thus:

Archilochus also wrote fables before Æsop;[32] and even anterior to these is the fable of The Belly and the Members, and those given in Holy Scripture. But, without question, Æsop was a true inventor of fables, for it is not to be believed for a moment that Greek genius (and this was the genius of Æsop, whatever his parentage) was not equal to such a task.

Doubtless many later, as well as earlier, fables[55] are included under the general designation of 'Æsopian,' by virtue of their resembling in the characteristics of brevity, force and wit the inventions of the sage.

Æsop in all probability did not write out his fables; they were handed down by word of mouth from generation to generation. At length they were collected together, first by Diagoras (400 B.C.), and later by Demetrius Phalereus, the Tyrant of Athens (318 B.C.), under the title of 'The Assemblies of Æsopian Fables,' long after the sage's death. This collection was made use of both by the Greek freedman Phædrus, during the reign of Augustus, in the early years of the Christian era, and later by Valerius Babrius, the Roman (230 A.D.). Later again, towards the end of the fourth century, a number of them were translated into Latin by Avienus.

The Æsopian fables are distinguished by their simplicity, their mother-wit and natural humour. A score of examples exhibiting these qualities might be cited. A few, not the best known, will suffice:

The Wolf and the Shepherds.—'A wolf peeping into a hut where a company of shepherds were regaling themselves with a joint of mutton—"Lord," said he, "what a clamour would these men have raised if they had caught me at such a banquet!"'

The compression and humour of this fable are[56] remarkable, and the obvious moral is: 'That men are apt to condemn in others what they practise themselves without scruple.'

The Dog and the Crocodile bids us be on our guard against associating with persons of an ill reputation. 'As a dog was coursing the banks of the Nile, he grew thirsty; but fearing to be seized by the monsters of that river, he would not stop to satiate his drought, but lapped as he ran. A crocodile, raising his head above the surface of the water, asked him why he was in such a hurry. He had often, he said, wished for his acquaintance, and should be glad to embrace the present opportunity. "You do me great honour," returned the dog, "but it is to avoid such companions as you that I am in so much haste."'

Again, The Snake and the Hedgehog. 'By the intreaties of a hedgehog, half starved with cold, a snake was once persuaded to receive him into her cell. He was no sooner entered than his prickles began to be very annoying to his companion, upon which the snake desired he would provide himself another lodging, as she found, upon trial, the apartment was not large enough to accommodate both. "Nay," said the hedgehog, "let them that are uneasy in their situation exchange it; for my own part, I am very well contented where I am; if you are not, you are welcome to remove whenever you think proper!"'

The fable (or rather story, for it is more an anecdote than a fable) of Mercury and the Sculptor reads like a joke of yesterday. In Mr. Cross's 'Life of George Eliot,' it is recorded that the great novelist (in a conversation with Mr. Burne-Jones) recalled her passionate delight and total absorption in Æsop's fables, the possession of which, when a child, had opened new worlds to her imagination, and she laughed till the tears ran down her face in recalling her infantine enjoyment of the humour of this story, as follows:

'Mercury once determined to learn in what esteem he was held among mortals. For this purpose he assumed the character of a man, and visited in this disguise the studio of a sculptor. Having looked at various statues, he demanded the price of two figures of Jupiter and Juno. When the sum at which they were valued was named, he pointed to a figure of himself, saying to the sculptor: "You will certainly want much more for this, as it is the statue of the messenger of the gods, and the author of all your gain." The sculptor replied, "Well, if you will buy these, I'll fling you that into the bargain."'

Again, take The Bull and the Gnat, intended to show that the least considerable of mankind are seldom destitute of importance:

'A conceited gnat, fully persuaded of his own importance, having placed himself on the horn[58] of a bull, expressed great uneasiness lest his weight should be incommodious; and with much ceremony begged the bull's pardon for the liberty he had taken, assuring him that he would immediately remove if he pressed too hard upon him. "Give yourself no uneasiness on that account, I beseech you," replied the bull, "for as I never perceived when you sat down, I shall probably not miss you whenever you think fit to rise up."'

Here, again, the humour is exquisite; but, indeed, that is a characteristic of nearly all the fables ascribed to Æsop.

The fable does not readily lend itself to the expression of pathos. Perhaps the only really pathetic fable is that of The Wolf and the Lamb, and it is also one of the very best. In this there is a touch of genuine pathos, unique in its character. Hesiod's Hawk and Nightingale,[33] and The Old Woodcutter and Death, as told by La Fontaine, are not wanting in pathos.

The applicability of the fables of Æsop to the circumstances and occurrences of every-day life, in the highest walks as in the humblest—for the nature in both is human, after all—gives them peculiar value. This, and their epigrammatical character, so conspicuous in the best, combined with the humorous turn that is given to them, impresses them upon the memory.

In such repute have the Æsopian fables always been held, that the most learned men in all ages have occupied themselves in translating and transcribing them. Socrates relieved his prison hours in turning some of them into verse.[34] In the days of ancient Greece, not to be familiar with Æsop was a sign of illiteracy.[35]

We have seen how other of the ancients collected and disseminated them. Coming down to later times, one of the first printed collections was by Bonus Accursius (1489,) from a MS. in the Ambrosian Library at Milan. To this was prefixed the Life by Planudes, written a century before. Another edition of the same was published by Aldus in 1505. The edition of Robert Stephens, published in Paris in 1546, followed; then came the enlarged collection by Neveletus, from the Heidelberg Library, in 1610. Later, Gabriele Faerno's 'One Hundred Fables' are Æsop given in Latin verse. So also with most of the collections by modern fabulists, La Fontaine, Sir Roger L'Estrange, Dr. Samuel Croxall,[60] La Motte, Richer, Brettinger, Bitteux—they are all largely Æsop, with added pieces of later invention.

'Æsop has been agreed by all ages since his era for the greatest Master in his kind, and all others of that sort have been but imitations of his original.'[36]

Of the popularity of Æsop's fables in book form during last century and the beginning of this, we can scarcely form any conception in these days of cheap literature in such variety and excellence. Along with the Bible and 'The Pilgrim's Progress,' Æsop may be said to have occupied a place on the meagre bookshelf of almost every cottage.

The editions of Æsop in English are innumerable, but the most noteworthy, in the different epochs from the age of the invention of printing downwards have been: Caxton's collection (1484); the one by Leonard Willans (1650); that by John Ogilby (1651); Sir Roger L'Estrange's edition (1692); Dr. Croxall's collection (1722); that of Robert Dodsley (1764); and the Rev. Thomas James's Æsop (1848).

It is remarkable that the majority of those who have busied themselves in translating and editing Æsop have won fame and (shall we say?) immortality through that circumstance alone. Take the names in order of time, and it will be seen that the[61] men are remembered chiefly or only (most of them) by reason of their association with the Æsopian fables: Demetrius Phalereus, Phædrus, Babrius, Avienus, Planudes, Bonus Accursius, Neveletus, even down to La Fontaine, L'Estrange,[37] Croxall, and James. The Æsopian fable has indeed a perennial life, and its votaries have rendered themselves immortal by association therewith.

Writers of much erudition, and in many countries, have vied with each other in learned research in this branch of literature, and in endeavours to trace the history of fable. Among the French we have Pierre Pithou (1539-96), editor of the first printed edition of Phædrus; Bachet de Meziriac, who wrote a life of Æsop (1632); Boissonade, Robert, Edelestand du Meril (1854); Hervieux and Gaston Paris. Of German writers there are Lessing, Fausboll, Hermann Oesterley, Mueller, Wagener, Heydenreich, Otto Crusius (1879), Benfey, Mall, Knoell, Gitlbauer; Niccolo, Perotti, Archbishop of Siponto (1430-80), and Jannelli, among the Italians; amongst Jewish[62] writers, Dr. Landsberger. Of English writers we have Christopher Wase, Alsop, Boyle, Bentley, Tyrwhitt, Rutherford, James, Robinson Ellis, Rhys-Davids, G. F. Townsend, and last but not least, Joseph Jacobs, in his scholarly 'History of the Æsopic Fable.'

[29] Antiquary in 'The Club.'

[30] 'Conviv. Sapient.'

[31] Boothby's translation.

[32] Priscian.

[34] 'Being exhorted by a dream, I composed some verses in honour of the god to whom the present festival [of the sacred embassy to Delos] belongs; but after the god, considering it necessary that he who designs to be a poet should make fables and not discourses, and knowing that I myself was not a mythologist, on these accounts I versified the fables of Æsop, which were at hand, and were known to me.'—Socrates in Plato's 'Phædo.'

[35] Suidas.

[36] Sir William Temple.

[37] Goldsmith, in his 'Account of the Augustine Age of England,' remarks: 'That L'Estrange was a standard writer cannot be disowned, because a great many very eminent authors formed their style by his. But his standard was far from being a just one; though, when party considerations are set aside, he certainly was possessed of elegance, ease, and perspicuity.' Notwithstanding this considerable estimate of L'Estrange, it may be said that he is now remembered chiefly by his association with the Æsopian fables.

Cowper: The Task (altered).

Phædrus, who wrote the fables of Æsop in Latin iambics, and added others of his own, was born at the very source of poetic inspiration, on Mount Pierius, near to the Pierian spring, the seat of the Muses, in Thrace, at that time a portion of the Roman province of Macedonia, and of which Octavius, the father of Augustus Cæsar, was Proconsul, during the last century before the Christian era. Like Æsop, he too was a slave in early youth, but being taken to Rome, he was manumitted by Augustus, and occupied a place in the household of that Emperor. Here he acquired the pure Latinity of his style, and in later years wrote the well-known fables in the collection that bears his name. His fables are in five books,[64] and were published during the reign of Tiberius and subsequent emperors.

In the prologue to his third book, addressed to Eutychus,[38] he thus alludes to his birthplace, and disavows all mercenary aims in his literary pursuits:

His object, as he declares, was to expose vice[65] and folly; in pursuing it he did not escape persecution, for Sejanus, the arbitrary minister of Tiberius (who had now succeeded to the imperial purple), took mortal offence at certain of the apologues which he suspected applied to himself, and, 'informer, witness, judge and all,' laid the iron hand of power heavy upon the fabulist. Phædrus, whose early years of slavery had left no taint of servility upon his character, was too independent to stoop to insolent power, and resented the treatment to which he was subjected. Thus beset, and probably largely owing to this cause, his last years were spent in poverty. Amidst the infirmities of age he compares himself to the old hound in his last apologue, which being chastised by his master for his feebleness in allowing the boar to escape, replied, 'Spare your old servant! It was the power, not the will, that failed me. Remember rather what I was than abuse me for what I am.' A lesson which even at the present day may sometimes find its application. Phædrus prophesied his own immortality as an author, and his boast was that whilst Æsop invented, he (Phædrus) perfected.

Babrius,[40] a Latin, did for the Æsopian fable, in Greek choliambics, what Phædrus, a Greek, accomplished for them in Latin iambics. He is[66] believed to have lived in the third century A.D., and to have composed his fables in his quality of tutor to Branchus, the young son of the Emperor Alexander Severus.[41] His collection of Æsopian fables in two books was known to ancient writers, who refer to him and quote his apologues, but, like other literary treasures, it was lost during the Middle Ages. Early in the seventeenth century, Isaac Nicholas Neveletus, a Swiss, published (1610) an edition of the fables of Æsop, containing not only those embraced in the work of Planudes, but additional fables from MSS. in the Vatican Library, and some from Aphthonius and Babrius. He further expressed the opinion that the latter was the earliest collector and writer of the Æsopian fables in Greek. Francis Vavassor, a French Jesuit, followed with comments on Babrius on the same lines; so also another Frenchman, Bayle, in his 'Dictionnaire Historique'; Thomas Tyrwhitt and Dr. Bentley in England, and Francisco de Furia in Italy, also espoused the idea first suggested by Neveletus, and adduced further proofs in support of it. Singularly enough, the accuracy of the forecast of these scholars was established by the discovery in 1840, by M. Minoides Menas, a Greek, at the Convent of St. Laura on Mount Athos, of a veritable copy of Babrius in Greek choliambic verse. The[67] transcript of Menas was first published in Paris in 1844. The first English edition was edited by Sir George Cornewall Lewis in the original Greek text, with Latin notes, and afterwards (1860) translated into English by the Rev. James Davies, M.A., and they now form the most trustworthy version of the Æsopian fables.

[38] 'The Charioteer of Caligula,' Bücheler.

[39] From the translation of the fables of Phædrus into English verse by Christopher Smart, A.M.

[40] Sometimes spelt 'Gabrias.'

[41] Jacobs: 'History of the Æsopic Fable,' p. 22.

Shakespeare: As You Like It.

'Fables,' says Aristotle, 'are adapted to deliberate oratory, and possess this advantage: that to hit upon facts which have occurred in point is difficult; but with regard to fables it is comparatively easy. For an orator ought to construct them just as he does his illustrations, if he be able to discover the point of similitude, a thing which will be easy to him if he be of a philosophical turn of mind.'[42]

The truth of this is exemplified in the use which has been made of the apologue by orators in all ages, but especially in early times.

The following instances of the application of fables to particular occasions are recorded. The fable of The Belly and the Members, which is reputed[69] to be the oldest in existence, is of sterling excellence, as well as of venerable antiquity.[43] Its lucid moral is truth in essence. The logic of its conclusion is as invulnerable as the demonstration of a proposition in Euclid. There is no gainsaying it, turn it how we may, and, with all due deference to Montaigne, only one moral is deducible from it. This is solid bottom ground and bed rock, safe for chain-cable holding; safe for building upon, however high the superstructure. Striking use was made of it by Menenius Agrippa when the rabble refused to pay their share of the taxes necessary for carrying on the business of the State.

In the 'Coriolanus' of Shakespeare, Menenius, the Roman Consul, is introduced in character,[44] and recounts the apologue to the disaffected citizens of Rome. Thus the dramatist, in his superb way:

The oldest fable in Holy Scripture, having been spoken or written about six centuries before the time of Æsop, is that of The Trees in Search of a King, recounted by Jotham to the men of[72] Shechem, and directed against Abimelech,[45] wherein it is shown that the most worthless persons are generally the most presuming: