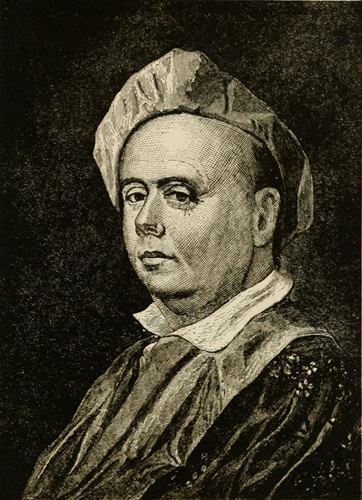

CAPTAIN JOHN MARSTON, 1715-1786

Landlord of the “Golden Ball” and “Bunch of Grapes”

OLD BOSTON TAVERNS

AND

TAVERN CLUBS

BY

SAMUEL ADAMS DRAKE

NEW ILLUSTRATED EDITION

WITH AN ACCOUNT OF

“Cole’s Inn,” “The Bakers’ Arms,” and “Golden Ball”

BY

WALTER K. WATKINS

Also a List of Taverns, Giving the Names of the Various Owners

of the Property, from Miss Thwing’s Work on “The Inhabitants

and Estates of the Town of Boston,

1630-1800,” in the Possession of the

Massachusetts Historical

Society

W. A. BUTTERFIELD

59 BROMFIELD STREET, BOSTON

1917

Copyright, 1917, by

W. A. BUTTERFIELD.

he Inns of Old Boston have played such a part in its history that an

illustrated edition of Drake may not be out of place at this late date.

“Cole’s Inn” has been definitely located, and the “Hancock Tavern”

question also settled.

he Inns of Old Boston have played such a part in its history that an

illustrated edition of Drake may not be out of place at this late date.

“Cole’s Inn” has been definitely located, and the “Hancock Tavern”

question also settled.

I wish to thank the Bostonian Society for the privilege of reprinting Mr. Watkin’s account of the “Bakers’ Arms” and the “Golden Ball” and valuable assistance given by Messrs. C. F. Read, E. W. McGlenen, and W. A. Watkins; Henderson and Ross for the illustration of the “Crown Coffee House,” and the Walton Advertising Co. for the “Royal Exchange Tavern.”

Other works consulted are Snow’s History of Boston, Memorial History of Boston, Stark’s Antique Views, Porter’s Rambles in Old Boston, and Miss Thwing’s very valuable work in the Massachusetts Historical Society.

THE PUBLISHER.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | Upon the Tavern as an Institution | 9 |

| II. | The Earlier Ordinaries | 19 |

| III. | In Revolutionary Times | 33 |

| IV. | Signboard Humor | 52 |

| V. | Appendix; Boston Taverns to the Year 1800 | 61 |

| VI. | Cole’s Inn | 73 |

| VII. | The Bakers’ Arms | 76 |

| VIII. | The Golden Ball Tavern | 80 |

| IX. | The Hancock Tavern | 89 |

| X. | List of Taverns and Tavern Owners | 99 |

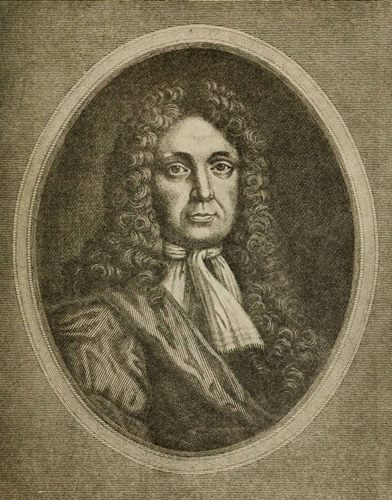

| Capt. John Marston | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| The Sign of the Lamb | 17 |

| The Heart and Crown | 18 |

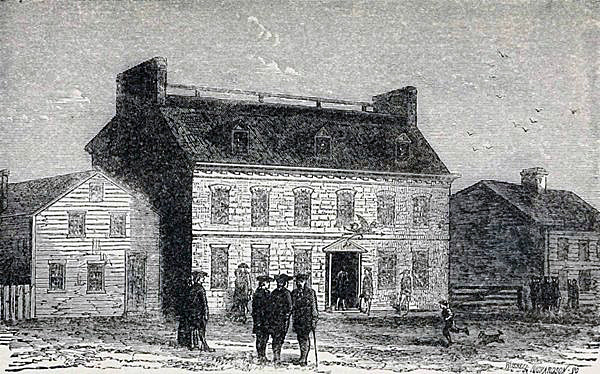

| Royal Exchange Tavern | 24 |

| Portrait of Joseph Green | 26 |

| Portrait of John Dunton | 28 |

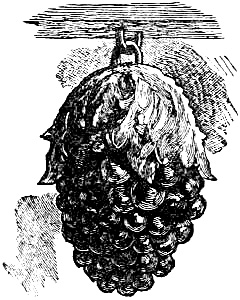

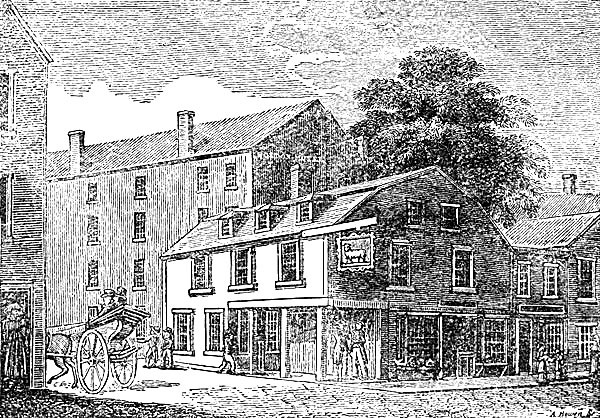

| The Bunch of Grapes | 34 |

| Cromwell Head Board Bill | 44 |

| The Cromwell’s Head | 44 |

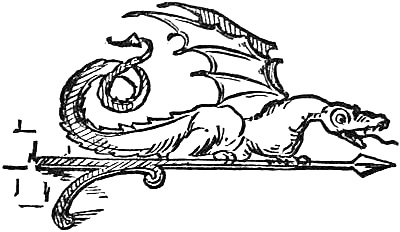

| The Green Dragon | 46 |

| The Green Dragon Sign | 47 |

| The Liberty Tree | 50 |

| The Brazen Head | 51 |

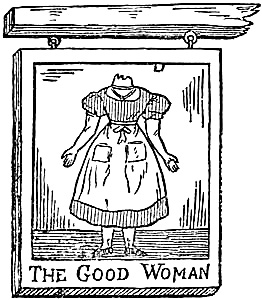

| The Good Woman | 52 |

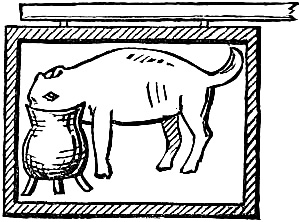

| The Dog and Pot | 53 |

| How Shall I Get Through This World? | 54 |

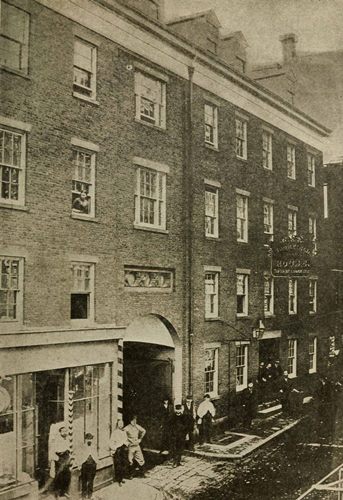

| The Crown Coffee House | 62 |

| Old Newspaper Advertisement | 64 |

| Julien House | 65 |

| The Sun Tavern | 68 |

| The Three Doves | 70 |

| Jolley Allen Advertisement | 70 |

| The Bakers’ Arms | 75 |

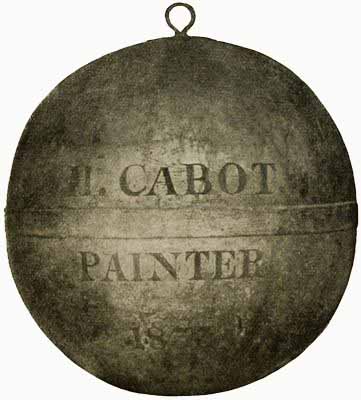

| Sign of Bunch of Grapes | 80 |

| Sign of Golden Ball | 80 |

| Map showing Location of Cole’s Inn | 88 |

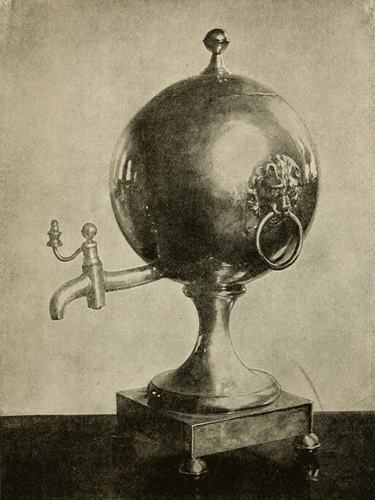

| Coffee Urn | 90 |

| Map of Boston, 1645 | 98 |

| Bromfield House | 102 |

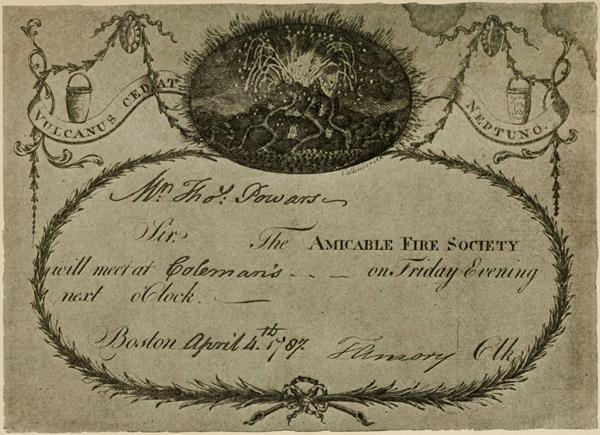

| Fireman’s Ticket | 104 |

| Portrait of Governor Belcher | 106 |

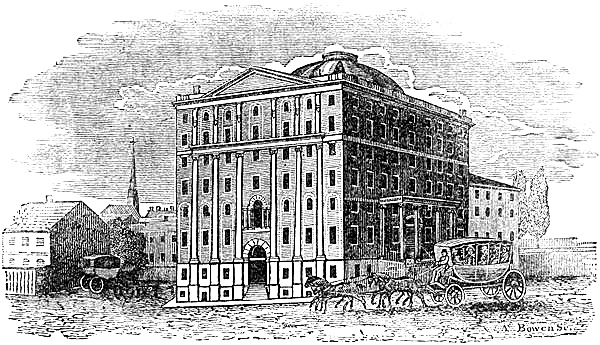

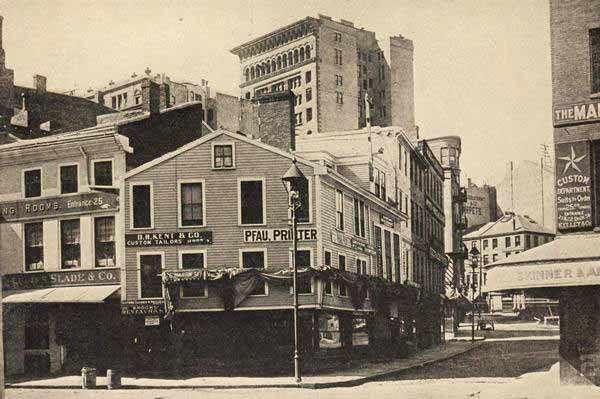

| Exchange Coffee House, 1808-18 | 108 |

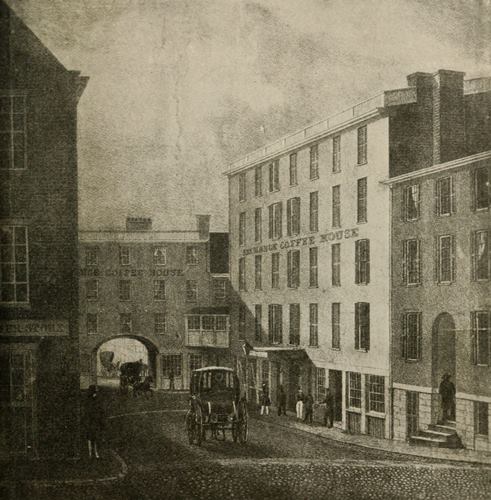

| Exchange Coffee House, 1848 | 110 |

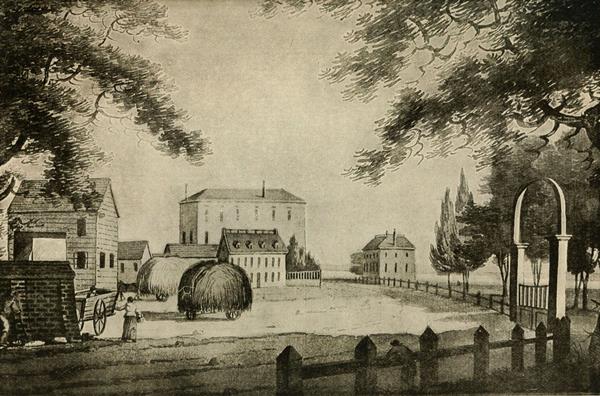

| Hatch Tavern | 112 |

| Lamb Tavern | 114 |

| Sun Tavern (Dock Square) | 122 |

| Bonners’ Map of Boston, 1722 | 124 |

UPON THE TAVERN AS AN INSTITUTION.

he famous remark of Louis XIV., “There are no longer any Pyrenees,” may

perhaps be open to criticism, but there are certainly no longer any

taverns in New England. It is true that the statutes of the Commonwealth

continue to designate such houses as the Brunswick and Vendome as taverns,

and their proprietors as innkeepers; yet we must insist upon the truth of

our assertion, the letter of the law to the contrary notwithstanding.

he famous remark of Louis XIV., “There are no longer any Pyrenees,” may

perhaps be open to criticism, but there are certainly no longer any

taverns in New England. It is true that the statutes of the Commonwealth

continue to designate such houses as the Brunswick and Vendome as taverns,

and their proprietors as innkeepers; yet we must insist upon the truth of

our assertion, the letter of the law to the contrary notwithstanding.

No words need be wasted upon the present degradation which the name of tavern implies to polite ears. In most minds it is now associated with the slums of the city, and with that particular phase of city life only, so all may agree that, as a prominent feature of society and manners, the tavern has had its day. The situation is easily accounted for. The simple truth is, that, in moving on, the world has left the venerable institution standing in the eighteenth century; but it is equally true that, before that time, the history of any civilized people could hardly be written without making great[Pg 10] mention of it. With the disappearance of the old signboards our streets certainly have lost a most picturesque feature, at least one avenue is closed to art, while a few very aged men mourn the loss of something endeared to them by many pleasant recollections.

As an offset to the admission that the tavern has outlived its usefulness, we ought in justice to establish its actual character and standing as it was in the past. We shall then be the better able to judge how it was looked upon both from a moral and material stand-point, and can follow it on through successive stages of good or evil fortune, as we would the life of an individual.

It fits our purpose admirably, and we are glad to find so eminent a scholar and divine as Dr. Dwight particularly explicit on this point. He tells us that, in his day, “The best old-fashioned New England inns were superior to any of the modern ones. There was less bustle, less parade, less appearance of doing a great deal to gratify your wishes, than at the reputable modern inns; but much more was actually done, and there was much more comfort and enjoyment. In a word, you found in these inns the pleasures of an excellent private house. If you were sick you were nursed and befriended as in your own family. To finish the story, your bills were always equitable, calculated on what you ought to pay, and not upon the scheme of getting the most which extortion might think proper to demand.”

Now this testimonial to what the public inn was eighty odd years ago comes with authority from one[Pg 11] who had visited every nook and corner of New England, was so keen and capable an observer, and is always a faithful recorder of what he saw. Dr. Dwight has frequently said that during his travels he often “found his warmest welcome at an inn.”

In order to give the history of what may be called the Rise and Fall of the Tavern among us, we should go back to the earliest settlements, to the very beginning of things. In our own country the Pilgrim Fathers justly stand for the highest type of public and private morals. No less would be conceded them by the most unfriendly critic. Intemperance, extravagant living, or immorality found no harborage on Plymouth Rock, no matter under what disguise it might come. Because they were a virtuous and sober people, they had been filled with alarm for their own youth, lest the example set by the Hollanders should corrupt the stay and prop of their community. Indeed, Bradford tells us fairly that this was one determining cause of the removal into New England.

The institution of taverns among the Pilgrims followed close upon the settlement. Not only were they a recognized need, but, as one of the time-honored institutions of the old country, no one seems to have thought of denouncing them as an evil, or even as a necessary evil. Travellers and sojourners had to be provided for even in a wilderness. Therefore taverns were licensed as fast as new villages grew up. Upward of a dozen were licensed at one sitting of the General[Pg 12] Court. The usual form of concession is that So-and-So is licensed to draw wine and beer for the public. The supervision was strict, but not more so than the spirit of a patriarchal community, founded on morals, would seem to require; but there were no such attempts to cover up the true character of the tavern as we have seen practised in the cities of this Commonwealth for the purpose of evading the strict letter of the law; and the law then made itself respected. An innkeeper was not then looked upon as a person who was pursuing a disgraceful or immoral calling,—a sort of outcast, as it were,—but, while strictly held amenable to the law, he was actually taken under its protection. For instance, he was fined for selling any one person an immoderate quantity of liquor, and he was also liable to a fine if he refused to sell the quantity allowed to be drank on the premises, though no record is found of a prosecution under this singular statutory provision; still, for some time, this regulation was continued in force as the only logical way of dealing with the liquor question, as it then presented itself.

When the law also prohibited a citizen from entertaining a stranger in his own house, unless he gave bonds for his guest’s good behavior, the tavern occupied a place between the community and the outside world not wholly unlike that of a moral quarantine. The town constable could keep a watchful eye upon all suspicious characters with greater ease when they were under one roof. Then it was his business to know[Pg 13] everybody’s, so that any show of mystery about it would have settled, definitely, the stranger’s status, as being no better than he should be. “Mind your own business,” is a maxim hardly yet domesticated in New England, outside of our cities, or likely to become suddenly popular in our rural communities, where, in those good old days we are talking about, a public official was always a public inquisitor, as well as newsbearer from house to house.

On their part, the Puritan Fathers seem to have taken the tavern under strict guardianship from the very first. In 1634, when the price of labor and everything else was regulated, sixpence was the legal charge for a meal, and a penny for an ale quart of beer, at an inn, and the landlord was liable to ten shillings fine if a greater charge was made. Josselyn, who was in New England at a very early day, remarks, that, “At the tap-houses of Boston I have had an ale quart of cider, spiced and sweetened with sugar, for a groat.” So the fact that the law once actually prescribed how much should be paid for a morning dram may be set down among the curiosities of colonial legislation.

No later than the year 1647 the number of applicants for licenses to keep taverns had so much increased that the following act was passed by our General Court for its own relief: “It is ordered by the authority of this court, that henceforth all such as are to keep houses of common entertainment, and to retail wine, beer, etc., shall be licensed at the county courts of the shire where[Pg 14] they live, or the Court of Assistants, so as this court may not be thereby hindered in their more weighty affairs.”

A noticeable thing about this particular bill is, that when it went down for concurrence the word “deputies” was erased and “house” substituted by the speaker in its stead, thus showing that the newly born popular body had begun to assert itself as the only true representative chamber, and meant to show the more aristocratic branch that the sovereign people had spoken at last.

By the time Philip’s war had broken out, in 1675, taverns had become so numerous that Cotton Mather has said that every other house in Boston was one. Indeed, the calamity of the war itself was attributed to the number of tippling-houses in the colony. At any rate this was one of the alleged sins which, in the opinion of Mather, had called down upon the colony the frown of Providence. A century later, Governor Pownall repeated Mather’s statement. So it is quite evident that the increase of taverns, both good and bad, had kept pace with the growth of the country.

It is certain that, at the time of which we are speaking, some of the old laws affecting the drinking habits of society were openly disregarded. Drinking healths, for instance, though under the ban of the law, was still practised in Cotton Mather’s day by those who met at the social board. We find him defending it as a common form of politeness, and not the invocation of[Pg 15] Heaven it had once been in the days of chivalry. Drinking at funerals, weddings, church-raisings, and even at ordinations, was a thing everywhere sanctioned by custom. The person who should have refused to furnish liquor on such an occasion would have been the subject of remarks not at all complimentary to his motives.

It seems curious enough to find that the use of tobacco was looked upon by the fathers of the colony as far more sinful, hurtful, and degrading than indulgence in intoxicating liquors. Indeed, in most of the New England settlements, not only the use but the planting of tobacco was strictly forbidden. Those who had a mind to solace themselves with the interdicted weed could do so only in the most private manner. The language of the law is, “Nor shall any take tobacco in any wine or common victual house, except in a private room there, so as the master of said house nor any guest there shall take offence thereat; which, if any do, then such person shall forbear upon pain of two shillings sixpence for every such offence.”

It is found on record that two innocent Dutchmen, who went on a visit to Harvard College,—when that venerable institution was much younger than it is to-day,—were so nearly choked with the fumes of tobacco-smoke, on first going in, that one said to the other, “This is certainly a tavern.”

It is also curious to note that, in spite of the steady growth of the smoking habit among all classes of people, public opinion continued to uphold the laws directed to[Pg 16] its suppression, though, from our stand-point of to-day, these do seem uncommonly severe. And this state of things existed down to so late a day that men are now living who have been asked to plead “guilty or not guilty,” at the bar of a police court, for smoking in the streets of Boston. A dawning sense of the ridiculous, it is presumed, led at last to the discontinuance of arrests for this cause; but for some time longer officers were in the habit of inviting detected smokers to show respect for the memory of a defunct statute of the Commonwealth, by throwing their cigars into the gutter.

Turning to practical considerations, we shall find the tavern holding an important relation to its locality. In the first place, it being so nearly coeval with the laying out of villages, the tavern quickly became the one known landmark for its particular neighborhood. For instance, in Boston alone, the names Seven Star Lane, Orange Tree Lane, Red Lion Lane, Black Horse Lane, Sun Court, Cross Street, Bull Lane, not to mention others that now have so outlandish a sound to sensitive ears, were all derived from taverns. We risk little in saying that a Bostonian in London would think the great metropolis strangely altered for the worse should he find such hallowed names as Charing Cross, Bishopsgate, or Temple Bar replaced by those of some wealthy Smith, Brown, or Robinson; yet he looks on, while the same sort of vandalism is constantly going on at home, with hardly a murmur of disapproval, so differently does the same thing look from different points of view.

[Pg 17]As further fixing the topographical character of taverns, it may be stated that in the old almanacs distances are always computed between the inns, instead of from town to town, as the practice now is.

Of course such topographical distinctions as we have pointed out began at a time when there were few public buildings; but the idea almost amounts to an instinct, because even now it is a common habit with every one to first direct the inquiring stranger to some prominent landmark. As such, tavern-signs were soon known and noted by all travellers.

SIGN OF THE LAMB.

Then again, tavern-titles are, in most cases, traced back to the old country. Love for the old home and its associations made the colonist like to take his mug of ale under the same sign that he had patronized when in England. It was a never-failing reminiscence to him. And innkeepers knew how to appeal to this feeling.[Pg 18] Hence the Red Lion and the Lamb, the St. George and the Green Dragon, the Black, White, and Red Horse, the Sun, Seven Stars, and Globe, were each and all so many reminiscences of Old London. In their way they denote the same sort of tie that is perpetuated by the Bostons, Portsmouths, Falmouths, and other names of English origin.

THE EARLIER ORDINARIES.

s early as 1638 there were at least two ordinaries, as taverns were then

called, in Boston. That they were no ordinary taverns will at once occur

to every one who considers the means then employed to secure sobriety and

good order in them. For example, Josselyn says that when a stranger went

into one for the purpose of refreshing the inner man, he presently found a

constable at his elbow, who, it appeared, was there to see to it that the

guest called for no more liquor than seemed good for him. If he did so,

the beadle peremptorily countermanded the order, himself fixing the

quantity to be drank; and from his decision there was no appeal.

s early as 1638 there were at least two ordinaries, as taverns were then

called, in Boston. That they were no ordinary taverns will at once occur

to every one who considers the means then employed to secure sobriety and

good order in them. For example, Josselyn says that when a stranger went

into one for the purpose of refreshing the inner man, he presently found a

constable at his elbow, who, it appeared, was there to see to it that the

guest called for no more liquor than seemed good for him. If he did so,

the beadle peremptorily countermanded the order, himself fixing the

quantity to be drank; and from his decision there was no appeal.

Of these early ordinaries the earliest known to be licensed goes as far back as 1634, when Samuel Cole, comfit-maker, kept it. A kind of interest naturally goes with the spot of ground on which this the first house of public entertainment in the New England metropolis stood. On this point all the early authorities seem to have been at fault. Misled by the meagre[Pg 20] record in the Book of Possessions, the zealous antiquaries of former years had always located Cole’s Inn in what is now Merchants’ Row. Since Thomas Lechford’s Note Book has been printed, the copy of a deed, dated in the year 1638, in which Cole conveys part of his dwelling, with brew-house, etc., has been brought to light. The estate noted here is the one situated next northerly from the well-known Old Corner Bookstore, on Washington Street. It would, therefore, appear, beyond reasonable doubt, that Cole’s Inn stood in what was already the high street of the town, nearly opposite Governor Winthrop’s, which gives greater point to my Lord Leigh’s refusal to accept Winthrop’s proffered hospitality when his lordship was sojourning under Cole’s roof-tree.

In his New England Tragedies, Mr. Longfellow introduces Cole, who is made to say,—

“But the ‘Three Mariners’ is an orderly,

Most orderly, quiet, and respectable house.”

Cole, certainly, could have had no other than a poet’s license for calling his house by this name, as it is never mentioned otherwise than as Cole’s Inn.

Another of these worthy landlords was William Hudson, who had leave to keep an ordinary in 1640. From his occupation of baker, he easily stepped into the congenial employment of innkeeper. Hudson was among the earliest settlers of Boston, and for many years is found most active in town affairs. His name is on the[Pg 21] list of those who were admitted freemen of the Colony, in May, 1631. As his son William also followed the same calling, the distinction of Senior and Junior becomes necessary when speaking of them.

Hudson’s house is said to have stood on the ground now occupied by the New England Bank, which, if true, would make this the most noted of tavern stands in all New England, or rather in all the colonies, as the same site afterward became known as the Bunch of Grapes. We shall have much occasion to notice it under that title. In Hudson’s time the appearance of things about this locality was very different from what is seen to-day. All the earlier topographical features have been obliterated. Then the tide flowed nearly up to the tavern door, so making the spot a landmark of the ancient shore line as the first settlers had found it. Even so simple a statement as this will serve to show us how difficult is the task of fixing, with approximate accuracy, residences or sites on the water front, going as far back as the original occupants of the soil.

Next in order of time comes the house called the King’s Arms. This celebrated inn stood at the head of the dock, in what is now Dock Square. Hugh Gunnison, victualler, kept a “cooke’s shop” in his dwelling there some time before 1642, as he was then allowed to sell beer. The next year he humbly prayed the court for leave “to draw the wyne which was spent in his house,” in the room of having his customers get it elsewhere, and then come into his place the worse for liquor,—a[Pg 22] proceeding which he justly thought unfair as well as unprofitable dealing. He asks this favor in order that “God be not dishonored nor his people grieved.”

We know that Gunnison was favored with the custom of the General Court, because we find that body voting to defray the expenses incurred for being entertained in his house “out of ye custom of wines or ye wampum of ye Narragansetts.”

Gunnison’s house presently took the not always popular name of the King’s Arms, which it seems to have kept until the general overturning of thrones in the Old Country moved the Puritan rulers to order the taking down of the King’s arms, and setting up of the State’s in their stead; for, until the restoration of the Stuarts, the tavern is the same, we think, known as the State’s Arms. It then loyally resumed its old insignia again. Such little incidents show us how taverns frequently denote the fluctuation of popular opinion.

As Gunnison’s bill of fare has not come down to us, we are at a loss to know just how the colonial fathers fared at his hospitable board; but so long as the ‘treat’ was had at the public expense we cannot doubt that the dinners were quite as good as the larder afforded, or that full justice was done to the contents of mine host’s cellar by those worthy legislators and lawgivers.

When Hugh Gunnison sold out the King’s Arms to Henry Shrimpton and others, in 1651, for £600 sterling, the rooms in his house all bore some distinguishing name or title. For instance, one chamber was called[Pg 23] the “Exchange.” We have sometimes wondered whether it was so named in consequence of its use by merchants of the town as a regular place of meeting. The chamber referred to was furnished with “one half-headed bedstead with blew pillars.” There was also a “Court Chamber,” which, doubtless, was the one assigned to the General Court when dining at Gunnison’s. Still other rooms went by such names as the “London” and “Star.” The hall contained three small rooms, or stalls, with a bar convenient to it. This room was for public use, but the apartments upstairs were for the “quality” alone, or for those who paid for the privilege of being private. All remember how, in “She Stoops to Conquer,” Miss Hardcastle is made to say: “Attend the Lion, there!—Pipes and tobacco for the Angel!—The Lamb has been outrageous this half hour!”

The Castle Tavern was another house of public resort, kept by William Hudson, Jr., at what is now the upper corner of Elm Street and Dock Square. Just at what time this noted tavern came into being is a matter extremely difficult to be determined; but, as we find a colonial order billeting soldiers in it in 1656, we conclude it to have been a public inn at that early day. At this time Hudson is styled lieutenant. If Whitman’s records of the Artillery Company be taken as correct, the younger Hudson had seen service in the wars. With “divers other of our best military men,” he had crossed the ocean to take service in the Parliamentary forces, in which he held the rank of ensign, returning home to[Pg 24] New England, after an absence of two years, to find his wife publicly accused of faithlessness to her marriage vows.

The presence of these old inns at the head of the town dock naturally points to that locality as the business centre, and it continued to hold that relation to the commerce of Boston until, by the building of wharves and piers, ships were enabled to come up to them for the purpose of unloading. Before that time their cargoes were landed in boats and lighters. Far back, in the beginning of things, when everything had to be transported by water to and from the neighboring settlements, this was naturally the busiest place in Boston. In time Dock Square became, as its name indicates, a sort of delta for the confluent lanes running down to the dock below it.

Here, for a time, was centred all the movement to and from the shipping, and, we may add, about all the commerce of the infant settlement. Naturally the vicinity was most convenient for exposing for sale all sorts of merchandise as it was landed, which fact soon led to the establishment of a corn market on one side of the dock and a fish market on the other side.

The Royal Exchange stood on the site of the Merchants’ Bank, in State Street. In this high-sounding name we find a sure sign that the town had outgrown its old traditions and was making progress toward more citified ways. As time wore on a town-house had been built in the market-place. Its ground floor was[Pg 25] purposely left open for the citizens to walk about, discuss the news, or bargain in. In the popular phrase, they were said to meet “on ’change,” and thereafter this place of meeting was known as the Exchange, which name the tavern and lane soon took to themselves as a natural right.

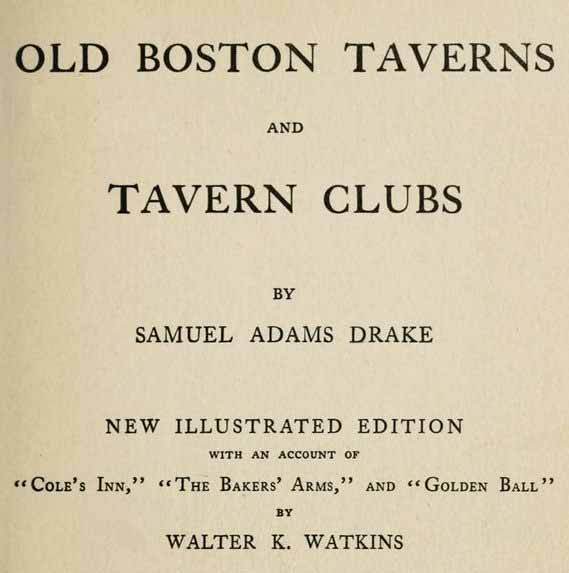

THE ROYAL EXCHANGE TAVERN (Merchants Bank site, State Street)

The tall white building, mail coach just leaving

A glance at the locality in question shows the choice to have been made with a shrewd eye to the future. For example: the house fronted upon the town market-place, where, on stated days, fairs or markets for the sale of country products were held. On one side the tavern was flanked by the well-trodden lane which led to the town dock. From daily chaffering in a small way, those who wished to buy or sell came to meet here regularly. It also became the place for popular gatherings,—on such occasions of ceremony as the publishing of proclamations, mustering of troops, or punishment of criminals,—all of which vindicates its title to be called the heart of the little commonwealth.

Indeed, on this spot the pulse of its daily life beat with ever-increasing vigor. Hither came the country people, with their donkeys and panniers. Here in the open air they set up their little booths to tempt the town’s folk with the display of fresh country butter, cheese and eggs, fruits or vegetables. Here came the citizen, with his basket on his arm, exchanging his stock of news or opinions as he bargained for his dinner, and so caught the drift of popular sentiment beyond his own chimney-corner.

[Pg 26]To loiter a little longer at the sign of the Royal Exchange, which, by all accounts, always drew the best custom of the town, we find that, as long ago as Luke Vardy’s time, it was a favorite resort of the Masonic fraternity, Vardy being a brother of the order. According to a poetic squib of the time,—

“’Twas he who oft dispelled their sadness,

And filled the breth’ren’s hearts with gladness.”

After the burning of the town-house, near by, in the winter of 1747, had turned the General Court out of doors, that body finished its sessions at Vardy’s; nor do we find any record of legislation touching Luke’s taproom on that occasion.

Vardy’s was the resort of the young bloods of the town, who spent their evenings in drinking, gaming, or recounting their love affairs. One July evening, in 1728, two young men belonging to the first families in the province quarreled over their cards or wine. A challenge passed. At that time the sword was the weapon of gentlemen. The parties repaired to a secluded part of the Common, stripped for the encounter, and fought it out by the light of the moon. After a few passes one of the combatants, named Woodbridge, received a mortal thrust; the survivor was hurried off by his friends on board a ship, which immediately set sail. This being the first duel ever fought in the town, it naturally made a great stir.

JOSEPH GREEN

Noted Boston merchant and wit, died in England, 1780

| SATIRE ON LUKE TARDY OF THE ROYAL EXCHANGE TAVERN By Joseph Green at a Masonic Meeting, 1749 |

| “Where’s honest Luke,—that cook from London? For without Luke the Lodge is undone; ’Twas he who oft dispelled their sadness. And fill’d the Brethren’s heart with gladness. For them his ample bowls o’erflow’d. His table groan’d beneath its load; For them he stretch’d his utmost art.— Their honours grateful they impart. Luke in return is made a brother, As good and true as any other; And still, though broke with age and wine, Preserves the token and the sign.” —“Entertainments for a Winter’s Evening.” |

We cannot leave the neighborhood without at least[Pg 27] making mention of the Massacre of the 5th of March, 1770, which took place in front of the tavern. It was then a three-story brick house, the successor, it is believed, of the first building erected on the spot and destroyed in the great fire of 1711. On the opposite corner of the lane stood the Royal Custom House, where a sentry was walking his lonely round on that frosty night, little dreaming of the part he was to play in the coming tragedy. With the assault made by the mob on this sentinel, the fatal affray began which sealed the cause of the colonists with their blood. At this time the tavern enjoyed the patronage of the newly arrived British officers of the army and navy as well as of citizens or placemen, of the Tory party, so that its inmates must have witnessed, with peculiar feelings, every incident of that night of terror. Consequently the house with its sign is shown in Revere’s well-known picture of the massacre.

One more old hostelry in this vicinity merits a word from us. Though not going so far back or coming down to so late a date as some of the houses already mentioned, nevertheless it has ample claim not to be passed by in silence.

The Anchor, otherwise the “Blew Anchor,” stood on the ground now occupied by the Globe newspaper building. In early times it divided with the State’s Arms the patronage of the magistrates, who seem to have had a custom, perhaps not yet quite out of date, of adjourning to the ordinary over the way after[Pg 28] transacting the business which had brought them together. So we find that the commissioners of the United Colonies, and even the reverend clergy, when they were summoned to the colonial capital to attend a synod, were usually entertained here at the Anchor.

This fact presupposes a house having what we should now call the latest improvements, or at least possessing some advantages over its older rivals in the excellence of its table or cellarage. When Robert Turner kept it, his rooms were distinguished, after the manner of the old London inns, as the Cross Keys, Green Dragon, Anchor and Castle Chamber, Rose and Sun, Low Room, so making old associations bring in custom.

It was in 1686 that John Dunton, a London bookseller whom Pope lampoons in the “Dunciad,” came over to Boston to do a little business in the bookselling line. The vicinity of the town-house was then crowded with book-shops, all of which drove a thriving trade in printing and selling sermons, almanacs, or fugitive essays of a sort now quite unknown outside of a few eager collectors. The time was a critical one in New England, as she was feeling the tremor of the coming revolt which sent King James into exile; yet to read Dunton’s account of men and things as he thought he saw them, one would imagine him just dropped into Arcadia, rather than breathing the threatening atmosphere of a country that was tottering on the edge of revolution.

But it is to him, at any rate, that we are indebted for a portrait of the typical landlord,—one whom we[Pg 29] feel at once we should like to have known, and, having known, to cherish in our memory. With a flourish of his goose-quill Dunton introduces us to George Monk, landlord of the Anchor, who, somehow, reminds us of Chaucer’s Harry Bailly, and Ben Jonson’s Goodstock. And we more than suspect from what follows that Dunton had tasted the “Anchor” Madeira, not only once, but again.

JOHN DUNTON, Bookseller, 1659-1733

George Monk, mine host of the Anchor, Dunton tells us, was “a person so remarkable that, had I not been acquainted with him, it would be a hard matter to make any New England man believe that I had been in Boston; for there was no one house in all the town more noted, or where a man might meet with better accommodation. Besides he was a brisk and jolly man, whose conversation was coveted by all his guests as the life and spirit of the company.”

In this off-hand sketch we behold the traditional publican, now, alas! extinct. Gossip, newsmonger, banker, pawnbroker, expediter of men or effects, the intimate association so long existing between landlord and public under the old régime everywhere brought about a still closer one among the guild itself, so establishing a network of communication coextensive with all the great routes from Maine to Georgia.

Situated just “around the corner” from the council-chamber, the Anchor became, as we have seen, the favorite haunt of members of the government, and so acquired something of an official character and[Pg 30] standing. We have strong reason to believe that, under the mellowing influence of the punch-bowl, those antique men of iron mould and mien could now and then crack a grim jest or tell a story or possibly troll a love-ditty, with grave gusto. At any rate, we find Chief Justice Sewall jotting down in his “Diary” the familiar sentence, “The deputies treated and I treated.” And, to tell the truth, we would much prefer to think of the colonial fathers as possessing even some human frailties rather than as the statues now replacing their living forms and features in our streets.

But now and then we can imagine the noise of great merriment making the very windows of some of these old hostelries rattle again. We learn that the Greyhound was a respectable public house, situated in Roxbury, and of very early date too; for the venerable and saintly Eliot lived upon one side and his pious colleague, Samuel Danforth, on the other. Yet notwithstanding its being, as it were, hedged in between two such eminent pillars of the church, the godly Danforth bitterly complains of the provocation which frequenters of the tavern sometimes tried him withal, and naïvely informs us that, when from his study windows he saw any of the town dwellers loitering there he would go down and “chide them away.”

It is related in the memoirs of the celebrated Indian fighter, Captain Benjamin Church, that he and Captain Converse once found themselves in the neighborhood of a tavern at the South End of Boston. As old comrades[Pg 31] they wished to go in and take a parting glass together; but, on searching their pockets, Church could find only sixpence and Converse not a penny to bless himself with, so they were compelled to forego this pledge of friendship and part with thirsty lips. Going on to Roxbury, Church luckily found an old neighbor of his, who generously lent him money enough to get home with. He tells the anecdote in order to show to what straits the parsimony of the Massachusetts rulers had reduced him, their great captain, to whom the colony owed so much.

The Red Lion, in North Street, was one of the oldest public houses, if not the oldest, to be opened at the North End of the town. It stood close to the waterside, the adjoining wharf and the lane running down to it both belonging to the house and both taking its name. The old Red Lion Lane is now Richmond Street, and the wharf has been filled up, so making identification of the old sites difficult, to say the least. Nicholas Upshall, the stout-hearted Quaker, kept the Red Lion as early as 1654. At his death the land on which tavern and brewhouse stood went to his children. When the persecution of his sect began in earnest, Upshall was thrown into Boston jail, for his outspoken condemnation of the authorities and their rigorous proceedings toward this people. He was first doomed to perpetual imprisonment. A long and grievous confinement at last broke Upshall’s health, if it did not, ultimately, prove the cause of his death.

[Pg 32]The Ship Tavern stood at the head of Clark’s Wharf, or on the southwest corner of North and Clark streets, according to present boundaries. It was an ancient brick building, dating as far back as 1650 at least. John Vyal kept it in 1663. When Clark’s Wharf was built it was the principal one of the town. Large ships came directly up to it, so making the tavern a most convenient resort for masters of vessels or their passengers, and associating it with the locality itself. King Charles’s commissioners lodged at Vyal’s house, when they undertook the task of bringing down the pride of the rulers of the colony a peg. One of them, Sir Robert Carr, pummeled a constable who attempted to arrest him in this house. He afterward refused to obey a summons to answer for the assault before the magistrates, loftily alleging His Majesty’s commission as superior to any local mandate whatever. He thus retaliated Governor Leverett’s affront to the commissioners in keeping his hat on his head when their authority to act was being read to the council. But Leverett was a man who had served under Cromwell, and had no love for the cavaliers or they for him. The commissioners sounded trumpets and made proclamations; but the colony kept on the even tenor of its way, in defiance of the royal mandate, equally regardless of the storm gathering about it, as of the magnitude of the conflict in which it was about to plunge, all unarmed and unprepared.

IN REVOLUTIONARY TIMES.

uch thoroughfares as King Street, just before the Revolution, were filled

with horsemen, donkeys, oxen, and long-tailed trucks, with a sprinkling of

one-horse chaises and coaches of the kind seen in Hogarth’s realistic

pictures of London life. To these should be added the chimney-sweeps,

wood-sawyers, market-women, soldiers, and sailors, who are now quite as

much out of date as the vehicles themselves are. There being no sidewalks,

the narrow footway was protected, here and there, sometimes by posts,

sometimes by an old cannon set upright at the corners, so that the

traveller dismounted from his horse or alighted from coach or chaise at

the very threshold.

uch thoroughfares as King Street, just before the Revolution, were filled

with horsemen, donkeys, oxen, and long-tailed trucks, with a sprinkling of

one-horse chaises and coaches of the kind seen in Hogarth’s realistic

pictures of London life. To these should be added the chimney-sweeps,

wood-sawyers, market-women, soldiers, and sailors, who are now quite as

much out of date as the vehicles themselves are. There being no sidewalks,

the narrow footway was protected, here and there, sometimes by posts,

sometimes by an old cannon set upright at the corners, so that the

traveller dismounted from his horse or alighted from coach or chaise at

the very threshold.

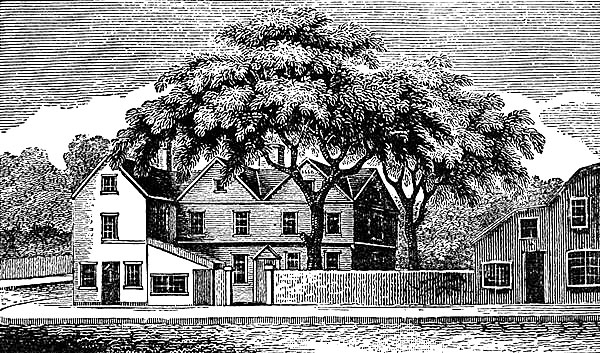

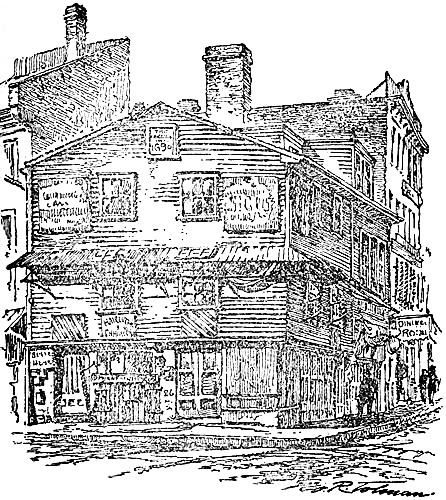

Next in the order of antiquity, as well as fame, to the taverns already named, comes the Bunch of Grapes in King, now State Street. The plain three-story stone building situated at the upper corner of Kilby Street stands where the once celebrated tavern did. Three gilded clusters of grapes dangled temptingly over the door before the eye of the passer-by. Apart from its[Pg 34] palate-tickling suggestions, a pleasant aroma of antiquity surrounds this symbol, so dear to all devotees of Bacchus from immemorial time. In Measure for Measure the clown says, “’Twas in the Bunch of Grapes, where indeed you have a delight to sit, have you not?” And Froth answers, “I have so, because it is an open room and good for winter.”

THE BUNCH OF GRAPES

This house goes back to the year 1712, when Francis Holmes kept it, and perhaps further still, though we do not meet with it under this title before Holmes’s time. From that time, until after the Revolution, it appears to have always been open as a public inn, and, as such, is feelingly referred to by one old traveller as the best punch-house to be found in all Boston.

When the line came to be drawn between conditional loyalty, and loyalty at any rate, the Bunch of Grapes became the resort of the High Whigs, who made it a sort of political headquarters, in which patriotism only passed current, and it was known as the Whig tavern.[Pg 35] With military occupation and bayonet rule, still further intensifying public feeling, the line between Whig and Tory houses was drawn at the threshold. It was then kept by Marston. Cold welcome awaited the appearance of scarlet regimentals or a Tory phiz there; so gentlemen of that side of politics also formed cliques of their own at other houses, in which the talk and the toasts were more to their liking, and where they could abuse the Yankee rebels over their port to their heart’s content.

But, apart from political considerations, one or two incidents have given the Bunch of Grapes a kind of pre-eminence over all its contemporaries, and, therefore, ought not to be passed over when the house is mentioned.

On Monday, July 30, 1733, the first grand lodge of Masons in America was organized here by Henry Price, a Boston tailor, who had received authority from Lord Montague, Grand Master of England, for the purpose.

Again, upon the evacuation of Boston by the royal troops, this house became the centre for popular demonstrations. First, His Excellency, General Washington, was handsomely entertained there. Some months later, after hearing the Declaration read from the balcony of the Town-house, the populace, having thus made their appeal to the King of kings, proceeded to pull down from the public buildings the royal arms which had distinguished them, and, gathering them in a heap in front of the tavern, made a bonfire of them, little imagining,[Pg 36] we think, that the time would ever come when the act would be looked upon as vandalism on their part.

General Stark’s timely victory at Bennington was celebrated with all the more heartiness of enthusiasm in Boston because the people had been quaking with fear ever since the fall of Ticonderoga sent dismay throughout New England. The affair is accurately described in the following letter, written by a prominent actor, and going to show how such things were done in the times that not only tried men’s souls, but would seem also to have put their stomachs to a pretty severe test. The writer says:—

“In consequence of this news we kept it up in high taste. At sundown about one hundred of the first gentlemen of the town, with all the strangers then in Boston, met at the Bunch of Grapes, where good liquors and a side-table were provided. In the street were two brass field-pieces with a detachment of Colonel Craft’s regiment. In the balcony of the Town-house all the fifes and drums of my regiment were stationed. The ball opened with a discharge of thirteen cannon, and at every toast given three rounds were fired and a flight of rockets sent up. About nine o’clock two barrels of grog were brought out into the street for the people that had collected there. It was all conducted with the greatest propriety, and by ten o’clock every man was at his home.”

Shortly after this General Stark himself arrived in town and was right royally entertained here, at that time[Pg 37] presenting the trophies now adorning the Senate Chamber. On his return from France in 1780 Lafayette was also received at this house with all the honors, on account of having brought the news that France had at last cast her puissant sword into the trembling balance of our Revolutionary contest.

But the important event with which the Bunch of Grapes is associated is, not the reception of a long line of illustrious guests, but the organization, by a number of continental officers, of the Ohio Company, under which the settlement of that great State began in earnest, at Marietta. The leading spirit in this first concerted movement of New England toward the Great West was General Rufus Putnam, a cousin of the more distinguished officer of Revolutionary fame.

Taking this house as a sample of the best that the town could afford at the beginning of the century, we should probably find a company of about twenty persons assembled at dinner, who were privileged to indulge in as much familiar chat as they liked. No other formalities were observed than such as good breeding required. Two o’clock was the hour at which all the town dined. The guests were called together by the ringing of a bell in the street. They were served with salmon in season, veal, beef, mutton, fowl, ham, vegetables, and pudding, and each one had his pint of Madeira set before him. The carving was done at the table in the good old English way, each guest helping himself to what he liked best. Five shillings per day was the usual charge, which was[Pg 38] certainly not an exorbitant one. In half an hour after the cloth was removed the table was usually deserted.

The British Coffee-House was one of the first inns to take to itself the newly imported title. It stood on the site of the granite building numbered 66 State Street, and was, as its name implies, as emphatically the headquarters of the out-and-out loyalists as the Bunch of Grapes, over the way, was of the unconditional Whigs. A notable thing about it was the performance there in 1750, probably by amateurs, of Otway’s “Orphan,” an event which so outraged public sentiment as to cause the enactment of a law prohibiting the performance of stage plays under severe penalties.

Perhaps an even more notable occurrence was the formation in this house of the first association in Boston taking to itself the distinctive name of a Club. The Merchants’ Club, as it was called, met here as early as 1751. Its membership was not restricted to merchants, as might be inferred from its title, though they were possibly in a majority, but included crown officers, members of the bar, military and naval officers serving on the station, and gentlemen of high social rank of every shade of opinion. No others were eligible to membership.

Up to a certain time this club, undoubtedly, represented the best culture, the most brilliant wit, and most delightful companionship that could be brought together in all the colonies; but when the political sky grew dark the old harmony was at an end, and a division[Pg 39] became inevitable, the Whigs going over to the Bunch of Grapes, and thereafter taking to themselves the name of the Whig Club.[1]

Under date of 1771, John Adams notes down in his Diary this item: “Spent the evening at Cordis’s, in the front room towards the Long Wharf, where the Merchants’ Club has met these twenty years. It seems there is a schism in that church, a rent in that garment.” Cordis was then the landlord.[2]

Social and business meetings of the bar were also held at the Coffee-House, at one of which Josiah Quincy, Jr. was admitted. By and by the word “American” was substituted for “British” on the Coffee-House sign, and for some time it flourished under its new title of the American Coffee-House.

But before the clash of opinions had brought about[Pg 40] the secession just mentioned, the best room in this house held almost nightly assemblages of a group of patriotic men, who were actively consolidating all the elements of opposition into a single force. Not inaptly they might be called the Old Guard of the Revolution. The principals were Otis, Cushing, John Adams, Pitts, Dr. Warren, and Molyneux. Probably no minutes of their proceedings were kept, for the excellent reason that they verged upon, if they did not overstep, the treasonable.

His talents, position at the bar, no less than intimate knowledge of the questions which were then so profoundly agitating the public mind, naturally made Otis the leader in these conferences, in which the means for counteracting the aggressive measures then being put in force by the ministry formed the leading topic of discussion. His acute and logical mind, mastery of public law, intensity of purpose, together with the keen and biting satire which he knew so well how to call to his aid, procured for Otis the distinction of being the best-hated man on the Whig side of politics, because he was the one most feared. Whether in the House, the court-room, the taverns, or elsewhere, Otis led the van of resistance. In military phrase, his policy was the offensive-defensive. He was no respecter of ignorance in high places. Once when Governor Bernard sneeringly interrupted Otis to ask him who the authority was whom he was citing, the patriot coldly replied, “He is a very eminent jurist, and none the less so for being unknown to your Excellency.”

[Pg 41]It was in the Coffee-House that Otis, in attempting to pull a Tory nose, was set upon and so brutally beaten by a place-man named Robinson, and his friends, as to ultimately cause the loss of his reason and final withdrawal from public life. John Adams says he was “basely assaulted by a well-dressed banditti, with a commissioner of customs at their head.” What they had never been able to compass by fair argument, the Tories now succeeded in accomplishing by brute force, since Otis was forever disqualified from taking part in the struggle which he had all along foreseen was coming,—and which, indeed, he had done more to bring about than any single man in the colonies.

Connected with this affair is an anecdote which we think merits a place along with it. It is related by John Adams, who was an interested listener. William Molyneux had a petition before the legislature which did not succeed to his wishes, and for several evenings he had wearied the company with his complaints of services, losses, sacrifices, etc., always winding up with saying, “That a man who has behaved as I have should be treated as I am is intolerable,” with much more to the same effect. Otis had said nothing, but the whole club were disgusted and out of patience, when he rose from his seat with the remark, “Come, come, Will, quit this subject, and let us enjoy ourselves. I also have a list of grievances; will you hear it?” The club expected some fun, so all cried out, “Ay! ay! let us hear your list.”

[Pg 42]“Well, then, in the first place, I resigned the office of advocate-general, which I held from the crown, which produced me—how much do you think?”

“A great deal, no doubt,” said Molyneux.

“Shall we say two hundred sterling a year?”

“Ay, more, I believe,” said Molyneux.

“Well, let it be two hundred. That, for ten years, is two thousand. In the next place, I have been obliged to relinquish the greater part of my business at the bar. Will you set that at two hundred pounds more?”

“Oh, I believe it much more than that!” was the answer.

“Well, let it be two hundred. This, for ten years, makes two thousand. You allow, then, I have lost four thousand pounds sterling?”

“Ay, and more too,” said Molyneux. Otis went on: “In the next place, I have lost a hundred friends, among whom were men of the first rank, fortune, and power in the province. At what price will you estimate them?”

“D—n them!” said Molyneux, “at nothing. You are better off without them than with them.”

A loud laugh from the company greeted this sally.

“Be it so,” said Otis. “In the next place, I have made a thousand enemies, among whom are the government of the province and the nation. What do you think of this item?”

“That is as it may happen,” said Molyneux, reflectively.

[Pg 43]“In the next place, you know I love pleasure, but I have renounced pleasure for ten years. What is that worth?”

“No great matter: you have made politics your amusement.”

A hearty laugh.

“In the next place, I have ruined as fine health as nature ever gave to man.”

“That is melancholy indeed; there is nothing to be said on that point,” Molyneux replied.

“Once more,” continued Otis, holding down his head before Molyneux, “look upon this head!” (there was a deep, half-closed scar, in which a man might lay his finger)—“and, what is worse my friends think I have a monstrous crack in my skull.”

This made all the company look grave, and had the desired effect of making Molyneux who was really a good companion, heartily ashamed of his childish complaints.

Another old inn of assured celebrity was the Cromwell’s Head, in School Street. This was a two-story wooden building of venerable appearance, conspicuously displaying over the footway a grim likeness of the Lord Protector, it is said much to the disgust of the ultra royalists, who, rather than pass underneath it, habitually took the other side of the way. Indeed, some of the hot-headed Tories were for serving Cromwell’s Head as that man of might had served their martyr king’s. So, when the town came under martial[Pg 44] law, mine host Brackett, whose family kept the house for half a century or more, had to take down his sign, and conceal it until such time as the “British hirelings” should have made their inglorious exit from the town.

After Braddock’s crushing defeat in the West, a young Virginian colonel, named George Washington, was sent by Governor Dinwiddie to confer with Governor Shirley, who was the great war governor of his day, as Andrew was of our own, with the difference that Shirley then had the general direction of military affairs, from the Ohio to the St. Lawrence, pretty much in his own hands. Colonel Washington took up his quarters at Brackett’s, little imagining, perhaps, that twenty years later he would enter Boston at the head of a victorious republican army, after having quartered his troops in Governor Shirley’s splendid mansion.

Major-General the Marquis Chastellux, of[Pg 45] Rochambeau’s auxiliary army, also lodged at the Cromwell’s Head when he was in Boston in 1782. He met there the renowned Paul Jones, whose excessive vanity led him to read to the company in the coffee-room some verses composed in his own honor, it is said, by Lady Craven.

From the tavern of the gentry we pass on to the tavern of the mechanics, and of the class which Abraham Lincoln has forever distinguished by the title of the common people.

Among such houses the Salutation, which stood at the junction of Salutation with North Street, is deserving of a conspicuous place. Its vicinity to the shipyards secured for it the custom of the sturdy North End shipwrights, caulkers, gravers, sparmakers, and the like,—a numerous body, who, while patriots to the backbone, were also quite clannish and independent in their feelings and views, and consequently had to be managed with due regard to their class prejudices, as in politics they always went in a body. Shrewd politicians, like Samuel Adams, understood this. Governor Phips owed his elevation to it. As a body, therefore, these mechanics were extremely formidable, whether at the polls or in carrying out the plans of their leaders. To their meetings the origin of the word caucus is usually referred, the word itself undoubtedly having come into familiar use as a short way of saying caulkers’ meetings.

The Salutation became the point of fusion between[Pg 46] leading Whig politicians and the shipwrights. More than sixty influential mechanics attended the first meeting, called in 1772, at which Dr. Warren drew up a code of by-laws. Some leading mechanic, however, was always chosen to be the moderator. The “caucus,” as it began to be called, continued to meet in this place until after the destruction of the tea, when, for greater secrecy, it became advisable to transfer the sittings to another place, and then the Green Dragon, in Union Street, was selected.

The Salutation had a sign of the sort that is said to tickle the popular fancy for what is quaint or humorous. It represented two citizens, with hands extended, bowing and scraping to each other in the most approved fashion. So the North-Enders nicknamed it “The Two Palaverers,” by which name it was most commonly known. This house, also, was a reminiscence of the Salutation in Newgate Street, London, which was the favorite haunt of Lamb and Coleridge.

The Green Dragon will probably outlive all its contemporaries in the popular estimation. In the first place a mural tablet, with a dragon sculptured in relief, has been set in the wall of the building that now stands upon some part of the old tavern site. It is the only one of the old inns to be so distinguished. Its sign was the fabled dragon, in hammered metal, projecting out above the door, and was probably the counterpart of the Green Dragon in Bishopsgate Street, London.

THE GREEN DRAGON TAVERN

As a public house this one goes back to 1712, when[Pg 47] Richard Pullen kept it; and we also find it noticed, in 1715, as a place for entering horses to be run for a piece of plate of the value of twenty-five pounds. In passing, we may as well mention the fact that Revere Beach was the favorite race-ground of that day. The house was well situated for intercepting travel to and from the northern counties.

THE GREEN DRAGON.

To resume the historical connection between the Salutation and Green Dragon, its worthy successor, it appears that Dr. Warren continued to be the commanding figure after the change of location; and, if he was not already the popular idol, he certainly came little short of it, for everything pointed to him as the coming leader whom the exigency should raise up. Samuel Adams was popular in a different way. He was cool, far-sighted, and persistent, but he certainly lacked the magnetic quality. Warren was much younger, far more impetuous and aggressive,—in short, he possessed all the more brilliant qualities for leadership which Adams lacked. Moreover, he was a fluent and effective speaker, of[Pg 48] graceful person, handsome, affable, with frank and winning manners, all of which added no little to his popularity. Adams inspired respect, Warren confidence. As Adams himself said, he belonged to the “cabinet,” while Warren’s whole make-up as clearly marked him for the field.

In all the local events preliminary to our revolutionary struggle, this Green Dragon section or junto constituted an active and positive force. It represented the muscle of the Revolution. Every member was sworn to secrecy, and of them all one only proved recreant to his oath.

These were the men who gave the alarm on the eve of the battle of Lexington, who spirited away cannon under General Gage’s nose, and who in so many instances gallantly fought in the ranks of the republican army. Wanting a man whom he could fully trust, Warren early singled out Paul Revere for the most important services. He found him as true as steel. A peculiar kind of friendship seems to have sprung up between the two, owing, perhaps, to the same daring spirit common to both. So when Warren sent word to Revere that he must instantly ride to Lexington or all would be lost, he knew that, if it lay in the power of man to do it, the thing would be done.

Besides the more noted of the tavern clubs there were numerous private coteries, some exclusively composed of politicians, others more resembling our modern debating societies than anything else. These clubs usually[Pg 49] met at the houses of the members themselves, so exerting a silent influence on the body politic. The non-importation agreement originated at a private club in 1773. But all were not on the patriot side. The crown had equally zealous supporters, who met and talked the situation over without any of the secrecy which prudence counselled the other side to use in regard to their proceedings. Some associations endeavored to hold the balance between the factions by standing neutral. They deprecated the encroachments of the mother-country, but favored passive obedience. Dryden has described them:

“Not Whigs nor Tories they, nor this nor that,

Nor birds nor beasts, but just a kind of bat,—

A twilight animal, true to neither cause,

With Tory wings but Whiggish teeth and claws.”

It should be mentioned that Gridley, the father of the Boston Bar, undertook, in 1765, to organize a law club, with the purpose of making head against Otis, Thatcher, and Auchmuty. John Adams and Fitch were Gridley’s best men. They met first at Ballard’s, and subsequently at each other’s chambers; their “sodality,” as they called it, being for professional study and advancement. Gridley, it appears, was a little jealous of his old pupil, Otis, who had beaten him in the famous argument on the Writs of Assistance. Mention is also made of a club of which Daniel Leonard (Massachusettensis), John Lowell, Elisha Hutchinson, Frank Dana,[Pg 50] and Josiah Quincy were members. Similar clubs also existed in most of the principal towns in New England.

The Sons of Liberty adopted the name given by Colonel Barré to the enemies of passive obedience in America. They met in the counting-room of Chase and Speakman’s distillery, near Liberty Tree.[3] Mackintosh, the man who led the mob in the Stamp Act riots, is doubtless the same person who assisted in throwing the tea overboard. We hear no more of him after this. The “Sons” were an eminently democratic organization, as few except mechanics were members. Among them were men like Avery, Crafts, and Edes the printer. All attained more or less prominence. Edes continued to print the Boston Gazette long after the Revolution. During Bernard’s administration he was offered the whole of the government printing, if he would stop his opposition to the measures of the crown. He refused the bribe, and his paper was the only one printed in America without a stamp, in direct violation of an Act of Parliament. The “Sons” pursued their measures with such vigor as to create much alarm among the loyalists, on whom the Stamp Act riots had made a lasting impression. Samuel Adams is thought to have influenced their proceedings more than any other of the leaders. It was by no means a league of ascetics, who had resolved to mortify the flesh, as punch and tobacco were liberally used to stimulate the deliberations.

THE LIBERTY TREE

[Pg 51]No important political association outlived the beginning of hostilities. All the leaders were engaged in the military or civil service on one or the other side. Of the circle that met at the Merchants’ three were members of the Philadelphia Congress of 1774, one was president of the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts, the career of two was closed by death, and that of Otis by insanity.

SIGNBOARD HUMOR.

nother tavern sign, though of later date, was that of the Good Woman, at

the North End. This Good Woman was painted without a head.

nother tavern sign, though of later date, was that of the Good Woman, at

the North End. This Good Woman was painted without a head.

Still another board had painted on it a bird, a tree, a ship, and a foaming can, with the legend,—

“This is the bird that never flew,

This is the tree which never grew,

This is the ship which never sails,

This is the can which never fails.”

[Pg 53]The Dog and Pot, Turk’s Head, Tun and Bacchus, were also old and favorite emblems. Some of the houses which swung these signs were very quaint specimens of our early architecture. So, also, the signs themselves were not unfrequently the work of good artists. Smibert or Copley may have painted some of them. West once offered five hundred dollars for a red lion he had painted for a tavern sign.

DOG AND POT.

Not a few boards displayed a good deal of ingenuity and mother-wit, which was not without its effect, especially upon thirsty Jack, who could hardly be expected to resist such an appeal as this one of the Ship in Distress:

“With sorrows I am compass’d round;

Pray lend a hand, my ship’s aground.”

We hear of another signboard hanging out at the extreme South End of the town, on which was depicted a globe with a man breaking through the crust, like a[Pg 54] chicken from its shell. The man’s nakedness was supposed to betoken extreme poverty.

So much for the sign itself. The story goes that early one morning a continental regiment was halted in front of the tavern, after having just made a forced march from Providence. The men were broken down with fatigue, bespattered with mud, famishing from hunger. One of these veterans doubtless echoed the sentiments of all the rest when he shouted out to the man on the sign, “’List, darn ye! ’List, and you’ll get through this world fast enough!”

“HOW SHALL I GET THROUGH THIS WORLD?”

In time of war the taverns were favorite recruiting rendezvous. Those at the waterside were conveniently situated for picking up men from among the idlers who frequented the tap-rooms. Under date of 1745, when we were at war with France, bills were posted in the town giving notice to all concerned that, “All gentlemen sailors and others, who are minded to go on a cruise off of[Pg 55] Cape Breton, on board the brigantine Hawk, Captain Philip Bass commander, mounting fourteen carriage, and twenty swivel guns, going in consort with the brigantine Ranger, Captain Edward Fryer commander, of the like force, to intercept the East India, South Sea, and other ships bound to Cape Breton, let them repair to the Widow Gray’s at the Crown Tavern, at the head of Clark’s Wharf, to go with Captain Bass, or to the Vernon’s Head, Richard Smith’s, in King Street, to go in the Ranger.” “Gentlemen sailors” is a novel sea-term that must have tickled an old salt’s fancy amazingly.

The following notice, given at the same date in the most public manner, is now curious reading. “To be sold, a likely negro or mulatto boy, about eleven years of age.” This was in Boston.

The Revolution wrought swift and significant change in many of the old, favorite signboards. Though the idea remained the same, their symbolism was now put to a different use. Down came the king’s and up went the people’s arms. The crowns and sceptres, the lions and unicorns, furnished fuel for patriotic bonfires or were painted out forever. With them disappeared the last tokens of the monarchy. The crown was knocked into a cocked-hat, the sceptre fell at the unsheathing of the sword. The heads of Washington and Hancock, Putnam and Lee, Jones and Hopkins, now fired the martial heart instead of Vernon, Hawk, or Wolfe. Allegiance to old and cherished traditions was swept away as ruthlessly as if it were in truth but the[Pg 56] reflection of that loyalty which the colonists had now thrown off forever. They had accepted the maxim, that, when a subject draws his sword against his king, he should throw away the scabbard.

Such acts are not to be referred to the fickleness of popular favor which Horace Walpole has moralized upon, or which the poet satirizes in the lines,—

“Vernon, the Butcher Cumberland, Wolfe, Hawke,

Prince Ferdinand, Granby, Burgoyne, Keppell, Howe,

Evil and good have had their tithe of talk,

And filled their sign-post then like Wellesly now.”

Rather should we credit it to that genuine and impassioned outburst of patriotic feeling which, having turned royalty out of doors, indignantly tossed its worthless trappings into the street after it.

Not a single specimen of the old-time hostelries now remains in Boston. All is changed. The demon demolition is everywhere. Does not this very want of permanence suggest, with much force, the need of perpetuating a noted house or site by some appropriate memorial? It is true that a beginning has been made in this direction, but much more remains to be done. In this way, a great deal of curious and valuable information may be picked up in the streets, as all who run may read. It has been noticed that very few pass by such memorials without stopping to read the inscriptions. Certainly, no more popular method of teaching history could well be devised. This being done, on a liberal scale, the[Pg 57] city would still hold its antique flavor through the records everywhere displayed on the walls of its buildings, and we should have a home application of the couplet:

“Oh, but a wit can study in the streets,

And raise his mind above the mob he meets.”

APPENDIX.

BOSTON TAVERNS TO THE YEAR 1800.

he Anchor, or Blue Anchor. Robert Turner, vintner, came into possession

of the estate (Richard Fairbanks’s) in 1652, died in 1664, and was

succeeded in the business by his son John, who continued it till his own

death in 1681; Turner’s widow married George Monck, or Monk, who kept the

Anchor until his decease in 1698; his widow carried on the business till

1703, when the estate probably ceased to be a tavern. The house was

destroyed in the great fire of 1711. The old and new Globe buildings stand

on the site. [See communication of William R. Bagnall in Boston Daily

Globe of April 2, 1885.] Committees of the General Court used to meet

here. (Hutchinson Coll., 345, 347.)

he Anchor, or Blue Anchor. Robert Turner, vintner, came into possession

of the estate (Richard Fairbanks’s) in 1652, died in 1664, and was

succeeded in the business by his son John, who continued it till his own

death in 1681; Turner’s widow married George Monck, or Monk, who kept the

Anchor until his decease in 1698; his widow carried on the business till

1703, when the estate probably ceased to be a tavern. The house was

destroyed in the great fire of 1711. The old and new Globe buildings stand

on the site. [See communication of William R. Bagnall in Boston Daily

Globe of April 2, 1885.] Committees of the General Court used to meet

here. (Hutchinson Coll., 345, 347.)

Admiral Vernon, or Vernon’s Head, corner of State Street and Merchants’ Row. In 1743, Peter Faneuil’s warehouse was opposite. Richard Smith kept it in 1745, Mary Bean in 1775; its sign was a portrait of the admiral.

American Coffee-House. See British Coffee-House.

Black Horse, in Prince Street, formerly Black Horse Lane, so named from the tavern as early as 1698.

Brazen-Head. In Old Cornhill. Though not a tavern, memorable as the place where the Great Fire of 1760 originated.

Bull, lower end of Summer Street, north side; demolished 1833 to make room “for the new street from Sea to[Pg 62] Broad,” formerly Flounder Lane, now Atlantic Avenue. It was then a very old building. Bull’s Wharf and Lane named for it.

British Coffee-House, mentioned in 1762. John Ballard kept it. Cord Cordis, in 1771.

Bunch of Grapes. Kept by Francis Holmes, 1712; William Coffin, 1731-33; Edward Lutwych, 1733; Joshua Barker, 1749; William Wetherhead, 1750; Rebecca Coffin, 1760; Joseph Ingersoll, 1764-72. [In 1768 Ingersoll also had a wine-cellar next door.] Captain John Marston was landlord 1775-78; William Foster, 1782; Colonel Dudley Colman, 1783; James Vila, 1789, in which year he removed to Concert Hall; Thomas Lobdell, 1789. Trinity Church was organized in this house. It was often described as being at the head of Long Wharf.

Castle Tavern, afterward the George Tavern. Northeast by Wing’s Lane (Elm Street), front or southeast by Dock Square. For an account of Hudson’s marital troubles, see Winthrop’s New England, II. 249. Another house of the same name is mentioned in 1675 and 1693. A still earlier name was the “Blew Bell,” 1673. It was in Mackerel Lane (Kilby Street), corner of Liberty Square.

Cole’s Inn. See the referred-to deed in Proc. Am. Ant. Soc., VII. p. 51. For the episode of Lord Leigh consult Old Landmarks of Boston, p. 109.

Cromwell’s Head, by Anthony Brackett, 1760; by his widow, 1764-68; later by Joshua Brackett. A two-story wooden house advertised to be sold, 1802.

Crown Coffee-House. First house on Long Wharf. Thomas Selby kept it 1718-24; Widow Anna Swords, 1749; then the property of Governor Belcher; Belcher sold to Richard Smith, innholder, who in 1751 sold to Robert Sherlock.

Crown Tavern. Widow Day’s, head of Clark’s Wharf; rendezvous for privateersmen in 1745.

THE CROWN COFFEE HOUSE (Site of Fidelity Trust Building)

[Pg 63]Cross Tavern, corner of Cross and Ann Streets, 1732; Samuel Mattocks advertises, 1729, two young bears “very tame” for sale at the Sign of the Cross. Cross Street takes its name from the tavern. Perhaps the same as the Red Cross, in Ann Street, mentioned in 1746, and then kept by John Osborn. Men who had enlisted for the Canada expedition were ordered to report there.

Dog and Pot, at the head of Bartlett’s Wharf in Ann (North) Street, or, as then described, Fish Street. Bartlett’s Wharf was in 1722 next northeast of Lee’s shipyard.

Concert Hall was not at first a public house, but was built for, and mostly used as, a place for giving musical entertainments, balls, parties, etc., though refreshments were probably served in it by the lessee. A “concert of musick” was advertised to be given there as early as 1755. (See Landmarks of Boston.) Thomas Turner had a dancing and fencing academy there in 1776. As has been mentioned, James Vila took charge of Concert Hall in 1789. The old hall, which formed the second story, was high enough to be divided into two stories when the building was altered by later owners. It was of brick, and had two ornamental scrolls on the front, which were removed when the alterations were made.

Great Britain Coffee-House, Ann Street, 1715. The house of Mr. Daniel Stevens, Ann Street, near the drawbridge. There was another house of the same name in Queen (Court) Street, near the Exchange, in 1713, where “superfine bohea, and green tea, chocolate, coffee-powder, etc.,” were advertised.

George, or St. George, Tavern, on the Neck, near Roxbury line. (See Landmarks of Boston.) Noted as early as 1721. Simon Rogers kept it 1730-34. In 1769 Edward Bardin took it and changed the name to the King’s Arms. Thomas Brackett was landlord in 1770.[Pg 64] Samuel Mears, later. During the siege of 1775 the tavern was burnt by the British, as it covered our advanced line. It was known at that time by its old name of the George.

Golden Ball. Loring’s Tavern, Merchants’ Row, corner of Corn Court, 1777. Kept by Mrs. Loring in 1789.

General Wolfe, Town Dock, north side of Faneuil Hall, 1768. Elizabeth Coleman offers for sale utensils of Brew-House, etc., 1773.

Green Dragon, also Freemason’s Arms. By Richard Pullin, 1712; by Mr. Pattoun, 1715; Joseph Kilder, 1734, who came from the Three Cranes, Charlestown. John Cary was licensed to keep it in 1769; Benjamin Burdick, 1771, when it became the place of meeting of the Revolutionary Club. St. Andrews Lodge of Freemasons bought the building before the Revolution, and continued to own it for more than a century. See p. 46.

Hancock House, Corn Court; sign has Governor Hancock’s portrait,—a wretched daub; said to have been the house in which Louis Philippe lodged during his short stay in Boston.

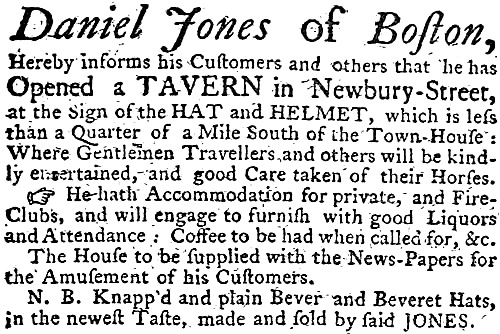

Hat and Helmet, by Daniel Jones; less than a quarter of a mile south of the Town-House.

Indian Queen, Blue Bell, and —— stood on the site of the Parker Block, Washington Street, formerly Marlborough Street. Nathaniel Bishop kept it in 1673. After stages begun running into the country, this house, then kept by Zadock Pomeroy, was a regular starting-place for the Concord, Groton, and Leominster stages. It was succeeded by the Washington Coffee-House. The Indian Queen, in Bromfield Street, was another noted stage-house, though not of so early date. Isaac Trask, Nabby, his widow, Simeon Boyden, and Preston Shepard kept it. The Bromfield House succeeded it, on the Methodist Book Concern site.

BOSTON NEWS-LETTER, FEB. 15, 1770

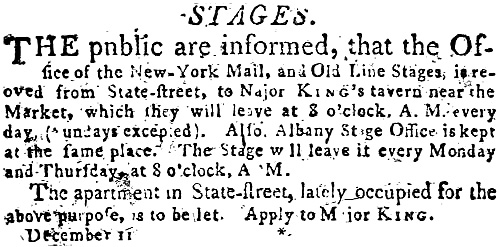

COLUMBIAN CENTINEL. DEC. 11, 1799

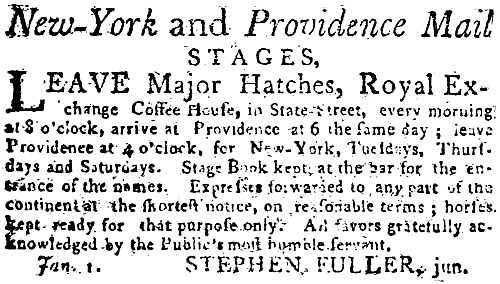

COLUMBIAN CENTINEL, JAN. 1, 1800

JULIEN HOUSE.

Julien’s Restorator, corner of Congress and Milk streets. One of the most ancient buildings in Boston, when taken down in 1824, it having escaped the great fire of 1759. It stood in a grass-plot, fenced in from the street. It was a private dwelling until 1794. Then Jean Baptiste Julien opened in it the first public eating-house to be established in Boston, with the distinctive title of “Restorator,”—a crude attempt to turn the French word restaurant into English. Before this time such places had always been called cook-shops. Julien was a Frenchman, who, like many of his countrymen, took refuge in America during the Reign of Terror. His soups soon became famous among the gourmands of the town, while the novelty of his cuisine attracted custom. He was familiarly nicknamed the “Prince of Soups.” At Julien’s[Pg 66] death, in 1805, his widow succeeded him in the business, she carrying it on successfully for ten years. The following lines were addressed to her successor, Frederick Rouillard:

JULIEN’S RESTORATOR.

I knew by the glow that so rosily shone

Upon Frederick’s cheeks, that he lived on good cheer;

And I said, “If there’s steaks to be had in the town,

The man who loves venison should look for them here.”

’Twas two; and the dinners were smoking around,

The cits hastened home at the savory smell,

And so still was the street that I heard not a sound

But the barkeeper ringing the Coffee-House bell.

“And here in the cosy Old Club,”[4] I exclaimed,

“With a steak that was tender, and Frederick’s best wine,

While under my platter a spirit-blaze flamed,

How long could I sit, and how well could I dine!

“By the side of my venison a tumbler of beer

Or a bottle of sherry how pleasant to see,

And to know that I dined on the best of the deer,

That never was dearer to any than me!”